The Navy Department Library

Pearl Harbor: Why, How, Fleet Salvage and Final Appraisal

by Vice Admiral Homer N. Wallin

PDF Version [57.2MB]

USS Arizona Memorial at Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor:

Why, How, Fleet Salvage and Final Appraisal

by

Vice Admiral Homer N. Wallin

USN (Retired)

with a Foreword by

Rear Admiral Ernest McNeill Eller, USN (Retired)

Director of Naval History

Naval History Division

Washington: 1968

Foreword

Pearl Harbor will long stand out in men's minds as an example of the results of basic unpreparedness of a peace loving nation, of highly efficient treacherous surprise attack and of the resulting unification of America into a single tidal wave of purpose to victory. Therefore, all will be interested in the unique volume that follows. It is Admiral Wallin's own handicraft, with only minor modifications by this staff.

The Navy has long needed a succinct account of the salvage operations at Pearl Harbor that miraculously resurrected what appeared to be a forever shattered fleet. We were delighted when Admiral Wallin agreed to undertake the job. He was exactly the right man for it -- in talent, in perception, and in experience. He had served intimately with Admiral Nimitz and with Admiral Halsey in the South Pacific, has commanded three different Navy Yards, and was a highly successful Chief of the Bureau of Ships.

On 7 December 1941 the then Captain Wallin was serving at Pearl Harbor. He witnessed the events of that shattering and unifying "Day of Infamy." His mind began to race at high speeds at once on the problems and means of getting the broken fleet back into service for its giant task. Unless the United States regained control of the sea, even greater disaster loomed. Without victory at sea, tyranny soon would surely rule all Asia and Europe. In a matter of time it would surely rule the Americas.

Captain Wallin salvaged most of the broken Pearl Harbor fleet that went on to figure prominently in the United States Navy's victory. So the account he masterfully tells covers what he masterfully accomplished. The United States owes him an unpayable debt for this high service among many others in his long career.

Following graduation at the Naval Academy in the Class of 1917, Ensign (and later Lieutenant) Wallin entered into the Navy' s then Construction Corps. He intensively studied ship construction in all its intricate facets, then he went on to various efficiently performed duties. At the time of Pearl Harbor Captain Wallin was serving as Battle Force engineer and was charged with overall responsibility for fleet repair and alterations. So he was in the thick of the Pearl Harbor attack from its onset.

When I asked him to write the account of the salvage I expected a well

--v--

written one from his experience, his profound mind, his thoroughness, his broad perception, and his skill in expressing himself in writing. What we got, as the reader will note, is not just salvage, but a succinct summary of international aggression during the '30's -- the surprise attack that inevitably followed weakness in face of aggression, -- and the resurrection and superb service of the fleet that suffered treachery. At first some of us looked upon the three as strange shipmates. But the more we thought about it the more we came to the conclusion that they made a unique team. Someone who had lived through all these, had thought about them at the time, had intimate personal contact in the attack and full responsibility for salvage had told them as the connected story they are - the three acts in a giant drama of world struggle.

Admiral Wallin has written with tireless effort to portray the truth. Whether or not one agrees with all that he says about the events through Pearl Harbor (and I do with all but a few), the reader can know that Admiral Wallin has assiduously sought just the truth. We sent him large cargoes of manuscript material and photographs to add to his own extensive collection. We supplied him with books or titles in numbers for his wide range of reading of published works in addition to the manuscript -- he is one of the few people who has seriously read the 39 volumes of the Pearl Harbor Congressional Hearings.

Rear Admiral F. Kent Loomis, Commander C. F. Johnson, Dr. William Morgan, Dr. Dean Allard, and others of us read the manuscript offering suggestions. Commander Victor Robison's assistant in the Curator Section, Mrs. Agnes Hoover; searched far and wide to obtain photographs to supplement the good ones supplied by Admiral Wallin. Dr. Allard, Mr. Bernard Cavalcante, and Miss Sandra Brown ably edited the manuscript for publication and have carried the burden of building a manuscript into a book. Mrs. Robert Winters of Fort Washington, Forest, Maryland, prepared the competent index to this volume. The story, however, is Admiral Wallin's and a significant one it is.

A host of Americans should thank Admiral Wallin for this work. May it help strengthen in the United States our sense of responsibility of service, our readiness to resist tyranny wisely, our integrity and devotion to the cause of liberty and dignity of man under God. May it also help to strengthen in all American minds understanding of the vast role the sea has played in America's destiny and is still to play. In the words of President Kennedy: "The sea means security. It can mean victory.

E. M. ELLER

Rear Admiral, USN (Retired),

Director of Naval History.

--vi--

Preface

Ever since the successful completion of Fleet Salvage at Pearl Harbor in 1942, I have frequently been importuned to write a comprehensive report of that gratifying outcome of the Pearl Harbor disaster. However, in view of other work and avocations, and especially because of the immensity of the task, if it was to be authentic, I was negatively inclined, -- at least until a more propitious time.

It was not until the early part of 1965 that the Director of Naval History, Rear Admiral Ernest M. Eller, U.S. Navy, Retired, persuaded me to take the pen in hand. His argument was that the Pearl Harbor Salvage Operation should be made a matter of historical record, and could in addition serve as a ready reference book for any future work of that nature; also that he knew of no other person who could write a reasonably authentic account with the data and information still available. So, in a way, I was "Hobson's Choice" if the work was to be done at all.

Fortunately, I had rather complete files covering the work, inasmuch as through the years I had become some sort of "pack rat" on technical records pertaining to my specialty of ship design, construction, and repair. Although I had turned over most of these files and photographs to the Bureau of Ships of the Navy Department, they were returned to me when I agreed to undertake the writing job.

Despite the fact that nearly a quarter of a century has elapsed since the event a great portion of the impact of my experiences at Pearl Harbor and the salvage work is still quite clear in my memory. At that time I was Material Officer on the staff of Vice Admiral William S. Pye, commander of the Battle Force of the Pacific Fleet. Therefore the handling of the damage sustained by ships of the fleet immediately became of first concern to me as an existent responsibility. Within a short time I was relieved of all other duties and ordered to full time work as Fleet Salvage Officer.

Ever since those days I have at times pondered the events which occurred before and after the Japanese air raid, and have often wished that the American people might have obtained a more correct understanding of the "Whys and Wherefores." It bothered me greatly when, following the

--vii--

attack, so many Americans and so much of our news media took a "Who dunnit" attitude toward the disaster and seemed to be more anxious to blame military negligence and inattention to duty rather than to gain a right appraisal of the panorama of events. Perhaps it is an element of human nature to accuse individuals and to find scapegoats whenever distasteful events occur.

Consequently, with the knowledge of one who was on the scene at the time, and of one willing to undertake a vast amount of research from official and other sources, I agreed to proceed with the salvage write-up, -- provided I could at the same time pinpoint the situation which pertained in the fleet and in our relations with Japan at that period.

In order to do this with some semblance of authenticity I have reviewed a goodly portion of the testimony given before the Roberts Commission in December 1941 and January 1942, the Hart Investigation in 1944, the Hewitt Inquiry of 1945, the Naval Court of Inquiry of 1944, the Army Investigation in 1944, the Congressional Investigation of 1945, and the State Department releases published in 1953. This latter has been drawn upon freely as it is the official report of the United States' Foreign Policy from 1931 to 1941 inclusive, and is entitled Peace and War. Also I have read a considerable number of books and reports on the Pearl Harbor attack, some written by Japanese participants. Virtually all of this information has the advantage of hindsight so far as evaluation is concerned and is therefore of inestimable value in piecing together a momentous event which requires retrospection as a primary ingredient.

The Pearl Harbor episode brought forth multitudinous opinions and convictions, some highly emotional and some pertaining to personalities. Others were based on cold logic and technical facts. In the over-all we must all agree that the event which set off a cruel and bloody war is fraught with many lessons and guideposts for the future. I have endeavored to pinpoint a few of these which are particularly worthwhile, and have striven honestly to be fair to all persons who were involved in any way either before, during, or after the event.

The final appraisal of the Pearl Harbor attack is given in Chapter XV. It reveals indisputably that the Japanese government made a great mistake in attacking Pearl Harbor, as it did also in other aspects of the struggle for dominance in the Pacific. There is now no doubt that the attack resulted from the gross unpreparedness of the American military forces, as was

--viii--

attested by the 1945 statement of President Truman and the 1965 statement of Admiral Nimitz.

I am indebted to the Director of Naval History and his staff for invaluable assistance throughout, and of course for general guidance. That office has furnished much valuable data and information such as official damage reports from the Bureau of Ships, descriptions of rehabilitation work from various naval shipyards, pertinent excerpts from ships' logs, and so forth.

Also, I am most grateful to the Commandant of the Thirteenth Naval District, Rear Admiral William E. Ferrall, U.S. Navy, and his staff for much assistance, including office space and equipment, some secretarial work, and a widespread spirit of cooperation and helpfulness.

HOMER N. WALLIN,

Vice Admiral, USN (Retired).

--ix--

Contents

| Page | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Foreword | v | ||

| Preface | vii | ||

| Index | 365 | ||

| Chapter I | INTRODUCTION | 1-8 | |

| Chapter II | THE TRENDS TOWARD WAR | 9-24 | |

| 1. | Basic Causes of War | 9 | |

| 2. | Germany's Insatiable Appetite for Aggression | 9 | |

| 3. | The Aggressions of Italy | 12 | |

| 4. | The Brutal Aggressiveness of Japan | 14 | |

| Chapter III | PROBLEMS AND DILEMMAS OF THE UNITED STATES AND EVENTUAL PREPAREDNESS FOR WAR | 25-40 | |

| 1. | American Attitudes and Policies | 25 | |

| 2. | Retrenchment in Military Preparedness | 26 | |

| 3. | Diplomacy at Work to Prevent War and to Improve Preparedness for War | 28 | |

