The Navy Department Library

Chapter 3: War Begins

History of US Naval Operations: Korea

Part 1. The Decision to Intervene

Part 2. The Far East Command

Part 3. First Days of Naval Action

Part 4. Air Strikes, Coastal Bombardment, Flank Patrols

Part 1. The Decision to Intervene

On 25 June 1950, at 0400 in the morning, the North Korean People's Army, with seven infantry divisions and one armored brigade in the line, and with two more infantry divisions in reserve, struck south across the parallel. In Korea it was Sunday, a favored day for starting modern wars.

In Washington, half a world away and half a day behind in time, it was the middle of a summer Saturday. President Truman was out of town, visiting his family in Missouri. In the offices of government, in the State Department in Foggy Bottom and in the Pentagon across the river, only duty personnel were at work. As evening came, press rumors of a Korean crisis drifted into the State Department, and then, at twenty-six minutes past nine, a dispatch reporting the invasion was received from Ambassador John J. Muccio in Seoul. Around the town the telephones began to ring. Echelon by rising echelon the officers of the Department of State were summoned. Before midnight came the Secretary of State had reached the President by telephone, and the Secretary General of the United Nations had been notified of the emergency.

Sunday in Washington was a day of frenzied activity. Two hours after midnight Secretary Acheson again telephoned the President, the decision to seek action of the Security Council was made, and at three in the morning the request was formally presented to Secretary Lie. Hastily summoned, the members of the Security Council met at three that afternoon, but with the Soviet delegate in self-imposed absence. By this time a report of the invasion had been received from the United Nations Commission on Korea, and the United States had prepared a resolution on this breach of the peace which called upon the North Korean People's Republic to desist from aggression. By a vote of nine to nothing, Yugoslavia alone abstaining, the resolution was approved. While these measures were in train at Lake Success the United States government was in emergency action. Throughout the morning the Secretary of State, the Secretary of the Army, and the military chiefs were in conference at the Pentagon. In the afternoon, in response to another call from Secretary Acheson, President Truman flew back to the capital. In the evening the President and his military and diplomatic advisers held a meeting at Blair House which began with dinner and which lasted until ii o'clock. Here the first decisions leading to American commitment in Korea were taken.

The situation which confronted the United States that Sunday evening was sufficiently obscure. Aggression had been committed. The cold war had become hot. But the aggression was local, the general emergency had not begun, and along the rest of the cold war's battleline prospects were unpredictable. At Blair House the discussion ranged from Korea to Formosa, to the implications of the invasion for Japan and the Philippines, and to the strength of Russian forces in the Far East. The possibility of Russian or Chinese intervention in Korea was raised, but to those present seemed remote. Over and above these concrete questions, to which concrete answers could at least be hazarded, there weighed heavily on the minds of all the memories of the 1930's. All present had lived through the agonizing series of crises which had marked the world's descent into the second great war, and whose very names - Manchuria, Ethiopia, the Rhineland, Munich - had become emotional symbols. If, as seems quite possible, Stalin was encouraged in the Korean venture by memories of democratic impotence in the Manchurian crisis, he overlooked one factor of central importance: his principal antagonist in 1950, the man from Missouri, was also a student of history.

In the light of these memories, and with the overpowering feeling that aggression, once unchecked, might sweep all before it, certain preparatory decisions were taken. American civilians and dependents were to be evacuated from Korea by sea and air; to cover this evacuation air and naval action in defense of the Korean capital, of the harbor of Inchon, and of Kimpo airfield was authorized. The Seventh Fleet was to be started north from the Philippines so as to be more readily available should things get worse. Shipment to Korea of ammunition and of military hardware under the Mutual Defense Assistance Program would be expedited by all available means. Shortly after eleven the meeting broke up, and the military chiefs hastened to the Pentagon to communicate the decisions to General of the Army Douglas MacArthur, USA, Commander in Chief, Far East Command.

Monday the 26th was another day of action. Around the world, outside the Iron Curtain, the news of the invasion of South Korea had shocked governments and peoples alike. But although feelings were both indignant and apprehensive, few saw any likelihood of direct action; the salvation of the Republic of Korea was up to the South Koreans. In the morning President Truman announced the decision to expedite arms aid to the Rhee government under the MDA Program, but no mention was made of the movements of American armed forces. In the evening a second conference of the military and civilian chiefs took place. On the far side of the globe, as the meeting began, ships and aircraft were evacuating Americans from Korea and the Seventh Fleet Striking Force had sortied from its bases in the Philippines and was steaming north.

The decisions taken at this second Blair House meeting were far-reaching. The Secretary of State had come with positive recommendations. His suggestion that air and naval support be given the Republic of Korea under sanction of the Security Council resolution of the day before, that increased military aid be extended to the Philippines and IndoChina, and that Formosa be neutralized, met with general approval. The need for rapid action made this use of force appear imperative; the continuing overestimate of the ROK Army, and the confidence that neither Soviets nor Chinese would intervene, made it appear sufficient. Little thought seems to have been given the question of whether to commit ground forces. The recommendations were accepted by the President, and a directive was at once sent General MacArthur authorizing him to use his air and naval forces against the invading army south of the 38th parallel, and instructing him to neutralize Formosa by the use of the Seventh Fleet.

This news was made public at noon on Tuesday the 27th. Following an earlier meeting with congressional leaders at the White House, the President announced that pursuant to the action of the Security Council he had ordered naval and air support of the Republic of Korea, and that he had instructed the Seventh Fleet to prevent either an attack on Formosa from the mainland or an invasion of China by the forces of Chiang Kai-shek. The mood of other governmental bodies matched his own: the House of Representatives extended the Selective Service Act by a vote of 315 to 4; in the Senate the action was unanimous. In the afternoon the Security Council met again at Lake Success to vote on an American-sponsored resolution which called upon members of the United Nations to assist the Republic of Korea in repelling the attack. Action was for a time delayed while the Indian and Egyptian delegates sought vainly to obtain instructions from their governments, but in the evening the vote was taken and the resolution passed.

Following so rapidly upon the President's announcement of American action, this move by the United Nations led to an extraordinary rise in spirit throughout the western world. For the first time within memory the democracies seemed to have produced a leader who would stand fast in time, and little heed was paid to Soviet denunciation of the U.N. action as illegal. But while hearts were high the news was increasingly bad: the forces of the Republic of Korea were disintegrating, the invaders were advancing almost unopposed, the capital of Seoul had fallen. On Thursday the 29th the gloom increased. The armies of the Korean Republic were proving weaker than anyone had expected and those of North Korea stronger; the threat of American air and naval action was dearly ineffective. In the afternoon the National Security Council met at the White House; inevitably, since the show of force seemed to have accomplished nothing, the discussion turned to the question of whether to commit ground troops. Here, in unexpected form, was the prospect of that war on the mainland of Asia against which all military authorities had warned. For such a war there were no plans, no detailed estimates of the forces required. These, indeed, could only be guessed at, although doubtless it was still possible to postulate a distinction between policing a minor power like North Korea and warring with a more serious opponent. Although the discussion seems to have drifted in the direction of commitment, decision was deferred pending the receipt of further information from General MacArthur, who had flown to Korea for a personal reconnaissance of the battle front.

Shortly after midnight the report from the Supreme Commander came in. In a telecon discussion in the first hours of Friday morning General MacArthur stated that the line could not be held without American help, and recommended the immediate movement of one regimental combat team to the Korean front as nucleus for a possible buildup to two divisions for early offensive action. This in time would prove a notable underestimate of the required force, but the view that the invaders would cease and desist, once confronted by U.S. Army contingents, was shared in Washington. In any event the highest authority on the spot, the man who would be responsible for conducting the campaign, had spoken. The decision could not be deferred. A little before five in the morning the Secretary of the Army telephoned the President to tell him what General MacArthur had reported. The President said to send the troops.

Here was the full commitment, although its ultimate magnitude was as yet unforeseen. On the morning of Friday, 30 June, after meeting with the Secretaries of State and of Defense, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and congressional leaders, President Truman made public the new decisions. General MacArthur was authorized to bomb north of the 38th parallel as governed by military necessity, a naval blockade of North Korea would be proclaimed, and "certain supporting ground units" would be committed to action.

