The Navy Department Library

NAVAL HISTORICAL FOUNDATION PUBLICATION

The Reincarnation of John Paul Jones

The Navy Discovers Its Professional Roots

PDF Version [23.3MB]

Officers of the Foundation

President-------Admiral James L. Holloway III (87)

Directors |

Vice Presidents |

| Admiral G.W. Anderson (87) | Captain E.I. Beach (88) |

| Admiral Arleigh Burke (88) | Captain Victor Delaney (Treasurer)(87) |

| Rear Admiral John D. H. Kane, Jr. (88) | Vice Admiral James H. Doyle, Jr. (Executive V.P.)(87) |

| Admiral William N. Small (89) | Rear Admiral Arthur G. Esch (87) |

| Rear Admiral Elliot B. Strauss (Chairman)(89) | Vice Admiral Charles H. Griffiths (Secretary)(89) |

| Mrs. J.S. Taylor (89) | Vice Admiral Forrest S. Petersen (89) |

| Admiral Jerauld Wright (89) |

Honorary Vice Presidents

Honorable W. Graham Claytor, Jr. (89) |

Admiral J.A. Lyons, Jr. (1) |

| Rear Admiral Ernest M. Eller (89) | Admiral Wesley L. McDonald (89) |

| Admiral S.R. Foley, Jr. (89) | Honroable J.W. Middendorf, II (89) |

| Admiral Thomas B. Hayward (89) | Admiral Thomas H. Moorer (87) |

| Vice Admiral Edwin B. Hooper (89) | Vice Admiral James B. Stockdale (89) |

| General P.X. Kelley USMC (1) | Admiral Harry D. Train II (89) |

| Honorable John T. Koehler (87) | Admiral C.A.H. Trost (1) |

| Admiral Paul A. Yost, Jr. USCG (1) |

Trustees

Captain James T. Alexander (89) |

Vice Admiral J.L. LeBourgeois (89) |

| Captain William H. Alexander (89) | Mr. Robert E. Lee (87) |

| Rear Admiral Herbert H. Anderson (89) | Rear Admiral R.F. Marryott (1) |

| Rear Admiral Thomas E. Bass, III (88) | Rear Admiral Albert R. Marschall (87) |

| Vice Admiral Harold G. Bowen (88) | Vice Admiral William I. Martin (88) |

| Admiral James B. Busey (1) | Vice Admiral Charles S. Minter (88) |

| Vice Admiral Dudley I. Carlson (1) | Dr. William J. Morgan (88) |

| Mr. Calvin H. Cobb, Jr. (87) | Vice Admiral Lloyd M. Mustin (88) |

| Vice Admiral George C. Dyer (88) | Rear Admiral W.T. Piotti, Jr. (1) |

| Mr. William J. Flather, III (87) | Admiral A.M. Pride (88) |

| Rear Admiral T.E. Flynn (1) | Admiral James S. Russell (89) |

| Mr. William H. Gorman (88) | General L.C. Shephard, Jr. USMC (1) |

| Admiral Charles D. Griffin (88) | B/General E.H. Simmons USMC (1) |

| Mr. James V. Holcombe (87) | Rear Admiral Roger E. Spreen (89) |

| Rear Admiral John P. Jones, Jr. (1) | Captain J.K. Taussig (87) |

| Vice Admiral Robert Y. Kaufman (87) | Commander Middleton G.C. Train (87) |

| Lieutenant General V. Krulak, USMC (89) | Rear Admiral Edward K. Walker, Jr. (1) |

| Vice Admiral William P. Lawrence (89) | Vice Admiral J.B. Wilkinson (1) |

The Reincarnation of

John Paul Jones

The Navy Discovers Its

Professional Roots

By

James C. Bradford

Foreword by

William James Morgan

Washington, DC.: Naval Historical Foundation

c1896

Cover Illustration:

An Eighteenth-Century plaster bust of John Paul Jones by Houdon presented to the Naval Historical Foundation by Mrs. George Nichols.

FOREWORD

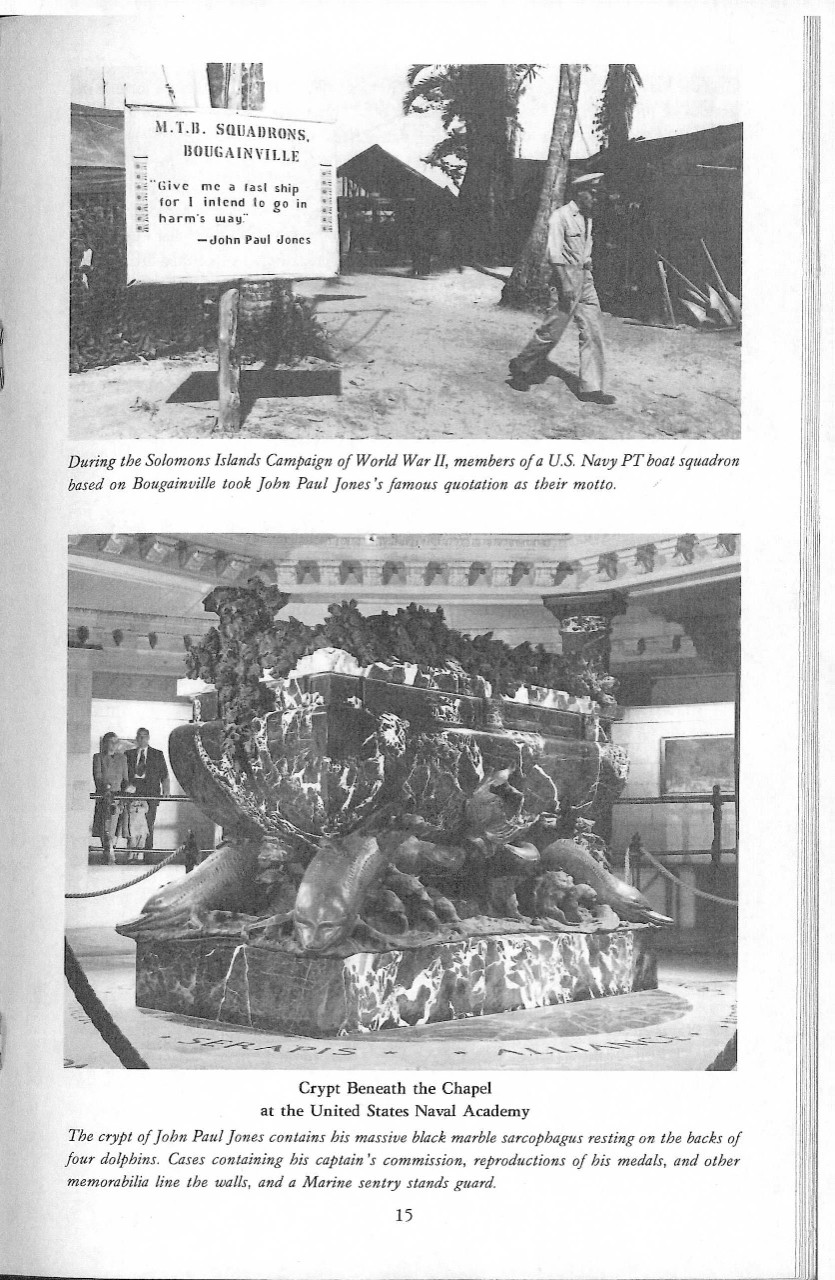

It is firmly held in the minds and hearts of the American people that among those who forged the Navy’s most cherished traditions. John Paul Jones stands in the forefront. His daring and courage as the cannon roared, and his defiant, “ I have not yet begun to fight,” have been chronicled by scores of writers since the early days pf the Republic. Thousands come annually to pay homage to the intrepid sea fighter at his final resting place in a magnificent crypt beneath the Naval Academy Chapel.

Professor Bradford, formerly on the Naval academy faculty, currently teaches history at Texas A&M University and is editor of the Papers of John Paul Jones. In this excellent study, the author does not retell the oft-repeated account of Jones’ heroics and success in battle. Rather he examines in depth the dramatically altered perception and image of John Paul Jones from hat of pirate to the embodiment of wisdom and nobility as portrayed in the literature. Dr. Bradford also provides a scholarly analysis of the impact of Jones and his thinking on naval education, organization and the qualities required in a naval officer---- all essential components of today’s professional U.S Navy.

This well conceived study can be read with profit and pleasure by a wide audience.

WILLIAM JAMES MORGAN

Editor, Naval Documents of the

American Revolution

PREFACE

The study is an outgrowth of a project undertaken in 1979 to collect and edit copies of all extant John Paul Jones papers. Since Jones is one of America’s great heroes, his letters have been avidly sought by collectors and many are no longer accessible to researchers. One way to trace the existence of documents is to consult early biographies whose authors made use of Jones’s letters before they dropped form sight. In doing so I was impressed by the variations in the views of Jones presented by different authors. These inconsistencies do not simply reflect the passage of time, he availability of new source materials, or the development of new perspectives as the discipline of history matured--- though these factors are certainly involved. Equally, if not more important, was the motivation of many authors who, writing with a purpose, sought lessons from Jones’s life or sought to use him to support various programs or to instill certain qualities in their readers. These shifts in characterizing Jones and the uses made of him are the focus of this study. Jones’s image in novels, plays, and even motion pictures could have been addressed but it was determined to limit this study to non-fiction works, or at least to works presented as non-fiction, and to the use made of Jones by the Department of the Navy and some of its branches.

I am indebted to a number of individuals from whose advice this study has benefited. An early version was delivered at a meeting of the Southwestern Social Science Association where fellow panelist K. Jack Baeur of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and the commentary of the discussant, Dean C. Allard, Senior Historian of the Naval Historical Center, both stimulated new lines of thought. Frank Uhlig, Jr., publisher of the Naval War College Review, saved me from errors and Dale T. Knobel and Chester S.L. Dunning, colleagues at Texas A&M University, gave critical readings to a later draft and suggested more felicitous phraseology. It was the idea of Captain David A. Long, Executive Director of the Naval Historical Foundation, to include Augustus C. Buell’s fabricated, but influential “Jones letter” as an appendix. Carole R. Knapp of the Texan A&M Department of History typed the manuscript. To each of these individuals I express my thanks. The flaws which remain are, of course, my own.

