The Navy Department Library

Beans, Bullets, and Black Oil

The Story of Fleet Logistics Afloat in the Pacific During World War II

by

Rear Adm. Worrall Reed Carter

USN (Retired)

with a Foreword by

The Honorable Dan A. Kimball

The Secretary of the Navy

and an Introduction by

Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, USN (Retired)

who helped turn back the Japanese at Midway and later took from them the Gilberts, Marshalls, Marianas, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa

Contents

| Chapter | Page | |||||

| Foreword | v | |||||

| Introduction | vii | |||||

| Preface | xi | |||||

| I. | Pre-World War II | 1 | ||||

| II. | The Service Force | 7 | ||||

| Laboring Giant of the Pacific Fleet | 7 | |||||

| III. | Early Activities | 11 | ||||

| Asiatic Fleet in Dutch East Indies | 12 | |||||

| Logistics of Raiding Forces | 17 | |||||

| Coral Sea | 21 | |||||

| Midway | 21 | |||||

| IV. | In the South Pacific | 23 | ||||

| Taking the Offensive | 23 | |||||

| Guadalcanal | 28 | |||||

| Logistic Outlook | 30 | |||||

| V. | Logistic Organization and Sources, South Pacific | 35 | ||||

| Damages and Repairs | 35 | |||||

| VI. | Building Up in the South Pacific | 49 | ||||

| VII. | The Southwest Pacific Command | 63 | ||||

| Early Logistics | 63 | |||||

| VIII. | In the Aleutians | 69 | ||||

| IX. | Operation GALVANIC (the Gilbert Islands) | 87 | ||||

| Mobile Service Squadrons Begin Growing | 90 | |||||

| Service Squadron Four at Funafuti | 91 | |||||

| X. | Service Squadron Ten Organizing at Pearl | 95 | ||||

| Relationship of the Service Administrative Squadron Eight | 96 | |||||

| XI. | Early Composition and Organization of Service Squadron Ten | 105 | ||||

| Ordnance Logistics | 107 | |||||

| Administration of Ordnance Spare Parts and Fleet Ammunition | 108 | |||||

| XII. | The Marshall Island Campaign | 115 | ||||

| The Truk Strike | 121 | |||||

| XIII. | Multiple Missions | 129 | ||||

| The Palau and Hollandia Strikes | 129 | |||||

| Marcus and Wake Raids | 132 | |||||

| Submarine Bases at Majuro | 133 | |||||

| Growth of Service Squadron Ten at Majuro | 134 | |||||

| XIV. | Operation FORAGER, the Marianas Campaign | 137 | ||||

| Floating Logistic Facilities | 138 | |||||

| Servicing the Staging Amphibious Forces | 140 | |||||

| Replenishment of Fast Carriers | 143 | |||||

| XV. | FORAGER Logistics in General and Ammunition in Particular | 149 | ||||

| Service Squadron Ten at Eniwetok | 163 | |||||

| XVI. | STALEMATE II: The Western Carolines Operation | 171 | ||||

| Preparations at Seeadler Harbor and Eniwetok | 173 | |||||

| XVII. | Logistic Support at Seeadler and at Sea | 185 | ||||

| Service Unit at Seeadler | 185 | |||||

| Oilers With the Fast Carrier Group | 190 | |||||

| Ammunition, Smoke, Water, Provisions, Salvage | 197 | |||||

| XVIII. | Further STALEMATE Support | 207 | ||||

| Medical Plans and Facilities | 207 | |||||

| 210 | ||||||

| Service Unit at Seeadler | 210 | |||||

| With the Fast Carriers | 212 | |||||

| Squadron Ten Prepares to Move | 213 | |||||

| XIX. | Service Squadron Ten Main Body Moves to Ulithi | 217 | ||||

| Reduction to Minimum at Eniwetok | 220 | |||||

| Improvement in Salvaging | 225 | |||||

| XX. | The Philippines Campaign | 233 | ||||

| Forces and Vessels | 233 | |||||

| Logistic Support of the Seventh Fleet | 237 | |||||

| Battle of Leyte Gulf | 243 | |||||

| XXI. | Logistic Support of the Third Fleet | 249 | ||||

| Submarine Attacks at Ulithi | 259 | |||||

| XXII. | Leyte Aftermath | 267 | ||||

| Ormoc Bay and Mindoro Landings | 267 | |||||

| Admiral Halsey on the Rampage | 271 | |||||

| "Bull in the China Sea" | 272 | |||||

| Some Dull Routine at Ulithi | 276 | |||||

| Another Midget Attack - Ammunition Ship Mazama Hit | 278 | |||||

| XXIII. | Iwo Campaign | 281 | ||||

| Fifth Fleet Relieves Third | 281 | |||||

| Forces and Vessels | 281 | |||||

| Logistics Prescribed | 282 | |||||

| Logistics Support Group - Service Squadron Six | 283 | |||||

| Service Squadron Ten Still Busy | 291 | |||||

| XXIV. | Service Squadron Ten Grows Up | 293 | ||||

| The Guam Base | 303 | |||||

| Seventh Fleet Logistic Vessels and Bases | 306 | |||||

| XXV. | Operation ICEBERG: The Okinawa Campaign | 311 | ||||

| The Forces Involved | 312 | |||||

| Staging Logistics | 317 | |||||

| XXVI. | Activities at Saipan and Ulithi | 323 | ||||

| XXVII. | Logistics at Kerama Retto for the Okinawa Operation | 331 | ||||

| Suicide Plane Attacks | 335 | |||||

| XXVIII. | Expansion of "At-Sea" Support by Service Squadron Six | 355 | ||||

| XXIX. | Support Activities at Leyte-Samar | |||||

| Service Squadron Ten Main Body Moves to San Pedro Bay | 370 | |||||

| Naval Bases on Leyte-Samar | 373 | |||||

| Reorganization of Service Squadron Ten | 379 | |||||

| Dysentery in Fleet Anchorage | 382 | |||||

| Service Force Pacific Absorbs Service Force Seventh Fleet | 383 | |||||

| XXX. | Okinawa After 1 July 1945 | 385 | ||||

| Operations Under Service Squadron Twelve | 388 | |||||

| The Move to Buckner Bay and Service Activities There the Remaining Days of the War | 392 | |||||

| XXXI. | The Giant Takes Off His Armor | 399 | ||||

| Surrender | 399 | |||||

| Changes in Logistic Services | 399 | |||||

| Getting Back Toward Peace Routine | 400 | |||||

| Pipe Down | 403 | |||||

| Appendix | 405 | |||||

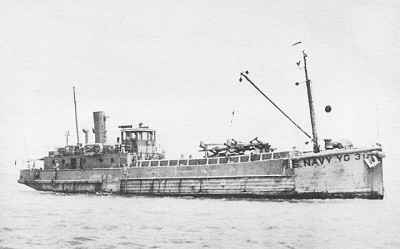

| The appendix contains a list of commanding officers of service vessels under Commander Service Force Pacific, photographs of vessels and small craft representative of the principal types engaged in logistic support activities under Commander Service Force Pacific, and a glossary of abbreviations. | ||||||

List of Photographs

| Page | |

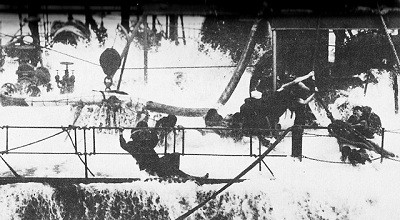

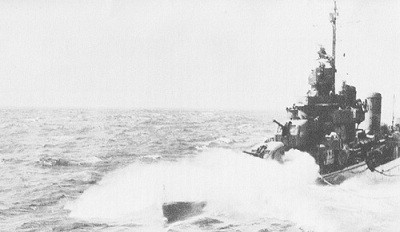

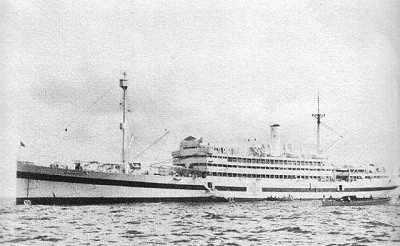

| Neosho fuels Yorktown in heavy sea | 19 |

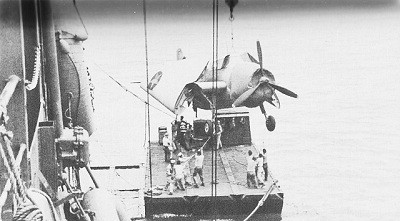

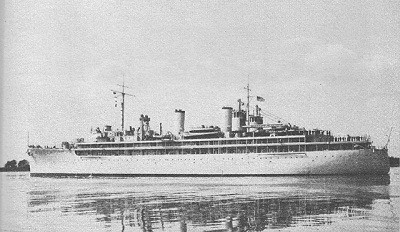

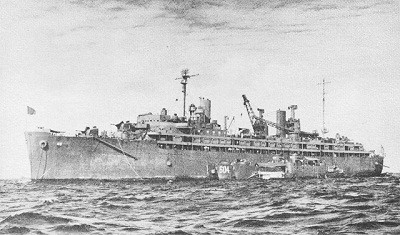

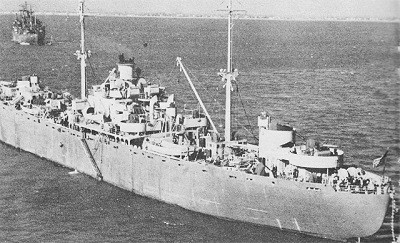

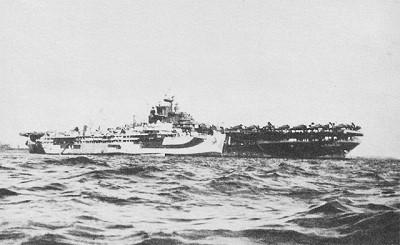

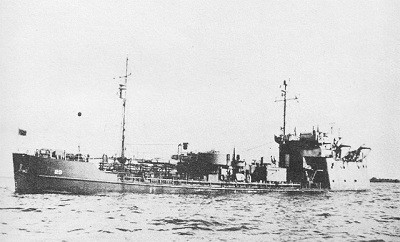

| Kitty Hawk supplying planes to the Long Island | 29 |

| USS Kitty Hawk at Pallikulo Bay, New Hebrides, unloading torpedo plane to self-propelled 50-ton barge | 31 |

