The Navy Department Library

Combat Narratives

Solomon Islands Campaign: IX Bombardments of Munda and Vila-Stanmore, January-May 1943

OFFICE OF NAVAL INTELLIGENCE, UNITED STATES NAVY 1944

PDF Version [54.1MB]

NAVY DEPERTMENT

Office of Naval Intelligence

Washington, D. C.

1 October 1943.

Combat Narratives are confidential publications issued under a directive of the Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet and Chief of Naval Operations, for the information of commissioned officers of the U.S. Navy only.

Information printed herein should be guarded (a) in circulation and by custody measures for confidential publications as set forth in Articles 75 ½ and 76 of Navy Regulations and (b) in avoiding discussion of this material within the hearing of any but commissioned officers. Combat Narratives are not to be removed from the ship or station for which they are provided. Reproduction of this material in any form is not authorized except by specific approval of the Director of Naval Intelligence.

Officers who have participated in the operations recounted herein are invited to forward to the Director of Naval Intelligence, via their commanding officers, accounts of personal experiences and observations which they esteem to have value for historical and instructional purposes. It is hoped that such contributions will increase the value of and render ever more authoritative such new editions of these publications as may be promulgated to the service in the future.

When the copies provided have served their purpose, they may be destroyed by burning. However, reports acknowledging receipt or destruction of these publications need not be made.

(Insert Signature)

REAR ADMIRAL, U.S.N.,

Director of Naval Intelligence.

II

Foreword

8 January 1943.

Combat Narratives have been prepared by the Publications Branch of the Office of Naval Intelligence for the information of the officers of the United States Navy.

The data on which these studies are based are those official documents which are suitable for a confidential publication. This material has been collated and presented in chronological order.

In perusing these narratives, the reader should bear in mind that while they recount in considerable detail the engagements in which our forces participated, certain underlying aspects of these operations must be kept in a secret category until after the end of the war.

It should be remembered also that the observations of men in battle are sometimes at variance. As a result, the reports of commanding officers may differ although they participated in the same action and shared a common purpose. In general, Combat Narratives represent a reasoned interpretation of these discrepancies. In those instances where views cannot be reconciled, extracts from the conflicting evidence are reprinted.

Thus, an effort has been made to provide accurate and, within the above-mentioned limitations, complete narratives with charts covering raids, combats, joint operations, and battles in which our Fleets have engaged in the current war. It is hoped that these narratives will afford a clear view of what has occurred, and form a basis for a broader understanding which will result in ever more successful operations.

(Insert Signature)

ADMIRAL, U.S.N.

Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet, and Chief of Naval Operations.

