Adapted from U.S. Navy. Naval History Division. Riverine Warfare: The U.S. Navy's Operations on Inland Waters. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1969.

The Navy Department Library

Riverine Warfare

The U.S. Navy's Operations on Inland Waters

| Forword Introduction The Early Period from the Revolutionary War Through the War of 1812 |

||

| The American Revolution | ||

| Benedict Arnold on Lake Champlain | ||

| The War of 1812 | ||

| Commodore Joshua Barney's Flotilla in the Chesapeake The Defense of New Orleans |

||

| The Middle Period: 1815 Through the 19th Century | ||

| Routing the Pirates in the Caribbean River War in the Everglades War With Mexico River Warfare During the Civil War |

||

| The Modern Period | ||

| World War II The River War in Vietnam |

||

| An Imposing Riverine Environment Operation JACKSTAY DECKHOUSE V Seventh Fleet Naval Gunfire Support Naval Advisory Group and the Vietnamese RAGs The Coastal Surveillance Force The River Patrol Force Mobile Riverine Force Operation SEA LORDS |

||

The United States Navy has fought on rivers at home and abroad throughout its proud history. In the War for Independence, daring American Sailors employed small boats--even row galleys--against the mighty warships of the Royal Navy operating on colonial waterways. In the War of 1812, hard-fighting U.S. naval units on the Mississippi River helped General Andrew Jackson defeat a major British assault on New Orleans. The only way the Navy could combat hostile Seminole Indians in the trackless expanse of the Florida Everglades during the 1830s was to embark armed Sailors and Marines in small boats that penetrated deep into enemy territory. U.S. naval expeditions up the Tabasco River were an important aspect of the Mexican War of 1846-1848.

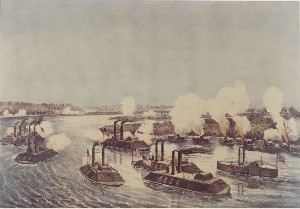

From the first days of the Civil War, Union and Confederate naval forces battled for control of the Mississippi, the most strategically vital river in North America. Employing ironclad warships in conjunction with U.S. Army troops, the Navy's Mississippi Flotilla bombarded and then seized one Confederate fort after another. Admiral David G. Farragut earned lasting fame when forces under his command fought their way past the bastions guarding the mouths of the Mississippi and captured New Orleans, gateway to the American interior. Riverine units enabled Union General Ulysses S. Grant to envelope and ultimately compel the surrender of enemy forces besieged at Vicksburg. Loss of the Mississippi split the Confederacy and helped bring about its defeat.

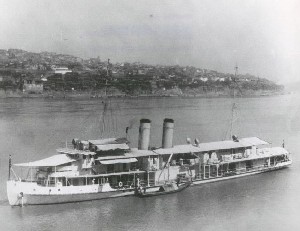

The early years of the 20th century found the Navy once again mounting river operations in support of U.S. foreign policy. Naval vessels provided gunfire support and transported troops and supplies on rivers in the Philippines to subdue Filipino rebels. For decades before World War II, U.S. Navy warships steamed up and down China's broad Yangtze River protecting American missionaries and traders, battling brigands, and promoting U.S. diplomatic interests. In addition to deploying hundreds of thousands of troops ashore in major landing operations in the Pacific and the Mediterranean during World War II, Navy amphibious units transported Allied ground forces across the Rhine River for the final defeat of Nazi Germany.

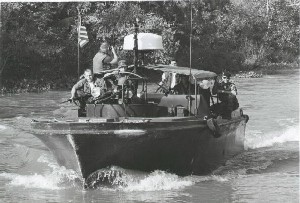

One of the most memorable chapters in the Navy's riverine warfare history was the hard-fought struggle for control of the waterways of the Republic of Vietnam. The U.S. Navy, as had the French navy during the First Indochina War of 1946-1954, and the Vietnam Navy in the years afterward, recognized the critical importance of the rivers and canals of South Vietnam for warfighting and waterborne commerce. With the onset of major combat operations in Vietnam during the mid-1960s, the Navy established the River Patrol Force and the Army-Navy Mobile Riverine Force whose charge was to secure the Mekong Delta. During the enemy's Tet Offensive of 1968 and the Sea Lords Campaign of later years, American and Vietnamese river units fought well and hard against a resilient Vietnamese Communist foe. While the Vietnam War ended in failure for the United States and the Republic of Vietnam in 1975, the experience left us with a wealth of information on the nature of modern riverine warfare. Insights abound on the most successful strategies, tactics, techniques, boats and craft, weapons, and equipment employed during the Vietnam War.

Consistent with the emphasis in recent years on "green water" and "brown water" operations, beginning in 2005 the Navy worked to establish a riverine warfare capability in the Naval Expeditionary Combat Command. The purpose of the new riverine warfare units, as stated in the Quadrennial Defense Review of 6 February 2006, will be to carry out "river patrol, interdiction and tactical troop movements on inland waterways."

To support that effort, the Naval Historical Center is posting this 1969 publication, Riverine Warfare: The U.S. Navy's Operations on Inland Waters. Viewers should understand that while the style and presentation of the work may seem dated, and we have reproduced it with minimal editorial change, it presents a concise summary of a significant episode in the U.S. Navy's modern combat history. If "the past is prologue," Riverine Warfare should shed light on one important aspect of the Navy's current and anticipated operations along inland waterways.

Edward J. Marolda

Senior Historian

Naval Historical Center

March 2006

Sea power's first advantage to the United States is that it keeps the enemy's main forces overseas. It controls the oceans for our use, denies them to the foe, and makes his coasts the frontier of war rather than those of America.

Nor does sea power stop at the hostile coastline; it projects the Nation's total power in a resistless tide inland beyond the coast. The long arm of sea power reaches inland with guns, with planes, with missiles like Polaris, and wherever water will float a boat. These complement and facilitate other national power projected ashore by the sea. In our lifetimes we have repeatedly had dramatic examples of the benefits this power brings to America--during World War II, Korea, and now Vietnam where Marines and Sailors fighting ashore, Seabees who build or fight, the large Army and Air Force components, all depend upon the logistic support as well as the shield and striking might of the U.S. Navy.

Operations on or projected from inland waters have come to be called "riverine warfare." Here fighting craft, tailored as necessary to the environment, bring combined operations the unique advantages of Power based afloat--greater mobility, ease of concentration, swift shift of objectives, speed, flexibility, versatility, and surprise.

If water permits, large ships like cruisers and destroyers blast aside opposition. For shallower depths many types of small warcraft develop to fit the need. We have seen this occur throughout United States history since riverine operations on small or large scale have entered into most of the limited or world wars that seem our fate. In these wars, through riverine operations as well as on the oceans, the U.S. Navy has well served our Nation and the hope of freedom to come for all men and women.

Since 1776 many revolutions have steadily increased the advantages of sea based compared to land based national power. This trend has greatly increased the influence of powerful fleets on the oceans. It has similarly affected riverine warfare. Consequently naval units of many types play an increasing role in the watery maze of South Vietnam.

We best serve the present and future when we understand the past. So it seemed appropriate to prepare this brief survey of riverine warfare that has helped shape United States history from the struggle for freedom in the American Revolution to the struggle for freedom against tyranny of communism in this second half of the 20th century.

In most projects of this office many dedicated people contribute. This account does not vary from the pattern. During periods of temporary active duty with us, Lieutenant Commander R.K. Pierce, USNR, a zealous able worker now a minister, developed a basic long narrative and from it a shorter one. This was modified and added to by several of us in the office including Rear Admiral F. Kent Loomis, Dr. W.J. Morgan, Dr. Dean C. Allard, Captain W.R. Deloach, and Commander Earl Mann.

The numerous details of publication for the first edition were ably carried out in Dr. Morgan's section. The brochure met wide appeal, making it necessary to issue this revision. It has received the generous attention of readers from the United States to Vietnam, including the commanders of most fleets. Space prevents mentioning all who helped, but I would like to note the large contributions of Admiral John J. Hyland, Vice Admiral F.J. Blouin, Vice Admiral W.F. Bringle, Vice Admiral L.M. Mustin, Vice Admiral E. R. Zumwalt, Rear Admiral K. L. Veth, and their staffs at the time, Captain R.S. Salzer, Captain W.C. Wells, Commander E.P. Stafford and Commander R.E. Mumford. Their modifications and updating appear from page 35 on. Mr. Robert L. Scheina and Mr. Don R. Martin have handled the publication details with energy and efficiency.

