The Navy Department Library

Bayly's Navy

By Vice Admiral Walter S. Delany, United States Navy (Retired)

Washington, D.C.: Naval Historical Foundation © 1980

Preface

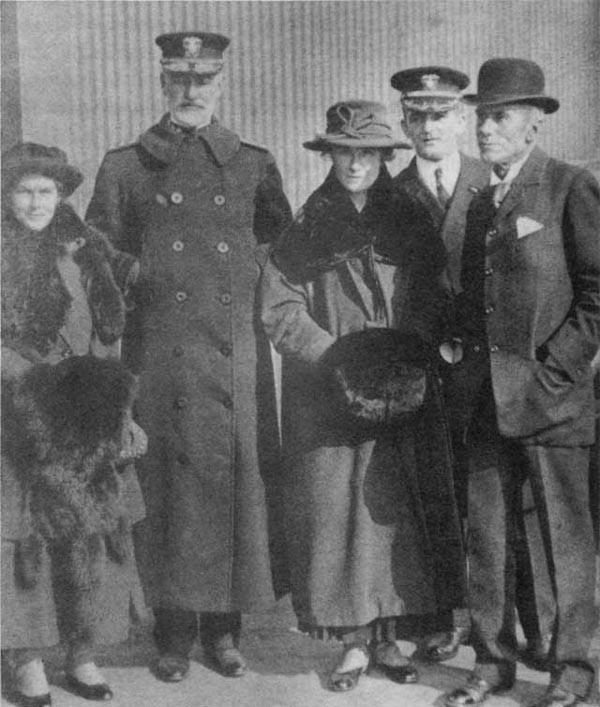

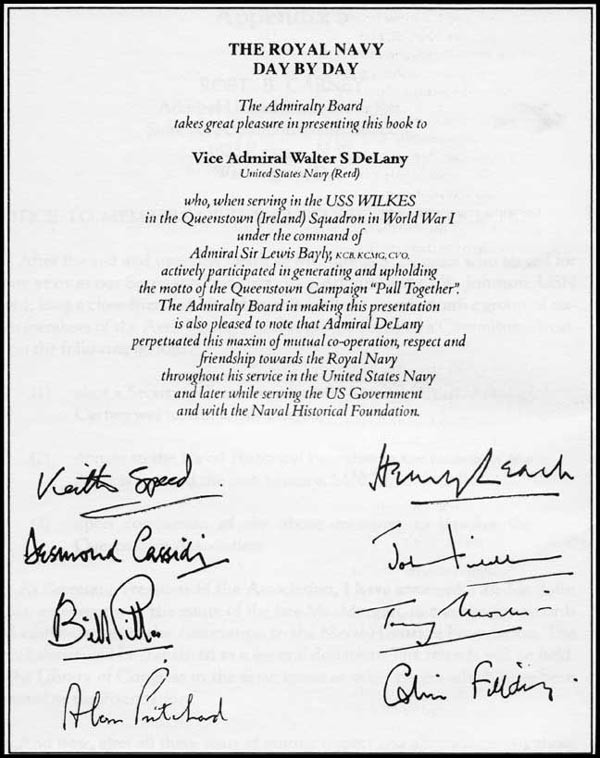

The 1967 Spring Report of the Naval Historical Foundation---50 years after the arrival of the first U.S. destroyers at Queenstown, Ireland, in World War I---presented a short story of the close and harmonious relationship that prevailed between the personnel in the ships of the U.S. and British navies serving together under British Vice Admiral Sir Lewis Bayly, KCB, KCMG, CVO. They did so within the mutually accepted meaning of the slogan "PULL TOGETHER," which was displayed on a signal board secured to the inboard bulkhead abreast the starboard main deck gangway landing of the tender USS Melville, moored in Queenstown Harbor. The board was placed there at the suggestion of Sir Lewis and with the complete concurrence of Captain J. R. P. Pringle.

That this respect and affection, which started in Queenstown among so many officers of the two navies dedicated to the same objective, and would extend through practically their entire later naval service lives, is a tribute to the significance which the seagoing navies attached to the words "PULL TOGETHER." It expressed the basic human relations element of a command structure.

It seems appropriate and opportune that this pamphlet should be a follow through on that 1967 Report. It is intended to emphasize how today, as in 1917, these words can be applied to tasks of several bodies directed towards a common objective. Where that objective is the portrayal of the history of the U.S. Navy and its role in the security of the country, the understanding and application of the words are significant.

Our members have also favorably endorsed the choice of "PULL TOGETHER" as the title of our newsletter.

The sources for this pamphlet are primarily the files of the Queenstown Association, which came to the Foundation when the Association was

--ii--

disbanded in 1961; Pull Together!: The Memoirs of Admiral Sir Lewis Bayly, published in 1939; the private collection of Mr. John C. Reilly, Jr., Ships Histories Branch, Naval Historical Center; and the official files and records of that office.

The author had fourteen months service on the Wilkes at Queenstown, was an original member of the Queenstown Association, and was an acquaintance of the Secretary of that Association. He has drawn on his memory to add to the content of this article. The voluntary editing and review support which Dr. William J. Morgan and Dr. Dean C. Allard, of the Naval Historical Center, extended to him are gratefully acknowledged.

WSD

--iii--

[B L A N K]

--iv--

In MemoriamOn 21 September 1980, when this small publication was still in page proof, Vice Admiral Walter S. DeLany peacefully embarked upon the great voyage beyond earth's last horizon. His was a long and distinguished career of service to the Navy, the Nation and to the Foundation. Admiral DeLany's zest for life and his ability to infuse the spirit of "Pull Together" into the Foundation's affairs remain as a living monument to be cherished and nurtured. |

--v--

The Queenstown Campaign:

Clearing the Sea Lanes to Britain

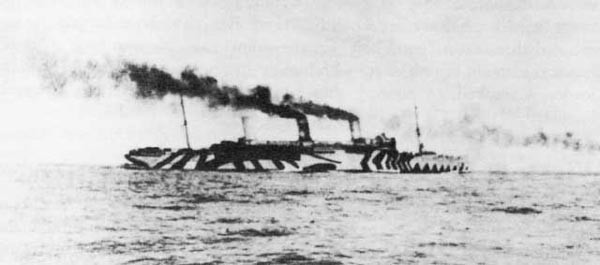

On 24 April 1917, the destroyer Wadsworth (DD-60) with Commander J. K. Taussig in command; in company with Conyngham (DD-58), Commander A.W. Johnson; Porter (DD-59), Lieutenant Commander W.K. Worthman; McDougal (DD-54), Lieutenant Commander A. P. Fairfield; Davis (DD-65), Lieutenant Commander R. Zogmaum; and Wainwright (DD-62), Lieutenant Commander F. P. Poteet, sailed from Boston under sealed orders. These were l100-ton, broken deck four-pipers with four 4-in./50 Cal. single-purpose guns and four triple-tube 21-in. torpedo mounts. Later classes of destroyers had one-pounder anti-aircraft guns mounted on the after deckhouse and forward of the bridge.

Opening their orders fifty miles at sea, they learned that the British Admiralty had requested the cooperation of a division of destroyers in the protection of commerce near the coast of Great Britain and France. With that information, they set their course for Queenstown, Ireland.

It is doubtful, however, if any of the skippers knew the actual circumstances which had led directly to these orders. They were, of course, familiar with the heavy losses the German submarines were inflicting on Allied shipping. They had an appreciation of the serious effect these losses were having on the British war effort and the welfare of the Allies. What they did not know was that, in early 1917, Ambassador Page had emphasized the seriousness of the situation to the U.S. Government and strongly recommended

--1--

that an admiral be sent to England immediately to consult. Rear Admiral W. S. Sims, then President of the Naval War College, was selected for the mission.

Because of the tense situation then existing between the governments of the United States and Germany, and the imminence of war between them, Sims was directed to go secretly under an assumed name and in civilian clothes. He and his aide, Commander J. V. Babcock, sailed on 31 March on board the American liner New York for Liverpool as J. V. Richardson and S. W. Davidson to carry out their confidential instructions. On 6 April 1917, while they were still at sea, war was declared on Germany. Although the ship had hit a mine off Liverpool on 9 April 1917, there was no delay in their arrival in London. After just five days in consultation with the First Sea Lord, Admiral John R. Jellicoe, and others including the King, Sims urged the Navy Department to send immediately the maximum number of destroyers and light surface craft it could assemble to the vital spot in the submarine campaign---Queenstown.

Destroyers Sent to Queenstown

It must be remembered that although the mission of these U.S. destroyers was the destruction of German submarines and protection of shipping, there were at that time no accepted and effective antisubmarine warfare doctrines or procedures to govern such destroyer operations.1

Nor were these destroyers equipped with any special anti-submarine weapons except, initially, the hand-thrown 50-pound depth charge, or "ashcan" as it was commonly called. There were no arrangements to launch them, and ships picked the strongest man in the crew to heave them over the stern when attacking a suspected periscope, oil slick, or unsuspecting whale. The charges were made in two parts which separated when they hit the water. One part acted as a float and the other as the explosive charge. The depth to which the charge sank was controlled by a line hand-wound on a spindle. When the charge sank to that depth, it was triggered and blew up.