III

Charts and Illustrations

| Facing page | |

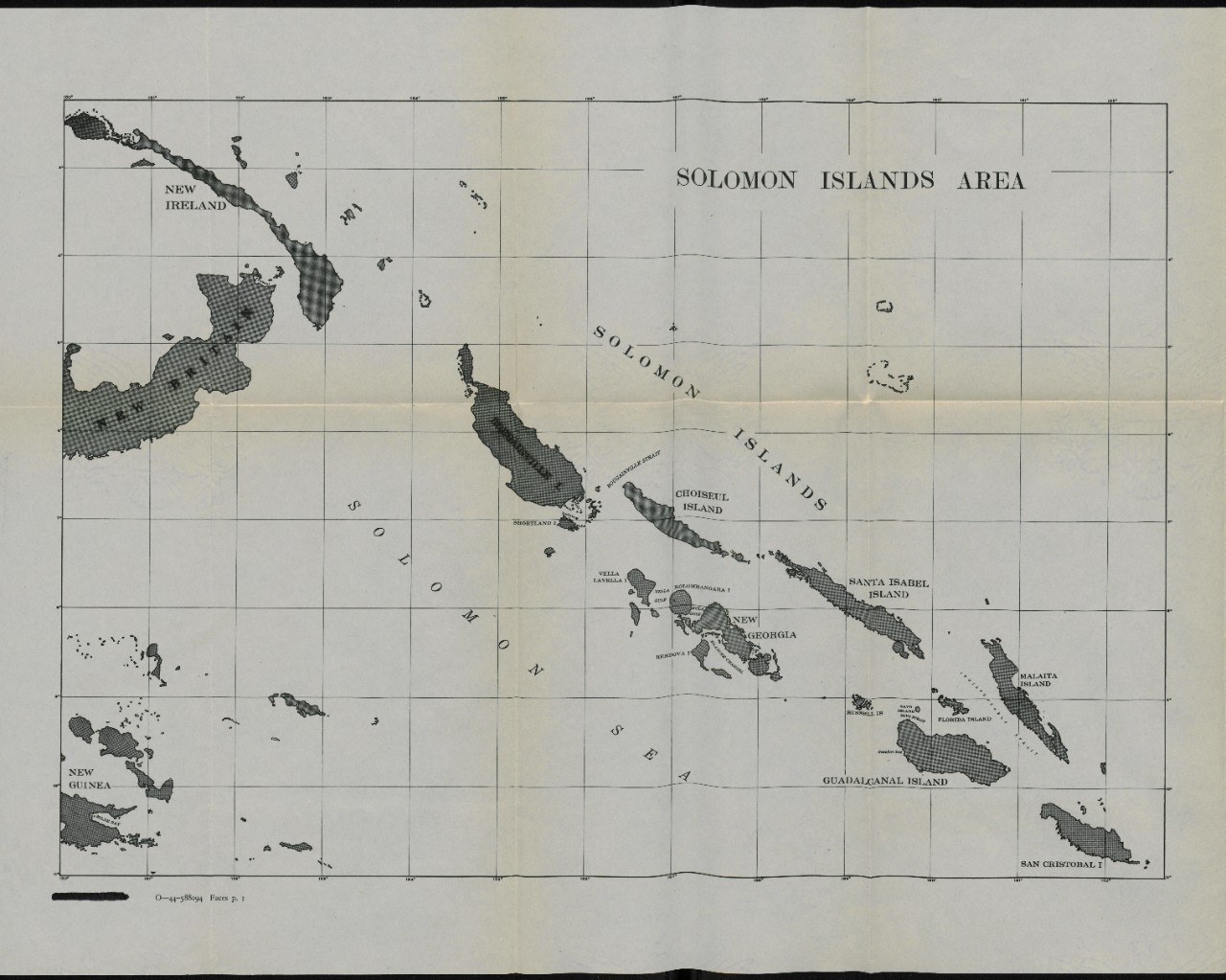

| Chart: Solomon Islands Area | |

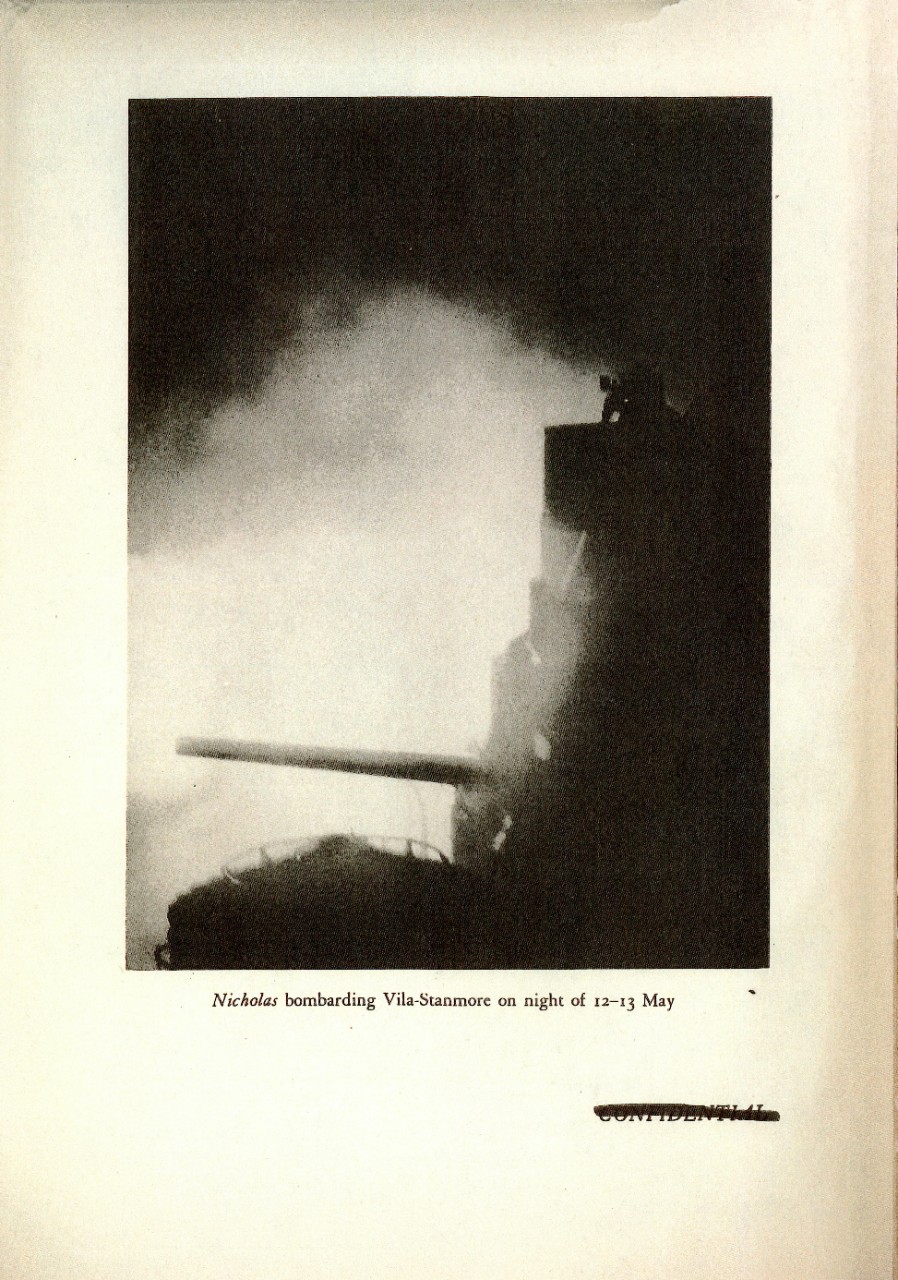

| Illustration: Nicholas bombarding Vila-Stanmore | 1 |

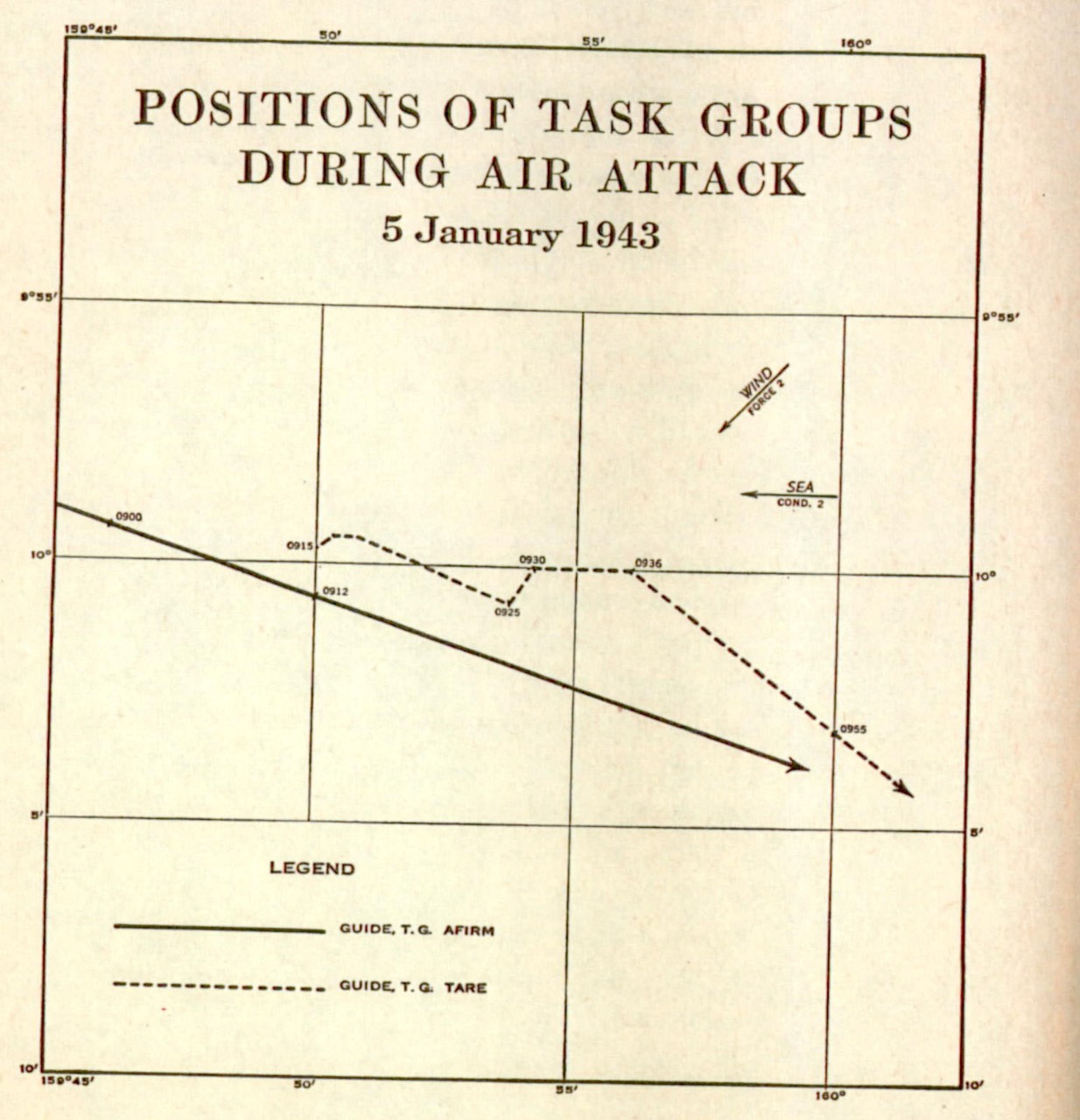

| Chart: Track during air attack, 5 January on page | 14 |

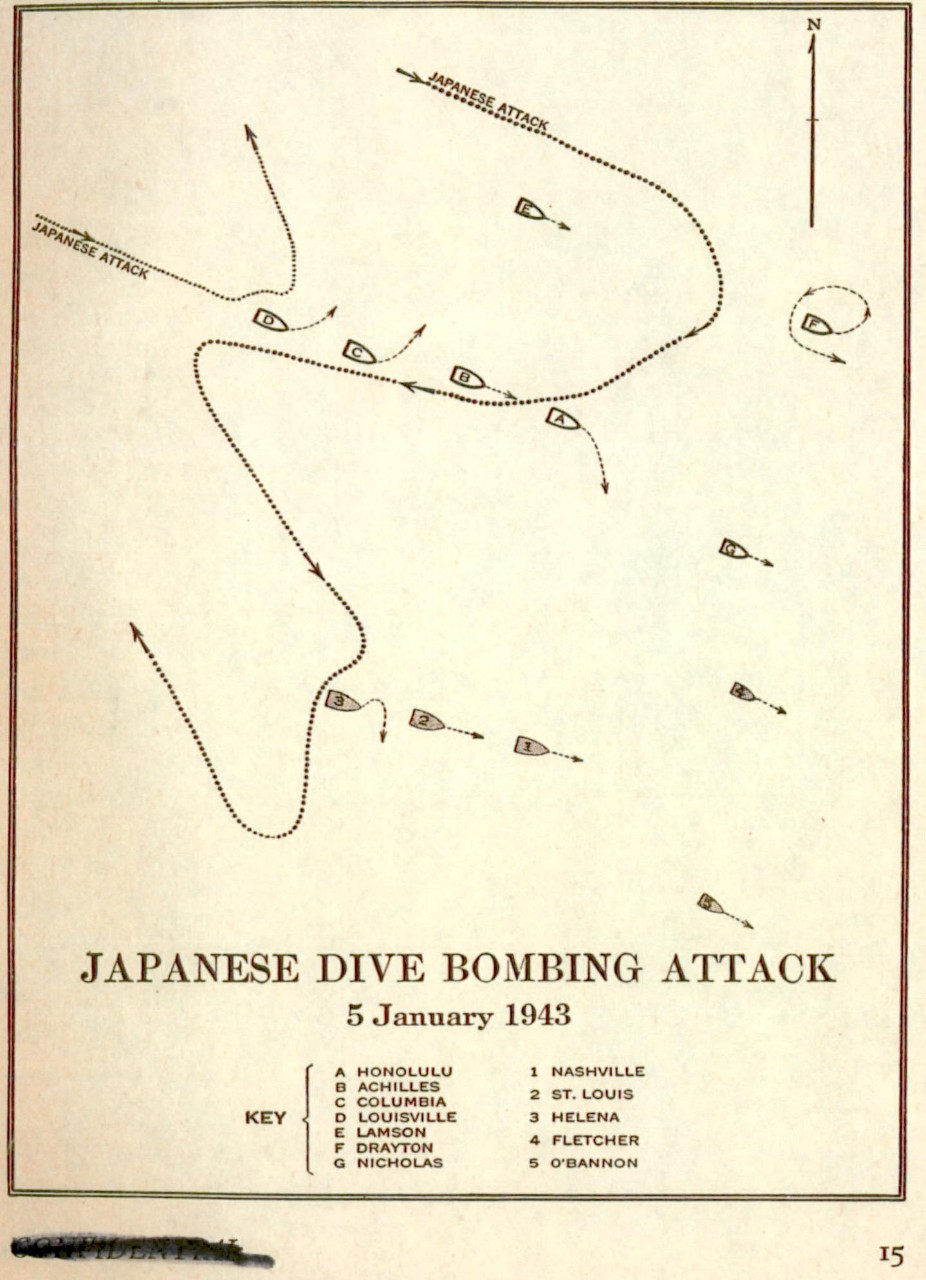

| Chart: Diagram of air attack, 5 January on page | 15 |

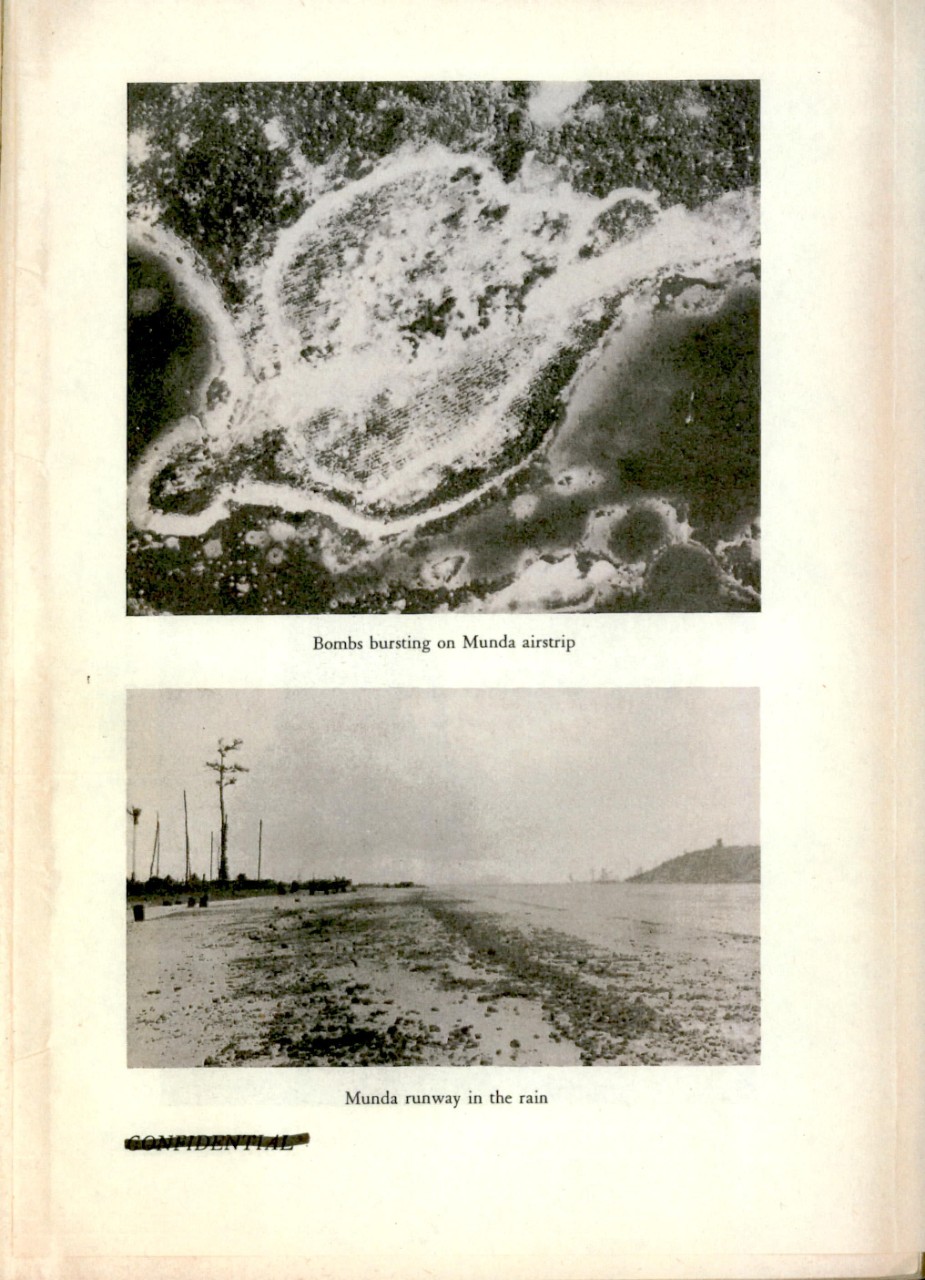

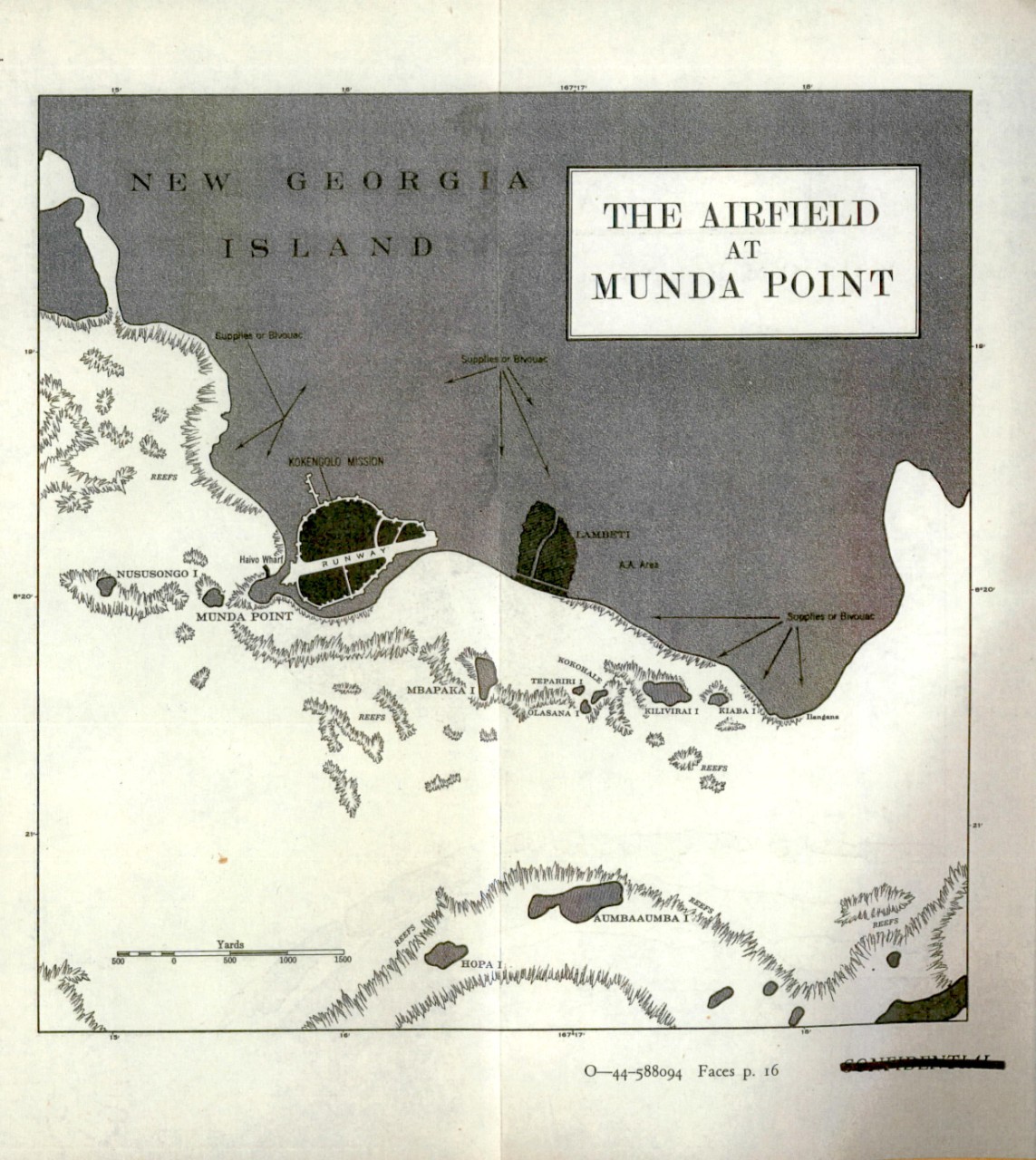

Chart: Munda airfield Illustrations: Bombs on Munda Munda airstrip |

16 |