No one can know the outcome of the Vietnamese war. But if we continue with integrity, courage, and fortitude we will win. We must win for we fight for a great cause. None has expressed this better than Lieutenant William Roark, USN. Shortly before he flew from his carrier the last time, to be lost in combat over North Vietnam, he wrote these words of deep moral conviction and courage to his wife--words all Americans should read and heed:

I don't want my son to fight a war I should have fought. I wish more Americans felt that way. I'm not a "warmonger" it will be me who gets shot at. But it's blind and foolish not to have the courage of your convictions.

I will not live under a totalitarian society and I don't want you to, either. I believe in God and will resist any force that attempts to remove God from society, no matter what the name.

This is what we all must do if we believe in what the Founding Fathers stood for.

E.M. Eller

Rear Admiral, USN (Retired)

Director of Naval History

Riverine Warfare - The U.S. Navy's Operations On Inland Waters

On board our Navy river boats, the seaman's eye and bamboo pole are used to navigate, while far at sea satellite navigation systems guide our ships.

Admiral Thomas H. Moorer, USN

The American Navy has repeatedly demonstrated the potency of sea power as an instrument of national policy, and the remarkable flexibility with which it can strike. The Navy exists, first of all, to keep the peace, and failing that, to fight on the high seas for their control, essential to national defense. It exists to fight in coastal waters, to blockade, or to project the United States total power in amphibious assault. It exists to drive this power into an enemy's inland waterways to give the concentration, mobility, flexibility, and potency of sea power so uniquely contributes. "The mobility and versatility of our naval forces," in the words of President Lyndon B. Johnson, "are a constant reminder to any aggressor that this country has the means to act quickly and decisively to protect the interests of the United States and the Free World."

The unfolding saga of sea power, from the high seas to the coastal waters and into the inland waterways, is being demonstrated and reaffirmed in all its potency and versatility in Vietnam today. There, while the powerful ships and aircraft of the Seventh Fleet provide our forces with secure control of the seas across the vast ocean to the gates of San Francisco, close-in forces project the tentacles of sea power in a wide gamut of activities extending from amphibious operations to a strangling blockade-type coastal surveillance, to any kind of air and gunfire support mission. With the control of the high seas and coastal waters assured, naval forces are then able to move inland along the restricted waterways of Vietnam's rivers, canals, and swamps projecting strength afloat deep into the heart of that country in the many forms of riverine warfare.

Riverine warfare is a convenient term for any projection of sea power into inland waters including rivers that open to the sea. It may take on an many different shapes and forms as there are different inland waterways into which sea power may be thrust, and different national objectives which it exists to support. Theaters of riverine confrontation may vary from an archipelago or river basin to deltas, bayous, swamps, rice paddies, streams, or lakes. National objectives may vary from early 19th century punitive actions against Caribbean pirates to the "limited wars" of the nuclear era. The rich history of naval and combined operations on inland waters is filled with examples illustrating the significance and the wide variety of forms this particular capability of sea power may assume.

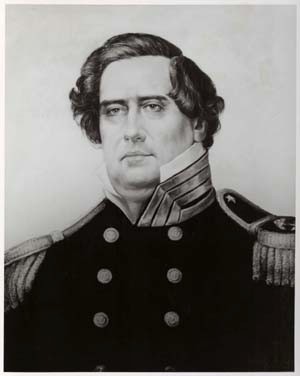

From Benedict Arnold's bold operations on Lake Champlain in 1775-76 to riverine warfare in Vietnam today, Americans afloat have sought the enemy wherever he may be found. Sometimes the opposing naval forces have been roughly equal as in Oliver Hazard Perry's battle on Lake Erie in 1813. Sometimes the U.S. Navy has been markedly weaker. Joshua Barney's defense of Chesapeake bay and tributaries against the British attack on Washington in 1814, and Commodore Daniel Patterson's stand at the Mississippi River approaches to New Orleans in 1814-15 are both examples of a hastily assembled river force intended to halt or delay a large enemy amphibious assault on a major United States city.

Matthew Calbraith Perry's naval expeditions 74 miles up the Tabasco River during the Mexican War, like David Glasgow Farragut's 110-mile transit of the Mississippi River to take New Orleans in 1862, illustrate the action of a major naval unit against an inland city reached only after a lengthy and arduous river transit. Small boat action against the Caribbean pirates and many aspects of the current war in Vietnam illustrate the use of small, armored and unarmored boats with limited endurance operating in restricted waters against a specific hostile target--a pirate's den, or a contraband-laden junk. The naval operations deep in the Florida Everglades against the Seminole Indians in 1836-42, in the swamps and deltas of the Mississippi River system during the Civil War, and the river war against communists in South Vietnam illustrate still another type of river warfare where naval forces alone or in combined operations are pitted against an elusive enemy capable of hitting and melting into the forbidding morasses that they know so well.

This small publication covers in varying detail each of these instances of naval warfare in restricted waters. It should be noted at the outset, however, that these are but illustrative examples from U.S. naval history rich in experience in this relatively unheralded yet important facet of sea power. It is the kind of sea power characterized by extreme navigational hazards: shallow uncharted waters, fluctuating currents, shifting river beds, unknown rapids, and inadequate charts. It is an aspect of sea power in which the convolutions of the terrain through which the waterways pass, such as high river banks, sharp bends, and dense foliage increase the threat of ambush and attack from a concealed enemy. And, it is a function of sea power requiring the same extremely versatile and flexible response called for constantly on the greater seas. President Abraham Lincoln well characterized this mud-churning form of warfare in giving the Union Navy credit for its irreplaceable contributions to victory in the Civil War:

. . . Nor must Uncle Sam's web-feet be forgotten. At all the watery margins they have been present. Not only on the deep sea, the broad bay and the rapid river, but also up the narrow muddy bayou and wherever the ground was a little damp, they have been and make their tracks.

A significant condition of riverine warfare is that one of the two opposing forces holds control of the high seas adjacent to the inland waterways where confrontation occurs. This permits the strong sea power to press into the inland waterways in the first place. During our early history the British controlled the high seas even though that control was valiantly contested by a small but aggressive American Navy and privateers. Therefore American riverine strategy in the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812 was largely defensive, but flavored with characteristic boldness.

The battles on Lake Champlain in 1776 and 1814, and on Lake Erie in 1813, resulted from British attempts to open the way for their armies to overrun and divide the American nation. The riverine defenses of Washington in 1814 and of New Orleans in 1814-15 were defensive and intended to halt or delay large British amphibious forces in their efforts to take those cities. In each case the slight American naval force was quickly developed to meet the threat, and represented an expedient cross between what ships were available and what the character of the surrounding waterways required.

I. The Early Period from the Revolutionary War Through the War of 1812

The American Revolution

It is certain that the Revolution would have failed without its Sailors.

Gardner Allen

Benedict Arnold on Lake Champlain

The first significant example of riverine warfare in the American Revolution occurred on Lake Champlain in 1775-76. This 136-mile-long lake with its connecting waterways to the north and south joins Canada with the heart of the original colonies near New York City. These waterways, thus, were a prime invasion route, and a bitter struggle for possession marked every conflict in the area through the War of 1812. At the outbreak of the revolutionary War, American leaders understood that the British would attempt to separate New England from the other colonies through control of the Lake Champlain route. Anticipating the threat, Colonels Ethan Allen and Benedict Arnold took Ticonderoga on 19 May 1775 and Crown Point a few days later. These early successes also netted badly needed cannon and munitions.

Arnold, making a bold bid to control the Lake, hastily armed a captured topsail schooner and immediately pressed north to the British base at St. John's on the Richelieu River. In a daring, pre-dawn riverine raid, Arnold's small force completely surprised the British garrison defending St.. John's and captured a British 70-ton sloop. Arnold also took or destroyed numerous small boats, stores, provisions, and arms before returning to Lake Champlain. With the ships and boats they had thus accumulated, the Americans had in one stroke gained control of Lake Champlain, thwarting British plans for that campaign season--a strategic victory of great consequence.

The next year was taken up in part with the unsuccessful American attack on Quebec. When large British reinforcements arrived in the St. Lawrence River in May of 1776, the Americans at Quebec fell back along the Richelieu River and evacuated Canada. Halting briefly at St. John's in June, with General Burgoyne's infantry in hot pursuit, the patriots escaped to the safety of Lake Champlain. Both sides now engaged in a furious shipbuilding race for the Lake.

