The Navy Department Library

German Submarine Activities on the Atlantic Coast of the United States and Canada

PDF Version [38.9MB]

NAVY DEPARTMENT [BR] OFFICE OF NAVAL RECORDS AND LIBRARY

HISTORICAL SECTION

Publication Number 1

GERMAN SUBMARINE ACTIVITIES

ON THE

ATLANTIC COAST

OF THE

UNITED STATES AND CANADA

1920

NAVY DEPARTMENT

OFFICE OF NAVAL RECORDS AND LIBRARY

HISTORICAL SECTION

***********

Publication Number 1

GERMAN SUBMARINE ACTIVITIES ON

THE ATLANTIC COAST OF THE

UNITED STATES AND CANADA

Published under the direction of

The Hon. JOSEPHUS DANIELS, Secretary of the Navy

WASHINGTON

GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1920

GERMAN SUBMARINE ACTIVITIES ON THE ATLANTIC COAST OF THE UNITED STATES AND CANADA.

PUBLICATION NO. 1, HISTORICAL SECTION, NAVY DEPARTMENT.

************

ERRATA.

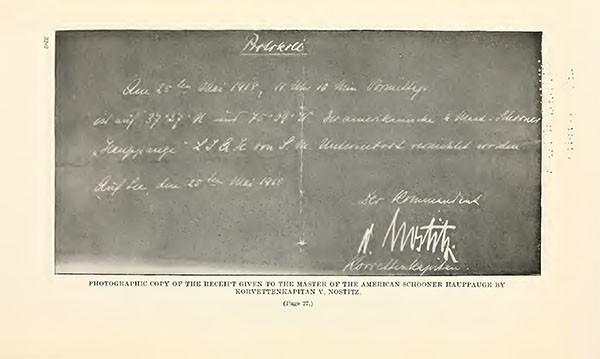

Page 23. line 10, strike out “Kapitan Van Nostitz und Janckendorf and insert Korvettenkapitän (Lieutenant Commander) von Nostitz und Jaenckendorf.

Page 24, after line 15, insert Note: The British steamship Crenella"> was formerly the Canadian steamship "Montcalm." The two names were confused in the dispatches and consequently the discrepancy.

Page 30, after line 14, insert Note: While it would have been possible for "U-151" to have been in the vicinity of the battleships on June 1, it is improbable that the attack of the battleships was on that submarine. The prisoners from the “Hattie Dana" "Hauppauge " and "Edna" were not released from "U-151" until June 2, and they do not make any mention of the encounter and would most likely have known of it.

Page 34, line 37, strike out "United Shipping States Board" and insert United States Shipping Board.

Page 36, after line 5 insert a new paragraph, viz:

The loss of the “Texel" had a direct bearing upon the plan of operations for the “United States Naval Rail way Batteries in France." That ship was one of those chosen to transport a cargo of material for that remarkable enterprise, and her loss necessitated the selection of another vessel.

Page 38, strike out lines 11 to 26 (both inclusive) and insert in lieu thereof after line 10 The official list, made later, shows that 272 survivors were landed at New York, viz:

Crew—1 stewardess and 91 men; total 92.

Passengers—58 females, 118 males, and 4 infants: total 180. Other survivors from the "S. S. Carolina ” were accounted for on June 4. At 1.45 p. m. lifeboat No. 5. containing 8 women and 21 men landed through the surf at the foot of South Carolina Avenue, Atlantic City, N. J. The same day the British steamship "Appleby " picked up from lifeboat No. 1, 9 members of the crew and 10 passengers and carried them to Lewes, Del. The first loss of life charged to enemy submarine activity off the American Atlantic coast was recorded when the survivors from lifeboat No. 1 were picked up by the steamship "Appleby" and reported that while trying to weather the rough sea that arose during the night their boat had capsized, about 12.15 a. m., June 3, and it was later found that 7 passengers, the purser, and 5 members of the crew were missing and were lost.

On June 3, at 4 p.m., the Danish steamship "Bryssel" picked up the abandoned lifeboat No. 1.

--1--

Page 41, line 36, after the words “found nothing” insert Note: The encounter of the U. S. S. “Preble” was too far north to have been with “U-151.''

Page 44, line 20, after the word “schooner" strike out “Ella Swift” and insert "Ellen A. Swift."

Page 44, line 22, after the word “whaler" strike out “Nicholson ” and insert “A. M. Nicholson.”

Page 46, strike out footnote 14 and insert 14 The joint attack by the battleship “South Carolina" and U. S. "S. C. 234 ” occurred in Lat. 38° 26' N., Long. 74° 40' W. and was too far north and west to have been on, “U-151.""Besides Capt. Ballestad says, in his testimony, that from 6.20 p. m.. on June 8, to 6.20 a. m., June 9, his ship followed the submarine at a slow speed, without stopping, on a course east, southeast, easterly, and they did not encounter the battleship.

Page 50, after line 20 insert Note: 12 lives were lost on the “Tortuguero.”

Page 56, line 24, strike out “Grand Island" and insert Grand Manan Island.

Page 56, line 20, strike out “Grand Island" and insert Grand Manan Island.

Page 50, in footnote 20, strike out “ Elizabeth Von Bilgie " and insert Elizabeth Van Belgie.

Page 88, after line 6 insert Note: There was no loss of life on the two fishing vessels, "Cruiser" and "Old Time." All matched shore in safety.

Page 91, line 23, strike out “tampion” and insert tompion.

Page 94, line 13, strike out “Brazilian” and insert American.

Page 95, line 4, strike out words ‘‘The day after” and insert Two days after.

Page 96, line 44. after the word “longitude" (line 43) strike out “58°” and insert 68°.

Page 105, line 38, strike out “October 10" and insert October 18.

Page 106, line 11, after the word “Constanza" insert Note: The British Admiralty give the name as “ Constance," 199 gross tons. The vessel was salvaged.

Page 118, line 33, strike out “August ” and insert October.

Page 124, line 34, strike out “August” and insert September.

Page 133, line 14, after the words Norwegian S. S. strike out “Breiford ” and insert Breifond; also in line 16, same correction.

Page 133, after paragraph 6 insert new paragraph, viz:

Besides the three rescued by the “Breiford" five other men, including one dead, were picked up by the American steamship “Lake Felicity" and taken to Newport, R. I. The five men clung to pieces of the pilot house, on which they remained for 12 hours. One died after 9 hours of exposure. A total of 30 lives was lost, including this man.

Page 134, line 9, strike out the words “The crew of 11 men came in the Inlet with the captain in one of their own boats; the balance of the crew landed on North Beach, Coast Guard Station 112,” and insert in lieu thereof: Of the crew, consisting of 29 men, the captain and 11 men came in the Inlet in one of their own boats and landed at Coast Guard Station 112. Another boat with 11 men landed on North Beach and 6 men were found missing and lost.

--2--

Page 140, table No. 1, strike out “Notre Dame de Lagarde, F. V. 145. B. Aug. 22” and insert “Notre Dame de 1a Garde, F. V. 145. B. Aug 21.

Page 157, line 27, second column, strike out “Brieford” and insert Breifond.

Page 100, line 51, strike out “Brazilian” and insert American.

CORRECTIONS CHART NO. 1.

CHART TRACK OF U-151.

May 19 (S. S. Nyanza). Insert sign showing vessel attacked but not sunk in lat. 38° 21' N., long. 70° 05' W.

May 21 (S. S. Crenella). Change sign to indicate vessel attacked but not sunk.

June 13 (Llanstephan Castle). Lat. 38° 02' N., long. 72° 47' W.

Change sign to indicate vessel attacked but not sunk.

June 18 (S. S. Dwinsk). Lat. 38° 30' N., long. 61° 15' W. Should have sign indicating vessel sunk.

CHART TRACK OF U-156.

July 23 (schooner Robert and Richard). 60 miles SE. of Cape Porpoise. Should be July 22.

August 8 (S. S. Sydland). Insert sign showing vessels sunk in lat. 41° 30' N., long. 65° 22' W.

Note: Sign indicating vessel sunk on August 8, on chart track of U-117 should be on track of U-156.

August 20 (Triumph and fishing fleet). 52 miles SW. of Cape Canso, N. S., approximately lat. 44° 31' N., long. 60° 30' N. Change sign to indicate vessels sunk.

August 22 (Notre Dame de 1a Garde). Lat. 45° 32' N., long. 58° 57' W. Should be August 21.

August 27 (near Cape Canso, N. S.). Strike out sign indicating vessel sunk.

CHART TRACK OF U-140.

July 19 (U. S. S. Harrisburg). Lat. 45° 33' N., long. 41° W. Should be July 14.

July 19 (S. S. Joseph Cudahy). Lat. 41° 15' N., long. 52° 18' W. Should be July 18.

July 26 (S. S. British Major), approximately lat. 38° 42' N., long. 60° 58' W. Change sign to indicate vessel attacked but not sunk.

July 30 (S. S. Kermanshah). Lat. 38° 24' N., long. 68° 41' W. Change sign to indicate vessel attacked but not sunk.

August 10 (U. S. S. Stringham). Lat. 35° 51' N., long. 73° 21' W. Change sign to indicate vessel attacked but not sunk.

August 13 (U. S. S. Pastores). Lat. 35° 30' N., long. 69° 43' W. Change sign to indicate vessel attacked but not sunk. September 7 (S. S. War Ranee). Lat. 51° 27' N., long. 33° 24' W. Should be September 5, and sign changed to indicate vessel attacked but not sunk.

--3--

CHART TRACK OF U-117.

August 8 (S. S. Sydland). Lat. 41° 30' N., long. 65° 22' W. Strike out sign indicating vessel sunk. Should be on chart track of U-156.

August 14 (schooner Dorothy B. Barrett). Lat. 38° 54' N., long. 74° 24' W. Change sign to indicate vessel sunk.

Aug. 15 (motor vessel Madrugada). Lat. 37° 50' N., long. 74° 55' W. Change sign to indicate vessel sunk.

August 22 (S. S. Algeria). Lat. 40° 30' N., long. 68° 35' W. Should be August 21.

August 25 (schooner Bianca). Lat. 43° 13' N., long. 61° 05' W. Should be August 24.

CHART TRACK OF U-155.

August 28 (S. S. Montoso). Lat. 40° 19' N., long. 32° 18' W. Should be August 27.

September 11 (S. S. Leixoes). Lat. 42° 45' N., long. 57° 37' W. Should be September 12, and sign indicating vessel sunk should be moved east to lat. 42° 45' N., long. 51° 37' W.

October 17 (S. S. Lucia). Insert sign indicating vessel sunk in lat. 38° 05' N., long. 50° 50' W.

CHART TRACK OF U-152.

October 16. Strike out sign indicating vessel sunk, approximately lat. 38° 05' N., long. 50° 50' W.

