The Navy Department Library

Introduction

Reflecting on his hard won freedom, he once stated emphatically, "the only master I have now is the Constitution," and when asked to describe himself, he answered, "I am a laboring man in the paint-shop in the Washington navy-yard." 1 Today Michael G. Shiner is famous for his diary chronicling events at the Washington Navy Yard and the District of Columbia from 1813 to 1869. Among the diary's better known passages are Michael Shiner's accounts of the War of 1812, the 1833 abduction of his family by slave dealers and the strike of 1835. In Michael Shiner's lifetime (1805-1880) few if any of his acquaintances or family knew of his diary. Only within the last few decades have scholars and historians begun to examine the manuscript closely. What follows is a brief account of Shiner's life, the context of his diary and a complete transcription of the manuscript.

Born in 1805, Shiner grew up near Piscataway, Maryland on land belonging to the Pumphrey family. His early life was closely bound to the property and fortunes of the brothers William Pumphrey Jr. (1761-1827) and James Pumphrey (1765-1832). Both men were Maryland famers and slaveholders. William Pumphrey Jr., owned a mid-size farm “Poor Man’s Industry” in Piscataway which he operated with enslaved labor and where the Shiner likely resided as a boy. William Pumphrey also owned residentail property in the District of Columbia where Shiner lived and worked. James Pumphrey too owned property in Prince Georges County but also resided in the District of Columbia. In the early entries, Shiner was working in the District of Columbia. (Clark, Edythe Maxey William Pumphrey of Prince George's County, Maryland, and his descendants. Anundsen: 1992.)

About 1828 Shiner married a young woman named Phillis. The young couple would have had the opportunity to meet regularly since their respective masters, the Pumphrey brothers, lived and worked in the District. Phillis was born in 1808, James Pumphrey purchased her in Virginia in 1817. For economic reasons the Pumphrey brothers most likely countenanced their living together near the Navy Yard. (District of Columbia Archives, Recorder of Deeds Office, James Pumphrey, Liber AP No. 40, dated 9 October 1817, p. 28.)

Slaveholders typically gave consent to marriage since any children born of such union were the slaveholder’s property. Despite Shiner’s extreme reticence regarding his private life, we know something of his family from other sources. The young couple had the following children: Ann, born 1829, Harriet, born 1830, Mary Ann born 1833, Joseph, born 1836, Sarah, born 1838 and Isaac M., born 1845. The Shiner’s were active in the Ebenezer Methodist Church where they took part in church adult classes then open to free and enslaved blacks.

For the first thirty years of the nineteen century, the navy yard was the Districts principal employer of enslaved African Americans. Their numbers rose rapidly and by 1808, muster lists reflect they made up one third of the workforce. The number of enslaved workers gradually declined during the next thirty years. Like many slaveholders William Pumphrey rented his young bondsmen to the new navy yard. Indeed the first surviving naval document specifically mentioning Michael Shiner is the “Muster Book of the U.S. Navy in Ordinary at the Navy Yard Washington City, from 1 January to 31 December, 1826.” On this muster roll Shiner is recorded as “Ordinary Seaman” with the notation he was first entered on the Ordinary rolls 1 July 1826.

In the early nineteenth century shipyard, the Ordinary was where naval ships were held in reserve, or for later need. Typically these older vessels had seen hard service abroad and were awaiting restoration, but due to the small naval appropriations of the era, repairs were not possible. Ships in Ordinary normally had minimal crews comprised of semi-retired or disabled sailors who stayed aboard to ensure that the vessels remained in usable condition, provided security, kept the bilge pump running, and ensured the lines were secure. Here enslaved African Americans worked as seamen, cooks, servants or laborers. The enslaved men assigned to the Ordinary, performed many of the most unpleasant and onerous jobs. For example, the Washington Navy Yard Station Log records for the week of 15 January 1827, they were assigned to scrape the hull of the USS Potomac, move timber from the saw mill, and help suppress a large fire at Alexandria. Positions in the Ordinary were attractive to slaveholders, because the wages were paid directly to the owners or their agents. Payments were regular, and most importantly the Navy Yard ensured day to day supervision and security. Slaveholders had to provide clothes and quarters. One concession Navy made was to include enslaved workers in the emergency medical care provided on the Yard. (W. Jones to Dr. Edward Cutbush, 23 May1813 RG45 NARA.)

