The Navy Department Library

US Naval Forces in Northern Russia (Archangel and Murmansk), 1918-1919

Prepared by Dr. Henry P. Beers

Download a PDF Version of US Naval Forces in Northern Russia (Archangel and Murmansk), 1918-1919 [9.5MB]

Administrative Reference Service

Report No. 5

U. S. NAVAL FORCES IN NORTHERN RUSSIA (ARCHANGLE AND MURMANSK),

1918-1919

Prepared by

Dr. Henry P. Beers

Under the Supervision of

Dr. R. G. Albion, Recorder of Naval Administration

Secretary's Office, Navy Department

Lt. Cmdr. E. J. Leahy, Director, Office of Records

Administration, Administrative Office,

Navy Department

Office of Records Administration

Administrative Office

Navy Department

November 1943

Administrative Reference Service Reports

1. Incentives for Civilian employees of the Navy Department: A Review of the Experience of the First World War, by Dr. Henry J. Beers. (Special Report, not for general distribution), May 1943.

2. U. S. Naval Detachment in Turkish Waters, 1919-1924, by Dr. Henry P. Beers, June 1943.

3. U. S. Naval Port Officers in the Bordeaux Region, 1917-1919, by Dr. Henry P. Beers, September 1943.

3A. U. S. Naval Port Regulations, Port of Bordeaux, France (Reproduction of 30 page pamphlet issued 19 March 1919) July 1943.

4. The American Naval Mission in the Adriatic, 1918-1921, by Dr. A. C. Davidonis, September 1943.

5. U. S. Naval Forces in Northern Russia (Archangel and Murmansk), 1918-1919, by Dr. Henry P. Beers, November 1943.

Note:

Attention is called to Report No. 3A, which reproduces a 30 page pamphlet, "U. S. Naval Port Regulations, Port of Bordeaux, France," published originally at Bordeaux by the naval port officer. It gives a comprehensive idea of the details of the routine functions of a port officer and might serve as a useful model for similar issues.

U. S. NAVAL FORCES IN NORTHERN RUSSIA (ARCHANGEL AND MURMANSK)

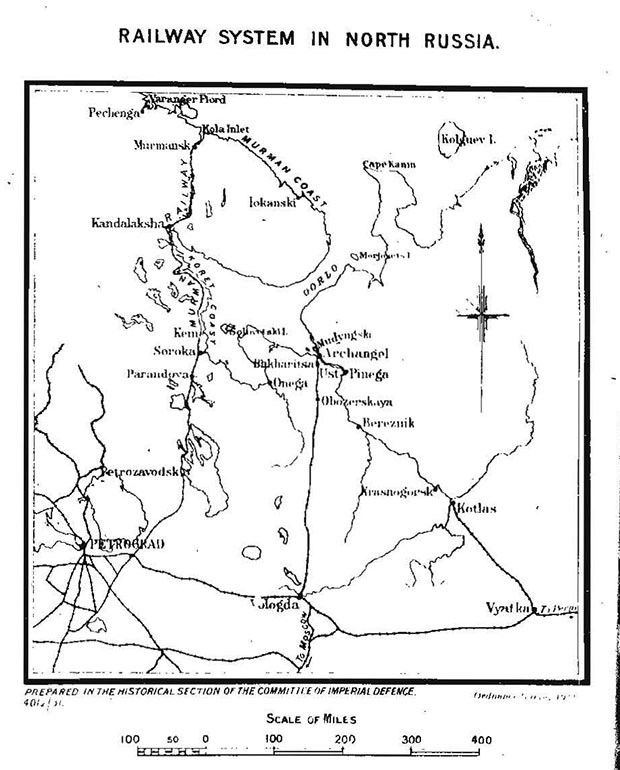

The outbreak of war between Russia and Germany in August 1914 had important effects upon North Russia. The closing of the Baltic ports of Russia and of the exit from the Black Sea through Turkey's joining the Central Power left her only the remote ports on the Arctic Ocean through which to secure military supplies and equipment from her Allies in western Europe, aside from the still more remote port of Vladivostok in Siberia. It became necessary therefore for Russia to develop the northern region to the greatest extent possible and with the greatest possible speed.

The only port of any size in Northern Russia in 1914 was Archangel, an imposing and well-built city located on elevated ground on the eastern bank of the North Dvina River where it branches into a number of streams, thirty-three miles from the White Sea. Founded in 1553, when an English trading factory was built there, Archangel had been Russia's only outlet to the sea for many years, but after the building of Petrograd by Peter the Great in 1702 it declined in importance although it continued to be visited by ships from England and the Netherlands. Far from peace time shipping routes, Archangel was 720 miles distant from Moscow and 760 miles from Petrograd. It was connected by river, canal, and rail with the south. In ordinary times it exported lumber, tar, flax, linseeds, and skins. To increase the capacity of the railroad, the terminus of which was at Bakaritza on the west bank of the North Dvina opposite Archangel, it was converted from a single to a double track line in 1916. A temporary railroad was built by the Russians to the port of Economia constructed by the

- 1 -

British sixteen miles down the river from Archangel in order to provide a place with a longer open season; this could be reached by ice breakers until the middle of January. The population of Archangel which in 1915 numbered 40,000, increased several fold and the imports many fold during the early years of the war.

Since Archangel was closed to shipping from November to May because of ice, which began forming in October at the headwaters of the North Dvina and progressed downstream to the White Sea, the Russians undertook the construction of a new port on the Murman coast 430 miles from Archangel. Although the Murman coast was farther north on the Barents Sea, a part of the Arctic Ocean, it was free of ice the year round because of the influence of the Gulf Stream, which passes north of Norway. Under imperial authority and at a cost of $60,000,000, a railroad was built during 1915-1917 by an army of laborers, foremen, and inspectors supervised by Russian engineers from Petrozavodsk, to which a line extended from Petrograd, to the Murman coast. Prior to its completion caravans of reindeer sleighs transported light articles and munitions by road to the south. Its northern terminus was a town of log huts built on a plain encircled by hills at a point on the eastern shore of the Kola Inlet twenty-five miles from the sea, which was at first known as Romanovsk and after the revolution of 1917 as Murmansk. The new port, a flask shaped bay, afforded sheltered anchorage for large vessels, and the narrowness of the Kola Inlet permitted stretching a boom across it to control the passage and provide protection against enemy raids. Here a shifting population of some 15,000 of Russians, Chinese and war prisoners supplied workmen for the railroad and stevedores for unloading ships. At Alexandrovsk, a port

- 2 -

founded in 1899 at the mouth of the Kola Inlet but considered unsuitable for development, because of high cliffs, were cable connections with England and Archangel. Through a branch cable running to Alexandrovsk, Murmansk had communication with those places. A telegraph line ran the length of the Murman coast from the Norwegian frontier via Alexandrovsk and Kola to Archangel.

Naval protection soon had to be provided for the Murman Coast, for the port of Murmansk was hardly begun before German submarines began to torpedo ships and lay mines off the coast. As the Russian Navy could furnish only an inadequate patrol, the British Navy undertook operations in this region in 1915 with a patrol squadron under Rear Admiral Thomas W. Kemp. Despite improved defense in 1916, German submarines accounted for forty vessels in that year. The patrolling and trawling detachments were further strengthened in 1917, but in the spring of that year the Russian Government requested the United States to dispatch at the earliest date possible a reinforcement of four patrol vessels and four destroyers. Captain Newton A. McCully, who was then serving as naval attaché at Petrograd, journeyed by rail to Archangel at the end of June 1917, investigated conditions there and at Murmansk, to which he traveled in a Russian trawler, and submitted a report in the following month. At this time the Russian commandant of the Archangel naval district was also commander-in-chief of the White Sea Fleet and had charge of communications and coastal batteries. Afloat the Russians divided control with the British White Sea Fleet, the Russians patrolling and trawling in the White Sea and its entrance as far as Sviati Noos, while the British operated west of that point. Admiral Kemp had certain rights of inspection and supervision in order

- 3 -

to expedite ship repairs at Archangel. He controlled shipping proceeding to that port where upon its arrival responsibility was transferred to the British Naval Transport Officer. Russian naval bases at Yukanskoe and Murmansk cooperated with the British. Admiral Kemp was usually stationed on the battleship Glory at Murmansk. Captain McCully stated that sending destroyers was of vital importance, if it was desired to encourage Russia to maintain opposition to the enemy. It was impossible at the time, however, for the U. S. Navy to meet other, apparently more urgent demands, and no destroyers were sent to Northern Russia. The British light cruiser Iphigenia, which it had been planned to allow to be frozen in at Archangel where Admiral Kemp and the naval transport office would remain, was withdrawn with all naval personnel in December 1917, following the Bolshevik revolution, to Murmansk where British forces continued in order to be in a position to influence conditions and to protect Allied refugees who were crowding into that port via the Murman railroad.

