The Navy Department Library

Interrogations of Japanese Officials - Vols. I & II

United States Strategic Bombing Survey [Pacific]

United States

Strategic Bombing Survey

[Pacific]

Naval Analysis Division

Interrogations of Japanese Officials

Volume 1

Foreword

The interrogations in this volume were conducted in TOKYO during the months of October, November, and December 1945 by officers of the Naval Analysis Division of the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey. While the original purpose of the interrogations was to gain evidence for an assessment of the role of airpower in the war with JAPAN, in the absence of any other body concerned with the conduct of this naval war, this purpose was broadened to include as wide a survey of wartime events as time and other restrictions would permit. The specific purpose of individual interrogations varied between that of obtaining comment and opinion from those very senior officers who were in a position to view the war as a whole, the discussion of specific operations and engagements with responsible commanders or other eyewitnesses and the elaboration and clarification of documentary material.

Although the Imperial Japanese Navy was abolished shortly after the surrender, and its personnel retired and dispersed, permission was obtained from General MacArthur to retain a nucleus of experienced officers at the Naval War College at HIYOSHI. In addition to being interrogated on their particular specialties and experiences, these officers performed research at the direction of the Naval Analysis Division and, together with the Japanese Naval Liaison Office, gave useful assistance in identifying and procuring other officers for interrogation.

Despite the cooperation of the Japanese, a number of unavoidable difficulties hindered the investigation. It was often a considerable problem to identify the proper individual for interrogation on a given subject, in many instances the most desirable candidates were dead, and in almost every case the selected officers had to be brought especially to TOKYO from all parts of JAPAN and even, in one case, from as far as SINGAPORE. All work was conducted by a small staff under pressure of time, without an adequate library, and in the face of an almost complete lack of original Japanese documents which had been either burned in air raids, or destroyed or hidden on surrender. Towards the end of the stay in JAPAN a quantity of hidden records were discovered; these have been returned to the United States and are now in process of translation, a work which will require a period of years to complete. In many instances, therefore, questions had to be explored entirely by interrogation with only partial or inaccurate war-time information as the starting point, with resultant delay and repetition.

So far as the question of veracity is concerned, it should be stated that almost without exception the Japanese naval officers interrogated were cooperative to the highest degree, and that no important attempt consciously to mislead the interrogator was ever noted. Accuracy on fine points was inevitably affected by the language problem which necessitated in most cases translation of both question and answer, by the specialized nature of the naval vocabulary which in some instances troubled the interpreters, and by the somewhat imprecise nature of the Japanese language itself. Allowance must also be made for the normal fallibility of human memory and in particular the memory of events months or years in the past which were witnessed under the intense strain of combat. Despite all these considerations it is felt that the interrogations provide an accurate picture of the war from the Japanese viewpoint, subject only to the qualifications that on important or disputed points of documentary confirmation should where possible be obtained.

The planned use of this material was, as has been noted above, as evidence for an evaluation of the role of airpower in the Pacific war. These interrogations, together with other material accumulated by the Naval Analysis Division, form the basis of reports to be submitted to the chairman of the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey. In view, however, of the wide range of subject matter covered, the important and in some cases unique qualifications of the Japanese officers interrogated, and the improbability that such an investigation will ever or could ever be repeated, it is believed that these interrogations form a body of source material indispensable to any future study of the war with Japan.

R A Ofstie

Rear Admiral, USN,

Senior Navy Member,

U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey.

--III--

[Blank]

--IV--

Contents

| Volume I: | Page |

| Foreword | III |

| List of Interrogations arranged numerically | VI |

| List of Interrogations arranged according to subject matter | IX |

| List of Illustrations | XIII |

| Index of Major Battles and Operations and Japanese Officials | XV |

| Interrogations 1-70 | 1 |

| Volume II: | |

| Interrogations 71-118 | 287 |

| Japanese Notes of Battles | 541 |

| Biographies of Interrogated Japanese Officials | 548 |

List of Interrogations

(Arranged Numerically)

(Arranged Numerically)

List of Interrogations

(Arranged by Subject Matter)

(Arranged by Subject Matter)

| The Aleutian Campaign: | page | Attrition, Training, Kamikaze - Con. | Page | |

| Attu and Kiska, Japanese Army gar- | Kamikaze Corps | 60 | ||

| sons on | 365 | Nav No. 12 - USSBS No. 62. | ||

| Nav No. 84 - USSBS No. 408. | Kamikaze Corps, Philippines and Oki- | |||

| Dutch Harbor, Carrier Aircraft Attack | nawa. Pearl Harbor, Attack on | 23 | ||

| on | 92 | Nav No. 6 - USSBS No. 40. | ||

| Nav No. 20 - USSBS No. 97. | Non-Combat Losses of Aircraft | 170 | ||

| First Destroyer Squadron, Japanese, | Nav No. 40 - USSBS No. 169. | |||

| Operations of | 299 | Production, Wastage and Strength, | ||

| Nav No. 73 - USSBS No.367. | IJNAF | 374 | ||

| Flying Boat Operation, Japanese, in the | 106 | Nav No. 86 - USSBS No. 414. | ||

| Aleutians | Training, IJNAF | 535 | ||

| Nav No. 23 - USSBS No. 100. | Nav No. 117 - USSBS No. 602. | |||

| Japanese Second Mobile Force and the | ||||

| Kiska Garrison from U.S. Prisoners of | 536 | Central Pacific, Marshalls, Gilberts, | ||

| War, Information on | Wake Island: | |||

| Nav No. 118 - USSBS No. 606. | Central Pacific, Japanese plans for | |||

| Japanese Twelfth Air Fleet in the Kuriles | 272 | Defense of | 165 | |

| and North Pacific | 102 | Nav No. 38 - USSBS No. 160. | ||

| Nav No. 67 - USSBS No. 311 | Central Pacific, Movements of Japanese | |||

| Kiska Garrison, Japanese Occupation of | Second Fleet in | 359 | ||

| Kuriles Operations. | Nav No. 82 - USSBS No. 396. | |||

| Nav No. 22 - USSBS No. 99. | Gilbert-Marshall Islands Operations | 86 | ||

| Komandorskis, Transports at the Battle | 207 | Nav No. 18 - USSBS No. 93. | ||

| of, 26 March 1943 | Gilberts-Marshalls Operations | 411 | ||

| Nav No. 51 - USSBS No. 205. | 97 | Nav No. 96 - USSBS No. 445. | ||

| Komandorski Islands, Battle of | Gilbert-Marshall-Marianas, Air Defense | |||

| Seaplane Operations. | of | 132 | ||

| Kurile Defense. | Nav No. 30 - USSBS No. 123. | |||

| Nav No. 21 - USSBS No. 98. | Gilbert-Marshalls Operation Naval | |||

| Komandorski Islands, Japanese Histori- | 399 | Strategic Planning | 143 | |

| cal Account of, March 1943 | Nav No. 34 - USSBS No. 139. | |||

| Nav No. 93 - USSBS No. 438. | Wake Island, Japanese Capture of | 370 | ||

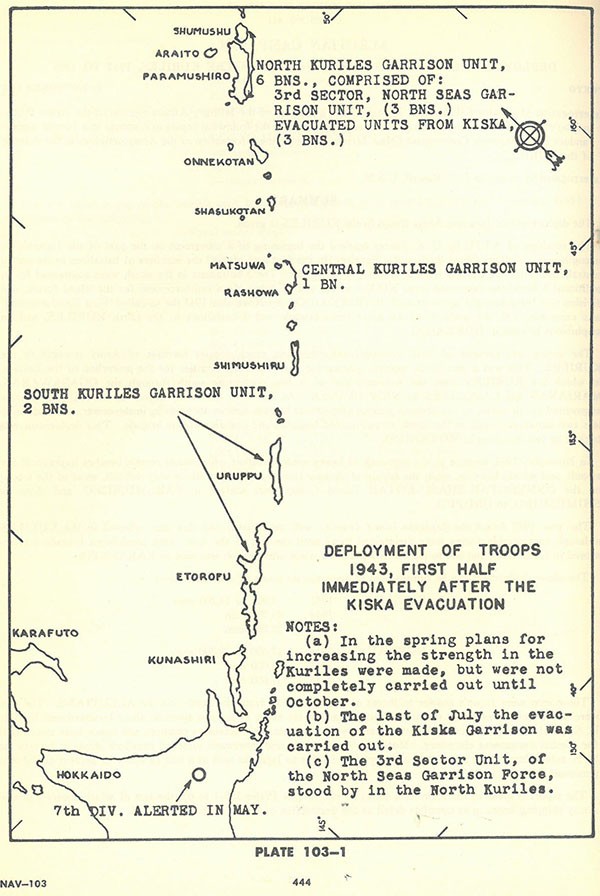

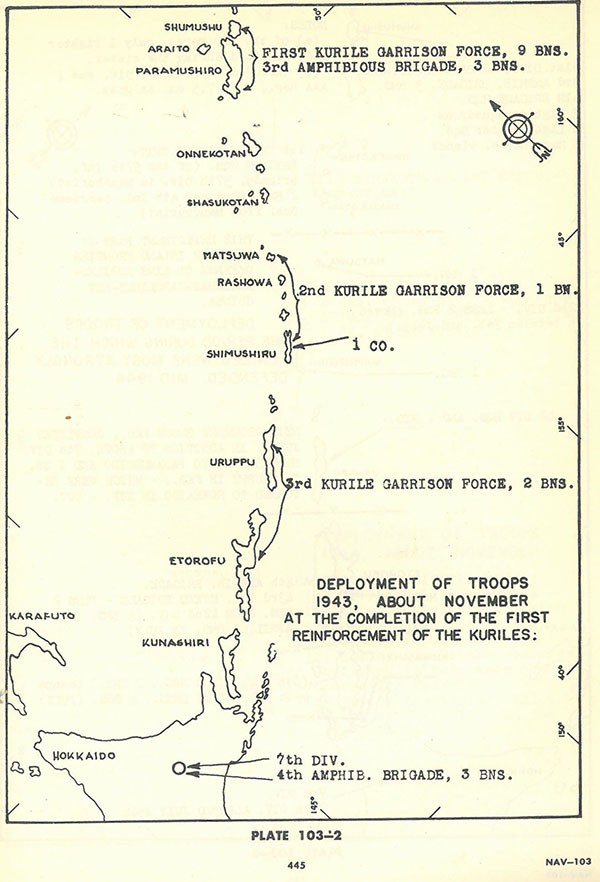

| Kuriles, Deployment of Japanese Army | 443 | Nav No. 85 - USSBS No. 413. | ||

| Forces in the | ||||

| Nav No. 103 - USSBS No. 461. | ||||

| Planning and Operations through No- | Convoy Protection - Escort Shipping: | |||

| vember 1942 | 108 | Convoys, Aircraft Escort of | 228 | |

| Nav No. 24 - USSBS No. 101. | Anti-Submarine Operations | |||

| Planning and Operations and Defense of | Nav No. 56 - USSBS No. 228. | |||

| the Kuriles, November 1942 - August | Convoy Escort and Protection of Ship- | |||

| 1945 | 110 | ping - South China Sea Area | 194 | |

| Nav No. 25 - USSBS No. 102. | Nav No. 47 - USSBS No. 199. | |||

| Convoy Protection of Shipping - Nether- | ||||

| Attrition, Training, Kamikaze: | lands East Indies - New Guinea Area | 201 | ||

| Aircraft Availability and Loss Reports | 204 | Nav No. 49 - USSBS No. 201. | ||

| Nav No. 50 - USSBS No. 202. | Escort and Protection of Shipping | 184 | ||

| Aircraft Ferrying & Pilot Attrition | Nav No. 45 - USSBS No. 194. | |||

| JNAF | 135 | Escort and Protection of Shipping | 212 | |

| Nav No. 31 - USSBS No. 129. | Nav No. 53 - USSBS No. 225. |

| Convoy Protection - Escort Shipping - | page | Midway - Continued | Page | |

| Continued | Midway - Eastern Solomons - Philip- | |||

| Escort and Defense of Shipping | 230 | pines | 269 | |

| Nav No. 57 - USSBS No. 229. | Nav No. 66 - USSBS No. 295. | |||

| Escort of Shipping | 455 | Midway - Savo Island - Solomons - | ||

| Nav No. 105 - USSBS No. 463. | Leyte Gulf | 361 | ||

| Escort of Shipping | 487 | Nav No. 83 - USSBS No. 407. | ||

| Nav No. 110 - USSBS No. 468. | Midway and Santa Cruz, Battle of; | |||

| Escort of Shipping | 491 | Cape Esperance and Coral Sea, Battles | ||

| Nav No. 111 - USSBS No. 469. | of | 456 | ||

| Japanese Convoy Escort, Organization | Nav No. 106 - USSBS No. 464. | |||

| and Development of | 440 | Midway, Solomons, Pearl Harbor | 65 | |

| Nav No. 102 - USSBS No. 460. | Nav No. 13 - USSBS No. 65. | |||

| Japanese Naval Escort of Shipping | 56 | |||

| Shipping Losses. | Mine Warfare and Countermeasures: | |||

| Nav No. 11 - USSBS No. 61. | Allied Offensive Mining Campaigns | 16 | ||

| Japanese Shipping Attacks on | 161 | Nav No. 5 - USSBS No. 34. | ||

| Nav No. 37 - USSBS No. 159. | Mine Counter-measures | 217 | ||

| Nav No. 54 - USSBS No. 226. | ||||

| Marianas, Palau, Formosa, Okinawa, Iwo | Mine Counter-measures and Shipping | |||

| Jima: | Losses - Osaka and Soerabaja Areas | 245 | ||

| Marianas Campaign, Shore-based Air- | Nav No. 59 - USSBS No. 251. | |||

| craft in | 396 | Mine Warfare | 116 | |

| Nav No. 91 - USSBS No. 434. | Nav No. 26 - USSBS No. 103. | |||

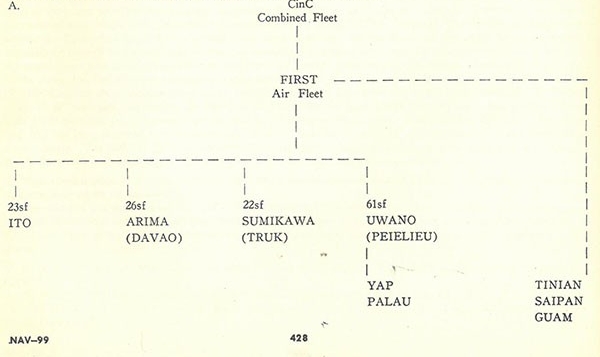

| Marianas, Shore-based Air in the | 428 | Mine Warfare in Shimonoseki Straits | ||

| Nav No. 99 - USSBS No. 448. | and Formosa Areas | 257 | ||

| Palau Strikes - Marianas | 432 | Nav No. 62 - USSBS No. 256. | ||

| Nav No. 100 - USSBS No. 454. | Mine Warfare | 267 | ||

| Philippine Sea, Battle of, 19-20 June | Nav No. 65 - USSBS No. 285. | |||

| 1944 | 7 | |||

| Nav No. 3 - USSBS No. 32. | Pearl Harbor, Attack On: | |||

| Philippine Sea, Battle of; Battle for Leyte | Pearl Harbor - Battle of Philippine | |||

| Gulf | 32 | Sea - Battle for Leyte Gulf | 122 | |

| Nav No. 9 - USSBS No. 47. | Nav No. 29 - USSBS No. 113. | |||

| Philippine Sea, Battle of - Pearl Har- | Pearl Harbor - Midway - Solomons | 65 | ||

| bor - Leyte Gulf, Battle for | 122 | Nav No. 13 - USSBS No. 65. | ||

| Saigon and Formosa. Carrier Aircraft | Pearl Harbor, Attack on; Kamikaze | |||

| Strikes on | 383 | operations in Philippines, Okinawa | 23 | |

| Nav No. 89 - USSBS No. 427. | Nav No. 6 - USSBS No. 40. | |||

| Yamato Group, The Attack on, 7 April | ||||

| 1945 | 136 | Philippine Islands, Japanese Occupation | ||

| Nav No. 32 - USSBS No. 133. | of | |||

| Philippines and Dutch East Indies, | ||||

| Midway | Operations of Japanese Naval Air- | |||

| Hiryu (CV) At the Battle of Midway | 4 | craft during Invasion of | 74 | |

| Nav No. 2 - USSBS No. 11. | Nav No. 15 - USSBS No. 74. | |||

| Midway, Battle of | 1 | Philippines and Dutch East Indies, Oc- | ||

| Nav No. 1 - USSBS No. 6. | cupation of | 25 | ||

| Midway, Battle of | 13 | Nav No. 7 - USSBS No. 33. | ||

| Nav No. 4 - USSBS No. 23. | Philippines and Dutch East Indies, Oc- | |||

| Midway, Battle of - Damage to Aircraft | cupation of | 71 | ||

| Carrier Soryu | 167 | Nav No. 14 - USSBS No. 67. | ||

| Nav No. 39 - USSBS no. 165. | Philippines and Dutch East Indies, Occu- | |||

| Midway and Eastern Solomons, Trans- | pation of | 357 | ||

| ports at; Battle of Tassafaronga | 249 | Nav No. 81 - USSBS No. 395. | ||

| Nav No. 60 - USSBS No. 252. | Philippines and Dutch East Indies, In- | |||

| vasion of | 83 | |||

| Nav No. 17 - USSBS No. 90. |

| Philippine Islands, Japanese Occupation | Page | Planning and Policies, Japanese - Con. | Page | |

| of - Continued | Japanese War Planning | 327 | ||

| Philippines, Invasion of | 275 | Nav No. 76 - USSBS No. 379. | ||

| Nav No. 68 - USSBS No. 331. | The Naval War in the Pacific | 502 | ||

| Second Fleet, Operation of Main Body of | 90 | Nav No. 115 - USSBS No. 503. | ||

| Nav No. 19 - USSBS No. 94. | Observations on the Course of the War | 284 | ||

| Nav No. 70 - USSBS No. 359. | ||||

| Philippine Islands, United States Re- | Observations on Japan at War | 384 | ||

| Occupation of: | Nav No. 90 - USSBS No. 429. | |||

| Cape Engano, Battle off, 24-25 October | Overall Planning and Policies | 422 | ||

| 1944 | 153 | Nav No. 98 - USSBS No. 447. | ||

| Nav No. 36 - USSBS No. 150. | Tokyo Air Defense | 118 | ||

| Cape Engano, Battle off | 277 | Nav No. 28 - USSBS No. 112. | ||

| Nav No. 69 - USSBS No. 345. | ||||

| First Air Fleet - Spring 1944 | 376 | Rabaul, New Guinea, Malaya Areas: | ||

| Nav No. 87 - USSBS No. 420. | Bismark Sea Convoy - 3 March 1943 | 500 | ||

| Leyte Gulf, Battle for, October 1944 | 219 | Nav No. 113 - USSBS No. 484. | ||

| Nav No. 55 - USSBS No. 227. | Celebes and Rabaul Area, Japanese Land- | |||

| Leyte Gulf, Battle for; Battle of Philip- | Based Air Operations in | 533 | ||

| pine Sea | 32 | Nav No. 116 - USSBS No. 601. | ||

| Nav No. 9 - USSBS No. 47. | Guadalcanal - Midway - Munda and Ra- | |||

| Leyte Gulf, Battle for - Battle of Philip- | baul | 191 | ||

| pine Sea - Pearl Harbor | 122 | Nav No. 46 - USSBS No. 195. | ||

| Nav No. 29 - USSBS No. 113. | KON Operation for Reinforcement of | |||

| Leyte Gulf - Savo Island - Midway - | Biak | 450 | ||

| Solomons | 361 | Nav No. 104 - USSBS No. 462. | ||

| Nav No. 83 - USSBS No. 407. | Malaya, Operation of 22d Air Flotilla | |||

| Philippines, Defense of, 1944 | 178 | in | 333 | |

| Nav No. 44 - USSBS No. 193. | Nav No. 77 - USSBS No. 387. | |||

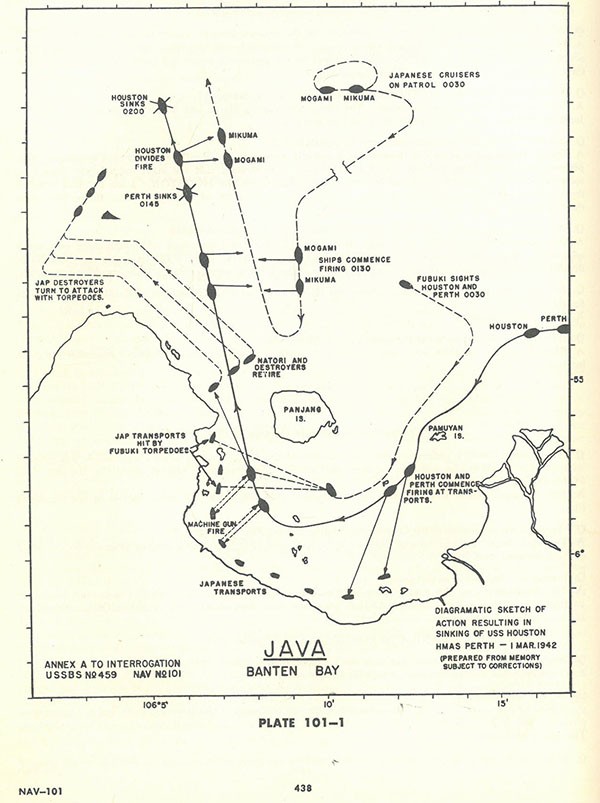

| Philippines, First Transportation Corps | New Guinea, Western, Japanese Naval | |||

