United States. 1947. Building the Navy's bases in World War II; history of the Bureau of Yards and Docks and the Civil Engineer Corps, 1940-1946. Washington: U.S. Govt. Print. Off.

The Navy Department Library

Building the Navy's Bases in World War II

Volume II (Part III, Chapter 26)

Chapter XXVI

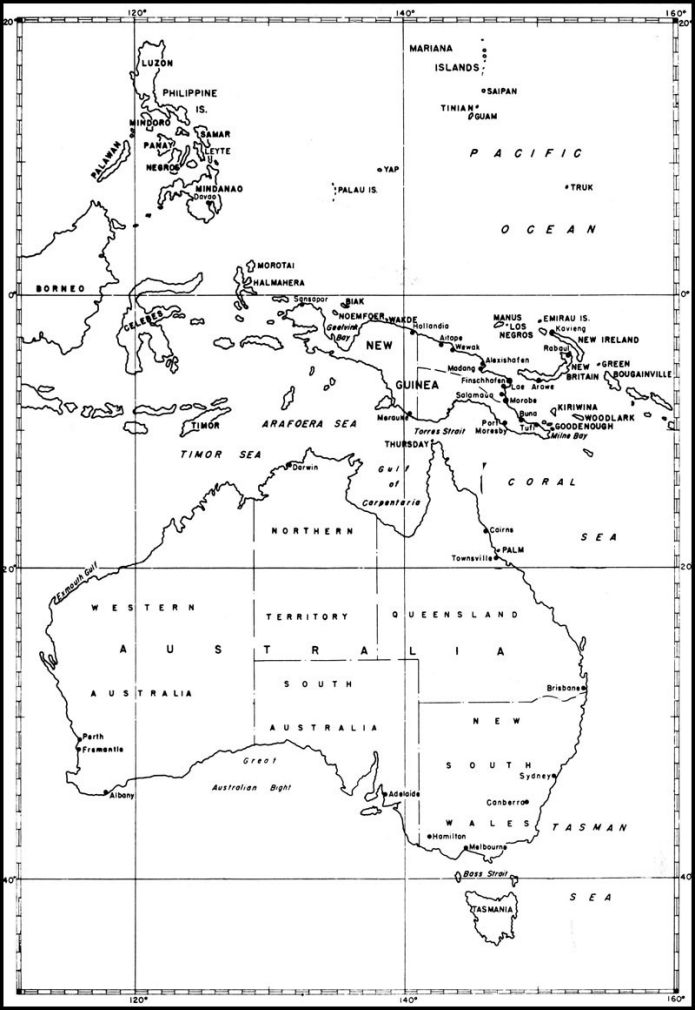

Bases in the Southwest Pacific

When the Japanese scored their initial successes in the Far East, the naval forces of the Allied powers retreated, fighting, through the Netherlands East Indies until they had fallen back to Australia. Refugee units and personnel from our Asiatic fleet began to arrive at northern and western Australian ports within a few weeks of the opening of the war.

The ensuing months showed a picture of considerable confusion. Cargoships, carrying supplies to destinations which had fallen to the enemy while they were en route, put in at Australian ports and were unloaded. The accumulation of such distress cargo created almost impossible problems of identification, storage, and protection, and much misdirection and loss of valuable material resulted. Gradually, however, storage space was found for Navy material in Brisbane, Sydney, and Melbourne on the east coast and at Fremantle on the west.

The major concern, however, was the development of facilities in Australia which would permit that island continent to serve as a secure base to support naval and military counter-offensives against the enemy. In April 1942, immediately after the command areas in the south Pacific were redefined, a board consisting of Australian and American representatives was convened to determine base-development requirements. It was understood from the beginning that Australia would provide the necessary construction labor and operating personnel and that the United States would be called on to supply only the materials and equipment that could not be obtained locally. Within a few weeks, plans had been formulated which appeared to satisfy the estimated requirements of the combined services and requests were forwarded to the United States for the materials and equipment which would not be available in Australia. Shipments were slow to arrive, however, and in the meanwhile the outcome of the battles of the Coral Sea and Midway had so changed the military situation that a thorough revision of the plans for base development was in order.

The general effect of the change was to shift major developments northward. The ports of Adelaide and Albany ceased to be important from a military standpoint, and Melbourne declined in importance as a center of activity after naval headquarters for Australia was moved to Brisbane in July 1942.

For the remainder of this first year of the war, work proceeded slowly on naval facilities, handicapped by Australia's severe manpower shortage. Base facilities for submarine maintenance and repair were put under way at Brisbane and Fremantle; PT-boat bases were developed at Cairns and at Darwin; repair and maintenance facilities to service escort vessels were established at Sydney and Cairns; and naval air bases were developed at Brisbane, at Perth, and on Palm Island, just northwest of Townsville. Moreover, a considerable amount of storage and supply space was obtained by lease of existing Australian facilities.

A few advance operating bases, particularly for submarines and PT boats, were also established during this period, at Merauke, on the southern coast of Dutch New Guinea, on Thursday Island in Torres Strait, and in Exmouth Gulf.

By the end of 1942, however, it was apparent that the shortage of manpower and materials in Australia was hampering the base-development program beyond the point of tolerance, and in January 1943 a request was made that naval construction battalions be assigned to expedite the construction work. In response to that request the 55th Battalion arrived in Brisbane on March 24, 1943.

In the meanwhile, it had been necessary to establish advance bases in New Guinea. In the earliest days of the war, Port Moresby on the southern coast of that island assumed considerable importance as a military debarkation point and as a destination of supplies for the forces resisting the

--277--

--278--

Japanese advance. Existing facilities were augmented by the Australians during 1942 and early 1943, particularly in connection with fuel storage. Milne Bay, at the eastern tip of New Guinea, had been occupied by Allied forces in the early summer of 1942 and a bomber strip had been built to permit air operations against enemy shipping and positions on the north coast.

In September 1942, the Japanese made a strong attempt against Port Moresby, their forces succeeding in pushing across the eastern New Guinea peninsula to within 30 miles of the port. Reinforcement of Allied ground forces and strong air support turned back the advance, however, and the enemy fell back upon his main base at Buna, on the north coast. A campaign by Allied forces to eject the Japanese from that base followed, its success signalized by the capture of Buna itself on December 14. Early in 1943 the northeast coast of New Guinea, from Buna, south, was finally cleared of the enemy.

In late 1943, after the Buna campaign had come to an end, our forces landed on Woodlark Island and Kiriwina Island, off the eastern end of New Guinea, with the intention of establishing air bases. Parts of the 60th and 20th Battalions participated in the landing on Woodlark; immediately thereafter the 60th set about the construction of the projected air strip. Army engineers undertook the airfield construction on Kiriwina, and in September, a detachment of the 20th Battalion was sent from Woodlark to Kiriwina to lend them assistance.

With Port Moresby, Milne Bay, Buna, Woodlark, and Kiriwina firmly in our possession, our next move was directed against the enemy's positions at Salamaua and Lae. Combining an overland drive from Buna and an amphibious assault, our forces succeeded in capturing both enemy bases by the middle of September. Maintaining the momentum of our advance, Finschhafen was taken on October 2, and by February 1944, all of the Huon peninsula was in our hands.

In November 1943, most of the 60th Battalion left Woodlark Island for Finschhafen to assist in the construction of an Army air strip and to build a naval base. During the months immediately succeeding, three more battalions arrived at Finschhafen to aid in establishing the then-forwardmost base in New Guinea.

The next move in our Southwest Pacific offensive was northward, directed toward the enemy's bases at Rabaul and Kavieng. On December 15, 1943, Army troops made landings on the southwest coast of New Britain, near Arawe, and on December 26, the 1st Marine Division went ashore at Cape Gloucester at the island's western tip. The 19th Construction Battalion was attached to the Marines and accompanied them in their landing.

In the meanwhile, our forces had established their positions in Bougainville, in the Solomons, to the east of Rabaul. Encirclement of that major Japanese base was carried forward another step by our invasion and occupation of the Admiralty Islands. On February 29, 1944, advance elements of the 1st Cavalry Division landed on the island of Los Negros on a reconnaissance mission. Finding the area lightly held, the division's mission immediately became one of invasion and occupation. Among the reinforcing elements sent ashore on March 2 were detachments from four of the construction battalions of the 4th Naval Construction Brigade, the 40th, 46th, 78th, and 17th. Development of Los Negros and Manus, the principal islands of the Admiralty group, during the succeeding months, yielded the largest and most important naval and air base in the Southwest Pacific theater. Facilities were established which, together with spacious Seeadler Harbor, made the base at Manus capable of supporting not only the 7th Fleet, attached to the Southwest Pacific command, but also a sizable portion of the Pacific Fleet as well.

Encirclement of Rabaul was completed by the occupation and development of Emirau, of the St. Mathias group, directly north of New Ireland. On March 20, 1944, Marines landed on the island to find it undefended. A few days later, construction battalions of the 18th Regiment, drawn from the Solomons, began to arrive and immediately started the construction of a naval base and two bomber fields for the Army. The once-important enemy base on New Britain was left to share the fate of other by-passed Japanese positions.

The momentum of our offensive was not permitted to run down. Aided by air support from naval carriers, Army forces on April 22 made successful landings on the New Guinea coast at Aitape and Hollandia, 400 miles and more to the west of Finschhafen. On May 9 the 113th Battalion arrived at Hollandia and set to work constructing naval-base facilities on Humboldt Bay to support

--279--

the 7th Fleet in its future operations, and fleet headquarters facilities in an upland area about 25 miles inland.

