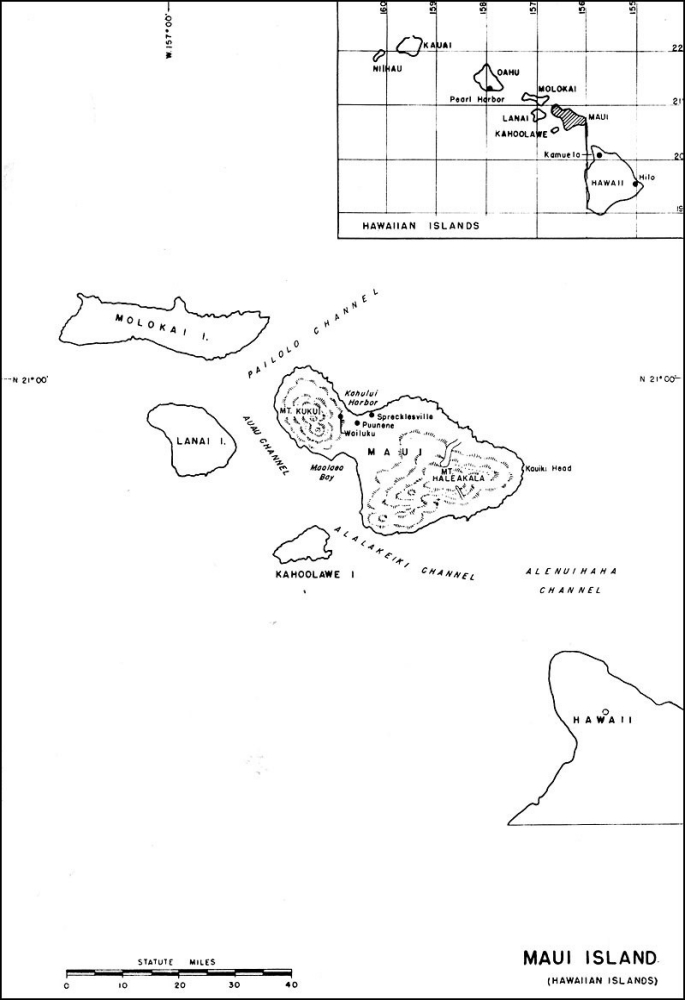

United States. 1947. Building the Navy's bases in World War II; history of the Bureau of Yards and Docks and the Civil Engineer Corps, 1940-1946. Washington: U.S. Govt. Print. Off.

The Navy Department Library

Building the Navy's Bases in World War II

Volume II (Part III)

Part III: The Advance Bases

Chapter XVIII

Bases in South America and the Caribbean Area, Including Bermuda

Part I - The Caribbean Area

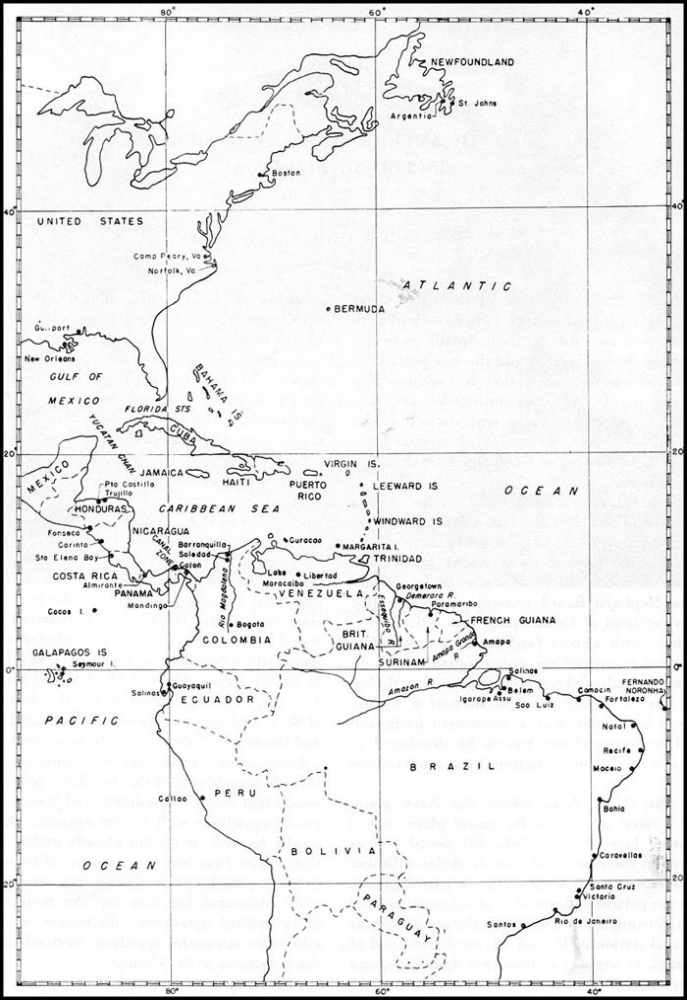

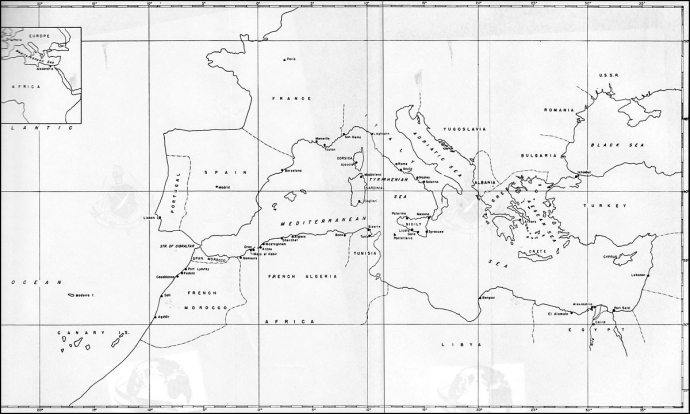

World War II development of the naval shore establishment throughout the Caribbean and Central American area divides itself broadly into two phases; the defense period and the war period.

Although the defense period is considered as beginning in July 1940, the construction program, as it evolved in the Caribbean area, dates from the fall of 1939, when the expansion of existing bases was begun, in line with recommendations of the Hepburn report.

With the exception of a radio station at San Juan, Puerto Rico, the naval shore establishment in the Caribbean in 1939 was confined to Guantanamo Bay, Cuba; the Panama Canal Zone; and a small area on the island of St. Thomas in the Virgin Islands. Hepburn Board recommendations called for development of Guantanamo into a fleet operating base with airport facilities to accommodate one carrier group and one patrol squadron. On St. Thomas, a small airfield occupied by the Marine Corps was to be expanded to support a Marine squadron of 18 planes on a permanent basis, and the adjacent waterfront was to be developed to serve a patrol-plane squadron in a tender-based status.

For the Canal Zone, where the Navy maintained a naval air station for patrol planes and a submarine base at Coco Solo, the board recommended an increase in the air facilities sufficient to accommodate seven squadrons of patrol planes, with a supporting industrial establishment capable of complete engine overhaul, and the establishment of a naval station at Balboa, on the Pacific end of the Canal, to support submarines, destroyers, and smaller craft.

For Puerto Rico, the board recommended the development of Isla Grande in San Juan harbor as a secondary air base, to contain facilities for one carrier group, two patrol-plane squadrons, complete engine overhaul, and berthing for one carrier.

Congress approved the base program as recommended by the Hepburn Board in May 1939, and partial financing was provided in the 1940 appropriation bill. The initial construction effort in the Caribbean area began in October with the award of a fixed-fee contract for the air-station development at San Juan, Puerto Rico.

Meanwhile, as 1939 drew to a close, the initial success of Axis aggression in Europe and the increasing submarine sinkings in the Atlantic, resulted in Congress again reviewing naval requirements. Recognizing that security hinged on ability to defend ourselves, Congress, pursuant to the recommendations of the Navy Department, authorized an additional 11-percent expansion in combatant-ship tonnage, with a concomitant increase in naval aircraft to 10,000 planes. The President signed the bill on June 14, 1940. The program for the development of shore facilities was immediately revised upward, and the scope of the Caribbean bases redefined.

Guantanamo, under the new program, was to furnish complete facilities for three patrol squadrons, eight carrier squadrons, and four additional patrol squadrons with tender support. The strategically located air station already under construction at San Juan was to be expanded to accommodate six patrol squadrons and two carrier groups, with additional facilities for the temporary use of two patrol squadrons with tender support. Facilities for ten patrol squadrons were scheduled for the air station at St. Thomas.

Development of the bases recommended by the Hepburn Board began immediately. Two contracts were awarded on June 17 and July 11 for work in

--1--

--2--

the Canal Zone, and a third on July 1, for Guantanamo. Because of St. Thomas's geographic proximity to Puerto Rico, the contract then under way at San Juan was expanded on July 8 to include the work on the neighboring island.

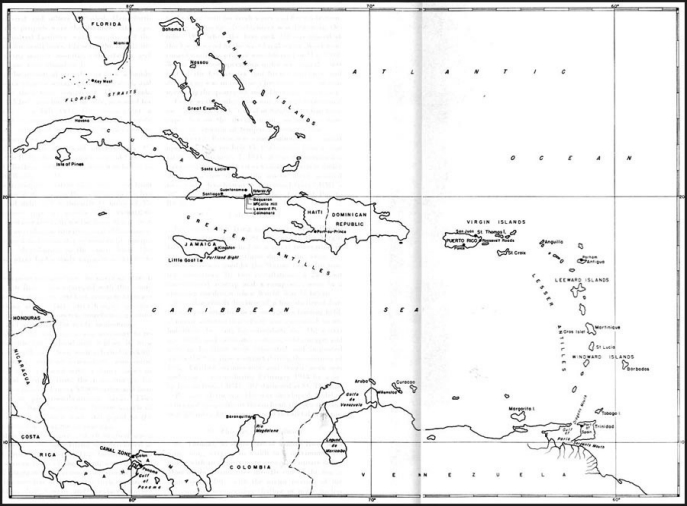

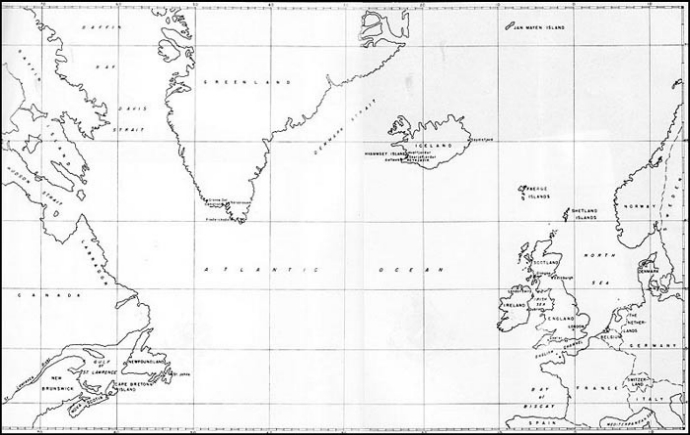

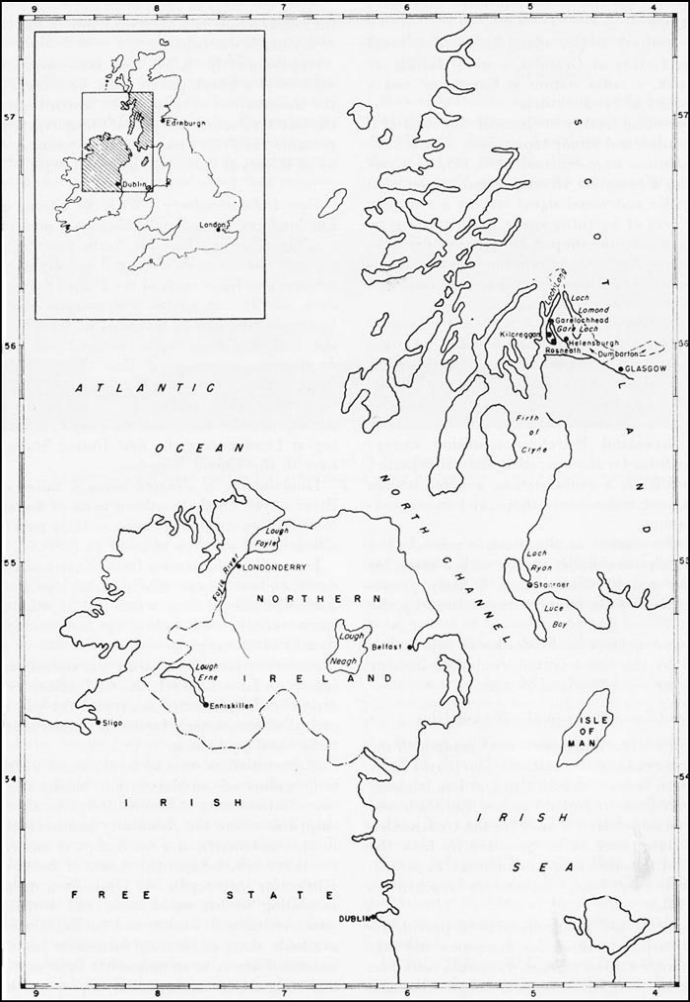

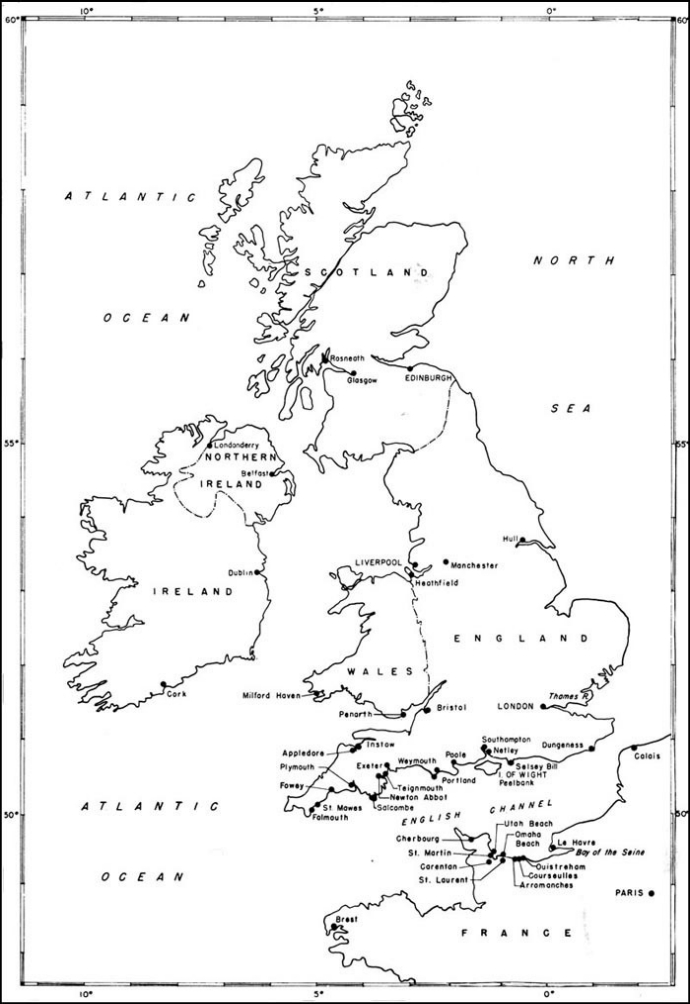

Meanwhile, the German submarine campaign was being prosecuted with telling effect. Britain had been severely affected by the general attrition of operations at sea, particularly in loss of destroyers. The United States needed extra bases to consolidate its defense in the Caribbean. Accordingly, the two governments entered into negotiations which culminated in the "Destroyers for Bases" agreement, signed September 2, 1940. Britain received fifty over-age destroyers. The United States received the right, under terms of a 99-year lease, to construct bases in eight British possessions, all in the Caribbean defense area, except one - Newfoundland (Argentia), which became part of the North Atlantic defense area discussed in Chapter 19. The southern group consisted of Bermuda, Jamaica, the Bahamas, Antigua, St. Lucia, Trinidad, and British Guiana.

On September 11, 1940, the President appointed a board, with Rear Admiral John W. Greenslade as senior member, to survey the naval shore establishment with a view to the requirements of the two-ocean Navy, at that time scheduled for accomplishment by 1946. Beginning its work in the Caribbean, the board, which included Army, Navy, and Marine Corps officers, participated in conferences with British experts to determine the exact location for the new bases. Tentative lease agreements were reached by the end of October 1940, but final agreements, together with decisions on such matters as customs, taxes, and wage rates for local labor, were not settled until March 1941.

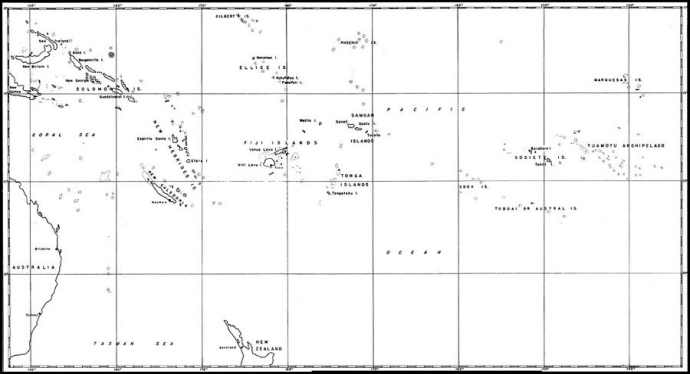

The Greenslade Board submitted its recommendations on January 6, 1941. Broadly conceived, these studies divided the strategic concept of our national defense into geographic areas, beginning in the North Atlantic and rotating clockwise through the Middle Atlantic, South Atlantic, Gulf, Caribbean, and Central America, completing the arc in the North Pacific. Insofar as they pertained to the Caribbean and contiguous areas in the Atlantic and the Pacific, they became the basic blueprint for all subsequent base development in that area.

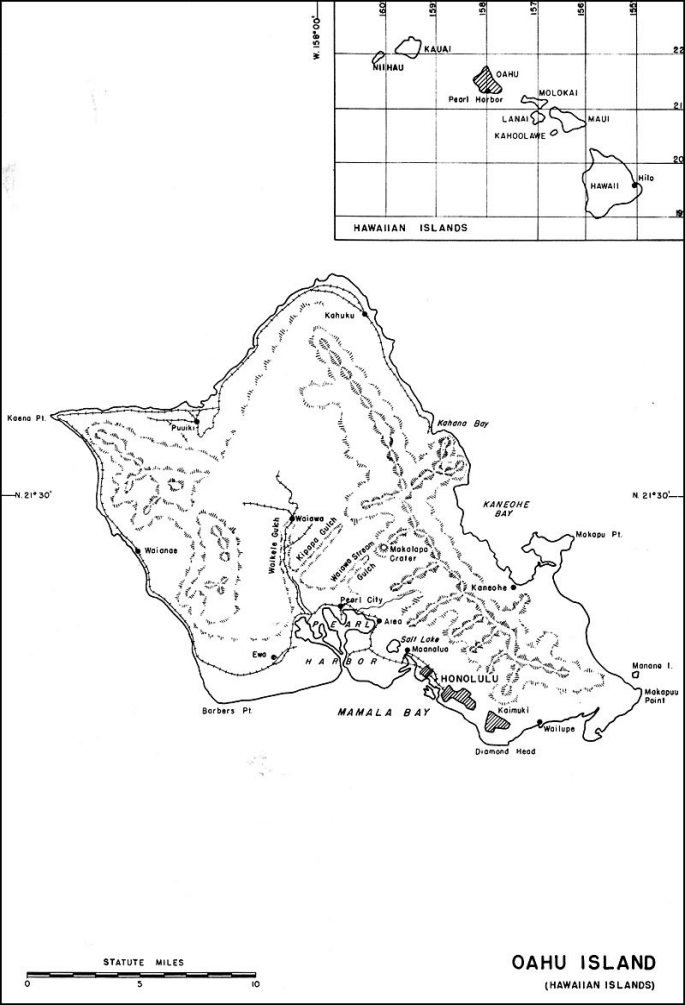

Naval defense of the Panama Canal, the focal point of our communications between the two oceans and South America, is, on the Atlantic side, primarily a matter of controlling the approaches to the Gulf of Mexico through the Florida Straits and the approaches to the Caribbean through the Yucatan Channel and the navigable passes of the greater and lesser Antilles. To accomplish this, the Greenslade Board divided the Caribbean into three areas, focusing major strength at Puerto Rico, Guantanamo, and Trinidad, each major operating base being supplemented by secondary outlying air bases to supply essential air surveillance.

At Puerto Rico, the Greenslade plan called for development of a major operating base as the keystone of the Caribbean defense, with facilities to include a thoroughly protected anchorage, a major air station, and an industrial establishment capable of supporting a large portion of the fleet under war conditions. Puerto Rico was to be the "Pearl Harbor of the Caribbean," furnishing logistic support to outlying secondary air bases developed on Antigua, St. Thomas, and Culebra.

Guantanamo was to be a major supporting base, capable of supplying limited maintenance, training, supply, and rest areas. It would also furnish a link in the supply chain from the Gulf area to other Caribbean bases. Jamaica and the Bahamas, as outlying secondary air bases, were to supply air surveillance in the Guantanamo area.

Bermuda was to be equipped to support carrier and patrol aircraft, cruiser, destroyer, and submarine forces capable of defense against strategical surprise on our middle Atlantic front.

Trinidad was to be organized as a subsidiary operating base, with major air facilities capable of supporting a large portion of United States naval forces. It was also to include training and advance-base operations projected to the south and east. Secondary air bases were to be located at St. Lucia and British Guiana, and emergency advance bases were to be placed along the northeastern coast of Brazil, each to be linked logistically to Trinidad and geared to the defense plan of that area.

Provision for adequate defense of the Canal from the Pacific presented a far more difficult problem. There were no potential sites for air bases, either on American soil or on territory which could be secured by lease or treaty. Only Cocos Island and the Galapagos group, the former controlled by Costa Rica and the latter by Ecuador, presented possibilities.

Early in 1940 the General Board of the Navy and

--3--

the Army-Navy Joint Board studied the subject and reached the conclusion that preparations must be made for the operation of constant air patrols over a wide area to the west of Panama. They recommended that patrol squadrons of seaplanes, supported partly by tenders and partly by shore installations, be based near Guayaquil on the Ecuadorian coast, in the Gulf of Fonseca in Nicaragua, and in the Galapagos. The Galapagos, it was decided, were to be the key installations, and they were subsequently fortified by both the Army and the Navy, under a program directed by the Army engineers.

By December 7, 1941, basic plans for the defense of the Caribbean and the Panama Canal were rapidly taking shape. The program was further expanded during 1942, with the development of bases at Salinas, Ecuador; Barranquilla, Colombia; Curacao, in the Netherlands West Indies; Puerto Castilla, Honduras; on the Gulf of Fonseca and at Corinto, Nicaragua; on Taboga Island, at the Pacific end of the Canal; and at Almirante, Chorrera, and Mandiga, in Panama. These were all small installations to support seaplanes, lighter-than-air craft, and small surface craft. A chain of air bases was also established along the coast of Brazil.

During the two years that followed, the tempo of construction activity increased steadily, reaching its peak in the early months of 1943. By that time the major features at each base had been completed and were being fully used by the occupying forces. The contractors' forces were withdrawn before the

--4--

year ended. Station maintenance, as well as minor items of new construction necessary for more efficient operations, was henceforth accomplished by Seabees or by local labor under the direction of the station Public Works Department.

As the progress of the war in Europe became more favorable to the Allied cause and the submarine threat diminished in the Caribbean during 1944, each of the Caribbean bases diminished in importance; consequently, all except the major installations at Trinidad, San Juan, Guantanamo, and the Canal Zone were reduced to a restricted or caretaker status by the fall of 1944.

San Juan, Puerto Rico

Except for a radio station and hydrographic office, the Navy had no installation on the island of Puerto Rico prior to 1939. Construction, which resulted in a major naval shore establishment, was accomplished under a single fixed-fee contract awarded on October 30, 1939.

In its original form, this contract comprised 44 related projects devoted primarily to the construction of the San Juan Naval Air Station on Isla Grande. Subsequent additions increased the scope to include base development on the islands of St. Lucia and Antiqua and the naval operating base at Roosevelt Roads.

Isla Grande is a 340-acre site in San Juan Harbor, between San Antonio Channel and San Juan Harbor. Except for an airstrip operated by Pan American Airlines and a small area occupied by the U.S. Public Health Service quarantine station, most of the site was a combination of mangrove swamp and tidal mud flats. Despite the necessity for dredging operations of considerable magnitude to reclaim the low-lying land, the site was selected because of contiguous waters ideal for seaplane operation, unrestricted air approaches, and the nuclear value of the existing airfield.

The layout prepared by the Bureau of Yards and Docks utilized the existing runway as the base of design for the air station. The seaplane operating area used the water frontage along the harbor, leaving the area between the two air activities for industrial and personnel structures. Seventy percent of the air station had to be built on a blanket of dredged fill. This site preparation, while an extensive operation, was accomplished simultaneously with, and as a by-product of, the dredging operation necessary to deepen the seaplane runways and the navigable reaches of both San Antonio and Martine Pena channels.

Facilities initially provided placed the station in the category of a major air base, equipped to serve two squadrons of seaplanes and one carrier group, with an industrial section. The major facilities of the seaplane area comprised two Navy standard steel hangars, an engine-overhaul shop, four seaplane ramps with connecting bulkhead, asphalt-paved parking areas, and a 450-foot concrete tender pier. The center line of the existing airfield was shifted slightly to conform more nearly with prevailing winds, the field was then lengthened, widened, and surfaced with asphalt to make a 5400-by-500-foot runway. This strip and a secondary north-south 2300-by-150-foot runway, together with a utility hangar, became one of the important bases of the Naval Air Transport Service in the Caribbean.

Located in an area frequented by high-velocity winds, most of the buildings were designed as permanent structures, using steel and masonry for industrial buildings and reinforced concrete for personnel units. Flat roofs and a cubical design gave an architectural treatment in keeping with local civilian practice. Pile foundations were necessary under all permanent structures, including underground pipe and duct lines, because of unstable soil conditions and a time schedule which demanded immediate use of filled areas.

The Tenth Naval District, including the Bahamas and the Antilles from Cuba to Trinidad, was established November 14, 1939, with San Juan designated as administrative headquarters. Buildings to house the district headquarters were begun in September 1940, on a tract of land bordering San Antonio Channel, directly opposite the air station. The buildings were one-story frame structures, equipped with cable lashings over the roof and anchored to the ground on either end as a safety measure against hurricanes. In addition, the Fernandez Juncos and San Geronimo quarters were erected to house headquarters personnel. Reinforced concrete and prefabricated steel-frame stucco construction was used.

A new quarantine station and hospital were undertaken simultaneously on a tract of land adjoining the district headquarters group. Built of reinforced concrete, these were constructed to replace the 40-year-old buildings of the U.S. Public

--5--

Health Service which occupied an area required for seaplane parking.

As the number of naval activities in the San Juan area expanded beyond the original air activity, the fixed dimensions of the Isla Grande site made necessary the purchase of additional land directly south of the air station.

The first of these new activities was a low-cost defense-housing project in suburban San Juan, designated as San Patricio. Added to the contract in October 1940, this facility comprised 200 duplex single-story structures built with prefabricated steel frames, concrete floors, and stucco exteriors.

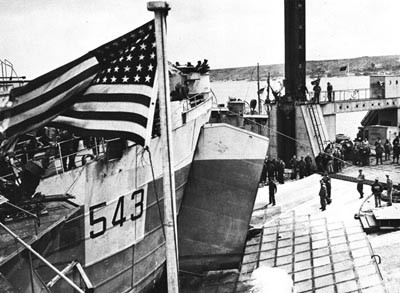

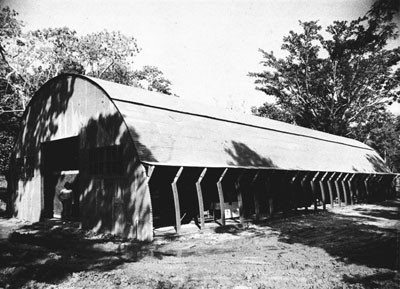

On February 13, the San Juan contract was further augmented to include construction at St. Lucia and Antigua, and to permit the assembling and fabricating of materials and equipment for temporary shore facilities to house a Marine detachment at each base. This latter item introduced the production-line principle to the construction of bases and was one of the early steps in the development of advance base structures.

As the summer of 1941 approached, gratifying progress was being made toward strengthening the air defenses in the Caribbean. Corresponding facilities necessary to support the Navy's surface craft in that area, however, were seriously deficient, and that at a time when the nation's ship yards were operating on a 24-hour basis, producing vessels for the authorized increase in ships for a two-ocean Navy. There were not drydocks between Charleston and the Canal Zone; nor, except for limited facilities at Guantanamo, were there any bases for repairs, fuel, and supplies.

In order to strengthen this weak link in our defenses, a major program of new construction was added on July 8, 1941, to the San Juan contract. This new program, in addition to the development of a major fleet base at Roosevelt Roads, provided operating and repair facilities in the San Juan area, additions to the air station, a radio station, and an ammunition depot.

Fortunately, the Insular Government had built a graving dock in San Juan Harbor, on a site contiguous with the air station. Functionally complete at the time, this 660-by-83-foot dock was taken over by the Navy in July. The approach channel was deepened and widened, a 600-foot approach pier built, and additional berthing provided by dredging and bulkheading a slip between the approach pier and an adjoining tender pier at the air station. Shops, storehouses, and other supporting industrial facilities were built in the area adjacent to the drydock, and a net depot was also developed.

In September 1941, a public works department was organized to serve all San Juan activities, except the naval air station for which a separate station public works department was established. The San Juan public works department performed station maintenance and operation functions as well as extensive new construction of projects not included in the contract. Except for the public works foreman and quarterman the entire mechanical and labor force comprised local Puerto Ricans, who responded well to a training program in building trades and other skills, under the direction of the public works officer.

Similarly, the combined clerical force of the district public works office and of the San Juan activities public works office, utilized Puerto Ricans under trained supervisors.

The extensive use of Puerto Ricans in mechanical trades and clerical work constituted an interesting innovation in this primarily agricultural land, and the employment of female clerical personnel on so great a scale broke centuries-old sociological precedents.

San Antonio Channel was also deepened to 35 feet adjacent to the north shoreline of the air station, and the waterfront improved with 2000 feet of quay wall and 2000 feet of sheet-pile bulkhead to accommodate carriers and other surface craft.

The San Juan section base, a complete facility equipped with barracks, administration building, warehouses, and waterfront improvements, was constructed under the same program, on a site adjoining the 10th Naval District headquarters.

The air station was improved and increased in all categories to give it complete facilities for the operation and maintenance of five patrol squadrons of seaplanes and one carrier group.

The ammunition depot, built on a 2100-acre site in the hills southwest of the harbor, at Sabana Seca, was planned and developed as a complete and self-contained facility equipped with roads, railroad spur, personnel structures, sewage-disposal unit, magazines, and storage structures.

Concurrently, the radio station, located on a reservation within the city of San Juan, was equipped with a bombproof communications building and a third antenna tower, 250 feet high.

Increased fuel storage, water supply, and hospital

--6--

facilities were required to keep pace with this growth. Consequently, a fuel depot at Catano and water development at San Patricio were added to the contract in October. The naval hospital was undertaken later, during January 1942, on a site adjacent to the housing project at San Patricio.

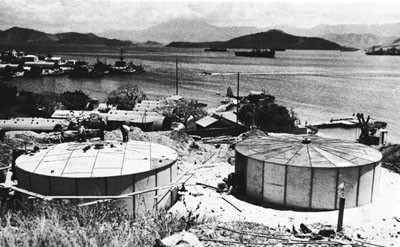

The fuel depot comprised seven 27,000-barrel pre-stressed concrete and three 27,000-barrel steel tanks, built into the hillside for concealment and protection; a timber pier, 350 feet long; a pumping plant, with heating equipment; personnel buildings; and a shop. All buildings were of reinforced concrete.

The San Patricio water development comprised two drilled wells, a filter plant of 500,000 gallons per day capacity, and a 200,000-gallon reservoir. A 10-inch main, laid under the Martin Pena Channel, served the air station, and a 6-inch main, under the San Antonio Channel, served the district headquarters and adjoining activities. The hillside location of the reservoir made possible adequate gravity pressure throughout the entire system.

Two hundred beds were provided at the naval hospital in a compact structure comprising a main central building with eight attached wings and a service building housing garages and heating units. All buildings were single-storied, with reinforced-concrete walls and timber roofs. Buttresses and steel ties held the roofs to the ground as a precaution against wind damage.

Maintaining the flow of materials became a trying and hazardous task subsequent to our entry into

--7--

the war. The Germans were quick to take advantage of their opportunity and made an incursion into our coastal waters in January 1942. During April and May, enemy submarines sank eight cargo-laden ships en route to Puerto Rico, resulting in costly delays on construction projects.

As 1942 drew to a close, the gradual completion of major construction operations at San Juan permitted a transfer of the major effort to Roosevelt Roads. Early in 1943, all dredging operations were completed, as were the water-filtration plant, the San Patricio housing development, and the ammunition depot at Sabana Seca. The drydock and repair unit were completed in March, and the main plane runway in April. The remaining activities were completed and the contract terminated by August 28, 1943.

New construction as well as station maintenance and operation at Roosevelt Roads was henceforth accomplished by the station public works department, augmented by CBMU 516, which arrived on August 26, 1943. The public works officer was given the additional title of officer in charge of new construction, under which he was vested with authority to hire both persons from the States and Puerto Ricans, giving them a modified civil-service status.

Roosevelt Roads

Roosevelt Roads, on Vieques Passage, at the eastern end of Puerto Rico, was intended to become the major fleet operating base of the Caribbean. As initially planned, it was to be equipped with a protected anchorage, a battleship graving dock, major repair facilities, fuel depot, supply depot, hospital, a major air station for both land- and seaplanes, and numerous other shore-based activities. These were to provide the necessary supporting services for 60 per cent of the Atlantic Fleet, and represented, in broad outline, the requirements indicated by the strategic situation as envisaged in the spring of 1941. It was a tremendous project, requiring five years to complete, at an estimated cost of $108,000,000.

The extreme eastern end of Puerto Rico was the only location on the island capable of accommodating a base of this magnitude, together with sufficient water area for development as a fleet anchorage. The Navy, accordingly, purchased 6680 acres at Ensenada Honda, Puerto Rico, and a substantial portion of the island of Vieques, including all of the western end, 7 miles east of Puerto Rico. Vieques Passage, between the two islands, was to be developed as an anchorage by constructing two breakwaters. The two sites were similar, with salt flats, mangrove swamps, and steep, weathered hills, some of which were 400 feet high.

In the early summer of 1941, the development of Roosevelt Roads was awarded to the fixed-fee contract then underway at the naval air station at San Juan. The initial award included the dredging necessary to provide channels from the mainland sites into Vieques Passage, the construction of approximately 14 miles of breakwater to provide a sheltered anchorage for the fleet, a battleship graving dock with complete accessories, a bombproof power plant, a large machine shop, and the construction plant and equipment necessary to accomplish a program of this magnitude. The contract was subsequently expanded from time to time, beginning in October 1941 and continuing through 1943, to cover the construction of a fleet supply depot, ammunition storage, personnel facilities, a 200-bed hospital, a section base, a net and mine depot, and a major air station for both landplanes and seaplanes.

No facilities of any kind were existent in May 1941 when work was begun at Ensenada Honda, on a tent camp and access roads.

When the year ended, the number of workmen had increased from 200 to 3000, a temporary construction camp with an expected life of five years had been built, dredging had been started on the approach to the drydock, and a pier had been completed which permitted material and equipment to be unloaded at the site rather than having to be trucked across the island from San Juan. Work was also begun on Vieques Island for the development of a quarry to furnish rock for the proposed breakwater.

The entry of the United States into the war had brought about changes in the plans for Roosevelt Roads. A review of the present and potential enemy naval forces in the Atlantic, the type of warfare conducted by the Axis in the Mediterranean, the necessity for maintaining a large portion of our major naval units in the Pacific, and the shortage of shipping and critical materials led to the decision to reduce the scope of the undertaking.

During February 1942, work was started on the section base, a 120-unit housing project, and an extensive system of roads designed to link the various shore activities then underway. Form work on the drydock was started in April and the first concrete poured in June. In August, certain items

--8--

were deferred and others curtailed. Henceforth the priority projects were the drydock with associated industrial facilities, water supply, and the air station for landplanes. Plans for the supply depot, receiving station, hospital, radio station, and seaplane base were abandoned.

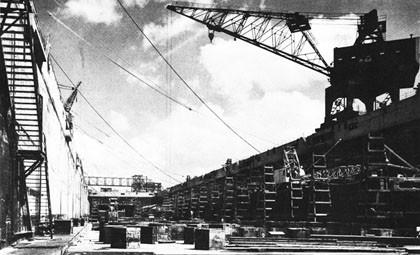

Within the industrial area the drydock, a bombproof power plant, a sewage pumping station, and a machine shop were completed. The drydock, 1100 by 155 feet, and built in the dry, was used for the first time in July 1943. The power plant, a bombproof structure with 4-feet-thick concrete walls, was equipped with two 5,000-kw steam-driven generators.

The drydock was dedicated on February 15, 1944, and the Bolles Drydock, in memory of Captain Harry A. Bolles, (CEC) USN, who was killed in Alaska in World War II.

The water-supply system obtained water from the tail race of the Insular Power Plant on the Rio Blanco and delivered it through 11 miles of 27-inch concrete pipe by gravity to a 46,000,000-gallon raw-water reservoir on the base. It was then treated by coagulation, filtration, and chlorination, and delivered to fresh-water reservoirs by pumps, for gravity distribution to the entire base. The treatment plant had a daily capacity of 4,000,000 gallons.

Of permanent construction, the naval air station at Roosevelt Roads was equipped with three concrete runways, 6,000 by 300 feet, concrete taxiways and parking area, a large steel hangar, quarters for personnel, a large concrete storehouse, gasoline storage, and magazines for ready ammunition.

In building the runways, it was necessary to remove unstable clay subsoil and replace it, to a minimum depth of 3 feet, with selected backfill, placed under controlled-moisture conditions. Shoulders were surfaced with a 3-inch layer of rolled coral dredged from the bay. Storage for gasoline was provided in six 50,000-gallon and four 250,000-gallon pre-stressed-concrete tanks. Elsewhere on the base, storage for 118,000 barrels of fuel and diesel oil were built and piped to the completed fuel dock at the section base.

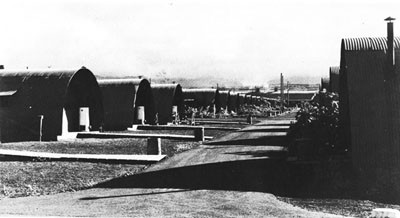

In addition to the quarry, which in itself was a major operation, Vieques Island was developed as a naval ammunition depot. This facility, located on the western third of the island, was equipped with 107 magazines and ammunition storage buildings of the concrete arch type for high explosives. Two 80-foot drilled wells and two large storage tanks were built for fresh water and fire protection.

The anchorage development was begun in October 1942 when the first rock fill was placed at the Vieques end of the west breakwater. Work continued until the project was deferred in May 1943. When the cease-operations order was issued, 7,000 feet of the breakwater had been completed, and everything was in readiness for major construction involving the quarrying and placing of 20-ton rock.

Field work under the contract was terminated on August 28, 1943. A total of $56,000,000 had been expended on the development, including a considerable amount of temporary construction.

Roosevelt Roads was commissioned as a naval operating base on July 15, 1943; more than a year later, on November 1, 1944, it was redesignated a naval station and placed in a caretaker status under the supervision of a public works officer, assisted by a small detachment of personnel from CBMU's 507 and 517 and a station labor force of Puerto Ricans.

Culebra Island

Culebra Island, lying midway between Puerto Rico and the island of St. Thomas in the Virgin Islands, was established as a naval reservation in 1917 and at various times during the years between wars was used by the Marine Corps for winter maneuvers. Its two installations, a 2400-foot sod-surfaced airstrip and a camp site, were in a rundown condition when World War II began.

Of value chiefly because of a fine sheltered harbor and potentialities as an emergency landing field, a minor construction effort was expended to rehabilitate the camp for immediate use. The sewerage, fresh- and salt-water systems, cold storage, and messing facilities were renovated and improved under the San Juan contract during the summer of 1942. Further maintenance and repair work was undertaken again during February 1944 by a detachment from CBMU 507 stationed at St. Thomas.

Because of the way the war developed, Culebra remained insignificant throughout the period, and in September 1944 was reduced to caretaker status.

St. Thomas, Virgin Islands

St. Thomas, 50 miles east of Puerto Rico, is 14 miles long, varying in width to a maximum of 4 miles, with an approximate area of 32 square miles. Most of the island rises directly out of the sea in high rocky cliffs, with the major portion of the surrounding water either shallow or made useless

--9--

by barrier reefs. On the south side of the island, however, there are three excellent bays, so situated that peninsulas and small islands form natural breakwaters. Two of these bays were developed for Navy use; Lindbergh Bay for seaplanes and Gregerie Channel for submarines and deep-draft vessels.

When, in July 1940, the fixed-fee contract operating at San Juan was extended to accomplish the development of St. Thomas, there existed on that island Marine air base, established in 1935, as well as a radio station and a submarine base, both dating from World War I. The air base, known as Bourne Field, comprised two 1600-foot sod-surfaced runways which were used by the Marines as an outlying training field; the radio station was a minor installation, and the submarine base had long since been abandoned as such.

The initial program called for improvements and additions to existing facilities to accommodate a Marine squadron of 18 planes on a permanent basis and a waterfront development to serve one patrol-plane squadron in a tender-based status.

The main east-west runway at Bourne Field was extended to a length of 4800 feet, and a 100-foot extension was added to the steel hangar, together with additional quarters, an administration building, additional gasoline storage, a cold-storage building and commissary, extensions to roads and services, and a new 60-bed dispensary and hospital. A concrete ramp, hangar, and utility shop were also built to accommodate seaplane operations in Lindbergh Bay.

Fifty low-cost housing units were added to the contract during October. Financed from National Defense Housing funds, these were built of prefabricated light-steel frames with concrete floors and stucco exteriors, identical with those built at San Juan. Reinforced concrete and structural steel were, in general, used for all other buildings, both

--10--

for permanency and as a precaution against hurricanes.

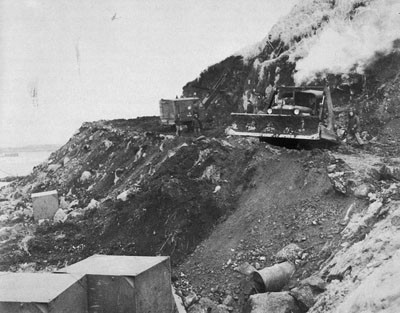

Due to the irregular terrain and the general presence of rock close to the surface, the runway extension was made by dredge-filling a marsh on the eastern end of the field. It was also necessary, because of the shallow soil overburden, to resort to drilling and blasting for practically all excavations necessary for foundations and underground services.

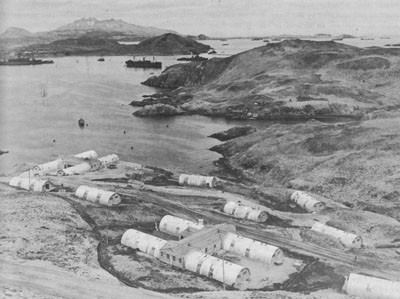

By midsummer 1941 the scope and purpose of St. Thomas had been redefined, in accordance with the Greenslade studies and the requirements of the two-ocean Navy and 15,000-plane program. As a consequence, the contract was again supplemented on July 8, 1941, to provide for further additions to the air station and the development of a completely new facility - a submarine base, on Gregerie Channel and adjacent to the air station.

Under the new construction program, the aviation shore facilities were expanded to meet the operational requirements of two Marine squadrons and the emergency operation of six patrol seaplanes. Additional barracks, services, magazines, recreational facilities, and fresh-water storage were built. Housing for service personnel, when completed, provided for 700 enlisted men in three barracks, one barrack for 40 officers, and 24 housing units for married non-commissioned and commissioned officers.

The waterfront development at the submarine base, built in dredge-deepened waters, comprised three finger piers, each 350 by 30 feet, and twelve 19-pile dolphins. Construction included quarters for 900 enlisted men and 42 officers, an administration building, storage buildings, torpedo overhaul shop, and a bombproof powerhouse in which were installed four 750-kva diesel-driven generators. Two 10,0000-barrel steel tanks, with a pump and filter plant, were installed for diesel-oil storage.

Fresh water for both the air station and the submarine base was obtained by collecting rainfall. Five hillside catchment areas, totaling 13 acres, were built by removing the foliage and thin layer of top soil from the underlying rock. The water thus collected was funneled into a number of concrete reservoirs, chlorinated, and pumped directly into the distribution pipe lines.

Under a later program, undertaken in October 1941, a section base and net and boom depot were

--11--

built on the waterfront adjacent to the submarine base. Two additional finger piers, one 500 feet and the other 350 feet long, were constructed, together with the necessary industrial buildings to house these activities. A new radio station, equipped with three 150-foot steel towers and a reinforced-concrete transmitter building, was also constructed to replace the inadequate station built in World War I.

Still further additions and improvements built during 1942 were directed toward bringing into better balance the facilities constructed under the initial development plan. The program was climaxed finally in December by a major increase in liquid-fuel storage and the paving of the east-west runway at Bourne Field. Two 100,000-gallon tanks, of pre-stressed concrete, for gasoline, and six of a similar type for diesel oil, with a capacity of 135,000 barrels, were built.

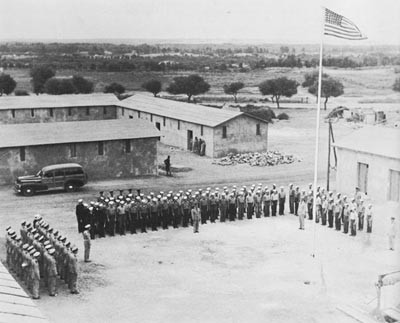

On June 11, 1943, CBMU 507, with a complement of 256 enlisted men and 4 officers, arrived at St. Thomas. The civilian contract was terminated 15 days later, the maintenance unit carrying to completion a number of buildings and installations left unfinished by the contractor. Using native labor to augment their own force, they also accomplished an extensive program of miscellaneous construction and improvements to facilitate better operation and make the base more nearly self-sustaining.

Guantanamo, Cuba

At the outset of the emergency, facilities in

--12--

existence at Guantanamo Bay comprised a naval station equipped with shops, storehouses, barracks, two small marine railways, a fuel oil and coaling plant, a Marine training station, and an airfield. The station, used by the fleet while on winter maneuvers, reflected the period of strict naval economy between wars, having been relegated to practically inactive status.

The site, acquired by lease from the Cuban government on July 2, 1903, for an annual rental of $2,000, completely encircles the bay and contains approximately 36,000 acres, of which 13,400 acres are land and the remainder water and salt flats. The greater part of the water is navigable, forming an excellent land-locked harbor, with depths ranging up to 60 feet.

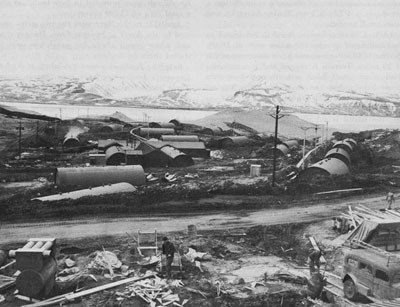

Initial development in the bay area consisted of an air station. By 1944, there had been developed a major naval operating base, equipped with ship-repair facilities, fuel depot, supply depot, and other related activities. These new facilities were accomplished under a single fixed-fee contract, awarded July 1, 1940; construction operations began two weeks later.

Included in the initial program were five major projects: a Marine Corps base for 2,000 men, a fuel-oil and gasoline storage depot, two airfields, and improvements to existing radio facilities.

Within the limits of the area under Navy lease, there were two sites suitable for airfields. One of these, McCalla Hill, adjacent to the eastern shoreline of the harbor entrance, was already developed as a field within the tract of land allocated to the Marine Corps. Leeward Point, directly west of McCalla Hill and across the bay entrance, offered the second site.

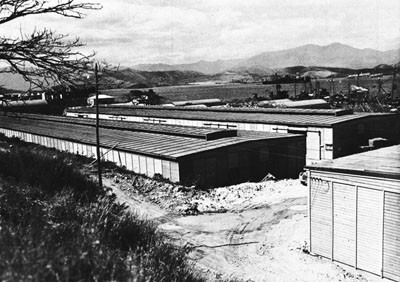

The area allocated to the Marine Corps was relinquished in order that the existing McCalla Hill airfield might be enlarged and a seaplane base be established there. In exchange, the Marine Corps was provided with a new and self-contained base for a force of 2,000 men, with all necessary utilities, such as barracks, administration buildings, dispensary, mess halls, storage buildings, laundry, roads. The buildings were of semi-permanent character, with concrete foundations, tile ground floors, wooden superstructure, and asbestos shingle or tile roofs.

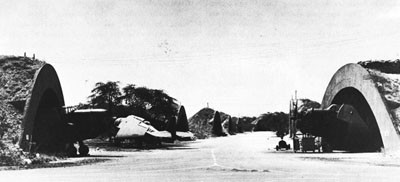

The airfield on McCalla Hill was equipped with three asphalt runways - one, 300 by 4900 feet, and two cross runways, 200 by 2300 feet - built to the limit of the land available. Warm-up platforms, a hangar and utility building, administration and operations building, magazines, quarters, barracks, and mess halls were provided. At the seaplane base, facilities installed included a concrete parking area of approximately 560,000 square feet, two seaplane ramps, each 100 feet wide, and a large, steel hangar.

At Leeward Point airfield, across the bay entrance, two runways, a hangar, storage facilities, distribution systems for water, diesel-oil, and gasoline, a small power plant, a magazine, a barrack and a small-boat landing were built. The main runway, 6000 feet long, and a cross strip, of 3500-foot length, were paved with asphalt 150 feet wide.

Fuel-oil storage, constructed under the original program, included 18 tanks of 25,000 gallons each and 10 tanks of 27,000 barrels each, grouped in tank farms at four separate locations. All were built of steel and located underground. Water lines, access roads, and chemical fire-fighting equipment were installed at each of the four locations. In addition to the pumping equipment and distribution lines which were installed to link these systems together, one ethyl-blending plant was provided for ethylizing raw gasoline.

Housing proved a problem from the very beginning of the construction period, for both continentals and Cubans. For those who lived in the two nearest Cuban cities, Caimanera and Boqueron, it meant a 5-mile boat ride each way or a much longer drive by automobile. To help relieve the situation, 200 low-cost homes, built in a community group on the reservation, remote from the area occupied by the principal naval activities, were added to the contract in October.

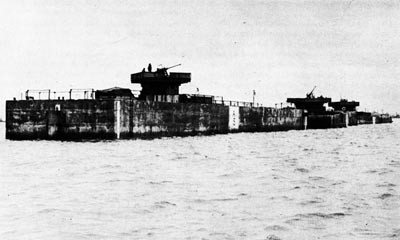

That month of October 1940 also saw a second major addition to the contract, which provided facilities needed for a fleet anchorage and operating base. Extensive dredging operations, totalling 16,000,000 cubic yards, were undertaken to deepen certain areas of the bay to permit mooring of deep-draft vessels. Also constructed were 17 destroyer, 10 cruiser, and 3 battleship moorings. These were of steel sheet-piling, cellular in design, filled with dredged material, and capped with concrete.

The October supplement to the contract also included three storehouses, a chapel, additions to an existing machine shop, a net and boom depot, and miscellaneous small projects.

For years, one of the main drawbacks to the development of Guantanamo Bay as a fleet operating base was the lack of fresh water. During the

--13--

early days, water had to be purchased on yearly contract from the neighboring cities of Caimanera and Boqueron, barged from there to the station, and pumped into storage tanks. This method of supply was costly, unreliable, and even dangerous when considered from the point of view of health. In 1934, Congress authorized the Navy Department to enter into a 20-year contract for water to be supplied to the station by pipe line. The pipe line was placed in operation in July 1939, water being obtained from the Yateras River, 10 miles distant, and pumped to the station through a 10-inch main.

As this system was definitely limited by the size of the pipeline, it became necessary, in view of the development planned for Guantanamo, to increase its capacity. This project, begun in September 1941, furnished an additional 2,000,000 gallons per day. A new pumping plant, installed at the Yateras River, pumped water through 50,000 feet of 14-inch main to two treatment-plants on the station. Midway along the pipe line a 500,000-gallon concrete reservoir was built for reserve water storage and as a fire precaution; three steel tanks, with a combined capacity of 2,000,000 gallons for treated water, were built on the station.

A new section base and an underground hospital were also begun during September 1941. The U-shaped pier, supported on timber piles, with a 260-foot base and two wings, each 350 by 30 feet, was built at the section base. Twelve barracks, each with a capacity fo 230 men, a mess hall, and a new machine shop were also provided.

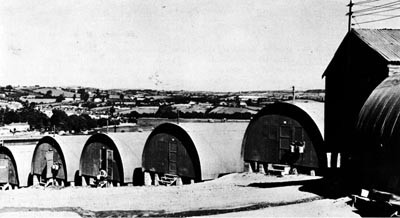

The underground hospital, a bomb-proof structure, comprising four concrete arch-type units built into a hillside, was fitted with 192 beds and complete hospital equipment, including two stand-by power plants for light and forced ventilation.

With the advent of war, the importance and value of Guantanamo was a major link in the chain of Caribbean defenses was reflected in the steady increase in construction activity throughout 1942. The capacity of the fuel depot was greatly expanded, beginning with the addition of a diesel-oil filter plant in February 1942, two 27,000-barrel pre-stressed concrete tanks in April, and seven 50,000-barrel tanks during May. These underground tanks were interconnected, with pipe-line extension, to a floating oil-dock in the fleet anchorage area.

A degaussing and deperming installation was authorized in March 1942; a 30-ton marine railway and a 3000-ton timber floating drydock, in June; and an anti-aircraft training center, in July. In November extensive ship-repair facilities and an auxiliary outlying airfield were begun.

Included in the ship-repair project were three timber piers, 625 feet, 1120 feet, and 250 feet long, respectively; a timber causeway, 400 feet long; and a 236-foot marginal wharf, the platforms of which were a composite of wood and concrete. Two large buildings, a repair shop and rigging loft, and several small industrial buildings were also included.

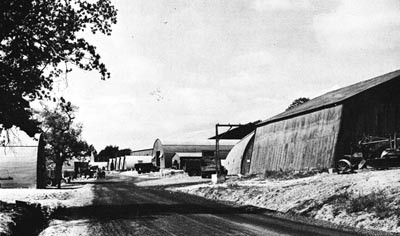

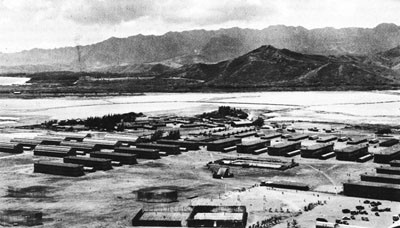

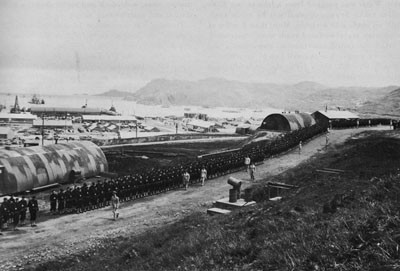

The outlying airfield, at Los Canos, 30 miles north of McCalla Hill Field at Guantanamo, was built to serve as an emergency landing field and as a training area for carrier-based aircraft. It was built on 450 acres of land leased from the Guantanamo Sugar Company and equipped with three 4500-foot runways, one of which was paved with a penetration asphalt surface, 150 feet wide. Quonset huts served for personnel housing and administration offices.

Upon completion of the Los Canos project in September 1943, this field, with the facilities provided at the McCalla Hill and Leeward Point fields, composed the naval air station, which supported the operation of three squadrons of patrol seaplanes, one carrier group of 90 planes, and one utility squadron, in addition to the temporary operation of four additional patrol squadrons with tender support and one additional carrier group with the parent ship present.

Upon the termination of the contract on September 30, 1943, the Public Works Department, augmented by 1800 men transferred from the contractors' payrolls, carried on all uncompleted contract projects. These consisted primarily of completing the ship-repair facilities and the installation of machinery in otherwise completed structures at various locations. The peak of operational activity was reached during the summer of 1944, when, because of the Allied advances in the European theater and the almost complete elimination of the submarine menace in the Caribbean area, orders were issued for the curtailment and consolidation of the activities at the base.

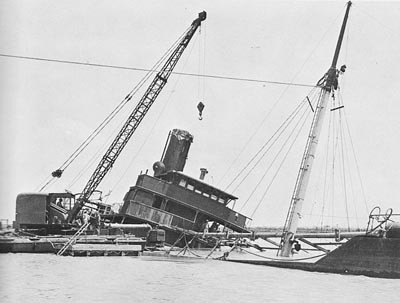

Haiti

Using Lend-Lease funds, the Navy constructed a 1000-ton marine railway at Port-au-Prince for use by the Haitian Coast Guard. This facility, built under

--14--

the Guantanamo contract, was completed in April 1944 and turned over to the Haitian government the following month. Except for the railway, no other construction was done on Haiti.

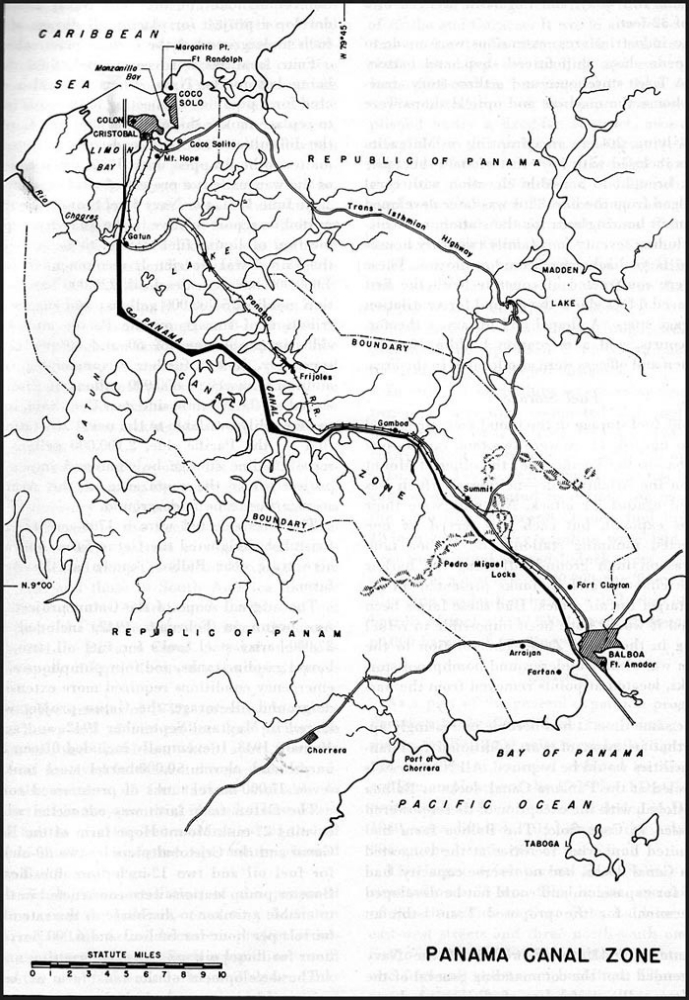

Part II - The Canal Zone

When anxious eyes were directed toward the defenses of the Panama Canal in the fall of 1939, the naval shore establishment then in existence in the Zone was limited on the Atlantic side to an air station for seaplanes and a submarine base at Coco Solo, a radio station at Gatun, and a small section base at Cristobal. On the Pacific side, at Balboa, were located the administrative headquarters of the 15th Naval District and, directly across the Canal, on the west bank, an ammunition depot. Another radio station, located at Summit, about one third of the distance from Balboa to Coco Solo, and a half a dozen fuel tanks at either end of the Canal, and a few minor installations completed the list. For fueling and ship repairs, the Navy was entirely dependent on the industrial plant owned and operated by the Panama Canal. These centered around a battleship graving dock at Balboa and a small dock, 390 feet long, at Cristobal on the Atlantic end of the canal.

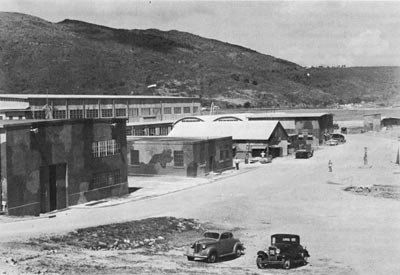

Using these existing facilities as a nucleus, the Navy began to strengthen and enlarge its installations during the summer of 1940. Guided by the Hepburn Board recommendations, the initial effort was undertaken by two fixed-fee contracts, awarded June 17 and July 11, and devoted primarily to enlarging the air station and submarine base at Coco Solo and constructing housing and a new office building at Balboa for the administrative offices of the 15th Naval District.

The scope of each contract was enlarged considerably during the pre-war period, as defense plans for the Canal were broadened and new installations authorized. When war was declared, several entirely new activities were well underway, with work concentrated in the Coco Solo area and on a new tract of land on the west bank of the Canal, directly across from Balboa.

By the end of 1940, work had begun on a new supply depot at Balboa, and on the Farfan Radio Station on the west bank, together with the enlargement of the two inland radio stations at Gatun and Summit. Two net depots were started in December, one at each end of the Canal, and during the same month a third contract was awarded for 1400 housing units, 1100 at Coco Solo and the remainder on the west bank at Balboa. The following summer two naval hospitals, one at Coco Solo and the other at Balboa, were begun.

That summer of 1941 also saw the start of intensive work on the development of a new naval operating base on the west bank at Balboa. With further expansion impossible along the congested waterfront, this west bank area became the locale for the major war construction effort in the Canal Zone.

The war years of 1942-1944 saw an enormous increase in the tempo of construction activity, the major effort being concentrated in three categories; fuel storage, ship-repair facilities, and the development of several advance bases to support distant air patrols. The Gatun tank farm on the Atlantic side, and the Arraijan farm, on the Pacific, were started in February 1942, and subsequently these huge storage reservoirs, 32 miles apart, were connected by a multiple pipe-line, installed under a fourth fixed-fee contract, awarded August 4, 1942 and completed in 1943.

In April 1942, work was started on a second graving dock adjoining the existing Panama Canal dock at Balboa, a bombproof command center, additional housing in the district headquarters area, and additional frame warehouses at the supply depot. In June, a third graving dock, to adjoin the other two at Balboa, was put under contract, and work was begun on two new marine railways, adjacent to the existing drydock at Cristobal. Meanwhile, the ammunition depots at Coco Solo and Balboa were enlarged, as were the facilities at the Coco Solo submarine base and air station and the Balboa operating base.

Advance bases were established during 1942 and 1943 on Taboga Island at the Pacific entrance to the Canal, on the Galapagos Islands off the coast of Ecuador, at Corinto in Nicaragua, Salinas in Ecuador, Chorrera and Mandinga in Panama,

--15--

Puerto Castillo in Honduras, and Barranquilla in Colombia.

The peak of construction activity was reached in the summer of 1943, and three of the four major contracts were terminated during the late fall of that year. After the termination of the fourth contract in April 1944, several smaller lump-sum contracts were awarded for minor additions and improvements and to care for current needs.

Two groups of Seabees, Detachment 1012, which arrived September 9, 1942, and Maintenance Unit 555, which arrived in December 1943 as a replacement for the first group, served in the 15th Naval District. Due to the difficulty of procuring civilian labor for work in outlying areas, both units were used mainly at the advance bases. Some of the men, however, were stationed within the Zone, to operate power houses and perform specialized maintenance work.

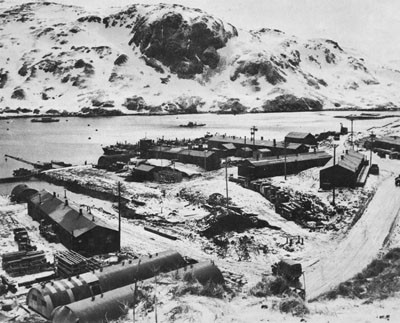

Coco Solo

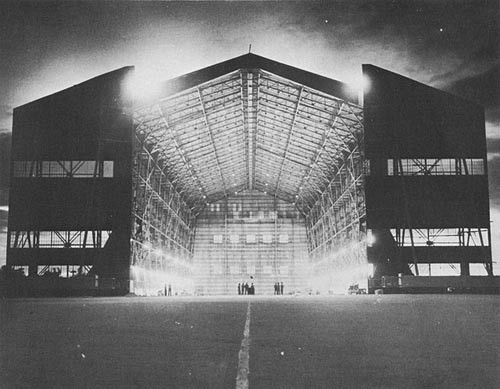

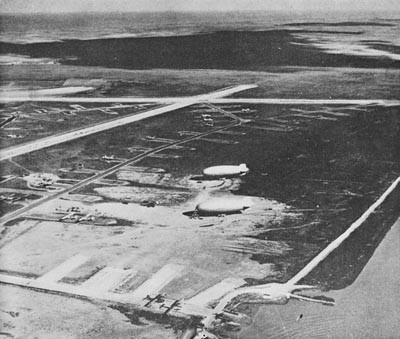

Naval Air Station. - The Coco Solo air station occupies 185 acres of hard land, on the east side of Manzanillo Bay. Existing facilities in 1939 included a small landing-field, three plane hangars, one blimp hangar, barracks, officers' quarters, three seaplane ramps, and a few miscellaneous buildings.

When the development of the station was begun on August 1, 1940, the approved plan contemplated expansion sufficient to serve seven patrol squadrons of seaplanes. The original site, though limited, was considered to be the most advantageous that could be found in the Canal Zone; consequently, maximum expansion was advocated rather than construction of an additional base in another locality.

The greatest single deficiency existing at the station was the lack of sheltered water for full-load take-off immediately adjacent to the base. There was a wide gap of open water between the eastern breakwater and Margarita Point, through which heavy ocean swells entered Manzanillo Bay, frequently making seaplane operations hazardous. In addition, the station lacked sufficient hangars, ramps, parking aprons, housing, storage, and repair facilities.

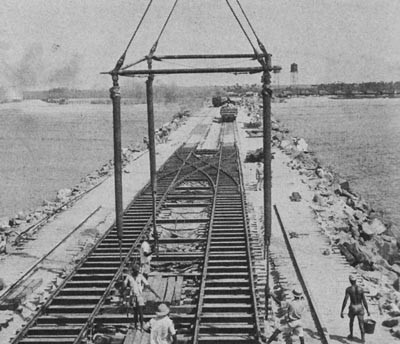

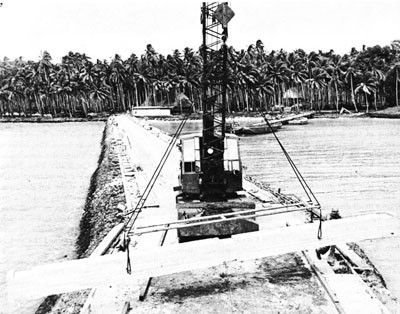

The initial construction effort, therefore, was concentrated on closing the 3800-foot gap in the Margarita breakwater. Rubble-mound construction, laid on a 15-foot coral mat, was used, the wall itself having a coral-fill core, covered with heavy rock and armored with pre-cast concrete blocks. It was built entirely from a temporary timber trestle, without the use of floating equipment other than the hydraulic dredge used for placing the foundation and core.

At the air station proper, three large steel hangars, four seaplane ramps, 700,000 square feet of concrete parking area, engine test stands, and a large aircraft assembly and repair shop were added to the operating area fronting on Manzanillo Bay. To make expansion possible, it was necessary to reclaim 30 acres of beach by dredge. A steel sheet-pile sea-wall, 2100 feet long, was driven to enclose two edges of this newly made land.

Other construction accomplished at the station included a barrack and mess hall for 1000 men, a new wing to an existing barracks to care for 400 men, a bombproof command center, an operations building, a large administration building to house the administrative offices of both the air station and the adjoining submarine base, and several large warehouses.

