The Navy Department Library

US Naval Port Officers in the Bordeaux Region, 1917-1919

Administrative Reference Service Report No. 3

U. S. NAVAL PORT OFFICERS IN THE BORDEAUX REGION, 1917-1919

Prepared by

Dr. Henry P. Beers

Under the Supervision of

Dr, R. G. Albion, Recorder of Naval Administration

Secretary’s Office, Navy Department

Lt. Cmdr. E. J. Leahy, Director, Office of Records

Administration, Administrative Office,

Navy Department

Office of Records Administration

Administrative Office

Navy Department

September 1943

U. S. Naval Port Officers in the Bordeaux Region

1917-1919

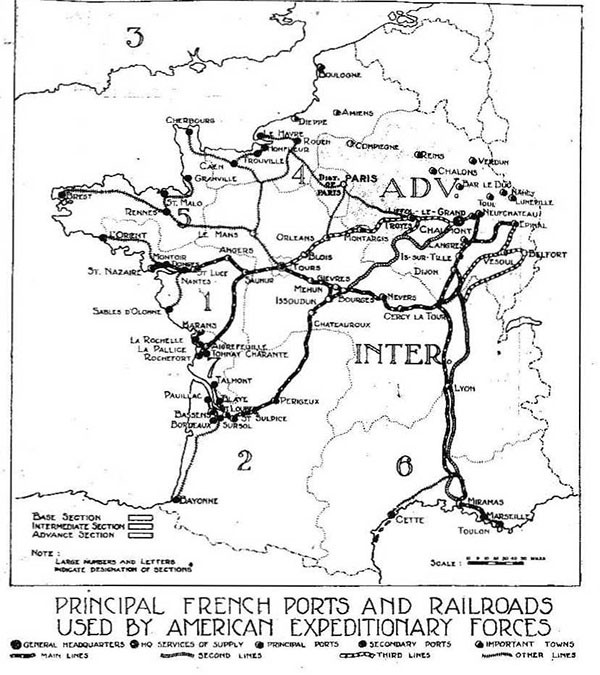

For the use of the American Expeditionary Force of the United States Army and American naval forces, it was necessary to acquire and develop extensive port facilities in France in 1917. Ports suitable for troop transports, cargo vessels, and naval patrol and escort vessels had to be found, so that the United States could get its men and material to the front and make its might felt in the struggle against Germany. During the preceding years of the war, the British had preempted the French Channel ports and the railroads leading from them to the front-lines also utilized for military operations—so that it was necessary for the United States to use the Bay of Biscay ports on the west coast of France. Besides being more remote from the front, a fact which increased transportation difficulties, most of these ports were not of sufficient depth to admit the largest ships and were poorly supplied with berths and facilities.

Since Bordeaux was the largest commercial port on the Bay of Biscay and third largest in the country, ranking after Le Havre and Marseilles, it was natural for it to become an American base. It was also natural for local interests to seek to attain this desirable end, and they did by instigating a report by a French military commission which recommended the establishment of a station for patrol vessels at Le Verdon, the use of Pauillac for discharging cargoes, troops, and animals, and the construction of new facilities at Bassens. An inspection of the ports on the west coast of France was made upon orders issued shortly after the declaration of war by a joint Franco-American commission. It reported that the early debarkation of American troops should take place at St. Nazaire, but it indicated that La Rochelle and Bordeaux would have to be used. Extensive improvements in the way of docks and railroad facilities were recommended for the last harbor, which should be kept unencumbered pending their completion. There appears to have been an examination of these ports by a Joint board of U. S. Army and U. S. Navy officers during this period. In June 1917 a Military Railroad Commission composed of American Array officers made a tour of the French front; they inspected the railroad lines connecting it with the

--1--

Bay of Biscay, and the ports of the bay, including those in the Bordeaux region; and they collected data which was used in planning the Army's transportation system in France.

The ancient city of Bordeaux, famous in the United States for the wines named after it that are produced in the neighboring country, is located on a semi-circle of the Garonne River sixty miles from the sea. Although not capable of accommodating the largest ocean liners of that day, the port of Bordeaux possessed considerable shipbuilding, repair, and supply organizations, in addition to being well protected from the weather, secure from naval attack, and remote from the usual zones of submarine activities. Twenty miles below Bordeaux at Bec d'Ambes the Garonne unites with the Dordogne River to form the Gironde River, a wide estuary which one naval officer who served on it likened to the upper half of Delaware Bay. Other ports on the Garonne-Gironde system employed by United States forces included Bassens, four miles below Bordeaux an the east bank of the Garonne, and Pauillac on the west bank of the Gironde twenty-five miles from its mouth, with wharfage for vessels too large to ascend to Bordeaux. At Le Verdon on the southern side near the mouth of the Gironde a great arm of the land provides a sheltered roadstead where vessels could be anchored pending the receipt of movement orders. From Le Verdon a railroad provided a further means of travelling to Bordeaux. Across the embochure from Le Verdon, lay Royan, one of the chief sea bathing resorts of France, which was useful chiefly because of its location as it lacked wharfage with discharge facilities.

Before the entrance of the Americans into Bordeaux, it had been developed as a revictualling base by the French. To increase its capacity for this purpose, new quays and facilities were constructed at Bordeaux, Bassens, Pauillac, and at Blaye on the east bank of the Gironde not far from Pauillac. So crowded were the docks on the river in 1915 that colliers were considerably delayed before getting berths. The total quantity of imports was greatly expanded while the exports were even more greatly reduced. But the advent of the Americans was to effect an even greater change in the economic life of the region.

--2--

The importance of the port facilities in France in the American military effort was realized by Rear Admiral Albert Gleaves, commander of the Cruiser and Transport Force of the U. S. Navy, who said that "the number of troops that may be landed in France at present depends not upon the success of the anti-submarine campaign, and consequent tonnage available and building, but upon the port facilities provided in France and England for the disembarkation of the troops and supplies that must come from America."

The U. S. Navy Department at the outbreak of the war had no plans for the organization of a port system and little idea of what would be needed in connection therewith. Following the decision of the government to aim merchant vessels, Rear Admiral William S. Sims was ordered towards the end of March 1917 to England to represent the Navy and keep it informed of developments.

On June 14, 1917, he was placed in command of our naval vessels abroad as Force Commander, U. S. Naval Forces Operating in European Waters. Secretary of the Navy Daniels informed Sims on May 8 that the French government had requested and the Navy Department was contemplating the establishment of temporary bases at Bordeaux and Brest. Sims approved—provided the destroyer bases did not suffer. Orders were issued by the Secretary on June 1 to Capt. William B. Fletcher to organize the vessels being fitted out for distant service as the U. S. Patrol Squadrons Operating in European Waters, to proceed to Brest, establish a base there, and begin operations in the waters adjacent to the French coast under the general command of Vice Admiral W. S. Sims. Slightly more than a month later Captain Fletcher reached Brest with his converted yachts, and, after locating his headquarters on shore at Brest, began operating with the French Navy against German submarines. His original complement of eight vessels was augmented by two additional squadrons of converted yachts in August and September, and by a destroyer squadron in October.

At the beginning of June, Comdr. John B. Patton, an officer of considerable experience in naval construction who had recently been recalled from retirement, received orders from the Chief of the Bureau of Navigation to proceed to Bordeaux, France and take command of the naval base to be established there. He could get no definite

--3--

orders in the department as to what his exact duties were to be, but, knowing that he would have to establish the base, he asked for and was assigned an engineer officer, a paymaster, and several yeomen. He was told by the French naval attache in Washington that the Navy Department had agreed to establish two naval bases in France. Arriving in Bordeaux in the Espagne on July 18, he reported by letter to Admiral Sims and to Captain Richard H. Jackson, the Navy Representative in Paris. After seeing them and Captain Fletcher subsequently in Paris, he was still without specific instructions from the American Naval authorities so he proceeded along the lines already worked out by the French, who had planned the development of a coaling and supply station at Pauillac for the use of the naval patrol and escort vessels operating along the coast.

