The Navy Department Library

Solomon Islands Campaign: XI

Kolombangara and Vella Lavella, 6 August - 7 October 1943

Office of Naval Intelligence. United States Navy

1944

PDF Version [53.9MB]

COMBAT NARRATIVES

Solomon Islands Campaign: XI

Kolombangara

and

Vella Lavella

6 August – 7 October 1943

Office of Naval Intelligence, United States Navy

1944

NAVY DEPARTMENT

Office of Naval Intelligence

Washington, D. C.

1 October 1943.

Combat Narratives are confidential publications issued under a directive of the Commander in Chief, U. S. Fleet, and Chief of Naval Operations, for the information of commissioned officers of the U. S. Navy only.

Information printed herein should be guarded (a) in circulation and by custody measures for confidential publications as set forth in Articles 75 ½ and 76 of Navy Regulations and (b) in avoiding discussion of this material within the hearing of any but commissioned officers. Combat Narratives are not to be removed from the ship or station for which they are provided. Reproduction of this material in any form is not authorized except by specific approval of the Director of Naval Intelligence.

Officers who have participated in the operations recounted herein are invited to forward to the Director of Naval Intelligence, via their commanding officers, accounts of personal experiences and observations which they esteem to have value for historical and instructional purposes. It is hoped that such contributions will increase the value of and render ever more authoritative such new editions of these publications as may be promulgated to the service in the future.

When the copies provided have served their purpose, they may be destroyed by burning. However, reports acknowledging receipt or destruction of these publications need not be made.

{SIGNATURE}

REAR ADMIRAL, U. S. N.,

Director of Naval Intelligence

II

Foreword

8 January 1943.

Combat Narratives have been prepared by the Publication Branch of the Office of Naval Intelligence for the information of the officers of the United States Navy.

The data on which these studies are based are those official documents which are suitable for a confidential publication. This material has been collated and presented in chronological order.

In perusing these narratives, the reader should bear in mind that while they recount in considerable detail the engagements in which our forces participated, certain underlying aspects of these operations must be kept in a secret category until after the end of the war.

It should be remembered also that the observations of men in battle are sometimes at variance. As a result, the reports of commanding officers may differ although they participated in the same action and shared a common purpose. In general, Combat Narratives represent a reasoned interpretation of these discrepancies. In those instances where views cannot be reconciled, extracts from the conflicting evidence are reprinted.

Thus, an effort has been made to provide accurate and, within the above-mentioned limitations, complete narratives with charts covering raids, combats, joint operations, and battles in which our Fleets have engaged in the current war. It is hoped that these narratives will afford a clear view of what has occurred, and form a basis for a broader understanding which will result in ever more successful operations.

{SIGNATURE}

E. J. KING

ADMIRAL, U.S.N.,

Commander in Chief, U. S. Fleet, and Chief of Naval Operations.

