The Navy Department Library

Chapter 12: Two More Years

History of US Naval Operations: Korea

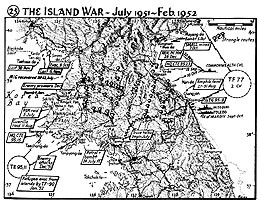

Part 1. July 1951-February 1952: Stabilized and Peripheral War

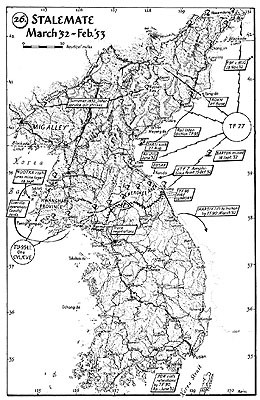

Part 2. March 1952-February 1953: Stalemate

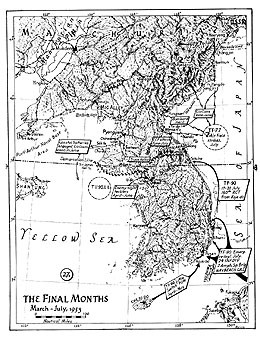

Part 3. March-July 1953: Progress, Crisis, Conclusion

Part 1. July 1951-February 1952: Stabilized Front and Peripheral War

At Kaesong the first few days of talk were not auspicious, occupied as they were by U.N. efforts to control Communist propaganda activity, by argument over the administration of the neutral area, and by procedural disputation. Nevertheless, in the course of little more than two weeks, an agenda was adopted and the delegates proceeded to address themselves to the question of a cease-fire.

Although hostilities were to continue until agreement had been reached, the commencement of negotiations made for optimism, and ComNavFE thought it necessary to warn of possible acts of treachery. Ground action, nevertheless, continued to diminish: six months of grinding frontline warfare had ended, the battleline had been stabilized on favorable ground, and except in the Iron Triangle and on the Soyang River, United Nations activity was limited to patrolling and to the improvement of defensive positions. But since the enemy was busily engaged in bringing down new units to replace those chewed up in the spring offensives, and was bending every effort to improve his logistic position, interdiction perforce continued. For the next two years, as hopes of peace continued to be frustrated, the burden of offensive action was to lie principally upon the Air Force and the Navy.

The prospect of an early armistice had already been reflected in the movements and composition of the Amphibious Force. With the departure of Admiral Thackrey in June the number of Amphibious Force flag officers in the Western Pacific dropped from two to one; at the end of the month a recommended reduction in the Far Eastern deployment of larger PhibPac ships to one AGC, seven APAs, and two AKAs had been approved by CincPacFleet; in time the allowance of LSTs would also be cut down. Concurrent with this diminution of strength, however, there arose the requirement of supporting the U.N. armistice delegation, and a special task element of one AGC, one APA, and an LST helicopter base was formed and stationed at Inchon to provide logistic and communications services. And at the same time other units of Task Force 90 were assisting in a special operation to the northward.

This affair, of the greatest importance for technical intelligence, involved the recovery of a downed Russian MIG. For although U.N. aviators were by now well acquainted with this high-performance fighter, Communist reluctance to engage in combat far from base had prevented acquisition of a specimen for closer examination, and a previous search by west coast ships for one reported on the sandbars of the Yalu Gulf had proved fruitless. On 9 July, however, word was received from JOC that a MIG was down in shoal water off the mouth of the Chongchon River; Sicily, back again in the Far East as relief for Bataan, was ordered to search, and the American officers in charge of west coast underground activities, "Leopard" on Paengnyong Do and "Salamander" on Cho Do, were instructed to alert their people. But the reported position was 15 miles in error, the weather was foggy, and the aircraft, awash only at low water, was hard to see; not until the11th did planes from Glory find the MIG a couple of miles offshore and 33 miles north of the Taedong estuary.

This location, less than 10 minutes flying time from the enemy’s Antung airfields, was both risky and navigationally difficult. But photographs indicated that recovery might be practicable, every effort was ordered by ComNavFE, and the commanding officer of Ceylon worked out a plan. On 18 July an LSU equipped with a special crane was borrowed from CTF 90 and sent up to Cho Do in the LSD Whetstone. The next day’s effort ended with the LSU fast on a sandbar, but on the 20th, with air cover from Glory, with Belfast stationed to warn of air attack, and with Cardigan Bay on hand for fire support, a U.S. Navy helicopter operating from the British carrier buoyed the site and Glory aircraft led the LSU through the sandbars. By evening the engine had been recovered and the major portions of the airframe located; next morning the pieces were loaded on the LSU. In the afternoon Sicily pilots sighted 32 MIGs heading for the area, but foggy weather prevented contact, no trouble ensued, and on the 22nd the LSU and its precious cargo were embarked in the LSD Epping Forest and the MIG brought back to Inchon.

Along both coasts, as talks began, action continued. On the western shore British Commonwealth, ROK, and U.S. units carried out a number of small bombardments and raids. At Wonsan in the east, activity increased as the enemy worked to expand his truck traffic and to develop his coastal defenses: reports from agents within the city made frequent mention of the presence of Soviet advisors, of the massing of troops, of possible shore-based torpedo firing facilities, and of the installation of batteries of impressive size, including a "Stalin gun" said to have been hauled out to Hodo Pando by 12 horses. Sufficient credence was placed in these reports to produce the "Wonsan Special" of 5 July, in which Task Force 77 helped out the bombardment group by devoting its entire day and 247 sorties to the city. And further confirmatory evidence was soon forthcoming.

At 1637 on the afternoon of the 17th, shore batteries opened on the destroyers O’Brien, Blue, and Cunningham from three sides of the Wonsan swept area. The ships at once went into the War Dance, an evasive maneuver originated in May by Brinkley Bass and Duncan, steaming in an ellipse at 22 knots and firing on batteries in each sector as their guns came to bear. As enemy fire continued heavy, Task Force 77 was called upon for air support; at 1650, and again an hour later, an LSMR was brought in from the outer channel to deliver a long-range rocket barrage against enemy gun positions. By 1830 the batteries on Hodo Pando, Umi Do, and the tip of Kalma Pando had been silenced or had checked fire, but a new group of emplacements at the base of Kalma Pando presently opened up. By this time Helena and New Jersey had been started in from Task Force 77, and HMS Morecambe Bay, en route to Songjin, had been diverted to Wonsan. At 2000 in she came to join the dance, and for another hour, until darkness descended, shooting continued. Despite many very near misses no ship had been hit, and the single casualty was treated by the application of a Band-Aid, but the more than 500 splashes observed and the far larger number of rounds returned made the so-called "Battle of the Buzz Saw" a very respectable engagement. Late that night Helena reached the outer channel, to be followed by New Jersey in the morning, and since something heavier than 5-inch gunfire seemed needed, both ships stayed on for two days of heavy-gun bombardment.

Prospects nevertheless seemed warm, and future policy deserving of consideration. To the Seventh Fleet staff the value of the Wonsan foothold seemed dependent on the future intentions of CincFE, a view which was communicated to the higher levels for comment. But there, owing to the commencement of armistice talks, planning was largely in abeyance, and answer came there none. In the absence of guidance from above, Admiral Martin decided, as an interim measure, to hold the harbor islands for bargaining purposes. It was to prove a long interim.

Offshore, despite the hindrance of the July fogs, Task Force 77 continued to provide aircraft for close support, armed reconnaissance, and interdiction. Since requests from JOC for support of the battleline seldom exceeded 30 sorties a day the main effort was invested in a continuation of Operation Strangle, the attempt to cut truck traffic between 38°15’ and 39°15’, and in a return to bridge breaking. Here foggy weather, increased antiaircraft, and the recent emphasis on close support had worked in favor of the enemy; the bridge cuts south of Songjin had been eliminated, and few breaks existed in the line. But by month’s end things were again under control, and a new program of systematic photography was underway to provide information for a new key bridge list.

At Kaesong, following agreement on the agenda, the delegates in late July took up the question of a demarcation line. Here the Communists, who by now had suffered a net loss of territory, insisted on the 38th parallel. But since an armistice would bring an end to the blockade, and to air and naval action against enemy territory, the U.N. negotiators, for their part, sought compensation in a line north of the existing front. From this discussion there soon arose the question of who in fact controlled the territory of the Yonan and Ongjin peninsulas, south of 38° and west of the Imjin River.