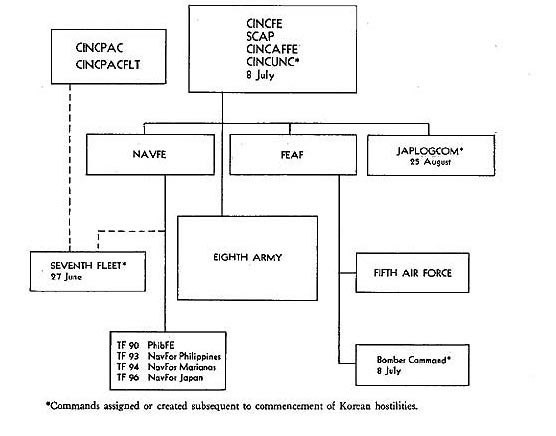

Part 2: The Far East Command

Despite optimistic statements issuing from the upper levels, the readiness of the United States for war in the summer of 1950 was very doubtful. For the war with which the country found itself confronted, this was the more the case. The Army had a total of ten combat divisions, all but one understrength. The Marines had two, both undermanned. The Navy was in the process of being cut down and even the Air Force, despite public and congressional favor, had been forced to narrow its focus and channel its capabilities.

The interaction of budget ceiling and strategic plan had led to emphasis on long-range bombardment and the European theater, an emphasis reflected in the deployment of American strength. The ground forces were divided between the continent of Europe, the continental United States, and occupation duty in Japan. The Navy's larger half was in the Atlantic. The weight of the Strategic Air Command and of other Air Force units lay at home and in the forward European bases. On the assumption that the first and most important Communist objective was Western Europe, it may be said that this deployment proved itself. No war came there. But for the war that did come this posture was more than a little awkward.

American forces in the Orient in 1950 were organized into the presumably unified command of General MacArthur, Commander in Chief Far East Command, who was also, as Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, responsible for the occupation of Japan. Occupation responsibilities bulked large at Headquarters, but in addition to these duties General MacArthur was charged with the defense of Japan, Okinawa, the Marianas, and the Philippines. To enable him to carry out these missions, forces of all three services had been assigned CincFE.

Notwithstanding the European orientation of strategy, the needs of the Japanese occupation had brought a large proportion of American ground strength to the Far East. On paper, Army Forces Far East was not unimpressive: its four divisions - the 7th, 24th, and 25th Infantry Divisions, and the dismounted 1st Cavalry Division - organized as the United States Eighth Army, were commanded by Lieutenant General Walton H. Walker, USA, who had been one of Patton's corps commanders in France. But all of Walker's divisions were understrength, with only two battalions to a regiment, and were undertrained and underequipped as well. No Army theater headquarters had been established, but the functions of such an organization were carried out by CincFE's staff.

The Far East Air Forces, the air component of General MacArthur's command, were commanded by Lieutenant General George E. Stratemeyer, USAF. In June 1950 FEAF contained five fighter and two bomber wings, a transport wing, and miscellaneous support units making up a total of some 1,200 aircraft. The principal mission of the Far East Air Forces, the air defense of Japan, Okinawa, Guam, and the Philippines, was reflected in the order of battle: of the 553 aircraft in organized units, 365 were F-80C jet fighters [Lockheed F-80 Shooting Star]. These aircraft, which had recently replaced the piston-engined F-51 Mustang [North American], had, as befitted their intended purpose, comparatively high performance. But their combat radius without external fuel tanks was limited to100 miles; with external fuel no bombs could be carried, and their operation required sizable modern airstrips. The efficiency of General Stratemeyer's command suffered from certain deficiencies of material, its engineering support was inadequate, and training had been restricted by budget cuts.

Joint training by the Army and Air Force in Japan had been minimal, in part owing to the defensive nature of their missions, in part to the emphasis in all American military planning on strategic rather than tactical air operations. The Air Force, it should be said, had indeed proposed some exercises at the division level which would involve a working out of the mechanics of air support, and had suggested the creation of a Joint Operations Center. But occupation duties and the lack of suitable maneuver areas had adversely affected ground force readiness, and the Army, not wishing to sacrifice its program of small-unit training, had declined the offer. The result was that such joint exercises as were held were small in scale, and formal and cut and dried in nature.

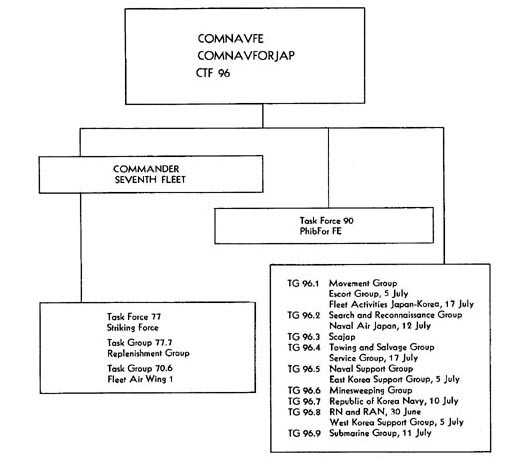

Despite these limitations, the main strength of the Far East Command lay on the ground and in the air. Only a little over a third of the Navy's active strength was in the Pacific, only a fifth of that was in the Far East, and the naval component under Vice Admiral C. Turner Joy was very small. But although Naval Forces Far East was largely a housekeeping command, ComNavFE did control, in Task Force 96, a small amount of fighting strength, and in Task Force 90 the nucleus of an amphibious force.

The combat units of Task Force 96, Naval Forces Japan, were fast and able ships, but none mounted anything larger than a 5-inch gun. Juneau, Captain Jesse C. Sowell, flagship of Rear Admiral John M. Higgins' Support Group, was a younger sister and namesake of the light antiaircraft cruiser sunk by a Japanese submarine in 1942 while retiring after the Battle of Guadalcanal. With a designed displacement of 6,000 tons, she had a speed of better than 33 knots and mounted a main battery of 16 5-inch dual purpose guns. The four ships of Captain Halle C. Allan's Destroyer Division 91 - Mansfield, De Haven, Collett, and Swenson - were 2,200-ton, 35-knot ships of the Sumner class, completed in 1944 and mounting six 5-inch guns each.

Table 2. - NAVAL FORCES IN JAPANESE WATERS, 25 JUNE 1950

| TASK FORCE 90. Amphibious Force, Far East. | Rear Admiral James. Henry Doyle, USN |

| Mount McKinIey (AGC-7), Flagship | 1 Amphibious Command Ship |

| Cavalier (APA-37) | 1 Amphibious Transport |

| Union (AKA-106) | 1 Amphibious Cargo Ship |

| LST 611 | 1 Landing Ship Tank |

| Arikara (ATF-98) | 1 Fleet Tug |

| TASK FORCE 96. Naval Force, Japan. | Vice Admiral Charles Turner Joy, USN |

| Task Group 96.5. Support Group. | Rear Admiral John M. Higgins, USN |

| Task Unit 96.5.1. Flagship Element. | Captain Jesse C. Sowell, USN |

| Juneau (CL-119), Flagship | 1 Light Cruiser |

| Task Unit 96.5.2. Destroyer Element. | Captain Halle C. Allan, Jr., USN |

| Destroyer Division 91: Mansfield (DD-728) (Flagship), De Haven (DD-727), Collett (DD-730), Lyman K. Swenson (DD-729) |

4 Destroyers |

| Task Unit 96.5.3. British Commonwealth Support Element. | Comdr. I. H. McDonald, RAN. |

| HMAS Shoalhaven | 1 PF. |

| Task Unit 96.5.6. Submarine Element. | Lt. Comdr. Lloyd. V. Young, USN |

| 1 Submarine | |

| Task Group 96.6. Minesweeping Group. | Lt. Comdr. Darcy. V. Shouldice, USN |

| Mine Squadron 3: | |

| Mine Division 31: Redhead (AMS-34), Mockingbird (AMS-27), Osprey (AMS-28), Partridge (AMS-31), Chatterer (AMS-40), Kite (AMS-22) |

6 Coastal Marine Sweepers. |

| Mine Division 32: Pledge (AM-277) (Flagship),2 Incredible (AM-249),3 Mainstay (AM-261),3 Pirate (AM-275), 3 |

4 Minesweepers. |

__________

1 On loan from Seventh Fleet.

2 In reduced commission.

3 In reserve.

In addition to this small fighting force, ComNavFE controlled a variety of auxiliary ships. The most important of these were those of Amphibious Group 1, Rear Admiral James H. Doyle: the command ship Mount McKinley, the attack transport Cavalier and the attack cargo ship Union, LST 611, and the fleet tug Arikara. This group, which held the tactical designation of Task Force 90 in the Naval Forces Far East organization, had recently arrived in Japan to conduct a program of amphibious training with units of the Eighth Army.

