The Navy Department Library

The Japanese

Smithsonian Institution War Background Studies Number Seven

By John F. Embree

(Publication 3702)

City of Washington

Published by the Smithsonian Institution

January 23, 1943

CONTENTS

| Page | ||

|---|---|---|

| Introduction | 1 | |

| Origins | 1 | |

| The mythological story of origin | 1 | |

| Racial and cultural origins | 5 | |

| The feudal period | 8 | |

| National social structure | 11 | |

| Group rule and rotating responsibility | 11 | |

| Political framework | 11 | |

| Economic framework | 13 | |

| Recent trends | 15 | |

| Family and household | 17 | |

| Family structure | 17 | |

| The household | 18 | |

| Age | 19 | |

| Position of women | 20 | |

| Cycle of life | 21 | |

| Birth and infancy | 21 | |

| Formal education | 23 | |

| Marriage | 25 | |

| Death | 26 | |

| Religion | 26 | |

| Buddhism | 27 | |

| Shinto | 28 | |

| The seasons | 30 | |

| Religion as a form of social control | 34 | |

| Concluding remarks | 34 | |

| Cultural homogeneity and borrowing | 34 | |

| Popular misconceptions regarding the Japanese | 36 | |

| Appendix: Facts and figures | 39 | |

| References and selected bibliography | 41 | |

ILLUSTRATIONS |

||

|---|---|---|

| PLATES | ||

| 1. | Izanami and Izanagi | 6 |

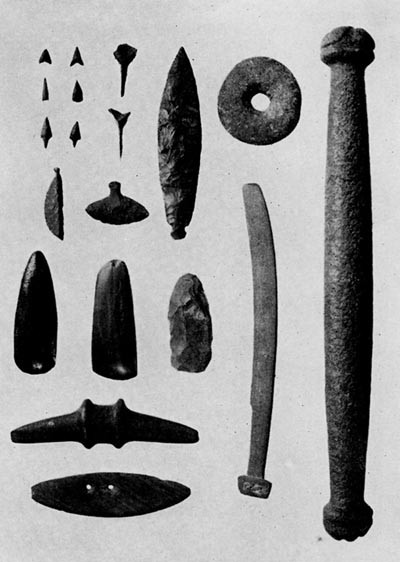

| 2. | Neolithic stone implements | 6 |

| 3. | 1, Man with Ainu trait of hair on face and body 2, Man with Malayan trait of wavy hair |

6 6 |

| 4. | 1, Tile-roofed house of a landowner 2, Thatch-roofed farmer's house |

6 6 |

| 5. | 1, Prefectural road running through a country town 2, A main street in Tokyo |

14 14 |

| 6. | 1, Imperial theater, Tokyo, 2, New Diet building, Tokyo |

14 14 |

| 7. | 1, Preparing a rice field for planting Cooperative labor group transplanting rice seedlings |

14 14 |

| 8. | 1, Wood carriers resting on a steep mountain path 2, Rest period during work at rice transplanting |

14 14 |

| 9. | 1, Marriage 2, Naming ceremony |

22 22 |

| 10. | 1, Childhood 2, Boy Day (May 5) |

22 22 |

| 11. | 1, Death Household shrine |

22 22 |

| 12. | 1, Radio exercises in the school yard 2, Young men of high school age in drill uniforms at a school celebration |