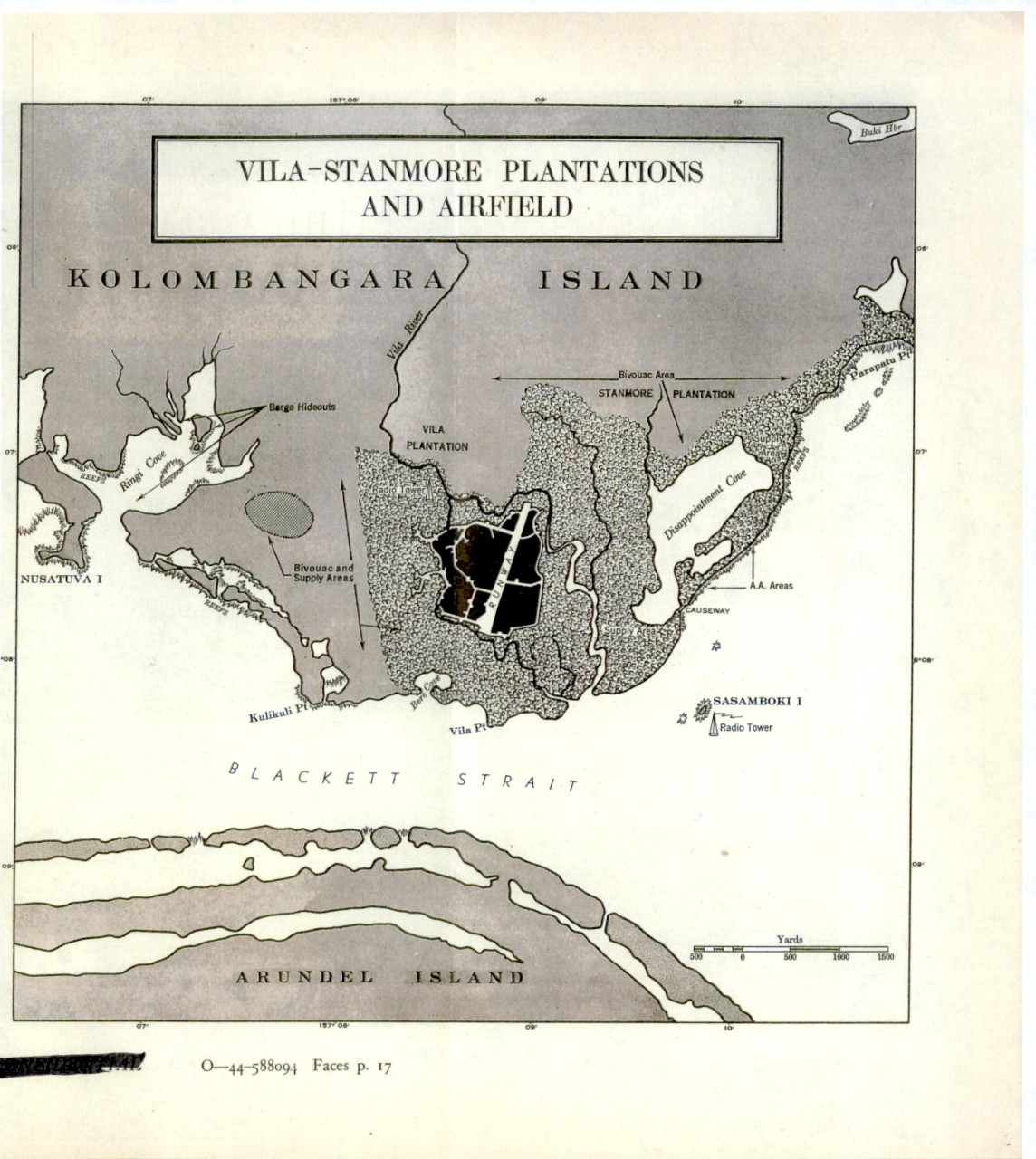

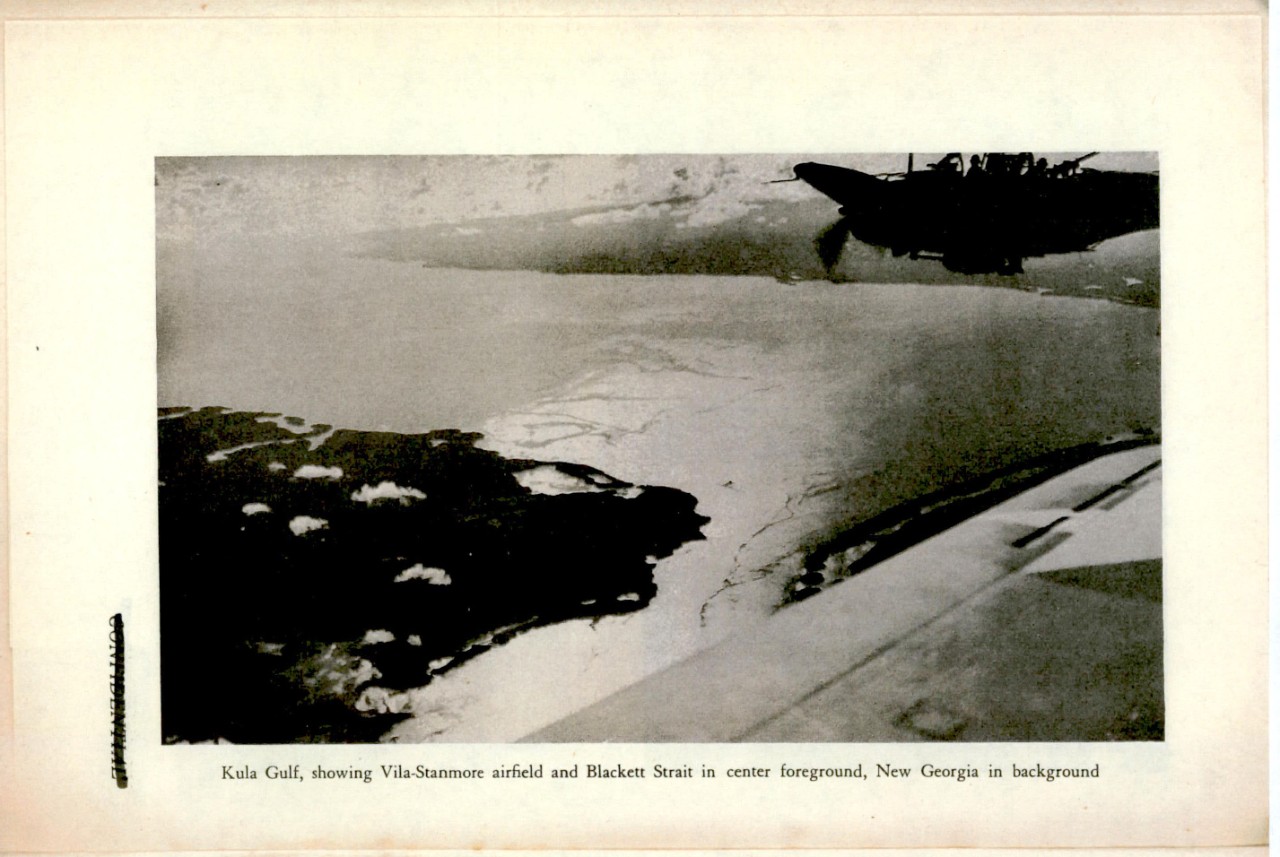

Chart: Vila-Stanmore airfield Illustrations: Kula Gulf |

17 |

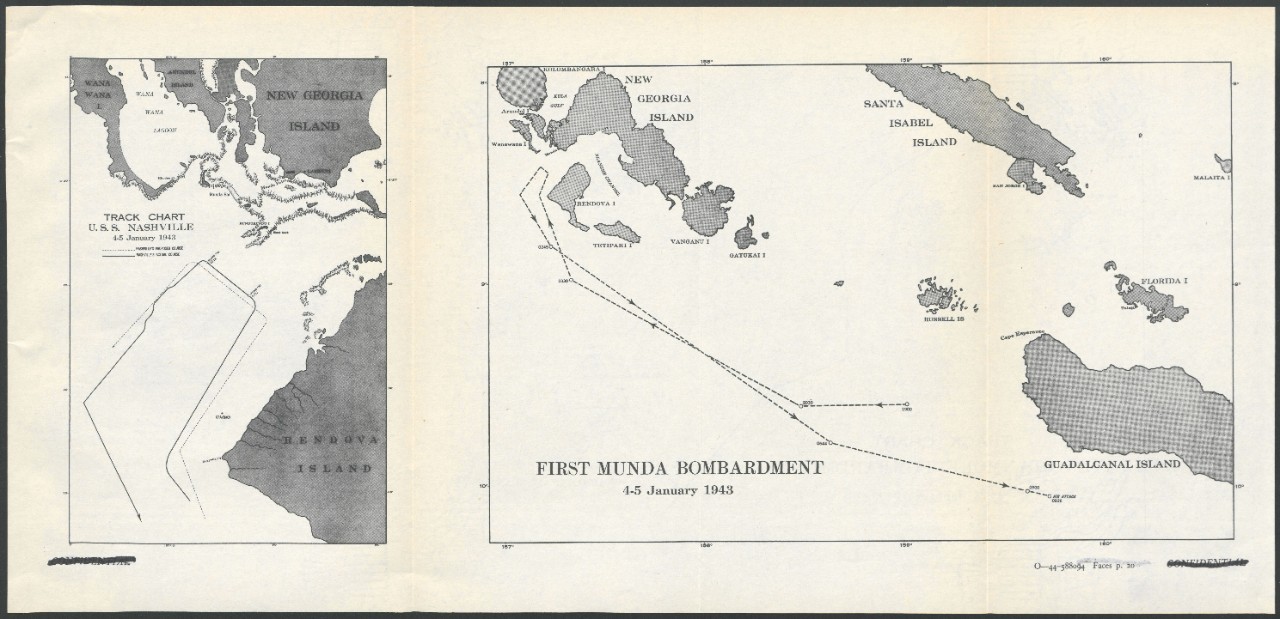

Charts: Munda bombardment, 4-5 January Track of Nashville, 4-5 January |

20 |

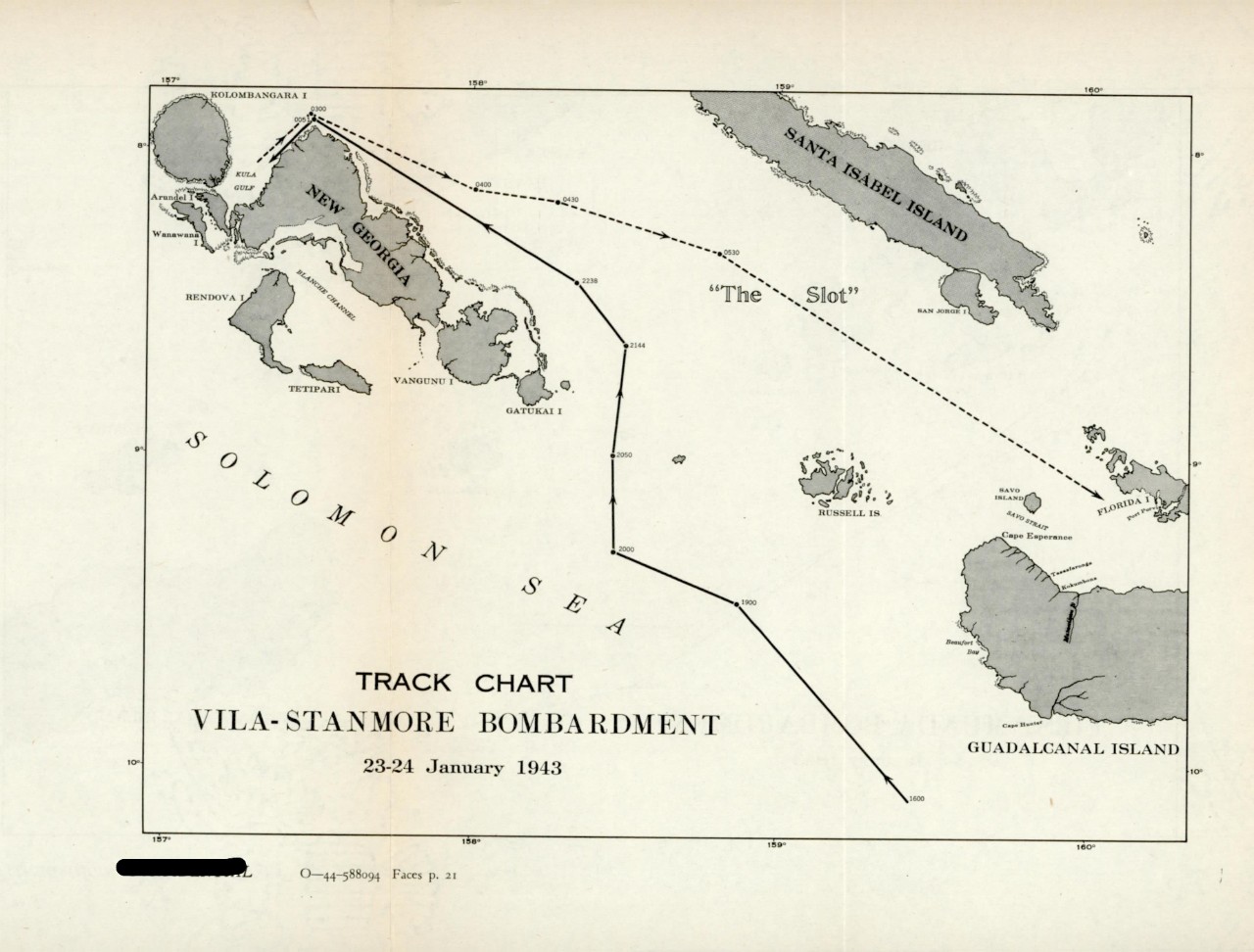

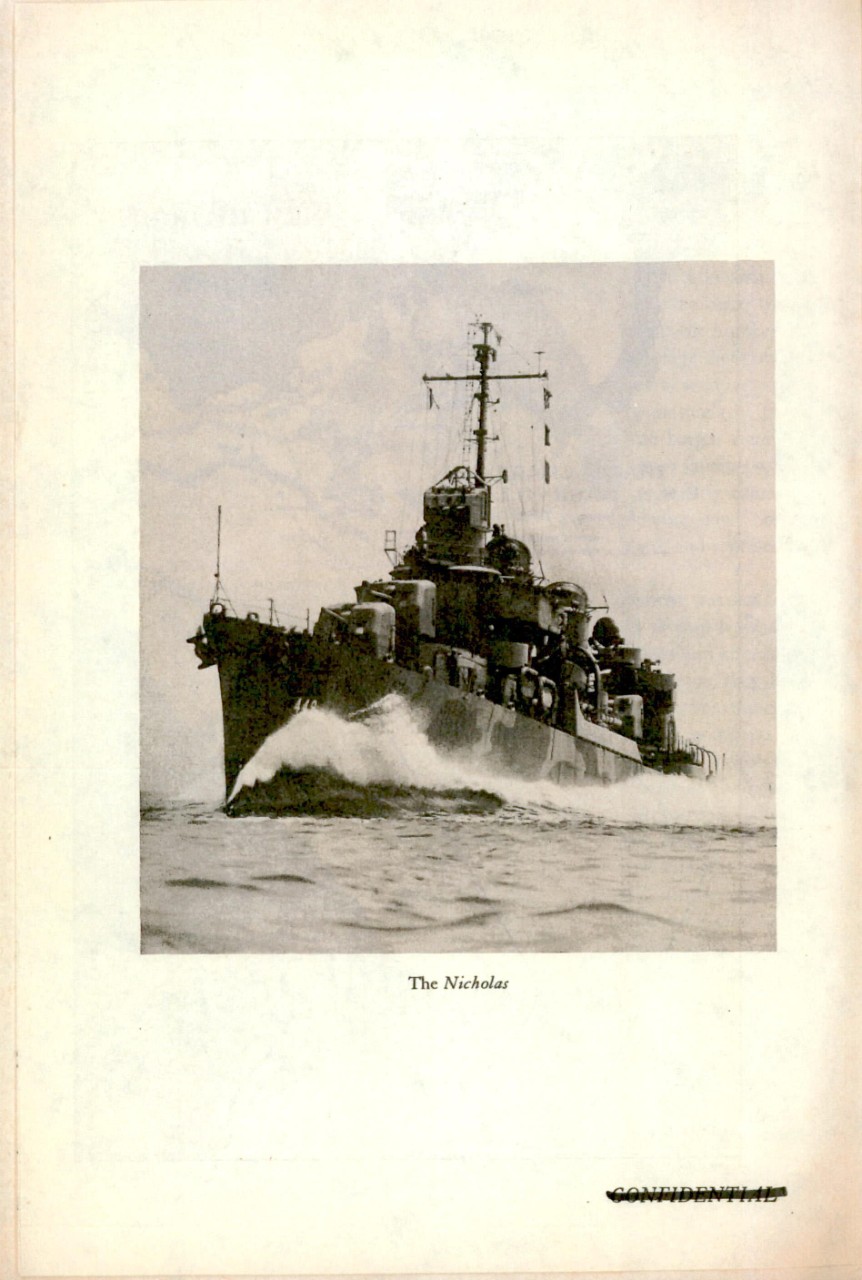

Chart: Vila-Stanmore bombardment, 23-24 January Illustrations: The Nicholas |

21 |

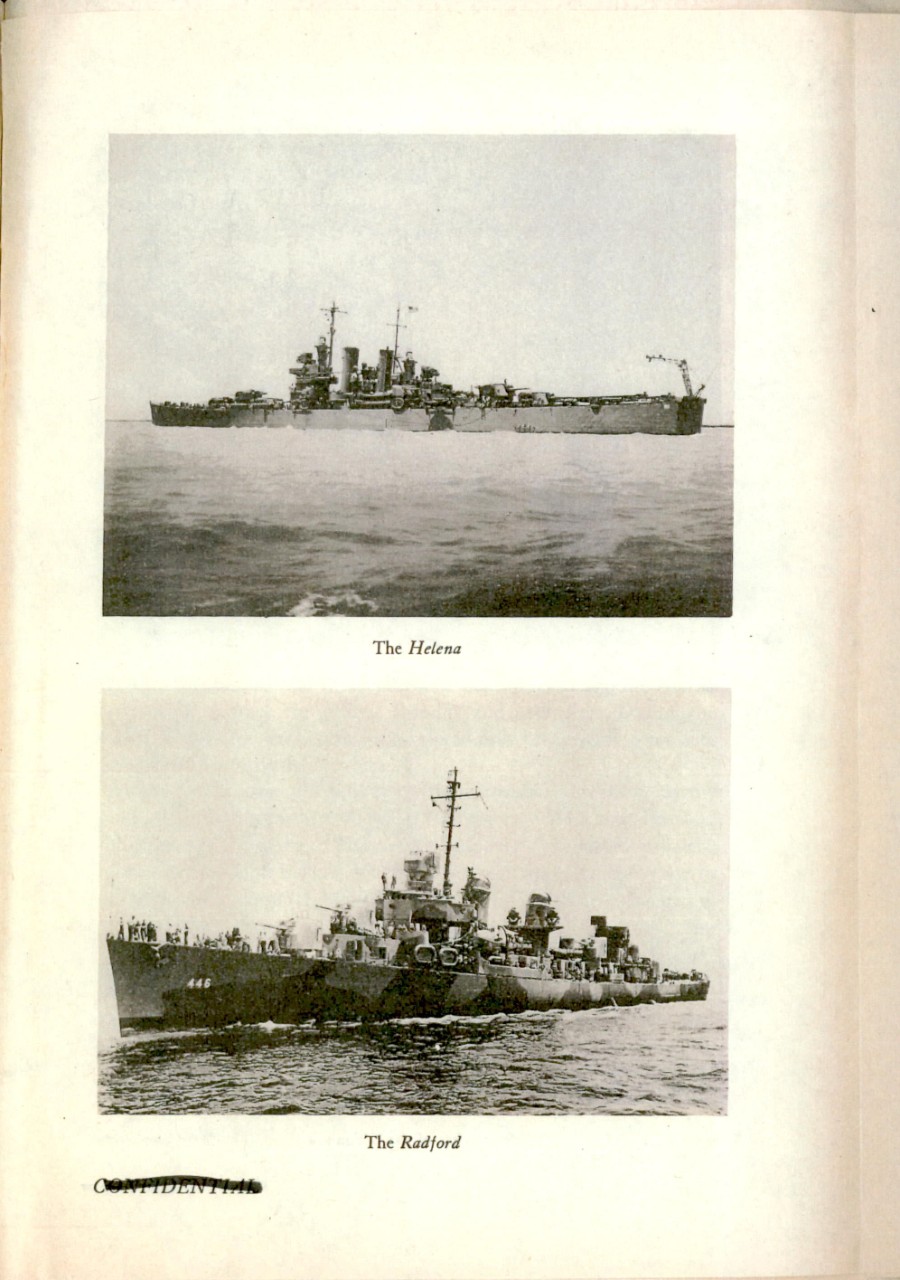

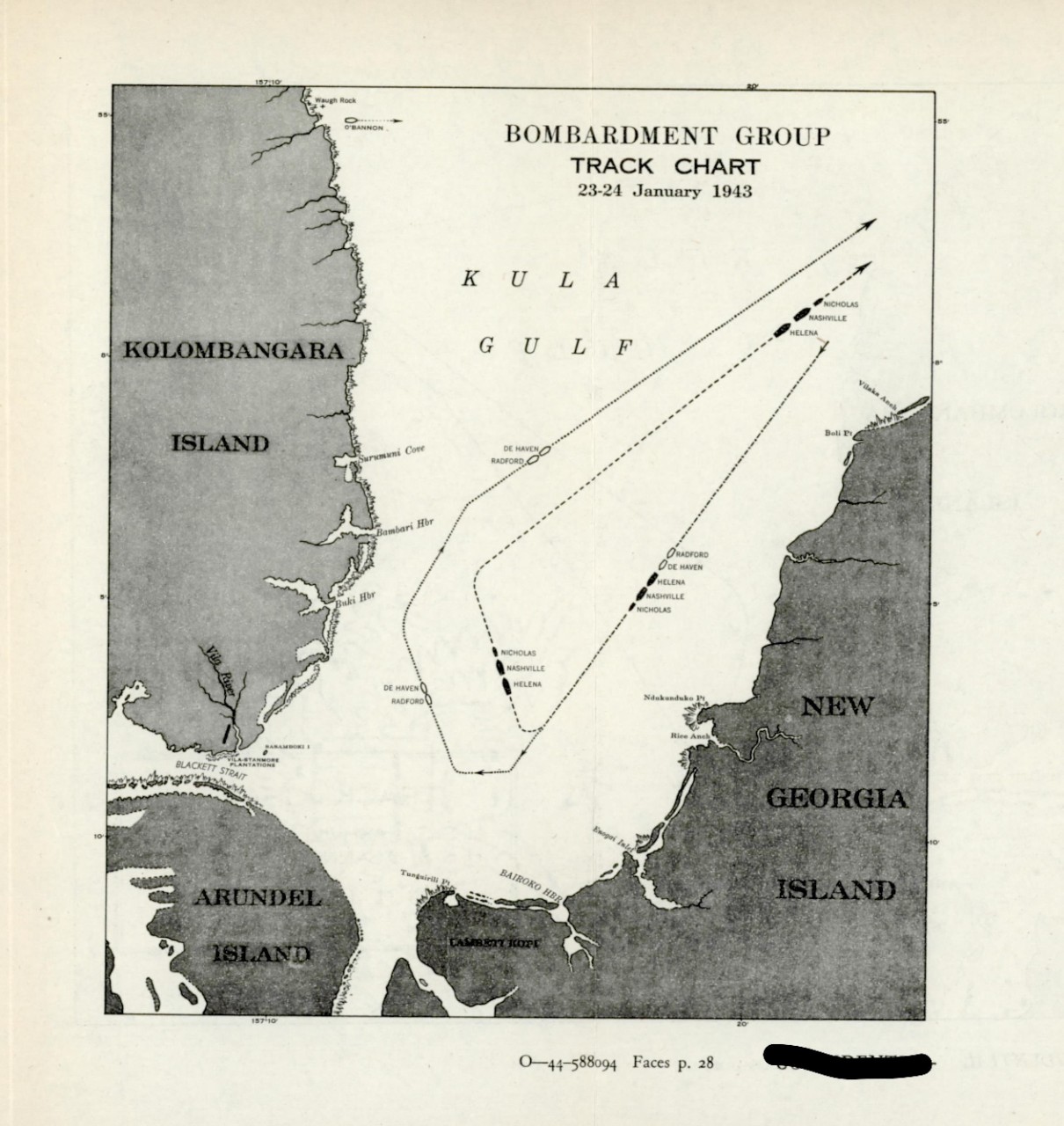

Chart: Bombardment group track, 23-24 January Illustrations: The Helena The Radford |

