The Navy Department Library

The Naval Bombing Experiments Off the Virginia Capes - June and July 1921

By Vice Admiral Alfred W. Johnson, Ret.

1959

It fell to my lot to command the aircraft in the bombing experiments off the Virginia Capes in the he summer of 1921.

I am therefore persuaded by brother officers that it might be of benefit to naval history, and posterity, if I should set forth the facts concerning those experiments. More especially does this seem advisable because of the distortion of those facts in published accounts of the experiments, and of the part played in them by Brigadier General William Mitchell, who commanded the Army airplanes that participated with Navy and Marine Corps aircraft in some of the experiments.

In this, my account of the bombing experiments which I offer to the Naval Historical Foundation, I give the names of Navy and Marine Corps aviators who participated in the bombing, as well as of Army aviators who took part, so that no one who reads this may get the impression that General Mitchell was the only participant. I also mention the controversies that preceded and followed the bombing experiments.

This paper is in three parts -- Background, Bombing Operations, and Aftermath.

It may be recalled that World War I saw the advent of fairly extensive employment of aircraft in warfare. The armies and the navies of the principle powers at war had their own air forces. On the Western front, at the end of the war, about 6000 Allied and about 2700 German planes faced each other. On the Italian front, about 600 Austrian and 800 Italian planes. Due to the relatively short range of the planes, bombing operations were confined to nearby targets. Along the seacoast, a fairly large number of seaplanes, dirigibles, blimps, and kit balloons operated against submarines.

Organization of Air Forces.

It was universally agreed after the war that airplanes would play a more vital role in future warfare, but there were sharp differences of opinion as to how air forces should be organized for future employment. Britain separated her aviation from her army and her navy, and merged the two branches into a single organization controlled independently of the Army and her Navy. The United States did not separate her aviation from her Army and her Navy. Neither did Japan. Their Navies, consequently, were able to develop naval air power freely. During World War II, the United States and Japan were the only two naval powers whose navies fought "Carrier aircraft to carrier aircraft" in battles which decided the outcome of the war in the Pacific.

Note: -- The absorption of Britain's efficient Naval Air Service by centralized Royal Air force in 1918, and the consequent withering of her Naval Air Arm, left her in 1942 relatively a second rate Navy as compared to our own. To revitalize her naval air arm, Britain, on two occasions modified her system of air organization - once during World War II, and once afterwards; and each time to conform more and more closely with he system of organization for U.S. Naval Aviation.

General Mitchell Advocates Single Air Service.

After World War I, General Mitchell, who commanded the Army Air Service in Pershing's Army in France during the war, returned to America and began a vigorous campaign to organize and to operate US Military aviation on the British pattern - this is, he advocated merging US Army and US Navy aviation into a single separate organization, entirely independent of the Army and the Navy, and co-equal to them.

In his drive for a single air service, Mitchell proclaimed that airplanes could sink battleships. He declared that aviation would make ground armies and surface navies obsolete - a prophecy that has yet to be realized. He maintained that aircraft therefore should be controlled, developed, and operated by a single centralized government agency, completely independent form the Army and the Navy.

Navy Opposes Single Air Service.

Our Navy vigorously opposed Mitchell's proposal. It foresaw that airplanes would play an increasingly important role in naval warfare, and insisted that it be free to develop naval air power, and to operate aircraft according to its needs to the same extent as in the case of its other weapons. Otherwise, our Navy would soon become obsolete.

Army Not in Favor of Mitchell's Proposal.

Our Army also opposed Mitchell's proposal, but less vigorously than our Navy. The Army's aviators, generally, favored Mitchell's ideas, and, after his death, continued his crusade for a single air service. Gradually they acquired for the Army Air Services, an increasing measure of autonomy, in marked contrast to the other organic arms of the Army, and, in 1942, one may say, it became a semi-autonomous organization.

Finally, in 1947, the Army Air Force was legally separated from the Army by the passage of the so called Unification Act. The Act, officially known as the National Security Act of 1947 as amended in 1949 established a Department of Defense, and in it a Department of the Air Force. It also changed the name of the War Department to the Department of the Army. The Department of the Navy remained unchanged in name.

Naval Aviation Remains with the Navy.

