The Navy Department Library

Market Time (U)

CRC280

CENTER FOR NAVAL ANALYSES

1401 Wilson Boulevard

Arlington, Virginia 22209

Operations Evaluation Group

By: Judith C. Erdheim

September 1975

Prepared for:

Office of Naval Research

Department of the Navy

Washington, D.C. 20350

Office of Chief of Naval Operations (Op03)

Department of the Navy

Washington, D.C. 20380

Table of Contents

| Page | |||

| Foreword | iii | ||

| Summary | iv | ||

| Background | 1 | ||

| NVN Resupply System | 1 | ||

| Group 125 Infiltration | 1 | ||

| WBLC Infiltration | 2 | ||

| Coastal Transshipment | 3 | ||

| Other Seaborne Resupply | 3 | ||

| Pre-Market Time Vietnamese Coastal Surveillance | 4 | ||

| First Trawler Infiltration Era: February 1956-March 1968 | 8 | ||

| Market Time under the Seventh Fleet and NAG | 8 | ||

| Planning the Operation | 8 | ||

| Assignment of Forces | 8 | ||

| Building Up an Intelligence Capability | 16 | ||

| TF 115 Established | 18 | ||

| Setting Up Barriers and Increasing Force Levels | 18 | ||

| Search Tactics | 21 | ||

| Arrival of PCFs | 22 | ||

| Enemy activity | 23 | ||

| Market Time under ComNavForV | 24 | ||

| Multitrawler Infiltration Attempt Following Tet | 26 | ||

| Market Time Status at NavForV Takeover | 27 | ||

| Secondary Market Time Missions | 28 | ||

| Naval Gunfire Support (NGFS) | 28 | ||

| Psychological Operations | 28 | ||

| Coastal Surveillance Operations | 29 | ||

| Turnover of Market Time Assets to VNN | 31 | ||

| Pause in Trawler Infiltration Activity: March 1968 to August 1969 | 34 | ||

| Enemy Resupply | 34 | ||

| Coastal Surveillance Operations | 34 | ||

| CTF 115 Becomes More Aggressive | 37 | ||

| Second trawler Infiltration Era: August 1969-April 1972 | 40 | ||

| Increase in Seaborne Infiltration Attempts | 40 | ||

| NVN Coordinating Units | 40 | ||

| Progress of Vietnamization | 41 | ||

| Penetration Exercises | 42 | ||

| Covert Surveillance | 44 | ||

| SL-8 Trawlers | 44 | ||

| Other Enemy Activity | 45 | ||

| Cloud Concept | 45 | ||

| New Air Patrols | 48 | ||

| Photoreconnaissance | 50 | ||

| Change in Priorities | 50 | ||

| Enemy Seaborne Infiltration and Transshipment Activity | 50 | ||

| Status of Vietnamization | 52 | ||

| Final Stage: May 1972-January 1973 | 54 | ||

| Progress of Vietnamization | 54 | ||

| Conclusions | 56 | ||

| Bibliography | 57 | ||

| Appendix A - Characteristics of VNN PCE and PGM | A-1--A-2 | ||

| Appendix B - Characteristics of Surface Craft Assigned to Market Time | B-1--B-6 | ||

| Appendix C - Characteristics of VP Aircraft assigned to Market Time | C-1--C-3 | ||

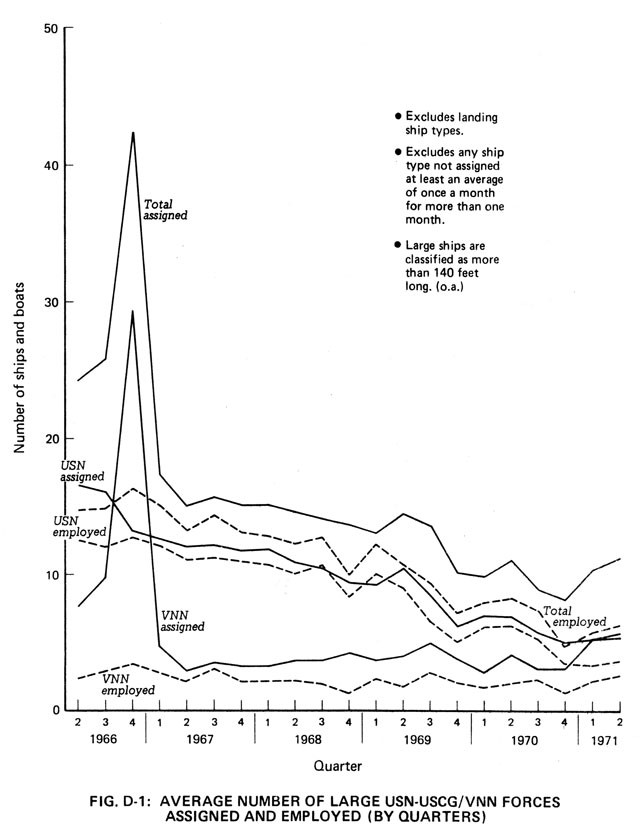

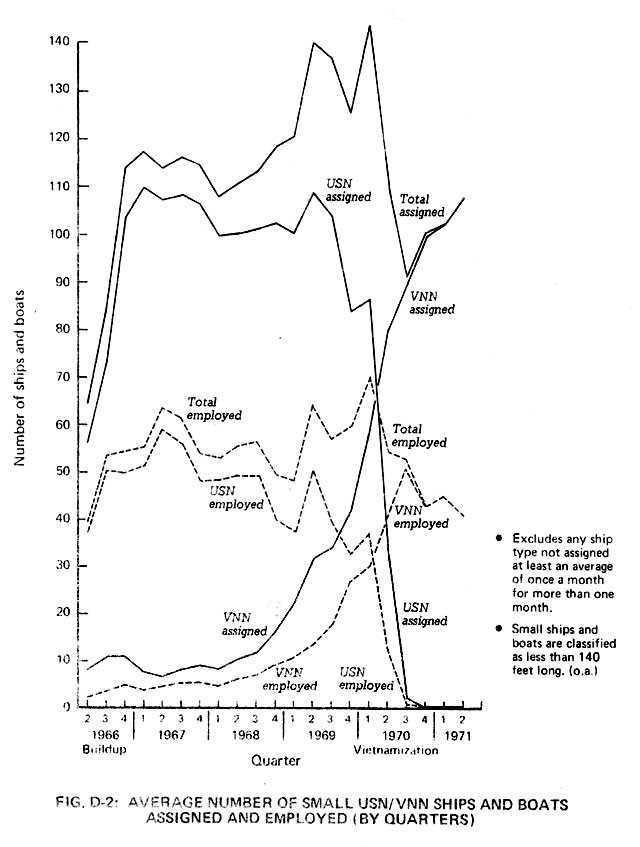

| Appendix D - Market Time Surface Craft Force Levels | D-1--D-5 | ||

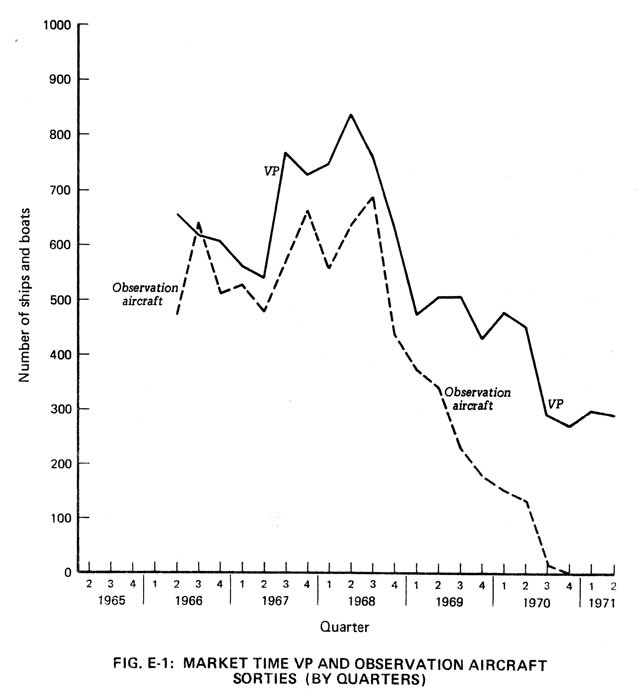

| Appendix E - Market Time Aircraft Force Levels | E-1--E-3 | ||

| Appendix F - Group 15 Inventory and Trawler Characteristics | F-1--F-3 | ||

| Appendix G - Trawler Infiltration Attempts | G-1--G-3 | ||

| Appendix H - Suspected Merchant Ship Smuggling on Mekong River | H-1--H-4 | ||

| Appendix I - Rules of Engagement | I-1--I-15 | ||

| Appendix J - Major Findings from Market Time Questionnaire | J-1--J-2 | ||

--i/ii--

FOREWORD

In addition to the documents listed in the bibliography appearing at the end of the main text, this research contribution is based on interviews and correspondence with Market Time participants; responses to a questionnaire prepared by the author; COMNAVFORFIVE, CINCPACFLT, CINCPAC, COMSEVENTHFLT, and CTF 115 message traffic; fact sheets; command histories; NAVFORFIVE in-house working papers, memoranda, and drafts of briefings and studies; and information provided by CIA and DIA.

Most of this information (except that provided by the intelligence agencies) can be found in the Vietnam Command Files and the COMNAVFORFIVE Provenance Files at the Naval History Division Archives. The author expresses her appreciation to Oscar Fitzgerald of the Naval History Division for his patience and help in using these files. The author, of course, assumes full responsibility for her interpretations of these documents.

--iii--

SUMMARY

Market Time was established in March 1965 as a coastal surveillance operation to prevent seaborne infiltration of supplies from North Vietnam (NVN) into South Vietnam (SVN). The objectives of the operation were soon expanded to include prevention of coastal transshipment of enemy supplies within SVN.

This research contribution summarizes Market Time in terms of the threat, the U.S. Navy-Coast Guard/Vietnamese Navy (VNN) response to the threat, limitations that might have affected this response, and the operation's effects on the enemy. The discussion includes the enemy's need for re-supply, possible infiltration routes, the potential for seaborne infiltration, and known infiltration. Secondary missions of Market Time such as naval gunfire support (NGFS) are examined only as they affected Market Time's coastal surveillance mission.

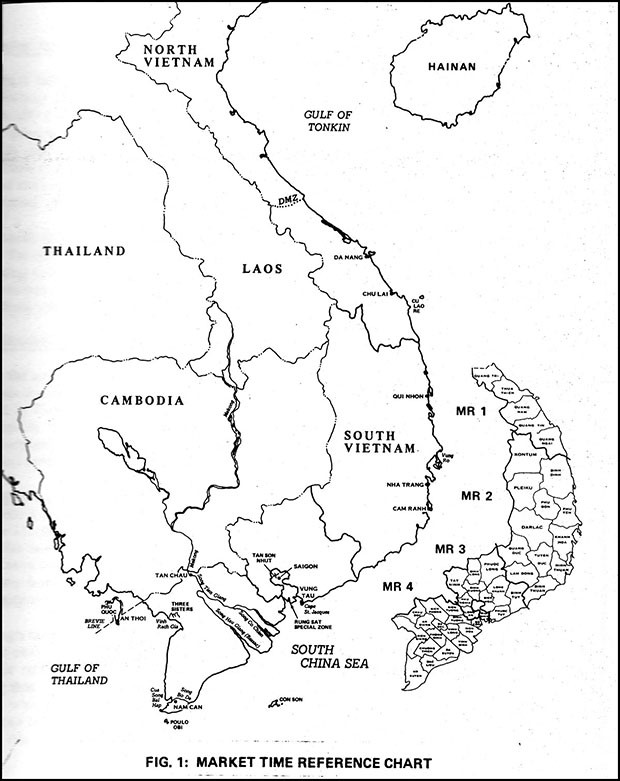

There were several methods of seaborne infiltration facing market Time. Trawlers under the control of NVN Naval Transportation Group 125 would either infiltrate directly over a beach or off-load onto sampans and junks several miles offshore. Trawlers were capable of carrying 100 to 400 tons of cargo. Waterborne logistic craft (WBLC) infiltrated below the 17th parallel to Military Region (MR)-1 of SVN (Figure 1); and enemy trans-shipment was done by small boats within SVN coastal waters. These small craft would mingle with the thousands of similar boats used for fishing and transportation along the coast of SVN.