22 22 |

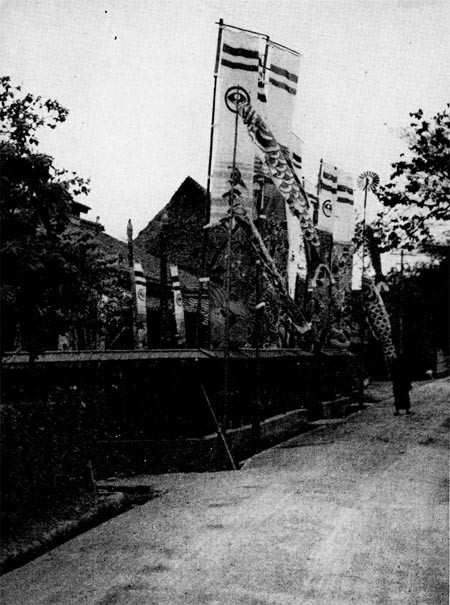

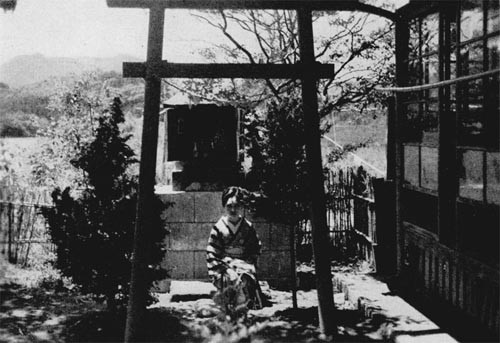

| 13. | 1, Inari shrine and geisha girl 2, Festival in a country town |

34 34 |

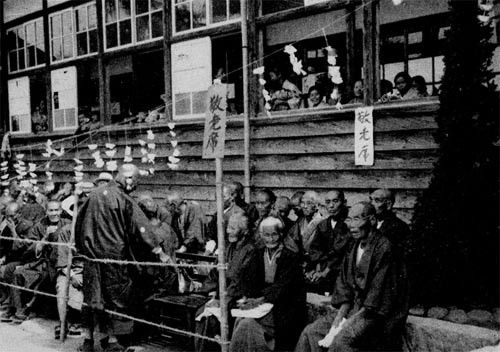

| 14. | 1, Respect for the aged 2, Cooperative labor on the neighborhood roads |

34 34 |

| 15. | 1, Sericulture 2, Fishing | 34 34 |

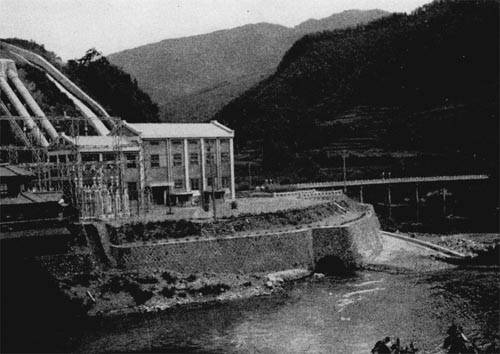

| 16. | 1, Transportation 2, Water power |

34 34 |

| TEXT FIGURES | ||

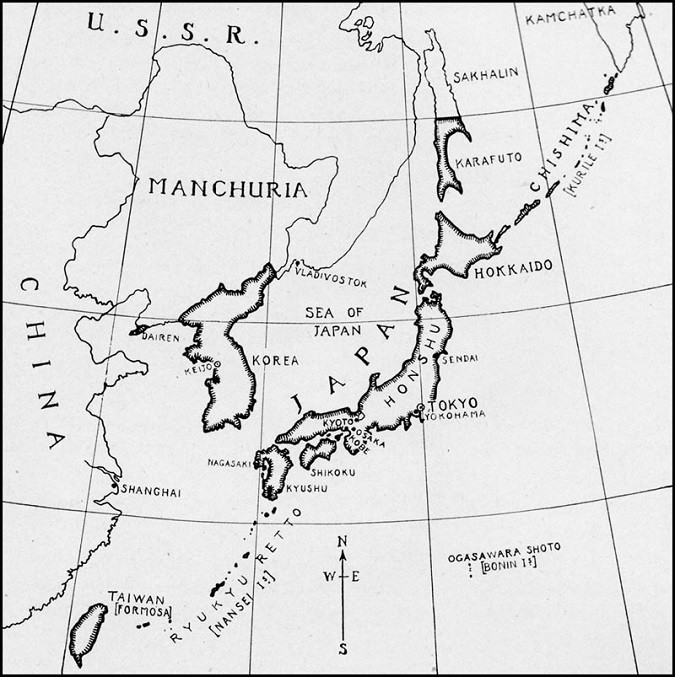

| 1. | Map of the Japanese Empire | vi |

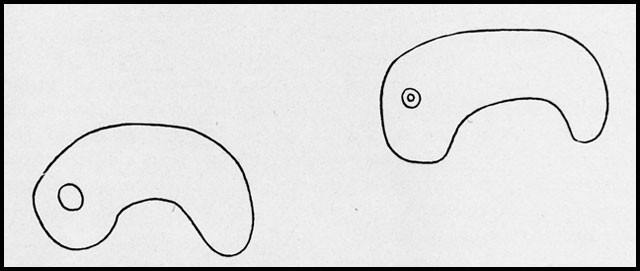

| 2. | Curved jewels from a sepulchral mound | 6 |

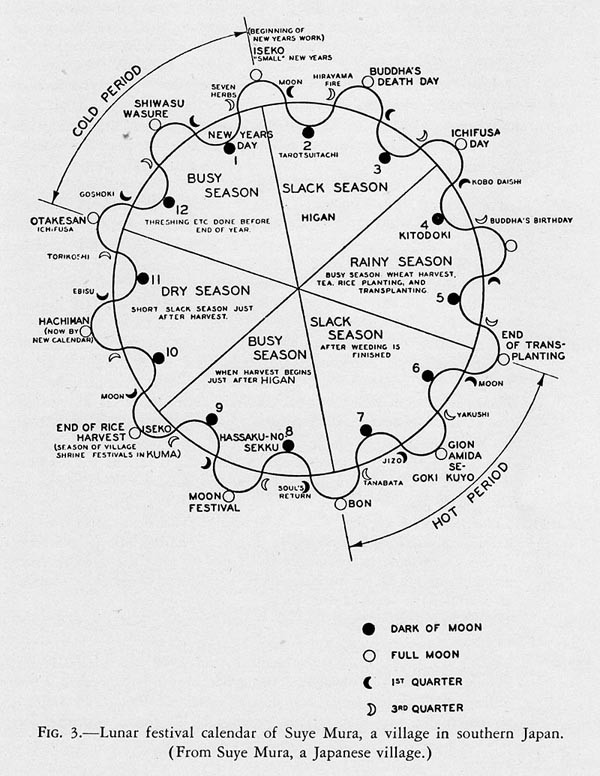

| 3. | Lunar festival calendar of Suye Mura, a village in southern Japan | 31 |

--iii/iv--

--vi--

The Japanese

By John F. Embree

Assistant Professor of Anthropology

University of Toronto

(With 16 Plates)

Introduction

The people of Japan have suddenly forced themselves upon the attention of a nation whose citizens have known little or nothing of them in the past, or have regarded them as quaint Gilbert and Sullivan folk in kimono who could never really learn how to fly an airplane. We have learned to our cost the error of this attitude.

In the pages that follow, a brief account is given of the origins and present social structure of the Japanese nation. There is nothing "mysteriously orential" about Japanese. Like other human beings, their thoughts and acts are conditioned by early training and cultural environment - the better these are understood, the better the behavior of the people may be understood and predicted.

Because most people are already familiar with them, descriptions of material culture such as house types and clothing have been largely ignored in this background study. The same applies to descriptive accounts of Japanese art and literature. Instead, emphasis is laid on the social and historical aspects of Japanese culture which are at once unfamiliar to Occidentals and of special importance in determining Japanese attitudes and behavior.

Origins

The Mythological Story of Origin

Like most insular peoples, the Japanese regard themselves as a race apart. This idea of uniqueness is carried to the extreme of claiming lineal descent from the gods who first created Nippon,1 the sacred land wherein they dwell. Some understanding of Japanese attitudes toward the world may be gained by a reading of their myths of origin, myths which to many Japanese are fundamental articles of faith.

--1--

In the beginning there was nothingness. Then a series of gods were born "in the Plain of High Heaven" who did little but exist until the advent of a male and female pair called Izanagi and Izanami. Izanagi dipped a heavenly jeweled spear into the deeps, and the drops that fell from it as he withdrew it formed the islands of Japan.

Performing a special marriage ceremony Izanagi and Izanami followed each other around a heavenly august pillar, and she greeted him, "Ah what a fair and lovely youth." He greeted her in return and they were married.2 But their first children were "not good" and by divination it was found that there had been an error in the wedding ceremony. The man, not the woman, should have spoken first. So the whole ceremony was repeated with Izanagi opening the conversation. Thus male superiority was assured for all time.

After having many offspring Izanami finally gave birth to a fire god, in the process of which "her august private parts were burnt and she sickened and lay down." Then Izanagi, distraught at the death of his wife, wished to follow her to the other world. When he came to the gate she warned him not to look in because she was already in the ugly process of dissolution. He did so anyway and was horrified by what he saw. Izanami, angry with shame, sent the Ugly Female of Hades to chase her inconsiderate spouse. As he fled, Izanagi

took his black august head-dress and cast it down, and it instantly turned into grapes. While she picked them up and ate them, he fled on; but as she still pursued him, he took and broke the multitudinous and close-toothed comb in the tight bunch (of his hair) and cast it down, and it instantly turned into bamboo-sprouts. While she pulled them up and ate them he fled on. Again later (his younger sister) sent the eight Thunder-Deities with a thousand and five hundred warriors of Hades to pursue him. So he, drawing the ten grasp sabre that was augustly girded on him, fled forward brandishing it in his back hand; and as they still pursued, he took, on reaching the base of the Even Pass of Hades, three peaches that were growing at its base, and waited and smote (his pursuers therewith), so that they all fled back. [Chamberlain, 1932.]3

Then Izanagi blocked up the gate to Hades and Izanami said, "If thou do like this I will in one day strangle to death a thousand of the folks of the land." Izanagi countered, "If thou do this then I will in one day set up a thousand and five hundred parturition houses." Thus it came about that for every 1,000 people who died 1,500 would be born, a sufficient cause in itself for Japan's dense population!

--2--

After this polluting contact with death Izanagi purified himself by washing. In the course of this washing a number of deities were born. The name of the deity born as he washed his left eye was Amaterasu o Mikami, the Sun Goddess; the deity born as he washed his right eye was Tsuki Yomi No Kami, the Moon God; and the god born as he washed his august nose was Susano-o No Mikoto, His Swift Impetuous Male Augustness.

This last deity, Susano-o, was indeed an impulsive and troublesome person. One day he appeared outside a house where his sister Amaterasu was overseeing eight of her weaving women and suddenly threw in the window the hide of a piebald horse, "flayed with a backward flaying." This strange and unexpected act scared the wits out of the weaving women and caused them to prick themselves in a shocking manner.

This and other misdemeanors of Susano-o so terrified and angered the Sun Goddess that she closed behind her the door of the Heavenly Rock Dwelling, thus bringing darkness to the whole Plain of High Heaven. The 800 myriad deities gathered in the land of the Tranquil River of Heaven and bid the deity Thought Includer to think of something. So he thought of a plan. First he ordered a metal mirror to be made, and a string of 500 curved jewels. Then a divination was performed and a ritual enacted. Finally he called on an old female deity with a flower in her hand to perform a dance on a wooden platform. She danced vigorously, causing the boards to resound, and as the dance achieved momentum she drew out her breasts and let down her skirt. The grotesque scene caused the gods to laugh. Hearing the laughter the Sun Goddess, having expected gloom to overcome the world when she retired, was surprised and curious so she opened the door a crack to see what was happening. One god handed her the mirror and another shut the door behind her. Thus by a combined appeal to feminine curiosity and vanity, the Sun Goddess was enticed from the cave and light came again into the world.

During the age of the gods thousands of deities came into existence, thus providing deities as ancestors for most of the important tribes and clans of early Japan, spirits for the mountains and streams, and patron gods for the villages. It is this myriad pantheon of deities and the rituals associated with them that makes up what is today called Shinto.

The transition period between myth and history is the arrival on the scene of Jimmu Tenno as the first historical ruler of Japan and the man who first succeeded in bringing together under one rule a number of separate tribes. Jimmu was born in Kyushu in 660 B.C. according to Japanese orthodox history, or about A.D. 1 according to more critical

--3--

historians. After conquering the tribes of northern Kyushu and southern Honshu, he established a permanent imperial line that has existed unbroken, if occasionally tangled, from his day to the present.

In A.D. 712 a history of Japan was compiled called the Kojiki and in 720 another called the Nihongi.4 In these two books, the oldest Japanese records, there is told the story of the origin and early history of the Japanese and their rulers. These books were originally compiled with the aim of sanctifying the rule of the imperial family then in power. In this purpose the books have succeeded notably as evidenced by the fact that Hirohito is of the same dynasty as Jimmu and by the fact that it as through appealing to these old records that scholars in the nineteenth century were able to aid in "restoring" power to the emperor whose powers had been gradually usurped by the Tokugawa Shoguns over a period of two and a half centuries.