Although the Unification Act separated the Army from its aviators, it welded aviation to the Navy. The Act definitely specified that Naval Aviation should continue to remain as an integral part of the Navy, and that the Marine Corps should remain part of the Navy.

That is how aviation for national defense developed organically in the United States. I mention it here, as there was some question concerning organization and command in connection with the bombing experiments, and the question has arisen not infrequently since then. There are many reasons why the Army and the Navy, and the Air Force did not see eye to eye on organization for national defense, but there were no valid or ethical reasons for some of the methods pursued by some of the partisans who disagreed on the organization of our armed forces.

Publicity

I think that our Navy learned as much about publicity from those experiments as it did about bombing battleships. Naval officers then regarded "publicity" to advance their own, or the Navy's interests as unprofessional, and unethical, whereas advocates of a single air service, and General Mitchell, the spokesman, had no such inhibitions. Consequently Mitchell got a good press, and the Navy no press, or a bad one. Mitchell was news; his works made colorful copy.

When various persons suggested to the Navy Department that experiments be made to demonstrate the effectiveness of aerial bombing by using warships as targets for airplanes, that fact was not published, but when General Mitchell announced that he had repeatedly requested that a warship be turned over to "us" and that the "Army and Navy hadn't seen fit to do it," it made headlines.

Secretary of War asks for Ships for Use as Targets.

The Secretary of War finally did ask the Navy Department for ships to be bombed by Army airplanes. When Secretary of the Navy, Josephous Daniels informed him that the Navy had no ships for that purpose at that time, some newspapers reported it in a way to give the impressions that Daniel's refusal was inspired by the Navy's fear that General Mitchell might sink the ships. Mitchell became a national celebrity before the bombing experiments started.

Secretary Daniels and Publicity.

Secretary Daniels had no distaste for publicity. He liked it and made use of it frequently. He was popular with the newsmen, but apparently did not believe that airplanes could sink battleships. When he heard that Mitchell was going about the country claiming that airplanes could sink battleships, Daniels countered by declaring that he, Daniels, would stand on the bridge of any battleship when any planes attempted to bomb it, or words to that effect. His boast was played up in the press and was used with telling effect against the Navy after the ships were sunk in the bombing experiments of 1921. Daniels was nowhere near the ships that were bombed. He went out of office with President Wilson's administration when Harding became President.

Daniels may, or may not, have been truthful when he told the Secretary of War that the Navy had no ships to spare for bombing, and the newsmen who implied that he was lying may or may not have known at the time that two of our Navy's battleships, the Indianaand the Massachusetts had already been sunk in some unpublished ordnance experiments; that one of our battleships, the Oregon,had been promised to the state of Oregon as a war memorial; and another battleship, the Iowa, was being converted into a radio controlled target ship for use of the Fleet in various forms of moving target practice at sea.

However, our Navy soon acquired some warships to be used as targets for bombing.

Navy Acquires Ships for Use as Targets.

The United States, as a result of the Versailles Treaty, acquired eleven ex-German warships and decided to bring them to the United States and use them as targets in experiments with guns and aerial bombs. Daniels then could no longer say that the Navy had no ships available for bombing.

How We Acquired the German Warships.

It may be recalled that when the German Navy surrendered to the Allied Powers at the end of World War I, its warships were apportioned among them with the understanding that they would destroy or demilitarize the ships before a fixed date (August 9, 1921).

The United States, in this way, acquired six U-boats, three destroyers, one cruiser, and one battleship. We would have acquired more if the German crews of the surrendered ships had not sunk 9 battleships, 5 battle cruisers, 7 or 8 light cruisers, and 49 destroyers at Scapa Flow, when the British ships assigned to guard them were temporarily absent one day. The Germans simply opened the seacocks of the ships and watched them sink. Then the crews went aboard the battleship Baden, which they left afloat as the ship to receive them.

The ships allotted to the United States were the battleship Ostfriedland, and the cruiser Frankfurt, destroyers G-102, S-132, V-43, and submarines U-117, U-140, U-111, UB-48 and others.

