The Navy Department Library

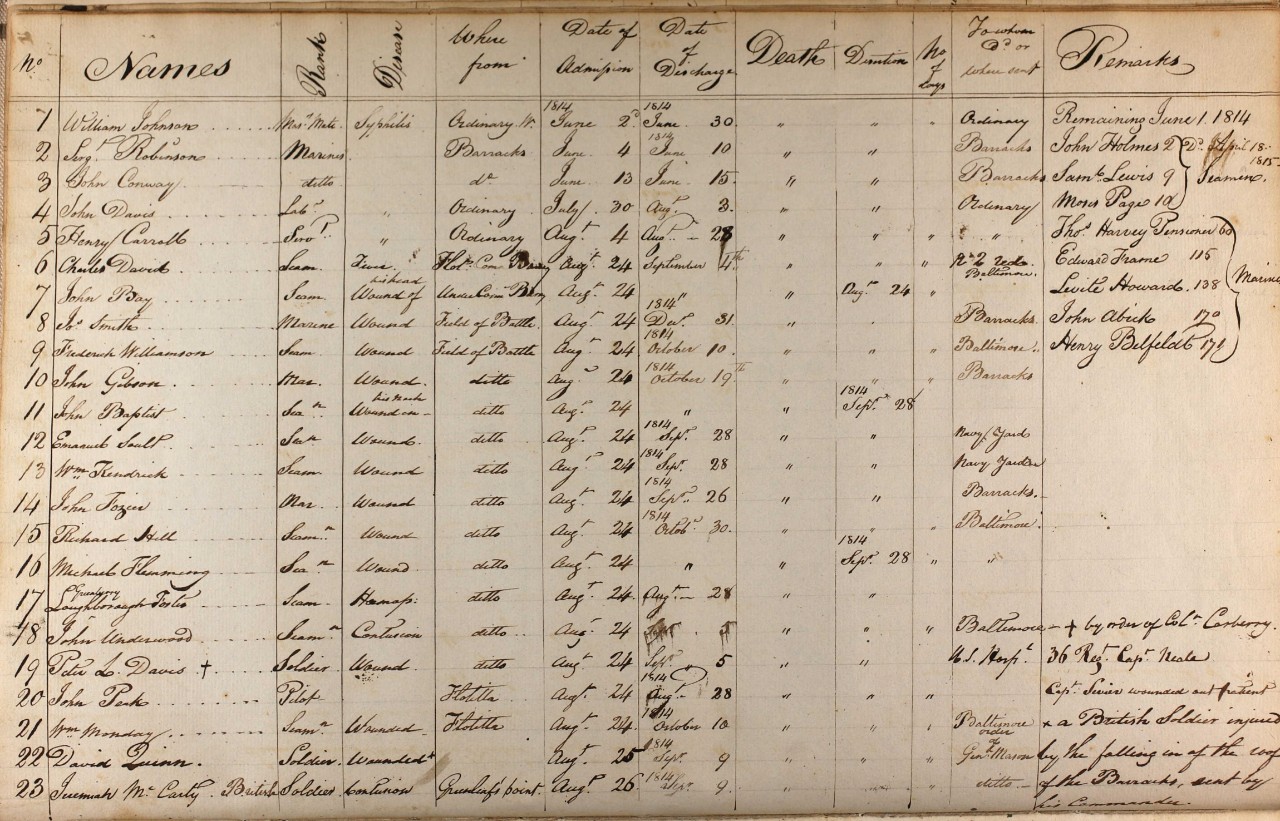

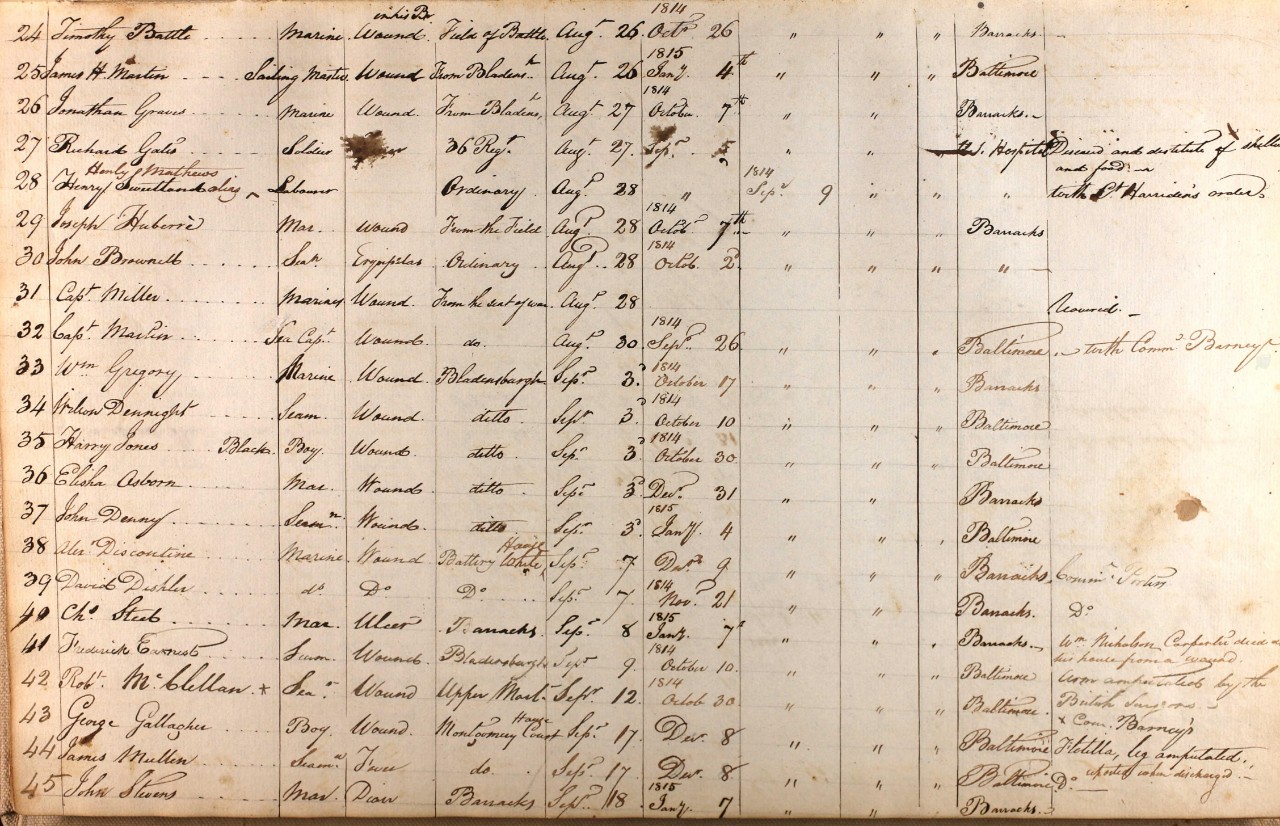

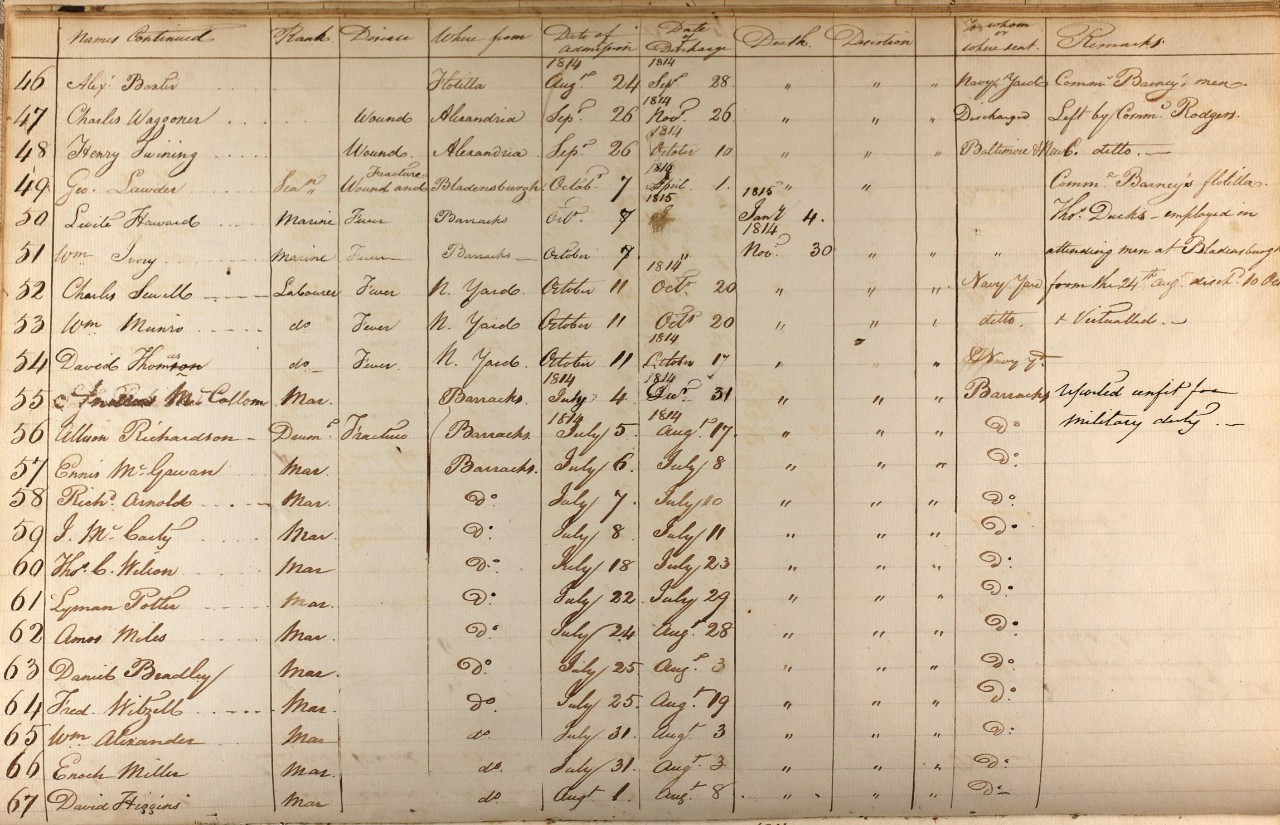

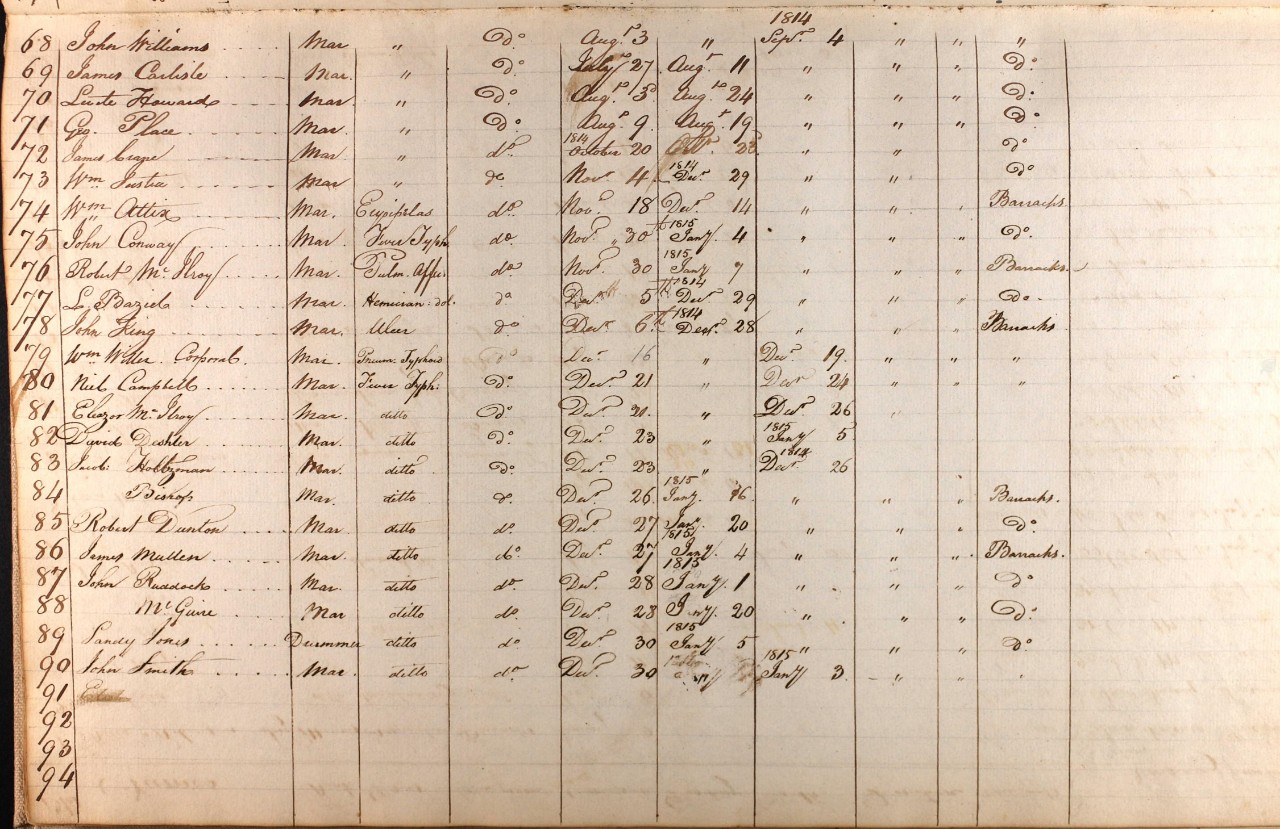

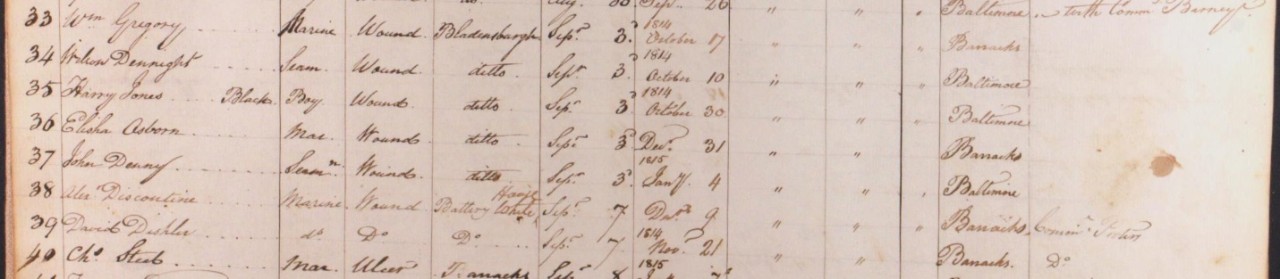

Register of Patients at Naval Hospital Washington DC 1814

With The Names of American Wounded From The

Battle of Bladensburg

Transcribed with Introduction and Notes by John G. Sharp

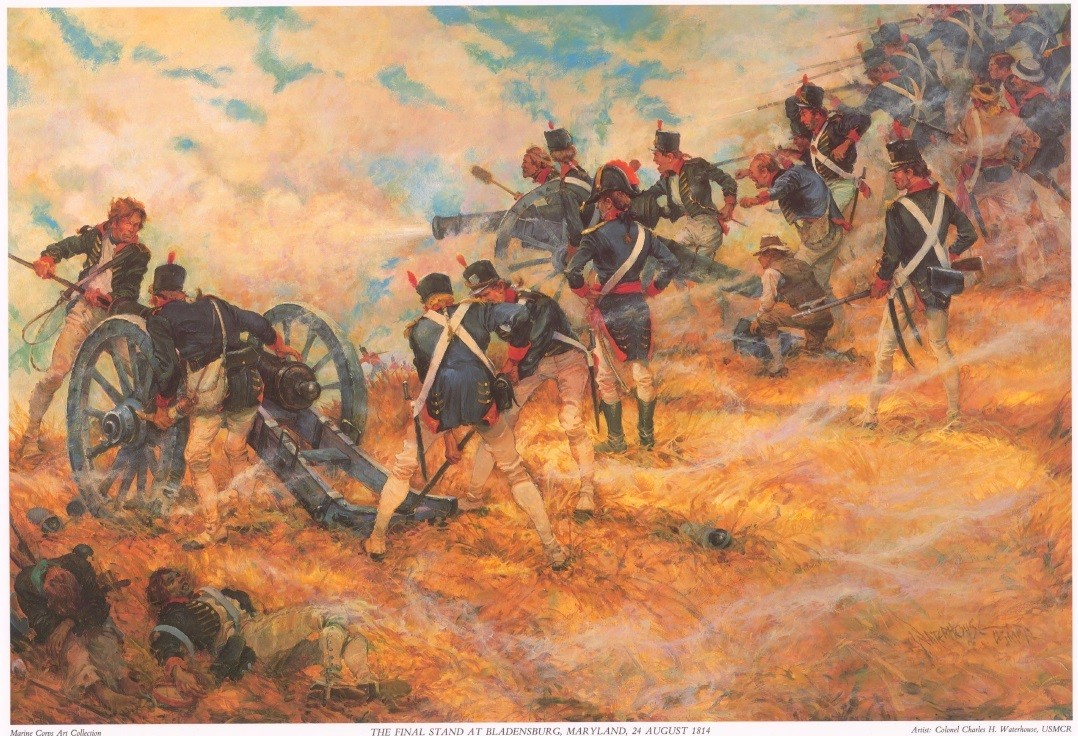

On 24 August 1814 following the British defeat of American forces at Bladensburg Maryland, the Naval Hospital, Washington DC, served as the main treatment center for many American and a few British casualties. At Bladensburg the American forces were made up largely of raw militia who had never seen combat or squeezed a trigger. By contrast the well trained British regulars had been hardened by years of victories under Lord Wellington in Spain. The British by superior discipline and tactics quickly drove the poorly trained militia into a panicked and hasty rout back into the city.1 The American collapse was quickly followed by the British capture of Washington; for the Americans Bladensburg was a catastrophe.2 Toward late afternoon that hot and