William Pumphrey became ill in the summer of 1827 and died in August of that year. Prior to his death he made a will leaving everything to his wife Mary and their children. In this will Pumphrey wrote that all his slaves, including Michael Shiner, were to be sold as “term slaves”, each for a specified period of time, and afterwards manumitted:

“My slaves to be sold for a term of years this winter my debts to pay (to wit) Nell, aged about 37 to serve for the term of two years; Michael, aged about 22 to serve fifteen years; Thomas, aged about 16 to serve twenty; Henry, aged about 10 to serve twenty six; Cornelius aged about 8 to serve twenty two; Warren aged about 6 to serve twenty four years; Leath aged about 4 to serve twenty four; Charlotte aged about 2 years to serve twenty six.” (Prince Georges County Register of Wills, William Pumphrey, 12 August 1827, Liber TT #1 folio 423)

Following Pumphrey’s death all his slaves were sold as term slaves to various buyers. Each slave mentioned in the will was to serve for the designated term and then be freed. Pumphrey's actual motivation to change his bondsmen from slaves for life to term slaves may have arisen from his Methodist principles or simply the need to secure greater economic benefit for his estate. Regardless, most term slaves spent the majority of their productive years in bondage.

On September 8, 1828, Thomas Howard, Clerk of the Yard, purchased Shiner from the Pumphrey estate. The final estate inventory reflects this sale as, “Negro Michael sold to Thos. Howard for cash $250.00.” (Prince Georges County Register of Wills (Inventories) William Pumphrey Liber TT 7, Folio 218.)

Howard paid a high price but certainly knew the young man’s value. Howard would recoup his investment many times for in his position he oversaw the keeping and scheduling of all labor free and enslaved. This unique position gave him ample opportunity to observe and assess Shiner’s character and work record. Shiner was healthy and in the prime of life and Howard ensured he was steadily and profitably employed. For Shiner the sale to Howard meant he would remain in the District with Phillis, continue to work at the Navy Yard, and retained the prospect of freedom.

Four years later on December 4, 1832, Thomas Howard died and his last will stipulated:

“having purchased a Negro Man named Michael Shiner for the term of fifteen years only, and having promised to manumit and set him free at the expiration of eight years, if he conducted himself worthy of such a privilege, it is my will and desire and I hereby set free and manumit the said Michael Shiner, at the expiration of Eight years from the date of said purchase.” (Archives of the District of Columbia District of Columbia, Orphans Court (Probate) Court, Records Group 2, Records of the Superior Court, Will of Thomas Howard, 1832 Box 11.)

Despite Shiner’s prospective manumission his diary entries for 1833 reflect the continuing danger and precariousness of life for an enslaved family. Slaveholder James Pumphrey’s death on 3 March 1833 placed Phillis and the children in grave jeopardy. Shiner’s brief and heart felt record of June 1833 is all he relates regarding Phillis or his family. His writes simply that his wife and the children “wher snacht away from me and sold” on the street of Washington by slave dealers and confined to their jail in Alexandria.

James Pumphrey’s death was the catalyst for the sale as he died intestate and to pay debts, his family needed to raise cash quickly. His oldest son Levi Pumphrey, was appointed administrator. Levi then purchased Phillis Shiner and two of her children on 27 April 1832 for $295. (Probate Court, Estate Records Group 2, Records of the Superior Court, Inventory of James Pumphrey 11 April 1832, O.S. 1559.)