A third category of force at Admiral Joy's disposal consisted of the units of Mine Squadron 3, which were engaged in check-sweeping World War II minefields. Minron 3 contained six 136-foot, wooden-hulled, diesel-engined craft, and four 184-foot, twin-screw Admirable class AMs; but three of the latter were in caretaker status and the fourth, Pledge, in reduced commission. Finally, ComNavFE controlled a number of Japanese-manned ships belonging to the Shipping Control Administration, Japan - Scajap - which were employed in logistic support of the occupation and in repatriation of former Japanese prisoners of war from the continent of Asia.

The activities of Admiral Joy's headquarters, like those of the forces it controlled, had been limited to the peaceful routine of an occupation force. The staff totaled only 28 officers and 160 enlisted men. There were four officers in the operations section, five in plans, four in communications. Since the activities of naval aviation in the Western Pacific were centralized at Guam, the NavFE staff had no air or aerology departments. Although two officers qualified in mine warfare were authorized, none was aboard. Like everyone else in the armed services, Commander Naval Forces Far East had based his plans on the assumption of a major conflict with the Soviets which would be centered elsewhere. The operation plans in effect in June of 1950 were concerned with such matters as passive defense, security under air attack, and the evacuation of American citizens in emergency.

Naval base facilities in Japan were minimal. There was no logistic command, no representative of Service Forces Pacific Fleet to plan, coordinate, or procure. At Fleet Activities, Yokosuka, there was a minor ship repair facility which could perform routine upkeep, but which lacked specialized shops for torpedoes or for electronics repair; a supply section adequate to the support of the roughly 5,000 naval personnel and dependents in Japan and Japanese waters; an ordnance facility with some 3,000 tons of ammunition; and a naval hospital whose capacity had recently been reduced to 100 beds. At Sasebo in western Kyushu, where the Imperial Japanese Navy had formerly maintained a major base, there was an excellent harbor with extensive drydocking facilities. But other equipment was at a minimum, and the on-board complement was only 5 officers and 100 enlisted men. And neither Yokosuka nor Sasebo was well supplied with the material for underwater harbor defense.

The single naval air base in Japan was the Naval Air Facility, Yokosuka, which supported two or three flying boats loaned by the Seventh Fleet for search and rescue missions. NAF Yokosuka had been but recently commissioned, rehabilitation of the buildings was still underway, only about five percent of the area of the former Japanese seaplane base was Navy-controlled, and Eighth Army was using the landing strip as a park for vehicles. As for land-based naval aviation, its total strength in Japan consisted of one target tow plane for antiaircraft gunnery training.

Fortunately, however, Task Force 90 and Task Force 96 were not the only naval units in Asiatic waters. Based in the Philippines, 1,700 miles to the southward, and under the command of Vice Admiral Arthur D. Struble, there lay the Seventh Fleet, the principal embodiment of American naval power in the Western Pacific. Yet while rejoicing in the title of fleet, Struble's command, in Second World War terms, amounted to little more than a few small task units. There was a carrier "group" with its screen, a submarine group, the two patrol plane squadrons of Fleet Air Wing 1, an evacuation group concerned with the safety of American citizens in emergency, and a variety of minor supporting units. The logistic group, which contained a small station reefer, a destroyer tender, and an oiler on shuttle service, constituted the total mobile fleet support in the Western Pacific, and was hard pressed to supply even the small Seventh Fleet.

Table 3. - SEVENTH FLEET, 25 JUNE 1950

| SEVENTH FLEET | VICE ADMIRAL Arthur D. STRUBLE, USN |

| Task Group 70.6. Fleet Air Wing 1 | Captain Edward K. Grant, USN |

| VP 28 | 9 Consolidated P4Y-2 Privateer |

| VP 47 | 9 Martin PBM-5 Mariner |

| Task Group 70.7. Service Group. | Captain James R. Topper, USN |

| Piedmont (AD-17) (Flagship | 1 Destroyer Tender. |

| Navasota (AO-106) | 1 Oiler. |

| 1 Store Ship. | |

| Mataco (ATF-86) | 1 Fleet Tug. |

| Task Group 70.9. Submarine Group. | Comdr. Francis W. Scanland |

| Segundo (SS-398) (Flagship), Catfish (SS-339), Cabezon (SS-334)1 Remora (SS-487)2 |

4 Submarines |

| FIorikan (SS-ASR-9) 3 | 1 Salvage Ship |

| TASK FORCE 77. STRIKING FORCE. | VICE ADMIRAL Arthur. D. STRUBLE, USN |

| Task Group 77.1. Support Group. | Captain Edward L. Woodyard, USN. |

| Rochester (CA-124) (Fleet Flagship) |

1 Heavy Cruiser. |

| Task Group 77.2. Screening Group. | Captain Charles W. Parker, USN |

| Destroyer Division 31 [ less Keyes and Hollister plus Radford and Fletcher]: Shelton (DD-790), Eversole (DD-789), Radford (DD-446), Fletcher (DD-445) |

4 Destroyers |

| Destroyer Division 32: Maddox (DD-731), Samuel L. Moore (DD-747), Brush (DD-745), Taussig (DD-746) |

4 Destroyer |

| Task Group 77.4. Carrier Group. | Rear Admiral John. M. Hoskins. |

| Valley Forge (CV-45) (Flagship) | 1 Carrier |

___________

1 Relieved by Pickerel (SS-524),11 July.

2 On loan to Naval Forces Japan.

3 Relieved by Greenlet (ASR-10), 30 June.

The Fleet's principal base of operations was on the island of Luzon, where the Navy, following the war, had developed new facilities at Subic Bay and an airfield at Sangley Point. Peacetime operations of the Seventh Fleet were under the control of Commander in Chief Pacific Fleet, Admiral Arthur E. Radford, but standing orders provided that, when operating in Japanese waters or in the event of an emergency, control would pass to Commander Naval Forces Far East. There were, however, certain problems implicit in this arrangement: Admiral Radford's area of responsibility included potential trouble spots outside the limits of the Far East Command; lacking an aviation section on his staff, the control of a carrier striking force and of patrol squadrons would present problems for ComNavFE; Admiral Struble was senior to Admiral Joy.

Although early postwar policy had called for the maintenance of two aircraft carriers in the Western Pacific, the reductions in defense appropriations had made this impossible: for some time prior to January 1950 no carrier had operated west of Pearl; current procedure called for the rotation of single units on six-month tours of duty. In these circumstances Admiral Struble's Seventh Fleet Striking Force, Task Force 77, was made up of a carrier "group" containing one carrier, a support "group" containing one cruiser, and a screening group of eight destroyers. The duty carrier in the summer of 1950 was Valley Forge, an improved postwar version of the Essex class, completed in 1946, with a standard displacement of 27,100 tons, a length of 876 feet, and a speed of 33 knots. Flagship of Rear Admiral John M. Hoskins, Commander Carrier Division 3, Valley Forge had reported in to the Western Pacific in May, at which time her predecessor, Boxer, had been returned to the west coast for navy yard availability. The 25th of June found Valley Forge, with the destroyers Fletcher and Radford, in the South China Sea, one day out of Hong Kong en route to the Philippines. Admiral Struble was in Washington; Admiral Hoskins, upon whom command of the Seventh Fleet had devolved, was at Subic Bay; the carrier's commanding officer, Captain Lester K. Rice, was acting as ComCarDiv 3.