It is from Amaterasu, the Sun Goddess, that the Japanese imperial family traces its descent and as the years have gone by this goddess - neither the first deity nor a creator deity - has come to be the most sacred and important figure in the Japanese pantheon. Today her spirit is worshiped at the sacred shrine of Ise, and all events of national importance are reported to her by the Emperor in person.

The moon deity is today relatively unimportant.

Susano-o, the Impetuous Male, however, is very important. The Japanese frequently associate their national and individual character with that of this rough, uncontrollable god who once so offended his relative Amaterasu that she hid in a cave. Susano-o is associated with storms and characterized by irrespressible animal spirits, and when Japan the modern nation throws into the halls of the League of Nations the piebald hide of a Manchurian incident, or when Japanese soldiers irrepressibly rape Chinese girls, this is complacently attributed by many Japanese to the spirit of Susano-o.

The mirror and set of jewels used in the ceremony before the cave where Amaterasu hid, together with a sacred sword given her by Susano-o, were handed down to one of her descendants and today comprise part of the sacred treasures of the imperial line. The mirror, supposed to be the original, is kept at the great shrine of Ise, the jewels at the imperial palace, and the sword at Atsuta shrine. Ritual dances performed at Shinto shrines are regarded by some as being formalized versions of older more freely sexual dances, and just such dances as that performed by the old female deity before the cave of the Sun Goddess may be danced and enjoyed today at drinking parties in rural areas of Japan.

--4--

Racial and Cultural Origins

The findings of anthropology are less specific, and certainly less entertaining than those of mythology, but they are more complex and present many interesting problems.

Basically of Mongoloid stock, the peoples who inhabit the collection of volcanic islands known as Japan are of mixed racial origin. As with other old populations, it is impossible to state with exactitude the time and source of the various early migrations. Lying off the great Asiatic continent, Japan has drawn her peoples and much of her culture from the north, south, and central coastal regions of this mainland region since the dawn of history.

The aboriginal peoples known today as Ainu and characterized physically by hairy chests and faces, probably came into Japan from an early Caucasoid stock of eastern Asia. The hairy Kumaso referred to in early accounts of Kyushu and the existence in some parts of the Ryukyus of an Ainu-like type indicate that originally men of the Ainu type lived in all parts of Japan. Today they exist as a distinct ethnic group only in the northern island of Hokkaido, though the occasional man with hair on his chest attests to an Ainu strain in the modern Japanese population. The majority of the more Mongoloid peoples came into Japan via Korea from time to time over a period of centuries. Many of the early influences which modified Japanese culture such as porcelain and writing came via the Korean peninsula within historic times.

From the south came a Malayan or southeast Asiatic strain, accounting for the occurrence of wavy hair among modern Japanese. The rare occurrence of frizzy hair indicates also a small but definite strain of Negrito in some southern areas. Incidentally, straight hair is the traditional Japanese ideal. For a woman to have wavy hair is a tragedy because wavy and curly hair is considered to be like that of an animal. However, in urban areas, despite the protests of male patriots, permanent waves are now quite common - or were before the war.

Bearing in mind the fact that present-day Japanese people are the result of extensive racial intermixture and that there is considerable variety of individual types, we may summarize the Japanese physical traits as; Tan skin color, straight or wavy black hair, dark eyes, facial and body hair frequent in the men, and legs short in relation to trunk. Also of frequent occurrence, though by no means always present, is the epicanthic fold (the Mongoloid eye), and, in infants, the Mongoloid spot in the small of the back.

On the average it may be said that Japanese, in contrast to Chinese, are more likely to have wavy hair, a beard, and short legs. But, owing to the

--5--

variability of physical type and the predominate Mongoloid strain, it is impossible to distinguish on purely physical grounds between individual Japanese and Chinese. The differences in dress, language, and general mental outlook between an educated Japanese and an educated Chinese are due, not to racial, but to cultural background.

There is no positive archeological evidence of a Paleolithic culture in Japan, in contrast to China, where some of the oldest forms of man and his culture have been discovered. The earliest phases of culture are Neolithic - stone arrowheads and chisels, some bone implements including a bone harpoon, some colored pottery. Earthen images give us knowledge of the practice of facial tattooing and the use of red clay and bone combs. Necklaces of bone and of stone were common, in striking contrast to modern Japanese culture where such feminine ornaments as necklaces and earings are absent. The stones of the Neolithic necklaces are shaped like animal teeth, and are much like those used in the ceremony to entice the Sun Goddess from her cave. Evidences of pit dwellings similar to those used by certain peoples of northeast Asia have also been discovered in Neolithic sites. On the whole the evidence of archeology indicates two definite influences: an Ainu-Tungusic culture from northeast Asia, and a Malayan culture from the south.

Coming now to the early historic period, as described in the earliest written texts compiled in the eighth century, we find a culture that was characterized by agricultural, hunting, and fishing communities strung along the coasts, and up the courses of the larger streams. Most of the people of this period were preliterate, though writing had come to Japan early in the fifth century. The material culture included the bow and arrow, swords and knives of iron, the fire drill, a weaving shuttle, the sickle, the pestle and mortar, and the quern.

Plate 4

Navigation was evidently little developed as there are few references to anything but a single-oared boat.

Houses of this period bear resemblances to structures in Malaysia, being constructed of wood with thatched roofs. There was a raised platform for sitting and sleeping. In the center of the floor was a fire pit, while windows, when present, were very small. In the mountain areas of Japan some homes of poorer peasants are still much like this.

In addition to regular houses there were parturition houses, one-roomed, windowless huts where a woman retired to give birth to a child. A woman was regarded as ritually unclean during this period. (Even to this day a menstruating woman or a woman who had just given birth is not allowed inside a Shinto shrine.)

If a death occurred, the old dwelling was destroyed or abandoned and a new one erected elsewhere. Death, like blood, was regarded as unclean.

Paddy-field rice was then, as now, the basic crop and basic food, and rice wine the favorite drink. Other vegetable foods included bamboo shoots, beans, ginger, millet, seaweed, and peaches.

In the field of social organization, polygamy was common among the upper classes and a man frequently married two women, who were sisters. Marriage involved an exchange of gifts. Children received personal names from their mothers at a special naming ceremony, but there were at this time no family names.

As in parts of Malaya today there was a period of tolerated sex freedom in adolescence. A young man visited young girls at night, then finally brought his choice back publicly to his parent's house. Women, then as now, were expected to be faithful, but no such duty was required of the husband.

Thou, . . . indeed, being a man, probably hast on various headlands that thou seeist, and on every beach headland that thou lookest on, a wife like the young herbs. But I, alas! being a woman, have no spouse except thee. (Chamberlain, 1932.)

Head chopping, much practiced by the samurai in feudal times, may have had its origin in head-hunting customs of this period, customs presumably similar to those of tribes in Formosa and the northern Philippines.

Religious beliefs and practices included elements similar to those of both northeast Asia and of Malaysia, many spirits of the woods, the rivers and the sea, and shamans or mediums who were frequently women. Many of the native rituals were of a purificatory nature.

A number of local kingdoms arose in Kyushu about the beginning of our era, some of them considerably influenced in their development by

--7--

contact with Korea. Gradually these kingdoms extended northward till by the seventh century the one in Yamato became uppermost and eventually gained control of all Japan as far north as Sendai. The historic period began in 712 when, in order to establish its line as legally superior to other kingdoms and dynasties, the Yamato court had the Kohiki compiled.

The Feudal Period

Skipping over the long and interesting history of Japan from the eighth century of strong Chinese influence, the tenth century, a brilliant court epoch in which the literary arts flourished, the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries of civil wars, we come to the era of internal peace and cultural consolidation, known as the Tokugawa period. In order to understand the people of modern Japan, it is necessary to know something of this stage in Japanese history because of its strong influence on contemporary Japanese culture.

For over 200 years - from 1615 to 1868 - the Tokugawa feudal regime remained in power. The Tokugawa government was essentially a military dictatorship carried on in times of peace, and after its initial battles against previous rulers, its main purpose was to preserve the peace by means of a feudal and military form of government with as little social change as possible.

The emperor, as sacred and nominal political head of the state, resided in the court capital of Kyoto, while the Tokugawa set up actual government in Yedo (now called Tokyo). The country was divided into feudal fiefs, each with a lord or daimyo having full control of responsibility in his own province to keep law and order and to raise taxes. The Tokugawa themselves were simply the largest and most powerful of such feudal lords with the largest estates and hence the greatest wealth and power. To prevent revolution against their leadership, the Tokugawa required each lord to spend a part of the year in Tokyo and while at home to leave his wife and children behind in the capital as hostages. The mass of the people were farmers owing allegiance and taxes to the lords of their respective districts and under the control of samurai, the soldiers of the lord.

