Olympia I (Cruiser No. 6)

1895–1957

The first U.S. Navy ship named for the capital city of the state of Washington.

I

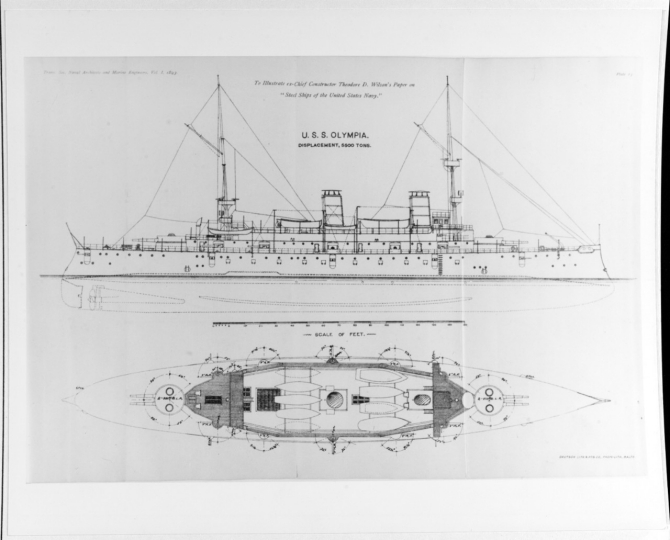

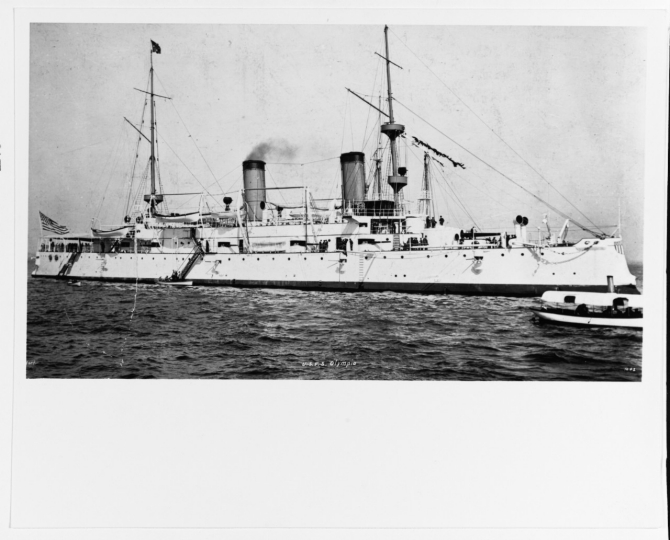

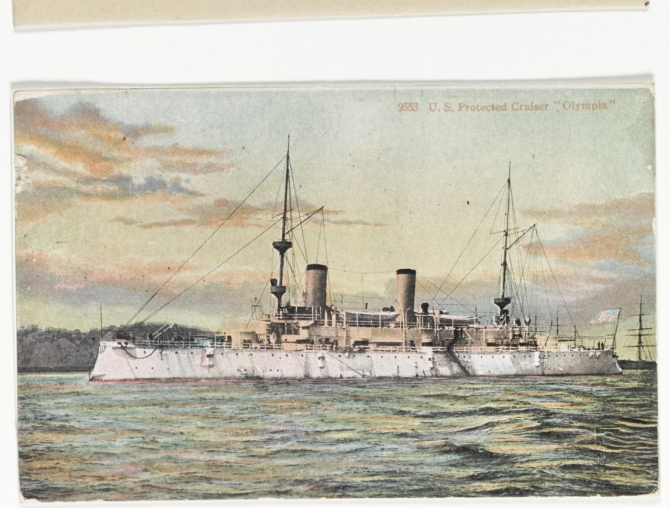

(Cruiser No. 6: displacement 5,586; length 344'1"; beam 53'; draft 21'6"; speed 20 knots; complement 411; armament 4 8-inch, 10 5-inch, 4 6-pounders, 6 1-pounders, 6 18-inch torpedo tubes; class Olympia)

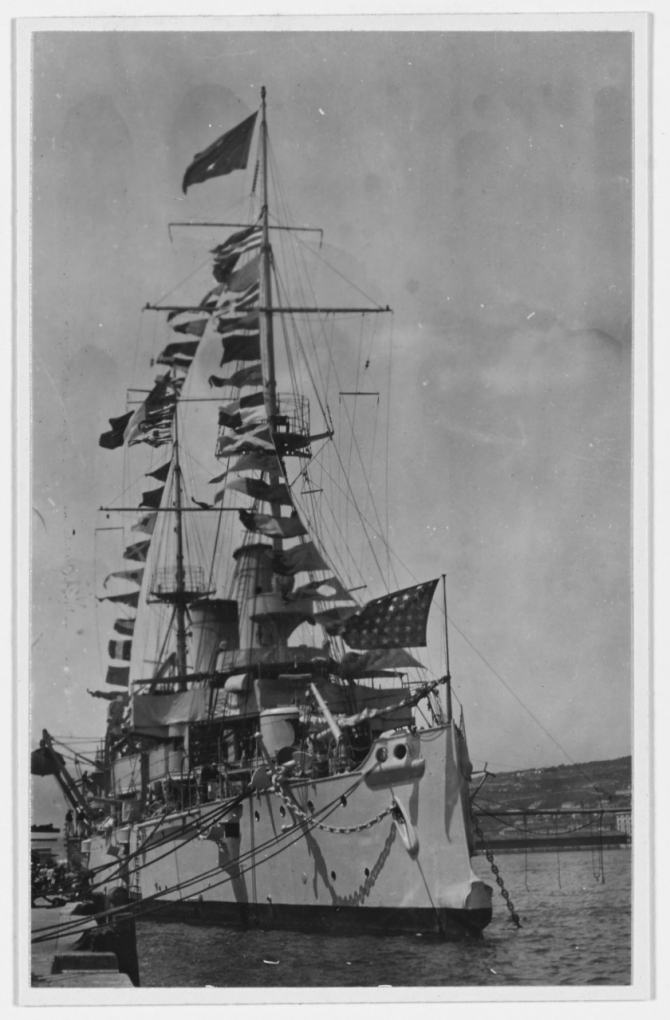

The first Olympia (Cruiser No. 6) was laid down on 17 June 1891 at San Francisco, Calif., by Union Iron Works; launched on 5 November 1892; sponsored by Miss Ann B. Dickie; and commissioned on 5 February 1895, Capt. John J. Read in command.

Built to a unique design, Olympia incorporated many innovative features including: electric priming for her main battery of guns; a refrigeration system; and electrical generators and electrical service for lighting and ventilation. In addition, she helped to pioneer the use of wireless communication equipment in the United States Navy.

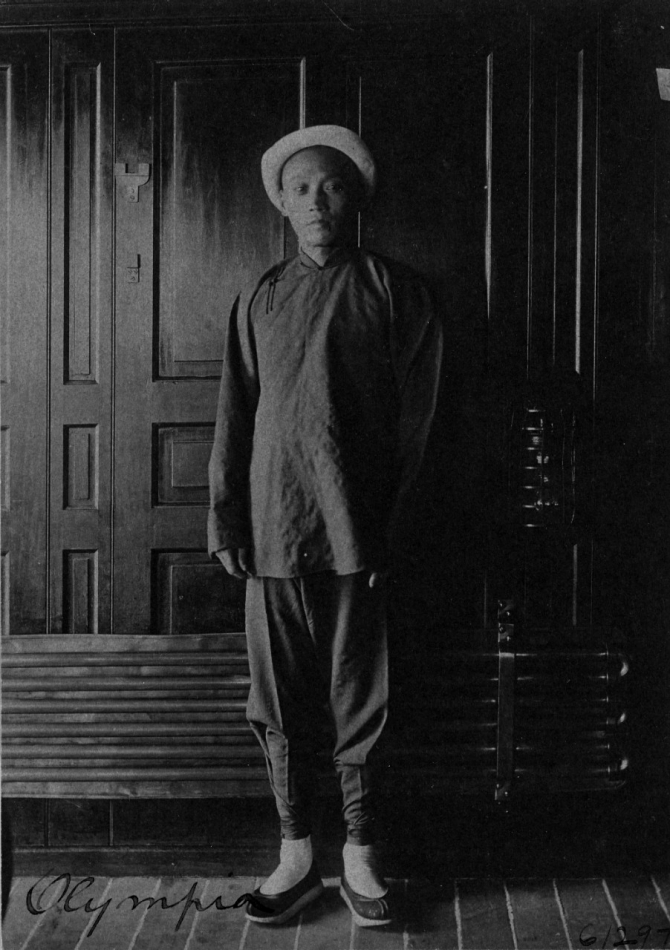

Olympia began her first operational deployment when she set out from Mare Island Navy Yard, Calif., on 25 August 1895 to join the Asiatic Squadron. The cruiser coaled in the Sandwich Islands (Hawaiian Islands) when she lay to at Lāhainā Roads off Maui and then Honolulu (6 September–12 October and 13–23 October, respectively). Olympia turned her prow westward as she resumed her voyage across the Pacific but severe weather marred her crossing and caused repeated fires in the coal bunkers. The ship nonetheless reached Yokohama, Japan, where Rear Adm. Frederick V. McNair, who commanded the squadron, broke his flag in her (9 November–10 December). The ship cruised in Japanese waters into the New Year, visiting Yokosuka (18–30 December), returning to Yokohama (30 December 1895–21 January 1896), and then visiting Kōbe on 22 January and Nagasaki (24 January–3 March).

The ship then made for Chinese waters and visited Woosung (Wusong) (4–9 March and 20 March–9 May), and from there proceeded with the squadron to Chefoo (Yantai) (12–20 May). The cruiser then fell out of the squadron and visited Chemulpo, Korea, before continuing on to Vladivostok, Russia, where she took part in celebrations for the coronation of Czar Nicholas II (23 May–2 June 1896). Olympia returned to Japanese waters and spent the summer at Yokohama, alternatively carrying out target practice, swing ship for deviation of compass, and accomplishing maintenance (8 June–12 October). Into the New Year she visited Kōbe (13–15 October), Yantai (18 October–9 November), and Nagasaki (11 November 1896–23 January 1897). Olympia fired at targets and participated in a torpedo exercise while at Hong Kong (26 January–3 April), and came about for Japanese waters, where she put in to Yokohama (8 April–23 May and 13 June–) and Okayama (24 May–12 June). The Bureau of Steam Engineering inspected the ship and observed that after nearly two years of steaming her engines and boilers remained in “good condition.”

On 30 November 1897, Commodore George Dewey received orders to assume command of the Asiatic Squadron and he proceeded by steamer, relieving McNair on board Olympia on 3 January 1898. An insurrection had broken out in Cuba against the Spanish in 1895, and at 2140 on 15 February 1898, an explosion in the forward third of battleship Maine, anchored in Havana harbor, destroyed the ship, killing 266 men. The incident outraged Americans, who used the slogan “Remember the Maine!” to press for war against Spain, who many Americans suspected of planting a mine.

Olympia was scheduled to return to the United States, but Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt telegraphed Dewey on 25 February 1898:

“Secret and confidential. Order the squadron, except Monocacy, to Hongkong. Keep full of coal. In the event of declaration of war Spain, your duty will be to see that the Spanish squadron does not leave the Asiatic coast, and then offensive operations in Philippine Islands. Keep Olympia until further orders.”