Largely untouched by war, and but lightly held by the enemy, the coastal parts of Hwanghae Province were subject at any time to descents from the sea, or to raids by partisans operating from the offshore islands. At the end of June ROK guerrillas with naval support had landed south of Yonan to destroy two ammunition dumps; in the following weeks raids were carried out against the mainland opposite Cho Do. On the evening of 24 July, as the question of the demarcation line arose, CTF 95 received a message from Admiral Joy asking for a show of strength in the Han River estuary as close as possible to Kaesong. Admiral Dyer at once committed all but one of his west coast frigates to this operation, Glory was ordered from Sasebo to join Sicily, and a check sweep of the entrance to Haeju Man was undertaken to permit the entry of heavy bombardment ships.

Two-carrier operations were carried out from 26 to 29 July; from the 27th to the 29th the heavy cruiser Los Angeles shot up targets on the western shore of Haeju Man; in the Han the Commonwealth frigates bombarded the northern bank. For these operations in the estuary the finest kind of seamanship was necessary: U.S. and British charts of the area differed widely, and none showed any very reassuring depths; the liquid medium in the Han, brown soup rather than clear water, was lined with rocks; currents reached eight to ten knots, and so poor was the holding ground that on one occasion Comus dragged while steaming to both anchors.

Although targets for bombardment, obtained from JOC and from the Leopard organization, were generally unprofitable, and although enemy reaction was for the moment nil, the demonstration was more concerned with capabilities than with accomplishments. By early August, despite intermittent groundings, the bombarding ships had succeeded in penetrating upstream to fire on Yonan from the southeast and northward up the Yesong River; on the 17th three of the frigates found 400 enemy troops along the river bank and gave them a thorough shelling. Late in the month, on the urging of Admiral Scott-Moncreiff, a survey of the river was begun by a UDT detachment in the APD Weiss, and the channel was buoyed by the fleet tug Abnakz.

By this time the optimism which had accompanied the opening of armistice talks was dead. In early August negotiations had been briefly suspended by General Ridgway in protest against Communist violations of the neutral zone; late in the month, following an incident apparently fabricated to suggest that U.N. aircraft had bombed the conference site, the Communists in turn refused to talk; only in late October, with transfer of the conference site to Panmunjom, were plenary sessions resumed. These events governed the progress of the fighting. In mid-August General Van Fleet launched a limited offensive on the eastern coastal strip; with the breakdown in negotiations he ordered a larger effort east of the Hwachon Reservoir in X Corps zone.

Once again fire support was needed on the coastal road. On 17 August a special bombardment group, Task Group 95.9, was formed to assist the ROK advance into the difficult hill country south of Kosong; composed initially of New Jersey, Toledo, and two destroyers, this group continued through various changes of ships and of designation to support the eastern end of the battleline through August and into September.

Once again, also, an amphibious demonstration was called for to assist the forward movement. On 27 August a minesweeping group composed of three AMS and the LSD Whetstone moved into the objective area at Changjon, to be followed in due course by Helena, three destroyers, and an LSMR, and on the 30th by New Jersey and another destroyer. On the 30th and 31st the beach and adjacent troop and gun positions were bombarded and subjected to air strikes; offshore, where the transport group lay to, the boats were lowered, formed into waves, and headed for shore, before being recalled and hoisted in. But although the demonstration was more elaborate than its predecessors, it remained questionable what diversionary impact had been created, or whether anything over and above the bombardment damage had been accomplished.

The main effort, however, was inland, and there on the 31st the attack began as the Marine Division, fresh from a six-week rest, pushed northward up the Soyang Valley, while the 2nd Division pressed forward on its left. By 18 September the Marines had reached their objectives, as did the 2nd Division in mid-October. West of the Hwachon Reservoir, IX Corps was also pressing forward, and by 21 October was looking down upon Kumsong. Seventh Fleet planners had by this time produced a follow-up plan, known as "Wrangler," which involved withdrawing the Marines from X Corps, embarking them at Sokcho, and landing them in assault at Kojo to link up with the advance of IX Corps. But on 24 October, after a month of haggling by liaison officers, the Communists asked that talks be resumed, and "Wrangler" never came off.

The northward advance of the Marines since their February commitment to the Wonju front had brought them steadily closer to the Sea of Japan. Late September found the division on the upper waters of the Soyang River where its right, though still west of the Korean divide, was less than ten miles from the sea. This proximity to tidewater raised possibilities of naval gunfire and maritime logistics which were quickly embraced.

In this extremely mountainous country the enemy, deeply entrenched on the reverse slopes, was hard to reach. Since artillery could not touch him, and since air support was in short supply and unpredictable in quality, resort was had for the first time in a year to naval gunfire. On 20 September New Jersey was sent in to provide support; on the 23rd, after liaison officers had been sent out by helicopter and radio communication had been established, ranging rounds were fired; on the next two days, and again on 2 and 3 October, 16-inch fire was called down upon the backsides of the enemy with destructive and demoralizing effect. On 17 October New Jersey returned to the task, and for five days late in the month support was provided by the heavy cruiser Toledo. Intermittently throughout the winter this work continued, with the ships firing at ranges of 11 to 16 miles, their shells sailing over 2,000-foot mountains and across the Nam River valley to embed themselves amidst the enemy’s supply concentrations and command posts.

The proximity of the sea also held logistic promise. In contrast to the ROK I Corps on the coast, always largely supported by sea, the Marines in September were dependent on their railhead at Wonju, 91 bad road miles away, a situation which required greatly increased allowances of motor transport, communications gear, and heavy engineer equipment. Now, however, encouraged by the prospect of "Wrangler," a road was cut through the mountains to the sea, Sokcho in the ROK zone was pressed into use as a supply port, and an adjacent airstrip was employed as division airhead. The impressive consequence of this shift to seaborne supply was the addition to the division’s monthly potential of an estimated 8,000 to 10,000 combat man-days.

In somewhat similar manner Marine air units attempted to base themselves on the sea. MAG 12, with its main base at Pusan West, had been increasing its output and decreasing commuting time by staging through a forward field near Wonju; in July this field was closed, and in August forward operations were shifted to a coastal strip near Kangnung. But Kangnung has no harbor, and although use of this strip greatly improved the sortie rate, the exposed nature of the coastline complicated logistics. Original plans to bring supplies in across the beaches foundered when the broaching of an LST showed the beach to be unsatisfactory. Resort was next had to unloading at Chumunjin, but at the cost of a 17-mile trucking requirement over inferior roads. In early September the construction of a pontoon causeway near Kangnung eased the situation until its destruction by winter weather necessitated further recourse to Chumunjin.

Still, if the complications of beach logistics forced the working hands to a variety of expedients, the support provided by MAG 12’s neighbors was unsurpassed. The broaching of the LST, with its vital load of POL and ordnance, brought an immediate response from the population of nearby fishing villages. Sampans were lashed together to form a causeway, and then overlaid by pierced steel planking across which the cargo was manhandled ashore. Twenty-four hours of continuous effort finished the job, and as no pay would be accepted by the Koreans the best the Marines could do was to set up a fund for the families of fishermen lost at sea.

Day after day throughout the summer the fast carriers continued the effort at interdiction. On 22 August a new face appeared in the Far East with the arrival of Essex, first of her class to enter World War II and first also to reach Korea following modernization to provide more powerful catapults, larger elevators for planes and bombs, and most importantly a larger gasoline capacity and an improved fueling system to cope with the insatiable demands of jet aircraft. Embarked in Essex was Air Group 5 with one squadron of ADs, one of F4Us, one of F9Fs, and one of the McDonnell F2H Banshee, an excellent twin-jet fighter, larger, heavier, and superior in performance to the F9F, although still, like all U.S. aircraft except the F-86, inferior to the MIG in speed and maneuverability.