The air group of Valley Forge, Carrier Air Group 5, Commander Harvey P. Lanham, was the first in the Navy to attempt the sustained shipboard operation of jet aircraft. Its complement of 86 planes was made up of two jet fighter squadrons with 30 Grumman F9F-2 Panthers; two piston- engined fighter squadrons equipped with the World War II Vought F4U-4B Corsair; and a piston-engined attack squadron of 14 Douglas AD-4 Skyraiders. Over and above these five squadrons the group contained 14 aircraft, principally ADs, which were specially equipped and modified - "configurated" in current Navy jargon - for photographic, night, and radar missions. The fighter squadrons had enjoyed considerable jet experience prior to receiving their Panthers and moving aboard ship; the group as a whole had conducted extensive training in close support of troops with the Marines at Camp Pendleton, California.

The submarine force under the operational control of Commander Seventh Fleet, administratively organized as Task Unit 70.9, consisted of four fleet submarines and a submarine rescue vessel; its principal activity had been in antisubmarine warfare training exercises with units of the Fleet and of Naval Forces Far East. One of the four boats, Remora, was at Yokosuka on loan to ComNavFE; Cabezon was at sea en route from the Philippines to Hong Kong; Segundo, with Commander Francis W. Scanland, the task unit commander, was at Sangley Point in the Philippines; Catfish was at Subic Bay. The submarine rescue ship Florikan was at Guam, where she was about to be relieved by Greenlet. No submarine tender was stationed in the Western Pacific, but limited quantities of spare parts and torpedo warheads were available from the destroyer tender Piedmont at Subic Bay.

Patrol plane activity in the Western Pacific, another Seventh Fleet monopoly, was centralized at Guam under control of Commander Fleet Air Wing 1, Captain Etheridge Grant, who served also as Commander Task Unit 70.6 and Commander Fleet Air Guam. For long-range search and reconnaissance in the theater Captain Grant had at his disposal two squadrons of patrol aircraft. Patrol Squadron 28, a heavy landplane squadron with nine PB4Y-2 Privateers, the single-tailed Navy modification of the Liberator, was based at Agana, Guam. At Sangley Point, Luzon, Patrol Squadron 47 operated nine Martin PBM-5 Mariner flying boats. In addition to these two squadrons and their supporting organizations, Fleet Air Wing 1 had a small seaplane tender, Suisun, which on 25 June was moored in Tanapag Harbor, Saipan.

For Captain Grant the impending crisis would not prove wholly unfamiliar, for the outbreak of war in December 1941 had found him commanding a seaplane tender in the Philippines. But his situation on 25 June was a somewhat scrambled one, for a second Mariner squadron, VP 46, was moving into the area as relief for VP 47, and the take-over process had already begun. Homeward bound, their tour in distant parts completed, the PBMs of VP 47 were widely dispersed. Two were at Yokosuka on temporary duty with Commander Naval Forces Far East, two were at Sangley Point, two were in the air and on their way, and three had already reached Pearl Harbor.

Such then was America's Western Pacific naval strength in June of 1950. Combat units assigned to ComNavFE and Commander Seventh Fleet totalled one carrier, two cruisers, three destroyer divisions, two patrol squadrons, and a handful of submarines. Not only was this a limited force with which to support a war on the Asiatic mainland: its southward deployment, with the principal base facilities at Guam and Luzon, made it ill-prepared for a campaign in Korea.

Yet if forces, bases, and plans alike seemed inadequate to the challenge of Communist aggression, there were certain mitigating factors. To employ force, whether for police action or for war, on the far side of an ocean, is to conduct an exercise in maritime power for which fighting strength, bases, and shipping are essential. Unplanned for though the emergency was, a sufficient concentration was still possible. The occupation forces in Japan contained a large fraction - four of ten Army divisions - of American ground strength. FEAF's air strength was by no means inconsiderable. Naval forces in the Far East could be reinforced, from the west coast in the first instance, in time from elsewhere. Limited though the fleet bases were in the narrow sense, in the larger context the base was Japan, and the metropolis of Asia offered many advantages in the form of airfields, staging areas, industrial strength, and skilled labor. Additionally, and by no means least, there existed and was available a sizable Japanese merchant marine, which could help to provide the carrying capacity without which control of the seas is meaningless, and which could be employed to project the armies and their supplies to the far shore.

The war in Korea, moreover, was in a sense a suburban war, and one must go back to 1898 to find in the American experience a parallel to this proximity of base and combat areas. The distances between Key West and Cuba and between Sasebo and Pusan are much the same. It could be argued, perhaps, that Admiral Joy's situation presented certain parallels to that of Admiral Cervera, but there was at least one notable difference: in 1950, despite the withdrawal of the entire occupation force, the populace of Japan proved reliable; in 1898, despite the presence of a Spanish army, the populace of Cuba did not. Doubtless to the Communists Korea seemed the most promising spot for aggression. In many ways it was also the area where the United States could best extemporize a reply.

Part 3. First Days of Naval Action

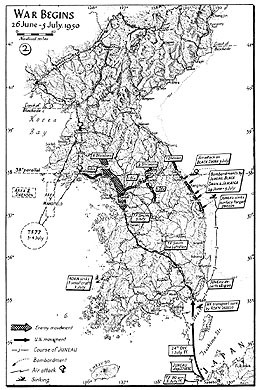

The main thrust of the Communist invasion, three infantry divisions with armored and air support, was directed initially toward the capital at Seoul. Poorly disposed for defense and considerably outnumbered at the scene of action, the Army of the Republic of Korea broke under the weight of the attack; the government fled to Taejon; Seoul fell. As the enemy pressed southward down the road toward Suwon the South Korean Army appeared to be in the process of dissolution. On 30 June, after describing its heavy losses of supplies and equipment, General MacArthur had concluded that it was no longer capable of united action, and that only by commitment of American ground forces could the Han River line be held. At sea the invasion was accompanied by a number of small unopposed landings along the east coast, which were magnified by rumor both as to number and as to location. These maritime efforts, which extended as far south as Samchok, would end with the arrival of United Nations naval forces, but in the first crucial hours of the war they were confronted only by the Navy of the Republic of Korea.

This Navy had its principal establishment at Chinhae, just west of Pusan, where the Japanese during their occupation had developed a considerable naval base with docks, barracks, petroleum storage, and a marine railway. Next in importance was the base at Inchon, seaport of the capital city, and rudimentary facilities had been established at Mukho and Pohang on the east coast, at Pusan and Yosu on the south, and at Mokpo and Kunsan on the shore of the Yellow Sea. At Inchon, on 25 June, there were four YMS, two steel-hulled ex-Japanese minecraft (JML), and the ROK Navy's single LST. At Mokpo, at the southwestern tip of the peninsula, there were two YMS and some small craft. Nine YMS were in the Pusan-Chinhae area along with some small craft, as was also the recently arrived PC 701, Bak Du San, purchased by subscription of naval personnel. Three other PCs had been obtained from the United States, but these were still in the Hawaiian Islands, and so was the Chief of Naval Operations.

With all ships on the western and southern coasts, no strength was immediately available to oppose the east coast landings. Nevertheless the ROK units at once put to sea, and on the evening of the 25th there took place the most important surface engagement of the war. Northeast of Pusan PC 701, Commander Nam Choi Yong, ROKN, encountered a 1,000ton armed steamer with some 600 troops embarked, and sank it after a running fight. Since Pusan, the only major port of entry available for the movement of supplies and reinforcements to South Korea, was at the time almost wholly defenseless, the drowning of the 600 was an event of profound strategic importance.

In Tokyo the 25th of June found the headquarters of Naval Forces Far East settled down for a normal peacetime weekend. Then the telephone rang, and when the Lieutenant Colonel of Marines who was Staff Duty Officer that day picked up the receiver he found himself talking to the Military Attaché at Seoul. This conversation put an end to holiday routine. Within minutes the headquarters had shifted to a state of readiness, and overnight it became clear that war, at least of a sort, was at hand. The unexpected nature of the Korean involvement and the speed with which the crisis broke meant that most NavFE planning, like that of other military headquarters, had to be thrown out the porthole. But it was at least possible to salvage so much of it as was concerned with the evacuation of American citizens. On the 25th, as American civilians and their dependents were ordered out of the Seoul area by Ambassador Muccio, ComNavFE instructed Admiral Higgins to send Mansfield and De Haven to cover the exodus from the port of Inchon. The evacuation was an interservice affair: on the 26th, as the destroyers were steaming west to cover the departure from Inchon, Air Force fighters orbited over the harbor; on the 27th loading of refugees was also commenced at Pusan, FEAF transport aircraft began to fly personnel out of the capital's airfield at Kimpo, and Air Force fighters destroyed seven enemy aircraft in the area of Seoul.