Later on, when 300-pound charges fitted with variable depth settings were developed, they were stowed in two fore-and-aft tracks secured to the after open deck. They could be rolled overboard in an attack by releasing them singly from a hand operated pull on the bridge. Y-guns were an added and later installation for projecting these charges to safe distances abeam.

In addition, "fighting lights" were installed. These were red and green lights which could be flashed together as an emergency recognition signal. They were the initial IFF (identification, friend or foe) installation. These installations, as

--2--

well as changes to the forward bulkhead of bridges to provide enclosed protection for the watch standers against the foul weather, were usually accomplished at a dockyard in Liverpool.

Remember, too, that neither sonar nor radar was a part of ships' installations. In fact, many of the destroyers did not have gyro compasses on board, and the master magnetic compasses required careful and repeated compensation, especially when topside ready ammunition stowage for the forward 4-in./50 Cal. guns was changed. One l100-tonner, USS Wilkes, before she left the States as an escort for the first troop convoy to leave New York for St. Nazaire, had what was called a "Fessenden Oscillator" installed. It was supposed to be a submarine detector, but was not successful in such tests conducted with U.S. submarines in Long Island Sound and with British submarines in the Solent Channel off Portsmouth, England.

--3--

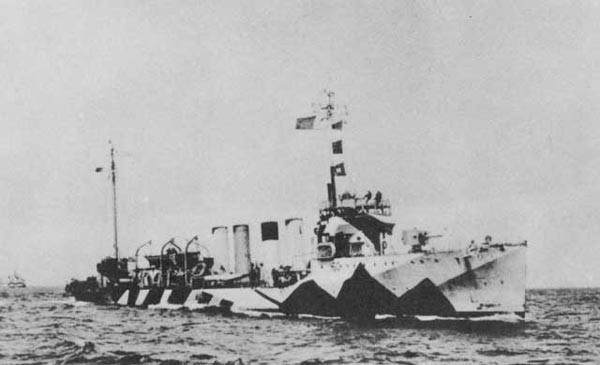

Wilkes also had its hull painted with a new camouflage design by Henry Bittinger, the Navy specialist in the Bureau of Ships. His idea was to paint out shadows such as overhangs, the under side of guns, etc., with merging tones of gray and white paint. This was not acceptable in the war zone where the "dazzle" design replaced it.

The Leaders: Sims and Bayly

Rear Admiral Sims was eminently qualified for this special command of U.S. Naval Forces operating in European waters. From 1897 to 1900, he had been Naval Attache to France, Russia, and Spain. Through his ability and perseverance, he had been responsible for the great improvement in naval gunnery. He had been a student at the Naval War College and a member of the staff there. In 1913, he had been in command of the Torpedo-boat Flotilla, Atlantic Fleet, where he again was responsible for developing destroyer tactics and doctrine. He was outspoken, fearless, extremely able, but not without a sense of humor.

--4--

In command at Queenstown at that time, in fact since 22 July 1915, was Vice Admiral Sir Lewis Bayly, RN. He had previously commanded the First Battle Squadron in the Grand Fleet. His reputation as a thorough, exacting, strict, arbitrary, and forceful officer was well known throughout the Royal Navy and by those of the U.S. Navy who knew him during his tour of duty as Naval Attache in Washington. He, like Admiral Sims, had been commodore of destroyer flotillas, and was credited with the development of the tactics and operating doctrines of the light forces of the British Navy. It is a coincidence, too, that like Admiral Sims, Sir Lewis had served as President of the Royal Naval College before his assignment to Queenstown. It is not too surprising, then, that an attitude of mutual respect and understanding developed between them which permeated the entire command. Sir Lewis recalled his meeting with Admiral Sims by saying: "In April 1917 I was sent for to the Admiralty and saw Jellicoe, who had gone there as First Sea Lord after leaving the Grand Fleet, and Sir Edward Carson, the First Lord. They told me that the U.S.A. was about to come into the War, and that a number of U.S. destroyers would be sent over to Queenstown and be put directly under my orders. I was then introduced to Admiral Sims, of the United States Navy, and returned to Queenstown."2

Admiral Sims' biographer, Elting E. Morison, in Admiral Sims and the Modern Navy, writes:

For the men of both nations who served there, the base has become a precious memory.... The splendor of its success has hidden many of the difficulties that lay in the way of that success. To a few officers, Admiral Bayly remained 'Old Frozen Face.' At times, in his pride in the men under him, he exceeded his authority and reprimanded American officers to their chagrin and mortification.... The enlisted men of both countries, upon occasion, irritated one another. Inevitable difficulties and frictions frequently could not be solved by ordinary salvation of command, an appeal to rules and regulations. Adjustments had to be made by instinct, tact, and intuition. Upon the leaders, Admiral Bayly, Admiral Sims, and Captain Pringle, fell the heavy burden of the command. To all of them belongs the credit for a great achievement. With this triumvirate quite properly belongs another, Miss Violet Voysey [Admiral Bayly's niece and hostess]. Each man appealed and not in vain to this young woman. 'Petticoat influence' has seldom been used by woman with such wise restraint.

An example of the spirit of cooperation that sprang up between the United States and British navies, which was so successfully forged by Admiral Bayly, Admiral Sims, and Captain Pringle, occurred while the author's ship, USS Wilkes, was in port at Portsmouth, home of HMS Victory.

HMS Victory was Lord Nelson's flagship at the Battle of Trafalgar. At the

--5--

time of this incident, Victory was painted white and moored in an accessible part of the harbor. Wilkes was moored to a dock close to that berth. When getting underway for an exercise, someone in Wilkes' fireroom did not put a tip in the oil burner nozzle. Result: huge billows of black, oily smoke belched out of the stack on the first engine bell. The wind carried it down onto the Victory. The Wilkes' skipper put the ship back alongside the dock, put the chief engineer and some firemen into the motor whaler and sent them to the Victory with cleaning gear, apologies, and offers to clean up any effects of the smoke. Fortunately, that was not necessary, but the gesture was greatly appreciated and duly acknowledged. That closed the books on both sides.

The Command at Queenstown

The Queenstown Command as set up in 1915 stretched from the Sound of Mulls to Ushant, covering all the western approaches of Ireland, the Irish Sea, St. Georges Channel, Bristol Channel and the entrance to the English Channel. Patrol vessels initially assigned to the Command were "Flower" class 1200-ton, coal-burning sloops (Bluebell, Zinnia, etc.) with 16-17 knot maximum speed, plus trawlers, drifters, motor launches, and submarines. The convoy system had not been started, and trawlers were assigned to work off-shore as escorts and hunters, with sloops patrolling specified areas on trade routes unless assigned for valuable ship escorts.

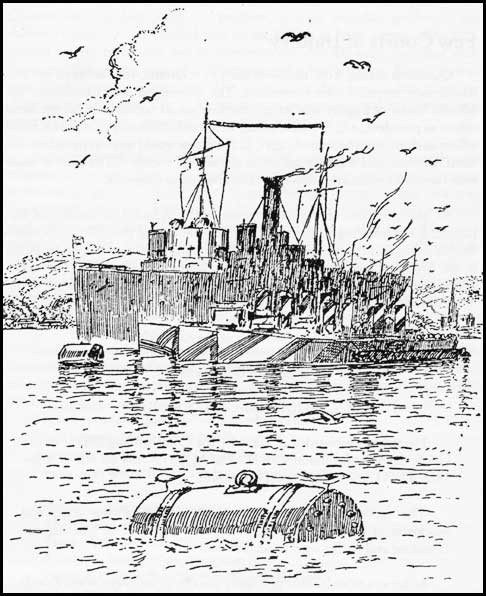

Mention must be made too of a special class, the so called Mystery Ship (or "Q" Ship). About 30 of these were used at different times. They were usually tramp steamer hulls, ballasted and compartmented to give added floatation if torpedoed. In addition, 4-in. or 5-in. rapid-fire guns were hidden in upper deck compartments within the silhouette. The ship was bait for enemy submarines and cruised in shipping lanes where submarine attacks were most likely. If torpedoed, the "panic party" abandoned ship. There was always a "phoney" captain with ship's papers in that party. The "fighting party" stayed on board waiting for the submarine to surface. When it did and it became a good target, the ship's sides in the gun compartments were dropped, and the ship began shooting at the enemy submarine.

The most famous of these was the Farnborough (Q-5), commanded by Captain Gordon Campbell (later Vice Admiral, VC, DSO), which sank the U-83 after his own ship had been torpedoed by that German sub. For this, he was given the Victoria Cross. He also commanded the mystery ship Pargust, which was torpedoed but managed to sink the submarine, and the Dunraven, which was sunk after a lengthy battle with a submarine. He later became Admiral Bayly's flag captain in command of his cruises.

In 1917, the Queenstown commander was given admiral rank and made Commander in Chief, Western Approaches.3

--6--

--7--

American Destroyers Arrive

The arrival of the first U.S. destroyers at Queenstown has been told in picture and story. The night before their arrival, Admiral Sims and his staff came down to Queenstown and stayed at the Admiralty House. During the evening, there were a series of explosions which were explained as caused by minesweepers exploding the mines that the German submarines had laid in the harbor entrance against the arriving destroyers. The next day, the sloop Mary Rose met the destroyers and escorted them into the harbor.

