Barbary Wars

1801–1805 and 1815

During the 17th and 18th centuries, state-sanctioned pirates from the Barbary States (Morocco, Tunis, Tripoli, and Algiers) would seize unprotected merchant ships off the coast of North Africa and demand ransoms from the crews’ families and governments. The general practice at the time was to simply pay “tributes” to the pirates for safe passage in the Mediterranean instead of confronting them militarily. With the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1783 that formally ended the American Revolution, the United States hoped it would enter a new era of global free trade. However, without the protection of the powerful British Royal Navy, American merchants quickly found themselves defenseless against Barbary pirates. At the time, the high seas were the most economically viable way to transport goods and the Mediterranean was vital to American prosperity. Presidents George Washington and John Adams chose to pay tributes to the Barbary pirates, but the bribes failed to ensure full protection and were subject to the shifting mmods of the bashaw of Tripoli, the bey of Tunis, the sultan of Morocco, and the dey of Algiers. With ransom amounts escalating, newly elected President Thomas Jefferson sent America’s reestablished Navy to confront the Barbary powers. In 1815, President James Madison sent a naval force to the Mediterranean to finish what Jefferson had started, and finally put an end to the Barbary States' threats toward American merchants.

First Barbary War: The Tripolitan War

In December 1800, the Bashaw Yusuf Karamanli of Tripoli presented the United States’ government with an ultimatum: increase tribute to $225,000 or face war. After years of rising ransoms and never-ending negotiations for captured ships and crews, President Jefferson decided to use force to ensure American maritime security in the Mediterranean. Previously, Jefferson, as secretary of state, had taken a hard line against Barbary piracy. Now, in May 1801, he ordered a Navy squadron led by Commodore Richard Dale to blockade Tripoli and to attack any interfering Barbary ships. Lieutenant Andrew Sterett, commander of the schooner Enterprise, won the first American victory of the conflict on 1 August, when he defeated the 14-gun corsair Tripoli after a fierce, but one-sided battle. Enterprise did not suffer a single casualty during the engagement, but because Congress had not formally declared war, Sterett was unable to take the ship as a prize. Instead, he ordered the battered pirate ship into port and his crew threw all of the enemy's guns overboard. The next victory for Enterprise came on 17 January 1803 when, after spending months carrying dispatches, convoying merchantmen, and patrolling, the ship defeated Paulina, a Tunisian ship under the charter of the bashaw of Tripoli. On 22 May, Enterprise ran a 30-ton craft ashore, and for the next month it and other ships of the Mediterranean Squadron cruised inshore, bombarding the coast and sending landing parties to destroy enemy small craft. Later that year, Enterprise joined the frigate Constitution to capture Tripolitan ketch Mastico. Refitted and renamed Intrepid, the ketch was provided to Enterprise's commanding officer, Lieutenant Stephen Decatur, Jr., for use in a daring expedition to burn frigate Philadelphia, which had been captured by the Tripolitans after running aground in the harbor of Tripoli. Decatur and his crew carried out the daring mission perfectly, destroying Philadelphia and thus preventing Tripoli from using the frigate in its fleet.

In August 1804, Mediterranean Squadron commander Commodore Edward Preble detailed Decatur with leading another attack on Tripoli Harbor, during which he boarded enemy gunboats and rescued several American prisoners. During the bloody battles, Decatur’s brother James, in command of a U.S. gunboat, was killed while engaging a Tripolitan vessel. During the subsequent pursuit and boarding of that ship, a wounded sailor, Reuben James, saved Stephen Decatur's life by inserting himself between his commanding officer and a sword-wielding corsair.

Although Decatur was the most-remembered hero of the First Barbary War, Army Captain William Eaton led the conflict’s most daring raid. Eaton, the former consul of Tunis, established an alliance between the United States and former Bashaw of Tripoli Hamet Karamanli, who had been deposed by his brother Yusuf Karamanli. In the spring of 1805, Eaton and Hamet Karamanli marched an army of 400 Arab and Greek mercenaries across the Libyan desert and attacked Tripoli’s city of Derna. They easily captured the city with the help of three American ships under the command of Master Commandant Isaac Hull. Before the force could continue on to Tripoli, U.S. Consul-General Tobias Lear and Danish Consul Nicholas Nissen reached a peace settlement with the bashaw. The agreement stipulated that after paying a $60,000 ransom, the United States no longer needed to pay tribute to Tripoli. Americans celebrated the treaty as a victory for free trade. Hamet returned to exile in Egypt, Eaton returned to America, and the war with Tripoli came to an end.