Major Phases of Trawler Infiltration Activity

Enemy seaborne infiltration as perceived by U.S. forces can be divided into five major phases of trawler infiltration activity:

Pre-Market Time infiltration (1962-1965).

First trawler infiltration era (February 1965-March 1968).

Pause in trawler infiltration attempts (March 1968-August 1969).

Second trawler infiltration era (August 1969-April 1972).

Wrap-up (April 1972-January 1973 cease-fire).

Knowledge of the enemy's seaborne infiltration activity before March 1965 is very sketchy. Enough is known, however, to establish the Mekong Delta as the focus of pre-Market Time seaborne infiltration.

--iv--

--v--

First Trawler Infiltration Era

The first infiltration era dates back to the February 1965 discovery of a trawler that had successfully infiltrated Vung Ro Bay. During this era, trawler infiltration attempts focused on MR-1 and--2 as well as the VC-infested Delta region in southern SVN (MR-4). There had been an influx of North Vietnamese army (NVA) main forces into MR-1 and--2 during 1965, and attempts were made to resupply those troops from the sea. These attempts were crisis-oriented; 8 of 12 trawlers between March 1965 and March 1968 approached the coast even through they must have realized they were under surveillance. All were either totally or partially destroyed.

The North Vietnamese attempt to land four trawlers simultaneously in February 1968, after the Tet offensive, was the best example that the enemy was responding to a crisis by attempting to resupply his forces rapidly from the sea. Market Time forces destroyed three of the trawlers; the fourth aborted its mission. Large amounts of medical supplies were salvaged from one of the destroyed trawlers.

Hiatus in Detected Trawler Infiltration Attempts

After the unsuccessful four-trawler effort in March 1968, no trawler infiltration attempt was detected by Market Time for a year and a half. By 1968, Market Time was considered by Commander, Naval Forces Vietnam (COMNAVFORFIVE) and Commander, Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (COMUSMACFIVE) to be an effective deterrent against seaborne infiltration. It could have been that the disastrous March attempt to land four trawlers had forced the enemy to reconsider alternate resupply routes.

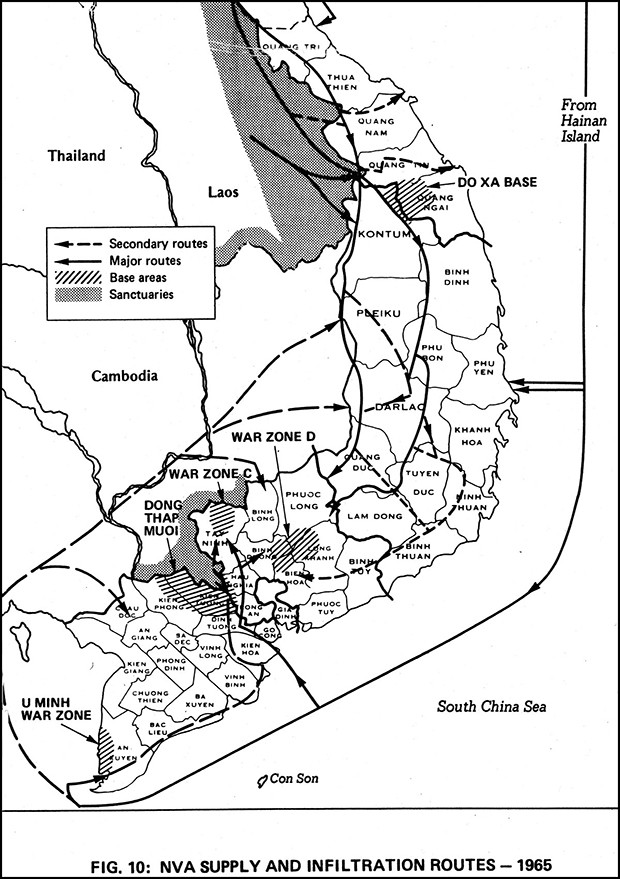

During this period, the North Vietnamese were using Cambodia as a base area to resupply MR-3 and -4 and southern MR-2 in SVN. From October 1966 through July 1969, there were 11,000 to 19,400 tons of military supplies delivered by Chinese ships to Sihanoukville destined for VC and NVA elements. Although direct delivery to SVN by sea would have been far simpler than the Cambodian route, Sihanoukville was open while Market Time hindered seaborne infiltration. The VC/NVA therefore turned to Cambodia as a resupply route to southern SVN.

Although many Market Time participants felt that no trawler evaded the barriers during that year-and-a-half hiatus, later information suggests that it would have been possible for an infiltrator to evade detection. But there is no intelligence information suggesting that any such infiltration occurred between March 1968 and August 1969. In any event, with free access to Cambodia, there was no critical need for the enemy to use seaborne infiltration for southern SVN. MR-1 and -2 wee taken care of by the overland route (Ho Chi Minh Trail), which had been expanded.

--vi--

Second Trawler Infiltration Era

The second trawler infiltration era began with the detection of an NVN trawler in August 1969. There were to be 38 detected trawler infiltration attempts during this era, which ended with the destruction of a trawler in international waters on 24 April 1972. Two of the 38 attempts were discovered to have been successful.

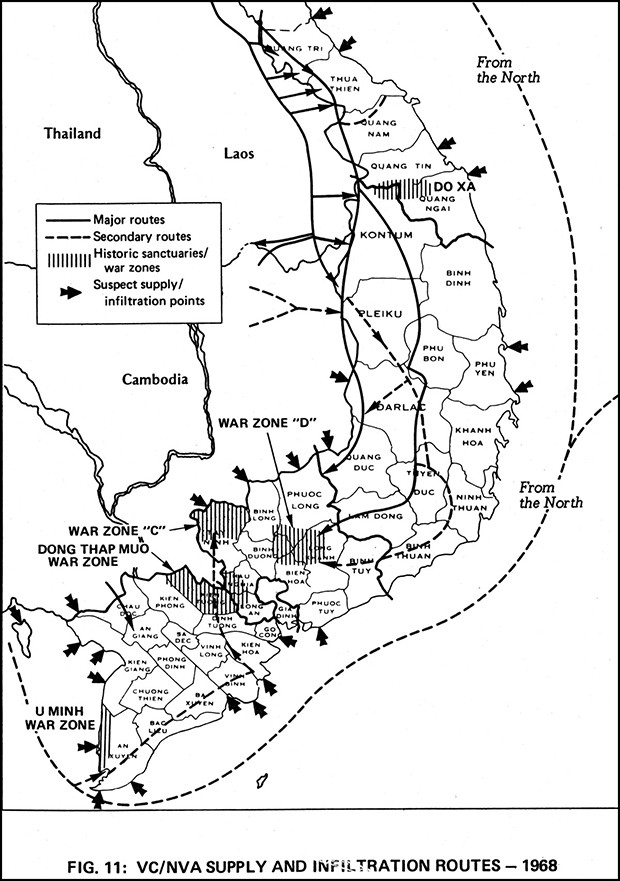

During the Summer of 1969, Prince Sihanouk of Cambodia placed an embargo on shipping arms through his country to the VC/NVA forces in SVN. Although the embargo was temporarily lifted, it was reimposed permanently by late 1969. Sihanouk's ouster in March 1970 and U.S./SVN cross-border operations into Cambodia that Spring permanently halted communist shipments through Sihanoukville. The communists then turned to the sea once more to resupply their forces in southern SVN.

This second era brought several trawler infiltration tactics that had not been observed during the first era. From 1969 on, the trawlers generally aborted their missions when they realized they were under surveillance; previously, most of them had tried to complete their missions. Group 125 had little to lose when its trawlers simply returned home instead of closing the coast under surveillance to what was often a future and fatal conclusion.

A new type of trawler, the SL-8, was detected in an infiltration attempt during February 1971. This trawler was larger and more seaworthy than any used before. It could carry 400 tons of cargo, compared with the 100 tons that trawlers previously detected could carry.

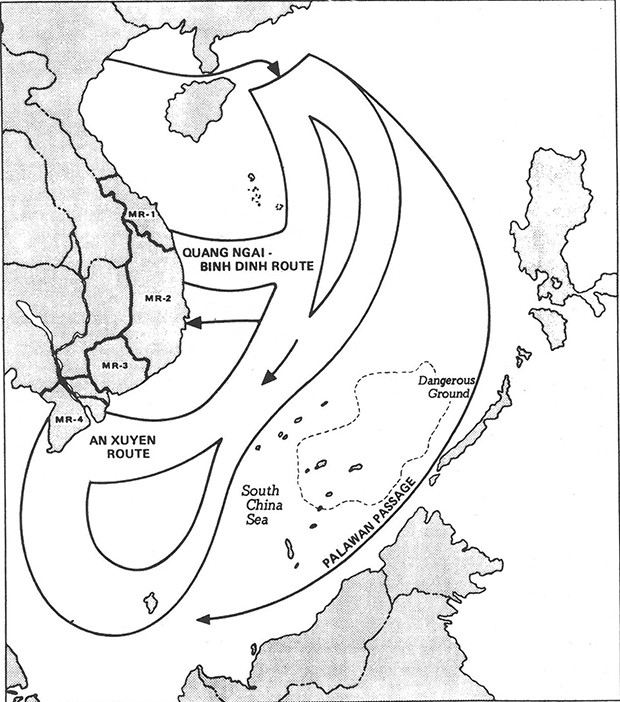

NVN trawlers evidently had begun to use a new route for seaborne infiltration in December 1971.Until then, the trawlers presumably had to transit the gap between the Dangerous Ground and the SVN coast.The new route took the trawlers through the Palawan Passage and back to SVN, circumventing the established Market Time air patrol areas. About the same time the new trawler route was discovered, it seemed that the North Vietnamese were trying to flood Market Time barriers by sending down three to four ships within 10 to 25 days. This tactic had not been observed since February 1968.

Wrap-Up

After the VNN destroyed a trawler in international waters in April 1973, no other infiltrating trawlers were detected. There are two possible explanations. One is that the destruction of a trawler on the high seas could have convinced the North Vietnamese that they would no longer have the option of aborting before entering SVN's waters once under surveillance. The second explanation may be that Group 125 trawlers could have been trapped in Haiphong during operation Pocket Money, the May 1972 mining of ports in NVN. Although there was evidence suggesting the Group 125 trawlers used Hainan Island, it is not clear whether its facilities and assets had been moved form Haiphong before Pocket Money.

--vii--

In mid-1972, Group 125 was eliminated.

NVN established a new seaborne infiltration group, which used smaller fishing vessels purchased and registered in SVN.

Market Time Operations

At first, Market Time was under the control of COMSEVENTHFLEET, but the operation was soon transferred to the Naval Advisory Group (NAG), subordinate to MACV. NAVFORFIVE was established as a separate command in April 1966, with Task Force 115 delegated responsibility for Market Time.

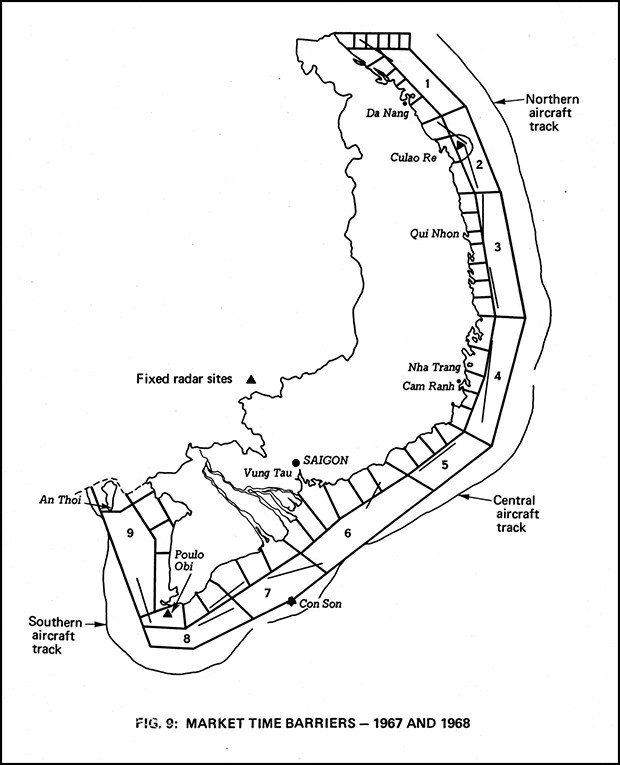

Five Coastal Surveillance Centers were established: Danang, Qui Nhon, Nha Trang, Vung Tau, and An Thoi. These centers coordinated coastal surveillance activities of the VNN and U.S. Navy. CTF 115 originally operated out of Saigon; he later moved to Cam Ranh Bay.