humid August day, the first carts with seriously injured troops and the walking wounded made their way to the naval hospital and private residences. Many of the injured seamen and marines were suffering from gunshot and shrapnel wounds. The 1814 Register of Patients at the Naval Hospital, Washington DC enumerates ninety patients; of these eighty-four were military and six civilian. Thirty-three of the incoming patients recorded in August and September were American seamen, soldiers, and marines wounded at Bladensburg or subsequent engagements. One British soldier, Jeremiah McCarthy (no.23.), was also treated at the hospital for a contusion. That August, while the various wards quickly filled with battle causalities, the majority of patients were suffering from a variety of non-combat ailments such as fractures, concussions, typhoid fever, venereal diseases, and ulcers.

The 1814 register provides a unique glimpse of the aftermath of battle and a record of the lives of individual sailors, marines, soldiers, and civilians from their admission to discharge. Naval regulations required all hospitals and ships afloat to keep a register of patients. Today this register, which covers the period 2 June to 30 December 1814, is one of our most important primary sources for the names and units of American casualties at Bladensburg. For modern historians the register is an overlooked source as it remains one of the few documents in which the names of the enlisted wounded are enumerated. Scholars differ significantly as to the exact number of battle casualties. Due to wartime conditions, the dead and wounded were only haphazardly recorded and many documents lost or destroyed. The exact number of casualties may never be known, though one recent estimate concludes the British suffered 64 dead and 185 wounded, while the American losses are given as ten to forty killed, forty wounded, and one hundred captured.3 The majority of those wounded were first treated on the field of battle. This register denotes two such instances: Frederick Ernest, Seaman (no.41), and George Gallagher, Boy (no. 43). Both sailors endured amputations in the field. Ernest arm was amputated by the British surgeon at Bladensburg while Gallagher’s leg was removed. The designation “Boy” in the early United States Navy was given to young enlisted men 12 to 18 years of age who served as seaman. Most “Boys” were usually rated Ordinary Seaman at age 18.