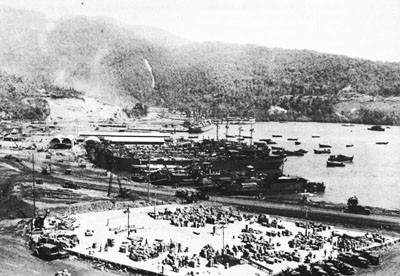

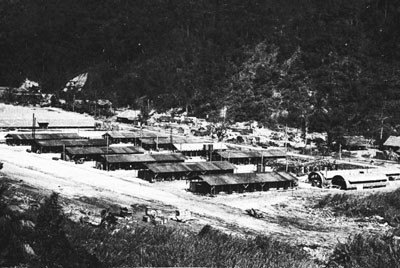

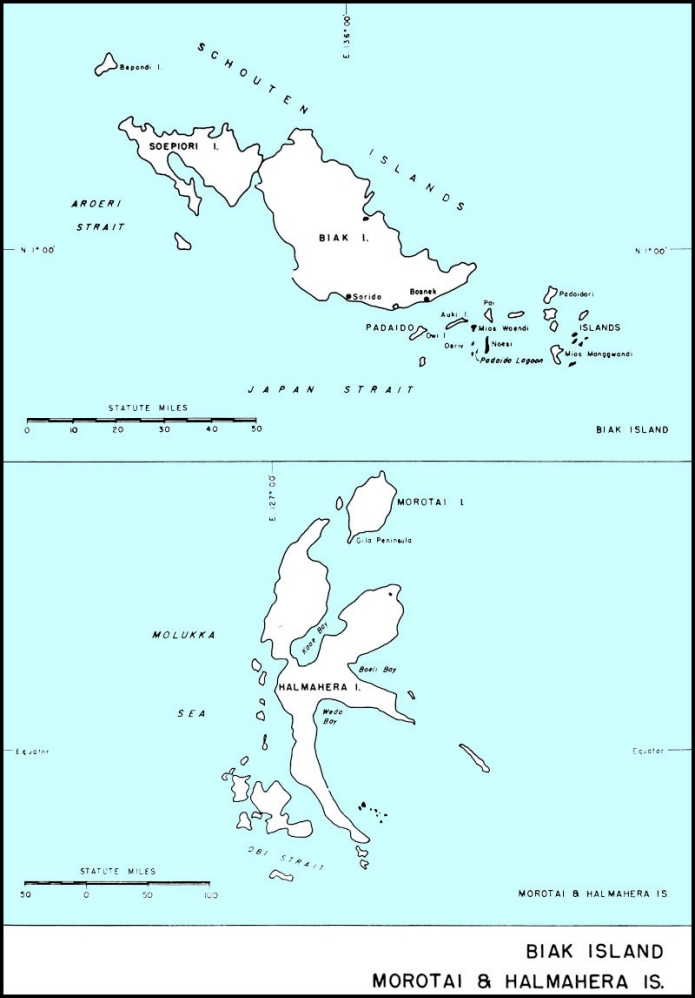

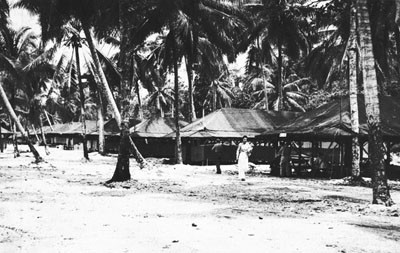

The establishment of our position at Hollandia had cut off more than 50,000 Japanese troops to the eastward, and our command of the sea approaches foreclosed their support or reinforcement. Our control of the remaining portions of the New Guinea coast was not far off. In May, our forces assaulted and occupied the island of Biak, the neighboring island of Noemfoor in July, and Sansapor, at the western tip of New Guinea, on July 30. Our control of the New Guinea coast was now complete. By that time, Japanese air strength had almost disappeared in the entire area and our offensive steadily gained momentum. On September 15 our forces invaded and occupied the island of Morotai, north of Halmahera; the reconquest of the Philippines clearly lay ahead.

Australia

Brisbane - Operating bases in the Australian area for patrol and escort craft were needed to anchor the far end of our long supply line to the Southwest Pacific. Accordingly, it was directed early in the war that there be provided in Brisbane, a base to support task forces, submarines, and escort craft.

Brisbane, the capital of Queensland, with a population of 370,460, is located on the Brisbane River, about 14 miles from the east coast. Moreton Bay, at the mouth of the river, affords suitable anchorage for vessels of draft not exceeding 33 feet.

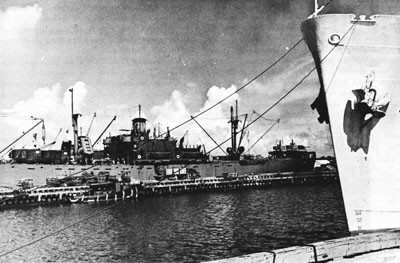

United States naval activities in Brisbane began on April 14, 1942, when the tender USS Griffin and her company of submarines tied up at New Farm Wharf, where existing installations consisted principally of wharves and wool-storage sheds. In order to provide the necessary equipment for a naval supply depot, part of these facilities were rented and paid for under reverse Lend-Lease.

Shortly thereafter a submarine supply and repair base was established; necessary facilities were rented or leased from the Australians and renovated by Australian construction men to meet the Navy's needs. Although harbor facilities were limited, the base was eventually expanded until it became the largest United States naval base in continental Australia. Existing buildings and Australian materials and labor were used when available; however, some Seventh Fleet units brought with them prefabricated buildings which were set up by their own men or by the Seabees.

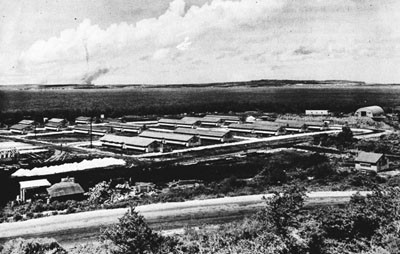

Seabees played no part in the establishment of the base until March 24, 1943, at which time the 55th Battalion arrived and established a base for themselves at Eagle Farm, 5 miles northeast of Brisbane, later used as a staging camp for the Seabees in the Southwest Pacific and known as "Camp Seabee." After two weeks in Australia, half of the battalion was sent to New Guinea, while the other half continued work on the camp and also began to build a mine depot. By June 10, other detachments had been sent north to Palm Island and Cairns, leaving only 250 men in Brisbane.

The 84th Battalion landed at Brisbane on June 19, 1943, and moved immediately into Camp Seabee. Here, orders were received sending approximately half the battalion to Milne Bay, New Guinea. The portion of the battalion left in Brisbane assisted the 55th Battalion in constructing the mine depot, additional barracks at Camp Seabee, a Merchant Marine anti-aircraft training station, and Mobile Hospital No. 9. During May and June of 1943 the 60th Battalion staged in Camp Seabee and aided forces there in the construction of projects then under way.

On January 20, 1944 the 544th CBMU arrived to take over all maintenance in the area.

In addition to the projects already mentioned, the Seabees built an advance base construction depot, containing 90,000 square feet of warehouse space and 53 acres of open storage; established a naval magazine at the mine depot by erecting 52 storage huts, 20 by 50 feet. At Hamilton, they renovated existing structures to give a ship-repair unit 5,000 square feet of shop space, and built a wharf, 40 by 130 feet. In addition, many small jobs were done by the Seabees as additions to, or in conjunction with, work performed by the Allied Works Council, including the building of access roads serving the newly constructed warehouses.

The 55th performed logging operations during a period of acute lumber shortage, and also established and operated a river-gravel plant which supplied all the concrete aggregate required at Brisbane by the United States Navy. They also operated a disintegrated-granite pit which provided surfacing material for roads and open-storage areas.

--280--

The Australians had not previously used this disintegrated granite as a surfacing material, but it proved thoroughly satisfactory.

Mobile Hospital 9 arrived at Brisbane with sufficient prefabricated buildings to set up 500 beds; it was later expanded to accommodate 1,000 beds, and subsequently 3,000. All buildings were of prefabricated metal, with the exception of a storehouse, theater-recreation building, laundry, and a sewage pumphouse, and the power plant. All construction was performed by Seabees, with the assistance of station personnel.

No air strips had to be built, for the local airport at Archerfield was made available, and air strips built for the United States Army at Eagle Farm were also used by Navy planes. In addition to 100,000 square feet of existing plane-parking areas, 192,000 square feet and 180,000 square feet were added to Archerfield and Eagle Farm, respectively. Repair shops and a parachute tower were erected, and two hangars, 248 by 105 feet each, which had been built for the Army, were turned over to the Navy. Leave areas, accommodating 250 men each, were built for naval personnel at Toowoomba, west of Brisbane, and at Coolangatta, on the sea, 65 miles south of Brisbane.

Local labor and materials were used almost exclusively. Australian labor also built a seaplane base on the south bank of the Brisbane River about 3 miles below the city. The existing finger pier was utilized, with barges attached at the outer end to facilitate loading and unloading operations. All station personnel and plane crews were quartered at this site.

The first major installation to be discontinued was the mine assembly depot, which was dismantled and crated in January 1944. The moving of Seventh Fleet headquarters to Hollandia, prior to the Philippines campaign, greatly decreased activities as Brisbane, and many of the facilities were returned to the Australians.

Townsville. - At Townsville, on the northeast

--281--

coast of Australia, a section base was set up to service convoy and combatant ships operating in the forward areas of the Solomons and New Guinea.

Land was acquired rent-free, from the Townsville Town Council, for the site of a fleet post office, and a frame building, occupied in the middle of April, was built entirely by Australian labor for this activity.

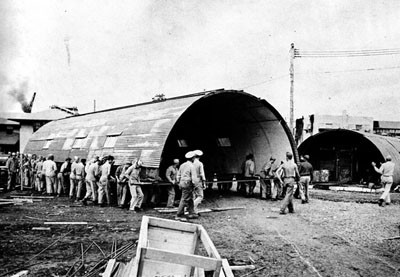

A naval magazine, 45 miles from Townsville, was completed August 23, 1943. It consisted of four prefabricated magazine huts and two wooden-frame buildings for barracks and mess hall. Local labor and some local materials were used. A 120-bed hospital, consisting of a group of quonset huts, was begun October 22, 1943 on the shores of Rose Bay, near Townsville, by Company C of the 55th Battalion and was operative by December 20, 1943.

