United States. 1947. Building the Navy's bases in World War II; history of the Bureau of Yards and Docks and the Civil Engineer Corps, 1940-1946. Washington: U.S. Govt. Print. Off.

The Navy Department Library

Building the Navy's Bases in World War II

Volume I (Part II)

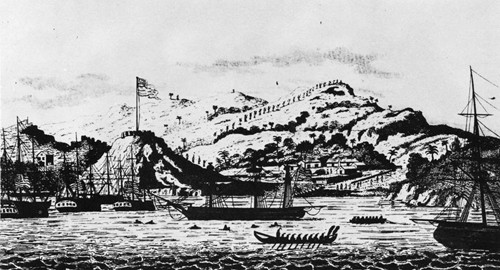

Navy's First Advance Base

Madisonville in Massachusetts Bay in the Marquesas Islands, some 800 miles northeast of Borabora, was established by Commodore David Porter to repair the frigate Essex after its historic voyage around the Horn in 1813. The Essex, which was the first American warship to visit the Pacific, is shown, with her prizes, in this old print, published in London in 1823.

In his book, A Voyage to the South Seas in the Years 1812, 1813, and 1814, Commodore Porter wrote that "agreeably to the request of the chiefs, I laid down the plan of the village about to be built. The line on which the houses were to be placed was already traced by our barrier of water casks. They were to take the form of a crescent, to be built on the outside of the enclosure, and to be connected with each other by a wall twelve feet in length and four feet in height. The houses were to be fifty feet in length, built in the usual fashion of the country, and of a proportioned width and height.

"On the 3d November, upwards of four thousand natives, from the different tribes, assembled at the camp with materials for building, and before night they had completed a dwelling-house for myself, and another for the officers, a sail loft, a cooper's shop, and a place for our sick, a bake-house, a guard-house, and a shed for the sentinel to walk under. The whole were connected by the walls as above described. We removed our barrier of water casks, and took possession of our delightful village, which had been built as if by enchantment."

___________

Foreword

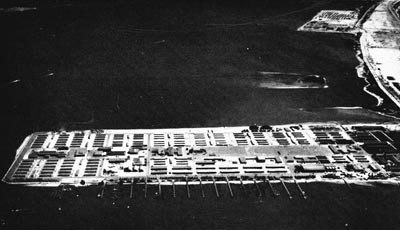

Because the Navy cannot operate without repairs and supplies, bases are as important as are ships and planes and personnel. The 1940 Navy had no properly equipped advance base other than Pearl Harbor. In the succeeding five years, the Bureau of Yards and docls built or supervised the building of more than 400 advance bases for the Navy in the Atlantic and the Pacific areas, at a cost of $2,135,427,881. More than 10 million dollars, each, was spent at eighteen areas on foreign soil.

| Guam | $280,795,700 | ||

| Leyte-Sumar | $215,603,201 | ||

| Manus | $131,757,843 | ||

| Okinawa | $113,715,453 | ||

| Saipan | $63,352,622 | ||

| Trinidad | $45,704,394 | ||

| Argentia | $44,912,927 | ||

| Espiritu Santo | $36,369,925 | ||

| Tinian | $35,158,275 | ||

| Bermuda | $34,983,064 | ||

| Subic Bay | $34,916,587 | ||

| Noumea | $24,297,449 | ||

| Eniwetok | $23,085,079 | ||

| Ulithi | $18,580,273 | ||

| Peleliu | $18,489,159 | ||

| Iwo Jima | $15,462,733 | ||

| Manila | $13,349,589 | ||

| Milne Bay | $11,101,000 |

All except Trinidad, Argentia, Espiritu Santo, Bermuda, Noumea, and Milne Bay had to be captured from the enemy and cleared of debris before contruction could begin. Fifteen of these eighteen bases were in the Pacific. As we progressed across that ocean, islands captured in one amphibious operation were converted into bases which became springboards for the next advanbce.

Advance bases were set up for various purposes. At first, they were mainly air bases, such as those in the South Pacific, at Borabora and Tongatabu, for use in protecting our lines of communication with Australia. Gradually, this changed to the staging bases for the anchoring, fueling, and refitting of armadas of transports and cargo ships, and for replenishing mobile support squadrons which accompanied the combat forces. As we progressed farther and farther across the Pacific, it became necessary to set up main repair bases for the maintenance, repair, and servicing of larger fleet units. Floating drydocks made it possible to repair battle damage and disabilities so that ships could be kept in the battle line without having to return to continental bases, or even to the Hawaiian islands, but even the floating drydocks needed a base.

The first large advance base set up in the Pacific was at Espiritu Santo; the next was a main repair base at Manus in the Admiralty Islands. A base, capable of supporting one-third of the Pacific fleet, was contructed at Guam; another was established at Leyte-Samar; a third was in process of construction at Okinawa when the Japanes surrendered.

Facilities to maintain these bases, including personnel structures, piers, roads, shops, utitlies, in large measure duplicated the type of facilities found at any continental navy yard. There was also provided the replenishment storage necessary to restock every type of vessel with fuel, ammunition, and consumable supplies; as well as food. The stocks on hand at Guam by V-J day would have filled a train 120 miles long. For fuel supply alone, 25,000,000 barrels of bulk fuel were shipped to the pacific in June 1945 for military purposes. At Guam, one million gallons of aviation gasoline were used every day.

As Admiral Kind pointed out in his final report to the Secretary of the Navy, had it not been for 'this chain of advance bases the fleet could not have operated in the western reaches of the Pacific without the neccessity for many more ships and planes than it actually had.' A base to supply or repair a fleet 5000 miles closer to the enemy multiplies the power which can be maintained constantly against him and greatly lessens the problems of supply and repair. The scope of the advance base program is indicated by the fact that the personnel assigned directly to it aggregated almost one fifth of the entire personnel of the Navy....including almost 200,000 Seabees.... In the naval supply depot at Guam there were 93 miles of raod. At Okinawa alone there were more than fifty naval construction battalions building roads, supply areas, airfields and fleet facilities for what would have been one of the gigantic staging areas for the final invasion of Japan.

As our advance came nearer to the Japanese islands, the rear areas which had been the scene of combat operations in earlier months were utilized for logistic support. In the South Pacific, for example, more than 400 ships were staged for the Okinawa operation. They received varied replenishment services, including routine and emergncy overhaul as required. Approximately 100,000 officers and men were staged from this area alone for the Okinawa campaign, including four Army and Marine combat divisions plus certain headquarters and corps troops and various Army and Navy service units. Concurrently with the movement of trrops, large quantities of combat equipment and necessary material were transferred forward, this contributing automatically to the roll-up of the South Pacific area. Similarly in the Southwest pacific area, Army service troops were moved with their equipment from the New guinea area to the Philippines in order to prepare staging facilities for troops deployed from the European theater. The roll-up was similarly continued and progress made in reducing our installations in Australia and New Guinea.

Bases as a vital factor of sea power have been well defined by Admiral Nimitz.

'Sea power,' he declared, 'is not a limited term. It includes many weapons and many techniques. Sea power means more than the combatant ships and aircraft, the amphibious forces and the merchant marine. It includes also the port facilities of New York and California; the bases in Guam and in Kansas; the factories whicxh are the capital plant of war; and the farms which are the producers of supplies. All these are elements of sea power. Futhermore, sea power is not limited to materials and equipment. It includes the functioning organization which has directed its use in the war. In the Pacific we have been able to use our naval power effectively because we have been organized along sound lines. The present organization of our Navy Department has permitted decisions to be made effectively. It has allowed great flexibility. In each operation we were able to apply our force at the time and place where it would be most damaging to the enemy.'

Part II: The Continental Bases

___________________

Chapter VIII

Navy Yards and Graving Docks

Initial expansion of the continental navy yards to meet the requirements of the enlarged fleet antedated slightly the war emergency, starting in 1938, shortly after Congress authorized an increase in the fleet of about twenty per cent.

At that time there were eight navy yards in operation for the primary function of construction and repair of naval vessels. Three of these - at Portsmouth, N.H., Boston, Mass., and New York, N.Y. - had been established in 1800, two years after the Department of the Navy was created as an independent organization. In 1801, the Navy took over an existing yard at Norfolk, Va., which had originally been built by the British before the Revolution and was subsequently leased to the Federal Government by the Commonwealth of Virginia. The Philadelphia Navy Yard, also created in 1801, was moved in 1875 from its original site in southeast Philadelphia to the present League Island site, which had been acquired and developed during the four preceding years. In 1854, the Navy Yard, Mare Island, Calif., was established to provide support for the naval defense of the newly won Pacific Coast. In 1891, a second Pacific Coast yard was established at Bremerton, on Puget Sound, Wash., and designated Navy Yard, Puget Sound. Finally, in 1901, a new navy yard was established at Charleston, S.C., replacing an earlier plant at Port Royal, S.C.

The Navy Yard, Washington, D.C., which had been one of the four original yards created in 1800, had subsequently become primarily a naval gun factory, and no longer performed the functions of shipbuilding and ship repair except to a minor degree.

The older navy yards, and to a lesser extent the more recent yards, had undergone progressive evolution and piecemeal development during the years, as the ships of the fleet evolved from the frigates and sloops of Revolutionary days to the complex and varied types of the modern navy. Although they had undergone considerable expansion during World War I, none of the yards was fully equipped to cope with the building and repair requirements of the two-ocean Navy of World War II, and most of them were congested, obsolescent, and poorly arranged.