| 4. | Hardening of Public Opinion | 31 | |

| 5. | Assistance to Friendly Nations | 33 | |

| 6. | Military Preparedness Measures | 35 | |

| Chapter IV | THE FLEET AT PEARL HARBOR | 41-58 | |

| 1. | Why Was the Fleet There? | 41 | |

| 2. | Army-Navy Defense of Pearl Harbor | 43 | |

| 3. | Reconnaissance | 44 | |

| 4. | Radar | 48 | |

| 5. | Operation of the Fleet | 50 | |

| 6. | How Powerful Was the Fleet? | 51 | |

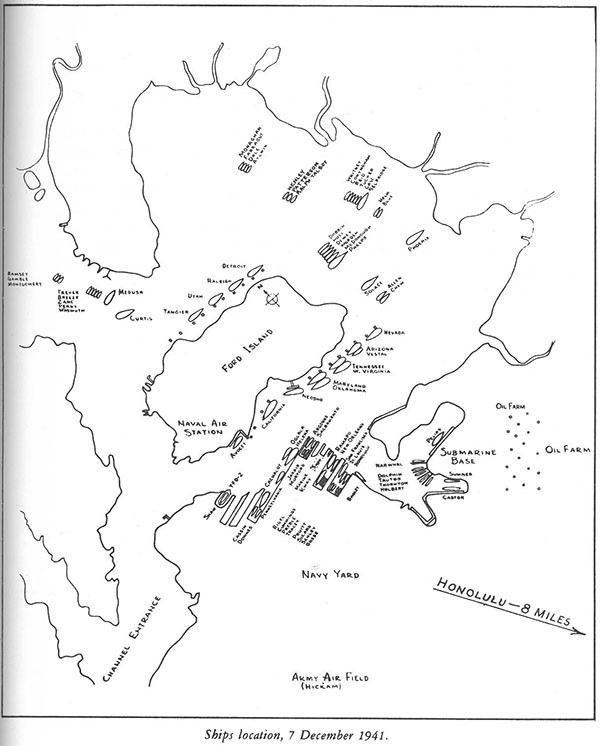

| 7. | Where Were the Fleet Ships on 7 December? | 54 | |

| Chapter V | IMMINENCE OF WAR | 59-82 | |

| 1. | Breakdown of Diplomacy | 59 | |

| 2. | Japan's Knowledge of Pearl Harbor | 60 | |

| 3. | America's Knowledge of Japan's Intentions | 65 | |

| 4. | Warning to the Fleet | 74 | |

| 5. | What Information Did Hawaii Not Receive? | 79 | |

| Chapter VI | JAPANESE ATTACK, STRATEGY, AND TACTICS | 83-98 | |

| 1. | Preparedness, War Games, and Drills | 83 | |

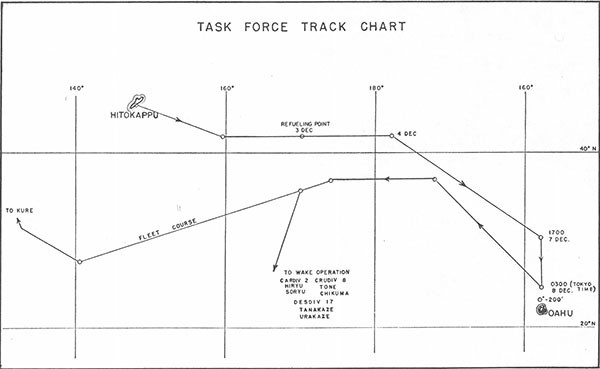

| 2. | Assembling of Attack Force | 85 | |

| 3. | Route of the Pearl Harbor Attack Force | 85 | |

| 4. | The Attack Force | 88 | |

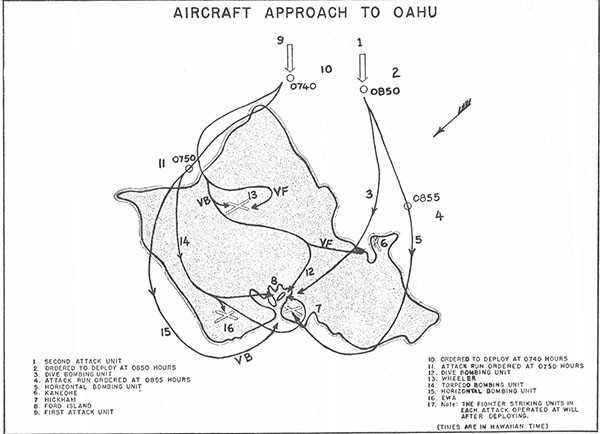

| 5. | The Attack | 88 | |

| 6. | Direction of Attack | 94 | |

| 7. | Submarines | 94 | |

| 8. | Japanese Losses | 94 | |

| 9. | Japanese Estimates of Damage to the Americans | 96 | |

| Chapter VII | RESULTS OF JAPANESE SURPRISE AIR RAID | 99-112 | |

| 1. | Sunday Was a Day of Rest in Hawaii in Peacetime | 99 | |

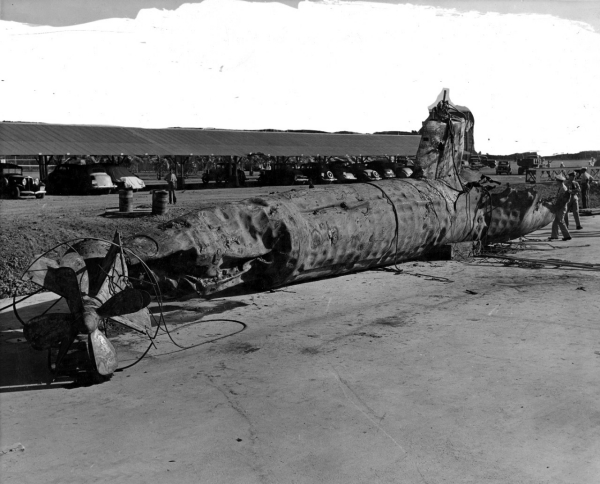

| 2. | Submarines | 100 | |

| 3. | We Are at War | 100 | |

| 4. | All Air Bases Immobilized | 101 | |

| 5. | Ships Attacked by Torpedo Planes | 102 | |

| 6. | Inboard Ships Hit by High-level Bombers | 104 | |

| 7. | Losses in Honolulu | 105 | |

| 8. | Officers and Men Aboard Ship and Fit for Duty | 105 | |

| 9. | Anti-aircraft Batteries Which Opposed the Japanese Planes 106 | 106 | |

| 10. | Deeds of Heroism | 108 | |

| 11. | Total Dead and Wounded in the Services | 108 | |

| 12. | Sabotage | 108 | |

| 13. | State of Mind of Military Personnel | 109 | |

| Chapter VIII | WASHINGTON'S RESPONSE TO THE JAPANESE ATTACK | 113-124 | |

| 1. | Military and Civilians Taken by Surprise | 113 | |

| 2. | Declaration of War | 114 | |

| 3. | Secretary of the Navy Visits Pearl Harbor | 114 | |

| 4. | The Roberts Commission | 115 | |

| 5. | President Roosevelt's Fireside Chat | 116 | |

| 6. | Admiral Kimmel and General Short Relieved | 117 | |

| 7. | Admiral C. W. Nimitz Takes Command | 118 | |

| 8. | Admiral Ernest J. King Becomes Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. Fleet | 118 | |

