The Navy Department Library

German Naval Communication Intelligence

Battle of the Atlantic Volume III

by OP-20-G

SRH-024

Battle of the

Atlantic

Volume III

German Naval

Communications Intelligence

SRH-024

National Security Agency

Central Security Service

Table of Contents

Chapter I

Organization and Working of

German Naval Communications Intelligence

- In relation to German naval organization.

- Subdivision of 4 SKL "Marinenachrichtendienst," naval communication service.

- 4 SKL/III "Funkaufklärung" (radio intelligence).

- The German radio intelligence bulletin and the handling of ULTRA.

- Concentration of German communication intelligence on Allied convoy traffic.

- Use of non-radio intelligence material.

-- 1 --

1. In relation to German naval organization.

The German naval intercept service and related intelligence activities formed part of the division of Naval Communications, which in turn formed one of the six numbered "Naval War Staffs." Late in 1944 these war staffs were as follows:

| OKM | Naval High Command | Grand Admiral Dönitz |

| Stabschef SKL | Vice Chief of Naval Staff | Vice Admiral Meisel |

| 1 SKL | Operations | Rear Admiral Hans Mayer |

| 2 SKL/BdUop | U-boat Operations | Rear Admiral Godt1 |

| 3 SKL | Intelligence | Rear Admiral Otto Schulz |

| 4 SKL | Communications | Rear Admiral Stummel |

| 5 SKL | Radar Research | Commander Meckel |

| 6 SKL | Hydrography & Meteorology | Vice Admiral Fein |

2. Subdivision of 4 SKL "Marinenachrichtendienst," naval communication service.

Chef MND: Rear Admiral Stummel

I. Central Office: Captain Möller.

II. German Communications: Captain Lucan

Radio communications, stations, frequencies, etc.

Naval codes and ciphers. Security.

Recognition signals.

Landlines.

III. Radio Intelligence: Captain Kupfer

Intercept, traffic analysis, low-grade recoveries.

Cryptanalysis.

__________

1. Dönitz retained high command of the submarine force. Godt was the U-boat Command's staff officer for operations.

-- 2 --

IV. Radar: This section was formed in August 1943, in an attempt to combat Allied location of U-boats and included research on Allied non-radar location devices as well as radar. Special effort went into construction of search receiving equipment.

Location: After bombardment of Berlin in November 1943, Section I moved to Koralle with Dönitz and staff. Sections II and III moved to Bismark and later to Eberswaldo. When the Russians reached the Oder in 1945, 4 SKL moved to Wilhelmshaven area. (Ultra/ZIP/ZG/337)

3. 4 SKL/III "Funkaufklärung" (radio intelligence).

a. Intercept net.

The intercept net was organized, in part at least, into naval D/F divisions (MPA), naval D/F main stations (MPHS), and naval D/F subsidiary stations (MPNS). Before the loss of Italy the German navy probably maintained about 50 intercept stations covering the Black Sea, Mediterranean, Baltic, Arctic, and Atlantic waters. Emphasis in the case of Atlantic stations was of course on British naval and RAF traffic, including radio traffic. Of particular interest was MPA Flanders, located in the Castle of Saint Andries near Bruges, where the operators captured from U-664 (Graef) were trained.2

In addition to interception, D/F work and the training of B-Dienst operators, MPA Flanders received and broke low to medium grade British naval traffic, such as Loxo and Foxo. Some of the other principal outlying stations performed similar intelligence duties, and issued routine summaries for their respective areas. B-groups were also maintained on various command staffs in occupied territory, to whom were sent daily recoveries of delivery groups and lettered coordinates for English position reporting system.

__________

2. U-664 was sunk by a U.S. Navy aircraft on 9 August 1943. Eight crew members were lost and 44 captured.

-- 3 --

b. Headquarters of 4 SKL/III.

All high grade naval traffic was forwarded to 4 SKL/III in Germany, together with D/F's, traffic analysis, and low-grade decoding results. The home station was organized into two sections, according to the Japanese Naval Attaché: "Auswertung" (Evaluation) and cryptanalysis. The number of workers was said to be 800 in the early part of 1944, but it is not clear whether this figure applied to both sections or cryptanalysis alone.

1. "Auswertung" (Evaluation).

The full extent of this section's functions is not at present known but its various subdivisions covered the following activities:

Intercept of enemy traffic.

Reconstruction of letter coordinates (from position reporting systems such as SP 02274).

Recovery of delivery groups. (Ultra/ZIP/ZG/3 10)

The above duties suggest that the evaluation section was responsible for D/F correlation and traffic analysis in general.

2. Cryptanalysis.

The internal organization and workings of this section are as yet little known. After the armistice with Italy, officers of the Italian naval communications intelligence organization (SIS), informed the Allies that they had worked in close collaboration with the Germans, and yet the Italians had never found out much about the inside of the German organization. Rome and Berlin had exchanged technical information and captured cryptographic documents, Rome, however, in the role of a subordinate. Neither maintained a permanent liaison with the other, although visits were exchanged. (GC&CS Intel Memo #66)

-- 4 --

4. The German radio intelligence bulletin and the handling of ULTRA.3

A German naval radio intelligence bulletin, dated 23 June 1944, was captured in Italy in September 1944. A weekly publication, this bulletin offered the most complete cross section ever seen here of 4 SKL/III's work. Just what section of 4 SKL/III compiled it is not clear, but it contains a large amount of material that would probably come from the "Auswertung" section. Presumably a correlation room existed, to which were passed the final results of the entire communications intelligence organization. The bulletin is carefully organized and apparently follows a relatively fixed form.

a. Distribution of the bulletin.

According to the introductory printed pages, 25 copies of the bulletin were made, 22 of which were distributed and 3 held in reserve. This distribution list is considerably longer than is customary in the case of U.S. Navy radio intelligence bulletins.

Distribution outside of Naval High Command (8 copies):

Naval Group Command West, Staff (located at Paris and in charge of naval surface units based on Biscay and Channel ports as well as coastal defense and Channel convoys).

Battle Group (Task group Tirpitz and 4th Destroyer Flotilla in northern Norway)

Comsubs Norway/Admiral Northern Waters at Narvik

Naval Liaison with Werhmacht Field Headquarters

German Naval Command Italy

___________

3. These bulletins are on file at the National Archives, Washington, D.C. Records of the National Security Agency, "German Navy Reports on Intercepted Radio Messages (B./X.B. Berichte), 8 September 1939-23 March 1945," SRS-548, SRS-1166 and SRS-1870. Record Group 457, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

-- 5 --

10th Flieger Corps via Air Fleet 3 (West Europe)

GAF Lofoten (the part of the Luftwaffe responsible for reconnaissance on Arctic convoys for Russia)

Small Battle Units Command (set up early in 1944, in charge of midget submarines, explosive motor boats, special commandos for mining and sabotage)

Distribution within Naval High Command:

6 copies to various sections of COMINCH and CNO including U-boat operational command (i.e. Chief of SKL, 1 SKL section, 2 SKL/BdU op)

4 copies to ONI (3 SKL)

1 copy to radar and electronics research (5 SKL)

3 copies within 4 SKL itself including one to the DNC

b. Grades of radio intelligence information and its dissemination by dispatch.

Two kinds of radio intelligence information are distinguished according to their source:

""B-Reports" or "B-Information": based on traffic analysis and reading of open or encoded messages.

"X-B-Reports" or "X-B-Information": based on the decryption of high grade traffic.

The captured bulletin contained both "B" and "X-B", the latter being distinguished from the former by framing or boxing in heavy black lines. To avoid any uncertainty which might arise in the interpretation of the information presented in the bulletin a standard form is indicated for degrees of reliability. Any unqualified statement could be taken as certain on the part of the reader. It should be noted, however, that this highest degree of reliability could apply to a good D/F fix as

-- 6 --

well as to a decrypted statement. "Probably" or "approximately" and "presume" or "presumably" qualified the lesser degrees of reliability in that order. In addition to the bulletin, "X-B situation reports" were issued daily by radio. No examples of these have been seen here. GC&CS describes them as daily summaries, sent out over the signature of the radio intelligence organization, which contain information from all intelligence sources, but mainly from the B-service itself. (ZIP/ZG/233, p. 1)

In addition to the above standard dissemination, radio intelligence material of an urgent operational nature might be sent by dispatch provided it was properly paraphrased and made no reference to source. This practice was to be limited to the most exceptional circumstances, particularly in the case of "X-B" information, for, as pointed out by the bulletin's printed introduction: "Should the enemy learn that X-B reports are obtained by the deciphering of his radio messages," he would destroy the work of months - even years - by changing his cipher data, and thus one of the most important sources of information for the execution of the naval war would be destroyed. Had the German navy observed these instructions more carefully, it might have been impossible for the Atlantic Section to demonstrate the existence and source of "X-B" information.

c. Captured bulletin's information, its organization and scope.