October 18 (S. S. Briarleaf). Lat. 36° 05' N., long. 49° 12' W. Should be October 17.

| List of illustrations | Page. 4 |

| Preface | 5 |

| Foreword | 7 |

| Table showing arrivals aud departures of German submarines | 7 |

| Steps taken by the Navy Department to protect shipping along the Atlantic coast | 8 |

| Dispatches from Force commander in Europe giving necessary information to prepare to meet attacks | 9 |

| The Deutschland | 15 |

| Visit of German U-53 to Newport, R. I. | 18 |

| The cruise of the German U-151 | 23 |

| The cruise of the German U-156 | 50 |

| The cruise of the German U-140 | 70 |

| The cruise of the German U-117 | 82 |

| The cruise of the German U-155 | 100 |

| The cruise of the German U-152 | 106 |

| Cable cutting by U-151 | 119 |

| United States and Allied radio service adequate for transaction of important official business in case the cables had all been cut | 121 |

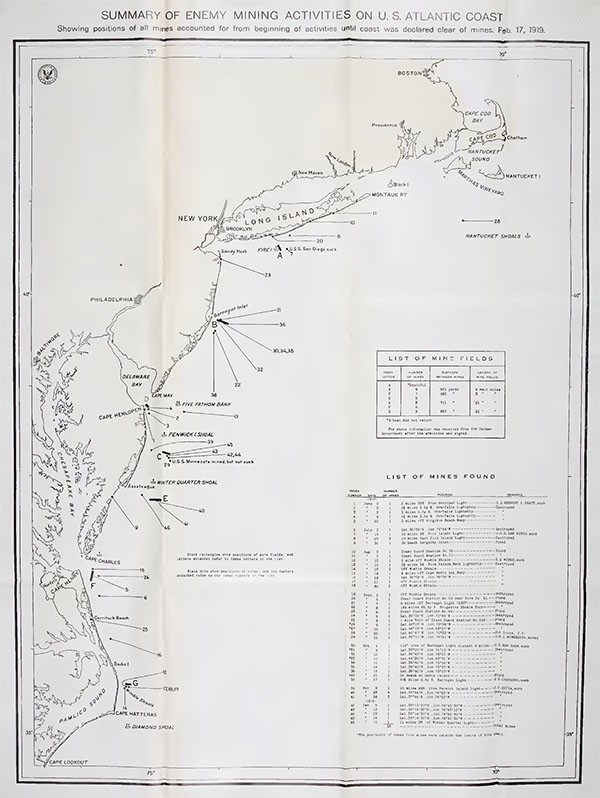

| Mine-laying operations | 122 |

| Submarine mines on the Atlantic coast of the United States | 125 |

| Mine-sweeping ships by naval districts | 135 |

| Mine-sweeping operations on the Atlantic coast | 136 |

| Table No. 1: Vessels destroyed by submarines acting on the surface using gunfire and bombs in western Atlantic | 139 |

| Table No. 2: Vessels destroyed by submarines submerged and firing torpedoes. | 140 |

| Table No. 3: Vessels damaged or destroyed by mines | 141 |

| Appendix | 143 |

Folded charts:

| 1. German submarine activities in the western Atlantic waters | In pocket. |

| 2. Enemy mining activities on the Atlantic coast | In pocket. |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

| Facing page— | |

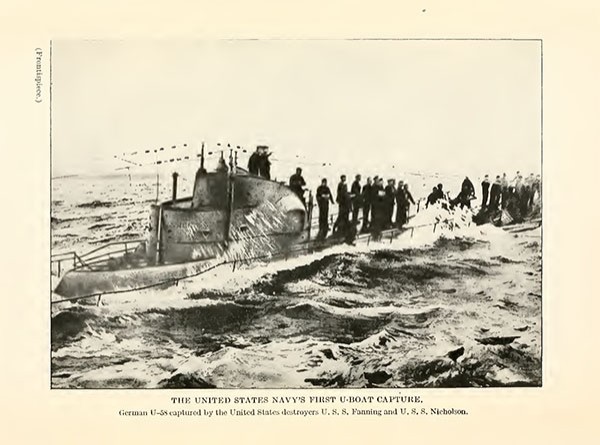

| The United States Navy’s first U-boat capture, German U-58 captured by the United States destroyers U. S. S. Fanning and U. S. S. Nicholson | Frontispiece. |

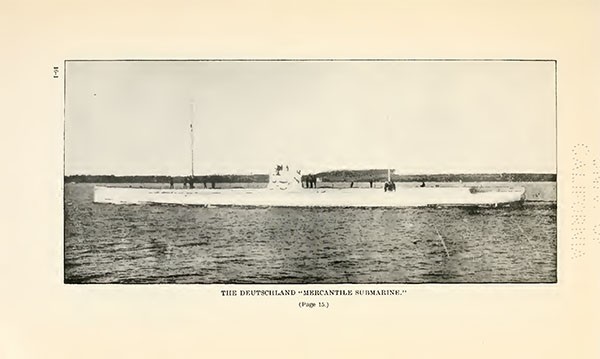

| The Deutschland "Mercantile Submarine" | 16 |

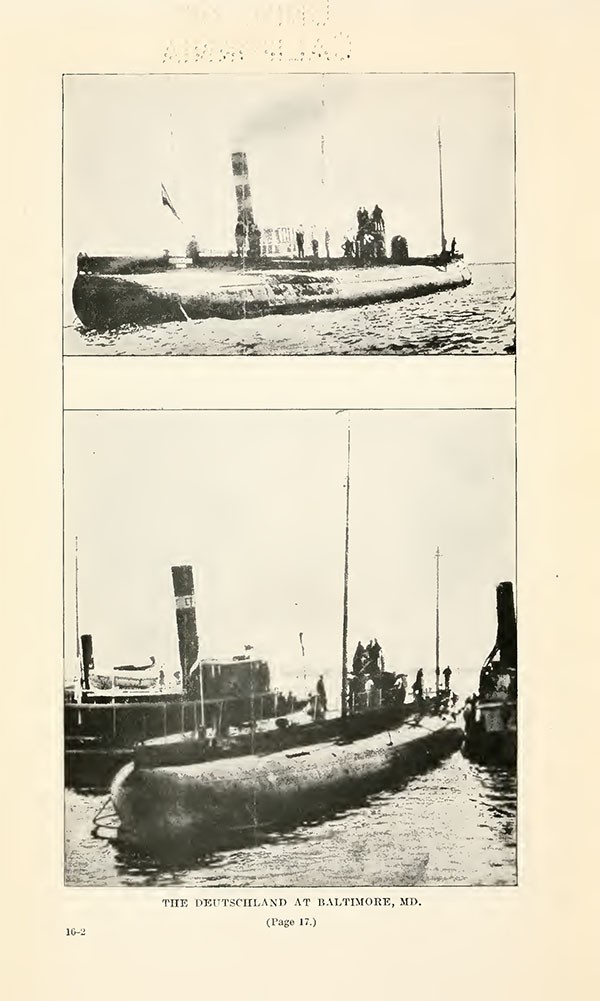

| The Deutschland at Baltimore, Md. (Two prints) | 16 |

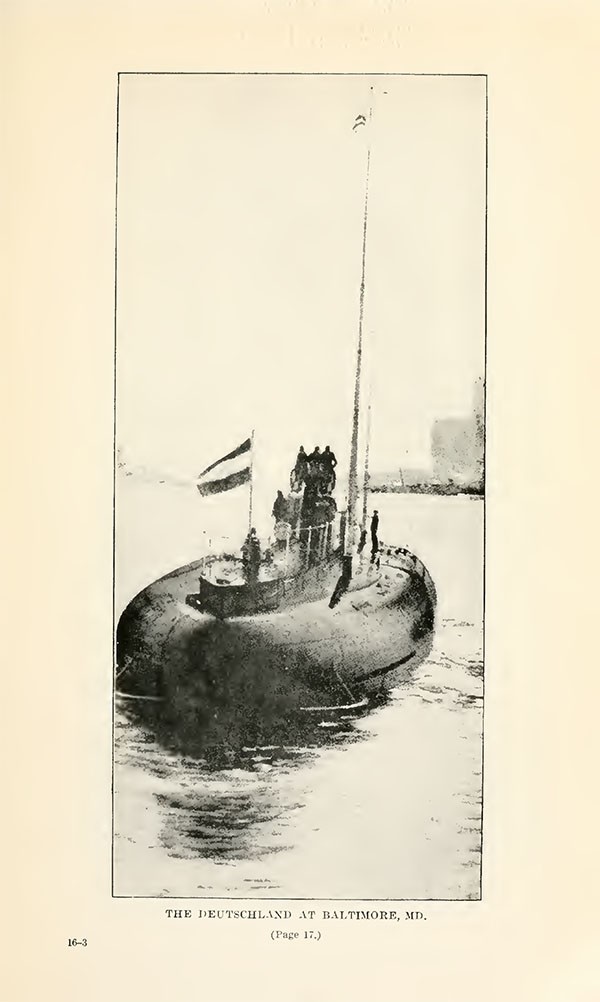

| The Deutschland at Baltimore, Md | 16 |

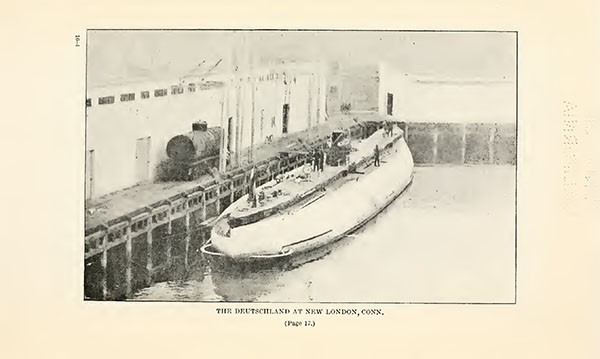

| The Deutschland at New London, Conn | 16 |

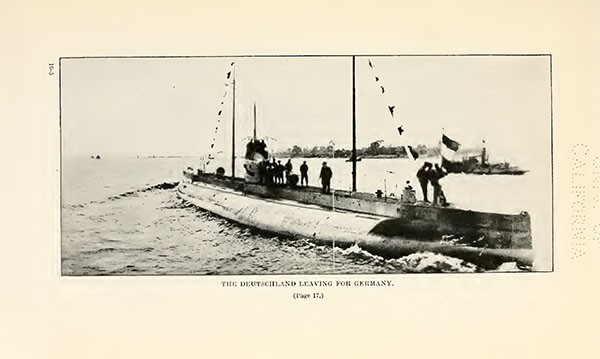

| The Deutschland leaving for Germany | 16 |

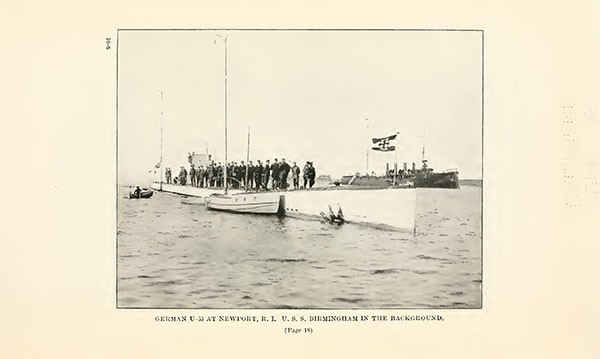

| German U-53 at Newport R. I. U. S. S. Birmingham in the background | 16 |

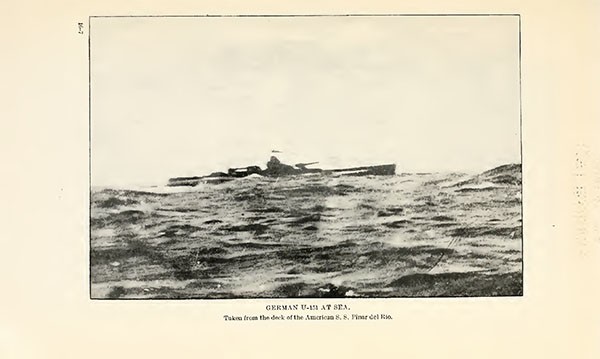

| German U-151 at sea. Taken from the deck of the American S.S. Pinar del Rio. | 16 |

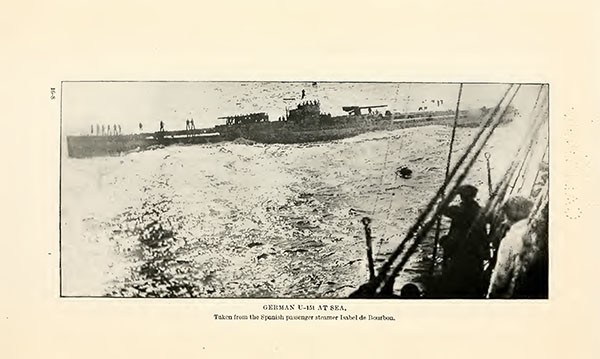

| German U-151 at sea, from the Spanish passenger steamer Isabel de Bourbon.. | 16 |

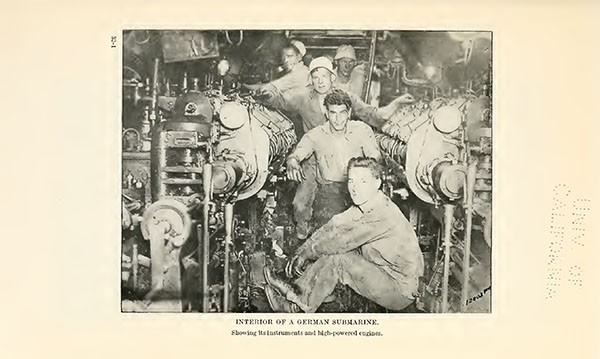

| The interior of a German submarine showing its instruments and high-powered engines | 32 |

| Photographic copy of the receipt given to the master of the American schooner Hauppauge by Korvettenkapitan v. Nostitz | 32 |