Dewey thus gathered Olympia, protected cruisers Boston, Capt. Frank Wildes in command, and Raleigh (Cruiser No. 8), Capt. Joseph B. Coghlan, and Concord (Gunboat No. 3), Cmdr. Asa Walker, and Petrel (Gunboat No. 2), Cmdr. Edward P. Wood. Capt. George F.F. Wilde, Capt. Wildes’ relief, arrived but Wildes volunteered to remain with Boston and led her into battle. Dewey’s lack of logistic support compelled him to purchase two British steamers, Nanshan, which could carry 3,000 tons of coal and he acquired on 6 April, and Zafiro three days late. The Americans loaded both ships with coal and supplies in anticipation of protracted operations. President William McKinley Jr., asked Congress for the authority to intervene in Cuba, on 11 April, and eight days later, Congress authorized him to use force to expel the Spanish from the island.

Events raced toward a confrontation and on 17 April revenue cutter McCulloch, Capt. Daniel B. Hodgson, U.S. Revenue Cutter Service in command, joined the Asiatic Squadron. Secretary of the Navy John D. Long telegraphed Dewey at Hong Kong on 21 April, informing him that the U.S. had begun a blockade of Cuba and that war would likely break out at any moment. The ships were meanwhile painted battle gray.

Baltimore (Cruiser No. 3), Capt. Nehemiah M. Dyer in command, reached Hong Kong on 22 April 1898. Baltimore and McCulloch brought additional ammunition, which was desperately needed as the prevailing economies in naval expenditures reduced the ammunition available to the ships to only 60% of their allotted requirements. Their arrival proved fortuitous for the Americans, because on 25 April Congress declared that a state of war with the Spaniards had existed since 22 April.

“War has commenced between the United States and Spain,” Secretary Long instructed Dewey. “Proceed at once to Philippine Islands. Commence operations at once, particularly against the Spanish fleet. You must capture vessels or destroy. Use utmost endeavors.”

The British, however, informed the commodore that he must leave the neutral port within 24 hours. Dewey possessed inadequate charts of the Philippines and lacked intelligence information on the Spaniards and their defenses, and wanted to receive the latest intelligence from the American consul at Manila, Oscar F. Williams, who was expected daily. The American squadron moved to Mirs Bay on the Chinese coast, about 30 miles east of Hong Kong, to await a circulating pump for Raleigh and Williams’ arrival. They spent two days drilling, distributing ammunition, and stripping the ships of all wooden articles, which could add to the damage of fires on board ship caused by enemy gunfire. Olympia hoisted in all boats except whaleboats, and lowered and secured for action whaleboat davits, on 26 April. A “carpenters’ gang” worked on enlarging the hatch for hoisting 6-pounder and 1-pounder ammunition abaft the cabins. Almost immediately after Williams arrived on 27 April, the American squadron departed for the Philippines, in search of the ships of the Spanish Pacific Squadron.

In a meeting called by Spanish Governor-General of the Philippines Basilio A. y Dávila on 15 March, Rear Adm. Patricio Montojo y Pasarón, in command of the Spanish naval forces in the colony, had expressed his opinion that the onslaught of the U.S. ships would annihilate his squadron. The Spanish Pacific Squadron consisted of seven unarmored ships -- cruisers Reina Christina, Castilla, Don Juan de Austria, and Don Antonio de Ulloa, protected cruisers Isla de Luzón and Isla de Cuba, and dispatch vessel Marqueres del Duero -- carrying 37 heavy guns and weighing a total of 11,328 tons. Castilla possessed a wood hull, and Montojo grimly assessed her as “merely…a floating battery incapable of maneuvering on account of the bad condition of her hull.” The admiral broke his flag in Reina Christina. The Americans deployed a stronger squadron, eventually consisting of six steel vessels mounting 53 guns and displacing 19,098 tons. Four of these ships had armored decks. In addition, many of the Spanish sailors lacked training and experience.

Montojo entertained few illusions as to the outcome of a battle, and recommended fortifying the entrances to Subic Bay, northwest of Manila, and moving his ships there to await the attack. If the Americans bypassed Subic and anchored in Manila Bay, it was thought, Montojo could sneak up on them during the night and inflict some damage. The governor general agreed, however, the admiral did not track the derisory progress of the work in Subic Bay. He sailed Reina Christina, Castilla, Don Juan de Austria, Isla de Luzón, Isla de Cuba, and Marqueres del Duero to Subic on 27 April, but discovered “with disgust” that the Spaniards had not emplaced the authorized shore batteries on Isla Grande, the island that guarded the mouth of the bay, or the torpedoes [mines] in the channels. Montojo convened a council of his captains and they reluctantly agreed to come about and prepare for battle in Manila Bay “under less unfavorable conditions” — a telling reflection of Montojo’s lack of confidence in his chance of victory.

The Spaniards set sail for the capital at 1000 on 29 April 1898, transport Manila taking Castilla in tow, and anchored that afternoon in line of battle at Cañacao, between Cavite and Sangley Point, shallow water protecting the ends of their line: Reina Christina, Castilla, Don Juan de Austria, Don Antonio de Ulloa, Isla de Luzón, Isla de Cuba, and Marqueres del Duero. The admiral may have deployed them in that area to protect Manila’s plaza from falling shots, as well as to ensure that his sailors could jump overboard and swim ashore in the event of a debacle. His (apparently) humanitarian motives frustrated his tactical disadvantages, however, because they deployed his ships outside the range of most of the shore batteries, rendering their support ineffectual. In addition, gunboats Argos and El Coreo and mail steamer Isla Mindanao lay to in the harbor but did not take part in the battle, and Manila joined cruiser Velasco -- in the process of having her boilers overhauled -- and gunboat General Lezo -- undergoing repairs -- at the Roads of Bacoor, which effectively put them out of action.

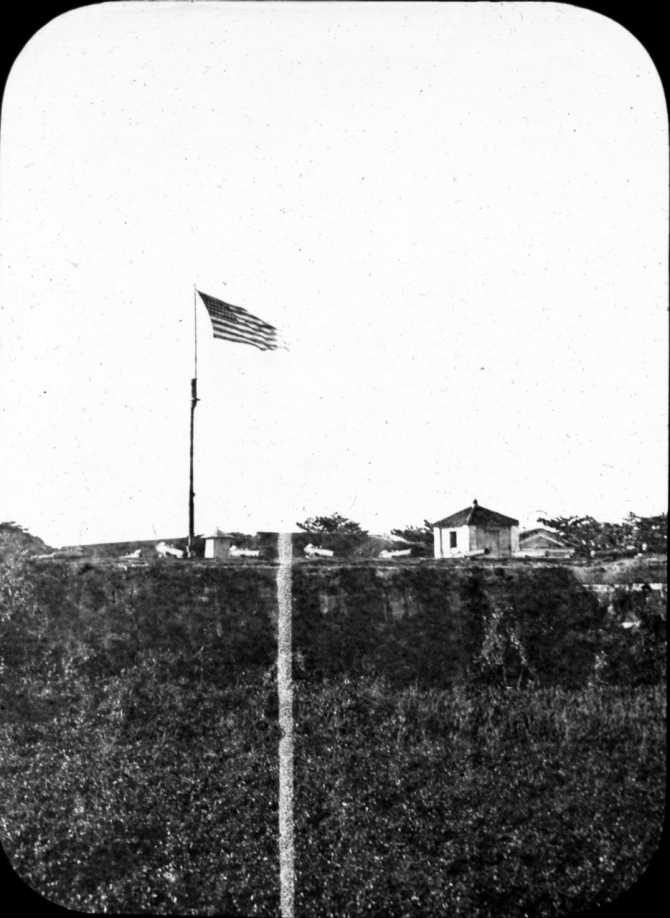

The defenders neglected to mine the entrances to Manila Bay because they believed that the depth and width of the water precluded mines’ usefulness in stopping ships from slipping in under cover of darkness. The Spanish shore batteries included: the islands of Caballo, El Fraile, and Corregidor that covered the entrance to the bay; Fort San Antonio Abad in Manila; Sangley Point to defend their naval station; Fort San Felipe, which protected Cavite Island and their naval shipyard; and Cañacao and Malate, situated not far from Sangley Point and Manila, respectively. The Spaniards supplemented these batteries with guns they removed from their ships, but the majority of the emplacements comprised guns of light caliber and limited range. Montojo afterward estimated that the ships and shore emplacements totaled 76 guns, but added that the ordnance was also “short of rapid fire.” A battery of 9.4-inch guns emplaced in San Antonio Abad could reach the U.S. ships, but only if they closed the range.

The Americans’ voyage to the Philippines proved peaceful though punctuated by daily battle drills. Olympia unstocked both bower anchors and lowered anchor davits for action on 27 April, and two days later broke out sheet chains to protect 5-inch ammunition hoists, as well as engaging fleeting sheet chains along bulkheads about the 5-inch hoists. Before the battle crewmen also flaked the heavy sheet chains up and down over a buffer of awnings against the sides in wake of the 5-inch ammunition hoists and afforded a stanch protection, and placed iron and canvas barricades in various places to cover gun crews and strengthen moderate defenses.

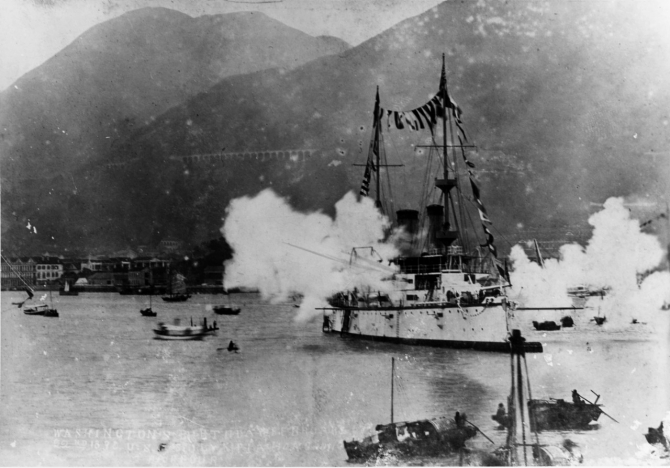

The squadron arrived off Cape Bolinao, Luzon, before dawn on 30 April 1898. Dewey sent Boston and Concord to reconnoiter Subic Bay during the afternoon watch, but finding the bay empty of warships they quickly rejoined the squadron. After a final meeting of ships’ commanding officers on board Olympia, the squadron resumed its voyage to Manila Bay at reduced speed, so as to arrive off the capital at about midnight, and reached a point off the harbor entrance at 2330. The Spaniards at Subic Bay meanwhile telegraphed Montojo, warning him of the approaching menace and costing Dewey the element of surprise.

Rumors circulated among the Americans that the Spaniards had mined the entrances to the harbor but Olympia led the ships in column, followed by Baltimore, Raleigh, Petrel, Concord, Boston, and McCulloch. The two supply ships brought up the rear as the darkened American ships steamed at eight knots through Boca Grande, the passage into Manila Bay between Corregidor and Caballo Islands to the north and El Fraile to the south. The Corregidor batteries ignored the squadron’s passage and the ships had almost passed when soot in McCulloch’s smokestack caught fire, alerting the battery on El Fraile, which fired several ineffectual shots, at about 0200 on 1 May 1898. Some of the ships switched on their search lights and illuminated the batteries, and Raleigh, Concord, Boston, and McCulloch returned fire with a couple of rounds each, and the squadron soon steamed out of range. The garrison nonetheless warned Montojo by telegraph, and the admiral directed that his ships light off their boilers and drop their masts, and notified the arsenal and the city’s plaza to prepare for battle. Two hours later he ordered the ships to clear for action.