The naval station at Pauillac was located in the neighboring hamlet of Trompeloup, thirty miles from Bordeaux, where a steel and concrete wharf was available for use. Here with the approval and assistance of the French authorities Commander Patton began the development of a base for the use of the American naval vessels which were just then arriving on the coast of France. He acquired land, rented buildings, contracted for coal, and began the construction of another wharf from piling and planks. The transformation of vineyards, industrial plants, and pastures into a naval base comprising storage buildings, housing for personnel, and repair facilities went ahead under the direct supervision of Lieut. Louis L. Bernier, a native of France long a resident of the United States and an experienced ship repair man who had enrolled in the Naval Reserve Force and accompanied Patton to Bordeaux. Admiral Sims, to whose headquarters in London Commander Patton had been reporting his troubles, sought in August to obtain authorization from the Navy Department for the expenditure of $150,000 on the proposed base, but Admiral William S. Benson, the Chief of Naval Operations, responded that it was not the department's policy to commit itself to the establishment of shore bases except for aviation purposes to a greater extent than the military situation absolutely demanded and that it was the intention to supply two repair ships for the use of the small craft operating on the French coast. Sim's rejoinder was that the situation demanded a shore establishment at Pauillac and that furnishing mother ships

--4--

would be diverting valuable trans-Atlantic tonnage.

In reply Admiral Sims was informed that the U. S. S. Panther and the U. S. S. Bridgeport would be sent to France, This decision forced the discontinuance of the work on the repair shop at Pauillac much to the disappointment of the French, but the preparations for its use as a coaling station went ahead. A former laundry building furnished accommodations for the men to be attached to the station, and ample storerooms.

At Bordeaux in the meantime Commander Patton had been organizing the staff of the American Naval Base. Its organization, as prescribed in a general order of July 31, 1917, comprised several departments. The office of the Commanding Officer or Port Officer, consisting of Commander Patton, a chief yeoman and 3 yeomen, was concerned with the movements of vessels, log books, personnel records, the Bureau of Navigation, and communication. Paymaster F. B. Colby acted as disbursing officer, supply officer, and accounting officer and was concerned with general administration, contracts, requisitions, pay roll, storehouses and supplies, ordnance stores, and commissary department. He was assisted by a chief yeoman and a yeoman. The industrial department was under Lieutenant Bernier and comprised a civil engineer, an electrician, a chief petty officer, and ten men. Surgeon H. Shaw, Assistant Surgeon L. Hays, and four hospital corpsmen composed the medical department, which took care of the sick bay, hospital arrangements, and sanitary inspection. At the end of September, nineteen enlisted men were included in the personnel at Bordeaux; these increased to only twenty-four at the end of 1917.

To look after the interests of American ships which were beginning to arrive in considerable numbers at French ports, Admiral Sims ordered Comdr. Frank P. Baldwin to duty as naval port officer at St. Nazaire and Commander Patton to additional duty in the same capacity at Bordeaux. The latter’s orders were issued to him on September 24, 1917 and designated him as naval port officer at Bordeaux, Pauillac, and Bassens, Admiral Sims notified Rear Admiral Fletcher, Commander,

U. S. Patrol Squadrons Operating on the French Coast, that these officers were to be under his orders and described their duties as follows:

--5--

5. SHIPPING

He should control all U.S. Shipping, permitting no vessel to sail except under his orders, and in regular organized convoys. The term "U.S. Shipping" is to be construed as embracing troop transports, chartered supply-vessels carrying any supplies, Naval supply vessels, all vessels under charter to the U.S. Government, and such other U.S. Merchant vessels as may visit the port in question. Some difficulty may be experienced in controlling U.S. vessels which are not under charter by the Government, but by working with the French authorities, it may be possible to withhold the clearance of such vessels until they express willingness to car[r]y out orders. All Allied shipping in British waters is now required to travel in convoy, regardless of nationality, and the U.S. Government is shortly to require all vessels to leave home ports in convoy. In order to reduce shipping losses on this side it is necessary to take a firm hand and dispatch our vessels in such a way as to provide the greatest security.

6. TROOP TRANSPORTS AND STORE SHIPS

The Naval Port Officer should be informed by you of the prospective arrival of Troop Transports and Store Ships, and all arrangements made for their escort into port. In the case of vessels of the same classes outward bound they are to be detained in port, or at a safe anchorage in the vicinity of the port, until a convoy can be formed and a suitable escort provided. The Naval Port Officer must keep you informed as to the dates of readiness for sailing of such vessels, and permit none of them to sail except in convoys. This will, probably, result in the delay of some ships, but it will ensure safety, and it seems probable that a regular outward bound convoy from a suitable port may be arranged to sail about once every eight days. In such convoy can be placed any Allied westbound merchant vessels. Your duty with respect to these convoys will be to see that they are provided with suitable escort

--6--

and to give instructions as to time of sailing. Ordinarily they should leave the French coast just before dark, so as to pass through the most dangerous areas by night, and be escorted for about forty-eight hours. You would also prescribe the route to be pursued through the danger zone upon information furnished from London or Paris or derived from the local French authorities.

7. The internal organization of the convoy will be the responsibility of the Senior Officer of the convoy, who should provide the necessary instructions for zigzagging, behavior under attack, dispersal, rendezvous, etc. As it is probable that the Naval Port Officer will frequently be consulted on these matters, he should be kept supplied with all the latest information as to tested and approved methods, so that he may give proper advice on request.

8. AIRCRAFT

The Naval Port Officer should, whenever possible, arrange for the co-operation of the French Coastal Air Stations to assist our inward and outward bound convoys. This may be accomplished by your office, but the Port Officer should have full authority to communicate direct with the local French authorities as well.

9. MINESWEEPING

The Naval Port Officer should, by constant communication with you and with the local French authorities keep himself fully informed as to the state of the approach channels, the progress of mine-sweeping operations and the results of such operations, and should keep you similarly informed.

10. COAL AND OTHER SUPPLIES

The Naval Port Officer should keep you informed as to the amount of coal and other supplies on hand and the amounts desired from time to time.

--7--

11. INFORMATION

The Naval Port Officer should interview the Captain or Master of every U. S. Man-of-War, Transport, Supply Ship, and other vessels entering his port, for the purpose of bringing out any criticisms they may have to make as to difficulties of entering the ports, lack of pilots, patrols, etc., and any suggestions they may have for improvements. These matters are of urgent importance, particularly in connection with our Troop Transports and Supply Ships. Conditions that may be handled by the local French authorities should be taken up direct with them.

12. CO-ORDINATION

It will be the duty of the Naval Port Officer to keep in constant and close touch with the U.S. Array representatives and the French authorities at the ports to work in close harmony with them and to use every endeavor to avoid friction and clashes of authority.

13. COMMUNICATIONS

The Naval Port Officer will have complete charge of the communication office at his port. He will be given the services of a Communication Officer, whenever such detail is found possible, and will, also, be furnished with a Communication Staff of the necessary size.

14. At St. Nazaire Assistant Paymaster Cunnungham is, at present, detailed as Communication Officer, and he will continue at that capacity until such time as another officer can be sent for that duty. Paymaster Cunningham has certain additional duties in connection with disbursements which he will continue to perform. A separate letter will be written going into the duties of the Communication Officer in more detail.

15. The Communication Officer at each port will, under the instructions of the Port Officer, and with his advice, assistance and co-operation, handle all matters in regard to communications,

--8--

make suggestions for improvement and make provision for keeping a secret file of all important messages; also, he will take steps to guard against secret communications falling into the hands of any but Commissioned Officers, or such member of the Communication Force as it may be found necessary, owing to shortage of personnel, to entrust them to.

16. It is particularly necessary that the prospective dates of arrival of Troop convoys and Supply convoys be kept secret, and be communicated to the French authorities and the U.S. Army authorities only in sufficient time to permit them to make the proper preparations for their reception.

17. REPORTS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

All reports made by the Naval Port Officer should be made to you direct, the most secret and rapid means of communication being utilized. The Naval Port Officer should, however be authorized to communicate direct with my Staff Representative in Paris and with other Naval Port Officers in cases of urgent necessity. He should, in all cases, immediately furnish you with copies of his communications.