Dredging operations at the air station were also extended to furnish coral fill for the construction of new runways at Army's adjacent France Field. When that field was completed, 1700 feet of concrete taxiway, 66 feet wide, was built to connect the two stations. The Navy, henceforth, used Army facilities for the operation of its landplanes in the Coco Solo area.

Submarine Base. - Established in 1917, and later modernized, the submarine base occupied a 130-acre peninsula bounded on the north by Margarita Bay and on the west and south by Manzanillo Bay. Important additions to all existing facilities were accomplished under the wartime construction program begun during the fall of 1940, developments being confined entirely within the limits of the existing boundaries.

A mole pier, 300 feet wide, enclosed with steel sheet-piling, was built as an extension to the original north quay wall, to provide additional berthing space and increase the basin area. This pier, paved with concrete, was equipped with water, oil, and air lines, a railway spur, a large transit shed, several storehouses, and shop buildings. The south quay was likewise extended a distance of 500 feet and equipped with water, oil, and electric services. A net depot, comprising a large storage building and a 16,000-square-foot paved weaving-slab was

--16--

--17--

built along this quay, and the basin dredged to a depth of 32 feet.

In the industrial area, extensions were made to the torpedo shop, ship fitters' shop, and battery shops. A large storehouse and a three-story structure to house the machine and optical shops were erected.

A low-lying, 20-acre area fronting on Margarita Bay was inclosed with 3200 feet of steel sheet-pile seawall, brought to a usable elevation with coral fill dredged from the bay. This was later developed as the main housing area for the station, construction including seventy four-family two-story houses and two large bachelor-officer dormitories. These units were constructed of concrete, with the first floor placed 6 feet above the ground for ventilation and garage space. A chapel and library, a theater, tennis courts, and a recreation building for enlisted men and officers were also located in the area.

Fuel Storage

In 1940, fuel storage in the Canal Zone presented a serious hazard. There were two tank farms - one at Balboa, on the Pacific side; the other at Mount Hope, on the Atlantic side - neither of which was protected against air attack. Not only were their positions exposed, but each was served by one unprotected pumping station. The Balboa tank farm was on high ground adjoining the harbor entrance channel, and its tanks presented an excellent target for air attack. Had these farms been destroyed it would have been impossible to refuel shipping in the Canal Zone. The solution to the problem was clearly underground bombproof storage tanks, located at points removed from the harbor.

At the same time, it had become increasingly apparent that in event of war, additional fuel-handling facilities would be required. All Navy vessels were fueled at the Panama Canal docks at Balboa and Cristobal, with the exception of diesel-powered craft based at Coco Solo. The Balboa farm had only limited bunkering facilities at the congested Panama Canal docks, had no reserve capacity, had no land for expansion, and could not be developed as a terminal for the proposed Trans-Isthmian pipeline.

In January 1941, the Secretary of the Navy recommended that the commanding general of the Canal Zone call a conference of all interested parties, including the governor of the Canal Zone and the commandant of the 15th Naval District, to develop a project for placing all storage of liquid fuels underground at the earliest practicable date.

Four localities were considered, final decision being left to the Navy. Plans were also considered for a pipe line connecting both coasts in order to replace tanker shipment through the Canal, but the difficulties and cost of construction caused that matter to be dropped until 1942, when the course of the war made it a project of vital urgency.

In June 1941, the Navy Fuel Storage Board submitted its report relative to the quantity, type, and location of liquid fuel storage to be provided in the 15th Naval District. It recommended fuel oil, 1,000,000 barrels; diesel oil, 220,000 barrels; aviation gasoline, 5,900,000 gallons; and suggested distribution of storage on the Pacific and Atlantic sides in proportions of 60 and 40 percent, respectively. It was further recommended that an additional reserve 3,800,000 gallons of gasoline be stored on the Atlantic side near Coco Solo, in order to be readily available to the naval air station, and that on the Pacific side, 2,100,000 gallons of reserve gasoline storage be combined into a single project under the cognizance of the Army. All storage was to be underground.

The sites selected were a 1700 acre tract, near Cristobal, designated the Gatun farm, and an 820-acre tract near Balboa, known as the Arraijan farm.

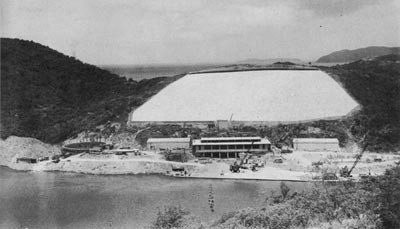

The original scope of the Gatun project, which was begun in February 1942, included fifteen 27,000-barrel steel tanks for fuel oil, two 27,000-barrel gasoline tanks, and four pumphouses. When emergency conditions required more extensive underground oil-storage, the Gatun project was enlarged in May and September 1942, and again in January 1943. It eventually included fifteen 27,000-barrel and eleven 50,000-barrel steel tanks and seven 27,000-barrel tanks of pre-stressed concrete.

The Gatun tank farm was connected with the existing 27-tank Mount Hope farm of the Panama Canal and the Cristobal piers by two 20-inch lines for fuel oil and two 12-inch lines for diesel oil. Booster pump stations were constructed in the line to enable a tanker to discharge at the rate of 8,000 barrels per hour for fuel oil and 6,000 barrels per hour for diesel oil.

The development of the tank farm at Arraijgan progressed concurrently with the project at Gatun. Planned originally to consist of eighteen 27,000-barrel

--18--

and two 13,500-barrel tanks, the Arraijan farm eventually included two 13,500-barrel and twenty-six 27,000-barrel steel tanks, four 27,000-barrel and six 50,000-barrel pre-stressed concrete tanks, and four pump houses. Two 18-inch and one 12-inch pipelines connected the farm with the fueling piers at Balboa. The tanks, pump-houses, all design details, and method of construction were similar to the Gatun project.

To provide reserve storage for aviation gasoline, seven 13,500-barrel steel tanks were installed in the naval magazine area, adjacent to the Coco Solo air station. This project, which likewise was begun in February, eventually expanded to include five additional tanks of 27,000-barrel capacity for ready diesel-oil storage to supply the submarine base. These were connected through an 8-inch pipe to the eight 25,000-gallon tanks at the air station. The diesel tanks were, in similar fashion, connected with the Panama Canal tanks at Mount Hope, the fueling piers at Cristobal, and, eventually, with the tank farm at Gatun, making the entire system mutually flexible.

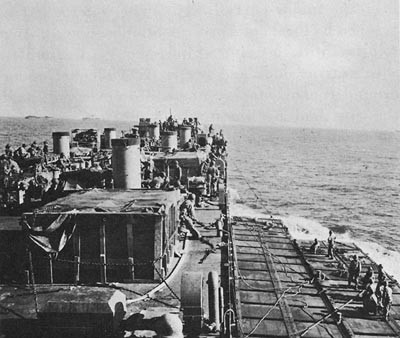

Japanese seizure of the oil fields in the Netherlands East Indies during the early days of the war made it necessary to rely entirely on the Americas for oil deliveries to the Pacific theater of operations. With a large portion of the United States refineries located along the Gulf of Mexico and the East Coast, and those in South America likewise accessible from the Atlantic and Caribbean, fuel deliveries to the Pacific depended upon the use of tankers and the Panama Canal. A certain and continued supply of liquid fuel was a strategic imperative.

During the summer of 1942, German submarines took a heavy toll of our tanker fleet plying the Atlantic and the Caribbean, which, apart from the loss of oil involved in these sinkings, seriously reduced the number of fast tankers available to transport oil in the quantities needed. These losses were a matter of grave concern in view of the oil demands involved in future operations planned for the Pacific campaign.

Accordingly, the installation of the proposed pipe line across the Isthmus, connecting the Gatun and Arraijan tank farms, became a project of immediate military necessity. Such a pipe line would confine the use of older, smaller, and slower tankers to a shuttle service between the fueling piers at Cristobal, the supply sources along the Gulf of Mexico, and the huge refineries at the Dutch islands of Aruba and Curacao. It would also serve to eliminate tanker traffic through the Canal and materially speed up the loading and return of the large, fast tankers carrying oil to the Pacific.

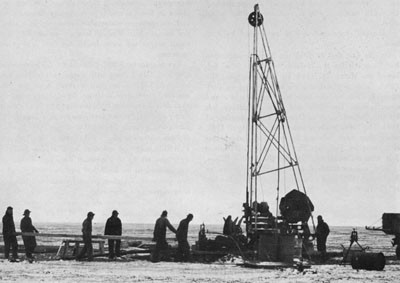

The installation of this pipe line was accomplished under a fixed-fee contract, awarded specifically for this purpose, on August 4, 1942. As initially planned, the project called for the installation of one 20-inch and one 10-inch welded-steel pipe lines, each 33 miles long, connecting the Gatun and the Arraijan tank farms. Construction was started in October.

In addition to one Canal-crossing, 4 miles of the run was under the waters of Gatun Lake. The rugged terrain and jungle along the route presented many problems in ditching, grading, and placing of the pipe itself. Even Gatun Lake had to be cleared of submerged obstacles.

In spite of an unduly severe rainy season, the two pipe lines were completed and used for the first time on April 18, 1943. By the end of 1943 the entire system was completed and in full operation.

In April 1944, a year after the first test had been run, work was started to double the capacity of the pipe line. A second 20-inch fuel line and a 12-inch line to carry gasoline were laid directly over the original 20- and 10-inch pipes.

Built at a cost of $20,000,000, the Trans-Isthmian pipe line was built to handle a daily flow of 265,000 barrels of fuel oil, 47,000 barrels of diesel-oil and 60,000 barrels of gasoline.

Housing

As a part of the general expansion program undertaken in the Canal Zone, two housing developments, totaling 1400 units, were built to provide for the families of married enlisted personnel and civilian employees of the 15th Naval District. These units, built under a contract awarded in December 1940, were divided, 1104 being on the Atlantic and 296 on the Pacific end of the Canal.

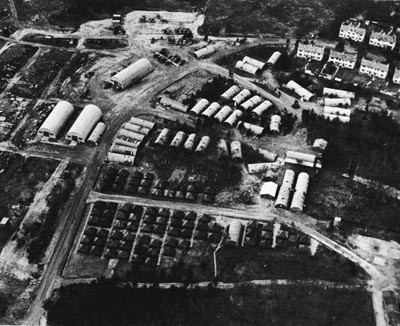

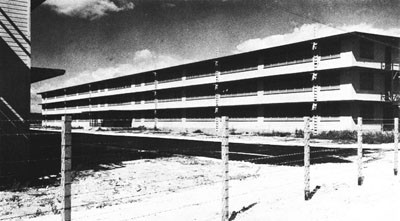

The larger development, Coco Solito, was constructed on a 33-acre, filled-in site, one mile south of the air station at Coco Solo. Laid out with six east-west streets and three north-south ones, Coco Solito contained 91 twelve-unit, one eight-unit, and one four-unit apartment buildings. The structures were of similar type and design, three stories high, of concrete and frame, with galvanized-iron roofing

--19--

and the ground floors available for garages and laundries.

The housing area at the Pacific end of the Canal encircled San Juan Hill on three sides, spreading over approximately 100 acres of rolling ground which required considerable clearing and leveling. It included 66 four-unit apartments, 2 officers' houses, 2 bachelor officers' quarters, and 5 B-1-type barracks, together with several community buildings, storehouses, a public-works shop, administration, subsistence, and service buildings.

At Lacona, 296 apartments for civilian personnel were completed in December 1941. This group comprised 24 twelve-unit and one eight-unit apartment houses.