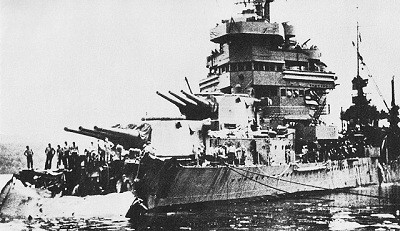

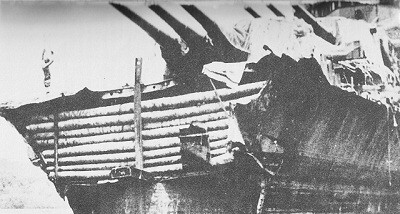

| Minneapolis, bow blown off | 44 |

| Minneapolis, bow repaired with coconut-palm tree trunks | 45 |

| Honolulu at Tulagi with bow damaged by "dud" torpedo | 56 |

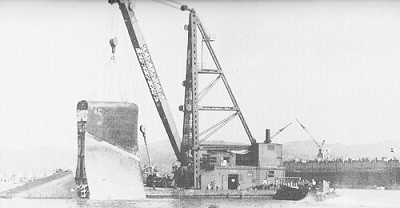

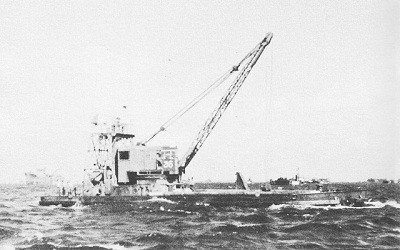

| Ortolan raises two-man submarine | 59 |

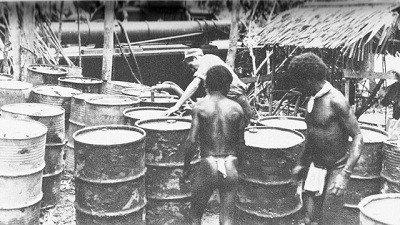

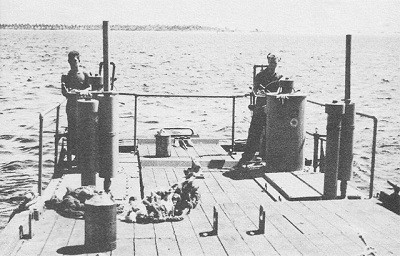

| PT boat fueling depot Base No. 8, Morobe, New Guinea | 65 |

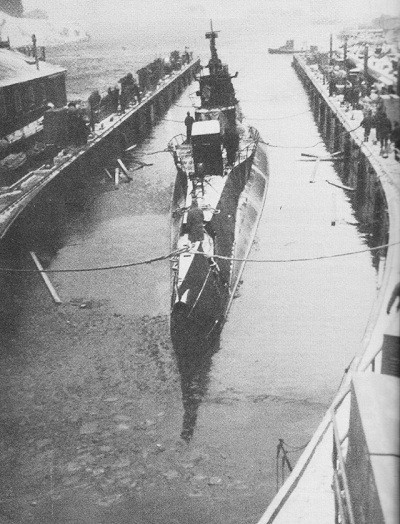

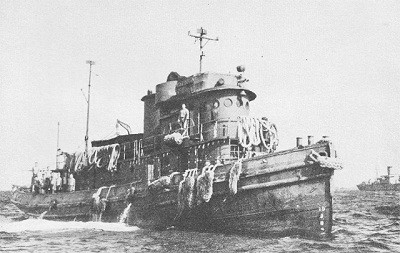

| Submarine undocking from ARD-6 Dutch Harbor | 70 |

| Sweepers Cove, Adak, Aleutian Islands | 71 |

| Finger Bay, Adak Island | 72 |

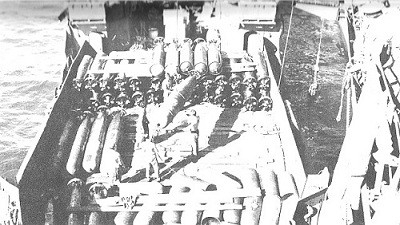

| Torpedoes being hosted aboard Lexington | 113 |

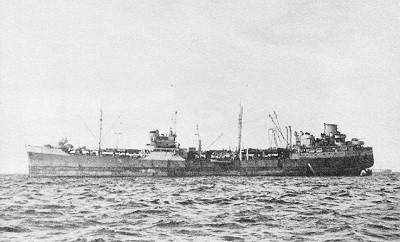

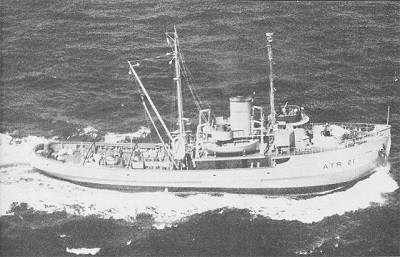

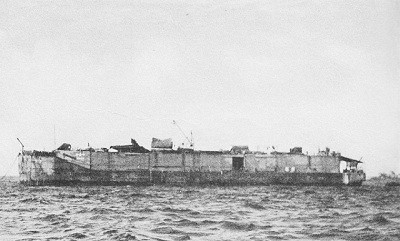

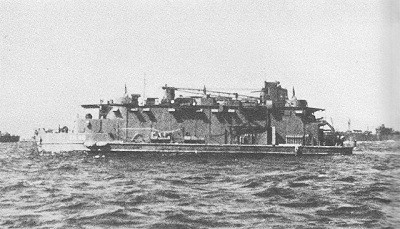

| Small floating drydock | 124 |

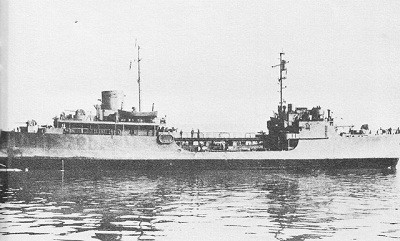

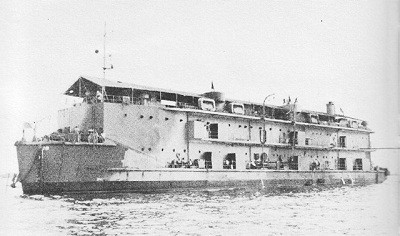

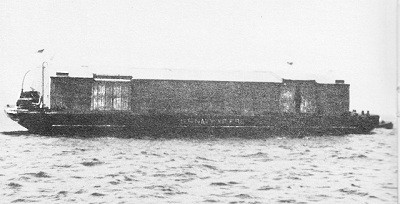

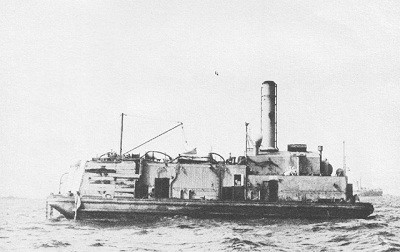

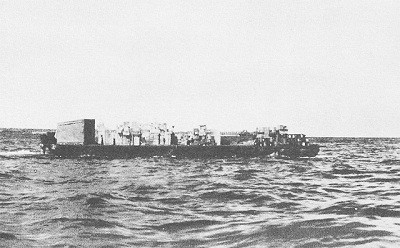

| The concrete stores barge Quartz, one of the many of this type construction | 127 |

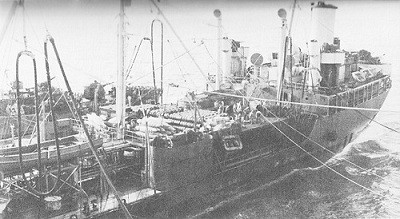

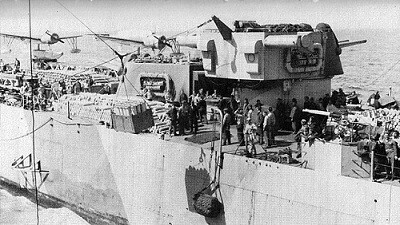

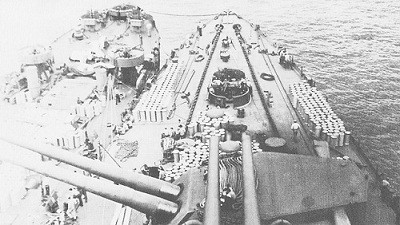

| Ammunition ship Shasta loading 14-inch powder and shells onto the New Mexico | 155 |

| New Mexico sending 14-inch H.C. shells to the magazines | 156 |

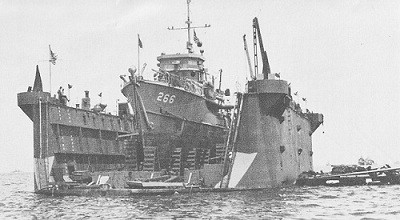

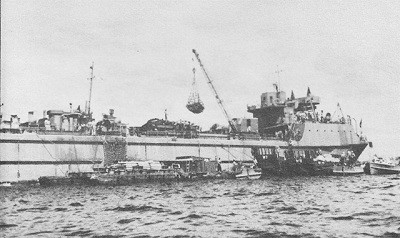

| Ships in Eniwetok, Marshall Islands | 164 |

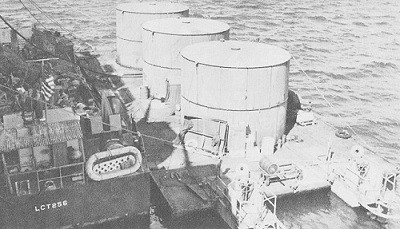

| An LCT alongside the Yorktown | 166 |

| Ships in Seeadler Harbor, Manus Island, in the Admiralty Islands | 186 |

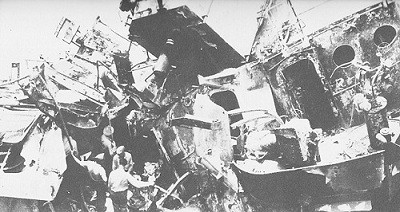

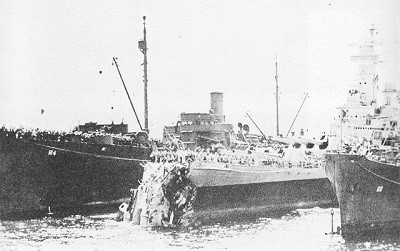

| Argonne damaged by the blowing up of the Mount Hood | 187 |

| The Boston fueling a destroyer | 192 |

| Fueling from both sides | 195 |

| Gasoline lighter and an LCT alongside the carrier Intrepid | 198 |

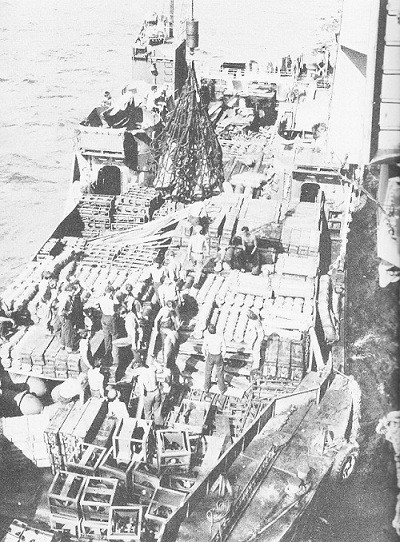

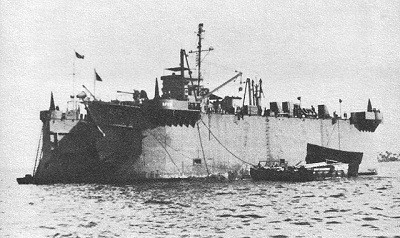

| Transferring bombs from LST to the carrier Hancock at sea | 199 |

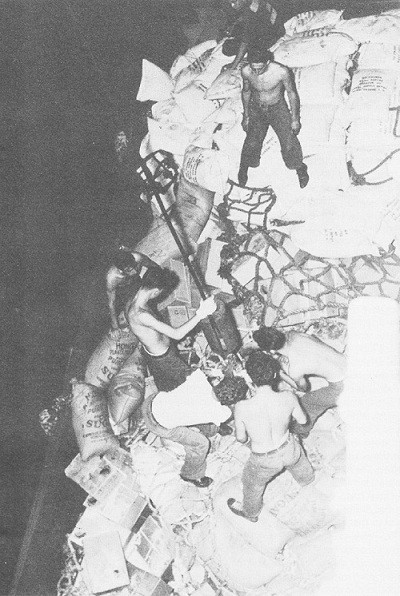

| Taking sugar on the carrier Lexington at night | 202 |

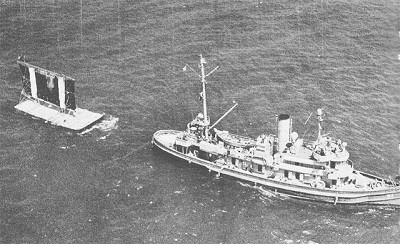

| The Houston - what holds her up? | 227 |

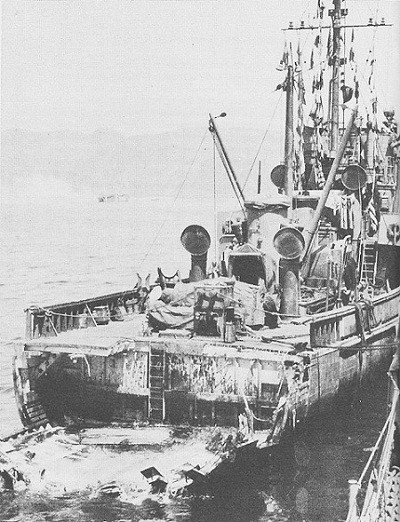

| The Reno hard hit and barely afloat | 229 |

| The Mississinewa torpedoed by a midget | 260 |

| One of the midgets | 262 |

| Load of powder midway between the Shasta and the cruiser Vicksburg at sea | 285 |

| Randolph damaged by suicide plane | 297 |

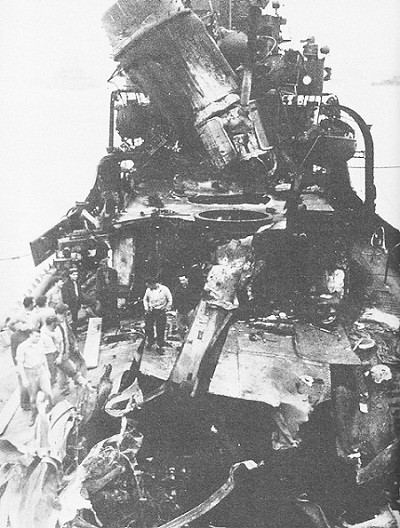

| Franklin hit hard | 298 |

| Closeup of the Franklin | 299 |

| Pittsburgh in a drydock, Guam | 304 |

| Bow of Pittsburgh, towed in, cut up, and restored to the ship | 305 |

| Destroyer Newcomb damaged by suicide attacks | 334 |

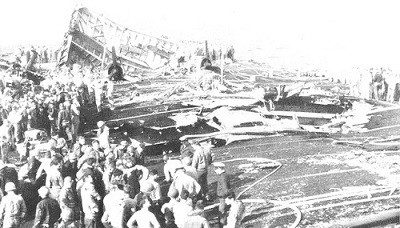

| Damage to the flight deck of Sangamon | 336 |

| Damage to Kiland's flagship, Mount McKinley | 338 |

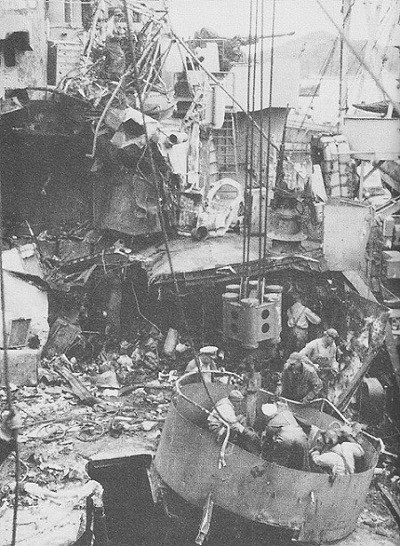

| Damage to the destroyer Hazelwood | 341 |

| Pennsylvania low in water after being torpedoed by plane | 342 |

| Maryland taking turret-gun powder | 344 |

| YMS-92, stern blown off | 352 |

| The oiler Cahaba fueling the battleship Iowa and the carrier Shangri-La on a smooth day | 360 |

