The Navy Department Library

Destroyers at Normandy

Naval Gunfire Support at Omaha Beach

Destroyers at Normandy

Naval Gunfire Support at Omaha Beach

By William B. Kirkland Jr.

Foreword by

James L. Holloway III

Edited by

John C. Reilly Jr.

Naval Historical Foundation

Washington, D.C. 1994

Published: Navy Museum Foundation, a project of the Naval Historical

Foundation, Washington Navy Yard, DC, 2002

Contents

| Foreword | V | |

| Preface | vii

|

|

| Prologue | ix | |

| I. Ships and Men | 1 | |

| II. DESRON 18 and OVERLORD | 11 | |

| III. Assault in the Morning | 21 | |

| At Pointe du Hoc | 27 | |

| With the 116th RCT | 29 | |

| With the 16th RCT | 35 | |

| With the 18th RCT | 52 | |

| IV. Breakout in the Afternoon | 57 | |

| V. The Days That Followed | 71 | |

| VI. The End of the Line | 75 | |

| VII. Ex Scientia Tridens | 81 |

Foreword

As the 50th Anniversary of the D-Day landings in Normandy is observed, most of the commemorative events and historical reminiscences are concerned with the experiences of the troops that fought their way ashore and then regrouped to begin the drive across France to the Rhine that gave the Allies victory in Europe. That is understandable. Europe has always been considered as the Army’s main theater of operations in World War II, just as war in the Pacific was considered the U.S. Navy’s victory. Because of these generalizations, attention to the key contributions of the "subordinate service" can all too easily be diminished. The role of the U.S. Navy in the Normandy invasions is an important example of this kind of oversight. The landings in Normandy and the defeat of the German army were the Army’s tasks and clearly among its finest hours. Nevertheless, the military victory could not have happened without the naval forces to move the armies across the Channel, to put the troops ashore on the assault beaches, and then to provide the naval gunfire that, with close air support, enabled the assault forces to break out of the beachhead.

This monograph provides firsthand accounts of Destroyer Squadron 18 during this critical battle upon which so much of the success of our campaign in Europe would depend. Their experience at Omaha Beach can be looked upon as typical of most U.S. warships engaged at Normandy. On the other hand, from the author’s research it appears evident that this destroyer squadron, with their British counterparts, may have had a more pivotal influence on the breakout from the beachhead and the success of the subsequent campaign than was heretofore realized. Its contributions certainly provide a basis for discussion among veterans and research by historians, as well as a solid, professional account of naval action in support of the Normandy landings.

Captain Kirkland’s manuscript was edited and prepared for publication by Sandra J. Doyle and Wendy Karppi. John C. Reilly Jr. reviewed it in detail, consulting the original sources and inserting annotations and emendations as necessary, and selected photographs and maps.

JAMES L. HOLLOWAY III

--vi--

Preface

In the summer of 1944 the Allied armies invaded Europe by crossing the English Channel to Normandy. The story has been told many times. The writings of the senior commanders give the overview of the planning, the decisions, and the execution from the high perspective. From military and naval historians we learn about operational details, and the successes and failures of combat units. Still other writers, especially those who were there, tell us of the individuals who fought, and some who died, and of their heroism and fears, joys and sorrows, on those desperate days between 6 and 9 June 1944.

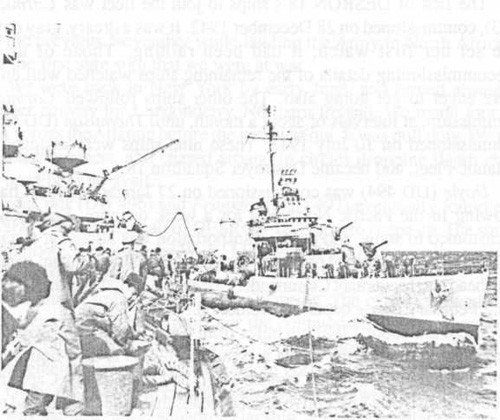

Thirty-three American and three British destroyers were engaged at the Normandy beaches, backed up by six destroyer escorts (DE) and high-speed transports (APD). Eight ships of Destroyer Squadron (DESRON) 18, with the three British destroyers, were in the front line at Omaha Beach. Destroyer Division (DESDIV) 34 and DESDIV 20 were on the line at Utah Beach. Before the first troops went ashore Corry (DD 463) struck a mine and sank. After the first hour the three British "cans" withdrew on schedule, and the ninth ship of DESRON 18, Frankford (DD 497), joined the others near the surf line.

This story reports the events at Omaha Beach as seen from afloat and ashore, integrated as well as the unit records permit, and illuminated by eyewitnesses. The purpose is to show the intimate relationship between the soldiers of the 1st and 29th Divisions and DESRON 18, a relationship that helped make victory possible at this key landing beach called Omaha.

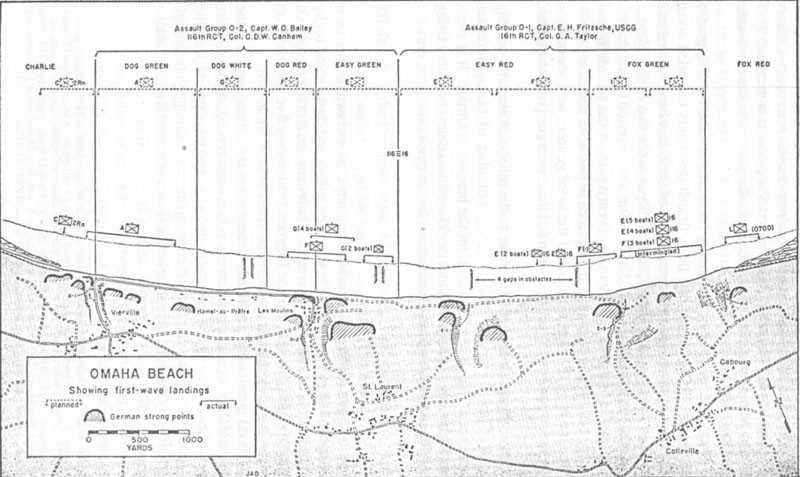

The assault on Omaha Beach can be divided into three well-defined engagements, which took place simultaneously on adjacent landing beaches. At the west end of Omaha the battle for Pointe du Hoc occupied the 2d and 5th Ranger Battalions, supported by Satterlee (DD 626) and Thompson (DD 627). In the center, on beaches called Dog and Easy Green, the 116th and 115th Regimental Combat Teams (RCT) of the 29th Infantry Division landed, supported by Carmick (DD 493) and McCook (DD 496). On Easy

--vii--

Red and Fox beaches, to the east, landed the 16th, 18th and 15th RCTS of the 1st Infantry Division, supported by Emmons (DD 457), Baldwin (DD 624), Harding (DD 625), and Doyle (DD 494). Frankford, DESRON 18’s flagship, cruised the landing area and demonstrated the aggressiveness needed from these destroyers in their first major battle.

The sequence of all three engagements followed a similar pattern: minesweeping, debarkation from transports, prelanding bombardment, and assault landings in three successive waves. After the assault waves went ashore, the destroyers fired at targets of opportunity to help the infantry break out of the landing beaches. Call fire, directed by fire control parties ashore, led to the final clearing of the landing beaches allowing armor and transport move inland. The progress of each phase of the action was quite different; none followed the prepared script.

After three days of battle, nearly three thousand soldiers from the 1st, 4th and 29th Divisions were casualties. Three destroyers, a destroyer escort, a heavily laden troopship, and numerous amphibious craft had been sunk. These losses attest to the ferocity of the battle for the Normandy beaches.

William B. Kirkland Jr.

Captain, USN (Retired)

Alameda, California

--viii--

Prologue

On the morning of 6 June 1944 James E. Knight, a soldier in the 299th Combat Engineer Battalion of the 1st Infantry Division, found himself pinned down on the rocky shoreline at Omaha Beach by German artillery and machine guns dug in on the bluffs overlooking the beach. He and hundreds of other American soldiers were trapped between the murderous fire of the defenders and the rising tide behind them.

Late in the morning Knight saw a destroyer come into the shallows behind him and fire over his head at the German strong points. Soon he and the others were able to leave the beach and move inland. He remembers the ship as Frankford, and suggested that someone research the facts and see if Frankford, by herself, might have turned the tide of the Omaha landing — and, possibly, the whole Normandy invasion. (Knight, 124-26)

Frankford, however, was not alone. She was flagship of Destroyer Squadron 18, commanded by Captain Harry Sanders, and more than one destroyer nearly put her bow in the sand to break the German wall at Omaha Beach. The author, gunnery officer of Doyle, has undertaken the research suggested by James Knight, and believes he is right in his assumption that naval guns were instrumental in turning the tide. Eight ships of DESRON 18, plus Emmons and three British destroyers, backed up the heroic efforts of the soldiers of the 1st and 29th Divisions, and had a large share in starting them on the road to victory.

* * *

In his action report Commander W. J. Marshall, commander of Destroyer Division 36, writes: "At 0617 (H minus 13 minutes) LCT(R)s [British landing craft converted to fire bombardment rockets] commenced firing rockets, drenching the area just inland from the beaches. Fire from this beach was temporarily silenced and the entire area covered with heavy smoke and dust. Troops landed and proceeded up the beach into the smoke."

--ix--

The action report of Baldwin (DD 624) records:

0619-0637: "Closed beach ahead of boat wave, firing guns 1 and 2 [the two forward 5-inch guns] in assigned target area and ahead of troops landing. Minimum range to beach 1,800 yards."

And from Doyle (DD 494):

0630: "‘H’ hour. Commenced indirect fire on target ... to aid in clearing beach exit now completely obscured by smoke and dust."