Meanwhile, on October 25, 1943, another detachment of the 55th Battalion had arrived at Townsville to build a second hospital, on a site 10 miles north of the city. This hospital, also consisting of quonset huts, had a capacity of 100 beds.

The base remained in operation until July 1944, when a detachment of the 84th Battalion began dismantling it and crating material for shipment to a forward area.

Sydney. - The capital of New South Wales, a modern, well-developed city, with a population of 1,250,000, provided a major repair base, an operations and maintenance base for escort craft, and a major port of debarkation.

United States naval facilities at Sydney, consisting of a supply depot, an ammunition depot, and Base Hospital 10, were constructed by civilian contractors,

--282--

under the auspices of the Australian Allied Works Council, on reverse Lend-Lease. The construction program was not initiated until the summer of 1943.

Storehouses for the supply depot were constructed of standard Australian wood-frame buildings and by rental of existing space. For the ammunition depot, twenty concrete magazines, 25 by 50 feet, and two 30-by-100-foot units were erected.

Base Hospital 10 occupied a small civilian hospital, which was augmented by standard barracks, ward buildings, an operating center, galley and mess hall. The normal capacity of the hospital was 200 beds, with a maximum emergency accommodation of 500 beds.

Commercial port facilities were used. The Australian government had under construction during 1943 and 1944 a graving dock, 1094 feet long and 140 feet wide, with a depth of 401/2 feet. Facilities ashore were simultaneously developed equivalent to those of a destroyer tender. During the summer of 1944, a detachment of 90 men from the 84th Battalion was stationed at Sydney to repair the USS Venus.

By July 1944, plans had been formulated for the elimination and reduction of our naval facilities at Sydney, with the exception of the ammunition depot, at the earliest practicable date.

Palm Island. - Palm Island, within the Great Barrier Reef, north of Townsville and 20 miles off the coast of Australia, was selected as a naval air station with facilities for the operating and overhauling of patrol bombers.

Palm Island, the largest of several closely grouped small islands, is triangularly shaped and contains 23 square miles. With the exception of a few small areas, the terrain is rugged from the water's edge. The air station overlooked a large stretch of sheltered water, ideal for seaplane operations.

On July 6, 1943, a detachment of 2 officers and 122 men of the 55th Battalion was sent from Brisbane to Palm Island to construct the station. As all the material could not be shipped at one time, a similar detachment, with 1,500 tons of material, was sent from Brisbane to Townsville by rail. Half of this detachment remained in Townsville to unload, store, and reload this material. No local labor and little native material were used, but coral aggregate for concrete was obtained and the entire

--283--

1,500 tons moved to Palm Island by such small craft as became available.

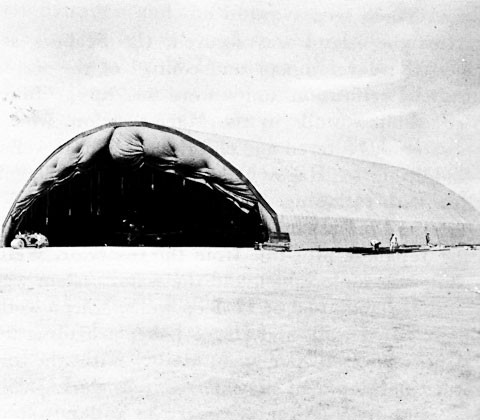

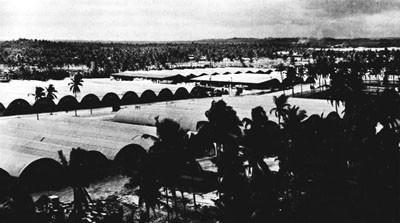

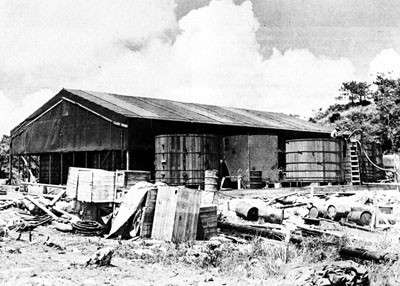

The Seabees on Palm Island set up a camp with all necessary facilities for 1,000 men. Concrete-surfaced seaplane ramps and a seaplane parking area large enough for 12 planes were constructed. Three nose hangars were built, and moorings for 18 planes were provided in the bay. A tank farm with a capacity of 60,000 barrels of aviation gasoline was constructed, using 2000 feet of shore pipeline and 1,200 feet of submarine pipeline. All buildings were wood frame.

No local labor and little native material were used, but coral aggregate for concrete was obtained from off-shore reefs at low tide.

By September 23, 1943, when personnel for the operation and maintenance of the base began to arrive in large numbers, the major facilities of the base were ready for operation. A month later the base was completed with the exception of the tank farm, construction of which was in progress, and a small portion of two nose hangars. On October 25, the Seabees began moving out, leaving a group of 35 men to complete the nose hangars and other miscellaneous minor jobs, after which the detachment rejoined the battalion at Townsville on November 8.

In addition to the construction of the facilities already listed and the unloading of construction equipment and material, some 3,500 tons of base operational and maintenance equipment and supplies had been unloaded by the Seabees between July 6 and October 22. They had also set up and maintained their own camp.

Housing and operational facilities were fully utilized from October 25, 1943, to May 1, 1944, with an average of four planes per day repaired. On June 1, 1944, a detachment from the 91st Battalion arrived to dismantle the camp, and by September 1, 1944, work was completed, with 5,000 tons of material and equipment loaded on ships for forward areas.

Darwin. - In order to fulfill an agreement with the Australian government, whereby the United States Navy was to supply mines to the Royal Australian Air Forces operating out of Darwin, a mine depot was established there. Facilities were later expanded to service United States submarines and PT boats operating off the northwest coast of Australia.

Darwin, on the northern coast of Australia, occupied a peninsula between Clarence Strait and Frances Bay. With a peacetime population of 3,000. Darwin had no industries, serving only as a port of call for coastwise shipping and as a base for pearling luggers. A civil airfield and a RAAF airfield on the other side of the strait provided air facilities.

The first echelon of Company B, 84th Battalion, arrived at Darwin on August 28, 1943, and immediately commenced work on the construction of a 500-foot PT-boat slip, and shortly thereafter erected a quonset warehouse. Existing facilities proved to be inadequate; hotels and private residences were renovated and used as quarters, and existing stores and warehouses were utilized, overflow space being provided with tents and new construction. Commissioning of this section base took place on November 21, 1943.

In January 1944, work was commenced on 12 magazine huts, with a detonator locker in the magazine area on Frances Bay, just south of the RAAF field. Roads were built. This construction, augmented by a warehouse and an assembly shed, was completed by April 6.,/P.

During January 1945, the Seabees also built a base camp, consisting of 22 huts, supply tents, and accompanying accommodations. A radio unit with necessary equipment and three quonset huts were set up at Adelaide River, 77 miles from Darwin.

Cairns. - Our base was planned to provide logistic support and hospital facilities to serve advance bases and operational forces afloat.

Cairns, on Trinity Bay on the east coast of Australia, is in a sub-tropical region, temperatures often exceeding 100°F. Much of the flat coastal area along the bay is mangrove swamp, requiring considerable fill to make it usable for construction purposes. By dredging, the harbor was kept at a depth of 22 feet.

On October 6, 1943, a detachment of 3 officers and 223 men from the 55th Battalion arrived at Cairns to set up an escort base on the site of [a] small PT repair base, which had been erected by various service units, with no planned construction layout. Practically all installations, however, were ultimately incorporated in the base. Although built to accommodate one PT boat, the wharf accommodated several more by nesting.

Escort Base One was set up for destroyer repair, mine maintenance, patrol-craft repair headquarters, and supply. The work of grading, filling,

--284--

and erecting buildings was taken over by the Seabees upon their arrival. Construction by the 55th Battalion included a galley and mess hall for 1,000 men, hospital facilities with complete installations for 50 patients, administration and operational facilities, all necessary buildings for radar and repair, ships' stores, fleet post office, storage and base roads.

Ninety days were required for the initial development of Cairns, completion date being January 1, 1944. Major obstacles were poor drainage and unstable material for structures and roads. These were overcome by using disintegrated granite as fill, installing culverts, grading, and ditching.

Development beyond the original plans included construction of a 40-ton floating drydock, a 600-foot timber wharf, and four 5,000-gallon water tanks. Time required for these developments was thirty days, with the final job completed January 31, 1944. The detachment then returned to Brisbane.

Late in December, it had been decided to provide ammunition-storage facilities, but as participation in this project would prolong too greatly the Seabees' service in a tropical area, another detachment arrived from Brisbane, December 30, 1943. At the dump site, 7 miles inland from the main base, the Seabees set up 18 prefabricated ammunition-storage huts, a frame barrack, and all other necessary camp facilities, which were completed March 19, 1944.

Apart from these projects, the 19th Battalion,

--285--

in July 1943, assisted the U.S. 6th Army Engineers in the construction of a large Army operating base, which included a drainage project, power plant, railroad, camp sites, and other facilities.

The naval base was used extensively for repair of all types of small craft and destroyers. During the construction period, as well as upon completion, the base was taxed to capacity.

CBMU 546 started roll-up late in 1944, and by January 7, 1945, all usable material had been sent to forward areas.

Merauke, Dutch New Guinea

Merauke, approximately 2 miles from the mouth of the Merauke River, on the southern coast of Dutch New Guinea, was selected as the site for a base to support PT squadron units, as well as operations of Allied Army, Navy, and Air components.

The area around Merauke consists largely of low land, covered with mangrove swamps interspersed with ridges of more stable sandy clay. The climate is tropical, with an average annual rainfall in excess of 100 inches.

A detachment of 4 officers and 233 enlisted men from the 55th Battalion arrived at Merauke on May 8, 1943, to construct the PT-boat base. As the town jetty had been destroyed by Japanese bombs, material and equipment had to be beached by unloading into leaky scows, which were towed to a makeshift wharf.

