The Navy Department Library

Merchant Ship Shapes

ONI 223M

Division of Naval Intelligence - Identification and Characteristics Section

PDF Version [16.1MB]

RESTRICTED

ONI 223-M MERCHANT SHIP SHAPES

NAVY DEPARTMENT

Office of the Chief of Naval Operations,

Washington, D. C.

1. ON I 223-M, Merchant Ship Shapes, is one of a series of handbooks on ships and their identification and reporting prepared by the Division of Naval Intelligence for the use of fighting forces and naval personnel in training. The first of this series, ONI 223, Ship Shapes, deals with warship types and nomenclature. A similar treatment of merchantmen is presented herewith.

2. Since a large proportion of cargo ships now in operation belong to one of the several standard types which have been developed in the present war or

survive from World War I, considerable stress has been laid on the appear ance of such vessels. In many circumstances identification of nonstandard ships may prove too difficult, and the appearance of functional types— passenger ships, tenders, cargo carriers, etc.― has been discussed in some detail so that reporting and identification by type may at least be effected.

3. ONI 223-M is issued with the hope that it may prove of service to the fighting forces in the development of accurate methods of identification of merchant vessels.

R. E. SCHUIRMANN,

Rear Admiral, U. S. Navy,

Director of Naval Intelligence.

Op-16-P-2 A10-3/EN3-10 Serial No.716 U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE : 1944 16-39462 -1

RESTRICTED

1

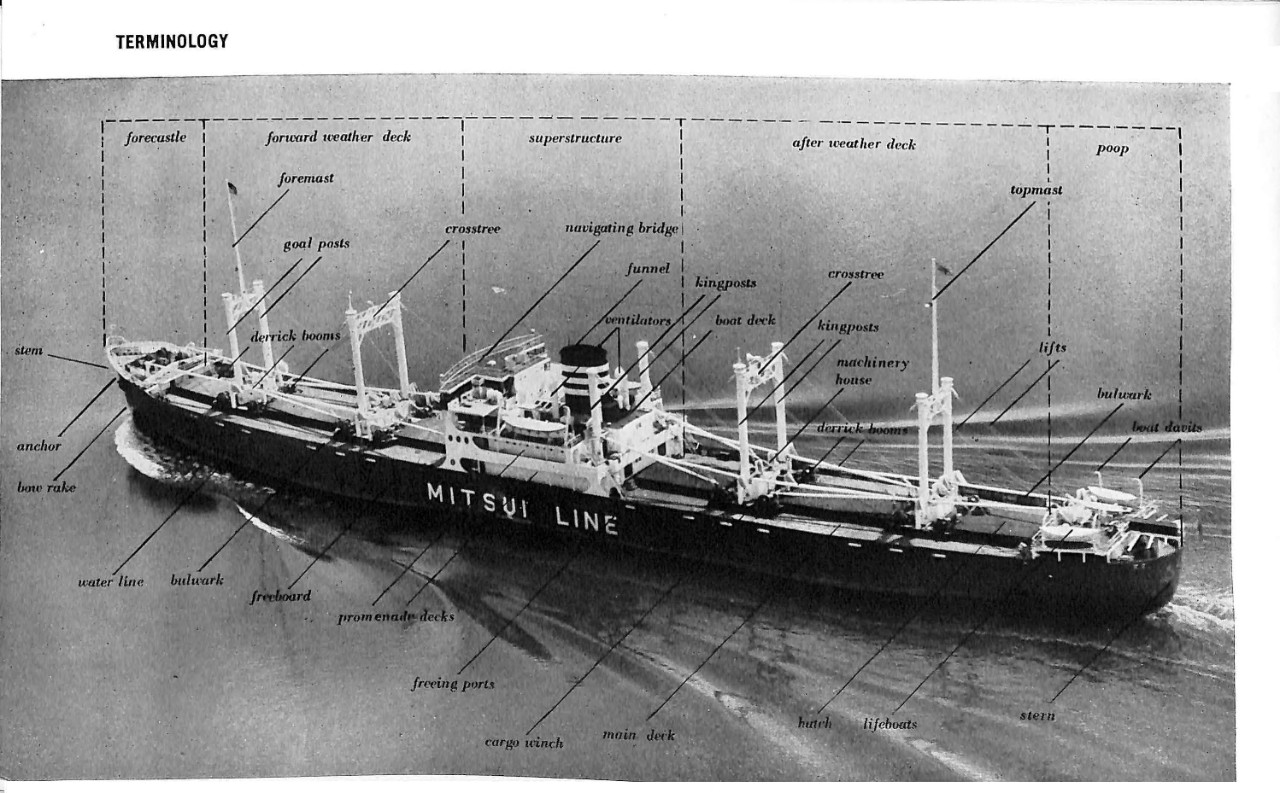

ONI 223-M TERMINOLOGY

| ABAFT - Behind or the rear of any part of a ship. | ENGINES AFT - Term used to describe a vessel stern. | MOTORSHIP - A ship driven by internal combustion engines |

| AFT - Near or toward a ship's stern | ||

| AMIDSHIPS - In the general vicinity of the center of a ship's length. | ENSIGN - A national flag flown by naval or merchant ships. | POOP - An island at the after end of a ship |

| ASTERN - Behind a ship's stern, or backwards | FLUSH - Level, free from breaks or irregularities. | PORT - Left side of a vessel, when facing forward. |

| ATHWARTSHIP - Across a ship (at right angles to the fore and aft line). | FORE - Adjective used as a prefix indicating forward or leading position. | PORT, LIGHT - An opening in the side of a ship's hull or deck structure. |

| BALLAST - Material carried to give a vessel stability when empty of cargo; usually water or sand. | FORE and AFT - Lengthwise (of a ship). | PORT, FREEING - Openings in bulwarks at deck level to perit egress of water. |

| BEAM - The greatest breadth of a ship's hull. | FORECASTLE - A raised island at the forward part of a ship. | QUARTER DECK - The part of rhe upper deck between the stern and mainmast. |

| BOOM - A heavy spar for handling cargo; usually attached to the base of a mast or kingpost. | FORWARD - Toward the bow. | RAKE - A term denoting fore and aft inclination from the vertical. This applies to masts, funnels, bows, sterns, etc. |

| BOTTOM - The underwater part of the hull, extending from the keel to the curved portion of the ship's sides. | FREEBOARD - Vertical distance from the waterline to the topmost continuous weather deck. | RIGGING - The ropes and cables that support or oerate the masts, spars, and booms of a ship. |

| BOW - The forward end of a ship. | GALLEY - The space on a ship in which food is prepared and cooked. | SAMSON POST - Same as kingpost. |

| BRIDGE - A high athwartship platform on the forward part of a ship's superstructure, including in its central portion an enclosed pilothouse. | GOALPOSTS - Double kingpost placed athwartships, with tops connected by a light truss. | SHEER LINE - The longitudinal line of a ship's deck at the intersection of a deck and sides. |

| BULKHEAD - Partition walls which subdivide the interior of a ship's hull | HALYARDS - Light lines or ropes used for hoisting signals, flags, etc. | STAY - Rope or wire used to support a mast, spar, or funnel. |

| BULWARK - A short, solid continuation of the ship's hull above the edge of an exposed deck giving protection against weather loss of material or personnel overboard | HATCH,HATCHWAY - An opening in a deck through which cargo may be handled; aslo smaller openings for personnel or ventilation. | STARBOARD - The right-hand side of a vessel, when facing forward. |

| BUNKER - A hull compartment used for stowage of coal or oil fuel. | HOLO - A Space below decks, used for stowing cargo. | STEAMSHIP - A ship driven by steam engines, whether fueled by coal or oil. |

| CATWALK - Narrow exposed fort-bridge connecting the hull islands. | HULL - The shell or body of a ship, including island but excluding built-on structures, such as deckhouses and superstructure. | STEM - Extreme forward part of a vessel's bow. |

| CRANE - Mechanical device used for hoisting or moving heavy weights. | ISLAND - Full-width sections of the hull rising one deck above the main weather deck. | STERN - The extreme after end of a ship. |

| DAVIT - A device for carrying, raising, and lowering lifeboats. | JURY MAST - temporary light mast. | STERN POST - Vertical rudder post in the stern of a vessel. |

| DECK - The "floors" of a ship's structure; included are the main deck weather deck, first, second, third decks, forecastle deck etc. | KEEL - A full-length, centerline strength member to which a ship's ribs are attached | STORM DECK - The extended portion of the center island either fore or aft the structure. |

| DECKHOUSE - An isolated element of a ship's superstructure which may occur at the base of a mast, on the poop, etc. | KINGPOST - A short vertical post used to support a derrick boom; may be single or in pairs. | SUPERSTRUCTURE - A structure or structures built above a vessel's hull. Includes pilothouse bridge, galley house, deckhouses, etc. |

| DRAFT - The depth of a ship below the waterline varing with load conditions. | KNOT - A unit of speed, equaling one nautical mile (6080.2 feet) an hour. | WATERLINE - A line on the hull representing the water level when the ship is in loaded condition. |

| DECKHOUSE - An isolated element of a ship's superstructure which may occur at the base of a mast, on the poop, etc. | LADEN (VESSEL) - Designates condition when vessel is fully loaded. | WEATHER DECK - The uppermost deck that is exposed tothe weather, exclusive of hull islands which may be built upon it. |

| DRAFT - The depth of a ship below the waterline varying with load conditions. | LIGHT (VESSEL) - The opposite to laden; empty of cargo. | WELL (DECK) - An area of weather deck situated between hull islandss. |

| LIST - Inclination of a ship to one side from the vertical. | WHEEL HOUSE - Deckhouse in which the steering wheel is located usually aft. |

3

INTRODUCTION

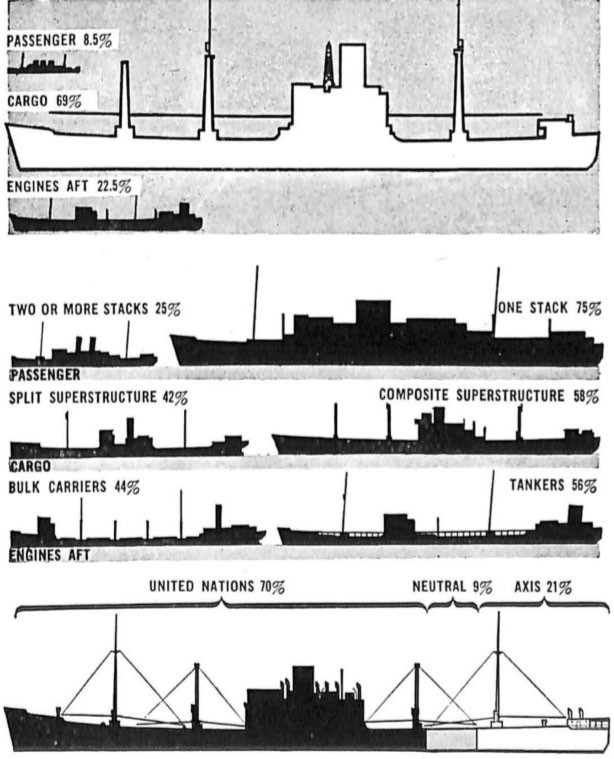

Merchant ships, in their wartime function of moving supplies close to the battle fronts and to advance bases, constitute vital factors in the prosecution of a war. It is important that an observer be able to tell more than that a merchant ship is a friend or enemy, since its type, probable size, and cargo may have considerable significance in forming an estimate of the character of the vessel and its part in an enemy's strategy. Each merchant ship has a particular function in the task of supplying over seas combat forces. This function will of ten provide an initial clue as to a ship’s type. For each of the three essential functions of merchant ships-to transport passengers, freight, or bulk cargo-a particular type of ship has been developed. The most important structural elements which serve in differentiating these ty pes arc those that occur above deck lines-superstructure, funnels, masts, kingposts, island s, etc. Some or all of these elements appear in all vessels and an accurate arrangement of their size, number, location, and relative arrangements will lead to determination of the type of a ship under inspection. In the case of passenger ships, for example, large consolidated structures - of passengers - occur amidships. This structure is surrounded by promenade |

decks. Additional living space is indicated by the many rows of ports along the sides of the ship's hull. Since freight carrying is only a secondary function of passenger ships, their loading equipment-the vertical "kingposts" and masts from which booms are swung - is less in evidence than in vessels designed as cargo carriers. Since extensive accommodations for passengers are not required on freighters, their superstructures usually consist of only a bridge, with one or two short decks for the crews' living facilities. Freighters usually carry a large amount of loading equipment in the form of heavy masts, kingposts, and booms to handle cargo which is towed in a number of separate watertight compartments or holds, running the length of the ship. IN the majority of cases the engines are placed amidships, and funnels, bridges, and other elements of the superstructure are located in a roughly central position. Bulk loads such as grain, ore coal, and oil are, however, usually transported by another type of cargo vessel. While small superstructures, consisting of bridges and parts of crew’s quarters, are usually located forward or amidships, engines and machinery are located aft, permitting holds to extend without interruption from bow to engines at the stern. Tankers are the most common and the most important of these ships which are easily distinguished by the location of their funnels. |

4

FUNCTION AND APPEARANCE

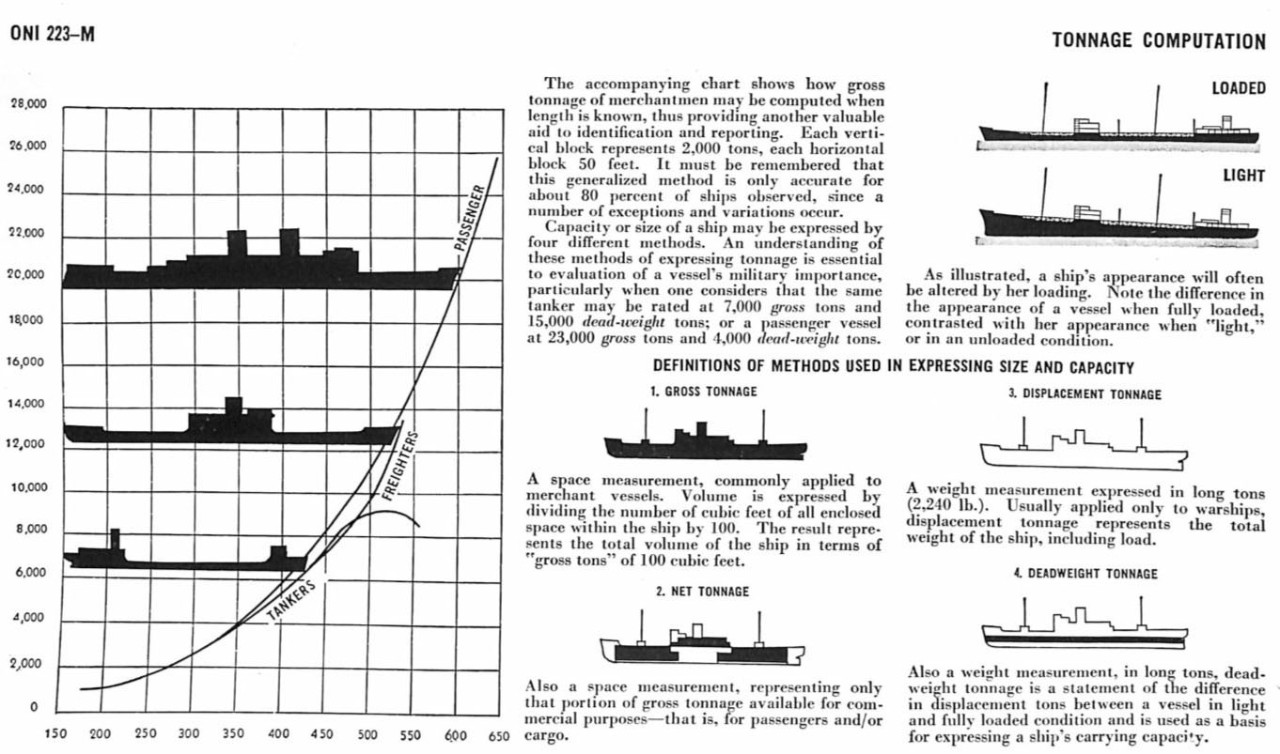

To illustrate the degree to which function deter· mines the appearance of a merchant ship, cross-sections of each of the three general types are shown. In these diagrams, the relation of cargo space (black), machinery space (gray), and living quarters (white) clearly indi cates functional differences, which are in turn reflected in the external appearance of all ships.

German Liner – SCHARNHORST

A Passenger-Cargo ship, showing the characteristi cally large superstructure. Notice the small proportion of cargo space and the large amount of space de voted to the machinery required to drive these large, fast ships. The many passenger decks contain cabins, restaurants, and luxurious recreational facilities.

"FORT" Class - British Standard Design

A modern Freighter, showing the many heavy king posts and booms which service the large cargo holds. Living quarters for the crew, and space required for the ship's machinery, arc comparatively small.

American Oiler - OHIO

A Tanker, typical of most modern "engines-aft" de signs. Notice the location of the engines and funnel, far aft, and the long, continuous hold adapted to handling liquid or bulk cargo. Living quarters and machinery require the same relative amount of space as in freighters.

Having grouped all merchant ships into three types according to their general functions, consideration must now be given to variations within each category.