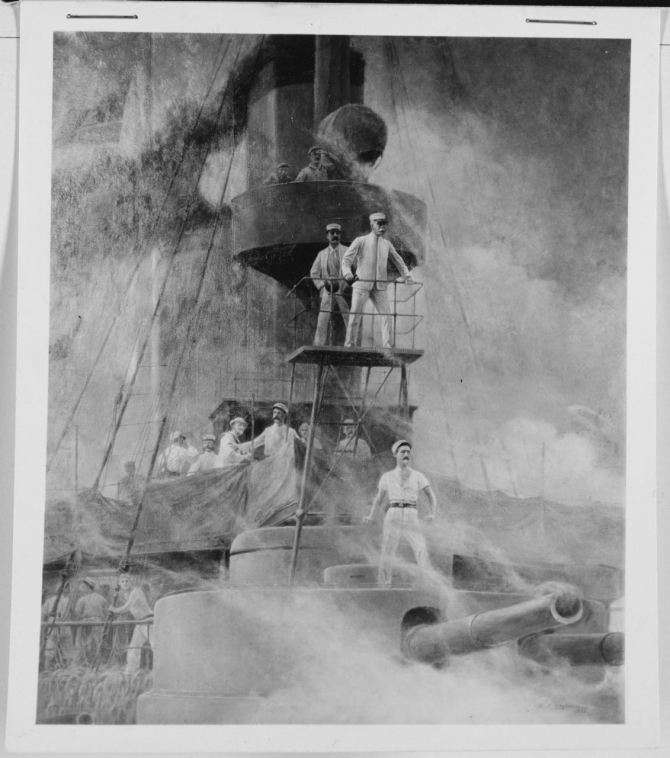

The U.S. squadron caught sight of the lights of Manila at about 0300 and slowed, so as to arrive off Manila by daybreak. The day dawned very warm, clear, and fair, with light airs to gentle breezes from the east. The outline of the city appeared at 0505 and several Spanish batteries there and two at Cavite opened fire ineffectually, but Dewey did not order his ships to return fire because of their ammunition shortages. Finding no ships off Manila, Dewey turned toward Cavite Island and there sighted the Spanish squadron. The shore batteries on Cavite and Sangley opened fire on the intruders but without effect. The commodore directed Capt. Charles V. Gridley, Olympia’s commanding officer, to engage the enemy.

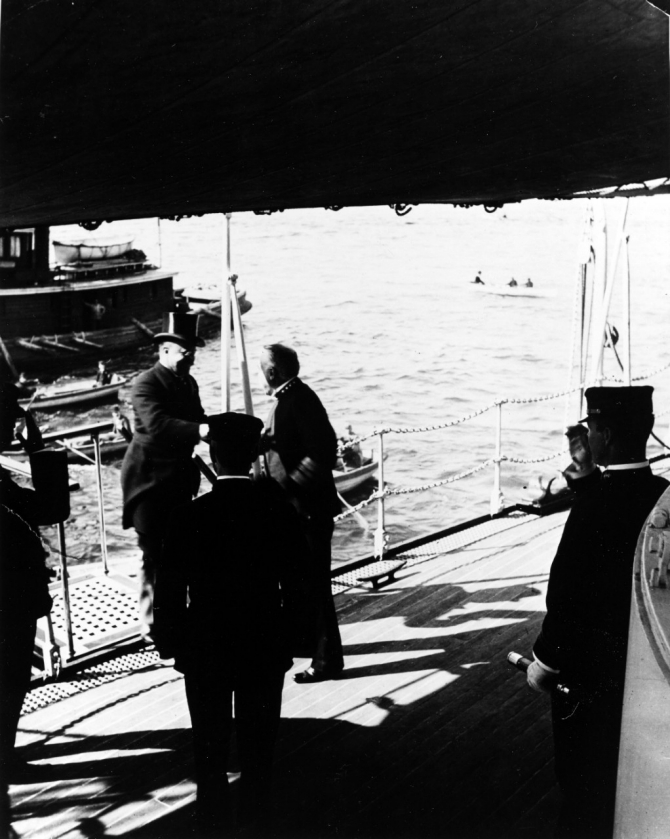

“At 5:40 when we were within a distance of 5,000 yards,” Dewey recalled, “I turned to Captain Gridley and said, You may fire when you are ready, Gridley...The very first gun to speak was an 8-inch...of the Olympia…”

The commodore elaborated in a letter to Secretary of the Navy William H. Moody on 18 September 1903: “When we had reached what I considered a proper and effective range, the distance being reported by the navigator, I said, as I remember it, to Captain Gridley, with whom I was on such terms of intimate acquaintance that I rarely addressed him by his title,” You may fire when you are ready, Gridley.” I did not say this in the usual tone of a military order, but merely as a part of a conversation which we were carrying on.”

Olympia’s forward turret fired several ranging shots. Gridley, who was in ill health, gamely directed Olympia’s fire from her conning tower, obtaining the range by cross bearings from the standard compass and the distance taken from the chart. Reina Christina slipped her cable and started ahead with her engines, Montojo explaining his decision to enable the flagship “not to be involved by the enemy.”

When Olympia reached the five fathom curve off Cavite the flagship turned to the westward, bringing her port battery to bear. After passing the entire Spanish line, she came about to the eastward firing her starboard battery again. Olympia led the line three times to the eastward and twice to the westward, pounding the enemy from a range varying from 5,000 to 2,000 yards until their fire slackened. Some of her 8-inch guns failed to fire on their electric priming and had to revert to percussion priming. The electric priming batteries of the 5-inch guns functioned unreliably, and the ammunition performed poorly. Several 5-inch shells became detached from their casings on loading and had to be rammed out from the muzzle, and some of the casings jammed in loading and in extracting.

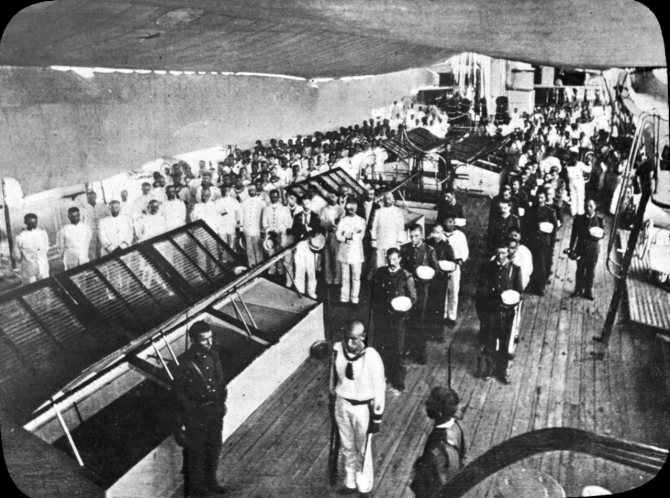

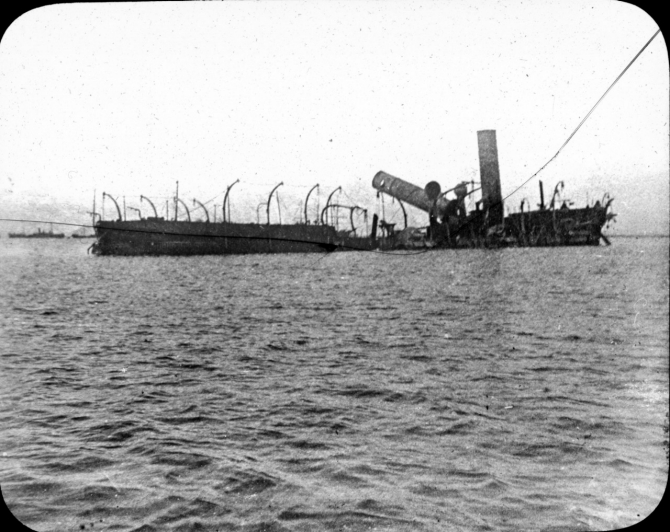

A few of the ships ceased firing more than once on account of the smoke, but resumed when the smoke cleared. At one point Olympia’s lookouts reported a “torpedo boat” closing to within 500 yards of the ship’s starboard bow, and marine sharpshooters opened fire, though the enemy boat turned out to be an unarmed Filipino launch attempting to flee the fighting. The ship’s marines again opened fire at another point in the battle, and shot about 1,000 rounds in total. At 0735 the commodore received a disturbing report that only 15 rounds of five-inch ammunition remained per gun. He accordingly withdrew from action to take stock of the available ammunition, and sent the crews to breakfast. While the men ate, several heartening things occurred. First, the commanding officers of the other ships made their reports of the action to the commodore on board Olympia. They indicated that the Spanish had inflicted only inconsequential damage to the squadron, and felt that they had battered the enemy. Second, Dewey received the information that they possessed adequate ammunition supplies to continue the fighting. Finally, the pall of smoke that shrouded the enemy squadron through most of the action cleared and revealed the devastation the U.S. gunfire had wrought, with multiple Spanish ships aflame and many sinking. The Americans resumed firing at 1115 and rapidly destroyed the Spanish squadron.

Montojo grimly described the American fire as “numberless projectiles” hurtling toward his ships. The Spaniards fought bravely, but Dewey summarized their fire as “vigorous, but generally ineffective.” An American shell struck Reina Christina’s forecastle, knocking out her four rapid-firing guns and showering splinters from the mast that wounded the helmsman, but Lt. Jose Nunez took the wheel “with a coolness worthy of great commendation” and steered the ship through the maelstrom of fire. A round knocked down the mizzenmast, bringing down the national flag and admiral’s ensign, but crewmen defiantly raised their colors again. The Spanish suffered horrifically, however, and another round exploded in the officer’s country, which they used as a hospital, killing the wounded men evacuated there and “covering the hospital with blood.” Another shell burst within the after magazine, and when the ammunition began to cook off, Montojo ordered the magazine flooded. The rain of shot continued and the admiral reluctantly ordered all the magazines flooded to prevent further loss of life, and the ship sank. Don Luis Cadarso, her commanding officer, valiantly attempted to save crewmen while they abandoned ship until a round killed him. As the cruiser went down, Montojo shifted his flag to Isla de Cuba and continued the fight, directing some of his surviving ships to make their final stand in the shallow waters of Bacoor Bay. Dewey ordered Concord and Petrel to take advantage of their shallow draft, and close the range inshore and finish off some of the enemy vessels. The enemy shore batteries continued to fire until Dewey warned them that he would shoot at the city if they did not cease fire, which they summarily did, Cavite raising a white flag at 1215. Fifteen minutes later, Dewey ordered the squadron to cease firing and the ships anchored peacefully off the town overnight, shifting the next day to anchorages off Cavite. “I beg to state to the Department,” the commodore reported, “that I doubt if any Commander-in-Chief, under similar circumstances, was ever served by more loyal, efficient and gallant captains than those of the squadron under my command.”

The pivotal battle paved the way for American influence to grow across the Far East. The Spaniards suffered at least 381 men killed and wounded, but although they hit the American ships a number of times none of the vessels sustained serious damage. Two U.S. officers and six enlisted men suffered wounds, none serious. Francis B. Randall, R.C.S., McCulloch’s chief engineer, died of a heart attack while attempting to stop the blaze from the cutter’s stack. Four of Olympia’s company sustained minor injuries: Lt. Carlos G. Calkins bruised his right knee by striking it against a ladder; Boatswain’s Mate 1st Class John Heany injured the little and ring fingers of his right hand from a gun recoil; Ordinary Seaman Olaf Forstrom cut his head over the right eye brow while opening a gun breech; and Seaman Ralph Shay sliced his left foot slightly with an axe while cutting away some gear. Enemy fire that struck Olympia: indented plate 1½ inches on the starboard side of the superstructure just forward of the second 5-inch sponson; slightly tore up three planks in the wake of the forward turret on the starboard side of the forecastle; damaged the port after shrouds of the fore and main rigging; slightly damaged the strongbacks of the gig’s davits, a 6-pounder shell cut a hole in the frame of the ship between frames 65 and 66 on the starboard side below the main-deck rail; carried away the lashing of the port whaleboat davit; carried away one of the rail stanchions outside of the port gangway; and indented the hull on the starboard side one foot below the main-deck rail and three feet abaft the No.4 coal port.