The cruiser Frankfurt and the three destroyers allocated to the US, were among the ships sunk at Scapa flow. They were salvaged and taken to Rosyth to be ready for the voyage to America. The submarines, manned by US crews came directly to American under their own power, from Harwich, England where the German U-boats had been sent from Germany to surrender in England. The battleship Ostfriedland had been badly damaged by a mine after the Battle of Jutland and was being repaired in Germany when the German High Seas Fleet proceeded to Scotland to haul down the German colors. When repairs were finished, the Ostfriedlandproceeded to Rosyth to join the Frankfurt and three destroyers. There the Germans turned the Ostfriedland over to Captain Julius F. Helweg of the US Navy who, with a detachment of officers and men of our Navy, brought the ships to America. Commodore Helweg, now retired and living in Washington, has told me the story of how he got the ships here. With the Ostfriedland towing the Frankfurt,and a minesweeper towing each destroyer, and $65,000 to cover expenses, they proceeded to France and picked up the 14-inch guns of the Navy's railroad battery, secured the guns on the Ostfriedland's deck and then made their way in company across the Atlantic to the New York Navy Yard.

The ships were given a careful and detailed study in New York with a view of ascertaining their strong and their weak points for the benefit of our ship designers. Under the supervision of Commander H. Van Kouren, later Chief of the Naval Bureau of Ships, the ships were prepared for the bombing experiments, and towed to Lynn Haven Roads, Virginia to await their turn for the bombing off the Virginia Capes. Admiral Van Kouren had given me an account of his experiences with the ships at the Navy Yard, and of his inspections of the Ostfriedland during the bombing experiments. I append his account to this paper.

Previous Experience in Bombing Ships.

No warships, except perhaps a few submarines were damaged by aerial bombs in World War I as far as I know. Four Turkish ships at anchor in the Sea of Marmora were sunk by British torpedo planes in August 1915, and German torpedo planes sank the British steamer Gena on May 1st, 1917. The German battle cruiser Gorben, after she and the cruiser Breslau escaped from the British Fleet in the Mediterranean early in World War I, ran aground near the Dardennelles. She remained aground six days. While aground, she was bombed by enemy airplanes frequently.,They dropped about 270 bombs and hit her three or four times. The Goben then got afloat and steamed away at 15 knots. The bombs probably were small ones.

Our Navy planned to learn all it could about the action and effectiveness of bombs of different types and weights dropped by airplanes on ships of each of the four German types acquired, and to experiment with the rest of the ships with guns. It decided to bomb with small bombs first and then with bigger ones winding up with the biggest - the 2000 pound bombs - unless the ship sank before that. To learn more about functioning of the bombs and the protection afforded in the design and construction of each of the ships, a board of officers from all the services was appointed to inspect the ships between attacks and to report on the damage done by each type of bomb.

The exercises with the ex-German warships were planned in practically their final form in December 1920. Announcement of the plans was made by Secretary of the Navy Daniels, after he approved the recommendations of the Joint Army and Navy Board. This Board, the predecessor of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in World War II, was then composed of the following Army and Navy officers:

| Army | ||

|---|---|---|

| Major General Payton Marsh | Chief of Staff of the Army | |

| Major General William Haan | Director of Army Operations | |

| Brig. General Henry Gerow | War Plans | |

| Navy | ||

| Admiral Robert M. Coontz | Chief of Naval Operations |

|

| Rear Admiral John H. Oliver | Naval Plans |

|

| Captain Benjamin F. Hutchinson | Ass't. Chief of Naval Operations | |

| Notes: - I mention the names of these officers because the anti-Navy Press after the experiments derided the Joint Army and Navy Board for the conclusions it reached from the experiments. | ||

Atlantic Fleet to Conduct Experiments

It was decided that the experiments would be carried out off the Virginia Capes by the US Atlantic Fleet during the months of June and July, 1921.

Bombing Experiment Not a Publicity Stunt.

The Navy proposed to conduct the tests as a research and development project and not as a publicity stunt. It intended to carry out the experiments in the same orderly way that it did its experiments with the battleship Indiana in October-November 1920 and with the Massachusetts in January 17-18 1921 and as the British did in their bombing and gun tests against the ex-German Baden; and as the French did in their various ordnance experiments against the ex-German battleship Thuringen, and against the ex-Austrian battleship Prince Eugen, soon after the Indiana tests.