JCB

THE REINCARNATION

OF JOHN PAUL JONES

The Navy Discovers Its Professional Roots

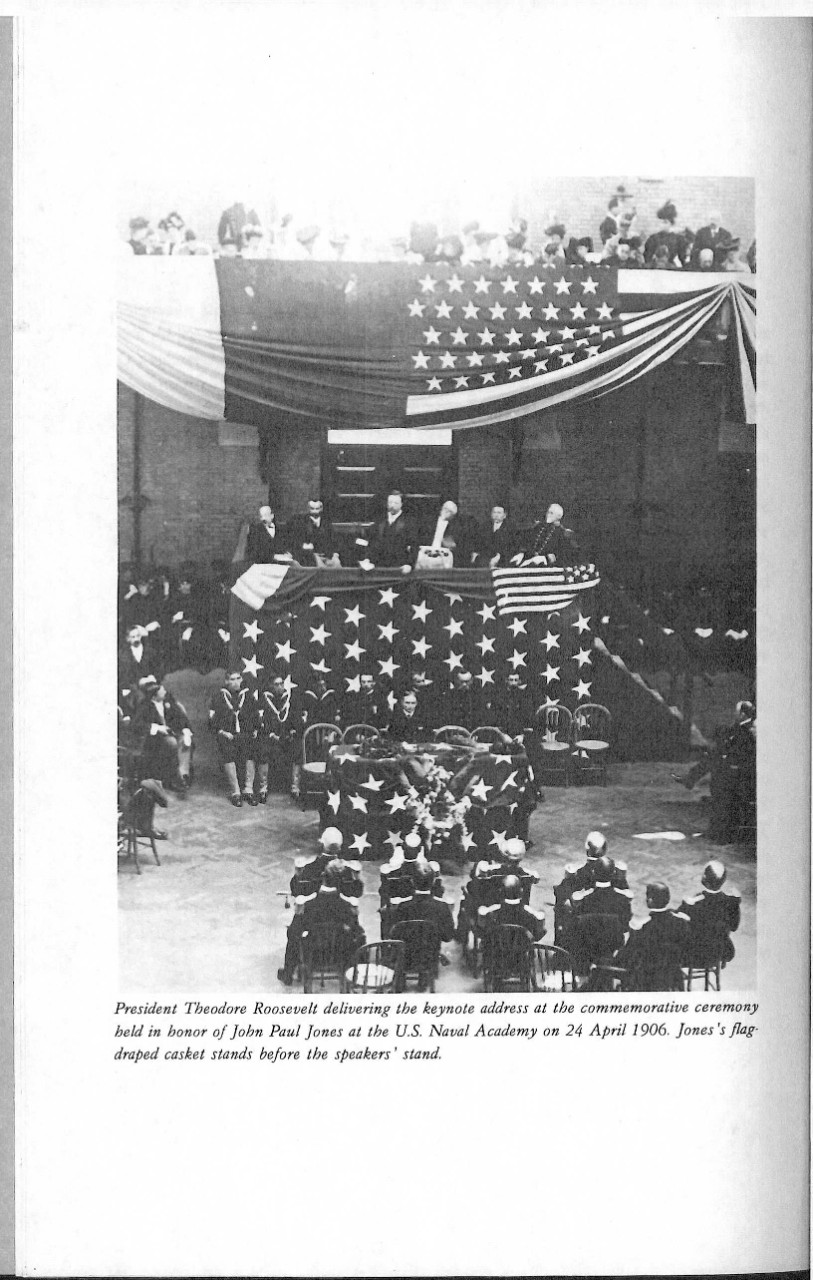

As the strains of “The Star Spangled Banner” died, Secretary of the Navy Charles J. Bonaparte rose, walked to the lectern, and began to speak to the audience assembled at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis. “We have met to honor the memory of that man who gave our Navy its earliest traditions of heroism and victory.” With these words the Secretary introduced President Theodore Roosevelt who welcomed the dignitaries present and sketched highlights from Jones’ career:

The future naval officers, who live within these walls, will find in the career of the man whose life we this day celebrate, not merely a subject for admiration and respect, but an object lesson to be taken into their innermost hearts...every officer...should feel in each fiber of his being and eager desire to emulate the energy, the professional capacity, the indomitable determination and dauntless scorn of death which marked John Paul Jones above all his fellows.

Before the podium stood the star-draped casket containing the body of Jones, recently returned to the United States after lying for over a century in an unmarked grave in France. The ceremony capped a series of activities which included a White House reception and an official visit by a French naval squadron. Congress ordered the publication of a commemorative volume whose introduction stated,” There is no event in our history attended with such pomp and circumstances of glory, magnificence, and patriotic fervor.”1 This may have verged on hyperbole, but there can be no doubt that the splendor surrounding America’s reception of the remains of John Paul Jones and their retirement in a crypt below the chapel of Naval Academy stood in sharp contrast to the treatment accorded him at the time of his death in Paris over a hundred years before.

In July of 1792, as Jones lay mortally ill in rented rooms near the Luxembourg Palace, America’s Minister to France, Gouverneur Morris, seemed troubles to find time between social activities for a visit to his deathbed and when he learned of his death ordered as inexpensive a burial as possible. The French Legislative Assembly intervened and, wishing to “assist at the funeral rites of a man who has served so well the cause of liberty,” took charge of the arrangements. Two days later Jones was laid to rest in a Protestant cemetery outside the city walls. Gouverneur Morris was giving a dinner party that evening and did not attend. Such was the sad ending to the life of the man whom Benjamin Franklin had once considered the chief weapon of American forces in Europe and whom Thomas Jefferson had described as the “principal Hope of [America’s] future efforts on the ocean.”2

What kind of a man was Jones to be so heralded during his lifetime, ignored at the time of his death, and honored a century later? The answer is complex just as Jones was complex.

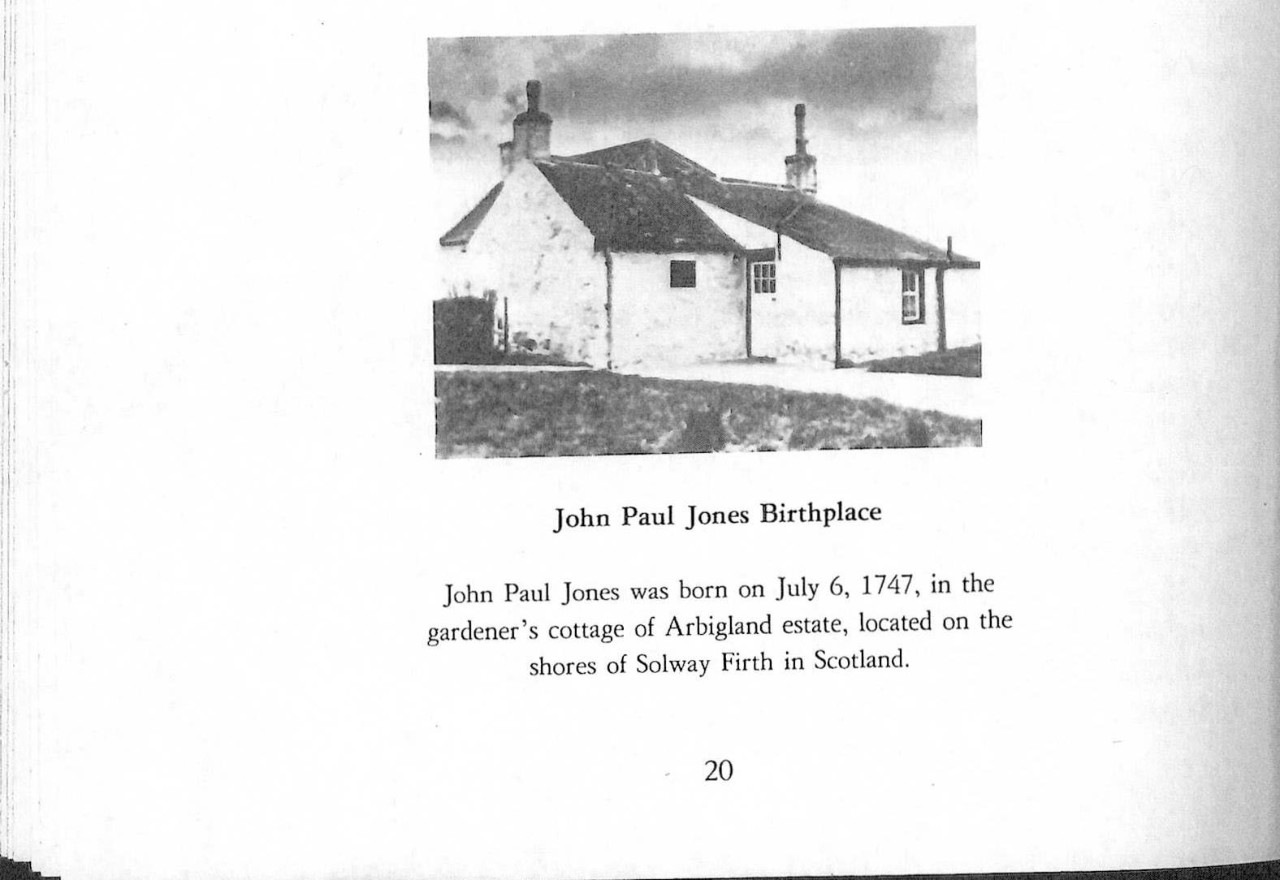

1

From humble origins he rose through sheer force of character and combat success to pre-eminence in the Continental Navy. When the war ended the nation believed it had little need for a naval force and disbanded the Continental Navy. Jones deplored the action. More than any other American of his era he wrote about naval policy and offered suggestions to foster professionalism in the service, but political leaders ignored his advice. Jones spent most of the postwar decade in Europe, first as a diplomatic agent seeking to collect prize money owed to Americans from the Revolution, then as an admiral in the navy of Catherine the Great. His death, just days after his fifty-fifth birthday, brought to an end a full life, one so colorful and played out against so broad a stage as to seem the work of a novelist. It was also a life in which one can find many themes ad through which Jones has been viewed, the themes picked out by authors for emphasis, and the uses made of hi tell as much about the writers and their times as they do about Jones.

There is material aplenty for such a study. Jones has been the subject of at least thirty biographies and over forty chapbooks. He has fascinated novelists. James Fenimore Cooper, Alexandre Dumas, Herman Melville, William Makepeace, Thackeray, and Sarah Orne Jewett each made him a major figure in one of their works. Poets as disparate as Walt Whitman and Rudyard Kipling include him in their writings. It is clearly beyond the ability of this study to analyze such a vast array of literature. Instead, its focus will be on the image of Jones in broad terms, the attitudes of naval officers toward him, and the use the U.S. Navy has made of Jones. The shifts which took place in these images, attitudes, and uses indicate much about the navy as an institution and about its officers.