5

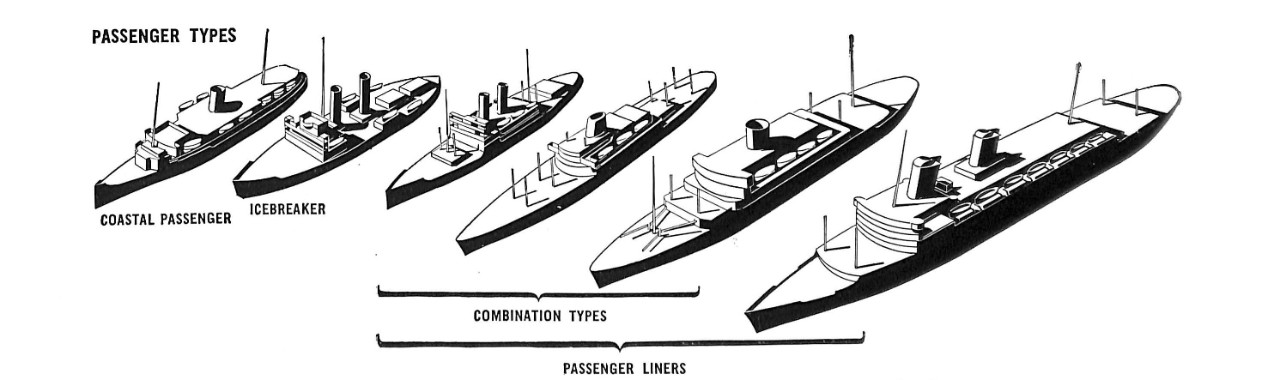

PASSENGER LINERS

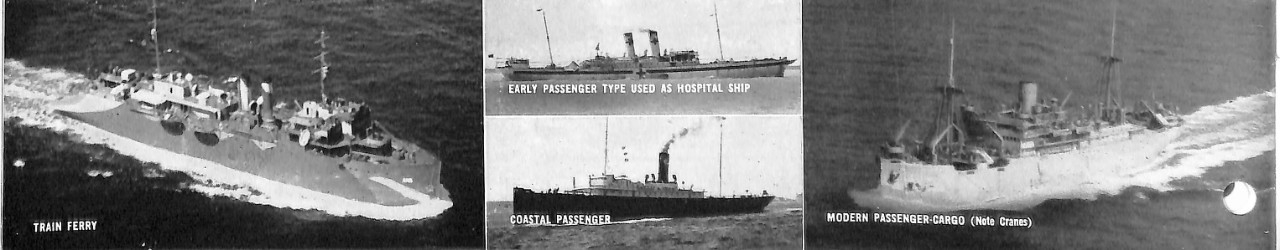

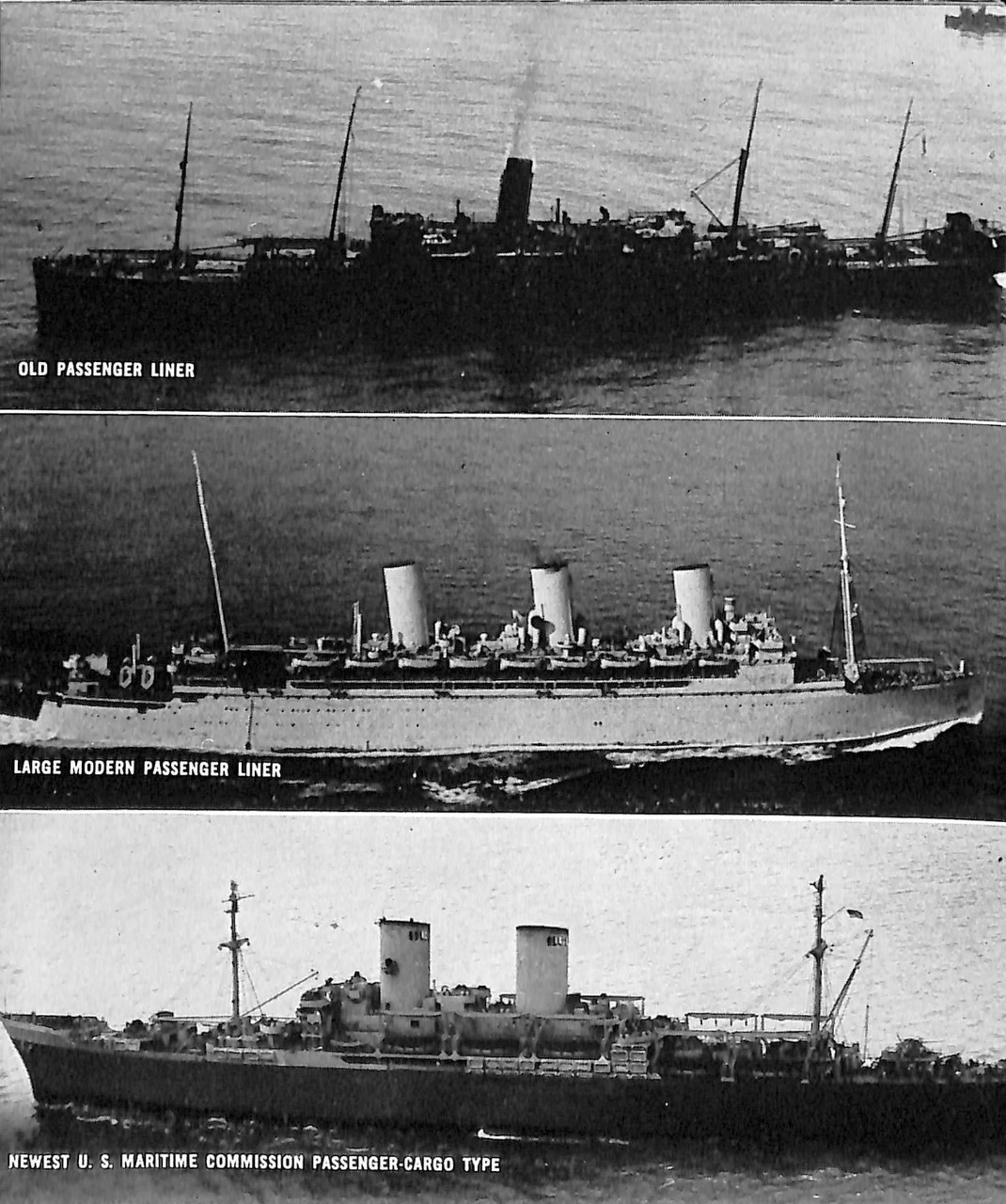

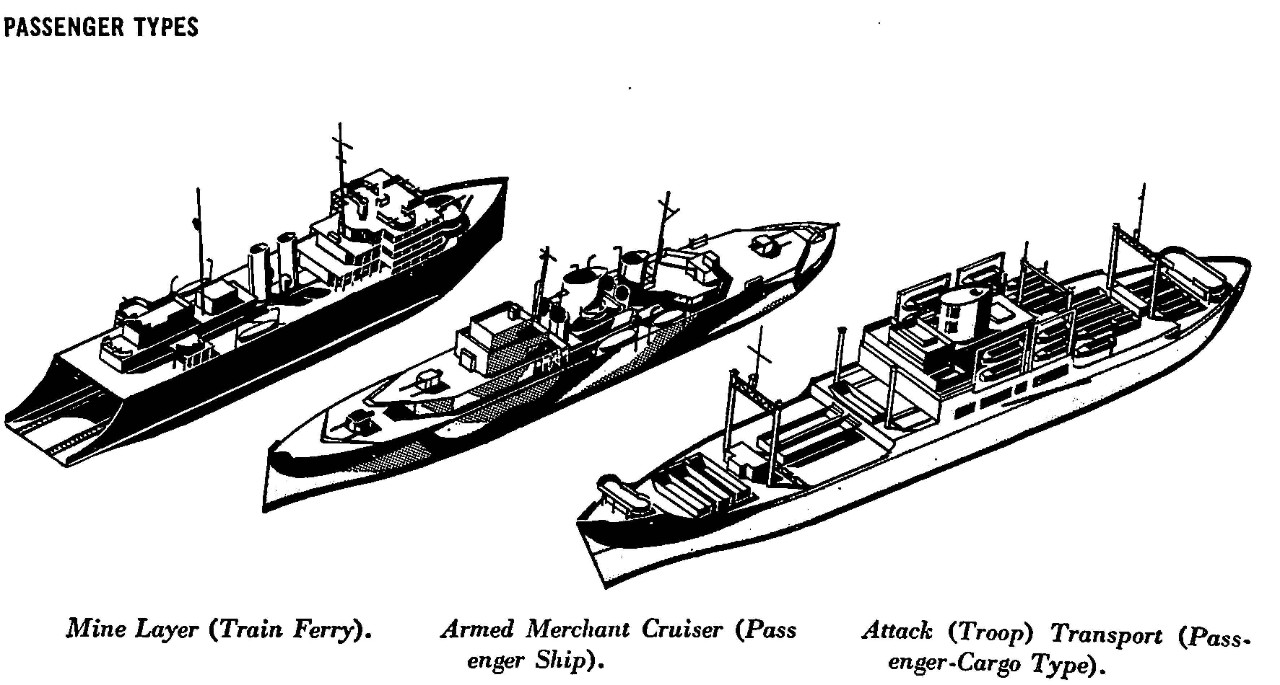

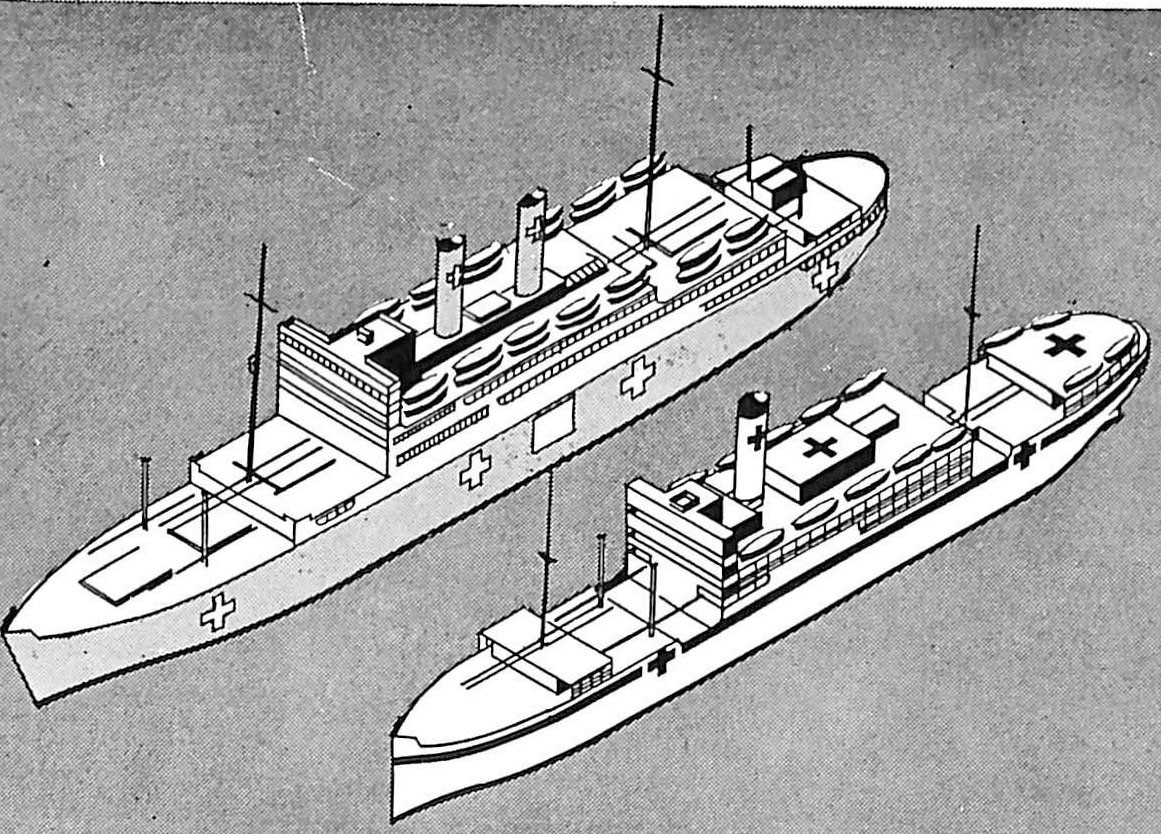

| Passenger vessels constitute the smallest numerical group of all merchantmen.They may range in length from 200 to 1,000 feet, and are principally identified by their large superstructures, which consist of decks covering over one-third of the ship's length. While most passenger ships have one funnel located amidships, many have from two to four. For the sake of convenience | all multi-funneled ships are here classed as passenger types, although some multi-funneled ice breakers and train ferries fall within this group. During wartime, _these vessels operate as troop transports, fleet tenders, and hospital ships, while others have been converted to armed merchant cruisers, aircraft carriers, or submarine supply ships. Shown and briefly discussed here are the various types for passenger vessels that are likely to be encountered. |

ONI 223M

COASTAL PASSENGER SHIPS-These ships frequently resemble liners. Their size is therefore often greatly over-estimated. Their very long superstructures, with many lifeboats, usually cover most of their length . Stacks range from one to three in number and presence of two masts is common. Designed for short-sea service, they run such routes as U. S. coastwise, English cross channel, Mediterranean, or the Japanese Inland Sea. Ships of this type normally are 250 to 350 feet in length, with a gross tonnage of 1,000 to 3,000 tons, and speeds of 18 to 24 knots.

ICE BREAKERS -These ships clear frozen sea lanes, usually serving at the same . time as cargo-passenger vessels. Ships of this type are usually of Russian, Japanese, and Scandinavian registry. They range from 200 to 335 feet in length, with a gross tonnage of 1,600 to 5,600 tons and speeds of 10 to 16 knots.

LINERS AND PASSENGER·CARGO VESSELS -Extremely long, low massive super structures with large stacks, many lifeboats and rafts, and two or more masts are distinctive features of the liner. Designed as high-speed luxury ships, comparatively few are in war service. Combination passenger - cargo liners have shorter superstructures, carry kingposts and cranes for handling cargo, and accommodate a limited number of passengers. These vessels con stitute a fairly large group. For the most part, liners are now under the control of the United States, Great Britain, and Japan. Neutral Sweden operates a few as repatriation ships. Liners vary from 450 to 1,000 feet in length, from 10,000 to 80,000 in gross tonnage, with speeds ranging from 14 to 32 knots.

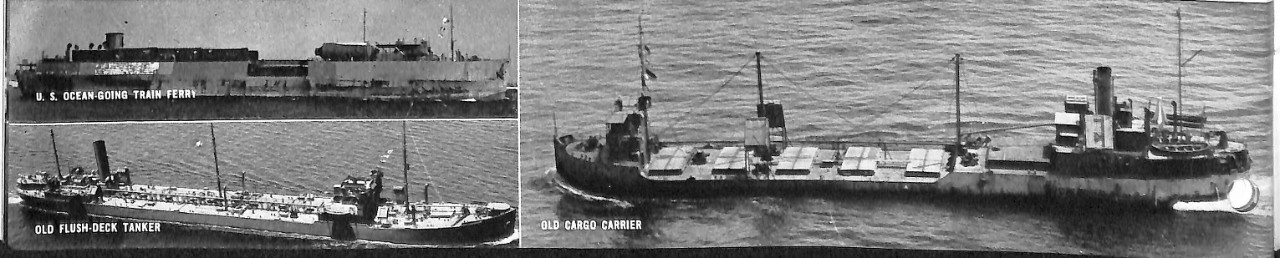

TRAIN FERRIES-These ships may be recognized by their long, high super structures, broad beam, and low, open sterns. A few are "double-enders." Paired funnels, placed abreast, occasionally occur in this type, leaving the hold free for railroad cars. This small category is made up of ships owned by the United States, Great Britain, Japan, and a few Baltic countries. They vary from 200 to 300 feet in length, with a gross tonnage of 500 to3,000 tons, and speeds of 12 to 16 knots.

7

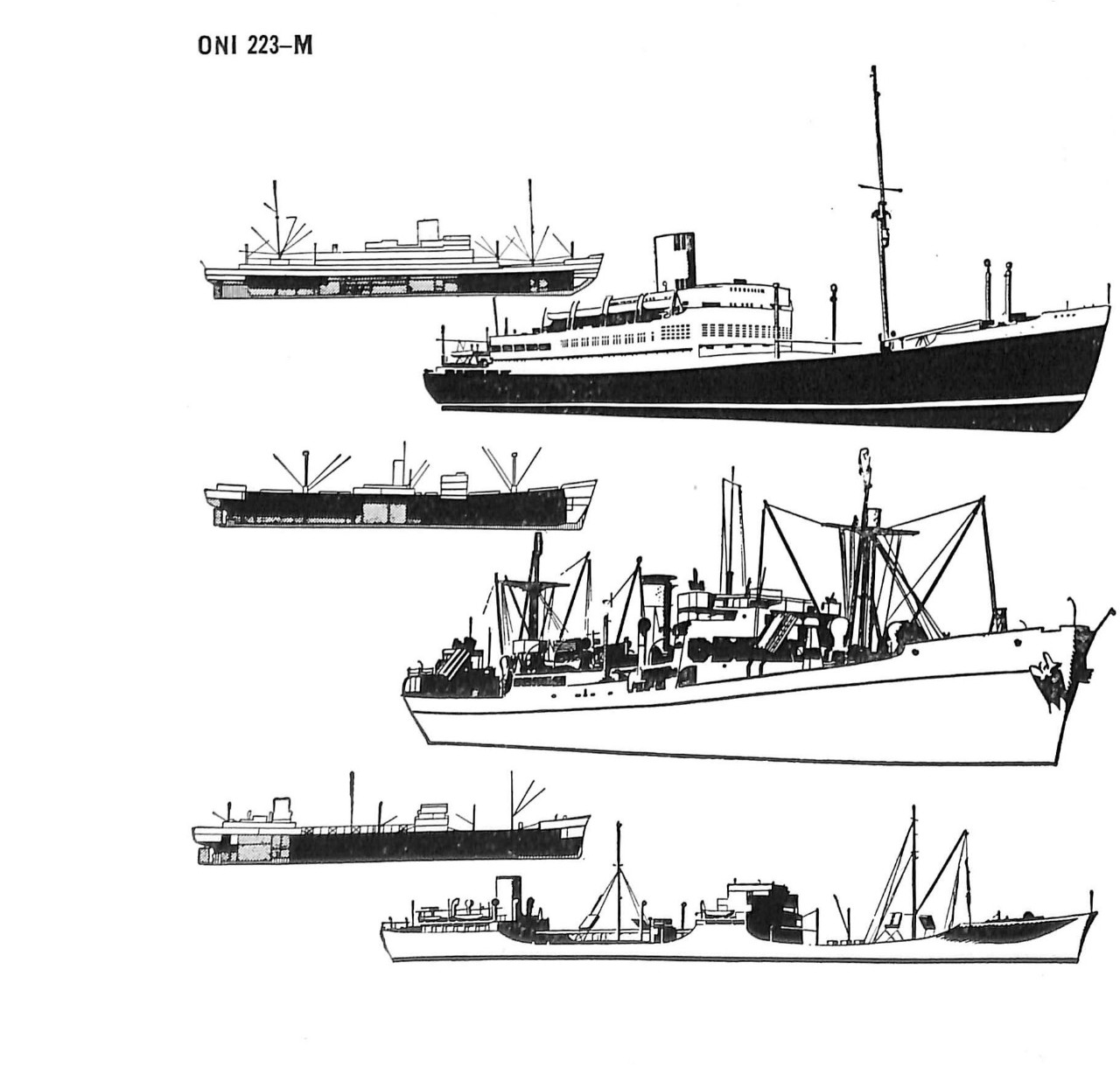

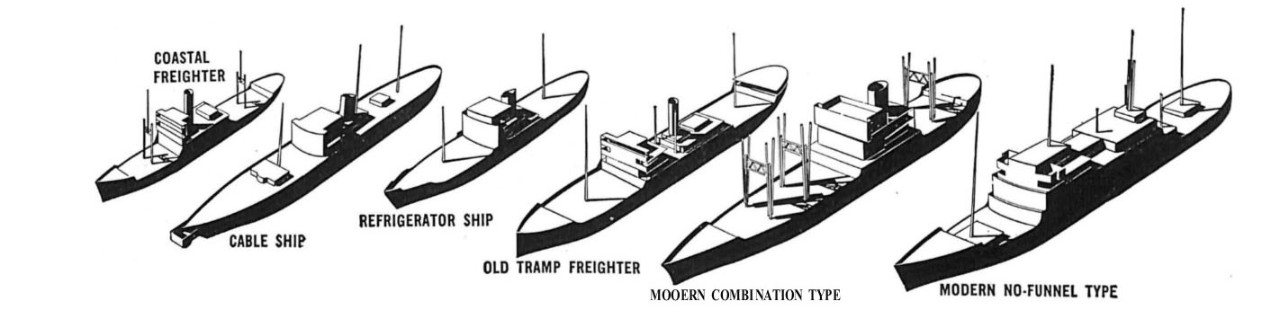

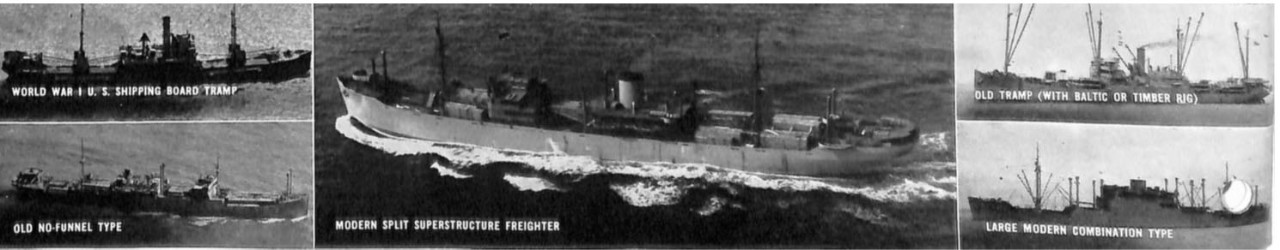

CARGO TYPES (Engines Amidships)

Cargo carrying vessels constitute the largest numerical group of merchant men under all flags. They range in length from 150 to over 500 feet and may be identified by their short superstructures, always less than one-third the length of the ship. A cargo carrier's superstructure will fall into one of two types- "Composite" or "Split." A superstructure is considered composite when bridge and decks form a single block. Split superstructures are divided so that a definite |

break for a cargo hatch exists between bridge and deckhouse. All of these ships have small single stacks except in the case of a few modern Diesel freighters in which no stack will he apparent. These vessels are not only used to transport freight and war material during wartime, but may he employed as raiders, mine layers, tenders, patrol vessels transports, or hospital ships. Their wartime functions are more varied than those of any other merchant type. |

ON I 223-M

COASTAL FREIGHTERS-These short-rang e craft strongly resemble oceangoing types. Superstructures are usually of the composite type, with few masts and kingposts. In war time they are usually, employed as cargo or store ships, sometimes as patrol or mine craft. Their lengths vary from 100 to 350 feet, their tonnage from 100 to 5,000 gross tons, with speeds of from 10 to 22 knots.