| 9. | Admiral Nimitz's Policy of a "Limited Offensive" | 120 | |

| 10. | Halsey's Early Raids | 121 | |

| Chapter IX | OBSERVATIONS AND STATEMENTS MADE BY SURVIVORS | 125-160 | |

| 1. | Condition of Ships at 0755 | 125 | |

| 2. | Impressions and Actions on USS West Virginia | 126 | |

| 3. | Impressions and Actions on USS Oklahoma | 132 | |

| 4. | Impressions and Actions on USS Arizona | 136 | |

| 5. | Impressions and Actions on USS California | 140 | |

| 6. | Impressions and Actions on USS Utah | 146 | |

| 7. | The Performance of USS Nevada | 150 | |

| 8. | Impressions and Actions on USS Maryland | 152 | |

| 9. | Impressions and Actions on USS Tennessee | 156 | |

| Chapter X | OTHER SHIPS' OFFICIAL REPORTS | 161-174 | |

| 1. | Destroyers | 161 | |

| 2. | Battleships | 165 | |

| 3. | Cruisers | 165 | |

| 4. | Miscellaneous Auxiliary Ships | 168 | |

| 5. | Submarines | 169 | |

| 6. | Oglala | 170 | |

| Chapter XI | "ALL HANDS" ENGAGED IN SALVAGE WORK | 175-188 | |

| 1. | Priority of Work | 175 | |

| 2. | Helping Each Other and Repelling Enemy Attacks | 176 | |

| 3. | Freeing the Trapped Men | 176 | |

| 4. | Salvage Operations from Argonne | 178 | |

| 5. | Start of Salvage Organization | 179 | |

| 6. | Recovery of Ordnance Material | 186 | |

| 7. | Medical Help for Wounded or Burned | 186 | |

| Chapter XII | GETTING THE LESS DAMAGED SHIPS READY FOR ACTION | 189-202 | |

| 1. | USS Pennsylvania, Battleship (Launched in 1915) | 189 | |

| 2. | USS Honolulu, Cruiser (Launched in 1936) | 191 | |

| 3. | USS Helena, Cruiser (Launched in 1939) | 192 | |

| 4. | USS Maryland, Battleship (Launched in 1920) | 192 | |

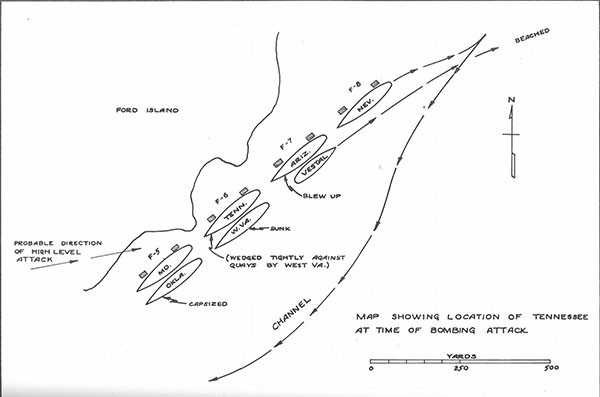

| 5. | USS Tennessee, Battleship (Launched in 1919) | 193 | |

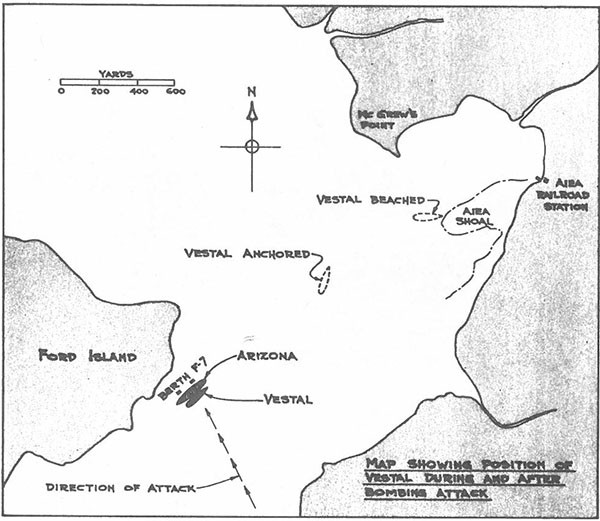

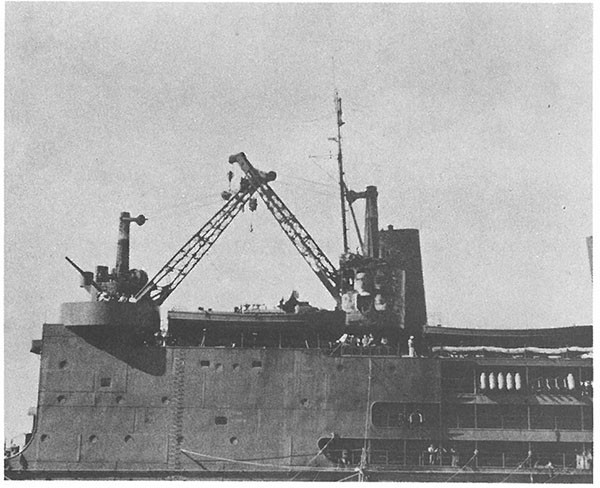

| 6. | USS Vestal, Repair Ship (Launched in 1908) | 194 | |

| 7. | USS Raleigh, Cruiser (Launched in 1922) | 195 | |

| 8. | USS Curtiss, Seaplane Tender (Launched in 1940) | 197 | |

| 9. | USS Helm, Destroyer (Launched in 1937) | 198 | |

| Chapter XIII | SHIPS SUNK AT PEARL HARBOR | 203-272 | |

| 1. | USS Shaw, Destroyer (Launched in 1935) | 203 | |

| 2. | Floating Drydock Number Two | 205 | |

| 3. | The Tug Sotoyomo | 206 | |

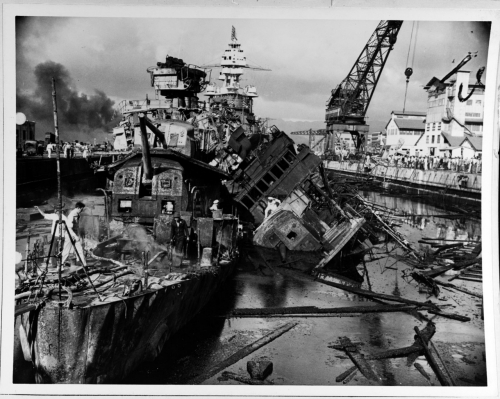

| 4. | USS Cassin (Launched in 1935) and Downes (Launched In 1936) | 206 | |

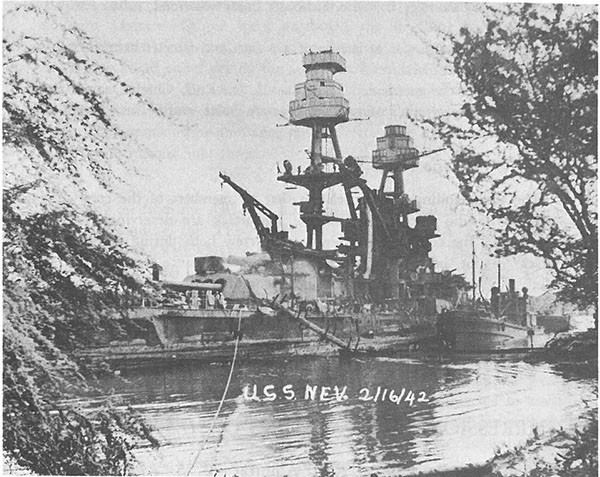

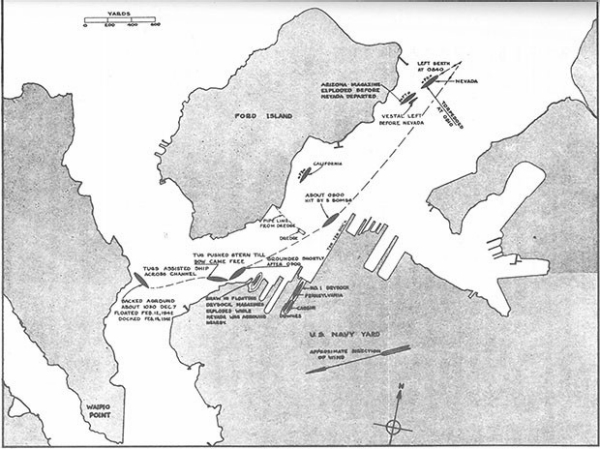

| 5. | USS Nevada Battleship (Launched in 1914) | 211 | |

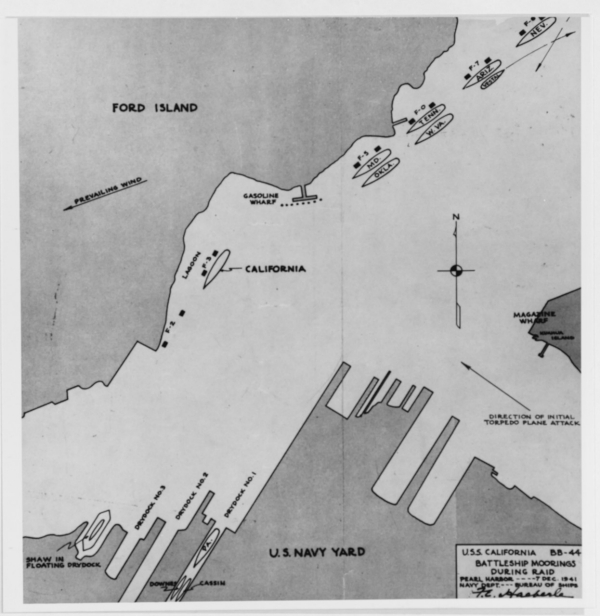

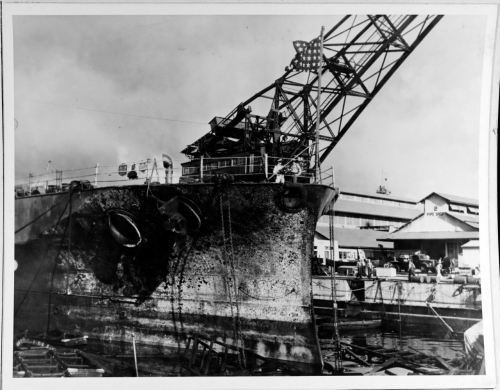

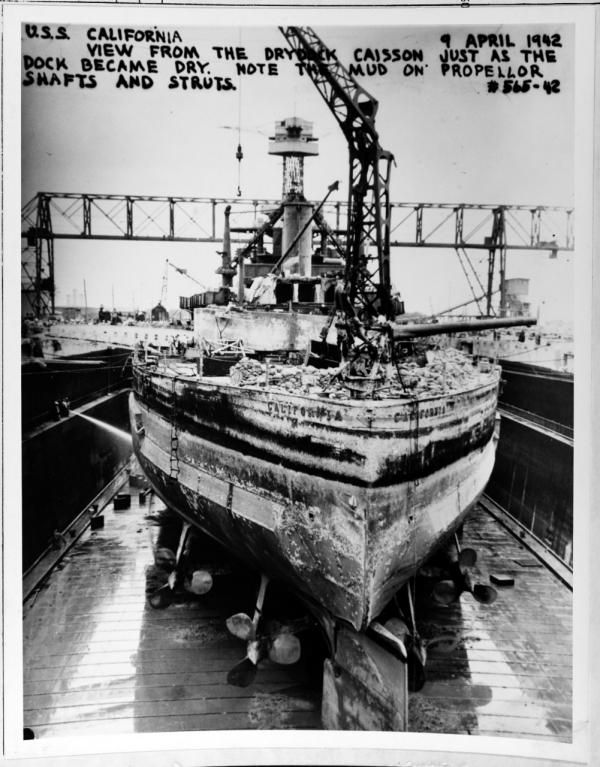

| 6. | USS California, Battleship (Launched in 1919) | 222 | |

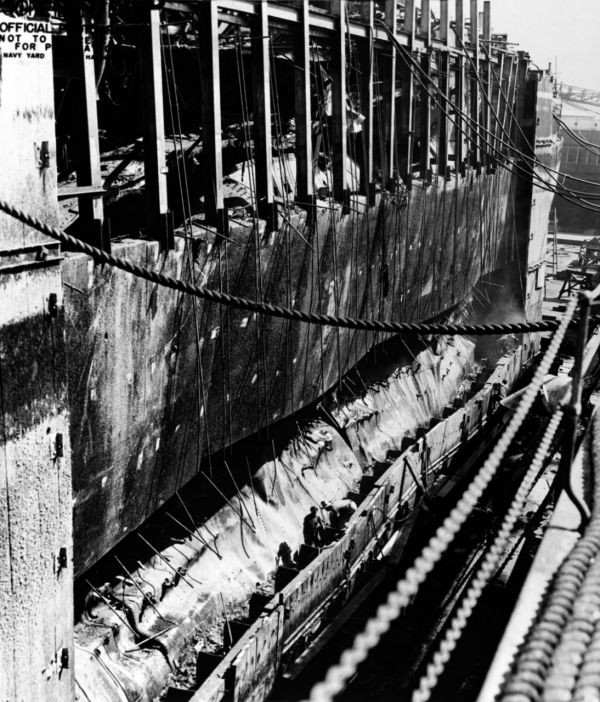

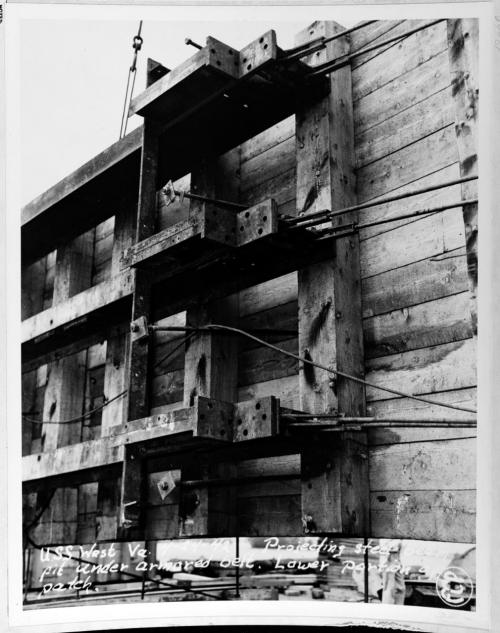

| 7. | USS West Virginia Battleship (Launched in 1921) | 233 | |

| 8. | USS Oglala (Launched in 1907) | 243 | |

| 9. | USS Plunger (Launched in 1936) | 252 | |

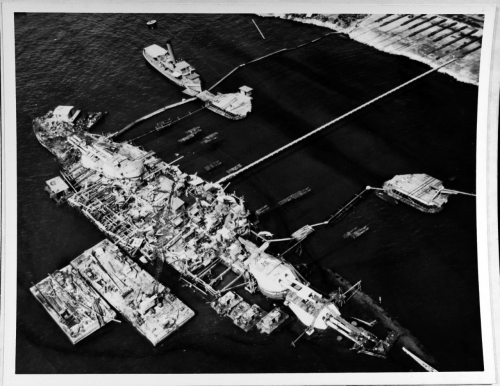

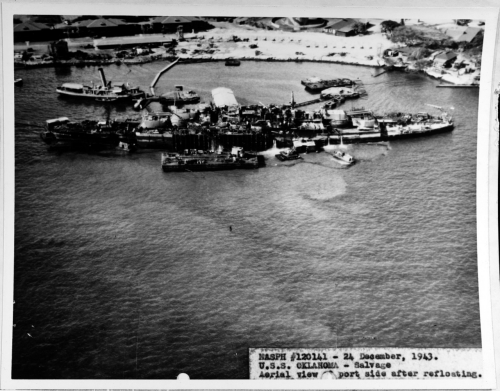

| 10. | USS Oklahoma, Battleship (Launched in 1914) | 253 | |

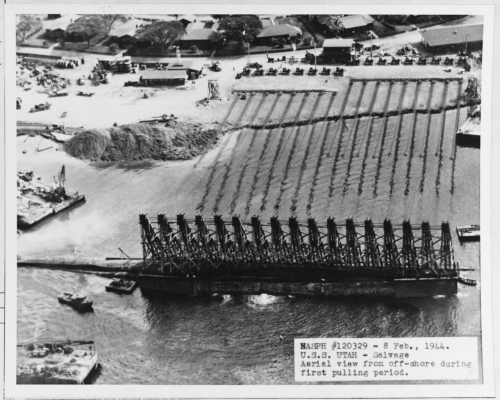

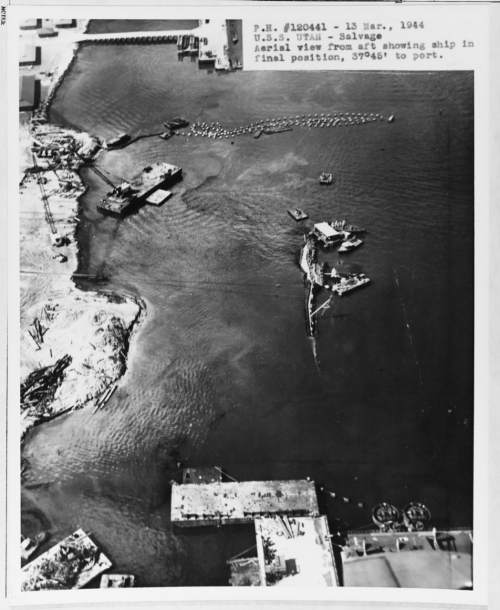

| 11. | USS Utah, Former Battleship (Launched in 1909) | 262 | |

| 12. | USS Arizona, Battleship (Launched in 1913) | 267 | |

| Chapter XIV | CONDITIONS WHICH PREVAILED OR WERE ENCOUNTERED IN SALVAGE WORK | 273-286 | |

| 1. | Lack of Material | 273 | |

| 2. | Fire Hazards on the Ships Themselves | 273 | |

| 3. | Salvage of Ordnance Material | 274 | |

| 4. | Electrical Equipment | 275 | |

| 5. | Japanese Torpedoes and Bombs | 276 | |

| 6. | Diving Experience | 277 | |

| 7. | Deadly Gas Encountered on Most Ships | 277 | |

| 8. | Gasoline Explosions | 279 | |

| 9. | Electric-Drive Battleships | 280 | |

| 10. | Classified Correspondence and Personal Property | 280 | |

| 11. | Removal of Human Bodies | 280 | |

| 12. | Cleaning of Compartments | 281 | |

| 13. | Work Performed by the Navy Yard | 281 | |

| 14. | Use of Sunken or Damaged Ships in the War Effort | 282 | |

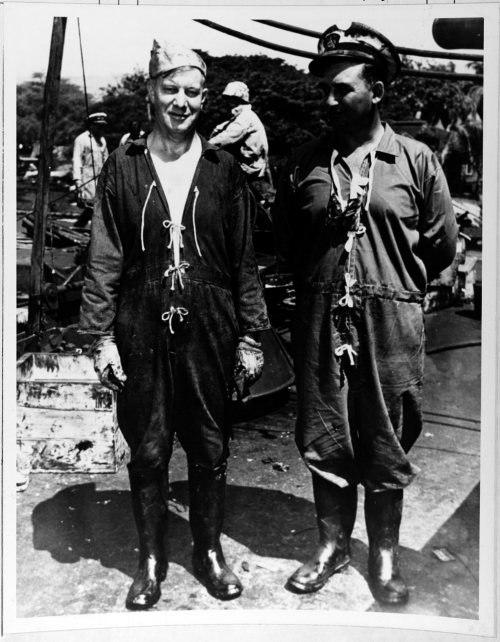

| 15. | Spirit of the Salvage Crew | 283 | |

| Chapter XV | FINAL APPRAISAL OF PEARL HARBOR ATTACK | 287-296 | |

| 1. | Japan's Mistake in Attacking Pearl Harbor | 287 | |

| 2. | Other Mistakes Made by the Japanese | 291 | |

| 3. | United States' Aversion to War | 292 | |

| Appendices | 297-363 | ||

| A. | Survivors' Statements and Actions | 297 | |

| B. | Restoration of Unwatered Compartments and Machinery of Sunken Ships | 328 | |

| C. | Gas Hazard and Protection Against Gas | 337 | |

| D. | Electric-Drive Machinery of Battleships | 339 | |

| E. | The Salvage of USS West Virginia | 342 | |

| F. | The Plan for the Salvage of USS Oklahoma | 356 | |

| G. | Ships Present at Pearl Harbor and Vicinity, 7 December 1941 | 362 | |

--xi - xv--

Chapter I

Introduction

[1]

[Blank]

[2]

Chapter I

Introduction

7 DECEMBER 1941 marked an abrupt turning point in world history. The treacherous Japanese air attack on the United States Fleet at Pearl Harbor and the Army Air Forces in Hawaii triggered a World War of unprecedented proportions.

On 8 December 1941 the Congress of the United States declared war on Japan, whereupon Germany and Italy three days later, on 11 December 1941, declared war upon the United States. Their action was in compliance with their mutual assistance treaty with Japan known as the Tripartite Pact of 27 September 1940. It is worthy of note that the United States did not formally enter the European War until after Germany and Italy declared war on the United States.