The Americans faced two additional threats at sea during the tense days following the battle. The U.S. victory opened the possibility of a foreign power seizing control of the Philippines in the wake of the Spanish collapse, and the Germans coveted the islands. German Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs Bernhard H.K.M. von Bülow ordered Rear Adm. E. Otto von Diederichs to dispatch ships of the German East Asia Squadron to the Philippines. Cruiser Irene, Capt. Ernst Obenheimer in command, reached Manila Bay on 6 May, and brazenly steamed into the harbor without stopping to receive observer instructions. “I remember as we steamed up the Bay,” Chief Boatswain Ernst Heilmann of Irene’s company subsequently recalled, “all eyes were directed towards Cavite where the victorious American ships were anchored and further inshore could be seen all that was left of the Spanish Armada, partly submerged, and laying on their beam ends.” Dewey chose to overlook the Germans’ boldness, but German reinforcements reached the islands during the next three months, logistics issues imposing delays in their deployment. Cruiser Cormoran stood into Manila Bay on 9 May, and Diederichs broke his flag in protected cruiser Kaiserin Augusta and reached the bay on 12 June. Additional cruisers included Kaiser, which arrived on 18 June, and two days later Prinzess Wilhelm and transport Darmstadt, loaded with nearly 1,400 troops. Cruiser Gefion also made for the Philippines during the confrontation.

Diederichs triggered repeated incidents, frequently ordering his ships to shift their anchorages overnight without notifying the Americans, and landing men who trained in some of the abandoned Spanish fortifications. The Germans outnumbered -- and outweighed -- Dewey by the beginning of July. Many of their crewmen lacked experience, however, because the Germans routinely exchanged up to half of their ships companies every two years, and they furthermore suffered from supply problems. Diederichs outraged the Americans when he slipped Dávila, whom the Spaniards dismissed because they feared he would surrender Manila, out of the islands on board Kaiserin Augusta on 5 August and carried the governor-general to Hong Kong.

Tensions further mounted when the Germans violated U.S. blockade regulations. One morning rumors circulated that the fighting between the Spaniards and the insurgents threatened to trap a pair of German businessmen near Subic Bay, and Irene steamed from Manila Bay suddenly, reaching Isla Grande by noon. Spaniards gathered on the beach frantically signaled the Germans, who lowered a cutter that went ashore and discovered that the Filipino insurgents had driven the Spanish troops from nearby Olongapo to the island, and they desperately requested evacuation of some severely wounded Spanish soldiers, as well as priests, women, and children. Capt. Obenheimer briefly contemplated the situation, and then replied that he would comply and return in the morning. Irene stood up the bay but shortly, under the lee of the island, the Germans sighted Companie de Filipina, a merchant steamer out of Olongapo taken by the insurgents, apparently heading toward the island. Obenheimer pointedly reminded the Filipinos that their flag was not recognized on the high seas and they hauled it down and raised a white flag, but during the night Companie de Filipina came about for Manila Bay, where the insurgents alerted the Americans of the incident. Irene meanwhile anchored overnight, and the following morning evacuated a wounded Spanish soldier, a priest, ten women, and 20 children. Irene passed Concord and Raleigh, en route to capture Grande, as she stood into the harbor to Cavite, and the Americans saw the evacuees sitting on the poop deck. Dewey protested the Germans’ actions, but a combination of diplomatic overtures by both sides, as well as the Germans’ belated recognition that they lacked support among the Filipinos, led to their withdrawal following the fall of Manila. Austro-Hungarian, British, French, and Japanese ships also aggravated the crisis at times when they sailed into Philippine waters.

In addition, Cámara’s Flying Relief Column, a Spanish squadron under the command of Rear Adm. Manuel de la Cámara, steamed for the Philippines to engage the Americans and relieve the beleaguered Spanish garrison. His squadron comprised battleship Pelayo, armored cruiser Emperador Carlos V, cruisers Patriota and Rapido, destroyers Audaz, Osada, and Prosepina, and transports Buenos Aires and Panay, and theoretically outweighed the U.S. Asiatic Squadron. Cámara sailed from Spanish waters on 16 June and reached Egypt on 7 July, but fears that American battleships operating in the Caribbean would cross the Atlantic and bombard Spanish ports led them to order Cámara to come about, and he returned to protect Spain, thus missing action in either the Philippines or the Caribbean.

Despite gaining the victory at sea, the Americans initially faced the problem of projecting their power ashore. The Spaniards deployed an estimated 40,000 troops throughout the Philippines, comprising 26,000 regulars and 14,000 militia, including as many as 9,000 around the capital. The U.S. squadron took control of the arsenal and navy yard at Cavite Island, where sailors and marines landed and destroyed the guns and magazines on 2 and 3 May. Baltimore and Raleigh forced the batteries on Corregidor to surrender on 3 May, paroling the garrison and spiking the guns, and the following day the Americans towed off Manila from where she had been run aground at Bacoor and made her a prize. Dewey cabled Washington that although he controlled the bay, however, he required 5,000 troops to seize the environs ashore. The Army dispatched substantially more men than the commodore requested, and 10,844 soldiers under the command of Maj. Gen. Wesley Merritt, USA, reached the islands before the end of the war.

A medical survey meanwhile condemned Capt. Gridley and Capt. Benjamin P. Lamberton relieved him on 25 May 1898. Gridley started for home but died on board Occidental & Oriental Steamship Company passenger liner Coptic while she prepared to sail from Kōbe, Japan, on 5 June. His wife, two daughters, and a son survived him, who had remained in the United States. Dewey strongly recommended that Gridley be advanced ten numbers in the promotion list, as a partial reward for his ability and judgment, and the Navy subsequently advanced him six numbers. Gridley was buried at Lakeside Cemetery in Erie, Pa. Four guns captured from the Spanish arsenal at Cavite were emplaced at his gravesite.

In addition in May, Dewey ordered McCulloch, which the Americans used to carry dispatches between the Philippines and Hong Kong, to return from the British colony with Filipino insurgent Emilio Aguinaldo y Famy and about a dozen of his men. The commodore hoped to learn more about the Spanish garrison, and welcomed any distraction the Filipino rebels might provide by their raids against the Spanish troops. The cutter brought Aguinaldo to the Philippines, and he boarded Olympia and discussed with Dewey tentative plans to drive the Spaniards from the islands. Aguinaldo landed and began to recruit men and seize Spanish arms, but Dewey and the American consuls in the Far East overestimated their ability to control the consequences of these actions, which included Aguinaldo’s expectation that the United States would support his demand for the colony’s independence.

“You must exercise discretion most fully in all matters,” Secretary Long cabled Dewey on 26 May, “and be governed according to circumstance which you know and we can not know. You have our confidence entirely. It is desirable, as far as possible, and consistent for your success and safety, not to have political alliances with the insurgents or any faction in the islands that would incur liability to maintain their cause in the future.”

By the time American forces were prepared to assault Manila in August, however, the potential problems of cooperating with the rebels became apparent to Dewey and Merritt. The Spanish garrison of Manila also feared retribution by the insurgents and preferred to surrender to the Americans, secretly negotiating with Dewey via the Belgian consul. The American commanders reached an oral agreement with Dávila to surrender the city after a brief naval bombardment and infantry assault. On the morning of 13 August Olympia, Raleigh, Petrel, and gunboat Callao, accompanied by tug Barcello, opened fire and Merritt’s troops went forward. After sharp fighting in some quarters the Spanish surrendered, allowing the Americans to occupy Manila — and keeping the Filipino insurgents out of most sections of the city. The United States and Spain signed a peace protocol on 12 August, but word of this did not reach Manila until four days later and the treaty did not come along until 10 December 1898.

Olympia steamed in Philippine waters until she returned to the China coast on 20 May 1899. Next month she set sail for home and thus missed taking part in the fighting during the Boxer Rebellion in China. Olympia passed through the Suez Canal into the Mediterranean, and at one point grounded, bending the blades of her starboard propeller. The ship reached Gibraltar on 4 September, and then crossed the Atlantic running on her port engine alone, starting the starboard engine less than a day before she hove to off Tompkinsville, N.Y., amidst great public fanfare on 26 September. The National Camp of the Patriotic Order Sons of America were convened at New Haven, Conn., and sent the ship a telegram welcoming her home:

The undersigned committee, selected by the National Camp of the Patriotic Order Sons of America, now in National Convention assembled, to send its greetings, desire to express to you, the welcome of the 250,000 of its members upon your safe return to your native land. In all your perils, trials and dangers for the glory of the flag we love,

Our hearts, our hopes, our prayers, our tears,

Our faith triumphant o’er our fears,

Were all with thee, were all with thee.

The crew reacted to the greeting with “shouts of applause.” The ship, returned to her white and spar color scheme, took part in the Dewey Day Naval Parade in New York harbor three days later. Following the celebration, Olympia steamed to Boston, Mass., which she reached on 10 October. The cruiser completed her first extensive overhaul and upgrade at Boston Navy Yard (16 October 1899–8 February 1902), decommissioning there on 8 November 1899. Sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens made a gilded bronze figurehead for the ship, commemorating her victory at Manila Bay. In addition, the work included alterations in the following areas: removing all of the torpedo tubes and sealing the torpedo apertures; enlarging the pilothouse; extending the after bridge and installing a signal house on the aft bridge deck; upgrading her ammunition handling gear, as well as the coal loading and handling gear; replacing the wood joiner bulkheads with light-gauge steel bulkheads and thermal insulation; installing larger electrical generators, and electric turning gear for turrets; and replacing the steam turning engines.

President McKinley commissioned the George Dewey Peace Jubilee Medal to honor the commodore for his victory. The medal attained its name because it was to have been awarded to Dewey during the public Peace Jubilee held in Philadelphia, Pa., to commemorate the end of the war, on 25 October 1899. For unknown reasons, the medal was not awarded at that time and subsequently disappeared. Many years later, retired Warrant Officer George Hubbard of Waterloo, Iowa, found the medal being sold at a flea market. Hubbard, a collector of memorabilia, added the medal to his collection and then contacted the Naval Historical Center. On 1 May 2005, the 107th anniversary of Dewey’s victory, dignitaries from the Philippine Embassy, Naval Order of the United States, Rear Adm. Jan C. Gaudio, Commander Naval District Washington, and the Naval Historical Center met on board Olympia’s fantail, preserved at Philadelphia (see below), for the formal presentation of the medal to the National Museum of the United States Navy. “The acquisition of this medal,” Dr. Edward Furgol, the museum’s curator, explained, “closes the chain of events celebrating Dewey’s spectacular victory at Manila Bay. We already have his official medals, sword, and uniform.”

Recommissioning in January 1902, Olympia spent the next four years roving the Caribbean, Atlantic, and Mediterranean, protecting American citizens and interests from danger. The ship was fitted for wireless telegraphy during work at Boston Navy Yard (2 June–12 July 1902), and then joined the North Atlantic Squadron, serving first as flagship for the Caribbean Division. Olympia then (15–17 July) steamed up the Hudson River and attended the dedication of the Stony Point Battlefield, N.Y., commemorating the battle fought between the Continentals and the British for possession of the strategic bastion on 16 July 1779. The cruiser coaled in New York (17–23 July), and then steamed with the squadron off Menemsha Bight and Woods Hole, Mass., New London, Conn., and Block Island, N.Y. (24 July–11 August), a sojourn broken only by performing dispatch duty to Newport, R.I. on 31 July and 9 August. Olympia planted targets and buoys off No Man’s Land, Mass., on 11 and 12 August, and then coaled and rejoined the squadron, continuing training in Massachusetts’ waters off Menemsha Bight, Woods Hole, Rockport, and Great Point, Nantucket, through the end of the month. The ship cut cables in Vineyard Sound near Woods Hole and off Lobsterville, Mass., on the first two days of September, and trained off Block Island, Cerebus Shoal, and Buzzards Bay. She then carried out practice firing by bombarding shore fortifications at Clark’s Point near New Bedford, Mass., on 3 September, and overnight shelled Forts H.G. Wright, Michie, and Terry in Long Island Sound. Olympia maneuvered with other ships off Hortons Point, L.I., the following day, and on 5 and 6 September bombarded the fortifications at Newport during a simulated night attack against that naval station. The cruiser rejoined the squadron but required repairs in Boston (8 September–16 October) and docking, painting, and coaling in New York (17–26 October).