The situation facing the British, in its simplest terms, was that in order to utilize the Lake Champlain-Lake George-Hudson River highway to split the colonies, they first had to dispose of Arnold's naval force.

In riverine war, as on the oceans, a force in being often plays a strategic role far greater than its size. From their shipyard at St. John's, the British rapidly prepared a reasonably powerful fleet of 29 vessels. Several were built in England, knocked down, and reassembled at St.. John's. The enemy squadron consisted of the ship Inflexible, 18; the schooners Maria, 14; and Carleton, 12; the radeau Thunderer, 6 (24-pounders), 6 (16-pounders), and two howitzers; the gondola Loyal Convert, 7; 20 gunboats, each carrying either nine 9 or 24-pound brass fieldpieces; and four longboats, each carrying one carriage gun. Captain Thomas Pringle, RN, commanded the force that sailed with about 670 trained, disciplined Sailors and Marines, and a total firepower of eighty-nine 6- to 24-pounder cannon.

Spurred on by the restless driving force of Benedict Arnold, the Americans sought to keep pace with the British at their Skenesborough shipyard, near the southern end of Lake Champlain. They worked with a poverty of resources using green timber and a hastily assembled force of carpenters. Drawing on his earlier experience as a Sailor and his newly acquired knowledge of the waters in which he would fight, Arnold prepared specifications for a new type of gondola particularly suited to his task. He wanted a small vessel of light construction that would be fast and agile under sail and oar. The greater maneuverability Arnold sought to gain would, he hoped, offset somewhat the disadvantages of restricted waters and fighting against the slow-sailing, deeper draft, heavier British ships whose strength he could not match.

Fifteen American vessels fought off Valcour Island, including the sloop Enterprise, 12; the schooners Royal Savage, 12; Revenge, 8; and Liberty, 8; eight of Arnold's specially built gondolas; and three galleys. Arnold manned his squadron with about 500 men from the troops available to him at the time and from those General Philip Schuyler was able to gather along the seacoast--"the flotsam of the waterfront and the jetsam from the taverns." Knowing that British preparations neared completion, Arnold headed north with pitch still oozing from the ships' pine planking. Now a brigadier general in the Continental Army, Arnold commanded from the galley Congress. Training his green troops as he went, he searched for the best place to fight.

On 10 October Arnold found what he thought was an ideal place west of Valcour Island to stand and give battle. The water was deep and the passage narrow enough so that only a few enemy ships could take him under fire at one time. The British failed to reconnoiter and sailed past Valcour Island the morning of 11 October under a stiff north wind. They then had to tack slowly and approach from the leeward at a distinct disadvantage.

The close battle raged all afternoon. Three-quarters of Arnold's ammunition was expended and his ships badly cut up. He took advantage of a north wind and a dark foggy night to slip through the anchored British ships in a daring escape. By noon on 13 October, the British began to overhaul the weary and straggling American vessels. One by one most of the American ships were captured or run aground and destroyed. Arnold reached Ticonderoga on 14 October and reported his losses as follows:

Of our whole fleet, we have saved only two galleys, two small schooners, one gondola, and one sloop. General Waterbury with one hundred and ten prisoners were returned by Carleton last night. On board of the Congress we had twenty-odd men killed and wounded. Our whole loss amount to 80 odd. The enemy's fleet were last night three miles below Crown Point; their army is doubtless at their heels.

With control of this "inland sea," the British quickly took Crown Point. General Horatio Gates and Arnold prepared to defend Ticonderoga against imminent attack. But the British did not come, by land or sea. The winter season was well advanced; the enemy was compelled to withdraw into Canada temporarily abandoning their invasion plan.

Thus, despite losing the Battle of Valcour Island, Arnold's riverine force had scored a strategic victory of far-reaching influence. By delaying the British advance south for a year, until the American army was strong enough to defeat Burgoyne's army at Saratoga in October 1777, Arnold achieved what Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan called a decisive victory. After Saratoga, France openly joined the Americans, transforming the contest "from a local to a universal war, and insured the independence of the colonies." French naval power, wisely integrated by George Washington in large combined operations, ultimately tipped the scale at Yorktown. It was as Washington said, "the pivot upon which everything turned."

The art of war is the same throughout; and may be illustrated as really, though less conspicuously, by a flotilla as by an armada.

Alfred Thayer Mahan

Similar significant examples of warfare on restricted waters occurred a generation later on Lake Erie and Lake Champlain. For brevity we cover only the first. The strategy of the War of 1812 centered about inland waterways. Initially, the British controlled the Great Lakes facilitating capture of Detroit and invasion of Ohio. In September 1812 Commodore Isaac Chauncey, USN, was ordered to command the lakes on the Erie-Ontario frontier to thwart British invasion from that direction. Chauncey immediately established bases, purchased lake craft, built green-timber ships and laboriously brought men and supplies from the distant seaboard. British naval forces likewise strengthened their position.

In March 1813 Master Commandant Oliver Hazard Perry, USN, arrived to take charge of naval activity on Lake Erie under the overall command of Chauncey on Lake Ontario. Commodore R.H. Barclay, RN, was his opponent on Lake Erie. Under Perry and Barclay a shipbuilding race, similar to that on Lake Champlain in 1776, accelerated rapidly. Neither side could spare adequate men and supplies for lake Erie. Therefore Perry and Barclay, like Benedict Arnold before them, labored under a paucity of resources as they raced to readiness for the decisive showdown. Initially had the advantage in ships but through remarkable drive and leadership, Perry overcame this obstacle and his ships sped to completion.

Having closed the gap in ships, Perry went after the enemy and on 10 September 1813 joined in desperate battle. He had an advantage of nine ships to six, and a 50 percent advantage in weight of fleet broadside. The British guns, however, were generally of much greater range, and there was a considerable danger of the Americans being beaten before they could come to close quarters in the very light wind prevailing.

Many things went wrong in the battle--they do in war--and a measure of a great commander is how he rises to the crises. Amidst shattered ships and death, Perry's star seemed to have set. One of his two heavy ships did not close the enemy. Unsupported, his flagship Lawrence became a shambles. Decks ran with blood, 80 percent of the crew were casualties, defeat seemed inevitable. But not to Perry. Embarking with a courageous boat crew he rowed across the shot-splashed waters, clambered on board the uninjured Niagara, sang out rapid orders, and steered to victory: "We have met the enemy, and they are ours."

Through energetic leadership Perry had assembled a fleet within a few months that gave the United States control of Lake Erie, the upper lakes, and the adjacent territory, and assured the all-important capability to move freely on these vital water arteries. It had far-reaching effect upon the future of the United States. With control of the Lake and resulting combined operations into Canada, the United States clinched her claim to the Northwest territory. A greater nation would result.

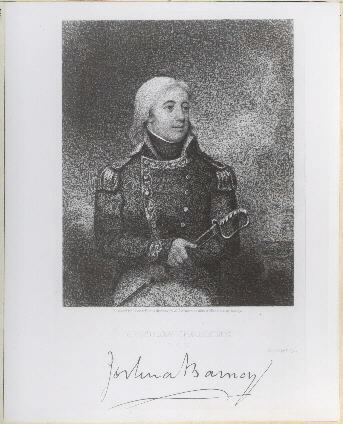

Commodore Joshua Barney's Flotilla in the Chesapeake

In 1814 Commodore Joshua Barney's defense of the approaches to Washington illustrates another mode of riverine warfare from that early period. Following their successful peninsular campaign against Napoleon, the British detached seasoned troops from Wellington's army in an effort to bring the American war to a rapid end. Enemy strategy was to follow up a series of punitive diversionary raids against major seaboard cities with a drive against New Orleans from the Gulf of Mexico and a large-scale invasion via the same Lake Champlain highway that Benedict Arnold's squadron had defended so ably almost 40 years earlier. The valiant and indefatigable Commodore Thomas Macdonough would again ensure British failure ashore by his victory afloat--September 1814, in the fiercely fought Battle of Plattsburg.