| in Defense of - USS Houston and | Land-Based Air Operations in | 287 | ||

| HMAS Perth, Sinking of, March | Nav No. 71 - USSBS No. 360. | |||

| 1942 | 436 | New Guinea Area, Japanese Naval Opera- | ||

| Nav No. 101 - USSBS No. 459. | tions in | 409 | ||

| Philippines, Midway, Eastern Solomons | 269 | Nav No. 95 - USSBS No. 441. | ||

| Nav No. 66 - USSBS No. 295. | New Guinea Area, Japanese Army Air | |||

| Samar, Battle off, 25 October 1944 | 147 | Force in | 404 | |

| Nav No. 35 - USSBS No. 149. | Nav No. 94 - USSBS No. 440. | |||

| Samar, Battle off, 23-26 October 1944 | 171 | Rabaul | 209 | |

| Nav No. 41 - USSBS No. 170. | Nav No. 52 - USSBS No. 224. | |||

| Surigao Strait, Battle of | 235 | Rabaul Area, Ship Operations in | 397 | |

| Nav No. 58 - USSBS No. 233. | Nav No. 92 - USSBS No. 435. | |||

| Surigao Strait, Battle of | 341 | Rabaul, Air Operations by Japanese | ||

| Nav No. 79 - USSBS No. 390. | Naval Air Forces Based at | 413 | ||

| Nav No. 97 - USSBS No. 446. | ||||

| Panning and Policies, Japanese: | 21st Air Flotilla | 379 | ||

| The Air War - General Observations | 497 | Nav No. 88 - USSBS No. 424. | ||

| Nav No. 112 - USSBS No. 473. | ||||

| Japanese Naval Planning | 176 | Solomon Islands: | ||

| Nav No. 43 - USSBS No. 192. | Coral Sea Battle, 7-8 May 1942; Battle | |||

| Japanese Naval Planning After Midway | 262 | of Eastern Solomons | 29 | |

| Nav No. 64 - USSBS No. 258. | Nav No. 8 - USSBS No. 46. | |||

| Japanese Naval Plans | 352 | Coral Sea, Battle of, and Solomon Islands | ||

| Nav No. 80 - USSBS No. 392. | Operations | 53 | ||

| Japanese War Plans and Peace Moves | 313 | Nav No. 10 - USSBS No. 53. | ||

| Nav No. 75 - USSBS No. 378. | Coral Sea and Cape Esperance Battles; | |||

| Midway and Santa Cruz Battles | 456 | |||

| Nav No. 106 - USSBS No. 464. |

| Solomon Islands - Continued | page | Solomon Islands - Continued | page | |

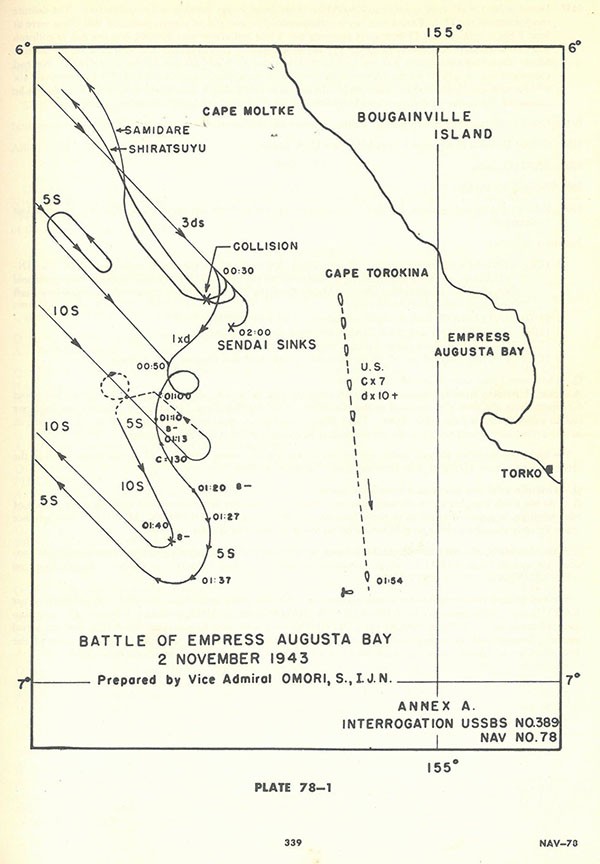

| Empress Augusta Bay - 2 November | Solomons, Transports at Eastern; Battle | |||

| 1943 | 337 | of Tassafaronga, 30 November 1942; | ||

| Nav No. 78 - USSBS No. 389. | Transports at Midway | 249 | ||

| Guadalcanal- Midway - Villa | 141 | Nav No. 60 - USSBS No. 252. | ||

| Nav No. 33 - USSBS No. 138. | Solomons Campaign, Japanese Army | |||

| Guadalcanal - Midway - Munda - | Air Forces in | 501 | ||

| Rabaul | 191 | Nav No. 114 - USSBS No. 485. | ||

| Nav No. 46 - USSBS No. 195. | ||||

| Midway - Eastern Solomons - Philip- | Submarine and Anti-Submarine Operations: | |||

| pines | 269 | Anti-Submarine Operations, Aircraft | ||

| Nav No. 66 - USSBS No. 295. | Escort of Convoys and | 228 | ||

| Savo Island, Battle of, 9 August 1942 | 255 | Nav No. 56 - USSBS No. 228. | ||

| Nav No. 61 - USSBS No. 255. | Anti-Submarine Equipment and Train- | |||

| Savo Island - Midway - Solomons - | ing | 259 | ||

| Leyte Gulf | 361 | Nav No. 63 - USSBS No. 257. | ||

| Nav No. 83 - USSBS 407. | Anti-Submarine Warfare | 309 | ||

| Solomons Campaign, 1942-43; Battle of | Nav No. 74 - USSBS No. 371. | |||

| Eastern Solomons, 23-25 August 1942; | Submarine Attacks on Japanese Con- | |||

| Battle of Santa Cruz, 26 October 1942 | 77 | voys | 465 | |

| Nav No. 16 - USSBS No. 75. | Nav No. 107 - USSBS No. 465. | |||

| Solomons, Midway, Pearl Harbor | 65 | Japanese Submarine Operations | 467 | |

| Nav No. 13 - USSBS No. 65. | Nav No. 108 - USSBS No. 466. | |||

| Solomon Islands Actions 1942-43 | 470 | Submarine Warfare | 291 | |

| Nav No. 109 - USSBS No. 467. | Nav No. 72 - USSBS No. 336. | |||

| Japanese Airborne Magnetic Detector | 197 | |||

| Nav No. 48 - USSBS No. 200. |

List of Illustrations

Note. - Plates for illustrations are numbered according to the Nav No. of the interrogation in which they appear; i. e. Annexes A, B, and C for Nav No. 9 are numbered Plate 9-1, 9-2, and 9-3.

| Plate | Title | Page |

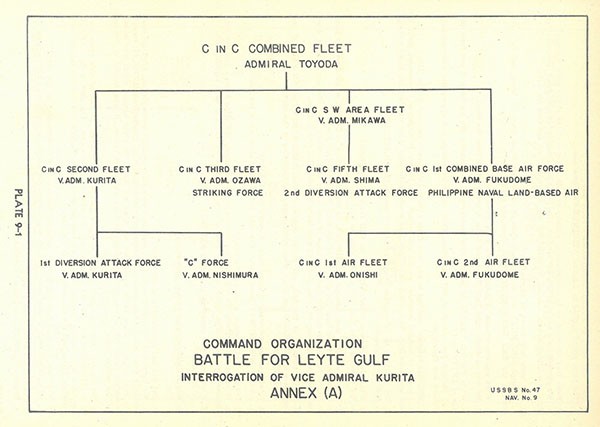

| 9-1 | Command Organization - Battle for Leyte Gulf | 35 |

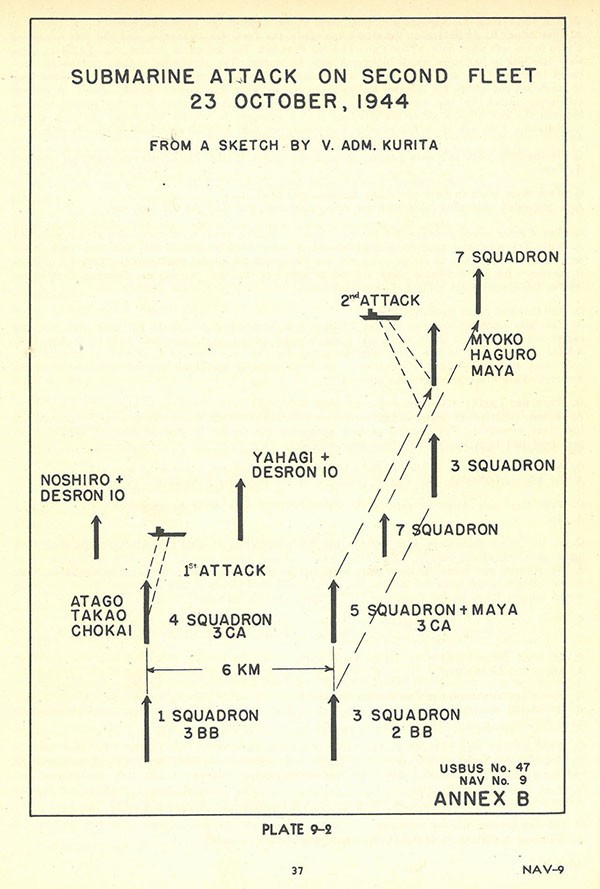

| 9-2 | Submarine Attack on Second Fleet, 23 October 1944 | 37 |

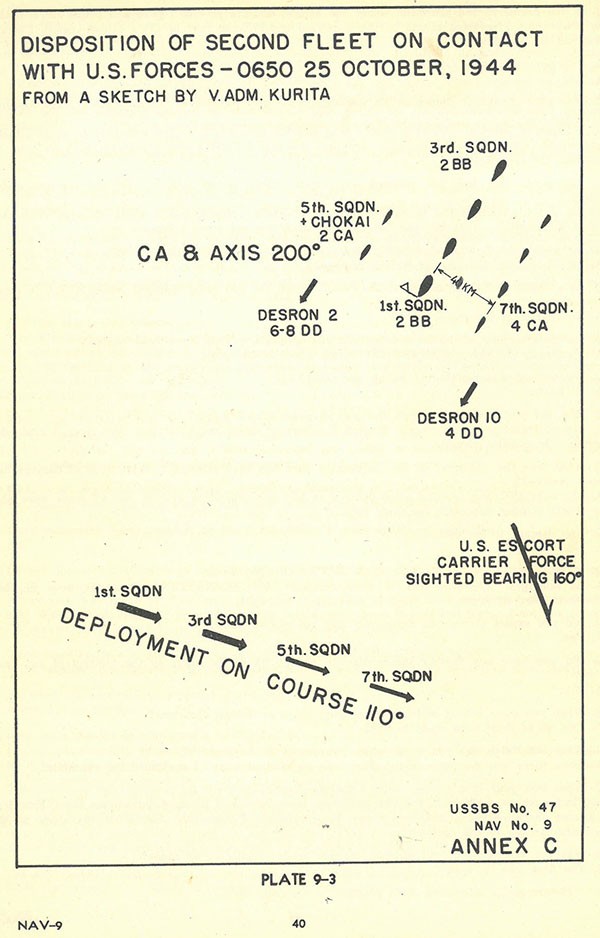

| 9-3 | Disposition of Second Fleet on Contact with U.S. Forces, 25 October 1944 | 40 |

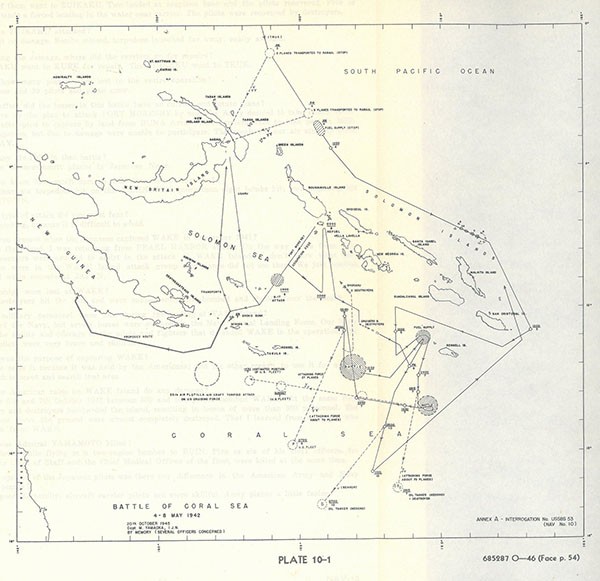

| 10-1 | Track Chart, Battle of Coral Sea, 4-8 May 1942 | facing p. 54 |

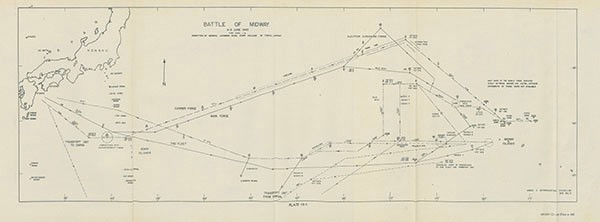

| 13-1 | Track Chart, Battle of Midway, 4-6 June 1942 | facing p. 68 |

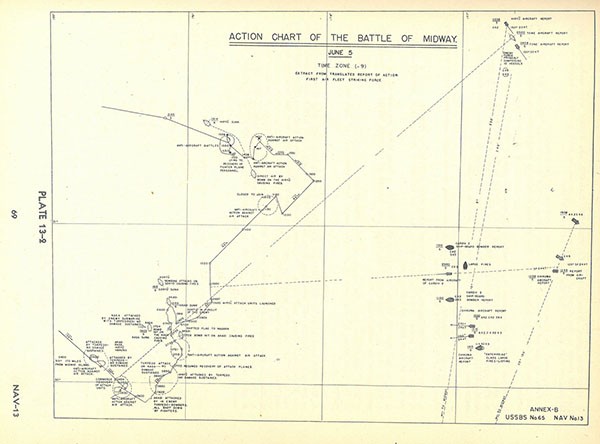

| 13-2 | Action of the Battle of Midway, 5 June 1942 | 69 |

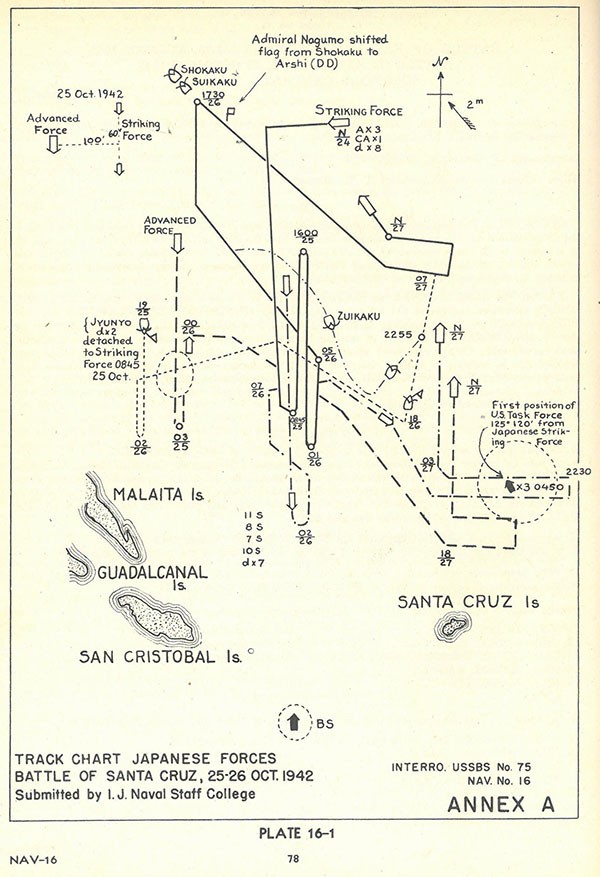

| 16-1 | Track Chart Japanese Forces, Battle of Santa Cruz, 25-16 October 1944 | 78 |

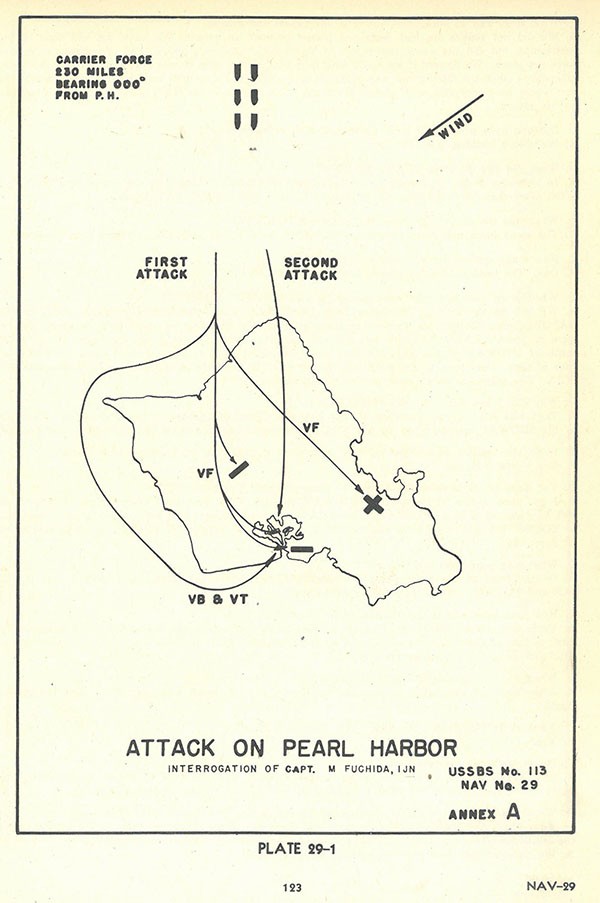

| 29-1 | Attack on Pearl Harbor | 123 |

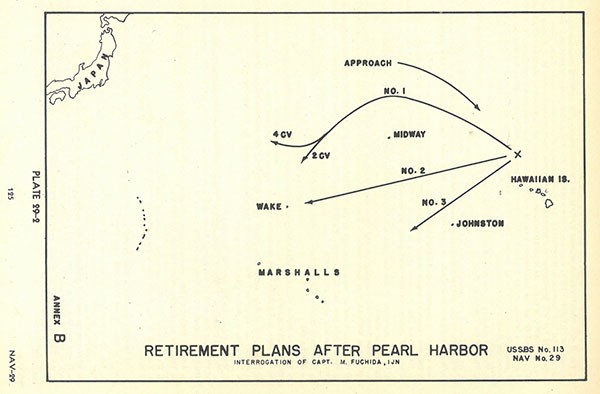

| 29-2 | Retirement Plans after Pearl Harbor | 125 |

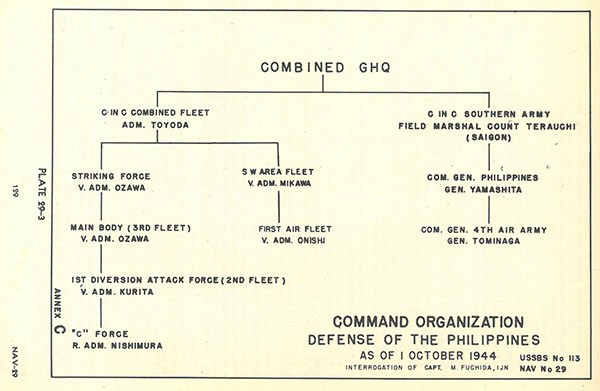

| 29-3 | Command Organization, Defense of the Philippines, 1 October 1944 | 129 |

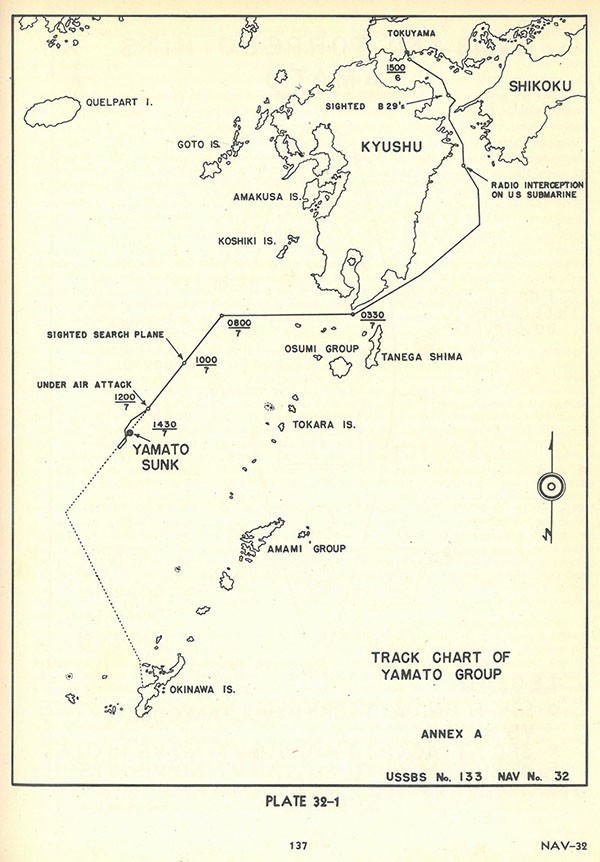

| 32-1 | Track Chart of Yamato | 137 |

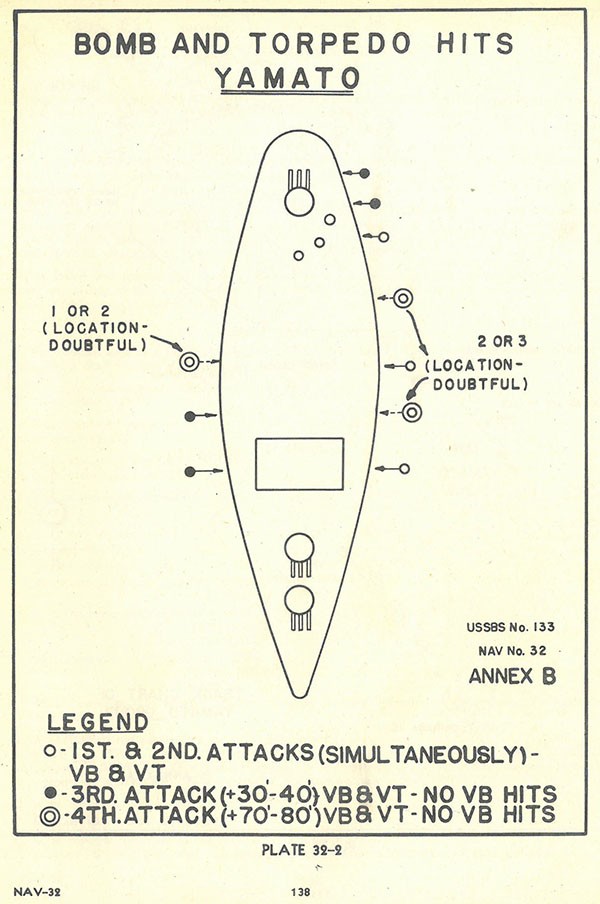

| 32-2 | Bomb and Torpedo Hits on Yamato | 138 |

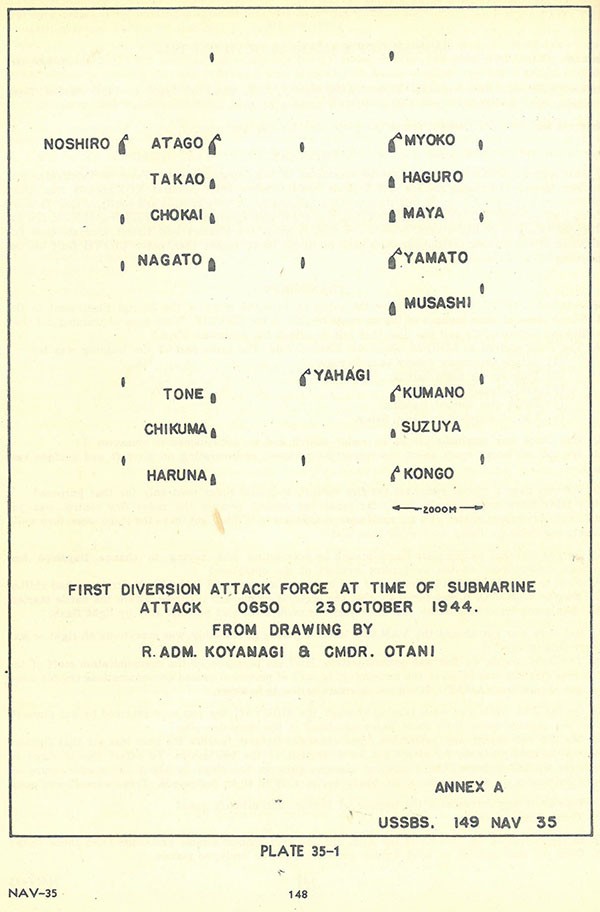

| 35-1 | First Diversion Attack Force at Time of Submarine Attack, 23 October 1944 | 148 |

