Roskill, S.W. The War at Sea, 1939-1945, Vol. 1. The Defensive. (London: Her Majesty's Stationary Office, 1954): 553-570).

The Navy Department Library

Disaster in the Pacific, December 1941

Chapter 26 of The War At Sea 1939-1945, by Captain S.W. Roskill, Royal Navy

"First there will be ... fortitude - the power of enduring when hope is gone.... There must be patience, supreme patience. ... There must be resilience under defeat ... a manly optimism, which looks at the facts in all their bleakness and yet dares to be confident."

John Buchan. The Great Captains, Homilies and Recreations (1926), p. 88

The last chapters have described the unceasing struggle waged during the second half of 1941 in the Atlantic, in our home and coastal waters, in the Mediterranean and on the broad oceans. Throughout this period the Royal Navy had borne a tremendous burden and worked continuously to the limit of its resources. Each and every one of the ever-changing demands had been met and, at one period, it had seemed that reward might soon be reaped. Then, in the last month of the year, just when the dawn of a more hopeful day seemed to be breaking on the horizon, it was blotted out by the gloom of our heaviest disasters.

The reversal of the favourable trend in maritime affairs had first been felt in the Mediterranean theatre, as has already been told, but worse was to follow.

The possibility of war with Japan had, since pre-war days, never been far from the minds of the Chiefs of Staff and of the Admiralty. The pre-war naval plans had stated that British maritime strength was inadequate to ensure the control of our home waters, to contribute to the war against Italy in the Mediterranean and to fight Japan in the Far East as well.1 If Japan actively joined the Axis powers the Mediterranean would have to be left to the French Navy. By no other means could an adequate fleet be sent to the East. Little was it foreseen that, when the occasion actually arose there would be no French fleet to hold the Mediterranean. But the total loss of French maritime power did not alter the need to send substantial British naval strength to the East as soon as it could be done without undue risk to the vital home theatre, and plans to do so were repeatedly considered during 1941. The Admiralty was under no illusion

____________________

1. See pp. 41-42.

--553--

regarding the great proportion of our total strength which would have to be sent out if the Eastern Fleet was to be able to fight the Japanese Navy on anything like equal terms, though the Prime Minister was inclined to consider its estimates of Japanese naval strength exaggerated. However, the Naval Staff adhered firmly to the view that the real requirement was to send out a powerful and balanced fleet, composed of all types of ship, including battleships and at least one aircraft carrier.

For the history of the gradual development of the Japanese plans to exploit the opportunity for further southward expansion, which the defeat of France and the tremendous preoccupations of Britain offered to her, the reader must refer to other volumes of this series. Here we need only remark that at the end of July 1941, when the German attack on Russia had reduced the danger of Soviet action in the north, the Japanese sent troops to Saigon in Indo-China and, shortly afterwards, made an agreement with Vichy France for the 'joint defence' of that country. Thus were the real designs of the Japanese leaders made clear, for it had always been realized in London that the nation which held in strength the coast of Indo-China, with its excellent base at Kamranh Bay, would control the whole South China Sea.1 The validity of this opinion was soon demonstrated, since, once the necessary land, sea and air bases in Indo-China had been securely occupied, the Japanese increased pressure on Thailand (Siam) and finally, in December, invaded that country. Their forces had now reached the threshold of Malaya and the East Indian archipelago, and it was not to be expected that a challenge could long be deferred.

But while these important moves were in progress the attention of the Admiralty and Chiefs of Staff, for all their many cares and anxieties at this time, was constantly turning to the need to reinforce the Eastern Fleet. In particular, when, in August, the Prime Minister had telegraphed from the Atlantic Conference that the President of the United States was shortly to present the Japanese with a note making it plain that any further southward advance would probably mean war, the Chiefs of Staff considered what active steps should be taken. At the beginning of August the only effective capital ships in the Home Fleet were the King George V and Prince of Wales; of the Mediterranean Fleet's battle squadron the Warspite had been seriously damaged off Crete and was to be repaired in America. This left Admiral Cunningham the Queen Elizabeth, Valiant and Barham. Force H, at Gibraltar, had the Nelson and Renown. The Malaya, lately in Force H, the Repulse and Royal Sovereign were refitting in home dockyards, while the Rodney and Resolution were refitting in

