An non-circulating original copy of this publication is located in the Navy Department Library Special Collection.

The Navy Department Library

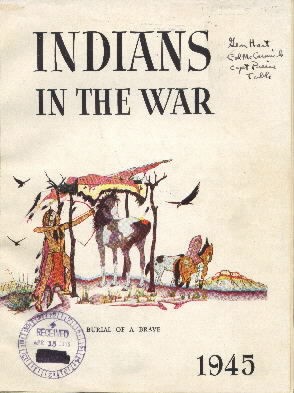

Indians in the War 1945

1941-1945

In Grateful Memory

of

Those Who Died

In the Service of Their Country.

They Stand in the Unbroken Line

Of Patriots Who Have Dared to Die

That Freedom Might Live, and Grow,

And Increase Its Blessings.

Freedom Lives,

And Through it They Live--

In a Way That Humbles

The Undertakings of Most Men.

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Indians in the War

| Honor for Indian Heroism | 1 |

| Awards for Valor (Lists) | 9 |

| Ceremonial Dances in the Pacific, by Ernie Pyle | 12 |

| A Choctaw Leads the Guerrillas | 14 |

| An Empty Saddle | 15 |

| We Honor These Dead (Lists) | 16 |

| Navajo Code Talkers, by MT/Sgt. Murrey Marder | 25 |

| Indians Fought on Iwo Jima | 28 |

| Wounded in Action (Lists) | 30 |

| Indians Work for the Navy, by Lt. Frederick W. Sleight | 42 |

| To the Indian Veteran | 44 |

| Indian Women Work for Victory | 49 |

| Prisoners of War Released | 50 |

| A Family of Braves | 51 |

| Indian Service Employees in the War | 53 |

The material in this pamphlet was collected for the 1945 Memorial Number of Indians at Work, before the magazine was discontinued because of the paper shortage. Many devoted workers spent much time and effort to get these stories, and the photographs which accompany the lists were loaned by the families of the boys whose names will be found here. We wish to express our gratitude to all of those who made this record possible.

The casualty lists and the lists of awards and decorations continue those begun in Indians at Work for May-June 1943 and carried on in the November-December 1943, May-June 1944, and September-October 1944 issues. They are not complete, and it is hoped that when the peace has come, the whole story of the Indian contribution to the victory may be gathered up into one volume.

Awards of the Purple Heart have not been indicated here because every soldier wounded in action against the enemy is entitled to the decoration, and the award should be taken for granted.

NOVEMBER 1945

United States Department of the Interior--Office of Indian Affairs

Chicago 54, Illinois

Haskell Printing Department

2-15-46--15,000

Honor for Indian Heroism

The war has ended in victory for the United Nations, and after a troubled period of readjustment and reorganization, peace will come at last. The story of the Indians' contribution to the winning of the war has been told only in part, and new material will be coming in for many months. As one of the Sioux boys says, "As a rule nowadays the fellows don't go in for heroics." But already the Indian record is impressive. In the spring of 1945, there were 21,767 Indians in the Army, 1,910 in the Navy, 121 in the Coast Guard, and 723 in the Marines. These figures do not include officers, for whom no statistics are available. Several hundred Indian women are in the various branches of the services. The Standing Rock Agency, North Dakota, estimates that at least fifty girls from that jurisdiction are in uniform.

The Office of Indian Affairs has recorded 71 awards of the Air Medal, 51 of the Silver Star, 47 of the Bronze Star Medal, 34 of the Distinguished Flying Cross, and two of the Congressional Medal of Honor. There are undoubtedly many more which have not been reported. Many of these ribbons are decorated with oak leaf clusters awarded in lieu of additional medals. It is not unusual to see an Air Medal with nine oak leaf clusters, or twelve, or even fourteen.

The casualty lists are long. They come from theaters of war all over the world. There were many Indians in the prison camps of the Philippines after the fall of Bataan and Corregidor, and later there were many more on Iwo Jima and Okinawa. There were Indians in the 45th Division in Sicily and Italy. They were at Anzio, and they took part in the invasion on D-Day in Normandy. A Ute Indian, LeRoy Hamlin, was with a small troop which made the first contact with the Russians across the Elbe on April 25. Another Ute, Harvey Natchees, was the first American soldier to ride into the center of Berlin. Pfc. Ira Hayes, Pima, of the Marines, was one of the six men who raised the flag on the summit of Mt. Suribachi. Once in a while, an Indian diving into a foxhole when shells began to burst, would find himself face to face with another member of his race, and they would start talking about Indian problems as they waited for the enemy fire to cease. When there was only one Indian in an outfit, he was inevitably called Chief, which amused him and perhaps pleased him a little.

The Indian people at home have matched the record of their fighting men. More than forty thousand left the reservations during each of the war years to take jobs in ordnance depots, in aircraft factories, on the railroads, and in other war industries. The older men, the women, and the children, who stayed at home, increased their production of food in spite of the lack of help. The Indians invested more than $17,000,000 of restricted funds in war bonds, and their individual purchases probably amount to twice that sum. They subscribed liberally to the Red Cross and to the Army and Navy Relief societies. The mothers of the soldiers organized War Mothers clubs in their communities, and every soldier received letters and gifts while he was in the service. The clubs helped to entertain the boys who came home on furlough, and now that the war is over, they are making plans for war memorials in honor of the fallen.

Reflecting the heroic spirit of Indians at war in every theater of action, the list of those specially selected to receive military honors grows steadily. We shall never know of all the courageous acts performed "with utter disregard for personal safety," but the proved devotion of all Indian peoples on the home front and the conspicuous courage of their sons and daughters in the various services entitle them to share in common the honors bestowed upon the few here noted.

1

Congressional Medal of Honor

The blue star-sprinkled ribbon of the highest award of all is given for "conspicuous gallantry at the risk of life above and beyond the call of duty." Relatively few of these medals have been given, and the nation may well be proud of the fact that two Indians thus far have won it. The story of Lt. Ernest Childers, Creek, was told in Indians at Work for May-June 1944; that of Lt. Jack Montgomery, Cherokee, in the January-February number, 1945.

Distinguished Flying Cross

The highest aviation honor is given for heroism or extraordinary achievement while participating in aerial flight. The ribbon is blue, with a white-bordered red stripe in the center and white stripes near the ends. Thirty or more Indians have been awarded this medal thus far, and their stories have been told in various issues of Indians at Work.

Mention has already been made of Lt. William R. Fredenberge, Menominee, of Wisconsin, who wears this ribbon and also has the Air Medal with seven oak leaf clusters. The citation for the DFC reads as follows:

"Lieutenant Fredenberg demonstrated superior skill in the execution of a dive-bombing attack upon a heavily defended marshalling yard wherein he personally destroyed three locomotives and thereafter in the face of heavy and accurate enemy fire remained in the target area strafing installations until his ammunition was exhausted. The outstanding flying ability and tactical proficiency which he exhibited on this occasion reflected the highest credit upon himself and his organization."

Sgt. Shuman Shaw, a full-blood Paiute from California, was wounded on his third mission as a tail-gunner on a B-24 Liberator, but he stayed with his guns and shot down two of the enemy, with three more probably destroyed. During his 22nd mission, while raiding strategic installations at Budapest, he was again seriously wounded. On both occasions he was given plasma. Sgt. Shaw has the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Air Medal with three oak leaf clusters, the Presidential Unit Citation, and the Purple Heart with oak leaf cluster.

Air Medal, Distinguished Flying Cross

Harold E. Rogers, Seneca from Miami, Oklahoma, was reported missing in action on July 3, 1944, when his plane failed to return from a mission over Budapest. Sgt. Rogers had flown 25 missions with the 8th Air Force in England, and then served as instructor in the United States for six months. He went back into action, this time with the 15th Air Forced, based in Italy. He wore the Air Medal with nine oak leaf clusters, and the Distinguished Flying Cross. The Purple Heart was awarded to him posthumously. His wife, a Potawatomi from Kansas, who now lives in Hollywood, was a student at Haskell Institute with her husband and Sgt. Rogers was studying law at the time

2

he entered the service. He also attended Sherman Institute and Riverside Junior College.