The governmental system of the Tokugawa was characterized by a rotation of responsibility and a set of ethical principles calculated to preserve the peace of the country through a series of careful controls. The responsibilities of high officials were rotated form time to time or divided in such a way as to avoid any monopoly of power by one person. This system extended right down to the small kumi or group of five persons who formed the unit of rural control. This aspect of the feudal

--8--

government is important because today, in rural regions and in the Tokyo government, there are similar features of divided and rotated responsibility.

Among the ethical principles of government were the virtues of filial piety and loyalty to one's superiors, which were constantly stressed. Farmers were urged to be industrious, samurai to be loyal and spartan. One aim of such an ethic, as manipulated by the government, was to preserve unchanged the system of social classes. Even today similar exhortations to industry, frugality, and loyalty are given to the people.

Further to prevent political troubles, a system of government agents was maintained to give reports on conditions in the various provinces. This early internal intelligence system is the precedent for the thorough system of internal secret police maintained by the contemporary Japanese government.

Laws were broad in nature, often not known to the people, and they frequently carried different punishments for offenses by persons of different classes. The people were then as now, expected to do as they were told without asking questions. The common people of Japan even today have a remarkable, unquestioning faith in all that comes from government sources.

There was a fairly rigid system of social classes, each with its own occupation, forms of dress, and types of law, all prescribed by the government. Below the Tokugawa rulers and the feudal lords there was the military caste or samurai who, as peace extended in area and time, came to have little to do and so developed such leisure-time rituals as the tea ceremony. Next in rank came the farmers and artisans, the producers of the country. Below them legally came the merchants, but these merchants frequently had a stronger economic base than either farmer or artisan - a dysfunctional aspect of the system that eventually helped to upset the whole feudal organization. At the bottom of the social scale were pariah groups, such as the Eta, concerned with the tanning of hides and other work involving slaughtered animals.

Christianity, which had gained a foothold in certain sections of Kyushu, was ruthlessly suppressed because of the fear that through the Portuguese and other missionaries it might lead to political trouble from within and the encroachment of foreign powers from without. In order to check the growing power of the Shinshu sect of Buddhism, it was split into two sections (east and West Hongwanji). Otherwise religion was left pretty much to itself and, after the enforced split of the Shinshu church, Buddhist priests had little to do with politics. The same was true of Shinto so far as the priesthood was concerned, although certain Shinto scholars eventually made use of Shinto texts to justify the overthrow of the Tokugawa regime.

--9--

Agriculture received attention from the government, which realized its importance to the state, but little thought was given to the well-being of the farmer as an individual. More than one agrarian revolt occurred despite the severe repression of them by the government.

In the city during this period the popular theater - Kabuki - developed, as well as puppet shows and an elaborate demimonde of geisha and prostitutes. Both actors and geisha were favorite subjects of the color-print artists who reached their height at this time. The merchants, who had plenty of money, were the chief patrons of the theater and the arts, and well as of the courtesans. The government frequently issued restrictive laws, but to little effect. In recent years the Japanese government has again shown its concern about the "morals" of its urban people by closing dance halls and prohibiting all kinds of sentimental songs.

In addition to the many controls within the country, the Tokugawa, after expelling the early missionaries and teachers, prohibited all foreign trade except for a small, rigidly controlled trickle through Dutch traders at Nagasaki. There was also a prohibition on the building of seaworthy ships, and no Japanese was allowed to leave the country on pain of death. At the very period when European nations were expanding, creating vast colonial empires, Japan deliberately shut herself off from the very fields she has gone forth to conquer today.

Thus, over a long period of time, Japan was able to consolidate her culture and create a people with remarkably uniform cultural values and ways of life. But a culture is never completely static no matter how isolated, and there were enough changes going on within Japanese society eventually to make unworkable the feudal controls originally set up by the Tokugawa. Merchants gained power while samurai and even feudal lords lost it after two centuries of peace. Shinto scholars came to the conclusion that the Tokugawa had usurped the powers of the emperor and that Shinto was in danger of being completely assimilated to Buddhist theology.

So when Perry came to knock forcibly at the gates of Japan, the Tokugawa were unable to refuse an invitation to deal with foreigners, especially an invitation that was backed by superior firearms. This capitulation so weakened their position at home that they were soon overthrown, and in the name of restoring power to the emperor a new regime was established in 1868, thus inaugurating the Meiji era - the era when Japan once again opened her arms to a foreign culture, this time Western culture. In the course of a generation she transformed her economy from one of self-sufficient agriculture to one of industry dependent on foreign markets and overseas raw materials, a transformation so great that it led to no less than four foreign wars in 15 years.

--10--

National Social Structure

Group Rule and Rotating Responsibility

Japan's national social structure still retains many features of Tokugawa feudal days, despite the drastic economic changes of the past 80 years. At the apex of the structure is the emperor, in whose name all acts of national importance are carried out. The governmental control in Tokyo follows a number of different lines, and the control at the various levels of responsibility is the function of groups, or is carried out by a rotation of individuals rather than by a single, permanent responsible head. Thus in the Tokyo government there is a whole group of individuals, including members of the privy council, the prime minister, and the army and navy ministers, all important, who collectively determine national policy in agreement with Japanese tradition, internal conditions of the country, and the world situation. By the Japanese system the heavy responsibility of national government is too great for any mere human being - hence one of the important functions of the sacred emperor is to serve as the individual in whose name national policy is carried out. Another function of the emperor, as a symbol of the national tradition and as the "father" of his people, is to reinforce the social solidarity of Japan.

The ruling group serves as an advisory body to the emperor and comes to its decisions, as a rule, only after considerable discussion and compromise. In the cabinet organization, for example, the prime minister is not the leader of the group, but rather the coordinator of the group and he cannot act without the agreement of the army and navy ministers. To affect governmental policy, therefore, it is necessary to affect representatives of several groups, not simply one or two.

Political Framework

There are a number of recognized administrative units from the national government in Tokyo to the little village or mura government of the rural areas. A mura or village is a collection of hamlets with locally elected officials. There is no county unit recognized administratively today, so the next unit above the village is the prefecture or ken, of which there are 47 in all. Each prefecture has a governor appointed form Tokyo and a locally elected prefectural legislature. Above the prefecture comes the government in Tokyo made up of (1) a new, comparatively ineffective diet or parliament, the members of which are nationally elected by male voters aged 25 or over, (2) a vast and strong bureaucracy, and (3) a small body of important men who rotate as heads of ministries, members of the privy council and advisors to the emperor. These include military men,

--11--

men of the old nobility, and a fair percentage of men who have risen from the ranks against great odds.

The system of group rule is old in Japan and extends all the way down to the smallest village hamlet. The headship of a hamlet usually rotates from year to year, from one house head to another, so that no one person carries the burden of the responsibility indefinitely. The village headman, as against the hamlet head, is usually elected from the body of councilors (elected by adult men of the village) for a number of years, and may be frequently reelected. In any important matter of local government such as the budget, the headman can act only after extensive discussion with, and after complete agreement of, the village councilors. He is usually a person well liked by most of the villagers. Thus there is a definite local democratic system for local affairs within Japan.

The village headman has two important functions in the national social structure: (1) to serve as official intermediary between the people of the village and all outsiders, official or unofficial; (2) to keep peace within the village. He is expected to take a personal fatherly interest in the welfare of his villagers, even acting as arbitrator in a quarrel between a villager and his wife.

The headman's function as middleman between the village and extra-village government bodies is typical of many aspects of Japanese life, where the go-between plays an important role. In marriage arrangements, in the purchase and sale of livestock and property, in delicate negotiations between two people or two social groups, it is the Japanese pattern to employ a neutral third party to act as go-between. In this way is avoided the face-to-face bargaining which might lead to argument or irreparable loss of face to one party or the other.