18. ARMED GUARDS

Whenever a vessel carrying a Naval Armed Guard enters a Port Officer's port he is to inspect the Guard, or have it inspected by a competent representative, and should make to you, for further transmission to me, a report covering the following points and any others that may suggest themselves in individual cases:

(a) Vessel - from - to

(b) Master

(c) Officer or P. O. in charge of guard

(d) Number, calibre, and condition of guns

(e) Arrangement and condition of magazines

(f) Personnel

(g) Organization

--9--

(h) Co-operation between guard and ship personnel.

(i) Food

Especial attention will be paid to the question of uniforms and personal neatness of guards, as the appearance of these men will have a considerable effect on the opinion of a very large number of people as to the general efficiency of our Navy.

19. As the appointment of Naval Port Officers is a new departure, the duties of such Officers cannot be prescribed completely and with exactness. Much must be left to the individual, and, in the discharge of his duties, it will be necessary that he exercise good judgment, tact and discretion, in order to avoid friction with the local authorities, both French and U.S. Army. He must, on the one hand, avoid unwarranted assumptions of authority, and he must, on the other hand, use every endeavor to advance the common cause, which is that of the safe and prompt entry and dispatch of Troop Ships, Supply Ships and other vessels. It is particularly important that between you and the Port Officer there shall be a feeling of mutual confidence, and a constant exchange of information. It is also very important, as has already been stated, that the prospective movements, both outward and inward, of U.S. vessels, be protected by secrecy, by the greatest possible use of the convoy plan, and by the provision of suitable escorts. If these objects are successfully accomplished minor difficulties and failings will have no bearing on the final general result.

On October 19, 1917 Rear Admiral Fletcher communicated to Commander Patton secret instructions as follows:

1. You will be the Port representative at Pauillac, Bordeaux and Bassens, France, of the Commander U.S. Patrol Squadrons Operating on French Coast.

--10--

2. You will, as far as is possible, be informed in advance of the arrival of U.S. Shipping Government chartered or private, bound for ports on the Gironde River.

3. You will similarly inform the Squadron Commander as to the dates when such vessels are ready to leave your ports, and as far in advance of departure as possible.

4. If such vessels are bound north or south along the French Coast, they will take advantage of the regularly constituted convoys.

5. You will report the names, speed and size of vessels bound off shore in order that instructions may be issued for them to proceed to such points as may be designated for assembly and escort in convoys.

6. You will arrange as may be necessary for the departure of vessels in Coastal convoys. Information concerning submarines and mines should be obtained by the Masters of vessels at the latest possible moment before leaving your port, from the offices of the French Port Authorities on the Gironde. Port authorities must also be kept informed of the sailings so that such preparations as are desirable and necessary may be assured by mine draggers and local escort, by air as well as by water.

7. Should convoys proceed from sea direct into the Gironde, escorted by American vessels, this office should be informed as far in advance as is possible, of the channels which are safe and can be used, through the Naval Port Officer and the C.D.P.B.

8. Lines of communication from and to you are entirely French. It will be necessary to work with them and through them in order that both French officials and ourselves may be informed of the existing situation. Every endeavor is being made by the Commandant Supérieur to perfect the Communication system. All delays in the receipt

--11--

or transmission of messages will be reported, so that the cause may be followed up.

9. Report weekly the amount of coal belonging to the Navy received and expended, and the amount remaining on hand. At the end of the month, report the amount received and expended during the month, and the amount remaining on hand.

10. Your attention is invited to paragraph 11 of Enclosure "A", reference (a), and to enclosure "B". These matters will be made the subject of report to the Squadron Commander as soon as possible after receipt of the information. Attention is also invited to paragraphs 12, 15, 17, 18 and 19 of reference (a), Enclosure "A".

11. In connection with the movements of vessels, attention is particularly called to the necessity of absolute secrecy of your codes and coding apparatus, and the secrecy of all despatches concerning the movements of all vessels. All messages received or sent will be entered when decoded, or upon coding, in ink in a record book. Access to this book will be had only by yourself and such persons as are thoroughly reliable. Copies will be limited to these absolutely necessary, marked secret, made only by a reliable person and delivered by such a person, marked "To be opened by addressee only."

12. Every endeavor will be made to work to the common cause of producing efficient service and cheerful and loyal cooperation within our own force, and with the representatives of our sister service, and with those of our Ally, the French.

American ship arrivals were not very numerous at Bordeaux in 1917, for the movement of troops and supplies across the Atlantic did not get well under way until the following year. Moreover the docks then under construction at Pauillac and Bassens were not ready for use until the latter year. In December 1917 there was discharged at Bordeaux 9,800 tons of general cargo, 28,300 tons of coal, and 6,600 tons of lumber.

--12--

These quantities were to be multiplied many times in the next year.

The development of the aviation program of the Navy in France resulted in the establishment of several air stations in the Bordeaux region as a part of the system which eventually was completed along the coast for patrol, escort, and reconnaissance purposes. In view of the plan to erect at Pauillac an aviation assembly and repair plant, general storehouses, and barracks for the distribution of enlisted aviation personnel throughout France, Capt, Hutch I. Cone, Commander, U. S. Naval Aviation Forces, Foreign Service, recommended to Admiral Sims on November 22, 1917 that the naval base at that place be changed to an aviation center and placed under his command. A naval air station was commissioned at Pauillac on December 1, and on the twenty-second Admiral Sims removed it from the command of the U. S. Naval Base Bordeaux. The assembly and repair plant eventually spread over a considerable acreage of vineyards and occupied the village of Trompeloup near which the air station was located. Here knocked-down aeroplanes received from the United States were assembled, tested, and flown to the operating fields. Other aviation activities in the region included a flying school at Moutchic (Lacanau), and an operating field at Arrachons. A lighter than air station was begun at Gujan-Mestras, but it was not completed before the end of hostilities.

To effect coordination over American naval activities in France, the Navy Department directed Admiral Sims on January 4, 1918. to designate Rear Admiral Henry B. Wilson, who had succeeded Captain Fletcher in command of the U.S. Patrol Squadrons Operating on the French Coast on November 1, 1917, as "Senior U. S. Naval Officer in France," and to direct him to organize his forces according to a general plan comprising six principal fields of activity: (1) naval forces afloat; (2) port organization and administration; (3) aviation; (4) intelligence; (5) communication; and (6) supply and pay. In addition to these matters he was also to take up with French authorities and the U. S. Army any questions that arose, provided they were not of such character that they should be handled by Sims or the department. He was directed in connection with the port organization

--13--

and administration to divide the west coast of France into three districts with headquarters at Brest, St. Nazaire, and Bordeaux under officers of command rank. Upon receipt of this order Admiral Sims called Wilson, Jackson, and Cone to London for a conference in which an agreement was reached relative to the reorganization of the forces in France. Admiral Sims then drew up some detailed instructions covering the organization of the forces in France, which were sent to Wilson who, as Commander, U. S. Naval Forces in France, was to have charge of all floating naval forces permanently assigned to duty on the channel and Atlantic coasts of France. For the administration of the port organization he was instructed to establish district headquarters at Brest, Lorient, and Rochefort; these places were chosen by Sims instead of those indicated by the Navy Department because they were the French Prefectures Maritimes and the sites of French navy yards. The proximity of the American and French headquarters would facilitate liaison between the naval forces of the two countries. The district organization was considered desirable because it was believed that the direct routing of ships from the United States to ports of destination would be necessary.

