The Navy Department Library

Wartime Diversion of U.S. Navy Forces in Response to Public Demands for Augmented Coastal Defense

by

Adam B. Siegel

Center for Naval Analysis

4402 Ford Avemeu Post Office Box 16268 Alexandria, Virginia 22302-0268

APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE; DISTRIBUTION UNLIMITED

The author is a Research Specialist at the Center for Naval Analyses. Mr. Siegel has a Master's Degree in Russian Area Studies from Georgetown University and is currently enrolled in the Naval War College. The views expressed within are those of the author and they do not necessarily represent those of CNA, the U.S. Navy, or any part of the U.S. government.

Professional Paper 472 / November 1989

The Wartime Diversion of U.S. Navy Forces in Response to Public Demands for Augmented Coastal Defense

by

Adam B. Siegel

A Division of

Hudson Institute

CENTER FOR NAVAL ANALYSES

4402 Ford Avenue Post Office Box 16268 Alexandria, Virginia 22302-0268

ABSTRACT

The Soviet Union might choose to operate a small number of nuclear-powered attack submarines in U.S. coastal waters during a war with the United States. The effects of such operations on U.S. public opinion could require the U.S. Navy to redeploy Navy assets away from forward operations to augment coastal defenses. During past conflicts, American military forces have, in fact, been diverted from other missions precisely to counter perceived threats to the Continental United States (CONUS). In some instances, the diversion was driven less by a purely military evaluation of the threat than by a public outcry for reassuring defensive measures. This paper examines the U.S. experience with threats to CONUS or coastal waters during four wars (the Civil War, the Spanish-American War, World War I, and World War II). It attempts to place real, present concerns about the public's possible future reaction to Soviet SSN operations off the U.S. coasts within a broader historical context.

--iii--

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

In the event of a U.S.-U.S.S.R. conflict, the Soviet Union might choose to operate a small number of nuclear-powered attack submarines in U.S. coastal waters. This paper considers the possibility that the effects of such operations on U.S. public opinion could require the U.S. Navy to redeploy Navy assets away from forward operations to augment coastal defenses. During past conflicts, American military forces have, in fact, been diverted from other missions precisely to counter perceived threats to the Continental United States (CONUS). In some instances, the diversion was driven less by a purely military evaluation of the threat than by a public outcry for reassuring defensive measures. The paper examines the U.S. experience with threats to CONUS or coastal waters during four wars (the Civil War, the Spanish-American War, World War I, and World War II). It attempts to place real, present concerns about the public's possible future reaction to Soviet SSN operations off the U.S. coasts within a broader historical context.

Soviet submarine-launched conventional-SLCM attacks could result from a variety of motivations. Purely military objectives could be the dominant Soviet motive, and facilities such as the Pentagon, airfields, or operating bases might be prime targets. Attacks might also originate from a Soviet imperative to respond in kind to any U.S. attacks on the Soviet Union. No matter what the specific motivating factor or targets of Soviet SSN operations off the coast, the public reaction, especially to cruise-missile strikes on coastal targets, could lead to a political imperative for the Navy to commit additional assets to eliminate the submarine threat beyond the forces already involved in antisubmarine warfare (ASW) operations in coastal waters. Such a requirement would almost inevitably draw forces away from potentially more important operations elsewhere in the world.

This paper highlights relevant episodes in the U.S. historical experience in a search for insights about what happened - and why. U.S. forces were, in fact, diverted to face threats to coastal regions in each of the wars examined. Military judgement as to the appropriate defenses was not always the leading factor in the decision to divert forces.

Early in the Civil War, for example, marauding Confederate raiders presented a threat to Union shipping off the New England coasts. Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles resisted pressures to divert ships to hunt down the Confederate ships and concentrated upon tightening the blockade on southern ports. It was not until the blockade was tightly in place that the U.S. Navy began to divert large numbers of ships to hunt the raiders.

At the beginning of the Spanish-American war, public fears were fueled by inaccurate news commentaries about the strength of the Spanish Navy. Concern that the Spanish fleet would bombard coastal cities created a political imperative for greatly augmented coastal defenses. The Navy, unable to resist the political pressures, was forced to splinter its Atlantic squadron so ships could make port calls to reassure the public.

Upon the U.S. entry into World War I, Navy leadership was divided as to the best naval strategy for conducting the war. Fears that German U-boats or even elements of the German High Seas Fleet could operate off the U.S. coast fueled arguments against deploying substantial forces to the Eastern Atlantic to aid in the protection of shipping. The Navy leadership's concern over U-boat operations in the Western Atlantic, which did not materialize until mid-1918, delayed the U.S. Navy's full participation in the main battle against the German underseas fleet.

For their assistance at various stages of this paper, the author would like to thank Peter Perla, Brad Dismukes, and Art Maloney of the Center of Naval Analyses, Dean Allard of the Naval Historical Center, Robert C. Mikesh of the Smithsonian Institution, and David F. Trask. While their assistance was invaluable, the author assumes all responsibility for the work.

--v--

In World War II, the U.S. faced a variety of threats to its coast. The shock that followed Pearl Harbor led to major augmentation of west coast defenses, including the diversion of a coastal artillery unit, en route the Philippines, to the Washington coast. In May 1942, prior to the Battle of Midway, civil defense officials, fearing a Japanese raid, distributed the nation's stock of gas masks to the civilian populace of California. Later in the war, even more exotic threats emerged. Over a six-month period, the Japanese launched 9,300 balloon bombs in the world's first intercontinental bombing campaign. Fighter squadrons were used to intercept the balloons and paratroopers were deployed to fight forest fires that might be caused by the incendiary bombs. In early 1945, the Navy countered far-fetched but potentially serious threats to both coasts. In late March, a carrier task force was formed off San Francisco to protect the city from a feared Japanese raid during the scheduled U.N. Conference on International Organization. In April, two U.S. Navy hunter-killer groups stalked and destroyed Group Seewolf, six U-boats that were feared to be carrying rockets to attack New York City.

The situations in which diversions of disproportionate forces to defend CONUS occurred seem to fall into three main categories:

Excess force available: At the end of both the Civil War and World War II, when faced with a threat, the Navy had enough assets available to devote significant forces to defensive operations without seriously affecting the conduct of offensive operations.

Military disagreement in threat assessment: During the opening months of U.S. participation in World War I, it appears that it was the military split over the nature and severity of the threat that caused a misallocation of resources not public pressure.

Political leadership ill-informed: At the beginning of the Spanish-American War, the Navy failed to convince the political leadership of the logic of its preferred force employment pattern. This failure quickly led to political pressure on the Navy to divide the Atlantic squadron in response to public outcries for direct and perceptible defense measures.

Despite the difficulties involved in applying lessons of the past to any future Soviet threat, it seems that the most dangerous situations arise when the political-military decision-makers are badly informed about the actual military situation. Under those circumstances, the military leadership may respond to unexpected setbacks with undue caution, and the political leadership may respond to public pressure by calling for obviously defensive military redeployments. Furthermore, such public pressure is most likely to build in a situation when the general populace remains ill-informed about the actual military situation. The historical experience of the United States indicates that, when the military leadership has clearly and coherently articulated the basis for its deployments and operations, the political leadership has generally acquiesced to the professional judgment of the military commander, despite the possibility of threats to CONUS and even in the face of adverse public pressure.