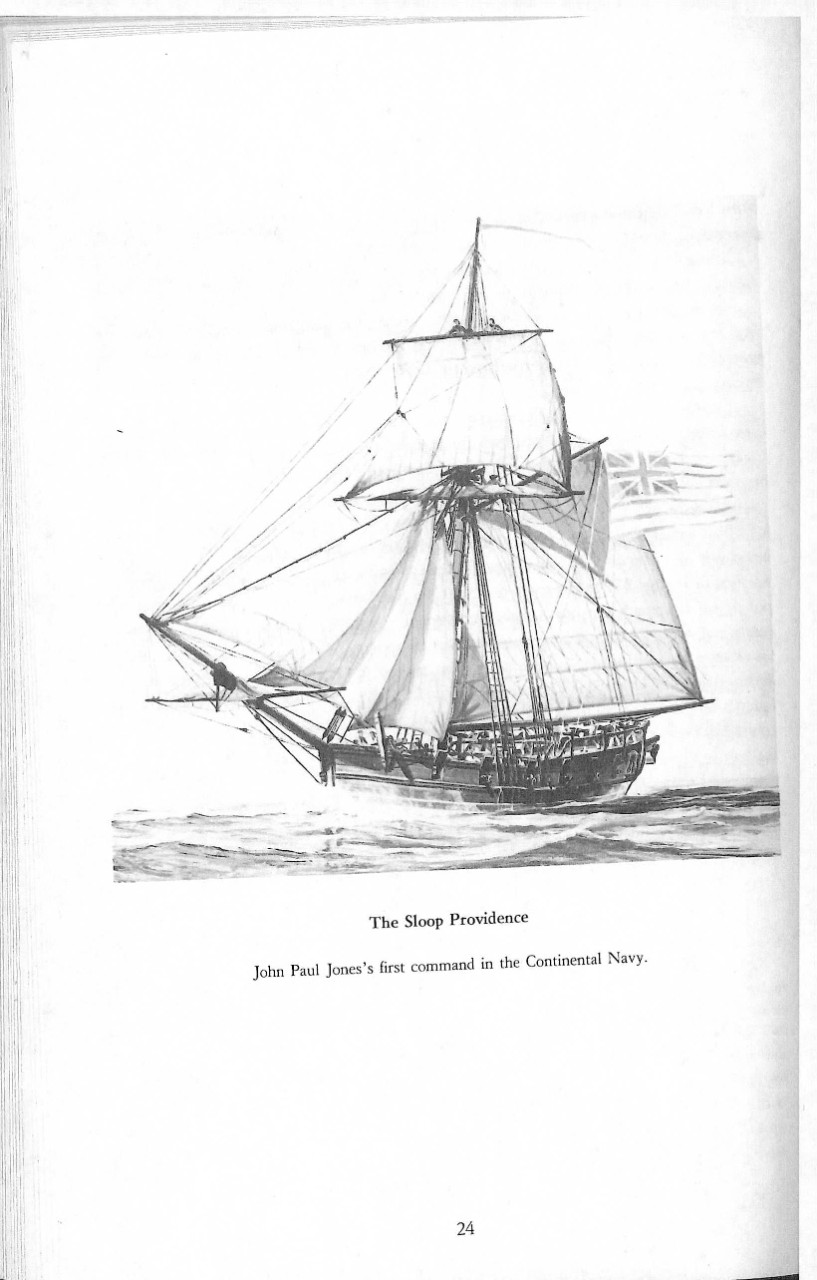

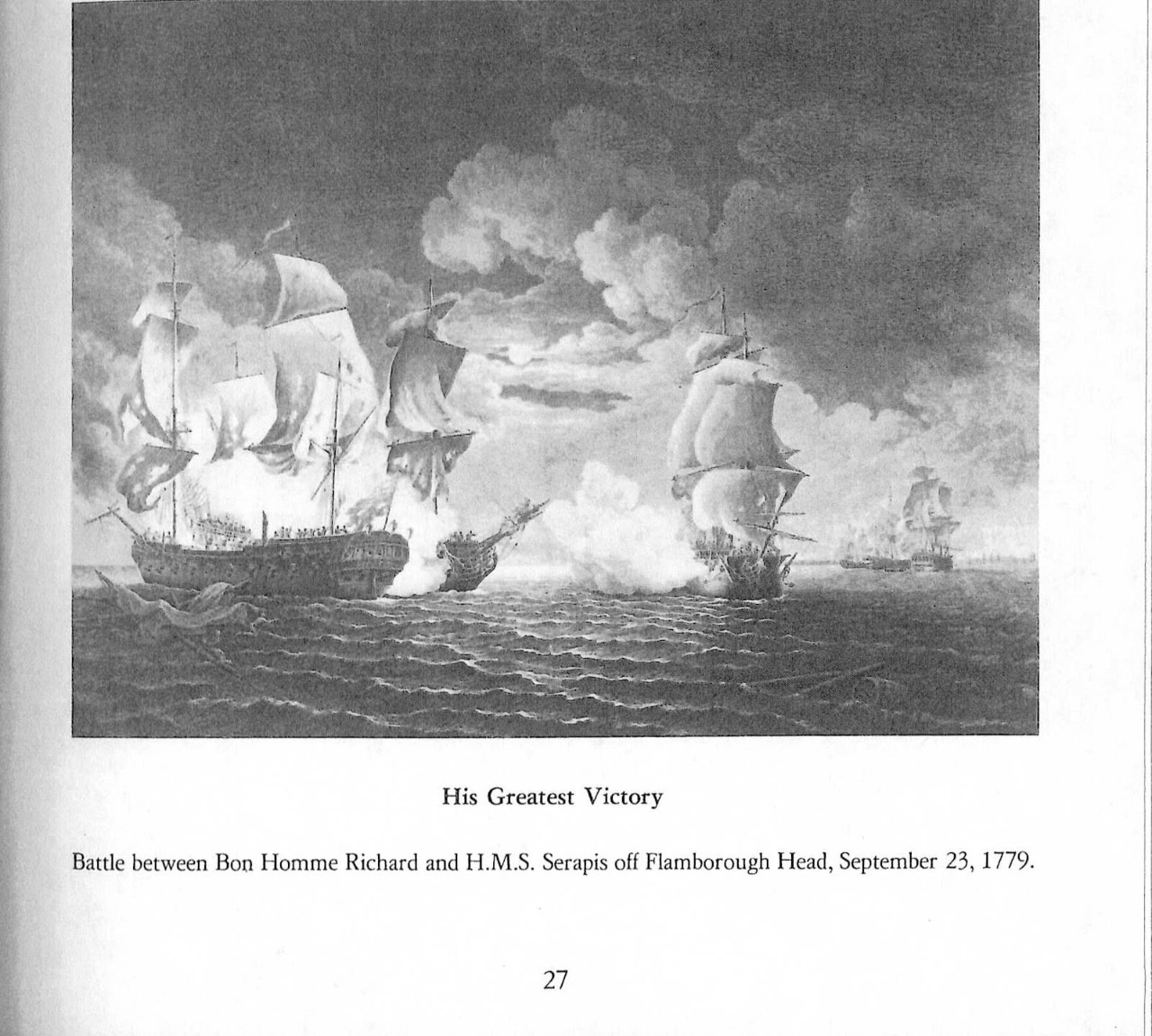

During the nineteenth century Jones was idolized by popular writers and extravagantly praised as a man of action. Virtually all biographers focused on his life at sea and devoted as many as half their pages to his exploits in command of the Ranger and the Bonhomme Richard. John Henry Sherburne wrote the first book-length biography of Jones. It appeared in 1825 at the start of the Romantic Period in American literary history. “Romantics” rebelled against the lifeless logic of the preceding Age of Reason and placed greater value on intuition and feeling than on education and reason. Men of action struggling against overwhelming odds were preferred to men to contemplation. It was a transitional era in political as well as literary terms. The nostalgic American tour of the aged Marquis de Lafayette and the deaths of Thomas Jefferson and John Adams on July 4, 1826, the fiftieth anniversary to the day of the Declaration of Independence, forced upon Americans a sense of generational change. John Quincy Adams, the last president with Revolutionary credentials, and also the last president to wear knee-breeches and a wig, was in the White House. Jacksonian Democracy with its self-confidence, optimism, and faith in the common man and the future of the United States was clearly on the horizon. It was a time when Americans wanted heroes. They were not alone. Only a few years later Thomas Carlyle would, in his Heroes and Hero-Worship (1841), state that a nation’s entire history could be told in terms of its heroes. Carlyle and others, like J.S. Froude, believed that nations needed heroes to instill patriotism and other estimable qualities.3

John Paul Jones was a prime candidate for heroic treatment. To Jacksonians he was a self-made man who fit the words of Calvin Colton: “Ours is a country, where men start from a humble origin...and where they ca attain to the most elevated positions, or acquire a large amount of wealth, according to the pursuits they elect for themselves.”4

2

Born the son of a Scottish gardener, Jones rose by dint of his own exertions to a position of leadership in the American Revolution and to become an admiral in the Russian Navy. In a recent study of hero-making in the Antebellum Navy, K. Jack Bauer has shown that “the most honored individual was John Paul Jones.” He was the only naval officer to have a frigate named for him before the Civil War and was the subject of nineteen of the thirty-one biographies written of American naval officers.5

