The Navy Department Library

UNITED STATES NAVY AT WAR

Second Official Report to the Secretary of the Navy

Covering Combat Operation March 1, 1944, to March 1, 1945

By Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King

*2*

12 March 1945

Dear Mr. Secretary:

Twelve Months ago I presented to the late Secretary Knox a report of the progress of our naval operations and the expansion of our naval establishment since the beginning of the war.

Long before the war Frank Knox saw clearly and supported strongly the necessity for arming the United States against her enemies. He knew that a powerful Navy is essential to the welfare of our country, and fought with all his energies to build a Navy that could carry the attack to the enemy. How well he succeeded is now a matter of history.

The manner in which the Navy has carried the attack to the enemy during the twelve months from 1 March 1944 to 1 March 1945 is the subject of the report, which I present to you at this time.

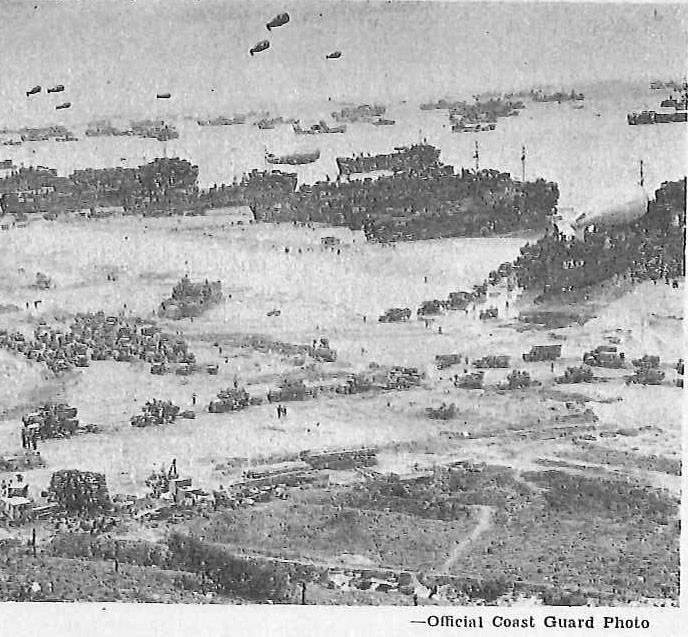

In reading this report, attention is especially invited to the significant role of amphibious operations during the entire period. In fact, amphibious operations have initiated practically all of the Allied successes during the past three years.

Ernest J. King [signature]