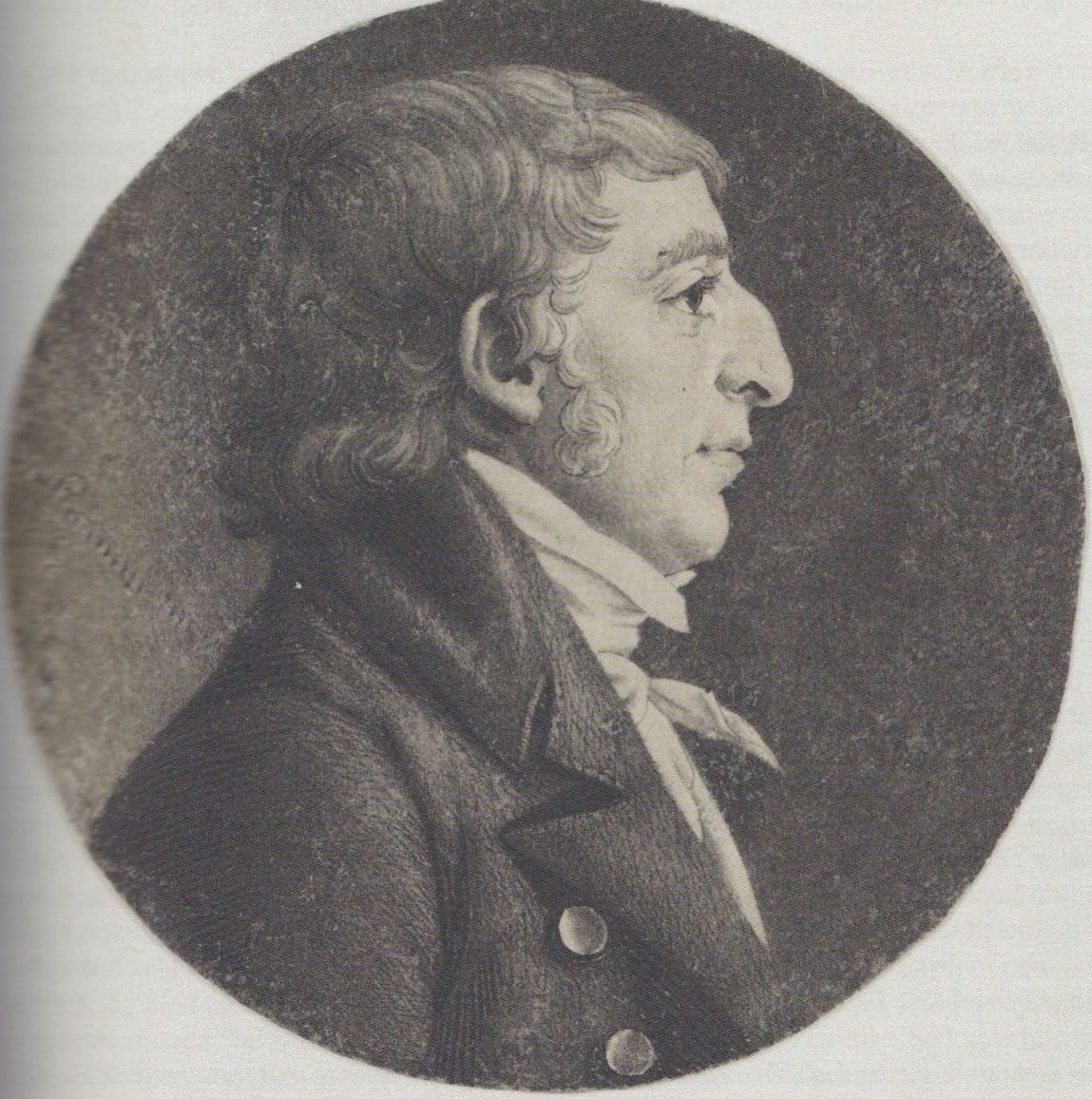

Bladensburg was one of the worst days for American arms, though a few units and individuals performed heroic service. Notable among them were Commodore Joshua Barney‘s 500 sailors and the 120 marines under Captain Samuel Miller (31), who inflicted the bulk of British casualties and were the only effective American resistance during the battle.4 Barney's men, with two 18-pounder guns and three 12-pounder guns drawn from the Washington Navy Yard, were posted astride the Washington turnpike. Civilians from navy yard volunteered too, among them was master blacksmith Benjamin King who accompanied Miller’s Marines into battle. King took charge of a disabled gun, and was instrumental bringing that gun into action.

Captain Miller remembered King’s gun “cut down sixteen of the enemy.”5 Charles Ball, an enslaved man who had formerly worked in the navy yard, and fought with Commodore Barney, recalled:

I stood at my gun, until the Commodore was shot down, when he ordered us to retreat, as I was told by the officer who commanded our gun. If the militia regiments, that lay upon our right and left, could have been brought to charge the British, in close fight, as they crossed the bridge, we should have killed or taken the whole of them in a short time; but the militia ran like sheep chased by dogs.6

Ball was not alone, for Barney’s flotilla group included numerous African Americans who provided artillery support during the battle. Prior to the battle, Barney on being asked by President James Madison “if his negroes would not run on the approach of the British?” replied: “No Sir…they don’t know how to run; they will die by their guns first.”7

The Commodore was correct, the men did not run, and a large part of his men were in fact killed or wounded. Barney a veteran of the American Revolution led by example though age fifty-five; he refused to retreat and was severely wounded with a bullet lodged deep in the thigh that surgeons were unable to extract. Commodore Barney and Captain Miller’s steady example gave their men courage and resolve. One such man was sailor Harry Jones (no.35), apparently a free black who was also wounded in the final action at Bladensburg. Due to the severity of Jones wounds, he remained a patient at the hospital for nearly two months.

African Americans like Charles Ball and Harry Jones, played a significant role in the American war effort, modern estimates place the number of black sailors serving in the War of 1812 at 15-20 % of naval manpower.8

Despite such courageous action the battle was a shattering defeat and quickly over. Most of the American militia simply fled the field with no destination in mind, or deserted the ranks to see to the safety of their families. African American diarist Michael Shiner 1805 -1880 detailed the general panic he witnessed as a nine year old, living near East Capitol Street. Shiner wrote:

[The Americans] fled in confusion and they had ceased firing at Blades Barge [Bladensburg] and At that time the Americans wher flying through the City comerder [Commodore] Barnney were taken prisoner and colnal samul Miler [Samuel Miller] then the British Armmy taken up ther line of march for Washington wher a number of the British soldiers felled in their ranks on the way to Washington from Blades Barge by the loss of blood Between the eastern toll gate and Blades Barge the British solders fell in holes to the right and left and still the British armmy continued the march on Washington.9

The last act of the battle was fought at close quarters with bayonets, pistols, and swords.

A final desperate Marine counter attack was not enough; Barney and Miller’s forces were overrun. In all out of the total of 114 Marines, 11 were killed and 16 wounded. Most of those listed in the register as wounded at Bladensburg probably suffered shrapnel or gunshot in this climatic moment of battle. British Admiral Sir George Cockburn later on surveying the field, complemented Barney for his courage, paroled him and bought him into Bladensburg for medical care on a litter. Captain Samuel Miller (31) whose arm was badly wounded was quickly paroled and bought to the naval hospital for treatment where he remained from August 28, 1814 to September 9, 1814. Barney on 29 August 1814 reported:

I received a severe wound in my thigh, Capt. Miller was wounded, Sailing Master Warner Killed, act. Sailing Master Martin killed & sailing Master Martin [James H. Martin (no. 25) ]wounded... Three of my officers assisted me to get off a Short distance - but the great loss of blood occasioned such a weakness that I felt compelled to lie down. I requested my officers to leave me, which they obstinately refused, but being Ordered they obeyed, only one remained.10

For his gallant service in this action, Miller was brevetted to the rank of Major.