A new 12-inch water main replaced the former 8-inch one supplying Balboa, and a 750,000-gallon water reservoir was built on San Juan Hill to serve naval activities.

Hospitals

To care for the large increases in personnel which accompanied the expansion of the naval establishment, a new 200-bed naval hospital was built on a 40-acre tract of high land, on the north side of the new Trans-Isthmian Highway, about 3 miles from the Coco Solo air station. This facility consisted of a four-story structure, with additional buildings for quarters, laundry, garage, and sewage plant, all of reinforced concrete. It was commissioned in September 1942, and later enlarged by the addition of two temporary wards of frame construction, to provide 500 beds.

A second hospital was built on a 50-acre tract adjoining the operating base on the Pacific side. Construction of this 400-bed facility was begun in the late fall of 1941. It was commissioned August 15, 1942, and put to immediate use, though only partially completed.

All the buildings were of temporary frame construction, one-story high, and well ventilated. They included six standard H-type wards, connected by covered passageways, quarters, and administration building, and laboratories, messhalls, and garages. Location and general layout were chosen so as to be readily adaptable if permanent structures were eventually erected on the site.

Ammunition Storage

The naval magazine area at Coco Solo, originally completed in 1937, was more than doubled both in storage capacity and in area, during the war-construction period. Under the initial program, begun in November 1940, new additions were confined within the original area of 700 acres. After war was declared, further increase in storage facilities was ordered and the area of the reserve increased to 1500 acres, of which 140 were devoted to the Coco Solo tank farm. Both the earlier work and the later additions required a considerable amount of clearing, excavating, and road building. Altogether, 40 storage structures of various types, ranging from concrete arch-type underground magazines for high explosives to frame storehouses, were built.

The capacity of the existing West Bank Ammunition Depot, commissioned in September 1937, was increased fourfold during the period from 1941 to 1943, a total of 47 ammunition magazines being built, of which 34 were concrete arch-type high-explosive magazines.

These were linked together by a system of access roads, and the newly developed area enclosed by 7 miles of wire fencing. In addition, sentry stations, telephone lines, quarters for assigned personnel, and a temporary mine-anchor storage building were included in the development.

Radio Stations

The two major radio stations, located at Gatun and Summit, were considerably enlarged, and a third, known as the Farfan Radio Station, was installed at Balboa.

At the Gatun station, three existing towers were removed and replaced by three 150-foot steel towers; a new two-story reinforced-concrete, bombproof transmitter and command post was added.

To the station at Summit, which had been completed in 1935, were added housing, an extension to the transmitter building, a new bombproof transmitter and receiving building, and a 300-foot and an 800-foot tower.

Erecting the 800-foot tower presented an unusual construction problem. Approximately 135,000 cubic yards of excavation were necessary to level the surrounding terrain before placing the ground grid-system, which comprised 240 bare copper wires extending radially for a distance of 600 feet. The 20-foot square tower rested on a single, huge insulator and was supported vertically by eight equally spaced guy cables, attached at a height of 515 feet.

The Farfan Radio Station, an entirely new development,

--20--

located on an 860-acre reservation south of the Balboa operating base, was equipped with complete services. The installation included five steel towers, a two-story bombproof operations building, and housing facilities.

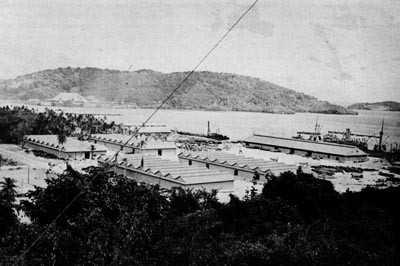

Cristobal

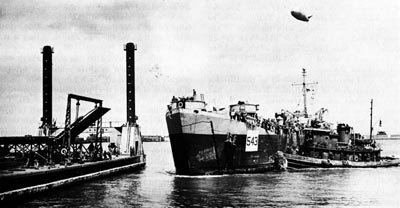

The Panama Canal maintained its ship-repair facilities serving the Atlantic end of the canal at Cristobal. These, comprising the Mount Hope shops and a graving dock, 390 feet by 80 feet, were supplemented by two marine railways of 1000-ton and 3000-ton capacities and a 1000-foot marginal wharf.

As a part of the fuel-storage program, the dock was equipped with fuel, diesel-oil, and gasoline pipe lines to facilitate the transfer of liquid fuel to the Gatun tank farm. Dredging to a depth of 35 feet provided an adequate turning basin in the vicinity of the marine railways and the marginal wharf.

The old section base at Cristobal was supplemented by new buildings to house and feed 450 men assigned to the inshore patrol.

Balboa

An area opposite Balboa, the only practical location for the expansion of waterfront facilities at the Pacific entrance, had been under study for several years as a possible site for a submarine base. In the summer of 1941, the development of a small operating base was begun at a point where a pier had been built four years previously, to afford access to the ammunition depot. An extension was made to this pier and two new finger piers were added.

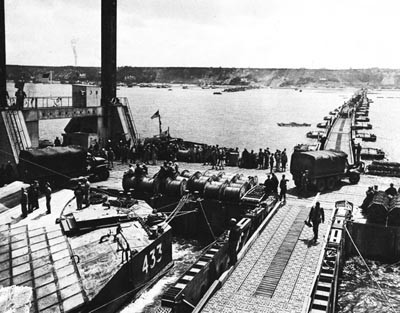

The two new piers, each 40 by 704 feet, were built of reinforced concrete. Concrete piles were cast at the concrete plant at Fort Randolph, on the Atlantic side, then producing piles for the Margarita breakwater, and shipped through the Canal. Pipe tunnels built into the piers provided space for fuel-oil, water, and power lines. The original ammunition depot pier was lengthened 220 feet and the waterfront area dredged to provide a 45-foot depth alongside the old pier, and a 33-foot depth at the new ones. A fourth pier, 1000 feet long, north of the ammunition pier, was planned and the necessary dredging completed, but the project was cancelled.

Several hundred feet out from the shoreline a head quay, or transverse wharf, 50 by 834 feet, was built to join the inboard ends of the three piers. A fill of dredged material was to be placed behind the quay, but after filling had progressed behind the first completed section, a serious slide damaged that portion of the quay. The damaged part was not rebuilt, and no more fill was placed.

An industrial area for the new base, adjacent to the piers, was provided with shops for repair and overhaul of torpedoes, batteries, communication equipment, and other items of comparable magnitude. In addition, a three-story general storehouse, 100 by 300 feet, was erected to house top-off stores for Pacific-bound convoys.

South of the industrial area, a net and boom depot was established, equipped with a steel-frame net and boom building and several temporary storehouses. In addition, the depot was provided with a paved area of 12,000 square feet for net weaving and 74,000 square feet for storage.

The 15th Naval District headquarters area, covering 40 acres, was increased to 65, and a new, 3-story, reinforced-concrete office building, a bombproof command center, and additional housing for service personnel were built.

A four-story concrete store house, 80 by 220 feet, adjacent to the Balboa piers, completed in November 1941, formed the nucleus of the Balboa supply depot. After our entry into the war, when the Zone became the last stopping-off place for vessels en route to the Pacific, eight temporary frame structures, each 50 by 300 feet, were erected on an 18-acre plot, half a mile north of the main warehouse. These structures were completed in March 1943, together with a sorting and handling shed and a 75,000-square-foot lumber-storage yard. A much-needed refrigerator storehouse to replenish ships' food-lockers was completed during May 1944.

During World War I, when the construction of the Pacific terminal of the Canal was under discussion, it was decided to build two graving docks at Balboa; one to take any vessel that could pass through the canal locks and the other to care for smaller ships. Construction of both was started, but only the larger, known as Drydock Number 1, was completed. When work on the smaller dock, Drydock Number 2, was stopped, early in 1915, the head wall and south side wall had been completed and the floor of the dock excavated into rock to the required depth. Thereafter, Dock Number 2 was carried in the shore development plans as an essential project to be provided at Balboa.

After the outbreak of World War II, Drydock

--21--

Number 2 was approved as a project in January 1942, and construction began immediately. It was redesigned to accommodate two destroyers or two submarines abreast, and a third dock for small vessels was built alongside, so located as to use the north wall of Dock Number 2 as one of its own.

All three drydocks share the use of the adjoining shops operated by the Panama Canal.

A pumping plant and electrical substation, a wharf along the north wall of Dock Number 3, a pier between Docks 2 and 3, and a cellular sheet-pile extension of the north and south walls of Dock Number 2, to form an approach pier, aiding the lateral control of vessels during docking operations, were also built. Some new machinery was purchased and installed in the Panama Canal shops to improve the repair capacity. By the end of 1943 the total repair facilities available in the Canal Zone were estimated as equal to those at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.

Part III - The Destroyer Bases

The eight bases, popularly known as "Destroyer Bases" because of their acquisition from Britain in exchange for over-age destroyers, operated to advance our sea frontier several hundred miles into the Atlantic on a broad arc, with Argentia, Newfoundland, as the north anchor and Trinidad as the south anchor, with Bermuda between. Individually and collectively they were of significant value in that they afforded strategically located sites upon which to base tactical and patrol aircraft for the control of the Caribbean.

Development and fortification of each base took into account the limitations imposed by location and character of terrain. Santa Lucia, in the Windward Islands, Antigua, Jamaica, British Guiana, and the island of Great Exuma in the Bahamas were equipped as secondary air bases and the remaining three, Trinidad, Bermuda, and Argentia, as major air bases. For immediate strategic reasons, Trinidad, Bermuda, and Argentia were given top priority and eventually became important bases for the operation of ships as well as planes. Argentia is discussed in the chapter dealing with bases in the North Atlantic.

A major air base, as visualized by the Greenslade Board, was to be equipped with complete facilities for operation, storage, and supply, engine overhaul, and complete periodic general overhaul of all types of planes. A secondary air base was a smaller installation, having facilities primarily for the operation, routine upkeep, and emergency repair of aircraft.

At the very beginning of their construction history these bases shared a common plan calling for the installation at each of emergency shore facilities to house a Marine detachment. This phase of their development was initiated by the Bureau of Yards and Docks on October 30, 1940, by assigning to the fixed-fee contract then operating at San Juan, the task of purchasing the necessary materials and equipment in advance of operations on the site. This beginning permitted the preliminary work attending a project of this magnitude to progress simultaneously with the negotiations attending the transfer of these Crown lands.

The Greenslade Board submitted its recommendations to the Secretary of the Navy on October 27, 1940, and tentative leases for the lands required were drawn, based on these findings; the necessary topographic and hydrographic surveys were begun. Remoteness of the sites, unknown bidding conditions, and the pressing necessity for speed contributed to the decision to undertake the construction at each location by negotiated cost-plus-fixed-fee contracts.

At first, there were some difficulties as the local governments did not have a clear picture of the agreement between the British and the United States governments concerning the use of the leased areas, and it was necessary for the Bureau to secure temporary leases in order to avoid delaying construction until such matters as customs, taxes, wharfage fees, and wage rates for local labor could be settled. The Navy Department received authority to enter Bermuda, Trinidad, and British Guiana, on January 3, 1941; Antigua and St. Lucia, on January 13; Great Exuma, March 27. The Jamaican government authorized entry into Little

--22--

Goat Island on January 16. Final lease agreements for all the bases were consummated March 27, 1941.

Trinidad

The strategically important island of Trinidad, commanding a vulnerable approach to the Panama Canal and the South American trade routes, lies off the coast of Venezuela. It is roughly 35 by 55 miles, with two long, narrow peninsulas extending westward toward the continent to form the Gulf of Paria, completely landlocked except for two easily guarded channels, each 7 miles wide.