Fleet Admiral

Commandant in Chief, United States Fleet

and Chief of Naval Operations

The Honorable James Forrestal,

Secretary of the Navy,

Washington, D. C.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

| Page | |

| LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL | 2 |

| I--INTRODUCTION | 3 |

| II--COMMAND AND FLEET ORGANIZATION | 5 |

| United States Fleet | 5 |

| Organization of United States Naval Forces in the Pacific | 5 |

| Organization of United States Naval Forces in the Atlantic-Mediterranean | 8 |

| III--COMBAT OPERATIONS: PACIFIC | 8 |

| Hollandia and Fast Carrier Task Force Covering Operations | 9 |

| Marianas Operations | 11 |

| Progress Along New Guinea Coast | 15 |

| Western Carolines Operations | 16 |

| Reoccupation of Philippine Islands | 18 |

| Assault on Inner Defenses of Japan | 25 |

| Continuing Operations | 27 |

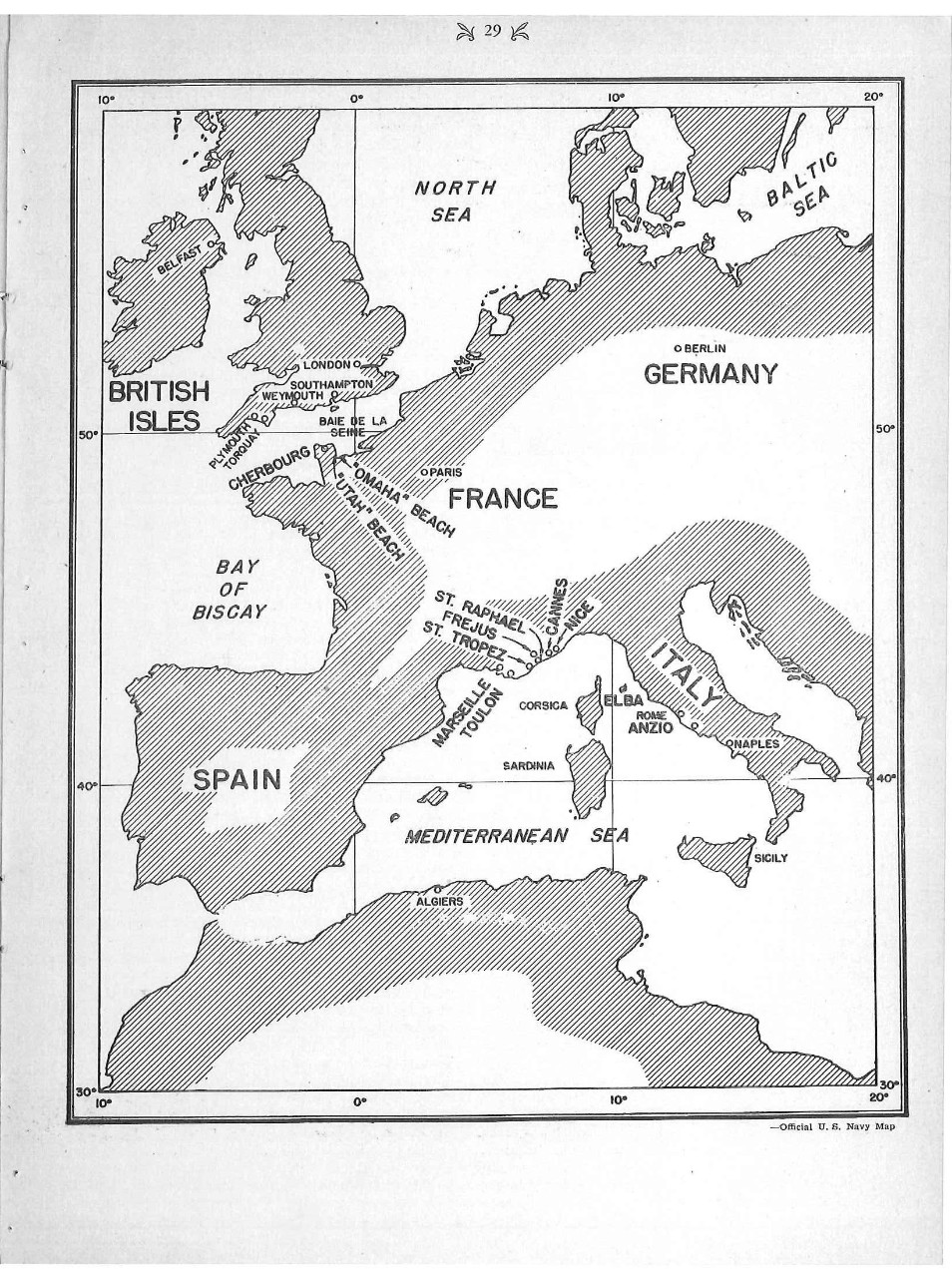

| IV--COMBAT OPERATIONS: ATLANTIC-MEDITERRANEAN | 28 |

| United States Atlantic Fleet | 28 |

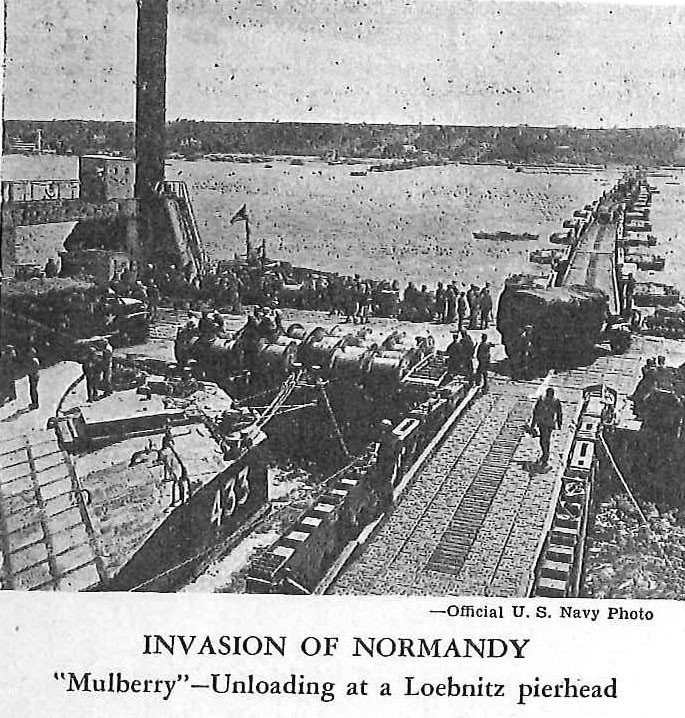

| United States Naval Forces in Europe-The Normandy Invasion | 30 |

| Eighth Fleet-Italy | 34 |

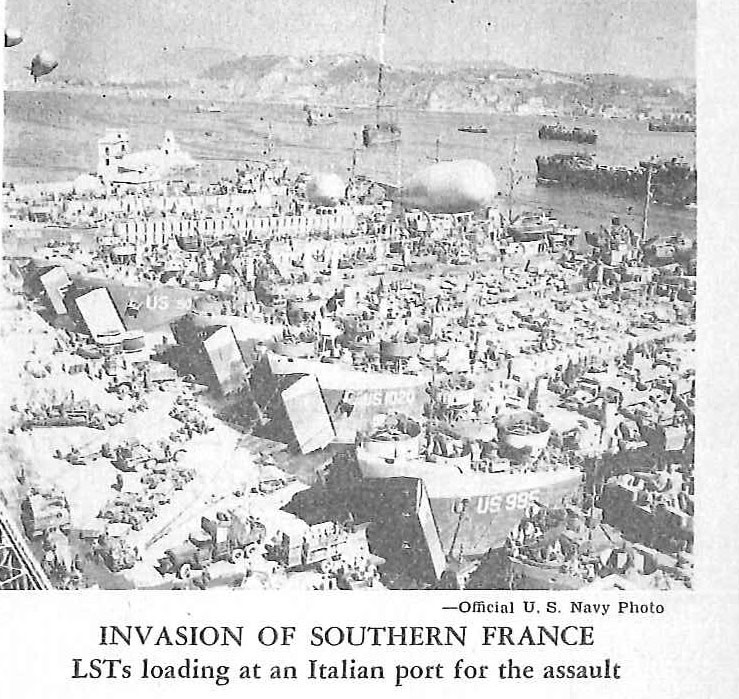

| Eighth Fleet-Invasion of Southern France | 35 |

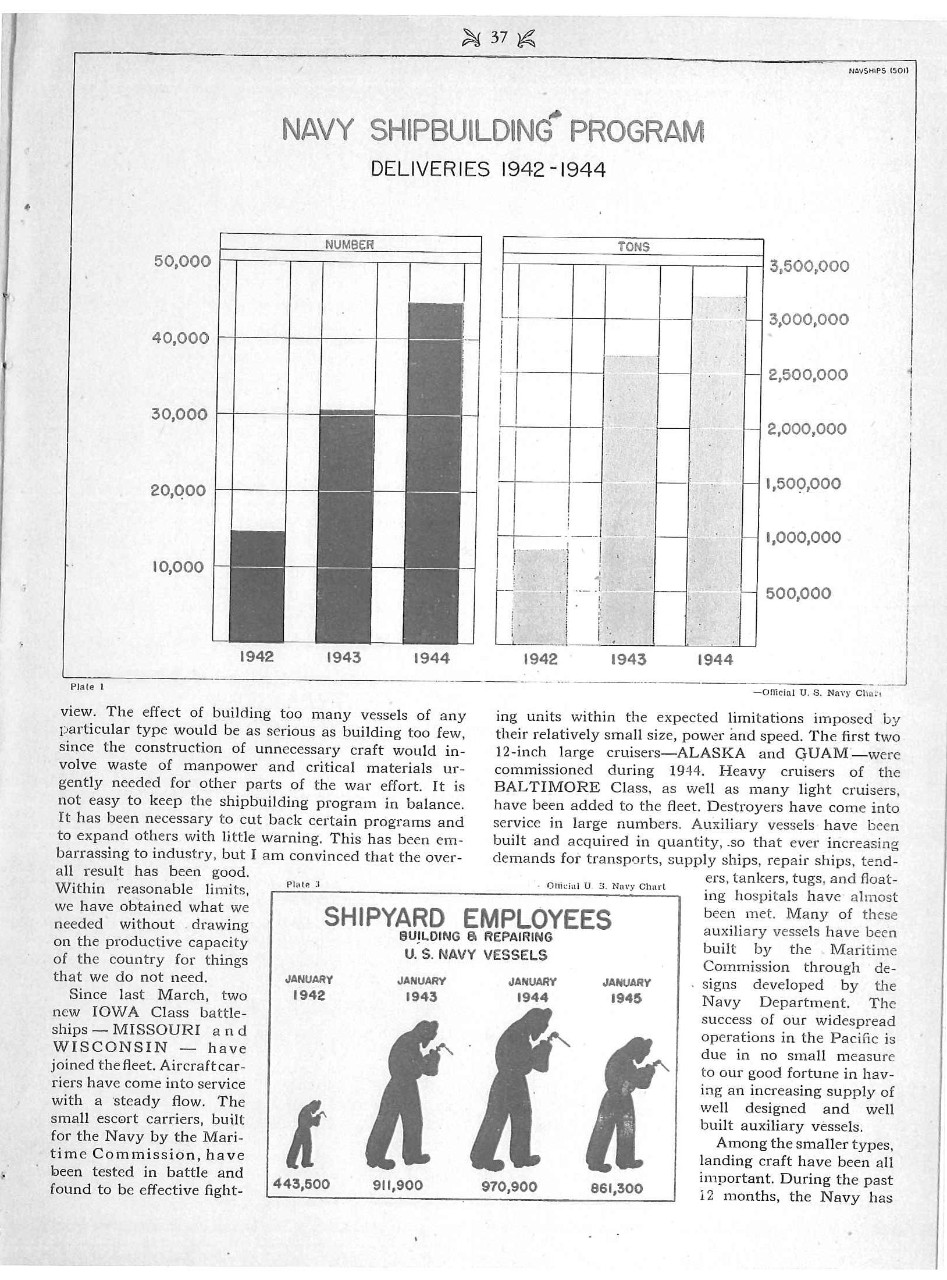

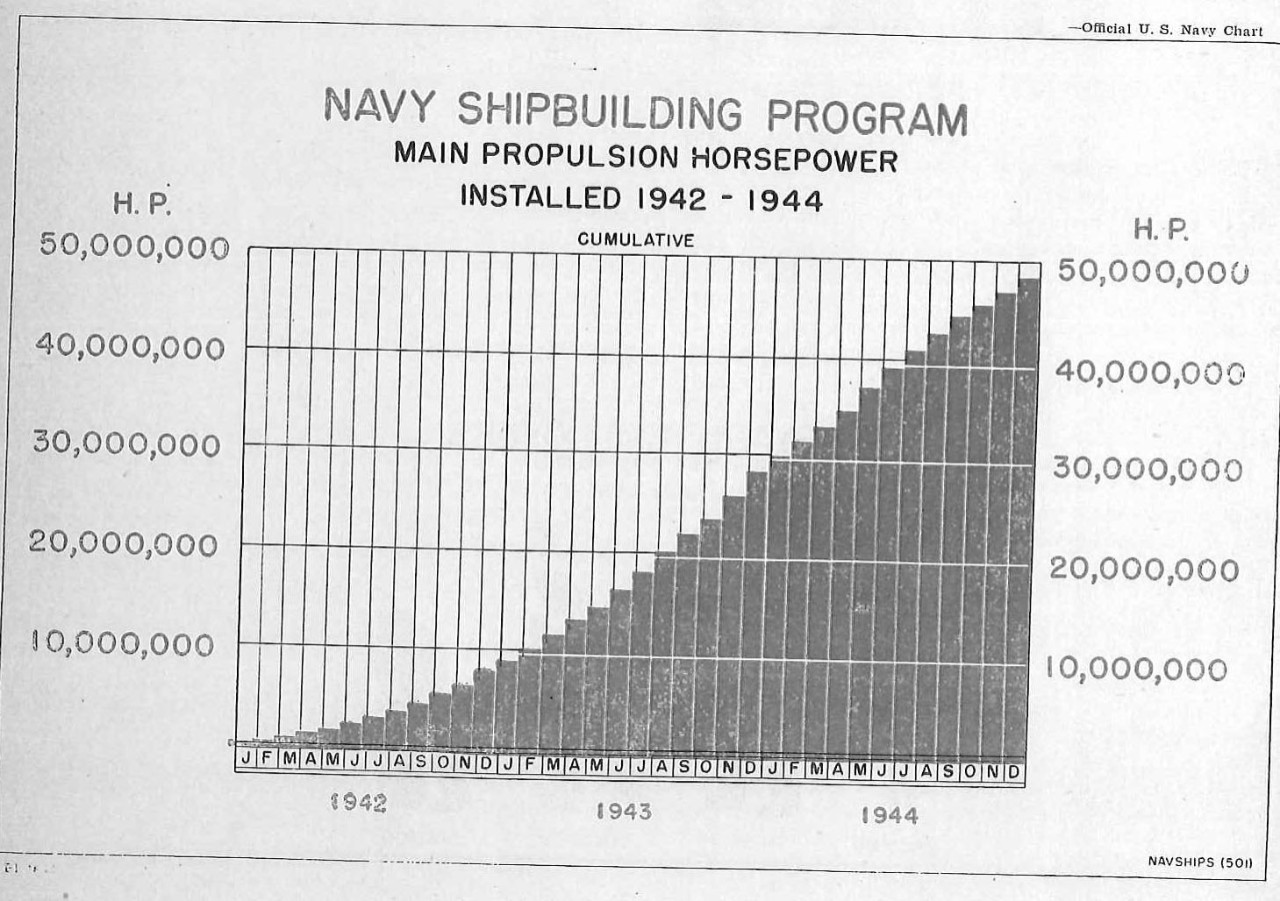

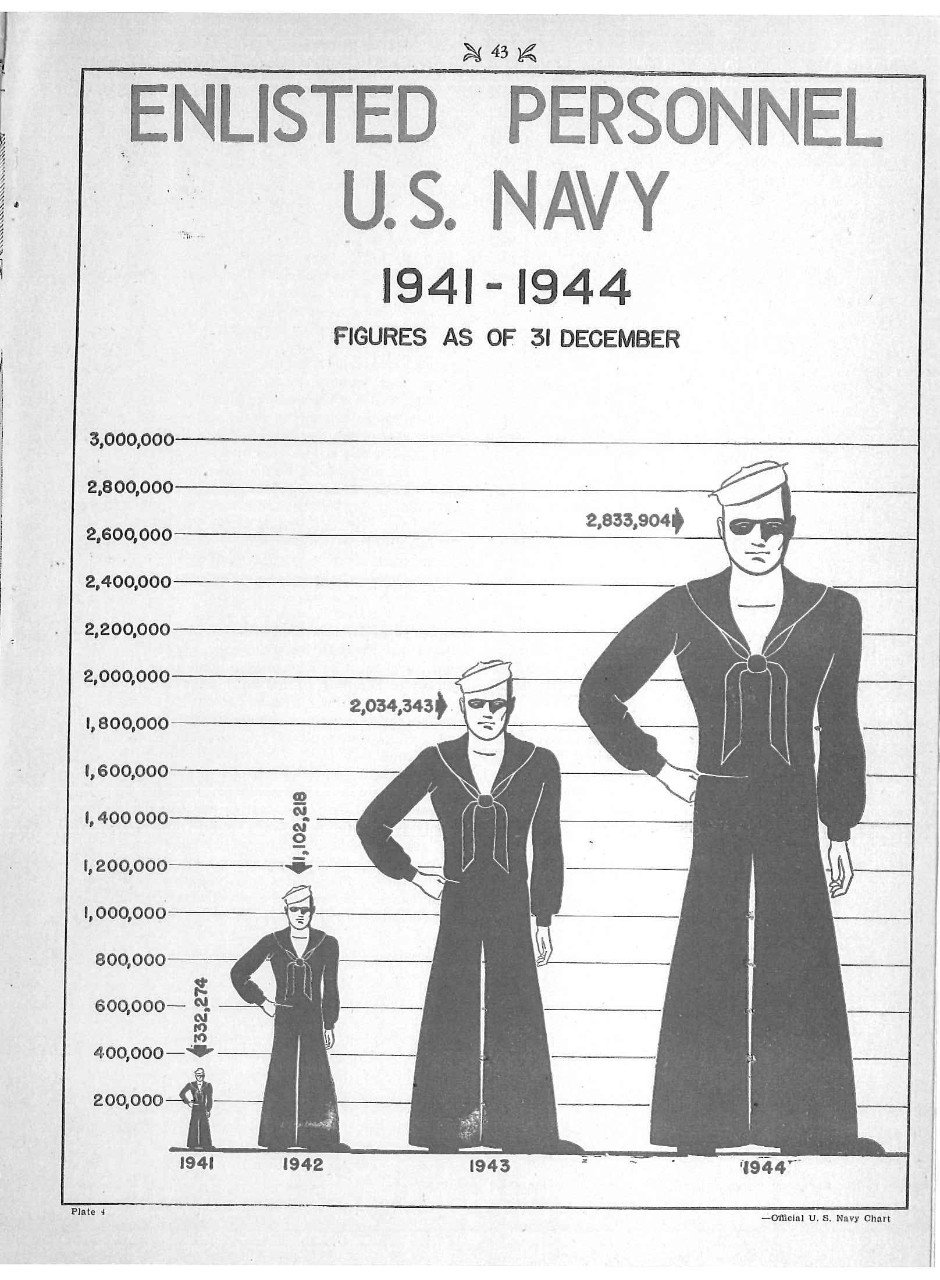

| V--FIGHTING STRENGTH | 36 |

| Ships, Planes and Ordnance | 36 |

| Personnel | 36 |

| Supply | 44 |

| Health | 45 |

| The Marine Corps | 46 |

| The Coast Guard | 46 |

| VI--Conclusion | 47 |

* COVER ART: Front-Official U.S. Navy Colorphoto Inside--Official U.S. Navy Photos Back--Associated Press, by Joe Rosenthal |

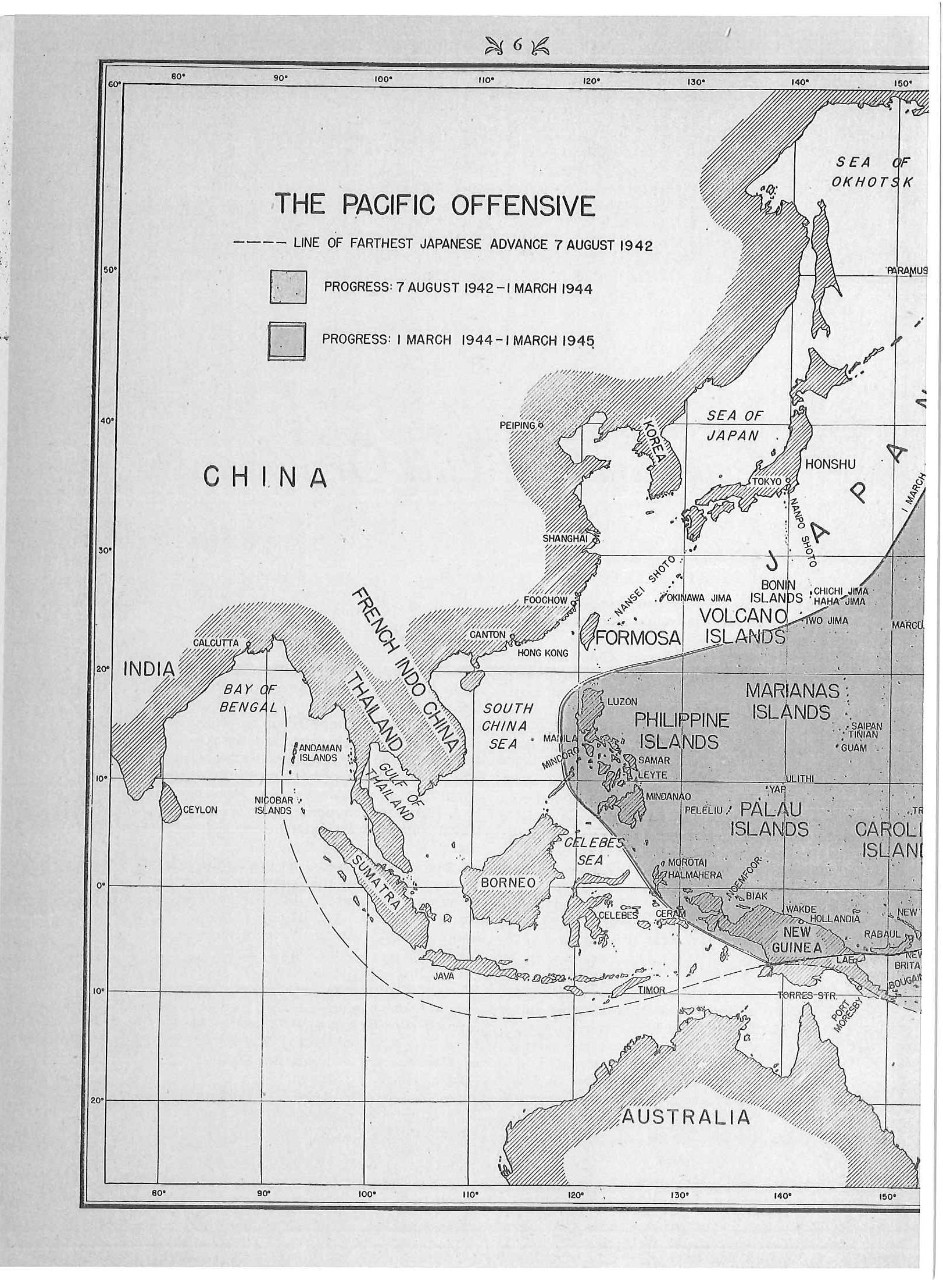

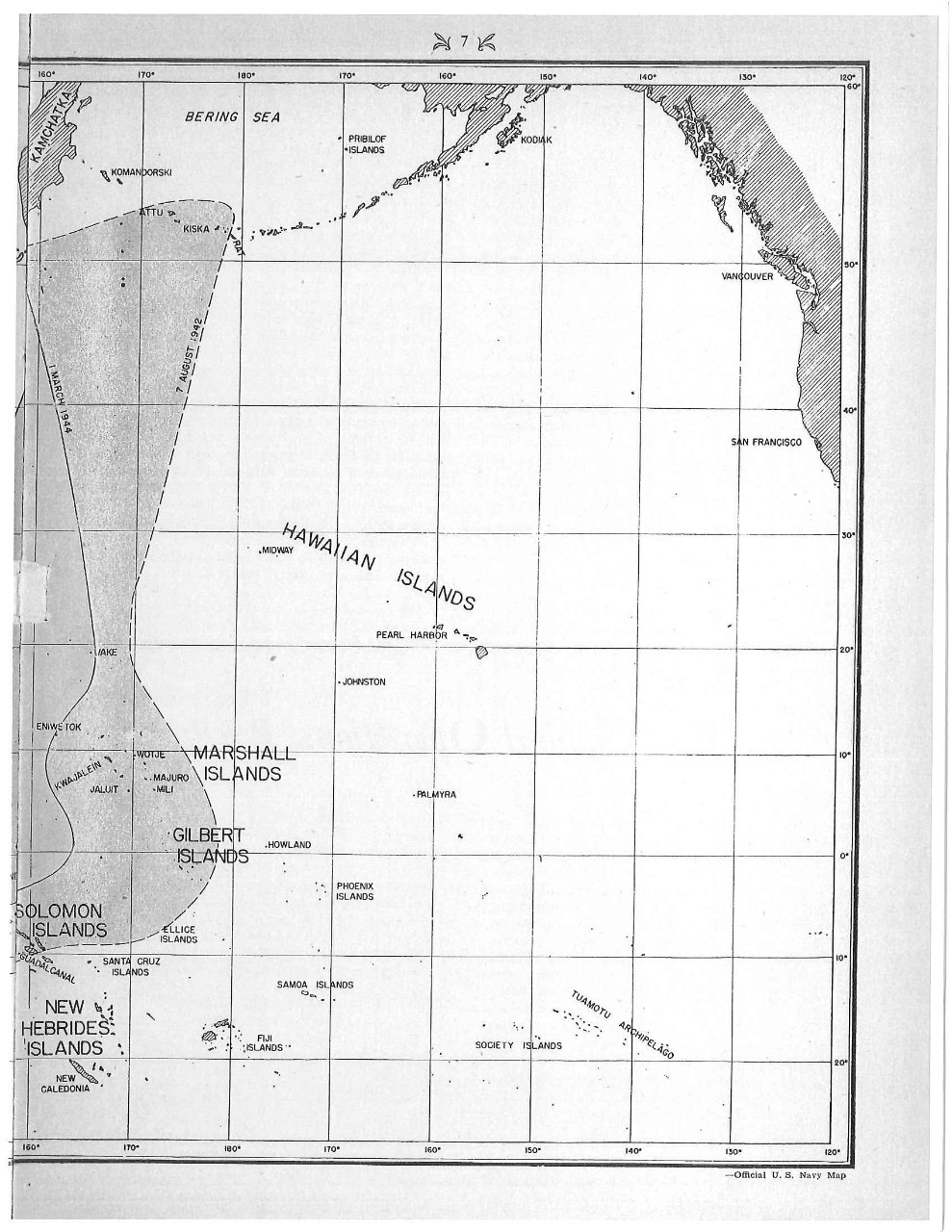

I – Introduction

My previous report presented an account of the development of the Navy and of combat operations up to 1 March 1944. This report covers the twelve months from 1 March 1944 until 1 March 1945. Within this period the battle of the Pacific has been carried more than three thousand miles to the westward – from the Marshall Islands into the South China Sea beyond the Philippines-and to the Tokyo approaches. Within this same period the invasion of the continent of Europe has been accomplished. These success have been made possible only by the strength and resolution of our amphibious forces, acting in conjunction with the fleet.

During these twelve months, there occurred the following actions with the enemy in which the United States Navy took part:

20 March 1944

Landings on Emirau Island, St. Matthias Group, northeast of New Guinea

Bombardment of Kavieng, New Ireland

30 March-1 April 1944

Carrier Task Force Attacks on Western Carolines

22 April 1944

Landings in Hollandia Area, New Guinea

29 April-1 May 1944

Carrier Task Force Attacks on Central and Eastern Carolines

17 May 1944

Landings in Wakde Island Area, New Guinea

19-20 May 1944

Carrier Task Force Attacks on Marcus Island

23 May 1944

Carrier Task Force Attack on Wake Island

27 May 1944

Landings on Biak Island, Dutch New Guinea

6 June 1944

Invasion of Normandy

11-14 June 1944

Preliminary Carrier Task Force Attacks on Marianas Islands

13 June 1944

Bombardment of Matsuwa Island, Kurile Islands

15 June 1944

Landings on Saipan, Marianas Islands

15-16 June 1944

Carrier Task Force Attacks on Iwo Jima and Chichi Jima, Volcano and Bonin Islands

17 June 1944

Capture of Elba, Italy

19-20 June 1944

Battle of the Philippine Sea

23-24 June 1944

Carrier Task Force Attacks on Pagan Island, Marianas Islands

24 June 1944

Carrier Task Force Attack on Two Jima, Volcano Islands

25 June 1944

Bombardment of Cherbourg, France

26 June 1944

Bombardment of Kurabu Zaki, Pramushiru, Kurile Islands

2 July 1944

Landings on Noemfoor Island, Dutuch New Guinea

*4*

4 July 1944

Carrier Task Force Attacks on Iwo Jima, Chichi Jima and Haha Jima, Volcano and Bonin Islands

21 July 1944

Landings on Guam, Marianas Islands

24 July 1944

Landings on Tinian, Marianas Islands

30 July 1944

Landings in Cape Samsapor Area, Dutch New Guinea

4-5 August 1944

Carrier Task Force Attacks on Iwo Jima and Chichi Jima, Volcano and Bonin Islands

15 August 1944

Invasion of Southern France

31 August-2 September 1944

Carrier Task Force Attacks on Iwo Jima, Chichi Jima and Haha Jima, Volcano and Bonin Islands