Note: -- The absorption of Britain's efficient Naval Air Service by centralized Royal Air force in 1918, and the consequent withering of her Naval Air Arm, left her in 1942 relatively a second rate Navy as compared to our own. To revitalize her naval air arm, Britain, on two occasions modified her system of air organization - once during World War II, and once afterwards; and each time to conform more and more closely with the system of organization for U.S. Naval Aviation.

It was Admiral Sir Percy Scott, the great gunnery expert of the Royal Navy who asserted that the new weapons made battleships obsolete. It was Admiral of the Fleet, Sir John Fisher, First Lord of the Admiralty, father of the Dreadnought type of Battleship, who said that the surface battleship would be superseded by a submersible battleship. It was Admiral Scheer, Commander of the German High Seas Fleet in the Battle of Jutland, who asserted that battleships were obsolete. Like General Mitchell, they were more of less right, but when did battleships really become obsolete?

Indiana and Massachusetts Experiment

Our Navy tested the Indiana to determine what degree of protection her watertight compartments and double bottom would afford her against underwater explosions of charges of TNT of different weights, placed at different distances from her hull and at different depths below the surface of the water. These explosions were like actual explosions of mines, torpedoes, depth charges, and aerial bombs that fall close alongside of a ship. In addition, charges of TNT were exploded at different locations on her deck and she was bombed by planes with water filled bombs.

The purpose of the tests against the Massachusetts, in January, 1921 was to ascertain how much protection her upper side armor and her armored belt afforded her against the direct fire of the guns of the coast artillery batteries near Pensacola, Florida at a range of 4000 yards.

The ship was towed to a spot in shallow water near the ship channel at that distance from the guns which bombarded and sank her there. Did that make battleships obsolete? I don't think so judging from what happened afterwards. The sinking of the Massachusettsby the guns of Fort Barrancas did not result in the abolition of battleships. It coincided strangely enough, or nearly coincided, with the abolitions of US seacoast fortifications and later abolitions of the US Coast Artillery Corps of the Army. Nor did the sinking of theOstfriedland result in the immediate abolition of battleships. It stimulated the development of bombs and airplanes, and improvement in the design of battleships. I think it noteworthy that the battleship Massachusetts (which I happened to serve in during the Spanish War) was shot at by the batteries guarding the entrance to the harbor of Santiago Cuba in 1898 as well as by the batteries guarding Pensacola in 1921 and that 21 years later, 1942, a new battleship named Massachusetts while supporting the landing of the American Army in North Africa (November 8, 1942) was shot at and hit by the forts guarding Casablanca.

Likewise a new Indiana, 21 years after the Ostfriedland was bombed and sunk, was in the Battle of the Philippine Sea on 19 and 20 June covering the operation at Saipan in 1944 with Spruance's 5th Fleet, which made it possible for General Curtiss Le May's big bombers to attack Japan.

Atlantic Fleet Returns to the United States.

The Atlantic and Pacific Fleets with their flying boats were at Panama for joint exercises in January and February 1921 when Admiral Wilson, Commander-in-Chief of the Atlantic Fleet received orders from the Navy Department to conduct the experiments scheduled for June and July off the Virginia Capes that year. The planes with the fleets were of the F5L and the NC (Navy Curtiss) type - the latter being the same type of plane that made the first trans-Atlantic flight from Newfoundland to the Azores in 1919. If I am not mistaken, our planes with the fleets at Panama were the first to fly from the United States to the Canal Zone, and from the Canal Zone to the United States. They were then the only airplanes that operated continuously at long distances from the United States as self-supporting units relying solely on their ships in sheltered waters for logistic support.

Note: Out Navy's aircraft carriers, and ship catapults, were perfected after the bombing experiments of 1921. That enabled our ship borne planes to reach any part of the world where their ships could go. It gave our country the only authentic intercontinental bombing planes with which to wage war. For example, Jimmy Doolittle's flight from the Hornet.The attack on Pearl Harbor couldn't have happened but for the mobility of the Japanese naval air-arm, and the war we fought against Japan could not have been won but for the aircraft of our naval aircraft carriers. In November 1942, the US Strategic Bomber Command couldn't support the landing of the American Army in Africa, because its fighter planes couldn't reach Africa. The only air support our Army got in the landings was from the US Navy air-arm. Doolittle and Hap Arnold admitted that, but Billy Mitchell died before World War II and never knew it.

Let us keep that in mind, and not get confused by the propaganda that has been poured ever since the Ostfriesland was sunk in 1921.