If the captured copy of the 23 June 1944 issue is a fair sample, the German naval radio intelligence bulletin shows the advantage which comes from centralizing the correlation of all interception results. (The captured bulletin covers the period from 12-18 June) It includes studies on topics of current operational interest such as the reconstruction of Atlantic convoy cycles as well as charts showing locations of contacts and attacks reported by Allied units.

At the request of OP-20-G, U.S. Navy Communications Security section (OP-20-X) examined the document but found "no evidence that U.S. cryptographic systems have been successfully attacked." Other than the monitoring of BAMS circuits, German attention was concentrated on British naval circuits, most of which had been subjected to close analysis. Although the information on US-Gibraltar convoys was as

-- 7 --

accurate as far as it went, it was not classified by the Germans as "X-B." Information on US-UK convoys, however, was in part classified as "X-B." No report has been received from the British on the sources of the German information given in the bulletin but these sources would presumably be described as "low-grade."

5. Concentration of German communication intelligence on Allied convoy traffic.

The captured bulletin tends to confirm the natural supposition that the German navy's communication intelligence organization would concentrate its energies on serving the most important operational part of the navy, the U-boat, and thus would specialize in Allied convoy traffic. That the enemy was adept at exploiting all sources in arriving at a clear and current picture of the convoy situation was shown many times in U-boat traffic. There were exceptions, but on the whole German radio intelligence did furnish the U-boat navy with that essential requisite for the successful prosecution of the U-boat war: good convoy intelligence.

The stereotyped nature of convoy traffic may have simplified the German problem so that analysis and delivery group recoveries would suffice to keep the convoy chart well posted and up to date. Against this background, however, they were able at times to read actual convoy messages in combined cipher and thus clarify and correct their plots as well as accumulate invaluable knowledge of convoy habits and procedures.

6. Use of non-radio intelligence material.

It will be noted that four copies were routed to 3 SKL (German Naval Intelligence) and that the daily "X-B" situation report drew on non-communication sources. The captured bulletin of 23 June, however, contains little that can be traced directly to outside sources except for the use of agents' reports in connection with Gibraltar convoys. The extent to which German radio intelligence organization was itself responsible for the correlation of its own material with that from non-radio intelligence sources is not known. The fact remains that it undoubtedly furnished the most important intelligence for U-boat Command. Before discussing German convoy intelligence,

-- 8 --

it is necessary to review the kinds of information sent to U-boats at sea, with particular reference to the various sources, both radio intelligence and non-radio intelligence, which were acknowledged in U-boat traffic.

-- 9 --

Chapter II

Intelligence Disseminated to U-boats and the Sources Acknowledged in U-boat Traffic

-- 11 --

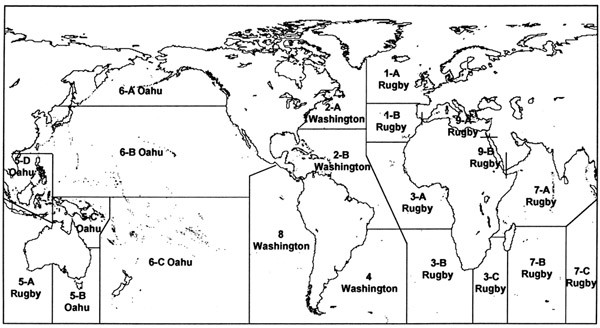

Areas for Broadcasts to Allied Merchant Ships (BAMS)

-- 12 --

1. Dissemination to U-boats at sea.

A constant effort was critically made to inform U-boats at sea of any intelligence which might assist them in their task. Thus, in addition to information on convoys and independents, both general and particular in its application for the offensive war, hundreds of messages concerned Allied anti-submarine activities. Intelligence for the U-boats defensive war included not only the number and disposition of anti-submarine units, whether surface or air, but also tactics, armament, and especially anti-submarine location devices. From time to time general estimates of Allied defenses for the various U-boat operational areas were added to the voluminous files of instructions which U-boats were obliged to carry and which were kept up to date by radio transmissions. The nature and tempo of the U-boat war required, in German eyes at least, a reliance on radio communications not only for the dissemination of current intelligence for offensive operations but also every scrap of information that could be gotten together on Allied defenses. Hence the reader of U-boat traffic was supplied with a surprisingly large background for judging German anxieties, suspicions, fears, and misconceptions, together with plans and hopes, or expedients, for counter action. As the U-boat task changed or as the conditions surrounding its execution altered, the intelligence sent to the U-boats was modified.

2. The course of the war as reflected in intelligence sent to U-boats at sea.

a. During the winter offensive, 1942-1943.

Intelligence disseminated to U-boats during the winter offensive of 1942-1943 was almost altogether on convoys, with emphasis on UK-US lanes. Other intelligence was issued only in so far as it bore upon or could be worked in with the convoy offensive. Intercepts of Allied contact and attack reports were rarely repeated on U-boat circuits, and then merely to request

-- 13 --

a clarification from the U-boat concerned.4 Reports of merchant sinkings in distant areas were occasionally relayed on appropriate circuits with requests for the identity of the U-boats responsible for the sinkings.

b. During the summer of 1943.

As the U-boat went on the defensive and sought out distant areas of operations, a distinct type of U-boat message gradually became a commonplace, and was to remain such: namely, the repetition of Allied contact and attack reports. The Allied reports became a kind of substitute for U-boat unit transmissions in view of the increasing need for radio silence on the part of the U-boat. The general defense situation reports for the Atlantic became remarkable for length and for new editions. Instead of convoy intelligence on the old scale, traffic situation reports of distant coastal areas and the Caribbean were on the air.

c. Resumption of convoy offensive. Winter 1943-1944.

The renewal of the North Atlantic convoy offensive brought back the convoy intelligence messages. Indicative of German difficulties in finding the convoys of an enemy who was reading almost everything the German navy put on the air and reading it currently was the appearance of new types of intelligence messages: the relay of D/F fixes on Allied unit transmissions and special reports from intercept parties onboard U-boats. Allied knowledge of the U-boats whereabouts was reflected in the constant flow of messages which endeavored to analyze the success of Allied location devices.

The repetition of contact and attack reports continued, increasing noticeably in the spring of 1944, particularly for the Biscay area, and gradually working around to include the Indian Ocean as well. The disposition and habits of U.S. Navy CVE groups were pressing concerns which necessitated

___________

4. For example - see 1034/2 January 1943: B-Service report of attack on U-Boat in 08°N - 55°W.; Mohr (U-124) replied. Also 1324/5 February 1943 to Group Nordsturm: "We have two English reports of attack." Gretschel (U-707) replied.

-- 14 --

revisions of current orders of the defense situation in an effort to determine where and when U-boats might safely surface. Attempts were made to evaluate all underwater sounds reported by U-boats in terms of new kinds of Asdic, search buoys, counter-devices for the acoustic torpedo, bluff, or marine biology.

d. After the summer of 1944.

The German attempt to fight with an outmoded U-boat which could not escape detection by a superior enemy gradually filled U-boat traffic with messages concerning the problem of U-boat defense. A time was reached when U-boat traffic seemed to reflect more Allied activity than German activity. With the introduction of the schnorchel U-boat German interest in underwater sound was intensified and concern with Allied radar remained as acute as ever. Operational intelligence messages became very detailed accounts of Allied shipping in coastal areas. In April 1945 the "Harke" gesture towards a revival of convoy warfare was accompanied by convoy intelligence indicating that the convoy plot had been kept up to date even though not used.

3. Sources acknowledged in U-boat traffic.

A summary of the various sources of intelligence which were acknowledged in U-boat traffic will not contain any startling revelations, for these sources are the ones which the enemy is expected to have. They should be borne in mind, however, for it was against this background that one had to judge possible sources when no acknowledgment was given.

4. Aerial reconnaissance.

It was not always possible to know when convoy intelligence could be accounted for by GAF sightings, even when the convoys were in the areas of GAF range, for acknowledgments were not consistently made. Such a source could usually be presumed with a degree of safety in the Mediterranean, along the English-Gibraltar convoy lane, along the Arctic route to Russia, and to some extent over the western approaches to Great Britain. Attempts were made in the spring

-- 15 --

of 1944 to home U-boats on UK-US convoys by means of special long range aircraft in the area of 20°W.

5. Submarine reconnaissance and observations of enemy conduct.

Submarines were themselves used in the effort to accumulate detailed observations of shipping and defense in distant coastal areas. The cumulative results were customarily repeated as "Situation and Traffic Reports" for the benefit of U-boats about to enter the area concerned. Some of this information could be traced to a particular U-boats own transmitted reports, but here again there was no certainty on many points. U-boat war logs were sometimes acknowledged as the source.