After getting the civilians out the next step was to get some ammunition in, under the accelerated MDA Program ordered by President Truman on the 25th. During the days of their imperial greatness the Japanese had talked of constructing a tunnel under the Korean Strait, but this grandiloquent scheme never reached the stage of action and the road to Korea remained, as in the days of Hideyoshi, a sea road. Ammunition from stocks available in Japan was therefore hastily loaded onto two ships bearing the agreeably symbolic names of Sergeant Keathley and Cardinal O'Connell. The operation order covering this movement was sent out by Admiral Joy's headquarters in the early hours of the 27th, and in the course of the next two days sergeant and prelate sailed forth to war.

The decision to give air and naval assistance to the Republic of Korea was made at Blair House on the evening of Monday the 26th, Washington time, midday of the 27th in the Far East. At 2015 that evening Admiral Joy's Operation Order 5-50, the basic order of the Korean naval campaign, was issued. In this dispatch ComNavFE informed his forces that President Truman had ordered the fullest possible support of South Korean units south of the 38th parallel "to permit these forces to reform," and had instructed the Seventh Fleet to take station to prevent either a Communist invasion of Formosa or the use of that island for operations against the mainland. Task Group 96.5, composed of Juneau and the four destroyers of Desdiv 91, was designated the South Korea Support Group, instructed to base at Sasebo, and ordered to patrol Korean coastal waters, oppose hostile landings and destroy vessels engaged in aggression, provide fire support to friendly forces, anti cover shipping engaged in evacuation or in carrying supplies to South Korea. Five and a half hours later the order was amplified to designate as primary targets for the attention of the task group the coast and off-lying islands from Tongyong, west of Pusan, to Ulsan on the east, and the east coast sector between Samchok and Kangnung.

On the evening of the 27th, when ComNavFE's operation order was promulgated, Admiral Higgins' Support Group was widely dispersed. The flagship Juneau, with the task group commander embarked, was leaving Sasebo to investigate a reported North Korean landing on the island of Koje Do, southwest of Pusan; in the Yellow Sea De Haven was escorting a Norwegian freighter with the first evacuees from Inchon, while Mansfield awaited the sailing of a second load in a Panamanian ship; Collett and Swenson had been ordered down from Yokosuka to Sasebo. Early on the 28th Juneau anchored off the southeastern shore of Koje Do, a party was sent ashore by whaleboat, difficulties in communication with the inhabitants were somehow surmounted, and the fact established that the island remained peaceful and undisturbed. Following this check on his southern area of responsibility, Higgins headed north, and in the afternoon put the landing party ashore at Ulsan with similar result. With evening Juneau again got underway, and continued up the coast to patrol the area between Samchok and Kangnung, which was reported to have been occupied by the enemy.

In Korea the situation was shrouded in uncertainty, and available intelligence was both fragmentary and confusing. False reports had caused the investigation of Koje Do and Ulsan, and a more tragic instance of misdirected effort was now to follow. At 0203 on the morning of the 29th, in 370 25' N, Juneau detected two groups of surface ships by radar. Since the South Korean Navy was reported to have retired south of 37o, fire was opened, one target sunk, and the others dispersed. But the information, unfortunately, was in error: the ROK retirement was still in progress, the sunken target was the South Korean JML 305, and the action gave rise to Korean reports of a Russian cruiser in the Samchok area.

On the 29th, as Juneau continued her patrol, Admiral Higgins ordered Swenson, which had now reached Sasebo, to rendezvous with Mansfield in the Yellow Sea. During the day De Haven joined the flagship, and at 2311 Juneau commenced firing the first bombardment of the war. At Mukho half an hour's deliberate shooting, conducted with searchlight illumination and with target advice from an ROKN lieutenant, brought the expenditure against enemy personnel of 16 rounds of influence-fused 5-inch and more than 400 rounds of 5-inch antiaircraft common, with what were felt to be excellent results.

The invasion of South Korea found Admiral Doyle's Amphibious Group busy with its training duties. On the morning of the 25th Task Force 90 got underway from Yokosuka, with elements of the 35th Regimental Combat Team embarked, to conduct landing exercises outside Tokyo Bay. Although operations were carried out on the 26th and 28th, in accordance with the training order, the attention of both teachers and pupils was progressively distracted by reports of happenings in Korea. During the second landing observers from the Far East Air Forces were ordered back to their stations; on completion of the exercise the ships returned at once to Yokosuka to debark the troops. On 30 June, as a movement of ground forces into Korea appeared increasingly probable, all ships of the Amphibious Group were placed on four-hour notice for getting underway. No reports of enemy mining had as yet come in, although in time there would be plenty, but there was no lack of tasks for the small ships of Minron 3. The eight AMS were at once deployed on picket duty, harbor defense, and convoy escort. In this they were joined by Pledge, the only operational AM, while at Yokosuka the work of activating the other ships of Mindiv 32 was at once begun.

It was late on the 30th, Tokyo time, that President Truman approved the commitment of American troops. Early the next afternoon Admiral Joy's headquarters issued its Operation Order 7-50 assigning 16 Scajap LSTs to Admiral Doyle, and instructing him to lift the 24th Infantry Division, Major General William F. Dean, USA, from Fukuoka and Sasebo to Pusan. Pursuant to this order CTF 90 got underway at once with Mount McKinley, Cavalier, and Union, escorted by HMS Hart, and headed for Sasebo. The uncertainty which still existed as to the dimensions of this war was not diminished during the journey. Two doubtful sound contacts on submarines were reported by Hart, depth charges were dropped, and at midday of the 3rd, while rounding the southwestern tip of Kyushu, visual sighting of a surfaced submarine was made.

Admiral Doyle's ships reached Sasebo on the afternoon of the 3rd, only to find that the 24th Division had already begun its move. Two infantry companies with supporting artillery had been flown to Pusan on the 1st, and the rest of the division was hastily loading in locally available shipping to follow by sea. Since the situation seemed under control, the ships of Task Force 90 were retained at Sasebo for other employment.

While the few American naval units in Japanese waters were being committed to the support of the Korean Republic, Admiral Joy's command was increasing in size. Following the decision at the first Blair House meeting to start the Seventh Fleet toward Japan, a dispatch from the Chief of Naval Operations had directed its commander to send his carrier striking force, his submarines, and necessary supporting units, to report to ComNavFE at Sasebo. This order reached Admiral Hoskins on the 26th as the Valley Forge group was entering Subic Bay. At 0515 on the 27th, after emergency replenishment, the Striking Force sortied, accompanied by Piedmont and Navasota, and headed north. On the afternoon of the same day Admiral Joy assumed operational control, but feeling that Sasebo, in the rapidly developing circumstances, was a little close to the Russian air concentration at Vladivostok, diverted the force to Okinawa.

ComNavFE's Operation Order 5-50, issued that evening, instructed the Seventh Fleet to conduct surface and air operations to neutralize Formosa. On the morning of the 29th, pursuant to these instructions, Admiral Hoskins made his presence felt by flying 29 F4Us and ADs up Formosa Strait. At 0630 in the morning of 30 June Task Force 77 reached Okinawa and dropped anchor in Nakagusuku Wan, now known as Buckner Bay in honor of the commanding general of the Tenth Army, killed in June 1945 in the moment of victory. At this base, strategically located between Korea and Formosa, the fleet did have the protection of distance, but there were no antisubmarine defenses other than those provided by the force's own destroyers, and no stocks of ammunition.

The Seventh Fleet submarines, in the meantime, were also moving northward. Segundo and Catfish took on full loads of torpedo warheads from Piedmont at Subic Bay on the 26th, and on the next day sailed for Sasebo. Cabezon made a fast turnaround at Hong Kong and joined with the others on the 28th off the northern tip of Luzon. Revised orders from Commander Seventh Fleet changed their destination also from Sasebo to Okinawa, and there they arrived on 30 June, to be joined next day by the submarine rescue vessel Greenlet from Guam. At Buckner Bay new orders were received, and on the 3rd Greenlet and her three charges sailed in company for Yokosuka.

