Butler, Henry F., Mrs. I Was a Yeoman (F). Washington, DC: Naval Historical Foundation, 1967. [Copyright by Naval Historical Foundation.].

The Navy Department Library

I Was a Yeoman (F)

By Mrs. Henry F. Butler

[Estelle Kemper]

Foreword

The Naval Historical Foundation is pleased to present for its members, the personal experience of a Yeoman (F) who just about 50 years ago was among those who invaded the sacred ranks of the bell-bottomed man's navy.

Those members who are old enough will in all probability have recovered from the shock of their initial impression of these feminine tars. The younger members will have grown accustomed to the modern version of the yeomanette who are such an important asset to the Navy of today.

The Foundation is indebted to Mrs. Henry F. Butler who kindly consented to this publication from a collection of material she has graciously presented.

Copyright – Naval Historical Foundation

I Was a Yeoman (F)

[p.1]

Springtime, 1918, was the loveliest of all Virginia springs, it seemed to me. The whole earth was sunny, warm, and fragrant with box, magnolia and honeysuckle.

In June I graduated from college, in Virginia, and in spite of the sobering effect of a world war, our commencement was carried on in the traditional manner. There were tree plantings, daisy chains, organdy dresses alternating cap and gown, gaiety tinged with nostalgia, and the inevitable words of wisdom and advice in stirring commencement addresses.

Perhaps our college felt the impact of war more than most, for, having offered its buildings for use as a Veterans’ Hospital, it was preparing to move from its flowery campus into city quarters.

Because "raised" in the South and fed on stories of the "war between the states," I had come to think of war as a sort of prehistoric phenomenon. When I found myself actually living in the midst of an almost-global shooting war I was stunned.

In College I had participated in all the war work open to students (largely, sewing for Belgian Orphans) but being young, and taking myself pretty seriously, I felt that if I could once get a full-time war job I might turn the world upside down, pronto, and bring back the relaxing, happy days of peace.

Perhaps I suffered from a Jeanne d' Arc complex, and visualized myself riding forth on a white horse on a great mission for Peace. And, being romantic as well as young, I may have got my white horse symbol from "Lady Godiva." Who knows?

Whatever was back of my seriousness, the minute I had my diploma safely tucked under an arm, I started a mad search for a war job in Washington.

My parents were often disturbed by my precipitations, and my impatience with preliminaries. Mother wished that I would get a good rest from college and then begin to think of a job. Father saw no reason why I could not find plenty of war work in Richmond. He warned me that Washington, in wartime, was a dangerous place for a girl, and that if I went to the capital city, I should "expect to be insulted on every street-corner."

To ease these fears somewhat, I agreed to stay temporarily with friends of the family who lived on the Virginia side of the Potomac. That would mean that my address would still be Virginia, rather than Washington.

Also I was to follow a clue I had for a civilian position in the Army with the Military Intelligence Division, and M.I.D. had a rather dignified, highbrow sound to the family.

Another safeguard they arranged was that I be met at the Washington station by a young Ensign, whom I had properly met in Virginia, at the home of a cousin. With such escort, the first day, at least, should be safe from the street-corner peril.

So I set forth -- in a railway coach, instead of on a white horse -- but with the serious intention of making over the world.

[p.2]

On arrival in the wicked city I was met by the Ensign, as planned, but since he too was young and filled with patriotic fervor, he had dreamed up a wonderful plan for me. He suggested that if I really wanted to serve my country, I should join the Navy.

Allowing women in any branch of the armed services was a recent innovation, and I had not heard that the Navy was enlisting women. Even to my crusading spirit the Ensign's suggestion was somewhat startling.

But why not join the Navy?

If not a white horse, why not a sea-worthy boat?

If the Navy needed me, I was hers.

So it was, that before even telephoning to the friend of a friend in Military Intelligence, I set off for the New Navy Building to see what was what.

To this day I have never been able to figure out why the Navy wanted to enlist girls in 1918. It had plenty of civilian clerks, and the (Yeoman (F)) were never more than clerks, but that is all beside the point.