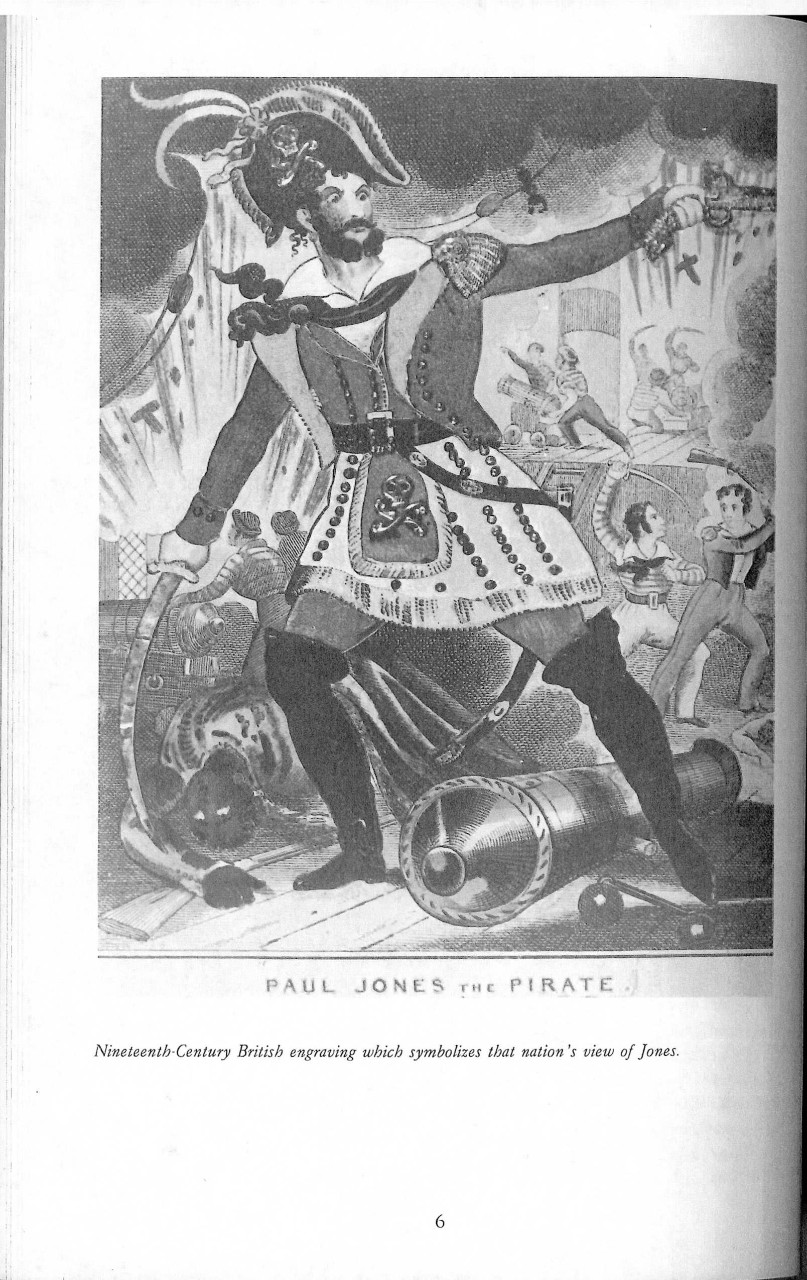

Jones early attracted the attention of chapbook writers.. The first were English and the titles indicate their characterization of Jones: The Life, Voyages, Surprising Incidents, and contained a Variety of Important Facts, displaying the Revolution of Fortune that this Naval Adventurer underwent and The Interesting Life, Travels, Voyages and Daring Engagements, of that Celebrated and Justly Notorious Pirate, Paul Jones; containing numberous Anecdotes of Undaunted Courage, in the Prosecution of his Nefarious Undertakings. The first work was published in London in 1802. The second appeared a year later. It was a reworking of the first but contained the misleading note that it was “Written by Himself.” A dozen other versions of the same work appeared on both sides of the Atlantic during the next two decades under various but similar titles. In all the works Jones was an audacious and brave leader. American versions usually deleted terms like “corsair” and “pirate” substituting “justly renowned Commander” and “Celebrated Seaman, Commodore.” None delved into his motivation or discussed his ideas.6

John Henry Sherburne’s is both the first full-length biography of Jones and the first to be based on primary source materials. Sherburne consulted government documents, sought out people who had known Jones, and borrowed correspondence from Thomas Jefferson. The result was a fuller, more accurate portrait of Jones, but one not entirely different from previous works.

In his introduction Sherburne characterized Jones as “an example worthy of imitation” and set the tone of his biography by drawing attention to Jones’s “chivalric spirit and undaunted valor…active disposition and nautical skill.” Sherburne called his “labors...for the furtherance of the American cause… incessant [and] indefatigable” and judged him to have been “generally successful in his enterprises scarcely ever failing in an undertaking or expedition, unless through the jealousy or disobedience of others, or in the clemency of the weather.” The biographer believed that “The present work…will redeem his name from the odium hitherto cast upon it [by] the venal British press.”7

For the next three-quarters of a century there was virtually no change in the image of Jones presented by writers on either side of the Atlantic. In Britain he remained at best a corsair with few redeeming characteristics beyond bravery and audacity. In America he became a venerated hero of the Revolution. His signature was avidly sought by autograph collectors until its value reached a point surpassed only by those of Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln, Hamilton, Franklin, and at times John Adams.

American naval officers did not rank him so highly. Many officers in the United States Navy even refused to acknowledge the link between their service and the Continental Navy in which Jones served. In 1812 a farewell dinner was held in Washington to honor an officer being transferred. It was attended by senior Navy Department civilians and all the senior commissioned officers in the capital at the time. After the meal a series of twenty-seven toasts were offered, none of which mentioned John Paul Jones or any action during the

3

Revolutionary War. Such occurrences have led Christopher McKee, a prominent student of the naval officer corps, to conclude that, “for the U.S. Navy of 1812 its mythic as well as its institutional history began only with 1798 and the Quasi-War with France.”8 A number of writers reflected and, perhaps, reinforced this attitude. In 1815 Isaac Bailey authored a collection of essays entitled American Naval Biography which included sketches of eighteen officers beginning with Thomas Truxtun and Edward Preble. A lithograph entitled “Naval Heroes of the United States” included eight officers: Perry, Decatur, Macdonough, Bainbridge, Preble, Dale, Berry, and Barney.9

There were exceptions to the rule, of course. Sherburne was a civilian employee of the Navy Department when he wrote his biography of Jones and Alexander Slidell Mackenzie was a lieutenant on active duty in the U.S. Navy when he wrote his two-volume biography of Jones in 1841. Still, the attitude persisted among officers. In 1915 retired Admiral French E. Chadwick stated that “There were two navies: that of the Revolution which disappeared wholly in 1785: and that of to-day, which had its origin in 1794.”10

Most general histories of the navy included the Continental Navy and John Paul Jones. James Fenimore Cooper included Jones in both his History of the Navy of the United States of America and his Lives of Distinguished Naval Officers (1846). The view presented of Jones was similar to that accorded him by Cooper in one of his earliest novels, The Pilot (1823), in which he focused on Jones’ seamanship and courage when in danger. Nothing was said of professionalism. John Ledyard Denison’s Pictorial History of the Navy of the United States (1860) described Jones’s voyages but said nothing about his character or professionalism. Edgar S. Maclay’s A History of the United States (1896) and John R. Spears’ five-volume History of Our Navy (1897-1898) treated Jones similarly. The title of George F. Gibbs’ 1900 book, Pike and Cutlass: Hero Tales of Our Navy is indicative of the contents of most naval histories of the era.

Nineteenth-century British authors were equally consistent. Jones would not have appreciated his inclusion with Blackbeard, Henry Morgan, and others in a book entitled Interesting Lives and Adventures of Celebrated Pirates (London, 1840) nor would he have taken pride in the use of an engraving of the battle between the Bonhomme Richard and the Serapis as the frontispiece for T. Douglas’ Lives and Exploits of the Most Celebrated Pirates and Sea Robbers (1841) or in the title of J.K. Laughton’s 1887 magazine article, “Paul Jones, the Pirate.” In what is perhaps a reflection of his Anglophilism, Theodore Roosevelt labeled Jones a “daring corsair” in his 1888 biography of Gouverneur[sic] Morris. Corsairs were technically above pirates because their capture of enemy ships were legal, unlike those of pirates who acted without legal authority. Such a distinction appears to have been lost on Rudyard Kipling whose 1890 poem “The Rhyme of the Three Captains” contains a heading referring to “the exploits of the notorious Paul Jones, an American Pirate.” Over half a century later, Sir Winston Churchill called Jones a “privateer” in his The Age of Revolution (1957), as did the editor of a volume of Lafayette papers in a caption to a portrait of Jones. Jones of course, never held a privateering commission or engaged in piracy. The realization of this might be what prompted someone to “correct” the British Library Catalogue. In the entry for “Jones (John Paul)Chevalier, See Paul afterwards Paul Jones(J). Pirate” someone crossed out “Prate” and substituted “Admiral of the Russian Navy.” The index manuscripts in the National Library of Scotland, in comparison, identifies him

4

as “Jones, Paul, Scottish Adventurer.” Such views have not prevented the British from invoking the name of Jones and quoting him served their purposes. Thus during the Battle of Britain, prior to American entry into World War II, Albert Alexander, the First Lord of the Admiralty, called up the spirit of Jones and in a radio broadcast told Americans that Jones’s defiant “I have not yet begun to fight” expressed exactly the sentiments of the British people in their struggle against Germany.11

At the turn of the century beginnings of a shift in Jones’ image is noticeable. The pivotal work in this change was Augustus C. Buell’ two-volume biography of Jones, which was first published in 1900. The timing was excellent. The U.S. Navy was accorded the lion’s share of credit for American victory in the War with Spain and things nautical were in vogue. It was the era also of the sailor-scholar Alfred Thayer Mahan whose work marks a transition in the naval historiography. Like his predecessors he devoted most of his attention to naval operations and battles; but like his contemporary progressive historians, he sought lessons from the past to influence current policy. He found few “lessons” in the life of John Paul Jones, and little of relevance in the entire history of the Continental Navy. Indeed, the commerce raiding engaged in by Jones and the Continental Navy was not in any way applicable to the type of navy Mahan hoped to see develop in the United States. Thus, when Mahan wrote two articles on Jones for the popular Scribner’s Magazine he chronicled the cruises of the Ranger and the Bonhomme Richard. Only in a closing paragraph did he address the topic of professionalism. After summarizing Jones’ postwar career, he pleaded that a lack of space precluded his quoting from a 1783 letter from Jones to Robert Morris regarding the navy, but said that this letter and Jones’ “undiminshed earnestness for professional improvement . . . afford striking indications of that comprehensive professional intelligence which, when combined with the daring in enterprise, and the endurance in action, shown by Jones, gives the best antecedent tokens of the great general-officer that might have been.”12

The sense of professionalism alluded to by Mahan was one of the dominant themes of the Progressive Movement, a major force in America at the turn of the century. Progressives stressed the importance of organizational structure, and of developing specialized managerial skills through education. Such values permeated the literature of the period and are essential to understanding the shift in the image of Jones that occurred during the era. Buell, an engineer reflected the managerial ethic of Progressivism when he wrote about Jones. It is possible also that he was following the lead of Mahan whose articles on Jones appeared two years before the publication of Buell’s biography.

History was not a new subject to Buell. He had published his Civil War memoirs when working as a journalist in the 1880s. In the preface to his next project, the Jones biography, he lamented that his subject had “left no family to preserve with filial care the voluminous and valuable records he had prepared” but said that “ a real history of Paul Jones” need not be based only on “his own literary relics.” These could be augmented by “the records of his contemporaries and colleagues [to produce for the first time a biography that would be correct] in detail as to the actual life and the real character of the man.” The result was a biography which liberally mixed fact and fiction to support a theme reflected in the title Buell gave to the work: Paul Jones: Founder of the American Navy. When Buell lacked documentary evidence to support the view he wished to present f Jones, he simple invented it. The most important bogus documents invented by Buell were two journals ostensibly

7

kept by Jones in 1787 and 1791 and a collection of correspondence between Jones and Joseph Hewes supposedly kept somewhere in North Carolina.

Bogus letters from Jones to Hewes were very influential in shifting the image of Jones. Joseph Hewes represented North Carolina in the Continental Congress and served as chairman of the committee charged with directing naval affairs. Buell fabricated a letter from Jones to Hewes dated 14 September 1775 (Appendix 1) which Buell asserted “embodies the logic and philosophy of naval organization and the elements of sea-power to-day quiet as fundamentally as it did then, or as they ever can be embodied under any conditions conceivable in the future.”13 Buell next told of Hewes submitting the letter to George Washington prior to forwarding it to Congress. During the next decade a number of individuals questioned the authenticity of sections of Buell’s work. To one of these the author responded that in writing his book he was "careless about preserving documentary evidence, [and that] for this reason, about all I can do now is to say that those who take sufficient interest in my statements to read them must accept them as authority, so far as I am concerned, without ‘ going behind the returns. “14

Buell’s work somehow escaped discredit and remained popular. In 1905 he published a biography of Andrew Jackson and in the following year his Jones biography was republished with a supplementary chapter by General Horace Porter, the American Ambassador to France who had located Jones’ body and arranged its return to the United States.

