The Navy Department Library

Seventh Amphibious Force - Command History 1945

Seventh Amphibious Force

Command History

10 January 1943 - 23 December 1945

--i--

Contents

| Page | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foreword | v | ||||

| Part I | Narrative Summary | I-1 | |||

| Part II | Command, Staff Organization and Administration | II-1 | |||

| (a) | Staff Organization and History | II-1 | |||

| (b) | Amphibious Training of Ground Forces by SEVENTH Amphibious Force | II-10 | |||

| (c) | Special Problems, Functions and Organizations | ||||

| 1. | Echelon Movement of Amphibious Shipping | II-27 | |||

| 2. | Beach Parties | II-31 | |||

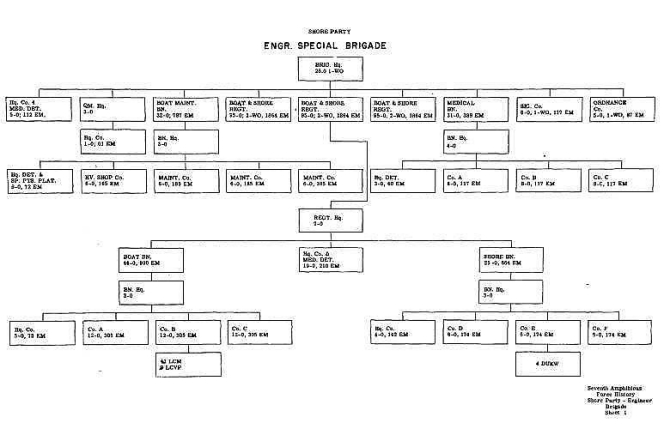

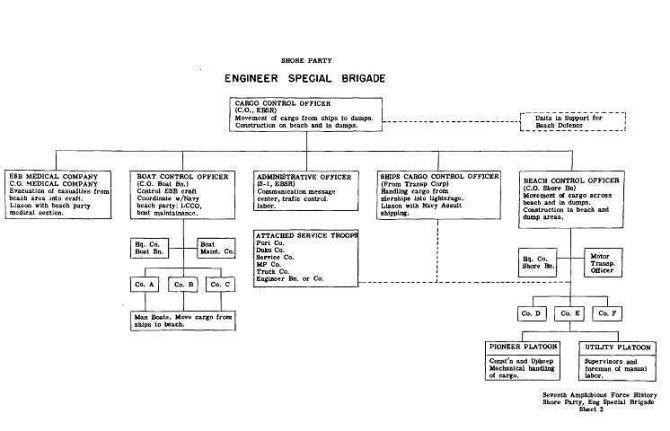

| 3. | Engineer Special Brigades (Shore Parties) | II-39 | |||

| 4. | Landing Craft Control Officers - SEVENTH Amphibious Force Representatives | II-46 | |||

| 5. | Assignment of Australian and British Ships | II-48 | |||

| (d) | Special Operations | ||||

| 1. | Minesweeping - Philippines and Borneo | II-51 | |||

| 2. | Movement of Service Units, Supplies and Equipment from Rear to Forward Bases | II-57 | |||

| (e) | Medical Services and Casualty Care | II-61 | |||

| (f) | Air Support Operations | II-80 | |||

| (g) | Administrative Command | II-86 | |||

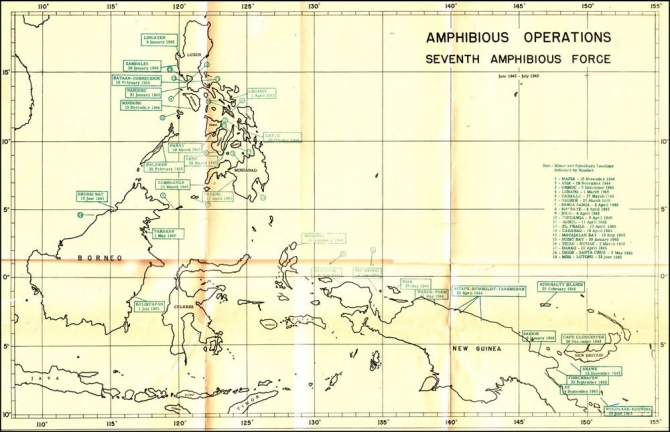

| Annexes | (A) | Chart of the Pacific Area Showing Operations by the SEVENTH Amphibious Force | |||

| (B) | Designation of Operation Plans and Operation Orders for Major Amphibious Operations | ||||