____________________

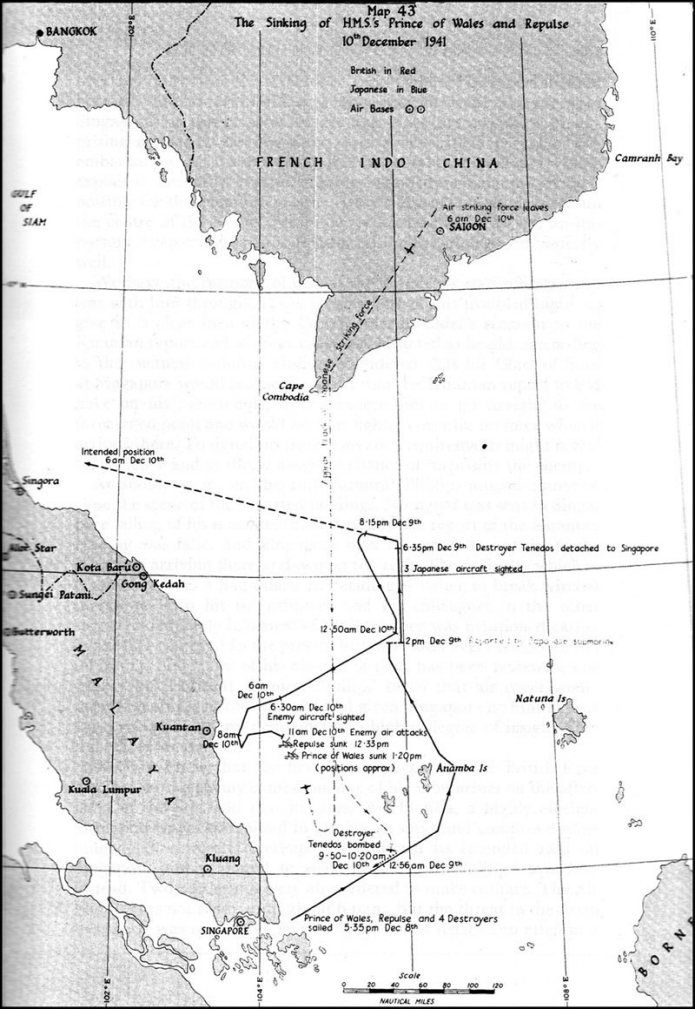

1. See map 43 (facing p. 565).

--554--

America. Lastly, the Ramillies and Revenge belonged to the North Atlantic Escort Force. Bearing in mind that the Tirpitz was known to be ready, or nearly ready, for operations and that the Italians were certainly superior to Admiral Cunningham's strength, it was plain that little, if any, margin of safety existed. The Chiefs of Staff recommended that, by mid-September one battleship from the Mediterranean should be sent east - either the Barham or the Valiant - and that four more battleships of the R class (all un-modernized ships) should follow by the end of the year. The first part of this proposal had not been carried out when the Barham was sunk on the 25th November. The possibility of substituting the Valiant was eliminated when, three weeks later, she and the Queen Elizabeth were damaged and immobilized in Alexandria harbour.1 No additional cruisers were to be sent, nor could any fleet destroyers be spared until American assistance in the Atlantic could take fuller effect. An aircraft carrier, probably the old Eagle, was, to go. Such a force had no chance of fighting the Japanese Navy but, if based on Ceylon, should, in the Chiefs of Staff's opinion, be able to prevent the disruption of our traffic in the Indian Ocean, at any rate for a time. It was intended that this should be the first stage of a long-term plan, which could not materialize before March 1942, to build up in the Indian Ocean, prior to sending to Singapore, a fleet which would finally be comprised of seven capital ships, one aircraft carrier, ten cruisers, and some two dozen destroyers. The Prime Minister did not like the Admiralty's proposals for sending out the first reinforcements and has stated his reasons.2 He wished instead to build up in the Simonstown-Aden-Singapore triangle a small but powerful force of fast modern battleships which, he considered, would have a deterrent effect on further Japanese aggression; and he drew an analogy between the influence of the Tirpitz on the Home Fleet and the suggested influence of a small but powerful eastern squadron on Japanese naval dispositions. The First Sea Lord had wished, in the first place, to use the four R-class battleships to protect the Indian Ocean routes and later, probably in December and January, to reinforce them with the Nelson, Rodney, and Renown which he desired to base on Ceylon, not on Singapore. None of the new King George V class battleships could, in Admiral Pound's view, be spared from home waters 'unless the U.S.A. (could) provide a sufficiently strong striking force of modern battleships capable of engaging [the] Tirpitz and be prepared to allow one of their ships to replace one of our own King George V class if damaged'. On the 28th of August the First Sea Lord replied to the Prime Minister's note pressing for one of the modern battleships to be sent east, and stated

____________________

1. See pp. 534 and 538.

2. See W.S. Churchill. The Second World War, Vol.III, pp. 523-525.

--555--

the full and considered reasons why he could not recommend it. The basic difference in the two points of view was that the Admiralty's force would be defensive, but would be well placed strategically in the centre of a most important theatre, whereas the Prime Minister's force was potentially offensive and was to be based far forward, but in an area which the enemy was threatening to dominate. It proved impossible to reconcile the two points of view and the matter was not discussed again until mid-October, when the Foreign Office drew attention to certain ominous signs of Japanese intentions and asked for the question of capital ship reinforcement to be discussed by the Defence Committee.

At the meeting on the 17th of October the Prime Minister repeated his previous arguments; the First Lord demurred at his proposal to send out the Prince of Wales, while the Foreign Office considered that her arrival would, from the point of view of deterring Japan from entering the war, have a far greater effect politically than the presence in those waters of a number of the last war's battleships. This was a rather different argument than the Prime Minister's but lent general support to his view. The discussion ended by the Prime Minister inviting the First Lord to send as quickly as possible one modern capital ship, together with an aircraft carrier, to join up with the Repulse at Singapore. He added that he would not come to a decision on this point without consulting the First Sea Lord, but in view of the strong feeling of the Committee in favour of the proposal, he hoped the Admiralty would not oppose this suggestion. The First Lord agreed to discuss the matter with Admiral Pound and to make recommendations in a few days' time.

