Winds of War, Winds of Change: The U.S. Naval Academy During the World War II Era

During World War II, the U.S. Naval Academy went into high gear to produce quality officer material for the two-ocean war. While only 5 percent of the total number of serving naval officers in the war were academy graduates, the school produced the professional core around which the Navy’s unprecedented expansion from 119,088 uniformed personnel in 1938 to 3,405,525 in 1945 could occur. Nearly all of the war’s key naval leaders—including William Halsey, Class of 1904; Ernest King, ’01; Chester Nimitz, ’05; and Raymond Spruance, ’06—were graduates. Altogether, alumni from 54 classes participated in the war. Between 1941 and 1945, the academy contributed more than 7,500 officers to the fleet. The losses for the classes of 1934, 1935, 1936, and 1937 were 12, 14, 16, and 14 percent respectively. The overall loss rate for academy graduates serving in the war was 6 percent. The war not only served to validate the academy’s very existence, but also brought about tremendous change. The war period and the years immediately thereafter led to the creation of new curricula, new facilities, and new ideas about naval education. Expanded classes of midshipmen from different demographic groups and new faculty recruited from civilian schools and the ranks of wartime veterans changed the institutional culture of the academy. This new blood set the institution on a course to evolve beyond its traditional place as a highly prestigious officer-training academy to a top-ranked academic institution in its own right.

The Naval Academy went on a wartime schedule in the summer of 1940 following the German attack on France, Congress’s decision to implement a peacetime draft, and President Roosevelt’s decision to extend “aid to Britain short of war.” A three-year curriculum was designed for the Class of 1943 and its successors. Moving some coursework to the summer months made it possible for the academy to squeeze 88 percent of its four-year curriculum into the newly accelerated program. The Navy recruited civilian educators to replace officer instructors dispatched to the fleet, and commissioned these new instructors into the Naval Reserve. Summer cruises were postponed and midshipmen trained on local waters, thus becoming the “salty sailors of the Chesapeake.”

To further increase officer output, the number of appointees allowed for each Congress member was moved from four to five. The academy also reinstated a Naval Reserve officer training program (NROTC) similar to the one that had been instituted in World War I to help make up for officer shortfalls. The first class of college graduate midshipmen reported for duty in February 1941. In May of that year, the Naval Academy graduated its first class of 583 reserve ensigns. In all, the Naval Academy trained and commissioned 3,319 reservists through this program and 4,304 regular officers via the traditional academy.

Sunday, 7 December 1941, was a normal day on campus complete with chapel, touring visitors, and a hop at Smoke Hall. The dance was still going when word began circulated of the attack. Guards escorted all visitors out the gates and small craft put out to secure the waterfront. Shortly afterward, blackout blinds were installed and lower decks of buildings became air raid shelters. Midshipmen took turns serving on fire watches and guard patrols. As one class of 1943 member described it, “The academy went wild with excitement.” But, despite increased security, life on campus retained a surprising degree of normalcy throughout the war. Rear Admiral John R. Beardsall, ’08, a former naval aid to President Roosevelt, served as the superintendent for much of the war. Under his command, the academy continued to run smoothly. The Navy provided the academy with a constant stream of new knowledge about developments in naval tactics and technology as well as the latest training equipment. Officers fresh from combat returned to the academy to teach lessons learned from the war, and the athletic program was restructured to guarantee 100 percent participation. A 22-acre playing field was created from dredged landfill off Cemetery Point. The academy also considered expanding its grounds by annexing the campus of St. John’s College, but eventually gave up on the idea.

Many traditional social functions and athletic events endured during the war years, including intercollegiate football. As one member of the Class of 1944 explained, “Of course, we read about the war in the newspapers and we expected that we’d be getting back into it, but it didn’t really worry us. We were eighteen or nineteen years old, and in the final analysis the war wasn’t something that concerned us at the moment. We wanted to have a good time while we could.” Once in the war, however, these men assumed their leadership roles with the utmost seriousness. Lieutenant Richard M. McCool, Jr., a 1944 Naval Academy NROTC graduate, typified the remarkable transformation that took place for many of these young men shortly after graduation. Just a year out of the academy, he commanded the landing craft support ship LCS(L)-22 during the battle of Okinawa. On 10 June 1945, he assisted in recuing survivors of a kamikaze attack on a nearby destroyer. The next day, his own ship was attacked by two suicide aircraft. The ship’s gunners shot down one, but the other crashed into McCool’s station in the conning tower, engulfing the area in flames. Although suffering from shrapnel wounds and painful burns, he rallied his concussion-shocked crew and initiated immediate firefighting measures. He then rescued several crew trapped in a blazing compartment, even carrying one wounded man to safety despite his own serious wounds. He continued damage control efforts until other ships arrived to assist. McCool received a Medal of Honor for his heroism. The Navy recently named its 13th San Antonio–class amphibious transport dock ship in his honor.