When schnorchel U-boats undertook a close-in blockade of British ports during the winter of 1944-1945 their situation reports on British coastal waters became especially detailed and systematic. The "Halm" ("Blade of grass") series of Offiziers sent to U-boats on the 13-14 February 1945 offered a correlation of information on shipping which undoubtedly used non-U-boat sources. By such means U-boats were given a clear and accurate summary against which to judge the significance of their own observations.

In addition to reconnaissance, U-boats were required to make special reports on Allied location devices, briefs of which were transmitted by radio. In this way it was possible to follow the struggles of the U-boat with Allied radar, from reports of radar transmissions intercepted on the early U-boat search receivers through all the subsequent attempts to isolate the mysterious source of Allied superiority. A numbered series of "Experience Messages" kept U-boats informed of Allied antisubmarine behavior and German interpretations.

6. Agents.

a. Gibraltar area.

Information from agents, as seen through U-boat traffic, was confined largely to the Gibraltar area: Ceuta, Cape Tres Forcas, Gibraltar, Alboran, Cape Spartel. The Germans followed all ship movements in and out of the Straits. Cape Spartel would report size and composition of an inbound convoy and

-- 16 --

its escort, giving exact time of sighting, line of bearing, and speed. Gibraltar would follow up with what ships had put in to or out of Gibraltar. German aerial reconnaissance would pick up the convoy after it had passed into the Mediterranean. All of this information was relayed on Mediterranean U-boat circuits, or on Atlantic circuits in the case of an outbound convoy. Clandestine traffic from the agents themselves was available to the Atlantic Section. 5

b. Agents elsewhere.

Particularly active in 1943 were the agents at Lourenco Marques and in the Cape Town area. Their traffic was also available to the Atlantic Section. It was possible to identify information passed to U-boats with specific reports which had gone in from these agents - both Italian and German. Occasionally information, presumably from agents, was disseminated on independent ships out of Takoradi, Lagos, Egypt, Persian Gulf, etc. In 1945 agents furnished information of a minefield off Fastnet, Ireland.

In addition to details on shipping in the Gibraltar area, Japanese Military Attaché traffic from Lisbon to Berlin carried much information on trans-Atlantic convoys including dates of departure from the U.S. A "reliable" Italian agent claimed the U.S. Naval Attachés office in Lisbon as the source of his report on the disposition of the U.S. fleet. (PPB 33, 3 November 1944) The reports of agents in England were seen in clandestine traffic via Spain. There is at least one case in which the sailing date of a US convoy (UGS 27) was attributed to an agent's report. (2013/16 December 1943 to Alsterufer and Osorno) As a rule, however, German U-boat traffic reflected only a small part of an organization which was apparently extensive and active but whose outline could not be discerned.

___________

5. The majority of the clandestine traffic received in the Atlantic Section came from the U.S. Coast Guard and other government agencies. These documents are now on file at the National Archives, Washington, D.C. Records of the National Security Agency, "Messages of German Intelligence/Clandestine Agents, 1942-1945," SRIA 01-1550, SRIB 017361, SRIC 01-4164, and SRID 01-73. Record Group 457, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

-- 17 --

7. Prisoners of war and survivors of encounters at sea.

Statements from survivors were occasionally passed immediately to Control by U-boat commanders. On one such occasion information on an England bound convoy (SC 118) was forwarded while the operation was still in progress. U-266 (Jessen) sank a straggler and captured the ship's captain and engineer. Within a few hours Jessen transmitted the following:

Prisoner's statement: Rudloff's convoy approximately 45 ships of which 15 are tankers. Broad formation, 10 columns. Destination North Channel. Inner and outer defense. Steamer frequency at present 50 meters.

Convoy formation: 10 columns, each with 4 to 5 ships. Distance between columns 900 meters. Distance between ships 550 meters. Speed 7-8. (2031/6, 0047, 0120/7 February 1943)

Some information on the general routing of convoys and independents in the South Atlantic and on the Caribbean-New York run was gained in this manner. With the increasing effectiveness of Allied anti-submarine measures U-boats were urged to take prisoners, especially from aircraft shot down, and interrogate them on tactics and devices for U-boat location. In December 1943, a prisoner from a Wellington helped materially in dispelling German fears of submarine location by amazingly effective search receivers.

8. Radio interception.

a. Direction finding.

Prior to the fall of 1943 little or no attempt had been made to supply U-boats with current D/F's. Beginning with the resumption of the North Atlantic battle, however, U-boat circuits relayed an increasing number of fixes on Allied unit transmissions. During January 1944, for example, no less than 51 D/F fixes were sent to U-boats in the North Atlantic. The area covered was usually north of 40°N and east of 30°W, but a few fixes were made as far west as 56°W. It does not appear that effective use was or could be made of this information by

-- 18 --

U-boats at sea, although a certain amount of correlation with the current convoy chart was attempted from shore for their immediate benefit.

b. Traffic analysis.

Acknowledgments of traffic analysis as a source of information were sometimes seen in Mediterranean traffic, and more frequently in Arctic U-boat traffic. In 1944-1945 U-boats in the Far East were furnished with the results of Japanese traffic analysis on the movements of major fleet units in the Indian Ocean. Although acknowledgment of traffic analysis as a major source of information on Atlantic convoys was extremely rare, it was assumed in the Atlantic Section that German knowledge of the convoy cycles came principally from this source, particularly in view of the stereotyped nature of convoy traffic. GC&CS recognized that valuable information on Atlantic convoys was gained through the recovery of delivery groups and the study of call signs, on which it was known that German communication intelligence placed considerable emphasis. (see ZIP/ZG/252, p. 4). Captured German documents have confirmed the extensive use of traffic analysis not only in reconstructing convoy cycles but also in the correct identification of convoys by designator and number.6 RAF Coastal Command traffic was also exploited in connection with convoy movements. The GAF communications intelligence organization work in close collaboration with the navy in such matters.

c. Allied transmissions in plain language or in self-evident code.

The repetitions of merchant vessel distress signals, BAMS submarine contact and attack reports, and aircraft reports on U-boats were frequently acknowledged by the phrase "according to B-Service." It became quite evident that German intercept service guarded the BAMS circuits with care and that U-boat Command correlated these reports with his submarine tracks, issuing orders and reprimands on the basis of them. The Atlantic Section watched the repetitions of these reports in

___________

6. In addition to the naval radio intelligence bulletin of 23 June 1944 already referred to, see ZIP/SAC/P. 7, a GAF radio intelligence bulletin.

-- 19 --

German traffic and invited COMINCH's attention to the advantages derived from them by the enemy.

d. Interception by U-boats.

Although there are a few cases of U-boat monitoring on the international distress frequency in connection with attacks on merchant shipping, U-boat traffic does not show this to have been of any importance. It was certainly never stressed by Command. The only serious attempt, by U-boats at sea, to exploit Allied radio transmissions was that made on convoy voice traffic, for which trained operators were provided in 1943. (See "B-Dienst Aboard U-boats" in Chapter V) The most persistent attempt at interception of Allied transmissions was that directed against radar. In addition to warning for the individual U-boat, radar interception was intended to build up a knowledge of Allied radar characteristics and tactics. Early in 1944 certain U-boats were equipped with special search gear and trained men to carry out "Feldwache" tests in an effort to determine what frequencies the Allies might be using which the standard U-boat receiver could not pick up.

--20--

Chapter III

German Intelligence on Allied Convoys in the Atlantic

- "Convoy expected."

- In relation to cipher compromise.

- Convoy chart for blockade runners, December 1943 - January 1944.

- North Atlantic convoys.

- US-North Africa convoys.

- Notable failures to disseminate information on US-Gibraltar Convoys.

- UK-Africa convoys.

- Analysis of convoy communications made by Atlantic Section; Recommendations submitted to COMINCH.

-- 21 --

1. "Convoy expected."

The enemy possessed at all times a reasonably clear picture of Atlantic convoys with varying degrees of accuracy as to the routes and day by day plotting. Although independents were not neglected, information on convoys was obviously more important for the U-boat war. Even when group operations were abandoned, knowledge of convoy gathering and dispersal points, ports of entry and departure, and the shipping lanes in coastal areas remained essential. As a rule, convoys were referred to in terms of general course, e.g. "north eastbound convoy," followed by area and date of expected arrival, the area usually being the patrol line itself. In only a few cases, during the fall of 1943, were convoys ever referred to in U-boat traffic by initials (e.g. 1626/16 September 1943, "ON," "ONS" to Group Leuthen). That the enemy knew the correct convoy designators and numbers, however, was clearly show in blockade runner traffic (December 1943 - January 1944), to say nothing of the evidence now available in captured documents.