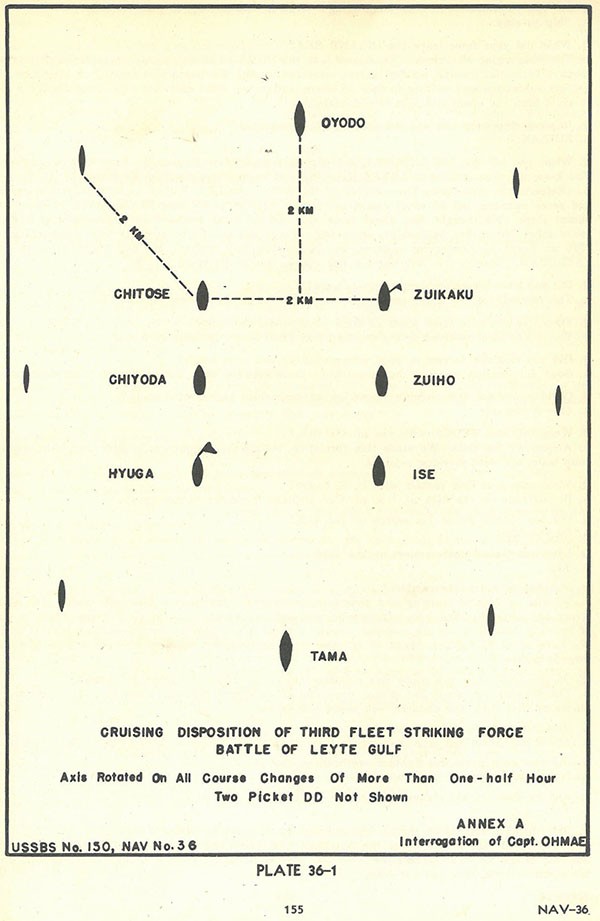

| 36-1 | Cruising Disposition of Third Fleet Striking Force, Battle of Leyte Gulf | 155 |

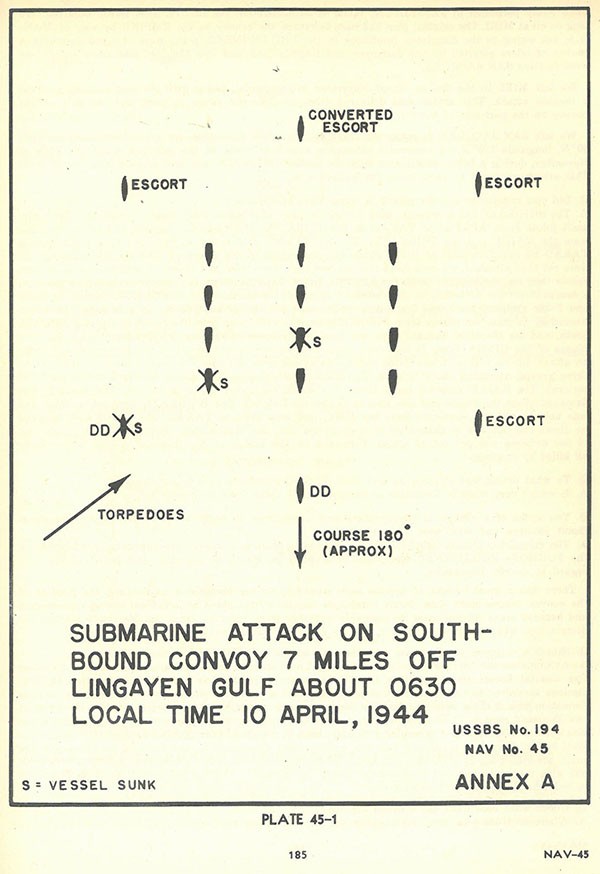

| 45-1 | Submarine Attack on Convoy 7 miles off Lingayen Gulf, 10 April 1944 | 185 |

| 45-2 | Submarine Attacks on Convoys off Borneo and Indo-China Coast, 4 or 5 and 10 November 1944 | 187 |

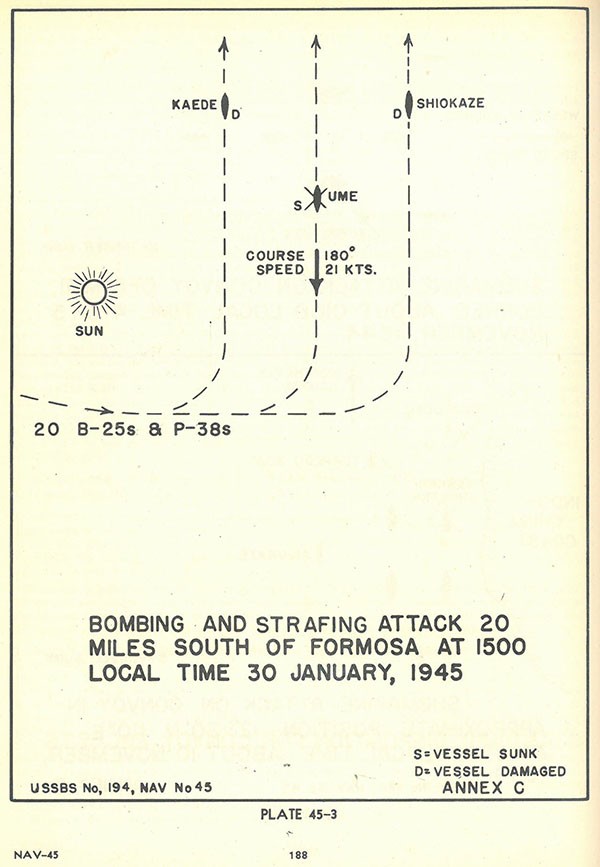

| 45-3 | Bombing and Strafing Attack on Japanese Convoy 20 miles South of Formosa, 30 January 1945 | 188 |

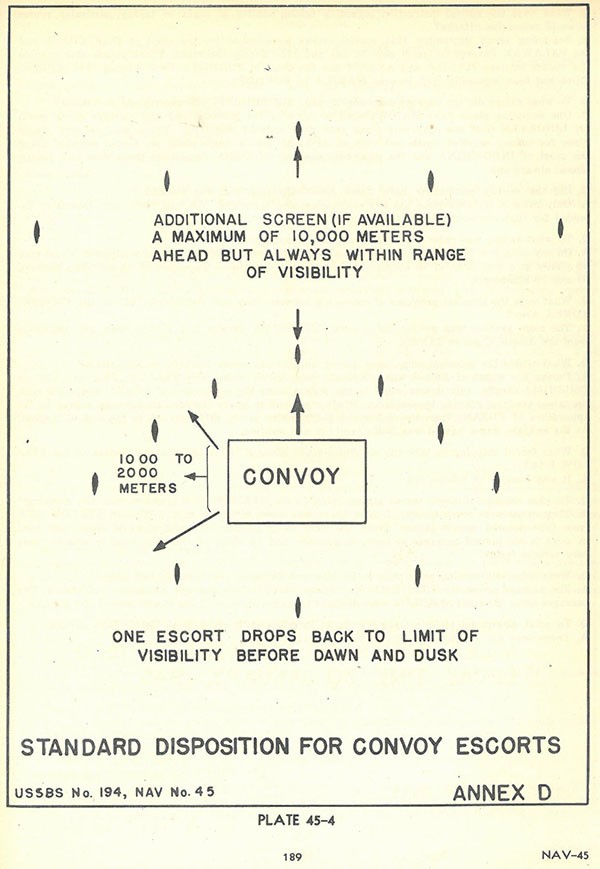

| 45-4 | Standard Disposition for Convoy Escorts | 189 |

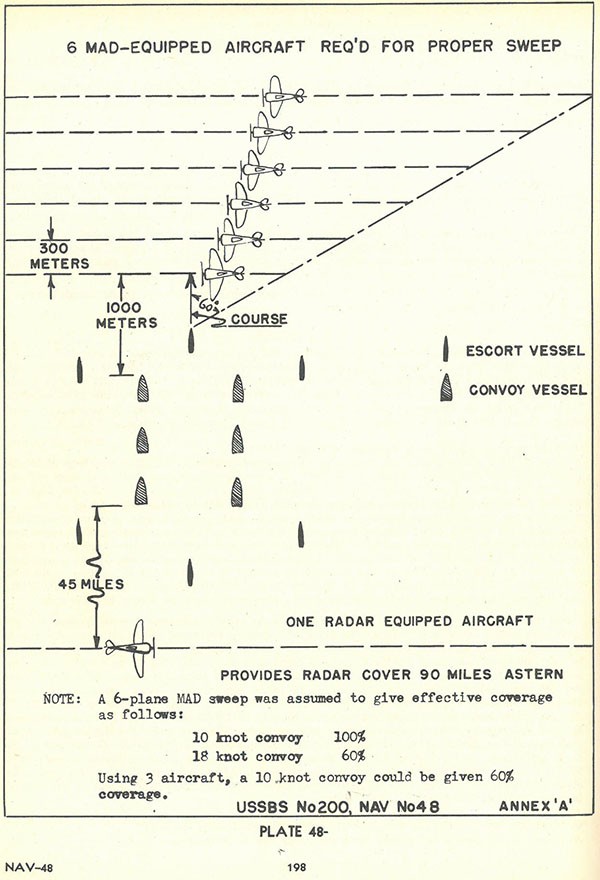

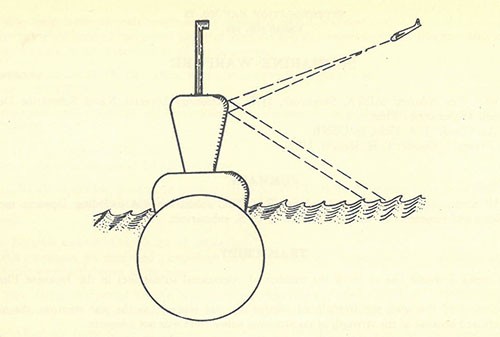

| 48-1 | Use of MAD Equipped Planes in Convoy Escort | 198 |

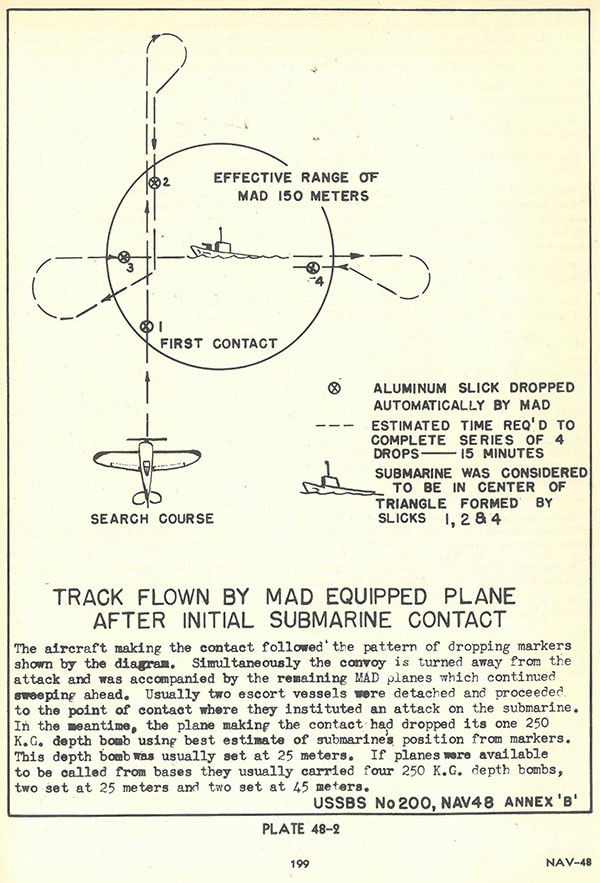

| 48-2 | Track Flown by MAD Equipped Plane after Initial Submarine Contact | 199 |

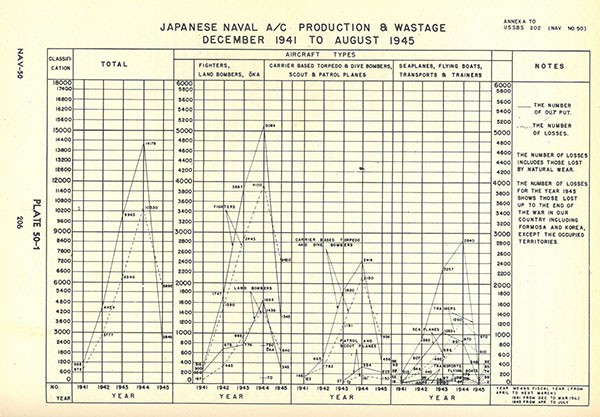

| 50-1 | Japanese Naval Aircraft Production and Wastage, December 1941 - August 1945 | 206 |

| 50-2 | Japanese Naval Aircraft Losses, December 1941 to August 1945 | facing p. 206 |

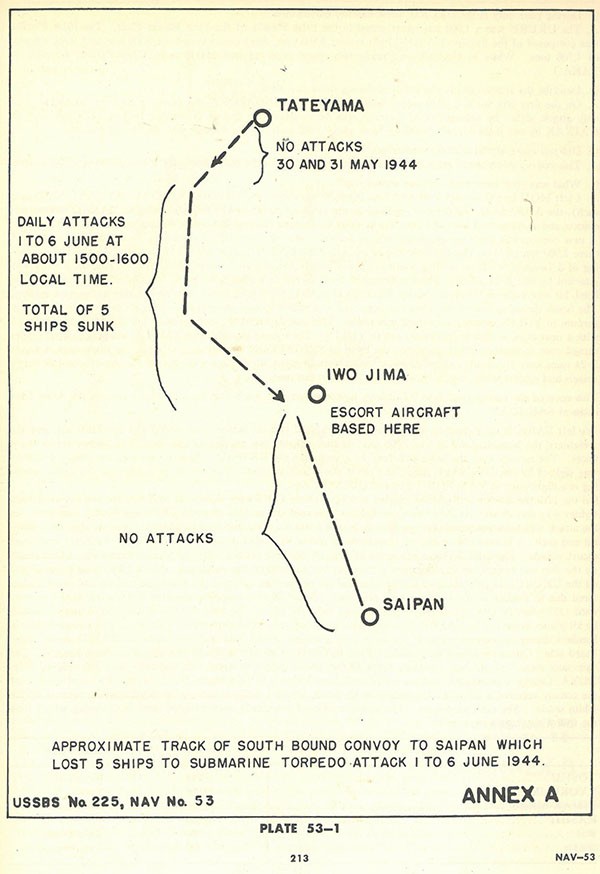

| 53-1 | Approximate Track of South Bound Convoy to Saipan, June 1944 | 213 |

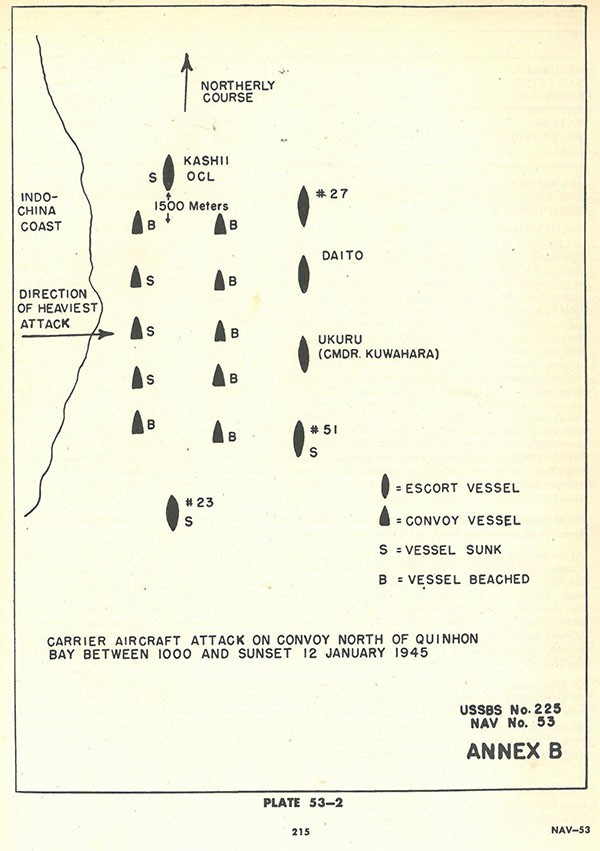

| 53-2 | Carrier Aircraft Attack on Convoy North of Quinhon Bay, 12 January 1944 | 215 |

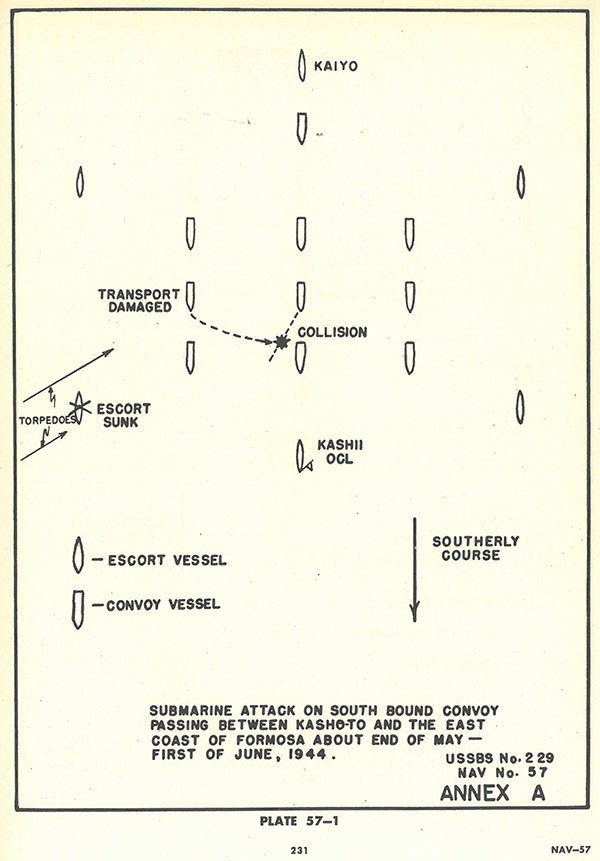

| 57-1 | Submarine Attack on Convoy between Kasho-To and Formosa, June 1944 | 231 |

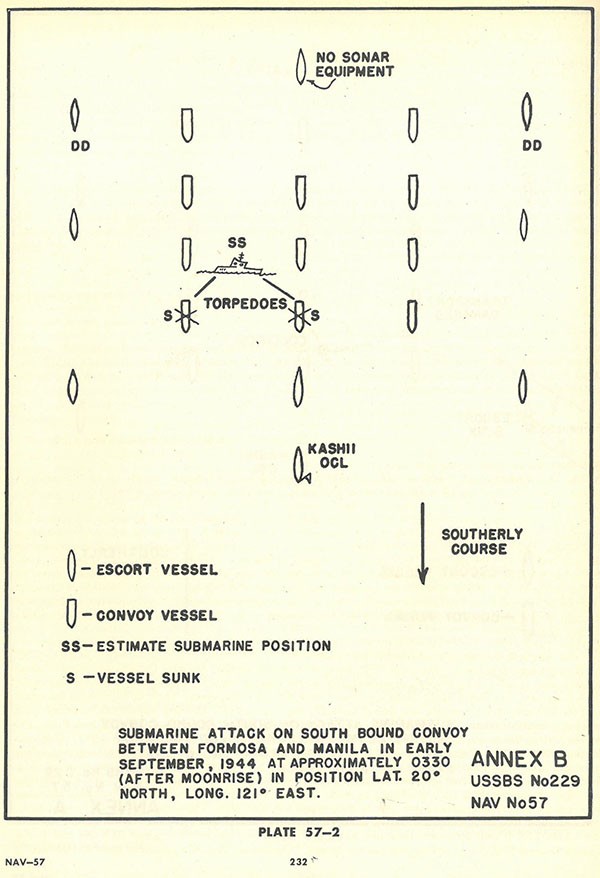

| 57-2 | Submarine Attack on Convoy between Formosa and Manila, September 1944 | 232 |

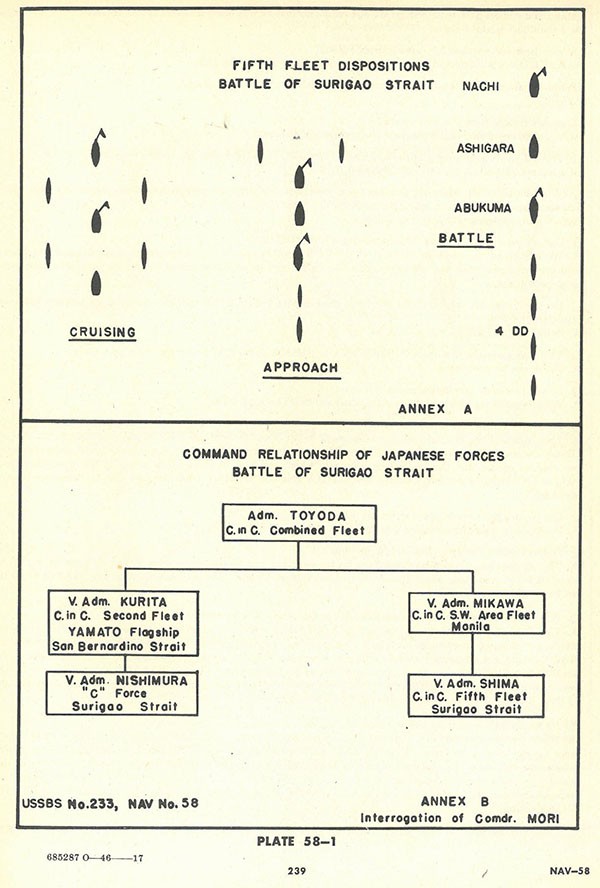

| 58-1 | Fifth Fleet Disposition and Command Relationship, Battle of Surigao Strait | 239 |

