The Navy Department Library

The Russian Navy Visits the United States

The Russian Squadron in New York, 1863

PDF Version [19.2MB]

FOREWORD

The story of the relations between the United States and Russia during our Civil War is not an

oft-told tale.

In this pamphlet, the Foundation attempts to acquaint its readers with some of the international involvement at that time. It also gives some of the highlights of the visits of the Atlantic and Pacific Squadrons of the Russian Navy to United States Atlantic and Pacific ports.

In spite of ideological differences, national interests and fear of a common foe often produce international partnerships with far-reaching results. Such a partnership between the United States and Russia, two countries which were the very antithesis of each other, is considered to have contributed to preventing European intervention in our Civil War and to keeping an Anglo-French alliance from interfering in the Russian-Polish dispute.

Lincoln found this relationship in the best interests of the welfare of the Nation. His policy was built on his confidence in America. He had faith in democracy and believed that a strong and united America with unchallengable [sic] power could maintain a lasting peace for his country.

On 27 February 1860, at Cooper Union, Lincoln said:

Neither let us be slandered from our duty by false accusations against us, nor frightened from it by menaces of destruction to the government, nor dungeons to ourselves. Let us have faith that right makes might, and in that faith let us to the end dare to do our duty as we understand it.1

Copyright- Naval Historical Foundation- 1969

THE RUSSIAN NAVY VISITS THE UNITED STATES

During the Civil War, all of the world powers were technically neutral. On 13 May 1861, the day Charles Francis Adams arrived in London as the United States Minister to the Court of St. James, and before official news of the blockade of the coast line of the seceded States had been received in that country, Great Britain issued her formal proclamation enjoining strict neutrality upon her subjects. France, Spain, The Netherlands, Brazil and other maritime nations followed with similar proclamations. This action was not favorably received in the North because it meant the recognition of the Confederate flag on the high seas. In addition, it granted Confederate ships privileges in neutral ports equal to those offered ships of the Federal government.

Just prior to the Civil War, however, the trials which democracy in the United States was experiencing was of interest to many of the world powers. It was in the interest of some to see the Union split in two. Independence of the Confederacy would weaken a growing and dangerous commercial competitor. “King Cotton” could rule again. A divided United States was of interest to others because that would, in their opinion, weaken the effectiveness of the Monroe Doctrine and the prospect of its enforcement. The point of common interest, however, was who was to be the winner in the event of a divided United States.

In England, the landed aristocracy had much in common with their counterparts in the Southern states. The working class, however, was sympathetic to the North for its anti-slavery attitude as upholding the cause of free white labor. The British government could find it quite expedient, therefore, at least to proclaim neutrality. Actually, so long as England considered the objective of the war as extending only to the restoration of the Union, rather than to the freeing of the slaves, the sentiment was against the North. A divided United States gave Britain a sense of greater security.

That was not a situation peculiar to Great Britain. Early in 1861, Spain had occupied the revolting island of Santo Domingo. On that occasion Edouard de Stoeckl, the Russian Minister to the United States, advised his government that Garcia y Don Gabriel Tassara, the Spanish Minister to the United States, assured him that “…if Lincoln dared to threaten Spain, his government would immediately recognize the independence of the Southern Confederacy…”2 In Prussia, only the Junker class was in sympathy with the South. The masses in that country were enthusiastic for the cause of the North and many volunteered to serve in the Union Army.

France, under Napoleon III, was probably the most persistent European anti-Northern country. Striving for world power and prestige, it was pleased at the prospect of a divided United States

1

that would be less effective in the enforcement of the Monroe Doctrine, which Napoleon considered as standing in the way of his plans for a French colonial empire. The political chaos then prevailing in Mexico led him to conclude that it offered an appropriate jumping-off place for devitalizing the Doctrine. The Emperor laid plans to establish Archduke Maximilian on the throne in Mexico. The Archduke was a brother of the Austrian Emperor which enhanced the sentient for the South in the Vienna Court. As early as April 1861, the French Minister, Henri Mercier, made overtures to Lord Lyons, the British Minister, and Edouard de Stoeckl, the Russian, to have them obtain the authority of their respective governments to recognize the Confederacy when the considered “the right time” had come.3 Actually, Mercier’s moves were unproductive because neither of them was willing to act.

The only important European country which was not openly anti-Northern was Russia. In fact, the attitude of the Russian government was so especially friendly as to be noticeably contrasting with that of other European nations. Russian officers volunteered for and fought in the Northern armies. Colonel John B. Turchin, the “Mad Cossack,” was court-martialed after his men helped to sack the Southern city of Athens. He, nevertheless, was appointed Brigadier General and marched with Sherman to the sea.4

The contrast in which Russia, with its absolutism, favored a democratic North, while the monarchical classes throughout Europe favored the South is to be noted. Russia was certainly no champion of democracy, but it was to her interest in the balance of power to favor a strong, and united United States.