Energy and courage would overcome weakness of national preparation on the lakes where ocean fleets could not reach; but it was different where these mighty ships could sail. We had failed to build a strong Navy so we would now suffer the disastrous consequences along the seaboard. It was too late to correct this, but Joshua Barney laid before the government the next best course--a well-conceived plan to defend the river approaches to Washington with a force that could be quickly built and easily manned. His plan included such characteristic riverine functions as harbor and coastal defense, harassment and destruction of enemy units, and intelligence collection. "Barney's flotilla," however small and inconsequential in open battle, would threaten British lines of communication in their assault on Washington. The attackers would be compelled to reckon seriously with the threat. Thus, the riverine force would serve the primary purpose for which it was created--throw off balance and delay the enemy advance. It was the best we could do with what we had.

Barney's plan was promptly accepted. Throughout the winter of 1813-14, as the British forces gathered at the mouth of the Chesapeake, Barney speeded construction and recruited men. Finally, in April he sailed from Baltimore on a brief shakedown cruise with 10 barges, the cutter Scorpion, the gunboat No. 138, and 550 men. The initial cruise brought out alterations needed to make the barges more seaworthy. Barney also discovered that the British had established a base at Watt's Island in Tangier Sound off the mouth of the Potomac.

Throughout June and July Barney hounded the enemy wherever he could and kept the capital informed of their gathering strength and movements. Meanwhile, in response to the threat from Barney's force, the British amassed a barge flotilla with the full realization that they could not move on Washington so long as Barney's force stood in the way.

On 1 June, after a brief skirmish, Barney routed a British advance detachment. Its purpose, however, had been to sound out American strength. On 8 June a much stronger British force of 15 barges entered the Patuxent, with schooners and frigates backing them up off the mouth. Barney, fox-like, retreated into a deep, 6-mile-long inlet called St. Leonard's Creek where he moored his barges in a line from shore to shore 2 miles from the mouth. Using rockets, which, though not as accurate, had a greater range than Barney's guns, the British barges could haul up out of Barney's range. There they peppered the Americans with these frightening, if not overly dangerous, missiles.

Not one to accept such a situation sitting still, Barney upped anchor and rowed down on the British. The enemy barges fled for the safety of their larger ships. Barney followed as long as he considered wise then returned to his original position. Later in the afternoon of the same day, the British came on again, and were chased back. A rocket landed in one of Barney's boats, killing a man and wounding three.

The morning of 10 June, the enemy came after him in force with 21 barges, towing two schooners, each of which mounted two 32-pounders, and a total strength of 800 men. Barney had 13 barges and 500 men. The British came on with flags flying, music playing, and the Sailors cheering as if victory were already theirs. A general melee developed. The British went reeling back; Barney in hot pursuit. His fire on a schooner blocking the narrowest part of the creek was devastating. Only when a frigate and sloop-of-war opened on his barges did Barney break off the attack. He was truly a thorn in the lion's paw.

Two of the British frigates remained off St. Leonard's Creek, tightly blockading the American flotilla. On 26 June Barney decided to break out with a coordinated land-river move. On the night of the 25th, he secretly mounted two long 18-pounders on a high bluff overlooking the mouth of the creek within range of the British ships. Then at dawn of the 26th, he drove on the powerful frigates with his barges. Unfortunately, his shore battery had been improperly placed, and the cannon consistently overshot the target, leaving Barney's barges unsupported to face the frigates' fire. Nevertheless, he so punished these British ships that they withdrew, and the American barges made good their escape from the creek.

Now Barney moved out into the Patuxent River, and, until the British appeared in full force to march on Washington, he stalked and harassed them constantly. By Friday, 19 August 1814, when word was received that British concentration in the Chesapeake Bay reached two 74-gun ships-of-the-line, a 64, eight frigates, seven transports, and a number of brigs and schooners--23 sail in all--Barney reported that Rear Admiral Cockburn, the British commander, had announced that he would dine in Washington on Sunday. Washington was thrown into a panic and Barney was ordered to take his flotilla as high up the Patuxent as possible and then march with 400 of his men to join in the defense of the capital city. His instructions to the shipkeepers were: "If the enemy advance on you with an overwhelming force, destroy the flotilla by fire."

On 20 August the British troops disembarked at Benedict, Maryland, only 35 road miles from Washington. The following afternoon Admiral Cockburn led his fleet of barges, tenders, and armed boats crowded with Marines and artillery to capture Barney's flotilla. This would not be. As the formidable British force hove into sight, the American barges, with flags flying, blew skyward. Barney and his detachment of Sailors ashore made a last gallant stand at Bladensburg though supporting troops broke and ran. With nothing else in their way, the British marched on into Washington, burning it on 24 August. In September they attacked Baltimore, with less success, in part because of the stout efforts of sailors manning batteries ashore. Out of the British dramatic night bombardment of Fort McHenry were born the words of the immortal "Star Spangled Banner."

Despite the ultimate British success against Washington, Barney's operations on the Patuxent and Potomac rivers are an excellent example of the effectiveness of riverine defenses against a large-scale amphibious invader. Using vessels especially designed for operating in shoal water and flats, and manned by local people familiar with both the waters and surrounding terrain, Barney's force generated and sustained a threat to the British that was out of proportion to its size. The enemy was actually defeated in a number of hot skirmishes with Barney's flotilla. They could not dispatch small ships, brigs or schooners on any significant expedition while Barney snapped at their flanks. They were stymied until their main force arrived from Bermuda. Only when Barney's flotilla had been destroyed did the British march on Washington, and then along a road paralleling the river so that the armies could keep in constant touch with their ships. The feeble defense of Washington in no way matched Barney's foresighted and brave efforts on the rivers or the fight put up by him and his men on the field at Bladensburg.

The effective use of Barney's gallant squadron should not blind us, however, to a truth of far greater significance. The burning of Washington shows clearly that in defense, riverine forces are a last gasp and poor substitute indeed for a real navy. As John Paul Jones had said long before, "Without a respectable Navy - Alas America!"

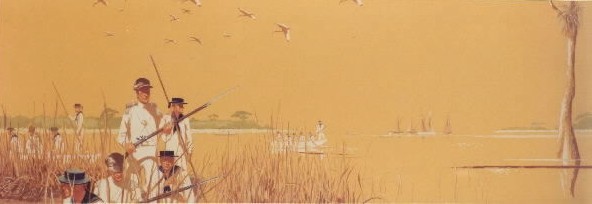

Commodore Daniel T. Patterson exhibited insight and courage like Barney's in defense of the river approaches to New Orleans against the attacking British. He predicted correctly that the British would strike at New Orleans rather than Mobile, and further, that their advance would be along the shortest route through Lake Borgne, east of New Orleans and Lake Ponchartrain. He deployed his riverine force of five gunboats, two small tenders, and his two largest craft Carolina, 14, and Louisiana, 16, so that the approaching enemy was forced to meet and destroy them before advancing on New Orleans. He thereby gained the crucial time that Andrew Jackson needed for his historic defense of the city. Patterson achieved maximum results from a makeshift naval squadron whose total strength did not match one British ship-of-the-line.

Briefly, the sequence of events was as follows. Between 8 and 12 December 1814, the British invasion fleet gathered in force off the Chandeleur Islands and began preparations to take New Orleans. Meanwhile, Commodore Patterson readied his riverine defenses of the city. He used trees and large A-frames to obstruct the shallow bayous and canals leading from Lake Borgne to the narrow strip of land beside the Mississippi over which the British Army would move. Gunboats were assembled and Patterson's largest ship, the unfinished Louisiana, was readied as a floating battery. Carolina and Louisiana took station in the river at New Orleans, and Lieutenant Thomas ap Catesby Jones sailed with the five gunboats and two tenders to Lake Borgne.

The British followed the course Patterson had foreseen. They planned to transport 7,000 men in open boats 62 miles from their anchorage off Cat Island to Bayou Bienvenu at the head of Lake Borgne. But first, Lieutenant Jones' gunboats had to be eliminated. Vice Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane sent to lake Borgne an expeditionary force of nearly 1,000 men in 42 barges, each armed with a 12- to 24-pounder. The battle was joined on 14 December. Although the American position was untenable before such overwhelming odds, Jones and his men put up a gallant, spirited defense which had the desired effect--delay the enemy to give General Jackson the time he desperately needed to assemble troops and prepare defenses.

On 23 December, the British finally penetrated Bayou Bienvenu 9 miles below the city. Had they pushed on immediately, they might have taken New Orleans; instead they camped for the night. The Carolina silently moved downstream and shelled the sleeping Britishers, creating near panic. Meanwhile, Jackson attacked. Although he was repulsed and the threat to the city remained great, his boldness paid off. Major Lacarriere Latour reported:

The result of the affair of the 23rd, was the saving of Louisiana; for it cannot be doubted but that the enemy, had he not been attacked with such impetuosity, when he had hardly effected his disembarkation, would, that very night, or early next morning, have marched against the city, which was not protected by any fortification, and which was defended by hardly five thousand men, mostly militia.