Except at the highest levels, there is a combination of locally elected and government-appointed officials. While the Japanese government is to a large degree authoritarian and paternalistic, there is also present a strong element of democracy. One reflection of this is the fact that no one likes to hold a position of responsibility for too long. Another is the way in which, while things of national importance are decided unequivocally from Tokyo, things of local importance are left to the local governments. In the village or mura the headman is locally elected, as are the village councilors, but the agricultural advisor is appointed by the prefectural department of agriculture, and the village school teachers are appointed by the prefectural department of education. The local Shinto priest receives his appointment from the prefectural government, but he is usually a local man recommended by the local headman. Thus local affairs are locally administered but agricultural efficiency and formal education, being

--12--

of national importance, are directed by government officials indirectly controlled from Tokyo via the prefectural governments. Members of the prefectural assembly are popularly elected by men of the prefecture, but the prefectural governor is appointed from Tokyo.

Economic Framework

Economically as well as politically, villages, towns, and cities have interrelations, but the economic network has a different pattern from the political one. Instead of the ties being primarily from Tokyo to prefecture to village, they tend to emphasize the economic interdependence of urban and rural societies.

In the predominantly rural areas of wet rice agriculture and sericulture - and this includes with some modification coastal fishing areas - a typical pattern is a series of small country towns, each with its own collection of satellite villages. The towns in turn are related to the small cities, urban centers which are frequently the sites of old county seats or the castles of feudal lords. These in turn are economically tied to the great metropolitan centers of a million or more population.

The basic tie between the town and the village results from the fact that the town serves as a trade center for its region. From time to time and on special market days, people from the villages, especially women, visit the town to sell farm products (except rice - rice is sold through regular rice brokers or through a farmers' cooperative). Unless there is a special market, most of the selling is to some dealer in the town. With the money thus obtained, or with other money, the villagers will buy manufactured goods - farm tools, noodle cutters, cloth goods, some special cake or candy. Except for the cake and candy, most of these goods are manufactured not in the town but in some large industrial center and reach the small town retailer through a traveling agent or via an agent in the nearest small city.

Thus the shops in the country towns serve simply as economic go-betweens so far as supplying the farmer with manufactured products is concerned. But the townsmen depend in a very fundamental way on the neighboring villages for food and for fuel (charcoal). They purchase these with profits from retail sales to countrymen and also through profits from some special services to traveling officials and traveling salesmen. These "special services" include hotels and geisha houses.

The geisha houses provide another social link between town and village, since most of the girls who work in them come from the villages, usually from poor families, the girl selling her services because of family debts.

--13--

Her patrons, however, are not villagers. Geisha houses make their money either from visiting travelers or from some local businessman giving a banquet, or some traveling agent entertaining a number of local businessmen as a means of creating good will.

There are other relations between town and village of a social and ceremonial nature, which serve to emphasize those which are basically economic. For instance, each country town has its own special Shinto shrine housing its own particular patron deity or deities. Annually, on the day sacred to the deity, a great ceremony and festival is held. The chief purpose of the festival is a special ceremony at the shrine and there is often a ceremonial procession of the deity through the streets of the town. Associated with this religious rite there are many secular entertainments such as wrestling bouts and performances of local dances by visiting village groups, as well as formalized dances by girls of village origin from the local geisha houses. Thousands of people form the villages attend such festivals, and these people, of course, bring a lot of money to the local tradesmen; as a consequence, the tradesmen are usually generous contributors to the shrine committee when it is collecting money. Important events such as the opening of a new school or other public building may also serve as a pretext for a carnival. For villager and townsman alike the festival, with its crowds and varied entertainments, serves as an enjoyable recreation from daily routine labor.

There are also other social ties between individuals living in villages and those living in town. A well-to-do villager, for instance, may send his daughter to the town's girls' school, or his son to its agricultural college. A village headman may serve on a Red Cross committee or be a member of a hospital association with headquarters in the town. Marriage ties may associate a man with someone in the town on a kinship basis. This last tie is, however, more likely to occur between village and village, since the average townsman would regard marriage with a rustic villager as beneath him.

The country town and its cluster of villages thus forms a closely interrelated economic and social unit. It is to be noted that the lines of social communication are, except for marriage, between village and town, not between village and village. There is another set of ties, that between the country towns and the commercial county center or small city, but again not among the small towns themselves. One more economic fact of social significance is that country roads led to the towns, and connecting the country towns are prefectural roads which lead to prefectural capitals. Ultimately, all roads lead to Tokyo.

--14--

Plate 5

Plate 6

Plate 7

Plate 8

Recent Trends

Japan is essentially an old, stable, peasant society suddenly transformed into an industrial nation. While the urban growth has been great, the rural areas have changed but little so far as population is concerned, and together with this population stability goes a remarkable cultural stability in the realm of religious and social affairs. The important developments in rural Japan are of an economic nature and introduced through outside agencies - improved agricultural techniques brought in by governmental agricultural advisers, improved transportation and communication facilities by means of railroad and telegraph, electricity, and manufactured clothing as a result of national industrial development. These changes in rural life have made greater mobility possible for farmers, but as compared with city people rural Japanese are still relatively immobile.

These same new facilities also make it possible for the Tokyo government better to control all areas of the country by keeping in closer touch with them, maintaining government appointed police, school teachers, and agricultural advisers in every little rural village.

Some interesting social forms have been carried over into modern industry from feudal days. The master-apprentice relation has been extended to the modern factory. (A large section of modern Japanese industry is decentralized in small shops of less than a dozen workers.) The traditional rights and obligations of both master and apprentice are maintained - the master to house, educate, and train; the apprentice to work, be obedient, and learn.

For large-scale textile and other industries, girls are brought in from rural areas to work under conditions which, while good from their point of view, are definitely paternalistic and restricted. The employer houses the girls in dormitories, sees that they are fed, and may even provide instruction in such traditional female arts as flower arrangement and the tea ceremony. The girls are trained to be efficient in factories but are given no chance or promise of advancement. The girls, however, are not in industry for life, but simply to earn enough to get married and go on through life as good wives and mothers.

One important aspect of this situation whereby modern industry operates in a social framework of traditional Japanese feudalism is that industrialism has produced in Japan remarkably few changes in social structure and family organization.

For Japan as a whole the great increase in nonrural population and the developments of industry have brought with them some social strains and difficulties, despite the careful controls surrounding the development of a

--15--

Japanese machine age. First, there is the frequently observed social and cultural gap between Japanese city people with their radios, movies, and automobiles, and the Japanese villagers who still use foot-powered rice threshers and whose recreation consists largely in folk song and folk dance enlivened by locally brewed rice wine. This social distance sometimes results in ignorance of farmers' needs by urban dwellers and mistrust of merchants and capitalists by farmers. This is especially significant when it is realized that the farmers and the army often see eye to eye. The financial fluctuations associated with a money economy, little understood by either farmer or soldier, make it easy for the army to use the urban capitalists as scapegoats in their appeals for support from farmer and worker.

Another strain on Japanese society has been the growing need of Japan for markets for her manufactured goods and easy access to raw materials such as wool and cotton to feed her new factories. In a world of free trade this problem would not be serious, but in the twentieth-century world of high tariffs, a new industrial nation is seriously handicapped especially if she is small in area and lacking in extensive overseas colonies. This situation explains in part Japan's attempt to solve her troubles by invading Manchuria in 1932, attacking China in 1937, and overrunning Malaysia in 1942.

During recent years, there has been a remarkable consolidation of the whole of Japanese social organization. Wherever possible there has been an amalgamation of several similar organizations overlapping in function to create a new single organization more or less under government control. For example, in 1940 all political parties dissolved themselves in the interest of national solidarity. This remarkable self-dissolution also took place among the numerous labor organizations. The number of newspapers and news agencies has been reduced until today there is only one official Japanese news agency, Domei, and all foreign-controlled newspapers have been taken over by Japanese. This gives the Tokyo government greatly increased powers in affecting public opinion. Numerous power companies have been consolidated and brought under greater government control. Everything foreign has been Japanized. The most drastic of these antiforeign moves was the Japanization of Christian missions whereby all direct foreign influence was done away with, most foreign missionaries edged out of the country, and the Bible revised to conform with Shinto mythology.

What is happening appears to be partly a reaction from two generations of extensive change in Japanese culture due to contact with the West: the growth of industrialism with a consequent weakening of family

--16--

solidarity, and contact with different social and religious systems with a consequent development of critical scholarship. Government leaders have begun to reconsolidate the nation as did the Tokugawa before them by uniting all competing factors under strong centralized control and by excluding foreigners and foreign ideologies from the country. These moves have been spurred by the rebuffs Japan has met from Western nations whenever she has attempted to expand. The most acute emotional stimulus of this nature was, perhaps, the American Exclusion Act of 1924 with its implication of racial inferiority.

