The Navy Department Library

Guadalcanal Campaign

The Guadalcanal Campaign

by Major John L. Zimmerman, USMCR

Historical Section, Division of Public Information

Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps

1949

Contents

| Forword | iii | ||

| Preface | iv | ||

| Special Prefatory Note | v | ||

| Chapter I. | Prelude to the Offensive | 1 | |

| Advance of the Japanese | 1 | ||

| U.S. Countermeasures | 4 | ||

| U.S. Means Available | 10 | ||

| Accumulation of Intelligence | 14 | ||

| Planning and Mounting Out | 19 | ||

| Rehearsals and Movement to the Objective | 22 | ||

| Chapter II. | Landings on Tulagi and Gavutu-Tanambogo | 26 | |

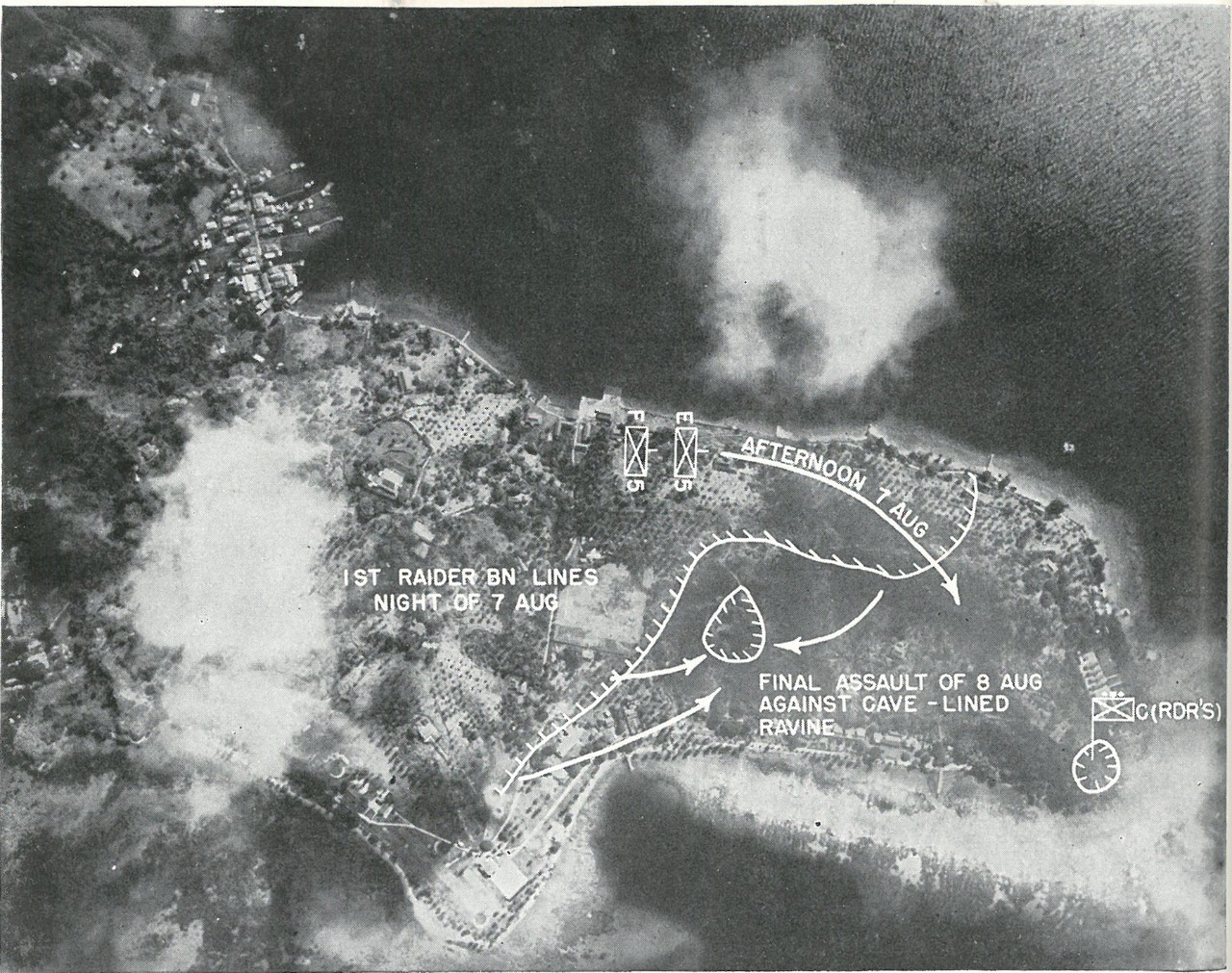

| Tulagi. The First Day | 26 | ||

| Tulagi. The First Night and Succeeding Day | 31 | ||

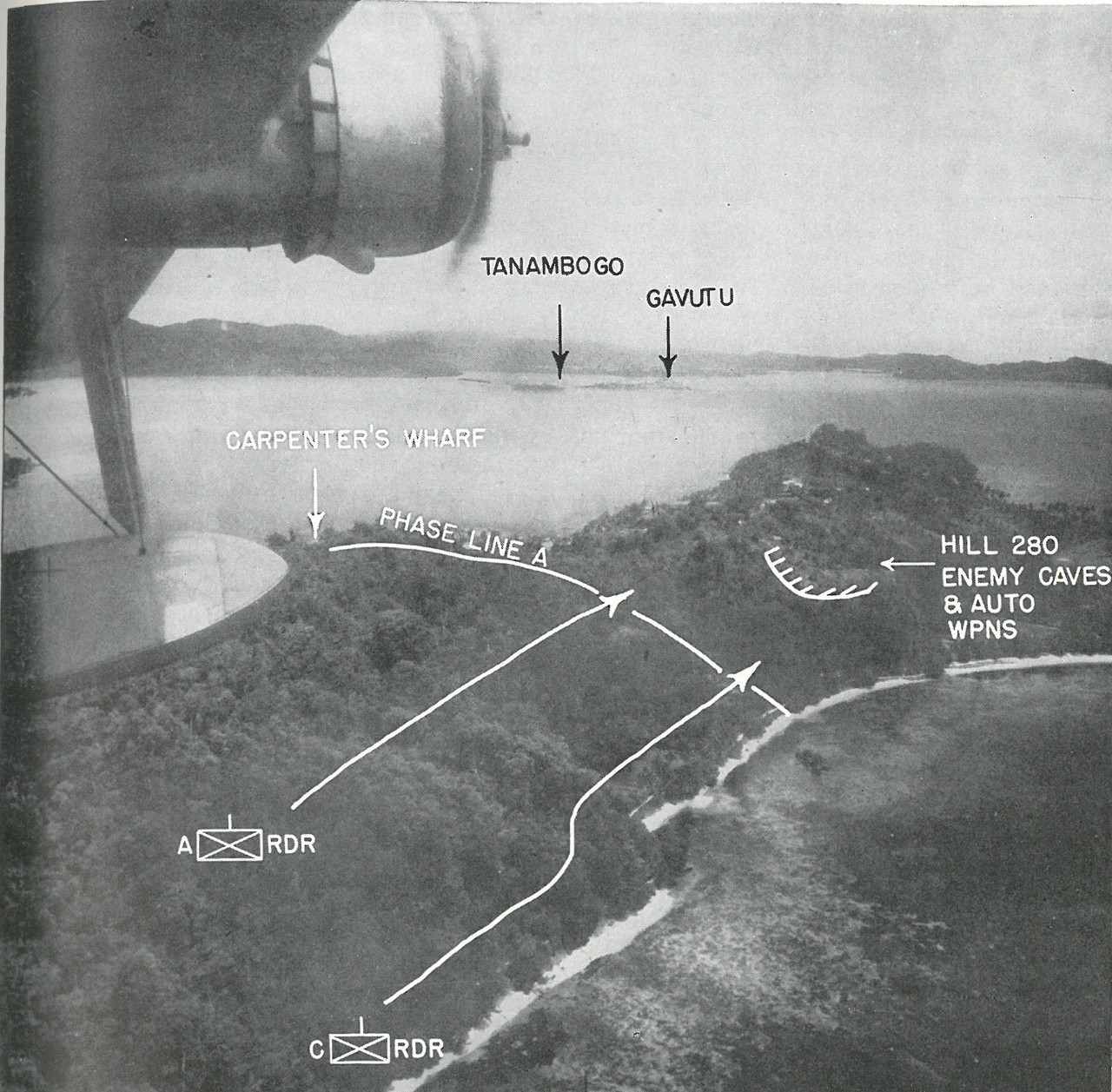

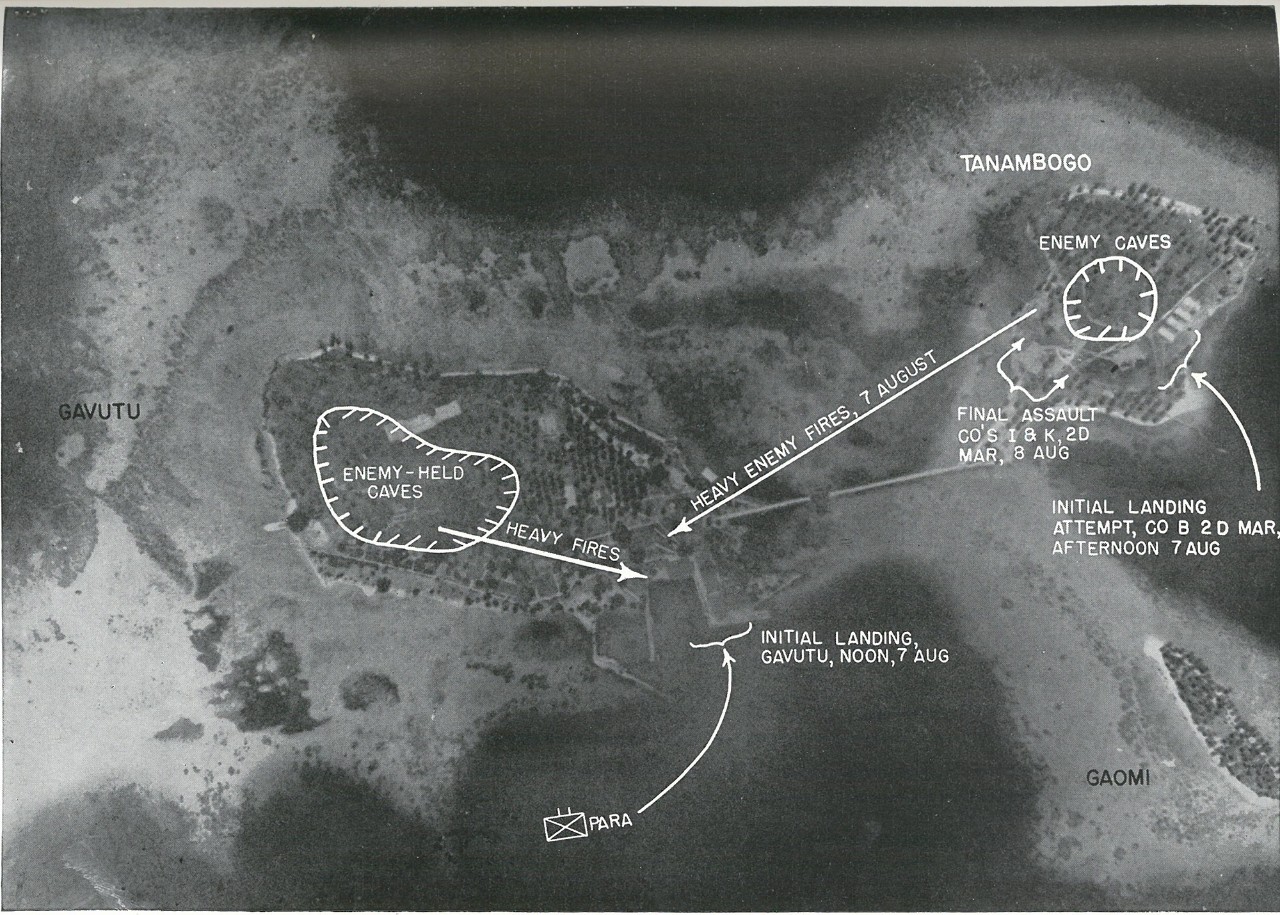

| Landings on Gavutu-Tanambogo | 33 | ||

| Chapter III. | Guadalcanal - The First Three Days | 41 | |

| Intelligence Situation | 41 | ||

| The First Day | 44 | ||

| General Vandegrift's Change of Plan | 47 | ||

| The Naval Withdrawal | 49 | ||

| Withdrawal of Task Force 62 | 52 | ||

| Chapter IV. | Establishment of the Perimeter and Battle of the Tenaru | 55 | |

| The Goettge Patrol | 58 | ||

| First Action along the Matanikau | 60 | ||

| The Brush Patrol | 61 | ||

| Beginning of Air Support | 62 | ||

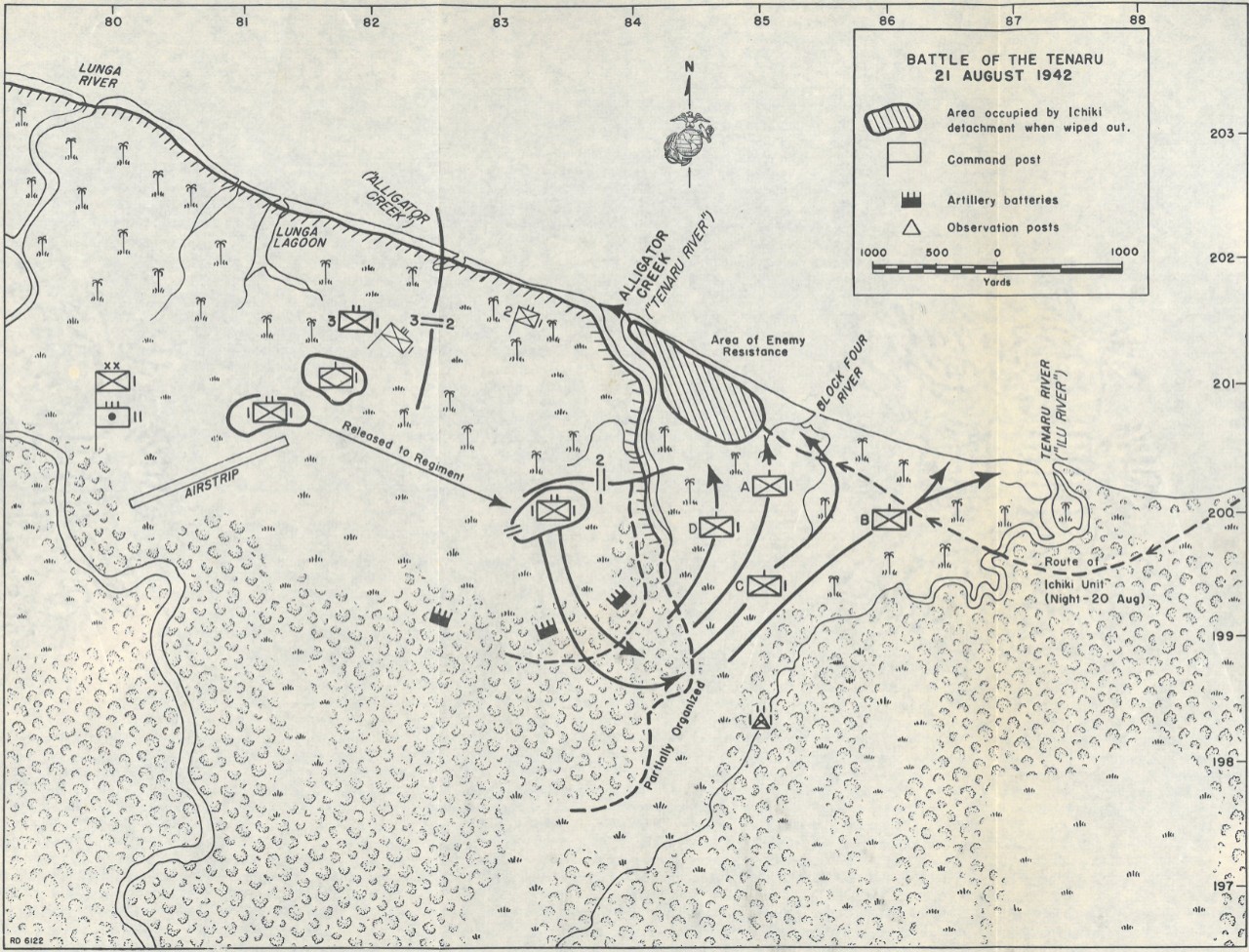

| Battle of the Tenaru | 65 | ||

| Chapter V. | The Battle of the Ridge | 73 | |

| Second Action along the Matanikau | 77 | ||

| The Tasimboko Raid | 79 | ||

| Gathering Strength | 82 | ||

| The Battle of the Ridge | 84 | ||

| Chapter VI. | Development of the Perimeter and Actions to the West | 92 | |

| Coming of the Seventh Marines | 93 | ||

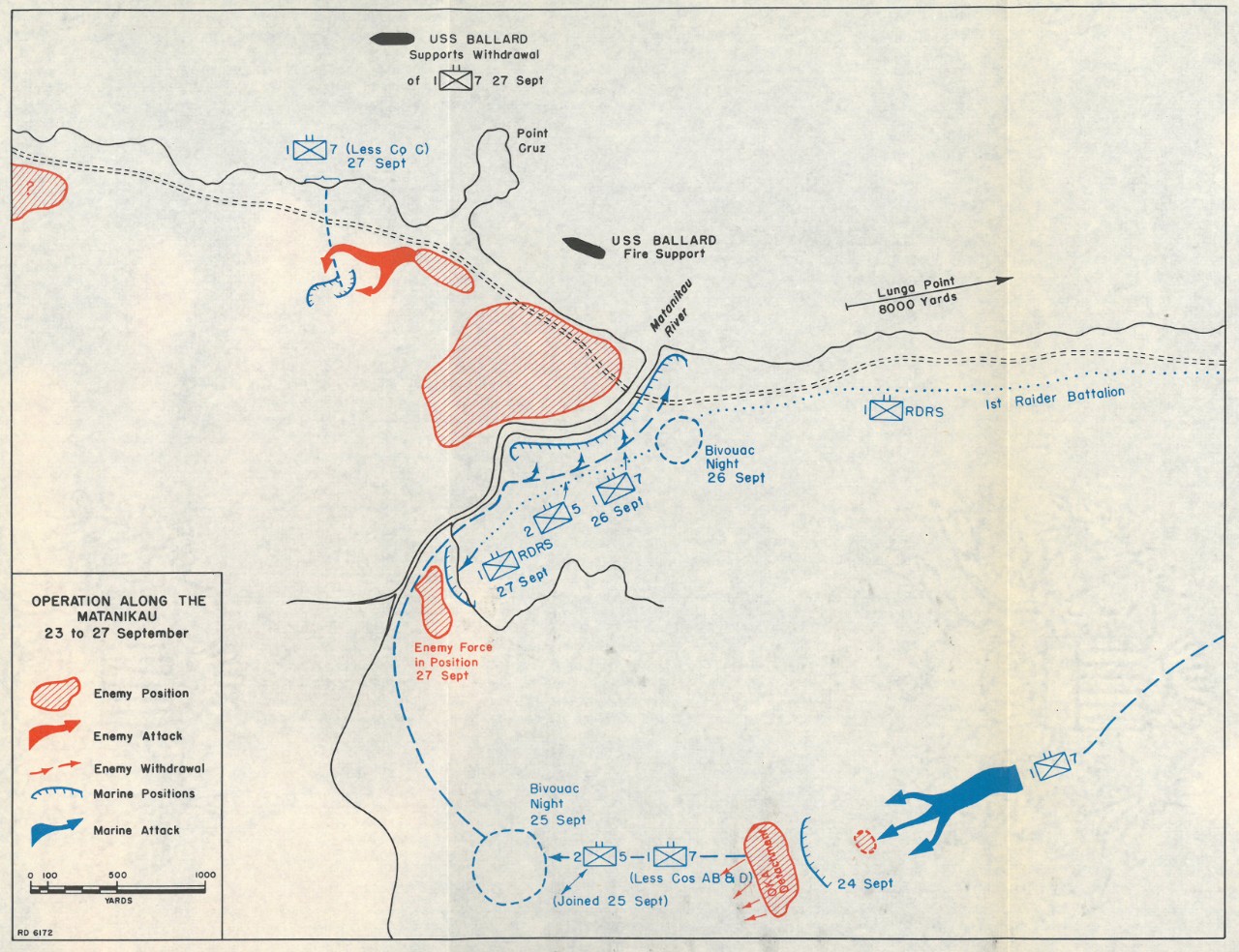

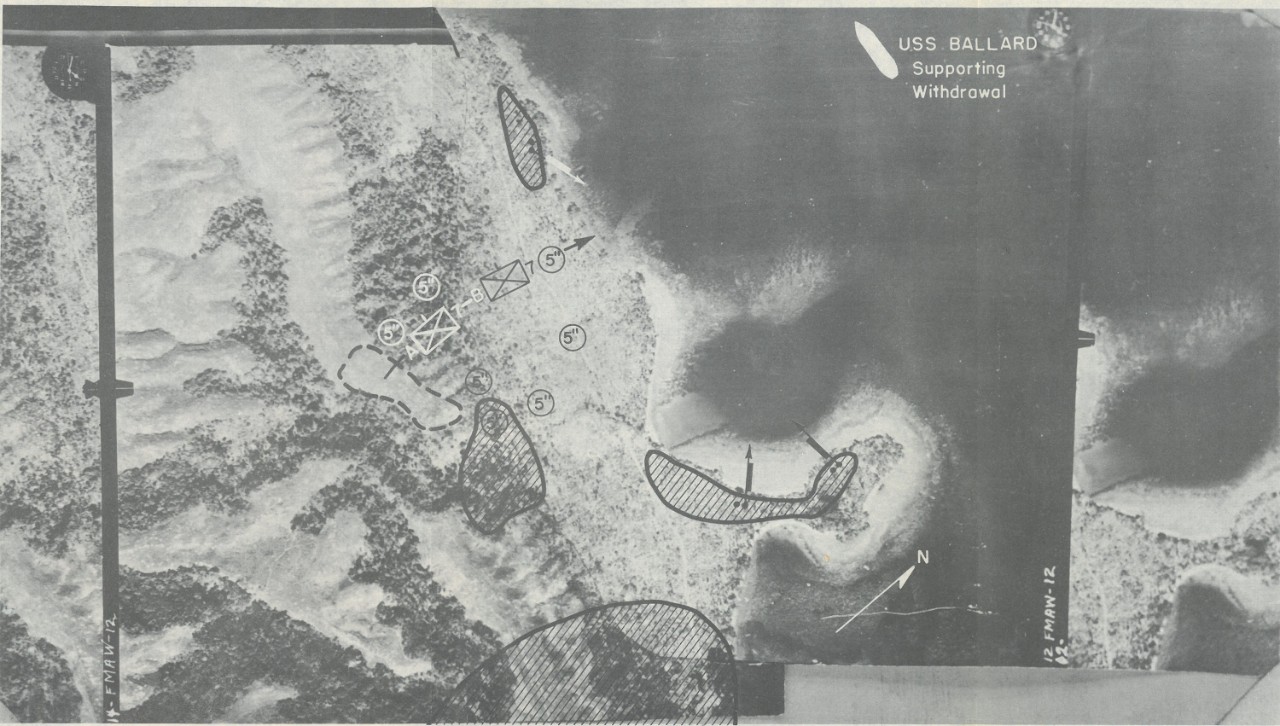

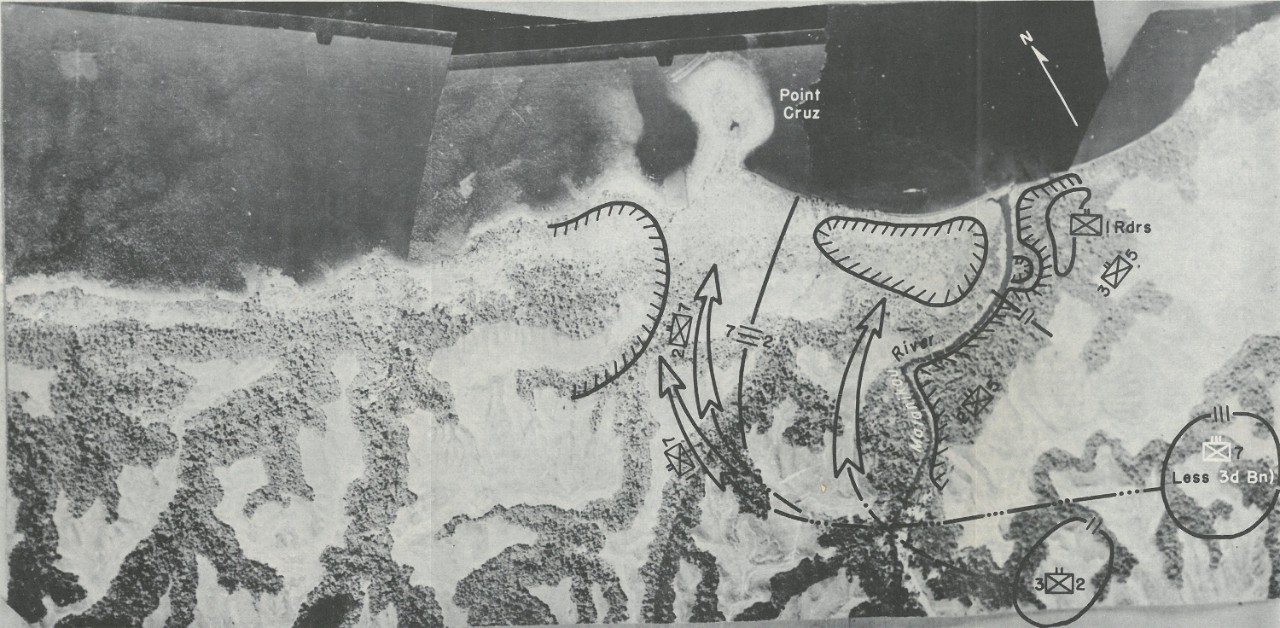

| Action on the Matanikau, 24-26 September | 96 | ||

| Actions on 7-9 October | 101 | ||

| The Battle of Cape Esperance | 104 | ||

| Chapter VII. | Expansion to the West and the October Attack on the Airfield | 106 | |