The deck log of Carmick (DD 493) records:

0647: "German Shore Battery opened fire on this ship."

0650: "German Shore Battery silenced by Main Battery of this ship. No damage resulting from enemy fire."

This seemed a promising opening, but within the half-hour things started to go wrong. Confused by loss of visibility in the smoke, about half the landing craft coxswains lost their way. Pushed along by the strong eastward set of the tidal current, many landed east of their designated objectives; some troops came ashore outside the landing area entirely.

German gunners, defending the five beach exits [so-called five draws or openings in the bluffs facing the beaches between Vierville and Cabourg], pounded the first wave. Demolition teams suffered from German fire and were hampered by the tangled condition of the beaches. The destroyers went dutifully into the second phase of their work, firing at targets behind the beach. It was nearly 0900 before it became clear to the destroyer skippers that something was wrong.

Doyle fired on a German gun overlooking the eastern exit to Colleville. Carmick saw American tanks stalled in the Vierville draw and, in cooperation with the tankers, knocked the first hole in the defenses. Landing craft from follow-on boat waves began milling around off the beach as their coxswains looked for places to land.

--x--

When Frankford, with Captain Harry Sanders aboard, closed the beach about 0900 things began to happen. All destroyers were ordered to the beach to help break through the defenses. This was the hour of crisis. Satterlee was picking off enemy gun emplacements at Pointe du Hoc.1 McCook reported that she knocked one enemy gun off the edge of the cliff, and that another "flew up in the air."2 Vierville was taken by 1100.

At the eastern end of Omaha Beach Frankford, Doyle, and Emmons were hitting hard at three exits while Baldwin blasted away at German guns near Port-en-Bessin. Baldwin was hit twice by light artillery, with no casualties. At 1043 McCook reported picking up a radio message saying that American troops were advancing. Harding was leading their way, dropping salvos up the draw toward Colleville. By 1600 St. Laurent-sur-Mer was occupied by 29th Division troops. Colleville was in a vice, set up by 1st Division troops approaching from two draws. The Germans here surrendered the next morning.

How this team of destroyers arrived at this particular place in history, and made the landings at Omaha Beach succeed, is the story to be told.

___________

1. Often incorrectly identified as Pointe du Hoe in many publications and documents.

2. There was no artillery at Point du Hoc on D-Day. Six 155mm guns had been mounted there to command Omaha and Utah Beaches, making its capture an essential feature of the assault plan. When the Rangers fought their way onto the point, they found the battery empty; the guns had been moved inland and replaced by wooden dummies. McCook’s gunners would have had no way of knowing this.

--xi--

I

Ships and Men

In the years after World War I the United States Navy gradually wore out the several hundred four-stack, flushdeck destroyers built to keep the sea lanes open during World War I. Very few of these destroyers had been completed in time to see active service before the Armistice.

Early classes of destroyers, authorized in 1898 and commissioned in 1902-1903, had weighed in at 408 to 480 tons. Early service demonstrated the value of the new type and the need for more displacement for satisfactory operation with the fleet. By the time the United States entered World War I, the Navy had 67 destroyers in commission, with seven more on the way. All had raised forecastles and ranged from 720 tons to 1,000. The war prompted rapid construction of the 1,090- to 1,190-ton "flushdeckers." Two hundred and seventy-three of these were laid down between 1917 and 1919. By the Armistice 37 were in service; five were canceled after World War I ended. The remaining ships were in commission by 1922, though postwar budget cuts soon sent most into reserve.

These early destroyers were built for speed, endurance and seaworthiness, designed to keep pace with the battleships and cruisers of their day and to launch massed torpedo attacks at an enemy’s battle line. Main battery guns — 4-inch 50-caliber in all but a few of the "flushdeckers" — were secondary armament to their torpedo tubes. Destroyers were fitted with underwater sound gear and depth charges during World War I to fight submarines, and in the postwar years they were called on to screen the battle line from submarine attack. These 1,100-tonners were the heritage that led to the 1,620-to 1,630-ton Benson and Gleaves classes and the 2,100-ton Fletchers of World War II.

--1--

By the beginning of the 1930s it was clear that new destroyers of improved design were needed. Despite their speed, the "four-pipers" were notorious for lack of cruising radius and for wet decks in even moderate seas. In rough weather the forward gun could not be manned. The torpedo tubes on the main deck were often made unserviceable by salt water. There was no adequate submarine detection equipment on board, with no room for the newer underwater sound devices, and limited stowage for antisubmarine weapons. Thus began a design evolution and limited construction of new destroyer classes.

In each year after 1931 a few ships were laid down, initially limited by the 1,500-ton standard displacement ceiling imposed by the London naval limitation treaty. "Standard displacement" was a legal concept established by the Washington Treaty in 1923; it measured the displacement of a warship fully manned, armed, supplied, and ready for sea, but without fuel or reserve boiler feed water. The first of the new destroyers were eight Farraguts, 1,365-tonners completed in 1934-35 with two stacks and new dual-purpose 5-inch 38-caliber guns. Sixteen 1,450-ton Mahans and eight 1,850-ton Porter-class "leaders" came into service during 1936-1937. In 1937 two Dunlaps, near-sisters to the Mahans, appeared with two single-stacked 1,500-ton Gridleys and eight similar Bagleys. Between 1937 and 1939 five single-stacked Somers class 1,850-tonners with improved steam plants went into commission. Two more Gridleys appeared in 1938, followed in 1939-1940 by ten single-stacked Benhams and twelve ships of the Sims class on a slightly enlarged displacement of 1,570 tons to permit improvements. To improve dryness forward, a problem with the earlier flushdeckers, the new ships were built with raised forecastles. Torpedo tubes were placed above the main deck in the later destroyers for the same reason. Boiler uptakes were trunked into one or two stacks to gain valuable centerline deck space. In the earlier destroyer classes the four boilers were grouped together in two firerooms, with the engine room — two engine rooms in the Sims class — aft. Keeping the firerooms together and combining the uptakes allowed more deck space topside, but a hit in the right place could disable both firerooms, or both engines, and leave a ship dead in the water.

The fiscal 1938 program included the first eight of what would become two large classes of two-stack destroyers, 1,620-tonners with their two firerooms and two engine rooms arranged in alternating sequence and so connected that a ship could operate on either half of her engineering plant. This "split-plant" arrangement meant added weight, but also gave a better chance of surviving a torpedo hit. These ships were designed to carry five 5-inch guns and three quad torpedo tubes, with .50-caliber antiaircraft (AA) machine guns, and became the beginning of the Benson (DD 421) class.

--2--

Eight more Bensons were funded in fiscal year 1939. Designers added more AA machine guns, put light armor around the bridge and gun director, and replaced the quad torpedo tubes with two new quintuple mounts. This arrangement seemed better than the original design, and the Navy decided to incorporate these changes in the first eight ships. Meanwhile, a new high-temperature steam plant had been selected for the 1939 destroyers, and it was retroactively included in two 1938 ships being built by Bath Iron Works. The new two-stackers now began to fall into groups, some built with the new high-pressure machinery and others with lower-temperature plants.

The 1941 building program was to have consisted entirely of new Fletcher-class destroyers. By 1940 the pace of war was heating up in Europe and in China, and 72 more Benson-pattern ships were ordered during 1940 and early 1941. Beginning with Bristol (DD 453), later ships of the class were built with four 5-inch guns instead of five to make room for new topside weights. Combinations of building programs, armaments, and engineering plants led to some confusion in class designations during the war years. Ships of the original 1938 design were called the Benson class. The high-temperature ships of the 1939 program were first called the Livermore (DD 429) class; since DDs 423 and 424 were built to the same standard, they eventually came to be called the Gleaves (DD 423) class. The early four-gun ships were originally called the Bristol class; as time went on, all the five-gun ships lost one gun to improve stability and make room for antiaircraft guns, and the Bristol distinction lost its meaning. The 96 ships built to the basic Benson concept eventually came to be known as the Benson and Gleaves classes, the difference lying in their machinery. As the war went on they all became tactically alike and operated together. It was from the Gleaves class that DESRON 18 was selected. (Friedman, 95-107)

In 1940 two shipbuilding contracts were let to the Seattle-Tacoma Shipbuilding Corporation. The first, on 9 September 1940, called for five Gleaves-class ships with hull numbers 493-497. The second, on 16 December, called for five more numbered DDs, 624-628. These 1,630-ton destroyers were originally manned by 18 officers and 220 men who served the four 5-inch 38-caliber dual purpose guns, 40mm and 20mm automatic AA guns, and five 21-inch torpedo tubes, with side-throwing K-guns and stern tracks for depth charges. The ships weighed 2,500 tons at full-load displacement and were 348 feet long with a beam of 36 feet and a maximum draft of 17 feet 5 inches. They had four superheated oil-fired boilers that delivered 825-degree steam to two geared turbines producing 50,000 horsepower to drive them at trial speeds of 37 knots. They were equipped with sonar as well as search and fire-control radar. (Fahey, 20-27)

--3--

--4--

--5--

The first of DESRON 18’s ships to join the fleet was Carmick (DD 493), commissioned on 28 December 1942. It was a dreary, gray day when she set her first watch; it had been raining. Those of us in the precommissioning details of the remaining ships watched with envy. We were eager to get going also. The other ships followed Carmick into commission, at intervals of about a month, until Thompson (DD 627) was commissioned on 10 July 1943. These nine ships were assigned to the Atlantic Fleet, and became Destroyer Squadron 18.

Doyle (DD 494) was commissioned on 27 January 1943. It had been snowing in the Pacific Northwest for a week or more. Seattle was not accustomed to snow, and public transportation was almost at a standstill. Still, the full crew turned out when the commissioning pennant went to the masthead and Lieutenant Commander Clarence E. Boyd assumed command. On 2 February Doyle departed Bremerton for San Diego.