On the 20th of October the proposal was again discussed by the Chiefs of Staff with the Prime Minister in the chair, and the First Sea Lord then developed the Admiralty's case more fully. He said that the deterrent which would prevent the Japanese moving south would not be the presence of one fast battleship, because they could easily afford to detach four modern ships to protect any southward-bound invasion force. But if the two Nelsons and four Royal Sovereigns were at Singapore they would have to detach the greater part of their fleet 'and thus uncover Japan' to the American Navy, on whose active co-operation in the event of a Japanese attack the First Sea Lord relied. It will be noted that this was somewhat different from the Admiralty's first proposal that the four old battleships should be based in the Indian Ocean. The Prime Minister said that he did not foresee an attack in force on Malaya, but chiefly feared raids from fast and powerful warships against our trade - to counter which the Royal Sovereigns would be useless - and the earlier argument of the Foreign Office about the political effect of sending out the Prince of Wales was restated.

--556--

The views of the First Sea Lord were plainly irreconcilable with those of the Prime Minister and of the Foreign Office. He therefore yielded so far as to suggest that the Prince of Wales should be sent to Capetown at once, and that her final destination should be decided after she had arrived there. This proposal was accepted by the Defence Committee, but next day, the 21st of October, the Admiralty told all British naval authorities that the Prince of Wales would leave shortly for Singapore. Though the Admiralty thus appears to have gone beyond the decision of the Defence Committee, it is likely that their signal, in spite of its categorical wording, was intended merely to give the authorities advance information of a probable redistribution of our forces. It is certain that such movements would never have been ordered by the Admiralty without higher approval. As recently as the 10th of October, when the Admiralty had told Admiral Cunningham about the intended dispatch of reinforcements to the Indian Ocean, the Prime Minister minuted to the First Sea Lord that no such fleet movement was to be carried out until approved by him or the Defence Committee. Furthermore on the 31st of October and the 5th of November Mr Churchill told the Dominion Prime Ministers that, in order further to deter Japan, we were sending the Prince of Wales to join the Repulse in the Indian Ocean, and she would be noticed at Capetown quite soon. But, added the Prime Minister, her movements would be reviewed when she had reached Capetown, because of the danger of the Tirpitz breaking out into the Atlantic. It is, however, plain that the Prime Minister considered that the battleship's onward voyage was very probable. On the last day of October he told the Chiefs of Staff so; and on the 1st of November he asked the First Sea Lord what his plans were if it was decided that she should go on to Singapore. When Admiral Pound replied that he intended 'to review the situation generally just before the Prince of Wales reaches Capetown', Mr Churchill assented.

Meanwhile, the battleship had left home waters on the 25th of October flying the flag of Rear-Admiral Sir T. Phillips, who had been given the rank of Acting Admiral. Though we cannot be sure regarding what Admiral Phillips himself thought about the future movements of his flagship, there seems to be little doubt that he considered his destination to be Singapore, and never expected the decision to be reviewed, let alone altered, after he had reached Capetown. The Prince of Wales reached Capetown on the 16th of November, and if a review of her future movements then took place no record of it has been found in the Admiralty's or the Prime Minister's papers; the Chiefs of Staff and the Defence Committees certainly did not consider the matter again.

Before Phillips had reached Freetown the Prime Minister telegraphed to Field Marshal Smuts introducing the Admiral and

--557--

suggesting that they should meet. The South African Prime Minister readily agreed, and Phillips therefore left his flagship at Capetown to fly to Pretoria. We have no record of the conversations which took place there, but on rejoining his flagship Admiral Phillips told his Chief of Staff (Rear-Admiral A. F. E. Palliser) that Smuts agreed with the policy of sending the two capital ships to Singapore as a deterrent against further Japanese aggression, and that in order to accomplish such a purpose he considered it essential to give publicity to the movement. This was the actual intention of the British Cabinet. None the less on the 18th of November, Smuts telegraphed to the Prime Minister expressing his serious concern over the division of Allied strength between Hawaii and Singapore into 'two fleets... each separately inferior to the Japanese Navy...'. 'If the Japanese are really nippy', added the Field Marshal, 'there is here (an) opening for a first class disaster'.

On the 11th of November, before Admiral Phillips had reached Capetown, the Admiralty ordered the Prince of Wales and Repulse to meet in Ceylon and proceed in company to Singapore. This message may have resulted from the review of the battleship's movements which the Prime Minister and First Sea Lord had intended to make but, if that is the case, we have no record of the decision nor of who was present when it was taken. On the 23rd the Prime Minister mentioned to the Foreign Secretary that the most important current naval movements were those of the Prince of Wales and Repulse, which would soon be at Singapore.

The Repulse (Captain W. G. Tennant) had arrived in Durban on the 3rd of October with a W.S. Convoy, and had thereupon been detached to the East Indies Station. The new aircraft carrier Indomitable, which had also been earmarked for the Far East, had, as we have already been told, been put out of action by accidental grounding. The Prince of Wales reached Colombo on the 28th of November and there met the Repulse for the first time. The Admiralty now ordered Admiral Phillips to fly to Singapore ahead of his flagship, and thence on to Manila in order to co-ordinate plans with the Dominion, Allied and American Navies. Phillips replied that he considered it of great importance to make contact with the Commander of the United States Asiatic Fleet, and that he intended to make a two- or three-day visit to Manila early in December.

From the foregoing brief account of the discussions which led to the dispatch of the two capital ships to Singapore it will be seen that the main purpose of the move pressed on the Admiralty by the Defence Committee was the political one of deterring Japan from further aggression. Bearing in mind that it was not known in London that Japan was, in fact, on the brink of war such a purpose was

--558--

certainly reasonable; for it was still by no means certain that, in the event of a Japanese attack on ourselves, America would enter the war. It may therefore be felt that an attempt to deter a third powerful nation from joining our enemies, at any rate for a time, had to be made - even at the price of accepting great risks. None the less it seems that, had we possessed clearer knowledge of Japan's imminent intentions, the Admiralty's anxiety regarding the exposed position of Admiral Phillip's force deepened, and on the 1st of December they suggested to him that the tow capital ships should leave Singapore. The Admiral was, in fact, considering a similar move at the time, and his staff was investigating the possibility of using Port Darwin in North Australia temporarily. Two days later the Admiralty suggested that Admiral Phillips should try to get some destroyers of the American Asiatic Fleet sent to Singapore and take the two big ships away from the threatened base to the eastwards. On reading this message the Prime Minister remarked that the ships' whereabouts should become unknown as soon as possible. On the same day, the 3rd of December, Admiral Phillips reported his intention to send the Repulse and two destroyers on a shore visit to Port Darwin. They sailed on the 5th but were recalled the next day when intelligence reached Singapore that a Japanese troop convoy had been sighted off the south coast of Indo-China steering west.

Mr. Churchill has recorded that by the evening of the 9th of December, when we were now at war with Japan, there was general agreement in London that the ships 'must go to sea and vanish among the innumerable islands'.1 But by then it was too late to implement this strategy, for the squadron was already at sea seeking the Japanese landing forces.

It will be appropriate next to consider the strength and disposition of the other Allied forces in the Pacific. The Commander-in-Chief China (Vice-Admiral Sir Geoffrey Layton) had three of the old light cruisers of the D class and two old destroyers at or near Singapore. Two Australian destroyers were also in the area. There were three more old destroyers and eight motor torpedo-boats at Hong Kong, and Admiral Phillips had with him four fairly modern destroyers, which was all that could be spared to him for anti-submarine screening. The light forces allocated to Admiral Phillips, who succeeded to Admiral Layton's command on the 8th of December, were therefore of mixed classes and performance and very weak in numbers. In Australian waters there were three cruisers, two

____________________

1. W. S. Churchill. The Second World War, Vol. III, p. 547.

--559--

destroyers and one Free French light cruiser, while the two New Zealand cruisers were at Auckland. The Dutch naval forces in the East Indies were, on paper, considerable. Three light cruisers, six destroyers and thirteen submarines were based on Java. Admiral Layton was already controlling some of the Dutch submarines, but little progress had been made towards wielding all these widely scattered ships into a single fleet under unified command.

The Americans had an advanced force known as the Asiatic Fleet (Admiral Thomas C. Hart, U.S.N.) comprising three cruisers, thirteen destroyers, and twenty-nine submarines based on Manila, but their main strength, the Pacific Fleet, was at Pearl Harbour, nearly 6,000 miles from Singapore, under Admiral Husband Kimmel. It consisted of nine battleships, three aircraft carriers, twelve heavy and nine light cruisers, sixty-seven destroyers and twenty-seven submarines. The relative strengths of the combined Allied naval forces and those of Japan in the Pacific do not, therefore, show a great disparity on paper, except in aircraft carriers. They are tabulated below.

Table 26. Allied and Enemy Naval Forces in the Pacific,

December 1941

| Capital ships |

Aircraft carriers |

Seaplane carriers |

Heavy cruisers |

Light cruisers |

Destroyers | Submarines | |

| British Empire | 2 | --- | --- | 1 | 7 | 13 | --- |

| American | 9 | 3 | --- | 13 | 11 | 80 | 56 |

| Dutch | --- | --- | --- | --- | 3 | 7 | 13 |

| Free French | --- | --- | --- | --- | 1 | --- | --- |

| Total | 11 | 3 | --- | 14 | 22 | 100 | 69 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japan | 10 | 10* | 6 | 18 | 18 | 113 | 63 |

* 6 Fleet carriers, 4 light fleet carriers

But whereas the Japanese fleet was fully trained, with all its different arms closely integrated, and could rapidly be concentrated at any desired point, the Allied forces were widely dispersed and were not trained to work and fight together; each had its own commander, and rapid concentration was out of the question. The eyes of each nation had been focused more on the defence of its own territories than on creating a unified strategy to protect the whole theatre and, in marked contrast to the great share now taken by the United States in the Atlantic battle, no corresponding policy had been agreed for joint defence in the Pacific. Nor could such a policy, if approved by the respective governments, have led immediately to creating a unified fleet. In the Pacific the problem of supply over the vast

--560--

distances involved will always be the controlling factor and, at this time, there were no properly developed bases between Pearl Harbour and Singapore which Allied ships, squadrons and aircraft could use.