The publication of Buell’s biography coincided with a major transition period for the U.S. Navy. In the decades on either side of 1900 the last vestiges of the old coastal defense, commerce raiding Navy gave way to the battle fleet of the modern Navy. The keel of the U.S.S Iowa, the first modern American battleship, was laid in 1891 and the ship commissioned four years later. The victory over Spain confirmed the rise of the U.S. Navy to world status and the ascension to the presidency of Theodore Roosevelt in 1901 insured its favored position at home. Congress tacitly accepted the naval renaissance of the nineties and the President’s commitment to building a second navy only to Britain’s when it appropriated funds to lay the keel for at least one battleship a year between 1899 and 1918 (with the exception of 1908 when Americans shipyards were filled to capacity). A total of thirty three battleships were laid down in the two decades between 1891 and 1911. Work began on another eight before Woodrow Wilson’s 1916 call for “Navy Second to None” expanded this commitment.15

The naval renaissance brought with its renewed interest in officer training which ushered in a “Golden Age” at Annapolis. Theodore Roosevelt visited the Academy several times during his presidency and it was he who dispatched the cruiser squadron to bring John Paul Jones’s body from France. As Academy officials sought to instill a new sense of professionalism in the midshipmen, the elaborate ceremony surrounding the return of the body John Paul Jones, the building of his crypt beneath the chancel of the Academy chapel, and the arrival of visitors to pay him homage, made Jones an obvious symbol. Buell’s book provided the material. Academy officials drew from it a number of quotations. Most popular was Jones’s description of the qualities of an officer:

It is by no means enough that an officer of the navy should be a capable mariner. He must be that, of course, but also a great deal more. He should be as well a gentleman of liberal education, refined manners, punctilious courtesy, and the nicest sense of personal honor… He should be the soul of tact, patience, justice, firmness, and charity. No meritorious act of a

8

subordinate should escape his attention or be left to pass without its reward, even if the reward is only a word of approval. Conversely, he should not be blind to a single fault in any subordinate, though, at the same time, he should be quick and unfailing to distinguish error from malice, thoughtlessness from incompetency, and well-meant shortcoming from heedless or stupid blunder.

This was reproduced in a variety of Academy publications including Reef Points, the “Annual Handbook of the Brigade of Midshipmen.” The first edition of Reef Points appeared in 1905 and it has been updated ever since. The Jones quotation remains in the current edition even though it has been shown to come from the bogus 14 September 1775 letter invented by Buell. It is reproduced under the heading “Qualifications of the Naval Officer” and carries a credit line reading “based on letters of John Paul Jones.” This credit line is certainly more accurate than earlier ones, some of which actually cited the bogus letter by date. It remains inaccurate since the only difference between the fraudulent letter as printed in Buell and Reef Points are the addition in the Reef Points of three commas, the deletion of a hyphen, the capitalization of two words, and the reversal of two words. The changes in punctuation were made so that Buell’s writing would conform to modern usage, “Navy” was probably capitalized for emphasis, and the two words were probably simply transposed by error. In any case, the words continue to be repeated to midshipmen because it is simply too good a quotation to give up. This use also reflects an attitude that “If he didn’t write it, he should have.” Concisely it sums up the qualities that the Academy tries to instill in its graduates. Since its founding in 1845 its mission has been “to prepare midshipmen morally, mentally, and physically to be professional officers in the naval service.” A 1981 Washington Post article restated this mission, followed it with “John Paul Jones, the American Navy’s oldest hero and the Academy’s patron saint, put it this way,” and then reproduced the first paragraph from the bogus Buell letter.16

In a recent history of the early Naval Academy, one of its graduates introduced his chapter on “Officer and Gentlemen: The Annapolis Ideal” with the bogus quotation from Reef Points calling it the answer one is most likely to receive if a new plebe is asked, “What is a naval officer?” The Academy graduate refers to it as “only one of a host of definitions, quotations, and sayings memorized and spat out in knee-jerk fashion by new midshipmen as part of their introduction to Academy life. Most are nonsensical . . . but the words of John Paul Jones are not nonsense. To the contrary, they connote what might be called the Annapolis ideal. . . .”17

In his study of the "Golden Age of Annapolis" and the "naval aristocracy" it produced, Peter Karsten calls Jones the "highest of all the naval heavenly hots" and testifies to the pervasiveness of the bogus quotation invented by Buell. It "was (and still is) afforded the highest rites in the cabins, wardrooms, statrooms, and homes of Mahan's messmates, " one of whom said that the question was " the first thing greet our eyes int he morning, the last thing at night, a constant reminder of that perfect officer character which we should ever strive to emulate."18

That they had the desired effect is testified to by Vice Admiral Horner N.Wallin: When I entered the Naval Academy in 1913 each midshipman, on his day of entry was given a book of rules for that institution, and a pamphlet giving certain statements by John Paul Jones. These were taken from his various letters, and compiled by Augustus C. Buell. The words in the pamphlet were indeed an inspiration to young men. Some of these follow [and the Admiral quoted a passage from the spurious 14 September letter].19

10

Within the Academy certain departments made use of various sections of the letter. Between the World Wars the Department of English, History, and Government spliced together the opening sentences of the second and third paragraphs to produce a quotation endorsing the study of English: “It is by no means enough that an officer of the navy should be a capable mariner. He must be of that, of course, but also a great deal more. He should...be able to express himself clearly and with force in his own language both with tongue and pen.” Variations of this, often with the middle sentence deleted, were printed on examination books and placed in frames in classrooms to inspire midshipmen. Perhaps it reflects the feeling of the liberal arts faculty at the technologically orientated institution that has led them to seek a kind of legitimacy by quoting Jones.

The Naval Academy was not the only branch of the service to make use of Jones as a symbol of professionalism. in leadership classes at Officer Candidate School fledging officers learn to “Praise in public, admonish in private” and that an officer, in Jones’s “words,” “should be the soul of tact, justice, firmness, and charity. No meritorious act of such a subordinate should escape his attention or be left to pass without its reward, [etc.].”

John Paul Jones, with his many affairs of the heart, would seem an unlikely candidate for praise by Chaplain Corps, but in the late 1950’s he was cited as an example of an officer who was concerned about the religious life of his men and who was tolerant of divergent religious groups. Instructors at the Chaplain School in Newport, Rhode Island, told their students that Jones carried a Protestant chaplain four years later. The change was made, the students were told, because Jones wished to have a chaplain of the faith of the majority of his crew. The story makes a good point but is probably apocryphal. Little is known of the clergymen who served as chaplains under Jones, but the story is not supported by extant records. In the summer of 1778 Jones expected to receive command of five French ships and sought the assistance of a contact in Paris is obtaining a chaplain. When Jones wrote that “for political Reasons it would be well if he were also a Clergyman of the protestant profession,”20 he did not refer to the crew which being French was almost certainly composed of Roman Catholics, but to political considerations in America where virtually all members of the Continental Congress were Protestants.

Chaplain School Instructors also credited Jones with setting the precedent for flying the church pennant over the American flag as a signal that divine services were in progress. Finally, it was suggested that chaplains could site Jones as an example of an officer who held divine service on board his ships if any of them encountered a commanding officer who was reluctant to hold them. Jones may have held worship services, but there is no mention of them in his surviving logbooks or any of his correspondence.21

The Bureau of Navigation incorporated sections of the letter in it “Report on Fitness of Officers” in the early part pf the century. In 1920 Naval War College President Rear Admiral William S. Sims sent a memorandum to the Bureau of Navigation stating that “since 1960 it has been established [that 14 September 1775 letter from John Paul Jones to the Marine Committee] is a forgery” and should not be quoted in the Report on Fitness of Officers. Sims, who commanded American naval forces in Europe in World War I, and won a Pulitzer Prize for history for his co-authorship of The Victory at Sea (1920), quoted a dated September 14, 1775, Jones never wrote it.”22

11

NAVAL WAR COLLEGE

NEWPORT, RHODE ISLAND

2 July 1920

From: Rear Admiral William S. Sims, U.S. Navy

To: Bureau of Navigation

Subject: Quotation, on page 3 of Report on Fitness of

Officers, from the alleged letter of John Paul Jones

to the Marine Committee, Septemeber 14, 1775.

1. Sinve 1906 it has established not only that this letter, quoted in "Paul Jones, Founder of the American Navy: A History. By Augustus C. Buell, " is a forgery, but that the Marine Committee, stated to have been appointed by the Congress in June, 1775, and to have invited John Paul Jones to lay before the Committee such information and advice as may have seemed to him useful in assisting ther said Committee to discharge its labors, never existed.

2. On September 15, 1908, the Librarian of the Navy Department addressed a letter to the Honorable Frank W. Hackett, in which he stated: "As to the alleged letter dated September 14, 1775, Jones never wrote it."

Memorandum by Admiral William S. Sims

12

Sims was not the only naval official to be skeptical of Buell’s work. Four entries in the “Chronology” in the John Paul Jones Commemoration volume (1907), including the 14 September 1775 letter, contain a footnote reading: “ Buell, ‘Paul Jones , Founder of the American Navy.’ These Statements are not supported by the Journals of the Continental Congress.”23

In a move reflecting a change in British attitude toward Jones, two instructors at the Royal Navy College, Dartmouth, honored the man Britons often called a pirate by including a Jones letter--- one of the few documents not of English origin--- in the volume of Select Naval Documents they compiled for the use of naval cadets in 1922. The letter, from Jones to French Admiral Kersaint in 1791, contains an analysis of French naval principles and is another of Buell’s forgeries. The British editors discovered this and deleted it from their 1936 edition noting in their preface that is had “been proved spurious.” This was not the end of the letter, though, because only a decade ago Liddell Hart included it in the collection of documents he edited entitled The Sword and the Pen.24

The fact that these particular Jones quotations were bogus does not detract from the main point being made in citing them: The image of John Paul Jones underwent a significant alteration in the early twentieth century. This change survived the discrediting of Buell and probably would have taken place had he never invented Jones letters. Popular interest in the Navy and the return of Jones’s body inspired a number of works. Two of these, Norman Hapgood’s Paul Jones (1901) and M. MacDermot Crawford’s The Sailor Whom England Feared (1913), were “mainly potted Buell,” and other authors, e.g., Valentine Thomson in Knight of the Seas (1939), added inventions of their own.25 Phillips Russell’s 1927 John Paul Jones, Man of Action could be added to the list, but there were other, more accurate, biographies of Jones appearing during this same period. The most important was Anna DeKoven’s two-volume Life and Letters of John Paul Jones which appeared in 1913. In her preface she noted that “The fame of Paul Jones has been the sport of romance and the plaything of tradition” and stated that “No one of the ten biographies of Jones which have been written may properly be called adequate.” She promised “to present a final and truthful estimate of his life and character.” The result was an accurate and more complete biography of Jones of the nineteenth-century life and times variety. Other volumes followed. The two best, Lincoln Lorenz’s John Paul Jones: Fighter for Freedom and Glory (1943) and Admiral Morison’s John Paul Jones: A Sailor’s Biography (1959) focus on the operational aspects of jones’ career, but neither neglect his role as a strategist or naval theorist.