| Action at Gurubusa and Koilotumaria | 112 | ||

| The Attack of 21-28 October | 113 | ||

| Matanikau Phase | 114 | ||

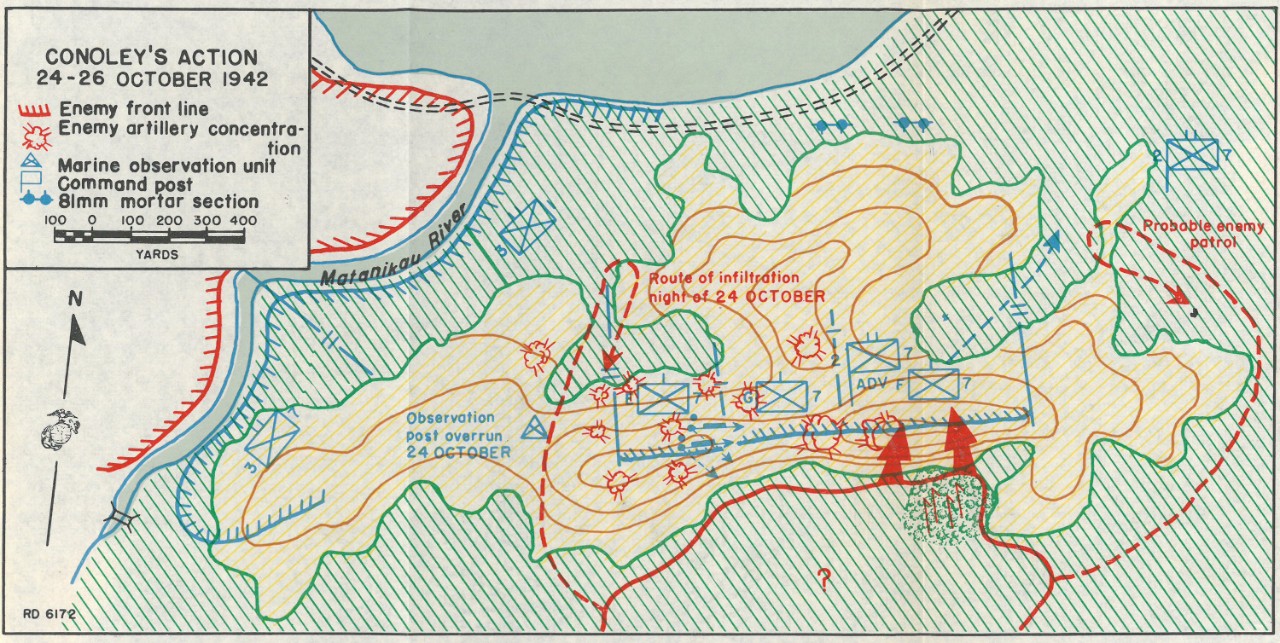

| The Inland Phase--24-26 October | 117 | ||

| The Enemy Situation--21-28 October | 123 | ||

| The Battle of Santa Cruz | 126 | ||

| Chapter VIII. | Critical November | 128 | |

| The Aola Base | 128 | ||

| Further Action on the Matanikau | 130 | ||

| The Koli Point Action | 133 | ||

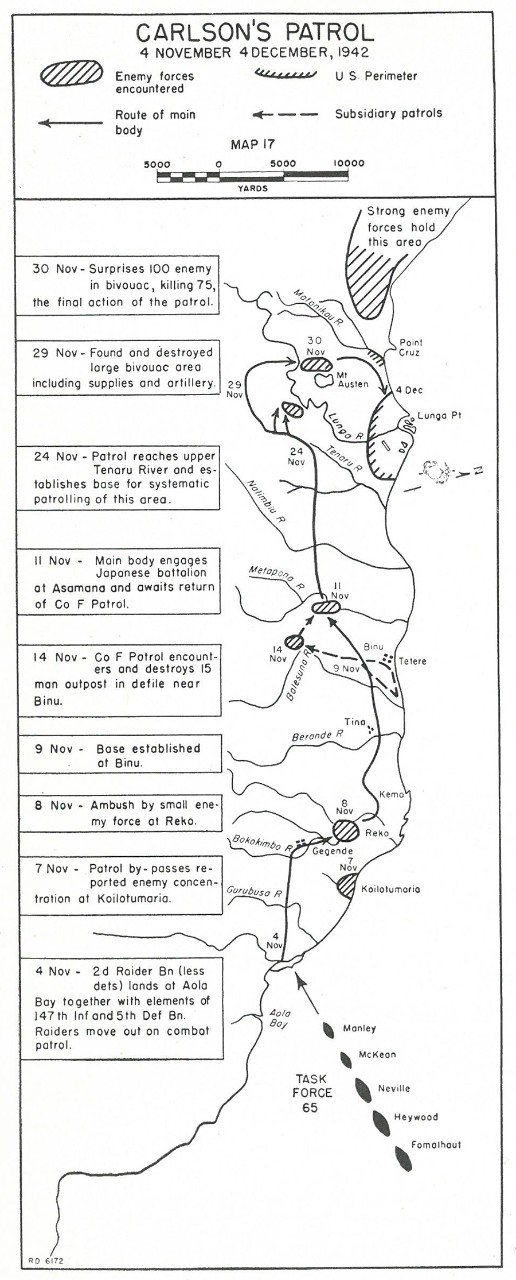

| The Second Raider Battalion | 141 | ||

| The Battle of Guadalcanal | 145 | ||

| Chapter IX. | Final Period - 9 December 1942 to 9 February 1943 | 156 | |

| Relief of the 1st Division | 156 | ||

| Coming of the 2d Division | 159 | ||

| Patrol of the 132d Infantry | 162 | ||

| The Final Drive | 162 | ||

| Chapter X. | Conclusions | 165 | |

| Appendices | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| A. | Casualties | 168 | |