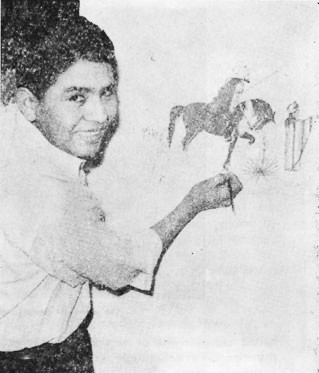

Silver Star to a Young Artist

A soldier who is cited for gallantry in action, when that gallantry does not warrant the award of a Medal of Honor or a Distinguished Service Cross, is given the Silver Star.

This decoration was awarded posthumously to Ben Quintana, a Keres, from Cochiti Pueblo. According to the citation, Ben was "an ammunition carrier in a light machine gun squadron charged with protection of the right flank of his troop which was counterattacked by superior numbers." The gunner was killed and the assistant gunner severely wounded. "Private Quintana," the citation continues, "refused to retire from this hazardous position and gallantly rushed forward to the silenced gun and delivered a withering fire into the enemy, inflicting heavy casualties. While so engaged he was mortally wounded. By this extraordinary courage he repulsed the counterattack and prevented the envelopment of the right flank of his troop. Private Quintana's unflinching devotion to duty and heroism under fire inspired his troop to attack and seize the enemy strong point."

With Ben Quintana's death the country has lost one of its most promising young artists. At the age of 15, he won first prize over 80 contestants, of whom 7 were Indians, for a poster to be used in the Coronado Cuarto Centennial celebration. Later, he won first prize and $1,000 in an American Magazine contest in which there were 52,587 entries.

Silver Star for Sherman Graduate

Captain Leonard Lowry, a graduate of Sherman Institute, also wears the Silver Star. he was a first lieutenant at the time of the citation, which says: "He was advancing with an infantry force of 500 men when they were halted by the enemy and the leading elements were pinned down. It was imperative that this force get through. Lt. Lowry assumed command and directed temporary security measures. He then organized a small combat patrol and personally led it in storming the enemy elements that were delaying the unit's advance." Capt. Lowry has been wounded several times.

Led the Way for Tanks

The Shoshones proudly claim Marine Pfc. Leonard A. Webber, of Fort Hall, Idaho, who received his Silver Star "for gallantry and intrepidity while serving with the Second Marine Division, during action against enemy Japanese forces on Tarawa, Gilbert Islands, from November 22 to November 23, 1943. During this period, when radio communication was out, he performed duties as runner between the tank battalion command post, tanks, and infantry front line positions, with utter disregard for his own personal safety in the face of heavy enemy gunfire. His skill and devotion to duty contributed greatly to the maintaining of communication of tank units. His conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity were in keeping with the highest tradition of the United States Naval Service."

Later, for action in 1944, Leonard Webber, now a Corporal, received the Bronze Star. This decoration is awarded for meritorious or

3

heroic achievement or service, not involving participation in aerial flight, in connection with military operations against an enemy of the United States. The citation for the Bronze Star reads:

"For meritorious achievement in action against the enemy on Saipan and Tinian, Marianas Islands, from 15 June to 1 August, 1944, while serving as a reconnaissance man in a Marine tank battalion. With aggressive determination and fearless devotion to duty Corporal Webber reconnoitered routes of advance for tanks in the face of intense enemy fire. On one occasion, he led a tank platoon over exceedingly dangerous and perilous terrain, while under heavy mortar and small-arms fire, to support the infantry advance and make it possible for his tank platoon to inflict severe casualties on the enemy. His cool courage and outstanding ability contributed in a large measure to the success of the tank operation. His conduct throughout was in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service."

Silver Star for a Cherokee

The mother and father of Pvt. Blaine Queen received the Silver Star posthumously awarded to their son for heroism in action in Germany. Pvt. Queen, a Cherokee from North Carolina, was with a platoon engaged in sharp action with the enemy. They were under heavy fire from nearby enemy positions, and when their ammunition began to run dangerously low, Pvt. Queen volunteered to leave his foxhole and go for the needed supplies. As he ran he was mortally wounded, but in spite of his wound he kept on toward his destination until death overtook him.

A Potawatomi Leads the Way

Pfc. Albert Wahweotten, Potawatomi from Kansas, received the Silver Star from his commanding general last February in Germany. According to the citation, Pfc. Wahweotten, armed with an M-1 rifle and a bazooka, worked his way 200 yards beyond the front lines to a house occupied by the enemy. In spite of heavy fire, he crawled to within ten yards of the house, which he set on fire with the bazooka. Then he went into the burning building and captured twelve Germans, eliminating the last enemy resistance in the town.

Initiative, Bravery, and Gallantry

An Iowa-Choctaw, also from Kansas, was another winner of the Silver Star for gallantry in action against the Germans. When his superior officer was disabled, Pfc. Thurman E. Nanomantube took over the duties of section leader of a heavy machine gun section, and with complete disregard for his own safety ran

4

across fifty yards of open ground, swept by heavy fire, in order to help a gunner whose gun was not working properly. When the battalion was pinned down by artillery fire, he gave first aid to two wounded men and handled another skillfully in order to keep him from becoming the victim of combat exhaustion. The citation praises Pfc. Nanomantube for his initiative, bravery, and gallantry.

Decoration for a Papago

An engineers outfit, in combat for 165 continuous days on Luzon, needed the bulldozer which Pfc. Norris L. Galvez, Papago of Sells, Arizona, was driving up the road. Pfc. Norris was told that the Japs had two automatic weapons firing across the road ahead, but he decided that the bulldozer must go through and unhesitatingly drove the unprotected machine through the field of fire, an action which brought him a citation and the Silver Star.

Hero's Son Receives Medal

Alec Hodge is only six years old, but he knows what war means. He knows, too, the pride with which soldiers receive their medals, for on Alec's small chest was recently pinned the bronze Star posthumously awarded to his father, Pfc. Otto Hodge, a Yurok-Hoopa, who was killed in action in Italy. The youngster stood straight, as befits the son of a warrior, and listened to the words of the citation: "For heroic achievement in action against the enemy from September 10 to September 23, 1944."

Then he solemnly shook the proffered hand of brigadier General Oscar B. Abbott, who made the award. The ceremony was held at the Arcata Naval Auxiliary Air Station near Eureka, California, on April 6, 1945.

Alec has two uncles in the service. One, Fireman Henry Hodge, is on sea duty in the South Pacific, while the other, Pvt. James Hodge, is serving in Europe. Both uncles are graduates of Sherman Institute and are the sons of Mrs. Carrie Hodge of Trinidad, California.

Ordeal by Fire

The citation accompanying the Bronze Star Medal awarded to Pvt. Houston Stevens, Kickapoo from Shawnee, Oklahoma, reads:

"For heroic achievement near St. Raphael, France, on 15 August 1944. Struck by an aerial bomb as it neared shore during the invasion of Southern France, LST 282 was burning fiercely and ammunition aboard was exploding continuously. Unmindful of the intense heat and the exploding ammunition, Pvt. Stevens manned a 50-caliber machine gun located within ten yards of the explosion. Though his hair and eyebrows were singed by the spreading flames, he remained at his post and continued to fire the gun at the enemy plane. By his devotion to duty, Pvt. Stevens prevented additional damage by the plane. His action reflects credit upon himself and the armed forces of the United States."

With the Famous Ivy Leaf

Sgt. Perry Skenandore, Oneida from Wisconsin, wears two rows of ribbons, as well as the blue bar for the Presidential Unit Citation. He has been awarded the Silver Star, the Bronze Star with oak leaf cluster, and the Soldier's Medal. His European theater ribbon carries three battle stars and the bronze arrow which stands for the invasion of Normandy. Sgt. Skenandore is a member of the 4th Infantry Division, the Ivy Leaf, a fighting outfit which is described by a Stars and Stripes correspondent as follows:

"After 199 days, ending March 9, in continuous contact with the German army, the 4th Division closed a chapter that carried it through some of the most famous battles of the present war.

"Starting on August 24 with the headlong rush into Paris, which they liberated the next day, the 4th's men never lost sight of the grey-uniformed Wehrmacht until they had it on the run towards the Rhine.

"Included in the nearly seven months of grinding up Nazi hordes were the mad dash across Northern France and Belgium; the liberation of such towns as Chauny, St. Quentin, St. Hubert, Bastogne, and St. Vith. The doughs never stopped their eastward drive until they had bowled through the Siegfried Line. the 4th Division was the first unit to enter German soil on September 11.