6-14 September 1944

Preliminary Carrier Task Force Attacks on Palau Islands

7-8 September 1944

Carrier Task Force Attacks on Yap

9-10 September 1944

Carrier Task Force Attacks on Mindanao, Philippine Islands

12-14 September 1944

Carrier Task Force Attacks on the Visayas, Philippines Islands

14-15 September 1944

Carrier Task Attacks on Mindano, Celebes and Talaud

15 September 1944

Landings on Peleliu, Palau Islands Landings on Morotai

17 September 1944

Landings on Angaur, Palau Islands

21-22 September 1944

Carrier Task Force Attacks on Manila, Philippine Islands

23 September 1944

Landings on Ulithi

24 September 1944

Carrier Task Force Attacks on the Visayas, Philippine Islands

28 September 1944

Landings on Ngesebus, Palau Islands

9 October 1944

Bombardment of Marcus Island

10 October 1944

Carrier Task Force Attack on Okinawa Island, Nansei

11 October 1944

Carrier Task Force Attack on Aparri, Luzon, Philippine Islands

12-15 October 1944

Carrier Task Force Attacks on Formosa and Luzon

18-19 October 1944

Carrier Task Force Attacks on Northern and Central Philippines

20 October 1944

Landings on Leyte, Philippine Islands

21 October 1944

Carrier Task Force Attacks on Luzon and the Visayas, Philippine Islands

23-26 October 1944

Battle of Leyte Gulf

5,6,13,14,19,25 November 1944

Carrier Task Force Attacks on Luzon, Philippine Islands

11 November 1944

Carrier Task Force Attack on Ormoc Bay, Leyte, Philippine Islands

11-12 November 1944

Bombardment of Iwo Jima, Volcano Islands

21 November 1944

Bombardment of Matsuwa Island, Kurile Islands

7 December 1944

Landings at Ormoc Bay, Philippine Islands

8, 24, 27 December 1944

Air-surface Attacks on Iwo Jima, Volcano Islands

14, 15, 16 December 1944

Carrier Task Force Attacks on Luzon, Philippine Islands

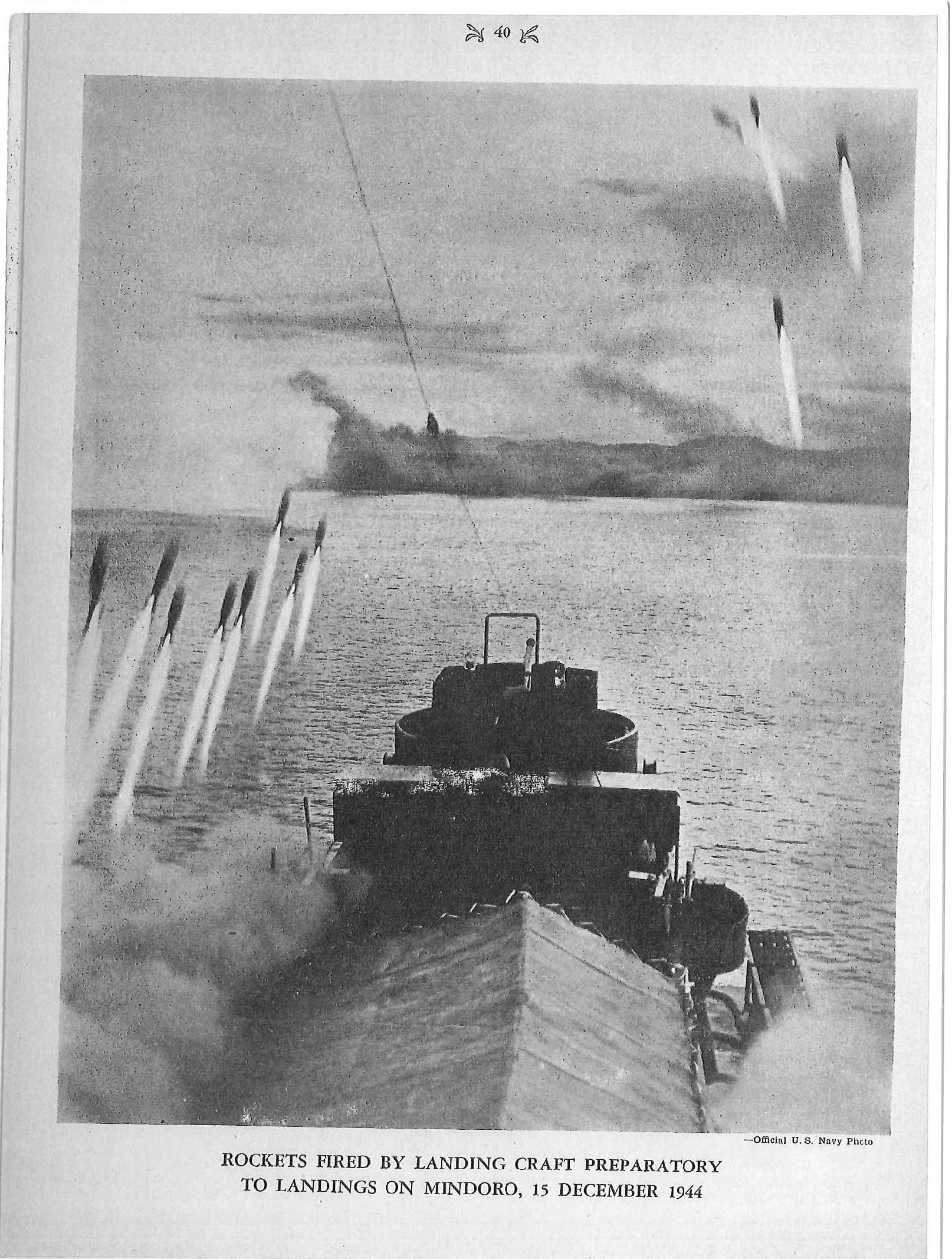

15 December 1944

Landings on Mindoro, Philippine Islands

3-4 January 1945

Carrier Task Force Attacks on Formosa

5 January 1945

Bombardment of Suribachi Wan, off Paramushiru, Kurile Islands

6-7 January 1945

Carrier Task Force Attacks on Luzon, Philippine Islands

9 January 1945

Landings at Lingayen Gulf, Luzon, Philippine Islands

Carrier Task Force Attack on Formosa

12 January 1945

Carrier Task Force Attack on French Indo-China Coast

15 January 1945

Carrier Task Force Attack on Formosa

16 January 1945

Carrier Task Force Attack on Hong Kong, Canton and Hainan, China

21-22 January 1945

Carrier Task Force Attack on Formosa and Nansei Shoto

24 January 1945

Air-surface Attack on Iwo Jima, Volcano Islands

29-30 January

Landings in Subic Bay Area, Luzon, Philippine Islands

31 January 1945

Landings at Nasugbu, Luzon, Philippine Islands

13-15 February 1945

Bombardment of Manila Bay Defenses, Philippine Islands

14 February 1945

Landings on Mariveles, Luzon, Philippine Islands

16 February 1945

Landings on Corregidor Island, Luzon, Philippine Islands

16-17 February 1945

Carrier Task Force Attack on Tokyo

19 February 1945

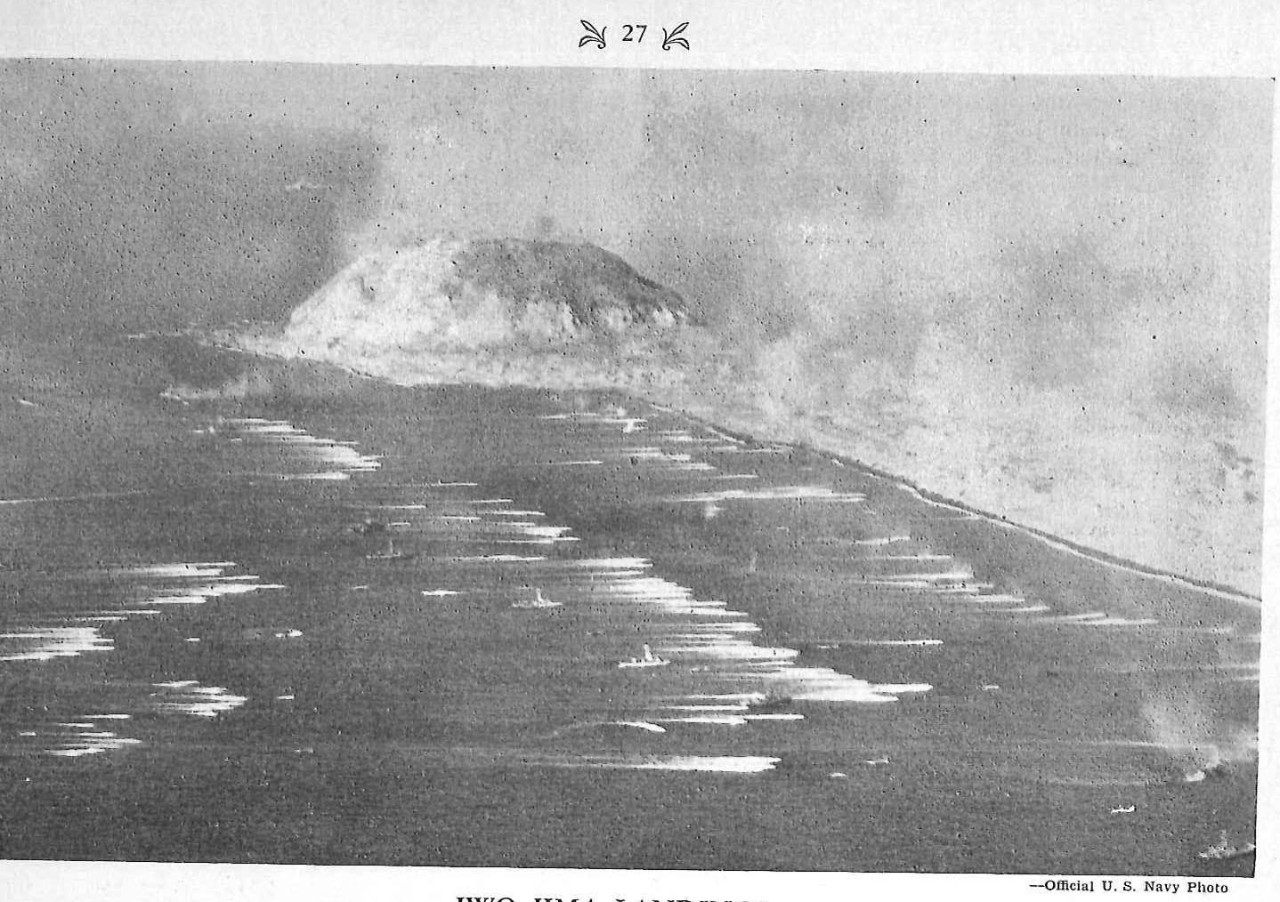

Landings on Iwo Jima, Volcano Islands

Bombardment of Kurabu Zaki, Paramushiru, Kurile Islands

25-26 February 1945

Carrier Task Force Attack on Tokyo and Hachijo Jima

28 February 1945

Landings on Palawan, Philippine Islands

[All dates are given as of local time of the area of the action.]

No listing of actions with enemy, however complete, can include the ceaseless and unrelenting depredaphases of the war they operated by themselves far beyond the range of any of our surface ships or aircraft. Their constant presence in the westernmost reaches of the Pacific limited the freedom of the enemy’s operations: their frequent and effective attacks depleted his shipping and diminished his logistic as well as his combatant strength. The rapid advance of our other forces, both sea and air, has been due in no small measure to the outstanding success with which our submarine activities have been carried on in waters where nothing but submarines could go. During the current phases of the war, our submarines are not only continuing independent operations but are also working in concert with the task fleets which are now exerting such heavy pressure on the Japanese.

The account of combat operations in this report is

*5*

based on special summaries recently made by the fleet commanders concerned. In some instances, this information will be found to differ slightly from communiques previously issued, due to the subsequent accumulation of additional facts. However, it should be understood that there has been no opportunity yet for an exhaustive analysis from an historian’s point of view of the great mass of operational reports in my files. I can furnish at this time no more than outline sketches of the highlights of combat operations. The preparation of carefully documented historical studies is underway, but the results will not be available during the progress of the war.

Limits of space further require that this account of combat operations be restricted to those actions, which have had a significant or decisive effect upon the progress of the war. Similarly, because of the greatly magnified scale of the operations described, it has been impossible to cite the names of individual ships and commanders in most cases. To retain any semblance of continuity, it has been necessary to omit the details of the constant activity of many naval air, surface, and shorebased units, which have performed invaluable services of patrol, supply and maintenance on a vast scale. Land-based planes and PT boats have incessantly harassed the beleaguered Japanese garrisons which have been by-passed in our progress across the Pacific. Seabees and other naval forces on shore have made great contributions to the conversion of islands seized in amphibious operations into useful bases for further attack upon the enemy. Countless ships and planes have contributed to the safe progress of troops and supplies along far-flung lines of communications. The operations of these forces, which have frequently involved bitter combat with the enemy, cannot, because of the nature of this report, be further elaborated upon.

II- Command and Fleet Organization

UNITED STATES FLEET

The basic organization of the United States Fleet has remained unchanged during the twelve months covered by this report.

The Headquarters of Commander in Chief, United States Fleet, located in Washington since December 1941, has continued to function as originally conceived, but with the growth in complexity and volume of work, I felt the need of assistance in matters of military policy concerning both the United States Fleet and the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. Consequently, the post of Deputy Commander in Chief, United States Fleet and Deputy Chief of Naval Operations was created, and on 1 October 1944, Vice Admiral R. S. Edwards reported for duty in that capacity. On the same date Vice Admiral C. M. Cooke, Jr., reported as Chief of Staff to Commander in Chief, United States Fleet, and Rear Admiral B. H. Bieri reported as Deputy Chief of Staff.

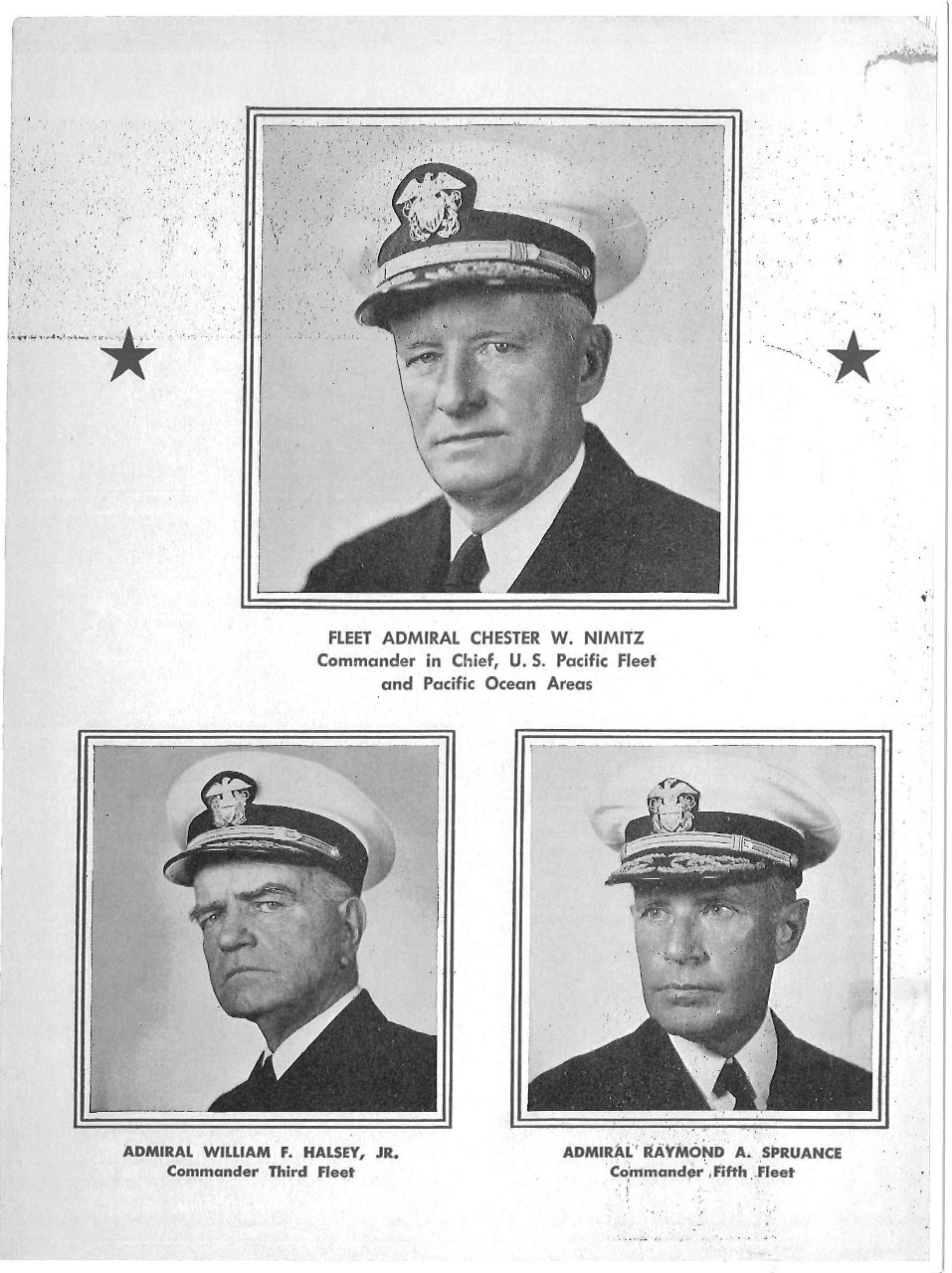

ORGANIZATION OF UNITED STATES NAVAL FORCES IN THE PACIFIC

United States Pacific Fleet

Operations in the Pacific Ocean Areas continue under the command of Fleet Admiral C. W. Nimitz, Commander in Chief, U. S. Pacific Fleet and Pacific Ocean Areas. As the scene of operations moved into the far western Pacific, Fleet Admiral Nimitz’s headquarters at Pearl Harbor became increasingly remote. Therefore, in January 1945 advance headquarters, were established at Guam, from which the Commander in Chief could supervise operations more closely.

Seventh Fleet

The Seventh Fleet (Vice Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid, Commander) continues to operate in the Southwest Pacific Area. Vice Admiral Kinkaid is under the command of General of the Army Douglas MacArthur, Commander in Chief of that Area.