Thus the Pearl Harbor attack brought the full potential of the United States into the European War which had continued since September 1939 and which up to that time seemed destined to bring victory to the aggressors. But, as a consequence of United States involvement, an all-out war was touched off around the globe. The tide of battle was gradually turned against Hitler's Nazi Germany and Italy's Fascist Mussolini. Their dictatorships, as well as the brutal militarism of Japan, were doomed to ignominious defeat. The war lords of Japan's efficient military machine eventually suffered complete rout, and were doomed to humiliating defeat and unconditional surrender. The defeat of these three powers was accomplished only after a long series of bloody battles, land, sea, and air, which continued at an ever-increasing tempo for nearly four years.

The titanic world struggle not only changed territorial boundaries and governmental framework, but affected basically the whole fabric of civilization, even the manner of living and the peoples' attitudes, standards, and ways of life. Indeed, the consequences of Japan's surprise attack on Pearl Harbor and Hawaii were world-shaking, and they are of a continuing nature which will influence history in all phases for years yet to come.

The immediate result of the Pearl Harbor attack was seeming disaster to the sea power of the United States, but this proved only temporary. The

--3--

psychological effect on fleet personnel was to arouse a fighting spirit which turned disasters into victories.

Among the American civilian population too, the attack unified wide diversities of viewpoint and opinion, and solidified the total population in a spirit of willing sacrifice and determined effort which gave unlimited support to the armed forces. The mobilization of moral, mental, physical, and spiritual effort produced a miracle of production such as has never been imagined by man. The output of ships, airplanes, tanks, guns, and landing craft was astronomical. Likewise, the over-all logistic support to the millions of Americans and their Allies who manned these weapons of war, was quite beyond calculation.

Thus, the Japanese militarists who had planned the Pearl Harbor attack over many months of careful and arduous preparation triggered for themselves a disaster quite the opposite of their dreams of conquest. Rather than conquerors they became the supine victims of their own machinations. The Japanese. government had been led into violating its solemn agreements signed at The Hague in 1907 not to attack another nation without a declaration of war or an ultimatum. That government was entirely dismantled and re-instituted as a democratic government by a generous and compassionate America.

So, in retrospect, the ambitions of the military forces of Japan, which culminated in the treacherous attack on the Fleet and Hawaiian Air Forces, proved calamitous. Its perpetrators failed entirely to understand that unrighteousness, although flourishing for a time, cannot eventually prevail in a world whose major powers stand for peaceful pursuits and fair dealing. The Japanese government failed miserably in underestimating the recuperative power of its newly made enemy and the American potential for all-out combat. The success of the Japanese attack was more than compensated for by the aroused moral and spiritual powers of the American people as they applied themselves to the task before them.

However, it must be recognized that the Japanese performed a masterful job in planning, preparing, practicing, and executing the attack. The efficiency of all aspects was well-nigh unbelievable, especially by people who habitually underestimated the capabilities of the Japanese. It is worthy of note that the weapons employed by Japan were the airplane and the aerial torpedo. Both of these were developed by the United States, but not as efficiently as used by the Japanese. Why? Because the United States was unprepared for war due to a public fetish that preparedness invited international misunderstanding and eventual conflict.

--4--

So, before outlining the damage wrought and the remedial measures taken, it seems appropriate to describe in some detail the strategy and tactics employed in delivering the attack, and why it was so successful. Thereafter we might cover the Fleet's response to the onslaught, the effect on specific ships, remedial action taken including details of salvage operations, and so forth. But first it would seem profitable to pinpoint the basic causes underlying and overlying the international situation which set off the holocaust.

Although much has been written regarding the world turmoil which developed during the 1930's, a short and specific recounting of the fateful events which culminated in World War II is necessary. Now it is quite clear that the war was the result of wanton military aggression by Germany, Italy, and Japan, and that the United States was forced to take up arms against these predatory forces if freedom and peace were to survive in the world. These basic facts have never been fully comprehended by the American people; neither have they understood how it was possible for the Pearl Harbor disaster to occur. One of the purposes of this book is to enlighten the public on these points, especially the new generations. Such is a responsibility of historical writings, and it is particularly important that the oncoming personnel of the Navy and the other military services should have a ready reference from which to select guidelines when confronted with comparable problems and circumstances. It is well to take account of the words of George Santayana: "Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it."

