The Navy Department Library

Religions of Vietnam

MACV Office of Information APO 96222

Command Information Pamphlet 11-67

April 1968

Introduction

Animism

Taoism

Confucianism

The Life of Confucius

Teachings of Confucius

Confucianism In Vietnam

Confucianism and the Family

Buddhism

Buddha

Buddha's Teachings

Nirvana

Buddhism After Buddha

Major Buddhist Divisions

Buddhism in Vietnam

Effects On Vietnamese Life

Terms, Symbols and Sacred Objects

Hoa Hao

History

Hoa Hao Beliefs

Cao Dai

Basis of Cao Daism

Major Doctrines of Cao Dai

Organization

Holy City of Tay Ninh

Influence in Vietnam

Christianity

Roman Catholicism

Protestantism

Religion in Everyday Life

Some knowledge of religion in Vietnam is fundamental to an appreciation of every phase of Vietnamese life, because religious beliefs richly color almost every Vietnamese thought and act, and affect the way they react to us and what we do.

We come from a different culture than the Vietnamese. Regardless of our individual faiths, we all have been conditioned by the concepts of our Judeo-Christian culture.

In large part, Vietnamese culture and religion differ greatly from what we are accustomed to. Therefore we may at first find them strange.

To avoid offending and even alienating a people with traditions just as old or older than ours we must develop understanding and tolerance of their religion, their values, their way of thinking and acting.

Religious freedom is one of the principles on which our nation was founded, the right of each person to believe and worship as he pleases. We will find in Vietnam a tradition of religious tolerance inherited from the ancient Buddhists.

To the Vietnamese, and to hundreds of millions of people in Asia, their religious beliefs are sacred, as sacred to them as our beliefs are to us, and perhaps more a part of their lives than ours are of ours. In Vietnam, then, we can do no less than try to understand and respect the beliefs of the people.

Vietnam has no state religion. Often it is considered a predominantly Buddhist nation, but this classification can be misleading. One simplified classification lists 20 per cent as Buddhists, 20 per cent as non-Buddhists and 60 per cent as nominal but non-practicing Buddhists.

All the world's great religions can be found in Vietnam. At least four major beliefs have had a profound impact on the people and their culture and are reflected subtly or obviously in behavior and customs. These are Animism, Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism.

Christianity entered Vietnam later and is now a religious force. Other beliefs such as Bahaism also have gained followings. Underlying all is a prevailing ancestor veneration.

The result is a blend or synthesis of beliefs in which the forms and practices are peculiarly Vietnamese. Buddhism in Vietnam is unlike Buddhism in-for instance-Thailand.

Catholics may practice ancestor veneration and Buddhists may adhere also to the principles of Confucianism. Relatively few people could be said to be purely of one religious belief although they may say they are when asked.

Differences in religious practices may vary also from one level of society to another-westernized urban to traditionalists to rural villagers.

The Viet Cong are well aware of the importance of religion in Vietnamese life. They use people's beliefs in any way they can, although they do not always respect the beliefs.

Our conduct in this country must reflect respect for the symbols and places held sacred, must take these things into account when we enter areas on operations, must consider them in psychological operations, and must recognize their influence during social contacts.

This pamphlet provides a general explanation of the major religions in Vietnam and illustrates symbols and places that an American should recognize.

The influence of animism can be found to some degree in the beliefs and practices of the majority of Vietnamese, although more so in the rural area. Animism, also called the "people's religion," is the religion of the Montagnards.

Animism is a belief in spirits, both of dead persons and those of some inanimate objects such as stones, rivers, mountains and trees. This belief holds that each person has a spirit, which continues to exist even after death has claimed its possessor.

Because the spirit continues an independent existence, it must be cared for properly and provided with its needs and desires in its spirit state. Unattended spirits may become angry, bitter or revengeful and seek to re-enter the earthly life, which would create havoc in numerous ways.

As spirits are associated with people, Animists believe them to be greedy, deceptive, unpredictable, and possessing every trait known to man. Normally, the spirits of departed good people do not create too much concern if the proper rites are performed at the appropriate times, especially those rites which will send them happily on their way to the spirit world.

Those who die violently as in accidents or war, are killed by tigers, women who die in childbirth or who die childless, or those whose bodies are not recovered and properly buried or cremated; all cause great fear, because their spirits are embittered by such a fate and are hostile to individuals, families or communities.

Throughout his life the Animist is fearful of offending the spirits that can cause him harm. He tries to worship and live his everyday life in such a manner as not to offend them, and to placate them in case he has unwittingly offended.

Because the Animist believes that the spirits are somewhat humanized, he believes that they can be influenced as humans are, and that the same capacity for doing good and evil. Basically, the animist seeks to influence his gods and spirits by elaborate ceremonies, flattery, cajolery and sometimes by angry words and actions in almost exactly the same manner that men are influenced.

The Animist does not view himself as a helpless or passive victim of the invisible spirit world, but as one who by the use of the proper formulas can achieve his own goals. In his continuous power struggle with the spirit world he grapples for the best advantages so that he may avoid that which otherwise seems certain and dreadful.

The Animist spends much of his thought, effort, energy, and wealth in observances and rites which will cause the spirits to do the will of the worshiper and which will placate those spirits that can do him harm.

To do this, elaborate rituals and ceremonies are conducted and offerings, sometimes blood sacrifices, are made. These are accompanied by incantations and prayers.

Surrounded as he is by the spirit world, the Animist is constantly on the lookout for those spirits who demand immediate attention, a situation which cannot be ignored with impunity. To aid in this search he seeks help from the important man of his village, the sorcerer. (In northern Vietnam the sorcerer is of less importance than the village chief or clan chief.)

Americans, too, should show special respect to these persons because of the place of esteem they hold in the Animist community.

The Animist also places great emphasis on omens which may come in dreams or may appear as signs for these are believed to be sent by the spirits to warn of future evil or good.

A dog sneezing at a wedding is a sign that the marriage is not a wise one, and normally the ceremony is halted immediately. The track of an animal across a path in the jungle may be an indication of evil and the traveler may return home to seek advice on whether to continue his journey.

The Animists see sickness and death as being spirit-related and so take measures particularly to protect children. Parents may give children nicknames, often very unfavorable ones, and keep the real name in strictest confidence in order to decoy the spirits away from a child.

A similar custom is related to the fact that boys are more highly regarded than girls, therefore if a boy is sickly, he may be dressed as a girl or one earring put in a boy's ear in order to fool the spirits into thinking that the child is a girl.