TIMBER CARRIERS-These are medium-sized freighters with masts and king posts widely spaced on forecastle and poop in order to clear a large continuous cargo bold. Bows are usually plumb and sterns of the counter type. The greater number of ships of this type have been built by the United States, Great Britain, Japan, and the Baltic states, and serve as excellent bulk carriers for military cargo. Their lengths range from 250 to 300 feet, their tonnage from 1,000 to 2,000 gross tons, and speeds from 7 to 11 knots.

CABLE SHIPS-Ships of this special type are often mistaken for yachts. Used by the United States; Great Britain, Japan, and Germany, these ships may be used in their designed capacity or be converted to mine layers. Their lengths vary from 150 to 350 feet, their tonnage from 900 to 5,300 gross tons, and speeds from 10 to 16 knots.

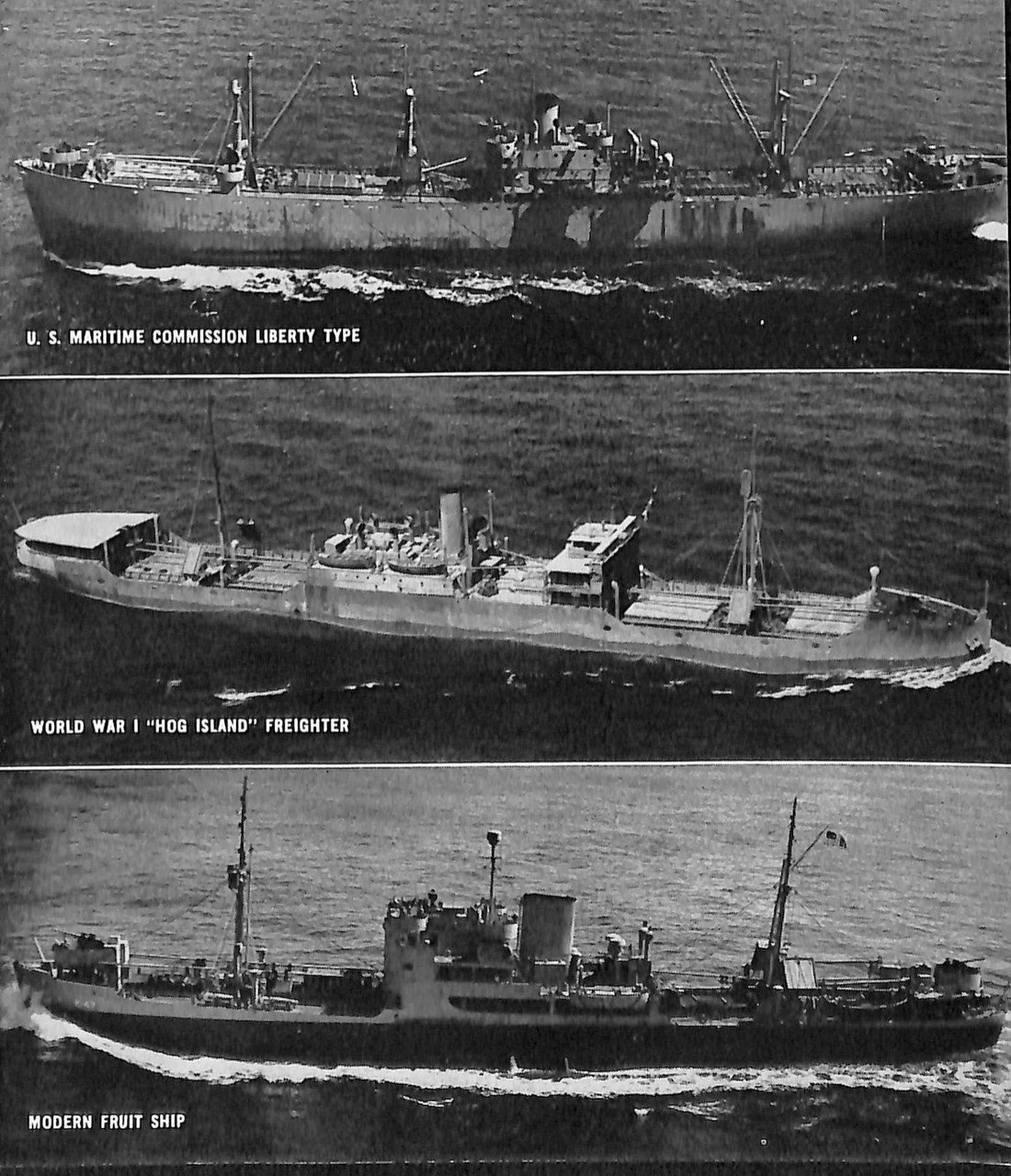

FRUIT SHIPS-Fast modern type motor hips used for the rapid transport of refrigerated meat and fruit, these ships usually have short composite super structures and a few light masts or kingposts. In wartime they may be used as raiders, mine layers, or escort craft. Lengths may vary from 250 to 350 feet, tonnage from 3,000 to 4,000 gross tons, and speeds from 15 to 20 knots.

OLD FREIGHTERS (TRAMPS)-These ships are the most frequently observed of all merchant types and may be recognized by their split superstructures, plumb bows, counter sterns, and tall thin stacks. Masts and kingposts are usually few. Lengths vary from 250 to 400 feet, tonnage from 4,000 to 8,000 gross tons, speeds from 6 to 14 knots.

MODERN FREIGHTERS-This type consists of large ships, with numerous king posts and lasts, large low stacks, raked bo.ws, cruiser sterns, and, usually, composite type superstructures. A few ships in this group, being Diesel driven, have no stacks. This type has absorbed most of the pre-war and war time building program. They carry all types of cargo and as many as twelve passengers. In wartime they are used as raiders, combat-loaded cargo ships, auxiliary cruisers, tenders, and supply ships. Lengths vary from 350 to 550 feet, tonnage from 9,000 to 10,000 gross tons, and speeds from 14 to 24· knots.

9

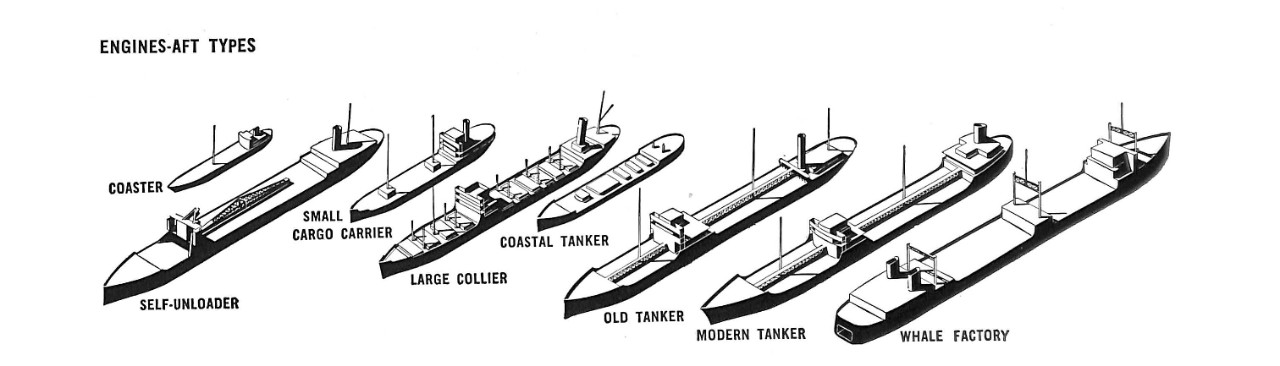

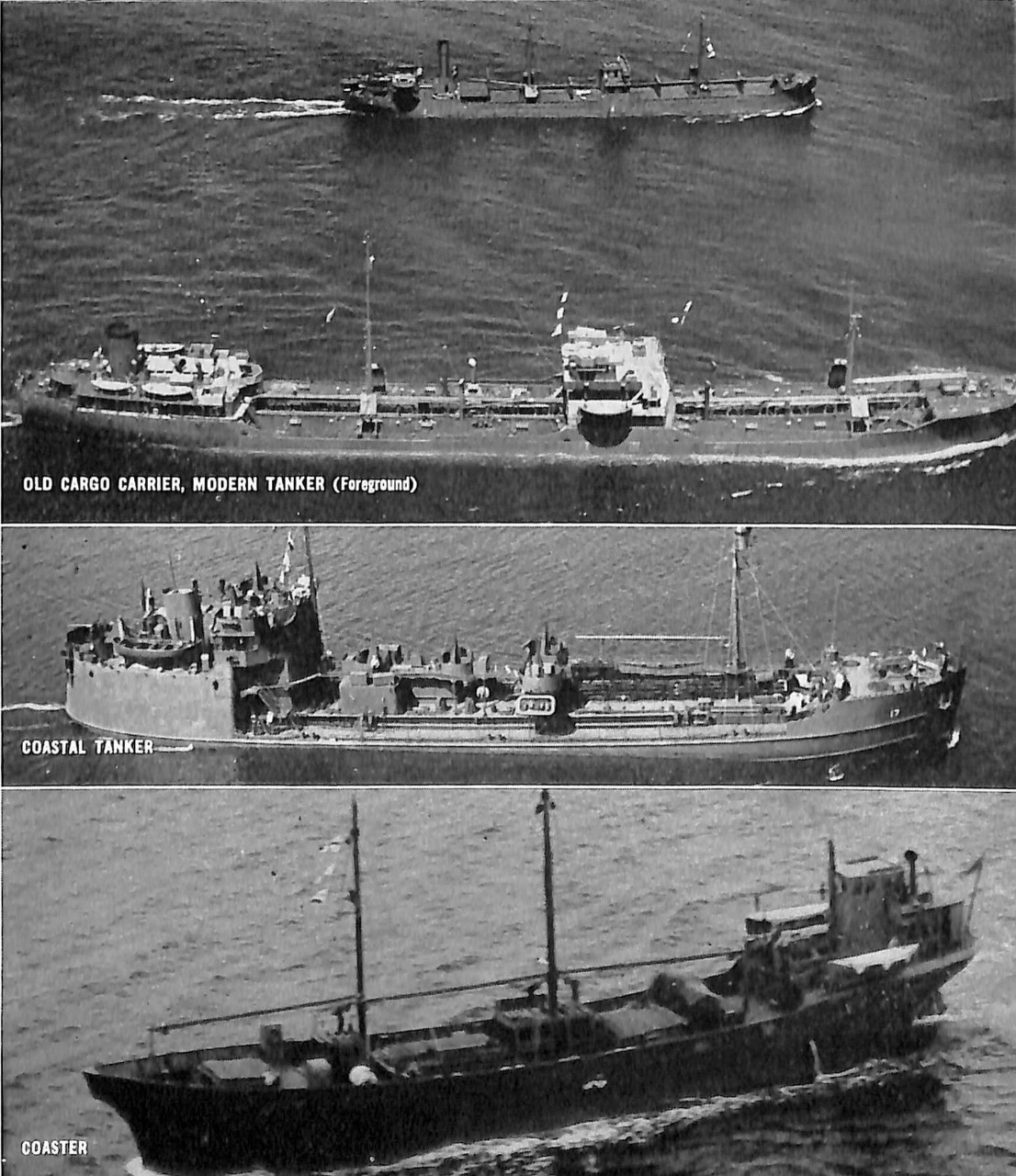

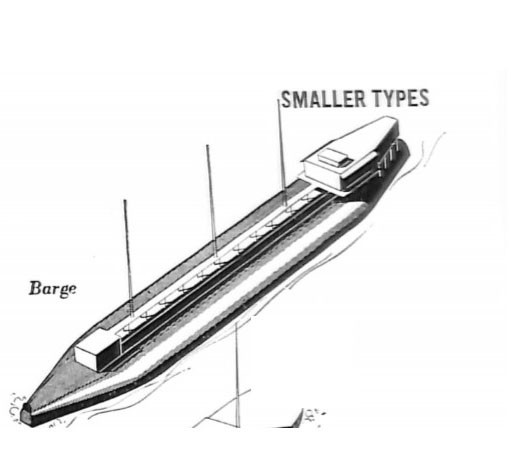

| Vessels with engines aft are "bulk" carriers, the nature of whose cargo re quires use of a single continuous hold. The size and shape of these tankers, ore carriers, coasters or whale factories vary considerably. In this type engines (and therefore funnels) are always situated far aft, but the bridge may appear on the poop, forecastle, or amidships. | Although of comparatively recent design, these ships form a growing pro portion of present-day merchant shipping. During wartime, ships of this type are used mainly for the purpose for which they were initially designed, especially in the case of oil and gasoline transports, but some may be altered to take on the added function of tenders or be converted to aircraft carriers. |

ONI 223-M

COASTERS-The smallest of the cargo types, these ships often resemble large trawlers, since presence of a bridge on the poop, a single mast, and large continuous batch characterize both types. Employed as short-haul craft, these types appear in great numbers and with a wide variation in appearance. Coasters may vary from 100 to 300 feet in length, from 500 to 1,500 gross tons, with speeds of from 7 to 12 knots.

CARGO CARRIERS-A numerically large type in all merchant fleets, these ships transport bulk cargo such as ore, grain, coal, timber, and large unit cargoes such as locomotives, boats, etc. Mostly older vessels, these ships usually have plumb bows, counter sterns, very large hatches, and many heavy masts and/or kingposts. Self-unloaders, which carry their own large conveyor machinery, belong to this group. They may vary from 200 to 620 feet in length and from 1,000 to 5,000 gross tons, with speeds of 8 to 12 knots.

TANKERS-Used by all nations as bulk liquid-fuel carriers, these ships have been retained during the war in this important function. The bridges of most tankers are located amidships, with a catwalk connecting hull islands. A few light masts and booms, and usually a pair of kingposts constitute their cargo handling gear. Newer types can be distinguished by raked bows, cruiser sterns, and large stacks situated well aft on the poop. Occasionally a trunked deck- or no-funnel type is seen. Exceptionally large deck space may be used advantageously for deck loads. For coastwise traffic, a smaller type of vessel has been designed, with small superstructure, normally situated aft, and a very low trunked hull. Tankers range from 360 to 550 feet in length 6 000 to 12,000 gross tons, and 10 to 18 k nots in speed.

WHALE FACTORY-A slipway in the stern, with two straddling funnels and long open -decked hull, render ships of this type unmistakable. A very small num ber of these ships, owned mostly by British, Scandinavian, and Japanese companies, have been designed for the processing of whales. In wartime these ships are used as cargo_ or fuel carriers, or mar serve as mother ships to minor naval craft or submarines. These vessels will vary from 500 to 600 feet in length, 10,000 to 20,000 gross tons, with speeds of 10 to 15 knots.

SEA TRAIN-A few of these vessels fall within the engines-aft classification. These constitute the only ships so classified that arc not bulk carriers.

ENGINES-AFT PASSENGER TYPES-A limited number of these vessels exist, but will be easily identified as passenger vessels by the length of their super-structures.

11

A large proportion of the world's merchant ships have been converted to regular naval service, are manned by naval personnel and used entirely in connection with military operations. Every type of merchant ship discussed on the foregoing pages has been converted to fulfill one of a variety of military functions, and often extensively refitted.

During the early phases of the present war many merchant conversions performed duties usually assigned only to naval vessels, a practice which was rapidly discontinued in allied navies with the development of naval ship building programs. Many merchant ships have, however, been retained as naval auxiliaries. Examples are shown on these pages of the types most frequently converted, and of those that have undergone most radical alteration.

The greater numberof the world's merchant ships, while they carry naval guns and gunners, are still operated by private shipping companies rather than by the armed services.

TRAIN FERRIES-The design of former train ferries adapts them for use as landing ships and mine layers. A number of other types of merchant men have also been converted to mine laying.

PASSENGER SHIPS-Expeditionary forces of un precedented size have required the use of many vessels of the passenger type. Combat-loaded for actual invasion operations, these ships will often accommodate all the landing craft and equipment required by the troops they carry.

Larger ships have frequently been converted to armed merchant cruisers through installation of heavy deck guns and are used as convoy escorts and in support of landing operations. Many are now being returned to troop transport duty. A few passenger types are also being used as; tenders, repair. ships or hospital ships.