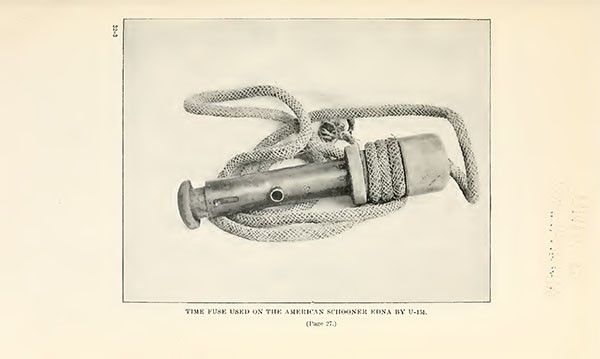

| Time fuse used on the American schooner Edna by U-151 | 32 |

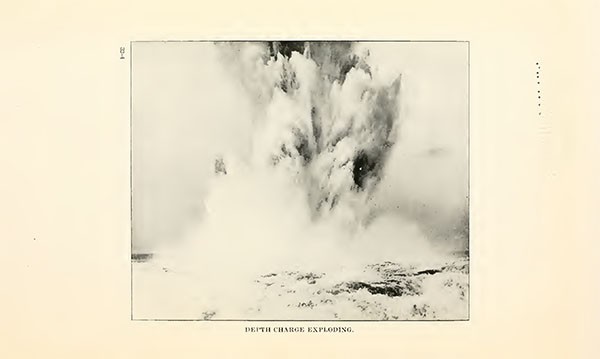

| Depth charge exploding | 32 |

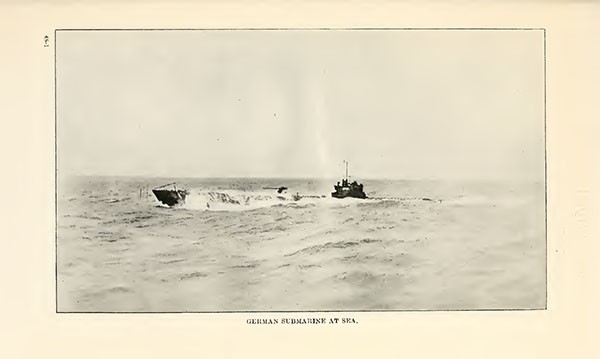

| German submarine at sea | 48 |

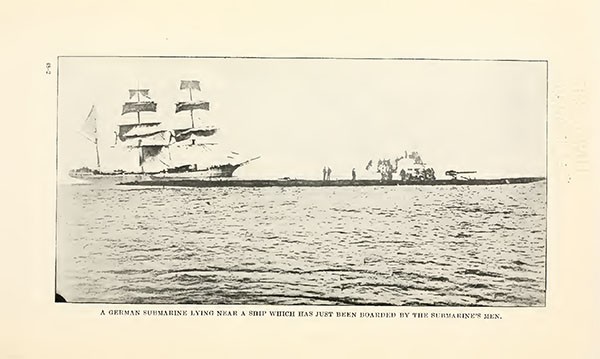

| A German submarine lying near a ship which has just been boarded by the submarine’s men | 48 |

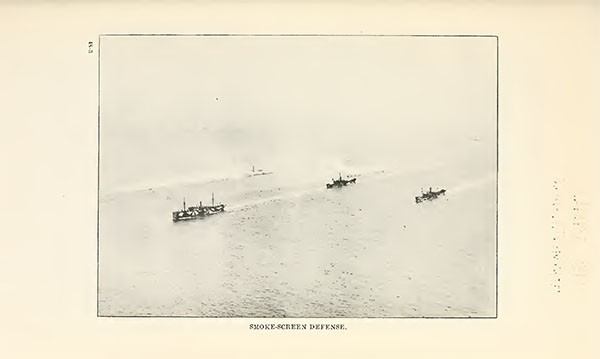

| Smoke-screen defense | 48 |

| War on hospital ships | 48 |

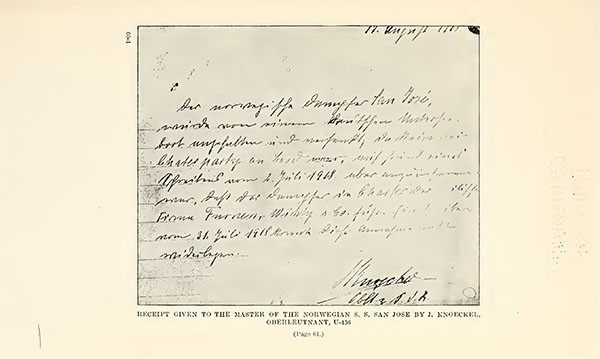

| Receipt given to the master of the Norwegian S. S. San Jose by J. Knoeckel, Oberleutnant U-156 | 60 |

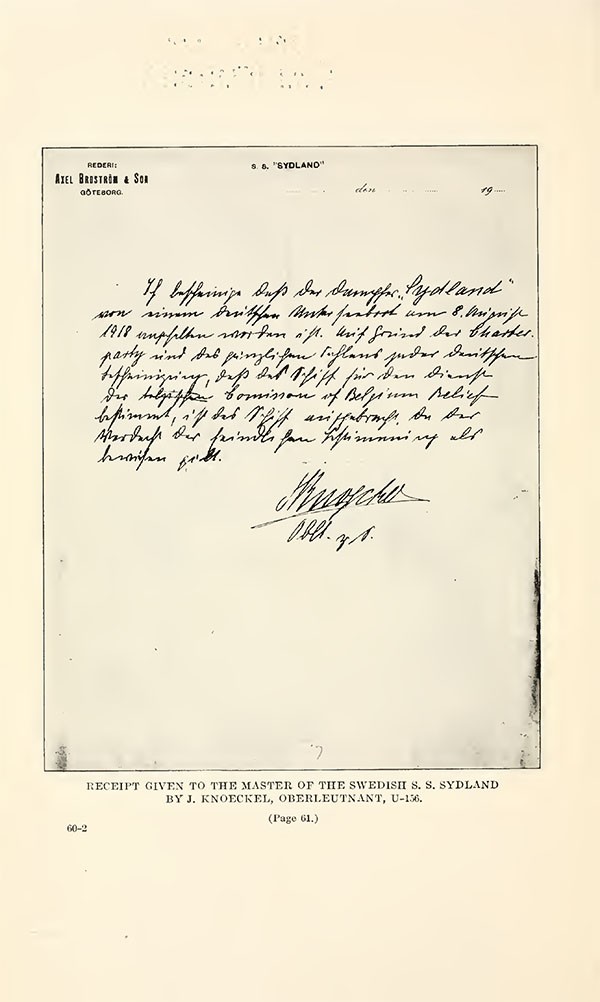

| Receipt given to the master of the Swedish S. S. Sydland, by J. Knoeckel, Oberleutnant U-156 | 61 |

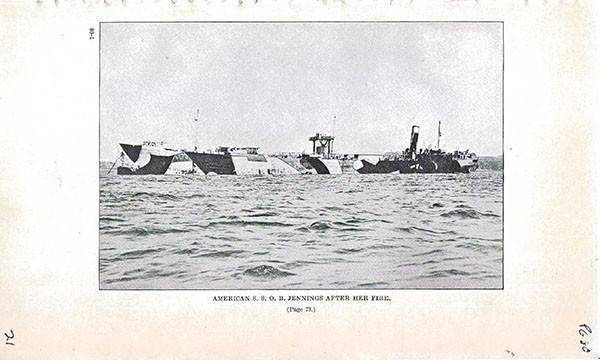

| American steamship O. B. Jennings after her fire | 80 |

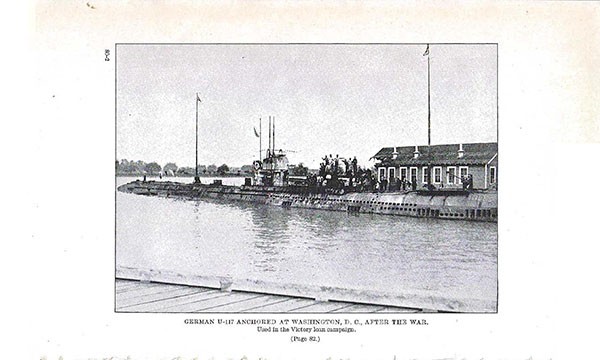

| German U-117 anchored at Washington, D. C., after the war. Used in the Victory loan campaign | 80 |

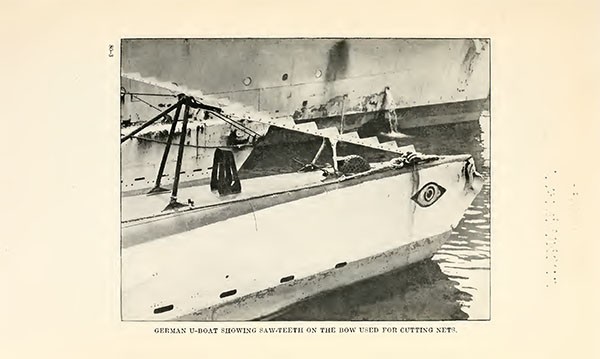

| German U-boat showing saw-teeth on the bow used for cutting nets | 80 |

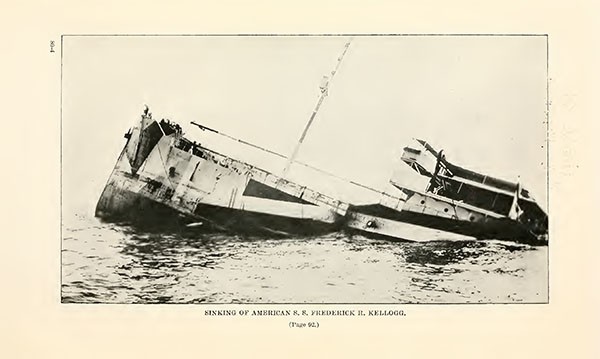

| Sinking of American S. S. Frederick R. Kellogg | 80 |

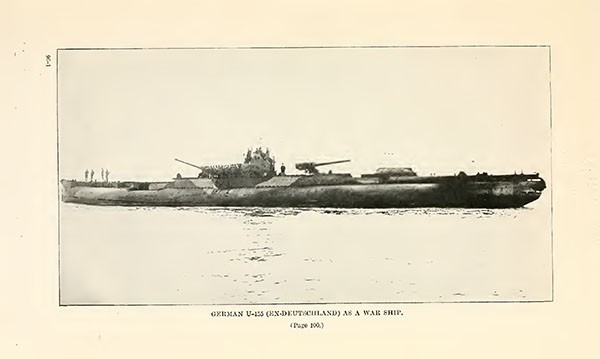

| German U-155 (ex-Deutschland) as a war ship | 96 |

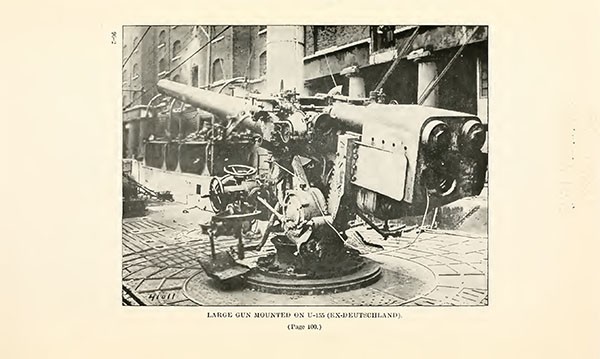

| Large gun mounted on U-155 (ex-Deutschland) | 96 |

| German U-155 (ex-Deutschland) after surrender anchored within the shadow of the famous Tower Bridge, London | 96 |

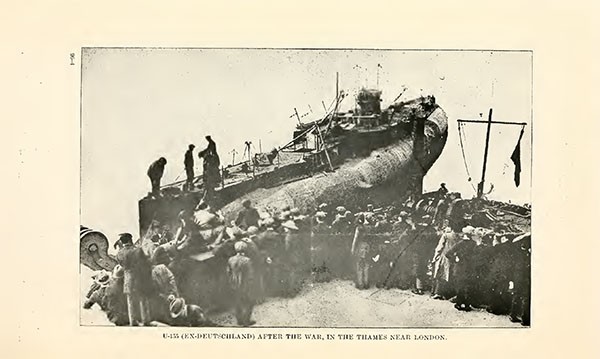

| U-155 (ex-Deutschland) after the war in the Thames near London | 96 |

| Survivors of the U. S. A. C. T. Lucia leaving the ship | 112 |

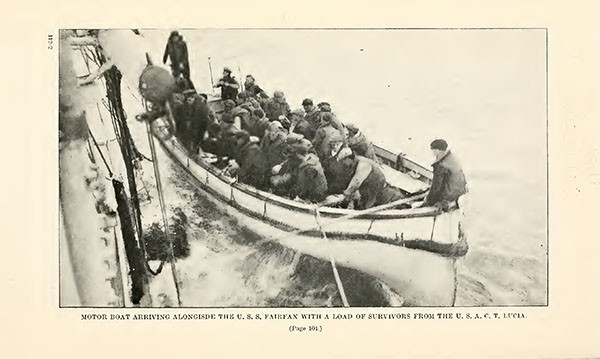

| Motor boat arriving alongside the U. S. S. Fairfax with a load of survivors from the U. S. A. C. T. Lucia | 112 |

