The Navy Department Library

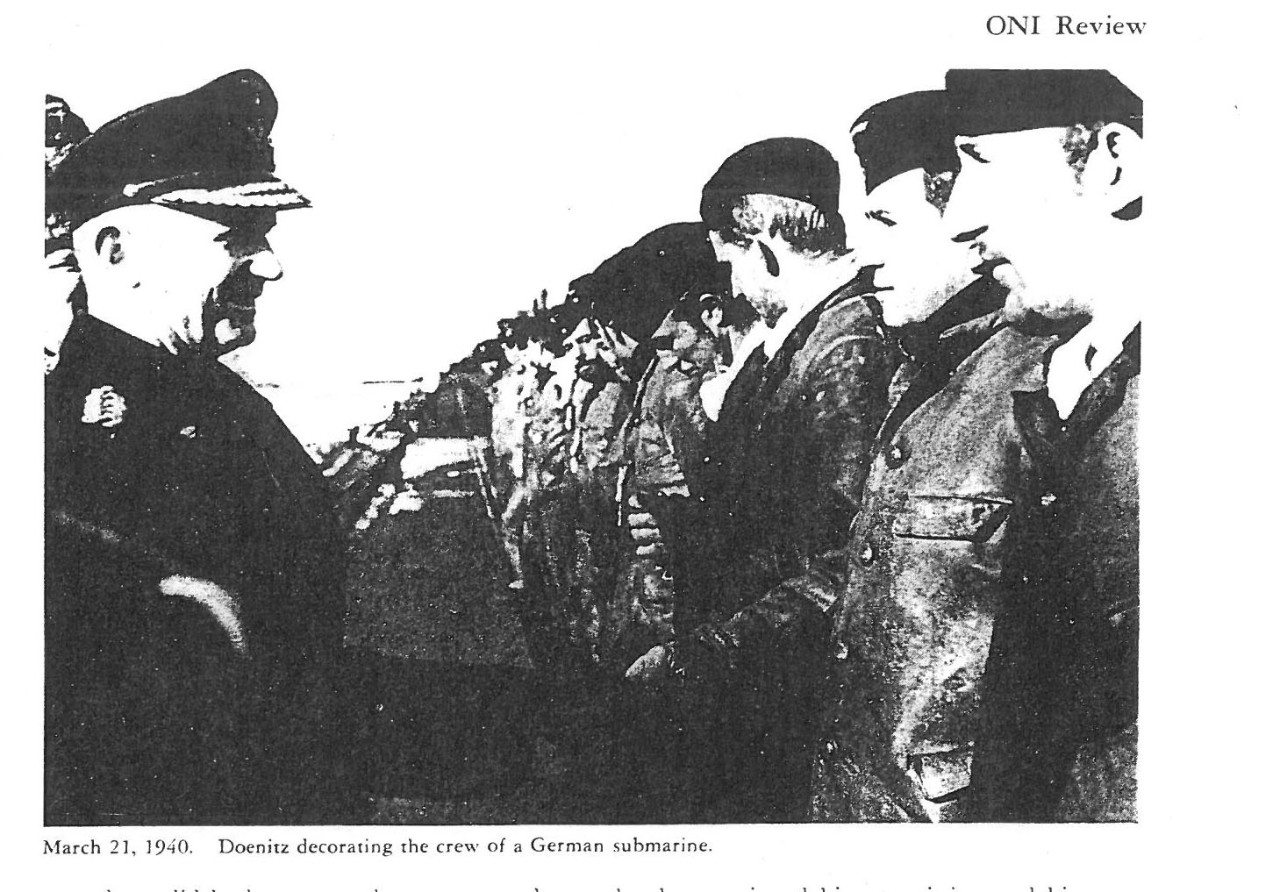

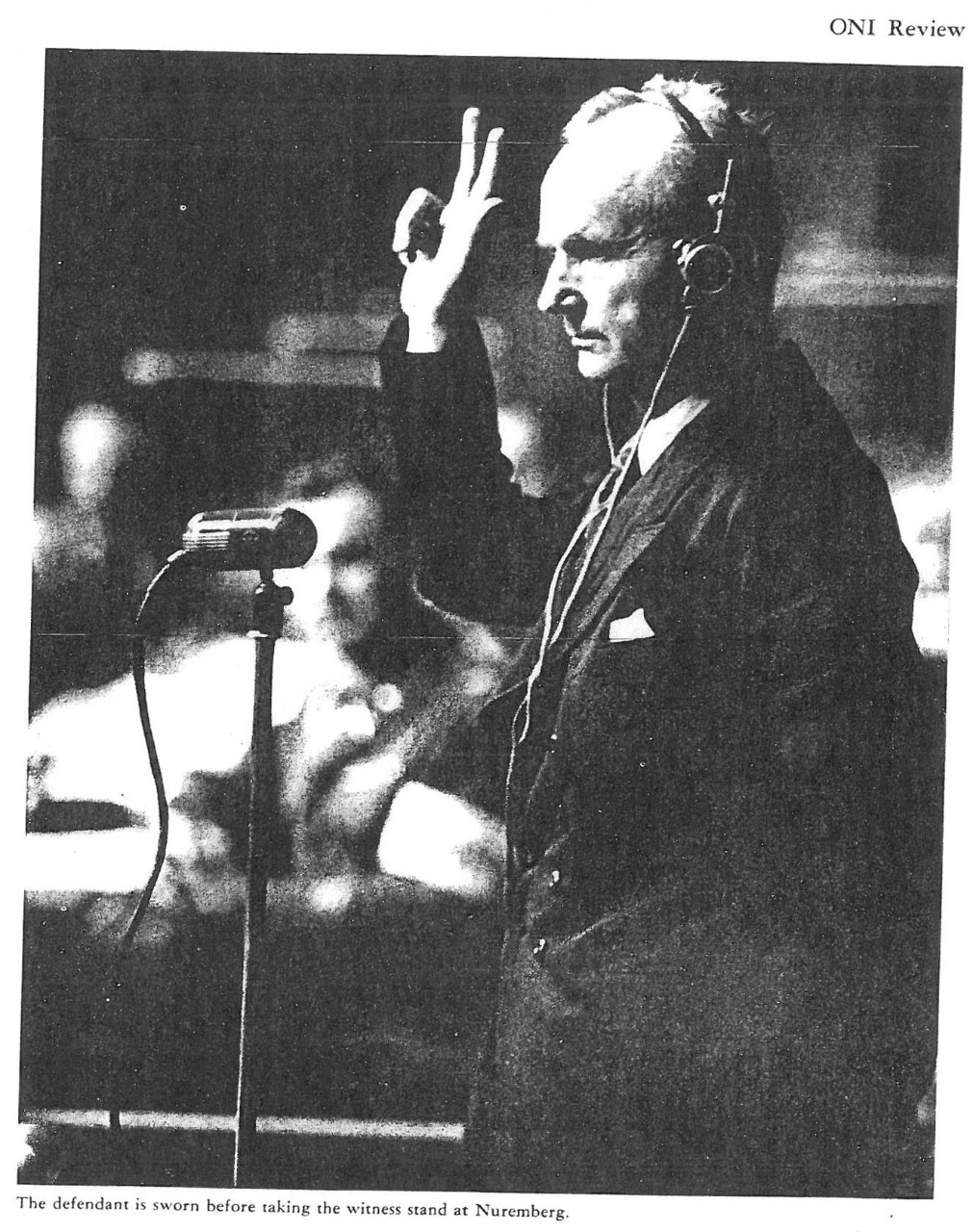

The Trial of Admiral Doenitz

The following article is condensed from the report of three United States naval officers who were designated to attend the war crimes trial at Nuremberg for the purpose of studying the cases of Grand Admiral Erick Raeder and Grand Admiral Karl Doenitz.

Download a PDF Version [6.8MB]

There exists one distinct anomaly in the Nuremberg trials and that is the prosecution of military persons. The profession of arms is an honorable one and is recognized by all nations. No soldier has ever been called before an international tribunal to give an account of his military deeds on a battlefield. It is submitted in this procedure, however, that Grand Admiral Karl Doenitz, Grand Admiral Erich Raeder, Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, and Colonel General Alfred Jodl are not being tried for what they did as soldiers in representing their country in battle, but for what they did in precipitating an unnecessary war, and for the manner in which they ordered, directed, and conducted that war. While Raeder and Doenitz are generally charged with the same offenses, the specific acts to which they have to answer are for the most part different.

The charges against Grand Admiral Karl Doenitz fall into two categories. On the political level he stands charged with promoting the preparation for aggressive war and participating in the planning of war of aggression in violation of treaties. On the military level, first in the position of flag officer submarines, and after 30 January 1943 as commander in chief of the German Navy, he stands charged with authorizing, directing, and participating in war crimes and crimes against humanity, especially against persons and property on the high seas. During the last weeks of the war, as Hitler’s successor, he stands charged with ordering the continuation of hopeless war.

The political charge is especially interesting. It involves the problem of how far the soldier can go in preparation of war without inciting the very war against which he claims to be preparing. The wording of the indictment and the outline of the case against Doenitz charge him with preparations for offensive war from the very fact that he prepared the U-boat arm, planned its use in war, dictated its methods of warfare, and sent it to its war stations in the weeks immediately preceding the outbreak of hostilities. The defense attempted to prove that in all this Doenitz was merely a naval officer faithful to his trust and obeying the orders of his political superiors. Under direct examination, Doenitz readily admitted that he prepared his flotilla in the tactics of commerce warfare, but commerce warfare under the prewar German prize ordinance, which embodied the limitations of summons and of safeguarding crew and passengers as laid down in the London Naval Treaty.