The process of joining up (if a girl) was simple and speedy: first, an interview by a chief clerk, and then a physical exam' at the Naval Hospital, an oath of allegiance and, presto, one was a "Yeoman (F)," signed up for four years!

My Chief Clerk was friendly and pleasant. He may have guessed that I had never been inside a real office in my life, for girls trained in business routines were even scarcer in those days than girl college graduates.

When the Chief Clerk asked me my "typing speed," I remembered that I had used my father's ancient Blickensderfer, for typing letters and college papers, by the "hunt and peck" system, and replied quite casually, "Oh, I guess around two hundred words a minute."

I had no idea that I was claiming a record, and the fatherly Chief Clerk undoubtedly knew that I was more ignorant than boastful (or dishonest), so, without testing me on the typewriter, he made out my application papers and sent me off to the Naval Hospital.

Since the Navy had been a thoroughly masculine branch of the armed forces, it was geared to deal with men and not women. It had given us a masculine rating with a modifying "(F)," probably to be sure that some harrassed personnel officer wouldn't order us to sea! And when it came to giving us a physical examination, it followed the procedure for male recruits.

So, arriving at the Hospital I soon found myself putting off my clothes and my Jeanne d'Arc role, perforce, for the part of Lady Godiva. Then I joined a long line of stripped females, holding bath towels around their middles, shivering in spite of the hot summer day.

We stood in a resounding corridor leading to the doctor's office. Some of those unhappy female recruits were sobbing nervously.

[p.3]

Male recruits may not mind being herded together in the "altogether," but those poor, stripped feminine patriots were a sorry sight, as they cringed in that open hallway, waiting to be scrutinized by a strange doctor in Navy uniform.

Had any one of them been able to sneak back to her little pile of clothing in the disrobing room, without the fear of running into a sailor (M), I rather guess that line in the corridor might have dwindled all too quickly.

Only the fear of prying eyes, or worse, saved a lot of Yeomen (F) for the U.S. Navy. Or that is my bet.

One weeping girl said to me: "You act like you didn't mind having no clothes on!"

In an effort to reassure her (and myself) that doctors - (M) or (F) - were quite impersonal about nudity (I hoped so, surely) I said as nonchalantly as I could: "Oh, after the first couple of times you get used to this sort of thing."

I am afraid that my answer was somewhat misconstrued, for that girl always carefully avoided me when we met, later on, in the Navy building.

As I remember it, there was only one weary, over-aged M.D. responsible for examining that long line of girls, and he was not one bit interested in anything but getting through his work and home to supper.

He weighed us, measured us, listened to our hearts, and passed us along at furious speed.

Then we were sworn in, and that afternoon I was a Yeoman (F), 2nd class, and was measured for a uniform.

Since all men enlisting in the Navy were assigned to a ship, the Yeomen (F) were assigned to an old boat called something like "The Thetis" (I have forgotten the name, but I imagine she was a tug), which had been sunk in the Potomac River, some time before. Thus the Navy saved masculine face and still insured for itself an ever-beached female service! As for me, my seaworthy boat was sunk, so again I turned my thoughts to a capering white horse!

I reported for duty that same afternoon, and by nightfall felt like an old hand. After dinner I phoned my family in Richmond. My father answered the phone and I told him proudly that I had joined the Navy. Never immune to my bomb-shells, he gulped and said quickly: "I'll call your mother."

When I repeated my announcement to her, she was stunned into silence for a moment, then asked weakly: "Oh, sister, can you ever get out?"

The poor dear probably saw me in bell-bottom trousers, swabbing decks, keeping close to the rail, for I was not born to the sea!

However, in no way daunted by my family's lack of enthusiasm for my piece of news, I felt greatly pleased with myself. I had gone the limit in my effort to end the war, and end it fast.

