The Navy Department Library

The Battle of Savo Island August 9th, 1942 Strategical and Tactical Analysis

Part I

PDF Version [129.3MB]

The Battle

of

Savo Island

August 9th, 1942

Strategical

and

Tactical Analysis.

U. S. Naval War College

1950

NAVPERS 91187

Prepared By

Department of Analysis

Naval War College

Commodore Richard W. Bates, USN (Ret)

Commander Walter D. Innis, USN

Table of Contents

| PAGE | |||||

| Foreword | i-ii | ||||

| Table of Contents | iii-xxii | ||||

| Zone Time | xxiii | ||||

| Principal Commanders | xxiv-xxv | ||||

| Introduction | xxvi | ||||

| Brief Narrative of the Battle of Savo Island | xxvii-xxx | ||||

| Chapter I | The Strategic Area | 1-4 | |||

| (a) | General Discussion | 1-3 | |||

| (b) | Tulagi-Guadalcanal Area | 3 | |||

| (c) | Weather | 4 | |||

| Chapter II | Japanese Arrangements | 5-14 | |||

| (a) | Japanese Command Relations | 5-6 | |||

| (b) | Information Available to Japanese Commanders | 7-8 | |||

| (c) | Japanese Land and Tender Based Aircraft | 8-10 | |||

| (d) | Japanese Search and Reconnaissance | 10-11 | |||

| (e) | Japanese Disposition of Naval Forces | 11-13 | |||

| (a) | Disposition at 0652 August 7th | 12 | |||

| (1) | Support Force and Chokai | 12 | |||

| (2) | Escort Force | 12 | |||

| (3) | Auxiliaries 25th Air Flotilla | 12 | |||

| (4) | Submarines | 12 | |||

| (f) | Japanese Tasks Assigned | 13-14 | |||

| (g) | Japanese General Concept | 14 | |||

| Chapter III | Allied Arrangements | 15-42 | |||

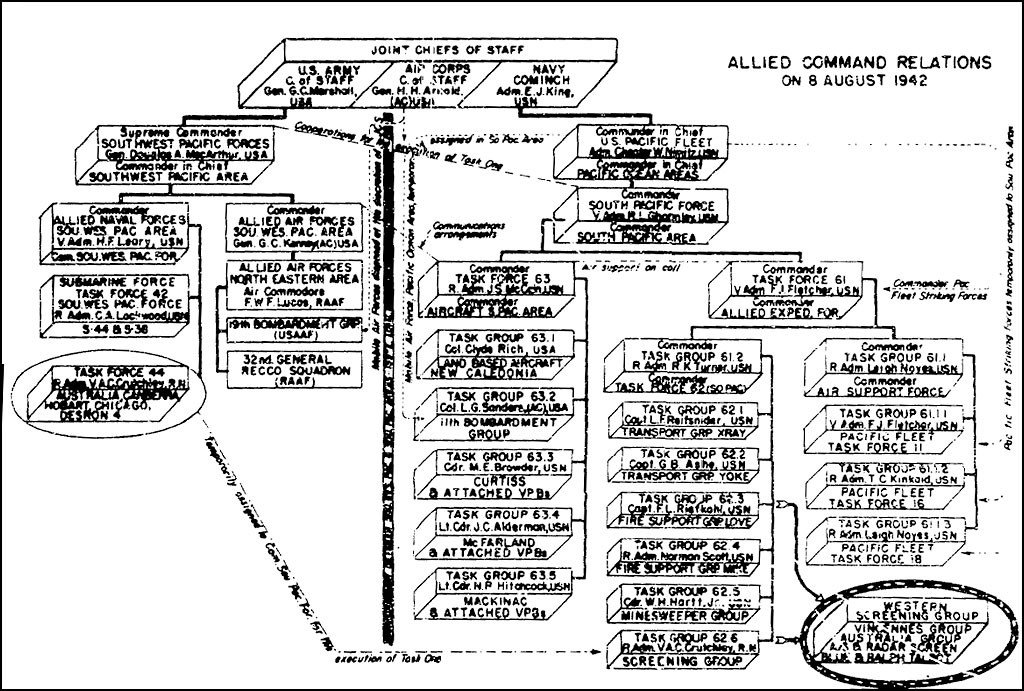

| (a) | Allied Command Relations | 15-19 | |||

| Tasks CINCPOA | 15 | ||||

| Tasks COMSOPAC | 15 | ||||

| Tasks COMSOWESPAC | 16 | ||||

| Admiral Nimitz Becomes CINCPOA | 16 | ||||

| Vice Admiral Ghormley Becomes COMSOPAC and COMSOPACFOR | 16 | ||||

| General MacArthur Becomes COMSOWESPAC | 16 | ||||

| Command Relations Between Australian and American Naval Officers | 17 | ||||

| Joint Chiefs of Staff Assign New Missions--Task ONE to COMSOPAC | 17 | ||||

| COMSOPACFOR is Designated as Task Force Commander for Task ONE | 17 | ||||

| COMSOPACFOR Issues Operation Plan | 18 | ||||

| Commander Expeditionary Force (CTF 61) Issues Operation Plan | 19 | ||||

| (b) | Information Available to Allied Commander | 19-21 | |||

| (c) | Allied Land and Tender Based Aircraft | 21-25 | |||

| (1) | South Pacific (SOPAC) | 21-23 | |||

| (2) | Southwest Pacific (SOWESPAC) | 23-25 | |||

| (d) | Allied Search and Reconnaissance | 26-31 | |||

| (1) | South Pacific (SOPAC) | 25-27 | |||

| (2) | South Pacific | 27-31 | |||

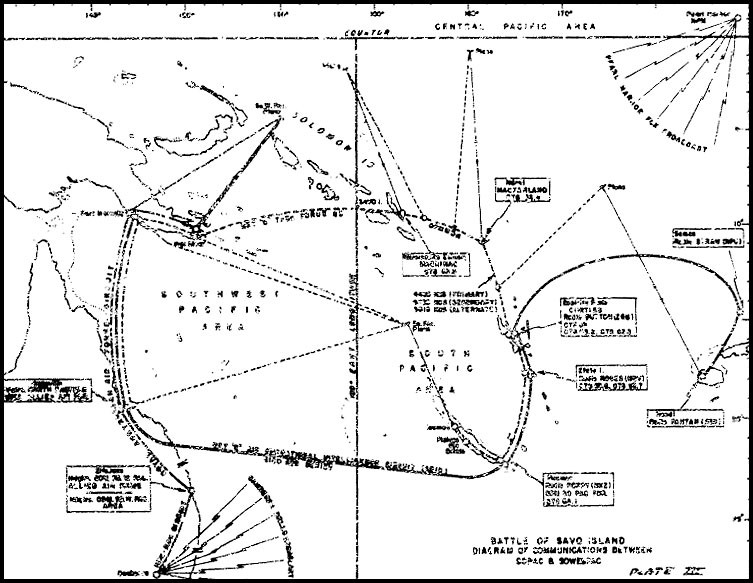

| (e) | Communications Arrangements Between COMSOPAC and COMSOWESPAC | 31-32 | |||

| (f) | Allied Deployment of Naval Forces | 32-37 | |||

| (1) | Approach to Guadalcanal-Tulagi Area | 32-34 | |||

| (2) | CTG 61.1 Operates his Carriers | 34-35 | |||

| (3) | Approach TG 61.2 (TF 62) (Amphibious Force) | 35 | |||

| (4) | Deployment of SOWESPAC Submarines | 35-36 | |||

| (a) | Deployment of S-44 | 35-36 | |||

| (b) | Deployment of S-38 | 36 | |||

| (5) | Deployment of Allied Forces at 0652 August 7th | 36-37 | |||

| (a) | TG 61.1 Air Support Force | 36 | |||

| (b) | TG 61.2 (TF 62) (Amphibious Force) | 36-37 | |||

| (c) | Submarines | 37 | |||

| (g) | Composition of Forces and Tasks Assigned | 37-40 | |||

| (1) | Composition of Forces | 37-38 | |||

| (a) | TG 61.1 (Air Support Force) | 37 | |||

| (b) | TG 61.2 (TF 62) (Amphibious Force) | 37-38 | |||

| (2) | Tasks Assigned | 38-40 | |||

| (a) | TF 61 (Allied Expeditionary Force) | 38 | |||

| (b) | TG 61.1 (Air Support Force) | 39 | |||

| (c) | TG 61.2 (TF 62) (Amphibious Force) | 39 | |||

| (h) | The Allied Plan | 40-42 | |||

| (i) | General Summary | 42 | |||

| CHAPTER IV | JAPANESE REACTION 0652 August 7th | 43-51 | |

| (a) | Operations of Japanese Cruiser Force | 43-50 | |||

| Tulagi is Attacked by Allied Forces | 43 | ||||

| Commander Outer South Seas Force Estimates the Situation | 43-44 | ||||

| Commander 5th Air Attack Force Makes Additional Searches and Launches Two Air Attack Groups | 45-46 | ||||

| Commander Outer South Seas Force Organizes Cruiser Attack Force | 46 | ||||

| Rabaul is Attacked | 47 | ||||

| Japanese Air Attack Hits Allied Shipping at Tulagi-Guadalcanal | 47 | ||||

iv

| PAGE | |||||

| Commander Outer South Seas Force Decides to Command Cruiser Force | 48 | ||||

| Japanese Air Attack Hits Allied Shipping at Tulagi-Guadalcanal | 48 | ||||

| Commander Outer South Seas Force Receives Intelligence Summary about Allied Forces | 48-49 | ||||

| Commander Cruiser Force Departs with Cruiser Force for Tulagi | 50 | ||||

| (b) | Movements of Japanese Submarines | 51 | |||

| CHAPTER V | ALLIED OPERATIONS (0652 - 2400 August 7th) | 52-71 | |||

| (a) | Operations of CTF 62 (Commander Amphibious Force) | 52-54 | |||

| Zero Hour Set for Guadalcanal and Tulagi | 52 | ||||

| Allies Land on Guadalcanal, Tulagi and Gavutu | 52 | ||||

| TF 62 Struck by First Japanese Air Attack | 53 | ||||

| TF 62 Struck by Second Japanese Air Attack | 53 | ||||

| CTF 62 Becomes Concerned Over Japanese Capabilities | 53 | ||||

| CTF 62 Requests CTF 63 to make Additional Searches | 53-54 | ||||

| CTF 62 is Erroneously Informed by COMSOPACFOR that Enemy Submarine is Nearby | 54 | ||||

| CTF 62 is Informed by COMSOWESPAC of Contact on Enemy Cruiser Force North of Rabaul and of contact on Six Unidentified Ships in St. Georges Channel | 54 | ||||

| (b) | Operations of Allied Screening Group | 54-61 | |||

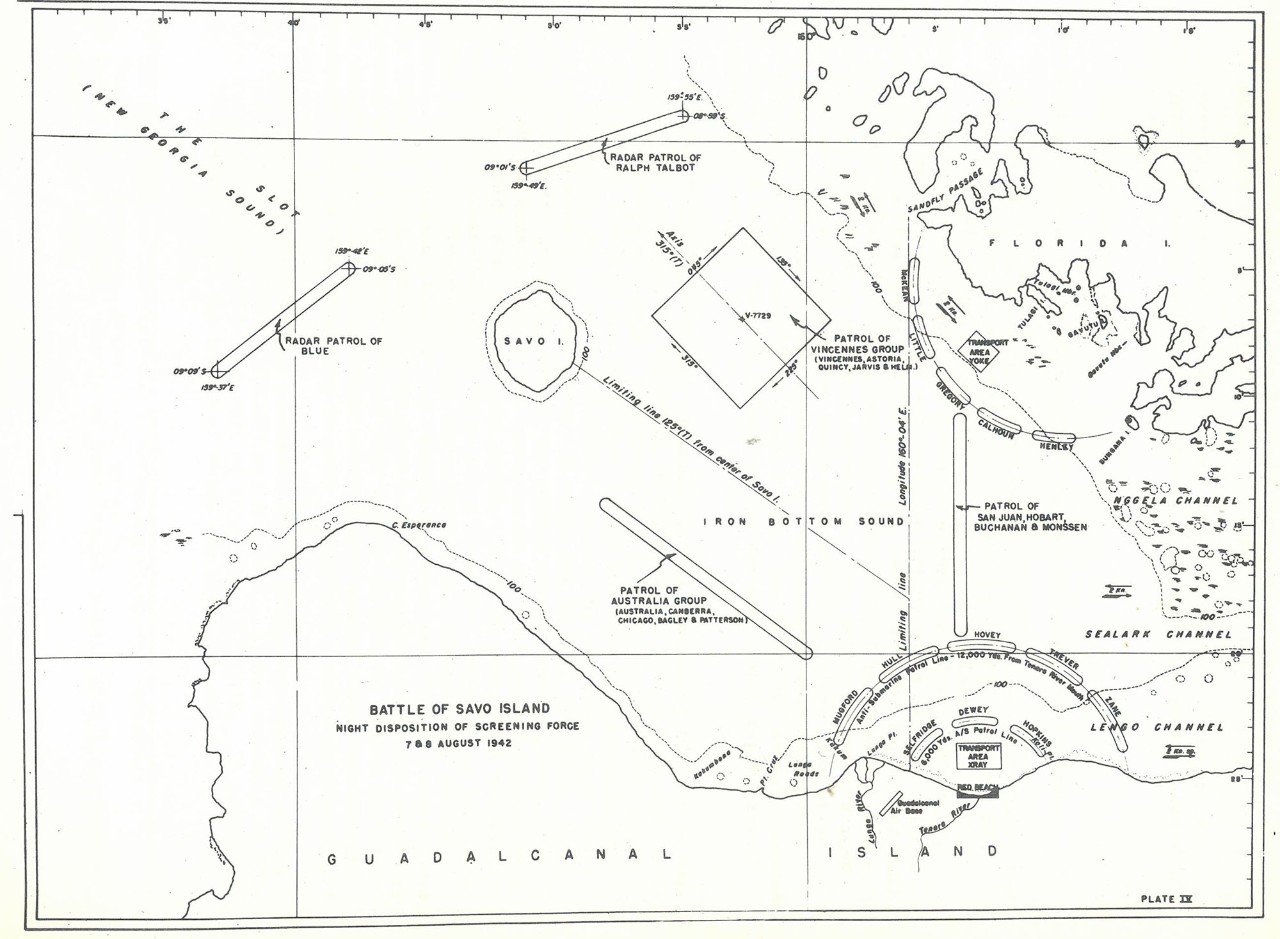

| (1) | Night Disposition | 55-56 | |||

| (a) AUSTRALIA Group | 55 | ||||

| (b) VINCENNES Group | 55 | ||||

| (c) SAN JUAN Group | 55 | ||||

| (d) RALPH TALBOT and BLUE | 56 | ||||

| (e) Remaining Destroyers | 56 | ||||

| (2) | CTG 62.6.1 Instructions | 56-57 | |||

| (3) | Discussion of Night Disposition | 57-61 | |||

| (c) | Operations of CTF 61 (Commander Expeditionary Force) | 61-64 | |||

| CTF 61 Remains in SARATOGA | 61 | ||||

| Communications for Air Operations | 61-62 | ||||

| CTF 61 Hears of Carrier Type Bombers Over Guadalcanal and Re-estimates Situation | 62 | ||||

| Directs Air Operations South of Cape Henslow for August 8th | 62-63 | ||||

| Discussion of This Order | 63-64 | ||||

| Intercepts CTF 62's Request to CTF 63 for Additional Air Search | 64 | ||||

| Receives CTF 62's Summary of Operations for August 7th | 64 | ||||

| (d) | Operations of CTG 61.1 | 64-68 | |||

| Weather Conditions | 64 | ||||

| WASP Air Support Group Destroy Japanese Seaplanes at Tulagi | 65 | ||||

| Provides Combat Air Patrol | 65 | ||||

- v -

| PAGE | ||||

| Provides Air Search and Reconnaissance | 65-66 | |||

| Hears that Carrier-Type Bombers Have Attacked Transports and Re-estimates the Situation | 66 | |||

| Discussion of New Day Launching Position | 67 | |||

| Suffers Aircraft Losses | 67 | |||

| (e) | Operations of Allied Submarines | 68-69 | ||

| (1) Operations of S-38 | 68-69 | |||

| (2) Operations of S-44 | 69 | |||

| (f) | Operations of CTF 63 (Commander Aircraft South Pacific Force) | 69-70 | ||

| (g) | Operations of Commander Allied Air Forces SOWESPAC | 70-71 | ||

| Sights Japanese Cruisers North of Rabaul | 70 | |||

| Contact Reports Delayed 11.5 Hours | 71 | |||

| Sights Six Unidentified Ships in St. Georges Channel | 71 | |||

| CHAPTER VI | JAPANESE REACTION | |||

(0000 August 8th to 2400 August 8th) |

72-82 | |||

| (a) | Operations of Commander Cruiser Force | 72-78 | ||

| Launches Search Planes from Cruisers | 72-73 | |||

| Sights Lockheed Bomber at 1020 | 73 | |||

| Recovers Search Planes | 74 | |||

| Receives Report of Situation Tulagi - Guadalcanal from Pilot of AOBA | 74 | |||

| Decides Carry Out Night Attack | 75 | |||

| Issues Instructions for Night Action | 75-76 | |||

| Receives Report of Japanese Bombing Attacks on Allied Shipping at Tulagi - Guadalcanal | 77 | |||