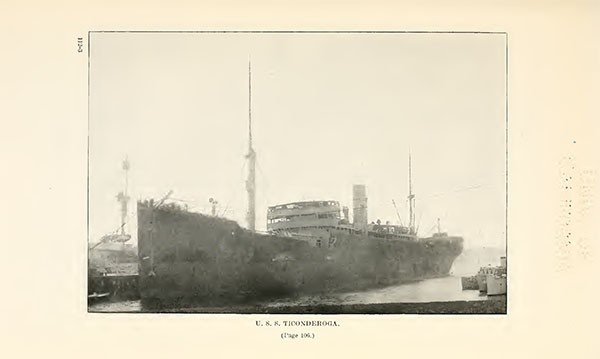

| U. S. S. Ticonderoga | 112 |

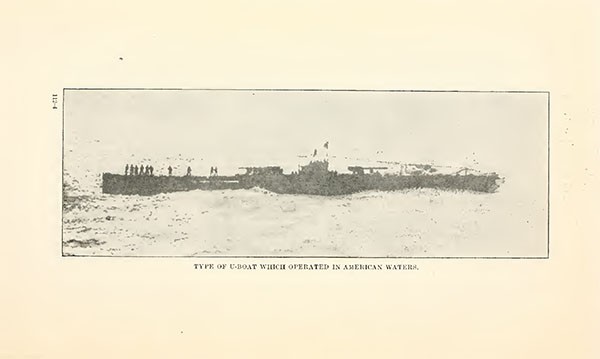

| Type of U-boat which operated in American waters | 112 |

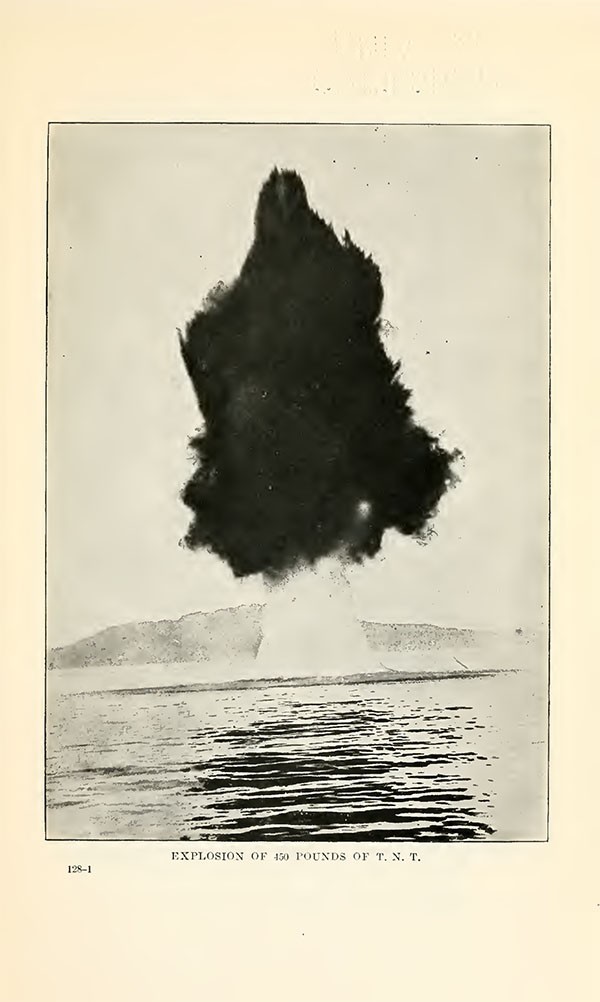

| Explosion of 450 pounds of T. N. T | 128 |

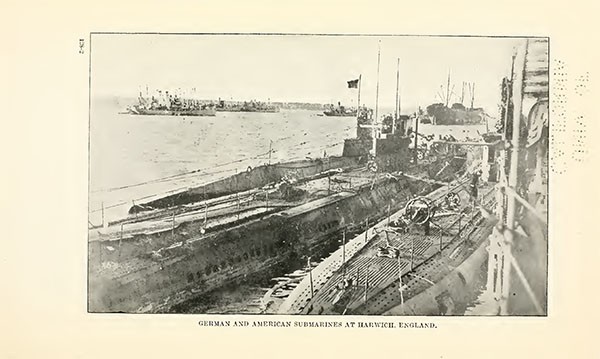

| German and American submarines at Harwich, England | 128 |

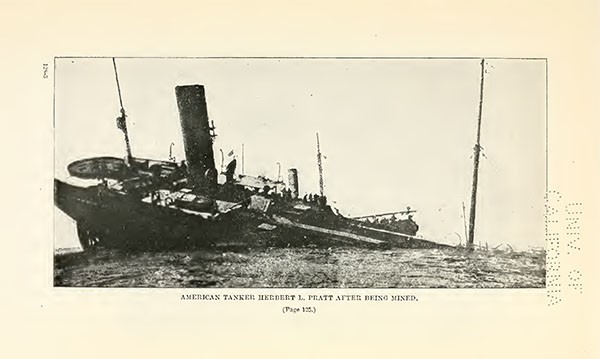

| American tanker Herbert L. Pratt after being mined | 128 |

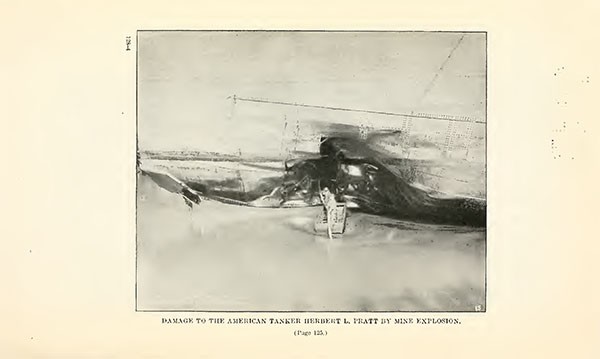

| Damage to the American tanker Herbert L. Pratt by mine explosion | 128 |

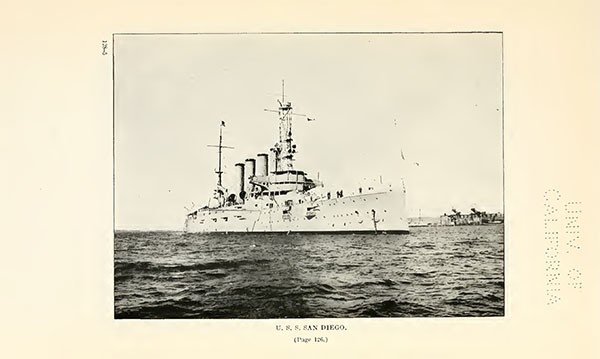

| U. S. S. San Diego | 128 |

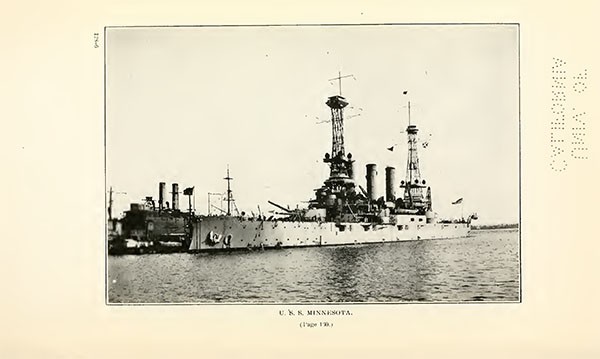

| U. S. S. Minnesota | 128 |

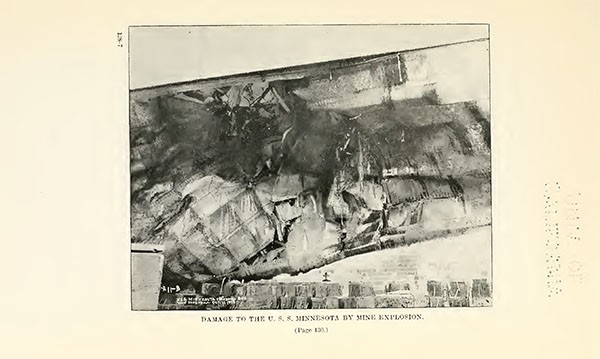

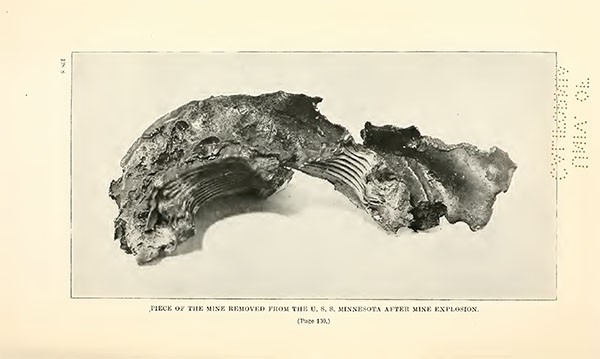

| Damage to the U. S. S. Minnesota by mine explosion | 128 |

| Piece of the mine removed from the U. S. S. Minnesota after mine explosion. | 128 |

--4--

____________

The preparation of the data for this article has occupied the time of a large part of the personnel of the Historical Section of the Navy Department for several months.

It has been attended with great difficulties. The reports of the sightings of submarines have been without number, and great care has been exercised to try to corroborate or validate the reports, and all have been rejected which do not answer such conditions as to accuracy. It is believed to be strictly accurate with the information available at the present time.

The two charts accompanying the report, which were prepared through the kindness of the United States Hydrographic Office, are intended to show as clearly as possible the operations of the submarines. On Chart No. 1 are printed the tracks of all the operating vessels. On Chart No. 2 is shown the location of all the mine fields with the number of mines in the area covered and when and how they were removed or destroyed.

The information received as to the number of mines in each area and the reports of their destruction leave little or no doubt that the Atlantic coast is free from any danger as to mines.

C. C. Marsh,

Captain, U. S. Navy (retired),

Officer in Charge, Historical Section, Navy Department.

December 12, 1919.

--5--

GERMAN SUBMARINE ACTIVITIES ON THE ATLANTIC COAST OF THE UNITED STATES AND CANADA.

______________

FOREWORD.

In defining in this article what should be considered as the American Atlantic coast, the meridian 40° west longitude is adopted arbitrarily to separate the submarine activities on the European coast from those on the American coast.

It is not believed necessary to go into the discussion based on opinions or surmises during the early years of the war in Europe as to whether or not an attack by the Germans would be made on the American coast. Therefore, the operations herein described are those which actually took place in the year 1918, with a description of the preliminary cruises made by the Deutschland and the U-53 in the year 1916.

Of course, it must remain a matter, more or less, of conjecture as to what was actually the object of the cruises made by the Deutschland in 1916. Apparently they were both purely commercial voyages. The voyage of the U-53 assumes more a character of a path-finding expedition. This vessel was a strictly combative vessel. It is interesting to note that on the arrival of this vessel at Newport, the commanding officer stated to the American submarine that he did not need or want a pilot to enter Newport, and that he wanted no supplies or provisions or materials of any kind.

In order to keep clear in the mind of the reader the dates and tracks of the several vessels, there is given here a condensed table of arrivals and departures.

Table showing arrivals and departures of German submarines off United States Atlantic coast or west of longitude 40°.

| Name or number. | Left Germany. | Arrived off Atlantic coast or longitude W. 40°. | Left Atlantic coast. | Arrived Germany. |

| Deutschland (1st) | June 14, 1916 | July 9, 1916 | Aug. 1, 1916 | Aug. 23, 1916. |

| U-53 | About Sept. 20, 1916 | Oct. 7, 1916 | Oct. 7, 1916 | Nov. 1, 1916. |

| Deutschland (2d) | Oct. 10, 1916 | Nov. 1, 1916 | Nov. 21, 1916 | Dec. 10, 1916. |

| U-151 | Apr. 14, 1918 | May 15, 1918 | July 1, 1918 | Aug. 1, 1918. |

| U-156 | About June 15, 1918. | July 5, 1918 | Sept. 1, 1918 | Struck mine in North Sea about Nov. 15, 1915 sunk. |

| U-140 | About June 22, 1918. | July 14, 1918 | do | Oct. 25, 1918. |

| U-117 | July, 1918, first part | Aug. 8, 1918 | do | In October, 1918, was towed in. |

| U-155 (formerly the Deutschland). | August, 1918, first part. | Sept. 7, 1918 | Oct. 20, 1918 | Nov. 15, 1918. |

| U-152 | August, 1918, latter part. | Sept. 29, 1918 | do | Do. |

| U-139 | September, 1918, first part. | Did not get west of 43-40 N., 30-50 W. | Not on Atlantic coast. | Do. |

--7--

The appended Chart No. 1 gives in detail the cruises of all these vessels. These tracks and all the data accompanying them are in accordance with all the data available at this time. It is possible that further data in the future will possibly require some corrections, but the main facts are correct.