The fervor with which all this reorganization has been carried out by some Japanese patriots suggests more than simply a reaction - it suggests a cultural-religious revivalism. With many non-European groups, after extensive disorganizing contact with Western culture, a violent religious revivalism sets in characterized by a desire to renounce anything Western and go back to the ways of the ancestors. Such a reaction serves to give the group a new feeling of social solidarity and to create new faith in the native beliefs which have been undermined by contact with Western culture. This phenomenon has occurred among Bantu tribes in Africa, Indian tribes in North America, and Melanesian tribes in New Guinea, but when it occurred, the non-Western group had no effective means of getting rid of the foreigner and his influences. Japan, with Western armaments and industrialism, is in a much better position to carry out in action her antiforeign cultural revival.

Family and Household

Family Structure

The structure of the Japanese family is based on a patrilineal and patriarchal principle whereby each family has continuity for ages unending through the kinship tie extending from father to son to grandson. In order to preserve the unity and continuity of the family, it is the duty of a son to marry and produce male descendants. If no son is born a man may adopt a boy and so create a male descendant by a legal fiction. Any misdeed of a son or daughter is a reflection on the family name - a name that should never die out and should never be tarnished. Within the family the father is head of the house but the wife takes care of household affairs, child education, and preliminary marriage arrangements.

For matters of great importance, a marriage, a death, buying or selling of land, the house head calls in members of the extended family to come together as a family council to celebrate, mourn, or consult as the occasion demands.

--17--

While an individual has many duties toward his family - obedience to parents, especially father, good conduct outside the home, and care for the ancestral spirits - the family also has duties toward the individual, especially that of caring for him in all times of crisis. If, for instance, a member of the family has gone to the city and failed, he may come home and again share the family roof and board.

The family is the basic unit of civil control, each house head in a town or village being responsible to the local authorities for the good conduct of his household. In the system of military control nearly every family plays a part either through having a son as a conscript soldier or through having an ex-soldier as a reservist. The reservists, being more numerous and being older, form the important local units of military control, taking charge of local activities such as seeing off new soldiers for the barracks, supervising school drills, and participating in all local group activities of importance. Furthermore every reservist in a family serves as a living example to the sons of the household of the military duties of a Japanese.

In religious matters the family is the most important unit in the Buddhist organization, and the Buddhist priest is the important ritualist in funeral services and memorial ceremonies for the spirits of the deceased. The kin tie through the generations is actively maintained by daily ancestor worship at the household Buddhist shrine. In matters of family solidarity the family group attitudes and the Japanese Buddhist beliefs and practices reinforce each other.

Popular Shinto is not important in family affairs except insofar as it provides a body of common beliefs and practices for all members of the group. State Shinto on the other hand, with its emphasis on the familial aspect of the nation - a father emperor with subject children - points up the individual family organization by indirectly endorsing the scheme of a male head of the family who is responsible for the members of his family, who in turn owe him love and self-sacrifice.

The Household

Among the very poor, family and household are synonymous, but most families, even those of rural farmers, have also at least a maidservant or a manservant or both, living with them under the same roof. These servants are usually contracted for and paid on a yearly basis, the wages often going directly to the parents of the young girl or young man. The servant lives with the family, sleeping in the same house and, in rural areas, eating at the same table. On the occasion of some big holiday or festival the master gives the servant some pocket money to spend and at

--18--

New Year provides a new set of clothing. Thus the servant becomes almost one of the family and is indeed often a nephew or niece - the child of some less well-to-do relative. Like a son or daughter, the servant is expected to show loyalty to the employer, and the employer for his part is expected to look after the servant's welfare. Usually a young man or woman works out as a servant for a few years, setting up his or her own household after marriage.

Occasionally, some relative of the head or of his wife other than their parents or children may be living in the house as a part of the household.

The household, thus composed, is the basic unit of Japanese civil life. In rural regions, on all cooperative labor, each household, not each family or each man, is expected to contribute one worker.

The house which serves as the home of this closely knit group is usually well protected by sacred talismans against evil and sickness. They may be passed by the front gate or in the kitchen. Within the main room there is the sacred Buddhist alcove for the ancestral tablets, and a Shinto shelf near it. These sacred things are usually near the tokonoma a special alcove for flowers and a decorative scroll. (The tokonoma is the honorable part of the room, and when guests attend a banquet, they are arranged in order of age and prestige, down from the alcove.) Up in the rafters there is still another sacred protection which was placed there in a special ceremony when the framework of the house was first constructed. In some rural areas a bit of the first drink of the evening is dropped into the fire pit for the spirits.

The characteristic house type is one on low piles, made of light wood and surmounted by a thatch or tile roof. The general structure is similar to that found in parts of the Philippines and elsewhere in Malaysia, though many architectural details are peculiar to Japan. There are vast differences in quality according to the wealth and social position of the occupants. Whereas a poor farmer dwells in a two-room cottage with floor mats somewhat the worse for wear, and rafters blackened by smoke from the fire, a nobleman lives in a two-story structure of a dozen or more rooms, each one with immaculate mats and beautiful woodwork.

Age

Both in the family and in Japanese society as a whole, there is a strong emphasis on age. This is especially true among men. Boys or men of the same age are especially close, and the words of an older man carry weight simply because of the age of the speaker.

The first son in a family enjoys not only the favored position in matters of inheritance, but in education and attention as well. Even the kinship

--19--

terms reflect this strong emphasis on age. While there are terms for elder brother and younger brother, there is no term simply for brother. A young person could never become an important political or social leader in Japanese society.

Position of Women

The position of women in Japan is what is usually called, by American standards, low. In evidence of this it may be noted that women in Japan cannot vote, as a rule they are not educated beyond the high-school level, and a man may divorce his wife at will although she cannot divorce him, against his will, except for serious cause.

Furthermore, men in urban and upper-class groups, when they go out for social functions, leave their wives at home. If female society is desired, it is obtained by hiring geisha girls to sing and entertain.

In the home a woman by tradition is expected first to obey her father, then after marriage to obey her husband, and finally, in widowhood to obey her eldest son. In taking the evening bath, it is first the master, then the older sons, and finally, the wives, daughters, and servants.

Educational emphasis, beginning even before primary school, is to make a woman dutiful and patient. This produces in the middle classes a very sweet and docile woman, the Japanese ideal of wife and mother. Among the upper classes women sometimes receive higher education, occasionally have an opportunity to travel abroad, and are encouraged to master some cultural art such as playing the musical koto or performing the tea ceremony. Since these upper-class women have servants and are not expected to do household chores, they can devote more time to cultural and intellectual matters, but they are still expected to be dutiful wives and rarely accompany their husbands to any social events outside the home.

Among the poorer classes and on the farm, women are more the social equals of men. The economic interdependence of husband and wife may have something to do with this - a farmer whose wife is a good farmer and at the same time a good manager of the household would hesitate to insult her or treat her badly for fear she might leave him or simply lie down on the job. Socially, also, women of the rural and lower classes have greater equality and at parties and banquets both men and women may participate, drinking, singing, and dancing. A farmer's wife is much freer in act and speech than a middle or upper-class woman would ever dare to be.

Prostitution in Japan is regulated by the government. Regular prostitutes (joro) are usually signed on for a period of 2 or 3 years. While formerly a father could sell his daughter without her consent, this is no

--20--

longer true. However, in a poor family, if a father puts pressure on his daughter to sign a contract there is no concerted public opinion to back up any objections she may have to the proposition.

Geisha, in contrast to joro, are girls who have been trained in playing the samisen, singing, and in general providing pleasant female company at a banquet. In rural hostelries the distinction between geisha and joro is so thin as to be invisible, but in cities such as Tokyo the distinction is marked, and the successful geisha are usually girls of considerable wit as well as training. Geisha are courtesans with traditions stemming from the court ladies of old Japan, while joro are simply members of the oldest profession.

In recent years women have been organized into civic and patriotic organizations to assist at reservist reviews, air-raid drills, etc. This is a new development in Japanese life, quite contrary to the tradition that woman's place is in the home or in her husband's field. Indeed, it has taken a good deal of urging from school teachers and other government officials to get these organizations under way. In urban areas, however, they are rather important. This is, perhaps, a significant development which will do more to change the traditional family pattern in Japan than either urbanism or industrialism.