--vi--

CONTENTS

| Illustrations | ix |

| Tables | ix |

| Introduction | 1 |

| The Postulated Soviet Threat | 3 |

| The Historical Experience | 5 |

| The Civil War | 6 |

| The Spanish-American War | 7 |

| World War I | 10 |

| World War II | 15 |

| Reaction to Pearl Harbor | 16 |

| Japanese I-Boat Operations Off the West Coast | 18 |

| Operation Paukenschlag: U-Boat Operations Off the East Coast | 22 |

| Reactions to the Halsey-Doolittle Raid 1942 to the End of the War | 23 |

| Midway and the Aleutians | 23 |

| Submarines Shell the Coast | 24 |

| GLEN Floatplane Attacks on Oregon | 25 |

| FuGo: Japanese Balloon Bombing, The First Intercontinental Air Raids | 27 |

| The Japanese Experience, in Conclusion | 30 |

| The Saboteur Threat | 30 |

| Reducing the Defenses, Calculating Risk | 32 |

| Seaborne Threats to CONUS, 1945 | 33 |

| World War II, in Conclusion | 34 |

| Lessons of the Historical Experience | 36 |

| Conclusion | 38 |

| Bibliography | 39 |

--vii--

ILLUSTRATIONS

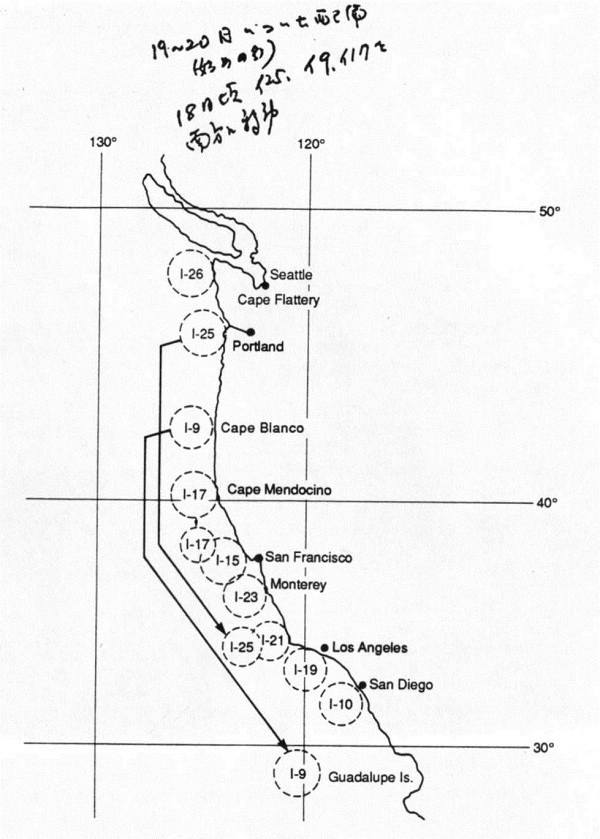

| Figure 1 | Japanese Submarine Patrol Areas Off the Pacific Coast | 20 |

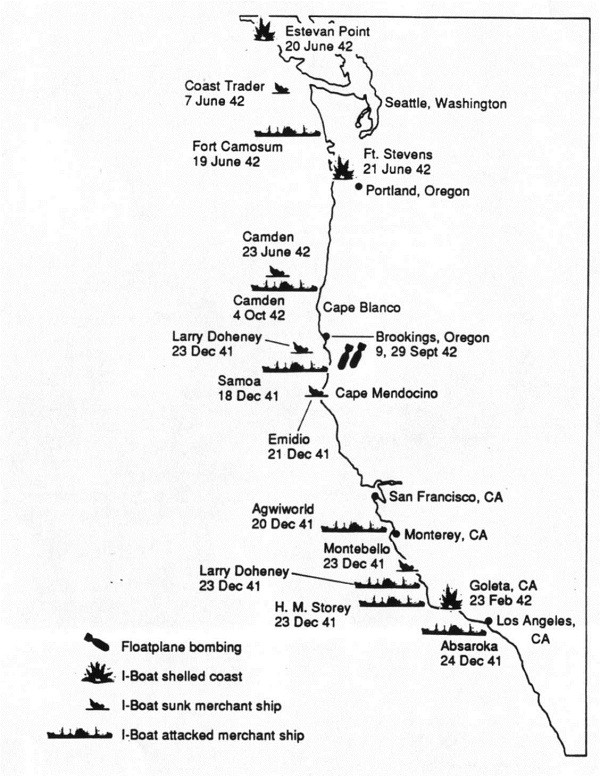

| Figure 2 | Japanese Submarine Operations Off the Pacific Coast | 21 |

TABLES

| Table 1 | German Submarine Operations in the Western Atlantic During World War I | 11 |

| Table 2 | Japanese Submarine Operations Off the Pacific Coast | 19 |

| Table 3 | Chronology of Japanese Balloon Bomb Activities | 28 |

--ix--

INTRODUCTION

In the event of a U.S.-U.S.S.R. conflict, the Soviet Union might choose to operate a small number of nuclear-powered attack submarines in U.S. coastal waters. This paper considers the possibility that the effects of such operations on U.S. public opinion could require the U.S. Navy to redeploy Navy assets away from forward operations to augment coastal defenses. During past conflicts, American military forces have, in fact, been diverted from other missions precisely to counter perceived threats to the Continental United States (CONUS). In some instances, the diversion was driven less by a purely military evaluation of the threat than by a public outcry for reassuring defensive measures. The paper examines the U.S. experience with threats to CONUS or coastal waters during four wars (the Civil War, the Spanish-American War, World War I, and World War II). It attempts to place real, present concerns about the public's possible future reaction to Soviet SSN operations off the U.S. coasts within a broader historical context.

Soviet submarine-launched conventional-SLCM attacks could result from a variety of motivations. Purely military objectives could be the dominant Soviet motive, and facilities such as the Pentagon, airfields, or operating bases might be prime targets. Attacks might also originate from a Soviet imperative to respond in kind to any U.S. attacks on the Soviet Union. No matter what the specific motivating factor or targets of Soviet SSN operations off the coast, the public reaction, especially to cruise-missile strikes on coastal targets, could lead to a political imperative for the Navy to commit additional assets to eliminate the submarine threat beyond the forces already involved in antisubmarine warfare (ASW) operations in coastal waters. Such a requirement would almost inevitably draw forces away from potentially more important operations elsewhere in the world.

This paper does not address the likelihood that a Soviet threat to the coast might materialize. Nor does it attempt to extrapolate from historical experience into the present and future to recommend policies for handling a potential public outcry. Rather the objective is to try to generalize from the past about the most likely conditions that could lead to pressure for the redistribution of forces, and to identify options open to military leaders that might best deal with that pressure. Further analysis would be required to develop the contemporary plans and policies that are implied.

This research is based mainly on secondary works, which provided enough information to reach general conclusions. More exhaustive examination of primary evidence could well turn up interesting nuance or detail. However, it is unlikely that additional research would alter the main findings.

Civilian and military responses to threats to U.S. territory or coastal waters have varied widely. On one extreme, during the Spanish-American War, public hysteria along the eastern seaboard led to a fragmentation of the fleet, as Navy ships made port calls in New England to reassure the public in the face of a feared (but implausible) Spanish threat. On the other end of the spectrum, Japanese seizure of the Aleutians and some uncertainty about Japanese intentions did not deflect important U.S. Navy elements from participation in the pivotal Battle of Midway despite considerable concern over the possibility of Japanese strikes against California. A principal question to consider, therefore, in examining the historical record is whether the U.S. military perceived the response to be inappropriate to the threat. If so, the next question is whether that disparity between requirements and the actual response was due to pressure from the civilian community.

This examination of the U.S. experience with threats to the coast provides a context within which to examine the potential threat of Soviet SSN operations near the U.S. coasts. In essence, it seems that the principal issue facing U.S. commanders has been that they must be prepared to face a public challenge to their methods and means of operations; that the possibility exists that the

--1--

military's evaluation of the threat and the political leadership's requirement to assuage a worried public could lead to different conclusions about the proper military response. With the growth of mass media and proliferation of pollsters and their increased importance in the U.S. political process, public opinion will probably influence military decisions to a greater extent in the future than in the past. Thus, the public perception of the military situation could become paramount even more readily than in the past. If it is generally believed, especially by the political leadership, that the proper forces have been allocated to antisubmarine warfare (and anti-air warfare) missions and that the threat is being countered in the most appropriate manner, the buildup of pressure great enough to force an irrational military response seems unlikely. If, on the other hand, the public perception of the military situation is ignored, public concern might produce sufficient political pressure that force allocations would be determined less by military judgment than by political expedience.

The discussion begins with a broad outline of the postulated Soviet threat. It proceeds to an examination of the U.S. historical experience with threats to the coast or coastal waters and concludes by highlighting the lessons of this experience and their relevance today.

--2--

THE POSTULATED SOVIET THREAT

The threat posed by Soviet nuclear-powered attack submarines operating off the coasts of the United States is multi-faceted. Not only might they potentially threaten SSBNs as they enter or exit port, but Soviet SSNs operating in U.S. coastal waters could pose a threat to Navy ships and sealift transiting to and from CONUS and could be targeted against other types of shipping in a campaign reminiscent of the German U-boat attacks of early 1942 off the east coast. The threat could also extend ashore, both with conventional or nuclear-armed missiles. (The possibility that the Soviets might have or might in the future develop a Tomahawkskii cruise missile with both nuclear- and conventionally-armed variants should not be ignored.) The Soviets could also employ submarines to insert Spetsnaz units to conduct sabotage operations. However, this last possibility should not in itself create additional demands upon U.S. Navy assets (which would already be engaged in the antisubmarine war) but instead would add to pressures upon the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and other police agencies.