Levi’s purchase was the result of an agreement to sell Phillis and the children to the notorious slave dealers Armfield and Franklin. Acting as a middleman, Levi sought to gain a quick profit since the firm constantly advertised their ability to pay top price. Their advertisement appeared in the Daily National Intelligencer 14 July 1832:

CASH IN MARKET

We wish to purchase one hundred and fifty likely Negroes of both sexes from 12 to 25 years of age, field hands; also mechanics of every description. Persons wishing to sell would do well to give us a call, as we are determined to give higher prices for slaves than any purchaser who is now, or may hereafter come into this market.

All communication promptly attended to. We can at all-time be found at our residence, West end of Duke Street, Alexandria, D.C.

FRANKLIN & ARMFIELD

After a few harrowing weeks, Shiner was able, with intervention and assistance of wealthy and powerful connections, to gain the release of Phillis and the children from Alexandria Jail and to secure their manumission. A recently discovered document by Leslie Anderson, Alexandria Public Library Reference Librarian reveals Shiner’s struggles were not over, for on 26 March 1836 in the Circuit Court of the District of Columbia he filed a petition for freedom, declaring that he was “ unjustly, and illegally held in bondage’ by the executors of Thomas Howard’s estate Ann Nancy Howard and William E. Howard.

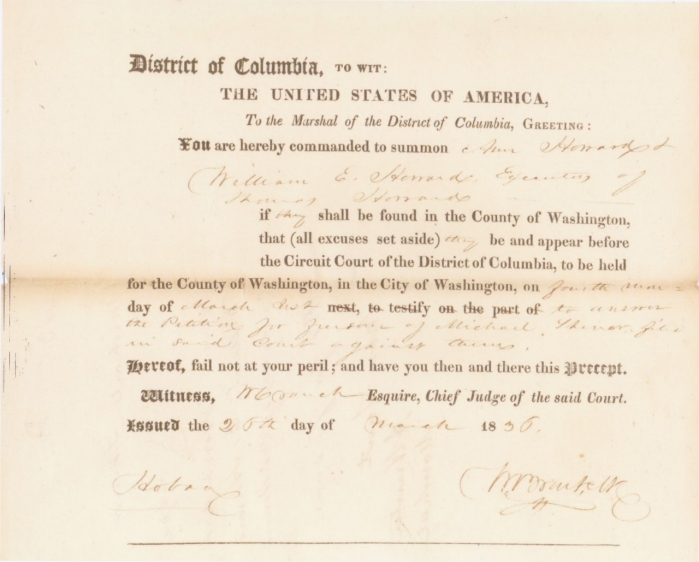

District of Columbia, TO WIT:

THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

To the Marshal of the District of Columbia, GREETING:

YOU are hereby commanded to summon Ann Howard & William E. Howard, Executors of Thomas Howard if they shall be found in the County of Washington, that (all excuses set aside) they be and appear before the Circuit Court of the District of Columbia, to be held for the County of Washington, in the City of Washington, on fourth mon day of March inst next, to, testify on the part of to answer the Petition for freedom of Michael Shiner filed in said Court against them.

Hereof, fail not your peril; and have you then and there this Precept.

Witness, W.G. Cranch Esquire, Chief Judge of the said Court.

Issued the 26th day of March 1836.

Hoban W. Brent, clk

Exactly what prompted this action is unknown, perhaps Shiner feared that the Howard’s were plotting to ignore or set aside the promised manumission. Ever resourceful Shiner engaged the services of future District Attorney for the District of Columbia James Hoban Jr. a son of the first architect of the White House. The Circuit Court folder for this petition contains no other documents, in all likelihood the Howard’s manumitted Shiner in 1836 in accord with Thomas Howard’s will. Here and elsewhere Shiner’s courage, determination, winning personality and ability to form lasting connections with wealthy and influential people gave him the protection of powerful patrons.