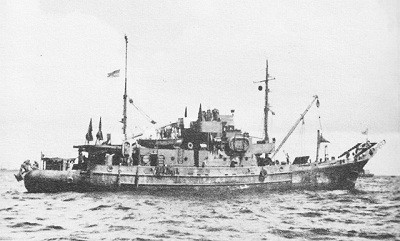

| The Ocelot - "Spotted Cat" - Carter's flagship | 372 |

| The Ponaganset loading fresh water at Balusoa Water Point, Samar | 377 |

| Raising a Jap midget by net layers | 391 |

| News of the surrender of Japan | 395 |

| Celebrating the good news | 396 |

List of Charts

| Title | Page |

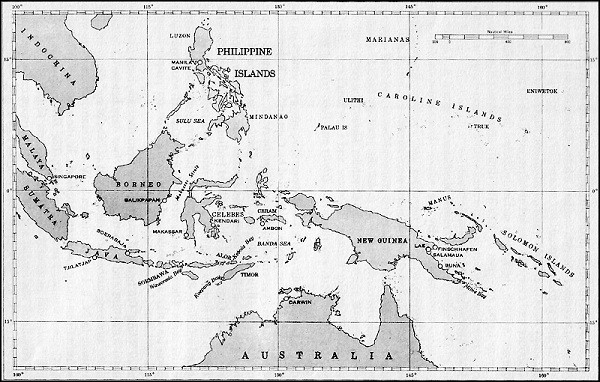

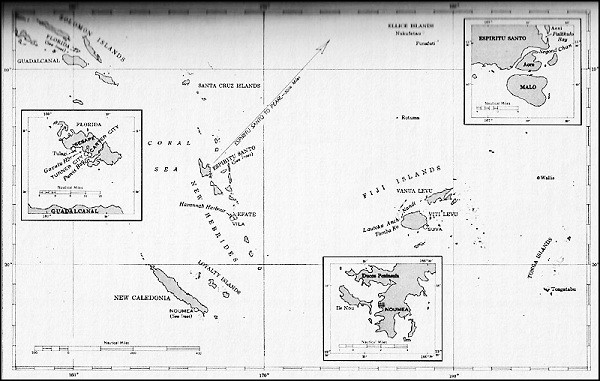

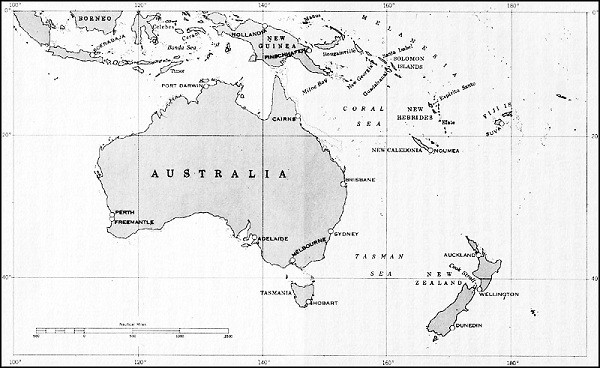

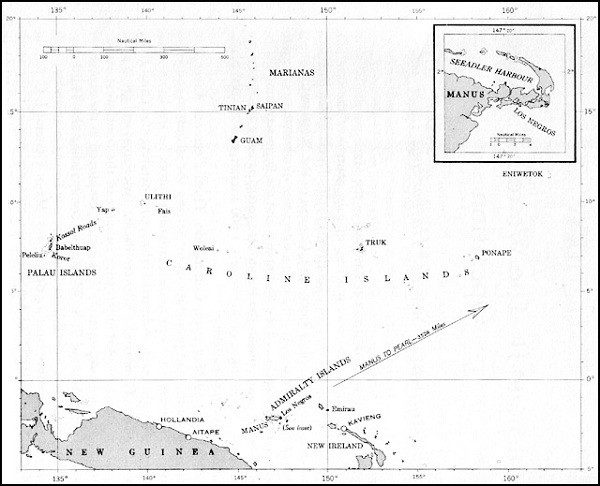

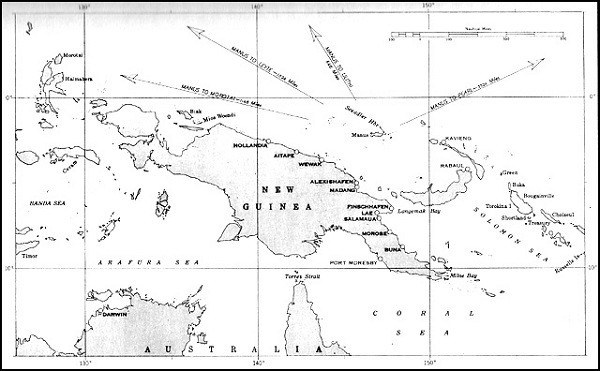

| Southwest Pacific, Australia, New Guinea, Borneo | 14 |

| New Hebrides | 27 |

| Australia | 62 |

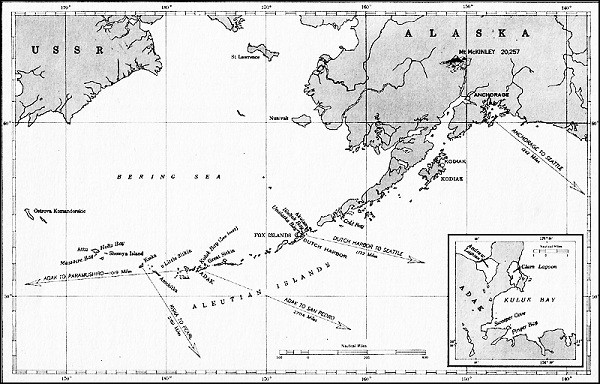

| Aleutian Islands | 74 |

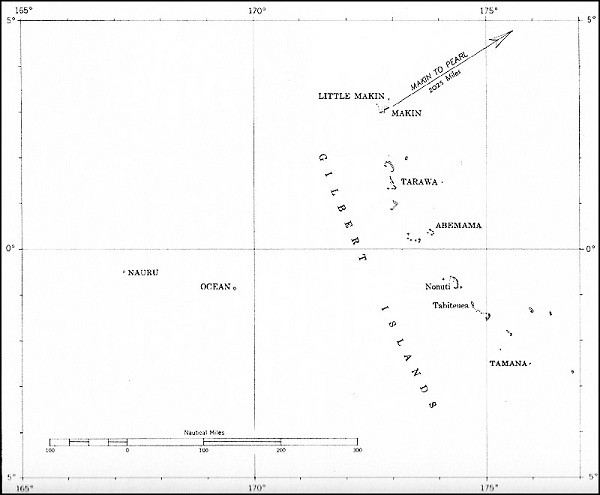

| Gilbert Islands | 88 |

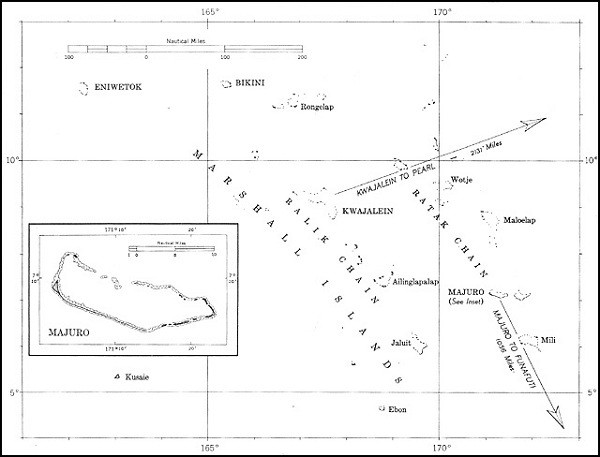

| Marshall Islands | 116 |

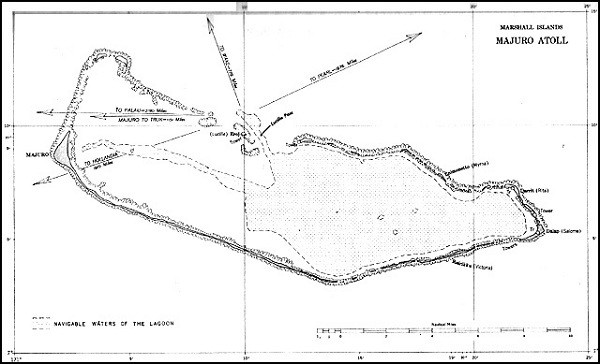

| Majuro Atoll | 119 |

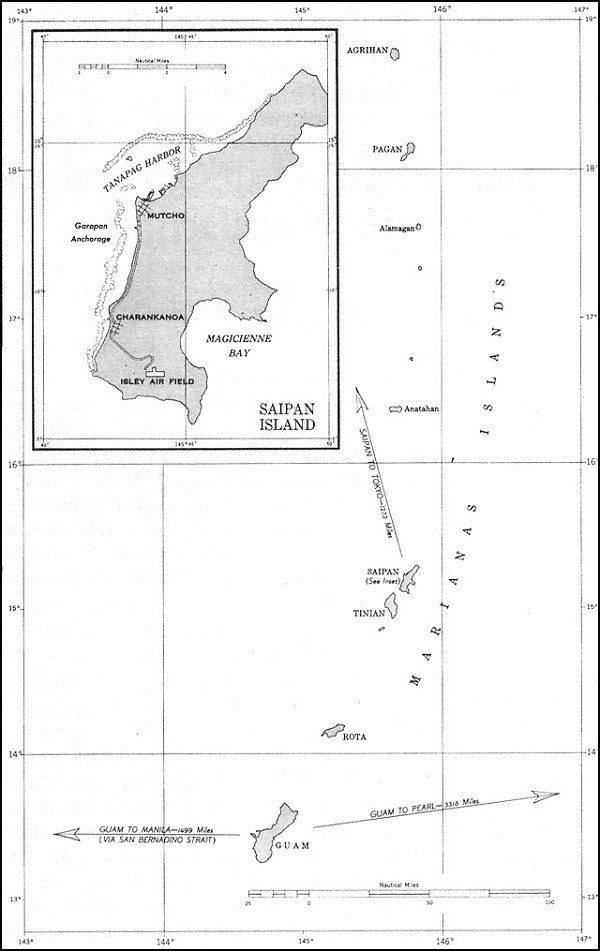

| Marianas Islands | 150 |

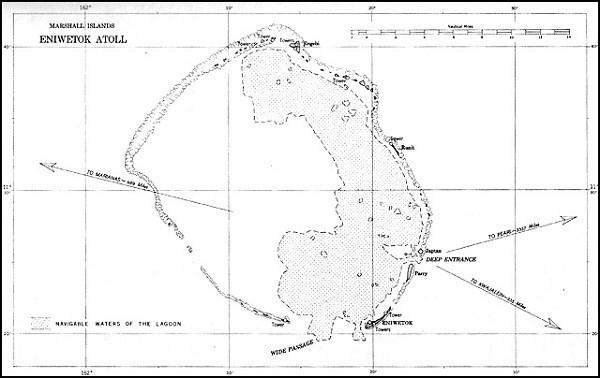

| Eniwetok Atoll | 153 |

| Caroline Islands | 172 |

| New Guinea (and small part of Australia) | 181 |

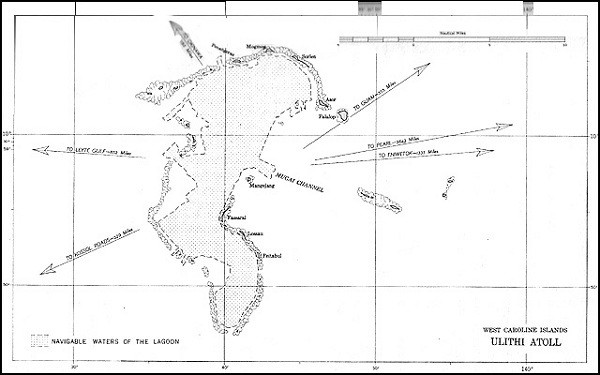

| Ulithi Atoll | 223 |

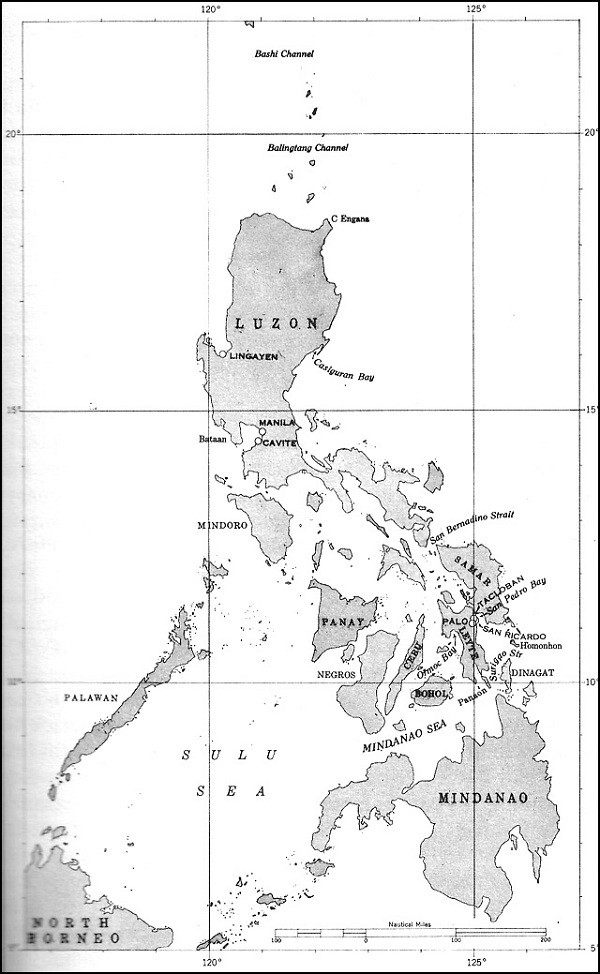

| Philippines | 235 |

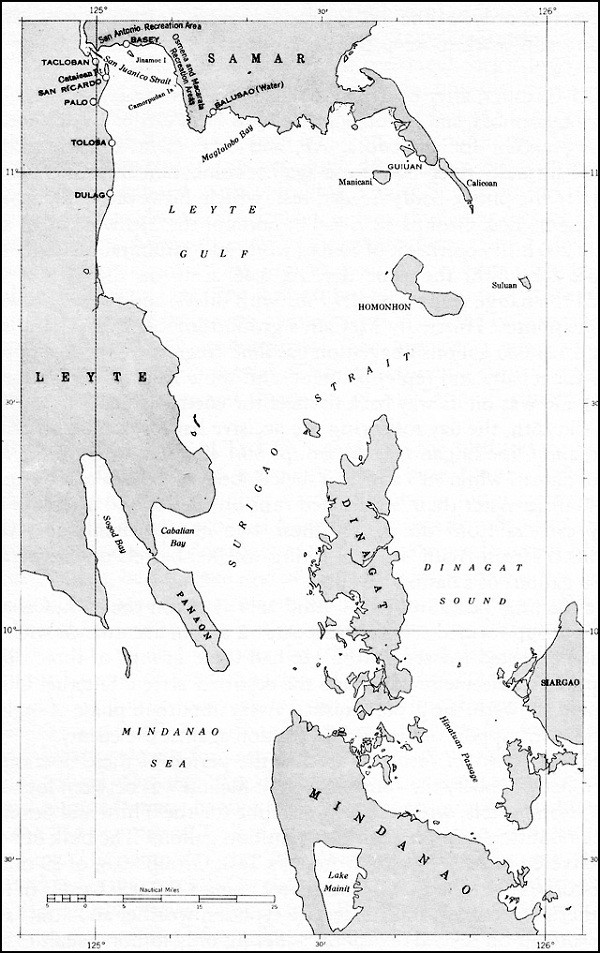

| Leyte Gulf - Surigao Strait - Samar - Leyte | 252 |

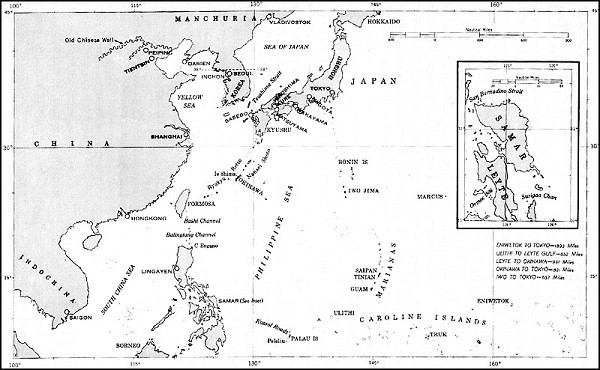

| China, Japan, and the Philippines | 273 |

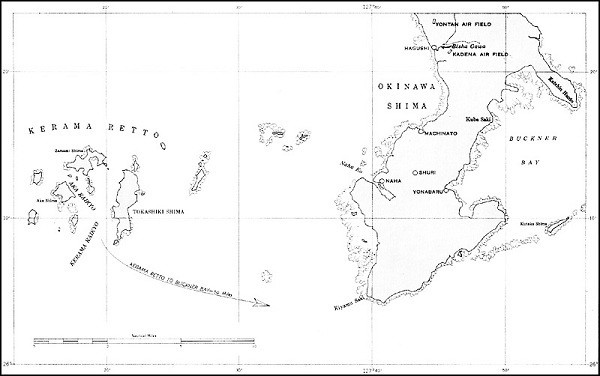

| Kerama Retto | 332 |

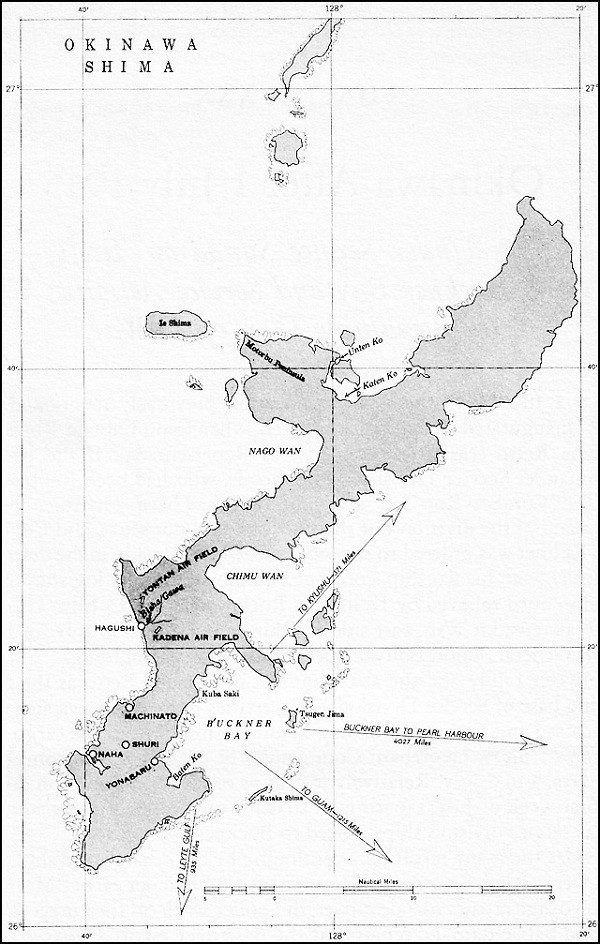

| Okinawa Shima | 386 |

Foreword

Victory is won or lost in battle, but all military history shows that adequate logistic support is essential to the winning of battles.

In World War II, logistic support of the fleet in the Pacific became a problem of such magnitude and diversity, as well as vital necessity, that all operations against Japan hinged upon it. The advance against the enemy moved our fleet progressively farther and farther away from the west coast of the United States, from Pearl Harbor, and from other sources of supply. To support our fleet we constructed temporary bases for various uses, and we formed floating mobile service squadrons and other logistic support groups. These floating organizations remained near the fighting fleet, supplying food, ammunition, and other necessities while rendering repair services close to the combat areas. This support enabled the fleet to keep unrelenting pressure upon the enemy by obviating the return of the fleet to home bases.

Because of the knowledge gained during his South Pacific service and particularly from his experience as Commander of Service Squadron Ten, the largest of the mobile squadrons, Rear Admiral W.R. Carter was chosen to write this history of logistics afloat in the Pacific. The opinions expressed and the conclusions reached are those of the author.

/s/

Dan A. Kimball

Secretary of the Navy

6 February 1952

--v--

Introduction

by Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, USN (Retired)

A sound logistic plan is the foundation upon which a war operation should be based. If the necessary minimum of logistic support cannot be given to the combatant forces involved, the operation may fail, or at best be only partially successful.

In a war, one operation normally follows another in a theater and each one is dependent upon what has preceded it and what is anticipated. The logistic planning has to fit into and accompany the operational planning. The two must be closely coordinated, and the planners for each must look as far into the future as they can in order to anticipate and prepare for what lies ahead.

A history of the sum total of American logistics during World War II would be forced to cover a tremendous field. The present volume deals only with naval logistics in the Pacific. As such, its scope is limited to a not-too-great portion of our entire national logistic effort. However, the area involved - the Pacific Ocean - is the one where our maximum naval effort was expended. Distances in that ocean were very great, and the resources available to us from friendly countries in the Western Pacific were comparatively minor, in both variety and quantity. Nearly everything our forces required had to come from or through the United States, with the exception of the large amounts of petroleum products originating in the Caribbean area and moving west through the Panama Canal.