The Soviets are unlikely to pursue all these options simultaneously, due to the relatively few modern, survivable SSNs (and, thus, limited payloads) that are likely to be available in the near future. This limitation grows if one considers the other missions that are likely to be high priorities for the Soviet SSN fleet (such as the defense of Soviets SSBNs in the bastions). Therefore, the Soviets will likely concentrate their assets on one or two of these target sets. Which mission would have the highest priority is highly scenario dependent.

A basic tenet of Soviet strategy calls for "suppressing the potential of an opponent's war economy.... It envisages ... demoralizing the populace and the personnel of the armed forces.... This task... should be performed by the destruction of vitally important targets on an opponent's territory."1 Although discussed in the context of a strategic strike, attacking the enemy's will to resist his "moral-political potential" would also be important during a conventional conflict

Even so, a Soviet conventional-SLCM attack upon the U.S. mainland might seem unlikely unless the U.S. has attacked the Soviet homeland. It seems plausible that the Soviets might consider using conventional SLCMs for "analogous-response" strikes against the U.S. following any U.S. strike against targets on Soviet soil.2 This revenge motive should not be discounted. The Japanese placed great emphasis on devising means for striking back at the United States following the Halsey-Doolittle raid. The first (only) intercontinental air strike campaign, the Japanese 1944-45 balloon-bombing campaign, resulted from this emphasis. The Soviets may not feel as driven as the Japanese high command, who believed in April 1942 that they had failed in their duty to protect the emperor. On the other hand, the Soviets express strong feelings about "Mother Russia" and Soviet weaponry can be expected to be much more accurate and lethal than the Japanese balloon bombs. Development of a conventionally-armed cruise missile would allow the Soviets to make such strikes against CONUS with much greater ease than any of the threats considered in this paper and thus would present the most serious non-nuclear threat to CONUS since the War of 1812.

Strikes against targets ashore, and the specific targets attacked, can be used as a means of communication between belligerents. The Soviets might feel compelled to use such conventional

___________

1. RAdm. N.P. V'yunenko, Capt. 1st B.N. Makeyev, and Capt. 1st V.D. Skugarev, Voyenno-morskoy Flot: rol', perspektivy razvitiya, ispolzovaniye (The Navy: Its Role, Prospects for Development, and Employment), ed. by Fleet Adm. S.G. Gorshkov, Moscow, Voyenizdat, 1988, p. 38.

2. Analogous response is a pre-INF treaty Soviet term referring to a Soviet desire to respond analogously to U.S. use of European-based GLCMs and Pershing IIs to conduct nuclear strikes on the Soviet Union (i.e., with nuclear weapons not launched from Soviet territory). It does not seem unreasonable to conceptualize a Soviet requirement for some sort of conventional strike "analogous response" capability. This conjecture is based on this analyst's understanding of Soviet military theory.

--3--

SLCM attacks on U.S. territory to signal to the American leadership that they are not only able but also willing to respond in kind to U.S. actions. One can argue that the Soviets might decide to strike CONUS as a means of dissuading further U.S. strikes onto Soviet territory. Therefore, conventional SLCM strikes against CONUS might not be simply retaliatory, but might also be a source of leverage (combined with diplomatic initiatives) to induce the U.S. political leadership to oppose further strike operations against Soviet territory.

In addition, any Soviet presence off the coast will carry with it the specter of nuclear warfare. If the United States and Soviet Union are in a global conventional conflict in the early 1990s, absent a startling breakthrough in the strategic defense or arms control arenas, the entire war will be colored by the possibility of nuclear escalation. Soviet submarine operations off or against CONUS will carry this threat closer to the shores in the public mind. While the U.S. would remain just as vulnerable to ballistic missiles, the threat nearby might dominate the public perception of the possible escalation of the conflict to nuclear war. Thus, if Soviet submarines launched conventional SLCM strikes against coastal targets, every missile could possibly foster a panic response that the next warhead might be a nuclear one. In such an environment, the public's demands for extensive ASW and air defense measures could be politically irresistible.

In one sense, the threat is not limited solely to actual Soviet operations.1 The specter of Soviet submarines could create an atmosphere of extreme anxiety along the coast even without Soviet deployments in the Eastern Pacific. During the Spanish-American War, Spanish ships never entered the waters off the east coast, but this possibility preoccupied the public until the main Spanish squadron was sunk in Cuban waters. In the event of a global war, the public mood is likely to be quite tense in the U.S. One prominent commentator, reminding the American public of the past Soviet proclivity for operating submarines off the U.S. coast, could create a public demand for stepped-up ASW activity even in the absence of a real threat. This demand could be translated into a political imperative for a more publicly visible (even if not particularly effective) ASW effort in coastal waters.

The scope and nature of any potential threat can be characterized by several different factors. Do the attacks occur only at sea (in coastal waters so that there is public knowledge of the events) or are they against land targets? Are the targets primarily "military" in nature or are overtly civilian targets being struck? When, in the war, does the attack occur? And, finally, is the attack limited to a single incident or does it appear to be part of a campaign over a wide expanse of territory? For example, a continuing Soviet campaign of conventional-SLCM strikes on major coastal cities, which cause significant civilian casualties, could create an atmosphere of hysteria among U.S. coastal region inhabitants. (The U.S. has never faced a situation where the enemy was causing large numbers of casualties ashore. Thus, this extreme case has no historical foundation on which to base an evaluation.) On the other hand, the sinking of just one minor merchant vessel well out of sight of land seems unlikely to create an atmosphere in which U.S. Navy force deployments would be determined by public hysteria rather than by military logic.

____________

1. Only the future threat posed from the Soviet submarine operations is considered in this paper. Other potential wartime threats to CONUS exist that are not considered, such as the possibility of Cuban air or sea raids against the Atlantic or Gulf coasts or of a widespread terrorist threat in the midst of a Third-World conflict.

--4--

THE HISTORICAL EXPERIENCE

In all her wars from the Revolutionary War through World War II, the United States has faced some form of threat to her borders, coast, or coastal waters. Through these experiences, the U.S. response has differed - both militarily and in the public perception of the threat. This section examines various episodes of threats to U.S. coastal regions over the past 130 years.

The most important question to examine is whether the military response to the perceived threat was in accordance with the military judgment of the time. If the response was disproportionately large, did non-military pressure force it? It is very difficult to determine cause and effect relationships between a public reaction to a threat and the military response to the threat. The following discussion of each episode considers the general nature of the threat, portrays the public reaction to that threat, and outlines the military response. Where the available evidence permits, it highlights the connections between the public response to the threat, the political imperatives placed upon the military leadership, and the possible effects on the resulting military response.

Several issues seem most important in this examination of the historical record. These include the civilian reaction to the threat, the state of coastal defenses as perceived by the military and the population at large, whether a strategic diversion of U.S. forces occurred, and the degree of unity among military decision-makers about how to respond. Key questions addressed include the following:

Civilian Reaction: What effect did attacks or threats of attacks have on civilian morale? How did the political leadership respond to the public mood? Did the military or other parts of the government attempt to prevent or defuse negative public reactions to the threat? If so, how? What other factors accounted for the public perception of the situation?

Coastal Defense: How did the existence and cognizance of coastal defense capabilities affect the public's perception of the threats to the coast? As well, how did the public's perception of threats affect the development of coastal defense? (This paper does not delve deeply into the question of coastal defense.)

Diversion: Did threats against or attacks on U.S. territory or coastal waters serve to divert U.S. forces from the uses preferred by the military leadership? What consideration did military planners give to possible civilian reactions to hostile activity against CONUS?

Unity of Decision Making: Did the military leadership have a common perception of the military dimensions and importance of the threat? If so, was this common agreement as to the severity of the threat successfully conveyed to the political leadership and to the public?

In examining the question of whether threats to a nation's homeland force a disproportionate response, the number of possible historical examples to examine is large. This examination is limited to the American historical experience and, more specifically, the U.S. experience with threats to the coast during the Civil War, Spanish-American War, World War I, and World War II. Prior to the Civil War, in the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, the U.S. Navy faced the overwhelming naval power of Great Britain. From the Civil War on, the U.S. Navy was dominant or at least had the potential for fully contesting command of the sea close to the United States. These later experiences of the U.S. Navy seem most relevant to the question of what future reactions might be to a threat to the U.S. coast or coastal waters.