Now free, the Shiner’s quickly prospered. The U.S. Census for the District of Columbia dated 1 June 1840, reflects Michael Shiner and his family enumerated for the first time as a "free colored.” As a freeman he worked steadily as a painter at the Navy Yard, was able to save money and provide for his family. Phillis Shiner died sometime prior to 1849. The 1850 District of Columbia U.S. census enumerated Michael Shiner as living in Ward 6 a free black man, aged 46. The family was listed as: Jane 19 years (Jane Jackson second wife), Sarah 12, Isaac 5, and Braxton 6 months. Shiner continued to work at the Washington Navy Yard until sometime after 1870.

Shiner begins his entries in 1813, the year of the British invasion of North America. We know from other evidence that in that year, he was only eight or nine years old. Because of this, what we have for this first section of his manuscript is an important narrative memoir in which he recollects the important events he had witnessed in his youth. What Shiner wrote in "his book" was apparently simply for his own remembrance. In his Diary, Michael Shiner concentrates primarily on the public events in his life along with some limited but important personal incidents.

Many of his observations can be linked with other contemporary records and in each case they ring genuine; from his description of the gleam of British soldiers' bayonets to his recounting of painful conversations with such people as "Mrs. Reid" (see August 1814). Shiner is frequently cited by modern scholars for his riveting account of the August 24 1814 British entry into Washington DC., as are his entries for the subsequent chaos, burning of public buildings, the providential storm, and British departure. Where was he living in 1814 and could he have seen the events he narrates? While I was working with noted author Tonya Bolden we discovered a document that answers this question:

District of Columbia

County of Washington

On the 18th day of April A.D. 1878 before the undersigned a Notary public for the said District personally appeared Michael Shiner who being duly sworn deposed and says,: I am now 73 years of age. For the last sixty six (66) years I have been a resident of Washington City. For the last 53 years I have lived near the Naval Hospital and for 13 years previous to that time I lived near the capitol. At the time of the battle of Bladensburg in 1814 I was living with my master near where Grant Row now is in on East Capitol Street. I was acquainted with Edward Foster from 64 years up to the time of his death. He was a volunteer in Captain William Doughty ‘s Rifle Company of what then known as the 6th Ward. There was a number of other companies in Washington at that time commanded by Captains Burch, (Field Artillery to which my master belonged) Fifth Ward; Captain Caldwell of Cavalry 5th Ward, Captain William Moore militia Company 5th Ward, Joseph Cassin Volunteer Infantry, Captain Thomas Hughes Militia Company and Captain Stulls Rifle Company. I knew that Mr. Edward Foster served in his Company until after peace was proclaimed and then returned to his work at Washington Navy yard as a draughtsman and shipbuilder. I was intimately acquainted with him from the time I was a small boy up to his death. I was employed at the navy yard myself for 47 years. I know that he (Mr. Foster) was at the Battle of Bladensburg because I have heard him speak of it and I saw him in Captain Doughty’s company when they came in from Bladensburg. The British army followed our army and burned first the large dwellings at the corner of 5th and Maryland avenue Gen’l Ross ‘s horse was shot down from that house. They then burned the buildings then on A Street near the Capitol. I was an eye witness to all this. All this was done on Wednesday the 24th day of August 1814. The British staid in Washington until Friday night and then left. My master’s name was William Pumphrey. I have no interest in this claim or in its prosecution.

his

Witness Michael X Shiner

James E. Waugh mark

W. G. Fletcher

Sworn and subscribed befor me on this 18th day of April A.D. 1878

James E. Waugh

Notary Public

Michael Shiner signed the above document with an X. Typically signing with an X mark meant an individual was illiterate, partially literate, or infirmed. The 1850 US Census enumerator questioned his literacy, however, the 1860 US Census taker attested to his literacy. For further evidence that Shiner was known to possess the ability to read and write, see, “The Education of Michael Shiner.”

In 1878 Shiner provided a deposition in the War of 1812 pension claim of Edward Foster. Ever proud of being present when history was made, Shiner recounted, “I was an eye witness to all this.” He then goes on to note “At the time of the battle of Bladensburg in 1814 I was living with my master near where Grant Row now is in on East Capitol Street.” As Tonya Bolden writes the East Capitol Street house on morning of 24 August 1814; was an excellent site to observe history in the making.