The hasty redeployment of the Seventh Fleet also affected the patrol planes, and the homeward voyage of Patrol Squadron 47, so recently begun, was destined not to be completed. The two Mariners at Yokosuka were at once assigned to local antisubmarine patrol; those en route and those which had reached Pearl Harbor were recalled to the Western Pacific. One plane was lost in an accident at Guam, when it missed its buoy, grounded, and sank, but by 7 July six PBMs were operating out of Yokosuka. Two for the moment remained in the Philippines, but these would shortly fly north to Japan, as aircraft from the incoming VP 46 reached Sangley Point and Buckner Bay.

With the transfer of Seventh Fleet forces to his operational control, Admiral Joy acquired all immediately available American naval strength. Considering the unpredictable responsibilities of his situation this was little enough, and a most helpful addition soon came in the form of British Commonwealth units commanded by Rear Admiral Sir William G. Andrewes, KBE, CB, DSO, RN, Flag Officer Second in Command, Far Eastern Station. On 29 June, following the vote of the Security Council for military assistance to the Republic of Korea, the British Admiralty placed Royal Navy units in Japanese waters at the disposition of ComNavFE; on the next day similar action was taken by the Australian government; in Canada three destroyers were ordered to prepare to sail; from New Zealand came promise of the early dispatch of two frigates.

Commonwealth naval strength in Japanese waters was by no means inconsiderable. Andrewes' command included Triumph, a 13,000-ton light carrier, completed in 1946 and operating about 40 aircraft; two 6-inch gun cruisers, heavily armored Belfast, the largest cruiser in the Royal Navy, and Jamaica; three destroyers and four frigates. The hospital ship Maine, soon to be added to the force, was for some time to be the only such vessel available for the evacuation of casualties from Korea. In the absence of American naval air bases in Japan the Royal Australian Air Force seaplane base at Iwakuni on the Inland Sea, which was at once made available, was to be of great assistance.

Table 4. - COMMONWEALTH NAVAL FORCES, 30 JUNE 1950

| TASK GROUP 96.8. BRITISH COMMONWEALTH FORCES. | |

REAR ADMIRAL SIR W. G. ANDREWES, RN. |

|

| HMS Triumph (R 16) | 1 Light Cruiser |

| HMS Belfast (C 35) (Flagship), HMS Jamaica (C 44) | 2 Light Cruisers |

| HMS Cossack (D 57), HMS Consort (D 76), HMAS Bataan | 3 Destroyers |

| HMS Black Swan (F 116), HMS Alacrity (F 57), HMS Hart (F 58), HMAS Shoalhaven (F 535) | |

On the evening of the 29th ComNavFE requested Admiral Andrewes to send Jamaica and the frigates to join Admiral Higgins' Support Group, and to proceed with his flagship Belfast, the carrier Triumph, and the two British destroyers to Okinawa and report to Commander Seventh Fleet. Early in the morning of the 30th Admiral Joy assumed operational control of Andrewes' forces, and in the evening modified Operation Order 5-50 to include the Commonwealth units for Korean operations only, thus exempting them from the neutralization of Formosa and the Pescadores, which remained a purely American affair.

With these augmented but by no means extravagant forces Admiral Joy confronted his tasks. He was required to evacuate American citizens, support the Republic of Korea, blockade the North Korean coastline, and at the same time to remain prepared for the unpredictable in connection with Formosa, the protection of his flanks, and a possible expansion of the conflict. And as his responsibilities and his forces grew, further difficulty was presented by the inadequacy of his staff and of those of subordinate commands. The total strength, officer and enlisted, of the NavFE staff at the end of June was 188; by November it would have reached 1,227. But in the first weeks, before reinforcements arrived, the job had to be done with what was on hand. Rarely in the history of 20th century warfare can so many have been commanded by so few.

It was not done without effort. The Plans Section went to heel and toe watches, 12 hours on and 12 off. The Operations Officer moved in a cot and did such sleeping as he could in his office; his people found themselves working a 12-hour day, with an additional four-hour night watch four days out of five. For Communications the situation became a nightmare as high-precedence traffic skyrocketed; in the first days the load of encrypted messages went up by a factor of 15, and was further complicated by great quantities of interservice and United States-British dispatches. Somehow they made do Even as anguishcd requests were sent off to Washington for more personnel, the round the clock efforts of those on the spot were accomplishing the reorganization and redeployment of available naval strength. To Naval Forces Japan had now been added the Seventh Fleet and British Commonwealth units; with these accessions Admiral Joy had gained all that would be available until reinforcements could come from afar. This strength was organized in three principal groups: Naval Forces Japan, the Seventh Fleet, and the Amphibious Force.

Of these, Admiral Doyle's Amphibious Force Far East, Task Force 90, had been moved forward from Yokosuka to Sasebo, where it was awaiting instructions. Under the direct control of ComNavFE, Task Force 96, Naval Forces Japan, was engaged in various tasks. The long range aircraft of VP 47 had been organized as the Search and Reconnaissance Group, Task Group 96.2, under Captain John C. AIderman, Chief of Staff to Commander Fleet Air Guam, who had been on leave in Japan at the onset of hostilities and found himself shanghaied for this purpose. In Korean waters the Support Group, Task Group 96.5, originally consisting of Juneau and Destroyer Division 91, had been reinforced by Jamaica, Shoalhaven, and Black Swan, and Alacrity was about to join up. Although Admiral Andrewes' ships had received the designation of Task Group 96.8, these for the moment were divided between the Support Group and the Seventh Fleet Striking Force, which had reached Okinawa on 30 June. Joined on the next day by Triumph, Belfast, Cossack, and Consort, Task Force 77 remained for the moment poised between Korea and Formosa.

No less difficult than the problems of concentration and control of forces were those of their support. The shore activities of Naval Forces Japan had been centralized at Fleet Activities Yokosuka, with the secondary base at Sasebo in what approximated caretaker status. But although the workload at Yokosuka was at once increased, as activation of reserve minesweepers and frigates was begun, war in Korea soon reversed the roles of the two bases. Sasebo is more than 500 miles closer to Pusan, a fact of obvious importance and one emphasized by the original orders from the Chief of Naval Operations to the Seventh Fleet. At Sasebo an immediate expansion was undertaken, and effort made to provide more personnel; the lack of antisubmarine defenses brought urgent action to provide at least a token patrol off the entrance, and this was accomplished on the 29th.

Two more organizational problems faced Admiral Joy in the first hectic days: the provision of some sort of escort for shipping en route to Pusan, and the establishment of the blockade of North Korea, recommended by the Chief of Naval Operations on 30 June and ordered by the President next day. These matters were dealt with by ComNavFE in Operation Order 8-50 promulgated on 3 July and effective on the 4th, which made further refinements in the organization of Task Force 96.

Escort of shipping between Japan and Korea had so far been on a wholly catch-as-catch-can basis: Arikara and Shoalhaven had been so used on 1 and 2 July, Jamaica and Collett on the 3rd. But now provision was made for an Escort Group, Task Group 96.1, with a commander and units to be assigned when available. Shortly the job would be turned over to the frigates under Captain A. D. H. Jay, DSO, DSC, RN, commanding officer of Black Swan.

Blockade and inshore work south of latitude 37o was assigned the ROK Navy, shortly to become Task Group 96.7, with such assistance as might become available from the Far East Air Forces and from any NavFE units that happened by. For the coastline north of 37o separate East and West Coast Support Groups were established: in the east the job was entrusted to Admiral Higgins' Task Group 96.5, in the west to the Commonwealth units of Task Group 96.8. The northern limits of the blockade were set at 41oon the east coast and at 39o30' in the west, well south of the northern frontiers, and the precaution implicit in these boundaries was emphasized by a specific admonition to all units to keep well clear of Manchurian and Russian waters. Important though this statement of policy was, it remained for some time of purely academic importance, for emergency calls for gunfire support along the coast were such as to limit the blockading forces to only intermittent sweeps north of the 38th parallel.