Olympia then made for the warmer waters of the Caribbean, reaching San Juan, P.R., on Halloween, and taking part in establishing a naval station at Culebra Island east of Puerto Rico (1 November–5 December). She sailed in company with Cincinnati (Cruiser No. 7) during a “search problem” (training exercise) (9–19 December), and with Machias (Gunboat No. 5) and Nashville (Gunboat No. 7) spent Christmas at Basse-Terre, St. Kitts (20–26 December). Olympia coaled at St. Thomas in the Danish West Indies (27–20 December 1902), and entered the New Year at Culebra. Olympia served as the flagship there on 3 February 1903, and accompanied by transport Panther made the round of nearby ports, visiting Port of Spain, Trinidad (5–6 February), Pointe a Pitre, Guadeloupe (7–11 February), and returning to Basse-Terre (11–14 February). The cruiser then carried out target practice off Culebra (16–19 February), coaled at San Juan (24 February–8 March), and resumed her practice shooting off Culebra (8–15 March).

Honduran conservative Manual Bonilla overthrew Gen. Terencio Sierra as that country’s president on 1 February 1903. Bonilla suppressed liberals throughout Honduras, and during the ensuing turmoil Rear Adm. Joseph B. Coghlan broke his flag in Olympia in command of a squadron that sailed in Honduran waters to protect Americans in the country: Raleigh, Cmdr. Arthur P. Nazro in command; San Francisco (Cruiser No. 5), Capt. Asa Walker in command; Marietta (Gunboat No. 15), Lt. Cmdr. Samuel W. B. Diehl in command; and Panther, Cmdr. John C. Wilson in command. The ships sailed from Culebra on 15 March, and reached the waters off Puerto Cortez on 21 March. Olympia, Marietta, and Panther steamed initially off Puerto Cortez (21–22 March) where tensions flared, and William P. Alger, the American Consul, requested assistance. Consequently, on 23 March Marietta landed 13 marines to protect the United States Consulate, who remained until the end of the month. Olympia meanwhile patrolled the waters off Ceiba (22–23 March) and Puerto Sierra (23–24 March). She then landed a detachment of 30 marines, under the command of Capt. Henry W. Carpenter, USMC, and Midshipman Edwin G. Kintner, to guard the Steamship Wharf at Puerto Cortez. These men returned to the ship on 26 March. The cruiser sailed in company with Raleigh and Marietta off Puerto Cortez (24 March–11 April), and ships of the squadron at times also visited the ports of La Ceiba, Puerto Sierra, Trujillo, and Tela, where they reported stable political conditions. Olympia came about for home following the Honduran crisis, and joined battleships off Pensacola, Fla. (14–23 April). She completed an inspection at the Southern Drill Grounds, Va. (28–30 April), lay to at Hampton Roads while awaiting orders, and then (4–12 May) accomplished repairs in drydock and coaled at Newport News, Va.

Olympia returned to Cuban waters and awaited the Cuban Commission -- which worked on normalizing relations between the United States and Cuba -- while at Santiago de Cuba (16–27 May 1903), and in company with Nashville and converted yacht Vixen surveyed a site for a coaling station at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba (27 May–15 July). Olympia turned her prow northward and sailed up the east coast of the United States, coaling at East Lamoine, Maine (20–22 July) before rendezvousing with the fleet off Bar Harbor for a search problem (22 July–5 August). The cruiser scouted for the other ships (5–8 August), returned to East Lamoine to coal, and rendezvoused with the fleet off Bar Harbor for additional steaming (9–12 August). Olympia anchored in Smithtown Bay, L.I., on 14 and 15 August, and then (15–17 August) took part in a Naval Review at Oyster Bay. The ship afterward came about and rendezvoused with the fleet off Rockland, Maine (19–24 August), and sailed in the waters off Maine during Army and Navy maneuvers: Casco Bay on 26 and 27 August; Richmond Island (27–29 August); and Portland on 29 August. A storm interrupted the exercise as it swept through the area and compelled Olympia to seek shelter at Provincetown (30 August–1 September). The following day the ship gamely stood out to sea as the tempest passed and she rejoined the fleet off Menemsha Bight. She steered southerly courses and anchored at Lynnhaven Bay, Va., overnight on 3 and 4 September, and then completed repairs at Norfolk Navy Yard, Va. (4 September–17 December).

Following the ship’s yard work she steamed for Panamanian waters. The United States sought the exclusive right to build and control an interoceanic canal across the Panamanian Isthmus -- then under Colombian rule -- and during the autumn, rising tensions threatened to engulf the region in conflict. The U.S. dispatched ships to the area and at 1730 on 2 November Nashville, Cmdr. John Hubbard in command, anchored at Colón to protect Americans there. Just before midnight Colombian troopship Cartagena entered the roadstead and anchored near the U.S. gunboat, and began disembarking 474 Colombian soldiers during the forenoon watch. Rumors circulated that the troops intended to march on Panama City to ensure order, but at 1800 on 3 November Panamanians seeking independence rose against the Colombians. Hubbard landed a detachment of marines, Lt. Cmdr. Horace M. Witzel in command, shortly after noon on 4 November, and they established positions at the railroad office, blocking the Colombian soldiers from taking a train into the city. The marines returned to the ship overnight, but some landed again the following morning and reoccupied their positions.

Additional U.S. ships reached the area and landed bluejackets and marines during the succeeding days, including Olympia, which sailed off the embattled country’s coast during part of the crisis. Olympia rejoined the flagship off Colón on 23 December, spent Christmas Eve and Christmas coaling at Chiriqui Lagoon, Panama, and then patrolled off Colón. On 27 December the cruiser carried United States Minister A.M. Beaupré to Columbia from Colón to Cartagena, Columbia, where he negotiated with that government. Olympia protected American interests in Panamanian waters into the New Year, patrolling off Colón (28–30 December 1903, 6 January–9 February, 21 February–16 March, and 21–24 March 1904), and breaking her patrols to coal at Chiriqui (31 December 1903–6 January and 10–20 February 1904) and at Portobello, Panama (16–21 March). Olympia then came about and coaled at Guantánamo Bay (27–29 March), and practiced her gunnery off Pensacola (2–24 April). The cruiser shifted from the Caribbean Squadron on 20 April when Rear Adm. Theodore F. Jewell, Commander European Squadron, broke his flag in Olympia at Pensacola. The ship accomplished voyage repairs and coaled while in drydock at New Orleans, La. (25 April–3 May), and then rejoined the fleet for a cruise in the Caribbean (4–18 May), visiting Pensacola on 4 and 5 May, Guantánamo Bay (9–13 May), and coaling at St. Thomas (16–18 May). Jewell next took the three ships of the squadron -- Olympia, Baltimore (Cruiser No. 3), and Cleveland (Cruiser No. 19) -- to Horta at Fayal in the Azores, where the ships coaled on 28 May and then prepared to resume their voyage to Lisbon, Portugal, but they received word of a crisis looming across the Atlantic.

Moroccan Sharif Mulai A. er Raisuni, known as “The Raisuli” to most Americans, kidnapped a man and a boy he erroneously believed to be U.S. citizens, Ion H. Perdicaris and Cromwell O. Varley, from Perdicaris’ villa in Tangier, Morocco, on 18 May 1904. The British, French, Germans, and Spanish all vied for control of Morocco, alternatively presenting extravagant gifts to Sultan Abdelaziz, in the hope of gaining coaling concessions for their ships. Raisuni apparently resented the foreigners’ influence and sought to embarrass the sultan, demanding a ransom for the safe return on his hostages. “Situation serious,” U.S. Consul Gen. Samuel R. Gummere telegraphed to the State Department the following day, “Request man-of-war to enforce demands.”

The U.S. initially sent the South Atlantic Squadron, Rear Adm. French E. Chadwick in command, to Tangier to compel the release of the hostages. Chadwick broke his flag in Brooklyn (Cruiser No. 3) and the squadron, also consisting of Castine (Gunboat No. 6), Machias (Gunboat No. 5), and Marietta, set sail on easterly courses, put in to Santa Cruz at Tenerife in the Canary Islands briefly on 28 May, and reached Tangier on 30 May. On that day, Brooklyn landed a detachment of a dozen marines equipped with side arms led by Capt. John T. Myers, USMC, who secured the U.S. Consulate and Ellen Perdicaris, the Greek expatriate’s wife.

Meanwhile, Jewell received orders to reinforce Chadwick and directed the European Squadron to set course for Tangier. Olympia, Baltimore, and Cleveland reached that port on the first of the month, raising the number of U.S. warships there to seven. The European powers also took a keen interest in the proceedings and the British dispatched battleship Prince of Wales from their Mediterranean Fleet, which arrived at Tangier on 7 June. The audacity of the kidnapping and the affront to the U.S. incensed many Americans. “It should be clearly understood,” Hay cabled Gummere on 9 June, “that if Mr. Perdicaris should be murdered, the life of the murderer will be demanded, and in no case will the United States be a party to any promise of immunity for his crime.” The Navy and the State Department considered plans to land bluejackets and marines from the ships and deploy them inland to rescue the hostages, a grim prospect considering the large number of tribesmen Raisuni could potentially summon and the immense logistic problems to be overcome.

President Theodore Roosevelt and Secretary of State John M. Hay responded sternly to the situation, the secretary cabling Gummere on 22 June: “The United States Government wants Perdicaris alive or Raisuli dead. No marine should be landed, however, or custom-house seized without specific directions from the Department.” Joseph G. Cannon, Speaker of the House of Representatives, read the first sentence of the telegram to the delegates gathered at the Republican National Convention at the Chicago Coliseum. The news electrified the delegates and they broke into an uproar, demanding U.S. military action. Cannon (apparently) did not receive the second sentence of the ultimatum, however, and thus the public remained largely unaware of Hay’s cautionary admonition. Olympia hove to off Tangier during most of the incident (1–8 and 11–29 June), interrupting her vigil to coal at Gibraltar (8–11 June). Following a flurry of negotiations Raisuni received the ransom and returned Perdicaris and Varley on 21 June, and on 27 June the ships came about. The motion picture The Wind and the Lion, released in 1975, dramatizes the incident.

Olympia then sailed in the Mediterranean, beginning her round of calls on that sea by spending Independence Day coaling at Gibraltar (29 June–5 July 1904). The ship entered the Mediterranean and visited Trieste, Austria-Hungary (12–24 July), Corfu, Greece (26–31 July), and Villefranche-sur-Mer, France (3–7 August). Disturbances at Smyrna (Izmir) in the Ottoman Empire (Turkey), however, obligated her to steam off that port to protect Americans (12–15 August). Olympia returned with the squadron to Gibraltar (22 August–3 September), and then sailed in the Atlantic, calling at Cherbourg, France (7–12 September) and Christiania (Oslo), Norway (15–22 September), before she came about in company with Cleveland and Des Moines (Cruiser No. 15) to have her condensers repaired at Gravesend, England (24 September–1 November). Olympia then returned to the “Rock of Gibraltar” (6–10 November), and coaled -- with Cleveland -- in dry dock at Genoa, Italy (13–22 November). Olympia turned her prow westward and coaled and took on stores -- with Cleveland and Des Moines -- at Gibraltar (25–30 November), and then, adequately provisioned, crossed the Atlantic with the squadron by westerly courses. Cleveland and Olympia detached and took on coal while spending Christmas at Bridgetown, Barbados (11–28 December), and Olympia greeted the New Year at Basse-Terre (29 December 1904–11 January 1905).