| B. | Bibliography | 170 | |

| C. | Native Help | 173 | |

| D. | Medical Experience | 176 | |

| E. | Station List | 181 | |

| F. | Marine Corps Aces | 189 | |

| Illustrations |

|---|

| Men Who Took Tulagi |

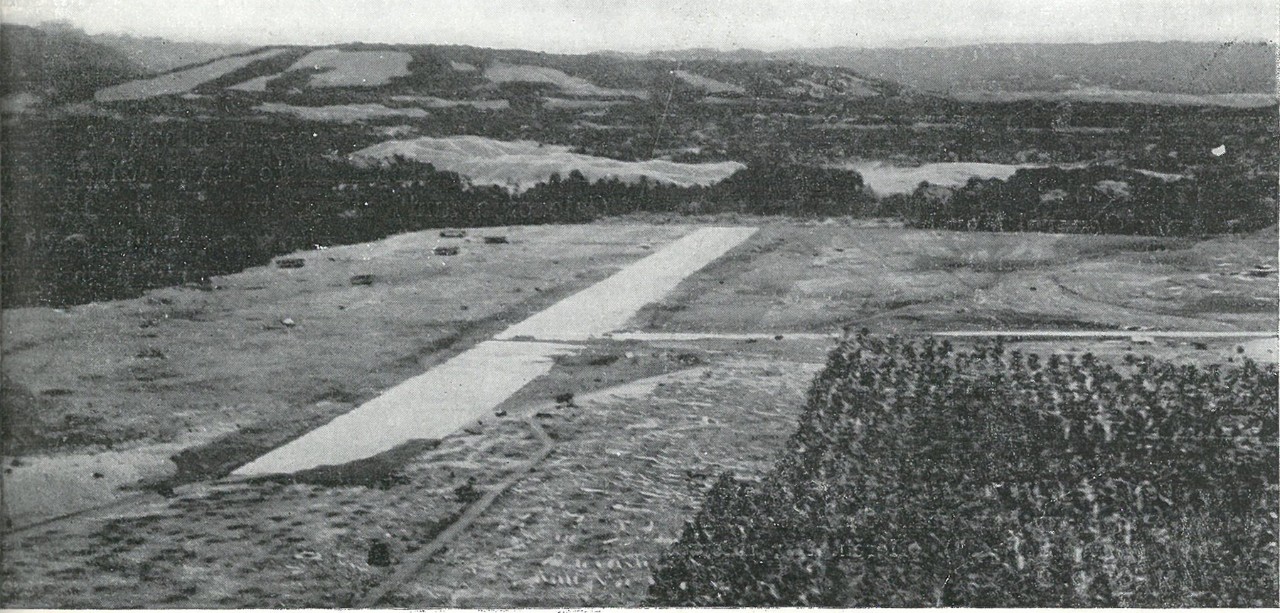

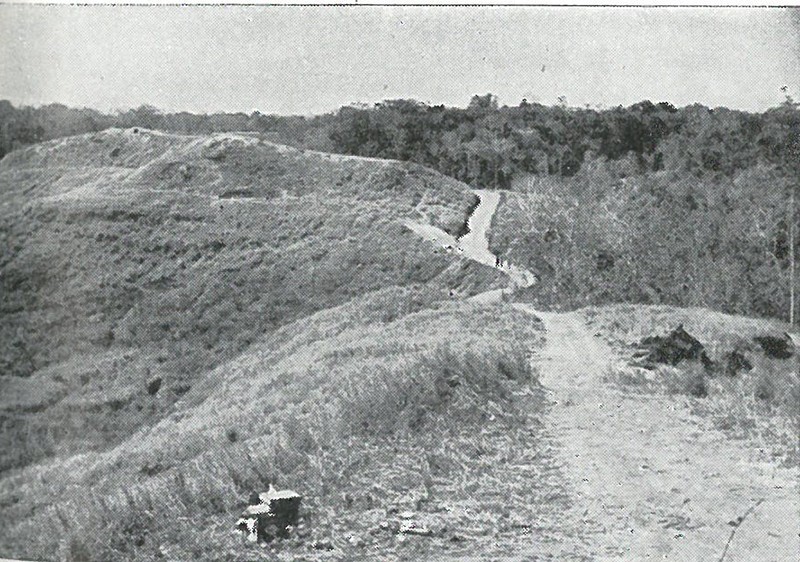

| The Japanese Commenced An Airstrip |

| Gen. A. A. Vandegrift |

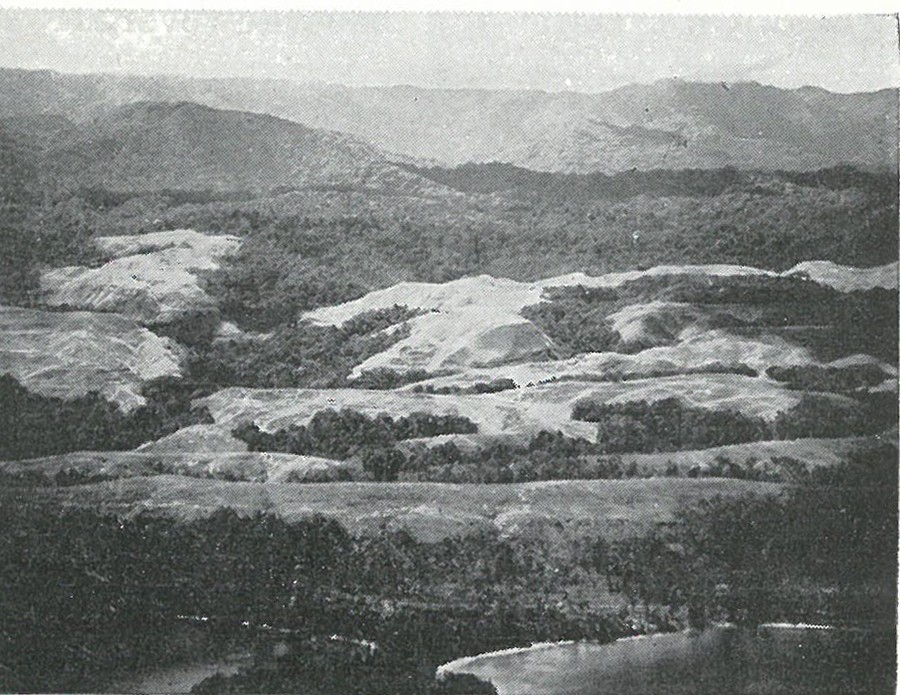

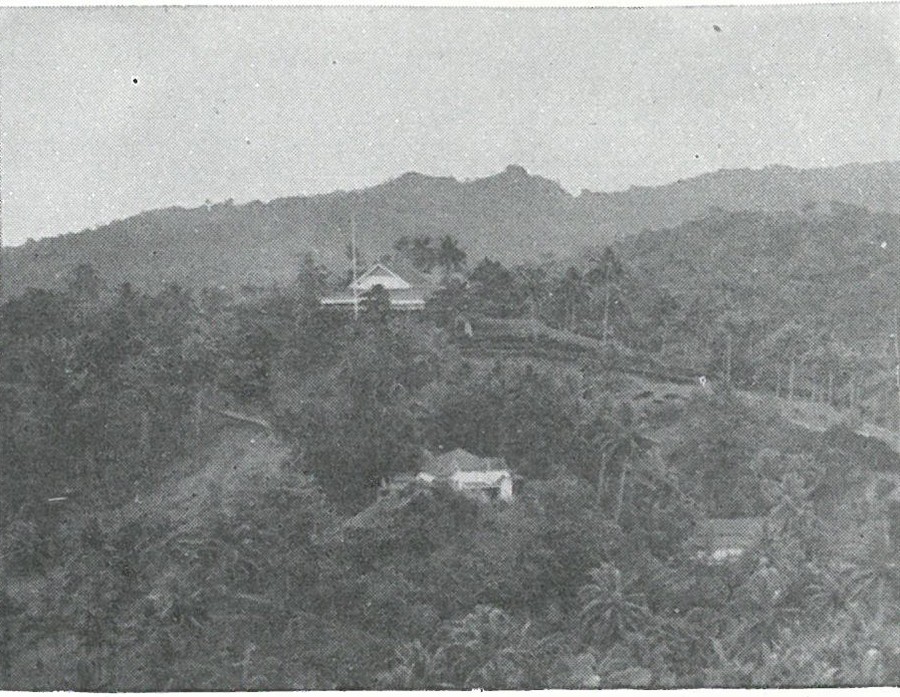

| Guadalcanal Presents A Varied Terrain |

| South Pacific Jungle |

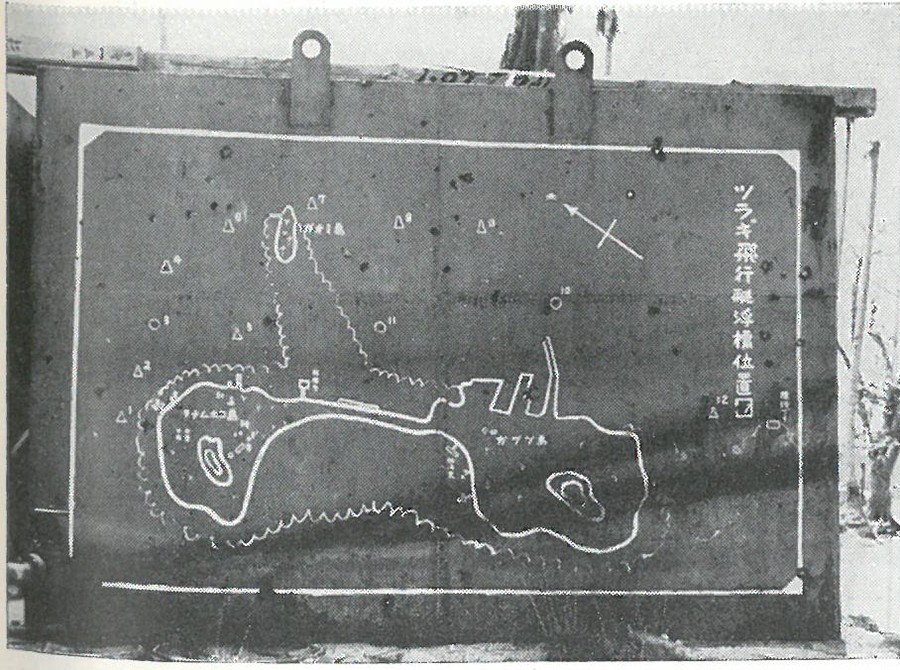

| Crude Maps |

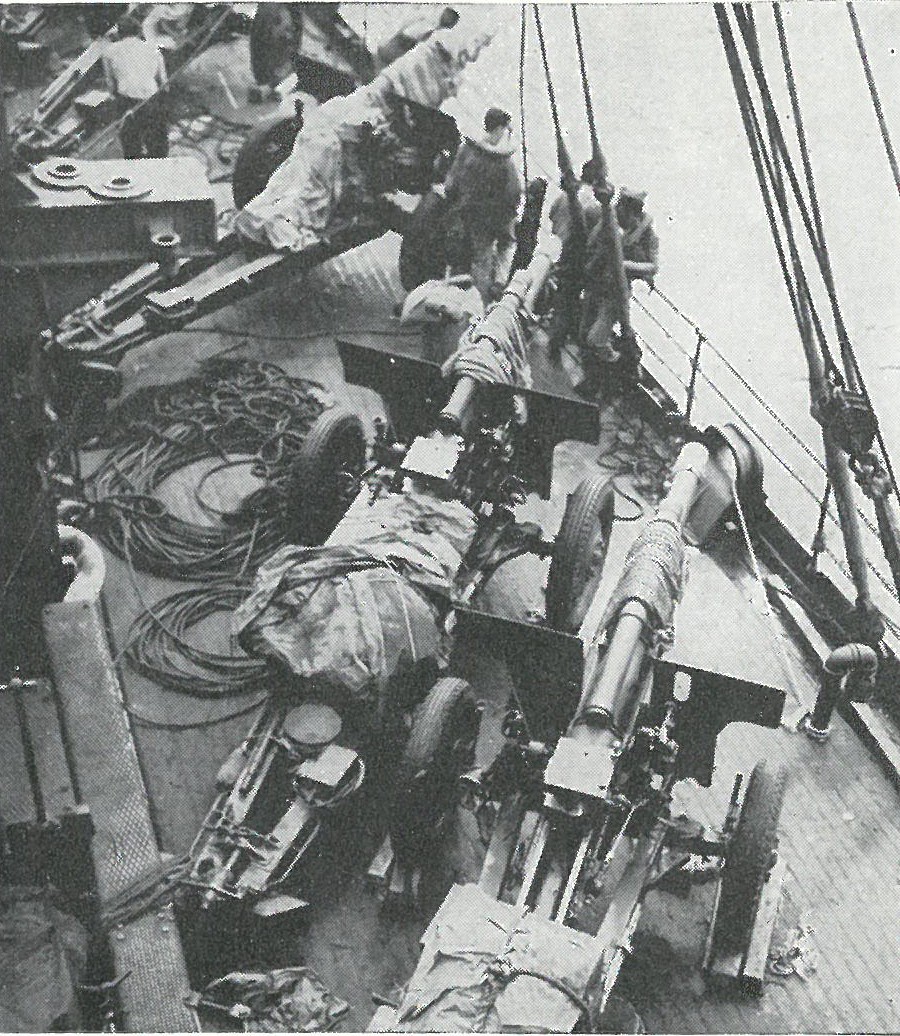

| Enroute to the Objective |

| Advance Along Tulagi |

| Final Assaults on Tulagi |

| Japanese Seaplane Anchorage, Gavutu-Tanambogo |

| Surprise Was Impossible |

| Gavutu and the Causeway |

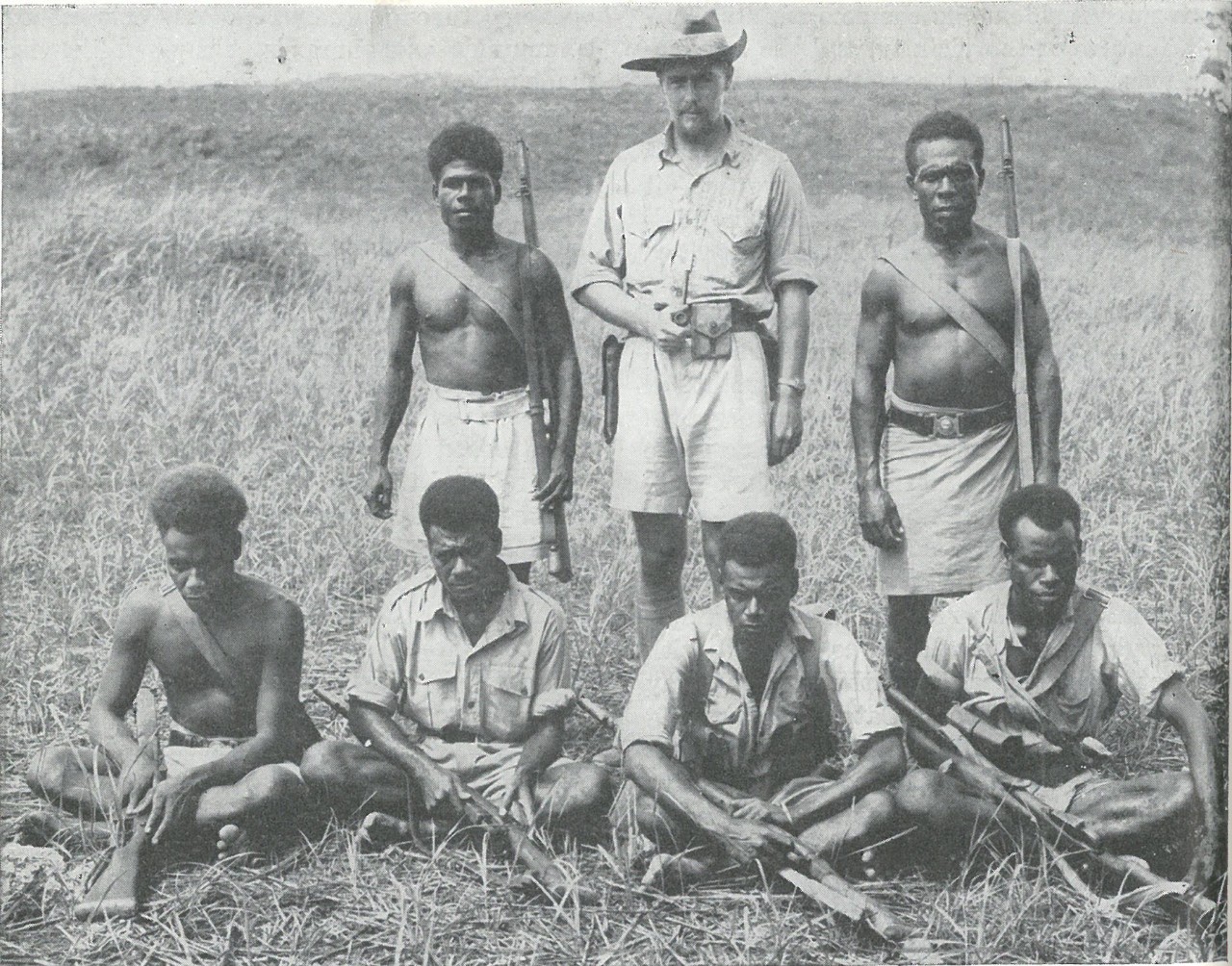

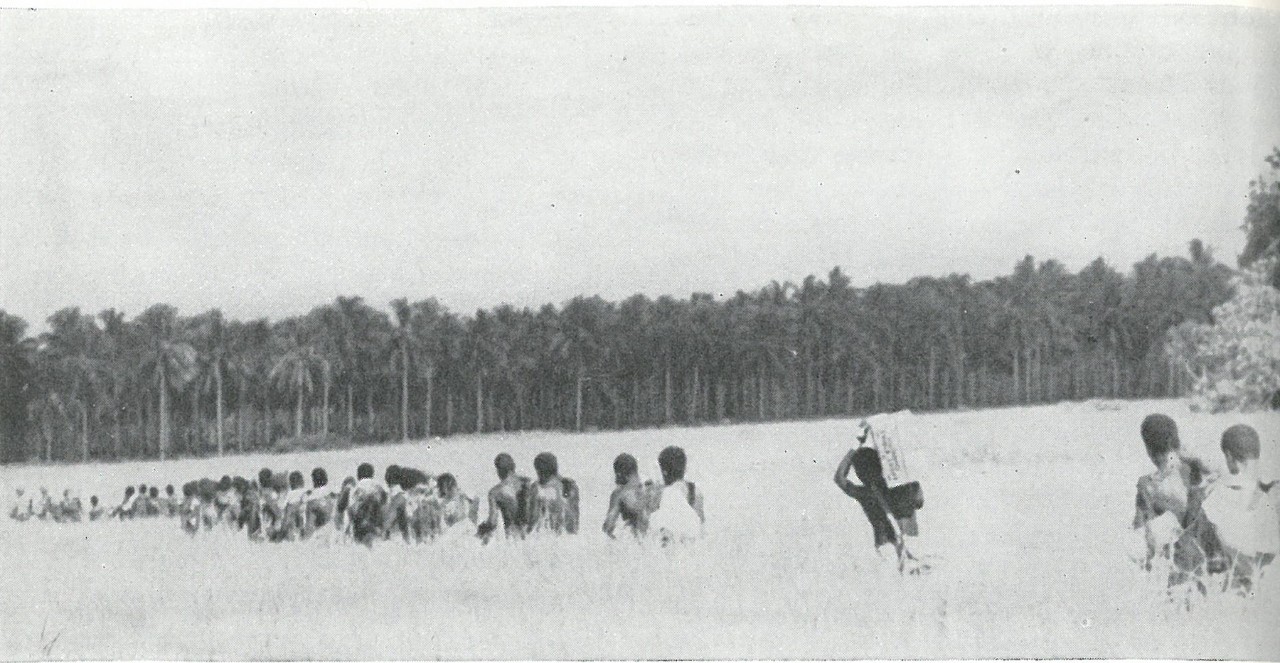

| Loyal Natives |

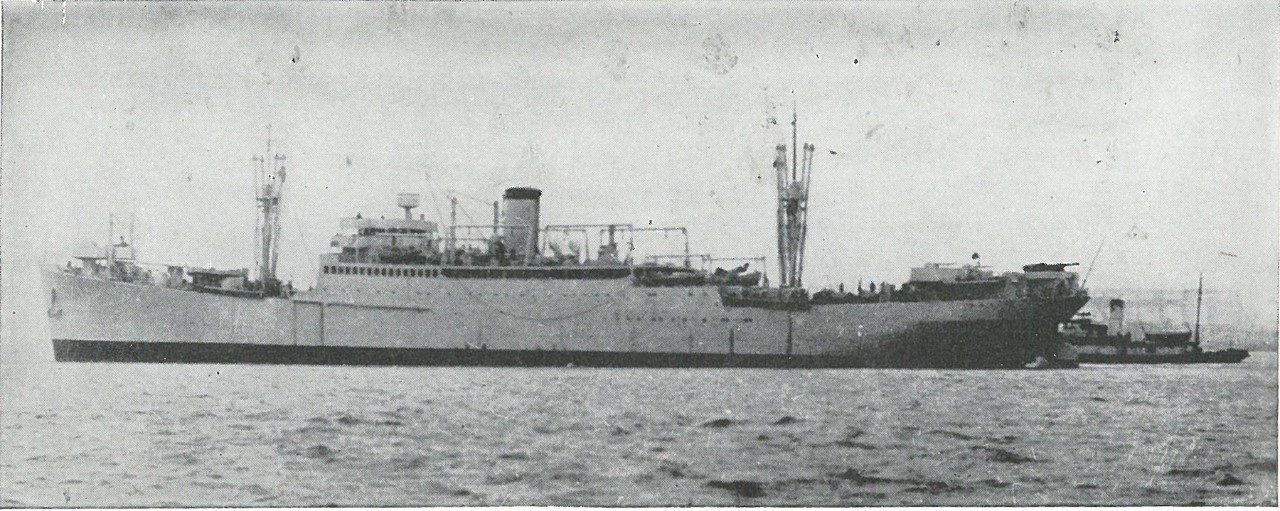

| The Transport, George F. Elliot |

| Victim of Savo Island |

| The Existence of the Fleet Marine Force |

| Beach Defenses |

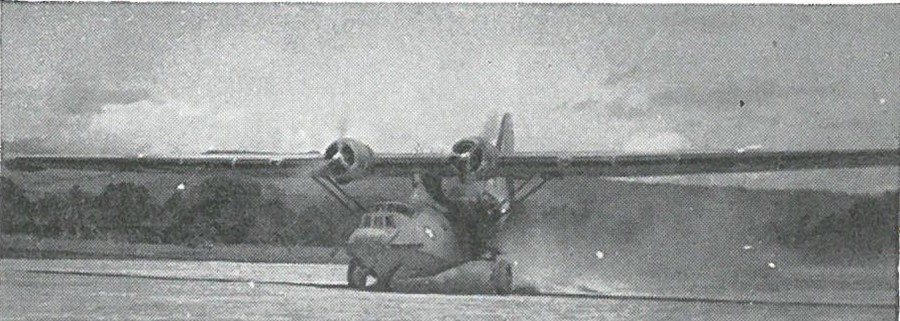

| First Plane to Land |

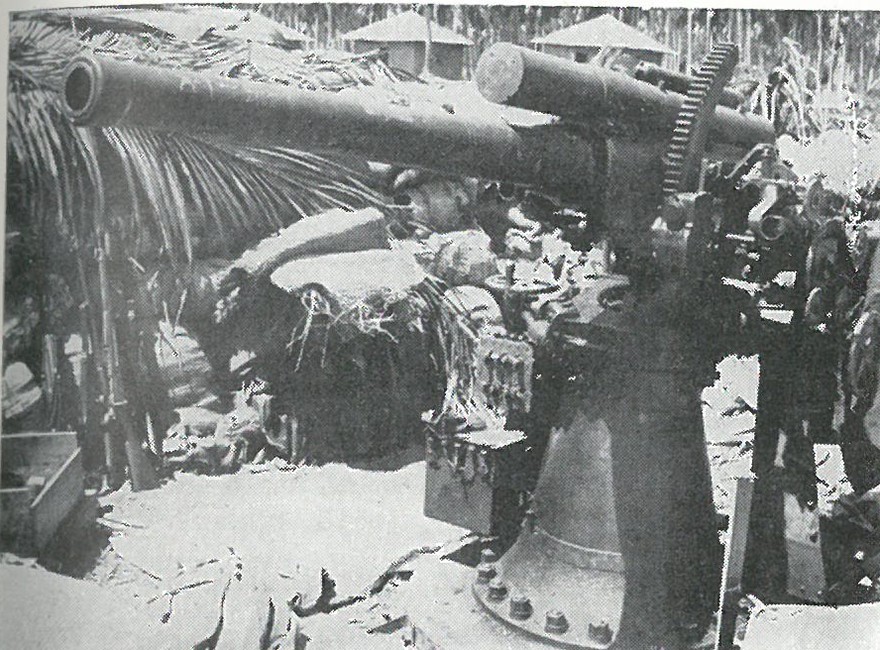

| Using Captured Japanese Guns |

| 90mm Anti-Aircraft Guns |

| Loser at Tenaru |

| Sgt. Maj. Vousa |

| The Japanese Suffered Total Casualties |

| Carrier Torpedo Planes |

| Five Army P-400s Arrived |

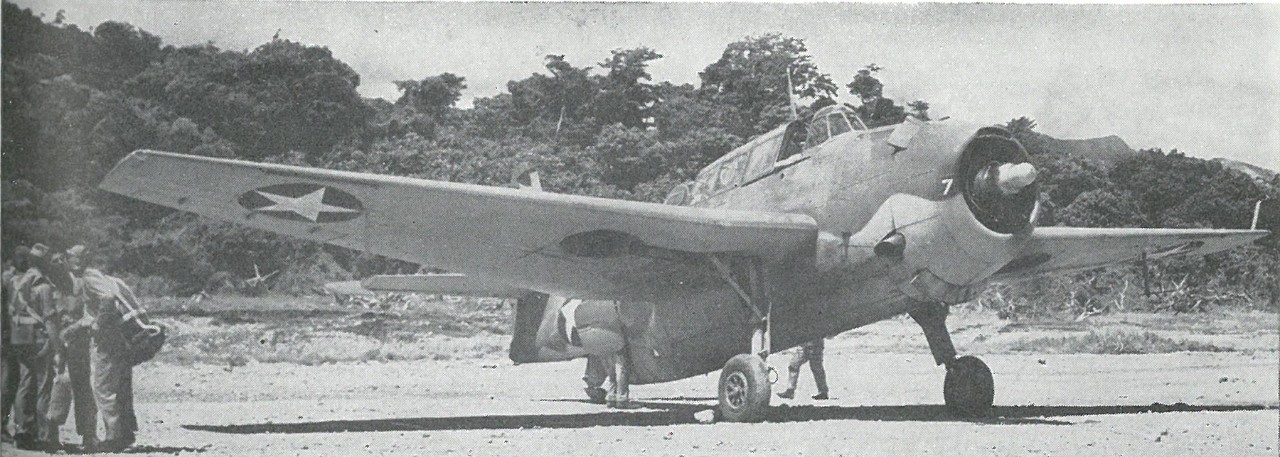

| Marine Fighter Planes |

| Maj. John L. Smith |

| Marine Fighters |

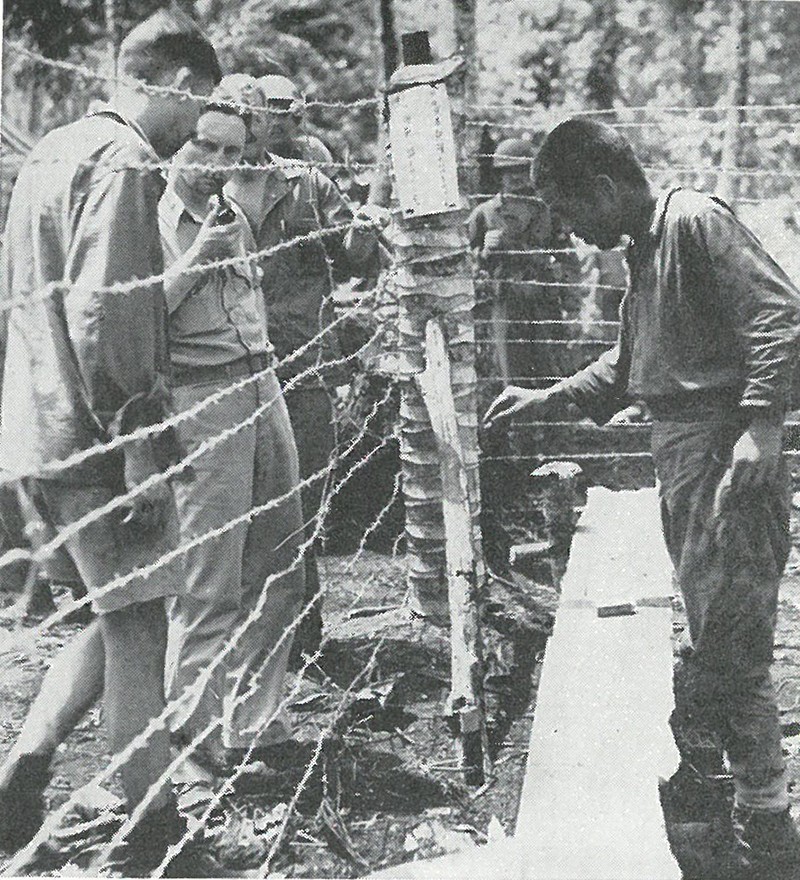

| Kawaguchi Brigade Headquarters |

| Maj. Gen. Roy S. Geiger |

| Luckier at Home Than at Edson's Ridge |

| Where the Tide Turned |

| Wire Protected the 1st Marines' Positions |

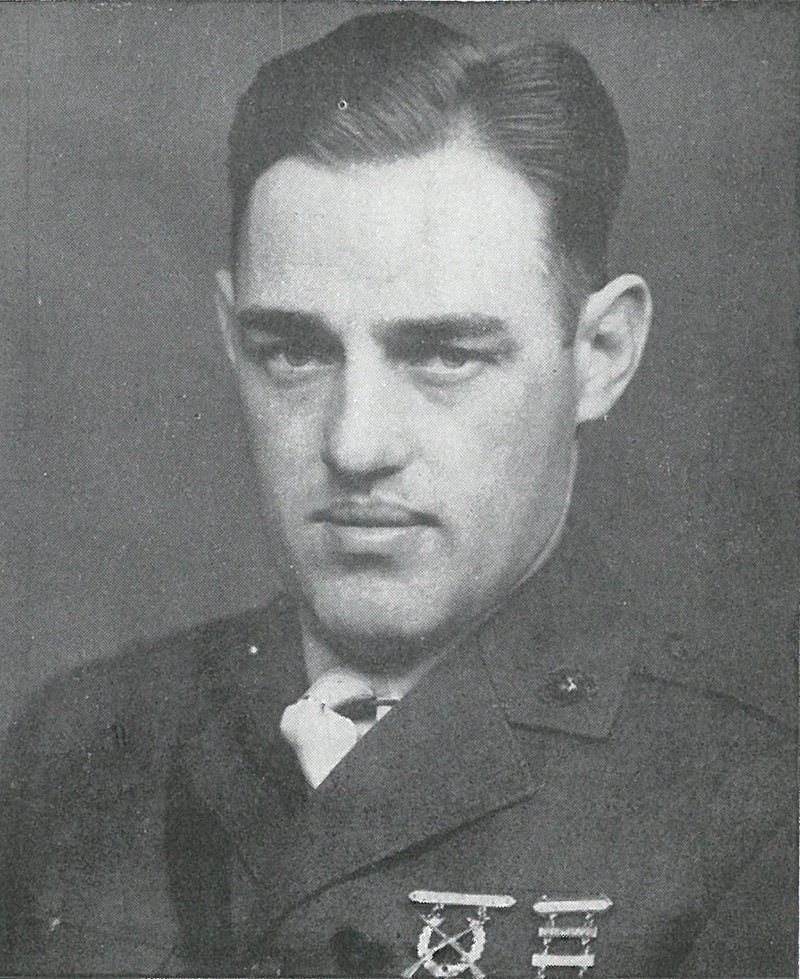

| Col. Merritt A. Edson |

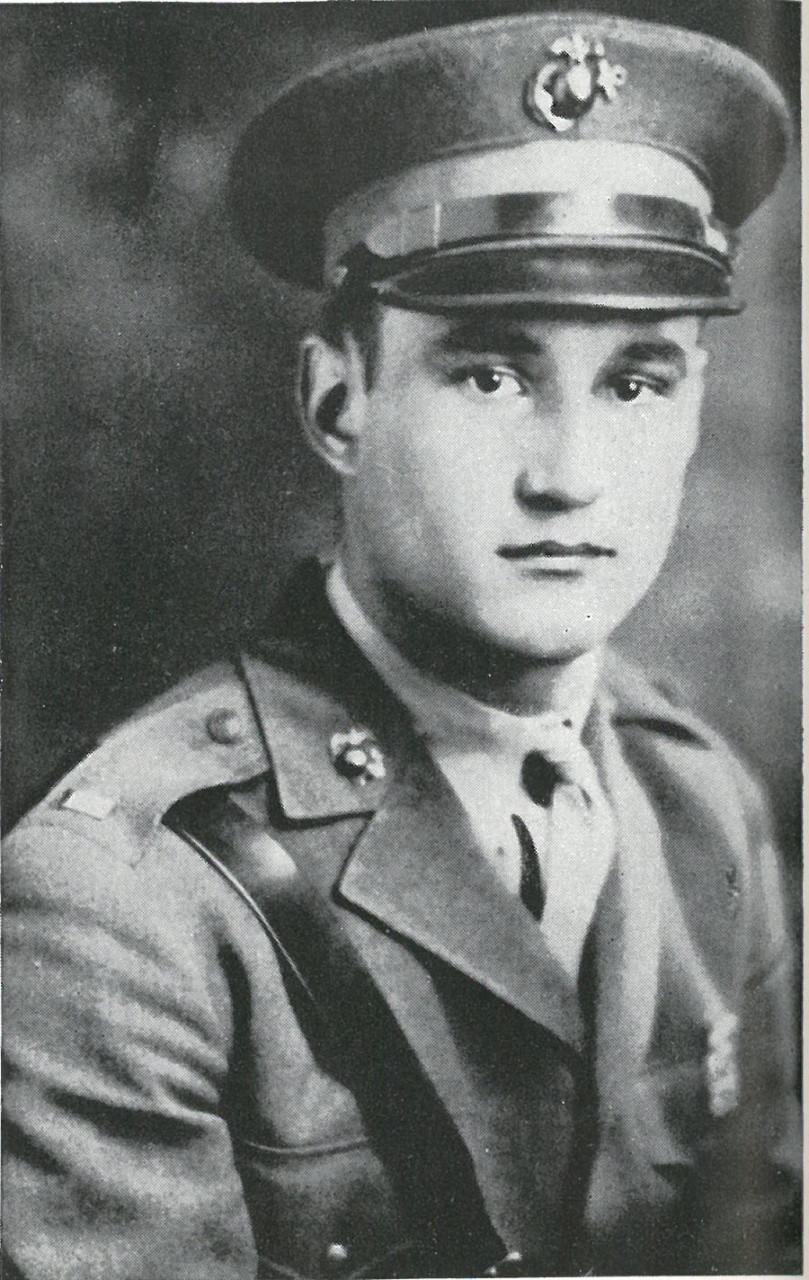

| Maj. Kenneth D. Bailey |

| Patrolling Intensified |

| Advanced Air Base Operations |

| Heavy Pressure on the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines |

| The Japanese Had The Advantage |

| In a Tight Spot |

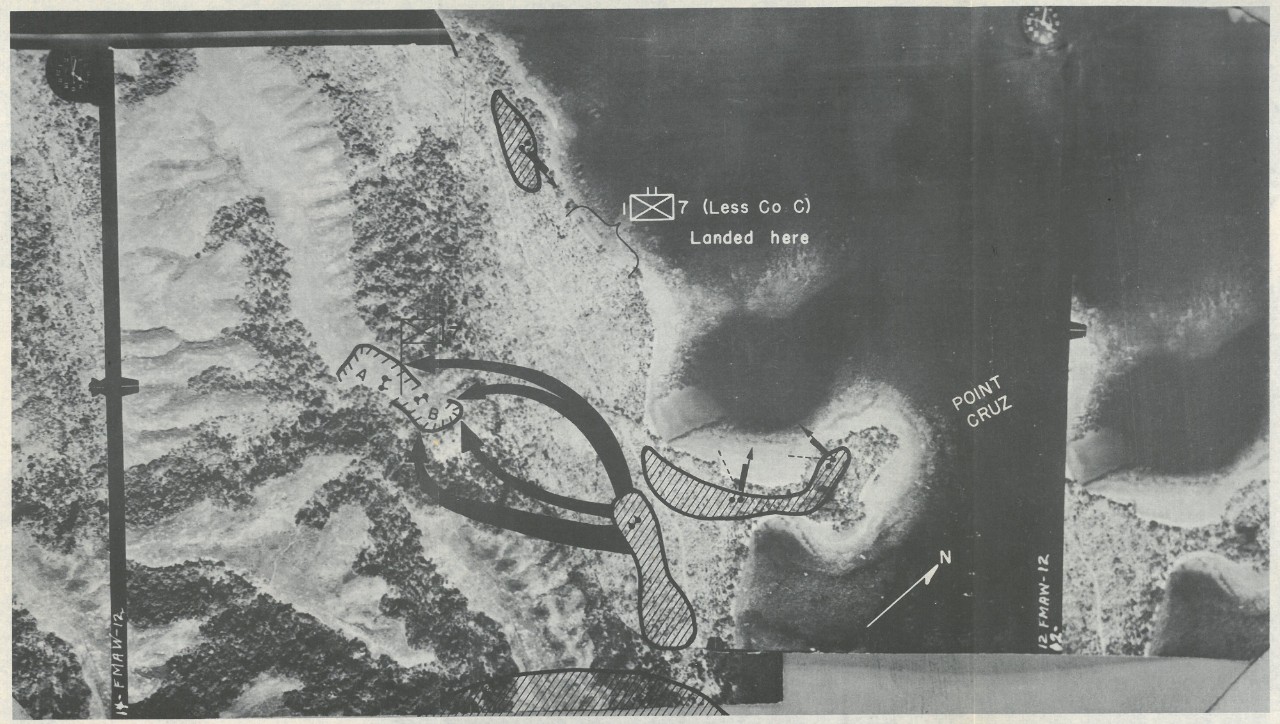

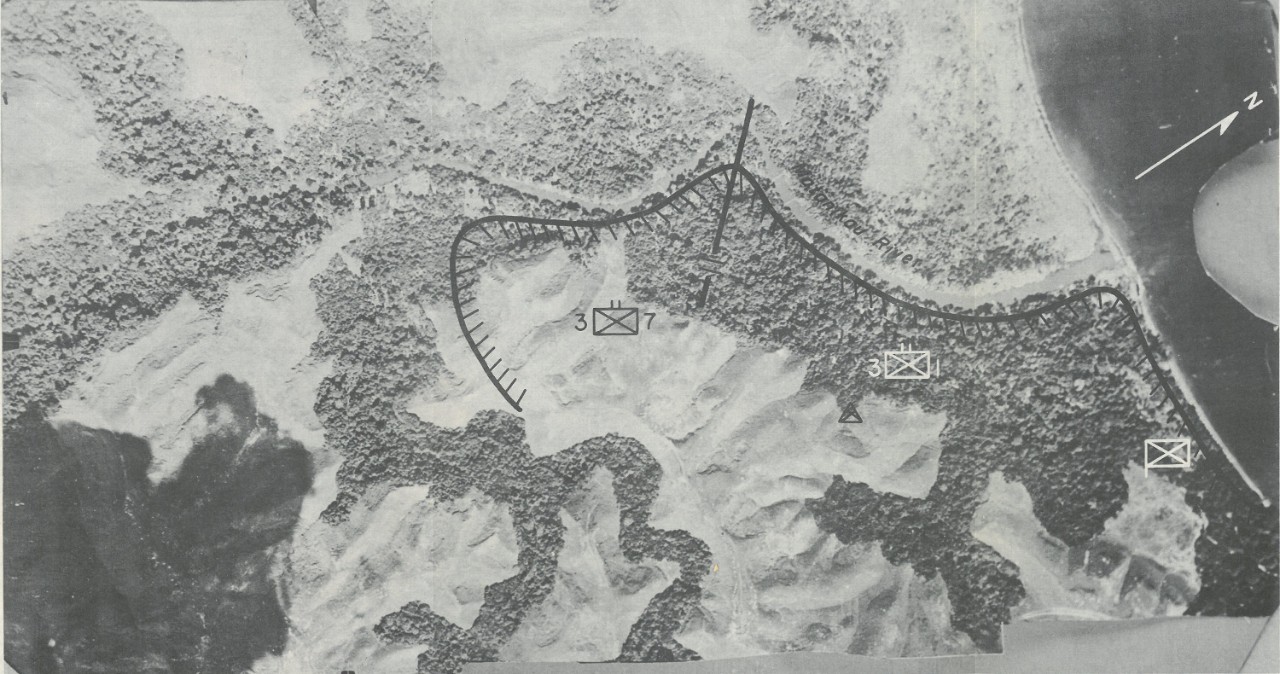

| Action on the Matanikau |

| Horseshot Defense Along the Matanikau |

| Lt. Col. Harold W. Bauer |

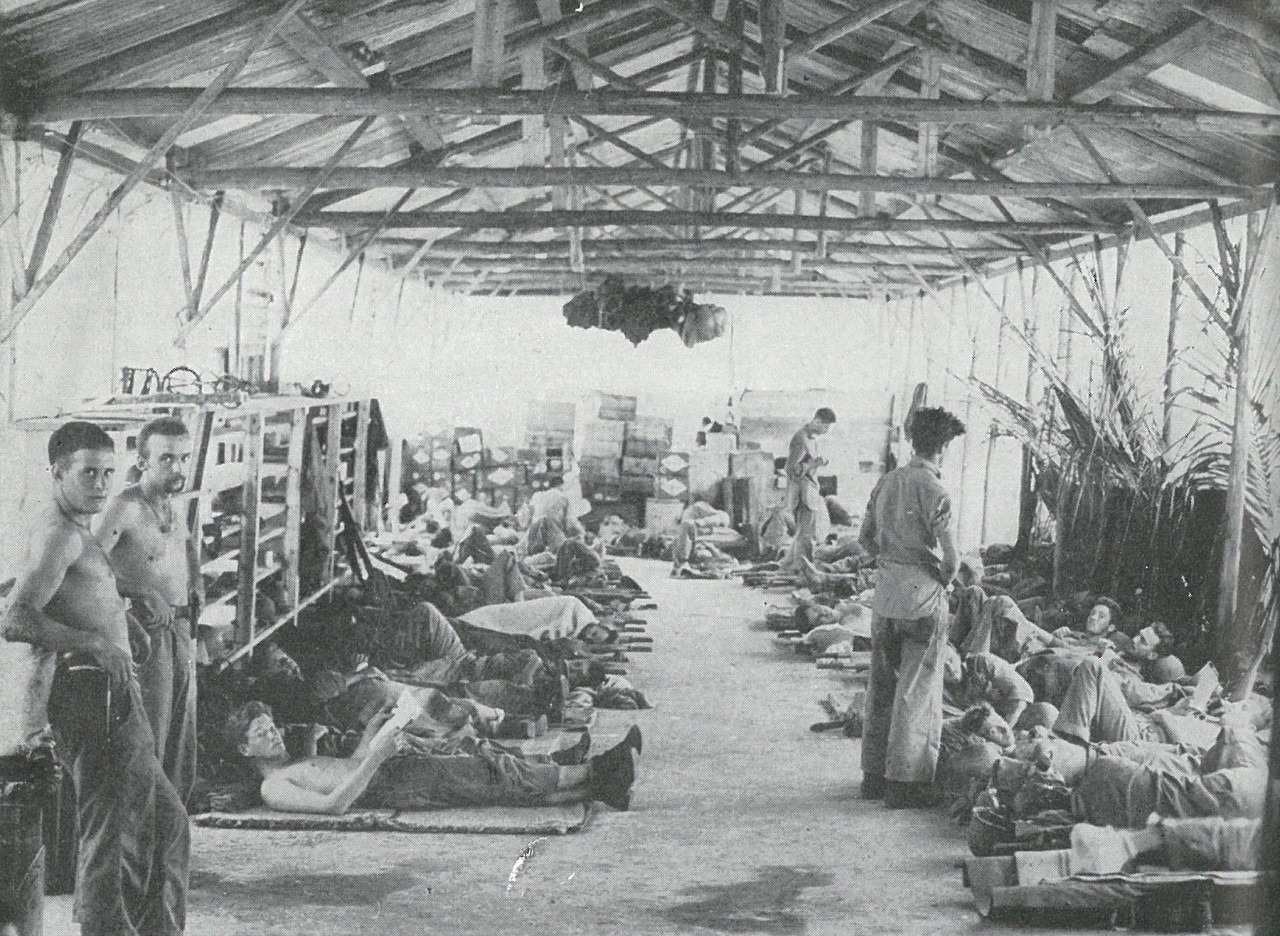

| Malaria Began to Make Itself Felt |

| Air Evacuation |

| Capt J. J. Foss |

| The Operation Bogged Down |

| With Bow Over Dry Land |

| Native Help Payed Off |

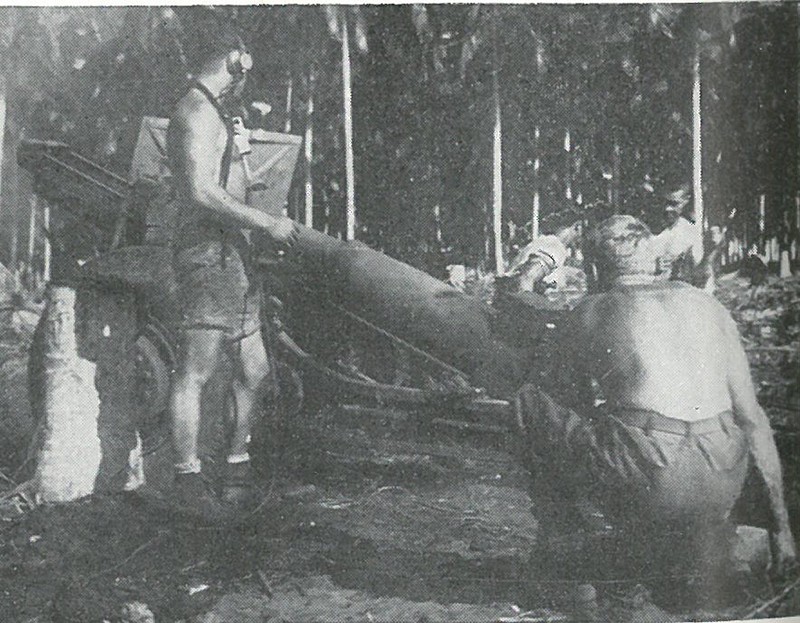

| "Pistol Pete"? |

| Japanese Medium Tanks |

| Scientific Extermination |

| Sgt. John Basilone |

| Unremitting Japanese Air Attacks |

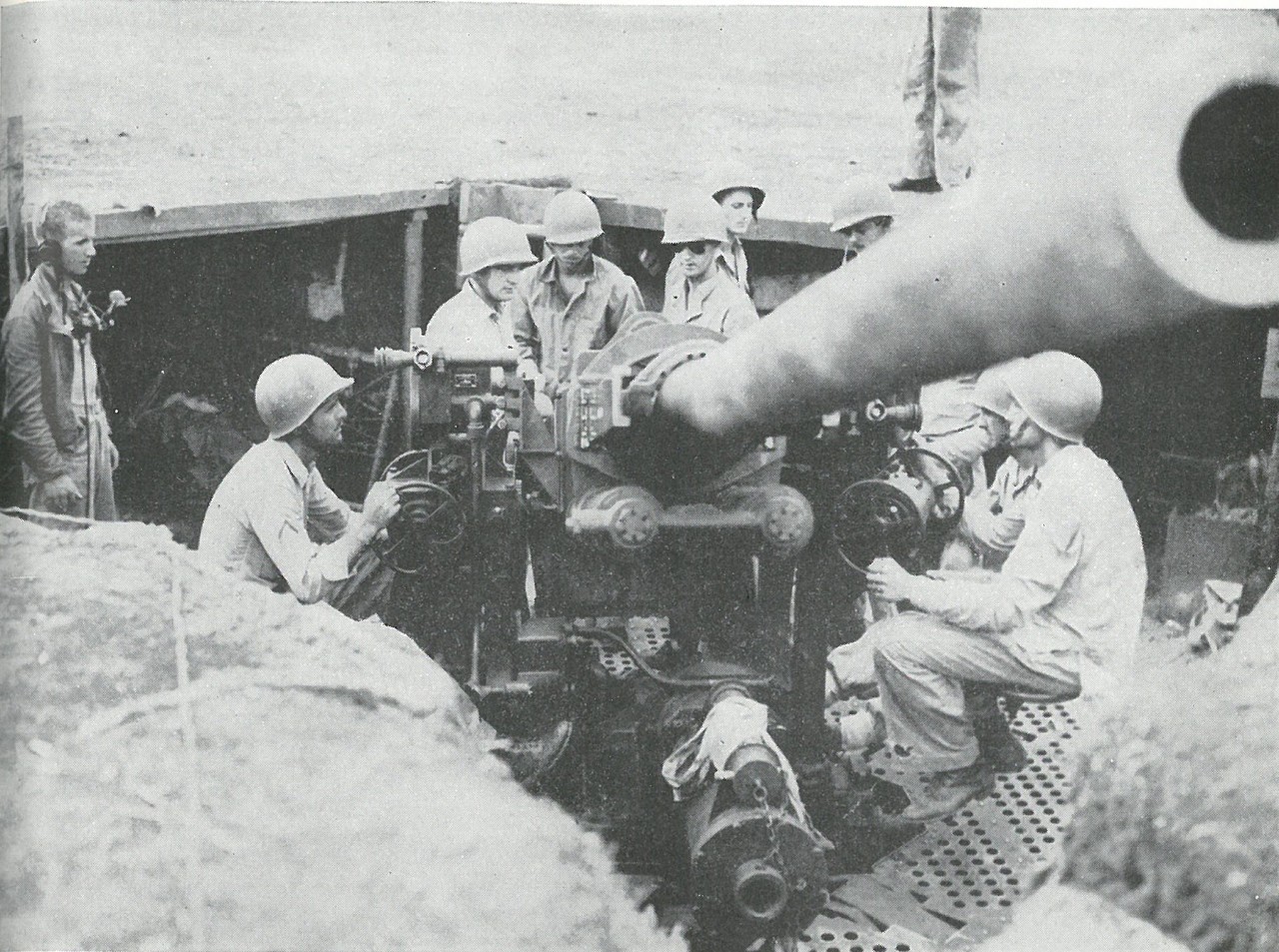

| Anti-Aircraft Gunners |

| Sgt. Mitchell Paige |

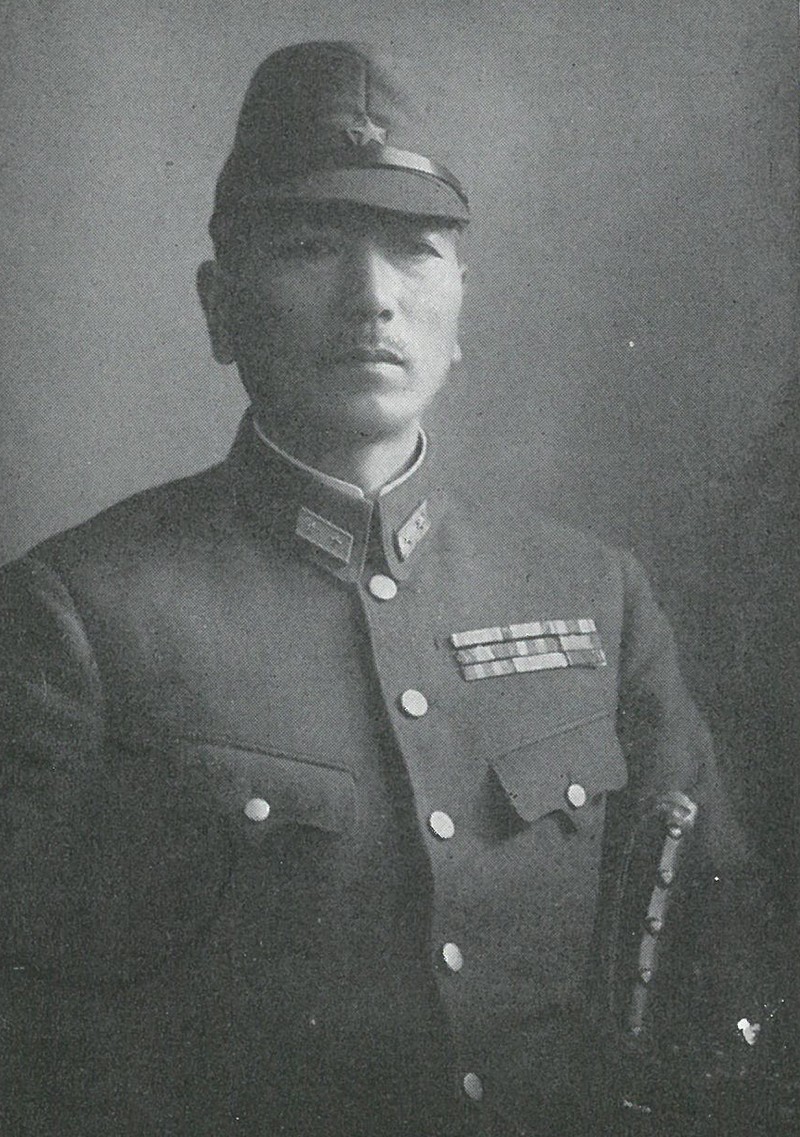

| Lt. Gen. Hyakutake |

| Vandegrift's Opponent |

| The Commandant Inspects |

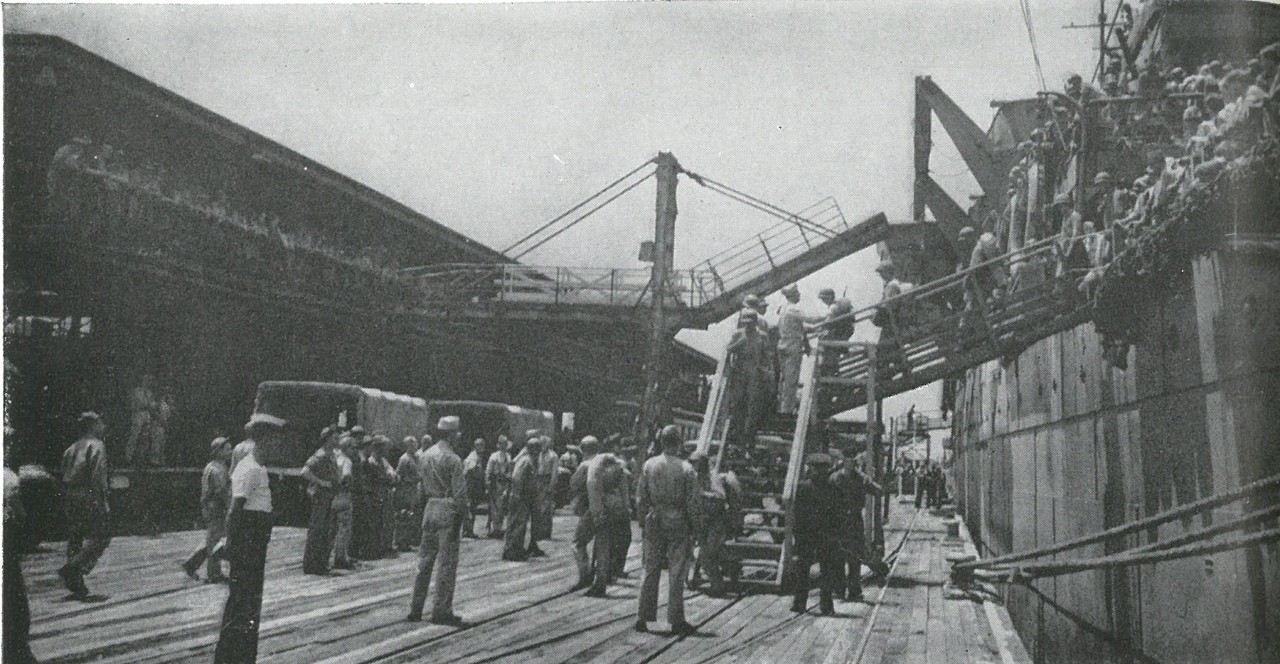

| Additional Units Arrive |

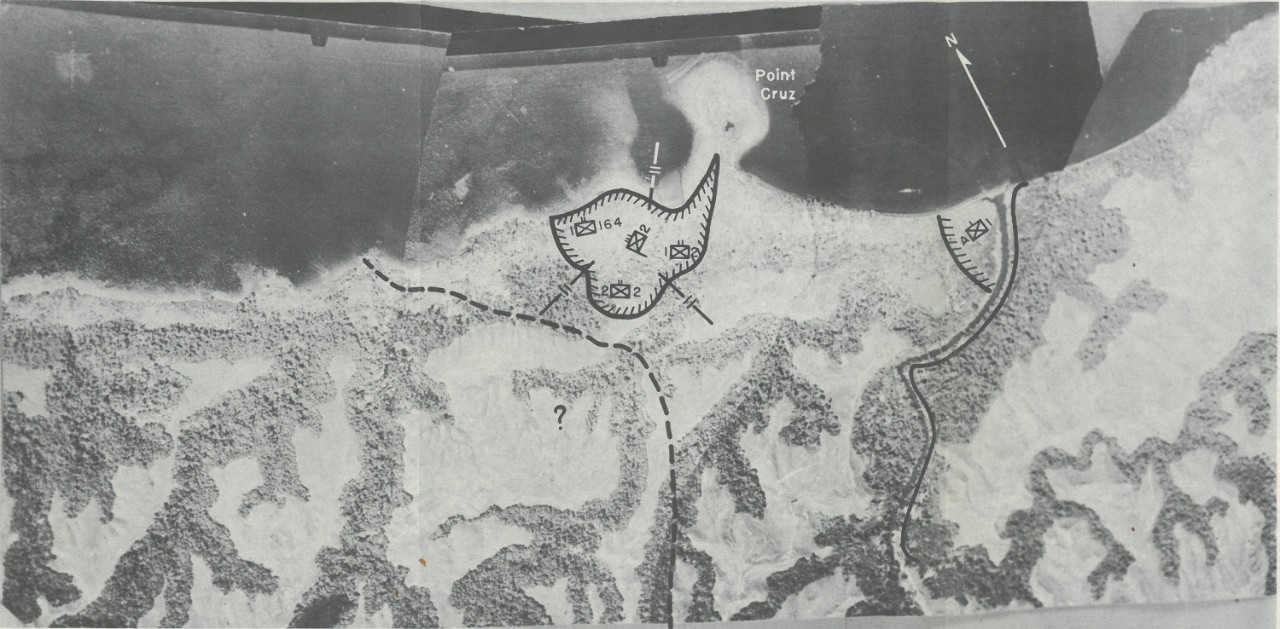

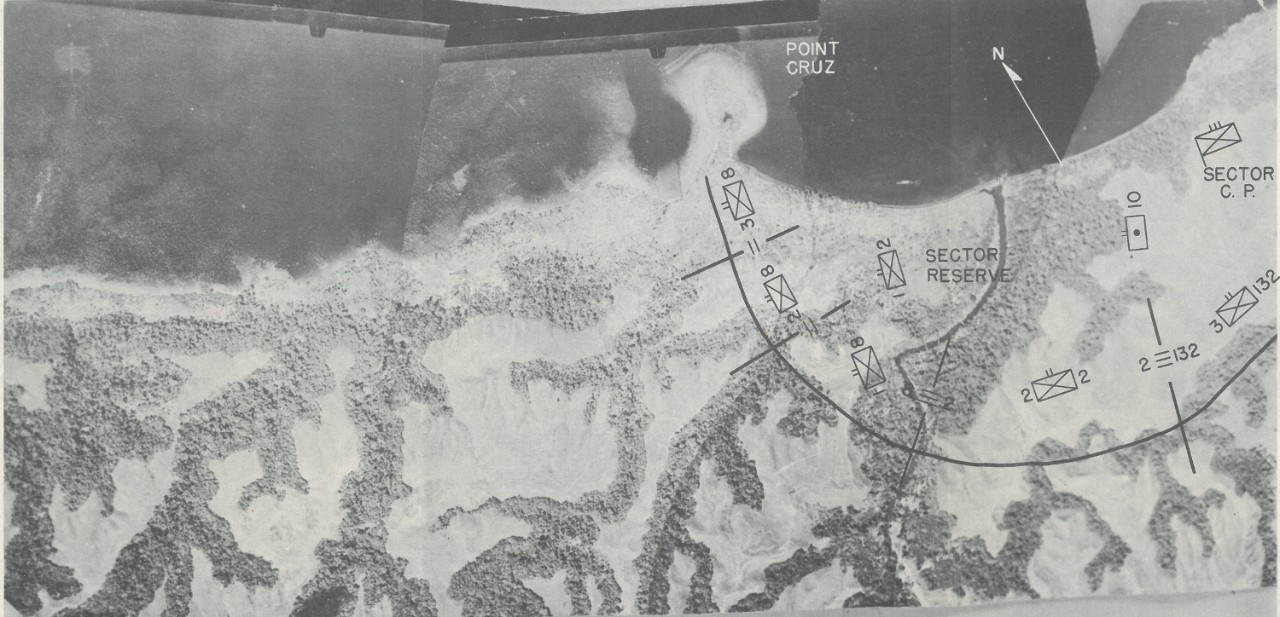

| Operations Above Point Cruz |

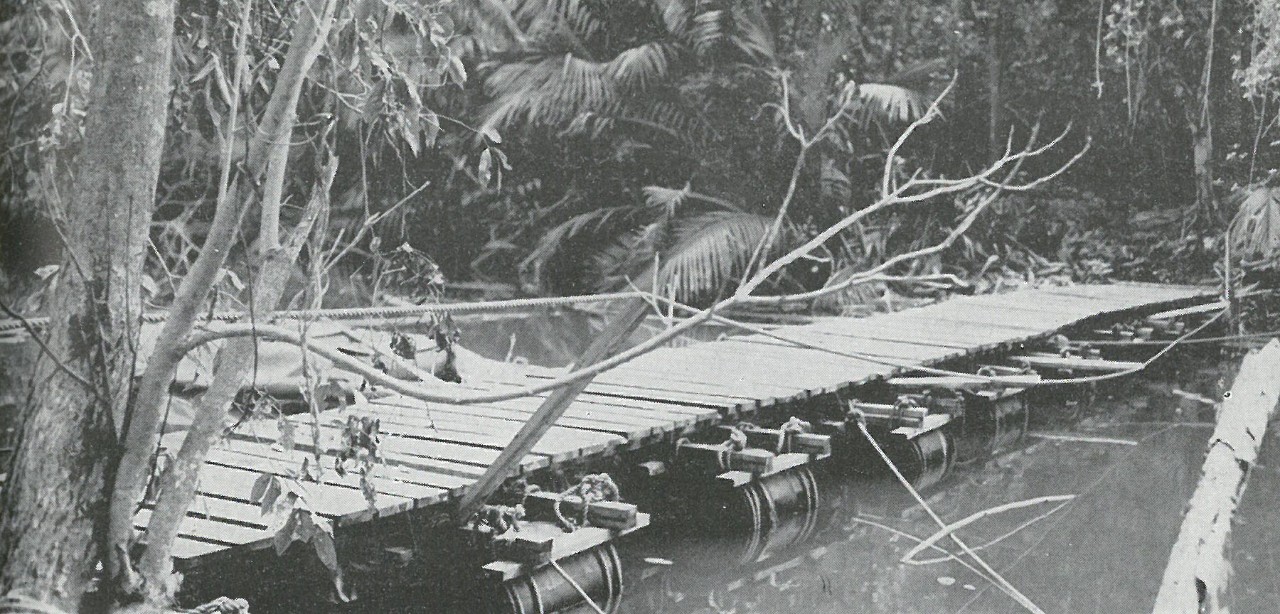

| The Engineers Succeeded |

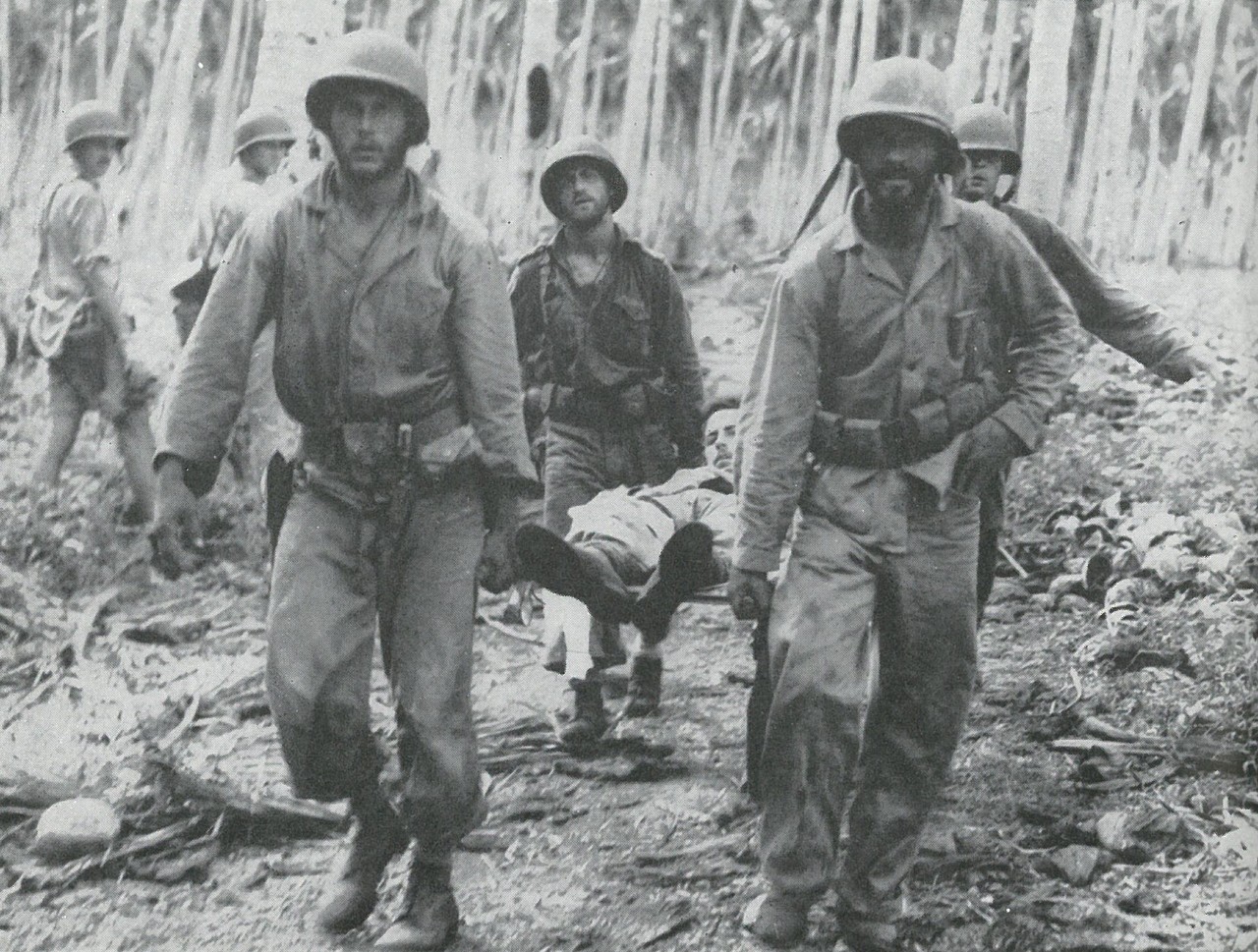

| Heavy Casualties Were Suffered |

| Gunfire Support by Day, Torpedoes by Night |

| Carlson's Raiders on the March |

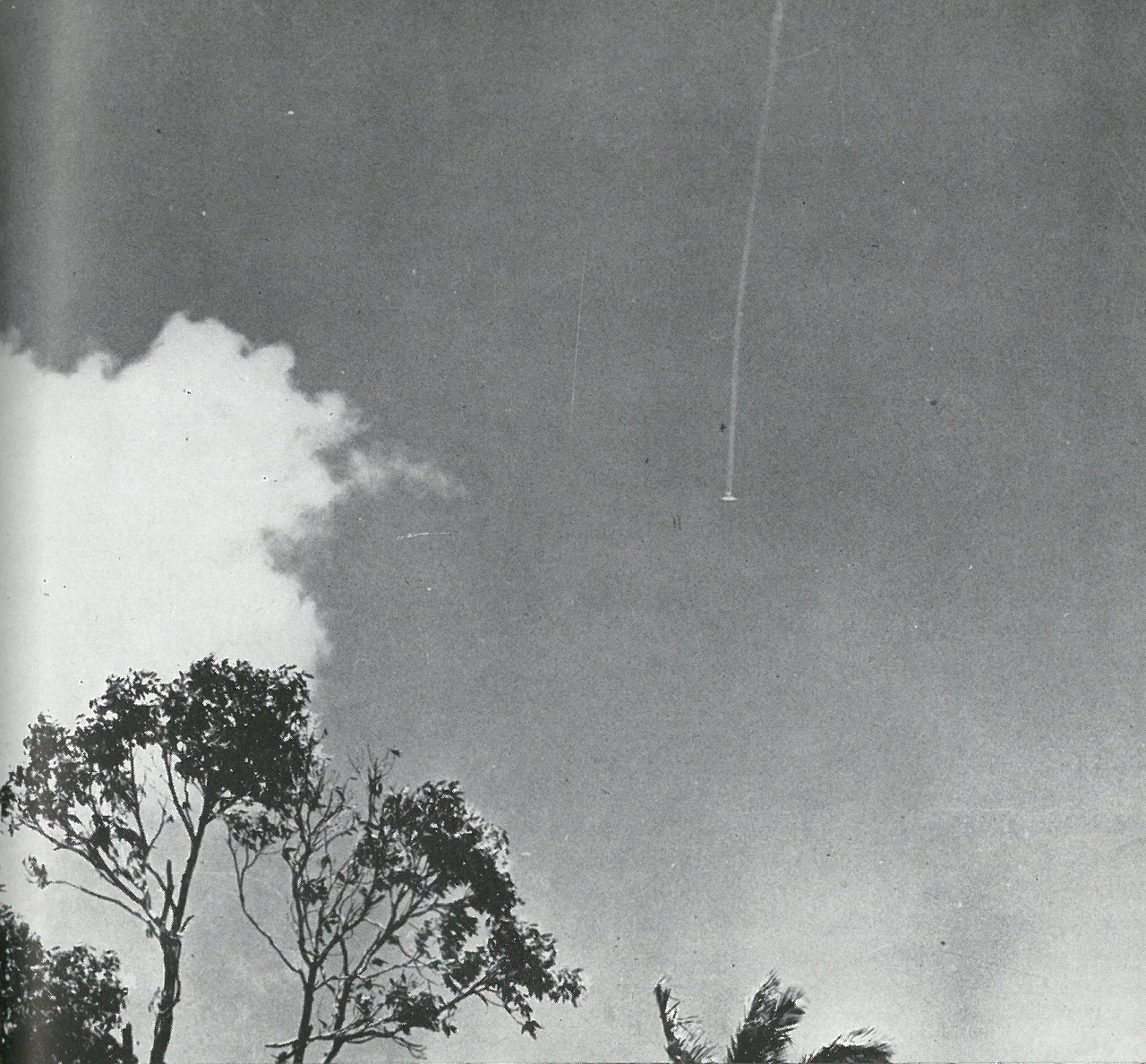

| Plummeting Down |

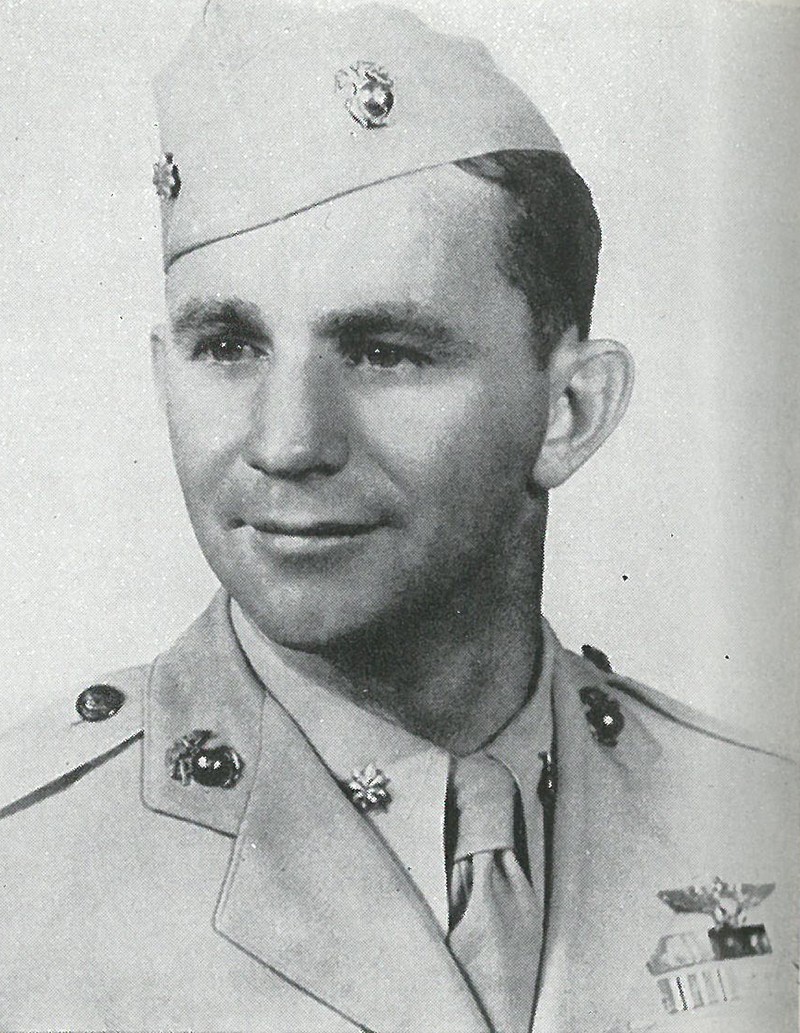

| Maj. R. E. Galer |

| On The Way Out |

| Maj. Gen. Patch, USA |

| The Army Arrives |

| Matanikau Positions in December |

| Inside the Stockade |

| Guadalcanal was the Turning Point |

| Maps |

|---|

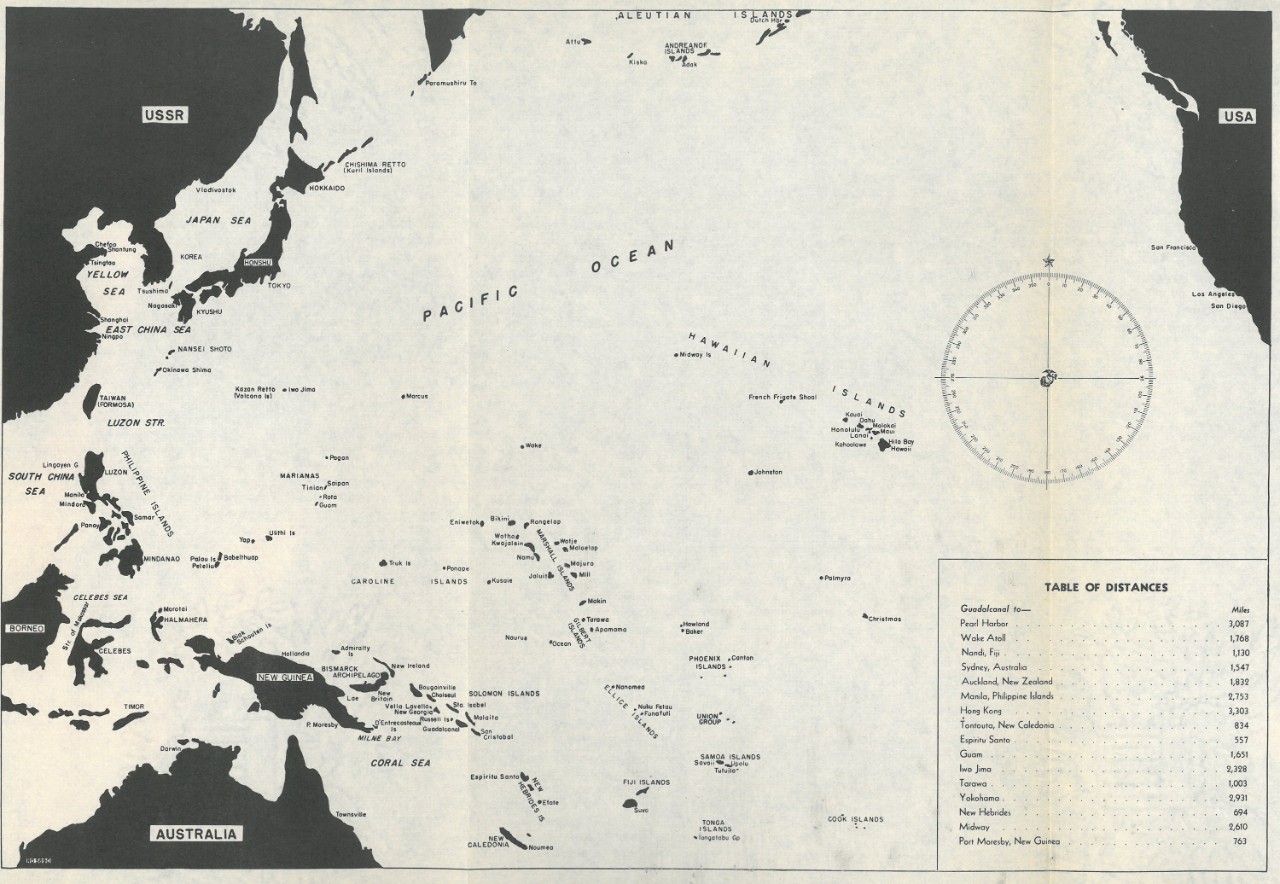

| Guadalcanal and Florida Islands |

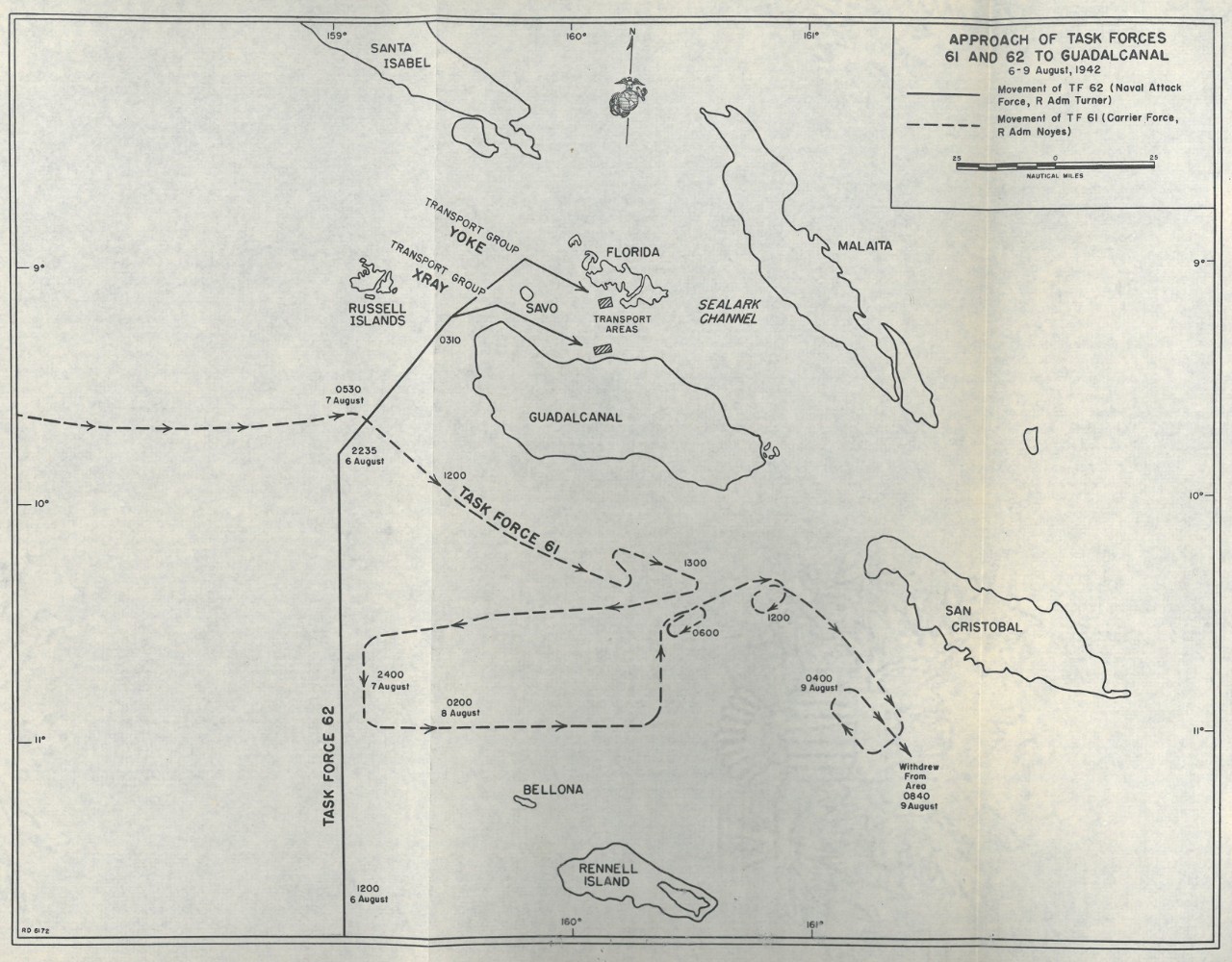

| Approach of Task Forces 61 & 62 to Guadalcanal |

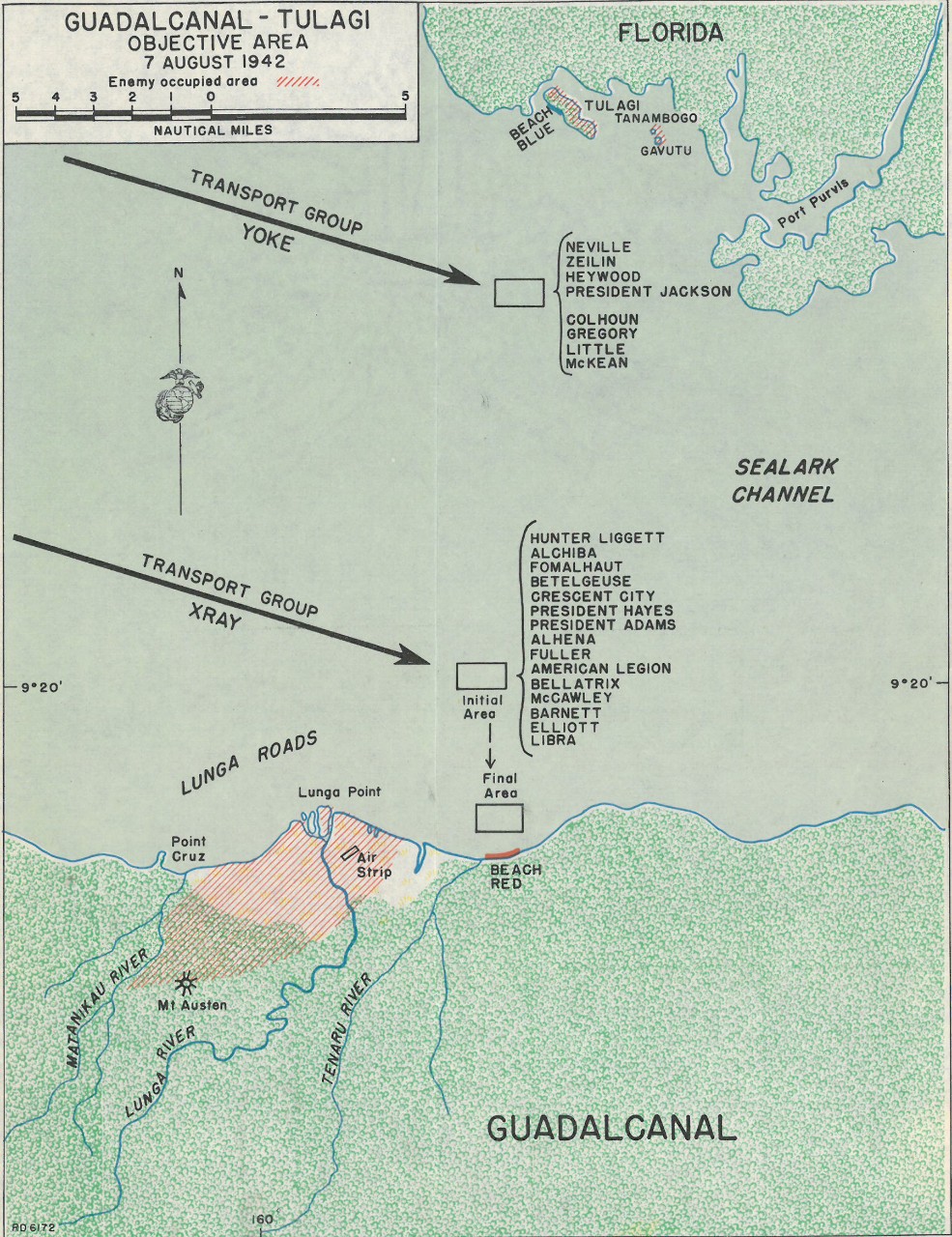

| Guadalcanl-Tulagi Objective Area |

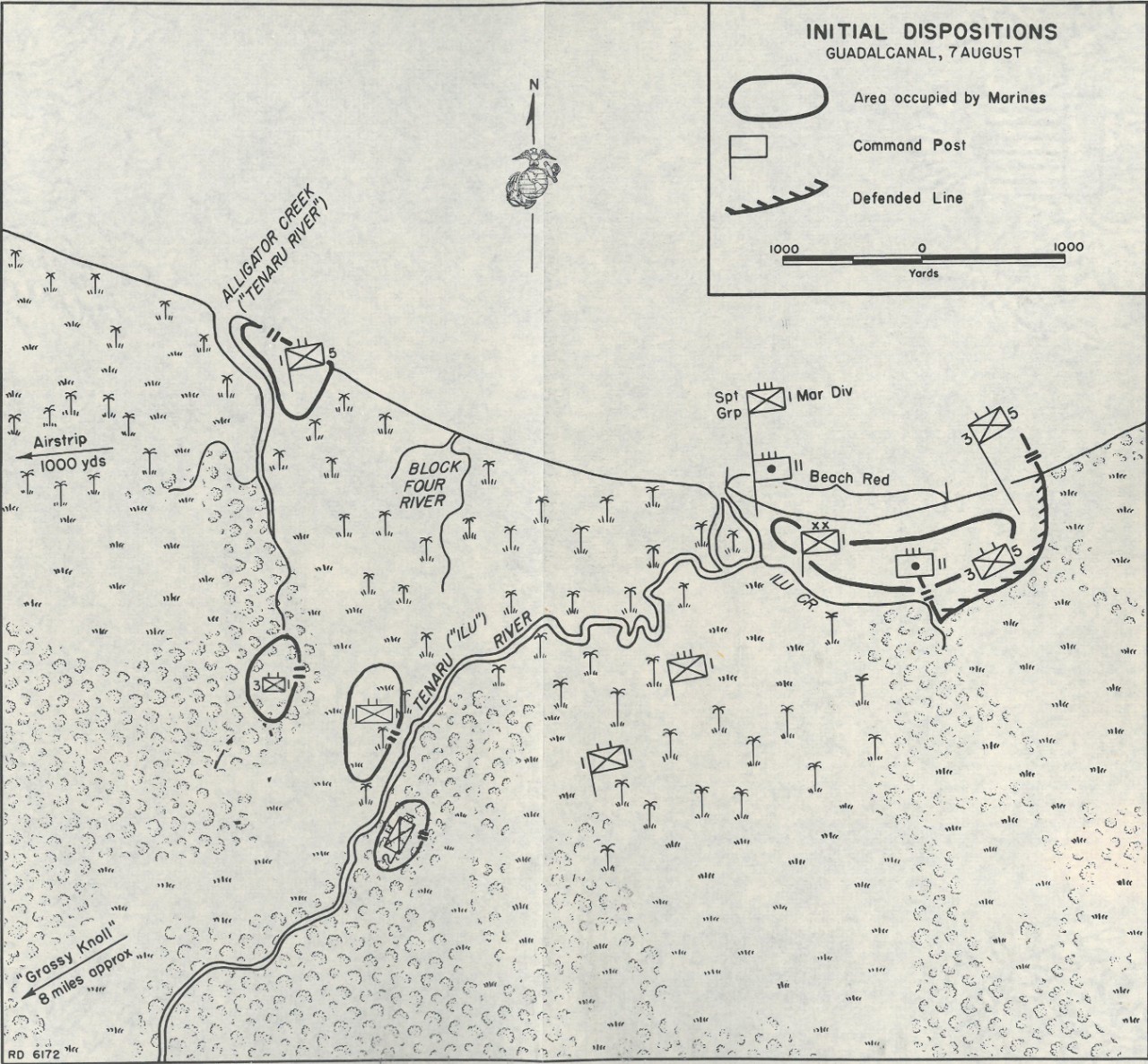

| Initial Dispositions-Guadalcanal, 7 August 1942 |

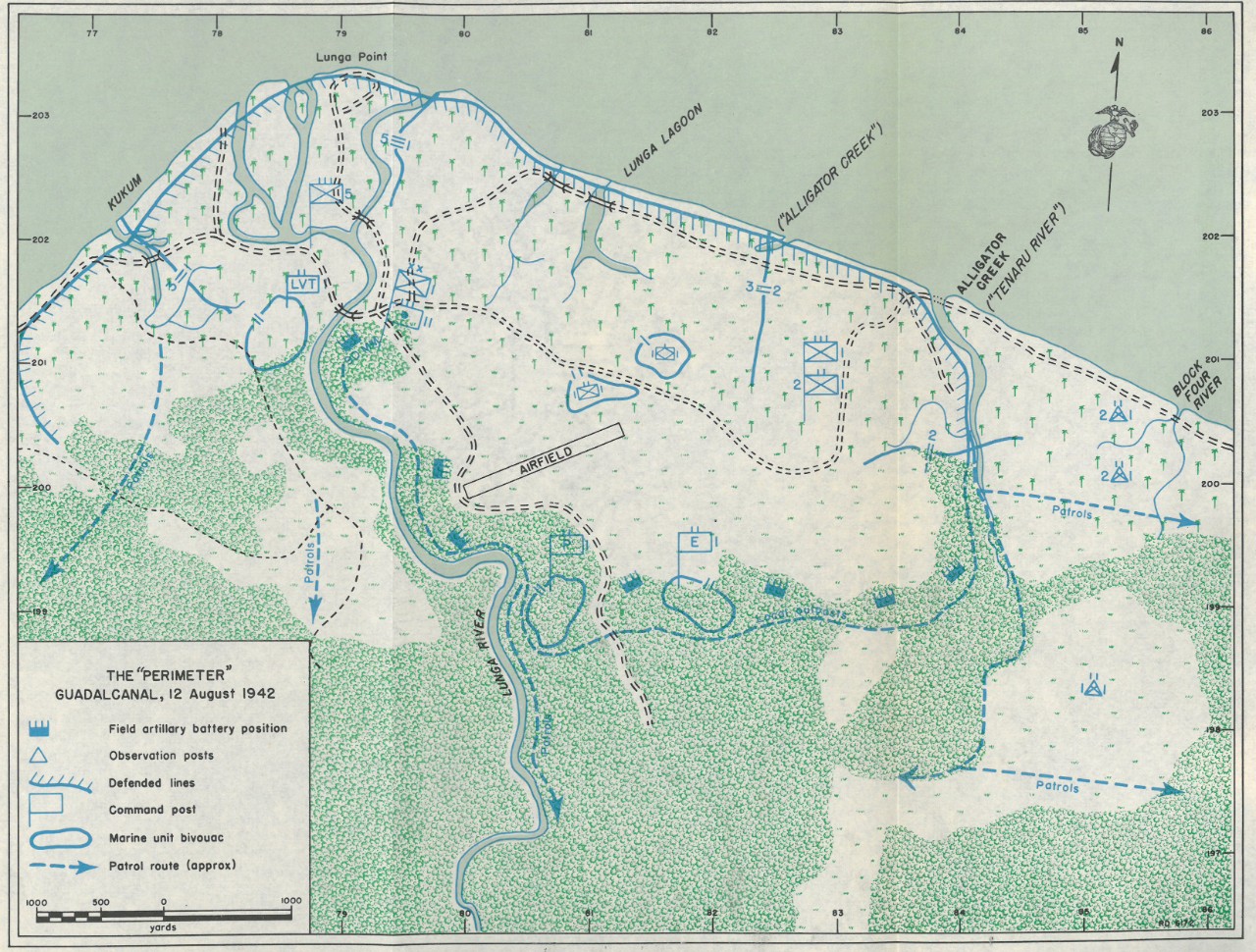

| The Perimeter |

| Battle of the Tenaru, 21 August 1942 |

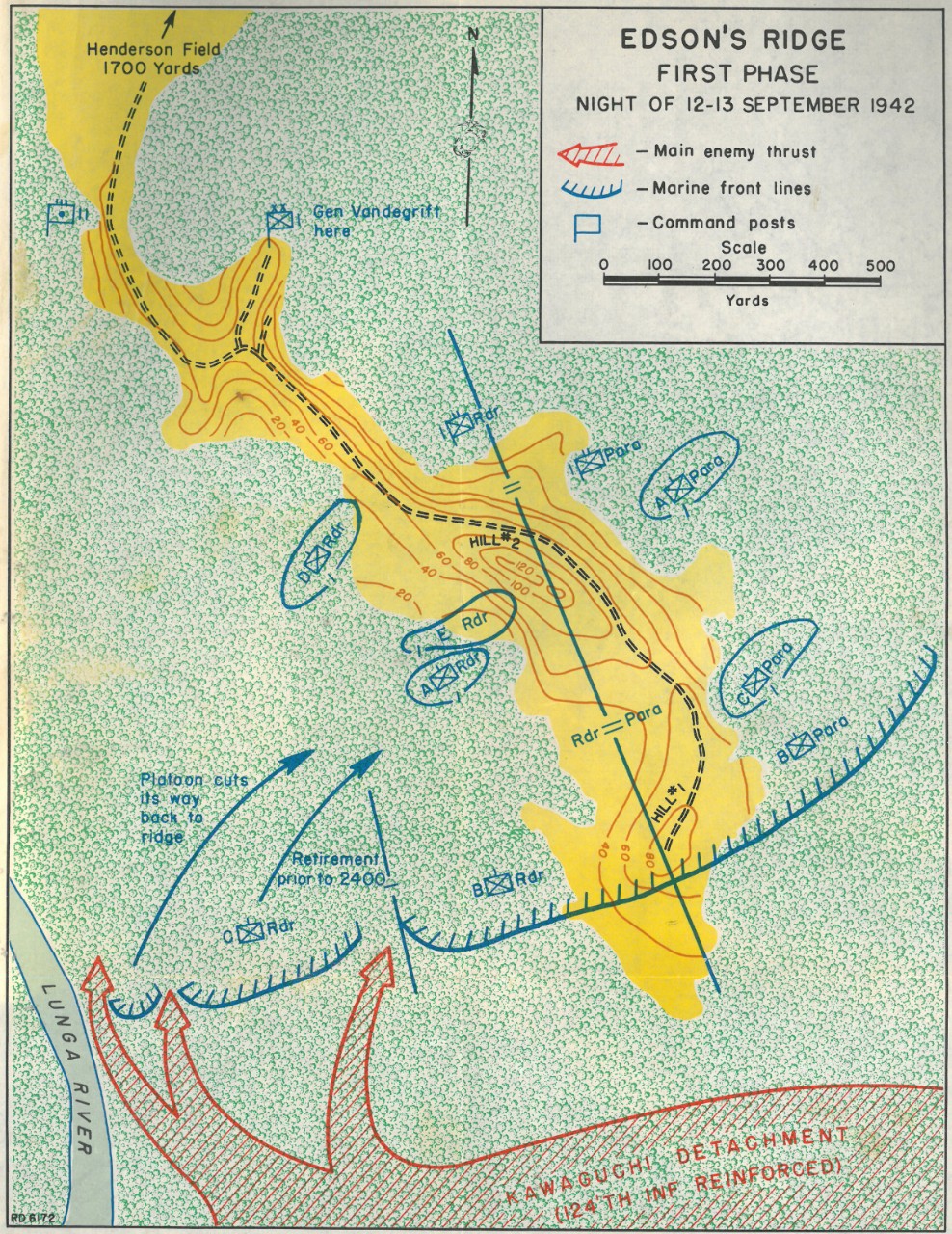

| Edson's Ridge-First Phase |

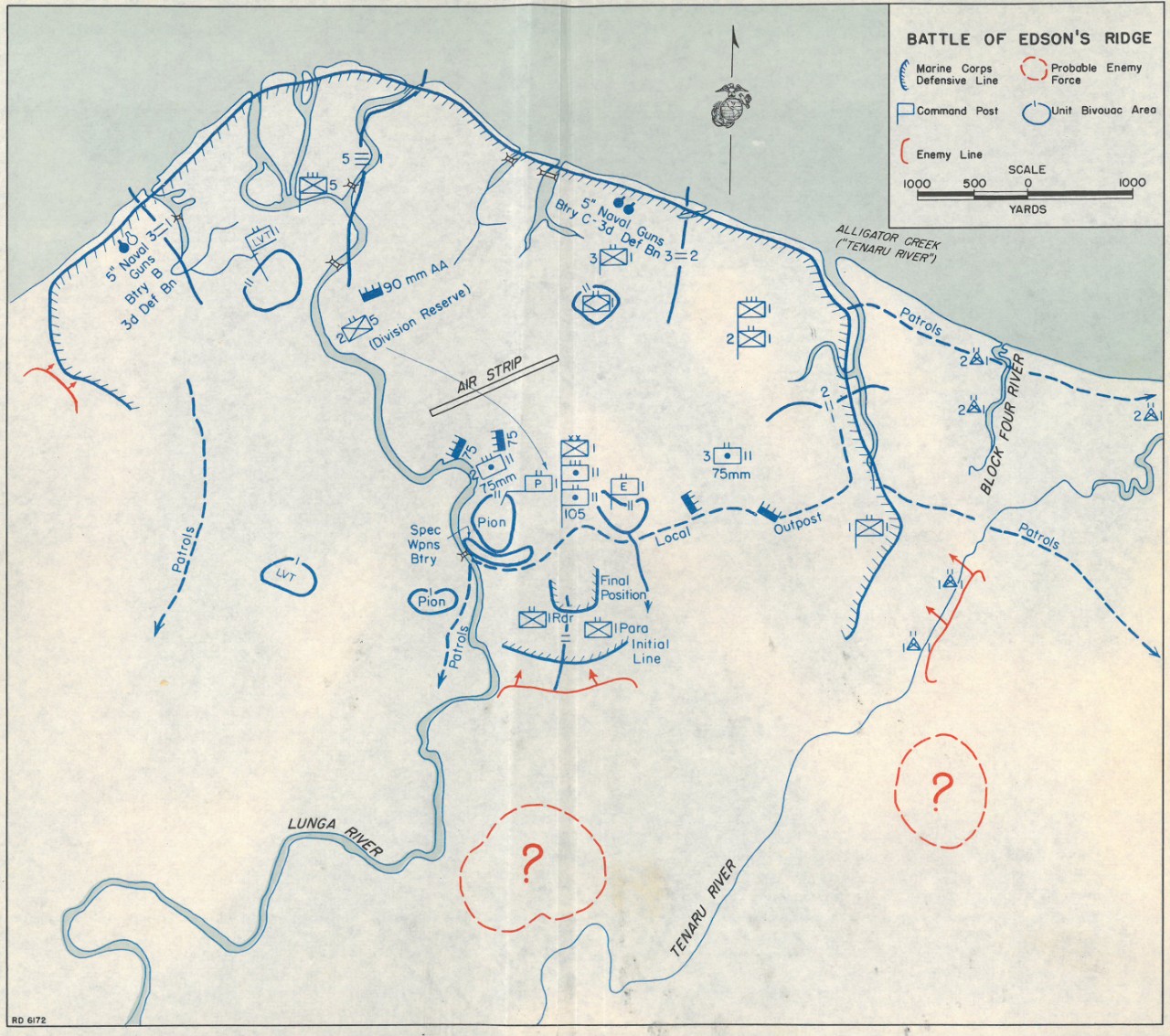

| Battle of Edson's Ridge |

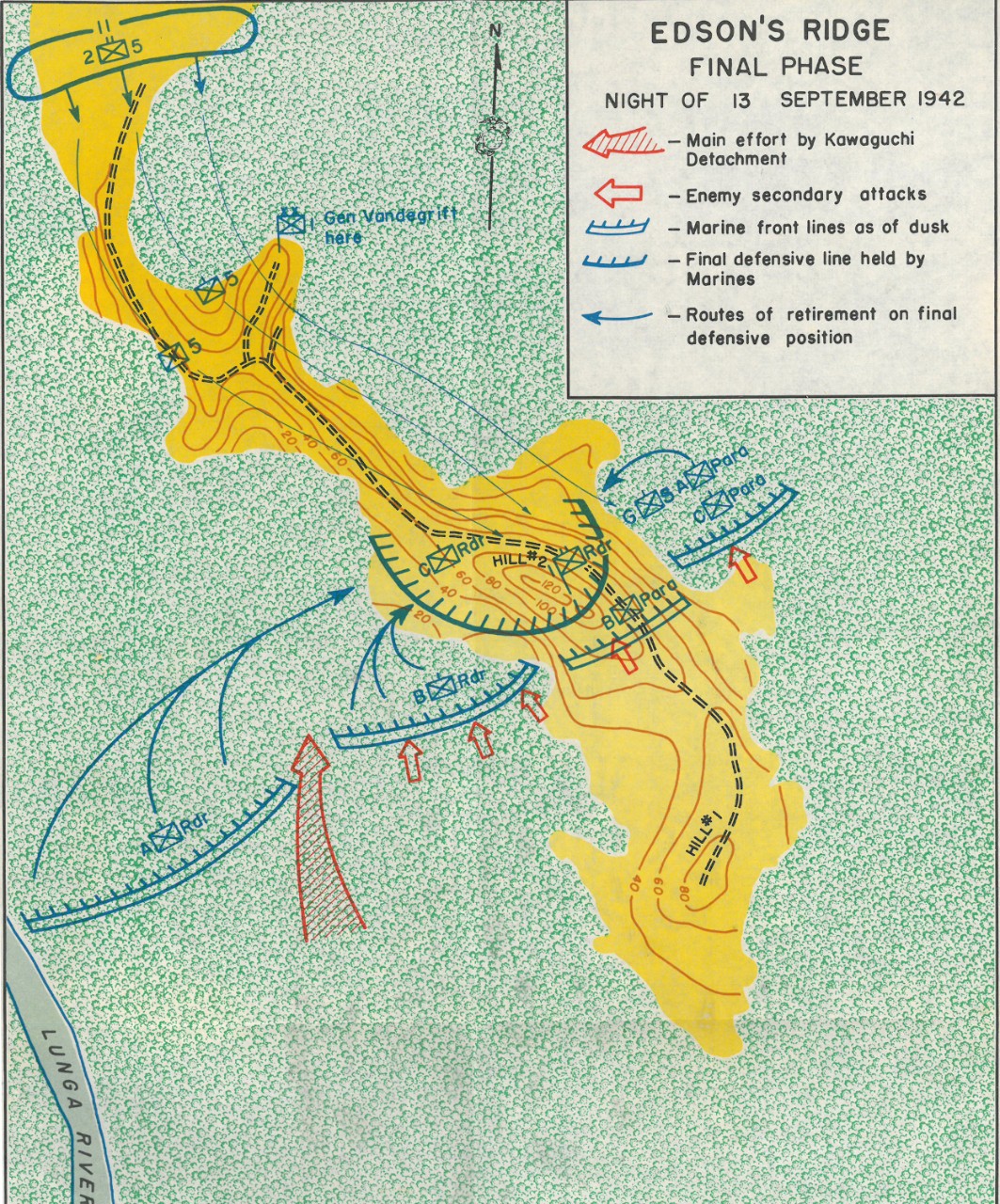

| Edson's Ridge-Final Phase |

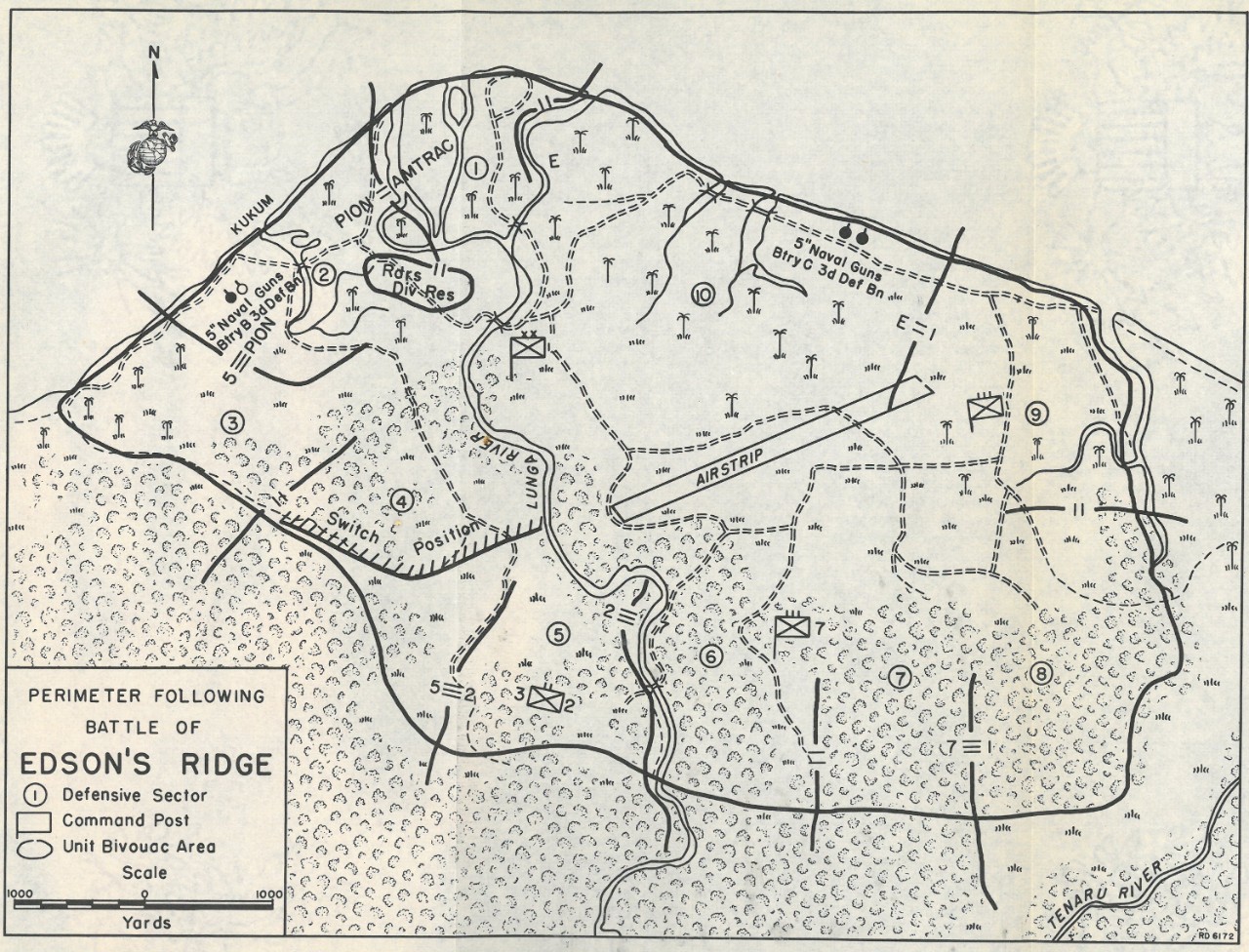

| Perimiter Following Battle of Edson's Ridge |

| Operation Along the Matanikau, 23 to 27 September |

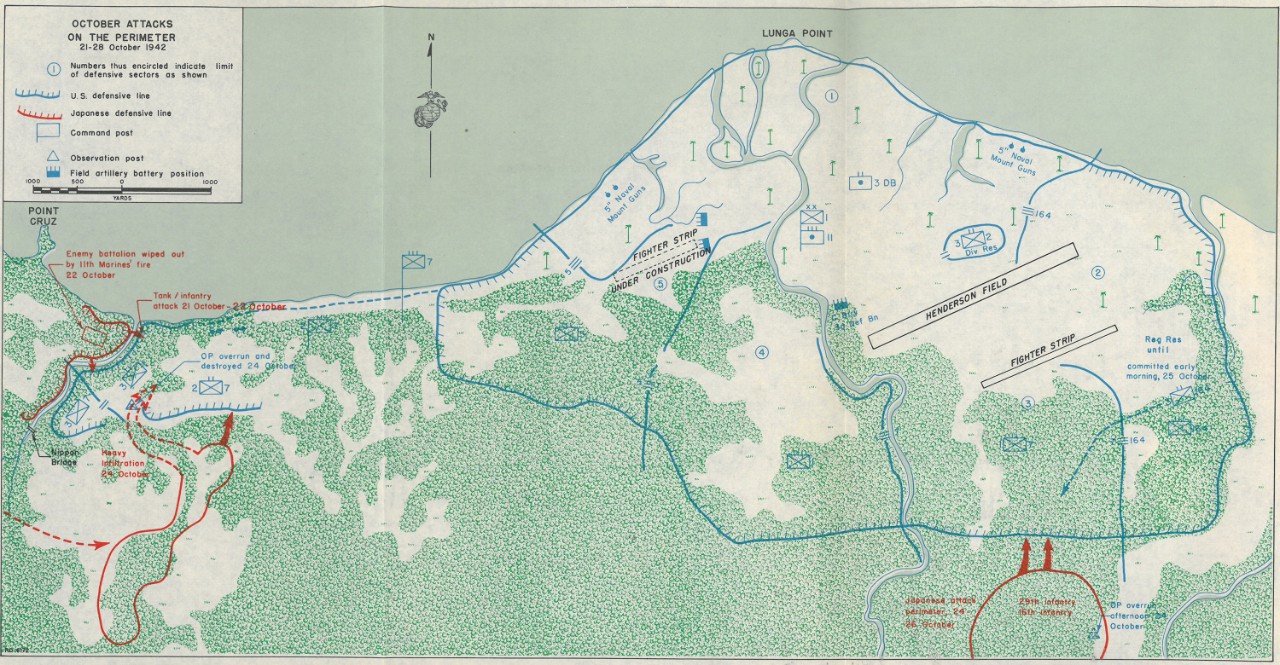

| October Attacks Along the Perimeter |

| Conoley's Action, 24-26 October 1942 |

| Carlson's Patrol: 4 November-4 December 1942 |

Forword

As one who participated in the long-drawn campaign of Guadalcanal, I cannot find more appropriate words to characterize that operation than those of my predecessor, General Vandegrift, in his special prefatory note.

To him, as to many thousands of other U.S. Marines, living and dead, our nation and our Corps owe gratitude for the readiness, discipline, and esprit which enabled the Fleet Marine Force to launch and win America's first offensive in World War II.

/s/

C.B. Cates,

General, U.S. Marine Corps,

Commandant of the Marine Corps

Preface

THE GUADALCANAL CAMPAIGN, a monograph prepared by the Historical Division, Headquarters, United States Marine Corps, is the fifth of a series of operational monographs designed to present to both the student and the casual reader complete and factually accurate narratives of the major operations in which the Marine Corps participated during World War II. As a sufficient number of monographs are brought to completion, these in turn will be edited and condensed into a single operational history of the Marine Corps in World War II.

The preparation of this monograph has been attended by certain problems of a special nature. The campaign was the first great offensive of the war, and it was begun in the greatest urgency. The units engaged were not as fully indoctrinated with the necessity for submitting full and complete reports as were the participants in later operations. The art of combat photography, later developed to such magnificent degree, was ax yet in its infancy. The hectic nature of the first few weeks on Guadalcanal was such as to make difficult, if not impossible, anything that was not closely and unmistakably connected with the business at hand--fighting.

Full assistance and cooperation have been given by all of whom they were requested. Individuals and various Government agencies have lent their aid whenever they were asked for it. The Office of Naval History, Naval Records and Library, and the various activities of the Army Historical Division must be mentioned as having been particularly kind and helpful. Similar acknowledgment must be made to the Marine Corps Schools for cartographic assistance, and to the Photographic Section, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, for help with pictorial matter. Photographs are U.S. Marine Corps, Navy, or Army official. Lieutenant Colonel Robert D. Heinl, Jr. of the Historical Division, participated extensively in the final editing of this work and supervised its cartographic planning. Captain Samuel E. Morison, USNR, and Commander James Shaw, his assistant, made many valuable suggestions and supplied much helpful material, while Mr. Walton L. Robinson was generous with the invaluable information he has collected concerning the Japanese naval order of battle. Mr. Robert Sherrod, historian of Marine air operations, rendered generous help in many phases, as did Captain Edna L. Smith, USMCR, his assistant.