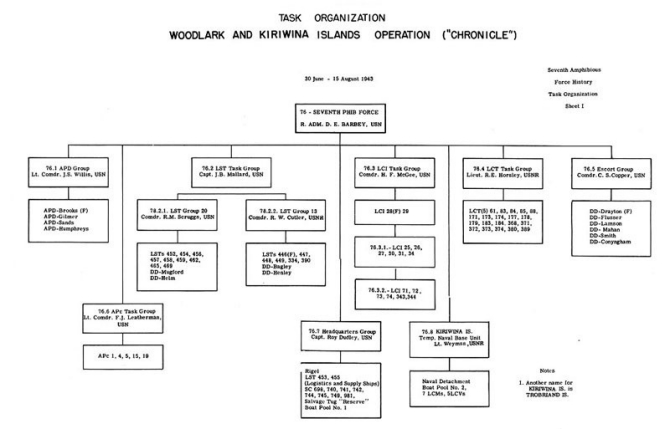

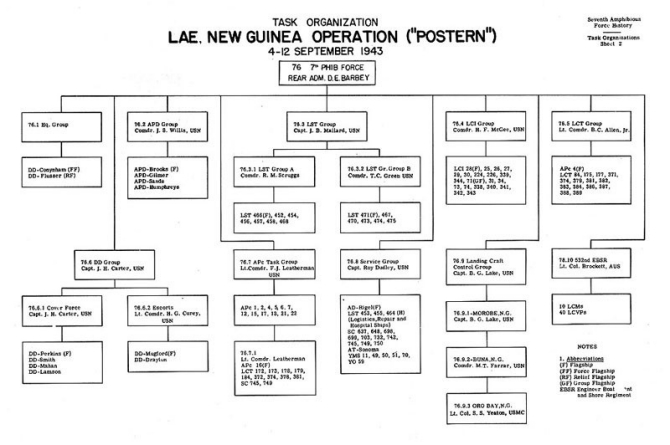

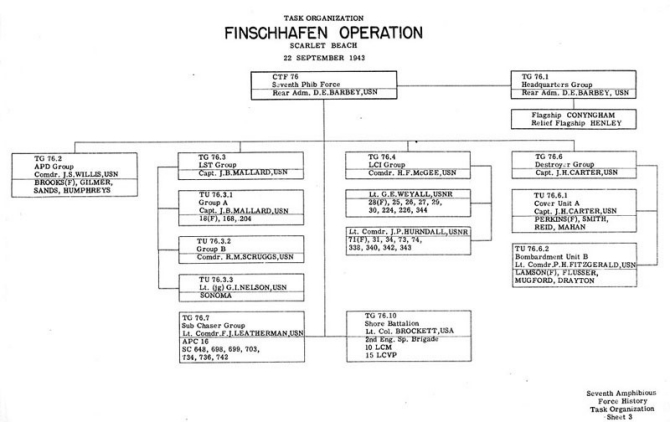

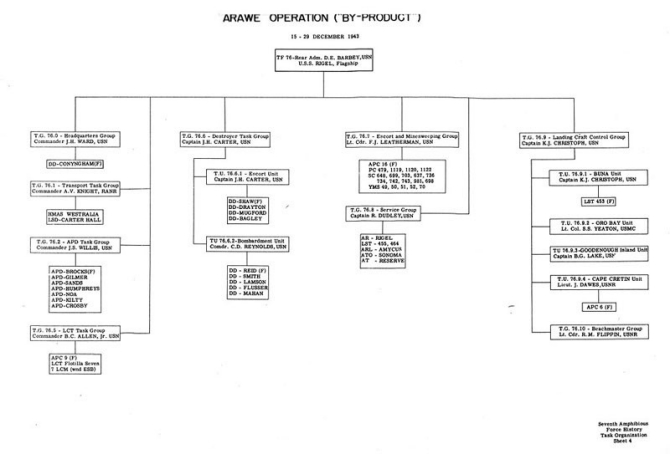

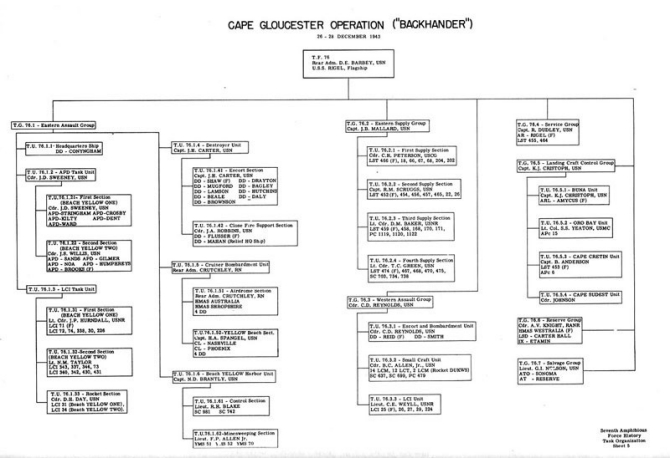

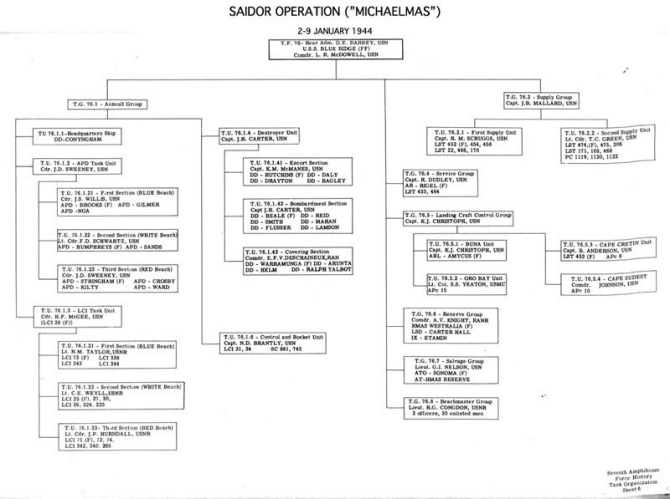

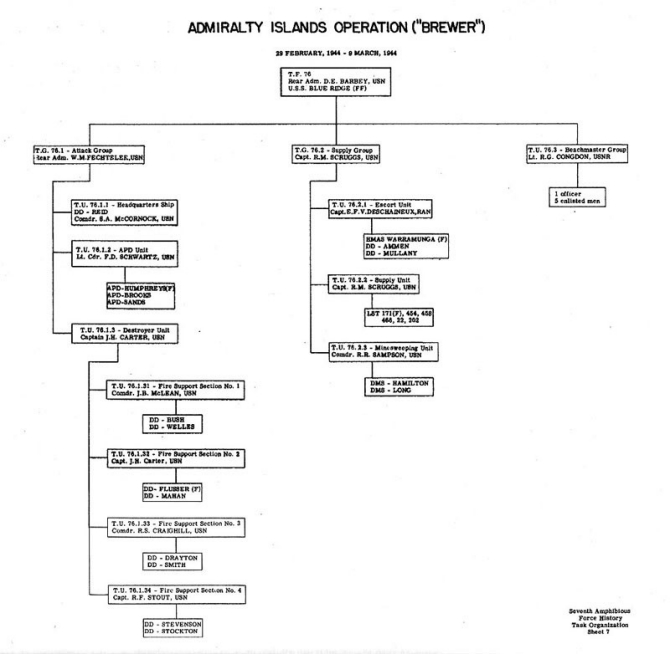

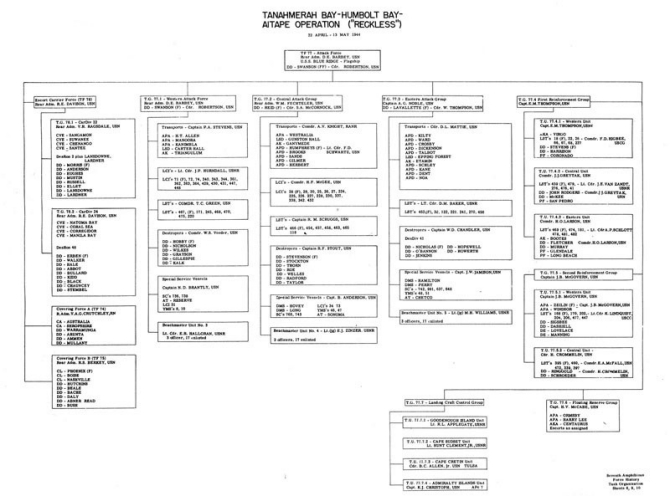

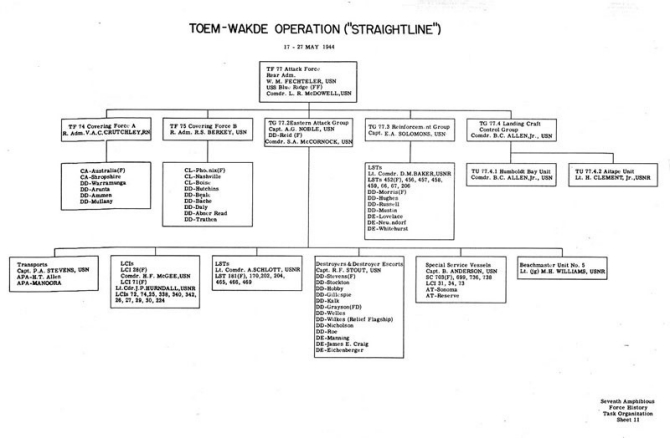

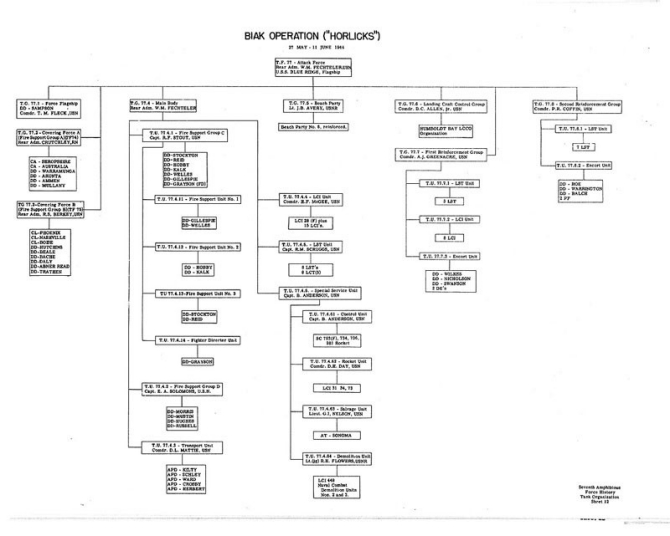

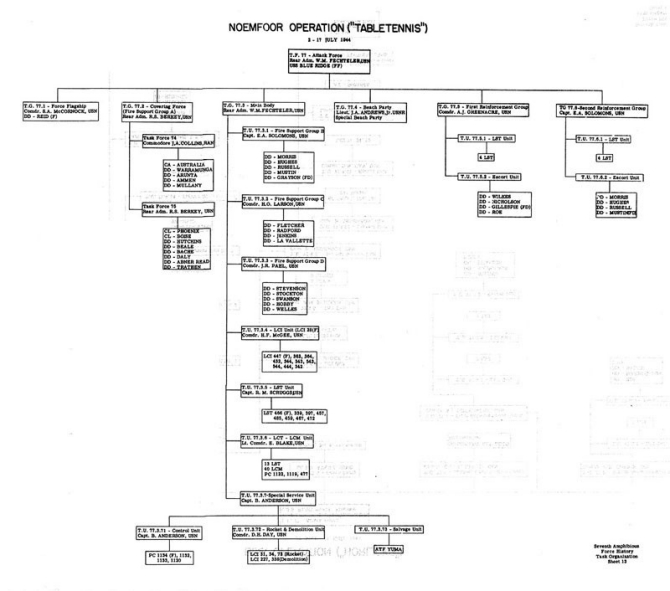

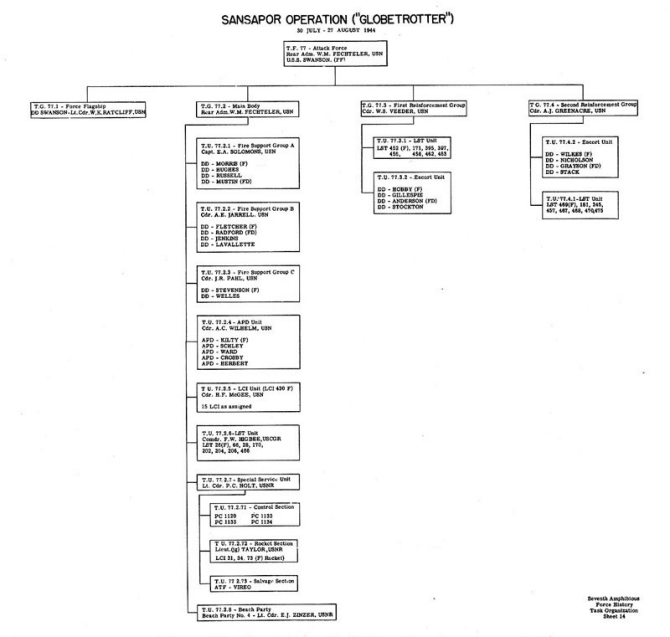

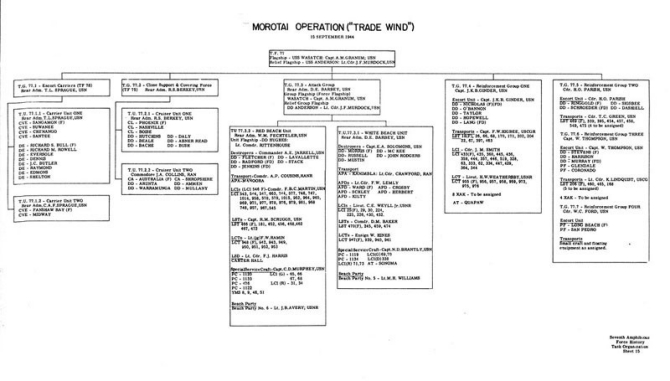

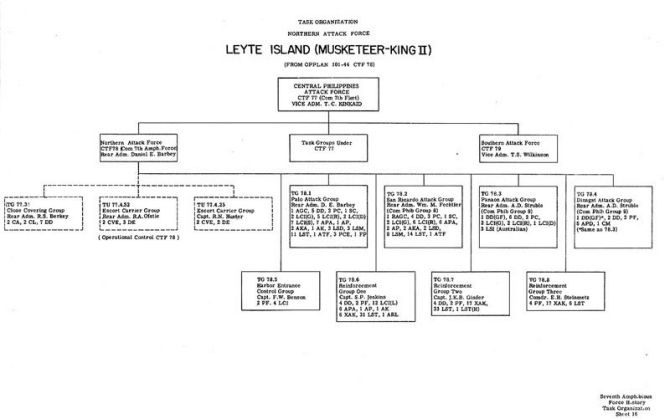

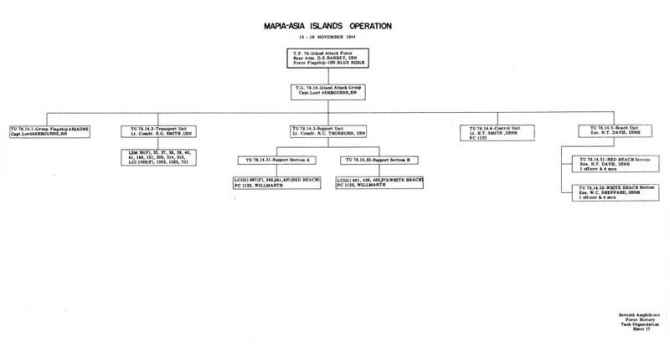

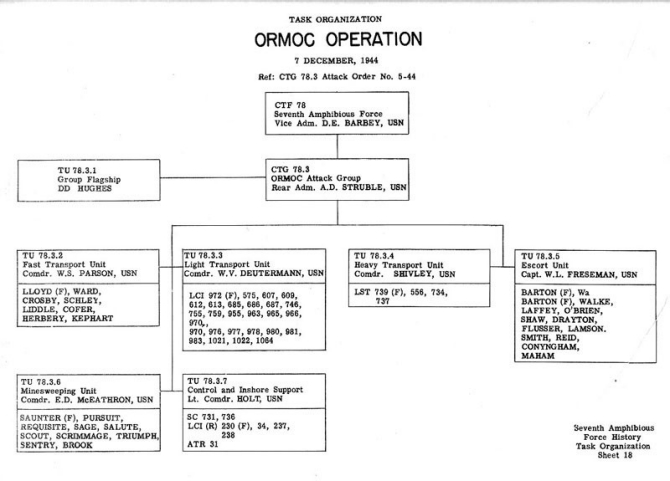

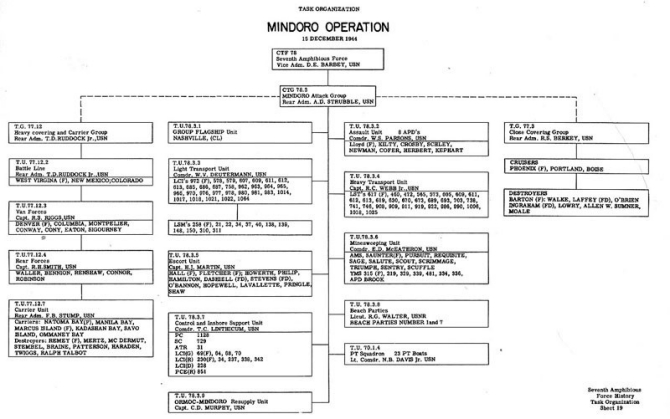

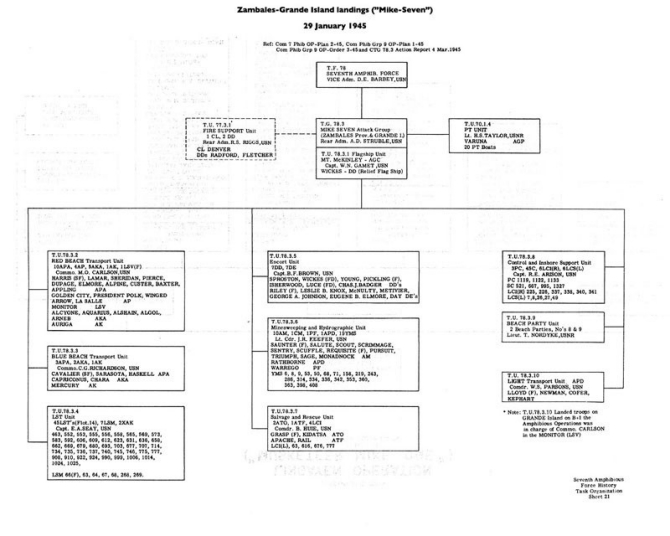

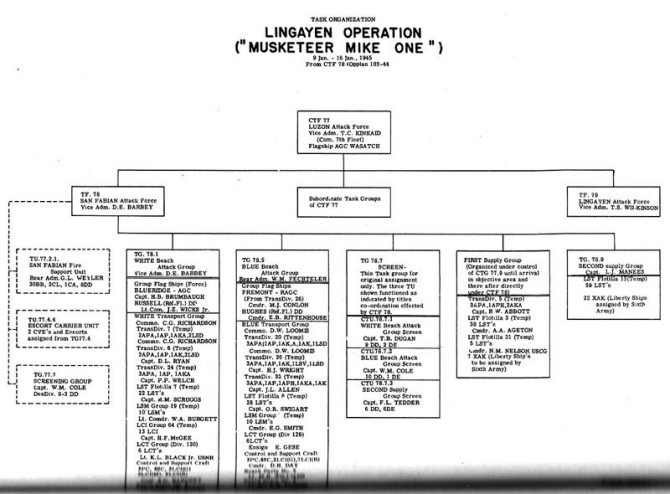

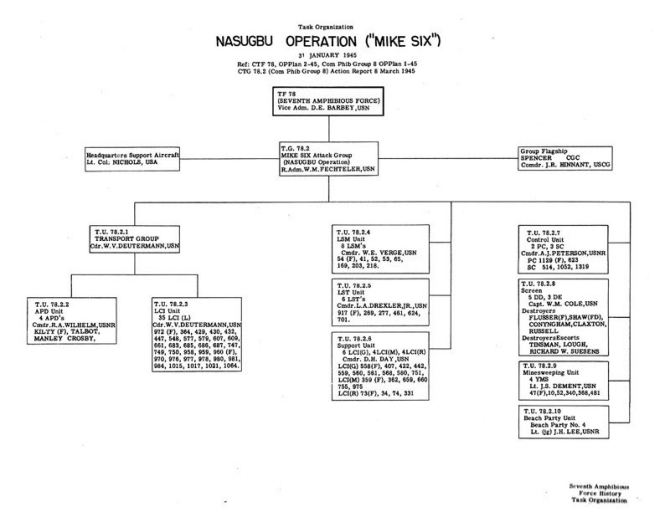

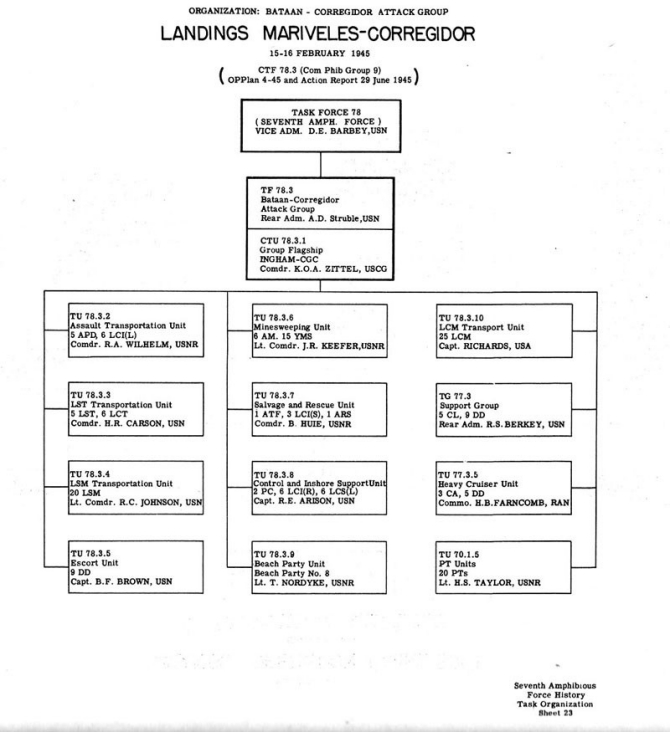

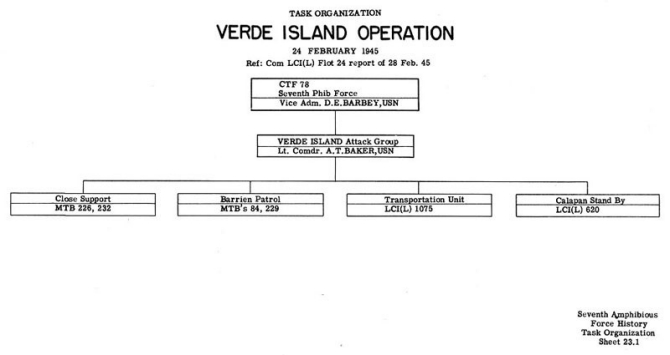

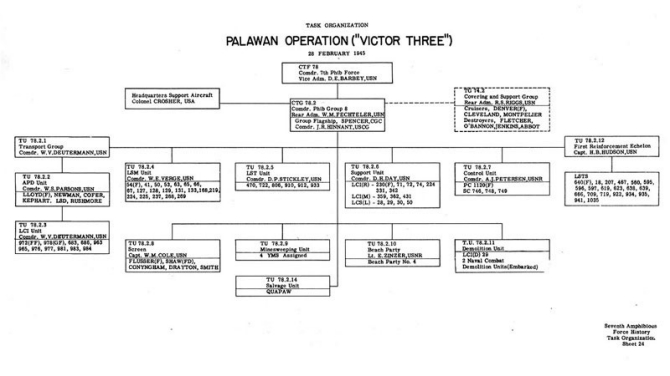

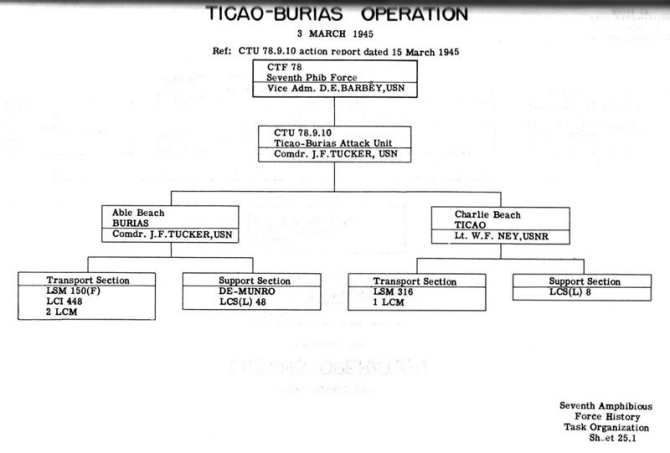

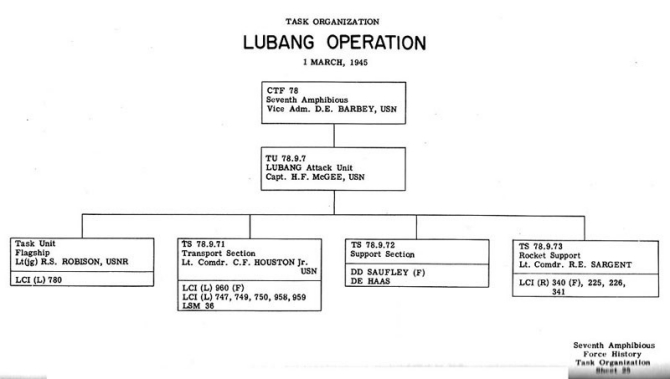

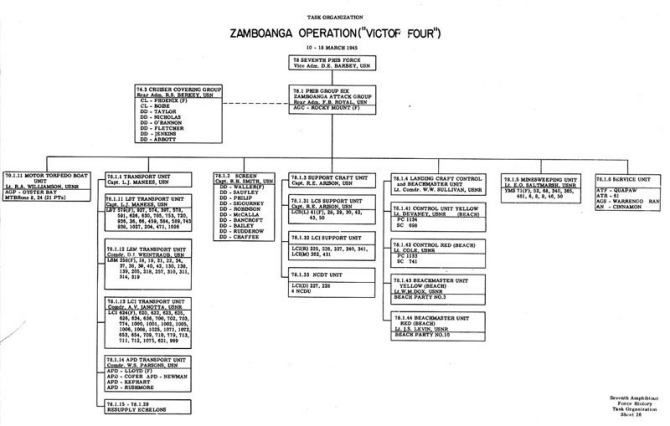

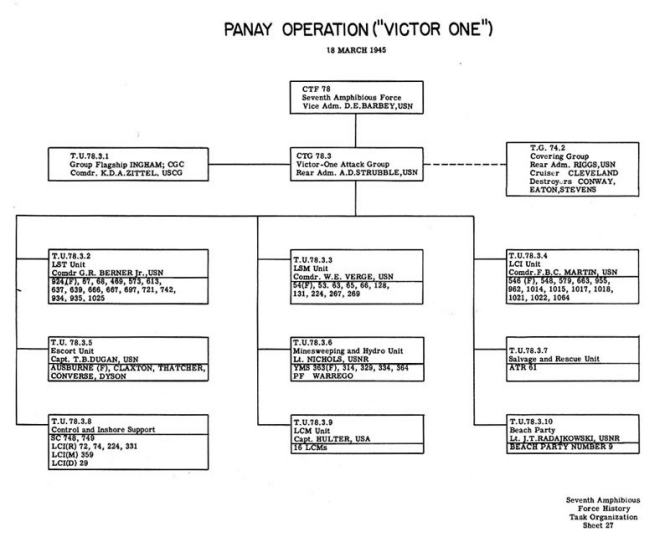

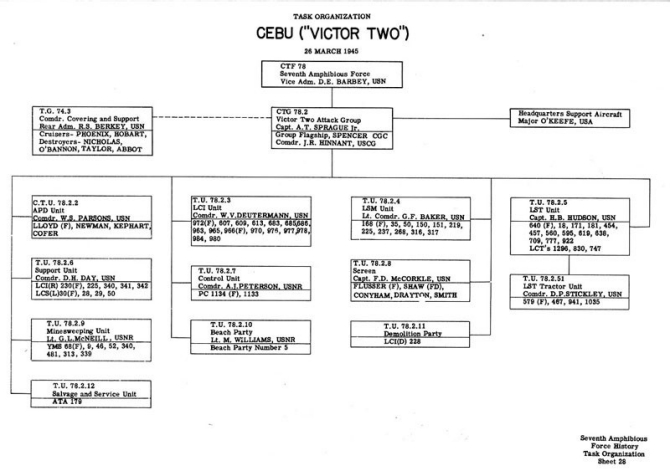

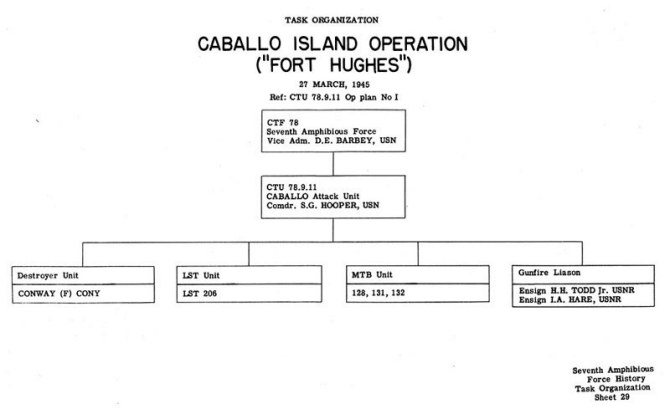

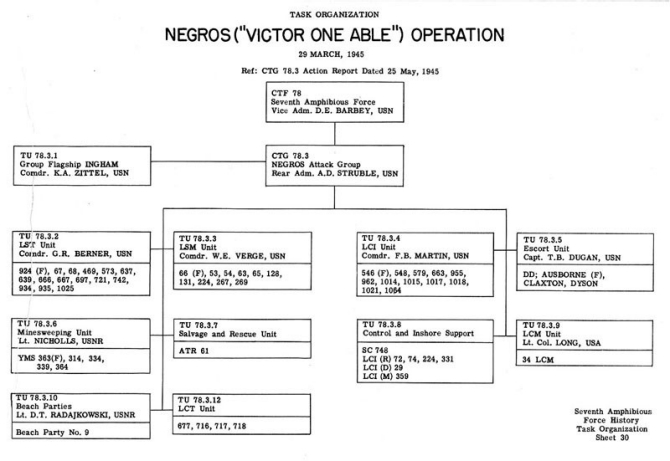

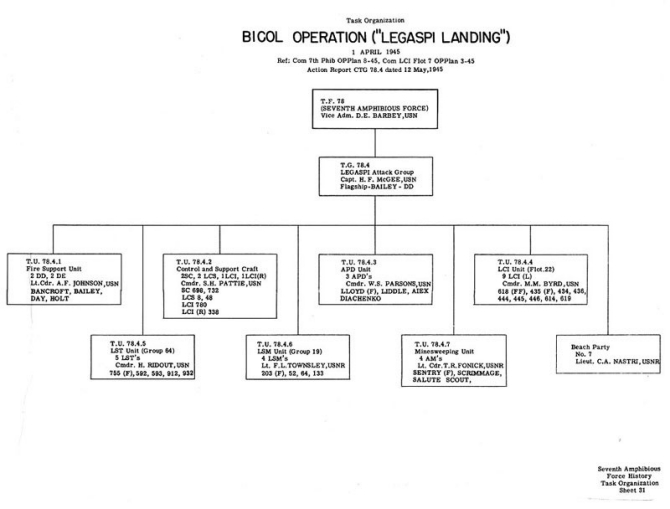

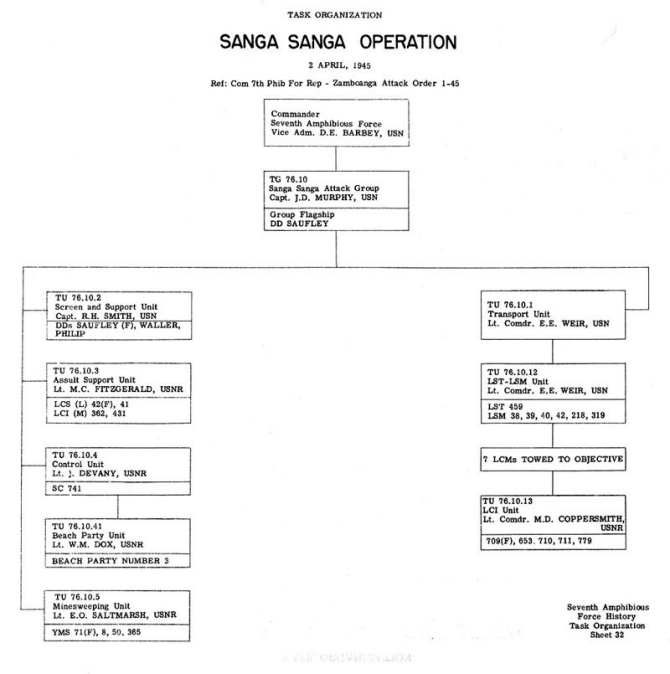

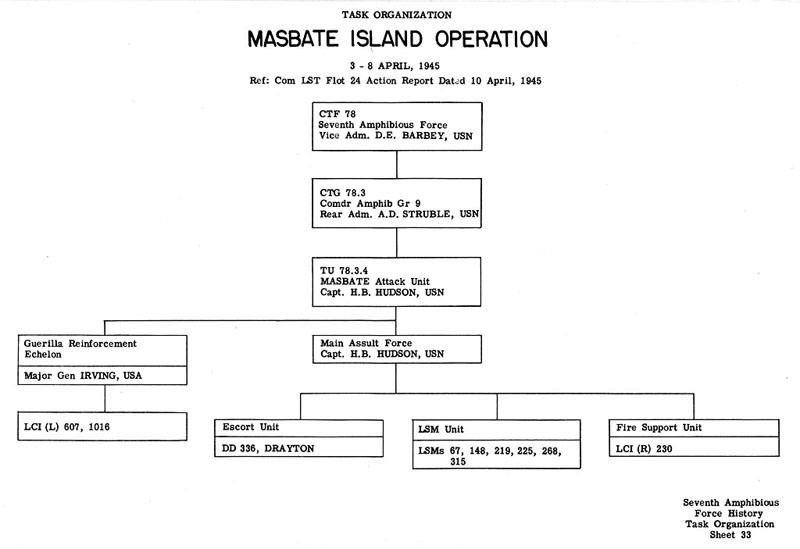

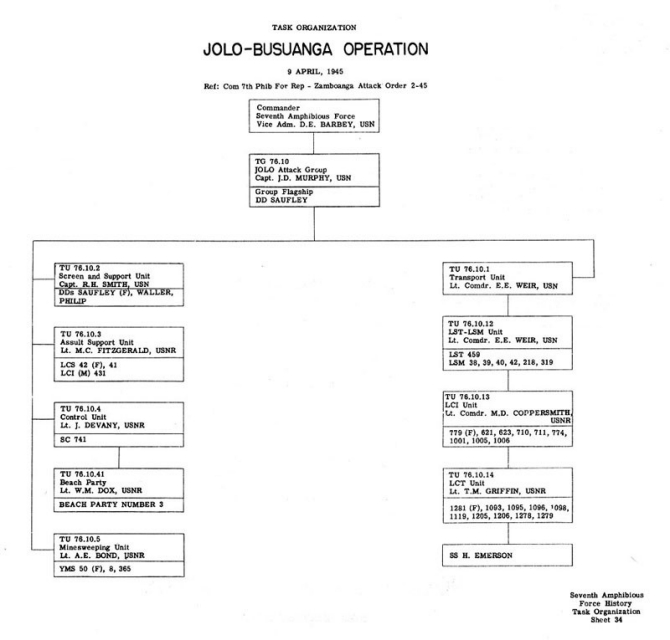

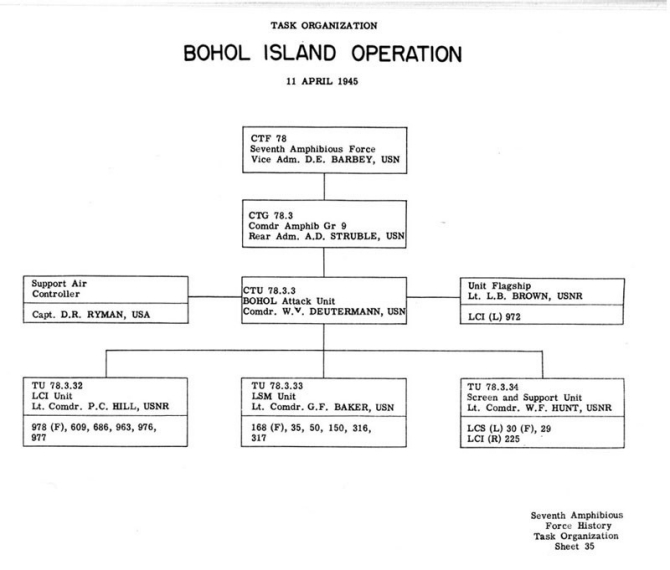

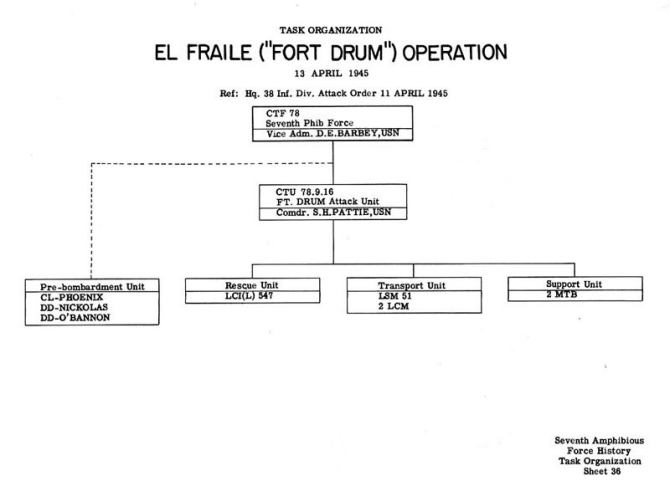

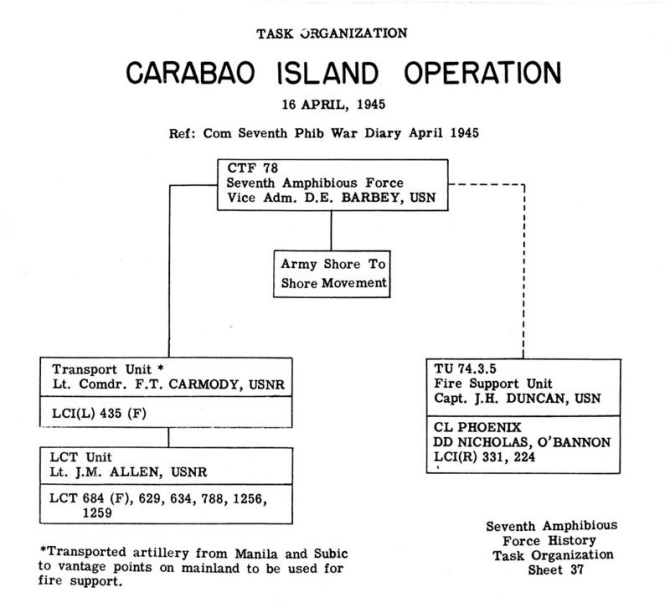

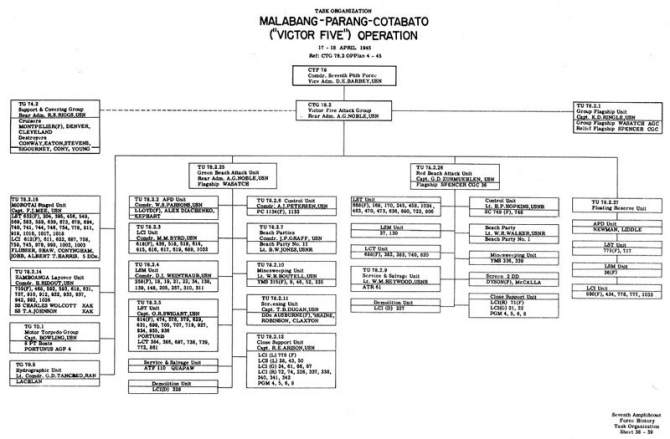

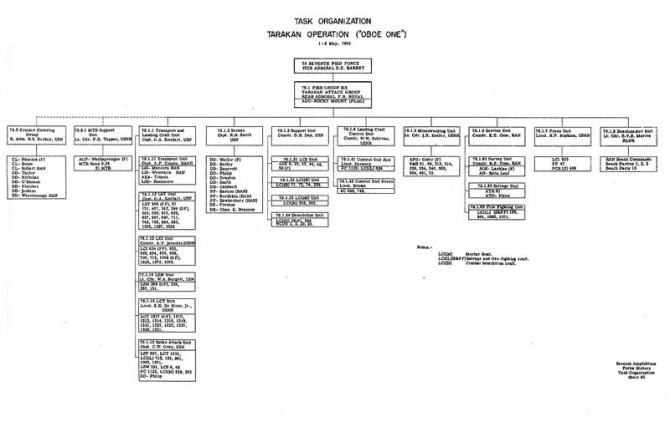

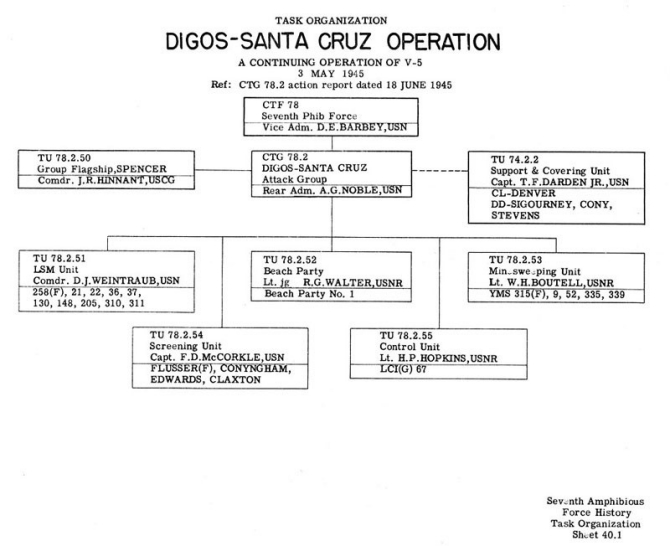

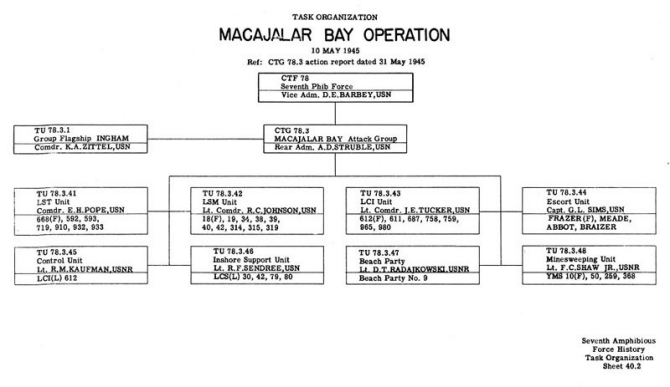

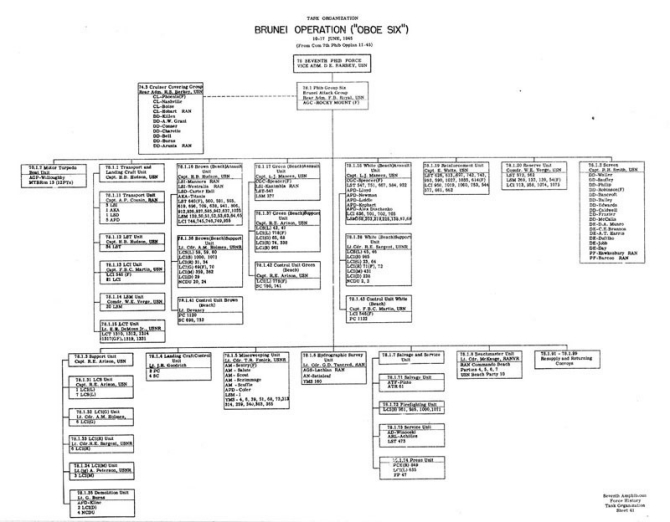

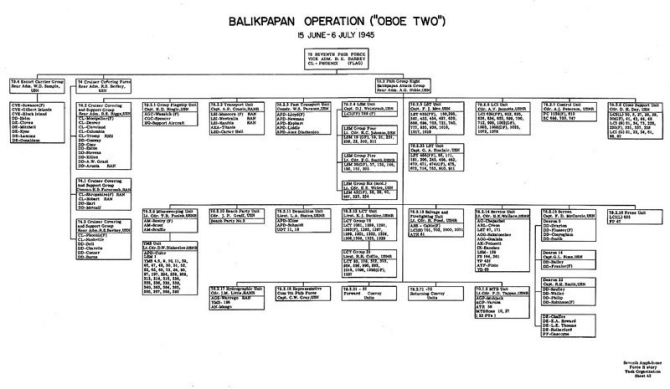

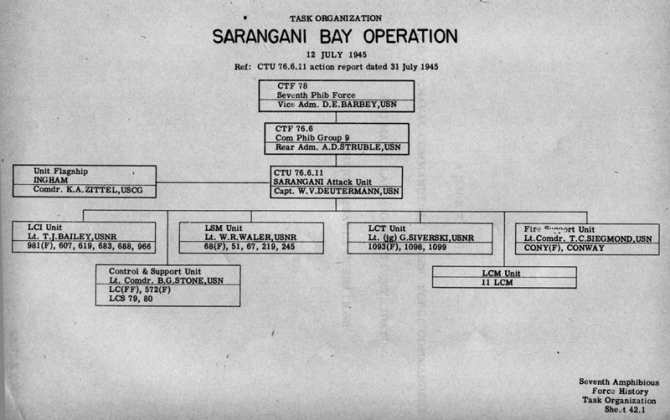

| (C) | Charts of Task Organization of Forces | ||||

| (D) | List of Naval Commanders, Landing Force Commanders and Major Landing Units | ||||

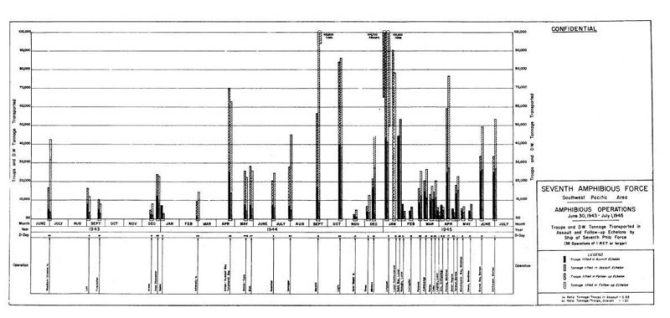

| (E) | Table and Chart Showing Troops and Cargo Transported in Major Assault Operations | ||||

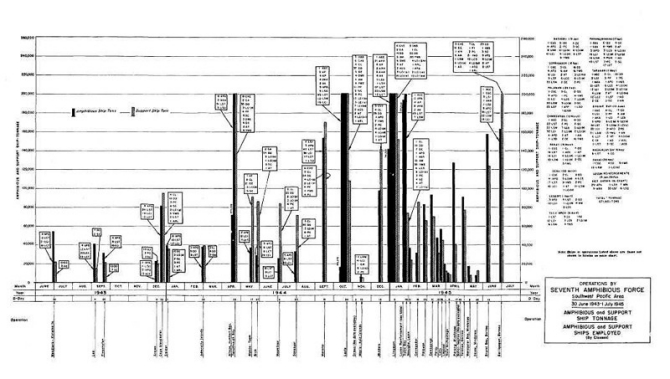

| (F) | Chart Showing Number and Displacement Tonnage of Amphibious and Supporting Ships Employed in Major Operations | ||||

| (G) | Miscellaneous Data | ||||

| (H) | List of Code Names used to designate Operations, Geographical Locations and Task Forces in the Southwest Pacific Area | ||||

| Illustrations | Page |

|---|---|

| Vice Admiral DANIEL E. BARBEY, USN | Frontispiece |

| Rear Admiral WILLIAM M. FECHTELER, USN, Deputy Commander and first Commander Amphibious Group Eight | I-18 |

| Vice Admiral BARBEY with Rear Admiral ARTHUR D. STRUBLE, USN, Commander Amphibious Group Nine and Rear Admiral WILLIAM M. FECHTELER, USN, Command Amphibious Group Eight | II-25 |

| Vice Admiral BARBEY with Rear Admiral FORREST B. ROYAL, USN, Commander Amphibious Group Six | II-50 |

| Commodore RAY TARBUCK, Chief of Staff and Rear Admiral ALBERT G. NOBLE, USN, Former Chief of Staff and later Commander Amphibious Group Eight | II-78 |

--iv--

Foreword

For almost three years, the SEVENTH Amphibious Force trained its personnel, fought a determined enemy, and carried Allied troops forward with accelerating pace and swelling power. Its strength and its success derived from the qualities of the individuals who composed it - foresight, courage, indefatigable energy, resourceful "know-how", the will to endure danger and suffering and hardship.

I am tremendously proud of the performance of the officers and men of the SEVENTH Amphibious Force, and, that others may more fully share my pride in their accomplishments, I hope that a more complete history some day will be written.

We have collected here the material from which the future historian may frame an outline for a more finished and detailed work. Our purpose has been to record significant incidents and conditions, dates and statistics, methods and opinions of participants, while they are fresh in the minds of those who were a part of the SEVENTH Amphibious Force.

Supplements to this Command History will deal separately with the amphibious phases of the various campaigns in which the SEVENTH Amphibious Force took part.

/signed/

DANIEL E. BARBEY,

Vice Admiral, U.S. Navy,

Commander Seventh Amphibious Force.

U.S.S. Estes

SHANGHAI, CHINA

23 December 1945

Narrative History

Seventh Amphibious Force

10 January 1943 - 23 December 1945