There is, therefore, given in the following pages a brief account of the commercial cruises of the Deutschland and the preliminary cruise of the U-53, and somewhat at length, the cruises of all the submarines that operated off the American coast. The cruise of U-139 is shown on the chart, but not referred to in the text, as she never got west of longitude 30-50 and therefore does not properly belong in the operations of the submarines off the United States Atlantic coast.

STEPS TAKEN BY THE NAVY DEPARTMENT TO PROTECT SHIPPING ALONG ATLANTIC SEABOARD.

Anticipating such attacks from German submarines, the Navy Department on February 1, 1918, appointed a special board to make recommendations as to the methods to be taken to provide for "defense against submarines in home waters." The report of the board, with certain alterations, was approved by the Chief of Naval Operations on March 6, 1918. (Note: Report in full of the special board, with alterations, will be found in the Appendix, page 143.) In accordance with the recommendations of this board, the following steps were taken:

1. Submarines placed and ready to operate as soon as information received of enemy:

Colon.

New York.

St. Thomas.

Long Island area.

Key West.

Boston.

Galveston.1

Halifax.1

Chesapeake.

2. Shipping:

(а) Shipping should be kept going with the least possible delay, at the same time taking all possible offensive measures to remove the danger.

(b) Approach routes adopted for Atlantic seaboard for westbound ships. Now in force for New York, Delaware, Chesapeake, and being extended to whole seaboard, including Caribbean and Gulf.

(c) Convoy lanes adopted and in force for all eastbound shipping. Aircraft escort convoys to 50-fathom curve and as far as possible beyond until dark. This escort is in addition to submarine chasers and destroyers.

(d) Coasting trade to hug the coast, keeping within 5-fathom curve. Only smaller and less valuable ships placed in coastal service. Coastal protections to be handled by districts through which shipping passes.

(e) Diversion of ships for entire Caribbean and Gulf coast. Shipping out of Gulf of Mexico to be routed north or south of Cuba as most expedient, depending on circumstances at time. Ships sail by day close in shore under protection patrol craft or at night by offshore diverted routes. Independent sailings to be adhered to unless situation becomes so acute as to warrant convoys.

_____________

1 Not yet effective.

--8--

3. War warnings:

Vested in Navy Department except such as inquire immediate action and are authentic. War warnings not to be given unless presumed to be authentic.

4. District defense:

(а) Nets and defensive mine fields; no offensive mines.

(b) Air patrol.

(c) Listening stations on lightships and elsewhere. Submarine bells stopped.

(d) Sweeping sendee at shipping points.

(e) Limited escort offshore by chasers and nine destroyers retained for purpose.

(f) Patrol craft at focal points to answer rescue calls.

5. Intelligence Section:

Coast patrols have been organized and system of communications perfected to obtain information of enemy.

Secret service has been expanded, particularly in Gulf and Caribbean areas, and Secret Service is in touch with British sendee.

6. Wireless:

All route-giving officers in Europe have been instructed to warn all shipping approaching Atlantic seaboard not to use wireless for communicating instructions.

DISPATCHES FROM FORCE COMMANDER IN EUROPE.

The following dispatches from the force commander in Europe, arranged chronologically, gave the Navy Department necessary information to prepare for and meet the attacks which followed;

April 28, 1917.—With regard to submarines entering and leaving their bases, and their approximate whereabouts while operating, the Admiralty is able to maintain information that is fairly exact.

Of the thirty-four mine U-boats two for some days were not located, and the Admiralty was on the point of informing us of the probability of their being en route to the United States when their whereabouts were discovered. It is the Admiralty’s belief now that at present none are likely to be sent over and that the present effort of the submarines which is successful will be kept up off the Channel entrance.

April 11, 1918 (No. 6352) (quoted in part).—The Department will be kept supplied with all information obtainable here as to the probability of hostile operations on home coast.

May 1, 1918 (7289).—Admiralty informs me that information from reliable agents states that a submarine of Deutschland type left Germany about nineteenth April to attack either American troop transports or ships carrying material from the States.

So far as known the Germans formed conclusions that: Nantucket Shoals and Sable Island direct to Europe.

Second: Material transports go from Newport News to a point south of Bermuda and then to Azores and thence to destination.

It is thought that the submarine is taking a northern route across Atlantic, average speed five knots.

None of new class of cruising submarines ready for service.

Admiralty experience with Deutschland class establishes following conclusions: They generally operate a long distance from shore and seldom in less than one hundred fathoms.

Their single hulls are very vulnerable to depth-charge attack.

They rarely attack submerged.

There is but one known instance of attack against convoy and but two of torpedo attack against single vessels, one being unsuccessful. They attack by gun fire almost exclusively.

The most effective type to oppose them is the submarine.

They shift their operating area as soon as presence of submarine is discovered. Admiralty requests Admiral Grant be given a copy of this cablegram.

--9--

May 15,1918 (7289).—Information contained in this cable is given me by the British Admiralty and is necessarily somewhat paragraphed for transmission, but I have every reason to believe it is authentic. There appears to be a reasonable probability that the submarines in question may arrive off the United States coast at any time after May twentieth and that they will carry mines.

English experience indicates the favorite spot for laying mines to be the position in which merchant ships stop to pick up pilots. For instance, for Delaware Bay the pilots for large ships are picked up south of the Five Fathom Bank Light Vessel. This in our opinion is one of the most likely spots for a submarine to lay mines.

As regards information possessed by Germany on subject of antisubmarine patrol. They have from various neutral sources information that a patrol is maintained off most of the harbors and especially off Chesapeake Bay. A neutral has reported that the patrol extends as far as Cape Skerry.

It should be noted that except for mine laying, submarines of this class always work in deep water and that the Germans have laid mines in water in depths up to seventy fathoms. So far as is known there is no reason why they should not lay mines in depths up to ninety fathoms.

The foregoing completes the information furnished by British Admiralty. The following is added by me.

There are circumstances which render it highly important that nothing whatever should be given out which would lead the enemy even to surmise that we have had any advance information concerning this submarine, even in the event of our sinking her, and that such measures as are taken by the department be taken as secretly as possible and without public disclosure of the specific reasons.

I venture to remind the department in this connection that the employment of surface vessels to patrol against this submarine would probably result at best in merely driving her from one area to another, whereas the employment of submarines against her might lead to her destruction. It is suggested that having estimated her most probable areas of operation submarines be employed in a patrol as nearly stationary as may be, some of them covering the point south of Five Fathoms Bank Light Vessel, remaining submerged during the day with periscopes only showing. Of five submarines certainly destroyed in four days three were torpedoed by British submarines.

June 4, 1918—(9029).—It is practically certain that there is but one submarine on Atlantic coast, which is probably U-151.

June 7, 1918—(9120).—Military characteristics of U-151 from latest Admiralty information as follows:

Length 213 feet 3 inches breadth 29 feet 2 inches surface draft 14 feet 9 inches displacement surface 1700 tons submerged 2100 tons Engine 1200 horsepower speed 11 knots and a half surface speed 8 knots submerged fuel stowage 250 tons including stowage in ballast tank, endurance surface 17,000 miles at 6 knots submerged 50 miles at 7 knots armament 2-5-9 guns two 22 pounders one machine gun six torpedo tubes 4 bow 2 stem complement 8 officers 65 men: U-151 is converted mercantile submarine Deutschland type commander probably Lieutenant Commander Kophamel formerly in command of Pola submarine flotilla. In cruising last from September 10th to December 20th approximately U-151 was out over 100 days during this period 9 steamers and 5 sailing vessels total 45,000 tons sunk by gunfire, about 400 ammunition carried for each gun, limited number of torpedoes carried—maximum of 12. Submarine may be equipped to carry and lay about 40 mines.

June 29, 1918—(357).—Second cruiser submarine at sea. At present off west coast of Ireland. Her field of operation not yet known. Can not reach longitude of Nantucket before July fifteenth. Shall keep Department informed.

July 5, 1918—(655, our 357).—Enemy cruiser submarine outward bound, reported July 4 about 45 N. 30 W. proceeding southwesterly.

--10--

July 24, 1918.—Admiralty has received reliable information indicating that U-156 is intended to operate in Gulf of Maine but if foggy there to shift operations off Delaware.

July 26, 1918.—Admiralty report on reliable authority that harbor works, cranes, etc., at Wilmington are considered by Germans as favorable objectives for bombardment. This and other similar information is transmitted for such use as the department can make of it although apparently of not very great value.

August 1, 1918.—It is considered probable by Admiralty that a new mine-laying type submarine is on its way to American coast, and that possibly she is the one engaged by S. S. Baron Napier on July 26th in lat. 45-26 N. long. 32-56 W. at 0838. It is estimated this submarine can reach longitude Nantucket Lightship August 2nd. It is said that this type is a great improvement over U-71-80, larger than ordinary U-boats and carries following armament: One six-inch gun, one four-inch gun, two anti-aircraft guns, forty-fives. Also carries torpedoes but number of tubes unknown.

August 6, 1918.—Following cable received by British commander in chief "As submarines reported western Atlantic are at present between New York and Chesapeake Bay area, vessels from UK below speed 13 knots are being routed north of area if bound New York, south if bound Chesapeake Bay and north or south if bound Delaware Bay latter being sent by X or Z routes respectively if necessary and then hug coast. Latter case will be specified in report sent in accordance with paragraph 8 approaching routes." As the agreement with Navy Department is that after general plans meet with joint approval we will handle the diversion routes at this end for westbound ships, this cable does not accord. It happens in this particular case to route ships direct through area of operations of the only two submarines at present on this coast. British C.-in-C. concurs in general scheme that westbound diversion better be handled from this end.

August 7, 1918.—We feel so certain that mine-laying submarine will operate in Vineyard Sound and Nantucket Sound August 30 that counter measures in mining are recommended.

August 9, 1918.—Admiralty informs that two converted mercantile type submarines will probably leave Germany middle of August for American coast. One of them will probably lay mines east of Atlantic City and Currituck. The other off St. Johns, Newfoundland, Western Bay, Newfoundland and Halifax. These submarines estimated to reach American waters about second week of September.

August 10, 1918.—Return routes of submarine now on American coast expected to be somewhat as follows: Submarine off Cape Hatteras at present by same return route as U-151. Submarine off Halifax at present approximately along parallel 44 north from longitude Halifax to about 50 degrees west. Mine-laying submarine after laying her mines expected to operate between Cape Race and Halifax.

September 2, 1918.—Return route of mine-laying submarine now off American coast expected somewhat as follows: Vicinity Cape Race through an approximate position 54 degrees north 27 degrees west.

September 9, 1918.—S. S. Monmouth reports that on September 7th she was chased in about 43.00 north 45.50 west. Should this report prove reliable submarine would be one of two converted mercantile type which were expected to sail from Germany about the middle of August and she could reach the American coast about September 15th. It is known that the other had not left Germany on September 2nd.

September 16, 1918.— U-152 believed to be proceeding to America, appears to have been submarine which sunk Danish S. V., Constanza 62.30 N. 0.35 W. at 1400 September 13. She is expected to operate to southward of steamer route and lay mines east Atlantic City and southeast Currituck. It is estimated she can reach longitude Nantucket first week October.

October 3, 1918.—Not for circulation. It appears that U-152 was in about 44 degrees north 39 degrees west, September 30th and is not likely therefore to reach

--11--

longitude Nantucket before about October 12th. Evidently U-139 was submarine which sunk two ships by gunfire in about 45.30 north 11.00 west October 1st and is therefore not proceeding America at present. Her commanding officer Arnauld de 1a Periere is firm believer in attack by gunfire.

In addition to the above dispatches the following letter from the force commander in Europe was received.

U. S. Naval Forces Operating in European Waters,

U. S. S. "Melville," Flagship,

30 Grosvenor Gardens, London, S. W., April 30, 1918.

Reference No. 01. 1641G.

From: Commander, U. S. Naval Forces in European Waters.

To: Secretary of the Navy (Operations).