For most of the operation, U.S. forces performed coastal surveillance with three barriers - air, outer surface, and inner surface. VNN junks and patrol craft helped U.S. forces, but the did no become an integral part of the operation until Vietnamization.

Air Barrier

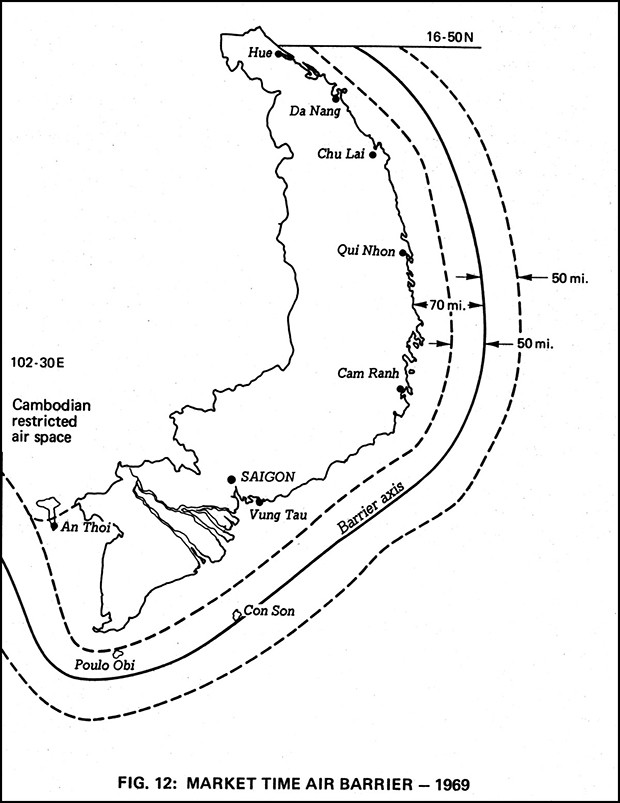

The air barrier was first flown by P-2s, P-3s, and P-5s. During the operation, VP aircraft flew from a seadrome and from five different bases (two in SVN, one in Thailand, and two in the Philippines). Apparently, the personnel ceiling in SVN was responsible for the out-of-country bases. By January 1969, P-2s and P-5s had been phased out of Market Time, and P-3s alone flew the patrols.

During the first few years of the operation, Market Time patrols experimented with many different tracks. The tracks most generally flown covered the southern part of SVN to Vung Tau and the sector fro Vung Tau north. One leg of the track was flown over the coast, and other 40 to 60 n. mi. offshore and parallel to the coast. In 1967, the patrols were flown off the northern and central southern sectors of SVN parallel to and 70 n. mi. from the coast, with a permitted deviation of 50 n. mi. on either side of the track. Every contract was to be investigated.

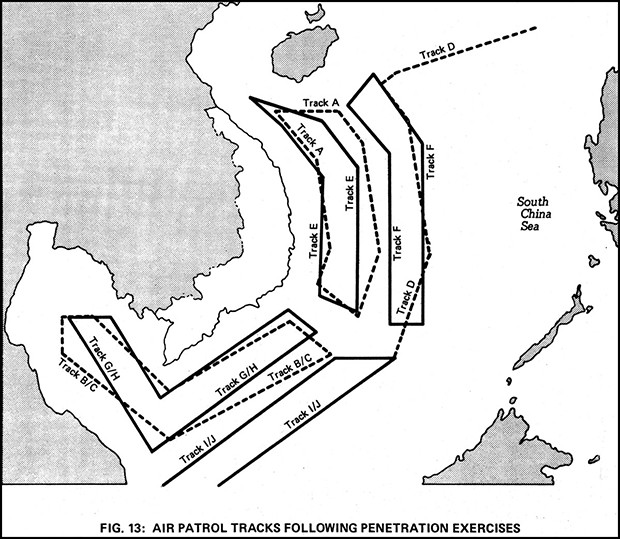

By January 1969, one P-3 flew a barrier from the demilitarized zone (DMZ) to Phu Quoc, 70 n. mi. offshore. A P-3 could cover the entire coast in a single sortie. But after a series of penetration exercises conducted by Seventh Fleet ships, the barrier was recognized as being susceptible to infiltration, for two reasons. First, the fixed tracks of the P-3s could be taken advantage of by an informed infiltrator. Second, the P-3s could not identify contacts at night. New daytime-only patrols wee instituted. The patrols were extended eastward and randomized so that an informed infiltrator could not penetrate the barrier; flight paths were also shifted back and forth to 20 n. mi. on either side of the tracks.

--viii--

(U) Along with the new patrols came a change in the Market Time concept of operations. Until 1970, Market Time practiced overt surveillance of trawlers; they were tracked until the Market Time units were sure the mission had been aborted. In the second trawler infiltration era, this practice of overt surveillance might have encouraged more attempts. Trawler crews knew that there would be nothing to lose if they were to abort before reaching SVN waters (12 n. mi. offshore) since the Market Time Rules of Engagement (ROE) prohibited VP aircraft from engaging trawlers in international waters. This meant trawlers could attempt infiltration and break off when they came under surveillance. COMNAVFORFIVE analysts concluded that the Market Time practice of overt surveillance of enemy trawlers did not damage the enemy while it tied up U.S. assets.

(U) By the end of 1970 Market Time forces were directed to maintain covert surveillance whenever possible. The fist time covert surveillance was successfully practiced (during November 1970), a trawler was destroyed.

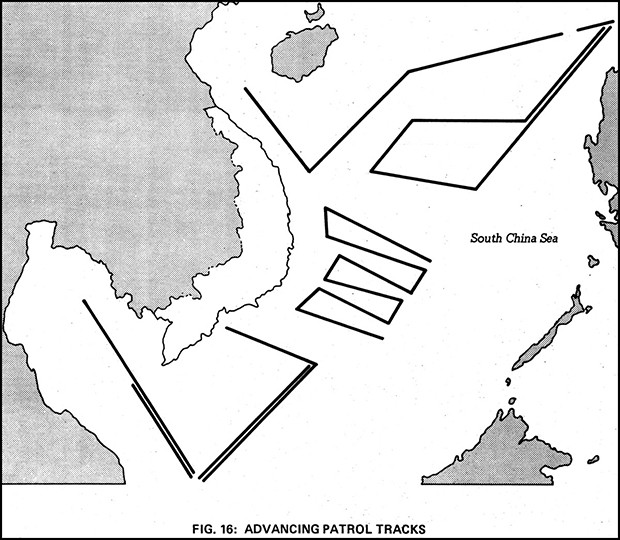

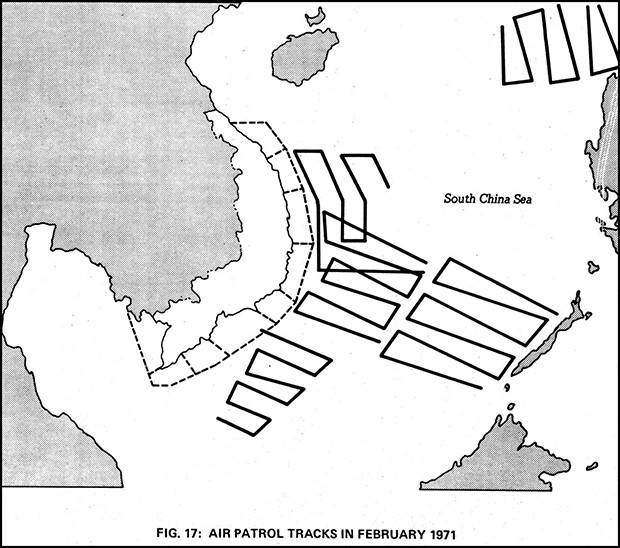

(U) In 1971, the air patrols were changed in reaction to intelligence suggesting that MR-4 was the target of trawler infiltration attempts. The trawlers probably passed through the choke point between the Dangerous Ground and the SVN coast. The new patrol, an "advancing" patrol, was based on aknowledge of trawler capabilities and destination. If the information were correct, trawlers would not be able to evade the advancing patrol. (U) There was a change in emphasis for Market Time air patrols during 1971. Instead of investigating every contact, the patrols began to concentrate on the smaller contacts. It was the smaller contacts that would prove to Group 125 trawlers; the primary mission of Market Time was to prevent infiltration by these trawlers, not to track merchant ships.

(S) There were other changes in priorities affecting Market Time during 1971. Information from photoreconnaissance flights over NVN and Hainan was provided to Market Time. Every time these photos indicated that a Group 125 trawler had left its home part, the information was passed to a U.S. submarine off the Chinese coast. If the trawler passed through the Hainan Straits and headed south, the submarine would contact Market Time aircraft. The submarine also tracked the SL-4 destroyed by the VNN in April 1972.

(C) In February 1972, after it had been determined that trawlers were transiting the Palawan Passage enroute to SVN, an advancing patrol was established to cover that passage and the Dangerous Ground. Adequate intelligence had provided an input to the development of the Market Time air patrols.

--ix--

Surface Barriers

The outer surface barrier was patrolled by deeper-draft vessels - DERs, MSOs, and MSCs and later, WHECs and PGs. Once the outer barrier was divided into nine large sectors in 1965, no major change was made for the remainder of the operation.

Vietnamization brought a winding down of U. S. Navy activity, and there were fewer sectors covered as the outer barrier came under VNN control. The area covered by the ships varied over the years from 10-15 to 12-40 n. mi. offshore.

The inner surface barrier was patrolled by shallow-draft PCFs and WPBs from inshore to the area manned by outer barrier ships. U. S. Navy/Coast Guard participation in the inner barrier peaked at 84 PCFs and 26 WPBs. The boats were assigned inshore areas of operation within the nine sectors.

Patrols suffered at the tip of An Xuyen Province because support bases for inner-barrier craft were too widespread. A major improvement in coverage of this area came during Vietnamization, when a base was established at Nam Can in the heart of VC controlled territory at the tip of An Xuyen Province.

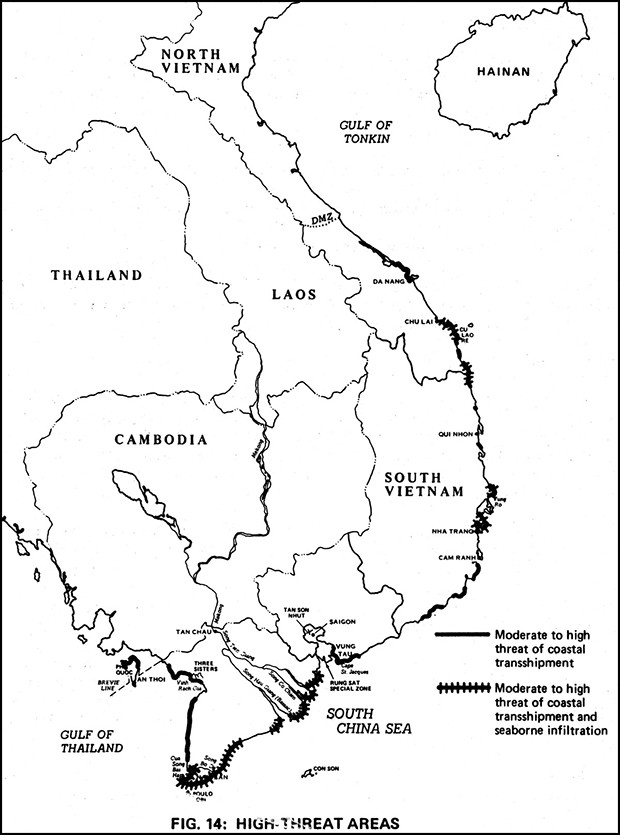

A major change in the concept of the inner barrier came in 1971 after the South Vietnamese had assumed responsibility for the inner barrier for several months. High-threat areas of the coast wee pinpointed and the inner-barrier craft formed into task units. The objective to the task units or "Clouds," was to change the former fixed patrols and concentrate forces in areas that were prime targets for transshipment or infiltration. Single boats were left to patrol low threat areas.