Command History of the Seventh Amphibious Force

PART I

Narrative Summary

The SEVENTH Amphibious Force was in existence for less than three years. In that time it participated in every assault landing in the Southwest Pacific Area and took part in the occupation landings following the successful completion of the war. Allied troops were transported and landed in assault on NEW GUINEA, BISMARCK ARCHIPELAGO and the HALMAHERAS, in the major campaigns which regained the PHILIPPINE ISLANDS and the operations which secured control of the SULU ARCHIPELAGO and parts of BORNEO. Preparations were being made for participation in the amphibious assault on JAPAN when the abrupt capitulation of the Japanese changed all plans. The Force thereafter was employed in transporting Army troops to KOREA, Marines to NORTH CHINA, Chinese forces from SOUTH CHINA to ports in NORTH CHINA and in repatriation of the Japanese from KOREA and the CHINA COAST.

Initially the SEVENTH Amphibious Force was known as the Amphibious Force, Southwest Pacific. On 15 December 1942 Rear Admiral Daniel E. Barbey received orders from Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet, to establish this force and he assumed command on 10 January 1943.

From January 1943 until September 1943, when assault operations commenced, Admiral Barbey was employed:

In the organization of the Amphibious Force, Southwest Pacific.

In the training of amphibious ships arriving from the United States.

In the training of Army Units in amphibious operations.

In the movement of Army, Marine, and Australian units to forward areas in anticipation of future operations.

Subsequent operations of the SEVENTH Amphibious Force to the time of the Japanese surrender can be divided into three general phases:

I-1

- September 1943 - September 1944 - Amphibious landings on the Eastern and Northern Coast of New Guinea, in New Britain, Admiralty Islands, and at Morotai in the Halmaheras.

October 1944 - February 1945 - Amphibious landings at Leyte, Mindoro, Lingayen and supporting operations in Luzon culminating in the Bataan-Corregidor landings on 15-16 February 1945.

February 1945 - July 1945 - Amphibious landings together with extensive minesweeping operations in the Central and Southern Philippines, Sulu Archipelago, and Borneo.

Organization and Training

The entire strategic concept of the military campaign to drive the Japanese from their positions in the Southwest Pacific Area was predicated on amphibious operations. When he assumed command of the Amphibious Force, Southwest Pacific - a force in name only - in January 1943, Admiral Barbey had three immediate problems:

Creation of an amphibious force

Training of amphibious ships

Training of army units

Creation of an Amphibious Force

LCTs and smaller craft began to arrive in the Southwest Pacific Area in December 1942 as part of a program to establish a large pool of LCTs, LCMs, and LCVs or LCPs primarily for use in training Army troops. The LCTs were shipped in three sections and assembled at Sydney, after which they were assigned with other landing craft to the amphibious training establishments at Port Sydney, New South Wales (about sixty miles below Sydney), and Toorbul, Queensland (about fifty miles north of Brisbane). Three flotillas of LCTs and landing craft for the units established at the various training centers were eventually obtained under the program.

The Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet assigned LST Flotilla Seven to the Amphibious Force, Southwest Pacific and the ships, many carrying LCTs, arrived at intervals between April and July 1943. The flotilla consisted of two groups of LSTs built on the west coast, and one group, manned by Coast Guard personnel, which had participated in the North African campaign.

I-2

The ships of LCI Flotilla Seven, also assigned to the Southwest Pacific Force, commenced to arrive in April 1943.

No APAs or AKAs were originally assigned to the Amphibious Force, Southwest Pacific, because of the pressing need for transports in other war theatres. Because of the need for at least one ship of each type for troop training, the Henry T. Allen (APA 15) and the Algorab (AKA 8) were assigned to the force in 1943, and reported at Sydney, the former in March and the latter in September. The Titania (AKA 13) replaced the Algorab in June 1944. Two other ships, the Blue Ridge (AGC 2) and Carter Hall (LSD 3) reported for duty in December 1943.