III

Charts and Illustrations

| Facing page | |

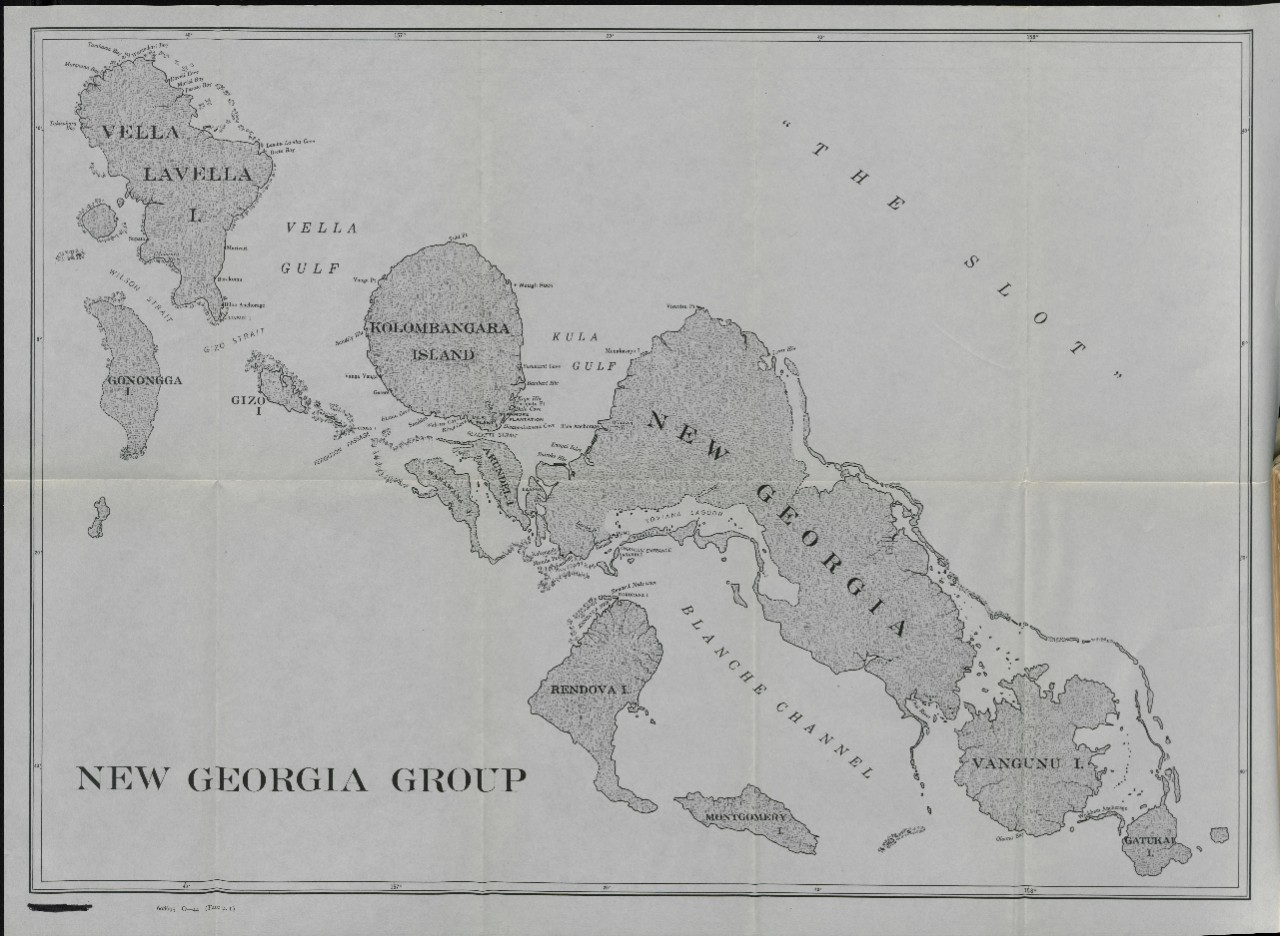

| Chart: New Georgia Group. | |

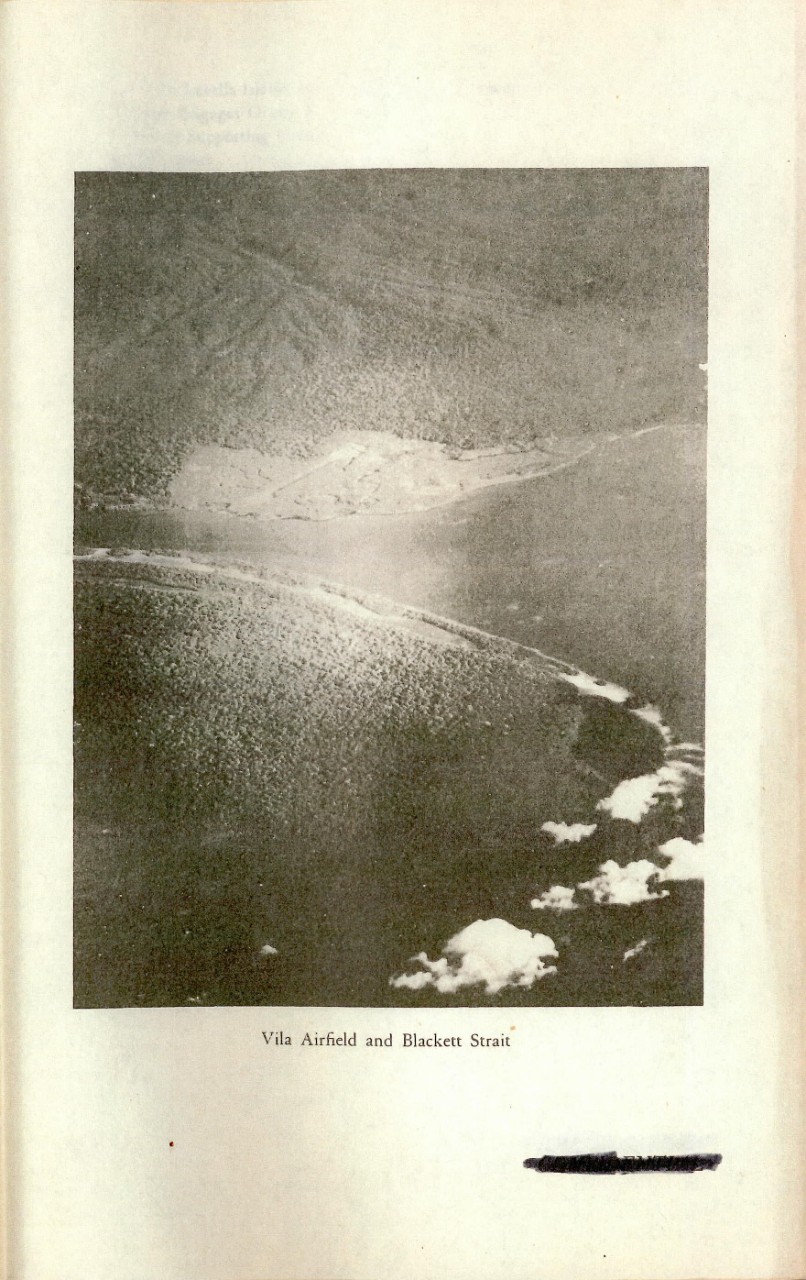

| Illustration: Vila Airfield | 1 |

| Diagrams illustrating Battle of Vella Gulf: | |

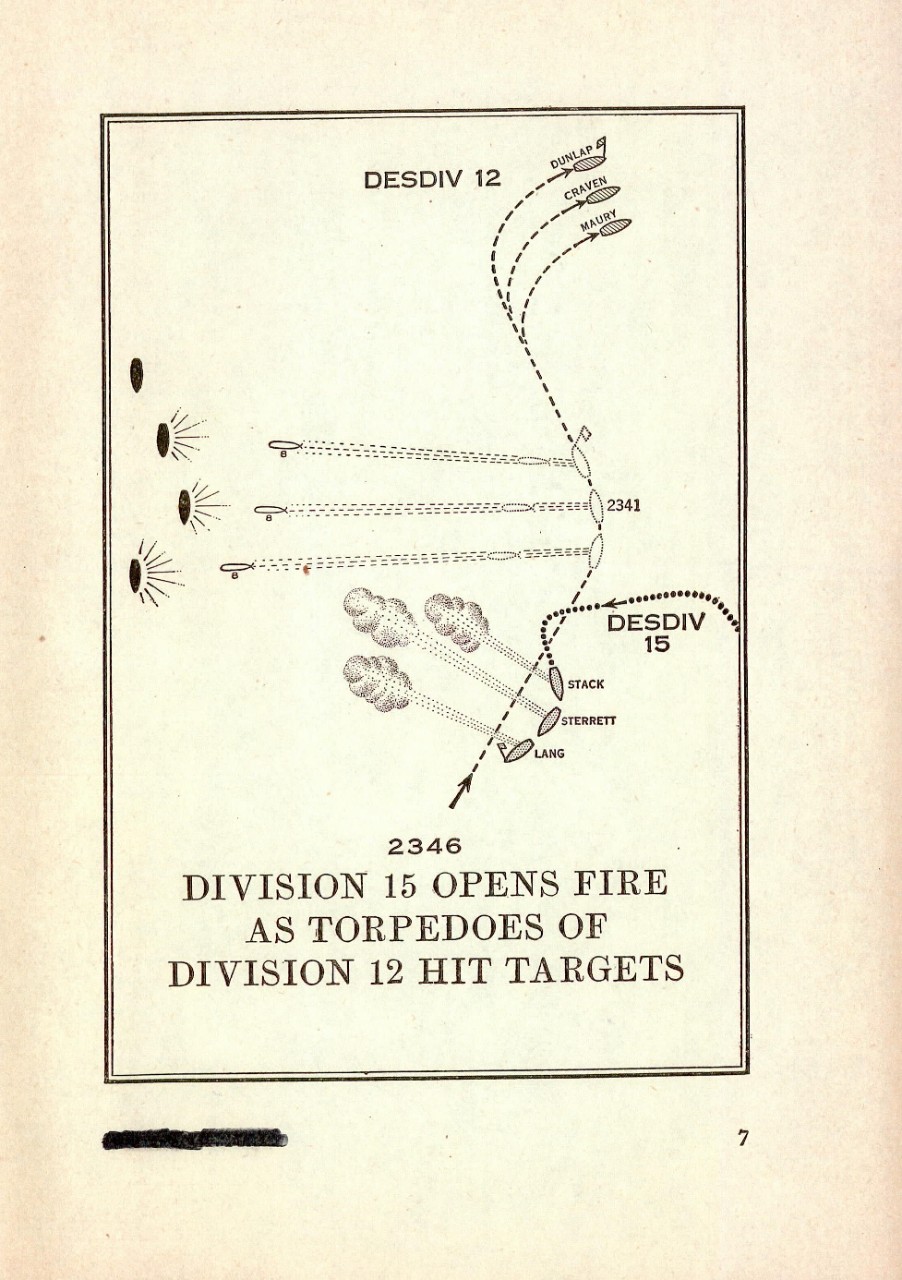

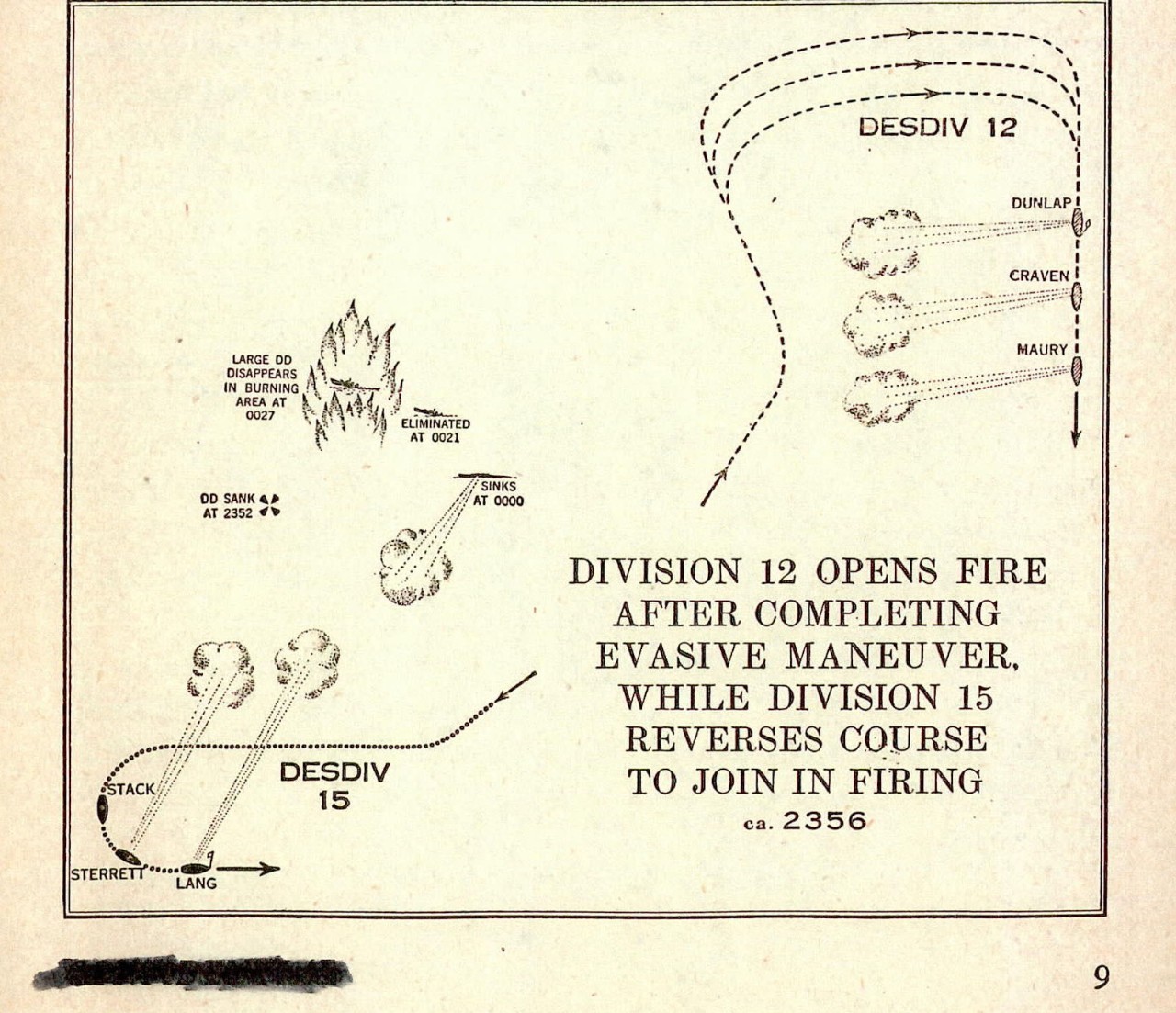

| DesDiv FIFTEEN opens fire (2346) | on page 7 |

| DesDiv FiFTEEN opens fire (2356) | on page 9 |

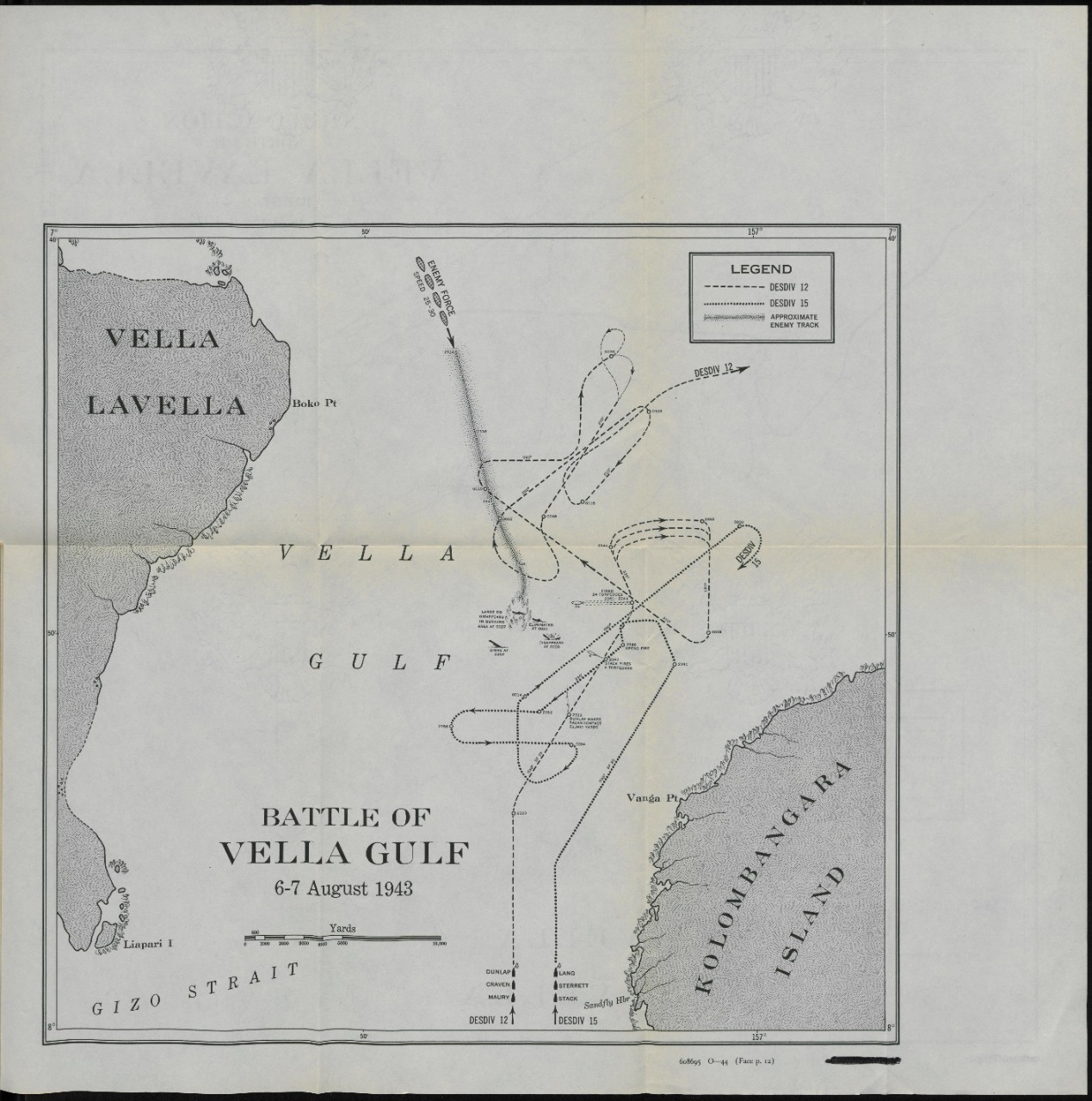

| Chart: Battle of Vella Guf. | |

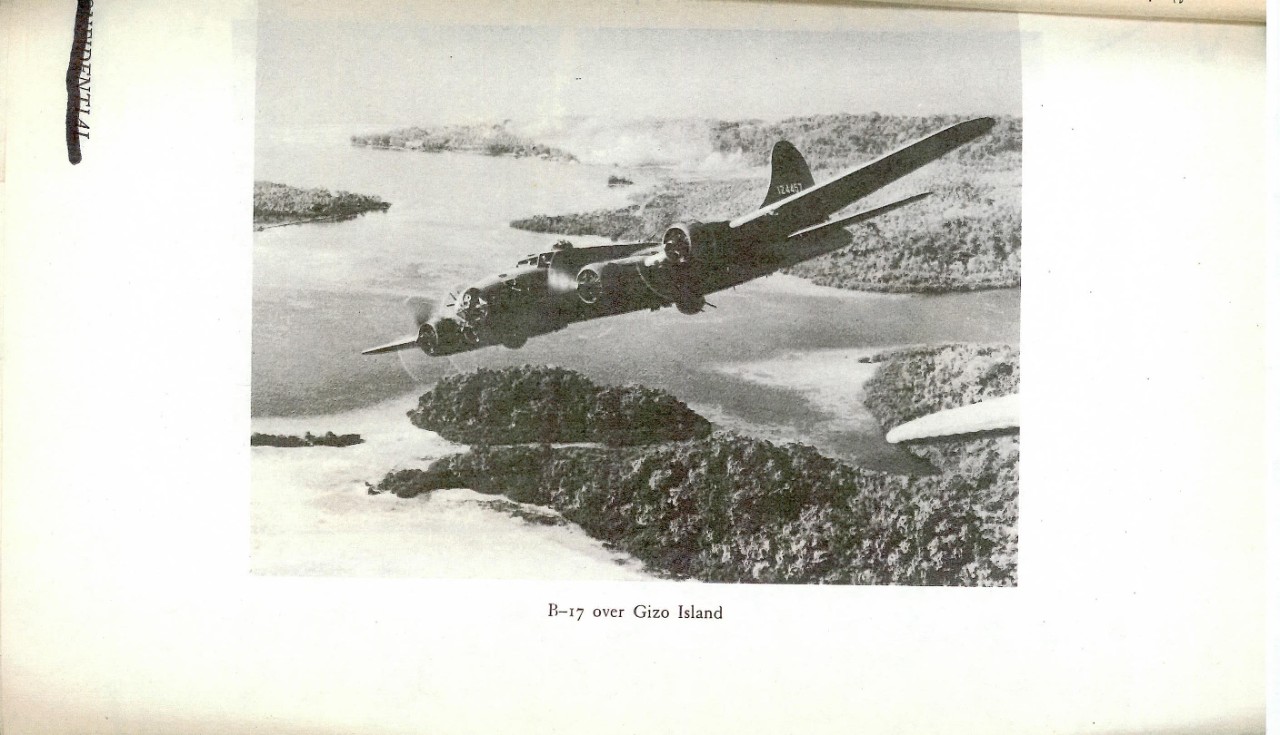

| Illustration: B-17 over Gizo Island | 12 |

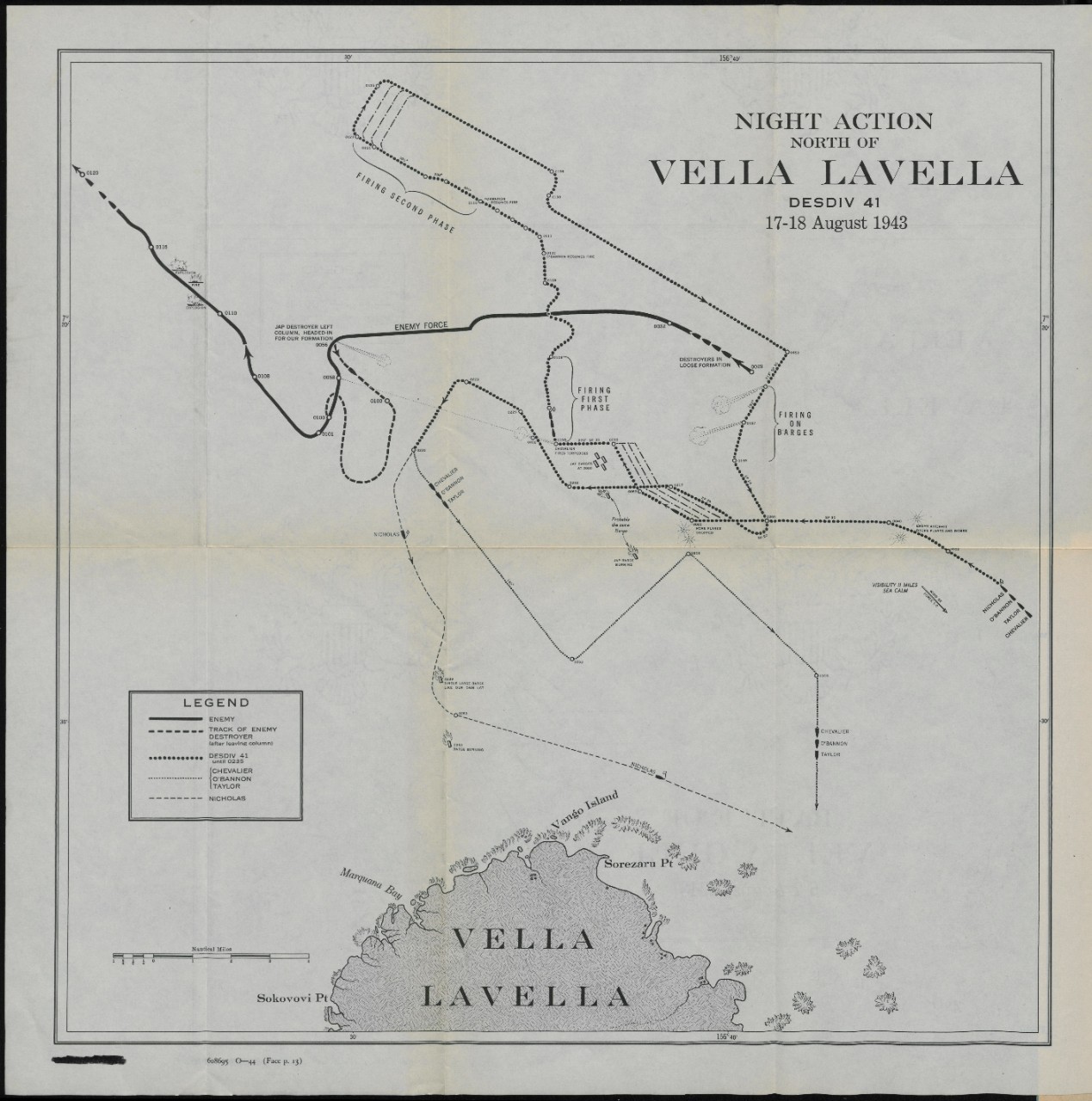

| Chart: Night Action 17-18 August. | |

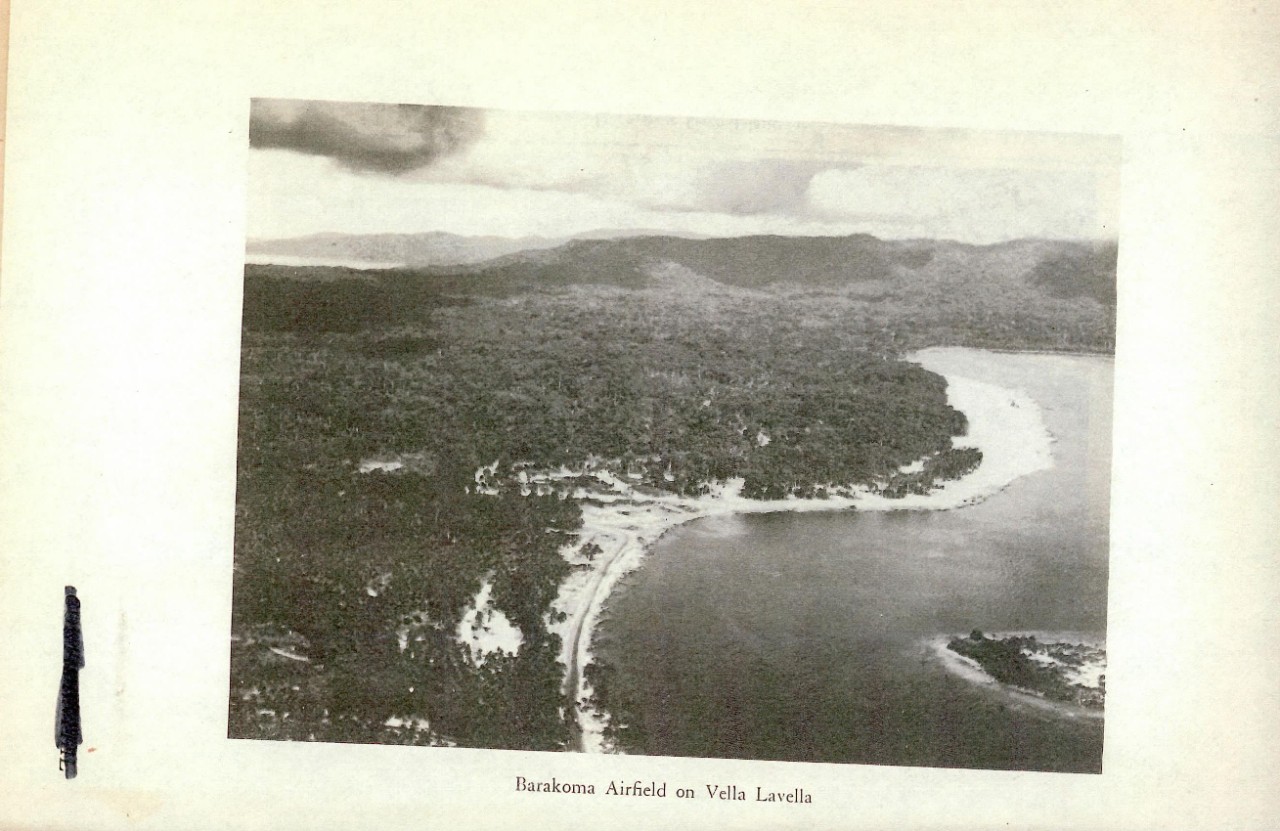

| Illustration: Barakoma Airfield | 13 |

| Illustrations | between pages 26 and 27 |

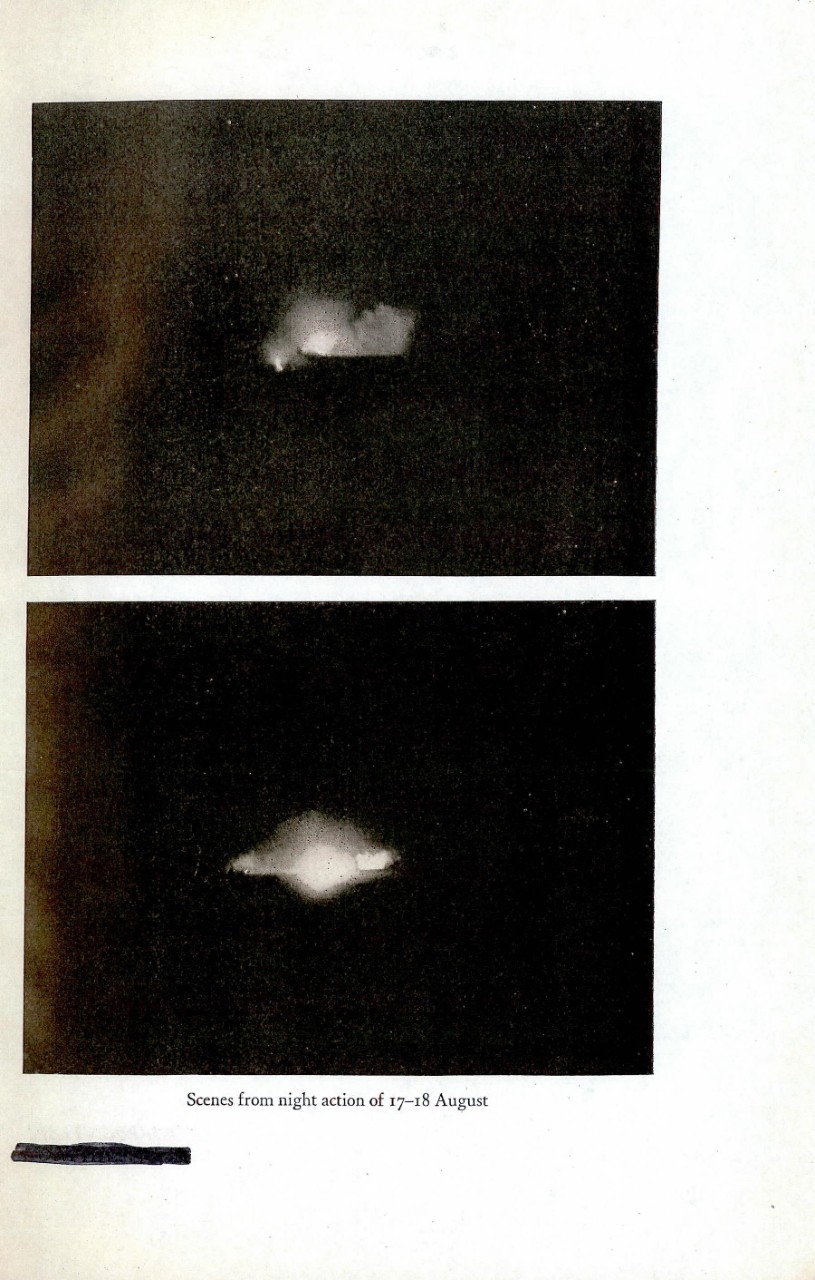

| Scenes from action 17-18 August. | |

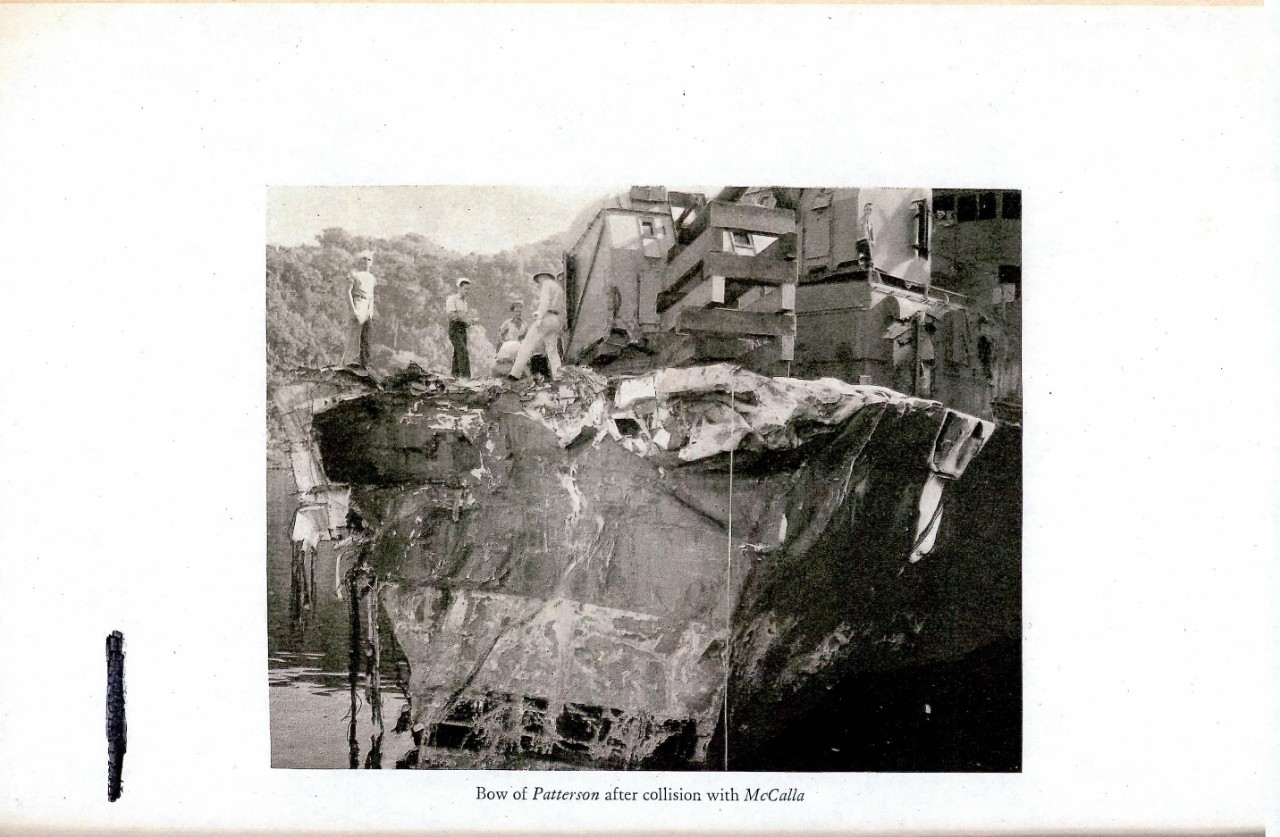

| Bow of Patterson after collison | |

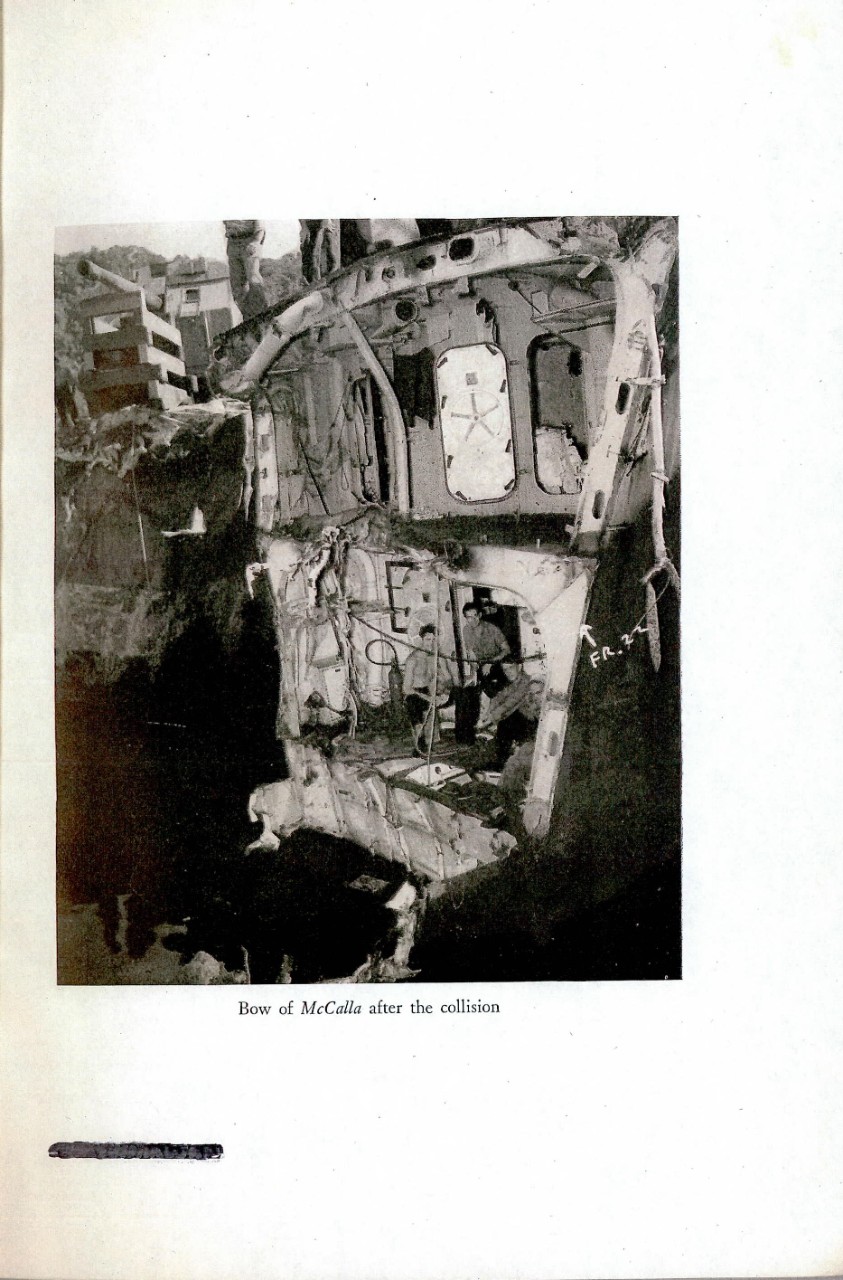

| Bow of McCalla. | |

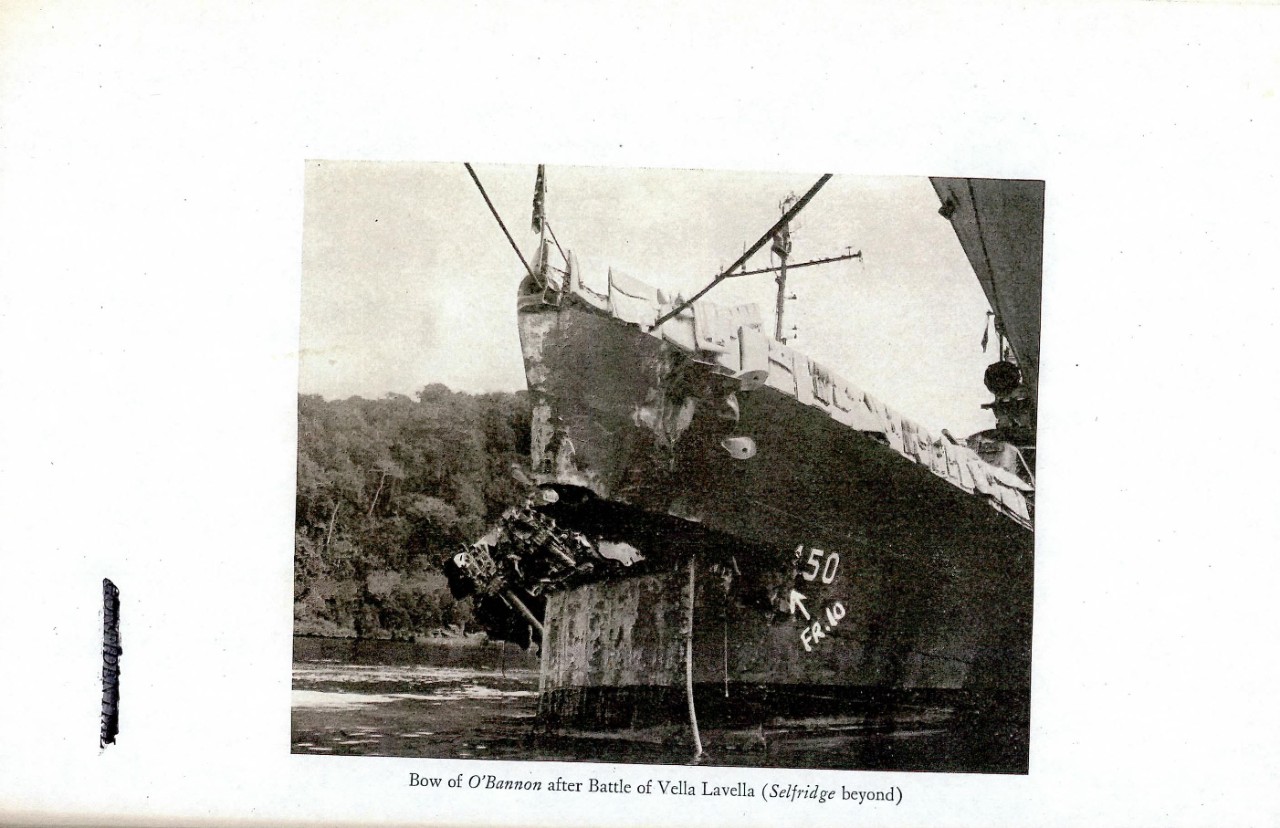

| O'Bannon after Battle of Vella Lavella. | |

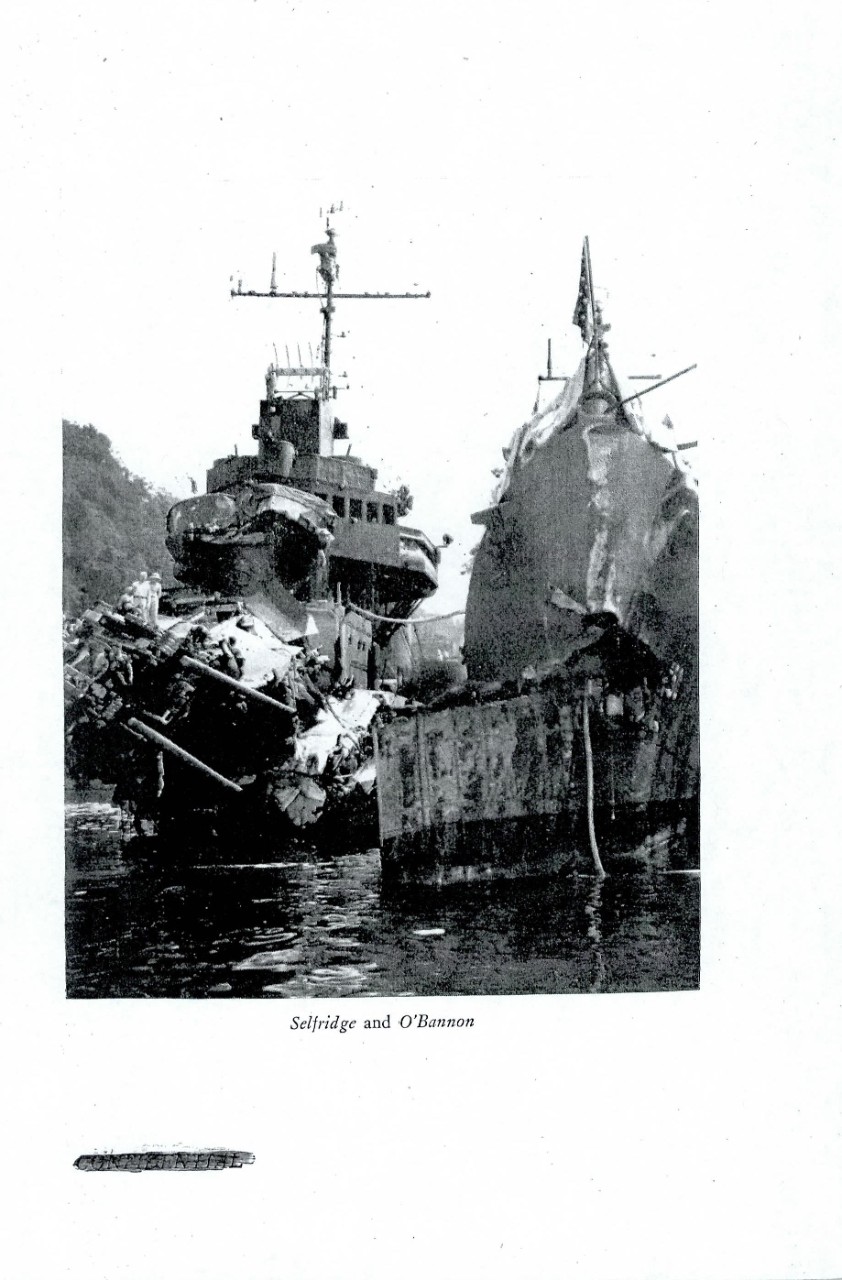

| Selfridge and O'Bannon. | |

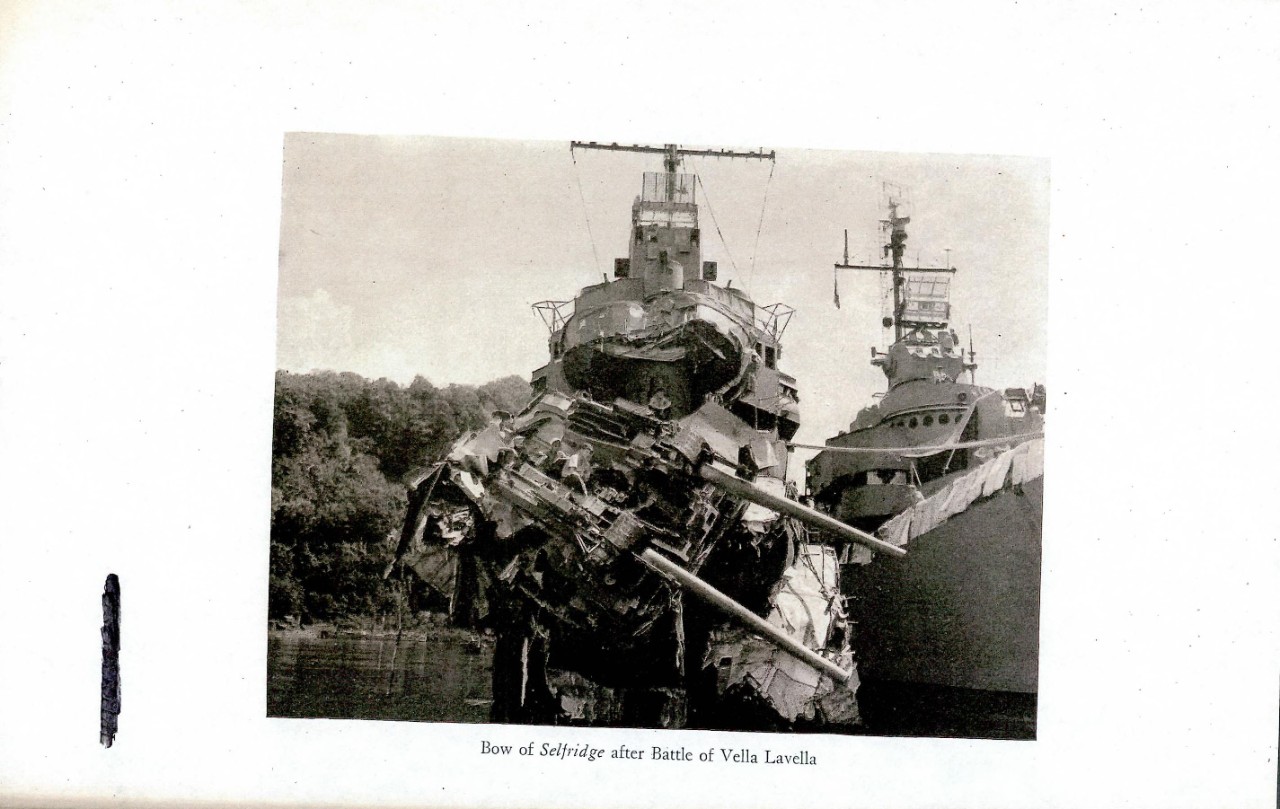

| Selfridge after Battle of Vella Lavella. | |

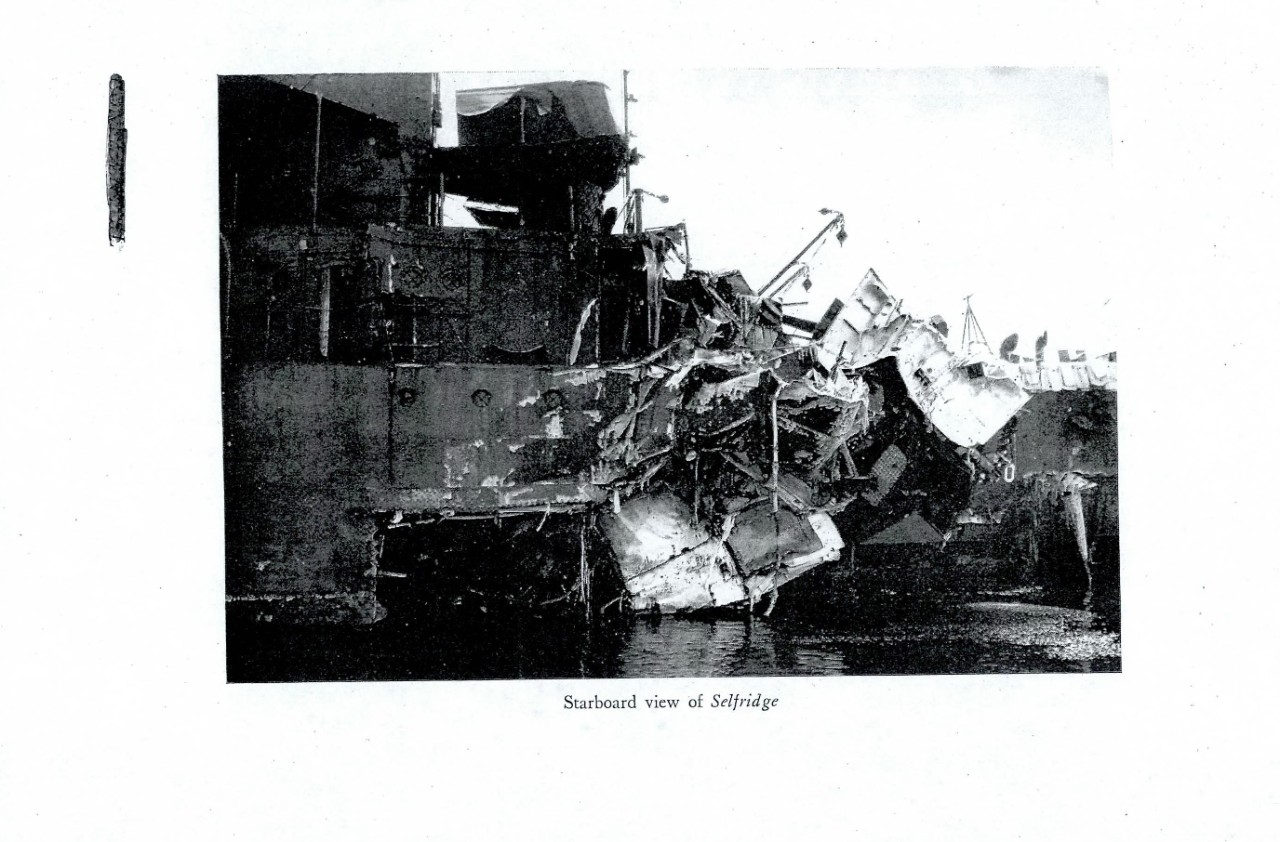

| Starboard view of Selfridge. | |

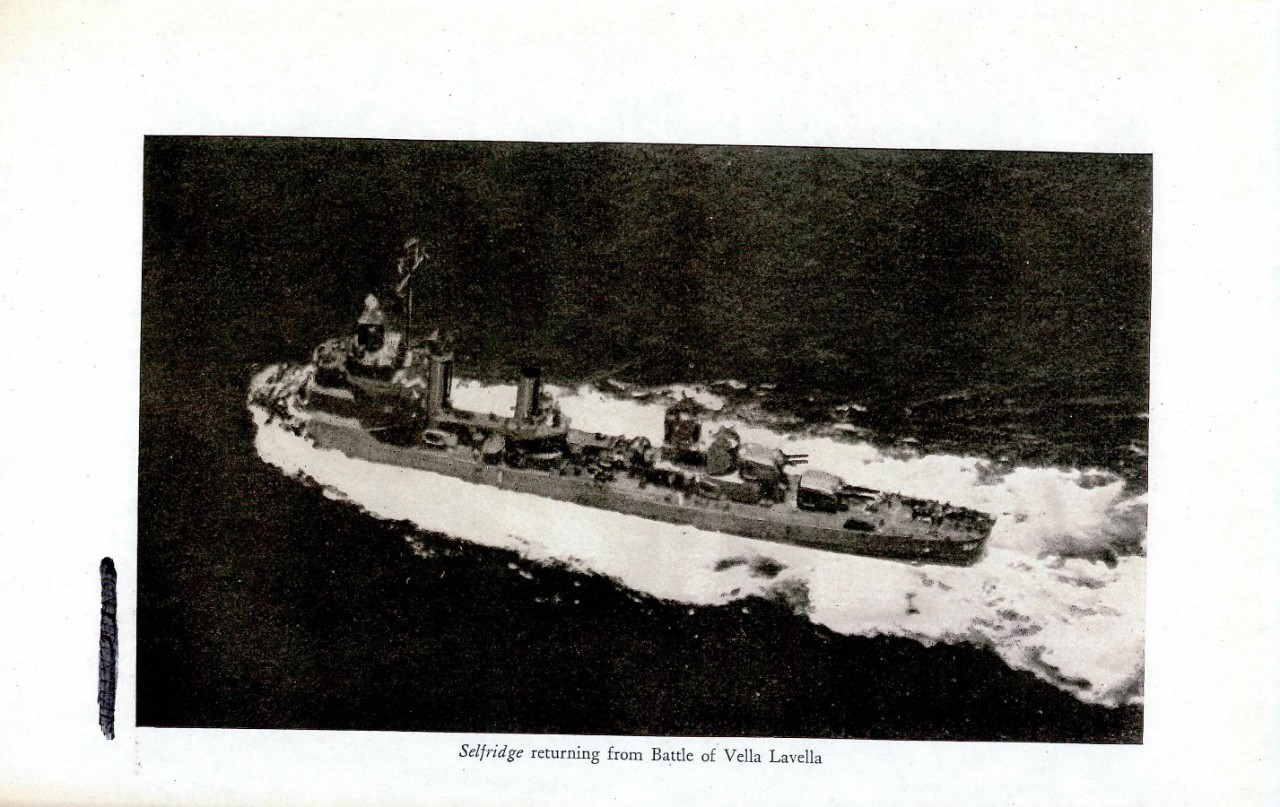

| Selfridge returning from Battle of Vella Lavella. | |

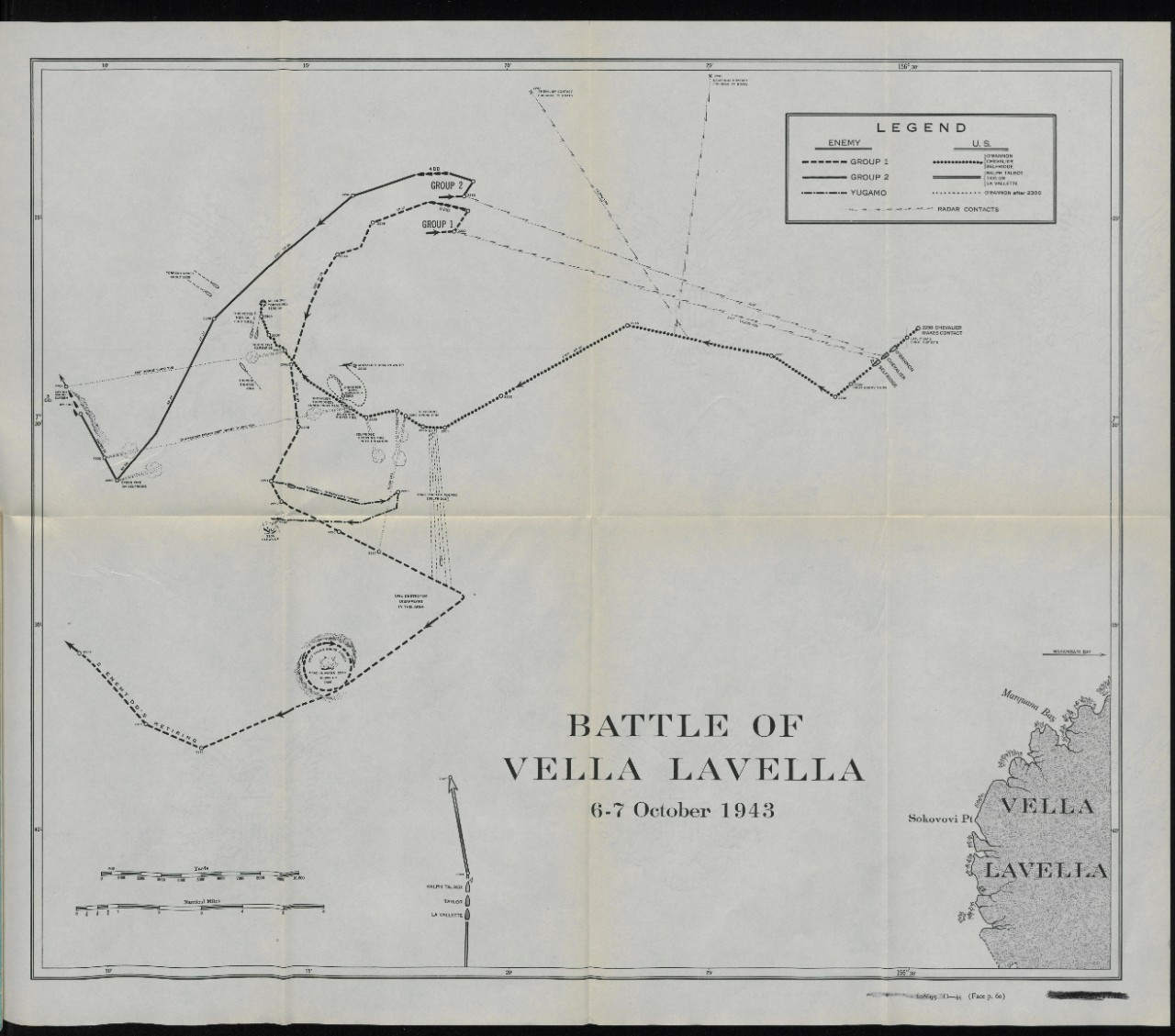

| Chart: Battle of Vella Lavella, 6-7 October. | |

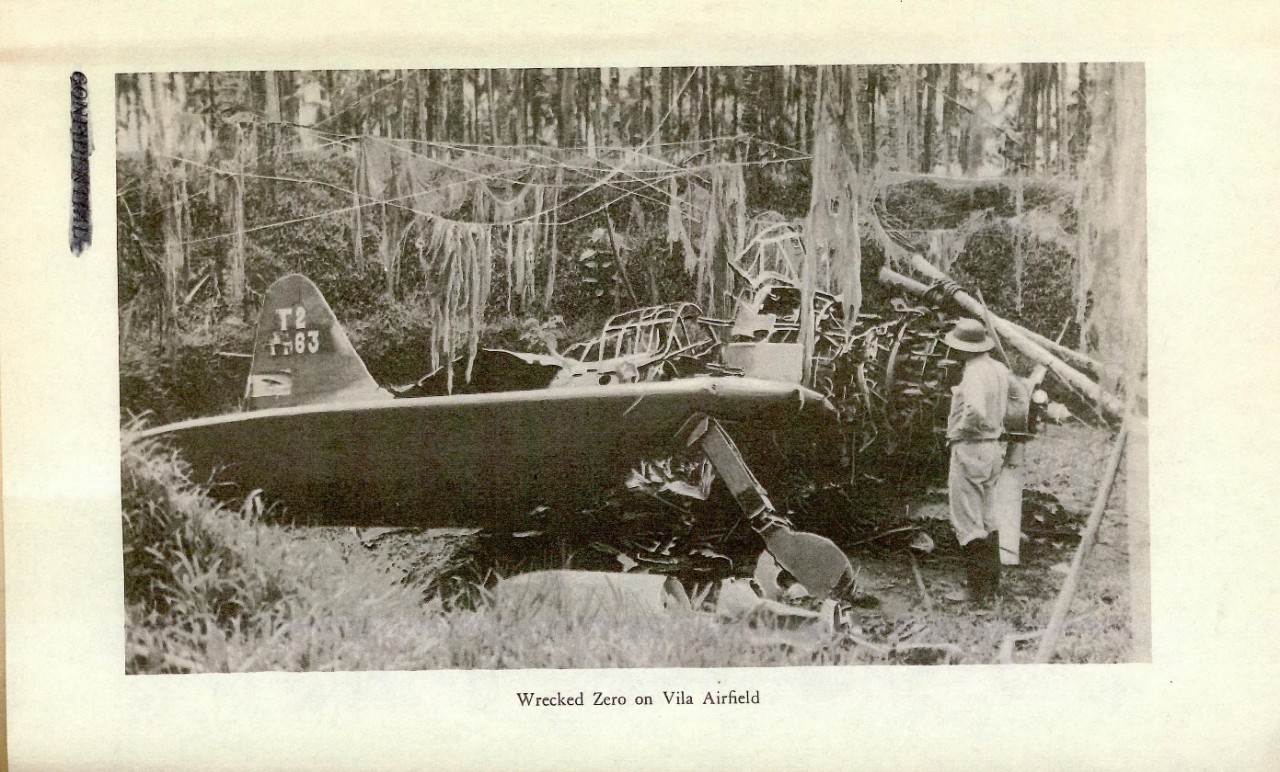

| Illustration: Wrecked Zero on Vila Airfield | 60 |

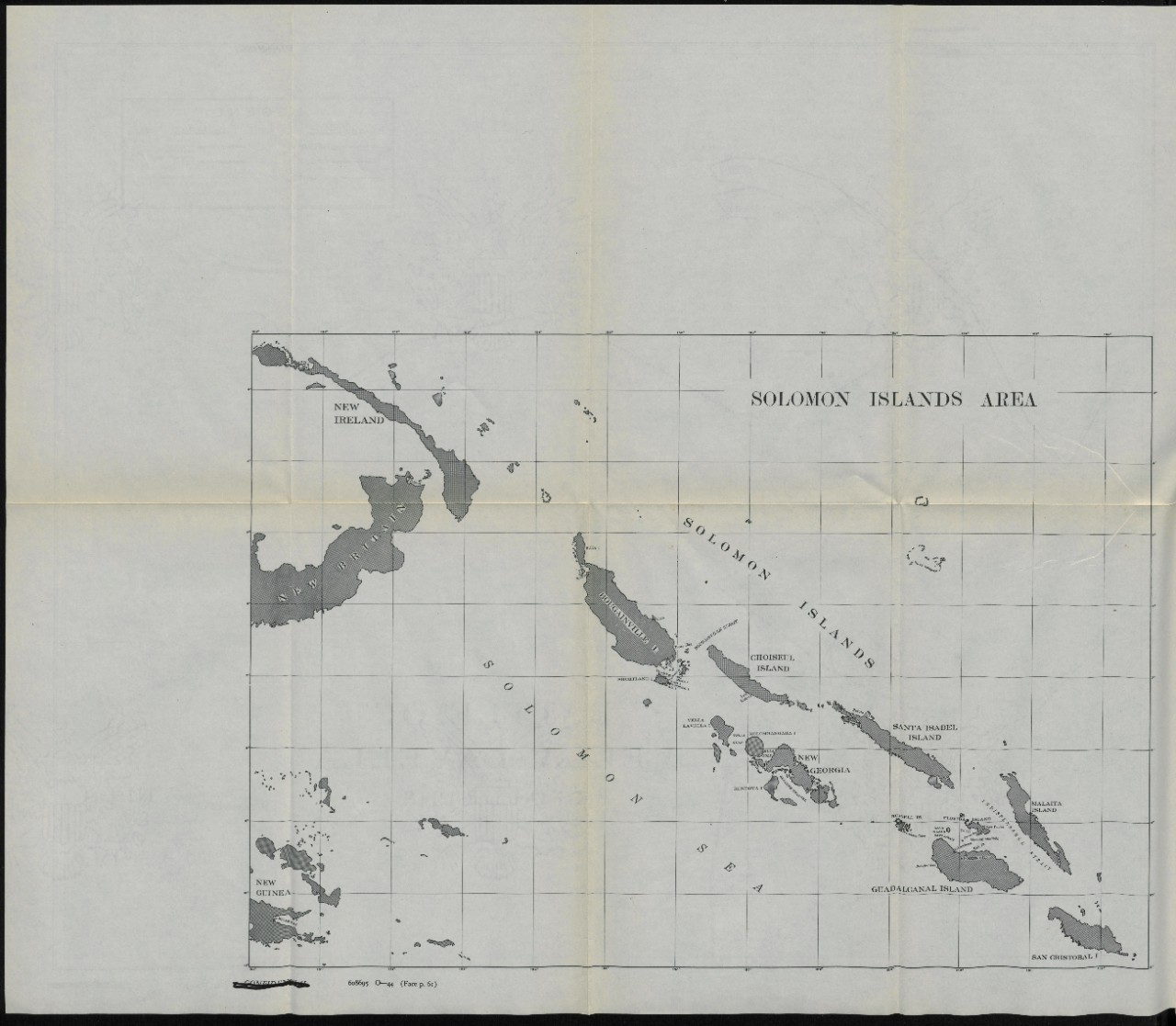

| Chart: Solomon Islands Area. | |

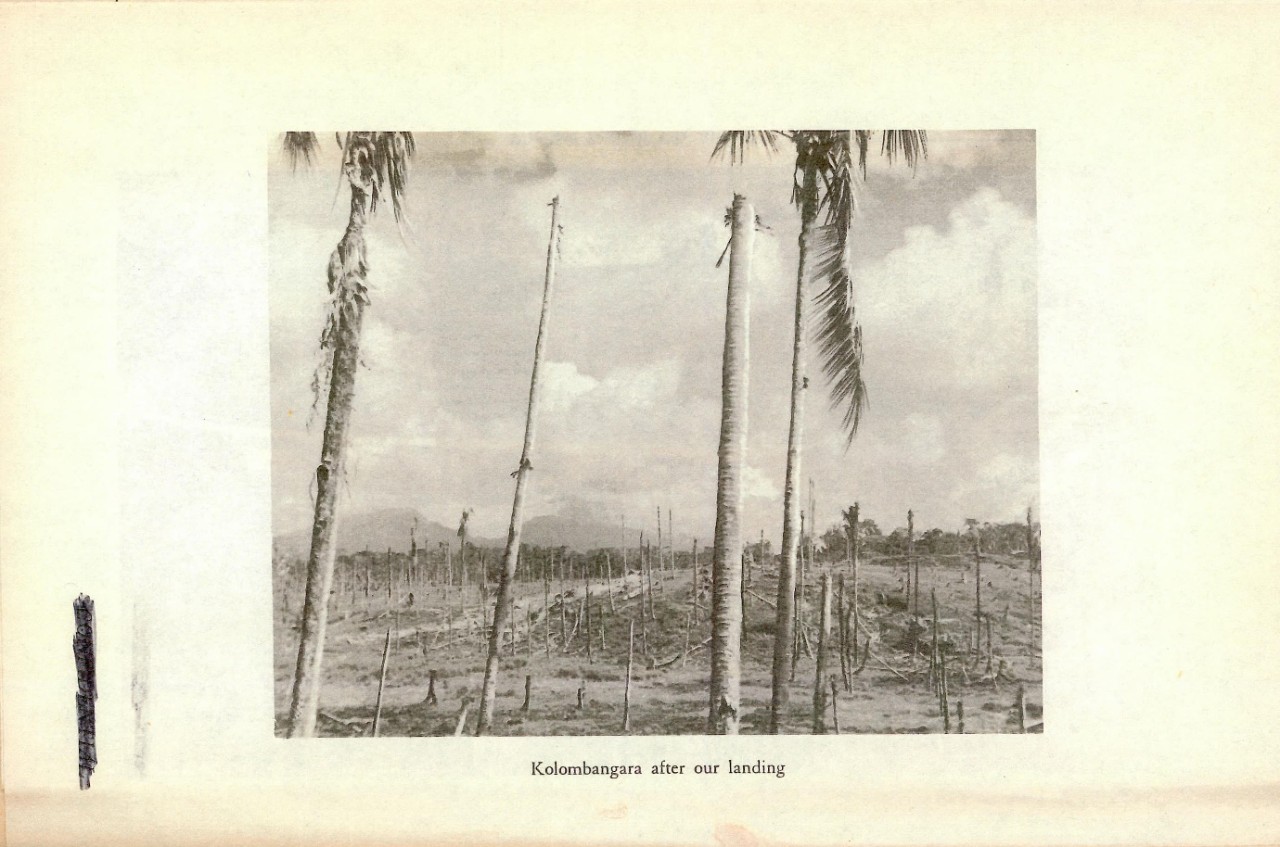

| Illstration: Kolombangara after our landing | 61 |

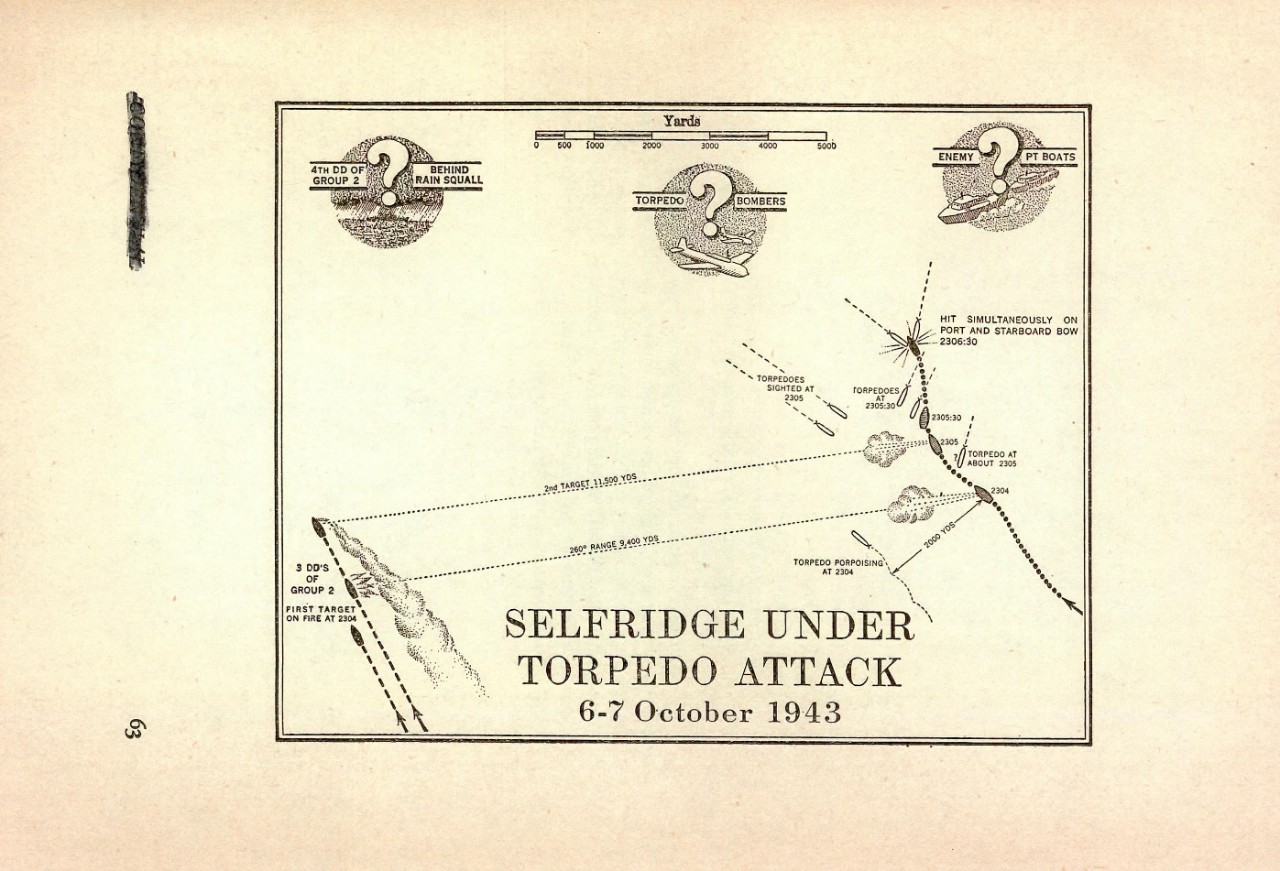

Diagram: Selfridge under torpedo attack |

on page 63 |

IV

Contents

| Page | |

| Introduction | 1 |

| Battle of Vella Gulf, 6-7 August 1943 | 2 |

| Preliminary Arrangements | 2 |

| Approach | 4 |

| Engagement | 5 |

| Conclusions | 11 |

| Destruction of Barges, 9-10 August | 12 |

| Landing on Vella Lavella, 15 August 1943 | 14 |

| Strategic Considerations | 14 |

| Task Force Organization | 15 |

| Preliminary Operations | 17 |

| Approach and Landing | 18 |

| Antiaircraft Action | 19 |

| Operations Ashore | 22 |

| Night Action off Vella Lavella, 17-18 August 1943 | 22 |

| Preliminary Maneuvers | 23 |

| Engagements with Destroyers | 24 |

| Destruction of Barges | 27 |

| Conclusions | 28 |

| Supplying Vella Lavella, 17 August-3 September 1943 | 28 |

| Second Echelon | 29 |

| Third Echelon | 31 |

| Fourth and Fifth Echelons | 32 |

| Passage of Command | 33 |

| Blockading Operations, 1 September-5 October 1943 | 34 |

| Minelaying West of Kolombangara | 35 |

| PT Boat versus Barge | 36 |

| Air Combat and Patrol | 38 |

| Evacuation of Kolombangara | 40 |

| Battle of Vella Lavella Iland, 6-7 October 1943 | 47 |

| Military Situation | 47 |

| Preliminary Movements | 48 |

| Contact and Approach | 50 |

| Action with Group I | 52 |

V

Battle of Vella Lavella Iland, 6-7 October 1943--Continued. |

Page |

| Selfridge Engages Group II | 55 |