It is interesting to note that our wartime enemies are now our closest friends. Japan, Germany, and Italy enjoy the compassion and generosity of America, and are industrial leaders in their parts of the world. When we speak of Germany we mean, of course, West Germany, under the influence of the United States and her Allies. East Germany is a satellite of Russia and has been subjected to Soviet influence rather than to the influence of the Western World.

Changes have also occurred among Allies in the war, including Russia and China. Russia has been the mother country of communism and has been our principal adversary for at least twenty years while she has fomented unrest throughout the world. China, whom we befriended against Japan, has fallen to communism and has turned out to be our mortal enemy. Strange indeed are the anomalies that occur in international relations.

--5--

[Blank]

[6]

Chapter II

The Trends Toward War

[7]

[Blank]

[8]

Chapter II

The Trends Toward War

1. BASIC CAUSES OF WAR

Warfare with its tremendous sacrifice in lives and treasure is abhorrent to all civilized people. Some wars of the past have been considered justified when waged for religious or idealistic purposes, such as to right the wrongs imposed upon a people. But here we are concerned with warfare based primarily on aggression and greed. History tells us that armed conflict is and always has been a fact of life whenever covetous governments desire their neighbors' property, or whenever thirst for power dictates the purpose and aim of officials in control. In such circumstances the relative weakness of the intended victim is a contributing factor. It has been proved that it is impossible for a nation to run away from a bad situation, to believe that a serious situation does not exist, or that freedom is not involved.

Peace-loving people teach and preach that national aggression and military force do not pay. But that would depend, it seems, whether or not the aggressor is met and repelled by a more powerful force in which hopefully righteousness adds to the power. This fact is true among nations even as among citizens who are menaced by criminals and bandits.

2. GERMANY'S INSATIABLE APPETITE FOR AGGRESSION

One of history's outstanding examples of wanton aggression and thirst for power is Hitler's Germany. Following his coming to power in 1933 Hitler initiated an armament build-up and psychological aggression which were awesome to all peace-loving nations. Even so, the various acts of aggression were gradual and limited, as if to make them somewhat natural and more acceptable to the victims and to onlookers. In effect, Germany pursued the "Nibble Theory" by taking a little here and later a little there, but always professing a fervent desire for peaceful practices and an end to expansive

--9--

ventures. Coupled with this were the appeasement policies of the leading world powers interested in world stability, but nonetheless trying desperately to avoid coming to grips with a formidable aggressor.

It is of immense importance to review the germination of the European War because it became a direct threat to American security, and certainly an indirect cause for the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. In addition, the experience of European nations with Nazi Germany was in many ways parallel to America's experience with pre-war Japan.

The record shows that Hitler became Chancellor in Germany's government in 1933. In 1934, he took the title of Fuehrer, which means in effect "all-powerful leader," and set out to build up the peoples' desire for expansion and the establishment of a so-called "New Order" in Europe.

Some of the significant steps taken before and after the declaration of the war in Europe were the following:

a. In 1933 Hitler denounced and quit the League of Nations. Violation of several provisions of the Versailles Treaty which ended World War I followed in short order.

b. In 1936 Germany violated the Locarno Treaty of 1925, which guaranteed the status quo in Western Europe, and reoccupied the Rhineland.

c. In 1936 Germany joined Italy in entering the Spanish Civil War.

d. In March 1938 Germany annexed Austria in violation of its pledge made in July 1936.

e. In September 1938 Hitler demanded control of part of Czechoslovakia. This aroused all major nations to the danger of general war, whereupon England's Prime Minister Chamberlain journeyed to Munich to confer with Hitler in order to avoid war in Europe. The result was that Great Britain, France, Germany, and Italy met and agreed to Hitler's demand for taking over that part of Czechoslovakia called Sudetenland.

f. Six months later, in March 1939, Germany took over most of Czechoslovakia in violation of the agreement made at Munich.

g. By this time Hitler had put in high gear the persecution of the Jews in Germany and the annexed territories, such that President Roosevelt "could scarcely believe that such things could occur in a twentieth century civilization." 1

h. At this point the United States appealed to Hitler and Mussolini

_____________

1. Peace and War, United State Foreign Policy 1931-1941, Department of State Publication, United States Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 1942, p. 58. Hereafter cited as Peace and War.

--10--

for assurance of no further attacks on independent States of Europe and the Near East. Neither replied directly. The American Secretary of State, Cordell Hull, stated that all other nations were confronted with the "tragic alternatives of surrender or armed defense.2

i. In August 1939 Hitler demanded the return to Germany of Danzig, which was declared a free city in the Versailles Treaty. Following this demand Great Britain and France warned Germany that in compliance with their treaties with Poland, aggression against Poland would mean war.

j. At this point the President of the United States appealed to Germany, Italy, and Poland to agree to settle their differences by direct negotiation or by arbitration. While Poland replied favorably, no direct reply was made by Germany because, the German Ambassador explained, the invasion had already begun due to the uncooperative attitude of Poland.3 Thus with the invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939 the European War began.

k. As the tempo of war developed, Germany asserted its power in every direction, especially its aggression toward neutral and unoffending nations.

l. In April 1940 Germany took over Denmark without opposition, and soon occupied Norway after overcoming Norway's spirited but futile resistance. This was denounced by the United States.

m. Then Belgium and the Netherlands were invaded and subjugated, as well as Luxembourg, in May 1940.

n. Early in 1941 Germany went to the assistance of Italy in its faltering invasion of Greece. By April 1941 the German forces overran both Greece and Yugoslavia and persuaded Rumania, Bulgaria, and Hungary to join the Tripartite Pact.

o. In June 1941 Germany attacked Russia in violation of their nonaggression pact.

p. Following its declaration of war in 1939, Germany carried on a vigorous submarine campaign against merchant ships, and gradually expanded its campaign against ships of neutral nations with little or no consideration for the safety of the crews.

q. By September 1941 Germany had sunk numerous American owned merchant ships in the Atlantic, and had attacked U.S.S. Greer. The first shots were fired in the Battle of the Atlantic.

_____________

2. Ibid., p. 63.

3. Ibid., p. 66.

--11--

USS Greer was attacked by a German submarine on 4 September 1941.

r. On 17 October 1941 Germany torpedoed U.S.S. Kearney in the North Atlantic causing severe damage and killing eleven men. Later in the month, destroyer Reuben James was sunk by a U-boat and lost 115 officers and men.

3. THE AGGRESSIONS OF ITALY

Although Germany's aggressions covered a larger field of action, Italy's predatory acts were even more devoid of presumed justification. Whether Mussolini copied Hitler, or vice versa, is not clear, but both came into office originally as purported socialist reformers and developed into absolute dictators in the fateful years between 1934 and 1941. Both exercised emotional leadership over their populations to a degree which bordered on hypnosis, and thus they had full and loyal civilian support in their nefarious ventures.

a. As early as 1934 diplomatic circles were aware that Mussolini was making preparations to take over some territory in Africa. Defenseless Ethiopia was selected as his first victim, and in October 1935 Italian armed forces invaded that country. Emperor Haile Selassie resisted valiantly, but his primitive forces were no match for Italy's army and navy. The conquest of Ethiopia was completed by May 1936.

--12--

b. The League of Nations became interested in this aggression and declared that Italy had violated her obligations under the Covenant and recommended commercial and financial sanctions against Italy. The imposition of sanctions by world powers was regarded with some fear and indifference; consequently the limited sanctions that were imposed proved wholly ineffective.

c. The United States held that Italy violated the Kellogg-Briand Pact of 1928 which renounced war as an instrument of national policy.

d. Together with Germany, Italy participated in the Spanish Civil War in 1936, contrary to commitments previously made.

e. Together Germany and Italy formed the Berlin-Rome Axis and Germany and Japan signed the Anti-Comintern Pact against Russia in late 1936.

f. In November 1937 this Pact was expanded to include Italy, the same having been under negotiation among the three powers since 1934-35.

g. In March 1939, when Hitler took Czechoslovakia, Mussolini's Fascist legions occupied Albania on Good Friday, 7 April 1939.

h. When Germany invaded Belgium, The Netherlands, and France in May 1940 the United States appealed to Italy to refrain from participation and thus extending the war. Mussolini replied: "Italy is and intends to remain allied with Germany and that Italy cannot remain absent at a moment in which the fate of Europe is at stake." 4

i. In September 1940 Germany, Italy, and Japan announced to the world that they had signed a treaty of alliance which provided mutual assistance -- political, economic, and military -- and recognized the leadership of Germany and Italy in establishing a "New Order" in Europe, and the leadership of Japan in establishing a "New Order" in Greater East Asia.

j. When the German Army was at the gates of Paris in June 1940, Italy declared war on France and Great Britain. Then it was that Winston Churchill called Mussolini "a jackal for plunging a knife into the back of his prostrate neighbor."

k. Italy invaded Greece in October 1940 but was unable to overcome its brave defenders. When the Italian Army was forced to retreat into Albania, Germany came to Italy's assistance. The result was that Greece and Yugoslavia fell to the Axis Powers in April 1941. Then Rumania, Bulgaria, and Hungary joined the Tripartite Pact, thus extending the war.

_____________

4. Ibid., p. 72.

--13--

4. THE BRUTAL AGGRESSIVENESS OF JAPAN

Japan's program of belligerency and expansion had been in operation for nearly ten years prior to signing the treaty of alliance with Germany and Italy. However, Japan made common cause with Hitler and Mussolini as early as 1934. Japan's pattern of expansion, conquest, and terrorism was quite similar to that of Germany, especially with regard to expressing idealistic motives and promises while still moving forward with new invasions and increased demands. Japan's record of treaty violation and aggression exceeds those of either Germany or Italy. This fact should be comprehended and understood by any person interested in the basic causes of the war which was started at Pearl Harbor. Let us therefore list some of the important items:

a. Following World War I Japan was granted a mandate over the islands formerly held by Germany in the Marshalls and Carolines. Contrary to stipulations in the Treaty of Versailles the Japanese proceeded to fortify certain islands and to build military bases in those islands, and to deny entry to the islands by foreigners. It might be noted parenthetically that the later capture of these formidable bases in World War II cost the United States thousands of casualties.

b. In 1931 the Japanese Army invaded Manchuria and set up a puppet government under the name of Manchukuo. The United States protested this action as an act of war in cynical disregard of Japan's obligations under the Kellogg-Briand Pact and the Nine Power Treaty of 1922 regarding the principles and policies to be followed concerning China.5 The United States declared that it would not recognize any arrangement which impaired the rights of its citizens in China.6

c. For several months in 1932, Japan occupied Shanghai and refused to consider the proposals for peaceful settlement put forth by Great Britain, France, Italy, and the United States.

d. In 1932 Japan developed an internal campaign of public animosity towards foreign nations, especially the United States, even proposing war if necessary. Self-confidence was stimulated by the constant reminder that the Japanese military forces had always proved invincible.

e. In 1933 Japan extended the boundaries of Manchukuo by occupying the province of Jehol in North China.