Finally, thanks must be given those officers and men who, having participated in the actions described, willingly and helpfully gave of their store of knowledge for the sake of allowing an accurate narrative to be written. in all cases their assistance has been invaluable, and in all cases it was cheerfully give.

/s/

John T. Selden,

Brigadier General, U.S. Marine Corps,

Director of Marine Corps History.

iv

Special Prefatory Note

HEADQUARTERS U.S. MARINE CORPS

WASHINGTON

December 5, 1947

We struck at Guadalcanal to halt the advance of the Japanese. We did not know how strong he was, nor did we know his plans. We knew only that he was moving down the island chain and that he had to be stopped.

We were as well trained and as well armed as time and our peacetime experience allowed us to be. We needed combat to tell us how effective our training, our doctrines, and our weapons had been.

We tested them against the enemy, and we found that they worked. From that moment in 1942, the tide turned, and the Japanese never again advanced.

A.A. Vandegrift

General U.S. Marine Corps

[Note: Original is a handwritten letter.]

page v

Chapter I: Prelude to the Offensive

The Guadalcanal Campaign, the first amphibious offensive operation to be launched by the United States in World War II, was undertaken by the United States Navy and Marine Corps in August, 1942, just eight months after the Japanese had struck their initial blow at Pearl Harbor. The objective of this campaign, which was set in motion on short notice with the most limited means, was the initial step in a program designed to safeguard our imperiled lines of communication to Australia and New Zealand, which were in turn vital to the success of future operations projected in the South and Southwest Pacific theaters.1

The Advance of the Japanese

Commencing with the advantages conferred upon them by surprise, the initiative, and carefully laid plans the Japanese swept through East Asia, the Indies, and much of Melanesia during the first six months of 1942. The milestones of their advance were Wake, Guam, Singapore, Bataan-Corregidor, and all the Netherlands East Indies. With the southward sweep of the seemingly irresistible advance, they seized first Rabaul, on 23 January 1942, and then Bougainville, in the Northern Solomons, two months later. In Rabaul they secured a prize of great strategic worth, for it served not only as a bastion for the great central position at Truk, but also as a point of departure for further offensives to the south.2 Bougainville, together with other subsidiary positions down the chain of the Solomons, was intended to be a key outwork to Rabaul and an intermediate station in their relentless thrust toward the all-important, slender U.S. line of supply and communications from the Hawaiian Islands to Australia and New Zealand.

At the tip-end of the enemy's line down the Solomons lay the British port of Tulagi and the then little-known island of Guadalcanal.3

Having meanwhile secured, unresisted, positions at Lae, Salamaua, and Finschafen on the northern coast of new Guinea, as well as stepping-stones at Choiseul, Vella Lavella, and the Treasury Islands, the Japanese seized Tulagi, with its superb harbor, on 4 May 1942.4

At this time, the British-Australian garrison at Tulagi consisted merely of a few riflemen of the Australian Imperial Force, some members of the Royal Australian Air Force,

______________

1. JCS Directive 2 July 1942.

2. "The Japanese Threat to Australia." Samuel Milner. In Military Affairs, Volume XXIX, number 1, April 1948. The author says further, "Rabaul, in short, was the key to Japanese offensive action in the South and Southwest Pacific."

3. Perhaps the only group of Americans who had ever heard of the island was that which comprised the readers and admirers of Jack Londong. One of his better short stories, The Red One, had the island as its setting, under the older form of the name--Guadacanar.

4. Earl Jellicoe, the famous British Admiral who commanded at jutland, had recommended after a visit of inspection immediately after World War I, that the Tulagi Harbor be developed as a major fleet base for the defense of the Empire.

--1--

a member of the Australian Naval Intelligence, the Resident Commissioner for the area, the civil staff, and a few planters and missionaries. All nonessential civilians had been evacuated. Among those who remained, however, were the coastwatchers, experienced and courageous men who had in most cases spent their lives in this area, and who now were prepared to retire in to the bush, where, the secret radio-transmitters, they could observe and report the Japanese movements, whether by land, sea, or air.

The Japanese descent on Tulagi was preceded by a heavy air raid on 1 May. The next day, a coastwatcher on Santa Isabel Island reported two enemy ships in Thousand Islands Bay, and it was thereupon decided to evacuate the area completely.5

The British Resident Commissioner and the Anglican bishop (The Right Reverend Walter Hubert Baddeley) removed to Malaita; other designated civilians proceeded to Savo and Guadalcanal to establish coastwatching stations. The military and naval personnel, with a few civilians, crossed to nearby Florida and thence to the southern tip of Guadalcanal and out of the area. The Reverend Henry De Klerk, Society of Mary, remained at his post, the mission of Tangarare, on the southern coast of Guadalcanal, and other priests and nuns of the same missionary order likewise refused to leave their posts.

The enemy landing was accomplished by a force from the 3d Kure Special Landing Force from the cruiser-minelayer Okinoshima, which flew the flag of Rear Admiral Kiyohide Shima. The force consisted of a machine gun company, two anti-tank gun platoons, and a number of laborers, all divided in two groups. That which landed on Tulagi was commanded by Lieutenant Juntaro

________________

5. The Coastwatchers. Commander Eric A. Feldt, O.B.E., R.A.N. pp. 78 and 79.

--2--

Maruyama, while the Gavutu detachment was led by Lieutenant (j.g.) Kakichi Yoshimoto.6

The enemy force went ashore without opposition and in accordance with plans based on aerial reconnaissance. Defensive positions were set up immediately. Base construction and improvement of existing facilities were initiated. Coastwatcher stations were established at Savo Island; and at Taivu, Marau Sound (on the southeastern tip), Cape Hunter (on the south coast near Tangarare), and Cape Esperance, all on Guadalcanal. This activity was under the personal supervision of Lieutenant Yoshimoto.7

No immediate steps were taken by the enemy to develop air fields, although the plains on Guadalcanal, 17 miles away to the southward, offered excellent terrain for the purpose. All initial effort was bent toward establishing harbor facilities and a seaplane base at Tulagi, and toward developing the coastwatcher system mentioned above. A full month passed before surveying parties and patrols were put ashore near the mouth of the Lunga River. Late in June the survey was completed, and early in July construction work was undertaken in earnest on the airstrip.

The only check received by the enemy to their almost machine-like occupation of Tulagi came on the very day of their landing.8 United States Navy carrier aircraft, operating from Yorktown, of Task Force 17 (Rear Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher, USN) caught the enemy amphibious shipping concentrated in Tulagi Harbor and attacked, sinking the destroyer Kikutsuki and several smaller craft, and damaging another destroyer, Yuzuki and the cruiser-minelayer, Okinoshima.9 (Okinoshima was sunk one week later

____________

6. Enemy Operations on Guadalcanal August 7, 1942 to February 9, 1943. Prepared by Captain John A. Burden, USA (MC) and disseminated through the Office of the Assistant Chief of Staff, Headquarters Western Defense Command and Fourth Army, Presidio, San Francisco, on 23 June 1943, p. 1. The same information, with more elaborate detail is found in an untitled manuscript by Captain Eugene Boardman, USMCR, who was the Language Officer attached to me 2d Marines (see below). Manuscript in possession of author, referred to hereinafter as Boardman ms.

7. The Boardman ms.

8. The Coastwatchers, pp. 81 and 82.

9. Enemy Operations on Guadalcanal, p. 1.

--3--

north of the Solomons, on 11 May, by the American submarine S-42.)10 A number of seaplanes likewise were destroyed by Fletcher's strike, and shore installations received heavy damage.11

Short of this local check, and of that received a few days later at the battle of the Coral Sea, which will be discussed briefly at a later point, the enemy was undisputed in possession of the Solomon Islands as far south as Guadalcanal. From this base it would be possible to strike at Northern Australia, New Guinea, and the New Hebrides; it would likewise be possible to protect the until now wide open left flank of forces operating against Northern New Guinea and the United States' lines of air and surface communication with New Caledonia and the Antipodes.12

U.S. Countermeasures

Shortly after the fall of Rabaul, when it became obvious that the enemy intended an expansion to the southeast from the newly conquered Southeast Asia area, plans to contain his advance began to be formulated. On 18 February, Admiral Ernest J. King, Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet, wrote the Chief of Staff, U.S. Army, saying that he considered it necessary to occupy certain islands in the South and Southwest Pacific. For this purpose it would be necessary to have Army troops for garrison, and King requested Marshall's approval.13

In reply, General Marshall wanted to know why King considered such a course necessary, and asked whether he had thought of using Marines for the garrison task. He asked to be told what King's complete plans were, and closed by saying:

In general, it would seem to appear that our effort in the Southwest Pacific must for several reasons be limited to the strategic defensive for air and group troops.14

In reply, King was more specific. He stated flatly that bases must be established at Tonga and Espiritu Santo, and challenged the statement of policy contained in Marshall's letter by saying that the general scheme for the Pacific must be not only to protect the lines of communication but also to set up strong points whence offensives could be mounted against the enemy in the Solomon Islands area and in the Bismarck Archipelago. In stressing the need for an early offensive, he laid down certain principles which he considered indispensable.