Largely cut off from outside sources of military supplies during the winter of 1914-1915 because of the lack of an ice free port on the Arctic, the Russians suffered military defeat at the hands of the Germans in 1915-1916, and were not able thereafter to make effective resistance. The Czar was deposed in a revolution in March 1917, and a provisional government was established. Not long after seizing power in November 1917, the Bolsheviks effected an armistice and began negotiations for a separate peace with the Central Powers. Excessive demands on the part of Germany prevented this from being immediately accomplished, resulting in February 1918 in the termination of the armistice by the Germans and their advance into Russia. By May they occupied both the rich granary of the Ukraine and Finland. The German

- 4 -

occupation of Finland placed her in a position to advance into North Russia; occupy Archangel and Murmansk; seize the huge quantities of military stores transported to those places from the United States, Great Britain, and France which in the 1917 season amounted to over two million tons; establish submarine bases from which they could raid Allied shipping routes; utilize as a base for the seizure of Spitzbergen; seize the Russian naval vessels in the White Sea; and entrench themselves so as to cut off Allied trade with North Russia after the war. These were apprehensions which it was only good military sense to contemplate. The defeat of Russia was a staggering blow to the Allies, for it meant the end of the German eastern front and the resultant transfer to the western front in France of large bodies of German troops. The occupation of Russia by Germany placed it in a position to benefit from the great resources of raw materials and the vast supply of man power of the conquered nation. To prevent Germany from reaping as far as possible the advantages of her victory over Russia, the Allies decided to intervene in Northern Russia in an affort [sic] to rebuild a Russian army about an Allied force as a nucleus and recreate an eastern front.

Early in 1918 the British sent the cruiser Cochrane to reinforce Admiral Kemp and requested naval assistance from France and the United States. On vessels sent to evacuate refugees some Royal Engineers were carried to Murmansk in order to perform demolitions in the event of a withdrawal. The Cochrane arrived on March 7 and the French cruiser Admiral Aube on the 19th.

The Allied intervention at Murmansk in the spring of 1918 was effected upon the invitation of the local Soviet, which had been

- 5 -

formed following the Bolshevik revolution, and with the approval of the Central Soviet at Moscow, which was desirous of obtaining supplies and military equipment from the Allies with which to suppress the factions wanting to continue the fight against the Central Powers. The Soviet government, it might be added, had no means at the time of opposing the Allies. Early in March representatives of Great Britain and France agreed with the Murmansk Soviet that supreme authority in the region was to remain with the Soviet, that the Soviet shou1d have representation on the military council which was to direct military matters, that the Allied representatives would not interfere with the internal affairs of the region, and that the Allies would supply food and war materials. Shortly afterwards, on March 9, 200 British marines from the Glory and 100 French marines from the Admiral Aube were landed at Murmansk. This small beginning was soon enlarged upon. Rear Admiral Kemp in command at Murmansk had instructions to protect and further Allied interests but not to commit himself to land military operations away from the port; he might utilize the crews of the ships to stiffen local resistance. A Finn attack upon Pechenga was repulsed in May by a force of British and Russians.

American participation in the Allied intervention in Northern Russia resulted from representations of the British government and American representatives in Russia. It was also favored by the Russian officials at Murmansk who distrusted the British and feared that once they were established in the region they would never depart. Admiral William S. Sims, Force Commander, U. S. Naval Forces Operating in European Water, whose headquarters were at London, forwarded with his indorsement on March 3, 1918 a request from the British

- 6 -

Admiralty for the dispatch of an American warship to Northern Russia to give material assistance and to impress the Russians. The Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral William S. Benson, replied that after conferring with the Department of State it had been decided not to send a cruiser to Murmansk for the present. A note on the same subject was received by the Department of State from the British Embassy on March 5. During March and April the Murmansk officials were in touch with Lieut. Hugh S. Martin, U. S. A., an assistant military attaché of the American Embassy in Russia, who had been sent to Murmansk by Brig. Gen. William V. Judson, chief of the American Military Mission in Russia, and the Ambassador in Russia, David R. Francis. Towards the end of April, Lieutenant Martin went to Vologda, to which Ambassador Francis had retired a month before, with a plan for American intervention. Mr. Francis had communicated his approval of intervention in March and continued to espouse it although nothing came of the plan presented to him by Martin.

Early in April, not long after the Germans began their great drive on the western front, following the transfer of troops from Russia, Admiral Benson again communicated with Admiral Sims concerning the need for an American naval vessel in Northern Russia and was assured that the British Admiralty still regarded it as necessary. The old cruiser Olympia, the former flagship of Admiral George Dewey, which had been engaged in convoy escort duty on the Atlantic under the command of Capt. Bion Boyd Bierer, after a lengthy retirement preceding the war, was selected for the Northern Russia assignment. Sailing from the Charleston Navy Yard, where it had been given some over-hauling to fit it for the rigorous duty ahead, on April 28, it

- 7 -

reached Scapa Flow on May 13, and after bunkering continued a week later on the voyage to Murmansk which was reached on May 24. Here it found an assortment of British, French, and Russian naval vessels all under the command of British Rear Admiral Thomas W. Kemp. Captain Bierer at once called upon Admiral Kemp on the Glory, the captain of the Amiral Aube, and the Murmansk Soviet and established official relations with them. With all the force under his command Captain Bierer was subject to orders from Admiral Kemp. According to arrangements made by Admiral Sims with the British Admiralty, the Olympia and the other American warships which subsequently arrived in Northern Russia were supplied by the British Navy, whose means were more ample and convenient for this purpose. Certain supplies, however, were received from the United States.

Among a number of passengers carried by the Olympia was Brig. Gen. Frederick C. Poole of the British Army, who had been selected by the Allied Supreme War Council as commander-in-chief of the Allied forces in Northern Russia. This appointment not only made him the superior of Rear Admiral Kemp but also gave him command of operations in both the Murmansk and the Archangel regions. Since operations in Northern Russia were bound to be amphibious in character and since the British were in the best position to handle such operations, it was good planning from a military viewpoint to put a British officer in command, but politically it would have been better to have designated an American officer, for of all the Allied nations the Americans were best liked and most trusted by the Russians.

The Allied force at Murmansk was augmented at the time of General Poole's accession to the command by the arrival of British marines

- 8 -

and infantry. Other elements in the force included French and Serb soldiers who had reached Murmansk on their way from Russia to France, Red Finns, Russians and Poles enlisted in a Slavo-British legion by the British, and Bolshevik troops who were cooperating with the Allies at this time. General Poole had expected to find a strong body of Czechs at Murmansk as arrangements had been made with the Soviet government for their transportation there from Omak, Siberia where they had collected after being liberated as prisoners of war following the Treaty of Brest-Litvosk, but a Bolshevik army had intercepted them. When news reached Murmansk at the end of the first week in June of the approach of Finnish troops to cut the Murman railroad, the Murmansk Regional Soviet authorized an Allied advance south of Kandalakaha, 200 miles to the south and the farthest point reached by foreign troops up to that period. To take the place of the troops that were dispatched to the south, 8 officers and 100 seamen were landed at Murmansk from the Olympia on June 9. Several writers state in their accounts that this force consisted of marines, but there were no marines serving on the Olympia while it was stationed in Northern Russia. These men were quartered in large, well-lighted barracks in the southern part of the town with the British marines that had been landed recently and performed guard duty, and the officers lived in a sleeping car. The passage of winter had brought to life swarms of mosquitoes which greatly troubled all living flesh in the region. General Charles C. M. Maynard arrived on June 23 with a thousand British troops. He found General Poole on board the Glory discussing the condition of the White Sea with Admiral Kemp, who in the following month paid a visit to Archangel. General Maynard took charge of the

- 9 -

Murmansk area where a force was necessary to keep open communications with England and France, and attempted to recruit Russians for service against the Germans; he was subordinate to General Poole.