Sea Frontiers

On 15 April 1944 a series of changes in the command organization of waters along the Pacific coast of the United States was made. The Northwest Sea Frontier which had been composed of the Northwestern Sector (Oregon and Washington) and the Alaska Sector, was abolished. The Northwestern Sector was incorporated into the Western Sea Frontier, and the Alaska Sector was established as the Alaskan Sea Frontier (Vice Admiral F. J. Fletcher, Commander). At the same time the 17th Naval District was created including the Territory of Alaska and its waters. This change consolidated all sea frontier and correlated activities on the west coast of the United States under the Commander, Western Sea Frontier (Vice Admiral D. W. Bagley), and incidentally brought the jurisdictional limits of the naval sea frontiers into conformity with the Army defense organizations on the Pacific coast of the United States.

On 8 November 1944, the functions of the Commander, Western Sea Frontier, were greatly enlarged in scope in order to afford more effective logistic support for war operations of United States forces in the Pacific. On 17 November 1944, Admiral R. E. Ingersoll assumed duties as Commander, Western Sea Frontier, relieving Vice Admiral Bagley.

On 28 November.1944, Vice Admiral Bagley relieved Vice Admiral R. L. Ghormley as Commander, Hawaiian Sea Frontier.

The Philippine Sea Frontier (Rear Admiral J. L. Kauffman, Commander) was established as a separate command under Commander Seventh Fleet (Southwest Pacific Area) on 13 November 1944.

*8*

ORGANIZATION OF UNITED STATES NAVAL FORCES IN THE ATLANTIC—MEDITERRANEAN

United States Atlantic Fleet

The U. S. Atlantic Fleet (Admiral Ingersoll, Commander in Chief, until 15 November 1944, when relieved by Admiral J. H. Ingram) consists of the forces operating in the United States area of strategic responsibility, which is, roughly, the western half of the Atlantic Ocean. The Fourth Fleet, operating in the South Atlantic, is a unit of U. S. Atlantic Fleet. Vice Admiral (now Admiral) Ingram was Commander Fourth Fleet until November 1944, when relieved by Vice Admiral W. R. Munroe.

United States Naval Forces, Europe

U. S. Naval Forces, Europe (Twelfth Fleet), Admiral H. R. Stark, Commander, is an administrative command, embracing all United States naval forces assigned to British waters and the Atlantic coastal waters of Europe. Admiral Stark is responsible for the maintenance and training of all United States naval units in his area. For operations connected with the invasion of the continent of Europe, he assigns appropriate task forces to the operational control of the British Admiral commanding the Allied naval contingent of General of the Army Dwight D. Eisenhower’s supreme command, which embraces all Army, Navy and Air elements involved in activities connected with the Western Front.

United States Naval Forces, Northwest African Waters

U. S. Naval Forces, Northwest African Waters (Eighth Fleet), Vice Admiral H. K. Hewitt, Commander, includes all United States naval forces in the Mediterranean. Vice Admiral Hewitt is under the British naval Commander in Chief of the Allied naval forces in the area, who is, in turn, under the command of the Supreme Commander of the area (formerly General of the Army Eisenhower, later Field Marshal Sir Henry Maitland-Wilson, at present Field Marshal Alexander of the British Army).

Sea Frontiers

There are four sea frontiers in the Western Atlantic The Eastern Sea Frontier (Vice Admiral H. F. Leary Commander) consists of the coastal waters and adjacent land areas from the Canadian border to Jacksonville. The Gulf Sea Frontier (Rear Admiral [now Vice Admiral] Munroe, Commander, until 17 July 1944, when relieved by Rear Admiral W. S. Anderson) consists of the coastal waters from Jacksonville westward, including the Gulf of Mexico, and adjacent land areas. The Caribbean Sea Frontier (Vice Admiral A. B. Cook, Commander until 14 May 1944, when relieved by Vice Admiral R. C Giffen) consists of eastern Caribbean and adjacent Iand and water areas. The Panama Sea Frontier (Rear Admiral H. C. Train, Commander, until 1 November 1944 when relieved by Rear Admiral H. C. Kingman) consists of western Caribbean waters, adjacent land areas and those waters of the Pacific constituting the western approaches to the Panama Canal. The Commander of the Panama Sea Frontier is under the Commanding General at Panama. The other western Atlantic sea frontier commanders are directly under Commander in Chief of the United States Fleet.

The Moroccan Sea Frontier (Commodore B. V. McCandlish, Commander) is under Commander Eighth Fleet.

III- Combat Operations Pacific

During the year 1944, the whole of the United States Navy in the Pacific was on the offensive. My previous report, summarizing combat operations to 1 March 1944, showed the evolution by which we had passed from the defensive, through the defensive-offensive and offensive-defensive stages, to the full offensive. To understand the significance of our operations in the account which follows, the reader. must be aware of the basic reasons behind them.

The campaign in the Pacific has important elements of dissimilarity from the campaign in Europe. Since the “battle of the beaches” was finally won with the landings in Normandy last June, the naval task in Europe has become of secondary scope. The European war has turned into a vast land campaign, in which the role of the navies is to keep open the trans- Atlantic sea routes against an enemy whose naval strength appears to be broken except for his U- boat activities. In, contrast, the Pacific war is still in the “crossing the ocean” phase. There are times in the Pacific when troops get beyond the range of naval gun support, but much of the fighting has been, is now, and will continue for some time to be on beaches where Army and Navy combine in amphibious operation: Therefore, the essential element of our dominance over the Japanese has been the strength of our fleet. The ability to move troops from island to island, and to put there ashore against Opposition, is due to the fact that on command of the sea is spreading as Japanese navy strength withers. As a rough generalization, the war in Europe is now predominantly an affair of armies, while the war in the Pacific is still predominantly naval.

The strategy in the Pacific has been to advance on the core of the Japanese position from two directions. Under General of the Army MacArthur, a combined Allied Army—Navy force has moved north from the Australian region. Under Fleet Admiral Nimitz, a United States Army-Navy-Marine force has moved west from Hawaii. The mobile power embodied in the major combatant vessels of the Pacific Fleet has, sometimes united and sometimes separately, covered Operations along both routes advance, and at the same time contained the Japanese Navy.

In November 1943 South Pacific forces secured beachhead on Bougainville, on which airfields were

*9*

constructed for the neutralization of the Japanese base of Rabul on New Britain. Simultaneously Southwest Pacific forces were working their way along the northern coast of 'New Guinea.

In November 1943 Pacific Ocean Areas forces attacked the Gilbert Islands, and at the end of January 1944 the Marshall Islands—the first stepping stones along the road from Hawaii. To control the seas and render secure a route from Hawaii westward, it was not necessary to occupy every atoll. We could and did pursue a “leap frog" strategy, the basic concept of which is to seize those islands essential for our use, by-passing many strongly held intervening ones which were not necessary for our purposes. This policy was made possible by the gradually increasing disparity between our own naval power and that of the enemy, so that the enemy was and still is unable to support the garrisons of the by-passed atolls. Consequently, by cutting the enemy’s line of communicating bases, the isolated ones became innocuous, without the necessity for our expending effort for their capture. Therefore, we can with impunity by-pass numerous enemy positions, with small comfort to the isolated Japanese garrisons, who are left to meditate the fate of exposed forces beyond the range of naval support.

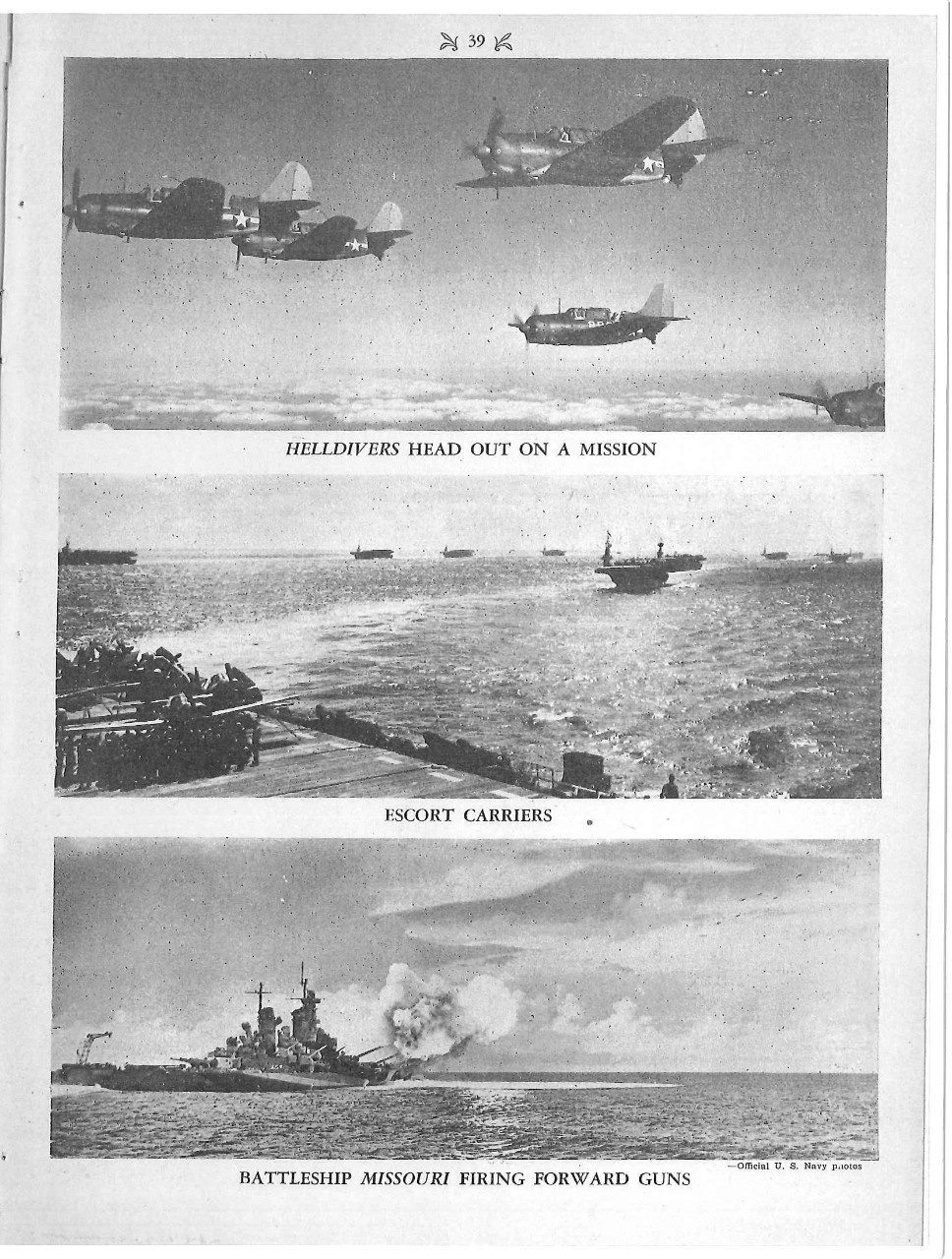

This strategy has brought the Navy into combat with shore-based air forces. It has involved some risks and considerable difficulty, which we have overcome. However, as we near the enemy’s homeland, the problem becomes more and more difficult. During the first landing in the Philippines, for example, it was necessary to deal with the hundred or more Japanese airfields that were within flying range of Leyte. This imposed on our carrier forces a heavy task which we may to become increasingly heavy from time to time. While shore-based air facilities are being established as rapidly as possible in each position we capture, there will always be a period following a successful landing when control of the air will rest solely on the strength of our carrier-based aviation.

The value of having naval vessels in support of landings has been fully confirmed. This renewed importance of battleships is one of the interesting features of the Pacific war. The concentrated power of heavy naval guns is very great by standards of land warfare, and the artillery support they have given in landing operations has been a material factor in getting our troops ashore with minimum loss of life. Battleships and cruisers, as well as smaller ships, have proved their worth for this purpose.

As I pointed out above our advance across the Pacific followed two routes. At the opening of the period covered by this report, General of the Army MacArthur’s forces were working their way along the northern coast of New Guinea, while Fleet Admiral Nimitz, by the capture of the Gilbert and Marshall Islands, had taken the first steps along the other route. The narrative which follows begins with the operations leading to the capture of the Gilbert and Marshall Islands, had taken the first steps along the other route. The narrative which follows begins with the operations leading to the capture of Hollandia on the north coast of New Guinea.

HOLLANDIA AND FAST CARRIER TASK FORCE COVERING OPERATIONS

On 13 February 1944 the final occupation of the Huon Peninsula in Northeast New Guinea was completed. The occupation of the Admiralty Islands on 29 February 1944 by General of the Army MacArthur’s forces and of Emirau in the St. Matthias group, north of New Britain, by Admiral W. F. Halsey’s forces on 20 March had further advanced our holdings. In these two operations, the amphibious attack forces were commanded respectively by Rear-Admiral W. M. Fechteler and Rear Admiral (now Vice Admiral) T. S. Wilkinson. On 20 March 'battleships and destroyers bombarded Kavieng, New Ireland.

The enemy had concentrated a considerable force at Wewak, on the northern coast of New Guinea, several hundred miles west of the Huon Peninsula. Hollandia, more than two hundred miles west of Wewak, had a good potential harbor and three airstrips capable of rehabilitation and enlargement. In order to accelerate the reconquest of New Guinea, it was decided to push far to the northwest, seize the coastal area in the vicinity of Aitape and Hollandia, thus by-passing and neutralizing the enemy’s holdings in the Hansa Bay and Wewak areas. This operation was made possible by the availability of the fast carrier. task force of the Pacific Fleet to perform two functions, namely to neutralize enemy positions in the Western Carolines from which attacks might be launched against our landing forces or against our new bases in the Admiralties and Emirau, and to furnish close cover for the landing.

Carrier Task Force Attacks on Westem Carolines

Under command of Admiral R. A. Spruance, Commander Fifth Fleet, a powerful force of the Pacific Fleet, including carriers, fast battleships, cruisers, and destroyers, attacked the Western Carolines. On 30 and 31 March, carrier-based planes struck at the Palau group with shipping as primary target. They sank 3 destroyers, 17 freighters, 5 oilers and 3 small vessels, and damaged 17 additional ships. The planes also bombed the airfields, but they did not entirely stop Japanese air activity. At the same time, our aircraft mined the waters around Palau in order to immobilize enemy shipping in the area.

Part of the force struck Yap and Ulithi on 31 March and Woleai on 1 April.

Although the carrier aircraft encountered active air opposition over the Palau area on both days, they quickly overcame it. Enemy planes approached the task force on the evenings of 29 March and 30 March but were destroyed or driven off by the combat air patrols. During the three days’ operation our plane losses were 25 in combat, while the enemy had 114 planes destroyed in combat and 46 on the ground. These attacks were successful in obtaining the desired effect, and the operation in New Guinea went forward without opposition from the Western Carolines.

Capture and Occupation of Hollandia

The assault on Hollandia involved a simultaneous three-pronged attack by Southwest Pacific forces. Landings at Tanahmerah Bay and, 30 miles to the eastward, at Humboldt Bay trapped the Hollandia airstrips situated 12 miles inland. The third landing, an additional 90 miles to the eastward at Aitape, provided a diversionary attack, wiped out an enemy strong point, and won another airstrip. Approximately 50,000 Japanese were cut off and the complete domination of New Guinea by Allied forces was hastened. The operation was under the

*11*

command of General of the Army MacArthur. Three separate attack groups operated under a single attack force commander, Rear Admiral (now Vice Admiral) D. E. Barbey, who also commanded the Tanahmerah Bay attack group. Rear Admiral Fechteler commanded the Humboldt Bay group and Captain (now Rear Admiral) A. G. Noble the Aitape group. This amphibious operation was the largest that had been undertaken in the Southwest Pacific Area up to that time. Over 200 ships were engaged. A powerful force of carriers, fast battleships, cruisers and destroyers from the Pacific Fleet. commanded by Rear Admiral (now Vice Admiral) M. A. Mitscher, covered the landings.

Throughout 21 April, the day before the landings, the carriers launched strikes against the airstrips in the Aitape-Hollandia area, which had previously been bombed nightly since 12 April by land-based aircraft. On the "night of 21-22 April, light cruisers and destroyers bombarded the airfields at Wakde and Sawar. The amphibious landing took place on the 22nd, and on that and the following day planes from the Pacific Fleet carriers supported operations ashore, while keeping neighboring enemy airfields neutralized. Prepared defenses were found abandoned at Aitape: at Hollandia and Tanahmerah Bay there were none. The enemy took to the hills and the landings were virtually unopposed. Once ashore, all three groups encountered difficulties with swampy areas behind the beaches, lack of overland communications, and dense jungles. In spite of these obstacles, satisfactory progress was made. At the end of the second day the Aitape strip had been occupied and fighters were using it within twenty-four hours. The Hollandia strips fell a few days later.

As soon as the airstrips were in full operation and the port facilities at Hollandia developed, we were ready for further attacks at points along the northwestern coast of New Guinea.