Trouble was encountered in selecting a camp site in the swampy terrain. Drinking water was obtained from seepage wells, and then purified. Timber for the construction of a 300-foot pier and a smaller one for PT boats did not arrive until July 15; work was then started immediately, and both were completed by September 3.

The air strip, 150 by 6,000 feet, was commenced on June 28, 1943; eight days later, it accommodated its first plane. This strip was able to handle one squadron of fighter planes and several medium bombers. Twenty miles of roads connected the strip with the town and with gasoline and fuel dumps.

As Merauke at this time was within easy range of enemy air bases, it was subject to numerous strafing and bombing raids. On May 11, three days after arrival, the Seabees experienced their first bombing raid; they sustained no casualties but lost some gear and equipment. Numerous alerts and attempted raids followed, but there were no more bombings until September 9, by which time all assignments had been completed.

Facilities of this base, both harbor and airfield, were used extensively, daily reconnaissance missions and bombing flights being flown from the strip.

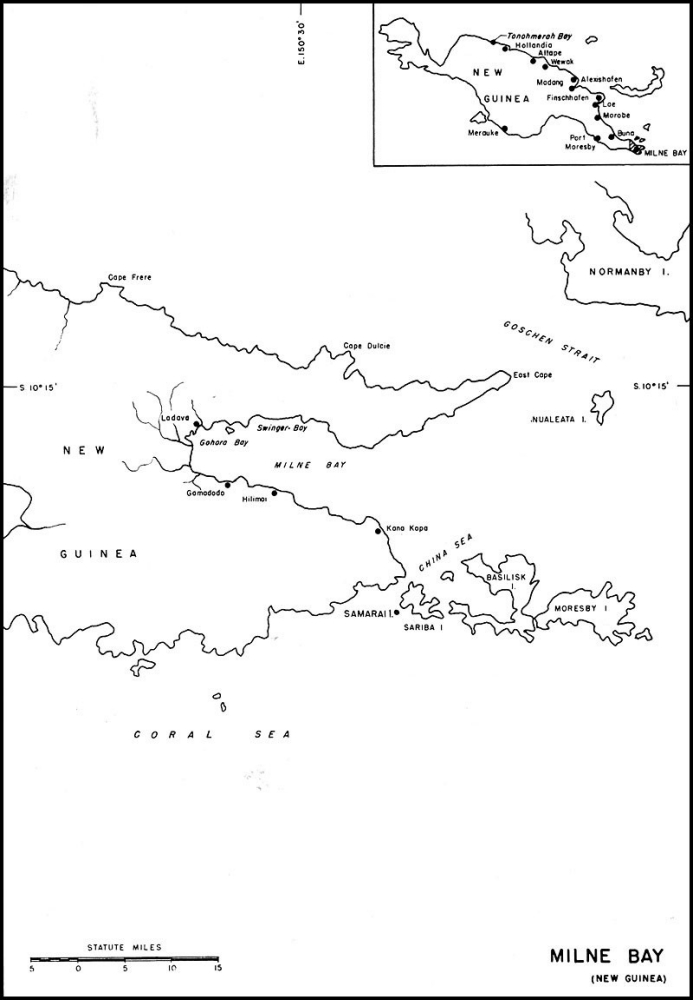

Milne Bay

The naval base at Milne Bay was developed to relieve overcrowded ports on the east coast of Australia and to provide facilities nearer the enemy. The major installations consisted of a transshipment and staging area, major overhaul facilities for PT boats, and a destroyer base.

Milne Bay, on the southeastern extremity of New Guinea, is 20 miles in length, with an average width of 7 miles, affording an extensive protected harbor. A dense, swampy, jungle plain extends inland from the narrow coral and mud beaches to the Owen Stanley Mountains. The climate is tropical, with high humidity and heavy rainfall. Population is extremely sparse.

The first Seabees, one company of the 55th Battalion, arrived in Milne Bay on May 23, 1943. Their mission was to construct PT Advance Base Six at Kana Kopa, on the south side of the bay. Personnel had unloaded supplies and set up a few tents. As the Allied forces moved up the coast of New Guinea, it was found that the major engine-overhaul base at Cairns, Australia, was too far behind the lines to be practicable; accordingly, it was decided to enlarge the base at Kana Kopa.

Despite excessive tropical rains and adverse soil conditions, the Seabees had the base in operation five weeks after work was started, in time for its boats to strike the Japanese at Salamaua and Nassau Bay on June 29 and 30. In four months this small detachment also installed facilities for housing and feeding 800 men, shops and storehouses of quonset huts, three 15,000-gallon water tanks, a tank farm of four 1,000-barrel fuel tanks, a timber pile wharf, and two pontoon drydocks for PT boats.

This base was completed in the scheduled time, despite adverse weather conditions and disease. Severe rains often caused knee-deep mud, and in some places men worked waist-deep in the churned earth. In pouring concrete, it was necessary to keep the slabs under cover, so temporary shelters were erected. An ingenious system for building quonset

--286--

--287--

huts from the top down was later devised to eliminate the construction of temporary structures for protecting the concrete. Mud sills were set, and on them, blocks were placed at intervals to support a quonset hut, which was then erected. The concrete floors and foundations were then poured under the completed hut.

Milne Bay is in one of the most malaria-ridden areas in the world, and in spite of a rigorous preventive campaign, from 23 to 39 percent of the personnel was incapacitated from this cause alone. This, combined with tropical skin diseases also prevalent, had a pronounced and detrimental effect on the speed with which the project was built.

On July 8, 1943, two companies of the 84th Battalion arrived and immediately began to unload. A temporary camp was set up on the beach, near the native village of Gamadodo. By the middle of August, a permanent camp was nearly complete and work had been started on the supply and ammunition depots, though a major portion of the heavy equipment had not yet arrived.

Construction specified in the original planning was essentially complete by the end of December. After clearing the site, 81/2 miles of roads were built, and housing and messing facilities in the staging area for 4,000 men, a dispensary and sick bay for 50 patients, a 40-by-900-foot wharf, 20 quonset and frame warehouses, 54,400 cubic feet of cold-storage space, and 10 ammunition magazines were constructed.

In these developments, more than 400,000 cubic yards of sticky, water-soaked gumbo were moved. A sawmill was set up and supplied all except a small portion of the lumber used. A large portion of the available manpower was engaged in stevedoring until the arrival of a detachment of the 15th Special Battalion in December.

On July 31, 1943, a small detachment of the 84th was sent to the island of Samarai, southeast of

--288--

Milne Bay, to construct a small seaplane base. Work was somewhat delayed due to serious material shortages and changes in original plans, but in 42 days the project was substantially complete.

The main features were a 50-foot ramp, leading to a nose hangar and a 40,000-square-foot parking area. Barracks, messing and galley space for 220 men and 50 officers, together with water, power, sanitary, and refrigeration facilities complemented them. Aviation-gasoline storage was provided by the erection of four 1000-barrel steel tanks.

In addition, this same group of men was assigned the task of building a small seaplane operating base in Jenkins Bay, on the north coast of near-by Sariba Island, consisting of a camp for 130 men, a small boat pier, communications building, offices, and general storehouses.

The 91st Battalion, arriving October 21, 1943, relieved a small group of the 84th who were building the base headquarters at Ladava, on the western end of the bay. About one-fourth of the battalion remained at Ladava to improve the camp and construct piers, jetties, roads, electric and communication systems, warehouses, a hospital unit, and facilities for housing 75 officers and 1,000 men.

Another detachment was detailed to construct a destroyer repair unit at Gohora Bay, half a mile south of Ladava. This project included numerous shops and warehouses, piers, jetties, roads, and housing facilities for 30 officers and 1,000 men. The principal problem confronting this detachment was one of terrain; the site to be used was under water at high tide, necessitating a large amount of fill, which had to be hauled more than 5 miles by truck, over poor roads.

The remainder of the battalion went to Hilimoi, about 5 miles east of Gadadodo, to relieve the detachment of the 84th constructing a 500-bed hospital there. This project was expanded to include a recuperation center for 3,000 men. At the same time, a small detail was sent to Swinger Bay, in the northwest corner of Milne Bay, to start an amphibious training center.

A portion of the staff of the 12th Regiment, part of the 3rd Brigade, reached the area on November 29, 1943, and set up headquarters at Ladava. All

huts from the top down was later devised to eliminate the construction of temporary structures for protecting the concrete. Mud sills were set, and on them, blocks were placed at intervals to support a quonset hut, which was then erected. The concrete floors and foundations were then poured under the completed hut.

Milne Bay is in one of the most malaria-ridden areas in the world, and in spite of a rigorous preventive campaign, from 23 to 39 percent of the personnel was incapacitated from this cause alone. This, combined with tropical skin diseases also prevalent, had a pronounced and detrimental effect on the speed with which the project was built.

On July 8, 1943, two companies of the 84th Battalion arrived and immediately began to unload. A temporary camp was set up on the beach, near the native village of Gamadodo. By the middle of August, a permanent camp was nearly complete and work had been started on the supply and ammunition depots, though a major portion of the heavy equipment had not yet arrived.

Construction specified in the original planning was essentially complete by the end of December. After clearing the site, 81/2 miles of roads were built, and housing and messing facilities in the staging area for 4,000 men, a dispensary and sick bay for 50 patients, a 40-by-900-foot wharf, 20 quonset and frame warehouses, 54,400 cubic feet of cold-storage space, and 10 ammunition magazines were constructed.

In these developments, more than 400,000 cubic yards of sticky, water-soaked gumbo were moved. A sawmill was set up and supplied all except a small portion of the lumber used. A large portion of the available manpower was engaged in stevedoring until the arrival of a detachment of the 15th Special Battalion in December.

On July 31, 1943, a small detachment of the 84th was sent to the island of Samarai, southeast of

--288--

Milne Bay, to construct a small seaplane base. Work was somewhat delayed due to serious material shortages and changes in original plans, but in 42 days the project was substantially complete.

The main features were a 50-foot ramp, leading to a nose hangar and a 40,000-square-foot parking area. Barracks, messing and galley space for 220 men and 50 officers, together with water, power, sanitary, and refrigeration facilities complemented them. Aviation-gasoline storage was provided by the erection of four 1000-barrel steel tanks.