That night, the skippers of the destroyers had their first dinner in the War Zone with the Admiral and his "only niece." As each new division of U.S. destroyers arrived, the skippers were treated the same way. Between May 1917 and the Armistice, there were 92 U.S. ships in the Queenstown command: two destroyer tenders, 47 destroyers, one submarine tender, seven submarines, one mystery ship, 30 sub-chasers, one minelayer, and three tugs.

The submarines arrived in 1917 with the tender Bushnell with Captain T. C. Hart in command (later Superintendent of the Naval Academy and Commander in Chief, Asiatic Fleet). They were based at Berehaven on the west coast of Ireland. The sub-chasers also arrived in 1917 with Captain A. J. Hepburn in command (later Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet) Seaplanes arrived the same year at Queenstown with Commander F. R. McCreary in command, at Wexford on the southeast extremity of Ireland under Commander V. O. Herbster, and also in Northern Ireland. The mystery ship was the Santee, commanded by Captain D. C. Hanrahan (former Cushing skipper) and a volunteer ship's company. She had a short life because she was torpedoed off Kinsale, within 24 hours, on her maiden cruise. The German submarine never did surface, and the ship was brought back to Queenstown under tow. It was general1y suspected that German intelligence was quite on to the U.S. Navy's effort in this field of anti-submarine activity.

American Naval Officer on Royal Navy List

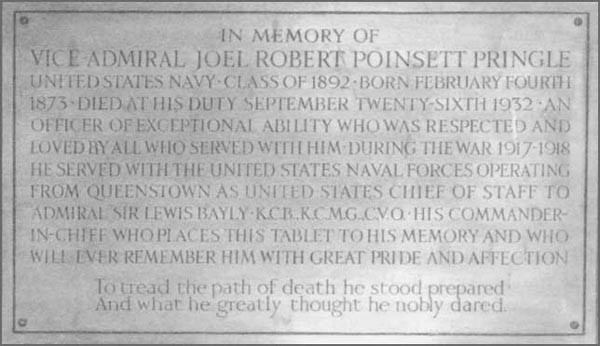

The two destroyer tenders were Melville (Captain H. B. Price) and Dixie (Captain J. R. P. Pringle). Captain Pringle, an outstanding officer, was the American Senior Officer Present at Queenstown and represented Admiral Sims in the Area. A destroyer sailor who had commanded the Perkins, he later commanded Flotilla Two of the Atlantic Fleet as additional duty in command of Dixie. Later, he became chief of staff to Admiral Bayly, who wrote, "I resolved when the U.S. destroyers arrived that I would deal with them directly

--8--

as regards their orders and duties, but I would in no way interfere with their internal discipline, which, though different from ours, is no doubt good. Consequently Captain Poinsett Pringle, the senior U.S. naval officer, took charge of al1 disciplinary matters. I made him my U.S. Chief of Staff, and as such entered him in the Navy List---the first time a foreign naval officer has appeared in the Navy List of an Admiral's staff." Admiral Bayly added:

"Captain Poinsett Pringle would have been an outstanding officer in any navy. A thorough disciplinarian, with a wel1-balanced mind and a lightning brain, he was a perfect man to handle the U.S. destroyer captains, to get the most work out of them, and to keep them smiling. He was one of the greatest friends I have ever made, my beau ideal of what a naval officer should be."4

--9--

As further evidence of the excellent command relations prevailing between the two seniors, the Admiral again writes, "In the summer of 1917 the Admiralty wrote suggesting ...I should take some [leave] now. I wrote back ... on condition that Admiral Sims should hoist his flag in place of mine during the week I was away.... On the morning of my departure my flag was hauled down and Admiral Sims' Admiral flag took its place, and he made Queenstown his headquarters. My niece and I in a U.S. Cadillac car, driven by a U.S. naval chauffeur, went for a motor drive round the coast of Ireland and to visit some of my bases."5

Admiral Sims wrote to Captain William Veazie Pratt who was assigned to the Chief of Naval Operations in May of 1917 that Admiral Bayly had written him as follows, "If I go on leave from June 18th to June 23rd, would you like to run the show from here during my absence? I should like it (and you are the only man of whom I can truthfully say that), your fellows would like it, and it would have a good effect all round." To this Sims replied on 1 June 1917 that

the suggestion was the surprise of my life. I will not attempt to express

--10--

my appreciation of the honor you have done me, or my gratification for the confidence your suggestion implies.

While I have never yet had occasion to hesitate to accept, or unduly feel the weight of, any of the lesser responsibilities of my service, I would hesitate to accept this were it not that I would simply be carrying out your plans, by your methods and with the assistance of a staff trained by you.

Under the circumstances I shall be more than glad to act as your representative, particularly as I assume that in case of an unforeseen problem of a serious nature I can fall back upon your more mature experience....

Please present my best repects to Mademoiselle Voysey, my fellow conspirator in our common cause.6

Number One Duty: Sink Submarines

Four days after arrival of the first destroyers, they went on their initial patrol. The schedule was normally five days at sea and two or three in port. These and all other destroyers and sloops in the command operated under the same broad instructions. They had three specific duties: to destroy submarines, to protect and escort mechantmen, and to save the crews and passengers of torpedoed ships. Number one priority was sinking submarines, even if there were men and women in boats or struggling in the water. Periscopes were to be shelled and not rammed to avoid decoys attached to mines. Ships were always to zig zag and never to steam at less than 13 knots.

A British signalman always spent one month on board each arriving U.S. destroyer to train the U.S. men in the British system.

Ships had orders to keep their radio room informed of their position every two hours. In case of an accident, the operator would send the ship's position without further orders.

Everything did not always come up roses for all hands when they came to Queenstown. Those familiar with destroyers in the old Navy know that a real characteristic of a good leading chief was his ability to forage. His store rooms always had many "you never know when you might need this" items which did not appear on the books. This was especially true when the word got around that their ship was getting ready to go to the war zone overseas. The store rooms were filled with spare parts, extra mooring lines, tools, and other items that "just happened" to find their way on board. These carefully laid plans, however, went overboard when the destroyers arrived at Queenstown. To the

--11--

complete disgust of these far-sighted chiefs, they found a station order which required ships to land for common use all except a minimum quantity of stores, spare parts, etc., for the specific purpose of lessening the ship's draft. To decrease the over-horizon range at which the ships could be seen, the topmast had to be housed and the radio antennea replaced.

In his book Pull Together published after retirement, Admiral Bayly wrote, "It is a great tribute to both British and U.S. captains that I never had a signal 'Request instructions'. Their orders were to do what they considered the best thing to do when in doubt, and very well they did it." He added, "I always saw the captains of escort ships of both Navies the morning after their return to harbor and the morning before they sailed: the former because there was always something to learn from them, the latter to make sure that they understood what they had to do."

Paperwork Kept to Minimum

Of interest to today's Navy is the fact that there was practically no paperwork other than operational orders and official reports. Ships operating on a five-day out and two or three-day in-port schedule had no time for paperwork. Unlike the customary work requests to be "submitted in quintriplicate for approval" and then await work commencement, when returning ships neared the entrance to Queenstown Harbor they would exchange recognition and distinguishing signals by flashing light with the signal station on the beach. They also requested any important repairs and supplies needed. Before entrance, the destroyer would have been assigned berths at the oil jetty or numbered mooring buoy without any inquiries from the ships. As soon as the ship was secured, all unnecessary fires were allowed to die out, and machinery needing repairs was disabled. It was known that the ship, except for an emergency, would be in port for three days. The convoy schedules and work was planned accordingly. Incoming destroyers were fueled in pairs at the jetty. As the fueling was completed, the ships were moved by tugs to their next mooring.

Even before the destroyers had secured in their assigned berths, motor launches from the tenders mothering the destroyers would be alongside, with repair officers, fresh provisions, mail, and necessary repair and replacement parts. The crews of the tenders were on duty around the clock to provide such services. Since each destroyer averaged about 6,000 miles per month under all kinds of weather, these hard working and devoted tender crews certainly rate the high regard in which they were held by all the operating destroyer personnel.

The dockyard officers were told that there would be no defect lists and that they must keep an account of the money expended on British and U.S. ships.

--12--

--13--

This was done and in 1919, when the war was over, the Admiralty sent a statement over to the U.S.A. of accounts which had been paid.

Few Courts of Inquiry

Questions arising from incidents such as collisions, etc., between the two navies were bound to need attention. The Command issued an order that when a Court of Inquiry was set up, the first would consist of a British naval officer as president, a U.S. naval officer as second member, and a British naval officer as third. For the second court, U.S. officers would serve as president and third member, and a British officer as the second member. The records show only two such courts were convened, both related to collisions.

As an indication of the decisiveness of the Admiral in matters of this nature, it is interesting to cite the finding in the case of the collision between the USS Shaw and the British liner Aquitania while the latter was under escort in the English Channel. The helm of Shaw jammed at almost full left rudder and turned her across the big ship's bow. Result---the Shaw's bow was cut off. The Admiral's recommendation was typical1y to the point:

To The Secretary of the Admiralty

Date 13th October 1918

1. H.M.S. AQUITANIA & U.S.S. SHAW --- Collision

Herewith is forwarded a report by the Commanding Officer of the U.S.S. SHAW of collision with H.M.S. AQUITANIA on 9th October 1918. The U.S.S. SHAW is at Portsmouth.