| (b) | Operations of Commander Fifth Air Attack Force | 78-81 | ||

| Launches Air Searches | 79-80 | |||

| Launches Air Attack | 80-81 | |||

| (c) | Operations of Japanese Submarines | 81-82 | ||

| CHAPTER VII | ALLIED OPERATIONS | 83-103 | ||

| (0000 August 8th to 2400 August 8th) | ||||

| (a) | Operations of CTF 62 | 83-91 | ||

| Informs TF 62 Enemy Submarine Might Enter Area That Day | 83 | |||

| Receives Word of Small Japanese Surface Forces Heading South | 83-84 | |||

| TF 62 is Attacked by Japanese Planes Damaging GEORGE F. ELLIOTT and JARVIS | 84 | |||

| Orders GEORGE F. ELLIOTT Sunk | 85 | |||

| Intercepts CTF 61 Dispatch Recommending Withdrawal of Carriers | 85 | |||

| Received Contact Report that Two Enemy Destroyers, Three Cruisers and Two Seaplane Tenders or Gunboats are Headed South | 86 | |||

vi

| PAGE | |||

| Also Receives Contact Report of Two Japanese Submarines Headed Towards Tulagi | 86 | ||

| Estimates the Situation and Decides No Enemy Night Attack | 87 | ||

| Calls Conference of CTG 62.6 and Commanding General, First Marine Division | 87 | ||

| CTG 62.6 Departs Western Screen and Fails to Notify Commander VINCENNES Group | 87-88 | ||

| CTF 62 Holds Midnight Conference | 89-90 | ||

| RALPH TALBOT Sights Enemy Plane and Broadcasts Warning | 80 | ||

| (b) | Operations of CTF 61 (Commander Expeditionary Force) | 91-95 | |

| Launches Air Search | 91 | ||

| Recommends Withdrawal of Carriers | 91-95 | ||

| (c) | Operations of CTG 61.1 (Air Support Force) | 95-97 | |

| Launches Air Search | 95 | ||

| Launches Additional Air Search | 96 | ||

| (d) | Operations of Allied Submarines | 98 | |

| (1) Operations of S-38 | 98 | ||

| (2) Operations of S-44 | 98 | ||

| (e) | Operations of CTF 63 (Commander Aircraft South Pacific Force) | 98-100 | |

| Launches Routine Searches | 98 | ||

| Results of Searches | 98-99 | ||

| (f) | Operations of Commander Allied Air Forces SOWESPAC | 100-103 | |

| Launches Routine Searches | 100 | ||

| RAAF Hudson Contacts Japanese Cruiser Force at 1025 | 100 | ||

| RAAF Hudson Contacts Japanese Submarine I-121 | 100 | ||

| Contact Report Delayed in Transmission to CTF 62 | 101 | ||

| RAAF Hudson Contacts Japanese Cruisers at 1101 | 101-102 | ||

| Contact Report Delayed in Transmission to CTF 62 | 102-103 | ||

| CHAPTER VII[I] | MEANS AVAILABLE AND OPPOSED | 104-105 | |

| (a) | Forces Engaged | 104 | |

| (1) Allied Force | 104 | ||

| (2) Japanese Cruiser Force | 104 | ||

| (b) | Strength and Weakness Factors | 104-105 | |

| CHAPTER IX | OPERATIONS OF JAPANESE CRUISER FORCE | 106-109 | |

| (0000 August 9th to 0132 August 9th) | |||

| (a) | The Approach | 106-109 | |

| Forms Cruising Disposition | 106 | ||

| Receives Intelligence of Allied Forces From Cruiser Plane | 106 | ||

| Alerts Battle Stations | 107 | ||

| Sights Allied Destroyer BLUE | 107 | ||

| Superiority of Japanese Night Naval Detection | 107 | ||

| Maneuvers to Enter Iron Bottom Sound | 107-108 | ||

| Enters Iron Bottom Sound | 109 | ||

vii

| PAGE | |||

| CHAPTER X | OPERATIONS OF ALLIED SCREENING GROUPS | 110-113 | |

| (0000, August 9th to 0132, August 9th) | |||

| (a) | Operations of BLUE | 110-11 | |

| (b) | Operations of CHICAGO Group | 111 | |

| (c) | Operations of VINCENNES Group | 111-112 | |

| (d) | Operations of RALPH TALBOT | 112 | |

| (e) | Operations of SAN JUAN Group | 112-113 | |

| CHAPTER XI | OPERATIONS OF JAPANESE CRUISER FORCE | 114-124 | |

| (0132, August 9th to 0150, August 9th) | |||

| (a) | Action with CHICAGO Group | 114-120 | |

| CHOKAI Sights the JARVIS | 114 | ||

| CHOKAI Sights the CANBERRA and CHICAGO | 115 | ||

| CHOKAI Sights the VINCENNES Group | 115 | ||

| CHOKAI Fires Four Port Torpedoes at CANBERRA and CHICAGO | 116 | ||

| COMCRUDIV SIX Sights CHICAGO Group | 116 | ||

| YUNAGI Decides to Attack JARVIS | 117 | ||

| CHOKAI Commences Firing | 118 | ||

| Japanese Cruiser Planes Drop Aircraft Flares | 118 | ||

| FURUTAKA Fires Guns and Four Port Torpedoes | 118 | ||

| Changes Course to 050°(T) | 119 | ||

| AOBA Fires 8-inch Battery and Three Torpedoes at CANBERRA | 119 | ||

| CRUDIV EIGHTEEN Changes Course to the Northeast | 120 | ||

| YUNAGI Reverses Course | 120 | ||

| Cruiser Force Breaks up into Two Groups - Eastern and Western | 120 | ||

| (b) | Approach to the VINCENNES Group | 121-124 | |

| CRUDIV EIGHTEEN Sights VINCENNES Group | 121 | ||

| KAKO Fires Three Torpedoes at CHICAGO | 121 | ||

| KAXO Fires on CANBERRA | 121 | ||

| FURUTAKA Fires One Torpedo at PATTERSON | 121 | ||

| FURUTAKA Fires at CANBERRA | 122 | ||

| CRUDIV EIGHTEEN Engages PATTERSON | 122 | ||

| CHOKAI Fires Four Torpedoes at VINCENNES | 122 | ||

| CHOKAI Changes Course to 069°(T) | 123 | ||

| FURUTAKA Fires Three Torpedoes at CANBERRA | 123 | ||

| Summary of Torpedo Firing Against CHICAGO Group | 123 | ||

| Position of Ships at 0150 | 124 | ||

| CHAPTER XII | OPERATIONS OF ALLIED SCREENING GROUP | 125-150 | |

| (0132 August 9th to 0150 August 9th) | |||

| (a) | Action of CHICAGO Group with Japanese Cruisers | 125-138 | |

| Conditions of Readiness | 125 | ||

| Weather Conditions | 126-127 | ||

| (1) Action by CANBERRA | 127-129 | ||

| Sights Four Enemy Torpedoes and Two Enemy Ships | 127 | ||

| Is Heavily Hit by Gunfire | 128 | ||

| Sights Additional Torpedoes Which Miss | 128 | ||

viii

| Page | ||||

| Commanding Officer Killed and Ship Disabled | 129 | |||

| Damage Received | 129 | |||

| (2) Action by CHICAGO | 129-133 | |||

| Sights Aircraft Flares Over Area X-RAY | 129 | |||

| Sights Three Enemy Ships | 130 | |||

| Fails to Notify Command | 130 | |||

| Sights Three Additional Torpedo Wakes | 131 | |||

| Hit by Torpedo (KAKO's) | 131 | |||

| Observes Gunfire Flashes | 132 | |||

| Fires Star Shells to Port | 133 | |||

| Hit by Enemy Shell | 133 | |||

| (3) Action by BAGLEY | 133-135 | |||

| Sights Number Unidentified Ships | 134 | |||

| Observes Enemy Salvos Landing Short of CANBERRA | 134 | |||

| Fails to Report Contact | 134 | |||

| Turns to Port and Fails to Fire Starboard Torpedoes | 134 | |||

| Observes Aircraft Flares Over Area X-RAY | 134 | |||

| Fires Port Torpedoes at CRUDIV EIGHTEEN | 134-135 | |||

| Turns Left to Scan Passage Between Guadalcanal and Savo Island | 135 | |||

| (4) Action by PATTERSON | 135-138 | |||

| Sights Enemy Ship (FURUTAKA) | 135 | |||

| Goes to General Quarters | 136 | |||

| Broadcasts Contact Report by TBS and Blinker | 136 | |||

| Turns to Port and Attempts to Fire Starboard Torpedoes But Fails to do so | 136 | |||

| Broadcasts Contact Report by TBS | 137 | |||

| Opens Fire on CRUDIV EIGHTEEN | 137 | |||

| Hit by One Enemy Shell | 137 | |||

| Succeeds in Hitting YUBARI | 138 | |||

| (b) | Operations of VINCENNES Group | 138-145 | ||

| (0132 August 9th to 0150 August 9th) | ||||

| Conditions of Readiness | 138 | |||

| Weather Conditions | 139 | |||

| Information Available to Commanding Officers | 139 | |||

| Commander VINCENNES Group Estimates the Situation | 140 | |||

| Concern Over Possible Submarine Attack | 141 | |||

| Sights Aircraft Flares | 141 | |||

| WILSON and HELM go to General Quarters | 142 | |||

| Commander VINCENNES Group Re-estimates the Situation | 142 | |||

| PATTERSON's Warning Message Received by QUINCY, VINCENNES and WILSON | 143 | |||

| QUINCY goes to General Quarters | 143 | |||

| VINCENNES goes to General Quarters | 144 | |||

| QUINCY Observes Enemy Ships | 144 | |||

| Commander VINCENNES Group Increases Group's Speed to Fifteen Knots and Awaits Developments |

144 | |||

viii

|

PAGE | ||

| Gunnery Officer ASTORIA Requests Unsuccessfully That General Quarters be Set | 145 | ||

| VINCENNES, QUINCY and ASTORIA are Illuminated by Enemy Searchlights | 145 | ||

| (c) | Operations of BLUE | 146-147 | |

| Unaware of Passage of Japanese Cruiser Force | 146 | ||

| Sights Four Flares and goes to General Quarters | 146 | ||

| Endeavors to Report Enemy Planes to Officer-in-Tactical Command | 147 | ||

| (d) | Operations of RALPH TALBOT | 147 | |

| Hears PATTERSON's Contact Report and goes to General Quarters | 147 | ||

| (e) | Operations of CTG 62.6 (AUSTRALIA) | 147-149 | |

| Decides to Remain in Transport Area X-RAY | 148 | ||

| Fails to Inform CTF 62 or Commanders VINCENNES and CHICAGO Groups | 148 | ||

| Sights Aircraft Flares Vicinity Area X-RAY | 149 | ||

| Observes Gunfire From AUSTRALIA Group as well as in Direction VINCENNES Group | 149 | ||

| (f) | Action by SAN JUAN Group | 149-150 | |

| Sights Aircraft Flares | 150 | ||

| Observes Firing | 150 | ||

| Hears PATTERSON's Warning | 150 | ||

| Goes to General Quarters | 150 | ||

| CHAPTER XIII | OPERATION OF JAPANESE CRUISER FORCE | 151-167 | |

| (a) | Actions Between Japanese Eastern Group and VINCENNES Group | 151-162 | |

| Commander Cruiser Force Changes His Objective | 151 | ||

| CHOKAI Sights ASTORIA | 152 | ||

| CHOKAI Commences Fire on ASTORIA, AOBA on QUINCY, KAKO on VINCENNES Employing Searchlights | 152 | ||