12

Wartime functions

ONI 223-M

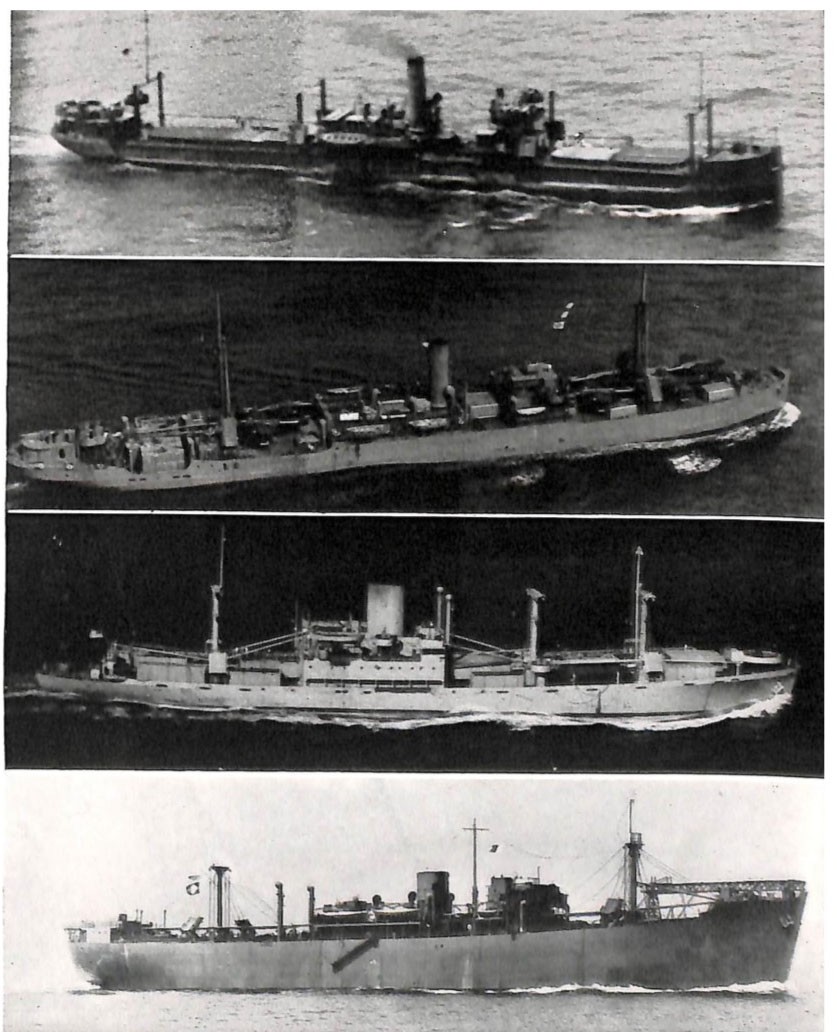

OLD FREIGHTERS-Unsuited to most other naval uses older freighters have been successfully used as coastal mine layers, AA ships, and as hospital ships (by the Japanese). Conversions to aircraft transports and seaplane tenders have also been frequent in the Japanese merchant marine.

MODERN FREIGHTERS-To keep pace with naval expansion and extended operations, many larger cargo ships have been converted to tenders and supply vessels for destroyers, submarines, PT boats, and patrol planes.

FRUIT SHIPS- These German freighter conversions, called Sperrbrechers, are combination escort, mine sweeping and AA ships. The Japanese have converted fruit ships to similiar purposes or used them as raiders.

TANKERS-These vessels, when they can be spared, have occassionally been employed as tenders for submarines, PT boats, and patrol aircraft. An additional temporary deck is often built over the wells, making them useful carriers of heavy deck cargo.

WHALE FACTORIES-Easily altered to serve as tankers and bulk carriers, these hughe vessels are also believed to be used by the Japanese as tenders for PT boats, midget subs, and landing craft, as well as aircraft transports and tenders.

FISHING CRAFT- Trawlers, drifters, whalers, and other fishingg craft, mine sweepers, AA ships, plane rescue craft, or coastal transports.

Many smaller modern merchantmen have been equipped for convoy-escort, patrol and minesweeping detail, or to serve as mother ships to fleets of small mine sweepers.

| A | Anti-Aircraft Ship (Old Freighter | E | Patrol and Escort Craft (Trawler) |

| B | Attack Cargo Ship (Modern Cargo Type) or Aircraft | F | Supply Ship and Tender (Tanker) |

| Transport | |||

| C | Tenders and Repair Ship (Modern Cargo Type) | G | Supply Ship and Tender (Whale Factory) |

| D | "Sperrbrecher" Blockade Runner and Raider (Fruit Ship) | H | Patrol Craft (Whale Killer) |

13

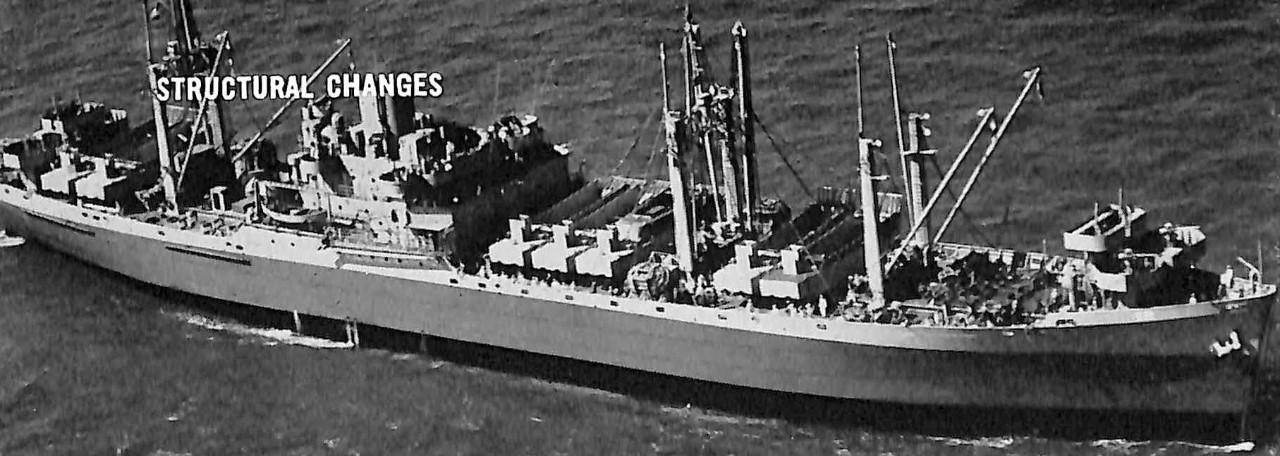

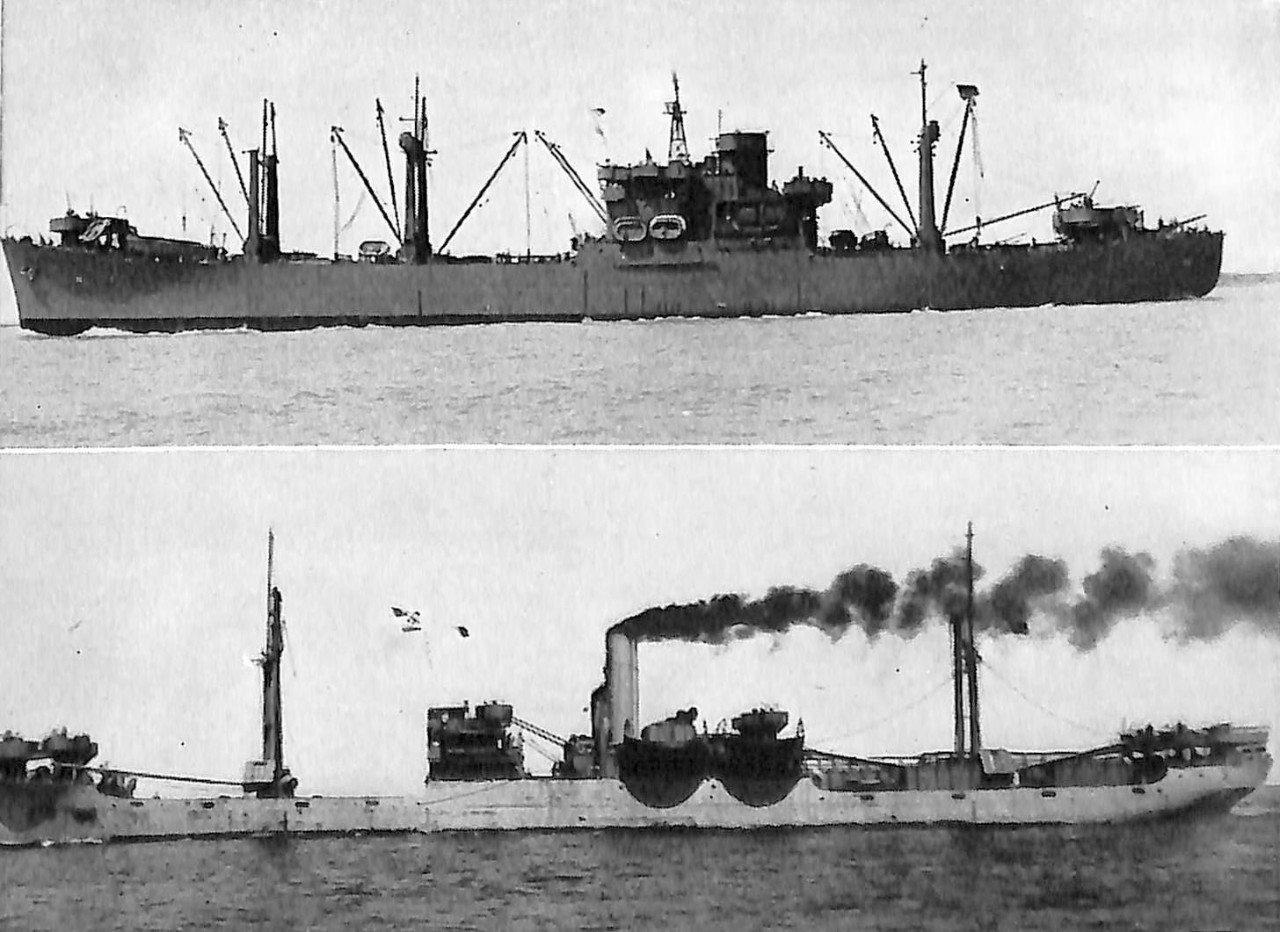

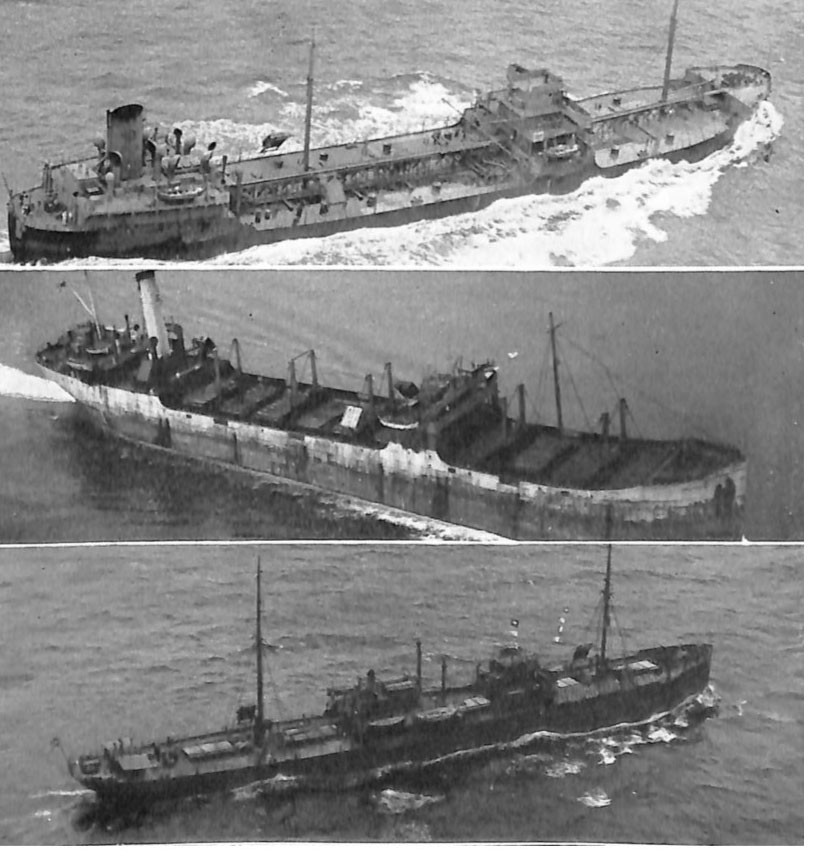

The appearance of most merchant ships has been altered as a result of conversion to military use. A typical Unite States Navy merchant auxiliary is illustrated above. Notice the prominent gun platforms fore and aft; landing craft as deck cargo, alterations to and elimination of king posts, stripped superstructure and lowered stacks. These changes are typical of wartime conversions.

The following changes are commonly mad e in merchantmen when converted to wartime use.

1. ARMAMENT.-Usually limited to the addition of gun platforms on forecastle and poop and of machine gun positions on superstructure.

2. SUPERSTRUCTURE.-Minor alterations occur in order to clear fields of fire and to facilitate handling of life rafts and landing craft.

3. DECK CARGO.-All types of ships during wartime carry a maximum of deck cargo, which of ten radically alters their appearance.

4. STACKS.-Usually cu t down; dummy funnels are removed from two- or three-stackers.

5. RIGGING, MASTS, K1NGPOSTS.-Rigging is stripped to essentials, masts reduced, and king-posts frequently eliminated. Tall antenna masts are occasionally added to kingposts or set up on the superstructure.

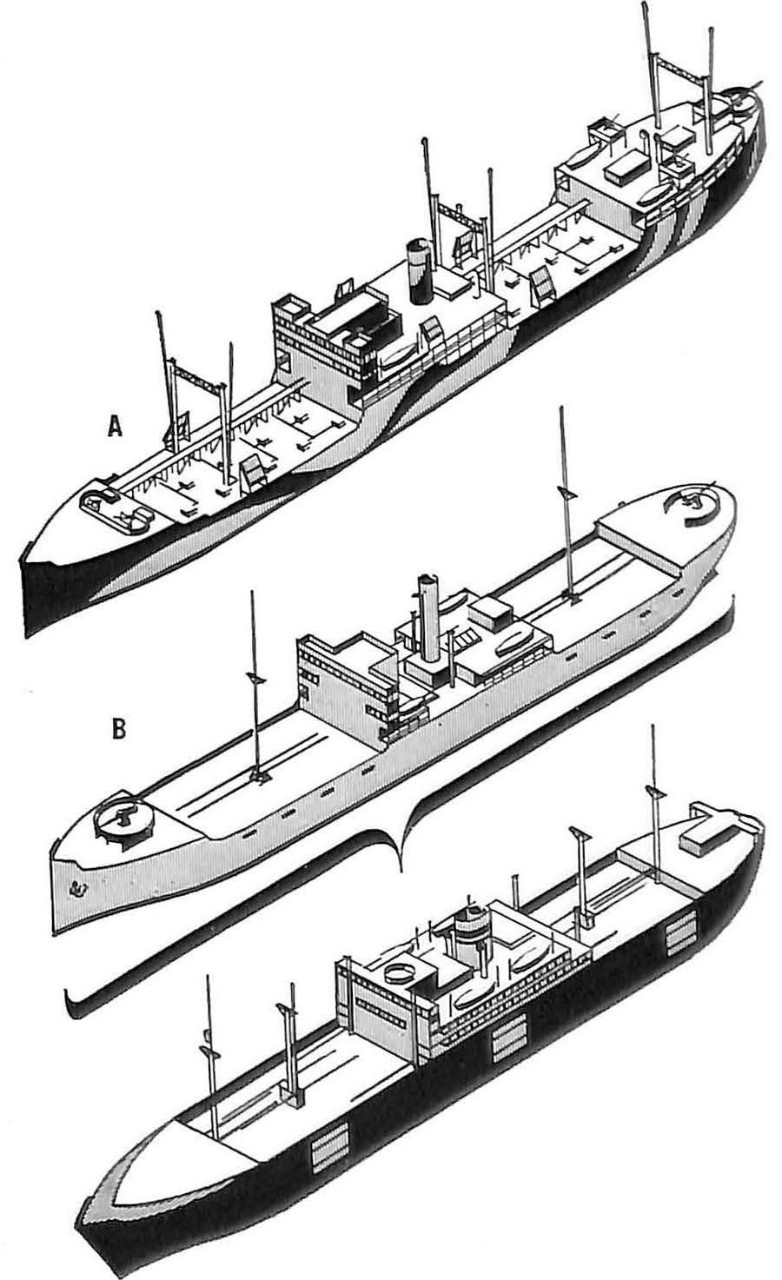

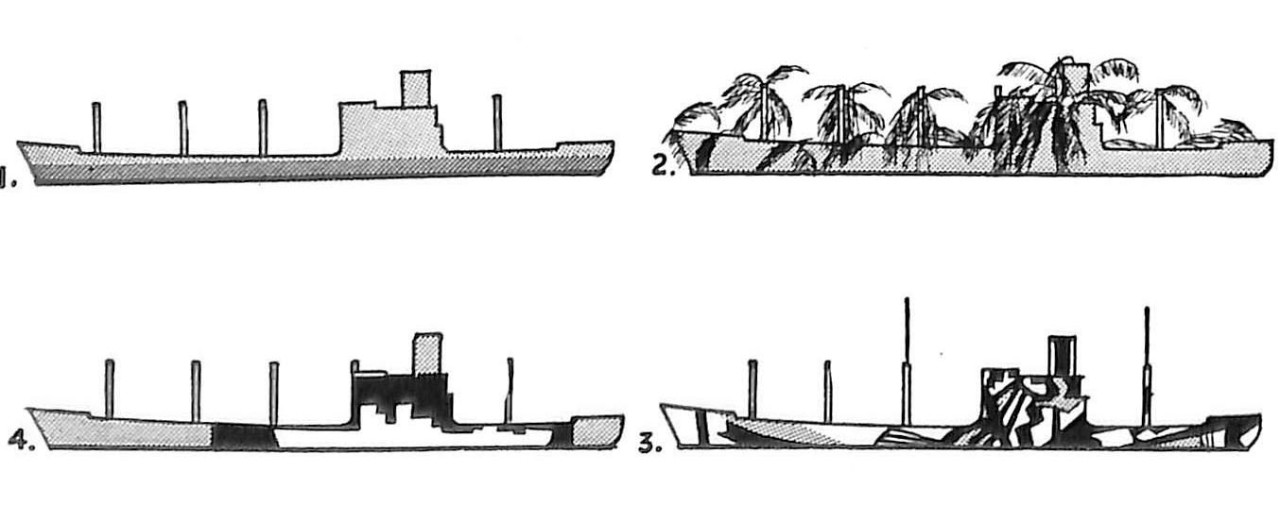

The length to which structural camouflage can be carried is illustrated in the two merchant ships at the right.