The report shows the coolness, knowledge of the ship, and quickness of decision which I should have expected of Commander Glassford and a ship commanded by him.

As far as a mixed Court of Inquiry usually formed here when British and U.S. ships are concerned, it does not seem to me to be necessary in this case, as I do not see how H.M.S. AQUITANIA would have known that U.S.S. SHAW's helm had jammed, or how she could have avoided her.

Lewis Bayly

Admiral

Commander-in-Chief

--14--

Sailors Relaxation

Recreation for the U.S. enlisted personnel was an initial problem in Queenstown. To help solve the problem, a large walled-in garden in the Admiral's grounds was handed over to the C.O.'s of both nations. The U.S. erected a large recreation hut to accommodate 200-300 men, equipped with desks, reading rooms, and a hall for music and other activities. British ratings were made honorary members. The money for this project was given by Americans in London. The U.S. also put up its own hospital in Queenstown manned with its own personnel.

With the small size of the town, lack of recreation facilities and even religious differences, liberty was a problem in Queenstown, and personnel were permitted to go to Cork by train. It soon became apparent that this was creating difficulties for all hands. The U.S. sailors had no other place to spend their money which was of sizeable amounts compared to that earned by local males. Obviously, the American blue jackets became popular with girls in Cork. The reverse was true of their boy friends. The result was free-for-alls in Cork and an order prohibiting British and U.S. officers and men to go within three miles of Cork on any pretense. It was learned that Cork suffered a loss of about 4,000 pounds sterling per week as a result of that order.

Humor and optimism are recognized assets of every sailor. This was true in Queenstown as the following, from the pamphlet "DOPE (From the dictionary---Dope: an intoxicating drug, anything calculated to stupefy)," will show:

There was an old "Melville" who lived at a Buoy,

She'd so many children she had to employ

Another to nurse 'em---old "Dixie" by name:

I really can't blame her for I'd do the same.

10 little "U" boats setting out in line,

1 bent her hydroplanes, then there were 9.

9 little "U" boats sang "The Hymn of Hate,"

1 sung too loudly, then there were 8.

8 little "U" boats thought they'd get to Heaven,

1 found he'd missed it, then there were 7.

7 little "U" boats, full of nasty tricks,

1 met an airship, then there were 6.

6 little "U" boats did a record dive,

1 burst his "innards," then there were 5.

5 little "U" boats tried to make a score,

1 attacked a convoy, then there were 4.

4 little "U" boats, busy as could be,

1 sighted Campbell, then there were 3.

--15--

3 little "U" boats, feeling rather blue,

1 ran himself ashore, then there were 2.

2 little "U" boats' cruise was nearly done,

1 found a minefield and that left 1.

1 little "U" boat staggered back to port,

Said that strafing England was not as easy as he thought.

Convoy System Implemented

It was not until late 1917 that the convoy system for shipping was put into use. Even then it was not completely acceptable to some in both navies as an effective solution to the protection against submarine attacks. In addition, it was not popular with merchant skippers who disliked cruising in controlled formations. Once the system was in use, both objections disappeared, and shipping losses to submarines began to decrease. As relates to Queenstown, there were only 13 coal-burning sloops really available for extended convoy requirements. When they were augmented by the long-legged, oil-burning U.S. destroyers, the system became feasible and was adopted.

The number of escorts assigned to a convoy generally depended on the number of merchant ships and their cargoes. The commanders of escorts were either U.S. or British as assigned in the operation orders. The meeting rendezvous and routing of the convoy after pickup depended on the eventual destination of the ships after the breakup of the convoy. Those ships onrouted through the English Channel were met by British channel escorts to destined ports. Before the large troop convoys began, the Queenstown destroyers could handle troopships destined for French ports. When the big push started in France and the large troop convoys were being routed to French ports, the American base in Brest was enlarged, and Rear Admiral Henry G. Wilson was placed in command. The number of escort vessels in that command was augmented by transferring the Queenstown destroyers with two condensers in their engineering plant to the Brest command to meet these added requirements. Queenstown destroyers continued to escort ships destined for British ports.

Leviathan's Crossing

The first large American troopship to make the Atlantic crossing with troops was the USS Leviathan, a former German liner. Launched at Hamburg in 1914, she could sustain a speed of 20 knots across the Atlantic regardless of weather. She had 14 watertight compartments, 46 Yarrow coal-burning boilers, and eight Parson turbines driving four 4-bladed propellors measuring 14 feet from tip to tip. On 15 December 1917, she left her pier in Hoboken in a heavy

--16--

snow storm for the crossing, bound for Liverpool. It is reported in the history of this ship that Leviathan had 7,254 troops and 2,000 crew on board for this initial trip.

Of course, a pilot was mandatory for ships entering Liverpool. On her maiden voyage, to avoid the necessity for her to "lie-to" outside the Mersey River to pick up such a pilot, he was put on board an escort destroyer in Queenstown for transfer to the big ship at the rendezvous. That didn't work, because the weather was so bad in the area that the transfer could not be made. The rough weather prevailed until the ships turned into the Irish Sea, where the transfer was finally made. Both ships maintained a steady course and speed. The destroyer came alongside, and a line was passed to the destroyer from the top deck of the liner with a bowline in the destroyer's end. This was put around the pilot under his arms. He stood on the outboard side of the destroyer deck just abaft the break on the forecastle. Timed to match the motion of the two ships, he was given a great big run across the deck and was swung aboard through an open cargo port near the water line of the big ship. Even so, the ship missed the tide and had to wait outside the port while the escorting destroyer ran anti-submarine circles around her. The Leviathan entered port on the morning of 24 December, and the escorts lighted off all boilers to get back to Queenstown for Christmas.

The escorting destroyers and their personnel had a punishing trip. Some of the escorts lost their forecastle life lines, had the bridge forward bulkheads buckled, and windows smashed. The navigator of the destroyer with the pilot on board mentions finding the pilot standing in the passageway from the wardroom to the outside deck, where he was going to the bridge for his 4-8 a.m. watch. The pilot, with his spread feet and arms against the bulkheads, was a depressed looking person. The navigator, trying to make conversation said, "How goes it, pilot," and he could not be mistaken about the pilot's feeling

--17--

when after some expressive words he concluded with "Every bone in my bloody body aches from 'olding on in the - - - - ship."

Admiral Bayly went to sea on occasion on board the U.S. escorts with the idea of uniting the two navies more closely. He was anxious to note the behavior of the U.S. ships at sea and to study their methods of discipline. He always flew his admiral's flag when he did so, even though as he said, he appreciated that it was "good bait" for the submarines. He also took Admiral Sims and Captain Pringle to sea with him in the cruiser Active, commanded by Gordon Campbell, of mystery ship fame, to watch an exercise in depth charging.

Winter of 1917 - 1918

As the winter of 1917-18 approached and the usual unfavorable weather in the area promised to make the destroyer operations more uncomfortable and hazardous, the Admiral issued the following memo to all ships under his command:

The Commander-in-Chief wishes to congratulate Commanding Officers on the ability, quickness of decision, and willingness which they have shown in their duties of attacking submarines and protecting trade. These duties have been new to all, have had to be learned from the beginning, and the greatest credit is due for the results.

The winter is now approaching, and with storms and thick weather the enemy shows an intention to strike harder and more often: but I feel perfect confidence in those who are working with me, and that we shall wear him down and utterly defeat him in the face of all difficulties. It has been an asset of the greatest value that the two Navies have worked together with such perfect confidence in each other and with that friendship which only mutual respect can produce.

Some U.S. destroyers did receive weather damage. The Ammen rolled one of her stacks out, and had a tender replace it. Others lost boats, life lines, and smashed ports with attendant compartment flooding. The crews had to be real sailormen to hang on and continue at their necessary stations and duties. Some never did a cruise in such weather without the discomforts of sickness. A tale around Queenstown relates to one destroyer that picked up the captain and two crewmen in a boat from a torpedoed tramp. The destroyer skipper was concerned that the merchant skipper would not stay in the wardroom but continued to sit on a camp stool lashed to the engine room hatch amidships. In conversation in this connection, the merchant skipper is reported to have said he had been going to sea for 30 years but had never been on such a - - - active ship before. He had been all over the destroyer and found the camp stool to be

--18--

the most comfortable and that's where he was staying. The wardroom messman brought him his ration of sandwich and soup which was the menu for such weather.

During 1918, the Admiral requested and was given command of the British aircraft units on the west coast of England as well as in Ireland to obtain complete unity of command in the Irish Sea. Patrols of surface ships, convoy routings, etc., were adjusted to meet changing German submarine tactics. This applied especially to protection of troop transports sailing singly or in convoys.

On 4 May 1918, the following memo was issued by the Admiral to the U.S. naval forces under his command:

On the anniversary of the arrival of the first United States men-of-war at Queenstown I wish to express my deep gratitude to the United States officers and ratings for the skill, energy, and unfailing good-nature which they all have consistently shown, and which qualities have so materially assisted the War by enabling ships of the Allied Powers to cross the ocean in comparative freedom.

To command you is an honour, to work with you is a pleasure, and to know you is to know the best traits of the Anglo-Saxon race.