The fact that the prosecution had at its disposal almost the entire archives of the German Navy, which Doenitz said were purposely left for them, seems to indicated either that all records of more “offensive” preparations were completely destroyed, or, what is more likely, that Doenitz was telling the truth.

What the evidence failed to show was whether Doenitz was, as he consistently claimed, content merely to carry out his duty to perfect his squadrons against all general war contingencies, or whether he actually urged secret plans for their ruthless employment. To one who witnessed the trial and observed the faith of the defendant in his submarines and in the inevitability of their unfettered employment against merchant shipping once war came, it is difficult to believe that the could have kept this enthusiasm to himself.

Granted that Doenitz merely trained his submarines, can he escape the charge of sharing in the common plan or conspiracy as one of the Nazi group who conspired to bring on the war? Politically, his case seems a strong one. He was in command of the Emden in the Indian Ocean when the Nazis seized power. According to his own unshaken testimony, he saw Hitler on only four occasions prior to the war. Not until some

26

CONFIDENTIAL

[DECLASSIFIED]

years later did he become an honorary member of the Nazi party. He flatly denied Ambassador Messersmith’s affidavit which pictures him as often in Berlin in close association with the Nazi leaders. Nor was any evidence introduced to prove that Doenitz participated in the secret rearmament of Germany contrary to the Versailles Treaty. Doenitz’ assertion that in the years before the war, he never went beyond the general tactical training of the new submarines built in accordance with the Anglo-German Naval Agreement seems to be the truth.

Even if it cannot be proved that Doenitz promoted the preparation for war, it can be proved that he participated for war, it can be proved that he participated in the planning of the Polish and Norwegian campaigns to the extent of knowing in advance the intentions of his naval and political superiors. In the middle of May 1939 Doenitz knew that plans for the Polish war were being perfected to meet an actual date less than 4 months ahead. Unless Poland were to be the aggressor, this war would be in violation of the German-Polish Treaty and of the Kellogg-Briand Pact. Knowing this, should he, or indeed could he, have resigned his commission and his command? Or could he with a clear conscience go ahead with his share of the preparations, leaving it to the future to disclose whether aggressive war was the actual intention of the political leaders of the Reich? He chose the latter course, and, in extenuation, he can point out that history records scarcely a single case of a soldier who, in similar circumstances, acted otherwise.

By 2 August 1939, Doenitz received operational directives for the employment of U-boats “to be sent into the Atlantic by way of precaution in the event that the intention to carry out “Fall Weiss” (the Polish operation) remains unchanged.” He was given 10 days in which to hand in his own operations orders. Whatever he was before 2 August 1939, from that date on Karl Doenitz became a war planner.

The prosecution made much of the sailing of the Atlantic submarines, proving that they must have left at least a week before the German attack on Poland. Doenitz readily admitted these “prophylactic” measures. Had the tribunal not ruled that evidence of similar action on the part

27

CONFIDENTIAL

of Germany’s enemies was inadmissible, he would have proved from the records of German listening stations that British submarines, which must also have sailed well before the declaration of war, were in the German bight near Heligoland on 1 September 1939.

The case of the prosecution against Doenitz for the planning of the invasion of Norway does not seem to be a strong one. Doenitz claimed hat as flag officer submarines he merely gave his opinion, when asked for it, on the value of Norwegian bases. As for the invasion itself, he naturally knew of it in advance.

It is not so much as flag officer submarines, nor even as commander in chief, that Doenitz stands accused of political, in distinction to military, crimes. Rather it is as a confirmed Nazi and in his role as a member of the Reich cabinet, or more specifically, as one of the small group who were constantly at Fuehrer’s headquarters, conferring on high level military and political problems and building up the structure of the war, which, in the last analysis, circumscribed and dictated the decisions of Hitler himself.

How far can Karl Doenitz be considered to have been a thorough Nazi, responsible for indoctrinating the half million officers and men of the navy with theories of racial pride and racial hatred which led to the enslavement of conquered peoples and the slaughter of Jews? Here again the record is not absolutely clear. Doenitz, faced with quotations from his own statements supporting the Nazi ideology, strove to picture his Nazism as no more than loyalty to his soldier’s oath to the Fuehrer, and a call for wartime unity in the service under his command.

It is not easy to accept Doenitz’s explanation that he became the heir to Hitler’s mantle, not because he was a known and fanatical Nazi, but solely because he was the senior officer of an “independent service.” To grant this would be to doubt the Nazism of Hitler himself.

The prosecution sought to throw the blame for continuing the war on Doenitz’s shoulders. He replied that he continued the war merely to disengage the armies in the east and bring them into central Germany as a rear guard for the thousands of German civilians who, in his view, would thus escape from certain slavery under the cruel heel of the “Bolshevist hordes.”