In addition, this same group of men was assigned the task of building a small seaplane operating base in Jenkins Bay, on the north coast of near-by Sariba Island, consisting of a camp for 130 men, a small boat pier, communications building, offices, and general storehouses.

The 91st Battalion, arriving October 21, 1943, relieved a small group of the 84th who were building the base headquarters at Ladava, on the western end of the bay. About one-fourth of the battalion remained at Ladava to improve the camp and construct piers, jetties, roads, electric and communication systems, warehouses, a hospital unit, and facilities for housing 75 officers and 1,000 men.

Another detachment was detailed to construct a destroyer repair unit at Gohora Bay, half a mile south of Ladava. This project included numerous shops and warehouses, piers, jetties, roads, and housing facilities for 30 officers and 1,000 men. The principal problem confronting this detachment was one of terrain; the site to be used was under water at high tide, necessitating a large amount of fill, which had to be hauled more than 5 miles by truck, over poor roads.

The remainder of the battalion went to Hilimoi, about 5 miles east of Gadadodo, to relieve the detachment of the 84th constructing a 500-bed hospital there. This project was expanded to include a recuperation center for 3,000 men. At the same time, a small detail was sent to Swinger Bay, in the northwest corner of Milne Bay, to start an amphibious training center.

A portion of the staff of the 12th Regiment, part of the 3rd Brigade, reached the area on November 29, 1943, and set up headquarters at Ladava. All

--289--

units in the Milne Bay area were assigned to this command and worked under its direction.

The 105th Battalion, which reached Milne Bay in January 1944, was given the job of completing the amphibious training center at Swinger Bay. This project comprised housing for 1,500 men in quonset huts, a large frame galley and mess hall, several quonset storehouses, class rooms, and shops, and the development of about 2,000 feet of waterfront. In all, more than 250,000 yards of dirt were moved in grading this project.

Soon after the 105th landed at Swinger Bay, a detachment was sent to Hilimoi to assist the 91st in their work on the hospital. Another group of about 150 men was sent to Gamadodo to set up a sawmill, augmenting the one already in operation by the 84th, and to build an additional Liberty-ship pier.

As work on the amphibious training center neared completion, men thereby released were moved to Gamadodo until eventually only enough were left at Swinger Bay to carry out maintenance and minor construction.

Arriving with the 105th was the 528th CBMU, which took over completion of naval headquarters at Ladava as well as maintenance of naval facilities in that area. Shortly thereafter, Pontoon Assembly Detachment 3 debarked at Gamadodo and commenced operations.

February 1944 saw the arrival of the 115th Battalion, which carried on the construction of the advance base construction depot, begun by the 84th. In March, the 118th Battalion landed and assisted the 115th until the depot was complete, their primary function then becoming its operation.

By the middle of 1944, most naval installations were complete. Original plans for Gamadodo were constantly expanded, and before our forces had advanced far enough to render this base unimportant, the following developments had been constructed and were in use: a magazine, a staging area with all facilities to care for 10,000 men, a supply depot, a pontoon assembly depot which was assembling pontoon cells as well as barges, and a large advance base construction depot which included a spare-parts warehouse, housed in what was probably the largest building in New Guinea - 120,000 square feet in area.

While work continued on some minor unfinished construction, dismantling was started on facilities which had fulfilled their purpose and were no longer needed by advancing forces. By July 1945, the advance base construction depot had been torn down and crated, and was waiting shipment to a forward area. By October, the hospital at Hilimoi had been readied for shipment north. At Gamadodo as soon as a building was vacated, crews went to work salvaging material which would be needed in the Philippines and Okinawa.

Port Moresby

The naval base at Port Moresby was established to provide major communication facilities and advance headquarters for the Seventh Fleet.

Port Moresby, on the southeastern coast of New Guinea, has a protected waterway, 5 miles long by 3 miles wide, with a sand and clay bottom affording excellent holding ground for anchorage. Temperatures are relatively mild, with rainfall uniform in distribution and not excessive.

A detachment of 70 men from the 55th Battalion arrived at Port Moresby on June 20, 1943. An Army base for forward operations and supply was already in existence there.

The construction project consisted of a radio station, to be used also as a communications center, and Port Director facilities. Constructed at the radio station were 10 quonset huts for living quarters, water supply and storage equipment, 2 transmitter and generator buildings, roadways, and parking areas. The station was placed in operation on July 15, 1943, and 8 additional quonset huts were erected by January 12, 1944.

The Port Director facilities in the original plan were to consist of 17 quonset huts for living quarters and offices, storage facilities, a water-supply system, a generator building, and roads. Work was begun July 28, 1943, and the project was ready for use within a month. As subsequent enlargement became necessary, 19 quonset huts were added and the port Director facilities became known as naval headquarters.

All construction was accomplished by the original 70 men augmented by 50 men sent from a detachment of the 55th working at Milne Bay. This contingent provided the additional labor required from late September until December 1943, at which time they returned to Brisbane with 20 men of the original detachment. No native materials or labor were used.

A detachment of CBMU 546 arrived on April 3,

--290--

1944, to relieve the 55th, which had carried on with routine maintenance after completing the construction program. During October the roll-up of this base was under way, and was completed by November 1, 1944.

Woodlark Island

Woodlark Island, lying northeast of Milne Bay, was occupied by United States forces on June 30, 1943, for the purpose of developing a supporting base to provide air cover for Allied operations along the northeastern coast of New Guinea.

The island has a rolling terrain, covered with dense jungle. Coral barrier reefs surround it except at Guasopa Bay, the principal harbor, which is accessible through two passages. Limited channel depth restricted the use of the harbor, but LST's could be brought to the beach for operations. Small supply ships anchored just offshore.

The task force which occupied Woodlark Island in a surprise landing on June 30, 1943, included Army and Marine units, the 60th Construction Battalion, and a naval base unit to which about 500 men of the 20th Construction Battalion were attached. Enemy resistance was light. The men of the 20th were assigned the construction of housing, roads, and services. The 60th had as its mission the construction of an airfield and accessory facilities.

On July 2, the first echelon of the 60th Battalion began clearing and grading for the airstrip; 12 days later a coral-surfaced strip, 3,000 by 150 feet, was ready for operations. Work continued on the airfield, and by mid-September the runway was completed to a length of 6,500 feet, with a maximum width of 225 feet. A parallel taxiway, 6,000 feet long, with a minimum width of 60 feet, a dispersal loop, and 110 hardstands were completed by October 12.

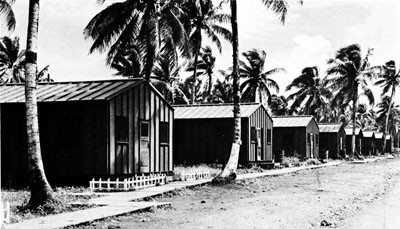

Meanwhile, the 20th Battalion concentrated on road and housing construction and the establishment of a water system. The first project after landing had been the cutting of trails into the coconut plantations and the surrounding jungle to allow immediate dispersal of all equipment and supplies. These trails were later developed into suitable roads, and by October, a 30-mile network of good hard roads had been completed. Housing was generally in floored and screened tents, although eight prefabricated wooden buildings and nine quonset huts were provided for the Army Air Force, and a small hospital.

Three 3-by-7-pontoon barges were assembled and turned over to the naval base unit for operation. One 2-by-12-pontoon string was assembled and anchored offshore for use as a PT-boat pier. The Seabees also did considerable repair work on landing craft, picket boats, and PT boats.

Ample water supply was procured locally from several rivers. A sawmill, which was set up, provided 15,000 board feet of lumber per day. A coral pit for road and airstrip surfacing material was also operated.

Spasmodic enemy bombings continued throughout the construction period at Woodlark, causing only minor damage and no casualties to the Seabees.

By November 1, 1943, all Seabees had been detached from Woodlark, with the exception of 309 men of the 60th Battalion who remained for maintenance duties until March 1944.

Kiriwina

Kiriwina Island, the largest of the Trobriand group, lying off the extreme eastern tip of New Guinea was occupied by United States forces on June 30, 1943, in a virtually unopposed landing, its capture being simultaneous with further landings by U.S. forces on New Georgia and on the New Guinea coast. It was intended to use Kiriwina as an air base to support future moves against the Japanese in New Guinea.

Near the center of this densely wooded island, which is 25 miles long and 6 miles wide at its broadest point, the United States Army Engineers constructed a coral-surfaced airstrip, 6,000 by 150 feet, for fighter and bomber operations. In September 1943, at the request of the 6th Army, 12 officers and 306 men of the 20th Battalion were sent to Kiriwina to assist in the airfield development.

The principal task of the Seabees was the construction of two taxiways, one 7,000 feet long, with 25 fighter hardstands; the other, 5,300 feet long, with 16 bomber hardstands. The first taxiway was completed on October 12, two days ahead of schedule, in time to support a major air raid against Rabaul. About a week later, the second taxiway was completed and the Seabees turned attention

--291--

to the erection of operations buildings and camp facilities for aviation personnel.

The projects assigned to the battalion were completed by October 28, 1943, when the Seabees returned to Woodlark.