| Arrival of Supporting Group | 57 |

| Enemy Losses | 59 |

| End of a Campaign | 60 |

| Notes on the Japanese Torpedo Attack in the Battle of Vella Lavella | 61 |

| I. Chevalier | 61 |

| II. Selfridge | 62 |

| Appendix A: Supply Echeleons to Vella Lavella | 66 |

| Appendix B: Symbols of U. S. Navy Ships | 67 |

| Appendix C: Designations of U. S. Naval Aircraft | 69 |

VI

Kolombangara and Vella Lavella

6 August – 7 October 1943

INTRODUCTION

The capture of the airfield at Munda Point on 5 August 19431 ended the first phase of our northward march through the New Georgia Group. Despite the fact that a total of 1,671 Japanese dead was counted and that heavy additional casualties were known to have been inflicted by Allied naval, artillery and air bombardments, some Japanese were able to withdraw to the north and effect a junction with other troops holding out at Bairoko Harbor, the last major center of Japanese resistance on New Georgia. A few others, probably high-ranking officers for the most part, were evacuated by barges to the enemy base at Vila-Stanmore on Kolombangara. This road of escape, however, was effectively denied to the majority of the survivors by our light surface vessels, which reported intercepting and sinking several troop-carrying barges in Kula Gulf during the final stages of the fighting at Munda.

Meanwhile, as two columns of our ground forces pushed through the jungle in pursuit of the fleeing enemy, Army engineers and Navy Seabees began reconstruction of Munda airfield, which was found to be in reasonably good condition despite the intensive bombardments which preceded its capture. Allied use of the airstrip, it was felt, would effectively neutralize the field at Vila-Stanmore, besides bringing our fighters and bombers within much closer range of the enemy’s last three remaining air bases in the Solomons – Kahili, Ballale and Buka.

Even though partially neutralized, the base at Vila-Stanmore remained a stumbling block in the path of our northward drive. Indications were that the Japanese had no intention of withdrawing from the area, despite the fact that its potential usefulness had greatly diminished. It was believed, on the contrary, that the enemy intended to augment his garrison there, and to this end was preparing to move in troops and equipment from the north in barges and destroyers under cover of darkness.

___________

1 See Combat Narrative, “Operations in New Georgia Area, 29 June – 5 August 1943”.

1

THE BATTLE OF VELLA GULF, 6-7 AUGUST

Preliminary Arrangements

The work of preventing these reinforcement operations fell to our destroyers and PT boats. For some weeks they had been systematically searching out enemy supply concentrations throughout the New Georgia Group. As our offensive against Munda gained momentum, they had contributed in no small measure to the success of the operation by breaking up enemy reinforcement attempts. Now the task would have to be continued in the waters surrounding Kolombangara.