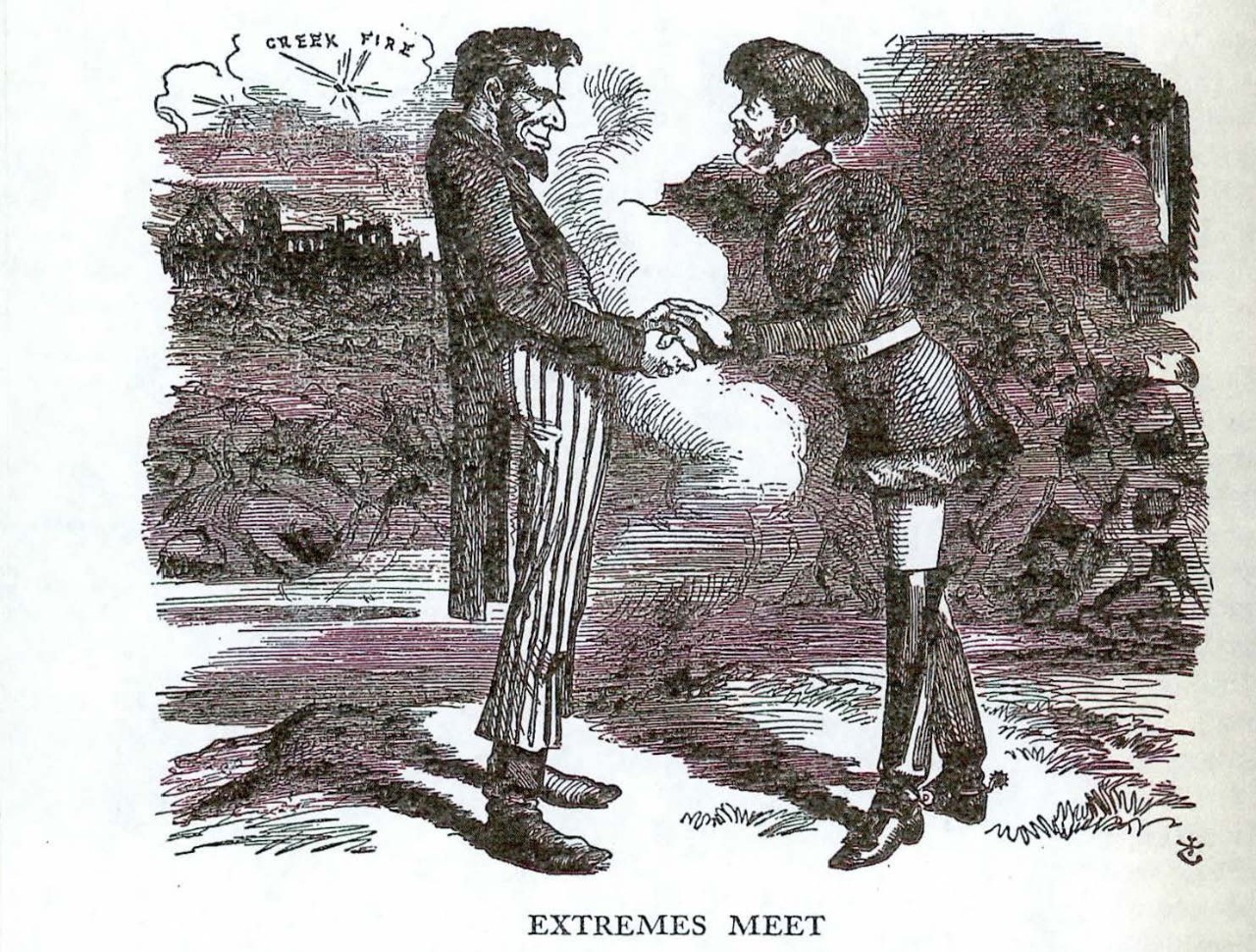

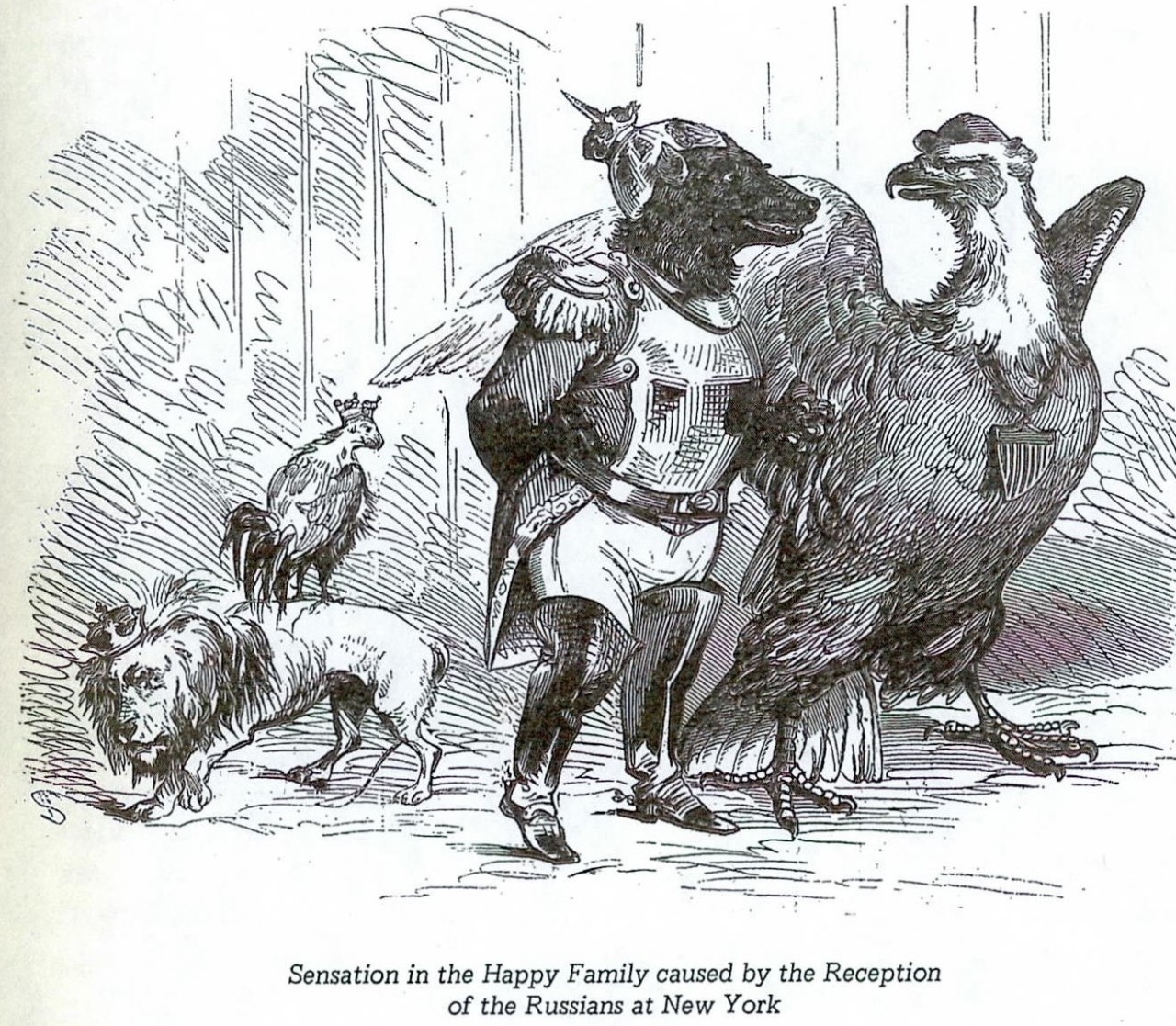

Then, too, there was the problem common to both the United States and Russia: Lincoln and his seceding States and Alexander II, his rebellious Poles. The London PUNCH ran a cartoon that had Lincoln saying to the Czar:

Imperial son of Nicholas the Great,

We air in the same fix, I calculate,

You with your Poles, with Southern rebels I,

Who spurn my rule and my revenge defy.5

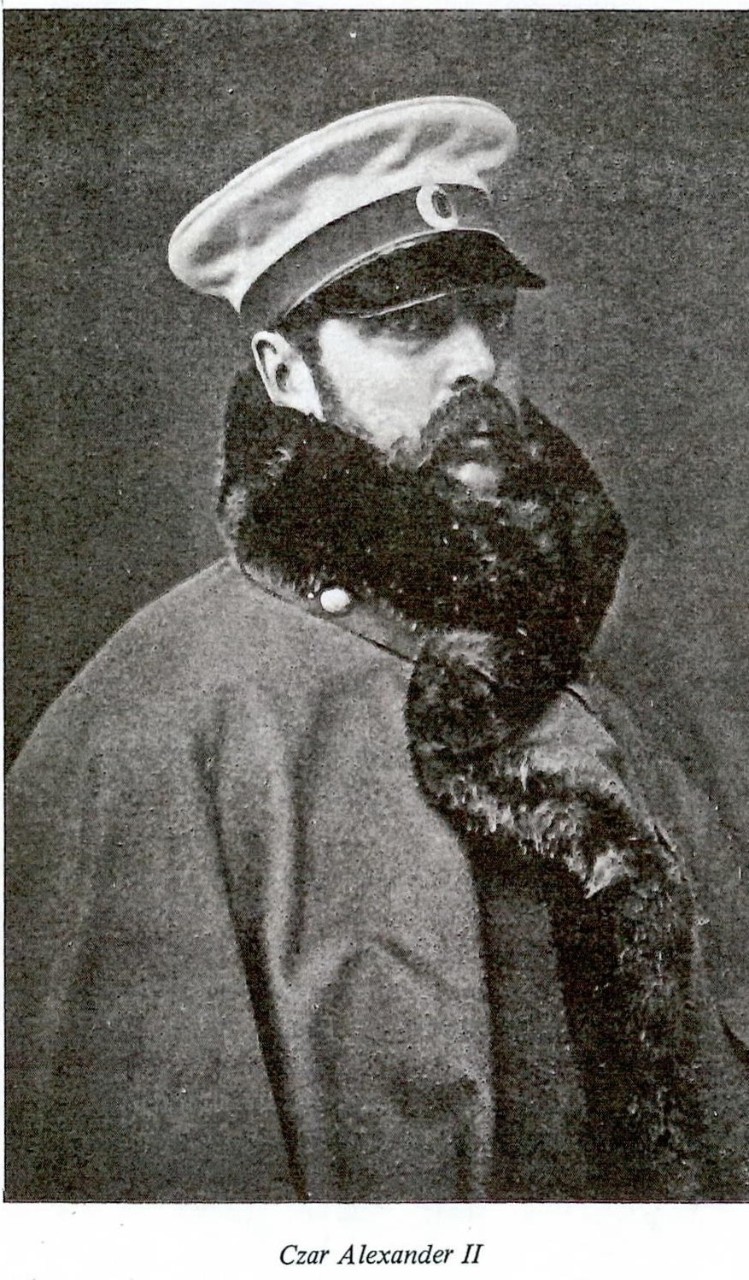

The Poles were restless because of the political condition which had been imposed on them by the former Czar, Nicholas I. They had expected a change for the better from his successor, Alexander II. When this did not happen, discontent grew and, in February 1861, open opposition became apparent. During the next two years, it ballooned to such proportion that it became the concern of most European nations. It was climaxed in 15 January 1863 when Russian police invaded many homes in Warsaw to seize males for army service.

Prussia sided with Russia in this matter and, in February 1863, concluded a military convention binding the two nations to put down the Polish revolt. Bismarck offered to send military assistance to the Czar. France, England and Austria joined against the Russians.

2

Napoleon III was especially favorable to the Polish cause because his Minister of State was Count Walewska. France was successful in getting these other countries to join her. In successive but unanswered notes to Russia, they contended that by reason of the Congress of Vienna in 1815, the Polish question was an international one; all signatory nations, therefore, should have a voice in the solution of the problem and would countenance no outside interference.

The Polish problem was a delicate one for the American people. They appreciated the good will of the Czar, but they were also sympathetic to the cause of liberty to which the Poles were dedicated. The influx of Catholic immigrants intensified interest in the Roman Catholic Poles. Aid committees were set up, funds were raised and mass meetings in behalf of the Poles were held throughout the North. Senator Charles Sumner, Chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee, created a sensation in New York. In a speech, he broke a lance for the oppressed Poles, belittled the friendship of Russia and declared in effect that Switzerland was the only real friend the United States had in Europe.6

The State Department followed a course guided by our national interest. Secretary Seward gave courteous refusals to the requests of both France and Great Britain that the United States might join in a mediation scheme to help the Poles. In addition, the United States was looking toward the end of the war and telling France to get out of Mexico. It was not a love for the Czar that kept the UnitedStates [sic] out of the Polish problem, but rather a decision in accord with the prevailing foreign policy. Russia was deeply appreciative of this attitude. Other nations were not—and the London TIMES wrote, on 15 October 1863: “No American can see anything wrong in a Polish war to which that carried on in Virginia and Tennessee bears so strong a resemblance.”

It will be recalled, too, that in 1861 Alexander II issues a manifesto freeing about twenty million serfs. This was done without a civil war. Naturally, the anti-slavery group in the North was pleased with this action of the Czar. Horace Greeley, in the New York TRIBUNE applauded the Christianity of the Czar and condemned the attempt of the South to “make slavery perpetual.” The Richmond EXAMINER replied with its own comparison by saying that Alexander was enslaving the Poles while freeing the serfs; and Lincoln was trying to free black slaves while subjugating white Southerners.7 The Russians could not forget the outspoken sympathies which the United States had expressed during the Crimean War. The mutual feelings were further strengthened by the attitude of both countries toward Great Britain. At that time, United States and Russia were trying to build their industrial power behind tariff barriers. England, with a strong industrial base, was a free trader.

3

The United States Congress, in 1861 (after enough Southern senators had withdrawn), had passed the Morrill Protective Tariff Act. When Cassius Clay, who was then American Minister in St. Petersburg, made a speech favoring protectionism, he was enthusiastically applauded by his Russian audience.8 Of course, the Czar was not embarrassed by public opinion in his own country. As the New York NATION remarked, pro-Northernism was a wise policy for the Russians. If the Union won, it would be grateful; if the South won, it would be so elated that it would quickly forget its grievance against Russia.

The relationship, at this time, between the United States and Russia— “two of the most mismatched international bedfellows in all recorded history”—is hard to explain.9 The two had a common rival in Great Britain, which acted as an incentive to bring strength

4

and encouragement to both nations when they most needed it. And, although poles apart ideologically, realistic international politics came into play to have them meet in political collaboration. As early as 10 July 1861, Prince Gortchakov, the Russian Minister for Foreign Affairs, speaking for the Emperor, sent a lengthy note to Edouard de Stoeckl, Minister Plenipotentiary to the United States which was intended for Lincoln’s eyes. The last two paragraphs are especially interesting:

I do not wish here to approach any of the questions which divide the United States. We are not called upon to express ourselves in this contest. The preceding considerations have no other object than to attest the lively solicitude of the Emperor, in presence of the dangers which menace the American Union, and the sincere wished which His Majesty entertains for the maintenance of that great work, so laboriously raised, which appeared so rich in its future.