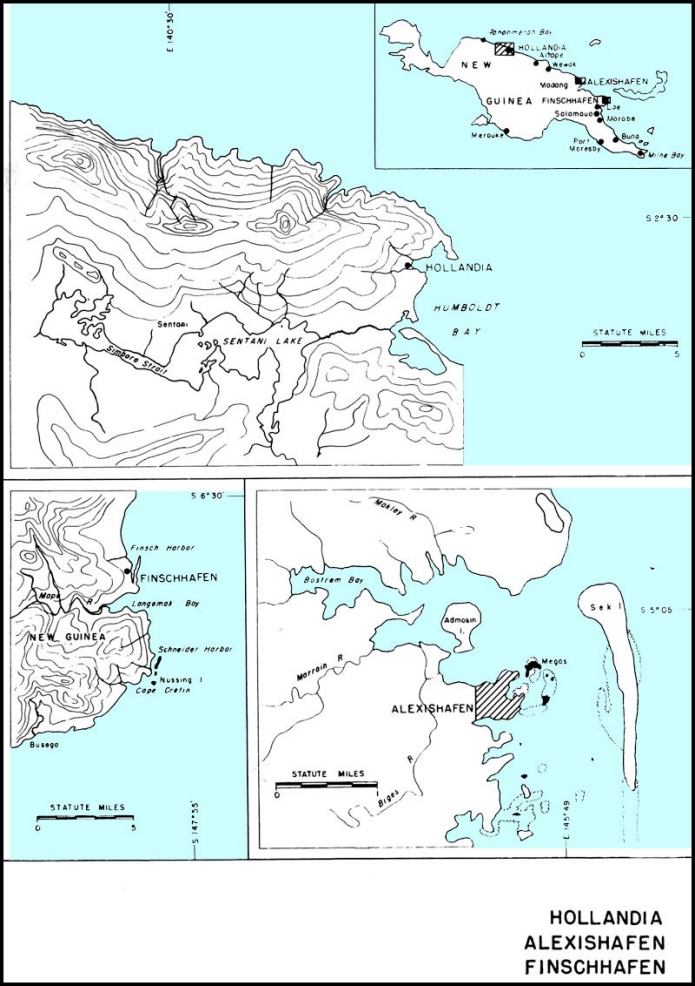

Finschhafen

The advance base at Finschhafen was established to provide supporting facilities for the accommodation of light naval vessels, such as PT boats and amphibious craft, to maintain a staging area for naval units participating in further forward movements, and to serve as a staging and supply point for the Seventh Fleet.

Finschhafen is on the eastern coast of British New Guinea; its harbor affords excellent shelter for moderate-size vessels and anchorages ranging from 5 to 45 fathoms. Climate is sub-tropical, with heavy rainfall.

The base was constructed on a narrow coastal plain backed by mountains. The major part of the area was jungle, with a top soil of deep black mud, underlain by poor-quality coral.

The first naval representatives to arrive at Finschhafen were members of the 60th Battalion, in early November 1943. This battalion, less one company which had remained at Woodlark, aided the Army in completing an airstrip and later developed a naval base.

Landing from LST's in Langemak Bay, near Finschhafen on November 5, the 19 officers and 658 men found the beach a morass as a result of heavy rains the previous night. Trucks and other rolling stock were unable to move more than 100 feet from the ships. The LST's were unloaded, however, and the next morning the work of clearing the beach began. A temporary dump and the camp site selected were about 300 yards from the beach, but in spite of every effort by the Seabees and a company of Army engineers, the road to this site was impassable for four weeks.

As a result, it was impossible for the Seabees to render any assistance to the 808th Army Aviation Engineer Battalion on the airstrip until November 16. The Seabees were assigned the job of rough-grading and mat-laying on the northern half of the field and of producing coral for fine-grading the entire area. In spite of the lack of equipment for road building, this strip was operating by the December 5 deadline.

The 78th Battalion landed at a point south of Finschhafen on December 9, and the 40th Battalion arrived at Finschhafen December 16, on the first Liberty ship to enter this zone. The 46th Battalion landed on the south side of Langemak Bay on January 6 and established a camp site adjoining the area occupied by the 78th Battalion.

Work on base construction was begun December 24. On January 5, 1944, the 808th Army Aviation Engineers departed, leaving the remaining airfield construction and maintenance to the 60th Battalion. The 60th built hardstands for fighters and medium bombers at Dreger Airfield, an aircraft repair area adjacent to the airstrip, four 2,000-barrel aviation-gasoline tanks, complete with piping and pumping units, and a 200-foot pile-and-timber jetty. Assistance was rendered on these projects by the 46th and 78th Battalions.

In the early months of 1944, an operating base for the support of two PT-boat squadrons was built by the 60th Battalion, the facilities including a 30-by-60-foot pier, a torpedo pier, one finger pier, two unloading piers, and 84-foot repair pier, a complete camp, warehouses, torpedo shop, and other work shops. During the late summer of 1944, the 91st Battalion, which had reported in July, improved these facilities with frame buildings and quonset huts for ships, warehouses, quarters, and recreation buildings.

Waterfront facilities were developed early in 1944. The 46th Battalion built four timber piers, each 330 feet long and 30 feet wide, with necessary approaches for Liberty ships.

Progress was slow, for it was impossible to obtain suitable piping, and the material into which the piles were driven was very soft and considerable penetration was needed to attain the required bearing. Two pontoon wharves, with bridge approaches, were erected, and covered storage in prefabricated buildings was provided at the cargo ship piers. Until the arrival of the 19th Special Battalion in late January, detachments of the several units handled stevedoring.

Base facilities were constructed by the 60th and 78th Battalions. These installations included a 500-man camp of framed and screened tents, quonset huts for administration use, and a 300-bed hospital. Base Hospital 14 consisted of ten 20-by-48-foot quonset huts for dental, surgery, storage, and ward facilities, with nine framed tents for additional wards.

Installations at the supply depot included four

--292--

--293--

6,800-cubic-foot refrigerators, twenty prefabricated warehouses, a 40-by-80-foot timber-and-coral-fill wharf, and ten 20-by-50-foot standard prefabricated steel magazines. The 78th also built a fuel-oil tank farm of five 10,000-barrel tanks, with all necessary piping.

Staging areas were established at Finschhafen for both Army and Navy personnel. The 40th Battalion built an Army staging area for 17,000 men, with camp and storage facilities, 14 LST loading ramps and 15 miles of two-lane roads with several timber bridges. During the summer of 1944, the 91st Battalion began construction of the naval staging area for 2500 men, with necessary camp and storage installations and roads. This project was about 75 percent complete on November 1, 1944, when orders were received to curtail further work at the base.

From March to June 1944, the 102nd Battalion, while restaging, assisted in minor construction activities. CBMU's 545 and 543 reported in February and April 1944, respectively, in time to aid in the major construction at the base.

Native labor was used, where available, for clearing brush and for logging and milling operations. The 60th Battalion set up a sawmill in November 1943, and the Army furnished the logs. This sawmill was later taken over by the 46th Battalion. Coral for the roads and the airstrip was secured from a nearby coral pit, operated by the Seabees.

Major obstacles to construction were heavy rains and occasional enemy bombings, which caused the Seabees some casualties.

All major projects at the base were curtailed in November 1944, and by January 1945, roll-up by CBMU 543 was well under way. The base was disestablished

--294--

April 1, 1945, and all facilities were turned over to the Army.

Cape Gloucester

On December 26, 1943, when the 1st Marine Division went ashore at Cape Gloucester, on the northwest tip of New Britain, it was accompanied by the 19th Construction Battalion, whose mission was the building of roads for supplies and access during the assault, and the preparation of beaches and piers for landing craft.

Reconstruction of two enemy airstrips, which were the principal objectives of the attack and from which United States planes could continue raids against Japanese-held Rabaul and Kavieng, was carried out by the 1913th and 841st Army Aviation Engineer Battalions. The strips were captured by the Marines on December 30, and next day the American flag was raised over all Cape Gloucester.

Road construction, with necessary bridges, continued throughout the Seabees' stay. Pulverized volcanic slag produced a surface so hard that even after continual truck traffic, the tread of a large bulldozer did not cut into the surface.

A new method of "drilling" holes for blasting was developed on this work. A 75-mm armor-piercing shell, fired into a rock ledge by a General Sherman tank, left a hole about 10 inches in diameter and 10 feet deep which could be quickly prepared for a dynamite charge.

Waterfront construction consisted of a rock-fill pile-and-crib finger pier, 130 feet long and 50 feet wide, a 160-foot rock-fill approach jetty for a cargo-ship berth, landing-craft unloading pier, and a 350-foot seawall of piles and log-facing, backed with large boulders.

The 19th Battalion, the only Seabee group at Cape Gloucester, was attached to the First Marine Division and left with the division in late April for the Russells. During the first weeks, continuous enemy air raids resulted in 5 men of the battalion killed and 24 wounded.

Manus

A major naval and air base, capable of service, supply, and repair to forces afloat, air forces, and other Allied units in the forward area, was established early in 1944, at Manus, in the Admiralty Islands, about 300 miles north of Lae, New Guinea, and, apart from the St. Matthias group, the northernmost group of island in the Southwest Pacific area. Manus lay close to the enemy line of communication between Truk and Rabaul, and also near the route between Kavieng and Wewak.

Manus and Los Negros comprise the major islands of the Admiralty group, which includes some 160 small islands and atolls and three first class harbors. Manus, about 50 miles long and 15 miles wide, is the largest island of the group. The terrain, which rises to a maximum elevation of 3,000 feet near the center of the island, is of volcanic origin, principally basalt, which weathers to a thick, reddish, clayey gumbo.

Seeadler Harbor, one of the largest and best in the Southwest Pacific, lies within the ellipse formed by Manus, the curving shore of adjoining Los Negros, and the reef-bound islands to the north. Its protected waters are capable of accommodating a large fleet of capital ships. Los Negros, roughly crescent in shape, is separated from the much-larger Manus by a narrow passage. The island is low and, for the most part, swampy, with coral just below the topsoil.

The first echelon of the 4th Construction Brigade, consisting of part of the 40th Battalion and small detachments of the 46th, 78th, and 17th Battalions, landed at Hyane Harbor, Los Negros, on March 2, 1944, with the first reinforcements to the original group of 1,000 Army troops, who had landed two days earlier. Only a small beachhead then existed. Enemy resistance, which had been severe, was overcome by March 4.

The Seabees' first job was to rehabilitate Momote airstrip, which had been sized on February 29, by a reconnaissance party of the First Cavalry Division. Although the airstrip was in our hands, the enemy occupied the surrounding areas, and 2 officers and 100 men from the 40th Battalion were placed in the front lines to reinforce the Army unit holding the area. These Seabees remained in this advanced position for two nights, withstanding three enemy attacks. For this action, the 40th was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation.