To supplement the Amphibious Force, the Australian Government provided three passenger ships which had previously been used as merchant cruisers, to be converted into Landing Ships, Infantry (LSI), the British counterpart of APAs. The conversion of the Manoora was completed in February 1943, the Westralia in June and the Kanimbla in September, and each immediately joined the force. These three LSIs plus the Henry T. Allen and the Titania served with the SEVENTH Amphibious Force until the end of the war.

The Rigel (AR 11) was assigned to the Seventh Amphibious Force, to provide repair and maintenance facilities for the ships of the force. Subsequently two LSTs, each with a Landing Craft Maintenance Unit embarked, augmented the maintenance facilities for a force that was constantly expanding and dispersed over a wide area. The facilities in these LSTs were increased until eventually they were reclassified as ARLs, and in December 1943 a third ARL joined the force. All these repair facilities remained under the operational control of Commander SEVENTH Amphibious Force until 30 June 1944 when Commander SEVENTH Fleet directed their transfer to Service Force, SEVENTH Fleet.

Except for a very short use of the Henry T. Allen in March 1943, Commander SEVENTH Amphibious Force was without a flagship until June 1943 when he and part of his staff moved aboard the Rigel. During the early assault operations, Commander SEVENTH Amphibious Force, with a small operational staff, used the Conyngham (DD 371) as his flagship, while the rest of the staff remained in the Rigel. When the Blue Ridge (AGC 2) arrived in the Southwest Pacific in December 1943, she became the force flagship and continued in that capacity until June 1945 when she returned to Pearl Harbor for overhaul and major alterations.

I-3

Training of Amphibious Ships

In the early period of activity in the Southwest Pacific Area, no organized training program for ships and landing craft similar to those of the Atlantic and Pacific Training Commands could be adopted. Ships had to be constantly engaged in troop training or in moving Army units to forward areas in preparation for imminent amphibious operations. However, the operations for occupation of Woodlark and Kiriwina Islands in June 1943 revealed the definite need for ship training, and as a result, an intensive ship training program was carried out in the Townsville-Cairns area of Australia prior to the first assault landing at Lae in September 1943.

Training of Army Units

Commander SEVENTH Amphibious Force organized and established an Amphibious Training Command for troop training at Port Stephens on 1 March 1943. This command absorbed the existing facilities of the Joint Overseas Operation Training School (U.S. Army) and the amphibious training facilities of HMAS Assault (Royal Australian Navy). In June 1943 the Amphibious Training Command was shifted to Toorbul and in an endeavor to maintain troop training in the vicinity of the staging areas, the Command was again moved forward to Milne Bay. However, the advance of our forces along the New Guinea coast was so rapid that three mobile training units had to be organized in order to train troops in forward areas. In March 1945, the Amphibious Training Command was transferred to Subic Bay, Luzon, to prepare for training troops for the prospective landings in the Japanese home islands.

The amphibious training curriculum was divided into two phases: intensive instruction of officers at the Training Center, followed by practice landings by Regimental Combat Teams under the direction of their own officers with mobile groups of instructors from the Amphibious Training Command serving as supervisors. A detailed account of the participation of Army, Marine and Australian Divisions in this training program is contained in a separate section of Part II.

Assault Operations

New Guinea: Bismarck Archipelago: Morotai

September 1943 - September 1944

The amphibious landing at LAE by the 9th Australian Division on 4 September 1943 was the first of a series of assault landings along the New Guinea coast, in the Bismarck Archipelago and in the

I-4

Halmaheras designed to provide staging areas, minor naval bases, and airfields to support the major assault on the Philippine Islands. From September 1943 to September 1944, the SEVENTH Amphibious Force made 14 major landings in these areas involving the movement of approximately 300,000 men and 350,000 tons of supplies and equipment.