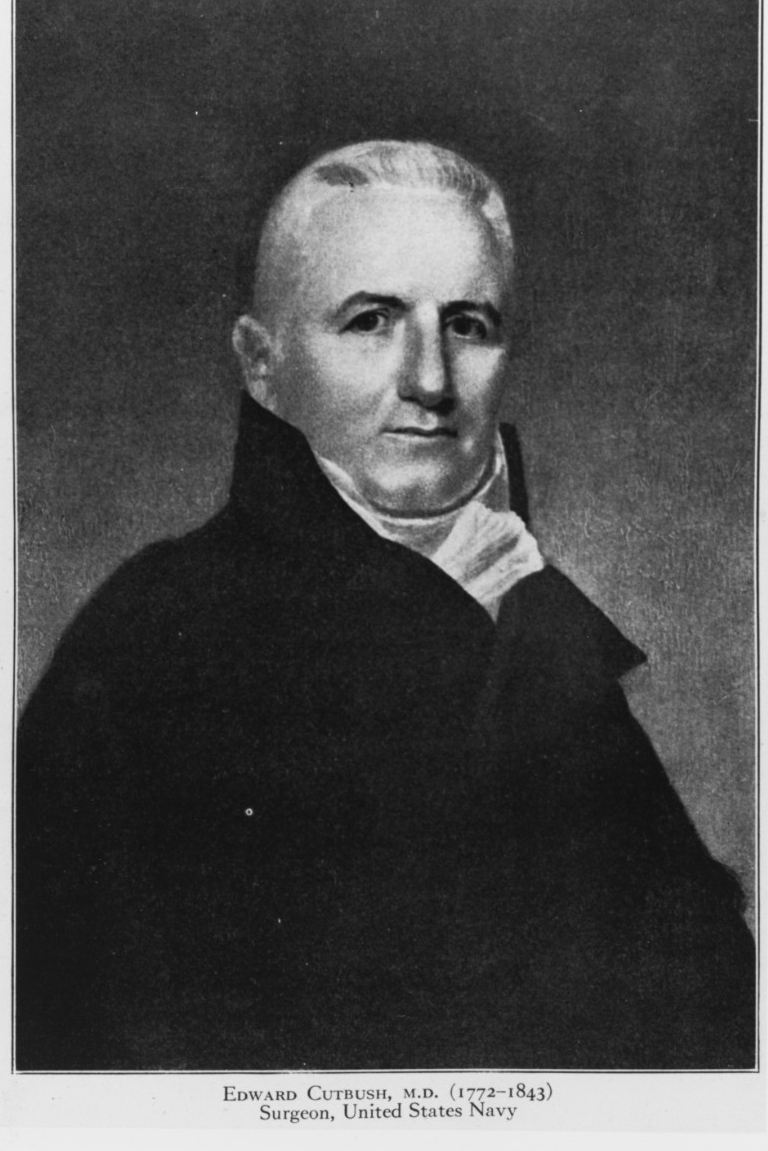

In 1814, the Naval Hospital Washington was still a makeshift affair, occupying a building near the corner of Pennsylvania Avenue and 10th Street, Northwest Washington DC. Navy had rented the building in 1812 at $200 per annum. This first hospital was probably a three story brick house, build in the federal style with most rooms utilized as wards and a small apothecary shop on the ground floor.11 No records survive of how this naval hospital was staffed. In his published writings, however, Dr. Edward Cutbush recommended each naval hospital have at least one physician/surgeon, one assistant surgeon, one steward to act as purser for supplies, one assistant steward to act as ward master, a number of nurses, a cook, a laundress and a guard. Due to the number of patients with serious battle wounds and injuries during August and September 1814, it is likely the staff was supplemented by other medical practitioners. From its inception the Naval Hospital Washington’s chief mission was the treatment of sailors and marines. To this the Secretary of the Navy on 23 May 1813 specifically directed that treatment and care be extended to: “…Master or laboring Mechanic or common laborer employed in the navy yard shall receive any sudden wound or injury, while so employed in the Yard; he shall be entitled to temporary relief.” The Secretary then further directed slaves employed in the navy yard similarly be afforded medical attention, with “a reasonable compensation [from the slaveholder] for such medical and hospital aid he may receive …”12

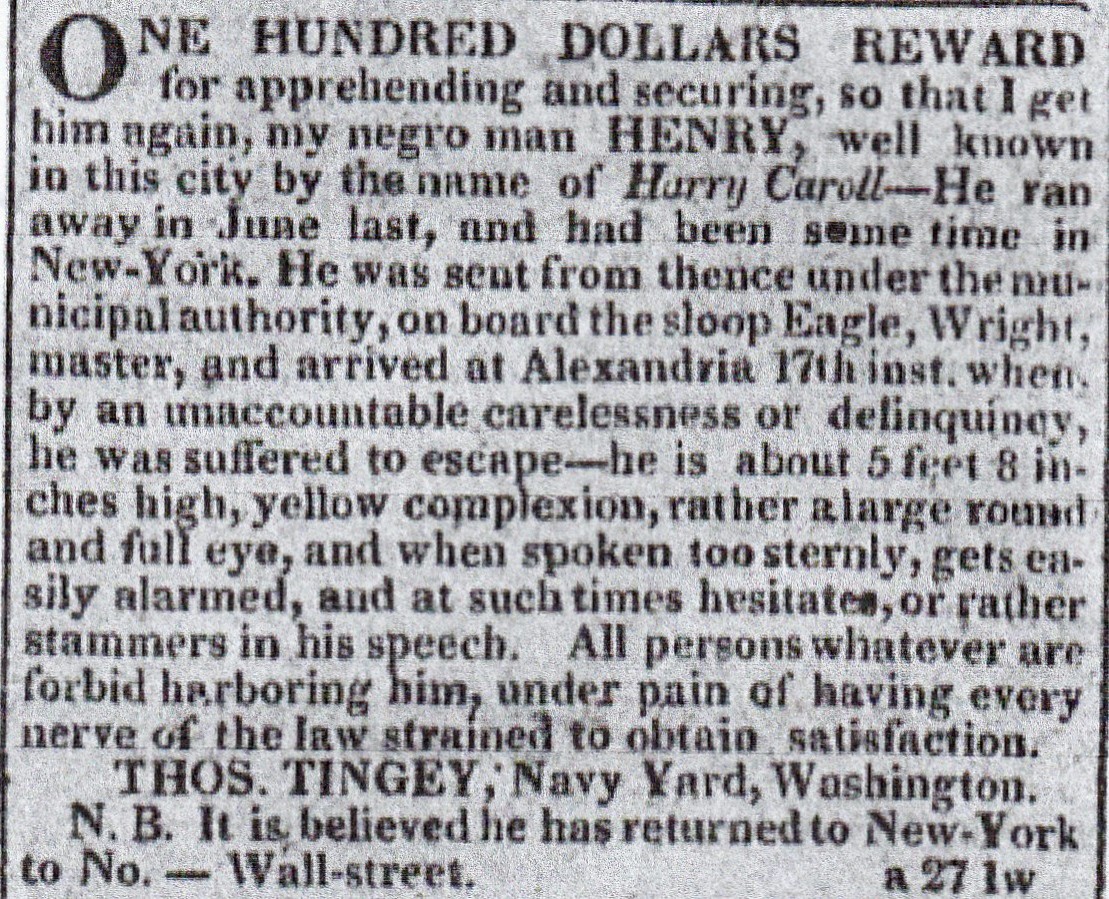

The 1814 Register of Patients provides the names of wounded officers and enlisted men, their rank, unit, the nature of their injury or illness, the date admitted, and date of discharge. Recorded in the remarks column is the outcome of each patients stay at the hospital, with the date of their discharge or death. In the same record some civilian navy yard workers are listed, among them Commodore Thomas Tingey’s enslaved black “Servant,” (no.5) Henry Carroll.13 In early records servant was a common euphemism for slave. However other documents confirm in June 1817 Henry Carroll aka Harry Carroll made a bold bid for freedom and that he escaped to New York City. Carroll’s capture in New York and subsequent his second escape in 1818 while being held in Alexandria Virginia and later recapture is established for his name is again listed on an August 1827 entry in the register as “Commodore’s Servant”.

As the British troops marched into Washington, the Americans were in full retreat and holding the navy yard became impossible. At the navy yard, Commodore Tingey, in compliance with orders to prevent capture of stores and ammunition, set off a gigantic blaze that consumed most structures and several vessels.