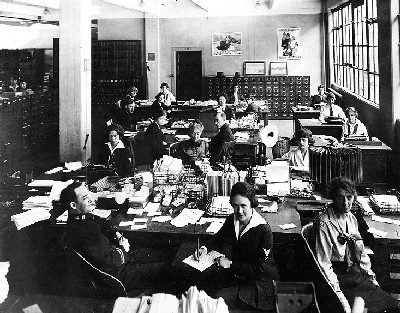

I was given a desk in the Supply Section of the Division of Aeronautics of the Bureau of Steam Engineering. Aeronautics apparently had been as great an innovation to the traditional floating navy

[p.4]

as "lady sailors" were, and the old sea-dogs who ran the show had tried to fit each into its existing pattern. The Bureau of Steam Engineering had charge of building ships' engines, so a Division of Aeronautics had been added which supervised building gasoline engines, propellers and incidental equipment for the ships of the air. The Division of Aeronautics was subdivided into as many sections as it had separate functions — the Engine Section, Propeller Section, and so on. In the same manner, to the Bureau of Construction and Repair which had charge of building ships' hulls and rigging had been added a "D.A." which supervised building hulls and wings for flying boats.

The job of the Supply Section D.A., Bu.S.E. to which I was assigned was to keep aeroplane parts flowing to the factories where planes were being assembled, and to our naval air stations and bases at home and abroad as spare parts to keep our planes flying.

There were no barracks or mess halls for Yeomen (F) and we were given an allowance to "find" ourselves. Virginia was too far from the Navy Building for easy transportation, so pretty soon I had a room in Washington, and was eating dinners with a group of seven Vassar "grads," who had come en masse from a small mid-Western town, and had joined the Navy, rented a House and hired a maid.

We were together in office and out and had quite a lot of fun, when there was any let-up in our long hours at the Navy Department.

[p.5]

We worked six days a week regularly, sometimes on Sundays, and often late into the night, for all of us were imbued with patriotic ardor and with the sense of our own responsibility to the war effort.

Our officers worked as long hours as we did, and as cheerfully.

I am not sure just what our salaries were, but I know that we had less than $150.00 a month each, and never received (or expected) any such things as "overtime."

My room rent was around $35.00 a month, and food costs were terrific. I bought shoes and stockings and nothing else, yet I seldom had enough cash to allow me to pay for the last few meals before pay day, so I had to call on friends. I was more fortunate than many of the Yeomen (F), for I did have friends in and near Washington, and was often invited out to dinner.

We had "dates," but usually with young Naval officers who were as "broke" as we were, so we contended ourselves with Sunday picnics, or automobile rides, and few parties. One attractive talented young officer, whose mother depended on him for support, lived in a country shack, walked several miles to town every day to save carfare, ate a fifteen cent dish of spaghetti for lunch, and cooked his own dinners at the shack. Picnic suppers at his place were great treats.

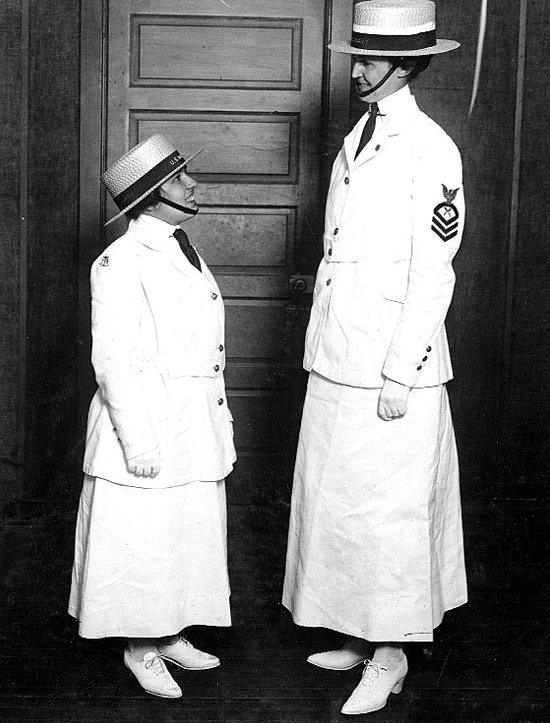

But there was one test to our patriotism which almost proved our downfall — our uniforms.