The amphibious landing at LAE, in the Huon Gulf, on the northeast coast of New Guinea, was made by Australian troops of the Ninth Division, A.I.F., in conjunction with a parachute and airborne landing in the Markham Valley. The operation at LAE progressed so swiftly that it was evident that the same troops could begin amphibious landings at FINSCHHAFEN earlier than originally planned. FINSCHHAFEN landings were made on 22 September 1943 and the whole operation progressed smoothly. There was relatively little initial resistance by shore based forces at either LAE or FINSCHHAFEN but enemy air attacks in strength commenced in both areas about noon on D Day, followed by night attacks of small groups of enemy planes. Ships leaving the landing areas and re-supply echelons were under persistent and determined air attacks until airfields were developed and aircraft brought forward to neutralize nearby Japanese air bases. This same general pattern of air resistance first adopted by the Japs at LAE and FINSCHHAFEN continued throughout the New Guinea campaign.

The 112th Cavalry Regimental Combat Team was landed at ARAWE, New Britain, on 15 December 1943 against strong enemy opposition. The plan called for two landings; an advance echelon of 300 men to land in rubber boats from APDs one hour before dawn, and the main force to land after sunrise in LVTs and landing craft from the Carter Hall (LSD 3) and Westralia (LSI). In the expectation of preserving the element of surprise, planners recommended that no naval gunfire be used to support the advance echelon. Surprise was largely unsuccessful, however, for two reasons: (a) the enemy had been forewarned by the landing of amphibious scouts on the same beach several days earlier, and (b) bright moonlight enabled the Japs to spot the movement. The advance echelon was repulsed with 50% casualties. The main landing, supported by excellent naval gunfire, was successful. As a result of this experience, the SEVENTH Amphibious Force never again omitted naval gunfire support in order to achieve surprise.

The splendid execution of the amphibious landing at CAPE GLOUCESTER, New Britain, on 26 December 1943 was a tribute to the

I-5

professional skill of the 1st Marine Division. The navigational problems involved in the long over water movement of a large number of landing craft and the skillful handling of these craft in the landing areas were particularly gratifying features of this operation. It was in this operation that Commander SEVENTH Amphibious Force inaugurated the employment of Landing Craft Control Officers who were responsible for guiding the landing craft through the reefs to the designated beaches. The direction of landing craft by a senior officer has since become standard practice in all assault operations.

The third amphibious landing by the SEVENTH Amphibious Force within 18 days was made at SAIDOR on 2 January 1944 as soon as landing craft could be released from the Cape Gloucester operation. The assault forces were the 126th Regimental Combat Team of the 32nd Division which were landed in order to establish advance bases from which aircraft and light naval forces could operate to secure control of the Vitiaz Straits Area.

The Amphibious landing in the ADMIRALTY ISLANDS on 29 February 1944 was intended as a reconnaissance-in-force to prepare for the main landing scheduled for 1 April 1944, to be executed in conjunction with simultaneous landings by the Central Pacific Forces in the vicinity of Kavieng, New Ireland. Negros Island was selected for the advance landing after air reconnaissance had revealed only a small enemy force there, but doubts arose as to the actual condition existing when amphibious scouts insisted there were large enemy troop concentrations on this island. To definitely determine the enemy strength, a squadron of the 1st U.S. Cavalry Division (dismounted) landed at NEGROS on 29 February 1944. Possibly because of the excellence of the supporting naval gunfire directed against defensive installations near the beach, the landing force met little resistance on the first day, and the situation was deemed sufficiently secure that the 40th Construction Battalion landed at once to develop the airfield at Mamote. However, the third day brought confirmation of the advance reports of the amphibious scouts, as Japanese resistance developed in great strength. The success of the entire operation was in danger until the arrival of reinforcements, especially artillery, which were rushed forward from New Guinea. During the engagement the "Sea Bees" assumed the role of combat troops, and served with such credit that the battalion was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation.

I-6

The AITAPE-HUMBOLDT BAY-TANAMERAH landings on 22 April 1944 represented the most ambitious amphibious undertaking to date in the Southwest Pacific. It was the largest overseas movement undertaken in that area and it effectively by-passed and cut off the strong enemy garrisons in the vicinity of Wewak. Excellent strategic surprise was effected. The Japanese had moved forward heavy reinforcements to the Wewak area in anticipation of attack, and as a result there was only nominal resistance where the landings were actually made. Carrier based planes were used for the first time for landing support, and APAs and AKAs assisted in transporting 25,000 troops for the three simultaneous landings. Fast carriers from the Pacific Fleet furnished support.

Experience in amphibious warfare has taught that: (a) assault echelons should carry a minimum of supplies, sufficient only for immediate needs, and (b) preliminary reconnaissance and photo-interpretation can be very misleading unless skillfully evaluated and analyzed. These lessons were learned again during this operation. At Hollandia, a large amount of supplies were brought in to beach dumps and insufficiently dispersed. On the evening of D Day, a lone enemy plane dropped a single bomb in the concentrated supply area and the resulting fire destroyed all the supplies landed that day, the equivalent of 11 LST loads. In the Tanamerah Bay area, photo intelligence had reported a road behind the beach. During the landing it was discovered that the "road" was an unfordable swamp which made it necessary to unload supplies at Humboldt Bay, forty miles distant. The results could have been disastrous for the Tanamerah Attack Force had the enemy opposition been stronger. Fortunately, these mishaps did not seriously affect the success of the landings.

The next amphibious operation was at WAKDE ISLAND on 17 May 1944 followed on 27 May 1944 by the landing on BIAK ISLAND. The Biak operation was not originally contemplated but was quickly conceived and planned when it became evident that the air strips at Hollandia would not be ready to support heavy bombers for some months. Several calculated risks were accepted in the execution of the Biak landing in order to meet the early date set. However, the landing and unloading were conducted with unanticipated success although the troops met considerable resistance. A minor reversal was successfully recouped two days after the initial landings when LCTs evacuated an Army battalion which had been cut off at one point by a large enemy force. Naval gunfire was effectively employed for several days to support the troops in their advance against the strong enemy positions.

I-7

On 2 July 1944 an assault landing was made at NOEMFOOR ISLAND and on 30 July 1944, the final landing of the New Guinea campaign was made at SANSAPOR.

Rear Admiral W. M. Fechteler, USN, Deputy Commander SEVENTH Amphibious Force, directed the amphibious operations at WAKDE, BIAK, NOEMFOOR and SANSAPOR while Rear Admiral D. E. Barbey, USN, was on temporary duty in the United States. Ships that participated in these four landings and in the resupply echelons that followed were under constant threat of attack by a strong Japanese surface force concentrated in the Philippine-Borneo-Netherlands East Indies Area. During this period, the Pacific Fleet was concentrated far to the north in the Marshalls-Marianas Area, and the combatant units of the SEVENTH Fleet would have been entirely inadequate at the time to withstand an attack of enemy heavy units. The failure of the Japanese Navy to attempt to capitalize on this opportunity to retard the advance and prevent the consolidation of our ground force positions is an unexplained aspect of the enemy's strategy.

The amphibious landings at MOROTAI in the Halmahera Islands took place on 15 September 1944, when over 50,000 troops disembarked in record time without opposition but under very difficult landing conditions. There was one other operation, relatively small, in the same area in November 1944. Under the direction of Commander SEVENTH Amphibious Force and under the immediate command of Captain Lord Ashbourne, RN, in the British minelayer Ariadne, United States troops transported in LSMs and LCIs landed unopposed to establish radar and loran stations on ASIA and MAPIA ISLANDS as aids to future naval operations.

Capture of the Philippines

October 1944 - February 1945

The projected increase of the SEVENTH Amphibious Force began to be realized in August 1944. Between then and November the Force was increased threefold by the addition of three LST Flotillas, four LCI Flotillas, three LCT Flotillas, and one LCS(L) Flotilla. Also many transports from the Pacific Fleet joined the force under the temporary operation control of Commander SEVENTH Amphibious Force.

Original plans for the capture of the Philippines provided for an amphibious landing at Sarangani Bay, Mindanao, but on 15 September

I-8

1944, Commander SEVENTH Amphibious Force was advised that the initial assault would be made at Leyte, and plans were revised accordingly. The changes were the result of the new strategic concepts, arrived at in early September, which stepped up the tempo of the whole program of war against Japan.

The amphibious landings at LEYTE, Philippine Islands, were made on A day, 20 October 1944, preceded by minor landings on Dinagat and Homonhon Islands at the entrance to Leyte Gulf on A-3 and A-2 days respectively. Commander SEVENTH Fleet was in overall command of the ships engaged in the Leyte Operation; Commander SEVENTH Amphibious Force was responsible for landing the XXIV Army Corps on the Southern Beaches in the vicinity of Dulag; and Lieutenant General Walter Kreuger, Commanding General SIXTH Army was responsible for securing LEYTE and the adjacent island of SAMAR.

In this operation the fire support ships did not operate directly under the amphibious force commanders, but under Commander Battleships (Rear Admiral Oldendorf) temporarily operating with part of his force under the SEVENTH Fleet, who served as Commander Support Force during the Leyte Operation. He conducted the preliminary bombardments prior to the landings and thereafter covered the amphibious forces during the Battles of Surigao Straits and Samar.

The amphibious landings were eminently successful, but the supporting ships suffered from suicide air attacks, effectively employed against our naval forces for the first time. Fortunately ships of the SEVENTH Amphibious Force in the assault echelon were lightly loaded and were able to unload and depart on the first day, with the result that the large transports were out of the landing area before the suicide attacks commenced.

When Commander SEVENTH Amphibious Force left Leyte for Hollandia to begin preparations for the Lingayen Operation (which was originally scheduled for 20 December 1944), Commander Amphibious Group 8 (Rear Admiral Fechteler) was designated to remain at Leyte. He was relieved as SOPA, LEYTE on 16 November 1944 by Commander Amphibious Group Nine (Rear Admiral Struble) who directed subsequent amphibious operations in the area.

The advance of the ground forces on Leyte was seriously threatened by the arrival of substantial Japanese reinforcements

I-9

landing at Ormoc on the west coast. On short notice, Commander Amphibious Group 9 skillfully planned and directed an amphibious landing at ORMOC on 7 December 1944. One week later, on 15 December 1944, he made another successful landing on MINDORO and conducted the resupply echelons in support of this landing as long as the Japanese air threat existed. His flagship was hit by a suicide plane while enroute to Mindoro, and his Chief of Staff, several other members of his staff, and several members of the staff of the Landing Force Commander were killed. Ships of the SEVENTH Amphibious Force suffered high personnel casualties and heavy material losses from suicide air attacks during the ORMOC and MINDORO operations. However, these two landings contributed materially to the final capture of Leyte and to the success of the impending operations on Luzon.

The amphibious landing at LINGAYEN on 9 January 1945 followed the same general organization plan used at Leyte. Commander SEVENTH Fleet was in overall command of the landing; Commander SEVENTH Amphibious Force landed the I Corps on the northern beaches; and Commander THIRD Amphibious Force landed the XIV Corps on the southern beaches. Initial opposition to the landing was not strong but it stiffened as the troops moved from the beachhead to the hills just beyond, and naval gunfire support was used for several weeks. Fire support ships and minesweepers suffered substantial losses during the preliminary minesweeping and preassault bombardment. If the enemy had concentrated air attacks on transports with the same effectiveness achieved against supporting ships, the Lingayen operation might not have succeeded.

After the Lingayen Landings, matters of first importance were the immediate reinforcement of the Philippines, and the exploitation of the rapid advance of the SIXTH Army down the Luzon plain. The SEVENTH Amphibious Force assumed the task of transporting troops to accomplish these ends. A major portion of those amphibious ships from the Pacific Fleet which had participated in the Leyte and Lingayen operations were made available to Commander-in-Chief Southwest Pacific Area until 15 February 1945, and under the operational control of Commander SEVENTH Amphibious Force, they were immediately employed in a rapid turnaround which brought six divisions from Leyte and New Guinea to Luzon within a month.

After LINGAYEN, the amphibious operations of the SEVENTH Amphibious Force assumed a new pattern to meet the need for

I-10

simultaneous operations for the earliest control of the entire Philippine Archipelago. Vice Admiral Barbey during this phase acted as the Attack Force Commander and assumed overall control of operations assisted by three Rear Admirals as Group Commanders. These were Commanders Amphibious Groups 8 and 9, regularly assigned to the Southwest Pacific Area, and Commander Amphibious Group 6 (Rear Admiral Royal), assigned temporarily from the Pacific Fleet. Individual operations were under the command of these group commanders or, in some cases, under command of subordinate officers of the Force.

The first of the consolidating operations took place on 29 January 1945, when one division and regimental combat team were landed near Subic, Zambales Province, followed on 31 January 1945 by the 11th Airborne Division landing at NASUGBU, South of Manila Bay, which assisted materially in the capture of the Capital. During the same period, three more divisions were landed at Lingayen, and a fourth at Mindoro.

The BATAAN-CORREGIDOR operation on 15 February 1945, was a combined air bombardment-naval bombardment-airborne-amphibious attack. The intensity of the air bombardment, the excellent timing of airborne and amphibious operations, and the accuracy of the naval gunfire support by cruisers and destroyers reduced what might have been a long and costly campaign to one successfully concluded in a few days. The amphibious phase of the operation was commanded by Commander Amphibious Group 9, Rear Admiral Struble.

Consolidating and Minesweeping Operations Throughout the Philippines and Borneo

February 1945 - July 1945

In February 1945, Commander SEVENTH Amphibious Force was charged with the clearance of minefields and reopening of ports and sea routes in the Philippine Area. The opening of Manila Bay to shipping was given first priority. Though a relatively small number of minesweepers were available for this difficult task, Manila was open as a port before 1 March 1945, not quite two months after the first troops had landed in Luzon. The clearance of Philippine water was by far the largest minesweeping operation of the war up to that time. Including the Borneo operations, over 1300 mines (both Allied and Japanese) were destroyed in more than 8,000 square miles swept

I-11

during continuous operations which lasted five months. Six AMs and approximately 25 YMS did the job.

While fighting on Luzon was still in progress, the campaign for the recapture of the remaining islands in the Philippines and for the control of Borneo and the Netherlands East Indies was begun. Between February and May 1945 more than sixteen landing operations were conducted in the central and Southern Philippines, and three major operations on the east and west coast of Borneo.

The first in the series was the landing of a regimental combat team of the 40th Infantry Division at PUERTA PRINCESSA, PALAWAN ISLAND by Commander Amphibious Group 8, Rear Admiral Fechteler, on 28 February 1945. In this operation there were no losses by either Army or Navy. When PUERTA PRINCESSA was secured, air bases were established which enabled the air force to gain control over the China Sea.

On 10 March 1945 in another amphibious operation under Rear Admiral Royal, Commander Amphibious Group 6, two regimental combat teams also of the 40th Infantry Division, were landed at ZAMBOANGA. In April, landings at JOLO, TAWI-TAWI, and on SANGA-SANGA ISLAND conducted by the same troops achieved control of the Sulu Archipelago.

The next series started on 18 March 1945 when two regimental combat teams landed in the vicinity of ILOILO, PANAY under Commander Amphibious Group 9. This was followed on 26 March 1945 by landing two regimental combat teams on CEBU with Acting Commander Amphibious Group 8 (Captain A. T. Sprague) in command. Over a two months period Commander Amphibious Group 9 conducted landings on NEGROS ISLAND: BOHOL ISLAND, and additional landings on CEBU and PANAY.

During March and April, amphibious landings were also made on LUBANG ISLAND, TICAO-BURIAS ISLANDS, MASBATE ISLAND, CABALLO ISLAND, CARABAO ISLAND, EL FRAILLE ISLAND, and at LEGASPI, LUZON. These operations were all commanded by subordinate officers of the SEVENTH Amphibious Force, usually flotilla or group commanders. In one of these operations, the landing of one Regimental combat team at LEGASPI on 1 April 1945, low-level bombardment prior to D Day supplanted naval gunfire with very effective results.