Admiral Phillips now carried out his intention to visit his American colleague at Manila, and left Singapore by air for the Phillipines on the 4th. We have no detailed record of the conversations which took place, though the memory of the staff officer who accompanied Admiral Phillips tells us that Admiral Hart revealed his main anxiety to be the safety of the sea supply line from the east to the Philippines and that General MacArthur, on the other hand, wanted the British Squadron to come to Manila at once and expressed high hopes of repelling a Japanese landing. The two Flag Officers reached agreement on certain matters of policy though much was, probably inevitably, left nebulous. The agreement was signalled by Admiral Hart to Washington, whence the Navy Office passed it to the Admiralty on the 7th. It may be of interest to summarise that message.

The two Commanders-in-Chief accepted that in the early stages of war with Japan the initiative was bound to rest with the enemy. 'Definite plans cannot be drawn up', they said; 'the most we can do is decide (the) initial dispositions that appear best.' The importance of preventing the Japanese penetrating the 'Malay barrier' was stressed. The dispositions decided on were, firstly, that 'the British battle fleet would be based on Singapore and act as a striking force against Japanese movements in the China Sea, the Dutch East Indies or through the Malay Barrier'. Secondly, a cruiser striking force was to be based on eastern Borneo, Soerabaya and Port Darwin in order to cover and escort convoys in those waters. 'Minimum cruiser forces for escort work were to be retained in Australian and New Zealand waters and in the Indian Ocean. The importance of co-ordinating their own actions with those of the American Pacific Fleet was next urged, and they asked to be told of the time-table for the movement of the Pacific Fleet westward against the main Japanese strongholds in the Pacific Islands.

To set up a joint headquarters was considered 'impractible at this time', and strategic control was to remain 'with the respective Commanders-in-Chief', who would work together 'under the principle of mutual co-operation'. Tactical command was to be exercised on the same principles as in the Atlantic. Finally it was hoped to obtain the agreement of the Dutch, Australian and New Zealand authorities to these arrangements 'next week', after which details would be worked out by the two staffs. Admiral Phillips told the First Sea Lord that, in addition to the matter contained in the formal

--561--

agreement, he and Hart, had also decided that Singapore was unsuitable as the main base for future offensive operations, that Manila was the only possible alternative and that measures were in hand to enable the British battle fleet to move there by the following 1st of April. The tentative dispositions of the warships controlled by the two Commanders-in-Chief (or which they hoped to control) were as follows: -

SINGAPORE

Battleships: Prince of Wales, Repulse, Revenge, Royal Sovereign

Cruisers: Mauritius, Achilles (N.Z.), Hobart (Australia), Tromp or de Ruyter (Dutch) and possibly Australia (Australian).

Destroyers: Ten British, six Dutch, four American.

SOERABAYA-BORNEO-PORT DARWIN

Cruisers: Houston (U.S.), Marblehead (U.S.), Cornwall, Java (Dutch).

Destroyers: four American.

AUSTRALASIA

Cruisers: Australia or Canberra (Australian), Perth (Australian), Leander (N.Z.) and three armed merchant cruisers.

INDIAN OCEAN

Cruisers: Exeter, Glasgow, nine of the older 'C', 'D' and 'E' classes and five armed merchant cruisers.

On the particular issue of the U.S. Navy helping to fill the serious destroyer shortage in his fleet, which the Admiralty had raised, Admiral Phillips said that Admiral Hart's understanding was that we would build up our destroyer strength as the battle fleet was reinforced. Of the destroyers at present controlled by Hart 'one Division is at Balik-Papan (in East Borneo) and will proceed to Singapore on the declaration of war'. But before this message had reached the Admiralty the whole of the intentions of the two Commanders-in-Chief had been frustrated, and their first steps towards building an integrated command system in the Pacific rendered obsolete.

At 8 a.m. on Sunday, the 7th of December, six Japanese aircraft carriers struck deadly blows, without warning, on the United States Pacific Fleet in Pearl Harbour.1 Their aircraft attacked in two waves, the first consisting of forty torpedo-bombers, fifty high-level bombers and a like number of dive-bombers while the second comprised fifty high-level and eighty dive-bombers. About eighty fighters escorted the striking forces, whose strength and skill were indeed formidable.

____________________

1. For a graphic account of the Pearl Harbor attack see S. E. Morison, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, Vol. III (Oxford U.P., 1948), pp. 80-146.

--562--

Within half an hour the Japanese had accomplished almost the whole of their object - the annihilation of the American battle fleet. The battleship Arizona was wrecked, the Oklahoma had capsized, the West Virginia was sunk and the California was sinking. The Tennessee and Nevada were seriously damaged. Only the Pennsylvania, which was in dock, and the Maryland escaped major injuries. Shore airfields had suffered badly but, fortunately, the great dockyard and the fuel storages were not heavily attacked. And, by good chance, an important part of the Pacific Fleet, including the aircraft carriers Lexington and Enterprise, thirteen cruisers and about two dozen destroyers, were at sea at the time of the attack, while the carrier Saratoga was on the west coast of America.

But American maritime power in the Pacific was temporarily extinguished, and all hope of successfully disputing control of the South China Sea and South-West Pacific was extinguished with it. The remaining forces of all the nations involved had either to be withdrawn at once or left to fight impossible odds to the finish. The latter course was chosen and, though their last fights made little or no difference to the enemy's progress, the gallantry of the ships and of their crews in tackling vastly superior numbers in one hopeless fight after another will always be a glorious episode in the annals of their services.

