California V (BB-44)

1921–1959

California was admitted to the Union as the 31st state on 8 September 1850.

V

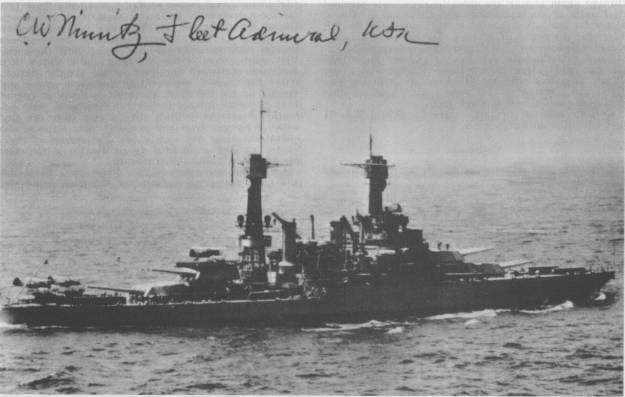

(BB-44: displacement 32,300; length 624'6"; beam 97'4"; draft 30'3"; speed 21 knots; complement 1,083; armament 12 14-inch, 14 5-inch, 4 3-inch, 2 21-inch torpedo tubes; class Tennessee)

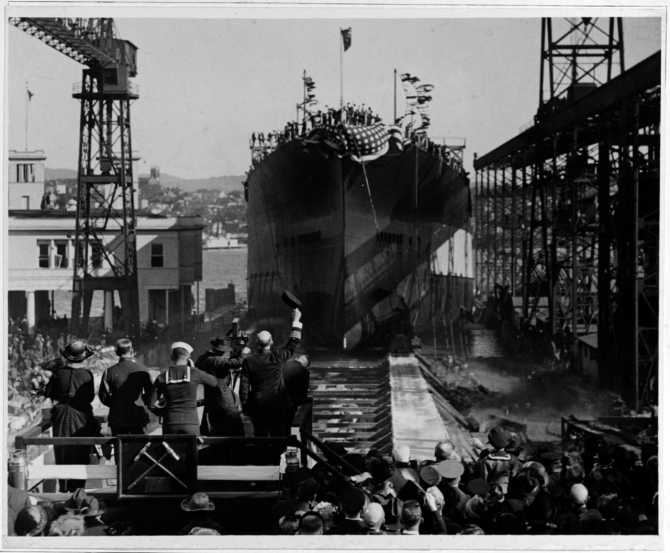

The fifth California (Battleship No. 44) was launched on 20 November 1919 at Vallejo, Calif., by Mare Island Navy Yard; sponsored by Mrs. Barbara S. Zane, daughter of Governor William D. Stephens of Calif.; redesignated as BB-44 on 17 July 1920; and commissioned on 10 August 1921, Capt. Henry J. Ziegemeier in command.

California slides down the way during her launching ceremony at the Mare Island Navy Yard on 20 November 1919. The group standing on the christening stand to the lower left of the photograph includes Mrs. Barbara S. Zane, daughter of the state’s Governor William D. Stephens and the ship’s sponsor (on the left), a Navy captain lifting his hat to the battleship, a motion picture cameraman, and a bugler. (Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph NH 55016)

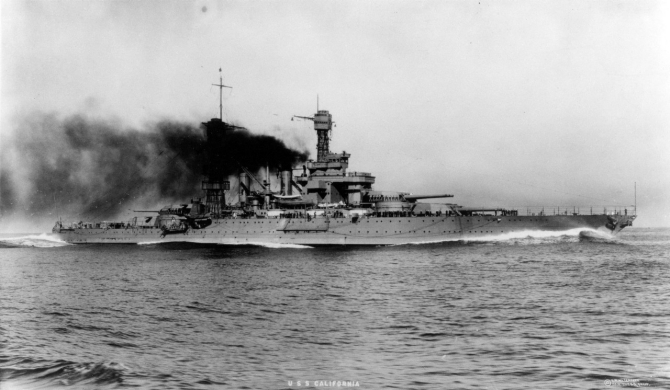

The ship makes smoke and churns through the placid Pacific with the “bone in her teeth” while working up, circa 1921. (O.W. Waterman of San Diego, Calif., Collection of Lt. Cmdr. Abraham DeSomer, donated by Myles DeSomer, 1975, Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph NH 82114)

For 20 years from 1921 until 1941, California served first as flagship of the Pacific Fleet, then as flagship of the Battle Fleet (Battle Force), U.S. Fleet. Her annual activities included joint Army-Navy exercises, tactical and organizational development problems, and fleet concentrations for various purposes. “Battle efficiency was her stock in trade,” the Navy’s Office of Public Information glowingly described the ship’s operations during one of those problems.

Lt. Dixie Kiefer made the first night take-off in a plane from a ship when he launched from California in San Diego Harbor, Calif., on 11 November 1924. Kiefer was born in Blackfoot, Idaho, on 4 April 1896, and graduated from the Naval Academy in 1918. “Good-natured, impulsive, generous,” the academy’s annual, The Lucky Bag described the young man, “he makes friends everywhere, and when he gets the ordeal of reporting aboard ship over with, he will make a good officer and, in an emergency, mighty fine ballast.” Kiefer became a naval aviator and served with Observation Squadron (VO) 2 during the event. A full moon lighted the night, and officers in dress blue uniforms swarmed around the catapult and Kiefer’s plane, a Vought UO-1 (BuNo. A-6494). The ship trained her searchlights on a dredge about 1,000 yards away to illuminate the area of the launch, and at 2146 the plane hurtled into the night. The pilot relied on the moon light when he ‘landed’ in the water. Bureau of Aeronautics Weekly News Letter No. 76 of 24 November 1924 observed that “the shot was a success in every respect and illustrates the degree of expertness in handling catapults on shipboard which has been obtained since this development was incorporated in battleship installations during the last two years.” He repeated the operation at 2300 on 13 November, and the following day launched from California while she steamed at sea about 50 miles from San Diego, communicated with the ship, and then flew ashore. Kiefer went on to become a highly decorated officer until his tragic death in a plane crash on Armistice Day 1945.

In January 1925, the Navy decided to operate Fighting Plane Squadron (VF) 1 from battleships, and overhauled the Curtis TS-1s of the squadron, installing new engines and fitting them with pontoons. The squadron reported to the Battle Force on 31 March, and cranes slung the planes over the side and they launched from the water. The ships laboriously retrieved their erstwhile charges when the planes returned to the water and the cranes hauled them back on board.

California held the ‘Battle Fleet Finals’ of the boxing and wrestling contests for the championship of the battle fleet on board on 23 May 1925. Men enjoyed fruit punch, sandwiches, cake, and cigarettes while cheering on their favorite contestants, who competed from multiple ships across the fleet. Among the winning bouts of the finals, California’s TM2c E.J. Zidick defeated S1c S.J. Dembrowski of hospital ship Relief (AH-1) by decision during a light heavyweight (175 pounds) boxing match. CSMTH2c William Honeycutt of Tennessee (BB-43) defeated California’s Sgt. A.M. Dalton, USMC, in a light heavyweight wrestling match. The flagship, however, fared poorly in two other matches, when FN1c F. Sigford of Tennessee defeated California’s WT2c Gazza Havyer in the lightweight (135 pounds) wrestling category, and SM3c J. L. Rich from Pennsylvania (BB-38) won against S1c V.B. Russell of California in the middleweight (160 pounds) wrestling.

Measles had infected a reported 469,924 people across the United States in 1920, at least 7,575 of whom died from the disease. Navy doctors thus took the disease seriously and carefully studied reported cases in the fleet. Some 78 ships reported one or more cases of measles in 1923, and in 1925 California reported an outbreak, emphasizing that more than 20 maximum incubation periods intervened, followed by a fresh importation of infection — with an outbreak. The medical staff experienced difficulty identifying and tracking the disease, however, because men went ashore on liberty and new drafts arrived frequently. The ship handled 11 drafts composed principally of men from all four naval training stations and from the receiving ships at San Francisco and Puget Sound, consisting altogether of 1,337 men, that year. California reported only three cases of mumps during the year, however, and they did not give rise to secondary cases. Men fresh from the training stations may have lowered the immunity indices of the ships to which they were transferred, but men infected by mumps in liberty ports where the disease was prevalent probably introduced it to the ships company.

California also accomplished an overhaul at Puget Sound Navy Yard at Bremerton, Wash., in 1925. The Navy meanwhile conducted an experiment concerning increasing the accommodations and improving the comfort of crewmen by substituting bunks for hammocks on board California and Oklahoma (BB-37). The fleet surgeon of the Scouting Fleet believed that the bunks represented the “most radical improvement of living conditions on board ship ever attempted by the Navy,” but opinion remained divided among officers, and the fleet surgeon of the Battle Force disagreed and advised against further installations until extended use proved their superiority over hammocks. The Navy eventually introduced bunks, as well as the later steel ones that sailors dubbed “racks”.

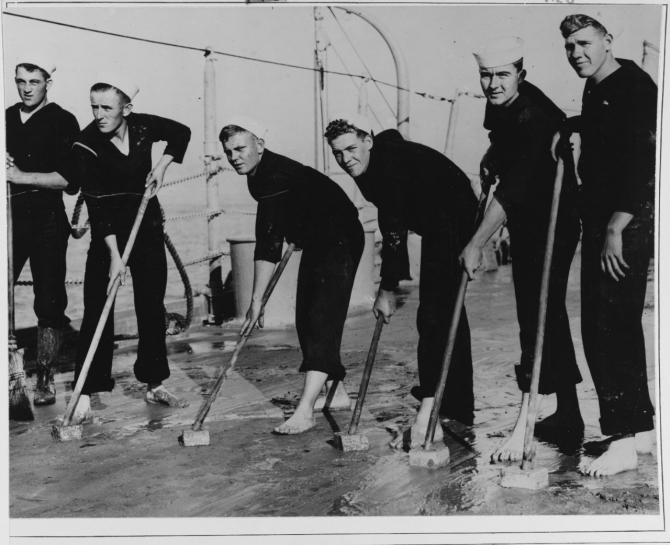

Officers of the ship’s company pose with Dorothy Devore, a silent film star and comedian on board the ship at San Pedro, Calif., 1925. Devore (22 June 1899–10 September 1976) was cast in 36 films during a career spanning two decades. Lt. Abraham DeSomer stands third from the right. Note the caps in the barrels of the triple 14-inch guns, and the overall cleanliness of the ship, the deck of which has likely been holystoned for the event. (Collection of Lt. Cmdr. Abraham DeSomer, donated by Lt. Col. Russell DeSomer, USAFR, 1975) (Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph NH 103839)

Barefoot sailors appear less than enthusiastic about arduously holystoning the battleship’s deck, circa 1920s. The ship’s company eventually nicknamed their holystoning teams the “California Rockettes.” (Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph NH 903215)

In the summer of 1925, California led the Battle Fleet and a division of cruisers from the Scouting Fleet on a very successful good-will cruise to Australia and New Zealand, calling at Pago Pago in American Samoa.

Men of the ship’s company dance with their partners and pose for the camera during California’s annual ships ball, 9 April 1926. (Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph UA 570.36)

California and 67 other ships of the Battle Force, its screen, and auxiliaries steam into San Francisco Bay for a brief visit, 18 June 1926. Capt. William H. Standley, California’s commanding officer, exchanges salutes with Brig. Gen. Smedley D. Butler, USMC (both of whom stand just left of the center of the picture). Note the marine guard and ship’s band to the right. (Courtesy of the San Francisco Maritime Museum) (Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph NH 68840)

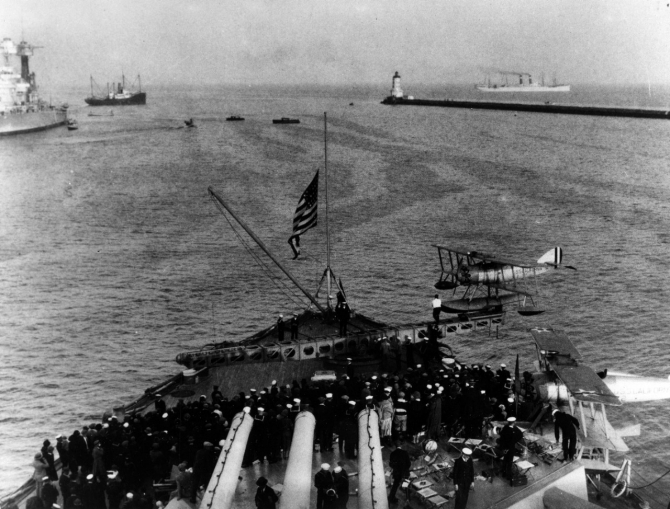

Sailors gather on the fantail to watch the ship launch a Vought UO-1 or FU-1 during Navy Day festivities off Los Angeles, Calif., in the late 1920s. Note the ship’s colors at half-mast to honor fallen veterans. (Courtesy of the San Francisco Maritime Museum) (Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph NH 68847)

California participated in many exercises during the 1920s and here leads a line of battleships through a deceptively calm sea off the California coast. The three ships next in line (in no particular order) are believed to be Colorado (BB-45), Maryland (BB-46), and West Virginia (BB-48), followed by Tennessee (BB-43) and several older battlewagons. (U.S. Navy Photograph 80-G-695093, National Archives and Records Administration, Still Pictures Branch, College Park, Md.)

Assistant Secretary of the Bureau of Aeronautics Edward P. Warner proved an energetic appointee and he inspected the fleet in the San Pedro and San Diego areas, observing flight tactical exercises, in 1926. He was flown from and to the deck of aircraft carrier Langley (CV-1), and took flight in a seaplane catapulted from California and observed fleet tactics from the air. The battleship routinely embarked up to three Vought UO-1s of Torpedo and Bombing Plane Squadron (VT) 2 during the year. Five turret-type catapults were meanwhile installed on board California, Colorado (BB-45), Maryland (BB-46), and West Virginia (BB-48), and the latter ship also received a turntable quarter deck catapult. California took part in the Naval Review by President Calvin Coolidge off Hampton Roads, Va., on 4 June 1927.

The actions of the ship’s company while on liberty and leave provide a glimpse of the personal lives of sailors during this period. California reported a rate of 137 per 1,000 cases of sexually transmitted diseases in 1927 and 118 per 1,000 in 1928. The highest incidence of one of the diseases studied -- gonorrhea -- per day resulted from liberty in San Francisco, followed (in order) by Seattle, Wash.; Sydney, Australia; Los Angeles, Calif.; and Auckland, New Zealand. The medical officer surmised that the availability of “bootleg liquor” and women contributed to a dangerous combination in that regard, and that well-meaning local authorities sometimes inadvertently exacerbated the problem by allowing men in uniform to travel on street cars in San Francisco or on all forms of public transportation in Sydney for free. Los Angeles figured less prominently because local officials made a “considerable effort” to limit the “sources of infection” and the women also plied their trade some distance from the ship’s berths. The New Zealanders isolated known prostitutes, and both of the latter cities provided a host of other amusements and amenities for the men going ashore. Honolulu proved even less appealing, because after the initial excitement of visiting the tropical island of Oahu, the men discovered few amusements and often preferred to remain on board ship. California also completed an overhaul at Puget Sound in 1928, but her evaporators deteriorated to such an extent that the Navy completed renewed them during the yard work.

The annual fleet problems concentrated the Navy’s power to conduct maneuvers on the largest scale and under the most realistic conditions attainable. California temporary switched oceans while she participated in Fleet Problem X and Fleet Problem XI in the Caribbean early in the new decade. Despite adverse weather during Fleet Problem X, commanders exercised in maneuver to gain tactical superiority over ‘enemy’ forces, and in the employment of light forces and aircraft in search operations (10–15 March 1930). Aircraft carriers Lexington (CV-2), Saratoga (CV-3), and Langley, minelayer Aroostook (CM-3) -- which operated as an aircraft tender -- and lighter-than-air aircraft tender Wright (AZ-1) also participated. Developments included an appraisal of the suddenness by which air power completely reversed engagements, and of planes that bombed and strafed battleships. Observers also recognized the shortcomings of the scouting planes in the inventory. In addition, failures in recognition led to ships shooting at friendly planes, and cruiser gunfire ‘damaged’ Langley.

Lexington, Saratoga, Langley, Wright, and Sandpiper (AM-51) took part in Fleet Problem XI in the Caribbean (14–18 April 1930). The problem focused on scouting and in concentrating dispersed forces, and in how concentrated forces attacked dispersed opponents. Unfavorable weather and visibility complicated the exercise. Light cruiser Richmond (CL-9) briefly “fired” her 6-inch guns at Lexington on 16 April. The umpire ruled that the shots knocked-out six planes on the flight deck, and evaluated the failure of Lexington’s other aircraft to lay smoke as a serious tactical omission. Two nights later ‘Black’ battleships Tennessee and West Virginia mistakenly identified their carrier Saratoga as ‘Blue’ Lexington and opened fire at her from a range of 9,000 yards with their 14 and 16 inch guns, respectively. The umpire subsequently ruled Saratoga out of action but not before her planes dropped 11 1,000-pound bombs from an altitude of 10,000 feet on Blue battleships prior to the problem’s conclusion. Experience from Fleet Problem X the preceding month and in this exercise led the Bureau of Aeronautics to call for the establishment of several “semi-permanent task groups [each] consisting of carrier, cruisers and destroyers,” the necessity for radios to equip all airplanes, the development of “proper type” scouting planes, the increase of the size of scouting squadrons to eighteen aircraft, and of the value of extreme long range patrol planes.

The battlewagon came about from Cuban waters following the second problem and steamed northward to New York City. She full-dressed with other ships while President Herbert C. Hoover reviewed the fleet from on board Salt Lake City (CL-25) off the Virginia capes on 20 May 1930, and six days later set out from Hampton Roads for her return voyage to the west coast. California again turned her prow northward that summer of 1930 and visited Port Angeles, Wash. (7–11 July), operated in the Puget Sound area through 11 August, and then steamed to San Francisco for a brief port call (17–24 August), before returning to San Pedro. California and the other battleships and their screens steamed from San Pedro to the San Diego area and from there to Panamanian waters (1 January–1 April 1931).

Langley, Lexington, and Saratoga, together with aircraft tenders Wright, Patoka (AO-9), and Swan (AM-34), fought across the Eastern Pacific toward Panamanian waters during Fleet Problem XII, which comprised strategic scouting, the employment of carriers and light cruisers, the defense of a coast line, and the attack and defense of a convoy (15–21 February 1931). The essence of the problem concerned action between a fleet strong in aircraft and weak in battleships, and a fleet that reversed these strengths. Rigid airship Los Angeles (ZR-3) took part in her first problem as a scout but her “extreme vulnerability” generated controversy. Aircraft checked but did not stop the advance of the battleship fleet and despite inferior air support the battleship fleet defeated the carrier fleet. The limitations of carriers became apparent in that their aircraft expended half of their fuel and ammunition in just two days and without replenishment the carriers would have been forced to retreat had the exercise continued. In addition, many heavy cruisers lacked sufficient stability for catapult and recovery operations.

California operated in the Puget Sound area (1 July–16 August 1931), visited San Francisco through the end of the month, and then returned to San Pedro. The ship’s authorized planes usually comprised one assigned to Adm. Richard H. Leigh, Commander Battle Force, who wore his flag in the battleship, and up to three scouts, and during this period she embarked three Vought O3U-1s. Strong winds, heavy seas, and frequent and heavy rain squalls accompanied by foggy mist delayed Advanced Practice C, an exercise off San Nicholas Island in southern Californian waters, early in 1932. On 15 January, Arizona (BB-39), California, and West Virginia carried out the exercise during rain squalls and mist, which caused the point of aim target to be “very indistinct” to the gunners during Phase A (direct fire), and “completely obliterated” the aim point during the subsequent phases (indirect fire). The evaluators observed, however, that since Phase B represented enemy ships laying smoke screens to shut out the point of aim, they considered the training a valuable opportunity in real battle conditions.

Minesweeper Grebe (AM-43) took frigate Constitution in tow and joined nearly 130 Navy ships, including Lexington, California, and Tennessee, in a visit to Long Beach, Calif., on 9 March 1933. The restored frigate, commonly known as “Old Ironsides,” was on a three year tour of the United States, and rendezvoused with the fleet for anticipated liberty. At 1755 the very next day, however, an earthquake with an estimated magnitude of 6.25 Ms occurred in Long Beach. Many buildings with unreinforced masonry walls collapsed and at least 120 people perished. Oil derricks in Huntington Beach toppled, and windows in downtown Los Angeles broke, sending glass shards falling into the streets. The National Geodetic Survey estimated that the Catalina Channel sank 359 feet, and the earthquake damaged many of the docks in Los Angeles Harbor. The Navy deployed 4,000 sailors and marines, including men from California, to assist the Army, American Legion, American Red Cross, and volunteers from multiple churches and organizations in the recovery effort, and to maintain order and prevent looting. The earthquake damaged some electrical connections between Constitution and the shore but the hardy frigate otherwise emerged unscathed, and on 19 March she resumed her voyage, though visited the city again on her southward passage that October. The disaster led to the state of California issuing stricter building codes.

California continued to serve as the flagship of the Battle Force during 1934–1935, but operated within Battleship Division (BatDiv) 4 along with Colorado, Maryland, and West Virginia. Three separate exercises designed to enhance realism comprised Fleet Problem XV in the Caribbean and in Panamanian waters (19 April–12 May 1934). Planes “sank” Saratoga and put Lexington out of action. On 6 May six Grumman FF-1s from Lexington “shot down” rigid airship Macon (ZRS-5) — although she transmitted a sighting report of the carrier. Observers noted the liability of airships in fleet operations and counterbalanced their great cost, slow speed, and vulnerability unfavorably with their value as scouts. The increase of the fleet problems in complexity and duration led umpires to initiate periodic recesses to rest crews. The lessons learned included the inefficiency of battleship and cruiser plane handling. Following the problem, the fleet stood in to Gonaives Bay, Haiti, until 25 May, and then sailed for New York, arriving on 31 May. That same day, off the Ambrose Channel Lightship, Pennsylvania led Lexington and Saratoga; the battle line; and a series of lesser ships in review past President Franklin D. Roosevelt embarked on board Indianapolis (CA-35). Then with Indianapolis in the lead, the ships entered New York Harbor and anchored in the North River.

California next took part with the fleet in a series of tactical exercises as the battleships steamed from the Panama Canal to San Pedro (27 October–9 November 1934). The ship embarked three O3U-3s of VO-4B during the exercises, one of which normally operated as the admiral’s “barge”. Destroyers carried out practice attacks against the fleet by day and night, joined by planes during the daylight hours. The voyage culminated in Exercise Z, in which Lexington, Macon, Wright, light cruisers simulating battleships, and the boats of Submarine Division 12 -- flagship Bonita (SS-165), Barracuda (SS-163), Bass (SS-164), and Dolphin (SS-169) -- attacked the fleet. Following those exercises, California, Colorado, Maryland, West Virginia, and Ranger (CV-4) took part in a landing exercise on San Clemente Island off southern California on 15 November. Mobile target ship Utah (AG-16), store ship Bridge (AF-1), and submarine tender Holland (AS-3) represented transports for the marines from San Diego. Evaluators learned that the fleet could rapidly concentrate “a considerable force” and, without preliminary training “land them effectively”. Destroyers and planes laid smoke to screen the movements of the marines “from ship to shore”, and the ships largely coordinated and timed their gunfire, aircraft operations, and boat movements as planned.

The five phases of Fleet Problem XVI covered a vast area from the Aleutian Islands to Midway, Territory of Hawaii, and the Eastern Pacific (29 April–10 June 1935). Severe weather hampered the operations in Alaskan waters, but the problem demonstrated the value of Pearl Harbor as a base when the entire fleet with the exception of the large carriers was berthed therein. Patrol and marine planes took the major aerial role during landing exercises when combined forces launched a strategic offensive against the enemy. During her first fleet problem Ranger joined Langley, Lexington, and Saratoga in the Main Body of the White Fleet. The slowness of sending patrols on 30 April enabled ‘Black’ submarine Bonita to close within 500 yards and fire six torpedoes at Ranger as she recovered planes, and for Barracuda to fire four torpedoes from 1,900 yards. Planes pursued the submarines and a dive bomber caught Bonita on the surface and made a pass before she submerged, but the ease with which the boats penetrated the screen boded poorly for the ships. A mass flight of patrol squadrons marred by casualties subsequently occurred from Pearl Harbor via French Frigate Shoals. The evaluators noted that the problem demonstrated the necessity of developing antisubmarine “material and methods”; the importance of training in joint landing operations; the lack of minesweepers capable of accompanying the fleet at higher speeds; and the slow speed of the auxiliaries.

California passes beneath the Golden Gate Bridge as she enters San Francisco Bay, circa January–June 1937. (Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph NH 73001)

California served briefly with BatDiv 2, and the division made a cruise to Hawaiian waters (7 July–22 August 1937). California and Tennessee passed through the Panama Canal and then (6–11 March 1938) visited Ponce, P.R. While training California’s 5-inch guns fired poorly at radio-controlled target planes, and evaluators reported that her performance “served to point out deficiencies in material, procedures and training, and have furnished a basis for further investigation and progress.”

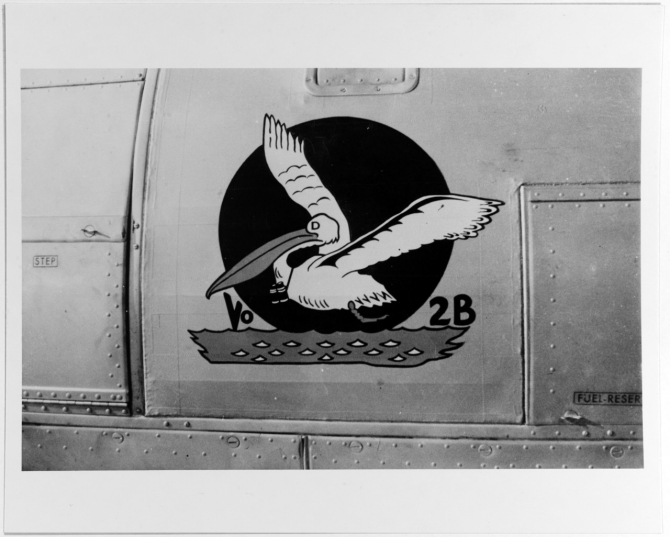

A close up view of the port side of the fuselage of one of the Curtiss SOC-3 Seagulls of Observation Squadron (VO) 2B embarked on board the ship, shows the squadron’s Pelican insignia, circa 1938. (Courtesy of Howard F. Ailes, Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph NH 80519)

California also became involved in introducing radar to the fleet. Adm. William D. Leahy, Chief of Naval Operations, held a policy conference on 1 May 1939 to reach decisions concerning the manufacture and installation of radar equipment. Based upon reports from researchers and the fleet, Leahy and the attendees recommended procuring 20 exact copies of the experimental XAF radar. The Bureau of Engineering demurred because researchers sought to further improve the system, so the planners compromised and the Navy contracted for ten sets. The service disclosed details of the XAF to engineers at Western Electric Co. Laboratories on 18 May, and the following day to engineers at Radio Corp. of America (RCA). Officers and engineers presented the complete specifications for what they called “radio range equipment” for the prospective bids by the two companies prior to 15 June, but in lieu of contracting for the initial 20 sets, the bureau decided to purchase only six and contracted for them with RCA in October 1939, with the understanding that the Naval Research Laboratory would assist in every possible manner. The XAF was delivered to the contractor the following month, and, designated CXAM, delivered to the fleet and fitted in California, Yorktown (CV-5), and heavy cruisers Chicago (CA-29), Northampton (CA-26), and Pensacola (CA-24) in May 1940. Despite insufficient funding, those researchers succeeded in developing a detection system that eventually revolutionized naval warfare.

Fleet Problem XX consisted of two separate phases around the Hawaiian Islands and Eastern Pacific (April–May 1940). The exercise involved coordinating commands, protecting a convoy, and seizing advanced bases to bring about a decisive engagement. The lessons learned included: the ability of carriers to alter the caliber of their aircraft weapons by changing squadrons; the tendency of commanders to overlook carriers’ limitations and assign them excessive tasks; the necessity for reliefs for flight and carrier crews under actual war conditions; the success of high altitude tracking by patrol aircraft; and the lack of success of low level horizontal bombing attacks. Following the problem on 7 May, President Roosevelt ordered the fleet to remain in Hawaiian waters, in an effort calculated to help deter further Japanese expansionism. California thus shifted her home port to Pearl Harbor. The global crisis compelled the Navy to cancel Fleet Problem XXII scheduled for 1941. The ship completed an overhaul that spring on 15 April 1941, and her bluejackets and marines then spent a week seeing the sights of San Francisco when the ship visited the bustling port.

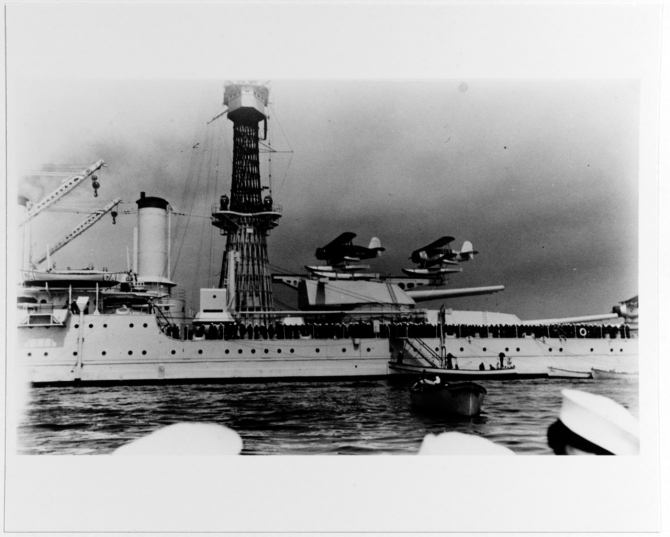

The liberty party prepares to go ashore in this glimpse of the ship in the days leading up to the Japanese onslaught, taken in 1940. Note the very large letters CAL painted on to the side of the boat on the left, and the three Curtiss SOC-3s on the catapults atop Turret III and aft. The Seagull with the dark markings is the Flag Plane assigned to Vice Adm. William S. Pye, Commander Battleships, Battle Force. The boat in the foreground is from light cruiser Detroit (CL-8). (Courtesy of Howard F. Ailes, 1974) (Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph NH 80516)

California lay moored starboard side to Berth F-3, along the southern side of Ford Island with other dreadnoughts of the Battle Force in “Battleship Row,” when the Japanese launched their aerial attack on 7 December 1941. The weather was clear with scattered clouds. The ship prepared to undergo a material inspection, and consequently, her watertight integrity was not at its maximum. She used Boiler No. 1 for auxiliary purposes, and had set Material Condition X-Ray, except for voids A-146-V, A-148-V, A-184-V, A-186-V, A-188-V, A-137-V, A-139-V, B-119-V, B-123-V, and B-109-V, which were open preparatory to complete necessary maintenance work. The warship was fueled to 95% capacity. Some 400 rounds of .50 caliber ammunition lay at machine guns no.1 and no. 2, and ready boxes contained 50 rounds of 5-inch antiaircraft ammunition. All other ammunition was stored in the magazines. Two of the 5-inch weapons, guns no. 1 and no. 2, had been designated as the ready guns. The Americans largely practiced Sunday routine, however, and the ship did not man her battery, with the exception of machine gun nos. 1 and 2.

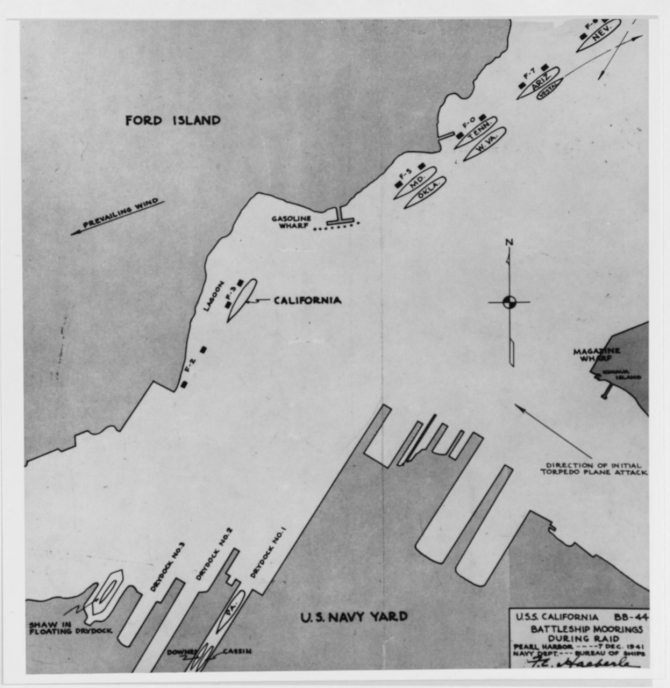

Following the Japanese attack of 7 December 1941, the Bureau of Ships prepares this chart showing California’s position on that morning, compiled on 28 November 1942. The plan shows California at Berth F-3 along the southern side of Ford Island -- just left of the center of the picture -- though does not indicate all of the ships in the harbor. The chart also shows the directions that Nevada (BB-36) and repair ship Vestal (AR-4) -- both to the upper right -- take during the battle to attempt to escape the attackers, and to the lower right the first wave of enemy Nakajima B5N2 Type 97 carrier attack planes -- labeled “torpedo planes” -- that savage Battleship Row. (War Damage Report No. 21 U.S.S. California Torpedo and Bomb Damage, December 7, 1941 Pearl Harbor, Plate I, Collection of Vice Adm. Homer N. Wallin, donated in 1975, Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph NH 83108)

California sounded general quarters at 0750, and all hands began to man their battle stations and to set Condition Zed. Lt. Cmdr. Marion N. Little, the ship’s first lieutenant, was the senior officer present on board, and immediately took command and ordered the gunners to man their guns, and for the ships company to make preparations to get underway. Lt. Cmdr. Frederick J. Eckhoff, the navigator, relieved the officer-of-the-deck and assisted Little. Lt. George Fritschmann, the senior gunnery officer, manned control and took charge of all of the batteries. Cmdr. John H. Skillman gathered fire-fighting equipment ashore, including new (and filled) extinguishers unloaded on the landing.

Japanese Mitsubishi A6M2 Type 0 carrier fighters strafed the ship as sailors and marines manned their battle stations. At 0803 her men opened fire with the “ready guns” on the attacking planes, but shortages of ammunition impeded their fire. Lt. Cmdr. Henry E. Bernstein, the communication officer, had the head of department duty but was sitting in his room half-dressed when the attack began. Bernstein ran to the quarterdeck and observed two Japanese Nakajima B5N2 Type 97 carrier attack planes approaching the ship perpendicular to her at an altitude of less than 100 feet and as he moved aft, saw them drop their torpedoes. He rushed to insure that the crew broke out the keys for the magazines and promptly began distributing ammunition, and then took his station in the conning tower.

Torpedoes tore into the ship’s port side near frame 100 at 0805. The deadly weapons punched a hole about 40-feet long, extending from the first seam below the armor belt to the bilge keel. The torpedoes struck almost simultaneously, the first one forward between frames 46–60, and the second one aft, between frames 95–109. Their effect, due largely to the incomplete setting of Conditions Yoke and Zed, proved far reaching and disastrous. The ship commenced listing to port and ominously strained her mooring lines, and Lt. Cmdr. Little ordered counter-flooding of the starboard voids to limit the list to 4 degrees. The 3rd deck flooded as water poured through the open manholes of the voids underneath, however, and aft through loose manhole covers and leaky deck seams. The blasts ruptured fuel oil tanks forward, introducing water into the fuel system and before the crew could clear it, the ship lost light and power at a critical time. The flooding of compartments in proximity to the torpedo hits prevented the necessary access to make possible some control of damage.

Aichi D3A1 Type 99 carrier bombers dove on the ship at least three times between 0815 and 0915, attacking successively from the starboard bow, from ahead, and from port bow. One of the first planes dropped a bomb that burst close aboard the starboard side, causing a minor sized hole amidships between the armor belt and gallery deck, denting shell plating and pulling some rivets thru. Another bomb near missed on the port side forward, between frames 2–20, causing minor damage. Numbers 2 and 4 5-inch guns fired at the carrier bombers, and BM1c W.S. Fleming was wounded yet coolly directed his men to man and fire No. 4 5-inch gun. The forward machine guns claimed to splash one of the attackers at about 0830, and two minutes later, the ship claimed to contribute to shooting down a second plane. Multiple ships and men ashore blazed away at the Japanese, however, and verifying the claims proved difficult. Four bombs splashed close aboard between the bow and the northern quay of Berth F-2 at 0840, showering the ship with lethal fragments that sliced into the starboard upper structure. Five minutes later Cmdr. Earl E. Stone, the executive officer, returned to the ship from ashore and took command.

A bomb, possibly a battleship armor piercing shell fitted with tail vanes, struck the upper deck abreast of Casemate No. 1 near frame 59, inboard from the starboard side, at 0845. The bomb tore through the ship into her vitals, ricocheted from the 2nd deck inboard and exploded in A-611. The blast ruptured the forward and after bulkheads of the compartment, as well as the overhead of A-705, and sprang the armored hatch leading into the Machine Shop, which men could not close again. The bomb completely destroyed the watertight integrity of the first and second decks between frames 26 and 100 approximately, and between the second deck and the machinery spaces (third deck) reached by the large centerline hatch about frame 65. Engineering crewmen lit off the after four boilers with cold oil and natural draft, restoring light, power, and pressure on the fire main at about 0845, which they maintained until 1000. A fire nonetheless erupted below the main deck as a result of the bomb explosion, at about 0905, and within ten minutes engulfed Casemate Nos 3, 5, and 7. The forward machine guns fired intermittently until the first attack in that area ended at about 0915. Capt. Joel W. B. Bunkley, the commanding officer, returned to the ship and relieved Cmdr. Stone at that time and at one point, Vice Adm. William S. Pye, Commander Battle Force, also returned to California.

Many crewmen endangered themselves bravely carrying wounded shipmates to safety, bringing ammunition to gunners, and battling the flames. Gunner Jackson C. Pharris took charge of the ordnance repair party on the third deck when the first Japanese torpedo struck the ship almost directly under his station. The concussion hurled Pharris against the overhead and back to the ship, stunning him. Pharris nonetheless acted on his own initiative and set up a hand-supply ammunition train for the antiaircraft guns, and the men passed up 62 rounds from magazines to the guns. Water and oil poured in to the ship where the port bulkhead had been torn up by the deck, and oil fumes overcame many of the remaining crewmen. Pharris accordingly ordered the shipfitters to counterflood in an effort to save the ship, and despite falling unconscious from the noxious fumes and the pain of his wounds, he persisted in his desperate efforts to speed up the supply of ammunition, at the same time repeatedly risking his life to enter flooding compartments and drag unconscious shipmates to safety who were gradually being submerged in oil. Pharris saved the lives of many of his shipmates and helped California respond during the attack, and subsequently received the Medal of Honor.

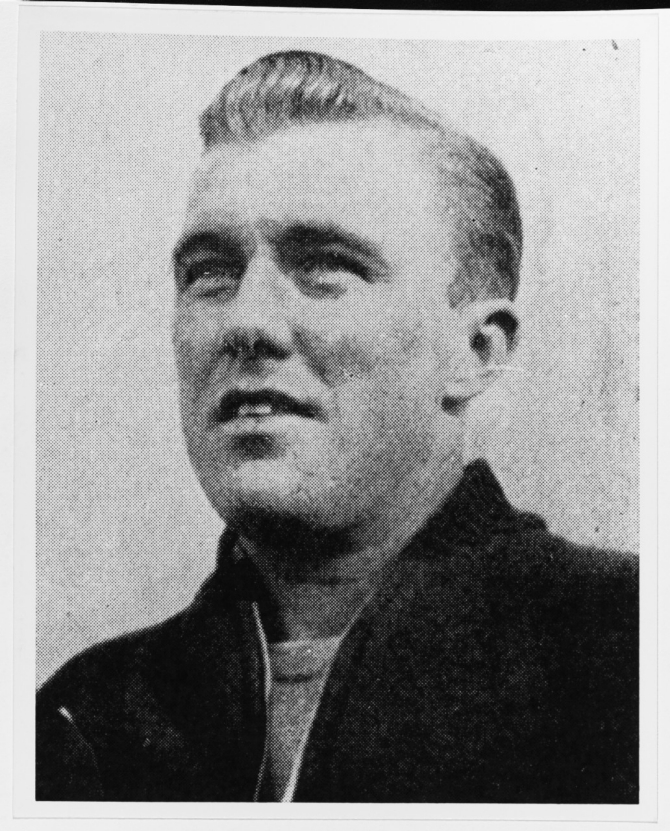

A halftone reproduction of a photograph of Gunner Jackson C. Pharris, who receives the Medal of Honor for his extraordinary conduct on board on 7 December 1941. The award later disappears after Pharris died on 17 October 1966, however, and his daughter stores the medal in a safe deposit box but then unexpectedly passes away. As the medal is not covered in her will, it becomes the property of the State of California. New legislation allows the state to contact the family to reunite them with the medal, and on 2 October 2007, Vice Adm. Terrance T. Etnyre, Commander Naval Surface Forces, oversees a ceremony at his headquarters in San Diego to return the medal to Pharris’ family. “It is my distinct honor to remember a surface force hero and to reunite a family with a lost family treasure,” Etnyre observed. “On behalf of my family,” Lt. Col. Jackson Pharris II, USMC (Ret.), the Gunner’s son, said, “I would like to thank you very much for returning it to us…I would like to accept it on behalf of those who have served in the past and those who are serving today.” (Unattributed U.S. Navy Photograph NH 106422, Photographic Section, Naval History and Heritage Command)

Ens. Harold C. Jones and Ens. Ira W. Jeffrey organized a party to bring ammunition up from below until both men were killed. A couple of sailors attempted to drag 23-year-old Jones to safety, but he ordered the men to leave him before the magazines exploded, and subsequently received the Medal of Honor posthumously. RMC Thomas J. Reeves entered a burning passageway on his own initiative, and helped pass ammunition to the gunners until fire and smoke overcame him. Reeves also afterward received the posthumous award of the Medal of Honor. MM1 Robert R. Scott manned his battle station at the air compressor until water and oil began flooding the compartment. As the survivors evacuated the compartment they implored Scott to join them, but he bravely refused and stayed at this station until overcome, Scott, too, receiving the Medal of Honor posthumously.

MM1 Robert R. Scott valiantly sacrifices himself for his ship and fellows during the Japanese attack, and afterward receives the posthumous award of the Medal of Honor. (Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph NH 92308)

Pay Clerk H.A. Applegate and EM3 B.F. Pavlin courageously took a boat and crossed to other ships to obtain ammunition, all while under fire. Boatswain S. Osmon was wounded but disregarded his wound and pain and continued to direct a party that attempted to repair the damage, and to rescue wounded men. Flames burned Cmdr. Jesse D. Jewell, MC, about his face and arms, yet he continued to administer first aid to the injured. Ensigns Edgar M. Fain, R.B. Canfield, Charles W. Gunnels Jr., Cary H. Hall, Stanley C. Hall, Robert D. Kirkpatrick Jr., Charles J. Lyden, Thomas P. McGrath, Archibald T. Nicholson Jr., Thomas J. Rudden Jr., Robert L. Settle, and William W. Walker “displayed outstanding qualities of leadership, bravery, and coolness” while fighting fires and rescuing men. SN2c Thomas J. Gary retrieved at least three men, each time bravely returning to the fray despite the danger, until he died while attempting to rescue another man.

Electrician Ray S. Linn had just sat down for breakfast in the warrant officer’s mess room when the ship sounded general quarters. “I heard a distant rumble,” Linn recalled, “glanced out the port hole on the port side of the ship, and saw a black airplane with rising sun insignias.” Linn went to the main control room, and worked with his men to lighting off both engine rooms. About five minutes after the first torpedo hit the steam pressure slowly dropped to zero. The sailors learned that salt water contaminated and clogged some the fuel lines and they worked feverously to clear the lines and to get fuel oil. The second torpedo hit and shortly afterward they received an unnerving report that a bomb struck the ship and started a large fire forward. Linn noted that they boosted the fire main pressure to well over 100 pounds and had steam pressure on one boiler to furnish light and power from the after engine room. Sailors meanwhile abandoned the forward engine room, and the after engine room reported main set ready to come in on line, but steam pressure again dropped to about 100 pounds. The crewmen held off putting in the after main set because of low steam pressure, and then orders came over J.V. phones to abandon ship — but were then belayed. Word spread that the hatch or port thrust buckled, and Linn told his shipmates to check the logs and see that it was secure, before they abandoned that area. When they received the order to abandon ship, they dogged down (closed) all of the hatches, and Linn checked the motor rooms, found them clear of men, and reported to topside, where he joined men who successively started putting pumps in various holds and commenced pumping.

Ens. Edward R. Blair Jr., was still dressing in the forward bunk room when the ship sounded general quarters. The first torpedo struck as he left the bunkroom, quickly followed by the second. Men set Zed on the main deck hatches so that in order to get topside he opened the escape hatch. In the boat deck Ens. Robert B. Canfield, USNR, acted as starboard battery officer and Ens. Cary H. Hall as port battery officer, so Blair rushed up to sky control to man a director, both of which proved inoperative. On the way up he noticed that the gunners at Machine Gun Nos 1 and 2 were rapidly running out of ammunition, only having available the 400 “ready” rounds on that station. Working on his own initiative, Blair therefore gathered a working party of about ten men from the vicinity of the No. 1 5-inch gun to bring up machine gun ammunition. They opened the amidships forecastle hatch, which led to the shaft leading to the forward torpedo hold, and Blair afterward reported that despite enemy planes assaulting the battleship, the men paid no heed to the attackers and “worked quickly and eagerly.” The working party opened five Zed hatches including the armored deck hatch to get to the .50 caliber ammunition, but Blair believed that the need for the bullets warranted the risk involved. The young ensign surmised that the torpedo hits would prevent him accessing the .50 caliber magazine via the 3rd deck, which would have required opening a similar number of Zed hatches. Blair broke out the belted ammunition, about 1,600 rounds, and distributed it among eight men, 200 rounds to a ready box, one ready box to a man, each of whom he directed to a station. The sailors struggled up the shaft with their heavy loads, a task compounded by the ship’s list, and they could use only one hand to chink the vertical ladders in the shaft.

He began belting up new ammunition when the bomb hit, Blair comparing the attack to how “the concussion of a 5 inch/51 caliber [gun] feels when you are sitting in the pointer’s seat.” Two glass gauges broke and diesel oil ran out on the deck, and as he closed the valves, he reflected that the Navy should do away with glass gauges on a battleship. The men could hear water running “close at hand” from a leak forward, and Blair dispatched the remaining man topside with all of the ammunition they could carry. A gunners mate remained with the men and he instructed him to bring the clipping machine with him, but it never reached topside. When the ensign went back for it 30 minutes later the torpedo hole was completely flooded. When Blair headed for the main top, he noted that the main deck starboard side was a wreck; men crawled out of the starboard forecastle hatch in a dazed condition, some badly burned; and he saw that the bomb had ripped a hole near No. 3 5-inch Gun, from which smoke trickled out. The maintop did not have ammunition, so he retraced his steps. On the main deck near the forecastle hatch amidst smoke and debris, Blair spotted the ammunition scattered over the deck, with a dead man beside each ready box. Fire prevented him from accessing all but two of the ready boxes, but he directed sailors to take the ammunition to nos. 1 and 2 .50-caliber machine guns. He returned to the maintop hoping to find the clipping machine and the boxes of loose ammunition brought out last from the magazine. Sea1c Shelton and another man, both exhausted, brought up ready boxes, and they belted about 100 rounds by hand until they heard the orders to abandon ship.

When the battle began Ens. William A. J. Lewis proceeded at once to his battle station in the forward engine room. Other sailors made their way through the tumult and manned the room within a few minutes, and Lewis gave the order to set all condition on the damage control fittings. As Lewis worked with the other men to prepare the ship to sortie, the first torpedo hit, knocking out about one half of the lights in the machine shop, and about one fourth of the lights in the engine room. Lewis inspected the area and the machinery appeared to continue to function without visible damage, so he ordered a main feed pump put on the line along with both main fuel oil pumps. They began warming up the main plant when they received a report that water contaminated the fuel oil for boiler no. 1. Steam pressure dropped rapidly, so Lewis and his men secured from warming up the main set, secured the main circulator, and the steam fuel oil pumps. The second torpedo suddenly struck and large quantities of smoke blew down the ventilator blowers, so they secured the ventilators.

Smoke continued to pour in, however, and men passed the word that gas was present. The engineering team detected only powder gases and did not put on their gas masks, but the smoke continued to thicken and Lewis subsequently directed some of the men to put on their masks. The masks offered limited relief because they took certain irritating particles out of the air and protected their eyes. The smoke seemed to result from burning paint rather than powder, but as it took effect on the men Lewis ordered all hands except the talker on the upper level to go down to the lower level where the air seemed somewhat better. The forward part of the engine room became very hot and the metal in some places was too hot to touch. The paint consequently began to blister, generating greater paint fumes. Lewis and his men did not hear the first order to abandon ship, but when the second order was passed he directed them to leave their stations and go up the after hatch. They did so but terrifyingly, could not open the watertight door above the hatch. They then tried to open the forward hatch but the metal in that area was so hot that they believed a fire raged just above them. The sailors grabbed fire extinguishers from the engine room, wrapped themselves in extra clothes, and began to try to force the forward hatch. Men above heard their efforts and assisted them in opening the hatch and they escaped. The fire blazed just forward of them so they proceeded aft and came up on deck. Lewis described the conduct of his men as “excellent”, but observed that the fire in A-611 produced such heat and smoke in the forward engine room as to make its operation possible only with great difficulty.

Sailors feared that the ship’s assigned planes would cause a gasoline fire hazard and attempted to move 2-0-5, a Vought OS2U-3 (BuNo. 5353) of Observation Squadron (VO) 2, away from the ship, but the Kingfisher capsized and sank at 0925. Many of the ships that the enemy struck leaked oil into the harbor, and just after 1000 oil on the surface of the water enveloped the battleship, starting multiple fires that grew to intense heat that threatened men on the forecastle. Bunkley conferred briefly with Pye and ordered abandon ship at 1002, but at 1015 cancelled the order as the prevailing wind blew some of the fire away, tugs came alongside to help battle the flames, the blaze from the water cleared the ship, and the crew manned battle stations topside, joined by large numbers of men returning from the beach. The ship fought without light or power, and without fresh or salt water service. Pye meanwhile transferred his flag ashore to the Submarine Base.

Burning oil spreads across the ship and she lists precariously to port, 7 December 1941. Men arrive from other ships and from ashore on board boats to battle the blaze, and oil leaks from the stricken ship. (Courtesy of Sue Grosz, U.S. Navy Photograph UA 564.24, Photographic Section, Naval History and Heritage Command)

At about 1030 a man reported to YNC S. R. Miller on the flag bridge that be had just escaped from Central Station by the trunk leading into flag conn. Miller told Ens. McGrath on the signal bridge, and the ensign led Miller and two other chiefs, CQM C.E. Stover and CEM Campbell, into flag conn to investigate. The men obtained a line and lowered McGrath through the trunk to central station, but fuel oil flooded from vents and they feared that the vapors would overwhelm McGrath, as well as the possibility of the list continuing until the ship capsized. McGrath staunchly persevered and found some men in a compartment under central Station that his party could rescue by cutting a hole through the deck of central station. He returned up the trunk to flag conn with his welcome news, but grimly added that oil would soon flood the deck of central station and that when that occurred, it would be too late to cut a hole through the deck. GM3 V.O. Jensen took some nearly men to the foundry and quickly obtained an acetylene cutting outfit. The rescuers called for volunteers, and many men on the boat deck offered to help but they only needed a few and directed many of the volunteers to resume fighting fires. McGrath, Campbell, PO1c Roundtree, and the chosen men entered central station through the trunk, and Jensen and his men lowered the cutting outfit down to them, and they then procured a sledge hammer and some chisels and also lowered them. The rescuers proceeded to cut an escape hole in the deck, and fumes almost felled McGrath and Campbell before they completed the desperate task. The men above attempted to rig a blower in the conning tower tube but the power failed, and vapors struck down the first sailor who worked with the cutting torch, but another experienced crewman took his place. Time proved of the essence in that leaking fuel oil gradually rose toward the hole and the rescue party risked touching off a fire. The men cut the hole in the deck just before oil flooded station, and Miller noted that the men involved “acquitted themselves equally as well to the best traditions of the Naval Service.”

Ninety eight men died as a result of the battle, and 61 sustained wounds. The ship defiantly remained afloat initially, but she listed 8 degrees to port and settled considerably with a three and a half foot trim by the bow. Tugs and minesweepers rendered assistance, including Vireo (AM-52), which moored alongside the stricken battleship at 2100, and additional vessels including Bobolink (AM-20) and water barge YW-10. The firefighters extinguished the blaze overnight, and worked to pump out the water using portable pumps, which lacked the power to siphon the water from the ship. The ship thus gradually settled into the mud, and men measured her mean draft as 44 feet by Tuesday afternoon (9 December), and the following day 50 feet as she settled firmly into the mud. By Thursday morning the maximum draft had increased to 57 feet, indicating that California lay embedded about 16 feet into the mud with only her superstructure remaining above the surface, and with a final list to port of 5½ degrees. The depth of the water below the ship sounded at approximately 40 feet, and the muddy bottom ran to a depth of 90 feet, over coral.

Minesweepers Bobolink (AM-20) (left) and Vireo (AM-52) and water barge YW-10 (both off the battleship’s stern) struggle to keep California afloat, 8 or 9 December 1941. (Courtesy of Vice Adm. Homer N. Wallin, 1975, Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph NH 95569)

A floating crane removes the ship’s battered “basket” mainmast during her salvaging, 13 February 1942. (Courtesy of Vice Adm. Homer N. Wallin, 1975 (Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph NH 55038)

The recovery efforts continued unabated and men laboriously pumped California free of water, and on 25 March 1942 refloated her. At 1315 on 5 April a vapor explosion occurred in way of the forward near miss damage, however, most likely caused by fuel oil vapor and hydrogen sulfide gas in A-201-A. The blast ruptured and blew off the patch that the salvagers had fitted over the hole, and damaged doors and hatches on and below the 3rd deck forward of frame 21, permitting more extensive flooding. Two pumps eventually controlled the flooding and men reinstalled the patch. The battered ship entered Dry Dock No. 2 at Pearl Harbor for repairs on 9 April, and on 7 June emerged under her own power.

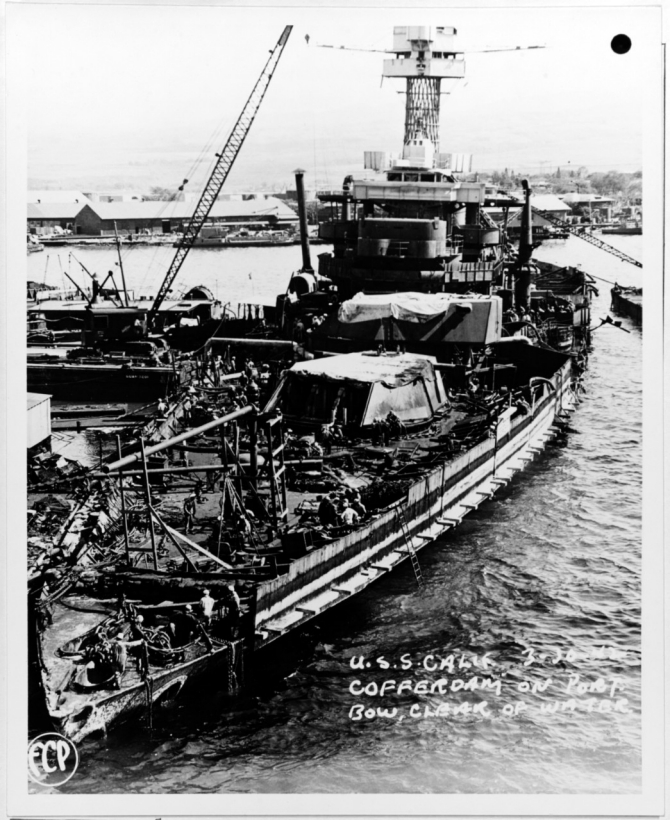

Workmen repair the ship after she is raised and moored at Pearl Harbor, 30 March 1942. Note the cofferdam installed along her port bow and the forward turrets with their guns removed. (Courtesy of Vice Adm. Homer N. Wallin, U.S. Navy Photograph NH 55036, Photographic Section, Naval History and Heritage Command)

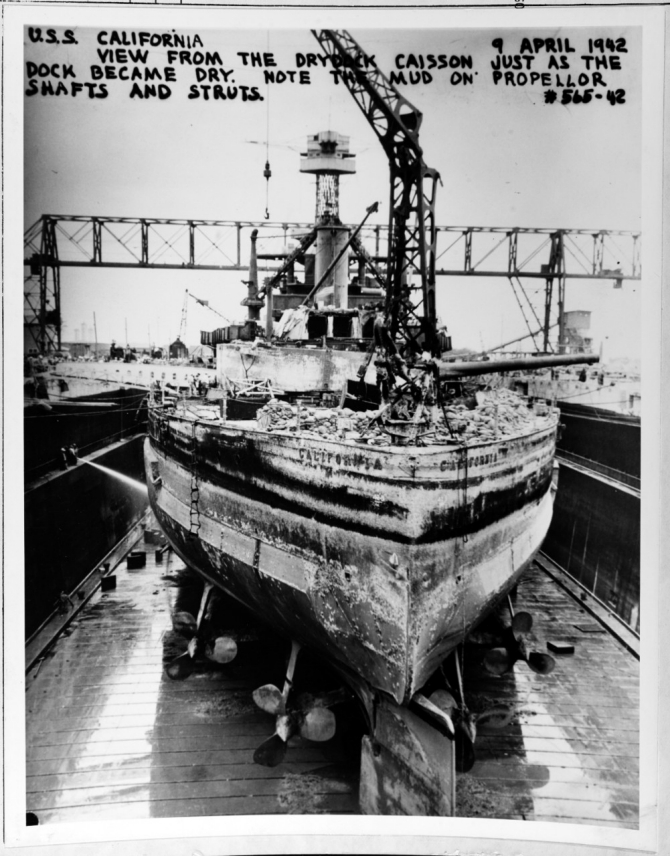

California enters Dry Dock No. 2 at Pearl Harbor for repairs, 9 April 1942. Shipyard workers have just drained the water from the dry dock, exposing the mud on her propeller shafts and struts. (Unattributed U.S. Navy Photograph NH 64483, Photographic Section, Naval History and Heritage Command)

California returned to sea on 10 October, rendezvoused with Gansevoort (DD-608) at 37°45ˈN, 133°W, and slowly but steadily made her way to Puget Sound Navy Yard, where she underwent repairs and a major reconstruction (20 October 1942–31 January 1944). The project required sheering the warship clean of guns and superstructure and stripping her down to the second deck level. The work included giving the ship greater beam, underwater protection, and stability; replacing her secondary battery with 16 5-inch guns; installing new fire control systems and greater close-defense armament; and nearly 154 miles of electric cable. In addition, following the Japanese attack, the CXAM radar was removed and the Army installed it ashore on Oahu.

California stood out of the yard on 31 January 1944 for a rigid curriculum of standardization trials and from there steamed southward for her shakedown off San Pedro. The battleship’s newly installed guns cracked out in structured firing tests, and the crew, many of them fresh from continental training stations, practiced seamanship drills and, more grimly, first aid and fire-fighting. Workers overhauled the machinery a final time and the ship packed her storage spaces with provisions while at San Francisco in April, and on 5 May the city’s skyline faded into the horizon as the ship passed beneath the Golden Gate Bridge and set out for Operation Forager — the invasion of the Marianas.

The ship practiced shore bombardment off Kaho’olawe Island, about seven miles southwest of Maui in the Hawaiian Islands. On 31 May 1944, California moved out, and reprovisoned and refueled at Roi-Namur in Kwajalein Atoll on 8 June. At 0800 two days later she sailed westward as part of Task Group (TG) 52.17, Fire Support Group 1, Rear Adm. Jesse B. Oldendorf in command, who broke his flag in Louisville (CA-28). Eastern FM-2 Wildcats of Composite Squadron (VC) 10, flying from Gambier Bay (CVE-73), and FM-2s of VC-5, embarked on board Kitkun Bay (CVE-71), flew overhead to cover the ships during their voyage. While en route Cmdr. Forrest R. Bunker, the executive officer, passed the word over the public address system and revealed their objective: Saipan. The battleship reached the eve of action on 13 June. Sailors showered and shaved, put on clean underclothes, and laid out clean dungarees and turned in, their attention to hygiene intended to prevent infection in case they were wounded. The ship sounded reveille an hour before dawn on 14 June, and the crew rose and walked to the mess decks for breakfast. Many of the men were lost in their thoughts and the chow lines moved quickly as they often ate in silence.

California rounded the northern tip of Saipan as the sun rose on a clear day with excellent visibility and a smooth sea, and catapulted her two OS2U-3s aloft to spot the shooting. The battleship moved to her assigned naval gunfire support position off the west coast of the island, steaming principally between Mutcho Point and Agingan Point. At 0558 the ship opened fire from a range of 14,500 yards against Japanese artillery batteries, pillboxes, trenches, and supply dumps located near Garapan, the capital of the island.