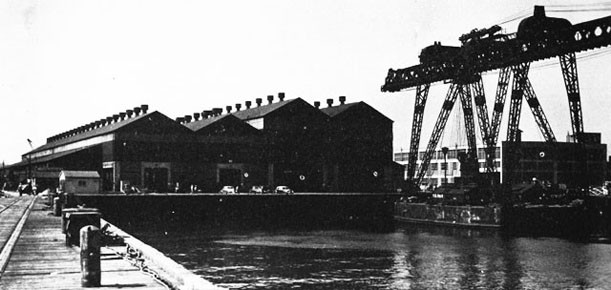

Some relief had been afforded at Boston through the partial development of an annex at South Boston, in an area contiguous to the Commonwealth Dock, a 1,200-foot drydock originally built by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts and subsequently acquired by the Navy. Partial relief of unsatisfactory conditions at Mare Island, occasioned by heavy silting of Mare Island Strait, had also been achieved by use of privately owned facilities at Hunters Point, on San Francisco Bay and within the city limits of San Francisco.

In the period between 1920 and 1938, only a moderate amount of important construction was accomplished at navy yards. A large machine shop was built at Puget Sound in 1934; a sheet metal and electrical shop was built at Norfolk in 1936; and a graving dock was undertaken at Mare Island in 1937. However, a considerable amount of work of lesser magnitude was accomplished during this period, partly under naval public work appropriations, but principally through allocations from National Industrial Recovery Administration, Civil Works Administration, Works Progress Administration, and Public Works Administration appropriations for unemployment relief during the Depression. Subsequent events demonstrated beyond question the wisdom of this constructive and effective use of relief funds. Without the rehabilitation, modernization, and improvements that were accomplished in this manner, the navy yards would have been critically unprepared for the emergency.

The Construction Program

Between 1938 and 1945, a total of $590,000,000 was expended for construction and improvements at navy yards.

The program was initiated by an appropriation

--169--

of $20,045,000 for public works at navy yards in the Naval Appropriation Act of 1938. These funds, which seemed so large at the time but which, in retrospect, were extremely modest, were earmarked by Congress for specific projects to overcome recognized deficiencies and to meet, in part, the enhanced needs of the Vinson fleet expansion bill of 1938.

In the fall of 1938, the Chief of the Bureau of Yards and Docks prepared a comprehensive plan for the improvement of the naval shore establishment, based on a survey of overall requirements for these purposes. This plan, which was issued on January 1, 1939, contemplated total expenditures of $330,000,000. Of this total amount, the sum of $75,000,000 was proposed for correction of accumulated deficiencies at navy yards, and $70,000,000 additional was proposed for yard improvements needed in connection with the Vinson fleet expansion program. Projects at navy yards thus represented 44 per cent of the total plan.

During the fiscal years 1939 and 1940, funds were provided by Congress under the appropriation "Public Works, Navy," for navy yard projects totalling

--170--

$116,000,000, in support of this program. In addition to projects for the improvement of existing yards, these appropriations provided $6,000,000 for the acquisition and initial development of the privately owned facility at Hunters Point and $19,750,000 for the acquisition and development of a similar facility at Terminal Island on San Pedro Bay, Calif.

By mid-1940, with the 1939 plan barely half financed, the Navy was faced with a further expansion of unprecedented proportions. The "Two-Ocean Navy" Bill, passed in July 1940, shortly after the fall of France, superimposed an expansion of 70 per cent in the fleet on top of the 20 per cent Vinson expansion of 1938 and an additional 11 per cent expansion which had been authorized earlier in 1940.

Money for the ships of this two-ocean Navy was appropriated to the Bureau of Ships, which, in turn, allotted funds to the Bureau of Yards and Docks for the construction of facilities needed to build and repair the additional vessels.

Between July 1940 and December 1941 the Bureau of Ships transferred more than 250 million dollars of its "two-ocean Navy" money to the Bureau of Yards and Docks for work at navy yards. In the same period only about 33 million dollars was appropriated directly to the Bureau of Yards and Docks for navy yard work. Ten million dollars of this latter amount were for an annex to the New York Navy Yard, to be established on recently filled land at Bayonne, N.J.

While the Navy was gathering its added momentum, a board headed by Rear Admiral John W. Greenslade was redetermining the basic needs of the shore establishment. The board's report, dated January 6, 1941, reiterated the Hepburn Board recommendation that the establishment on each coast should be able to maintain the entire Navy, in this case the authorized two-ocean Navy. This objective could be attained by setting up a shore strength capable of maintaining 60 per cent of the Navy on a single-shift working basis or 100 per cent of the Navy on a three-shift basis.

--171--

In July 1940, when the two-ocean Navy was authorized, the fleet had 1058 ships in commission, including some ships of the 20-percent program, already completed. The new program contemplated an ultimate deployment, by 1946, of more than 2000 ships.

A large part of the new shipbuilding and most of the additional repair and overhaul work entailed by these programs devolved on the navy yards.

The public works program at these yards during the last eighteen months of peace, was concentrated on providing, with the utmost dispatch, the vast expansion of facilities needed for the effective accomplishment of this herculean task.

When war came, substantial progress had been made by the Bureau and its field forces in the execution of this work, for which more than $350,000,000 had been made available. Many individual projects were usably complete by December 7, 1941, well ahead of schedule. Their early availability contributed significantly to the rapid mobilization of the fleet and the speedy conversion of merchant vessels taken over by the Navy.

Actual war, however, demanded ships in numbers far greater than the Navy had planned for its two-ocean strength. The anti-submarine campaign required many novel classes of ships, such as destroyer escorts, corvettes, frigates, and escort carriers. The long-range strategic plans called for a vast fleet of vessels of entirely new types - landing ships and craft of every description - for the prospective amphibious operations. By mid-1945 there were more than 10,000 ships in active commission, exclusive of small landing craft. Much of the construction and some of the repair of these combatant and auxiliary vessels was performed at private shipyards, or at new emergency shipyards financed in part or in whole by the Navy. Nevertheless, the volume of work imposed on the navy yards continued to increase to proportions undreamt of before the war. It was repeatedly necessary to revise drastically upward the estimates of requirements which, when first submitted, had seemed extravagant to many in authority.

The superb record of productive accomplishment by the navy yards would have been impossible of attainment without the early start made in planning and providing the plant facilities required and the unprecedented rate at which the public works programs were consummated.

Twenty-percent expansion. - The first significant

--172--

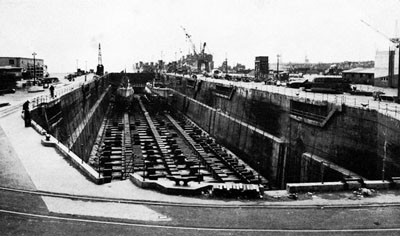

project initiated after the appropriation of funds for the 1938 expansion was a graving drydock at Puget Sound Navy Yard. In 1938, Puget Sound was the one navy yard on the West Coast with a dock big enough to accommodate the existing battleships. Ships too large for that 867-foot dock were being planned, and at least one drydock for their repair was obviously needed on the West Coast, to serve the Pacific Fleet. Work was started on 1,000-foot drydock, No. 4 at Puget Sound in the fall of 1938. A year later, construction was begun on a second large dock at Puget Sound. In April 1940, work began on Drydock No. 4 at Mare Island. Of 435-foot length, this dock was designed for repairing submarines, destroyers, and small merchant ships.

Construction of major facilities at the two West Coast navy yards took place earliest in the expansion period because most of the fleet had been moved to the Pacific in the mid-thirties, increasing the need for major facilities to serve that area. The Vinson program of 1938 intensified this need.

The bulk of the Navy's new ship construction was accomplished in East Coast yards. Repair facilities were generally adequate for the needs of the Vinson program, because of the small proportion of the fleet operating in the Atlantic, but extensive increases of the shipbuilding facilities were mandatory.

Two-Ocean Navy Expansion. - The authorization of the two-ocean Navy in 1940 involved both radical increases in the scope of the public works program at navy yards and new concepts in shipbuilding practice as applied to capital ships.

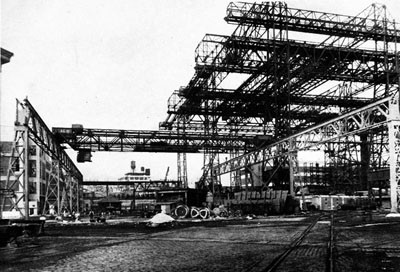

By dint of major reconstruction, involving extensions and strengthening of the groundways and

--173--

overhead crane structures, it was possible to build the new battleships of the North Carolina and Iowa classes, assigned to the East Coast shipbuilding navy yards, on existing inclined shipways. Many unprecedented problems were faced and solved on these projects. The Iowa class had a nominal displacement of 45,000 tons, based on London Treaty standards, and an actual displacement of more than 55,000 tons. To permit safe launching of these vessels, with a launching weight of more than 32,000 tons, it was necessary to provide quadruple launching ways, 6000-ton triggers, and substructures at the pivoting points capable of supporting 18,000 tons instantaneous pivoting pressure. These were the heaviest ships ever launched from inclined ways.