(A) A tanker, a primary target for submarines, now masquerades as an ordinary engines-amid ships cargo ship. The midships island has been built up, dummy stacks and kingposts installed and other minor changes made.

(B) An old tramp may pose as a modern freighter by clever use of wood, canvas, plating, and paint. Funnels, kingposts, and vents are easily created from plates, piping, or oil drums. Bows, sterns, and islands are altered in character by use of the same materials. Raiders are equipped with large workshops for this purpose.

14

1. Up to the time of writing, most allied and Japanese merchantmen have been painted gray. Camouflage is often used for naval auxiliaries by both sides.

2. Dazzle camouflage frequently appears on German, Japanese, British, and Italian mer chantmen.

3. For inshore work, the Japanese sometimes cover their vessels with palms or boughs, or paint them to resemble rocks.

4. A ship silhouette is sometimes painted on a vessel's side, to confuse range.

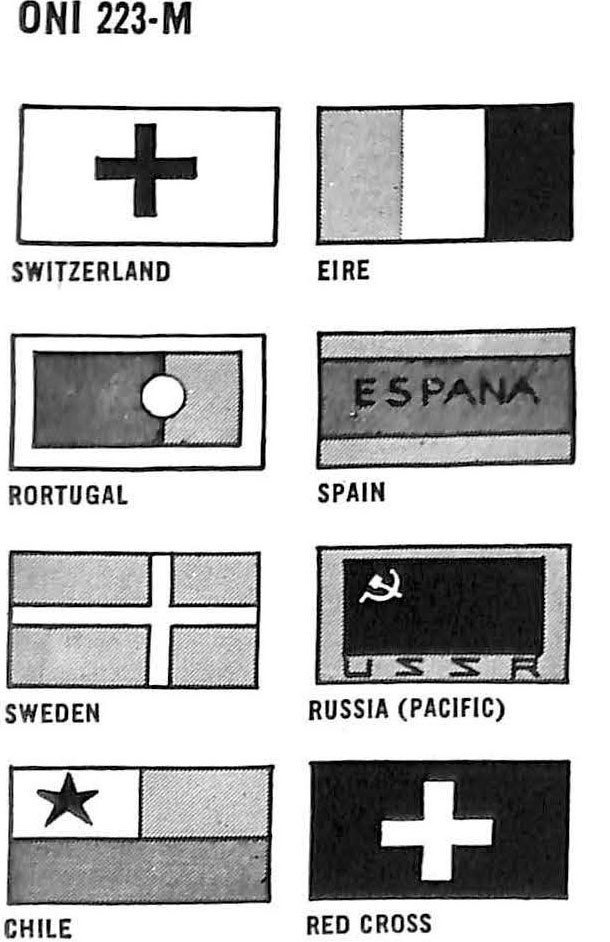

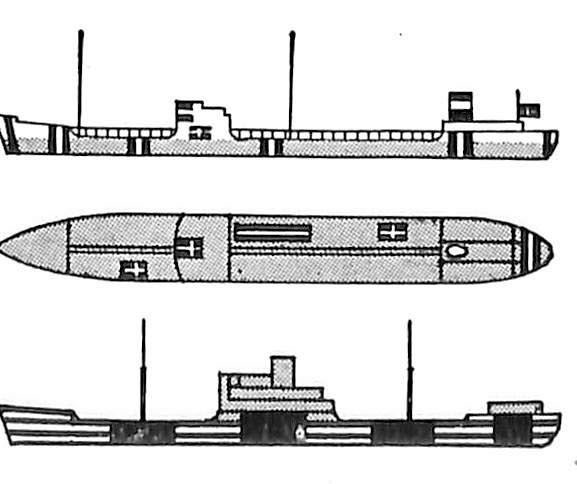

SAFE CONDUCT VESSELS-International agree ments guarantee the safe conduct of belligerent or neutral ships serving two functions. These ships are conspicuously painted in accordance with a fixed procedure (see drawings at right).

A. Vessels engaged in repatriation of war prisoners, or in carrying diplomats. Markings: Green hull, with white crosses.

Hospital ships, which are distinguished by white hulls, a green band, red crosses and are illuminated at night.

NEUTRAL MARKINGS-Neutral merchant vessels are required to display their national insignia and name of country on their hulls; these markings may also appear on wooden signs ecrected midships or on the after super-structures.

Some countries such as weden (tanker) and Argentia (freighter), have added even more conspicuous markings.

15

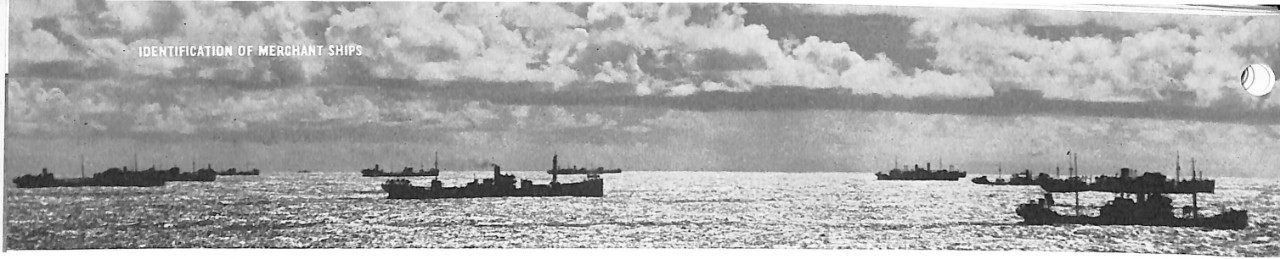

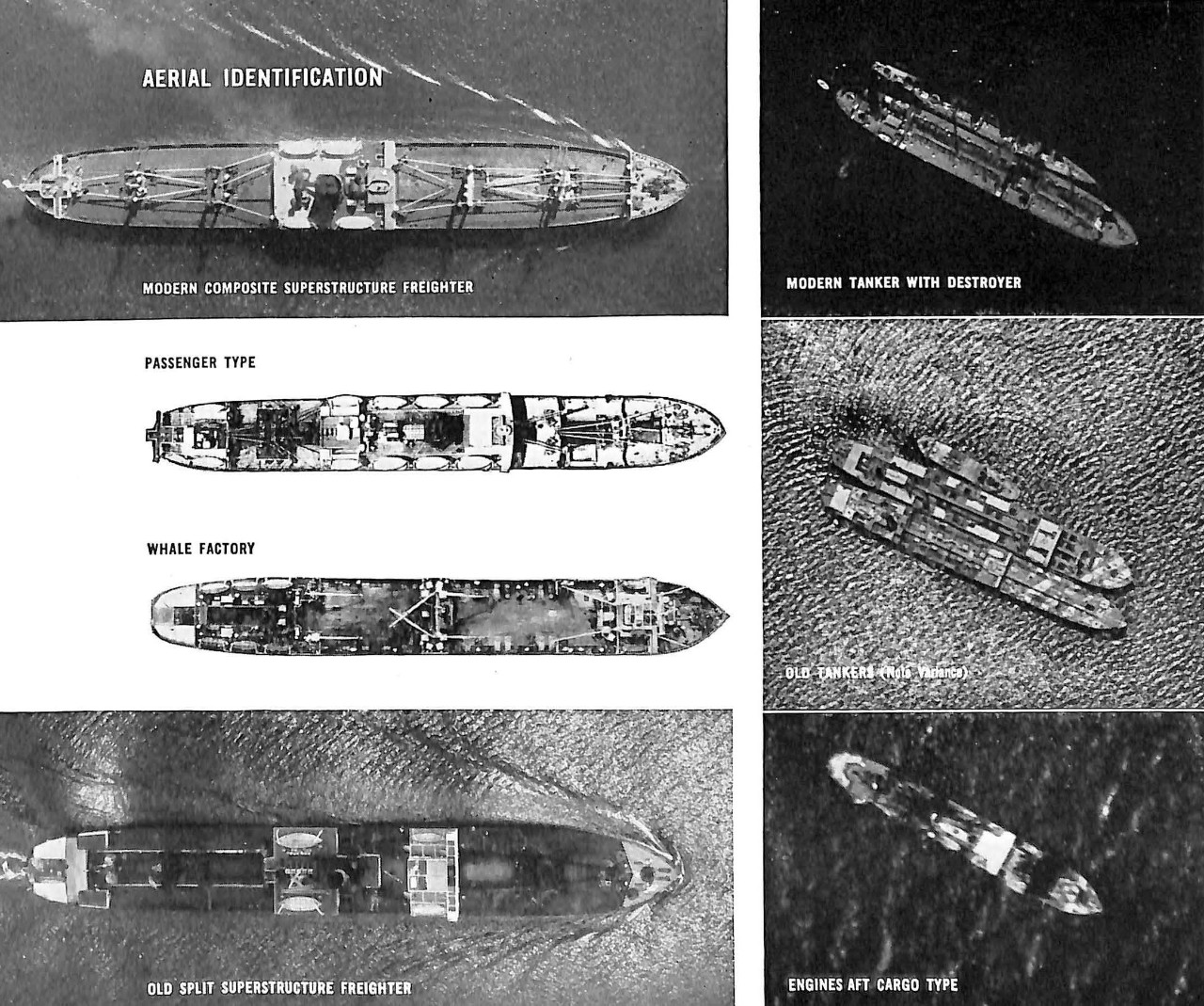

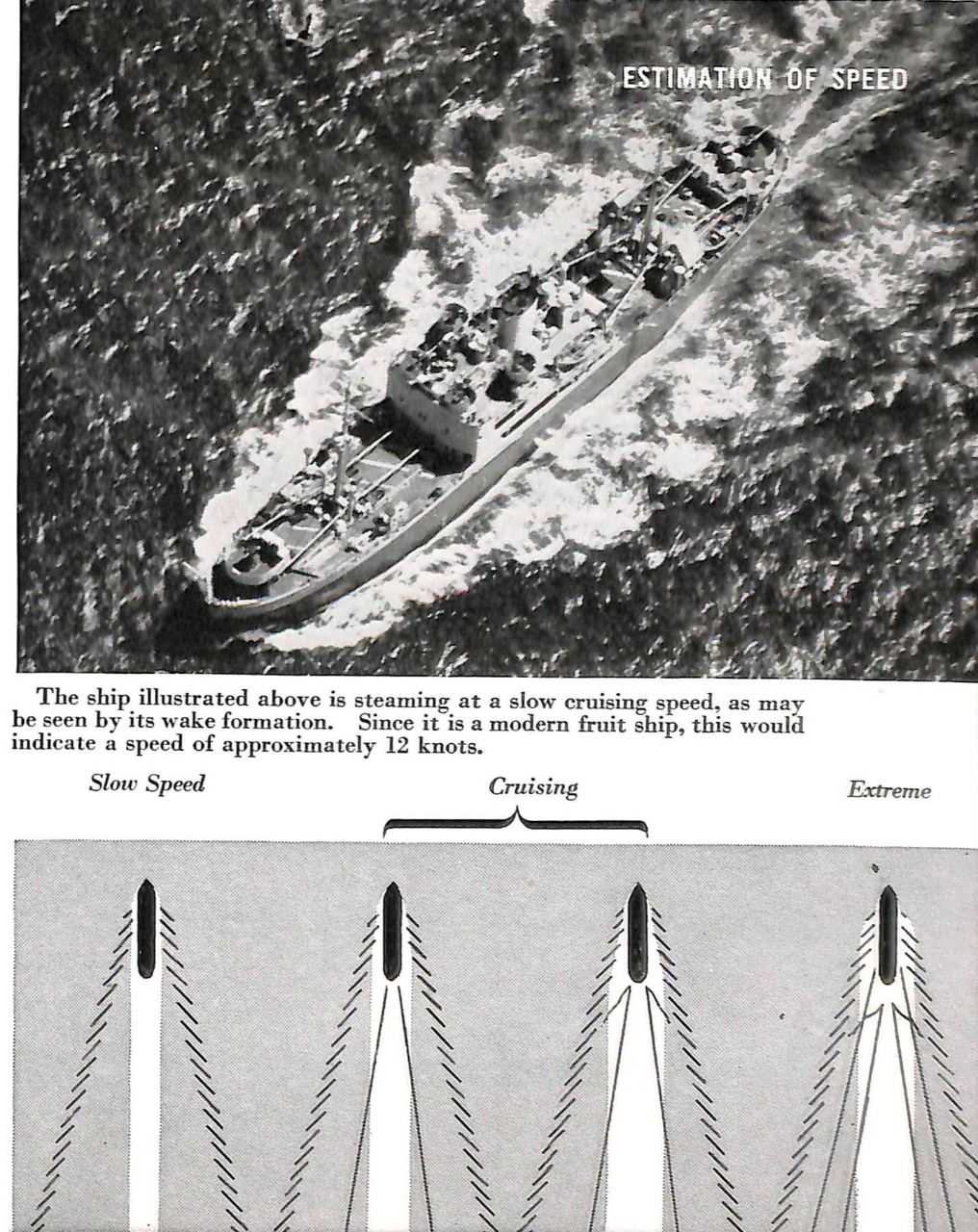

The tendency to overestimate the size of a vessel observed from the air is a common one. This is found to be particularly true of observation from high altitudes.

Hull shape cannot be used in determining size, length, or tonnage of merchant ships, although useful in distinguishing warship types.

A reliable estimate of length may often be obtained through study of structures or installations of a ship observed.

Depend able standards may be applied in estimating the length of merchant vessels through the following factors:

1. Most lifeboats, which are readily visible, are 30 to 35 feet long.

2. Motor launches, usually few in number, are about 50 feet long.

3. Cargo hatches, varying from 18 to 24 feet square, average 20 feet.

4. Life rafts are usually either of the short types, 8 1/2 feet long, or of the long type, 18 feet over-all.

16

17

DESIGN TRENDS

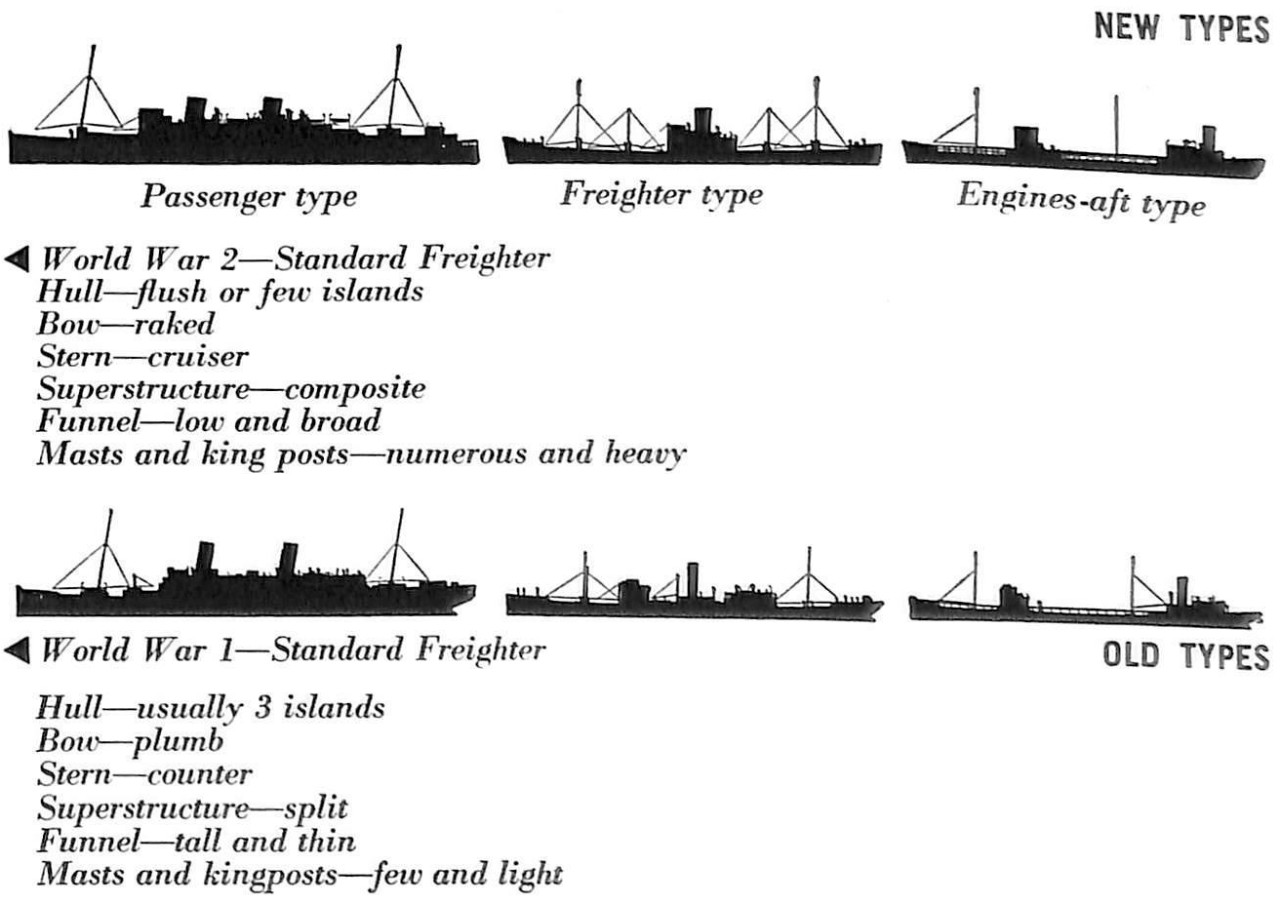

An understanding of general trends in merchant-ship design will help the observer in determining a ship’s age. It is possible to form a reasonably accurate estimate of the actual speed of which a ship is capable if her building date can be approximated.

For reporting purposes, it is only necessary to distinguish between new and old types. The marked differences in the design of these two groups are illustrated by accompanying photographs, which show the development of standard freighter design over a period of 25 years.

The differences in design apparent in these two ships are, generally speak ing, common to all types of merchantmen, as may be seen in the silhouettes on this page.

Smoke may also be used as a guide in determining the age of merchant ships. Generally speaking, old ships burn coal, while most mod ern vessels are oil burning. Coal smoke emerges from the funnel in black, billowy clouds, but quickly disperses. Oil burners rarely emit smoke, but when seen it is dense and greasy, and remains in clouds for a long time. A few modern types burn Diesel oil and make no smoke, although small gray puffs of vapor may be seen.

18

ONI 223-M

Determination of a merchant ship's speed will depend largely on a knowledge of its type and age. Once these factors are known, it is a relatively simple atter to estimate a ship's speed within the small range of its capabilities.