The captured airfield consisted of a 4,000-foot strip and a number of dispersal areas, none of which was in service, due to poor construction methods and design and to bombing by our forces. The Seabees began work on March 3, the morning after landing, and continued for several days, despite constant sniping and the loss of bulldozers to other activities. The condition of the strip was such that 14,000 cubic yards had to be filled and graded

--295--

before matting could be laid, as local coral material proved unsuitable as surfacing.

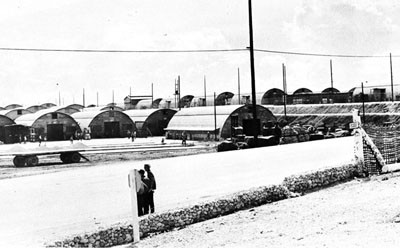

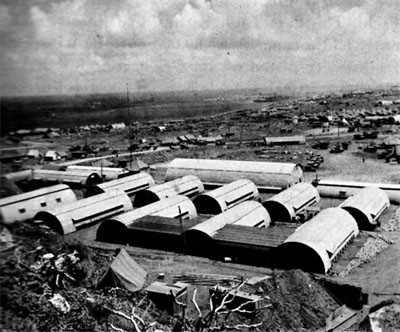

On March 10, RAAF fighters arrived and began operations, although construction continued until June 1, 1944, when the facilities were turned over to the Army for maintenance. Completed installations consisted of an airstrip, 7,800 by 150 feet, with taxiways and hardstands for 90 fighters and 80 heavy bombers, a 17,000-barrel aviation-gasoline tank farm with fuel jetty for small tankers, bomb storage revetments, roads, operations buildings, and personnel facilities.

Construction of an additional airfield (Mokerang) was the major project of the 104th Battalion, which arrived on April 1, 1944. An Army engineer aviation battalion assisted throughout the operation. The original plan called for a bomber runway, 8,000 by 200 feet; a taxiway, 8,500 by 125 feet, with hardstands and service areas for 50 bombers. This project was completed as scheduled, on April 22, with the use of additional equipment from other battalions. The first landings of 307th Bomber Group planes had taken place on April 21.

The original taxiway was later enlarged and two additional taxiways built. Other installations included a 30,000-barrel tank farm, quonset-hut shops, and personnel facilities. A second bomber strip of equal size, added to the plan, was built by Army engineers aided by Seabee equipment and operators.

By July 1944, the Seabees had constructed numerous other facilities in the Hyane Harbor area, including a 500-bed evacuation hospital for the Army. Waterfront construction consisted of two cargo-ship wharves, a repair pier with fixed crane, and a fuel pier, 800 feet long, to serve major ships.

Facilities at the pontoon assembly depot, operated by PAD 1, which arrived June 19, 1944, involved a pontoon pier, four prefabricated steel buildings for warehouses, shops, and offices, structural steel factories, and a personnel camp of 40 huts with all utilities for 50 officers and 500 men. The depot could assemble 900 pontoon cells per month.

An aviation supply depot was established as the central procurement, storage, and issuing agency for all such material and equipment in the Southwest Pacific area. For this activity, the 46th Battalion erected 24 steel warehouses, each 40 by 100 feet, and 83 quonset huts for administration and personnel. Facilities for an aviation repair and overhaul unit were set up, consisting of 25 steel buildings, 40 by 100 feet, for shops, a personnel camp for 1,000 men, roads, and all utilities. A naval airstrip, 5,000 by 150 feet, with hardstands, a 7,000-barrel aviation-gasoline storage farm, a parking area, warehouses, and a personnel camp were also built. The section base at Hyane Harbor was provided with facilities for small-boat repair, including a wharf, personnel camp, and shops.

In April 1944, two additional locations on Los Negros were selected for development, one at Papitalai Point and one at Lombrum Point.

The projects at Papitalai Point were assigned to the 58th Battalion, which arrived on April 17, 1944. The next day, survey crews were sent ashore to select a camp site. Constant heavy rainfall and the unfavorable terrain, however, made progress difficult. Quarters were finally erected on coconut-log footings at least 2 feet above the ground.

The first major construction assignment was the building of a 30-foot primary road from Lombrum Point to Papitalai Point.

For a drydock storage area and personnel camp, the 58th built seven 40-by-100-foot warehouses, 29 quonset huts, a mess hall, a galley, a water system, and a coconut-log, coral-fill jetty, 40 by 80 feet, the site of which required considerable fill.

Heavy rains, which turned the area into a mass of mud, considerably delayed construction of a PT-boat overhaul base and personnel camp; however, it was found that coral from a nearby deposit furnished a measure of stability. Due to the lack of available access roads, a jetty had to be built entirely by hand labor. Installations upon completion consisted of seven 40-by-100-foot warehouses, three quonset huts, one 30-by-50-foot wood-frame building, and a frame galley and mess hall.

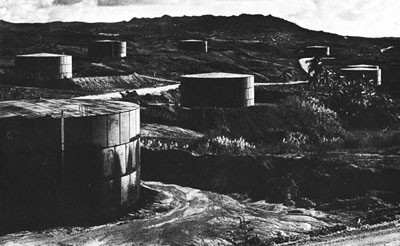

The major project at Papitalai, a tank farm with sufficient storage of fuel and diesel oil to supply a large base and major units of the fleet, was begun on June 23. Lack of suitable coral for surfacing again proved a handicap. Material for tank foundations had to be ferried across the harbor, and roads deteriorated to such an extent that corduroying was the only solution. However, the schedule to complete 25 tanks by August 15 was met despite the difficulties encountered, and work continued until 63 tanks were erected, each having a 10,000-barrel capacity. A two-way pumping system and a drum-filling plant completed the farm, which was split into sections, making it possible to operate from any single unit or series of units.

The 11th Battalion was the first unit to land at

--296--

--297--

--298--

Lombrum Point, on April 17, 1944. A permanent camp was set up and work begun on three main projects - a seaplane repair base, a ship repair base, and a landing-craft repair base.

For the landing-craft repair base, the Seabees erected six warehouses and shops, two quonset huts for administration buildings, and frame quarters and messing facilities, with all camp utilities. A 250-ton pontoon drydock was provided for docking LCT's, LSM's, and smaller landing craft.

Facilities at the ship-repair base combined docking, repair, and supply services equivalent to those furnished by auxiliary ships. Docking equipment consisted of a 100,000-ton sectional dock capable of handling battleships, a 70,000-ton sectional dock capable of handling most major ships, and an 18,000-ton steel floating dock.

The seaplane base at Lombrum Point was established to furnish operational, service, and repair facilities. Installations included a 50-by-250-foot concrete seaplane ramp, one steel nose hangar with a concrete deck, an 8,000-barrel aviation-gasoline tank farm, a pontoon pier for small boats, four 40-by-100-foot prefabricated shops, quonset-hut shops, and camp facilities.

Development of base facilities on Manus Island was initiated by the 5th Construction Regiment, composed of the 35th, 44th, and 57th Battalions, which landed between April 14 and 20, 1944. There was no enemy resistance, although Army patrols killed three snipers on the beachhead and captured several prisoners in the vicinity during the next ten days. For six weeks, the Seabees maintained perimeter guards at their camps.

The principal installations were made for the supply depot, which was to serve shore-based activities in the Admiralties as well as all forces afloat in the area. The Seabees erected 128 storage buildings, 50 refrigerators, each containing 6,800 cubic feet, built open-storage areas, 5 miles of access roads, an LST landing beach, and two major piers, one 800 feet and the other 500 feet long. Ultimately, the storage floor space was extended to give the equivalent of 180 storage buildings. This was accomplished by lean-to additions. These facilities were located along the Lorengau airstrip,

--299--

which had been found unsuitable for operational development. The depot was commissioned on July 2.

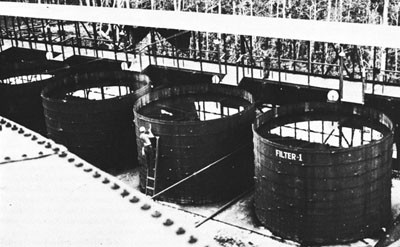

A major development undertaken by the various units of the Seabees at the Manus naval base was the construction, operation, and maintenance of a water-supply system, capable of producing 4,000,000 gallons per day.

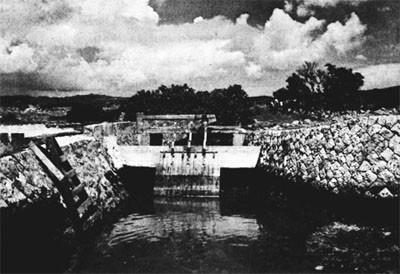

Two primary systems were developed. The Lorengau system, with its source of supply the Lorengau River, produced a daily average of 2,700,000 gallons. The Lombrum system, utilizing five small streams and impounding reservoirs, produced an average of 600,000 gallons per day.

In addition, 23 unit water systems in outlying areas, using portable purification units, could draw 850,000 gallons per day from shallow wells.

Treatment of both primary supplies incorporated aeration, sedimentation, coagulation, filtration, and chlorination, producing a quality of water that was considered very good for all purposes.

Distribution was accomplished from a gravity-flow system; however, auxiliary pumps were spotted in the lines to boost the pressure in the event of an emergency.

The main reservoir of the Lorengau system had a capacity of 2,142,000 gallons, augmented with five 10,000-barrel steel tanks, one 1,000-barrel steel tank, and various wood-stave tanks at the population centers.

The Lombrum system was tied in with a main 420,000-gallon reservoir and wood-stave tanks.

All distribution mains were steel pipe, ranging from 6 to 12 inches in diameter. Laterals and auxiliaries were from half inch to 4 inches in diameter.

The administration area for the entire Admiralty base was located at the mouth of the Lorengau River. Facilities included 48 quonset huts for officers,

--300--

a 2,000-man mess hall, 10 quonset huts, signal towers for base communications, all utilities, and a timber pier. On May 4, the 4th Brigade headquarters were moved from Los Negros to Manus.