There are about 1,040 sea miles from Cape Flattery, on Washington’s northwest coast, to Point Loma at San Diego. This is a 48-hour run at 22 knots cruising speed. But Clarence Boyd had other ideas. Captain A. L. Gebelin, then Doyle's executive officer, recalls that once the ship had reached Cape Flattery, Boyd ordered Chief Engineer Sam Rush to put on the turns.

Doyle passed Cape Flattery abeam to port at about 1730. It was already dark. By about 2345 Cape Disappointment and the mouth of the Columbia River were abeam and the Western Sea Frontier’s Movement Report Office (MRO) challenged Doyle's speed of advance. Captain Boyd didn’t hear too well in the middle of the night.

At 1300 the next day course was changed to south-southeast and Doyle cleared Point Reyes. As the ship passed the Golden Gate she got another challenge from the MRO. Again the message got mislaid. Boyd, after all, was a very experienced skipper with several destroyer tours in his record. If he was to take this one in harm’s way he needed to know how fast and how far. The passage was made in 30 hours, with time to kill off San Diego waiting for daylight in order to pass through the harbor defense nets.

February days were intense shakedown times. It was underway at 0700, pass through the nets, and proceed with exercises until dark. There was seldom a day to catch up on the endless paperwork. In March Doyle sailed from San Diego for Panama, enroute to New York.

Carmick and Doyle met in New York, and Endicott (DD 495) arrived shortly afterward. In April 1943 the three destroyers sailed as part of the screen of a slow convoy bound across the lower latitudes for Casablanca. In that harbor the French battleship Jean Bart lay, on an even keel but badly wrecked by the main battery of the battleship Massachusetts (BB 59) the previous November while landing the Army in North Africa. This was the first sure sign that we were at war.

--6--

We were back in New York by early June, and turned around with another convoy for Londonderry, Northern Ireland. We made four round trips across the Atlantic before the year was out. It was dull duty. We picked up sonar contacts, and chased around in circles dropping depth charges, but usually to no avail.

McCook (DD 496) and Frankford (DD 497) eventually found us, and DESDIV 35, the first half of DESRON 18, began to shape up. The squadron commodore, Commander W. K. Mendenhall Jr., occasionally rode Doyle or one of the others.

The small squadron staff was a tight fit. The captain moved into his small sea cabin to make room for the commodore in his stateroom. The staff members bumped us around in wardroom country. Despite the inconvenience, we and the commodore got to know each other.

On board Frankford crowding and discomfort went with the duty, since she was the designated squadron flagship. The small irritations which the rest of us suffered from time to time were endemic in the leader. Commodore Mendenhall was a "hard driver" who aimed to have the best destroyer squadron in the Atlantic Fleet. We all rose to his challenge; Frankford rose a little higher.

* * *

The Division scattered as we helped shake down new major warships in the sheltered waters off Trinidad in the British West Indies. Doyle screened the cruiser Quincy (CA 71) and did plane guard duty for the carriers Bataan (CVL 29) and Wasp (CV 18). The other ships of DESDIV 35 did likewise. We learned fast, steaming and station-keeping with the big boys.

While operating with Bataan, Doyle played target for her small air group. One day a Grumman TBF torpedo bomber dropped a practice "fish," which would have been a sure killer. It hit Doyle between frames 130 and 132 on the port side, leaving a big dent in her hull plating, then dove under the keel and hit the starboard propeller. Doyle shook pretty hard before the "black gang" got her stopped. That ended that cruise.

It took four days to get Doyle into drydock at the Charleston, South Carolina, Navy Yard. By the end of February she was back in Casco Bay with a new propeller. Here, on 24 March 1944, the nine ships of DESRON 18 mustered together for the first time since leaving the builder’s yard in Seattle.

--7--

All of the squadron’s commanding officers were Naval Academy graduates; their class year and ultimate rank are shown.

DESRON 18 CAPT Harry Sanders, USN '23 (VADM)

Frankford (DD 497) CDR James L. Semmes, USN ’36 (CAPT)

DESDIV 35 CAPT Harry Sanders, USN

Carmick (DD 493) CDR Robert O. Beer, USN ’32 (RADM)

Doyle (DD 494) CDR Clarence E. Boyd, USN ’28 (CAPT)

Endicott (DD 495) CDR Wilton S. Heald, USN ’27 (RADM)

McCook (DD 496) LCDR Ralph L. Ramey, USN ’35 (CAPT)

DESDIV 36 CDR Wm. J. Marshall, USN ’25 (VADM)

Baldwin (DD 624) LCDR Edgar S. Powell, USN ’34 (CAPT)

Harding (DD 625) CDR George G. Palmer, USN ’30 (RADM)

Satterlee (DD 626) LCDR Robert W. Leach, USN ’33 (RADM)

Thompson (DD 627) LCDR Albert L. Gebelin, USN ’34 (CAPT)

Captain Harry Sanders had served as aide to Admiral Ernest J. King in 1941 when King was Commander in Chief, Atlantic Fleet. Sanders went to sea after Pearl Harbor when King became Commander in Chief, United States Fleet (COMINCH). He had only recently departed the Mediterranean after commanding Destroyer Squadron 13 from September 1943 until February 1944, including the landings at Salerno and Anzio. Captain Sanders relieved Commander Mendenhall as COMDESRON 18 in mid-March 1944. On 26 March Commander James G. Marshall relieved Commander Clarence Boyd of command of Doyle. During the preceding six months all of DESRON 18’s commanding officers, except Commander Palmer in Harding (DD 625), had been replaced.

Nineteen forty-four brought other important changes. Most of the lieutenants who became department heads at commissioning had been ordered to newer destroyers and replaced by last year’s ensigns, now lieutenants (junior grade). In Doyle, for example, the Executive Officer, Lieutenant Commander A. L. Gebelin left to take command of Thompson. He was relieved by Lieutenant E. J. "Ted" Sweeny. Where the commissioning complement included six lieutenants and two lieutenants (jg), it now stood at three lieutenants and eight lieutenants (jg). Of the original eight ensigns, four remained as lieutenants (jg), and ten new ensigns were on board. The wardroom, which had been crowded at 18 souls, now held 21 officers. At commissioning four of Doyle's officers on board were Naval Academy graduates; by 1944 she had two. This type of officer turnover happened in all nine ships of the squadron. Changes among the enlisted men were just as dramatic. In Doyle Walter Foley was promoted from

--8--

shipfitter first class to Warrant Carpenter and moved to wardroom country. Jack Gwin, from Texas, was a machinist’s mate second class in Doyle's commissioning crew, and was now a chief petty officer. Ed Miller came aboard as a torpedoman’s mate second class and made first class the hard way, by taking BuPers [Bureau of Naval Personnel] promotion exams. With only a few exceptions the sailors were reserves called up from Kansas, Illinois, North Carolina and the Bronx. Few had seen salt water, but they became outstanding Navy men who learned their jobs well and gave superb performance when it was due.

On 18 April 1944 DESRON 18 departed Boston as part of Task Group 27.8 under Rear Admiral Morton L. Deyo (Commander Cruiser Division 7) in the heavy cruiser Tuscaloosa (CA 37), with the veteran battleship Nevada (BB 36), bound for England.

--9--

[Blank]

--10--

II

DESRON 18 and OVERLORD

DESRON 18 came to Devonport by way of Plymouth, in southwest England, on 28 April 1944. None of the officers or men, save perhaps the commodore, had any idea what they were to do that summer; but these were now a skilled and well-schooled group of young men. The nine ship captains were 34 years of age, plus or minus a few years. Not many others were over 30.

By twos and fours the ships sortied daily for drills and high-speed maneuvering off the coast in the area of Eddystone Light. At day’s end, back in the narrows of Plymouth Sound, each would pick up a mooring buoy and often take alongside a British counterpart. This thoughtful gesture, no doubt justified as a means of getting allied crews acquainted before sharing a battle, had a keen side effect.

No sooner were mooring lines secured than our "Brit" opposite numbers were on board for coffee and a quick tour. There followed a return visit to splice the mainbrace, courtesy of His Majesty George VI. After dinner we gathered in the American ship for ice cream and a movie. When the "flick" was done the non-watchstanders again visited the Brit for more honest Scotch. And so passed some pleasant days of Anglo-American camaraderie when shore leave was limited.

According to one story there was an exception to the "pick up the buoy" routine. Frankford, with COMDESRON 18 embarked, was always assigned a pierside berth. Commodore Sanders assumed this was in deference to his rank and position. Lieutenant (jg) Richard Zimmerman, (USNA ’43) Frankford’s CIC [Combat Intelligence Center] officer, thought otherwise. This young bachelor made the acquaintance of a lovely British

--11--

WREN (Women’s Royal Navy Service), Phyllis Saunders, who was posted to the Port Director’s Office. She had much to say about day-to-day berthing assignments. She also knew that Dick could hit the beach much sooner from pierside than from any mooring buoy in the river. And so it was.

Three of the British DDs berthing with DESRON 18 were Melbreak, Talybont, and Tanatside, "Hunt Type III" class of "escort destroyers" of 1,087 tons, 264 feet long at the waterline with four 4-inch guns and light AA guns, designed as fast antiaircraft and antisubmarine escort ships. Their 19,000 horsepower gave them about 25 knots. (Lenton & Colledge) They operated with DESRON 18 at Omaha Beach.

* * *

Before the first of May, the squadron shifted to Weymouth Bay, behind Portland Bill. On the night of 3 May DESRON 18 was underway for Phase I of Exercise Fabius I, screening transports of the 11th Amphibious Force heading for Slapton Sands. Five days earlier this had been the scene of a tragedy.

During an invasion rehearsal in the early hours of 28 April, the day we arrived at Plymouth, German motor torpedo boats, called "E-boats" by the Allies, torpedoed two LSTs of the Utah Beach landing force whose British escort had become disabled and could not leave port. Because of a command foulup Rear Admiral Don T. Moon, the Utah force commander, was never notified of the gap in his screen. This raid cost us LST-507, LST-531, and 638 American soldiers and sailors. (Morison, XI, 66-67) To keep this from happening again, DESRON 18 now escorted 16 transports and 21 LSTs of the Omaha Beach landing force. (Doyle war diary)

Early on 5 May DESRON 18, less Thompson, formed up off Plymouth to escort nine transports north to Scotland. The Officer in Tactical Command (OTC) was Commander Transport Division 3 in the attack transport Charles Carroll (APA 28). The convoy also included Henrico (APA 45), Samuel Chase (APA 26), Anne Arundel (AP 76), Dorothea L. Dix (AP 67), Thomas Jefferson (APA 30), Thurston (AP 77), and British troopers Empire Anvil and Empire Javelin.

On 9 May DESRON 18 was again underway for Slapton Sands for shore bombardment drill. On the 12th Carmick and Endicott escorted the ammunition ship Nitro (AE 2) to Dunoon Bay, Greenock, Scotland.

After Slapton Sands the rest of DESRON 18 went north to Scotland for shore bombardment practice and got acquainted with our Shore Fire Control Parties (SFCP), each made up of one Navy and one Army officer, with a small team of Army radiomen.

--12--

DESRON 18 was based in the River Clyde. Sometimes we moored in Dunoon Bay, Greenock, in Kilbrannan Sound off Sanda Island, or across the North Channel in Belfast Lough, Northern Ireland. The squadron exercised at every conceivable evolution. We practiced defense against E-boats in something called "video" exercises. We fired AA practice at towed sleeves off Black Head, Northern Ireland. We practiced shore bombardment with our Shore Fire Control Parties, and escorted the "big boys" while they did their practicing.

On 25 May DESRON 18 was ordered south as escort for twelve transports. At 1100 the squadron, less Frankford, departed Belfast Lough and joined the convoy. We found Destroyer Division 119 in company. These were new Allen M. Sumner-class ships: Barton (DD 722), Walke (DD 723), Laffey (DD 724), O’Brien (DD 725), and Meredith (DD 726), all commissioned between the end of December 1943 and mid-March 1944. Captain William L. Freseman (USNA ’22), COMDESRON 60, took charge and formed us in tight columns on either flank of the column of troopers. The commodore led the pack in Barton from a station about 2,000 yards ahead of the formation; the rest of DESDIV 60 deployed on either bow. DESDIV 35 took station to port of the convoy, while our DESDIV 36 deployed to starboard.

Down the Irish Sea we went, southbound in the swept channel at about 25 knots. Around 0400 the watch had just changed as we passed St. Goven’s Lightship abeam to port and prepared to take the formation 90 degrees left into the Bristol Channel. Suddenly a blip showed on Barton's radar screen, identified as a ship northbound in the center of the narrow channel. We intercepted right at the turning point.

The "loner" was the American Export Line steamer Exhibitor, who had no idea she was confronting a fast 25-ship naval convoy and maintained course and speed in the center of the channel. The destroyermen, at least, had radar and could sense the real world of racing ships around them as we whipped through the left turn while crowding into less than half the channel width. Sleeping destroyer captains, suddenly called to the bridge, had to quickly grasp the tactical situation and judge if the OOD [Officer of the Deck] had made the correct move.

I recall that, when my boss in Doyle suddenly realized I was steaming parallel to the nearest transport at a distance of about 100 yards, his heart must have jumped, but he left the conn to me as he watched Endicott and the freighter slip by about 150 yards on the port side.

Doyle's war diary says Exhibitor passed down our starboard side, which would have placed her between Doyle and the line of troopers. I was Officer of the Deck (OOD), and remember it as told above. This is confirmed by correspondence from Jim Arnold, who was OOD of McCook.

--13--

Endicott, ahead of us, fared poorly. Captain Heald found his way onto the very dark starboard bridge wing. He took one look at the troopship close aboard, called for left full rudder — and cut across Exhibitor's bow. It was a good clean hit. Endicott lost her bow; the freighter survived. The rest of us raced on down channel, heads-up for German E-boats rumored to be about. Endicott hove to and estimated damage, and then limped into Milford Haven, Wales, escorted by Carmick. On 28 May Endicott transferred ammunition, and her secret orders for Operation Neptune [the naval part of Overlord] to Emmons (DD 457), commanded by Commander Edward B. Billingsley. Our squadron mate, Endicott, missed the action at Omaha Beach.

We delivered our transports to Weymouth Bay, behind Portland Bill, on 27 May and anchored at 0132 in dense fog. On the night of the 28th Portland was the target of a heavy German air raid. DESRON 18 hove to short stay, ready to up anchor and sortie if necessary, fearful the Germans would see the crowd of ships anchored in the bight of Portland Bill. We held our fire and watched as the guns ashore blazed away at the bombers held in the searchlight beams. We heard the bomb explosions and saw the flashes, followed by flames of things ashore burning. McCook took a near miss that knocked the SG surface-search radar antenna off the foremast and jammed the 5-inch gun director’s FD fire-control radar and optical rangefinder against the stops. We never fired a shot, but knew we were now in harm’s way.

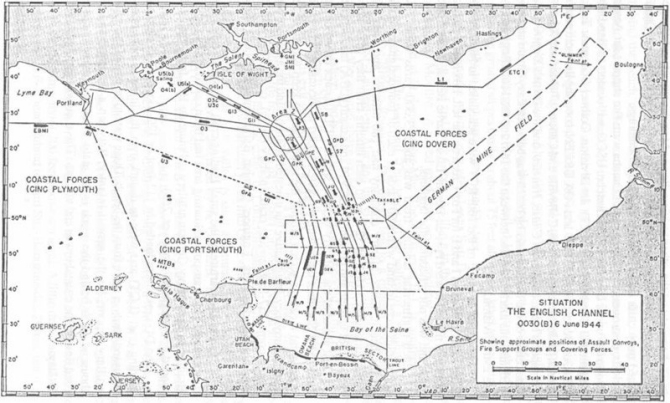

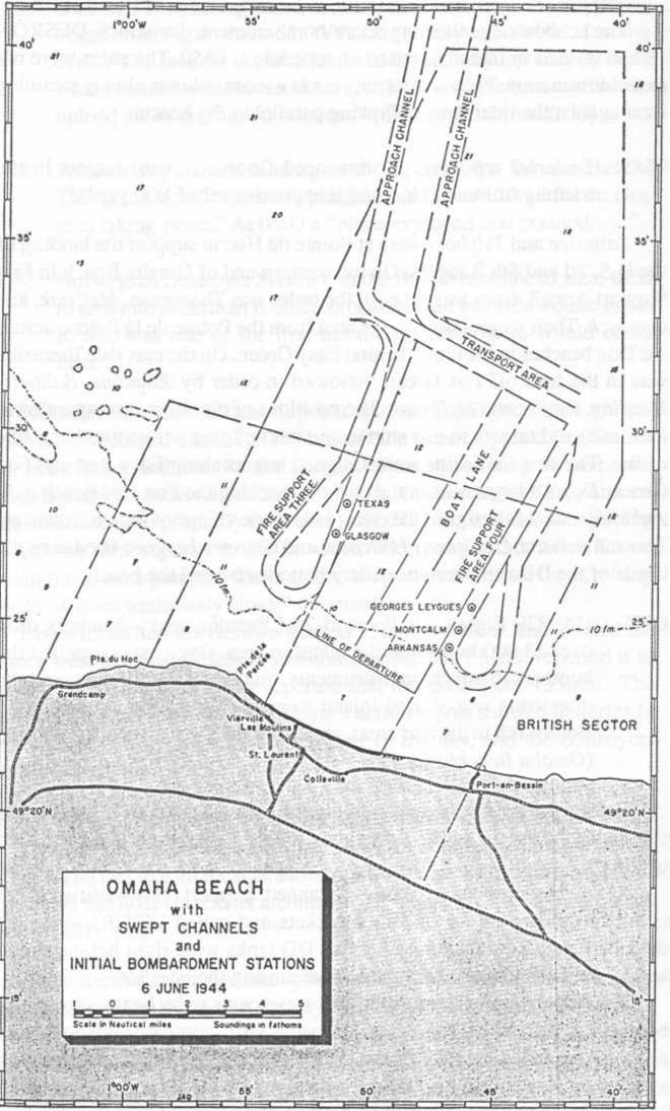

* * *

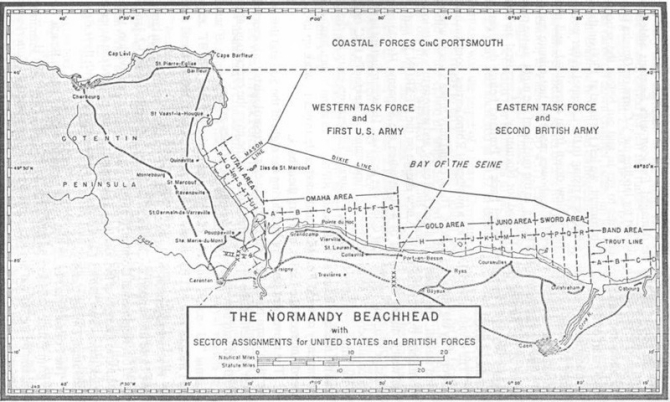

The Western Task Force (Task Force 122), under Rear Admiral Alan G. Kirk in the heavy cruiser Augusta (CA 31) and carrying Lieutenant General Omar Bradley’s U.S. First Army, included over 200 naval vessels of all types. TF 122 was organized into TF 125, Assault Force "U," aimed at Utah Beach under Rear Admiral Don P. Moon. TF 124 was Assault Force "O," headed for Omaha Beach under Rear Admiral John L. Hall, with Major General L. T. Gerow’s V Army Corps. Admiral Hall and General Gerow were in the command ship Ancon (AGC 4), a sophisticated amphibious headquarters ship whose very existence was classified. Rear Admiral C. F. Bryant’s Bombardment Group included the battleships Texas (BB 35) and Arkansas (BB 33), with four light cruisers — the British Glasgow and Bellona, with the French Montcalm and Georges Leygues — and the eight remaining ships of DESRON 18 with their three British teammates. The Escort Force, which provided the screen, included three more U.S. and two British destroyers, with three American destroyer escorts and two French frigates.