On 4 August, the day before Munda finally fell, Comdr. Frederick Moosbrugger, commanding a Task Group of six destroyers, reported to the headquarters of Rear Admiral Theodore S. Wilkinson on Guadalcanal and was informed that the Admiral wished to make a sweep of Vella Gulf with two destroyers and a number of motor torpedo boats, with the object of intercepting and disrupting enemy barge traffic. Conversations on this subject with MTB officers led to the calling of a conference to meet the following day aboard the destroyer Dunlap (Lt. Comdr. Clifton Iverson) at Purvis Bay. Attending this conference were Comdr. Moosbrugger as Commander of Task Group MIKE;2 Comdr. Rodger W. Simpson, ComDesDiv FIFTEEN in TG MIKE; Comdr. R. W. Calvert, ComMTB Flotilla ONE; Lt. Comdr. Henry Farrow, and other MTB officers. At this conference the MTB representatives presented “much valuable information” regarding barge traffic and destroyer sightings in the Vella Gulf area, and tentative plans for an operation were worked out. The operation did not materialize because of the need for the MTB’s elsewhere, but the information obtained at the conference proved invaluable in the action that was to follow.

Comdr. Moosbrugger, as CTG MIKE, had the following vessels at his disposal:

DesDiv TWELVE (less Gridley), Comdr. Moosbrugger.

Dunlap (F), Lt. Comdr. Iverson.

Craven, Lt. Comdr. Francis T. Williamson.

Maury, Comdr. Gelzer L. Sims.

___________

2 Numbers identifying task forces have been omitted from all Combat Narratives for reason of security. In place of these numbers will be found the Navy flag name for the first letter of the surname of the commanding officer of a task force.

2

DesDiv FIFTEEN (less Wilson), Comdr. Simpson.

Lang (F), Comdr. John L. Wilfong.

Sterett, Lt. Comdr. Frank G. Gould.

Stack, Lt. Comdr. Roy A. Newton.

Late in the afternoon of 5 August, he received a dispatch from Admiral Wilkinson directing him, with his two divisions, to sortie from Tulagi at 1230 on 6 August, proceed to Vella Gulf by a route south of the Russells and Rendova so as to arrive at Gizo Strait at 2200, and make sweeps of the Gulf, avoiding minefields. If he made no enemy contacts by 0200 on 7 August, he was to return at maximum speed to Port Purvis, passing north of Kolombangara. Admiral Wilkinson later informed Comdr. Moosbrugger that he believed the Japanese intended to reinforce the Vila-Stanmore area during the night of 6 August, using destroyers and possibly a cruiser.

The following morning Comdr. Moosbrugger invited Comdr. Simpson to a breakfast conference. The battle plan adopted was one previously conceived for a similar situation by Comdr. Anleigh A. Burke, who had been relieved by Comdr. Moosbrugger just prior to this operation. The following assumptions were made: (a) there was a remote possibility that enemy submarines might be encountered in Gizo Strait; (b) Gizo Strait was not minded; (c) enemy MTB’s might be operating in the Vella Gulf area; (d) enemy snoopers would be active; (e) enemy troop-carrying barges equipped with the equivalent of 40 mm guns might be encountered in the Gizo Strait area, close to the fringing reefs north and west of Gizo Island, in the Blackett Strait area, and near the western shore of Kolobangara Island; (f) enemy destroyers would approach either from the north through Vella Gulf, or through Wilson Strait and Gizo Strait (the latter seemed improbable, as our PT boats had thoroughly combed that area); (g) enemy cruisers might be present; (h) the enemy force might consist of two groups, well separated; (i) the enemy surface forces would be at a disadvantage, their decks loaded with troops; (j) the element of surprise was in our favor, and must be exploited; (k) in a night surface engagement under favorable conditions, the destroyer’s primary and most devastating weapon was the torpedo; and (l) that American gunfire was superior to that of the Japanese.