Some works have placed even more emphasis on these and other aspects of professionalism. The popular writer Gerald W. Johnson entitled his biography of Jones The First Captain (1947). On the dustcover flap his approach is summed up: Jones “was the first true professional among our naval officers, and as such, the first to understand that the navy as an implement of peace may be no less valuable than it is as a weapon of war….Paul Jones won his fights against the British and the Turks, but the fight of the man of genius to get his ideas accepted goes on forever. His ideal of the naval officer not merely as a combatant but as an instrument to serve the nation’s purpose is perhaps more valuable today than it was in his time.” In his opening chapter Johnson presented his thesis:

John Paul Jones . . . won naval battles[,] laid the foundation of our prestige on the high seas[,] devised strategical and tactical expedients [and] designed better ships…better gunnery practices [and] better rules and regulations for the Navy.

13

But in addition he designed something else more important than all these things put together. He designed the modern American Officer....26

This is quite a shift in image from “the daring corsair, Paul Jones” described by Theodore Roosevelt almost eighty years before.27

There is plenty of evidence in authentic Jones papers to support the characterization of Jones as a professional without resorting to Buell’s fabrications. his 21 January 1777 letter to the Marine Board, his 1777 “A Plan for the Regulation, and Equipment of the Navy, Drawn Up at the Request of the Honorable The President of Congress,” (Appendix 2), and his October 1783 letter to Agent of Marine Robert Morris provide ample evidence that Jones had an appreciation of professionalism far in advance of his contemporaries.28

An excerpt from the first letter was used by the Naval Academy as early as 1876 and between 1895 and 1913 was “posted on the first leaf of the note-books used by midshipmen in [the English] department”.29

....none other than a gentleman, as well as a Seaman both in Theory and Practice is qualified to support the Character of a Commission Officer in the Navy, nor is any Man fit to command a Ship of War, who is not also capable of communicating his Ideas on Paper in Language that becomes his Rank....

In 1928 article, L.H. Bolander, Librarian at the Naval Academy, accurately quoted the authentic letter explaining that Buell” compiled” his spurious document. Bolander clearly implied that the Academy should employ the genuine rather than the fraudulent document.”30 Yet for some reason, perhaps because Buell wrote so well, navy people have resisted disposing of his counterfeit letters. Leland P. Lovett, for example, reproduced the bogus 14 September 1776 letter an appendix to his 1959 Naval Customs, Traditions, and Usage. He entitled it “Qualifications of the Naval Officer: A Collection from Jones’s Reports and Letters in Modern Version as Arranged by A.C. Buell” and justified its inclusion by saying that “mr. Buell drafted a letter that covered many of Jones’s suggestions and opinions; and, although this literary sharpness is not condoned, the Buell letter of Jones is quoted as the essence of that brave, dashing officer’s code. . . .”31

Rear Admiral Ralph Earle and Carroll Storrs Alden, former Head of the Department of English, History, and Government at the Naval Academy, used the other two authentic documents in preparing their essay on Jones for Makers of Naval Tradition. In their preface the authors stated that “it is their hope that the youths studying to become officers will by means of this book be led to realize more fully their debt to the great men who have preceded them in the Service.” Their essay on Jones, one of thirteen officers chosen for inclusion, identified contributions made by Jones: “Organization was his first great contribution to the Service. His second contribution [was] daring and enterprise . . . doubtful viruses except as they are based on sound strategy and tactics. After the war Jones made a further important contribution to the American Navy in his sound ideas of preparedness by education.” To support and illustrate this last point Alden and Earle quoted briefly from Jones’ 10 October 1783 letter to Robert Morris in which he proposed the formation of “a fleet of evolution.”32

This letter to Morris (Appendix 3) is particularly interesting because it clearly illustrates the shift in emphasis among Jones biographies. Virtually all Jones biographies have used the letter. In the nineteenth century, authors tended to quote from the sections of the letter dealing with operations and questions of rank. Robert Sands, for example, reproduced extracts

14

from the letter in a six-page appendix to his 1830 biography of Jones but did not include the sections of the letter advocating the formation of a “Fleet of Evolution” or the establishment of “Academies…at each Dock-Yard, where [officers] should be taught the principles of every Art and Science that is necessary to form the character of a great Sea Officer.”33 The description of the letter in the letter in the Calendar of John Paul Manuscripts prepared by the Manuscripts Division of the Library of Congress in 1903 hints at the other topics discussed in the letter, but clearly does not single them out as being particular importance when it says that “It gives also his ideas upon the organization of the United States Navy and the lessons which may be learned from the experience if European nations and France in particular.” Three times as much space is devoted to describing its other contents.34

The letter was first published virtually in its entirety in the 1907 Commemoration volume. Anna DeKoven quoted separate sections of the letter, including the passage on officer education, in three places in her 1913 biography. She believed that Jones sent only the section of the letter dealing with his rank to Morris.35 Regardless of this, the evolution in the use of the document was complete by the time of Alden and Earle who quote only the section on officer education. Lincoln Lorenz continued this use of the letter. In his 1943 biography he quoted only brief sections of the letter, none of which dealt with operations or even Jones’ disappointments with regard to rank, and stated that “the leadership which Jones was prepared to assume in building the Navy is measurable...by his communication intended for Morris.”36 Even Samuel Eliot Morison, writing A Sailor’s Biography which emphasizes operations, omitted all sections except those dealing with Jones’s idea of “sending a proper person” (himself) to Europe to study foreign navies, his comments on the weaknesses exhibited by British, French, and Dutch navies, and his proposals for officer education. No mention was made of sections dealing with Jones’s career during the war or his belief that he was dealt with unfairly in terms of rank. Instead of using its contents to support Jones’ claim to high rank, as other authors, Morison ignored such contents and calls it “one of the most thoughtful and prophetic of Jones’s letters on naval subjects.”37

The dramatic shift in the use made of this letter reflects the metamorphosis of Jones from a fighting sailor in the nineteenth century into a prescient proto-professional naval officer in the twentieth century. Jones would appreciate the irony of this transformation. As the revolutionary War neared its end, he had written to Captain Hector McNeill, a fellow officer sadly saying, “In the course of near Seven Years Service I have continually Suggested what has occurred to me as most likely to promote [the] honor [of our navy] and render it serviceable to our Cause; but my Voice had been like a cry in the Desert.”38

By 1900 many Americans were willing to listen. A heightened interest in the Navy brought by the Spanish-American War was strengthened by Theodor Roosevelt, one of America’s most naval-minded presidents. Progressive historians, like Mahan, were seeking lessons from the past.39 The rediscovery of John Paul Jones’ body just as the time that the U.S. Naval Academy was being rebuilt and his reentombment in the magnificent sarcophagus made him the most visible symbol of America’s early naval heritage. This is not to argue that twentieth-century naval theorists and authors looked to Jones for ideas. Rather they looked to him to find support for ideas and plans suggested by modern circumstances. It comes as no surprise that the image of the John Paul Jones who emerged in this era was quite different from the image of half a century before. During the six decades between the publication of Alexander Slidell Mackenzie’s biography of Jones and that of Augustus C.

16

Buell in 1900 a transformation had taken place in the U.S. Navy, a transformation reflected in the treatment of John Paul Jones. Lieutenant Alexander B. Pinkham’s assessment of Jones epitomized the nineteenth-century view: “It was [John Paul Jones] who... created the spirit of my country’s infant Navy with his fight against the Serapis,”40 The title of Gerald W. Johnson’s biography, The First Captain: The Story of John Paul Jones epitomizes the twentieth-century view. Neither view is either totally correct or totally false. In 1960 Morris Janowitz wrote that “The history of the modern military establishment can be described as a struggle between heroic leaders, who embody traditionalism and glory, and military ‘managers,’ who are concerned with the scientific and rational conduct of war.”41 Jones defies placement in either category. Over time Jones seems to have been shifted from the heroic to the managerial category. But this is more a matter of emphasis than of substance.

There is evidence in Jones’s career and his writing to warrant placing him in either or both categories and that evidence is compounded by the myths that surround virtually every facet of his life. The Jones legend has grown bit by bit---anecdote by anecdote, chapbook by chapbook, pseudo-biography by pseudo-biography--- until the myth threatens to obscure the substance. If the general public knows Jones the heroic man of action more than it does Jones the professional naval officer, this is not surprising. More people are likely to have formed their images of Jones from passing mentions in textbooks and literature, from the dozen “popular” biographies, or from the 1959 Hollywood movie than ever have or ever will read his papers or any of the more scholarly biographies.

Admiral Morison, whose John Paul Jones: A Sailor’s Biography best combines accuracy, readability and brevity, was keenly aware of the problem of separating “the real Jones” from the myths and images enveloping him. In the preface to his 1959 biography Morison writes that “I have adopted the principle. . . . If a story conflicts with known facts about Jones, I reject it; if it fits in with or supplements ascertained facts, and is intrinsically probable, I tell it. But I have not taken up space and the reader’s time to refute all the nonsense that has been written about Paul Jones.” This said, Morison devotes six appendices to refuting some of the more enduring Jones legends. It is perhaps the labor of sifting through these myths and legends that led Morison to the assessment that “it is easier to write a novel about a complex character like Paul Jones than to write a biography.”42

It is also this complexity of character as well as the legends that accounts for the continuing fascination that Jones holds for modern Americans. John Paul Jones was at the same time both a heroic man of action and indomitable spirit and a prophet of American navalism.

17

NOTES

1. [Charles W. Stewart, comp], John Paul Jones Commemoration at Annapolis, April 24, 1906 (Washington, 1907), 13. 16

2. Thomas Jefferson to William Carmichael, 12 August 1788, Julian Boyd, ed., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, 21 vols. to date (Princeton, 1950-), XIII, 503.

3. Thomas Carlyle, Heroes and Hero-Worship (London, 1841); J.A. Froude, Short Studies on Great Subjects, 2 vols. (London, 1867)

4. Calvin Colton, Junius Tracts (1844), quoted in John G. Cawelti, Apostles of the Self Made Man: Changing Concepts of Success in America (Chicago: 1865), 39.