"History has recorded their successful but

5

bloody Battle of the Huertgen Forest and their magnificent stand before the city of Luxembourg in those dark days of December, when, according to Lt. Gen. George Patton, Jr., 'a tired division halted the left shoulder of the German thrust into the American lines and saved the city of Luxembourg.'

"From this action the Ivy Leaf Division went over to the offensive, crossing the Sure River and eating into the bulge the enemy had built up. Switching to the St. Vith sector, they fought their way through the Siegfried Line in exactly the same place where they had pushed through in September. This made four times they had passed through the maze of steel and concrete that was once considered almost impregnable."

Sgt. Skenandore has a good deal to tell about his division and its accomplishments against the Nazis, but little information about himself. The ribbons, however, speak for him.

Held the Lines

The Bronze Star Medal was awarded to Corporal Calvin Flying Bye, Sioux, of Little Eagle, South Dakota, "for heroic achievement in Germany on 29 and 30 November 1944. . . . During these two days, when his division attacked a fortified enemy town, communication lines between the forward observer and his battalion were severed. In spite of heavy enemy fire which was falling not more than 15 yards from him, he checked the lines and constantly maintained them without getting any sleep for 48 hours. His courage and devotion to duty reflect great credit upon himself and the military service."

An Alaskan Scores

Pfc. Herbert Bremner, Tlingit, of Yakutat, Alaska, has been given the Bronze Star for heroic action in Holland:

"While the Anti-Tank Platoon which was supporting the assault battalion was moving its weapons forward to engage four enemy tanks which were holding up the progress of the battalion, two of the prime movers were damaged by intense mortar and machine gun fire, and it was necessary to repair them before they could be used to move the weapons into position. Without regard for his personal safety, Private Bremner manned the machine gun, which was in an exposed position on top of one of the vehicles. His determined, accurate fire forced the enemy tanks to withdraws, thus permitting the battalion to advance to its objective. The high standard of courage of Private Bremner was a large factor in enabling the battalion to gain its objective and is a distinct credit to this soldier and the military service."

Inspired His Comrades

Marion W. McKeever, Flathead, from Montana, was awarded the Bronze Star posthumously "for meritorious achievement in connection with military operations against the enemy at Bougainville, Solomon Islands, on March 10, 1944. During a counterattack to destroy the enemy forces, when his platoon made an advance against enemy positions, Pvt. McKeever moved up aggressively to engage the enemy. Moving up as far as possible he crossed a machine gun lane and the enemy opened fire, killing him instantly. Because of his daring movement in spite of the heavy fire, he was one of the most forward men of the platoon. His action was cool and brave and was an inspiration to all who served with him."

The Bronze Star for an Infantryman

A posthumous award of the Bronze Star Medal was made to Cpl. Jack E. Mattz, Yurok-Smith River Indian from Grants Pass, Oregon. During an assault on enemy lines in Holland, Cpl. Mattz crept forward toward a dugout containing a large number of the enemy, killed several of them with his sub-machine gun, and when his ammunition ran out, accounted for the rest by using hand grenades. A few hours later he was killed by shell fire.

Saved by Partisans

Two Indian gunners with the 15th Air Force, based in Italy, had similar stories to tell of parachute jumps in Balkan territory. S-Sgt. Cornelius Wakolee, Potawatomi, from Kansas, was forced to bail out over Yugoslavia when his Liberator bomber was hit by heavy flak. He was reported missing on October 14, and returned to duty some six weeks later, after a long walk, guided across enemy-held

6

territory by Yugoslav partisans. Some months afterward, T-Sgt. Ray Gonyea, from the Onondaga Reservation, New York, made a similar jump and landed in a village held by the partisans, who helped him and his crew back to their base--after an hilarious celebration. Sgt. Gonyea holds the Air Medal with two oak leaf clusters, and the Purple Heart. Sgt. Wakolee has three clusters to the Air Medal.

Purple Heart, Four Cluster

Danny B. Marshall, Creek, from Holdenville, Oklahoma, has evaded death dozens of times and has been wounded eight times. Five of his wounds required hospital treatment, but the other three times he had first aid and did not report at a hospital. He has been hit in the face, head, arms, leg, and back, and has the Purple Heart with four clusters, the Bronze Star, the Good Conduct medal, the Combat Infantryman's Badge, and five battle stars for service in Italy, including the Anzio beachhead and Rome, and the invasion of Southern France.

A Submarine Veteran

"The greatest thrill of all," said John Redday, Sioux, from South Dakota, "was to pass through the golden Gate and set foot again on American soil." This remark was made after 21 months' service in a submarine patrolling South Pacific waters. During this time the sub sank fourteen and damaged seven enemy vessels. Among them was one of Japan's largest freighters, which was destroyed by gunfire alone.

The thrills and dangers of submarine warfare were many, according to Redday. Once a sub-chaser, disguised as a transport, discovered them while they were surfaced, and depth charges fell all around them before they could submerge. The charges were so terrific that the overhead motors were sheared off. Another time an enemy destroyer caught their propguard with a grappling iron and pulled them forty feet toward the surface before they could get away. In escaping they dived far below normal depth and the pressure was so great that water leaked in from all sides.

Redday was transferred to the Veterans' Hospital at Minneapolis a year ago because of tuberculosis, and is slowly improving in the free air of his homeland.

A Navajo Fights on Two Fronts

Dragging one wounded soldier, helping support another, his own back and legs torn by shrapnel, a twenty-year-old Navajo made his way across three hundred yards of knee-deep snow. Safe in his own lines again, he did not bother to go to the aid station. This is only one of the stories told about Sgt. Clifford Etsitty, a star patrol scout of the Western front. Another time he was within 30 yards of the enemy when a machine gun opened up on his patrol. "The Chief," as he is known in the Army, flattened out and with six shots finished the half-dozen Nazis who barred his way.

Etsitty received his first Purple Heart on Attu, where he killed 40 Japs in 20 days. This was night ambush detail. Clad in white snow suits, the soldiers lay in wait for enemies and

7

picked them off as they approached. The cold, dangerous work ended when a bursting mortar shell smashed the Navajo's jaw and sent him to the hospital for seven months. As soon as he was discharged, he was sent to the 99th Division and continued his remarkable career on the German front.

Foresight and Sound Decision

The Bronze Star has also been received by Staff Sgt. David E. Kenote, Wisconsin Menominee, "for meritorious service in connection with military operations against an enemy of the United States, in France, from 1 August 1944 to 31 October 1944. Sgt. Kenote inaugurated a system of stock records and a procedure for requisitioning which enabled the Adjutant General, Third United States Army, successfully to supply and distribute War Department publications and blank forms to Third Army troops. The foresight of this non-commissioned officer, and his careful planning and energetic execution achieved continuous supply during all phases of a rapidly moving operation. His plans were simple and workable, and his decisions were sound. The zealous devotion to duty of Sgt. Kenote reflects great credit upon himself and the military forces of the United States."

8

Awards for Valor

9 |

Awards for Valor

10 |

Awards for Valor

11 |

Ceremonial Dances in the Pacific

(One of the last stories written by Ernie Pyle before his tragic death on Ie Island was about the Indians of the First Marine Division on Okinawa. It is reprinted here by permission of Scripps-Howard Newspapers and United Feature Syndicate, Inc. The ceremonial dances, according to Marine Combat Correspondent Walter Wood, included the Apache Devil Dance, the Eagle Dance, the Hoop Dance, the War Dance, and the Navajo Mountain Chant. Besides the Navajos, Sioux, Comanche, Apache, Pima, Kiowa, Pueblo, and Crow Indians took part in the ceremonies.)

By ERNIE PYLE

Okinawa--(By Navy Radio)--Back nearly two years ago when I was with Oklahoma's 45th Division in Sicily and later in Italy, I learned that they had a number of Navajo Indians in communications.

When secret orders had to be given over the phone these boys gave them to one another in Navajo. Practically nobody in the world understands Navajo except another Navajo.

Well, my regiment of First Division marines has the same thing. There are about eight Indians who do this special work. They are good Marines and are very proud of being so.

There are two brothers among them, both named Joe. Their last names are the ones that are different. I guess that's a Navajo custom, though I never knew of it before.

One brother, Pfc. Joe Gatewood, went to the Indian School in Albuquerque. In fact our house is on the very same street, and Joe said it sure was good to see somebody from home.