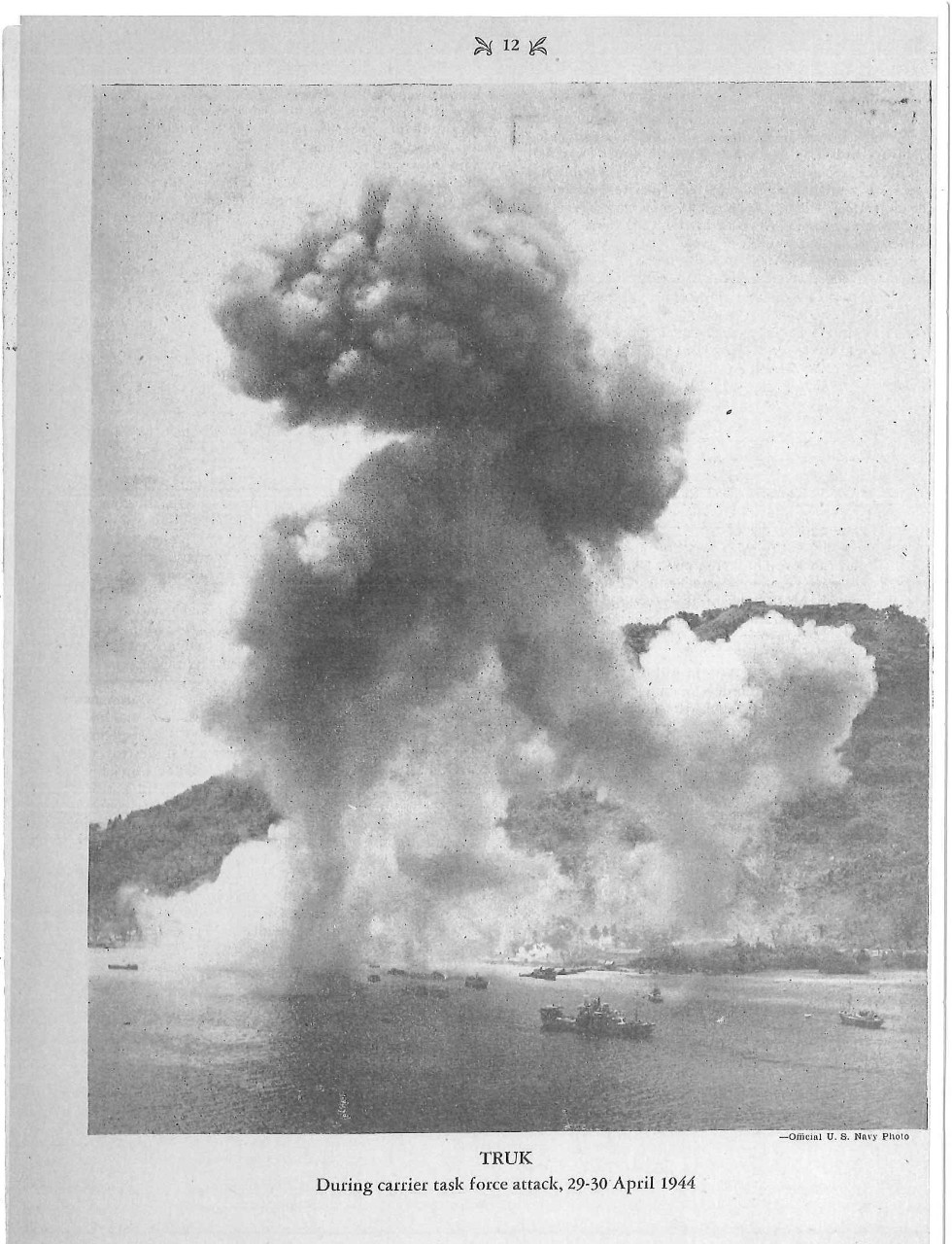

Carrier Task Force Attacks on Central and Eastern Carolines

Returning from support of the Hollandia landings, The fast carrier task force attacked Truk on 29 and 30 April. Initial fighter sweeps overcame almost all enemy air opposition by 1000 on the morning of the 29th, and there after over 2200 sorties, dropping 740 tons of bombs, were flown against land installations on Truk Atoll. Our planes encountered vigorous and active antiaircraft fire, but did exceedingly heavy damage to buildings and installations ashore. One air-attack was attempted on our carriers on the morning of the 29th, but the approaching planes were shot down before they could do damage. Our plane losses in combat were 27 against 63 enemy planes destroyed in the air and at least 60 more on the ground.

For over two hours on 30 April a group of cruisers and destroyers bombarded Satawan Island, where the enemy had been developing an air base. Although existing installations were of little importance, the bombardment served to hinder the enemy’s plans and furnished training for the crews of our ships. Similarly, a group of fast battleships and destroyers, returning from Truk, bombarded Ponape for 80 minutes on 1 May. There was no opposition except for antiaircraft fire against the supporting planes.

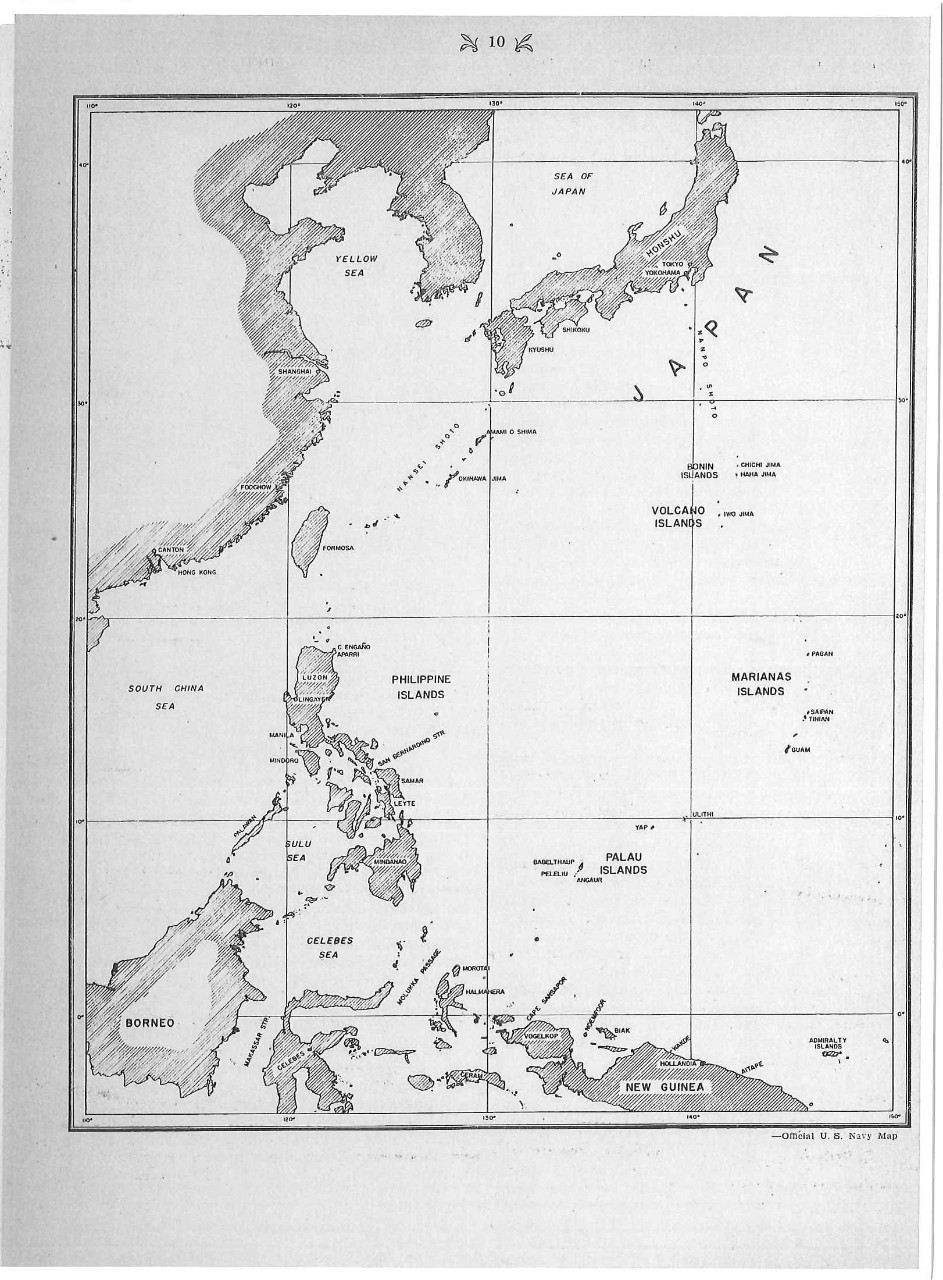

MARIANAS OPERATIONS

During the summer of 1944. Pacific Ocean Areas forces captured the islands of Saipan, Guam and Tinian, and neutralized the other Marianas Islands which remained in the hands of the enemy. The Marianas form part of an almost continuous chain of islands extending 1350 miles southward from Tokyo. Many of these islands are small, rocky, and valueless from a military viewpoint, but others provide a series of mutually supporting airfields and bases, like so many stepping stones, affording protected lines of air and sea communications from the home islands of the Japanese Empire through the Nanpo Shoto [Bonin and Volcano Islands] and Marianas to Truk; thence to the Eastern Carolines and Marshalls, as well as to the Western Carolines, the Philippines and Japanese-held territory to the south and west. Our occupation of the Marianas would, therefore, effectively cut these admirably protected lines of enemy communication, and give us bases from which we could not only control sea areas further west in the Pacific but also on which we could base aircraft to bomb Tokyo and the home islands of the Empire.

As soon as essential points in the Marshall Islands had been secured, preparations were made for the Marianas operation. Admiral Spruance, who had already conducted the Gilberts and Marshalls operations, was in command. Amphibious forces were directly under Vic Admiral R. K. Turner and the Expeditionary Forces were commanded, by Lieutenant General Holland M. Smith, USMC. Ships were assembled, trained, and loaded at many points in the Pacific Ocean Areas. More than 600 vessels ranging from battleships and aircraft carriers to cruisers, high-speed transports and tankers, more than 2,000 aircraft, and some 300,000 Navy, Marine and Army personnel took part in the capture of the Marianas.

Enemy airbases on Marcus and Wake Islands flanked on the north our approach to the Marianas. Consequently, a detachment of carriers, cruisers, and destroyers from the Fifth Fleet attacked these islands almost a month before the projected landings in order to destroy aircraft, shore installations, and shipping. Carrier planes struck Marcus on 19 and 20 May and Wake on 23 May. They encountered little opposition and accomplished their mission with very light' losses due to anti-aircraft fire.

From about the beginning of June, land-based aircraft from the Admiralties, Green, Emirau and Hollandia kept enemy bases, especially at Truk, Palau, and Yap well neutralized. The fast carriers and battleships of the Fifth Fleet, under Vice Admiral Mitscher, prepared the way for the amphibious assault. Carrier planes began attacks on the Marianas on 11 June With the object of first destroying aircraft and air faculties and then concentrating on bombing shore defenses 1n preparation for the ' coming amphibious landings. They achieved control of the air over the Marianas on the first fighter sweep of 11 June and thereafter attacked air facilities, defense installations, and shipping in the vicinity.

Initial Landings on Saipan

Saipan, the first objective, was the key to the Japanese defenses; having been in Japanese hands since World

*13*

War I. its fortifications were formidable. Although a rugged island unlike the coral atolls of the Gilberts and Marshalls. Saipan was partly surrounded by a reef which made landing extremely difficult. To prepare for the assault scheduled for 15 June, surface ships began to bombard Saipan on the 13th. The fast battleships fired their main and secondary batteries for nearly 7 hours into the western coast of Saipan and Tinian Islands. Under cover of this fire, fast mine sweepers cleared the waters for the assault ships, and underwater demolition teams examined the beaches for obstructions and cleared away such as were found.

The brunt of surface bombardment for destruction of defenses was borne by the fire support groups of older battleships, cruisers and destroyers, which preceded the transports to the Marianas and began to bombard Saipan and Tinian on 14 June.

Early on the morning of 15 June the transports, cargo ships. and LST’s of Vice Admiral Turner’s amphibious force came into position off the west coast of Saipan. The bombardment ships delivered a heavy, close range pre-assault fire, and carrier aircraft made strikes to destroy enemy resistance on the landing beaches. The first troops reached the beaches at 0840, and within the next half hour several thousand were landed. In spite of preparatory bombing and bombardment, the enemy met the landing force with heavy fire from mortars and small calibre guns on the beaches. Initial beachheads were established not without difficulty, and concentrated and determined enemy fire and counter attacks caused some casualties and rendered progress inland slower than was anticipated.

The 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions landed first and were followed the next day by the 27th Army Infantry Division. Although Saipan had an area of but 72 square miles, it was rugged and admirably suited to delaying defensive action by a stubborn and tenacious enemy. The strong resistance at Saipan, coupled with the news of a sortie of the Japanese fleet, delayed landings on Guam.

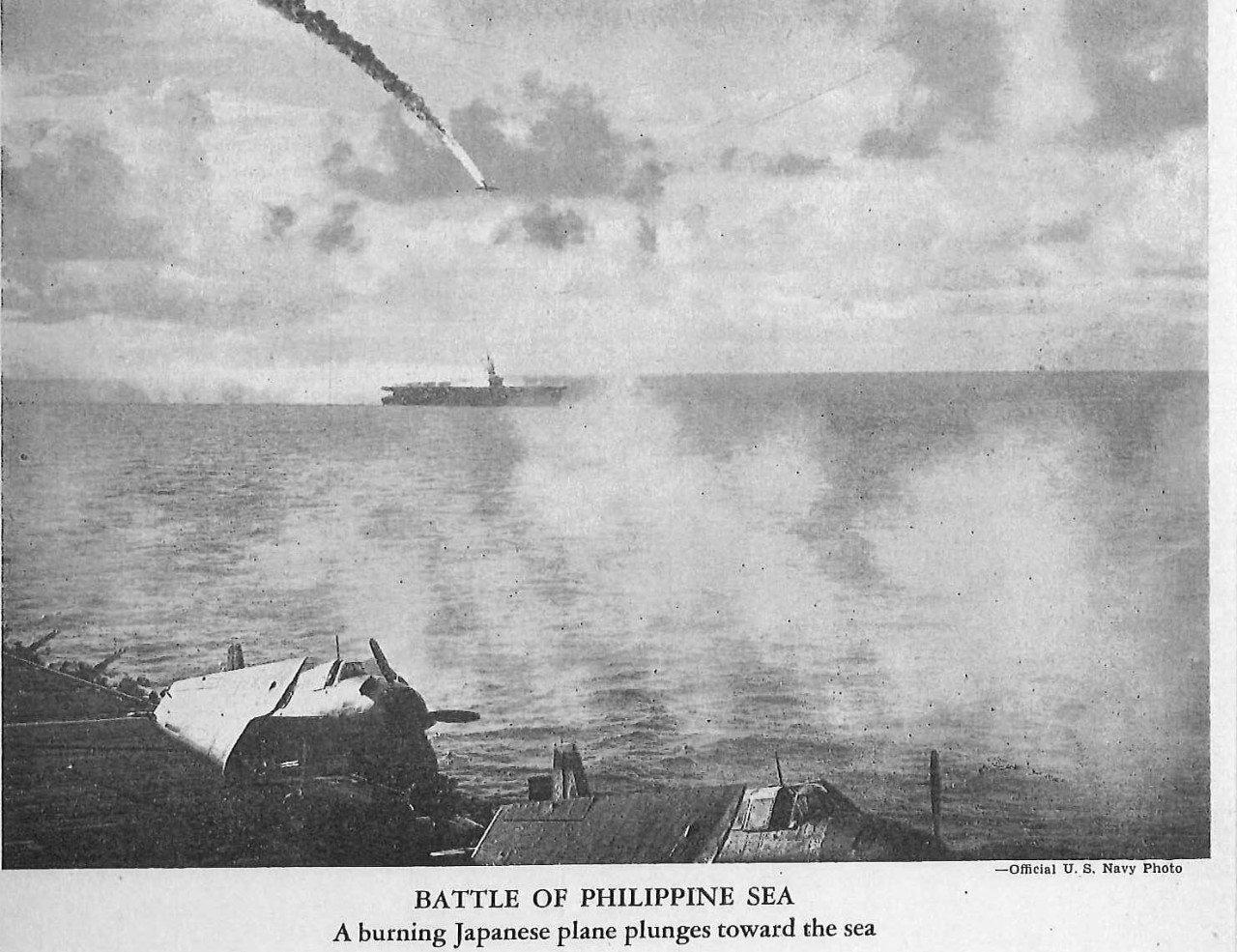

Battle of the Philippine Sea

This sortie of the Japanese fleet promised to develop into a full-scale action. On 15 June, the very day of the Saipan landings, Admiral Spruance received reports that a large force of enemy carriers, battleships, cruisers and destroyers was headed toward him, evidently on its way to relieve the beleaguered garrisons in the Marianas. As the primary mission of the American forces in the area was to capture the Marianas, the Saipan amphibious operations had to be protected from enemy interference at all costs. In his plans for what developed into the Battle of the Philippine Sea, Admiral Spruance was rightly guided by this basic mission. He therefore operated aggressively to the westward of the Marianas, but did not draw his carriers and battleships so far away that they could not protect the amphibious units from any possible Japanese “end run” which might develop.