The prosecution attempted to show that even before he succeeded Hitler, Doenitz was a political personality. From 30 January 1943 when he became commander in chief, Doenitz ranked as a Reich minister. According to the prosecution, whatever he might have been before, he was thereafter no longer a mere naval officer carrying out his orders, but a naval statesman, responsible jointly for the actions of other department heads of cabinet rank. The proof of this charge is not clear from the evidence. Documents showed that after Doenitz became commander in chief of the navy, he visited Hitler’s headquarters 119 times. It was further proved that ministers, whose responsibilities included affairs beyond military matters, were present at these meetings. Doenitz was unshaken in his testimony that these ministers met merely to hear to briefing of the developments on the fronts during the last 24 hours, and to suggest immediate countermoves; they did not formulate policy.

Just as the student of naval affairs can scarcely believe that Doenitz as flag officer submarines worked in an isolated political vacuum, so the student of government can scarcely credit his statement that as commander in chief of the navy he dealt solely with naval affairs. One document at least proves that Doenitz was consulted on questions of the highest political importance. In February 1945 he was asked for the Navy’s comment on Hitler’s announced intention to abrogate the Geneva Convention. Doenitz replied:

“From the military point of view there are no grounds for this step as far as the conduct of the navy at sea is concerned… Even from the general point of view it appears to the C-in-C Navy that this measure would bring no advantages. It would be better to carry out the measures considered necessary without warning and all costs save face with the outer world.”

Confronted with the evidence of his “cynicism and opportunism,” Doenitz sought to picture himself as one who could never advise breaking a treaty so strongly embedded in the conscience of the world as the Geneva Convention. He further stated that by “the measures considered necessary” he referred to the contemplated measures against the German troops in the west who were deserting to the Allies. Whether he meant that Germany would now so mistreat Allied prisoners by putting them in bombed cities that the Allies would retaliate and desertion would no longer promise safety to the German deserter, he failed clearly to state. The prosecution left the suspicion that this indeed was what he meant.

We may now turn to the more complicated charge that Doenitz “participated in war crimes

28

CONFIDENTIAL

including especially crimes against persons and property on the high seas.”

Germany began the war against merchant shipping in accordance with her prize ordinance, which provided for summons and search and for the placing of crews and passengers in a place of safety, as stipulated in the London Treaty. Britain, on her part, entered the war with her merchant ships still unarmed. Even after guns were put aboard, she sought to direct their use in a “defensive” manner. The Admiralty instructions to merchant ships, issued the year before the war, had fallen into German hands. They directed that even in the stage of the “defensive” use of weapons, merchant skippers were to defend themselves against any U-boat whose obvious intention was to capture their ship.

The conduct of Britain and Germany during the first weeks of the war at sea was like that the two boxers each hoping and expecting that the other will strike the first foul blow, and each prepared instantly to retaliate. To Britain’s charge, which is fully proved, that Germany conducted war against shipping with increasing disregard for international law which was conceived to protect life and property from arbitrary attack at sea, Doenitz replied this development “had to come.”

All the old problems of commerce warfare reappeared in the record of Doenitz’ trial, belligerent conduct by merchant ships, contraband, blockade, war zones, commerce control, unneutral service and finally the rescue or nonrescue of survivors.

Although Doenitz admitted that he had his plans ready, he emphasized the apparent reluctance with which German submarine forces progressed from prize ordinance to utter ruthlessness. At each step he sought to prove that his forces acted in retaliation for breaches of international law by the enemy. The record, as brought out by the trial, is far from clear. To dispose of one well-known incident, he asserted that the commander of U-30, who sank the passenger liner Athenia on 4 September 1939, acted contrary to specific orders to spare all passenger liners, even if armed or in convoy. The very fact that he admitted the U-30’s log was altered for “political purposes” shows how anxious Germany was, at least in the early days of the war, not to jeopardize civilians and neutrals at sea. As Doenitz put it:

“We remembered the tremendous power of English propaganda in the last war.”

Except for the Athenia, mistaken for an auxiliary cruiser and torpedoed at night, German’s record in the early weeks of the war is not a bad one. Not until 29 October 1939 was permission granted to attack passenger ships when sailing under escort, and not till 17 November could armed passenger liners be attacked. All this at a time when the British Expeditionary Force was crossing to the Continent.

Ruthless action against enemy cargo ships came more quickly. At first they were to be destroyed only after the safety of the crew had been assured. As early as 24 September, ships using their radios on being summoned were to be subject to immediate attack. This permission was very soon extended to cover merchantmen who used their radios on sighting a submarine, thus before they were summoned. Darkened ships presented a difficult problem. A memorandum dated 22 September recommended that they be sunk without warning, that this order be passed by word of mouth, and that all night sinkings be justified by an entry in the submarine’s log to the effect that the target was thought to be an enemy cruiser. Admiral Doenitz and his principal witness, Admiral Wagner, chief of the Operational Division of the Naval Staff, stoutly maintained that this memorandum represented the “ideas of some young staff officer,” that it was never approved or put into effect, and that, when attacks without warning on darkened ships were permitted, definite orders to that effect were actually issued.