Original plans contemplated two separate hospitals, but these were consolidated into one 1,000-bed unit, Base Hospital 15. Facilities included 42 quonset huts, a 1,000-man mess hall, 8 wards, 5 operating rooms, storage facilities, administration, dental, and laboratory installations, and all utilities. A receiving station was also established, containing facilities for 5,000 men in 292 quonset huts, with frame galleys and mess halls.

Two additional air bases were constructed on the nearby small islands of Ponam and Pityilu.

At Ponam a fighter base, to provide minor repair and overhaul facilities for carrier-based planes, together with housing facilities for pilots and crews, was established by the 78th Battalion in the summer of 1944. Installations consisted of a coral-surfaced airstrip, 5,000 by 150 feet, a 5,000-foot taxiway with a parking area, 6,000 feet square; 34 quonset huts for repair shops and operations; a 1,500-man camp; and an 8,000-barrel tank farm with sea-loading line for aviation gasoline. Fifty per cent of the work area was swamp land, requiring fill, all of it coral, blasted and dredged from the ocean bed.

The 71st Battalion set up a base for carrier planes on Pityilu, to care for one patrol squadron, to service and repair all types of carrier-based planes, and to provide storage for 350 of these planes, with camp accommodations for 350 officers and 1,400 men. The coral-surfaced runway measured 4,500 by 300 feet, with taxiway and three parking areas. Prefabricated steel huts were erected for administration, operations, and shop use. Other facilities included a 7,000-barrel aviation gasoline

--301--

tank farm with sea-loading line, one prefabricated nose hangar, and munition dumps. This work was accomplished in May and June 1944, with assistance from Company C of the 58th Battalion. Later, the field was extended 1,000 feet; parking areas were increased; the camp was enlarged to accommodate 2,500 men; and the dispensary was developed into a 100-bed hospital with all facilities.

The eastern end of Pityilu Island was cleared, graded, and made into a fleet recreation center to accommodate 10,000 men at one time.

Stevedoring for all naval activities was handled by the 20th, 21st, and 22nd Special Battalions.

Although little native labor was employed, native woods and coral were used in abundance.

Arriving September 17 and 18, 1944, the 63rd Battalion was assigned to a wide variety of work. An ammunition depot, consisting of concrete-floored storage buildings, with sorting warehouses, and quonset huts for personnel, was built, together with additional warehouses for the supply depot. Maintenance of all facilities, including roads, boats, and electrical equipment, as well as coral excavation, was also assigned to the battalion. In addition, both a concrete batching plant and a sawmill were set up and operated. These activities, with improvements to docking facilities and extensive power line installations, were carried out before the 63rd departed for Manila on March 25, 1945.

The 140th Battalion landed at Manus on June 17, 1944, two companies being detailed to Ponam and Pityilu, respectively. On Manus, the 140th assisted the 63rd in the establishment of the ammunition depot, later taking over the entire maintenance and development.

On V-J Day, the 140th Battalion, the 20th and 22nd Special Battalions, CBMU's 561, 587, and 621, and PAD 1 were still in the Admiralties. All units were engaged in stevedoring and in general maintenance and repair.

Emirau

Continuing the Pacific strategy of by-passing Japanese strong points and occupying intervening islands to aid in cutting the enemy's lines of communication and supply, and to provide landing

--302--

fields for our shore-based bombers in the coming attacks on Truk, Yap, and Palau, the island of Emirau was occupied on March 20, 1944. In addition to landing fields, the island was to be developed as a naval base, a PT operating base, and a minor repair base.

Emirau, one of the many small islands of the Bismarck Archipelago, lies 250 miles north of the once strongly fortified Japanese base of Rabaul, New Britain. The Truk Islands are 600 miles due north, and Yap and the Palau group are 800 miles to the northwest.

The island is approximately 2 miles wide, and 8 miles long in an east-west direction, with an arm in the central section jutting northward for about 21/2 miles. The shoreline border of flat land, several hundred feet in width, rises several feet above sea level, and is broken by a parallel cliff formation, which rises abruptly, 75 to 185 feet above the sea at most points, to a comparatively level plateau of about 4,000 acres. The island is covered with light vegetation, second-growth timber, and some heavy forest. Hamburg Bay, a fair harbor, lies on the northwest coast. The climate is tropical, with high humidity and heavy rainfall. About 300 natives inhabit the island.

Emirau was occupied without enemy opposition, March 20, 1944, by two battalions of the 4th Marine Division. Main contingents of the 18th Construction Regiment, comprising the regimental staff, Battalions 27, 61, 63, and the 17th Special Battalion, arrived with the second and third echelons of the division on March 25 and March 30. These contingents were augmented April 14 by the 7th Construction Battalion.

All construction was assigned to the 18th Regiment for distribution among its battalions; the work was inter-related as far as possible, no battalion being assigned projects solely of one type or in one area.

The 27th Battalion took over the construction of the naval base headquarters, PT Base 16, the small-boat pool, Hamburg Bay harbor developments, an LCT floating drydock and slip, and a portion of the roads.

The construction of the main road arteries, aviation housing facilities, ammunition-storage buildings, the runway at North Cape Field, some of the

--303--

building at the PT base, and sawmill operation comprised the work of the 61st Battalion.

The 63rd assisted in the operation of the sawmill and work on the aviation shops, camps, roads, the airfield, harbor facilities, storage warehouses, magazines, and bomb and aviation-gasoline dumps.

To the 77th Battalion fell the task of constructing taxiways and hardstands on Inshore and North Cape airfields, aviation shops, and camps, bomb dumps, and the construction, maintenance, and operation of the aviation-gasoline tank farm.

The Inshore Field runway and approach zones, aviation shops and camps, radio range and radio direction finder stations, and the road and causeway at the eastern end of the island were built by the 88th Battalion.

The two airfields, Inshore and North Cape, were both heavy bomber strips, 7,000 by 150 feet, and coral surfaced, as were the warm-up areas at each end of the fields. Inshore Field had 35 double hardstands capable of parking 210 fighter or light-bomber planes. There were 42 hardstands on North Cape Field, with space for parking 84 heavy bombers. Both fields had all necessary facilities for operations, including a control tower, field operations building, field lighting, and a dispensary. All buildings used for supplies and servicing were of prefabricated steel or wooden frame. Screened and decked tents housed 1,050 officers and 4,200 enlisted aviation personnel.

A tank farm for aviation gasoline was installed with three 10,000-barrel and nineteen 1,000-barrel tanks, two tanker moorings with anti-torpedo nets, two sea-loading lines, and a gravity distribution system to six truck-filling points. In connection with this farm, an adequate reserve of more than 40,000 barrels was maintained in drums. The ammunition and bomb dump provided covered storage, steel magazines, and revetments.

Three hospitals were built on the island. The naval base hospital, with a capacity of 100 beds, and the 24th Army Field Hospital, with beds for 160, were both located in the southwestern tip of the island. Acorn 7 Hospital, located on the extreme northern tip of Cape Ballin, had facilities for 150 patients.

The anchorage in Hamburg Bay accommodated five capital ships; Purple Beach, on the Bay, with three finger piers and one 77-by-120-foot slip was sufficient to handle seven LCT's. On this beach were also eight pier cranes, refrigerators with a capacity of 42,400 cubic feet, six 40-by-1,000-foot warehouses, and approximately 400,000 square feet of open-storage space, which permitted the handling of 800 tons of cargo a day. An LCT floating drydock was also maintained in the Bay. All other beaches on the island were unsuitable for efficient cargo handling; however, five beaches on the western coast were improved to accommodate thirteen LCT's.

Communication facilities consisted of two wooden transmitter buildings with concrete floors, two 16-by-32-foot revetted wood-frame power plants, and two quonset-type receiver stations.

The naval base was established at the southwest tip of the island. Facilities constructed for its operation consisted principally of wooden frame, canvas-covered structures, replaced later by quonset-type buildings, when urgent airfield facilities had been provided.

Quarters and messing for 560 officers and men, engine overhaul and repair shops, a magazine, a total of 350 feet of coral-fill piers, a signal tower, and all the necessary utilities for a PT base, were erected on the island of Eanusau, just off the southwest tip of Emirau. The small-boat pool was also installed there, consisting of a camp for 250 men and 15 officers, 4 quonset-type dry-storage buildings, shops, a sick bay, an armory, a generator plant, ships' service, a personnel pier, and a signal tower. Connecting the various activities and camps were a total of 40 miles of 40-foot coral-surfaced, all-weather highway.

In July 1944, CBMU 502 arrived to relieve the construction battalions of maintenance work. By August, construction was complete, with the exception of minor additions.

The 61st Battalion left in July, and by the middle of December, all construction forces, with the exception of the maintenance unit, had left. The 502nd, by that time, was engaged in dismantling quarters and buildings as soon as they were vacated, and crating equipment no longer needed. By the end of May 1945, the roll-up was complete, except for installations which were to remain on the island, and on June 6 the 502nd departed for Manus.

Hollandia, New Guinea

The naval base at Hollandia was established to provide logistic support to services afloat and later to become a supply base for the invasion of the

--304--

Philippines. It was to include a base for convoy escorts, a supply depot, a repair base for destroyers and lighter craft, and an ammunition depot. In addition, it was to be advance headquarters of the Seventh Fleet.

Hollandia is located on Humboldt Bay on the north coast of Dutch New Guinea. This area has a tropical climate, with heavy rainfall.

Generally throughout the Hollandia region the terrain is rocky, erosion having caused a jumble of hills and bluffs, some of which exceed 1,000 feet in height. Fresh water is extremely scarce except in the Hollandia valley. A reef, composed of soft coral and silt, lies close along the shore. Humboldt Bay, adequate and well protected, provides the only extensive anchorage between Wewak, about 200 miles to the east, and Geelvink Bay, some 350 miles to the west.

Naval facilities at Hollandia were extensive, including a staging area, fleet postoffice, Seventh Fleet advance headquarters, and a fueling depot. All facilities were located near Humboldt Bay, with the exception of advance headquarters, which was about 12 miles west of the bay, and the fueling depot on Tanahmerah Bay.