Attached to the Olympia were workmen of various crafts who were kept busy while the ship was at Murmansk working upon ships in that port. After assisting in overhauling and repairing the Russian destroyer Kapitan Yourasovski, a detail of fifty men from the Olympia was assigned to duty on board it. In succeeding weeks working parties were engaged on the merchant ships Porto and Stephen and the Glory. Because of the shortage of stevedores, assistance was also given in discharging and loading vessels.

Following the establishment of peace with Germany in the treaty of Brest-Litvosk, the Bolshevik government under German pressure sought to effect the removal of the Allies from Murmansk. It presented notes of protest to the Allied representatives in Russia against the continuance of Allied warships in Russian harbors and sent a demand which was received in Murmansk on June 16 for the departure of these vessels. In view of this situation the British troops which were still on board ship were landed on June 26 under orders of General Poole. The Murmansk Regional Soviet, after consulting with the Allied representatives, decided to defy the order from Moscow. This decision was affirmed by a mass meeting at which the Allied officers, including Captain Bierer, made addresses in which they appealed to the local population to continue the fight against the Germans. Along with General Poole and Capitaine Petit of the Amiral Aube, Captain Bierer signed an agreement With the Murmansk Regional Council on July 6 in which it was provided that the

- 10 -

region would be defended against the Germans and that the Allies would furnish military supplies and equipment, foodstuffs, manufactured goods, and funds which were to be charged against the government debt of Russia, and that the internal government of the region was to be exercised by the Murmansk Regional Council. This accord, which opened the region to Allied penetration, was provisionally approved by Admiral Sims in a cable to Captain Bierer of August 3 and by the Department of State in October. The Moscow government protested against the Allied occupation as an invasion of Soviet territory and declared that it would be resisted. While on a trip on the Murman railroad to the south, General Maynard encountered Red Guards, a force of railroad defense troops raised by the Soviet Government, on the way to drive the Allies out of Murmansk; he was successful in disarming them and the local population along the railroad and so established control of it. In July British forces assisted by the newly arrived light cruiser Attentive and the carrier Nairana occupied Kem and Soroka, towns on the Murman railroad which were on the shore of the White Sea. Thus was inaugurated a state of undeclared war with the Bolsheviks which was to endure until late in the succeeding year. In this state of affairs it became the design of the Allies to effect a junction with White Russian forces under Admiral Kolchak fighting their way westward along the Siberian railroad and then to overthrow the Bolsheviks by force of arms. A part of the same general scheme was another Allied expedition which was landed at Vladivostok on the Pacific coast of Siberia and assistance rendered the forces of General Denikin and General Wrangel in South Russia. Thus from an anti-German the expedition was transformed into an anti-Bolshevik enterprise.

- 11 -

As the continued presence of Bolshevik forces at Archangel constituted a threat to the Allied occupation of Murmansk, an invasion of the former region was planned by the Allied officers, who no doubt regarded it as a more strategic base for operations. Sir Eric Geddes, First Sea Lord, who came on a visit with the British reinforcements, advised the War Cabinet to order an early landing. But General Poole decided to await the arrival of more Allied forces. The removal of Ambassador Francis and the other Allied ambassadors from Vologda, where they would have been cut off by the seizure of Archangel, their arrival at Kandalaksha on July 30, after a train journey to Archangel and a voyage across the White Sea, which movements were reported to General Poole by Ambassador Francis, who was the dean of the diplomatic corps, enabled the expedition to embark on the same date. It comprised the Attentive, the Nairana, the Amiral Aube and was preceded by six armed trawlers. The Olympia remained at Murmansk, but Captain Bierer accompanied the force on board the H. M. S. Salvator with General Poole and his staff. More ships left on the 31st carrying British and French troops and on the S. S. Stephen were three officers and fifty-one men from the Olympia. The force on the warships and the transports included only about 1500 troops, but the offensive power of the naval vessels added greatly to the total strength. After bombs dropped by aircraft from the Nairana and shells fired by the Attentive subdued the Russian battery on Modyugski Island 30 miles north of Archangel, both that place and Economia were occupied on August 2, and on the following day the Bolsheviks, who during the winter had succeeded in removing most of the military stores that had accumulated at Archangel were driven out of Bakaritza. After the

- 12 -

landing at Archangel, forces were sent south on the railroad, and on the Dvina River combined military and naval operations were undertaken. Special efforts had been made by Moscow itself to effect the shipment to interior points of the valuable stores, most of which were consequently lost to the Allies, and some of which apparently reached German hands to be used for fighting the Allied troops. The debt for the stores was repudiated by the Bolsheviks who did not consider themselves responsible for obligations incurred by the imperial government of Russia. After the loss of Archangel, the Bolsheviks anticipated a descent upon Moscow and began overtures to the Germans for help. The Bolsheviks thereafter were naturally hostile towards the Allies who by this time had also landed in Siberia.

The part played by the U. S. Navy in the taking of Archangel was of no particular moment, for only the small landing force commanded by Lieut. Henry F. Floyd was involved. Of this force half were soon sent up the Dvina River with Allied troops in an attempt to push the Bolsheviks farther south; they encamped at a point near the junction of that river with the Vaga. A small detachment of an officer and twelve men was employed in patrolling the Archangel-Vologda railroad between Isakogorka and Tundra. The rest of the force assisted in training a Russian Allied Naval Brigade which was organized at Archangel. A party of twenty-two bandsmen arrived shortly from the Olympia and was probably used to soothe the local population and entertain the occupying forces. The Russian destroyer Kapitan Yourasovski, which was largely manned by American bluejackets, was also at Archangel in August. Captain Bierer inspected Archangel and Bakaritza and their vicinities, and conferred with Admiral Kemp

- 13 -

and the other British naval officers concerning the use to be made of the Russian ice breakers, trawlers, patrol vessels, and steamers; which were found at Archangel, and the formation of the Russian Allied Naval Brigade. With Admiral Kemp on the Salvator he departed for Murmansk on August 19. Ambassador Francis, who in the meantime had traveled to Murmansk only to reach there after the departure of the expedition, returned to Kandalaksha and then to Archangel where he arrived with the diplomatic corps on August 9 and established the embassy. The dispatch of American soldiers to Northern Russia was urged by the British and by Ambassador Francis. The British pleaded inability to furnish adequate forces because of the demands of the situation in France and the lack of troops in England. Francis reported that the forces in Northern Russia were inadequate and that the arrival of Americans would enhearten the Russians. On a visit to Paris he urged a force of 100,000 men. Having taken the first step, the United States Government now took the next step and became fully involved in the war with the Bolsheviks. General Pershing, the Commander of the American Expeditionary Force, was opposed to the intervention in Northern Russia because it meant diverting troops from the front in France, but President Wilson was persuaded to consent and ordered the sending of troops.

The American consul at Archangel, Felix Cole, realized what intervention would lead to and addressed a long communication to Francis, which was forwarded to the Department of State, setting forth potent reasons against it. He believed that our involvement would result in increasing demands for ships, men, and money, and materials; that to hold the region and the railroads and rivers leading to the south would require widespread operations and extensive forces; that the ground had

- 14 -

not been properly laid and that active support wou1d not be afforded by the Russians; that it would be necessary to feed the entire population; that the Bolsheviks would oppose it; that it would not be effective in a military way against Germany; that it would damage our relations with the Russian people; and that like other invasions of foreigners into Russia it would be swallowed up. He did, however, favor the dispatch of strong naval forces to Archangel, Murmansk, and the White Sea. That there was wisdom in his words subsequent events proved, but they were words from afar.