With the mobility and freedom of choice sea-based power provides, Patterson's small ships striking from the British flank had significant effect giving our army "a manifest advantage." The enemy now delayed again while laboriously bringing heavy guns from the distant fleet to counter the ships. Jackson energetically used the priceless time to strengthen defenses across the narrow neck of land between the river and the swamp. By Christmas day the British had brought heavy fleet guns ready to dispose of Patterson's tenacious fighting ships. The Carolina was destroyed, but Louisiana continued effective fire until the end of the campaign on 19 January. When the British advanced to attack, the naval flanking fire abeam of Jackson's ramparts had especially devastating effect. General Jackson had high praise for Patterson's riverine effectiveness: "To your well directed exertions must be ascribed in a great degree that embarrassment of the enemy which led to his ignominious flight."

Riverine warfare during the revolution and the War of 1812 was characterized by timely and critically important actions on lake, bay, and river. Small but dedicated, the bravely and wisely led forces afloat demonstrated beyond question the Navy's inherent capability and flexibility whether called upon to operate on the ocean, coastal seas, or inland waters far removed from salt spray--and the vital meaning of all to America's destiny.

II. The Middle Period: 1815 Through the 19th Century

Following the War of 1812, the U.S. Navy again dispatched ships to the Mediterranean to restore peace. Close to home the small but capable Navy controlled the seas adjacent to our coasts and inland waters to the great benefit of freedom of the seas for everyone. An offensive strategy against buccaneers and other intruders became possible. Instead of hastily constructing riverine defenses against an enemy who dominated the seas, rivers, or lakes, a respectable U.S. Navy on the ocean confronted any aggressor, real or potential. Now, whether hunting down pirates in longboats through Caribbean inlets and lagoons, or waging guerrilla war against hostile Indians in Florida swamps and bayous, United States riverine warfare took an offensive turn. For the next generations, whether the United States used large seagoing ships, river "ironclads," "tinclads," "cotton clads," rafts, or canoes to transit long tortuous rivers, the Navy ably demonstrated the flexibility and adaptability in riverine warfare that has become a part of our proud and meaningful heritage. It is now well proving out in Vietnam.

Routing the Pirates in the Caribbean

The average citizen is quite unaware of certain minor wars and activities in which his navy's part has yielded results beyond price or praise.

Rear Admiral Casper F. Goodrich, USN

The first riverine warfare in the middle period was against pirates who had long infested the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico. The rapid growth of American commerce in Caribbean and Gulf waters after the War of 1812 spurred freebooting activity. By the early 1820's, nearly 3,000 corsair attacks had been made on merchant ships. Financial loss was staggering; murder and torture common. Finally spurred to action in 1822, the United States formed the West India Squadron under Commodore James Biddle to meet the pirates head on.

Biddle mounted daring raids with open longboats in which crews operated for days at a time in burning sun or storm. They reached into uncharted bays, strange inlets, lagoons, and small treacherous rivers to ferret out the criminals. Lieutenant James Ramage's assault on a pirate lair near Bahia Hondo, Cuba, illustrates this duty in the steaming tropics. Ramage reported:

I despatched our boats with forty men under command of Lieut. Curtis in pursuit of these enemies of the human race. The boats having crossed the reef, which here extends a considerable distance from the shore, very soon discovered, chased, and captured a piratical schooner, the crew of which made their escape to the woods.

Curtis very judiciously manned the prize from our boats and proceeded about ten miles to leeward, where it was understood the principal depot of these marauders was established. This he fortunately discovered and attacked. A slight skirmish here took place, but, as our force advanced, the opposing party precipitately retreated. We then took possession and burnt and destroyed their fleet consisting of five vessels, one of them a beautiful new schooner of about sixty tons, ready for sea with the exception of her sails. We also took three prisoners; the others fled to the woods.

With heavy ships (like Constellation of early fame) forming the backbone of the force and serving as seagoing bases for the small craft, the squadron steadily reduced piracy. Time after time over the years, operations like Ramage's showed the Navy's determination, boldness, resourcefulness. Among them we might cite one other example, a joint British-American expedition.

In April 1825 an attack under Lieutenant McKeever in USS Sea Gull, a steam galliot, first U.S. naval steamer to see action on the high seas, destroyed another buccaneer base east of Matanzas, Cuba. McKeever led the barge Gallinipper into the mouth of the Sagua La Grande River where masts were sighted amidst the river bank foliage. He attacked immediately. The schooner lying in the river quickly surrendered, but then treacherously opened fire. After a hot action the pirate ship was taken and the base leveled.

The Navy's aggressive and persistent assault on piracy paid off. Buccaneering, increasingly hazardous and less profitable, withered and the naval squadron was gradually reduced in the late twenties.

The struggle against Caribbean pirates embodied many of the demands of riverine warfare in Vietnam today - boat expeditions and cutting-out parties in the intense heat of often uncharted waters; pursuit of a mobile, elusive, and ruthless enemy thoroughly familiar with the waters and terrain. Armed shallow-draft vessels were a must but the supply rarely met the need. Nevertheless, by capturing or destroying over 60 ships, eliminating corsair dens, and driving the "Jolly Roger" from the sea, the Navy rendered an invaluable service to citizens and commercial interests of the United States and other nations.

The officers and men of the squadron have undergone every species of privation and toil. Their patient endurance, and cheerful alacrity in the discharge of every duty, evince their high state of discipline; and merit the highest commendation.

Lieutenant John T. McLaughlin, USN

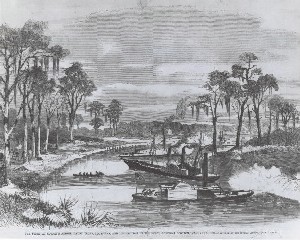

The next decade, the Seminole and Creek wars in Florida, 1835-42, produced another riverine conflict even more like that waged in the Mekong Delta of Vietnam a century and a quarter later. In 1832 Congress passed the Indian Removal Act to relocate the Florida tribes on reservations west of the Mississippi. Many Seminoles and Creeks refused to leave and vowed to resist removal.

The Seminoles massacred an Army detachment under Major Francis Dade northeast of Tampa in December 1835. Almost immediately more soldiers moved into the state, and Commodore A.J. Dallas' West India Squadron landed parties of Marines and seamen.

The futility of fighting a shadowy enemy completely at home in the swampy wilderness of the Everglades and the rivers of West Florida quickly led the Army to request naval assistance, "to ply up and down the Chatahoochie River, for the purpose of transporting the necessary supplies, of keeping open communications, and operating against the Indians." With one of the first naval units so assigned was Passed Midshipman J.T. McLaughlin. His varied duties with the Army demonstrated the close coordination between river and land forces often demonstrated throughout our history in joint operations large and small. McLaughlin not only transported supplies and kept vital communication lines open, but served as aide-de-camp to Lieutenant Colonel A.C.W. Fanning, USA. He was seriously wounded by Indians at Fort Mellon in February 1937.

As the pace of war quickened, the Navy's riverine force grew. Three small schooners, procured in 1839, Flirt, Wave, and Otsego, operated in the inlets along the coast to chart the water, harass the Indians and protect civilian settlers. Besides the schooners, McLaughlin, now a lieutenant commanding the naval force, gathered large numbers of flat-bottomed boats, plantation canoes, and sharp-ended bateaux to penetrate the bewildering Everglades maze. Tents and blankets frequently served as make-shift sails. The men of McLaughlin's "Mosquito Fleet" were as mixed as the vessels, and numbered over 600 Sailors, soldiers, and Marines operating about 150 craft, mostly canoes. One participant described their joint efforts as follows:

There was at one time to be seen in the Everglades, the dragoon [soldier] in water from three to four feet deep, the Sailor and Marine wading in the mud in the midst of cypress stumps, and the soldiers, infantry and artillery, alternately on the land, in the water, and in the boats. . . . Here was no distinction of corps, no jealousies, but a laudable rivalry in concerting means to punish a foe who had so effectually eluded all efforts. Comforts and conveniences were totally disregarded, even subsistence was reduced to the lowest extremity. Night after night, officers and men were compelled to sleep in their canoes, others in damp bogs, and in the morning, cook their breakfast over a fire built on a pile of sand in the prow of the boat, or kindled around a cypress stump.

Correspondence between Lieutenant McLaughlin and the Secretary of the Navy reveals the wide range of "Mosquito Fleet" operations, resembling the reports from the Mekong Delta today. In cooperation with the Army, McLaughlin's entire force penetrated the Everglades to attack and destroy the Indian stronghold of Abraka (or Sam Jones). The riverine assault group patrolled and explored the interface between the coastal waters and the open sea as well as the navigable inland waterways. They sliced hundreds of miles into tributaries and swamps covered with cypress trees, rotting stumps, and "occasional glimpses of open water." They aided distressed mariners and civilians ashore. They raided the Indians, and destroyed their supply caches and crops. Often they laboriously hauled their boats overland, from one body of water to another. Finally, McLaughlin established or kept secure the all-essential communications between Army units and scattered settlements.

The similarity of sea power in a riverine environment in the Seminole Wars and Vietnam is vivid. First, the fundamental goal was control of waterways to reestablish internal order and restore normal activity. Second, the waterways were not only restricted waters in every sense, but they crisscrossed the soil so completely that land transportation was totally inadequate and the character of the neighboring terrain became paramount. The absolute dependence of Navy upon Army and Army upon Navy gave the whole force a homogenous character of a single tactical entity closely integrated and interdependent. The ever-changing character of the waterways from deep and wide to narrow and shallow required an extremely versatile force in which various type vessels met different needs dictated by the terrain and available water. Not again until the campaigns on the Mississippi River during the Civil War would the Navy face such a riverine challenge.

The service was arduous, the exposure to unhealthy influences great, and the localities gave the enemy decided advantages of successful resistance; yet, with an indomitable courage and fortitude, the officers and men met and overcame all difficulties.

Secretary of the Navy John Y. Mason

The Navy added to its growing experience in inland waters during the Mexican War, 1846-48. Examples are two daring river raids against the city of San Juan Bautista de Tabasco. When hostilities opened, the U.S. Navy's Home Squadron under Commodore David Conner blockaded the Mexican Gulf coast. The blockade forced the enemy to use inland waterways and overland routes to move supplies. San Juan Bautista, 74 miles up the Tabasco River from the port of Frontera, was the center of a large traffic in war materials.

Although the Tabasco River had ample depth to accommodate vessels of any draft that could be conveniently taken across the bar at Frontera, there were serious obstacles to a river assault against San Juan Bautista. The river current was strong, and dense vegetation along the banks provided excellent cover for riflemen and cannon. There was an extremely hazardous "S" shape bend called "Devil's Turn" and two strategically placed forts guarded the approaches to the city.

An operation like this with sailing vessels alone would have had little chance of success. But the world and the U.S. Navy were in the early stages of a revolution that would vastly increase the capabilities of sea-based power against the land. Steam propulsion that had begun commercially a generation earlier on inland waters had developed to the point that it could be tried in smaller ocean going ships. The Home Squadron in the Gulf of Mexico benefited from this first stage of the revolution, having several small steam ships-of-war.

On 23 October 1846, the U.S. Navy's expeditionary force, under Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry, crossed the bar and took Frontera with little resistance. Then with three steamers, four other vessels, and a landing party of 200, Perry pressed upriver to San Juan in just 33 hours. The expected resistance from the fortified position 9 miles below the city did not materialize; the Mexican garrison fled as the American ships closed.

In position before San Juan at noon on the 25th, Perry demanded surrender. The mayor returned an insolent reply, the ships opened fire on the city's flagstaff, and at the third round, the flag fluttered down. The commodore complied with the foreign consuls' appeal to spare the town but seized two steamers, five schooners and a number of smaller vessels to deny them to the gunrunners. One prize ran aground, and the Mexicans opened on Perry's squadron with small arms fire. In turn, the ships' cannon raked the streets.

Neither of the two towns was occupied, but Frontera was closely blockaded for about 6 months following the expedition. When the naval blockade was lifted contraband again flowed over land and river through these points. Thus, by June 1847, Perry was ready to ascend the Tabasco River a second time.

From recent experience he knew the hazards faced on the river and before the city. Perry assembled a larger and skillfully trained group for his second punitive expedition. Long an advocate of infantry drill and landing party training, Perry formed a Naval Brigade. He organized 2,500 officers, seamen, and Marines into infantry and artillery divisions under the command of Captain J. Mayo, USN. Mayo was humorously styled "the acting Adjutant-General for the time." To carry the men and protect them during the river move and assault, Perry's flotilla included four small steam warships (Scorpion, Spitfire, Scourge, Vixen) towing six schooners, bomb brigs and numerous ships' boats.

The force started upriver on 14 June against a 4-knot current. At the first elbow of the "Devil's Turn," the lead ships came under small arms fire from snipers concealed in the dense chaparral on the banks. Ships' fire promptly silenced the enemy, but obstructions had been placed in the river around the turn which was covered by well-manned breastworks on the opposite shores. After reconnoitering the obstructions and coming under attack from the breastworks, Perry landed the Naval Brigade to march the last 9 miles to San Juan.

While Perry led his Sailor-brigade through swamp and jungle, the ships, temporarily commanded by Lieutenant David Dixon Porter, worked their way through the obstructions. Together the Americans afloat and ashore routed 600 Mexican troops at Accachappa and moved on to Fort Iturbide just below San Juan.

Fort Iturbide boasted a main battery of six guns, and some 400 infantrymen lined the entrenchments. The American steamers advanced steadily into this fire. Then under the protective cover of the ship cannonade, Porter launched a small but determined landing party at the fort. The defenders took flight before the charge, and the American flag was flying over the fort when Perry and his brigade came on the scene.

This foray against San Juan presented problems inherent in sending a sizable naval group into a narrow hazardous river. Perry's force functioned as a single coordinated tactical entity in a temporary inland penetration against an objective deep in enemy country. The Tabasco River operations exemplified the use of versatile sea power in restricted and dangerous waters to carry out a specific mission. Civil War experience brought such naval operations to the level of a fine art.

So did the U.S. Navy begin to open a new era in war with new promise for freedom that sea power nurtures and sustains. In the War of 1812, the U.S. Navy had had the first steam warship, Fulton, which saw no combat service. A decade later, with its little harbor tug Seagull operating against the pirates in the Caribbean, the U.S. Navy first used steam in combat on the high seas. Now it had put into combat several better steam warships in amphibious and riverine operations.

Steam propulsion had come slowly to the deep sea because of many problems besides low powered, often faulty engines and boilers. Crucial among these were high fuel consumption with resulting short cruising range. Hence for many years navies with world duties used steam mostly as auxiliary to sails.

For amphibious and riverine operations, however, even the limited capacity steam propulsion of the time brought sea power significant new advantages in attack against the land. Ships could now operate independent of wind and tide. They could strike faster. They could more readily outflank and change objective, increasing the ancient superiority of surprise sweeping in from over the horizon.

Steam was the first of many revolutions that have steadily increased the advantages of sea-based strength--and the end is not in sight. Nuclear energy, guided missiles, and Polaris submarines speed up the shift; a prophecy and warning of vast import to America.

River Warfare During the Civil War

Fighting is nothing to the evils of the river--getting on shore, running afoul of one another, losing anchors, etc.

Admiral David Glasgow Farragut

Wise and vigorous use of strength afloat played a decisive role in the Civil War. The south had no navy at the outset, and the ever-increasing predominance of the Federal Navy gave the Union vital control of the sea at all stages. Union naval strategy quickly crystallized into three broad areas: (a) blockade the Southern coast to strangle the already industrially deficient area; (b) amphibious assault and capture of ports and coastal strong points that not only greatly hurt the South directly but also forced her to disperse defenses over wide areas; (c) split the Confederacy along the Mississippi and its tributaries using these inland river highways to crush the divided parts in a vice-like squeeze.

The effective 3,000-mile blockade, and the complete imbalance between Northern and Southern strength afloat confined most naval warfare to coastal and inland waters. That is, if the world-wide success of CSS Alabama and other Confederate commerce raiders be excepted.