The study of our naval logistic effort in the Pacific, as outlined in the present volume, brings out our dependence on both shore bases and mobile floating bases such as are exemplified by Service Squadron Ten. Each had its advantages, and neither alone could have done the job.

In the early days of the war, when the fighting was principally in the South and Southwest Pacific, we had around our bases good-sized land masses, which permitted the construction of shore facilities. Shipping then was scarce and at a premium, and large numbers of ships could not be spared for conversion to the special purposes of a mobile floating base. Furthermore, our advance against the enemy then was not so rapid

--vii--

in its movement as it became later. Shore bases continued to be close enough to the fighting front to retain practically their full usefulness.

When we started planning in the summer of 1943 for operations in the Central Pacific, it was obvious that the geography of the area which we hoped to capture had characteristics very different from those of the South Pacific. We did not know how fast we would be able to move ahead, but we did know that in the Gilberts, Marshalls, and Carolines, many of the islands had splendid protected anchorages in their lagoons. However, the land areas surrounding the lagoons were very small. These islands were only large enough, as a rule, to enable us to construct the always necessary air strips and to take care of the requirements of the atoll garrison forces. Truk, which we bypassed, in the Carolines, was an exception geologically in that there were some fairly large but rugged islands in the middle of its magnificent lagoon. Exceptions also were Kusaie and Ponape, which were large rugged islands without any protected anchorages big enough to be of interest to us. The Marianas we knew had some good-sized islands in the group, but we also knew that not one of them had a protected anchorage large enough for fleet use.

This geography meant that the logistic support for our fleet during operations in the Central Pacific would have to be primarily afloat, in what developed into the mobile service squadron - first Service Squadron Four at Funafuti in the Ellice Islands and then Service Squadron Ten at Majuro in the Marshalls. The small beginnings of the idea in Service Squadron Four were absorbed into Service Squadron Ten soon after the latter came into being in February 1944 at Majuro.

The growth of Service Squadron Ten, its movement across the Pacific to successive bases at Eniwetok, then Ulithi and then Leyte, and its continuous and most efficient service to the fleet at these and numerous other bases where it stationed ships and representatives as our operations demanded, are achievements of which all Americans can be justly proud, but about which most of them have little or no knowledge.

The actual furnishing of logistic support to ships at sea is an essential part of this picture. At first it was confined to fuel, but as we pushed westward toward Japan and as the tempo of our operations increased, our fleet had to remain for longer and longer periods at sea. This reached its peak in the Okinawa operation, which lasted for over 3 months and during all of which it was necessary to keep strong fleet forces from the fast carrier force in a covering position. The fine work of Service Squadron Six under Rear Admiral D.B. Beary, USN, enabled this to be done.

--viii--

The author of this book, Rear Admiral W.R. Carter, USN (Ret.), is well qualified by experience to write about naval logistics in the Pacific during World War II. At the outbreak of war and during its early months he was Chief of Staff to Commander Battleships Pacific Fleet, Rear Admiral Walter S. Anderson, USN. When that command changed, Captain Carter (as he was then) was most insistent that he remain at sea in the Pacific, and if possible that he be sent wherever there was fighting. His demands resulted in his being sent to the South Pacific in the fall of 1942, where he became Commander Naval Bases. Here he helped to build up the shore bases which supported our early operations in the Solomons. Later, after a South Pacific organizational change which originated in the Navy Department, he returned to Pearl Harbor and was then sent to the Aleutians. After returning to Pearl Harbor, he worked up on paper the organization of Service Squadron Ten.