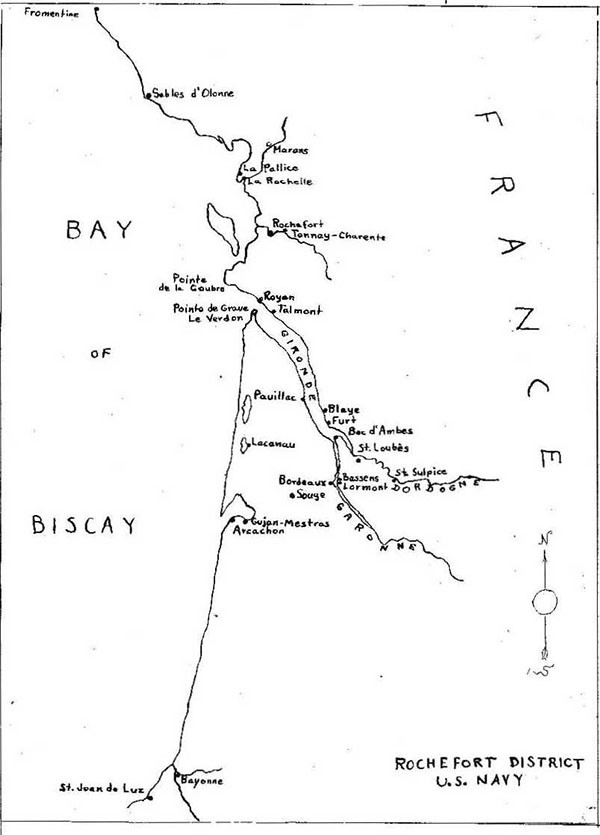

The district organization was set up by Admiral Wilson in an order of January 18 addressed to the district commanders. Their mission was to safeguard the passage of American troop and store ships and to cooperate with the French naval forces for the protection of shipping and for the conduct of submarine warfare. The limits of the districts were described; those for the Rochefort District extending from Fromentine on the north to the Spanish border on the south—a 280 mile stretch of coast. The district commanders were charged with the following duties: operations of vessels that might be placed under their command; command, administration, repairing, and supply of vessels assigned to their districts; development and maintenance of adequate naval port facilities; establishment and maintenance of prompt and certain communication; supervision of American shipping and of United States naval personnel on merchant ships. The naval port officers were subject to their orders. Movements of ships were to be reported directly to the Commander, U. S. Naval Forces in France. Captain Henry H. Hough was placed in command

--14--

of the Brest District, Capt. Thomas P. Magruder the Lorient District, and Capt. Newton A. McCully the Rochefort District.

Captain McCully left Brest in the U. S. S. May on January 20 to assume his command at Rochefort. He did not proceed directly to that place, however, for, pursuant to orders from Admiral Wilson, he visited Lorient, St. Nazaire, Bordeaux, Pauillac, and Le Verdon and conferred with officials at those places before arriving at Rochefort at the end of the month. He went ashore there on February 5 to organize and establish the district headquarters. His duties as district commander were in addition to his command of the Squadron 5, Patrol Forces, Atlantic Fleet, which he had been exercising since the previous October. Upon completing his tour, McCully reported that the district comprised the ports of La Pallice, Rochefort, Bordeaux, Arcachon, Bayonne, and St. Jean de Luz, the most important section being that of the Gironde. He recommended that central direction of the work of the district would be best located in the entrance to that river at Royan, but the move was never approved. Other suggestions included the location of a station ship for communications and escort duty and repair ship at Le Verdon, port officers at La Pallice and Bordeaux, and naval base commander and staff at Pauillac.

The district organization remained in use throughout the war. To the original three districts was added in April 1918 a fourth at Cherbourg of which Comdr. David F. Boyd was given command. After his experience with the district organization during the war, Admiral Wilson reported towards its close a strong approbation of the system, which provided the necessary decentralization of administration, particularly of details, required to successfully perform the operations of the Navy connected with the protection of American ships. It was not merely enough, in his opinion, to decentralize matters, for they also had to be placed in charge of officers of considerable rank who could command the respect and attention of French officials and U. S. Army officers. Placing the districts under officers of rank also made it more difficult for the French to obtain control of them. He believed that the character of the work performed by the district commanders

--15--

justified the rank of rear admiral and recommended that rank for McCully and Hough.

On the same day that he issued instructions to the district commanders Admiral Wilson issued other directions to naval port officers, which described their mission and duties as follows:

1. Your mission and duties are summarized as follows:

MISSION: To facilitate the berthing, discharging, and prompt sailing of U.S. troop and store ships.

DUTIES:

(a) To cooperate fully with the U.S. Army and French authorities with a view to expediting despatching of vessels,

(b) To immediately inform the Commander in France and your District Commander of the arrival of all U.S. vessels at your port. The Force Commander and the Army headquarters will be informed by the Commander in France.

(c) To interview Commanding Officers or Masters of all U.S. ships on arrival as to incidents of voyage and their needs.

(d) Inspect the U.S. Navy armed guard crews and radio men on U.S. vessels other than regular commissioned U.S. Naval vessels.

(e) To assist in the supplying of vessels with fuel and supplies insofar as this can be properly handled by the Navy.

(f) To pay naval members of armed guards on presentation of memorandum rolls or other necessary vouchers, and to furnish them with clothing and small stores.

--16--

(g) Investigate offenses committed by U.S. Navy personnel on vessels other than regular commissioned U.S. Navy vessels.

(h) Investigate and take necessary action on Admiralty cases involving U.S. Navy.

(i) Keep Commander in France informed of the readiness of vessels and of the speed of which they are capable through the danger zone.

(j) Transmit sailing orders received from the Commander in France or District Commander.

(k) Indoctrinate Masters as to precautions to be observed within the danger zone and familiarize them with the prescribed convoy doctrine.

(l) As near as possible prior to sailing, furnish convoy and escort commander with the latest information in regard to submarine and mine activities.

(m) Keep Commander in France informed weekly as to the amount of coal belonging to the Navy on hand, the amount expended and received.

The foregoing instructions were taken almost verbatim from Sims' orders to Wilson, being modified slightly to suit the local situation.

Some special instructions were sent by Wilson to Commander Patton at Bordeaux. These stated that the district commander at Rochefort was responsible for reporting U. S. ship movements in La Pallice, La Rochelle, and Rochefort and the Naval Port Officer at Bordeaux for those in the ports of Pauillac, Bassens, Bordeaux, and Le Verdon. Until direct telegraph and telephone communication was provided between Bordeaux and Le Verdon he was to depend upon the French

--17--

commandant at the latter place for reports on ship movements there.

Admiral Wilson was dissatisfied with the retention at Bordeaux of an officer, who had been assigned there for the purpose of establishing a repair base, as a Naval Port Officer and requested his replacement by a younger man with executive ability and lots of steam. London naval headquarters finally arranged with Wilson and Cone for the transfer of Commander Patton to the post of commandant of the Aviation assembly and repair plant at Pauillac. When the change occurred on February 10, 1913, he was succeeded temporarily as Naval Port Officer at Bordeaux by Lieutenant Bernier. On May 28 the position was taken over by Commander Ralph P. Craft, who was detached for the purpose from the U. S. S. Aphrodite on which he had been serving recently as escort commander on the Verdon convoy. In June the port office at Bordeaux embraced the following departments: naval port officer, marine superintendent, assistant naval port officer, patrols and inspections, repair officer, medical officer, coding officer, radio repair station, pay and disbursing office. Shortly afterwards patrols and inspections seem to have been assigned to separate officers. An organization outline for September 21, 1918 lists the members of the staff as follows:

| Naval Port Officer | Comdr., U.S.N. |

| Assistant Naval Port Officer | Lieut., U.S.N.R.F. |

| Engineer Officer | Lieut., (j.g.), U.S.N. |

| Inspections and Docks | " U.S.N.R.F. |

| Correspondence Officer | Ensign " |

| Patrol Officer | " " |

| Communication | " " |

| Radio Repair, Bassens | " " |

| District Medical Inspection | Comdr. (Medical) |

| Medical Officer (2) | Lieut " |

| Pay and Disbursing Officer | " (Pay), U.S.N. |

The enlisted personnel attached to the naval port office included a number of yeomen and seamen of different classes employed as correspondence, communication, mail and pay clerks, messengers, automobile, motor cycle, and truck drivers, repair gang, and in the dispensary run by the medical officer. Until October 1918 these

--18--

men were put upon subsistence; they were then barracked in a remodeled chateau about a mile from the port office. As this building did not provide sufficient accommodations, portable barracks were erected in a public park nearby. Suitable equipment was installed in these barracks to keep them in proper sanitary condition. Better discipline was possible through having the men in barracks.