Subject: Areas of Operations of Enemy Submarines.

Reference: (a) My cable #6352 of 11 April.

1. Submarines along Atlantic seaboard.—Since the beginning of submarine warfare it has been possible for the enemy to send a submarine to the Atlantic seaboard to operate against allied shipping. The danger to be anticipated in such a diversion is not in the number of ships that would be sunk, but in the interruption and delays of shipping due to the presence of a submarine unless plans are ready in advance to meet such a contingency.

A more serious feature is that the department might be led to reconsider its policy of sending antisubmarine craft abroad. It is quite possible for the enemy to send one or more submarines to the Atlantic seaboard at any time. The most likely type of submarine to be used for such operations would be the cruiser submarine.

2. Cruiser submarine.—At the present time there are only 7 cruiser submarines completed. All of these are of the ex-Deutschland type, designed originally as cargo cruisers and now used to assist in the submarine campaign. Ten others of greater speed have been projected, but none have been completed, and the latest information indicates that the work on these vessels is not being pushed. This is rather to be expected owing to the small amount of damage done thus far by cruiser submarines. These submarines sink only 30,000 to 40,000 tons of shipping in a four-months’ cruise.

3. Cruiser submarines now in sendee make only about 11 1/2 knots on the surface, with perhaps a maximum of 7 knots submerged. They handle poorly under water and probably can not submerge to any considerable depth. On account of their large size they are particularly vulnerable to attack by enemy submarines. It is probably for this reason that the cruiser submarine has always operated in areas well clear of antisubmarine craft. If this type of vessel proceeded to the Atlantic seaboard it would undoubtedly operate well offshore and shift its areas of operations frequently. Thus far, with one exception, which occurred a few days ago, the cruiser submarine has never attacked convoys and has never fired torpedoes in the open sea, although vessels of this type have been operating for 10 months. All attacks have been by gunfire, and as these cruiser submarines are slow, they can attack with success only small, slow, poorly armed ships.

4. If cruiser submarines are sent to the North Atlantic seaboard no great damage to shipping is to be anticipated. Nearly all shipping eastbound is in convoy and it is unlikely that any appreciable number of convoys will be sighted, and if sighted will probably not be attacked. The shipping westbound is independent, but is scattered over such a wide area that the success of the cruiser submarine would not be large, and war warnings would soon indicate areas to be avoided.

[Note.—Later evidence indicates two cases of attack against single ships; in one case the vessel was struck and the other missed by two torpedoes.—Wm. S. S.]

--12--

5. As there are only 7 cruiser submarines built, we are able to keep very close track of these ships. At the present time one of these vessels is operating off the west coast of Spain, en route home, two are in the vicinity of the Canaries, one is in the North Sea bound out, and three are in Germany overhauling. I have the positions of all of these cruiser submarines checked regularly, with the idea of anticipating a cruise of any of these vessels to America. These vessels are frequently in wireless communication with one another, as well as with the small submarines, and they receive messages regularly from Nauen. Their attacks against ships furnish an additional method of checking their positions, and I hope that we will be able to keep an accurate chart of all the cruiser submarines, so as to be able to warn the department considerably in advance of any probable cruise of these vessels out of European waters. At the moment the only one that might cross the ocean is the one now coming out of the North Sea, as the other three have been out too long to make a long cruise likely.

6. Small submarines.—There is greater danger to be anticipated from the small submarine—that is, submarines of a surface displacement not exceeding about 800 tons. These vessels can approach focal areas with a fair degree of immunity, and can attack convoys or single ships under most circumstances. The number of torpedoes carried by these vessels is small, however, not exceeding 10 or 12, and the damage by gunfire would not be serious except to slow, poorly armed ships.

7. There seems little likelihood, however, that small submarines will be sent to the Atlantic seaboard. These vessels would have to steam nearly 6,000 miles additional before arriving at their hunting ground. This would mean a strain on the crew, difficulty of supplies and fuel (although their cruising radius is sufficient), absence from wireless information, liability to engine breakdown, unfamiliarity with American coast, and so forth, all for a small result on arriving on the Atlantic seaboard.

8. The small submarines at present operating around the United Kingdom can discharge their torpedoes and start home after about 10 days’ operations. In one case, U-53, which is considered a remarkably efficient submarine, exhausted all torpedoes after 4 days’ operations in the English Channel.

9. It is certain that if the enemy transfers his submarine attack in any strength to America the submarine campaign will be quickly defeated. The enemy is having difficulty in maintaining in operation under present conditions any considerable number of small submarines. The average number around the United Kingdom at any time does not exceed about 10. The number is not constant but seems to be greater during periods of full moon.

10. Declared zones.—If submarines are to operate regularly on the Atlantic seaboard, it is quite probable that the enemy will make a public declaration extending the present barred zones. Public declarations were made January 31, 1917, setting limits to the barred zone and these were extended by proclamation on November 22, 1917; January 8, 1918; January 11, 1918.

The barred zone around the Azores was declared in November, 1917, but a cruiser submarine operated in the vicinity during June, July, and August, 1917. The barred zone around the Cape de Verde Islands was declared January 8, 1918, but a cruiser submarine was operating off Dakar and in the Cape de Verde Islands in October and November, 1917.

It is evident that the enemy might at any time, without warning, send a submarine to the Atlantic seaboard; but for repeated operations there he would probably declare a barred zone. The declaring of such a zone open to ruthless warfare would weaken all the arguments used to justify the declaring of zones in European waters. We know that the enemy would produce arguments if the military advantage warranted, but the advantage of operations in America should prove so small as not to justify the embarrassment in extending the barred zone.

--13--

11. Future submarine operations.—The enemy is working on a new type of cruiser submarine with a speed of about 17 knots and the same battery as the Deutschland type. It is doubtful if this type of vessel will be handy under water and it is assumed that the bulk of her work will be done by gunfire.

Convoys escorted by cruisers would have little to fear from this type of submarine; but slow vessels poorly armed would be at a disadvantage. There is some doubt, however, as to whether a convoy of vessels, even without a cruiser escort, would not make it interesting for the submarine. Altogether the type is not greatly to be feared; but it is realized that this type of vessel would have considerable advantage over the present Deutschland type of cruiser submarine.

12. Around the United Kingdom the small submarine seems to be committed, for the present, at least, to inshore operations.

In February of 1917 there were some 30 sinkings to the westward of the 10th meridian, extending as far as the 16th meridian; but in February of this year there were no sinkings west of the 8th meridian. In March, 1917, there were 40 sinkings west of the 10th meridian, extending as far as the 18th meridian, but in March, 1918, there were no sinkings west of the 8th meridian. In April, 1917, there were 82 sinkings west of the 10th meridian, extending to the 19th meridian, while in April, 1918, practically all of the sinkings have been east of the 8th meridian, there being only 4 sinkings west of this meridian, operations not extending beyond the 12th meridian. So far as can be ascertained the enemy are concentrating efforts on building submarines of about 550 tons surface displacement.

13. The changes of areas in which submarines operate have undoubtedly been brought about by the introduction of the convoy system. Submarines operating well to the westward have small chance of finding convoys and have the disadvantage of having to attack convoys under escort if found. By confining their operations to areas near shore submarines enjoy the advantage of alway's having a considerable quantity of shipping in sight, as well as of finding many opportunities either by day or night to attack ships that are not under escort or in convoy. This is necessarily so, as there is a considerable coasting trade, cross-channel trade, and numbers of ships proceeding to assembly ports, all of which sailings are either unescorted or poorly escorted, and the submarine finds many opportunities for attack without subjecting himself to the danger that he would encounter in attacking escorted convoys.

14. It is hoped during summer weather to make a wider use of aircraft and small surface craft to protect coastal waters. Whether results will be successful enough to drive the submarine farther offshore remains to be seen. Every indication at present seems to point to the submarines continuing their operations near the coast.

15. The convoy system has given us a double advantage:

(a) It has brought the submarine closer in shore, where more means are available for attacking it.

(b) It has given protection and confidence to shipping at sea and made the submarine expose himself to considerable risk of destruction in case he elects to attack a convoy.

There are many indications that the submarine does not relish the idea of attacking convoys unless the escort is a weak one or a favorable opportunity presents itself through straggling ships or otherwise. About 90 percent of the attacks delivered by submarines are delivered against ships that are not in convoy.

16. Department’s policy.—I fully concur in the department’s present policy, namely, retaining on the Atlantic seaboard only the older and less effective destroyers, together with a number of submarine chasers and the bulk of our submarines. The submarine campaign will be defeated when we minimize the losses in European waters. If the enemy voluntarily assists us by transferring his operations to the Atlantic seaboard his defeat will come the sooner.

--14--

17. There is always the likelihood that a submarine may appear off the American coast. In the same manner, and this would be fully as embarrassing, submarines may begin operations west of the 20th meridian. The losses from all such operations must be accepted. We are certain that they will be small, and will not, for many reasons, be regularly carried on.

18. I see nothing in the submarine situation to-day to warrant any change in the present policy of the department. The situation is not as serious as it was a year ago at this time. The Allies are getting better defensive measures and are increasing offensive measures against the submarine, many of which are meeting with success. The help of the U. S. Navy has materially aided in defeating the submarine campaign. Present information indicates that we are at least holding our own with the submarine, and that submarine construction is slowing down rather than speeding up. During the first quarter of 1918 we sank 21 enemy submarines, and the best information indicates that not more than 17 new boats are commissioned. With the coming of better weather it is hoped that the situation will further improve.

19. There seems no sound reason for assuming that the enemy will transfer operations to the Atlantic seaboard, except possibly in the case of the cruiser submarines. These vessels have thus far done little damage to shipping, and it might prove good strategy to send them to our coast. In any event no great danger is to be anticipated from the present type of cruiser submarine, and adequate steps can be taken to deal with these vessels if they arrive on the Atlantic seaboard.

20. This letter was prepared prior to the dispatch of my cable No. 7289 of May 1.

THE DEUTSCHLAND.

The German submarine Deutschland, the first cargo-carrying U-boat, left Bremen with a cargo of chemicals and dyestuffs on June 14, 1916, and shaped her course for Heligoland, where she remained for nine days for the purpose, so her captain, Paul Koenig, stated, of throwing the enemy off the scent if by any means he should have learned what was being attempted.

The Deutschland was manned by a crew of 8 officers and 26 men— the captain, 3 deck officers, 4 engineer officers, 6 quartermasters, 4 electricians, 14 engineers, 1 steward and 1 cook.

Because of the danger by way of the English Channel, which was heavily netted, Capt. Koenig laid his course around the north of Scotland, and it was while he was in the North Sea that most of the submergence of the Deutschland (about 90 miles in all) took place. Usually the U-boat traveled on the surface, but on sighting any suspicious ship she would immediately submerge, occasionally using her periscopes. According to Capt. Koenig’s account, she was submerged to the bottom and remained for several hours.

The Deutschland resembled the typical German U-boat, but carried no torpedo tubes or guns. Her hull was cigar-shaped, cylindrical structure, which extends from stem to stern. Inclosing the hull was a lighter false hull, which was perforated to permit the entrance and exit of water and was so shaped as to give the submarine a fairly good ship model for diving at full speed on the surface and at a lesser speed submerged. The dimensions and some of the characteristics of the Deutschland were as follows: Length, 213 feet 3 inches;

--15--

beam, inner hull, about 17 feet; beam, outer hull, 29 feet 2 inches; depth, about 24 feet; depth to top of conning tower, about 35 feet; draft (loaded), 16 to 17 feet; displacement, light, 1,800 tons—submerged, 2,200 tons. Speed on the surface, 12 to 14 knots per hour—submerged, 7 1/2 knots; fuel oil capacity, 150 tons normal, and maximum 240 tons.

At 7 1/2 knots per hour she could remain submerged for 8 hours; at 3 1/2 knots per hour, 40 hours; at 1 1/2 knots per hour, 96 hours. Cargo capacity, about 750 tons. The Deutschland was equipped with two vertical inverted, four-cycle, single-acting, nonreversible, air-starting engines of 600 horsepower each; Diesel, Krupp type; diameter of cylinders, about 17 inches; shaft, about 6 inches.

She had two periscopes of the housing type, one in the conning tower and one offset, forward of the conning tower. Her electric batteries consisted of 280 cells in two batteries of 140 cells each. There were two motors on each shaft, each motor being 300 horsepower. She was fully equipped with radio apparatus, installed in a sound-proof room. The radio set was in forward trimming station. Two hollow masts were used, height about 43 feet above the deck; length of antenna, about 160 feet. Masts were hinged and housed in recesses in starboard superstructure. They were raised by means of a special motor and drum.