The two fleets with their flying boats left Panama in February for the U.S. The Atlantic Fleet of Gunatanamo, Cuba carried out battleship long-range target practice with aircraft spotting, and antiaircraft gunnery. The destroyers held torpedo practice. The big boats conducted machine gun gunnery practice against towed target sleeves; and live bombing practice against towed surface targets.

Note: At latter practice, the minesweeper Sandpiper, towing a target raft about 400 yards astern, had her condenser damaged by the explosion of a 100 pound live bomb that fell fairly close to her. The impact, or water-hammer of the explosion was transmitted through the inboard and outboard delivery pipes to her condenser causing the tubes to leak at the ferrules and salting up the condenser.

In relating this story to General Mitchell on board the Shawmut in Hampton Roads, we came to the conclusion that the near misses when we bombed the ships there would probably cause more damage to them than direct hits.

The Atlantic Fleet Air Force which I commanded then consisted of the flying boats already mentioned, of a squadron of two-seater wheel planes (VE-7's Chance Vought) also fitted with attachable floats, a kite balloon squadron, all of Guantanamo and torpedo-bomber squadron at Yorktown.

Lieutenant Harry B. Cecil commanded the flying boat squadron (Cecil went down with the Akron off Barnegat Light in 1933). Lieutenant Virgil C. "Squash" Griffin (Griffin was the first man to fly off the deck of a U.S. carrier, 17 October 1922) commanded the two-seater land planes which were in training for carrier landings. Lieutenant Victor B. Herbster commanded the kit balloon squadron, which were flown from the battleships of the Atlantic Fleet for ship spotting. Lieutenant H. T. (Culis) Bartlett commanded the torpedo-bomber squadron of Martins.

The aircraft tenders were the U.S.[S.] Shawmut, my flagship; the destroyer Harding, Lieutenant Commander Albert C. "Putty" Read, who flew the NC-4 across the Atlantic in 1919; and the minesweeper Sandpiper, Lieutenant Johnson commanding.

On completion of the exercises off Guantanamo, the Atlantic Fleet, including the Atlantic Fleet Air Force, departed for Hampton Roads to carry out the exercises with the U.S.S. Iowa and the ex-German warships scheduled for June and July.

The fleet returned to Hampton Roads the latter part of April after an absence of four months. On arrival there the fleet was reviewed by President Harding. It then prepared for the bombing experiments.

Navy Invites Army to Participate in the Bombing

In February 1921, the Navy invited the Army to participate in the bombing experiments with Navy and Marine Corps planes. The invitation to Secretary of War Baker from Secretary Daniels included plans for the experiments.

The War Department accepted the invitation and notified the Navy Department that it agreed with plans except that it requested that the Army be authorized to make at least two hits with the largest size bombs in service - the 2000 pound bomb. The Navy Department agreed to this and it was so stated in Admiral Wilson's printed instructions to the fleet dated May 25, 1921, governing the exercises with the Iowa and ex-German warships. A copy of these instructions is attached to this account of the bombing.

General Mitchell Assigned to Command Army Planes

The War Department designated General Mitchell, Assistant Chief of the Army Air Services to command Army planes taking part in the exercise.

The instructions dated May 25, 1921, called for the following exercises:

| 21 June | U-117 bombing by aircraft |

| 22 June | U-140, U-111, UB-48, attack by Destroyer Div. 36 |

| 26 June | Search and bombing of Iowa with dummy bombs |

| 13 July | Destroyer G-102 bombing by aircraft |

| 18 July | Cruiser Frankfurt bombing by aircraft |

| 20 July | Battleship Ostfriesland bombing by aircraft |

While the fleet was in the Caribbean training for war, Mitchell was flying about the country saying that airplanes could sink battleships and make conventional armies and navies obsolete. The people of our country were in just the right mood to accept this estimate. They were tired of war; they had just finished winning the "war to end all wars," and had made the world "Safe for Democracy." They wanted President Harding to "bring the country back to normalcy." They believed airplanes would provide a cheap and easy way to win wars, and make the country safe from invasion. If "a thirty thousand dollar airplane can sink a forty million dollar battleship," why build battleships? "The cost of national defense," Senator Borah said, "is breaking the backs of our tax-burdened people," or words to that effect.

Note: The United States built no battleships for 17 years, between 1922 and 1939, because the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922 limited this country to 18 battleships, afterward reduced to 15, none of which could be replaced until it was at least 20 years old. We were obliged to scrap about 30 battleships including battle cruisers as a result of the treaty. All the battleships and battle cruisers under construction were scrapped, except two battle cruisers that were converted into aircraft carriers. Our total tonnage was reduced to 135,000 tons.

[The Admirals and National Defense]

The "sea-minded" admirals who were responsible for our naval policy and the Navy's state of readiness for war may have under-rated the airplane; the "air-minded" generals may have over-rated the airplane; but the admirals were more concerned with war on the high seas, and on islands and continents across the seas than with the ability of airplanes to sink battleships close to our shores. "The Admirals" were not worried when the coast defense batteries at Pensacola battered and sank the Massachusetts two miles away; nor did it excite them greatly when emotional pundits and reporters professed that airplanes had made navies obsolete. But it annoyed "sea-minded" admirals when the anti-Navy press echoed Mitchell's complaint that the battleship Ostfriedland was anchored too far from Langley Field for a fair test between airplanes and battleships. However, the real issue between our Navy and the crusaders for a single air service was not about battleships versus airplanes, but whether our Navy was to be free to develop naval air power and use it in war. Congress gave the answer when it passed the National Security Act of 1947.

General H.H. Arnold, first Chief of the Air Force after the passage of the Act, gives a very clear picture of the controversy between General Mitchell and the Navy. He says in his book Global Mission (Harper & Brothers, New York, 1949), page 110:

So Mitchell's fight with he Navy over the battleships, was not just a simple fight between the Army, the Navy, and the little Air Service. It was really a battle of ideas, involving airminded people and non-airminded people in both services. But Mitchell's constant use of the Press to put his ideas across over-simplified the question .... Regardless of where they were all air-officers did what they could to keep the Air Arm before the public.

Unlike the present day battles for headlines and newspaper space waged by the Services in their jurisdictional disputes over aircraft, missiles, satellites and spaceships, our Navy in 1921 had no public relations agency. That came after the bombing experiment. It is an illuminating story.

Purpose of the Experiments (3 View Points)

One should consider the purpose of the experiments from the view points of the public, the Navy, and the flyers.

The public wanted to know whether airplanes could sink battleships and make surface navies and armies obsolete about which they had heard so much.

The Navy wanted to test various types of Army and Navy aerial bombs as weapons against ships of different types, and to test the capabilities of Army and Navy aircraft in simulated war conditions as far as possible.

The flyers wanted to show that they could sink ships by bombing them. There was much rivalry among the flyers too as to which service would make the highest scores and deliver the coup de grace. They looked upon bombing largely as one would a sporting event in which the contestants would be governed by the same rules.

Army and Navy aerial bombs of all types and weights in service were used in the experiments - from the smallest to the biggest - from the Army's small 25 pound Cooper fragmentation bombs for use against exposed personnel, and the Navy's antisubmarine 163 pound bomb - to the heavy Navy armor-piercing bomb and the Army's 2000 pound demolition bomb, the heaviest bomb that could be carried by current types of aircraft in service with fuel enough to make them of any use in naval warfare. The bombs differed in types of construction, types of fuses used, and purpose for which they were designed.

Bombs with the greatest penetrating power had thicker heads and heavier bodies and carried less weight of explosive than bombs of the same weight designed with lighter casings in order to carry greater explosive charge. There were bombs with nose fuses, tail fuses, and both nose and tail fuses as well as instantaneous and delayed action fuses. The light case bombs had greater mining effect with near misses than the armor piercing type, and less effect against gunshields, splinter bulkheads, superstructures and protective decks, but the ones designed for penetrating power had to be dropped from higher altitudes.

There was much talk about precision of "pin pointing" in bombing from high altitudes safe from antiaircraft gun fire and much speculation about the affectiveness of antiaircraft artillery against planes at any altitude. But nothing could be proved in the experiments off the Virginia Capes because of low ceilings and unmanned and unarmed target ships.

Note: This inability of high altitude horizontal bombers to pin-point naval ships underway at sea was proved in World War II. I am told that no US naval warship was hit by a Japanese high flying plane when the ships were underway at sea. The many that were sunk by Japanese planes were sunk by dive bombers and torpedo bombers and Kamikazes.

The inability of antiaircraft guns to hit high flying planes or at least to down them with any degree of success was proved in tests before the war. With the development of electronics, electronic fire control systems, and the perfection of the proximity fuse early in World War II, the picture reversed and anti-aircraft gun fire became a very effective weapon and added new life to the battleship.

When the War Department accepted the Navy's invitation to participate in the bombing experiments, copies of the printed instruction and orders issued by the Commander-in-Chief of the Atlantic Fleet, Admiral Henry B. Wilson, which governed the operations were sent to all units concerned, including all aircraft - Army, Navy, and Marine Corps.

The instructions dated May 25, 1921, copy enclosed, placed the Commander of the Battleship Force, Vice Admiral Hilary P. Jones, in charge of all operations for the month of June, and Rear Admiral A. H. Scales, Commander of Battleship Division Five, in charge of all operations scheduled for the month of July. The Commander of the Atlantic Fleet Air Force, Captain A. W. Johnson, was placed in charge of air operations, under the overall command of Captain S. H. R. Doyle, Commanding Naval Air Station, Hampton Roads, who was placed in charge of the air base at Hampton Roads and of communications between that base and the bases at Yorktown and Langley Field and other bases that might be established. Lieutenant Commander Jules James, US Navy, was detailed as Chief Censor, and was to be given detailed instructions later as to the policy which would govern his censoring of press matter in connections with the exercise.

I attended the conferences at the Navy Department in May as Fleet Representative to discuss the final plans for the bombing with representatives of the War and Navy Departments. Others attending were: Captain Tommy Kurts of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, Commander Ken Whiting representing the Director of Naval Aviation, and Captain W. C. Watts, Judge Advocate General of the Navy. Representing the War Department were General Mitchell, Assistant Chief of the Army Air Services, and Major Thomas B. Milling from Langley Field, Mitchell's executive officer during the bombing operations. There were some others whose names I do not recall now.

I had not met Mitchell before, but we became well acquainted afterwards.

At the opening conference, Captain Kurtz stated its purpose. It was at once apparent that General Mitchell did not agree with the Navy Department's plans for the experiments. He though we should bomb the ships with everything we had and sink them as fast as we could.

Captain Kurtz at the conference on May 10th, made it clear that the primary purpose of the bombing experiments was to learn as much as possible about the effect of the explosives rather than about tactical methods.

Captain Watts explained that the experimental bombing was to ascertain the damage on certain types of naval vessels of certain intensive weapons of different types. The limitations as to the size of the bombs and number of hits required were prescribed after careful study of the material bureaus - not by the operating end of the Navy. Captain Watts said, "It would be unsatisfactory for instance to drop a 2000 pound bomb on the destroyer and end the thing right there - the experiment would be robbed of its value. All this elaborate program was submitted to the War Department, and was accepted with the exception of the two hits allowed for the heaviest bomb." Nevertheless, it was decided to let Mitchell have the destroyer to play with any way he wanted to.

The Shawmut, my flagship, and mother ships of the Atlantic Fleet Air Force were to be stationed close to the target and direct the air operations from there, to signal when the attacking units should leave their bases to attack, and to give them weather reports at the target.

Much time was spent in discussing the exercises to be conducted with the radio controlled target ship Iowa. General Mitchell finally decided not to participate with his planes, and that the attack would be meaningless [unless] the ship was bombed with live bombs. He said he would like to know how the air force was to be handled. He was told that the Iowa experiment and all the operations with the German ships was under the overall command of the Commander-in-Chief of the Atlantic Fleet. He said, "The Commander of the Air Force of the Navy will be over the Commander of the Air Force of the Army, and that is contrary to law." Commander Whiting piped up that that applied only to special occasions.

Mitchell said he understood that these are really ordnance tests, and that the Navy wanted to examine the ships after each attack. Captain Kurtz told them that, "We want to examine the cruiser and the battleship after each attack. The submarine and the destroyer we don't care about."

General Mitchell called attention to the site selected for the target; (seventy miles east of Langley Field), and preferred one closer to shore. He suggested a location off Hatteras thirty miles from shore were you can get 100 fathoms. Captain Whiting pointed out that that would mean that we would have to establish another base for the airplanes to take off from. One hundred fathoms is too deep for anchoring.

Note: The newspapers afterwards made quite a point of this, claiming that the Navy purposely selected a location far from the Langley Field to make it hard for the Army planes to reach the target.

The spot chosen was in the area known by the Navy as the Southern drill grounds where the Fleet conducted target practice and other exercises. It was clear of the shipping lanes; the water was not too deep for anchoring the target ships, yet deep enough so that when the ships were sunk, their wreckage would not endanger the ships operating in the locality, and there was ample searoom for the Fleet to witness the tests. The Navy Department or US Government has paid over $100,000 in damages to fishermen and yachtsmen whose boats have run afoul of the old battleship Texas, which was sunk by the Navy in gun tests in Chesapeake Bay near Langley Field in 1911.

We discussed many other matters; identification of targets, radio communications, safety precautions, visual signals, etc. A line of destroyers were to be stationed seven miles apart between Langley Field and the target to point the way and to rescue any planes that had forced landings, and twenty destroyers were to be stationed in the area to be searched in the Iowa problem to rescue planes forced down.

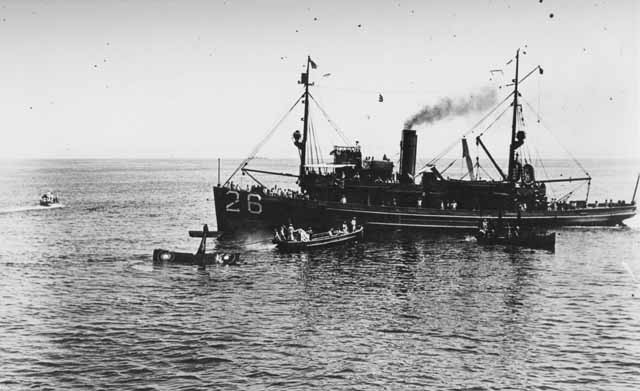

Note: The only casualties during the experiments were one Marine Corps plane and one F5L ran short of gas mentioned later. One Army Handley Page bomber landed in the water and was wrecked and Lieutenant Colonel Culver landed in the water in his scout plane (see picture). The only death was in an accident during bombing practice with the old Texas mentioned above. Captain Douglas of the Air Force who had been assigned as my aid aboard the Sawmut was flying back to Washington and collided with a formation of Army bombers attacking the Texas and crashed close to the Texas and was drowned. At General Mitchell's request I sent Putty Read in the Harding with divers to recover the body. While divers were down, a formation of bombers from Langley Field flow over the spot and rendered a salute in honor of Douglas by dropping one or more salvos of bombs and then returned to Langley Field. The concussion of the bombs frightened the divers, but none were hurt.

Mitchell suggested that an attack be made on one of the targets with torpedo planes using warheads instead of exercise heads. His suggestion was not adopted as it was decided to attack with aerial bombs only as the purpose of the tests was to find all we could about them. Bartlett commanded the Navy's torpedo and bombing squadron of Martin bombers and actually did attack a division of four battleships steaming at seventeen knots off the Capes after the tests were over. He made a fine score, but of course used exercise heads on the torpedoes. Had Mitchell's suggestion been carried out at a ship target, using live warheads, the many failures with our torpedoes early in World War II in the Pacific might have been foreseen as the case of some of the bombs after the bombing experiments. [Not true, entirely different warheads used later]

When the conference were ended, Kurtz asked Mitchell if everything was clear to him and if he was satisfied to which he replied in the affirmative.

The historical significance of the bombing experiments is that they marked another milestone in the age old competition between the attacking weapon and passive defense - like the spear against the shield - the gun against armor, and then the aerial bomb against an armored ship. But psychologically it marked the beginning of the long series of disputes among the services over the cognizance of weapons; first between the Air Force and the Navy over aviation, and later between the Air Force and the Army and the Navy over missiles.

Note: Adapted from: Johnson, Alfred Wilkinson. The Naval Bombing Experiments Off the Virginia Capes: June and July 1921, Their Technological and Psychological Aspects. Washington, DC: Naval Hsitorical Foundation, 1959. The original fragile document is available for examination at the Navy Department Library. It is unavailable for inter-library loan.

[END]