In staging operations of the type which he envisaged, the amphibious forces involved must be replaced at once by garrison troops, in order that they might prepare for further operations. Instead of serving as garrison troops, Marine would best be employed in amphibious assaults and other advanced work.15

Occupation of certain strategically important islands began on 12 March. On that day Noumea, the capital of New Caledonia, was entered by a mixed force of U.S. Navy and Army, and the construction of a major air base at nearby Tontouta was immediately set afoot. On 29 March the 4th Defense Battalion (reinforced), Fleet Marine Force, landed at Port Vila, on the island of Efate, in the New Hebrides, to the north of New Caledonia, and less than two months later the island of Espiritu Santo was occupied and organized for defense by a combined force of Marines (from the 4th Defense Battalion and Marine Air Group 21), Naval Construction units, and Army personnel. At each of the latter two locations, naval and air base construction was begun with the maximum speed consistent with the slender means at hand.

While these initial counter-deployments of U.S. forces were in progress, the Japanese

______________

10. Japanese Naval and Merchant Shipping losses During World War II by All Causes. Prepared by the Joint Army Navy Assessment Committee, February , 1947. (Navexos P-468) (Hereinafter referred to as JANAC). p. 2.

11. Boardman ms.

12. ASAFISPA Report, p. 1.

13. Letter, CominCh to CofS, U.S. Army, 18 February 1942. Naval Records and Library. (Hereinafter NRL.)

14. Letter, Marshall to King, 24 February 1942, NRL.

15. Letter, King to Marshall, 2 March 1942. NRL.

--4--

had clashed with elements of the U.S. Pacific Fleet in the Battle of the Coral Sea, which took place on 7-8 May 1942, almost contemporaneously with the occupation of Tulagi. In this engagement, although it can hardly be said that a decisive U.S. victory had been gained, the enemy at least sustained a considerable check, losing a light carrier, the Shoho, together with 80 planes, and suffering severe damage to the big fleet carrier Shokaku.16 Moreover, a projected enemy invasion of South Papua was forestalled.

The United States forces in turn lost the USS Lexington, one of the familiar and much-loved aircraft carriers of the prewar Fleet. More important, however, than the actual losses of either side, was the fact that this engagement forced the Japanese to postpone - tentatively until July of 1942, as they now planned - the seaborne invasion of Port Moresby, on the south coast of New Guinea.17

Concurrently with these developments, Admiral King's plans for operations in the South Pacific began to be implemented. On 10 April he warned General Holcomb that the 1st Marine Division, currently attached to me Amphibious Force, Atlantic Fleet, would be sent to the South Pacific in May, probably to Wellington, N.Z.18 In reply, General Holcomb requested that the division be transferred to the Marine Corps prior to detachment for duty overseas.19

Two events of early June gave point and immediacy to what, up to the time, had been tentative planning. American air reconnaissance, confirming reports from coastwatchers stationed nearby, had observed that the Japanese were planning an air field on the Lunga Plains. This made it clear to Admiral King at least that the time had come to carry out that portion of Joint Chiefs of Staff's decision of 14 March which dealt with applying pressure to the enemy and containing him where possible.

At the time, another event far distant from the Southern Solomons brought about a decisive turn of circumstances in favor of the United States.

On 4 and 4 June, 1942, some 150 miles northwest of Midway Atoll, the combined attacks of carrier- and shore-based Navy and Marine air virtually annihilated the carrier-based air power of the Japanese Combined Fleet. Four enemy carriers - Kaga, Akagi, Soryu, and Hiryu - were sunk, as well as the heavy cruiser Mikuma, and with them went the flower of the Japanese Navy's carrier groups. More than 250 enemy aircraft had been destroyed, and, what was worse, the trained pilots, the teamwork, and the organization which go into the highly coordinated operations of a carrier air group, had likewise been wiped out. For the time being, the Japanese Navy was as much off balance - perhaps even more so - than the United States Pacific Fleet after Pearl Harbor.20

The advantage accruing to the United States forces in the Pacific as a result of the decisive victory did not escape the attention of the astute MacArthur. On 9 June Nimitz noted that the General suggested an immediate assault upon Rabaul, by now Headquarters of the enemy 8th Base Force. MacArthur said that, if he were given a division of troops well trained in amphibious assault techniques, and naval support to include two carriers, he would undertake the task himself.21 The suggestion

_____________

16. The Campaigns of the Pacific War. United States Strategic Bombing Survey (Pacific), 1946. (Hereinafter referred to as USSBS.) pp. 52 and 53.

17. 1947 Memorandum by Brigadier General William E. Riley, giving certain information he gleaned while serving on staff of Admiral E.J. King, U.S.N., in 1942, hereinafter cited as Riley Memo.

18. Memo, CominCh and CNO to Commandant Marine Corps, 10 April 1942, NRL.

19. Letter, Commandant Marine Corps to CominCh, April 1942. NRL.

20. For details of Marine Corps participation in the Battle of Midway, refer to Marines at Midway, by LtCol Robert D. Heinl, Jr., official Marine Corps account of the action.

21. War Diary, CinCPac, June, 1942. NRL. MacArthur was not the only commander in the Pacific who was in favor of immediate action. A fortnight before, Nimitz had written, on 28 May, to the General suggesting a raid on Tulagi by the 1st Raider Battalion, a Marine Corps unit. MacArthur advised against the scheme on the basis of insufficient force, and Ghormley concurred. The idea was dropped. Actually, six battalions, including the same 1st Raiders, were employed in reducing the position.

--5--

was rejected by the Navy on the grounds that American carrier strength, notwithstanding a present imbalance in enemy forces, was not sufficient to justify risking two of these invaluable ships in an operation that would make necessary their maneuvering in a severely restricted area, exposed to constant danger from enemy land-based aircraft.22

Following the great success at Midway, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, both alarmed by the steady and rapid southward extension of Japanese power through the Solomons, and quickened by the momentary breathing-space b ought by our victory at Midway, undertook a reconsideration of basic U.S. strategy in the Pacific.

As in now well know, the fundamental strategic policy of the United States and Great Britain, as conceived at the outbreak of hostilities in 1941, had been to concentrate upon the defeat of Germany, with a definite second priority being accorded the effort against Japan.23 In line with this policy, only such means had been apportioned to the Pacific war as would, in the judgment of the strategic planners, enable us to contain the Japanese, almost on their own terms. With this end in view, it had likewise been decided that no land offensive would be mounted in the Pacific before the fall of 1942, and that earlier operations would be limited to those necessary to establish and maintain our lines of communication to the Antipodes and to set up a few advanced bases required either for containment of the enemy or as springboards for the offensives in prospect. As we have seen, deployment for these purposes had commenced well prior to the Battle of Midway.

Now, however, the threat by the Japanese to our line of communication--and indeed, the ominous possibility that our precariously situated advanced outposts in the New Hebrides might be swallowed up--impelled a re-examination of possible courses of action in the Pacific.

On 25 June, King sent out two communications. He advised Nimitz and the Commander, Southwest Pacific Force,24 that the Joint Chiefs of Staff had directed that an offensive be launched against the enemy forces in the Lower Solomons. Santa Cruz Island was to be seized and occupied, as were Tulagi and adjacent areas in the Solomons. Permanent occupation forces would be Army troops from Australia. The target date was about 1 August, and the operation was to be under the direction and control of CinCPac.25

On the same day, however, he addressed a memo to Marshall, in which he said that it was urgent that the United States seize the initiative. He pointed out that a golden opportunity had passed--ideally, the offensive should have been launched about 3 June, when the main currents of Japanese strength were running toward Midway and Alaska. He urged that Marshall give favorable attention to the plan for attacking the Japanese in the Solomons area.

Marshall's answer, sent out next day, indicates clearly that despite the fact that an offensive had been directed, there was still no complete meeting of the minds between him and his Navy opposite number.

This time it was the question of command that gave the General pause. He did not agree that the proposed operation should be under Navy command. He pointed out that the are involved lay wholly within the Southwest Pacific, and he suggested strongly that General MacArthur was the only officer available capable of exercising command. He pointed out further that "we should not be bound by lines drawn on a map" and added that to his mind it would be most unfortunate

_______________

22. Letter, Nimitz to MacArthur, 28 May 1942. NRL.

23. Riley Memo.

24. Two days before, an interesting message had been sent Ghormley by Nimitz. Very early in the morning of 23 June, Nimitz gave his subordiante the tally of the Midway victory, and suggested that the carriers consequently made available for other employment might be used by Ghormley as support for an operation aimed at driving the Japanese out of the Solomon Island. War Diary, ComSoPac, June 1942. NRL.

25. Dispatch, ComonCh to CinCPac and ComSoWesPacFor (with information copies to ComSoPac and Chief of Staff, USA), 25 June 1942. NRL.

--6--

to bring in another commander at that time to carry out the operation.26

King stood fast. On the same day which saw General Vandegrift receiving first warning of the impending campaign from ComSoPac in Auckland, the Admiral sent a final uncompromising memo to Marshall. He said unequivocally that the operation must be under Nimitz, and that it could not be conducted in any other way. After the amphibious phase was over, then control would pass to MacArthur. The command setup must be made with a view toward success, said the Admiral, but the primary consideration was that the operation be begun at once. In answer to Marshall's plea that the area lay within MacArthur's bailiwick, he pointed out that all the forces involved would come, not from MacArthur, but from the South Pacific, and he included two prophetic statements. He expressed doubt that much aid at all could be got from the Southwest Pacific area (since the nearest bomber base in that area lay 975 miles from Tulagi) and said:

I think it is important that this [i.e. seizure of the initiative] be done even if no support of Army Forces in the South West Pacific is made available.27

In fact, Southwest Pacific air support during the assault was negligible, and no ground troop support was ever forthcoming from that area.

In the meantime, and in line with earlier plans for a more deliberate assumption of the offensive, a significant development had taken place in the command structure of the Pacific Ocean area. A huge geographic wedge, bounded on the north by the equator, on the west by 160º West Longitude, and extending indefinitely southward, had been designated the South Pacific Area. Vice Admiral Robert L. Ghormley, USN, had been selected to command it, under Nimitz.28

Upon arrival in Pearl Harbor, Ghormley found out that whereas he was to command the South Pacific Area and South Pacific Force, including all air, sea, and ground forces (save ground troops actually assigned the mission of defense of New Zealand) within the area, his powers hardly matched his responsibilities. Nimitz advised him that from time to time task forces would be sent on missions within his area. In such cases, Ghormley's degree of control consisted only of the ability to direct that such task force commanders carry out their assigned missions. Only in extraordinary circumstances would he exercise local control and initiative.29

There were three steps in e establishment of Ghormley's command. on 22 May he set up his command post aboard the USS Rigel in the Harbor at Auckland, N.Z., as Prospective Commander, South Pacific Area and South Pacific Force. On 10 June he moved ashore to the New Government Building in the city of Auckland, still as Prospective Commander. On 19 June, satisfied at last that he had established adequate communications, he assumed full title and command.30 He still anticipated a possible offensive in the fall.

On 25 June, he received dispatches telling him of an impending operation, to be mounted from his area and employ his forces. He was directed to begin planning at once with this in mind. The forces to be employed would be organized by CinCPac, and execution of the plan would be by directive from the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Two days later he was warned that Army participation in the operation, which had been assumed, might be delayed.31

Four days later, when General Vandegrift had been told of the plans and directed to make preparation, as will be described below, more definite information came to Ghormley

_____________

26. Letter, Marshall to King, 26 June 1942. NRL.

27. Letter King to Marshall, 26 June 1942. NRL.

28. Until 15 April, Ghormley had been Special Naval Observer at London and Commander, U.S. Naval Forces in Europe. Probably more converant with the European situation than anyone else in the Navy, he was recalled to Washington, given an ominous mission and a hurried briefing, and sent on his way within a fortnight. He was warned by Admiral King that probably in the coming Fall an offensive would be begun from his area, but that it was impossible to give him proper tools for carrying out his mission. Ghomley ms.

29. War Diary, ComSoPac, May, 1942. NRL.

30. War Diary, ComSoPac, June, 1942. NRL.

31. War Diary, ComSoPac, June, 1942.

--7--

--8--

from Nimitz. Ghormley was told that he would command the operation, and that the joint forces would be under command of Vice Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher, who would assume command when he reported with Task Force 11 at rendezvous prior to movement to the target area. one week later, on 4 July, he received the Joint Chiefs' detailed plan.

The Commander, South Pacific Area, was faced with the two-headed problem of mounting an offensive at an almost impossibly early date with a barely adequate force. A slight amelioration of the time problem was offered when the target date was set back one week (see below); the problem of adequacy of means remained until the operation was well under way.

The Joint Chiefs of Staff directive of 2 July, relayed by Nimitz to Ghormley late the same day, set out succinctly the military aims of the moment for the war against Japan in the South Pacific and Southwest Pacific areas. The ultimate aim was the seizure and reduction of New Britain, New Ireland, and New Guinea. The purpose was, as we have seen, the removal of a serious threat to the lines of communication between the United States and Australia and New Zealand.

The realization of the ultimate goal involved the accomplishment of three tasks. First, it would be necessary to seize and occupy Santa Cruz, Tulagi, and the adjacent areas. Second, the rest of the Solomon Islands would have to be occupied and defended, as would Lae and Salamaua and the vicinity. Third Rabaul and the surrounding territory would be taken.

The general considerations were that the Joint Chiefs would determine the forces, the timing, and the passage of command, that the date for undertaking Task 132 would be about 1 August, and that throughout all three tasks, tactical command of the amphibious forces would vest in the Naval Task Force Commander. For Task 1, CinCPac would designate the forces to be used, for Tasks 2 and 3, the selection would be left to General MacArthur. Effective on 1 August, the boundary of the South Pacific Area was to be moved one degree west, to 159º East Longitude. It was assumed that Ghormley would be the Task Force Commander for Task 1, "which he should lead in person in the operating area." Ghormley was directed to confer with MacArthur.33

The result of the conference, at which MacArthur and the Admiral found themselves in complete agreement, was that a dispatch was sent jointly by them to King and Marshall. In essence, the message urged strongly that the proposed operation be postponed until such time as American strength in the South and Southwest Pacific had been built up sufficiently - especially in the matter of air power - to provide adequate support for the assault.34

The Joint Chiefs of Staff replied to the effect that although all arguments presented by Ghormley and MacArthur were valid, it was imperative that the operation go forward. Additional shipborne aircraft and surface forces would be made available. Thirty-five heavy bombers, presently in Hawaii, would be supplied by the Army, which also planned to "take al the follow-up measures possible in support of the seizure and occupation of the Tulagi Area."35 The message also directed Ghormley to itemize to the Joint Chiefs additional forces essential to the success of the operation and not available to him.

Ghormley, in turn, replied that he considered the forces available--or to be made available in accordance with the Joint Chiefs' assurances - to be adequate for the immediate

_______________

32. During the concept and planning stage, Task 1 was given the code name PESTILENCE. The actual operation of the assault on Tulagi and Guadalcanal carried the designation WATCHTOWER, while Guadalcanal itself, as a place, was called, appropriately, CACTUS.

33. War Diary, ComSoPac, 4 July 1942, NRL.

34. Upon receipt of this plea, King wrote Marshall, noting that whereas three weeks before, MacArthur had wanted to move straight to Rabaul, he now objected to an assault upon a much less formidable target. He pointed out that if the Japanese were permitted to consolidate their holding at Tulagi, they would be in a position to harass the United States base at Efate and lines of communications. Memo, King to Marshall, 10 July 1942, NRL.

35. Ghormley ms, pp. 52 and 53.

--9--

task, provided that General MacArthur have sufficient means for interdicting hostile aircraft activities on New Britain, New Guinea, and the Northern Solomons. His reply contained the following prophetic words:

I desire to emphasize that the basic problem of this operation is the protection of surface ships against land based aircraft attack during the approach, the landing, and the unloading.36

General MacArthur, again seeing eye to eye with Ghormley, requested planes, and more planes for the purpose of supporting the operation.

And so, while King's reiteration of attack, size the initiative, and do it now was beginning to take on the throbbing insistence of a war drum, and while Marshall was temporizing in his replies to him, the plans for the offensive began to be implemented. On 10 July Admiral Nimitz sent Ghormley his operation order covering the proposed seizure of Tulagi and Guadalcanal. The operation was to bear the name WATCHTOWER.

U.S. Means Available

When Ghormley received his first warning order, on 25 June, the 1st Marine Division, Fleet Marine Force (or FMF, as usually abbreviated) under the command of Major General Alexander Archer Vandegrift, was in process of moving from the United States to Wellington, New Zealand. The advance echelon37 had arrived on 14 June, and the rear was at sea.

This division, which in fact constituted the major available Marine Corps unit in readiness for employment on short notice38 was itself understrength by about one-third, one of its rifle regiments, the 7th Marines (reinforced),39 having been temporarily detached on 21 March 1942 to become part of the 3d Marine Brigade, on duty in Samoa.

Other FMF units were deployed at this time to the maximum capacity of the Marine Corps throughout the Pacific, both within and outside Admiral Ghormley's area. American Samoa was defended by the 2d and 3d Provisional Marine Brigades, the 2d, 7th, and 8th Defense Battalions (of the Marine Corps) and the 1st Marine Raider Battalion. At Palmyra, Johnston, Midway, and the Hawaiian Islands other FMF troops, mainly defense battalions or aviation units, were likewise disposed to form a thin screen of defense for outlying Allied bases and lines of communication. Of a total strength of 142,613, the Marine Corps had 56,783 officers and men serving overseas at the time.

When decision to strike was reached, the 1st Marine Division was in process of moving from the United States to New Zealand, for what General Vandegrift thought was to be several months of training.40 The first echelon of the division had arrived at Wellington in organizationally-loaded ships and

_______________

36. Ghormley ms, p. 54.

37. Final Report, Phase I, p. 1, and Annex A to that document. The advance echelon consisted of the 5th Marines (reinforced), Division Headquarters, and certain division troops, and was embarked in the Elektra, Del Brazil, and Wakefield. The rear echelon, consisting of the 1st Marines (reinforced) and the rest of the division troops was on board the Lipscomb Lykes, Alcyone, Libra, Alchiba, Mizar, Ericcson, Elliot, and Barnett. The ships were not combat loaded.

38. The 2d Division was at Camp Elliott, California, being whipped into shape after losing many of its experienced officers and men to newly formed regiments. One of its rifle regiments, the 8th Marines (reinforced) was also in Samoa, having departed the United States in January, 1942. Another, the 6th Marines, had recently returned from seven months in Iceland.

39. The use of odd numbers for all components of the Division bears explanation here. There was a division on each coast--the 1st at New River, North Carolina, the 2d at Camp Elliott, near San Diego, California. Current practice made all components of the East Coast unit odd numbered, while the corresponding components of the West Coast division bore even numbers. This practice was in process of disappearing at the time--the 9th Marines, for example, was formed at Camp Elliott from a cadre supplied by the 2d Division and received its preliminary training with that division.

40. General Vandegrift was under the impression that his division would not be called upon for combat prior to the early part of 1943. Division Commander's Final Report of Guadalcanal Operation, April 1943. Phase I (Hereinafter Final Report). In Marine Corps Records (hereinafter MCR). Vandegrift was not at this time aware of tentative plans for the fall of 1942.

--10--

had begun to unload and go into camp. They second echelon was at sea, likewise in organizationally-loaded vessels, and was not expected to arrive until 11 July, less than three weeks before the target date.

To supplement the Marine Forces enroute to, or already on duty in the South Pacific, Army ground and service troops were not to be found at New Caledonia,41 the Fiji Islands (where they had been sent to replace a New Zealand Division withdrawn for defense of New Zealand), Tongatabu, and the New Hebrides. These forces, together with Army air units within the area, initially were controlled directly by Ghormley. On 1 July, however, CominCh informed him that Major General Millard Harmon, USA, was to be appointed to command of all Army forces in the South pacific Area, with the title of Commanding General, South Pacific Area. Harmon, in turn, would be under Ghormley's command and responsible directly to him.42 The appointment was made and Harmon began his duties late in July.

Within the naval structure of the Pacific Ocean Areas, Ghormley, as we have seen, occupied the position, under Admiral Nimitz, of a major subordinate of limited autonomy. Specifically, his powers were as follows:

1. Nimitz from time to time would order Task Force Commanders to report to Ghormley for duty, with missions already assigned.

2. Ghormley, in turn, would direct such commanders to carry out their assigned missions (as given them by Nimitz).

3. "The Commander, South Pacific Force would not interfere in the Task Force Commander's mission unless circumstances, presumably not known to the Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Fleet, indicated that specific measures were required to be performed by the Task Force Commander. The Commander, South Pacific Force would then direct the Task Force Commander to take such measures"43

The naval strength that could be called upon to operate in support of Ghormley's offensive was small in point of number of ships, albeit included in that number there was considerable power. Three aircraft carriers, with a strength of about 250 planes, were available, as were a number of light and heavy cruisers, two new battleships, and the requisite screening vessels and auxiliary craft. Transports and cargo vessels were at a premium, and would continue so for several months.

In air strength, an indispensable adjunct to modern amphibious operations, the picture was by no means as bright. In addition to the approximately 250 carrier aircraft mentioned above (available to him only under certain conditions), Ghormley could muster 166 Navy and Marine Corps planes (including two Marine Corps squadrons--VMF-212 and VMO-251), 95 Army planes, and 30 planes from the Royal New Zealand Air Force. This total of 291 aircraft was under the command of Rear Admiral John S. McCain, USN, whose title was Commander Aircraft South Pacific and who was under Ghormley's command.44

Taken all in all, therefore, Ghormley could rely on the services of a small, highly trained striking force of ground troops, consisting of less than one Marine division with its supporting organic units, surface forces of fluctuating and never overwhelming power (which nevertheless represented the maximum which Admiral Nimitz could spare) and an extremely scanty array of land based aircraft. He had no assurances of reserve ground troops for the coming operation (although plans were under way to release both the 7th and 8th Marines from their Samoan defense missions)45 and he had been advised that garrison forces would have to come from

________________

41. The New Caledonia force, composed mainly of National Guard units, became the Americal Division on 24 May 1942 under command of Major General Alexander Patch, USA. The division served throughout the war without a numerical designation under the name which was formed by combining syllables of American and New Caledonia.

42. Ghormley ms, p. 42. Ghormley confesses to an initial dislike of the idea. He later came to look upon Harmon as one of the finest administrators and coordinators he had ever met. (Information given in interview in January, 1949).

43. War Diary, ComSoPac, 9 May 1942. NRL.

44. History of Marine Corps Aviation in World War II, Robert Sherrod, 1949.

45. Relief for 7th Marines was to leave the United States on 20 July (PICADOR Plan) and that for the 8th on 1 September (OPIUM Plan). War Diary, ComSoPac, June 1942.

--11--

--12--

the troops within his area who already were committed to base defense.46

The general structure organized to employ these resources against the Japanese was laid down in Nimitz' order to Ghormley of 9 July, and Ghormley's Operation Plan 1-42 of 17 July 1942.47

Ghormley, exercising strategic command, set up his organization in three main groups:

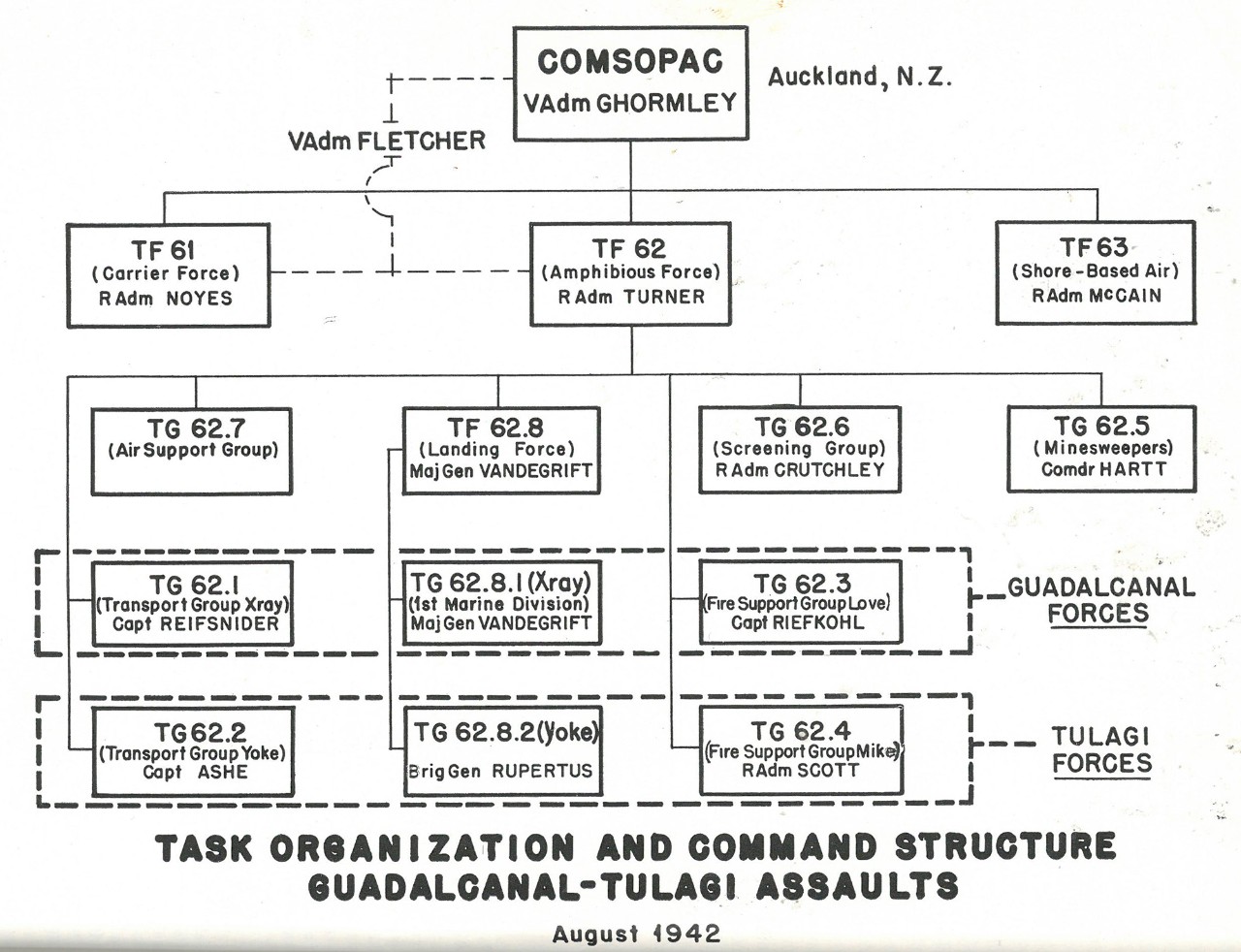

The Carrier Force (Task Force 61) commanded by Rear Admiral Leigh Noyes, was composed of elements of three task forces from Nimitz' area--11, 16, and 18. It would include three carriers - Saratoga, Enterprise, and Wasp - the fast new battleship North Carolina, five heavy cruisers, one so-called antiaircraft cruiser, and 16 destroyers.