A reinforcement of American troops consisting largely of the 339th Infantry totaling 4600 men reached Archangel on the troop ships Somali, Tydeus, Nagoya from England on September 4, 1918. At the time of their arrival, these men were not in good shape for battle, for they had been attacked by an epidemic of influenza during the voyage. Their commanding officer, Col. George E. Stewart, had directions to report to General Poole and operate under his orders. Part of these troops were sent to the south along the Dvina and the railroad while others were stationed in Archangel and vicinity. Wherever they went and wherever other Allied troops served, they went usually under British officers, for the British adopted the practice of giving temporary promotions to their officers so they would out-rank the other Allied officers. Some additional American Troops arrived at the end of September with other forces under General William E. Ironside. The American forces were by far the most numerous in the Archangel region, but they had to fight under a British general. Colonel Stewart was given quarters in a steam heated building, modern and roomy where he enjoyed considerable comfort and no authority, and where he remained for the winter.

- 15 -

Although they conferred with the British, the American officers were not on a confidential basis with them.

A naval passenger on one of the troop transports, Lieut. Sergius M. Riis, U. S. N. R. F., became attached to the American Embassy at Archangel as acting naval attaché. Since he had had previous experience in the Arctic and could speak Russian, Esthonian, and Finnish, he was a valuable addition not only to the embassy but to the whole circle of American officers in Northern Russia all of whom utilized his services on occasion.

Although the United States Government dispatched navel and military forces to Northern Russia, it did not commit itself to full-fledged military intervention in Russia. The policy of the government was announced in a public statement issued on August 3, the day after the occupation of Archangel. In this the considered opinion was expressed that military intervention in Russia would not be in the interest of her people and would be more likely to result in using them than in serving them, even if it were successful in creating an attack upon Germany from the east. Military action was admissible only to help the Czecho-Slovaks against the armed Austrian and German prisoners who were attacking them and to steady efforts at self-government or self-defense by the Russians. "Whether from Vladivostok or from Murmansk and Archangel, the only present object for which American troops will be employed will be to guard military stores which may subsequently be needed by Russian forces and to render such aid as may be acceptable to the Russians in the organization of their own self-defense." No interference with the political sovereignty of Russia or intervention in her internal affairs was contemplated.

- 16 -

Ambassador Francis was informed in a telegram of September 26 that as there was no hope of effective help from the Russians, the United States would cooperate militarily only to guard the ports themselves and the neighboring country. General relief could not be undertaken nor would more American troops be sent to Northern Russia. The substance of these documents was communicated by Admiral Sims to Captain Bierer, who acquainted his forces with their import.

After the arrival of military reinforcements at Archangel, most of the landing force and the bandsmen were returned in the middle of September from that place to the Olympia at Murmansk. No American soldiers were landed at Murmansk until April 1919 when two companies of transportation troops arrived to run the Murman railroad. But the U. S. Army was represented at Murmansk by two intelligence officers, Lieut. H. S. Martin and Lieut. M. B. Rogers. The former acted as American consul prior to the arrival of Maurice C. Pierce to fill that position in January 1919.

At the time of the Allied occupation of Archangel, its government passed into the hands of anti-Bolshevik officials headed by the veteran socialist, Nikolai Vasilyevich Chaikovsky, who had spent many years of his life in England and the United States as an exile. This government was put in office with the help of Allied agents and became subservient to the Allied Commander, General Poole, being guided by him and the Allied ambassadors. A proclamation was issued announcing the establishment of the Supreme Administration of the Northern Region, which was a provisional body intended to function only until the formation of a central democratic government in Russia. This government was replaced early in October by the Provisional Government of

- 17 -

the North, which allowed representation to middle classes groups. Mr. Francis made repeated complaints to Washington about the high-handed methods employed by General Poole in the conduct of affairs. The general was called to England in October to report on matters in Northern Russia and did not return, being replaced by General William E. Ironside, who proved to be a more conciliatory officer. The maintenance of independent commands at Archangel and Murmansk was difficult so at this time General Ironside was given command only at Archangel, and General Maynard was accorded complete charge at Murmansk. In the following month Rear Admiral John F. E. Green became senior British naval officer in Northern Russia, succeeding Rear Admiral Kemp who returned to England. Upon Chaikovsky's departure in January 1919 to engage in anti-Bolshevik agitation at the Paris peace conference, he was succeeded by Major General Eugene Miller, an officer of the old Russian army, who filled the posts of minister of foreign affairs and commander-in-chief as well as that of governor general. Murmansk came under the Archangel government, and after the beginning of November 1918 it was governed by a deputy governor named Yermoloff; he worked closely with General Maynard who had been in practical charge of civil affairs for sometime previous, owing to the virtual retirement or the Murmansk Council.

After the landing of American soldiers at Archangel, the Navy Department took up with the Department of State the matter of assigning a rear admiral to duty in Northern Russia. The latter department communicated to Ambassador Francis the plan to send Rear Admiral Newton A. McCully, who had previously served under him as naval attaché at Petrograd, and the reply was received that this officer would be very acceptable. Rear Admiral McCully was selected because of his

- 18 -

familiarity with Russia and the Russian language acquired during a tour of duty in the Far East as an observer with Russian military and naval forces during the Russo-Japanese war and during his tenure of the position of naval attaché in Russia from 1914 to 1917. Before his departure from Russia in 1917 he had made a brief Visit to Northern Russia, as already mentioned and submitted a report concerning the dispatch of American naval forces to that region. In the spring of 1917 he served for a short time with the American Mission to Russia and in the fall of that year, after his return to the United States, with a Russian Mission to the United States. When orders were sent him on September 26, 1918 to assume the post in Northern Russia, he was serving at Rochefort, France in charge of a U. S. Naval District embracing that portion of the French coast from Fromentine to the Spanish border and in command of Squadron 5, Patrol Force, Atlantic Fleet. He proceeded early in October to London where he made arrangements with Admiral Sim's staff for his new duty.

Confidential instructions for the guidance of the Commander, U. S. Naval Forces, Northern Russia were given McCully by Sims on October 10. In regard to policy he was directed to call promptly on the Ambassador and to consult with him freely, and to read the President's proclamation on Siberian intervention and the dispatch of the Department of State to the Ambassador in Russia. Like Captain Bierer to whom these pronouncements had been communicated, as has been seen, he was to shape his policy accordingly. He was to cooperate with the Allied military and naval forces so far as the foregoing policies permitted. Cordial relations were to be maintained with the Senior U. S. Army Officer. He was to support the local Russian government, except when its actions

- 19 -

were contrary to the interests of the Russian people, as the United States wished to be known as a friend. In regard to the operations of his forces he was to be under orders of the senior naval officer of the Allies in Northern Russian waters, who was then Rear Admiral Kemp, R. N., of H. M. S. Glory. Such ordnance equipment was to be taken as would permit interchangeability of supplies with the Allied forces. Care was to be exercised by the medical officer against contagious diseases that might spread among the population and be communicated to the naval personnel, and precautions were to be adopted against frostbite and scurvy. In supplemental orders of the 15th he was authorized to issue orders transferring officers within his command and travel orders. This was a useful authority and even resulted in the Commander, U. S. Naval Forces in Northern Russia issuing travel orders to Rear Admiral Newton A. McCully. He could order no officer home except on the recommendation of a board of medical survey. Reports were to be made of changes, arrivals, and departures of officers.

Rear Admiral McCully arrived at Murmansk on October 24 under escort of the Kapitan Yoursaovski on board the French cruiser Gueydon, which had been sent to replace the Amiral Aube, and on the afternoon of that day he read his orders before the assembled crew of the Olympia, raised his flag on that vessel, and assumed command of the U. S. Naval Forces in Northern Russia, the designation thereafter used. He brought with him an aid, Ensign Jay Gould, U. S. N. R. F., and a party of enlisted men including three for duty with his staff. He received official calls from the captains of the Glory and the Gueydon, the Russian General. Zvegintsov, the commander of the French force ashore, and Lieutenant Rogers, U. S. Army. As the chief officers in Northern Russia were then at Archangel, Rear Admiral

- 20 -

McCully sailed for that place on October 26 on the Olympia, leaving Ensign Oliver E. Cobb, U. S. N. R. F., a storekeeper, and a seaman ashore in Murmansk for special temporary duty.