The cruiser took part in winter maneuvers off Culebra (12 January–17 February 1905), and then in company with Kentucky (Battleship No. 6), Missouri (Battleship No. 11), and Des Moines off Guantánamo Bay (20 February–18 March). Olympia took a welcome break from her operations and visited Havana, Cuba (20–25 March), following which she carried out target practice off Pensacola (27 March–30 April). The ship coaled at Dry Tortugas, Fla. (2–4 May), but she turned southward to respond to a burgeoning crisis in the Dominican Republic. Olympia protected American interests while alternatively steaming off Dominican ports: Monte Cristi (7–9 May, 21 July, 31 August–7 September, 1–5 October, and 15 October–2 November); Sánchez (10 May, 22–28 September, and 10–13 December); and Santo Domingo (11–18 May, 28–30 September, and 10 November–9 December). The cruiser broke her patrols periodically by coaling and carrying out small arms practice at Guantánamo Bay (20–24 May, 3–30 August, 8–16 September, 6–19 October, and 3–8 November) and visiting Kingston, Jamaica (26 July–2 August). She came about just before the holidays, visited St. Thomas (18–22 December), and conducted target practice at Culebra (22 December 1905–19 January 1906), before returning to Hampton Roads, where some men took leave while the crew prepared the ship for decommisioning. Olympia was placed out commission on 2 April 1906 at Norfolk Navy Yard.

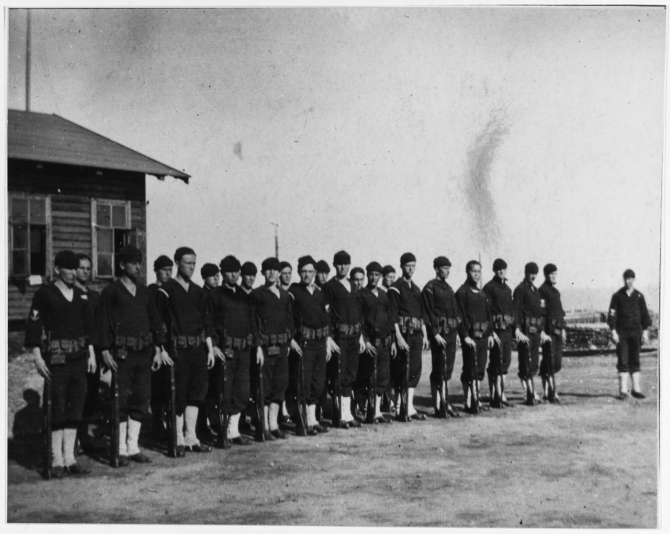

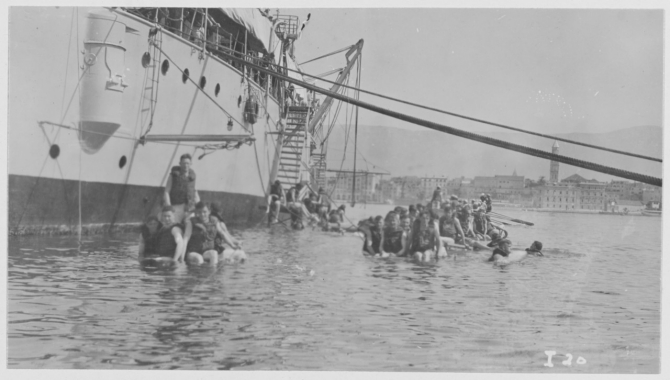

For six years Olympia remained largely out of commission, first at Norfolk, then at Annapolis, recommissioned during three summers for midshipmen training cruises. A number of the naval officers who subsequently attained senior rank and led the Navy to victory during two world wars served either on board Olympia, or in the ships of the squadron, of which she operated as the flagship, during these cruises. All of the 6-pounder guns and mounts on the berth deck were removed, and spaces formerly used by junior, senior, and warrant officers were modified in order to accommodate midshipmen. She recommissioned on 15 May 1907 at Norfolk for the first such voyage and visited: Lynnhaven Bay (1–3 and 8–9 June); embarked the midshipmen at the Naval Academy at Annapolis, Md. (3–8 June); put in to or lay off Hampton Roads (9–14 June); Newport News (14–19 June); Annapolis (19–20 June); York Spit in Chesapeake Bay (21–22 June); New York City (24–28 June); New London (29 June–22 July and 26 July–1 August); Newport (22–24 July); Bradford, R.I. (24–26 July); Smith Point, Md. (21–22 August); Cornfield Harbor, Md. (22–25 August); and disembarked her midshipmen (25–26 August), before decommissioning on 26 August 1907).

The veteran cruiser completed repairs (16 March–20 May 1908) before she recommissioned for a second such cruise with the Naval Academy Practice Squadron, embarking midshipmen at the Naval Academy (21 May–8 June), and lying to off: Cove Point (10–12 June), Solomons Island on 12 June, and Piney Point, Md. (15–16 June); Rappahannock Spit (16–17 June) and Hampton Roads, Va. (17–22 June and 22–25 August); Block Island on 24 June; New London (29 June, 3–6, 10–13, 17–20, and 24–27 July); Oregon Hills, L.I. (30 June); Gardiners Bay (13–17 and 23–24 July); Bradford (20–23 July); Newport (30 July–3 August); Boston (5–11 August); Portsmouth, N.H. (11–14 August); and Bath, Maine (14–19 August), before returning her midshipmen to the Naval Academy (27 August–23 November). She then completed work at Norfolk (27 November 1908–8 March 1909).

Olympia entered reserve status (9 March–7 June 1909) and followed that the next summer by again steaming with the Naval Academy Practice Squadron. The ship embarked her midshipmen at the Naval Academy and visited: Solomons Island (7–9 June and 25–26 August); Hampton Roads (10–14 June); Gardiners Bay (16–18 and 21–25 June, 6–9, 12–16, and 19–23 July); New London (18–21, 25–28, and 30 June, 9–12, 16–19, and 23–26 July); Newport (26–29 July and 19–23 August); Boston (30 July–3 August); Gloucester, Mass. (3–5 August); Portsmouth (5–7 August); Portland (7–10 August); Bath (10–15 August); and Bar Harbor (16–17 August), before disembarking the midshipmen at the Naval Academy on 26 August 1909 and being placed in reserve. She steamed to Charleston, S.C. (2–6 March 1912), to serve as barracks ship for the men of the reserve torpedo group, until she was placed in ordinary in 1914. Later that year the aging cruiser then completed a refit at Charleston Navy Yard, recommissioning on 2 January 1915.

In 1914 and 1915, Haitian Gen. Jean V. G. Sam led a revolt and on 25 February 1915 was “elected” president of the embattled island republic. Shortly thereafter, Dr. Rosalvo Bobo became increasingly frustrated with the country’s growing ties to the United States and rebelled against Sam. The Americans dispatched reinforcements to oversee the crisis, and while Olympia steamed in the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean, she ranged briefly in Haitian waters. Following the ship’s deployment to the crisis, she was decommissioned on 9 June 1915 at Charleston. As war approached the United States, however, Olympia underwent a major refit at Charleston Navy Yard (July–November 1916). Her original main battery of four 8-inch guns was removed, along with the armored barbettes and turrets. In addition, she was rearmed with 12 4-inch guns, ten of which replaced her 5-inch guns.

The ship was recommissioned on 30 October 1916, and steamed en route from St. Thomas to Norfolk Navy Yard when the U.S. declared war on 6 April 1917. On 13 April Rear Adm. Henry B. Wilson, Commander Patrol Force Atlantic Fleet, broke his flag in Olympia. While en route from Tompkinsville to Gardener’s Bay, L.I., for gunnery practice on 25 June, she grounded on Cerberus Shoal in Block Island Sound, holing the hull in several locations on the port side. The cruiser listed to port, and bluejackets threw blankets overboard in an attempt plug the holes while pumps worked to de-water the ship. Olympia was beached in shoal water and later salvaged and towed to New York Navy Yard, where she accomplished repairs in drydock and then additional work at Tompkinsville (13 July 1917–6 February 1918). The ship was again rearmed, this time with ten 5-inch guns. These weapons replaced the 4-inch guns on the forward and after platforms and in the superstructure, with exception of the midship gun positions at frame 47. Furthermore, an “oscillator” -- a “submarine signaling device” -- was installed in the hull bottom.

Following the yard work, Olympia made for Halifax, Nova Scotia, and upon arriving at that port on 9 February 1918, she received a message that Naval Overseas Transportation Service (NOTS)-manned cargo ship Hatteras (Id. No. 2142) was in distress and requested immediate assistance. After loading a cargo of steel and grain in Maryland, Hatteras had joined a convoy at Norfolk and sailed for Bordeaux, France, on 26 January. On 4 February the convoy ran into a severe North Atlantic storm, and Hatteras' steering gear broke down completely. As it turned out, however, the disabled ship headed back to Boston using a jury-rigged steering system, arriving 11 days later, and did not require assistance. Olympia then received word that steamers Clarane and Clara also needed help, only to discover that they were otherwise provided for and she came about, returning to Tompkinsville on 17 February. The cruiser then escorted British merchantmen en route to and from New York and the war zone (12–23 March). The ship turned over her charges to destroyers and on 4 April arrived at Hampton Roads.

The Russian Civil War meanwhile swept through that empire. The Bolsheviks, known as ‘Reds,’ and the ‘Whites’ -- a disparate mix of people loyal to the Romanovs or at least opposed to the Reds -- fought across fronts measuring thousands of miles. The Allies felt betrayed by the Russian withdrawal from the war, and sought to recover huge stores of munitions they had shipped to support them, and intervened in the fighting. On 8 April Vice Adm. William S. Sims, Commander, Naval Forces Operating in European Waters, wired Adm. William S. Benson, Chief of Naval Operations (CNO), reporting that the British Admiralty believed it desirable for an American warship be at Murmansk, Russia. Sims noted the lack of a suitable vessel to send from his forces, but added, “that a pre-dreadnaught battleship or armored cruiser from home waters be sent.” In reply the following day, Benson cabled Sims that the only vessel “which might be possibly made available for this duty is USS Olympia.” Sims approved Olympia’s selection, and recommended that she proceed via Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands.

Workmen hurriedly completed alterations to Olympia’s interior spaces to accommodate the assortment of men required for her mission, while in dry dock at Charleston Navy Yard (15–28 April). The cruiser sailed on 28 April 1918, anchoring off Kirkwall in the Orkneys on 13 May. Olympia bunkered and then stood out of Scapa Flow for Russian waters at 0413 on 20 May, and reached Murmansk at 2252 on 24 May. A chaotic situation greeted the ship and the Allies feared that the Germans and Finns on the one hand, or the Bolsheviks on the other, might attack their forces in the area.

On 8 June 1918, therefore, the ship, in accordance with orders from Rear Adm. Thomas W. Kemp, RN, Commander British North Russia Squadron and the senior Allied naval officer afloat, landed a party 108 men -- nearly a fourth of her crew -- under the command of Lt. Henry F. Floyd to join a detachment of British Royal Marines. Logistics issues constrained the British to continue to occupy the barracks slated for the Americans, however, and Floyd and his sailors returned to Olympia at 1919 that evening. The following day the men landed again and manned positions around the port, Floyd later received the Russian Order of St. Ann 3rd Class with Crossed Swords for his service in the campaign.