Operations proceeded during the remainder of 1918 under the same coordinated and pleasant arrangements. Finally, the war was over, and the Commander in Chief sent the following to all ships:

The Commander-in-Chief congratulates all British and United States officers and crews under his command on the splendid victory achieved, which their loyalty, ability, and ever-ready energies have so greatly assisted. It will always be a source of great pride to him to have been so closely associated with them in this great war.

Admiral Bayly said in his book that it was "quite impossible" for him to name all the United States officers who had won his admiration for their "ability, energy, and never failing readiness to carry out any operations, however difficult, or even apparently impossible, because it would include them all...."

Finally, at year's end, the following memo was addressed to the Admiralty:

Commander-in-Chief's Office

Queenstown

December 31,1918

Sir,

1. Be pleased to lay the following letter before Their Lordships, with a

--19--

view (should they agree) to its being forwarded to the Navy Department, Washington, D.C., U.S.A., through Admiral W. S. Sims, U.S.N.

2. Sea-fighting having ceased on this station on the signing of the Armistice, and the fighting units of the U.S.A. that were stationed on the Coast of Ireland having completed their work, and been withdrawn, it appears to me opportune to make a few remarks as a record of what is probably a unique situation---viz., U.S.N. Forces operating entirely under a British Admiral in British waters.

3. When each of the various units arrived here they found themselves confronted by an entirely new situation. They were faced by an unprecedented kind of warfare and new methods of attack, and found themselves operating in waters which were strange to them and in unfamiliar types of weather.

4. They at once set to work with all their energies to learn the new methods: there was no foreign feeling about them, not a sign of jealousy, no impatience at receiving their orders from a foreign Admiral; they were singleminded in their endeavours to do their utmost for the common cause, and in consequence they proved to be a most valuable asset to the Allies, and assisted magnificently to save a very dangerous situation.

5. It is hard to express in words the singleness of purpose which animated them, the eagerness with which they set themselves to learn all the methods which had been tried, and to improve these methods so as not to lose any chance of possible success. It should be remembered that success in this submarine war is not only measured by the number of submarines sunk (except in the case of mystery ships and other craft whose sole duty is to sink them), but by the number of ships, crews, and cargoes preserved from an attack, and in this they have every reason to be most proud of their success, though the actual numbers can never be known, as we can never know the number of attacks that were prevented by their constant vigilance and ability.

6. It appears to me reasonable to make a few remarks on each type that came over:

(1) Destroyers. They were at once sent out to patrol certain areas, mostly west of the Fastnet; later on they were formed into escorts for convoys, and when a chance came they were formed into hunting squadrons.

Frequently they were under the orders of British officers, such as when they were in an escort whose senior officer was a British commander or lieutenant commander in a sloop; frequently they had British officers under them; and it is greatly to the credit of both that there never was a question, a doubt, or any sign of anything but perfect co-operation.

--20--

(2) Submarines. They were handed over to Captain M. H. Nasmith in the Ambrose at Berehaven to learn the new method of warfare. Thanks to his infinite tact and well-proven ability, and to their keenness and eagerness to learn, they were soon able to take up the duties of a sea-patrol, and under Captain T. C. Hart, U.S.N., and Commander W. L. Friedell, U.S.N., who relieved him, they were able to keep their patrols in any weather and to be relied on to keep their patrol waters clear.

(3) Seaplanes and Kite Balloons. They proved to be a very valuable asset to the station; their difficulties in the matter of being housed in a foreign country and operating in unfamiliar weather over strange lands were considerable. They soon grappled with the situation, and proved to be most useful. Commander F. R. McCreary,U.S.N., took infinite trouble to get the greatest value out of them, and for the short time during which they operated they were most useful.

(4) Chasers. The chasers came in at a late season, September, and before starting to operate had to learn the appearance of the coast, and the navigational necessities such as tides, currents, appearance of headlands, etc. They were untried, being a new type of craft, and commanded by officers who had no previous fighting training. But thanks to their plucky energy which declined to see difficulties, and owing to the great ability and tact of Captain A. J. Hepburn, U.S.N., who was in charge of them, they soon grappled with an unfamiliar situation, and would soon have become a great asset in working with the seaplanes off the coast.

(5) Repair Ships*. Without these the work could never have been done. Working complete twenty-four hours in three shifts of eight hours each; sleeping among the noise of the machinery; always ready for extra work when an unexpected accident happened, or an unforeseen call was made on a destroyer that was being dealt with---they never failed me. Captain J. R. P. Pringle, of the Melville, and Captain H. B. Price, of the Dixie, were not only always ready to do the expected, but used their utmost endeavours to be prepared for the unforeseen, and the result was such as their country has reason to be proud of.

(6) Battleships at Berehaven. Although the battleships were not directly under my operative orders, Admiral T. S. Rodgers laid himself out to meet my wishes in every way, and did all that was possible to help at Berehaven whenever he had an opportunity to do so. He worked with me when his

*See page 8. Note change in Tender commands during period of assignment to Admiral Bayly's command.

--21--

squadron was ordered to sea, and always showed that his intention was to be an integral part of the U.S. Forces operating off the coast of Ireland as long as it was in tune with his other orders to do so.

7. It is proper to place on record the behaviour of the men on shore, which was excellent. A men's Club was built for their entertainment, and thanks to Captain J. R. P. Pringle's discipline (he being the senior U.S. officer in the port) there was practically no trouble on shore. Even when, owing to the hostile attitude of certain of the inhabitants of Cork, it was necessary to put the city and a radius of three miles outside out of bounds to British and U.S. officers and men the situation was accepted and no trouble ensued.

8. Finally, I wish to acknowledge the generous, broadminded help which I have always received from Admiral W. S. Sims, U.S.N. From first to last he has worked with me for the Allied cause in a way which has compelled the admiration of all concerned.

I have the honour to be, Sir,

Your obedient Servant,

Lewis Bayly

Admiral

Commander-in-Chief

A report entitled Summary of Activities of U.S. Naval Forces Operating in European Waters in 1919, prepared in London shows that the destroyers and other units of the Bayly Queenstown Navy did the jobs assigned to them in highly competent and cooperative performances. The Queenstown naval command was the second largest in the war; only Brest, the center of troop convoy activity, was greater. There were almost 7 ,000 personnel in Ireland at the end of the war, and 59 vessels of all types. In the 20 months, the forces in Queenstown supplied 91 percent of the escorts for 360 convoys. The success of the convoy system can be judged by the sinkings. In December 1917, roughly 350,000 tons of Allied shipping were lost, while in October 1918 only 112,000 tons were lost.

The Fanning was the only U.S. destroyer that sank a German submarine. The following account of the action, which includes the capture of the enemy crew, is part of the Queenstown Association Collection of papers held by the Naval Historical Foundation and was written by Fanning's commanding officer, Lieutenant A. S. Carpender:

--22--

--23--

17 November, 1917

1. At Queenstown, Ireland.

2. At 1115 stood out of harbor with Escort for OQ 20, Nicholson (Flag), Conyngham, Cummings, Warrington, Jacob Jones, Zinnia & Cullist. On passing Daunt escort scouted in force for ten miles from East to West (Mag) preparatory to Convoy's coming out of harbor.

3. Convoy headed out of harbor & when five miles south (Mag) from Daunt began to form up in four columns, 2 ships in each column.

4. The four leading ships, & second ships in three right columns had formed up, & rear ship of left column was closing, when at 4:10 pm., position 7 miles South (Mag) from Daunt, this vessel sighted a foreign periscope, three points on port bow, distance about 400 yds, & headed across bow at about 2 knots with about 10 inches of periscope showing. Fanning, at that time was turning, with left rudder, into position covering left rear flank and was distant about 1000 yds. from S. S. Welshman, the second ship in second column.

5. Fanning turned with left rudder, increasing speed to 20 knots working up to full power, and righted rudder to swing into position for dropping charges. Depth charge was dropped, vessel stood on, on turn. Soon the conning tower of submarine was seen to come to surface, Nicholson, who was heading down into her position astern headed for spot & dropped charge near sub, & as she turned, opened fire with her stern guns. Fanning turned in Nicholson's wake & opened fire, but after third shot from bow gun, submarine surrendered.

6. Fanning went alongside, while Nicholson covered, & picked up prisoners 4 officers & 36 men, one of the men died after being taken on board Fanning.

7. Submarine sank alongside, evidently being scuttled.

8. The submarine was the German S-M U58, Captain Lieutenant Gustav Ausberger, Commanding, who surrendered to comdg officer of Fanning,& gave parole for his officers. Officers & men were made prisoners-of war.

9. It was ascertained that the vessel was wrecked & made helpless & unmanageable by the depth charge dropped by Fanning. Her motor driving gear, & oil leads were wrecked,& she went down to about 200 feet, where she blew tanks & came to surface helpless.

10. Fanning returned to Queenstown, anchoring in lower harbor, where prisoners were transferred under guard to Melville. Burial service was read by Comdg officer, over dead German sailor, & vessel then proceeded to sea &

--24--

buried dead German, with full Military honors. On completion of burial, Fanning returned & anchored in lower harbor.