It would be easy to suggest, after the event, that the succession of defeats and disasters which now impended could have been avoided if only the governments of the countries concerned had concentrated all their forces in good time and at one selected base - presumably Singapore. But, for political as well as strategic reasons, it was impossible for the American Government to move the Pacific Fleet there before the outbreak of the war, and without that powerful fleet the enemy's control of the adjacent seas could not be disputed. It would be equally easy to suggest that, once it was obvious that the enemy's maritime control could not be disputed, all naval forces should have been withdrawn. But it was unthinkable for the navies to abandon the land and air forces to carry on the unequal fight alone, or to make no attempt to save the big civilian populations. In fact, once there, the ships had to fight as best they could with what they had, for they were committed to playing their part in the hopeless struggle. It was that requirement which, in the end, dictated the movements of Admiral Phillip's ships.

Attacks on Hong Kong, the Philippines and various Pacific islands, and the invasion of Siam and Malaya started simultaneously with the raid on Pearl Harbour; but here we can only consider the invasion of Malaya. On the 6th of December a large number of Japanese

--563--

transports, under powerful escort, was sighted off the south-west point of Indo-China steering for the Gulf of Siam. The first landings directed against Malaya took place on the night of 7th-8th at Singora on the 'neck' of the peninsula, in Siam, and at Kota Bahru, just inside the Malayan frontier.1 All our airfields in the north of the Federation were heavily attacked at the same time.

Admiral Phillips decided that, given good fighter support and provided that he could achieve surprise, the chance of destroying enemy reinforcements and of cutting their line of supply, so that those on land might be thrown back, was not unfavourable, since none of the modern Japanese warships had so far appeared in the area. The prospects were discussed on board the flagship on the morning of the 8th and the Admiral's views were supported by all the officers present at the meeting. Air reconnaissance to the northward of his course and fighter cover over the scene of his intended raid - for such it was - were requested. At 5.35 p.m. on the evening of the 8th, the Prince of Wales, Repulse, and four destroyers left Singapore and steered to the north-east. Admiral Phillips left his chief of staff at Singapore to act as his representative and to co-ordinate the naval requirements with those of the other services.

In the early hours of the next morning, the 9th, a message was received in the Prince of Wales from Admiral Palliser reporting that the fighter protection requested off Singora on the 10th could not be provided. A warning that strong Japanese bomber forces were believed to be stationed in southern Indo-China was also passed. The first of the two essential conditions laid down by Admiral Phillips had passed; but he decided, none the less, to carry on, provided that he was not sighted by enemy aircraft during the 9th. He intended to make a lunge, with the heavy ships only, at the enemy landing forces at Singora early on the 10th. On the afternoon of the 9th Japanese naval aircraft were sighted by the flagship and the second condition, that of surprise went the way of the first. Admiral Phillips thereupon decided that the risks involved had become unacceptable and at 8.15 p.m. he reversed course for Singapore, when disturbing reports about Japanese air strength in the north and the disintegration setting in on shore were now being received. Shortly before midnight an 'Immediate' signal was received in the flagship from Admiral Palliser. It said: 'Enemy reported landing Kuantan, latitude 3 50' North', but gave no indication of the reliability of the report. Kuantan was much further south of the point at which Admiral Phillips had originally intended to attack and, moreover, was not far off the squadron's return course.2 It was

____________________

1 & 2. See Map 43 [next page].

--564--

over 400 miles from the airfields of Indo-China. The report made it necessary for Admiral Phillips to reconsider his decision to return to Singapore for two reasons. In the first place the possibility of surprising an enemy landing force during the critical period of disembarkation was attractive, and it was natural that he should wish to exploit it. Secondly, a road running inland from Kuantan made it possible for the enemy to cut the Army's line of communications up the center of the Malay Peninsula by landing there. It was an important, even critical point, as Admiral Phillips understood perfectly well.

We have the memory of one of the Admiral's staff officers, who was with him throughout the greater part of this troubled night, to give us a clear idea of the Commander-in-Chief's reaction to the Kuantan report and of the reasons why he acted as he did. According to that witness Admiral Phillips considered that his Chief of Staff at Singapore would realise the effect that the Kuantan report would have on his movements, would expect him to go straight to the threatened point and would arrange fighter cover for his force when it arrived there. To signal his intentions and requirements might reveal his presence and so throw away his chance of surprising the enemy.

At about 1 a.m. on the 10th Admiral Phillips altered course to close the scene of the reported landings. No signal was sent to Singapore telling of his new intention. Actually the report of the Kuantan landing was false, and Singapore took no action to anticipate the squadron arriving there at dawn on the 10th. The difficulty which so often faces a flag officer in deciding whether to break wireless silence to keep his subordinates and his colleagues in the other services adequately informed of his intentions was mentioned earlier in another context. In the present instance, after every reason for not informing Singapore of his change of plan had been reviewed, one cannot but feel that Admiral Phillips' belief that air cover would meet him off Kuantan, when he had given Singapore no hint that he was proceeding there, demanded too high a degree of insight from the officers at the base.