Joe has been out here three years. He is 34 and has five children back home whom he would like to see. He was wounded several months ago and got the Purple Heart.

Joe's brother is Joe Kellwood who has also been out here three years. A couple of the others are Pfc. Alex Williams of Winslow, Ariz., and Pvt. Oscar Carroll of Fort Defiance, Ariz., which is the capital of the Navajo reservation. Most of the boys are from around Fort Defiance and used to work for the Indian Bureau.

The Indian boys knew before we got to Okinawa that the invasion landing wasn't going to be very tough. They were the only ones in the convoy who did know it. For one thing they saw signs and for another they used their own influence.

Before the convoy left the far south tropical island where the Navajos had been training since the last campaign, the boys put on a ceremonial dance.

The Red Cross furnished some colored cloth and paint to stain their faces. They made up the rest of their Indian costumes from chicken feathers, sea shells, coconuts, empty ration cans and rifle cartridges.

Then they did their own native ceremonial chants and dances out there under the tropical palm trees with several thousand Marines as a grave audience.

12

In their chant they asked the great gods in the sky to sap the Japanese of their strength for this blitz. They put the finger of weakness on the Japs. And then they ended their ceremonial chant by singing the Marine Corps song in Navajo.

I asked Joe Gatewood if he really felt their dance had something to do with the ease of our landing and he said the boys did believe so and were very serious about it, himself included.

"I knew nothing was going to happen to us," Joe said, "for on the way up here there was a rainbow over the convoy and I knew then everything would be all right."

13

A Choctaw Leads the Guerrillas

In April 1945, after more than three years as a guerrilla leader in the Philippines, Lt. Col. Edward Ernest McClish came home to Okmulgee, Oklahoma, where his family, who had refused to believe him dead, waited for him. Some of his story has been told in American Guerrilla in the Philippines, by Ira Wolfert, and other details have been added in a report given to the Public Relations Bureau of the War Department by Col. McClish. It is an extraordinary tale of accomplishment against great odds.

Lt. Col. McClish, a Choctaw, who graduated from Haskell Institute in 1929 and from Bacone College two years later, was called to active duty in the National Guard in 1940, and early in 1941 he arrived in the Philippines, where he became commander of a company of Philippine Scouts. In August he went to Panay to mobilize units of the Philippine Army there, and as commander of the Third Battalion he moved his men to Negros, where they were stationed when the war broke out. Late in December they crossed by boat to Mindanao, and there all the Moro bolo battalions were added to McClish's command.

The Japanese did not reach Mindanao until April 29, 1942, shortly before the American capitulation on Luzon, and Col. McClish's men fought them for nearly three weeks. When forces on the island finally surrendered, McClish, a casualty in the hospital, some distance from headquarters, was fortunately unable to join his men. Instead of capitulating he began to organize a guerrilla army.

By September 1942, he had an organization of more than 300 soldiers, with four machine guns, 150 rifles, and six boxes of ammunition. Some American and Filipino officers had escaped capture and joined the staff. In the early stages of the organization, McClish got word of a Colonel Fertig, of the Army Engineers, who was working along similar lines in the western part of Mindanao, and he managed to reach Fertig by travelling in a small sailboat along the coast. The two men decided to consolidate their commands, and Colonel Fertig asked McClish to organize the fighting forces in the four eastern provinces of the island as the 110th Division.

Organization was at first very difficult. Independent guerrilla bands had sprung up all over the island, some of them composed of robbers and bandits who terrorized the villages. Some were anti-American, says Colonel McClish. Most of them lacked military training and education. But slowly the work proceeded. The bandits were disarmed and jailed; the friendly natives were trained, and young men qualified to be officers were commissioned. By the spring of 1943 McClish had assembled a full-strength regiment in each of the three provinces, a fourth had been started, and Division headquarters staff had been completed.

Simultaneously with the military organization, civil governments were set up in each province. Wherever possible, the officials who had held jobs in pre-war days were reappointed, provided that they had not collaborated with the Japanese. Provincial and municipal officials worked hand in hand with the military, and helped greatly to build up the army's strength.

Because of the shortage of food, reports Colonel McClish, a Food Administrator and a Civil and Judicial Committee were appointed to begin agricultural and industrial rehabilitation. Army projects for the production of food and materials of war were begun throughout the Division area, and all able-bodied men between the ages of 18 and 50 were required to give one day's work each week to one of these projects. They raised vegetables, pigs, poultry, sugar cane, and other foods. The manufacture of soap, alcohol, and coconut oil was started. Fishing was encouraged. In some of the provinces food production was increased beyond the peacetime level. The civilians realized that they were part of the army, and that only a total effort could defeat the enemy.

The public relations office published a newspaper, and headquarters kept in communication

14

with the regiments in each province by radio, by telephone (when wire was available), or by runner. The guerrillas acquired launches and barges which had been kept hidden from the Japanese, and these were operated by home-made alcohol and coconut oil. Seven trucks provided more transport, but it was safer and easier to use the sea than the land. In order to maintain their motor equipment, they "obtained" a complete machine shop from a Japanese lumbering company in their territory.

From September 15, 1942, to January 1, 1945, while McClish's work of organization and administration was continuing, his guerrilla forces were fighting the Japanese, and more than 350 encounters--ambushes, raids on patrols and small garrisons, and general engagements--were listed on their records. One hundred and fifteen men were killed and sixty-four wounded. Enemy losses were estimated at more than 3000 killed and six hundred wounded. The guerrillas finally made contact with the American forces in the South Pacific and supplied them with valuable information about the enemy which was extremely helpful when the time for the invasion of the Philippines came at last. They did their part in bringing about the final victory in the Pacific.

An Empty Saddle

"If I should be killed, I want you to bury me on one of the hills east of the place where my grandparents and brothers and sisters and other relative are buried.

"If you have a memorial service, I want the soldiers to go ahead with the American flag. I want cowboys to follow, all on horseback. I want one of the cowboys to lead one of the wildest of the T over X horses with saddle and bridle on.

"I will be riding that horse."

Such were the written instructions left by Pvt. Clarence Spotted Wolf, full-blood Gros Ventre, with his tribesmen. He was killed December 21, 1944, in Luxembourg.

Pvt. Spotted Wolf was born May 18, 1914. He entered the service in January, 1942, and a year later was transferred to a tank battalion. He went overseas in August, 1944.

On January 28, in Elbowoods, North Dakota, the memorial service he had foreseen was held in his honor. It was an impressive ceremony. The Stars and Stripes presided over the winter-bare hills where Clarence Spotted Wolf's family and friends carried out his wishes. There were soldiers; there were cowboys; and his own saddle had been placed on the T over X horse, which was led in the procession. It is pleasing to fancy the spirits of brave warriors long departed watching benignly from the Happy Hunting Grounds.

As for the empty saddle--who knows?

15

We Honor These Dead

16 |

17 |

18 |

19 |

20 |

21 |

22 |

23 |

24 |

Navajo Code Talkers

by

W/T Sgt. Murrey Marder

Marine Corps Combat Correspondent

Reprinted by permission of The Marine Corps Gazette

Through the Solomons, in the Marianas, at Peleliu, Iwo Jima, and almost every island where Marines have stormed ashore in this war, the Japanese have heard a strange language gurgling through the earphones of their radio listening sets--a voice code which defies decoding.

To the linguistically keen ear it shows a trace of Asiatic origin, and a lot of what sounds like American double-talk. This strange tongue, one of the most select in the world, is Navajo, embellished with improvised words and phrases for military use. For three years it has served the Marine Corps well for transmitting secret radio and telephone messages in combat.

The dark-skinned, black-haired Navajo code talker, huddled over a portable radio or field phone in a regimental, divisional or corps command post, translating a message into Navajo as he reads it to his counterpart on the receiving end miles away, has been a familiar sight in the Pacific battle zone. Permission to disclose the work of these American Indians in marine uniform has just been granted by the Marine Corps.

Transmitting messages which the enemy cannot decode is a vital military factor in any engagement, especially where combat units are operating over a wide area in which communications must be maintained by radio. Throughout the history of warfare, military leaders have sought the perfect code--a code which the enemy could not break down, no matter how able his intelligence staff.