Part 4. Air Strikes, Coastal Bombardment, Flank Patrols

With Supplies and troops on the move, and with gunnery ships converging on the Korean coast, it remained to reach inland by air. Air strikes could destroy the North Korean Air Force. Air strikes could harass the invading formations, interrupt their supply, and so help in the ground battle which was about to be joined. Air supremacy, indeed, seemed the key to modern war: without it victory was impossible; with it victory followed as the night the day. Its attainment was a matter of utmost urgency.

The Far East Air Forces had been committed, along with the Navy, to the support of thc Korean Republic on 27 June; like the Navy they had already seen action. On the first day of the invasion Air Force fighters on patrol over the Sea of Japan had been fired on south of the parallel by a small North Korean convoy; two days later transport planes had flown American nationals out of Kimpo and fighters covering the evacuation had destroyed some enemy aircraft; the first missions in support of the ROK Army had been dispatched on the 28th.

Like the rest of the defense establishment, FEAF had planned on a different war. The 19th Bombardment Group at Guam, the only such unit in the Far East, was trained for strategic attack. The equipment and training of the fighter groups stationed in Japan had been tailored to the mission of air defense, a responsibility which the coming of war in Korea did little to diminish, and which, for a time, it promised perhaps to emphasize. Nevertheless the decision to commit American forces was followed by a rapid movement of the bombers to Okinawa, whence they flew their first missions against the invader, and by concentration of available fighter strength in the Fukuoka area in Kyushu, where the Fifth Air Force, Lieutenant General Earle E. Partridge, USAF, set up an operations center. But although these Kyushu airfields were the closest available to Korea, the limited endurance of the F-80C permitted it to remain only very briefly in the target area, and effective operations waited upon the establishment of Korean bases, the manufacture of new wing tanks, or a change in aircraft type.

Lack of target information for the bombers and the limited capabilities of Air Force fighters placed great premium upon carrier-borne aviation. Never, perhaps, had the virtues of free movement upon the face of the waters shone so brightly, even to those who had long derided this instrument of war. On 29 June, as his Seventh Fleet Striking Force was approaching Buckner Bay, Admiral Struble flew into Tokyo from Washington. By presidential proclamation and NavFE operation order the mission of the Seventh Fleet was the neutralization of Formosa, but the rapid deterioration of the situation in Korea raised pressing questions concerning its employment there. Early on the 30th Struble queried his staff by dispatch as to how soon Valley Forge and Triumph could conduct a first strike in the area of the 38th parallel, and in a conference with General MacArthur, Admiral Joy, and General Stratemeyer, the decision was reached to strike objectives in the Pyongyang area. First emphasis would be given to the airfield complex of the North Korean capital, second priority to the railroad yards and to the bridges over the Taedong River. Following these discussions Struble flew on to Okinawa to rejoin his force, and early in the evening ComNavFE promulgated Operation Order 6-50 governing the employment of the carrier striking force.

The prospect of operating this mixed force presented some problems, owing to the differences between British and American aircraft types and to the fact that Triumph's maximum speed of 23 knots was 10 knots slower than that of Valley Forge. But the British were eager to go; many of their officers had had experience in joint operations in the Second World War and the two forces had recently held joint maneuvers; the advantages outweighed the difficulties. Although obscurity still surrounded the intentions of Communist submarines, Seventh Fleet forces had already reported two contacts, one some distance off Okinawa, one at the entrance of Buckner Bay; the Seventh Fleet submarine commander was therefore drafted as antisubmarine warfare adviser to ComCardiv 3. On the evening of 1 July Task Force 77, now enlarged to two carriers, two cruisers, and ten destroyers, sortied from Buckner Bay and headed northwest and north toward the launching area in the Yellow Sea.

Along the Korean coastline, following the Mukho bombardment of the evening of the 29th, Juneau and DeHaven had continued on patrol. The British cruiser Jamaica had reported to Admiral Higgins by radio at 1940, and had requested a rendezvous, and on the next day Black Swan also checked in by dispatch. But radio communications had become clogged, owing to the sudden expansion of high-precedence traffic, and communications with the British were for the moment worst of all: the instructions for a rendezvous never reached the British ships, and his allies had to seek out Admiral Higgins by intuitive means.

Nevertheless the clans were gathering. On the west coast, where Swenson had joined Mansfield on 30 June, the patrol of arcas Yoke and Zebra continued without contact with the enemy. On the east coast, following conferences with southbound ROK naval personnel, Juneau returned to Mukho to expend a further 43 rounds of 5-inch VT against troop positions and a shore battery. Collett came up from Pusan, where she had embarked ROK interpreters, signalmen, and liaison officers for distribution throughout the force, and at 2200 Jamaica joined. On the 1st, Alacrity and Black Swan arrived, and the day was spent in patrolling the coast and reorganizing the Support Group. DeHaven and Collett were detached to Sasebo to fuel and to escort troopships to Pusan; Alacrity was ordered into the Yellow Sea to relieve Mansfield in Area Yoke; Juneau, Jamaica, and Black Swan continued on east coast patrol.

On the morning of 2 July the South Korean Support Group returned to action. At 0615 bow waves were sighted close inshore, and investigation disclosed four torpedo boats and two motor gunboats heading north from Chumunjin, whither they had escorted ten motor trawlers loaded with ammunition. As the cruisers put on speed to intercept the enemy, the torpedo boats, with more bravery than discretion, turned to attack. Fire was opened at 11,000 yards, and by the time the range had closed to 4,000 one PT had been sunk and one stopped, a third was heading for the beach, and the fourth was escaping seaward. The final score of the engagement was three torpedo boats and both gunboats destroyed, and two prisoners taken by Jamaica. Following this first engagement with the North Korean Navy, also in effect the last, the cruisers bombarded shore batteries at Kangnung, and late in the day Jamaica was sailed for Sasebo to fuel.

The 3rd of July saw a number of dispersed skirmishes around the Korean coastline. Along the convoluted western shore Communist activities ha(l extended far south of the formal battleline, and in the evening the ROK YMS 513 caught and sank three small boats unloading military supplies at Chulpo. On the east coast Juneau finished off the ammunition trawlers at Chumunjin, and the British frigate Black Swan was subjected to the first enemy air attack of the war.

Although the North Korean Air Force, in the first days of conflict, had performed useful services in demoralizing ROK troops, its strength in any serious terms was small. Estimates of its composition as of the outbreak of hostilities varied between some 75 and 130 aircraft, none of very recent types. But on 2 July ComNavFE had alerterted the Support Group against possible air attack, and at 2012 on the 3rd two enemy fighters, thought to have been Stormoviks, came in on Black Swan from over the land and out of the haze, inflicted minor structural damage, and escaped without being hit. Fortunate in their evasive action, these pilots were doubly fortunate in their assignment that day, for their colleagues back at Pyongyang had just received a thorough working over by the aircraft of Task Force 77. In any event such attacks were not to be soon repeated: the efforts of Seventh Fleet and Fifth Air Force fighters and the airfield attacks by Bomber Command speedily demobilized the North Korean Air Force. Black Swan's experience remained for some time unique, and not until 23 August did another U.N. ship undergo attack from the air.

Since the evening of 1 July Task Force 77 had been steaming north from Buckner Bay, and by early morning of the 3rd Admiral Struble's Striking Force had reached the designated launching point. There, in the middle of the Yellow Sea, the force was some 150 miles from the target area, but only 100 miles from Chinese Communist airfields on the Shantung Peninsula and less than 200 miles from the Soviet air garrison at Port Arthur. The air defense problem, therefore, was potentially somewhat larger than the size of the North Korean Air Force would indicate; like the submarine situation, it required a certain investment in defensive measures. At 0500 Valley Forge launched combat and antisubmarine patrols; beginning at 0545 Triumph flew off 12 Fireflies and 9 Seafires for an attack on the airfield at Haeju, and 15 minutes later Valley Forge commenced launching her strike group. Sixteen Corsairs loaded with eight 5-inch rockets each, and 12 Skyraiders carrying i,60~pound bombloads were launched against the Pyongyang airfield. When the propeller-driven attack planes had gained a suitable headstart, Valley Forge catapulted eight F9F-2 Panthers, whose higher cruising speed would bring them in first over the target area. No serious opposition was encountered by the American jets as they swept in over the North Korean capital. Two Yaks were destroyed in the air, another was damaged, and nine aircraft were reported destroyed on the ground. For the enemy, this sudden appearance of jet fighters more than 400 miles from the nearest American airfield was both startling and salutary. Quite possibly, as one American commander observed, it may have deterred a sizable commitment of aircraft to North Korean bases.