11. Complete report in detail is appended, marked A, and also list prisoners.

18 November, 1917

1. Got underway at daylight & moored to #2 buoy, later being shifted to fuel ship.

19 November, 1917

1. At Queenstown, Ireland.

2. Admiral Sir Lewis Bayly, R.N. Commander in Chief South Coast of Ireland, accompanied by the Chief of Staff, U.S. Destroyer Flotilla Operating in European Waters, came on board and, by direction of the Admiralty, published a cablegram from admiralty, copy appended, re-encounter with and destruction of Enemy submarine U-58. The officers and crew at quarters during publishing of orders. After publishing the Admiralty cablegram, the C-in-C personally congratulated the crew on destruction of U-58.

The following U.S. ships of the Queenstown force sustained major damage as a result of action. The Cassin had her stern blown off by a German submarine torpedo but was salvaged. The Jacob Jones was the only destroyer sunk by a submarine. The Shaw, which had her bow cut off while escorting HMS Aquitania, was also salvaged. The Manley, serving as a convoy escort, had her stern blown off by the explosion of her own depth charges in a collision with HMS Montagana, and was towed to Queenstown and salvaged. The Wilkes had her bow badly damaged in a collision with a French patrol craft in a dense fog off Brest. She backed into Davenport for repairs and resumed her duty. Several bent bows and some topside damage incident to minor collisions and the weather were "serviced" by local facilities.

--25--

Queenstown Association:

In the Spirit of 'Pull Together'

Giving Meaning to a Motto

In July 1919, Admiral Bayly retired after nearly 50 years of service, over 47 of which were sea time. He returned to Plymouth Hoe to say good-bye to those with whom he had served.

The spirit of loyalty and cooperation that was fully accepted and practiced by all hands in interservice relations throughout the organization began as soon as the U.S. destroyers arrived at Queenstown. Quite appropriately, the motto which expressed that relationship was "PULL TOGETHER."

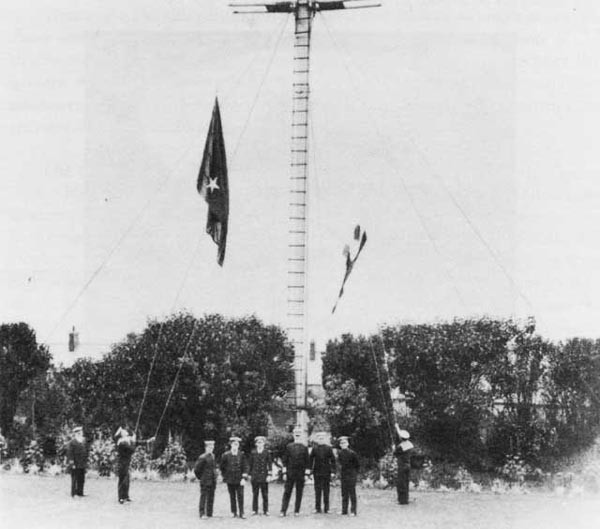

The origin of the motto is attributed to words inscribed on a signal board from a sunken German submarine that had been picked up at sea. It was mounted, at the suggestion of Sir Lewis, on the topside bulkhead of the Melville just inboard of the starboard gangway maindeck platform. It was within this framework of understanding and appreciation of a job to be done in a spirit of cooperation and mutual respect that the American and British forces continued to operate.

This was not a motto pulled out of Admiral Bayly's hat. It represented his concept of the spirit that had to prevail between the personnel of the two navies within his command, where both were dedicated to a single and accepted objective, i.e., win the war. He used these same words to title his book, Pull Together! The Memoirs of Admiral Sir Lewis Bayly, KCB, KCMG, CVO, which he dedicated to "V.V. who made me write it." He finished writing it just before being taken very ill in May 1938. It was published after his death in February 1939 by his so fondly remembered niece, Miss Violet Voysey, and had forewords by President Franklin Roosevelt from the White House dated October 26, 1938; and Admiral Sir Roger Blackhouse, GCB, CGVO, CMG, his life long service friend from the Admiralty, Whitehall, dated January 1939.

--26--

Another publication was the pamphlet Pull Together, which he had printed for private circulation only. It contained the report he made to the King after his visit to the United States in 1934.

In his book Victory at Sea, Admiral W. S. Sims said that Admiral Bayly "always referred to his command as 'my destroyers' and 'my Americans,' and woe to anyone who attempted to interfere with them or do them the slightest injustice! Admiral Bayly would fight for them, against the combined forces of the whole British navy, like a tigress for her cubs.... Relations between the young Americans and the experienced Admiral became so close that they would sometimes go to him with their personal troubles; he became not only their commander, but their confidant and advisor."

Admiral Sims continued: "Admiralty House was always open to our officers they spent many a delightful evening there around the Admirals fire, they were constantly entertained at lunch and at dinner, and they were expected to drop in for tea whenever they were in port."

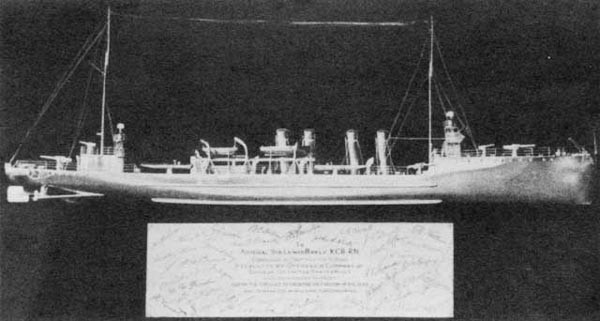

The respect and affection which the officers in Queenstown had for Admiral Bayly was first shown by the presentation made to him by about 40 of the commanding officers who had served under him. It was a silver half-model of a four-stack broken deck U.S. destroyer named "The U.S.S. PULL TOGETHER," mounted on a wooden backboard. The signatures of all the donors were engraved on the plaque.

--27--

The "PULL TOGETHER" spirit was so completely a part of the relations among the officers of the Queenstown forces, that the incentive and enthusiasm of Lieutenant Junius S. Morgan, to continue it through the creation of a peacetime organization led to the formation of the Queenstown Association. The first recorded meeting and dinner of the Association was held at the Ritz Carlton Hotel in Philadelphia on 3 January 1920, and the following minutes taken:

Upon motion duly made and seconded, it was unanimously voted that membership in this Association be limited to Commissioned Officers of the United States Navy, who prior to the signing of the Armistice on November 11, 1918, were based on and operated from Queenstown; together with such other Commissioned Officers of The Irish Command who prior to January 8, 1919, had signified their desire to join the Association.

Upon motion duly made and seconded, it was unanimously voted that Officers of the Royal Navy who were based on and operated from Queenstown are elected honorary members of this Association.

Upon motion duly made and seconded, it was unanimously voted that insofar as possible an annual meeting and dinner will be held at least once in every year; the date and place to be determined by the Officers and Executive Committee.

The following officers were unanimously elected:

Honorary Presidents: |

Admiral William S. Sims, |

Upon motion duly made and seconded, it was unanimously voted that an Executive Committee be appointed by the President to act in an advisory capacity and to assist in the activities of the Association.

Upon motion duly made and seconded, it was unanimously voted that Miss Violet Voysey be elected an honorary member of this Association.

The Secretary reported that approximately 750 notices regarding the formation of this Association were mailed; approximately 400 replies were received; all replies were favorable to the formation of the Association with the exception of one. Notices were sent to al1 those for

--28--

whom any address could be found in the time available; this list is being largely increased for future needs.

There were 93 persons present.

The President stated he has now under consideration the appointment of the Executive Committee, and an announcement will shortly be made relative thereto.

Upon motion made and seconded meeting adjourned.

Junius S. Morgan, Jr.

Secretary

The dinner menu for this meeting was ingenious. It included Bantry (a bay on the West Coast of Ireland) Oysters, Potage Haulbowline (dockyard at

--29--

Queenstown), Sea Bass Ballycotton (headland on the South Coast of Ireland), Roast Chicken Dixie (the tender which Captain Pringle commanded), Potatoes O'Brien (the ship on which Lieutenant Junius Morgan had served), Peas Poinsett (the third given name of Captain Pringle), and Bombe Fanning (the U.S. destroyer that sunk the U-58).

The year 1921 was a gala one for the Association. The dinner was held at the Biltmore in New York on 19 February. Both Admiral Sims and Admiral Bayly, who was making an around-the-world cruise with his niece, were present, in addition to some 80 members. Fortunately, the records contain the pamphlet which it is believed was sent to members and in which the speeches delivered that evening are printed. It would seem appropriate to quote from that part of Admiral Sims' speech which refers to the only female Honorary Member of the Association. He said:

Although our Old Man at Queenstown had all the qualities necessary for getting the maximum services out of his forces, still we believe that he owed not a little of his success to the chief member of his staff. The chief of staff was an incredibly charming and amazingly competent person with the heart of a woman and all the best mental qualities of a man without any of man's defects-the Right Hand Man of "Uncle Lewis", otherwise known as the "Only Niece"-Miss Violet Vosey. To this most admirable hostess of Admiralty House we owe a debt of gratitude not only for keeping Uncle Lewis always in a good humor, but for her sympathetic kindness to all the Yankee people, for her charming hospitality, her excellent afternoon tea and such cakes as could be made on the war ration of sugar.