During the summer, additional Allied reinforcements arrived in northern Russia, including soldiers of the U.S. Army’s 339th Infantry Regiment and 310th Engineers. Crewmen from Olympia busily repaired ships in port and performed stevedoring service. In addition, they took possession of the dilapidated but repairable Russian torpedo-boat destroyer Kapitan Yourasovski on 17 July 1918. Built in 1899 at the Schichau yard in Danzig, Germany, the ship had served in the Siberian Flotilla and the Baltic Fleet, before being transferred to the north. After reconditioning the vessel, she was placed into service as a patrol vessel under the Imperial Russian Navy with a crew of 50 men from Olympia’s company and ten Russians. Kapitan Yourasovski patrolled those cold waters until late 1918 or early 1919, at which time she was placed out of service.

The fighting continued and an allied expeditionary force under the command of British Army Maj. Gen. Frederick C. Poole, Allied commander-in-chief designate, North Russia, and including 27 men from Olympia, seized and occupied the Russian port of Arkhangelsk (31 July–1 August 1918). On 3 August, Capt. Bierer and 27 more men from the ship arrived. The sailors then rode a White Russian train down the railway toward Vologda. The Bolsheviks slugged it out with the train on 6 August, killing one of the Allied troops and wounding 11. The following day, Olympia’s 22-piece band left Murmansk to help raise the morale of the Allied troops at Arkhangelsk. Ens. Donald M. Hicks and 25 of the ship’s crewmen from the train joined a mixed Allied force on 10 August, and moved up the Dvina River from Arkhangelsk toward Kotlas on board small river steamers/barges. They disembarked and marched to Tegora, reaching the town on 15 August and fighting an estimated 250 Bolsheviks. In the ensuing five hour battle, Olympia’s Seaman George D. Persche was wounded, one British officer was killed, four Frenchmen died, and one Polish fighter fell. For his “conspicuously courageous part in all the fighting and marching,” Hicks later received the Navy Cross.

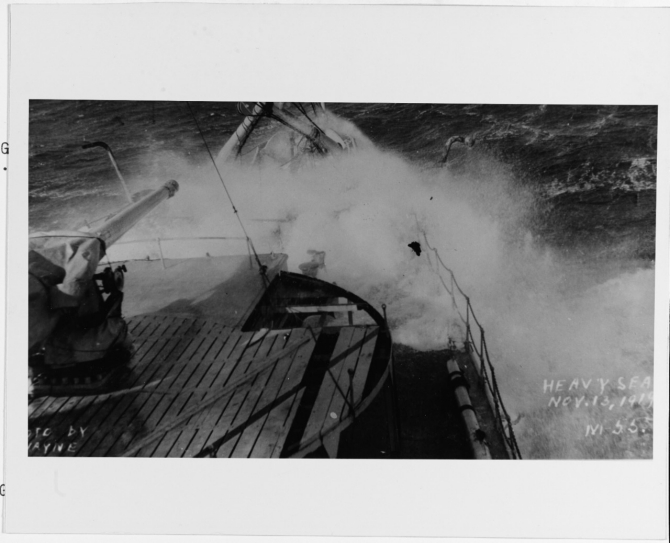

The last of Olympia’s bluejackets and marines returned from Arkhangelsk on 14 September, after nearly 14 weeks ashore. Rear Adm. Newton A. McCully Jr. and 35 men -- mostly of his staff -- arrived at Murmansk on board French armored cruiser Gueydon on 24 October. At 1603 that afternoon, McCully broke his flag in Olympia as Commander U.S. Naval Forces, Northern Russia. Olympia weighed anchor at Murmansk at 1300 on 26 October, crossed the White Sea, and anchored at Arkhangelsk at 0752 on 29 October. American flagged merchantman Ascutney and NOTS-manned freighter West Gambo (Id. No. 3220) were among the Allied ships that also entered Arkhangelsk while Olympia lay at the port. West Gambo set out in a convoy from New York on 18 September and arrived on 12 October with a load of flour for the International Red Cross, discharged her cargo, loaded 4,000 tons of ballast, and proceeded for Glasgow, Scotland, on 2 November, where she bunkered and sailed on 24 November for New York. McCully meanwhile shifted his flag ashore on 6 November, and the ship detached six men to assist the admiral, while Lt. Sergius M. Riis, USNRF, led another three to Arkhangelsk. David R. Francis, the ailing U.S. Ambassador to the Whites, boarded Olympia and at 0725 on 9 November the ship stood down the Northern Dvina River for the last time, anchoring at Murmansk at 0823 on 11 November 1918. She set sail at 0700 on 13 November, plowed through heavy seas that dislodged planking on the forward gun platform, and moored at Invergorden, Scotland, at 1210 on 18 November.

The ship then completed voyage repairs in dry dock at Portsmouth, England, until the day after Christmas 1918 she turned her prow southward and made for the Mediterranean to serve with the Inter-Allied Patrol in maintaining peace in the Balkans in the wake of the collapsing Austro-Hungarian Empire. The cruiser celebrated New Year’s Eve at Gibraltar, and on 5 January 1919, Adm. Benson directed Rear Adm. Mark L. Bristol to hoist his flag on board Olympia and sail to the Adriatic to assume duties as Commander U.S. Naval Forces Eastern Mediterranean. As it turned out, however, tumultuous events also erupted during the fall of the Ottoman Empire, and Bristol proceeded instead via Paris, France, to serve as the Navy’s Senior Naval Officer Present, Turkey, reaching that troubled land on 25 January. Bristol later assumed additional duty as the U.S. High Commissioner in Turkey.

Rear Adm. Albert P. Niblack, Commander U.S. Patrol Squadrons Based on Gibraltar, therefore broke his flag in the ship at 1550 on 10 January 1919, while in passage to Venice, Italy. Olympia reached Valetta, Malta, on 15 January, stood out to sea the following day, and visited Brindisi, Italy, where she received instructions on how to navigate through the minefields just outside the harbor of Venice, as well as routing instructions for Fiume, Austria. The ship moored at Venice on 21 January, and the next day Niblack assumed his duties as Commander U.S. Naval Forces Eastern Mediterranean. On 21 February, Niblack shifted his flag to Maury (Destroyer No. 100), that took him to Pola, Italy.

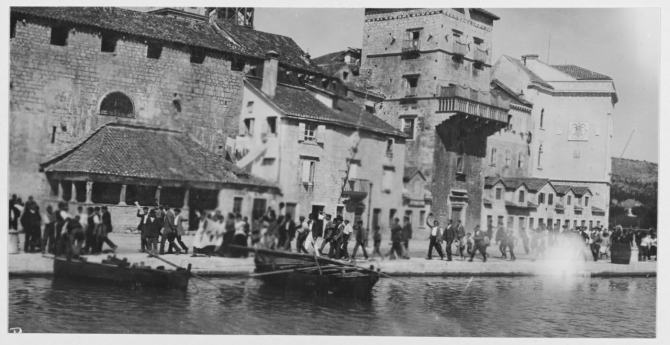

The following day, Olympia reached Spalato [Split], Croatia, which the Allies selected as the naval base for the zone patrolled and protected by American forces under the terms of the Austro-Hungarian armistice. The ship anchored in Cavale Castelli between two former Austro-Hungarian pre-dreadnaught battleships, Radetzky and Zrinyi — both of which served briefly under U.S. colors. Olympia’s aging radio proved inadequate for maintaining communications, and Israel (Destroyer No. 98) initially anchored at the mouth of Canale Grande at Venice, where she passed on the cruiser’s messages to the land line for transmission to Paris and beyond.

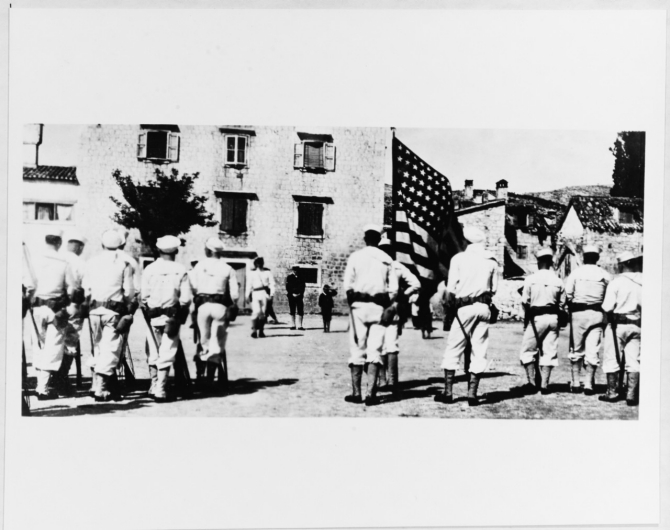

Political disturbances caused many problems and Lt. Cmdr. Richard S. Field landed on 25 February 1919 and assumed duties as the Chief Officer of the Inter-Allied Patrol, a force the ship reported as “maintaining tranquility ashore in Spalato.” Lt. Floyd led a patrol of a dozen men equipped with rifles from Olympia that cooperated with other sections of the patrol in the city. Olympia coaled at Brindisi (16–20 March), and Rear Adm. Philip Andrews relieved Niblack on board the ship on 26 March. The admiral hauled down his flag on Olympia and shifted to Stribling (Destroyer No. 96) on 5 April, but broke his flag in the cruiser again on 19 April. Olympia steamed to Fiume on 10 and 11 July, where Andrews transferred his flag to Pittsburg (Armored Cruiser No. 4) on 19 July. The following day, Olympia returned to Spalato, reaching that port on 21 July.

The ship next observed the Turkish War of Independence when she steamed (18–23 August 1919) to Constantinople [Istanbul]. From that crossroads of the Orient she began a voyage into the Black Sea, stopping at Batum, Russia; Trebizond [Trabzon] and Kerasunt, Turkey; the Turkish port of Unich [Űnye], where she rescued Americans from the vortex and transported them to Samun, Turkey; and continued to Sinub, İnebolu, and Sungal, Turkey, before returning to Constantinople on 8 September. Olympia made for Smyrna (13–14 September), and then came about for Spalato (16–19 September).

![Olympia rounds the headland at Trebizond [Trabzon], Turkey, the ancient Byzantine and Turkish fortress visible atop the cliff, August 1919. (R.E. Wayne K-89, U.S. Navy Photograph NH 122302, Photographic Section, Naval History and Heritage Command) Olympia rounds the headland at Trebizond [Trabzon], Turkey, the ancient Byzantine and Turkish fortress visible atop the cliff, August 1919. (R.E. Wayne K-89, U.S. Navy Photograph NH 122302, Photographic Section, Naval History and Heritage Command)](/content/history/nhhc/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/o/olympia/_jcr_content/body/image_98792610.img.jpg/1475779067528.jpg)

Dalmatian Italian Count Fanfogna led three truckloads of armed irregulars across the armistice line at Trogir (Traù), Dalmatia, and surprised and captured the small Serbian garrison there, on 23 September 1919. The senior Italian naval officer present asked Capt. David F. Boyd Jr., Olympia’s commanding officer, to maintain peace between the Serbian and Italian troops. Boyd dispatched Lt. Cmdr. Field and Cmdr. Marony, an Italian naval officer from protected cruiser Puglia, by automobile to Trogir, while he took Olympia and Cowell (Destroyer No. 167) to the port. Boyd landed a small guard of crewmen -- 101 lightly equipped men from the cruiser -- at Trogir, and the men temporarily diffused the situation. The Italians had already been induced to return, but they left behind an army captain and several soldiers, and the Americans protected them from retribution by the Serbs by placing them in an Italian motor boat and turning them over to the Italian Navy. The Serbians assured the Americans that they would restore order and not harm the Italian civilians, the bluejackets and marines returned to the ships, and Olympia retired to Spalato that evening. Adm. Enrico Millo, the Italian Governor of their occupied portions of Dalmatia, sent his senior officer to thank Boyd for his prompt intervention.

The internecine quarrels that plagued the region continued, however, and the ship hove to at Trogir again (27 September–25 October 1919). Rear Adm. Harry S. Knapp, Commander U.S. Naval Forces Operating in European Waters, observed that Rear Adm. Andrews’ “tactful firmness” kept the “friction along the armistice line between Serbians and Italians…from causing serious results.” Olympia came about and on 28 October reached Valetta, and the following day entered dry dock to have her bottom cleaned in preparation for the return voyage. Olympia departed Malta on 1 November, stopped at Gibraltar (5–9 November), and then passed westward through the strait and battled heavy seas before reaching Charleston on 24 November.

Olympia was made ready for further Adriatic duty that winter and visited New York (14–17 February 1920), before setting out across the Atlantic for the Mediterranean. She reached Gibraltar (5–8 April), and then returned to the Dalmatian Coast, arriving at Spalato on 14 April. The next day Rear Adm. Andrews transferred his flag from Pittsburg. The ship ranged between Venice, points on the Dalmatian Coast -- Ragusa, Spalato, and Gravosa (4 May–29 September), and during that time, Olympia was reclassified to a heavy cruiser (CA-15) on 17 July 1920. She accomplished an overhaul in a floating dry dock at Pola (1–9 October), steamed between Venice, Brioni Island, and Spalato, and on 7 November assisted with the transfer of Radetzky and Zrinyi when those two pre-dreadnaughts were taken in tow out to sea and handed over to the Italians.

The cruiser steered a course from Spalato to Venice on 15 November 1920, but the next day received orders to come about and proceed immediately to the Black Sea to rescue refugees fleeing from the Bolsheviks and trapped in the Crimean Peninsula. Olympia made speed but while she rounded the southern coast of Greece on 17 November received additional orders directing her to return to Venice as the Allies completed evacuating the fugitives. Shortly after her arrival in Venice three days later, however, the ship received further word of the dreadful plight of 2,500 refugees landed at Ragusa. The cruiser reached that port and her crewmen cared for the people, who suffered from hunger, lack of shelter, and the outbreak of smallpox and typhus.

Olympia bluejackets and marines provided fuel for heating and cooking, soap and towels, clothing and food, and the medical officer and his team treated the sick and inaugurated what sanitary measures they could in such dire circumstances. On Christmas Day 1920, the refugees gave the ship two touching testimonials thanking them for their help, one from the men and the other from the women and children, which the crew framed and hung in the captain’s cabin. Rear Adm. Andrews transferred his flag to destroyer Sturtevant (DD-240) and Olympia came about from the Adriatic on 26 April 1921. The ship stopped briefly at Naples, Italy (29 April–4 May) and Gibraltar (8–11 May), and arrived at Philadelphia Navy Yard on 25 May. Rear Adm. Edward Simpson Jr., Commander Train, Atlantic Fleet, shifted his flag from heavy cruiser Columbia (CA-16) to Olympia on 9 June. The ship hove to off Lynnhaven Roads (Lynnhaven Bay — 15–29 June), visited New York (30 June–11 July), and then made several cruises between Lynnhaven Roads and the Southern Drill Grounds -- about 50 miles off the Cape Charles Light Vessel -- to prepare for the bombing of the German ships.

The services began a series of controversial bombing tests off the Virginia capes in 1921. The Navy planned the evaluations to provide detailed technical and tactical data on the effectiveness of aerial bombing against ships, and of the value of compartmentation in enabling vessels to survive such damage. Three USN Curtiss F-5L flying-boats initiated the evaluations on 21 June when they dropped 12 bombs from 1,100 feet that sank German submarine U-117 in 12 minutes following the first hit. Army bombers sank German destroyer G-102 on 13 July. Five days later German light cruiser Frankfurt sank beneath 74 bombs dropped by USAAS and USN aircraft. Bombing runs against German battleship Ostfriesland began on 20 July when USAAS, USN, and USMC planes dropped 52 bombs, ending the next day when Army Martin MB-2s sank the battlewagon with 11 1,000 and 2,000-pound bombs. Olympia observed the attack on Ostfriesland on 21 July, and then came about, reaching New York the next day. The incident escalated the controversy when the Army refused to allow investigators to board Ostfriesland and their planes continued their runs until they sank the ship. Further tests sank more ships.

Rear Adm. Lloyd H. Chandler relieved Rear Adm. Simpson as Commander Train, Atlantic Fleet, on board Olympia on 30 July. The cruiser spent the rest of the summer operating off: Lynnhaven Roads (2 and 23–24 August and 6 September); Hampton Roads (21 August and 19 September); Cape Henry, Va., on 25 August; and New York (26 August–6 September). The ship completed work in dry dock at Norfolk Navy Yard (20–23 September), returned to Lynnhaven Roads (23–25 September), moved to Hampton Roads that day, and then stood out for Melville, R.I., on 28 September. Fog obliged her to stop off Montauk Point, L.I., overnight and she proceeded the next day, arriving at Melville on 30 September, and then returning southward.

On 3 October 1921, Olympia sailed from Philadelphia for Le Havre, France, to bring the remains of the Unknown Soldier home for interment in Arlington National Cemetery. She visited Plymouth, England (14–23 October), and then crossed the English Channel and moored at Pier d’Escale at Le Havre on 24 October. A special train departed from Paris with the Unknown Soldier in the midmorning of 25 October, and pulled into La Havre at about 1300. American and French representatives, including a U.S. Army honor guard, French troops and sailors, a French band, and mounted gendarmes greeted the train and its hallowed passenger. Thirty French soldiers removed the floral pieces from the train and took position in the column for the procession to the docks. The American body bearers then carried the casket from the funeral car and placed it on a caisson, while the band played “Aux Champs” and school children showered the entourage with flowers as it proceeded along the Boulevard Strassbourg. When they reached the pier at 1430, French Minister of Pensions André Maginot presented the Ordre national de la Légion d’honneur, that country’s highest military award, to the Unknown Soldier. United States marines on the pier presented arms, and the cruiser’s band played the French and American national anthems and Chopin’s “Funeral March” as the bearers solemnly carried the soldier on board. Rear Adm. Chandler broke his flag in Olympia and led a group of Allied officers and dignitaries that followed the casket onto the ship. They secured the casket to the aft gun platform, and a guard of sailors stood watch over him.

Destroyer Reuben James (DD-245) and six French destroyers escorted Olympia as she set out for home at 1528. The French destroyers fired a 17-gun salute as the column cleared French territorial waters and then fell astern at 1650. Olympia reached the Virginia capes and proceeded up Chesapeake Bay and anchored at the mouth of the Potomac on 7 November. At 2000 the following day she continued up the river, anchoring at Indian Head, Md., at 0200 on 9 November. The cruiser resumed her voyage at 1238 on that rainy day, joined by North Dakota (BB-29) and Bernadou (DD-153) as she stood up the channel to the nation’s capital, exchanging salutes from Fort Washington and Mount Vernon during her passage, and mooring at about 1600 at the Washington Navy Yard, D.C. Brig. Gen. Harry H. Bandholtz, USA, who commanded the Military District of Washington, led a welcoming entourage that included: Secretary of War John W. Weeks; Secretary of the Navy Edwin Denby; Gen. of the Armies John J. Pershing, USA; Adm. Robert E. Coontz, CNO; and Maj. Gen. John A. Lejeune, USMC, Commandant of the Marine Corps. Olympia fired a 21-gun salute, buglers on board sounded attention, and the boatswain piped the Unknown Soldier over the side, the ship’s band playing the “Funeral March,” followed by the national anthem. The 3rd Cavalry Regiment’s band played “Onward Christian Soldiers” as the procession, escorted by cavalry troopers, made its way toward additional ceremonies at 1608, culminating in interring the Unknown Soldier in Arlington National Cemetery on 11 November.

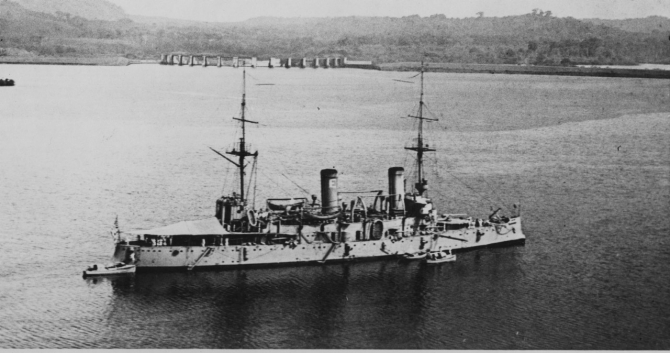

On 15 November the ship stood down the channel and reached the Philadelphia Navy Yard the following day. Capt. Thomas L. Johnson relieved Rear Adm. Chandler on board Olympia on 12 December. On 27 December 1921, Capt. Louis R. de Steiguer relieved Johnson. The ship steamed in Cuban waters early in the New Year, stopping at Guantánamo Bay on 11 January 1922, operating in the Gulf of Guacanayabo (12 January–3 February), and putting in to Guantánamo Bay the following day before returning to League Island at Philadelphia on 27 April. Two days later, de Steiguer transferred his flag to hospital ship Relief (AH-1). Olympia carried out repairs in dry dock at Philadelphia Navy Yard (16–18 May), and then trained midshipmen during the summer. The ship reached Hampton Roads on 22 May, embarked the men at the Naval Academy on 26 May, and then steamed in company with Delaware (BB-28), Florida (BB-30), and North Dakota to the Caribbean. Olympia stood into the entrance of the Panama Canal and anchored in Gatun Lock on 13 June, coaled at Colón (19–20 June), and visited: Port Castries, St. Lucia (26 June–3 July); Basse-Terre (4–7 July); Culebra (7–21 July); and San Juan (21–25 July). The cruiser then turned toward northerly climbs and visited Halifax (1–13 August), came about and coaled at Hampton Roads on 17 August, and on 22 August moved to Lynnhaven Roads and then the Southern Drill Grounds, anchoring there the same day. She returned to Philadelphia on 1 September, where she was decommissioned on 9 December 1922. That year she was also reclassified to a light cruiser (CL-15). Olympia was briefly placed on exhibit during the Philadelphia Sesquicentennial Exposition in 1926, and on 30 June 1931 was redesignated as an unclassified miscellaneous auxiliary (IX-40).

The Navy’s oldest steel ship still afloat is preserved as a shrine by the Cruiser Olympia Association, Inc. of Philadelphia. CNO Fleet Adm. Ernest J. King assigned the ship -- in caretaker status -- to the North Star Preservation Group on 27 June 1944. The group carried out some limited maintenance on the ship in dry dock beginning the following April, her first drydocking in nearly 23 years. During this work they covered her stacks to prevent rainwater from collecting within the ship. On 23 July 1954, the 83rd Congress enacted H.R. 8247, Public Law 83-523: ‘An Act to provide for the restoration and maintenance of the United States ship Constitution, and to authorize the disposition of the United States ship Constellation, United States ship Hartford, United States ship Olympia, and United States ship Oregon and for other purposes.’ The act proved the catalyst whereby the Navy prepared Olympia for donation to a private organization for conservation.

The Navy declared Olympia unfit for further naval service and stricken from the Naval Register on 2 January 1957. The ship was transferred to the Cruiser Olympia Association under U.S. Code 7308 during a ceremony attended by senior officials of that group, the Keystone Drydock & Repair Co., and the service in the office of Secretary of the Navy Thomas S. Gates Jr., on 11 September of that year. On 19 September the cruiser was towed to Keystone, which accomplished the repairs that made her “safe and presentable” for the public (February–4 October 1958). Keystone underwrote the cost of the work, and the association then reimbursed the company following a fund-raising campaign.