Off the entrance to the Dvina, Rear Admiral McCully was met on October 28 by Lieutenant Riis and proceeded with him and Ensign Gould on a small tug to Archangel to which the Olympia continued on the following day. He reported to Rear Admiral Kemp and Ambassador Francis and called on Mr. Chaikovsky, Mr. Duroff, the governor general of the northern provinces, Francis Lindley, the British commissioner, Joseph Noulens, the French Ambassador, the Italian charge, General Ironside, and Colonel Stewart. Ambassador Francis was in need of a major surgical operation, and, pursuant to arrangements which had been made by the State and Navy Departments, Rear Admiral McCully had him taken on board the Olympia on November 6 for conveyance to England. The Rear Admiral apparently took the Ambassador's place in the American Embassy, while Ensign Gould and 6 men went ashore for duty with the flag and three others for service with Lieutenant Riis, who continued to serve as acting naval attaché. There were still eleven other men at Archangel serving under Ensign Donald R. Hicks, U. S. N. R. F., with the Allied Naval Brigade. The Olympia left Archangel on November 8 under the command of Captain Bierer, whose service in Northern Russia was ended on the departure of the ship from Murmansk on November 13 for Scotland. Mr. DeWitt Clinton Poole, the former consul general at Moscow, who had been appointed special assistant to the ambassador with the rank of counsellor, took the ambassador's place.

After his arrival in England, Captain Bierer proceeded to London for consultation with Admiral Sims and to Paris for consultation with

- 21 -

Admiral Benson. Early in the following year he was ordered home, and in Washington he submitted a report to the Office of Naval Intelligence in which he stated that he had received a deep founded impression that the British and French took a special interest in Northern Russia and particularly the British who because of its resources and possibilities hoped that conditions would so shape themselves that they would be able to secure control or domination of the region.

It seems to have been the intention to have had the Olympia return to Northern Russia, but this did not happen, and for several months after its departure the U. S. Naval Forces in Northern Russia had no forces aside from the personnel stationed ashore. Not a single naval vessel was attached to the command, although a rear admiral had the assignment. An additional vessel had been asked for by Captain Bierer after the occupation of Archangel, but none was provided. When Rear Admiral Green proposed in November to decommission the Kapitan Yourasovaki, Rear Admiral McCully was obliged to request that the United States naval personnel then on board that destroyer be allowed to remain until the return of the Olympia.

The armistice of November 11, 1918 had no effect on the Allied intervention in Northern Russia although the need to frustrate German designs no longer existed. It was officially explained that the approach of winter made evacuation impractical and that it would amount to desertion of the Russians who had come to the support of the intervention. The occupation continued because it afforded a means by which the European members of the occupying forces might affect the situation in Russia, which was then developing into a civil war between the Reds (Bolsheviks) and the Whites (tsarists).

- 21a-

At the time of the departure of the Olympia, the United States naval personnel in Northern Russia was disposed as follows: McCully, Gould, Riis, and Ensigns D. M. Hicks and C. S. Bishop in Archangel, the last two being attached to the Allied Naval Brigade as instructors; Ensign J. M. Griffin, U. S. N. R. F., at Onega; Ensign O. E. Cobb as communication officer at Murmansk; eleven enlisted men attached to the flag office in Archangel; and section leaders at Onega (1), Shekuvo (6), and Murmansk (2). Comdr. Wallace Bertholf reported for duty to Rear Admiral McCully at Murmansk on December 12 and was immediately sent on a trip to Archangel with instructions to observe the conditions of navigation between the two places, particularly as to ice in the White Sea and its entrance; and after reporting to the American Embassy to investigate conditions in Archangel and the vicinity. During this mission he reached the front lines south of Archangel in time to be present while advance positions of the Allies were under bombardment.

Rear Admiral McCully's chief concern after his arrival in Northern Russia was to acquaint himself with conditions there both at the ports and in the interior; for this purpose his enforced sojourn on shore gave him ample opportunity. Accompanied by Ensign Gould and Col. J. A. Ruggles, Capt. E. Prince, and Lieut. H. S. Martin, of the United States Military Mission at Archangel, he left that place on November 7 and reached Obozerskaya about 90 miles south on the railroad on the same day. The advance post of the Allied forces at this time was only a few miles south of that point. From Archangel he took passage on the ice breaker Sviatogor with Ensign Gould, two yeomen, and two mess attendants on November 25 for Murmansk, reaching there in two days, which

- 22 -

was the length of the usual voyage between the two ports. The Murman railroad was the scene of McCully's next inspection trip, which began on November 29 when he boarded a train at Murmansk with Ensigns Gould, Cobb, and H. C. Taylor, and Lieut. Rogers of the U. S. Army. For this journey General Maynard placed at their disposal his special car, in which the start was not made until the 3oth because of the engine's running off the tracks. The party went as far as Soroka, the headquarters of the detachment guarding the southern end of the railroad. Although it was located in the southwestern part of the White Sea, this place was nearly 500 miles from Petrograd by rail. The Allied forces were only 25 miles south of Soroka by this time. In the middle of December, McCully visited Alexandrovsk which he found occupied by a small detachment of troops and by cable and telegraph employees who were discontented because of the poor rations allowed them. The scarcity of decent accommodations in Murmansk led Rear Admiral Green to insist that McCully establish his living quarters on the British armed yacht Josephine.

Having visited both regions under Allied occupation in Northern Russia, Rear Admiral McCully forwarded a general intelligence report to Admiral Sims on December 20 in which he presented information concerning political, financial, military, naval, and economic conditions. He reported that the Allied forces controlled about two-thirds of Archangel province, south to the points already mentioned in connection with his trips and west to the border between Finland and Karelia. Concerning naval conditions there was little to report, for there had been no naval operations. Neither then nor later did the Bolsheviks have nava1 forces on the open sea, their operations on water being confined by Allied superiority to the rivers and lakes. Part of the

- 23 -

Allied naval forces had gone into winter quarters at either Archangel or Murmansk; the French vessels were at the former place, and the Glory and British armed yachts were at Murmansk, which had the advantage of being open all winter. Ice breakers were employed to keep the route between the two ports open as long as possible.

The foregoing report was one of a series of such periodic reports submitted by McCully to Admiral Sims. These general intelligence reports were factual in character and contained information which was obtained through the efforts of McCully and the officers under his command; it was not supplied to him by the British. Besides these reports which were fairly lengthy, weekly reports such as had been submitted by Captain Bierer were continued. The topics covered by them included the following: vessels present, operations, enemy activities, miscellaneous, recommendations and suggestions, miles steamed during the week, hours at anchor or moored, hours under way, fuel consumed in port, fuel consumed under way, miles per ton of coal. The weekly reports were generally brief and could not have been of great value to Admiral Sim's staff, but they do contain some data which, for historical purposes, supplement that to be found in other documents. In addition, special reports were submitted now and then when events required them.

Part of the naval personnel which had been serving in Northern Russia departed during December and January. In the former month Ensign Gould left on the Yaroslovna, which had on board the French Ambassador, M. Noulens, while in the latter Ensign Taylor and fifteen enlisted men departed on the Aspasia for England, and to the same country went Ensigns Hicks, Bishop, and Griffin with thirteen men on the Junin.

- 24 -

The receipt at Murmansk of an inquiry from Archangel at the end of January 1919 as to the means existing there for the evacuation of Archangel indicated an alarming situation and caused Rear Admiral McCully to embark on the ice breaker Alexander to undertake a personal investigation. Upon his arrival in Archangel on February 5 he conferred with the United States diplomatic and military representatives, the officials of the provisional government, and the British military and naval officers. He learned that the situation was serious but not critical and so reported in a telegram to Admiral Sims. A strong Bolshevik offensive launched in the preceding month had forced the retirement of American and Allied forces from Shenkurst, a town on the Vaga River which was the most important position south of Archangel. The military situation of the Allied forces at this time was regarded by the American military attaché as very unsatisfactory; they were scattered in small detachments; communications were slow and difficult; the enemy forces were superior in number of men and quantity or artillery; and it appeared that further withdrawals would have to be made.