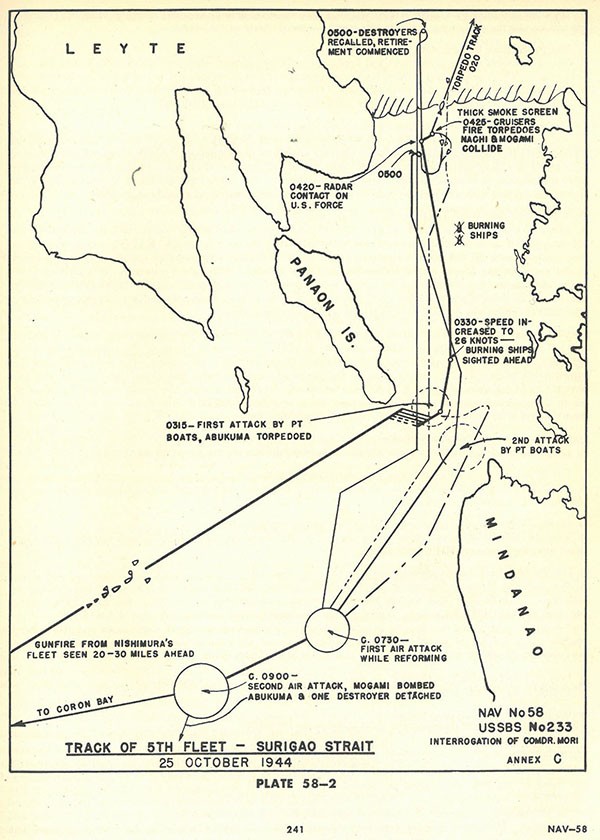

| 58-2 | Track of Fifth Fleet - Surigao Strait | 241 |

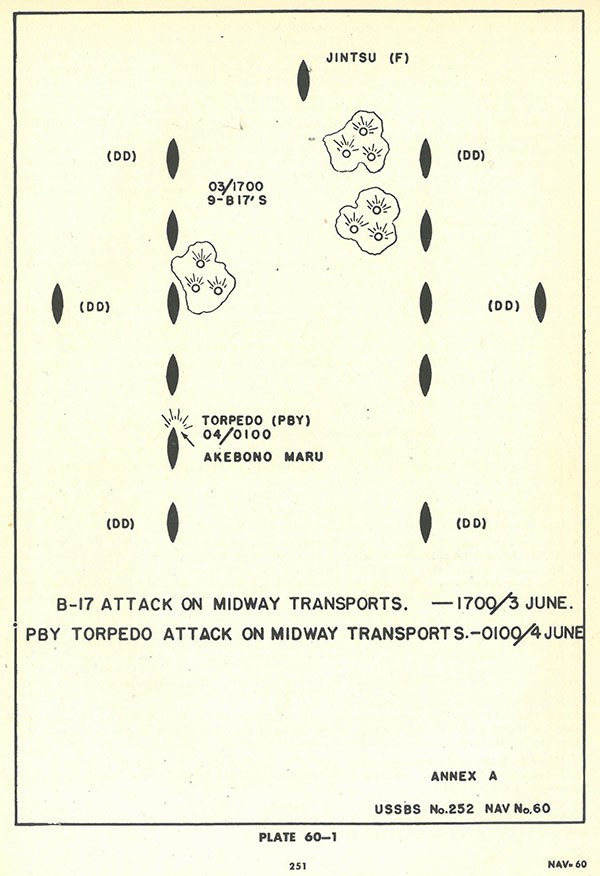

| 60-1 | B-17 Attack on Midway Transports, 3 June 1942; PBY Torpedo Attack on Midway Transports, 4 June 1942 | 251 |

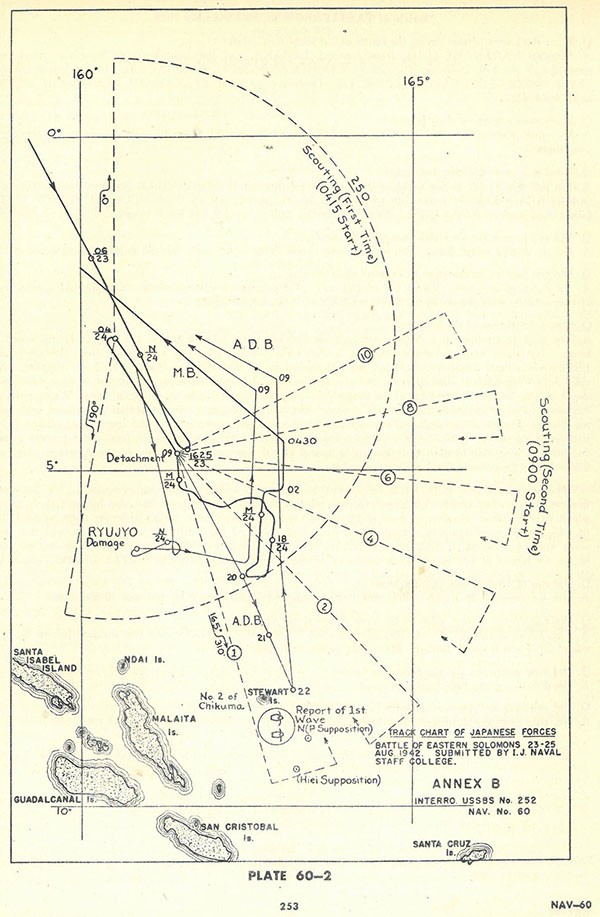

| 60-2 | Track Chart of Japanese Forces, Battle of Eastern Solomons, 23-25 August 1942 | 253 |

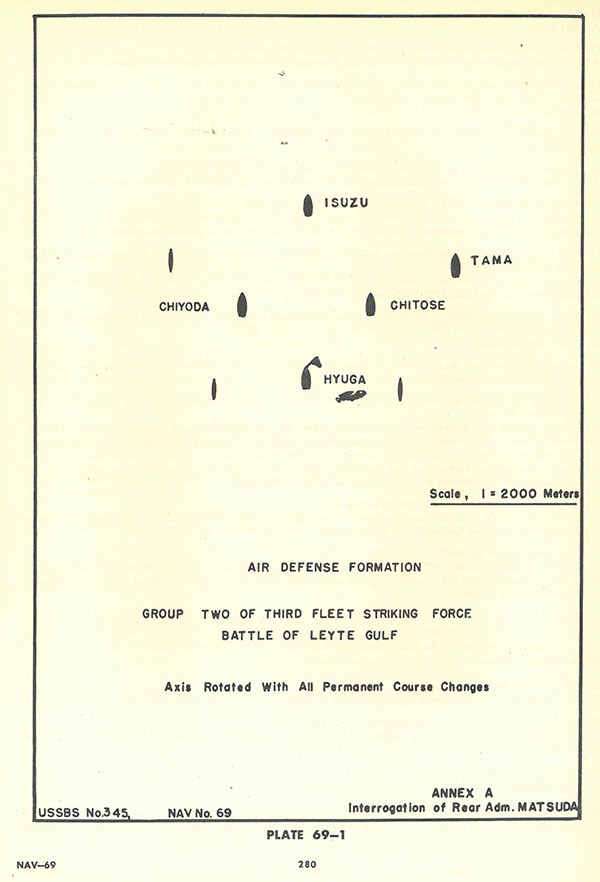

| 69-1 | Air Defense Formation, Battle of Leyte Gulf | 280 |

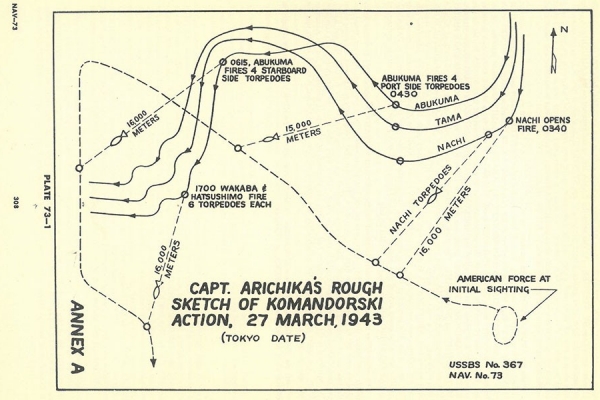

| 73-1 | Rough Sketch of Komandorski Action, 27 March 1943 | 308 |

| 78-1 | Battle of Empress Augusta Bay, 2 November 1943 | 339 |

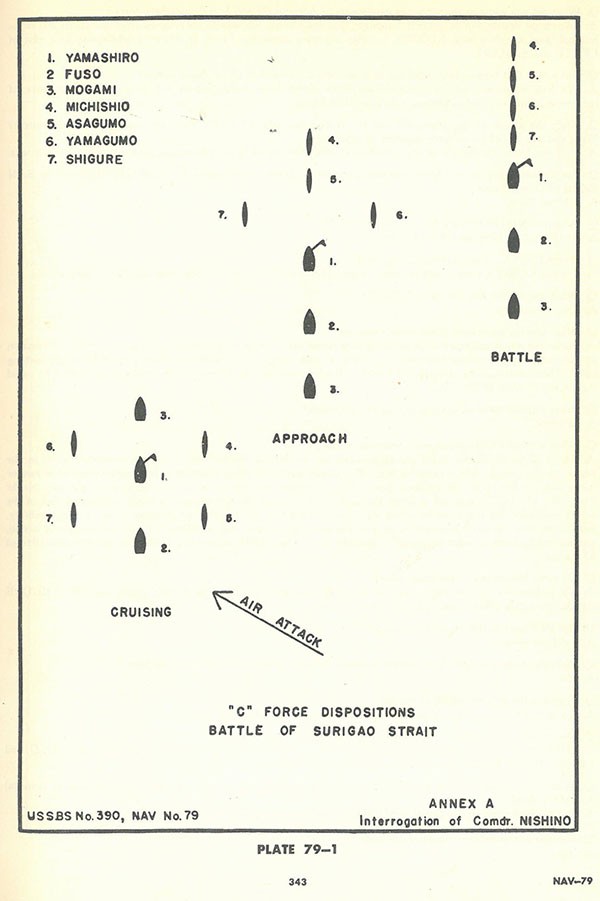

| 79-1 | "C" Force Dispositions, Battle of Surigao Strait | 343 |

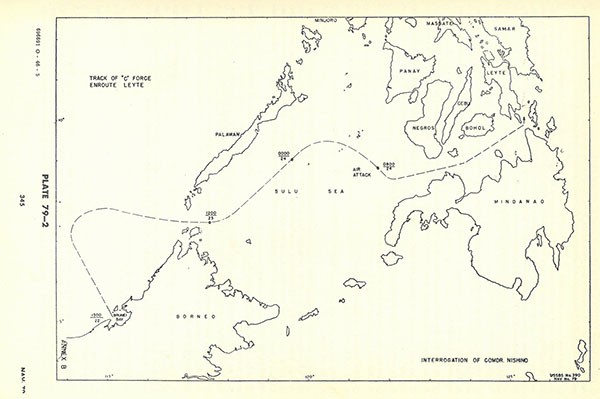

| 79-2 | Track of "C" Force Enroute Leyte | 345 |

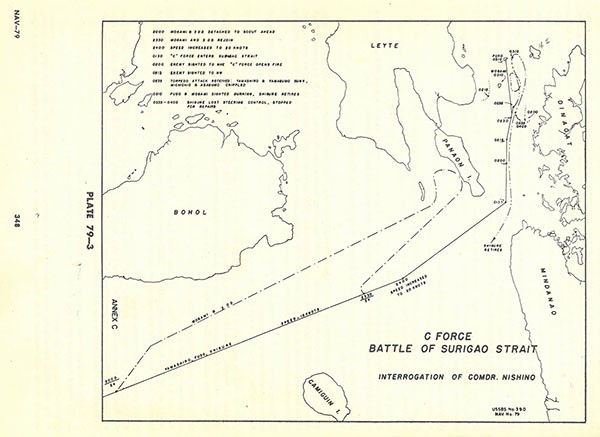

| 79-3 | Track of "C" Force, Battle of Surigao Strait | 348 |

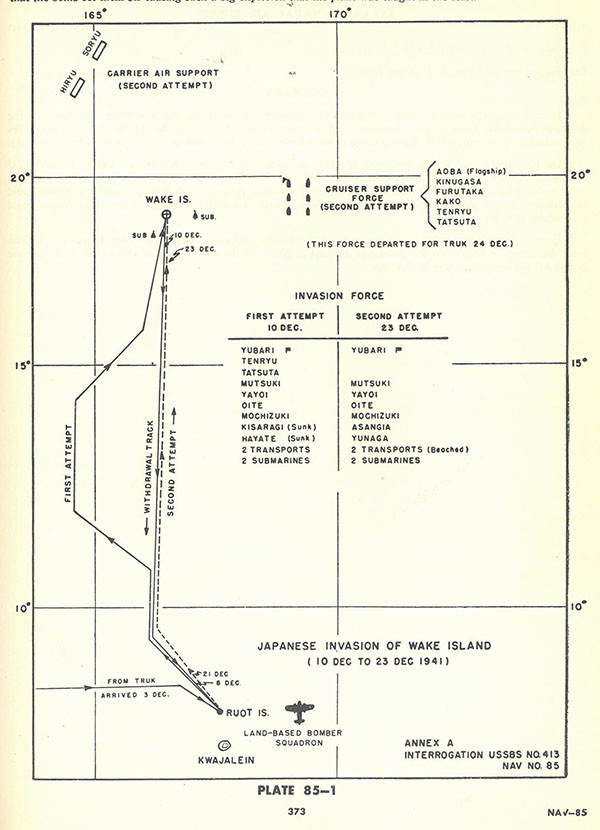

| 85-1 | Japanese Invasion of Wake Island, 10-23 December 1941 | 373 |

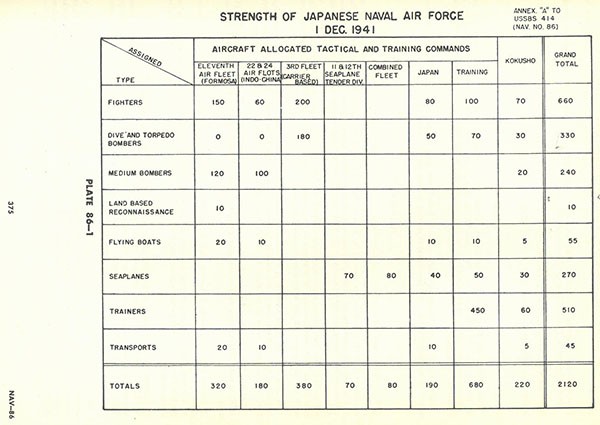

| 86-1 | Strength of Japanese Air Force, 1 December 1941 | 375 |

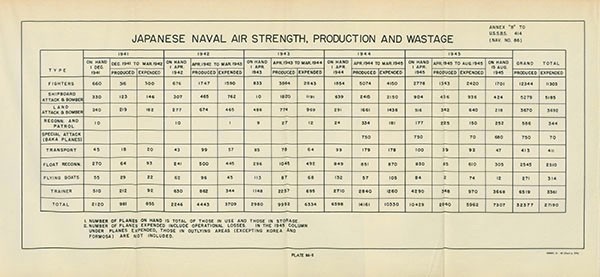

| 86-2 | Japanese Naval Air Strength, Production and Wastage | facing p. 374 |

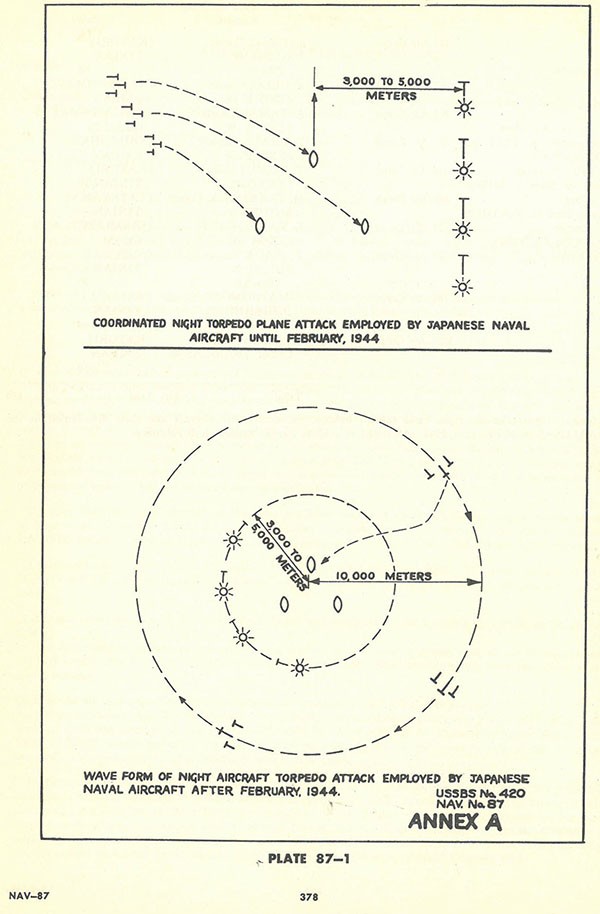

| 87-1 | Diagrams of Night Torpedo Attacks employed by Japanese Naval Aircraft, February 1944 | 378 |