I-12

On 17 April 1945, Rear Admiral Noble who had succeeded Rear Admiral Fechteler as Commander Amphibious Group 8 directed a two division landing by the X Corps at PARANG and MALABANG in the Cotabato area of Mindanao. The landing areas had previously been secured by guerrillas, and troops moved quickly overland and captured DAVAO. Meanwhile, naval support forces moved into DAVAO GULF and destroyed suicide boats, midget submarines, and their bases. Elements of the X Corps moved northward from Davao and met increasing Japanese resistance in the mountainous part of Central Mindanao. To assist in enveloping the remaining Japanese, Commander Amphibious Group 9 landed a regimental combat team at MACAJALAR BAY and on 1 June 1945 he assumed responsibility for support of the entire Mindanao Operation while Commander Amphibious Group 8 withdrew to prepare for the Balikpapan operation.

Owing to the importance of preparation for the invasion of Japan, plans for control of the Netherlands East Indies were restricted to the capture of strategic areas in Dutch and British Borneo. The first operation took place on 1 May 1945 when a brigade group of the 9th Australian Division, equivalent in size to a regimental combat team, landed at TARAKAN, Dutch Borneo. Commander Amphibious Group 6 conducted this landing which was unopposed, following effective air strikes, naval bombardment, and minesweeping operations. An unusual feature of the TARAKAN operation was the extreme tidal range encountered and the fact that LSTs beached in mud instead of sand. Seven LSTs were stranded in mud for 11 days. Another was the iron rails set upright in the mud to form beach obstacles. Such obstacles had not been encountered previously and no Underwater Demolition Team had been assigned to remove them. However, the Royal Australian Engineer Unit undertook and successfully accomplished the job on D-l Day.

Commander Amphibious Group 6 conducted the second landing in Borneo on 10 June 1945 at BRUNEI BAY; (The original date of 22 May was extended to permit the arrival of support units and supplies from Australia). This was an extensive operation involving the simultaneous landings of one brigade group of the 9th Australian Division on LABUAN ISLAND and another on the mainland adjacent to BRUNEI BAY. Subsequent operations resulted in the capture of the rich oil area of MIRI-LUTONG .

The untimely death of Rear Admiral Royal occurred at sea while his flagship was enroute to Leyte following the Brunei Bay operation.

I-13

The final amphibious assault landing in Borneo was made on 1 July 1945 at BALIKPAPAN. Vice Admiral Barbey was in overall command of this operation with Commander Amphibious Group 8 directly responsible for landing the 7th Australian Division. Many elements of this division had been transported the entire distance from Australia in LSTs of the SEVENTH Amphibious Force. The following factors made BALIKPAPAN an extremely difficult amphibious operation:

A very shallow beach gradient which did not permit fire support ships nearer than five miles out from the beach.

Shallow waters thickly sown with magnetic mines.

Landbased air support operating from bases more than 400 miles away.

These difficulties were overcome by the excellent work of the minesweepers, intensive naval bombardment, and three Escort Carriers of the Pacific Fleet which contributed air support.

The Borneo operations were unique in the respect that serious difficulty was encountered with previously sown allied magnetic mines. The Fifth Air Force and RAAF had planted numerous magnetic mines, many incapable of self-sterilization, in the shallow waters of TARAKAN, BRUNEI BAY, and BALIKPAPAN, and pre-assault sweeping was conducted for several days in each of these three areas. At BALIKPAPAN where the threat of magnetic mines was especially great, minesweeping continued for two weeks before the landing. No serious difficulty was encountered in clearing Japanese mines. However, off LUTONG, the sweeping groups swept one enemy field of 600 mines all more than 80 feet deep. The field had obviously been designed as a defensive measure against Allied submarines. Because of the slight gradient of the ocean bottom near LUTONG, Japanese tankers were obliged to anchor three miles from the beach and load oil through long pipe lines, thus being particularly exposed to submarine attack.

Throughout the BORNEO operations, the small minesweeping group attached to the SEVENTH Amphibious Force did an outstanding job in spite of heavy losses - about one ship damaged or lost for every two magnetic mines destroyed.

I-14

Post War Operations

Although it was not realized at the time, the BALIKPAPAN operation was the last for the SEVENTH Amphibious Force which completed a two-year combat record of 56 amphibious assault landings involving overwater movement of a total of more than a million men.

During July and August 1945, ships of the SEVENTH Amphibious Force were engaged in the roll-up of men and material from New Guinea, the Solomons, and Admiralty Islands. Many of the same ships had carried the same troops to those ports in assault landings a year or two before. During this period, the SEVENTH Amphibious Force also was engaged in redistributing Army Units, and preparing plans for the final assault on the Japanese homeland.

15 August 1945 had been set for the transfer of the SEVENTH Amphibious Force from the SEVENTH Fleet to the Amphibious Forces, Pacific Fleet, where it was to have a status comparable to the THIRD and FIFTH Amphibious Forces. Administrative and training functions of the force were to be transferred to the Administrative Command, Amphibious Forces, Pacific Fleet, and the ships to various commands, primarily the Philippine Sea Frontier.

When the Japanese surrendered on the very day the transfer was to take place, plans were quickly revised, and the SEVENTH Amphibious Force continued under the operational control of the SEVENTH Fleet. The movement of the XXIV Corps for occupation in KOREA and movement of the III Marine Amphibious Corps for similar duties in NORTH CHINA were begun immediately. Upon completion of these lifts, the SEVENTH Amphibious Force transported the 8th, 13th and 52nd Chinese Armies from South to North China ports and simultaneously began the repatriation of Japanese from Korea and North China. Commanders Amphibious Groups 7, 8 and 13 were in immediate command of these various phases.

On 19 November 1945, Vice Admiral Barbey assumed command of the SEVENTH Fleet, and simultaneously delegated the responsibility for continuation of the repatriation program to Commander Amphibious Group 8. The same date marks the end of the operations of the SEVENTH Amphibious Force, for while it

I-15

continued as a command, and Vice Admiral Barbey retained his title as Commander, the flagship with the staff embarked, proceeded to the Atlantic. On 23 December 1945, the SEVENTH Amphibious Force was finally disestablished. The organization, which Vice Admiral D. E. Barbey created, trained, and led, had completed its task.

I-16

PART II (a)

Staff Organization and History

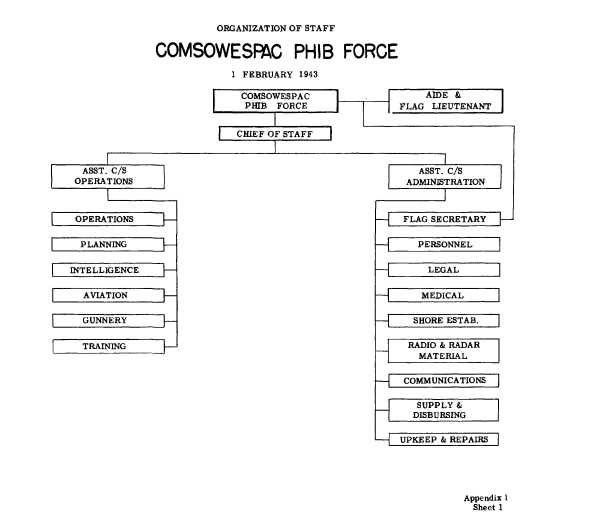

Rear Admiral DANIEL E. BARBEY, USN, assumed command of the Southwest Pacific Amphibious Force on 10 January 1943. By 1 February 1943 the Staff was complete, and established in headquarters ashore at BRISBANE, AUSTRALIA. The Staff of Commander Southwest Pacific Amphibious Force was initially organized as shown in Appendix 1, Sheet 1.

The first concern of the Commander Southwest Pacific Amphibious Force was the establishment of base facilities for landing craft and the initiation of amphibious training for all branches of the armed forces in preparation for forthcoming operations. By 13 March 1943, the following had been activated under his jurisdiction and control:

Headquarters, Southwest Pacific Amphibious Force, BRISBANE.

Amphibious Training Command, PORT STEPHENS, NEW SOUTH WALES.

Landing Force Equipment Depot, PORT STEPHENS.

Naval Landing Craft Depot, TOORBUL POINT, QUEENSLAND.

Naval Landing Craft Depot, MACKAY, QUEENSLAND.

On 15 March, 1943 Commander Southwest Pacific Amphibious Force became Commander Amphibious Force, Seventh Fleet.

The U.S.S. Henry T. Allen reported for duty as flagship, and on 17 March, 1943 the staff moved aboard. However, the ship was in poor material condition and also was needed urgently for use in amphibious training and transportation of troops. As a consequence the Staff remained aboard only a short time.

For the WOODLARK-KIRIWINA Islands Operation, the Commander Amphibious Force SEVENTH Fleet, took forward an advance echelon of his staff to serve as an operating group. This echelon, which embarked in the USS Rigel on 22 June, 1943, consisted of the following officers: Operations, Assistant Operations,

II-1

Aviation, Aerology, Medical and Communications plus the necessary communication watch officers and enlisted personnel. The rest of the staff under the Chief of Staff remained at the BRISBANE headquarters.

During the conduct of actual operations, commencing with Woodlark-Kiriwina and concluding with AITAPE-HUMBOLDT BAY-TANAMERAH operation Admiral Barbey used a destroyer as a flagship. At these times three or four watch officers and necessary communication personnel accompanied him. The remainder of the forward echelon, usually engaged in operational planning, remained in the Rigel.

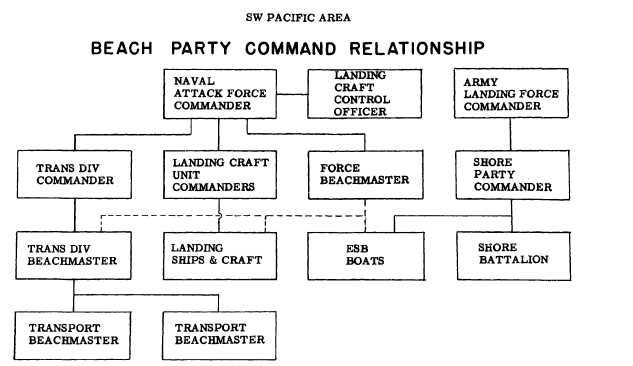

For the purpose of controlling the movements of the large number of landing craft employed in widespread Southwest Pacific Areas, certain officers of the staff of Commander Seventh Amphibious Force, known as Landing Craft Control Officers, were established in various New Guinea ports. In assault operations Landing Craft Control Officers directed the movement of landing craft to the beach. After the assault phase ended and the attack force commander left the area, they assumed entire control of shipping for the immediate support of the landing force. In the rear areas, the LCCO in each port controlled the movement of amphibious ships, primarily the echelons scheduled for re supply.

On 15 August 1943, when the Amphibious Forces throughout the Pacific were reorganized, Commander Amphibious Force, Seventh Fleet became Commander Seventh Amphibious Force.

In December 1943, the U.S.S. Blue Ridge (AGC 2) reported as flagship, and on 18 December the rear echelon embarked in the Blue Ridge and moved forward to Buna, New Guinea, where the forward echelon transferred from the Rigel. A Progress Section for material and supply remained at Brisbane.

On 27 January 1944, Rear Admiral W.M. FECHTELER, USN, reported as Deputy Commander Seventh Amphibious Force. He served in this capacity, acting as Attack Group Commander in several operations, until 1 October 1944, when Amphibious Groups were established in the U.S. Fleet and he was ordered as Commander Amphibious Group Eight.

The frequency of operations and the rapid movement forward during the period 30 June 1943 to 1 May 1944 resulted in a need for

II-2

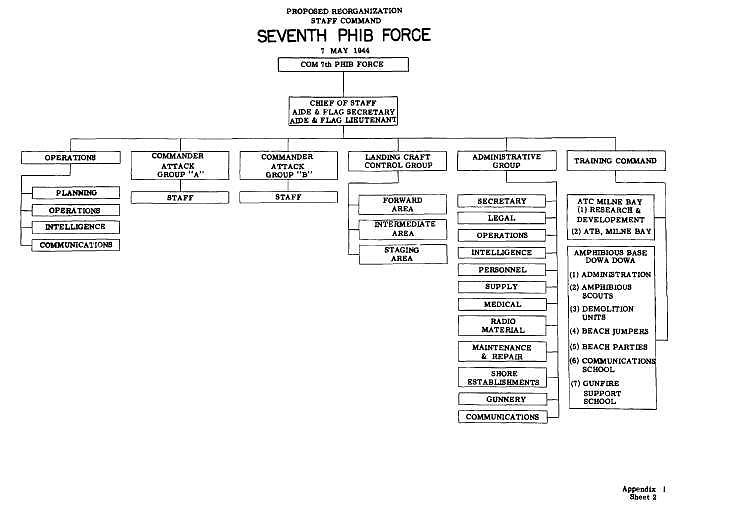

more staff personnel. The requirements fell generally into two categories: Officers to command attack operations and the various phases thereof, and officers to control the movements and logistics of amphibious shipping at numerous points. On 7 May 1944 it was proposed to reorganize the Staff as shown in Appendix 1, Sheet 2, but this proposal was not approved, and the Staff organization continued to function without attack group commanders.

With the approach of the Leyte Operation, it was considered desirable to again divide the staff, since the Blue Ridge was to take part in the operation. The Staff had grown considerably as the size of the force increased, and it was difficult to maintain the entire staff in one ship. On 7 October 1944, the "Administrative Group of the Staff of Commander Seventh Amphibious Force" was established in the U.S.S. Henry T. Allen with Captain H. J. NELSON, USN, as Commander Administrative Command, Seventh Amphibious Force. The mission of the Administrative Command was defined:

"To provide the necessary personnel, training, and logistic requirements and to maintain in a satisfactory condition the ships assigned to this force in order to enable Commander Seventh Amphibious Force to provide transportation and close support for amphibious operations against enemy held positions.

To carry out all the administrative functions and to take over any other duties that can be delegated to it in order that Commander Seventh Amphibious Force may have the minimum amount of details and influence distracting him from his combat missions."

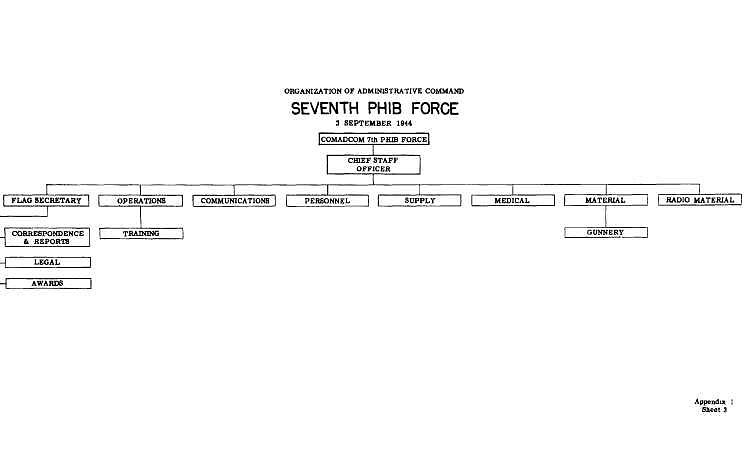

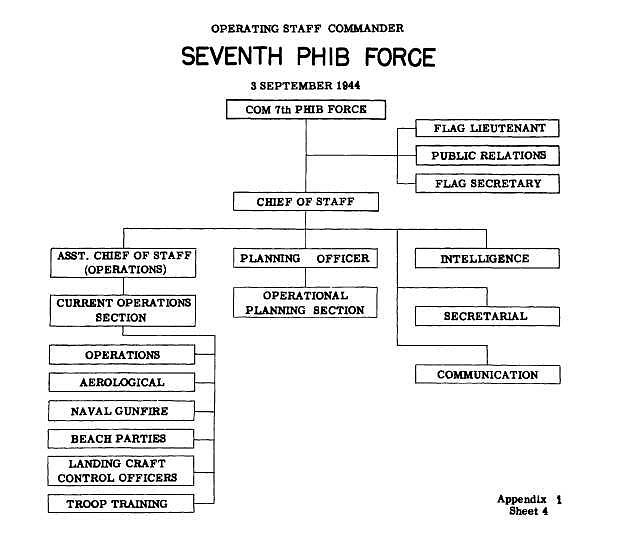

The administrative Command was organized as shown in Appendix 1, Sheet 3. The operating Staff was organized as shown in Sheet 4.