Sea Lords Induces Change

A major change in the concept of operations for the task forces under COMNAVFORFIVE included Market Time in 1968. The fairly passive patrols had previously been restricted to the coast. In 1968, patrols became more aggressive as PCFs became part of the Sea Lords operation to clear MR-4 waterways of VC. PCFs participated in raids up the canals and rivers of the Delta. Increased gunfire support was emphasized for both inner and outer barrier craft.

Vietnamization Induces Changes

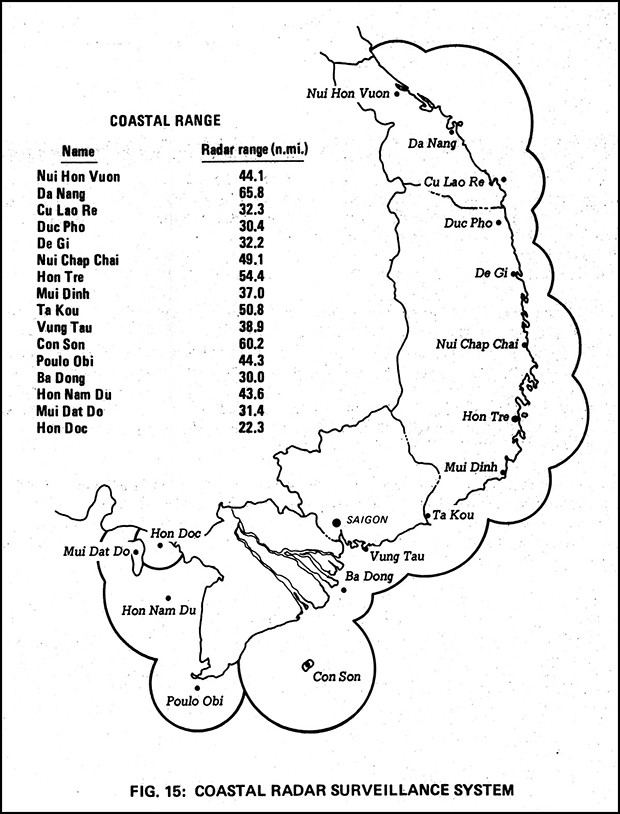

As the U. S. Navy removed some of its Market Time assets, a replacement had to be found for the P-3s, whose detection capability had been essential to the operation. A coastal radar system was developed, and by mid-1972, 15 coastal stations and a radar ship had been turned over to SVN. But these stations lacked the identification capability of the P-3s, providing surface forces reaction times of only hours instead of the two to three days provided by the P-3s.

--x--

The radar system served as the impetus for development of the "Cloud" concept. This concept was designed to meet the need for a strong inner barrier reaction force, since by the time a contact was detected by the radar system and the information disseminated, it could well be the job of inner barrier assets to intercept the infiltrator. Task units might be able to handle an infiltrating trawler, but individual boats certainly did not have adequate firepower.

By December 1972, VNN had taken over the inner barrier, the outer barrier, and the coastal radar system, and CTF-115 was dissolved. An adequate replacement had not yet been found for U.S. Navy VP aircraft, which were still flying Market Time surveillance missions at the time of the cease-fire. The radar system could not provide the same reaction time and coverage that the P-3s did. The aircraft never were scheduled to be turned over to the South Vietnamese.

--xi--

BACKGROUND

NVN RESUPPLY SYSTEM

NVN has been organized to direct infiltration into SVN since 1959. During that year, VC needs for out-of-country resupply in SVN began to increase. Possible infiltration routes were the Ho Chi Minh Trail (first upgraded in 1959), Cambodia (used at least since 1964), and the sea.

Seaborne infiltration was recognized as a possible means of resupply as early as 1961. Cargo that took 170 days overland to reach the VC/NVA in SVN reached them in a few days by sea with far less manpower expended.

There were several methods of seaborne infiltration that Market Time ultimately had to face. In the early 1960s, trawlers capable of carrying 60 to 100 tons of supplies infiltrated directly to the beach or offloaded onto smaller craft several miles offshore. During Market Time, trawlers capable of carrying 100 to 400 tons of cargo appeared as infiltrators. Smaller craft infiltrated below the 17th parallel to MR-1, or performed resupply functions as coastal transshippers within SVN.

Group 125 Infiltration

Trawlers under the operational control of NVN 125th Naval Transportation Group had been resupplying the VC in SVN at least since 1962. The trawlers were also used to transport key personnel in limited numbers.

When a trawler crew learned via radio contact with rear services groups ashore that it would be unsafe to attempt a landing, they often dropped the cargo overboard in fishnets. The cargo, in watertight containers, was marked with buoys. When the area was safe, sampans and junks retrieved it. A trawler could not be legally intercepted in international waters. Junks and sampans that picked up the contraband were very difficult to identify among the 64,000 similar SVN fishing boats off the coast. When the coastal radar system began to operate in 1971, it could be eluded by the trawler crews' transferring their cargo to junks and sampans just outside the range of the AN-TPS 62; that range averaged about 23 n.mi.

There is some question as to just when Group 125 was established and to what NVN command it was subordinated. Sources agree that there was an organization in the late 1950s that was responsible for maritime infiltration into SVN and possibly for other communist resupply missions. The same sources indicate that Group 125 was probably formed about 1960, and certainly by 1962.

--1--

(C) Originally under NVN's naval command, Group 125 subsequently was probably responsible to the NVN high command. Because of the high-level control of Group 125, NAVFORFIVE intelligence section estimated in December 1970 that Group 125 had access to the most current information from all VC and NVA intelligence organizations.

(C) Group 125 trawlers originally operated out of Haiphong, but in mid 1966 as U. S. bombing of the Haiphong area intensified, they probably moved to Hainan. Two years later, with the bombing halted, the trawlers began to reappear in Haiphong. In 1972, an NVN prisoner revealed that infiltration trawlers regularly used the port of Hsin Hsing on Hainan. Use of this port would have eased trawler infiltration attempts while Haiphong was quarantined.

(C) Members of Group 125 wee fanatic communist who remained aloof from other naval personnel. The 125th maintained cover as a meteorological outfit. On infiltration missions, the ships were disguised as innocent trawlers from other Asian countries. Their hulls were generally painted a drab color for camouflaging when beached in SVN. Interrogation reports revealed that the crews of some of the trawlers had orders to raise mainland China's flag when they were in danger of being fired upon.

(U) Security was extremely tight. The crew members' knowledge was severely restricted to a need-to-know basis, as was information available to the cadre who made the trip. Each trawler had a self-destruct system to preserve the secrecy of the organization and its mission and to prevent supplies and personnel from falling into enemy hands. The self-destruct system also indicted that the loss of these trawlers was not too important to NVN because of increased Chinese maritime support.

WBLC Infiltration

(C) Another enemy transportation group was in charge of infiltration by WBLCs across the 17th parallel. It was learned in 1965 that the VC would take South Vietnamese craft and crews to NVN, load supplies, and return to SVN.

(C) There is little documentation of the organizational structure behind the activities of the communist WBLCs that crossed the 17th parallel with supplies and personnel. According to the CINCPAC Infiltration Study of 24 July 1967, a transportation group was established in NVN during mid 1966 to organize the flow of supplies into SVN by WBLCs. There was no indication this group was associated with Group 125. WBLCs infiltrating to SVN probably originated from the coastal area between Ben Thuy (between the 18th and 19th parallels) and the 17th parallel. Another organization, the Vinh Linh Sea Transport Unit, was also responsible for supply movement to northern MR-1. This unit sent supplies from Vinh Linh (just north of the DMZ) to SVN by sampans and small junks within the surfline.

--2--

Coastal Transshipment

(U) In addition to these different infiltration methods, Market Time had to cope with intra-SVN enemy transshipment by junks and sampans. Transshipment was aided by the fact that much of the 1,000-st. mi. SVN coast was not under SVN control. Coastal transshipment seems to have been a purely local phenomenon. Some of the areas in which transshipment occurred were traditional routes that were consistently reported over the years. The route from the Three Sisters area across the Vinh Rach Gia in MR-4 was such a route. Transshipment also took place when inland routes were made hazardous or inconvenient by geography, weather, or allied operations. Transshipment along the coast of MR-1 and--2 was the safest and easiest method of redistribution of supplies in these areas. After Sea Lords began to interdict communist resupply routes in MR-4, there were increased reports of transshipment along the coast.

(U) Market Time forces rarely captured contraband from the thousands of junks they searched. Arms and ammunition could be easily jettisoned before a search. The VC could produce false papers, and the distinction between legitimate food shipments and enemy resupply efforts was generally impossible to make.

(U) Some infiltration occurred in the Gulf of Thailand from Cambodia by small boats, but like transshipment, this seemed to be under local control. Many of the coastal area accessible to transshippers were inaccessible to deeper draft coastal surveillance patrol craft.

(U) Beginning in 1970 reports of coastal transshipment in MR-4 were used by NAVFORFIVE to illustrate trends. Most of the reports were low level and unconfirmed, but NAVFORFIVE suggested that the overall number of such reports indicated that in 1972 an increase in coastal transshipment was occurring. The problem with this approach was that each report of transshipment activity did not deal with the same number of craft or people, so that more reports involving fewer junks and sampans might not mean an increase in activity. No adequate measure of effectiveness was developed to gauge Market Time's ability to intercept or otherwise hinder enemy coastal transshipment.

Other Seaborne Resupply

(C) In addition to direct seaborne infiltration into SVN, there were other forms of communist seaborne resupply with which Market Time did not deal. Form October 1966 to July 1969, the communists delivered between 11,000 and 19,400 metric tons of military supplies to Sihanoukville destined for the VC in MR-3 and 4. There is also a theory, proposed by the Naval Ocean Surveillance Information Center (NOSIC), that merchant ships smuggled arms up the Mekong River for the VC. This theory was never proven conclusively but evidence suggests it is plausible (Appendix H). There is also a possibility that the arms and munitions were smuggled into SVN by junks that lightered the supplies from merchant ships off the SVN coast.

--3--

PRE-MARKET TIME VIETNAMESE COASTAL SURVEILLANCE

For the first half of 1962, the U.S. Navy and the VNN participated in coastal surveillance exercises. The earliest patrols began in December 1961 with units from U.S. Minesweeping Division 73 and VNN patrol craft (PC)--174 foot submarine chasers--operating just south of the 17th parallel. Seventh Fleet aircraft also made periodic reconnaissance flights.

In February 1962, the patrols extended their limits from 30 n. mi. offshore to the Paracel Islands. By early March, the U.S. was authorized to patrol north of the 17th parallel as long as U.S. ships avoided the waters off NVN. This change was sparked by the discovery of North Vietnamese junks that would simply cross the 17th parallel when they were spotted south of that line. To train the SVN, the U.S. placed shipriders aboard the VNN PCs, and the Vietnamese placed liaison officers aboard U.S. ships. Since there was no authorization for U.S. ships to board and search suspicious contacts, radar was used to vector VNN units to the scene.

Also in February 1962, a patrol was established in the Gulf of Thailand between An Xuyen Province and Phu Quoc Island. The objectives were the same as the northern patrol: train and improve the Vietnamese, determine the extent to VC infiltration, and prevent infiltration. U.S. forces stayed clear of the Cambodian border; the Vietnamese units usually operated in the shallow waters of the Gulf of Thailand, not in company with U.S. destroyer escorts. The system of shipriders and liaison officers instituted in the northern patrol was incorporated into this exercise, as was the U.S. radar vectoring of VNN units to a contact.

The record of both patrols through March 1962 confirmed a lack of extensive seaborne infiltration of VC supplies into SVN. The U.S. Navy determined that enemy infiltration by sea was limited to high-priority shipments of vital material and key personnel.

SVN official must have feared VC seaborne infiltration. In December 1963, SVN established a blockading force around An Xuyen Province to counter communist infiltration there by way of Phu Quoc and other VC-controlled islands in the Gulf of Thailand. One section of the blockade covered the west coast of An Xuyen Province, another covered the east coast of An Xuyen, and another section covered Phu Quoc.