During this visit to Archangel, Real Admiral McCully made another trip on the railroad to Obozerskaya on February 7, continuing on the next day to the advance positions. These he found to be under continuous bombardment by the Bolsheviks who employed observation balloons in directing their fire. By this time the American troops had adapted themselves to the climate and the British rations and were in exceptionally healthy condition and in a better state of morale than when McCully previously saw them. Reinforcements supplied by the Murmansk command had marched overland from Soroka and strengthened the forces in this region.

- 25 -

Reaching Murmansk on board the S. S. Beothic on February 23, Rear Admiral McCully found the U. S. S. Yankton in port and immediately took up his quarters aboard it. Under Comdr. Richard S. Galloway this vessel had reached there on February 8, bringing, for duty with McCully, Lieut. Adolph P. Schneider, U. S. N., Lieut. Milton 0. Carlson, U. S. N., and Ensign Maxwell B. Saben, U. S. N. R. F. It also brought equipment for a radio station, and, after the approval of McCully was obtained of the preliminary arrangements which had been made during his absence, the erection of the station was begun on Soviet Hill by working parties from the Yankton. Previously communication had been had through the cable and the radio on the British and French naval vessels, but these methods had proved unsatisfactory. After its completion the naval radio station was strong enough to intercept messages from the United States, Honolulu, and European countries. Lieutenant Carlson was placed in charge of the station in April. On March 15 the Yankton stood down the Kola Inlet to Alexandrovsk where it remained anchored with the Rear Admiral on board until April 4 when it returned to Murmansk. Commander Bertholf reported to McCully on board the Yankton at the end of March; from about this time he functioned as chief of staff.

Right after his return to Murmansk from Archangel, Rear Admiral McCully sent a cablegram on February 25 to Admiral Sims and followed it with a report on the 28th in which he recommended the dispatch of naval reinforcements to Northern Russia. Stating that the military situation in the Archangel region was precarious and that the Allied forces along both the Archangel-Vologda railway and the Murman railway were insufficient, he urged stationing vessels at both Archangel

- 26 -

and Murmansk and providing another to cruise along 1600 miles of coast and visit other ports. One of the vessels should be suitable for a flagship which the Yankton was not, and one ship should serve as a supply ship for the others because great difficulties and uncertainties were being experienced in constantly shipping stores, and these usually arrived in a pillaged condition as a result of their being proached by the crews of the British merchant marine whose morale had deteriorated. As the Allied forces on the Dvina would be at the mercy of the Bolshevik vessels which would be released at an earlier date from the frozen waters of the upper Dvina, he recommended a detachment of twelve submarine chasers with a tender for operations on that river. These would be necessary he stated, if military operations were to be undertaken in the spring. In case relief were to be extended on a large scale, naval port officers would have to be appointed at Archangel, Kem, and Murmansk. Admiral Benson, to whom the request of McCully was referred, advised the department to prepare the Sacramento, a cruiser of the Denver class, and three Eagle boats for duty in Northern Russia, because, as he stated, although our future policy in the region had not been decided upon, it was necessary to meet the situation which had arisen. He also directed Admiral Sims to keep the sub-chasers which it had been planned to return to the United States in readiness.

Two U.S. Naval vessels the Galveston and the Chester arrived at Murmansk on April 8 with 310 men of the 167th U. S. Engineers and forty British replacement troops. Shortly before, the S .S. Stephen had brought in 350 men of the 168th U. S. Engineers and other Allied troops. Brig. Gen. Wilde P. Richardson came on the Chester to take

- 27 -

over the command of the United States troops in Northern Russia; he soon proceeded with his staff and Rear Admiral Green on the ice breaker Canada to Archangel where he superseded Colonel Stewart. After effecting a readjustment of the naval personnel attached to the three naval vessels by making transfers to the Yankton, the Galveston and the Chester sailed for England on the 13th.

It was a month later when the naval reinforcements ordered by Admiral Benson for Northern Russia began to arrive. The cruiser Des Moines, Capt. Zachariah H. Madison, put into Murmansk on May 13 while the Yankton was on a cruise in the White Sea, but it encountered the latter vessel at Ivanovski Bay on the 17th. McCully transferred his flag to the Des Moines on the next day and proceeded to Archangel while the Yankton went to Murmansk. At the latter place arrived on the 22d the Sacramento, Comdr. Otto C. Dowling, and the Eagles 1, 2, and 3 after a week's voyage from Inverness, Scotland. With Commander Bertholf and Lieut. Peter J. Bukowski aboard, the Sacramento on June 5 reached Archangel where the commanding officer reported to McCully on the Des Moines and paid visits to the H. M. S. Cyclops and the Gueydon. The port was a busy place during that month, for American and French troops were being brought in from

the interior and evacuated. Rear Admiral McCully, who since his arrival there on the 26th had been conferring with Allied and Russian officials, inspected Eagle No. 1 after its arrival there with Eagle No. 3; Eagle No. 2 also reached that port on June 11. A week later the Yankton escorted into Archangel sub-chasers 95, 256, and 354, which it had met off Vardo, Norway; together with the British tanker Birchol they completed the 1975 run from Inverness, Scotland in 12 days.

- 28 -

Towards the end of April McCully seems to have contemplated dividing his forces into two divisions, the first consisting of the cruisers and the Eagles to guard the bases at Archangel, Kem, and Murmansk, and the second consisting of the sub-chasers to operated in the North Dvina River but he had no opportunity to perfect the arrangement. To the officers of the vessels then attached to his command, he issued instructions on April 25 to cultivate close and cordial relations with all the officials in the region and to prepare monthly intelligence reports. Near the end of May he established the Eagle boats as a weekly dispatch service between Murmansk, Archangel and Kem to carry dispatches, mail, and military, naval or diplomatic officials and light freight of an urgent or perishable character; it was to be available for both Russian and Allied use. Passengers, however, had to make their beds on the open decks and provide their own protection. The service was operated by the U. S. naval port officers in cooperation with other port officials in the region. Subsequent instructions stipulated that the dispatch vessels might carry as freight gold, silver or jewels under special circumstances and that bills of lading might be given for them, charges made, and responsibilities assumed. Rear Admiral Green regarded this service as an expensive luxury having no connection with naval operations. To a considerable extent this opinion was probably correct.

The staff of the Commander, U. S. Naval Forces in Northern Russia consisted in the spring of 1919 of Commander Bertholf as senior aide and acting chief of staff, Ensign Cobb as aide and flag lieutenant, and Ensign Saben as aide and flag secretary. Bertholf during this period shuttled back and forth between Archangel and Murmansk.

Shifting to the Sacramento on June 15, McCully left Archangel

- 29 -

that day and after visiting Sosnovaya Bay and Keret Bay anchored at Kem harbor. At this place he stayed on Eagle No. 1 for a day and on the Des Moines for two days, and then at the invitation of General Maynard he accompanied him with Lieutenant Cobb on an inspection trip to the Murman railroad front. The party journeyed by train to Medvyejya Gora, a station on the Murman railroad at the northern tip of Lake Onega, which was then the advance base of Allied military and naval operations, and which was only 95 miles from Petrozvodsk farther down the lake. Though some places on the shore of the lake were in Allied possession, the Bolsheviks controlled the lake with a force of armed steamers and tugs. The Allied naval flotilla based at Medvyejya Gora did not have armament that could combat the Bolsheviks. This flotilla included two American motor sailers brought by train from Murmansk and launched on the lake on May 29, operating with crews of American bluejackets under the command of Lieut. Douglas C. Woodward. At the time of McCully's visit one of these boats was being prepared for shipment to the Yankton, and the British were negotiating for the other. The force on the Murman front, in McCully's opinion, was not sufficient for an advance, and the morale of the troops was not good as a result of the withdrawal of part of the Allied forces and the approaching retirement of the American engineer troops who had greatly improved the efficiency of the Murman railroad.