According to the defendant, all of these increasingly severe measures were justified as retaliations against Britain’s breaches of the letter or, more often, of the spirit of international law. Some substance is lent to this claim by the fact that Britain announced on 24 September 1939 that all British merchant ships would soon be armed. The prosecution asserted that arming was justified as a defensive measure, an assertion somewhat weakened by evidence that only three days later the Admiralty planned to fit depth charges on merchant ships capable of 17 knots, and that the Admiralty instructions to armed merchant ships capable of 17 knots, and that the Admiralty instructions to armed merchant ships dated 1938 contemplated to force the submarine to keep her distance, but engage, and, if possible, to destroy her. Doenitz in his direct examination said: “Merchant ships do not carry cannon merely for fun.”

The use or even the mere possession of radio was another point mentioned by the defendant to justify retaliation. It was brought out that,

29

CONFIDENTIAL

from the very beginning, British merchant ships had blanket orders to report the position of all submarines sighted in order thereby to assure their own safety and the safety of other merchantmen. According to the defense, they then became “part of the British Intelligence Service.” It was argued that the merchant ship capable of rendering contact reports and of engaging the submarine was indeed little different from the auxiliary cruiser.

The prosecution laid emphasis on the submarine clauses of the London Treaty, to which Germany acceded in 1936, which assured merchant ships immunity from attack and assured the safety of their crews and passengers except only in the cases of “persistent refusal to stop” or “active resistance to visit and search.” The treaty contains nothing to prohibit merchant ships from carrying guns, much less from carrying radio. The truth is, the London Treaty made effective submarine warfare against commerce impossible. Germany was both prepared and anxious to escape from its hampering limitations. It was obviously to her interests to picture herself as the injured party and to justify her action as retaliation. Retaliation, however, depends on timing, and here the evidence is far from clear, even assuming the claims of both sides to be correct.

In all this, the prosecution and the defense were dealing with unescorted merchantmen. Both sides granted that by accepting escort in convoy the merchantman loses her right to be duly summoned and searched. The intensification of submarine warfare was based on other developments which the defense sought to justify by other arguments. The most important of these developments was the proclamation of “war zones.”

During the first week of the war, the United States announced a war zone through which United States merchant ships were forbidden to sail because of the danger. We thus handed to the Germans a ready-made argument and already delineated zone. On 24 November, German merely overlaid our barred zone with her own “danger zone” in which neutral merchantmen were now warned they would sail at their peril.

The German justification for her war zones declaration was partially based on her alleged rights retaliate against Britain’s hunger “blockade.” In German eyes Britain had established a vast paper blockade of the entire Continent neutral and belligerent alike, and was enforcing it, not by risking her searching cruisers, but by extending her control even into neutral ports.

Doenitz’s theoretical justification of unlimited submarine warfare as a retaliation for unlimited and “illegal” blockade, was somewhat weakened by his admission that it was adopted haltingly and with measures of deception. From the evidence it is not clear whether these measures of deception were conceived by the politicians or by the navy itself.

Even before the declaration of the German danger zone, Doenitz’s submarines attacked neutral ships in European waters. There is no evidence that there were orders for such attacks. An order January 1940 directed that, in the war zone, Greek ships be treated as enemies.

During these months Germany was having marked success with the magnetic mine. It was now decided that in the Bristol Channel, whose waters are shoal enough to permit mining, and later along the entire coast with the hundred fathom curve, neutral ships might be torpedoed without warning, though submarine captains were ordered to fire only when the torpedo wakes would not be seen and fake their logs to furnish evidence for protesting neutrals that their ships were being lost in mine fields.

Although these and others were “political” orders issued to Doenitz by the commander in chief, he took considerable pains to justify them, rather than basing his defense, as he did in other cases, on the excuse that he was merely carrying out orders whose justice he, as a subordinate commander, had neither the opportunity nor the right question.

In February 1940, German shifted her ground from the anger zone theory to the theory of retaliation against Britain’s “illegal” blockade practices. Neutral merchantmen were now to lose their neutral rights if bound, even unescorted, to an enemy port or even if possessing a British navicert.

The fact that Doenitz, when questioned about this progression of ruthlessness, sought to justify it indicated that, as flag officer submarines, he was acting under orders which he felt could stand examination before the bar of history. The best that can be said for him is that he merely obeyed orders from higher authority and that they were such that a professional German sailor felt them to be justifiable war measures. The worst that

30

CONFIDENTIAL

can be said is that he himself suggested and planned the progression. There is much evidence to probe the former, little to prove the latter.