--5--

THE CIVIL WAR

During the Civil War, in the face of immense difficulties, the Confederate Government was able to mount a commerce raiding campaign with an assortment of ships. These ships raided shipping lanes worldwide and even had some success close off commercial centers on the Northern seaboard. Confederate privateers and raiders captured or destroyed nearly three hundred Union ships, with direct losses exceeding $25 million and even greater indirect losses (through higher insurance costs, shipping of goods in neutral ships, and the reflagging of Union merchant ships to neutral flags).1

In 1861, Confederate privateers enjoyed great success. On 17 April 1861, Jefferson Davis offered Southern ship owners letters of Marque, and, by early summer, the twenty such craft operating off the Atlantic coast had captured two dozen Northern ships. 2 The audacious nature of these operations created great hysteria among Northern ship owners. These ship owners and others concerned with maritime commerce placed great pressure upon the President and the Navy Department to divert ships from the blockade of the South to defend Northern harbors, patrol the coasts, guard fishing and shipping fleets, and to hunt the raiders. Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles decided to concentrate on strengthening the blockade: "What is there to prevent the Confederates from maintaining and equipping their fast cruisers except the unwearying vigilance of the blockading fleet?" 3 However, Welles' decision to concentrate the Navy's resources on the blockade was denounced as "pure madness." Editorials described Welles as "a man possessed," a "Rip Van Winkle snoozing" while the nation's seaborne trade expired.4 Yet Welles remained convinced that the blockade remained the answer to the privateering threat - and he was proven correct in this belief. The transition from privateering to naval commerce raiding began as early as June 1861 with the sailing of the first Confederate Navy commerce raider, CSS Sumter. Privateers soon disappeared from the seas due both to losses to Union ships (several Confederate privateer crews were in jail by the fall of 1861) and their inability to safely get their prizes past the blockade.

The new threat that emerged in the Confederate Navy's raiders was, potentially, a more serious one. Once past the blockade, these ships did not require the ability to reenter southern ports, as the goal was not the capture of Northern shipping and trade, but its destruction. Thus, these raiders increased shipping interests' pressure on the government for the dispatch of Union ships to pursue the Confederate vessels. In 1863, there was a general panic along the eastern seaboard when it became general knowledge in the North that there were sea-going ironclads

____________

1. Perhaps the most serious indirect cost was the damage done to the long-term health of the American merchant marine, whose continued decline can be traced from the Civil War. Due to Confederate activity, extra premiums for war risk rose to levels as high as 9 percent of insured value in 1863. Due to these high costs, large numbers of ships were registered under foreign flags. By mid-1864, according to one accounting, the U.S. merchant fleet had fallen from 5.2 to 1.7 million tons. Of the 3.5-million-ton reduction, just 110,000 was due to sinkings by Confederate raiders - most of the reduction was due to transfers to foreign flags to avoid the high insurance rates. Following the war, the U.S. recovered a relatively small amount of this shipping primarily due to laws that greatly restricted a return to the flag of any ship that had given up U.S. registry. (See George W. Dalzell, The Flight from the Flag: The Continuing Effect of the Civil War Upon the American Carrying Trade, Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 1940, pp. 237-262.) On the other side of the ledger, one estimate placed the direct value of vessels and cargo seized by Union blockade ships at $30 million. (Adm. David D. Porter, USN, The Naval History of the Civil War, Secaucus, NJ, Castle Books, 1984, p. 18. This is a reprint of the 1886 original edition of the book. Porter was heavily involved in the riverine campaigns of the Civil War and, for example, commanded the Union Navy forces at the Battle of Vicksburg.)

2. James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, New York, Oxford University Press, 1988, p. 315.

3. Porter, Naval History of the Civil War, p. 623.

4. As quoted in The Civil War: The Blockade, Runners and Raiders, Alexandria, VA, Time-Life Books, 1983, pp. 28-29.

--6--

building in England for the Confederates. Until the panic over the building iron-clads, there had not been great pressure for the deployment of ships off harbors along the New England coast, because most harbors already had some form of coastal fortification.

Welles continued to resist the pressure to dispatch Navy ships all over the globe until the Union Navy had built up enough strength so that sending ships on far-ranging missions would not weaken the blockade. The supreme Union military objective was the subjugation of the Confederacy, and the main Navy contribution to this goal was through the blockade of Southern ports and direct support to Army operations along the coasts and inland waterways. Any diversion from the blockading forces would be "strategically justified only on the ground of grave peril to some vital interest of the North."1

A few commerce raiders did not constitute a "grave peril." Confederate privateers and raiders created additional costs and inconveniences but did not affect the core Union war effort, nor seriously threaten the Union's coast or flow of commerce. While, as the war progressed, more Union ships were on the high seas seeking Confederate raiders (leading to such confrontations as the famous 1864 engagement when USS Kearsarge sunk CSS Alabama off the coast of France), this was a secondary effort. Thus, Welles maintained the Navy's prime focus on strengthening and maintaining the blockade throughout the Civil War, even in the face of great public demands for increased Navy protection of Union shipping.

THE SPANISH-AMERICAN WAR

At the beginning of the Spanish American-War, the public pressured the U.S. military to act in two contradictory directions. That the army land in Cuba as soon as possible was the first demand in a highly jingoistic atmosphere, the public wanted the Spanish "rape" of the Cuban people to be ended forthwith.

The second public demand was for forces (primarily naval) to be assigned to protect the Atlantic coast from possible raids by the Spanish fleet. In light of the potential threat from the Spanish fleet, army operations would wait for resolution of the situation at sea or would depend upon the Navy for escort protection. Rather than devoting the fleet to the blockade of Cuba and deploying it in the best position to intercept Spanish naval movements crossing the Atlantic, the Navy was forced to divert ships to patrol the coast in response to the public fears. Prior to the war, the Navy Department had directed "the preparation of a scheme for a 'mosquito flotilla' for coast defense" and "this auxiliary naval force finally composed forty-one vessels, distributed so as to protect important strategic points of the United States." This, however, was not enough to "allay the unwarranted terror felt by the inhabitants of the coast towns."2 Perhaps the greatest threat, then, that the U.S. Navy faced was not opposition by the Spanish at sea but interference with their operations from their own shores.

Politicians, reacting to the public hysteria, placed great pressure upon the Navy to provide protection for virtually every part of the eastern seaboard. Theodore Roosevelt, Assistant Secretary of the Navy at the start of the war, later summed up the situation as follows:

[A] fairly comic panic ... swept in waves over our seacoast... The state of nervousness along much of the seacoast was funny in view of the lack of foundation for it.... The Governor of one State actually announced that he would not permit the National Guard of that State to leave its borders, the idea being to

____________

1. Harold and Margaret Sprout, The Rise of American Naval Power, 1776-1918, Annapolis, Maryland, Naval Institute Press, 1966, p. 162-164.

2. John D. Long (Secretary of the Navy 1897-1902), The New American Navy, vol. 1, New York, The Outlook Company, 1903, pp. 160, 208.

--7--

retain it against a possible Spanish invasion. So many of the businessmen of the city of Boston took their securities inland to Worcester that the safe deposit companies of Worcester proved unable to take care of them. ... on Long Island clauses were gravely put into leases that if the property were destroyed by the Spaniards the lease should lapse. As Assistant Secretary of the Navy, I had every inconceivable request made to me. ... Congressmen ... Chambers of Commerce and Boards of Trade of different coast cities all lost their heads for the time being, and raised a deafening clamor and brought every species of pressure to bear on the Administration ... to distribute the navy, ship by ship, at all kinds of ports with the idea of protecting everything everywhere. 1

A Georgia congressman wanted a ship to protect Jekyll Island, according to Roosevelt,

because it contained the winter homes of certain millionaires. A lady whose husband occupied a very influential position ... came to insist that a ship should be anchored off a huge sea-side hotel because she had a house in the neighborhood. 2

The Navy sought to resist such pressures, for in essence, the Navy leadership understood the true weakness of the Spanish fleet and they desired not to divide the battle forces in light of what was viewed to be a very unlikely threat. However, the public perception of the threat was not influenced by the Navy's threat evaluation. Instead, the public heard from European (and some American) commentators who greatly magnified the capabilities of the Spanish fleet and disparaged the capabilities of the U.S. Navy.3 The Spanish Navy's view of its own capabilities demonstrates the true extent of the feared threat. Adm. Pascual Cervera y Topete, the commander of the Spanish fleet, feared that the American Navy would seize the Canary islands and would operate against shipping off the Spanish coast. He called for retaining the Spanish Navy in home waters, rather than steaming out "like Don Quixote ... to fight windmills and come back with broken heads."4 Cervera considered any thought of attempting action off the U.S. coast as "a dream, almost a feverish fancy. ... A campaign against that country will have to be ... a defensive one or a disastrous one."5 However, the Spanish Minister of Marine ignored Cervera's opinions and ordered the fleet to cross the ocean.