The interior of the cylindrical hull was divided by four transverse bulkheads into five separate water-tight compartments. Compartment No. 1 at the bow contained the anchor cables and electric winches for handling the anchor; also general ship stores and a certain amount of cargo. Compartment No. 2 was given up entirely to cargo. Compartment No. 3, which was considerably larger than any of the others, contained the living quarters of the officers and crew. At the after end of this compartment and communicating with it was the conning tower. Compartment No. 4 was given up entirely to cargo. Compartment No. 5 contained the propelling machinery, the two heavy oil engines, and the two electric motors. The storage batteries were carried in the bottom of the boat, below the living compartment. For purposes of communication, a gangway 2 feet 6 inches wide by 6 feet high was built through each cargo compartment, thus rendering it possible for the crew to pass entirely from one end of the boat to the other. The freeboard to the main deck ran the full length of the boat and was about 5 1/2 to 6 feet wide.

The cockpit at the top of the conning tower was about 15 feet above the water, there being a shield in front so shaped as to throw the wind and spray upward and clear of the face of the quartermaster or other observer. The forward wireless mast carried a crow's nest for the lookout.

--16--

The Deutschland made a safe passage through the North Sea, avoiding the British patrols. The rest of the trip was made principally on the surface. The weather was fine throughout. When off the Virginia Capes she submerged for a couple of hours because of two ships sighted of doubtful appearance. She passed through the Capes on July 9, 1916, at 1 o’clock a. m., and as she left Helgoland on June 23, the time of her trip was 16 days. The Deutschland arrived at Baltimore, Md., on Sunday, July 9, 1916. The total distance from Bremen to Baltimore by the course sailed was about 3,800 miles. Her cargo consisted of 750 tons of dyestuffs and chemicals, valued at about $1,000,000, and which was discharged at Baltimore.

The Deutschland remained at Baltimore 23 days and took on cargo for her return trip—a lot of crude rubber in bulk, 802,037 pounds, value $568,854.84; nickel, 6,739 bags, 3 half bags, weight 752,674 pounds, value $376,337; tin in pig, 1,785 pigs, weight 181,049 pounds, value $108,629.40. Goods were billed to Bremen and no consignee was stated.

She left Baltimore on August 1, 1916, and arrived at the mouth of the Weser River at 3 p. m., August 23, 1916. "The Berliner Tageblatt," of August 24, 1918, said:

The voyage was at the beginning stormy; later on was less rough. There was much fog on the English coast, and the North Sea was stormy. The ship proved herself an exceedingly good seagoing vessel. The engines worked perfectly, without interruption. Forty-two hundred (4,200) sea miles were covered, one hundred (100) under water.

She was made ready and reloaded with another cargo of dyestuffs and chemicals for her second voyage to the United States within a week. Her health certificate was issued by the American vice consul at Bremen on September 30, 1916. She was ready to go to sea again on October 1, 1916, but was held until October 10, 1916, for possible word concerning the Bremen. The last voyage to the United States covered 21 days, being somewhat retarded by hard weather. She arrived at New London, Conn., on November 1, 1916; discharged her cargo of dyestuffs and chemicals and, in addition, securities said to be to the value of 1,800,000 pounds sterling. Her return cargo was said to contain nickel and copper; 360 tons of crude nickel which had come from Sudbury, Canada, and had been purchased in 1914.

She left New London, Conn., on November 17, 1916, but half a mile from Race Rock Light in Block Island Sound, R. I., where the tide runs heavily, she rammed the American Steamship T. A. Scott, Jr., gross 36 tons, which sank in about three minutes. On account of the collision the Deutschland had to return to New London for repairs. She again left New London on November 21, 1916. Her voyage occupied 19 days, arriving at the mouth of the Weser on December 10, 1916.

--17--

Some time after her return to Germany she was converted into a warship and furnished with torpedo tubes and two 5.9-inch guns. Her war activities were continued as U-155.

The Deutschland as the U-155 left Germany about May 24, 1917, and operated principally off the west coast of Spain, north of the Azores, and between the Azores and the Madeira Islands; then under the command of Lieut. Commander Meusel, on a cruise which lasted 103 days, during which she sank 11 steamers and 8 sailing vessels, with a total tonnage of 53,267 gross tons.

She attacked by gunfire the American Steamship J. L. Luckenbach, 4,920 gross tons, on June 13, 1917, at 7.15 p. m., in latitude 44° N., longitude 18° 05' W., but the ship escaped.

Among the sailing vessels sunk was the American schooner John Twohy, 1,019 tons gross, which was sunk by bombs placed aboard, after her capture about 120 miles south of Ponta Delgada and approximately in latitude 35° 55' N., longitude 23° 20' W., on July 21, 1917, at 6 a. m.

Also the American bark Christiane, 964 tons gross, was sunk by bombs placed on board after her capture off the Azores and approximately in latitude 37° 40' N., and longitude 20° 40' W., on August 7, 1917, at 6 p. m. She returned to Germany about September 4, 1917.

The Deutschland again left Germany about January 16, 1918— Commander Eckelmann apparently having succeeded Lieut. Commander Meusel—on a cruise which lasted about 108 days, during which time she sank 10 steamers and 7 sailing vessels, with a total gross tonnage of 50,926 tons, viz, 2 British steamers (armed), 5 Italian steamers (armed), 2 Norwegian and 1 Spanish steamer (unarmed), 4 British, 2 Portuguese, and 1 Spanish sailing vessel. From the Norwegian Steamship Wagadesk, which was captured and afterwards sunk, she took 45 tons of brass, which she took back to Germany. During the cruise she operated between the Azores and Cape Vincent off the coast of Spain, and the entrance to the Straits of Gibraltar.

She returned to Germany about May 4, 1918.

In August, 1918, she began her famous cruise on the American coast.

VISIT OF THE GERMAN SUBMARINE U-53 TO NEWPORT, R. I., OCTOBER 7, 1916.

On October 7, 1916, between the two visits of the German commercial submarine Deutschland to the United States, the German submarine U-53 entered the port of Newport, R. I., under the command of Lieut. Hans Rose.

--18--

At 2 p. m. October 7 a code message was received from the U. S. submarine D-2, stating that a German man-of-war submarine was standing in. A few minutes later a Gorman submarine was sighted entering the harbor of Newport. The submarine was first sighted 3 miles east of Point Judith, standing toward Newport, and the D-2 approached and paralleled her course to convoy the German submarine while in sight of land. Upon arrival at Brenton Reef Lightship, the captain of the German submarine requested permission from D-2 to enter port, which permission was granted by the D-2. The German captain stated that he did not need a pilot. The D-2 convoyed the submarine into Newport Harbor. She was flying the German man-of-war ensign and the commission pennant and carrying two guns in a conspicuous position.

Upon approaching the anchorage the U-53, through the captain of the U. S. D-2, signaled the U. S. S. Birmingham, Rear Admiral Albert Gleaves commanding, requesting to be assigned to a berth. She was assigned to Berth No. 1, where she anchored at 2.15 p. m.

The commandant of the naval station, Narragansett Bay, R. I., sent his aide alongside to make the usual inquiries, but with instructions not to go on board, as no communication had yet been had with the health authorities. At 3 p. m. the commanding officer of the U-53, Lieut. Hans Rose, went ashore in a boat which he requested and which was furnished by the U. S. S. Birmingham. He called on the commandant of the Narragansett Bay Naval Station. He was in the uniform of a lieutenant in the German Navy, wearing the iron cross; and he stated, with apparent pride, that his vessel was a man-of-war armed with guns and torpedoes. He stated that he had no object in entering the port except to pay his respects; that he needed no supplies or assistance, and that he proposed to go to sea at 6 o’clock. He stated also that he left Wilhelmshaven 17 days before, touching at Heligoland.

The collector of customs located at Providence, R. I., telephoned and asked for information as to the visit of the German submarine, and when told that she intended to sail at 6 p. m., he stated that under the circumstances it not be practicable for either him or a quarantine officer to visit the ship.

Following the visit of the captain, the commandant sent his aide to return the call of the captain of the U-53 and to request that no use be made of the radio apparatus of the vessel in port.

The submarine was boarded by the aide to the commandant, and immediately afterwards the commander of destroyer force’s staff. In reply to inquiry the following information was obtained.

The vessel was the German U-53, Kapitän Lieut. Hans Rose in command. The U-53 sailed from Wilhelmshaven and was 17 days out. No stores or provisions were required and that the U-53

--19--

proposed to sail about sundown on the same day; that the trip had been made without incident, on the surface, and had passed to the northward of the Shetland Islands and along the coast of Newfoundland.

The following of interest was noted: Length above the water, about 212 feet; two Diesel Nürnberg engines, each of 1,200 horsepower; each engine had six cylinders; maximum speed, 15 knots; submerged speed, 9 to 11 knots.

The captain stated with pride that the engines were almost noiseless and made absolutely no smoke except when first starting. She had four 18-inch torpedo tubes, two in the bow and two in the stern; the tubes were charged and four spare torpedoes were visible. Each pair of tubes was in a horizontal plane. They could carry 10 torpedoes, but part of the torpedo stowage space was utilized to carry extra provisions. The torpedoes were short and they said their range was 2,000 yards. The guns were mounted on the deck, one forward and one aft. The forward gun looked to be about 4-inch and the after one about 3-inch—short and light. The muzzles were covered and water-tight. They had vertical sliding wedge breechblocks, with a gasket covering cartridge chamber water-tight. They carried a permanent sight with peephole and cross wires, and on it was a receptacle evidently to take a sighting telescope. The steel deflection and elevation scales, cap squares, etc., were considerably rusted. The guns were permanently mounted on the deck and did not fold down. A gyro compass with repeaters was installed. The control seemed to be similar to that of the American submarines. There were three periscopes, which could be raised or lowered, and the platform on which the control officer stood moved with the periscope; one was about 15 feet high above the deck and the others several feet lower. One of the periscopes led to the compartment forward of the engine room for the use of the chief engineer and the third was a periscope for aeroplanes. There was stowage space for three months’ supplies of all kinds. The complement consisted of the captain, the executive and navigating officer, ordnance officer, engineer, electrical and radio officer, and crew of 33 men. The officers were in the regulation uniform, new and natty in appearance. The crew wore heavy blue woolen knit sweaters, coats and trousers of soft, thin black leather lined with thin cloth, top boots and the regular blue flat cap. They were freshly shaved or with neatly close-trimmed beard or hair, all presenting a very neat appearance.

All the electrical machinery and appliances were manufactured by the Siebert Schumann Co., except the small motor generator, taking current from storage batteries and supplying electric lights which gave excellent illumination throughout the boat, and there was no trace of foul air anywhere.

--20--

The radio sending and receiving apparatus was in a small separate room on the starboard side. The radio generator was on the port side in the engine room.

There were two antennae—one consisted of two wires, one on each side about three-eighths of an inch in diameter, extending from the deck at the bow to the deck at the stern and up over supporting stanchions above the conning tower, with heavy porcelain insulators about 4 or 5 feet from deck at each end and from each side of the supporting stanchions. The other was an ordinary three-wire span suspended between the masts and was about 3 feet high on the starboard side. These masts were about 25 feet high and mounted outboard over the whaleback; were tapered, of smooth surface, hinged at the heel, each with a truss built out about 3 feet near the heel for leverage, to which secured, and from which led through guide sheaves along the side, a galvanized one-half inch wire rope for raising and lowering. The masts were hinged to lie along the top of the outer surface along starboard close to the vertical side plate of the superstructure. They claimed to have a receiving range of 2,000 miles.

A flush wood deck, about 10 feet wide amidships, extended the entire length. This was built of sections about 2 inches thick, each about 30 inches square and secured to the supporting steel framework by bolts. Each section had several holes about inches by 4 inches cut through to allow passage of the water. The sides of the superstructure framework were inclosed by thin steel plates reaching nearly to the hull. The inner body of the hull was divided into six watertight compartments. They had very little beam and suggested that a large amount of available space was devoted to oil storage.

There were three main hatchways—one from the conning tower to the central station, one into the forward living space, and the other into the after living space.

Patent anchors were housed in fitted recesses in the hull just above the torpedo tubes. Electric motor-driven anchor chain winch outside the hull under the bow superstructure. There was a galvanized-wire towing hawser about 1 1/4 inches in diameter, shackled to the nose leading aft along the port side of the hull, stoppered on with a small wire, to the port side of the conning tower, so that the heaving line fastened to its end could be hove from the conning tower. They had a small electric galley with coppers, etc. Small room for the commanding officer amidships forward of the central; officers’ room farther forward of same. Two-tier bunks about 18 inches wide for about half the crew in two other compartments. Hammocks for about half the crew. Small wash room nicely fitted and a toilet for the officers and another for the crew. The life buoys had a cork sphere, about 10 inches in diameter, attached by a long small line.