On 22 November 1944 the Progress Section (in Australia) was discontinued and its personnel returned to the Administrative Command.

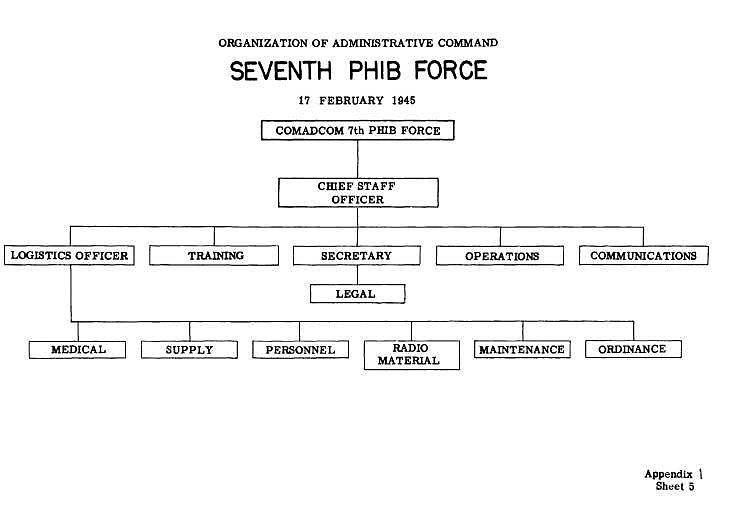

On 17 February 1945 the Administrative Command was augmented by a logistics officer, whose duty was to coordinate all sections having to do with logistics of any type (see Appendix 1, Sheet 5.

Beginning in early February 1945, the Blue Ridge based in the

II-3

Manila-Subic Area and the Henry T. Allen in Leyte. With the progressive occupation of the Philippines, it became necessary to provide representatives in many ports to control amphibious shipping. By 1 May 1945 the Staff had representatives in Manila, Lingayen, Subic, Mindoro, Palawan, Leyte, Hollandia, Zamboanga, Malaban, Tarakan, and Morotai.

On 7 June 1945 the operating staff moved aboard the U.S.S. Ancon (AGC 4) and the Blue Ridge returned to Pearl for overhaul.

On 13 August 1945 the Ancon departed for service in connection with the occupation of Japan, and the operating staff was temporarily housed in the U.S.S. St. Croix (APA 228) until it moved aboard the U.S.S. Catoctin (AGC 5) on 28 August.

On 15 August 1945 the Seventh Fleet became a unit of the Pacific Fleet, and Commander Seventh Amphibious Force reported to Commander Amphibious Forces, Pacific Fleet. The Administrative Command Seventh Amphibious Force also reported to Commander, Amphibious Forces, Pacific Fleet and became the Administrative Command, Amphibious Forces Pacific Fleet, Philippine. Since Commander Amphibious Forces, Pacific Fleet became the type commander, it was not necessary for the operating Staff to absorb a major portion of the function previously performed by the Administrative Command. However, a logistics subsection was added to the operations section. The staff has since performed with a gradual reduction in personnel due to demobilization, but with no essential change in organization.

II-4

II-5

II-6

II-7

II-8

II-9

PART II (b)

Amphibious Training of Ground Forces by

Seventh Amphibious Force

Introduction

The amphibious training of Army troops was assigned as a Navy responsibility by action of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. In conformance with this, General Headquarters of the Southwest Pacific Area issued a directive on 8 February 1943 which charged the Southwest Pacific Amphibious Force with the conduct and coordination of all amphibious training, except training for close-in-shore, shore-to-shore-operations of the Engineer Special Brigades. It will be noted that in this particular function only, that of amphibious training of army troops, Rear Admiral BARBEY was to be directly responsible to General Headquarters and not through the Commander Southwest Pacific Force as he was in all other matters.

All amphibious training activities then functioning were placed under his command. These were:

(a) Joint Overseas Operational Training School at Port Stephens, New South Wales. This activity had been operating directly under General Headquarters and was engaged in a program of basic amphibious training for officers of the United States and Australian Armies. An Australian infantry battalion with a battery of artillery served as school troops and gave landing demonstrations on the battalion landing team scale. A naval advanced base unit of 3 officers and 40 enlisted men with 40 landing craft of the 36' LCP type was attached to this school. This advanced base unit was also engaged in instructing Royal Australian navy personnel in the operation of the U.S. type of landing craft.

(b) At Toorbul, Queensland, another naval unit of 3 officers and 60 enlisted men with 10 landing craft of the 36' LCP type were also engaged in elementary training of Royal Australian Navy personnel in the handling of landing craft.

(c) At Camp DOOMBEN, Queensland, in the vicinity of Brisbane were 21 officers and 250 enlisted men who had been trained in

II-10

the operation of landing craft and who were awaiting the arrival of landing craft from the United States. These personnel were later transferred to the Amphibious Training Command at Port Stephens when that Command was established.

(d) The Royal Australian Navy had an amphibious training base at Port Stephens, known as HMAS Assault. On 25 February 1943 the Australian Commonwealth Naval Board directed that the HMAS Assault and also the Australian Landing Ship Infantry HMAS Manoora be placed under the operational control of Commander Southwest Pacific Amphibious Force. The HMAS Kanimbla and Westralia, two additional LSIs were to be similarly assigned as soon as their conversions had been completed.

Amphibious Training in Australia

Initial Operations

On 1 March 1943, the Joint Operational Overseas Training School, HMAS Assault and U.S. Advanced Base Unit were all combined to form the Amphibious Training Command under temporary command of Captain K. J. CHRISTOPH, USN. He was relieved the following month by Captain J. W. JAMISON, USN who had had considerable experience in amphibious training in the Atlantic and who had served as Beachmaster during the North African Landings.

The Seventh Division, Australian Imperial Forces were the first troops scheduled for amphibious training. In preparation for the large scale training, special training was conducted for selected officers of the division. Subjects covered were shore and beach parties, communications, naval gunfire support, air support, amphibious scouting and the duties of transport quartermasters. Sixty four officers attended these courses.

The Seventh Division was unable to meet its date for troop training because of difficulties in organization, lack of replacements, and the large number of personnel down with recurrent malaria. It was estimated that the division would not be ready to commence training until the end of April.

The Commander Southwest Pacific Amphibious Force recommended that the First Marine Division, then in the

II-11

vicinity of Melbourne, be made available for training. This was approved and training of this division was conducted in the Dromana Beach Area, Port Phillip, Victoria, from 28 March until 15 May. During this period officers of the Seventh Australian Division observed the training of the Marines but no troop training was given this division.

The HMAS Manoora and USS Henry T. Allen were initially used for amphibious training of the First Marine Division. The H.T. Allen had arrived in the area on 13 March from the South Pacific. The material condition of this ship was such that it had to be withdrawn from training on 10 April for a five weeks overhaul availability at Sydney. It was planned that LSTs, LCIs and LCTs as they became available in the area would take part in this training, commencing about 15 April. Such craft however were required for the movement forward of troops as soon as they arrived. Only the Manoora remained available for training, embarking one battalion landing team at a time.

Pattern of Training

While refresher training of First Marine Division was proceeding at Port Phillip, preparations were made for training troops at Port Stephens. Standard operating procedures were developed for Shore Parties, Naval Gunfire Support and Air Support, Landing Force Communications, Transport Quartermasters, and Combat Loading, Conduct of Troops aboard Amphibious Ships and Craft, Technique of the Soldier in Debarking from Amphibious Ships and Craft.

The 32nd Infantry Division was the first unit to attend the Amphibious Training Center. The method of instruction was found to be successful and was adopted as a pattern for all future training. A staff and command course, specialist course and course for troop instructors was given prior to training of troop units.

Officers attending staff and command courses were; Division or Assistant Division Commander; Intelligence, Operations, and Logistic Officers; Division, Regimental and Battalion Staffs; Division Engineer; Division and Regimental Surgeons; Regimental and Battalion Commanders.

The first week of the staff and command course consisted of

II-12

lectures, discussions and demonstrations covering all phases of amphibious operations. The second week was devoted to a school problem which required students to prepare plans, field orders, and administrative orders for a Regimental Combat Team landing. RCT and BLT Staffs worked as groups in solving this problem.

The Specialists School was divided into sections. Communications attended by division, regimental and battalion communication officers; Naval Gunfire Support by forward observers, liaison officers and S-3s of Field Artillery Battalions; Shore Party by selected officers of Engineer Battalion, Pioneer Platoons and Infantry units; Transport Quartermaster section which was attended by two officers from each Battalion; Medical by Division, Regimental and Battalion Surgeons.

Students in the Specialists School attended those first week lectures and discussions of the Command and Staff Course which were of general interest to all. The balance of the two week period was spent on the particular specialty with lectures, discussions, school problems, and practical work.

The assistant troop-instructor school was held for each RCT one week before scheduled troop training for that unit. It was attended by one officer and one half of the non-commissioned officers from each company, battery, or similar unit. The purpose of this course was to provide personnel qualified to instruct and correct the individual soldier during troop training and therefore stressed technique of embarkation, debarkation, individual procedure aboard transports, wearing of equipment, etc.

Officers attended the Staff and Command and Specialist Schools on a temporary duty status. During troop training, all Commanding Officers retained command of their units. The Amphibious Training Center published the schedule of training and the Troop Commanders executed it. Instructors acted as supervisors of training and advisors to the Commanding Officers of units undergoing training.

In May 1943, the Combined Operations Training School at Toorbul, Queensland was turned over to Commander Seventh Amphibious Force. This school had been operated by the 1st Australian Army and had been training separate Infantry Battalions, Anti-Aircraft Groups, and Armoured Brigades.

The Amphibious Training Center, Cairns, Queensland was

II-13

established on 25 June 1943. Captain P. A. STEVENS, USN, former Commanding Officer of the USS Henry T. Allen, was assigned as Commanding Officer. The 2nd Engineer Special Brigade consisting of amphibious trained Army Troops, was located at Cairns and was placed under the operational control of Commander Seventh Amphibious Force for use in training the 6th and 9th Australian Divisions.

Units Trained

Following is the training accomplished by amphibious training centers in Australia during 1943:

| Unit | ATC | Inclusive Dates |

|---|---|---|

| 32nd U.S. Inf. Div. | ||

| Staff & Command & Specialists School | Port Stephens | 31 May - 14 June |

| Troop Training | Port Stephens | 16 June - 28 August |

| 1st U.S. Cav. Div. | ||

| Staff & Command & Specialist Schools | Port Stephens | 2 - 16 August |

| Troop Training | ||

| 1st Brigade | Port Stephens | 13 Sept - 4 October |

| 2nd Brigade | Toorbul | 13 Sept - 4 October |

| 9th Australian Div. | ||

| Troop Training | Cairns | 1 July - 10 August |

| 6th Australian Div. | ||

| Troop Training | Cairns | 16 August - 8 Sept. |

| 24th U.S. Inf. Div. | ||

| Staff & Command & Specialist School | Port Stephens | 15 - 30 September |

| Troop Training | Toorbul | 5 Oct. - 11 Dec. |

II-14

| Unit | ATC | Inclusive Dates |

|---|---|---|

| 41st U.S. Inf. Div. | ||

| Staff & Command & Specialist School | Toorbul | 6 - 18 Dec. |

| Troop Training | Toorbul | 20 Dec. - 29 Jan. |

Ships & Craft Available

Throughout this entire period training was severely handicapped by the lack of equipment and particularly by the lack of necessary number of ships and landing craft. No more than four transports (1 APA and 3 LSIs) were available at any one time. While training was in progress at Port Stephens, Toorbul, and Cairns, simultaneously, only two transports were available; the other two (Henry T. Allen and Westralia) were lifting troops from Australia to New Guinea in preparation for forthcoming operations. An average of one LST, four LCIs, 3 LCTs, 40 LCVs, and 8 LCMs was available at each of the Centers during the period of training. Because of this shortage of equipment, improvisation had to be made. At times LSTs were rigged with debarkation nets and used as transports, carrying as much as a battalion landing team aboard. Ships sides were built over the water and troops debarked over these into landing craft, simulating debarkation from transports.

Shore Parties

Although Engineer Special Brigades were arriving in this theater, they were required for immediate operational use and were not available as Shore Parties during training of the several divisions. As a result, General Headquarters directed that the divisions concerned organize Shore Parties for use in training. This situation was not desirable but it did make some units cognizant of the Shore Party problem. On the other hand most troops did not take the Shore Party training seriously, since it was generally believed that Engineer Special Brigade units would be provided for operations against the enemy. Also most divisions were unable to obtain adequate and sufficient mechanical equipment for proper Shore Party; i.e., bull-dozers, cranes, trucks, trailers, etc.

II-15

Naval Gunfire Support

Because of the dearth of combatant ships during this period, officers who were being instructed in naval gunfire support had little opportunity for practical exercises with such ships.

Sickness

During their training periods the 1st Marine Division, the 32nd U.S. Infantry Division and the 6th and 9th Australian Divisions were as much as 30% below strength because of recurrent malaria among the troops.

Amphibious Training, New Guinea Area

General Headquarters. Southwest Pacific Area on 11 January 1944 directed that training at ATC TOORBUL be discontinued by 5 February 1944 after completion of training of the 41st Infantry Division and that personnel, equipment and records be moved to ATC, MILNE BAY, NEW GUINEA. This directive was complied with; the ATC at MILNE BAY was commissioned on 26 January 1944 and the remaining facilities at TOORBUL were turned over to the Australian Army.

The Amphibious Training Center, Milne Bay, established on the shore of Stringer Bay, consisted of a boat pool, repair shops, quarters for assigned personnel, one large lecture hall (40' × 100' quonset hut) and seven small classrooms (20' × 40' quonset hut) with a mock-up ship's side build out over the water and rigged with debarkation nets. This was the same type installation used at the Centers in Australia except that quarters or mess facilities were not available for students since it was anticipated that units trained at this center would be staged in the Milne Bay area and would be able to commute to ATC from their camp.

Course of Training

The course of training at ATC Milne Bay followed the same pattern as used at the Centers in Australia; Staff and Command and Specialists School, Assistant Troop Instructors Course, and finally, Troop Training.

The 6th U.S. Infantry Division entered the training period on 28 February 1944. In addition to the customary officers' schools

II-16

during the first two weeks, each RCT was to have three weeks training using transports, LCIs, and LSTs. However, on 8 April training had to be suspended because all available transports and larger type landing craft were required for the forthcoming Aitape-Humboldt Bay-Tanamerah Operation.

As training would be at a halt until completion of the initial phases of this operation, ATC instructors were detailed as observers with the various elements of the Task Force and Landing Force. This move was particularly valuable to instructors because it afforded them an opportunity to observe two divisions, the 24th and 41st, in their first amphibious operation since completing training at the ATC Toorbul.