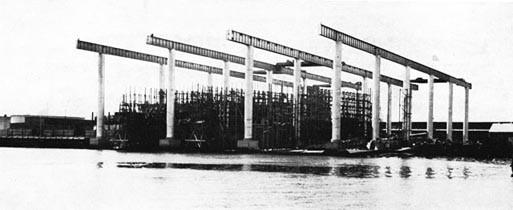

The new expansion program included five battleships of the Montana class, with a London Treaty displacement of approximately 58,000 tons and a true displacement of nearly 70,000 tons. These ships, whose dimensions were predicated on the availability of the third set of Panama Canal locks, had a beam greater than the clear space between the crane supports of the existing shipways. It was necessary to provide either new shipways or shipbuilding drydocks. The latter were selected; first, to avoid the problems and hazards involved in launching ships of such unprecedented size, and, second, to gain the advantages in ease of access, facility of construction, and simplification of weight-handling operations inherent in the use of drydocks.

Construction was begun on the first two superdocks, at Norfolk and Philadelphia, in June 1940.

--174--

These docks were 1092 feet long and 150 feet wide. In 1941, a second shipbuilding dock was started at Philadelphia and two similar docks were undertaken at the New York Navy Yard. All these docks were built by the tremie method and were completed, ready for laying of keels, in from 17 to 21 months, as compared with prior times of three to eight years.

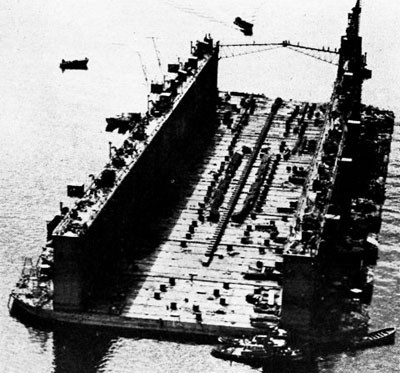

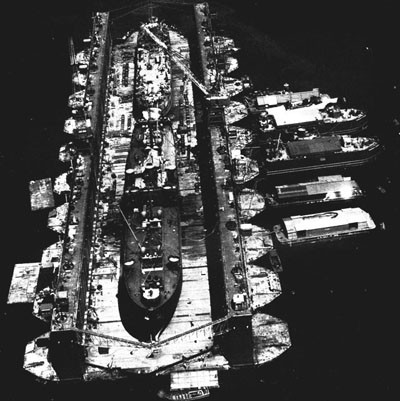

Subsequent events in the progress of the war dictated the later abandonment of the program for building these super-battleships and the construction, instead, of aircraft carriers of the Midway class. A large number of carriers and other smaller vessels were built in these docks, in time to play an active part in the Navy's brilliant fleet operations in the last two years of the war.

In August of 1940, the first of two important moves was made to provide adequate ship repair facilities on the West Coast when work was started on the new repair facility at Terminal Island, San Pedro, Calif.

For many years, the Navy had been supporting the fleet in the Pacific from two navy yards, at Puget Sound and Mare Island, with supplementary repair facilities for smaller vessels at the Destroyer Base, San Diego. Puget Sound was the home yard for the capital ships; Mare Island was limited, by shallow water and continuous silting, to vessels of cruiser size and smaller. The facility at Terminal Island was started with the acquisition of land, the enlargement of the area by filling, and the construction of a 1092-foot drydock and accessory shops, waterfront and weight-handling facilities.

The second move to increase repair facilities on the West Coast was made with the acquisition, in November 1940, of a privately owned ship repair yard at Hunters Point, on San Francisco Bay, within the county limits of San Francisco, with which the Navy had previously had an operating agreement. When taken over, this yard contained two drydocks, one 1000 feet long. The expansion of this shipyard was initiated in December 1940, when a large assembly shop was started alongside the larger dock.

Development of both Terminal Island and Hunters Point was continued through the entire war period, and both yards, originally designated as naval dry docks, were ultimately elevated to the status of naval shipyards at the same time that the titles of the old navy yards were changed, for organizational reasons, to naval shipyard. Two additional 700-foot docks were built at Terminal Island in 1942-1943, and three drydocks for submarines were built at Hunters Point in 1943-1944.

On the East Coast, ship repair facilities were augmented by the development of a new repair base at Bayonne, N.J., immediately adjacent to the Bayonne Supply Depot. This project included a 1092-foot drydock, initially conceived for the repair and voyage overhaul of the huge transatlantic liners entering New York harbor, for which there were no existing facilities. This base was developed to a well-integrated small repair facility by the addition of quay walls, shops, and utilities, and ultimately became the Bayonne Annex of the New York Navy Yard.

The New York yard was greatly expanded by the acquisition of four successive parcels of highly developed and expensive urban property which increased its land area from 120 to 195 acres, and by the construction of a large number of shops, storehouses, piers, and other facilities, which converted a congested and obsolescent yard into a modern, well equipped, and exceptionally efficient plant.

Similar expansions of facilities were made progressively at all the other navy yards on the East Coast, including additional shipbuilding docks for smaller vessels at Portsmouth and Charleston, a dock for the construction of escort vessels at Boston, a cruiser repair dock at the South Boston Annex, and small docks in private yards at Savannah and Philadelphia.

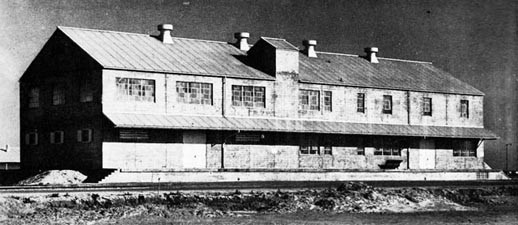

Portsmouth

One of the four oldest United States navy yards, the Portsmouth Navy Yard was established in 1800, on the Piscataqua River, south of Kittery, Maine. The old yard area was purchased in two separate sections: Dennet's Island, 58 acres, in 1800, and Seavey's Island, 105 acres, in 1866. Subsequent acquisitions brought the area up to 243 acres. The navy yard was built on a ledge formation. Except in filled reclaimed areas, only a thin layer of earth covered this ledge.

Major war construction at this submarine building yard included two drydocks, additional shipbuilding ways, several piers, two large storehouses, and power plant improvements.

Improvement of the Portsmouth yard began in March 1939, when a contract was let for an extension of the shipbuilding ways. In May and July,

--175--

work began on an addition to the shipfitters shop, and in August a contract for construction of a machine and pipe shop was let. Meanwhile, work was getting under way on an addition to the electrical generating equipment.

In 1940, a fifth groundway for submarine building was installed alongside the existing ways and covered with a roofed craneway. Later in the year, the fitting-out pier was extended to add 775 feet of berthing space. The yard's building capacity was further increased by construction which began in 1941. In April, dry dock No. 1 was placed under contract. This dock was 435 feet long and 91 feet wide at the entrance. Its primary purpose was submarine construction, but a depth of more than 21 feet over the blocks enabled the docking of submarines, destroyers, and small merchant ships for repairs.

The next Portsmouth project was a pier to handle the fitting-out of ships built in the new dock. This project, which was begun in October, comprised a concrete quay wall on steel girders and piles, enclosing a V-shaped point, and made available 12 acres of filled land and 2088 linear feet of berthing for fitting-out purposes.

That same month, work began on an important power-plant improvement. As at other navy yards, at Portsmouth the increased shipbuilding activities were demanding a greater amount of electric power than the pre-defense Navy power plant could produce. The Portsmouth problem was aggravated by the fact that only direct current was generated at the yard. In recent years a demand for alternating current, which had to be bought from the outside, had arisen by substantial additions of alternating current-using equipment. Before the Navy could start making its own alternating current, the use of outside power reached a 6,000-kw peak. The improvement contract called for three 120,000-pound-per-hour boilers and two 3,500-kw turbo-alternators, together with auxiliary equipment, removal of old generating equipment, and enlargement of the power plant building. One boiler and one generator were subsequently eliminated and diverted to another project of higher priority elsewhere.

Expansion continued in November with the award of a contract which included a three-story permanent storehouse, 220 feet long by 100 feet wide, two temporary storehouses, 200 feet by 80

--176--

feet, and one temporary storehouse, 160 feet by 80 feet.

Shortly after the war began, in February 1942, work began on a permanent six-story addition to the general storehouse, and on a submarine building basin, an addition to the submarine groundways, a sub-assembly building, and a utility building. The basin was built 366 feet by 84 feet in plan. In March 1943, a contract was let for a galvanizing plant. Other national defense and war projects at Portsmouth provided submarine barracks, an extension to the naval prison, and lesser facilities.

Only Dry Dock No. 1 presented unusual construction problems. The dock, 91 feet wide and 435 feet long, was built to dock submarines, destroyers, and small merchant vessels. Originally designed as a pressure-relieving type dock, in which the hydrostatic uplift was relieved by a system of vertical drains, Portsmouth Dry Dock No. 1 was redesigned as a gravity type dock because of soil conditions unfavorable to the lighter type. The primary difficulty was the construction of an effective cofferdam. Three rows of steel sheet piles were driven and impervious material was cast against the outboard row. The cofferdam section was unwatered with deep well pumps and well points. Part of the cofferdam difficulties were attributable to the presence of uneven ledge rock, against which the piling could not be adequately seated.