28 |

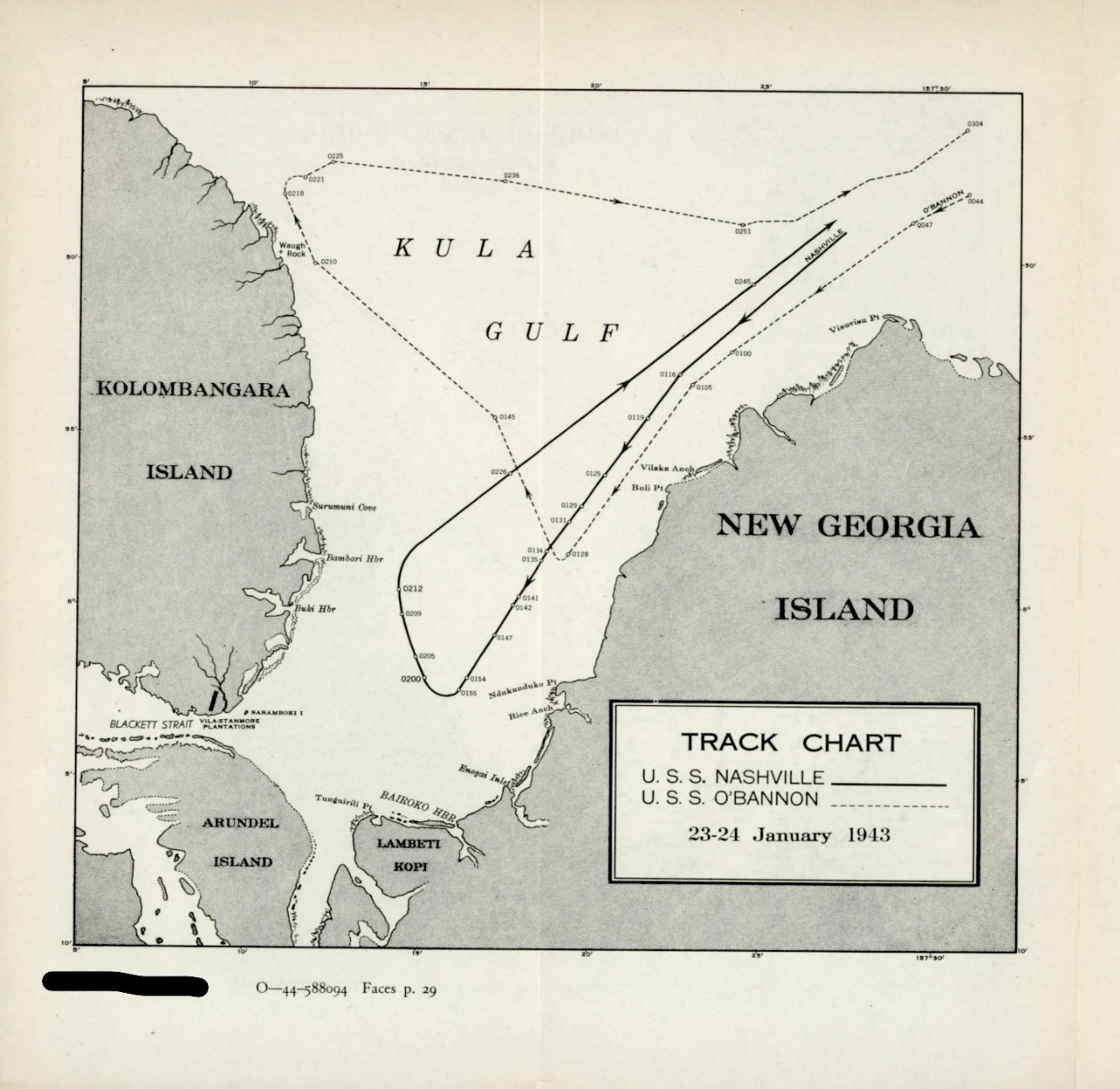

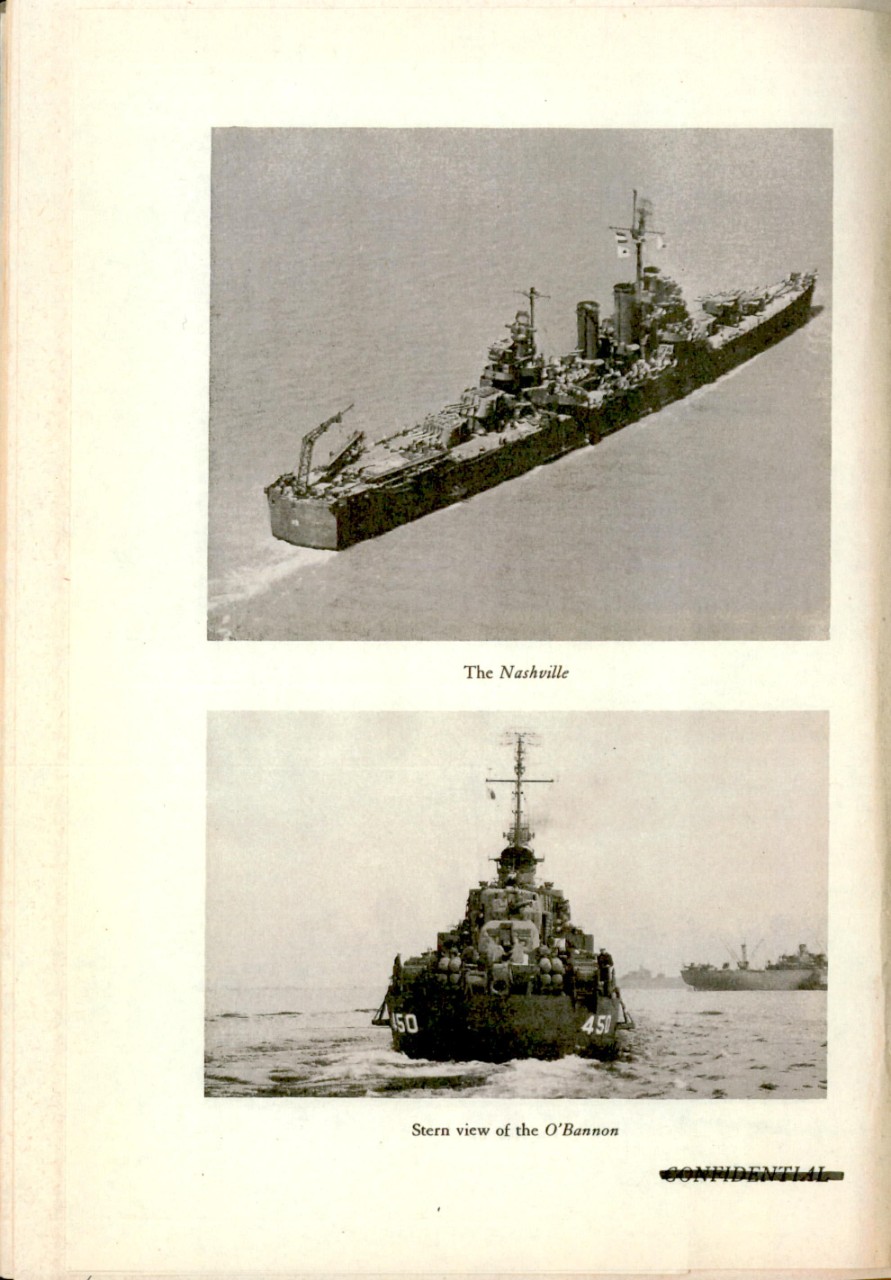

Chart: Track of Nashville and O'Bannon, 23-24 January Illustrations: The Nashville The O'Bannon |

29 |

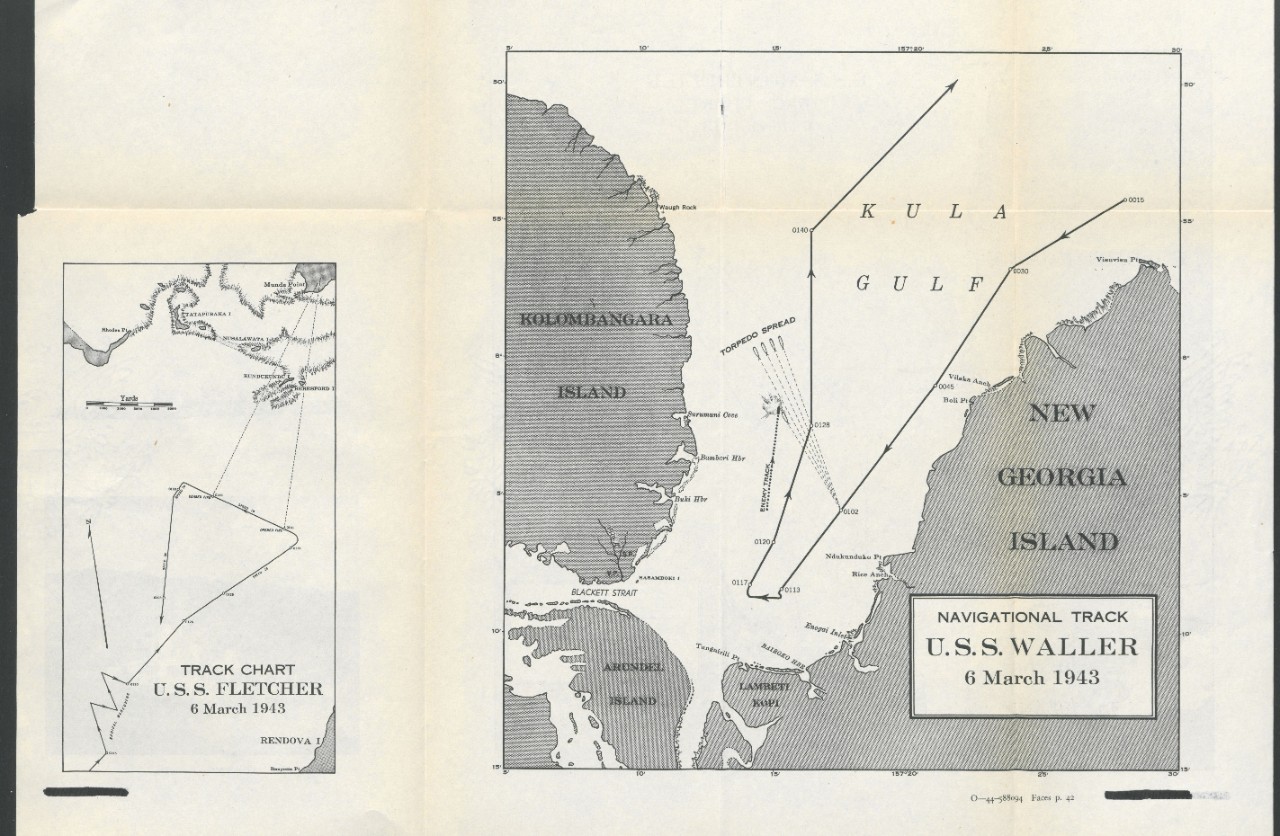

Charts: Track of Waller, 6 March Track of Fletcher, 6 March |

42 |

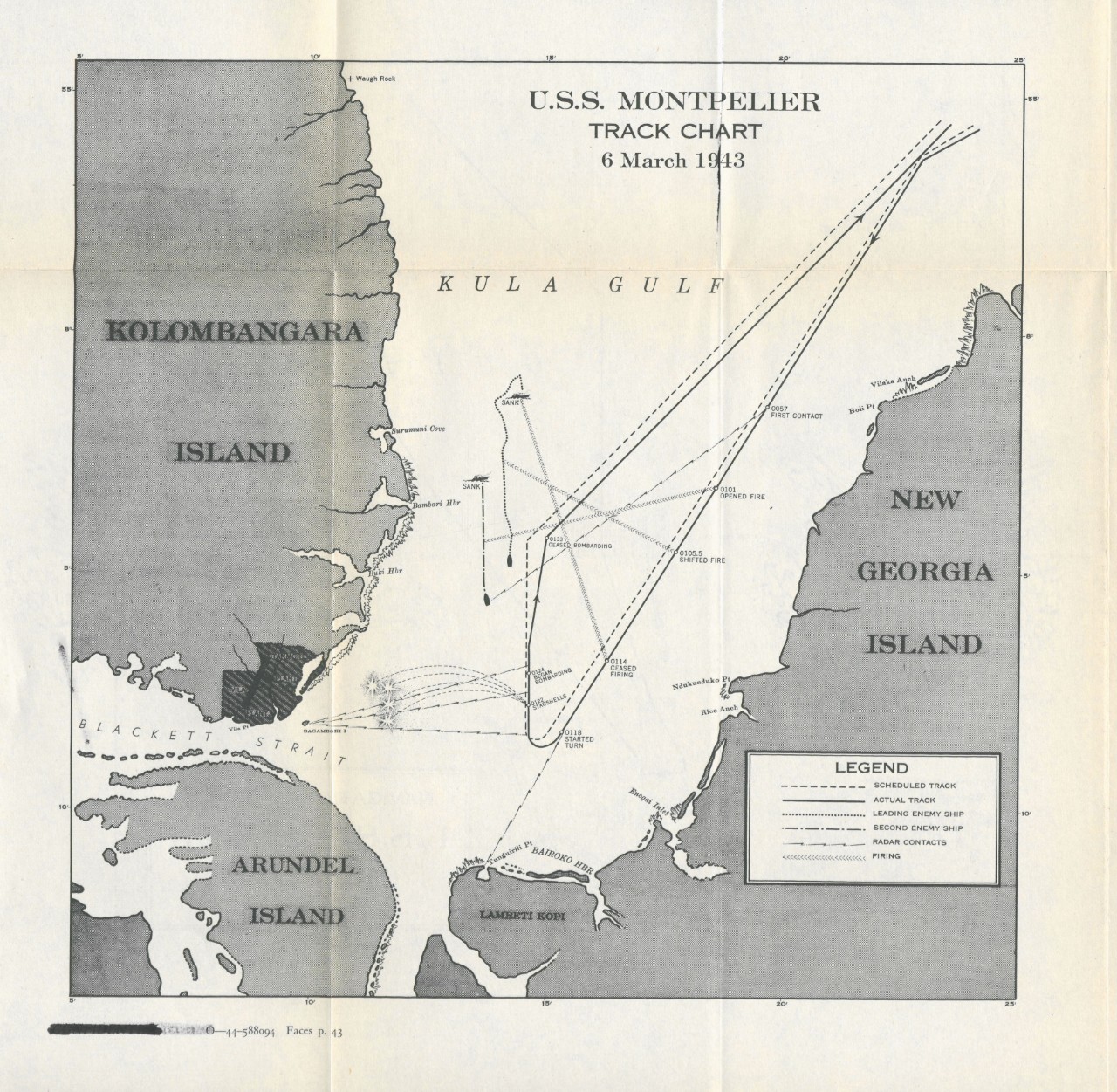

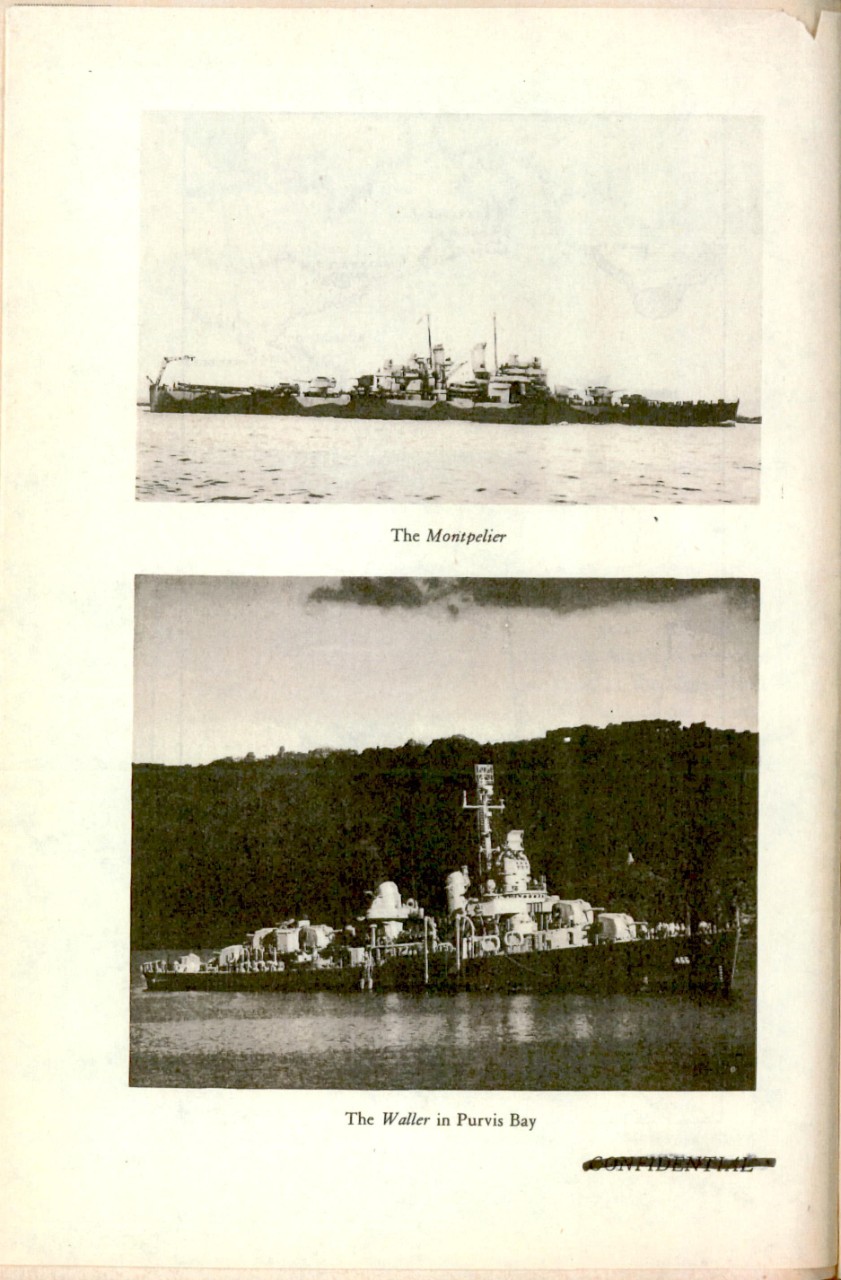

Chart: Track of Montpelier, 6 March Illustrations: The Montpelier The Waller |

43 |

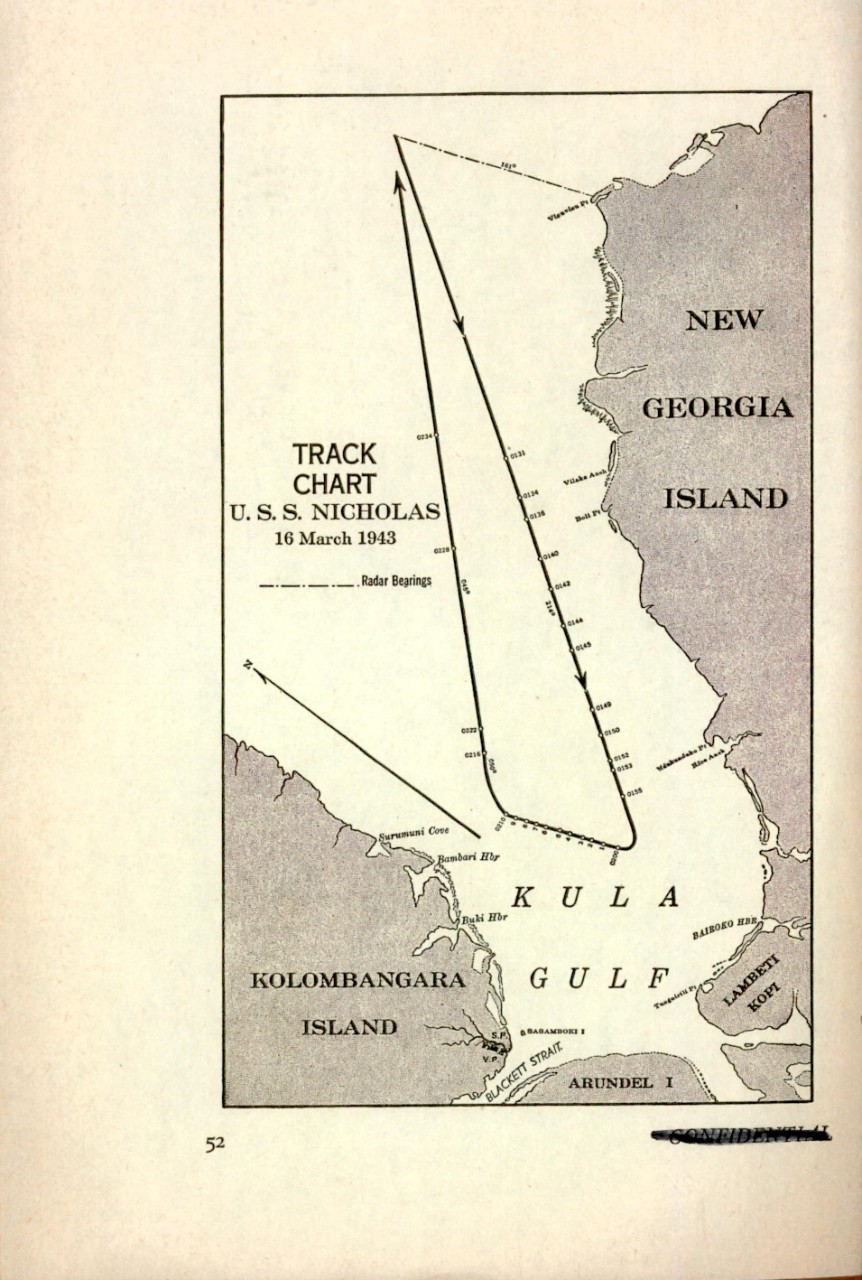

| Chart: Track of Nicholas, 16 March on page | 52 |

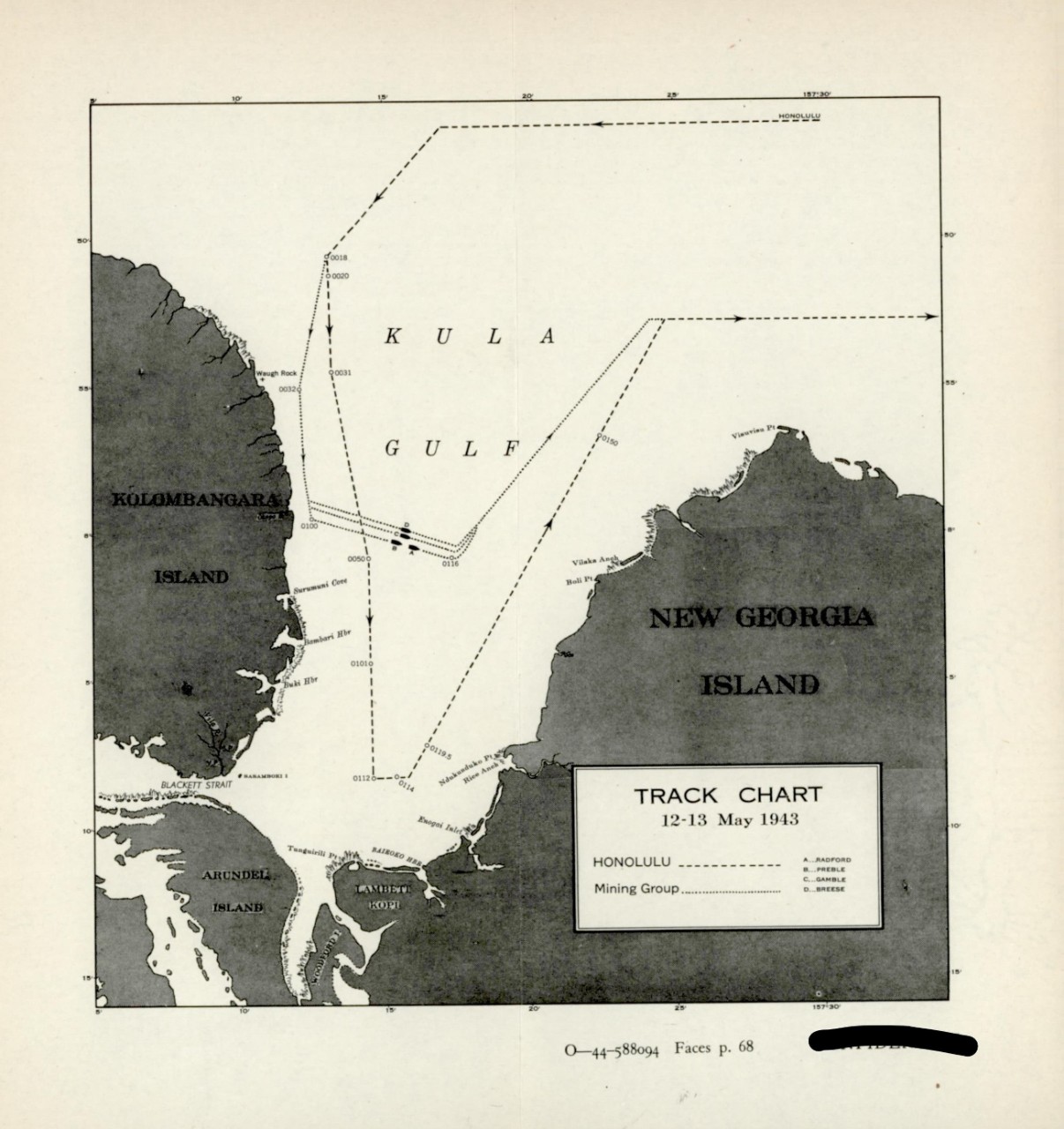

Chart: Bombardment and mining track, 12-13 May Illustrations: The Preble The Jenkins |

68 |

IV

Contents

BOMBARDMENTS OF MUNDA AND VILA-STANMORE

| Page | |

| First Bombardment--Munda--4-5 January 1943 | 1 |

| Preparations | 3 |

| The bombardment | 7 |

| Retirement | 11 |

| Results | 17 |

| Second Bombardment--Vila-Stanmore--23-24 January 1943 | 18 |

| Preparations | 19 |

| The bombardment | 23 |

| Retirement | 28 |

| Results | 30 |

| Third Bombardment--Munda and Vila-Stanmore--5-6 March 1943 | 32 |

| Preparations | 33 |

| Approach to Vila-Stanmore | 36 |

| Bombardment of Vila-Stanmore | 40 |

| Approach to Munda | 43 |

| Bombardment of Munda | 44 |

| Results | 46 |

| Fourth Bombardment--Vila-Stanmore--15-16 March 1943 | 48 |

| Preparations | 49 |

| The bombardment | 50 |

| Results | 53 |

| Fifth Bombardment--Munda and Vila-Stanmore--12-13 May 1943 | 54 |

| Interim activities | 54 |

| Preparations | 58 |

| Approach to Vila-Stanmore | 63 |

| Bombardment of Vila-Stanmore and mining of Kula Gulf | 64 |

| Retirement from Kula Gulf | 70 |

| Bombardment of Munda | 71 |

| Results | 73 |

| Appendix I: Designations of U.S. naval ships and aircraft | 75 |

| Appendix II: List of published Combat Narratives | 79 |

V

Bombardment of Munda and

Vila-Stanmore

I

FIRST BOMBARDMENT—MUNDA

4-5 January 1943

THE month of December 1942 was a comparatively quiet one for American Naval forces in the Solomon Islands area. Following the Battle of Tassafaronga on 30 November, when United States ships opposed a strong enemy reinforcement attempt, both sides occupied themselves in strengthening their positions and preparing for the next major operation. For our part, this included continuing efforts to eliminate the Japanese from Guadalcanal Island and developing the defenses of the area. The enemy also continued to strengthen his positions to the north, and to hack new air bases out of the coconut forests on the islands of the New Georgia group.

Both sides made wide use of smaller surface craft and aircraft in efforts to hamper and harass each other’s attempts at consolidation. In this field we were particularly successful. The cumulative effect of our submarine, aircraft, and surface ship attacks was a considerable total loss to the enemy at little cost to ourselves.1

On Guadalcanal, the opposing lines were fairly well established between the Matanikau River and Tassafaronga, 12 miles west of Henderson Field. The main Japanese base was at Cape Esperance, near the northwest corner of the island, about 25 miles from Henderson. American surface and air patrols were constantly on the alert to prevent the passage of supply and reinforcement vessels through the Savo strait to the principal enemy landing points. The task was complicated, however, by the fact that the Japanese held all the islands to the north and west, and could land cargo and even troops around the cape on the west side

---------------------

1 At least 14 Japanese ships, including 2 cruisers, 6 destroyers, 4 cargo ships and 2 transports were believed to have been sunk. Eleven more—2 cruisers, 7 destroyers and 2 cargo ships—were damaged or possibly sunk. Two destroyers suffered possible damage.

1

of the island with relative impunity without running the strait. The well-known “Tokio Express,” composed of fast cargo vessels and destroyers loaded in the nearby islands to the north, was still operating regularly to Guadalcanal, and was as regularly attacked by our aircraft and PT boats.

The enemy’s intentions at this time were not clear. Reports of airfields under construction, new troop concentrations, and increasingly large convoys led to the conclusion that some major move was planned. From one point of view, it seemed possible that he might be building up a strategic defensive in the Solomons preparatory to a large-scale drive elsewhere.2 On the other hand, his evident preparations and strenuous material developments in the Solomons indicated a possibility that he might initiate a strong offensive to recapture Guadalcanal.

Supporting this latter belief was the unusual Japanese activity at Munda on New Georgia Island. Late in November, information was received that the enemy had started construction of an airfield there. On 24 November, our heavy bombers practically destroyed the Munda warehouses and wharf, as well as the nearby enemy-occupied village of Lambeti, but saw no airfield. Aerial photographs on the 26th likewise revealed nothing, but the reports persisted. Logic seemed to back up the information, for the Munda area, lying only 150 to 200 miles from our bases on Guadalcanal, offered protected anchorages and terrain suitable for military installations. Finally, on 3 December, a photographic reconnaissance mission brought back proof that an airfield had not only been started, but was well along toward completion, although still screened by coconut trees. On the 9th of the month, the field was observed to be about 90 percent complete, with antiaircraft positions, dispersal areas, and shelters in the process of construction.

The potential threat this airfield offered was obvious. After its discovery on 3 December, aircraft from Guadalcanal attacked it regularly, bombing and strafing gun emplacements, buildings, and runways. In one month, B-17’s from Espiritu Santo and Guadalcanal with lighter planes from Henderson Field dropped between 150 and 200 tons of bombs on Munda field and its environs, while small groups and single planes harassed the area by night. Despite this continuous attack, a fighter

--------------------

2 Early in December the Japanese began to increase their strength in New Guinea and the Dutch East Indies.

2

strip was completed and Zeros were operating from it by Christmas; and by 29 December it was operative for bombers.

Some of the aerial attacks on Munda seemed to promise specular success, yet none interrupted Japanese use of the installations for more than a day or two. On 24 December, American dive bombers and fighters carried out a particularly heavy attack, shooting down 4 Zeroes over the field. Twenty more were caught taking off. Ten of these were shot down by our Grunmans, while the remaining planes were destroyed at one end of the runway by dive bombers. Two more fighters were strafed in revetments, and SBD’s silenced weak antiaircraft fire. All our planes returned.

At noon the same day American aircraft returned to bomb the runway, meeting no AA, and sighting only one undamaged Zero on the ground; and that afternoon a reconnaissance flight over the field saw no enemy planes and met no AA. Yet by the 31st it was seen that the field had not only been repaired for fighters but was also in use for the first time by medium bombers.

PREPARATIONS

The comparative ineffectiveness of our aerial bombing was but one of the factors CINCPAC considered when it was decided to carry out a ship bombardment of Munda. Incident to this decision was the necessity of insuring the uninterrupted landing of Army troops, who were by this time rapidly replacing Marines on Guadalcanal. The replacement officially began on 9 December, when Maj. Gen Vandegrift of the Marine Corps turned over his command to Maj. Gen Patch of the Army, and continued steadily throughout the month. By early January, approximately 58,000 American troops were stationed in the Guadalcanal-Tulagi area, of whom 31,600 were Army forces.

A particularly large movement of personnel was scheduled for 4 January, when a convoy which had left Noumea on New Year’s Day was due to arrive at Guadalcanal. The group was made up of six transports and one cargo vessel, carrying the last increment of the 25th Division, U.S. Army. After unloading, the transports were to embark the 7th Marines, and depart late in the afternoon of 5 January for Melbourne. It was obviously desirable that the enemy learn as little as possible regarding this operation, and that the landing and loading be carried out speedily with a minimum of aerial or surface interference.

3

The South Pacific naval force was at this time stronger than it had been for some time, since powerful reinforcements had arrived during December and early January. Thus it was determined that a sizable fleet detachment could be made available to screen and provide a diversion for the troop movement.

The logical way to accomplish this, it seemed to COMSOPAC, would be by a heavy bombardment of Munda. Such an operation would serve the dual purpose of drawing any nearby Japanese fleet elements to waters more than 100 miles from Guadalcanal, and of striking a hard blow at the enemy’s most immediate threat to our positions.

A dispatch from COMSOPAC on 30 December created the task organization for the operation. Task Force LOVE,3 with 3 battleships and 4 destroyers under Rear Admiral Willis A. Lee, Jr., was to cover the transport operation, while Task Force AFIRM, with 7 cruisers and 5 destroyers under Rear Admiral Walden L. Ainsworth, was to assist in the coverage and provide the diversion. As a preliminary move, aircraft from Guadalcanal were to strike Munda and Buin repeatedly during the days immediately preceding the bombardment. When the weather permitted they were also to strike at Rabaul.4

For a time, on the night of 2-3 January, it seemed as if the American plans might be jeopardized when a large enemy destroyer force was reported operating off the northwest end of Guadalcanal, in an evident attempt to supply and reinforce Japanese troops on the island. Originally there were 10 destroyers in the formation. However, a fighter-escorted Flying Fortress sighted the group south of Shortland Island during the early afternoon of the 2nd, and several hours later the ships were intercepted by dive bombers about 20 miles southwest of Munda.

One enemy destroyer was left burning fiercely, and a second appeared to be sinking. A near-hit was scored on a third. One of 10 accompanying Zeros was shot down. Late in the evening of the 2nd, MTB’s from Guadalcanal met the remaining vessels north of the island, scoring a hit on one destroyer and three probable on two others. The upshot was that the Japanese failed to land any troops, but did dump overboard, in the hope that they would drift ashore, a large amount of supplies, includ-

-------------------------

3 Task Force numbers have been omitted from Combat Narratives for reasons of security. In place of these numbers will be found the Navy flag names for the first letter of the surname of the commanding officer of a Task Force.

4 A total of 15 Japanese ships were hit in these operations, some of which were undoubtedly destroyed.

4

ing ammunition in watertight containers. MTB’s and submarine chasers destroyed all visible supplied in the water the following morning.

Preparations for the bombardment of Munda were worked out by the various ship commanders at a conference held by Rear Admiral Ainsworth aboard the Louisville on 2 Januarys, while the combined Task Forces were standing up from Noumea to the Solomons. Particularly careful planning was needed, since the operation would be the first in which the Navy would coordinate surface, submarine, and aircraft units in a night bombardment.

Two major factors had to be considered before detailed planning could begin. First, there was the problem of taking the enemy by surprise; secondly, maximum practicable retirement from Japanese land-based air forces had to be effected before daybreak the following morning, making use of American air coverage which would be provided both by the larger vessels and by Guadalcanal. The time and duration of the bombardment depended on these two factors. A study of these, as well as the distance tables from Guadalcanal, amount of destroyer fuel, and other points, led to the decision to open fire at 0100 on the 5th, and to bombard for about one hour.

The submarine Grayback,5 Lt. Comdr. Edward S. Stephan, had already received orders to take station as a navigational aid two miles to the northwest of Banyetta Point on Rendova Island. By using her bearings, the bombardment Task Force could more easily come up on its navigational track, the determination of which was facilitated by peculiarities in the outlying rocks and land masses of the coral reefs off Munda. One of these, a 70-foot nubbin named Beresford Island (Black Rock), just to the right of Kundukundu Island, formed a perfect range for the open fire bearing of 018o directly in line with the center of the target area.

Unit commanders involved in the operation were of the opinion that the Curtiss scout-observation planes carried by the cruisers were not well adapted for night work of this magnitude. Fortunately COMAIRSOPAC

---------------------------

5 This submarine had aboard at the time a seaman who was convalescing from one of the most unusual operations on record. His appendix had ruptured while the Grayback, was on war patrol in enemy waters. The ship surfaced at night while a pharmacist’s mate, assisted by a lieutenant as anaesthetist, opened the patient’s abdomen and washed the peritoneal cavity with alcohol and sulfanilamide powder. A rubber band held the incision open, spoons from the galley served as retractors, and a pair of long-nosed pliers from the engine room was used to remove bits of the appendix. Ether was administered through a Momsen Lung. Post-operative condition was reported excellent.

5

had agreed to supply radar-equipped Black Cat planes6 for spotting during the bombardment. Lt. Comdr. Dennis S. Crowley, aviation officer on the staff of Rear Admiral Ainsworth, together with the operations officer for COMAIRSOPAC, drew up the coordinating plans for the spotting, and an aircraft radio set was obtained from the Enterprise for communication with the planes and the submarine.

Lt. Comdr. Crowley and two trained aviation spotters left Espiritu Santo for Guadalcanal on 2 Januarys, and flew over Munda in their Black Cats on the nights of the 2nd and the 3rd in preparation for this big show on the 4th. The planes arrived over Munda Point at about midnight on each of these nights, and harassed the airfield area with 500-pound bombs, 30-pound demolition bombs, mortar shells, and flares. On both nights, the attacks lasted for a period of from 2 to 2 ½ hours. The planes experienced moderate to heavy AA fire from gun positions located approximately in accordance with information on charts issued to Commander Task Force AFIRM. On the night of the 3rd, the Black Cats sighted one or more aircraft with red and green lights over the target area, possibly float Zeros on reconnaissance from Rekata Bay. No attacks were made, however, and it was believed that the enemy was unable to sight the camouflaged PBY’s.

The following was the Task Group organization for the bombardment:

Task Group Commander, Rear Admiral Ainsworth.

3 Cruisers:

Nashville (F), Capt. Herman A. Spanagel.

St. Louis, Capt. Colin Campbell.

Helena, Capt. Charles P. Cecil.

2 Destroyers: Capt. Robert B. Briscoe.

Fletcher, Lt. Comdr. Frank L. Johnson.

O’Bannon, Comdr. Edwin R. Wilkinson.

Fire control plans called for the ships to come on the range at 10-minute intervals, with a firing leg 3 miles long and a speed of 18 knots. After the vessels reached the “Commence Firing” position, they were expected to use the bearings of the islands previously noted, as well as a “Mark” from the patrol plane which would be stationed over the center of the firing area. Ships were to open fire on a generated bearing, elevation to be in stable element by plotting room director. All batteries were to

-------------------

6Consolidated PBY “Catalina” patrol bombers, painted black for invisibility at night, capable of longer flight and more sustained operations than the SOC’s.

6

fire in automatic control, salvo fire to be followed by continuous rapid fire or rapid salvo fire when they were sure they were on the target. All spots by the spotting plane were to be to the center of the target area. After establishing the range and deflection to the center of the firing area, each ship was to cover the entire target area by shifting the mean point of impact to take the grid squares in succession and distribute the bombardment fire. The fire effect per hundred-yard square had been calculated to be the equivalent of four 75-mm. shots per minute. Since this was approximately one-fourth of the weight estimated to be required to neutralize hostile troops, it was considered fairly heavy for this type of operation. Actually, when the Nashville arrived at the rendezvous, it was discovered that the ships had more 6” ammunition aboard than was expected. After rounding up all the 6” bombardment projectiles available, the Task Force Commander found that he would have almost 1,100 rounds per vessel. The rate of fire, in this case, would be about 7 shots per gun per minute. Ten shots per gun per minute was set as the rate for the 5” 38-caliber guns of the destroyers.

THE BOMBARDMENT

The night of 4 January was very dark, with an overcast sky and passing showers. At 2000 local time,7 southwest of the Russell Islands in position 09o 36’ S., 158o 38’ E., Task Group AFIRM separated from Task Group TARE,8 and stood up toward Rendova Island at 26 knots, keeping well clear of the coast. Steaming order was the Nashville, St. Louis, and Helena, with the Fletcher and O’Bannon providing a screen.

The vessels navigated darkened, using SG radar for their fixes, echo ranging gear to ascertain the approximate location of reefs shown on their

--------------

7 All times are Zone minus 11.

8 Task Group Commander, Rear Admiral Mahlon S. Tisdale.

4 Cruisers:

Honolulu (F), Capt. Robert W. Hayler.

Louisville, Capt. Charles T. Joy.

HMNZS Achilles, Capt. C.A.L. Mansergh.

Columbia, Capt. William A. Heard.

3 Destroyers, Comdr. Laurence A. Abercrombie:

Drayton, (F), Comdr. Jacob E. Cooper.

Lamson, Comdr. Philip H. Fitz-Gerald.

Nicholas, Comdr. William D. Brown.

This Task Group was to spend the night patrolling the waters off Guadalcanal.

7

charts, and fathometers to verify soundings. A Catalina with radar searched ahead for enemy forces as far north as the approaches to Buin.

At approximately 2330, while still well clear of Munda, ach of the cruisers launched one scout observation plane for standby purposes, illuminating ship momentarily to do so. The planes carried a total of 12 flares, to be dropped only if ordered. According to directions, they proceeded to a prearranged position behind Rendova Island and over Blanche Strait. When the surface bombardment started, they were to fly to seaward and over the surface formation to warn of the approach of enemy surface forces, and to radio any bombarding vessel which might be running into navigational dangers.

By this time a heavy black raincloud hanging in the direction of Munda was seen to be moving slowly to the eastward, and stars became dimly visible overhead. In the faint light, Rendova Island came up distinctly to starboard, and the Nashville was able to take approximate tangents on the entrance to Blanche Strait. Land masses showed up clearly on the SG radar as the vessels closed Banyetta Point, while positions taken were observed to check closely with the dead reckoning track.

The Grayback, which had been patrolling off Montgomery Island, had meanwhile surfaced and was proceeding to her rendezvous. At 0025 on the 5th she arrived on station. Shortly thereafter the darkened column rounded the point and stood up toward the agreed position. Radar showed both the area ahead and that to the westward to be clear, and the Nashville signaled by blinker tube to the ships astern to start opening distance for the bombardment. At 0032 the Grayback was picked up exactly in position. The submarine flashed her challenge, “AFIRM POSIT”, which was answered by the flagship.9

Upon passing the Grayback, All vessels slowed to 18 knots for the approach. The islands and rocks on the coral reefs began to show up clearly on the position plotting indicator at about 7 or 8 miles distance. These together with Banyetta Point on the artboard quarter gave excellent bearings to determine accurately the ships’ positions.

The Nashville made her turn to the firing course, 309o T., just before 0100. At that moment the Black Cat over the center of the Munda target area began calling out “Mark, Mark, Mark! ; but because of the presence of high land behind the plane, the Nashville’s FC radar had

-------------------

9 No blinker tube signals were made toward the beach at any time, and no TBS or voice radio was used from sunset until after the Nashville opened fire.

8

difficulty in distinguishing its bearing and IFF signals. The fire control radar, however, got excellent bearings on Beresford Island. The generated bearing was cranked in, and the Nashville opened up on the line. She fired her first salvo at 0102. The first spot from the Black Cat was “Up 500; no change in deflection.”

The initial firing point was on bearing 198o at a distance of 13,400 yards from the center of the target area. The Nashville, moving down the firing line on the prescribed course, fired her second salvo which was spotted ‘No change.” She then walked her pattern up and down the airfield runway and over both previously located dispersal areas. In about five minutes the flagship went to rapid continuous fire; observers reported that the stream of tracers from her guns looked as though she were playing a fiery hose on the enemy position. The Black Cat spotter estimated that 95 percent of her projectiles landed in the target area. At least one good fire was started south of the runway.

At 0113 the Nashville ceased firing and stepped up her speed to 25 knots as the St. Louis moved onto the line. The St. Louis commenced firing at almost the exact moment the Nashville ceased, but her first few salvos were some distance to the right of the target area. The Black Cat sent a left spot several times, and after a few moments the St. Louis shifted fire and dropped a salvo close to the runway. A “No Change’ spot wad transmitted over both circuits. The ship then distributed its fire along the target area, covering the installations thoroughly. By the time she moved off the line at 0124 she had started several large fires, one of which was still burning when the vessels left the area for the return trip. Spotters estimated that 65 percent of her fire landed on the target.

Some Japanese counterfire, which had broken out during the Nashville’s bombardment, was directed at the St. Louis, but became more and more sporadic and unenthusiastic. The return fire was detected from the ships by observing tracers rise from the vicinity of the airfield, with an occasional slight flash as the guns fired. The tracers were all dull red in color. They travelled along the general line of the fire being delivered by our forces, in the opposite direction, slightly below the American 6” trajectories. The tracers could not be observed after mid-point, and no splashes were seen at any time. It is probable that all projectiles fell considerably short of the bombarding vessels.

Meanwhile a curious phenomenon had occurred. While the Nashville was nearing the end of her firing course, lookouts on the Fletcher, at

9

the head of the destroyer column, reported a large ship dead ahead at a distance of 4,000 to 5,000 yards, in line with Point Rhodes. The sighting was verified by several officers and men, but the SG radar, trained on the object, persisted in a negative report. Immediately the sighting was communicated over TBS to the OTC, while the Fletcher’s torpedo battery was trained to firing bearing, speed was increased to 25 knots, and course changed left with hard rudder. With this maneuver the bearing of the phantom began to draw rapidly to the left, although the target angle remained constant. Puzzled by this impossible behavior, the Squadron Commander and the Fletcher’s captain ordered torpedo fire held up. At about this time the Nashville ceased fire, and the phantom immediately disappeared.10 Tension relaxed as the only possible explanation of the contact became apparent—that what the Fletcher had picked up was her own shadow created by reflection of the Nashville’s gunfire on the light haze to seaward. As the St. Louis took up the bombardment, however, a similar phenomenon appeared to the Nashville, and for a few moments she opened fire with her five-inch and automatic weapons at a “phantom torpedo boat on the starboard bow.”11

At 0125, a minute after the St. Louis moved off the line, the Helena opened fire, her first salvo falling short and to the left. The Black Cat sent “right” and “up” spots, and the Helena shifted accordingly until the projectiles began to hit on the point. She then started a thorough coverage of the target area, to the accompaniment of spots of “beautiful, excellent,” from the Black Cat, and about midway through her firing period caused a large explosion near the field. The Helena then sprayed the beach area to the north of the point, causing another large explosion on a hillside north of the runway. Finally, as she steamed down the line, she scattered a few salvos to the eastward of the strip. Eighty percent of her shots had struck home when she ceased firing at 0136.

Now it was the turn of the destroyers. Moving in on a course 500 yards outside their previously assigned 11,000-yard line,12 the Fletcher, which had doubled back astern of the Helena, and the O’Bannon opened

----------------------

10 A radarman 3/c on the Fletcher was seen to shake his fist at the SG screen, and heard to shout, ‘Oh, you bastard, if you let us down now!”

11 Intelligence reports of a Japanese bombardment of Guadalcanal in October revealed that the enemy had experienced similar troubles. Captured documents included reports of a Japanese destroyer squadron chasing American destroyers and torpedo boats out of the area. None of our light forces was in the area during the bombardment.

12 A sound sweep had indicated that the shoals southwest of Kundukunda Island extended farther to sea than charts revealed.

10

fire almost simultaneously at 0140, the O’Bannon in position approximately 750 yards astern. Their first salvos landed directly in the target area, and as they steamed along their firing course they effectively covered the beach areas south of the runway along Munda Point and well up to the north of the point along the coast. One large explosion, probably from a gun position or an ammunition dump, was noted just north of the point, and five small fires were started. The enemy replied weakly and caused no damage.

RETIREMENT

At 0150 the Fletcher and the O’Bannon ceased fire and stepped up their speed to 32 knots as they raced to take station ahead of the cruisers. All ships closed up rapidly. At 0225 the destroyers arrived in position, and the group zigzagged on course 125o T., with many minor course changes, toward the assigned rendezvous with Task Group TARE, covered by the spotting Black Cats which searched the area ahead with radar until dawn. The retirement course wad laid well to the southward to give a wide berth to a reported nest of midget submarines off the southern end of New Georgia Island. Fighter coverage from Guadalcanal, consisting of four F4F’s, was picked up and identified by radar shortly before 0700, when the vessels were about 30 miles south of the Russell Islands, and arrived overhead a few moments later. The bombardment group, which had frequently changed speed as well as course, then settled down to a pace of 28 knots.

At 0900, in latitude 10o 00’ S., longitude 159o 40’ E., the Task Groups made their rendezvous. Each group at this time had three planes in the air as close-in antisubmarine patrol, and the bombardment group was momentarily expecting the arrival of its three SOC’s which had been used st Munda and which had proceeded to Tulagi after the retirement began. Task Group AFIRM, when contact was made, was steaming st 28 knots and zigzagging, while Task Group TARE, which had spent the night patrolling off Guadalcanal, was approaching from the east southeast. When the two had come within signaling distance, Task Group AFIRM hoisted the signal “I am recovering planes,” and slowed to 15 knots on course 135o T. Task Group TARE hauled around astern of the bombardment group, paralleling it well clear on the port hand, and also proceeded to launch and recover planes.

Suddenly at 0936, just south of Cape Hunter, Guadalcanal, six of a

11

group of about 10 Aichi 99 dive bombers attacked the combined groups. There had been absolutely no realization of the presence of enemy planes until the attack began. Some of the ships were in Condition ONE,13 some in Condition THREE;14 furthermore the Honolulu was holding battery and fire control drills which included dives by her own planes. The surprise element was due to several factors. In the first place, most of the vessels had apparently not been informed that they were to have fighter plane coverage; and after the friendly fighters arrived, they did not know the total number assigned. Thus little attention was paid to the Japanese planes because of their resemblance to the covering Grummans. Secondly, a PBY passed over the formation through the Grummans just before the attack, adding to the impression of purely American air activity. Thirdly, the enemy approached from the direction of Henderson Field, whence our planes would normally come. And in the fourth place, the proximity of high land on Guadalcanal made radar detection extremely difficult. Noteworthy in this connection was the fact that all SC radars on all our ships were operating at the time of the attack. There was no way for them distinguish our planes from the Japanese, however, because few of the Grummans were showing IFF signals. Some of the ships had been tracking the Grummans for some time, and on the Achilles,15 at least, observers were certain that they saw the enemy planes in advance, but mistook then for our own. Whatever the reasons might have been, it was only a matter of seconds before the Aichis had made their approach and were coming down over the formation in a 75o glide.

At the time of that attack, the Honolulu, Achilles, Columbia, and Louisville of Task Group TARE, which seemed to be the principal objective of the dive bombers, were in column in that order. They were heading on course 120o T. at about 15 knots, almost directly into the sun which bore 112o T. at about 47o altitude. A second or two before the attack, speed of the guide was increased to 27 knots and the rudder swung hard left to bring the ship to 100o T., as the Task Force guide on which the Honolulu was taking station had just zigged to port. At this moment the Honolulu’s Sky Forward was returning to its ready position from the drill action, when the director picked up four planes in their dive

-----------------------------

13 Complete readiness.

14 One-third readiness.

15 This was the same Achilles which helped harry the Graf Spee into the River Plata in December 1939.

12

and the control officer gave the dive bomber attack local control signal on the warning howlers. Commence firing was not given.

The three lead planes screamed into their low dive from almost directly ahead of the Honolulu. They had already loosed their bombs when the Honolulu managed to fire one ineffective round each from guns No. 2 and 8. The first bomb landed about 25 yards from the vessel’s port side, almost exactly abreast of Turret No. 1, temporarily drowning out the communications of Sky Forward with a towering pillar of water. The ship was turning to port at the time, and when the blast column had starboard battery picked up the planes as they came over the ship, the starboard battery firing in local control, shifting to director control on receipt of word from the director.

The second bomb was also a near-hit, landing about 50 yards from the bow and slightly to starboard. Almost immediately a third bomb exploded between 25 and 50 yards from the starboard beam, directly abreast of No. 3 5” gun.16 Meanwhile the 1.1” mounts on the port side which had been holding loading drill were frantically shifting clips, but the planes were out of range before they were able to fire. The starboard battery, however, got off 20 rounds, while the starboard 1.1”mounts fired 96 rounds and the 20-mm.’s expended 237 rounds. These may possibly have shot down one bomber, since observers saw machine gun bullets entering a wing of the last attacker, and a Japanese plane caught fire soon afterward and dived into the water.

As the bombers passed over the Honolulu, they headed for the Achilles, second ship in line, astern and somewhat to port. The New Zealand cruiser had sighted the Japanese planes a few minutes earlier flying at 12,000 to 15,000 feet in a diamond formation, but had identified them as Grumman “Wildcats” and had assumed them to be a defensive formation from Guadalcanal. The first sign of hostile character noted was when the enemy broke formation and peeled off into their dives, leaving the Achilles barely time to man her AA guns.

The third bomber in the formation17 divided though what fire could be thrown up from the three already-manned 20-mm. guns and dropped one bomb, probably 250 pounds,18 which struck squarely on the roof of the

-----------

16 These explosions littered the Honolulu’s decks with bomb fragments.

17 This plane is believed to have dropped no bombs at the Honolulu.

18 The extremely localized damage led some observers to believe that it was a smaller bomb, or possibly one which failed to detonate completely.

13

Achilles’ No. 3 Turret, penetrating and exploding on the cradle of the right gun. The gun house was completely wrecked, and nine of the personnel were killed. Two were missing and presumed killed, two later died of wounds, and at least eight were wounded. The explosion blew the right side of the turret, made of one-inch plate, into the sea, and split

the roof, also of one-inch plate, into its component halves. One half was thrown onto the quarter-deck, the other half tossed vertically into the air where it turned upside down and landed on the turret again. The left gun was undamaged, but the bore of the right was distorted.

Fortunately the remote effects of the blast and fragmentation aboard the Achilles were practically nil. Fires were confined to the turret and

14

were easily extinguished. There was no damage whatever in No. 4 Turret, although the front glass of the after searchlight was broken, several wireless aerials carried away, and a few small fragments reached as far as the foremast. The pedestal of the 20-mm. gun mounted on top of No. 3 Turret remained attached to half the roof by one bolt, and landed

with it on the quarterdeck. The Achilles took the damage in her stride, and never lost position. Her AA fire continued throughout the brief engagement. The quick extinguishing of the fire was especially fortunate, a she had several boats in close proximity to the bombed turret and had not been de-painted to the same extent as the American ships.

The Columbia, third vessel in line, put her rudder over full left and went to flank sped as the bomb struck the Achilles. As she did so, one Aichi, which apparently was just beginning its dive on her, was intercepted by a Grumman, and fell smoking into the sea. After swinging left about 45 degrees, the Columbia reversed her rudder and opened fire with her 20-mm. and 40-mm. batteries on two planes to starboard. At this moment a single plane was observed heading toward the ship from starboard, and was immediately taken under fire by 5” battery. Luckily the Columbia scored no hits, for the plane was soon identified as friendly.

The Louisville, which was trailing the Columbia, zigged radically to port and opened fire as soon as the attacking planes came within range. One of the planes peeled off in a high, fast gliding dive to starboard directly into the Louisville’s fire from 5” batteries, 20-mm.’s and 1.1” quadruples. It never got a chance to drop its bombs, because at about 800 yards distance, before it reached the release point, 20-mm. shells ripped into its fuselage. The Aichi immediately began to lost altitude, and later another dive bomber came in low and fast from directly astern, with the evident intention of strafing the Louisville’s decks. Like its predecessor, this plane never reached the ship, but in the face of heavy AA fire maneuvered violently, turned away, and retired to port after being hit by a few shells. Unfortunately one of the Louisville’s 1.1” shells was a premature and exploded the barrel of the gun, wounding one of the crew.

As the remaining planes passed over the rear of the column, they swung hard left and attempted to attack the St. Louis and the Helena of the bombardment group 4,000 yards away. These vessels, however, had already had sufficient warning, and put up a terrific AA barrage. The first plane came in a low, fast glide, directly into the curtain thrown up by six of the St. Louis’ 5” 38-caliber guns. The second salvo struck the plane directly, just as it wildly released its bomb. In a matter of seconds, the Aichi was in the water.

The remainder of the attackers swung on past the Helena, which first turned left to unmask the port battery then right to unmask the starboard.

16

One of the planes came in high and fast over the Helena’s stern from port. The ship immediately opened up with her 20-mm. and 40-mm. batteries, but it was several seconds after “Commence Firing” before the dive bomber came within range. In barely a minute, the Helena had scored a definite hit, and the bomber crashed near its predecessor, having jettisoned its bomb harmlessly from an altitude of approximately 2,500 feet. The St. Louis, meanwhile, continued to fire. It is believed that one of these vessels damaged a third Aichi before driving the rest off.19

This phase marked the end of the enemy attack. After crossing the Helena’s stern, the remaining Aichis turned abruptly and fled to the north, hotly pursued by Grummans and Lockheed P-38’s from Guadalcanal.

RESULTS

Because of the thorough planning, careful preparation, and efficient execution of the first bombardment of Munda, it was disappointing to learn that enemy aircraft were using the field again in less than 18 hours.20 This must be attributed, however, rather to excellent repair work by the Japanese than to any ineffectiveness on the part of the ships involved, for photographs of the target taken the next morning showed that the area had been “thoroughly worked over.” Pilots on reconnaissance at that time reported they met practically no AA fire from the locations bombarded. Automatic weapon fire was received from the islands just south of the airfield, and from the woods just to the east of the field. None of the AA was as heavy as three-inch. Spotters and observers agreed that the bombardment was the most destructive and efficient—available targets considered—which had been delivered to the Japanese up to that date.

Perhaps the best interpretation of the bombardment was given by CINCPAC when he said, “As a diversion . . . and as a deterrent against air attack on Guadalcanal during troop replacement, the operation was of value.”

He qualified this statement, however, by adding, “The damage to airfields or other land positions is so transient that ship should not ordinarily be risked to bombard airfields and other positions except in close support of ground operations.”

-----------------

19 The O’Bannon reported seeing a total of five planes burning in the water.

20On the afternoon of 5 January coast watchers herd antiaircraft warming up at Munda.

17

II

SECOND BOMBARDMENT---VILA-STANMORE

23-24 January 1943

During the month following the first bombardment of Munda, American troops rapidly consolidated their positions and strengthened their reserve bases in the Guadalcanal-Tulagi area. The development of Port Purvis and Tulagi as fleet harbors afforded increasingly satisfactory sites for fueling and repairing ships, while the completion of a million-gallon bulk gasoline stowage area on Guadalcanal facilitated air operations from Henderson Field.

Meanwhile our campaign to drive the enemy from the island slowly got underway. Ground forces, supported by ship and air bombardments, methodically reduced many Japanese strong points, and by the fourth week of January had overcome resistance on the high land southwest of Henderson Field, captured Kokumbona, and were approaching Tassafaronga to the west. By midmonth, operations were proceeding so favorably that plans were developed for outflanking the enemy by a troop landing on the northwest coast of Guadalcanal. Tank landing vessels were brought in to Tulagi, and on the 19th and 220th of the month Maj. Gen. Patch, commander of the ground forces in the area, visited Beaufort Bay on reconnaissance in the destroyer Nicholas.

Aerial reconnaissance had revealed considerable enemy activity in the Japanese island bases to the north and west, with heavy shipping concentrations at Rabaul, smaller groups at Buin, and vigorous base development projects in the New Georgia Islands. There was still no evidence, however, to clarify the direction of the next enemy thrust. Many indications still pointed to New Guinea, where Japanese air and ground strength were steadily on the increase, despite losses from Allied air attacks. One important movement from Rabaul to Lae, for example, consisted of four transports escorted by two cruisers and four destroyers. It reached its destination despite the loss of one more ships and damage to several others. On the other hand, the continued possibility existed that the Japanese would endeavor to regain Guadalcanal. They were going to

18

considerable effort to keep their airfields at Munda and elsewhere in serviceable condition under continuous aerial bombardment and the “Tokio Express” still ran periodically with supplies for the remaining troops on Guadalcanal.

Japanese destroyers at this time were particularly active in the waters northwest of the American bases. Early in the morning of 12 January, off Cape Esperance, eight PT boats tackled a Japanese force of 10 destroyers, sinking 1 and scoring possible hits on two others. Two more destroyer groups were sighted off Savo Island on the night of the 14th, and American search planes scored at least one hit on one of the vessels. On the morning of the 15th PT boats torpedoed three of these destroyers, and dive bombers later scored bomb hits on two more. On the nights of 20 and 21 January small groups of enemy reconnaissance planes bombed Espiritu Santo, and for three successive nights, beginning 20 January, the enemy harassed Henderson Field from the air, making as many as eight attacks in one night.21

Meanwhile our aircraft from Guadalcanal carried out several heavy attacks on the Japanese airfield at Munda, but did not succeed in seriously impeding its progressive development or hindering enemy air operations. On the contrary, not only did enemy shipping to Munda increase, but the base at the Vila-Stanmore Plantations on nearby Kolombangara Island.22 assumed increasing importance as a staging point for the advanced Munda Field. Evidence that an airstrip was also under construction at Vila-Stanmore was verified by photographs on 22 January, showing a 6,000 foot runway 90 percent cleared. Such a development had been suspected for some time, and its portent thoroughly considered and discussed. Both protected by and sustaining this field at Munda, an air base as Vila-Stanmore could constitute a highly effective menace, both offensively and defensively, to future American operations throughout the Solomon Islands area.

PREPARATIONS

A close study of available information led to some interesting conclusions concerning actual and potential Japanese activity at the base at Vila-Stanmore. The first report of Japanese occupation on 31 December

-------------------

21 It was perhaps not coincidental that the Secretary of the Navy and CINCPAC were inspecting these bases at the time.

22 The plantations were situated on opposite banks of the mouth of the Vila River-Stanmore Plantation to the west and Vila Plantation to the east. (See chart.)

19

revealed that the enemy had stationed 400 troops in the area. Two weeks later, on 13 January, detailed reports by native scouts revised the number to 4,000, indicating that the Japanese considered the base to be of increasing importance. The first enemy troops evidently used the plantation houses, which were easily visible from the sea and air, as quarters; later, however, the main plantation house at Vila was dismantled and rebuilt in the bush near the western boundary of the cultivated land. Slit trenches were dug in the nearby jungle, and two guns of unknown size were moved from their exposed positions on Vila Point to the better cover of the plantation. The Japanese evidently used a considerable number of barges to supply the base, unloading them at night and hiding them under cliffs along the shore during daylight. Frequent reports were received of barge and cargo vessel traffic to the island. Two particularly large movements were noted—one on 28 December when 28 barges were reported moving through Diamond Narrows, the other on 10 January when 22 more were seen in the same area. Larger ships apparently came in from Faisi, unloaded, and returned to Faisi the following day. Some of their cargo would then be loaded on the hidden barges, and sent down to Munda under cover of darkness.

The experience gained in the first Munda bombardment was not particularly conductive to optimism over the lasting effect of ship bombardments on land bases and airfields. As diversionary actions and screening operations for more important moves in other areas, however, they had been shown to possess considerable value. It should be remembered that at this time extensive troop replacements were still going on in Guadalcanal. Furthermore, it was necessary that preparations for the anticipated amphibious operations on the northwest coast of the island be effected with as much secrecy as possible. Our advanced Solomons bases had been lately receiving a good deal of unpleasant enemy attention which, if continued for any length of time, might prove embarrassing to our plans. Accordingly, on 19 January, COMSOPAC issued operation orders to bombard Vila-Stanmore on the night of the 23rd and 24th, paying particular attention to plantation buildings, bivouac areas, ammunition supply dumps, storehouses, gun emplacements, docks, and any ships or barges present.

Task Force AFIRM, which had so ably shelled Munda, was once again assigned to furnish the bombardment group.23 After studying operational

---------------

23 The Task Force was now at Espiritu Santo.

20

plans, Rear Admiral Ainsworth chose for this purpose his flagship, the Nashville (Capt. Spanagel), the Helena (Capt. Cecil), and the destroyers Nicholas (Lt. Comdr. William D. Brown), DeHaven (Comdr. Charles E. Tolman), Radford (Lt. Comdr. William K. Romoser), and O’Bannon (Lt. Comdr. Donald J. MacDonald).24 Capt. Robert P. Briscoe in the Nicholas commanded the destroyer unit.

The support section of the Task Force was composed of the Honolulu, (Capt. Robert W. Hayler), the St. Louis (Capt. Colin Campbell). And the destroyers Drayton (Comdr. Jacob E. Cooper), Lamson (Comdr. Philip H. Fitz-Gerald), and Hughes (Lt. Comdr. Herbert H. Marable). Destroyer were under the command of Comdr. Laurence A. Abercrombie. With Task Force ROGER25 under Rear Admiral DeWitt C. Ramsey, it was to protect the bombardment; Task Force ROGER was to remain southeast of Rennell Island, and Comdr. Abercrombie’s group was to operate around Guadalcanal, protecting convoys moving in to the island. An air group from the Saratoga, based on Henderson Field, was to be in the air at the time, ready for possible action against attacking enemy planes.

The proposed bombardment presented, in general, the same problems of approach and retirement which had been encountered in the Munda expedition. Certain important differences, however, had to be taken into account. In the first place, the fact that the Vila-Stanmore operation was to be a second venture in the same direction, together with the possibility that visibility would be good, made Rear Admiral Ainsworth “quite dubious” as to the likelihood of arriving at the bombardment point undetected. Secondly, the narrow confines of Kula Gulf---the only feasible firing area—offered little room for a maneuvering, and would leave the ships increasingly liable to “boxing in” as they penetrated deeper to an effective bombardment line. In order that these difficulties might be minimized as much as possible, it was decided that the Force should steam into the Gulf in column, two destroyers leading the cruisers and two screening behind. The O’Bannon was to take the lead, 5,000 yards in advance of the Nicholas, and make a sweep of the Gulf following the general path which the other vessels were to take. In no case, however, was she to awaken enemy suspicious by going farther south than latitude

---------------------

24 Only 2 cruisers were assigned because of a local shortage of 6” high capacity ammunition.

25 Task Force ROGER was composed at this time of the carrier Saratoga (F), the cruiser San Juan, and the destroyers Saufley, Maury, McCall, and Fanning. The Case joined the Force on the morning of 23 January.

21

08o 05’—little more than half the distance from Visuvisu Point to the firing line. Without joining the bombardment, the O’Bannon was then to take station off Waugh Rock, avoiding detection if possible, and cover the firing group by preventing the approach of enemy surface units from the north. Upon completion of the O’Bannon’s sweep, the bombardment vessels, still in the same order, were to turn to the firing course—slowing vessels, still in the same order, were to turn to the firing course—slowing to 15 knots because of the restricted waters and prospective navigational difficulties—and open fire after they were headed out.

No submarine was available for the navigational duties which the Grayback had performed during the bombardment of Munda; but because of easily identifiable landmarks and the proven accuracy of radar navigation, it was not felt that one was needed. Nor were scout observation planes from the cruisers to be used, the Munda experience having shown that Black Cats were far superior for spotting on this type of operation. However, in addition to the two Black Cats required for spotting the bombardment, a Catalina equipped with radar was to be used for screening purposes during the firing and retirement.

The difficulties presented, when considered in the light of aerial photographs of the Vila runway and dispersal areas, led Rear Admiral Ainsworth to decide on a firing plan rather different from that employed at Munda. The two cruisers—the flagship leading—were to come on the firing leg in column, where the Nashville would take as her point of aim the north end of the cleared runway where it met the Vila river. The Helena, scheduled to arrive at the “open fire” bearing two minutes later, was to concentrate on the plantation buildings. This plan provided about 2,500 yards separation between the “open fire” points of the two cruisers---a spread which they were to eliminate by working their fire toward one another’s targets. It was believed that the separation, together with the difference in “open fire” time, would give the Black Cats a good opportunity to distinguish the separate salvos. The average range this plan afforded was between 11,000 and 13,000 yards.

After the Helena stood on to the range, the DeHaven and the Radford were to close to about 7,500 yards to take the plantation buildings and the adjacent river areas under fire. Upon turning off the range, the destroyers were to increase speed to 30 knots to over the flank of the retiring cruisers. As they steamed out of the Gulf, they were to put a heavy fire into Buki and Bambari Harbors, small bays north of the plantations, on the chance that some enemy shipping might be there. By this almost

22

simultaneous bombardment, as contrasted with the separate firing employed at Munda, it was hoped that any enemy resistance would be smothered, while the sty of the ships in hostile waters would be considerably lessened.

Early on 21 January, Task Force ROGER left Noumea to transport the Saratoga’s air group to Henderson Field. On the following day, having fueled and taken on ammunition, Task Force AFIRM sortied from Espiritu Sano, laying course to the west of Guadalcanal. While both Forces were en route, on the night of 22-23 January, Black Cats carrying the spotters for the firing group went out on a harassing mission over Munda, partly to deceive the enemy as to our intentions toward Vila-Stanmore, and partly to familiarize the spotters with the procedure to be followed the next night. The following day, from dawn until mid-after-noon, planes from Henderson Field repeatedly attacked the air base at Munda, bombing and strafing runways and revetments, seeking to neutralize the field for the bombardment that evening.

THE BOMBARDMENT

Task Force AFIRM, including the bombardment and support groups, took cruising formation after leaving Espiritu Santo and zigzagged west of Guadalcanal. All during the day and night they steamed at 21 knots, the cruisers in line of divisions, the destroyers forming an antisubmarine screen. Japanese reconnaissance planes picked up the ships at about 1030 the morning of the 23rd, southwest of the island, and shadowed them off and on during the remainder of the day, keeping for the most part just out f sight. During this time Henderson Field provided fighter coverage ranging between 7 and 12 planes. On several occasions sector radar coverage reported bogies on the screen, and the fighters were vectored out after the snoopers. Occasionally various vessels of the Force caught glimpses of the shadowers, and reported to the fighters that they appeared to be flying quite low; but our planes were never able to locate the elusive Japanese. The ships could see the fighters go out and could hear them talking to one another; but the shadowers would always come back on the screen after short intervals, and undoubtedly made frequent reports of the position of the Force.

Finally, at 1840, the fighter escort left to return to Guadalcanal. Five

23

minutes later, another Japanese reconnaissance plane appeared from the West.26

Immediately after sunset, clouds shut in from the east and the whole sky became overcast. By 1900 the Force had reached latitude 09o 30’ S., longitude 158o 50’ E., just southwest of the Russell Islands, and had turned once again toward the west in the hope that enemy shadowers would mistake its destination. At 2000, in position latitude 09o 25’ S., longitude 158o 31’ E., the support group turned about and steamed back toward the south around the southern end of Guadalcanal. Although the moon had risen, the overcast made the night very dark. Amid scattered rain squalls, the bombardment group swung due north into New Georgia Sound and, satisfied that its change of course had gone undetected, set out at 26 knots for Vila-Stanmore.

Assuming Condition of Readiness TWO, with full boiler power, the bombardment group steamed to the north for an hour and three-quarters, the cruisers in column and the destroyers forming a circular screen. At 2144 course was changed to 326o T., and at 2238 to 298o T. At about 0014 on the 24th, while the ships were standing along and well out from the north New Georgia coast with the objective less than two hours away, they were picked up by three planes showing small white wingtip lights and large white lights in the tail portions of their fuselages. For a few moments these were thought to be the spotting Black Cats, and the CTF “inwardly cursed” them for their display of lights. It was soon noticed, however, that they were somewhat too straight in the fuselage to be Catalinas. A moment later they began challenging the vessels, using the single letter character UNCLE. For more than an hour they circled the O’Bannon, finally disappearing just as the leading destroyers turned into Kula Gulf. By this time they had been definitely identified as Mitsubishi twin-engined bombers. Apparently, however, they remained in doubt as to the identity of the Force (although they much have thought it excessively cautious in not answering the challenge), for they did not attack, despite being in position to do so many times.

The navigational problem involved in entering the Gulf in the blackness offered little difficulty because of the excellent functioning of the SG radar. Sasamboki Island, low and close to the land, did not stand out.

----------------

26 At about this time one of the Black Cats passed over the Fence and headed toward Munda, thereby possibly giving the Japanese the impression that this was our objective.

24

with the boldness of the offshore rocks at Munda, but nevertheless was picked up clearly. Tunguirili Point, on the other hand, stood out sharply, and gave an excellent cross bearing. As the Force entered the Gulf, the O’Bannon and the Nicholas swept ahead of the other ships for enemy vessels, but encountered none. At 0128 the O’Bannon, satisfied that the bay was clear, turned northward toward her station off Waugh Rock, and the bombardment vessels, having slowed to 17 knots, steamed unopposed toward the firing line.

At 0155, as the Nashville turned to the bombardment leg, both cruisers made contact with their spotting planes, already over the target, on voice and keyed secondary frequencies. At 0200, exactly on schedule, the Nashville opened fire, her point of aim being the north end of the runway at the junction of the Vila River. The spotters’ task was complicated at first, because their orientation point was the tip of land at the east bank of the river mouth some 2,800 yards south of the initial target. Fast salvo fire (7.5 seconds) was employed for a minute or two until the first spot reported that the shells were landing near the center of the air strip. After correcting down 6, left 150, the Nashville shifted to continuous fire, setting parallax range on infinity and using vigorous rocking in deflection to effect wider lateral displacement of fire. She then covered the area from the center of the runway south and west through the dispersal areas, and walked her fire over the two reported dump areas west of the south end pf the runway and north of the plantation buildings, starting numerous small blazes of short duration. The spotters estimated that 95 percent of her projectiles struck in the target area, only on salvo landing in the water.

Two minutes behind the Nashville, at 0202, the Helena swung onto the line and fired two ranging salvos with her main battery. The first salvo landed in the water a little short of the Vila planation buildings. The second, however, struck in the plantation building area. On receipt of a spot, the Helena shifted down 5 and opened fire with her 5” battery, the main battery going to continuous fire. Thereafter the Helena’s salvos covered the land area north and west of the plantation buildings from 1,800 yards north to 1,000 yards west of the south end of the runway. She also worked over the area east of the plantation as far as the Vila River. As in the case of the Nashville, 95 percent of the Helena’s fire was spotted in the target area. Material and personnel on both cruisers

25

functioned smoothly and efficiently---so efficiently that the commanding officer of the DeHaven, waiting his turn to begin bombardment, noted six salvos from the Nashville alone in the air at one time.27

The Nashville had been firing for about 6 minutes when her Black Cat suddenly interrupted its spots to report an unidentified vessel attempting to escape through Blackett Strait.28 The Helena was immediately ordered to attack, but could not locate the ship, either visually or by radar. The DeHaven, which at this time was within 3 ½ miles of the beach, was also notified by TBS. She, too, made a radar search, but found nothing and reported that she “couldn’t have helped seeing a ship had there been one there.”29

Eight minutes after the Nashville’s initial salvo, the Nicholas, whose primary mission was to act as a screen ahead of the heavy ships, opened fire on the causeway at the entrance to Bambari Harbor. She had previously learned from the Black Cat that both cruisers were placing their salvos in the proper target area, and had determined by radar sweep that Buki and Bambari Harbors were free of enemy shipping. In the next 3 minutes she fired 65 rounds of 5” projectiles, and when the Nashville ceased firing and turned to 052o for the retirement, the Nicholas also broke off her bombardment and resumed her screening station on the cruiser’s starboard row.

The DeHaven and the Radford, trailing the cruisers, continued on their entrance course for 4 minutes after the Helena had turned to the firing line. At the end of this time the DeHaven swung to 270o T., and maintained that heading for another 4 minutes, the Radford continuing as before. On the Expiration of this second period, the DeHaven turned to the firing course (340o T.), and at 0209, with Sasamboki Island bearing 269o T., opened fire on the Vila plantation buildings. No fires were visible in this area until the DeHaven began her bombardment, but im-

------------

27 CTF stated later that he believed that the cruiser fire killed or injured many of the reported 4,000 Japanese troops on the island.

28 Observers on the Nashville reported sighting “the usual torpedo wake.” Upon interrogation the next day, however, several of them changed their minds.

29 After conferring with the spotters following the bombardment, CTF reported that in all probability an enemy vessel was entering Blackett Strait when the bombardment started, then turned around and stood out. The spotters were apparently in error in assuming that the ship was standing out of Vila River and into the strait. After the bombardment force had left the area, reconnaissance planes saw a cargo vessel and a small unidentified ship steaming out of the bay. A destroyer and a cargo ship arrived at Faisi the following morning.

26

mediately thereafter flames shot up in tall pillars.30 The DeHaven continued salvo fire for 30 seconds waiting for a spot from Black Cats. When this was not forthcoming, she shifted to rapid fire, convinced that she was hitting in the right place.31 At 0219 she changed course to 030o nT., and increased speed to 30 knots, opening fire on Buki Harbor, at 0220. After two minutes she shifted her fire to Bambari Harbor, and at 0226 ceased firing and changed course to 055o T., to regain the formation.

The Radford, close on the heels of the DeHaven as they entered the Gulf, held to her original course of 216o T. until 0207, when she swung to the firing leg coincidentally with the DeHaven’s turn. By this maneuver, she lengthened the distance between her and her sister ship, and set her bombardment line somewhat farther offshore than that of the DeHaven.

At 0209 she, too, opened fire, her first salvos hitting in the assigned areas east and west of the plantation buildings. Bombardment was begun by using then tangent of land at Stanmore Plantation as a point of aim in train, and 9,000 yards range was set on the computer for elevation. From this initial range setup, generated ranges were used and arbitrary deflection and range spots of 100-yard steps were applied every 3 seconds to cover the target area. The large fire which broke out as the destroyers began their shelling spread further with each impact, punctuated every few seconds by tremendous explosions and billowing flames reaching high above the tops of the coconut trees. By the time the destroyers left the area, the conflagration had spread over an area 300 yards square, centering on the plantation buildings. As they completed the bombardment, one of the Black Cats increased the devastation by dropping two 500-pound bombs just north of the edge of the blaze, adding considerably to the flames and causing the fire to spread inshore. The second Cat dropped two bombs near the plantation buildings with unobserved results.

At 220, following the lead of the DeHaven, the Radford ceased firing, swung to course 030o T., and increased her speed to 30 knots. Two minutes later, while speeding out of the bay, she commenced firing into Buki Harbor, shifting targets in a few moments to Bambari Harbor. At 0229

------------------

30 Comdr. Tolman later reported to CINCPAC: “We naturally assumed that we had hit the jackpot with the first nickel, but have since been informed that the fires were actually started by the cruisers. I find my crew a little hard to convince.”

31 It was learned after the DeHaven ceased fire that no spots were received because all the plugs in the transfer panel in Radio Central jumped out with the first salvo, and continued to jump out with succeeding salvos.

27

she ceased fire and changed course to 055o T. to take her station astern of the retiring group.

Throughout the bombardment, enemy counterfire was weak and completely ineffective—so weak that only two of the vessels reported it, and none thought it worthy of reply. The DeHaven noted slight antiaircraft fire from the beach during her initial run. Al though some of the bursts appeared directly above her, she assumed that they were directed at the Black Cats. The Nashville, some minutes after she opened fire, observed antiaircraft shells bursting a thousand or more yards short of the ship. At times her tracers, with those of the Helena, almost converged on the enemy gun positions in deflection, but the range was obviously too great to hit.

RETIREMENT

The formation for retirement called for the O’Bannon, after leaving her picket station off Waugh Rock, to join the Nicholas, one on either bow of the Nashville, while the DeHaven and the Radford closed up on either quarter of the Helena. In this arrangement, the group would present a boxed antiaircraft formation. Events soon proved the wisdom of this plan.

At approximately 0230, when the DeHaven and the Radford had just passed Bambari Harbor about 4,000 yards offshore, they ceased fire and swung to course 055o T. to close the cruisers. Behind them near Stanmore Plantation the flames were growing, overshadowing the conflagration at Vila. As they rushed to take them assigned positions in the screen, a green glow lit the sky over Kolombangara Mountain. A moment later a bright white flare dropped astern. Although no planes were seen, it was apparent that the Japanese had discovered the bombardment group’s position and could be expected to attack.

For the next half hour, flares fell in quick succession from enemy planes invisible in the overcast. The pattern and colors of the pyrotechnics seemed to indicate a hitherto encountered Japanese method of tracking the course of the vessels and marking off points from which to start an attack. Green and red aerial flares, burning very brightly, would box the formation, and would be followed by light floats which illuminated the surface of the water.

At 0259 the O’Bannon took her prescribed station on the Nashville’s port bow, and the flagship increased her speed to 29 knots. Almost

28

immediately the cruisers, which had already begun an aerial search with their SC radars, made contacts with enemy planes. The overcast, through which was glowing faintly the watery disk of the moon, prevented all but the most fleeting visual contacts with the enemy; but it undoubtedly served to screen the ships just as effectively. The bombardment group, steering a direct course, steamed steadily toward the mouth of the Gulf until, at 0310, a particularly large flashing white light was sighted on the water dead ahead. The Nicholas, on orders of the CTF, left the screen at full speed to investigate. She found a large lighted float, apparently dropped by enemy planes to stake out and mark the path of the formation. It appeared that when the floats were dropped, they would act first as a flare suspended from a parachute, dropping slowly to an altitude of about 500 feet. At this point they would plummet into the water, where they would exhibit for some times a series of bright flashes, similar to a navigation light.

By 0314 the DeHaven and the Radford had reached their stations on the port and starboard quarters of the Helena, and the formation was complete. Surface visibility remained about 8,000 yards, with the pale moonlight diffused by the dense cloud cover. The destroyers could be seen from the cruisers at 4,000 yards with the unaided eye. The Black Cat spotters reported that the wakes of the cruisers, extending at least five miles, could occasionally be seen from 6,000 yards altitude. At 0331, when radar indicated that the planes were definitely closing, the Helena was ordered to track the nearest ‘bandit” and open fire. During the next few minutes she opened up sporadically at several promising contacts, but made no definite hits.

At 0350, with flares still falling and an increasing number of enemy planes maneuvering in the clouds, the Radford reported a sound contact with an enemy submarine. The contact disappeared almost immediately, and before it could be tracked down a black squall appeared ahead and to starboard. Rear Admiral Ainsworth at once ordered course changed to 095o T., and the vessels, still in formation, slipped out of the comparative visibility into the cover of the rain. From that time until an hour later, when the ships were well out of the Gulf, the weather befriended them. As soon as they would emerge from one squall another would appear approximately on their course. By keeping under this series of temporary covers at least 75 percent of the time, the vessels complicated the task of the enemy planes. With the formation steaming at 30 knots, coming

29

into the open only occasionally, and with the Japanese unable to attack from ahead without flying directly through the squalls, the danger of torpedo or bomb attack was greatly lessened.

A few moments after 0400, an enemy float plane came momentarily into the clear, and was engaged by the antiaircraft batteries of the Helena and the O’Bannon, which may have succeeded in shooting it down. At that moment another surface radar contact was made—this time by the Nashville. The first report showed an undetermined number of small ships bearing 050o R. In a minute or two, this was revised to two small boats, bearing 060o R. The exact nature of the contact was never determined, for the American vessels slipped into another squall, and the radar pips soon died away.

The next heavy concentration of planes approached the formation at 0434, and all ships except the DeHaven, whose SC radar was not working, opening fire simultaneously. At 048, the Radford picked up on her FD radar an invisible plane about 23,000 yards distant, apparently directly approaching the ship from starboard. Tracking was started at 18,000 guns which could be brought to bear. At a range of about 4,000 yards, while the plane was still invisible and firing was in full radar control, the pip abruptly disappeared from the screen. At that moment, two points forward of the starboard beam, a plane burst through the overcast and crashed into the sea. Although direct confirmation was, of course, impossible, it seemed most probable that the Radford scored a hit by using radar aim alone—one of the first examples of a ship shooting down a plane and sighting it only when it crashed.

At 0441 the Japanese planes apparently gave up their attempt to attack and turned back to their bases. A few final shots were fired at an unidentified shadowing plane by the O’Bannon shortly before dawn, but no further action developed. At 0620 a fighter patrol of five P-38’s from Guadalcanal arrived over the formation and escorted it to Tulagi, where it joined the remainder of the Task Force.

RESULTS

As in the case of the bombardment of Munda, the permanent results o she shelling, aside from an unknown number of troops killed and extensive material destroyed, were practically nil. The bombardment

30

group had barely reached Tulagi before the enemy undertook repair of damage and replacement of supplies. Reconnaissance reports indicated that three cargo ships arrived at Vila-Stanmore from the north the evening after the bombardment, and numerous other vessels followed on succeeding days. Construction of the air base continued at a rapid rate, seemingly little affected by the bombardment. The field was completed, and aircraft were operating from it, by early February.

Spotters and ships’ officers agreed that the damage wrought, judging from the flames, was far greater st Vila-Stanmore than at Munda. Rear Admiral Ainsworth, in a report to CINCPAC, stated that this fact might possibly be due to luck, but added that “the supposition must hold that there was very little at Munda to hit, and that there were plenty of Japs and stores at Vila.”

He added, however, “The fact is inescapable that the Japs have gone right ahead and built two airfields in spite of constant bombing by aircraft and two bombardments by surface vessels. We may destroy large quantities of gasoline and stores, and we may render these fields unusable at critical times, but the only real answer is to take the fields away from them.”

31

III

THIRD BOMBARDMENT—MUNDA AND VILA-STANMORE

5-6 March 1943