2. In relation to cipher compromise.

The "convoy expected" messages came from a background of correlation which included all the sources mentioned in the preceding chapter, with the addition of important punctuation from the reading of convoy dispatches in combined cipher. General convoy intelligence is being discussed here before going into cipher compromised (for which, see the next chapter), because the latter represents a refinement of the "convoy expected" messages, both from the German point of view and from that of the Atlantic Section.

There is no way of determining at present to what extent information from cipher compromise was interwoven with the standard convoy expectations. For the most part general convoy intelligence and expectations of particular convoys were not sent in the Offizier cipher which was shown by experience to be the normal means for relaying decryption intelligence. There could be no assurance, however, that decryption intelligence had not played a part in patrol line

-- 22 --

shifts and formations not ordered by Offizier. There is no reason to believe that the Germans were always consistent in observing their own security regulations.

3. Convoy chart for blockade runners, December 1943 - January 1944.

The most complete single statement of German convoy intelligence ever seen here in German naval traffic came in a series of messages to homebound blockade runners in December 1943 and January 1944. These messages apparently reproduced the enemy's current convoy chart for the North Atlantic, including the Gibraltar lanes. The convoys then at sea were correctly identified both by designators and numbers, and accurate information on convoy cycles, speeds, and general routing was given.

a. US-UK convoys, general:

1. Convoys from Halifax to England (abbr. "HX") and Sidney-Canada-England convoys (abbr. "SC") and English convoys (abbr. "ON" or "ONS") generally navigate a great circle from which deviation occurs only if threat from U-boat warrants. Therefore convoys are paired on fixed lanes. The northern portion of these fixed lanes is by far the most navigated." (0105/17 December 1943 ALLE 66)

2. "HX" and "ON" convoys have a day's run of 204 miles. "SC" and "ONS" a day's run of 180. "HX" and "ON" convoys run at intervals of 6 and 7 days alternately, "SC" and "ONS" at intervals of 13 days.

3. Stragglers are to be expected after every convoy. They are routed on constantly changing courses." (0253/17 December 1943 ALLE 67)

b. US-Gibraltar convoys, general:

| Designations: | "UG" = US to Gibraltar "GU" = Gibraltar to US Add "S" for slow and "F" for fast (1054/22 January 1944) |

-- 23 --

| Cycle: | 10 Days |

| Speed: | 204 miles per day (8.5 knots) for "S" (0854/5 January 1944 ALLE 91) |

| Route: | Between 32°N and 36°N from 63°W to Gibraltar (0854/5 January 1944 ALLE 91) |

| Escort: | ... varies. Details not exactly known here. Far ranging reconnaissance by aircraft and close escort by destroyers and destroyer escorts must be assumed. |

c. Dead reckoning for particular convoys.

On 16 December 1943 blockade runners Osorno and Alsterufer received dead reckoning estimates for the following convoys: HX 270, SC 149, ON 215, ONS 25, and UGS 27. On the 18th, England Mediterranean convoys KMS 36, MKS 33, and MKS 34 were added. (1900, 1933, 1948, 2013/16 December 1943 DAN 7-10; 1013, 1037, 1102/18 December 1943 DAN 3335).

Dead reckoning plots on GUS 26 and UGS 30 were sent 5 January, (0854/5 January 1944 ALLE 91). The convoy identifications were correct. Dead reckoning estimates for US-UK convoys were given in terms of successive "standing lines." For example, convoy HX 270 was plotted for 18 December as being somewhere along a line extending from 51°N - 36°W to 43°N - 35°W. The "standing lines" for HX 270 and SC 149 ran approximately from the standard eastbound convoy route "B" on the north to standard route "C" on the south and did in fact lie across the route taken by these convoys. Had any one of the "standing lines" west of 30°W been occupied by U-boats after the fashion of the preceding winter, contact would have been made at about the estimated time. Group Rugen, then in the area east of 30°W, was informed of these "eastbound" convoys,

-- 24 --

but, strangely enough, the timing given to the U-boats was not as accurate as that given to the blockade runners. The plotting of ON 215 and ONS 25 was rather poor. GUS 26 and UGS 30 were plotted with fair accuracy in the area between the Azores and Bermuda.

4. North Atlantic convoys.

Accumulated evidence indicates that convoys which were not "expected" by U-boats were simply those in which the enemy could not take an operational interest. As the North Atlantic began to fill up with U-boats in January 1943, the number of "convoy expected" messages increased, accompanying the formations of lines for practically every major eastbound convoy from the middle of January to the end of May. On the whole a high standard of accuracy was maintained.

Convoy diversions were sometimes learned from decryption in time to rearrange U-boat patrol lines appropriately. In addition, the large number of U-boats and the pattern of their arrangement in groups tended to negate convoy diversions by covering the major possible diversion routes. Contacts were thus made by U-boats other than those for which the convoy was originally intended. German knowledge of the entire convoy situation was in this way constantly clarified and amplified.

During the summer of 1943 there was no check on the convoy plot such as had been furnished by U-boat operations. Despite this lack, convoy expectations began again promptly and accurately with the resumption of the North Atlantic offensive in September 1943. More "convoy expected" messages marked the unsuccessful campaign of 1943-1944 than the campaign of the preceding winter. From an average of about 7 a month during the winter campaign of 1942-1943, these messages rose to an average of about 10 per month during the following winter.

This increase signified the lack of success, reflecting not only a carry-over of unused patrol lines but also the willingness of patrol lines to take westbound as well as eastbound convoys. Furthermore, convoy intelligence assumed a new function in 1943-1944 which had been unheard of in the North Atlantic during the preceding winter; warning to U-boats of the possibility of encountering carrier borne aircraft and

-- 25 --

other forms of anti-submarine activity. Of the 38 HX and SC convoys which sailed for England from 13 September 1943 to 22 February 1944 no less than 34 were referred to in U-boat; of the 35 ON and ONS convoys during the same period, 27 were mentioned.

There are several instances in which U-boat Command showed a knowledge that could not have been gained simply from convoy cycle plotting, quite apart from the presumed and confirmed cases of cipher compromise. For example, when Group Coronel was formed in December 1943 to operate against "a slow westbound convoy." Command must have known not only that ONS 24 and ON 214 were not proceeding on similar routes, as had been customary, but also that it was ONS 24 which was taking the northerly route. The insight which the Germans gained solely by analysis of the heavy volume of stereotyped combined cipher traffic on US-UK convoys probably found supplementary information in local British "low-grade" communications.

5. US-North Africa convoys.

Although the German navy had no advance information the North African landings in November 1942, they had no difficulty in building up a knowledge of US-North African convoys from agents in the Gibraltar area, traffic analysis, and GAF reconnaissance. In addition a large amount of convoy radio traffic in the Mediterranean was sent in combined cipher. U-boat group operations functioned with a smoothness comparable to that on the US-UK lanes, but no lack of intelligence seems thereby indicated. There are, however, the possible failures of intelligence which are discussed in paragraph 6 below.

a. To summer 1943. Operational intelligence.

During the only period in which U-boat groups kept vigil on the US-Gibraltar lane (winter 1942-1943) at least 4 eastbound convoys were "expected," one of the UGS 6, on the basis of cipher compromise. Only one westbound convoy, GUS 4, is known to have been awaited; cipher compromise also played a part in this case. The best operations, with the possible exception of UGS 6, seem to have resulted from accidental contacts. Group Delphin's destruction of the tanker

-- 26 --

convoy TM 1 in January was due to an early sighting by a Uboat bound for the Trinidad area. COMSUBs recognized the target, however, as the first Trinidad-North Africa convoy. When U-boats (Group Trutz) returned to the US-Gibraltar lane in June 1943, after an absence of two months, they were certainly provided with good intelligence; in fact the formation of Group Trutz must have been due in large part to compromise of Flight 10's routing dispatch. The enemy was also aware of GUS 7A and, later, of GUS 8A, but did not show any realization in traffic of UGS 9 which was proceeding near Flight 10.

b. Interest increases in winter 1943-1944.

Information on US-Gibraltar convoys did not reappear in U-boat traffic until the fall of 1943, when U-177 (Gysae), returning from an extended patrol off South Africa, was given dead reckoning positions for UGS 18. The positions were a good 10 degrees ahead of the convoy's progress, indicating a German plotting at 10 to 10.5 knots whereas the convoy was making 9. Gysae received the information primarily for warning. Warning seemed the purpose of subsequent dissemination of intelligence on these convoys, which increased noticeably during the winter. In December dead reckoning plots on convoys UGS 26 and GUS 23 were sent out to five U-boats which were crossing the lane.