Cycle of Life

Birth and Infancy

As with Chukchee and other northeast Asiatic tribes, a Japanese woman does not cry out in childbirth, for to do so would bring shame upon her. This tabu on showing pain is probably associated with old tabus surrounding childbirth as a ritually unclean event, an event to which it is well to draw as little attention as possible. In modern Japan this attitude has been assimilated to the growing pride in race and culture that has characterized the Japanese of recent decades. According to the intellectuals the Japanese woman is not ashamed but rather she is too proud to cry out as her child is born.

In rural areas the afterbirth is usually buried somewhere in the yard and the father walks over it. This guarantees that the child will respect and obey his father. If a dog or some other animal were to walk over it before the father, then the child would fear that animal - a situation to be avoided. Certain foods such as pumpkin are to be avoided by the new mother, and certain foods such as ame candy and tai fish are considered beneficial. Neighbors usually visit the new mother and bring her gifts of such good foods.

--21--

Sex is something of great concern to Japanese as to other people. While sexual intercourse and childbirth are both carried out as privately as possible, there is plenty of public joking on the subject. Even the new-born infant is made the subject of jocular remarks, a baby boy being called taiho (cannon) and baby girl gunkan (warship).

The child's first introduction to society is at his naming ceremony, which is held 3 or 5 days after birth. On this occasion near neighbors - one from each household - and relatives living not too far away come to a little party given by the parents in honor of the new child. The midwife, as the professional expert involved in the child's birth, is also invited. Each guest except the midwife brings a gift of kimono material for the infant as well as rice and wine - this in exchange for the feast food and wine to be consumed at the party.

The actual ceremony of naming may be done in a number of ways. One is for the guests present to write names on slips of paper and place these in a bowl in the tokonoma. The midwife, with the aid of sacred wine and a Buddhist rosary, selects one slip and reads the name on it after which the child is passed from guest to guest as each takes a drink and pronounces the name thus selected. In this way the new child acquires a name and a limited personality while the local community becomes aware of a new member.

The birth of the child, if a first child, especially a first son, gives the new wife added status in the eyes of her husband's family and also makes her now a full-fledged member of her husband's community. In rural areas, after the birth of a child a woman may give up some of her maidenly reserve, begin to smoke and drink a little and engage in occasional broad banter.

The next stage in a child's life is a more religious one. At 31 days if a boy, 32 if a girl, a child is taken to the local village Shinto shrine for a ceremonial introduction to the patron deities of the village. This ceremony, known as hiaki, is performed by the village Shinto priest. Hiaki marks also the lifting of a number of tabus. The child may now be carried across water, and the mother may now again sleep with her husband.

For about a year the new child, especially if a boy, is the favored one in the family. At any time he may drink milk from his mother's breast and whatever he cries for will be given him. At the same time, however, he is rigidly trained in cleanliness. Together with his mother he has a daily deep bath in very hot water. The strong emphasis on the daily bath among Japanese is best understood by considering the general emphasis of Shinto on ritual cleanliness. Furthermore, with the rule that no shoes may be worn inside the house and the necessity of keeping the floor mats clean,

--22--

Plate 9

Plate 10

Plate 11

Plate 12

the child is trained at an early stage not to wet or dirty either himself or the mats.

Another complication that enters the young child's life and one that comes as a shock to him after all the loving attention he has been receiving from his parents, is that produced by his mother having another child. She now devotes her attention to the newcomer and the 1- or 2-year old is turned over to the care of an older brother or sister or nursemaid who is by no means so attentive to his every whim as was his mother. As a result, there may be weeks of frequent temper tantrums.

This early period in a Japanese child's life is important in an understanding of his adult personality. The motherly affection coupled with the severe toilet training and culminating in the sudden loss of attention when the next child is born creates an early sense of insecurity which in turn produces an adult who is never absolutely sure of himself and who through compensation may become almost paranoic. There are a number of social usages in Japan that fit into this interpretation of the adult personality pattern. For instance, the emphasis on face -i.e., the elaborate provisions for avoiding an open insult or slight of a social equal, thus avoiding injury to his amour propre. One standard mechanism providing for this avoidance of embarrassment is the go-between through whom any delicate negotiations between individuals or families are carried out. Loss of face is also avoided in another social usage found in the governmental structure whereby it is a group rather than an individual who assumes responsibility. The adult manifestation of the temper tantrum resulting from lack of attention or fancied slight is assassination, and the deep shame felt from real or threatened loss of face is manifested by suicide. On a national scale, the fierce pride in race and culture may be in part associated with this characteristic Japanese adult personality and in part with the cultural revivalism referred to in a previous chapter.

Formal Education

At about the age of 3 or 4 a youngster becomes part of a small age group and begins the slow process of learning to get along with his contemporaries. Even in these early years a boy will receive special educational influences different from those of his sister. On a walk to some beauty spot a mother may tell her young daughter to walk behind her brother because she is the lady while the boy is the gentleman. A first son as he grows up will be given preferred treatment over his younger brothers.

Formal education begins at the age of 6. To begin with, the official Shinto priest of the local shrine performs a ritual and hands out the

--23--

first book of ethics and patriotism. After the shrine service the child attends school for the first time as a student, dressed in a school uniform. Here he forms his first associations with contemporaries beyond his immediate neighbors or relatives. The ties of men who have been classmates are often very strong in adult life; even stronger than those between a man and his wife.

The school day commences with the teachers leading their pupils in radio exercises in the school yard. For 10 minutes every morning the entire youth of the nation simultaneously goes through the same daily dozen to the shrill directions of the same government radio station.

The school itself is often anything but comfortable and warm, a feature that fits in with a Japanese tradition that one learns best when not too comfortable. It also aids in another basic aim of Japanese education - training in the virtues of frugality and self-discipline.

The Japanese school teachers, trained in government normal schools, are torch-bearers of the Japanese way. Skeptics may appear in the ranks of businessmen, college students, and ordinary civil servants, but almost never among school teachers. More than once a Japanese teacher has lost his life in an attempt to save the emperor's portrait from the flames of a burning school building.

The curriculum includes in the early years liberal doses of songs including a first-year song on the beautiful soldier, and lessons in ethics - i.e., filial piety, cooperativeness, and reverence for the emperor. The major problem, however, is that of learning to read and write. The Japanese script is a combination of Chinese ideographs and a native syllabary of 51 symbols. To make things more complicated, there are two forms of the syllabary, the square cut kata-kana and the cursive hira-gana. To be able to read, one must learn the ideographs that are used in all adult newspapers, magazines, and books - characters that may be used either phonetically or semantically. From this it should be clear that to be literate in Japanese is a major feat in itself. This situation means that in the primary grades the Japanese have little time left over from ethics, reading, and writing for the study of much in the field of the natural and social sciences. While today every child goes to school for 8 years, very few go on to high school or college. Thus the urban intellectual class, which includes the governing group, is very small in relation to the masses who, while they can read and write, known only what the government may tell them in regard to either Japanese history or world events.

The basic aims of Japanese education are to produce literate and peaceable subjects - subjects with sufficient knowledge to compete in the modern world, but not enough to question the ways of the governing

--24--

groups. (The present government no doubt is aware of the fact that scholars had a hand in the downfall of the Tokugawa regime.)

School buildings and grounds may be used for civic affairs not directly connected with the children. Town meetings and banquets may be held there, and often the annual inspection of military reserves takes place in the school grounds. On this occasion all the women don patriotic women's association uniforms and act as hostesses to the visiting military, who in return are frequently very haughty toward the local gentry. The reservists (men who have returned from the barracks) line up for inspection by the visiting officers. The inspection is followed by strong nationalist speeches to the soldiers and special lectures to the women. Thus once a year the local community has its attention drawn to war.

After leaving grammar school most young people in rural areas begin their apprenticeship in farming, either aiding their parents or working for some other family as manservant or maidservant. From some areas, large numbers of girls go to work in factories for 2 or 3 years before marriage. At the age of 21 conscription takes, in peace time, from a fourth to a third of the young men for a period of military training. On their return a marriage is arranged.

Marriage

Marriage in Japan is a distinctly family affair. In the delicate negotiations and investigations into family background a go-between is essential. Gifts are exchanged between bride and groom before and at marriage. Most of the gifts of the bride's family, such as footgear, and packages of tea, come in pairs. The wedding ceremony consists of an exchange of rice wine between bride and groom and bride and groom's father to seal the bonds of marriage and indicate that the bride has entered a new family.5 There is no priest involved in the ceremony; instead the go-between is the master of ceremonies.