The patrol units consisted of one to three PCEs (185 foot patrol escort craft), four PGMs (102 foot patrol motor gunboats), an LSIL (159 foot light infantry landing ship), and an oiler and light cargo ship to replenish the patrol force. (Appendix A describes characteristics of the PCE and PGM.) Each ship operated with several junks. The Coastal Force junks patrolled inshore in groups of two or three, and the Sea Force ships patrolled out to 10 n. mi. offshore.

--4--

One of the anti-infiltration procedures adopted was biweekly air reconnaissance by SVN air force planes with U.S. and Vietnamese naval observers aboard. These flights covered the area from Phu Quoc to Con Son Island. Several Seventh Fleet P-2s (see Appendix C) monitored Sea Force and Coastal Force activity in the Gulf of Thailand. The need for establishing prohibited zones was recognized, and U.S. advisors recommended relocating fishing villages so that local fishermen would not be in restricted areas.

In 1964, the Sea Force patrolled the entire coast of SVN, with about half the force underway daily. The force consisted of 40 ships at the beginning of 1964 (and acquired four more before the end of the year). Initially, the Coastal Force was a paramilitary organization of motorized and sail-only junks. Under the Military Assistance Program, a new more seaworthy series of junks, Yabuta junks, was built. In October 1964, the U.S. Naval Advisory Group (NAG) was investigating a small, meal hulled patrol boat for VNN use and was considering the U.S. commercially available aluminum Swift boat; the Swift would later become an integral part of Market Time.

With these early coastal patrol efforts came the groundwork for the Market Time concept. The Vietnamese, with U.S. shipriders and with more patrol ships, were considered capable of doing an effective coastal surveillance job. The effectiveness of Vietnamese patrols was questionable in light of later evidence suggesting that at least 40 trawlers (60 to 100 ton capacity) had infiltrated before Market Time. The areas of emphasis for the earliest patrols were the 17th parallel and the Gulf of Thailand. These were traditional areas of high coastal transshipment activity, while the destination of the trawlers appears to have been the mouths of the Mekong.

Before Market Time, U.S. Navy advisors had reported that efforts of the SVN Coastal Force and Sea Force patrols were rather half hearted with a great reluctance to patrol at night. According to MACV, two incidents in early 1965 provided the immediate impetus for Market Time.

From 11 to 24 January 1965, U.S. Navy P-2s flew 14 random flights over Vietnamese patrol areas along the entire SVN coast and observed many VNN craft at anchor instead of patrolling. Emphasis was on night surveillance, and effective communication between U.S. aircraft and VNN patrol units and shore bases was proven to be feasible. After the VNN deputy chief of naval operations made one of these flights, patrol units showed a marked improvement.

On 16 February 1965, a helicopter on a medical rescue mission discovered a camouflaged ship in Vung Ro Bay. This ship, with a cargo capacity of 100 tons, was sunk by air strikes. Diving operations proved it to be a North Vietnamese infiltrator. Large arms caches found in the area indicated that other such trawlers had successfully infiltrated.

--5--

(U) MACV originally seems to have downplayed the VC/NVA capability for waterborne infiltration but later accepted a "significant" portion of VC infiltration as taking place by sea. The NAG, although subordinate to MACV, did not take the infiltration threat from the sea as seriously. The NAG March 1965 Monthly Historical Summary implied that while there were frequent reports of sea infiltration, almost none of those indicating large-scale activity was believable. The Vung Ro Bay discoveries, that publication stated, proved only that large-scale infiltration existed. At the same time, the Summary suggested sea infiltration as a strong possibility because of the appearance of arms and ammunition similar to those discovered at Vung Ro Bay in other parts of SVN. There was a possibility, however, that these munitions were delivered through Cambodia and not directly infiltrated by sea.

(U) The most significant infiltration information available at the time Market Time was established is contained in the "Buckley Report," published in February 1964. That study reached conclusions similar to the March 1965 NAG Summary--that there was no hard intelligence proving large-scale infiltration of supplies or men by sea. Although there were many reports of such activity, reliability of these reports was questionable. According to the Buckley Report, information concerning the infiltration of special personnel and articles needed by the VC did not indicate that such infiltration ever occurred south of Saigon.

(U) Two early Market Time commanders apparently believed at first that the threat of sea infiltration was not particularly significant. One suggested that there was no real evidence of infiltration that MACV wanted the U.S. Navy to prevent. As late as June 1965, the other commander would not accept sea infiltration as a fact anywhere but at Vung Ro Bay.

(U) In Summer 1965, General William C. Westmoreland (COMUSMACV) reiterated his belief that 70 percent of VC infiltration took place by sea. CTG 115. 4, in the Gulf of Thailand, commented that he had seen no evidence to support this contention. COMUSMACV and the Market Time commanders continued to disagree for a few years about how much seaborne infiltration was taking place.

(U) While adequate information on the scope of enemy infiltration seems to have been lacking at the inception of Market Time, evidence accumulated later confirms the existence of extensive seaborne infiltration before Market Time and seriously questions the Buckley Report's assertion of no infiltration south of Saigon. Documents captured in April 1965 reveal that between January 1964 and January 1965, two trawlers a month infiltrated MR-4 and a VC medical cadre captured in June 1965 revealed that from 1960 through October 1964, 20 trawlers infiltrated, destined for the mouths of the Mekong.

(C) The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) indicates that while the magnitude of the enemy infiltration effort into the rest of SVN before Market Time is difficult to assess, such an effort did indeed exist. The CINCPAC/CINCPACFLT Infiltration Study of July 1967 listed these

--6--

reports of possible trawler infiltration before Market Time; 20 in 1963, 15 in 1964, and six to seven in 1965.

(C) Similarly, the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) believes that before 1965 at least 40 trawler infiltration attempts were made, peaking in late 1964 and early 1965. If there were, in fact, at least 40 trawler infiltration attempts before Market Time, COMUSMACV's assertion that much of the VC/NVA resupply was by sea seems plausible.

(C) While VC captured in June 1965 suggested that at least some of the trawlers were 60 ton capacity ships, DIA believes that the trawlers used for infiltration during the early period were capable of carrying 100 tons of cargo. The DIA estimate corresponds with later inventories of NVN trawlers used for infiltration (Appendix F). The June 1965 interrogation is in accord with DIA's belief that the Mekong Delta--and more specifically Kien Hoa Province-- was probably the destination of early infiltrators. DIA also suggested An Xuyen as a probable destination. The early Market Time concept of steel hulled trawler infiltration was thus based on inadequate intelligence.

--7--

FIRST TRAWLER INFILTRATION ERA:

FEBRUARY 1965-MARCH 1968

MARKET TIME UNDER THE SEVENTH FLEET AND NAG

Planning the Operation

ComUSMACV held a meeting in Saigon from 3 to 10 March 1965 to plan a combined U.S. Navy/VNN coastal surveillance patrol operation. On 15 March, President Johnson authorized Seventh Fleet patrols off the SVN coast. The operation was given its unclassified name, Market Time, on 24 March.

Establishment of the operation was based on these assumptions:

Seaborne infiltration of SVN had been taking place and would continue unless preventive measures were taken.

Such activity took the form of coastal infiltration by steel-hulled trawlers and wood-hulled junks.

There were only limited U.S. Navy shallow-draft patrol craft available.

The U.S. was not yet authorized to board and search, and such authorization was required.

Because of the limited number of U.S. Navy shallow-draft boats, the original plan for detecting and preventing coastal infiltration directed the U.S. Navy to help the South Vietnamese increase the quantity and quality of their searches of small craft. Since the U.S. Navy initially had no boarding authority, U.S. ships detected, tracked and reported suspicious contacts to VNN units, then would vector them to the contacts. A VNN liaison officer was to be assigned to each U.S. unit, and the NAG, in turn, assigned U.S. officers as advisors for junk division, Sea Force patrol ships, and the coastal surveillance centers.

Market Time originally came under the operational control of ComSeventhFlt because the U.S. first planned to commit only large patrol ships to the surveillance operation. VADM P. P. Blackburn, ComSeventhFlt, became the first Market Time commander, Commander Task Force (CTF) 71. The NAG, subordinate to MACV, served as the link between the Seventh Fleet and the VNN.

Assignment of Forces

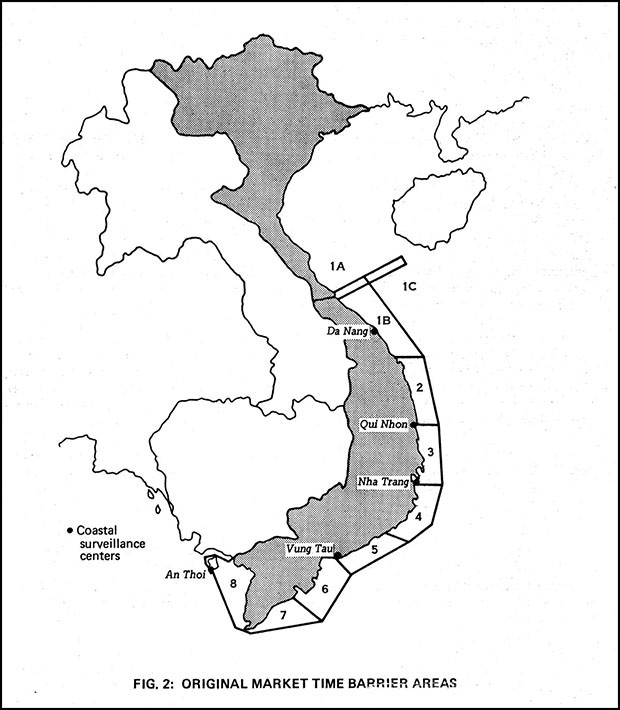

At the beginning of the operation, the coast of SVN was divided into 8 patrol areas, with at least one ship assigned to each area. Five coastal surveillance centers (CSCs) were established--at Danang, Qui Nhon, Nha Trang, Vung Tau, and An Thoi--to

--8--

coordinate the VNN and U.S. Navy units. (Figure 2). A barrier 40 n. mi. long and 10 n. mi. wide was established at the 17th parallel, with at least 3 U.S. ships on station, a P-3 continuously on station, and an EC-121 flying at night to within 50 n. mi. of the Chinese island of Hainan.

For the first 3 months of Market Time, TF 71 averaged 15 ships (destroyers and minesweepers) on station. In June and July, the destroyers were replaced by 14 DERs, most of them about to be decommissioned; appendix B describes the patrol craft used in Market Time. The DERs were more efficient ships for countersea infiltration work because they burned less fuel, had superior endurance, and had better electronic capabilities.

The concept of the U.S. Navy's role in Market Time was changed in April at a meeting of SecDef, SecNav, and CinCPac with a decision to purchase 20 Swift boats from Seward Seacraft. (Appendix B). One Swift boat (PCF) was estimated to replace 5 Vietnamese Coastal Force motorized junks. The Swift boat could handle up to 36 hours on patrol, although 24 hours was preferable. The Swift radar would vector Vietnamese junks to suspicious contacts in the inshore areas and would lead Coastal Force units otherwise unable to operate at night, to junk concentrations. A MACV study in April 1965 suggested that Market Time obtain 54 Swift boats by 1 January 1966.

One of the more important factors that brought about the decision to expand the U.S. Navy's role in Market Time must have been the observation that the Coastal Force and the Sea Force were half-hearted in their patrols. Another factor involved the VNN PGMs; their crews were originally supposed to have given moral support to junk crews, and they were supposed to have aided and encouraged the junks on night patrols. But the PGM did not prove to have the necessary shallow-water capability.

While expansion of the U.S. Navy's role in Market Time was being conceived at the April conference, another type of shallow-draft patrol craft was discussed. The 82-foot Coast Guard Cutter (WPB) seemed to be the best available boat for coastal surveillance operations. The Coast Guard agreed to loan 17 WPBs to the Market Time force; these units began arriving in June.

Since the nature of the U.S. Navy's role in Market Time had expanded to include shallow-water surveillance, the operational control of the Coastal Surveillance Force was transferred in April to the NAG, subordinate to MACV. The NAG would have to expand its resources, since its role would encompass an operational as well as an advisory command.

As the operation was building up its force levels, photoreconnaissance aircraft finished a survey of the entire SVN coast during April. P-2 aircraft based at Tan Son Nhut and P-3s (see Appendix C) based at Sangley Field in the Philippines patrolled the coast from Vung Tau to the DMZ. In May, a P-5 seadrome was established to help the P-2s at

---9--

--10--

Tan Son Nhut with the southern coastal patrol. Through July, the aircraft tracks were varied to randomize the patrols and to experiment with different tracks, and 2 aircraft were to be on station at all times.

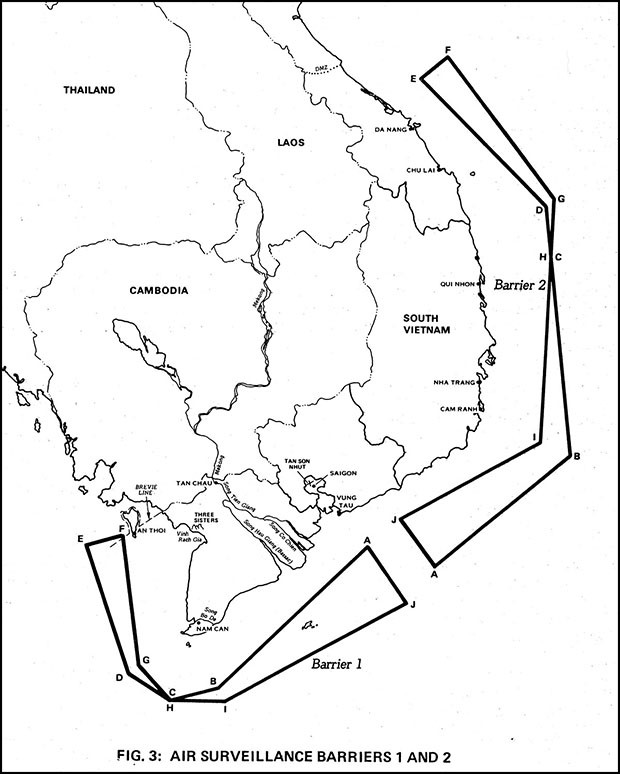

Barriers 1 and 2 were flown during the greater part of the period between 30 May and 30 July (see Figure 3, with Barrier 1 flown by P-2s from Tan Son Nhut or P-5s from Con Son Seadrome and Barrier 2 flown by P-3s from the Philippines. The aircraft were to report steel-hull contacts to the area commanders. These barriers were aimed at locating all contacts within 45 n. mi. of either side of the track.

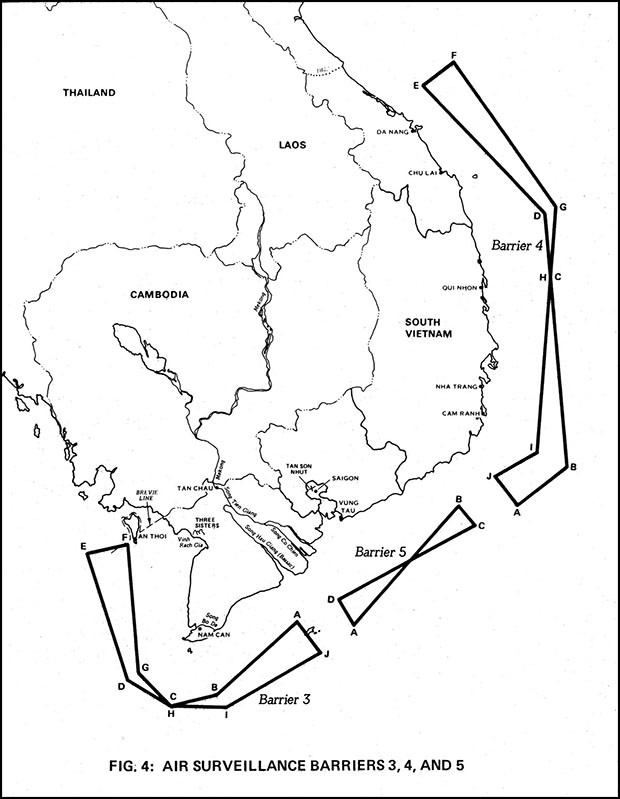

Barriers 3, 4, and 5, flown by P-2s, P-3s, and P-5s, respectively, offered a greater probability of detection with continuous coverage than did Barriers 1 and 2 (90 vs. 70 percent). (Figure 4). Because of the small number of P-2s at Tan Son Nhut, however, Barrier 3 could not be continuously covered.

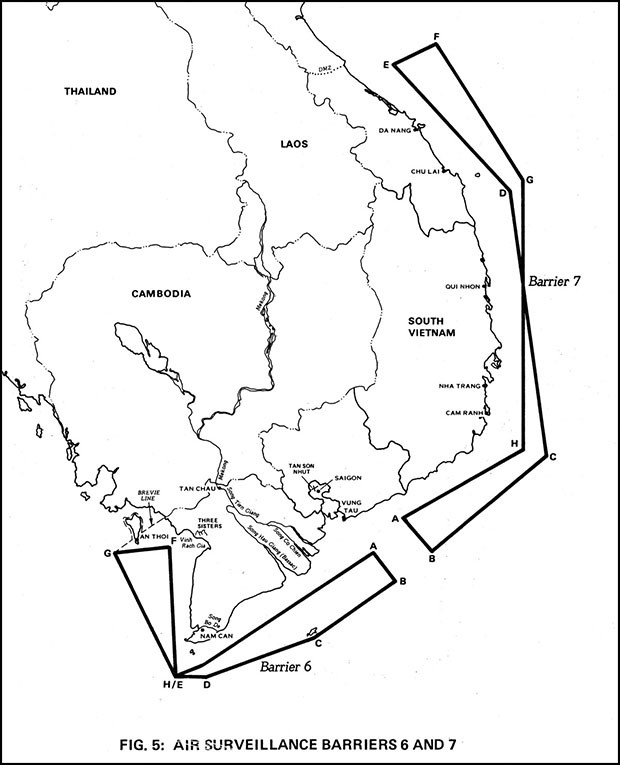

Barriers 6 and 7 were devised to bring the tracks inwards towards the SVN coast. (Figure 5). This concept was coordinated with the surface forces being stationed within 12 n. mi. of the coast. The air patrols were directed to concentrate on all targets within 40 n. mi of the coast, since surveillance beyond that range was not practical in relation to the effort expended.

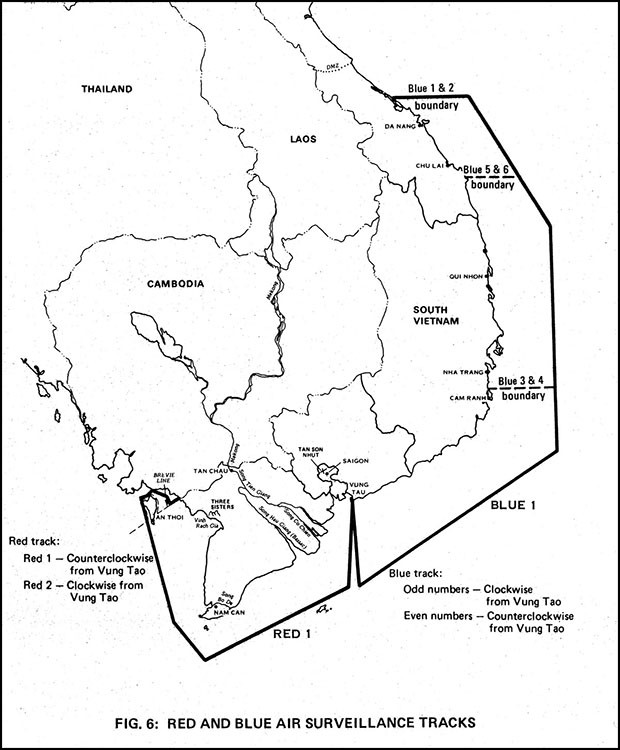

Market Time air patrols were most commonly flown on the Blue and Red tracks (Figure 6). Aircraft on these tracks maintained surveillance on coastal areas in addition to randomly searching for steel-hulled contacts up to a distance of 40 n. mi. from the coast. One leg of the patrols was flown inshore, and the other was flown 40 n. mi. out to sea.

Through the entire operation and on whatever track they were flown, the VP patrols observed and determined normal coastal and off-shore junk or ship traffic patterns. They reported to the CSCs all deviations that could suggest infiltration routes or operations in progress. The aircraft investigated and reported all ships that could not be identified and were within 40 n. mi. of the coast of SVN or on a course toward the coast. To exchange information, VP aircraft established voice contact with VNN coastal groups and Sea Force Ships and with U.S. Navy task groups, task units, and patrol ships when they were nearby. The aircraft were prepared to be vectored to investigate contacts when requested to do so by surface forces.

During daylight, contacts were "rigged" (photographed) and their positions, descriptions, courses, and speeds passed to the CSC. At night, vessels were identified by their running lights or by coded light interrogation response between the aircraft and the contact ship. Suspicious contacts warranting further identification were illuminated by air-dropped flares.

--11--

--12--

--13--

--14--

--15--

In May 1965, new rules of engagement (ROEs) authorized Market Time units to board and search vessels not clearly engaged in innocent passage within the 3-n. mi. territorial limits of SVN and within a contiguous zone extending 12-n.mi. offshore. Beyond the 12-n.mi. limit, the U.S. Navy was authorized to search any vessel believed to be South Vietnamese. (See Appendix I).

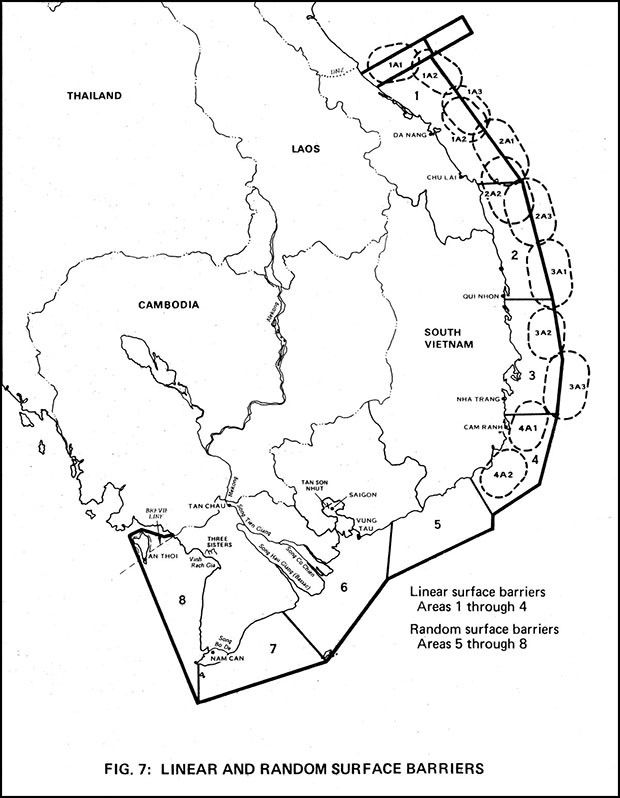

Different surface patrol concepts were tried during May. Instead of patrolling randomly, 12 of the 15 Market Time ships patrolled the 4 northern areas in predetermined courses parallel to the coast so there would be continuous radar coverage of the northern SVN coast. Random patrolling was continued by the remaining 3 ships in the 4 southern areas, which were supposedly less conducive to seaborne infiltration (Figure 7).

Whether the southern areas were, in fact, less conducive to sea infiltration is debatable. But at the time, discoveries of junk traffic across the 17th parallel and the Vung Ro Bay incident gave credence to the idea.

In mid-July, another surface patrol concept was tried as an experiment. Market Time ships began to patrol only within 12 n. mi. of the coast, deemphasizing possible contacts beyond the contiguous zone. This concept was intended to have the psychological effect of visible proof to both the enemy and the South Vietnamese that the U.S. Navy was supporting the VNN.

In July, before the turnover to NAG, SecDef ordered 34 more PCFs to equal the number proposed in the April MACV Market Time study. The Coastal Force was formally integrated into the VNN, an important psychological step for Coastal Force crews. By mid-July TF 71 destroyers had been replaced by DERs. Before Market Time was turned over to NAG, 17 WPBs had arrived. Nine were sent to An Thoi to form CG Division 11, and the remaining 8 were sent to Danang to form CG Division 12.

With expansion of the U.S. Navy's role in Market Time to include shallow-water patrols, support plans for the WPBs and Swifts had to be developed. Until YR-71 (a floating workshop) arrived at Danang and ARL-38 (a 328-foot former LST repair ship) arrived to anchor off An Thoi in mid-September, 2 LSTs (landing ships) supported the WPBs.

During the first 5 months of the operation, the U.S. Navy had gathered information on the types of vessels likely to infiltrate and the areas most conducive to enemy infiltration. Market Time developed a detailed knowledge of local operating areas, including fishing patterns, tides, VC-controlled areas, population distribution, and shipping traffic.

Building Up an Intelligence Capability

During Summer 1965, there was still no evidence suggesting the extent of enemy seaborn resupply. ComPatForSeventhFlt's final Market Time report at the end of July

--16--

--17--

noted that Market Time's effectiveness was hampered by very inadequate intelligence. CTF 71 received intelligence summaries from MACV, but reliability of these summaries was questioned. Except for the discoveries at Vung Ro Bay and a few other isolated incidents, there was very little hard intelligence. The available information was totally inadequate to assist in determining the position of Market Time forces.

Chief, Naval Advisory Group (CHNAG) started to build a Market Time intelligence network before he actually took control of the operation. The intelligence community usually dealt only with land and air warfare. It had to be reoriented to an awareness of the sea infiltration problem.

A Navy captain joined the intelligence section of MACV's staff. An agent network funded by MACV was set up by the VNN. U.S. Navy intelligence officers in Vietnam increased from 6 at the beginning of Market Time to 32 by July, with at least one intelligence officer at each CSC and 5 at NAG headquarters. By January 1967, of the 38 NILO officers, 23 were concentrated in the Delta in support of Market Time and Game Warden (the riverine operation).

TF 115 Established

On 31 July 1965, TF 115 under NAFG was activated when TF 71 was deactivated by ComSeventhFlt. CinCPacFlt, through ComSeventhFlt, retained the logistic support responsibility for TF 115.

RADM Ward, CTF 115 and CHNAG, added another patrol area off the coast of MR-4, which made a total of 9 patrol areas, each 30 to 40 n. mi. deep and 8 to 120 n. mi. long, with one DER in each area (Figure 8) or an MSO or MSC if not enough DERs were available. U.S. Navy Market Time operations were controlled from CTF 115 surveillance operations center in NAG headquarters, Saigon, while the VNN patrol operations were coordinated with U.S. Navy operations from the CSCs.

Setting Up Barriers and Increasing Force Levels

After the transfer of operational control of Market Time from ComSeventhFlt to CHNAG in July, there were no further major changes until the September conference in Saigon. There, the conferees discussed, among other topics, ComUSMACV's recommendation that additional patrol ships be made available to Market Time to increase the number of offshore patrol stations continuously manned from 9 to 25. The conference was attended by representatives from CinCPac, CinCPacFlt, OPNAV, and NAG. A study was conducted, refining the concept of operations for Market Time and recommending adjusted force levels based on the best available information of the nature of the threat.

--18--

--19--

That study (Landis Study) estimated that the VC needed to infiltrate 14 tons per day to maintain their level of operations.1 If the 14 tons were supplied by sea, they could have been moved by one 100-ton-capacity vessel every 7 days, by 28 junks of ½-ton capacity each day, or by combinations of the two. It was decided that the aspect of the threat most difficult to interdict--infiltration and transshipment by junks--should be the basis for developing a concept of operations. It was further determined that a 20-percent attrition would be unacceptable to the enemy. With increased force levels to achieve this attrition, it was assumed that Market Time would have a substantial capability against steel-hulled trawlers.

The study group suggested establishing 3 barriers--an air barrier and outer and inner surface barriers. The air barrier was to be flown with 2 tracks manned continuously. The Red Track was usually flown by P-2s from Tan Son Nhut or P-5 seaplanes, and the Blue Track by P-3s from Sangley Field in the Philippines (Figure 6). Both tracks consisted of one leg over the coast and the other 40 n.mi. offshore. In addition, small single-engine aircraft (L-19s) made two daily flights over the coastline; aircraft with sidelooking airborne radar flew intelligence and night missions; and a Vietnamese C-47 flew two to three surveillance flights a week over area 9 near the Cambodian border.

The remaining 2 barriers were to be patrolled by surface craft. The outer surface barrier, 10-15 n.mi. offshore, was manned by DERs, MSOs, and MSCs. The Landis Study suggested a formula that required the equivalent of 11, 17-knot ships on station. The inner barrier was to be patrolled by Swifts, WPBs, and VNN junks. Thirty more Swifts (for a total of 84) and 9 more WPBs (for a total of 26) were ordered. The first Swifts were scheduled to begin arriving in November. The Landis Study assumed maximum utilization of the VNN forces, implying that about 100 VNN units would operate inshore close to their coastal group bases, and 16 VNN patrol craft would be on station in the inner barrier.

Cam Rahn Bay, Vung Tau, Qui Nhon, and Cat Lo were planned as PCF support bases in addition to Danang and An Thoi after additional PCFs were ordered. By October, it was clear that ARL 38, which had arrived in September, could accommodate only 2 PCF crews.

A recommendation was made to house other crews in tents ashore. At the end of 1965, with 8 PCFs stationed at An Thoi, the crews lived in tents on Phu Quoc Island. (Since the island was largely controlled by the VC, 2 Regional Force companies were stationed there to protect the Market Time forces.)

__________

1. Various estimates of enemy war material needs are presented throughout this research contribution. These estimates cannot be correlated with each other, and the sources do not adequately explain how the estimates were determined. They are given here to indicate official beliefs at given times throughout the operation.

--20--

Search Tactics

A concept for the investigation and search of junk concentrations was developed in October in Operation Roundup. Aircraft were to observe junk groups to determine their location and number. Patrol units would then surround the junks at night so that, in the morning, the junks could be forced into preplanned inspection areas. This exercise was tested in November off the mouth of the Cau Co Chien River, but without air surveillance. The initial exercise failed. A week later, with aircraft surveillance, junk concentrations were found and the concept was again tested. This time it worked.

By Spring 1966, U.S. Navy ships were boarding and searching about 15 percent of the junks they detected; the VNN searched additional junks along the coast. The 200 or so small craft of the Sea Force and Coastal Force had little or no ability to patrol at night. Night searches were handled by U.S. Navy shallow-draft PCFs and WPBs. The Coastal Force operated close inshore trying to prevent VC transshipment, while Sea Force ships patrolled further out to sea. Patrol areas were chosen by size, location of SVN coastal zone boundaries, areas of responsibility of VNN coastal groups, and coastal districts.

Two types of investigations were conducted by Market Time forces among the wood-hulled ships and boats: inspections and boardings. In an inspection, the patrol ship closely approached the junk, viewed its exposed cargo and observed the actions of the crew, or the Vietnamese liaison officer (when there was one) questioned the crew. In a boarding, the patrol ship sent a detachment aboard to check paper, inspect the cargo, and question the crew.

Different search tactics were used, including random searching and searching the nearest uninvestigated junk. In the former tactic, a junk in the searcher's assigned area was randomly selected for boarding. In the latter, the object was to search the largest possible number of junks in the surveillance zone. The disadvantage of the nearest-uninvestigated-junk tactic was that the infiltrator could evade by ensuring there was always another boat between it and the searcher. When detained by U.S. Navy or Coast Guard crews, suspects or cargo were turned over to the Vietnamese.

There was a trend toward an increased surveillance effort shown in the numbers of junks and people searched as the end of October 1965 approached, but the effort seems to have decreased in November. This decline may have been a combination of low Vietnamese morale and the northeast monsoon, which reduced both the numbers of patrolling craft and fishing craft. In addition, U.S. Market Time forces had problems with the VNN because of units that would report themselves "on patrol" as long as they wee out of Saigon. After a meeting between CHNAG and VNN's Chief of Naval Operations about VNN investigation procedures, the VNN units were made to take the terms "on patrol" and "investigation" more literally.

--21--

In November, for the first time, and again in December, heavy weather curtailed some Market Time activities.

The WPBs on the 17th parallel had to be called into Danang because of high seas. As Market Time participants learned, operations on the east coast of SVN were hampered during the northeast monsoon (November and December). And during the southwest monsoon (June and July), the Gulf of Thailand was excessively rough.

Arrival of PCFs

PCFs began to arrive in SVN at the end of October; by the end of 1965, 8 Swifts were stationed at An Thoi to form Boat Division 101. In January 1966, 6 more PCFs arrived to form Boat Division 102 at Danang based at first on YR-71 and then on YFNB-21 (barracks and workshop craft) until the arrival of an APL (barracks craft). In February, Boat Division 103 was activated at Cat Lo, and the Swifts patrolled the RSSZ in conjunction with 9 WPBs that also arrived at Cat Lo in February to form CG Division 13. The PCF divisions had 1½ crews/boat; the more seaworthy WPBs had one crew per boat.

In January and February, the Swifts started a series of exercises to determine their most effective use in Market Time. These exercises included gathering hydrographic information and examining DER support of the PCFs. PCFs were found to work effectively only in seas of 6 feet or less. Underway refueling from a DER was feasible, increasing a Swift's time on station from one to 120 days.

Similar exercises were held to determine how well WPBs could function away from their shore bases. It was demonstrated that 3 WPBs could function at a distance of more than 100 n. mi. from their bases when supported by a DER. The effectiveness of vectoring WPBs to targets detected by the DERs was also demonstrated. The combined effort of PCF/WPB/DER units resulted in more aggressive patrols and increased morale.

In the future, the use of DERs as mother ships for the PCFs would depend on the distance the PCF had to patrol from its base and on the nature of the junk traffic to be searched. In areas where junk traffic did not transit from the outer barrier to the inner barrier such as off Cam Ranh Bay, close coordination between DER and inner-barrier patrol craft was unnecessary. U.S. Navy efforts were not well coordinated with the efforts of the VNN junks (until Vietnamization began), although direct liaison between all the U.S. Navy and VNN forces was encouraged for information exchange.

Using the experience gained in the January/February exercises, Market Time forces participated in four special operations during March. Operation Jack Stay was combined U.S. and Vietnamese Marine thrust into the VC-controlled RSSZ. Some Market Time units (9 WPBs and 6 PCFs) were used to patrol the major rivers of the RSSZ in an operation designed to prevent both infiltration and exfiltration of the VC in the RSSZ to protect the main shipping lanes to Saigon. The three other special operations were more similar to a blockading operation that took place in February. (That operation was based on intelligence reports of enemy movements in an area ashore; it supported land operations.)

--22--

(U) The four operations reiterated the concept of the DER as mother ship for PCFs and WPBs in situations when it was necessary for the smaller craft to be too far from their shore bases to make their normal patrols. The DER/WPB/PCF team proved to be more efficient than the MSC or the MSO/WPB/PCF team. The minesweepers lacked space to berth the extra PCF crews and radio equipment with which to communicate with coastal groups and within a minesweeper's own task group. The exercises demonstrated that rapid deployment and concentration of forces were feasible to meet a threat anticipated by intelligence reports.

(U) Under NAG, the Market Time force composition and barrier configurations were established. The inner barrier was manned by the VNN Sea Force and Coastal Force. U.S. Coast Guard WPBs and U.S. Navy PCFs were added. Larger U.S. Navy ships (DERs, MSOs, and MSCs) patrolled offshore in the 9 patrol areas. U.S. Navy VP aircraft flew mainly two patterns (the Red and Blue tracks). Under the NAG, operational tactics were experimented with, and DER/PCF/WPB teams worked to coordinate their patrolling activities. There was little coordination between the VNN Sea and Junk Force and the Swifts.

Enemy Activity

(U) As Market Time progressed, more information on enemy activity came to light, suggesting that the VC had used and would continue to use seaborne infiltration to transport supplies into SVN. At the end of April 1965, a large arms cache was discovered in Kien Hoa as a result of 3 months of intelligence work (started before the operation was officially established). This cache was found to be at a more permanent site than that at Vung Ro Bay, and it included 6 Chinese portable flamethrowers. This was the first known instance of flamethrowers entering SVN. Intelligence officials determined that the weapons were to have been distributed north and west of Saigon and surmised that they had probably been delivered by sea.