It is the cruelty which inevitably accompanies unlimited submarine warfare which forms the crux of the charges against Doenitz. As flag officer submarines and later as commander in chief, did he violate the demands of humanity in callousness or ruthlessness toward shipwrecked survivors? Again the record is not clear.

Early in 1940, Standing Order 154 went to U-boats:

“Do not pick up survivors and take them with you. Do not worry about the merchant ship’s boats. Weather conditions and the distance to land play no part. Have a care only for your own ship and think only to attain your next success as soon as possible. We must be harsh in this war. The enemy began the war in order to destroy us, so nothing else matters. [Signed] DOENITZ.”

Both Doenitz and his witness made much of the point that this was purely a nonrescue order, necessary to prevent young captains from risking their boats through mistakenly giving in to the seaman’s desire to help the shipwrecked.

With the entry of the United States into the war, Germany turned from the destruction of ships to the killing of merchant seamen, seeking to exploit its “scaring off” effect on merchant marine recruits. On 14 May 1942, Doenitz, in conference with Hitler, spoke of the new magnetically detonated torpedo, which, by its “back breaking” explosion, would kill most of the crew and sink the ship so quickly that the others would or could not save themselves.

The records show that on 3 January 1942, Hitler discussed merchant shipping with the Japanese ambassador:

“Merchant ships would be sunk without waring with the intention of killing as many of the crew as possible… We are fighting for our existence and our attitude cannot be ruled by humane feelings. For this reason he must give the order…that U-boats were to surface after torpedoing and shoot up the lifeboats. Ambassador Oshima heartily agreed… and said that the Japanese, too, are forced to follow similar methods…”

Neither captured records nor evidence at the trial indicated that such an order was ever issued. According to Raeder’s affidavit, Hitler broached the idea at the conference of 14 May 1942, where the new torpedo was discussed, and both he, as commander chief, and Doenitz, as flag officer submarines, rejected the idea flatly.

The nonrescue order 154 soon was superseded by an order so severe in its wording that it could be interpreted as a directive not only not to rescue but actually to kill. The Laconia incident apparently gave the excuse. The Laconia, carrying British soldiers and civilians, including women and children, and Italian prisoners with their Polish guards, was torpedoed on the night of 12 September 1942 by U-156. The submarine’s log read:

“2207 Standing by to leeward to await sinking.

“2226” During a loop to windward heard Italian cries for help. Fished for people. Italian prisoners of war from North Africa. Ostensibly 1200-1800 to them on board.”

Captain Hartenstein of U-156 immediately disregarded the standing nonrescue order and took aboard 90 survivors. He so informed flag officer submarines. Doenitz immediately radioed three other German submarines to proceed to help U-156. The next morning Captain Hartenstein broadcast a request for help, promising not to attack any ship joining him in his rescue work. He spent the day helping survivors, both enemy and allies, into the scattered lifeboats. He took a hundred more aboard despite Doenitz’ radio directing that he keep his boat clear for diving. The rescue work was continued for the next two days with two more German submarines now joining in, and a French cruiser due the next day.

At 100, 16 September, U-156, now crowded with survivors and towing five lifeboats, was circled by a “four –engine bomber of American design.“ She signaled the plane by lantern, inquiring for location of the expected French cruiser, and, further to indicate her rescue operations, displayed a Red Cross flag on her bridge. Despite this, the same or a similar plane returned soon and bombed U-156, very nearly sinking her by a close miss amidship. The next day, U-506, the third submarine participating in the rescue, reported an attack by a seaplane while crowded with survivors.

Doenitz now held what he described as a “very spirited conference” with his staff. Obviously the U-boats then in the area where Laconia sank must be kept clear for underwater operation. Apparently the sternest of his staff officers sug-

32

CONFIDENTIAL

gested pushing the survivors overboard, but Doenitz rejected this advice. He sent a radio to U-156 concurring in action in discontinuing rescue operations, and he later advised U-507 to cast off her tow of lifeboats containing English and Poles. The next day all submarines in the area were ordered to keep clear for crash diving, taking “all measures ruthlessly including the discontinuance of rescue.” To U-507, inquiring what to do with the women and children she had on board, he replied: “Keep clear for crash diving. Transfer all but Italians to lifeboats.” The next day U-507 transferred her Italians to the French cruiser, and placed the English women and children in lifeboats after they had spent the night aboard. Doenitz replied: “Action disapproved. Boat was sent to rescue Italians, not Englishmen and Poles.”

The Laconia incident has been given in some detail, as it forms the background of the order of 17 September 1942. Seventeen September was the day of the bombing of U-506, the day after the bombing of U-156. The order reads:

“To all commanding officers:

“1. No. attempt of any kind must be made at rescuing members of ships sunk, and this includes the picking up of persons in the water and putting them in lifeboats, righting capsized lifeboats, and handing over food and water. Rescue runs counter to the rudimentary demands of warfare for the destruction of enemy ships and crews.