_____________

5. Ibid., pp. 4 and 5.

6. Ibid., p. 3.

--14--

f. When the League of Nations in 1933 adopted a report finding Japan an aggressor in China and acting wrongly in principle, the Japanese delegation walked out and the Japanese government gave notice of withdrawal from the League of Nations.

g. In response to the American protests against aggression and disregard of treaty rights, Japan in early 1934 advised the United States it had no intention of making trouble with any other power, and that no question between Japan and the United States was incapable of amicable solution.7 During diplomatic exchanges however, when the United States insisted on adherence to treaties including trade and commercial agreements, Japan gradually put forth a claim of super-sovereignty over parts of Asia on the basis of its special rights and responsibilities.8

h. In 1934 Japan gave notice of its refusal to renew the 1922 Treaty for the Limitation of Naval Armament.

i. By 1935 Japan had considerable domination over China and was building up its military strength. Japanese diplomats repeatedly pointed out that Japan was destined to be the leader of oriental civilization and criticized former Japanese government officials for "signing agreements which could not be carried out if Japan wanted to progress in the world."9

j. At the London Naval Conference in 1935-1936 Japan asked for naval parity with Great Britain and the United States. When this was not agreed to by the other powers Japan withdrew from the Conference and refused to abide with any limitation on naval armament.

k. During these times the United States emphasized the importance of amicable conferences and such principles as equality in commercial and industrial affairs without resorting to force or threats of force. Japan expressed general agreement, and its diplomats frequently regretted the misunderstanding and misapprehension of the United States as to Japan's intentions, and gave assurance that their armaments were not intended for war against anybody, especially the United States.10

l. Encouraged by the apparent improvement in the general progress and spirit of the people in Germany and Italy a group of Japanese Army officers fomented a mutiny which was directed toward setting up military control of national policies. The Japanese Army did many things to force the government to pursue a policy of expansionism in China.

______________

7. Ibid., pp. 18 and (This viewpoint was expressed many times.)

8. Ibid., pp. 38 and 39. (Kurusu, Yoshida, and others put forth this argument.)

9. Ibid., p, 38. (Kurusu's statement to the U. S. Embassy in Tokyo, 23 December 1935.)

10. Ibid., p. 39. (Statement by Yoshida.)

--15--

m. On 25 November 1936 Japan and Germany signed their Anti-Comintern Pact, which foreshadowed the similar patterns of aggression which each nation was to follow.

n. In July 1937 the Marco Polo Bridge incident occurred. This was a planned clash between troops of Japan and China, which resulted in Japanese occupation of additional Chinese territory including Peiping in North China. At this point the United States addressed a note to all nations regarding the fundamental principles and international policy toward peaceful existence. The United States offered its good offices to compose differences between China and Japan and to negotiate an agreement. The diplomats of Germany and Italy agreed but Japan refused on the ground that the objectives and principles could only be attained in the far eastern situation by full recognition and realization of the actual particular circumstances of that region.11 As Japan poured more manpower and engines of war into China, the United States warned of the serious consequences to peace, goodwill, and cooperation as compared to the distrust and antipathy being generated among world powers by the brutal policies pursued by the Japanese government.12

o. The Assembly of the League of Nations on 6 October 1937 adopted a report stating that Japanese activities in China violated Japan's treaty obligations. The United States, though not a member of the League, proclaimed a similar position.

p. The following month nineteen nations assembled at a conference in Brussels to consider peaceful means for ending the Japan-China conflict. Japan refused to attend on the ground that the dispute applied only to Japan and China and was outside the provisions of the Nine Power Treaty. All members of the conference except Italy went on record opposing Japan's position.13

q. On 12 December 1937 the United States was shocked by the air-bombing and destruction of the United States gunboat Panay and three United States merchant vessels on the Yangtze River, followed by the machine gunning of crews and passengers. The United States demanded formal apologies, complete indemnification, and assurances against future attacks on American nationals and property in China, or any unlawful interference whatsoever with its legal rights and appropriate business. To this

_____________

11. Ibid., pp. 44 and 45.

12. Ibid., p. 47.

13. Ibid., pp. 49 and 50.

--16--

strong representation Japan replied favorably, expressed profound regret, and fervently hoped that friendly relations would not be affected by this unfortunate affair.14

USS Panay was sunk by Japanese aircraft, 12 December 1937.

r. In November 1937 Italy became a partner of Japan in the Anti-Comintern Pact.

s. After Germany's subjugation of the Netherlands in May 1940, Japan expressed some concern as to the status of the Netherlands Indies. The United States informed Japan and the world that any alteration of the status quo would prejudice the cause of stability, peace, and security of the whole Pacific area on account of the importance of the area's rich resources of oil, rubber, tin, and other commodities.15

______________

14. Ibid., p. 51.

15. Ibid., p. 89.

--17--

t. Early in June 1940 Japan delivered a full-scale bombing raid on Chungking, endangering American lives and property. The United States' protest was answered by Japan's request for the removal of our nationals. A few days later 113 Japanese aircraft repeated the bombing. Thereafter, Japan requested all nations to remove from China all troops and war equipment which they might have in that area.

u. During these times the Japanese occupation forces in various parts of China harassed and assaulted American citizens, destroyed their property, and even attacked missions and missionary hospitals. This was part of a terrorist campaign to compel foreigners to evacuate.

v. Upon the fall of France in June 1940 Japan asked the French government at Vichy for rights and military bases in the French possessions in Indo-China. This request was backed by an ultimatum and threats of force, but even while awaiting a favorable reply the Japanese occupied strategic points. The Japanese had occupied the island of Hainan in 1939, which is abreast of Indo-China.

w. On 27 September 1940 Japan signed a treaty of alliance with Germany and Italy which provided for mutual assistance in the establishment of Japanese leadership of a "New Order" in Asia, and for German-Italian leadership of a "New Order" in Europe. This was highly important to Japan's objectives, and it was a clever move on the part of Germany and Italy. It was intended to require the United States to defend itself in the Pacific and thus to reduce her strength in the Atlantic. In case the United States should enter the European conflict its military forces, especially its Navy, would be divided between the Atlantic and the Pacific.

x. At about this time the United States announced discontinuance of steel and scrap exportation to Japan. This was in accordance with the Export Control Act of July 1940. Japan immediately protested this action as an "unfriendly act," whereupon Secretary of State Hull stated that it was "amazing" that, after violating American rights and interests, to question this sort of response, especially when in the subjugation of China the United States is called unfriendly unless we sit on the sideline cheerfully and agreeably as these acts go on.16

y. Many discussions were held between the diplomats of the United States and Japan to improve a deteriorating situation. The United States pointed out Japan's program of expansion by military force, together with

_____________

16. Ibid., p. 94. (The above is a paraphrase of Secretary Hull's reply to Ambassador Horiguchi.)

--18--

intensive construction of military and naval armament, and the openly declared intention to achieve and maintain by force of arms a dominant position in the Western Pacific. Secretary of State Hull cautioned that Japan's "best interests lay in the development of friendly relations with the United States and with other countries which believed in orderly and peaceful international processes."17

z. In January 1941 the United States Ambassador to Japan, Joseph C. Grew, reported rumors that Japanese military forces planned a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor in case of trouble with the United States.

aa. Beginning in March 1941 continuous conferences were held in Washington between Japanese Ambassador Nomura and the State Department for the settlement of differences with regard to the Japanese policy which was sloganized as a "New Order in Greater East Asia." As it turned out, this included taking territory by force and violating freedom of trade and freedom of the seas.

bb. In May 1941 Japan proposed a settlement based on recognition by the United States of Manchukuo, recognition of peaceful expansion of Japan to the south, and discontinuance of United States material assistance to China. In return Japan would guarantee the neutrality of the Philippine Islands. The Japanese were not willing to commit themselves unreservedly to a policy of peace, and would not abandon their ties with Hitler and Mussolini.18 However, the Department of State wrote a comprehensive statement in which important concessions were made to Japanese policy, but with reservations intended to exert a restraining influence.19

cc. In the summer of 1941 Hitler pressured the French Vichy Government to grant Japan military base rights in Southern Indo-China. These became effective in July 1941 whereupon the President of the United States proposed neutralization of Indo-China so that all nations could carry on trade and commerce. Japan rejected this proposal. Then on 1 August, the United States imposed an oil embargo on Japan.

dd. For several years military control of the Japanese government had been in the ascendancy. Almost full army control had been gained by threat, pressure, and assassination. The conservative elements, even including the Emperor, were shunted aside. Premier Konoye was required to resign in October 1941, and the new premier was Army General Hideki Tojo. Thus

____________

17. Ibid., p. 113.

18. Ibid., p. 116.

19. Ibid., p. 117.

--19--

the militaristic element was in full control of Japan and took over the government with the purpose of consolidating their aggressions in China and proceeding with the "Greater East-Asia Co-prosperity Sphere."

ee. In return for discontinuance of the United States' trade restrictions, Japan offered to cooperate in a development of natural resources and trade in the southwest Pacific. There was a Japanese threat to move into Thailand and to dominate the Indian Ocean while efforts of Germany and Italy were aimed at the Near and Middle East. At the same time the survival of Great Britain was in serious doubt.

ff. Japanese diplomats now proposed a conference between their Premier Konoye and President Roosevelt to reach an overall settlement. But they were unwilling to agree in advance on the basic principles which the United States had consistently championed and which Japan had consistently violated. But, as always, the Japanese stated that they "had no intention of using 'without provocation,' military force against any neighboring nation."20

gg. On 3 November 1941 Ambassador Grew explained to the United States government that the militaristic government of Japan could not be stopped, and that war could not be averted by the imposition of economic embargoes or sanctions. On 17 November 1941 he suggested that vigilance against sudden Japanese naval or military attack was essential.21

hh. In November 1941 Japan's special envoy, Mr. Kurusu, arrived in Washington and endeavored with the help of the Japanese Ambassador to justify Japan's situation, which was really fully understood by our State Department. He had nothing new to offer on the crucial question of Japan's aggressions. The United States promised that if Japan would indicate some peaceful intentions they would be well responded to.22

ii. Since Japan's expressions of peaceful intent contained qualifications and restrictions, and did not budge from the fundamental objectives stated by its military leaders, the United States under date of 26 November 1941 made crystal clear its position. The American note was sent when it was fully realized that the long drawn-out negotiations to improve the relations between the two governments were failing.