Lieutenant Richard M. McCool, Jr., is presented with the Medal of Honor by President Harry S. Truman at the White House, Washington, DC on 18 December 1945. The medal was awarded for conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity while McCool was commanding officer of USS LCS(L)-22 off Okinawa in June 1945 (80-G701648).

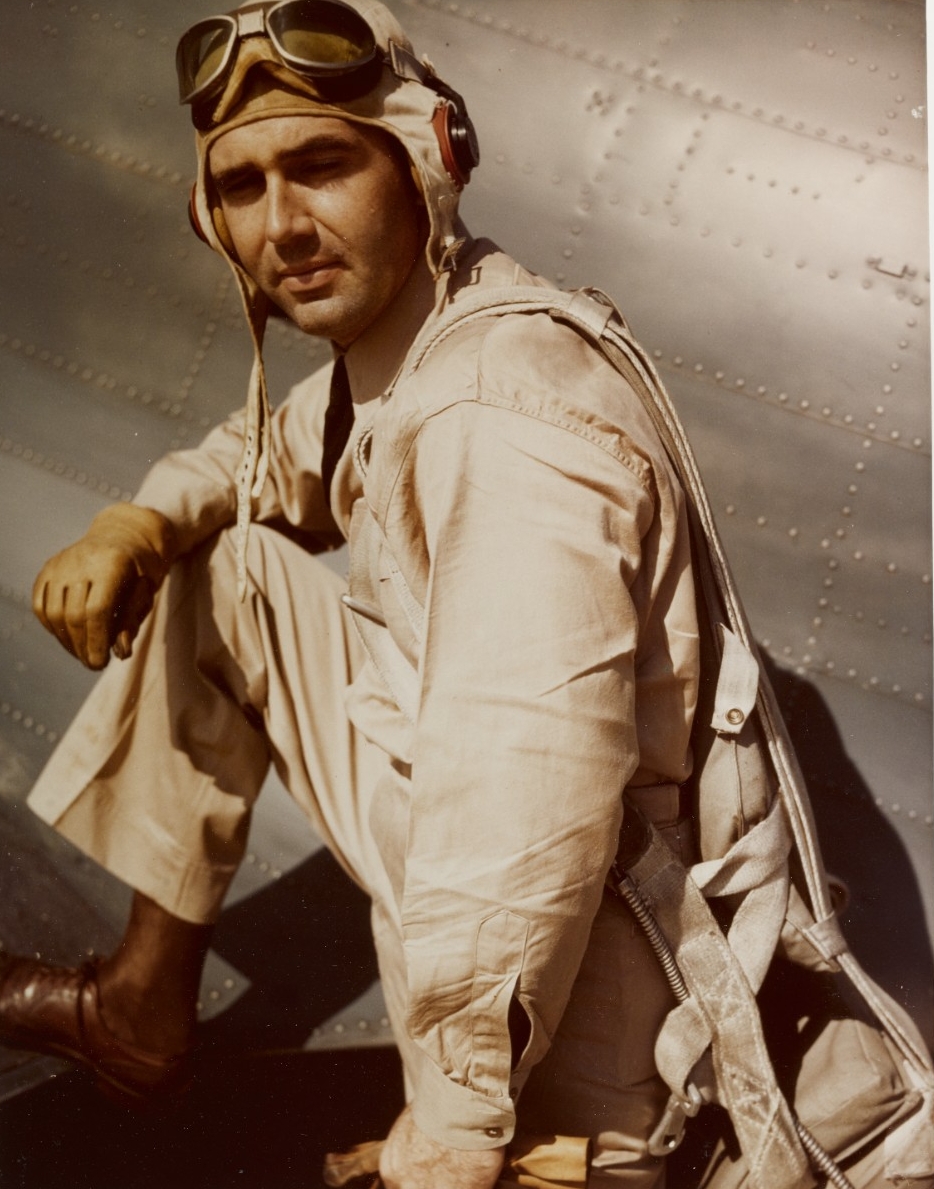

All told, 27 alumni were awarded the Medal of Honor, all of them in the Pacific, 14 of them posthumously. The Navy’s first Medal of Honor recipient in World War II was Lieutenant Edward “Butch” O’Hare of the Class of 1937. On 20 February 1942, O’Hare placed his F4F Wildcat fighter between his ship, the Lexington (CV-2), and an advancing enemy formation of nine twin-engine bombers. Without hesitation, alone and unaided in his aircraft, he repeatedly attacked the formation, downing five of the bombers and severely damaging a sixth with his machine guns. “As a result of his gallant action—one of the most daring, if not the most daring, single action in the history of combat aviation,” reads his citation, “he undoubtedly saved his carrier from serious damage.” O’Hare also emerged from the mission as the Navy’s first flying ace. He later died in combat in November 1943 during a night attack against a Japanese bomber. The international airport in Chicago is named in his honor.