It was at this dinner that the Association presented the Bayly Bowl to the Admiral. This was a large silver bowl inscribed as follows:

--30--

From the Queenstown Association composed of Officers of the United States Navy, who served under his command during the World War, to Admiral Sir Lewis Bayly, RN, an Honorary President of that Association, and a Master of his Profession. Presented to him upon the occasion of the Associations Dinner given in his honor in New York City on February the nineteenth, nineteen hundred and twenty-one as a testimonial ofloyalty and affection.

Sir Lewis' remarks that evening were quite apparently made with deep emotion. He repeatedly emphasized the cooperative and cordial relationship that prevailed between the forces in his command. He related an instance which happened in the ship bringing him to New York when he was met and escorted by a Navy blimp and seaplanes. A lady American passenger remarked to him, "what a magnificent thing it must be for you to be a British Admiral." His reply in true Bayly fashion was, "you are making the greatest mistake in your life, that has nothing to do with being a British Admiral at all. It is the greatest proof that has ever been seen of a true friendship between 250 or 300 people."7

It was in the same year, 1921, that the British branch of the Queenstown Association was inaugurated at a dinner in the Criterion Restaurant in London on 9 June in honor of Admiral Sims. British officers who served in Queenstown between May 1917 and November 1918 were made eligible for membership. Sir Lewis Bayly and Admiral Sims were made Honorary Presidents, Miss Voysey was made an Honorary Member. These officers were elected:

President - Rear Admiral F. M. Leake, DSO

Member - Commander G. W. H. Heaton, DSO

Member - Lieutenant Commander E. K. Chatterton, RNVR

Honorary Secretary - Commander S. C. Douglass

Subsequent to 1921, there were dinners at the Columbia Country Club in Washington, D.C., in 1924, and at the Harvard Club in New York in 1925-30. At the latter, Admiral Sims presided.

It was about this time that the Association established the Bayly Fund, which was to be used by Sir Lewis to purchase a suitable home for himself and his niece. The fund grew to about $15,000 and the Admiral bought a comfortable home which he called "Fawns," which was at Wellington Avenue, Virginia Waters, Surrey.* He sent autographed photos of the house to the Association and a copy is in the records. He lived there until 1937 when in-

* Letters exchanged between Junius Morgan and Sir Lewis concerning this fund are attached as appendices 1 and 2.

--31--

creasing age and failing health caused him to sell "Fawns" and move into Arlington House Flat in central London where he could be more comfortably quartered. During his occupancy of "Fawns," in addition to losing 260 pounds sterling of his pension by acts, the maintenance of the house and other expenses took a heavy toll on his finances. When the house was sold before his death, there was little money left for the welfare of his niece and himself.

There were no further Association meetings until 1934. In 1932, however, J. R. P. Pringle, who had been President of the Association since its start, died. He was then a vice admiral in command of the battleships of the Battle Force. Appropriate arrangements were made by the Association for representation at the burial in the Naval Academy cemetery.

The Fleet came to New York in 1934, and the Association took advantage of that visit to hold a real get-together. Sir Lewis was invited to come over. He accepted, and with his "Chief of Staff Officer," Miss Voysey, arrived in New York in the Aquitania on 18 May. He brought with him a brass tablet which was to be presented by him at the U.S. Naval Academy as a personal memorial to Vice Admiral Pringle. The Secretary of the Navy had approved the presentation for installation in a naval command, and the Naval Academy had been selected. Admiral Bayly had obtained approval of the content of the inscription from the King. According to the Admiral's own story of his arrival with the tablet he said, "An officer of the Air Force was given the tablet to fly with it to Annapolis, with orders that if for any reason he failed to do so, he was to disappear and never to be seen again."8

Sir Lewis' schedule had been prepared by the Association and handed to him on his arrival (see Appendix 3). It provided that throughout his stay in the

--32--

United States, he would be under the guidance of Association members. He spent one day, 21 May, in Philadelphia with the First Naval District Commandant, then Rear Admiral Hepburn, and others. He was in Washington from 22-24 May. On the 23rd, he went to Annapolis to present the Admiral Pringle Tablet to the Naval Academy. In his presentation talk, he said about Admiral Pringle, "I have spent my whole life at sea and I have been thrown in contact with all sorts and condition of men in the world, and I have lost the greatest friend I have ever had, and the United States a most valuable servant."

During his stay in Washington, he had lunch with the President and Mrs. Roosevelt at the White House. He arrived back in New York on 29 May and, on 31 May, boarded the USS Indianapolis to be with the President to take the review of the Fleet as it steamed into New York Harbor. He visited with Admiral Sims in Boston for two days and then, as he reports, "We left Boston at 10:30 a.m. on Monday with Lieutenant Kane who drove us about 50 miles to Newport, Rhode Island, where we were to stay with his wife and Mrs. Pringle."9 He was back in New York for the Association dinner on 8 June at the Harvard Club. On that occasion, 99 members were present where he presided. The next day, after lunch on board the carrier Lexington, he returned to England by oceanliner.

Upon his arrival, he gave a full report of his visit to the King and the Admiralty. The London Times on 30 July 1934 carried Admiral Bayly's own article in which he gave the full details of his visit. The newspaper's editorial on that date noted: "In the world at this moment there is only too much evidence that hatred and savagery are quick to spread. Friendship and good will also it seems will spread and endure and Admiral Bayly's visit to the United States will turn many a gaze upward toward one of the serenest glances in a wild and stormy sky."

It was in this same year, 1934, that the Association took action to memorialize Vice Admiral Pringle. The new wing at the Naval War College, named Pringle Hall, has been completed that year. The Association procured a portrait of the Admiral, and on 18 May 1936 with appropriate ceremonies, it was unveiled in that Hall.

The records show that 1934 was the last big dinner of the Association when both Honorary Presidents attended.

Admiral Sims died in September 1936. After the war, he had again been President of the Naval War College until he retired in 1922. He continued his interest in the Association until his death. He was buried in Arlington Cemetery after funeral services at St. John's Episcopal Church in Washington. The Association and members sent flowers and messages of condolence to Mrs. Sims and attended the funeral. In 1939, a 1570-ton destroyer, the USS Sims (DD-409) was named in his honor and christened by Mrs. Sims. The ship was

--33--

sunk in the Battle of the Coral Sea in May of 1942. The second USS Sims (DE154) was commissioned in April 1943 and was decommissioned at Green Cove Springs, Florida, in April 1946. A third USS Sims (FF-I059) was commissioned in January 1970.

Admiral Bayly died on 16 May 1938. His body was cremated after a simple service at the Side Chapel at St. Michaels. An Association letter from Junius Morgan to Mr. Roger Williams, giving a description of the funeral by Violet Voysey, is included as Appendix 4.

In September 1938, Rear Admiral A. W. Johnson, commander of the Atlantic Training Squadron, sent a letter to Mr. Morgan relating to the disposition of the silver model of the destroyer "Pull Together," which had been presented to Admiral Bayly during the war by the captains of the U.S. destroyers serving at Queenstown, and also the Silver Bowl which was presented to him in 1921 in New York by the Queenstown Association.

The silver model was bequeathed by Admiral Bayly to HMS Vernon, the Torpedo School at the Royal Naval Dockyard, Portsmouth, England, where he had served as a young officer many years before. It was presented by Miss Voysey at a ceremony held on 15 July 1938. Present at this ceremony were British Naval officers from HMS Vernon and the Royal Naval Dockyard and American officers from the USS New York, USS Texas, and USS Wyoming, which were in port at that time.10

The Silver Bowl* was bequeathed to Miss Voysey, who wished to have it presented to the U.S. Naval Academy "in memory of Admiral Bayly and of the friendship existing between the officers of the British and American Navies who served under his command during the World War." The cup was brought back to the U.S. in the USS New York and, on 24 August 1938, was turned over to the Superintendent of the Naval Academy for safe keeping until a formal ceremony could be held.

To comply with the donor's request, an additional inscription was engraved on the cup by Tiffany of New York. It read:

This Cup is presented to the United States Naval Academy in Memory of Admiral Sir Lewis Bayly KCB KCMG CVO Royal Navy, Commander in Chief of the Western Approaches during the World War, who had under his Command 10,000 Officers and Men of the United States Navy. In giving it into the Care of the Naval Academy it is hoped

* Originally presented as "bowl" Later referred to as "cup" when presented to the Naval Academy.

--34--

that it will serve as an inspiration to all present and future Midshipmen of the pull-together Spirit which existed at Queenstown between the Royal Navy and the United States Navy where they served together for the Common Cause. Presented by Violet Voysey, niece of Admiral Sir Lewis Bayly.

The cup was presented to the Naval Academy in a formal ceremony in Dahlgren Hall on 2 December 1938.

It was intended to hold another big dinner in New York when the Fleet was scheduled to visit the World Fair being held there. That visit of the Fleet was cancelled incident to rising tensions in the Pacific which necessitated the Pacific Fleet's return to that coast after winter maneuvers in the Atlantic.

With the death of Admiral Bayly, the Association became increasingly interested in the welfare of his niece. The sale of the Admiral's book, Pull Together, did not reach expected numbers and, as previously noted, funds available for her livelihood were meager. The members of the Association, therefore, contributed to a fund which was deposited for her welfare for the remaining years of her life. Miss Voysey died on 19 November 1943 at which time the remainder of the fund was returned to the Association treasury.

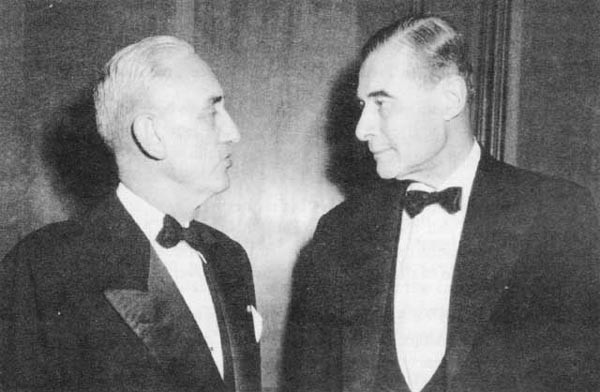

There were get-together dinners in New York at the Harvard Club in December 1941, May 1946, May 1948, 1950, 1953, and 1955. Another dinner was held at the Metropolitan Club in Washington in 1957. This was the last time the members got together. Usually about 60 members attended these dinners.

The Association was completely informal and non-dues paying. Funds for any extra requirements were obtained by voluntary contributions of interested members. Those attending dinners paid only the charges incident to those friendly get-togethers. On 3 March 1961, 40 years after the first meeting, about 375 members remained on the Association's mailing list.

Upon the death of both Admirals Bayly and Sims, who were the Honorary Presidents, it was agreed that the senior member on active service in the U.S. Navy should become President, and the next senior, the Vice President. This was never quite completely resolved. Due to the informality of the Association, however, no real problems arose. In accord with the above, Rear Admiral A. W. Johnson became President upon the death of Vice Admiral Pringle.

Many officers who had served in Queenstown kept an active interest in the Association. It would be correct to say, however, that none had a more active one and did more work to keep the Association alive than Mr. Junius S. Morgan

--35--

who was Secretary-Treasurer during its life. He had been a lieutenant in the O'Brien at Queenstown, and his personal efforts in behalf of the Association were tireless. He ran most of the dinners, did all of the fund raising, maintained records, mailing lists, etc. After the 1955 meeting, it was agreed to make an appropriate presentation in appreciation for his work on behalf of the Association. On 22 November 1955, a silver cigar box was given to him inscribed:

"]unius Spencer Morgan

With affectionate regards of his friends in the

Queenstown Association"

After the death of Mr. Morgan in 1960, a consensus of the members who had participated in the activities of the Association agreed to the suggestion of Admiral Robert B. Carney11 that the Association should be disbanded. The funds remaining in the treasury were given to the Naval Historical Foundation, as were the records of the Secretary (see Appendix 5).

Nothing is more indicative of the spirit and understanding which started in May 1917, and carried on through the life of the Association until 1961, than the expression contained in Admiral Bayly's letter to the Secretary of the Navy as published in General Order No. 490 dated 27 July 1919 by the Navy Department. It is quoted herewith:

--36--

"GENERAL ORDER |

NAVY DEPARTMENT, WASHINGTON, D.C., July 21,1919. |

1. The following letter is published for the information of all concerned:

THE FAWNS, ERMINGTON,

S. Devon, England, June 4, 1919.

To Franklin D. Roosevelt,

Assistant Secretary of the Navy.

Sir: I wish to be allowed to say how very proud I am to have received so kind and courteous a letter from you; and how honored I feel at your appreciation of the results of the combined work done on the Queenstown station during the war. The fact that you permitted your ships to be put under the command of a British admiral was a very high honor to our navy; but the unity, excellent good feeling, and the success of our two navies working together, could never have existed had it not been for the determination of the United States officers who were stationed there to make it a success, and for the ability they brought with them which enabled them to do so. And the fact that the United States officers came over with the intention of not only working with us as allies, but also as friends, is shown by the constant communications that pass between us, although the sea warfare has been over for many months, and the Atlantic separates us from actual meeting. I have commanded many ships and squadrons and have spent the greater part of my life at sea, and can truly and honestly say that a finer lot of seamen and gentlemen I have never commanded. However hard the work, however dangerous the duty, they never failed me.

It is with deepest regret that I shall never again have the chance of working with a force which no one is more proud of than I am. I wish you and your splendid destroyers the best of good fortune.

Yours, most respectfully,

(Signed) Lewis Bayly, Admiral.

2. This heartfelt commendation from Admiral Sir Lewis Bayly, R.N., who is held by the United States Navy in the highest respect, esteem, and affection, is a source of the utmost pride and gratification to the entire naval service.

Josephus Daniels

Secretary of the Navy

--37--

Notes

1 Intelligence Confidential Bulletin No.1, U.S. Fleet, "Notes on Defense Against Submarines," H. T. Mayo, 6 April 1917, and Intelligence Confidential Bulletin No.2, U.S. Atlantic Fleet, "Submarine Operations and Methods of Offense and Defense Against," 4 May 1917.

2 Bayly, Pull Together! The Memoirs of Admiral Sir Lewis Bayly K.C.B. K.C.M.G. C. V.O. London: George C. Harrap & Co., 1929, p. 218.

3 Admiral Sims is reported to have been instrumental with the First Sea Lord of the Admiralty in making this promotion effective.

4 Bayly, pp. 222-23.

5 Bayly, p. 234.

6 Morison, Elting E. Admiral Sims and the Modem American Navy. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1942, p. 381. The last paragraph of Sims' letter is particularly significant. It is generally accepted that he had arranged with Miss Voysey to put the idea of his taking command at Queenstown in Admiral Bayly's head.

7 Speech by Admiral Sir Lewis Bayly to the Queenstown Association's dinner meeting, New York, NY, 19 February 1921.

8 From a privately printed and circulated pamphlet, "Pull Together: Account of My Visit to U.S.A. 16th May to 9th June, 1934," by Admiral Sir Lewis Bayly, p. 4. Since there was no "Air Force" at that time, the officer Sir Lewis referred to was a Naval Aviator.

9 The Lieutenant Kane is the father of Rear Admiral John D. H. Kane, ]r., presently Director of Naval History.

10 Rear Admiral Elliott B. Strauss, presently Secretary of Naval Historical Foundation, was the Flag Lieutenant to Admiral Johnson on this occasion.

11 Admiral Robert B. Carney, USN (Ret.), is the Chairman of the Board of Directors of the Naval Historical Foundation.

--38--

Appendix 1

New York, October 8, 1930

My dear Admiral:

Long before you receive this letter you will have been advised by the Manager of Lloyd's Bank, Portsmouth, of the receipt of a sum for your credit. There is little that any of us here can add to what has been said before in regard to this and we all hope that you will accept this evidence of the affection and regard of your American officers in the spirit in which it is meant. Many have contributed to it and all with the greatest pleasure in being able to do something to show their affection for their former chief. In writing you I am acting as a messenger from ll your associates at Queenstown in 1917-19.

With best regards to Miss Voysey and yourself, I am

Very sincerely yours,

(Signed) JUNIUS S. MORGAN, JR.

Admiral Sir Lewis Bayly,

The White Cottage,

Waltham St. Lawrence,

Berks., England.

--39--

Appendix 2

October 24, 1930 |

c/o Lloyds Bank, 'Commercial Road, Portsmouth. |

My dear Morgan:

I write with a very deep sense of gratitude for the most real affection shown by your letter that exists between the U.S. Queenstown Association and me. The wonderful gift which my U.S. Naval Officers have sent touches us both very deeply, and we are both overwhelmed with their most thoughtful kindness. It is certainly without parallel and I find it very difficult to express in writing my real feelings with regard to it, but you may be assured that when we have been able to find a house its value to us will be greatly increased by the knowledge that it has been given by those who came over to help us in the war and have honored us with their affection through the years that have passed since it was over. When you came over in 1917, I knew that, having the same sea traditions we should work together as if the same nation; but that the friendship between us which the war produced should have continued through the following years of peace was more than I dared to expect, though I greatly hoped for it, or at least that we should not lose touch with so many real friends. There are many guiding forces in the world, but none has a greater power and rests on a more secure foundation than true friendship and it is that which binds us together, and when I pass on, the gift will remain with Miss Voysey reminding her of the happy days when the U.S. Officers did all they could to show her how they valued all her friendship and kindness.

Yours very sincerely,

LEWIS BAYLY.

--40--

Appendix 3

Schedule prepared for me by the Queenstown Association and handed to me on my arrival in New York

MARK VI.

| May 18th | .. | Friday (add) | .. | To be met by Mr. Morgan, probably by Captain Dewar, R.N. (and possibly by Admiral Stirling) and a representative of Commandant, 3d District. Tablet will be taken by an officer to Floyd Bennett Field, thence by plane to Naval Academy to be delivered to Superintendent (Officer in Charge, Buildings and Grounds). |

| May 19th | .. | Saturday | .. | New York. |

| May 20th | .. | Sunday | .. | New York. |

| May 21st | .. | Monday | .. | Arrive Philadelphia (Hepburn). |

| May 22nd | .. | Tuesday | .. | Arrive Washington. (To be met at station by Admiral and Mrs. Chandler, Fairfield and Bryant.) Leave cards at White House, call on Secretary of the Navy-and on British Embassy in afternoon, British Naval Attache to arrange. Tea at Country Club, five to seven p.m. (Rear Admiral and Mrs. Bryant.). |