Essex’s first month in the theater was one of developmental progress. Operationally a new first in interservice cooperation was effected when 23 F9F and F2H fighters escorted 35 B-29s in a strike against Najin, a Communist storage center on the northeast coast beyond the range of Air Force fighters and but 17 miles from the Soviet boundary. In materiel also an advance took place, following a serious accident in which a damaged F2H floated over the barriers and into parked aircraft, causing a gasoline fire which destroyed 4 planes, killed 7, and injured 27. Lacking propellers to catch the barricades, floating jets had always been hard to stop, and the ultimate solution of the angled deck was still some years away; but the Essex incident brought an effective interim measure in the installation of a ten-foot barrier of wire and nylon tape as a last-resort midships arresting device.

For the most part, however, the work went on, day after day, in routine fashion. "Strangle" operations against the North Korean road net continued into September, as did attacks on key rail bridges. Across the peninsula Fifth Air Force also continued its efforts against road traffic, but with a progressive tendency to shift to a new concept, still under the rubric "Strangle," which called for the destruction of railroad trackage in the optimistic hope that this would force the enemy to wear out his motor transport. In this effort, officially begun on 19 August, the carriers soon joined; a month later, on orders from CincFE, all close support was halted to permit full concentration on interdiction; on the last day of September, following a conference between Air Force and Navy commanders, it was decided to emphasize rail cutting supplemented by the destruction of a small number of key bridges. The Navy’s part began fast with 131 track cuts in the first three days of October, and as the enemy’s repair parties were poorly deployed to meet the new tactic, both Air Force and carrier airmen managed to stay ahead while the flying weather remained good.

At intervals throughout the fall the work of the fast carriers in the Sea of Japan was augmented by the Commonwealth light carrier. On 18 and 19 September, at the suggestion of Commander Seventh Fleet, CTF 95 put on a special two-day air, gun, and rocket effort against Wonsan, in which the air strikes were provided by HMS Glory. On 10 and 11 October a similar operation against the Kojo area, with air strikes from HMAS Sydney, and with a mixed U.S., British, and Canadian screen, was carried out by Rear Admiral Scott-Moncreiff in Belfast. Late in November Scott-Moncreiff returned again with Belfast and Sydney, and with a screen still further internationalized by the addition of a Dutch destroyer, to spend two days in banging up Hungnam.

In the east, along the 300 miles of enemy coast, the ships of Task Force 95 continued to provide fire support, to patrol and bombard, and to besiege the cities of Wonsan and Songjin. In July the Royal Marine Commando, whose varied experiences had taken it under the sea in Perch, up to thc reservoir with the Marines, and into enemy country near the mouth of the Taedong River, had arrived at Yo Do for a six month’s tour of duty; after some practice raids against the Wonsan mainland the Royal Marines began a series of autumn operations, landing from an APD to attack targets along the northeastern coast. On 5 September, on orders from Seventh Fleet, CTF 95 instructed the minesweepers to clear a lane between Wonsan and Hungnam to bring the western shore of the Korean Gulf within gunfire range. One month later, as the job was being finished, New Jersey, Helena, and some destroyers bombarded the Hungnam area for the first time since the X Corps evacuation, destroying an oil refinery and some ammunition dumps. But although the clearance of Hungnam had been successful not everyone had heard the details, and on 7 October the destroyer Small got outside the swept area and was mined with considerable damage and heavy casualties.

The efforts at interdiction by Fifth Air Force in the west and Task Force 77 in the east, together with surface ship bombardment of accessible coastal pressure points, had placed a heavy load upon the Communists. Their Department of Military Highway Administration, charged with road repair, had grown to a total of some 20,000 men, and the railroad repair organization was estimated of equivalent size. But despite all, it still seemed impossible to cut the flow of supplies below the enemy’s requirements. Persistence and diligence in repair, a determination to get supplies through, and the small logistic requirements of Communist forces had resulted in continuous improvement of the enemy’s front line logistic situation: his soldiers were better fed than ever before, his number of tanks had increased, and his expenditure of artillery ammunition had risen from 8,000 rounds in July to 43,000 in November. For one side, at least, negotiation had proven profitable.

Not only were supplies getting through, but some 500 heavy antiaircraft guns and almost 2,000 automatic weapons had by now been emplaced in North Korea, and U.N. aircraft were suffering increasing losses. The increase in coast artillery, first noted at Wonsan, had extended along the shore, with the result that U.N. vessels could no longer move close in or lie to while firing. At sea the possible submarine threat continued to preoccupy naval commanders, while in the air enemy strength continued to grow.

Steadily increasing totals of MIG sorties were being reported by Air Force fighter pilots on northern patrols–180 on 2 October, more than 300 on 29 November–while the availability of light bombers and propeller-driven attack planes was no longer a matter of question. Following an Air Force query as to carrier jet capabilities in the northwest an F2H sweep was sent off to MIG Alley; no contact was made, and this maximum-range effort was not repeated, but the menace remained. Noting the increase in Communist air strength and the concurrent effort to activate North Korean airstrips, ComNavFE in early November informed his command that enemy aircraft had been sighted south of Pyongyang, and directed heavy ships not to operate north of Wonsan without air cover. On 27 November a flight from Bon Homme Richard was attacked by MIGs near Wonsan, and on subsequent occasions contrails were sighted high overhead. In early December, as the Amphibious Force began an interchange of Army units between Hokkaido and Inchon, CincFE instructed FEAF and the West Coast Carrier Element to provide cover for all troop movements in the Yellow Sea.

Nevertheless, despite the enemy’s increasing material prosperity, the movement of the battleline had continued northward, the U.N. retained command of the air over most of North Korea, the U.N. navies controlled the coasts, and bombardment at Wonsan, Songjin, and in the Han River estuary remained a daily affair. On 28 September CTF 95 made an inspection trip up the Han in the Australian frigate Murchison, only to be opened on by mortars, small arms, and light field guns. Contemporaneously with this first instance of the long-awaited enemy reaction, indications that the Communists were about to abandon their insistence on the 38th parallel brought requests from the U.N. delegation and from EUSAK for more gunfire.

Admiral Dyer at once ordered the Han River operation intensified. The Yellow Sea carrier was directed to bomb the northern banks daily and to provide air spot and CAP for the bombarding frigates. On 3 October Black Swan steamed up the river to draw enemy fire, whereupon 13 F4Us from Rendova attacked the gun positions; and for the balance of the month, as carrier aircraft burned off the cover on the northern bank, the noise of the bombardment was wafted to the negotiators at Kaesong. By October’s end an effort originally scheduled for a few days had lasted a hundred, and like the destroyers at Wonsan the frigates in the Han estuary had become fixed.

On 25 October, as the enemy returned to the truce table, the U.N. negotiators proposed the establishment of a four-kilometer demilitarized zone based generally on the existing line of contact. On 5 November the proposal was accepted, together with a U.N. proviso that the line be that existing when final agreement was reached. A week later General Ridgway directed Eighth Army to cease offensive operations and commence an active defense of existing positions. By the 27th the front had been mapped and accepted by both sides, and a bait provided for the Communists by a U.N. undertaking to accept this line should the armistice be conduded within a month.

With this agreement, frigate bombardment in the Han River was terminated and ground action again diminished. Along the entire front, from the Imjin to the sea, the Communists pressed the fortification of defensive positions. But as the ground battle tapered off into patrolling, the enemy commenced an offensive effort in a new sphere, and the seat of war was transferred to the offshore islands.

These islands, acquired during the U.N. advance in late 1950, had since that time been employed as bases for raids and for intelligence activities. On the eastern shore the picture was a fairly simple one: except for those in Wonsan harbor only four islands of importance lie along this coast, and of these the two largest, Mayang Do on the 40th parallel and Hwa Do off Hungnam, were enemy controlled. Northeast of Songjin, however, the Yang Do island group, two miles offshore, accommodated intelligence personnel moving in and out of North Korea, and in time would become an ROKN PT operating base; off the bomb line on the 39th parallel the little island of Nan Do was employed as a base for Task Force Kirkland, a EUSAK unconventional warfare organization.

In the west the situation was more complex. On Tokchok To, off Inchon, the Air Force navigational equipment evacuated in December had been reinstalled in February, and similar gear had been emplaced on Paengnyong Do on the 38th parallel. Along the southern shore of Hwanghae Province, from the Han estuary to Korea’s western tip, numerous coastal islets were employed as bases by partisan groups, of which Leopard Force was the most notable. Off the Chinnampo approaches, the important islands of Sok To and Cho Do supported guerrilla and clandestine operations, and an Air Force desire to install radar facilities and rescue helicopters on Cho Do waited only on improved security. To the northward in the Yalu Gulf a group of islands, seized by the ROK Navy in November 1950, contained numerous anti-Communist guerrillas.