The other dock constructed at Portsmouth during the emergency period was Dry Dock No. 3. This structure was a double submarine building dock with an overall width of 84 feet; each entrance section was 39 feet wide. The depth of the dock was 17 feet over the blocks, and the length was 366 feet. A filled cellular cofferdam was used in the construction. During unwatering operations, a 2-foot bulge occurred on one side of the cofferdam. This was corrected by tying cellular coffer to concrete deadmen.

Boston

Another of the four navy yards established in 1800 was the Boston Navy Yard. The main yard was located in Charlestown between the Mystic and the Charles rivers, in Boston Harbor; the South Boston Annex to the yard was located on the main ship channel to the harbor, 2 miles seaward from the main yard.

Both the Boston Navy Yard and the South Boston Annex were built, to a large extent, on filled flat land. The area of the main yard, which was 123 acres before war expansion began, was increased to 143 acres in 1941 and 1942. The annex was increased from 106 acres to 231 acres. One of the principal Boston assignments in World War II was the construction of escort vessels.

At the navy yard, early improvements included a shipway, begun in August 1940 and completed in August 1941. These ways, designed to accommodate two destroyers, were of concrete construction supported on timber piles, and were equipped with a utility building constructed under the inshore portion of the ways.

At the same time, work was started on the improvement of the main yard power plant, including the addition of an 80,000-pound-per-hour boiler, a 5,000-kw extraction turbine generator, and a 5,200-cfm air compressor.

In October 1940, work was initiated on a project for a 7-story light shop building, 186 by 134 feet; subsequently, a number of other shop and storage projects were constructed under the same contract. In April 1941, construction of a 9-story concrete storehouse, 173 by 195 feet, was begun, a project later increased by the addition of a 7-story extension, of steel construction, 173 by 200 feet. Several other improvements and extensions of storage and shop structures were included. The original storehouse was completed in October 1941; supplementary projects extended the life of the contract to August 1943.

In October 1941, work was started on a shipbuilding drydock for escort vessels. This dock was 518 feet long and 91 feet wide, with a depth over the blocks of 17 feet. The dock was of the relieving type, with weep holes to allow the ground water, which would otherwise cause uplift, to flow into the dock, whence it was removed by drainage pumps.

Many other scattered projects were undertaken during the course of the war for the improvement of the waterfront, modernization of ships, and provision of special facilities.

South Boston

At the South Boston Annex, work was started in March 1940 on a quay wall and wharf and on a machine shop 1,300 feet long and 500 feet wide. The following spring a new power plant project

--177--

was undertaken, to provide six boilers, a compressor and a primary connection to the Edison system. An additional waterfront project, comprising two 980-foot timber piers and a steel sheet pile bulkhead, was started in the sumer of 1941, followed in September by construction of an additional shop 420 feet long and 120 feet wide.

In December 1941, work was started on a graving dock, 693 feet long, 91 feet wide at entrance, and 32 feet deep over the blocks, for the repair of cruisers. This dock, which was built inside a cellular steel pile cofferdam, was completed and placed in service in March 1943. The cofferdam was later incorporated as part of Piers 5 and 6.

Work was also undertaken in 1941 on a 500-man barracks for ship's crews, necessitated by the fact that with three-shift repair work, the crews could not be quartered aboard.

The expansion of the Annex continued with the construction of an additional 900-foot pier, started in the fall of 1942, a rigger's shop, a paint shop, and a general shop, started in November of that year, and extensive improvements and additions to utilities, streets, tracks, and equipment.

New York

Another of the four yards established in 1800 was the New York Navy Yard, located on Wallabout Channel on the Brooklyn side of the East River, between the Manhattan and the Williamsburg bridges.

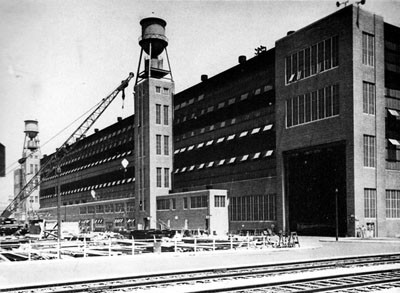

The New York yard has undergone more major alterations during its history than any other major station, particularly in the Cob Dock area, due partly to the changing size and character of vessels and partly to the small and irregular site located in a congested metropolitan area. The improvements installed during the pre-war emergency period and during the war years constituted the most comprehensive and complex reconstruction program undertaken at any yard and in many ways involved the most difficult engineering problems, particularly in regard to foundations and to reducing interferences with productive operations.

Prior to 1938, there were four drydocks, ranging from a small 349-foot stone dock to the 695-foot brick-lined concrete battleship dock No. 4. The latter was noteworthy because of the unique methods used in its construction, after conventional methods had repeatedly failed. The entire perimeter was composed of rectangular concrete wall caissons, sunk by the pneumatic method. The floor was also supported on pneumatic caissons.

The assignment of the contract for the building of the North Carolina to the yard necessitated the lengthening of this dock by 32 feet, so the ship could be docked, if necessary, after launching or during outfitting.

A project for a V-notch extension, authorized in 1938, was successfully accomplished, despite extreme difficulties occasioned by the treacherous site conditions and the proximity of the central power plant, by sinking the entire extension as a unit by compressed air methods.

The structural shop was extended by the addition of two shop bays for the fabrication of special treatment steel armor, one of which was surmounted by an additional mold loft.

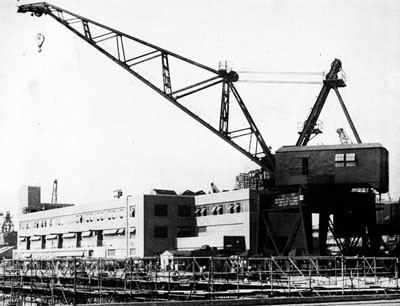

Work was also begun on construction of a new 350-ton hammerhead crane for installing turrets and guns aboard the new battleships. This crane, like its counterpart at Norfolk, was of the turn-table type, rather than a pintle crame. The crane was provided with two main 175-ton trolleys, arranged in tandem on a single track, which could be operated independently or jointly, an auxiliary 50-ton trolley, with a reach of 190 feet, and an auxiliary crane of 15-ton capacity traveling on top of the main rotor or hammerhead. These installations gave these cranes a capacity of 350 tons at 115 feet reach, 175 tons at 150 feet, 50 tons at 190 feet, and 15 tons at an extreme reach of 240 feet.

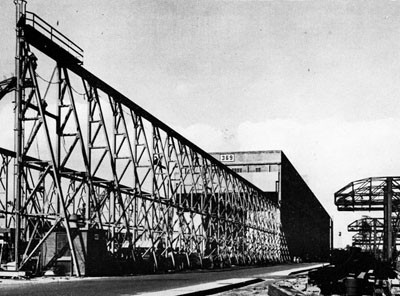

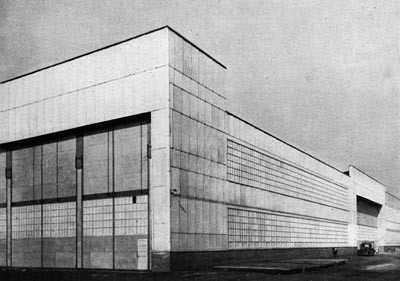

In 1939, work was started on a new turret and erection shop located at the extreme west end of the yard. This project involved the acquisition of some additional land, and extensive demolition and site preparation. The building was a single bay structure, 800 feet long, 100 feet wide, and 105 feet high. The south half was equipped with welding facilities and with a mold loft. The north half was provided with two 175-ton bridge cranes for handling turrets. The crane runway was extended outside the building over a turret barge slip, the end of the building being closed by a unique group of mechanically operated doors providing almost full opening of the end of the building. This project was completed in 1940.

Shipways No. 2, which had been completely reconstructed, partly by WPA forces and partly by contract, to take the North Carolina, was further

--178--

strengthened and extended to take the 45,000-ton battleship Iowa, the shipways crane structure was extended, and the old 40-ton bridge cranes on this structure were replaced by new 50-ton cranes, specially designed to avoid significant increases in the loads on the structure.

In July 1940, the improvement of shipways No. 1 was started and two small sub-assembly shops were built between the shipways and Dry Dock No. 1. Improvements to the power plant were also undertaken, including a 150,000-pound-per-hour boiler, two 5000-cfm compressors, and alterations to the building.

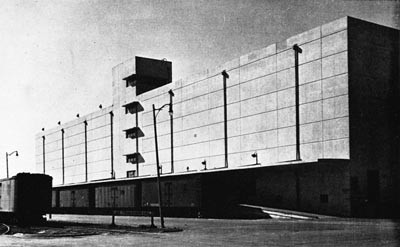

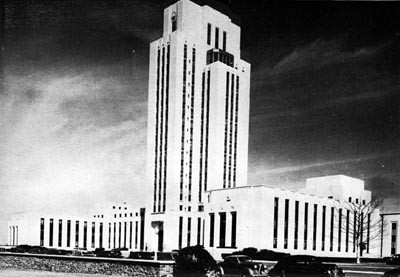

Work was also started in July 1940 on a 16-story office and storage structure. This building was of reinforced-concrete construction, the storage floors being of flat slab design and the office floors of beam and girder type. The storage floors were windowless, with mechanical ventilation. This exceptionally heavy structure was supported on drilled-in piles, consisting of 30-inch steel cylinders sunk to rock, which varied from 120 to 140 feet below the surface. Cores were drilled into the rock for distances of 5 to 10 feet, and the shafts were filled with concrete encasing heavy H-columns. Exceptional speed was made on the construction of the superstructure.