While the U.S. Navy was able, to some extent, to "avoid frittering away our naval strength by assignment of vessels before every port of the Atlantic and Gulf coasts," substantial diversions still occurred. As Secretary of the Navy John D. Long later wrote:

Apologies are profuse now for the fears of Spanish bombardment entertained by certain coast cities and towns, but in April 1898 there was insistent demand for

___________

1. Theodore Roosevelt, An Autobiography, New York, The MacMillan Company, 1913, pp. 220-221.

2. Roosevelt, Autobiography, p. 221.

3. The absurdities of some of these commentaries are impressive. Many commentators called the U.S. Navy a mercenary navy, with too many foreign sailors (i.e., immigrants) who would be unwilling to risk their lives in battle. Commentators of this ilk thus discounted the physical capabilities of the U.S. Navy's vessels, believing that their crews would desert at the earliest opportunity if war seemed likely to occur. At the same time, these commentators added into calculations Spanish ships that were not yet in the fleet, ships that were obsolete and used for training, and ignored significant readiness problems. This last factor was also one the U.S. Navy was unaware of. See F.E. Chadwick, The Relations of the United States and Spain: The Spanish-American War, vol. 1, New York, Scribner's Sons, 1911, pp. 28-46.

4. As quoted in: David F. Trask, The War with Spain in 1898, New York, Macmillan, 1981, p. 65.

5. Letter of Adm. Cervera to the Spanish Minister of Marine, 16 February 1898. As quoted in Chadwick, Relations of the United States and Spain, p. 99. For a discussion of the Spanish naval strategy debate, see Chadwick, pp. 94-126.

--8--

protection, and the department was compelled to modify the rule of concentration as the guide of its conduct during the war. 1

Thus, the main Atlantic fleet was divided in two, with the "Flying Squadron" deployed at Hampton Roads rather than Key West with the rest of the fleet in order to cover the east coast from the Spanish threat.2 In mid-May, powerful elements of the squadron, including the protected cruisers USS Columbia and USS Minneapolis, were detached to form the "Northern Patrol Squadron" to cruise the waters between Rhode Island and Maine. These ships called at different ports to reassure the local inhabitants, who were terrified by "the specter of Adm. Cervera."3

The "specter of Adm. Cervera" was not simply a civilian fear, however. Troop movements from New York to Florida were made by rail rather than sea "because the fleet of the Spanish Navy...was abroad somewhere on the high seas, location unknown."4 And as long as Cervera's location remained unknown, the Atlantic fleet remained in two distinct forces: the first blockading Cuba, and the Flying Squadron guarding against a possible Spanish descent on the east coast.

The Spanish Navy's greatest value was as a fleet-in-being - its ability to restrict the U.S. Navy's operations simply through its existence. The Spanish government sacrificed this role when it ordered Cervera's ill-prepared and outnumbered squadron across the Atlantic. As soon as Cervera's squadron was discovered in the Caribbean, the U.S. fleet was able to concentrate against it and destroy it.

Following the war, the problems of preventing such a public outcry in a future conflict were examined. Following Mahan's logic in his analysis of the war,5 which stressed a means for visibly reassuring the public, a much greater investment in harbor and seacoast defense in the United States was one of the legacies of the war. Speaking at the Naval War College in 1908, Roosevelt said:

Let the port be protected by the [Army's] fortifications; the fleet must be foot-loose to search out and destroy the enemy's fleet; that is the function of the fleet; that is the only function that can justify the fleet's existence.... For the protection of our

____________

1. Long, New American Navy, pp. 206, 208. The Navy Department's efforts to avoid significant diversions were sometimes less than candid with the President. For example, in his autobiography Roosevelt writes of the instance that "stood above the others. A certain seaboard State contained in its Congressional delegation one of the most influential men in the Senate and... in the lower house. These two men had been worse than lukewarm about building up the navy, and had scoffed at the idea of there ever being any danger from any foreign power. With the advent of war the feelings of their constituents, and therefore their own feelings, suffered an immediate change, and they demanded that a ship be anchored in the harbor of their city as a protection. Getting no comfort from me, they went "higher up" and became a kind of permanent committee in attendance upon the President.... Finally the President gave in and notified me to see that a ship was sent to the city in question. I was bound that, as long as a ship had to be sent, it should not be a ship worth anything. Accordingly a Civil War Monitor, with one smoothbore gun ... was sent to the city in question, under convoy of a tug. It was a hazardous trip for the unfortunate naval militiamen, but it was safely accomplished; and joy and peace descended upon the Senator and the Congressman, and upon the President whom they had jointly harassed. Incidentally, the fact that the protecting war-vessel would not have been a formidable foe to any antagonist of much more modern construction than the galleys of Alcibiades seemed to disturb nobody." Roosevelt, Autobiography, p. 221.

2. Trask, War with Spain, p. 87.

3. G.J.A. O'Toole, The Spanish-American War: An American Epic - 1898, New York, W.W. Norton & Co., 1984, p. 209.

4. As quoted in: O'Toole, Spanish-American War, New York, p. 210. That Army transports might be intercepted at sea was considered a viable possibility, thus railroads were used rather than allowing transports to sail unescorted.

5. A.T. Mahan, Lessons of the War with Spain, Boston, Little, Brown & Co., 1899.

--9--

coasts we need fortifications; not merely to protect the salient points of our possessions, but we need them so that the Navy can be foot-loose.1

The existence of powerful, coastal fortifications served the Navy's interests in more than one way. These fortifications would protect Navy bases from seaborne attack (which, of course, was a central Navy concern). Less directly, but perhaps more saliently in light of the Spanish-American war experience, strong defenses along the coast, according to this logic, would provide a strong sense of security to the public. This, it was thought, would do much to avert the kind of public panic which threatened to fragment the fleet at the beginning of the conflict

Some military commentators disagreed with this approach. They suggested that the least expensive option would be to educate the public as to the low threat against the U.S. coastlines and the proper role of a navy.2 One study pointed out "that at every important point our fixed defenses were more than strong enough to drive off the Spanish fleet.... That there was panic among the denizens of our Atlantic States is a fact, but this panic was not justified by the paucity of our coast-defenses. ... Our brethren of the army had done their work too well and no such paucity existed." The chosen policy, it was argued, had "started on the road" that would bring "a continuous battery from Maine to Texas ..." and that the coastal defense policy's real effect was to "weaken the public confidence in our true coast-defense the sea-going fleet." It was argued that "the most important lesson of the war ...is the danger that uninstructed public opinion may usurp the direction of naval policy, [emphasis added]"3

WORLD WAR I

At the beginning of America's involvement in World War I, two months after the German resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare on 1 February 1917, a debate over the proper role of the U.S. fleet occurred between various parts of the naval leadership. Simply put, RAdm. William S. Sims, commander of U.S. Navy Forces Operating in European Waters, believed that the United States should move its forces, especially escort and mining forces, to English waters as rapidly as possible. Sims believed that the greatest threat facing the Allies, and thus the U.S., was the German submarine campaign against shipping in the Eastern Atlantic. The Secretary of the Navy, Josephus Daniels, and Chief of Naval Operations, Adm. William S. Benson, believed that the main elements of the fleet, including most ships suitable for convoy escort operations, should remain in the Western Atlantic to protect the U.S. coast against a threat from German submarines and, potentially, Germany's High Seas Fleet. In addition, some officers feared that deploying the fleet overseas would risk it at the far end of an uncertain supply line (in light of the U-boat threat). An additional element of this discussion focused on the substantial ongoing naval shipbuilding program. Sims argued that the building of capital ships should be halted so that the ship yards could concentrate on construction that would aid in the antisubmarine war. Benson, on the other hand, believed that this would put at risk long-term U.S. interests, especially in the event of a British collapse and a concentration of the German, Japanese, and, potentially, surrendered British navies against the U.S. coast. This debate waxed and waned, but after several months President Wilson made the decision to focus on escort operations in the Eastern Atlantic.4

___________

1. As quoted in: Emanuel Raymond Lewis, Seacoast Fortifications of the United States, Annapolis, Maryland, Leeward Publications, 1979, p. 99.

2. See Sprout, Rise of American Naval Power, Annapolis, p. 236.

3. Captain Caspar F. Goodrich (USN), "Some Points in Coast-Defense Brought Out By the War with Spain," USNI Proceedings, n. 2, (1901): pp. 231, 234.