The number of independent agencies on these islands led at times to situations of considerable complexity. In August 1951 one observer noted that Yo Do in Wonsan harbor was crowded with uncoordinated delegations from nearly every organization operating in Korea, and that the masses of amateurs commuting to and from the mainland created hazards for the skilled agents. In the west a FEAF outfit which operated its own private navy, and the organizations controlled by Leopard at Paengyong Do and by Salamander at Cho Do, cooperated well with the blockading force. But other groups, too mysterious to mention, were less considerate, and when NavFE headquarters proved unable to influence the state of affairs, Admiral Scott-Moncreiff ordered the apprehension and detention of all unidentifiable travellers. By autumn this particular situation had improved, but by this time the enemy was showing interest in the islands, while the armistice talks had adversely affected the morale of anti-Communist North Korean guerrillas.

Giving thought to their future status in the event of a cease-fire, many of these now became double or triple agents, or went over to the Communists. At Sok To a mutiny of the garrison and landing force was caught in the nick of time by Leopard, and 300 prisoners were removed to the southward. On 30 August Royal Marines and stokers from Ceylon made a descent upon a west coast target designated by Leopard Force; Leopard himself accompanied the raiders and no trouble was expected, but someone had leaked and the opposition was waiting. On Cho Do, in early September, an attempt on the life of Salamander was made by one of his own ex-agents. But not all developments were adverse. On 24 September, supported by gunfire from Comus, Leopard’s Sok To agent led a small raid against the Amgak peninsula, and returned with nine prisoners including a North Korean colonel and his concubine. The colonel, recently transferred from Wonsan, reported that he was fed up with the war; the comments of his lady have unfortunately not been preserved.

In this situation of tension and uncertainty the enemy, in early October, began to exert pressure. On the 9th, 600 invaders from the mainland landed on the large Yalu Gulf island of Sinmi Do, and although the garrison held for a time with support from Cossack and Ceylon, reinforcements arriving across the tidal mud flats forced withdrawal on the 12th. On the 30th Cayuga reported receiving a hundred rounds of artillery fire from the Amgak peninsula opposite Sok To; in the Yalu Gulf the island of Taehwa Do, where friendly forces had concentrated, was attacked by aircraft on 6 November in the first confirmed enemy employment of light bombers in Korea. That night Ka Do and Tan Do, two of the smaller northern islands, were seized by the Communists in a night amphibious attack.

Since the U.N. delegation hoped to use the islands as counters to trade off against the Kaesong area, these events served to stimulate some interest. From Commander Seventh Fleet came a request for an inventory of west coast islands, and from EUSAK a hope that Taehwa Do would be held. Although he felt the northern islands were not worth the effort required to defend them, Admiral Scott-Moncreiff on 9 November ordered a destroyer to patrol the area during the hours of darkness. Shortly Commander Seventh Fleet appeared in the Yellow Sea on an inspection tour; on the 12th, with air spot from HMAS Sydney, his flagship New Jersey fired her final Korean bombardment and her 3,000th 16-inch round of the war at troop concentrations reported by Leopard Force.

Winter by now had come again bringing strong winds, cold, and the first snows to the northern Yellow Sea. Nightly, nevertheless, ships of the blockading force went up to Taehwa Do; in the course of the month guerrilla raids supported by naval units were conducted against enemy-held islands in the Yalu Gulf; but the proximity of these positions to enemy airfields prevented daylight surface support or carrier air patrol. On 27 November the subject of the offshore islands came up for discussion at Panmunjom, and at once the Communists stepped up their efforts.

Although the enemy carried out a successful raid against Hwangto Do in Wonsan harbor on the night of the 28th, his principal effort was in the west. On 30 November, as CincFE warned that the islands had become critical to the negotiations and adjured his island commanders to make preparations for defense, Fifth Air Force fighters intercepted a formation of 12 twin-engine bombers heading for Taehwa Do with an escort of 16 propeller fighters and 50 MIGs, and destroyed the greater part of the bomber force. Nevertheless the island was lost that night to a well-planned amphibious assault supported by artillery from Ka Do, and of some 1,200 guerrillas and inhabitants only about a quarter got out. This affair was followed almost immediately by further enemy shore-to-shore attacks which seized six small coastal islets in Haeju Man, and by reports of extensive troop movements in Hwanghae Province. These events brought a review of the island situation.

Responsibility for island defense was at this time somewhat obscure. Tokchok To and Paengnyong Do had for almost a year been charges of CTG 95.1; other islands where U.S. intelligence activities or equipment were operative were under the control of CincFE; the Korean-occupied islands were pretty much on their own. The loss of Taehwa Do had brought increased patrolling by west coast ships and a request for reinforcement of the Cho Do, Sok To, and Paengyong Do garrisons; on higher levels various proposals for the institution of small boat patrols, reinforcement of the islands by air, and the like, were bandied about; in the south ROK Marine units were alerted for movement to the threatened islands. On 7 December Admiral Dyer received the loan of Manchester from Commander Seventh Fleet, and followed by Ceylon proceeded west at speed to Cho Do. But the attitude of higher echelons remained obscure, no reinforcements were available from EUSAK, and Commander Seventh Fleet was reluctant to become too deeply involved.

At Cho Do and Sok To, Admiral Dyer found morale improved by the news that the islands would be defended, but the situation was still precarious, Island commanders, intelligence officers rather than Marine or Army line, were inexperienced in organizing defenses; since the guerrillas were all natives of North Korea, security was inherently poor; conversation with Leopard indicated the great desirability of getting the refugees out and the ROK Marines in as fast as possible. An LSD and some AMS were brought in to keep the Sok To anchorage swept and to strengthen the small craft patrol, and arrangements were made for the LSTs bringing up the ROK Marines to remove the refugees. With this much accomplished, and with an apparently growing small boat menace to the Wonsan harbor islands, CTF 95 proceeded to the east coast.

Hardly, however, had he reached Wonsan when word was received of attacks on two small islands inboard of Sok To, and between 16 and 18 December, despite support from U.N. ships and aircraft, an enemy force of about 600 overran these positions. With the situation apparently still deteriorating, CTF 95 again headed west, and on the 18th took over as officer in tactical command on the west coast. By the 20th the ships on anti-invasion duty near Cho Do included Manchester, Ceylon, and two destroyers, and the question of responsibility for island defense was at last beginning to jell.

Despite the fact that all islands north of 38° were conceded by the U.N. negotiators on 21 December, failing an armistice agreement the defensive requirement remained. On 6 January responsibility for the overall defense, local ground defense included, of designated islands on both coasts, was assigned the Navy and delegated to CTF 95. So far as east coast islands were concerned only Nan Do, off the bombline, had not previously been a naval responsibility; in the west, however, Sok To and Cho Do in the Chinnampo approaches, Taechong Do in the Sir James Hall group, and Taeyongpyong Do south of Haeju were added to the list. On the 9th an Army-Navy-Air Force island defense conference was held aboard Wisconsin, following which the West Coast Island Defense Element was organized with a U.S. Marine officer in command, with headquarters on Paengnyong Do, and with two battalions of ROK Marines distributed among critical islands.

Already the LSTs of Task Force 90, which had brought the defenders in, had begun to evacuate refugees: by 22 December about 9,000 had been lifted out and by late January some 20,000 had been transported south to Kunsan. Constant patrolling of the threatened areas was undertaken, and an LST with armed small boats was provided for inshore work. In mid- January, in an effort to suppress the artillery effort against Cho Do and Sok To, CTF 95 went north in Rochester to bombard the Amgak peninsula in coordination with a Marine air strike from Badoeng Strait. By early February the enemy had retired from a number of the captured islets in Haeju Man and off the Ongjin peninsula, in part apparently owing to bombardment by rocket ships, in part to inability to support his forces. By March these islets were being reoccupied by anti-Communist partisans and a number of enemy efforts to attack across the mud flats had been thrown back by naval gunfire.