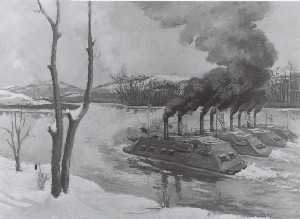

Commander John D. Rodgers, commencing riverine operations, selected vessels and readied a force under Army control on the northwestern waters. He centered operations at strategically located Cairo, Illinois, where the Ohio and Mississippi rivers meet. At this point Union vessels could influence the river traffic of three states, Illinois, Kentucky, and Missouri. Commander Rodgers purchased and converted river steamers into wooden gunboats Tyler, Lexington, and Conestoga.

In addition, Commander Rodgers, through the War Department, contracted for seven new gunboats to be named after cities along the rivers they were defending. These "city class" ships, the "backbone of the river fleet," were 175 feet long and had a 50-foot beam. A casemate covered the entire ship with heavy armor protecting the forward part. To reduce draft, they had lighter armor amidships and astern (on the theory that most of the fighting would be head-on), hence they were vulnerable in these areas. The boats were built to carry 13 large guns each. Because of the need to get them out quickly, they mounted any guns available, a collection of old fashioned 42-pounders supplied by the Army, and some 8-inch and 32-pounder Navy guns.

For several decades steamships had developed on the western rivers where the calm waters and ready accessibility of fuel favored the early crude engines. Hence the gunboats went to war relatively independent of wind and current. They were part of a broad revolution in naval design and warfare that would play a key role in keeping the Union intact. They became the spearhead which dismembered the Confederacy along the Mississippi.

While the "city classers" were being built, the three original wooden gunboats contributed decisively to ultimate Union victory. These ex-river sidewheelers, unarmored and vulnerable, could not have stood up to a seagoing warship or a fort but they accomplished far-reaching results. In a land of few and poor roads they controlled the broad highway of the rivers. Speeding back and forth on the rivers, they provided many of the same advantages sea based power enjoys on the oceans:

- Mobility and speed of movement of large bodies of troops and supplies.

- Concentration of troops and heavy artillery of ships at the point of decision.

- Surprise.

- Flexibility in strategy and tactics that permitted swift adjustment to emergencies, omnipresent in war, to seize fleeting opportunity and to gain victory out of disaster.

Overcoming vast difficulties, Rodgers converted, manned, armed, and got the three river steamers to Cairo on 12 August. They not only protected this strategic junction of the Ohio and Mississippi rivers, but Rodgers at once vigorously put them to use in reconnaissance up and down the rivers. On these operations they gathered important intelligence, drove Confederate troops from commanding positions that would have blocked use of these key highways by the Union and closed the streams to the Confederates who gravely needed them. Strong Southern sentiment prevailed on both banks of the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. The presence of the gunboats in these early days awed secessionists, gave heart to unionists and encouraged middle-roaders to oppose secession. As Admiral Mahan wrote, they were of inestimable service "in keeping alive attachment to the Union" and in preventing the secession of the border states of Kentucky and Missouri.

Tyler and Livingston convoyed 3,000 of General Grant's men to Belmont, Missouri, and rendered fire support to the operations. When a large Confederate reinforcement arrived, the gunboats kept up a canister and grape barrage which allowed Grant to reembark his outnumbered troops and withdraw--giving him another lesson in the benefits of mobile strength afloat.

The three wooden gunboats accomplished much. They could not, however, take the offensive against forts the Confederates erected at Columbus on the Mississippi below Cairo, at Fort Henry on the Tennessee River just below the Kentucky border, or nearby at Fort Donelson on the Cumberland. The semi-ironclads built for this purpose were commissioned by Flag Officer Andrew H. Foote in mid-January. Foote had relieved Rodgers. Now he had the spearhead to split the Confederacy from the north. At once he and General Grant pressed for permission to attack, and on 2 February the combined forces sailed up the Ohio en route to assault strategic Fort Henry.

Grant's troops embarked in transports at Cairo and Paducah and following Foote's gunboats advanced on Fort Henry. The soldiers were landed 5 miles above the fort according to prearranged plans for a combined assault on 6 February. However, the troops made slow headway in the mud and the gunboats attacked alone. They opened fire at 1,700 yards which was briskly returned by the shore batteries. Foote pressed on knocking out all but four of the Confederate guns. Essex was disabled and other ironclads were struck, but Foote closed to point-blank range pouring a hail of fire into the fort until it surrendered.

Now the value of inland sea power became bitterly apparent to the South. With Fort Henry captured, it was as if a dike had been breached by raging seas. The wooden gunboats, USS Conestoga, Lexington, and Tyler swept up the Tennessee River, burning, destroying, capturing. Giant explosions, towers of smoke by day and columns of fire at night, marked their course as they ranged south across Tennessee, the edge of Mississippi and into northern Alabama until stopped by the shallows of Muscle Shoals. Most disastrously for the South, she lost heavily in river steamers, and with them the mobility they gave for military operations.

Meanwhile, wasting no second, Foote sailed to Cairo the evening of the 6th with three damaged ironclads to prepare for the assault on Fort Donelson. He saw the vast potential in breaching the Confederate defenses at the center. From far up in Kentucky, south and west to the Mississippi at Columbus, all hung in the balance. Fort Donelson would open the second door for the flood of Union power to sweep into the South. With the center broken, collapse would follow.

The significant possibilities opening for the Union and the disaster awaiting the South had resulted in considerable part not only from Foote's indomitable drive to get the ships ready and to make them effective, but also from his bold leadership in action. He indeed deserved Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles' congratulations: "The labor you have performed and the services you have rendered in creating the armed flotilla of gunboats on the Western waters, and in bringing together for effective operation the force which has already earned such renown, can never be overestimated. The Department has observed with no ordinary solicitude the armament that has so suddenly been called into existence, and which, under your well-directed management, has been so gloriously effective."

Though the Confederate gunners had manned their weapons well, General Johnston, CSA, noted the results of the action: "The capture of that Fort [Henry] by the enemy gives them the control of the navigation of the Tennessee River, and their gunboats are now ascending the river to Florence . . . Should Fort Donelson be taken it will open the route to the enemy to Nashville, giving them the means of breaking the bridges and destroying the ferryboats on the river as far as navigable."

Fort Donelson on the Cumberland river proved more difficult as it could subject the gunboats to a destructive plunging fire. Eight days after Fort Henry fell, however, the combined forces of Foote and Grant moved boldly against the strong point on the Cumberland. This time the furious Southern gunnery forced the gunboats to withdraw. Shots holed the flagship St. Louis about 60 times and each of the other ships took 20 or more hits. Pilot houses were battered. Both St. Louis and Louisville had their steering gear shot away, leaving them to drift helplessly downstream. In the fierce fight, 54 officers and men were killed or wounded, including Foote.

Nevertheless the Confederate suffered from the gunboats' fire and, as General Grant emphasized, they had a controlling role in the campaign that had grim consequences for the South. Without the gunboats and the use of the river highways they ensured, he could not have attacked at all in the early months.

Under renewed combined attack afloat and ashore, Fort Donelson surrendered on 16 February. In panic the Confederates abandoned their strong positions in Kentucky. On the Mississippi they retreated down to Island Number 10. Nashville, in central Tennessee on the Cumberland River, with its mountains of stores and important manufacturing facilities so gravely needed by the South, swiftly fell as Foote's gunboats pushed rapidly up the Cumberland convoying troops. Added to irretrievable losses of territory, munitions, and men, the Confederacy faced even graver and darker days. Behind the powerful gunboats Union armies were poised to sweep southward in combined operations--irresistible wherever water reached.

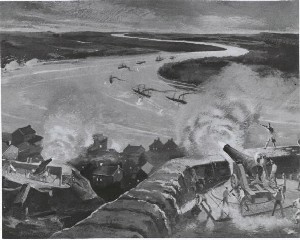

Meanwhile far to the south another great threat gathered on the water to drive in like a hurricane. On 2 February 1862, the same day Grant and Foote had sailed from Cairo for the capture of Forth Henry, Flag Officer Farragut in Hartford departed Hampton Roads for the Gulf of Mexico and his destiny.

Farragut arrived on 20 February off Ship Island where the British fleet had assembled nearly half a century earlier for the assault on New Orleans that failed. The British at that time had not dared to sail their heavy ships against the Mississippi current with American fortifications barring the way. However, sea power now had new dimensions. Steam had freed navies of the vagaries of wind, tide and current. It had come to give them new capabilities for assault against the land and for riverine operations.