(U) At this time, a key VC official was captured. Documents were found pinpointing the district of Thanh Phu in Kien Hoa Province (MR-4) as a major sea infiltration area. The documents indicated a large ship anchored 3 to 5 n. mi. offshore twice a month to be offloaded by 3 motorized sampans.

(U) A VC who was knowledgeable about sea infiltration stated that from January 1964 to November 1965, an average of 2 steel-hulled ships per month infiltrated arms and ammunition into An Xuyen.

(C) The first trawler detection since February took place on 31 December off An Xuyen Province. The trawler aborted its mission and returned to Chinese waters. Photography proved that this trawler was similar to the one discovered at Vung Ro Bay. Since this trawler had a Chinese nationalist flat painted on it, the U.S. commander on Taiwan began to send NAG the name, registry number, estimated date od departure and estimated date

--23--

and location of arrival of all Chinese Nationalist trawlers to ensure detection of further infiltration attempts under the guise of that neutral flag.

MARKET TIME UNDER COMNAVFORV

On 1 April 1966, U.S. Naval Forces, Vietnam (NavForV) was established as the Naval component commander for ComUSMACV.

Later that year, two things happened outside of Market Time that ultimately affected seaborne infiltration--the Sea Dragon Operation and the opening of Sihanoukville to communist bloc nations.

Sea Dragon, consisting of U.S. and Australian ships and support aircraft dedicated to interdicting NVN's coastal logistics traffic between the 17th and 20th parallels, went into effect in November. By the end of 1966, this operation had destroyed 382 WBLCs and damaged 325, many of them headed for SVN. During the 2 years of Sea Dragon, the numbers of WBLCs crossing the 17th parallel dropped sharply, except during standdown periods.

In December 1966, Sihanoukville was opened to communist bloc nations, providing logistic military support the VC/NVA in MR-4 and-4 and in southern MR-2. Any great pressure for sea infiltration into the Delta would have been certainly eased and possibly eliminated by the impunity with which the VC could now transport supplies through Cambodia to the Delta by the extensive inland waterway network and land routes in MR-4.

In May 1966, soon after NavForV was established, TF 115 detected a trawler heading for MR-4. The trawler was destroyed by Market Time forces but much of its cargo was retrieved. The most significant item recovered was 120mm. mortar ammunition manufactured in China in 1965; it was the first time this type of ordnance had been discovered in SVN. In addition, the discovery of 12. 7mm. APO ammunition manufactured in China in 1965 also indicated a shortage of ammunition for communist troops in SVN.

Another infiltrating trawler heading for MR-4 was captured in June. Some of the ammunition boxes that were salvaged were dated 1966, implying the communists had a rapid distribution system.

The disagreement between NavForV and MACV on the extend of seaborne infiltration came up again in August 1966. ComUSMACV was told about infiltration from the sea in MR-2 and-3, proven by cart tracks and arms caches on the beaches. CTR 115 did not agree with this theory.

--24--

As more PCFs arrived, incident with junks increased, probably an indication that much of the infiltration/transshipment was not being detected. The more Market Time forces there were available, the more activity they discovered. By the end of 1966, 96 WBLCs had been destroyed, and large quantities of medical supplies, ammunition, and equipment seized.

Another trawler infiltration attempt was detected in December. But the trawler, probably headed for Binh Dinh province, aborted its mission. In January 1967, however a trawler was detected offloading onto Sampans near the mouth of the Bo De River in MR-4. After an exchange of gunfire with Market Time forces, the trawler exploded possibly as a result of a self-destruct system. The hull was never found and, therefore, no contraband located. Salvage operations were hindered because the exact location of the trawler had not been plotted, and the general area was controlled by the enemy.

In March 1967, another steel-hulled trawler attempting infiltration into Quang Ngai was detected by Market Time forces. It was destroyed by its own crew, but some cargo was recovered.

Most reports of enemy waterborne activity in this area (off the coasts of MR-1 and-2) were hearsay from low-level sources. In March, a high-level information source became available on seaborne deliveries into enemy MR-5.2 That source was a 39-year-old North Vietnamese major who defected ("rallied") to the South Vietnamese on 25 March 1967 in Quang Ngai province. His credentials stated that he was the training officer in enemy MR-5; he said that more than half the supplies to MR-5 came by sea during 1965 and 1966. (MR-5, by his definition, included the coastal provinces between the southern borders of Thua Thien and Khanh Hoa provinces.)

He estimated that, so far in 1967, only 20 to 30 percent of MR-5 supplies had arrived by sea. Although his statement corroborated earlier low-level reports, they failed to clarify the type of supplies included in the sea-borne infiltration.

In April, as corroboration for the defector's report, there were increasing low-level reports indicating that seaborne infiltration and coastal resupply were being used to meet the logistical requirements of VC/NVA forces in northern Binh Dinh and southern Quang Ngai Provinces. By April, however, the number of low-level reports infiltration by sea in SVN from Cambodia had decreased.

__________

2. The VC and North Vietnamese had their own system of subdividing SVN into military regions.

--25--

The commander of CG Division 11 in the Gulf of Thailand felt, early in March, that the VC had been driven to inland canals and that intracoastal traffic had been eliminated. There is no way to corroborate this; but it is plausible in light of the VC's freedom to use Cambodia without harassment. Despite Sea Dragon, there were still frequent reports in April 1967 of the infiltration of troops and supplies from NVN by WBLCs just below the DMZ.

In July, ComNavForV said there had been a marked decrease in seaborne infiltration because of the effectiveness of Market Time and increased control of the coast by friendly military assistance forces. Market Time forces had been concentrated in areas shown by intelligence to be infiltration points. In July, perhaps because of the extra vigilance of Market Time forces off MR-1, TF 115 forces detected a steel-hulled trawler attempting infiltration into Quang Ngai province. The trawler was run aground and the cargo salvaged.

By July 1967, the enemy was probably moving less than 5 percent of out-of-country requirements of Class II, IV, and V3 materials by sea, and that most of the seaborne infiltration to MR-1 was by WBLCs.

Multitrawler Infiltration attempt Following Tet

With the fighting during Tet in February 1968, there was a decrease in routine activity for Market Time forces. The fighting prevented indigenous junk and sampan traffic from using many inland waterways as access to the ocean, and bad weather inhibited normal activity of the watercraft.

During late February, 5 trawlers were detected attempting to infiltrate. One trawler aborted its mission before reaching SVN's contiguous waters. Several days later, on 28 and 29 February, 4 trawlers came under Market Time surveillance as they approached the SVN coast in MR-1,-2, and-4. This was the first detected coordinated multiple infiltration attempt. It was obviously a crisis-oriented effort after the heaviest fighting of Tet, as evidenced by the large quantity of emergency medical supplies--particularly blood plasma--carried by one of the trawlers. Three of the trawlers were destroyed and the fourth aborted its mission.

After this attempted multitrawler infiltration, no other infiltrating trawlers were detected until August 1969.

__________

3. Class I - food and water.

Class II - weapons, vehicles, signal equipment, and clothing.

Class III - POL.

Class IV - construction material.

Class V - ammunition, etc.

--26--

Before 1965, trawler infiltration focused on the Delta. In 1965, there was an NVN main force buildup in MR-1 and-2, so the trawler infiltration effort was expanded to include northern SVN. MR-3 potential beach sites failed to meet most security requirement, and the support organization needed to meet infiltrated supplies was never generated. Supplies were moved across rivers to MR-3 from the Mekong estuaries.

In the first trawler infiltration era, there were two main trawler corridors--the Quang Ngai-Binh Dinh corridor and the an Xuyen corridor (Figure 8). The upper section of the corridor roughly parallel the Hong Kong-Singapore/Shanghai-Singapore routes, probably to serve as cover for the trawlers and to simplify navigation. During that time, the trawlers did not seem inclined to abort their missions. The attempts were probably designed to meet specific short-term supply needs, as illustrated by the 4 simultaneous attempts following the Tet offensive. In addition, 3 trawlers tried to take advantage of Christmas' and New Year's stand-downs.

Market Time Status at NavForV Takeover

After NavForV was established, CTF 115 spent the rest of 1966 building up to the force levels suggested by the Landis Study. But a review of the Landis Study in July 1966 showed that some of the assumptions on which it was based were no longer valid.

The intelligence estimates of VC resupply requirements in SVN were revised. The VC/NVA were credited with the ability to infiltrate 269 tons a day by land and river lines of communication (LOCs) through Laos. But as additional forces were infiltrated, their resupply requirements would exceed land and river LOC capabilities by late 1966. The intelligence section of MACV expected a renewed emphasis on the seaborne route.

Not only was the estimate of the threat revised, but it was pointed out that all the positions recommended by the Landis Study had not yet been filled. While CTF 115 waited for the remainder of his requested forces, the primary emphasis of the surface effort was on random patrols within assigned zones rather than on establishing a perimeter barrier around a defended zone.

In addition, the Landis Study had assumed that 100 SVN coastal units and 16 SVN patrol craft would be available to patrol the coast. An average of 100 inshore units were on station, but only 10 patrol vessels were available; these were equipped with unreliable radar. Although the Landis Study had implied that an attrition rate of more than 20 percent attrition could be expected on steel-hulled trawlers penetrating the outer barrier, the need to increase this attrition rate (especially in high-threat areas) was determined in mid-1966.

The TF 115 OpOrder of April 1966 estimated that the total VC requirements for one day of operations could be met by 180 medium-sized junks. The OpOrder further noted that

--27--

there was no effective control of motorized junks licenses to operate in SVN waters. ComNavForV initiated a junk-boarding/manifest-reporting program to build up a knowledge of coastal and riverine traffic, and areas for housing detainees were set up.

Secondary Market Time Missions

Once the basic operating concepts were learned, Market Time forces began to participate in operations secondary to their main mission. In addition, until Game Warden was started in May, WPBs and PCFs participated in river patrols.

As a result of a January MACV directive to develop defenses of major harbors in SVN, Market Time activities expanded into harbor defense (operation Stable Door) in mid-April 1966. A harbor entrance control post, radar surveillance, and surface-craft patrols were to be established at each major port.

Market Time forces increased their support of ground operations during 1966 and 1967 to prevent enemy infiltration/exfiltration. From one of these support operations, Tee Shot V, came three emergency action plans for Market Time units to establish barriers or concentrated area inspections of junks and sampans. These plans were to be executed rapidly with minimum communications. Plan Line Plunge established a barrier perpendicular to the coast to intercept traffic parallel to the coast; plan End Around placed a barrier parallel to the coast to intercept traffic travelling perpendicular to the coast; and plan Corral established a specific area of search when closer-than-normal scrutiny of a junk concentration was required.

Naval Gunfire Support (NGFS)

By mid-1967, NGFS of ground forces bean to increase as a secondary Market Time mission. As freedom of movement was denied to the enemy inland, exfiltration operations became more important, resulting in more opportunities for NGFS. Originally, NGFS had been frowned upon as interfering with coastal surveillance.

Psychological Operations

Another mission of Market Time was well underway in 1966: the psychological operations (PsyOps) program. This program was calculated to counter VC propaganda, warn junk and sampan crews against evading an intensive U.S. Navy or VNN search of an area, and make contacts that might be a good source of intelligence. In the course of a day's search, kits of soap, dehydrated milk, sewing kits, cooking oil, toothpaste, cigarettes, and Kool Aid, among other items, were often distributed to junk and sampan crews to compensate for the burden of submitting to search.

--28--

But questions were raised about the value of such a giveaway program. Or, as the 1967 Coastal Division 13 Commander commented in his end of tour debrief: "The goodie bags get you little more than a highly indignant attitude on the part of the Vietnamese when you show up without them."

There was also some question as to how effective the leaflet programs would be if many members of the local population were illiterate. On the other hand, there seems to be no disagreement that first-aid treatment and towing of stranded local craft was a substantial way to accomplish PsyOps goals.

Another form of PsyOps more substantial than the giveaway program was the support by some U.S. Navy and Coast Guard units of SVN institutions such as orphanages. By August 1966, the Island Adoption Program was underway in the Gulf of Thailand. Under this program, each Gulf of Thailand Market Time unit was assigned a specific island, together with the responsibility of furnishing education and informative materials to counter VC propaganda, providing medical treatment, and improving the civilian-military relationship.

Coastal Surveillance Operations