During the last week in June all of the vessels attached to the command assembled in the Gulf of Kandalaksha in the northwestern portion of the White Sea to engage in target practice. McCully joined the proceedings, following his return from the Murman front, at Kiv Bay on June 27 on board sub-chaser 95, which had picked up him and Lieutenant Cobb at Popov (Port of Kem) on the preceding day. The rear admiral's

- 30 -

flag flew from the Des Moines, Sacramento, and then the Yankton; on board the last he reached Popov on July 1. With a liberty party of officers and men he went that day on subchaser 256 to Solovetsky Island where on the eastern side of Blagopoluchia haven was a monastery, which was evidently worth the trip for it contained six churches, gardens, cattle yards, and one of the richest sacristies in Russia, constituting a shrine visited by thousands of pilgrims every summer. He continued on the Yankton to Archangel on the 3rd carrying as passengers Lieutenant Rogers, of the American Military Mission at Kem, and an army sergeant. The Des Moines and the subchasers also steamed to Archangel, after the practices were ended, while the Sacramento went to Murmansk.

A phase of activities of the U. S. Naval Forces in Northern Russia - that concerning the naval port officers - which has only been referred to thus far in these pages can now be treated in a continuous fashion. One of the principal duties engaged in by McCully as District Commander at Rochefort, France from February to October 1918 had been the direction of a system of naval port officers located at ports in that district but chiefly in the region of Bordeaux on the Gironde-Garonne River. Thus he had a good background for this aspect of affairs in Northern Russia.

The shipping boom experienced by the ports of Archangel and Murmansk during the war when Russia was an active participant on the Allied side collapsed after her defeat by Germany. The Bolshevik revolution was the signal for the Allies to cease the exportation of war materials to those ports, for they had no desire to strengthen the arms of the Reds nor through them the Germans. When McCully visited Archangel in July 1917, he observed in the harbor sixty-five steamers discharging, awaiting discharge; loading, or discharged, and nine sailing vessels.

- 31 -

At this time about 120,000 tons of goods were being unloaded monthly; indeed, so much was received that year that an immense quantity had to be stored in the open without adequate protection at Bakaritza, pending shipment on the overworked railroad. Immediately after the Bolshevik revolution, however, the Allies instituted an embargo not by publicly announcing it but by withholding licenses for exports of war supplies to Northern Russia, this method being employed in order not to give the Russian people the idea they were being abandoned by the Allies. Early in 1918 the British Admiralty attempted to recover some of the stores at Bakaritza by offering food in exchange, but the Bolsheviks just continued hauling them away. Commerce with the ports of Northern Russia was not completely cut off, for after the Allied forces occupied the region they had to supply themselves with munitions and food and to feed the whole population which numbered three hundred thousand people. During the winter of 1918-1919 supplies unloaded at Murmansk were taken by rail to Kandalaksha and thence by sledges over the 200 mile frozen expanse of the White Sea to Archangel.

The British Navy, which entered Northern Russian waters early in the war to cooperate with the Russian Navy, obtained control of all shipping in both Archangel and Murmansk. By arrangement with the provisional government in Northern Russia this control was continued after the revolution of 1917, but, discontinued at Archangel after the British Navy retired from there in December 1917, but, following the Allied occupation of that port in August 1918, British naval officers again assumed charge. The Principal Naval Transport Officer (P. N. T. O.) at Archangel throughout the period of the intervention

- 32 -

was Commodore Richard Hyde, R. N., who had a number of assistants. During the war French vessels were consigned to the French Vice-consul and were discharged and loaded by the Hudson's Bay Company under the general charge of the chief British transport officer. He also handled the unloading of American vessels of which only six appear to have arrived at the port during 1917, though American supplies were brought in in great quantities, undoubtedly, in British and Russian vessels. A British port officer also operated at Murmansk, and later another was stationed at Kem. At all of these places there were Russian and French port officers as well. The British naval transport officers handled all matters connected with shipping; discharging, berthing, ballasting, fueling, repairing, supplying, and sailing. Apparently with the approval of the United States Government, the British, after the intervention began, continued the closing of the Russian Arctic ports, which had been decreed by the Russian Government in April 1916, to other than Allied vessels except by permit issued by the British Admiralty. But, judging from Commander Bertholf's report on his trip to Vardo, Norway in March 1919, the British kept this in their own hands by refusing permits. The exportation of Russian products from Archangel was prohibited by Moscow authorities at the time of the Allied intervention, but Allied control made this ineffectual, and, according to the historian, Strakhovsky, the British took away goods valued at 2,793,700 pounds and the French 821,300 pounds - at requisition prices. Indubitably commercial considerations - the opportunity to make a profit - played a part in the British administration of shipping, but then the British, like the French, had lost heavily by the Bolshevik repudiation of the debt for the goods supplied

- 33 -

Russia during the war.

The experiences of the S. S. Portonia, an American ship which reached Archangel in June 1917, reveal some of the difficulties ships encountered in that port. Captain McCully found the crew dissatisfied because they could not go ashore, because their quarters were insufficient, and because they could get no provisions. A number of the crew had no passports and without them the Russian authorities would not permit going ashore. The ship had no seal, and documents without seals were not recognized by the Russians. The ship had to be ballasted with 600 tons of coal at $50 a ton although that amount of cargo could have been loaded except for peculiar regulations by which American vessels were still regarded as neutrals and not eligible for cargo. To top everything else, the ship had no gun for protection against submarines.

Only a few American ships reached Northern Russia during the period of the intervention. In the first part of 1918 Ambassador Francis urged sending shiploads of foodstuffs to Archangel to relieve hunger among the Russian population, whose sources of supply had been interfered with by Czechoslovak operations along the Siberian railroad, to feed the Allied representatives at Vologda should they have to retire to the north, and for propaganda purposes. Not until after the Allied occupation of Archangel, however, when the need was greatly increased, were American ships routed there. The U. S. S. Aniwa and the U. S. S. West Gambo arrived in a convoy on October 12 with flour and Red Cross Stores. These were U. S. Shipping Board vessels operated by the Naval Overseas Transportation Service With naval crews and allotted by the U. S. Shipping Control Committee for this voyage to the British Ministry of Shipping. About the same time the S. S. Ascutney, another U. S. Shipping Board

- 34 -

vessel, arrived with a cargo of Red Cross supplies.

The Aniwa remained in port nearly a month, not departing until November 10. It reached the entrance to the Dvina in the evening of October 11, but remained there at anchor overnight. Early the next morning upon receiving a signal to proceed into the harbor, it went ahead a short distance and then stopped to pick up the pilot, who came from the light vessel stationed at the entrance, and a boarding officer. The latter soon shoved off, and the vessel followed the Dvina River channel under pilotage, anchoring at Archangel at 1:08 P.M. Over an hour and a half later a customs official and a lieutenant commander from the British transport office came aboard in separate tugs, the former to make an inspection and the latter with orders. During their visits the captain was ashore on official business. While the vessel awaited discharging, personnel attached to it, including liberty parties, went ashore. On the 14th a representative of the American consul came on board as did the representative of the British transport office, both of whom made subsequent visits. Throughout the stay in the port a guard was maintained on the ship and apparently on the shore nearby. Discharging began on the 18th and was completed on the 31st when the loading of 1200 tons of flax for ballast started. Two stevedores were detected in the act of smuggling flour off ship. Hatches were sealed by a customs officer. A representative of the American consul came aboard again on the 28th with papers for the captain. Rear Admiral McCully came aboard on November 1. Oil was pumped into tanks from the British S. S. Seattle beginning on the next day. After the loading was finished on November 9, British and Russian control officers came aboard. Before the departure on the 10th immigration officials visited the ship. A pilot conducted

- 35 -

it down the Dvina to the light ship where he was taken away in a small boat.

The experiences of the West Gambo were very similar to those of the Aniwa. In connection with the discharging of some ordnance supplies a visit was made by a British ordnance officer. Lieutenant Riis, the U. S. naval attaché, twice came on board this vessel whereas no mention is made in the log of the Aniwa of visits by him to it. Discharging began on the 16 and was completed on the 31st, a total of 6269 tons of flour. It departed from the dock under pilotage on the next day to take on fuel from the Seattle. Some passengers were brought on board for passage to the United States at the request of the American ambassador and with the consent of the naval authorities. Under orders issued by Commodore Hyde it proceeded to sea on November 2. No references were found in regard to its taking on cargo or ballast.