The period following naval assumption of responsibility for island defense brought two actions of some importance. On the northeast coast, after a month of careful preparation, the North Koreans mounted a raid on the Yang Do group by some 250 troops boated in sampans. Shortly after midnight on 20 February the New Zealand frigate Taupo, the DMS Endicott, and the destroyer Shelton were patrolling to the northward when an emergency dispatch reported Yang Do under fire from the mainland and invasion apparently imminent. Steaming at flank speed the ships reached the islands to discover bombardment continuing and fighting in progress ashore, but by this time radio contact had been broken. With daylight, however, the island commander came back on the air: all invaders on Yang Do had been either killed or captured, those on East Yang Do were departing for the mainland. There followed a spirited engagement in the two-mile strait in which Taupo and Endicott engaged some 15 sampans, destroying 10 and damaging the rest, and were themselves engaged by artillery from the mainland, while Shelton put up counter-battery fire. This was all very well, but on the west coast the enemy fared better, and in a successful assault on the night of 24 March seized a small island between Cho Do and Sok To and eliminated its defenders.

Although reports of enemy offensive plans continued to come in, and although artillery fire was persistently directed against Cho Do, Sok To, and their supporting ships, as well as against the islands at Wonsan, the enemy island offensive was limited in its success to the elimination of the foothold in the Yalu Gulf. At Cho Do improved defensive arrangements were followed by the installation of radar and antiaircraft weapons in February, and in March by a helicopter detachment; these facilities, together with naval patrol of the surrounding waters and a rescue B-29 which orbited overhead, made the Cho Do area a useful bail-out and rescue zone for pilots from the Yellow Sea carrier and from the Fifth Air Force. Elsewhere the offshore positions continued to provide bases for intelligence and guerrilla activity, while at Wonsan possession of the harbor islands paid an unexpected dividend. Some concern had been caused the U.N. Command by events such as the Sok To mutiny, and by reports that guerrillas were surrendering in response to an enemy offer of amnesty. But at Wonsan, on 21 February, reassurance was gained when at 0630 in the morning Brigadier General Lee Il, NKPA, reached Tae Do in a stolen sampan, with a briefcase full of top secret papers, a head full of top secret plans, and a strong desire to make himself useful.

As the war continued among the islands, along the coasts, and in the air over North Korea, so did the talks at Panmunjom. There, with agreement on the demarcation line, discussion had turned to arrangements for a ceasefire and to the question of prisoners of war. December and January brought abandonment by the U.N. of the northern islands, of the right to air reconnaissance over North Korea, and of a previously proposed limitation on Communist rehabilitation of airfields. But with the New Year the sticking point appeared in the question of forced repatriation of prisoners. Despite further U.N. concessions all progress ceased, while continued enemy pressure against the islands was indicative of no speedy peace.

Through the winter cold and winds and snow, naval and air operations went on. The Amphibious Force was engaged in further troop lifts between Korea and Japan. The units of Task Force 95 continued as before, the monotony interrupted only by a brief resumption of the Han River patrol, by rumors of.a Soviet submarine in the northeastern coastal area, and by the loss with all hands of an ROK PC, presumably by mining, at Wonsan. On the east coast the detachment of the ROK Capital Division to chase guerrillas in the southern mountains imposed additional burdens at the bombline, but the assignment of a heavy ship and of another destroyer to duty there enabled the remaining forces to hold the road while the extermination campaign went on. The load of the minesweepers was increased by the decision of CTF 95 to sweep the east coast from Kansong to Songjin every two weeks. As for the aviators, they were still working on the railroad.

Table 22.-COMMUNIST AND U.N. TRANSPORT, WINTER 1951-52

| Vehicles | Locomotives | Rolling stock | |

|---|---|---|---|

| North Korea | 6,000-7,000 | 275 | 7,700 |

| South Korea | 22,000 | 486 | 8,314 |

In the north the frugal and ant-like enemy continued to accumulate supplies and, as the table shows, to maintain with roughly half the logistic means of the U.N. a larger military establishment. At year’s end total U.N. strength in Korea was of the order of 600,000, and that of the Communists a third as much again, while EUSAK credited the enemy with the ability to launch a general offensive with a force of more than 40 divisions.

So spring came.

Part 2. March 1952—February 1953: Stalemate

Watch after watch, day after weary day, the war went on. The cold of winter passed, to be followed by the thaw and rains of spring, the haze and fog and steaming heat of summer, and the clear days of early autumn. In steady succession carriers and their air groups crossed the Pacific to take their tour of combat and depart; from the west coast of the United States destroyers crossed the ocean and from the Atlantic coast the world, operated for their allotted period, and returned again. In the Atlantic and Mediterranean the larger half of the U.S. Navy was also working on an accelerated schedule in a situation that was neither peace nor war. Throughout the establishment and on both sides of the world effort was called for from all hands, and particularly from the career personnel, laboring to accomplish an acceptable minimum of training while watching the steady disappearance of rated men and qualified reserves into the welcoming arms of American industry.

Stalemate existed, but stalemate brought no rest. Readiness had to be maintained; crews had to be trained; the enemy, ensconced in the northern half of the peninsula, had to be harassed, and if possible brought to terms. Day after day the F-86s went up to the Yalu, Air Force fighter-bombers and carrier aircraft ranged over North Korea, the gunnery ships continued on patrol, mines were swept. But month after month went by, and increasingly the question of what leverage to employ upon the enemy became more puzzling and more frustrating.

For the supporting forces and for the NavFE shore establishment, as well as for those on the line, life continued arduous under the twin pressures of operational load and Parkinson’s Law. The hazards of the sea continued to manifest themselves in run-of-the-mill casualties and breakdowns calling for the attention of the Service Force, while April brought a major tragedy when an explosion in Saint Paul’s forward 8-inch turret took 30 lives. In some areas, however, appropriate savings were effected: to economize on pilots and aircraft, pull-out altitudes were raised and passes over a target limited; to economize on fuel and ammunition Commander Seventh Fleet would soon restrict speed in transit and unobserved gunfire. Expenditure of aviation ordnance, however, continued apace, aided by the load-carrying characteristics of the AD, with the surprising result that by May 1952 Navy and Marine usage in Korea equalled their total for the entire war against Japan. In communications, too, economy was hard to come by, and multiplied circuits and augmented personnel struggled bravely but vainly against the loquacity of the human animal. The message count of late 1950, when great operations were afoot, was up by half again in 1952 though all remained routine; in the autumn an amphibious feint would double the peak reached during the amphibious strokes of two years before.

For the enemy, too, the war went on, the seasons passed. To a country hardly worth more devastation, and to men whose lives held little value for their rulers, U.N. aircraft and ships and artillery brought destruction and death. What the Communists thought they were accomplishing remains unknown. Their inability to deal with the situation in constructive terms, either for themselves or for the world at large, remained unimpeachable.

Once more in 1952 the coming of spring brought changes to the Far East. In Europe General Eisenhower gave up his command at SHAPE, and returned home to begin a career in politics. Summoned to succeed him, General Ridgway was in May relieved of his commands by General Mark W. Clark, USA, who had struggled in Italy with the problems of peninsular war and in Austria with those of negotiating with the Communists. This change at the top of the U.N. Command was paralleled throughout the echelons of Naval Forces Far East: the Marine Division and the Marine Aircraft Wing received new commanding generals; with the arrival of Rear Admiral Burton B. Biggs the Logistic Support Force got a flag officer at its head; in April the first of a new generation of carrier division commanders arrived in the person of Rear Admiral Apollo Soucek; in May Vice Admiral Joseph J. Clark become Commander Seventh Fleet and Rear Admiral Frederick W. McMahon, for four months ComCarDiv 5 in Valley Forge, relieved Admiral Ofstie as Chief of Staff of Naval Forces Far East.

Although rotation and relief had brought multiple changes in most Far Eastern billets there remained two commanders who had seen it all. Now, at long last, replacements for these veterans arrived. On 1 June Commander Luosey, who since the earliest days had administered the ROK Navy, was relieved. In May, after ten months of negotiations, Admiral Joy was succeeded as head of the truce team by Major General William K. Harrison, Jr., USA; in June, after nearly three years in peace and war as Commander Naval Forces Far East, he turned over his Tokyo command to Vice Admiral Robert P. Briscoe.