The range of cruising speeds of the various merchant-ship types is summarized below:

SPEED IN KNOTS

| Modern | Old | ||

| Luxury Liner | 21-32 | ||

| PASSENGER TYPES | Others | 16-21 | 12-16 |

| Freighter | 12-14 | 8-11 | |

| ENGINES-AMID SHIPS TYPES | Coaster | 10-12 | 7-9 |

| Tanker | 12-15 | 7-11 | |

| ENGINES-AFT TYPES | Cargo-Carrier | 10-12 | 10-12 |

| Coaster | 10-12 | 7-9 | |

| Whale Factory | 13-15 | 10-12 |

Once the cruising speed of a merchant-ship type has been determined it is possible to estimate its actual speed by a study of the ship's wake and bow-wave formation.

Wake may be described as the swirling, disturbed water trail left by the ships propellers. Under normal conditions the following assumptions can be made:

If the wake length is 2 X ship length = full speed, 1¼ X ship length = cruising, ½ X ship length =slow speed.

By comparing relative speed, such as full or slow, with the known cruising speed of a particular ship, an actual speed figure in knots may be estimated.

Another method based on the study of bow waves and their troughs is shown in the accompanying diagram. It is interesting to note that the leading bow wave always forms constant angle in relation to the ship's course, regardless of speed or hull form.

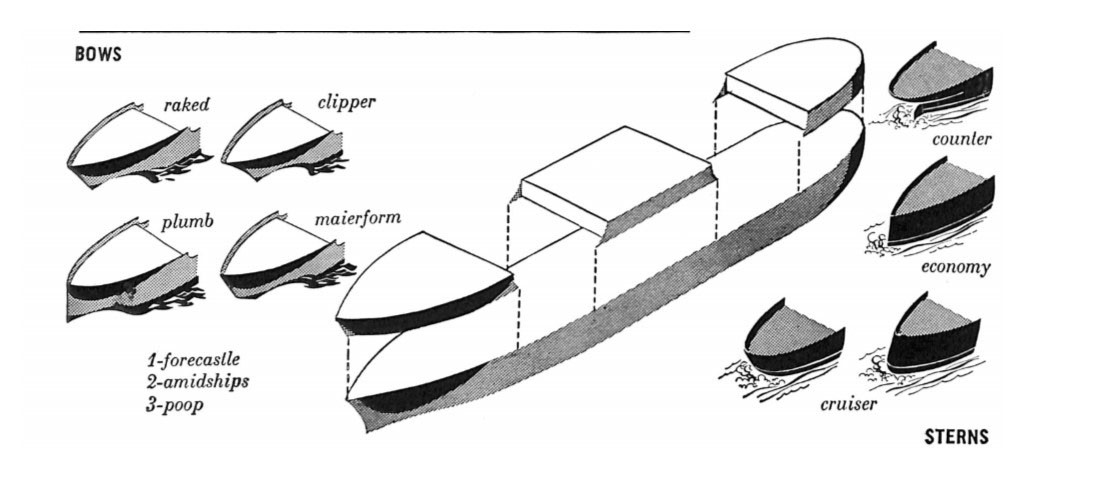

The amount of foam created by a hip's ow is often erroneously taken as an indication of speed. Actually this merely indicates hull design, since plumb bows will always cause more foam disturbance than the streamlined raked or Maierform types.

MERCHANT FLEETS OF THE WORLD

An over-all look at the world's merchant fleets gives sharpened perspective to the distribution of the types whose characteristics have been examined in the foregoing pages. From the standpoint of numbers, the predominant merchant ship type is the freighter. Tankers have assumed a new and fast-growing importance, while the construction of passenger types has naturally fallen off. The relative percentages of these types now operating are illustrated in the accompanying chart.

The commercial tonnage of the world is divided among the belligerent and neutral nations as shown. In the section that follows, standard types developed by individual powers are shown separately. Each profile, therefore, represents a large class of identical or similar ships.

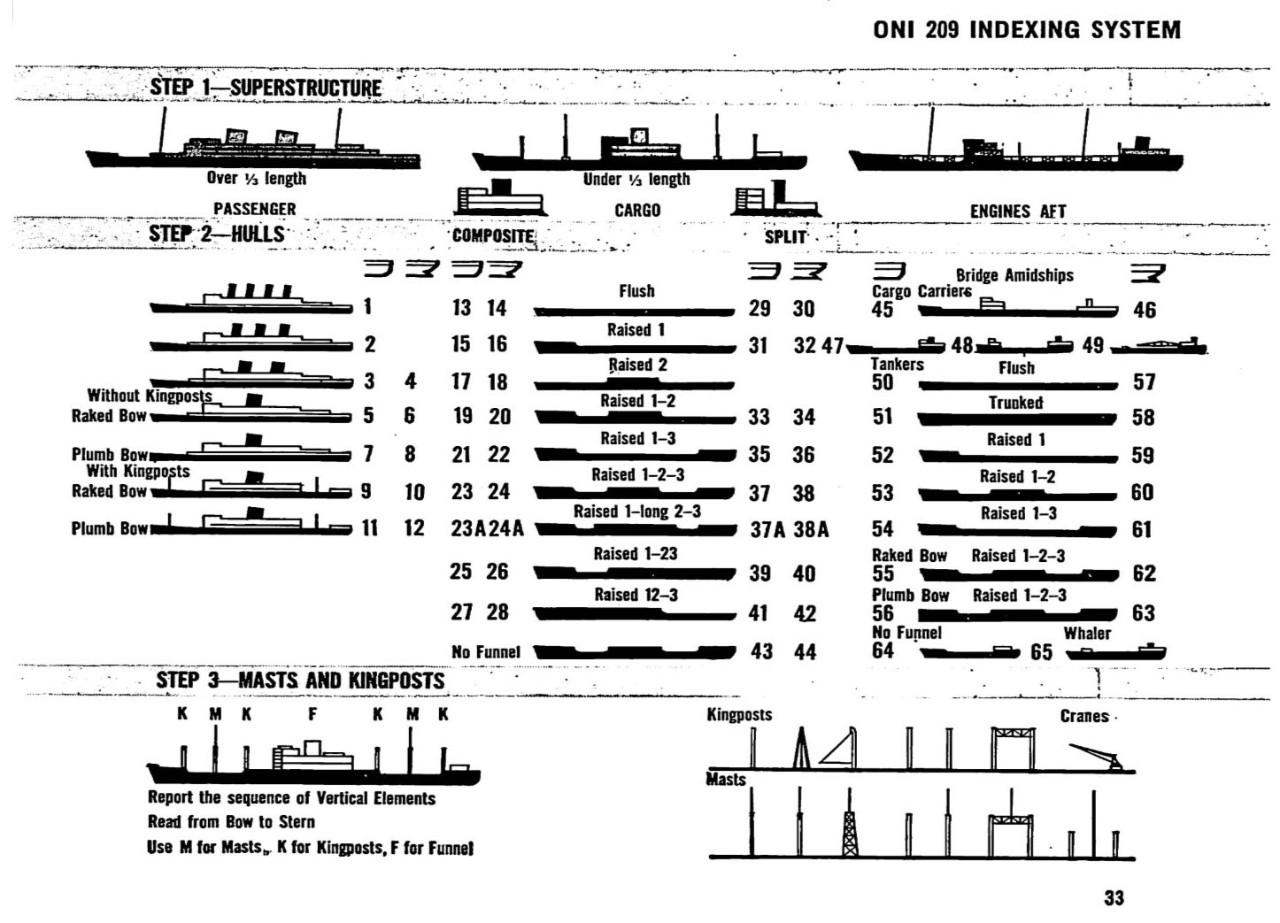

Unlike warships, merchantmen lack peculiar appearance characteristics which will serve to establish nationality. This has made necessary the development of a system of type classification without regard to nationality, which forms the basis for methods of descriptive reporting. The method used indexing ONI 209, A Manual of Merchant Ships, is briefly explained and illustrated on page 33. The most common standard national types of merchant ships, shown in the following pages, are accompanied by their type designations and by "coded" description based on this method.

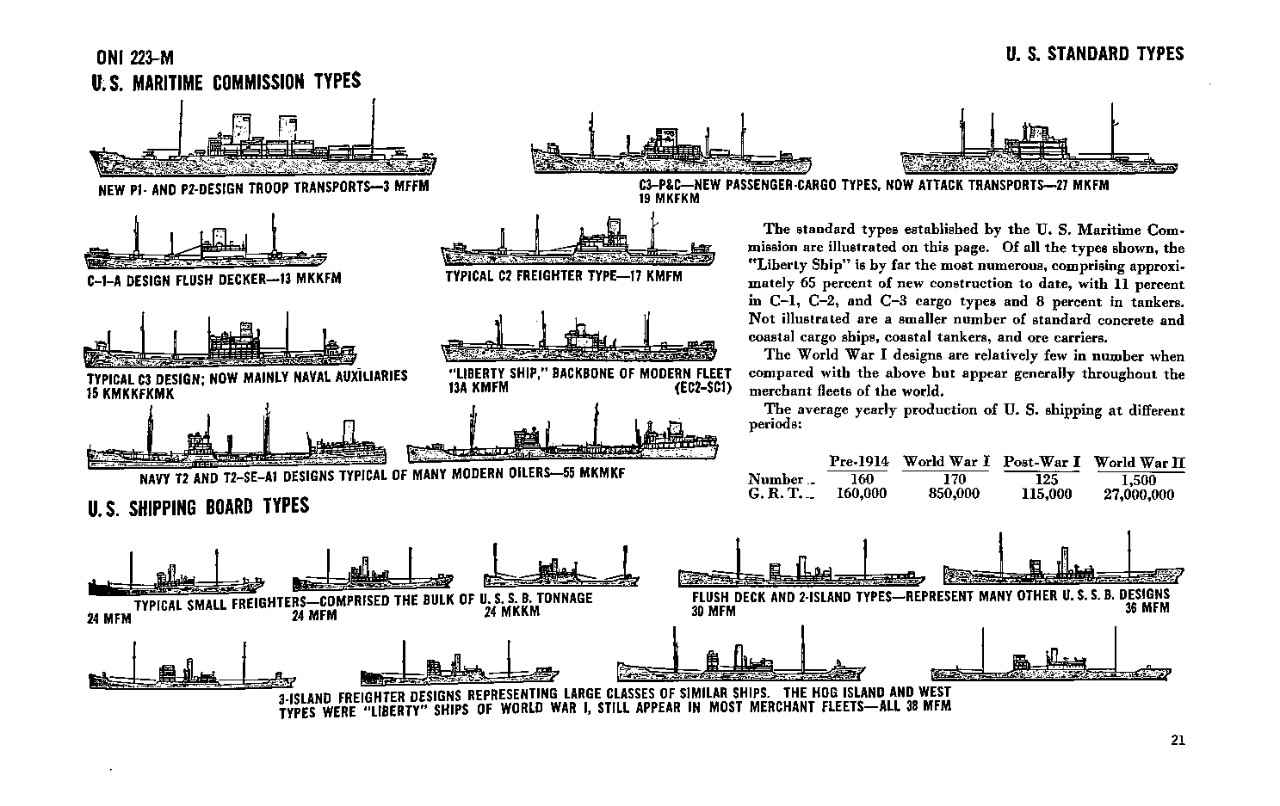

UNITED STATES

The First World War demonstrated the capacity of United States shipyards to develop mass production of merchant ships: Construction lagged after the Armistice of 1918. Not until 1936, when the United States Maritime Commission was set up to establish a Government-subsidized building program, was shipbuilding revitalized.

The result of the planning that went inot pre-World War II shipbuilding prgram is the staggering production in this, our third year as an active belligerent. After providing 20 million dead-weight tons for ourselves and our allies in 1943, American shipyards were geared to produce more shipping during 1944 than was produced in all the world in 1943.

A similiar program was undertaken durint the First World War under the United Slates, Shipping Board. Many standard types were constructed inAmerican Canadian, and Japanese shipyards, under a coordinated schedule which carried on until 1923. During the ensuing years these ships were sold and exxhanged so that today they are found in almost every maritime service, particularly in the Japanese and Russian merchant fleets.

20

ONI 223-M

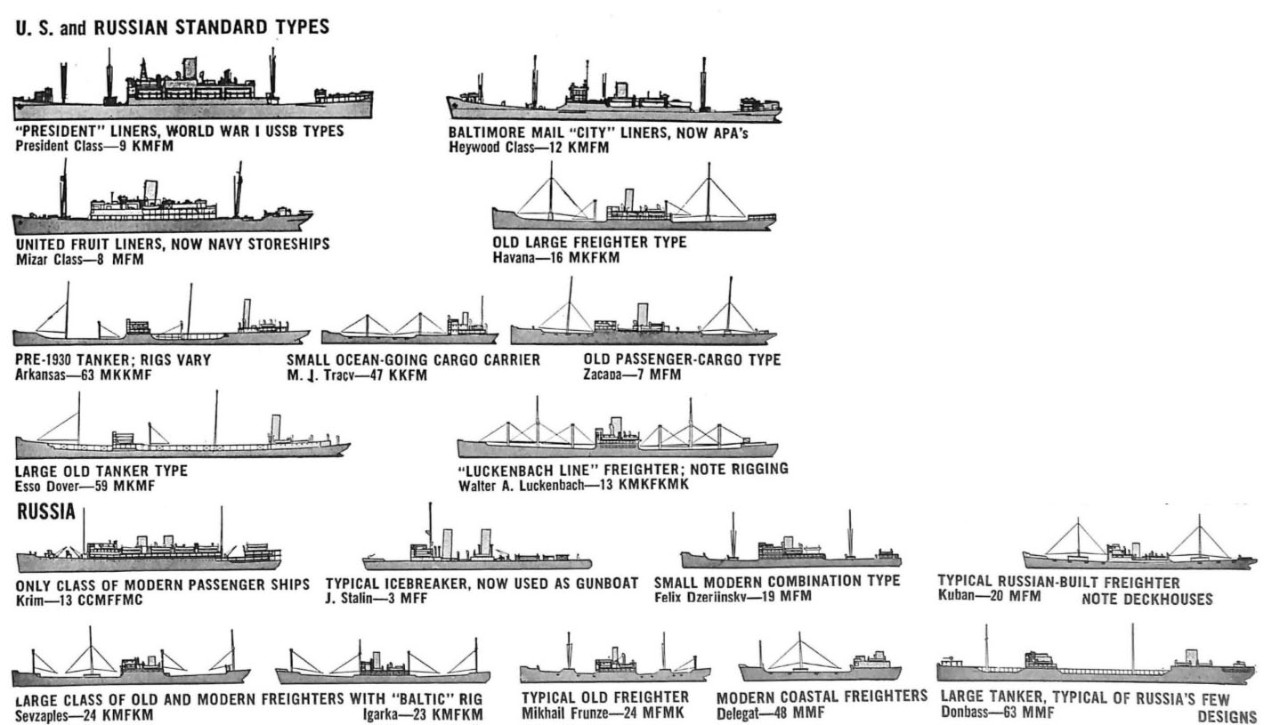

RUSSIAN AND U.S.

Many large classes of ships were completed in American yards during the period between the two war-time emergency building programs. The most representative types are shown on this page.

Before World War II, Russia had a comparatively small merchant fleet. Through Lend-Lease aid, the Russian merchant marine has increased greatly, particularly in the Pacific. Over one-half of Russian tonnage is foreign0built, and a large percentage consists of United States Shipping Board vessels, survivors of the World War I building program.

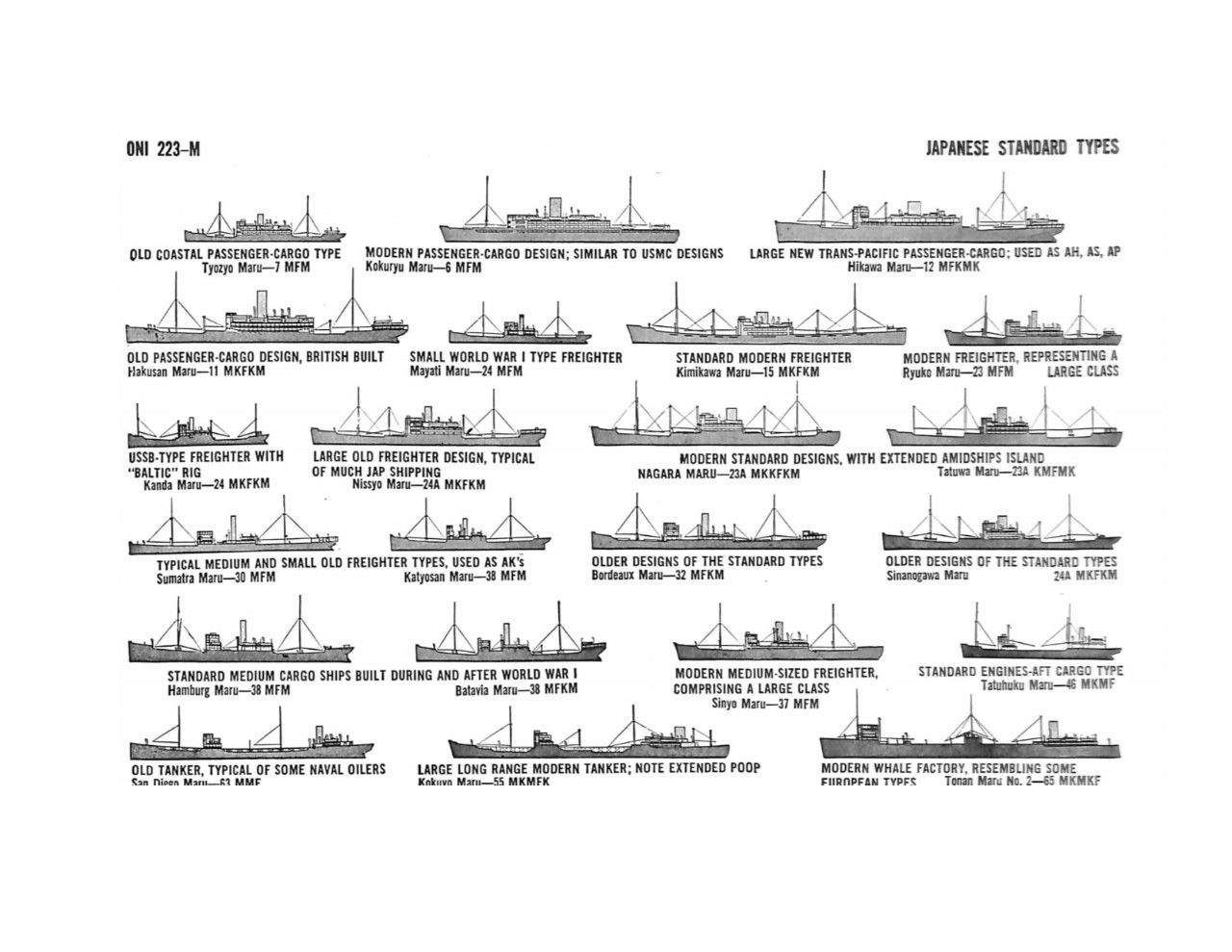

JAPANESE

The Japanese merchant fleet began to develop at the turnof the century when many British-built shis were acquired. During World War I, aid was given tt heir yard's under the United States Shipping Board program. Enlarging on these designs during the twenties, the Japanese developed a large trans-Pacific fleet. In the early thirties a new and vast fleet of fast modern freighters, tankers, and passenger-cargo ships was built, setting the tankers for almost all foreign shipping design. Emphasis is now places on smaller freighters and tankers.