While the Ascutney was engaged in taking on flax and coal, the Chief engineer on the morning of October 21 discovered a fire in the main cross bunker. He reported immediately to the captain, and the removal of coal from the bulkhead was begun in order to locate the fire. That afternoon the master made a report to the British transport office, but the officers sent aboard by Commodore Hyde did not enter the bunker, according to a statement of the chief engineer, and saw no fire. When summoned to Commodore Hyde's office on the 26th, Lieutenant Riis learned from him that the master of the Ascutney had called several times claiming there was a fire on his ship, which the Commodore disbelieved on the basis of reports submitted by his subordinates and charged the master with having a lively imagination and possibly other reasons for holding his ship in port as long as possible. Riis saw the master that day, and, after receiving from

- 36 -

him the assurance that there was a fire, suggested that he be informed if it got worse and he would arrange for a board of inquiry. It shortly got worse, being communicated to the cargo of flax, and help had to be afforded by both the Glory and the Olympia. To extinguish the fire the holds had to be flooded, and this forced beaching the ship on the flats opposite Archangel; then the holds had to be pumped out, the ship taken along side the dock and the cargo discharged in order that the wet portion could be landed and new cargo and coal loaded. Captain Bierer and other officers attached to the Olympia, constituting a board of investigation, conducted an examination of the ship during the first three days of November and submitted a report in which the conclusion was reached that the fire in the cross bunker had originated from spontaneous combustion and that the heat from it ignited the flax; no evidence of incendiarism was found. Slight damage was suffered by the vessel, but damage to the cargo of flax exceeded half a million dollars. So the remissness of the P. N. T. O. in not receiving with credence the master's report of the fire and taking prompt measures to discover and extinguish it turned out to be a costly mistake.

Theft as well as fire was experienced by the Ascutney. Of 119,000 cases of Red Cross goods shipped on this vessel, the Red Cross officials reported a shortage of 4564 cases and damage amounting to 50% to seventy bags of sugar for which a claim was made. Up to March 1919 this was the outstanding case of theft of cargo encountered by the U. S. Shipping Board.

Since they were promulgated during war time, the following regulations are of interest although they antedate the Allied intervention:

- 37 -

COMPULSORY REGULATION

relating to access to the shore from ships arriving at the Port of Archangel from abroad, and the visiting of such ships by casual strangers. Issued by the Commander-in-Chief of the Town of Archangel and of the White Sea District by virtue of Sec. 1 Para. 19 of Regulations regarding places declared to be under martial law. (Supplement to Art. 23 vol. 2 of the Civil Code).

1. All persons arriving at the port of Archangel on foreign-going vessels (including ships' crews) are required to be in possession of a passport or a document certifying to their identity with a photograph attached thereto. The Master of the ship is responsible for the fulfilment [sic] of this regulation.

Note. Consular certificates based on verbal declarations cannot in this case be considered to take the place of passports.

2. All subjects of neutral states and passengers on and crews of ships sailing under a neutral flag are absolutely forbidden to go ashore.

Note. The landing of passengers from neutral ships is permitted only on the authorization of Russian officials having special power to do so.

3. If there is no war material (Government or private) on a neutral ship and if at the same time the ship is not berthed alongside a military discharging area, the Master of such a ship and one of the crew selected by the Master alone have the right to go ashore. The Master is required immediately on arrival in the port of Archangel (il. e. at Chijovka) to notify the Port Defence Officer in writing of the person thus selected. When the said person is given leave to go ashore, the Master must provide him with a leave permit in the Russian language signed by himself and sealed with the ship's seal.

Note. If a neutral ship is moored alongside a military discharging area, and also as long as there is war material on a neutral ship, the Master is permitted, as an exception, to go ashore once only on the ship's business for a period not exceeding 8 hours and he must be accompanied by an officer from the Marine Transport Headquarters.

4. Russian and Allied vessels are divided into two categories A and B:

a) to category A belong all ships containing general war cargoes either Government or private, until such cargo has been discharged, and also all vessels without exception while they are lying alongside military discharging areas.

b) all other ships belong to category B.

5. Passengers and crews of allied ships in category A and such Russian ships in category A as still have on board high explosives (of the first category) undischarged, and also all subjects of allied states on board Russian ships in category A are absolutely forbidden

- 38 -

to go ashore.

Note. (1) The Master (or in his stead the chief Officer) of an allied ship in category A or a Russian ship with high explosives is permitted, as an exception, after the ship has stopped to go ashore once only on the ship's business and for a period not exceeding 12 hours.

Note. (2) Passengers on allied vessels in category A and Russian vessels With high explosives may be taken ashore only by the military authorities. Military units may go ashore with the permission of the local military authorities only if required to be present at discharging operations or for dispatch to their destination.

6. The crews of allied vessels in category B and all Russian vessels with the exception of those containing high explosives are permitted to go ashore on the responsibility of the Master under the following conditions:

a) The Master and the Chief Officer must not be absent from the ship at the same time;

b) The Chief and Second Engineers are also forbidden to be absent at the same time;

c) Not more than half of the crew may be absent from the ship at the same time;

d) The Master may grant permission to go ashore only to such persons as are in possession of passports or certificates of indentity [sic](with photographs attached) acknowledged as being in order by the Port Defence Officials at the entrance to the Port of Archangel (Chijovka);

e) Leave may only be granted to ship's officers (excluding the Master) and crews from 6 a.m. up to 10 p.m. and only on the issue of leave permits in the Russian language signed by the Master and sealed with the ship's seal.

Note. (1) Officers and crews of Russian ships, provided that they are Russian subjects, may be granted leave by Masters in exceptional cases for a longer period then is laid down in Sec. 6 above, but this period must not exceed three days.

Note. (2) When a Russian ship is lying alongside a military discharging area the passengers and crew of such a Russian ship may be allowed to pass through that area by means of a list of their names and if accompanied by one of the ship's officers and a Port Defence Official; the same list gives them the right of readmittance through the military discharging area to their ship, provided they are again accompanied by an officer and a Port Defence Official.

7. Persons who have obtained permission to go ashore from a ship

- 39 -

(Sections 3 and 6) must show their leave permits whenever required to do so by the local authorities. It is forbidden to go ashore wilfully [sic] without a leave permit or to return to the ship late.

8. If any person willfully [sic] goes ashore from a ship (without permission or in contravention of the rules laid down in Sections 2 and 5 of the present Regulations), the Master must immediately inform in writing the Defence Officer or the military discharging area or the harbour authorities through the Custom House official on the spot, and his Consul.

9. It is forbidden on the responsibility of the Master to admit on board vessels in category A any persons not possessing the regular permits of admittance to military discharging areas.

10. Persons guilty of infringing this Compulsory Regulation render themselves liable under administrative order to a fine not exceeding 3000 roubles, or to imprisonment for a period not exceeding three months, or to detention for the same period.

ll. This Compulsory Regulation comes into force on May 10th, 1917, and from that date as far as the Port of Archangel is concerned Regulation No. 956 of January 25th, 1917, is cancelled.

(signed) N. SAVITSKY Commander-in-Chief.

Archangel,

April 30th, 1917.

No. 4612.

- 40 -

The pilots who conducted the U. S. Naval vessels up the Dvina to Archangel were picked up at the light vessel at the mouth of the river or from the first appearance of ice to the close of navigation at the Modyugsi lighthouse. The captains usually conned the vessel along with the pilots in order to familiarize themselves with the channel, but because of a bar and the changeability of the channel in which dredging operations had been carried on for years it was the practice to take a pilot. In the harbor pilots were also employed in changing anchorages, docking, and taking the vessel away from the dock. The voyage down the river was also under pilotage. On the Kola Inlet pilots were employed to steer the vessels up to Murmansk, and they were also taken on board at Kem. A schedule of fees was established for pilot service and towage. Vessels were some times delayed at the mouth of the Dvina because the tide and daylight did not serve. Towards the end of the year with the approach of the Arctic night the hours of daylight became very short while in the summer there was daylight twenty-four hours in the day.