Simultaneously, work was started on a new receiving barracks for ships' crews. Because of the limited space in the yard, one city block, across Flushing Avenue from the yard, was acquired by condemnation and a 6-story fireproof reinforced-concrete structure, 200 by 350 feet, having six dormitory wings on either side of the central stem, was constructed. This structure, which had a nominal capacity of 2500 and a peak capacity of 4000, contained under one roof all the accessory facilities required for a complete receiving station.

In April 1941, a cost-plus-fixed-fee contract was let for the two shipbuilding drydocks, together with a new sub-assembly shop. This project was located at the east end of the yard and involved the reacquisition by condemnation of the Wallabout Market area. This tract, which was originally acquired by the Navy early in the 19th century, had been sold about 1890 to the City of New York, and a municipal market erected on the site. The displacement of this market, which was glutted with food stocks being held for rising prices, caused considerable difficulty; occupants were allowed

--179--

to remain as long as possible under revocable permits. At one time, 182 such permits were in force.

The project included extensive work on site preparation, including bypass roads and tracks around the site, removal of two navy yard piers and the causeway between the main yard and Cob Dock, elimination of the Brooklyn Eastern District railroad terminal, removal of four piers in the Marine Channel, and demolition of the market buildings.

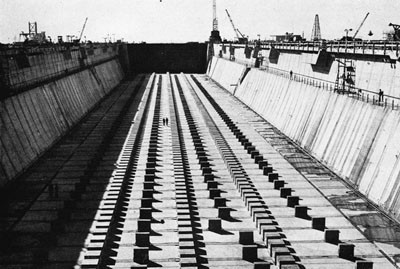

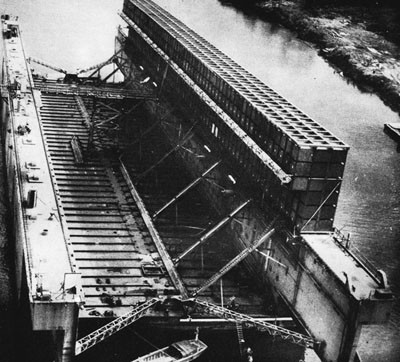

The drydocks, each 1092 feet long, 143 feet wide, and 38 feet deep over the blocks, were built by the tremie method. The docks were equipped with five 75-ton and ten 20-ton portal jib cranes.

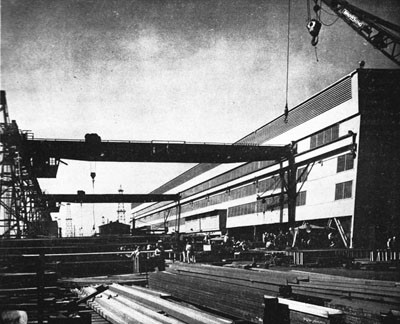

The sub-assembly shop, located at the head of the docks, was 800 feet long, 100 feet wide, and 105 feet high, with an attached steel storage shed alongside, 760 feet long, 83 feet wide, and 56 feet high. In general design the main shop was similar to the turret and erection shop previously constructed at the west end of the yard.

This contract was subsequently increased to include extensive improvements in the Kent Avenue area, on additional land acquired by condemnation, and in the Cob Dock area. The work included the construction of a huge twin-tube municipal outfall sewer, 2630 feet long, with a waterway of 264 square feet, the filling of the Kent Avenue Basin, and the construction of various service facilities.

The work also included the construction of piers J and K, which were of unusually heavy construction. The substructure consisted of a 3-foot concrete slab at tide level, supported on steel cylinders reinforced with three steel H-piles each, and filled with concrete. The coping walls, crane-track foundations, and service tunnels were erected on this slab, earth-fill placed, and concrete decks laid. These piers were designed for capital ship repair work and were equipped with exceptionally heavy utilities and services.

This project also included the removal of pier H, the construction of quay walls between piers J and K, the construction of a barge basin, a new railroad transfer bridge and classification yard, a scrap metal plant, a coaling plant, a 250-ton-per-day incinerator, and an assembly yard runway equipped with two 25-ton cranes. The total expenditures under this contract were $73,360,843.

A number of other major projects were executed under other contracts. The central power plant was completely removed and replaced with a modern plant on the same site, without interrupting service, by an ingenious and complicated sequence of successive piecemeal steps, and a new circulating water loop provided, at a total cost of $8,577,934.

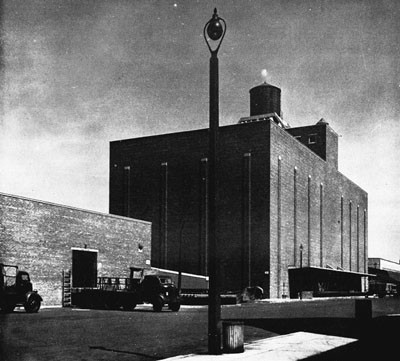

In 1941, a new foundry was erected on the Wallabout tract, and in the fall a 7-story ordnance shop building, 160 by 320 feet, was started on the site of the old foundry. A triangular 6-story extension was built on the structural shop to provide adequate office and personnel facilities. Late in 1941, a six-story steel-frame brick building, 350 by 100 feet, was started to house the material testing laboratory.

The same year, seven additional buildings were constructed, including a six-story paint and oil storehouse, a compressed-gas storehouse, a ship's superintendents' building, a three-story utility building at the fitting-out pier, and a motion picture exchange. In 1942, additional projects were undertaken, including a welding and fabricating shop, practically matching the sub-assembly shop in size, but of timber construction, and a sawmill, joiner, and boat shop, L-shaped, 290 by 440 feet, three stories high, and also of timber construction.

In 1943, the 350-ton hammerhead crane, which had started to settle, was underpinned and the quay wall strengthened and tied back to concrete deadmen.

Partly because the location and congestion of the yard dictated fireproof multi-story buildings and partly because the comprehensive program was planned in considerable detail and undertaken before materials became critically scarce, the New York Navy Yard was fortunate in obtaining the greater portion of its new facilities of permanent, fire-resistant construction.

The two shipbuilding drydocks were built in an area at the east end of the yard, partly within the earlier yard limits and partly on an acquired tract, which was previously a marine terminal and municipal market. The Brooklyn Eastern District Terminal contained a freight yard, car float transfer bridge, and freight houses. Also located on the Marine Channel were four freight piers operated by various railroads and a municipal refuse pier. The Marine Channel was separated from the yard basin by a causeway of heavy masonry construction which connected the Cob Dock area with the

--180--

main yard. Two cruiser piers projected into the yard basin from the causeway.

The location and orientation of the new docks was fixed within narrow limits by considerations of direct access, and by the requirements that the approach to old Dry Dock 4, which lay at right angles to the new docks, be kept clear. The situation necessitated extensive dredging of existing land, filling of water areas, and removal of the causeway, the two cruiser piers, and all the structures on the Marine Channel.

It was imperative that full access be maintained

--181--

to the Cob Dock, which was in full use for fitting out, repairing, and servicing ships. As soon as possession was obtained of the Wallabout Market area, by condemnation and declaration of taking, the structures west of Washington Avenue, were demolished, and temporary tracks, roads, and utilities installed around the construction site and contractor's working area, and across a new timber causeway built across the Marine Channel.

Dredging was started simultaneously in the navy yard basin and was carried through the causeway and into the market area as soon as these connections were in service. Six dredges were used to remove 2,300,000 cubic yards of material, at a maximum rate of 25,000 cubic yards per day, to a general depth of 63 feet, and a maximum depth of 72 feet, below mean low water. For the drydocks, a 2-foot layer of crushed rock was deposited and carefully leveled with a heavy drag.

Pile supports were required under the entire dock structures. More than 12,000 steel H-piles weighing 74 pounds per foot, from 30 to 70 feet long, were driven under water to 37.5-ton minimum bearing from floating drivers. Extremely accurate positioning was required to avoid interference with tremie forms. In some cases, clearances were less than 6 inches. Long telescopic leads, taut holding lines, and careful plumbing of leads were necessary to insure the precision required.

Tremie forms were used for the floors and lower side walls. The floor forms were 14 feet wide, 20 feet high, and 190 feet long, open top and bottom, and were prefabricated steel box trusses with corrugated steel sheathing and with the required reinforcement built in. The wall forms were similar but smaller, and included built-in frames to which steel piling could be attached to complete the sidewall cofferdam.

It was impossible to allot sufficient space in the yard for the fabrication of these forms. A tract of land on the New Jersey waterfront was leased, and the completed forms brought to the yard on car floats. The forms were placed by an improvised rig, consisting of two 100-ton stiff-leg derricks mounted on three 60-by-90-foot sections of an old timber floating drydock.

Floor forms were required only for alternate

--182--

blocks, as these blocks could be used as forms for the intervening spaces.