Another important concept, again widespread in Vietnam, is that the dead must be properly buried, with the correct ceremonies, or the spirit will forever wander. This belief is played upon in our psychological operations against the VC and NVA who are unable to give proper burials to many of their dead.

The enemy also makes use of the belief when they mutilate and decapitate bodies. In doing so, they harm not just the body but the spirit, too.

Various other customs are based on the fear of spirits and attempts to prevent their doing harm. Mirrors are placed in doors for a spirit will be frightened at seeing himself and not enter. Likewise red papers representing the god of the threshold may be fixed to doorposts to frighten spirits. Barriers may be erected along pathways leading to a village to stop spirits.

For every part of an Animist's life from birth to burial the spirits are his constant companion to be feared and placated and his belief about them control his every action.

Taoism (pronounced dowism) had its beginning in China. Lao Tse (the Old One) is generally credited with being its founder. It is essentially of Chinese origin and entered Vietnam with the conquering Chinese armies, unless the Vietnamese brought it with them when they migrated to the Red River delta from China.

Lao Tse lived about 600 B.C. making the religion he is said to have founded slightly older than Confucianism and Buddhism.

Essentially the Dao, or way, taught by Leo Tse is a road or way of life by which a man attains harmony with nature as well as with the mystical currents of the spiritual world. A Taoist accepts all things as they are and attempts to attune his thinking and actions to things as they are; never fighting against them.

Most Taoist worship, rituals and ceremonies are attempts to assist man to attune himself to the universe. To the Western mind it would appear that Taoists use magic, witchcraft, fortune-telling and astrology in their worship.

It may appear to one who adheres to one of the Western religions as mummery, but to the Taoist all his religious activities have a deep spiritual meaning.

Taoists are not usually spirit worshippers although there is an animistic flavor to Taoism, and some beliefs may seem similar. Taoists believe that God's spirit can animate inanimate objects, while animists believe that these objects have spirits of their own.

The basic doctrines of Taoism seem to the Western mind to be:

- The universe, including the nature of the physical and spiritual worlds, is supreme.

- For every positive factor in the universe there is an opposing negative factor.

- All these factors exert influence on all facets of the Taoist's life.

- The positive and negative factors are as they are and cannot be changed; however, by astrology and divining a Taoist priest can forecast which factor can be in greater power at a give day, month, or year.

- The universe is controlled by a mystical, almost mythical supreme being from whom occasional mandates come to rulers or priests.

- The elements-metal, wood, water, fire, and earth-form the basis for the religious rites of Taoism.

Taoists believe in one supreme being, the Emperor of Jade, and worship him, other deities who assist him, and ancestors.

The two principal assistants to the Emperor of Jade are Nam Tao and Bac Dau, who keep the register of all beings in the universe.

Although Taoism has a limited formal organization in Vietnam today, the concepts of Taoism are in evidence in the daily life cycle of the Vietnamese.

Many of the more basic beliefs and practices of Taoism have been absorbed into other religions found in Vietnam, and affect the cultural patterns.

These ideas are to be observed in older medical practices; the consultation of horoscopes and astrologers in making marriage arrangements, the selection of auspicious dates, and in the ceremonies of worship pertaining to Spring, Fall, the ploughing of the land and planting of the seed.

Like Taoism, and to some extent Buddhism, Confucianism came to Vietnam from China. In the mixture of religions and philosophies which have contributed to the moulding of the Vietnamese character, Confucianism has held an important place and will help us to understand much about the Vietnamese today. It is part of the cultural environment in which they are born.

Confucius, who lived 2,500 years ago, never attempted to found a religion but was content to be a scholar and teacher.

He introduced no new religious ideas and never professed to be original. Instead he held fast to ancient rites and customs, and his ethics were his chief contribution. He did not indulge in abstract philosophizing; for him man was the measure of all things.

In his teachings he combined politics, ethics, and education and imbued disciples with the spirit of reverence and devotion.

His ideas survived the inroads of other major religions and lived on while dynasties rose and fell for more than 25 centuries.

Confucius was born in Shantung, China, in 551 B.C., one of 11 children whose father died when Confucius was three. His early life was spent in poverty. Largely self-educated, he became China's most noted educator and learned man.

His Chinese name K'ung Fu-tze was Latinized to Confucius by Jesuit missionaries.

Confucius became an overseer of public lands at 19. A few years later he married, left this position and founded a school for instruction in conduct and government.

After 29 years of successful teaching he was appointed town magistrate when he was 51 and in four years advanced to chief justice of his state. The state ruler, Duke Ting, impressed with Confucius' teachings, followed them to the point of greatly improving his government and his people's lot. Then Confucius resigned.

The teacher-philosopher wandered for 13 years from state to state, trying to interest feudal lords in his ideas and ideals. This period of self-imposed exile, with its hardship and danger, helped spread his fame as a teacher and reformer and attracted many disciples.

When Confucius was 68 years old he returned to his home. There he completed work on the ancient Chinese classics, edited The Book of Songs (containing 308 songs and several anthems), wrote a chronicle of his native state and a book detailing the classic rites. He also began writing the Analects or Sayings of Confucius, which were completed by his disciples.

These writings became the foundation of Confucianism.

He died in 479 B.C., disappointed because his ideas were not adopted. But in 140 B.C., Emperor Han Wu-Ti made Confucianism a state religion.

Succeeding emperors built temples in his honor in every district of China, and imperial colleges were established which taught the Confucian Classics. Graduation from these schools, or passing an examination based on his teachings, opened the door to social and official life until 1912.

His emphasis on ancestral reverence continued into modern times. When the Tientsin-Pukow railroad was being built the railroad authorities were influenced by his descendants to divert it five miles from the town so as not to disturb his resting place. This year Red Guards desecrated Confucius' tomb, the first known exception to this tradition.

His teachings exerted such an influence on China and the rest of Southeast Asia that Confucius is recognized as one of the most influential men in world history.

"Learning knows no rank."

Confucius lived in a time of strife and anarchy. His teachings called, not for the salvation of the soul, but for good government and harmonious relations among men. He taught that men should be more conscious of their obligations than of their rights.

As taught in Vietnam today, followers of Confucius are charged with five obligations or ordinary duties:

1. Nhan-love and humility.

2. Nghia-right actions in expressing love and humanity.

3. Le-observation of the rites or rules of ceremony and courtesy.

4. Tri-the duty to be educated.

5. Tin-self-confidence and fidelity towards others.

There are nine conditions under which the individual correctly performs these duties. When the duties are performed under the nine conditions, the person reaches the goal of life which is achievement of the three cardinal virtues-the correct performance of three relationships. These are:

King and subject (Fatherland and citizen)

Teacher and pupil

Father and children

(References in English usually list five Confucian relationships as follows:

Ruler and subject, father and son, elder and younger brother, husband and wife, and friend and friend.)

Although subordination to the superior is directed in each case, the superior has duties and responsibilities toward the junior whether it be ruler to subject or father to children.

Reverence and respect are not owed the superior blindly. A son may, with respect, correct a father, and a people may withdraw the mandate from a ruler who does not truly fulfill his function. The individual's primary obligation is to his ruler, then his teacher, and finally his father although later Confucian teachings have stressed filial piety.

A general rule to be observed in relationships with others is: "Do not do to others what you would not want them to do to you."

One of the conditions for performance of the five duties was taught by Confucius in his work, the Chung Yung which has been translated as Doctrine of the Mean. Actually Confucius meant much more than is implied by the word "mean," or middle way.

He taught moderation and equilibrium, and harmony in actions, but advocated that a person might use the maximum means necessary. What he deplored was an excess beyond what is required to accomplish a desired end.

To this end, he taught "Recompense injury with justice, and recompense kindness with kindness."

As the object of all Confucian teachings was the perfect moral individual and a harmonious social order, the basis for obtaining these goals was the "superior, noble or princely man."

Such a man would know how he ought to live with moderation and harmony in everything. From this superior man would grow a harmonious family and a perfect state.

One of the most frequently preached Confucian doctrines was Government by Example. Government was to be in the hands of the educated and virtuous who by their example would bring about the perfect state.

One of the most frequently preached Confucian doctrines was Government by Example. Government was to be in the hands of the educated and virtuous who by their example would bring about the perfect state.

While Confucius was a humanist whose teachings were ethical, he recognized existing beliefs in a Supreme Being; by his teachings, insistence on the observance of existing rites and customs, he perpetuated religion as part of Confucianism.

Ancestor veneration was perpetuated also both by the precept of filial piety and the observance of rites for the ancestors. A basic Confucian precept and the basis of ancestor veneration is that children serve their parents, an obligation equally as binding after the parents' death as when they are living.

The Chinese Emperor Han Wu-Ti placed Vietnam under a military governor in 111 B.C., and for the next 900 years events in Vietnam were part of Chinese history.

In this period Chinese technology and culture came to Vietnam and were accepted under a rule of moderation and semi-independence.

The influence of Confucianism on early art was important, with the painters following his Doctrine of the Mean: neither too much nor too little; no overcrowding of details: not too many nor too bright colors, just enough to obtain the desired effect.

During the period of national independence (939-1404 A.D.) most of the Vietnamese people accepted Confucianism. Vietnamese writers were dominated by Confucianism and rarely veered from moralistic tales until 1925 when the author Hoang Ngoc Phach published the novel To Tam that marked a departure from Confucianist tradition.

In 1404 the Chinese reconquered the country and held it for 23 years. In 1427 the Vietnamese patriot Le Loi defeated the Chinese and, ruling under the name of Le Thai To, adopted a Confucian model of government which lasted for 360 years.

The influence of Confucianism on Vietnam was tenacious because it was rooted in the country's educational system until the 20th century. (Education consisted of a study of the Confucian classics and ethics.)

At first the schools taught only sons of royalty and other high officials, but in 1252 they were opened to students of varied backgrounds. By the beginning of the 15th century Confucian-type schools were operating in leading centers and education became the most cherished of ideals.

Confucian classics and ethics also were taught at elementary level in villages throughout the country.

Because of the scarcity of schools, the theater became a way to perpetuate Confucianism. The social relations of imperial Vietnam (emperor and subject, father and son, etc.) made the basis of stage plays. The five cardinal virtues of Confucianism (humanity, loyalty, civility, wisdom and justice) were promoted.

The Hat Boi, one of Vietnam's five major types of plays, is still influenced by Confucianism.

When Gia Long became emperor in 1802, centralized administration was strengthened. He and his successors zealously promoted Confucianism and their own image as Confucian father-figures of a harmonious and submissive Vietnamese national family.

In the 19th century, to be "educated" meant to be learned in the Confucian classics.

Schooled for centuries in Confucian principles, the rulers of Vietnam were unable to conceive of another kind of civilization and sought to isolate the country from alien religious ideas and from the modern world. In the 19th century this was no longer possible.

Under French rule, Confucianism declined. It encountered new ideas and forces, and long before the end of the colonial period it had lost its dominant position. The final blow to Confucian education was the French reform of civil service examinations which required training in the European education system rather than Confucian learning.

Its basic precepts, however, remained deeply imbedded in the morals and values of the people.

Confucianism is still important as a traditional source of attitudes and values among the peasantry.

The Vietnamese villager still tends to feel that the family is more important than the individual, to respect learning and to believe that Man should live in harmony with his surroundings. Therefore, the peasant takes the "dao" or way of Confucius, a harmonious path between all extremes of conduct. (The Confucian dao is ethical, while the Taoist dao of Lao Tse is mystical.)

Confucianism beliefs also contribute to the politeness of the Vietnamese.

The Confucian doctrine which commands children to respect their father and mother and honor their memory, provides strength, stability and continuity to the large family group. It is a powerful guardian of morality because of the fear of dishonoring the memory of ancestors.

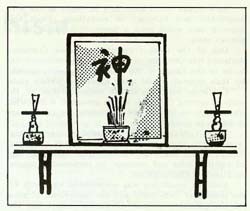

Rites for the ancestors continue as important ceremonies in Vietnam. Many Vietnamese homes have an alter dedicated to the family ancestors, decorated with candlesticks, incense bowls, flower trays and the tablet containing the names of ancestors who have died in the past five generations.

The ceremonies pay respect to the dead, preserve the family lineage, and care for the spirits of the departed who would otherwise wander homeless.

Offerings of food and symbolic votive papers are made by a male member of the family on whom falls responsibility for ancestor veneration on the anniversary of each ancestor's death and again after two years.

Ancestors are honored also on other special days including festivals, holidays, weddings and births.

Confucianists commemorate the anniversary of Confucius' birth on the 28th day of the ninth lunar month. The center of this birthday celebration is a temple (Temple of Souvenirs) dedicated to him in Saigon's Botanical Gardens.

Buddhism is the third of the great religions which have contributed to the molding of Vietnamese culture and character over the centuries. Buddha was a contemporary of Confucius, and the religion he founded entered Vietnam from both India, Buddha's home, and China. Today it is perhaps the most visible of Vietnamese religious beliefs.

According to accounts of his life, Buddha was an Indian prince born about 563 B.C., in a small kingdom in northern India between Nepal and Sikkim. His given name was Siddhartha and his family name Guatama.

Six days after his birth an astrologer predicted that he would become a great leader. It was also noted that if the child saw signs of misery he would renounce royalty and become a monk.

His father, doting and anxious that Guatama should succeed him as king, screened his son from all unhappiness and surrounded him with luxury. Whenever Guatama went out, the king sent messengers to clear the streets of anything that would suggest other than youth, health and strength.

His early life also included a marriage, but when Guatama was 16 he married his second wife, Yasodhara, said to be the most beautiful in the kingdom, who bore him a son.

Then, the legends say, Guatama escaped from the palace one day and met four divine messengers. The first three were disguised as an old man, a sick man, and a dead man. They revealed misery to Buddha.

The fourth, disguised as a monk, caused him to decide to renounce his wealth and family to seek the way of deliverance for mankind.

Stealing away from the palace, Guatama shaved his head and put on the saffron robes of a monk and began years of wandering and austerity in search of the truth.

Finally he came to rest under a Bo-tree (also "Bodhi" tree) at Buddha Gaya where he fasted and mediated. The truth he sought, the way to relieve man's suffering, was revealed under this tree. Buddha called this truth the "Middle Way," a way of moderation between the luxury of his youth and the asceticism of his wanderings. Finding the truth, he became Buddha, The Enlightened One.

After his enlightenment, Buddha traveled and preached, attracting large gatherings and making converts from all classes of society. Yellow-robed, clean-shaven monks of his order wandered tirelessly, preaching the doctrine of liberation.

Buddha, according to some, was 80 years old when he died in 483 B.C., on the same day of the year that he was born and on which he attained enlightenment.

"Lead others, not by violence, but by righteousness and equity."

The major teachings of Buddha are found in the Benares Sermon of Buddha which stressed the "Middle Way." That this "Middle Way" might be realized by humanity, Buddha proclaimed what are now known as the Four Noble Truths:

1. Existence (life) is a succession of suffering, or, to exist is to suffer;

2. Suffering is caused and created by desires or cravings; the ignorance of true reality allows ambition, anger, illusion, to continue to cause an endless cycle of existence;

3. The extinguishing of suffering can be achieved only by the elimination of desire;

4. The elimination of desire or craving can be achieved only through the Noble Eightfold Path.

The Noble Eightfold Path by which the Buddhist must strive to perfect himself consists of:

1. Right views

2. Right aspirations

3. Right speech

4. Right behavior

5. Right living

6. Right effort

7. Right thoughts

8. Right concentration

Buddha gave five Commandments or Prohibitions:

1. Do not kill;

2. Do not steal;

3. Do not be unchaste;

4. Do not lie;

5. Do not drink alcohol.

Karma and the Wheel of Existence

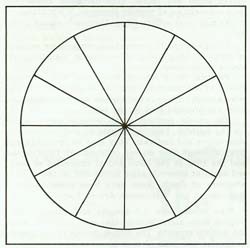

None of the Buddha's teaching is of great significance than the doctrine of Karma. The wheel, one of the earliest Buddhist symbols, stands for the unending cycle of existence through which life goes on by birth and rebirth.

According to the doctrine of Karma the sum total of a person's good or bad actions, comprising thoughts, words and deeds, determines his specific destiny in the next rebirth in the unending cycle of life.

As translated from The Gospel of Buddha by Paul Carus, Buddha taught that "All beings have karma as their portion: they are heirs of their karma; they are sprung from their karma; their karma is their kinsman; their karma is their refuge; karma allots beings to meanness or to greatness."

While Hinduism holds a similar belief in reincarnation, the wheel of existence and karma, Buddhism differs in that Buddha taught that there is no self, therefore, no actual transmigration of the soul or continuity of the individual.

Again from The Gospel of Buddha, Buddha said, "Therefore abandon all thought of self. But since there are deeds and since deeds continue, be careful with your deeds."

The individual is likened to the waves of the sea, separate, but part of the whole sea to which they return without identity. Men remerge with the whole of being or into the total universe.

In fact Buddhists technically prefer the term "demise" to death as they assert there is no death as life is not confined to one's body, but that the life force experiences a series of rebirth. In popular Buddhism, the adherent tends to think of himself as a candidate for rebirth.

As a man determines his Karma by his actions, he has made himself. This force, Karma, is held to be the motive power for the round of rebirths and deaths endured until one has freed himself from its effects and escapes from the Wheel of Existence.

The state to which the Buddhist aspires is Nirvana. It is a state of being freed from the cycle of rebirth or the Wheel of Existence. It is the final release from Karma and can be achieved only by long, laborious effort, self-denial, good deeds, thoughts, and purification through successive lives.

An exact definition of Nirvana seems unobtainable since Buddha refrained from describing this state. He called it the summit of existence, the enlightenment of mind and heart, the city of peace, the lake of ambrosia and peace, perfect, eternal and absolute.

It is the state in which Buddha's followers believe him to be now as a result of the Enlightenment which he achieved.

It was the lack of a clear definition of Nirvana that caused the Great Buddhist schism into two main sects. (These two divisions, Mahayana and Theravada or Hinayana, are discussed later.)

The teachings of Buddha are found in more than 10,000 ancient manuscripts written after his death by his disciples. Buddha had taught no divine object of worship.

At first Buddhists made no images but used symbols to remember him. A Bo-tree recalled his enlightenment. A wheel became a reminder of the law and a suggestion of eternal truth. His tireless journeys were recalled by his footprints carved in stone.

Symbols, relics, sacred writings and prayers were placed in dome-shaped structures called stupas and in temples and shrines as objects of veneration. As time passed the faithful began to worship Buddha images in elaborate temples.

As Buddhism spread it underwent many changes. Its speculative nature attracted scholars while its virtues and ceremonial observances appealed to the common people.

In the countries where Buddhism was carried by missionaries it adapted itself to the beliefs and forms of worship that were already there and added festivities of its own.

By the second century A.D., Buddhism had divided into two major branches: Theravada (the lesser vehicle or the teaching of the elders) also called Hinayana, and Mahayana (the greater vehicle). The two branches do not necessarily conflict but they emphasize different things.

Followers of Theravada Buddhism regard Guatama as the only Buddha and believe that only a select few will reach Nirvana. Every man following this branch must spend several months in the priesthood.

This is a minor division of Buddhism in Vietnam, found principally in the southern Delta provinces such as Ba Xuyen and An Giang where there are groups of ethnic Cambodians. Their number is estimated at 500,000 or more.

The "greater vehicle" of Mahayana theology teaches that everyone can strive toward a better world. The followers regard Buddha as only one of many Buddhas and believe that, theoretically, any person may become a Buddha-if not in this life, then in a future life-but those who attain Buddhahood are rare.

A pantheon of superhuman beings, Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, are recognized and venerated in Mahayana pagodas. A Bodhisattva is a saint who strives for perfection, or a person who relinquishes his own chance to enter Nirvana in order to help other achieve salvation.

The Greater Vehicle emphasizes worship before the image of Buddha in temples rather than a retired life of devotion. Men are not required to spend time as a priest in Mahayana. There are 16 denominations or sects of Buddhism in Vietnam, most of which are Mahayana.

The Thien (Zen), a school of Mahayana Buddhism, is a major school in Vietnam. Thien has 12,000 monks and 4,000 temples. It is also a key factor in other countries influenced by Chinese civilization such as China, Tibet, Korea, Japan and Taiwan.

Theravada Buddhism predominates in countries along the Indian Ocean including Thailand, Burma, Cambodia, and Laos.

Buddhism was introduced into Vietnam in the second century A.D., and was spread for the next four centuries by Chinese and Indian monks. This was the first of three stages in the spread of Buddhism in Vietnam.

Buddhism reached its greatest heights in Vietnam in the second stage which ran roughly from the seventh to the 14th centuries. With expulsion of the Chinese in 939, Confucian scholars with their Chinese education were exiled temporarily from political life and Buddhism received official support.

A second reason for its growth was that pagodas also served as repositories of culture.

Between 1010 and 1214, the Ly dynasty made Buddhism a state religion. Monks were used as advisers in all spheres of public life, a Buddhist hierarchy established, and many temples and pagodas built. This was the high-water mark for official support of Buddhism.

By the close of the eleventh century, Buddhism has planted its roots so deeply in Vietnamese culture that it was no longer considered an imported religion.

It had been the court religion; now it had filtered down to the villages and hamlets. Here mixed with Confucianism and Taoism it has become an indigenous part of the popular beliefs of the people.

The decline of Buddhism began with this adulteration of the pure religion and progressed with the lessening of official support. In the 15th century the rulers again favored Confucianism which continued as the more influential religion in public life until the present century.

The admixture of the three religions, Taoism, Buddhism, and Confucianism, continued and formed the religion of many Vietnamese. Rites and practices of animism also influenced popular beliefs.

A revival of the purer forms of Buddhism and the establishment of an Association of Buddhist Studies in Saigon in 1931 were halted by Word War II. Centers of Buddhist revival were opened also in Hanoi and Hue, where the movement became strongest.

Since 1948, although with temporary setbacks, Vietnamese Buddhist groups have strengthened their organizations, developed lay and youth activities, worked toward unifying the various branches and sects, and joined the World Buddhist Organization.

Buddhism today retains a deep influence on the mass of the people and its effects go far beyond religion, touching on behavior, the arts, and craft forms.

Buddhism presented to Vietnam a new look at the universe, the individual and life. It had a particularly strong effect on morals and behavior.

All the arts show the Buddhist influence. The creation of Buddha's image affected the arts of the entire Far East, for giving human characteristics to Buddha's image and to those of the Bodhisattvas opened up a whole new field in the arts.

Episodes from the life and teachings of Buddha as well as the effects of good and evil deeds have been the subjects for paintings, engravings and murals.

Sculpture, painting and architecture often have been inspired by two key virtues of Buddhism; purity and compassion.

Buddhism also served as a vehicle for bringing Indian and Chinese art to Vietnam, and influenced designs in lacquer work, weaving, embroidery, jewelry and metal work.

Most of the prose and poetry of the first independent national dynasty was written by Buddhist monks who exchanged their verse with the great poets of China.

The spiritual warmth and brilliance which drew thousands of followers to Buddha during his life and has drawn millions since, is illustrated in the literature based on his teachings and parables. One of the best known has become a folk tale allover the world: "What Is An Elephant?"

Nguyen Du's famous poem, "Kim Van Kieu," based on the teachings of Buddha, has been popular for more than a century. Vietnamese children memorize long passages from its 3,254 verses. One of the main factors that made it popular is its treatment of Karma.

The effect of Buddhism on Vietnamese life was summed up in Buddhism in Vietnam by Chanh-Tri and Mai Tho-Truyen:

"In Vietnam, Buddhist influence is not limited to the realm of art, letters and philosophy. It inspires the theater, serves as a guide for certain good customs, inspires stories and legends, provides suggestions for popular songs and proverbs."

In Vietnam the fourth day of the 15th lunar month, which normally comes in April or May, is observed as Buddha's birthday. It is a national holiday. The same day is commonly observed as the date of his death and of his enlightenment, although the eighth day of the 12th month is officially observed as the date of his enlightenment.

The first and 15th days of each lunar month are Buddhist holy days.

Terms, Symbols and Sacred Objects

The Three Jewels/Three Gems form the object of devotion in which every follower of Buddha puts his whole hope. They are Buddha, the Darma or teachings of Buddha, and the Sangha or order of Buddhist monks.

The Sangha is composed of the bonzes or monks and nuns and is basically supported by the laity, mainly through gifts which earn merit for the giver. Their shaven heads and yellow, gray or brown robes mark the renunciation of worldly pleasures. While Mahayana monks may wear saffron robes, Theravada monks always do.

Though normally vegetarians, monks may eat meat on occasion. They live a life of utmost simplicity, own almost no personal property.

Personal items allowed may vary, but in general consist of one undergarment, two robes, a belt, an alms bowl, a small knife or razor, a needle and a water strainer. They are proved food by the laity.

The monks perform many services and functions for the faithful. They participate in and lead religious observances and festivals. They may be invited to weddings although they do not officiate. At funerals they lead the rites in the home and at cremation or burial, and again at intervals after burial and on the first anniversary of death. Some have been commissioned as chaplains in the Vietnamese Armed Forces.

The monks care for temples and pagodas, teach religion. Some assist in charitable work and other health and welfare projects. The former preach in the pagodas on the 1st and 15th of each lunar month.

Particularly in rural areas, the monk may be the best educated person in the community and serve and an adviser in community affairs and as a teachers. More important to Buddhists, the bonzes are examples of the Middle Way of Life in the travel to Nirvana.

Nuns have been part of the Sangha since the Buddha established the role of nuns in his lifetime. Nuns observe similar but stricter rules than bonzes, are usually affiliated with pagodas though living in separate establishments.

Pagodas, shrines, temples: There are distinctions in purpose and use between these three but the untrained observer will not normally be able to distinguish among them. However, all are sacred. Unless permission is granted to leave shoes on, they should be removed before entering.

The pagoda (chua) is usually the largest, best constructed and most ornate building in Vietnamese villages. Even in cities, its appearance sets it apart.

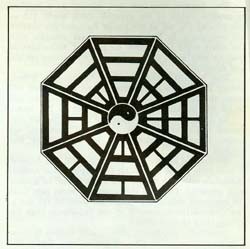

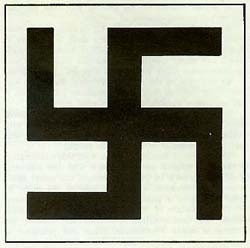

The pagodas of Vietnam are normally constructed in the highly decorated Chinese style. The dragon, the phoenix and other legendary figures are interwoven with Buddhist symbols such as the Wheel of Life and the Chu Van (swastika).

Pagodas are used for services but even more for private devotions. At the front of the main room before a statue of Buddha is an altar usually containing flowers, offerings of fruits, candle sticks, and incense.

The pagoda area may include rooms for instruction and quarters for the monks.

The Wheel of Life, earliest of Buddhist symbols, is a circle with eight or 12 divisions (spokes). The circle denotes the Buddhist concept of the endless cycle of existence. Eight spokes signify the Noble Eightfold Path and 12 spokes denote either the 12 principles of Buddhism or the 12-year calendar within an endless cycle of time. The symbol of Buddhist chaplains in the Vietnamese Armed Forces is the 12-spoke Wheel of Life held by the Hand of Mercy.

The Chu Van (swastika to most Westerners) is the symbol of Enlightenment, the achievement of Nirvana. It is often found on medals, decorating pagodas, or on the chests of Buddha statues as Buddhists believe it will appear on the chests of the Enlightened.

Buddha statues are normally the central figure in the pagoda and wherever found are held in sacred esteem.

Gongs or drums are used in pagodas and homes for three basic purposes: to announce the time of a service or meeting, to mark the different parts of a ceremony, and to set the tempo for chanting as an aid to one's meditation.

The drum of the pagoda is usually located on the porch and is used to alert the community that a service is beginning or ending.

Flowers are widely used for devotions in Vietnam on family alters, graves, in the pagoda, or for presentations when calling on bonzes or older relatives. In the temple, flowers symbolize the shortness of life and the constant change inherent in existence.

Incense is symbolic of self-purification and self-dedication and is offered in memory of Buddha and as a form of meditation. When joss sticks are burned, there are usually three to symbolize the Three Gems.

Lights, candles or lamps, symbolize Buddha's teachings which give light to the mind and drive away ignorance, replacing it with Enlightenment.

Food and water are placed before the altars of Buddha and symbolize that the best is first shared with him. As only the essence of food is essential for worship, the items are later retrieved and used.

Merit bowls, often incorrectly called "begging bowls" by Westerners, are the means by which the monks receive their daily food. The receiving of food symbolizes the monk's vow of poverty and the giving is a means of gaining merit for the giver.

The lotus blossom is a much-used Buddhist decoration. Buddha often used the lotus as an example, pointing out that though it grew in the water and mire, the beautiful flower stood above the impurities untouched. The bud is a popular offering to monks and pagodas. The seed may be eaten either green or dry. Roots are also eaten in salads, soup, or candied as dessert.

Buddhist beads consist of a string of 108 beads, each symbolizing one of the desires or cravings which must be overcome. The beads are used in meditation.

The Buddhist flag is composed of six vertical stripes of equal width. The first five, from left to right, are blue, yellow, red, white and pink or light orange. The sixth stripe is composed of five horizontal stripes of equal width in the same colors and order from bottom to top.

Each color signifies a different Buddhist virtue, but there is no consensus on which color represents which virtue. (The flag was designed in Ceylon in the 1880s by an American ex-Army officer, a Civil War veteran.)

Lustral water, or holy water, is water which as been poured over a Buddha statue under the proper conditions to gain some of the efficaciousness of the Buddha's virtues. It may be poured over the hands of a corpse at funerals or the hands of a bridal couple or sprinkled about a newly-built house. It should be treated in the same manner as the holy water of Catholic practice.

The Hoa Hao (pronounced wah how) is generally accepted as a Buddhist religion. Founded in Vietnam is 1939, it is a reform development of Theravada Buddhism which stresses simplifying doctrine and practice.

Found mainly in the Delta where it began, the Hoa Hao has a history of political and military as well as religious activity.

The Hoa Hao was founded by Huyen Phu So, who was born in 1919 at Hoa Hao Village, Chau Doc Province. At 20, after a life of weakness and infirmity, he was miraculously healed and began to proclaim his doctrines of Buddhist reform, giving them the name of his native village.

So's apparent power of healing, of prophecy (he foretold defeat of French in World War II, coming of Japanese and later of Americans), and his zeal and eloquence quickly gained him a large following. In time So was being called Phat Song, the Living Buddha.

Considering his teaching anti-French, the French exiled him to My Tho and Cai Be where he gained more converts. The French then placed him in a mental institution in Cholon, where So converted the psychiatrist in charge.

Declared sane and released, So was next exiled to Bac Lieu Province and then in desperation sent to Laos.

After the Japanese came, they insisted on his return in late 1942. With the Japanese defeat, So led the Hoa Hao into the National United Front, a group of nationalist organizations seeking Vietnamese independence. However, So would not accept Viet Minh leadership and the break led to open conflict between the Hoa Hao and the communists.

In April 1947 the Viet Minh ambushed and executed So in Long Xuyen, a fact still not discussed or accepted by all Hoa Hao followers, some of whom believe So is still alive. All believe that he will return.

Ever since, the Hoa Hao have been joined in implacable opposition to the Viet Cong. However, on other issues the sect divided has not had cohesive leadership.

Most of the Hoa Hao also opposed the Diem government, maintaining their own military forces (used against the Japanese, French and Viet Minh) up until reconciliation with the government in 1963.

Hoa Hao adherents are estimated at between a half-million and a million, although they claim two million. They are concentrated in An Giang and Chau Doc Provinces and are also influential in the provinces of Ba Xuyen, Bac Lieu, Chuong Thien, Kien Giang, Kien Phong, Phong Dinh and Ving Long.

Though the sect is united now only on religion, its background of military and political involvement growing out of a time of war and struggle make it a still a faction of some strength.

The appeal of Hoa Haoism is attributed to its simplicity and lessened demands on the peasants. The founder advocated a return to basic Buddhist precepts, the absence of elaborate temples, statues, monks and other outward forms of Buddhism. He stressed individual worship as the means of attaining a richer spiritual experience and working toward salvation.

The faithful are free to practice their religion whenever and wherever they please.

The four major precepts So taught are:

Honor parents

Love country

Respect Buddhism and its teachings

Love fellow men

So stressed four virtues which prescribe that marriage partners be faithful to each other, that children obey parents, and that officials be just, honest and faithful in behalf of their people even as parents care for their children.

Members of the Hoa Hao recite four prayers a day, the first to Buddha, the second to the "Reign of the Enlightened King," the third to living and dead parents and relatives, the fourth to the "mass of small people to whom I wish to have the will to improve themselves, to be charitable, and to liberate themselves from the shackles of ignorance."

These prayers are said before a small, simple altar in home or temple. The altar is covered with a maroon cloth as a symbol of universal understanding, because these Vietnamese accept maroon as the all-embracing color. Four magical Chinese characters, "Bao Son Ky Huong" (a scent from a strange mountain), adorn the cloth.

The only offerings sanctioned by the Hoa Hao are water (preferably rainwater) as a symbol of cleanliness, flowers as a sign of purity, and small offerings of incense.

The Hoa Hao have permitted some restricted forms of Confucianism and Animism such as the incense which is to chase away evil spirits, and prayers and offerings to Vietnamese national heroes and to personal ancestors.

Hoa Hao are forbidden to drink alcohol, to smoke opium, or to kill either buffalo or oxen for food. The ban on killing oxen and buffalo does not preclude eating beef when it is offered by a host. However, Hoa Hao must not eat either meat or greasy food on the first, 14th, 15th, or 30th days of the lunar month as these are days of abstinence.

The Hoa Hao celebrate the anniversary date of their founding on the 18th day of the fifth lunar month, gathering to listen to sermons and speeches.

The major pagoda is located in Hoa Hao Village, undoubtedly the center of the religious faith.

The Hoa Hao flag is rectangular in shape and solid maroon as the Hoa Hao believe that maroon is the combination of all colors and thus signifies unity of all people.

The Cao Dai (pronounced cow die) like the Hoa Hao is a distinct religion which originated in Vietnam and has been active politically and militarily; unlike Hoa Hao, however, the Cao Dai are not accepted by the Buddhists as Buddhists.

Cao Daism was organized in 1919 as an indigenous Vietnamese religion composed of "spiritism" and an ouija-board device called corbeille a bec (beaked bag), Taoism, Confucianism, Buddhism and Christianity. It has a Roman Catholic-type church organization.

It was formed in an attempt to create a universally acceptable religion in an area of the world where an intermingling of religious beliefs might be found in the same person.

The Cao Dai believe that there have been three major revelations of divinity to mankind.

The First Revelation was given to several missionary saints including a Buddhist, a Taoist, an ancestor worshipper and Moses. The Second Revelation came to Lao Tse, Confucius, Ca Kyamuni (for Buddhism), Jesus and Mohammed.

The Third Revelation was given by God to the Cao Dai founder Ngo Van Chieu on Phu Quoc Island in 1919. The name Cao Dai means the high, tower-shaped throne of the Supreme Emperor (God).

The major doctrines of the Cao Dai are:

- That Cao Daism is the Third Revelation of divinity to all men and supersedes or corrects previous teachings.

- Cao Daism worships the Absolute Supreme God who is eternal without beginning or end, who is the Creator of all, Supreme Father of all, and unique Master who created and creates all angels, buddhas and saints.

- Cao Daists believe in the existence of three distinct categories of invisible beings:

The highest deities composed of buddhas, saints, and angels; the medium beings which include sanctified spirits; the lower beings which include both phantoms and devils.

This belief includes the concept that all three orders must pass through human existence in order to help humanity and normally move from the lowest toward the higher forms. Of all living creatures, only man can become a devil or an angel because he has a special soul.

- Cao Daists believe that the human soul may go up or down the ladder of existence, and that man by his will and actions determines the direction.

- The ultimate goal of Cao Daism is the deliverance of man from the endless cycle of existence. Man possesses an immortal soul which must obtain release from the cycle for complete victory.

- The worship of ancestors is a means of communication between the visible and invisible worlds, between the living and the dead, and is a means of expressing love and gratitude to ancestors.

- Cao Dai ethical concepts teach equality and brotherhood of all races, the love of justice, the Buddhist law of Karma, Buddha's Five Commandments and Eightfold Path, and the Confucian Doctrine of the Mean.

- Cao Daism recognizes a pantheon of saints and deities which include Joan of Arc, Sun Yat Sen and Victor Hugo.

- Last, but not least, Cao Daists believe that divinity speaks to man through spiritual mediums using the corbeille a bec.

When this beaked bag is held two members of the Legislative Body of the Cao Dai over a board which holds the alphabet, the divinity causes his spirit to move the bag to spell out the divine communication. Such messages must be revealed at the Tay Ninh Temple.

The Cao Dai church has three major administrative sections, executive, legislative, and charity.

The Executive Body (Cuu Trung Dai) runs the temporal affairs of the church. The titular head, the Pope, is reputed to be the spirit of a Chinese poet. The position of Interim Pope (living head of the church) has been empty since 1934 due to an inability to agree on a successor.

Other members of the executive are cardinals, archbishops, bishops, monks, nuns, and some laity.

The Legislative Body (Hiep Thien Dai) is a 15-man college of spiritual mediums who regulate the use of the beaked bag.

The Charity Body (Co Quan Phuoc Thien) has the duty of caring for the sick and aiding the needy, orphans, handicapped, and aged.

Within the hierarchy of Cao Daism are three major branches: The Confucian group who wear red robes as a symbol of authority; the Buddhist group who wear yellow as the symbol of virtue and love; and the Taoists who wear blue, the color of peace. These colors are normally worn on special occasions; otherwise the clergy wear white and black robes.

Ordinary clergy may marry. All clergy are required to be vegetarians.

There are several sects of Cao Daists with centers throughout Vietnam but the center of the faith is at Tay Ninh City in the Tay Ninth Temple. It is built to the same pattern as other Cao Dai temples but in a more grandiose style. It sits in a large, well-ordered compound which includes a school, a hospital, an orphanage, a home for the aged and a residence for nuns.

The temple has nine floor levels, rising from the door to the altar, which represent the nine levels of spiritual ascension possible. The main altar is a huge globe symbolizing the universe. On the globe is painted a human eye which symbolizes the all-seeing eye of divinity. The eye, by which all Cao Dai altars can be recognized, is in other uses set within a triangle. (Americans will recognize it as the same eye and triangle as that on the back of our one-dollar bills.) Cao Dai laity must worship at least once a day in home or temple at one of four set times: 0600, 1200, 1800, or 2400 hours. |

Special occasions for services include 8 January, the anniversary of the First Cao Dai Revelation, and 15 August, which honors the Holy Mother of the founder.

Cao Dai use tea, flowers, and alcohol as offerings, representing the three elements of human beings; intelligence, spirit, and energy.

Five joss sticks are used in worship to represent the five levels of initiation; purity, meditation, wisdom, superior knowledge, and freedom from Karma.

The Cao Dai flag has three horizontal bars, red, blue, and yellow (from the top) representing the same attributes as the robes of the clergy.

The Cao Dai claim about two million members in the Republic of Vietnam, with the largest numbers concentrated west and south of Saigon. Other estimates put the number at about a million. In the disorganized times during and after World War II they acted in political and military roles, often largely controlling some provinces.

In general the Cao Dai have been anti-communist. They are still a major factor in Vietnam, particularly in areas where they form the major part of the population.

Christianity has a longer history in Vietnam than most Americans might suppose, dating back to the early 16th century when the first Roman Catholic priest landed in what is now South Vietnam.

Today Christianity must be considered one of the major religions, claiming approximately 11 per cent of the population of the Republic of Vietnam.

The comparatively high educational level of many of Vietnam's Catholic tends to place them in positions of influence.

Roman Catholics form the largest Christian group in Vietnam. The religion was brought to Vietnam during the 16th century and expanded during the 17th century. Alexandre de Rhodes, S.J., who was in Vietnam from 1624-1645 and who developed the present Vietnamese alphabet, headed one of the more prominent missions.

Catholicism persisted despite recurrent persecutions until religious freedom for all Christians was guaranteed by treaties with the French regime late in the 19th century.

Spokesmen for the church point out that cultural patterns not in conflict with church theology may be practiced. Thus, ancestor veneration is practiced in nearly all Vietnamese Roman Catholic homes.

Today the Roman Catholic Church counts 10.5 per cent of all South Vietnamese as members. This includes 650,000 Catholics who migrated from North Vietnam after the Geneva Accords of 1954.

There are two Archdioceses and 13 Dioceses in South Vietnam. The Archbishops, at Saigon and Hue, and the 13 Bishops all are Vietnamese but one-a French Bishop at Kontum. Heavy concentrations of Catholics are in urban areas of Saigon, Nha Trang, Hue, Qui Nhon, Dalat and Kontum. The Vietnamese Armed Forces have had priests serving as chaplains since 1951.

Protestantism was introduced at Da Nang in 1911 by a Canadian missionary, Dr. R.A. Jaffray, under the auspices of the Christian and Missionary Alliance. This international organization has more than 100 missionaries in Vietnam and has been largely responsible for the growth of Protestantism here.

Today missionaries from this organization are found throughout the Republic of Vietnam; they ceased their work in North Vietnam after the 1954 Geneva Accords.

One important outgrowth of this missionary work was the establishment of the Evangelical Church of Vietnam which as 345 churches and approximately 150,000 adherents. The church and the Christian and Missionary Alliance carry on extensive health, education, and welfare work. All Vietnamese protestant chaplains are pastors in the Evangelical Church of Vietnam.

As more missionaries came, most from Canada and the United States, Protestantism spread to Hanoi, Saigon and Dalat.

In more recent years, other Protestant groups have begun work in Vietnam. While their outreach has been less extensive, their impact has been significant in both religious and welfare activities.

Listed below are miscellaneous religious practices, beliefs and traditions which for reasons of clarity were omitted from the sections on particular religions. Many of these are so blended with Vietnamese daily life that they are not easily attributable to any one religious belief.

**********************************************

The lay (pronounced "lie") is a hand sign used both as a form of greeting and as the highest gesture of respect. In making this sign the hands are placed palms together, fingers pointing upward, in front of the chest. When showing respect to clergy or when worshiping, the hands are raised in front of the face.

Customarily, the lay is performed three times after lighting joss sticks in front of a pagoda. (Unless specifically invited to do so, it is not proper for those who are not members of the faith to light joss sticks.)

Funerals vary depending on locality, ethnic groups, religious beliefs and wealth and position.

Normally the chief mourner leads the funeral procession, followed by the hearse, religious objects, pictures of the deceased, women mourners in white, a band, and other mourners. Jokes about sickness and death should be avoided and the dead should be treated with the same respect that you would show in our society.

Graves in Vietnam vary from those in regular cemeteries to circular piles of dirt which may dot the countryside in paddies and fields.

Whatever found, graves should be respected and extra trouble taken not to desecrate them. The Vietnamese believe that desecration of a grave angers the spirits, causing an attack on the living.

The communal house (dihn), along with the pagoda and the market, is one of the places of greatest importance in any Vietnamese community.

The communal house is first of all a place to worship the protective genii of the village.

Secondly, it is the place to receive the king or, in more modern terms, to receive the representative of the government, the province chief or other officials; and a meeting place for the notables of the village.

Lastly, the communal house is a place for keeping memorial tablets to village dead who died without descendants to carry out their ancestor worship.

Over the door to a communal house will be found Chinese characters which mean "Long Life to the King," indicative of its purpose as a place to receive the king.

Spirit houses, little shelters like birdhouses ranging from simple to elaborate, are erected for the happiness of the spirits. They often contain candles and joss sticks. They reflect the belief in ancestor veneration and are vitally important to those who erect them.

Americans and Vietnamese see time differently.

For Americans, time is linear with a beginning, an end, and measured segments. For the Vietnamese, time is circular, unending and endlessly repeating the 12-year cycle. They have developed patience and the hope that Karma will improve their lot in their next existence.

The role of the family is particularly important in Vietnam, more so than that of the individual or society as a whole. Vietnamese concepts of family have been affected by Buddhism, ancestor veneration and Confucianism.

Each individual is a part of the family, a link to yesterday and tomorrow. The value placed on the family encourages large families, respect for the aged and conformity to what is best for the family.

Votive Papers, representing gold, silver, clothing, and other common objects, are burned to provide for the needs of ancestors or other persons being venerated.

In ancient custom, not only in Asia but also in other lands, the actual objects (sometimes including servants) were buried with the dead. The use of votive papers evolved as a more humane and less expensive way of caring for the spirits.

[END]