A higher percentage of newer ships exists under Japanese registry than under the flag of any other major maritime nation. Age of ships as of 1939:

Under 5 years, 37%; 5-20 years, 23%; over 20 years, 40%.

22

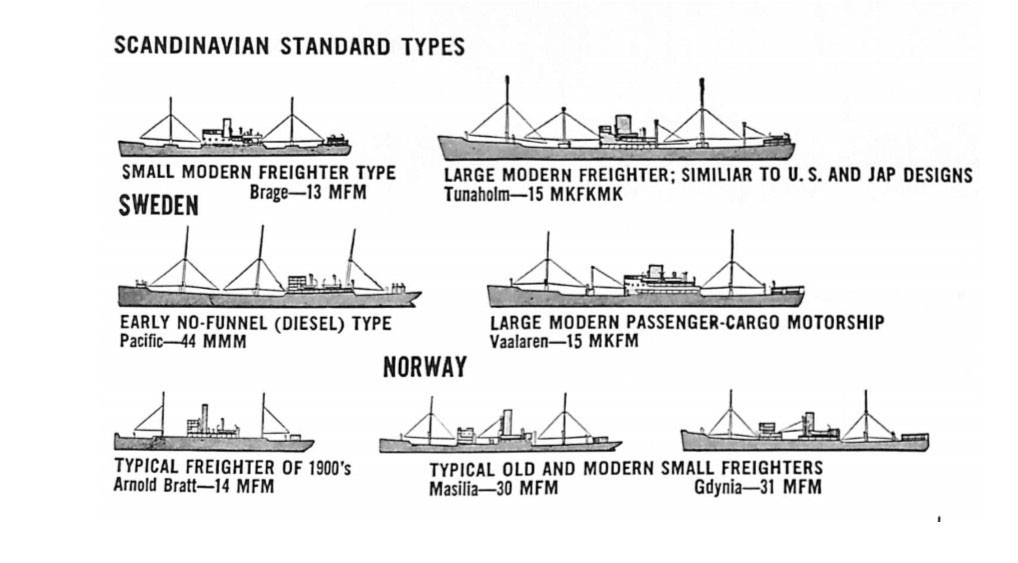

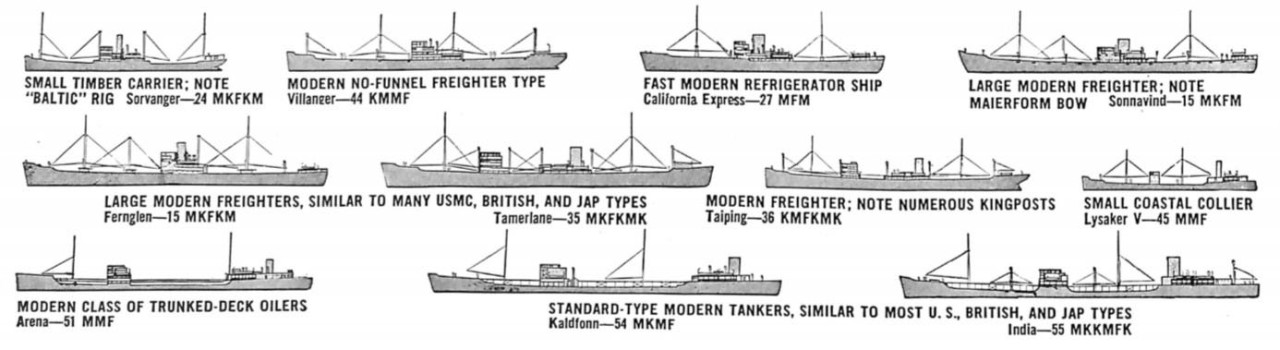

NORWEGIAN

Sweden and Norway have for many years maintained large merchant fleets. The Norwegian merchant marine alone exceeds al other countries except Great Britain in total shipping tonnage in operation. A great majority of rhese vessels are serving the allied cause. Sweden's shipbuilding program, which had been small, is now increasingly active.

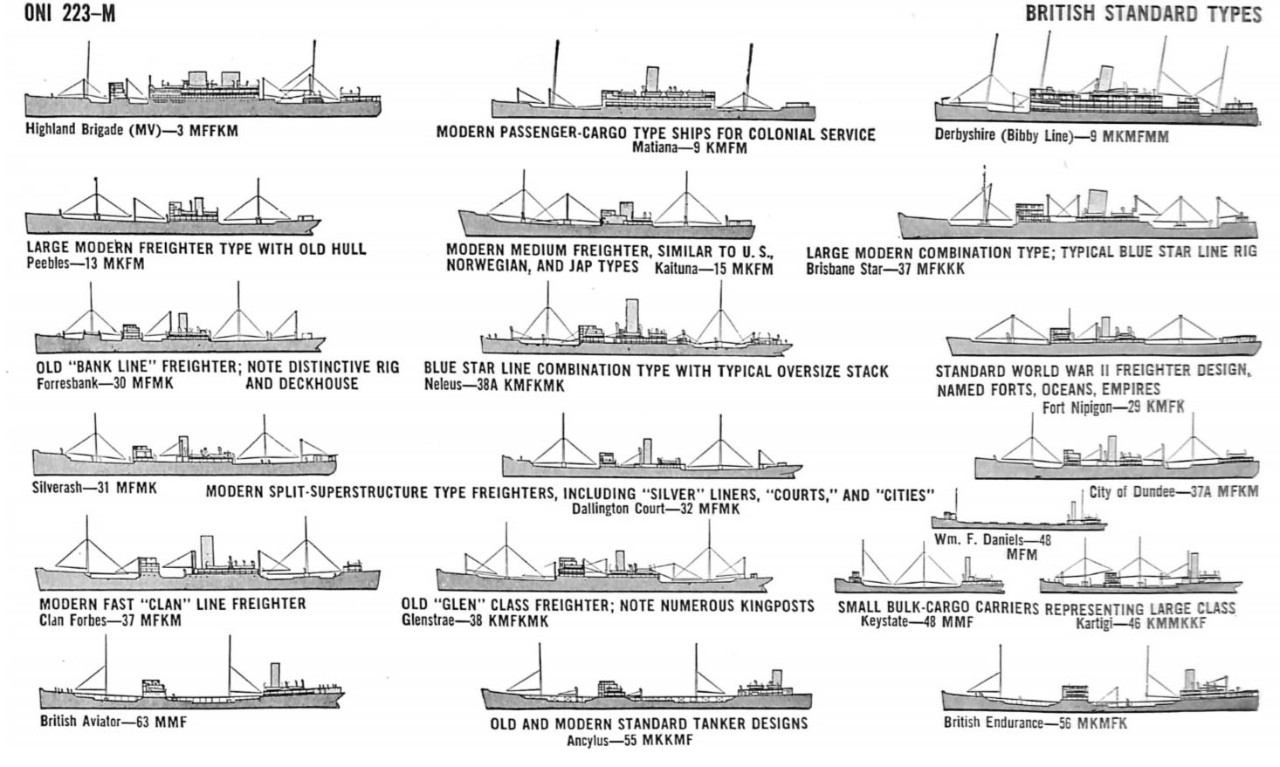

BRITISH

The British merchant marine has for centuries been the largest and the most progressive in the world. British shipyards not only built practically all the Empire's own bottoms, but have supplied a large proportion of the units of other merchant fleets.

Recently, British shipbuilders have joined the United States Maritime Commission in a joint policy of standardizing designs to speed up production. The result has been the launching of great quantities of standard British-designed freighters and tankers.

Age of the British mercantile navy in 1939:

Under 5 years, 25%; 5-20 years, 30%; over 20 yeras, 45%.

24

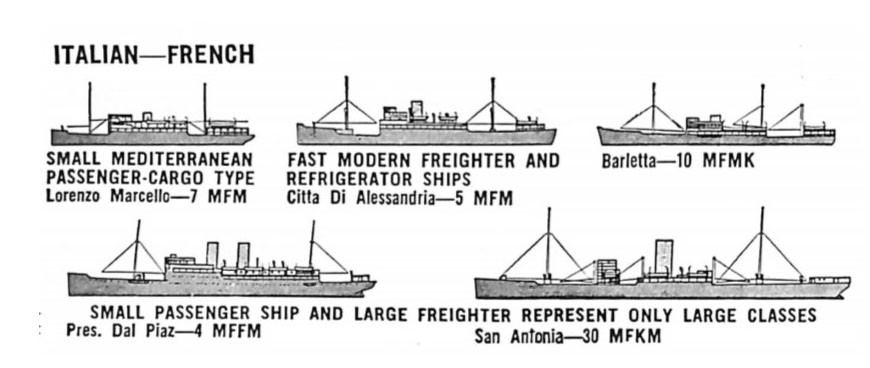

ITALIAN, FRENCH, GERMAN, STANDARD TYPES

ITALIAN AND FRENCH

Except for trans-Atlantic luxury liners, such as the Rex and the Normandie, the merchant fleets of these European nations had been of minor importance. The work horses of their fleets-the freighters and tankers were few in number, and are now largely in the hand s of the Germans.

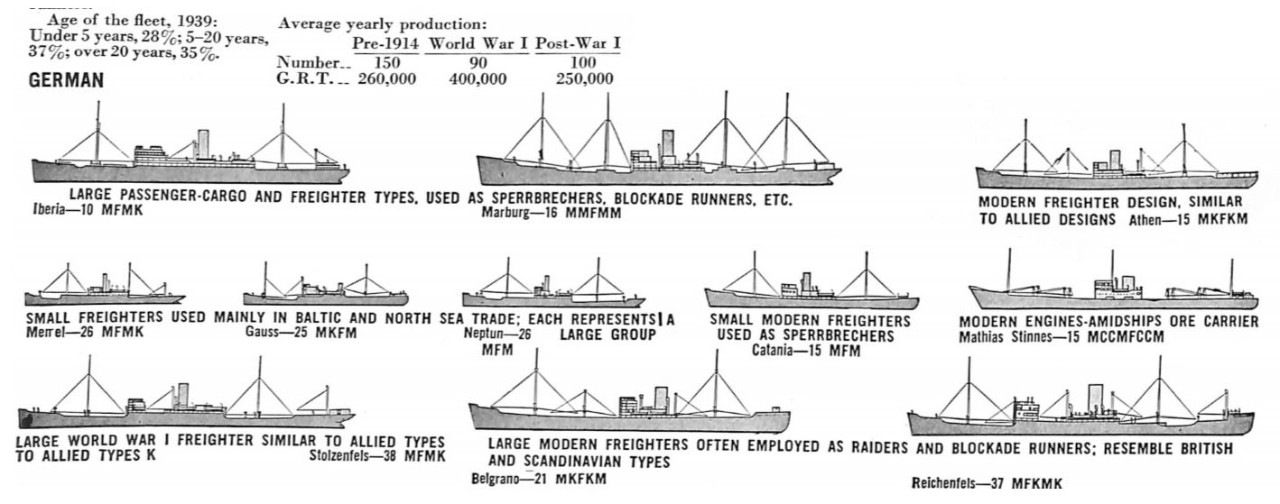

GERMAN

German shipbuilding, while it has been second in tonnage to that of Great Britain, has averaged only one-third to one-fourth of the yearly British total, and recently has been cut back sharply. Her own fleet, together with seizures, is being employed in coastwise trade, with some of the newest and fastest merchantmen detailed as raiders and blockade runners.

26

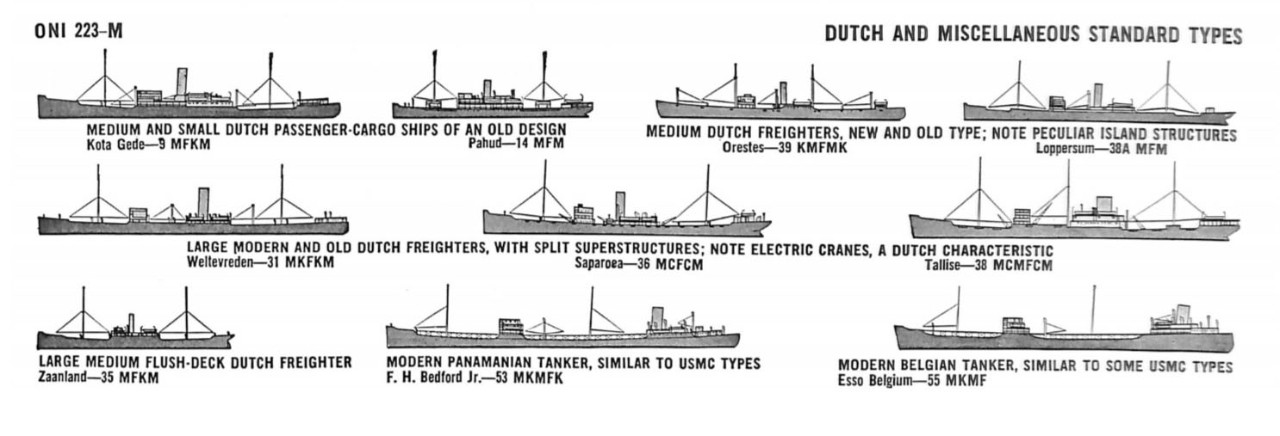

THE NETHERLANDS

Until their conquest by the Nazis, the Dutch despite the smallness of their homeland, were able to control one of the world's great colonial empires. The size strength, and efficiency of their merchant navy constituted a vital factor in Dutch economy.

Age of Dutch merchant fleet, 1939:

Under 5 years, 30%; 5-20 years, 36%;over 20 years, 34%.

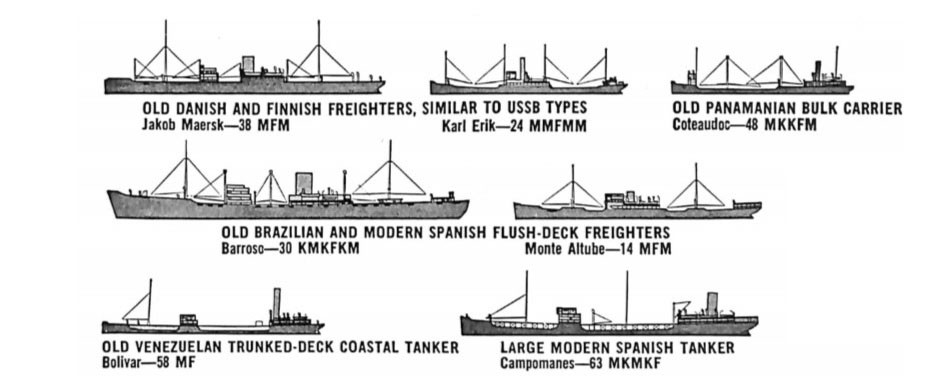

MINOR MARITIME NATIONS

Practically every country with a seacoast has a merchant fleet however small. Some of these lesser maritime countries, such as Panama, Belgium, Denmark , Finland, Brazil, Venezuela, and Spain are represented here. These nations and others, such as Greece, Ireland, Yugoslavia, Portugal, and China usually purchase their ships, which are frequently discards. Lend-lease, however, has come to the aid of some fleets. as in the case of Greece and China.

Average yearly production:

| Pre-1914 | World War I | Post-War I | |

| Number | 83 | 135 | 70 |

| G.R.T. | 65,000 | 135,000 | 125,000 |

27

ONI 223- M

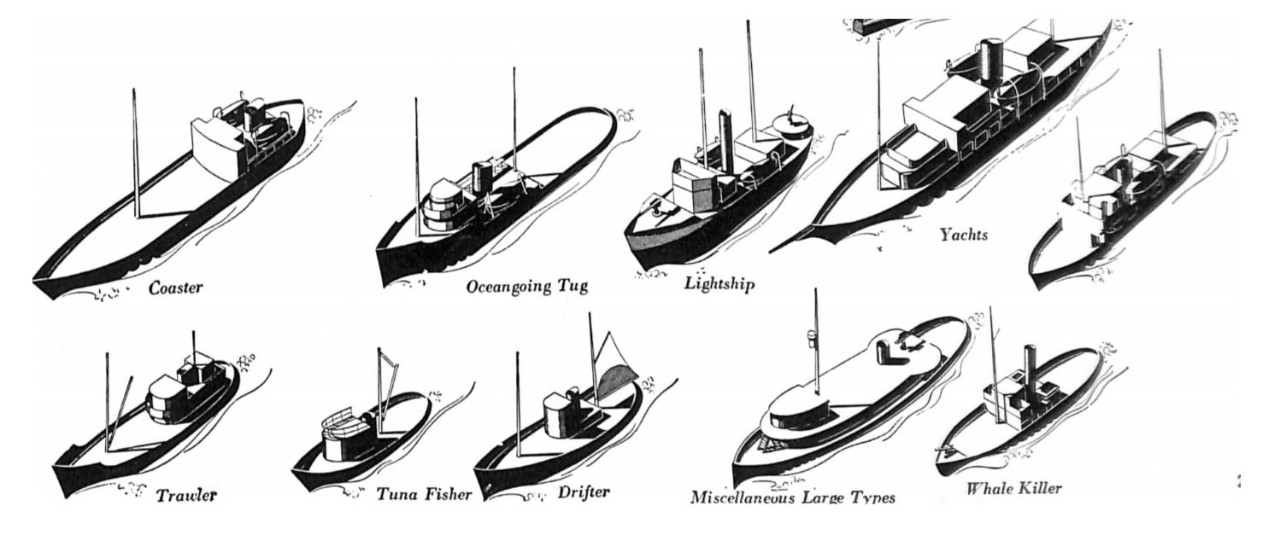

The smaller miscellaneous craft to be found in the vicinity of large ports and bases, en gaged in coastwise and near-seas trade, or scattered on fishing banks, constitute a rather extensive and locally significant group.

Shown on this page is a cross-section of the greatly varied types of fishing craft, which may use either motor or sails, or both, for propulsion.

Many minor types-especially the larger trawlers, coasters and yachts-have been used as emergency naval units. Most conversions of this sort are still being used by the British and Japanese Navies. Although numerous at one time, these vessels are being replaced in our navy by new patrol craft types.