As the faces changed so did the problems faced. In mid-March the command structure of the Western Pacific was modified by presidential order, and military responsibility for the Philippine-Formosa-Marianas area transferred from CincFE to CincPac; local responsibility, however, remained with Commander Seventh Fleet, in his capacity as Commander Formosa Defense Force, and standing orders dating from Struble’s time, to proceed to Formosa at best speed in the event of a serious invasion threat, continued in effect. In April the Japanese peace treaty became effective and that war, at least, was formally over. For Naval Forces Far East this had a variety of implications. Along with their sister services in Japan they had to transmute themselves from occupation forces into guests, a process facilitated by war in Korea which both demonstrated the virtues of available force and provided a sizable infusion of dollars for the Japanese economy. With the peace treaty came also the disestablishment of Scajap, the Navy-administered Japanese-manned shipping concern which had performed such yeoman service in support of the Korean campaign, and the transfer of its LSTs to MSTS contract operations. For the future, ComNavFE acquired new responsibilities in helping the Japanese to organize a Coastal Security Force, and in supervising the transfer of frigates and landing craft to Japanese control.

Within Korea, spring of 1952 brought a change of some importance in the move of the Marine Division from the Soyang River sector to the Imjin front. On the tactical level this shift was occasioned by concern at EUSAK for the defenses in the west; strategically, it reflected the final abandonment of plans for an east coast amphibious envelopment. For most of the troops this 160-mile movement across everyone else’s supply lines was carried out between 18 and 25 March by road, but the tanks, amphibian tractors, and much of the engineering equipment were lifted out from Sokcho by two AKAs, three LSDs, and ten LSTs from Task Force 90. The arrival of the Marines west of the Imjin, where they relieved the ROK 1st Division, made it for the first time possible to hold this position against determined attack, while their transfer to a coastal sector produced an extra dividend as an amphibious retraining program, conducted throughout the summer in the Tokchok Islands, was apprehensively observed by the enemy.

The continuing amphibious threat, together with U.N. occupancy of islands off the enemy’s shore, had by now brought the assignment of three North Korean corps and three CCF armies to coast defense. In March and April, enemy raids across the mud flats of Haeju Man against Yongmae Do were repulsed by gunfire from Commonwealth naval units; on the east coast enemy batteries on Mayang Do fired on minesweepers and patrolling ships. U.N. forces, for their part, continued to exploit the islands for their opportunities in evasion and escape, and as bases for guerrilla operations. Attacks by APD-borne detachments against the east coast rail line were resumed, but with diminishing dividends; in the west, coastal raids and incursions into the Haeju area were supported by the Yellow Sea carrier and by gunnery ships.

At Cho Do and Sok To, which with their valuable radar, weather, and helicopter detachments had become the Wonsan of the west, a series of intermittent engagements took place between ships, carrier and Fifth Air Force aircraft, and enemy coastal batteries. In July there was a brief flurry in the Yellow Sea as an island close to the tip of the Ongjin peninsula was invaded by a North Korean force embarked in junks and outboard motor-boats. As Belfast and Amethyst converged to assist the defenders, and as Marine fighter planes from Bataan answered the call, other west coast ships manned anti-invasion stations off Cho Do and Sok To; within two days only 5 of the 156 invaders were missing and unaccounted for. More trouble-some than the enemy were outbreaks of typhus on Cho Do and Paengnyong Do, but the epidemics were quickly controlled by a naval medical unit.

With the front remaining relatively quiet, the most conspicuous ground action of early 1952 was the campaign of Koje Do. On this island, 30 miles southwest of Pusan, camps had been erected to hold the more than 100,000 prisoners of war. Early in the year a screening program, intended to separate civilians from bona fide soldiers, had culled out some thousands of the former, who were then lifted by LST to mainland ports; it had also been violently resisted by organized prisoner groups. With the commencement of a second screening cycle, designed to separate those desiring repatriation from those who would resist it, disorder and violence increased; within the Communist-controlled pens the prisoners reigned supreme, and by their riotous activity provided grist for enemy propaganda mills. In May the capture of the camp commander by his charges provided embarrassing evidence of a need for reinforcement.

Five ROKN small craft were ordered to Koje to prevent escape by water; elements of the 187th Airborne Regiment were hastily flown from Japan to Pusan and lifted out by LST, while the rest of the regiment with its heavy gear was brought across by sea. For Task Force 90 the sudden calls resulting from the crisis on Koje Do meant that scheduled maintenance had to be foregone and training schedules modified, but in due course the campaign was won. New island sites for camps were selected by aerial reconnaissance, beach surveys for LST slots were carried out by the UDTs, Army engineers and equipment were lifted to the new locations to construct new compounds. On 10 June a new camp commander imposed control upon his intransigent wards, and in July Task Force 90 carried 37,000 prisoners to their new decentralized homes.

At Panmunjom no progress remained the order of the day. Enemy insistence on freedom to reconstruct the North Korean airfields, on a limitation on rotation of forces in Korea, and on crippling restrictions for the proposed Neutral Nations Supervisory Commission sufficiently impeded agreement. But the insuperable barrier to progress, which no concession could apparently move, was the reluctance of Communist prisoners to return home and the insistence of their governments on forced repatriation.

Behind his fortified front, his stubbornness in negotiation, and his vigor in propaganda, the enemy continued to increase his strength. In March, interrogation of prisoners indicated that great operations were impending. On 1 April the biggest air battle of the year occurred when 186 F-86s took on some 350 MIGs. Late in the month piles of construction material at the Pyongyang airbase evidenced continued intentions of rehabilitation. In May an unparalleled 4,000 vehicle sightings a night betokened an extremely active logistic effort. In the weeks that followed, increased aggressiveness brought the MIGs south as far as Sinanju.

On the east coast, as well, the growth in enemy capabilities was apparent. There, where the ships of Task Force 95 continued to patrol, bombard, and besiege, enemy gunfire steadily increased. From Kojo north to Chongjin the installation of radar, together with such devices as anchored ranging buoys, led to continued improvement in Communist fire control. March brought the heaviest shooting since the previous July, and April’s fall of shot was double that of March. Reports from captured and defecting personnel, which suggested that an assault against the Wonsan islands was in preparation, gained at least superficial confirmation from the discovery that the boatbuilders of the area had been mobilized, and that the bays west of Hodo Pando contained a large and increasing number of small craft.

By June the greatest troop and supply accumulations of the war were in evidence behind Communist lines, and intelligence indicated the imminence of a general offensive. There was also a rumor circulating, derived from POW interrogation, that the enemy proposed to kidnap the U.N. armistice delegation on the 25th, the second anniversary of the outbreak of war. No one can feel very safe when dealing with such people: as far back as April the Marines had formed a covering force to protect the truce team should the talks break down, and the new rumors brought further preparations. But June passed without difficulty and the anticipated offensive never came.

The naval siege of Wonsan was now well into its second year. Begun in order to take some pressure off Eighth Army and to get the gunnery ships on the offensive, it had by now become institutionalized: the officer in tactical command afloat enjoyed the additional honorific title of Mayor of Wonsan, and with changes of command there passed also a large gilt key to the city. But here too the passage of time, the size of effort, and the difficulty of damage assessment led inevitably to questioning. Certainly the extensive installation of shore batteries and antiaircraft, and the reported presence in the neighborhood of almost 80,000 troops, gave evidence that the effects had been considerable. On the other hand a sizable force was required to maintain the siege, defend the islands, and prevent remining of the harbor: in addition to four or five minesweepers, their tender and a tug, two or three destroyers were maintained permanently on station, and the expenditure of ammunition, much of it unobserved and unspotted, had been heavy. Demonstrable damage to the enemy hardly made up for this investment, which could only be justified by the argument that it held down large enemy forces, and by such incidental advantages as the flow of information gained through the infiltration of agents. Some now came to argue that the siege should never have been undertaken, but its long history made it difficult to abandon without apparent admission of defeat.