We now know that the first sighting report of the British force received by the enemy came from one of his submarines on the afternoon of the 9th, and that his 22nd Air Flotilla, a highly efficient formation which specialized in attacks on ships and comprised some ninety-eight aircraft, thereupon abandoned its intended raid on Singapore and prepared to strike at Admiral Phillips' squadron instead. Two battleships were also ordered to make contact. The Air Flotilla was not ready until about 6 p.m., but the threat to the troop transports was considered so great that it was decided to attempt a

--565--

night attack. The search was, however, unsuccessful and the aircraft returned to their base at about midnight. In the early hours of the 10th another Japanese submarine sighted Admiral Phillips' force and fired a salvo of torpedoes at it, all of which missed. She then surfaced and reported the British squadron to be on a southerly course. A new air search was promptly organized by the enemy. It was quickly followed by a striking force of some thirty bombers and fifty torpedo bombers.

As Admiral Phillips closed towards the coast at dawn, it was obvious that no enemy forces were in the vicinity where the new landings had been reported. While he was investigating some small craft sighted offshore, the first enemy air attack developed. The Japanese striking force had missed the British squadron on its southward run almost to the latitude of Singapore but now, by ill luck, found its quarry on the return journey. Soon after 11 a.m. attacks started, firstly by high-level bombers and then by torpedo bombers.1 They were of the very nature which Admiral Phillips had decided that he could not risk incurring while he lacked fighter protection. The Repulse was hit by a bomb in the first attack but was not very seriously injured. Then the first flight of torpedo-bombers came in and obtained two hits on the flagship, which damaged her grievously. A few minutes later another flight attacked the Repulse, almost simultaneously with a second bombing attack. Both were successfully avoided. Soon after noon Captain Tennant closed the flagship, now not under control, to try to help her. A third torpedo attack was now developing and, in spite of skilful manoeuvring, the Repulse received one hit. Almost simultaneously, the Prince of Wales, now apparently incapable of taking avoiding action, was again attacked and received four more torpedo hits in quick succession. It was now 12.23, and fresh waves of torpedo-bombers were still coming in. Three minutes later another hit jammed the Repulse's steering gear and placed her at the mercy of the blows now relentlessly pouring in on her. Three more torpedo hits in rapid secession sealed her fate and Captain Tennant, realizing that the end was near, ordered all his men on deck. His report of the last moments of the Repulse must be quoted verbatim. 'When the ship had a list of 30 degrees to port I looked over the side of the bridge and saw the Commander and two or three hundred men collecting on the starboard side. I never saw the slightest sign of panic or ill-discipline. I told them from the bridge how well they had fought the ship, and wished them good luck. The ship hung (for several minutes) with a list of about 60 or 70 degrees to port and then rolled over at 12.33.' The destroyers picked up 796 officers and men of her company of 1,309, including Captain Tennant.

____________________

1. See Map 43.

--566--

Meanwhile the Prince of Wales was in sorry state, steaming north at slow speed. At 12.44 she received a bomb hit which, however, did not greatly aggravate her damage. But she was settling rapidly in the water and listing heavily to port and was clearly doomed. At 1.20 p.m. she healed over sharply, turned turtle and sank. The destroyer Express had previously gone alongside to take off her wounded and men not required to fight the ship. She, the Electra and Vampire rescued 1,285 men of her complement of 1,612. Neither Admiral Phillips nor Captain Leach was among the survivors.

Thus this was the first act in the tragedy of the South Pacific played out to the end. Any previous doubts regarding the efficiency of the Japanese air force had been dispelled in no uncertain manner, for the attacks had been most skillfully carried out. At trifling cost to themselves they had, by sinking two capital ships at sea, accomplished what no other air force had yet achieved - and they had accomplished the feat at a distance of some 400 miles from their bases. From the British point of view the blow, coming so soon after the heavy losses suffered in other theatres, was very severe. Mr Churchill has told how he received the news from the First Sea Lord, and his later account of the disaster to a silent House of Commons is also on record.1 Though chance may have played a part in guiding the homeward-bound enemy striking force to the squadron's position, it had several times been reported by submarines and aircraft. It therefore seems unlikely that, even had Admiral Phillips not gone to Kuantan in search of a non-existent landing force, it would have escaped attack.

The divergent views expressed in the Chiefs of Staff and Defence Committees regarding the maritime strategy to be adopted in the eastern waters have already been discussed; and it has been told how the Admiralty's representatives at the crucial meetings accepted the eastward movement of the capital ships, albeit reluctantly. Had a modern aircraft carrier been able to accompany the force, as had originally been intended, such a squadron might well have exerted a cramping influence on the enemy's strategy, even though it would still have been inadequate to fight the Japanese fleet. Whether it was wise to persist with the deterrent plan after the Indomitable had been put out of action is open to argument.

As to the conduct of his operations after Admiral Phillips had arrived on his station and Japan had launched her attack, the attempt to destroy the enemy landing forces is surely not open to criticism; for the Admiral could not possibly ignore such a threat to the base on which our whole position in his theatre depended. The only

____________________

1. See W. S. Churchill. The Second World War, Vol. III, p. 551.

--567--

conclusion that can reasonably be drawn is that, after the tremendous events of the 7th of December had transformed the whole war and rendered all previous strategic considerations obsolete, it was inevitable that his ships should in the end, if not immediately share the fate of all other Allied forces in the area.