While some of the fast carriers and battleships were disposed to the westward to meet this threat, other carriers on IS and 16 June attacked the Japanese bases of Iwo Jima and Chichi Jima. During this strike to the northward our carrier planes destroyed enemy planes in the air and on the ground, and set fire to buildings, ammunition and fuel dumps, thus temporarily neutralizing those bases. and freeing our forces from attack by enemy aircraft coming from the Bonins and Volcanoes. The forces employed in the northward strike were recalled to rendezvous west of Saipan, as were also many of the ships designated to give fire support to the troops on Saipan.

On 19 June the engagement with the Japanese fleet began. The actions on the 19th consisted of two air battles over Guam with Japanese planes evidently launched from carriers and intended to land for fueling and arming on the fields of Guam and Tinian and a large-scale lengthy attack by enemy aircraft on Admiral Spruance's ships. The result of the day's action was some 402 enemy planes destroyed out of a total of 5-25 seen. as against 17 American planes lost and minor damage to 4 ships.

With further air attacks against Saipan by enemy aircraft unlikely because of the enemy‘s large carrier plane losses, and with its basic mission thus fulfilled, our fleet headed to the westward hoping to bring the Japanese fleet to action. Air searches were instituted early on the 20th to locate the Japanese surface ships. Search planes did not make contact until afternoon and, when heavy strikes from our carriers were sent out. it was nearly sunset. The enemy was so far to the westward that our air attacks had to be made at extreme range. They sank 2 enemy carriers, ‘2 destroyers and l tanker, and severely damaged 3 carriers, 1 battleship, 3 cruisers, l destroyer and 3 tankers. We lost only 16 planes shot down by enemy antiaircraft and fighter planes. Precariously low gasoline in our planes and the coming of darkness cut the attack short. Our pilots had difficulty in locating their carriers and many landed in darkness. A total of 73 plans were lost due to running out of fuel and landing crashes, but over 90 per cent of the personnel of planes which made water landings near our fleet were picked up in the dark by destroyers and cruisers. The heavy damage inflicted on the Japanese surface ships, and prevention of enemy interference to operations at Saipan, made these loses a fair price to pay in return.

The enemy continued retiring on the night of the 20th and during the 2lst. Although his fleet was located by searches on the 215t, planes sent out to attack did not make contact. Admiral Spruance‘s primary mission precluded getting out of range of the Marianas, and on the night of the let, distance caused the chase to be abandoned. The Battle of the Philippine Sea broke the Japanese effort to reinforce the Marianas: thereafter, the capture and occupation of the group went forward without serious threat of enemy interference.

Conquest of Saipan

During the major fleet engagement. land fighting on Saipan continued as bitterly as before. Between 15 and 20 June, the troops pushed across the southern portion of the island, gaining control of two enemy airfields. During the next ten days, from the 2lst to the 30th, the rough central section around Mount Tapotchau was captured. The Japanese, exploiting the terrain, resisted with machine guns, small arms and light mortars from caves and other almost inaccessible positions. This central part of the island was cleared of organized resistance. and the last stage of the battle commenced. By 1 July, the 2nd Marine Division had captured the heights overlooking Garapan and Tanapag Harbor on the west coast, while

*14*

the 4th Marine Division and 27th Army Division had advanced their lines to within about five miles of the northern tip of the island. From 1 to 9 July the enemy resisted sporadically, in isolated groups, in northern ‘Saipan. On 4 July the 2nd Marine Division captured Garapan, the capital city of the island. One desperate “banzai” counter attack occurred on 7 July, but this was stemmed and all organized resistance ceased on the 9th. Many isolated small groups remained, which required continuous mopping up operations; in fact, some mopping up, still continues.

While the campaign ashore went on, it was constantly supported by surface and air forces. Surface ships were always ready to deliver gunfire, which was controlled by liaison officers ashore in order to direct the fire where' it would be of greatest effectiveness. Carrier aircraft likewise assisted. Supplies, ammunition, artillery and reinforcements were brought to the reef by landing craft and were carried ashore by amphibious vehicles until such time as reef obstacles were cleared and craft could beach. The captured Aslito airfield was quickly made ready for use, and on 22 June Army planes began operation from there in patrols against enemy aircraft. Tanapag Harbor was cleared and available for use 7 July.

Japanese planes from other bases in the Marianas and the Carolines harassed our ships off Saipan from the time of landing until 7 July. Their raids were not large and, considering the number of ships in the area, these attacks did little damage. An LCI, was sunk and the battleship Maryland damaged. An escort carrier, 2 fleet ‘tankers, and 4 smaller craft received some damage, but none serious enough to require immediate withdrawal from the area.

While these activities went on in Saipan, the fast carriers and battleships continued to afford cover to the westward, and also to prevent the enemy from repairing his air strength in the Bonins and Volcanoes. On 23 and 24 June, Pagan Island was heavily attacked by carrier planes. Iwo Jima received attacks on 24 June and 4 July and Chichi Jima and Haha Jima on the latter date. The 4 July attack on Iwo included bombardment by cruisers and destroyers. These attacks kept air facilities neutralized and destroyed shipping.

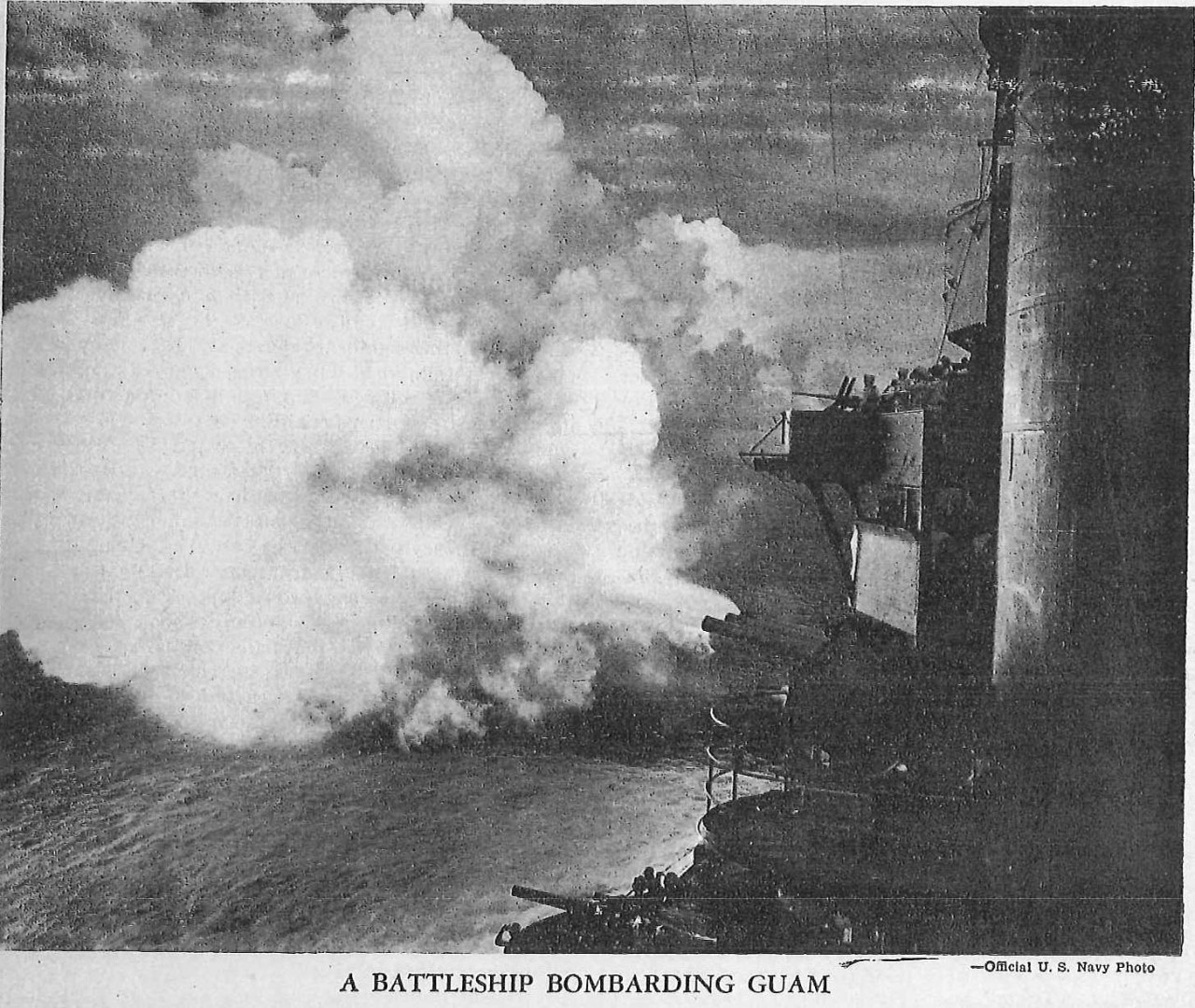

Reoccupation of Guam

As has been seen, the unexpectedly stiff resistance on Saipan, together with the sortie of the Japanese fleet, had necessitated a postponement of landings on Guam. This delay permitted a period of air and surface bombardment which was unprecedented in severity and duration. Surface ships first bombarded Guam on 16 June from 8 July until the landing on the 21st the island was

*15*

under daily gunfire from battleships, cruisers and destroyers, which destroyed all important emplaced defenses. This incessant bombardment was coordinated with air strikes from fields on Saipan and from fast arid escort carriers. The destruction of air facilities and planes on Guam and Rota, as well as the neutralization of more distant Japanese bases, gave us uncontested control of the air. The forces engaged in the reoccupation of Guam were under the command of Rear Admiral R. L. Conolly.

Troops landed on Guam on 21 July. As at Saipan the beach conditions were unfavorable and landing craft had to transfer their loads to amphibious vehicles or pontoons at the edge of the reef. With the support of bombarding ships and planes. the first waves of amphibious vehicles beached at 0830. There were two simultaneous landings: one on the north coast east of Apra Harbor and the other on the west coast south of the harbor. Troops received enemy mortar and machine gun fire as they reached the beach. The 3rd Marine Division. the 77th Army Infantry Division and the last Marine Provisional Brigade, under the command of Major General R. S. Geiger, USMC, made the landings: from 21 to 30 July they fought in the Apra Harbor area, where the heaviest enemy opposition was encountered.

The capture of Orote Peninsula with its airfields and other installations, made the Apra Harbor area available for sheltered and easier unloading. Beginning on 31 July, our forces advanced across the island to the east coast and thence pushed northward to the tip of Guam. While enemy opposition was stubborn, it did not reach the intensity encountered on Saipan, and on 10 August 1944 all organized resistance on the island ceased. Air and surface support continued throughout this period.

The elimination of isolated pockets of Japanese opposition was a long and difficult task even after the end of organized resistance. As at Saipan, the rough terrain of the island, with its many caves, made the annihilation of the remaining small enemy forces a difficult task. The enemy casualty figures for Guam illustrate the character of this phase. By 10 August, the total number of Japanese dead counted was 10,971 and 86 were prisoners of war. By the middle of November, these numbers had increased to 17,238 enemy killed and 463 prisoners.

Occupation of Tinian

The capture of Tinian Island, by forces commanded by Rear Admiral H. W. Hill, completed the amphibious operations in the Marianas in the summer of 1944. Located across the narrow channel to the southward of Saipan, Tinian was taken by troops who had already participated in the capture of the former island. Intermittent bombardment began at the same time as on Saipan and continued not only from sea and air, but from artillery on the south coast of Saipan. A joint naval and air program for “softening” the defenses of Tinian went on from 26 June to 8 July, and thereafter both' air and surface forces kept the enemy from repairing destroyed positions. There were heavy air and surface attacks on 22 and 23 July, the days immediately preceding the landing, and these completed the destruction of almost all enemy gun emplacements and defense positions. The landings, which took place on beaches at the northern end of Tinian, began early on 24 July. Beach reconnaissance had been conducted at night and the enemy was surprised in the location of our landing. Troops of the 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions landed in amphibious vehicles from transports at 0740 on the 24th. They met only light rifle and mortar fire, and secured a firm beachhead. Like Saipan and Guam, Tinian presented a difficult terrain problem, but enemy resistance was much less stubborn than on the other islands. On 1 August the island was declared secure, and the assault and occupation phase ended on the 8th.

Throughout this period, surface and air units provided constant close support to the ground troops. In addition, on 4 and 5 August units of the fast carrier task force virtually wiped out a Japanese convoy, and raided airfields and installations in the Bonin and Volcano Islands. Damage to the enemy was 11 ships sunk, 8 ships damaged, and 13 aircraft destroyed; our losses were 16 planes.

PROGRESS ALONG NEW GUINEA COAST

Before and during the Marianas operations, Southwest Pacific forces under General of the Army MacArthur engaged in a series of amphibious landings along the north coast of New Guinea. These operations were undertaken to deny the Japanese air and troop movements in western New Guinea and approaches from the southwest to our lines of communication across the Pacific, thus securing our flank. Unlike the Hollandia operation, which was supported by carriers and battleships of the Fifth Fleet, they involved the use of no ships larger than heavy cruisers.

Occupation of the Wakde Island Area

In order to secure airdromes for the support of further operations to the westward, an unopposed landing was made on 17 May 1944 by U. S. Army units at Arara, on the mainland of Dutch New Guinea, about 70 miles west of Hollandia. Under command of Captain (now Rear Admiral) Noble, a naval force of ‘cruisers, destroyers, transports and miscellaneous landing craft landed the 163rd Regimental Combat Team reinforced. Extending their beachhead on D-day along the coast from Toem to the Tor River, the troops made shore—to shore movements to the Wakde Islands on 17 and 18 May. By 19 May, all organized enemy resistance on the Wakde Islands had ceased.

Occupation of Biak Island

Because of the need for a forward base from which to operate heavy bombers, an amphibious assault was made on Biak Island, beginning on 27 May. The attack force, under the command of Rear Admiral Fechteler, composed of cruisers, destroyers, transports and landing craft, departed Humboldt Bay on the evening of 25 May and arrived off the objective without detection. Initial enemy opposition was weak and quickly overcome, but subsequently the landing force encountered stiff resistance in the move toward the Biak airfields. Air support and bombardment were furnished by B-24’s, B-25’s and A—20’s, while fighter cover was provided by planes from our bases at Hollandia and Aitape.

After the initial landing on Biak Island, the enemy, entrenched in caves commanding the coastal road to the airstrips, continued stubborn resistance and seriously retarded the scheduled development of the air facilities for which the operation had been undertaken. Furthermore,

*16*

it became apparent that the enemy was planning to reinforce his position on Biak. To counter this threat, a force of 3 cruisers and 14 destroyers under the command of Rear Admiral V. A. C. Crutchley, RN, was given the mission of destroying enemy naval forces threatening our Biak occupation. On the night of 8-9 June, a force of 5 enemy destroyers attempting a “Tokyo Express” run was intercepted by Rear Admiral Crutchley’s force. The Japanese destroyers turned and fled at such high speed that in the ensuing chase only one of our destroyer divisions, commanded by Commander (now Captain) A. E. Jarrell, was able to gain firing range. After a vain chase of about three hours the action was broken off.

Occupation of Noemfoor Island

On 2 July 1944, a landing was made in the vicinity of Kaimiri Airdrome on the northwest coast of November Island, southwest of Biak Island. The amphibious attack force, under the command of Rear Admiral (now Vice Admiral) Barbey, consisted of an attack group, a covering group of cruisers and destroyers, a landing craft unit, and a landing force built around the 148th U. S.Infantry Regimental Combat Team reinforced. Landing began at 0800, and all troops and a considerable number of bulk stores were landed on D-day. Prior to the landing nearby Japanese airfields were effectively neutralized by the 5th, Air Force.

Enemy opposition was feeble, resistance not reaching the fanatical heights experienced on other islands. There were not more than 2000 enemy troops on Noemfoor Island and our casualties were extremely light, only 8 of our men having been killed by D-plus—6 day. Again, forward air facilities to support further advance to the westward had been secured at a relatively light cost.

Occupation of Cape Sansapor Area

On 30 July 1944, an amphibious force, under the command of Rear Admiral F echteler, carried out a landing in the Cape Sansapor area on the Vogelkop Peninsula in western New Guinea. Rear Admiral R. S. Berkey commanded the covering force.

The main assault was made without enemy air or naval resistance. Beach conditions were ideal and within a short time, secondary landings had been made at Middleburg Island and Amsterdam Island, a few thousand yards off shore.

Prior to D-day Army Air Force bombers and fighters had neutralized enemy areas in the Geelvink- Vogelkop area and the main air bases in the Halmahera. On D-day, when it became evident that the ground forces would encounter no resistance, Army support aircraft; from Owi and Wakde were released for other missions and naval bombardment was not utilized. Again; casualties sustained were light“; one man killed, and minor damage to small landing craft.

This move brought our forces to the western extremity of New Guinea. It effectively neutralized New Guinea as a base for enemy operations, and rendered the enemy more vulnerable to air attack in Halmahera, the Molukka Passage and Makassar Strait. Enemy concentrations had been by-passed in our progress up the coast, but due to the absence of roads, the major portion of enemy transport was of necessity water-borne. Here our PT boats did admirable service, roaming east and west along the coast, harassing enemy barge traffic, and preventing reinforcements from being put ashore.