At 0910 California plastered the enemy troops ashore, her engines stopped and with little way on, when an enemy shell plunged toward the battleship from her port quarter, sliced into the upper deck aft of the fire control platform and penetrated deeply through three decks and exploded. The attack killed WT3c Henry Kelekian, USNR, seriously wounded two enlisted men, and lightly wounded the assistant navigator and seven enlisted crewmen. The hit knocked out the SK air search radar, put the exterior communication facilities within the pilot house out of action, and broke cables that started an electrical fire over the chart desk. California increased speed to “ahead one-third” and sounded fire call, and damage control teams played hoses onto the ensuing conflagration and despite heavy black smoke contained the damage. The fire control station temporarily shifted to main battery plot and the ship kept shooting. Capt. Henry P. Burnett, the ship’s commanding officer, summarized the harrowing episode by recommending “that greater sea room for maneuvering when operating against a firmly entrenched enemy with large caliber guns is essential”. Late in the afternoon the battleship recovered her Kingfishers, came about and headed out to sea for the night. Intelligence officers later identified the source of these attacks as a trio of 4.7-inch field guns hidden in the mouth of a cave on Tinian, which lay only a few miles across the channel from Saipan. The same battery also damaged Colorado and Norman Scott (DD-690) on 24 July — Tennessee knocked the guns out four days later.

The Americans spotted Japanese Type 95 light tanks or Type 97 mediums of the 1st Tank Division’s 9th Armored Regiment in Garapan at 0954 and California fired on them, observers reporting that she knocked out at least one and likely two of the armored vehicles. The Japanese returned fire at times and a concealed enemy gun emplacement on Maniagassa Island (Isleta Mañagaha) off Tanapag harbor fired on Maryland as the battleship steamed barely two miles offshore. The Japanese rounds fell short by about 1,000 yards, and California and Maryland silenced the battery with 5-inch salvoes. The resolute enemy artillery fired at the U.S. ships during the forenoon watch, and the water around Cleveland (CL-55) erupted in near misses as the enemy shells straddled the light cruiser, and a small caliber round hit Braine (DD-630), killing three men and wounding 15. Indianapolis and Birmingham (CL-62) unsuccessfully fired at the Japanese troops dug-in on Afetna Point, which rose between Beaches Green 2 and 3. California briefly withdrew from the battle shortly after noon, and the crew ate k-rations while the ship was ventilated, but Rear Adm. Howard F. Kingman, Commander BatDiv 2, directed California, Tennessee, and Birmingham to blast the enemy positions that afternoon, and planes flew bombing and strafing runs on the stubborn Japanese. California battled the enemy until 1830, at which time she came about, fell astern of Tennessee, and opened the range from shore overnight. The naval gunfire did not always prove effective because the ships often steamed at long ranges to avoid possible enemy mines in the shoals offshore, and because the gunners often lacked experience in shore bombardment and the aerial spotters failed to differentiate between the targets.

The following day on 15 June, California supported the 2nd Marine Division as the leathernecks stormed ashore. The ships company sadly bid farewell to WT3c Kelekian when he was buried at sea at 0411, and at 0429 manned general quarters. Minesweepers and Underwater Demolition Team (UDT) 5 went to work under the protective fire of California, Louisville, and Birmingham. California launched her Kingfishers at 0601 and opened fire at 0612. The battlewagon pounded Japanese positions near the southern part of Garapan, and then shifted fire to support the landings on Red 1, 2, and 3 Beaches. Spotters believed that Japanese troops entrenched in that area required additional bombardment and California fired 400 more 5-inch rounds than originally allotted. The enemy had zeroed in many of the landing areas and fought determinedly, and the ship’s crewmen agonized as the smoke partially cleared and they watched shells and small arms fire tear into the marines. The Japanese troops dug-in on Afetna Point laid down murderous artillery and mortar fire on the marines landing on Beaches Green 2 and 3, and the trio of ships concentrated their salvoes against the Japanese on Afetna Point until the landing craft reached 1,000 yards from the assault beaches at 0830 and three flares shot into the air, signaling them to shift their fire inland. California’s planes flew out of the battle to be reserviced by New Mexico (BB-40) in mid-morning and then returned to the fighting. Burnett reported that some “defects of organization and liaison became apparent” and California experienced difficulty contacting and obtaining information and spots from Shore Fire Control Party No. 23. The fighting to capture Afetna Point proved desperate and the leathernecks only overwhelmed the defiant enemy there by using flame throwers and hand grenades.

California meanwhile bombarded the Charan Kanoa sugar mill and a number of farms, but a Japanese lookout climbed into the smokestack at the blackened shambles of the mill and observed the Americans for several days. The Japanese repeatedly probed the marine lines that first harrowing night, attempting to infiltrate through gaps to the invasion beaches. Marine pickets detected hundreds of enemy soldiers attempting to work around their positions to the east of Beach Red 1 and north of the beachhead. California eventually established radio communications with Navy Liaison Officer No. 62 and at 1712 resumed cannonading the enemy, firing a total of 31 rounds of 5-inch ammunition from an average range of 9,000 yards into the advancing Japanese in Area 172D. Fighting raged throughout the night and ships firing from offshore proved instrumental in helping the marines hold their positions.

Enemy planes attacked some of the ships that night, but California could not track the intruders because of her inoperative SK radar, and the crew spent a tense night. The ship received a flash red at 1837 and sounded general quarters. Four planes, later identified as Nakajima B5N2 Type 97s, roared over the water about 1,000 yards ahead of the ship from left to right three minutes later. Multiple ships including California opened fire but missed as the intruders dropped bombs close aboard a destroyer and passed out of sight off the starboard bow. Two U.S. planes crossed over the stern of the ship and No. 6 40 millimeter gun opened fire and almost immediately ceased firing without hitting the aircraft. The lookouts and gunners relied on binoculars and Burnett understatedly reported that “the lack of SK radar and recognition equipment was keenly felt”.

The following day Japanese tanks counterattacked the marines and the shore team requested “continue fire…with full salvoes as rapidly as possible” into Area 191 (1,200 square yards). The ship consequently sent 1,399 rounds of 5-inch ammunition into the enemy -- an average of a shell per square yard -- without any initial confirmation from the shore team, though observers believed that the fire hit at least two tanks. Some of the ship’s gunners surmised that the Japanese may have “tapped” into the shore lines and misdirected their fire. Japanese planes attacked the ships operating offshore during the morning watch on 17 June, and at 0522 a bomber tentatively identified as a Mitsubishi G4M1 Type 1 attack plane [Betty] approached the starboard bow. The ship’s 5-inch guns started shooting at the Betty when it reached about 8,000 yards and continued firing for nearly four minutes without hitting the attacker, which changed course and flew out of range. At 0534 watchstanders sighted a Tony [Kawasaki Ki-61 Hien — Flying Swallow] on the port quarter, astern of Maryland, and California and Maryland’s 20 and 40 millimeter guns fired at the plane when it closed to 2,000 yards. The plane passed abreast of the formation and dropped a bomb that missed Maryland, swung to the right and passed across the column astern of California at a range under 1,000 yards. The fire from both ships splashed the Tony, which plummeted into the sea between the two battleship columns, and Prichett (DD-561) recovered the injured pilot.

Despite resistance from the Japanese Thirty-first Army, the marines established beachheads ashore and pushed inland. The enemy developed a comprehensive system of well-sited defenses that harmonized with the surrounding terrain. Many of these positions escaped naval bombardment and the supporting ships normally only knocked out these emplacements with direct hits. The continuing enemy opposition compelled Lt. Gen. Howland M. “Howling Mad” Smith, USMC, Commander Task Force (TF) 56, Expeditionary Troops, to reinforce the marines with the Army’s 27th Infantry Division on 17 June.

A Japanese plane, which the ship’s lookouts identified as a Tony, attacked California on 18 June. The Kawasaki approached the ship rapidly and low from astern, but the ship’s guns opened fire and drove the attacker off. During the confusion of the fighting, however, No. 5 40 millimeter gun, firing in automatic full director control, accidently fired into No. 3 5-inch gun mount, striking the left 5-inch barrel, and then sending a second round into the right barrel. Fragments lightly wounded several men, and investigators concluded that the accident likely occurred because the ship began the battle with her 5-inch guns in the “ready position” at 45° elevation, thus interfering with the lighter guns’ line of sight. The battleship then changed her procedures to train the 5-inch guns at 0° at the ready. California came about from the fighting at 1247 on 22 June, the following day refueled Conway (DD-507) and Phelps (DD-360), and at 1800 set out for Eniwetok in the Marshalls.

The battleship completed repairs at that atoll (25 June–16 July), where she held swim calls off the forecastle. In addition, recreation parties formed on the quarterdeck and self-propelled pontoon barges, which the men dubbed “sea mules”, took them to a recreational facility on Runit Island. Thousands of sailors and marines from ships anchored at the atoll packed onto the tiny isle, a thin strip of sand covered by a handful of coconut palm trees and undergrowth, and flanked by the sharp-edged coral. The Navy distributed two beers per man, but by the time the beer reached them it was usually warm. The thirsty crewmen nonetheless savored the opportunity for an all too fleeting respite from the war, and hundreds of discarded beer cans, empty beer cases, and bottles soon littered the isle. The lack of recreation proved disappointing, but some enterprising men from the ship’s company swam out to a partially sunken Japanese ammunition lugger and brought back some of their finds as souvenirs, until the executive officer put a stop to their dangerous endeavors.

California then returned to the Marianas to take part in Operation Stevedore — landings by the 3rd Marine Division, 1st Provisional Marine Brigade, and the Army’s 77th Infantry Division on Guam. California formed column on Tennessee as she set out from the lagoon during the afternoon watch on 16 July. Conway, McDermut (DD-677), McGowan (DD-678), and Dionne (DE-261) escorted the two battleships as the six vessels became Task Unit (TU) 53.1.16. While en route California launched her two operational OS2U-3s and Tennessee her OS2N-1 of VO-2 alternatively at dawn and dusk to hunt for enemy submarines, but the Kingfishers did not discover any boats stalking the ships. The ships sighted Rota and then Guam during the morning watch on 19 July, and that afternoon California’s band played a swing session for the crew on the forecastle as the battleship, McDermut, and McGowan detached and rendezvoused with TG 53.5.3 Southern Fire Support Group, Rear Adm. C. Turner Joy, in command, who broke his flag in Wichita (CA-45). California stood by within a screen of destroyers in an area north of Cabras Island about five miles off the northwest coast of Guam, and her men saw explosions erupt along the invasion beaches and “a large fire” burning in the capital of Agana (Hagåtña) as other ships pounded the enemy.

The next day California blasted the Japanese troops defending the island in the area of Tumon (Tomhom) Bay. A dense growth of small trees and brush covered the beach just north of Hilaan point north of the bay and made it difficult for the ship and her planes to accurately spot the enemy positions. A plane laid a smoke screen at 1000 to cover UDT-3 as the men attempted to mark Japanese obstacles and clear channels for the landing craft and amphibious tractors, but the smoke did not cover the swimmers and California consequently fired smoke. Some of the ship’s 40 millimeter guns also shot at the beaches to cover the swimmers, but fears that they might hit some of the men led them to cancel the fire. That afternoon the ship bombarded enemy soldiers that held out in buildings in the town, “walking” her shot from the extreme western end of Agana to a large stack that rose in the approximate center of the town, permitting the smoke and dust from the previous bursts to drift off. When California came about for the evening, however, her gunners noted that a large red water tower on a hill still stood despite the torrent of steel the ship had sent inland.

The battlewagon continued to support the landings and manned battle stations at 0500 on 21 July 1944. The ship launched her planes and observed other vessels firing star shell to illuminate the landing beaches, but the Japanese withheld their fire. As the sun rose an hour later, the sea rolled in slight easterly swells, and a gentle breeze touched the air from the east. Scattered showers during the morning later reduced the visibility to eight to ten miles. California’s heavy guns shelled pillboxes and antiaircraft gun emplacements near Tumon Bay, and machine gun nests and emplacements at a nearby school. One of the ship’s Kingfishers spotted additional machine gun nests and slit trenches near the beach, and she let loose with 5-inch salvoes. The ship’s storm of fire helped blast the way for the assault force that landed at 0830. The marines established their beachhead and the ship came about at 1000, secured from general quarters and recovered her scout planes, after firing 45 14-inch and 228 5-inch rounds during the morning. At 1500 she retired from the fire support sector, and later steamed north to Saipan.

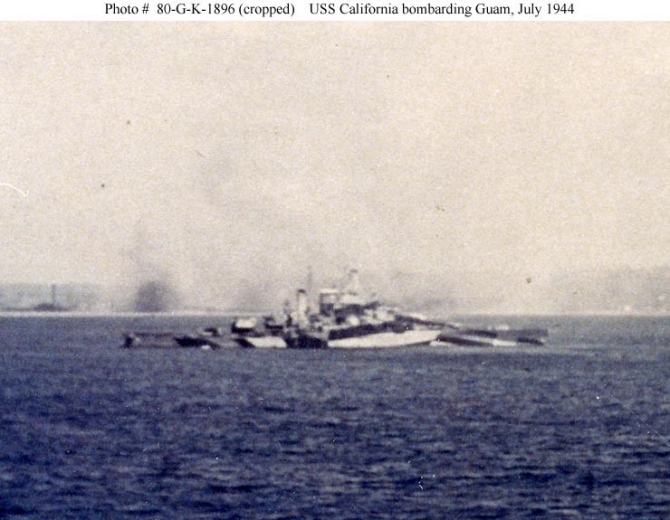

California pounds the Japanese troops on Guam, July 1944. S.C. Rotman, a sailor on board New Mexico (BB-40), snaps the picture from his ship during the battle. The battleship is painted in a distinctive camouflage pattern, likely Measure 32, Design 16-D. (Courtesy of S.C. Rotman, U.S. Navy Photograph NH 80-G-K-1896, National Archives and Records Administration, Still Pictures Branch, College Park, Md.)

California stocked up her magazines at Saipan and on 23 July reached her firing position off the central west coast of Tinian, under the direction of the task group’s Unit 1, led by Rear Adm. Kingman. Heavy and persistent rain delayed California and Tennessee for about 30 minutes, but they then unleashed their firepower against the Japanese coastal defense guns and military installations around the town of Tinian, in an attempt to divert the enemy from the actual landing beaches further to the north, and destroyed the town by hurling 480 14-inch and 800 5-inch shells into the settlement. California incurred problems accurately spotting the fall of shot, however, because orders prohibited her Kingfishers from flying over the island, a safety measure stemming from the large number of planes crisscrossing the area while flying close air support runs. In addition, USMC Stinson OY-1 Sentinels spotted for the leatherneck’s artillery and cruised back and forth across the battleship’s line of fire, compelling her to repeatedly check fire. A plane incurred a hung bomb while it attacked the Japanese and the device accidently released as the plane flew over the ships at 1231, splashing into the surf off California’s port quarter. California ceased all fire at 1700, recovered both her spotting planes, and fell in astern of Tennessee as they retired to the westward for the night.

On the morning of 24 July California worked down the west coast, giving gunfire support to the marines. The crescendo of bombardment led observers on board the ship to surmise that none of the Japanese could survive, yet the defenders opened mortar and automatic and light weapons fire as the marines landed. The ship reported that a “spectacular” explosion occurred close to the airfield near Ushi Point at 1145, most likely as naval gunfire touched off a fuel or ammunition dump. A large column of brownish white smoke rose in mushroom shape to a height of nearly 7,000 feet, and flames lapped at the base of the column for two days. California ceased fire at 1748 and recovered her planes, one of which just barely made it back before it ran out of gas. The fighting ashore continued unabated, however, and during the 2nd dog watch the ship fired at enemy soldiers east of Fabius San Hilo Point designated by the shore fire control party at a slow and deliberate rate. At 1954 she began firing one star shell about every fifth or sixth salvo, shooting 56 overnight. Several shells passed to seaward over the ship close aboard during the night, but crewmen could not discern if they originated from enemy artillery ashore or strays from U.S. artillery or ships.

The Japanese made a last desperate stand on the high ground of Tinian’s southern tip, and during the morning watch on the last day of the month, a gray day with a drizzle, California joined other ships as they fired a massive box barrage against the defenders. The ships then lifted their fire, and the marines advanced and flushed out the last organized resistance during the subsequent two days. “Your mission completed,” Kingman signaled the ship. “Proceed anchorage. Sorry we could not find more targets for you.” California returned to the fighting on Guam, shelling the dogged enemy by day, and shooting illuminating rounds and harassing fire by night. The seasoned battleship swung out of the line on 9 August, and then (12–19 August) refueled and replenished at Eniwetok.

California stood out of that anchorage in company with a small task force of battleships, cruisers, and destroyers, and two days later on the morning of 21 August 1944 crossed the equator. King Neptune set up his court atop Turret I and the ship reported that “the lowly pollywogs passed in judgement all day long before the Ruler of the Deep”. The Royal Barber shaved the supplicants in “fancy” styles, while the Royal Doctor provided strange remedies to cure them of their pollywog condition. The men kissed the Royal Baby’s belly, were sternly advised not to flirt with the Royal Princess, and climbed down a Jacob’s ladder hung over the side of the turret. While the “unfortunates” descended the ladder shellbacks drowned them with salt water from a fire hose, and two rows of shillelagh-wielding salts whacked them “unmercifully”, and they then crawled through a nylon antiaircraft target sleeve, only to be pounded full in the face by another fire hose while questioned about their pollywog status. Some men dazed by the experience replied “I’m a sailor [or marine]”, to which they received a further hail of blows from shillelaghs until they barked out their newly-won shellback status. It took time for the men to rinse the graphite, grease, saltwater soap, and vinegar taste from their mouths, but most afterward reflected proudly upon their rite of passage.

Barely a minute before reveille on 23 August 1944, however, Tennessee reared out of control with a steering casualty and her stern crunched into California’s port bow, tearing a large gash forward of Turret I. The night was dark, the sky about seven tenths overcast, and the visibility good. A moderate sea ran from the southeast and a fresh breeze blew from that direction. The ships steered 145° (all bearings are true unless otherwise indicated) at 15 knots, with Pennsylvania as the guide, the officer in tactical command in Louisville, and Tennessee steaming in formation off California’s port bow. Suddenly at 0448, Rear Adm. Kingman announced over a low frequency voice radio (TBS): “Steering casualty on Imperial.” Mere seconds thereafter California’s Combat Information Center (CIC) revealed that Tennessee closed to less than 800 yards and they could not reliably determine her position on SG radar. California put her rudder full right and backed the starboard engine full speed, and sounded collision quarters (without the siren). Both battleships normally kept their running lights off for security but they turned them on, but as California swung rapidly to a heading of about 175° Tennessee struck her on the port bow at about frame 21.

Tennessee pierced several crew berthing compartments assigned to the 2nd and 5th Divisions and water poured in, but although the collision injured a number of crewmen, no one died. The reaction of the impact separated the battleships and California continued to swing to the right on to a northwesterly course before the helmsman stopped the swing and brought her left to the emergency formation course of 235°. Rudder action reduced her speed to approximately ten knots. The collision distorted plating that trapped a number of men of the 2nd Division in berthing compartment A608L, and in order to rescue these men it became necessary to turn the ship away from the wind and seas to a westerly course at five knots. Sailors burned through the plating to free the men, shored the forward bulkhead in the sick bay ward, and eventually pumped and bailed the water out of the flooded spaces. The collision killed Sea1c Russell C. Gill, USNR, Sea1c Joseph Hairychin, USNR, Sea1c Harvey Mead, USNR, Sea1c Junior W. Metcalf, USNR, Sea1c Howard S. Nagel, USNR, Sea1c Fenton W. Samples, USNR, and Sea1c Martin J. Ward, USNR. In addition, one man sustained serious injuries and seven suffered minor injuries. Tennessee did not report casualties but sustained considerable damage that compelled her to come about and complete repairs at Pearl Harbor. California briefly resumed her voyage with the convoy, before completing repairs in advance base sectional dock ABSD-1 at Espíritu Santo in the New Hebrides (Vanuatu) (25 August–10 September). The ship’s fallen crewmen were transferred ashore to Naval Base Hospital No. 3 and then interred in Espíritu Santo Military Cemetery. Rumors circulated among the ships company not to stray far from the ship because of “head hunters” among the local islanders, but some of the friendly people rowed outrigger canoes over to the recreation area as the liberty parties went ashore, and sold the men beautiful sea shells they had gathered. The collision prevented California from supporting the marines as planned when they landed on Peleliu during Operation Stalemate II on 15 September.