| Plate | Title | Page |

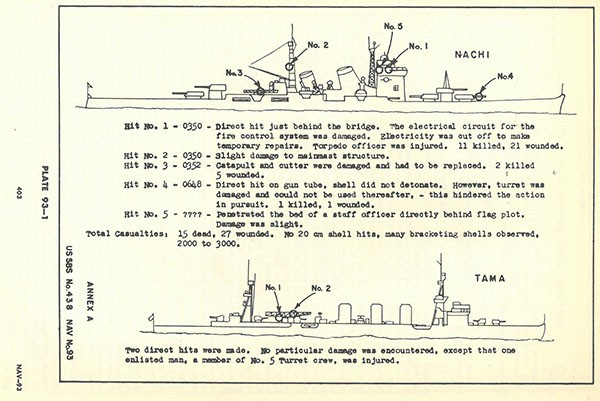

| 93-1 | Diagram of Bomb Hits on Nachi and Tama, Aleutian Campaign | 403 |

| 93-2 | Track Chart of Komandorski Engagement, 27 March 1943 | facing p. 402 |

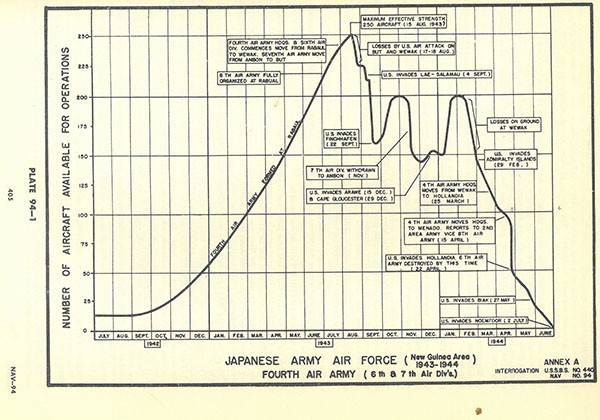

| 94-1 | Japanese Army Air Force - Fourth Air Army | 405 |

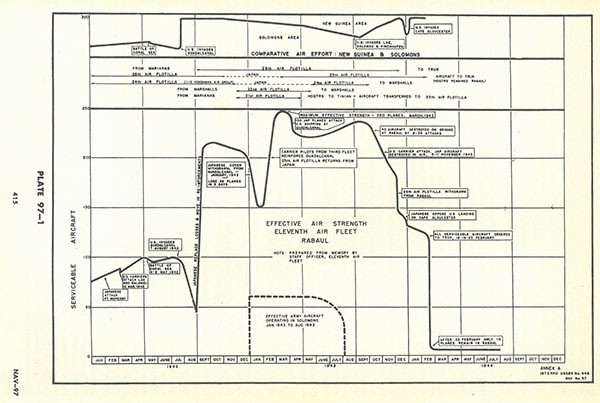

| 97-1 | Effective Air Strength - Eleventh Air Fleet - Rabaul | 415 |

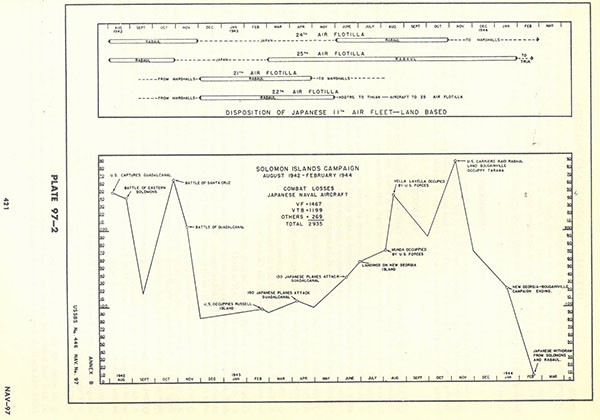

| 97-2 | Combat Losses - Japanese Naval Aircraft - Solomon Campaign | 421 |

| 101-1 | Track of Forces, Banten Bay, Java | 438 |

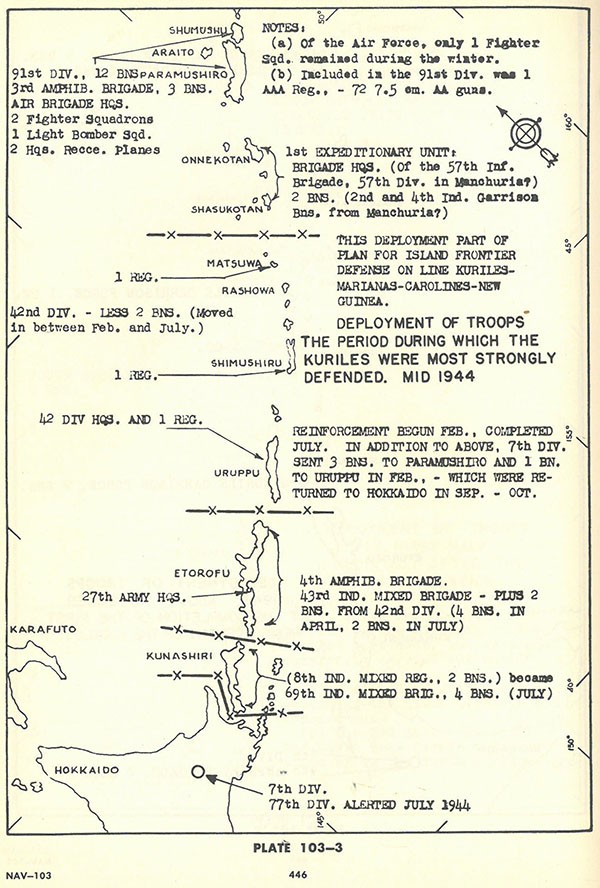

| 103-1 | Deployment of Troops (Kuriles), First Half 1943 | 444 |

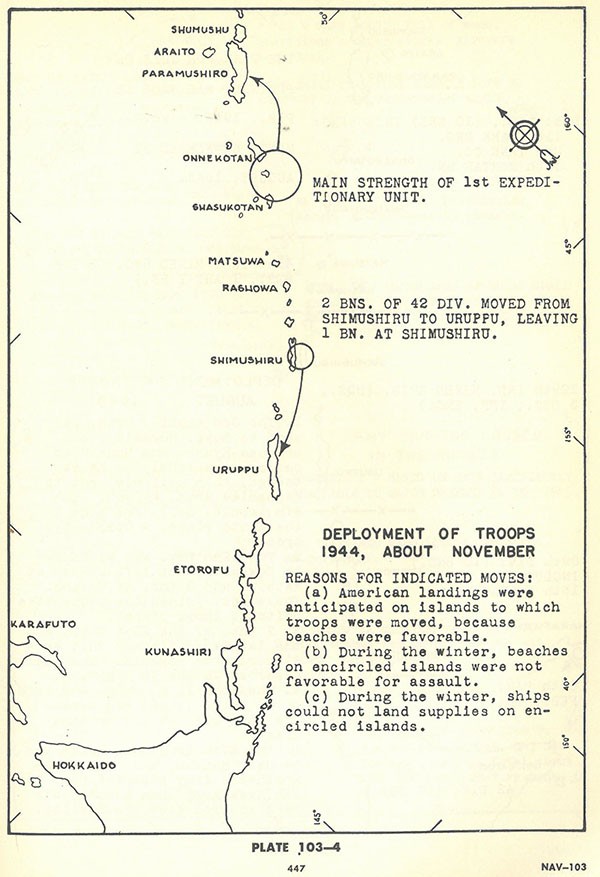

| 103-2 | Deployment of Troops (Kuriles), about November 1943 | 445 |

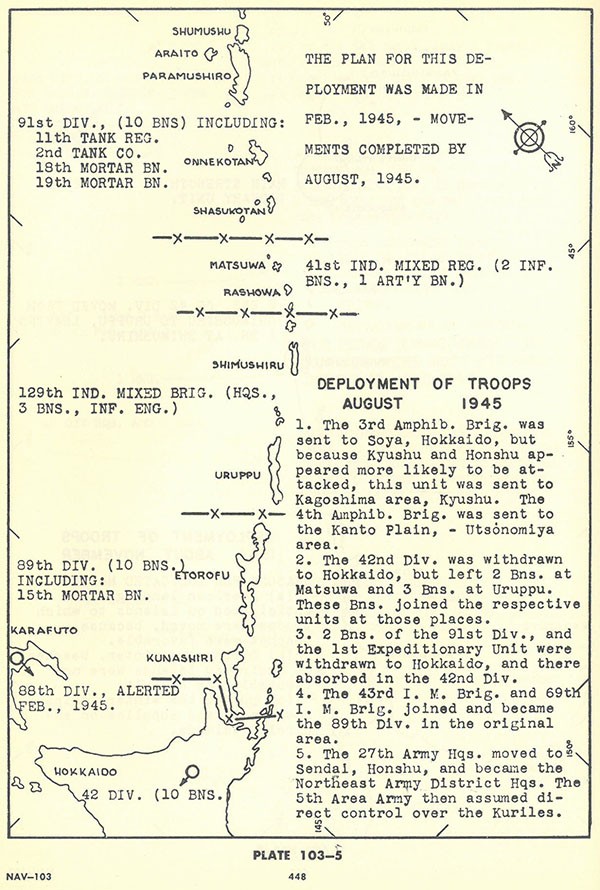

| 103-3 | Deployment of Troops (Kuriles), Mid 1944 | 446 |

| 103-4 | Deployment of Troops (Kuriles), about November 1944 | 447 |

| 103-5 | Deployment of Troops (Kuriles), August 1945 | 448 |

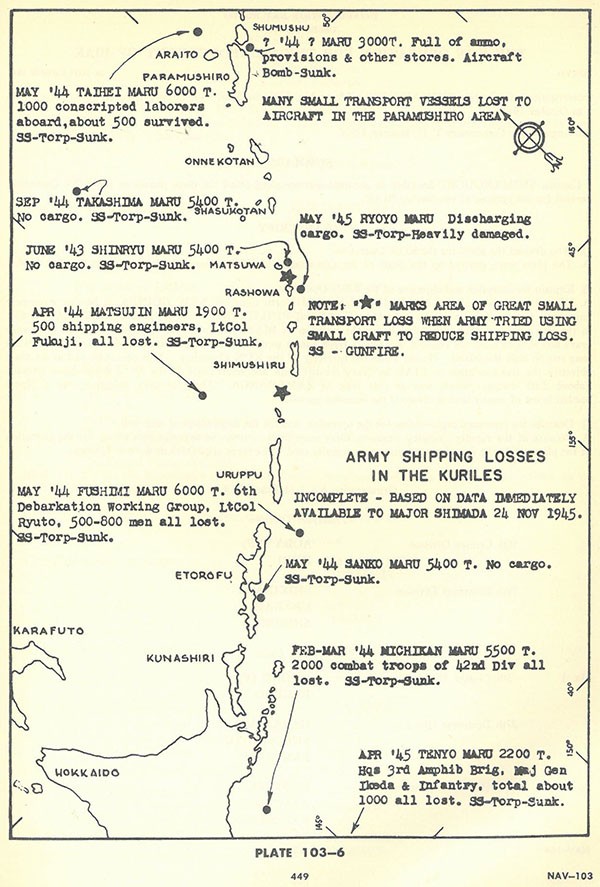

| 103-6 | Army Shipping Losses in the Kuriles | 449 |

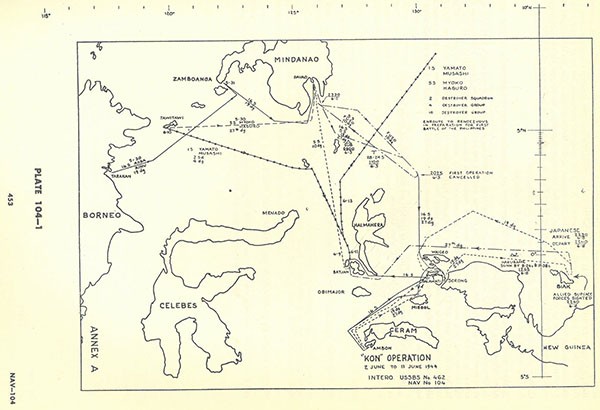

| 104-1 | "KON" Operation Track Chart, 2-11 June 1944 | 453 |

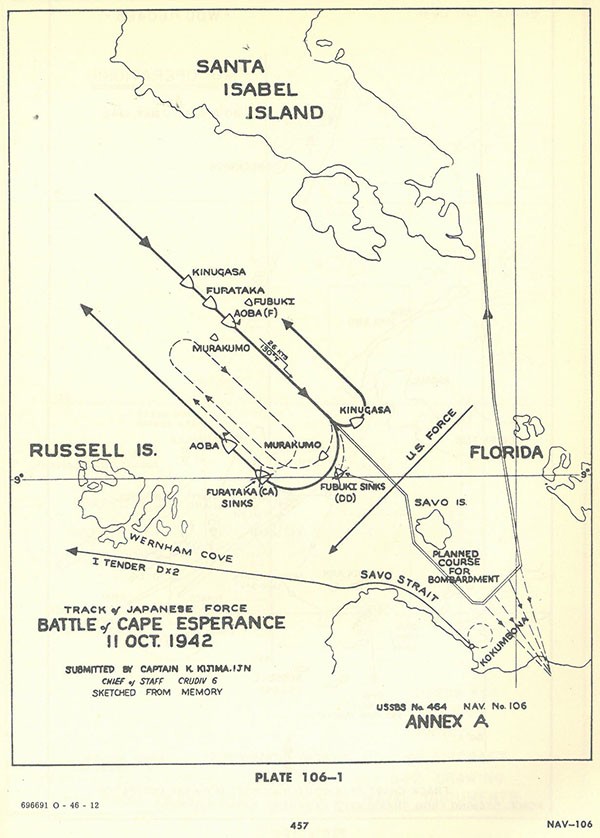

| 106-1 | Track of Japanese Force, Battle of Cape Esperance | 457 |

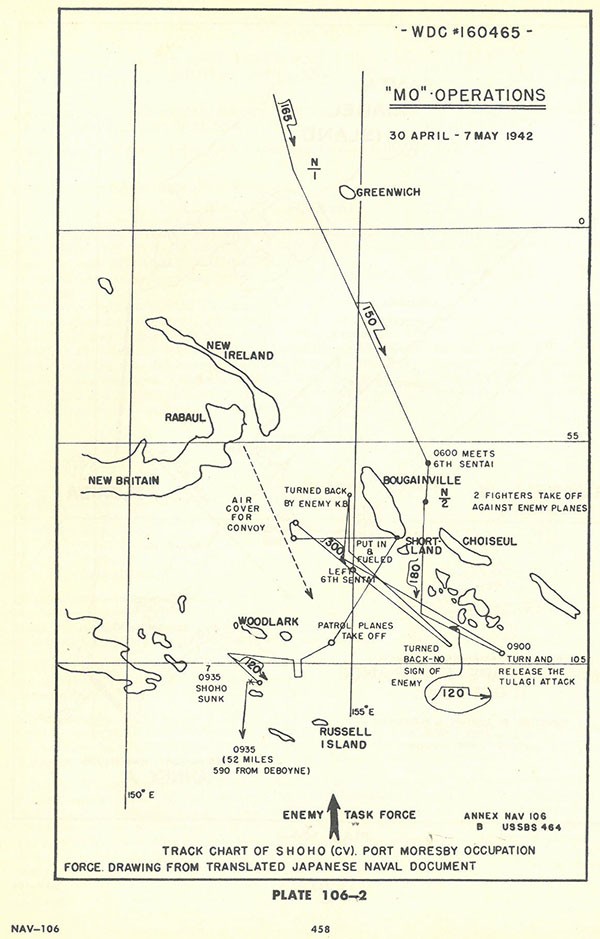

| 106-2 | Track Chart of Shoho (CV), "MO" Operations (Port Moresby) | 458 |

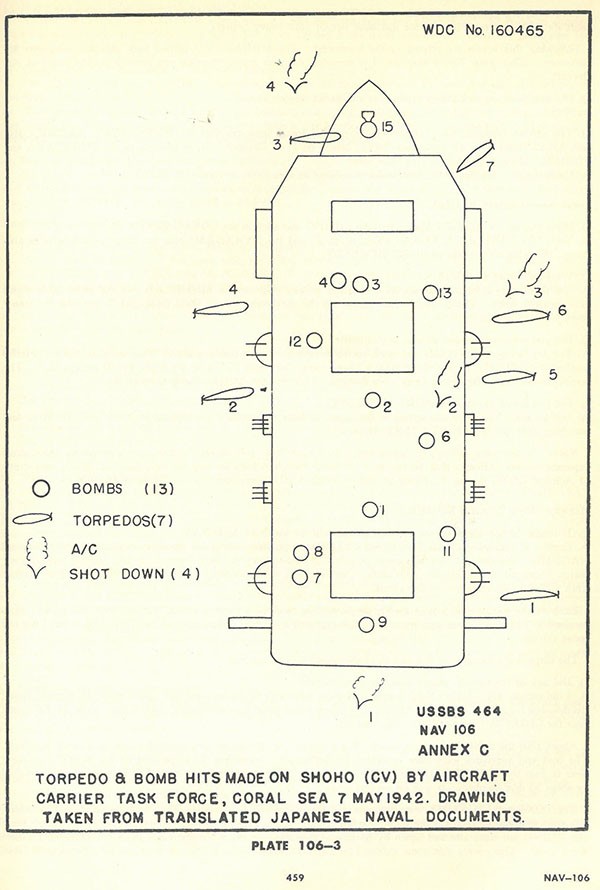

| 106-3 | Torpedo and Bomb Hits on Shoho (CV), Battle of Coral Sea | 459 |

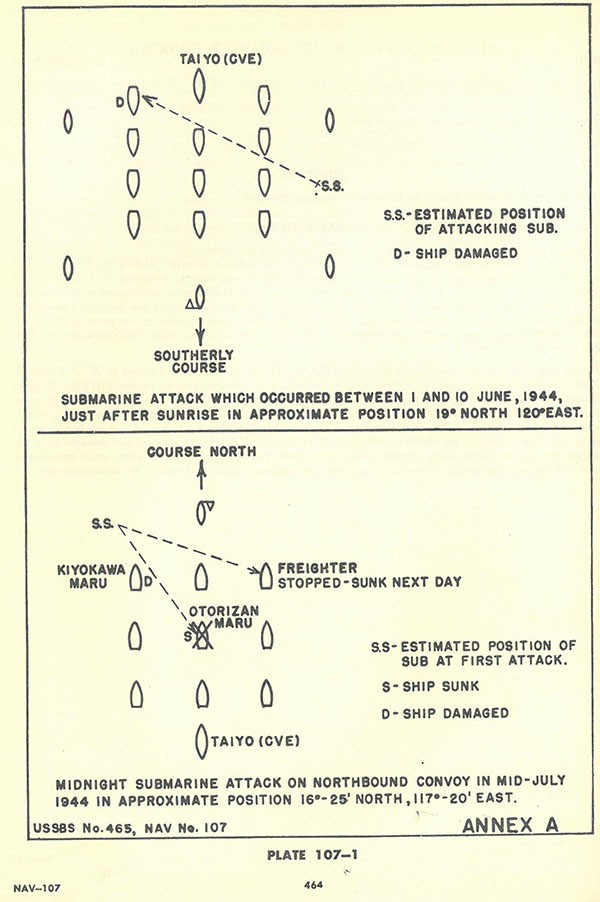

| 107-1 | Submarine Attack on Convoy North and West of Luzon, June-July 1944 | 466 |