jj. In early December 1941 there were threatening Japanese troop movements into Southeast Asia. When this was protested by President Roosevelt

_____________

20. Ibid., pp. 124 and 125.

21. Ibid., pp. 130 and 131.

22. Ibid., pp. 132 and 134.

--20--

Rear Admiral William R. Furlong, USN, Commander Minecraft, Battle Force, was in his flagship, USS Oglala, during the Japanese attack. He became Commandant of the Navy Yard, Pearl Harbor, on 25 December 1941.

on 2 December, Kurusu explained that they were for protection against Chinese troops, and that Japan was concerned lest the allied powers should occupy Indo-China.23

kk. On 6 December 1941 President Roosevelt transmitted a telegram to the Emperor of Japan appealing for cooperation toward eliminating any form of military threat, and for restoring traditional unity.

ll. Under date of 7 December 1941 Japan's reply to the 26 November message was delivered to Secretary Hull. The message was abusive and condemnatory, and ended with breaking off the negotiations. Secretary Hull said to the Japanese diplomats: "I have never seen a document that was more crowded with infamous falsehoods and distortions -- infamous falsehoods and distortions on a scale so huge that I never imagined until today that any Government on this planet was capable of uttering them."24

The world now knows that when the Japanese note was written their naval task force was on the way to attack Pearl Harbor, and the attack had

____________

23. Ibid., pp. 139 and 140.

24. Ibid., p. 142. (Secretary Hull's statement of 7 December 1941 to the Japanese diplomats.)

--21--

already been delivered more than an hour before the note was delivered by the Japanese diplomats. This certainly shows bad faith on the part of the Japanese. Their attack force was assembled and underway before the 26 November 1941 note was received by them; their basis for peace was premised upon an unbending attitude regarding Japanese policies in the Pacific; their continued diplomatic efforts were fraudulent because they knew that the United States would not agree to their demands. Even as late as 30 November 1941, General Tojo as Premier stated that the Japanese purpose was to purge East Asia; with a vengeance, of hostile British and United States influences.

--22--

Chapter III

Problems and Dilemmas of the United States and Eventual Preparedness for War

Chapter III

Problems and Dilemmas of the United States and Eventual Preparedness for War

1. AMERICAN ATTITUDES AND POLICIES

The gathering clouds of war in Europe and the Far East became more and more ominous to the United States during each of the half dozen years preceding the attack on Pearl Harbor. Because of our nation's firm commitment to peace there was much sympathy and concern among Americans for the victims of the aggression. In the early stages of unprincipled aggression abroad there seemed little need to worry about what was developing in other countries, or what our own welfare and eventual security might be. Yet as time went on and situations became more critical we found ourselves the only major world power that was not engaged in warfare. Even when our foreign trade and property were jeopardized and our citizens abroad were endangered we were reluctant to take decisive actions which might possibly embroil us in the worldwide conflict. Even while condemning the aggressor nations the large majority of our people demanded peace and neutrality for themselves.

As pressures mounted our diplomatic policy stood firmly for cooperative observance of law and order by all nations. Yet in most cases we found ourselves impotent in negotiating settlements for the benefit of world peace or our own interests. The unremitting efforts made by our country, as well as the efforts made by the victimized nations, proved that talk, discussion, and negotiation were almost futile. Aggressor nations are no more susceptible to logical argument than outlaws bent on plunder. Both operate by force of arms, and it requires force of arms to restrain them.

The major dilemma confronting the United States was whether to tolerate a wholly unsatisfactory world situation, or to resort to forceful intervention. Neither was acceptable nor really possible, but nevertheless the great prob-

--25--

lem of the United States was to determine how to restore peace and lawful practices among nations in a disrupted world without going to war. How to strengthen our diplomatic voice in the world without building a sufficient military force to back up adequately that voice was a real dilemma faced by our government.

A specific dilemma in the case of Japan's policy in China, the Secretary of State noted, was to come to amicable agreement with Japan but not at the expense of China.

A related dilemma was how to make preparations against the possibility of armed conflict when public opinion opposed military expenditures and seemed obsessed with the benefits of neutralism and perhaps by self-righteousness. These and other contradictory factors of our national life and well-being are touched upon in this chapter, as are the steps taken to reconcile opposing considerations.

2. RETRENCHMENT IN MILITARY PREPAREDNESS

For a dozen years or more after World War I the United States followed a program of drastic retrenchment in military preparedness. Much of this was quite in order because we had built up a gigantic military machine by the end of World War I, and there were in various stages of completion large naval building programs. The Washington Treaty for the Limitation of Naval Armament, signed in 1922 by the United States, Great Britain, Japan, Italy, and France was in this tradition.

But public opinion demanded much greater military curtailment to demonstrate America's support of the worldwide yearning for peace as exemplified by the various peace-keeping treaties of those years. Also, it is interesting to note that in the mid 1930's the Nye Committee of the United States Senate held numerous hearings to show that war was caused in large part by the manufacturers and vendors of armament and military equipment. It was pointed out that drastic reduction in the purchase of such materials would presumably tend toward peace.

Many peace organizations were active during those times in promoting general disarmament. In the absence of any over-all agreement among the world powers there was a strong feeling for "disarmament by example," the theory being that other nations would probably follow the strongest

--26--

nation in the world. Professional propagandists were likewise busy. The result was that throughout the 1920's the military forces of the United States were steadily reduced in effectiveness. Very few new ships were authorized, and manning levels in the military services were greatly curtailed. In short, the military services existed on a starvation diet.

However, when the economic depression began after 1929, the nation was fortunate that a portion of the Congressional appropriations for the National Industrial Recovery Act was assigned to a rehabilitation program in ship construction, but not without opposition from well-meaning organizations devoted to the hope of peace through disarmament. Included in this program of ship construction were a number of major vessels. The design and construction of such ships requires four to five years. But some of these became available and were of inestimable value in the early days of World War II. An important national benefit was the reactivation of the famished American shipbuilding trade which thus was available for the gigantic programs of production in the days ahead.

At this time there was no comprehension of the magnitude of the military needs which shortly would be thrust upon us. Of course, there was very little concern that such needs would require several years of lead time for the design, planning, development, and manufacture, or for the training of personnel for operation. The large portion of our population was determined to avoid war at any cost, and they were quite sure that the best way to avoid war was to avoid preparing for war.

Naturally the Congress reflected the viewpoint of public opinion. Although supporting most of the President's recommendations for national defense, in the late 1930's it acted otherwise repeatedly.

For example, in 1938 the House of Representatives barely defeated the proposed Ludlow constitutional amendment which would have required a popular vote as a prerequisite to a declaration of war by the Congress. Except for the strong representations made by the President and the Secretary of State this proposal would probably have been passed.1

Near the end of 1938 Secretary of War Woodring reported that despite improvements made, the United States stood eighteenth in relative strength among the standing armies of the world. In 1939 Congress refused to

______________

1 Peace and War, p. 52. (President Roosevelt wrote to the Speaker of the House on 6 January 1938, and Secretary Hull warned on 8 January 1938 that this proposal would hamstring the Government.)

--27--

modify the prohibition against U.S. merchant ships trading with friendly nations under attack, but did allow these countries to buy our war materials on a cash and carry basis.

Although the Congress approved calling up for active duty the Reserves and the National Guard, in August 1940 it was required that they be used only within the Western Hemisphere or in United States territories. As late as August 1940 Congress passed the first peacetime Selective Service and Training Act in our history by a small margin, but with the same restrictions as for the Reserves and National Guard. At about the same time Congress defeated a bill for improving the defenses of Guam, on the basis that the United States should not do anything to provoke or irritate Japan.

So while some progress was made in building up the national defense forces, public opinion was divided as to the advisability of doing anything which had the appearance of warlike measures. Except for the strong leadership and insistence of the President and Secretary of State, backed by U.S. naval and military leaders, our military structure might well have been quite impotent in late 1941 when World War II broke upon us.

3. DIPLOMACY AT WORK TO PREVENT WAR AND TO IMPROVE PREPAREDNESS FOR WAR

In a world beset with ever-increasing international outlawry, the diplomatic workload of a leading world power committed to peace and legal procedures among nations was enormous. The United States exerted every means to impress upon the offending nations the importance of peaceful processes and the avoidance of violence. Secretary of State Cordell Hull was a patient and reasonable man. He continuously emphasized the inviolability of treaties and agreements among the nations if peace and orderly progress were to be maintained. The logic of his arguments was clear to most people. And let it be said that his work during those critical years bears the stamp of excellence in building a framework of definite action which later could be properly taken. Together with President Roosevelt, the State Department took progressive steps toward exposing international outlawry, and in time toward taking specific action to oppose it. We might list a few of the most important steps which were taken. Many of the specific measures taken pertain primarily to problems in the Atlantic, but of course are clearly related to the problems presented by the Japanese in the Pacific. Many

--28--

of the steps taken by government officials were for the purpose of informing the American people of the implications of the world conflict, and alerting them to possible involvement if principles of peace and honor were to be preserved.

a. Freedom of trade and commercial activity as guaranteed by treaties and agreements were the subject of frequent notes and discussions. The situation became crucial when freedom of the seas became involved. Ultimately the United States took decisive action by instituting a naval patrol in the Atlantic in 1941.

b. When public opinion seemed willing to overlook violations of American rights in 1938 Secretary Hull warned that our security would be menaced if we abandoned our legitimate principles because of fear or unwillingness. Only by meeting our responsibilities and making our proper contributions to the firm establishment of a world order based on law "can we keep the problem of our own security in true perspective . . . ."2

c. When war broke in Europe in 1939 the United States declared its neutrality and also declared a Limited National Emergency. The embargo on the export of arms under the Neutrality Act was repealed in November 1939 so that some aid could be rendered to Great Britain and France.

d. In order to exert a restraining influence on Japan's warlike policies it was decided that the fleet exercises in May of 1940 would be held in the Hawaiian area. The Fleet remained in Hawaii after the maneuvers. This was a diplomatic decision, which was not concurred by all military leaders.

e. On 19 May 1940, President Roosevelt said, "We are shocked and angered" by the over-running of the Lowlands by the Germans and he said that it is a mistaken idea that the American republics are wholly safe from the impact of the attacks on civilization in other parts of the world.3 A month later, on 20 June 1940, the Secretary of State stated that, because of the imminent fall of France, never before has there been such a powerful challenge to freedom, that we could meet it only by retaining an unshakable faith in the worth of freedom and honor, of truth and justice, of intellectual and spiritual integrity, and by determination to give our all for the preservation of our way of life.4

f. When the Japanese bombed Chinese civilians the United States declared a "Moral Embargo" against Japan. The American government