Sailors, employees, and newly arrived hospital patients saw the inferno. Mary Stockton Hunter, an eyewitness to the vast conflagration wrote her sister:

Our important Navy –Yard was yet to be destroyed by our own hands – the most suicidal act ever committed. No pen can describe the appalling sound that our ears and the sight our eyes saw. We could see everything from the upper part of our house as plainly as if we had been in the Yard. All the vessels of war on fire-the immense quantity of dry timber, together with the houses and stores in flames produced an almost meridian brightness. You never saw a drawing room so brilliantly lighted as the whole city was that night.14

Although the hospital was located near the ship yard main gate, the wounded and sick remained safe throughout the brief British occupation, however, it was likely they had tense moments as they heard the explosions, smelled the smoke, and saw the navy yard ablaze. Despite the war, both sides generally respected hospitals and afforded care to the enemy wounded. Patients at the Naval Hospital were fortunate; Dr. Edward Cutbush 1772-1843, an experienced and energetic naval surgeon had recently transferred from Philadelphia to the Washington Naval Yard and was granted charge and direction of the: “Marine and Navy Hospital establishment and of the medical and hospital stores, which may from time to time be required for the use of the hospitals, or for the vessels of the United States equipped at this place.”15

Dr. Cutbush’s appointment to Washington DC was based on his long familiarity with hospital administration. A decade earlier he established the first naval hospital in 1804 in Syracuse, Sicily, to support fleet medical needs in the Barbary War. In his well-regarded 1808 text, Observations on the means of Preserving the Health of Soldiers and Sailors, Cutbush stressed sanitation in naval hospitals and ships. He recommended they be kept clean and orderly and all patients regularly washed and bathed. His practice emphasized rigorous cleaning, disinfecting, and ventilating hospitals and ships. For August 1814 the hospital register lists a monthly purchase of 12 lbs. of soap and vinegar, presumably for cleansing both patients and wards. Cutbush encouraged “the wards be kept as sweet and clean as possible” by frequent white washing with lye, potash and water. In his text he recommended the naval diet contain more vegetables and far less meat. In August 1814 the hospital purchased 324 ½ lbs. meat, 48 lbs. corn meal and 92 lbs. of vegetables probably reflecting the preference both patients and staff. The hospital records for that month show procurement of small amounts of whiskey and brandy possibly for use medicinally when mixed with opiates as laudanum. For illumination the hospital patients and medical staff relied on candlepower, ordering on average 12 lbs. of candles per month.

In his practice Dr. Cutbush specified the need for strict physical examinations of all recruits and patients. He continually reiterated that to eliminate infection, sailors and marines needed to wear their hair short, shave regularly, and wash themselves and their clothing.

Long before the germ theory of disease Dr. Cutbush stressed basic hygiene in all naval hospitals:

- Every patient on entering the hospital shall be washed, his linen shifted and hair combed.

- No dirty clothing or bedding shall be brought into any of the wards; but shall be deposited in the washhouse to be cleansed.

- The hands and face of every patient shall be washed, and the hair combed every morning; the feet shall also be occasionally washed.

- Every patient shall be shaved three times a week, viz. on Sunday, Tuesday and Friday; and shall change his linen as often as may be thought necessary.

- No person shall spit on the floors or walls of the hospital; but must endeavor to keep the house as clean as possible. No smoking of tobacco shall be allowed in the wards.

- No spirituous liquors shall be brought into the hospital on any pretense whatever. Every person who may be found intoxicated shall be punished.16

Notwithstanding these efforts, the real danger which lurked within the close confines of all nineteen century hospitals was infectious disease. One of the most virulent was typhoid fever or “Prussian Typhoid” transmitted to humans via bacterial infection. Typhoid first manifests as fever, stomach pains, headache, and a rash for many deaths usually followed within a one or two weeks. The movement of the disease was rapid. In late November 1814 typhoid fever struck the Marine Barracks in Washington DC hard; thirteen patients, all young Marines, were diagnosed with typhoid. A month later six of these young men had died. The disease quickly spread, and on 15 April 1815 the National Intelligencer of Washington DC wrote of typhoid like “epidemic” within the District of Columbia. During the War of 1812, the United States suffered 2,200 men killed in action or of wounds, while infectious disease, especially typhoid killed 13,000 Americans. Caused by bacterial infection, the disease is typically spread by poor hygiene and unsanitary conditions, such as contaminated food and water. In 1814, this swiftly moving disease with a high mortality was poorly understood as was its microbial origin. Medical isolation within the small confines of the naval hospital was simply impossible. Before antibiotics, the standard medical response of the era was bleeding and purging the patient with emetics. Typhoid epidemics again struck Washington in 1832, 1849, and 1866.17

A seamen’s life was hard, especially during wartime. Scholar Christopher McKee found that “desertion was a most serious problem for the pre-1815 navy.” McKee notes desertion was both a problem and a way of asserting independence often brought on by resentment of the conditions of seafaring life, with liquor frequently the trigger for men to leave. The 1814 register includes three wounded seamen John Bay (no.7), John Baptist (no. 11), and Michael Fleming (no. 16), who apparently had seen enough of war, battle and naval life and chose to desert. Seaman John Bay, suffering from “a wound of his head” deserted a short time after admission to the hospital. After a month in the hospital Seamen Baptist and Fleming deserted together on 28 September 1814, neither was apprehended. On reviewing naval desertion records McKee concludes “Of the hundreds of men who deserted …between 1798 and 1815 only a small fraction were ever caught or punished.”18

During the first three decades of the nineteenth century, the navy yard leased enslaved labor from local civilian and military slaveholders. In accord with the Secretary of the Navy’s direction, emergency medical care was provided to enslaved workers for a range of maladies and on the job injuries. Among these patients Henry Carroll (no.5) listed as “Servant” was in fact enslaved to Washington Navy Yard Commodore Thomas Tingey.19 Three years later, Carroll made a bold though unsuccessful bid for freedom.20

The British occupied Washington for only a few days, during which they burned both the U.S. Capitol and the White House. Following a violent storm and a freak tornado, and with the navy yard embers still smoldering, their army suddenly, and only 26 hours after they arrived, left the city moving toward Baltimore. On the British departure; civilian shipyard laborers like Harry Sweetland aka “Matthews” (no.28), Charles Sewell (no.52), William Munro (no. 53), and David Thompson (no. 54) on their discharge from the hospital wards, returned to their navy yard and saw the destruction was nearly total. This compounded the shock of military defeat, with the utter ruin of their workplace and means of livelihood. They and hundreds of their fellow mechanics and laborers were unemployed. Several of these men had served with the District of Columbia militia at Bladensburg. They had born the battle and were subsequently left with no income, no tools, and faced destitution.

On the navy yard conditions were bleak, architect Benjamin Latrobe reported to Thomas Jefferson:

Since the commencement of the War, the public buildings have afforded no employment … After the irruption of the British; their case was still more deplorable. The numerous mechanics of the Navy Yard were deprived of bread, and it is almost a miracle that many did not die with hunger and cold last winter. The situation of very respectable and once wealthy families has been described to me as inconceivably wretched; from the period of the invasion of the enemy to that of the appropriation for the repair and rebuilding of the public edifices.21

The Treaty of Ghent was signed on Christmas Eve 1814, however unbeknownst to the naval hospital patients due to the lack of effective communications; the treaty ended the War of 1812 between the United States of America and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Only in the New Year would the citizens of Washington DC and the hospital patients learn of the Treaty and the restoration of peace. On 8 January 1815, the recovering soldiers, sailors, and marines listed on this exceptional document, finally heard news of an overwhelming victory at New Orleans. At New Orleans American forces, led by General Andrew Jackson, emerged triumphant. The defeat at Bladensburg and destruction of the navy yard were heavy blows. As the New Year emerged though the nation was sustained by renewed optimism, determination, and resolve. Together in the coming years they would participate in rebuilding their navy yard, their city, and their country.