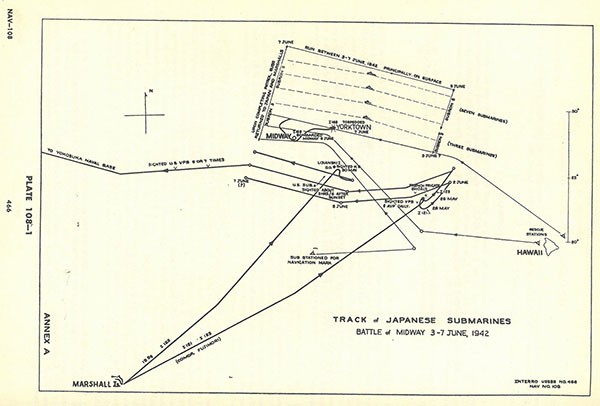

| 108-1 | Track of Japanese Submarines - Battle of Midway | 468 |

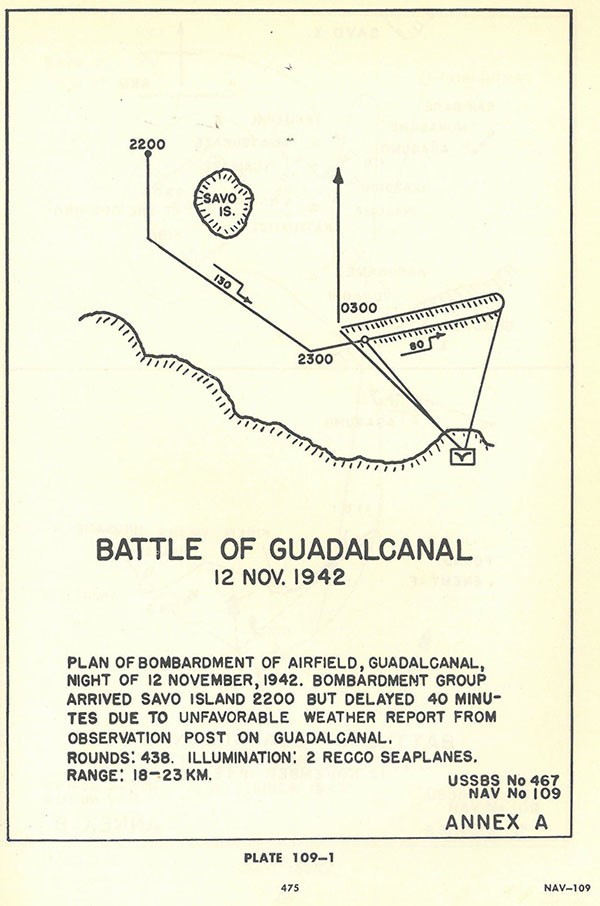

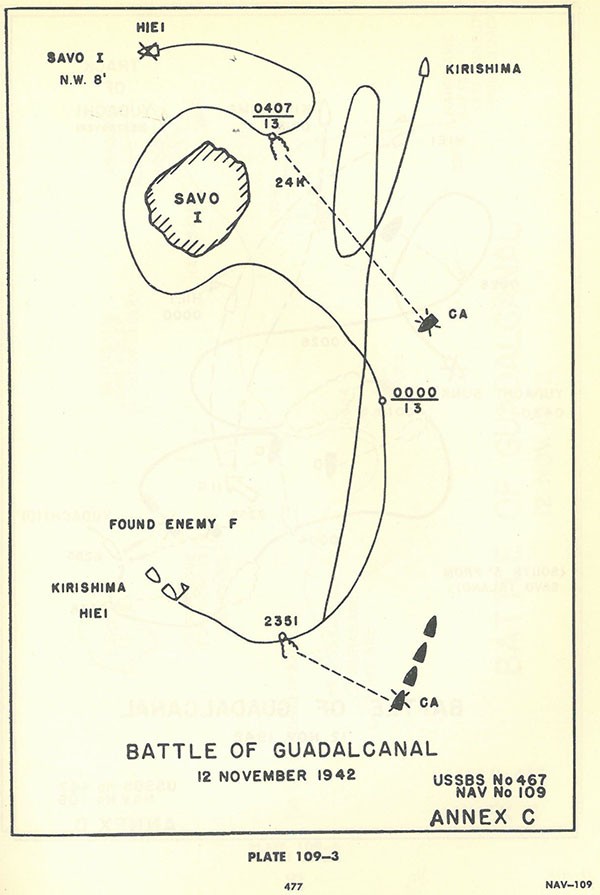

| 109-1 | Battle of Guadalcanal, 12 November 1942 | 477 |

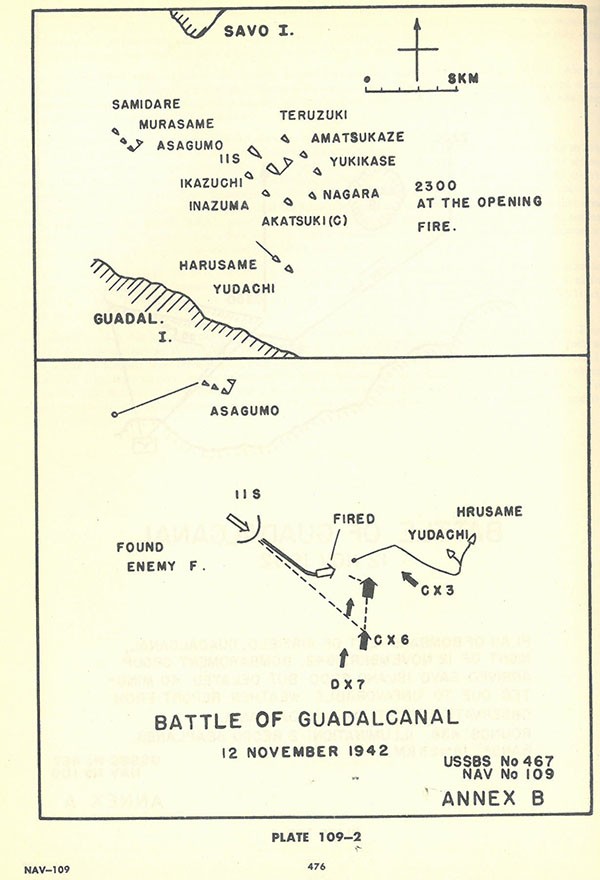

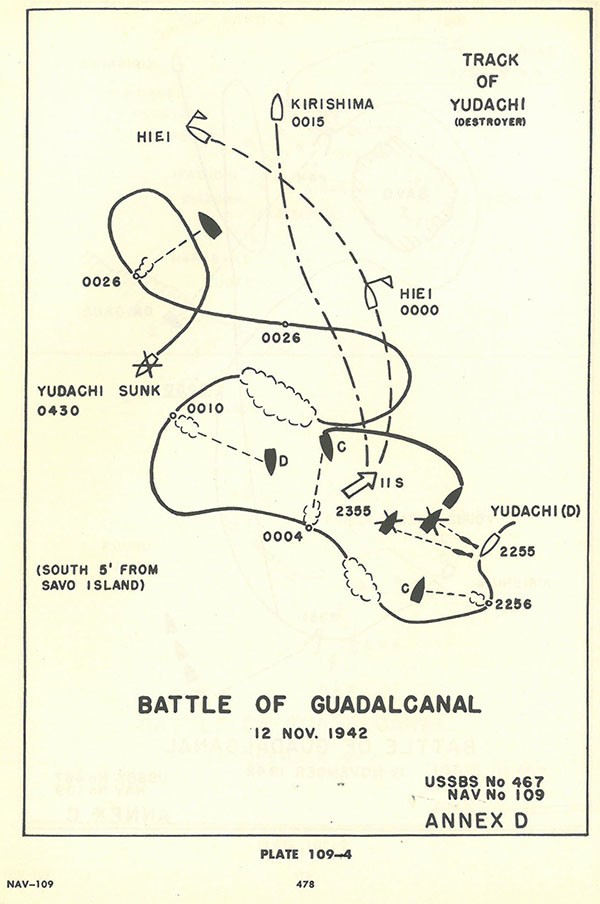

| 109-2 | Battle of Guadalcanal, 12 November 1942 | 478 |

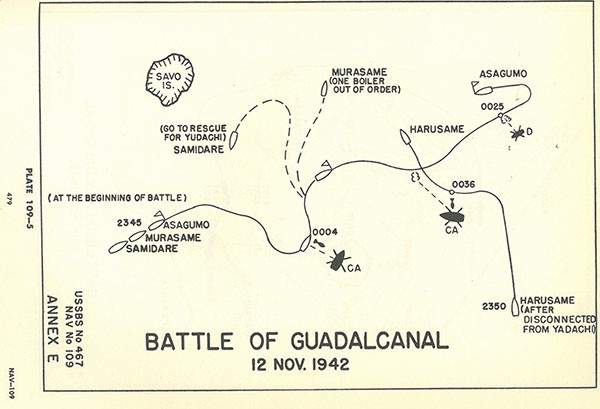

| 109-3 | Battle of Guadalcanal, 12 November 1942 | 479 |

| 109-4 | Battle of Guadalcanal, 12 November 1942 | 480 |

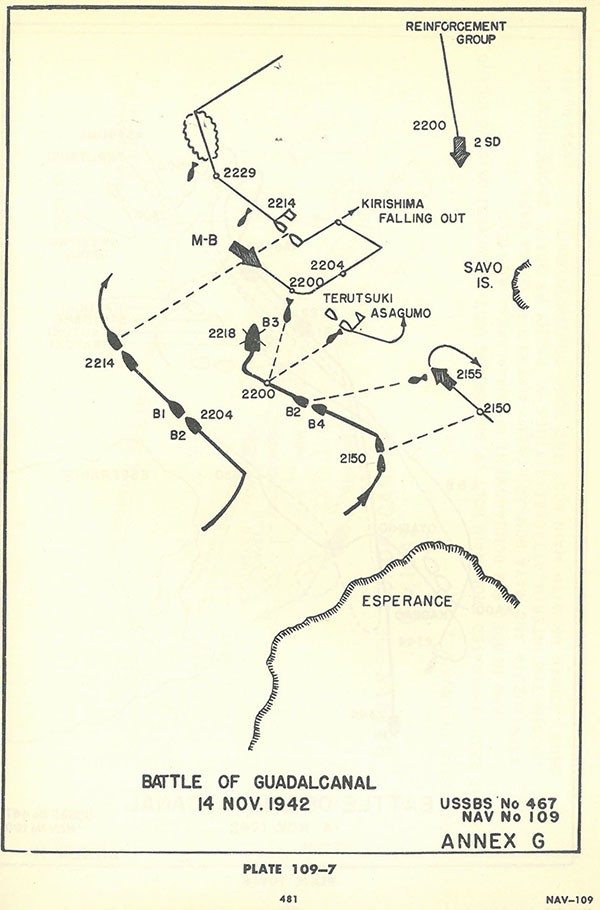

| 109-5 | Battle of Guadalcanal, 12 November 1942 | 481 |

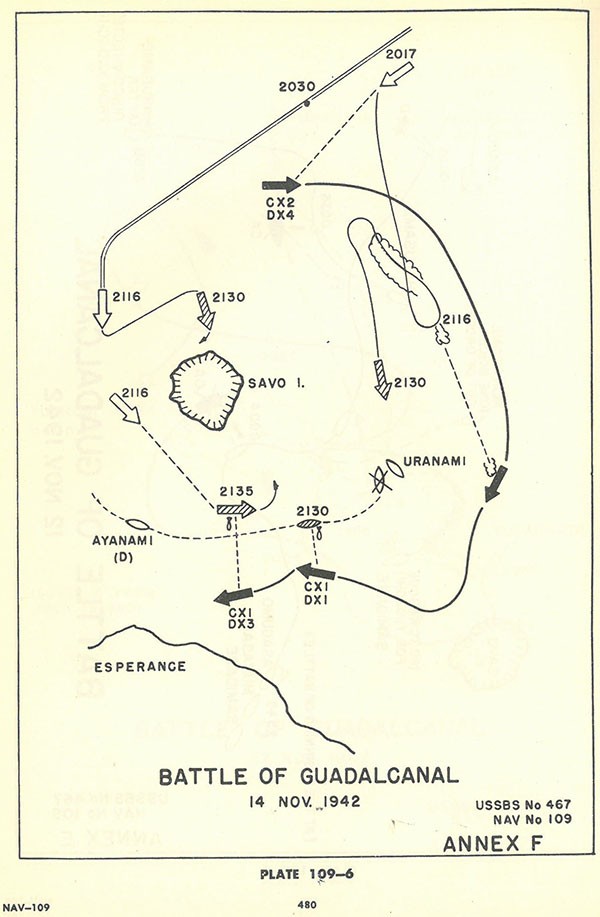

| 109-6 | Battle of Guadalcanal, 14 November 1942 | 482 |

| 109-7 | Battle of Guadalcanal, 14 November 1942 | 483 |

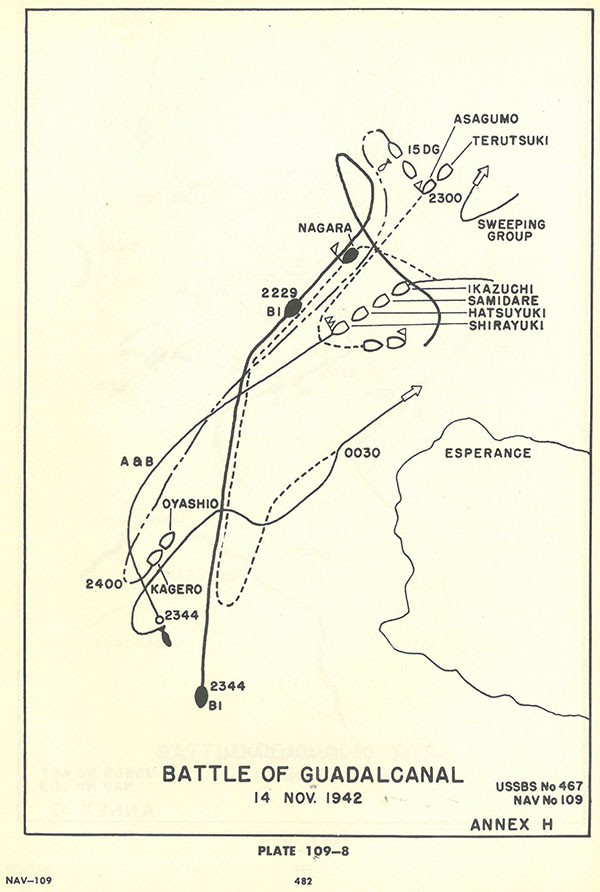

| 109-8 | Battle of Guadalcanal, 14 November 1942 | 484 |

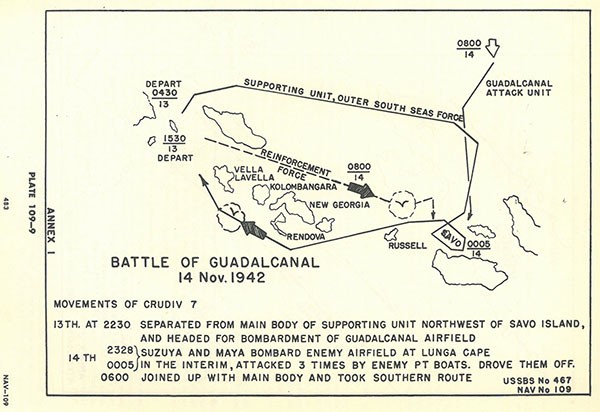

| 109-9 | Battle of Guadalcanal, 14 November 1942 | 485 |

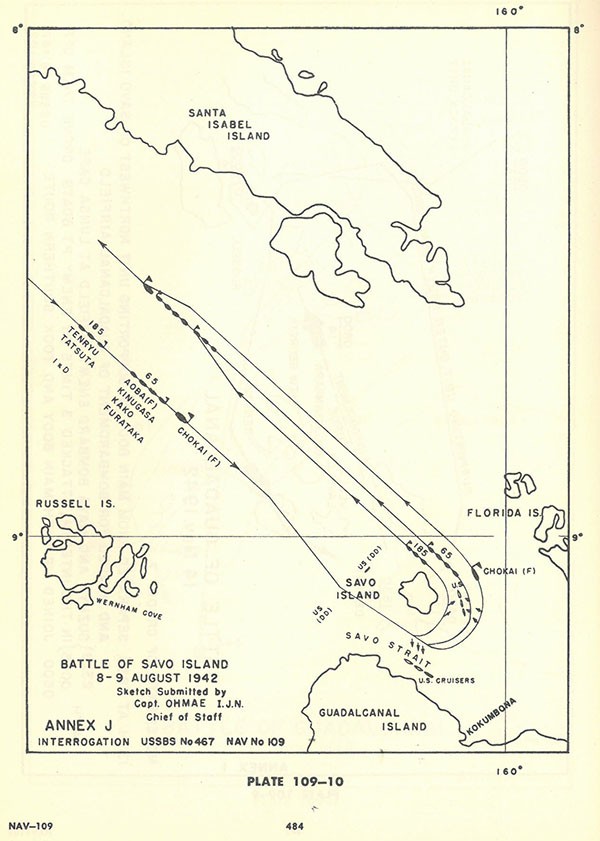

| 109-10 | Battle of Savo Island, 8-9 August 1942 | 486 |

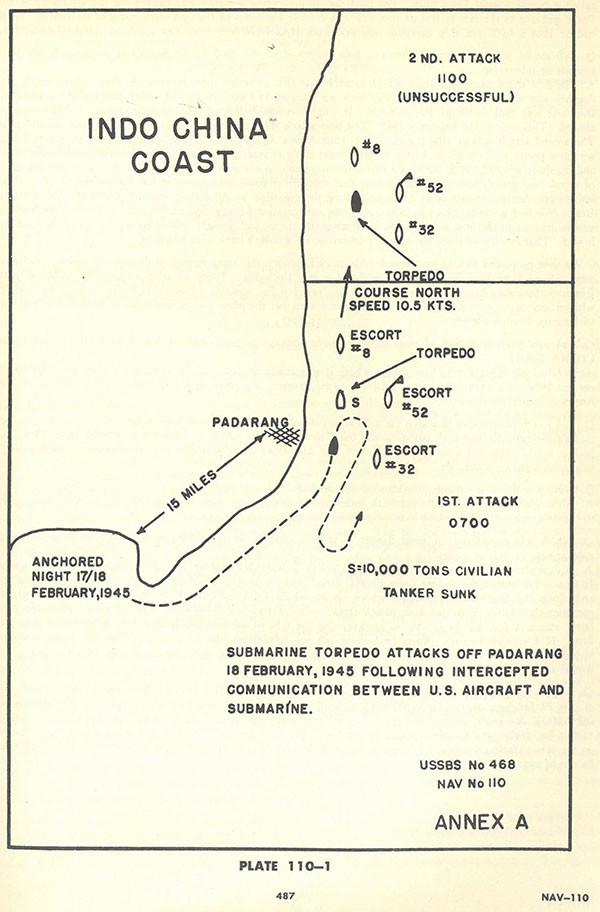

| 110-1 | Submarine Torpedo Attacks on Convoy off Padarang, 18 February 1945 | 489 |

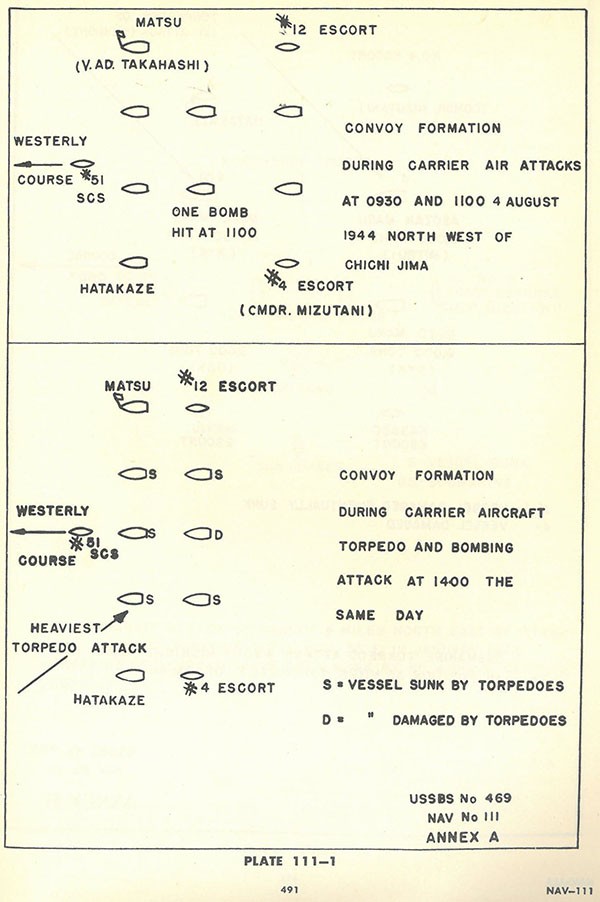

| 111-1 | Carrier Aircraft Attacks on Convoys, 4 August 1944 | 493 |

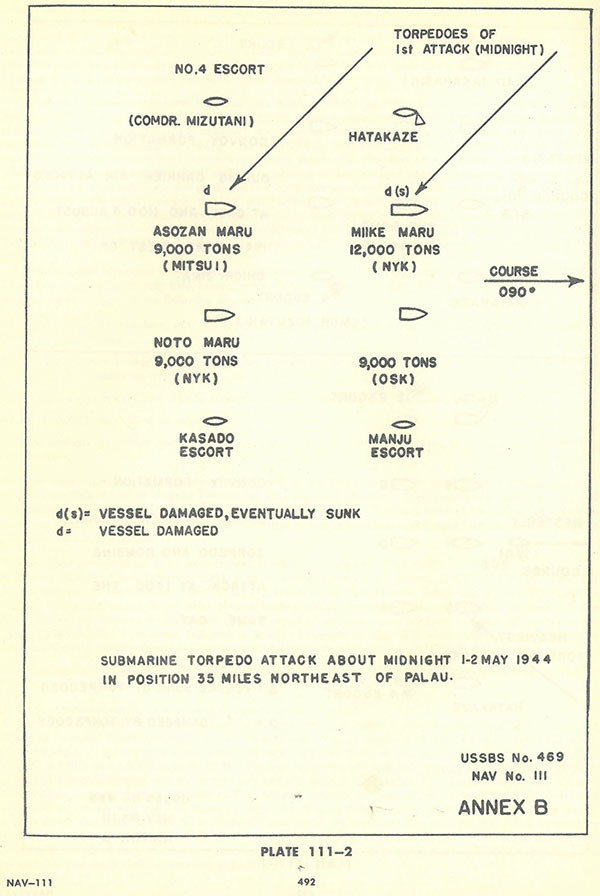

| 111-2 | Submarine Torpedo Attacks on Convoy Northeast of Palau, 1-2 May 1944 | 494 |

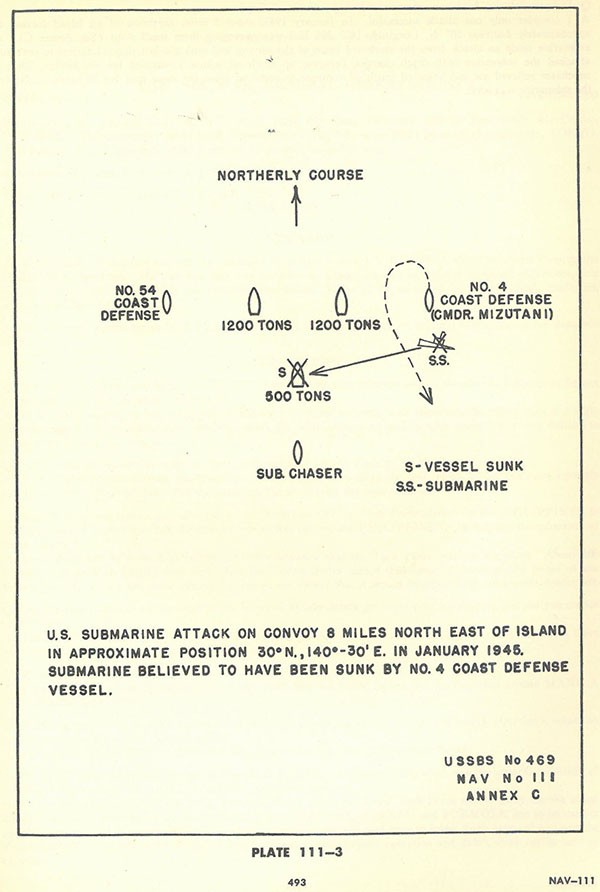

| 111-3 | U.S. Submarine Attack on Convoy, January 1945 | 495 |

>Index

(By Nav Interrogation Number)

(By Nav Interrogation Number)

| Aleutians - 20, 24, 25, 73, 118 | Marshall Islands - 13, 18, 30, 34, 38, 43, 96, 109, 115 | |

| "A" Operation - 9 | Midway (MI Operations) - 1, 2, 3, 4, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13, 16, | |

| AGO Plan - 3, 43, 71, 75, 95, 99, 104 | 20, 21, 22, 24, 25, 29, 31, 33, 34, 35, 39, 43, 46, 52, | |

| Attu - 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 51, 73, 84 | 60, 64, 66, 69, 70, 73, 75, 76, 83, 90, 98, 106, 109, | |

| Bombing Dive - 1, 2, 3 , 4, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13, 16, 17, 18, 28, 30, | 112, 115 | |

| 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 39, 41, 46, 52, 53, 60, 66, 82, 83, 89, 106, | Mines - 5, 11, 16, 26, 45, 46, 52, 54, 59, 62, 65, 92, | |

| 109, 111, 115 | 95, 100, 105, 110, 115 | |

| Bombing Torpedo - 2, 4, 8, 10, 11, 16, 32, 33, 35, 36, | Nagano, Osami, Admiral - 13, 80 | |

| 39, 40, 41, 46, 53, 60, 82, 83, 106, 109, 111, 115 | Netherlands East Indies - 5, 7, 11, 14, 15, 17 | |

| Bombing Horizontal - 1, 2, 4, 8, 9, 16, 17, 18, 21, 22, 23, | New Guinea - 57, 71, 94, 95, 97, 104, 115 | |

| 25, 29, 30, 33, 34, 37, 39, 40, 45, 46, 49, 52, 53 | Nishimura, Shoji, Vice-Admiral - 9, 29, 35, 36, 41, | |

| 56, 57, 60, 66, 83, 84, 94, 96, 104, 105, 106, 109, 110, 111, 112, | 44, 55, 58, 64, 69, 75, 79, 115 | |

| 115, 118 | Nomura, Kichisaburo, Admiral - 90 | |

| Cape Engano Battle - 36, 55 | Okinawa - 3, 5, 6, 12, 13, 115, 116 | |

| Cape Esperance - 106 | Ozawa, Jisaburo, Vice Admiral - 3, 9, 12, 29, 36, 41, | |

| Coral Sea - 3, 8, 10, 13, 35, 36, 43, 106 | 44, 55, 58, 64, 69, 75, 79, 99, 115 | |

| Dutch Harbor - 1, 2, 7, 13, 20, 23, 24, 73, 118 | Palau - 5, 11, 29, 72, 100, 115 | |

| Eastern Solomons (Battle of) - 8, 97, 106 | Philippine Sea (Battle of) - 9, 29, 55, 58, 69 | |

| Emperor - 12, 43, 76, 90 | Philippines - 3, 6, 7, 9, 12, 14, 15, 17, 29, 34, 36, | |

| Escort Shipping - 5, 11, 37, 45, 47, 49, 53, 56, 57, 74, | 37, 44, 55, 64, 72, 75, 90, 99, 101, 102, 112, 115 | |

| 102, 110, 111 | Port Moresby (MO Operation) - 8, 10, 95, 98, 106 | |

| Formosa - 9, 16, 29, 44, 55, 64, 69, 112, 115 | Rabaul - 3, 13, 16, 34, 38, 46, 52, 78, 82, 97, 115, | |

| French Indo China (Air Attacks on) - 53 | 116 | |

| Fuel Oil and Gasoline (Tankers) - 3, 7, 8, 9, 11, 13, | Radar - 1, 2, 3-4, 5, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 16, 18, 20, 22, 25, 30, 32, 33, | |

| 28, 29, 31, 34, 35, 36, 37, 41, 44, 47, 48, 55, 58, 59, 64, | 35, 36, 37, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 52, 55, 56, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 69, 72, 73, 74, 78, | |

| 66, 69, 70, 71, 72, 75, 76, 80, 90, 97, 110, 112, 115, 117 | 79, 84, 87, 97, 108, 110 | |

| Fukudome, Shigeru, Vice Admiral - 41, 44, 115 | Saigon - 89, 102, 115 | |

| Germany - 5, 8, 10, 12, 26, 65, 70, 72, 74, 80, 90,115 | Samar - 9, 35, 36, 41, 44, 66, 69 | |

| Gilberts - 8, 18, 30, 34, 38, 96, 109, 115 | San Bernardino Strait - 3, 9, 66, 75 | |

| Guadalcanal - 3, 13, 16, 31, 33, 43, 46, 70, 75, 76, 80, | Santa Cruz - 8, 16, 34, 97, 106 | |

| 83, 90, 97, 98, 106, 109 | Savo Island - 8, 16, 61, 83, 109 | |

| Hong Kong - 37 | Sho Operation - 3, 9, 12, 29, 36, 55, 64, 69, 72, 75, | |

| Houston - 7, 14, 17, 101 | 79, 99, 101, 112, 115 | |

| Iwo Jima - 28, 29 | Solomons - 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 9, 10, 13, 15, 16, 33, 34, 35, 38, 39, 40, | |

| Japan, Air Attacks on - 28 | 52, 60, 66, 69, 78, 82, 83, 89, 92, 97, 98, 114, 115, 116 | |

| Java Sea - 7, 14, 17, 68, 81 | Submarines (American) - 2, 3-4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 11, 13, 17, 21, | |

| Kamikaze - 6, 9, 12, 16, 36, 44, 55, 56, 75, 112, 115, | 22, 25, 34, 37, 39, 44, 45, 47, 48, 49, 53, 56, 57, 63, | |

| 116 | 67, 69, 70, 72, 73, 74, 75, 78, 80, 82, 83, 84, 90, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109, 110, 111, 115 | |

| Ketsu Operations - 6, 12 | Surigao Strait (Battle of) - 9, 41, 75, 79 | |

| Kiska - 13, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 51, 73, 84, 118 | Ta Operations - 37 | |

| Koga, Mineichi, Admiral - 34, 99, 100, 115 | Tassafaronga - 60 | |

| Komandorskis - 21, 25, 51, 73, 84, 93 | Ten Operation - 29 | |

| Kon Plan - 71, 94, 95, 104 | Toyoda, Soemu, Admiral - 3, 5, 9, 12, 29, 35, 36, | |

| Kula Gulf - 16 | 41, 55, 58, 64, 69, 75, 79, 99, 115 | |

| Kuriles - 21, 22, 25 | Truk - 3, 11, 16, 30, 34, 40, 87, 97, 110, 115 | |

| Kurita, Takeo, Vice Admiral - 9, 12, 29, 35, 36, 41, | Vella Gulf - 33 | |

| 44, 55, 58, 64, 69, 75, 79, 82, 115 | Vella La Vella - 16, 46, 109 | |

| Leyte Gulf - 9, 29, 35, 36, 41, 44, 55, 58, 64, 66, 70, | wake - 10, 30, 85 | |

| 72, 75, 76, 79, 83, 90, 101, 115 | Yamamoto, Isoroku, Admiral - 4, 10, 13, 20, 24, 55, | |

| Makassar Straits - 7 | 75, 90, 100 | |

| Manila - 11 | Yonai, Mitsumasa, Admiral - 43, 76, 90 | |

| 91, 95, 98, 99, 100, 115 | "Z" Operations - 43 |

Interrogation NAV No.1

USSBS No. 6

The Battle of Midway

TOKYO |

6 October 1945 |

Interrogation of: Captain AMAGI, Takahisa, IJN, Naval Aviator, Air Commander (observer) on CV HIRYU at PEARL HARBOR, Air Officer on CV KAGA at Battle of MIDWAY, 3, 4, 5 June 42.