Detailed plans for the entire operation were developed and transmitted to the commanding officers. The vessels involved were to pass through

3

Gizo Strait in column of division columns at 15 knots,3 entering Vella Gulf at moonset. On passing abeam of Liapari Island, DesDiv FIFTEEN was to form on bearing 1500 T. about 4,000 yards from DesDiv TWELVE and sweep at 15 knots on course 124 degrees T. within a mile or two of Gizo Reefs. Thence they were to head north, close under the west shore of Kolombangara, searching for barges. DesDiv FIFTEEN, equipped with 40 mm guns, was selected as the inshore division, and DesDiv TWELVE, with 44 torpedoes, was designated as the offshore division to engage any destroyers or heavier ships which might arrive earlier than expected. It was planned to destroy barges detected on this sweep only on condition that reports from the spotting Black Cats gave definite information that there were no destroyers or heavier ships in the area. If such information were not forthcoming, contacts on barges were to be passed up until the second trip around.

If destroyers or larger vessels were encountered, Division TWELVE would close to fire torpedoes, retire to about 10,000 yards until the torpedoes hit, then open gunfire. Division FIFTEEN was to cover Division TWELVE while the latter approached the enemy for torpedo attack. Unless the enemy discovered and opened fire on Division TWELVE during its approach, Division FIFTEEN was to wait until the torpedoes hit before opening gunfire. It would also make a secondary torpedo attack if a favorable opportunity was presented.

Approach

Task Group MIKE departed Purvis Bay, Florida Island, 6 August at about 1130. The departure one hour prior to the scheduled time was considered necessary because of the condition of the Maury’s engineering plant, which limited her speed to 27 knots. In the vicinity of Savo Island the task group assumed a special semi-circular antiaircraft formation with the Dunlap at the center and proceeded south of the Russells and Rendova Islands to Gizo Strait.

At 1730 a relay contact report was received from Plane One of Flight 15 saying that a Japanese force had been sighted at latitude 040 50’ S., longitude 1540 40’ E., course 1900 T., speed 15 knots. It was estimated that this force would reach Vella Gulf about midnight if it proceeded by direct route at a speed of 21 knots.

____________

3 The 15-knot speed was chosen because it made for efficient sound searches, produced a wake difficult for snoopers to detect, and permitted maintenance of the predetermined timetable.

4

Six Black Cats were assigned to CTG MIKE for coverage and search, operating in two groups of three each. Bad weather and radar trouble were encountered, however, and communication was never established with either group.