5. Stephen Decatur, Oliver Hazard Perry, William Bainbridge, and Silas Talbot tied for second place with only two biographies each. K. Jack Bauer, “ Forgotten Commodores: Hero-Making in the Antebellum Navy,” unpublished paper.

6. Don C. Seitz, Paul Jones: His Exploits in English Seas During 1778-1779 (New York, 1917), includes a bibliography of virtually all nineteenth-century works on Jones.

7. John Henry Sherburne, The Life and Character of John Paul Jones (New York, 1825), v-vii.

8. The dinner and toasts are reported in the National Intelligencer, 8 August 1812. The conclusion is by Christopher McKee, “Edward Preble and the ‘Boys’: The Officer Corps of 1812 Revisited,” in James C. Bradford, ed., “Makers of the American Naval Tradition: Command Under Sail” (Annapolis, 1985)

9. Isaac Bailey, American Naval Biography (Princeton), included ten to twenty-page sketches of Truxtun, Preble, Murray, Rodgers, Hull, Decatur, Jacob Jones, Lawrence, Bainbridge, Barry, Biddle, Alwin, and Macdonough. Works like American Naval Battles: Being a Complete History of the Battles Fought by the Navy of the United States, from 1794 to the Present Time (Boston, 1831), purposely omit the Continental Navy. The author chose 1794, the date of the establishment of the U.S. Navy as his starting date though the Navy did not engage in any battles until 1798. The Library of Congress lithograph is reproduced in Nathan Miller, The U.s. Navy: An Illustrated History (New York, 1977),74.

10. French E. Chadwick, The American Navy (Garden City, 1915), 280.

11. J.K. Laughton, “Paul Jones, the Pirate,” Fraser’s Magazine (London, 1878), 501-522; Theodore Roosevelt, Gouverneur Morris (New York, 1888); Winston Churchill, The Age of Revolution (London, 1957); Stanley J. Idzerda, ed., Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution (Ithaca, 1979), II: 259, Morison, Jones, 413.

12. Captain A. T. Mahan, “John Paul Jones in the Revolution,” Scribner’s Magazine, XXIV (1898), 22-36, 204-219. The quotation is from page 216.

13. August C. Buell, Paul Jones” Founder of the American Navy (New York, 1900), I: viviii, contain Buell’s statement concerning Jones’ papers and 2-37 contain the letter.

14. Augustus C. Buell to George Canby, 4 October 1901, printed in the Boston Transcript, 1 July 1905, p. 24. Milton W. Hamilton, “Augustus C. Buell, Fraudulent Historian,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, LXXX, 478-492, thoroughly discredited Buell among academic historians, his influence remained great enough among popular writers and the general public that Samuel Eliot Morison felt obliged to include an appendix entitled "Buell's Fabrications" in his John Paul Jones: A Sailor's Biography (Boston, 1959), 425-428.

18

15. The Battleship in the United States Navy (Washington, 1920) ,42-47 , Naval officers of the time were well aware of the shift. In his biography of John Rodgers, Charles Oscar Paullin divided American naval history into four periods, calling the 1880-1909 “The New Navy.” C.O. Paullin, Commodore John Rodgers, 1773-1838 (Cleveland, 1909), 13. Walter R. Herrick, Jr., The American Naval Revolution (Baton Rouge, 1966), and B. Franklin Cooling, Benjamin Franklin Tracy: Father of the Modern American Fighting Navy (Hamden, 1973) both identify Benjamin Franklin Tracy’s secretaryship (1884-1893) as a time of significant change.

16. Neil Henry, “Absorbing the Navy Mystique,” The Washington Post, 14 June 1981. The author substituted the word “manners” for “courtesy” in the last sentence.

17. Charles Todorich, The Spirited Years: A History of the Antebellum Naval Academy (Annapolis, 1984), 133.

18. Peter Karsten, The Naval Aristocracy: The Golden Age of Annapolis and the Emergence of Modern American Navalism (New York, 1972), 256. Karsten quotes Bowman H. McCalla.

19. Homer N. Wallin, “John Paul Jones,” typescript biographical sketch in Navy Department Library in the Naval Historical Center, Washington, D.C.

20. Jones to Henry Grand, 12 July 1778; Jones Lteerbook, U.S. Naval Academy, Museum.

21. Interview with Richard W. Stadelmann, who was a student at the Navy Chaplain School in 1957.

22. Sims to the Bureau of Navigation, 2 July 1920. William S.Sims Papers, Personal Files, Box 51; Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

23. John Paul Jones Commemoration, 165.

24. H.W. Hodges and E.A. Hughes, eds., Select Naval Documents (Cambridge, 1922), document 121; ibid., 2nd edition (Cambridge, 1936), vii. Basil Liddell Hart, The Sword and the Pen: Selections from the World’s Greatest Military Writing (New York, 1976) 137-139

25. Morison, Jones, 425-426

26. Gerald W. Johnson, The First Captain: The Story of John Paul Jones (New York, 1947), 4.

27. The old images are not dead. In The Age of Revolution (London, 1957), 203, Sir Winston Churchill, who should have known better, called Jones a “Privateer.” The 1959 motion picture “John Paul Jones” devotes much time showing Jones as a comfortable planter in Virginia whose estate was ruined by British marauders--a life and events totally without documentation.

28. William Bell Clark and William Jones Morgan, eds., Naval Documents of the American Revolution, 8 vols. to date (Washington, 1964-), VII, 1005-1007; VIII, 288-290. Jones to Morris, 10 October 1783. John Paul Jones Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress. Printed versions omit many of the ideas Jones Expressed in his first draft, but deleted from the shortened version sent to Morris.

29. Anna DeKoven, The Life and Letters of John Paul Jones, 2 vols.(New York, 1913). I, 132.

30. L.H. Bolander, “Two Notes on John Paul Jones,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, LIV (July 1928),546-548

31. Leland P. Lovette, Naval Customs, Traditions, and Usage (Annapolis, 1959), 321-323

19

32. Carroll Storrs Alden and Ralph Earle, Makers of Naval Tradition (Boston, 1942) [1925], vii, 14, 20, 30

33. [Robert Sands], Life and Correspondence of John Paul Jones (New York, 1830), 304-309. John Henry Sherburne printed more of the letter in his 1825 biography but misdated the letter 22 September 1782. This date was picked up by Benjamin Disraeli and John Malcolm in their 1825 and 1830 biographies.

34. Charles Henry Lincoln, comp., A Calendar of John Paul Jones Manuscripts in the Library of Congress (Washington, 1903), 187-188

35. DeKoven, Jones, I: 152-153, 189-194; II: 234-235

36. Lorenz, Jones, 505-508, following the lead of Sherburne misdates the letter 1782.

37. Morison, Jones , 334-335

38. Jones to McNeill, 25 May 1782. The Pierpont Morgan Library.

39. When he sought exemplary officers Mahan looked not to the U.S. or Continental navies, but to the Royal Navy of Great Britain. Mahan, Types of Naval Officers Drawn from the History of the British Navy (London, 1904). It is interesting to note that a British author, James R. Thursfield included only one American, Jones, in his Nelson and Other Naval Studies (London, 1920). The essay on Jones was also the only one “written specially for . . . a volume which deals . . . largely with Nelson and his crowning victory at Trafalgar” (p. vii).

40. Edouard A. Stackpole, A Nantucker Who Followed an Ideal in a Far Country (n.p., n.d.), 2-3.

41. Morris Janowitz, The Professional Soldier: A Social and Political Portrait (Glencoe, 1960), 21.

42. Morison, Jones, xii-xiii.

APPENDIX I

John Paul Jones to Joseph Hewes

dated September 14, 1775

(The Buell Fabrication)

As this is to be the foundation--or I may say the first keel-timber---of a new navy, which all patriots must hope shall become among the foremost in the world, it should be well begun in the selection of the first list of officers. You will pardon me, I know, if I say that I have enjoyed much opportunity during my sea-life to observe the duties and responsibilities that are put upon naval officers.

It is by no means enough that an officer of the navy should be capable mariner. He must be that, of course, but also a great deal more. He should be as well a gentleman of liberal education, refined manners, punctilious courtesy, and the nicest sense of personal honor.

He should not only be able to express himself clearly and with force in his own language both with tongue and pen, but he should also be versed in French and Spanish--- for an American officer particularly the former--- for our relations with France must necessarily soon become exceedingly close in view of mutual hostility of the two countries toward Great Britain.

The naval officer should be familiar with the principles of international law, and the general practice of admiralty jurisprudence, because suck knowledge may often, when cruising at a distance from home, be necessary to protect his flag from insult or his crew from imposition or injury in foreign ports.

He should also be conversant with the usages of diplomacy and capable of maintaining, if called upon, a dignified and judicious diplomatic correspondence; because i often happens that sudden emergencies in foreign waters make him the diplomatic as well as military representative of his country, and in such cases he may have to act without opportunity of consulting his civic or ministerial superiors at home, and such action may easily involve the portentous issue of peace or war between great powers. These are general qualifications, and the nearer the officer approaches the full possession of them the more likely he will be to serve his country well and win fame and honors for himself.

Coming now to view the naval officer aboard ship and in relation to those under his command, he should be the soul of tact, patience, justice, firmness and charity. No meritorious act of a subordinate should escape his attention or be left to pass without its reward, if even the reward be only one word of approval. Conversely, he should not be blind to a single fault in any subordinate though, at the same time he should be quick and unfailing to distinguish error from malice, thoughtlessness from incompetency, and well-meant shortcoming from heedless or stupid blunder. As he should be universal and impartial in his rewards and approval of merit, so should he be judicial and unbending in his punishment or reproof of misconduct.

21

In his intercourse with subordinates he should ever maintain the attitude of the commander, but that need by no means prevent him from the amenities of cordiality or the cultivation of good cheer within proper limits. Every commanding officer should hold with his subordinates such relations as will make them constantly anxious to receive invitation to sit at his mess-table, and his bearing toward them should be such as to encourage them to express their opinions to him freedom and to ask his views without reserve.

It is always for the best interests of the service that a cordial interchange of sentiments and civilities should subsist between superior and subordinate officers aboard ship. Therefore it is the worst of policy in superiors to behave toward their subordinates with indiscriminate hauteur, as if the latter were of a lower species. Men of liberal minds, themselves accustomed to command, can ill brook being thus set at naught by others who, from temporary authority ma claim a monopoly of power and sense for the time being. If such men experience rude, ungentle treatment from their superiors, it will create such heart-burning and resentments as are nowise consonant with that cheerful ardor and ambitious spirit that ought ever to be characteristic of officers of all grades. In one word, every commander should keep constantly before him the great truth, that to be well obeyed he must be perfectly esteemed.

But it is not alone with subordinate officers that a commander has to deal. Behind them, and the foundation of it all, is the crew. To his men the commanding officer should be Prophet, Priest, and King! His authority when off shore being necessarily absolute, the crew should be as one man impressed that the Captain, like the Sovereign, ”can do no wrong!"

