The Navy Department Library

Preface - History of US Naval Operations: Korea

Perpaps the simplest way to describe the Korean War is to say that it was different, for it fell, or seemed to fall, outside the pattern of all previous American experience. It was a surprising war in a surprising place at a surprising time, and one which imperatively called for answers to neglected problems of national defense. It was begun as a police action; it developed rapidly into an undeclared war of no small magnitude; it ended as an unpopular and seemingly profitless stalemate. It was conducted, at least in theory, less as a national enterprise in defense of an easily apprehended national interest than as an exercise in collective security under the aegis of the United Nations. And while partial precedents can doubtless be discerned in battles long ago, the package was a new and unsettling one.

In addition to differences such as these in the nature of the war itself, there were others which bear upon the historian. Since the enemy had no navy, the conflict lacks the drama inherent in the clash of fleets. Since the focus of action was always on land, the three services were pretty constantly mixed up in each other's affairs, and simple single-service history becomes an impossibility. The chronology of the struggle, in which a year of violent and dramatic action was followed by two of deadlock, poses problems of selection and emphasis and makes for injustice to those who came late on the scene. The absence, in notable contrast to the situation of 1945, of any appreciable quantity of enemy records, constitutes a further obvious difficulty.

Nevertheless, an attempt to tell the story of United States naval operations in Korea has seemed worthwhile. If many of the specific lessons of the conflict are now obsolete, the general principle remains: that for those who have abjured the offensive, the main problem is how to prepare for the unexpected, or more cynically, how to be surprised at least cost. If war is to remain a political act, the Korean experience seems worth contemplating for its demonstration that the neglected problems of stalemate may at times be as important as those of advance and retreat.

If the absence of contending fleets detracts from the excitement of the story, it also emphasizes the fact that since all war is an exercise in persuasion, naval activity has always been ultimately directed against the far shore. And finally, one may hope that caution will help to counteract the one-sided nature of the available source material.

To the puzzling question of how far to treat the actions of the other services, I have found no wholly satisfactory answer. I have attempted throughout to keep before the reader a general picture of the campaign, but to deal in detail with Army and Air Force operations only when they interacted with those of the Navy. But while this standard has seemed the only one possible, it should be made plain that it distorts the picture. For the Army it means that emphasis is on the hard times when help was called for, rather than on periods of prosperity when things were moving well; for the Air Force the vexed question of tactical support receives considerable attention, while the work of Bomber Command and of the fighter pilots up by the Yalu is scanted.

In some cases this procedure gives rise to questions of a certain delicacy. The Korean War took place at a time when the new defense establishment was suffering growing pains; the course of the conflict was such that divergent and strongly held views were put to the test; interpretation of the consequences is unavoidably controversial. Although I have not thought it possible to gloss over these matters, I cannot hope that my conclusions will please everyone. Perhaps, indeed, they will satisfy none: the manuscript has been read by those connected in one way or another with Army, Navy, and Air Force alike, all of whom (happily for different reasons) have disagreed with certain of the views expressed. In this connection it may be worth stating, for those who wonder how "official" this history is, that I have had full liberty to express my own opinions, and that there have been no deletions from the manuscript on security or other grounds.

One final caveat. Throughout the book I have referred to General MacArthur, and to his successors in supreme command, by their United States short title, CincFE, rather than as CincUNC, Commander in Chief United Nations Command. This usage has been employed as a matter of euphony only, and in no way indicates a desire on my part to de-emphasize the international nature of the campaign.

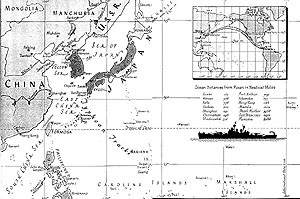

No one ever writes a book alone, and like all authors I have incurred heavy debts. I am grateful to those individuals, in and out of the armed services, who have been generous of their ti me in discussing the war and in criticizing the manuscript, and to others who on other occasions have contributed to my education in these matters. I must record my thanks to the administration of Swarthmore College for the grant of a leave of absence without which completion of the book would have been long delayed. Throughout the enterprise Rear Admiral P. M. Eller, USN (Ret.), the Director of Naval History, and his staff have been most helpful. Erwin Raisz has been both skillful and patient in working through the complex specifications for the maps which illustrate the volume. Karlene Madison's contribution went far beyond the military fortitude with which she typed and retyped. My wife and children have shown great forbearance.

| James A. Field, Jr. Swarthmore, Pennsylvania |