ATC Milne Bay resumed training of the 6th U.S. Infantry Division on 1 May and completed work with that division on 5 June 1944.

Mobile Training Units

As a result of the Aitape-Hollandia-Tanamerah Bay landings, Milne Bay became a rear area location and it was apparent that no other combat troops would stage from there. Transportation difficulties prevented movement of troops to Milne Bay for training. It was decided therefore to organize Mobile Training Units which figuratively would take the Training Center to the troops. Three such units were formed, each one capable of training one division. These units were composed of officers, transports and landing craft available to the Center. Since the 33rd U.S. Infantry Division was the only one on the training program which had had no previous amphibious work, officers of this organization attended the last Staff and Command and Specialists Course held at Milne Bay during the period 5-17 June 1944. Troop training for the 33rd was carried out at its staging area, Finschhafen.

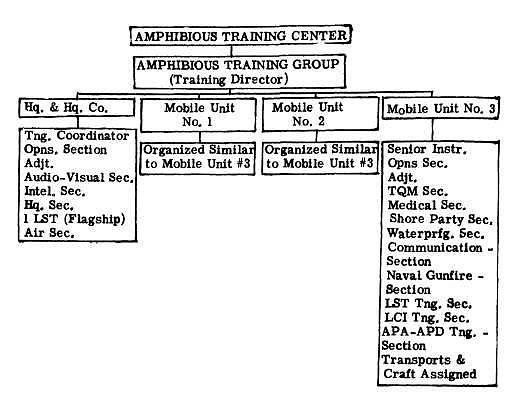

The remaining divisions on the program were given refresher training only, since they had all had basic amphibious work and had been in at least one amphibious operation. The following chart shows organization of the Amphibious Training Group based on the use of Mobile Training Units:

II-17

Units Trained

Following is a list of the units trained by the Amphibious Training Group, Seventh Amphibious Force, during the New Guinea Phase:

| Unit | Place | Inclusive Dates |

|---|---|---|

| 6th U.S. Inf. Div. | ||

| Staff & Specialist School | Milne Bay | 28 Feb. - 11 Mar. 1944 |

| Troop Training | Milne Bay | 13 Mar. - 8 Apr. & 1 May - 5 June |

| 33rd U.S. Inf. Div. | ||

| Staff & Specialist School | Milne Bay | 5 - 17 June 1944 |

| Troop Training | Finschhafen | 26 June - 29 July 1944 |

II-18

| Unit | Place | Inclusive Dates |

|---|---|---|

| 6th U.S. Ranger Bn. | ||

| Troop Training | Finschhafen | 17 - 29 July 1944 |

| 37th U.S. Inf. Div. | ||

| Troop Training | Bougainville | 13 July - 24 Aug. 1944 |

| 43rd U.S. Inf. Div. | ||

| Troop Training | Aitape | 28 Aug. - 26 Sept. 1944 |

| 31st, 33rd, 43rd Divs' Arty. 120th, 126th, 129th F.A. Bns. | ||

| Naval Gunfire Support | Aitape | 12 - 20 August 1944 |

| 112th U.S. Cav. RCT | Aitape | 28 Sept. - 12 Oct. 1944 |

| 25th U.S. Inf. Div. | ||

| New Troop Training | New Caledonia | 8 Sept. - 13 Oct. 1944 |

| 7th Australian Div. | ||

| Troop Training | Cairns, Aust. | 14 Oct. - 14 Nov. 1944 |

| 40th U.S. Inf. Div. | ||

| Troop Training | Cape Gloucester | 15 Oct. - 18 Nov. 1944 |

| 9th Australian Div. | ||

| Troop Training | Cairns, Aust. | 17 Nov. - 2 Dec. 1944 |

Ships and Craft Used

An average of 2 APA (LSI), 2 LST, 4 LCIs were available to each training unit during this period.

On 2 October 1944, six British LSIs reported to Commander

II-19

Seventh Amphibious Force and were assigned to the Amphibious Training Group for duty. These were HMS Clan LaMont, Glen Earn, Empire Mace, Empire Spearhead, Empire Arquebus, Empire Battleaxe. These ships were not satisfactory, but no other were available since other transports under control of Commander Seventh Amphibious Force were engaged in combat operations.

The LSIs carried only the British LCA (landing craft assault) which were personnel boats only, similar to the LCP(R). Davits could not take the LCVP without extensive conversion. The Amphibious Training Group issued two LCM(3)s to each ship. In addition, these ships had limited troop and cargo capacity - about 800 troops, eight 2-½ ton trucks and 20 1/4 ton trucks. Cleanliness and sanitation were not up to the standards maintained by ships of the United States Navy.

All LVTs and DUKWs in the Southwest Pacific Area were either in use on operations or being assembled in staging areas for future operations. None were available for training.

Shore Parties

As in previous training, the units involved were required to form Shore Parties from organic elements of the division. Again, the lack of mechanical equipment and sufficient engineer troops hampered complete and efficient Shore Party training. The most common source of Shore Party personnel was from one of the regiments not in training. This assignment was rotated among the three regiments of the division.

Naval Gunfire Training

During the period 12-20 August, 1944, forward observers of the 31st, 33rd, and 43rd U.S. Infantry Divisions and 120th, 126th, and 129th Field Artillery Battalions received training at Aitape with a destroyer division furnishing gunfire. Training was coordinated with combat missions of the 43rd Infantry Division operating in the Aitape sector. In this manner forward observers not only gained experience in working with firing ships, but found "live" targets and performed under combat conditions.

II-20

Philippine Phase

Establishment of ATC Subic

During the period of the Leyte and Lingayen operations, troop training was at a standstill since nearly all combat units were being employed in the Philippine Campaign. However, it was deemed essential to commence refresher amphibious training as early as practicable in preparation for the eventual invasion of Japan. Several areas along the Coast of Luzon, Philippine Islands, were reconnoitered and Subic Bay, Zambales Province was finally selected as the site for an Amphibious Training Center in the Philippines.

In early March 1945, General Headquarters directed that the ATC, Milne Bay, be transferred to Subic Bay and that preparations be made to train three Divisions simultaneously. Because most Army units would have a considerable number of officer replacements since their last amphibious operation, it was directed that a Staff and Command Course and Specialists School for officers be conducted prior to troop training of each division. The organization for this training was to be along the same lines as that used during the training in New Guinea - officer schools at the Center and troop training in the staging areas conducted by Mobile Training Units.

In early April 1945 the Amphibious Training Center, Subic Bay, was placed high on the construction priority list so that the first course could start by 12 June 1945. The completed installations at Subic Bay included facilities for the Amphibious Training Base, Headquarters Amphibious Training Group, lecture halls and class rooms for the Staff and Command and Specialists Schools, and quarters and mess for 300 officers.

Staff and Command and Specialists Courses

In accordance with General Headquarters' directive, a two-weeks Staff and Command and Specialists School proceeded all troop training. Increased emphasis was placed on such subjects as air support, naval gunfire support, and communications. As soon as it was known that JASCOs (Joint Assault Signal Company) would be assigned certain division's for training, a Specialists School for the Air Liaison and Shore Fire Control Sections of these units was initiated. The JASCO Shore Party Communications Sections were to receive instruction and training with the Shore Parties.

Since the Seventh Amphibious Force was to be transferred

II-21

to the control of Amphibious Forces Pacific on 15 August 1945, "Transport Doctrine, Amphibious Force Pacific Fleet" was used as a basis for all instruction. While this required some changes in technique, the basic doctrine was the same as previously taught in the Southwest Pacific Area.

Troop Training

Troop training was accomplished by sending Mobile Training Units to the divisions concerned rather than attempting to transport all divisions to Subic Bay. Training Units were organized in the same manner as those used in New Guinea and had in addition one transport division of four APAs and one AKA. The transport division commander was also the commanding officer of the Mobile Training Unit.

Because of the limited time for training, it was necessary to handle up to three divisions at once. Again the transports and landing craft had to be split three ways. The shipping allocated each training unit was only sufficient to lift one RCT. Thus exercises involving the embarkation and landing of an entire Army division could not be accomplished.

Units to be Trained

Following is a list of the units scheduled for training, including dates and location of training:

| Unit | Place | Inclusive Dates |

|---|---|---|

| 81st and Americal U.S. Inf. Divs. | ||

| Command & Staff & Specialists | Subic | 15 - 24 June |

| Troop Training | Leyte; Cebu | 1 - 23 July |

| 1st U.S. Cav, 40th, 33rd, Inf. Divs. | ||

| Command & Staff & Specialists | Subic | 13 - 22 July |

| Troop Training | Lucena, Luzon; Iloilo, Panay; Launion, Luzon |

30 July - 21 Aug. |

II-22

| Unit | Place | Inclusive Dates |

|---|---|---|

| 24th, 41st, 43rd U.S. Inf. Divs. | ||

| Command & Staff & Specialists | Subic | 11 - 20 Aug. |

| Troop Training | Lingayen, Luzon; Zamboanga, Mindanao |

28 Aug. - 19 Sept. |

ATC Organization

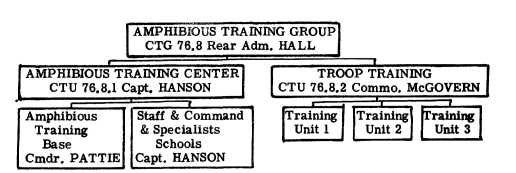

On 10 June 1945, Rear Admiral J. L. HALL, Jr., USN, Commander Amphibious Group 12, reported to Commander Seventh Amphibious Force for duty as Commander Amphibious Training Group. He succeeded Captain R. E. HANSON, USN, who had commanded the group since July 1944. Captain Hanson then became Commanding Officer of the Amphibious Training Center, Subic Bay and Commodore J. B. McGovern, USN, who had reported with Transport Squadron 16, was placed in charge of troop training.

The following diagram illustrates the Amphibious Training Group Organization:

Cancellation of Training

The cessation of hostilities brought about the cancellation of all amphibious training since the troop units concerned were required for the occupation of Japan and Korea. At this time the 81st and American Divisions had completed their course of training; the 1st Cavalry, 40th and 33rd Infantry Divisions had finished the Command and Staff and Specialists Schools and were midway in their troop training, and officers of the 25th, 41st, and 43rd divisions had started the Command and Staff and Specialists School.

II-23

At its end the Amphibious Training Group was embarked on one of the most extensive amphibious training programs of the war; initially the training of eight army divisions for the assault on Kyushu and later the same program for ten divisions for operations against Honshu.

II-24

II-26

PART II (c)

Special Problems, Functions

and Organization Within

Seventh Amphibious Force

Part II (c) (1)

Echelon Movement of Amphibious Shipping

General

During the New Guinea Phase of operations in the Southwest Pacific Area, Commander SEVENTH Amphibious Force had the responsibility of not only establishing the landing force in the assault area, but also of supporting it for a considerable period after the initial assault. This support consisted of bringing forward both reinforcements and resupply, and generally continued until the landing force had captured and developed an air field from which fighters and medium bombers could operate. Thereafter the responsibility for support of the operation would be assumed by U.S. Army Service of Supply (USASOS).

Movements of amphibious shipping in the Southwest Pacific were not by large convoys as was the practice elsewhere, but rather by small groups, sailed in frequent echelons. There were several reasons for employing such a system:

- Distances were relatively short, and fast turn-around of shipping was not only feasible but essential due to the small number of ships available.

- Japanese air threat, usually from the west, was always present.

- The jungles offered few exits from beaches, and disposal and dump areas were few and difficult to find.

- Satisfactory beaching areas for landing craft were limited by coral, shoals and other offshore navigational hazards.

II-27

Unloading and Dispersal of Supplies

The jungle vegetation along the New Guinea coast offered few landing beaches with satisfactory exits and disposal areas. Swamps often were located back of the beaches and clear areas and roads were almost non-existent. In addition the heavy jungle limited intelligence which could be derived from air photographs. Employment of scouts and periscope photographs from submarines also produced insufficient information. There were few white men with a knowledge of the area and these had no appreciation of the military problems involved. Their reports were usually too optimistic. As an example, what they would describe as a "good road" was never able to support our heavy equipment. Consequently, one of the assumptions in every plan had to be that poor unloading conditions would prevail.

Under such handicaps, the movement of supplies in the assault and early echelons exposed both the supplies and ships carrying them to serious danger of attack and destruction. This fact was strikingly demonstrated in the destruction of 11 LST loads of supplies by one bomb dropped from a single plane on the night of D day at HOLLANDIA, and in the successful air attack on the USS Etamin, an AK loaded with 5000 tons of cargo, which then had been unloading for six days at AITAPE during the same campaign. Nevertheless, there was always a tendency for Army planners to demand too large a proportion of equipment and supplies in the assault and early echelons. This was a natural tendency brought on by (a) a desire to be able to exploit any initial success and (b) fear that supply lines would be interrupted. Such concern was never warranted by experience. Echelons always arrived as scheduled and delivered supplies and equipment when needed.

Japanese Air and Submarine Threats

Japanese aircraft presented a constant threat to supply lines into the combat areas. Except at HOLLANDIA and MOROTAI all air protection was provided by land based aircraft and in these latter campaigns, carrier based air was only available for the early echelons. In the early campaigns, Japanese air bases practically surrounded, not only the objective areas but in some cases, as in the LAE and FINSCHHAFEN campaigns, also the staging areas. Later along the north coast of New Guinea the Japanese air bases were to the westward, whereas our fighters

II-28

had to come from the east. This meant that the Japanese were free to launch late afternoon attacks practically free from the danger of fighter interception.

It was therefore necessary that amphibious shipping and their escorting ships be exposed to this constant threat in as small numbers as possible and for as short of time as possible. During the LAE and FINSCHHAFEN campaigns, night unloading of reinforcement and resupply echelons was resorted to. Subsequent practice was to proceed to the objective area during darkness, unload in the early hours of daylight and move out of the objective area by 1000. This allowed more expeditious and efficient operations while substantially reducing the threat of enemy air attack.

Schedule of Resupply Echelons

The echelon system of reinforcement and resupply with its fast unloading, frequent turn-arounds and the relatively few ships employed required close timing and attention to detail by staff personnel planning these operations and exact execution by the operating personnel. It was necessary that loading time be limited and much mobile loading be done to obtain maximum use of few ships. Ships were scheduled to depart from the staging area at times and by routes best calculated to avoid enemy aircraft and to obtain maximum protection from our own land based cover. Plans were carefully made for ships to arrive in the objective area at the most propitious time, to be unloaded quickly and to depart before the Japanese reconnaissance discovered their presence. It was seldom that an LST remained more than 6 hours in the objective area. Sometimes when unloading did not progress satisfactorily, ships even departed with cargo still on board rather than to expose ship and cargo to danger of loss by air attack.

The usual practice in New Guinea was to sail LSTs and LCIs in echelons of about six, the LSTs normally being escorted by three destroyers and the LCIs by a similar number of SCs with one or more destroyers. In the earlier campaigns, from WOOD-LARK to FINSCHHAFEN, LCTs were also used for resupply and sailed in echelons, accompanied by an APc for navigational escort and some SCs. Later with increasing distances LCTs were generally towed to the objective areas and left there for use in unloading LSTs, APAs, AKs and merchant ships under control of USASOS.

II-29

Resupply in Philippines and Borneo Campaigns

The system of using small echelons of amphibious craft for resupply was employed until the MOROTAI campaign. The long distance involved in the LEYTE and LINGAYEN campaigns made it necessary to supplement amphibious craft with heavy merchant shipping sailed in convoy. In the later Philippine and Borneo campaigns the majority of amphibious ships were required for the numerous operations scheduled and therefore were not available for resupply functions. The reduction of the Japanese air threat in the Philippines made early use of merchant shipping for resupply feasible and it was successfully employed.