______________

2 Ibid., p. 55. (Secretary Hull's address in Washington, D.C. on 17 March 1938.)

3 Ibid., p. 73.

4 Ibid., p. 78.

--29--

appealed to manufacturers and exporters of aircraft parts and armaments not to send these products where they would be used against civilians.

g. In September 1940 American Ambassador Grew reported that Japan felt that she had a "golden opportunity." Japan, he said, was a predatory power and a fully opportunist nation seeking to profit through the weakness of others. She has been deterred from taking great liberties with interests of the United States because she respected our potential power, and she trampled on our rights in exact ratio to the strength of conviction that the United States public would not permit that power to be developed and used.5

h. Embargoes and sanctions against Japan were frequently considered and carefully evaluated as to risk of provocation. However, in July 1940 the Export Control Act authorized the President in the interest of national defense to prohibit or curtail the export of certain war materials, including scrap metal and oil.

i. In January 1941 President Roosevelt declared in his State of the Union Message to Congress that American security was threatened, that we supported resolute people resisting aggression, and that our own security would "never permit us to acquiesce in a peace dictated by aggressors or sponsored by appeasers."6

j. In March 1941 Congress passed the Lend Lease Act and appropriated seven billion dollars to aid friendly nations. President Roosevelt made a statement that this action ended any compromise with tyranny and the forces of oppression.7

k. On 27 May 1941 the President declared an "Unlimited National Emergency." A major objective was to authorize naval action to prevent the aggressors from gaining control of the seas.8

1. Following attacks on American merchant and naval ships in September and October 1941 President Roosevelt stated: "History has recorded who fired the first shot." We had sought no shooting war with Hitler, but we were not willing to pay for peace by permitting Hitler to attack our ships when they were on legitimate business.9

m. On 21 October 1941 Secretary Hull stated with regard to the Congressional authorization for American merchant vessels to carry cargoes to belligerents that the "paramount principle of national policy is the preserva-

_____________

5 Ibid., p. 92.

6 Ibid., p. 95.

7 Ibid., p. 96.

8 Ibid., pp. 101 and 102.

9 Ibid., pp. 110 and 112.

--30--

tion of the safety and security of the nation;" and the "highest right flowing from that principle is the right of self-defense."10

n. On 17 August 1941 President Roosevelt and Secretary Hull conferred with Japanese diplomats and delivered a note which contained the statement that the government of the United States "finds it necessary to say to the Government of Japan that if the Japanese Government takes any further steps in pursuance of a policy or program of military domination by force or threat of force of neighboring countries, the Government of the United States will be compelled to take immediately any and all steps which it may deem necessary toward safeguarding the legitimate rights and interests of the United States and the American nationals and toward insuring the safety and security of the United States."11

o. On 1 December 1941 Secretary Hull stated to Japanese diplomats that the United States would give all the materials Japan requires if the Japanese leaders will show some movement toward peace and discontinue bellicose threats and bluster.12

Thus it is seen that American diplomacy was active throughout the decade preceding Pearl Harbor, in endeavoring to restrain the aggressors on the one hand, and on the other, to educate the American people regarding the issues at stake and the threat to their freedom and security.

4. HARDENING OF PUBLIC OPINION

As the people became informed of the progress of events in Europe and Japan, and were alerted to the effects on American interests and principles, they gradually assumed stronger views against the three aggressor nations. Yet despite the actions of those nations, the clear mandate of the people was to refrain from war or the appearance of war.

There were wide differences of opinion as to the rightness or wrongness of every nation's actions, including our own. Some of these were based on race, nationality, or personal experience. Others were influenced by paid propaganda outputs in this country. But the great majority of the people were sincere and honest in their desire to avoid warfare if at all possible, and were willing to make concessions and even sacrifices to that end. There

_____________

10 Ibid., p. 111.

11 Ibid., pp. 123 and 124.

12 Ibid., p. 139.

--31--

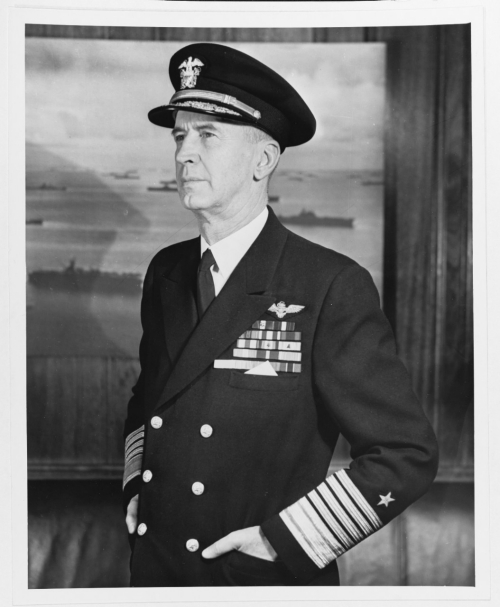

Rear Admiral Claude C. Bloch, USN, Commandant, Fourteenth Naval District on 7 December 1941.

--32--

were some who deprecated the mild and patient manner of the State Department over the years, and felt that any nation which violated our legitimate pursuits or hazarded our nationals abroad should be sternly dealt with. Such persons criticized the State Department for writing notes rather than acting forthrightly and forcibly.

The unprovoked bombing of USS Panay and three merchant ships in 1937 by the Japanese hardened the American viewpoint, as did the brutal attacks on missionary hospitals in China, and the terror-bombing of the Chinese people.

There was strong opposition to the exportation of scrap metal and oil to Japan before these items were embargoed in 1940 and 1941 especially when these commodities were in short supply in the United States. Yet Ambassador Grew stated that economic sanctions were more likely to cause war than to avoid it. This was one of the dilemmas which the Administration had to face. The Japanese, he explained, could not be bluffed or forced into submission. They would not "back down" as the Oriental psychology would consider this a "loss of face."

By 1941 the great majority of our people were quite aware of Japan's unprincipled behavior, but still regarded the Japanese people with some sympathy and with considerable admiration for their industriousness, objectiveness, arid national loyalty. But the ever-increasing tempo of Japan's depredations and the belligerent demands of their government changed attitudes of sympathy and admiration into anxiety and antipathy. When Japan took virtually full control of Indo-China in the summer of 1941 and demanded that Thailand grant special concessions, the American people approved our imposition of an oil embargo. Nevertheless public opinion tried hard to take these aggressions in stride, and it remained for the Japanese to solidify public opinion completely by the surprise attack on the American flag at Pearl Harbor.

5. ASSISTANCE TO FRIENDLY NATIONS

The American public seemed in large part to be naive regarding the full implications of the European War and the Sino-Japanese War. Our high government officials, however, were quite aware of the threats to American interests and eventual security. It soon became crystal clear that the basic contest was between the forces of predatory authoritarianism and the free

--33--

nations of the world. Therefore, regardless of personal attachment to one country or another, the effort and influence of the United States were naturally directed toward restraining the predatory powers and assisting the free nations. This diplomatic position became increasingly active and forceful each year as events became more threatening.

Our endeavors to render material support to the beleaguered free nations required some military protection. As the contest widened, the need for defense indicated the importance of greater military potency. Thus the American stance against world aggression gradually developed from the diplomatic stage to the economic, and finally to the military, culminating in the United States becoming, clearly, if not formally, allied with the free nations against the Axis Powers.

We have already mentioned some of the more significant measures of diplomacy; now we might consider a few of the more important steps taken to render assistance to the friendly nations.

a. American trade with China had been of importance to both countries for many years, and was essential to China in resisting Japan's depredations. From the start of the conflict we furnished assistance to China by shipping important materials to meet economic and military requirements. Such assistance to China was characterized by Japan as "an unfriendly act."

b. The Neutrality Acts of 1935 and 1937 placed a rigid embargo on the export of arms to all belligerents, and thus had an injurious effect on friendly nations which were comparatively deficient in military equipment with which to resist the aggressors. At various times President Roosevelt and Secretary Hull endeavored to persuade Congress to amend the Acts favorably to the victimized nations, but to no avail until November 1939 when the Acts were partially repealed. Although the Congress continued to stand firm for military neutrality, the apathy and complacency of the people were challenged and gradually broken down because of the shockingly predatory events abroad.

c. In June 1940 President Roosevelt reported that the United States would provide surplus material resources to Great Britain and France, and pointed out that this was in our self interest. In justifying this action he stated that we as a nation were concerned that "military and naval victory for the gods of force and hate would endanger the institutions of democracy in the western world," and that our sympathies were with these nations that were giving their lifeblood in combat against these forces.13

______________

13 Ibid., p. 74.

--34--

d. In September 1940 the American government agreed with Great Britain to transfer fifty old-type destroyers in exchange for long-term leases of certain bases in the Western Atlantic and Caribbean. These bases would be essential in case of war, which they eventually proved to be.

e. In December 1940 it was plain that the European aggressors intended to dominate all of Europe and ultimately the rest of the world. President Roosevelt proclaimed that the United States would act as the "Arsenal of Democracy," and stated that we must help defend the free world by furnishing needed materials. In January 1941 the President asked Congress to authorize the lending of arms and other assistance to such nations when this was vital to the interests of the United States.

f. Despite the bitter protests of isolationists Congress passed the Lend Lease Act in March 1941 and appropriated seven billion dollars to put it into effect. This Act permitted all direct military aid to Great Britain.

g. By 1941 the loss of British ships to German submarines exceeded the rate of production in the shipyards of both Great Britain and the United States. In order to deliver to Great Britain the material aid required, the United States instituted a naval patrol force to protect British ships in the Western Atlantic.

h. On 30 October 1941 Roosevelt informed Stalin of his decision to grant the Soviet Union up to one billion dollars of Lend Lease Aid to counter Hitler's invasion of Russia.

i. By November 1941 it was clear that the survival of Great Britain was essential to the whole free world, and therefore the United States removed virtually all restrictions on arms shipments to that nation.

j. In spite of continued protests of Japan we had for several years assisted China by furnishing military equipment for shipment over the Burma Road, which by 1941 was the only open route to China as all others had been blockaded by Japan.

6. MILITARY PREPAREDNESS MEASURES

The military capabilities of the United States in the early 1930's were small compared to what might be required to match the powerful forces of the Axis. This fact was fully realized by responsible government officials, but public sentiment was quite fixed in opposition to any warlike gestures, including the buildup of armament. Furthermore, the economic depression