--14--

DESRON 18, less the damaged Endicott with Emmons added, was assigned to provide fire support for landing the V Corps on Omaha Beach. To allow the minesweepers time to get in and out before the scheduled 0550 start of the naval bombardment, we left Portland at 1300 on the 4th, heading into a rough and windy sea rising in the Channel. After weeks of quiet summer weather a storm blew down from Greenland, and nearly crippled the invasion. General Eisenhower made his last-minute decision to delay the landings for 24 hours. In the middle of the night, as we neared Point Z, the turning point to head for Normandy, we received an urgent recall. We did a turnabout to get back to Portland before daylight; just another exercise.

The invasion force included a number of Rhino ferries, pontoon barges powered by big outboard motors. These could only make 5 knots when the wind was aft. They had been dispatched early, and were to turn south toward Normandy by mid-afternoon. A new ensign on the DESRON 18 staff had the watch during the night of 4 June when the Supreme Headquarters message ordering the 24-hour delay was received. He was reluctant to wake the commodore. Captain Richard Zimmermann, Frankford's CIC officer at the time, remembers that when Captain Sanders, up early on the 5th, read the message board he realized the Rhinos were about to turn southward. He urgently ordered Frankford and another destroyer to work up to flank speed, intercept the ferries, and turn them back.

The movement was repeated during the night of the 5th, and this time we didn’t turn back. General Eisenhower’s meteorologists had detected a clear spot behind the first weather front, and he gave the order to go ahead. We fitted into that narrow gap and put the armies ashore.

* * *

Five destroyers on the western flank of the main Omaha Beach landing gave close fire support to Captain W. O. Bailey’s Assault Group 0-2, landing the 116th Regimental Combat Team of the 29th Infantry Division, taking position to the right of the boat lane. The assault group included the American attack transports Charles Carroll and Thomas Jefferson, with their British equivalent, Empire Javelin.

The Pointe de la Percee was at the western end of Omaha Beach, with the grim Pointe du Hoc a further three miles away. Pointe Du Hoc was to be taken by the 2d and 5th Ranger Battalions, supported by Satterlee and HMS Talybont.

The units of the 116th to land on beaches Dog Green, Dog White, and Dog Red were, in order, Companies A, G and F; Company E was to land

--15--

--16--

--17--

on Easy Green. These units were to seize two of the beach exits, one leading to St. Laurent and the other to Vierville-sur-Mer. A company of Rangers went ashore on Charlie beach, just west of Dog Green; most of Charlie faced steep cliffs and was not scheduled for landings.

Six destroyers at the east end of Omaha were fire support for Assault Group 0-1 under Captain E. H. Fritzsche, USCG, with orders to "land 16th Regimental Combat Team (RCT), 1st Division, Colonel George A. Taylor USA, on Beaches EASY RED and FOX GREEN, covering the three eastern [beach] exits to Saint-Laurent, Colleville and Cabourg." (Morison XI, 130) Transports included Samuel Chase, Henrico, and the British Empire Anvil. The center of the Omaha landing beach was between Easy Green and Easy Red, and this marked the line between the 16th and the 116th Regiments of the 29th Division.

Companies E and F of the 16th RCT were scheduled to land on Easy Red, with Companies I and L for Fox Green on the left. Fox Red Beach lay farther to the left toward Port-en-Bessin. Like Charlie Beach, it faced steep cliffs and was not scheduled for landings.

Each regimental landing front was about 3,000 yards wide. Two companies were to land within 50 yards of each of four designated points on the beach. Each infantry company had 180 officers and men with supernumeraries added; at 32 men to each landing craft they filled six of the 36-foot vehicle and personnel (LCVP) and assault (LCA) landing craft.

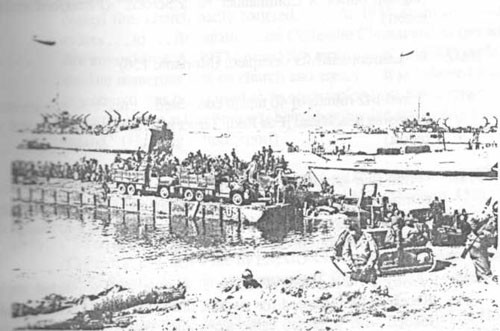

Just ahead of the infantry went 64 special "DD (duplex drive) tanks," Army M-4 Sherman tanks with propellers added to locomote through the water, and a canvas screen around the upper hull to keep water out and furnish buoyancy. Imaginative but untested. Right behind the assault groups would come 157-foot landing craft, infantry (large), or LCI(L), with the Division Headquarters, Engineer Combat Battalions, and Naval Beach Battalion.

The line of departure of the small landing craft was set 11 miles from the beaches. This transport unloading area had been called for by General Bradley to keep heavy German artillery at Pointe du Hoc from hitting the loaded troopships. (Eisenhower, 269)

The DD tanks were loaded in 112-foot or 120-foot open-decked tank landing craft (LCT) and were to debark over the lowered bow ramp a thousand yards or more from the beach. These were to be part of the critical artillery support for the assault infantry. Between a thousand and two thousand yards behind the beach is the main Vierville-Colleville coastal road linking the coastal towns and villages. This road was the objective for D-Day.

* * *

--18--

The shoreline behind the beaches at Omaha is quite varied. To the west, toward the Pointe de la Percee, a hundred-foot cliff rises vertically behind the beach, and rocks appear off shore. East of this, along Charlie Beach, the beach widens somewhat and the cliffs become rugged bluffs. Just east of Charlie Beach was the first exit, designated D-1. A paved road goes some 600 yards from the beach up a shallow draw to the village of Vierville-sur-Mer on the coastal road. At the entrance to D-1 the paved road from Vierville turns eastward and runs for a mile along Dog Green and Dog White beaches. Along this stretch the seawall at the high water line is 4 to 8 feet high. Along the paved road villas are spaced 50 to 100 yards apart; this group of houses is called Hamel-au-Pretre. Behind the villas the ground slopes easily to about 75 feet above sea level and continues, more gently, to level ground at about 120 feet.

A mile and a quarter east of D-1 was Exit D-3, at the dividing point between Dog Red and Easy Green. A village in the mouth of the draw is called Les Moulins. A paved road goes up the shallow draw to join the coast road at St.-Laurent-sur-Mer. The third exit, E-1, is another three-quarters of a mile eastward. This leads up the valley of a shallow stream called the Riviere Rouquet. The draw rises to a plateau about halfway between St.-Laurent-sur-Mer and the village of Colleville-sur-Mer. In this area the flatter ground above the beach is about 150 feet high, but the bluffs are not too steep. The bottom of the E-1 draw is wooded. A dirt road climbs from the beach along the west side of the draw into the outskirts of St.-Laurent. This exit served Easy Red beach.

About a mile east of Exit E-1 is a much larger, gentler, valley with a wide mouth at the beach and a paved road following its right side for three-quarters of a mile into the center of Colleville-sur-Mer. This was Exit E-3. Except for the last few hundred yards into Colleville, the road grade is very gentle. Because this little valley is such a natural route inland from the beaches, it was heavily defended by the Germans. This exit served Easy Red and part of Fox Green.

Continuing east from Exit E-1 to the next draw, the bluffs are rather steep and lead to cultivated fields between Colleville and a smaller village, Cabourg. There were a few buildings along this stretch. This exit draw was designated F-1, and served the eastern half of Fox Green. It was a short, steep climb for about 550 yards to an elevation of 165 feet above mean sea level. This is a slope of about 14 percent, difficult for heavy vehicles though a dirt road of sorts ran along the west side of the draw to Cabourg.

From the eastern end of Fox Green to Port-en-Bessin the bluffs are very steep, rising about 200 feet above sea level. A little draw, about three miles east of F-1, leads inland toward Ste.-Honorine-des-Pertes, but it has no beach.

***

--19--

The morning of 6 June was wet and windy; seas were 3 to 6 feet. Launching and loading the landing craft started just after 0400. It was rough going; some boats got dropped or smashed. Some men were dumped into the ocean, and others got fouled in the cargo nets that the troops used to climb down the sides of the transports to the landing craft. Soldiers got very seasick after being in the rough-riding small craft for over two hours.

The beaches at Normandy are very flat, and the tidal range quite large, and these conditions had a dramatic effect on events. The approximate tide levels at Port-en-Bessin, from action reports and correlation with recent tide tables, were as follows:

| Low | High | Low | High | |

| Time | 0552 | 1052 | 1810 | 2306 |

| Height (ft.) | +3.1 | + 22.9 | + 4.1 | +22.9 |

(Above chart datum, extreme low water; Spring Range 19.8 ft.)