At the time of the Marshalls operation Captain Carter secured a billet as a convoy commodore, which was consistent with his idea of getting closer to where the fighting was going on. When I found him in this capacity at Majuro shortly after we had taken Kwajalein, I told him to find a relief for his convoy billet and to start building up Service Squadron Ten at Majuro, which he did.

From February 1944 until July 1945, "Nick" Cater continued to run Service Squadron Ten and did a magnificent job, often under great difficulties. Just before the end of the war, Carter was ordered to Washington for a medical survey over the vehement protests of Admiral Nimitz and others in the Pacific. After being found physically fit he asked for reassignment to the Pacific, but the war ended before action could be taken on his request.

Commodore Carter was fortunate, as were all the rest of us, in having at all times the intelligent, generous, and wholehearted support of Vice Admiral W.L. Calhoun, USN, who as Commander Service Force in Pearl Harbor was Carter's immediate superior. Bill Calhoun's loyalty up to his boss, Admiral Nimitz, "down" to all his own command in the Service Force, and "sideways" to all the rest of us who needed his help and support, was something that could always be depended upon. Under the leadership of Admiral Nimitz, we had a combination that could - and did - go anywhere in the Pacific.

/s/

R.A. Spruance

--ix--

Preface

THIS IS NOT A STUDY in logistics. It is more a story of logistics. It is a story about the logistic services supplied to U.S. naval forces in the operating areas in the Pacific, 1941-45. It is largely an account of services rendered by means of floating facilities. It does not go into the magnificent production and supply by the industrial plants, shipyards, and naval bases of continental United States and Hawaii which made possible the floating bases of distribution and maintenance. This is a story of the support of the fleet into the far reaches of the Pacific in its campaign against the Japanese. It is the story of the distribution to the fleet of the sinews of war, at times, at places, and in quantities unsuspected by the enemy until it was too late for him to do much to oppose it. This book has little or nothing to say about the building, equipping, and fitting out of new vessels, or the manufacture and shipping of the thousands of tons of thousands of different items by continental sources, without which colossal accomplishment there could have been no drive across the Pacific. This account does not attempt to furnish complete statistical figures; such statistics are matters for the technical bureaus of the Navy. This is, rather, an attempt to spin a yarn of the logistics afloat in the Pacific Fleet, in order that those interested in naval history may realize that naval warfare is not all blazing combat.

I have been helped by several people, but most of all by Rear Admiral E.E. Duvall, USN (Ret.), my former Chief Staff Officer in Service Squadron Ten. Mere acknowledgment of the work he has done would be an injustice. He is practically the co-author and has furnished me with many useful suggestions. Just as he was every ready to tackle patiently any assignments during the war, so has he worked with me on this book. Duvall designed and made preliminary sketches for the sea-horse emblem, the spine, charts, and end-papers of the book.

My thanks go to Miss Loretta I. MacCrindle, Head of the World War II Classified Records Branch, Division of Naval Records and History, and her assistant, Miss Barbara A. Gilmore, for their help in digging up material from the acres of filing cabinets and for their tolerance of my disorderly use of it.

I am indebted to Miss Mary Baer, the Film Librarian at the Navy

--xi--

Photographic Center, for helping me with the illustrations.

The student cartographers under the direction of Mr. Leo M. Samuels and Mr. Fulton G. Perkins of the Hydrographic Office helped me with the charts.

The early typing was done by Miss Shirley Zimmerman, who proved herself almost a cryptanalyst in reading my writing. Norman L. Clark and Maurice O'Connor helped. The rewrite typing was done by YN3 Johnnie J. Freeman. I thank them all.

Rear Admiral John B. Heffernan, USN (Ret.), the Director of Naval Records and History, who got me into this history writing but who is not to be held responsible for anything found amiss herein, has been my boss and my backer. Without the facilities and encouragement which he has furnished me this neophytic effort would have failed.

This work originated in a request from the President of the Naval War College, Newport, R.I., and the project was approved by the Chief of Naval Operations on the recommendation of Vice Admiral R.B. Carney, then Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Logistics. The project has continued to receive the support and encouragement of Vice Admiral F.S. Low, now Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Logistics.

The original manuscript on file with the Division of Naval Records and History, which is much larger, goes into greater detail, and has a larger appendix section, is retained for official use. Commander A.S. Riggs, USNR, read the manuscript and did much of the work of cutting down to a more popular version and size. For his work I am very thankful and appreciative. It was not easy. For the final editing I am much indebted to Mr. L.R. Potter.

The sources of this book are official naval records, such as war diaries, logs, operation plans, and action reports, and therefore it is thought unnecessary to give individual case authentications to which very few readers ever refer and which makes for a great deal more printing and crowding of pages. A glossary has been included to acquaint the reader with the meaning of certain abbreviations and terms.

/s/

W.R. Carter

Rear Admiral, USN (Ret.)

Washington, D.C.

8 October 1951

--xii--

Chapter I

Pre-World War II

From 7 December 1941, when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, until they admitted defeat in August 1945, our fleet continuously grew. During those stirring and difficult times, the accounts of ship actions, air strikes, and amphibious operations make up the thrilling combat history of the Pacific theater. Linked inseparably with combat is naval logistic support, the support which makes available to the fleet such essentials as ammunition, fuel, food, repair services - in short, all the necessities, at the proper time and place and in adequate amounts. This support, from advanced bases and from floating mobile service squadrons and groups, maintained the fleet and enabled it to take offensive action farther from home supply points than was ever before thought possible, and this is the story which will be told here. But before telling this story, let us examine some of the ideas and accomplishments of fleet logistics in the years before World War II.

The advantages of logistics afloat and near the fleet operating area had long been recognized by many naval commanders, and no doubt by others who gave the matter analytical thought. There was some selfish opposition to its development by local politicians, merchants, and shipyards because of the wish to keep the activities where the disbursements would benefit the local shore communities directly. Also, there was some opposition in naval bureaus, and there was some skepticism on the part of some officers within the naval service as to the feasibility of accomplishing many of these services afloat. For example, it took a long time to satisfy everyone of the practicality of fueling under way at sea. Also, there were those who were skeptical of the capabilities of tenders and repair ships. Such vessels were looked upon as able to accomplish a certain degree of minor repair and upkeep, but for support of any consequence a navy yard or shipyard was for years thought necessary.

During World War I, the astonishing repairs accomplished by our two destroyer tenders at Queenstown turned many doubters into enthusiasts. In fact, the whole afloat work of servicing the destroyers at

--1--

Queenstown, a place with a very small naval shore establishment, was a praiseworthy accomplishment along lines of progress which furnished new concepts for naval consideration.

So, with the retrenchment and curtailment of naval appropriations and the transfer of the principal part of the U.S. Fleet to the west coast after World War I, the Base Force was formed as part of the fleet. This was, in fact, the beginning of the Service Force and its duty was service to the fleet, although it continued to be called the Base Force until the United States entered World War II. In concept and principle it was sound, and its organization for the work then deemed practical was good. As a result, valuable and efficient services were rendered to the fleet, and some ideas of greater future accomplishments took root. The fuel-oil tankers, fresh and frozen-food ships, repair ships, fleet tugs, and target repair ships were administered and operated by the Commander Base Force. Ammunition ships were administered and usually operated by Naval Operations (OpNav). The navy-yard schedule for overhaul was arranged but the allotment of funds for the work was controlled by the type commanders.

The destroyer tenders and submarine tenders were not administered or operated by the Base Force, and only occasional servicing jobs, either of emergency nature or beyond the capacity of the tenders, were performed directly on destroyers and submarines by the Base Force ships. The term "directly" is used because the Base Force often supplied the tenders with fuel, food, and ammunition, with which they in turn served the destroyers and submarines.

The Base Force also made arrangements for water and for garbage disposal, and usually ran the shore patrol. The distribution of the enlisted personnel was, in varying degrees (depending upon the ideas of the Commander in Chief), handled by the Base Force.

The flagship of the Commander Base Force (Rear Admiral J.V. Chase1) was a temporary one, the old fleet flagship Connecticut. She was soon scrapped. A Hog Island cargo vessel, the Procyon, which for a short time after World War I had been used as a target repair ship, was assigned and designs for her alteration to meet the administrative-staff requirements were tentatively drawn and sent with the ship from Norfolk to Mare Island Navy Yard, where the work was to be done. There was little or no knowledge or experience to draw upon these requirements.

__________

1. Admiral J.V. Chase had as his Chief of Staff, Captain W.T. Cluverius, who several years later became Commander of the Base Force. Admiral Chase was later the Commander in Chief of the U.S. Fleet.

--2--

Theory did not suffice, and practically new designs had to be drawn up with the assistance of Chase's staff after the arrival of the Procyon at Mare Island. When the work was well under way, the Board of Inspection and Survey chose that time to make its inspection of the ship, and considerable difficulty was encountered in convincing the Board that these alterations were necessary and should be completed. This further illustrates how little this logistic business of the Navy was understood.

The fleet air arm was a separate organization, with its own tenders and furnishing its own services, although while assigned for photographic, target, and some observation work the planes received temporary servicing from the Base Force. The aircraft tenders, like those of the destroyers and submarines, received some services from the Base Force which in turn were passed on to the planes. When the Langley, Lexington, and Saratoga joined the fleet, the Base Force took on the principal part of the responsibility for their fuel, food, and gun ammunition and made arrangements for regularly scheduled overhauls. All special equipment and planes, and many alterations due to experimental changes and improvements, were handled direct through the bureaus without reference to the Base Force.

Fueling under way at sea was instituted as part of the annual exercises, and fuel connections were designed and installed and "at sea" rigs were supplied in order to carry out this part of the schedule. Fueling under way at sea was then looked upon somewhat as an emergency stunt which might have to be resorted to in wartime, and therefore probably required occasional practice. Few ever thought it would become so routine a matter that it would be accomplished with ease in all kinds of weather except gales.

The era was one of rapid change and progress. In 1925 the operating force of the Navy consisted of 234 vessels, including 17 battleships, 15 cruisers of different types, a second-line carrier and 2 second-line mine layers, 6 destroyer-minelayers, 103 destroyers, 80 submarines, 1 fleet submarine in an experimental stage of development, and 9 patrol gunboats. To service these units afloat we had 75 other craft: Oilers, colliers, tenders, repair ships, store ships, 1 ammunition ship and 1 hospital ship, 25 mine sweepers, 2 transports, 8 fleet tugs, and miscellaneous small craft, a total of promising size. A good start had been made, the principal objections to formation of this element of the Navy had been overcome, and the Base Force had been established as a definite part of the United States forces afloat.

--3--

Unfortunately, just as we were ready to move to further accomplishment the depression years arrived, funds were severely restricted, and the Base Force came to a slowdown without opportunity for improvement and advancement in operating technique. This period was immediately followed by the Roosevelt years of emergency. The sudden expansion of all categories of naval personnel left little opportunity for anything but the fundamentals. In consequence, not great advance in Base Force technique or organizational coordination of fleet logistics was made until the war was in its second year.

The Navy Department knew that expansion of the fleet called for a proper balance in its auxiliaries; but, because of the lack of detailed knowledge, there was no sound formula for finding that balance. So it was estimate and guess, with the authorizations always a little on the light side because of the need for combat units whose construction alone would tax the capacity of the building plants. As a result, in 1940 the operating force consisted of 344 fighting ships, and to service them afloat 120 auxiliaries of various types. While in the 15 years from 1925 to 1940, destroyers, cruisers, and carriers had more than doubled in numbers, the auxiliaries had not. The most notable increase had been in seaplane tenders and oilers, but there were too few of the latter to permit their being kept with the operating units long enough to improve their at-sea oiling technique. Instead, they had to be kept busy ferrying oil.

During the first year of President Roosevelt's declared limited national emergency - 1940 - there were authorized 10 battleships, 2 carriers, 8 light cruisers, 41 destroyers, 28 submarines, a mine layer, 3 subchasers, and 32 motor torpedo boats - a total of 125 combat fleet units. Because of the lack of logistic knowledge and foresight, the auxiliaries ordered to service this formidable new fleet numbered only 12: 1 destroyer tender, 1 repair ship, 2 submarine tenders, and 2 large and 6 small seaplane tenders. The war plans, it is true, included the procurement and conversion of merchant ships for auxiliary and patrol purposes, but nothing came of this provision. Because of the shortage of merchant shipping, little could be done without causing injury elsewhere.