Transcription: These pages from the 1814 register are transcribed from The Register of Patients Naval Hospitals 1812 -1934 Vol. 45. National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 52 Records of the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery, Field Records Case Files for Patients at Naval Hospitals and Registers, Entry 45. The original manuscript has no pagination but generally is arranged chronologically except where noted. This register was begun 1 June 1813 by Dr. Edward Cutbush M.D. as “Admission Book for the Hospital Department City of Washington.” This transcription was made from photographic images of the register in the collections of NARA. I have striven to adhere as close as possible to the original in spelling, capitalization, punctuation, and abbreviation (e.g. "Do" or "do" for ditto or same as above) including the retention of dashes, superscript, underscores ampersands, and overstrikes. Where I was unable to print a clear image or where it was not possible to determine what was written, I have so noted in brackets. In the register columns, the ward clerks used quote marks frequently to signify a blank or empty space e.g. in the two columns labeled “Death” and “Desertion”. Where possible I have arranged the material in a similar manner to that found in the original register. On the register the entries of names in the right hand column titled “Remarks” do not correspond to the patient names listed as numbers 2-9 in left column. Instead these entries record the names of seamen and marines remaining in hospital as of April 18, 1815, see end note 21. Comments in the remarks column, do not necessarily correspond to patients enumerated in column one and listed in column two, e.g. patient number 40, is Ch[arles] Steel but the remarks column adjacent instead records, “Wm. Nicholson carpenter died at his home of a wound.” William Nicholson is not listed in the 1814 register as a patient. Likewise patient number 50 is Levite Howard however the remarks column adjacent Howard’s name refers to “Thos Ducks – employed in attending men at Bladensburgh [Bladensburg] from the 24th Augt…” Thomas Ducks is otherwise unknown and is not further listed in the register.

All August 1814, expenditures cited for hospital stores are derived and transcribed from the quarterly expenditures appendixes within The Register of Patients Naval Hospitals 1812 -1934 Vol. 45.

Click on the photographs below to see a transcribed list of patients with notes.

Appreciation: My gratitude to Andre B. Sobocinski Historian Naval Hospital, Bureau of Medicine and Surgery for his help with the location of the naval hospital in 1814. My thanks also to the wonderful staff of the Navy Department Library; they are all truly Sine qua non.

Dedication: To the memory of Corporal William Joseph Haden Jr. 4th Marine Division, USMC WWII - Semper fi.

John G. M. Sharp, May 2018

NOTES

All entries and discharge dates for U.S. Marine Corps enlisted personnel in the War of 1812 were taken from National Archives and Records Administration. Muster Rolls of the U.S. Marine Corps, 1798-1892. Microfilm Publication T1118, 123 rolls and Records of the U.S. Marine Corps, Record Group 127; National Archives in Washington, D.C. U.S. Marine Corps Muster Rolls, 1893-1958. Microfilm Publication T977, 460 rolls. All Naval and Marine Corps officer data is from Officers of the Continental and U.S. Navy and Marine Corps 1775 -1900 Naval History and Heritage Command http://www.history.navy.mil/books/callahan/reg-usn-c.htm

1. Anthony S. Pitch, The Burning of Washington The British Invasion of 1814, (Naval Institute Press: Annapolis 1997), 72-85 and Alan Taylor The Internal Enemy Slavery and War In Virginia, 1772 -1832 (WW Norton & Company: New York, 2013), 300-301. Architect Benjamin Latrobe writing to John Mason on 17 July 1807 observed, “Upon the whole I find that the Navy Yard cannot produce a single good rifleman.” Latrobe goes onto confide the mechanics of the navy yard had no leisure time in which to practice and recommended they better “organize themselves into a Company of Artilerists…” See The Correspondence and Miscellaneous Papers of Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Volume 2, 1805-1810, John C. Van Horne editor, (Yale University Press: New Haven, 1986), 453-454.

2. David Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848, (Oxford University Press: New York), 64.

3. David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler, Encyclopedia of the War of 1812, (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press: Annapolis 1997), 56.

4. Robert S. Quimby, The U.S. Army in the War of 1812 An Operational and Command Study Vol.1 (Michigan State University Press: East Lansing, 1997), 657.

Donald R, Hickey, editor, The War of 1812 Writing from America’s Second War of Independence. (The Library of America: New York 2013), 736.

5. Letter of Samuel Miller to James Madison, April 20, 1836. Captain Miller was Benjamin King’s commanding officer at Bladensburg; and states King, took charge of disabled gun and was instrumental bringing the gun into action assisting the gun crew “cut down sixteen of the enemy.” See Library of Congress, The James Madison Papers accessed at: http://lcweb2.loc.gov/ammem/collections/madison_papers/ For Benjamin King 1764-1840 see The Diary of Michael Shiner Relating to the History of the Washington Navy Yard 1799 -1869, John G. Sharp editor, Naval History and Heritage Command, 2015, p.18 note 18. https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/d/diary-of-michael-shiner/1813-1829.html

6. One of the best accounts is that Charles Ball born 1785. Ball served with Commodore Barney’s flotilla and later recounted his life in Slavery in the United States: A Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Charles Ball, a Black Man, Who Lived Forty Years in Maryland, South Carolina and Georgia, as a Slave Under Various Masters, and was One Year in the Navy with Commodore Barney, During the Late War (New York: John S. Taylor, 1837). Ball served at the Battle of Bladensburg and later helped man the defenses at Baltimore. In his 1837 memoir, Ball reflected on the Battle of Bladensburg: “I stood at my gun, until the Commodore was shot down… if the militia regiments, that lay upon our right and left, cold have been brought to charge the British, in close fight, as they crossed the bridge, we should have killed or taken the whole of them in a short time; but the militia ran like sheep chased by dogs.”

For Commodore Joshua Barney’s force see: Elizabeth Dowling Taylor, A Slave in the White House: Paul Jennings and the Madison’s (Palgrave MacMillen: New York, 2012), 49.

7. Elizabeth Dowling Taylor, A Slave in the White House: Paul Jennings and the Madison’s Palgrave (MacMillan: New York, 2012), p.49. See also Lauren McCormack, “I never had any better fighters:” Black Sailors in the United Sates Navy During the War of 1812 USS Constitution Museum http://www.asailorslifeforme.org/educator/activities/Black-Sailors-in-the-US-Navy-1812-Meet-the-Crew-War-of-1812-Resources-African-Americans.pdf

8. Many African Americans served as members of Commodore Barney's naval flotilla force. This force provided crucial artillery support during the battle. British commanders noted the effectiveness of Barney's unit, see University of Maryland http://www.lib.umd.edu/bladensburg/reputation-ruined/battle-of-bladensburg. For the estimate of 15 -20 %, of sailors as black in the War of 1812 see; Charles E. Brodine, Michael J. Crawford and Christine F. Hughes, editors, Ironsides! The Ship, the Men and the Wars of the USS Constitution (Fireship Press, 2007), 50.