Second Barbary War: The Algerian War

During the War of 1812 the Algerians sided with the British, although the British blockade along the Atlantic obstructed most American trade in the Mediterranean. Shortly after the end of the war, President Madison requested that Congress approve war against Algiers. Authorization came on 3 March 1815, and in May a 10-ship squadron led by Decatur sailed from New York for Algiers. An even larger force, led by Commodore William Bainbridge, was close behind. Decatur, as commander of Guerriere, captured Meshouda and in the skirmish killed corsair Raïs Hamidou. After inflicting further damages on the Algerian fleet, Decatur dictated terms of peace in the summer of 1815. The agreement stated that in return for the captured Algerian ships, the United States would no longer pay tribute and would enjoy full shipping rights. Additionally, Algiers would free all enslaved Americans, primarily former members of the merchant vessel Edwin, and provide them with $10,000 compensation. Unfortunately, the captives all perished on the journey home when their ship, Epervier, sank in the Atlantic. Although the Second Barbary War lacked the drama of the conflict with Tripoli, the defeat of Algiers won respect for America and marked a victory for free trade.

Aftermath

The 1815 defeat of Algiers signaled the beginning of the end of Barbary pirate dominance in the Mediterranean. Although Decatur’s fleet had secured great concessions from Algiers and Tunis, the United States knew that the Barbary powers had a long history of breaking agreements. In 1816, the Algerians attempted to renege on their agreement, and in response, President Madison deployed the U.S. Mediterranean Squadron, led by Commodore Isaac Chauncey, to protect U.S. shipping. In August of that year, a combined Dutch and British fleet attacked the city of Algiers and forced its leadership to release more than 1,000 European slaves. Several European powers continued paying the Algerians tribute as late as 1822. The Barbary States, although they did not capture any more U.S. ships, began to resume piracy in the Mediterranean, and despite punitive bombardments by the British, did not end their practices until the French conquest of Algeria in 1830.

*****

Significant Naval Engagements and Related Events

- 3 September 1783: Treaty of Paris was signed, ending the American Revolution. American ships were no longer protected by the British Royal Navy.

- 27 March 1794: President George Washington signed the Naval Act of 1794 into law, authorizing the construction of the U.S. Navy’s six original frigates to protect U.S. commercial vessels from attacks by Barbary pirates in the Mediterranean and nearby Atlantic waters.

- December 1799: United States agreed to pay Tripoli $18,000 per year to secure safety for American trade ships in the Mediterranean. Similar agreements with other Barbary powers were also made.

- March 1801: Tripoli declared war on the United States.

- 15 May 1801: President Thomas Jefferson sent a naval squadron commanded by Commodore Richard Dale to blockade Tripoli.

- 1 August 1801: Schooner Enterprise, commanded by Lieutenant Andrew Sterett, captured Tripolitan Admiral Raïs Mahomet Rous’ ship Tripoli after a bloody, one-sided battle. The event was considered the first U.S. naval victory of the Barbary Wars.

- 6 February 1802: Congress passed the “Act for Protection of Commerce and Seaman of the United States against the Tripolitan Corsairs,” essentially a declaration of war.

- 12 May 1803: Frigate John Adams captured Tripolitan frigate Meshouda.

- 31 October 1803: American warship Philadelphia surrendered after running aground in Tripoli harbor.

- 16 February 1804: Intrepid, commanded by Lieutenant Stephen Decatur, Jr., set captured Philadelphia on fire to avoid it being used as a Barbary warship.

- 3 August 1804: Commodore Edward Preble launched an attack on Tripoli that last through 11 September.

- 27 April 1805: After a two-month march across the Libyan aesert, Army Captain William Eaton, former Tripolitan Pasha Hamet Karamanli, and a group of mercenaries attacked Derna by land. Meanwhile, U.S. warships under Master Commandant Isaac Hull struck Derna from the sea.

- 10 June 1805: Treaty of Tripoli was officially signed. American merchant ships no longer had to pay tribute to Tripoli.

- 24 December 1814: Treaty of Ghent was signed, ending the War of 1812.

- 3 March 1815: With support from Congress, President James Madison declared war on Algiers.

- 15 May 1815: Commodore Stephen Decatur, Jr., commander of a 10-ship American squadron, departed New York for Algiers.

- 3 July 1815: After destroying several Algerian ships, Decatur negotiated for peace with Algiers. The treaty ended the practice of paying tributes, freed American and European slaves, and secured full American shipping rights in the Mediterranean.