Most codes are based on the codist's native language. If the language is a widely-used one, it also will be familiar to the enemy and no matter how good your code may be the enemy eventually can master it. Navajo, however, is one of the world's "hidden" languages; it is termed "hidden," along with other Indian languages, as no alphabet or other symbols of it exist in the original form. There are only about 55,000 Navajos, all concentrated in one region, living on Government reservations and intensely clannish by nature, which has confined the tongue to its native area.

Except for the Navajos themselves, only a handful of Americans speak the language. At the time the Marine Corps adopted Navajo as a voice code it was estimated that not more than 28 other persons, American scientists or missionaries who lived among the Navajos and studied the language for years, could speak Navajo fluently. In recent years, missionaries and the Interior Department's Bureau of Indian Affairs have worked on the compilation of dictionaries and grammars of the language, based on its phonetics, to reduce it to writing. Even with these available it is said that a fluency can be acquired from prepared texts only by persons who are highly educated in English and who have made a lengthy study of spoken and written Navajo.

One of the reasons which prompted the Marine Corps to adopt Navajo, in preference to a variety of Indian tongues as used by the AEF in the last war, was a report that Navajos were the only Indian group in the United States not infested with German students during the 20 years prior to 1941, when the Germans had been studying tribal dialects under the guise of art students, anthropologists, etc. It was learned that German and other foreign diplomats were among the chief customers of the Bureau of Indian Affairs for the purchase of publications dealing with Indian tribes, but it was decided that even if Navajo books were in enemy hands it would be virtually impossible for the enemy to gain a working knowledge of the language from that meager information. In addition, even ability to speak Navajo fluently would not necessarily enable the enemy to decode a military message, for the Navajo dictionary does not list military terms, and words

25

used for "jeep," "emplacement," "battery," "radar," "antiaircraft," etc., have been improvised by Navajos in the field.

The adoption of code talkers by the Marine Corps stemmed from a request for Navajo communicators by Maj. Gen. Clayton B. Vogel, then Commanding General, Amphibious Corps, Pacific Fleet. A report submitted with his request said a Navajo enlistment program would have full support of the Tribal Council at Window Rock, Arizona, Navajo Reservation.

Acting on this request the Marine Corps' Division of Plans and Policies in March 1942 sent Col. Wethered Woodworth to make a further report on the subject, and a test was made at the San Diego, Calif., Marine Base to determine the practicality of Navajos as code talkers.

The test revealed that the Navajos who volunteered for the experiment could transmit the messages given, although with some variation at the receiving end resulting from the lack of exact words to transmit specific military terms. For example, "Enemy is pressing attack on left flank" would come out "the enemy is attacking on the left."

Proper schooling in military phraseology, it was believed, could correct this variation, and the following month the Marine Corps authorized an initial enlistment of 30 Navajos to ascertain the value of their services.

The enlistment order required that recruits meet full Marine Corps physical requirements and have a sufficient knowledge of English and Navajo to transmit combat messages in Navajo. The recruits were to receive regular Marine training, attend a Navajo school at the Fleet Marine Force Training Center, Camp Elliott, Calif., and then receive sufficient communications training to enable them to handle their specially qualified talent on the battlefield.

All the recruits spoke the same Navajo basically, but there were certain word variations. In Navajo, the same word spoken with four different inflections has four different meanings. The recruits had to agree on words which had no shades of interpretation, for any variation in an important military messages might be disastrous. As might be expected in any group of youths, they were not equal in education or intelligence. Some of the military terms were very complex to the unschooled; all had to be able to understand them thoroughly in order to translate them into their native language. Some were not easily adaptable to communications work. It was difficult in several instances for non-Navajos to instruct the recruits in Marine Corps activities; a few marine instructors were unable to cope with the typical Indian imperturbability.

On the other hand, many of the recruits were well-educated, intelligent and quick to learn. A number had worked for the Bureau of Indian Affairs as clerks, and almost all the Navajos had the highly developed Indian sensory perceptions.

There were some recruits like PFC Wilsie H. Bitsie, whose father is district supervisor of the Mexican Springs, N. Mex., Navajo District. Bitsie became an instructor in the Navajo School at Camp Elliott for a time, and helped work out the much needed military terms. He went on to join the marine Raiders and at New Georgia his Navajo ability helped the Raiders maintain contact with the Army command at Munda while the marines knocked out Japanese outposts in the jungle to the north.

Other code talkers went with the Third Marine Division and the Raiders to Bougainville. There some manned distant outposts, maintaining contact in Navajo by radio. It was found best to have close friends work together in teams of two, for they could perfect their code talk by personal contact.

The men in their units learned that in addition to their language ability the Navajos also could be good marines. They could do their share of fighting and they made good scouts and messengers.

There had been concern in some quarters that dark-skinned Navajos might be mistaken for Japs. In the latter days of the Guadalcanal action one Army unit did pick up a Navajo communicator on the coastal road and messaged the marine command: "We have captured a Jap in marine clothing with marine identification tags." A marine officer was startled to find the prisoner was a Navajo, who was

26

only bored by the proceedings.

The code talkers went on into more campaigns, proving their ability, and the Navajo quota in the Marine Corps rose from 30 to 420. At their TBXs they transmitted operational orders which helped us advance from the Solomons to Okinawa.

It was found that the Navajos are not necessary at levels lower than battalions. For messages between battalions and companies the extra security is not required and speed is the paramount issue.

The III Amphibious Corps reported that the use of the talkers during the Guam and Peleliu operations "was considered indispensable for the rapid transmission of classified dispatches. Enciphering and deciphering time would have prevented vital operational information from being dispatched or delivered to staff sections with any degree of speed."

At Iwo Jima, Navajos transmitted messages from the beach to division and Corps commands afloat early on D-day, and after the division commands came ashore, from division ashore to Corps afloat.

Last April authority was granted to establish a re-training course for Navajos at FMFPac. Under this plan, five code talkers are taken from each division to attend an intensive 21-day course which gives emphasis to plane types, ship types, printing and message writing, and message transmission. These Navajos then return to their divisions to instruct the remaining men. It is emphasized that code talkers work out successfully only where interest is shown by the command and where training continues between operations.

As for the Navajos themselves, they probably are not any more enthusiastic about the concentrated schooling than most young marines would be about schooling, for they are amused at being regarded as different from other marines.

On rare occasions, though, they do lapse into some typical Indian gyrations. Ernie Pyle, in one of his last dispatches from Okinawa, described how the First Division's Navajos had put on a ceremonial dance before leaving for Okinawa. In the ceremony, they asked the gods to sap the strength of the Japanese in the assault.

According to a later report, when the First Division met the strong opposition in the south of Okinawa, one marine turned to a Navajo code talker and said,

"O.K., Yazzey, what about your little ceremony? What do you call this?"

"This is different," answered the Navajo with a smile. "We prayed only for an easy landing."

27

Indians Fought on Iwo Jima

Many Indians participated in the famous action on Iwo Jima. The most celebrated of these if Pfc. Ira H. Hayes, a full-blood Pima from Bapchule, Arizona, one of three survivors of the historic incident on Mount Suribachi, when six Marines raised the flag on the summit of the volcano, under heavy enemy fire. He served on Iwo Jima for 36 days and came away unwounded. Previously he had fought at Vella La Vella and Bougainville. Because of the nation-wide attention won by Rosenthal's dramatic photograph of the flag-raising, symbol and expression of the invincible American spirit, Hayes and his two comrades, Pharmacist's Mate John Bradley and Pfc. Rene A. Gagnon, were brought back to this country to travel extensively in support of the Seventh War Loan. In the photograph on the opposite page, Hayes is pointing out his position in the flag-raising patrol.

On May 1st, more than 1000 Indians of the Pima tribe gathered at Bapchule to pay honor to their fellow tribesman and to celebrate his safe return. A barbecue feast, under a canopy of brush, was followed by an impressive religious ceremony, with prayers led to Protestant and Catholic missionaries and songs by several church choirs. Mrs. Hayes, Ira's mother, asked two of the girl soloists to sing the hymn, "He Will Deliver."

The National Congress of American Indians gave a luncheon in honor of Hayes and his comrades in Chicago on May 19, at which a brief speech by Hayes was broadcast. At this meeting he was made first commander of the American Indian Veterans' Association. Pharmacist's Mate Bradley stated in an interview that Hayes was "a marked man on the island because of his cool level-headedness and efficiency." He refused to be leader of a platoon, according to Bradley, because as he explained, "I'd have to tell other men to go and get killed, and I'd rather do it myself," When he and the two others were ordered home to take part in the War Loan campaign, Hayes was reluctant to leave his fighting comrades, and, after a few weeks in the United States, requested that he be returned to overseas duty, where he felt he would be of greater value to his country.