In accordance with the battle plan, the Task Group arrived at Point Option, latitude 080 03’ S., longitude 1560 41’ E. at 2200, slowed to 15 knots and began a careful search for enemy craft. Upon traversing Gizo Strait DesDiv FIFTEEN formed on bearing 1500 T., distant 4,000 yards from DesDiv TWELVE. Our forces were disposed in a line of division columns with ships at intervals of 500 yards. At 2228 course was changed by division column movement to 1240 T. to sweep the reefs fringing Gizo Island and the approach to Blackett Strait. That done, course was changed to 0000 T. at 2250 for a sweep up the west coast of Kolombangara Island.

After the moon set at 2226 the night was extremely dark. The sky was completely overcast, with a ceiling at about 4,000 feet. Surface visibility varied from about 3,000 to 4,000 yards, depending upon the rain squalls that descended at frequent intervals. The wind was from the southeast, force 2. The sea was smooth, the Gulf being nearly landlocked. Our force was apparently not sighted by enemy planes throughout the approach.

The Engagement

2333 Dunlap makes radar contact.

2341-42 DesDiv TWELVE fires 24 torpedoes.

2344 CTG orders DesDiv TWELVE to execute “Turn 9.”

2346 Explosions seen on targets. DesDiv FIFTEEN changes course to 2300 T. and opens fire.

2351 Enemy destroyer turns over and sinks.

2352 DesDiv TWELVE changes course to 1800 T. to join in gunfire. Whole target area flame. Many explosions.

2355 CTG orders Dunlap to open fire on smaller ship. Other ships of division join in firing. DesDiv FIFTEEN changes course to 090 degrees T. and joins in firing.

0000 Target disappears.

0017 Enemy destroyer observed against flames of a large destroyer and sunk by gunfire from DesDiv FIFTEEN.

0027 Large enemy destroyer presumed sunk by torpedoes from DesDiv FIFTEEN.

At 2318 the flagship Dunlap reported what appeared to be a good radar contact bearing 0900 T., range 4,500 yards, and requested verification by

5

the other ships. Upon receiving no verification the contact was abandoned as false. At 2323 course was changed to 0300 T., speed to 25 knots to continue along the northwest coast of Kolombangara.

Shortly after discarding the first contact as a phantom, the Dunlap at 2333 made a second radar contact, bearing 3590 T., range 23,900 yards, and requested verification from other vessels. Craven confirmed the contact reporting, “I have three targets; looks mightly nice to me”; to which the Dunlap replied over TBS, “We have four.” Reports from the Combat Intelligence Center indicated that the enemy ships were in column, apparently using a shallow zigzag on course 1650 T. and 180 0 T., at speed between 25 and 30 knots.

At 2340, when the Dunlap’s Torpedo Officer announced a track angle of 2900 T., and the distance between the opposing forces was being closed at a rate of about 50 knots, CTG MIKE gave orders over TBS for DesDiv TWELVE to take course 3350 and prepare to fire torpedoes. DesDiv FIFTEEN turned by column movement to follow DesDiv TWELVE, then changed course to 2700 T. and then to 1900 T. The two division of TG MIKE now drew apart rapidly with Division TWELVE on a course that, if continued, would sweep the port flank of the enemy column while Division FIFTEEN was preparing to cut back on a southwesterly course to cross the bow of the enemy in excellent position to open gunfire.

Between 2341 and 2342 DesDiv TWELVE fired 24 torpedoes at a range of 4,300 to 4,820 yards. Since surface visibility at this time was less than 4,000 yards, none of the enemy ships had been sighted at the time of torpedo attack. At 2345 Division TWELVE made a simultaneous turn to the right to maneuver clear of possible enemy torpedo fire and to take station for further action, leaving Division FIFTEEN to engage the enemy with gunfire during the maneuver.

While results of the attack were awaited, the chief torpedoman’s mate of the flagship Dunlap reported to the bridge of his vessel that all torpedoes “appeared to run hot, straight and true.” At 2346 the first explosion was observed among the targets. There followed a series of violent explosions, variously reported as to number. The general consensus of opinion seems to have been that there were four hits on three vessels, occurring from left to right; these were followed by another series of violent explosions totaling between seven and ten.

The torpedo attack created such havoc among the enemy forces that from the time its results were observed it was evident that the battle

6

was won. Two ships were rocked by continuous explosions, and a third was enveloped in a mass of flame with successive explosions. The latter target was at first identified as a cruiser, though later information indicated that she was probably a large destroyer. Red flames and heavy black smoke proved unmistakably that she had been hit in her oil tanks. A large fire developed in the center of the explosions and spread over a considerable area.

It seems probable that the enemy did not know of the presence of our force until he was hit, since there were no indications of any evasive action taken by his ships. It was suggested that the position of our ships, close to the shoreline of Kolombangara may have prevented detection by Japanese radar. The enemy force seemed to be thrown into confusion from the start of the engagement. Some enemy gunfire was reported, but it was of short duration and entirely ineffective.

Immediately after the first torpedo explosion, Division FIFTEEN, now broad on the port bow of the enemy column, swung right on course 2300 T. to cut across its course, and opened fire with all guns. The Lang picked a target to the left of the flames by FD radar. An early hit illuminated the target, and the Sterett and Stack joined without signal in concentrating gunfire upon the same ship. About the third salvo, a yellow fire broke out amidships and spread rapidly. The target, now seen to be a destroyer, returned an ineffective fire, but under the combined pounding of three ships she rolled over and sank at 2352.

In the meantime the Stack discovered what was believed to be a good target in the area of the large destroyer that was aflame, and the Commanding Officer, Lt. Comdr. Roy A. Newton, ordered the starboard torpedo battery fired. It was believed that at least one hit was obtained, but results were obscured by the fire.

At 2352 Division TWELVE, having completed its evasive maneuver, changed course to 1800 T. by turn movement to join in the gunfire. At 2355 Comdr. Moosbrugger ordered his flagship to open fire upon a target southeast of the burning area. The battery of the Dunlap was immediately joined by those of the other two ships of Division TWELVE. At 2356, just as Division FIFTEEN was changing course to 090 degrees, gunflashes were observed coming from an enemy vessel, which was evidently firing on our division as it turned. This was the target upon which Division TWELVE had just opened fire from the opposite side. The Japanese destroyer was

8

now smothered by fire from both divisions and “literally torn to pieces.” She disappeared at 0000.

At 0003 the commander of TG MIKE ordered Division TWELVE to change course to 310 T. and pass a few thousands yards to the north of the flaming area. His purpose was to take a position near the northwest entrance to Vella Gulf so as to be prepared to intercept any other enemy force approaching.

Radar search indicated only one target remaining in the area, the bearing of which revealed it to be the large burning destroyer, which could be clearly seen at this time. Ships of both divisions took turn in keeping up and spreading the fires that raged topside. At 0010 there was a terrific explosion on this ship that mounted 600 to 700 feet in the air. Division FIFTEEN, which had been assigned “mopping up” duties, took course 0500 preparatory to finishing the burning ship with torpedoes. At 0017, when our ships were about ready to fire torpedoes, the procedure was interrupted by a rare and unexpected opportunity.

An apparently undamaged destroyer, not indicated on the radar scope, moved slowly into silhouette against the flames from the burning ship. Division FIFTEEN immediately opened fire at a range of less than 5,000 yards. All three ships began hitting at once, their salvos rending the topside and starting fires. An early salvo from the Sterett, striking just aft of amidships, evidently hit the enemy vessel’s magazine. After a violent explosion the bow of the destroyer rose to an angle of sixty degrees, and she sank stern first in a few seconds.

At 0020 CTG MIKE, being informed that Comdr. Simpson was going to sink the remaining ship with torpedoes, ordered Division TWELVE to change course to 0900 T. in order to clear range for Division FIFTEEN. Just at this point the Dunlap reported a torpedo to starboard and took an evasive turn. The same ship reported another torpedo at 0035 and a third at 0059. At none of these times, however, was a torpedo sighted from her bridge, and it was concluded that the reports were erroneous.

Comdr. Rodger W. Simpson in the meantime turned to the task of finishing the remaining Japanese ship, directing each ship of his division to fire two torpedoes at the burning vessel. Three violent explosions resulted. The target was said to have “looked like a bed of red hot coals thrown a thousand feet in the air.” At 0027, after more explosions, she disappeared from sight as well as from all radar screens in the force, and was presumed to have sunk. Oil and debris continued to burn in the area for an hour and a half.

Radar search revealing no further targets in the surrounding area, both divisions, after joining up and adjusting their formations, maneuvered to search the area of burning oil. Much burning wreckage cluttered the area, filling the air with a mingled smell of burning fuel, diesel oil and wood. Observing many survivors in the water, Comdr. Moosbrugger directed Division TWELVE to attempt to pick up some of them. However, at this time the Maury reported that engineering difficulties would probably prevent her from maintaining her speed, a maximum of 22 at that time, for more than an hour. At 0118, therefore, Comdr. Moosbrugger retired down the “Slot”4 with Division TWELVE after directing Comdr. Simpson of Division FIFTEEN to attempt to pick up survivors for intelligence purposes.

__________

4“The Slot” was previously designated on Solomon Island charts as New Georgia Sound. On later charts this bod of water is given the name of “The Slot”, in conformity with common usage.

10

Steaming through the survivor area at 25 knots, Division FIFTEEN required about four minutes to traverse waters that were filled with men clinging to rafts and wreckage. To the Commanding Officer of the Lang it seemed that “the sea was literally covered with Japs”—so thick that their bodies were seen to be thrown up in the phosphorescent wake of the vessel. From all sides the survivors lifted a cry that sounded like “Know-we, Know-we”, chanted in unison with considerable volume.5 “It was a weird unearthly sound punctuated at times by shrieks of mortal terror.” When speed was reduced and efforts were made to pick up survivors someone in the water blew a whistle, the chanting stopped and the men all swam away from the ship.

It was concluded from the number of men seen in the water, a number clearly in excess of that accounted for by the ships’ crews, that all four vessels were probably carrying troops and supplies to Kolombangara or reinforcements for Vila. Enemy casualties were thought to have been quite heavy, since there was no opportunity for orderly abandonment in the case of any one of them. Moreover, the area surrounding the large destroyer had been a flaming sea of oil, and the waters surrounding the other vessels had been smothered with gunfire, much of it 5-inch AA common.

Unable to get any Japanese survivors aboard, or to discover any other targets, Division FIFTEEN retired from Vella Gulf about 0200 and proceeded to Tulagi. The reassembled task group discovered no material damage to any ship and no personnel casualties whatever as a result of its highly successful engagement.

Conclusions

As is usual in these night actions, evidence as to the exact extent of the enemy’s losses is not conclusive. There seems to be no doubt that there were four Japanese vessels involved in the engagement. All the observers among our forces whose reports are on record believed that all four were destroyed. On the other hand, several Japanese survivors who were picked up later insisted that one of the destroyers escaped. Our own observers consistently refer to the “cruiser” present among the Japanese vessels. The gunnery officer of the Dunlap, who was in a good position for observation, identified it as belonging to the Kuma or the Natori class. Contrary to this, however, is the testimony of the prisoners, who

___________

5 The word was probably Kowai, a Japanese ejaculation of fear.

11

agreed (even to the names of the ships) that all fur of the ships were destroyers. At the present time, therefore, all that can be claimed conclusively are three destroyers sunk and one heavily damaged.

As a result of this battle heavy enemy reinforcements were prevented from reaching Kolombangara. This probably decided the Japanese to evacuate the Island instead of holding it. “Had they elected to defend it,” observed CINCPAC, “it would have cost us a diversion of effort, either in ground forces to take it by assault, or in air and surface forces to keep it neutralized as we by-passed it and moved further to the northwest.”

Destruction of Barges in Vella Gulf, 9-10 August

On 9 August Admiral Wilkinson received word from COMSOPAC that another Tokio Express composed of cruisers and destroyers appeared to be preparing another attempt to reinforce the garrison at Vila and that troop-carrying barges might be present also. Admiral Wilkinson ordered Comdr. Moosbrugger’s Task Group to proceed to Vella Gulf, arrive at Gizo Strait at 2200, and make a sweep of the Gulf to destroy enemy shipping.

Task Group MIKE was composed of the same ships that had fought the Battle of Vella Gulf on 6-7 August, except for the substitution of the Gridley, Lt. Comdr. Jesse H. Motes, Jr., for the Maury in DesDiv TWELVE and the substitution of the Wilson, Lt. Comdr. Walter H. Price, for the Stack in DesDiv FIFTEEN.

The two Division Commanders, Comdr. Moosbrugger and Comdr. Simpson, held a short conference before the departure of the task group. It was decided that the battle plan used on the night of 6-7 August would be followed and the same assumptions would be made. Since contact with the enemy had not been made on that occasion until our task group was nearly out of the Gulf, it seemed probable that the Japanese assumed that our ships had come up the Slot instead of through Gizo Strait. It was considered unnecessary, therefore, to vary the route on the 9th.

Task Group MIKE formed in the vicinity of Savo Island and took a course south of the Russells and Rendova Island. Three Black Cats were assigned to the group for scouting, but again no contact was established with any of the Cats during the night.

Entering Vella Gulf by way of Gizo Strait about 2258, the task group swept partly around Gizo Island, then at 2344 changed course to 0000 T.

12

to make a sweep of the western shore of Kolombangara. The sea was smooth, the wind from the southeast, force 4; the sky was overcast and visibility was between 700 and 3,000 yards.

Two radar contacts were made on small unidentified targets soon after the group entered the Gulf. The first contact, established at 2313, was probably a barge near the shore of Liapari Island. The second contact, probably another barge, was made at 2347 on the opposite side of the Gulf, off Sandfly Harbor, Kolombangara. The Task Group Commander ordered that neither target be taken under fire. His primary mission was to destroy the Tokio Express, and since radar search of the Gulf had not been completed he did not wish to reveal the presence of the task group.

Comdr. Moosbrugger changed course to 0300 T. at 0003, and increased speed to 25 knots. At 0014 a third radar contact was made which after a few minutes appeared to be three enemy barges. Radar search had been carried far enough by this time to indicate that there were no enemy destroyers in the Gulf. Believing that the Express might be approaching from the north, Comdr. Moosbrugger directed Division TWELVE to hold fire and continue northward, while Division FIFTEEN took the targets under fire.

At 0020 Division FIFTEEN sighted three barges at 1,000 yards and fired on these targets intermittently until 0032. The barges returned fire with 25 caliber machine guns, but caused no casualties. Two of these barges were possibly sunk and one damaged.

Division TWELVE completed a northern sweep of the Gulf, and Division FIFTEEN rejoined on the southward sweep of the coast of Vella Lavella. At 0018 the Gridley made contact on a target near Liapari Island that was thought to have been the barge located earlier near the same place. Five ships opened fire on this target which disappeared from all screens about 0137, and was believed to have sunk.

The Task Group turned northward again at 0138 and picked up another contact bearing 0640 T., distant 7,340 yards, which may have been one of the three barges engaged at 0020. The Group closed range and Division TWELVE and the Lang opened fire at 0151, continuing to fire for five minutes. The contact disappeared from the screen and was presumed to have sunk.

After operating in Vella Gulf for nearly four hours, Comdr. Moosbrugger retired through Gizo Strait and turned southward at 0241 to return to his base by the same route used in his approach.

13

In all seven radar contacts were made, two of which may have been twice contacted. Only brief glimpses of the targets could be gained. From this incomplete evidence it was estimated that they were barges between 80 and 100 feet in length. They were tracked at speeds up to seven knots. Their small caliber gunfire was ineffective, causing no casualties to our forces.

LANDING ON VELLA LAVELLA

Strategic Considerations

One week after the Battle of Vella Gulf another major step was taken in the Solomons Campaign. The capture of Munda and the consolidation of control over New Georgia had left Arundel Island, Kolombangara, and Vella Lavella, as well as several smaller islands, to be occupied. Of these, Kolombangara with a garrison of more than 5,000 Japanese troops, strong fortifications, and an airfield was easily the most formidable. Up until 12 July, Kolombangara had been scheduled as our next objective. On that date, however, when the fall of Munda seemed to be impending and it seemed likely that this airfield could be used to extend the range of our fighter cover, Admiral Halsey decided to cancel the earlier plan in favor of an assault upon Vella Lavella.

This decision marked an important departure from the strategy hitherto followed in the South Pacific. Our advance so far had been from one enemy-occupied and defended island to the next. The primary objective in both Guadalcanal and New Georgia had been an enemy airstrip. The new strategy was to by-pass the enemy defenses on Kolombangara and his airfield at Vila and advance our island perimeter many miles beyond to an island with negligible defenses and no airfield. Although there were significant differences, this strategy had been in part anticipated in the Aleutians Campaign when we by-passed Kiska and landed on Attu 11 May 1943.

Lying northwest of Kolombangara, athwart the path of the supply routes of enemy bases on that island, Vella Lavella would furnish bases for more effective patrol of both Vella Gulf and Blackett Strait. The latter provided the favorite rote for Japanese barges running supplies to the garrison at Vila. It was intended to establish a minor naval base and an airstrip on the island from which Japanese shipping and air bases of southern Bougainville might be attacked.

It was known that Vella Lavella had received little attention from the Japanese during their occupation of the Solomons in the summer of 1942.

14

Current intelligence reports estimated enemy strength in the island to be perhaps 250 men. These men, equipped with light antiaircraft guns, were concentrated principally on the northwest coast, from which they operated barge supply points.

The coastal area of Vella Lavella is a narrow strip varying in width from 100 yards to one mile. Beyond this the ground rises abruptly toward a central ridge from 2,000 to 3,000 feet in height. Apart from the coconut plantations along the coast, usually located opposite channels giving entrance through the main reefs, the country is overgrown with heavy jungle through which it is impossible to see more than a few yards.

On the night of 21-22 July, a party of six Army, Navy and Marine officers was landed on Vella Lavella by PT boat for the purpose of making a comprehensive reconnaissance of the southern part of the island. The party investigated Liapari Island, Biloa Anchorage, landing beaches, and a site for an airstrip. Taken off six days later, along with the rescued crew of a Catalina patrol plane, the reconnaissance mission reported suitable beaches and a site for a PT base at either Liapari or Nyanga. Because of good drainage, safe approaches, suitable beaches and bivouac areas, Barakoma was selected as the site for the landing and for the construction of an airstrip. Furthermore, the locality was not occupied by the Japanese and no opposition in force was expected.

Task Force Organization

Acting upon Rear Admiral Theodore S. Wilkinson’s recommendations, Admiral Halsey designated 15 August as D-day,6 and authorized a force composed of Naval, Army and Marine Units for the operation.

The composition of the main body of Task Force WILLIAM under command of Admiral Wilkinson was as follows:

Advanced Transport Group, Capt. Thomas J. Ryan, Jr.

TransDiv TWELVE, Comdr. John D. Sweeney

Stringham (F), Lt. Comdr. Ralph H. Moreau

Waters, Lt. Comdr. Charles J. McWhinnie

Dent, Lt. Comdr. Ralph A. Wilhelm

Talbot, Lt. Comdr. Charles C. Morgan

TransDiv TWENTY-TWO, Lt. Comdr. Robert H. Wilkinson

Kilty (F), Lieut. John W. Coolidge.

____________

6 It is an interesting coincidence that 15 August also became D-day for the landing on Kiska, which had been by-passed by the taking of Attu.

15

Ward, Lt. Comdr. Frederick W. Lemly

McKean, Lt. Comdr. Ralph L. Ramey

DesDiv FORTY-ONE, Capt. Thomas J. Ryan, Jr.

Nicholas (F), Lt. Comdr. Andrew J. Hill, Jr.

O’Bannon, Lt. Comdr. Donald J. MacDonald

Taylor, Lt. Comdr. Benjamin Katz

Chevalier, Lt. Comdr. George R. Wilson.

Cony (FF), Comdr. Harry D. Johnston

Pringle, Comdr. Harold O. Larson

Single Transport Group, Capt. William R. Cooke, Jr.

LCI Unit, Comdr. James M. Smith

LCI’s 61, 23, 67, 68, 332, 334, 222 (F), 330, 331, 333, 21, 22

DesDiv FORTY-THREE, Capt. William R. Cooke, Jr.

Waller (F), Comdr. Laurence H. Frost

Saufley, Comdr. Bert F. Brown

Philip, Lt. Comdr. William H. Groverman, Jr.

Renshaw, Lt. Comdr. Jacob A. Lark

Third Transport Group, Capt. Grayson B. Carter

LST’s 354, Lieut. Bertram W. Robb

395, Lieut. Alexander C. Ford

399, Lt. (jg) Joseph M. Fabre

DesDiv FORTY-FOUR (less Pringle, Cony), Comdr. James R. Pahl

Conway (F), Comdr. Nathaniel S. Prime

Eaton, Comdr. Edward L. Beck

SC’s 760, 761

Screen

DesDivs FORTY-ONE, FORTY-THREE, FORTY-FOUR7

MTB Flotilla CAST, Comdr. Allen P. Calvert

New Georgia MTB’s

18 MTB’s

Kolombangara MTB’s

8 MTB’s

Northern Landing Force, Brig. Gen. Robert B. McClure, U. S. A.

Troops

Headquarters Detachment

4th Marine Defense Battalion (less 155 mm Gun Group; Btry. D [90 mm];

1/2 Btry. G[S/L] and Tank Platoon).

35th Regimental Team (less certain detachments)

___________

7 After performing convoy duty to Barakoma beach these destroyers were to form a screen for landing operations.

16

Naval Base Force, Capt. George C. Kriner

58th Construction Battalion (less rear echelon)

Naval Base Units including Boat Pool No. 9

Preliminary Operations

During the week preceding the operation considerable air strength was reported in Kahili and Rabaul, and destroyers were observed in the Buin-Shortlands area. Photographs of the Rabaul area taken on the 13th revealed—besides 19 cargo vessels—two cruisers, five destroyers, six submarines, and smaller warships. Airdromes in the area held an estimated total of 271 aircraft. In the harbor were 25 floatplanes and four flying boats. All these hostile forces had to be taken into account in the plan of operations.

Surface forces of the Third Fleet were held in reserve to provide protection against any major enemy forces that might put in an appearance. Motor torpedo boats based on Rendova and Lever Harbor were to screen our forces by picket lines to the south, the west, and the northeast of Vella Lavella during the night of 14-15 August, returning to base at daylight on the 15th.

Shore-based aircraft from Munda were to support the operation. An attack upon Rabaul by aircraft from the Southwest Pacific Area was requested in view of the concentration at that point, but General MacArthur reported this to be impracticable because of other commitments.

In spite of adverse weather through most of the week preceding the attack on Vella Lavella, Allied planes struck at enemy bases and depots in the Vila, Buin and Rekata Bay areas. TBF’s and SBD’s dropped 36 tons of bombs on gun positions at Disappointment Cove and Kape Harbor, Kolombangara, on the 13th. On the 12th and 13th Liberators dropped a total of 49 tons of explosives on the airfield at Kahili, destroying many planes and shooting down 11 enemy fighters. The seaplane base in Rekata Bay was attacked seven times and the Vila airdrome was raided almost nightly during the week.

As a final preliminary to the action, an advance party was landed at Barakoma on the night of 12-13 August to mark the channels and beaches to be used by landing craft and to select bivouac and dispersal areas and defense positions. Another duty assigned this advance party, which consisted of only 25 men, was to take custody of a large number of Japanese prisoners reported to be held by native sentries. Upon arrival, however, it was discovered that no prisoners were in hand, but that several

17

hundred refugees from Kolombangara and survivors from the enemy ships sunk during the night of 6-7 August were at large. These Japanese were reported to be armed with hand grenades, clubs, and a few firearms. Reinforcement was immediately requested and after some delay the troops were moved in from Rendova by motor torpedo boats after dawn on the 14th.

Approach and Landing at Barakoma

In the meantime, loading of equipment and supplies on the LST’s at Guadalcanal had begun on 12 August and was completed the following day. On the 13th troops embarked, conducted a debarkation drill, and reembarked. At 2130 that evening at Kokumbona a single enemy plane came in low for an attack on the Eaton. The destroyer opened fire and observed its tracers hitting the approaching plane, which quickly ignited, whirled off to the west and crashed inland.

With the exception of one reinforced battalion of the 35th Combat Team which embarked in the Russells, all units of the Main Body of the Task Force embarked at Guadalcanal. The three Transport Groups, each with its screen of destroyers, departed independently on 14 August on a schedule arranged to time their arrival at Barakoma on the 15th as follows:

| Depart | Arrive | |

| Guadalcanal | Barakoma | |

| 14 August | 15 August | |

| Advance Transport Group | 1600 | 0610 |

| Second Transport Group | 0800 | 0710 |

| Third Transport Group | 0300 | 0800 |

It was hoped thus to avoid undue exposure to air attack by giving each group full use of the beaches and cutting to a minimum the time other groups would be kept awaiting opportunity to unload.

Admiral Wilkinson chose as his flagship the Cony, on which General McClure also embarked. The Pringle was designated primary fighter director ship with the Conway as relief. The O’Bannon and the Taylor, as bombardment ships, were to open fire on any shore battery which threatened our landing craft. Screening destroyers were to maneuver to seaward of the transport area.

The weather during the approach to Barakoma was excellent, the sea calm, the sky nearly cloudless, and at night there was a brilliant moon.

18

All Task Groups took the same course, lying south of the Russells and Rendova, thence north through Gizo Strait. Northwest of Rendova the three groups "leap-frogged.” Shortly before dawn the Third Group with LST’s was slowly overhauled and passed by the Second Group with the LCI’s, while almost simultaneously the Advance Group with the swift APD’s overtook and passed both the slower Groups. The Units finally entered Gizo Strait in correct order. So far, but for the approach of an enemy snooper plane which apparently passed without spotting our force, the passage had been uneventful.

The Advance Group arrived off Barakoma at the break of dawn and began unloading troops and equipment at 0615. Debarkation proceeded with dispatch, and was completed by 0715. The APD’s departed on the return trip to Guadalcanal at 0730 with a screen of four destroyers. It was with the beaching of the LCI’s of the Second Group at 0715 that the schedule was broken. It was discovered that only 8 of the 12 landing craft could be accommodated at one time by the three beaches. This condition plus an error in communications from the beach party delayed the completion of unloading the last four LCI’s until about 0900. In the meantime the LST’s had arrived at 0800 according to schedule and were awaiting their turn at the beach.

Antiaircraft Action

Friendly aircraft from Munda were overhead by 0605. Since the landing was carried out within 90 miles of Kahili, the largest Japanese air base in the Solomons, it was no surprise when the radar of the fighter director destroyer picked up bogies at 0747. The original raiding party was considerably larger than the number of planes that succeeded in breaking through to deliver the attack. Our fighters, which successfully intercepted the attack, were credited with shooting down many planes.

At 0759 between 15 and 20 enemy fighters and dive bombers commenced an attack on the destroyers of the screen, ignoring for the moment the more vulnerable targets presented by the beached LCI’s and the slow LST’s. The flagship Cony sustained three near hits, two within 50 yards of the ship, but there was no damage to the vessel and only one man was slightly wounded. Planes also dove on other destroyers, straddling the Philip’s bow narrowly and bracketing LST 395 with two near hits, but without damage to either. Antiaircraft fire from the attacked vessels was effective in helping drive off the attack. The Nicholas, O’Ban-

19

non, Taylor and Chevalier, still in the area during the attack, also joined in the firing.

The LCI’s completed unloading by 0900 and retired with all the remaining destroyers except the Conway and the Eaton. The Advance Group and the Second Group returned separately to Guadalcanal.

Between 0900 and 0915 the three LST’s beached and began unloading. LST 395 struck a ledge of broken coral short of dry land, necessitating the construction of a ramp. This was quickly accomplished with the aid of a bulldozer that had been placed in the bow of the ship for such a purpose. Difficulties in clearing jungle growth for space to deposit supplies, and in keeping at work the personnel assigned unloading duty threw the LST’s off schedules. Instead of departing at 1600 the Group did not retire before 1800.

Unloading proceeded laboriously under a burning sun and a perfectly clear sky. Visibility was so excellent that Corsairs and Kitty Hawks circling at altitudes up to 24,000 feet were clearly visible to the unaided eye.

After the attack of 0800 the ships remained unmolested until 1227 when the heaviest attack of the day began, continuing about 15 minutes. The Japanese planes, dive bombers of the Aichi 99 type plus Mitsubishi Zeros, were intercepted, but two groups consisting of eight to twelve bombers broke through and attacked. One of these groups attacked the beached LST’s; the other two struck at the destroyers. Bombers were seen circling at 14,000 feet and starting their glides, some of which were steep, others shallow.

The first bomber to dive on the Conway was shot down, crashing within 50 feet of that ship. Three of its bombs burst close off the ship’s starboard bow. The salvo from the second plane fell even closer on the starboard bow, one bomb within 20 yards. The third plane was shot down and crashed 500 yards from the Eaton. The next three bombers sustained no apparent damage, but their bombs missed badly.

Eight bombers came in high and fast out of the sun to attack the LST’s. Near hits were scored on two of the ships. No material damage was done, though one man was seriously wounded. One of the landing ships claimed to have downed two bombers with antiaircraft gunfire and another at least one.

Scarcely had the bomber attack been broken up when the Conway spotted seven fighters, Zeros and Vals, hedge hopping over a saddle in the ridge of the island, closing in for a strafing attack on the landing area.

20

The gun control officer of the Conway opened effective fire before the planes were sighted by the landing ships, and brought down one. Amply warned by the destroyer’s fire, the crews of the LST’s put up a tremendous fire from small and medium weapons which completely frustrated the attack. One of the landing ships claimed three planes, another two, and the third one plane shot down. Capt. Grayson B. Carter, commander of the Third Transport Group, considered the repulse of this attack “the highlight of the day.” In all, our forces reported they shot down ten planes in the noon attack.

Unloading was resumed and proceeded uneventfully until warning of a fourth attack came at 1724 from the Combat Air Patrol. This attack group, a large one coming in from the northwest, was intercepted and all but broken up by the Air Patrol. Only about eight single planes succeeded in getting through. They dived wildly, released bombs indiscriminately, and fled low over the water without inflicting any damage.

Shortly after this attack, the Third Transport Group completed unloading except for about 130 tons of cargo aboard two LST’s and retired at 1800 to avoid exposure to night attacks while without fighter cover.

Defense against air attacks during the day had been highly successful so far as the ships and their personnel were concerned. Ashore, however, twelve of the landing force had been killed and forty wounded, though damage to material was slight.

On the return to Guadalcanal under a brilliant full moon and a clear sky, two of the three Transport Groups were subjected to repeated air attacks. From five to eight Mitsubishi 97’s attacked the Second Group, consisting of 12 LCI’s and four destroyers, when it was south of Rendova Island. The planes attacked singly at intervals from 2050 to 2140, dropping, it was believed, six torpedoes in all. No hits were made, however.

As in the daylight attacks, it was the Third Transport Group that took the most prolonged punishment. Between 2034 and 2330 the Group underwent six horizontal bombing attacks, and for four hours the convoy was surrounded or partially surrounded by flares and float lights dropped by the enemy. The bombs were usually dropped in patterns of eight, and were thought to be not over 100 pounds in weight. So often were the awkward landing ships bracketed and straddled that one of their commanding officers was sure that LST meant “large slow target.”

21

All of these ships were sprayed with shrapnel. One reported some 200 holes punctured in bulkheads. Another reported 14 near hits from bombs within 100 feet of the vessel. The destroyers made frequent use of smoke screens. That our ships survived the attacks with only minor damage and insignificant casualties was attributed, among other things, to “a perfectly phenomenal supply of good luck.” Several officers commented on the excellence of Japanese night search and attack.

Operations Ashore

In the course of D-day the three Transport Groups had landed at Barakoma a total of 4,600 troops, including 700 Naval personnel; 2,300 tons of equipment and supplies, including eight 90-mm antiaircraft guns; 15 days’ supplies of all classes, and three units of fire, except for the 90-mm guns, for which one Marine Unit (300 rounds per gun) was landed. The supplies discharged were considered sufficient to sustain the landing party well beyond the scheduled arrival of the next echelon.

The 4th Defense Battalion of the Fleet Marine Force immediately upon landing began setting up antiaircraft guns in temporary shore positions. By 1530, sixteen 50 caliber machine guns, eight 20-mm, and eight 40-mm guns were in position. Marine gunners were credited with shooting down five enemy dive bombers during the day. By 1800 two searchlights were in readiness. During the night of 15-16 August shore installations were attacked 12 times by enemy planes, but only minor damage was inflicted.

Troops of the 35th Regimental Combat Team had landed without opposition and proceeded with their task of establishing a temporary defense perimeter. This was accomplished by noon without any Japanese resistance having been encountered, and field artillery was emplaced in temporary positions by 1700. In the meantime naval base units, including the 58th Construction Battalion, commenced work upon docks, ramps, roads, airstrips and dispersal areas.

NIGHT ACTION OFF VELLA LAVELLA, 17-18 AUGUST

Preliminary Maneuvers

Early in the afternoon of 17 August a plane contact with enemy forces from Bougainville was reported at Admiral Wilkinson’s headquarters. The report gave the location, disposition, course and speed of four destroyers making up a Tokio Express probably destined either for the relief of Kolombangara or an attack on the new base at Barakoma.

22

Admiral Wilkinson dispatched Capt. Thomas J. Ryan, Jr., commanding officer of Destroyer Squadron TWENTY-ONE, with four destroyers of Division FORTY-ONE to intercept the enemy force. Task Unit ROGER was organized as follows:

Nicholas (F), Lt. Comdr. Andrew J. Hill, Jr.

O’Bannon, Lt. Comdr. Donald J. MacDonald.

Taylor, Comdr. Benjamin Katz.

Chevalier, Lt. Comdr. George R. Wilson.

Forming column open order, distance 500 yards, in the order named above, the Task Unit departed Purvis Bay, Tulagi Island, at 1527, 17 August, and proceeded “up the Slot” at 32 knots, course 3050 T. This route took the force east of New Georgia Island to arrive at a position 30 miles bearing 3050 T. from Visu Visu Point, on New Georgia, at 2300, and thence north of Kolombangara.

According to the original plan, Capt. Ryan’s force was to be augmented by two destroyers from DesDiv FORTY-THREE, which was then screening the Second Echelon on its return from Barakoma. The Philip and the Saufley, under the command of Capt. William R. Cooke, Jr., were to join Task Group ROGER en route to intercept the enemy, and destroy barges expected to be under escort by the Japanese destroyers. However, upon hearing by TBS that the Waller, the third destroyer of DesDiv FORTY-THREE, was in difficulty, and knowing that Capt. Cooke was escorting LST’s through Gizo Strait, Capt. Ryan ordered the Philip and the Saufley to return to Capt. Cooke.

A minor casualty aboard the Chevalier threatened to diminish the strength of the Task Unit still further. At 1630 her number two main feed pump became steam-bound and necessitated the vessel’s dropping out of formation to make necessary repairs. Since the casualty had been foreseen, repairs were quickly made and the Chevalier rejoined at about 1655.

Between 2035 and 2253 numbers of bogies were tracked, closing and opening range. Some of these were probably friendly planes. At any rate no attack was made on the force. All hands were called to general quarters at 2210.