This is the most delicate of all the commanding officer’s obligations. No rule can be set for meeting it. It must ever be a question of tact and perception of human nature on the spot and to suit the occasion. If an officer fails in this, he cannot make up for such failure by severity, austerity, or cruelty. Use force and apply restraint or punishment as he may, he will always have a sullen crew and an unhappy ship. But force must be used sometimes for the ends of discipline. On such occasions the quality of the commander will be most sorely tried.

You and the other members of the Honorable Committee will, I am sure, pardon me for speaking with some feeling on this point. It is known to you, I presume, to the other gentlemen, your colleagues, that, only a few years ago. I was called upon in a desperate emergency and as a last resort to preserve the discipline requisite for the salvation of my ship and my fever-stricken crew, to put to death with my own hands a refractory and wholly incorrigible sailor. I stood jury trial for it and was honorably acquitted. My acquittal was due wholly to the impression made upon the minds of the jury by the testimony of my crew. . . . I do not reproach myself. But it is a case to illustrate the truth of what I have already said, namely, that the commander should always impress his crew with the belief that, whatever he does or may have to do, is right, and that, like the Sovereign, he “can do no wrong!”

When a commander has, by tact, patience, justice, and firmness, each exercised in its proper turn, produced such an impression upon those under his orders in a ship of war, he has only to await the appearance of his enemy’s topsails upon the horizon. He can never tell when that moment may come. But when it does come he may be sure of victory over an equal or somewhat superior force, or honorable defeat by one greatly superior. Or, in rare cases, sometimes justifiable, he may challenge the devotion of his followers to sink with him alongside the more powerful foe, and all go down together with the unstricken flag of their country still waving defiantly over them in their ocean sepulchre!

22

No such achievements are possible to an unhappy ship with a sullen crew.

All of these considerations pertain to the naval officer afloat. But part, and often an important part, of his career must be in port or on duty ashore. Here he must be of affable temper and a master of civilities. He must meet and mix with his inferiors of rank in society ashore, and on such occasions he must have tact to be easy and gracious with them, particularly when ladies are present; at the same time without the least air of patronage or affected condescension, though constantly preserving the distinction of rank.

It may not be possible to always realize these ideas to the full; but they should form the standard, and selections ought to be made with a view to their closet approximation.

In old established navies like, for example, those of Britain and France, generations are bred and specially educated to the duties and responsibilities of officers. In land forces generals may and sometimes do rise from the ranks. But I have not yet heard of an Admiral coming aft from a forecastle.

Even in the merchant service, master mariners almost invariably start as cabin apprentices. In all my wide acquaintance with the merchant service I can now think of but three competent master mariners who made their first appearance on board ship “through the hawse-hole,” as the saying is.

A navy is essentially and necessarily. True as may be the political principles which we are now contending, they can never be practically applied or even admitted on board ship, out of port or off soundings. This may seem a hardship, but it is nevertheless the simplest of truths. Whilst the ships sent forth by the Congress may and must fight for the principles of human rights and republican freedom, the ships themselves must be ruled and commanded at sea under a system of absolute despotism.

I trust that I have now made fairly clear to you the tremendous responsibilities that devolve upon the Honorable Committee of which you are a member. You are called upon to found a new navy; to lay the foundations of a new paper afloat that must some time, in the course of human events, become formidable enough to dispute even with England the mystery of the ocean. Neither you nor I may live to see such growth. But we are here at the planting of the tree, and maybe some of us must, in the course of destiny, water its feeble and struggling roots with our blood. If so, let it be so! We cannot help it. We must do the best we can with what we have at hand!

--------------------------------------

Extracted from Augustus C. Buell’s Paul Jones: Founder of the American Navy, Vol. 1, pp. 32-37 (New York, 1901).

Buell prefaced the letter by relating that “On the subject of personnel Jones addressed the committee in the form of a letter to Joseph Hewes. At the outset he said, personally, to Mr. Hewes: ‘I choose this form of communication partly because I can write with more freedom in a personal letter than in a formal document, and partly that you may have opportunity to use your judgment in revision before laying it before the Honorable Committee. Please, therefore, use all, or any part, or none of it, as your judgement may dictate.’ ‘ ‘

23

APPENDIX 2

A Plan for the Regulation and

Equipment of the Navy drawn up at

the Request of the Honorable the

President of Congress

Philadelphia 7th April 1777

Let a dockyard be Established at the most convenient and defensible Port within the Four Eastern States. Let another be Established at a proper Place, within the five middle States, and a third at a proper Place within the Four Southern States. Let the Navy be formed into three division, one Squadron to Rendezvous at each dockyard. Let a principal Commissioner, a Surveyor, a Treasurer and deputies if necessary with Clerks and Storekeepers &ca. be appointed for each dockyard.

Let it be the duty of the Commissioners to superintend the Building, Repair, Alteration, Victualling, Payment and Outfit of all Ships of War, let it be their duty to provide, and have in constant readiness sufficient Quantities of Provision, Anchors, Cables, Masts, yards, Sails, Rigging, Warlike, and Naval Stores, Slops, and all manner of Articles which are necessary for the speedy Equipment of Ships of War, let it be their duty to examine Warrant Officers and to recommend them to the Board of Admiralty, let it also be their duty to inspect into the state and Condition of each Ship as soon as she arrives in Port, and to call the Warrant Officers to account for the Expenditure of the Stores of heir respective departments, these Officers ought to make good all Wastage or Embezzelment.

Let it be the duty of any Continental Agent to Import such Articles as the Commissioners may direct for the use of the Navy, let it be their duty to Supply Ships of War when in Ports at a distance from the dockyards with such Stores and Articles as may be wanted, to enable the Agents to do this with conveniency and dispatch, let them have in constant readiness at some of the best outposts certain Quantities of such Articles as the Commissioners may Judge necessary, let it also be the duty of any Agents to Muster the Ships Company when in Port, and make return to the Commissioners on Oath.

Let all the Commissioners meet at Philadelphia, and hold a general Conference once a year, leaving deputies or Clerks to carry on the Business in their absence, let it then be their duty to settle all accounts, with the Board of Admiralty, or such Person or Persons as the board shall think fit to appoint, to whom they are always to be accountable for every part of their Conduct , let it be their duty to lay before the board, or whom the board may appoint the true State and condition of each Ship, of each dockyard, and of all Stores; to point out past Errors, and future Improvements, in the Construction of Ships, dry docks, Hulks, &ca. to suggest necessary institutions in the Marine department, and to furnish hints to Form a clear line of duty for each of the Navy warrant officers.

25

The principal Commissioner ought to be a steady Man of business, a Seaman, and compleat[sic] Mechanic, well skilled, in all respects, in the Construction, and Equipment of Ships of War, it will naturally be his duty to inspect the Conduct of the Surveyor and Treasurer.

The surveyor ought to be a Shipwright, a Man of great Activity and of sound Judgement, well acquainted with the qualities, and Properties of Ships of War, as well as all their materials and Stores.

The treasurer ought to be a Man of Business, & a complete Merchant, the purchase of Provision, and Ships &ca. as well as the Payment of the Men might Fall under his direction.

The authority of the Commissioner must by no means extend to the destination of Ships, or their internal Government, it being their Province only to keep the Navy in fit order for Sea service, and it being the Province of Commanders in the Navy to govern their Ships according to the Rules and Regulations established by the supreme Power of Congress, and to follow the Instructions which they may receive from the board of Admiralty, or their deputies, or from Senior or Flag Officers, consequently Commanders of Squadrons, or of single Ships have a right to call on the Commissioners or Agents for supplies, whenever hey are in want of them, being always accountable to Senior Officers in their division for their Conduct, but more especially so to the Board of Admiralty,

As the extent of the Continent is so great that the most advantageous Enterprise may be lost before Orders can arrive within the Eastern and Southern districts from the board of Admiralty, it will perhaps be expedient to appoint deputies for executing the Office of High Admiral, within these extreme districts to continue in Office only during Pleasure, and at all times accountable to the Board of Admiralty, Perhaps one Deputy to the Eastward, and another to the Southward may be found equal to the Business but the number in each department ought not to exceed three, they ought to be Men of inviolable Secrecy, who inherit much discernment and Segacity, and are endowed with consummate Knowledge in Marine affairs, besides pointing out proper Services for single Ships, and for Squadrons, it may be the duty of the deputies, with the assistance of three or more of the most Judicious Commanders of the Fleet, who may be named by the board of Admiralty to examine the abilities of Men, who apply for Commissions, and make report to the Board; also to examine divers Persons who now bear Commissions in the Service, and whose Abilities, and Accomplishments are very suspicious and uncertain, the board may do the same within the middle district, and by this means, the Navy will at a Period not far distant be Officered by Gentlemen and Men of Sense, instead of Men of no Education, with limited Capacities, whom nature never intended for a Rank superior to that of Boatswain.

It may also be expedient to establish an Academy at each dockyard, under proper Masters whoe’s duty it should be to Instruct the Officers of the Fleet, when in Port in the Principles, and Application of the Mathematicks, drawing, Fencing, and other manly Arts and Accomplishments.

It will be requisite that young Men serve a certain term in quality of Midshipmen, or Masters mate before they are examined for Promotion.

And the necessity of Establishing an Hospital near each dockyard, under the care of Skilful Physicians is self evident.

Jno P Jones

26

___________________________

John Paul Jones advocated a variety of naval reforms in letters to a number of correspondences, but this “Plan” is his only formal statement of recommendations. In 1779 he described the circumstances that led him to write it:

“The President of Congress [John Hancock] told me that as the Regulations of the Marine was [sic] then under Consideration I would be of Service if I would give in Writing the outlines of my Ideas on a Navy System. This I did with great pleasure.... “

There are signed copies of the plan in the manuscript collections of the American Philosophical Society and the Library of Congress. The Charleston [South Carolina] Library Society has a partial copy which is not signed by Jones but which is docketed in his hand. This transcription is made from the American Philosophical Society copy. For a transcription of the Library of Congress copy which has minor differences in capitalization and punctuation see Clark and Morgan, eds., Naval Documents of the American Revolution, VII, 288-289.

*Jones to the President of Congress, 7 December 1779, R.G. 360: Papers of the Continental Congress. Item 168: Letters and Papers of John Paul Jones, vol. II, 116, National Archives.

APPENDIX 3

Extract From

John Paul Jones to Robert Morris

Sir,

It is custom of Nations on the return of Peace to Honor, Promote, and Reward such officers as have served through the War with the greatest “zeal prudence and intrepidity.” And since my Country has, after an eight years War, attained the inestimable blessing of Peace and the Soverignty of an extensive Empire I presume that, as I have constantly & faithfully served through the Revolution & at the same time supported it in a degree wit my Purse, I may be allowed to lay my grievances before you, as the Head of the Marine. I will hope, Sir though you to meet with redress from Congress...