| KINUGASA Fires at CANBERRA | 152 | ||

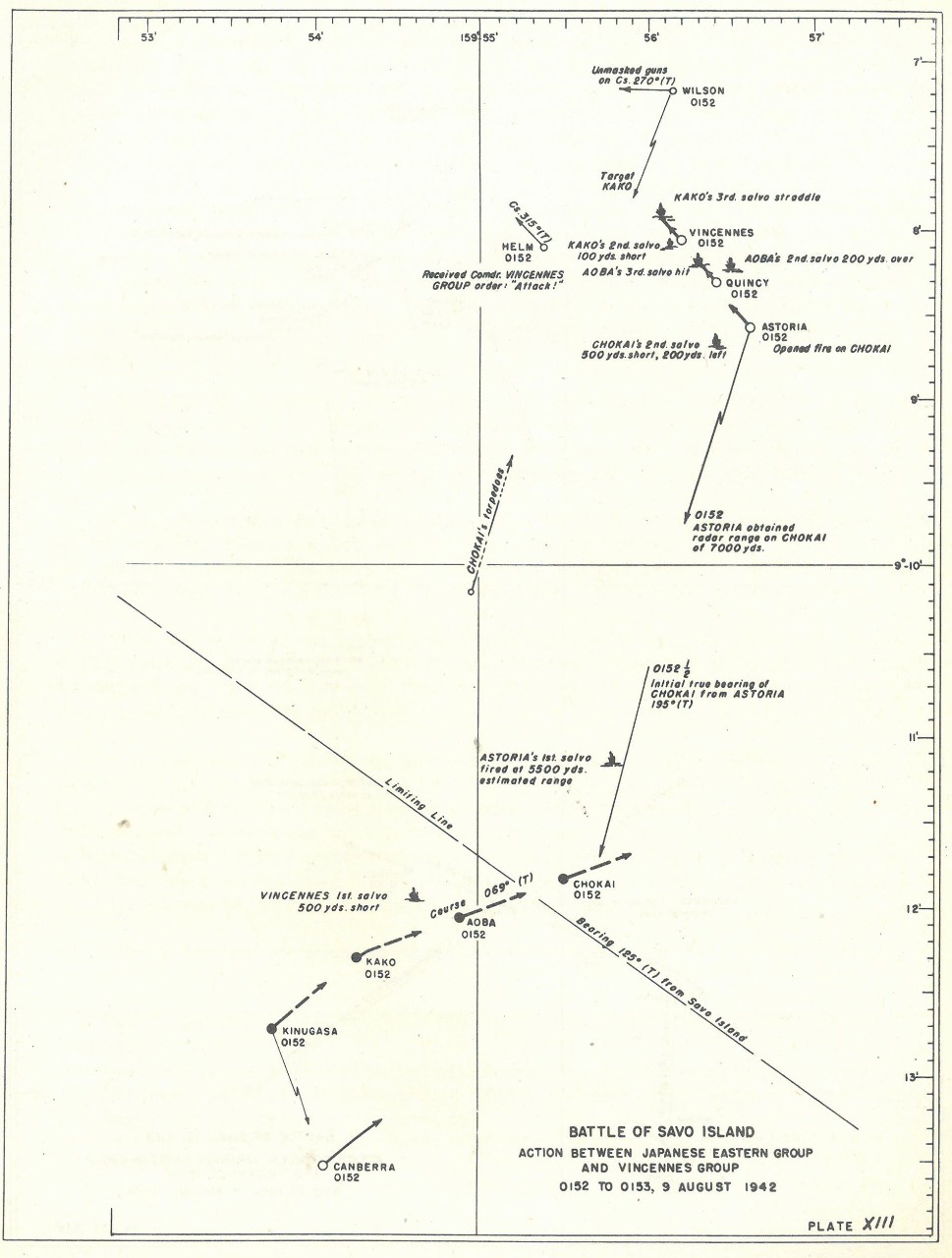

| Japanese Salvos are Short | 153-154 | ||

| Japanese Searchlight Technique | 154-155 | ||

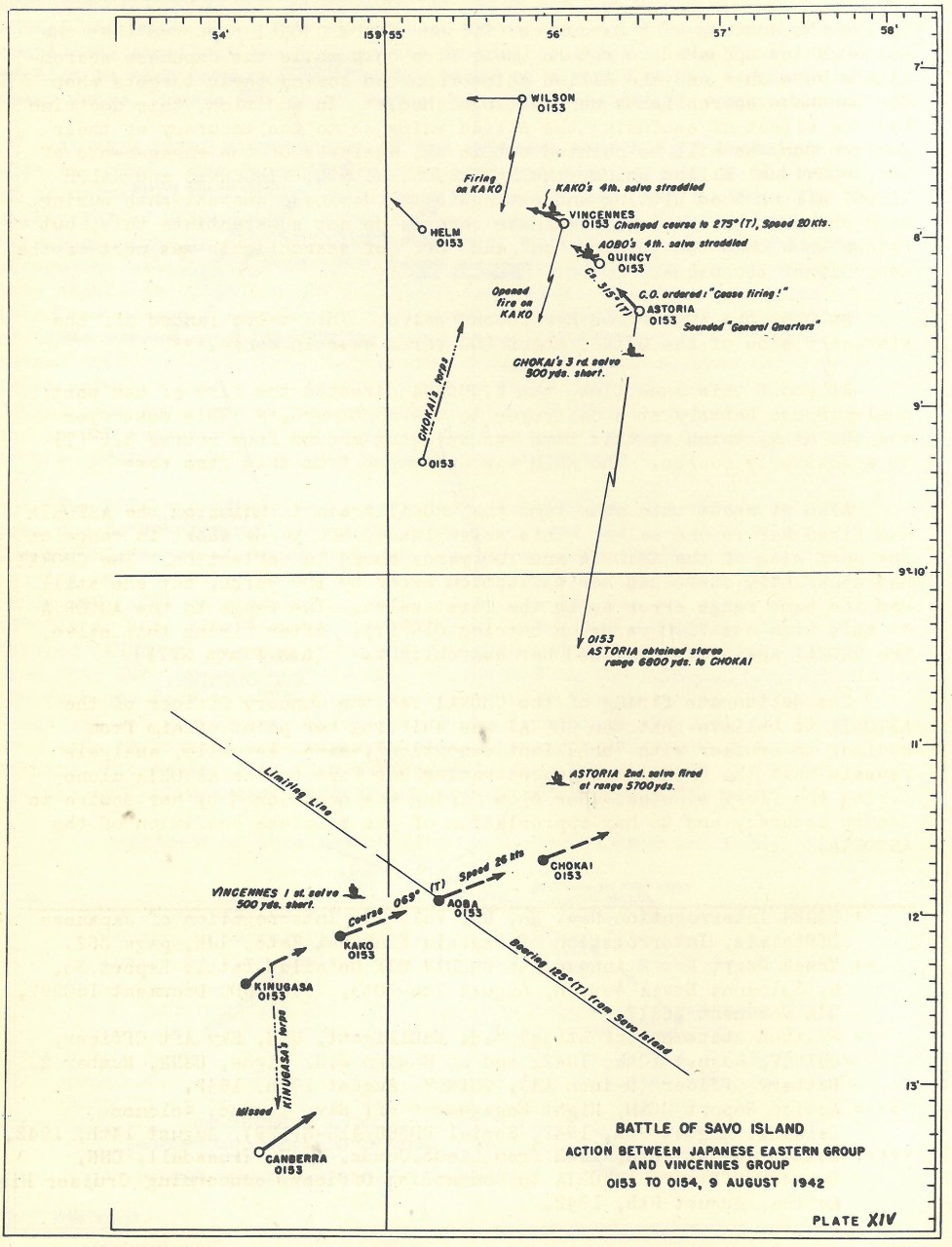

| AOBA Fires Second Salvo at QUINCY | 155 | ||

| KINUGASA Fires at HELM | 155 | ||

| CHOKAI Fires Second Salvo at ASTORIA | 155 | ||

| KAKO Fires Second Salvo at VINCENNES | 156 | ||

| AOBA's Third Salvo Hits QUINCY | 156 | ||

| KAKO's Third Salvo Hits VINCENNES | 156 | ||

| CHOKAI Fires Third Salvo at ASTORIA | 156 | ||

| KINUGASA Continues Firing at HELM | 156 | ||

| AOBA's Fourth Salvo Hits QUINCY | 156 | ||

| KAKO's Fourth Salvo Hits VINCENNES | 157 | ||

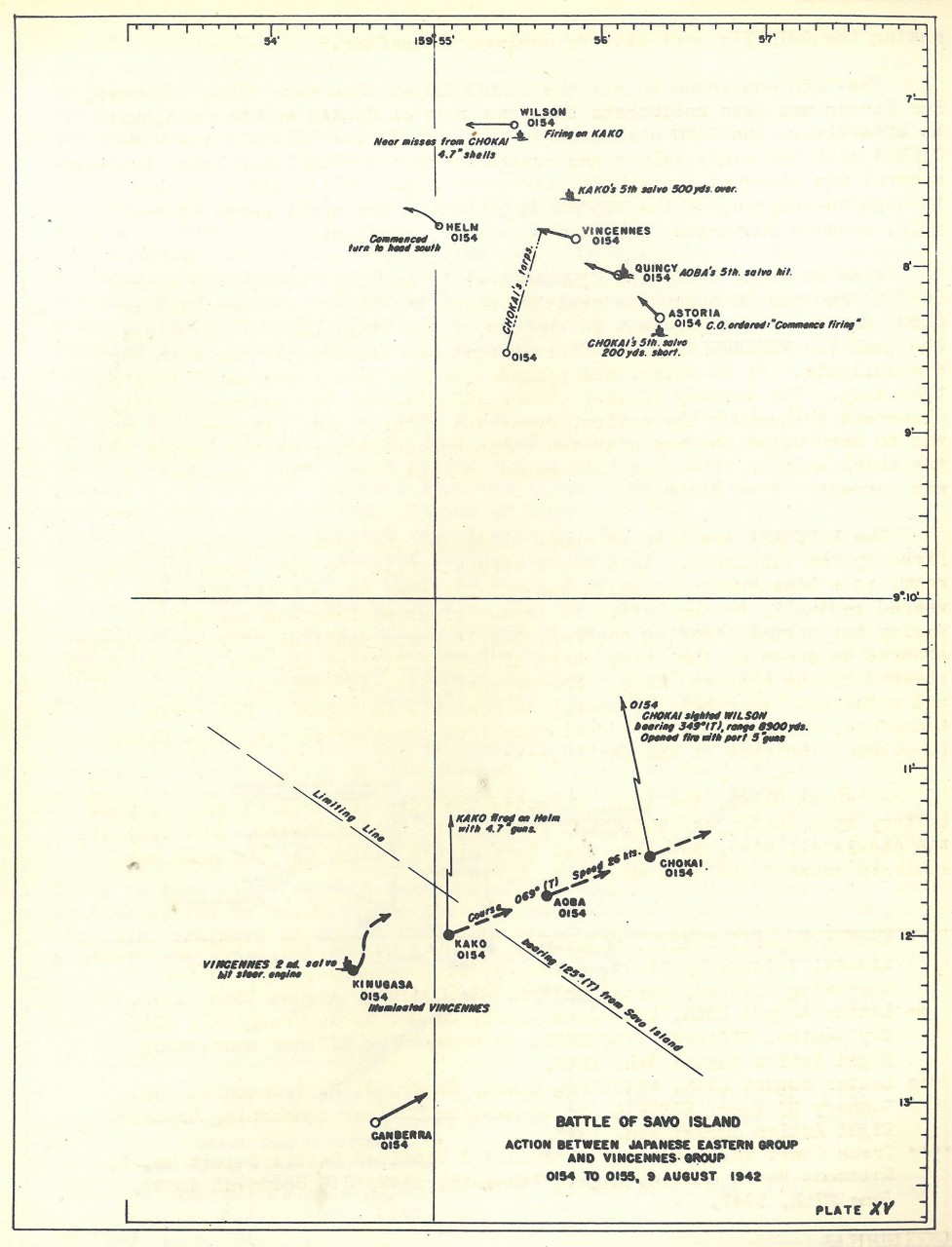

| KINUGASA Fires Four Torpedoes at CANBERRA | 157 | ||

| CHOKAI Fires at WILSON | 157 | ||

| CHOKAI Fires Fourth Salvo at ASTORIA | 157 | ||

x

PAGE |

|||

| AOBA's Fifth Salvo Hits QUINCY | 157-158 | ||

| KAKO Continues Hitting VINCENNES | 158 | ||

| KINUGASA Fires at VINCENNES | 158 | ||

| KINUGASA Hit by VINCENNES | 158 | ||

| AOBA Fires at HELM | 158 | ||

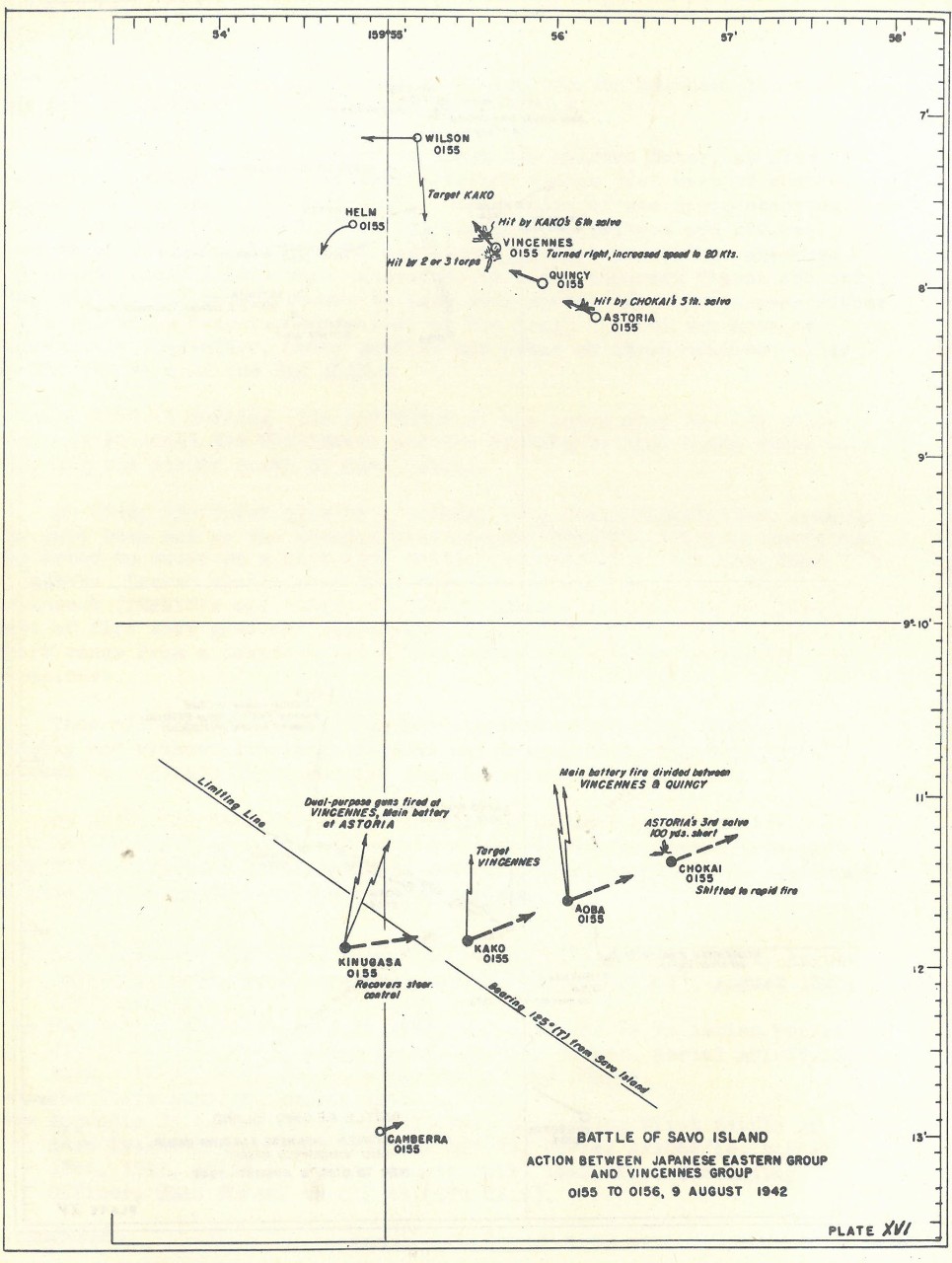

| AOBA's Sixth Salvo Hits QUINCY | 159 | ||

| AOBA Divides Fire Between VINCENNES and QUINCY | 159 | ||

| CHOKAI's Fifth Salvo Hits ASTORIA | 159 | ||

| KAKO Hits VINCENNES | 159 | ||

| KINUGASA Fires at VINCENNES, ASTORIA and HELM | 159 | ||

| CHOKAI Hits ASTORIA | 160 | ||

| KINUGASA Fires at VINCENNES | 160 | ||

| KINUGASA is Hit by PATTERSON | 160 | ||

| Commander Cruiser Force Closes Enemy and Observes that VINCENNES Group had Sunk | 160 | ||

| CHOKAI Falls Behind | 160 | ||

| (b) | Action Between Japanese Western Group and VINCENNES Group | 162-167 | |

| COMCRUDIV EIGHTEEN Avoids FURUTAKA | 162 | ||

| Changes Course to 000°(T) | 164 | ||

| Observes CANBERRA Sinking | 164 | ||

| FURUTAKA Opens Fire on QUINCY | 164 | ||

| COMCRUDIV EIGHTEEN Sights the VINCENNES Group | 164-165 | ||

| TENRYU Opens Fire on QUINCY | 165 | ||

| FURUTAKA Shifts Fire to VINCENNES | 165 | ||

| (c) | Action of YUNAGI with JARVIS | 166-167 | |

| Opens Fire on JARVIS | 166 | ||

| Breaks off Action | 166 | ||

| CHAPTER XIV | ALLIED OPERATIONS | 168-214 | |

| (0150 August 9th to 0200 August 9th) | |||

| (a) | Engagement of VINCENNES Group with Japanese Eastern Group | 168-203 | |

| VINCENNES Group is Illuminated by Searchlights | 168 | ||

| Commander VINCENNES Group Estimates the Situation | 168-169 | ||

| Decides to Maintain Course and Speed | 169 | ||

| Discussion of This Decision | 169-171 | ||

| (1) Action by VINCENNES | 171-178 | ||

| Trains on KAKO But Fails to Open Fire | 171 | ||

| Observes Enemy Salvos Landing | 171-172 | ||

| Fires Star Shells to Illuminate Enemy | 172 | ||

| Directs Destroyers HELM and WILSON to Attack | 172 | ||

| Is Heavily Hit | 173 | ||

| Fires First Salvo | 173 | ||

| Commander VINCENNES Group Re-estimates Situation | 174 | ||

| Decides to Close Enemy | 174 | ||

| Discussion of this Decision | 174 | ||

| Fires Second Salvo and Hits KINUGASA | 175 | ||

xi

| PAGE | |||

| Commander VINCENNES Group Decides to Turn Away | 176 | ||

| VINCENNES is Torpedoed and Slows Down | 176 | ||

| Commanding Officer Endeavors to Change Course to Port | 177-178 | ||

| Changes Course to Right and Fires Third Salvo | 178 | ||

| (2) Action by QUINCY | 178-187 | ||

| Commanding Officer Estimates Situation | 178-179 | ||

| Considers Searchlights Friendly | 179 | ||

| Directs Gunnery Officer Fire on Searchlights | 179-180 | ||

| Observes Enemy Salvos | 180 | ||

| Unable set Condition One Promptly | 180 | ||

| QUINCY is Hit | 182 | ||

| Maneuvers to Follow VINCENNES | 183 | ||

| Observes Japanese Western Group | 184-185 | ||

| Fires First Salvo | 185 | ||

| Continues to be Heavily Hit | 186-187 | ||

| (3) Action by ASTORIA | 187-198 | ||

| Gunnery Officer Requests General Quarters be Set | 187 | ||

| O.O.D. Fails to Call Commanding Officer | 187-188 | ||

| Observes Salvos Land off Port Side | 188 | ||

| Gunnery Officer Urgently Requests General Quarters be Set | 189 | ||

| Obtains Radar Range on Japanese Cruisers | 189-190 | ||

| Gunnery Officer Opens Fire | 190 | ||

| First Salvo | 190 | ||

| Quartermaster Sounds General Alarm | 191 | ||

| Commanding Officer Called | 191 | ||

| Fires Second Salvo | 192 | ||

| Commanding Officer Appears on Bridge and Orders "Cease Firing" | 192 | ||

| Discussion of this Order | 192-193 | ||

| Commanding Officer Observes ASTORIA Straddled and Hit | 194 | ||

| Orders "General Quarters" and "Commence Firing" | 194 | ||

| Fires Third Salvo | 195 | ||

| Hits CHOKAI With Machine Gun Fire | 195 | ||

| Commanding Officer Estimates Situation | 195-196 | ||

| ASTORIA is Heavily Hit | 196 | ||

| Fires Fourth, Fifth, Sixth and Seventh Salvos | 196-197 | ||

| (4) Action by HELM | 198-200 | ||

| Fires One Salvo | 199 | ||

| Estimates the Probable Situation | 199 | ||

| Ordered to Attack | 199 | ||

| Observes Own Cruisers on Fire | 199 | ||

| Changes course to South | 199 | ||

| (5) Action by WILSON | 200-203 | ||

| Observes Unidentified Ships Illuminating and Firing on VINCENNES Group | 200 | ||