Following the Panthers in, the Corsairs and Skyraiders bombed and rocketed hangars and fuel storage at the airfield. Both at Pyongyang and at Haeju enemy antiaircraft opposition was negligible, and no plane suffered serious damage. In the afternoon aircraft from Triumph flew a second strike, and a second attack was launched by Valley Forge against the marshalling yards at Pyongyang and the bridges across the Taedong River. Considerable damage was reported inflicted on locomotives and rolling stock, but the bridges survived this effort.

In view of the Formosan commitment, the carrier strikes had been originally planned as a one-day affair. But this had been modified during the approach, owing to the "rapidly deteriorating Korean situation," and General MacArthur had authorized the attack to continue as practicable beyond the first day. Targets for the second day, selected by CincFE, were designated by dispatch on the night of the 2nd, with first priority given the railroad facilities and bridges in the neighborhood of Kumchon, just north of the parallel on the main line from Pyongyang to Seoul, second priority to similar installations at Sariwon, halfway between the two capitals, and third priority to those near Sinanju, where the main road and rail lines from Manchuria cross the Chongchon River.

With a fine disregard of these instructions Task Force 77 celebrated the Glorious Fourth with further attacks on Pyongyang. This time a break was made in one of the Taedong River bridges, some locomotives were destroyed, and some small ships in the river were attacked. Antiaircraft opposition had increased somewhat over that of the previous day, four ADs were damaged, and one, unable to lower its flaps, landed fast and bounced over the barrier, destroying three planes and damaging six more. With completion of flight operations the Striking Force retired southward. On the 5th Admiral Andrewes, with Belfast, Cossack and Consort, was detached to join the blockading forces in compliance with orders from ComNavFE, Admiral Struble flew to Tokyo by carrier plane, and Task Force 77 continued on to Buckner Bay. There it arrived on 6 July, and there it was retained until the 16th.

On the east coast, on 4 July, Juneau and Black Swan worked up and down the shore between Samchok and Chumunjin, firing on bridges and on the coastal road. On the 5th Jamaica returned from Sasebo, Juneau retired to replenish fuel and ammunition, and for the next few days the bombardment duty was left in the hands of the British.

The 5th of July, which saw Task Force 77 retiring southward and Juneau completing her second tour of firing at coastal targets, saw also the beginning of the ordeal of the American foot soldier. As early as 27 June an Advance Command Group under Brigadier General John H. Church, USA, had been established at Suwon, some 25 miles south of Seoul, to help in reorganizing ROK forces and to expedite logistic assistance. But events soon demonstrated the optimism of this assignment, and on 30 June, with the arrival of the North Korean People's Army momentarily expected, this group was withdrawn to the southward. As ADCOM was retiring the first units of the 24th Infantry Division were being flown into Korea, and as the rest of the division was hastily embarking in Japan this advanced element, two infantry companies with supporting artillery under Lieutenant Colonel Charles B. Smith, USA, began its northward movement from Pusan. On the 5th Task Force Smith made contact with the enemy at Osan, south of Suwon, where it ran into an entire North Korean infantry division with armored support. From 0800 to 1500 the fight went on, at which time the survivors, outmaneuvered, outflanked, and most of all outnumbered, withdrew with the loss of all equipment save small arms. Twelve miles back down the road a larger force underwent the same fate, and the Americans were forced back on Chonan, where they would hold to 8 July.

The war was now ten days old. American citizens had been evacuated; a carrier air strike had been made against the enemy capital and the enemy air force; the east coast invasion route was under fire from naval guns. In the air the Far East Air Forces were putting forth their best efforts. On the ground the Army had engaged the enemy. Across the Korean Strait a stream of shipping was flowing into Pusan where, prior to the arrival of an Army port company, the unloading of 55 ships with 15,000 troops and 1,700 vehicles was handled by two ECA employees, Alfred Meschter and Milton Nottingham. In Korea the situation was being dealt with to the limit of the abilities of the forces available. There remained the problem of the northern and southern flanks.

What the dimensions of this problem might be, no one knew. If the invasion of South Korea had surprised the United States, and had shown how wrongly intelligence had heen evaluated, what faith could be put in estimates of Communist intentions elsewhere? Suddenly capabilities became important. The State Department had warned all hands on 26 June of the possibility that Korea was but the first of a series of coordinated moves; the military forces of the United States had gone on world-wide alert; in the Mediterranean the Sixth Fleet had put to sea. In the immediate theater of operations, no less than on the world scene, possibilities were unpleasant and visibility poor. The Joint Chiefs, it is true, had estimated that there would be no Soviet or Chinese intervention, but there was plenty of history, including a day at Pearl Harbor, to teach the outpost commander that estimates make poor weapons.

What of the northern neighhor, whose airfields at Vladivostok and Port Arthur flanked the Korean peninsula and were less than two hours flying time from Japan? What of the estimated four-score submarines based in the Vladivostok area? For the air threat, which had caused Admiral Joy to divert the Seventh Fleet to Buckner Bay, FEAF's fighter strength provided some counter, hut the submarine situation was less satisfactory. The excitement of the first week of conflict had brought forth eight reports of submarine sightings, ranging from Okinawa to the Sea of Japan, and while most were doubtless in error they at least posed serious questions. Harbor defense equipment was lacking in the Far East, and the shortage of antisubmarine units was acute: of the three American destroyer divisions in the theater, two were needed to provide a minimum sound screen for Valley Forge. Of necessity, therefore, the patrol planes of VP 47 were employed on local antisubmarine patrol and in the escort of shipping, and long range search had to await the coming of reinforcements.

What were the intentions of the Communist Chinese? In Korea their capabilities could for the moment be largely disregarded, but ComNavFE had been instructed to use the Seventh Fleet to neutralize Formosa, and to prevent attack in either direction across Formosa Strait. Here Chiang's forces presented no problem, but the Communists had the capability, and both thc Generalissimo and Admiral Struble thought an August effort wholly possible. The implications of such a development, added to the situation in Korea, greatly outweighed Admiral Joy's new accretions of force, and he may well have wondered what tools he was supposed to use to do this job. Some show of muscle, at least, had been made by Valley Forge as she steamed north, when she flew an air parade over Formosa Strait and the city of Taipei. But the chance that more would be required, as well as problems of logistic support, had made it necessary, following the Pyongyang strikes, to return Task Force 77 to Okinawa.

If Formosa was to be defended, coordinated planning was obviously necessary, and the state of Nationalist morale was such as to require stiffening. Arriving in Tokyo on the afternoon of 5 July, Struble had proposed a prompt resumption of carrier strikes, this time from the Sea of Japan. But decision on these was delayed, the talk turned to the Formosa problem, and the suggestion of a visit to that island was approved by General MacArthur. On the 6th, Commander Seventh Fleet flew back to Buckner Bay, and on the next day boarded a destroyer for a high-speed run to Taipei and two days of talks with the Generalissimo and the Nationalist military. Another few days would see the Formosa Strait under reconnaissance by planes of Fleet Air Wing 1, but the question of a surface patrol was more difficult. With the gunnery ships committed up to their ears in Korea, and with the situation there calling ever more urgently for Task Force 77, all that remained were the submarines of the Seventh Fleet. On 18 July Catfish was sailed from Yokosuka for a reconnaissance of the China coast, and was followed on the next day by Pickerel.

Finally, the northern sector, so great in undisclosed potentialities, was also brought under surveillance. On 7 July the first patrol plane reinforcements reached the Far East, and the long range P2V Neptunes of VP 6 were at once assigned to search in the Sea of Japan. On the 23rd the submarine Remora, escorted by Greenlet, headed north from Yokosuka for a patrol of La Pe'rouse Strait.

[End of Chapter 3]