That same year - 1940 - the Oakland, Calif., Supply Depot was acquired, and the existing port storage depots at several points, notably San Diego, Calif., Bayonne, N.J., and Pearl Harbor, T.H., were expanded. Still no one seemed to give much consideration to the delivery and distribution of supplies to ships not at those bases to receive them. The Base Force war plans for an overseas movement visualized two somewhat vague schemes. One was that the fleet would fight at

--4--

once upon arrival in distant or advanced waters and gain a quick victory (or be completely defeated), and the base would be hardly more than a fueling rendezvous before the battle. Afterward (if victorious), with the enemy defeated there would be plenty of time to provide everything. The other idea was that the advanced location would be seized, the few available repair and supply vessels would be based there, and the remaining necessary facilities would be constructed ashore. The action there was no assurance that the base could be held with the fleet not present. On the other hand, the fleet if present could not be serviced without adequate floating facilities while necessary construction was being accomplished ashore. So the idea of fleet logistics afloat was becoming more and more firmly rooted; only time was needed to make it practical, as our knowledge and experience were still so meager that we had little detailed conception of our logistic needs. Even when someone with a vivid imagination hatched an idea, he frequently was unable to substantiate it to the planning experts and it was likely to be set down as wild exaggeration. How little we really knew in 1940 as compared with 1945 shows in a comparison of the service forces active at both times.

In 1940 the Base Force Train included a total of 51 craft of all types, among them 1 floating drydock of destroyer capacity. By 1945 the total was 315 vessels, every one of them needed. The 14 oilers which were all the Navy owned in 1940 had leaped to 62, in addition to merchant tankers which brought huge cargoes of oil, aviation gasoline, and Diesel fuel to bases where the Navy tankers took them on board for distribution to the fleet. No less than 21 repair ships of various sizes had supplanted the 2 the Navy had 5 years before. The battleships had 3 floating drydocks, the cruisers 2, and the destroyers 9, while small craft had 16. Hospital ships had risen from 1 to 6, and in addition there were 3 transport evacuation vessels, while the ammunition ships numbered 14, plus 28 cargo carriers and 8 LST's (Landing Ship, Tanks). The number of combatant ships had increased materially, and it is natural to ask if the auxiliaries should not have increased comparably. The answer is, of course, yes. But the increase of combatant ships had been visualized, and the building programs were undertaken before the war began. It flourished with increased momentum during the early part of the war, long before the minimum auxiliary requirements could be correctly estimated and the rush of procurement started. The original planers had done their best, but it was not until the urgency for auxiliaries developed as a vital

--5--

element of the war that we fully realized what was needed, and met the demand. Merchant ships were converted whenever possible, and this, with concentrated efforts to provide drydocks and other special construction, produced every required type in numbers that would have been considered preposterous only a short time before.

--6--

Chapter II

The Service Force

Laboring Giant of the Pacific Fleet

At the time of the Japanese Attack on Pearl Harbor, Rear Admiral W.L. Calhoun commanded the Base Force there and had his flag in the U.S.S. Argonne. Overnight his duties increased enormously. Thousands of survivors of the attack had nothing but the clothes they wore, which in many cases consisted of underwear only. These naval personnel had to be clothed, fed, quartered, re-recorded, and put on new payrolls with the utmost expedition in order to make them available for assignment anywhere. There were hundreds of requests for repairs, ammunition, and supplies of all kinds.

Calhoun expanded his staff to three times its original size, and despite the excitement, confusion, diversity of opinion, uncertainty, and shortages of everything, he brilliantly mustered order from what could easily have been chaos. Calhoun, soon promoted to vice admiral, continued as Commander of the Service Force until 1945, and the remarkable cooperation, hustle, and assistance rendered by his command are unforgettable. This was especially true in the advanced areas. Any duty to which the term "service" could be applied was instantly undertaken on demand; this contributed enormously to the fleet efficiency, and, in consequence, to the progress of the campaign. No single command contributed so much in winning the war with Japan as did the Service Force of the Pacific Fleet. It served all commands, none of which could have survived alone. Neither could all of them combined have won without the help of the Service Force. It is deserving of much higher public praise than it ever received, and, most of all, its activities should be a matter of deepest concern and study by all who aspire to high fleet commands.

At the time of the Pearl Harbor attack the Base Force had a few more vessels than in 1940, but otherwise was substantially unchanged. Besides

--7--

the added vessels, it had a utility wing composed of three flight squadrons. In San Francisco it was represented by the Base Force Subordinate Command (Rear Admiral C.W. Crosse), which had been established in June of 1941 to give quicker and more direct service on the west coast and to aid in more efficient procurement and shipment for the mid-Pacific.

The early Service Force was organized around four squadrons: Two, Four, Six, and Eight. Squadron Two included hospital ships, fleet motion-picture exchange, repair ships, salvage ships, and tugs. Squadron Four had the transports and the responsibility for training. This was the tiny nucleus of what eventually became the great Amphibious Force, or Forces. Squadron Six took care of all target-practice firing and of the towing of targets, both surface and aerial. Six also controlled the Fleet Camera Party, Target Repair Base, Anti-Aircraft School, Fleet Machine Gun School, and Small Craft Disbursing. Squadron Eight had the responsibility for the supply and distribution to the fleet of all its fuels, food, and ammunition.

Growth and changes came. In March of 1942 the name was changed to Service Forces Pacific Fleet. Headquarters had already moved ashore from the U.S.S. Argonne to the Pearl Harbor Navy Yard, and later moved again to the new administration building of the Commander in Chief Pacific, in the Makalapa area outside the navy yard. Two years later, in July of 1944, the Service Force moved into its own building, a huge three-story, 600-foot structure adjacent to the CinCPac Headquarters. The organizational and administrative changes were dictated by the increasing requirements of the war. Squadron Four was decommissioned and its transports given to the Amphibious Force, as already noted. By the summer of 1942 the rapidly changing conditions of the war caused a further reorganization, and Service Force was realigned into four major divisions: Service Squadrons Two, Six, and Eight, and Fleet Maintenance Office. Except for some additional duties, the functions of the three numbered squadrons remained unchanged. The Fleet Maintenance Office took over all hull, machinery, alteration, and improvement problems involving battleships, carriers, cruisers, and Service Force vessels, while the Service Force Pacific Subordinate Command at San Francisco continued its original functions and expanded as the tempo of the war mounted. It became the logistic agency for supplying all South Pacific bases. By August of 1942, operations there were of such critical nature, with the campaign against the enemy in the Solomons and Guadalcanal about to begin, that the Service Force South Pacific Force was authorized to deal direct with Commander in Chief, Commander Service Force Pacific,

--8--

or Commander Service Force Subordinate Command at San Francisco.

As the war went on, the number of vessels assigned to the Service Force went steadily upward. With each new campaign our needs increased, and so did the number of ships. By September of 1943 the Service Force had 324 vessels listed, and in March no less than 990 vessels had been assigned, 290 of them still under construction or undergoing organization and training. Much of this increase was in patrol craft for Squadron Two and barges for Squadron Eight.

Barges and lighters of all types were being completed rapidly, but moving them from the United States to the areas of use was a problem. Having no means of propulsion, they had to be towed out to Pearl Harbor, and thence still farther westward, in the slowest of convoys. The departure of merchant ships and tugs hauling ungainly looking lighters and barges was not so inspiring a sight as that of a sleek man-of-war gliding swiftly under the Golden Gate Bridge and standing out to sea. Yet these barges, ugly as they were proved invaluable in support of operations at advanced anchorages.

A new Squadron Four, entirely different from its predecessor, was commissioned in October 1943 and sent to Funafuti in the Ellice Islands to furnish logistic support to the fleet. In February of 1944, Squadron Ten of a similar nature went to Majuro in the Marshalls, soon absorbed the Service Force until the end of the war. Just a year later - February 1945 - Service Force had been assigned 1,432 vessels of all types, with 404 of them still to report; and by the end of July 1945, a few weeks before hostilities ended, it had no less than 2,930 ships, including those of Service Force Seventh Fleet, over which administrative control had been established in June.

By squadrons this astonishing total of ships was as follows: Squadron Two, 1,081 ships; Six (new), 107; Eight, 727; Ten, 609; Twelve, 39; Service Force Seventh Fleet, 367. There were 305 planes in the Utility Wing. The total of personnel was 30,369 officers and 425,945 enlisted men, or approximately one-sixth of the entire naval service at the peak of the war. Squadron Twelve, nicknamed "Harbor stretcher," had been commissioned in March 1944 for the primary purpose of increasing depths in channels and harbors where major fleet units would anchor, or where coral reefs and shallow water created serious navigational hazards. By far the largest operation Twelve undertook was at Guam.

Squadron Six, newly commissioned in January of 1945, bore no

--9--

relationship to the former Mine Squadron of the same numerical designation. Six was the third link in a chain of service squadrons with the duty of remaining constantly near the striking forces or close behind them as they moved nearer Japan. Eight hauled the supplies from the west coast and the Caribbean areas to bases, anchorages, and lagoons in the forward area. Ten then took hold, but even its fine services were not as close as desired to task forces and major combat units when they wished to remain at sea for indefinite periods, and take no time between strikes to return to newly established anchorages in what had been enemy territory a short time before. So Squadron Ten in such cases passed on its supply ships to Six as ammunition, fuel, and provisions were needed, and the transfers were all made at sea. After discharging into the combat groups, the empty supply ships were passed back by Six to Ten to be refilled, or still farther back to Eight, which resupplied them from the west coast, Hawaiian, or other areas.

By spring of 1945 the organization of Service Force consisted of 12 principal sections, with the officers in charge of Force Supply, Fleet Maintenance, Over-All Pacific Naval Personnel, and Area Petroleum having additional duty of a similar nature on the staff of CinCPac also. There was a fleet chaplain who had a similar two-hat set-up.

The operating squadrons, coordinated with each other and organized as self-sufficient commands for internal regulations, were separate from these sections. Each one had its own commander, chief of staff, and appropriate administrative, communications, operations, supply, and maintenance sections. Directly under the Commander Service Force came the Deputy Commander Service Force Pacific and Chief of Staff. He in turn was supported by an Assistant Chief, two Special Assistants, and an Administrative Assistant. This latter officer controlled the usual staff functions and several special ones: Postal Officer, Legal Officer, Public Relations (later Public Information), and so on.

This rearrangement into two types of organization within the Service Force had a sound reason behind it. The earlier squadron scheme tended to narrow the use of the vessels assigned to activities of that squadron only. With the section scheme, in which vessels were all under control of the operations office, the broadest possible use of the vessels to meet special problems of any section could be more readily made. At any rate, the section scheme was gaining favor over the squadron when hostilities ended, and the functions of the various squadrons were being absorbed by the sections. The actual change-over to the final section organization was not, however, made complete until the fighting was over.

--10--

Chapter III

Early Activities

Asiatic Fleet in Dutch East Indies - Logistics of Raiding Forces - Coral Sea - Midway

After the Japanese bombing of the fleet at Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, the three battleships capable of steaming were ordered to the United States for repairs: The Maryland and Tennessee to Bremerton, the Pennsylvania to Hunters Point, San Francisco. The Colorado was already undergoing overhaul at Bremerton. When the work was finished, this group assembled on 31 March 1942 at San Francisco. There they were joined by the New Mexico, Mississippi, and Idaho, which had been rushed from the Atlantic. Together with a squadron of destroyers which had no tender, this seven-ship force based on San Francisco until late in May. The ships were serviced almost entirely from shore facilities. With the exception of targets, target-towing vessels, and planes they were given very little floating service.

On 14 April the force left port with the possibility of being used to assist in stopping the Japanese in their South Pacific drive toward Australia. No train (group of supply vessels) was available, so the ships were crammed with all the fuel, food, and ammunition they could hold. So heavily overloaded were they at the start that they were three to four feet deeper in the water than they were ever meant to be. The third or armored decks were all below the water line; none of the ships could have withstood much damage either above or below water. The Coral Sea action was fought before they could take part in it, the enemy backed off, and the force was not called upon. After staying at sea until their fuel was nearly gone and the fresh provisions exhausted, the ships returned to California at San Pedro.

No one concerned with it will ever forget the servicing of this force there. The San Pedro base had not been used by the fleet for 2 years, and

--11--

was practically without floating equipment. Upon notification of the prospective arrival, and the stores and fuel required, the base authorities called upon the citizens and local firms for action. The response was a magnificent demonstration of patriotic support by the entire community. Rich and poor, celebrities and unknowns, worked side by side on docks and vessels of all sorts, including yachts, operated in many instances by their owners. The job was completed in good time.

Of course, there was no problem of resupply of ammunition because the force had not been in action. If there had been, no doubt it could have been solved by the "incredible Yankee resourcefulness" of the Californians. However, the point to be observed in this maneuver is that the Navy was unprepared at this fleet base to do an efficient job of logistics for a small force of its ships, mainly because of its lack of floating equipment. In fact, the Navy was unprepared to do the job at all without the wholehearted community assistance. This battleship force continued to base on San Francisco until midsummer of 1942, when it moved to Pearl Harbor.