“2. Orders for bringing in captains and chief engineers still apply.

“3. Rescue the shipwrecked only if their statements will be of importance to your boat.

“4. Be harsh, having in mind that the enemy takes no regard for women and children in his bombing attacks on German cities.”

On the same date this order is recorded in the war diary of the flag officer submarines:

“The attention of commanding officers is again drawn to the fact that all efforts to rescue members of crews of ships which have been sunk contradict the most primitive demands for the conduct of warfare by annihilating enemy ships and their crews. Orders concerning the bringing in of captains and engineers still stand.”

The order and the war diary reference to it are high spots in the case against Doenitz. To evaluate their significance, we must, however decide (1) whether this was a special order meant for the three U-boats then engaged in the rescuing of Laconia’s survivors and mistakenly sent to all U-boats; (2) what significance to attach to the directive not to rescue and yet to bring in captains and engineers, and (3) whether this order was intended, not as another nonrescue order, but rather as a veiled hint to murder, and whether it was so interpreted by the German submarine service. It would seem that the fate of Karl Doenitz depends in part upon the tribunal’s answer to these questions.

The date of the order lends credence to the defense claim that this was a special order. Surely there can be no doubt that the bombings of 16 and 17 September were the reasons why it was issued. But why, then, was it sent all commanding officers rather than merely to the three commanding officers concerned in the Laconia rescue? Under direct later cross-examination, both Admiral Doenitz and Admiral Wagner, his chief of operations, were vague and uncertain in their answers. Doenitz failed to eradicate the impression that this was vindictive order.

The prosecution asked why submarine skippers again were specifically directed to capture merchant captains and engineers if the purpose of this order was to keep all U-boats under water. Doenitz replied that only one or two men were needed on deck during the search for the captain of a sunken ship, whereas general rescue operations require the presence of many of the crew topside.

The prosecution asked the reason for the statements “rescue runs counter to the rudimentary demands of warfare for the destruction of enemy ships and crews,” and “be harsh, having in mind that the enemy takes no regard of women and children.” Neither Doenitz nor is witness could answer these questions specifically. Though no admission of guilt could be wrung from Doenitz, the prosecution introduced testimony to show that at least one high-placed submarine officer did interpret this as an order to shoot survivors.

Captain Moehle of submarine headquarters Kiel, whose duty it was to brief submarine skippers on current orders before their departure on patrol, testified that he himself was in doubt as to the admiral’s meaning, and when next in Paris asked clarification from the admiral’s staff. There he was told the story of an outward-bound U-boat which sighted British airmen on a raft in the Bay of Biscay. Unable to take them aboard for lack for time, the submarine avoided them and continued on her mission. Her skipper so reported to Admiral Doenitz on his return.

33

CONFIDENTIAL

He was told that he had acted wrongly. If he could not capture the flyers he should have killed them on the raft to prevent their rescue and return to duty to fight against German submarines. Capt Moehle testified he repeated this story to submarine skippers who asked whether the order of 17 September meant to kill survivors.

Capt Moehle’s testimony was partially substantiated by a Lieutenant Heisig, who stated that Doenitz, lecturing to the graduating class of the submarine officers school, gave the order the same interpretation. The credibility of Heisg’s affidavit is weakened by the fact that it admittedly was in behalf of a submarine commander, Eck, then under indictment for actually shooting survivors and sinking their lifeboats. Heisig and been told that his testimony might save Eck but it could not harm Doenitz, since there already was enough evidence to hand him. As specific refutation to Heisig’s testimony, defense produced affidavits from other officers denying that Doenitz’s speech implied that survivors should be murdered. As a general refutation the defense submitted a voluntary affidavit signed by more than a hundred submarine officers to the effect that they do not interpret the Laconia order as an order to shoot survivors.

Eck denied that his action was based on the order of 17 September. He said he had to destroy the floating wreckage to prevent being spotted and sunk by scouting planes. Questioned about this, Doenitz refused either definitely to approve or to disapprove of Eck’s decision. He answered: “Captain Eck had to think of his boat had his crew.”

Two survivors’ affidavits and an extract from the log of U-105 were offered by the prosecution as evidence that three other German submarines fired on survivors. The defense sought to cast doubt on the affidavits.

Even if one grants that Doenitz never directly ordered the murder of the shipwrecked, it is evident that he welcomed the loss of life which his submarines were inflicting on merchant crews.

The presence of special rescue ships in convoys was to force Doenitz again very near to ordering the destruction of crews whose ships had been sunk. His top secret order of 7 October reads in part:

“To each convoy a so-called rescue ship is generally attached, a special vessel up to 3,000 tons which is designed to take aboard the shipwrecked after U-boat attacks. These ships are in most cases equipped with catapult planes and large motor boats. …They are heavily armed with depth charge throwers and very maneuverable, and are often taken for U-boat traps by commanders. In view of the fact that the annihilation of ships and crews is desired, their sinking is of great importance.”