4.For a discussion of the internal U.S. debate over the use of naval forces in the war effort, see David F. Trask, Captains and Cabinets: Anglo-American Naval Relations, 1917-1918, Columbia, Missouri, University of Missouri Press, 1972.

--10--

The ability of German submarines to operate in the Western Atlantic had been demonstrated before the U.S. entry into the war. In 1916, two German submarines crossed the Atlantic and raised the specter that the U.S. coast might be vulnerable to German submarines. (U-boats did not start actual war patrols off the coast until a year after the U.S. entry into the war. See table 1.) One of these U-boats, Deutschland, an unarmed "mercantile" submarine, ran the Allied blockade and entered east coast ports twice that year.1 The other, U-53, made a one-day courtesy port call in Newport on 7 October 1916 following a rough trans-Atlantic passage. The U-53 was tasked with attacking Royal Navy ships (which it did not encounter) that were patrolling for Deutschland. The day following the port call, U-53 attacked and sank five non-U.S. merchant ships in international waters off the U.S. coast.

Table 1. German Submarine Operations in the Western Atlantic During World War I

| Name/Number | Left Germany | Arrived off Coast | Left Atlantic Coast | Arrived Germany |

| Deutschland | 14 June 1916 | 9 July | 1 August | 23 August |

| U-53 | 20 Sept 1916 | 7 October | 7 October | 1 November |

| Deutschland | 10 Oct 1916 | 1 November | 21 November | 10 December |

| U-151 | 14 Apr 1918 | 15 May | 1 July | 1 August |

| U-156 | 15 Jun 1918 | 5 July | 1 September | Struck North Sea Mine, sunk |

| U-140 | 22 June 1918 | 14 July | 25 October | |

| U-117 | July 1918 | 8 August | Mid-October | |

| U-155a | Early Aug 1918 | 7 September | 20 October | 15 November |

| U-152 | Late Aug 1918 | 29 September | ||

| U-139 | Early Sept 1918 | while assigned to do so, did not operate off U.S. coast | ||

a) Formerly the Deutschland.

Source: "German Submarine Activities on the Atlantic Coast of the United States and Canada," Navy Department, Office of Naval Records and Library, Historical Section, Publication Number 1, Washington, DC, GPO, 1920, p. 7.

The public reaction to these five sinkings was enormous. A significant stock market fall and a jump in shipping insurance rates followed the U-53 attacks. RAdm. Bradley A. Fiske warned that "U-53 has shown us how accessible our shores are to Europe.... If U-53 got as far as the vicinity of Newport undetected, she could have gone into the harbor itself undetected, and could have sunk one or more of our battleships without our even knowing the cause of their sinking.... If one submarine could come across, a fleet could do the same." Fiske argued that, in

___________

1. After avoiding Royal Navy ships sent to intercept her, the Deutschland arrived in Baltimore, MD, on 9 July 1916 with a cargo of dyes, mail, and precious stones. The Deutschland was unarmed; and, after inspection, it was recognized as a merchant-vessel by the U.S. government. On 2 August, she departed for Bremen (arrived 24 August) with a cargo of zinc, copper, and nickel. The second voyage occurred in October/November, when the Deutschland visited New London. A second mercantile submarine, the Bremen, also sailed for the U.S., but it never arrived. Following her second voyage, the Germans modified Deutschland and her sister ships (there were a total of seven built or building, plus two long-range submarines designed from the keel up as war vessels) to carry torpedoes. (See: R.H. Gibson and Maurice Prendergast, The German Submarine War, London, Constable & Co., 1931, pp. 103-104, 111; Edwyn Gray, The Killing Time, New York, Charles Scribner's Sons, 1972, pp. 150-151, 225; and Dwight R. Messimer, The Merchant U-Boat, Annapolis, Naval Institute Press, 1988.)

--11--

case of war, the U.S. fleet would be required to stay on the east coast to prevent the imposition of a blockade.1

Public (and military) fears were not limited to a submarine campaign. One popular work of the war years prior to the U.S. entry into the war, America Fallen, postulated a German invasion of the United States following a negotiated settlement in Europe in 1916.2 While somewhat farfetched, this scenario was not totally unrelated to scenarios that had been examined in more serious fora. In the early 1890s, following German-American tension over Samoa, the German admiralty began to examine options for a conflict against the U.S. An 1899 plan called for a surprise assault on New York, while a January 1902 plan called for the seizure of Puerto Rico as an operating base for operations against the U.S. coast.3

In 1903, Proceedings republished with commentary an article from Scientific American on the path of a naval war between Germany and the U.S. as it had unfolded during one war game society's utilization of the "Jane Naval War Game". While the game ended in the U.S. side "winning," victory came at the cost of 60 percent of U.S. commerce, the destruction of 40 percent of U.S. coastal property and the weakening of the U.S. Navy.4 While these may have been considered unlikely scenarios, that the Germans might be capable of exerting force directly against the United States was of concern to the U.S. military leadership. In fact, the primary U.S. Navy planning for a war against Germany, Plan Black, focused on the probability of a major naval engagement on the high seas between the two nations' fleets.5

Thus, at the beginning of the war, these prewar concerns and the fears elucidated by Fiske and others were paramount in the thinking of many in the Navy Department. Sims, secretly sent to England just prior to the U.S. entry into the war, called for an immediate and total U.S. commitment to the ASW battle in the convoy approaches in the Eastern Atlantic because Britain seemed to be on the verge of being forced out of the war as a result of the merchant shipping losses to German submarines. And, with longer lasting implications, Sims argued that the entire U.S. shipbuilding effort should be focused on two types of shipping destroyers and other ASW-capable vessels, and merchant ships to replace the heavy allied losses and that the substantial U.S. production of major fleet units should be halted for the duration of the ASW emergency.

___________

1. Rear Adm. B.A. Fiske (USN), "What the Visit of the U-53 Portends to the United States," USNI Proceedings, n. 6, 1916, pp. 2038-2039. At the time of the U-53 visit to Newport, Fiske was finishing his last tour of duty with an assignment to the Naval War College.

2. The book outlines this scenario: Germany negotiates peace with a large indemnity ($15 billion) to Britain and France, but does not destroy any forces. Germany purchases St. Thomas from Denmark and deploys her fleet to the Caribbean. On 1 April, the day after the U.S. learns of the St. Thomas purchase, German troops land in Boston and New York, and the German Navy cripples the U.S. Navy through a surprise attack. Within a month, the U.S. is forced to accept a $20 billion indemnity thus Germany earns a $5 billion profit between the two conflicts. J. Bernard Walker, America Fallen, New York, Dodd, Mead & Co., 1915. One military reviewer wrote that "The author has made use of accurate information regarding our land forces to draw a vivid picture of possible consequences of our present unpreparedness for national defense.... The tragic events recited are supposed to take place on April 1, but granting only the element of surprise, there is no reason why they should not take place on any other day of the year." Infantry Journal, vol. XII, July-August 1915, pp. 163-165.

3. This somewhat fantasy planning essentially ceased in 1906 as the Admiralty Staff increasingly turned its attention to questions of a European conflict. See Carl-Axel Gemzell, Lund Studies in International History 4: Organization, Conflict, and Innovation: A Study of German Naval Strategic Planning, 1888-1940, Stockholm, Esselte Studium, 1973, pp. 70-73.

4. See: Fred T. Jane, "The Naval Wargame," pp. 595-660, and LtCdr A.P. Niblack, USN, "The Jane Naval War Game in the Scientific American," pp. 581-593, USNI Proceedings, n. 107, September 1903.

5. Clay Blair, Jr., Silent Victory: The U.S. Submarine War against Japan, vol. 1, Philadelphia, J.B. Lippincott, 1974, pp. 21-22.

--12--

Benson and Daniels, on the other hand, believed that a threat existed against the U.S. coast that required keeping the fleet in reserve. They perceived a multidimensional threat that was not limited to the German submarine fleet (and Sims' assertions that Great Britain was near collapse strengthened their concern that the German High Seas Fleet would threaten the U.S. directly when Britain fell). They also looked with concern at the Japanese in the Pacific (following a 1912-1913 war scare in the Pacific) and at the possibility of a U.S.-U.K. confrontation following the war. The fear that the Allies might collapse (leaving the U.S. to face Germany and, perhaps, Japan alone) and the desire to achieve the shipbuilding goal of acquiring a Navy second to none both encouraged hesitation over modifications in the shipbuilding program. On 20 April 1917, the Navy's General Board met and presented its views on the question of whether to continue the capital ship building program. The Board thought it necessary to consider not only the present emergency but also the possibility of "a war resulting from the present one in which the United States may be confronted by Germany and Japan operating conjointly in the Atlantic and Pacific; it is also possible that we may have to meet these two powerful navies without allies to restrict the operations of the German fleet"1 Thus, Sims' requests for the rapid deployment of Navy assets to the British Isles and the realignment of U.S. shipbuilding efforts faced great resistance in Washington.

Despite the debates, however, the Navy was the only service prepared to make an immediate contribution to the war effort and it quickly started deploying forces to England. On 4 May 1917, the first flotilla of six destroyers reached the Irish coast. By 1 July, 28 of the 52 available U.S. destroyers were on station in Europe. At this point, deployments to England slowed. The Navy Department withheld dispatch of the remaining destroyers for a variety of reasons. While some were in need of repair, the primary concerns were hesitation over further dividing the battle fleet and demands for destroyers for patrols along the east coast.2 Sims vociferously argued for the deployment of all available ships to the Eastern Atlantic.

For months, the Navy Department and Sims battled via trans-Atlantic cable. President Wilson finally resolved the issue by supporting Sims' emphasis on the protection of merchant shipping in the area of the British Isles3 and, therefore, in favor of a shipbuilding program that emphasized vessels for the submarine war over continued expansion of the main battle line. This was never wholeheartedly adopted as Navy policy and while, at the height of the effort, some 370 ships were in Eastern Atlantic or Mediterranean waters, this was out of a total of over 1,500 Navy units and included less than 15 percent of Navy personnel. 4 Adm. Benson stated his war priorities in this manner:

____________

1. Trask, Captains and Cabinets, p. 102.

2. Trask, Captains and Cabinets, p. 77.

3. As early as late summer 1917, as convoying eased the submarine crisis, the debate shifted to whether the USN should concentrate on protecting shipping to England or on protecting U.S. troop transports. As Captain William V. Pratt (USN) wrote, "The impelling reason of the British was protection to food and war supplies in transit. Our basic reason was protection to our own military forces in crossing the seas.... The most important future cross water operations" were those that would ensure "safe transportation of American troops to French soil." On this issue, Sims did not have his way, and the USN emphasis was placed upon safely transporting the U.S. Army to France. See: Mary Klachko, Admiral William Shepherd Benson: First Chief of Naval Operations, Annapolis, Naval Institute Press, 1987, p. 70-71; and, Dean C. Allard, "Anglo-American Naval Differences During World War I," Military Affairs, vol. XLIV, n. 2, April 1980, pp. 76-77.

4. Elting E. Morison, Admiral Sims and the Modern American Navy, New York, Russell & Russell, 1942, p. 369. The personnel figure is potentially misleading. The percentage of the Navy's manpower in training camps, assigned to transports and cargo ships carrying troops to Europe, and manning the fleet's battleships (few of which were deployed to the Eastern Atlantic) must have been enormous.

--13--

My first thought in the beginning, during, and always, was to see first that our coasts and our own vessels and our own interests were safeguarded. Then ... to give everything we had... for the common cause.1

In May 1918, the long-dreaded U-boat activity in the Western Atlantic began as U-151, the first of seven U-boats to operate off the east coast, arrived in its area of operations.2 This submarine, a converted mercantile submarine, cut telegraph cables, laid mines, and attacked shipping both on the surface (with gunfire, and by boarding and sinking with demolitions) and submerged (with torpedoes). After U-151's minefields, laid off Baltimore, "claimed their first victims ... a wild panic ensued on shore. German U-boats were reported everywhere, ships were hurriedly recalled to harbor by their owners, freight rates began to rise, and marine insurance premiums soared."3 The other U-boats to operate off the U.S. coast used the same techniques. An unusual twist was added near the end of August. A fishing boat, Triumph, was captured and used to attack other fishing boats near the Grand Banks.4

U-151's activities and those of the six other U-boats that deployed to the Western Atlantic came with very accurate prior warning from Adm. Sims in England, who erred, for example, by one day as to the arrival of U-151 off the east coast.5 Sims was well aware of the potential psychological dangers of the coming U-boat campaign and feared that undue pressure would be brought to bear to keep antisubmarine ships on the east coast.

There is no doubt in our minds over here, that what [the enemy] seeks to do is to produce a moral and political effect, and that as the result of these effects, he can induce the Allies to disintegrate their [anti] submarine forces.

For example, if by sending one submarine to America to plant the few mines he can carry, or to sink the few ships that he can sink, he can through the influence of his presence upon public opinion, force our Government to keep a large number of destroyers on the other side or in any service not connected with the real antisubmarine campaign, he will have succeeded admirably in his objective.

Of course I understand something about the effect of public opinion, but this public opinion must necessarily be an ignorant opinion viewed from a military standpoint. It would therefore seem that it was up to us to instruct this opinion so as to prevent the effect the enemy wishes to produce... This should not be difficult, as the question [explaining the purpose of the cruising submarines to the public] is one of marked simplicity.6

The seven German U-boats had great success. With the loss of just one submarine, over 150,000 tons of shipping were sunk in the Western Atlantic. Losses included the sinking of USS San Diego, an armored cruiser, and damage to the battleship USS Minnesota. Large numbers of

____________

1. As quoted in Allard, "Anglo-American Naval Differences," Military Affairs, pp. 75-76.

2. For a discussion of the German debate over whether or not to operate submarines off the U.S. coast, see: Holger H. Herwig and David F. Trask, "The Failure of Imperial Germany's Undersea Offensive Against World Shipping, February 1917 - October 1918," The Historian, vol. XXXIII, n. 4, August 1971, pp. 613, 617-623, 626. The Kaiser hesitated over deploying submarines to the Western Atlantic, hoping to avoid arousing "the less militant regions of the United States" and, thus, that pacifist elements in the United States might weaken the U.S. war effort.

3. Gray, Killing Time, p. 234.

4. Gibson and Prendergast, German Submarine War, pp. 309-310. The Triumph, as a German corsair, was responsible for the sinking of at least ten fishing vessels in the last weeks of August.

5. Gibson and Prendergast, German Submarine War, pp. 306-307.

6. Adm. W.S. Sims cable to Secretary of the Navy Benson, 17 May 1918. As quoted in Morison, Admiral Sims and the Modern American Navy, p. 411; and Trask, Captains and Cabinets, pp. 219-220.

--14--

U.S. Navy ships were active in the Western Atlantic to deal with this seven-submarine threat. In terms of the U.S. capability to wage war, however, the U-boat campaign itself had little effect. Just one ship involved in convoy operations was sunk, the British steamer Dvinsk, which was empty en route to Newport News for troops.1 The Navy Department's postwar study of the submarine offensive concluded that:

The German campaign, by means of submarines on the Atlantic coast of the United States, so far as concerned the major operations of the war, was a failure. Every transport and cargo vessel bound for Europe sailed as if no such campaign was in progress. All coastwise shipping sailed as per schedule, a little more care in routing vessels being observed. There was no interruption to the coast patrol which, on the contrary, became more active. The small vessels ... scoured the coast regardless of the fact that the enemy submarines were equipped with ordnance very much heavier than their own. There was no stampede on the Atlantic coast; no excitement; everything went on in the usual calm way and, above all, this enemy expedition off the Atlantic coast did not succeed in retaining on the Atlantic coast any vessels that had been designated for duty in European waters.2

It is true that the German submarine campaign off the east coast did not force a redeployment of U.S. Navy assets from Europe back to the U.S. However, prior to the U-boats' arrival, the fears of such a campaign had already contributed to the Navy's restraint for the year that the U.S. had been in the war. While the restriction on the U.S. Navy's activities and hesitation in modifying its building program reflected concerns in much of the populace, it resulted from a debate and concerns within the Navy itself rather than pressure from the civilian community. In examining the record, it is difficult to separate the military decision process from the atmosphere in which the decisions were made. It seems, however, that the debate over how best to utilize the Navy and what force to construct for the war centered on differing naval perspectives of the war and its imperatives rather than from undue or uninformed pressure on the Navy's leadership.

WORLD WAR II

During World War II, there were a number of threats to the U.S. coast and/or coastal waters that are relevant to the current research. These range from the significant German U-boat operations off the east and Gulf Coasts starting in January 1942 to the Japanese balloon-bombing campaign late in the war. Some of the incidents examined were not "real," but only perceived threats, such as the battle against Group Seewolf in April 1945, when it was feared that the Germans were attempting to use U-boats for launching rocket attacks against east coast cities. This section examines a number of these World War II experiences.