It is in this sense, sir, that I desire you to express yourself, as well to the members of the general government as to influential persons whom you may meet, giving them the assurance that in every event the American nation may count upon the most cordial sympathy on the part of our August master, during the serious crisis which it is passing through at present.10

Stoeckl hastened to have the note translated and sent to the President, with a copy to Secretary of State Seward. With permission of the Russian Minister, wide publicity was given to the note which lifted the morale of the North. On 9 September, Stoeckl advised Gortchakov that President Lincoln said to him: “Please inform the Emperor of our gratitude and assure His Majesty that the whole nation appreciates this new manifestation of friendship.” In that same year, when the TRENT affair, which almost brought the United States to the brink of war with England, was finally settled, another note of warm satisfaction was forthcoming from the Russian Foreign Minister. President Jefferson Davis, in his effort to win recognition from the Czar’s government, appointed Lucius Q. C. Lamar a Commissioner to Russia in November of 1862. He went to St. Petersburg, but Prince Gortchakov delayed his official reception to such an extent that Davis brought Lamar home.

The autumn of 1862 was a desperate period of the rebellion and a dangerous one from the standpoint of foreign intervention in the Civil War. On 31 October, Lord Cowley, British Ambassador to Paris, wrote that the French Premier, Drouyn de Lhuys, “by the Emperor’s orders” had informed him that a despatch [sic] was about to be sent to the French Ministers in London and St. Petersburg instructing them to request joint action to suggest an armistice of six months, including the suspension of the blockade, which would throw Southern ports open to commerce.12 This renewed the crisis in the British cabinet, and its decision not to participate in

5

the mediation was not announced until 13 November. Prior to that date, Lord Russell had been advised by Lord Napier in St. Petersburg that Russia would not join, but would support the French-British proposals through her Minister in Washington, “provided it would not cause irritation.”13

Two days after the decision of Great Britain, Bayard Taylor, the United States Chargé d’ Affaires in St. Petersburg, wrote Secretary Seward:

While I infer…that Russia would, to a certain extent, be inclined to take part in a movement which she foresaw to be inevitable to take part of England and France, rather than permit a coalition between these two powers from which she should be wholly excluded, the probable refusal of the English government announced today by telegraph relieves me from all apprehension of complications that might arise from the proposition. I stated to Prince Gortchakov, at our recent interview, my belief that England would not accede, and am very glad it so soon confirmed.14

In spite of the friendly attitude of Russia toward the North, and her willingness to join the mediation effort, it was really the attitude of Great Britain which was the deciding factor that avoided intervention in the war.

It is interesting to note that, when Great Britain learned of Lee’s invasion of Maryland, she decided to await results. The outcome at Antietam led Lincoln to launch his preliminary emancipation proclamation. On 22 September 1862, five days after McClellan’s defeat of Lee at Antietam, Lincoln summoned his Cabinet and declared:

I made a solemn vow before God, that if General Lee was driven back from Pennsylvania, I would crown the result by a declaration of freedom to the slaves.15

This led to a commitment to free the slaves as well as to preserve the Union.

If Antietam had been a decisive Confederate victory, it is possible that both France and Great Britain may have intervened even without Russia. It was Great Britain and not Russia that was the influencing power in the question of European non-intervention.

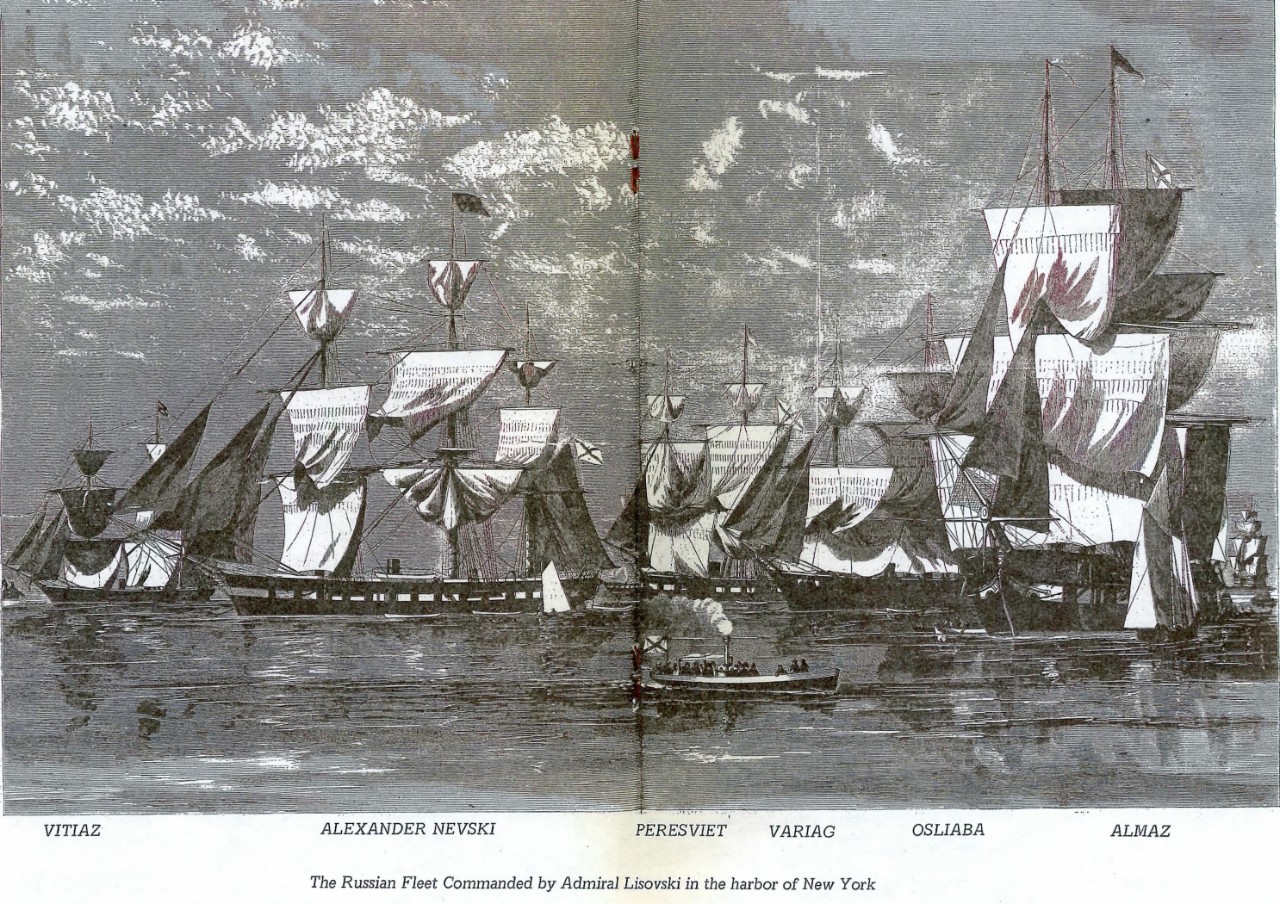

While all this was transpiring, one of the most unusual events in diplomatic and naval history occurred. Russia dispatched her Atlantic and Pacific Naval Squadrons to United States ports. They arrived in New York and San Francisco respectively in September 1863, at a time when the tide of war had turned in favor of the North at Gettysburg and Vicksburg. The fleets remained in United States waters for about seven months before being ordered to return to their homeland.

As early as January 1862, Grand Duke Constantine, General-Admiral of the Russian Navy, had plans for the navy in the event European nations started a war against Russia. Admiral Popov

6

was proceeding to take command of the Pacific Squadron at that particular time. He was instructed, in the event of war between Russia and a stronger power, to order his weaker ships to safe harbors and to use the remainder to destroy enemy commerce. He spent the summer of 1862 having his ships visit different ports in his command area, training his crews, and getting acquainted with the situation. He, himself, made Sitka, Esquimalt, and San Francisco—the last in late September. On return, he visited Honolulu and arrived in Nagasaki in November of that year.