The positions were much nearer the truth than those for UGS 18 had been, but they did not show any exact knowledge of the standard route. While not precise, they were still sufficiently accurate to have effected contact by a suitably disposed patrol line. From January to March 1944 each successive UGS and GUS convoy (UGS 27-34 and GUS 26-32) was referred to in terms of Gibraltar arrival or departure for benefit of U-boats trying to enter the Mediterranean. Thereafter such information was disseminated only on the few occasions when U-boats were ordered to individual patrols in the Gibraltar approaches.

6. Notable failures to disseminate information on US-Gibraltar Convoys.

One assumes that the Germans kept a current plot on UGS-GUS convoys in which some confidence was felt. It is therefore difficult to account for certain failures to warn supply

-- 27 --

submarines or to change their rendezvous positions during June, July and November 1943. Two supply submarines were sunk and one endangered in positions which either show poor convoy intelligence or a failure to correlate and use such intelligence as was at hand. Although no dead reckoning positions farther west than 37°W were ever given to the U-boats, blockade runners had been furnished with dead reckoning positions on UGS 30 and GUS 26 as far west as Bermuda. The latter had been originated by a non-U-boat section of the Navy (1 SKL), but it is hard to believe that U-boat Command (2 SKL/BdU op) did not have access to all available information and that it was not capable of plotting convoys all the way across with operational accuracy, or what was deemed operational accuracy.

a. Case of refueler Czygan's (U-118) sinking 1410Z/12 June 1943, in 30°49'N - 33°49'W by TG 21.12 (Bogue).

Plans for Czygan's refueling station in 30°45'N - 33°40'W were announced in U-boat traffic on 31 May. On 12 June he was sighted on the surface and sunk within six miles of this position. No change had been ordered in his rendezvous assignment despite German knowledge that between 31 May and 12 June considerable aircraft protected Allied shipping had passed through this area. At no time during this interim did Command show any real awareness of the true situation. He did know about Flight 10 and GUS 7A but he apparently knew nothing of UGS 9 or TG 21.12.

Czygan was warned late on 5 June that an eastbound convoy with aircraft escort could be expected on the 7 June, but this was after the Bogue had attacked the Trutz line. Command had Flight 10 in mind and not UGS 9. The danger from UGS 9 was much greater than that from Flight 10, for the latter had altered course to the north after passing through the Trutz line on 5 June while TG 21.12 had turned south to cover UGS 9, which was proceeding along 29°30'N.

Schnoor (U-460), another supply submarine, was in the immediate vicinity. Command showed no awareness of UGS 9 until after Manseck (U-758) had accidentally sighted a convoy and had been so heavily bombed for his trouble that he prepared Command for the loss of his boat, after having explained that he had been attacked by carrier borne planes.

-- 28 --

Manseck pulled off to the south. Not until then were the two supply submarines warned that Manseck's sightings were probably on an eastbound convoy and that they should watch out for carrier aircraft while going to Manseck's rescue. By following Manseck's southerly course Schnoor and Czygan were drawn out of harm's way. But after Manseck had been found, still afloat, and turned over to Schnoor's custody, Czygan returned to his original rendezvous assignment - in time to meet TG 21.12 on its return sweep.

It should be pointed out that the area south of the Azores had been used for refueling rendezvous' many times in the past without mishap. One might also argue that Command had every reason to believe the three to four day old wake of a convoy a safe place for a refueling rendezvous. Czygan's sinking, however, surely indicates, besides ignorance of UGS 9, that Command was unprepared for the offensive nature of the task group that might engage in free maneuvers of its own.

b. Case of refueler Metz (U-487) sinking 13 July 1943 in 27°15'N - 34°18'W by TG 21.12.

The important nature of Metz's assignment in July has been dealt with elsewhere. His loss was an irreparable misfortune. One might then expect that the best of German intelligence would have concentrated on his safety. Yet he had not quite arrived at his assigned rendezvous position, 27°09'N - 33°27'W, when he was sunk 131700Z July. Convoy and Routing's plot for GUS 9 at 132000Z was 27°01'N - 33°39'W, within nine miles of the rendezvous position assigned to Metz. In blocking the US-Gibraltar lane to the north of 30°N with Group Trutz, U-boat Command had contributed materially to the southerly routing of GUS 9 which had brought TG 21.12 to Metz.

c. Case of refueler Bartke (U-488) November 1943.

The loss of U-118 and U-487 may have started the policy of warning U-boats when crossing the US-Gibraltar lane, for this type of message was not seen during the summer of 1943. Gysae was warned in September. Nevertheless, Bartke was twice seriously endangered by convoys during his November cruise without receiving any warning from Control. While passing from one rendezvous position to another in the area

-- 29 --

mid-way between Bermuda and the Azores he was surely within 60 miles of GUS 19 on the evening of 7 November. Again on 9 November he crossed UGS 23's path not many miles ahead of that convoy. Bartke later reported that he had been depth charged and damaged on 8 November.

Approaching Biscay on his return cruise, Bartke was given a dead reckoning position on a Gibraltar-England convoy. Warning messages were not sent because of a near collision on the German U-boat chart; U-boats were warned, when warned, even on a remote chance of encounter. For one thing, Command's day by day knowledge of a U-boats position was not necessarily accurate. Hence it seems reasonable to suppose that Bartke would have been informed had the German chart shown any convoys at all between Bermuda and the Azores.

d. Comment on German intelligence US-Gibraltar convoys, August and September 1943.

As of 15 September 1943, U-boat Command gave the following account of US-Gibraltar convoy routes in Operational Order #56 (Nemo document):

"The convoy routes lie between 30°N and 40°N latitude; the convoys coming from America travel the southern part, those going to America in the northern part of the lane. Extensive detours, particularly to the south, after attacks on this traffic."

On 16 August 1943 Current Order #11 carried this statement to all U-boats at sea:

"For the protection of America-Gibraltar convoys, one or more carriers are located in the area CD (from 34° to 43°N - 26° to 35°W) and DF (from 26° to 34°N - 35° to 43°W). Many repulsed attacks and the unexplained loss of several submarines homeward bound testify to this. In sum, carrier-based aircraft can always be counted on in the whole sea area between Gibraltar, New York and 25 degrees North. All the machines, even carrier-based planes, are probably fitted with radar ..."

One assumes that the September information on convoy routes was available in June and July. Current Order #11, however, seems to

-- 30 --

speak directly from the costly experiences of June and July. And yet Operational Order #56 declares that:

"Since the spring of 1943 the enemy has assigned auxiliary carriers to the area between 25°W and 40°W, which is otherwise hard to patrol. These are escorted by from 2 to 4 destroyers, watch over the area mentioned and in case of U-boat attacks come to the aid of the endangered convoys."

Apparently the detailed implications of this paragraph were not anticipated, or, if anticipated, were left blank to be filled in by experience.

7. UK-Africa convoys.

At times inbound and outbound U-boats were informed of convoys on the UK-Gibraltar lane, either for purposes of operation or for warning. During the period from April to June 1943, five Offizier messages were sent to U-boats along the northwest African coast informing them of dead reckoning positions on UK-African convoys. These cases should be studied here to a limited extent only since the convoys were entirely British and no convoy files were available. It was later learned that GC&CS presumed these to be instances of compromise, probably derived from dispatches sent in Combined Cipher #3. (see Appendix 13 on "Cases of Presumed and Confirmed Compromise of Allied Communications 1943-1945)

8. Analysis of convoy communications made by Atlantic Section; Recommendations submitted to COMINCH

Because of the renewed persistence of convoy intelligence in German traffic in the fall of 1943 the Atlantic Section felt obliged to follow up its studies on cipher compromise by an examination of convoy communications procedure and habits. It was of course recognized that the tremendous convoy undertaking could not in practice satisfy all demands of security theory, but the apparent ease with which the German communications intelligence organization maintained its hold on Allied convoys, particularly US-UK, suggested that some improvement could be made in our own communications, quite apart from the introduction of Naval Cipher #5, which had immediately followed the demonstration of extensive compromise in Cipher #3.

-- 31 --

a. Findings.

It was found that standard procedure made the task of enemy traffic analysts easy. In addition to the heavy reliance on combined cipher, tables "M" and "S", with the subsequent overburdening of a weak system, the timing of many radio dispatches concerned with each convoy observed a pattern as regular as that of the sailings themselves. In the case of HX-SC convoys during the fall of 1943 the ocean route was broadcast by CINCCNA approximately four days prior to each sailing. On the day of sailing and at a set interval after the sailing, each convoy was again announced in the fixed pattern messages from ports of departure and from the authorities concerned with escort relief at the ocean meeting point. The ocean meeting point usually gave rise to exchanges of dispatches between escort commanders and shore commands. A convoy diversion would be followed immediately by a BAMS broadcast. In the case of US-Mediterranean convoys correct identifications in blockade runner traffic had aroused particular interest here, but intensive study of available data had failed to prove cipher compromise.