But the enemy, too, was concerned about Wonsan. One indication of the extent of his worries was provided by captured records of a war game conducted by North Korean division commanders in early 1952. This problem was concerned with a defense against a four-divisional assault at Wonsan, accompanied by subsidiary landings at Kojo and Hungnam, and by a northward thrust of Eighth Army through the Iron Triangle and the eastern mountains. Against this hypothetical maneuver, which bore a not too remote resemblance to U.N. planning, there were available to the North Koreans the two mobile artillery brigades which manned the Wonsan shore, three infantry divisions in the near neighborhood, and Chinese forces further inland. Interestingly, the exercise conceded inability to prevent a U.N. lodgment, and the scheme of maneuver emphasized an all-out counterattack on D plus 4. Interestingly also, and showing that spies are everywhere, the problem included among the assaulting units the 40th and 45th Infantry Divisions which, at the time the exercise was prepared, had just finished amphibious indoctrination in Japan and were preparing to be lifted to Korea.

Since the Navy, like it or not, appeared to be committed, steps were taken to improve the position at Wonsan. Island fortifications were strengthened; a clear statement from CTF 95 defined the primary mission of ships at Wonsan, as at Yang Do and Nan Do, as the defense of those positions; construction of an emergency airstrip on Yo Do was undertaken. This enterprise had been suggested the previous autumn, when the increased effectiveness of Communist antiaircraft had forced a number of damaged planes to ditch in Wonsan harbor. In the absence of a regular naval construction unit in the area the proposition had been put up to the Army and Air Force, in whose custody, in view of the continuing hopes of an armistice, it had languished for six months. In May 1952, however, permission was secured for the employment of Task Force 90's Amphibious Construction Battalion, and ComNavFE obtained the approval of CincFE. On 9 June a detachment of 3 officers and 75 men from ACB 1 was landed by LST, and began work under intermittent bombardment from Hodo Pando and Umi Do. The planned 2,400-foot runway had been estimated to be a 45-day project, but the Seabees did better than the planners, and in 16 days the strip was finished. The commanding officer of the construction battalion had predicted that salvage of one plane would more than offset the expense of the project, and if his cost accounting was correct the dividends were enormous: eight Corsairs from Task Force 77, damaged or low on fuel, were brought in safely in July, and in time twin-engined transports would arrive bringing the sinews of war and lady war correspondents. This success stimulated jealousy in the west, where the condition of the emergency beach strip on Paengnyong Do was such as to cause frequent damage in landing, and from the commanding officer of Badoeng Strait came a request for the provision of separate but equal facilities.

Along the familiar stretch of coast from Hungnam to Songjin the campaign against the east coast rail line continued. The effort had been simplified, early in the year, with the designation of 16 target areas, 5 of which were to be dealt with initially by carrier air and then kept out by surface gunfire, while the rest were assigned to heavy gun bombardment. As before, the targets were principally bridges, vulnerable tunnel entrances, embankments, and slide areas along the precipitous shore. As previously, the effort was comparatively successful: in the first half of 1952 less traffic passed along this stretch of railroad than along any other line north of Pyongyang-Wonsan. With time, however, and as the employment of Task Force 77 shifted from interdiction to strikes against strategic targets, the responsibility devolved increasingly upon the gunnery ships, while in the interest of economy in ammunition expenditure the shooting up of trains replaced the shooting up of track.

By now, indeed, the interdiction campaign had become the despair of all concerned, and at Air Force headquarters the publicity given the code name "Strangle" was bitterly regretted. Rails could be broken, trains shot up, bridges knocked down, and truck formations harassed, but the enemy continued, largely through night movement, to accumulate supplies in the forward areas. In this situation the inadequacies of U.N. night air capabilities rose again for discussion, and new efforts were undertaken to improve night work.

In May, Task Force 77 put on a series of night attacks, Operation Insomnia, in which six aircraft were launched at midnight and six more at o2oo for a time this tactic permitted unopposed attacks on heavily defended areas; on one occasion ii locomotives were trapped for later destruction by day strike groups. By July, in an effort to provide all-night operations without overloading ships’ companies, three teams of hecklers were being launched at dusk, of which one worked until midnight while the others landed ashore for later takeoff. But by autumn the lack of personnel to man key posts on a 24-hour basis, and the view of Commander Seventh Fleet that unless a special night carrier could be provided the emphasis should be on daytime operations, had led to diminished effort. Owing to the world situation and the shortage of operating carriers no such ship was ever made available, although an abortive attempt was to be made at war s end to do this locally, and the lack of night capabilities remained a major U.N. deficiency.

Through the spring of 1952 Task Force 77 had drifted slowly away from rail interdiction. Although in March the force was still averaging 133 rail cuts per operating day, increased attention was being given to small boat demolition so as to inhibit attempts to recapture offshore islands. In April a series of coordinated air-gun strikes on coastal cities was begun: at Chongjin on the 13th, 246 sorties from Boxer and Philippine Sea deposited 200 tons of bombs while Saint Paul, escorted by three destroyers and with spot from the carrier planes, kept up a daylong bombardment. In May a three-day effort, equally divided between Chongjin and Wonsan and supported by Iowa, was conducted in two installments when the original plans were frustrated by sea fog. But deserving targets were limited, and in June the work of the carrier air groups was shifted inland beyond gun range.

Diminishing and discouraging returns from interdiction and disillusion with the progress at Panmunjom had also led the staff of FEAF to seek alternative employment. Since the enemy was now amply supplied for offensive action, and since any offensive would bring him into the open and subject him to heavy damage, FEAF’s planners proposed to concentrate on maintaining air superiority in MIG Alley while maximizing the cost of war to the other side. In May, therefore, in a move somewhat parallel to the air-gun strikes by Task Force 77, Fifth Air Force sent large fighter-bomber attacks against concentrations of supplies, facilities, and equipment in the enemy rear.

This attempt to maximize enemy costs inevitably raised the question of the hydroelectric complex, the one important untouched target system in North Korea. These generating plants and their related distribution facilities had been brought to high development during the period of Japanese occupation. At Suiho on the Yalu River the world’s fourth largest hydroelectric plant, with an output of some 300,000 kilowatts, supplied power both to Korea and Manchuria; up in the mountains, in what had once been X Corps territory, the Chosin, Fusen, and Kyosen Reservoirs together produced an even larger quantity for the cities of the eastern coast. In the summer of 1950 proposals to attack the power complex had very sensibly been turned down on the ground that the bill for reconstruction would fall upon the American taxpayer; subsequently, in the effort to avoid Chinese intervention, the importance of the Suiho plant to Manchurian industry had led these targets to be placed off-limits. But as the armistice negotiations stretched out into 1952 the question was again raised by FEAF, as on a lower level by CTG 95.2, who was desirous of turning off the lights at Wonsan by shooting up the substation.

The timing was appropriate. In late April, in an effort to compose remaining differences at Panmunjom, Admiral Joy had offered to waive restrictions on airfield rehabilitation if the Communists would accept voluntary repatriation of prisoners and the exclusion of the U.S.S.R. from the Neutral Nations Supervisory Commission. But this offer was violently rejected, all progress ceased, and the meetings degenerated into propaganda about POW riots and bacteriological warfare. In this situation, comparable to the period in World War II when water barriers separated the principal belligerents, a turn to attritional bombardment, the slowest of all methods of war, was almost inevitable.

Early in June, FEAF put the proposition up to General Clark, and was given permission to plan the destruction of all hydroelectric plants except Suiho, which was still off-limits without JCS approval. But with the Chinese carrying the burden of the war for the enemy, the earlier rationale had disappeared, and since damage to Suiho offered a method of making trouble in Manchuria without crossing the border, approval from Washington was forthcoming. In Tokyo a date was selected which would permit the maximum carrier contribution and on 18 June FEAF alerted Fifth Air Force for strikes on the 23rd or 24th, weather permitting.

Since late January, four fast carriers had been present in the theater, working in teams of two. For the power plant attacks, arrivals and departures in the operating area were overlapped to provide, for the first time since December 1950, four on station at once. In another way the situation was a reminiscent one, for not since the strikes on the Sinuiju bridges in November of that year had the carrier attack planes crossed Korea to hit targets in MIG Alley. Joint planning between Task Force 77 and Fifth Air Force was begun at JOC on 21 June; on the 22nd flight schedules and ordnance plans were made up and navigational details worked out. The Suiho strike was to be a joint operation in which the carrier pilots had the place of honor; the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing was given the two Chosin installations; the Kyosen plants were assigned to other task force strike groups; those at Fusen were divided between the Navy and Air Force. Since Suiho, where heavy MIG opposition was expected, was the critical target, the other attacks were timed to follow it by a few minutes.

Early on the 23rd Boxer and Princeton were joined by Bon Homme Richard and Philippine Sea. Preparation for the launch was halted when the Air Force put off the strike owing to anticipated adverse weather. But in the course of the day the operation was rescheduled, H-Hour was set for 1600, and at 1410 the force began launching 35 ADs with 4,000 and 5,000- pound bombloads for the Suiho attack. Forming up at 5,000 feet, the Skyraiders crossed the coastline at Mayang Do and then, keeping low to the mountains to avoid radar detection, headed straight for the target. Fifty miles from Suiho they were overhauled by 35 F9Fs which had taken off 50 minutes later. Eighteen miles from the target the group commenced a climb to 10,000 feet, with one jet squadron going up to 16,000 feet as combat air patrol. Two miles from the target a high-speed approach was begun.

At 1600, precisely on schedule, the first squadron of Panthers dove on the gun positions on the Korean bank, closely followed by the ADs and by the other flak-suppression jets. Release altitude was at 3,000 feet and pull-out at 1,000; within a space of two and one half minutes the attacking aircraft delivered 81 tons of bombs. At the power house which was the main target red flames filled the windows, secondary explosions were reported, and photographs taken by the last ADs to drop showed smoke pouring from the roof. The antiaircraft batteries had opened as the attack began, heavy weapons and automatic fire was moderate and machine gun fire intense, but the defenses were overwhelmed. No plane was lost, and the only Skyraider to suffer serious damage made a successful wheels-up landing at Kimpo. Everyone else was back aboard by dinner time.

As the carrier group departed the attack continued with interservice cooperation of a high order. Beginning at 1610, 79 F-84s and 49 F-80s of Fifth Air Force, which had come up from the south to continue the pummeling, added a further 145 tons of bombs. Downstream, between Suiho and Antung, a total of 84 Sabre jets gave top cover against enemy MIGs. But while the Antung field is only 35 miles from Suiho, none of these gentlemen put in an appearance, and of 250 reported on the ground by Air Force pilots, two-thirds disappeared into interior Manchuria during the attack, a tactic for which, on the U.N. side at least, no firm explanation was ever devised.

While the attacks at Suiho were in progress the Chosin plants received the attentions of 75 aircraft from the Marine Aircraft Wing, a second group of 90 planes from Task Force 77 hit the Fusen plants along with 52 Air Force F-51s, and 70 carrier aircraft went in on Kyosen. These efforts were followed up the next day by carrier, Air Force, and Marine attacks on all three complexes, and on 26 and 27 June the Air Force returned to Chosin and Fusen. Then the picture taking and the photo interpretation began, but in North Korea and Manchuria the lights had already gone out.

The results appear to have been first-class. Something in the neighborhood of 90 percent of North Korean power production had been disabled; for two weeks there was an almost complete blackout in enemy country; even at year’s end a power deficit remained. But if liaison between the Air Force, Navy, and Marines was well nigh perfect, on the upper levels someone had forgotten to pass the word. The British had not been advised of the contemplated attacks, and in Parliament some ructions developed among the opposition.

Admiral Briscoe had requested a detailed breakdown of the strikes, and ten days later his operational intelligence officer provided it. The extent of the naval contribution revealed by this tally was such as to give ComNavFE cause for pride. Total Task Force 77 sorties against the plants on 23 and 24 June exceeded those of Fifth Air Force and Marines together, as did the weight of bombs dropped. On a service basis breakdown, Navy and Marine sorties were of the order of 700, as compared to some 400 by the Air Force, and Navy and Marine bomb tonnage amounted to more than two-thirds the total. These figures, however, are in a sense delusive, for they take no account of the F-86 top cover provided at Suiho, nor of the later Air Force attacks at Chosin and Fusen. Since FEAF had performed the preliminary planning, and since final preparations had been joint, it seems proper to conclude that all hands had done a good job to excellent purpose.

In the course of the summer of 1952 three more large interservice air operations took place. On 11 July 822 Air Force, Marine, and Navy planes, led by 106 from Bon Homme Richard and Princeton, struck Pyongyang gun positions, supply and billeting areas, and factories. Although weather prevented the carriers from launching more than one strike group and hindered shore-based operations, the demolition of designated targets was extensive, and encouraging reports were received of direct hits on a Communist brass hat air raid shelter. On 20 August a sizable combined Navy-Marine-Air Force effort was conducted against a large west coast supply area, and nine days later the enemy capital was subjected to the largest air attack of the war.

The seven weeks since the first joint strike on Pyongyang had seen renewed movement of troops and guns into the North Korean capital. To get these targets, as well as to provide food for thought in Moscow where Chou En-lai was conferring with the Soviets, another attack was laid on. On 28 August warning leaflets were scattered over Pyongyang, and on the next day 1,080 aircraft descended on the luckless city. Everyone and his cousin got into the act this time, for in addition to aircraft from Fifth Air Force, Task Force 77, and the Marine Aircraft Wing, the British carrier and the ROK Air Force also took part.

Over and above these cooperative efforts, the work of the fast carriers during the summer consisted principally of maximum-effort strikes against targets in eastern North Korea. These, insofar as possible, were directed against objectives which, like the hydroelectric system, had importance on both sides of the North Korean border. In July strikes against the small Funei complex near Musan, the smallest grid in North Korea, finished off the power plants within the Navy’s zone. Late in the month the Sindok lead and zinc mill, reportedly a considerable exporter to Iron Curtain countries, was three-quarters destroyed, and the magnesite and thermoelectric plants at Kilchu heavily damaged by Princeton strike groups.

The course of the war by this time had brought a northward displacement of remaining North Korean industrial facilities, and a concentration of new development along the Manchurian and Russian borders. In early August Rear Admiral Herbert E. Regan, ComCarDiv 1, had commented on the build-up of new industry near Aoji in the far northeast, and had urged attack upon these targets. One month later, in response to this request, the Joint Chiefs suspended for a single event their rule against air operations within 12 miles of Soviet territory. On 1 September, in the biggest all-Navy strike yet, morning and afternoon deck loads from Essex, Boxer, and Princeton went up to the north, and while the jets worked over oil storage and an iron mine at Musan and targets at Hoeamdong, the attack planes destroyed synthetic oil production facilities at Aoji. Other attacks in the far north followed at the border town of Hoeryong, at the Yalu bridge town of Hyesanjin, and on a munitions factory near Najin. On three days in October task force aircraft teamed with B-29s in strikes against North Korean objectives. By winter most known targets had been eliminated.

Taken in connection with the increasing boldness of enemy fighter pilots, the northward movement of carrier operations raised the prospect of collision. On the west coast, during the summer, aircraft from the British carrier and the American CVE had clashed repeatedly with MIGs; during the west coast strike of 20 August Princeton F9Fs had an inconclusive skirmish south of Sinanju; on 10 September a Marine flyer had made history by becoming the first pilot of a piston-engined aircraft to shoot down an enemy jet. On 13 September a two-carrier strike against Hoeryong, though unopposed, produced large numbers of bogeys orbiting 50 miles to the eastward over the Siberian border. On the 26th MIGs were sighted over eastern Korea, and in the first week of October two Corsairs were lost in the course of a series of engagements south of Hungnam.

This situation led to some excitement on 18 November as Kearsarge and Oriskany were again striking Hoeryong. The force was operating in 41°30', about 100 miles south of Vladivostok, with the cruiser Helena and a destroyer on search and rescue station halfway in to Najin. During the morning Helena tracked numerous high-speed radar contacts to the northward, which seemed to be flying a barrier patrol under ground control. At 1329 Raid 20, estimated at 16 to 20 aircraft, was approaching from the north, distant 35 miles. This contact or a part of it, estimated at eight aircraft, was also detected by Oriskany, and a four-plane division of F9Fs, which had descended to 13,000 feet owing to fuel pump failure in the leader’s aircraft, was vectored out with instructions not to engage unless attacked.