Doenitz was permitted to send an “interrogatory” to Fleet Admiral Nimitz, inquiring as to the methods of the United States Navy in its submarine warfare against Japanese commerce, and asking specifically our rules on sinking at sight, war zones, and the rescue or nonrescue of survivors.

In his reply, Fleet Admiral Nimitz stated that the United States announced specific war zones, that therin United States submarines attacked merchant ships without warning, except for hospital ships and ships under safe conduct, and that on general principles we did not rescue enemy survivors if undue hazard to the rescuing submarine would result or if she would thereby be prevented from accomplishing her mission. Although there were numerous cases of rescue recorded, rescue operations were of necessity limited, not only by the small passenger-carrying capacity of the submarine, but even more by “the known desperate and suicidal character of the enemy. Survivors did not come on board voluntarily. It was necessary to take them prisoner by force.” Such being the inherent limitations of our submarines and the peculiar character of our enemies, American submarine skippers could do little for the shipwrecked beyond furnishing provisions and life rafts in some instances. Nor would it have been possible to summon Japanese merchant ships since they were “usually armed and always sought to attack our submarines by any available means.”

Hitler, on 18 October 1942, signed a directive known throughout the service as the “Fuehrer’s Order”:

“All enemies on so-called commando missions. . . challenged by German troops, even if . . . in uniform . . . are to be slaughtered to the last man . . . even . . . if . . . they are prepared to surrender.

Individual commandos captured separately were to be “handed over to the SD” (security police). That, Doenitz admitted, meant they would be shot.

What guilt attaches to Doenitz for the navy’s share in carrying out the Fuehrer’s order? He admitted that as flag officer submarines he knew of the existence of the order, but said that, as the

34

CONFIDENTIAL

order exempted captives taken at sea, the submarine service was not directly concerned. After 30 January 1943, Doenitz was commander in chief, responsible for the conduct of the entire German Navy. The record shows that at least one case occurred, after that date, in which the navy was responsible for carrying out the “Fuerher’s Order.”

The record seems to prove that Doenitz was cognizant of the order’s implications. Only 10 days after he assumed command, a special staff memorandum on this subject was directed by the International Law Section of his Operations Staff to the Chief of Operations, Admiral Wagner, warning that shooting soldiers captured in uniform was not in accordance with the accepted laws and customs of war. The memorandum recommended a clarification of the navy’s responsibility. Wagner, according to his testimony, returned the memorandum with the comment that no further clarification was necessary.

This fact casts doubt on his subsequent denial, and the denial of Admiral Doenitz, that the shared the guilt for the execution of the crew of MTB 345. In July 1943 the British Motor Torpedo Boat 345 left the Shetlands on a mission to destroy German shipping and to lay mines in Norwegian waters. Attacked by superior German naval forces while hidden at the island of Apso, near Bergen, her captain destroyed his ship and surrendered himself and his crew as prisoners of war. They were interrogated by German naval intelligence officers, and, despite the recommendation of their naval interrogators that they be accorded prisoner-of-war treatment, they were turned over by the navy to the Security Police, on the suggestion, if not the insistence, of the naval commander in Norway, Admiral Schrader. Schrader later committed suicide.

Faces with this story, Doenitz denied all knowledge of it. He maintained that he was never informed. All that he would admit was, granted the facts were as the prosecution stated, there had been a “local mistake.”

The British sailor, Paul Robert Evans, who was one of the crew of a two-man torpedo fired against the Tirpitz in December 1942, was captured in uniform. He was executed a few weeks before Doenitz became commander in chief. Doenitz disclaimed knowledge and responsibility.

Such was the case of the United States, the French Republic, the United Kingdom and the USSR against Grand Admiral Karl Doenitz. This study does not pretend to argue the law, or even completely to state or evaluate the evidence. Its intention has been to review in brief the mass of documents and affidavits, and the long transcript record of assertion, denial and explanation on which the tribunal has based its verdict.

Since the above article was written, the International War Crimes Tribunal at Nuremberg has sentenced Grandadmiral Doenitz to 10 years imprisonment and Grandadmiral Raeder to life imprisonment. Doenitz was found guilty on two charges, namely Crimes Against the Peace (i.e., waging was that are illegal under International Law) and War Crimes (i.e., contravention of rules governing the conduct of warfare). Doenitz was found innocent of the charge of Conspiracy to Bring About War. Raeder, on the other hand, was convicted on all three of these charges. Both men were found innocent of a fourth charge, namely, Crimes Against Humanity.

* * *

35

CONFIDENTIAL

Source: Vol. 1, The ONI Review No.12, pgs 26-35, October 1946