The investigation of UGS-GUS communications for the period from November 1943 through January 1944, however, did show beyond question that traffic analysis of the Mediterranean end alone should suffice for maintaining and correcting knowledge of the convoy cycles. A surprisingly large amount of fixed pattern radio traffic was broadcast in the world-wide table of the combined cipher for the information of practically every Allied command of any description in the Mediterranean area. These dispatches followed a fixed timing in relation to the convoy's progress. The check made by agents at the Straits or by GAF reconnaissance seemed almost unnecessary as far as major convoys were concerned.

b. Recommendation.

The results of these studies were made available to U.S. Navy Communications Security and COMINCH. To eliminate the dependence on combined cipher in the Mediterranean the introduction of more cipher machines was hastened. For US-UK convoy communications certain remedial measures were drawn up and submitted to the Director of Naval Communications, who incorporated them in a memorandum for COMINCH (F-34). It was recommended that:

-- 32 --

"a. All shore authorities and ships in Western Atlantic be notified by dispatch that messages should be sent in "A" or "M" rather than in "M" or "S" Table when the 10th Fleet C&R is the only US authority included in the address.

b. All shore authorities and escort vessels in the Western Atlantic be notified by dispatch that messages addressed to US authorities in addition to 10th Fleet C&R, but of no immediate action is required, be sent as in (a), above, with appropriate passing instructions in the text.

c. CINCCNA make greater use of aircraft to carry home messages for ships and that such aircraft report last location of convoy rather than escorts break radio silence to report positions.

d. Admiralty modify convoy instructions particularly to stress the great danger of breaking radio silence and using homing procedure in the mid-Atlantic.

e. Admiralty and CINCCNA examine the standard reports required by shore authorities and escorts in connection with convoys with a view to eliminating unnecessary reports or stereotyped patterns."

-- 33 --

*** This Page Intentionally Left Blank ***

--34--

Chapter IV

Compromise of Naval Ciphers #3 and #5

(Anglo - US)

- Statistical summary, with comment.

- Fears of compromise, February 1943.

- Fears communicated.

- Further evidence, March 1945.

- Raubgraf - Convoy HX 229.

- Convoy TO 2.

- Convoy UGS 6.

- Compromise established, May 1943. Convoy HX 237

- Demonstration of compromised accepted. Action taken.

- More compromise - to 10 June 1943.

- Comment: The enemy's own ULTRA intelligence during U-boat decline.

- Compromise of Naval Cipher #5 feared. September 1943.

- German awareness of standard convoy routes.

- Evidence accumulates. SC 142 and U-220.

- HX 257, ON 203. COMINCH communicates apprehensions to First Sea Lord.

- Compromise of Naval Cipher #5 confirmed. October 1943 HX 261.

- SC 146 diversion compromised. November 1943.

- Indications of Combined Cipher compromise cease in U-boat traffic.

-- 35 --

1. Statistical summary, with comment.

For the period from January through June 1943 there are at least 39 cases in U-boat traffic of presumed or confirmed compromise of Allied naval radio communications. These cases are listed in Appendix 13 together with cases which appeared after this period. Appendix 12, taken from a British study, lists confirmed cases of cipher compromise for 1942. The enemy sources referred to in Appendix 12 were not available to the Atlantic Section of OP-20-G. Nearly all of the 39 cases for January - June 1943 whose sources have been identified involved Naval Cipher #3, tables "M" and "S," and it is probable that those whose sources were not identified likewise involved this cipher.

Tabulation for January - June 1943

(The case numbers refer to Appendix 13)

| Month | Precise Source Unknown |

Confirmed Source Identified |

Case | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| January | 3 | 1 | Case 1, British Naval Code | 4 |

| February | 4 | 1 | Case 5, Combined Cipher #3 | 5 |

| March | 3 | 1 | Case 3, Combined Cipher #3 | 4 |

| April | 2 | 1 | Case 3, Combined Cipher #3 | 3 |

| May | 7 | 8 (9) | 15 (16) | |

| June | 6 | 2 | 8 | |

| Total | 25 | 14 (15) | 39 (40) |

| (Appendix 13 contains 40 for this period rather than 39 with the addition of a case in May, taken from British records. The German message involved was not sent to U-boats. See case 5 for May.) |

| After the introduction of Naval Cipher #5 in June only two cases of confirmed compromised were recorded, one in October and one in November 1943. |

-- 36 --

a. Comment.

For a discussion of the delay in Allied counteraction the reader is referred to the chapter on German intelligence in Volume I. The present chapter's concern is with cipher compromise in relation to the Atlantic Section of U.S. Navy communications intelligence and to the information currently available to it. The tabulation above, however, incorporates a British study received after the compromise of Naval Cipher #3 had been definitely demonstrated here. In not one of the three cases listed above as confirmed for the period February through April 1943 was the compromised Allied dispatch available to the Atlantic Section. Nor were these dispatches found in the Navy Department's files.

2. Fears of compromise.

The highly successful attack on convoy ON 166 in February 1943 crystallized suspicions of cipher compromise, although compromise could not be demonstrated at that time. Last minute shifts in the patrol lines of Groups Ritter and Neptun at 2322A and 2330A on 18 February showed clearly that the German Naval High Command had abandoned the idea of operating on an expected eastbound convoy (HX 226) and was rapidly reforming his lines for a westbound convoy (ON 166). Within a few minutes of these changes, at 2349A/18 a third group of U-boats, Knappen was formed to swing out to the southeast of the Neptun-Ritter line and thus cut off any possible southerly diversion of the convoy.

It was Knappen that made contact on the morning of the 20th, U-604's (Höltring) hydrophones having picked up the convoy's screws. Three diversions had been sent to ON 166 on 17-18 February in Naval Cipher #3, table "S" as the convoy attempted to clear the U-boat area by proceeding on a southerly course. In addition, several position reports had been sent by the convoy before 17 February in table "S." That U-boat Command had accurate information on the convoy can scarcely be questioned.

The disposition and shifting of the U-boat groups between 18 and 20 February suggest knowledge of the convoy's diversion rather than reckoning based on the convoy's own position reports. Of the three diversions sent, the first

-- 37 --

one, 1001Z/17 February from CINCWA, seems the most likely suspect, not only from the point of view of the time lag, but also in view of the U-boat disposition. This first diversion would have sent the convoy through the Ritter line just to the south of its mid point. The straggler's route would have passed through Knappen's line.

3. Fears communicated.

On 26 February the Atlantic Section sent a memorandum to COMINCH calling attention to the extraordinary and effective sequence of changes in the U-boat line from 18 to 20 February, and the fear of compromise was orally communicated to COMINCH by the Commanding Officer of the Atlantic Section.

4. Further evidence, March 1943.

a. Raubgraf - Convoy HX 229.

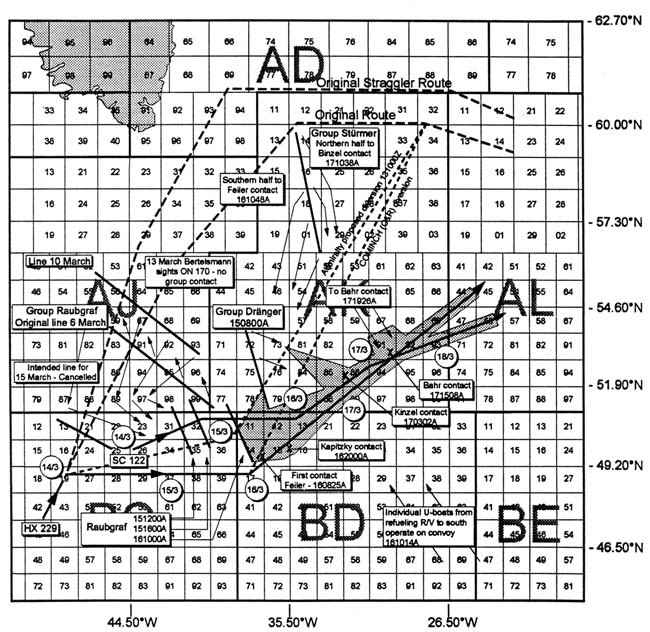

The Raubgraf operation in mid-March of HX 229 and SC 122, "the greatest success yet achieved against a convoy," was probably assisted in large part by a compromised diversion dispatch, sent in the world-wide table of combined cipher. U-boat traffic suggests that HX 229 was the one involved in compromise rather than SC 122, which was proceeding on approximately the same route with HX 229. After the operation was well underway Command recognized that he had two convoys, but the one first contacted and the one which Command seemed to be looking for was presumably HX 229 rather than SC 122. It will be helpful to list the critical Allied and U-boat dispatches in their chronological relation.