Concrete was mixed at a central mixing plant, served by belt-conveyor bridge from aggregate bins on the east side of Cob Dock. Cement was delivered in bulk and blown to the storage bins. Peak daily requirements were fourteen 800-ton barges of aggregates and two 5,000-barrel barges of bulk cement.

Concrete was delivered by pumping through a system of 8-inch pipes, with booster pumps where needed, for a maximum distance of 1100 feet, to the tremie barges, where it was discharged through hoppers into eight tremie pipes which could be raised and lowered as required. The concrete in a form, aggregating 1660 cubic yards, was placed in a continuous pour at a controlled rate in nine hours. More than 500,000 cubic yards of tremie concrete was placed.

The outer ends of the docks were built within sheet pile cofferdams. Temporary cofferdams were built across the dock, about 700 feet from the head wall, to permit starting ship construction before the outer ends were completed.

After the lower sidewalls were complete, the steel piling was mounted on preset framing, sealed into the concrete, and the docks pumped down. The finished floor and sidewall lining were then placed in the dry.

Backfill around the docks required 1,600,000 cubic yards of material, delivered by truck from borrow pits on Long Island. Crane tracks around the docks were supported on steel H-piles.

Bayonne

For years before the war, the need had been apparent for a major drydock in New York Harbor, capable of accommodating the largest transatlantic

--183--

liners entering the harbor and the capital ships of the Navy which could not pass under the Brooklyn Bridge to reach the navy yard without housing their top hamper.

It was originally proposed that the dock be built under the joint ownership of the federal government and the Port of New York Authority, but Congress rejected this method of subsidizing a non-federal agency. In October 1941, Congress appropriated funds for dock construction by the Navy. A site was selected on the New Jersey shore, at Bayonne, where a peninsula had been constructed of fill and partially developed as the Bayonne Port Terminal, and a contract was awarded in February 1941 for construction of the dock and its appurtenances. The outer portion of the area was allocated for the dock and for repair facilities; the inshore portion was developed as the Navy Supply Depot, Bayonne.2

The dock, which was 1092 feet long, 150 wide at the coping, and 43 feet deep over the blocks at mean high water, was located at the extreme end of the peninsula, facing the main ship channel. Like the navy yard docks, this structure was built by the tremie method.

The site was dredged to subgrade, a blanket of broken stone placed and leveled, foundation piles driven, and tremie forms set. The bottom forms were steel trussed boxes, 191 feet long, 14 feet wide, and 20 feet high, sheathed on the four sides with corrugated sheet metal, but open top and bottom. The reinforcement was prefabricated and assembled with these forms. Laid transversely to the dock's centerline, properly spaced, and filled with tremie concrete, they formed alternate blocks of the floor system, which was completed by filling the spaces between these blocks. The lower sidewalls were also built by tremie in similar but smaller forms; the upper part was built in the dry, inside a steel cofferdam supported on A-frames built onto the sidewall forms. An outboard cofferdam was built on an arc in 40 feet of water. It was of rip-rapped earthfill, with a steel sheet pile

____________________

1. [No footnote # in text.]

2. See Chapter 12.

--184--

corewall. A 25-foot-wide top carried a construction road.

After the tremie concrete was placed and the cofferdams were completed and closed, preparations for unwatering began. A system of drains was installed around the outside of the interior cofferdam to take surrounding seepage and to relieve the uplift seepage from under the dock. Sumps were installed at points along the drainage line, and pervious material was cast behind the interior cofferdam. A temporary 8,000-g.p.m. pumping installation unwatered the area to 20 feet, then twelve deep well pumps, totaling 30,000-g.p.m. capacity, were installed in the sumps alongside the interior cofferdam, and unwatering was completed. The effectiveness of the drainage system was demonstrated when it was found that three sump pumps operating on one side of the dock could maintain a satisfactory groundwater level on both sides of the dock.

Finish floor paving and wall construction proceeded in the dry. The floor slab was tied down to the tremie concrete by rows of hairpin dowels incorporated in the tremie concrete, and the slab was designed to take full uplift pressure in case of leaks through the tremie slab. The walls were formed directly on the tremie slab. The outer side had a vertical face, and the wall section varied from 20 feet 6 inches to 17 feet in thickness from the base to elevation 11 feet 6 inches, then stepped back 4 feet to a vertical rise to the top, which was 13 feet wide. Work was conducted from the dock floor and from the 30-foot level behind the interior cofferdam. Later, the area behind the walls was backfilled, the seaward cofferdam was removed, and the caisson gate, which had been erected and launched at the site, was placed in its seat. Alongside the drydock continuous drydock crane tracks were installed. Dock pumping facilities consisted of four main pumps with a rated capacity of 130,000 gallons per minute.

The project at Bayonne also included a heavy ship repair wharf, a machine and structural shop, 175 by 450 feet, a sheet metal, pipe, and electrical shop of the same size, a substation and compressor plant, a heating plant, and a cafeteria, and a complete system of roads, tracks, crane tracks, utilities, and weight-handling equipment.

Philadelphia

The Navy's second battleship building yard, at Philadelphia, was built on level League Island at the southern edge of the city, at the confluence of the Schuylkill and the Delaware rivers. The Delaware River and Bay provided a dredged 40-foot

--185--

channel to the Atlantic Ocean, 100 miles distant.

When the 20-percent fleet expansion was authorized in 1938, primary Philadelphia construction and repair facilities included one large and two smaller drydocks, two battleship building ways, and a lesser building ways. National defense and war projects extended the capacity of the building ways to accommodate construction of Iowa-class battleships and added two building drydocks which would accommodate the construction of super-battleships and aircraft carriers. Small ship repair facilities were augmented by the erection of two 3,000-ton marine railways.

The construction and repair capacity was approximately doubled between 1938 and 1945. Shop, storage, and other facilities were expanded in a similar proportion, as illustrated by a power-plant capacity increase from 12,500 to 21,875 kva output. The new docks were built side by side at the west end of the yard; each, 143 feet wide at entrance and 1092 feet long. One was built with a depth of 35 feet over the blocks and the other 38 feet 6 inches over the blocks.

The first Philadelphia expansion began in 1938 when an extension to the machine shop was started. A turret assembly shop, a structural assembly shop, and a pipe and copper shop were also placed under contract that year.

Like New York, Philadelphia had two battleship building ways in 1940. On one of these ways was the USS Washington, about to be launched. For the impending construction of the heavier battleships New Jersey and Wisconsin, it would be necessary to strengthen and extend both ways. The first such job began on Shipways No. 2 in February. Part of the ground ways was removed and rebuilt, and later a cofferdam was built at the outboard end of Shipways No. 2, to extend the working

--186--

length of the ways. In June, after the Washington had been launched, similar work was begun on Shipways No. 3. Work got under way in June on the first 1092-foot drydock, Dry Dock No. 4, and on a permanent 100-by-90-foot pier, needed for fitting out new vessels built at the yard and at nearby private shipyards. In August, an electric shop extension was begun. Power plant modification plans called for two additional 125,000-pounds-per-hour boilers with auxiliaries installed in the existing power plant.

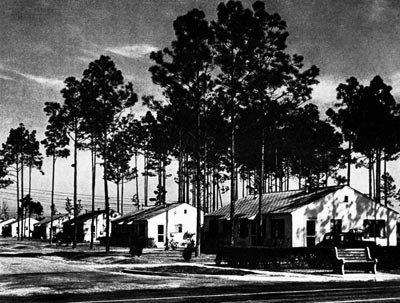

Housing for ships' crews was increased by work which began in late 1940. A three-story fireproof barracks to accommodate 1575 were built.

In May 1941, work was begun on the second 1092-foot shipbuilding drydock. Dry Dock No. 4 was well under way by May, but the Navy was anxious to start building ships in it; so a temporary cofferdam was installed in the body of the dock, to permit unwatering of the inboard end to allow shipbuilding prior to the completion of the outboard end. A contract was let for three 75-ton drydock cranes.

Other work initiated that spring included power plant improvements, a pattern shop extension, and a storehouse near the reserve basin. Twelve 20-ton jib cranes for the drydocks were ordered in June. Later, work began on an eight-story reinforced concrete storage building, 400 by 275 feet. Another permanent barrack for 875 men and 50 officers was placed under construction; later, a third story was added to increase the total capacity to 1500.

A project which reached the contract stage late

--187--

in the summer of 1941 was a four-lane lift bridge across the reserve basin. The bridge was 400 feet long, with a lift span of 240 feet. In September, work began on a 60-by-300-foot two-story service building and on a turbine testing laboratory.

In 1942, the construction of two 3,000-ton marine railways, with ways 900 feet long, was undertaken as a supplement to the drydock contract. Work began on the first railway in January and on the second in February. At the time work started on the second marine railway a change was made in the contract for the second 1092-foot drydock, providing for a depth over the sill of 43 feet 6 inches instead of 40 feet, at mean high water. A large open storage area for lumber and other materials was also developed at the northwest end of the yard.

Most of the remaining Philadelphia projects were for personnel structures, although in September, six 75-ton drydock cranes were ordered. In February, work began on a 2000-man temporary barracks project, and in March a project to house 500 students and 60 enlisted men was initiated. Later a four-story concrete frame and brick barrack was erected to house 2000 men.