Marriage is the greatest social event there is for the families concerned, for through marriage come children and on children the future welfare of the family depends. Through heirs a man's memorial tablets are properly cared for. Because of its importance relatives from far and near are invited. The neighborhood's interest in the event is usually recognized by a second special banquet whereby the new bride is introduced to the people of her husband's community.

In rural regions practically everyone is married unless feeble-minded or leprous. There is also a special fear of tuberculosis, which may act as a

--25--

barrier to marriage. Through the family arrangement of marriages, it is rarely that a man marries outside his social class.

At marriage a wife takes the Buddhist sect of her husband and his ancestors become her ancestors. She is buried in the husband's family graveyard. An exception to these general rules is marriage by adoption whereby a family with a daughter but no son adopts a husband for this daughter, who then changes his name to hers, and whose children become heirs of her family, not his.

Death

Death, the transition of the soul from earth to an afterworld, is largely the concern of the Buddhist priests. They are the ones who conduct the funeral and perform the memorial services for the dead. These services, attended by relatives, are performed every seventh day after the death for 7 weeks. The forty-ninth-day ceremony is known as hiaki and marks the end of intensive mourning during which relatives abstain from eating fish. There are also ceremonies on the first, third, and seventh years as well as other intervals up to the fiftieth and one-hundredth year after death. The purposes of these services is to insure the deceased a place in paradise. Only after the last of these is performed may it be said that a man ceases to influence the lives of the living.

In rural areas a funeral, like any other family event requiring assistance such as a fire or a house building, calls for aid from all the neighbors. They prepare funeral objects such as lanterns and coffin as well as dig the grave. The relatives meanwhile mourn the dead and give comfort to the immediate family.

A number of special beliefs attend a death. Picture scrolls are turned to the wall, the kimono of the deceased is folded the opposite way from that of the living and those who touched the corpse must later wash with salt water in order to purify themselves. There are many other special beliefs and tabus which vary considerably from district to district, as for instance the belief that an evil man may haunt the living in the form of a fire ball. In the Kojiki there is reference to the soul of a dead man flying away as a bird.6

Religion

In Japanese society the sacred aspects of life are more apparent than in Western society. This is due, in part at least, to the broad peasant base of Japanese society as well as to its long unbroken national existence.

--26--

The myriad native beliefs concerning birth and death, sickness and health, and the seasons of the year have grown up over centuries upon centuries of existence as a cultural system based on wet rice agriculture. Today the Japanese emperor, in the midst of a war fought with airplanes and baby submarines, continues to perform rituals associated with the planting and harvesting of rice, and Japanese children are told of their descent from Izanami and Izanagi, the primeval pair who founded the land of the fruitful rice ears.

Buddhism

Buddhism was introduced into Japan during the course of the sixth century, together with Buddhist sculpture and painting. Sponsored by Prince Shotoku, Buddhism rapidly gained ground and at one time even threatened to absorb all the native beliefs into its own system by interpreting Japanese deities as special manifestations of Buddhist divinities.

Nearly every family in Japan belongs to one Buddhist sect or another. The most popular one is Shinshu, according to the tenets of which if one has sincere faith in the savior Amida, one is sure to reach the western paradise after death. The traditional religion of the samurai is Zen, which emphasizes self-discipline as a means of enlightenment.

Buddhist household practices include the maintenance of a Buddhist shrine or alcove (Butsudan) in which are kept the ancestral tablets. Daily offerings of food and drink are made here as well as a brief ritual by members of the family. The household aspects of Buddhism help to give unity to the family group.

All matters concerning the afterlife, such as funerals and memorial services for deceased relatives, are looked after by the local Buddhist priest.

Most of the larger Buddhist sects have headquarters in Kyoto, the old prefeudal capital of Japan. Buddhist priests, after a period of training at the theological seminary in Kyoto, go out to some temple where they may spend a lifetime looking after the spiritual needs of their parishioners. Formerly Buddhist priests, as educated men, served as the teachers and leaders in their local communities and vital statistics were kept in the local temple archives. But today, with government-trained teachers and regular government census records, the Buddhist priest has lost much of his former power and prestige. He is subject to military conscription and has but little political power, since most active temple members are women and old people. He does serve one important function from the point of view of the government, that is soothing and keeping peaceful the common people with his talk of Amida's paradise.

--27--

In addition to the orthodox priestly aspects of Buddhism - temple services, funerals, and memorial services - there are many popular aspects of Buddhism that exist quite independently of any priest or temple. One of the important popular deities is Jizo, who is usually personified in stone as a priestly figure sitting by the roadside. Beliefs about Jizo are legion, but in general he is looked upon as a friend, a protector of children's souls, and a protector of dangerous places such as crossroads. Another popular Buddhist deity is Kwannon, Goddess of Mercy.7 A pregnant women often prays to Kwannon for a safe and easy delivery. In rural Japan there is usually a little neighborhood do or sacred house where children play and pilgrims rest. Within the do may be a figure of Jizo, Kwannon, or some other popular Buddhist deity such as Yakushi, God of Healing. There is no priest associated with the do. Its deity receives flowers and other offerings from neighbors, and on days sacred to its deity a little ceremonial food and drink is served to neighbors and pilgrims by a local do committee whose membership rotates from year to year within the neighborhood group.8 These popular deities and the neighborhood do serve to give a feeling of security to travelers and to the local neighborhood. They serve quite a different function from formal Buddhism with its emphasis on the soul and the afterlife.

Shinto

Shinto beliefs and practices fall into three classes: Popular Shinto, sect Shinto, and official or state Shinto. Shinto could almost be defined as those sacred beliefs and practices which are not Buddhist.9 In one form or another Shinto beliefs are held by practically all Japanese subjects regardless of their Buddhist affiliations.

In the realm of popular Shinto there are deities of good fortune, such as Daikoku and Ebisu whose images are found in every farmhouse; spirits of the well, of the land, and of the kitchen who add to the sacred aspects of home and household. There are deities of river and forest, of prosperity and good crops, patron deities of hamlets and villages - all included in the polytheistic beliefs of popular Shinto.

One of the most important of the popular Shinto deities is Inari, god of rice, good crops, fertility, and prosperity in general. Inari's messengers are

--28--

foxes and by his temple there are always to be seen the figures of foxes. Inari priests are usually men or women who have had a dream in which a fox commanded them to set up or maintain an Inari shrine. These priests are frequently faith healers curing the patients through the virtue of Inari's powers. They may also act as mediums, the spirit of Inari possessing their bodies and talking through their mouths.

Inari is also a deity of geisha and prostitutes, perhaps owing to the sexual connotations of Inari's function as god of fertility. Geisha regularly pay their respects to the nearest Inari shrine in order to gain his favor and so have many patrons.

The role of the fox as Inari's messenger is simply one of many supernatural roles played by the fox in Japanese folk belief. By popular tradition foxes have the power of bewildering the unwary by transforming themselves into beautiful women. Many is the tale of a man being seduced by such a fox woman and even marrying her and having children, only later suddenly to discover himself to have been bewildered. Dogs, who also have certain supernatural powers, can always detect a fox woman and will bark and snap at her.

The chief role of the dog, however, is a more malevolent one in the form of witchery by means of a dog's spirit. Those who have this power, usually crotchety old women, can perform black magic, bring ill luck and even death on their enemies. Such black magic is usually performed as a result of covetousness, envy, or jealousy.

Every village has a local village Shinto shrine housing the deity or deities who protect the village. These deities are looked after by the village Shinto priest, and it is to their shrine that infants are brought when a month old. Most Japanese soldiers take with them as an amulet a small package of earth from the village shrine or from the shrine of a sacred mountain in the region to protect themselves from harm in battle.

With the exception of black magic through the dog spirit, the sacred beliefs and practices of popular Shinto serve to give unity to local groups of people, or to heal the sick and give protection. Popular Shinto gives a man confidence in the face of the uncertainties of life, while orthodox Buddhism looks after his immortal soul.

In addition to such beliefs and practices, there are also 13 formally organized sects of Shinto, such as Teenrikyo, which are comparable in function to Buddhist sects. While the ordinary popular Shinto beliefs do not interfere with Buddhist beliefs, members of a Shinto sect are not members of a Buddhist sect.

The government distinguishes between beliefs such as the above and the special sacred beliefs and practices associated with nationalism, the

--29--