As the tide would rise about 20 feet between 0600 and 1100 on 6 June, by 0900 it would be going up at more than an inch every minute. This was helpful for retracting landing craft, but dangerous for soldiers taking cover on the beach from German gunfire.

From the tide levels it is clear the initial landings would beach several hundred yards below the high water mark. Shoreward was a seawall of sorts; beyond it the ground rose toward the fields and hedgerows of Normandy. Heavy smoke and dust from the bombardment had settled over the landing beaches by H-hour, 0630. To this was added a planned smokescreen in the 2-mile area between the landing craft line of departure — the "jumpoff" point from which they began their final assault run — and the beaches. The boat coxswains could not see landmarks after leaving the line of departure. Some were good at compass steering, but not well briefed on the strong tidal current running west-to-east along the beach. Others simply followed the boat ahead. The problem of smoke was worse on the eastern beaches. The destroyers were not much bothered; they had radar and a dry place from which to navigate.

--20--

III

Assault in the Morning

About 1800 on 5 June Doyle and Emmons escorted the Canadian sweepers of Minesweeping Flotilla 31 into the Seine estuary. Sunset was at 2206. The force was keeping Zone B Time, British Double Summer Time. After dark the small dan-buoys marking the swept channel showed feeble white lights to guide the amphibious vessels toward the beaches. At about 0400, after the minesweepers had cleared Fire Support Area 4, Harding and Baldwin (DD 624) joined, with British destroyers Tanatside and Melbreak. To the right of the boat lane in Fire Support Area 3 McCook, Satterlee (DD 626), and Carmick screened British sweepers of Minesweeping Flotilla 4; Thompson and HMS Talybont protected the rear. When the sweepers finished, the destroyers took station in Area 3.

Harding's first log entry for 6 June 1944 read: "0000. Ahead of USS ANCON, guide."

Carmick, close to the beach, noted that "by midnight the seas were calm, the wind force J, visibility four to six thousand yards, sky partially overcast, with a rising full moon." Captain Beer announced on the 1MC public-address system: "Now hear this. This is probably going to be the biggest party you boys will ever go to. So let’s all get out on the floor and dance." (Ryan, 162)

On board Doyle a visiting reporter from Yank, the Army news magazine, wrote that "since midnight we had watched the prelude to the big show ... First came the Pathfinders [lead planes that marked target areas with flares]. ... I watched five separate air attacks, each lasting not more than ten minutes." (Bernard)

--21--

| 0230: | On board Thomas Jefferson, about 12 miles offshore, assault troops began climbing down into LCVPs, 36-foot plywood-hulled landing craft. "The process ... was rendered difficult by the choppy seas, which caused some minor delays ... Thomas Jefferson was able to unload all its craft in 66 minutes." (Omaha Beachhead, 38) |

| 0430: | Thomas Jefferson's landing craft departed for Omaha Beach. Thompson noted "intense aerial bombardment of Point[e] du Hoc area taking place." At 0500 a "plane exploded and crashed. ..." |

| 0515: | Norwegian Destroyer Svenner, in the British beachhead area, tried to turn into a German E-Boat torpedo spread but didn’t quite make it. She was one of the first naval casualties; more would come later.1 |

____________

1. The first Allied naval casualty of Operation Neptune was the American minesweeper Osprey (AM 56), lost to a mine in the Channel on 5 June.

Just after 0530 the surface-ship war started. The French light cruiser Montcalm, anchored about 7,500 yards off the beach, opened fire first. It was both fitting and sad, for the French sailors were firing at their own homeland. Doyle and Emmons came under fire from enemy artillery around Port-en-Bessin and promptly fired back, with Harding and Baldwin joining in. And the Yank reporter in Doyle wrote, "German 155mm rifles, far on the left flank, were pumping shells around the pre-invasion task force, raising towers of foam ominously close." (Bernard)

Doyle identified the German guns as 75mm or 88mm, and located the battery west of Port-en-Bessin. Emmons, on the other hand, reported it to the east of the port. Harding reported that the guns were 155mm. The hand-drawn chart enclosed with Doyle's action report showed batteries in both places. These guns fired again later in the day, and the destroyers returned fire.

| 0530: | "One of the control vessels for Dog Beach drifted off station, which may explain some of the later troubles of approach in that sector. The fact that all the mislanded craft were east of their targets points to the tidal current as a contributing factor." (Omaha Beachhead, 40) |

There were no casualties among the British and Canadian minesweepers, nor among the Omaha Beach destroyers.

* * *

--22--

The scheduled prelanding shore bombardment, for which DESRON 18 had trained so intently, started on schedule at 0550. The ships were not in close formation. They were strung out in a loose column, slowly steaming west against the tidal current flowing parallel to the beach.

| 0548: | Satterlee reported: "Commenced firing ... (on) targets in the vicinity of Pte du Hoc, range approximately 5,000 yards." |

Satterlee and Talybont were at Pointe du Hoc to support the landing of the U.S. 2d and 5th Rangers. On the western end of Omaha Beach in Fire Support Area 3, from west to east, the order was Thompson, McCook, and Carmick. Their targets were in the area from the Pointe de la Percee across the Dog beaches to the bluffs behind Easy Green. On the east side Tanatside was in the lead off Fox Green, followed in order by Emmons, Baldwin, Harding, Doyle, and Melbreak. The positions of the ships corresponded to their assigned targets so one ship would not be firing across another’s line of fire. The first four ships were assigned targets along Easy Red and Fox Green; Doyle's target was in the cliff overlooking the Fox Red beach exit, and Melbreak was assigned the crossroads in the village of Sainte Honorine. Texas, Arkansas, Glasgow, Montcalm, and Georges Leygues fired over the heads of the DDs at German artillery batteries behind the beach.

| 0555-0614: | 329 Eighth Air Force B-24 Liberator heavy bombers drop over 13,000 bombs on the invasion area. Overcast compelled the bombers to attack on instruments, guided by Pathfinders, and the drop zone was shifted inland to avoid hitting the landing craft. Bombs fell in the rear areas, and had little effect on beach defenses. (Omaha Beachhead, 42) |

Baldwin somehow found herself in the boat lanes at 0617, leading the charge for the beaches, and "firing guns 1 and 2 in assigned area and ahead of troops."

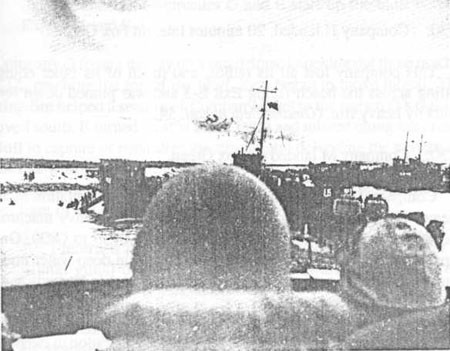

At 0625 bombardment ceased as planned. Support craft — British LCTs converted to fire salvos of 5-inch rockets and called LCT(R) — sent off their barrages. The seagoing Sherman DD tanks were right behind them, and by 0630 48 troop landing craft were closing the beaches.

The infantry companies in the first wave came in by boat sections, six boats — LCVPs or LCAs — to a company, with company headquarters sections due to land at 0700 in the next wave. The landing craft carried an average of 31 men and one officer, with a section leader and five riflemen in the bow. They were followed by a wirecutting team of four men to clear

--23--

--24--

--25--

the way through beach entanglements. Behind these were two BAR (Browning Automatic Rifle) teams of two men each, two bazooka [light antitank rocket launcher] teams, a four-man mortar team with a 60mm mortar, a two-man flamethrower crew, and five demolition men with TNT charges. A medic and assistant section leader sat in the stern. (Omaha Beachhead, 43)

During 35 minutes of prelanding bombardment the battleships and cruisers, DESRON 18, and the three British destroyers unloaded about

3,000 rounds on designated targets. Most of these had been located and identified from aerial photos. Cornelius Ryan notes that Major Werner Pluskat of the recently arrived 352d Division was surprised to find that the heavy shelling had not hit any of the twenty guns of the four divisional artillery batteries he commanded, emplaced in positions about half a mile behind the coast. Pluskat wondered if the naval gunners were shooting at observation posts under the impression that these were gun positions. (Ryan, 200)2

___________

2. The 352d Division’s artillery batteries were only part of what Ryan calls "the deadly guns of Omaha Beach": "There were 8 concrete bunkers with guns of 75 millimeters or larger caliber [75mm to 88mm]; 35 pillboxes with artillery pieces of various sizes and/or automatic weapons; 4 batteries of artillery [presumably Pluskat’s]; [about] 18 antitank guns [37mm to 75mm]; 6 mortar pits; 35 ["About 40" (Omaha Beachhead, 25)] rocket-launching sites, each with four 38-millimeter [32-centimeter] rocket tubes; and no less than 85 machine gun nests" (Ryan, 199n).

The only action reports that spoke to the scheduled aircraft bombing was McCook's entry at 0447, "Heavy bombing of beach defenses commenced." None of it, however, hit the beaches at Omaha. It is clear, from the events that followed, that the 35 minutes of naval artillery firing at intelligence- and reconnaissance-generated targets didn’t work either.

* * *

At H-hour real trouble started. Landing craft coxswains lost their bearings in the morning mist, deepened by smoke and dust kicked up by the bombardment. Many of them missed their assigned landing sectors. Of the 64 DD tanks, 27 made it to the Dog beaches but only five got ashore on the Easy beaches; the rest foundered on the way in.