The excavation for the drydocks was carried to a depth of 58 feet below mean low water, 224 feet wide at the bottom and 436 feet wide at the top, the bottom width setting up a clearance of 20 feet from the outside of the tremie concrete walls on either side. About 1,273,000 cubic yards of material was dredged in operations on Dock No. 4 and 1,576,000 cubic yards on Dock No. 5. After dredging operations were completed, a 4-foot mat of crushed stone was placed on the bottom and smoothed with a heavy drag. Steel piles, 12-inch "H" sections, were driven to a penetration of 57 feet. Tremie concrete was poured around the heads of the piles, which were used both for bearing and for resistance to uplift. Construction methods on both docks were similar. However, modifications

--188--

were made on No. 5 dock work in the light of experience on No. 4. On No. 5 the steel piles were cut before they were driven, which eliminated costly and time-wasting cutting by divers. The thickness of the walls and floors of Dock No. 4 was 14 feet with a 2-foot finished lining, whereas the monolithic floor of No. 5 was 15.5 feet thick and the lining was eliminated from the walls.

In order to advance the date of starting ship building in Dry Dock No. 4, a temporary cofferdam was constructed in the body of the dock near the outboard end, 860 feet from the head of the dock.

For repair of small ships, two 3,000-ton marine railways with a slope of 7/8 inch to the foot, were built at the reserve basin. Dredging for each marine railway covered an area 900 feet long by 26 feet wide. After dredging was completed, a 2-foot layer of gravel was spread on the bottom. About 1,300 piles of varying lengths were driven through the gravel bed. The initial pour of tremie concrete on the gravel and pile heads was 3 feet deep. A 175-pound rail on a 16-foot gauge carried a 400-foot steel cradle, which rolled on 184 double-flanged wheels. As built, each railway was 900 feet long, with a total rise of 64 feet.

Norfolk

Oldest of the navy yards, the Norfolk Navy Yard had been used by the British and by the Commonwealth of Virginia before its official establishment

--189--

in 1801. Located in Portsmouth, Va., across the Elizabeth River from Norfolk, the yard had an area of 665 acres at the end of World War II.

The land on which the yard was built was flat and alluvial. Facilities in existence there before the defense and war expansion periods included six drydocks, ranging in length from 325 feet to 1011 feet, five slips for mooring 21 vessels, one large shipbuilding ways, and shop, utility, and storage buildings to service the fleet repair and construction facilities.

One large drydock was built at Norfolk during World War II, and a servicing area for smaller vessels was developed at St. Helena, across the Elizabeth River from the yard.

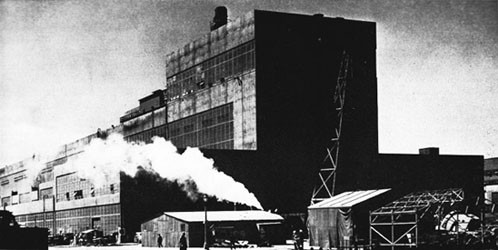

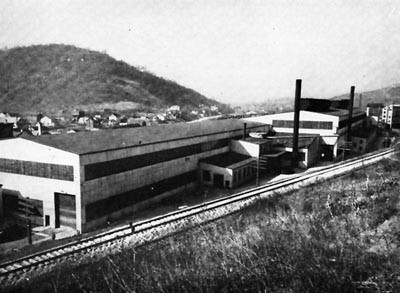

Emergency construction began in 1938 with the extension of the structural shop and foundry. In 1939, work was started on a 480-by-130-foot supply storehouse and an 880-by-110-foot sub-assembly shop. The sub-assembly shop was built between the building ways and the 1011-foot Dry Dock No. 4, the largest dock then in existence at Norfolk. Construction on the 1092-foot drydock began in June 1940. In July, construction started on a 130-by-480-foot three-story addition to the inside machine shop, and before the end of the year about a million dollars' worth of power plant improvements were under way, together with a number of minor bridge and wall cranes. Work started in 1941 included a 500-by-280-foot four-story fireproof storehouse and three hammerhead and six jib cranes.

In May 1942, after war had begun, 18 H-type barracks, to house 4,100 men, were ordered. In June, work began on the construction of a boiler shop and material storage building and of a field shop building. The boiler shop and storage building was one story high, 600 by 150 feet, on concrete footings. The field shop building was of reinforced concrete, 315 by 340 feet. Weight-handling equipment was augmented by the addition

--190--

of 59 bridge cranes, ranging from 10 to 25 tons in capacity.

The new Norfolk drydock was built under the same contract as drydocks Nos. 4 and 5 in Philadelphia. Of the same plan and dimensions, it was built deeper, for use in repairing as well as building capital ships. The bottom of the dock was tremie-cast, 18 feet thick, on steel "H" piles which served both as supports and anchors. After construction was started on the inboard end of the dock, placing tremie forms and concrete immediately behind the excavation, a temporary cofferdam was built around the outboard end. This cofferdam allowed ship construction to proceed before seating the caisson gates, and even before pouring the headwalls. After the cofferdam had been placed, the pumpwell, headwall, and caisson gate were installed in the dry. The crane tracks for the job cranes servicing the docks were pairs of standard-gauge rails on 40-foot centers.

St. Helena. - The St. Helena area of the Norfolk Navy Yard had only six small piers before 1942. During World War II, Navy built 47 buildings and four piers. The additional buildings included barracks, shops, and service buildings necessary for the repair of small vessels. The four new piers provided berthing for 22 small craft.

Charleston

The Charleston Navy Yard was established in 1901, on the Cooper River about 5 miles above its junction with the Ashley River at the city of Charleston. The area of the yard prior to the defense and war expansion programs was approximately 350 acres. It was increased to 710 acres between 1938 and 1945. The site, being alluvial with later extensive fill, required pile foundations for all except a few small structures in slightly higher areas.

Pre-defense facilities at Charleston included old Dry Dock No. 1, old small shipbuilding ways, and new cruiser ways built by PWA and WPA in the 30's. Major wartime expansion included both expansion within the old yard area and development of a new area to the south, including a small double building dock, temporary shops, and finger piers.

As at several other yards, defense construction began at Charleston in 1938, when the machine shop was extended. No further work was initiated until 1940, when two 60,000-pounds-per-hour boilers with auxiliaries were installed and three existing

--191--

turbo-generators were modified, all within the existing power plant.

The first significant contract at the Charleston yard, based on the two-ocean Navy program, was let in 1940 for a receiving barracks.

In April 1941, a small shipbuilding dock (No. 2) was placed under contract, as was a new boiler and a 5,000-c.f.m. air compressor, to provide the additional power which would be required in the use of the new dock. In the summer, work began on a temporary 500-man barrack, and in the fall a utility shop for the new dock was put under construction. Four 15-ton jib cranes also were ordered that fall.

Two 760-by-90-foot piers were begun for use in fitting-out ships built in the new dock. Called "finger piers," the structures had crane tracks and the electrical, compressed air, water and steam services, typical of fitting-out piers. They were built obliquely to the shore line, on the waterfront area which was later developed as a southward expansion of the yard's industrial facilities.

The last project initiated before the war began was an ordnance shop and storehouse, the first at Charleston. It was built 600 feet by 125 feet, one story high.

Early in March 1942, three temporary storehouses were started, and later in the month, two 50,600-barrel splinter-proof diesel-oil tanks were placed under contract. In April, six barracks were started.

In May, the significant southward expansion was initiated for the construction of escort vessels. Work included the two 365-foot building drydocks, and timber buildings to house machine, plate and shape, welding, assembly, electrical, pipe and sheet metal shop activities. Work also included another finger pier, built obliquely to the shore, parallel to those which had been put under construction during 1941.

Five 50,000-barrel and one 27,000-barrel underground prestressed concrete fuel-oil tanks were begun in June.

In March, the Navy had acquired an 85-are area

--192--

to the north of the main yard. Known as the Noisette Creek tract, it had been condemned for the purpose of establishing enlarged storage facilities for the yard. Work, which started at Noisette Creek in August, included two storehouses for storage of bar metals and boiler tubes, covered storage for gasoline and lubricating-oil in containers, a paint and oil storehouse, lumber storage, and a cold-storage building. Additional construction at Noisette Creek included an L-shaped wharf, with a 500-by-60-foot head and a 415-by-30-foot approach to shore, and a transit shed, 225 by 55 feet.

The first dock, No. 2, was built completely in the dry. Before cofferdam sheet piling had arrived on the site, excavation began at the inshore end. As soon as there was enough material excavated the first slab of floor concrete was poured. When sheet piling arrived, it was driven around the entrance of the dock, and excavation and construction were continued.

The small building docks were built adjacent to each other, 9 feet 7 inches deep over the blocks, each 98 by 365 feet, with two 42-foot entrances. The docks were composed of steel sheet pile walls tied back to anchor piles, structural concrete decks, and porous concrete underfloor mats. They were set on steel piles which, due to variation of soil conditions, in some cases were more than 90 feet long. In many cases the piling had to be spliced by welding. Excavation was handled by dragline after the steel sheet pile sidewalls, together with the anchor pile tie-back system, had been installed.

At Noisette Creek, 11 storage buildings were

--193--

built by August 1945. The Noisette Creek area had been occupied by a sawmill before its acquisition by the Navy, and the area was covered with a layer of sawdust topped by a layer of silt. This condition gave the impression of solid soil, but, when the surface was disturbed, the area became unstable. Pile foundations were used for storehouse construction over the buried sawdust.