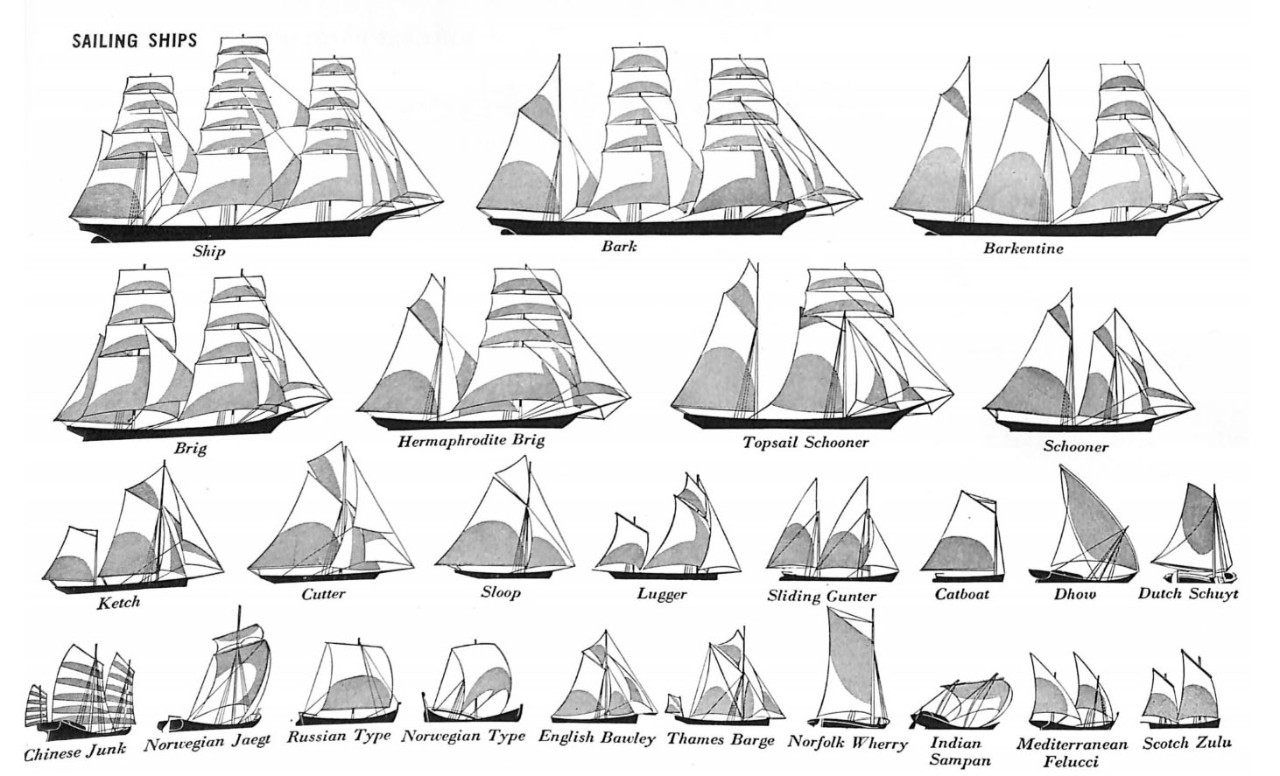

Sailing vessels (opposite page), which not so long ago dominated the high seas, have al most disappeared from some important sea routes, though they may still be seen in abundance in certain waters. Illustrated are the common types seen throughout the world.

29

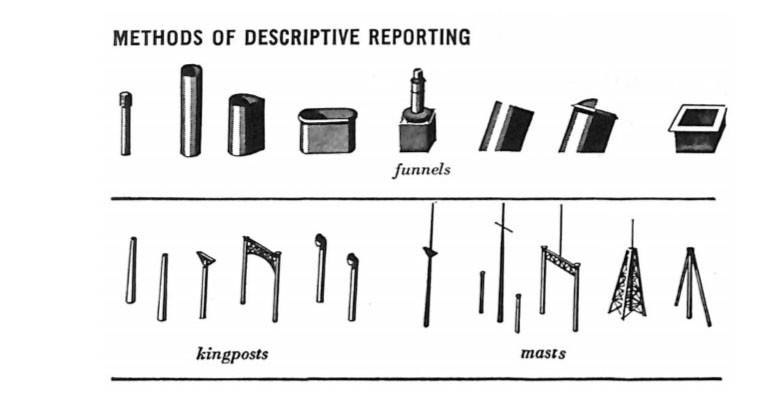

Description of a vessel's appearance by means of a code is a device that has been widely used for reporting and as a basis for the organization of published information. The indexing and arrangement of ONI standard merchant ship manuals is based on groupings of ships which share certain appearance characteristics.

Several other activities have developed methods of identification or descriptive reporting, which, in some instances, closely parallel the system devised by the Division of Naval Intelligence. Three methods arc in general use by the forces of the United Nations in different areas. As an observer in the field may be called upon to make use of any one of these method s, each is explained in the following pages. Theater commanders may thus com pare the merits of these systems in the light of the requirements of the area in which they operate, and form a conclusion as to which method appears most suited to their needs and duties.

All merchant ship reporting systems are based on the appearance and arrangement of elements of ship design discussed in general throughout the foregoing. Many of these systems, however, involve descriptive reporting of these elements in considerable detail. Of these factors, those which are necessary for the various coding systems outlined in the following pages are shown at the left. They may he studied in their many combinations through reference to the illustrations in other sections of the book.

30

ONI 223-M

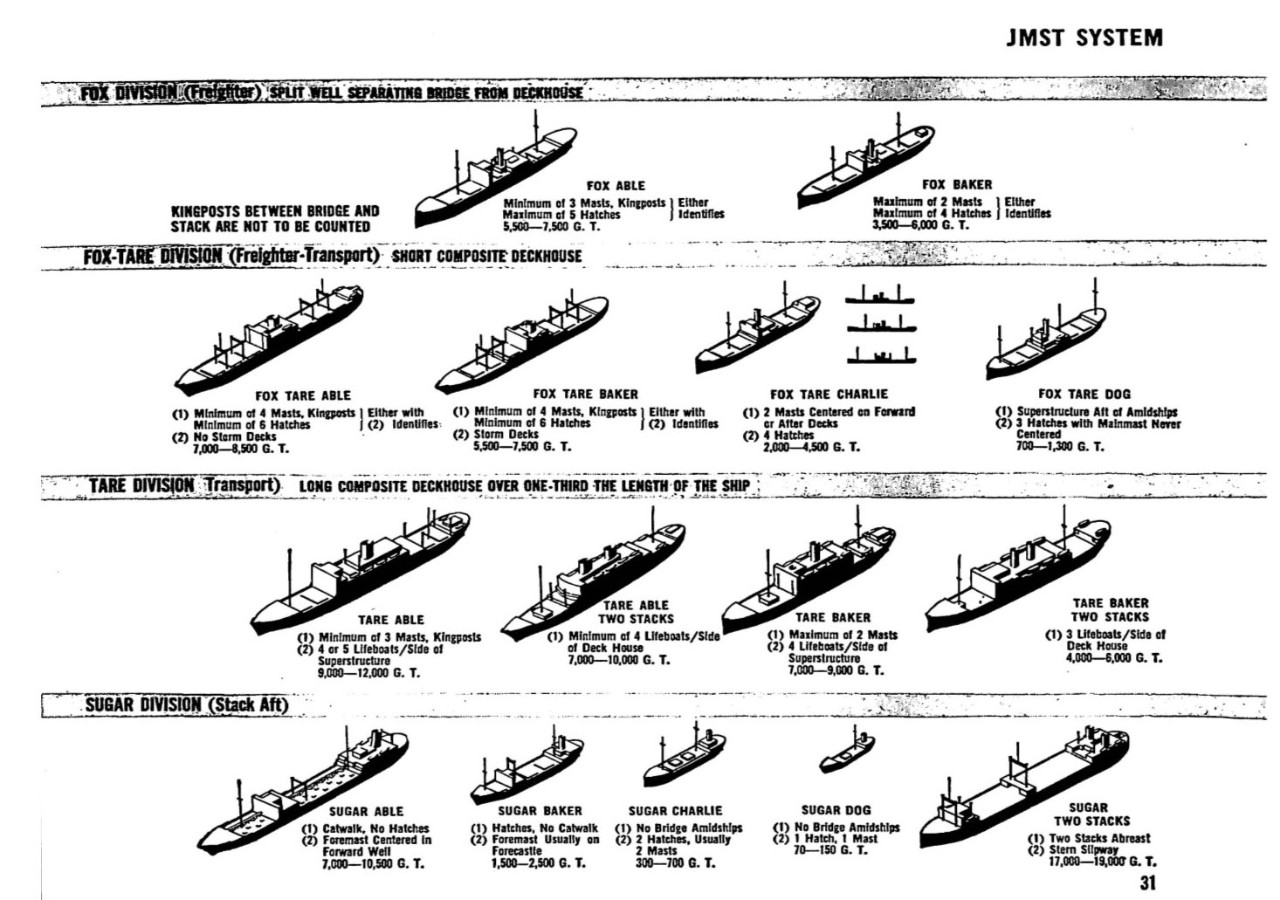

The first and simplest method is represented by JMST (Japanese Merchant Shipping Tonnage), developed by Allied Air Forces and Naval Intelligence in S. W. P. A. and now officially used in that theater. As reference to the chart will indicate, this method establishes certain basic appearance factors common to each important group of Japanese merchantmen, and provides the observer with information on the tonnage for individual ships coded designation for the type. This method is, therefore, essentially a means of arriving at certain general conclusions as to the type and size of a ship observed.

It cannot, however, be regarded as a means of effecting identification of a ship, and its general use will be inhibited by the fact that the system has been developed to take advantage of the characteristics of Japanese vessels only.

INSTRUCTIONS FOR USE

On sighting a ship, the following procedure is to be used:

1. Select a similar deckhouse for determination of division.

2. Determine the subdivision.

3. Ship will then be reported with the call signal of the selected subdivision; e.g., one freighter falling within subdivision ABLE will be reported as 1 FOX ABLE.

When details necessary for classification cannot be determined, the ship will be reported as MIKE VICTOR (merchant vessel) with estimate of tonnage. When a ship can be classified as to division, but not to sub- division, it should be reported as, for example, FOX UNCLE, (unidentified, with an estimate of tonnage.

All reports should begin with the number of ships of any type observed. An example would be: 1 FOX BAKER, 5 FOX-TARE CHARLIE, etc.

31

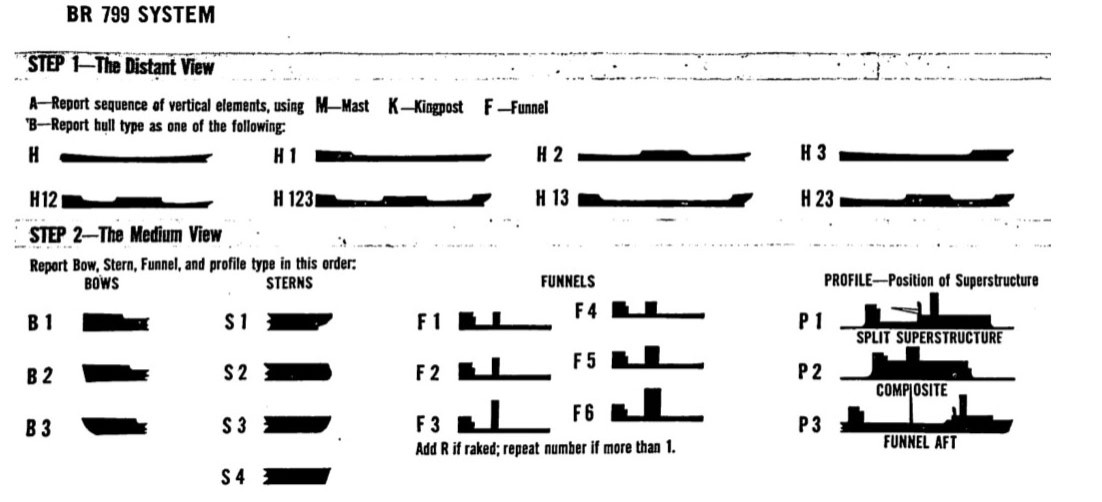

A pamphet issued by the Admiralty (BR 799) serves as a basis for detailed de scriptive reporting of a vessel with a view to positive identification.

The following is a partial reproduction of the text and diagrams promulgated by the Admiralty. This method is officially in use in many parts of the European Theater of operations.

It will be seen that this method, if followed to a conclusion, will in a very accurate statement of a ship's appearance. It has been the subject of criticism on the grounds that the elaborateness of the system imposes an undue burden upon the aerial observer, whose opportunity for detailed observation of hostile vessels may be limited, and whose ability to follow the prescribed sketching procedure may be inhibited by space and the necessity of operating his aircraft. For the use of personnel aboard surface vessels, however, there can be no question that the procedure, if accurately developed will result in a more detailed report of the appearance of an individual vessel than may be reached through any other method in general use.

An example of the application of this system may be shown by the coding of the taker shown in silhouette.

Distant View * 522-MMF-H123

Medium View * B2-S3-F11R-P3-M38-L42-T7

Close View * G-FL01-ML3Qs-AL8Q12-BR3Q5-FU10-FB19-LB8Q10-VT59Q10

All merchant ship reporting by this method is to be preceded by the code letters 522.

All features not indicated must be described in full.

| ST-(Similar to Signal letters) | CD-Cowl on funnel | ME-Motor Engines | ||||

| FL-Forecastle length | SL-Superstructure length | GN-Gun(s) | DC-Deck Cranes(s) | FB-Flyingbridge or catwalk | OF-OilFuel | DV-Davits |

| ML-Midcastle length | PD-Promenade Deck | VT-Ventilation | DB-Docking Bridge | CF-CoalFuel | LB-Lifeboat(s) | |

| AL-Aftercastle length | WD-Well Deck | FU-funnel (if position needed) | SE-Steam Engines | HD-Heavy Derrick9S) | SD-Standing Derrick(s) | |

| BR-Bridge length | DH-Deck House(s) |

32

ONI 223-M

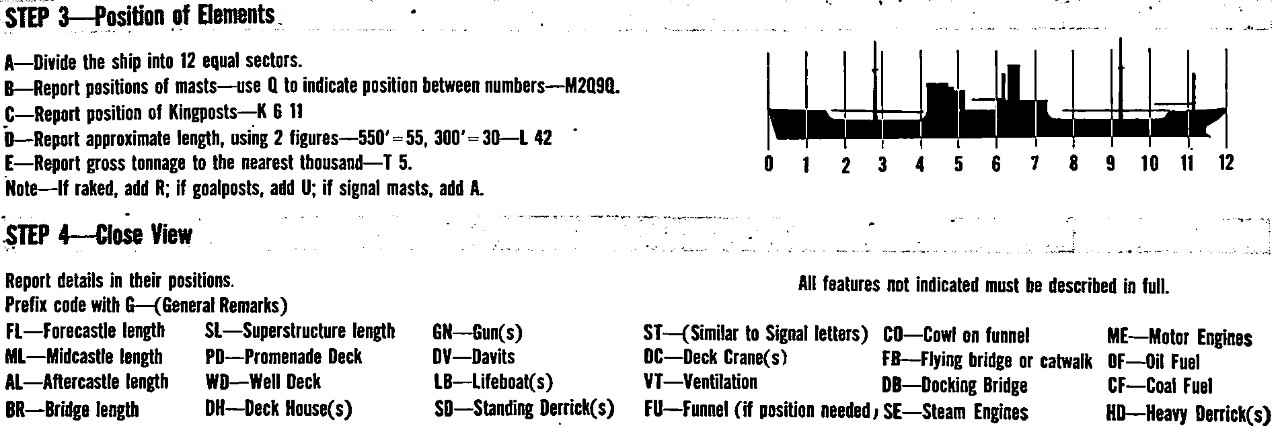

At about the same time that the BR 799 system was promulgated by the Admiralty, the Division of Naval Intelligence completed and gave wide dissemination to the first section of ONI 209 A Manual of Merchant Ships. In this publication the appearance of all known merchantmen is covered by a descriptive "coding" system in which ships are divided into seventy groups based on certain common appearance characteristics. These appearance groups, or types, form the basis for indexing the manual and are further broken down into smaller categories through sequence of masts, funnel kingposts and cranes, and relative length.

The merchant ship shown in profile under STEP 3 will serve as an example to illustrate the coding method used in preparing ONI 209.

Step One - The superstructure is seen to be composite cargo type.

Step Two - Its peculiar three-island hull immediately a 23A or 24A type. The cruiser stern design specifies it as being 23A.

Step Three - The sequence of vertical elements is shown to be, reading bow to stern, KMKFKMK.

Therefore, the completed coded description of this merchant ship is 23A-KMKFKMK. This code, together with an estimate of the ship's length, will identify any ship or class of ships by using ONI 209.

33

PITFALLS IN CODING

The process of descriptive reporting or "coding" outlined on page 33 was designed to facilitate classification of all merchant ships under separate appearance groups.

A great many exceptions and special variations of common practice occur in merchant ship design, and it is important that the more usual of these be recognized in order to avoid miscoding.

Differences between tankers and cargo carriers are often very slight and difficult to distinguish. Differentiation between these groups is important and a few general rules-of-thumb shou,d be kept in mind.

TANKERS generally have catwalks spanning the deck between islands. They carry only a few light masts and kingposts and the only visible hatches are small and few, used for ventilation only.

ENGINES AFT CARGO CARRIERS are designed with large hatches covering most of the main deck. They carry many large, heavy masts and kingposts, which are necessary to handle the bulk cargo.

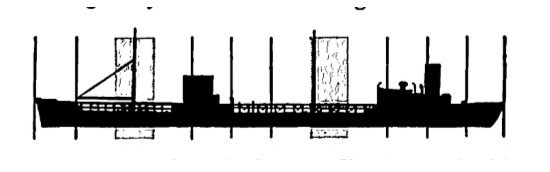

The old no-funnel type freighter shown here might at first glance be regarded as having a raised forecastle and center-island. Closer observation shows that this impression is creared by high bulwarks on a flush hull.

34

ONI 223-M

Despite the flush-bulled appearance created by trunking over the wells between islands, the ship illustrated has a raised forecastle and poop (or "raised 1-3") and should be so reported. The ship is an old split superstructure MKFKM freighter.

This old freighter incorporates an unusual feature. A small well is here introduced into an otherwise flush-deck design, either far forward, or aft as in this case.

Since the well is filled with deck cargo, this ship, seen in profile, might easily appear to be a flush-decker.

Certain variations will tend ro confuse an observer in reporting the vertical elements seen on a ship. In the USMC standard type illustrated, the correct sequential code is KKKFM. The forward kingpost supports a heavy-lift boom and not a mast as does the member located aft. The two light radio masts stepped on the after part of the superstructure are not included in the "coded description", since at distances they would not be visible.

Another example of rhe unusual rigs found in wartime is this standard British "Empire" type. Reading from bow to stern her sequence of vertical elements is MMFKK. The mast appearing in the split is stepped on the port kingpost, which otherwise would not be coded. The paired ventilators abaft the superstructure also serve as kingposts and are therefore coded as such. The bow catapult is used for launching "catafighters" for convoy protection.

35