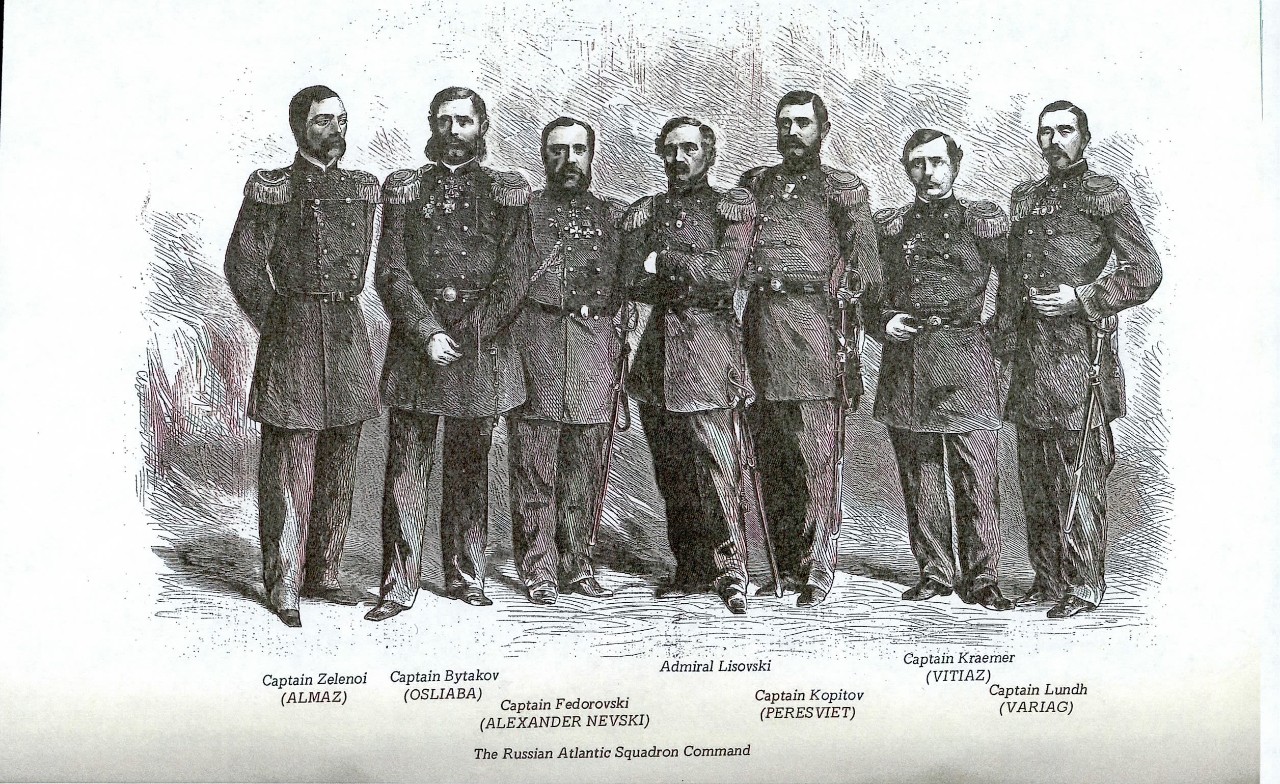

In June of 1863, when war appeared to be inevitable, General-Adjutant Krabbe, who was acting while the Grand Duke was absent in Warsaw, began to work on a plan of campaign. The fleet, comprised a small squadron in the Pacific, seven ships of various descriptions at Kronstadt, and one frigate in the Mediterranean. The Ships were of wooden construction, rigged for sail, but with auxiliary steam engines for use when necessary. It was realized that these ships could not stand up against the British navy. Krabbe did point out, however, in his report to the Emperor that they could be used as raiders. To insure [sic] their availability for such missions, the report included the warning that the ships should not be caught in icebound ports and British controlled waters; that they would have to be sailed to neutral ports; and, to avoid suspicion, would have to be dispatched swiftly. The intent of the plan and destination had to be kept a secret from all hands until the last moment. The Emperor subscribed to this proposal and preparations to carry it out began under the plans to be ready for two years foreign service. Rear Admiral Unkovski was offered command of the Atlantic Squadron. When he did not accept, Captain Lisovski was promoted to flag rank and given the command.

On 26 July 1863, Krabbe gave Lisovski his instructions as approved by the Emperor:

Your fleet is to consist of three frigates, three clippers, and two corvettes. In case of war destroy the enemy’s commerce and attack his weakly defended possessions. Although you are primarily expected to operate in the Atlantic, yet you are at liberty to shift your activities to another part of the globe and divide your forces as you think best. After leaving the Gulf of Finland proceed directly to New York. It would be preferable to keep all the ships in that port, but if such an arrangement is inconvenient for the American government you may, with the advice of our representative in Washington, dispose of the vessels among the various Atlantic ports of the United States. When you learn that war has been declared it is left to you how to proceed, where to rendezvous, etc. Our minister will help you in matters of supplies; he will have on hand a specially chartered boat to keep you informed of what is going on. Should you find out on the way that war has broken out begin

7

operations at once. If soon after reaching New York you deem it wise to go to sea to keep your fleet together until war is actually declared, but avoid the enemy, even commercial ships, so as to cover your tracks. If through our minister or some other reliable source you are told of the opening of hostilities dispose of your ships and plan your campaign as may seem best. Captain Kroun is preceding you to America to prepare for your coming. Study the Treaty of Paris so as to be well informed on matters of neutrality. Should you meet with Rear-Admiral Popov consult with him as to the course to be pursued. Communicate in cipher. Hand in person your secret instructions to the officers. Whether there is war or not make a study of the commercial routes, of the strength and weakness of the European colonies, of desirable coaling stations for our fleet, and of the economic and military importance of our own possessions. These instructions are made purposely general in order to give you a free hand to act according to your judgement and discretion.16

Admiral Popov, in command of the Pacific Squadron about the same time, was given similar instructions: “On receipt of news concerning the outbreak of warlike activities” to direct his ships towards vulnerable places of enemy power and inflict injuries on lines of trade communications. No place in these orders to the Squadron Commanders does one find instructions to help the North, or anything about “sealed orders,” or of turning the ships over to President Lincoln in case of foreign intervention to the American war.17

On 3 August, Popov wrote the Russian Minister of Marine that he had selected San Francisco, and gave as his reason:

I took such a decision because I do not have here any other information besides my own views, which tell me that our [Far Eastern] ports are unfavorable for the concentration, just as they do not represent any fortunate means either for provisioning the squadron or for the indispensable repairs…The republics of Central and South America do not seem inclined to turn us out of their ports, although they are indeed swamped with Poles. [But] they, too, as in Mexico, do not hinder either the French or the English from spying on our squadron in their roadsteads. There remains, therefore, the United States of America which England and France have worried to the utmost by their recent interference.18

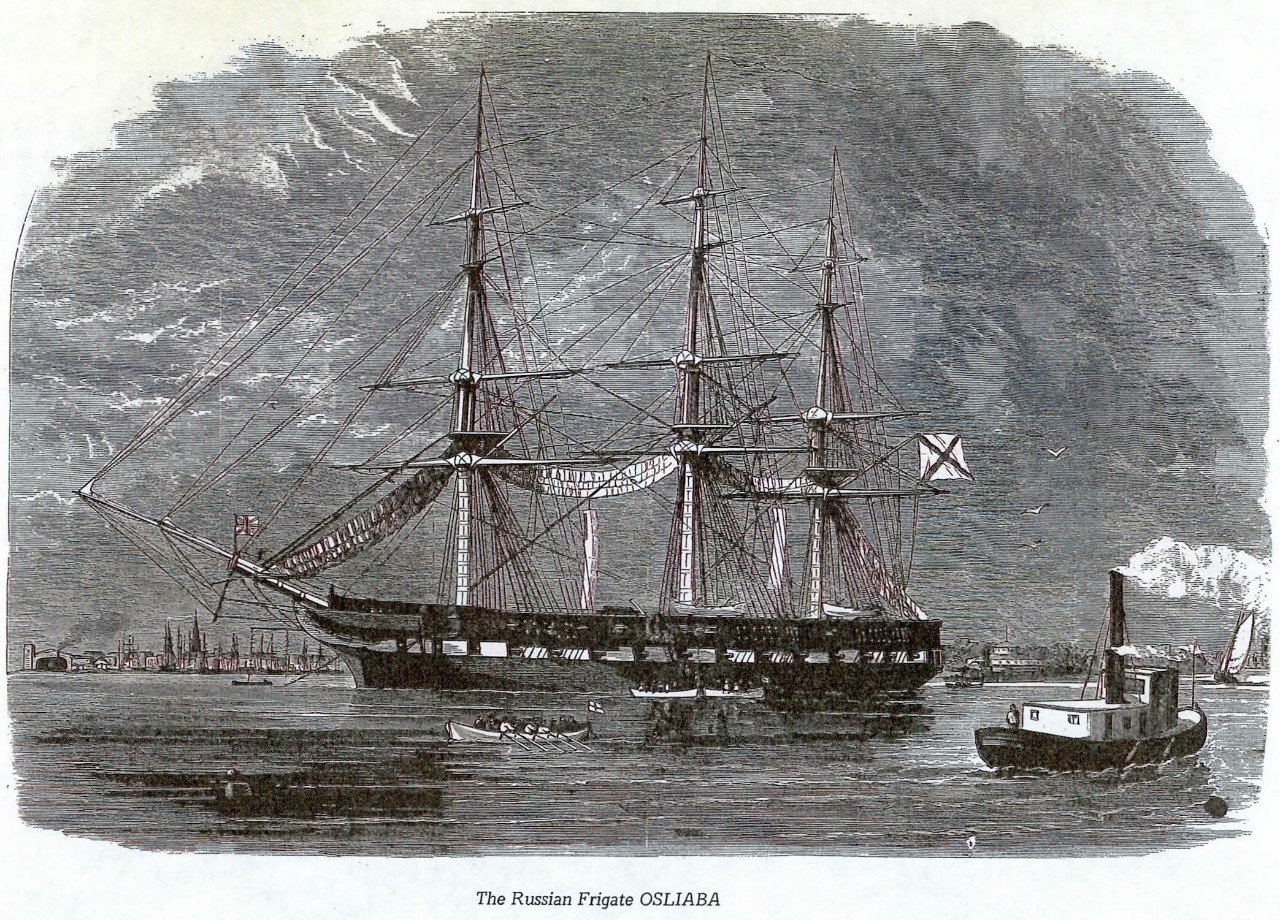

When orders were given to Lisovski and Popov, the frigate OSLIABA, then in Greek waters, was directed to sail for the United States. Enroute [sic], she was to stop in Portugal to get the latest information and to let it be understood that she was proceeding to Siberia. Actually, she was to keep on the trade routes between

8

Liverpool and the West Indies, with instructions where to join the Atlantic Squadron and what do [sic] do in case of war.

To prepare for the arrival of the ships in the United States, Captain Kroun was directed to proceed to New York and give Minister Stoeckl full information regarding the visits. Lisovski had written Kroun that he expected to arrive in New York in September. He said he would send one of his corvettes into the harbor to get information on the state of affairs. If war had not been declared, he would bring his entire squadron into port. IF it had been, then he would want provisions sent to him to arrive at Santa Catharina Island off Brazil between 1 and 20 November. He would also want supplies again in March 1864 at Lobito Bay, Benguela, Western Africa, and by 15 July in San Matias Bay, Port San Antonio, Argentina.

Lisovski called his officers together to acquaint them of their task and to give them his plans before departure from Kronstadt. These provided for a first rendezvous to be in the Little Belt; then for sailing in company via the north of the British Isles to New York as a destination. If after departing the Belt, they were picked up and trailed by the British and French fleets, it was to be presumed the latter were awaiting a declaration of war to attack. In that event, Lisovski would signal ships to disperse at the first favorable occasion to proceed singly to New York. Any show of an unfriendly act against the Russian fleet was to be met by offensive action. If it were learned during the passage that war had been declared, the plan called for the ALEXANDER NEVSKI to operate on the trade route between Liverpool and South America; the PERESVIET on the route England to the East Indies; VARIAG to operate south of the equator; VITIAZ between Cape Hope and St. Helena Island; ALMAZ to operate against enemy shipping from equator to five degrees north latitude. Should war be declared by 15 October, the ships would rendezvous at Santa Catharina Island.

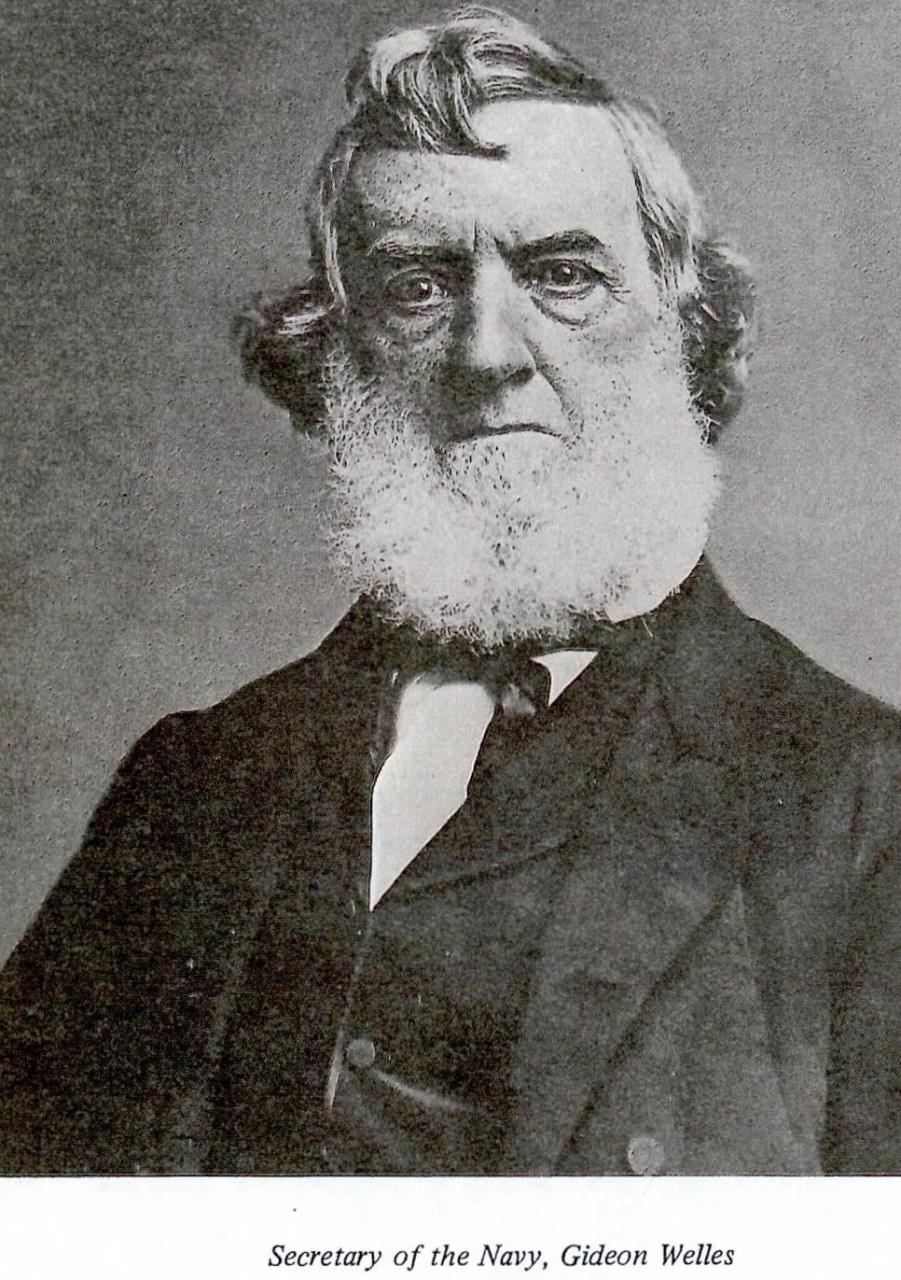

Of the seven ships in the Atlantic Squadron, only five were considered seaworthy enough to make the passage. Even those were not adequately equipped and prepared for this long voyage. They did, however, reach New York. The first to arrive, on 24 September, was the ALEXANDER NEVSKI, a screw frigate of 51 guns and the PERESVIET, a frigate of 48 guns. The VARIAG and VITIAZ, sloops of 17 guns, arrived two days later. Within three weeks, the ALMAZ and OSLIABA (a screw frigate of 33-8” guns manned by 450 sailors and Marines) made New York. The Secretary of the Navy, Gideon Welles, had been officially notified of the coming by Minister Stoeckl. Welles replied on 23 September 1863:

The Department is so much gratified to learn that a squadron of Russian war vessels is at present off the harbor of New York, with the intention, it is supposed, of visiting that city. The presence in our waters of a squadron belonging to His Imperial Majesty’s Navy cannot but be a source of pleasure

10

and happiness to our countrymen. I beg that you will make

known to the Admiral in command that the facilities of the

Brooklyn navy yard are at his disposal for any repairs that

the vessels of his squadron need, and that any other required

assistance will be gladly extended. I avail myself of this

occasion to extend through you to the officers of His Majesty’s

squadron a cordial invitation to visit that navy yard.

I do not hesitate to say that it will give Rear Admiral

Paulding very great pleasure to show them the vessels and

Other objects of interest at the naval station under his

command.19

Later, Welles wrote in his diary: “In sending them to this country there is something significant. What will be its effect on France and the French policy we shall learn in due time. It may be moderate; it may exasperate. God bless the Russians.”20