The location at Pauillac of the aviation assembly and repair station and its use as a port of discharge for material destined for the trans-Atlantic radio station being constructed by the U. S. Navy at Croix d'Hins greatly increased the shipping at that place. The escort vessels which convoyed the ships that arrived in the Gironde obtained at Pauillac coal imported from Cardiff, Wales. Water was available there, and fresh provisions could also be procured by ordering from Bordeaux, where liberty parties could visit for amusement in its theatres and cafes. After his transfer to Pauillac, Commander Patton acted as Naval Port Officer there until the arrival of Lieut. Herbert R. A. Borchardt, U. S. N. on March 10, 1918 to perform the duties of that position. He was succeeded in June by Lieut. George F. Keene U.S.N.R.F., who continued to serve until late in the year. When Comdr. Frank T. Evans relieved Patton, who was invalided home because of an attack of neuritis, as commandant of the aviation establishment at Pauillac in July, he removed his office to a more convenient location at Trompeloup, and at the request of the port officer, the communication officer, and the Army Transport Service officer who was stationed there provided them with space in the same building. When Ensign Andrew Robeson, U. S. N. R. F. was ordered to duty as Naval Port Officer at Pauillac towards the end of October, he was placed under the military supervision and control of the commandant of the naval air station, but he was directed to make reports concerning ship movements and the like to the District Commander, Rochefort.

The expansion of shipping on the Gironde River and the system of operations which was developed to handle it resulted in the establishment of other port officers, in part according to Captain McCully's original recommendations. At Bassens, which was operated as part

--19--

of the Bordeaux office, a U. S. Naval Dock Officer was stationed to act as liaison between the captains and masters of American ships and the French captain of the port in matters connected with mooring and navigation. A Communication or Liaison Officer was maintained on board the French station ship Marthe Solange at Le Verdon. A Naval Port Officer at Royan was used principally as a signal station to report ships entering and leaving the Gironde. This place was under the command of Lieut. William V. Astor from February to November 1918. An officer in the Naval Reserve Force, Lieutenant Astor had served during most of 1917 on his own yacht the Noma which he had presented to the Navy, and on the staff of the Naval Port Office at Bordeaux during the early part of the winter.

In addition to the naval port offices on the Gironde, others were established in Rochefort District during the first part of 1918 at Rochefort, La Pallice, St. Jean de Luz, and Sables d’Olonne. These ports were used by cargo vessels; La Pallice and neighboring La Rochelle and Marans being used particularly for discharging coal brought across from Great Britain.

Since the bulk of the American shipping to French ports during World War I was used to man and supply the American Expeditionary Forces, the U. S. Army organized a transportation system in France. The first convoy of troop transports reached St. Nazaire late in June 1917, and that was the scene of the earliest activities of the Army Transport Service. That convoy and all subsequent convoys sailing directly from ports of embarkation in the United States to French ports escorted by cruisers attached to the U. S. Cruiser and Transport Force, which was commanded by Rear Admiral Albert Gleaves, U. S. N. To supply and equip the 2,000,000 troops that eventually made up the A. E. F., it was necessary to build up a vast fleet of cargo carriers; most of these became attached to the Naval Overseas Transportation Service, which was established in the Navy Department in January 1918, following an agreement with the War Department and the U. S. Shipping Board by which the Navy was to man vessels entering the war zones. After studying the British and French organizations, General John J. Pershing, Commander-in-chief, American Expeditionary Forces, decided that the

--20--

responsibility for the movement of troops and supplies from the hold of the vessel at the port to the end of the railroad journey in the rear of the front lines should be vested in a transportation department, and on July 5, 1917 he established this system. William W. Atterbury, a former vice-president of the Pennsylvania Railroad, appeared in France at the end of August with orders from the Secretary of War appointing him Director General of Transportation, A. E. F. In the following month General Atterbury and a party of American and French officers inspected the ports on the Bay of Biscay and the railroads connecting them with the interior to secure information upon which to determine ways to improve the systems for the use of the U. S. Army. The list of projects drawn up included the extension of facilities at Bassens and Pauillac.

The selection by the Army of ports to be used as ports of disembarkation for troops and discharge of supplies resulted in the establishment at those ports of supply organizations known as Base Sections, superintendents of the Army Transport Service, and naval port offices. Base Sections came to be organized at St. Nazaire, Bordeaux, Le Havre, Brest, Marseille, and La Pallice. That at Bordeaux, the second one established, was called Base Section No. 2; it was commanded by Brig, Gen. William S. Scott and later by Brig. Gen. William D. Connor. Here towards the end of October 1917, an Army Transport Service Superintendent's office was opened by a major, who was succeeded by other majors and lieutenant colonels. The Base Section headquarters at Bordeaux was a much larger organization than the Naval Port Office, whose task was a subordinate one of considerable importance as it concerned the maintenance of the life line across the Atlantic.

The activities of the Army in the Gironde region were widespread. At American Bassens the Corps of Engineers constructed between August 1917 and April 1918 a pile dock containing ten berths, which was the largest construction of this type undertaken by the Army in France and which made Bassens its most efficient port. To distinguish it from French (old) Bassens the new port was called American (or New) Bassens.

The assignment of six berths for the Army at French

--21--

Bassens aided in the building of the new berths and provided a greater quantity of wharfage at this favorable point on the right bank of the river, affording access to railroads running to the front. A refrigerating plant was put up here by the Quartermaster Corps. Other dock installations were undertaken at nearby Lormont, at St. Loubes and St. Pardon on the Dordogne River, and at Talmont near Royan, but these were not completed before the Armistice. A number of camps were built around Bordeaux, including camps for laborers near Bassens, Genicart Camp and Grange Neuve Camp at Lormont, Camp Le Hunt at Le Courneau, a combined artillery and balloon training camp at Camp de Souge, and cantonments at St. Loubes, St. Sulpice, Gradignan, and Begles. There was a base hospital for troops at Bordeaux, a veterinary hospital at Carbon Blanc, a remount depot at Marignac, and a motor park at Bordeaux. To serve the port of Bordeaux, a great storage depot was begun at St. Sulpice, nine miles from Bassens in March 1918.

In late December 1917 Captain Jackson wrote Admiral Sims from Paris that the Navy would have to face the necessity of sending troop transports to Bordeaux, for the Array was preparing camps there for the reception of soldiers. Since the Navy escorted the troopships, this plan gave it some concern. Captain Jackson believed it would be safer to route the convoy directly to Bordeaux than to shunt transports south from St. Nazaire to Bordeaux as the voyage along the coast would be dangerous. On the last day of the year he notified Sims that General Pershing wanted Bordeaux used to the fullest extent for troopships and that the Army was then ready to receive troops there. Although the troop convoys had not vet become nearly as frequent as they would, difficulty was being experienced in handling those that were arriving at Brest and St. Nazaire, which were the principal ports utilized for the debarking of troops brought to France in American convoys. Hence the Army’s desire to use Bordeaux as a port of debarkation. Unwillingly the Navy yielded to Army pressure, for the despatch of troopships to Bordeaux meant the division of a convoy somewhere in the eastern Atlantic Ocean, which not only resulted in weakened escorts but put a severe strain on the Navy's ability to provide escort vessels. The dispersion of the troop transports was

--22--

a means of speeding up their return to the United States and so hastening the movement of troops abroad, and this was what was wanted in Washington.

Early in 1518 transports began arriving at Bordeaux, and in March 5,459 troops were landed principally from the Tenadores, Mercury, and Mallory. Smaller numbers were brought in on freighters in that and subsequent months. A somewhat higher number, 6,161, was disembarked in April chiefly from the Powhatan, MarthaWashington, and Rochambeau. Some of these transports made repeated trips to Bordeaux. Although these vessels were among the smaller transports, some of them had difficulty in entering and ascending the Gironde. The commanding officer of the Powhatan reported delays in waiting for the high tide to get over the bar at the mouth of the river and at Pauillac in waiting for a berth. As the engines had to be kept running while at anchor at this place in order to shift the ship with changing levels in the river, no opportunity was offered for overhauling work. Transports continued to arrive, however, landing around 11,000 troops in both May and June. From the Tenadores Admiral Wilson received word in July that it had rested in the mud while unloading. Finally the Army, because of the difficulties encountered on the Gironde, adopted the policy in August of sending transports to Bordeaux only when they carried a large amount of cargo in addition to troops and their equipment and of occasionally sending transports there in order to return troops to the United States. A total of 50,000 soldiers was debarked on the Gironde.

The Army Transport Service was represented on the Gironde not only at Bordeaux, where a superintendent had been stationed in October 1917, but also at Pauillac and at Bassens. Troop transports of too deep draft to ascend to Bordeaux were discharged at Pauillac under the direction of Major H. H. Haines, Army Transport Service superintendent. He also boarded transports on the way to Bordeaux to present orders to the officer in charge of the troops. The handling of the transports at Bassens where they were discharged by the Army, was in the hands of a Marine Superintendent, who was a lieutenant commander in the Naval Reserve Force. The officer who reported for this duty on October 26, 1917 was Henry W. Barstow, a former ship captain in the Clyde-Mallory

--23--

Line; he filled the position until June 1918. His duties took him on occasion to Bordeaux, Pauillac, and Blaye. He was provided for this Army service at the request of the general in command of the Line of Communications, the temn then used for the Army Services of Supply.

Although the Army and the Navy operated many D. S. Shipping Board vessels, that agency operated some itself. The U. S. Consul acted as the agent for the Shipping Board vessels, but he had only limited supervision. This position was filled throughout the war by George A. Bucklin. The Shipping Board vessels were assigned to French shipbrokers, to whose financial interest it was to delay a ship in port as long as possible. Mr.Bucklin found it necessary to keep constantly on the watch to see that the shipbrokers did not engage in improper practices and to insure rapid discharging, watering, coaling, ballasting, and clearing. He also found that through his intervention the passage of the vessels up the river through the hands of the various French officials could be expedited. His repeated requests that he be allowed to handle the vessels officially and thus prevent delays were denied by the government in Washington because it was necessary to continue peace time practices in order to maintain good relations with the French. Special permission was given the Army to unload powder ships, which were a menace to the installations and supplies at Bassens, but other ships loaded for the account of the French government continued to be consigned to private companies. Some improvement in matters resulted from the adoption of the suggestion made by Bucklin that the masters of the vessels be directed to communicate with the consul's office on their arrival and make it their headquarters while in port.

In a report to the State Department submitted in August 1918 Mr. Bucklin enumerated the causes that delayed vessels in port as follows; awaiting permit and orders to sail; left American registry; repairs and crew trouble; cargo for French government; awaiting berth; slow discharge and bunkering; awaiting convoy. Most delay was caused by the unavailability of berths. Shipping Board vessels were subject to more delay because their cargoes were often for the French and Swiss governments, which made securing berths more difficult.

--24--

Stevedores were poor and hard to find.

Despite these difficulties, the consul by collaborating closely with the Army and Navy officers stationed in the locality was able to assist in speeding up the turn around of the ships.

A further source of trouble for the consul was the crews of the Shipping Board ships which were necessarily a conglomeration of nationalities. So many seamen arrived in port without papers that in December 1917, Mr. Bucklin recommended that all Shipping Board vessels be manned by the Navy, a step he considered desirable to avoid trouble and delays to shipping.

Certain services were performed by the consul for the Navy. He took acknowledgments of and administered oaths to naval and military personnel, charging fees only for private business. He assisted in the repatriation of members of naval crews and made advances of money to naval signalmen.

Shipping Board vessels caused more trouble for the Naval Port Officers than either the Naval vessels or the Army transports. Their masters were often not capable men, owing to the decadence of the American merchant marine which had diminished the supply of trained officers, and they were frequently indifferent to the necessity for handling their vessels quickly. To the naval officers who reported upon activities of these vessels, it looked also as if they were not well administered; masters operated many of the ships without adequate instructions. Attempts by naval officers to expedite their handling brought forth exhibitions of ill will.

In October 1918 Admiral Wilson was authorized by Admiral Sims, who had instructions from Washington, to transfer to the N. O. T. S. any Shipping Board vessels on which crew conditions endangered the safety of lives or property. To accomplish this, District Commanders were directed by Admiral Wilson to request the necessary authority from him and to appoint a board to report on the circumstances of taking over a ship.

Just as the U. S. Navy and the U. S. Amy had to

--25--

work together in handling American vessels in French ports, it was necessary for both to work with French officials, for in their hands remained largely the control of ship movements, pilotage, berthing, and mooring. The region comprised in the Rochefort District coincided with the 4th Arrondissement or Department de la Gascogne in which the supreme authority was the Prefet Maritime at Rochefort. His organization included four divisions: the Patrol Marine Defense, Communications, and Land Defense. The Patrol Division administered the patrol and convoy system through subordinates at La Pallice, Le Verdon, and St. Jean de Luz and the aviation patrols operating from bases along the coast.

At La Rochelle, Bordeaux and Bayonne were commandants du port, who were naval captains whose duties were principally those of information and communication. Commandants des Fronts de Mer were stationed at La Rochelle, Royan, and St. Jean de Luz for purposes of sea defense and information.

Among the French officials stationed at Bordeaux the chief was M. Clavel, whose French title was le Lieut. Colonel du Ingénieur en Chef des Ponts et Chaussées Chef d’ Exploitation des Ports de Bordeaux at de la Gironde. He controlled American shipping in general but not in detail. Other French officers included a station commandant, a chief of Division of Patrol Ships of Gascogne, which also had a lieutenant attached to the U. S. Navy as a liaison officer, and an Inspector General of Department of Civil Engineering and Assistant Chief of Central Service of Military Operations of Ports. Commander Patton seems to have been supplied immediately with a French liaison officer. A French naval port officer and an administrator of marine were maintained at Pauillac, the latter representing the Navy Commandant at Bordeaux. At Le Verdon a French station ship, the Marthe Solange. served as an operation office for the convoy, and as a coaling, supply, and repair ship. The French Army of which the headquarters of the 18th Army Corps was in Bordeaux was also involved in the control of shipping as was the Bordeaux Chamber of Commerce and the Pilots Association.

The existence of war obliged the French to enforce certain requirements of vessels entering the Gironde in

--26--

order to safeguard the interests of the nation and to further its war effort. These requirements were enumerated in printed instructions which were presented to the masters of foreign vessels. Upon their arrival at the entrance to the Gironde the vessels were required to seal their wireless apparatus; to fill in an examination form; to hand in all ship's papers; to submit a list of the names of all persons on board; and to restrict persons from going ashore without the necessary permission. These requirements were designed to prevent the communication of information helpful to the enemy; to prevent the entrance of enemy agents and saboteurs; to apprehend suspected persons; and to secure data useful for handling the vessel while on the river. After mooring in the port the master had to furnish another list of the members of the crew with certain information and to restrict their landing without proper authorization. During the stay in harbor the movements of persons attached to the ship were strictly controlled through the issuance of identity cards and permits of circulation; communication with war prisoners was forbidden; only persons with the authorization of the marine authorities were to be allowed on board ship; persons boarding surreptitiously were to be reported, as were members of the crew leaving ships without permission. At sailing time inspectors bearded the ship to examine the identity cards and to obtain their return; the captain was to insure that no suspicious person was on board and to furnish the names of missing members of the crew, and before sailing the ship had to have a "sailing license." These regulations, established according to French laws, decrees, and orders of 1916 and 1917 were enforced by the Navigation Police, whose chief was stationed at Pauillac, where vessels were inspected on their way up the river. At this place a quarantine officer also boarded vessels to conduct a sanitary inspection.

In the ports of France, American troop and store ships were obliged to pay for pilotage, ballast, water, towage, and handling of lines. The French government remitted the sanitary and quay dues, and there were no custom house or passport charges. The pilotage fees were required by French laws and had to be paid whenever pilot service was offered even though it was not accepted. Considerable correspondence was exchanged

--27--

with the French government on this matter, the U. S. Navy taking the stand that it should not have to pay and the French insisting that payment had to be made, except in the case of American patrol vessels regularly assigned to the station. Admiral Wilson pointed out to the French the difficulty he would have in certifying to his government hills for pilotage in cases where the pilot's services had been refused. The Chief of Staff of the French Ministry of Marine took up the matter with Captain Jackson at Paris in April 1918 asking that it be referred to the government at Washington. In forwarding the communication from the Chief of Staff, Captain Jackson pointed out that the practice of paying the pilotage bill if required by port regulations even though pilotage had been refused was quite widespread and suggested issuing instructions accordingly. The matter was referred by the Chief of Naval Operations to the Judge Advocate General of the Navy Department who responded on May 11, 1918 by quoting a statement submitted by the State Department in the preceding year to the effect that the doctrine of international law was that all vessels were subject to the revenue and police regulations, including those in regard to pilotage of the territorial waters which such vessels might enter. United States vessels were subject to the rules and regulations of the French ports, and the controlling factor was not the nature of the certification of the pilotage bill but that the port regulations made its payment obligatory. This opinion was accepted as the official policy of the Navy Department, and Admiral Sims published it for the information and guidance of all forces in Europe in his circular letter no. 65 of July 16, 1918.