Whoever designed those Yeoman (F) uniforms I do not know, but it was no Mainbocher.

[p.6]

The skirts were straight, tight and of the most awkward length possible. The jackets were shapeless affairs, loosely belted in a sort of "Norfolk" attempt. The ensemble turned out to be about as flattering to the female form as our father's business suits would have been.

The hats were flat, blue sailor models, just the wrong size and shape for any girl who ever wore a hat, except when taking a comic part on the stage.

Our big blue capes were rather impressive, but, unfortunately, too heavy to wear except in extremely cold weather.

My seven Vassar friends and I tried on our new uniforms for the first time, and were struck dumb by what we saw in the mirror, and when we looked at each other.

Normally we were not a bad-looking lot. In those uniforms we could have been outdone in looks by the Salvation Army!

Well, we were a crestfallen crew - almost a tearful one. We did love our country, and did want to do our duty by the Navy, but how on earth could any country demand such a sacrifice?

Did it really make any difference, anyway, whether we wore the uniforms or not?

There were hundreds of civilian clerks in the Navy Department, and who would know the difference if we just hung away our uniforms in our closets and continued to wear our own clothes?

The Navy had offered no attempts at any special indoctrination for its girls; it provided no barracks, allowing us to live wherever we pleased, so there seemed little reason to wear uniforms (How we would have loved to wear such uniforms as the Waves were given in World War II!)

Sadly we made our decision, for it was a serious matter to all of us.

We went about our daily tasks as usual, and no one paid the slightest attention to our garb. Then, suddenly, one day each of the eight of us got an order to report to our Chief Clerk, Mr. Wrenn — and at once.

We filed into Mr. Wrenn's office, en masse, out of uniform, and unashamed.

Mr. Wrenn was like a hurt father. "What are you girls doing out of uniform?" he questioned us with a sad note of disappointment in his voice.

One of our number, smart little Irish girl, answered Mr. Wrenn with a sob in her voice: "Oh, Mr. Wrenn, our uniforms don't fit!"

Mr. Wrenn assumed a stern tone of parental authority: "You girls know where you can get a tailor, don't you?"

We nodded slowly, all eight of us.

"Well," said Mr. Wrenn in an encouraging voice: "You girls — every one of you — go to a tailor and ask him to make your uniforms fit. Come in here a week from today and let me take a look at you, properly dressed."

We were humble, said, "Yes, Mr. Wrenn," and filed out.

No tailor could have done anything with those uniforms so we saved our money, put the uniforms on a week from that day, wore

[p.7]

our capes over them on the street, and then marched to see Mr. Wrenn.

He was properly impressed and properly complimentary, and our interview was over.

After that we continued to leave the uniforms in our closets, and no one seemed to notice our dereliction. Then along came eight printed forms, ordering us to report at a certain hour, on a certain day, at the "White Lot" (down back of the White House) for Drill.

That was a blow. Six of the girls decided that our independence was at an end, but one of the Vassarettes and I were not willing to give up without a struggle. The six donned their uniforms again on the appointed day and joined the mob at the "White Lot." The seventh and I, in our own dark voiles, trailed them to watch the procedure. We kept behind some shrubbery, and out of sight, but ready to join the ranks if it seemed advisable.

A young C.P.O. (M) finally appeared on the scene with a stenographer's notebook in hand. He signalled to the Yeomen (F) for attention, and then called out casually, "Now let's get your names, one at a time."

The girls spoke out in turn and he listed them.

"Now," he said, "you'll start Drill next week. That's all for today."

The six who had got their names in the C.P.O.'s notebook went back the next week to the White Lot, and again we other two trailed them. Since nothing happened but a brisk walk around the White Lot, we saw no reason to join the walkers, and so we went back to the office and worked during "Drill" period. From that day on we were on the job while the others ambled around the White Lot.