xii

| PAGE | |||

| Opens Fire | 201 | ||

| Observes VINCENNES Group Under Heavy Fire | 201 | ||

| Slightly Damaged by CHOKAI Gunfire | 202 | ||

| (b) | Operations of CHICAGO Group | 203-210 | |

| (1) Action by CHICAGO | 203-207 | ||

| Fails to Appreciate Objective | 203-204 | ||

| Opens Fire on YUBARI | 204 | ||

| Hits TENRYU | 204 | ||

| Sweeps With Searchlights | 205 | ||

| Observes Gun Action in Direction of VINCENNES Group | 205 | ||

| Determines Extent of Damage Received | 206 | ||

| (2) Action by CANBERRA | 207 | ||

| (3) Action by PATTERSON | 207-209 | ||

| Proceeds Independently to Eastward | 207 | ||

| Discovers Had Failed to Fire Torpedoes | 208 | ||

| Opens Fire on KINUGASA | 208 | ||

| (4) Action by BAGLEY | 209-210 | ||

| Passes Under Stern of CANBERRA | 209 | ||

| Decides to Continue Scanning Operations | 210 | ||

| (c) | Operation of Radar and Anti-Submarine Screen | 210-211 | |

| (1) Operations of BLUE | 210-211 | ||

| (2) Operations of RALPH TALBOT | 211 | ||

| (d) | Operation of CTG 62.6 | 211 | |

| Observes Firing | 211-212 | ||

| Believes VINCENNES and CHICAGO Groups Coordinated | 212 | ||

| Decides Station AUSTRALIA Between Enemy and Area X-RAY | 213 | ||

| Decides Rendezvous Destroyers on AUSTRALIA | 213 | ||

| (e) | Operations of SAN JUAN Group | 213-214 | |

| CHAPTER XV | OPERATIONS OF JAPANESE CRUISER FORCE | 215-228 | |

| (0200 August 9th to 0220 August 9th) | |||

| (a) | Action Between Japanese Eastern Group and VINCENNES Group | 215-223 | |

| CRUDIV SIX Separates From CHOKAI | 215 | ||

| Discussion Thereon | 215 | ||

| KAKO and KINUGASA Shift Fire to ASTORIA | 215 | ||

| KINUGASA Fires Torpedoes at Area XRAY | 215-216 | ||

| AOBA Opens Fire on ASTORIA | 216 | ||

| KAKO Fires Four Torpedoes at ASTORIA | 216-217 | ||

| AOBA Shifts Fire to QUINCY | 217 | ||

| CHOKAI Observes ASTORIA Being Hit | 217 | ||

| CHOKAI Opens Fire on ASTORIA | 217 | ||

| CHOKAI Hit by Three Shells From QUINCY | 218 | ||

| KAKO Fires Two Additional Torpedoes at ASTORIA | 218 | ||

| AOBA Observes QUINCY Attacking Formation | 218 | ||

| KAKO Fires on QUINCY and WILSON | 219 | ||

| CHOKAI Illuminates VINCENNES and Opens Fire | 219 | ||

xiii

| PAGE | ||||

| AOBA Fires One Torpedo at QUINCY | 219 | |||

| KINUGASA Illuminates QUINCY and Opens Fire | 219 | |||

| CHOKAI is Hit by ASTORIA | 220 | |||

| Japanese Extinguish Searchlights and Cease Firing | 220 | |||

| Commander Cruiser Force Estimates Situation Decides to Withdraw | 220 | |||

| Discussion of this Decision | 220-222 | |||

| (b) | Action Between Japanese Western Group and VINCENNES Group | 223-227 | ||

| FURUTAKA Shifts Fire to VINCENNES | 223 | |||

| TENRYU Fires Six Torpedoes at QUINCY | 223 | |||

| YUBARI Fires Four Torpedoes at VINCENNES | 223 | |||

| TENRYU Fires on QUINCY | 224 | |||

| YUBARI and FURUTAKA Fire on VINCENNES | 224 | |||

| YUBARI Torpedo Hits VINCENNES | 224 | |||

| TENRYU's Torpedoes Hit QUINCY | 224 | |||

| TEURYU Opens Fire Momentarily on WILSON | 224-225 | |||

| YUBARI and FURUTAKA Cease Firing | 226 | |||

| TENRYU Illuminates RALPH TALBOT and Opens Fire | 226 | |||

| FURUTAKA Opens Fire on RALPH TALBOT | 226 | |||

| RALPH TALBOT is Lightly Hit | 227 | |||

| FURUTAKA and TENRYU Cease Firing | 227 | |||

| YUBARI Illuminates RALPH TALBOT and Opens Fire | 227 | |||

| FURUTAKA Re-opens Fire | 227 | |||

| (c) | Operations of YUNAGI | 228 | ||

| CHAPTER XVI | OPERATIONS OF ALLIED SCREENING GROUP | 229-261 | ||

| (a) | Action by VINCENNES | 229-235 | ||

| Fired on by FURUTAKA | 229-230 | |||

| Is Heavily Damaged | 230 | |||

| Fires Fourth and Fifth Salvos | 230 | |||

| Is Torpedoed by One Torpedo | 231 | |||

| Is Fired on by YUBARI | 231 | |||

| Engineer Force Secures Engine and Fire Rooms | 231 | |||

| Observes Two Destroyers Ahead | 231-232 | |||

| Gunnery Officer Informs Commanding Officer Battery is Out of Action | 232 | |||

| Considers He is Being Fired on by Friendly Ships | 232 | |||

| Continues to be Heavily Hit by FURUTAKA and YUBARI | 234 | |||

| Hoists U.S. Ensign | 234 | |||

| FURUTAKA and YUBARI Cease Firing | 234 | |||

| Is Fired on by CHOKAI for Several Salvos | 235 | |||

| (b) | Action by QUINCY | 235-243 | ||

| Fires Star Shells | 236 | |||

| Is Hit by AOBA | 237 | |||

| Is Fired on by TENRYU | 237 | |||

| Commanding Officer Estimates Situation | 237-238 | |||

| Decides to Close Enemy | 238 | |||

xiv

| PAGE | |||

| Fires Second Salvo | 238 | ||

| Is Hit by Two Torpedoes From TENRYU | 238 | ||

| Fires Third Salvo and Hits CHOKAI | 239 | ||

| Is Heavily Hit | 240 | ||

| Turret II Explodes | 240 | ||

| Commanding Officer Dies | 241 | ||

| Relief Attempts Beach Ship | 241 | ||

| Command Situation Within QUINCY in Utter Confusion | 242 | ||

| Is Hit by One Torpedo | 242 | ||

| Enemy Firing Ceases | 242 | ||

| (c) | Action by ASTORIA | 243-249 | |

| Is Being Heavily Hit by AOBA, KAKO and KINUGASA | 243 | ||

| Fires Eighth and Ninth Salvos | 243 | ||

| Unable Increase Speed | 245 | ||

| Fires Tenth Salvo | 246 | ||

| Is Fired on by CHOKAI | 246 | ||

| Fires 1.1 inch Guns and Hits AOBA | 246-247 | ||

| Fires Eleventh Salvo | 247 | ||

| Enemy Fire Slackens | 247 | ||

| Combat Effectiveness at this Time | 248 | ||

| Fires Twelfth (and last) Salvo and Hits CHOKAI | 248-249 | ||

| (d) | Action by HELM | 249-250 | |

| Prepares Torpedo BAGLEY | 249 | ||

| Reverses Course to Rejoin VINCENNES Group | 249-250 | ||

| Heads for Rendezvous North of Savo Island | 250 | ||

| (e) | Action by WILSON | 251-252 | |

| Shifts Fire to AOBA | 251 | ||

| Is Fired on by TENRYU | 251 | ||

| Ceases Firing | 251 | ||

| Avoids Collision with HELM | 251 | ||

| Resumes Fire on CHOKAI | 251-252 | ||

| Ceases Fire and Heads for Savo Island | 252 | ||

| (f) | Action by CHICAGO | 253-254 | |

| Heads to Westward to Investigate Firing | 253 | ||

| Fires Star Shells | 253 | ||

| Contacts BAGLEY | 253 | ||

| Fails to Report Activities to CTG 62.6 | 253-254 | ||

| (g) | Action by CANBERRA | 254 | |

| (h) | Action by BAGLEY | 254-255 | |

| (i) | Action by PATTERSON | 255 | |

| (j) | Action by BLUE | 255-256 | |

| Contacts Small Schooner | 256 | ||

| (k) | Action by RALPH TALBOT | 257-259 | |

| Is Temporarily Illuminated by YUNAGI | 257 | ||

| Is Illuminated by TENRYU | 257 | ||

| Is Fired on By Tenryu and FURUTAKA | 257 | ||

| Considers Enemy Ships Friendly | 257 | ||

| Received One Hit | 258 | ||

xv

PAGE |

|||

| FURUTAKA and TENRYU Cease Firing at Ralph Talbot | 257 | ||

| Is Illuminated and Fired on by YUBARI | 258 | ||

| Is Fired on by FURUTAKA | 258 | ||

| Opens Fire on Yubari | 258-259 | ||

| Is Heavily Hit | 259 | ||

| Fires Three Torpedoes at YUBARI | 259 | ||

| FURUTAKA Ceases Firing at RALPH TALBOT | 259 | ||

| (l) | Operations of CTG 62.6 (AUSTRALIA) | 260 | |

| Awaits Information | 260 | ||

| Orders Destroyers to Concentrate | 260 | ||

| (m) | Operations of San Juan Group | 260-261 | |

| CHAPTER XVII | OPERATIONS OF JAPANESE CRUISER FORCE | 262-271 | |

| (0220 August 9th to 2400 August 9th) | |||

| (a) | Withdrawal of Japanese Cruiser Force | 262-266 | |

| (1) Operations of Commander Eastern Group | 262-263 | ||

| Continues Retirement | 262-263 | ||

| (2) Operations of Japanese Western Group | 263-265 | ||

| YUBARI Fires on RALPH TALBOT | 264 | ||

| Reforms Formation | 264 | ||

| YUBARI Receives Slight Damage | 265 | ||

| YUBARI Ceases Firing | 265 | ||

| Continues Retirement | 265 | ||

| Rejoins Eastern Group | 265 | ||

| (3) Operations of YUNAGI | 266 | ||

| (b) | Operations of Japanese Cruiser Force 0340 to 0958 | 266-268 | |

| Assumes Original Column Formation | 266 | ||

| Prepares for an Attack | 267 | ||

| Considers Himself in Safe Waters | 267-268 | ||

| (c) | Separation of Japanese Cruiser Force 0958 | 268 | |

| (d) | Operations of Commander Japanese Cruiser Force 0958 to 2400 | 268-271 | |

| (1) Operations of Commander Bismarck Island Group | 268-270 | ||

| Retires Through Bougainville Strait | 268-269 | ||

| Estimates Situation | 269-270 | ||

| (2) Operations of Rabaul Group 0958 to 2400 | 270-271 | ||

| Retires Through Bougainville Strait | 270 | ||

| CHAPTER XVIII | OPERATIONS OF OTHER JAPANESE FORCES | 272-279 | |

| (a) | Operations of Commander Fifth Air Attack Force | 272-279 | |

| Receives Word of Night Action at Savo | 272 | ||

| Estimates Situation | 272 | ||

| Conducts Searches | 273-275 | ||

| Launches Air Attack Group | 276 | ||

| Probable Operations Air Attack Group | 276-277 | ||

| Hears of Retiring Allied Cruiser | 277 | ||

| Re-Estimates Situation | 277-278 | ||

| Decides Attack Retiring Allied Cruiser | 278 | ||

xvi

| PAGE | ||||

| (b) Operations of Japanese Submarines | 279 | |||

| CHAPTER XIX | OPERATIONS OF ALLIED SCREENING GROUP | 280-312 | ||

| (0220 August 9th to 2400 August 9th) | ||||

| (a) | Operations of CHICAGO Group | 280-289 | ||

| (1) Operations of CHICAGO | 280-283 | |||

| Commanding Officer is Interrogated by CTG 62.6 and Replies | 280 | |||

| Discussion of His Operations | 280-281 | |||

| Commanding Officer is Interrogated Again by CTG 62.6 and Replies | 281 | |||

| Opens Fire on PATTERSON Which Returns Fire | 282 | |||

| Ceases Firing | 282 | |||

| Joins SAN JUAN Group | 283 | |||

| Rejoins TF 62 | 283 | |||

| Summary of Shells Fired and Hits Received | 283 | |||

| (2) Loss of CANBERRA | 283-285 | |||

| Abandons Ship | 284 | |||

| Is Fired on by SELFRIDGE in Attempt to Sink | 285 | |||

| Is Fired on by ELLET by Mistake | 285 | |||

| Is Sunk by ELLET on Orders | 285 | |||

| Summary of Shells and Torpedoes Fired and Hits Received | 285 | |||

| (3) Operations of BAGLEY | 285-287 | |||

| Removes Survivors from ASTORIA | 286 | |||

| Discovers Many Additional Survivors Still on Board ASTORIA | 286 | |||

| Summary of Shells and Torpedoes Fired and Hits Received | 287 | |||

| (4) Operations of PATTERSON | 287-289 | |||

| Stands by CANBERRA | 287 | |||

| Removes Survivors | 288 | |||

| Engages CHICAGO, No Damage | 288-289 | |||

| Returns Area XRAY | 289 | |||

| Summary of Shells and Torpedoes Fired and Hits Received | 289 | |||

| (b) | Operations of VINCENNES Group | 289-297 | ||

| (1) Loss of VINCENNES | 289-290 | |||

| Abandons Ship | 289-290 | |||

| VINCENNES Sinks | 290 | |||

| Bureau of Ships Comments on Loss | 290 | |||

| Summary of Shells Fired and Hits Received | 290 | |||

| (2) Loss of QUINCY | 290-291 | |||

| Abandons Ship | 290 | |||

| QUINCY Sinks | 291 | |||

| Bureau of Ships Comments on Loss | 291 | |||

| Summary of Shells Fired and Hits Received | 291 | |||

| (3) Loss of ASTORIA | 291-296 | |||

xvii

| PAGE | ||||

| BAGLEY Removes Some Survivors | 292 | |||

| Commanding Officer Endeavors Salvage | 293 | |||

| Taken Under Tow by HOPKINS | 293 | |||

| Towing Operations Discontinued | 294 | |||

| Abandon Ship | 294 | |||

| ASTORIA Sinks | 294 | |||

| Bureau of Ships Comments on Loss | 295 | |||

| Summary of Shells Fired and Hits Received | 295 | |||

| (4) Operations of HELM and WILSON | 295-297 | |||

| Rescue Survivors from VINCENNES, QUINCY and ASTORIS | 296 | |||

| Summary of Shells and Torpedoes Fired and Hits Received | 297 | |||

| (c) | Operations of Radar and Anti-Submarine Screen | 297-301 | ||

| (1) Operations of BLUE | 297-299 | |||

| Contacts JARVIS | 298 | |||

| Rescue Survivors from CANBERRA | 299 | |||

| Summary of Shells and Torpedoes Fired and Hits Received | 299 | |||

| (2) Operations of RALPH TALBOT | 299-301 | |||

| Continues Engagement with YUBARI | 299 | |||

| Fires Torpedo at YUBARI | 300 | |||

| Makes one 5-inch Hit on YUBARI | 300 | |||

| Ceases Firing | 300 | |||

| Heavily Damaged Requires Assistance | 300 | |||

| Summary of Shells and Torpedoes Fired and Hits Received | 301 | |||

| (d) | Operations of CTG 62.6 in AUSTRALIA | 301-309 | ||

| Continues to Remain in Area XRAY | 301 | |||

| Queries His Groups as to the Battle | 301 | |||

| Receives Indefinite Replies | 301 | |||

| Queries Commander CHICAGO Group | 302 | |||

| Receives Laconic Reply | 302 | |||

| Receives CHICAGO's Amplifying Report | 303 | |||

| Informs CTF 62 of Battle | 303 | |||

| Queries PATTERSON | 303 | |||

| Receives Ambiguous Reply | 303 | |||

| Discovers His Destroyers are Concentrated at Wrong Rendezvous | 304 | |||

| Receives Report CHICAGO Heading Towards XRAY | 304 | |||

| Learns that CANBERRA is Heavily Damaged | 304 | |||

| Receives Orders Destroy CANBERRA | 305 | |||

| Directs COMDESRON FOUR Destroy CANBERRA if Cannot Retire by 0730 | 305 | |||

| Concerned About Night Action | 305 | |||

| Informs Australian Commonwealth Naval Board of AUSTRALIA's Condition | 306 | |||

| Hears of Damage to ASTORIA, QUINCY and RALPH TALBOT | 306 | |||

| Endeavors Obtain More Information | 307 |

xviii

| PAGE | ||||

| Learn from FULLER of Loss of QUINCY and VINCENNES and Damage to ASTORIA | 307 | |||

| Broadcasts Air Raid Warning | 307 | |||

| Hears of Further Damage to RALPH TALBOT | 307 | |||

| Learns Full Details of Night Battle | 308 | |||

| Retires with TF 62 to Noumea | 308 | |||

| (e) | Operations of SAN JUAN Group | 309-312 | ||

| CTG 62.4 Receives No Reports | 309 | |||

| Observes Ships on Fire and Apparently Sink | 309 | |||

| Observes Action Between CHICAGO and PATTERSON | 310 | |||

| Directs Ships of TG 62.4 Resume Daylight Screening Stations | 310 | |||

| Prepares for Battle in Transport Area | 310-311 | |||

| Receives Air Raid Alarm from CTG 62.6 | 311 | |||

| Detects by Radar Japanese Reconnaissance Plane | 311 | |||

| Rejoins Squadron YOKE as Screen | 311-312 | |||

| Retires with Squadron YOKE | 312 | |||

| CHAPTER XX | OPERATIONS OF ALLIED FORCES | 313-335 | ||

| (0000 August 9th to 2400 August 9th) | ||||

| (a) | Operations of CTF 62 | 313-322 | ||

| Advises CTF 61 Will Have to Retire TF 62 | 313 | |||

| TF 62 Gets Underway | 314 | |||

| Hears That CHICAGO Has Been Torpedoed | 315 | |||

| Learns That CTG 62.6 is not in Battle | 315 | |||

| Intercepts Dispatch Authorizing Retirement TG 61.1 | 315 | |||

| Hears CANBERRA is Heavily Damaged | 315 | |||

| Decides Retire TF 62 | 316 | |||

| Discussion of this Decision | 316 | |||

| Learns RALPH TALBOT Heavily Damaged | 316 | |||

| Becomes Concerned About Unloading Operations | 317 | |||

| Decides Remain Tulagi Area with TF 62 | 318 | |||

| Advises CTF 61 | 318 | |||

| Advises CTG 62.6 Concerning Damage to ASTORIA, QUINCY, RALPH TALBOT | 318 | |||

| Receives Contact Report on Unidentified Planes | 318 | |||

| Discusses Unloading Operations with Commanding General, First Marine Division | 319 | |||

| Reports Progress of Action to CTF 61 | 319 | |||

| Requests Admiral Fletcher's Plan | 319 | |||

| Air Raid Warning Causes Discontinuance of Unloading | 319 | |||

| Learns Full Details Night Battle | 320 | |||

| Orders Unloading Continued | 321 | |||

| Learns Will Obtain No Air Support From CTF 61 | 321 | |||

| Re-estimates the Situation | 322 | |||

| Decides Retire | 322 | |||

| TF 62 Retires | 322 | |||

xix

| PAGE | ||||

| (b) | Operations of CTF 61 | 323-327 | ||

| Hears Flash Reports About Night Battle | 323 | |||

| Receives Orders COMSOPACFOR Authorizing Retirement | 323 | |||

| Commences Retirement | 324 | |||

| Hears Additional Flash Reports | 324 | |||

| Takes No Action | 324 | |||

| Receives CTF 62's Request for His Plan | 325 | |||

| Receives Word that SARATOGA's Searches had been Negative but had Located JARVIS | 325 | |||

| Hears that CTF 62 Plans Retire | 325-326 | |||

| Advises COMSOPACFOR of Losses and Damages in Night Battle | 326 | |||

| Continues Retirement | 326-327 | |||

| (c) | Operations of CTG 61.1 | 327-330 | ||

| Weather Conditions | 327 | |||

| Receives Flash Reports of Night Action | 327 | |||

| Conducts Planned Search Operations | 327-329 | |||

| Locates JARVIS | 328 | |||

| Fails to Collect Information Concerning Night Battle | 328-329 | |||

| Continues Retirement | 330 | |||

| (d) | Operations of Allied Submarines | 330-331 | ||

| (1) Operations of S-38 | 330-331 | |||

| Sinks Japanese Transport Meiyo Maru | 330 | |||

| (2) Operations of S-44 | 331 | |||

| (e) | Operations of CTF 63 | 331-334 | ||

| Conducts Planned Search Operations | 331 | |||

| Misses Japanese Cruiser Force | 332 | |||

| Launches Air Attack Against Shipping in Rekata Bay | 333 | |||

| (f) | Operations of Commander Allied Air Forces SOWESPAC | 334-335 | ||

| Conducts Planned Search Operations | 334 | |||

| Contacts CRUDIV SIX | 334 | |||

| Contact Report Not Received in SOPAC | 335 | |||

| CHAPTER XXI | EPILOGUE | 336-338 | ||

| (1) Allied Operations | 337 | |||

| (2) Japanese Operations | 337 | |||

| (3) Situation as of 2400 August 10th | 337-338 | |||

| CHAPTER XXII | THE EFFECTS OF THE BATTLE | 339-341 | ||

xx

| PAGE | |||

| CHAPTER XXIII | BATTLE LESSONS | 342-366 | |

| 1. | Relation Between Strategy and Tactics | 343 | |

| 2. | Importance of Surprise | 344 | |

| 3. | Correct Location of the Commander of an Expeditionary Force | 344-345 | |

| 4. | Necessity for Making Every Effort to Accomplish the Objective | 345-346 | |

| 5. | Importance of Correctly Reporting Enemy Damages | 346-347 | |

| 6. | Discussion Concerning Division of Forces | 347-348 | |

| 7. | Capabilities vs. Intentions in Planning | 348-349 | |

| 8. | Importance of Setting Conditions of Readiness Promptly | 349-350 | |

| 9. | Influence of Technological Advantages on Naval Operations | 350 | |

| 10. | Commander Should have Operational Control over Shore-Based Aircraft Assigned | 350-351 | |

| 11. | Necessity for Providing Land and Tender-Based Aircraft Adequate in Numbers and in Training | 351-352 | |

| 12. | Fundamentals in Planning | 352 | |

| 13. | Necessity for Promptly Broadcasting Contact Reports | 352-353 | |

| 14. | Officer-in-Tactical-Command Should be Informed of the Various Changes in the Situation | 353-354 | |

| 15. | Advisability of Providing Battle Plans | 354-355 | |

| 16. | Importance of Advising Command of Changes in Officer-in-Tactical Command | 355 | |

| 17. | Employment of Commanding Officer as Group Commander as well not Recommended | 355-356 | |

| 18. | Gunnery Effectiveness Stems from Gunnery Training | 356-358 | |

| 19. | Necessity for Improvement of Professional Judgment in Command | 359-360 | |

| 20. | Functions of a Carrier Covering Force | 360-361 | |

| 21. | Importance of Damage Control Training | 361-362 | |

| 22. | Necessity for Maintenance of Reliable, Rapid and Secure Communications | 362-363 | |

| 23. | Importance of Correct Identification and Recognition | 363-364 | |

| 24. | Importance of Mobile Logistics Support in the Operating Area | 364-365 | |

| 25. | Task Organizations Should be Flexible | 365 | |

| 26. | Tactical Voice Radio Discipline Should be Maintained | 365-366 | |

| CHAPTER XXIV | Combat Appraisal of the Japanese Commander Cruiser Force | 367-369 | |

| * * * | |||

| Appendix I | Organization of Southeast Area Force at the Time of the Battle of Savo Island | 370-371 | |

| Appendix II | Organization of the South Pacific Force at the Time of the Battle of Savo Island | 372-374 | |

| Appendix III | Organization of Southwest Pacific Forces Which Assisted SOPAC Operations at the Time of the Battle of Savo Island | 375 | |

| Appendix IV | Summary of Japanese Damage | 376 | |

| Appendix V | Summary of Allied Damage | 377 | |

xxi

| TABLES, PLATES AND DIAGRAMS | |||

| PAGE | |||

| TABLES | |||

| 1 | Disposition of Usable Japanese Shore and Tender-Based Aircraft as of 2400 August 6th, 1942 | 9 | |

| 2 | Disposition of Allied Shore and Tender-Based Aircraft as of 2400 August 6th, 1942 | 22 | |

| 3 | Disposition of Allied Shore and Tender-Based Aircraft as of 2400 August 7th, 1942 | 70 | |

| 4 | Disposition of Allied Shore and Tender-Based Aircraft as of 2400 August 8th, 1942 | 100 | |

| Plates | |||

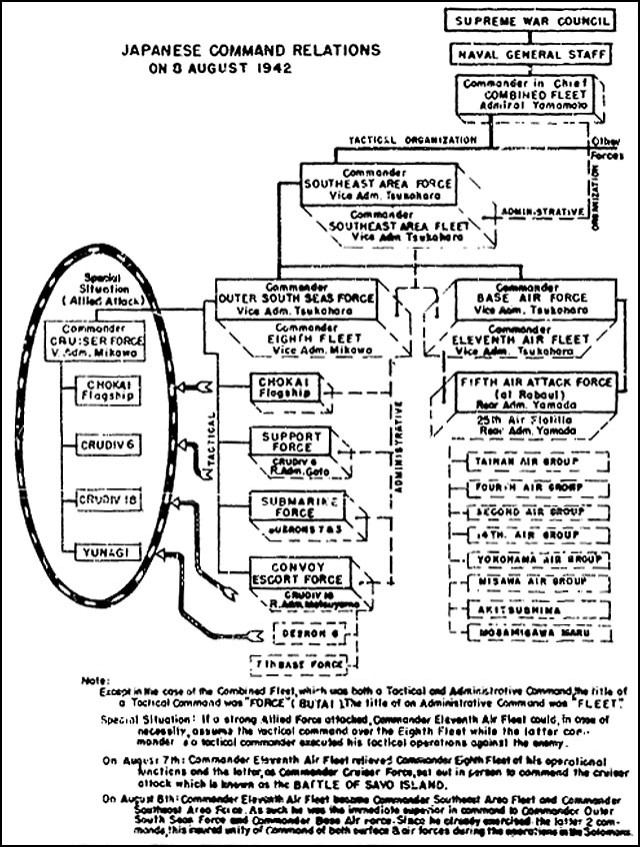

| I | Japanese Command Relations, August 8th | 6 | |

| II | Allied Command Relations, August 8th | 16 | |

| III | Communication Between SOPAC and SOWESPAC | 31 | |

| IV | Night Disposition of Allied Screening Force | 55 | |

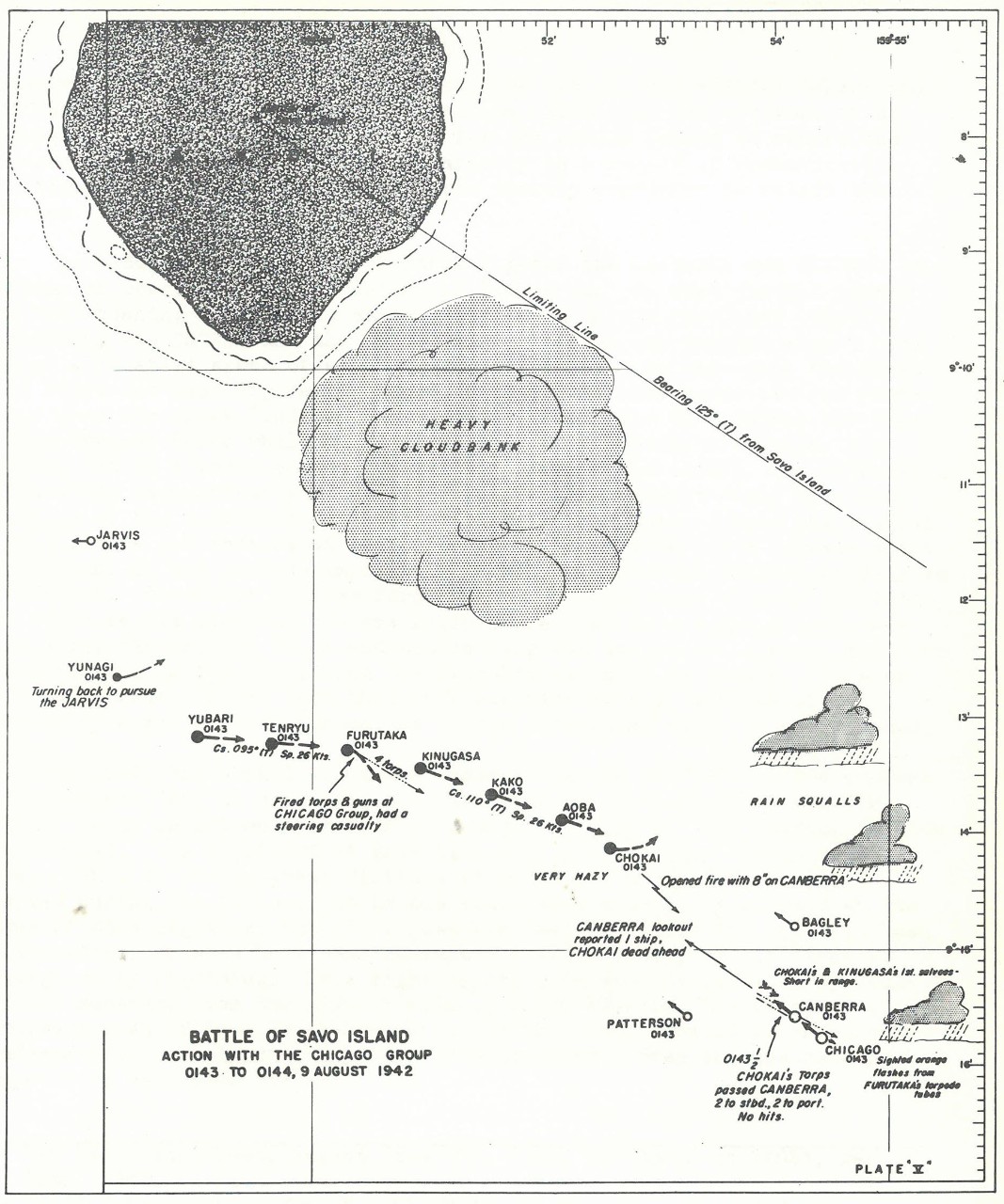

| V | Action With CHICAGO Group, 0143 to 0144 | 118 | |

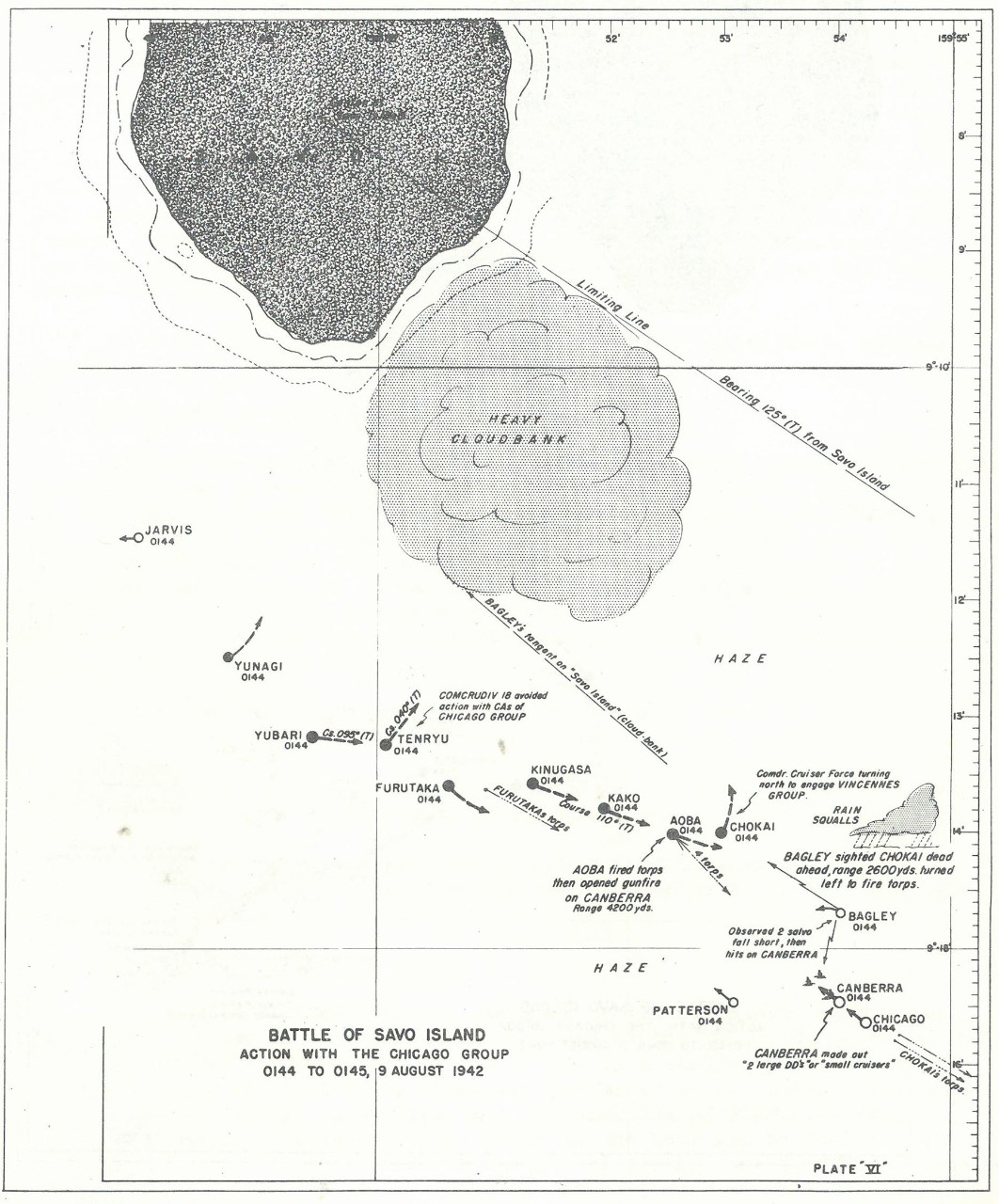

| VI | Action With CHICAGO Group, 0144 to 0145 | 119 | |

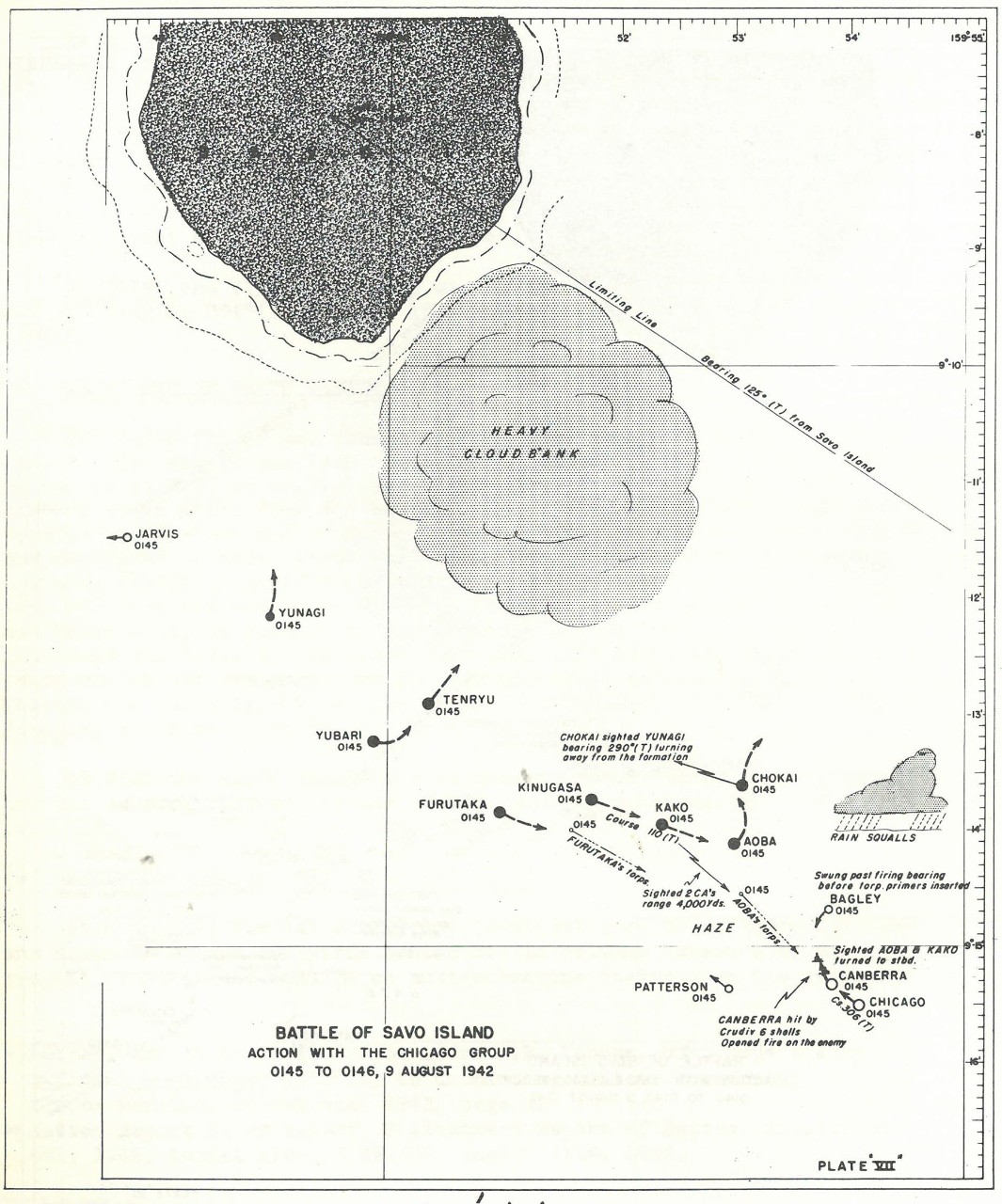

| VII | Action With CHICAGO Group, 0145 to 0146 | 120 | |

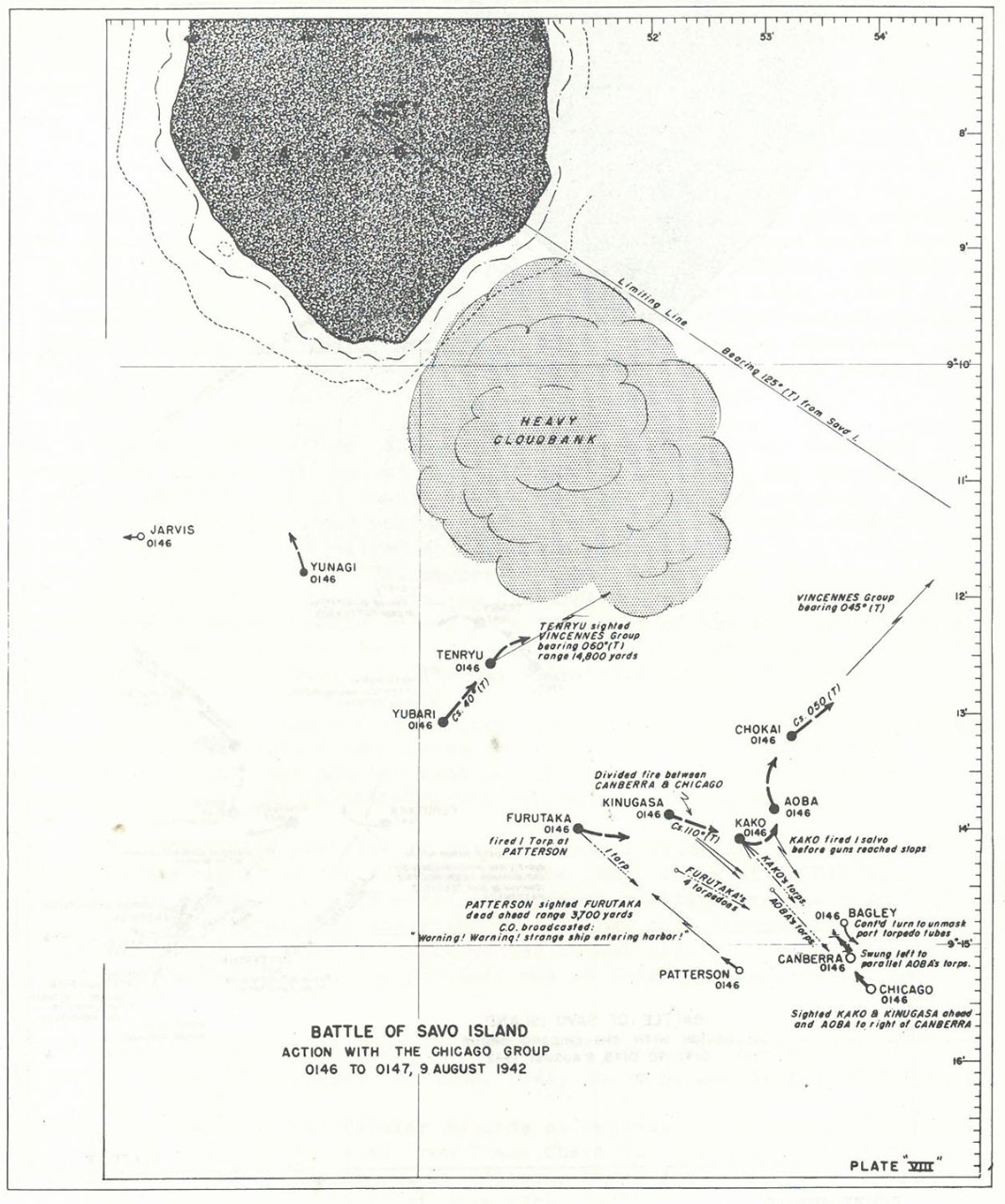

| VIII | Action With CHICAGO Group, 0146 to 0147 | 121 | |

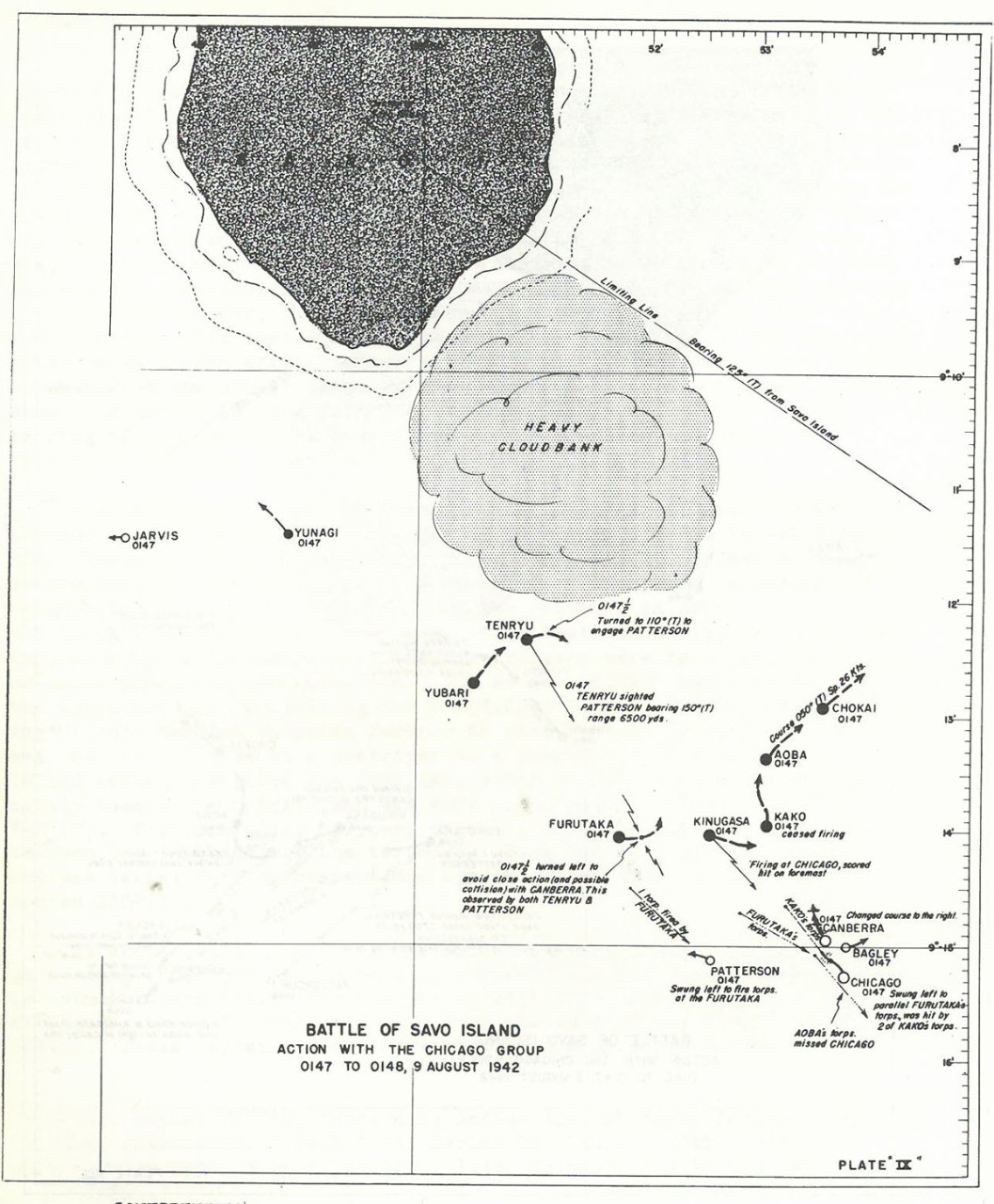

| IX | Action With CHICAGO Group, 0147 to 0148 | 122 | |

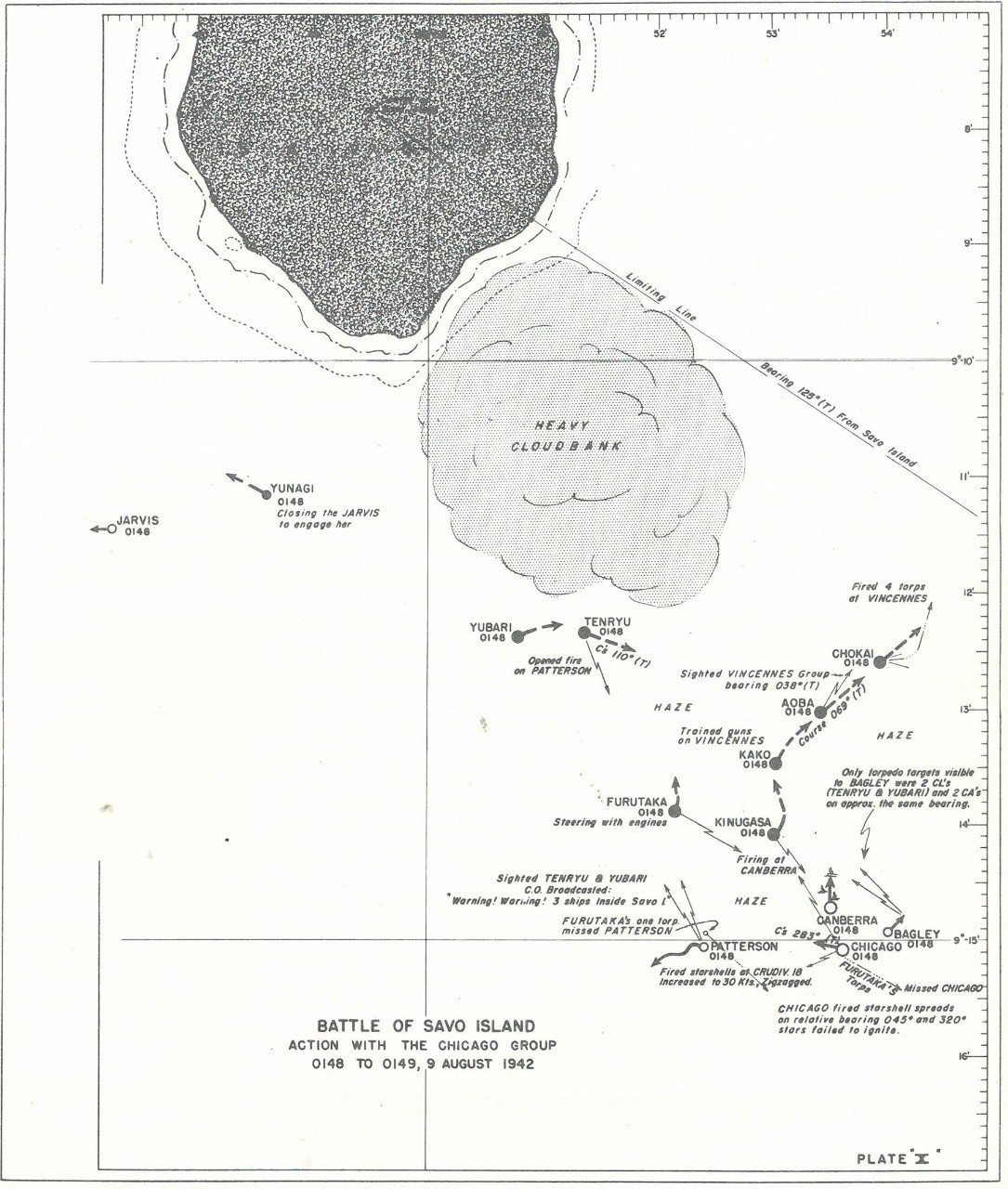

| X | Action With CHICAGO Group, 0148 to 0149 | 123 | |

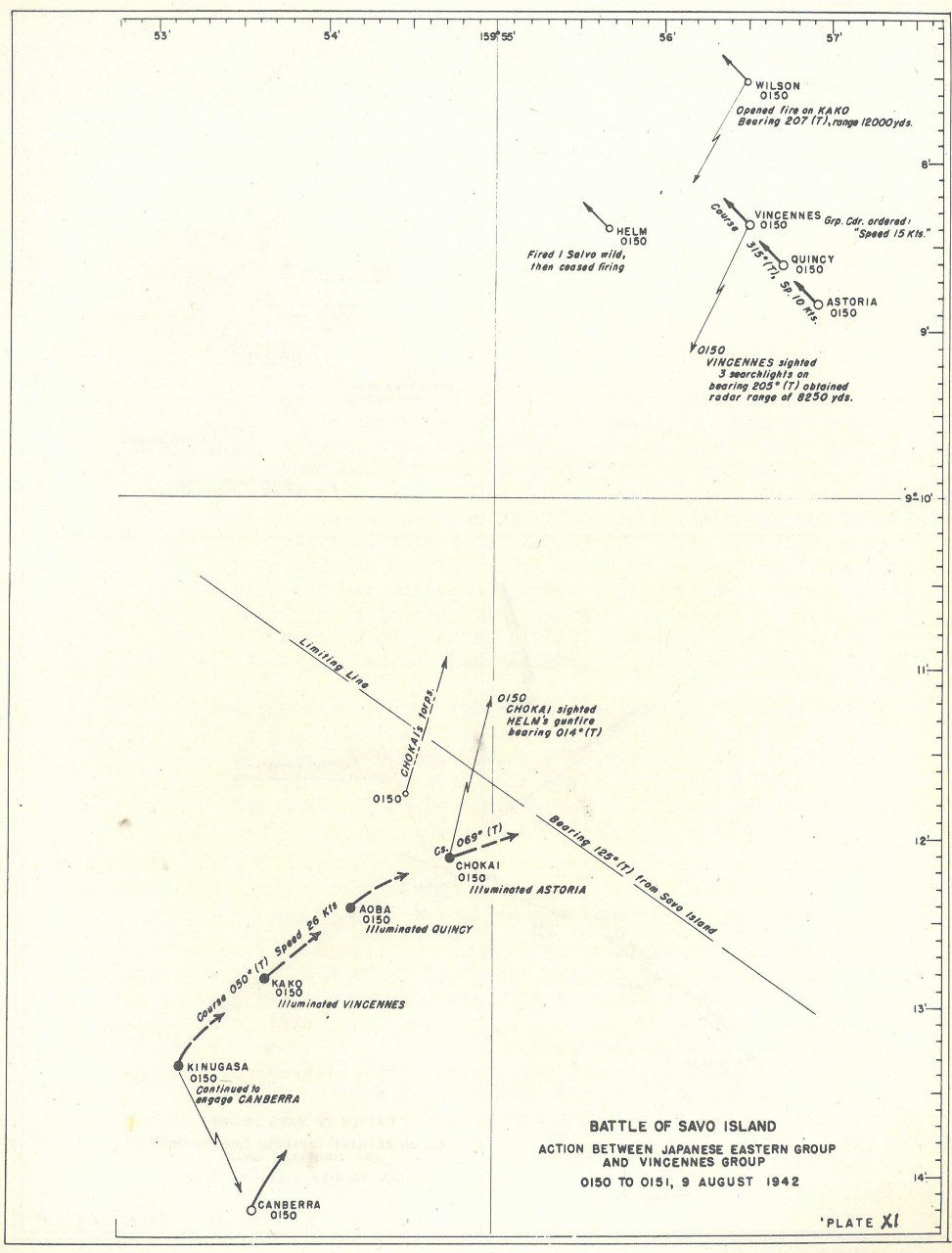

| XI | Action Between Japanese Eastern Group and VINCENNES Group, 0150 to 0151 | 152 | |