WESTERN CAROLINES OPERATIONS

Following closely upon the capture of the Marianas, Fleet Admiral Nimitz’s forces moved to the west and south to attack the Western Caroline Islands. Establishment of our forces in that area would give us control of the southern half of the crescent shaped chain of islands which runs from Tokyo to the southern Philippines. It would complete the isolation of the enemy held Central and Eastern Carolines, including the base at Truk.

Admiral W. F. Halsey, Jr., Commander Third Fleet, commanded the operations in the Western Carolines. Additions to the Pacific Fleet from new construction made an even larger force available to strike the Western Carolines than the Marianas. Nearly 800 vessels participated. Vice Admiral Wilkinson commanded the joint expeditionary forces which conducted landing operations. Major General J. C. Smith, USMC, was Commander Expeditionary Troops, and Vice Admiral Mitscher was again commander of the fast carrier force. Troops employed included the lst Marine Division and the lst Army Infantry Division.

Preliminary Strikes by Fast Carrier Task Force

Prior to the landings in the Western Carolines, wide flung air and surface strikes were made to divert and destroy Japanese forces, which might have interfered. Between 31 August and 2 September, planes from the fast carriers bombed and strafed Chichi Jima, Haha Jima. and Iwo Jima. Cruisers and destroyers bombarded Chichi Jima and Iwo Jima. They destroyed 46 planes in the air and on the ground, sank at least 6 ships, and damaged installations, airfields and supply dumps. Our forces lost 5 aircraft. On the 7th and 8th, planes from the same carriers attacked Yap Island.

Simultaneously, other groups of fast carriers devoted their attention to the Palau Islands where the first "Western Carolines landings were to take place. In attacks: throughout the group from 6 to 8 September, they did extensive damage to ammunition and supply dumps, barracks and warehouses.

The plan was for Pacific Ocean Areas forces to land; on Peleliu Island in the Palau group on 15 September, simultaneously with a landing on Morotai by SouthWest Pacific forces. In order“ to neutralize bases from which aircraft might interfere with these operations, carrier air strikes on Mindanao Island in the southern Philippines were made. These. attacks began on 9 September and revealed the unexpected weakness of enemy air resistance in the Mindanao area. On 10 September there: were further air attacks, as well as a cruiser- destroyer raid off the eastern Mindanao coast, which caught and completely destroyed a convoy of 32 small freighters.

The lack of opposition at Mindanao prompted air strikes into the central Philippines. From 12 to 14 September, planes from the carrier task force attacked the Visayas. They achieved tactical surprise, destroyed 75 enemy planes In the air and 123 On the ground, sank: many ships, and damaged installations ashore.

In direct support of the Southwest Pacific landing at Morotai, carrier task force planes attacked Mindanao, the Celebes, and Talaud on 14- 15 September. On the

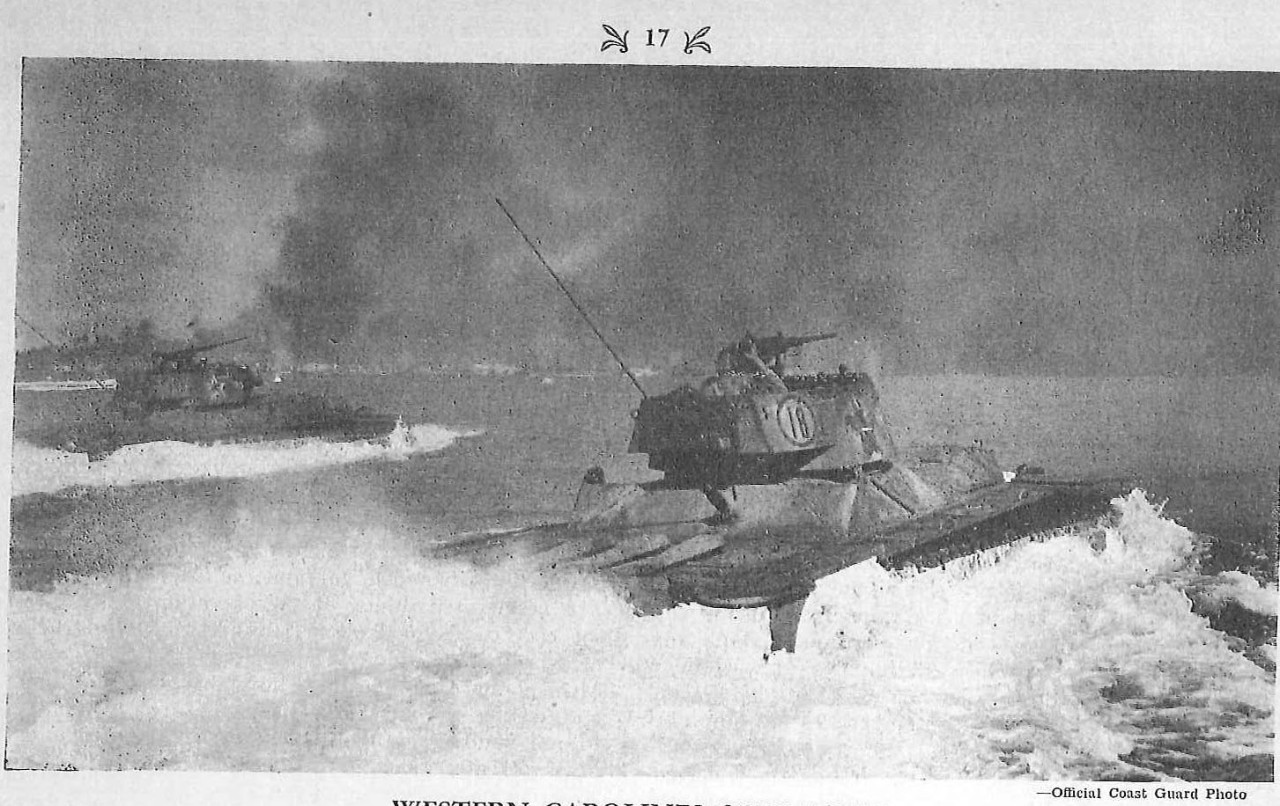

WESTERN CAROLINES OPERATION

Amphibious tanks moving ashore towards, Anguar, 17 September 1944

14th destrOyers bombarded the eastern coast of Mindanao. There was little airborne opposition and our forces destroyed and damaged a number of aircraft and surface ships.

Landings on Peleliu and Angaur

Ships and tr00ps employed in the Western Carolines landings came from various parts of the Pacific. Three days of surface bombardment and air bombing precedes, the landing on Peleliu. During this time mine sweepers cleared the waters of Peleliu and Angaur Islands and underwater demolition teams removed beach obstructions. The Peleliu landing took place on 15 September, the landing force convoys arriving off the selected beaches at dawn. Following' intensive preparatory bombardment, bombing and strafing of the island, units of the lst Marine Division went ashore. Despite difficult reef conditions, the initial landings were successful. The troops quickly overran the beach defenses, which were thickly mined but less heavily manned than usual. By the night of the 16th, the Peleliu airfield, which was the prime objective of the entire operation, had been captured. After the rapid conquest of the southern portion of the island, however, progress on Peleliu slowed. The rough ridge which formed the north— south backbone of the island was a natural fortress of mutually supporting cave positions, organized in depth and with many automatic weapons. Advance along this ridge was slow and costly. The Japanese used barges at night to reinforce their troops, but naval gunfire dispersed and destroyed many of them. Enemy forces had been surrounded by 26 September, although it was not until the middle of October that the assault phase of the operation was completed.

The 81st Infantry Division went ashore on Angaur Island, six miles south of Peleliu, on 17 September. Fire support ships and aircraft had previously prepared the way for the assault transports. Beach conditions here were more favorable than at Peleliu. Opposition also was less severe, and by noon of 20 September the entire is— land had been overrun, except for one knot of resistance in rough country. Prompt steps were taken to develop a heavy- bomber field on Angaur. Part of the Slst Division went to Peleliu on 22 September to reinforce the lst Marine Division, which had suffered severe casualties.

The southern Palau Islands offered no protective anchorage. Before the landings of the 15th, mine sweepers had been clearing the extensive mine fields in Kossol Roads, a large body of reef-enclosed water 70 miles north of Peleliu. Part of this area was ready for an anchorage on 15 September, and the next day seaplane tenders entered and began to use it as a base for aircraft operation. It proved to be a reasonably satisfactory roadstead, where ships could lie while waiting call to Peleliu for unloading, and where fuel, stores and ammunition could be replenished.

Marine troops from Peleliu landed on Ngesebus Island, just north of Peleliu, on 28 September, by a shore-to-shore movement. The light enemy opposition was overcome by the 29th. Later several small islands in the vicinity were occupied as outposts.

No landing was made on Babelthuap, the largest of the Palau group. It was heavily garrisoned, had rough terrain, would have required a costly operation, and offered no favorable airfield sites or other particular advantages. From Peleliu and ‘Angaur the rest of the Palau group is being dominated, and the enemy ground forces on the other islands are kept neutralized.

*18*

As soon as it became clear that the entire 81st Division would not be needed for the capture of Angaur, a regimental combat team was dispatched to Ulithi Atoll. Mine sweepers, under cover of light surface ships, began work in the lagoon on 21 September and in two days cleared the entrance and anchorage inside for the attack force. The Japanese had abandoned Ulithi and the landing of troops on the 23rd Was without opposition. Escort carrier and long range bombers kept the air facilities at Yap neutralized so that there was no aerial interference with landing operations. Although Ulithi was not an ideal anchorage, it was the best available shelter for large surface forces in the Western Carolines, and steps were taken at once to develop it.

Landings on Morotai

Occupation of the southern part of Morotai Island was carried out by the Southwest Pacific forces of General of the Army MacArthur to establish air, air warning and minor naval facilities. This action was further designed to isolate Japanese forces on Halmahera, who would otherwise have been in a position to flank any movement into the southern Philippines. It was timed simultaneously with the seizure of Palau by Pacific Ocean Areas forces. On 15 September 1944 an amphibious task force composed of escort carriers, cruisers, destroyers, destroyer escorts, attack transports and miscellaneous landing ships and craft, all under the command of Rear Admiral (now Vice Admiral) Barbey, approached Morotai. Practically no enemy opposition was encountered, and personnel casualties were light; difficulty was experienced, however, in beaching and unloading, due to coral heads and depressions in the reef adjacent to the landing areas.

Prior to D-day Army land-based planes from Biak and Noemfoor carried out heavy strikes on enemy air facilities in Ceram, Halmahera, northern Celebes, Vogel kop and southern Philippine areas. Carrier fighter sweeps combined with further bombing operations prevented hostile aircraft from reaching Morotai on D—day. Naval gunfire support was furnished by destroyers and two heavy cruisers. During subsequent covering operations we sustained our first naval loss in the Southwest Pacific Area, except for planes and minor landing craft, since the Cape Gloucester operations in December 1943; the destroyer escort SHELTON was torpedoed and sunk by an enemy submarine.

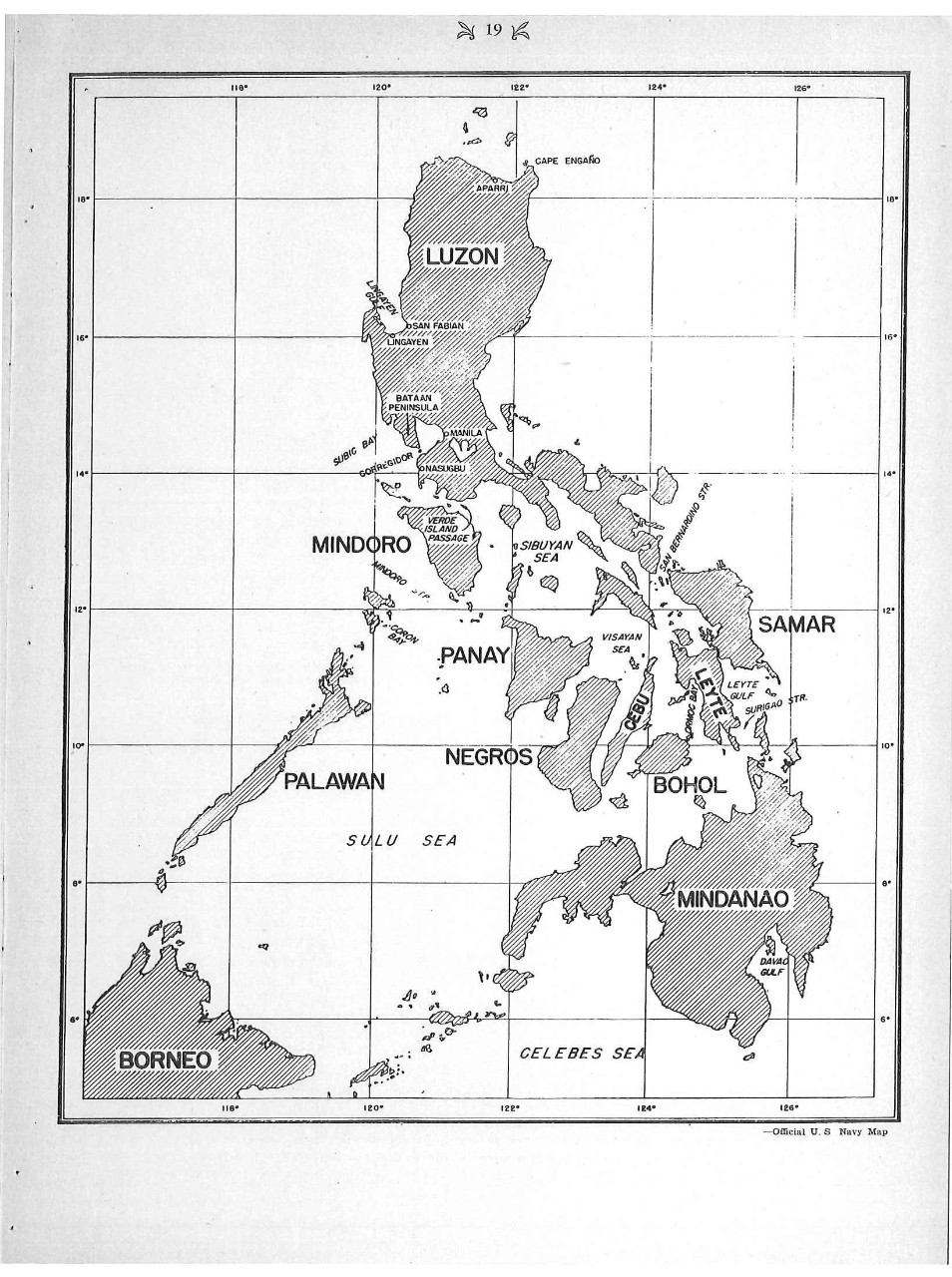

REOCCUPATION OF PHILIPPINE ISLANDS

After providing support for the Palau landings, the Third Fleet fast carrier task force returned to the attack on enemy power in the Philippines. From waters to the east, they conducted the first carrier attack of the war on Manila and Luzon. Under cover of bad weather the carriers approached without detection. On 21 and 22 September planes from the carriers attacked Manila and other targets on Luzon, inflicting severe damage on the enemy and suffering only light losses.

On 24 September carrier planes struck the central Philippines. They completed photographic coverage of the area of Leyte and Samar, where amphibious landings were to take place in October, and reached out to Coron Bay, a much used anchorage in the western Visayas. Many enemy planes and much shipping were destroyed. The light air opposition revealed how effective the first Visayas strikes of 10 days previous had been. Following the strikes of the 24th, the fast carrier task force retired to forward bases to prepare for forthcoming operations.

Initial plans for re-entry into the Philippines intended securing Morotai as a stepping stone with a View to landings by the Seventh Amphibious Force on Mindanao some time in November. The decision to accelerate the advance by making the initial landings on Leyte in the central Philippines was reached in middle September when the Third Fleet air strikes disclosed the relative weakness of enemy air opposition. It was decided to seize Leyte Island and the contingent waters" on 20 October and thus secure airdrome sites and extensive harbor and naval base facilities. The east coast of Leyte offered certain obvious advantages for amphibious landings. It had a free undefended approach from the east. suflicient anchorage area, and good access to the remainder of the central islands in that it commanded the approaches to Surigao Strait. Moreover, the position by passed and isolated large Japanese forces in Mindanao. The accelerated timing of the operation and choice of the east coast for landing required, however, the acceptance of one serious disadvantage—the rainy season. Most of the islands in the Philippines are mountainous and during the northeast monsoon, from October to March, land areas on the east sides of the mountains have torrential rains.

Forces under General of the Army MacArthur carried out the landings in the Philippine Islands. For this purpose many transports, fire support ships and escort carriers were temporarily transferred from the Pacific Fleet to the Seventh Fleet, which is a part of the Southwest Pacific command. The Central Philippine Attack Force, composed of Seventh Fleet units, greatly augmented by Pacific Fleet forces, was under the command of Vice Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid. This large force was divided into the Northern Attack Force (Seventh Amphibious Force, Rear Admiral [now Vice Admiral] Barbey commanding) and the Southern Attack Force (Third Amphibious Force, Vice Admiral Wilkinson commanding), plus surface and air cover groups, fire support, bombardment, mine sweeping and supply groups. It comprised a total of more than 650 ships, including battleships, cruisers, destroyers, destroyer escorts, escort carriers, transports, cargo ships,landing craft, mine craft, and supply vessels. Four army divisions were to he landed on D-day.