African Americans also fought on the British side with the British Colonial Marines in the attacks on Bladensburg and Washington DC. In 1813 Rear Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane formed the Corps of Colonial Marines. Cochrane deliberately recruited enslaved blacks with a promise of freedom for themselves and their families. These new black troops received the same training, uniforms, pay, and pensions as their Royal Marine counterparts. See William S. Dudley, editor The Naval War of 1812: A Documentary History Volume II. (Naval Historical Center: Washington, DC 1992), 324-325. British commanders later stated the new marines fought well at Bladensburg and confirm that two companies took part in the burning of Washington including the White House. Following the Treaty of Ghent, the British kept their promise and in 1815 evacuated the Colonial Marines and their families to Halifax Canada and Bermuda. See Alan Taylor The Internal Enemy Slavery and War In Virginia. 1772 -1832, (WW Norton & Company: New York, 2013), 300-305 and Appendix B.

9. The Diary of Michael Shiner Relating to the History of the Washington Navy Yard 1799 -1869, John G. Sharp editor, Naval History and Heritage Command, 2015, 6. https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/d/diary-of-michael-shiner/1813-1829.html

10. Michael J. Crawford, Christine F. Hughes, Charles E. Brodine, Jr., and Carolyn M. Stallings editors, The Naval War of 1812: A Documentary History Vol. III, 1814-1815, Chesapeake Bay, Northern Lakes, and Pacific Ocean, (Washington, DC: Naval Historical Center, 2002), 207-208.

Pitch, 82 - 83.

11. The first naval hospital (1811-1843) was established in a rented building near the Washington Navy Yard. Jack Edward McCallum, Military Medicine: From Ancient Times to the 21st Century (ABC: CLIO Inc.: Santa Barbara, CA, 2008), 221. Also see Historical Medical Sites in the Washington D.C. Area US National Library of Medicine https://www.nlm.nih.gov/hmd/medtour/oldnavy.html In 1812 Dr. Edward Cutbush rented a private building at the corner of Pennsylvania Avenue and 10th Street, Northwest Washington DC for use as a naval hospital. The rent was $200 per annum. Email to author 1 Dec 2016 from Andre B. Sobocinski Naval Hospital Bureau of Medicine and Surgery Historian citing article by E. Caylor Bowen. Bowen writes the naval hospital was located at the corner of Pennsylvania Avenue and 10th Street, southeast. This building may have been the very same building the navy used as an apothecary shop in 1802 (Square 948) located at the corner of Pennsylvania Avenue and 10th Street, southeast.

12. William S. Dudley, editor The Naval War of 1812: A Documentary History Volume II. (Naval Historical Center: Washington, DC, 1992), 124.

13. John G. Sharp, African Americans in Slavery and Freedom on the Washington Navy Yard 1799-1865 (Morgan Hannah Press: Concord, 2012), 12, Appendix B.

14. Mary Hunter, “The Burning of Washington, D.C.” New York Historical Society Quarterly Bulletin (1924): pp. 80 – 83 quoting Mary Stockton Hunter to Susan Stockton Cuthbert August 30, 1814.

15. William S. Dudley, editor, The Naval War of 1812: A Documentary History Volume II. (Naval Historical Center: Washington, DC, 1992), 124.

16. Edward Cutbush, Observations On the Means of Preserving the Health of Soldiers and Sailors: And On the Duties of the Medical Department of the Army and Navy: With Remarks on Hospitals and Their Internal Arrangement (Thomas Dobson: Philadelphia, PA, 1808), 207-210. For Dr. Cutbush in Barbary War, see: Andre Sobocinski The Early Years of Naval Hospitals 1804 to the Present, 2014. http://navymedicine.navylive.dodlive.mil/archives/6035

17. National Intelligencer Washington, DC, 15 April 1815, 2. During the War of 1812, the United States suffered 2,200 men killed in action or of wounds, while infectious disease, especially typhoid killed 13,000 Americans. See: Spencer Tucker, James R. Arnold, Roberta Wiener, Paul G. Piepaoli and John C. Frederick Encyclopedia of the War of 1812: A Political, Social and Military History, volume 1, (ABC-CLIO, 2012), 113.

18. Christopher McKee, A Gentlemanly and Honorable Profession the Creation of the Officer Corps, 1794 -1815. (Naval Institute Press: Annapolis, 1991), 248.

19. For the first thirty years of the nineteen century, the navy yard was the Districts principal employer of enslaved African Americans.Their numbers rose rapidly and by 1808, muster lists reflect they made up one third of the workforce.The number of enslaved workers gradually declined during the next thirty years. See:The Diary of Michael Shiner Relating to the History of the Washington Navy Yard 1799 -1869, John G. Sharp editor, Naval History and Heritage Command, 2015, Introduction, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/d/diary-of-michael-shiner/1813-1829.html

Early naval records such as musters and payrolls were created solely for financial purposes. The Department of the Navy, with some noteworthy exceptions (Letter Thomas Tingey to the Secretary of the Navy 25 April 1808) simply had no requirement for an employee’s racial or ethnic background. This makes the exact number of African American (enslaved and free) employed in any given year, is for the most part, extremely difficult to calculate. For 1808 the overall Washington Navy Yard civilian employee population, was 194, of which 64 are specifically enumerated as black, 6 of these individuals are listed as free, see: John G. Sharp, African Americans in Slavery and Freedom on the Washington Navy Yard 1799 -1865 (Vindolanda Press: Concord, CA, 2016 ), 74, and Appendix B. When Tingey purchased Henry Carroll is unclear, though “six slaves were registered in the 1810 census as part of the household.” See Gordon S. Brown, The Captain Who Burned His Ships Captain Thomas Tingey, USN, 1750 -1829, (Naval Institute Press: Annapolis, MD, 2011), 86.

20. In April and May 1818, Commodore Tingey posted the following reward notice for Carroll in newspapers in New York City and Washington DC:

ONE HUNDRED DOLLARS REWARD for apprehending, and securing, so that I get him again, my negro man HENRY, well known in this city by the name of Harry Carroll - He ran away in June last, and had been sometimes in New –York. He was sent from thence by the municipal authorities on board the sloop Eagle, Wright master, and arrived at Alexandria 17th inst. when, by an unaccountable carelessness or delinquency, he was suffered to escape - he is about 5 feet 8 inches high, yellow complexion, rather large round and full eye, and when spoken too sternly, gets easily alarmed; and at such times hesitates, or rather stammers in his speech. All persons whatever are forbid harboring him, under pain of having every nerve of the law strained to obtain satisfaction.

THOS. TINGEY; Navy Yard, Washington

N.B. It is believed he has returned to New -York to No. _ Wall- street.

Mercantile Advertiser. New York, New York 2 May 1818, 4.

Henry Carroll’s subsequent recapture is confirmed in the 1827 Register of Patients at Naval Hospital Washington DC and other naval records. In 1827 register Carroll is enumerated as patient number 60, “Servt to the Commanding Officer” and diagnosed with hepatitis. He remained in hospital from 29 August 1827 to 25 September 1827. Enslaved diarist Michael Shiner (1805 -1880), patient number 58, was also treated that August for a fever. While Carroll is not mentioned in the diary, the two men worked together in the shipyard ordinary. See Muster Book of the U.S. Navy in Ordinary at the Navy Yard Washington City, from 1 January to 31 December, 1826, National Archives and Records Administration Washington DC, Record Group 45, Entry, T829, Miscellaneous Records of the Office of the Navy Records and Library, Microfilm Roll 163: Washington Navy Yard , pp. 49 -50.

21. "Benjamin Latrobe to Thomas Jefferson 12 July 1815," in The Correspondence and Miscellaneous Papers of Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Volume 3, 1811-1820, John C. Van Horne editor, (Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, 1988), 667.

----------

[END]