Reaction to Pearl Harbor

Following Pearl Harbor, the nation was shell-shocked:

No American who lived through that Sunday will ever forget it. It seared deeply into the national consciousness, shearing away illusions that had been fostered for generations. And with the first shock came a sort of panic. This struck our deepest

__________

1. Gibson and Prendergast, German Submarine War, pp. 307.

2. "German Submarine Activities on the Atlantic Coast of the United States and Canada," Navy Department, Office of Naval Records and Library, Historical Section, Publication Number 1, Washington, DC, GPO, 1920, p. 141. The Navy Department's official assessment that "everything went on in the usual calm way" seems too positive, however, the most important point of this quote is correct: no disruption occurred in convoys to Europe.

--15--

pride. It tore at the myth of our invulnerability. Striking at the precious legend of our might, it seemed to leave us suddenly naked and defenseless."1

There were great fears not only among the public, but in the military as well, that the west coast would suffer from Japanese follow-up raids. Thus, the early months of the war saw frantic efforts to secure the west coast from any such Japanese efforts and, perhaps surprisingly, the east coast from any similar German act.

In an address to the nation, President Roosevelt stressed that the initial attack could be repeated "at any one of many points in both oceans and along our coast lines and against the rest of the hemisphere." The terrible lesson of Pearl Harbor should be clear to every citizen, "that our ocean-girt hemisphere is not immune from severe attack... We cannot measure our safety in terms of miles on any map."2 RAdm. Clark H. Woodward (ret.) suggested in a news commentary that the Japanese or their allies would probably make sporadic "hit and run" attacks against the U.S. to terrorize the population and to break morale. He warned that the nation should be prepared for "an unannounced air raid on some coastal town or industrial center at most any time - now that we have enemies across both oceans."3 Fiorello LaGuardia, Mayor of New York City and national Civil Defense chairman, warned that "the war will come right to our cities and residential districts..."4 Such commentaries fueled fears of further air attacks. Rumors and scares occurred on both coasts, but were particularly rampant on the Pacific coast.

Shortly after the Pearl Harbor attack, the captain of USS Fox (one of five WWI-era destroyers that were the primary U.S. Navy ships in the Northwest Sea Frontier) received a report that 24 enemy vessels were approaching the coast off Monterey.5 On 8 December, an enemy air raid was reported 100 miles west of San Francisco; Army planes claimed they fired on one of the two reported Japanese formations; and contact was made with and depth charges dropped on "submarines" in San Francisco Bay. Lt. Gen. John L. DeWitt, commander of the Western Frontier, countered any thoughts area citizens might have had that the Army was playing games to motivate them to practice their blackouts:

There are more damned fools in this locality than I have ever seen. Death and destruction are likely to come to this city at any moment. These planes were over our community for a definite period. They were enemy planes. I mean Japanese planes. They were tracked out to sea. Why bombs were not dropped, I do not know. It might have been better if some bombs had dropped to awaken the city.6

In fact, there were no Japanese planes in the area. Two days later, San Diego was blacked out when an air raid was reported. 7 On December 9, OPNAV warned Adm. Kimmel in Hawaii that:

___________

1. Marquis Childs, I Write from Washington, New York, Harcourt, Brace, & Co., 1942, p. 241.

2. Roosevelt 9 December 1941 radio address as quoted in: William A. Goss, "Air Defense of the Western Hemisphere," Chapter 8 in The Army Air Forces in World War II, vol. 1: Plans and Early Operations, January 1939 - August 1942, Wesley Frank Craven and James Lea Cate, editors, Office of Air Force History, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1948, p. 272.

3. Woodward 19 December 1941 commentary as quoted in: Martin V. Melosi, The Shadow of Pearl Harbor, College Station, Texas, Texas A & M Press, 1977, p. 4. Woodward had retired from the Navy just prior to the start of the war.

4. LaGuardia December 1941 statement as quoted in: Richard R. Lingeman, Don't you know there's a war on? The American Home Front, 1941-1945, New York, GP. Putnam's Sons, 1970, p. 35.

5. Grahame F. Shrader, The Phantom War in the Northwest, 1941-1942, self-published, 1969, p. 5.

6. Lingeman, Don't you know there's a war on? p. 25.

7. USN Administration in World War II, vol. 1, 163(a), Commander, Western Sea Frontier, 1945, p. 32.

--16--

Because of the great success of the Japanese raid on the seventh it is expected to be promptly followed up by additional attacks in order [to] render Hawaii untenable as a naval and air base in which eventuality it is believed [that the] Japanese have forces suitable for [the] initial occupation of islands other than Oahu, including Midway, Maui, and Hawaii. ...

Until defenses are increased it is doubtful if Pearl should be used as a base for any except patrol craft, naval aircraft, submarines or for short periods when it is reasonably certain Japanese attacks will not be made.1

Reinforcing west coast defenses was one of the greatest priorities in the Department of War following the Pearl Harbor attack. The U.S. had relied upon Hawaii and the fleet to provide a barrier to any serious threat to the west coast. On 9 December, Stimson reported to Roosevelt that "the present attack has left the West Coast unprotected."2 The official threat assessment categorized submarine operations off the coast as "highly probable" and stated that air raids could be expected against west coast targets.3 West coast air defense reinforcement was rapid; the first elements of a pursuit group from Michigan began to arrive in the Los Angeles area on the 8th. By 17 December, nine additional antiaircraft regiments had arrived on the west coast.4

While Japanese troop assaults against the west coast were considered unlikely, significant forces were deployed to face this potential "invasion" threat. The 218th Field Artillery, which had departed two weeks before the war from Fort Lewis, Washington, for the Philippines was 1,000 miles out to sea on 7 December. It was quickly ordered to return to reinforce coastal defenses. Within a week after Pearl Harbor, the 21,000 troops of the 41st division were "thinly scattered along the Washington coast from the Canadian border to the Columbia River and beyond in anticipation of an invasion."5 By the end of December, two additional divisions and many other smaller units were deployed to the west coast6

Secretary of War Stimson became frustrated with what he viewed as a Navy overemphasis and preoccupation with the securing of Hawaii and the west coast at the beginning of the war. Regarding opposition to options for relieving the Philippines, Stimson wrote in his diary:

We have met with many obstacles, particularly because the Navy has been rather shaken and panic stricken after the catastrophe at Hawaii and the complete upset of their naval strategy which depended upon that fortress. They have been willing to think of nothing except Hawaii and the restoration of the defense of that Island. They have opposed all our efforts for a counter-attack, taking the defeatist attitude that it was impossible before we even tried.7

___________

1. As quoted in: Gordon W. Prange, At Dawn We Slept, The Untold Story of Pearl Harbor, New York, McGraw-Hill Book Co., 1981, p. 585.

2. Goss, "Air Defense of the Western Hemisphere," Army Air Forces in WWII, p. 272.

3. "The category of defense for the Northwest Sea Frontier except UNALASKA, has been designated as 'Category C; UNALASKA as 'Category D'. 'Category C is a category of defense based on the assumption that the sea frontier will be subject to minor attack. 'Category D' is a category of defense based on the assumption that the area defined may be subject to major attack. Enemy submarine attacks on shipping in the coast waters of the Northwest Sea Frontier are highly probable. Enemy air attacks from carriers may be made upon military objectives and important industrial areas. Attempts at sabotage and sabotage activities may be expected." Headquarters, Northwest Sea Frontier, Seattle, Washington, 12 December 1941 Operation Order, Paragraph 1.

4. Byron Fairchild, ed., The United States Army in World War II: The Western Hemisphere, vol. 2: Guarding the United States and its Outposts, Stetson, Conn, 1964, p. 83.

5. Shrader, Phantom War in the Northwest, p. 7-8.

6. Fairchild, ed., United States Army in World War II: The Western Hemisphere, p. 83.

7. 14 December 1941 Stimson diary entry as quoted in: Prange, At Dawn We Slept, p. 585.

--17--

In the days following Pearl Harbor, military assets were diverted to coastal defense from what, in a calmer environment, would have been the preferred usage. However, it is unclear that such diversions occurred due to public pressure on the military for added defense against a threat. The result of surprise in war can be panic, and in the case of Pearl Harbor both the military and civilian world suffered from the surprise. Indeed, a sense of panic and shock pervaded the military as it did the civilian world, and thus, as always in such a situation, rationality might not have held sway in the decision-making process.

Japanese I-Boat Operations Off the West Coast