The Third Fleet, operating under Admiral Halsey, was to cover and support the operation by air strikes over Formosa, Luzon and the Visayas, to provide protection for the landing against heavy units of the Japanese fleet, and to destroy enemy vessels when opportunity offered.

Preliminary Strikes by Fast Carrier Task Force

Preparatory strikes to obtain information on installations, and to destroy air and surface strength, which might hinder our success in the Philippines, lasted from 9 to 20 October.

While a cruiser-destroyer task group bombarded and damaged installations on Marcus Island on 9 October, ships of the fast carrier forces were approaching the Nansei Shoto [Ryukyu Islands]. Long range search-planes and submarines “ran interference” for the force, attacking and destroying enemy search-planes and picket boats, so that our heavy forces achieved tactical surprise at their

*20*

objective. Carrier aircraft attacked Okinawa Island in the Nansei Shoto on 10 October. The Japanese apparently were taken by surprise. Not only was little airborne opposition met, but shipping had not been routed away from the area. Many enemy ships were sunk and airfields and facilities severely damaged.

On 11 October while the force was refueling, a fighter sweep against Aparri on the northern end of Luzon disorganized the relatively underdeveloped and lightly garrisoned fields there.

The next attack, on Formosa and he Pescadores, took place on 12 and 13 October. These strikes on aviation facilities, factory warehouses, wharves and coastal shipping, were expected by the enemy and, for the first time in this series of operations, a large number of enemy planes were over the targets and antiaircraft fire was intense. In spite of opposition, 193 planes were shot down on the first day and 123 more were destroyed on the ground.

At dusk on the 13th, part of the task force was skillfully attacked by aircraft and one of our cruisers was damaged. Although power was lost, the ship remained stable, due to prompt and effective damage control, and was taken in tow. With a screen of cruisers and destroyers, and under air cover from carriers, the slow retirement of the damaged ship began. At that time, the group was 120 miles from Formosa and within range of enemy aircraft on Okinawa, Luzon, and Formosa. Enemy planes kept the group under constant attack and succeeded in damaging another cruiser on the evening of the 14th. She also was taken in tow, and both vessels were brought safely to a base for repairs.

In order to prevent further air attacks while the damaged ships retired, the carriers launched repeated fighter sweeps and strikes over Formosa and northern Luzon on 14 and 15 October.

Beginning on 18 October the carrier planes again struck the Philippines. In strategical as well as direct tactical support of the landings of Southwest Pacific forces at Leyte on the 20th, the strikes of the 18th and 19th were aimed at the northern and central Philippines. On 20 October, some of the fast carriers furnished direct support to the Leyte landing and others conducted long ranged searches for units of the enemy fleet. Thus, Japanese airfields in and around Manila and in the Visayas were kept neutralized during the initial assault phase of the Leyte landing, while at the same time carrier planes from the Third Fleet furnished direct support to the landings by bombing and strafing beaches and interior areas on Leyte throughout the day. On 21 October, there were sweeps and strikes as far west as Coron Bay. Carrier planes also continued long-range searches with negative results.

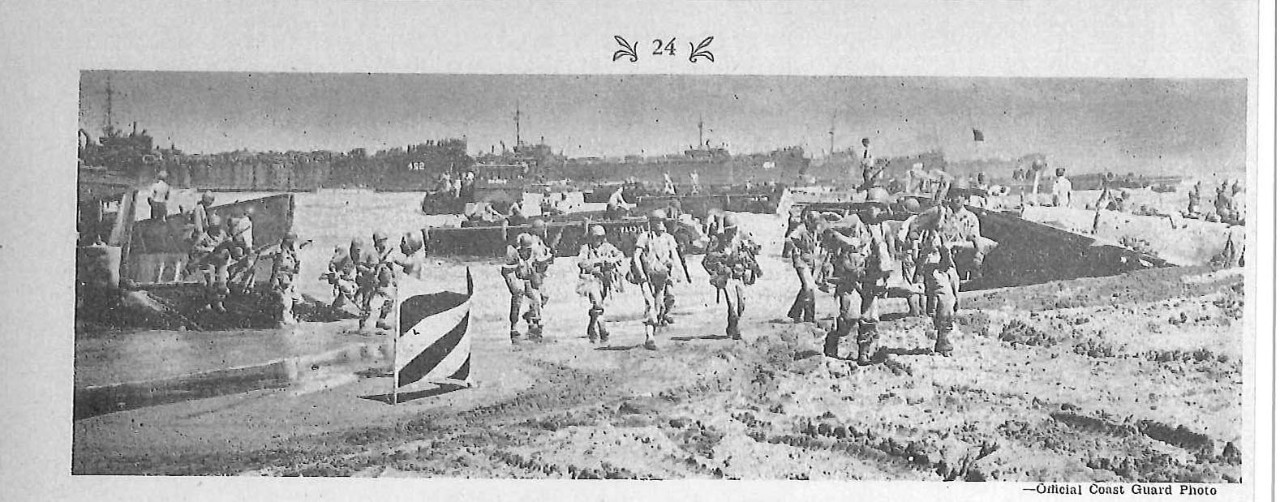

Leyte Landings

During the 9 days preceding the landing on Leyte, the task groups sortied from New Guinea ports and the Admiralties and moved toward Leyte Gulf. On 17 October (D-minus-3 day) preliminary operations commenced under difficult weather conditions. By D-day the islands guarding the eastern entrances to Leyte Gulf were secured. The approach channels and landing beaches were cleared of mines and reconnaissance of the main beaches on Leyte had been effected.

After heavy bombardment by ships’ guns and bombing by escort carrier planes had neutralized most of the enemy opposition at the beaches, troops of the 10th and 24th Corps were landed, as scheduled on the morning of 20 October. The landing were made without difficulty and were entirely successful. Our troops, were established in the central Philippines, but it remained for the naval forces to protect our rapidly expanding beachheads from attack by sea and air.

In the amphibious phase of the Leyte operation. YMS 70 sank in a storm during the approach and the tug Sonoma and LCI (L) 1065 were sunk by enemy action. The destroyer Ross struck a mine on 19 October and the light cruiser Honolulu was seriously damaged by an aerial torpedo on 20 October.

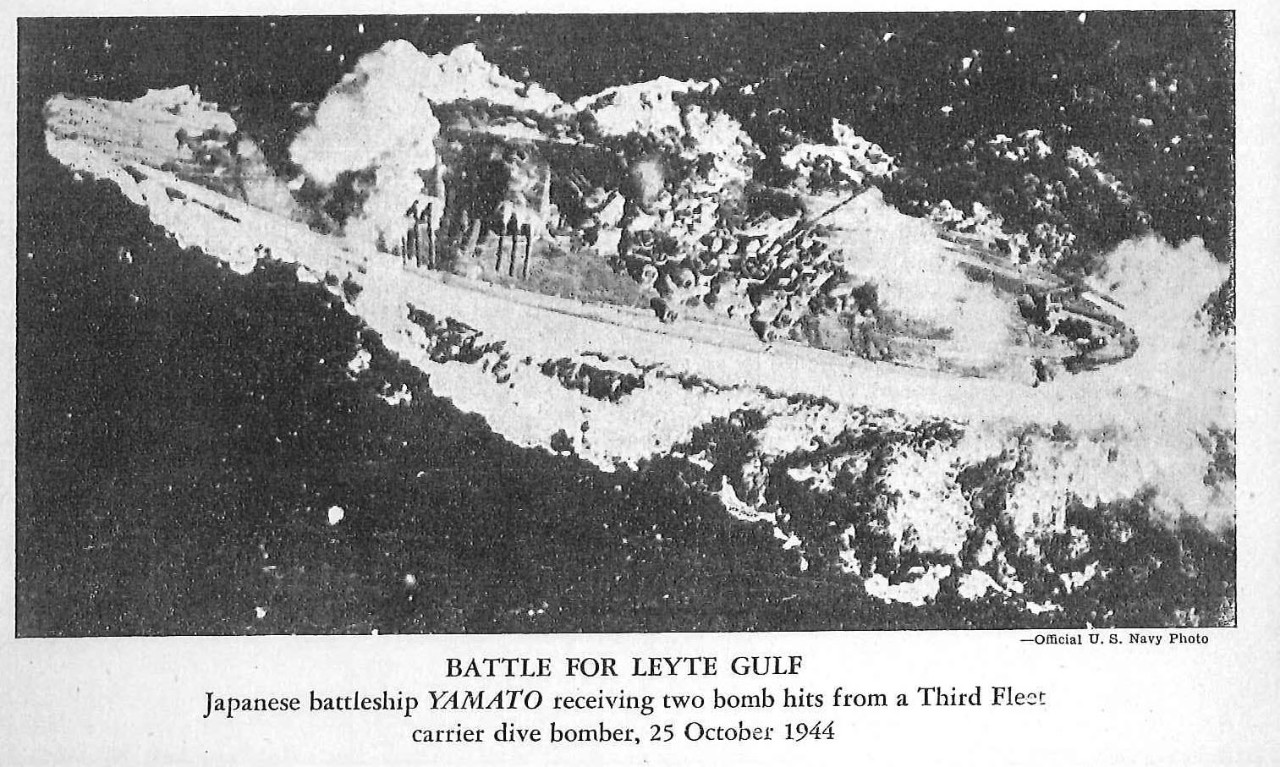

Battle for Leyte Gulf

The Leyte landings were challenged by Japanese naval forces determined to drive us from the area. Between 23 and 26 October, a series of major surface and air engagements took place with far reaching effect. These engagement, which have been designated the Battle off Samar, and the Battle off Cape Engano. They involved the battleships, carriers, and escort carriers, cruisers, destroyers and destroyer escorts of the Third and Seventh Fleets, as well as PT boats and submarines.

Three enemy forces were involved. One of these, referred to hereinafter as the Southern Force, approached Leyte through Surigao Strait and was destroyed there by Seventh Fleet units on the night of 24-25 October. A second, or Central Force, passed through San Bernardino Strait in spite of previous air attacks by Third Fleet carrier planes and attacked Seventh Fleet escort carriers off Samar on the morning of the 25th. Finally, a Northern Force approached the Philippines from the direction of Japan and was attacked and most of it destroyed by the Third Fleet fast carrier force on the 25th.

On the early morning of 23 October two submarines, Darter and Dace, n the narrow channel between Palawan and the Dangerous Ground to the westward discovered the Central Force, then composed of 5 battleships, 10 heavy cruisers, 1 or 2 light cruisers, and about 15 destroyers. These submarines promptly attacked, reporting four torpedo hits in each of three heavy cruisers, two of which were sunk and the third heavily damaged. Darter, while maneuvering into position for a subsequent attack, grounded on a reef in the middle of the channel, and had to be destroyed after her crew had been removed. Other contracts were made later in the day in Mindoro Strait and off the approach to Manila Bay, resulting in damage to an enemy heavy cruiser.

On the 24th carrier planes located and reported the Central Force (in the Sibuyan Sea) and the Southern Force (proceeding through the Sulu Sea) and the Sothern Force (proceeding through the Sulu Sea) sufficiently early to permit aircraft from Vice Admiral Mitscher’s fast carriers to inflict substantial damage.

The third enemy force, the Northern, was not located and reported until so late on the afternoon of the 24th, that strikes could not be launched against it until the next morning. While these searches and strikes were being made, the northernmost of our fast carrier task groups was subjected to constant attacks by enemy land-based planes.

*21*

Although about 110 planes were shot down in the vicinity of the group, one of the enemy aircraft succeeded in bombing the light carrier Princeton. Large fires broke out on the damaged carrier and despite heroic efforts of cruisers and destroyers to combat them, Princeton suffered a series of devastating explosions which also caused damage and casualties to ships along-side. After hours of effort to save the ship, it became necessary to move the task group to meet a new enemy threat (the reported sighting of the Northern Force), and Princeton was sunk by torpedo fire from our own ships. It should be noted, that Princeton was the first fast carrier lost by the United States Navy since the sinking of Hornet in the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands on 26 October 1942.

Battle of Suriago Strait

A part of the enemy’s Southern Force entered Surigao Strait in the early hours of 25 October 7 ships (2 battleships, 1 heavy cruiser and 4 destroyers) advanced in rough column up the narrow strait during darkness toward our waiting forces. The enemy was first met by our PT boats, then in succession by three coordinated destroyer torpedo attacks, and finally by devastating gunfire from our cruisers and battleships which had been disposed across the northern end of the strait by the officer in tactical command, Rear Admiral (now Vice Admiral) J. B. Oldendorf. The enemy was utterly defeated. This action is an exemplification of the classical naval tactics of “crossing the T”. Rear Admiral Orldendorf had deployed his light forces on each flank of the approaching colum and had sealed off the enemy’s advance through the strait with his cruisers and battleships. By means of this deployment, he was able to concentrate his fire, both guns and torpedoes, on the enemy units before they were able to extricate themselves from the trap. The Japanese lost, 2 battleships and 3 destroyers almost before they could open fire. The heavy cruiser and one destroyer escaped, but the cruiser was sunk on the 26th, by our planes. Other ships of the Southern Force which did not engage in the night battle were either later sunk or badly damaged by aircraft attack. In the night action, the destroyer Albert W. Grant, was severely damaged by gunfire, our other ships suffered no damage.

Battle off Samar

Throughout the 24th the Third Fleet carriers launched strikes against the Central Force which was heading for San Bernardino Strait. This force consisted of 5 battleships, 8 cruisers and 13 destroyers. As they passed through Mindoro Strait and proceeded to the eastward, our planes launched vigorous attacks which sank the new battleship Musashi-pride of the Japanese Navy, 1 cruiser and 1 destroyer, and heavily damaged other units, including the battleship Yamato, sister ship of Musashi, with bombs and torpedoes. In spite of these losses and damage which caused some of the enemy ships to turn back, part of the Central Force continued doggedly through San Bernardino Strait and moved southward unobserved off the east coast of Samar. Our escort carriers with screens, under the command of Rear Admiral T. L. Sprague, were dispersed in three groups to the eastward of Samar, with the mission of maintaining patrols and supporting ground operations on Leyte. Shortly after daybreak on 25 October, the Japanese Central Force, now composed of 4 battleships, 5 cruisers and 11 destroyers, attacked the group of escort carriers commanded by Rear Admiral C. A. F. Sprague. A running fight ensued as our lightly armed carriers retired toward Leyte Gulf.

*22*

The 6 escort carriers, 3 destroyers and 4 destroyer escorts of Rear Admiral C. A. F. Sprague’s task group fought valiantly with their planes, guns and torpedoes. Desperate attacks were made by planes and escorts, and smoke was employed in an effort to divert the enemy from the carriers. After two and one-half hours of almost continuous firing, the enemy broke off the engagement and retired towards San Bernardino Strait. Planes from all three groups of escort carriers, with the help of Third Fleet aircraft, which struck during the afternoon of the 25th, sank 2 enemy heavy cruisers and 1 destroyer. Another crippled destroyer was sunk and several other enemy ships were either sunk or badly damaged on the 26th as our planes followed in pursuit.

In the surface engagement, the destroyers Hoel and Johnston, the destroyer escort Roberts and the escort carrier Gambier Bay, were sunk by enemy gunfire. Other carriers and escort ships, which were brought into the fray sustained hits; these included Suwanee, Santee, White Plains and Kitkun Bay. Enemy dive bombers on the morning of 25 October sank the escort carrier Saint Lo. Approximately 105 planes were lost by Seventh Fleet escort carriers during the Battle for Leyte Gulf.

Battle off Cape Engano

Search planes from Third Fleet carriers had located the enemy Southern and Central Forces on the morning of 24 October, and had ascertained that they were composed of battleships, cruisers and destroyers, without aircraft carriers. As it was evident that the Japanese Navy was making a major effort, Admiral Halse reasoned that there must be an enemy carrier force somewhere in the vicinity. Consequently he ordered a special search by one of our carrier planes on the afternoon of the 24th of the enemy Northern Force-a powerful collection of carriers, battleships, cruisers and destroyers-standing to the southward.

During the night of the 24th-25th, our carrier task force ran to the northward and before dawn launched planes to attack the enemy. Throughout most of 25 October, the Battle off Cape Engano (so named from the nearest point of land at the northeastern tip of Luzon Island) went on with carrier aircraft striking the enemy force, which had been identified as consisting of 1 large carrier, 3 light carriers, 2 battleships with flight decks, 5 cruisers and 6 destroyers. Beginning at 0840 air attacks on these ships continued until nearly 1800. Late in the day, a force of our cruisers and destroyers was detached to finish off ships, which had been crippled by air strikes. In that day’s work all the enemy carriers, a light cruiser, and a destroyer were sunk, and heavy bomb and torpedo damage was inflicted on the battleships and other Japanese units.