Apollo 10 and NASA ─ Navy Collaboration in Search and Recovery Operations

Eight days after departing this planet for a manned mission to the moon on 18 May 1969, the command module of Apollo 10 reentered Earth’s atmosphere at 32 times the speed of sound. Thousands of miles but only minutes away, the crew of Princeton (CV-37) and others on board were waiting on the flight deck for the spacecraft to appear.[1] When they caught sight of the parachutes and Apollo, having slowed into a graceful descent, Navy personnel got right to work. The sequence of operations after splashdown determined life or death for astronauts rendered helpless and vulnerable upon their return to Earth.

By Apollo 10’s splashdown on 26 May 1969, the Navy could rely on a wealth of experience in the recovery of NASA spacecraft. The first such Navy-NASA collaboration had occurred almost exactly eight years prior with the splashdown of Freedom 7 upon its return from the United States’ first manned spaceflight. The Navy’s competencies and technologies made it possible for astronauts to survive the aftermath of an ocean landing.

In the case of Apollo 10, recovery happened in record time, the product of good weather conditions, a precise reentry, and highly skilled Navy personnel. Splashdown occurred in calm waters of the South Pacific less than three miles from Princeton, the amphibious assault ship tasked with recovering the astronauts and their spacecraft. From Princeton’s deck, Navy helicopters carried some of the Navy’s best swimmers, detached from Underwater Demolition Team 11, to Apollo 10’s command module.[2]

The swimmers had trained extensively for their role in helping NASA, and they must have known that their performance could easily determine the outcome of this kind of search and recovery operation. They had to reach the spacecraft right away in order to help the astronauts get away from what could soon turn into a deadly sinking.[3]

The men aboard Apollo 10’s command module were all test pilots and veteran astronauts: U.S. Air Force colonel and mission commander Thomas P. Stafford, U.S. Navy commander and lunar module pilot Eugene A. Cernan, and U.S. Navy commander and command module pilot John W. Young.[4] He and Cernan joined a long line of naval-aviators-turned-astronauts all the way back to Captain Alan B. Shepard Jr. (USN), the first American to go to space.[5]

The three men had lifted off at 12:49 p.m. EST and had a bumpy escape from the atmosphere, after which point the mission settled into routine but highly complex maneuvers that saw the lunar module and the command service module undocked, then docked, undocked, docked, and undocked again in the course of the journey to and from the moon.

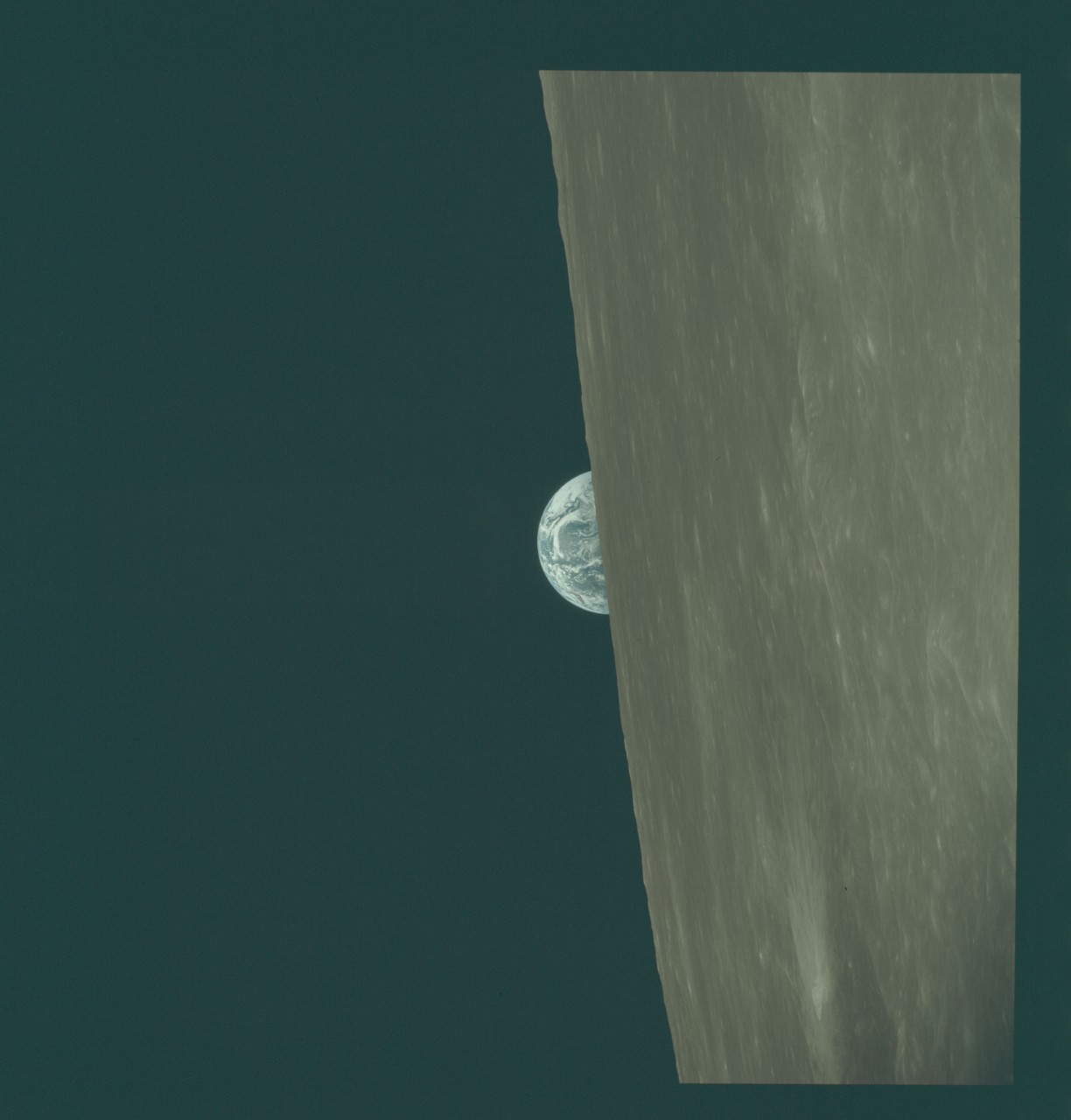

Building on successes of past missions, including Apollo 8, which orbited the moon on 24 and 25 December 1968, Stafford, Cernan, and Young became the first astronauts to orbit the moon in a spacecraft fully capable of landing a person on the moon. From just 15 kilometers above the moon’s surface, Stafford and Cernan were able to identify the landing area for future missions — a relatively flat strip which they called “U.S. 1” after the north-south highway connecting Fort Kent, Maine, to Key West.[6]

Having viewed the landing sites, overseen the production of lunar maps by robotic probes, and fulfilled all the other primary mission objectives, Cernan, Stafford, and Young wrapped up the final dress rehearsal for landing a person on the moon. As historian Greg Tomko-Pavia observes, the success of Apollo 10 “gave NASA planners the final bit of confidence they needed” in order to launch Apollo 11 in July of the same year.[7]

To help ensure the success of this next mission, the astronauts of Apollo 10 debriefed NASA and Navy officials and scientists on board Princeton. According to Glynn S. Lunney, chief of the Flight Director’s Office at NASA, the mission “went well, everything behaved well, and basically the whole system, hardware, and people, passed the clearance test that we needed to pass to be sure that we could go land on the moon on the next one.”[8]

For their efforts, the astronauts also enjoyed sumptuous meals organized by Princeton’s crew. In addition to eggs, any style, and crispy bacon for breakfast, there was filet mignon and passionfruit juice. Dinner featured a variety of delicacies: shrimp cocktail, broiled rock lobster tails, Southern fried chicken, potatoes lyonnaise, broccoli hollandaise, and — for dessert — baked Alaska, ice cream sundaes, strawberry shortcake, and apple pie à la mode.

Princeton next returned to her homeport of Long Beach, California, where the recovery ship (Hornet) for the next mission (Apollo 11) lay waiting. And it was aboard Hornet (CV-12) that NASA and Navy planners met to review Princeton’s after-action report and apply lessons learned to the search and rescue procedures for Apollo 11’s splashdown the following month.[9]

––Adam Bisno, Ph.D., Communication and Outreach Division, Naval History and Heritage Command, April 2019

[1] Scott W. Carmichael, Moon Men Return: USS Hornet and the Recovery of the Apollo 11 Astronauts (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2010), 21.

[4] Mark L. Evans and Roy A. Grossnick, United States Naval Aviation, 1910–2010, vol. 1: Chronology, fifth edition (Washington, DC: Naval History and Heritage Command, 2015), 374; Greg Tomko-Pavia, “Apollo 10,” in USA in Space, vol. 1: Air Traffic Control Satellites –– ITOS and NOAA Meteorological Satellites 1–678, third edition, edited by Russel R. Tobias and David G. Fisher (Pasadena, CA: Salem, 2006), 96–97.

[5] Stafford graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1952. See William David Compton, Where No Man Has Gone Before: A History of Apollo Lunar Exploration Missions (Washington, DC: NASA, 1989), 367–68. Cf. Eric Christensen, “Astronauts and the U.S. Astronaut Program,” in USA in Space (op. cit.), 1:188–189.

[6] Tomko-Pavia, “Apollo 10,” 99.

[8] Quoted in an interview in “Before this Decade Is Out…”: Personal Reflections on the Apollo Program, ed. Glen E. Swanson (Washington, DC: NASA History Office, 1999), 209.