The Amphibious Force (Task Force 62) commanded by Rear Admiral Richmond K. Turner, USN, included the FMF Landing Force,48 six heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, 15 destroyers, 13 attack transports, six attack cargo ships, four destroyer transports, and five minesweepers.

Shore-Based Aircraft (Task Force 63) under command of Rear Admiral J.S. McCain, USN (ComAirSoPac) included all aircraft in the area save only carrier-based naval planes.

Complicating the foregoing symmetrical structure was the presence of Vice Admiral Fletcher as tactical commander of the joint attack and support forces. (See footnote on Nimitz' Operation Order No. 34-42 above. Fletcher was already familiar to the Marines as a result of his role in the attempt to relieve Wake Island.49

Ghormley also announced that there would be a rehearsal in the Fiji area prior to departure for the assault and directed that all task force commanders arrange to hold a conference near the rehearsal area. He himself would move to Noumea about 1 August in order to comply with his orders to exercise strategic command within the operating area.50

By this time the planning and the resultant orders had taken final form. The target had been selected, the forces organized which were to strike at the target. The Navy had leeway, thanks to the 2 July directive which, by moving the South Pacific boundary one degree west, had made it possible for Ghormley's forces to operate without poaching in the territory of the Southwest Pacific.

Only one detail remained unsettled. The target date, set up first in the warning orders Ghormley received on 24 June and reiterated in the 2 July directive, was still 1 August and impossibly close. Vandegrift pointed out to Ghormley that the late arrival of his second echelon, taken in conjunction with an unforeseen stretch of bad weather, had so complicated his loading problem as to make it impossible to meet the date set. Ghormley agreed, suggesting that at least a week additional time would be needed. Nimitz concurred, passing along the request to King. King agreed to set back the date to 7 August, and Ghormley was so notified, with the stipulation that this was the latest date permissible and that every effort should be made to advance it if possible.51 The new date was incorporated in Ghormley's Operations Order 1-42, of 17 July 1942, in which the foregoing task force structure was set up and which contained the additional admonition that all

______________

46. Admiral King's effort to secure quick release for the assault troops was not successful. The Army's commitments to the European Theater were such that no units were vailable for such missions. Initially assured that air support and air replacements would be available, King was warned by Lieutenant General Joseph C. McNarney, USA, acting Chief of Staff, on 27 July that commitments in other areas would not permit further air reinforcements for the South Pacific--a dictum which King protested strongly in a memo to Marshall on 1 August. NRL.

47. Ghormley ms, pp. 54 and 58.

48. It will be noted that the landing force commander, General Vandegrift, was directly assigned as a subordinate within the command of the Amphibious Force Commander (Admiral Turner), a relationship that was to prove to be both unrealistic and troublesome.

49. See The Defense of Wake, by LtCol R.D. Heinl, Jr., the official Marine Corps narrative of that operation.

50. Ghormley ms, p. 59.

51. War Diary, ComSoPac, July, 1942. NRL.

--13--

ships of the joint force should fuel to capacity at the conclusion of the rehearsal.

Inasmuch as Admiral Turner's amphibious force (Task Force 62) was the one which included the Landing Force and which would carry out the actual assault and landings on Guadalcanal and Tulagi, the internal structure of that command requires our attention.

Like all such task forces it was subdivided into internal components, each known as a task group. One of these was that commanded by General Vandegrift, while others included fire-support ships, transports, minesweepers, and such other units as are required to carry out the naval phase of a landing operation. Within General Vandegrift's command there existed two principal subdivision, to which appropriate transport task-groups of Admiral Turner's force corresponded--namely, the units assigned, respectively, for the Tulagi and the Guadalcanal assaults. These will be described in detail at a later point.

Accumulation of Intelligence

From the intelligence point of view, the Guadalcanal-Tulagi landings can hardly be described as more than a stab in the dark. When General Vandegrift received his initial warning-order on 26 June 1942, neither his staff nor the local New Zealand authorities had more than the most general and sketchy knowledge of the objective area,52 or the enemy's strength and disposition therein. What was more, less than a month was available between the announcement of the mission and the scheduled date of mounting out, 22 July. During the four weeks at hand, every effort had to be, and was, bent toward piercing the fog of blank ignorance and some misinformation which enshrouded Guadalcanal and Tulagi.

As is the case with most tropical backwaters, the charting and hydrographic information was scanty and out of date. Recourse thus was automatically directed toward individuals with on-the-spot experience who could be discovered either in New Zealand or Australia. The accumulation, evaluation, and dissemination of this material fell to Lieutenant Colonel Frank B. Goettge, Intelligence Officer of the 1st Marine Division, Colonel Goettge's first step was to locate such persons, mainly traders, planters, ship-masters, and a few miners, who had visited or lived at Guadalcanal or Tulagi. A number of possible likely sources, he soon found, were now living in Australia, and, while his subordinates set about tabulating the formal data available, Goettge set out for Australia on 2 July, returning to New Zealand on the 13th.53

Long after the conclusion of the campaign, in the late winter of 1943, it was learned that Colonel Goettge's efforts deserved a better success than they had enjoyed. During his hurried trip to Australia, he arranged with the Southwest Pacific Area for maps to be made from a strip of aerial photographs and to be delivered prior to the sortie of the 1st Marine Division. These were never delivered, and the incident apparently was forgotten by the 1st Division staff.

After the arrival of the Division in Australia, however, Lieutenant Colonel Edmund J. Buckley, who succeeded Colonel Goettge as D-2, was asked by an Army officer whether the maps he had prepared had been useful. Further inquiry by Buckley brought to light the information that a special flight had been made, photographs taken, and a map made and sent to New Zealand. Nothing further was done in the matter at the time.

During the summer of 1948 a letter was sent to Dr. John Miller, an Army historian and former Marine, by Colonel E.F. Kumpe, of the Corps of Engineers. Pertinent extracts are quoted herewith through the courtesy of Dr. Miller:

Colonel E.J. Buckley, USMC, the G-2 of the 1st Marine Division following the death of Colonel Goettge is quite correct in his recollection. I was at that time the map chief for SWPA and also the Commanding Officer of the 648th Engineer Topographic

_______________

52. Final Report, Phase I, p. 3, and Annex E to that document. Admiral Ghormley was in no better shape in the matter. His most up-to-date chart of the area was one printed in 1908. Ghormley ms, p. 11.

53. Final Report, Phase I, p. 3 and Annex E.

--14--

Battalion which had recently arrived at Melbourne. The red rush job at that time was the preparation of photomaps for Guadalcanal. The photography was flown by Colonel Karl L. Polifka of the Air Force, now in Quarters 200 at Maxwell Field, and consisted of two strip along the north shore of the island. The following information is not a tale of woe, but a very distressing account of what eventuated at that time. The photographs were printed in the north, and the prints and negatives assigned A-1 priority for shipment to GHQ and subsequently to the map plant. They were diverted for approximately 10 days due to a whim of the Transportation Officer at Townsville, and subsequently delivered to the map plant. Unfortunately, I do not recall the specific date, but it was in advance of the operation.

At the base map plant three sets of duplicate prints were prepared and transmitted to Auckland, and a duplicate set of negatives was also prepared by hand. An additional set of prints was assembled in the form of a mosaic on a concrete floor as equipment had not yet been received and was compiled for civilian reproduction in Melbourne. Manuscript copies of these photo-maps were transmitted in three separate shipments to Auckland with request for bulk distribution.

No bulk distribution request was received and it was a matter of considerable surprise to discover that neither the photograph nor the photo-maps had been available to the 1st Marine Division. An informal investigation after the operation brought out the information that the maps had been lost in the tremendous pile of boxes incident to the organizing of the base establishment of South Pacific (SOPAC). Colonel Buckley stated on subsequent occasions that some oblique photographs captured from the Japanese were the only source of maps during the opening phase of the operation. On the second operation of the 1st Marine Division at Cape Gloucester, New Britain, they received the best maps then available for any operation in the western Pacific, both in the form of topographic maps and with a back printing of the photo-maps, and were duly grateful.

The story does not sound too good in its reflection on the coordination between theaters. However, in this particular case, every effort was made from the western Pacific to send forward all they had to meet the operational dates.

This unfortunate series of events was unknown and unsuspected at the time. All that was known was that a search carried out with great intensity failed almost utterly to produce usable and dependable maps and charts. The Marines were reduced to using what they could gather of the personal knowledge of former residents or travelers of the area.

The fruits of Colonel Goettge's inquiries may be summarized for the benefit of the reader, with appropriate corrections in terms of a general description of the area which would soon become so familiar to members of the 1st and 2d Marine Divisions.

Tulagi and Guadalcanal, the targets of the operation, are dissimilar physically. Tulagi is a relatively small island lying within an indentation of the coast of Florida, the largest island of the Nggela Group. It is a hilly mass, heavily wooded and with little level ground. Its chief importance lies in that it guards an excellent small harbor and is the seat of government of the British Solomon Islands.

To the east of its southern extremity lie two small, hilly islands, Gavutu and Tanambogo. A causeway connects the pair, of which Gavutu is the larger. They are by far the most important of Tulagi's peripheral islands.

Guadalcanal, on the other hand is a land mass about 90 miles in length whose long axis lies in a southeasterly-northwesterly direction. It presents a varied terrain, with plains, foothills, and mountains and with a range of vegetation that runs from grassy plains to true rainforest and jungle.

The mountain backbone of the island is parallel to the long axis. The slope to the southwest is abrupt, and there is little extensive plains country on that side of the

--15--

island. On the opposite coast, however, from the mouth of the Lunga River to the east, there is a wide belt of plains, cut by rivers and covered with jungles interspersed with broad patches of grass lands. These well watered plains are ideal for the development of copra plantations, for which purpose they have been used since the beginning of the century. Rainfall is extremely heavy, and changes in season are marked only by changes in intensity of precipitation. This, together with an average temperature in the high 80's, results in a humid, unhealthy climate. Malaria, dengue, and other fevers, as well as fungus infections, afflict the population.

Rivers are numerous, and from the military point of view may be divided arbitrarily in two classes. The first of these is the long, swift, relatively shallow river that may be forded at numerous points. Generally deep for a short distance up from its mouth, it presents few problems in the matter of crossing. Examples of this type are the Tenaru, the Lunga, and the Balesuna.

The second type is that of the slow and deep lagoon. Such streams are sometimes of inconsiderable length, as in the case of the Alligator Creek, and again are merely the coastal extremities of rivers of considerable size, as in e case of the Matanikau. This type, because of its depth and the precipitous nature of its banks, was an admirable defensive aid.

Beaches on both Tulagi and Guadalcanal were frequently treacherous because of the broad coral formations. In the vicinity of the Lunga, however, and in some spots farther to the northwest, it was possible to bring large craft almost to the shoreline because of the close-in steep-to.

Although this accumulation of data afforded much enlightenment beyond the little previously known, it included corresponding minor misinformation and many aggravating gaps, for detailed information in a form suitable for military operations was mainly lacking.

In spite of the number of years which had elapsed since initiation of the systematic economic development of the islands by the British, not a single accurate or complete map of Guadalcanal or Tulagi existed in the summer of 1942. The hydrographic charts, containing just sufficient data to enable trading schooners to keep from grounding, were little better, although these did essay to locate a few outstanding terrain features of some use for making a landfall or conducting forms of triangulation. In one case, in fact, Mount Austen (Mambulo was its native name) was assigned as an immediate objective, only to have the discovery made--after the Guadalcanal landing--that, instead of being but a few hundred yards away from the beaches, it actually lay several miles distant, across almost impassable jungle.54

The second and more profitable source of up-to-date information would of course be aerial photographs, but the paucity of long-range aircraft and suitably located bases, together with the short notice upon which planning had been launched, combined to restrict availability of aerial photos in the quantity and quality normally considered necessary for Fleet Marine Force landing operations.

Perhaps the most useful photographic sortie carried out prior to the Guadalcanal-Tulagi landings (except for the fruitless effort described previously) was that undertaken by an Army B-17 aircraft in which Lieutenant Colonel Merrill B. Twining (assistant operations officer (D-3) of the 1st Marine Division) and Major William B. McKean (member of the staff of Transport Squadron 26) conducted a personal reconnaissance of the landing areas. This flight took off from and returned to Port Moresby, New Guinea, on 17 July and was, in fact,

______________

54. This was the so-called "Grassy Knoll" assigned to the 1st Marines. Long-time Guadalcanal residents described it as lying virtually within the perimeter area ultimately occupied and defended by General Vandegrift, whereas its true location was six miles to the southwest. This discrepancy, unexplained for years, has given much cause for speculation to historians of the Guadalcanal campaign, some of whom have raised the question whether Mount Austen was really the "Grassy Knoll" which Goettge's informants had in mind. This school of thought suggests that the only feature which could possibly fall within the described limits would have been the high ground later to become known as Edson's Ridge.

--16--

the first occasion during the war upon which Guadalcanal was sighted by U.S. Marines. The route followed made landfall in the vicinity of Cape Esperance, then proceeded to Tulagi Bay (where float-equipped Zero fighters could be seen preparing to take off on intercept), and then swung on a return leg along the north coast of Guadalcanal from Aola Bay westward toward the intended beachhead. Photostrips were taken all the way. Just as the bomber approached Lunga Point, however, the critical point of the reconnaissance and the area in which the Japanese were reportedly developing the Guadalcanal air-strip, the Zero fighters, which had now gained altitude, swarmed down. In the resultant melee, photography was of course impossible, and visual observation became largely valueless. Under the circumstances, therefore, and because the "turn-back" point had now been well passed, the reconnaissance could not be retraced. Thus neither Twining nor McKean could obtain positive information as to me progress of the Japanese in completing their field although they could ultimately reassure General Vandegrift as to the evident suitability of the Lunga beaches for landing. The return trip to Port Moresby was rendered successful by Major McKean's supervision of the somewhat haphazard navigation, on the basis of his Naval Academy training of years gone by.55

The coastal map of Guadalcanal finally adopted as official by the 1st Marine Division (and employed, with such corrections as could later be developed, throughout the entire campaign) was traced from an aerial strip-map obtained by Colonel Goettge on his mission to Australia, and, while reasonably accurate as to general outline, contained no usable indications of ground-forms or elevations. The Goettge map--a section of which is reproduced in this monograph as an indication of the crudeness of the topographic material available--was distributed to units of the division prior to departure from Wellington. This was supplemented by aerial photos of Tulagi, Gavutu, and Tanambogo Islands, and these constituted, altogether, the sum of what the 1st Marine Division was to know of Tulagi and Guadalcanal prior to the landings.56

Of the enemy's strength, dispositions and activities, it was known to the U.S. planners--largely from coastwatcher reports57--that the Japanese forces had established their headquarters in the former British governmental seat at Tulagi, that they had occupied and installed defensive positions on nearby Gavutu and Tanambogo, and that their construction

_________________

55. Information this flight obtained from Historical Section interview with Col. William B. McKean, 18 February 1948.

56. Two aerial photos, taken on 2 August by a ComAirSoPac B-17 and developed aboard the USS Enterprise, were forwarded to Division Headquarters. They showed Tulagi defensive positions in sharp detail, and verified the reports of coastwatchers about the rapidly approaching completion of the air strip in the Lunga plains. Final Report, Phase I, Annex E, p. 5.

57. "The invaluable service of the Solomon Islands coastwatching system . . . cannot be too highly commnded." Final Report, Phase I, Annex E, p. 2.

--17--

forces were busily at work across the Sealark Channel on the Guadalcanal airfield project. We have also seen that coastwatching stations had been set up on Florida, Malaita, and Guadalcanal.

Estimates of enemy strength were by no means as definite or convincing as were the factual accounts of the defenses. Various intelligence estimates, prepared during July, gave figures as high as 8,400, while Admiral Turner's Operation Plan A3-42, issued at the rehearsals at Koro Island on 30 July, gave it as the Admiral's opinion that 1850 enemy would be found on Tulagi and Gavutu-Tanambogo,

--18--

and 5275 on Guadalcanal. Both figures were high. A count of enemy dead in the Tulagi and Gavutu area placed the number of defenders at about 1500 (including 600 laborers) while a study of positions, interrogation of prisoners, and translation of enemy documents on Guadalcanal proper indicated that about 2230 troops and laborers had been in the Lunga area at the time of the Marines' landing.58

Close and determined combat was anticipated with these forces; what the future held in the way of counterblows, the 1st Marine Division had no way of foreseeing.59

Planning and Mounting Out

Tactically speaking, the task assigned the 1st Marine Division was dual in character, not only because of the considerable physical separation between its two initial objectives, that is, Guadalcanal and Tulagi, but because hard fighting was expected during or immediately after the latter landing. On the other hand, it was hoped that the former beachhead could be secured without instantaneous enemy reaction. This duality had, as we have seen, shaped General Vandegrift's task-organization into two landing forces; Group X-Ray (Guadalcanal) and Group Yoke (Tulagi). It likewise guided the Marine commander in his assigned of units to these two groups.

To the Tulagi group--commanded by Brigadier General William H. Rupertus, assistant division commander to General Vandegrift--the latter assigned the 1st Marine Raider Battalion (Lieutenant Colonel Merritt

_______________

58. Final Report, Phase II, p. 8, and Boardman ms.

59. Nimitz was preoccupied with this very problem. On 17 July he wrote King saying that it would be unsafe to assume that the enemy would not attempt to retake the area to be attacked, and that if insufficient forces were assigned, the Marines might not be able to hold on. Dispatch, CinCPac to CominCh, 17 July 1942. NRL.

--19--

A. Edson); the 1st Parachute Battalion (Major Robert H. Williams); and the 2d Battalion, 5th Marines (Lieutenant Colonel Harold E. Rosecrans). These were then considered to be the best-trained units, and therefore more suitable for the sharp work ahead.60

The Guadalcanal group, under General Vandegrift's personal leadership, would comprise the other two combat groups (as they were then styled) within the 1st Marine Division,61 plus the balance of the division special and service troops.

The northern scheme of maneuver, that on Tulagi, called for a landing on the south shore by the 1st Raider Battalion and 2d Battalion, 5th Marines, in column in that order, the attack then wheeling right (east) and moving down the long axis of the island. This would be followed by further landings by the Parachute Battalion on Gavutu and Tanambogo, plus a mop-up sweep by a Battalion (less one company) along Florida Island's coastline fronting Tulagi Bay.

The scheme on Guadalcanal envisaged landing the 5th Marines (less 2d Bn) across a beach somewhat removed to the eastward from whatever defended beaches or other defenses which the Japanese might have set up in the Lunga delta. This unit, landing on the right half of the beach with two battalions abreast, was to be followed by the 1st Marines in column of battalions. The units thus landed would therefore be assured no more than minor resistance at worst, plus the subsequent opportunity of assembling and forming for an overland attack to the west from an established beachhead. These schemes of maneuver were embodied in 1st Marine Division Operation Order 7-42, issued on 20 July at Wellington.62

In the attack on an area supposed, altogether, to be defended by more than 5,000 enemy, it will be realized that a division less one-third of its strength (i.e., the 7th Marines, reinforced) would have little if any margin in reserve. To remedy this hazard, Admiral King proposed, on 27 June, that the 2d Marines63 (reinforced), including its supporting light artillery battalion (3d Battalion, 10th Marines) and normal reinforcing elements, be ordered from San Diego, combat-loaded, to serve as landing force reserve.64

While the foregoing operational plans were in process of preparation, and while the accumulation and collation of intelligence progressed as best it could, the Guadalcanal landing force found itself confronted by a logistic task of monumental proportions. This was the job of completely unloading its original shipping; sorting and reloading its equipment and supplies; and accomplishing all this with troop labor under an intolerable pressure of time.

The reason for this massive reshuffle was that, as originally mounted out from the United States, the 1st Marine Division's shipping had been organizationally loaded, that is, equipment and supplies had been stowed aboard ship to take maximum advantage of hold-space, rather than in the uneconomical but necessary method known as combat-loading, whereby items are placed so as to be ready for unloading in accordance with the priority of their necessity in an assault landing. Inasmuch as shipping was scanty and overburdened, and, as originally planned, the 1st Division would not be employed in

_______________

60. Final Report, Phase I, p. 4.

61. At this time, the standard phrase "regimental combat team" (RCT) had not come into uniform use. What we would now style an RCT was what Guadalcanal Marines labelled a combat group, that is, a rifle regiment with its direct-support artillery battalion, engineers, signal, medical, and other combined supporting elements. Within the so-called combat groups, similar battalion-sized aggregations were designated combat teams. This usage will be followed throughout this monograph.

62. This order did not reach the 1st Raider Battalion and the 2d Marines until these units joined the main force in the rehearsal area on 27 July.

63. This unit was to be employed to carry out projected landings at Ndeni, in the Santa Cruz Islands. Needless to say, these were never carried out, although occupation plans for Ndeni, always involving Marine forces, continue to appear in Admiral Turner's records until October, 1942.

64. "It is most desirable that 2d Marines be reinforced and combat unit loaded and ready upon arrival this area for employment in landing operations as a reinforced regimental combat team." War Diary ComSoPac, entry 27 June 1942.

--20--

combat immediately, no reason could have justified combat-loading at the time of the force's movement to New Zealand from the United States.65 Combat loading moreover, would have been made difficult by the fact that most of the vessels used were passenger ships and not specially equipped attack transports.66

Almost overnight, however, while the Marines were still enroute, the situation, as we have seen, had changed. An assault operation was now in immediate prospect, and, as a necessary concomitant, it would be essential that the equipment and supplies of the Marine units reached Guadalcanal and Tulagi combat-loaded. Thus, as soon as the troops could be disembarked at New Zealand, the onerous task of unloading, rearranging, and re-loading had to be set on foot and had to be completed at all cost prior to the date set for departure.

Aotea Quay, at Wellington, was the scene of this operation. It was inadequate in all ways save that it could accommodate five ships at a time. Labor difficulties with the highly unionized stevedores--it was not possible to provide the incentive of pointing out that the ships and men in them were about to go into action--resulted in the entire unloading and re-loading task being undertaken and carried through the Marines. Dock-side equipment was meager, and there was no shelter. Carton-packaged foodstuffs and other supplies deteriorated rapidly in the persistent cold windy rain of a "southerly," as did the morale of the men.67

The re-loading and reembarking of Combat Group A (5th Marines, reinforced) was accomplished smoothly, uncomplicated by the necessity for literally unloading and reloading at the same time which plagued the operations of the rear echelon. The group was embarked beginning 2 July and remained on board its transports to await the arrival of the rear echelon.68

The logistic problem facing the rear echelon was much more sever and complicated. Arriving on 11 July, this group was faced with the necessity of completely emptying and reloading its ships on a dock, to repeat, that was lacking in specialized equipment and in shelter for material that was being sorted. The task, moreover, had to be completed by 22 July.

The problem was solved by what must be regarded as heroic measures. The troops were not disembarked, save those who were to remain

_____________

65. It must not be thought, however, that the importance of combat loading was not fully realized. The following extract from a letter of R.K. Turner (then Assistant Chief of Staff (Plans) under Admiral Stark) to the Commander in Chief, United States Fleet, clearly demonstrates this point.

"It is also recommended that definite decision be made to send to New Zealand the 1st Marine Division, one Marine Defense Battalion, eight combat loaded transports and 3 combat loaded cargo vessels." This letter, having for its subject Command Relations for Pacific Ocean Area, bears no date, but from its place in archives it appears to have been written about 1 April 1942--a time when, of course, there were no plans for specific, immediate offensive.

66. Letter, General Vandegrift to CMC 4 February 1949.

67. Final Report, Phase I, Annex L.

68. Final Report, Phase I, p. 6.

--21--

in New Zealand as rear echelon personnel. All others, who already had been in cramped quarters during the long trip across the Pacific, were put to work in eight hour shifts, and work proceeded around the clock. Parties of 300 men were assigned to each ship.69

During the process of mounting out, certain modifications of the logistic plan had become necessary. As finally loaded, the marine force was carrying 60 days supplies, 10 units of fire for all weapons, the minimum individual baggage, ". . . actually required to live and fight," and less than half the organic motor transportation authorized for the Division.70