A second Indian, Louis C. Charlo, Flathead, from Montana, climbed Mount Suribachi with a Marine patrol shortly after the flag was raised on its summit. He was killed in action not long afterward, fighting to keep the Stars and Stripes on the mountain. Louis was the grandson of Chief Charlo of Nez Perce war fame, a leader who maintained his friendship with the white people throughout those trying times.

Among Indians listed as wounded on the island are Pfc. Ray Flood, Sioux, from Pine Ridge; Verne Ponzo, Shoshone, Fort Hall; Orville Goss, Sidney Brown, Jr. and Richard J. Brown,; Robert Spahe, Jicarilla Apache; Thomas Chapman, Jr., Pawnee, and William M. Fletcher, Cheyenne, from Oklahoma; Joseph R. Johnson, Papago, Arizona; Pfc. Glenn Wasson and Pfc. Clarence L. Chavez, Paiute, Nevada; and Richard Burson, Ute. from Utah. Killed were Pvt. Howard Brandon, Rosebud Sioux; Pfc. Clement Crazy Thunder, Pine Ridge Sioux, whose photograph appeared in the May-June 1943 issue of Indians at Work; Pfc. Adam West Driver, Cherokee, from North Carolina; Pvt. Eugene Lewis, Yurok, California; and Paul Kinlahcheeny, Navajo. Leland Chavez, S 1-c, Paiute, Nevada, is reported missing in action.

Sgt. Warren Sankey, Arapaho, from El Reno, Oklahoma, was one of the crew which first knocked out a Japanese tank on Iwo Jima.

28

Two Flathead Indian brothers, Daniel and John Moss, Marines from Arlee, Montana, met unexpectedly on Iwo Jima, and both came safely through the fighting. Their father, Henry Moss, served with the Marines in the First World War.

One of four survivors of his company is Pvt. Clifford Chebahtah, Comanche, of Anadarko, Oklahoma. Pvt. Chebahtah was injured on Iwo Jima and was granted a two weeks' furlough at home.

"I was lying in a foxhole when I saw our boys raise the flag on the top of the volcanic mountain of Suribachi, and cold shivers ran down my spine," he said.

29

Wounded in Action

30 |

31 |

32 |

33 |

34 |

35 |

36 |

37 |

38 |

39 |

40 |

41 |

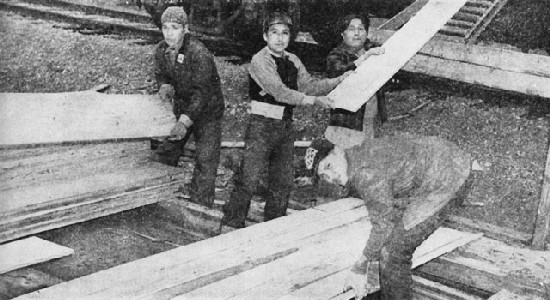

Indians Work for the Navy

By Lt. Frederick W. Sleight, USNR

The story of the American Indian and his efforts in this second great world struggle is not limited to the exploits of soldiers. Men and women too old or too young for service with the armed forces have volunteered for work in the war industries as well as in food production. This report on one of the U.S. Navy's greatest land-based activities illustrates the intense desire of the Indian people to serve where they are directly connected with the work of the war. The Naval Supply Depot at Clearfield, Utah, has as its aim and purpose general service to the fleet. It sends out a lifeline of supplies, pouring the essentials of successful warfare in an endless stream to the far points of the Pacific theatre.

The Depot was established in the Spring of 1943, to start the flow of vital materials to the Navy. At this time, down in the Rio Grande Valley of New Mexico, Indians were leaving home for military service. Ten per cent of the Pueblo Indians had gone into uniform. In the neighboring cities and the local communities help was urgently needed. The older men of the Pueblos, recognizing the emergency, decided to put an advertisement in the local papers offering their services for part-time work in the neighboring area. Soon trucks came pouring into the villages to pick up working parties, some even arriving from Colorado. When word of this project reached the offices of the Civil Service Commission in Denver, they sent a representative to Santo Domingo Pueblo to confer with John Bird, an Indian leader of political and social affairs.

John Bird was told about the new Naval Depot at Clearfield. The Civil Service understood that the Pueblo people wanted to help win the war; here at Clearfield was a place where men were needed, a place contributing directly to our successes in the Pacific. It was agreed that Pueblo men, if they went to work at Clearfield, would be allowed to go home during the summer months to plant and harvest their crops.

At the meeting called by John Bird, the Pueblos agreed that this was work which they wanted to do. The farm agent was convinced that if they came back and farmed in the summer months, the move to Utah for the rest of the year would be good. The task of recruiting men from all the Pueblos was given to John Bird, and he travelled from Taos on the north to Isleta on the south. Santa Clara, Jemez, and Santo Domingo gave the greatest number of workers. Sixty-two men came from Jemez alone. When they were examined and passed as physically fit by Indian Service doctors, they were ready to leave. About 150 men made up the first battalion that set out for Clearfield. The first contingent of work-hungry Pueblos, travelling in coaches reserved for them, arrived at the Navy Depot in December 1943.

Work assigned to the Indians has been varied. John Bird, who travelled with his people to Clearfield, has advanced to a supervisory position. He, like many of his men, has worked on the swing shift. Some of the men have been placed in the transportation division, and others have handled and loaded supplies destined for the ships at sea. Oscar Carlson, labor foreman at the Depot, says that the Indians--Shoshones, Apaches, Sioux, Navajos, Utes, as well as Pueblos--are outstanding workers. They understand instructions well. They are not shirkers on the job. He says, "I have never had an Indian in my office for disciplinary action."

The great problem of production, absenteeism, is unknown among the Indian population of the Depot. Indians are constantly on the job. Indian participation in the War Bond campaigns has been 100 per cent--another indication that the Indians are whole-hearted in their devotion to the cause for which their sons have fought.

For two springs the Pueblo people have gone back to their farms, but, the growing season over, they have returned, often bringing with

42

them new recruits to help with the big job. Mr. Carlson states that nearly all of the men return after a summer of farming, and that they all seem happy to come back. Further testimony comes in a report from the Security Department. This office, which handles all the policing of the area, has no record in the files any trouble initiated by the Indians.

From all quarters of the Depot have come similar reports. On the 10th of April, 1945, Rear Admiral Arthur H. Mayo, speaking at the ceremonies commemorating the second anniversary of the Depot's commissioning, said: "It is encouraging to know that many Pueblo Indians . . . have travelled north to the State of Utah in order to 'man the battle stations' at the Navy Supply Depot at Clearfield. I know that these fine people are doing a splendid job."

High credit should go to the Indian for an outstanding part in our victory. He has sacrificed more than most men who are doing this work. He has left the land he has known all his life and has had to travel to strange places where people often do not understand him and his way of living. In most cases he has left his family behind. He has had to forego attending the dances and other religious ceremonies that are so much a part of his life. He has had to work under foremen and supervisors, in a way that is new to him. It is an adjustment more difficult for him than for the white man who has known these conditions before.

For all these reasons, the Indian should receive the highest praise. In his quiet way he has shown that he too has a stake in this conflict, and by his personal qualities he has made himself liked by everyone. To men like John Bird, should go a special tribute. He helped interpret these modern problems to his people. When his brother Ted was killed in action in Germany last April, he flew home to comfort his mother and father. He has three other brothers in the armed forces overseas.

Like all Americans, these people look forward to the day when the soldiers will come home to a peaceful world. But these Indians have learned new skills and have acquired a new confidence in their own competence which should be very useful in the tasks of peace.

43

To the Indian Veteran

The Congress and the state legislatures have passed many laws providing various benefits for all veterans except those who have been dishonorably discharged from the armed services. Many of you know what these benefits are; but when you come home you will find at the agency someone who can tell you just how to apply for the benefits which you want, and what you must do to qualify. There is no distinction made between Indians and any other veterans. Every organization serving the veteran will serve you. Your Selective Service Board, to which you report within ten days after your return home, will have a counsellor to advise you; and the State agencies, the Red Cross, and other groups will provide information and counsel. The Indian Service will make every effort to direct you to the proper authority as quickly as possible.