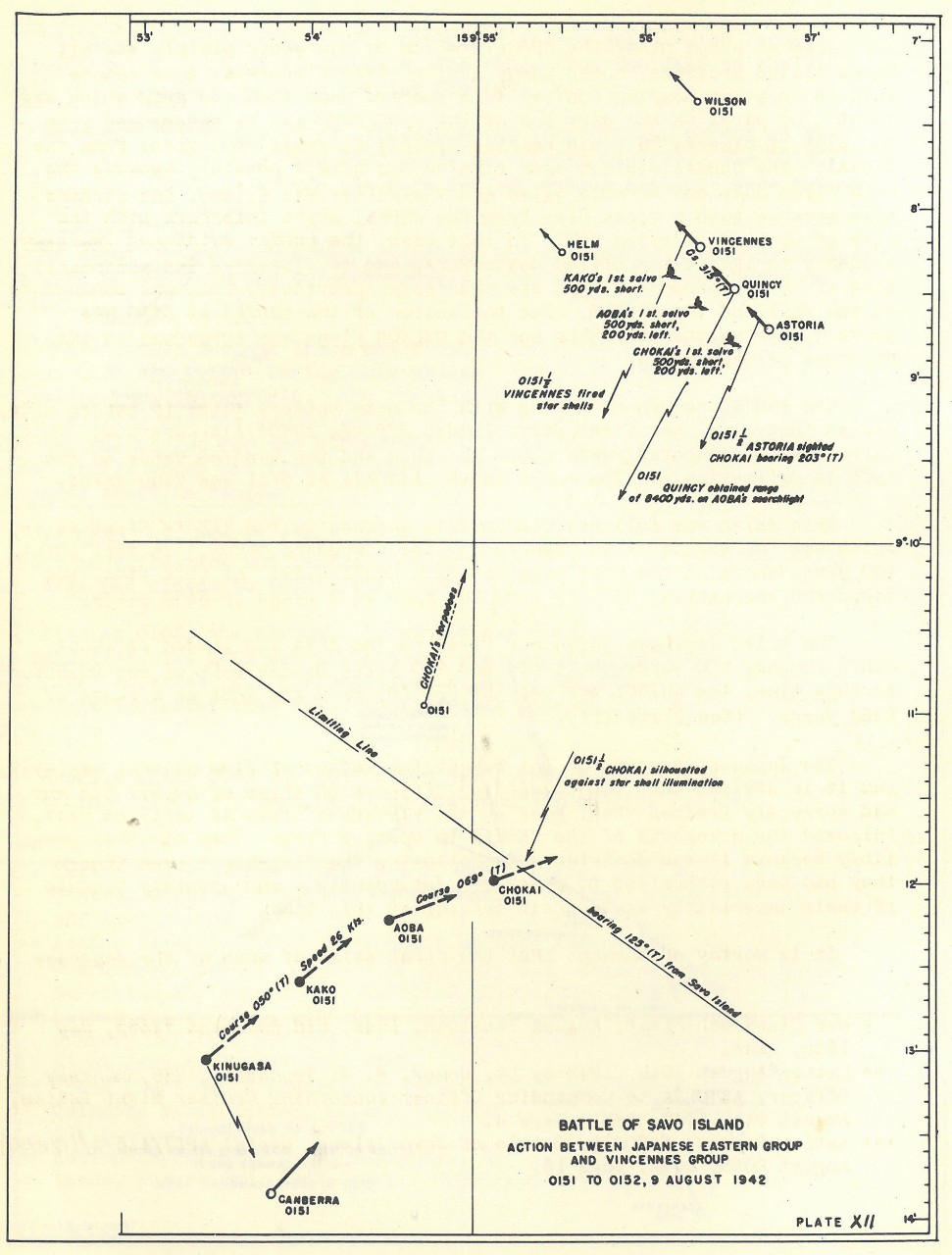

| XII | Action Between Japanese Eastern Group and VINCENNES Group, 0151 to 0152 | 153 | |

| XIII | Action Between Japanese Eastern Group and VINCENNES Group, 0152 to 0153 | 155 | |

| XIV | Action Between Japanese Eastern Group and VINCENNES Group, 0153 to 0154 | 156 | |

| XV | Action Between Japanese Eastern Group and VINCENNES Group, 0154 to 0155 | 158 | |

| XVI | Action Between Japanese Eastern Group and VINCENNES Group, 0155 to 0156 | 159 | |

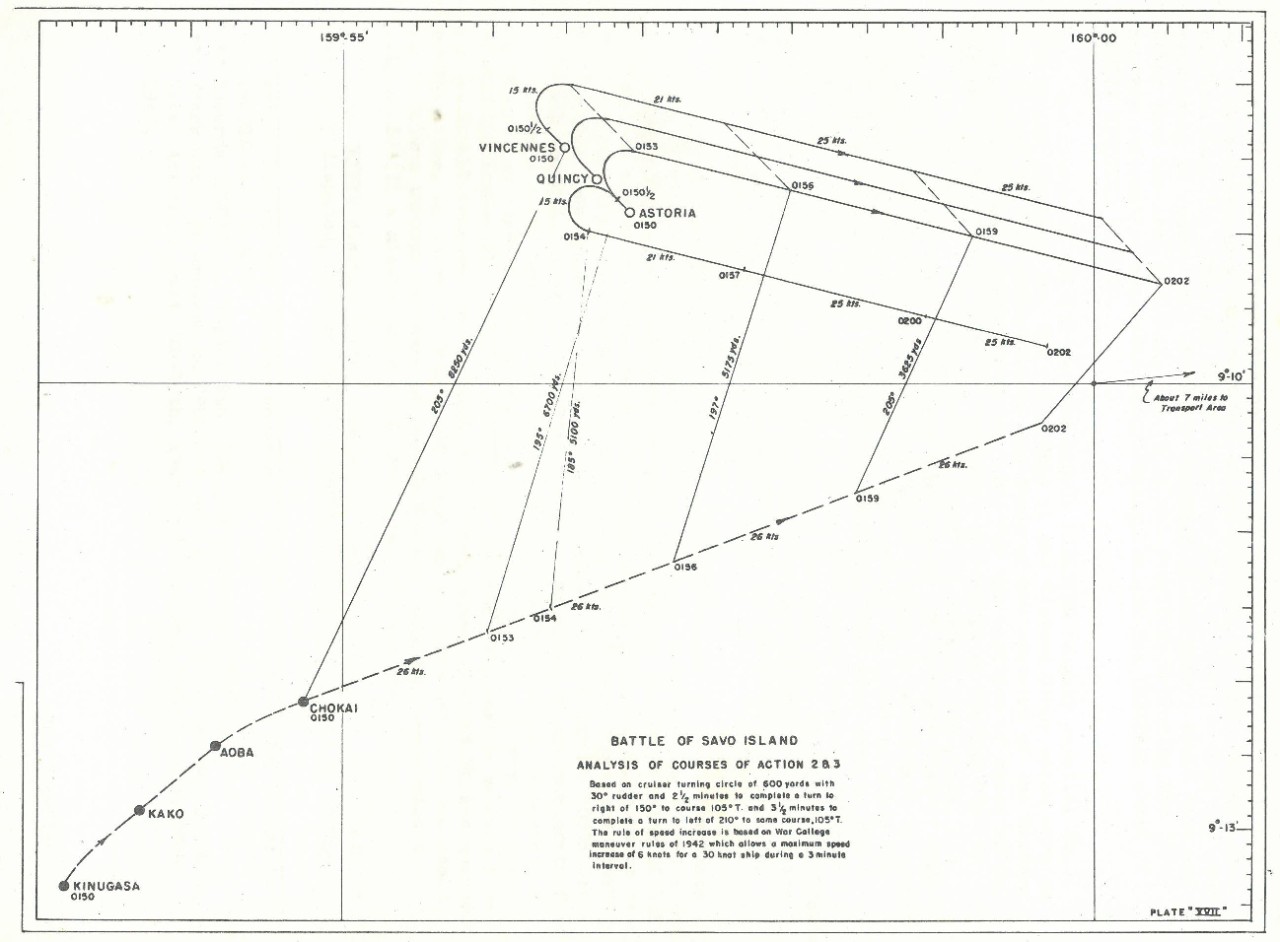

| XVII | Analysis of Courses of Action 2 and 3 | 169 | |

| DIAGRAMS | Follows | ||

| "A" | Strategic Area Chart | 377 | |

| "B" | Air Searches and Movement of Forces, 6 August | 378 | |

| "C" | Air Searches and Movement of Forces, 7 August | 381 | |

| "D" | Air Searches and Movement of Forces, 8 August | 385 | |

| "E" | Japanese Approach Past Radar Pickets, 0000 to 0132 | Chart "D" | |

| "F" | Action With CHICAGO Group, 0132 to 0150 | 387 | |

| "G" | Opening Plan of Action With VINCENNES Group 0150 to 0200 | 389 | |

| "H" | Final Phase of Action with VINCENNES Group, 0200 to 0220 | 394 | |

| "I" | Withdrawal of Japanese Cruiser Force, 0220 to 0240 | Chart "H" | |

| "J" | Composite Track Chart | Chart "I" | |

| "K" | Air Searches and Movement of Forces, 9 August | 398 | |

xxii

Foreword

This analysis of the Battle of Savo Island was prepared by the Naval War College. It is based on information from both Allied and Japanese sources which is wider and more complete than that available to writers on this subject up to this time. It endeavors to maintain, at all times, the viewpoint of the Commanders of the units involved on both sides.

Complete information from all sources was not available to this analysis. This was especially true concerning Japanese information. Unfortunately, sufficient translators were not available to provide all of the additional translations which the progress of the analysis indicated were desirable. New facts and circumstances, therefore, may come to light, from time to time, which may change some of the analyses produced herein.

In view of the critical nature of this analysis an effort has been made in certain important situations to place the critic in the position of the Commander in order to obtain the latter's point of view. In employing this system it is realized that although the critic can often succeed in placing himself sufficiently near the position of the Commander for any practical purposes, in many instances he may not succeed in doing so.

Because of the nature of this Allied defeat and the numerous controversies which have arisen concerning it, a complete background has been provided. In addition, when the time comes to analyze the other battles in the struggle for Guadalcanal, this material will be available.

The Battle of Savo Island was a real test of existing Allied and Japanese night tactical concepts as well as of the combat ability in night action of the various Commanders on both sides. The pages of history have invariably revealed defects in command in similar situations, and it would have been surprising had such defects not appeared in this action.

As a result of battle lessons learned, and ass quickly applied, the ability of the Navy to conduct warfare steadily improved during the course of the war. As time went on the lesson so often forgotten - that the test of battle is the only test which proves the combat ability of Commanders - was relearned. The ability or the lack of ability of the various Commanders in the art of war became apparent. Valor alone was shown to be insufficient, for valor is not an attribute of only one race, but is an attribute and a heritage of many races. The indispensable qualification for command, the art of war, was shown to be the ability in combat to apply the science of war to active military situations.

The present senior officers of the Navy are well aware of the reasons for changes in established doctrines and in the development of new ones. But this cannot necessarily be said of the Commanders of the future, who very probably will be inexperience in command in war.

--i--

Finally, all comments and criticisms are designed to be constructive. By indicating what appear to be sound and unsound decisions, and the apparent reasons for arriving at them, it is hoped to provide earnest thought among prospective commanders and thus to improve professional judgment in command.

--ii--

[Note: Table of Contents moved to beginning of project, pages iii - xxii.]

ALL TIMES IN THIS ANALYSIS, EXCEPT DISPATCH TIMES

ARE ZONE TIME (- 11)

DISPATCH TIMES ARE GREENWICH CIVIL TIME

--xxiii--

Principal Commanders

| American | ||

|---|---|---|

| Commander Screening Group, CTF 62.6 | Rear Admiral V.A.C. Crutchley, RN | |

| Commander Australia (Chicago) Group | Captain Howard D. Bode, USN | |

| Commander Vincennes Group | Captain Frederick Reifkohl, USN | |

| Commander San Juan Group, CTG 62.4 | Rear Admiral Norman Scott, USN | |

| ** | ||

| Commander Amphibious Force, CTF 61.2 or CTF 62 | Rear Admiral Richmond K. Turner, USN | |

| Commander Allied Expeditionary Force, CTG 61; also CTG 61.1.1 | Vice Admiral Frank J. Fletcher, USN | |

| Commander Aircraft South Pacific Force (COMAIRSOPAC), CTF 53 | Rear Admiral John S. McCain, USN | |

| Commander Southern Pacific Area (COMSOPAC) and Commander Southern Pacific Naval Forces (COMSOPACFOR) |

Vice Admiral Robert Ghormley, USN | |

| Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet (CINCPAC) and Pacific Ocean Areas (CINCPOA) |

Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, USN | |

| *** | ||

| Commander Allied Air Forces Southwest Pacific Area (COMAIRSOWESPAC) | Major General George C. Kenney, (Air Corps) USA | |

--xxiv--

| Commanding General South Pacific Area (COMGENSOPAC) | Major General Millard F. Harmon, (Air Corps) USA | |

| Commander Allied Naval Forces Pacific Area (COMNAVSOWESPAC) | Vice Admiral Fairfax Leary, USN | |

| Supreme Commander Southwest Pacific Area (COMSOWESPAC) | General Douglas MacArthur, USA | |

| Japanese | ||

|---|---|---|

| Commander Cruiser Force | Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa, IJN | |

| Commander Cruiser Division SIX | Rear Admiral Aritomo Goto, IJN | |

| Commander Cruiser Division EIGHTEEN | Rear Admiral Mitsuharu Matsuyama, IJN | |

| Commander 26th Air Flotilla | Rear Admiral Sayayoshi Yamada, IJN | |

| Commander Southeast Area, Commander 11th Air Fleet and Commander Outer South Seas Force |

Vice Admiral Nighigo Tsukuhara, IJN | |

| Commander in Chief, Combined Fleet | Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, IJN | |

--xxv--

Introduction

The Battle of Savo Island is an action of singular interest to students of naval history for several reasons: It was the first occasion in which Japanese and Allied naval forces had engaged in night battle since the Allies had assumed the offensive; it was a serious tactical defeat to the Allied forces, and finally it was a classic example of a powerful night raid by surface forces with the attendant features of surprise and withdrawal. During the early operations of 1942 Japanese and Allied surface forces had clashed in several minor night actions but no night surface actions had occurred between cruiser forces of approximately equal strength.

The battle resulted from the seizure by the Allies of the Tulagi-Guadalcanal area of the lower Solomon Island sin order to protect the Allied lines of communications to Australia and New Zealand. These lines were being menaced by the expansion of the Japanese in that direction.1

In order to check this expansion and to contain the Japanese within the already occupied area, limited countering moves had been undertaken by the Allies. In the Battle of the Coral Sea, May 7th, the Allies had prevented entirely by carrier air action, the capture of Port Moresby by sea. In the Battle of Midway, June 3rd-6th, the Allies had inflicted, almost entirely by air action, such losses on the Japanese in aircraft carriers as to force the abandonment by them of planned advances into New Caledonia and the Fijis. However, within the Solomon Islands, the Japanese had continued to advance.2

On May 2nd they had overrun the island of Tulagi where they were attacked by an Allied carrier task force on May 4th, just before the Battle of the Coral Sea. On July 4th they had commenced building an airfield at Lunga Point, Guadalcanal Island. Actually, they were building this airfield, as well as others in the Solomon Island chain, primarily for the protection of Rabaul which was to be one of the strong points of the Japanese southern perimeter.2

With the Allied seizure of Tulagi-Guadalcanal, the Japanese realized that failure to dislodge the Allies might seriously affect Japanese strategy in that area. They, therefore, put into force energetic counter-measures designed to dislodge the Allies form their precarious foothold. These counter-measures which began on August 7th were highlighted on the early morning of August 9th, by the night action known as the Battle of Savo Island.

______________

1. U.S. Navy at War 1941-1945, Official Report by Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King, USN, page 49.

2. Campaigns of the Pacific War, USSBS 1946, page 105.

--xxvi--

A Brief Narrative of the Battle of Savo Island

The directive of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, issued by COMINCH to CINCPAC on July 2nd, 10942, put into effect the Allied plan of denying the New Britain-New Guinea-New Ireland Area to the Japanese. This plan assembled an Allied force in the South Pacific area under COMSOPACFOR for the purpose of seizing, in its first phase, the Santa Cruz Islands, Tulagi and adjacent positions.

The Allies planned the above operations with the utmost secrecy. However, the Japanese Commander in the area knew that the Allies were reconnoitering frequently the Tulagi-Guadalcanal area, and that during August, the intensity of this reconnaissance had increased. He correctly assumed that the Allies would counterattack Japanese positions in the Solomons in the near future, though not as early as August 7th. However, he had not taken any special precaution, either of air search or of reinforcing outlying bases.

Meanwhile, COMSOPAPCFOR had organized an expeditionary force consisting of an Amphibious Force and an Air Support force, the latter composed of three single carrier task groups, to seize Tulagi and Guadalcanal. This force was to be supported by land-based support aircraft operating from islands in the SOPAC Area, as well as from SOWESPAC air bases.

The Allied Expeditionary Force successfully landed on Tulagi and Guadalcanal Island at daybreak on August 7th, having achieved complete surprise.

The Japanese immediately decided that it was necessary to drive the Allies out and employed their land-based air forces and their limited surface forces for this purpose. They conducted air attacks on the Allied transports and cargo ships at Guadalcanal during two successive days. On August 7th they launched two air attacks; on August 8th they launched one air attack. All of these attacks seriously interfered with the unloading operations, but they were otherwise ineffective.

Meanwhile, on August 7th, the Japanese Commander at Rabaul decided to attack the Allied shipping at Guadalcanal with surface ships as well as with aircraft. He therefore assembled a cruiser force consisting of five heavy cruisers, the Chokai, Aoba, Kako, Kinugasa, and Furutaka; of two light cruisers, the Tenryu and Yubari; and of one destroyer, the Yunagi, and at 1628 dispatched it, commanded in person by himself, to the Tulagi-Guadalcanal Area to destroy the Allied transports and cargo ships there. While this cruiser force was assembling off Rabaul, it was sighted at 1231 by allied bombers from SOWESPAC. This contact report reached COMSOPAC at 2400.

As this cruiser force moved south toward Guadalcanal, it was first sighted at about 1930, August 7th by the Allied submarine S-38 stationed off Cape St. George, New Zealand. The submarine was forced to submerge.

--xxvii--

Upon surfacing at about 2010 the submarine incorrectly reported the composition of the force as two small and three larger vessels. This report was received by COMSOPAC at 0738, August 8th.

Some three hours later or at 1025, August 8th, the cruiser force was sighted by an R.A.A.F. plane operating from Milne Bay, and was incorrectly reported as three heavy cruisers, two destroyers and two seaplane tenders or gunboats, Later on the same day, it was sighted at 1101 by another R.A.A.F. plane which reported it as two heavy or light cruisers and one unidentified vessel. The first report was received by COMSOPAC at 1845; the second report at 2136. The long delay in transmitting these reports denied COMSOPAC the opportunity of requesting an immediate attack by COMSOWESPAC planes. The Allied high command at Tulagi-Guadalcanal, incorrectly, decided that these ships were bound for Rekata Bay, there to set up an air base from which to bomb the Allied shipping in Iron Bottom Sound, commencing on August 9th.

Commencing at sunset each evening the transports and cargo ships of the Allied amphibious force were covered by a night screening disposition designed to meet Japanese surface ship attacks from all entrances to Iron Bottom Sound. The disposition was composed of an Eastern and Western Screening Group. The Western Screening Group which fought the Battle of Savo Island consisted of two anti-submarine and radar pickets, the Blue and Ralph Talbot, stationed west and north, respectively of Savo Island, and of two cruiser-destroyer support groups. One support group, the Australia Group, consisting of the Australia, Chicago, Canberra, Patterson and Bagley guarded the passage northeast of Savo Island.

During the night of August 8th at about 2055, the Commander of the Western Screening Group, in the Australia, left his group under the tactical command of the Commanding Officer, Chicago and stood into the Guadalcanal Area to attend a conference with Commander Amphibious Force and the Commanding General, First Marine division.

At this conference which was held at 2326, August 8th, Commander Amphibious Force decided to retire his force the following morning, because the carrier Commander had decided to retire. This would leave the amphibious forces without air cover or air support.

However, as many necessary supplies had not been landed, the Commander Amphibious Force decided to unload as much of the supplies as was possible throughout the night, and an effort was made to accomplish this.

After this conference, the Commander Western Screening Group remained in the Guadalcanal Area with the Australia, this reducing the Australia group by one heavy cruiser.

--xxviii--

The Japanese Cruiser Force entered Iron Bottom Sound at about 0132, August 9th, having passed the Allied destroyer Blue without being discovered. At 0236 this force surprised the Australia Group and aided by aircraft flares dropped by its own cruiser planes, opened fire with both guns and torpedoes. Within a matter of minutes, the Canberra had bee heavily. Hit and was out of action (it was finally by Allied destroyer torpedoes at 0800); the Chicago had been torpedoed in the bow and had had her speed considerably reduced; the Bagley had fired four torpedoes ineffectively, and the Patterson had broadcasted the contact before engaging the two Japanese cruisers. The Patterson was lightly damaged in this akin, none of the sips of then Chicago Group inflicted abs important damage on the Japanese ships.

During this phase of the action the Japanese Cruiser force broke up into three groups. One consisting of the, Aoba Chokai, Kako, and Kinugasa continued on towards the Vincennes group at twenty-six knots. It caught the Vincennes Group at 0100 by surprise and, employing both guns and torpedoes, succeeded in heavily damaging the three cruisers of that group. In accomplishing this the Chokai group passed under the stern of and along the starboard side of the Vincennes Group. Another group, consisting of the Tenryu, Yubari, and Furutaka passed along the port side of the Vincennes Group and employing guns and torpedoes increased the heavy damage caused by the first group. Both of these Japanese groups intermittently employed searchlights rather than star shells for illumination. As a result of the above damage, the Quincy sank at 0238, the Vincennes at 0250 and the Astoria at 1215. The third Japanese group consisting of the destroyer Yunagi turned away from the cruiser action and ineffectively engaged I a gun battle wait the retiring allied destroyer, Jarvis. Jarvis was sunk later in the day by air attack at about 1800, August 9th.

After this action, Commander Cruiser Force, because, because of a fear of Allied carrier-based planes, decided to retire rather than to remain for the purpose of destroying the Allied shipping at Tulagi and Guadalcanal. As he retired he engaged the Allied destroyer Ralph Talbot with the Tenryu, Yubari, and Furutaka.

The Japanese Cruiser Force, except for several hits, escaped from the entire action almost entirely unscathed. In its retirement, it succeeded in avoiding Allied search planes so that it received no damage from Allied air attacks. However, it was discovered by the allied submarine, S-38, on August 10th as a result of which the Kako was torpedoed and sunk.

The effects of this battle were serious insofar as the Allies were concerned. There was a shortage of heavy escort and bombardment ships in all sea areas and as the Allies were preparing to conduct the North African Invasion, as well as to conduct offensive operations in the Aleutians and to continue those already underway in the Solomons, the

--xxix--

loss of four heavy cruisers and one destroyer was immediately felt in all areas.

The Japanese on the other hand grossly exaggerated the Allied losses in surface ships and informed the world and the Japanese people by press and radio of their claims.

--xxx--

Chapter I

The Strategic Area

(a) GENERAL DISCUSSION

The strategic area involved in the combat and support operations of the Solomon Islands offensive extended from the Equator southward to the Tropic of Capricorn and from the 180th Meridian westward to the coasts of Australia and New Guinea. This over-all area, besides being entirely tropical, was oceanic. The total land mass of the small islands east of Australia and New Guinea is no greater than n the area of Celebes--or to use a more familiar example, no greater than the area of any one of the states of Washington, Missouri or Oklahoma.

The outstanding characteristic of this area is the chain of small islands extending from New Guinea to New Caledonia through the Bismarck Archipelago, the Solomon Islands, Santa Cruz Islands, New Hebrides and Loyalty Islands. These islands define the eastern boundary of the Coral Sea, including the Solomon sea north of the Louisiade Archipelago. As a series of potential air and sea bases, they constitute a barrier between Australia and North America.

This strategic area was adaptable to limited offensive operations. On the one hand, the Japanese could slowly extend themselves deeply into the South Pacific through the island chain to threaten the life-line from Australia and New Zealand to the United States. On the other hand, the Allies were provided with a route of advance toward Japanese strong points in the Western Pacific. They were also provided with an extremely advanced position from which to effect attrition upon the limited war potential of Japan. Consequently the strategic area became a theater of combat.

The strategic area was divided into two approximately equal areas by the boundary between the Southwest Pacific area and the South Pacific area along meridian 159 degrees East Longitude. This boundary passed through middle of Santa Isabel Island in the Solomons, and passed about 35 miles west of Guadalcanal Island. The Guadalcanal-Tulagi target area, wherein was fought the battle of Savo Island, lay wholly within the South Pacific area.

The threat of a large-scale overseas attack by the Japanese upon Australia and New Zealand through this area had been temporarily removed by the battle of the Coral Sea in May 1942 and the Battle of Midway in June of that year. However, the Japanese had continued to advance slowly thereafter by piecemeal penetration overland southward along the coast of New Guinea and by sea southward through the Solomons.

The relative positions of the Japanese and the Allies within this strategic area in August 1942 provided the Japanese with the more favorable military situation. The Allied positions in the south Pacific Area

--1--

were but lightly held, and consisted chiefly of airfields under construction which had been hurried to a degree of readiness for limited use in the days just prior to August 7th, 1942. These airfields were located on New Caledonia, Efate, Espiritu Santo, and in the Fijis. The Japanese positions in the Bismarck Archipelago, with their principal advanced base at Rabaul, were firmly held. Their positions at Kavieng, Rabaul, Las, Salamaua, and Buka were less firmly held and were being strengthened by a major effort in the development of airfields.* In improving these positions the Japanese had extended their occupation of New Guinea as far south as Buna, had occupied Florida Island in the Solomons, and had moved into the north-central shore love Guadalcanal Island on July 4th where they had immediately begun the construction of an airfield, harbor facilities, and other installations at large at Lunga Point.

It was apparent to the Allied High command that the firm establishment of the Japanese at Tulagi and Florida Island and its airfield at Guadalcanal would seriously hamper, if not prevent the Allies from establishing themselves in Espiritu Santo and Santa Cruz,** and that therefore the Japanese positions in the Solomons were a threat to vital links in the Allied communications. It was also apparent that the Allied positions relative to the Japanese were potentially less menacing.

The positions of the Japanese and the Allies, relative to the Guadalcanal-Tulagi area in air miles.

| Maramasike Estuary, Malaita (A) *** | 90 | miles |

| Rekata Bay, Santa Isabel (J) | 120 | " |

| Kieta, Bougainville (J) | 340 | " |

| Ndeni, Santa Cruz Islands (A) | 365 | " |

| Buka Island (J) | 392 | " |

| Rabaul, New Britain (j) | 540 | " |

| Milne Bay, New Guinea (A) | 565 | " |

| Espiritu Santo (A) | 580 | " |

| Kavieng, New Ireland (J) | 665 | " |

| Efate (A) | 715 | " |

| Port Moresby, New Guinea (A) | 745 | " |

| Plaines des Gaiac, New Caledonia (A) | 790 | " |

| Noumea, New Caledonia (A) | 875 | " |

| Townsville, Australia (A) | 970 | " |

| Nandi, Fiji Islands (A) | 1155 | " |

There were no allied harbors in the area suitably equipped to effect major repairs to damaged ships. The docking facilities at Pearl Harbor were about 4000 miles away via Fiji. At Sydney, which was about 2000 miles away from Savo Island via Noumea, there were repair facilities for

_______________

* ComSoWesPac Dispatch 081018 which is Part Five of Dispatch 081012, July 1942

** COMINCH Dispatch 102100, July 1942

*** (A) means Allied - (J) means Japanese

--2--

cruisers and smaller craft. In an emergency, smaller harbors in the area could be used for repairs, although they were not equipped with supporting activities or base facilities. In particular, these were Saint James Bay, Espiritu Santo Island, and Noumea, New Caledonia. The best harbor site in the Solomons was at Tulagi on Florida Island, but this position was exposed tom enemy attack and was, prior to the landing on august 7th, in Japanese hands.

(b) THE TULAGI-GUADALCANAL AREA

The Battle of Savo Island was fought in the body of water lying between Guadalcanal and Florida Island which became known among Allied Forces as Iron Bottom Sound. This sound is the southeastern extremity of the Slot (New Georgia Sound). Then 100 fathom curve off Guadalcanal and Florida Islands are 20 miles apart at the western end of this Sound and close on each other to a distance of one mile to form the Sealark channel at the eastern end of the Sound.

Savo Island lies between the western extremities of Florida and Guadalcanal Islands, and is an approximately round volcanic island with a diameter of 4 miles and with its highest peak at 1675 feet. The 100-fathom curve is nowhere more than 1200 yards distant from the shore of Savo Island, allowing an restricted navigation closed to its shores. Savo Island divides the western approaches to Iron bottom sound into two wide passages. The southerly passage between Savo Island and Cape Esperance on Guadalcanal is seven miles wide. The northerly passage between Savo Island and Florida Islands is seven miles wide.

At its eastern end, Florida Island is thirteen miles north of Guadalcanal Island and numerous shoal patches and reefs lie within the 100-fathom curves of each island on either side of Sealark channel. Through the fouled ground off Florida Island runs the Niggela channel. Through the shoals off Guadalcanal al runs the Longo channel which is three or four miles wide with depths of eighteen to thirty fathoms.

Strong tide rips are caused by the numerous shoals and irregularities in the bin the bottom between the eastern end of Florida and Guadalcanal Islands. The tidal currents set to the westward and to the eastward along the coasts of Florida and Guadalcanal Islands, following the trend of the coast line and attaining the velocity of two knots at springs.

The general depth of water in Iron bottom Sound is 200 to 400 fathoms between Lung Point on Guadalcanal and Tulagi Harbor. Tulagi Harbor is situated midway along the southern coast of Florida Island and is the principal port of the Solomon Islands. Westward of Tulagi Harbor there are no off-lying dangers, and the 100-fathom curve runs parallel with the coast about three miles offshore.

(c) WEATHER

In the Solomon Islands area there are two marked climatic seasons.

--3--

The northeast monsoon prevails from November to March. The southeast trade wind usually establishes itself by April and lasts until October. Winds are strongest during the season of the southeast trades, averaging 10-20mph. Average wind velocities are only rarely interrupted by the passage of a tropical cyclone.

It is hot throughout the year. Average monthly temperatures range from 81 degrees (F) to 84 degrees (F). Highest temperatures are recorded from November to April.

Throughout the year, average cloudiness amounts to about 5 tenths cloud cover. The cloudiest months are January, February and March. Apart from rare cyclones, other tropical depressions cause overcast skies of intermediate and high clouds. Lower type clouds prevail with local thunderstorms and rain squalls.

Thunderstorms normally occur over land during the afternoon and over the water in the early morning. Rain squalls may occur during any season of the year. Rainfall is abundant. The months of January, February and March are the wettest. At Lunga Point, Guadalcanal the average rainfall for July is 2.70 inches. At Tulagi, average rainfall is slightly greater.

Fogs at sea level are unknown. Reduced visibility is due to heavy downpours of rain, haze, or low clouds. A particularly heavy rain squall may reduce visibility to 100 yards over a limited area. Haze is prevalent during the season of the southeast monsoon. It may render objects indistinct in visibility of 15-20 miles.*

On a cloudy night in Iron Bottom Sound, visibility has been observed to be extremely low. Rain squalls seem to form over Savo Island almost every night of the year, causing heavy rain about 2330 and clearing about 0200 as they drift slowly southeastward.** On the night of August 8th-9th, this type of bad weather did not clear up. This will be shown in the discussion of the battle itself.

________________

* All of the above is from War Department publication SSC-677, survey of the Solomon Islands, March 15, 1943, Confidential.

** CTF 62 personal letter to Captain R.C. Parker, USN(Ret), Office of Naval History, Navy Department, Washington, D.C. dated 1948.

--4--

Chapter II

Japanese Arrangements

(a) JAPANESE COMMAND RELATIONS (Plate I)

All of the Japanese Fleets, including the Naval Air Fleets, excepting the China Seas Fleets, were under the Command of the Commander-in-Chief of the Combined Fleet. The Combined Fleet consisted of the mobile (mission) fleet which could operate anywhere in any area, and of the localized (area) fleets which were responsible for and restricted to certain geographical areas. The mobile fleet constituted the main striking force of the Combined Fleet. The area fleets were normally defensive in character and were generally unable to take any strong offensive action without assistance from the mobile fleet.* The mobile fleet consisted of the Main Body (First Division FIRST Fleet), the Advance Force (SECOND Fleet), and the Striking Force (THIRD Fleet),** the area fleets consisted of the Northern Force, later called Northeast Area Force (FIFTH Fleet) based at Horomushiro; the Inner South Seas Force (FOURTH Fleet) based at Truk, the Outer South Seas Force (EIGHTH Fleet) based at Rabaul and the Southwest Area Force (Combined Expeditionary Fleet) based at Surubaya.** In addition to the mobile fleet and the area fleets, the Combined Fleet consisted of the Base Air force (ELEVENTH Fleet) base on Tinian and the Advanced Expeditionary Force (SIXTH fleet) which was composed of submarines and was based at Kwajalein.** All tactical titles employ the term "Fleet" with the single exception that the title "Combined Fleet" was both administrative and tactical (Plate I)***

Prior to July 14th, 1942 the South seas Force was responsible for the defense of the Central and southeastern Pacific Area, including the Marshalls, New Guinea, and the Solomon Islands. However, due to the increasing importance of the Central and southeastern Pacific Areas and to the fact that there was an ever-increasing threat of an attack on the Solomons by the Allies, the Japanese High Command decided to split the South Seas Area into two areas, one, an Outer South Seas Area, the other, an Inner South seas Area. This split became effective on July 14th, 1942.****

The dividing line between the two areas thus formed was established as the line bearing 280°(T) from the juncture of the equator and Long.

________________

* Japanese Naval Organization, Change No. 11 to ONI 49, page 5.

** Enclosure, Submitted October 26th, 1945 by Rear Admiral Nakamura, IJN, in answer to USSBS Memorandum No. NAV-1, October 10th, 1945.

*** Japanese Naval Organization, Change No. 11 to ONI 49, page 33.

**** War Diary, 8th Fleet, August 7th, 1942, WDC Document 161259.

--5--

150° E. Commander Inner South Seas Force was assigned the responsibility for the defense of the area north of this line and Commander Outer South Seas Force for the defense of the area south of this line. In order to provide for unity of command, it was directed that in the event of an enemy attack in the above areas, the Commander ELEVENTH Air Fleet would, in case of necessity, exercise over the FOURTH, SIXTH, AND EIGHTH Fleets.*

Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa activated the EIGHTH Fleet on July 14th. On July 16th he hoisted his flag in the Chokai. On July 23rd he was assigned the Chokai and Cruiser Division SIX and became Commander Outer South Seas Force. On July 27th he formally assumed responsibility for the New Guinea and Solomon Islands operations.*

All land based air forces in this operation wee naval and were assigned to the FIFTH Air Attack Force** (25th Air Flotilla), which was based at Rabaul and was a subdivision of the ELEVENTH Air Fleet. The Commander of this attack force retained operational control over his component and its and cooperated with the Commander Outer South Seas Force. He remained at Rabaul to direct its activities. No Army air forces were assigned at this time.***