Asiatic Fleet in the Dutch East Indies

Our Asiatic Fleet had meanwhile moved south from the Philippines and into the Java area, joining with the British cruisers Exeter, Hobart, Perth, and Electra, which were accompanied by several destroyers, and the Dutch cruisers of the East Indies Force, DeRuyter, Java, and Tromp, also with a few destroyers. Many of these British and Dutch vessels were in use for convoying to and from Singapore, and real concentration in full strength was not attained until near the end. What joint action occurred was poorly coordinated, not only in tactics but in basing and servicing. The basing of our ships until 3 February on Dutch East Indies ports, particularly Soerabaja, was not too bad, except that there was a shortage of ammunition and torpedoes, and special equipment and spare parts for all types. Our submarines, however, based first at Darwin, later at Fremantle, West Australia.

The first part of our Asiatic Fleet, made up of the seaplane tender Langley, the oilers Pecos (Commander E. P. Abernethy) and Trinity (Commander Williams Hibbs), with the destroyers John D. Ford and Pope, left Manila 8 December and next day joined Admiral Glassford, whose flag was in the heavy cruiser Houston. With him were the light cruiser Boise and the destroyers Barker, Paul Jones, Parrott, and Stewart. The two forces

--12--

met to the south of Luzon and continued southward through the Sulu Sea. On 12 December the two cruisers left the formation and proceeded on special duty at greater speed.

The ships were in hostile waters, had no intelligence of the enemy's whereabouts, and everyone was keenly alert, every eye strained for possible danger. At 1115, the Langley suddenly opened fire on a suspicious object, range 6,000, first spot up 100. The dimly seen object turned out to be the planet Venus, which is sometimes visible during daylight in that particular atmosphere. No hits were made!

On 13 December the light cruiser Marblehead (Captain A.G. Robinson) joined, and the next day the whole detachment anchored in Balikpapan, Borneo, where the merchant liner President Madison, three Dutch tankers, and two British ships were already moored. Later submarine tenders Holland and Otus and cruisers Houston and Boise came in, together with the converted yacht Isabel, the auxiliary Gold Star, ocean tug Whippoorwill, the small seaplane tender Heron , the converted destroyer seaplane tender William B. Preston, and a few small craft. All the ships were fueled here, and the oilers Trinity and Pecos refilled with oil and gasoline.

Admiral Glassford divided his Task Force Five into two groups on the basis of speed. The fast group was headed by Captain S.B. Robinson in the Boise, the slower commanded by Captain A.G. Robinson in the Marblehead, and all, including the flagship Houston, sailed for Makassar in the Celebes, N.E.I., where the Houston left them for Soerabaja. There Admiral Glassford wished to hold preliminary conferences with the Dutch and British. The two groups remained at Makassar, holding drills and refueling, until 22 December, when they steamed out for their respective areas. The auxiliaries went to Darwin, which was soon found to be too far away, and too hazardous as well, to be any proper logistic base.

Patrol Wing Ten had had rough going from the start, both from operational hardships and from the enemy. Two days before Christmas, 1941, the surviving planes from Squadron 101 of "PatWing" Ten were sent to Ambon, in N.E.I. in Banda Sea S.W. of Ceram, where there were in the Celebes was our Patrol Squadron 22. The Heron, Childs, and William B. Preston did most of the servicing for these squadrons. The Australian command was cordial and the two organizations exchanged some operational and material support, but neither was strong enough to do what was called for in either reconnaissance or offensive strikes.

--13--

--14--

On 15 January 1942, 26 Japanese bombers and 10 fighters attacked Ambon. We lost 3 patrol planes and had others damaged. The next day, Patrol Squadron 101, of which only 4 planes were left, was ordered to Soerabaja. Patrol Squadron 22 held on for a few days longer at Kendari. On the 24th the Childs barely escaped a Japanese task force there, and it was clear that the end was not far off. Given another month of attention at the hands of an enemy who held control of the air whenever he chose to exercise it, no amount of logistics could save the situation. What was needed desperately and did not have was air power - bombers, fighters, and patrol - in sufficient strength to fight it out with the oncoming Japanese.

Admiral Glassford sent orders on 23 December 1942 making the oiler Trinity (Commander William Hibbs) Task Unit 5.5.3 and ordering her to Woworada Bay, Soembawa. The other auxiliaries were designated as the Train and sent to Darwin, which by order of the Chief of Naval Operations in Washington was made the logistic base. Since it was apparent that Darwin was too far away, the Trinity was used in some of the bays nearer the scene of operations. Later the oiler Pecos and the commercial tanker George D. Henry were taken from Darwin and put to more active use. Soerabaja was the main operating base until the final 3 weeks of the defense campaign in the Netherlands East Indies.

The Train consisted of the flagship submarine tender Holland (Captain J.W. Gregory), with Captain W.E. Doyle as Commander Base Force (Train) aboard; the submarine tender Otus (Commander Joel Newsom); the Gold Star, a general auxiliary (Commander J.U. Lademan); the seaplane tender Langley (Commander R.P. McConnell); the oiler Pecos (Commander E.P. Abernethy); the destroyer tender Blackhawk (Commander G.L. Harriss); the small seaplane tender Heron (Lieutenant W.L. Kabler); the converted destroyer seaplane tenders Childs (Commander J.L. Pratt) and William B. Preston (Lieutenant Commander E. Grant); and the converted patrol yacht Isabel (Lieutenant John W. Payne).

During January there was considerable moving about between Darwin, Woworada Bay, Keopang Bay, Timor, and Kebalas Bay, Alor Island, just north of Timor in the N.E.I. On 18 January the first refueling at sea in this campaign took place when the Trinity oiled the destroyer Alden at a speed of 10 knots. Again the tanker, on 7 and 8 February, refueled six escorting destroyers at 9.5 knots.

Four days previous - 3 February - the Japanese had bombed us out of Soerabaja, and on the 10th practically the entire Asiatic Fleet, with

--15--

Train, had gathered at Tjilatjap, Java. But there was not security anywhere. A week later, on 17 February, the Trinity had to go all the way to Abadan, Iran, for oil. The Japanese had shut off or captured every East Indian source except a very small supply from the interior of Java, so this dangerous voyage of more than 5,000 miles was necessary. The oiler Pecos was also scheduled to refill in the Persian Gulf, but was sunk - with the Langley survivors on board - by the enemy on 1 March, just after getting started for Colombo, Ceylon. The Train, in its short 10 days at Tjilatjap, put in some much-needed work on the worn, racked, and hard pressed ships of our striking force, and then most of its own vessels had to be sent off the Exmouth Gulf, West Australia, for the jig was nearly up in Dutch waters.

Usually ample fuel oil was available for this force, and some of the Dutch tankers were very efficient, but the method of distribution practiced by the Dutch bases was slow. Much of the oil was stored in the interior. The service from our tankers was faster, but in the circumstances these tankers could not be made available to all. Toward the last there was a shortage because of the dependency the naval ports had placed upon peacetime delivery from Borneo and Sumatra, rather than upon full development of interior Javanese oil sources. The Australian cruiser Hobart, for example, though undamaged, could not participate in the Java Sea battle on 27 February because she could not get fuel. Tjilitjap was the operating base for both Dutch and American striking forces after we were bombed out of Soerabaja. It was inadequate, but of course it was only a matter of days before it too became untenable.

Each successive raid by or encounter with Japanese planes left us with fewer ships. After her severe mauling on 4 February, the cruiser Marblehead was patched up, mainly by her own crew, so that she could start for home by way of Ceylon and the Cape of Good Hope. "Patched up" is a correct term, for we had no real facility for making what we ordinarily would have called temporary repairs according to Navy standards. It speaks well for the initiative and resourcefulness of the shot-up crew of the Marblehead - and the men of some other vessels - that the patchwork enabled the ship to function. The destroyer Stewart, however, had to be abandoned in a bombed and disabled condition in a bomb-wrecked Dutch drydock. The Japanese salvaged her and put her in service, only to lose her to our Navy in action. Grounding had damaged the Boise on 21 January so badly that she was beyond repair by available facilities. She was accordingly cannibalized - stripped, for the benefit of her sisters - of all ammunition and stores and sent limping off to Ceylon.

--16--

On 27 February the final attempt to slow the Japanese drive on the Netherlands East Indies was made by the Dutch Admiral Doorman. He had 5 cruisers and 10 destroyers left out of the combined Dutch, British, and American forces, not counting submarines and their tenders, and the old aircraft tender Langley, sunk a few days later. The after turret of the Houston was inoperative as a result of bombing on 4 February, and there was not facility for repairing it before going into action. Doorman failed, and the order was given to leave the Java Sea. Only 4 American destroyers could do so; all the other ships were sunk by the Japanese. Orders for the withdrawal to the Australian coast for some of the personnel on shore were accomplished only by extreme methods, as we did not have enough vessels. Not even the little shore material there for servicing could be moved. In this campaign there never was sufficient force available to stop or greatly delay the Japanese. No matter how adequate the logistics might have been, the outcome would not have been very different. This brief outline merely shows the relationship logistics bore to the situation.

Logistics of Raiding Forces

In January 1942 Vice Admiral Halsey with Task Force Eight and Rear Admiral F.J. Fletcher with Task Force Seventeen joined in raiding some of the Japanese-held islands of the Marshall and Gilbert groups. Task Force Eight consisted of the carrier Enterprise; cruisers Northampton, Salt Lake City, and Chester; the fleet oiler Platte; and seven destroyers. Task Force Seventeen consisted of the carrier Yorktown; cruisers Louisville and St. Louis; the fleet oiler Sabine; and five destroyers.

Task Force Eight had sailed from Pearl and Task Force Seventeen was just out from the United States. They were guarding the landing of Marines in Samoa when the raids were ordered.

While at sea the carriers and large vessels refueled on 17 January from the tankers Platte (Captain R.H. Henkle) and Sabine (Commander H.L. Maples), in two task groups, and the destroyers filled up from the larger ships of their own striking groups in latitude 09°30' S., longitude 169°00' W. This was repeated on 23 and 28 January. On the 28th the larger ships of the Enterprise group were topped off by the Platte in latitude 04°06' N., longitude 176°30'W. The strikes were made 1 and 2 February on Wotje, Maloelap, Kwajalein, Roi, Jaluit, Makin, Taroa, Lae, and Gugegive, and during the night of 2 February the destroyers again

--17--

refueled. After withdrawal the Yorktown group was fueled on the 4th from the Sabine, in latitude 11°00' N., longitude 163°00' W.

These raids seem to warrant a continuance, so on 14 February Halsey with the carrier Enterprise, two cruisers, seven destroyers, and the tanker Sabine sailed from Pearl Harbor for a raid on Wake Island. On the 22d he fueled his destroyers and took fuel from the tanker in latitude 25°30' N., longitude 167°00' E., approximately 300 miles north of Wake. He should have had another tanker in case he lost the Sabine, but unfortunately at that time tankers were almost as scarce as carriers. The strike was made on the 24th. Wake was bombed and shelled with excellent results and with the loss of only one plane. The Sabine meantime had retired to the northeast, and 2 days later she rejoined, refueling the destroyers once more. Again on 1 and 2 March in latitude 29°30' N., longitude 173°00' E., or thereabouts, the task group was refueled and started for a raid on Marcus Island, which was bombed by the Enterprise planes, again with the loss of but one plane. Meanwhile in the South Pacific Vice Admiral Wilson Brown with the carrier Lexington and support cruisers and destroyers started a raid on Rabaul. He was discovered, used up much of his fuel in high-speed maneuvers while beating off Japanese plane attacks, and canceled the raid.

Task Force Seventeen, the Yorktown group under Rear Admiral F.J. Fletcher, was on its way to the South Pacific. After fueling twice at sea from the Guadalupe (Commander H.R. Thurber) it joined the Lexington group under Brown in a raid on 10 March on Salamaua and Lae on the New Guinea coast in which considerable damage was done to enemy naval and transport vessels. On 12 March the destroyers fueled from the heavy cruisers Indianapolis and Pensacola. Two days later the force was joined by the tankers Neosho (Captain J.S. Phillips) and Kaskaskia (Commander W.L. Taylor), and refueled from them during the next 3 days.

Then came the very dramatic raid on Tokyo, the comparative value of which may never be fully decided. It kept carriers, tankers, other ships, and planes away from the South Pacific where they might well have been used to turn the balance from defensive to offensive weeks earlier. However, the heartening effect upon the nation may have been worth it. On 2 April, Task Force Eighteen, composed of the carrier Hornet (Captain Marc Mitscher), the heavy cruiser Vincennes, Destroyer Division Twenty-two, and the tanker Cimarron (Captain H.J. Redfield), sailed from San Francisco. On 8 April, Cimarron fueled destroyers Gwin

--18--

--19--

and Grayson. The next day which was set for fueling was too rough. On the 10th the Vincennes was fueled and on the 11th the remaining destroyers took some from the Hornet. On 12 April the Hornet supplied 400,000 gallons of fuel oil in latitude 38°30'N., longitude 175°00' W. On the next day Task Force Eighteen and Task Force Sixteen (Halsey) joined. The latter was composed of the Enterprise; cruisers Northampton, Nashville, and Salt Lake City; Destroyer Division Six; and the tanker Sabine. Three days later, 17 April (14 April was lost crossing the 180° Meridian), the Sabine fueled the Enterprise group, and the Cimarron did the same for the Hornet group, with some destroyers getting their fuel from the heavy ships. This was at latitude 35°'30' N., longitude 157°00' E., approximately. There the destroyers and tankers left the striking force and turned back on an easterly course. After dispatching the B-25's on their Tokyo mission the next day the whole force retired at high speed to the eastward and on 21 April were met and again fueled by the Cimarron and Sabine in latitude 35°45' N., longitude 176°00' E., approximately. Then all proceeded to Pearl, where it was hurry up all logistics and get off to the South Pacific where the Japs looked very threatening. The Hornet had to get new squadrons on board and some task-force and ship reorganization made. On 30 April, Task Force Sixteen (Hornet, Enterprise, and supporting vessels) sailed for the South Pacific.