If the first thing in your mind is employment, you probably know that you are entitled to get your old job back, or one with equal pay and standing, provided that you have completed your military service satisfactorily, that you are still able to do the job, that you apply for reinstatement within 90 days of your discharge, and that your employer will not suffer undue hardship by taking you back. Once you are on the job, you may not be dismissed without cause for the period of one year. This is true for Civil Service employees and for those in private industry. If you didn't have a job when you went into the military service, or if you don't want to go back to the job you left, you should apply to the nearest office of the U.S. Employment Service, or, if you want a Federal job, to the Civil Service Commission. You are entitled to preference for jobs in the Indian Service, both as an Indian and as a veteran, but you must of course qualify by training or by examination.

If you want to continue your education, there are many opportunities. Under the G.I. Bill of Rights (Public Law 346, 78th Congress), you are entitled to one year of school or college, if you have served at least 90 days, not counting the time spent in Army or Navy special training courses. You may choose the course you prefer, at any elementary school, high school, college, or vocational training institute on the list

44

approved by the Veterans' Administration, but you must be accepted as qualified by the school you select. A number of Indian Service schools have already been added to the approved list, and a number of special courses have been planned for returning servicemen.

If you are under 25, or if you can show that your education was interrupted when you went into military service, you may continue your education beyond this first year. For each month you spent in active service after September 16, 1940, and before the end of the war, you may have an additional month of schooling, but the total time cannot be more than four years. While you are studying under this program, the Veterans' Administration will allow you $50 a month for living expenses and will pay your tuition and other fees, including the cost of books, supplies, and equipment, up to $500 per year. If you have dependents, the subsistence allowance will be increased to $75 per month. If you receive payment for work done in connection with your study program, your allowance may be decreased, and if you take only a part-time course, you will not receive the full monthly benefit.

Commercial courses, courses in agriculture and stockraising, sheetmetal work, plumbing, drafting, automotive mechanics, carpentry, baking, cooking, machine shop work, masonry, painting and decoration, power plant operation, printing and binding, and many others, will be offered at eight or more Indian schools: Albuquerque Boarding School, Carson, Chemawa, Chilocco, Flandreau, Wingate, Haskell Institute, and Sherman. Not all of the courses will be available at each school, and other courses will be added from time to time. These courses will be available to non-Indians, if there is room enough, and the Indian veteran is not limited to a choice of Indian schools. You may take any course for which you can qualify, at any approved school.

If you have a disability resulting from your military service, the educational program offered under Public Law 16, 78th Congress, may be more helpful to you. Under this legislation, a disabled veteran may be allowed up to four years of vocational training, during which time he may receive a total pension of not less than $92 per month. If he has dependents, the allowance is larger.

The G.I. Bill also provides readjustment allowances for veterans who are unable to find work. Any unemployed veteran who has served 90 days or more and has been released without dishonorable discharge, or has been disabled in the line of duty, may receive a weekly readjustment allowance of $20, less any part-time wages he may receive in excess of $3. To be eligible for this allowance, the veteran must report regularly to a public employment

45

office; and if he fails to accept any suitable job offered to him, he is disqualified. He may also be disqualified if he does not attend a free training course available to him, or if he has left suitable work, or is discharged for misconduct. The readjustment allowance may be continued for 24 weeks, plus four weeks for each month of active service, up to a maximum of 52 weeks. If he is self-employed and he can show that his net earnings have been less than $100 in the month preceding the date of his application, he is entitled to receive an amount large enough to bring his earnings up to $100 for the month. Benefits under this legislation may not be claimed when five years have passed after the end of the war, and claims must be made within two years after the veteran's discharge from the military service or within two years after the end of the war, whichever date is later.

Veterans may have free hospital care, medical and dental services, through the Veterans' Administration, for any disabilities incurred in the line of duty in the service or aggravated because of such service.

The Servicemen's Readjustment Act of 1944--commonly called the G.I. Bill of Rights--also provides for certain benefits for veterans who want to borrow money to buy or build a home, to purchase a farm, farm equipment or livestock, or to acquire business property. The Federal Government will not make loans or extend any credit under this program. It says simply that if you can get a loan for these purposes from any lending agency, either public or private, such as a bank, corporation, or individual, the Veterans' Administration, on approving the loan, will guarantee one-half of the amount, up to $2000. The Administrator will also pay the first year's interest on the amount of the guarantees. This interest need not be repaid. The loan itself must be repaid according to the conditions under which it is made.

The lending agency to which you apply for a loan should be one of those serving your community. This organization should understand that you may receive a loan on the same basis as other veterans, even though you may conduct your operations on trust land belonging to you or on tribal lands operated under an assignment. It should be possible for you to get a loan without any security other than a mortgage on the property you are buying with the money loaned to you; but if other security is required, the Superintendent may approve a lien on trust property, other than land, as collateral. Trust land may not be given as security for these loans.

It should also be understood that the Superintendent may authorize a creditor to enter on the reservation to repossess equipment bought with borrowed money, if the loan should be in default.

If you want to qualify for a farm loan, you must show that you have had farming experience. If your loan is for the purchase of livestock, you must show that you have adequate range on which to run it. If you plan to buy farm machinery, you will have to show that you have land upon which the machinery will be used, and you must also describe your plan of operation and demonstrate that it will produce income enough to repay the loan.

In general, no restrictions will be placed upon property obtained under loans guaranteed under the Act, except those which the lending agency may require in order to protect the loan.

You should remember, too, that you have other ways to obtain a loan, if you are not eligible under the G.I. Bill. The Indian Service may be able to arrange a loan from revolving credit funds; or your tribe may offer to lend you what you need. There are many avenues to explore.

From time to time, Congress may make changes in the provisions of the G.I. Bill and other servicemen's legislation. Allowances for the unemployed veteran and for the veteran attending school may be increased. You are urged to take advantage of the program which you feel will be most useful to you. Get all the information available, consult with everyone who can be of help to you, and make full use of the opportunities which you have earned by your service to your country.

46

47

48

Indian Women Work for Victory

Indian women, anxious to help out during the war-created manpower shortage, have made an astonishingly large contribution to their country's needs. Thousands of them have left their homes to work in factories, on ranches and farms, and even as section-hands, to replace men who were vitally needed elsewhere. They have joined the nurses' corps, the military auxiliaries, the Red Cross, and the American Women's Voluntary Service.

Not content with this, they have given their services in many other and more unusual ways. More than 500 Eskimo and Indian women and girls worked day and night manufacturing skin clothing, mittens, mukluks, moccasins, snowshoes, and other articles of wearing apparel for our forces serving in cold weather or at high altitudes. An Alaskan Indian woman ran a trap line to make money for war bonds.

Cherokee girls wove and sold baskets, buying war stamps with the money. On the Eastern Cherokee reservation, women and girls planted and harvested the crops, and even drove tractors.

Forty Chippewa women formed a rifle brigade for home defense. An old Kiowa woman gave $1,000 to the Navy Relief Fund as her contribution. Osage women, draped in their brilliant blankets, spent long hours at sewing machines for the Red Cross.

In the West, a Pueblo woman drove a truck between Albuquerque and Santa Fe, New Mexico, delivering milk to the Indian school. She not only serviced her own truck but also helped at the school garage as a mechanic. Many Indian women became silversmiths, and made insignia for the armed forces. At Fort Wingate, New Mexico, the Navajo women's work ranged from that of chemists to truck drivers. Two Indian women in California served at a lonely observation post, driving the twelve miles to their position in a rickety old automobile.

The war plants had many Indian women on their rolls, working as riveters, inspectors, sheet metal workers, and machinists. An Indian girl was chosen at one plant to receive the Army-Navy E for her fellow-workers.

In the Indian forests, hitherto considered as providing work fit only for men, the Indian women learned to take over many tasks. Treatment for blister rust was given 80,182 acres of forest, mainly in the Lake states, and Indian women performed much of the labor. On the Menominee reservation in Wisconsin, fifty women replaced men at the mill. Crews consisting of two women and one man planted young trees to replace those cut down in the Red Lake forest in Minnesota. During the short period in the spring which is considered most advantageous for such planting, 90,700 trees were replaced on 238 acres of land. Indian women have "manned" fire lookout stations on the Colville and Klamath reservations. An Indian woman acted as guard at the Dry Creek station on the Yakima forest, and another learned to be a radio operator at the central camp on the Quinaielt reservation.