Toward midnight gun flashes were seen from the enemy force then under attack by our TBF’s. At 0025, one of our torpedo planes that had participated in the attack reported four enemy destroyers midway between

23

Vella Lavella and Choiseul Island on course 1200 T., speed 12 knots. Repeated efforts to obtain further information from planes, including two Black Cats, were unavailing because of poor radio reception at both ends.

Shortly before this report, the weather had cleared. A brilliant moon, almost full, which had been obscured by frequent rain squalls until 0010, now provided visibility for more than eleven miles. The sea was calm, the wind from the southeast between force 1 and 2.

Engagement with Destroyers

0029 O’Bannon reports surface contact.

0039 Enemy aircraft drops flares, scores near bomb hit on Nicholas.

0056 Enemy DD’s open fire.

0058 Nicholas opens fire followed by O’Bannon and Taylor.

0100 Chevalier fires five torpedoes.

0110-13 Explosions noted on two enemy destroyers, fire on third.

0121 Engagement with enemy destroyers broken off.

At 0029, when our forces were off the northeastern tip of Vella Lavella Island, in latitude 070 26’ 25” S., longitude 1560 45’ 05” E., the O’Bannon reported a surface contact bearing 3130 T., distance 23,000 yards. The Chevalier made contact at almost the same time, and the enemy was visible within two minutes. A number of barges were located between our formation and the enemy destroyers. Capt. Ryan ordered a series of changes in course in order to close the destroyers.

It was believed that enemy planes, which radar plot indicated had been circling Task Unit ROGER since 0014, had sighted and reported its presence to the enemy ships. With the assistance of spotting planes, excellent visibility, and a full moon, the enemy was in all probability aware of the presence of our ships when the O’Bannon first made radar contact. At any rate the Japanese destroyers had formed up and changed course as if to avoid engagement.

At 0039 enemy planes dropped flares that illuminated our formation and also a stick of bombs that landed about 100 yards off the starboard bow of the Nicholas at the head of our column.8 Eleven minutes later the planes dropped two more flares, just as our formation was passing near the group of enemy barges. These now appeared to consist of numerous small barges towed by two tugs, and two large ones. For the moment our ships passed them up, with the intention of returning later to destroy them.

___________

8The Commander of the O’Bannon believed these bombs fell 100 yards off the starboard quarter of the Nicholas.

24

At 0056, when the range was about 14,000 yards, the Japanese destroyers opened fire—about two minutes before our ships commenced firing. Initial enemy salvos were over our formation some 600 yards, though the pattern of gunfire was reported to be good, and the third or fourth salvo fell short, almost finding the range. The Chevalier received a near hit about 50 feet off the starboard beam, which drenched personnel on the bridge with its splash. For approximately two minutes after the enemy opened fire, the Nicholas, O’Bannon, Taylor and Chevalier were in column on course 2700, and three of the Japanese destroyers, also in column, were on a course of about 1800. For this prief period, while almost crossing our bow, the enemy gunners enjoyed a tactical advantage.9 Additional advantages of the enemy were a bright moon, against which our force was silhouetted, and the flares previously dropped by planes. After the first few salvos, however, enemy gunfire became gradually less accurate until at the close of the engagement shells were landing between two and three thousand yards short.

At about the time the Japanese opened fire, one of their destroyers swung out of formation to close range rapidly, apparently with the intention of firing torpedoes. Accepting the torpedo menace, Capt. Ryan continued to close range until 0058 when the formation executed a column right to open gunfire, coming to course 3500 T., all ships following the Nicholas without signal. At 0058 the Nicholas, and at 0100 O’Bannon and Taylor commenced fire upon the enemy column, at ranges varying from approximately 8,500 yards to 11, 350 yards.

At 0100 the Chevalier, rear ship in the column, fired five torpedoes spread 20, low speed, with full radar control at the enemy destroyer that had advanced out of formation bearing 3000 T., distant 6,800 yards. Immediately after firing her torpedoes she joined in the gunfire. The concussion from Gun No. 3 fired an additional torpedo. The targets at that time were on course 2000 T., speed 30 knots.

Soon after our ships opened fire the Japanese destroyers executed a turn to the northwest, deserted the barges, and fled at high speed. For a few moments after the enemy turned, our ships enjoyed a tactical advantage similar to that the Japanese had enjoyed when they first opened gunfire. Hits were reported on all four targets, some of which were believed badly damaged.

____________

9See track chart.

25

For ten minutes after we opened fire, radical maneuvers to avoid enemy torpedoes were necessary, during which firing had to be suspended intermittently. Japanese torpedo fire was quite accurate. Although none of our vessels was hit, one torpedo wake was reported to have crossed about 25 to 30 yards ahead of the Chevalier, and another to have passed close astern of the Taylor. The Nicholas also reported torpedo wakes.

The Task Unit had orders to fire torpedoes when ready. None of the vessels except the Chevalier, however, believed that the range was suitable for a torpedo attack, since torpedoes had been set on intermediate speed for the action. The Chevalier planned to fire a half salvo from mount two, but this jammed, and mount one had to be used. Torpedoes in the former were on intermediate speed; those in mount one on low speed. At 0110 observers on the Chevalier saw a heavy explosion on the bow of the rear destroyer in the enemy line and the Nicholas heard a distinct underwater explosion. The destroyer on which the explosion was observed turned left, decreased speed, and seemed to smoke heavily.

At 0111 the column reformed after evasive maneuvers, and a turn was made to the left on course 300 degrees T., which was roughly parallel to the course of the retiring enemy. Firing was continued at a range of 15,500 to 17,600. The Taylor and O’Bannon concentrated their gunfire on the third destroyer in the enemy line, obtaining a number of hits. An explosion was observed on this target, which also began to smoke.

In this phase of the action the Nicholas suffered serious casualties in her five-inch batteries. In guns Nos. 1 and 2, after approximately 200 rounds had been fired by each, the rammers failed to retract and jammed in the forward position. A cartridge also jammed in gun No. 4 and proved exceptionally hard to remove. The O’Bannon also suffered casualties in her No. 3 gun as the result of a dented cartridge case and rammer trouble, which caused the gun to miss about ten salvos. These casualties were remedied before the final phase of the action.

Believing that he could not afford to leave the enemy barges unmolested any longer, Capt. Ryan ordered the engagement with the destroyers broken off at 0121. At that time the column was closing with the enemy and hitting again. Three of the Japanese destroyers were still in sight, one of them well ahead of the other two. The third appeared to be dropping slowly astern. 10

_____________

10Capt. Ryan believed the four destroyers to be of the Fubuki-Amagiri class. O’Bannon and Taylor believed one was of the Terutsuki class. A Black Cat pilot was certain that one of the vessels was much larger than the other three and reported it to be a cruiser.

26

The extent of our success in this engagement is not definitely known. At 0128 observers on the Chevalier saw a heavy explosion on the enemy destroyer that had dropped astern, and about 0129 her silhouette disappeared from the horizon simultaneously with the disappearance of her pip from the SG radar screen. This was not the vessel which the Chevalier claimed to have hit with a torpedo. Lt. Comdr. MacDonald of the O’Bannon reported that no enemy vessels were observed to sink, and that his CIC11 officer reported that all four destroyers went off the SG screen out of range. A fighter pilot later reported sighting a burning destroyer off Warambari Bay at the northern tip of Vella Lavella, at 0620, 18 August. This may have been one of the destroyers engaged. All that can be positively claimed, however, seems to be two destroyers damaged. There was no damage to our ships or personnel.

Destruction of Barges

Upon breaking off action with the enemy destroyers, Task Unit ROGER reversed course to search for the barges passed earlier. At 0148 the O’Bannon’s radar showed the barges bearing 213 degrees T., distance 13,000 yards, in a position only slightly to the north of where they were originally sighted. Course was then changed to close and the order given to fire when ready. The radar screen revealed four or five contacts. Range was closed by simultaneous turns until visual contact was established. Some of the barges, not self-propelled, were towed by tugs, one of which 75 feet long with a flush deck and a cabin amidships, was probably of wood. The number of smaller barges under tow was indeterminate. When firing was opened about 0155 the barges scattered to the west at eight to ten knots. One sank and others disintegrated. Machine gun fire appeared to be as effective as the 5-inch battery for these targets. By 0227, after about 20 minutes of firing, only one barge of the original four or five remained on the radar screen, and it was left burning furiously.

At 0235 the O’Bannon reported a new surface contact bearing 183 degrees T., distance 8,000 yards. Capt. Ryan in the Nicholas turned south to investigate this contact, and ordered the Taylor, O’Bannon and Chevalier to continue their search for barges in the area of original contact. The Nicholas discovered one large barge similar to our LCT, set it on fire, and watched it burn intensely and sink at a range of less than 1,000 yards.

__________

11Combat Intelligence Center.

27

Another barge was set afire in the same area. In all, at least four large barges plus an indeterminate number of small barges were thought to have been destroyed. There was no evidence of gunfire or resistance of any kind from the barges.

At 0306 unidentified planes began an attack on the Task Unit. A stick of bombs fell across the O’Bannon, two landing close to the port quarter and two more ahead on the starboard bow; another stick dropped about 300 yards on the starboard beam of the Nicholas, and two bombs fell within 50 to 100 feet of the Taylor. The O’Bannon had already opened fire on these planes when IFF identified them as friendly. This identification, however, proved to be coming from our own ships, which had their IFF turned on at the time, and it was concluded that the planes were not friendly.

Proceeding south close to the reefs six miles off Vella Lavella, the Taylor, Chevalier and O’Bannon fired star shells at 0328 to illuminate the northeast coast of the island. No further targets were discovered. At 0400 the Nicholas, with Capt. Ryan, rejoined the formation, and a sweep of Vella Gulf was made. Aside from firing upon an unidentified plane, and another bombing attack which landed a stick of bombs close to the O’Bannon, the retirement to Tulagi was without incident.

Conclusions

The reason for the enemy’s precipitous desertion of his barges is a matter for speculation. The fact that no personnel was observed aboard the barges and that when set on fire they burned furiously with periodic explosions leads to the supposition that they were carrying supplies only. It seems probable that the combatant vessels were carrying troops. If so this might explain their reluctance to engage and their willingness to leave the barges unprotected.

The bright moonlight, which extended visibility to more than eleven miles, reduced the tactical advantage our forces enjoyed in their radar. Had maximum visibility been 6,000 yards or less, it seems probable that success against the destroyers would have been more nearly equivalent to that achieved in several other similar engagements in this area.

SUPPLYING VELLA LAVELLA

The amphibious phase of the Vella Lavella campaign continued for twenty days after the initial landing and was not complete until four

28

more echelons landed supplies, equipment, and personnel from Kokumbona and Kukum on the coral beaches of Barakoma. Although the enemy failed to oppose these operations with surface vessels, his air force did not neglect the opportunity our supply ships presented while moving slowly through the narrow waters of Gizo Strait and Blanche Channel or lying beached at Barakoma.

The 35th Regimental Combat Team, concerned with establishing and maintaining a defense perimeter, had accomplished its mission without meeting any resistance. Patrols made a few contacts with small unorganized groups of Japanese who offered no resistance and kept moving northward. The military situation had therefore remained virtually unchanged since midday of 15 August.

The Second Echelon

The Second Echelon, under the command of Capt. William R. Cooke, Jr., was scheduled to arrive at Barakoma two days after the initial landing. This consisted of LST’s 339, 396, and 460 screened by Destroyer Division FORTY-THREE (less Renshaw), including the Saufley, Philip and Waller (F), and SC 1266.12 Besides equipment and supplies, these ships were also transporting detachments of the 35th Combat Team, the 4th Defense Battalion, and the 58th Construction Battalion.

Departing from the Guadalcanal area on 16 August the echelon arrived at Barakoma at 1625 the following day. In planning the operation it had been thought that all echelons subsequent to the initial landing group could be more safely unloaded at night. Shortly after our fighter cover withdrew, two waves of enemy planes, one at 1850 and a second at 1910, attacked the beached vessels with bombs and strafing. Expecting the attacks to be continued through the night, Brig. Gen. McClure ordered the LST’s, though still not unloaded, to withdraw from the beach and return in the direction of Rendova pending further orders. With destroyers in screening stations the convoy proceeded down Gizo Strait. There the third enemy plane attack began at 2110, and continued for two hours and seventeen minutes.

From the first attack at 1850 on 17 August, the convoy was under almost continuous attack by enemy planes until about 0200, 19 August. With only brief respite, men were at general quarters stations for a period of about 36 hours. During the greater part of this period no air cover was

____________

12For organization of the 2nd Echelon see Appendix A.

29

present because of darkness or unfavorable weather conditions. Although the fighter director control ship reported repeatedly that enemy planes were in the vicinity, the attacks occurred as a surprise in all but the technical sense, in that they were made under conditions of reduced visibility, such as fog, low clouds, or through smoke screens. Enemy planes were invariably in attack positions before they could be sighted.

That the convoy suffered no damage as a result of these bombing and torpedo attacks was probably due in large part to the effectiveness of smoke screens laid by the destroyers, and also to the fact that the enemy for the most part chose the screening vessels, rather than the LST’s as targets. With radical maneuvers and intense gunfire, these ships escaped damage.

At 2237, while engaging bombing and torpedo planes, the Waller and Philip collided in the narrow waters of Gizo Strait. At the moment of collision both ships were laying smoke screens and making radical changes of course at approximately 30 knots. The Waller was engaging one plane while the radar screen showed two more approaching. Under the circumstances the accident was considered unavoidable. In a sideswipe collision the Waller struck the port side of the Philip. The damage was not serious enough to prevent the ships from continuing their screening duties through the night, though the following morning the Waller’s damage was found more extensive than had been thought originally, and it was considered necessary to send her to Tulagi.

The convoy continued toward Rendova until 0143, when the course was reversed to return in the direction of Barakoma. At 0220 flames suddenly burst from the ventilators of LST 396. It was quickly apparent that the fire was beyond control and that the ship would have to be abandoned. The burning ship launched its only boat and threw life rafts overboard. Capt. Cooke ordered the Saufley and SC 1266 to pick up survivors, which was accomplished without the loss of a single life. The rescue was effected under hazardous exposure to exploding ammunition and falling debris.

At 0232 a heavy explosion blasted out the after section of the main deck, and subsequent explosions tore the vessel apart, sending flames hundreds of feet in the air. She sank at 0320. The cause of the fire was not determined. No bomb hit was observed and there had been no underwater explosion. Although several theories were advanced to account for the first explosion, all the evidence indicated that a gasoline

30

vapor explosion occurred in the port shaft alley, and that this was the origin of the fire that rapidly destroyed the ship.13

After completing their rescues the Saufley and SC 1266 had to beat off yet another air attack before arriving at Barakoma. There they found that the LST’s had already beached at 0700. Before our ships left, enemy planes made two more bombing attacks. A near hit lifted LST 339 so high on the beach that she had difficulty in retracting. Damage inflicted upon enemy planes was impossible to assess with accuracy, but it was thought possible that four planes were shot down during daylight attacks and two during the night attacks. The convoy’s return to Guadalcanal after the unloading of the LST’s was completed without further attack, though the presence of bogies kept the men at general quarters until 0200, 19 August.

Third Echelon

With minor changes the First Echelon to Vella Lavella also acted as Third Echelon, which consisted of LST’s 354, 398 and 398 escorted by Destroyer Division FORTY-FOUR (less Cony) plus Pringle and SC 505. Departing Guadalcanal on 20 August these ships arrived at Barakoma at 0700, 21 August. En route up Gizo Strait, the formation was subjected at 0540 to torpedo, bombing and strafing attacks. Smoke screens and antiaircraft fire were used against the attack. The Pringle sustained slight damage as a result of strafing that killed two men and wounded several seriously.

After the LST’s were beached the destroyers retired to Rendova, and SC 505 took up off-shore patrol. At 1015 Aichi 99 bombers accompanied by Zeros appeared over the beach at high altitude, having penetrated our fighter air cover. The enemy planes, after maneuvering uncertainly, apparently in search of the destroyers that had already departed, attacked the SC but retired without pressing home their attack on the LST’s.

A third air attack, developing about 1515, was pressed home with determination against the LST’s by a formation of more than 20 planes, consisting of Aichi 99 dive bombers, Mitsubishi 97 torpedo bombers, and Mitsubishi Zeros. A few planes swerved off without dropping their bombs, and a few dropped their loads prematurely, but some ten planes dived steeply through intense antiaircraft fire directly upon the beached

___________

13See Bureau of Ships War Damage Report No. 46 for a complete description of the loss of LST 396.

31

vessels. Although there were no direct hits, bombs landed thickly in the area between and around the LST’s. Near hits, one within 25 feet, lifted the bow of one ship clear of the beach, knocked off a hatch cover, jammed the elevator, and knocked personnel on the main and tank decks off their feet. Bombs exploding on the beach covered the decks with coral rocks, some of them over 100 pounds in weight, knocked down gunners, and put about 50 percent of the LST batteries out of commission. A fire broke out on LST 398 but was quickly extinguished. In all, personnel casualties amounted to four killed and eleven seriously wounded.

The 58th Construction Battalion was highly commended for its zeal, not only in unloading but in fighting. Ignoring danger, the men of this Battalion carried out the Task Force Commander’s order to “go on and stay on till the job is done.” They continued at their task under the hottest attack, and manned batteries when their gunners were knocked out. Because of their excellent work, the LST’s were unloaded, except for a few tons remaining on two of the ships, and were able to withdraw at 1600. The return trip under escort was without incident.

Fourth and Fifth Echelons

The next two echelons were considerably more fortunate than previous ones in their experience with enemy aircraft. Improving weather, for one thing, enabled air cover from Munda to give more effective protection, and lessons learned from previous experiences could be profitably applied.