Meanwhile, Brown of Task Force Eleven had been relieved by Rear Admiral A.W. Fitch, who, with his flag in the carrier Lexington, had sailed from Pearl 16 April to join Rear Admiral F.J. Fletcher, with flag in the Yorktown. Fletcher was now senior task-force commander in the South Pacific. The Yorktown had been at sea since 17 February 1942, and since the Salamaua raid had fueled from the Tippecanoe (Commander A. Macondray) in March, and twice in April from the Platte. On 20 April the group reached Tongatabu, where it found fuel, some mail, and limited amounts and types of provisions, and enjoyed a few days of relaxation after 62 days of tension.

When Fitch left Pearl for the South Pacific, available information indicated early concentration of some enemy force there. Later, at Tongatabu, the news definitely suggested a threat in force by the enemy against Port Moresby on the south coast of New Guinea, and perhaps against New Caledonia or Australia. Fitch's Task Force Eleven - the carrier Lexington; cruisers Minneapolis and San Francisco; the destroyers Worden, Dewey, Dale, Aylwin, Farragut, and Monaghan; and the tanker Kaskaskia - had refueled once, on 25 April, at latitude 11°30' S.,

--20--

longitude 178°30' W. Meantime, Fletcher at Tongatabu got everything he needed except rest, and sailed 27 April for the Coral Sea. Fitch was diverted to join him there. On 1 May Fletcher refueled from the tanker Neosho, and during the 2d-3d Fitch did likewise from the Tippecanoe, which then departed for Efate in the New Hebrides. On 5 and 6 May 1942, Task Force Seventeen again refueled in the Coral Sea from the Neosho, which immediately thereafter was sent off to the southeast escorted by the destroyer Sims. The retiring point was not far beyond the range of visibility.

The battle of the Coral Sea will not be dealt with here except to note that the Neosho and her escort, the Sims, were discovered and destroyed by the enemy 7 May, and the following day the Lexington was lost and the Yorktown damaged. Meantime our planes had sunk the small enemy carrier Shoho, and severely mauled and all but sunk one of the two larger Japanese carriers. This apparently was more than the Japanese had bargained for, so the operation was discontinued and the enemy's combat units withdrew. The action therefore became a victory for Fletcher at what was probably the most critical period of the war thus far.

Nevertheless, if the withdrawal had not taken place, how much longer could Fletcher have held his position without a source of fuel near his force? We need not answer the question, but as a lesson for the future let us not forget the inadequacy of logistic support during the most critical battle in the Pacific up to that time. Fletcher's base at Tongatabu was 1,300 miles away, and Efate, where the nearly empty Tippecanoe had been sent, was more than 400 miles away.

Hardly had the smoke cleared away from the Coral Sea when the enemy was detected in preparations for another move in great strength. This time the objective was diagnosed as Midway, and Task Force Sixteen started out belatedly for the South Pacific, was recalled to Pearl. Fletcher was also ordered to Pearl with his battered Yorktown. There she was hurriedly patched up for the fight to come.

Along with plans for the expected sea and air battle, preparations were being made at CinCPac headquarters for the defense of Midway Island itself. That island needed personnel, planes, antiaircraft guns, ammunition, and certain stores, and needed them in a hurry.

The U.S.S. Kitty Hawk (Commander E.C. Rogers) had arrived at Pearl on 17 May 1942, and indeed this was fortunate, as few ships at that time had the crane capacity for unloading planes and heavy cargo at the dock at Midway. After unloading her stateside cargo at Pearl, the

--21--

Kitty Hawk was reloaded with the following: 28 planes (11 SBD's; 17 F4F4's) and Marine Air Groups 21 and 45; eight 3-inch AA guns, a Marine crew and ammunition to serve them; and more personnel and cargo. She got underway on the 23d and made her highest speed (17.1 knots) for Midway, arriving at 1918 on the 26th. Just 12 minutes after mooring alongside the pier, the Marines started unloading the AA battery and by the next morning it was in place to protect the airfield on San Island. In addition to unloading her important deck cargo she gave the station fuel oil and got clear on the 29th, only a few days before the Battle of Midway commenced. The Kitty Hawk had rendered substantial logistic support to the defense of Midway. In a congratulatory message to Commander Rogers, CinCPac commented upon the "unusually expeditious unloading at Midway."

The task forces which sailed from Pearl on 28 and 30 May to meet the enemy had the tankers Cimarron, Platte, and Guadalupe at sea near them, and refueled on 31 May and 1 June. After the battle, on 8 June 1942, they again refueled a little more than a hundred miles north of Midway Island. The beaten enemy retired, after losing all four of his participating carriers. Lacking certain information, we did not pursue with all the vigor possible, which is unfortunate for we had air superiority and our fast tankers might well have gone farther west in support of our task force had pursuit been carried somewhat farther.

Here at Midway we lost the Yorktown. We had not yet learned thoroughly the use and value of fleet tugs and salvage action.

--22--

Chapter IV

In the South Pacific

Taking the Offensive - Guadalcanal - Logistic Outlook

With the defeat of the Japanese at Midway a more nearly even balance of forces was accomplished, and it was time for us to attempt to take the initiative, to seize the offensive if possible. This was certain to be bitterly contested by the enemy, who might still hope to gain the upper hand if his South Pacific drive could be won. It was natural that this was where we must next stop and defeat him, so the Guadalcanal offensive was planned.

In April 1942, principal commands in the Pacific were:

- Pacific Ocean Area, Admiral C.W. Nimitz, Commander in Chief. This was further divided into two subordinate commands, the North and South Pacific.

- Southwest Pacific Area, General Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander Allied Forces.

- Southeast Pacific Area, a region of patrol command principally for security.

Vice Admiral Robert L. Ghormley since May 1942 had been Commander South Pacific. As such, he was charged with the conduct of the Guadalcanal operation under the over-all direction of Admiral Nimitz. Late in July 1942, not counting attack transports, which are considered combatant vessels, we had 15 logistic vessels there. The repair ship Rigel was at Auckland, N.A. At Tongatabu were the destroyer tender Whitney, hospital ship Solace, stores ship Antares, the fresh and frozen food ships Aldebaran and Talamanca, the ammunition ship Rainier, and two district patrol craft, YP-284 and YP-290, both with provisions. Two more YP's, the 230 and 346, were at Efate in New Hebrides. The seaplane tender Curtiss and the two small plane tenders McFarland and Mackinac, the former a converted destroyer, based at Noumea, New

--23--

Caledonia, while the limited repair ship Argonne sailed 10 July from Pearl for Auckland.

Besides these, the fleet oilers Cimarron and Platte were to be at Tongatabu to supply oil for the amphibious force ships staging there late in July, and the fleet oiler Kaskaskia was scheduled to leave Pearl 20 July. At Noumea there were to be 225,000 barrels of fuel oil brought by chartered tankers, and the same amount about 2 August. Over at Tongatabu the old, slow Navy tanker Kanawha (Commander K.S. Reed), with a capacity of 75,000 barrels, was a station oiler.

The chartered tanker Mobilube arrived at Tongatabu 10 July, but after fuel had been pumped from her into Rear Admiral Noyes' Wasp group of Task Force Eighteen, Rear Admiral Kinkaid's Enterprise group of Task Force Sixteen, and two of the transports, the President Adams and President Hayes, she pumped the rest of her cargo into the Kanawha and left for San Pedro 27 July.

The vital importance of an adequate supply of fuel, and its timely and properly allocated delivery to the vessels of the South Pacific for the campaign about to begin, was clearly recognized by Admiral Ghormley. The distances involved, the scarcity of tankers, and the consumption of oil by task forces operating at high speeds made the solution of this logistic problem difficult enough if the normal operating consumption was used for estimates. But what would constitute "normal" when the offensive was under way? Even more difficult to resolve was the margin of safety to cover unforeseen losses, excesses, or changes in operations. Furthermore, though Ghormley foresaw the situation and tried to anticipate it, his logistic planners were too few and had too little experience. That he had his fuel requirements constantly in mind is shown by his dispatches to Admiral Nimitz. Another thing that worried him was the lack of destroyers for adequate escort and protection of his tankers even when he had the latter. This shortage of destroyers was felt by the task force commanders also, and had considerable influence on all the operations.

In a dispatch of 9 July 1942 Admiral Nimitz said to Ghormley that he, Commander in Chief Pacific Fleet, would supply the logistic support for the campaign. Arrangements, he stated, had been made to have the oilers Cimarron and Platte accompany Task Force Eleven leaving Pearl for the South Pacific, and that the Kaskaskia would leave soon after about 20 July. The Kanawha would fuel Task Force Eighteen and then go to Noumea. The chartered tankers already mentioned as bringing 450,000 barrels of fuel to the port would be followed by others with

--24--

about 225,000 barrels a month for the carrier task force. Nimitz also promised other requirements, such as aviation gasoline, Diesel fuel, and stores for the task force, would be supplied as Ghormley requested.

All this sounded like a comfortable amount of fuel oil, and based upon past experience, no doubt seemed liberal to the estimators. But past experience was not good enough. To begin with, the Cimarron and Platte had fueled Task Force Eleven on its run down from Pearl. On 21 July the Platte was ordered to pump her remaining oil into the Cimarron, proceed to Noumea, and refill there from the waiting chartered tankers. She took aboard 93,000 barrels of that oil and rejoined Task Force Eleven.

On 28 July Admiral Ghormley ordered the ammunition ship Rainier (Captain W.W. Meek) and the tanker Kanawha to leave Tongatabu and proceed to the west side of Koro Island in the Fiji group. The ships were to arrive, escorted by Turner's amphibious Task Force Sixty-two, at the earliest practical time during daylight. The fleet tanker Kaskaskia was also ordered there to supply the needs of the Task Force which was to rendezvous there before proceeding to Guadalcanal.

The next day Ghormley ordered the commanding general on Tongatabu to load the coal-burning Morinda with one hundred 1,000-pound bombs, four hundred 500-pounders, and one hundred 100-pounders from the stocks available on shore. The Morinda was then to return to Efate, New Hebrides, filing her departure report to include route and speed of advance. The reason for this was that she had to go to Suva for coal and water to complete her trip to Efate.

While this was occurring, Task Force Sixteen, the Anzac Squadron, and part of the Amphibious Force joined Task Force Eleven and took all the Cimarron's remaining fuel. As soon as the Platte rejoined, the former tanker was sent to Noumea to refill. She cleaned out the tankers there, and on 1 August Admiral Ghormley sent word to Commander Southwest Pacific: "Urgently need additional fuel oil New Caledonia area as Bishopsdale, now empty, being dispatched to Brisbane to refill. Request you dispatch one tanker loaded with 50 to 100 thousand barrels as replacement." Before the Bishopsdale could clear the harbor she ran into a mine and was out of service. The 225,000 barrels due at Noumea in the chartered tankers E.J. Henry and Esso Little Rock had already been diverted, one tanker to Efate, one to Suva, so Ghormley could hardly be blamed for feeling uncomfortable about the fuel-oil situation. For his 3 carriers, 1 fast battleship, 11 heavy cruisers, 3 light cruisers, 40 destroyer-type ships, 19 large transports, 1 large and 3 small aircraft tenders, 8

--25--

service-force vessels, and 499 airplanes of carrier- and land-based types, the only other fuel he had not already mentioned were some small quantities of black oil in shore storage for patrol craft, and considerable tank and barreled gasoline at Tongatabu and Efate and a smaller amount in New Caledonia. To remedy this acute shortage, Admiral Nimitz on 1 August, after reading of the Bishopsdale's mishap, ordered the 2 large, fast tankers then available at San Pedro to proceed at the earliest possible moment to Noumea with black oil for diversion by Ghormley. This was in addition to the 200,000 barrels ordered delivered every 15 days. The Gulfwax was also ordered to sail from Pearl to replenish the storage supply at Samoa. The next day the tanker Sabine left San Pedro for the South Pacific, but could not reach the Fijis before 2 weeks had elapsed.