11

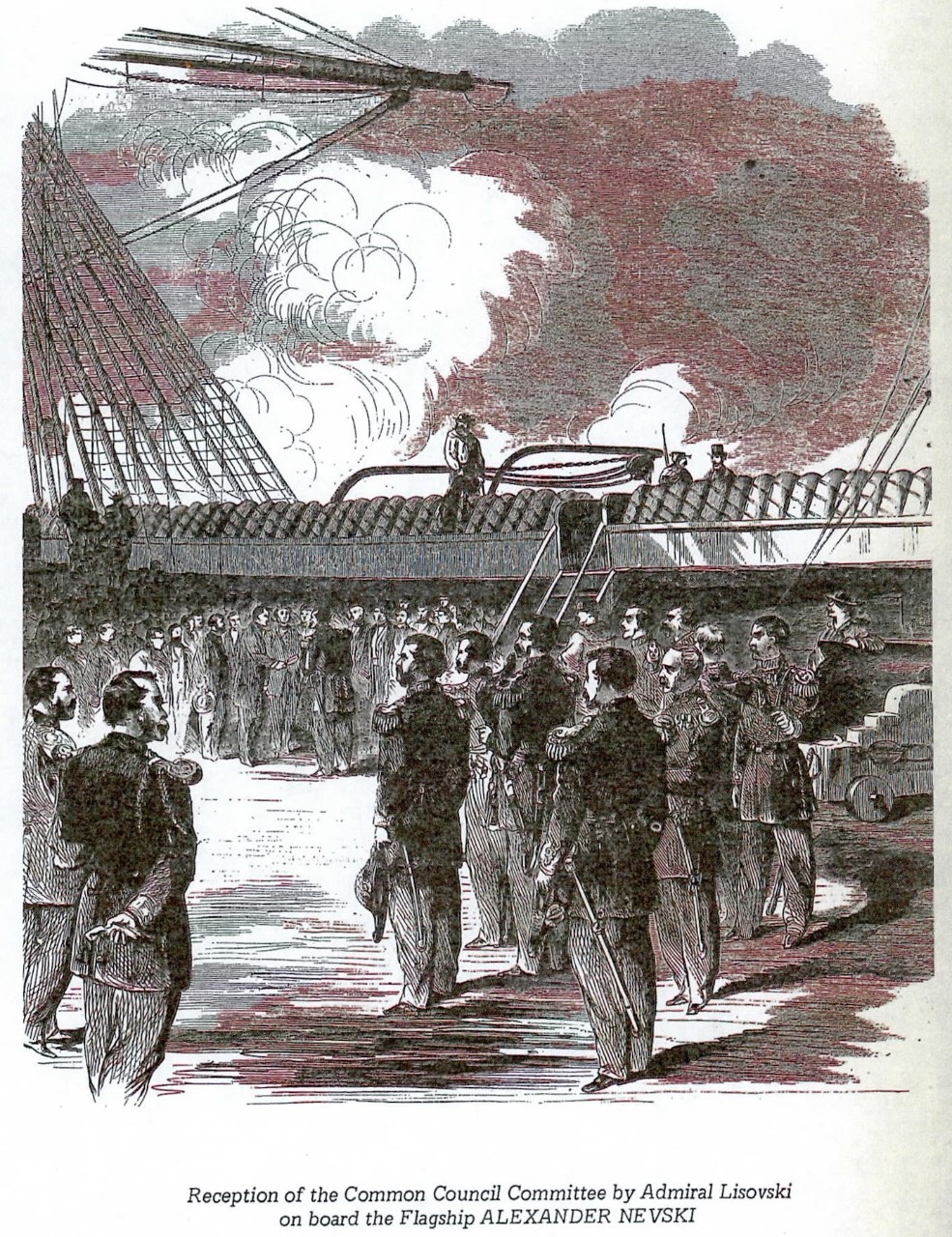

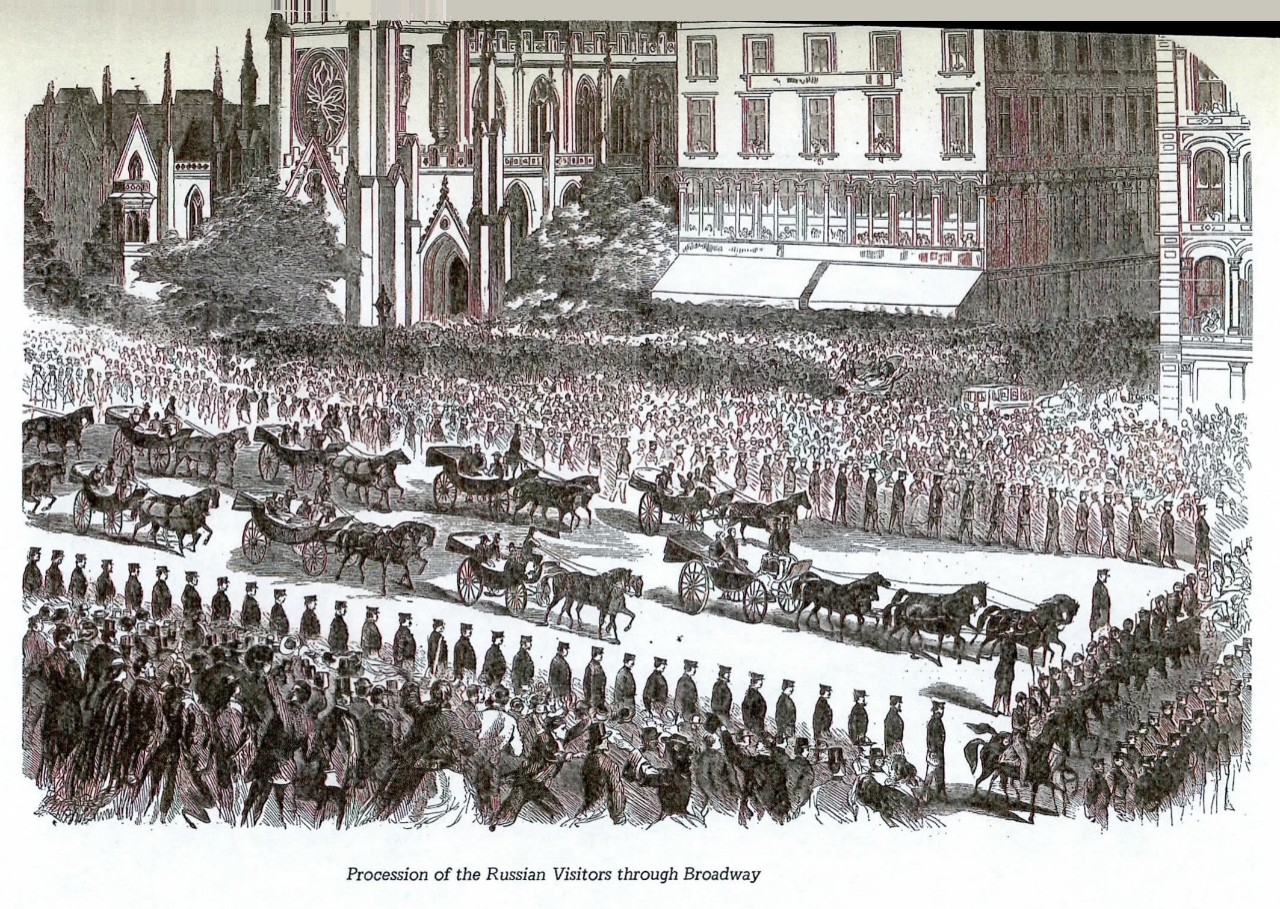

The ships and their crews received a warm welcome from the citizens of the city. The New York DAILY TRIBUNE carried the following article on 2 October 1863:

The “Joint Committee’ went out to welcome the Russian visitors. The band of the NORTH CAROLINA performed the beautiful Russian Nation Air, “God Save the Czar,” as

14

it passed the vessels, while the Russian seamen mounted the riggings to acknowledge the compliment by loud and hearty cheers. The band of the flagship ALEXANDER NEVSKY struck up “Yankee Doodle” in return. A dozen of the ships’ boats were awaiting the arrival of the committee and the invited guests were transferred to the deck of the Russian flagship…The officers of the Russian fleet were standing on the starboard side in full-dress uniform with the Admiral Lisovski at the head. The seamen were drawn up in line on the port side and forward on the starboard side. The officers present numbered nearly three-score and were of the grades known in the Russian Navy as Admiral, post captain, lieutenant, sublieutenant [sic] and midshipman. The uniforms of the Russian Navy are very attractive, being tastefully decorated with gold lace and embroidery about the collar and cuffs.

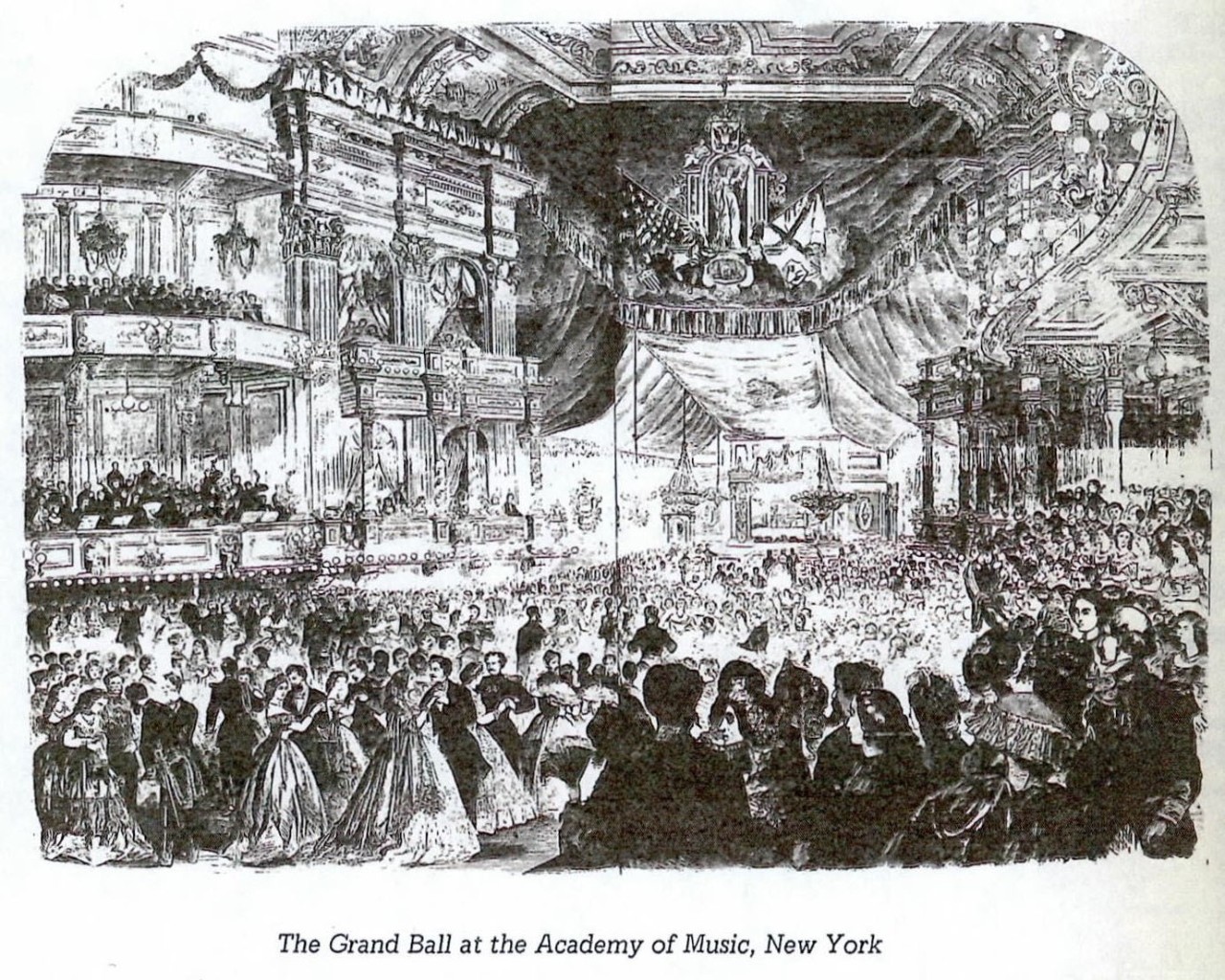

There was a banquet at the Astor House given for the Russian officers by the merchants and businessmen of the city. A grand ball was held in the Academy of Music on 5 November, with decorations of Russian and American flags and other items indicative of

16

the prevailing friendly relations. HARPER’S WEEKLY, quote from an account in the NEW YORK HERALD, described the affair:

Immediately after the Russians arrived the dance began…In truth it was a very wonderful and “indescribable phantasmagoria of humanity…” Alas! For the Russians. It is known or should be, that these Slavic [sic] heroes are not the largest of the human race—that they are small men in fact—and what is to become of small men in such a jam? Early in the night—indeed very soon after the dance began—We saw several of them in the embrace of grand nebulous masses of muslin and crinoline, whirled hither and thither as if in terrible torment, their eyes aglare, [sic] their hair blown out, and all their persons expressive of the most desperate energy, doubtless in the endeavor to escape. What became of them we cannot tell.21

As might be expected, the arrival of the Russian ships in New York came as a surprise to the British and French ships in that port and a shock to London. The Russian Ambassador to England, who had not been made aware of this move, expressed his concern to Gortchakov. The Russians were anxious to avoid any issue, and

17

Brunow was advised to reply to questions by saying the fleet was on a regular cruise to relieve other ships, and would probably remain in United States waters until the European situation cleared. In the meantime, the Russians in New York were careful to maintain friendly relations with the English and French. When their ambassadors visited the city, Lisovski called on them. Only Lord Lyons returned the call.

In December of 1863, the Russian squadron sailed up the Potomac and anchored near Alexandria. Secretary Welles ordered naval personnel to show the visitors “all proper courtesy.”22 There were parties ashore and afloat for all hands. A reception on the OSLIABA received much publicity, when General Dix and Mrs. Lincoln are reported to have toasted the health of the Czar, and the Captain of the ship responded with a toast to the President. It would be expected that the President and his lady would entertain the Russians, but this was not possible since Lincoln returned in poor health from his Gettysburg Address.

A few weeks after the arrival of the ships in New York, word flashed across the Continent that Admiral Popov, with the ships of the Russian Pacific Squadron, had entered San Francisco Bay on 12 October. His ships were the corvettes BOGATIR, KALEVALA, RINDA, and NOVIK, the clippers ABREK and GAIDAMAK. California was not unfamiliar to the Russians and Popov. He had visited it the year before and the Russians had established a settlement there by 1812. Then, too, their settlements at Ross and Bodega, California, originally founded to supply New Archangel (Sitka) another Alaskan ports with grain, were sold to John Sutter in 1841 for $30,000.

San Francisco gave a hearty welcome to the ships’ companies. Enthusiasm heightened after the Russians rendered valuable assistance in putting out a big fire in the city within three weeks after their arrival. Popov was so bold as to issue orders to fire on any Confederate ships that attempted to make the port. Rumor has it that Confederate cruisers were in the area and planned an attack on the city. The Admiral send copies of this order to Stoeckl in Washington and Krabbe in St. Petersburg. Their replied are interesting as indicative of the Russian attitude. Stoeckl said that as he understood Russian diplomacy, Russia was not concerned with either the North or South, but a United States. Russia had no right to interfere in the internal affairs of another nation and Popov should keep out of the conflict. He continued:

From all the information to be obtained here it would seem that the Confederate cruisers aim to operate only in the open sea and it is not expected that cities will be attacked and San Francisco is in no danger. What the corsairs do in the open sea does not concern us; even if they fire on the forts, it is your duty to be strictly neutral. But in case the corsair passes the forts and threatens the

18

city, you have then the right, in the name of humanity, and

not for political reasons, to prevent this misfortune. It is

to be hoped that the naval strength at your command will

bring about the desired result and that you will not be

obliged to use force and involve our government in a situation

which it is trying to keep out of.23

Gortchakov, likewise, disapproved of Popov’s plan and urged strict neutrality. In a letter to Krabbe on 27 January 1862 he said the Russian position was neutrality, although it had not been so declared. In a conversation with Bayard Taylor, who was then our Chargé d’Affaires, Gortchakov said, on 27 September 1862: “We desire above all things the maintenance of the American Union. We can not take any part more than we have done. We have no hostility to the southern people.”24

The squadron remained in United States’ waters until the late spring of 1864. On 26 April of that year, Gortchakov told Krabbe that the Emperor considered it was no longer necessary to keep the fleet in the western Atlantic. Orders were sent Lisovski and Popov to return to their respective bases. When the fleet got back to Kronstadt, it was received by the Emperor who thanked the crews for their services, and promoted some officers and men. It has been stated that the Emperor looked upon the American visit by his Navy as one of the noteworthy events of his entire reign.

It is not too difficult to see why the Russians decided to send the ships to American waters. Certainly they did not want to have locked in ice-bound ports. There were not ports in Europe from which they would be free to operate against British and French shipping. The situation in Europe was tense. On the other hand, there are paralleling circumstances in the relations between Russia and the United States that lead to this decision. Alexander II had freed the serfs. Lincoln was emancipating the slaves. Russia was fighting against Polish insurrection; the United States to put down rebellion. Both Russia and the United States were interested in developing their home industries through protective tariffs; England adhered to free trade. New York and San Francisco were the logical ports on which to base their squadrons to insure [sic] freedom of operations in the event this became necessary.

Undoubtedly, the visit gave much moral support to the North coming four days after the bloody defeat at Chickamauga. Writing to Bayard Taylor on 23 December 1863, Secretary Seward said, “In regard to Russia, the case is a plain one. She has our friendship, in every case, in preference to any other European power, simply because she always wishes us well, and leaves us to conduct our affairs as we think best.”25

Historian James Ford Rhodes put the effect of the visit on the whole nation in these words:

The friendly welcome of a Russian fleet of war vessels, which arrived in New York City in September; the enthusiastic reception by the people of the admiral and officers when offered the hospitalities of the city; the banquet given at the Astor House by the merchants and business men in their honor; the marked attention shown them by the Secretary of State on their visit to Washington “to reflect the cordiality and friendship which the nation cherishes towards Russia”: all these manifestations of gratitude to the one great power of Europe which had openly and persistently been our friend, added another element to the cheerfulness which prevailed in the closing months of 1863.26

Undoubtedly, this event made an unusual bit of diplomatic history. It can be said that Russia did not send its squadrons to our ports for our benefit. By doing so, however, it must be recognized that the Czar did render a distinct service. The United

20

States, on the other hand, was not too conscious of the contribution it was making to the Russian position and its status in Europe. Nevertheless it can be contended, that the United States did save Russia from a humiliating situation and even a war.

President Lincoln was assassinated on 15 April 1865. On 16 April 1866, an attempt was made to assassination Alexander II. His life was saved when a liberated peasant, Ossip Komissarov, hit the arm of the would-be assassin and deflected the bullet just as he pulled the trigger. The United States Minister Clay quickly extended the warm congratulations of his government on the safety of the Czar. The monarch replied: “I trust under Providence that our mutual calamities will strengthen our friendly relations and render them permanent.”27

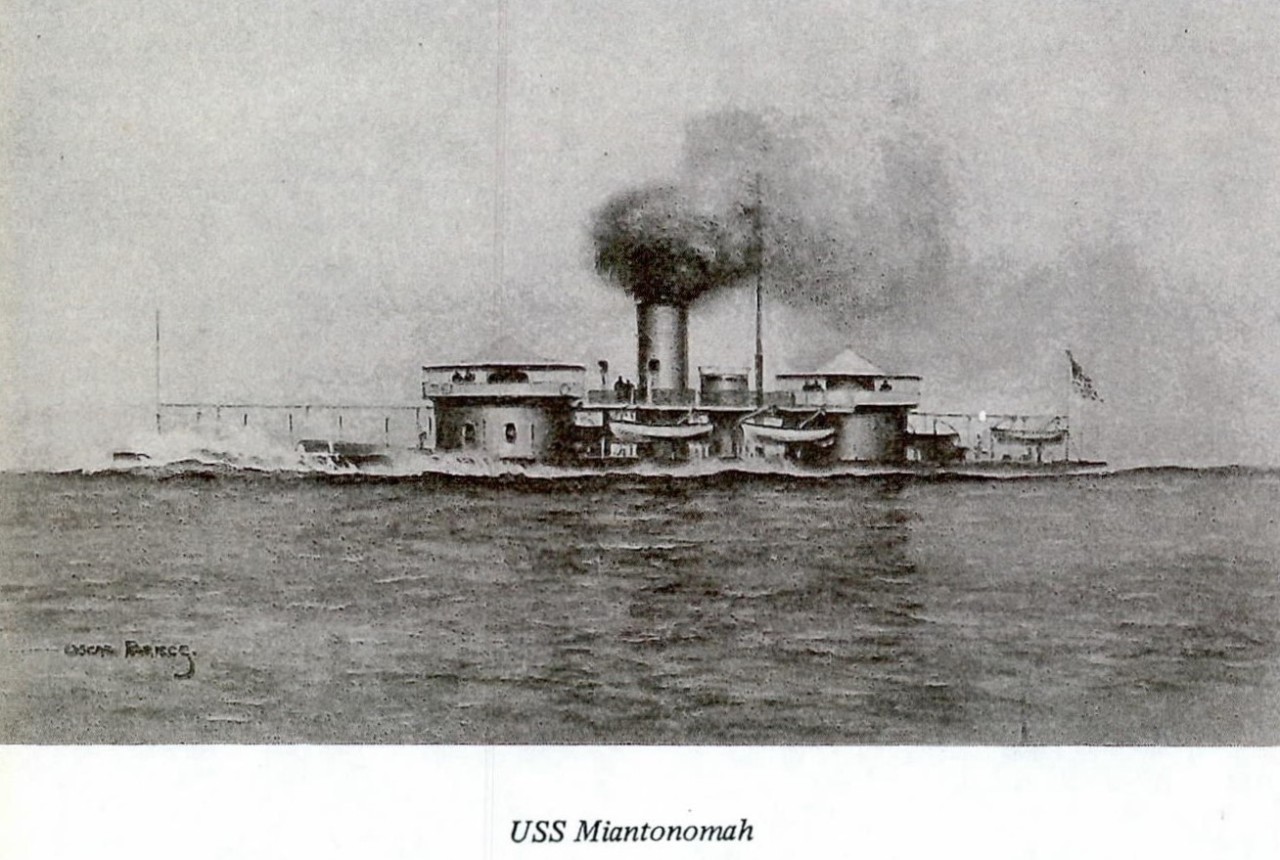

Congress passed a resolution authorizing a naval vessel to take a special envoy to Russia to express in person to His Imperial Majesty good will to “the twenty millions of serfs upon the providential escape from danger of the Sovereign to whose head and heart they owe the blessings of their freedom.”28 Assistant Secretary of the Navy Fox was selected to head the mission. The ironclad monitor MIANTONOMAH, accompanied by side-wheeler AUGUSTA, was assigned to carry the party to Kronstadt. Both sailed from Newfoundland on 5 June 1866. Stops were made enroute at Ireland, England, France, Denmark and Finland. Secretary Fox

21

presented the Resolution of Congress to the Czar on 8 August 1866. A round of receptions, banquets and balls were given in honor of the Americans. In Moscow, when Fox saw the Russian and American flags flying side by side, he said:

If the hearts of the Americans present could be uncovered, there would be found what I now behold, the flags of Russia and of America intertwined. May these two flags in peaceful embrace be thus united forever.29

PROLOGUE

A few months after Fox returned to the United States, the negotiations for the purchase of Alaska came to a climax.

The United States was actively interested in the resources of Alaska and our commercial position in the Pacific. A sum of five million dollars was mentioned as a possible purchase price for

22

the almost 600,000 square miles of the territory. This sum was not satisfactory to the Russians, but they did believe it merited study and consideration. The LinolnAdministration [sic] had come into Washington by the time the study was completed. By then, however, the Civil War had begun.

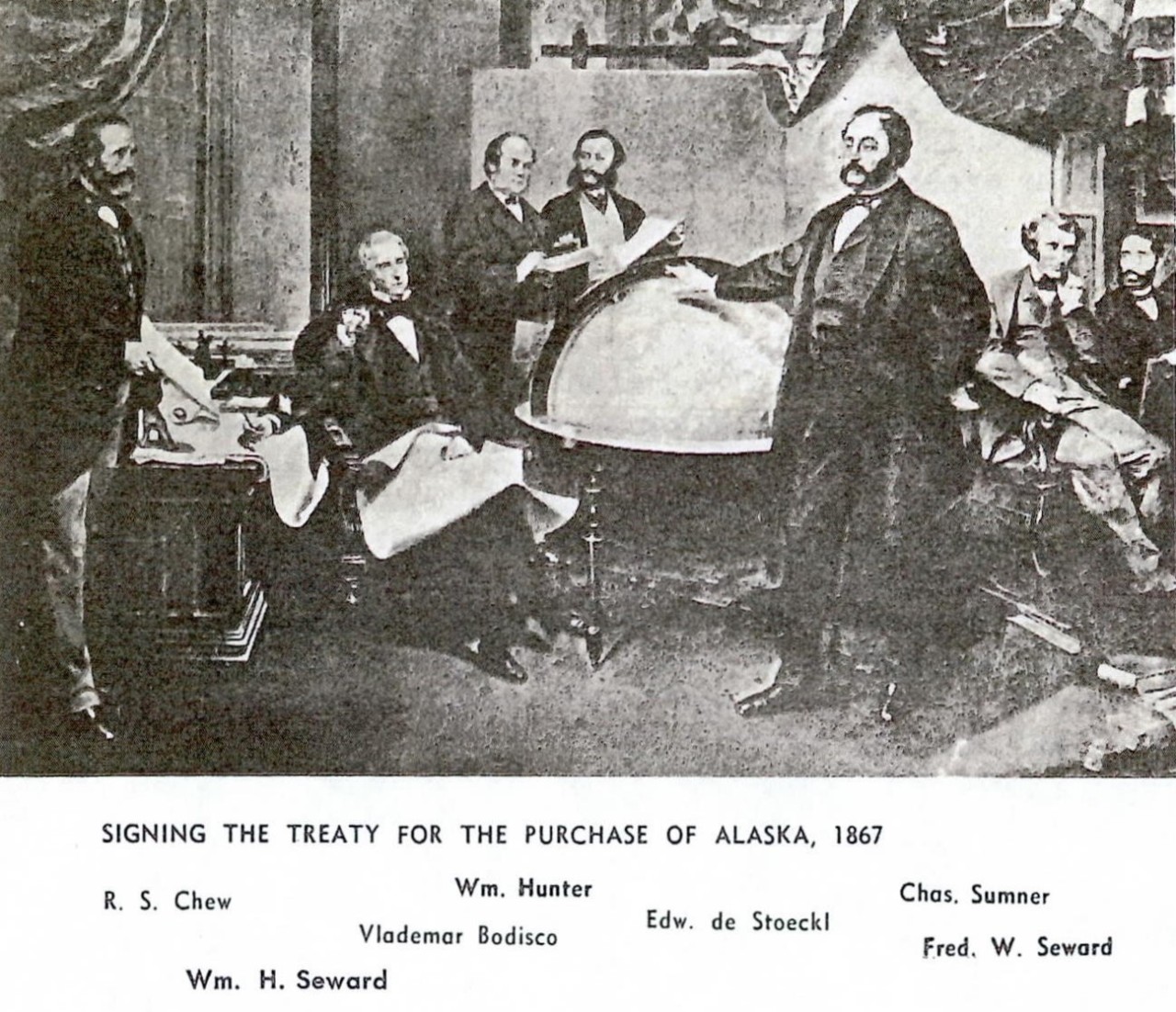

Lincoln did not live to see the sale completed. The Russian Minister advised Secretary Seward, on the evening of 29 March 1867, that his government was ready to compromise the asked and offered prices and a purchase price of $7,200,000 was agreed upon. Russian and United States representatives worked all that night on the wording of the treaty. By four in the morning of 30 March, the document was ready and it was duly signed and sealed. Alaska and the Aleutian Islands, rich in timber, fisheries, fur seals, minerals and oils were transferred to the United States at the fabulous price of about two cents an acre.

The treaty was duly ratified by theSenate [sic] by a vote of 37-2 and proclaimed in force by the President on 20 June 1867. Senator Sumner, who chaired the Committee on Foreign Affairs, made the principal address for ratification. There was a different reaction in the House, which was reluctant to appropriate money to purchase

the region referred to as “Seward’s Folly” and “Walrussia.” It was not until 14 July 1868 that the House by a 113 to 43 vote approved the bill appropriating the money to pay Russia. General Nathan P. Banks, who chaired the Committee on Foreign Affairs in the House, predicted that the Aleutian Islands would become “the drawbridge between America and Asia” over which we could carry our instructions and laws to the East, as well as to the islands of the Pacific.30

Before Congressional approval of the purchase, but with the consent of the Russian Government, President Johnson took possession of the territory at Sitka on 18 November 1867. Appropriate ceremonies were held. Two American gunboats, which had been despatched [sic] from Panama, were at anchor when the transport JOHN L. STEVENS arrived with Company F of the Ninth Infantry and Company H of the Second Artillery, under the command of Colonel J. Davis, to take part in the ceremony. General L. H. Rousseau, the official representative of the government, arrived in the OSSIPPE.

On the afternoon of 18 October 1867, General Rousseau, with American soldiers as an escort, landed and marched to the Governor’s palace. They were drawn-up beside the Russian garrison.

Captain Alexei Pestchaurof and Prince Maksoutoff represented the Czar. The Russian flag was lowered; the Stars and Stripes raised with salutes from both batteries. Alaska and the Aleutians then became a part of the United States, and President Johnson placed them under the War Department where they remained until 1877.

After the payment, there were rumors that part of the purchase price was, in reality, a repayment by the United States Government for expenses incident to the visit of the Russian fleets to this country. Ugly rumors persisted, too, that part of the money was used by Baron de Stoeckl as bribed for influence and votes for the purchase. The House ordered an investigation of these charges but could find no conclusive evidence that would warrant action against any individual. The Baron was invited to send a representative of the Russian Legation to make a statement concerning the matter but declined. The Committee did find that, of the $7,200,000, only $7,035,000 less bank commission was sent abroad. The remaining $165,000 was deposited to the credit of the Minister.31

Czar Alexander II was pleased with the deal and awarded Stoeckl with a gift of 25,000 rubles. The Baron was disappointed with this sum and, as soon as the transaction was completed, asked to be sent to “any other post” in the world so that he could forget the rough handling he had received from Congressmen, lobbyists, “mercenary editors,” and others in connection with the Alaskan transaction.32 His request was granted and, in October 1868, he was replaced by Constantine Catacazy, who quickly proved to be offensive to the United States. His forced recall ended the entente cordiale of the Civil War days.

24

NOTES

1. Abraham Lincoln’s Address at Cooper Union, New York, 27 Feb. 1860 – The Works of Abraham Lincoln, Speeches and Presidential Addresses, 1859-1865, edited by John H. Clifford & Marion Miller, VOL. V, p 42 (New York, 1907)

2. Central Archive, Moscow, Russia, Foreign Affairs 49, Manuscript Div., Library of Congress, Washington D. C., Dispatch, April 14, 1861 (no number); No. 24, April 14, 1861; No. 38, June 3, 1861.

3. Ibid, No. 23, April 14, 1861.

4. Albert Parry, John B. Turchin: Russian General in the American Civil War, Russian Review, I, 44-60 (April 1942).

5. London PUNCH, XLV, 169 (Oct. 24, 1863).

6. Charles Sumner, His Complete Works (Boston, 1900), X, 144.

7. Daily Richmond Examiner, VOL. XVII, 5 Oct. 1863, No. 173.

8. C. M. Clay, The Life of Cassius Marcellus Clay (1886), I, 415.

9. Albert A. Woldman, Lincoln and the Russians (New York, 1961), p. 121.

11. Central Archive, Moscow, Foreign Affairs 49, loc. cit., No. 57, Sept. 9, 1861.

12. Foreign Office, France, VOL. 1446, No. 1236.

13. Ephraim D. Adams, Great Britain and the American Civil War, (London, 1925), VOL. II, 63.

14. Taylor to Seward, Nov. 15, 1863 Diplomatic Correspondence (1863-1864) VOL. 2, pp.844-46 in U. S. Dept. of State Manuscripts 1860-1869, Washington, D. C.

16. A. M. M., D. K. M. M. (Arkhiv Morskogo Ministerstva, Dielo Kantseliarii Morskogo Ministerstva), No. 91, pt. I.

25

17. E. A. Adamov, Russia and the United States at the Time of the Civil War. Journal of Modern History, VOL. 2 (1930), pp. 603-7.

20. Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, edited by John T. Morse, VOL. I, 443, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1911.

21. Harper’s Weekly, VOL. 7 (Nov. 21, 1863), p. 746.

22. Welles Diary, op. cit., VOL. I, pp. 480-81.

23. Morskoi Sbornik, October 1914, p. 45.

24. Exec. Docs., 38 Cong., I Sess., II, 840 (1863-1864).

26. James Ford Rhodes. History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850, VOL. IV, 418, New York: Harper & Bros. and The Macmillan Co., (1893-1919).

27. James Rood Robertson. A Kentuckian at the Court of the Tsars. Berea, Ky.: Berea College Press, 1935.

28. Woldman, op. cit., p. 243.

29. Joseph Florimond Loubat. The Fox Mission to Russia in 1866, edited by John D. Champlin, Jr. (New York). D. Appleton & Co., 1879.

30. Congressional Globe, VOLS. 40-42, Appendix, pp. 386-88.

31. William A. Dunning, Paying for Alaska, Political Science Quarterly, VOL. 27 (1912) September.

32. Frank A. Golder, The Purchase of Alaska. American Historical Review, VOL. 25 (1919-20), p. 424.

Prints obtained from Harper’s Weekly, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, “Alaska” 1741-1953 by Clarence C. Hulley and Naval History Division, Office of Chief of Naval Operations.

26