--21--

The vessel appeared very orderly and clean throughout. It was especially noticeable that no repair work whatever was in progress. All hands, except officers and men showing visitors through the boat, were on deck, where the crew were operating a small phonograph. The engineer officer said that U-53 was built that year, 1916.

The captain stated that he would be pleased to have any officer visit his ship and would show them around. This privilege was taken advantage of by a number of officers from the destroyer force, and the aid to the commandant. All the officers who visited the ship were much impressed by the youthfulness of the personnel, their perfect physical condition, and their care-free attitude. One or two observers thought that the captain seemed serious and rather weary, but all agreed that the other officers and the crew seemed entirely happy and gave no indication that they considered themselves engaged in any undertaking involving hazard or responsibility. The freedom with which the officers and crew conversed with visitors and their willingness to show all parts of the ship was surprising. They stated that they were willing to tell all that they knew and to show all they had, this to officers and civilians alike.

The officers spoke our tongue with careful correctness, though not fluently, and answered all questions except when asked their names, which they courteously declined to give. When one officer was asked by one of the visiting officers whether he spoke English, he replied, ;"No; I speak American." All hands were very military in deportment, and whenever a man moved on duty he went with a run. As the boat entered and left the harbor, the crew was lined up on deck, at attention, facing vessels they passed. Upon leaving, they faced about and after passing and saluting the destroyer tender Melville, the officers and crew waved them caps to the last destroyer as they passed. The U-53 got under way at 5.30 p. m. and stood out to sea. It was learned that a letter to the German Ambassador at Washington was entrusted to a newspaper representative and by him was posted.

On October 8, 1916, the day after leaving Newport, the U-53 captured and sunk the following vessels off the coast of the United States, viz:

The British S. S. Stephano, 3,449 tons gross, 2 1/2 miles E. by NE. of Nantucket Light Vessel. The Stephano had American passengers aboard.

The British S. S. Strathmore, 4,321 tons gross, 2 miles S. by E. from Nantucket Light Vessel.

The British S. S. West Point, 3,847 tons gross, 46 miles SE. by E. from Nantucket Light Vessel.

The Dutch S. S. Blommersdijk, 4,850 tons gross.

The Norwegian S. S. Chr. Knudsen, 4,224 tons gross.

--22--

It was thought possible Unit the U-53 was accompanied by one or two other U-boats, as other U-boats marked U-48 and U-61 were reported. It is, however, likely that the report of three submarines was due to Capt. Rose’s having his number "U-53" painted out and substituting other numbers. He did this on four separate occasions and finally came into Germany about November 1 under the number "U-61."

THE CRUISE OF THE U-151.

The U-151 2, a converted mercantile submarine of the Deutschland type, commanded by Kapitän Van Nostitiz und Janckendorf, sailed from Kiel on April 14, 191S. Although her route to the American Atlantic coast is not definitely known, it is probable that she followed the more or less recognized path later taken by other enemy cruiser submarines to and from America.3 The U-151 was first located early in May, when the office of Naval Operations, Washington, D. C., received the following message from Kingston, Jamaica:

U. S. steamer engaged enemy submarine 2 May, 1918, lat. 46° N., long. 28° W.4

The position indicated by this message was a point about 400 miles north of the Azores.

On May 15, 1918, the British steamer Huntress, 4,997 gross tons, bound for Hampton Roads, reported that she had escaped a torpedo attack made by an enemy submarine in latitude 34° 28' N., longitude 56° 09' W.5

These reports were considered authentic. All section bases were ordered to be on the alert, and the following message was broadcasted by the Navy Department on May 16, 1918:

Most secret.—From information gained by contact with enemy submarine, one may be encountered anywhere west of 40 degrees west. No lights should be carried, except as may be necessary to avoid collision and paravanes should be used when practicable and feasible. Acknowledge, Commander in Chief Atlantic Fleet, Commander Cruiser Force, Commander Patrol Squadron, Flag San Domingo, Governor Virgin Islands, Commandants 1st to 8th, inclusive, and 15th Naval Districts. 13016.OPNAV.

The first definite information of the activity of the German raider off the American coast was received by radio on May 19 at 12.14 p. m. The Atlantic City radio intercepted an S O S from the American steamship Nyanza, 6,213 gross tons, advising that she was being gunned and giving her position as latitude 38° 21' N., longitude 70°

_____________

2 The Germans classified their submarines in three general groups: The U or ocean-going type, the UB, or coastal type, and the UC, or mine-laying type. The classification UD was made by the British Admiralty to designate the converted mercantile submarines, the Deutschland type, from others of the U class.

3 This in spite of the fact that the crew of the U-151 stated to prisoners that her route had been via the Danish West Indies, a Mexican port, and then up the Atlantic coast to her field of operations.

4 The identity of this vessel has not been established.

5 This position is about 1,000 miles east of Cape Hatteras.

--23--

W., or about 300 miles off the Maryland coast. That the submarine was proceeding westward into the waters of the fourth naval district was indicated by information received on May 20 from the master of the J. C. Donnell, who, upon his arrival at Lewes, Del., on that day, reported that this ship’s radio had intercepted a message from the American steamship Jonancy, 3,289 gross tons, on May 19, saying that she was being gunned and giving her position as 150 miles east of Winter Quarter Shoals. On May 21, at 11.15 a. m., the Canadian steamer Montcalm relayed a message to Cape May radio station from the British steamship Crenella, 7,082 gross tons, stating that a submarine had been sighted in latitude 37° 50' N., longitude 73° 50' W., a point about SO miles off the Maryland coast. Six shots were fired at the Crenella by the submarine, but no hits were registered. At 1 p. m. on the same day the Montcalm reported that the Crenella had escaped.

The information that merchant vessels had reported a German submarine proceeding toward the coast was immediately disseminated to the section bases, to the forces afloat, and to the commanders of the coast defenses. In addition to the regular patrols, detachments of sub-chasers were established and ordered, whenever practicable, to proceed to the positions given in S O S messages.

Subsequent information indicated that as the submarine approached the American coast she picked as her prey sailing vessels not likely to have means of communication by radio, and in attempting further to conceal her presence in the vicinity took as prisoners the crews of the first three vessels she attacked, the Hattie Dunn, the Hauppauge, and the Edna.

On May 26, 1918, the Edna, an unarmed American schooner of 325 gross tons, owned by C. A. Small, Machias, Me., was found abandoned near Winter Quarter Shoals Lightship. She was taken in tow by the Clyde Line steamer Mohawk. The schooner’s towing bitts carried away and she was abandoned by the Mohawk; later she was picked up by the tug Arabian and towed to Philadelphia, arriving May 29. An investigation made by the aide for information, fourth naval district, disclosed the presence of two holes, 20 to 30 inches in diameter, in the vessel’s hold just above the turn of the bilge, evidencing an external explosion.6 A time fuse was found, the extreme end of which had been shattered by an explosion. Thus, the naval authorities received the first visual evidence of the work of an enemy raider off the coast.

In interviews with the survivors of the Edna, who had been held as prisoners aboard the submarine until June 2, it was learned that the damage to the Edna had been inflicted by the enemy in an attempt to sink her, and that the vessels, Hattie Dunn and Hauppauge, had

_______________

6 See the story of Capt. Gilmore, of the Edna, p. 27.

--24--

been sunk earlier on the same day, May 25. At the same time definite information was gained concerning the identity and military characteristics of the submersible. Although there were no identifying marks, letters, or numbers on the hull, M. H. Sanders, mate of the Hauppauge, stated that he saw the letter and figures “U-151” at the foot of several bunks and on the blankets aboard the submarine; T. L. Winsborg saw the letter and figures on the hammocks and on the machine guns; other survivors noticed that tools, furniture, and equipment were similarly marked. These facts, together with a comparison of the photograph of the submarine known to have sunk the first ships, with photographs and silhouettes of submarines obtained from official sources, proved conclusively that the raider operating off the American coast was the U-151 of the Deutschland type. The description of the submarine as given by Capt. Gilmore of the Edna and Mate Sanders of the schooner Hauppauge, and by other survivors, was most complete. This description, together with the information gained from official sources, furnished the basis for the dissemination, on June 7, to all naval forces of the following data concerning the U-151:

Identity, U-151, Deutschland type of converted mercantile submarine, complement; 8 officers and 65 enlisted men; length, 213 feet 3 inches; breadth, 29 feet 2 inches; surface draft, 14 feet 9 inches; displacement (surface), 1,700 tons; displacement (submerged), 2,100 tons; engine, 1,200 H. P.; speed (surface), 11§ knots; speed (submerged), 8 knots; fuel storage, 250 tons, including storage of ballast tank; endurance (surface), 17,000 miles at G knots; endurance (submerged), 50 miles at 7 knots; armament, two 6-inch guns, two 22-pounders, one machine gun, six torpedo tubes—four in bow and two in stem; ammunition capacity, 400 rounds per each gun; maximum number torpedoes, 12; many time fuse bombs; equipped to carry and lay 40 mines; a two-kilowatt wireless set, and a portable set which could be rigged up in a few hours on a captured merchant vessel to be used as a decoy or as a mother ship. Submarines “U-converted mercantile type” are especially fitted with submarine cable-cutting devices.

That the U-151 carried a cable-cutting device is apparently borne out by the statements of Capt. Sweeney, of the Hauppauge, and of Capt. Holbrook, of the Hattie Dunn, describing a mysterious device on the deck of the submarine. Along the center line of the ship’s deck, fore and aft, there were two stanchions about 70 feet apart, around each of which a coil of 48 turns of 3/8-inch wire rope was taken. On one end of this rope, which was covered only with a coat of heavy grease, there was an eye splice, and at the other end there was a cable attached to some instruments and appliances hidden and carried in sets abreast of and on each side of the conning tower. Capt. Holbrook stated that on one occasion when the prisoners were below deck they noticed that the submarine gave a sudden lurch and listed on beam end. He was unable to state the cause of the lurch. As far as he could make out, the submarine was at the time, May 28,

--25--

off New York Harbor. It is possible that this lurch may have been caused by the submarine’s grappling with or cutting cables leading from New York. As a matter of fact, one cable to Europe and one to Central America were cut 60 miles southeast of Sandy Hook, on May 28, 1918. This device had disappeared when the prisoners came on deck on the morning of May 30.

The statements of survivors also furnished details concerning the procedure and the methods employed by the U-151 in her attack upon vessels. The first sinking by the U-151 off the American coast occurred when the Hattie Dunn, an unarmed American schooner of 435 gross tons, was attacked off Winter Quarter Shoals at 10.10 a. m. on May 25. Capt. C. E. Holbrook, master of the Hattie Dunn, tells the following story:

The Hattie Dunn sailed from New York on May 23, 1918, en route for Charleston, S. C., in ballast. On Saturday, May 25, about 10.10 a. m., when about 15 to 25 miles off Winter Quarter Lightship, I heard a cannon go off; I looked and saw a boat, but thought it was an American. That boat fired once; I started my ship full speed to the westward. He fired again, and finally came alongside and said:

"Do you want me to kill you?"

I told him I thought his was an American boat. He told me to give him the papers, and get some foodstuff. He then wanted me to get into his small boat, but I was anxious to get ashore, so I immediately got into one of my own boats and shoved off. He halted me because he did not want me to get ashore. He then put a man into my boat so that I would come back to the submarine. An officer and other men from the German submarine then boarded the schooner and after placing bombs about her ordered the crew of the Hattie Dunn to row to the submarine, which we did. The schooner was sent to the bottom by the explosion of the bombs in latitude 37° 24' N., longitude 75° 05' W. The second officer in command aboard the submarine gave me a receipt for my ship.

There were no casualties. The weather was fine and clear, the sea was calm.

We kept aboard the submarine until the morning of June 2. While we were aboard, the second officer and others of the submarine crew wrote some letters and gave them to me to mail. I told them I would not mail the letters if there was anything in them detrimental to my country. I handed them to the first naval officer I came to.

A few minutes later the U-151 made another attack in the same vicinity, which culminated in the sinking of the Hauppauge, an unarmed American schooner of 1,446 gross tons, owned and operated by R. Lawrence Smith, New York. Capt. Sweeney, master of the Hauppauge, gave the following information: