The Navy Department Library

The Incredible Alaska Overland Rescue

Naval Historical Foundation

Washington, DC,

1968

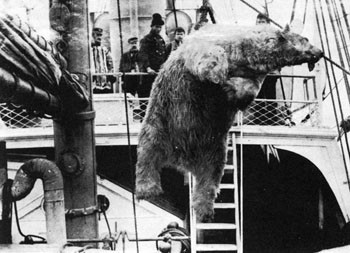

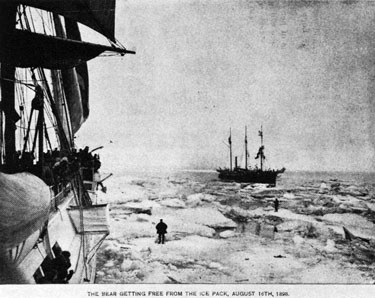

The Fall Report of 1 November 1967 showed selected displays from the current exhibit in the Truxtun-Decatur Naval Museum titled, "177 Years of Coast Guard History." In 1951, the Foundation had sponsored a similar exhibit, "United States Coast Guard in Action Since 1790." A ship's name always associated with the Bering Sea patrol cruises and rescues in Arctic waters which have been conducted over the years by the Revenue Cutter Service - Coast Guard since 28 January 1915 - is Bear.

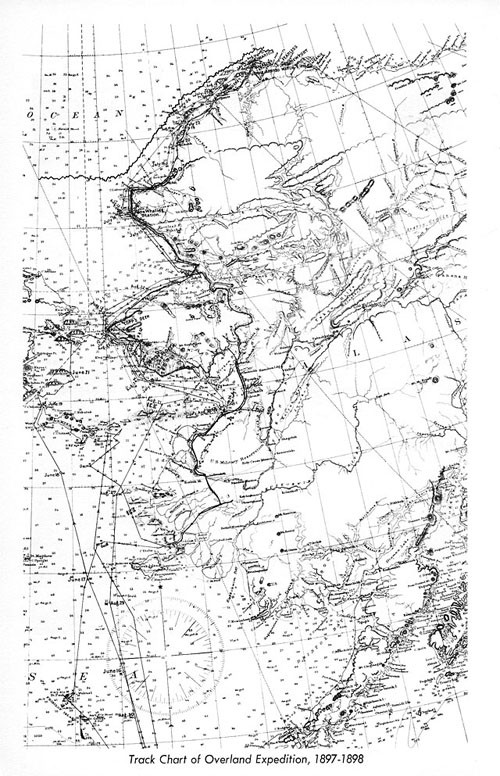

Seventy years have passed since the memorable overland expedition, of a selected crew from that cutter mushed 2000 miles from Nunivak Island to Cape Barrow to relieve from starving 275 men of the crews of ice-bound whalers. It is now a pleasure to publish the briefed report of the expedition which the Commandant of the Coast Guard has had prepared for the Foundation.

It seems appropriate to give a short history of Bear: Bear was built in 1874 by Alexander Stephen and Sons, Ltd., Linthouse, Goven, Scotland, as a sealing vessel; purchased by the Navy at St. Johns's, Newfoundland, 28 January 1884; and commissioned 17 March 1884, Lieutenant W. H. Emory in command.

Bear was purchased for use in the rescue of Lieutenant A. W. Greeley, USA, and his expedition, who were marooned in the Arctic. Bear and Thetis successfully rescued Greeley and the six other survivors at Cape Sabine, 23 June 1884. In April 1885 Bear was decommissioned and transferred to the Revenue Cutter Service.

She remained with the Revenue Cutter Service and Coast Guard until 1929, making 34 voyages to Alaskan and Arctic waters. Sold by the Coast Guard in 1929 to the City of Oakland, California, for use as a museum, she was used (as Bear of Oakland) by Rear Admiral R. E. Byrd during his Antarctic Expedition of 1933-35. Repurchased by the Navy 11 September 1939, she was commissioned the same day as Bear (AG-29). Following two voyages to the Antarctic (22 November 1939-5 June 1940 and 10 October 1940-18 May 1941), Bear served with the Northeast Greenland Patrol until returning to Boston 15 November 1943. She was decommissioned 17 May 1944 and transferred to the Maritime Commission 13 February 1948.

--i--

--ii--

THE COMMANDANT OF THE UNITED STATES COAST GUARD

WASHINGTON

Foreword

The dispatch of an overland expedition of crew members of the Revenue Cutter Bear in 1897 to rescue whalers marooned on the ice above Point Barrow, Alaska, is one of the true epics of the North. In carrying out this hazardous mission, involving a thousand-mile trek across the ice in the teeth of an Arctic winter, these men of the Revenue Cutter Service, our immediate ancestor, displayed a selfless courage and gallantry which won world fame for them and for their Service. Times have changed greatly since 1897, but the courage shown by these men is timeless.

The Coast Guard is grateful for the opportunity afforded it by the Naval Historical Foundation to make public the story of the Overland Expedition. In doing so, it is rendering a distinct public service.

[Signature]

W.T. SMITH

Admiral, U.S. Coast Guard

--iii--

The Incredible Alaska Overland Rescue

In early November, 1897, the Chamber of Commerce and the people of San Francisco brought to the attention of President William McKinley, that eight whaling ships were caught by the Arctic ice in the vicinity of Point Barrow, Alaska, and their crews were in danger of starvation. The situation for the whalers was believed so critical by the President that he ordered a rescue expedition formed.

Little hope was given for the whalers, by men who had explored and experienced the Arctic region. It was believed too late in the Fall to reach the marooned whalers by ship. However, trusting in the ability and resourcefulness of the Revenue Cutter Service (now called the Coast Guard), the Secretary of the Treasury, Lyman J. Gage, directed the veteran cutter Bear to prepare for a Winter rescue of the whalers.

The Bear, under the command of Captain Francis Tuttle, had just returned from her annual cruise to Point Barrow on the Arctic coast of Alaska. Upon the receipt of the Secretary's directive, Captain Tuttle began to assemble an all volunteer relief expedition. Next, he stocked the ship with ample provisions to enable the entire crew to winter-over in this area.

Knowing that the Arctic ice would not permit a cruise very far North, Captain Tuttle planned an overland relief expedition. This plan was also pursuant to a letter of instruction from Secretary Gage:

"Treasury Department

Office of the Secretary,

Washington, D.C., Nov. 15, 1897

SIR: The best information obtainable gives the assurance of truth to the reports that a fleet of eight whaling vessels are icebound in the Arctic Ocean, somewhere in the vicinity of Point Barrow, and that the 265 persons who were, at last accounts, on board these vessels are in all probability in dire distress. These conditions call for prompt and energetic action, looking to the relief of the imprisoned whale men. It therefore has been determined to send an expedition to the rescue.

Believing that your long experience in arctic work, your familiarity with the region of Arctic Alaska from Point Barrow, south, and the coast line washed by the Bering Sea, from which you but recently returned, your known ability and reputation as an able and competent officer, all especially fit you for the trust, you have been selected to command the relief expedition. Your ship, the Bear, will be officered by a competent body of men and manned by a crew of your own selection, The ship will be fully equipped, fitted, and provisioned for the perilous work in view, for such it must be under the most favorable conditions.

--1--

"It is of course well understood that at this advanced season of the year the route to the Arctic Ocean through the Bering Straits will be closed to you, and because of this known condition you will not attempt it. Therefore your efforts will be directed to establishing communication by means of an overland expedition with the whaling fleet, not only for the purpose of succoring the people, but to cheer them with the information that their relief and ultimate rescue will be effected as soon as the condition in Bering Straits will permit your command to advance.

With this purpose steadily in view, you will prepare an expedition of at least two commissioned officers and one forward or petty officer of your command, to undertake, from a landing that you will effect, the journey overland to Point Barrow. You will assign an officer to the charge of this expedition, furnishing him with such written instructions for the government of his party as, in your judgement and discretion, will dictate as most likely to further the success of the undertaking. This party should be prepared while you are enroute and be ready upon leaving Unalaska, bound north, to take advantage of the first opportunity afforded for a landing. They should be amply provided and fully equipped for arctic travel to successfully accomplish the trying journey and work which will be ahead of them from the landing point. You will make your own selection from the personnel of your command, volunteers preferred, of the officers whom you will deem best fitted, physically and otherwise, to encounter the hardships incident to the trip in view. There are several plans deemed feasible, all leading to the same end, by the adoption and execution of some one of which, the primary purpose of the expedition, as above given, can be accomplished. The first and great need of the whale men will probably be food. It is believed that the only practicable method of getting it to them is to drive it on the hoof. To effect this object and the other ends set forth above it is proposed:

First. That leaving Unalaska you proceed north with your command to Cape Nome, passing between Nunivak and St. Matthews Island, in sight of Nunivak; thence north between St. Lawrence Island and the coast of Alaska, carefully noting the extent and condition of the ice, if any is met, keeping well over to the mainland, the object being to ascertain where there is ice, or indications of it, in Norton Sound, If the way is clear, or you can by any means land the party on the north shore of Norton Sound, between Cape Nome and Cape Prince of Wales, natives can be communicated with at either Cape Nome, Sledge Island, Point Rodney, or Point Spencer. Should a landing be effected at any point named, or near it, a quantity of provisions previously made ready, should be landed and cached there, to be afterwards conveyed by the natives to the reindeer station at Port Clarence, and left in the care of Mr. Brevig. From the point of landing will begin the overland expedition from your command, above dwelt upon, and the officer placed in charge of it should be fully instructed upon the following general lines:

--2--

"1. Communicate as quickly as possible with W. T. Lopp, at Cape Prince of Wales; with a native named Artisarlook (generally known as Charlie), at Point Rodney. Failing these, then with Kittleson, superintendent Government reindeer station at Unalakaleet.

2. The purpose is to collect from the herds at Rodney and Cape Prince of Wales the entire available herds of reindeer, all to be driven to Point Barrow.

3. Mr. Lopp is to take charge of this herd and make all necessary arrangements for herders, sleds, and dogs; and the necessary food for use of the party must be landed from the ship. Such clothing as can be carried should be transported. It is suggested that a reindeer might carry a light pack, say 40 pounds.

4. Mr. Lopp must be fully impressed with the importance of the work in hand, and with the necessity of bending every energy to its speedy accomplishment.

5. He must also make arrangements, providing sledges and so forth, for transporting the overland expedition (from your command) to Point Hope.

6. When the deer are collected and the start made, the party from the Bear should travel with them as far as Kotzebue Sound, to make certain that they are properly started on their route.

7. That point being reached, one officer, and the necessary drivers should then push on ahead along the coast to Point Hope, leaving the other officers and Mr. Lopp to follow with the herd over the route selected to reach Point Barrow.

--3--

"8. Impress upon Mr. Lopp and the natives employed that they will be amply rewarded for their labor in furthering the object of the expedition.

9. Arriving at Point Hope, the expedition will probably get news of the condition of things at Point Barrow.

10. If it should not be known at Point Hope that the whaling fleet is icebound and its people in distress, inform the white people there of the fact that they will be expected to take care of such men as will be sent down later from Point Barrow.

11. At Point Hope the officer in charge of the expedition should, if possible, engage Jim 0'Hara at that place to guide the party to Point Barrow, together with as much provisions as can be transported.

12. Then push on, following the coast. En route parties of men may be met with, making their way to Point Barrow.

13. On this stretch of coast (between Point Hope and Point Barrow), at Point Lay, Ice Cape, Wainwright Inlet, and vicinity of Point Belcher, are natives who well know the situation at Point Barrow and can furnish aid in getting there.

14. Upon arrival at Point Barrow, the officers of the expedition should assemble, if possible, the masters of the ships, Charles Brower and Thomas Gordon, of Liebes's Whaling station, Mr. Marsh, Professor McIlhenny, and Edward Aiken, late of Point Barrow Refuge Station, ascertaining the situation, quantity of available provisions and clothing.

15. If the situation is found, as now anticipated, to be desperate, the officers must take charge in the name of the Government and organize the community for mutual support and good order, apportioning the provisions on hand, and slaughter as many reindeer as necessary (which it is hoped will have arrived) for food, to make all hold out until August 1898 when you will arrive in the Bear. Such reindeer as are left will be turned over to the Presbyterian Mission at Point Barrow.

16. The people at Point Barrow must be divided; some sent along the coast to Point Hope and others among the natives to the south.

17. In any event a part, if not all, of the people from the ships should be at Point Hope by July 1, where they can be reached and succored a month earlier than at Point Barrow by your ship.

18. No opportunity for hunting, sealing, or whaling, whereby the food supply maybe added to, must be neglected, and provisions must be made for the natives employed.

19. The officer in charge of the overland expedition from whatever point started, must be instructed to deal firmly and judiciously with every situation that may confront him, particularly after arrival at Point Barrow, he bearing in mind that he represents the Government on the spot.

20. Having succeeded in landing the overland expedition with adequate instructions, you will seek such harbor as you may deem proper to await results and the opening of navigation in Bering Straits.

--4--

"21. Before parting with the officers of the overland expedition you will instruct them to communicate with and report progress to you, should opportunity offer, giving Unalaska as your address, as you will doubtless return there for fuel and perhaps to winter.

Second. The aforegoing supposes that you will effect a landing and start the expedition from some point on the north shore of Norton Sound. If, however, because of insurmountable obstacles, such as imperiling your command or getting fast in the ice, not to escape until spring, you should fail to make a landing for your party, you will try St. Michael or the western end of Stuart Island. At St. Michael the officer in charge of the overland expedition will apply to the military commandant, Colonel Randall, USA, for transportation to Cape Prince of Wales, or engage Mr. Englestadt, at Unalakik, or St. Michael, where he may be wintering for the purpose, when your instructions given as above will be carried out.

Third. Finding it impossible to effect a landing at any point in Norton Sound, you will then try Cape Vancouver, on the north side of which is located a Catholic mission, where transportation can be obtained to Andreafsky, and thence to St. Michael, or you may effect a landing at some one of the villages on Nunivak Island, and cross the expedition on the ice to the mainland.

Fourth. Having exhausted effort and found it impossible to land at anyone of the named points north, then try Bristol Bay, anywhere from Cape Newenham to Ugaslik, where natives can be procured to convey the expedition to Togiak, Nushagak, or Ugashik. White men will be found at these places, or any of them, who can command and provide the necessary transportation to Bethel Mission, or to Lind's trading post, on the Kuskokwim River. There transportation can be procured to the Russian mission on the Yukon, and from there to St. Michael or Unalakaleet, where the instructions above given will become operative.

From whatever point the overland expedition is landed from the Bear its first aim will be to get the reindeer herd in motion for Point Barrow, and you will instruct the officer given charge that celerity of movements is of first importance; that he must, so far as possible, live on the country and change his teams for fresh ones as often as he can. You will be guided by circumstances in outfitting this expedition from the Bear:

1. As to the point at which it will be landed.

2. As to the facilities available for traveling expeditiously.

Fifth. If all the attempts to land the overland expedition on the Alaskan coast of Bering Sea should be prevented by the ice, then consider the possibility of sending the expedition by way of Katmai, in the Shelikoff Straits. Obtain all information relative to facilities and time on this route. You are aware that David Johnson made the trip from Bethel Mission, on the Kuskokwim River, to Katmai last winter in thirty-one days, and as he was in no haste it is thought his time can be materially shortened, if deemed practicable to attempt the journey to St. Michael by that route.

--5--

"Before leaving Unalaska bound north, make such preparations as maybe possible, even over the ice, if it promises success. Procure there dogs and kayaks, arrange with the Alaska Commercial Company for credit at any and all of their trading posts and connections, and gather all the information, relative to means of travel and the time required through the region from Bristol Bay to the Yukon.

Sixth. The routes and methods outlined in the foregoing are suggested for your consideration. You doubtless have formed plans of your own and believe such can be executed with better success. You will understand that your movements are not, by anything herein contained, in the least hampered. The whole situation may be summed up under two heads, to wit:

1. Food must be gotten to the starving men.

2. The best and most feasible method of doing this is to be adopted.

If the straits were open the whole thing would be comparatively easy of solution and accomplishment. That route being, to all intents and purposes, hermetically sealed, the next best course is to be attempted.

Before sailing from Seattle you will procure as many suitable sleds as you deem necessary, fitted with necessary appurtenances, as sleeping bags, etc.

You are hereby given full authority and the largest possible latitude to act in every emergency that may arise, and while impossibilities are not expected, it is expected that you, with your gallant officers and crew, will leave no avenue of possible success untried to render successful the expedition which you command. I transmit herewith orders to Lieut. Colonel Randal, United States Army, Commanding at Fort St. Michael, and to Mr. Lopp at Cape Prince of Wales, to extend to you and the overland expedition every facility and aid in their power. In the next summer, when you shall have carried to a successful termination the rescue of the people in the Arctic and have them safely on board the Bear, you will sail with all for San Francisco direct.

Mindful of the arduous and perilous expedition upon which you are about to enter, I bid you, your officers and men, Godspeed upon your errand of mercy, and wish you a successful voyage and safe return.

Respectfully yours,

L.J. Gage, Secretary

Captain Francis Tuttle, R.C.S,

Commanding U.S. Revenue Cutter Bear, Relief Expedition for the Whalers in the Arctic Ocean, Seattle, Washington"

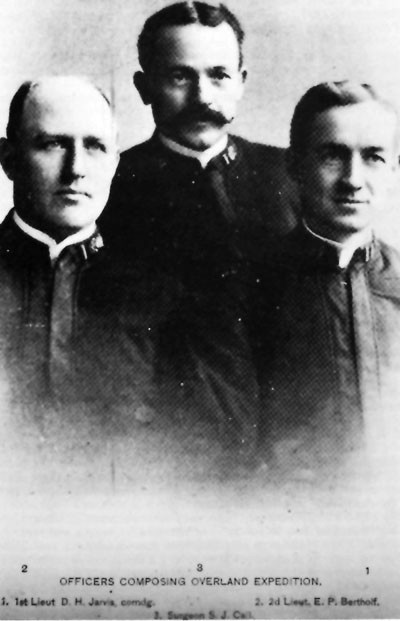

Acting on Secretary Gage's instructions, Captain Tuttle appointed an overland expedition consisting of First Lieutenant D.H. Jarvis, Officer in Charge; Lieutenant E.P. Bertholf; Surgeon S.J. Call and F. Koltchoff.

--6--

--7--

The Bear sailed from Port Townsend, Washington, on 30 November, 1897, and arrived ten days later in Unalaska, Alaska. From Unalaska, the Bear sailed to Cape Vancouver where the overland expedition was put ashore, on 16 December, near the village of Tununak. Ahead of the expedition lay over 1500 miles of desolate and frozen arctic frontier. The probability for its survival was small.

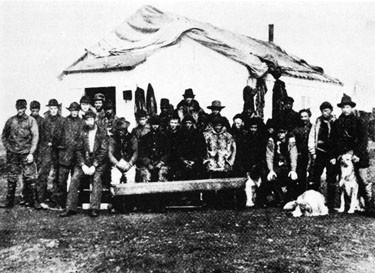

Jarvis acquired 1500 pounds of equipment and supplies which were loaded on four sleds, pulled by strong huskies. Also, a Russian guide and four Eskimos joined the expedition. At the beginning of the journey, progress seemed minimal to Jarvis and his officers. For these men, who had been seafarers most of their lives, the experience of driving sleds through the Arctic was new and dangerous. Except for a few missionaries, Jarvis and his officers were the first white men many of the Eskimos had seen in many years. Consequently, some of the Eskimos became alarmed as the white men entered their small villages.

On 20 December, Jarvis decided to break up his expedition. Some of his huskies were exhausted. He left lieutenant Bertholf, Koltchoff and the Russian guide behind with the exhausted huskies and pushed on with two good teams for Cape Prince of Whales. Bertholf and his men were to pick up fresh dogs in a couple of days and try to rendezvous with Jarvis at Kikiktaruk, near Cape Blossom.

After several days of sledding in moderate weather the temperature dropped to fifteen below zero. On the eve of Christmas, Jarvis noted in his report on the expedition that ". . . the temptation to remain over Christmas was great, but our mission would not permit any unnecessary delay." However, late Christmas day the expedition ran into a blizzard. Shell ice began to form on the surface of the snow, which cut the paws of the huskies. After the blizzard abated some of the natives in the expedition developed severe colds.

In the ensuing days, the expedition followed the Yukon River to its mouth and then struck out across the ice of Cape Romanof. At St. Michael, on 30 December, Jarvis completed the first stage of the journey. They obtained fresh huskies and pressed on their journey. Two days later, they met Mr. Tilton, who was the third mate aboard the Belvedere - one of the trapped whaling vessels. Tilton told Jarvis that he had left Point Barrow on 17 October and that the Orca, Freeman and Belvedere managed to get past Point Barrow and sailed as far southwest as the Sea Horse Islands before being trapped in the ice. The Orca was crushed and the Freeman had been abandoned. The crews of both these ships took refuge aboard the Belvedere. In addition, the Rosario was the whaling ship closest to Point Barrow with the Jeanette, Fearless and Newport spread out east of the point from 60 to 100 miles. The Wanderer, another whaler, had last been heard from in September and was believed to be about 500 miles east of Point Barrow.

--8--

Jarvis's expedition left Unalaklik on 5 January, 1898. Three days later, the snow became so heavy that snowshoes were necessary. The huskies kept sinking so deeply into the snow that they could no longer pull the sleds. So, Jarvis and his men began to tramp a path ahead of them with their snowshoes so that the huskies could pull the sleds.

Arriving at Golovin Bay on 11 January, Jarvis exchanged his sleds and huskies for Lapland freight sleds and reindeer. These sleds were shaped like small boats and were generally pulled by deer. Having mastered the huskies, Jarvis now had to learn the new technique of driving deer. Unlike the huskies, the deer were timid, nervous and consequently - easily frightened.

Jarvis's report, of 14 January, noted that his expedition was in a blizzard which increased in intensity as he drove north. He was relieved to reach the village of Opiktillik, because the deer had lost a great amount of strength and it became questionable whether they could be driven any further. Jarvis and his men crowded into a native hut to wait-out the blizzard. The wind blew hard for several days. Jarvis grew more restless as the blizzard continued and on 17 January, with the weather still foul, and because of worry about the loss of time, he lead his expedition into the full Arctic blizzard and below zero temperatures.

--9--

Jarvis's log noted: "We had to make the next village, some thirty-five miles away, for it was out of the question to pitch a tent in such weather. Tramping alongside the sleds and beating ourselves to keep warm, there were times when we anxiously looked for the protecting ice of Cape Nome. In the middle of the day we would see the sun, a red ball through the driving snow, but everything else on a level was a winding, blinding sheet. As we worked along, seeing nothing, buffeted about by the fierce gusts, it seemed as if we would certainly pay dearly for our temerity. In the afternoon the storm suddenly lulled, and we found ourselves under the lee of Cape Nome. We now breathed easier, and several hours later made our camp at the village of Kebethluk, on the west side of the Cape."

The following morning Jarvis and his men awoke to find that the village dogs had scattered their deer. A long chase ensued to round them up. Later that evening after they had been herded together, Jarvis found his feet dead-cold, so he spent the remainder of the night alternating in kicking one foot with the other so they would not freeze.

On 19 January, the expedition reached the home of Charlie Artisarlook and his family. At this point, the relief expedition would really begin. Jarvis explained to Artisarlook that his expedition needed fresh deer to complete the journey to Point Barrow. Jarvis assured Artisarlook that at a later date the U.S. government would return the same number of deer as he would borrow. After Artisarlook had a discussion with his wife, he agreed to provide Jarvis with fresh deer.

Jarvis ordered the deer herded and prepared to make the last 800 miles of the journey. Jarvis went on ahead to collect more deer at Port Clarence and left Surgeon Call behind to drive Artisarlook's herd. The first destination for Jarvis was Teller's Reindeer Station near Port Clarence. The journey was cold and the temperature dropped to a mid-winter low of forty degrees below zero.

On 24 January, Jarvis reached the home of Mr. Lopp, the Teller's Station superintendent. As a missionary, Lopp had spent many years training the natives to raise and care for their deer as the only guarantee against starvation during the Arctic Winters. In addition to asking Lopp for fresh deer, Jarvis requested he accompany the expedition for the remainder of the journey to Point Barrow. Mrs. Lopp bravely insisted that her husband join the expedition, even though she faced the winter alone with her children in a native village. Lopp agreed to join the expedition and succeeded in convincing the natives of the necessity of using fresh deer for the journey to Point Barrow. Therefore, 301 deer were given to Jarvis.

Several days passed before Call and Artisarlook arrived with additional deer. Before departing Teller's Station, Lopp managed to hire six of the most trusted and experienced deer herders in the region. The expedition now faced a hazardous 700 miles of mountainous Arctic-terrain and frequent blizzards. Time was important because Jarvis believed the whalers could not hold out much longer.

--10--

On 3 February, the expedition started out from Teller's Station with 18 deer-drawn sleds and 438 deer.

After a few days of sledding, it became evident that the sleds were too heavy and were tiring the deer. Jarvis decided to leave Lopp in charge of the herds while he departed for the nearest village to obtain huskies. Jarvis had considerable trouble obtaining huskies, because the natives in the region were poor and had few of them.

Jarvis had additional problems with the natives in the expedition. They were generally less disciplined than Jarvis, his officers, and Lopp, as this became manifest when early on the journey the natives consumed most of the food; after which, many of them abandoned the expedition, even though Jarvis tried to assure them that Bertholf would be waiting at Cape Blossom with a food train.

Jarvis had heard nothing from Bertholf since 20 December. Under Jarvis's plan, Bertholf and Koltchoff were to travel to Norton Sound and then strike across the mountains for the head of Kotzebue Sound. In that Bertholf had the provisions, the success of the rescue expedition depended upon his rendezvous with Jarvis at Kikiktaruk.

When Jarvis arrived at Kikiktaruk, near Cape Blossom, on 12 February, he was relieved to find Bertholf and the provisions. Jarvis felt he was falling behind his schedule for the journey to Point Barrow, so he decided to have Bertholf remain behind to wait for Lopp and the deer. Then Jarvis and Call set out for Point Hope, which was a week's journey away. Jarvis's log noted they left Kikiktaruk "... in ideal weather--42 degrees below zero."

Jarvis and Call arrived at Point Hope on 20 February and met a man who had just arrived after a month's journey from Point Barrow. The man reported that the condition of the whalers at Point Barrow was not dire, even though the food supplies were dwindling; they still had tea, coffee and flour available. He also informed Jarvis and Call that three deaths had occurred and scurvy was feared prior to his departure from Point Barrow.

As Jarvis was about to leave Point Hope, he learned that Lopp had crossed the ice on Kotzebue Sound with the deer, saving 150 miles, and was expected to arrive at the pre-established rendezvous point at the mouth of the Pitmegea River.

Jarvis's expedition left Point Hope on 6 March for the final 400 miles of the journey. When the expedition reached the mouth of the Pitmegea River, a note was found which was written by Lopp. Lopp stated that he and his deer crossed the mountains in six days. The sled deer were exhausted but the herd was in good shape. Jarvis wrote in his log, "The last great obstacle had been overcome; and though the cold, strong winds were hard to face, it was now a straight drive over level country to Point Barrow. Human nature could not accomplish more than had been done, so pushing on until nightfall, we went into camp, feeling we had things well in hand to go to the end of the journey."

--11--

Now Jarvis's objective was to catch up with Lopp and the deer. However, the wind and low temperatures made the progress of the expedition slow. On 15 March Jarvis wrote, "Our dreams of catching up with the herd were gone this morning, for the wind had increased during the night and by the time we awoke, it was blowing a gale. It was all we could do to keep the tent from blowing down, so we cut blocks of ice and built a barricade around our camp that kept off some of the wind, but it was anything but comfortable. During the day the thermometer registered 40 to 45 degrees below zero, which is unusually low with so much wind."

At this time, a new problem arose for Jarvis with the huskies, who according to custom were fed only on the trail. Their food supplies were nearly depleted, so they began to eat anything that was not metal or wood. They ate canvas, deerskin and ropes. When the huskies were being fed, Jarvis and his men had to club the larger and stronger ones to keep them from attacking the weaker to satisfy their hunger.

On 17 March Jarvis was greeted with the welcome sight of Lopp and the deer herd. Lopp and his men showed the marks of the blizzards they endured. There was no time for rest, so the expedition pushed on to Point Belcher, only 100 miles from Point Barrow, where they arrived on 25 March.

--12--

On 26 March, Jarvis found the marooned whalers of the Belvedere near the Sea Horse Islands. Now Jarvis had achieved his objective. His report read, ". . .we drew up alongside about four P.M. and going aboard announced ourselves and our mission, but it was some time before the first astonishment and incredulousness could wear off."

He was shocked at the appearance of the Belvedere¹s captain who looked as though he would not survive the winter. Only two meals a day were served to the thirty men on board. The Belvedere had on board a number of survivors of the Orca and Freeman, which had been lost.

Jarvis was too close to his goal to stop. His indomitable courage and driving sense of duty started him on the trail again the following morning. He camped the last night only fifteen miles from his destination. The following day the weather turned beautiful as Jarvis made a triumphant entry into Point Barrow. The expedition had made it! For the first time in the history of the North, an expedition had covered over fifteen hundred miles in the dead of winter.

Jarvis noted cooly upon arriving that "some of the officers of the wrecked vessels, whom we know, were stunned and it was some time before they could realize that we were flesh and blood. They looked to the south to see if there was not a ship in sight and others wanted to know if we had come up in a balloon."

--13--

With his arrival at Point Barrow, Jarvis found his work had just begun. Surgeon Call found a barracks with seventy-eight men living in filthy conditions. The room was so small they could hardly move about. Trying to keep warm, the men had burned seal oil lamps and were covered with lamp soot. The men were in a low state of morale from the cramped quarters, idleness and inadequate food. There were four cases of scurvy.

Jarvis energetically got to work, constructing new quarters, issuing soap and having the men clean their clothes. Sanitary regulations were instituted as well as inspections.

Lopp and the remaining elements of the expedition arrived at Point Barrow on 30 March. They had started the expedition with 448 deer and arrived with 382. After resting, he was given a huskie team to return to his home, along with dispatches for the Bear and Washington informing them of the expedition's success.

Jarvis had nearly five hundred unruly and discontented whalers on his hands. Most of their contracts expired early in the winter, so they deserted their ships. At the Point where they took refuge, there was no discipline and they frequently demanded from Jarvis that the U.S. Government feed them. Also, Jarvis had to keep the whalers and the natives apart. He cautioned the natives not to fraternize with the whalers, so that the latter could not take advantage of them.

--14--

Besides making inspection trips to distant ships to see that they received adequate rations, Jarvis also had to suppress mutinies and keep good order. Captain Millard of the Belvedere reported a mutiny on his ship, so Jarvis had to make the long trip to Sea Horse Island to settle the outbreak. [Jarvis was kept busy with the deer, which were fawning.] Now, everyone was awaiting the day when the ice fetters which were holding the whaling ships would be broken by the spring thaw. Surgeon Call was kept busy administering to whalers and natives alike. His practice ranged from frostbites to major amputations. He treated many cases between his arrival at Point Barrow and the arrival of the Bear. In this period, there was only one death, which was caused by heart disease.

The Bear left Unalaska on 14 June and was caught in the ice near St. Lawrence Island six days later. By 23 March, Captain Tuttle managed to squeeze his ship through the ice and get as far as Cape Prince of Wales. Here, Lopp reported the successful arrival of the relief expedition at Point Barrow.

The first drift ice was encountered near Cape Lisborne on 17 July. It took the Bear ten days to smash her way to Point Barrow. At five o'clock on the morning of 28 July 1898, the watch officers of the Bear sighted the relief station at Point Barrow. Jarvis and a large party of men came over the ice to greet the cutter. Jarvis was welcomed aboard by Captain Tuttle and hailed as a hero.

--15--

On 13 September 1898, after an absence of 9 months and 16 days, the Bear returned to her home port, Seattle, with another mission accomplished. Jarvis, his men of the expedition, and the Bear had become world famous. Seattle gave them a rousing welcome. This expedition had written a chapter of heroism in the far North that would be long remembered.

Official photographs of the U.S. Navy, U.S. Coast Guard and U.S. Signal Corps

--16--

[END]