"Naval gunfire had practically ceased when the infantry reached the beach; the ships were under orders not to fire, unless exceptionally definite targets offered, until liaison was established with fire control parties. Lacking this liaison, the destroyers did not dare bring fire on the strongpoints through which infantry might be advancing on the smoke-obscured bluffs." (Omaha Beachhead, 57)

The Special Engineer Task Force, made up of Navy underwater demolition teams and the 299th Army Engineers, methodically went about their business of blowing holes in the beach obstacles, but lost nearly half their numbers to German gunfire. The Army’s narrative notes that "casualties ... ran to 41 percent for D Day, most of them suffered in the first half-hour." (Omaha Beachhead, 42)

--26--

| 0708: | "Second Ranger Battalion landed at Pte du Hoc." (Satterlee action report) |

| 0710: | "... machine gun fire directed at this ship. Commenced firing ... at pillbox in vicinity of Pte du Hoc." (Satterlee action report) |

| 0710: | "... the first boat of the 2d Rangers ... to attack Pointe du Hoe [sic] landed ... to the east of the point. These boats were forty minutes late in arriving ... due to ... additional distance of transports ... and ... slow progress by the heavily loaded boats into wind and sea. Wind ... from ... West force ... (10-15) knots, sea ... from the west waves (2-4) feet high and moderate swells from North North West. Five ... or ... six out of the ten ... boats foundered ... between one ... and two ... hundred yards from the beach. Most of the Rangers ... reached the beach." (COMDESDIV 36 action report) |

| 0715: | "The fortifications at Pointe du Hoe [sic] had been under heavy fire ... to H minus 05 minutes. However this fire had been lifted according to schedule and when the Rangers landed fortyfive [sic] minutes later the Germans had filtered back into the fortifications and were waiting for them with machine guns, mortars, rifles and hand grenades. ... As the Rangers landed they found themselves pinned under the cliffs and were being rapidly cut to pieces. ... I immediately ordered SATTERLEE to close the point and take the cliff tops under ... fire. ... Her fire control was excellent and the |

--27--

| Rangers were enabled to establish a foothold on the cliff top. [Satterlee established communications with the Ranger shore fire control party at 0728.] As their Shore Fire Control Party advanced inland the remainder of the Rangers established communication with SATTERLEE by light and were thus enabled to rapidly call for close support fire. By this means SATTERLEE and later THOMPSON and HARDING were able to repel several enemy counter-attacks which otherwise would have wiped out this Ranger Battalion. ... The gallant fight of ... our Rangers against tremendous odds and difficulties was an inspiration to all naval personnel fortunate enough to witness this phase of the battle. The Rangers were magnificent." (COMDESDIV 36 action report) | |

| 0732: | "Commenced firing on targets designated by SFCP, initial range 2,600 yards." (Satterlee action report) |

Meanwhile—

| 0720: | Companies A & B, 2d Ranger Battalion, landed at their alternate objective on Dog Green behind the 1st Battalion Landing Team of the 116th Infantry Regiment, and were soon in trouble. |

These Ranger units were awaiting orders to back the assault at Pointe du Hoc. When nothing was heard after 15 minutes they followed their alternate orders to land at Charlie Beach and proceed up Exit D-1 toward Vierville. Approaching the beach, Lieutenant Colonel Max F. Schneider, 2d Ranger Battalion, saw conditions on the beach — Companies A and B of the 116th were scattered and taking losses—and ordered the Ranger boats to move further east. Even so, the boats carrying these Rangers came in on the east edge of Dog Green, and two landing craft were lost.

The two Ranger companies totaled about 130 officers and men; 62 reached the seawall. "Only a few hundred yards further east ... 13 out of the 14 craft carrying the 5th [Ranger] Battalion touched down close together, in two waves ... The 450 men of the battalion got across the beach and up to the sea wall with a loss of only 5 or 6 men to scattered small-arms fire." (Omaha Beachhead, 53)

| 0729: | Corry, her back broken, sank off Utah Beach. Twenty-two of her crew were lost, 33 more were wounded. (Roscoe, 349-50) |

| 0730: | "HMS TALYBONT departed [the beachhead area] (for screen duty) in accordance with previous instructions." (COMDESDIV 36 action report) |

With the 116th RCT—

| 0630: | The 743d Tank Battalion landed. (Omaha Beachhead, 42) |

The 743d brought its M4 tanks to the beach in LCTs. Company B landed on Dog Green at the mouth of the Vierville raw and was hit by German artillery. The battalion commander’s LCT was sunk off the beach, and all other officers but one lieutenant were illed or wounded. Eight of Company B’s 16 tanks landed and opened fire on the German defenses. Tanks of Companies A and C landed in good order to the east on Dog White and Dog Red. (Omaha Beachhead, 42)

| 630: | "Word received from OTC that some ships were firing into our own troops and for these ships to cease fire." (Carmick action report) |

| 0636: | Company A of the 116th Infantry Regiment landed as planned on Dog Green. (Omaha Beachhead, 45) |

Under fire within a quarter-mile of the shore, the infantry met their worst experiences just after touchdown. Small-arms fire and artillery concentrated on the landing areas. The worst was from converging fires from automatic weapons. Survivors reported hearing the fire beat on the ramps of the landing craft before they were lowered, and then seeing the hail of bullets whip the surf. (Omaha Beachhead, 44)

Several hundred yards of bluff west of exit D-3 (Dog Red) were obscured by heavy smoke from grass fires, apparently started by naval shells or rockets. Because of smoke, enemy guns were unable to deliver effective fire on that end of Dog Beach. (Omaha Beachhead, 45)

"One of the six LCAs carrying Company A foundered about a thousand yards offshore, and passing Rangers saw men jumping overboard and being dragged down by their loads. At H+6 minutes the remaining craft grounded in water 4 to 6 feet deep, about 30 yards short of the outward band of obstacles. Starting off the craft ... the men were enveloped in accurate and intense fire from automatic weapons. Order was quickly lost as the troops attempted to dive under water or dropped over the sides into surf over their heads. ... In short order every officer of the company ... was a casualty, and most of the sergeants were killed or wounded. The leaderless men gave

up any attempt to move forward and confined their efforts to saving the wounded, many of whom drowned in the rising tide. ... Fifteen minutes after landing, Company A was out of action for the day. Estimates of its casualties range as high as two-thirds." (Omaha Beachhead, 45-47)

| 0638: | "First landing craft containing men and material made landing on beach. Enemy lire severe from unknown points." (McCook action report) |

| 0640: | Company E of the 116th came ashore. This company missed the assigned beach — Easy Green and the western half of Easy Red — entirely and came ashore far to the eastward, some of its landing craft intermingled with units of the 16th RCT on Fox Green. (Omaha Beachhead, 47) |

Company F landed, almost on target, on Dog Red and Easy Green. They came ashore in front of the strong defenses of Exit D-3, the Les Moulins draw. Part of the company was screened by smoke, but lost their officers getting ashore; others, unprotected by smoke, took 45 minutes to get across the beach under heavy fire, losing half their numbers. (Omaha Beachhead, 47)

| 0647: | "German Shore Battery opened fire on this ship. 0650 German Shore Battery silenced by the main battery of this ship." (Carmick deck log) |

| 0650: | "Instead of coming in on Dog White, Company G landed in scattered groups ... [on Easy Green, leaving an unplanned thousand-yard gap between them and Company A]. The ... boat sections nearest Dog Red, where smoke from grass fires shrouded the bluff, had an easy passage across the tidal flat. ... Further east on Easy Green, the other sections of Company G met much heavier fire as they landed, one boat team losing 14 men before it reached the embankment." (Omaha Beachhead, 47) |

| 0700: | The first assault wave had failed. By this time Company A had been cut to pieces at the water’s edge. Company E was lost, and finally landed in the 16th RCT zone. Company F was disorganized by heavy losses, and scattered sections of Company G were trying to move along the beach to their assigned sectors. (Omaha Beachhead, 47) |

--30--

The later waves did not come in under the conditions planned for their arrival. The tide began flowing into the obstacle rows at 0700 and covered them by 0800 after the tide rose 8 feet. Obstacles were gapped in only a few places. The defense was not neutralized, and no advances had been made beyond the shingle. Mislandings continued. (Omaha Beachhead, 49) Company B of the 116th was scheduled to land on Dog Green. One section of Company B landed behind Company A and came under the same destructive fire that had wrecked Company A. Remnants of both companies mingled and struggled to survive. (Omaha Beachhead, 50) Company H landed, badly scattered. The 1st Machine-Gun Platoon and two mortar sections landed on Easy Red. Other segments of the company landed on Dog Red and Easy Green with heavy casualties. (Omaha Beachhead, 51)

| 0700: | Headquarters of the 2d Battalion of the 116th landed under heavy fire on Dog Red. |

The Battalion Commander was among the first ashore, and set to work trying to organize leaderless troops on the beach. Until about 0800 he had no radio and could not communicate with the scattered elements of his battalion. (Omaha Beachhead, 51)

| 0710: | Company C, scheduled for Dog Green, landed on Dog White. |

| 0716: | "Field gun observed firing on beachhead from approximately [map coordinates] 636928 [Pointe de la Percee], Commenced firing. ... 0755 Ceased fire on above target. Target destroyed." (Thompson action report) |

| 0730: | Company D, scheduled to land at 0710 on Dog Green, landed in scattered fashion and at various times on Dog Green and Dog Red. (Omaha Beachhead, 50, Map VI) |

To complete the disaster, the Headquarters Company of the 1st Battalion Landing Team, and Beachmaster unit for Dog Green, landed on Charlie Beach and lost from a half to two-thirds of their strength to small-arms fire crossing the tidal flat to cover under the cliffs. Sniper fire pinned them there most of the day. (Omaha Beachhead, 50)

--31--

| 0730: | Assault units were now lined up along the whole of the 116th Infantry Regiment’s portion of the landing beach. (Omaha Beachhead, 53) |