- 12 November 1815: Guerriere, commanded by Decatur, returned to New York City to a hero’s welcome.

- 5 December 1815: The Algiers Treaty was ratified by Congress.

- 15 December 1815: President James Madison declared that war with Algiers was over.

Suggested Reading

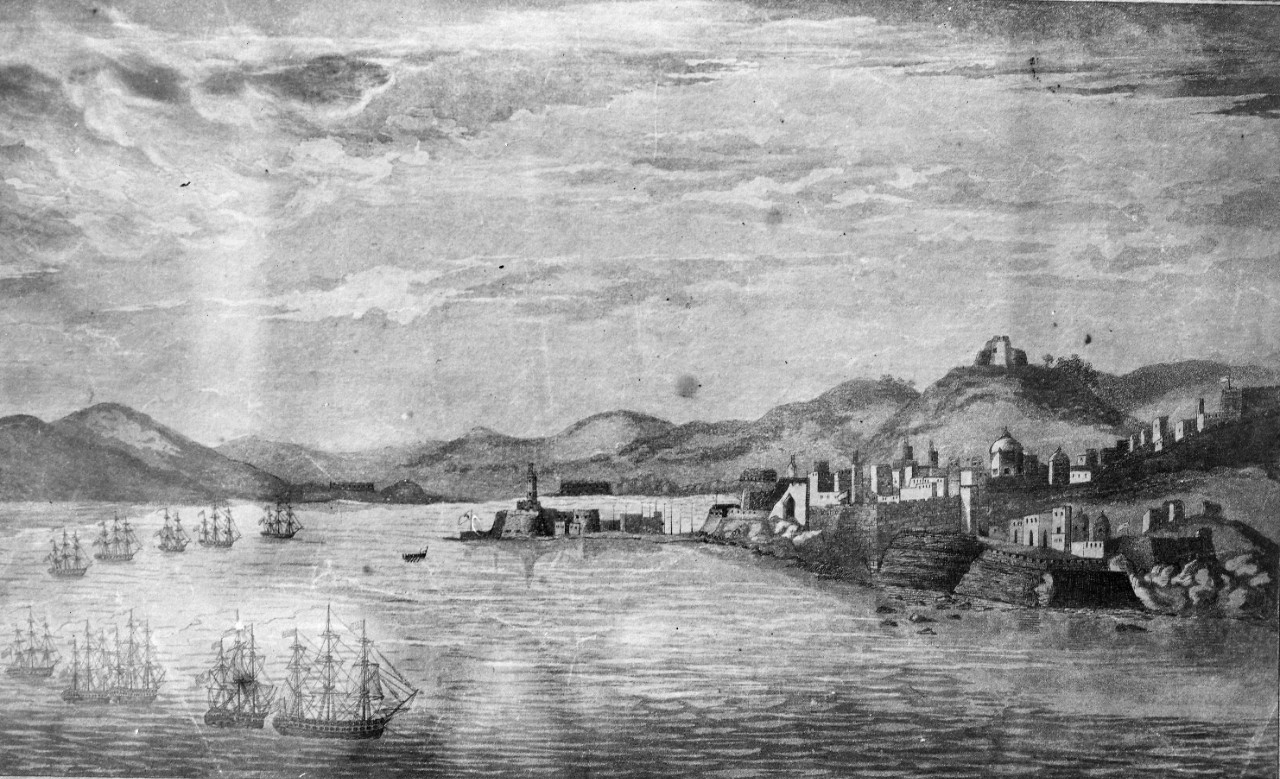

- Bombardment of Tripoli, 1804

- Edward Preble’s Leadership Qualities Analysis

- Battle of Derna, 27 April 1805

- Battle of Tripoli Harbor, 3 August 1804

- Brief History of the Seagoing Marines

- U.S. Navy’s Six Original Frigates

- Pirate Interdiction and the U.S. Navy

- Capture of the frigate Philadelphia

- Lieutenant Stephen Decatur's Destruction of Philadelphia, Tripoli, Libya

- The Navy: The Continental Period, 1775–1890

- Officers of Peculiar Skill: Petty and Forward Officers of the U.S. Navy, 1797–1860

- Surface Navy: Age of Sail

- Swords: The Cutlass carved its Niche in our Navy’s Annals

- Officers of the U.S. Navy/Marine Corps, 1775–1900

- The Reestablishment of the Navy, 1787–1801: Historical Overview and Select Bibliography

- Bibliography: Quasi-War with France and Barbary Wars

- Bibliography: Shipboard Life in the Navy, 1775–1899