Some difficulty was encountered in the construction of the oblique piers along the south waterfront. The piers were of reinforced concrete slab and girder deck construction supported on steel "H" section piles. Due to non-uniform soil conditions, it was necessary to use piling ranging in length from 60 feet to more than 100 feet. In some cases, adjacent piles had considerable length differentials, and, in many cases, piling more than 100 feet long was required, necessitating the use of welded splices. During pile-driving, there was a tendency, due to swift currents, for the slender piles to drift from their proper locations.

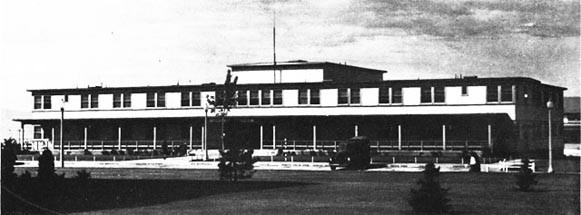

Puget Sound

Established in 1891 at Bremerton, across Puget Sound from Seattle, the Puget Sound Navy Yard, during World War II, had its area increased from 286 acres to 316 acres. Before the war, Puget Sound was the only battleship repair yard on the Pacific Coast. Its facilities included three drydocks and four piers, one of which mounted a 250-ton hammerhead crane. One of the drydocks was the Navy's initial shipbuilding dock. Shipbuilding and repair facilities at Puget Sound were increased during World War II by the construction of two more drydocks, both capable of docking battleships and carriers, and by the erection of two double shipbuilding ways large enough to build escort vessels. Service buildings and shop buildings for the new drydocks and shipbuilding ways were erected in an area south of the old industrial area.

The first construction at the yard after Congress authorized the 20-percent expansion of the fleet in 1938 was that of Dry Dock No. 4. The dock was

--194--

built with a depth over keel blocks of 43 feet, sufficient to allow a battleship to enter for repairs. The plan dimensions were 133 feet by 997 feet. A cofferdam was constructed around the outboard end of the dock so that work could be conducted in the dry. The cofferdam was an earth fill with a sheet-pile core. After excavation was completed, a gravel mat was leveled on the bottom, and the concrete floor was placed.

Dry Dock No. 5 was similar in size to No. 4. Construction procedure also as similar, except that the contract for No. 5 included a tunnel connection to No.4 to cross-connect the pumping systems.

The other increase in shipbuilding facilities at Puget Sound was the erection during 1942 of two double shipbuilding ways. Each pair was built 109 feet wide and 400 feet long. The major problem in the construction of these shipways arose in connection with driving 9300 piles for support of the shipways. It was considered that six pile-driving rigs would be needed to give proper construction progress. Only four rigs could be obtained, but the operation was speeded satisfactorily by jetting the piles.

Before the escort-ways job was started, however, other structures in support of the drydock program were put under construction. In August 1940, a 360-by-140-foot shipfitters assembly shop was started. Later in the year, work began on a fitting-out quay and pier, adjacent to the newest drydock. The project provided 700 feet of quay and a 700-by-120-foot pier, one side of which was an extension of the quay front.

Responsive to the passage of the 1942 appropriate act, a contract was let in May 1941 for another fitting-out pier. Overall size of the new pier was 90 by 730 feet. Work also started in May on the west quay wall, 1480 feet along the waterfront. A seven-story fireproof general storehouse, 450 by 150 feet, and an 800-by-120-foot fireproof supply pier were built under contracts which were awarded that summer.

Wartime construction began with the award on January 1, 1942, of a contract for two double shipways, 109 by 400 feet, a craneway, and an assembly platform for the construction of escort vessels. Extensions were made to the machine shop, including a main extension, six stories high and 170 by 280 feet in plan. In February, a storehouse, 450 by

--195--

160 feet, was placed under contract, as was also a steel-frame shipfitters shop with fabricating bays, 540 feet long by 300 feet wide by 80 feet high.

No major construction was initiated at Puget Sound in 1943. In 1944, in order to give the yard a connection with the railroads of the continent, a 5-mile spur was built to connect with the line between Shelton and Bangor.

Mare Island

Mare Island Navy Yard and its adjacent ammunition depot were the two oldest naval stations on the West Coast, having been established shortly after the admission to the Union of the California republic. Prior to the war expansion program the yard had an area of 635 acres. Facilities included three drydocks and two shipbuilding ways. By 1945, the yard covered an area of approximately 1500 acres, including much reclaimed land, and contained four drydocks and eight shipbuilding ways.

In March 1940, work started on the fourth drydock, which was to be 84 feet by 435 feet, with a depth of 20 feet over the blocks. While tremie walls and floors were being poured from the inboard end of the dock a row of steel sheet piling was driven on the line at the outboard end of the floor on the sill. This line of steel was used as the form for the tremie concrete sill and was cut off flush with the floor when the dock was finished. Dredging for the dock was followed by placement of a gravel mat, a foot thick. Through the mat, piles were driven, ranging in length from 40 to 80 feet, and tremie concrete was poured in alternate sections. The lower portions of the pumpwell and cross culverts were poured by the tremie method, and when the dock was unwatered for the finishing process these items also were finished. The unwatering

--196--

took place after the backfilling was completed.

Construction on the drydock was preceded by the construction of a 250-by-900-foot machine shop. After work began on the drydock a contract was let for a 500-foot freight pier with rail service to either side and for a finger pier and quay wall system which added 7,340 feet of berthing space for fitting-out vessels. Three 740-foot piers were built in the system.

West Coast building capacity was increased in May, when work began on a double ways for submarine construction. In November, another project included five double building ways, each 450 by 96 feet long, with crane and rail services, and a combined shop building adjacent to the ways. This project was located on the waterfront in an undeveloped area just north of Causeway Street. The site was filled with material dredged from the strait alongside, and a quay wall was built. The outboard end, for 137 feet, was built of concrete, and the inner end, 327 feet long, was a timber-framed deck. The entire structure was supported on wood piles. The outboard end was closed by a removable steel gate. During construction the concrete section was surrounded by a cofferdam of steel sheet piles.

A four-chambered cofferdam was constructed around the outboard end of the ways area, and a mat of crushed stone was placed inside as a suitable surface to receive tremie concrete. A week after the tremie concrete had been poured, the area inside the cofferdam was successfully unwatered. The outboard steel sheet piling was cut off to accommodate the prefabricated gates.

When work began on the first ways, another contract was let for power plant improvements to furnish power which would be needed for the increased building activity. A 150,000-pound-per-hour steam generator and a 6,000-c.f.m. compressor were installed in the existing power house. The contract later was expanded to include extensions and additions to the electrical distribution system.

Personnel facilities were increased by a project, initiated in the sumer of 1941, which included quarters for 1000 men and 50 officers.

An ordnance machine shop, 600 by 310 feet, was placed under contract in the fall.

In 1942, new projects included three storehouses; one of reinforced concrete, 100 by 400 feet, for paint and oil storage; a second, one-story, 400 by 160 feet, of wood-frame construction, for heavy materials; a third, one-story, 475 by 425 feet, of wood-frame construction, for the storage of spare submarine parts.

In January 1943, an unusual contract called for

--197--

the construction of 680 air-raid shelters, with a capacity of 27,200 persons.

Six barracks and an ordnance storehouse were started in 1944. The storehouse was a wood-frame building, 510 by 250 feet, one story high, with a mezzanine. Also in 1944, work began on a joiner and machine shop.

Hunters Point

One of the two new ship repair facilities established on the West Coast was the Hunters Point Naval Dry Docks, later redesignated as Naval Shipyard, Hunters Point. This development was initiated in 1940 by the acquisition of a privately owned plant, 48 acres in extent, which contained two graving docks, and with which the Navy had previously had a long-standing working agreement. This plant was situated on a point of land, half way between San Francisco and South San Francisco, on the west side of San Francisco Bay. Later acquisitions increased the total area to 583 acres.

The major construction projects at Hunters Point were a 1092-foot drydock, three 420-foot drydocks, and a major earth-moving job under which almost 8,000,000 cubic yards of earth were removed to cut down a hill to form a flat industrial area.

The first project to be placed under contract after the initial development began was a $675,000 quay wall, on which work began in July 1941. The large dock and bluff-removal project was started in January 1942, immediately after the United States entered the war. In April, the installation of 10 miles of sewer pipe and 10 miles of fresh-water lines was begun on the lands which were being leveled. At the same time, work was started on an additional drydock crane, an extension to the crane-track system, and on an assembly building.

In August 1942, agreements were made for 15 projects, which included utilities systems, connecting crane tracks from old Dry Docks 2 and 3 to those of the new 1,092-foot dock, additional weight-handling equipment, moving a Marine barrack, two ship's service buildings, two small storehouses, two small shop buildings, a dispensary, a cafeteria, and a transportation building. This work took place on the newly leveled land.

In June 1943, a timber wharf, 350 feet long, was put under construction, and a contract was let for the construction of the three small drydocks. Nos. 5, 6, and 7, for docking submarines and destroyers and, later, landing craft. Other work included four 40-ton diesel-electric cranes, 3 one-story frame

--198--

storage buildings, and a one-story frame building used as a boiler and blacksmith shop.