| 041704Z March | Original route for HX 229, sent in Naval Cipher #3, "M" |

| 1602Z/13 | HX 229 diverted; ordered to turn due east on reaching 49°N - 48°W. (J) Sent in Naval Cipher #3, "M" |

| (The presence of U-boats across the original route between Newfoundland and Greenland was known.) |

-- 38 --

Groups Raubgraf, Dränger, and Stürmer - HX 229 and SC 122, March 1943

-- 39 --

| 1214A/14 | Raubgraf ordered to form new line off Newfoundland for 15 March in expectation of a "north eastbound convoy" |

| (HX 229's original route would have bisected this line at about 50°30'N - 47°W) | |

| 1847A/14 | Before Raubgraf could reform on the line for the 15th, it was suddenly ordered to head for area 49°40'N - 42°15'W at high speed. |

| 1920A/14 | Raubgraf line ordered for 1200A/15 from 51°15'N - 42°05'W to 49°27'N - 40°55'W. "Get hold of eastbound convoy to which further groups can be detailed later." |

It is difficult to account for Raubgraf's sudden shift without assuming compromise. Between the time of the order for the first Raubgraf line and the high speed heading (1214A to 1847A/14), 5 Raubgraf submarines transmitted, two to give their positions and three to report land based aircraft.

There is nothing in these reports which could have justified Command's conclusion that a northeast convoy not yet sighted was turning into an eastward convoy. It was not until 2300A/14, more than four hours after Raubgraf's "diversion," that Command had anything like a sighting from a submarine. At that time Walkerling (U-91) reported having seen smoke clouds at 2030A in 49°57 'N - 46°45 'W, but he had been bombed and forced off by aircraft before he could investigate. Walkerling remained close, for he made contact on a destroyer the following evening. It was Feiler (U-653) who finally established contact on the convoy itself on the morning of the 16th. Feiler had been detached from the group and was headed for a refueler off to the southeast.

Meanwhile, Raubgraf U-boats were going through several maneuvers involving such fine points as a 15 mile shift to the south, accompanied by such phrases as "The convoy must be found!" (0443/15) During this interim Command was consistently putting his successive reconnaissance lines a few miles too far to the north for HX 229. The lines would have caught SC 122 had that convoy not been several hours ahead of the line schedule.

The possibility of a compromised dispatch to SC 122 can not be altogether excluded, for the heading point ordered at 1847A/14 actually lay between the routes of SC 122 and HX 229, but orders to U-boats showed no awareness of two

-- 40 --

convoys and U-boat maneuvers pointed to HX 229. German uncertainty as to the precise location of the convoy and Command's failure to arrange his U-boats with requisite precision before Feiler's accidental contact probably indicate that Command did not possess a complete recovery of the HX 229 diversion dispatch. It should be noted that neither in the case of HX 229 nor in the case of ON 166 were critical German messages sent in the Offizier setting.

b. Convoy TO 2.

On 18 March U-boats in the Trinidad area were informed by Offizier message of the expected arrival of a convoy (TO 2) at Trinidad on 21 March. The convoy's position as of 2000A/13 March was given along with three points on her ocean route. Her estimated time of arrival was explained by the Germans as based on dead reckoning with a speed of 13 knots. This Offizier was read on 22 March and in a memorandum of that date the Atlantic Section called COMINCH's attention to it, stating that "the message gives an accurate description of the convoy's course..." This judgment was not based on the convoy's dispatches, which were not available in OP-20-G but on the convoy position estimates of COMINCH Convoy and Routing.

When access to the convoy files had been gained later on, no dispatch could be found in TO 2's file which would have accounted for the 2000A/13 convoy position given in the German Offizier. The following correspondences, however, were found in NOIC Gibraltar's Secret 2242A/10 March to USS Roper and Decatur: sent in Naval Cipher #3, table "S":

| NOIC Gibraltar | German Offizier |

| Point F: 18°05'N - 43°56'W Point G: 15°02'N - 51°55'W Point H: 11°30'N - 60°02'W Speed of advance: 13 knots. |

"It is proceeding via 18°09'N - 44°02'W 15°09'N - 52°03'W 11°33'N - 60°09'W 13 knot (The above positions are the mid-points of German grid squares.) |

It was later learned that GC&CS traced the German Offizier to two Allied dispatches, on from Flag Officer Gibraltar on 10 March (2247A) and the other from FOC WAC on 13 March

-- 41 --

(1402), both in Naval Cipher #3, table "S". Neither of these dispatches was seen in the convoy files in COMINCH Convoy and Routing. Presumably the second of these dispatches contained the estimated position of the convoy for 2000A/13.

c. Convoy UGS 6.

In February some 5 U-boats of the 740 ton class departed France under orders Seewolf. Their heading point was deciphered as off Cape May, a decipherment soon confirmed by clarification from Control which resulted from an error by one of the U-boats. From area 42°N - 45°W Seewolf U-boats were suddenly diverted to the southward where they intercepted UGS 6 on 13 March, west and a little south of Flores. That the above operation involved the compromise of UGS 6's ocean route seemed highly probable, but gaps in German traffic (noon 7 to noon 9 March and noon 11 to noon 12 March) made complete investigation impossible. Evidence tending to confirm compromise in this case turned up in January 1944, when Marbach (U-953) was informed in Offizier setting that "until March 1943, traffic proceeded to port (Casablanca) via DJ 2196 (34°03'N 08°00'W)." (1517/19 January 1944) Point "Z" on the ocean route for UGS 6 was 34°04'N - 08°01'W.

5. Compromise established, May 1943. Convoy HX 237.

The Atlantic Section's wall chart on 8 May showed convoys HX 237 and SC 129 on a diversion route that would safely clear the south end of the long Rhein-Elbe patrol line whose position off Flemish Cap had been accurately fixed by decryption. At this point the current reading of traffic stopped temporarily, but U-boat contact seemed very unlikely. When B'B' short signals, with the group count known to be predominantly convoy sighting reports, were fixed by D/F the following afternoon in the convoy's path, it was clear that Rhein-Elbe submarines had made a rapid sweep to the southeast and had found the convoy, for there were no other U-boats in the general area at that time except the members of these groups. When the traffic became available, a few days later, attention was immediately concentrated on three Offizier messages. Grammatical variations of the crib "Ein erwarteter Geleitzug" (an expected convoy) were tried and the compromising information came out.

-- 42 --

a. Investigation of first Offizier.

| "2307 | ||

| To: (Groups) | Rhein and Elbe Offizier G |

|

| An expected convoy was in LD 2684 (BC 7684 = 43°57'N - 48°25'W) on 6 May 2330B. Precise course not known, but apparently eastward. Speed 9.3" | ||

A careful study was at once undertaken but for several day yielded no satisfactory result because the Atlantic Section had not received all the pertinent Allied dispatches. Not until access to Convoy and Routing had been gained via COMINCH submarine tracking room was it possible to find the source of compromise. The examination of the convoy files showed that German cryptanalysis had a good depth with which to work, for the diversion of the convoys, complicated by a bad fog off Newfoundland Banks, had led to frequent exchanges of dispatches between shore authorities and the escorts - all in Naval Cipher #3, table "S." On 7 May, for example, there were at least 6 transmissions from escorts (5 from C2 and 1 from W6). While there was no way of determining how many dispatches the Germans had read, the first Offizier could be traced without question to:

W6 Secret 062130Z to CINCCNA (in Naval Cipher #3, table "S") HX 237's position 43°56'N - 48°27'W, course 131, speed 9.5.

| Allied dispatch | German Information |

| Time: 2130Z 45°56'N 48°27'W |

"2330B 45°57'N (mid-point of 48°25'W German grid square) |

The Germans had apparently failed to make a complete recovery and remained in ignorance of the southerly diversion until the evening of 8 May.