The great increase in shipping on the Gironde River, the multiplicity of officers of various countries handling it, and the necessity for imposing war time restrictions produced a complicated and confusing situation, which was never entirely free of difficulties and friction throughout the period of the war. For an understanding of this situation, it is necessary to have a picture of the conduct of operations on the river.

Upon their arrival at the mouth of the Gironde River vessels were subjected to a rigid procedure which lasted during their sojourn. Entrance to the river through the protecting submarine nets stretched across

--28--

its mouth was under the watchful eyes of the escort vessels which had convoyed the ships to the river and the French patrol ship guarding the passage through the net, which was kept open at all times. Inside the net at Le Verdon was the French station ship Marthe Solange, an old sailing hulk, upon which was stationed the French officer in command of the convoy and the American Naval Communication or Liaison Officer, as he was later called. Information as to the probable date of arrival of vessels was communicated to the Naval Port Officer at Bordeaux, who notified the Army authorities when Army cargoes were involved. At Le Verdon roads the vessels were visited by the French Navigation Police and by the American Naval Liaison Officer, the latter to present a copy of the Port Regulations and to receive a filled in form containing information about the ship necessary for its handling. The radio apparatus was sealed and thereafter was unsealed only by the French authorities or by the U. S. naval district radio repair officer. Preparations were to be made for unloading the cargo while the vessels were still at the anchorage in order that no time would be lost after they reached the docks. Certain restrictions imposed upon the personnel of the ships by the French have been mentioned; others were stipulated by the U. S. Port Regulations. Liberty parties were allowed under no circumstances at Royan or St. Georges, but when vessels were to be at Le Verdon for several days parties were permitted ashore under an officer accompanied by patrol. Data concerning the arrivals and departures of ships was communicated to the Commander U. S. Naval Forces in France to whose staff it was useful in planning and directing the movements of convoys and patrol and escort vessels.

The passage up the Gironde and the Garonne was under the guidance of a series of French pilots each of whom collected a fee. Off the entrance the vessels were boarded by the Royan pilots, who saw them through the net to the anchorage at Le Verdon. The Le Verdon pilot took vessels as far as Pauillac, where inspections were made by the French Navigation Police and the sanitation authorities. Vessels with cargoes for Bassens or Bordeaux were taken to those places by the Pauillac pilot, and the mooring at those places was in the hands of still another pilot. The Bordeaux pilots had to be secured for subsequent changes of mooring at Bordeaux and

--29--

Bassens and for entrance into the basin at the former place. On the voyage downstream this procedure was reversed. Dock regulations for the port on the river were issued by the French captains of the ports and came to be incorporated into the U. S. Naval Port Regulations. So many pilots for a mere sixty miles of river were quite unnecessary, and the chief reason for having changes of pilots was to collect more fees. This, however, was not a practice peculiar to French ports.

Vessels were discharged by the service to which their cargoes were assigned. Most of the vessels containing cargo for the U. S. Navy were unloaded at Pauillac, where a Transportation Department developed under the supervision of a naval officer subordinate to the commandant of the Aviation Assembly and Repair Station. Crews of U. S. naval vessels wore required to assist in unloading in order to reduce the time spent in port. Work parties were organized to discharge certain holds on their ships, and when these were emptied the men were placed at liberty. The armed guards on board the ships were used as sentrys [sic] at the gangways and at the holds from which cargo was being taken. Assistance was given by the Naval Dock Officer at Bassens and the Naval Port Officer at Bordeaux through whom orders concerning the movements of vessels were arranged. Daily reports were submitted to them as to the handling of the winches and gear, the consumption of fuel, and the progress of the unloading.

Other services were performed by the Naval Port Officer Bordeaux. He handled all cable and telegraph communication and incoming and outgoing mail. He arranged for the transfer of naval personnel to other bases in France and for the return of personnel to the United States. Fuel, water, ballast and ammunition were arranged for by the Naval Dock Officer at Bassens.

Array cargo transports and troop transports were under the jurisdiction of the Army Transport Service from the time of their arrival at Le Verdon. Their berthing, discharging, watering, fueling, ballasting, and guarding were handled by the representatives of that service stationed at Pauillac, Bassens, and Bordeaux. The revised port organization for base ports such as

--30--

that of Bordeaux-Bassens instituted by the Army in May 1918 comprised Administrative, Operations, Troop and Cargo, Terminal Facilities, and Supplies Division, each having a number of officers. The responsibility for handling cargo from the ship's hold to cars, trucks, and warehouses was in the hands of the Chief Stevedore in the Troop and Cargo Division. The discharge of Army transports was facilitated by the practice of having on board an Army Quartermaster who was familiar with the manner in which they had been loaded.

The Medical Officer attached to the Naval Port Office had important duties connected with the health of ships' crew and sanitary conditions on board and ashore. Neither officers or crew members were allowed to leave the ship until the medical inspection had been passed. Members of the crew found to be infected with venereal diseases were confined to the ship; others having contagious diseases were hospitalized. A Naval dispensary was maintained at Bassens for the treatment of persons on the sick list and a dental office at Bordeaux. A report of the sanitary condition of the ship was made to the Naval Port Officer, Bordeaux. Ashes and garbage had to be placed on shore in proper containers—not dumped into the river. A medical officer acted as liaison with the Army for the evacuation of sick and wounded to the United States. Severe cases of sickness or injury were cared for in the Army Base Hospital at Bordeaux.

By the middle of 1918 American naval personnel were a familiar sight on the streets of Bordeaux, and at times there were hundreds of them on liberty. Although the conduct of these men was generally good, instances of disorderliness, rowdiness, and drunkenness in which persons were sometimes injured were sufficiently numerous to require the establishment of a Naval Patrol by order of the District Commander of June 21, 1918. The duty of maintaining order and enforcing liberty regulations devolved upon the patrol, and by arrangement with the French the jurisdiction of the patrol was extended to the personnel of American merchant ships visiting the city. Liberty was allowed between the hours of 8 A. M. and 9:30 P. M., but the patrol was on duty somewhat later in order to pick up stragglers. Persons granted liberty by the commanding officers of ships were

--31--

required to carry passes signed by their executive officers. Special passes were granted for attendance at theatres with the warning that violations of the spirit of the pass would result in disciplinary action. Advice as to the danger of infection from associating with prostitutes and the addresses of Army prophylactic stations were supplied; badly diseased red light districts were set up as restricted districts and men caught with disreputable women were punished. Other causes of arrest were disorder, intoxication, refusal to obey orders of patrol, and absent overleave [sic] or without leave. The Naval Patrol at Bordeaux consisted of personnel attached to the Naval Port Office. At Pauillac no permanent patrol was formed, and patrols were furnished by the ships landing liberty parties. A Naval Ferry operated between Bassens and Bordeaux was much used by naval personnel going to the latter on liberty. Since it was the largest city in the region, Bordeaux attracted liberty parties from naval activities throughout that part of France.

The Naval Port Officer held court two or three times a week, dispensing what might be called naval justice. If Naval Regulations or the rules for courts and boards held, well and good, if not, he used his ingenuity, like a frontier judge of the United States, and devised penalties to fit the crime or misdemeanor. Private American citizens with grievances against the Navy or the French, and French citizens, as well as Naval personnel brought their troubles to the Naval Port Officer.

In the military port of Bordeaux there were special dangers incident to the war which had to be countered. Deserters from the Allied forces were looking for means of escape, sometimes as stowaways on board ships in the harbor; German prisoners were utilized on the docks in labor gangs; spies sought means of communicating with ships; other agents attempted sabotage on ships and attempted to stir up dissatisfaction among their crews. Consequently guards had to be maintained constantly on ships and docks. American Naval personnel were warned against bands of courtesans engaged in collecting information for the enemy; these were not only of the street walking variety but also the educated, well-dressed type whose particular prey was Naval officers.

--32--

In 1918 a counter espionage system -was being developed by the U.S. Navy, which involved the assignment of intelligence officers to the headquarters of the French military regions to cooperate with the U.S. Array and French intelligence services. The district intelligence officer for Rochefort District was stationed at Bordeaux, and instructions were issued to the District Commander and the Naval Port Officer at Bordeaux to furnish him. with information and to assist him in his work. The officer assigned to Bordeaux at the end of February was Lieut. Comdr. William L. Stevenson, U.S.N.R.F. He performed some excellent work in organizing the counter espionage system in the 18th Army Region, in the opinion of his superior, Comdr. W. R. Sayles, the naval attache at Paris, but he did not establish proper relations with the District Commander at Rochefort and got into difficulties with his chief assistant, as a result of which both were disenrolled in June. The chief assistant became particularly unpopular with Commander Sayles because he represented himself as the naval attache in visits to ports south of Bordeaux. Lieut. Frederick C. Havemeyer, U.S.N.R.F. succeeded Stevenson at Bordeaux and remained there until the end of the war.

The material condition of ships was also a concern of the Naval Port Officer. Repairs beyond the capacity of a ship’s force were handled by the repair officer, who from the summer of 1918 had available for this kind of work a repair ship, the U. S. S. Panther. There were dry dock and ship yards in Bordeaux, where repairs were also made upon American vessels. The repair officer handled not only the naval vessels based on the coast but also troop ships and cargo vessels whether Navy, Army, or Shipping Board. Repairs were also made by Army establishments. The scarcity of shipping made it imperative to keep all vessels in operation as much of the time as possible. Radio repairs were taken care of by an office at Bassens.

The establishment of adequate communications was of unusual importance to the Naval Port Office at Bordeaux because of the distance of that port from the sea and because of its supervision of other port offices on the river. For months the American naval port office system was dependent upon the French lines of

--33--

communication, which had never been planned for the load now put upon them. In the summer of 1918 work was undertaken upon independent telephone and telegraph lines but progressed slowly, owing to the lack of material and to the indifference of the U.S. Army to building purely Naval lines. In July 1918 a submarine cable was laid between Royan and Le Verdon; it worked a few days and then failed because of poor insulation. By the end of 1918 the Navy had constructed a complete telephone circuit from Rochefort via Royan, Le Verdon, Pauillac, Bordeaux, and back to Rochefort. This system included two cables under the Gironde between Royan and Le Verdon. All port officers could also communicate at this time by telegraph with the District Commander. Radio schools were conducted at Bordeaux and Rochefort for coaching operators on ships.

The last service performed by the Naval Port Officer at Bordeaux and his subordinates at Bassens and Pauillac for U. S. ships was to get them started on the homeward voyage. A day or two before departure commanding officers called at the Naval Port Office for sailing orders. Ships ready to depart were required to make a search for stowaways, prepare a list of persons carried on board and a list of men left behind. After being cast off from the docks vessels which had been discharged by the Army again came under naval authority. The passage down stream was under the guidance of pilots, and at Le Verdon French officials came aboard for an inspection.

Le Verdon was the assembly point for convoys bound for the United States, which were referred to as the O. V. convoys and which were made up of vessels from the Gironde River ports and other ports on t he southwest coast of France. No vessels, except naval warships, were allowed outside of the nets guarding the entrance to the Gironde without naval escort. The O. V. (V. for Verdon) convoy was established towards the end of 1917 by the Commandant Superieur des Divisions de Bretagne at Brest, under a French naval officer on the Martha Solange. As the French escort was inadequate, several American yachts which had been serving farther north on the coast of France were based at Le Verdon early in 1918. The vessels usually assigned here during 1918 were the Aphrodite, Corsair, May, Nokomis,

--34--

Noma, and the Wakiva. Although orders for the convoys were issued by the French, the commander of the senior American escort vessel was given further information by the District Commander at Rochefort, on whose staff the Operations Officer had charge of the escort vessels assigned to the district. The senior escort commander communicated his final and secret instructions in a meeting attended by the ships' officers on the Marthe Solange. The usual procedure was for a group of three American and one French escort vessel to accompany the ships to sea for two or three days when they dispersed on divergent routes on the open sea, and then the escort returned to the Gironde. For the first 50 miles the escort, whose composition varied according to the number of craft available, was reinforced with gunboats and launches attached to the Gascony patrols.

In the sunnier of 1918 the number of ships in a convoy ranged from 22 to 56. With more or less regular .. periods for liberty and repairs, the monotonous escort trips went on and on. In these more southern waters there were few encounters with enemy submarines. Reports of the convoys were sent by the senior American officer to the District Commander. Between February and October 1918 twenty-four O. V. convoys comprising 457 ships were escorted from Le Verdon.

After April 1918 ships sailing from New York to Bay of Biscay ports were convoyed directly in what were called H. B. convoys. These convoys were operated by the British Admiralty, as were all other convoys of cargo ships crossing the Atlantic, until September when the U.S. Navy, having acquired experience in running convoys, took over the operation of the H. B. convoys; the more northern convoys traversing more dangerous routes remained under British control. The laden ships of the H. B. convoys were conducted by American or French cruisers to a rendezvous point off the French coast, where they were met by escort vessels which had brought out an O. V. convoy, and, whenever possible by destroyers from Brest, and taken to Le Verdon for distribution to the ports to which they were destined. This system required careful management and necessitated a constant flow of communication between Admiral Wilson's headquarters at Brest and Captain McCully's headquarters at Rochefort, in addition to communication

--35--

with the United States and the British Admiralty at London. Arrangements at first were for convoys every sixteen days, but by September there was a fast storeship convoy every four days in addition to slow convoys; they comprised an average of ten ships. The Navy Department at this time considered increasing the number of convoys, but Admiral Sims advised an increase in the number of ships on the convoys as the more numerous the convoys the easier it was for the submarines to find that and the more escort vessels needed. Of the total of 255 ships taken to the Bay of Biscay in twenty H. B. convoys 202 were American.

Ships coming to Le Verdon to join the O. V. convoys, ships brought to that place in H. B. convoys for distribution to other ports on the coast, and ships engaged in coastwise traffic were escorted in coastal convoys which operated along the entire coast of the Bay of Biscay. These coastal convoys were run by the French Navy, and the officer stationed on the Marthe Solange at Le Verdon received orders pertaining to them. American naval vessels composed three out of the eight units of escort vessels employed on the coastal convoys.

Pauillac served as a supply base for the American escort vessels. At the completion of each trip to sea, they ran up the river to coal from colliers anchored at that place or from the coal piles at Trompeloup. Here they also obtained other supplies, including water, provisions, clothing, lubricating oil, gasoline, and engineering and electrical stores. Monthly visits were made by one of the yachts to Brest for other supplies not procurable at Pauillac. Because of the difficulty of coaling the yachts there, due to the lack of berths, the District Commander recommended the acquisition of two lighters. To meet the need which would eventually exist for a shore base for the vessels assigned to the district, he suggested, in a report of August 1, 1918 Talmont as the most suitable place because of its superior location. The construction of oil tanks at Furt, which was progressing at this time, would have provided a store from which to supply oil burning destroyers for escort duty—had the war continued longer.

--36--

American troop transports were provided with escorts and routed by Admiral Wilson's headquarters at Brest. These were given preferential treatment over the cargo convoys because they carried our manpower and because they were larger and more valuable Alps. Convoys of transports routed to the Gironde under the escort of destroyers, which had met than at the rendezvous in the Atlantic, were reinforced at land fall positions by the American escort vessels attached to the Le Verdon station. It was sometimes necessary to weaken the regular Verdon convoys in order to accomplish this. Instead of being returned to the United States in the regular O. V. convoys, the troopships formed special O. V. convoys and were given destroyer escort to a safe distance from the coast, whence they proceeded alone, relying on their speed to evade any chance submarines that might be encountered.