Overcoming immense difficulties, Farragut got his heavy ships across the bar at the mouth of the Mississippi and in mid-April moved the whole fleet upriver to powerful Fort Jackson and Fort St. Philips whose more than 100 heavy guns guarded the approaches to New Orleans, During 5 days of bombardment by his mortar flotilla, built especially for riverine warfare, he continued the thorough preparation of his ships for the fight past the forts. Masts were lowered and excess gear stored ashore, weights shifted for optimum draft, cables laid as improvised side armor.

In the darkness of the midwatch, after 0200, 24 April, Farragut's fleet drove past in a wild stirring battle of ship against fort and ship against ship, as the small but valiant Confederate squadron gallantly engaged. On the 25th, steaming through a river of fire with burning cotton bales, merchandise and Confederate ships (including ironclads not completed in time), the fleet anchored at New Orleans. High water allowed the ships' guns to dominate the city over the levee top. A small squadron of ships manned by less than 3,500 men had captured the South's largest and wealthiest city. New Orleans, with its shipping facilities, was the only seaport where the South had any chance to match the Union's overwhelming power on the rivers. It was a critical blow from which the South could never recover. Sea power had joined in riverine warfare with a vengeance that was awful in its results to the loser, even darker in omens for the future.

To the north behind Foote's gunboats, catastrophe after catastrophe had continued to befall the South, whose armies alone could not match the overwhelming advantages the Union armies gained by having power afloat for joint operations. Instead of an artery of life for the Confederacy, the far-spreading streams of the Mississippi system had become highways of death to divide and destroy the South.

The three wooden gunboats had maintained control of the Tennessee River down across the state to Mississippi. They continued to keep the Confederates off balance, destroying, capturing, and preventing them from fortifying the banks. Advancing south along the river behind the gunboats, Grant's troops soon cut off western Tennessee from the rest of the state. In the battle of Shiloh on 6 April, when the Confederates suddenly fell on Grant's army and were on the point of victory, the gunboats poured a devastating fire upon the units that had turned Grant's river flank. This timely fire helped transform defeat into victory. Often throughout the vast riverine campaigns of the Civil War the concentrated mobile artillery of ships, brought speedily to bear at the point of crisis, would prove decisive, but seldom more strikingly than at Shiloh.

On the Mississippi the semi-ironclad gunboats steadily drove on with the Union armies cutting into the heart of the South like a flame. On 4 March, Foote's gunboats had occupied Columbus, "Gibraltar of the West." Outflanked by the rapid combined operations to the eastward, the Confederates abandoned this "impregnable fortress" leaving large quantities of ordnance and munitions. In riverine war, as on the oceans, a superior Navy often makes the "impossible" easy.

A month later, as Grant was wining at Shiloh to the eastward with the aid of the wooden gunboats, the next Confederate stronghold down the Mississippi, Island Number 10, suddenly fell after stubborn resistance. On 7 April the Confederates precipitantly abandoned it after two of Foote's gunboats ran past the fortification and made it possible for the Union army to cross the river in the rear of the fortifications. With little fighting, the Union forces again took a major stronghold, then called "The Key to the Mississippi," along with over 100 siege guns and large amounts of other materials the Confederates could ill spare. Mobile naval strength, making possible swift combined operations, had sealed the fate of the Confederacy on the upper Mississippi.

Now it knifed deeper into the core of the South. Less than a week after the fall of Island Number 10, Foote's flotilla steamed far downriver to Fort Pillow with the Union army of 20,000 men following astern in transports. At this last important fortification above Memphis, however, most of the Union army was detached to the eastward to join Grant at Shiloh. Hence Fort Pillow held out until evacuated by the Confederates on 4 June (by then Foote, suffering from his wounds, had been relieved by Captain Charles Henry Davis). Warships alone can accomplish wonders but riverine operations gain maximum effectiveness when the unique advantages of land forces combine with the matchless ones of the fleet. Their strengths do not simply add; they multiply to concentrate a nation's total power with awesome results.

The outnumbered Confederate river fleet now put up a last gallant defense, but the fall of Fort Pillow doomed Memphis, which surrendered as the Union fleet entered on 6 June. Steadily and fatefully the South was being dismembered along its river highways.

From New Orleans Farragut's heavy ships, suffering much damage in the restricted river waters, mounted the Mississippi to Vicksburg. Here was growing a mighty fortress with batteries high on the bluff that his ships' guns could not effectively reach. With his advance ships at Vicksburg in mid-May. Farragut could have captured the city if a few thousand troops had been assigned to him. When he ran past Vicksburg a month later in the early morning hours of 28 June, he had 3,500 soldiers for the combined operation; but now the Confederates had so strengthened the fortifications that Farragut estimated an army from 12,000 to 15,000 men was needed to capture it.

On 1 July Davis' flotilla joined Farragut's above Vicksburg. The spearheads from north and south had met. In a brief 5 months since Grant got underway behind Foote's gunboats for Fort Henry the whole complexion of the war had changed in the west. The South had suffered crippling losses in material, territory, and strategic position, which it never regained.

Vicksburg did hold out tenaciously for another year. During this time the warships, especially the river gunboats, were active in a myriad of operations. One of these has so many similarities to conditions in Vietnam a century later that it bears touching on. This was the effort to cut off Vicksburg by controlling the extensive water systems to the rear. The Yazoo River and Yazoo Pass expeditions were the result of this strategy.

Natural hazards on the Mississippi may be considered light when compared with those on the Yazoo. The Mississippi is wide and relatively deep, allowing some maneuvering room, but parts of the Yazoo were reclaimed bayou, with the river's course determined by man-made levees. In the bayou country the waters were sometimes no more than a foot in depth. Narrow watercourses and dense overhanging foliage made hard-going routine.

The river workhorses, the armored city-class gunboats, drew too much water for extensive use under these conditions. They saw some action in the bayous, but were constantly threatened by collision and marooning. Captain Henry Walke, who earlier had dashed past Island Number 10 in Carondelet, converted stern-wheelers for use on the narrow Yazoo. Pilot houses were lowered, boilers protected, and several light guns mounted. The thin iron sheets used for armor on the boats earned them the title "tinclads." Protected from musket and light field artillery fire, they could not stand up against heavy cannon. The Confederate's ingenious use of torpedoes was an added and constant menace in the Yazoo.

On 12 December 1862, as part of preparation for combined operations, Walke proceeded up the Yazoo sweeping torpedoes, as mines were then termed. Almost immediately he lost USS Cairo, first of some 40 Union craft to fall victim to Confederate torpedoes. Undeterred, he continued sweeping. His four light ironclads, four tinclads, two woodenclads, and two rams moved upriver in a coordinated minesweeping formation. Progress was tortuous but steady until arriving at Drumgould's Bluff, Mississippi. Here the Southerners had mounted a battery to keep the Yankees away from two gunboats under construction at Yazoo City. The exchange of fire was heated, but the gunboats were able to sweep the river clear of torpedoes to within a half-mile of the battery.

The ill-fated joint Yazoo Pass Expedition opened the first week of February 1863. Its purpose was to reach the rear of Vicksburg by a surprise move. An opening was to be made in the levee at Yazoo Pass through which the Union gunboats and troop carriers could enter and work up the Yazoo River above Haines Bluff.

Delay followed delay so that the surprise element was lost. Not until 25 February were obstructions sufficiently removed from the Pass to allow Lieutenant Commander Watson Smith's light-draft gunboats, transports, and coal barges to enter. The navigational dangers were incredible--tree stumps and floating logs stove in housings and fouled wheels; overhanging willows and vines snared and held on smokestacks. Best speed was a mile and a half in 1 hour. There was also the ever present threat of having retreat cut off by guerrillas.

When the bedraggled expedition reached the Tallahatchie River (joins with the Yalobusha to form the Yazoo River) the waters became more manageable. Here, however, the Federals unexpectedly faced a well-positioned cotton and earthen breastwork, Fort Pemberton. Several sharp engagements followed between fort and gunboats. Flooded conditions prohibited any troop landing to outflank the Southern gunners. The Yazoo Pass Expedition came to a grinding halt and fell back.

Admiral Porter tried again via a different route, Black Bayou. Porter found the going so tough through the dense forest that he made only four miles in 24 hours while snipers peppered his gunboats and the Confederates felled trees across his path. The back door to Vicksburg remained closed.

River warfare in the Yazoo delta highlighted a number of aspects of this projection of sea power; defensive minelaying and offensive minesweeping on a significant scale, and forays into outrageously difficult waters. Porter observed that "no one would believe that anything in the shape of a vessel could get through Black Bayou or anywhere on the route."