Some early entries do strongly suggest they were later reworked to provide additional detail, for example, the lengthy descriptions of the District of Columbia militia units, the colors of the soldier's uniforms and the names of their unit members. His recounting of the launches of the U.S.S. Columbus and the U.S.S. Saint Louis (see his entries for the years 1819, p. 17 and 1828, p. 27) imply that this part of his manuscript was finished as late as 1867. Some information in the diary, including militia unit members' names, could only have been listed after the events recorded. On these and similar occasions Shiner appears to have read and incorporated contemporary newspaper accounts, such as those found in the Washington Intelligencer for some events (e.g. U.S. Mexican War 1846-1848 and the Civil War 1861-1865).

After describing the British troop withdrawal at the conclusion of the War of 1812, Shiner proceeds chronicling the daily routine at the Washington Navy Yard. In these entries he provides illuminating and important details of early working conditions and social attitudes at Washington Navy Yard toward slaves and freeman. The Shiner diary also allows modern readers glimpses of evolving military/civilian relationships and the struggles of early federal workers for better pay and conditions of employment.

His later entries provide a valuable account of the volatility of the early District of Columbia, especially the crucial events of the year 1835. Here Shiner provides an important and unique account of the Washington Navy Yard labor strike which rapidly morphed into the "Snow Storm" of 1835 (p. 60). This strike helped fuel white anger into a bitter race riot led by mechanics from the navy yard. The riot required the active intervention of President Andrew Jackson and a strong contingent of U.S. Marines to finally bring under control.

Occasionally to relieve the pressure and pain of his everyday existence Michael Shiner, like many ship yard workers, drank too much and when he did (December 24-5, 1828 [pp 30-32], June 17, 1831 [pp 41-44], and September 6, 1835 [p. 66]), he records some very close calls with law enforcement (pp 30-32) and angry white workers. As a result of these near catastrophes, he took the temperance pledge. On December 4, 1836 (p. 74), he gave up liquor for good. Shiner's entires contain vivid descriptions of other perils early shipyard workers endured. In one particular harrowing incident on February 20, 1829 (p. 35) while working in a small boat he fell overboard and nearly drowned in the icy cold waters of the Potomac River and, as a result, later came close to freezing to death as he and his colleagues desperately searched for a fire. In other passages he shifts perspective and casts a careful eye to the heavens where he records notable celestial events such as total eclipses of the sun on February 12, 1831 (p. 40) and the Denali Comet of 1858 (p. 168).

Shiner's genuine love of the Washington Navy Yard, the City of Washington and his country are evident throughout the manuscript, see particularly the entry for June 1, 1861, on p. 178. After the Civil War, Shiner prospered, he was active in Republican Party politics and became an outspoken champion of black rights. A survivor of numerous perils Michael Shiner died in his home at 338 Ninth Street SE, on 16 January 1880, a casualty of an outbreak of smallpox. The death certificate stated he was seventy-five. He was buried in the Union Beneficial Association Cemetery on C Street. At his death he was a well-known figure and he was given a front page obituary in the 19 January 1880 issue of the Evening Star. The paper celebrated Shiner for having, “the most retentive memory of anyone in the city, being able to give the name and date of every event which came under his observation, even in his boyhood.” After his death, the manuscript came into the possession of the Library of Congress. The donor annotated it with the following tribute which nicely captures the man and his work: "This book is a very valuable book and is very interesting. It is worthy of perusal. The author Michael Shiner was a Patriot may he rest in peace." Time and neglect have destroyed the old cemetery and his grave marker but “his book” remains a true memorial to this “laboring man.”

__________

1. First quote: Critic-Record, Washington, DC, September 12, 1873, second quote: Report of Committees of the House of Representatives for the Second Session of the Forty-Second Congress. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1872. [See Shiner testimony on pages 471-473.]