Interrogated by: Captain C. Shands, USN.

Allied Officers Present: Captain S. Teller, USN; Captain J.S. Russel, USN; Lt. Col. Parry, USA; Comdr. J.T. Hayward, USN; Comdr. T.H. Moorer, USN; Lt. Comdr. J.A. Field, Jr., USNR.

SUMMARY

The KAGA (CV) in company with the CV's HIRYU, SORYU and AKAGI, and BB's KIRISHIMA and HARUNA and DD's composed the Air Striking Force approaching MIDWAY ISLAND from the West in support of an occupation force. This force had expected contact and attack by long range United States aircraft when between 500-1000 miles of MIDWAY and attack by short range aircraft from MIDWAY when within 300 miles. No attacks were made on the Carrier Force prior to the dive bombing attack the morning of 4 June. The presence of the United States Carrier was not known to this officer. Dive bombing attacks were most feared.

Several hours after sunrise on 4 June (Plus 12) dive bombers attacked that Japanese Carrier Group. Four direct hits were received by the KAGA from the dive bombers just prior to turning into the wind to launch the KAGA's air group (6 VF had been launched two hours before as CAP). The fires as a result of the attack ignited planes and ammunition which resulted in the sinking of the KAGA during the afternoon with the loss of 800, saving 1000 personnel. No other bomb hits were made on the KAGA. No horizontal bomb hits were received or observed on other ships of the formation, but it was reported the HARUNA (BB) just astern of the KAGA had also been hit by dive bombers. Captain Amagai stated that as a result of the damage to the aircraft carriers with consequent loss of air power, the decision was made to abandon the attempt to seize MIDWAY. The remainder of the Task Force returned to JAPAN.

TRANSCRIPT

Q. What aircraft carrier divisions were present at MIDWAY?

A. The Third Fleet or Third Task Force, commanded by Vice Admiral NAGUMO. Rear Admiral KUSAKA was Chief of Staff.

Q. Who were Captains of the Carriers at MIDWAY?

A. Captain Okada of the KAGA, Captain Kaka of the HIIRYU, Captain Yanagimoto of the SORYU and Captain Aoki of AKAGI. The first three were killed at MIDWAY.

Q. Were there any other forces such as Support Force or Occupation Force?

A. Believe there were two other forces for occupation, but am not sure of composition or relative location.

Q. Do you know what Force made simultaneous attack in ALEUTIANS?

A. JUNYO Aircraft Carrier No. 4 Squadron.

Q. What was purpose of ALEUTIAN attack?

A. It was a feint.

Q. Draw a diagram of the cruising disposition of the Aircraft Carriers.

( ) KIRISHIMA (BB) |

|

HIRYU (F) |

AKAGI (F) |

SORYU |

KAGA |

( ) HARUNA (BB) |

|

NAV-1

--1--

In daytime a circular formation was used, but at night a column was formed. Believe the Task Force Commander was on the SORYU.

Q. What was the composition of the KAGA's Air Group?

A. It was composed of 21 fighters (0) Type: 27 VB (99 Type); 18 VT (97 Type); same as all other carriers.

Q. What was the mission of the Carrier Task Group?

A. To attack MIDWAY, to help occupation.

Q. During your approach to MIDWAY did you expect to be attacked by American planes?

A. We had expected an attack by scouting planes at 1000 miles, and by bombing planes at 700 miles and by small planes at 300 miles.

Q. Did you see any planes during the approach to MIDWAY prior to the battle of 4 June?

A. No, but it was reported that an American plane was heard over the carrier formation at night, one or two days before the battle.

Q. Was the carrier formation attacked by long range bombers about 600 miles from MIDWAY, or were any air attacks made on the carrier force prior to the day of the battle (4 June, plus 12; 5 June, TOKYO time)?

A. No.

Q. Were any submarine attacks made on the carrier force during the approach?

A. No.

Q. When was the KAGA first hit?

A. It was hit by dive bombers two or three hours after sunrise, 4 June (5 June Tokyo time).

Q. How many bombs hit the KAGA?

A. There were four hits on the KAGA. The first bomb hit the forward elevator. The second bomb went through the deck at the starboard side of the after elevator. The third bomb went through the deck on the port side abreast of the island. The fourth bomb hit the port side aft. When the bombs hit, big fires started. Unable to see much because of smoke.

Q. Did any of the American bombers dive into the deck?

A. No, not on KAGA. Did not hear that any had dived on other carriers.

Q. Were any other ships hit by bombs at same time?

A. It was hard to see because of smoke, but I believe that the Battleship HYEI just astern of the KAGA was hit by dive bombers and a fire started on the stern of the HYEI.

Q. Was the KAGA attacked by horizontal bombers?

A. No.

Q. Was the KAGA attacked by torpedo planes?

A. I saw torpedo planes but do not think KAGA was attacked. No torpedo hits were made. However, while swimming in water several hours after attack saw a torpedo apparently fired from submarine strike side of ship at angle and bounce off. Didn't explode. Torpedo went bad.

Q. Were any other ships attacked by horizontal bombers?

A. Did not see any hit. Saw some pattern of bombs fall in water during day.

Q. Which type of attack most feared - torpedo plane, dive bomber, or horizontal bomber?

A. Dive bomber, cannot dodge.

Q. Were planes on board when ship was hit?

A. Yes, about 30 planes in hangar loaded and fueled, remainder on deck, six VF in air.

Q. Did bombs sink the ship?

A. Yes, gasoline and bombs caught fire. Ship sank itself, Japanese no need sink with torpedo.

Q. Was KAGA strafed by planes?

A. Was done during diving, one or two personnel and planes on deck were injured.

Q. When did it sink?

A. Same afternoon.

Q. What kind of planes made the attack - torpedo planes, dive bombers or horizontal bombers?

A. Dive bombers.

--2--

Q. In what order was attack made?

A. I think first high horizontal bombers, no hits. Then torpedo attack. Was dodged, no hits. Then dive bombers, 4 hits. Then more horizontal bombing about 400 meters away. No hits. Most attack all the same time.

Q. How many personnel lost when ship sunk?

A. About 800 lost. About 1000 saved.

Q. How many pilots saved?

A. About 40 pilots. About 50% pilots saved.

Q. How were the personnel rescued?

A. By cruisers and destroyers.

Q. How many airplanes did you expect to lose in the attack on MIDWAY?

A. It all depends upon Captain of ship. He expects about 1/3 do not come back.

Q. Were any KAGA planes launched to attack MIDWAY?

A. No, all planes on board except six fighters overhead. I heard that they landed on other ships. Other ships had launched planes to attack MIDWAY but KAGA planes were waiting for orders to launch and attack.

Q. How many protective fighters (CAP) were over carrier formation?

A. Normally 28. Two carriers supplied eight each, the other two carriers provided six each. This was normal patrol. If attacked, other planes rose to meet opposition.

Q. How long did fighters stay in air, and how were planes in air relieved?

A. Two hours. When the waiting planes get in air up high, then the former patrolling plane comes down and lands.

Q. When the carrier launched the patrol did it turn into the wind alone, or did all ships turn?

A. All turn in same formation. We use 14 meters wind over deck for landing and launching. If only few planes launched individual carrier turns into wind. If many planes launched or landed entire formation turns. When over 300 miles from target, carriers operate independently. When within 300 miles of target, all ships maneuver together.

Q. About how far apart were the ships in the formation?

A. A square formation about 4000 meters apart. When need much speed and wind, distance large. When wind and sea strong, the distance diminishes.

Q. Did the formation zigzag?

A. Yes.

Q. Were destroyers employed with the carriers when operating the planes?

A. Yes, sometimes, one, sometimes two destroyers would come from outside circular screen. They take station about 700 meters astern.

Q. How are fighter planes controlled in the air?

A. By wireless. A special officer controls the planes. He is a pilot, in his absence the anti-aircraft commander takes his place.

Q. How did the control officer know where to send the fighters?

A. By radar. It was an experiment at MIDWAY. Not too good.

Q. Did the KAGA have it?

A. No, island too small.

Q. What ships in the formation had radar?

A. HIRYU, maybe SORYU. Not sure of AKAGI, it is rather old ship. (JUNYO did not have it because it was a small converted merchant ship.)

Q. What did the radar look like?

A. It was a big wire grid. Kept rotating. Didn't work very well. Destroyers act as pickets and advise by voice radio if planes are coming. More radars put on ships middle of 1942 and used in SOLOMON ISLANDS operations.

--3--

NAV-1

Interrogation NAV No.2

USSBS No. 11

HIRYU (CV) at the Battle of Midway

TOKYO |

10 October 1945 |

Interrogation of: Captain KAWAGUCHI, Susumu, IJN, Air Officer on the HIRYU (CV) at MIDWAY.

Interrogated by: Captain C. Shands, USN.

Allied Officers Present: Brig. Gen. G. Gardner, USA; Lt. Paine Paul, USNR.

SUMMARY

The HIRYU was one of four aircraft carriers in the Japanese Striking Force supporting the planned occupation of MIDWAY Island, June 1942. When about 600 miles from MIDWAY a U.S. plane passed overhead but did not observe ships due to high fog. No aircraft attacks were made on the carrier group until about an hour after sunrise on 4 June when the formation was attacked by torpedo planes (B-26’s and TBF’s). No hits were made since the long dropping range permitted torpedoes to be easily avoided. A little later, the formation was attacked by high (approximately 18000’) horizontal bombers but no hits were made. The HIRYU launched planes against MIDWAY about sunrise then later against the U.S. Carrier Force. Although the KAGA, AKAGI, and SORYU had received damage during the day, the HIRYU was not hit until late afternoon when she received six hits from dive bombers setting her afire. Still later the same afternoon an unsuccessful bombing attack was made on the HIRYU by horizontal bombers at medium altitude. The fires resulting from the dive-bombing attack spread to the engine room during the night, rendering the ship helpless. She was sunk by torpedoes from a Japanese destroyer the next morning.

About sixty pilots were lost in the battle. About 500 out of the 1500 men on the ship were lost. This group of ships was not attacked during retirement, although search planes were seen. Visibility was poor. Surviving pilots of the battle were distributed between the ZUIKAKU, SHOKAKU, and SOLOMON Islands. These pilots later participated in the battle of SANTA CRUZ, 26 October 1945. As the war progressed the quality of pilots deteriorated due to insufficient training facilities, great attrition, and a shortage of fuel for training with the consequent necessity of using inadequately trained replacements.

TRANSCRIPT

Q. What was the number of the air fleet at MIDWAY?

A. It was of the Second Air Attack Force of the First Air Fleet.

Q. What ships were present in Carrier Force at MIDWAY?

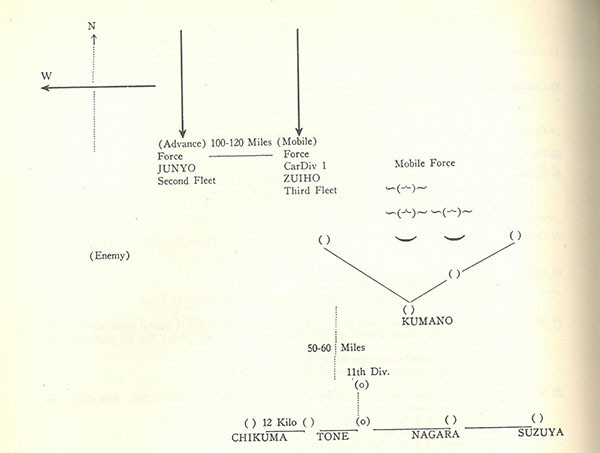

A.

| 1st Div (CV) | 2nd Div (CV) | |

| AKAGI (F) | HIRYU (F) | |

| KAGA | SORYU | |

| BB | CA | CL |

| KIRISHIMA | TONE | NAGARA |

| HARUNA | CHIKUMA | |

| About ten DD’s. |

| ( ) Kirishima | ||||||

| ( ) | ( ) Nagara | |||||

| ( ) | Hiryu (F) ( ) |

Akagi (FF) ( ) |

( ) | |||

| ( ) | ( ) | |||||

| Tone ( ) | Soryu ( ) |

Kaga ( ) |

( ) Chikuma | |||

| ( ) | ( ) Haruna | ( ) | ||||

( ) |

||||||

| ( ) | ( ) |

NAV-2

--4--

Q. When you left JAPAN what was the mission of the air fleet at MIDWAY?

A. It was to seize MIDWAY.

Q. What plans were made for the employment of MIDWAY following the seizure? Did they expect to run searches, go to PEARL HARBOR and the ALEUTIANS or to stop at MIDWAY?

A. Just to defend Midway. Heard of no other plans other than to seize and protect MIDWAY.

Q. What carriers were in the ALEUTIANS?

A. RYUHO and JUNYO; there was no 3rd division, the first and second divisions are in the attack body, the 4th at DUTCH HARBOR, the third did not exist.

Q. During the approach to MIDWAY did you expect an attack; if so, about how far out?

A. Think a two-engined scout plane looked us over once about 500-600 miles from MIDWAY the day before the battle; but the weather was so bad, we still didn’t expect an attack.

Q. Was your formation attacked by submarines at any time during the approach?

A. No, the first submarine attack was on the KAGA after the battle opened.

Q. When was the HIRYU first attacked?

A. On the 4th of June, two hours before sunset. (5 June Tokyo time.)

Q. Were you attacked by a B-17 formation (Four engined bombers) the day before the battle?

A. No, we didn’t get anything the day before but we were attacked by Boeings on the day of big battle and didn’t get hit. There was no attack on 3rd of June.

Q. Do you know of any ships that may have been hit by torpedoes from B-26’ or PBY’s?

A. Not a hit in those days of the battle on the carrier formation.

Q. Were you attacked with torpedoes in the morning of the battle of 4 June?

A. About an hour after sunrise, we were attacked by torpedo bombers.

Q. Were they single or twin-engined?

A. Mostly they were twin-engine, none of them hit. They were dropped at very great range and we were able to avoid them.

Q. Do you know if one of the twin-engined planes, after dropping the torpedo, flew into the deck of one of the carriers?

A. No, I was observing and know that did not happen.

Q. In the early morning of the 4th of June (5 June Tokyo time) did you receive an attack from high level horizontal bombers?

A. About two hours after sunrise some very high four engine planes attacked, maybe 5,000-6,000 meters, but did not hit anything.

Q. How and when was the HIRYU hit?

A. The HIRYU was hit six times during the fourth attack by dive bombers. One on forward elevator. Two just forward aft elevator. Lifts damaged. Fire. Many engineering personnel killed. The floor of the lift flopped against the bridge. We were unable to navigate.

Q. When the HIRYU was hit were any planes on board?

A. Very few about 20 planes had come back. They had been launched to attack American carriers after they returned from MIDWAY.

Q. Will you confirm the position of the island in relation to bow of ship?

A. AKAGI – port, SORYU – starboard, KAGA - starboard.

Q. Did any planes deliver an attack on the ENTERPRISE?

A. Yes, they did attack.

Q. How did they locate the ENTERPRISE?

A. From scout planes about 200 miles off to the east.

Q. Were you attacked by horizontal- bombers later that day?

A. It was about sunset the same day after the dive-bombers gave us six hits that we got about ten misses from Boeings. I think it was B-17’s or something else. It was medium altitude horizontal–bombing. I don’t think they were very high and was astonished at the distance away from the ship when they released bombs.

Q. How many bombs dropped?

A. About ten bunches.

Q. Where did they hit?

A. They didn’t hit – bombs landed about 500 meters away.

NAV-2

--5--

Q. Were any of the battleships hit at that time?

A. I think that something touched the KIRISHIMA or HARUNA in the stern, didn’t do much, no difficulty in navigation as a result.

Q. Was that a result of the horizontal-bombers?

A. No, this was the dive-bombing attack. One of them dived and dropped a bomb on the KIRISHIMA but horizontal bombs didn’t hit the KIRISHIMA.

Q. How were the other carriers hit?

A. All got hit from the dive-bombers.

Q. How were our torpedo planes shot down?

A. I think it was fighter planes in the main.

Q. How was your ship finally sunk?

A. The fire got to the engine rooms by the next morning and stopped the ship, whereupon a Japanese destroyer was called to sink it with torpedoes.

Q. How many men and pilots were lost on the HIRYU?

A. About sixty pilots and a total of 500 men of the crew of 1500.

Q. Why didn’t the occupation force and Grand Fleet continue on to MIDWAY?

A. Because we could not occupy the island having lost our air attack force.

Q. During your retreat did you sight any of our reconnaissance planes?

A. We saw five or six of your planes, on the morning of the 5th, but they didn’t attack us.

Q. Did the HIRYU or any of the other carriers or ships have radar?

A. No, not any. As soon as we got back they put them on the carriers. July 1942 both battleships and carriers received them.

Q. How did you control your fighters in the air?

A. At first at MIDWAY we set the courses on the ships and turned them loose on the first attack. No radio.

Q. Which kind of attack did you most fear, dive-bombing, torpedo or horizontal-bombing?

A. The worst is dive-bombing.

Q. Why?

A. You can’t avoid it, but you can avoid torpedoes at long range.

Q. Do you know if they intended to attack MIDWAY again?

A. All hands thought it was no use.

Q. Do you know if the attack on MIDWAY was instigated by the Army or Navy Command?

A. I believe it was a combined general staff decision.

Q. Did the loss of these carriers result in sending their pilots and aircraft into the SOLOMONS as land based planes?

A. Some of the pilots went back to JAPAN, some went to bases in the SOLOMONS, and some were assigned to the SHOKAKU and ZUIKAKU in the SOLOMONS Area.

Q. Do you know why they continued to send troops, planes and ships into the SOLOMONS in little groups instead of one big group?

A. There were not enough personnel and equipment at home to throw a big bunch in there, therefore they had to go in small increments.

Q. Do you know what influenced the decision to withdraw from the SOLOMONS?

A. I heard it was because we couldn’t supply them. I got very little on plans. Personally thought that Americans were landing too much around us and we should have to give up what we had and go on the defensive. I thought that because we had insufficient number of planes, we couldn’t hope to take offensive action. I thought it was defensive holding from that time on.

Q. Do you know if the Navy had planned for a short war or a long war?

A. We all thought that if it was a long war, the Navy would be finished, and we thought it would be a long war.

Q. What did you consider a long war?

A. If it was short it would be less than two years, something over five years if it were long.

Q. Was there any improvements in aircraft material or personnel during the war?

A. The pilots got worse but the planes got better.

NAV-2

--6--

INTERROGATION NAV NO. 3

USSBS NO. 32

THE BATTLE OF THE PHILIPPINE SEA, 19-20 JUNE 1944

TOKYO |

16 October 1945 |

Interrogation of: Vice Admiral OZAWA, Jisaburo, IJN, Commander in Chief of the Japanese Task Force in subject battle.

Interrogated by: Rear Admiral R. A. Ofstie, USN.

Allied Officers Present: Captain T.J. Hedding, USN; Captain D.J. McCallum, USN; Lieut. Comdr. J.A. Field, jr., USNR.

SUMMARY

The Battle of the PHILIPPINE SEA occurred on 19-20 June 1944 in the sea area west of the MARIANAS, and during the U.S. landing operations on SAIPAN. Major units of the opposing fleets were engaged. On the first day, Japanese carrier aircraft, coordinated with shore based Naval aircraft, carried out a large scale attack on U.S. Task Force 58. Approximately 400 enemy aircraft were shot down, with only moderate U.S. air losses and minor damage to our surface vessels. U.S. submarines sank two Japanese aircraft carriers on this day. On 20 June, at about sunset, U.S. carrier aircraft attacked the Japanese Fleet, sinking one carrier, seriously damaging a second, and sinking two and damaging one of the accompanying tankers.

Admiral OZAWA, who commanded the Japanese Fleet in this action, discusses Naval planning for this operation and movement of forces to the battle area, and gives details of the engagement on both days and subsequent retirement to home waters. He touches briefly on later planning, and offers miscellaneous comment and opinion on various features of the war.

TRANSCRIPT

Plans and Early Movements

Q. Admiral Ozawa, today we propose to discuss the First Battle of the Philippine Sea, 19-20 June 1944. At the beginning of this operation, say about the 10th of June, where were you based, and when did you start on the ensuing operation?

A. The entire fleet was at TAWI TAWI. Left there on or about 10th June (not sure of exact date), fueled in GUIMARAS STRAIT, and then south of MASBATE on to SAN BERNARDINO STRAIT, the due east refueling at sea at about Long. 130°. After refueling started battle here (referring to chart) at about long. 135°. Details are uncertain and approximate.

Q. Why was TAWI TAWI your base?

A. Because the original plan was to get out south of MINDANAO to approach either the Western CAROLINES or the MARIANAS. If this was impossible or inadvisable we meant to go through SURIGAO STRAIT. TAWI TAWI was the best location to meet these arrangements.

Q. What was the information on which this plan was based; why did the task force leave on the 10th of June?

A. The first possibility was that the American Fleet would come up from NEW GUINEA to attack PALAU; the second possibility was that the fleet would come to the MARIANAS. A radio from SAIPAN stated that your force was coming to the MARIANAS, so the task force left TAWI TAWI on receipt of that information.

Q. At that time were SAN BERNARDINO and SURIGAO STRAITS mined?

A. There were Japanese mines in both passages in certain places.

Q. What was the status of training of the Air Groups when you left TAWI TAWI; do you feel that they were well trained, completely trained, or what was your view?

A. The training was very insufficient because the airfield at TAWI TAWI was still under construction.

Q. Had the air groups done some training at SINGAPORE previous to that?

A. The First Squadron only had trained at SINGAPORE; the 2nd and 3rd Squadrons were trained in JAPAN.

NAV-3

--7--

Q. All pilots, however, could land on board in the daytime?

A. Yes, they were capable, but not at night.

Q. What were the basic plans for defense against American landings in the MARIANAS, and by whom were they prepared?

A. There were land-based planes at PALAU, YAP, and GUAM. They were here under direct command of the Combined Fleet, and not under Admiral OZAWA. These air forces, coordinating and cooperating with the task force, were to conduct operations against the American Task Force. This was the original plan of the Combined Fleet Headquarters.

Q. This was the AGO Plan, issued by Admiral Toyoda?

A. Yes, and Toyoda made the plan.

Q. Did you have a conference with Admiral Toyoda before the operation, regarding the plan?

A. The two Admirals had had no conference; Admiral Toyoda was in JAPAN, Admiral OZAWA was in SINGAPORE when the plan was originally received. It was an order from Admiral Toyoda.

Q. About when did the order come out?

A. Perhaps the end of April or beginning of May.

Q. You mentioned that the shore-based air force was under C-in-C Combined Fleet. Were they all Navy, or Army and Navy?

A. All Navy planes.

Q. There were no Army planes in the Islands?

A. There were no Army planes.

Q. What was Admiral OZAWA'S command status relative to these planes; could he give direct orders to them himself or did he have to go back to Admiral Toyoda?

A. They were under command of Admiral Toyoda.

Q. What was the means of arranging coordinated action once the operation started? Did Admiral OZAWA have to go to Admiral TOYODA to direct them?

A. The command was issued by Admiral TOYODA, and I was trying to work along the line of that command. As to the details of how the cooperation was done, I do not remember.

Q. What I meant was, could you, Admiral OZAWA, make decisions effecting shore-based air without reference to Admiral TOYODA?

A. That was done. The First Air Fleet Headquarters was at TINIAN, and the C-in-C of the First Air Fleet had the direction of the air force of all land-based planes.

Q. What was the approximate strength of the aircraft of the First Air Fleet in all those islands?

A. Altogether the land-based planes totaled about 500.

Q. Was that part of the AGO Plan?

A. Yes.

Q. Admiral, will you outline your initial plan; how you intended to strike at the beginning, and what you intended to accomplish here?

A. The first purpose was to attack the American Task Force in cooperation with land-based planes. The second consideration was to attack the landing force with the Second Fleet.

Q. What information did you have as to the strength of the American Task Force?

A. I received information that one task force was around here, about 200 miles south, and another task force was northwest of SAIPAN. These were reports from land-based scout planes.

Q. To go back; when you sortied from TAWI TAWI what did you think the total American strength was?

A. I did not receive any detailed information of the American Task Force but was inclined to think that the whole American Task Force was coming, complete, with about 12 or 13 carriers.

First Day, 19 June 1944

Q. What losses did you have on the first day and when did they occur relative to the time of initiating your attack?

A. Two carriers were sunk that day, the TAIHO and SHOKAKU.

NAV-3

--8--

Q. Give me details about the sinking of the SHOKAKU.

A. She was sunk by a submarine at one o'clock in the afternoon (not quite sure of details; was far from the scene). The first wave of planes had left the ship, and the submarine attack occurred before the second wave was launched. The first wave had not yet returned. I received a report that the carrier was afloat 2 or 3 hours after the hit.

Q. As for the TAIHO, what happened there?

A. It was a submarine torpedo at 0900 on the 19th. All the gasoline spread around in the hanger deck exploded, and because of this explosion the TAIHO sunk at perhaps 1100.

Q. Before launching the first wave?

A. After the first wave left and before the second wave was launched.

Q. You then transferred to what ship?

A. I transferred to the ZUIKAKU by means of a destroyer.

Q. During this period, when ships were lost and the 1st and 2nd waves of planes were sent out for the attacks, was the whole disposition fairly close together, say within 50 miles?

A. Within a range of 100 miles, the entire formation.

Q. What were the first reports you had of the results of the air attack on the American Task Force; when did you get reports and what were they?

A. I did not know until this operation ended and the planes returned. In other words, during the action I received no report of American damage, and never did receive full information.

Q. About how many planes did you send out; how many waves and how many planes?

A. The 1st wave was 300 planes altogether (not quite sure); the 2nd wave a very few planes on account of the two carriers being sunk, perhaps about 100.

Q. The other planes sank with the carriers?

A. Yes.

Q. About what total of planes did you have in all the ships before you came up there?

A. We brought altogether about 400 or 450 planes.

Q. And of those planes how many returned from the 1st and 2nd waves?

A. I do not recollect; but very few returned.

Q. Did you know whether a considerable number had gone in and landed at GUAM and TINIAN?

A. I received a report to that effect. I think they landed at GUAM and TINIAN.

Q. How were plans changed as a result of first days action?

A. The plan was changed to such an extent that the next day the ships were to go back west to refuel and then try to attack again. There were no changes in basic plan but a necessitated change in Japanese movements.

Q. Did you receive any new directive or intelligence from Admiral TOYODA as a result of the first day?

A. I received no report from Admiral Toyoda directly as a result of the first days action.

Q. When the 1st and 2nd waves were sent out, what were the flight commanders orders; what were they to attack, first priority - what was the plan?

A. The main order was to attack the carriers in conjunction with land-based planes; only to attack the carriers. Also the land-based planes were to attack carriers.

Q. This is the point, if attacks from all the planes were to be coordinated, was an effort made to strike at the same time?

A. The planes made formation (rendezvous) in individual squadrons, and every squadron was to take its individual target.

Second Day, 20 June 1944

Q. The next day you had very few planes; about how many left?

A. Perhaps a little less than 60, perhaps about 40 planes left on the ZUIKAKU of the entire First Air Squadron. About the same number of planes left in the 1st and 3rd squadrons.

Q. What was your plan to employ these planes on the 20th?

A. The day of the 20th was occupied by refueling, and keeping watch against submarines. Next attack was intended to be made on the 21st.

NAV-3

--9--

Q. During the day of the 20th while refueling, etc., and until late in the day, what information did you have on movements of the U.S. Task Force?

A. American scout planes interfered with the fueling operations, and the force had to go still further west. Fueling never was accomplished, and about evening the American bombing attack was received and resulted in the loss of one carrier in the 2nd Air Squadron.

Q. That was the HIYO?

A. Yes, and the JUNYO received serious damage. By result of that attack we had to change the refueling and attacking plan altogether. We abandoned original plans and retired to OKINAWA, and at the same time I received a dispatch from Admiral TOYODA that we should abandon the attack and return.

Q. That night you received the dispatch?

A. In the evening of the 20th I received orders to similar effect from Admiral TOYODA.

Q. With respect to the HIYO, can you tell me the details of the damage; did you sink her or did she sink from torpedo or bombing attack?

A. She sank on account of damage, mostly by bombing.

Q. How soon did she sink?

A. Perhaps 1-1/2 hours; she had very insufficient defense equipment because it was a converted carrier and had insufficient compartmentation and protection.

Q. Now with regard to the JUNYO. How much damage was done to her, and did you tow her or could she get away herself?

A. She received a bomb to right of the bridge aft. She received another bomb in some part, but even though damaged it did not affect the speed of movement or affect maneuvering. On account of the damage on the flight deck she could not use the airplanes.

Q. Were there any other ships damaged in that attack, that you know of?

A. I am certain there was no other damage on other ships.

Q. That applies only to the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Air Squadrons; or does it include the support force?

A. I remember clearly there was no other damage.

Q. Did you have reports on the tankers, which were near you then? Any damage to them?

A. Yes, I received a report on the tankers; 2 or 3 tankers were damaged.

Q. The entire fleet moved then to OKINAWA?

A. Yes, all the fleet retired to OKINAWA.

Miscellaneous Battle Comment

Q. What was the first time you thought you knew that the American Fleet had you located?

A. After 5 or 6 hours after we left SAN BERNARDINO STRAITS, I thought we were found by an American submarine or shore watchers.

Q. You had radar in all your ships then?

A. All ships were equipped with radar, but I was very doubtful whether or not our men had mastered the use of radar.

Q. In other words you had no reports by your own radars of any of our aircraft coming over and picking you up?

A. We got it not from radar but from interceptions of dispatches.

Q. That was the day before?

A. Five hours out of SAN BERNARDINO.

Q. About midnight of the 18th-19th, the night before the engagement, one of our patrol planes picked up your force. Did you know that?

A. No, I did not know that.

Q. Did you observe radio silence from the time you sortied until the time the action was initiated on the 19th?

A. Yes, but I think I did send out some radio message on the night of the 18th.

Q. For what reason did you break radio silence; was there an important message to be sent?

A. We sent a radio to instruct the land-based airplanes where to attack the American Task Force.

NAV-3

--10--

Q. Asking them where, or telling them the location of our task force?

A. Telling them mainly the place. It was already understood that the attack would be made in early morning. These instructions were sent to coordinate the action of land-based planes.

Later Plans, Movements, and General Comments

Q. After retirement to OKINAWA, what steps were taken to make new plans as a result of this action?

A. The force refueled at OKINAWA and received order from Admiral TOYODA to return to the INLAND SEA.

Q. Did you then have a conference with Admiral TOYODA, or what was done to prepare new plans as a result of the Marianas battle?

A. I reported verbally to Admiral TOYODA.

Q. And Admiral TOYODA then issued new plans?

A. Admiral TOYODA issued a new order. I didn't have any conference with him on this plan, and had no voice in framing the new plan.

Q. When you first approached the MARIANAS the night of the 18th-19th with your plan of attacking by air and then bringing the fleet in during the final approach, was the intention to come in straight toward SAIPAN, or to come from the south or from the north in a flanking approach? In other words, were you going to go in straight, or come from the side to get the transports?

A. The plan was to go in direct. It would take too much fuel to take the longer route, which had been considered, but we planned to go in straight and we did not change that plan during the approach. Perhaps a little southerly sag in the line of approach for the sake of air cover, but in the main plans agreed to were straight approach.

Q. What date did you get back to the INLAND SEA from OKINAWA?

A. We reached OKINAWA the 22nd or 23rd, immediately refueled and both the 3rd and 2nd Fleets departed either that night or the next morning for the INLAND SEA.

Q. How long did the fleets stay there in the INLAND SEA?

A. The 2nd Fleet and 3rd Fleet, excepting the carriers, stayed there about ten days and then all the able ships except the carriers of the 3rd Fleet joined the 2nd Fleet and departed for SINGAPORE. The 3rd Fleet carriers stayed in the INLAND SEA.

Q. The 2nd Fleet stayed in SINGAPORE until about time for the sortie for the Philippine landings?

A. They stayed in SINGAPORE and LINGGA and BRUNEI BAY.

Q. How long did the fleet stay at SINGAPORE?

A. The Fleet went to SINGAPORE area where damage was repaired for the ships requiring it, and training was undertaken at LINGGA by the balance of the fleet.

Q. The new plan put out by C-in-C Combined Fleet - Admiral TOYODA; what was the substance of that plan?

A. There was a new plan, dependent on the location of American operations. I think the plan was divided into three possibilities: An attack on the PHILIPPINES at LEYTE or around MINDANAO, FORMOSA or OKINAWA.

Q. That was the "SHO" Plan of operation?

A. It was the "SHO GO" operation.

Q. Will you express briefly what, in your opinion, was the effect of the Battle of the CORAL SEA in May 1942? What was the effect on planning; did it cause JAPAN to go on the defensive?

A. I was in SINGAPORE at the time so I do not know exactly what kind of effect that battle had on the plans. I do not think that the Battle of the CORAL SEA affected future main planning.

Q. Now the same thing with respect to the Battle of MIDWAY in which four carriers were lost; how do you feel about that?

A. I think that on account of the result of the MIDWAY battle the planning for future operations was very difficult on the side of JAPAN.

Q. Do you mean that at that point it had changed to the defensive?

A. Thereafter it became necessary to consider the naval operations as mainly defensive on account of loss of 4 carriers.

NAV-3

--11--

Q. Down in the South Pacific in the SOLOMONS, in the RABAUL-GUADALCANAL Area, there was a long period of fighting night actions in which we lost many ships and JAPAN lost many ships. Did that long period of attrition have some predominant effect on operations?

A. JAPAN lost quite a few ships, also damaged air force which made future planning more difficult.

Q. What is your personal opinion as to the relative importance to the whole war of the loss of Japanese Naval strength in ships, the loss of Naval air strength, loss of merchant shipping, and loss of oil?

A. First is the air force - the damage to air force means damage to all the rest. The other three are all dependent on damage to the air force.

Q. Now again down in the SOLOMONS, in the RABAUL-GUADALCANAL Area; you had heavy air losses there and for that reason that was an important campaign, is that correct?

A. Due to the damage of air forces they could not very well replace air force, therefore they could not replace anything else successfully to keep up the strength of RABAUL.

Q. Aircraft or pilots?

A. Same thing with pilots.

Q. Throughout the PACIFIC side of the operations, excluding CHINA; what was the approximate percentage of Japanese Naval aviation as against Japanese Army aviation that was employed?

A. If you include CHINA, then the forces of Army and Navy are about equal; but if CHINA is excluded I do not know.

Q. Wasn't there a predominance of Naval aircraft in the TRUK-RABAUL Area?

A. After MIDWAY there were very few carrier pilots who were assigned land bases in the SOLOMON Area; nearly all of them were reserved for other carrier duty. Excluding CHINA but including BURMA, JAVA and MALAYA, the Navy and Army were about equal. But if you mean the Pacific Ocean Area without the MALAY ARCHIPELAGO, it was almost exclusively Navy. There was some Army air strength in the NEW GUINEA Area, toward the end of the SOLOMONS operations.

Q. After the occupation of the MARIANAS did you feel there was any reasonable chance of defeating our fleet, or of destroying our airforces?

A. I did not know much about the replacement of airplanes, but I thought if the land-based airplanes were prepared to such an extent that they could counter American attack, then I thought there was a fair chance of defeating the American forces.

Q. To go further then. After the 2nd Philippine Operation in October 1944, when you had lost four carriers, then you had no strength to defeat our fleet except with shore-based aircraft. That was the plan then, to use shore-based aircraft?

A. That was then the only way to attack the American forces, with shore-based planes.

Q. In your personal opinion was there any particular outstanding weakness or strength, one way or the other, in the American Fast Carrier Forces? In other words, what were the weakest and the strongest features of the American fast carriers?

A. The particular strength of your task force is the use of radar, interception of radio messages, and intercepting by radar of Japanese air attacks which they can catch and destroy ("eat up") whenever they want to. That is the strength. The weakness we noticed in the beginning of the campaign was the slowness, the lack of maneuverability in case of torpedo attack. Towards the end maneuvering ability improved and we could not successfully deliver a torpedo attack in strength enough to sink anything.

Q. When was construction work on new Japanese carriers discontinued?

A. I do not know the exact date of the discontinuance of building new carriers but think that up to the very end of the war a very high priority was given to this construction.

Q. When did the Naval Air Force shift from carriers to shore bases; at approximately what time?

A. Right after the second Philippines campaign they shifted to a defensive plan, with carrier planes shore based.

(Note: Interrogation of Admiral OZAWA to be continued on Tuesday, 30 October 1945, at 0930)

NAV-3

--12--

Interrogation NAV No.4

USSBS No. 23

Battle of Midway

TOKYO |

9 October 1945 |

Interrogation of: Captain AOKI, Taijiro, IJN. Commanding Officer of AKAGI (CV) at Battle of MIDWAY. He was not a pilot.

Interrogated by: Captain C. SHANDS, USN.

Allied Officers present: Brig. Gen. G. GARDNER, USA; Cmdr. T. H. MOORER, USN; Lt. Cmdr. J. A. FIELD, Jr., USNR.

SUMMARY

The AKAGI was one of four aircraft carriers comprising the Eleventh Air Fleet, in the striking force at the planned occupation of MIDWAY ISLAND, June 1942. The CV’s were first attacked about 200 miles from MIDWAY, 2 hours after sunrise, 4 June by many planes carrying torpedoes, all of which were avoided. The first indication of the presence of the United States carriers was the dive bombing attack which scored two hits on the AKAGI. The AKAGI had launched half of her planes to bomb MIDWAY but forty were still being serviced when hit. No more were launched. 200 were lost and 100 wounded, out of a total complement of 1400. On the morning of the 5th a Japanese DD torpedoed and sank the AKAGI. The KAGA, SORYU, and HIRYU were sunk due to damage inflicted by dive bombers. No other damage was sustained from air attack by ships in the striking force except possible damage to one battleship’s superstructure. No planes seen on the 5th or later during retirement.

The loss of the CV’s caused plans for the occupation to be abandoned.

TRANSCRIPT

Q. What ships were present in the carrier force at MIDWAY?

A. AKAGI, KAGA, HIRYU and SORYU (all CV’s) HIYEI or HARUNA and KIRISHIMA (BB), TONE and CHIKUMA (CA), NAGARA (CL), about ten or twelve destroyers. AKAGI was in the Eleventh Air Fleet.

Disposition

| ( ) | ||||||||

| ( ) DD | ( ) DD | |||||||

| ( ) Kirishima (BB) | ||||||||

| ( ) DD | ( ) Hiryu (CV) | ( ) Akagi (CV) | ( ) DD | |||||

| ( ) (DD) | ( ) Soryu (CV) | ( ) Kaga (CV) | ( ) (DD) | |||||

| ( ) Hiyei (BB) | ||||||||

| ( ) (DD) | (Haruna) | ( ) (DD) | ||||||

| ( ) (DD) | ( ) (DD) |

Q. What were the other three units?

A. The Grand Fleet was there to act as support, commanded by Admiral YAMAMOTO.

Q. What was the mission of the Eleventh Air Fleet?

A. Simply to bombard MIDWAY by planes.

Q. What was the mission of the entire fleet?

A. That was to help. Entirely separate from this was the occupation force.

Q. Was the Air Fleet separate from the Grand Fleet?

A. Yes, of course it was under the Grand Fleet, but was a separate force.

NAV-4

--13--

Q. During the approach to MIDWAY when did you expect the first air attack?

A. About 500 miles from MIDWAY, but our carriers were first attacked in the morning about two hours after sunrise, about 200 miles from MIDWAY.

Q. What type planes made the first attack?

A. Torpedo planes, then dive bombers. First a great many torpedoes were dropped from planes, then dive bombers hit.

Q. Were any attacks made on the carrier force during the approach by B-17’s or PBY’s?

A. There were none. Torpedo planes in the morning of attack but no four engine bombers.

Q. Were any planes seen or heard during the approach the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd of June?

A. There was a high fog and the day before the action opened they heard one above the clouds in the day time.

Q. Was the AKAGI hit by any four-engined or horizontal bombers?

A. Not once.

Q. Were any ships hit by horizontal bombers?

A. I think all ships were hit by dive bombers.

Q. Did you lose any ships to submarines during approach?

A. No, none at all.

Q. On the day before the main action about 600 miles from MIDWAY, was the formation attacked by long range planes?

A. No.

Q. How was the AKAGI damaged?

A. Fire; two bombs by dive bombing about two hours after sunrise, (one started a fire at after elevator). Planes were loaded up with bombs inside the hanger and caught fire.

Q. Did you see any horizontal bombers over the formation at the time?

A. KIRISHIMA was under attack by horizontal bombing. It was not hit. Near misses.

Q. Were the AKAGI’s planes in the air?

A. About half of them were up attacking MIDWAY. We were servicing others in the hanger, about forty on board. We had high cover of 6 Zero Type fighters in addition.

Q. Was this the first group launched from AKAGI?

A. This was the first group launched from all the ships.

Q. Were any other planes launched from AKAGI to attack our carriers?

A. There was no second flight from the AKAGI.

Q. Which type of attack was most feared – horizontal, dive bombing or torpedo?

A. Diving, you can swing away from torpedoes, but the worst is dive bombing.

Q. Was AKAGI sunk as a result of those two bomb hits or was she sunk later by Japanese destroyers?

A. It did not sink by bombs. She was sunk by a Japanese destroyer’s torpedoes during the next morning. Engines were helpless, fire damage, could not navigate so gave up the ship; many engineers were killed. 200 were lost, 100 were wounded out of 1400 on board.

Q. How many pilots were saved; how many lost?

A. Six pilots were lost. Others landed and were picked up by destroyers.

Q. Why didn’t the task force continue to MIDWAY?

A. Too much damage to aircraft carriers, lost control of air.

Q. What other carriers or ships were lost?

A. KAGA, SORYU, HIRYU. No damage to battleships or serious damage to any other ships in our group.

Q. In what other operations was the AKAGI?

A. PERAL HARBOR was the first, she attacked at CEYLON and TRIMCOMALEE, next MIDWAY. MIDWAY was the only action in which I was aboard.

NAV-4

--14--

Q. Did our aircraft carrier raids on JAPAN affect the training of pilots during the war?

A. When your planes were attacking we had to stop training and so lost time besides training planes. However, we didn’t suffer much from the loss of training planes.

Q. Had the Navy planned on a war of long duration?

A. They were all talking that it would be long, but nobody hazarded a guess as to duration. As soon as it began we thought it would be a long war.

Q. About how many planes or pilots did you expect to lose at MIDWAY, that is from anti-aircraft and attack?

A. Because we had suffered so little at PEARL HARBOR at the beginning of the war, we thought we would get away with the same thing at MIDWAY. I think that other ships in the task force lost a good many pilots, but as far as my ship was concerned, we got off very easily.

Q. Did you have radar on the AKAGI?

A. No.

Q. Did any ships at MIDWAY have radar?

A. YAMATO, MUTSU and NAGATO in the Grand Fleet may have had it. There was no ship at MIDWAY or carrier which had it.

Q. Do you know when they were first installed and first used?

A. I don’t know but when I went to the arsenal at KURE, I saw the grids on the ISE and HYUGA. It was August 1942 after MIDWAY. I supposed that they must have been installed on better ships by then.

Q. While cruising to MIDWAY was radio silence observed?

A. There was radio silence.

Q. Was an interpreter radio guard stood on CW or voice frequency?

A. There was nothing but curiosity, but there was not a real guard.

Q. During passage to MIDWAY, were flight operations conducted or carried out?

A. Training flights for about two days (Weather bad); anti-submarine patrols every day. No combat air patrols.

Q. What number and types of planes were used for anti-submarine patrols?

A. 97 Type attack planes. Four planes were used for anti-submarine patrol, searching out at a distance of about 40,000 meters.