The war years at the Naval Academy not only produced a slew of war heroes, but also the academy’s first and only U.S. President, James Earl Carter, Jr., ’47. Midshipman Carter never made it to the fleet during the war, but did experience a wartime training cruise on USS New York (BB-34). “I manned a 40-mm anti-aircraft gun battery during the frequent alerts,” he wrote in his memoir, “and was responsible for cleaning the ‘after head’.... During rough weather the wastes were thrown onto the deck, drenching the floor and also those at the time who were using the toilet. This was not a favorite cleaning station.”

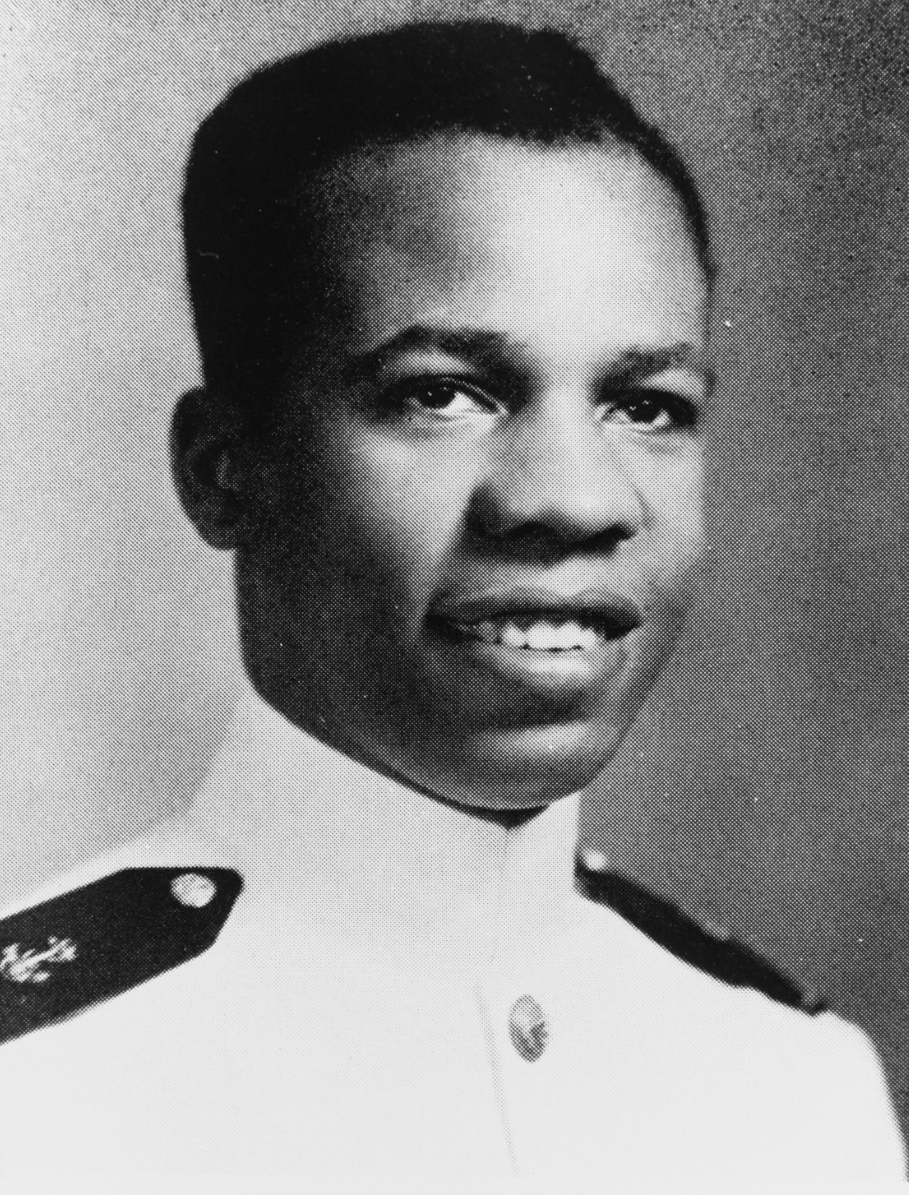

In addition to experiencing the rough discipline and hazing of the period (which included being hit by brooms or heavy aluminum pans by upperclassmen), Carter also bore witness to demographic changes at the academy brought about by the war. The number of regular midshipmen at the academy increased from 2,250 in 1920 to 3,000 in 1945. More and more midshipmen came from families not associated with the Navy and from regions of the country far from the coasts. In 1945, the academy admitted its sixth black midshipman, Wesley Brown. All prior attempts to graduate an African American had failed due in part to the harsh treatment these midshipmen received at the hands of racist upperclassmen. Given that many blacks had served honorably in the Navy during the war and by the end of the conflict comprised 5.5 percent of the force, it was imperative for the Navy to begin commissioning more black officers, especially from the academy. That Wesley Brown was able to graduate in 1949 is a testament to his unique character, the changing institutional culture of academy, and also the helping hand provided by a select group of upperclassmen, including Jimmy Carter, who ran on the cross-country team with Brown. Carter, who came from rural Georgia, received tremendous flak from other southern classmates for being an outspoken proponent of racial equality and an encouraging mentor for Brown. The Wesley Brown Field House stands today as a tribute to Brown and the academy’s commitment to equal opportunity.

World War II not only changed the demographics of the school, but also its entire philosophy of naval education. New types of warfare became more significant as the war progressed, including submarine warfare (Carter’s chosen specialty), amphibious operations (with its emphasis on the Navy-Marine team), and air warfare. Recognizing these changes, the Navy appointed Vice Admiral Aubrey W. Fitch, ‘06, who had commanded the Lexington group at the Battle of Coral Sea and later served as the Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Air, to replace Beardsall in August 1945. As the first aviator to become superintendent, he immediately set about expanding the academy’s aviation program by creating a new Department of Aviation. Plans were also made to establish a naval air station in Annapolis, but none was ever built. Seaplane trainers based in hangars on the Severn were utilized instead.

When the cease-fire came in the Pacific on 14 August 1945, the academy declared a two-day holiday, pandemonium broke out on Tecumseh Court, and the Japanese Bell rang endlessly. The Naval Academy celebrated its centennial during a week of celebrations in October 1945. In a newly reorganized brigade, 3,000 midshipmen marched in honor of the school that day—many in period uniforms from 1845, 1870, and 1900. But the end of the war also spelled potential trouble for the Naval Academy. To lead a large post-war Navy of 500,000, Secretary of the Navy James V. Forrestal put forth a plan to convert the academy into a two-year postgraduate commissioning school for young men who had already completed three years of college. Vice Admiral Louis E. Denfeld, ’12, convened a board to study the issue. The body, headed by Rear Admiral James L. Holloway, Jr., ’19, considered a number of options designed to increase the Navy officer corps, including the Forrestal plan. The one ultimately adopted by the Navy proposed expanding the Naval Reserve Officers Training Corps at civilian colleges and universities to fill the gap. The Holloway plan ultimately approved by Congress offered scholarships and stipends to students in programs at more than 50 schools in exchange for two years of service after graduation. The new NROTC program soon produced as many officers as the Naval Academy (and eventually many more) and made it possible to preserve the academy as a four-year academic institution. It also extended the presence of the Navy to places in the country devoid of ships and other visible symbols of the sea services, thus serving an important outreach role.

Holloway, a veteran of both World Wars and the father of future Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) James Holloway III, ’22, fittingly became superintendent in 1947. Under his tutelage, the school developed a balanced, basic curriculum comprised of fundamental sciences and humanities similar to the core curriculums offered at many top civilian schools such as Columbia University and the University of Chicago. Without ignoring professional military education, Holloway helped transform the school from what CNO Elmo Zumwalt, ’42, once called a “glorified trade school” to one of the top colleges in the United States (today ranked sixth in the National Liberal Arts Colleges category in Best Colleges, published by US News). Symbolizing this shift to a more academically credible curriculum was the decision of the Middle States Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools to provide the academy with its first academic accreditation in 1947.

World War II, in short, transformed the U.S. Naval Academy in very significant ways. The wartime leadership and heroism of academy graduates proved beyond doubt the value of the institution in producing future naval leaders. Rapid changes brought about by the war and the ease in which faculty and midshipmen alike responded to these changes set the stage for more dramatic evolution following VJ Day. After the war, a new generation of superintendents leveraged their wartime experiences to further modernize both the professional and academic curriculums of the school. The school also emerged from the war looking more like the United States in demographic terms (although much more work would need be accomplished in this area, especially with regard to minorities and eventually women). Finally, the war and subsequent Holloway plan insured that the U.S. Naval Academy would not become a two-year officer candidate school, but remain a four-year academic institution in its own right—one whose prestige would only grow stronger in the next decades.

—John Darrell Sherwood, PhD, NHHC History and Archives Division

____________

Sources

Robert J.

Schneller, Jr., Breaking the Color

Barrier: The U.S. Naval Academy’s First Black Midshipmen and the Struggle for

Racial Equality. New York: New York University Press, 2005.