49

Prisoners of War Released

Many Indians reported as prisoners of war have now been released and have come home again. Lt. Frank Paisano, Jr., a prisoner of the Germans, has returned to Laguna Pueblo, During his absence he was awarded the Air Medal, which his wife accepted in his name. Omar Schoenborn, Chippewa, once reported dead, was one of 83 men who escaped death when the prison ship carrying them to Japan was sunk off Leyte. He managed to swim ashore and to hide from the Japanese until the arrival of the American forces. Gilmore C. Daniels, Osage, who joined the Royal Canadian Air Force early in the war, spent nearly four years in a German prison camp before the advancing armies released him. Another Osage, Major Edward E. Tinker, a nephew of General Clarence Tinker, was taken prisoner when he crashed in Bulgaria, and was freed by the Russian advance.

Among the American prisoners released by the 6th Ranger Battalion from Cabanatuan Prison in the Philippines on January 30, 1945, was Major Caryl L. Picotte, Sioux-Omaha, formerly of Nebraska, but now stationed in Oakland, California.

50

Major Picotte was called to active duty with the Air Corps in September, 1941, and sent to the Philippines. On his arrival in Manila he was assigned to duty as Associate Engineering Officer at the Philippine Air Depot, Nichols Field.

After the Japanese air attack on Nichols Field, December 8, 1941, when most of the serviceable American aircraft were destroyed, Major Picotte assisted in the organization of a provisional Air Corps regiment which fought as infantry from January 1, 1942, until the capitulation of Bataan on April 9th of that year. He was in the famous Death March from Bataan to the first American prisoner-of-war camp at O'Donnell, covering 80 miles in three days with one meal of rice. In June he was moved to Cabanatuan, where he remained until released by the Rangers two and a half years later. During the last days before the fall of Bataan, he was recommended for the Distinguished Service Cross and the Silver Star.

Major Picotte comes of a distinguished Indian family. His grandfather was Joseph LaFlesche (Iron Eyes), the last chief of the Omaha tribe. His mother, Susan LaFlesche Picotte, was the first Indian woman physician and is remembered with veneration for her life of unselfish service to both Indians and Whites. The late Francis LaFlesche, distinguished ethnologist, was his uncle, and Suzette LaFlesche Tibbles, (Bright Eyes), who lectured throughout the civilized world and was the most famous Indian woman of the 1880's and 1890's, was his aunt.

Major Picotte reported that there were more than 300 Indians on Bataan and Corregidor. While in the prison camps he met and talked with many from all sections of the country. He added, "Their battle record, individually and as a whole, left nothing to be desired."

Not all the news of the prisoners of war is good. Some did not survive the rigors and the mistreatment in the camps, and some were lost in the torpedoing of several ships carrying prisoners of war from the Philippines to Japan. Others perished when another ship was bombed and sunk in Subic Bay. It is hoped that, as time goes on, more will be found alive and that the lists of released prisoners will grow.

51

A Family of Braves

Six grandsons of the Reverend Ben Brave, retired Sioux minister, have shown their patriotism by donning uniforms. Four went into the army, one into the Navy, and one into the Coast Guard.

Staff Sgt. Francis E. Brave received the Silver Star for gallantry in action, evacuating 30 German prisoners to the rear under enemy fire on Anzio beachhead. "During the two hours required for the trip," to quote the citation, "Sergeant brave had to wade through waist-deep water and frequently had to take cover from enemy tank and mortar shells; however, he controlled his prisoners and brought them to the proper collecting point. Sergeant Brave's gallant conduct made possible the early gathering of important information from the prisoners and reflects much credit on the Army of the United States."

Staff Sgt. Waldron A. Frazier, also a grandson of the Reverend Brave, served with the Second Troop Carrier Squadron for four years, during two of which he was stationed successively in China, India, and Burma. As crew chief of the "Thunderbird," one of the big transport planes, he had more than 125 hours of combat flying time, and he wore the Air Medal, the Pacific Theater Ribbon with two battle stars, and the American Defense Ribbon. His group won two Presidential Unit citations. Last December he was killed in a plane crash while being invalided home.

Nearly four hundred of "The Chief's" friends decided to do something in his memory. Accordingly, they bought for his little girl, Ilona Joyce, $1,025 worth of War Bonds, and sent a check for the $14.45 left over from the purchases. Among the donors were all ranks from majors to privates. "We hope that this little gift will help to give Ilona Joyce some of the things that Waldron would like her to have," they wrote.

The other four grandsons are doing well, and no doubt we shall hear brave stories of them. They are: Cpl. Alexander A. Brave, Sgt. Judson B. Brave, and Ronald H. and Donald H. Frasier, twins, who are in the Coast Guard and the Navy, respectively.

The Reverend Brave's son, Ben, was recently discharged from the Army for overage. A son-in-law, Lt. Frank Fox, is in the Army, and another grandson, John W. Frazier, Jr., has recently donned the uniform. Two grandsons-in-law, James Wilson and Russell DeCora, complete the family fighting group.

52

Indian Service Employees in the War

Twenty-one employees of the Indian Service gave their lives for the cause of freedom and justice, some of them in action against the enemy, some in training, some by accident, and some by illness. There will be more names to add to the list when the reckoning is completed. Captain Homer Claymore, pilot of a B-17 bomber in the 8th Air Force, has been missing for many months and must be presumed lost. He was employed as a baker at Pine Ridge before he entered the AAF. Lt. Orian Wynn, of the Consolidated Ute Agency, was reported missing after a raid on enemy territory from his base in Italy.

The prisoners of war released by the victorious armies of the United Nations include Soldier Sanders, baker at the Sequoyah School, Wallace Tuner, clerk at Jicarilla, and Marion Chadacloi, assistant at Navajo. They were all prisoners of the Germans. Cornelius Gregory, teacher at Fort Sill, spent eleven months interned in Sweden, following a raid on Germany during which his plane was damaged and had to land in neutral territory. Mrs. Etta S. Jones, teacher, who was captured when the Japanese invaded the island of Attu in June 1942, was found in a camp near Tokyo and brought back to the United States. Her husband, who was a

53

special assistant and operated the radio station on the island, was killed at the time of the invasion. Dr. Sidney E. Seid, formerly physician at the Chilocco School, survived more than three years' imprisonment in Japan.

Still to be heard from are Louis E. Williams, clerk at Pine Ridge, and Roy J. House, clerk at Jicarilla, who were made prisoners by the Japanese during the first campaigns in the Philippines.

Indian Service employees have won decorations for gallantry and courage. Lt. William Sixkiller, Jr., who died of wounds received in action on Saipan, received the posthumous award of the Silver Star. Another Indian Office employee, Sgt. Robert Duffin, wears the same decoration, awarded for exploits in Germany, and Philip Kowice, of the United Pueblos Agency, earned his Silver Star in the Italian campaign. Bronze Star Medals were awarded to Lt. James M. Ware, of the Osage Agency, who directed evacuation of the wounded in an Italian engagement, although seriously wounded himself; to Colonel E. Morgan Pryse, Director of Roads, for the construction of airfields in advance combat sectors; and to Major Delmer F. Parker, Physician at the Pawnee Agency, for his work as surgeon in the Pacific theatre. Capt. Louis J. Feves, furloughed from his position as physician at the Umatilla Agency, Oregon, won the Soldier's Medal when he went to the rescue of injured crew members of a bomber which had crashed on a heavily-mined reef in the Gilbert Islands.

The list of those wounded in action includes Henry McEwin (Engineer, Chilocco School), Walter W. Nations (Agricultural Extension Agent, United Pueblos), Nelson Thomson (Assistant, Navajo), Walter Campbell (Barber, Sherman institute), Franklin Gritts (Teacher, Haskell Institute), Michael Bordeaux (Clerk, Rosebud), James M. Ware (Clerk, Osage), Henry Garcia (Orderly, Navajo), and Morris James (Mechanic, Pine Ridge).

IN MEMORIAM

| Joe Singer | Assistant, Navajo Agency | May 10, 1942 |

| C. Foster Jones | Assistant, Alaska Service | June 8, 1942 |

| Percy Archdale | Clerk, Truxton Canyon Agency | February 7, 1943 |