-------

The Chief of the Bureau of Steam Engineering, Admiral Griffin, a brilliant and cultured officer, was always most courteous. But the second-in-command, a captain of the brass-bound, salty type, let it be known he still considered the Navy a man's world, and had it in for the skirts.

One Friday afternoon after two o'clock our bounding old Captain plunged into our office. Usually there were several officers and around twenty girls working there, but this afternoon there were only three or four of us girls, and the room looked pretty well abandoned.

Our Captain looked about and was visibly disturbed over something.

He roared at us: "Who's in command of this ship?"

Immediately my glamorous Vassar friend, Irish Carolyn, rose to her feet and saluted.

"I am, Captain," she replied in a deeply respectful voice.

The Captain was almost toppled over, but he came right back at her: "Are the girls who belong in this office still at lunch?"

His fog-horn tones were threatening.

[p.8]

Our Yeoman (F) replied sweetly. "Captain, this is Friday, you know. I imagine it's a matter of bones."

The Captain snorted violently and rushed headlong out of the office. He was making strange, gurgling sounds in the back of his throat.

In World War I there were no women commissioned officers except in the Nursing Corps. Chief Petty Officer was the highest rating open to us, and there were only a few of them.

Six months after my induction as a Yeomanette, I was recommended for a C.P.O. rating. The exam was easy and I missed out on only one question, "Where are the Ozarks?" (I'm still not sure); but then a general Navy order came out stating firmly that no more girls could be C.P.O.'s. This was after the Armistice, so the order was quite reasonable. But I should have liked to reach the grade of C.P.O., at least.

Well do I remember the morning of November 11, 1918.

I was standing beside my desk in the Navy Building, sharpening a bunch of pencils, when bells began to ring, and whistles to blow. Since the "False Armistice," everybody was a bit wary of reports of an end to the war, but this was the real thing. (Even now I have a superstitious feeling about pencil-sharpening. Whenever I have a problem, I wonder if sharpening a few pencils might not bring about its solution!)

The city was wild that night. I was with a group of revelers, and we did not manage to find a place to eat until nearly midnight. We ended up at a club, and our officer hosts flung all caution to the winds and ordered a steak dinner with Burgundy!

-------

Since Washington was new to me, I got a great kick out of attending special night sessions of Congress, when not working late at the Navy Building. One of my Vasser friends and I hold the distinction of having been in the elder Senator Lodge's office the night the Senate was in all-night session filibustering the League of Nations. We were looking for a Ladies Room about midnight and just wandered into Sen. Lodge's office to ask directions. His secretary was typing a long list of names, probably the list of senators who were backing Lodge to kill the League.

Since all of us disapproved of Senator Lodge and his opposition to the League, my friend and I often wondered if we could have kidnapped his secretary that night and saved the League of Nations.

-------

After the Armistice our Supply Section attended to the collection and disposition of Naval Aviation materiel no longer needed at our air bases in this country and overseas.

That work was necessary, but rather tedious.

Then came preparations for the Trans-Atlantic flight, and none of the Yeomen (F) can ever forget the excitement of those months.

[p.9]

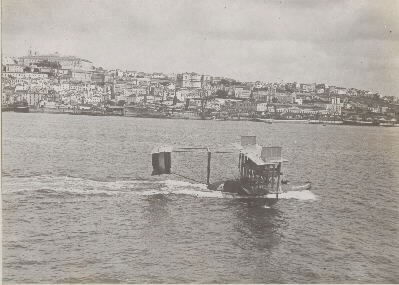

It is surprising how few people remember that the first crossing of the Atlantic Ocean by air was accomplished by our Navy.

During 1918 and 1919 several attempts at this great feat were made, and two such attempts were undertaken by the U.S. Navy — one by lighter-than-aircraft (the C-5) and one by flying boats.

The Navy dirigible, unfortunately, broke loose from its moorings north of Halifax, floated, without crew, out to sea and finally disappeared in the east.

However, the flying boat venture succeeded.

I happen to have a copy of the diary kept by the pilot-engineer of the successful Navy plane, the NC-4, and the facts of that memorable flight are gathered from Lt. Breese’s log, plus various items from our own memory.

There were some real inventive geniuses among the young officers who engineered that great adventure, and we Yeomen (F) always felt it a privilege to be entrusted with drawings and plans which had to be transported by special messenger to our Air Base at Anacostia.

After months of preparation the Navy was all set for the take-off of three planes assembled at Rockaway Beach. Since they were built by Curtiss they were called the (Navy-Curtiss) NC-1, 3 and 4, respectively. (The NC-2 had been cannibalized to replace damaged parts in the other planes.)

Commander Towers was in charge of the full expedition and commanded the NC-3, the Flag Ship. Lt. Commander Bellinger commanded the NC-1; Lt. Commander Read the NC-4.

On May 9, 1919, the NC-1, 3 and 4 were ready to leave Rockaway Beach en route to Trepassy Bay, Nova Scotia, which was to be the jumping off spot for the Trans-Atlantic hop.

All hands on board were given four-leaf clovers for luck, and, at 10 A.M., men in high boots waded into the water and turned the three planes so that their noses pointed to the open sea. Then the signal was given, and the planes rose from the water and started flying north along the shores of Lone Island, toward Halifax, their first stop.

U.S. destroyers were stationed along the course to be followed, first, up to Trespassy Bay, and then at approximately 150-mile intervals across the Atlantic to the Azores.

When about a hundred miles off Cape Cod, the NC-4 had engine trouble, and had to be brought down on the sea for repairs. A broken connecting rod had pushed out through the side of the crank-case of one engine, wrecking a water pipe of the cooling system.

Commander Read decided to taxi back to Chatham for repairs.

Lt. Breese observes in his diary: "An all-night run brought us there at day-break. A wonderful piece of navigation! Imagine landing somewhere in the open ocean, setting your course at an unknown speed, running all night, and at daybreak finding yourself just where you wanted to be!"

However, after replacing the damaged engine and making other repairs, the NC-4 was grounded at Chatham by bad weather until May 14.

[p.10]

On that day it finally got off and, after an all-day flight, arrived at Halifax. The crew went aboard the U.S.S. Baltimore for supper and the night after tying the "4" astern.

On May 15, the NC-4 again took to the air a little after 10 A.M., and that evening came down in Trepassy Bay, where the NC-1 and 3 were awaiting it.

That night the crews of the three planes slept aboard the U.S.S. Aroostook.

The engine which had been installed on the NC-4 at Chatham was not working properly and had to be replaced by a new Liberty. So it was that while the NC-1 and 3 were ready to leave Trepassy at about 4 P.M. on May 16, and were taxiing around the Bay, the NC-4 was frantically endeavoring to get its new engine started, and the crew were fearful of being left behind.

Finally, as his "last trump card," Lt. Breese went below and raised the ignition circuit from its normal 8 volts to 12. He was taking a chance of burning out the starting motor, but the moment was critical. He came back on deck, gave the signal, the pilot pulled the button, and with a roar the recalcitrant engine started. The other engines started easily and all three planes pulled into position. One and 4 took to the air, but 3 was too heavy to get off the water and, I believe, one man was taken off. Then around 5 P.M. all three started again, and this time the big hop was on, and so the three venturesome planes flew eastward into the night.

Lt. Breese noted in his diary: "The sun has set in a ball of red behind us, and the moon is rising off our port bow."

The crew of the NC-4 could periodically communicate by wireless with the destroyers which they occasionally sighted beneath them.

While the three planes endeavored to keep fairly near each other, they made no attempt to fly in close formation. Before long the NC-4 was well ahead of the others.

At dawn on May 17, the NC-4 encountered clouds, and later fog. The plane rose to 3,000 feet to escape the clouds, but since from that altitude it was impossible for the crew to see the land they hoped they were approaching, they dropped and flew close to the water where visibility was better.

Soon land was sighted off the starboard bow and after coming down once to take bearings, the NC-4 landed in the harbor of Horta, flying the American flag as a commissioned ship of the U.S. Navy entering the foreign port.

At Horta the NC-4 crew learned of the sad fate of the NC-1. It had been lost in fog, had made a water landing but in doing so had broken a wing panel. The crew were picked up by a tramp steamer while their poor flying boat, with both wings torn off by high seas, turned over and sank.

The NC-4 left Horta on the morning of May 20 and reached Ponta Delgada by nightfall.

There they found the crew of the NC-3, whose plane had been "shipwrecked for 72 hours" and had taxied into Ponta Delgada with only one motor running, and unable to continue the flight.

[p.11]

More engine trouble and bad weather, then the NC-4 was off again, this time alone.

On the evening of May 27 the "4" landed at Lisbon, with the whole city out to watch it.

Lisbon gave the crew a great ovation which lasted for nearly two days.

Then the NC-4 flew on to Plymouth, England, where ceremonies were held celebrating "the return of the Mayflower."

The Navy had completed the first ocean journey by air after eighteen days of mishaps, and lay-overs for bad weather. Two of the planes had failed to stand the gaff; only the NC-4 had made the grade.

In Washington our officers were in a state of wild excitement. We Yeomen (F) felt that we had played some slight part in this world-shaking accomplishment. In other words, we had done "yeoman service" for the first crossing of the Atlantic Ocean by air.

The NC-4 was returned to the United States where it continued its flying career until it finally came to rest at the Smithsonian Institution.

-------

Washington had a far greater war population in 1942-45 than in 1918, but World War II found the city somewhat better prepared to cope with the housing of its workers.

Washington boarding-house keepers capitalized on the influx of war workers, and often crowded six or eight girls into a normal size double room. We even heard tales of some girls sleeping on

[p.12]

cots in long dormitory rows, in Washington attics. Because of the bad living conditions in the city, the dreadful "Flu" epidemic in the autumn of 1918 quickly got beyond the bounds of medical control. These herded war workers died like flies, and the rows of piled up caskets along the tracks at Union Station were mute evidence of the city's unpreparedness for war-time crowds. I caught the dreaded bug but fortunately fell into the hands of a wonderful lady osteopath, who put me to bed right in her own apartment and would not let me get out until a high fever had been reduced to normal. So I was just plain lucky.

During the epidemic I went early to the office, armed with a big bottle of disinfectant and washed all desks and chairs and telephones with the bug-killer. Just the same, it seemed to me that every morning somebody else was missing from his or her desk, and all too often when I called a home phone number I learned that our clerk had died overnight.

We were winning the war in Europe, but for a few weeks Death seemed to have put his awful finger on our capital city.

In 1918 there was a general atmosphere in the capital of old fashioned patriotic fervor, which was the natural accompaniment of high hopes, and dreams of making the world safe for Democracy, once and for all. President Wilson's idealism fired every war worker.

There were flags and bunting everywhere, and a sort of perpetual Fourth of July atmosphere. Hundreds of war posters, many done by outstanding artists, plastered every available bill-board, trolley car and building.

There were no nightclubs then, but in hotels, cafes and restaurants, orchestras played and guests sang, with wild enthusiasm, the songs made popular by our "boys in the trenches." Among the favorites were "It's a Long, Long Way to Tipperary," "Over There," "Pack Up Your Troubles in Your Old Kit Bag and Smile, Smile, Smile."

In 1918 the term "cocktail lounge" was unknown. Naturally there was a certain amount of drinking, but as the law forbade the sale of liquor to anyone in uniform, the hotels, restaurants and cafes were pretty meticulous about conforming to it. Most drinking was done in private homes or in clubs.

Among my own circle of friends and acquaintances in Washington there was very little consumption of alcohol. We had little money to spend for drinks, and little time to indulge ourselves.

As for smoking — practically no girls or women smoked in public, and never in an office. Most of my girl friends had an occasional cigarette, either the old strong Fatimas or, going to the other extreme, the little violet-scented numbers. We usually enjoyed them in the privacy of our own bedrooms, and often blew our smoke out an open window.

There were only a few movie theatres and they were seldom crowded. However, mobs were attracted by Bond Rallies and Bond Raffles; and on Sunday mornings long lines formed outside churches

[p.13]

bright and early, in an effort to get seats. In 1918 Washington was hard-working, earnest city. Its enthusiasm was spontaneous, and needed little artificial stimulation.

Having jobs and doing our "duty" (as we saw it) fully compensated the Yeomen (F) in my acquaintance for their lack of money, lack of prestige, long working hours — even those uniforms — and we were sorry when the Navy gave us our "honorable discharges" in 1919.

Fortunately, most of us were still young enough to look forward to new worlds to conquer.

I do not know how many of the "Yeomanettes" re-enlisted in the U.S. Navy in World War II. Personally, I longed to become a "Wave."

It would have been good to hope for a better rank than that of able bodied seaman (F), and surely those lovely Wave uniforms would have brought joy to the hearts of any Yeoman (F) of the first World War!

The only distinction I won as a grounded Navy enlistee came after the Armistice in 1918. Every member of the services was issued a medal on a rainbow ribbon. This "Victory medal" was "general issue," but the then Secretary of the Navy personally presented mine to me, with the conventional kiss on each cheek. A little French, to be sure, but a very satisfactory honor!

-------

On a visit to Washington in 1922, I was eager to attend the final session of the Naval Disarmament Conference. Still riding the white horse, and also an old Navy hand, I felt that I was obliged to present on the day when the treaties were signed by the Great Powers. However, attendance at that memorial session was necessarily restricted, and I was told that even our Senators were allowed only one extra admission ticket each. There was no chance in the world for me to get into the conference chamber.

Though discouraged on all sides, I went to the Memorial Continental Hall that fateful morning to see for myself what the situation actually was.

There was a full line of armed guards surrounding the building, and then extra military at each door.

A steady stream of dignitaries were arriving, and even these important people, all bearing official admission tickets, were held up twice while their tickets were examined.

I tried every known wile on the first line guards, but to no avail. It seemed pretty hopeless.

Then I engaged one guard in conversation. I told him I was born and raised a Democrat. He said he was a Republican. Then I suggested that maybe a Democrat might turn Republican if he could see the Republican President, Mr. Harding.

I guess I got to be quite a pest, for, finally, in desperation, the guard said: "Oh, well! Go on in and tell the next guard you are Senator ____________'s daughter."

[p.14]

I obeyed with stifled alacrity, got by the second guard and into the conference chamber.

An usher seated me in the balcony just above the table where the treaties were spread out for signing. As the representative of each Great Power went up to the table I could read the signature he affixed to each document. It was a moving spectacle. I also saw President Harding very clearly, though I must confess the sight did not change my political affiliation.

To carry away some proof of my attendance at this great gathering I asked a Western Union boy to get for me the autograph of Sir Arthur Balfour. I still have it on a Western Union blank.

My friends and family had to believe that I had succeeded in attending that session when I produced that autograph.

When I explained that I had got into that closed session, as "Senator ___________'s daughter,” everyone gasped. "Why, he's a bachelor!" they said.

During World War II, I was seated at dinner, one evening (in Washington), beside a very youthful Army Captain. He was obviously hungry, and just as obviously, not in a conversational mood. He ate and ate, and as I felt there should be some sound from our end of the table, I talked and talked.

Finally I was exhausted, and also hungry, so I tried one bombshell to shock him out of his silence.

I said quietly, "You know I was a Wave in World War I." (He was too young to understand the term, "Yeoman (F)"!)

He was completely unimpressed. I began to eat. Then the young Captain inquired casually, "Were you a Wac in the Civil War?"

I handed him the palm.

[END]

Notes: All underlined words in the original publication have been changed to a bold font. The original manuscript of this memoir was transferred from the Naval Historical Foundation to the Navy Department Library’s historic manuscripts collection in the Spring of 2005.