After it was all over, the Chiefs of Staff asked the Commander-in-Chief, Far East, whether Admiral Phillips had asked for fighter cover while at sea, after he had abandoned his original plan, and whether Singapore had not been kept informed of his position and revised intentions. Air Chief Marshal Sir Robert Brooke-Popham replied that no such request had been made while the squadron was at sea, and that Singapore had not been told of the change of plan or kept informed of the ships' position. The first information of the enemy air attacks which he had received came when the Repulse reported that she was being bombed, and fighters were then immediately dispatched. They arrived in time to witness the rescue operations.

The loss of Admiral Phillips and of Captain Leech accentuated the tragedy. The former had been Deputy (and later Vice) Chief of Naval Staff for the first two grueling years of the war. He had been the right hand of the First Sea Lord, had borne an immense burden with unshakeable resolution and had won the complete confidence of the Prime Minister. At the age of only fifty-three and while still a Rear Admiral, he had been selected to command a fleet which it was planned to build up to great strength as soon as possible. All these plans, hopes and intentions were now in ruins.

In justice to Captain Leech and the Prince of Wales' company it must be mentioned that, throughout her brief life, she never had a proper chance to reach full efficiency as a fighting unit. Only a few weeks after she first joined the Home Fleet, and while still suffering from serious technical troubles, she was hurried out to fight the Bismarck. As soon as she had repaired the damage received she was sent to Newfoundland for the Atlantic Charter meeting - a mission which was bound to dislocate her internal economy and delay progress towards fighting efficiency. Then the long and hurried journey to the east began, and throughout that passage she lacked most of the aids, such as targets, necessary to improve her state. Admiral Phillips was well aware of this and his understanding of the condition of his flagship played a part in making him decide to turn back on the 9th of December. Even a fully efficient ship, however, could hardly have warded off the fate which overtook the battleship, and though her unsatisfactory condition is a minor issue compared with the strategic policy which placed her where she met her end, it is right that her exceptional difficulties should be left on record. With regard to the

--568--

Repulse it should be remembered that she was a very old ship, completed in 1916, and built for speed rather than strength. She had not been modernised and re-equipped to the same extent as her sister ship the Renown. It was hardly to be expected that such a ship could successfully withstand blows of a far more lethal power, and of a totally different type from those which she had been designed a quarter of a century earlier to resist. The lessons driven home by the tragedy of the Hood are partly applicable to this second disaster to a British battle cruiser. Parsimony towards the services in peace time will always bring such nemesis in war.

The only redeeming feature of the tragedy was the splendid conduct of the officers involved in it. The Royal Navy always seems to rise to its highest peaks of devotion and self-sacrifice in adversity. A young airman who flew over the scene while the destroyers were performing their work wrote to Admiral Layton these words: 'During that hour I had seen many men in dire danger waving, cheering and joking as if they were holiday-makers at Brighton.... It shook me, for here was something about human nature. I take my hat off to them, for in them I saw the spirit which wins wars'. The last, prophetic sentence was indeed true, as all our enemies were to learn in due time, but the events of the 10th of December 1941 made it certain that the road to victory must still be long and arduous.

The epilogue can briefly be told. On the 11th of December Admiral Layton rehoisted his flag as Commander-in-Chief of an Eastern Fleet now almost non-existent. Since the survivors of the American Pacific Fleet had withdrawn to their west coast bases, the way to complete domination of the seas washing the East Indian archipelago, beyond which lay Australia and New Zealand, was now wide open to the enemy.

As soon as he had resumed command Admiral Layton told the Admiralty that, if Singapore was to be held, reinforcements must be sent, and at once. But the truth was that such reinforcements did not exist and, even if the Mediterranean had been evacuated, we could not have sent out adequate strength in time to reverse the trend of the land campaign. On the 13th Admiral Layton, foreseeing that Singapore would soon be a beleaguered fortress and the naval base unusable, proposed to send everything he could, except his submarines, to Colombo, which, plainly, was the strategic centre round which our strength must be rebuilt. Next day the Admiralty approved his proposal and thus, under the impact of disaster, we reverted to the policy which the Admiralty had originally wished to adopt.

--569--

The problems of strategic control in the threatened area, however, had still not been solved. The survivors of the American Asiatic Fleet were controlled from Washington, and British, Dutch, Australian and New Zealand authorities still controlled the strategic dispositions of their own naval forces. But the Prime Minister arrived in Washington on the 22nd of December, having crossed the Atlantic in the Duke of York. Plans, necessarily of a long-term nature, to rebuild Allied maritime power in the Pacific were there formulated, and unified command of the A.B.D.A. (American-British-Dutch-Australian) area was agreed during his visit.

Meanwhile Hong Kong, attacked on the 8th of December, fell on Christmas Day and the slender naval forces left there were all destroyed. On the 16th Borneo was invaded, and by the capture of its airfields and harbours the enemy was able to outflank Malaya and to facilitate his further penetration southwards. The Dutch submarines mentioned earlier obtained some successes against troopships and supply vessels and, before the end of the year, two British submarines were ordered to Singapore from the Mediterranean. But submarines alone could not hope to check the enemy's progress, let alone stop it, and the year closed with unbroken storm clouds hanging on the eastern horizon.

--570--

[END]