"Five of the eight companies of the 116th RCT had landed with sections well together and losses relatively light. ... The weakest area was in front of Exit D-1; Dog Green, the zone of the 1st BLT, had almost no assault elements on it capable of further action." (Omaha Beachhead, 53)

| 0730: | "Regimental command parties began to arrive. The main command group of the 116th RCT came in on Dog White. ... From the standpoint of influencing further operations, they could not have hit a better point in the 116th zone. To their right and left, Company C and some 2d Battalion elements were crowded against the embankment on a front of a few hundred yards, the main Ranger force [5th Ranger Battalion] was about to come into the same area, and enemy fire from the bluffs just ahead was masked by smoke and ineffective. The command group was well located to play a major role in the next phase of action." (Omaha Beachhead, 53) |

The entire 3d Battalion of the 116th landed together about 10 minutes late, and east of their intended beaches. Only a handful of troops from the first wave had landed on Easy Green and the west half of Easy Red, part of the 16th RCT’s zone. With the 3d BLT ashore the beach was now fairly crowded. German small-arms fire was light. Despite few casualties, men tended to become immobilized after reaching shelter and reorganization was delayed because boat sections were mixed up. Sections landed on top of different units. Company M landed together, further east on Easy Red, but troops were tired after spending time in the cramped landing craft. Enemy fire was more intense from the strong points above Exit E-1. The company made the move toward the embankment as a body. Said one survivor, "the company learned with surprise how much small-arms fire a man can run through without getting hit." (Omaha Beachhead, 52)

| 0740: | LCI(L)-91, approaching Dog White, is struck by artillery fire. |

Disaster struck LCI(L)-91, carrying the backup headquarters unit of the 116th RCT Hit by artillery fire as she tried to get through the beach obstacles, she backed off and tried again. As she dropped her ramps a shell, or incendiary rocket, hit forward, killing everyone in the forward compartment. A sheet of flame went up. Five minutes later LCI(L)-92, approaching the same beach area,

--32--

had her fuel tanks set off by an underwater explosion. The two LCIs burned for hours. (Omaha Beachhead, 56)

| 0750: | Company C started toward the bluff between Exits D-1 (Vierville) and D-3 (Les Moulins). (Omaha Beachhead, 59) |

The first penetration on Dog White was made by Company C, of the 116th, and the 5th Ranger Battalion. Reorganization was spurred by Brigadier General Norman D. Cota, deputy commander of the First Infantry Division. Between Exits D-1 and D-3 the bluffs were steep and bare, but the climbing men found small folds and depressions for protection against small-arms fire. (Omaha Beachhead, 60)

Smoke gave protection. Empty trenches were found along the crest, and the troops then went ahead into flat, open fields and stopped as they took scattered machine-gun fire at some range from their flanks. Captain Berthier B. Hawks, the company commander, had a foot crushed coming ashore, yet climbed to the top of the bluffs with his men. (Omaha Beachhead, 62)

| 0810: | Rangers advanced across the beach road at Dog Green. |

The first groups up, a platoon of Company A and some men of Company E, went straight inland on a front of less than 300 yards. (Omaha Beachhead, 62)

| 0810: | "SFCP contact, asked for fire in area of T5. Ranging salvo was fired at a range of 17,000 yards, then unable to [hold] contact [due to] transmitter trouble on their part." (Carmick war diary) |

| 0830: | Carmick breaks the cease-fire order that had suspended supporting gunfire at H-Hour. |

"Early in the morning a group of tanks were seen to be having difficulty making their way along the breakwater road toward Exit D-1 [the Vierville draw]. A silent cooperation was established wherein they fired at a target on the bluff above them and we then fired several salvos at the same spot. They then shifted fire further along the bluff and we used their bursts again as a point of aim." (Carmick action report)

| 0830: | Rangers reached bluff top; last elements of assault troops left the sea wall. |

--33--

Other platoons were on top of the bluffs by 0830 and stopped to organize. Company D platoons had to clean out a few Germans from the trenches along the edge of the bluff, knocking out a machine gun. German mortars began to range in on the slope, knocking down General Cota and his aide and killing two men nearby. Just east of Dog White the beachhead was widened before 0900 by small parties from Companies F and B. (Omaha Beachhead, 62)

| 0830: | Elements of Company G arrive on Dog White. |

Four boat sections of Company G had arrived in fair condition on Easy Green at about 0700. Moving around other troops as they slowly headed westward under fire toward Dog White, units gradually got scattered and lost cohesion. Only fragments of Company G finally reached Dog White after the main action on that beach was over. The 2d BLT commander, Major Sidney Bingham, got some 50 men from Company F across the beach to attack Les Moulins. Their M1 semiautomatic rifles had gotten clogged with sand, and the troops could not put enough rifle fire on the German defenses. Bingham managed to get a squad most of the way to the top of the bluff east of Exit D-3, just across the mouth of the draw from Les Moulins, but they were unable to knock out a machine gun nest at the top of the bluff and had to withdraw. (Omaha Beachhead, 52)

| 0839: | "Commenced firing on pillbox which was delivering fire against beach. 0852 Ceased firing on pillbox - range fouled by Patrol craft. 0854 Commenced firing. 0858 Ceased firing. Pillbox demolished by direct hits." (McCook action report) |

| 0850: | "HMS TANATSIDE left Fire Support Area (previous orders to return to the screen)." (COMDESDIV 36 action report) |

An explanation is in order to account for the British "Hunt" class DDs being ordered to the outer screen so early in the assault. The reader will recall they were 1,087-tonners with 4-inch main battery guns, excellent ships for anti-E boat work and for ASW [antisubmarine warfare]. However, they lacked the modern fire-control computers and radar-equipped, gyro-stabilized gun directors that the Gleaves class had. The Brits had to be able to see their targets, while the Americans could deliver blind fire on map coordinates given by the shore fire control parties. This was an important distinction after the initial bombardment was completed.

--34--

| 0900: | Elements of Companies K, I, and L advance to the top of the bluff between Exits D-3 (Les Moulins) and E-1 (Vierville). |

Sections of Companies K and I were together on Easy Green; L and M were more scattered and to the east, on Easy Red.

"Since each boat team was supposed to make its own way past the bluffs to a battalion assembly area about a mile inland, no attempt was made to organize the companies for assault, and forward movement was undertaken by many small groups starting at different times, acting independently, and only gradually coming together as they got inland by different routes and with different rates of progress." (Omaha Beachhead, 63)

No resistance was met at the top of the bluff, where troops came out in open ground extending toward the village of St.-Laurent. Some took shelter behind a hedgerow some 200 yards from the bluff. Company K lost 15 to 20 men getting to the top shortly after 0900. Most of Company M’s boat sections landed together near the Exit E-1 strongpoints and came under heavy fire. They set up four machine guns and two heavy mortars in a gully and engaged German gun emplacements near Exit E-1. (Omaha Beachhead, 65)

* * *

It is clear from this record that by 0900, two hours after the third assault wave landed in the 116th RCT half of Omaha Beach, many units of infantry had reached the top of the bluffs and penetrated inland between Vierville and St.-Laurent. The destroyers had held their fire, as ordered, except when clearly seen targets were attacked with 5-inch fire, usually in response to some indication of need from the troops ashore. It was also becoming clear, however, that the overall situation on the beach was difficult. While the infantry moved inland, the support troops were bogged down with wrecked and damaged vehicles, tanks and artillery. The beachmaster would not have matters under control until later in the afternoon. Two LCIs were ablaze.

* * *

With the 16th RCT—

| 0630: | "Commenced indirect fire on target No. 2 intended to aid in clearing beach exit [Exit E-3, Fox Green] now completely obscured by smoke and dust." (Doyle action report) 741st Tank Battalion landed on Easy Red and Fox Green. |

--35--

"In the 16th RCT zone, only 5 of the 32 DD tanks (741st Tank Battalion) made shore; of Company A’s 16 standard tanks, 2 were lost far off shore by [sic] an explosion of undetermined cause, and 3 were ... put out of action very shortly after beaching. The surviving third of the battalion landed between E-1 and E-3 draws and went into action at once against enemy emplacements." (Omaha Beachhead, 42)

| 0650: | "Ceased fire. Total ammunition expended to present time — 364 rounds of 5"/38 caliber common" [common projectiles were general-purpose shells, capable of penetrating light armor and designed to attack shore and surface targets by blast and fragmentation]. (Doyle action report) |

Five sections of Company F, scheduled for Easy Red, landed on Fox Green intermingled with Company E of the 16th and Company E of the 116th.

These five boat sections were scattered from Exit E-3 to a point 1,000 yards east. Two sections landed together in front of the E-3 strongpoints. Mortars and machine guns downed about a third of the men before they could get as far as the shingle. Further east, the other three sections did no better; seven men from one landing craft made it to the shingle. Two of Company F’s officers survived the landing. (Omaha Beachhead, 48)

| 0700: | Company G, in the second wave, landed on Easy Red on target. |

The company landed in good order, but suffered most of its 63 casualties between boats and the shingle bank. They came in on top of three sections left from the first wave, one from Company E of the 16th RCT and two from Company E of the 116th. (Omaha Beachhead, 54)

| 0700: | Company K, in the second wave, landed on Fox Green. |

Elements of five companies were already ashore on Fox Green, scattered except for Company L. Company K, arriving at 0700, added to the mix with six sections, bunched in two groups that were not in contact with each other for some hours. Company K took 53 casualties on the beach.

| 0705: | Company L, scheduled for Fox Green, landed on Fox Red. |

Company L’s landing craft were carried eastward by the current, and landed 30 minutes behind schedule on Fox Red instead of in front of Exit

--36--