-- 43 --

b. Investigation of second Offizier.

| "0025/9 | ||

| To: (Group) | Rhein Offizier K |

|

| The expected convoy, according to sure report, is further south and further ahead than assumed. A patrol line must therefore be drawn up by 2000B on 9 May extending from CG 2927 (BD 7927 = 43°33'N - 34°55'W) to VA 9154 (CE 4154 = 39°45'N - 35°02'W). Maintain radio silence." | ||

Although there could be little doubt that the second Offizier derived its information from compromise, it was not possible to identify the specific Allied dispatch in question. It was clear that German Command had discovered the southerly diversion between 2015B and 2310B on 8 May, for at 2051 the failure of the U-boats to make contact had led to an order for a sweep on course 060, speed 8, thus indicating that a northerly route was deemed possible. At 2310B the order to sweep on course 060 was canceled and U-boats were put on course 120 at top speed. U-359 (Forstner) made contact the following afternoon in 41°N - 37°W. Any one of several dispatches between CINCCNA and convoy escort, which resulted from difficulties in trying to change course, would have yielded the information, especially CINCCNA 060900Z to W6 and CINCCNA 061530Z to escorts, both in table "S."

c. The third Offizier and the straggler rendezvous.

| "0952/11 | ||

| To: (Group) | Drossel Offizier X |

|

| Eastbound Clausen convoy will be in nav. sq. 9552 (44°21'N - 27°15'W) at 1600B May 11." | ||

The Clausen referred to in the third Offizier was the Commander of U-403. This U-boat had regained contact on HX 237 the preceding day, 10 May, by following an obliging tug until it rejoined the convoy. The tug was the ship Dexterous. It is mentioned because Dexterous was in part responsible for the broadcast of straggler rendezvous for the 11th that was sent to Group Drossel in the third Offizier.

-- 44 --

| Allied dispatch | German Information |

| (CINCWA Liverpool 090901) R/V 1400Z/11 in 44°22'N - 27°20'W |

1600B in 42°21'N - 27°15'W (mid-point of German grid square) |

Escort had informed CINCWA Liverpool that Dexterous had strayed and requested that she be informed of rendezvous position, adding that what books she held was not known. CINCWA Liverpool broadcast the rendezvous positions in 090901, which was sent in Naval Code #3, Auxiliary Vessel System SP 02358/44 and marked BAMS. It was assumed here that the message must have been repeated in Naval Cipher #3, as was the custom in such cases, but no such dispatch could be found in Convoy and Routing. There were other puzzling points for which satisfactory explanations could not be obtained. (For British conclusions see Appendix 13, case 4 under May 1943.)

6. Demonstration of compromised accepted. Action taken.

The demonstration of compromise was at once submitted to COMINCH. Meanwhile the British had arrived at the same conclusion and recommended certain precautions for the month of June until a new basic book (No. 5) could become effective. The insecurity of Naval Cipher #3 was attributed to:

(a) "compromise of portions of aviation base book due to heavy use over long periods.

(b) overload of "M" and "S" tables in spite of 10 day change.

(c) ease with which enemy can classify messages in Naval Cipher 3 due to distinctive combined call signs."

(ref. Ultra personal for Admiral King for First Sea Lord 072250, 072255, 072302 June 1943)

The proposed countermeasures consisted largely in weekly changes of "M" and "S" tables. In view of the continuing evidence of compromise, which increased markedly during this period, the interim cipher safeguards could not be accepted satisfactory. In consequence Naval Cipher #5 was brought into effect on 10 June.

-- 45 --

7. More compromise - to 10 June 1943.

During May and the first 10 days in June 22 cases of compromise (confirmed or presumed) appeared in U-boat traffic. Three of these cases are of particular interest to the U.S. Navy.

a. COMINCH submarine notices:

| COMINCH Sub Notice | German Offizier |

| Confidential 291613Z May (in part) "USS Herring on patrol within 20 miles of 54°N - 42°W. USS Haddo on patrol vicinity 51°N - 35°W" |

(Positions converted from grid) 153113/31 May "On evening of 29 May an American submarine was on patrol within 20 miles from 53°57'N - 41°55'W. Another one in 50°57'N - 34°55'W submerged by day, on surface at night." |

| Comment: While the last phrase in the Offizier did not appear in COMINCH, the Germans had presumably read it before and may have assumed that the last sentence in the sub notice, which they did not read, contained this ordinary and sensible conclusion. Time interval: 45 hours. |

|

| Confidential 051606Z Jun "Hake on patrol vicinity 53°20'N - 37°00'W. Haddo on patrol vicinity 51°00'N - 35°00'W. Herring 54°41'N - 28°48'W submerged by day enroute 54°45'N - 28°01'W. ETA 051800 thence to 54°01'N - 22°02'W. ETA 061800 surfaced at discretion." |

1729B/8 JUN "American sub Hake on 5 June patrolling area of 53°21'N - 37°05'W- sub Haddo in 51°03'N - 34°55'W." 2311B/8 JUN "USA submarine Herring was 54°39'N - 28°45'W on 5 June; course not known, proceeding submerged by day." |

| Comment: Time interval: 71 hours. |

|

b. Flight 10 (with note on GUS 7A).

COMINCH Secret 211944Z May informed CESF, NOB Bermuda, and others in Naval Cipher #3 that 19 British LCI(L)'s were to set sail about 24 May from Norfolk to Bermuda. NOB

-- 46 --

Bermuda was to direct from Bermuda to Gibraltar according to the ocean route which was given. In Offizier 1106B/24 May German Command ordered 16 U-boats to leave their stations in the North Atlantic and head at once for area 35°15'N - 42°05'W. The U-boats had to reach their destination by 2000B/31 May. An explanation was not forthcoming until 1832B/29 May:

"1. Action is planned against west-east convoy expected in the patrol line from 1 June to 6 June. Speed 8 - 8.5

2. Beginning 1 June an eastbound convoy is expected approximately in area of Struckmeier's position consisting of storm landing boats of 250 tons and of their attendant tankers protected by escorts...No operation against this. Take advantage of opportunities for shots against valuable targets (tankers). Do not report when you sight this convoy..."

The west-east convoy was undoubtedly Flight 10. The position of Struckmeier (U-608) should have been approximately 33°N - 43°W, since he was the third man from the south end of the line (Group Trutz), which had been ordered on 26 May to run due north and south along the 43rd meridian and from 39° to 32°N. It was to be occupied by 0800B/1 June. Position "H" for Flight 10 was given as 33°10'N - 43°15'W in the COMINCH dispatch referred to above.

Note on GUS 7A:

If it seemed peculiar for a long patrol line to expect a convoy at its southern end rather at the middle, this oddity may have been explained on 1 June (1021B) when Group Trutz was informed by Offizier that:

"Beginning noon today, count also on westbound convoy. When you sight it, operate on it."

The "westbound convoy," GUS 7A, would have passed through the northern half of the Trutz line, according to it original route would explain the peculiar formation of Trutz, as designed to catch two convoys at the same time, but would not account for the long delay in informing U-boats. CMSF 240300Z was not believed compromised, for it had been sent in ECM 38. The

-- 47 --

possibility of another source for compromise, however could not be excluded, since at this time daily position reports were being sent in Naval Cipher #3 by various shore authorities.

8. Comment: The enemy's own ULTRA intelligence during U-boat decline.

If one may judge from U-boat traffic, German ULTRA intelligence had never been better than it was just a that period when the decline in U-boat fortunes became so evident. The increase in ULTRA intelligence disseminated to U-boats during this period may and probably does represent a corresponding increase in the amount available. The way in which it was used, however, suggests a desperate and hurried attempt to give all possible information to the U-boats at sea. In trying to give his men an additional advantage, Command certainly disregarded security regulations - without compensation - for the risk he ran. In effect, he was sacrificing his best source of intelligence at a time when his fleet was incapable of using this intelligence.

The last U-boat group attempt in May to destroy an US-UK convoy (Group Mosel - HX 239) made use of a decrypted dispatch giving straggler rendezvous positions, yet the operation ended on 24 May in miserable failure. At least six U-boats were sunk, and Command had to stop the operation while the convoy was still in sight. As U-boat after U-boat was requested to "Report position at once" ("Standort sofort melden"), Command was trying to review the total situation in a series of long messages. He promised suitable changes in operational areas until such time as his boats could be provided with adequate protection against aircraft.

It was just 12 hours later that he ordered the southern heading to intercept Flight 10. German radio intelligence had surely influenced his choice of the Gibraltar lane as the place where he might find convoys less well defended. Our decryption of his plans, however, had led to the formation of the Bogue task group, which reached the Trutz patrol line before the convoys.

9. Compromise of Naval Cipher #5 feared. September 1943.

The dispersal of the U-boat fleet during the summer of 1943, following the abandonment of Atlantic convoy lanes,

-- 48 --

made it impossible to judge how effective the introduction of Naval Cipher #5 had been, since German information on convoys could not be put to any immediate operational use. Instead of convoy intelligence, U-boats were receiving relays of Allied contact and attack reports. With September's resumption of the offensive against convoys attention was again directed to the intelligence which appeared in the timing and arrangement of the patrol lines as well as in "convoy expected" messages to U-boats.

Group Leuthen was prepared for the initial attack with the familiar signs of convoy intelligence. In addition, two of Leuthen's 21 U-boats were equipped with intercept teams prepared to hear and D/F convoy voice traffic. At 1626B/16 September COMSUBs sent the following to Leuthen: