Commodore Robert Field Stockton: A Legacy of Accomplishment and Controversy

20 August 1795–7 October 1866

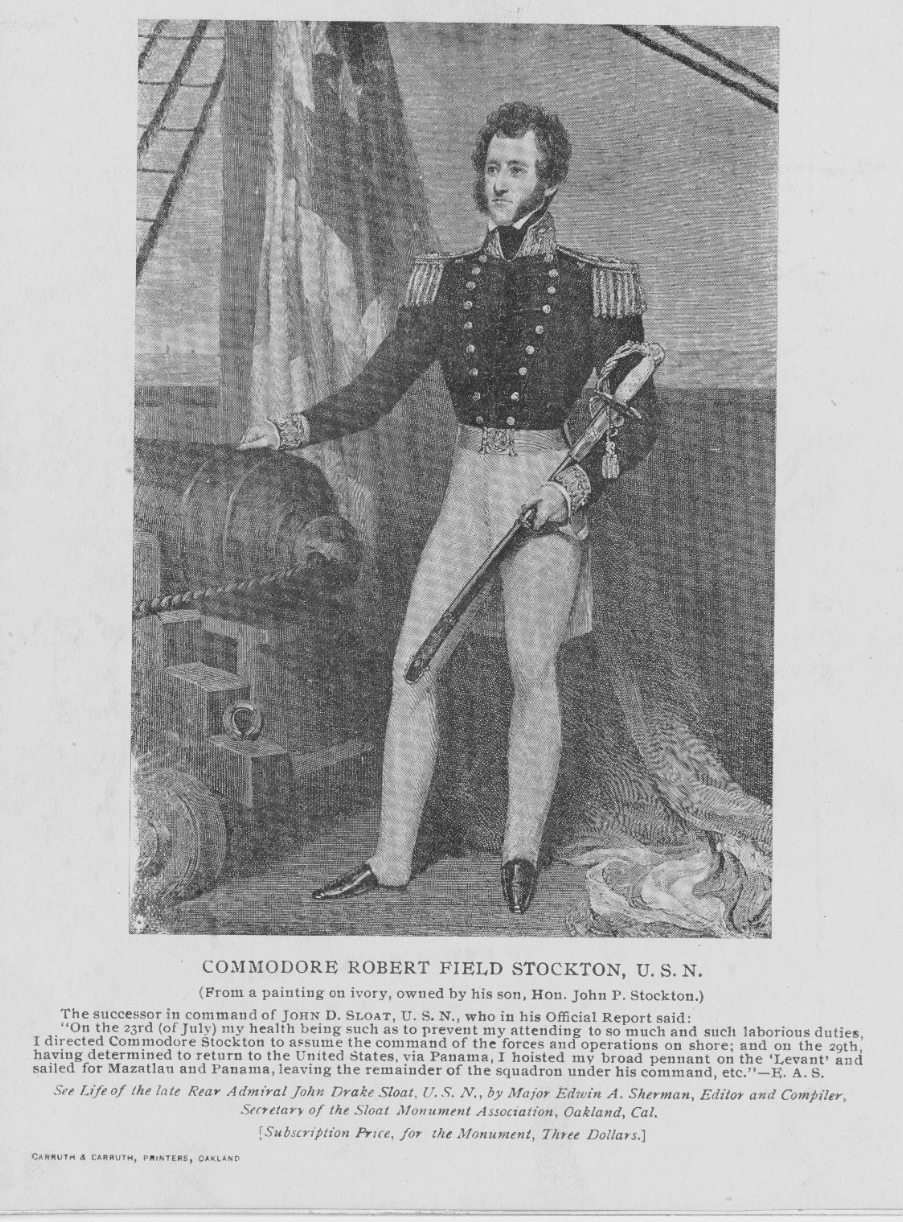

Commodore Robert F. Stockton, USN. Halftone reproduction of a 19th-century engraving, printed by Carruth & Carruth, Oakland, California, for the Sloat Memorial Association of Oakland. The original engraving was based on a painting on ivory owned by Commodore Stockton's son, the Hon. John P. Stockton. Stockton relieved Commodore John D. Sloat as commander of the Pacific Squadron in July 1847. U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph. (NH 44394)

Commodore Robert Field Stockton was a multifaceted man with a legacy of both accomplishments and controversy. Stockton had a successful naval career, but he was also known for being impetuous and pushing the bounds of his authority. He was recognized as a master diplomat, demonstrated by his roles in the establishment of Liberia in 1821 and in the annexation of Texas in 1845, but he was known to employ threats and violence as part of his negotiations. He distinguished himself as a captor of pirate ships engaged in illegal activity, but often employed pirate techniques in order to do so, including pushing the limits of the U.S. Navy’s authority in international waters and on foreign soil. He was a strong advocate for abolishing flogging in the U.S. Navy, but was involved in at least two duels, and threatened to cane a British sailor whom he had just shot in the leg. He intercepted and captured merchant ships carrying slaves, but employed slave labor on his investment properties in Virginia and Georgia.[1] Stockton also had a pivotal role in the annexation of California and surrounding territories to the United States during the Mexican-American War. After retiring from the Navy, he was elected as U.S. senator by the state of New Jersey in 1851.

At the age of 16, Stockton dropped out of college to join the Navy at the onset of the War of 1812. He served with distinction during the conflict, and was commissioned as a lieutenant in 1814. While serving in the Mediterranean aboard Erie, Stockton became an outspoken advocate for abolishing flogging as punishment aboard Navy ships. When he took command of Alligator in 1821, Lieutenant Stockton made a display of throwing the ship’s lash overboard. (In 1851, as a U.S. senator, Stockton would sponsor a bill to abolish flogging in the U.S. Navy.)

Stockton continued to live up to the nickname (“Fighting Bob”) that he had earned in the War of 1812 long after the war ended. He was involved in two documented duels in 1817 as a lieutenant serving on Erie. The first duel was in Naples, Italy, with a British sailor. This duel ended when Stockton shot his opponent in the leg. The other duel was with a midshipman aboard Erie, in which neither Stockton nor the midshipman hit one another before declaring that both were satisfied.[2]

In 1821, Lieutenant Stockton took command of the newly commissioned schooner Alligator. He had successfully petitioned Secretary of the Navy Smith Thompson to allow him to use Alligator to patrol the west African coast in search of American ships illegally engaged in the trafficking of slaves in violation of the 1807 Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves, and also to search for a location to resettle freed American slaves.

The effort to relocate freed slaves was not without controversy. A representative of the American Colonization Society, Dr. Eli Ayres, was on board Alligator to assist Stockton in the search for this new colony. The society was supported by Southern slaveholders, who were concerned that freed slaves would bolster the growing abolition movement and would embolden enslaved people to revolt. Frederick Douglass addressed this relocation effort in an 1852 newspaper editorial, stating, “There is no sentiment more universally entertained, nor more firmly held by the free colored people of the United States, that that this is their own, their native land.”[3]

Stockton and Ayres located land on the west African coast that would become Liberia and negotiated a contract with local African leaders (described as “kings” in Ayres’ accounts) to purchase approximately 140 acres. The Americans offered trade goods that included tobacco, gunpowder, rum, and items of clothing and household provisions, altogether worth about $300. Ayres kept a detailed account of the negotiations. A popular assertion that the African leaders were coerced at gunpoint, on the order of Stockton, to agree to the sale, has been challenged by some historians.[4] Some accounts, however, describe a scene in which Stockton, dressed as a civilian during the negotiations, deliberately drew and cocked a pistol, then gave it to Ayres, saying, ”…‘Shoot that villain if he opens his lips again!’”[5] Whether the African leaders were coerced or willingly agreed to the exchange, Liberia was established on the west coast of Africa in 1821.

After his success in Africa, Stockton sailed for home, capturing several vessels on this voyage back to the United States. He captured the Portuguese ship, Marrianna Flora, under dubious claims that the ship was engaging in piracy. The capture of Marrianna Flora was later declared illegal by the District Court of the United States at Boston, and the ship was ordered to be returned along with an award of a “large amount” as damages. Stockton appealed the decision, and the case eventually made its way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which found in his favor. Marrianna Flora was eventually returned to the Portuguese government, but the ship was surrendered out of comity rather than any admission by the U.S. government of wrongdoing on the part of Stockton or the U.S. Navy.[6]

Stockton also captured the French slave-trading ship Jeune Eugenie on his cruise home from Africa. Although the ship was not sailing under an American flag, and Stockton’s mission on Alligator was specifically to intercept American merchant ships acting in violation of the Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves, Stockton made the decision to expand his authority to any ships engaging in the trafficking of slaves, whether they displayed an American flag or not. Stockton’s reasoning was that any such vessel made it, ipso facto, a pirate, and therefore free for the taking. When the resulting case was heard by the U.S. Supreme Court, the court again ruled in Stockton’s favor. Associate Justice Joseph Story, who had also written the Marrianna Flora decision, stated that the slave trade was prohibited by both “universal law and by the law of France,” and therefore a French ship engaged in slave trafficking could be justly considered a pirate ship, and therefore had no international legal protections.[7]

After his return from Africa, Stockton continued to apprehend ships engaged in slave trading closer to home, primarily off the coast of Cuba. He made the bold move of pursuing pirates on shore if he was unable to capture them at sea. As described in A Sketch of the Life of Com. Stockton, Stockton “invariably followed them ashore, and hunted them down to their dens and hiding places. In this way he gave serious check to their nefarious depredations, and inspired them with a salutary terror of American retribution.” Stockton disregarded the fact that Cuba was Spanish territory at the time. “If the Spanish authorities were unable to restrain the inhabitants of Cuba from such atrocities, they had no reason to complain if, in hot pursuit, their shores were invaded for the purpose of chastising the enemies of all mankind.”[8]

In 1826, after 16 years at sea, the U.S. Navy granted Lieutenant Stockton extended shore leave in his home state of New Jersey. In addition to personal and business pursuits that included racehorses, politics (he actively opposed the reelection of President Martin Van Buren, and campaigned for William Henry Harrison[9]), and time with his family, Stockton studied naval architecture and gunnery. Stockton requested permission from the Navy to build a steam-powered ship-of-war. He successfully argued that England and France had outpaced the U.S. in steam technology in their navies. He was granted permission to build the first screw steam warship of the U.S. Navy, Princeton. It was completed in 1844, with Captain Stockton in command.[10]

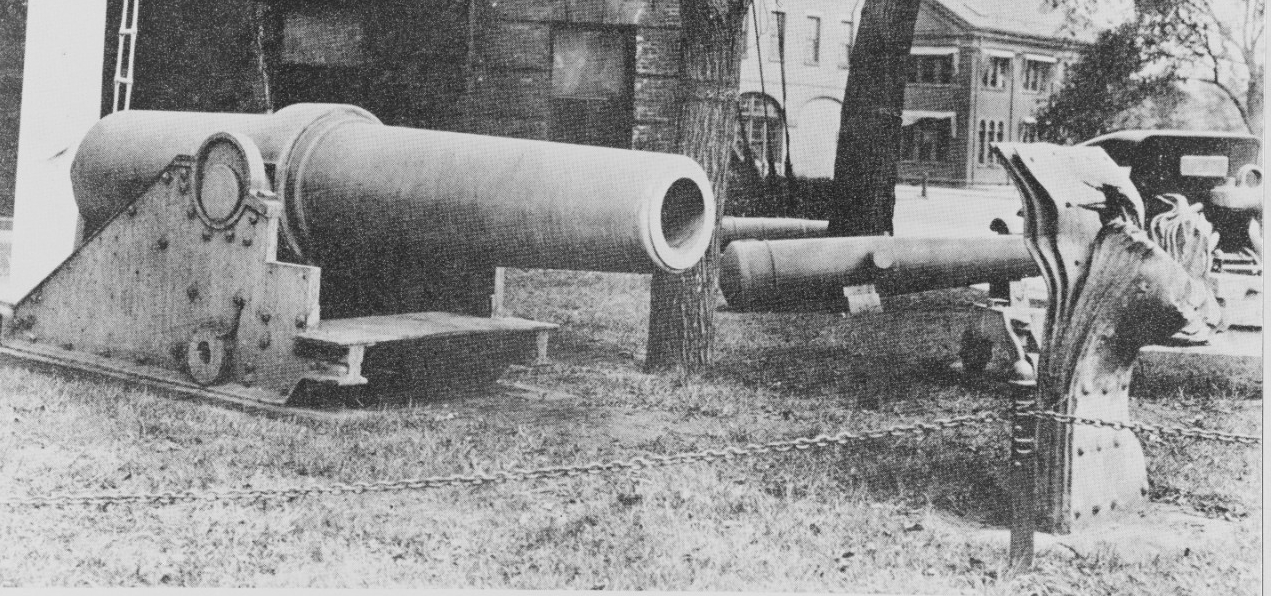

In February 1844, President John Tyler was almost killed while onboard Princeton during a demonstration of a new 12-inch, 27,000-pound cannon dubbed the Peacemaker, which Stockton had helped design with naval engineer John Ericsson. During a cruise on the Potomac, after successfully firing the cannon twice, its third round caused it to explode. Several people onboard Princeton were killed in the explosion, which would be the deadliest peacetime disaster of its time. These included Secretary of State Able P. Upshur; Secretary of the Navy Thomas Gilmer; Captain Beverly Kennon, Chief of the Bureau of Construction, Equipment, and Repairs; Representative Virgil Maxey of Maryland; Representative David Gardiner of New York; and a servant of the President. Representative Gardiner would have been President Tyler’s father-in-law had he lived to see his daughter become the First Lady.[11] John Ericsson had argued with Captain Stockton that the cannon was not ready for a demonstration, but Stockton had bragged of the cannon’s capabilities to President Tyler and insisted on firing the Peacemaker while the President was onboard Princeton—with disastrous results.[12]

A court of inquiry, convened in March 1844, exonerated Captain Stockton and his crew of any wrongdoing in the disaster. The court concluded, “In regard to the conduct and deportment of the captain and officers of the Princeton on the occasion of the deplorable catastrophe which occurred on the 28th of February last, the court feels itself bound to express its opinion that in all respects they were such as were to be expected from gallant and well-trained officers, sustaining their own personal character and that of the service:—marked with the most perfect order subordination, and steadiness.”[13]

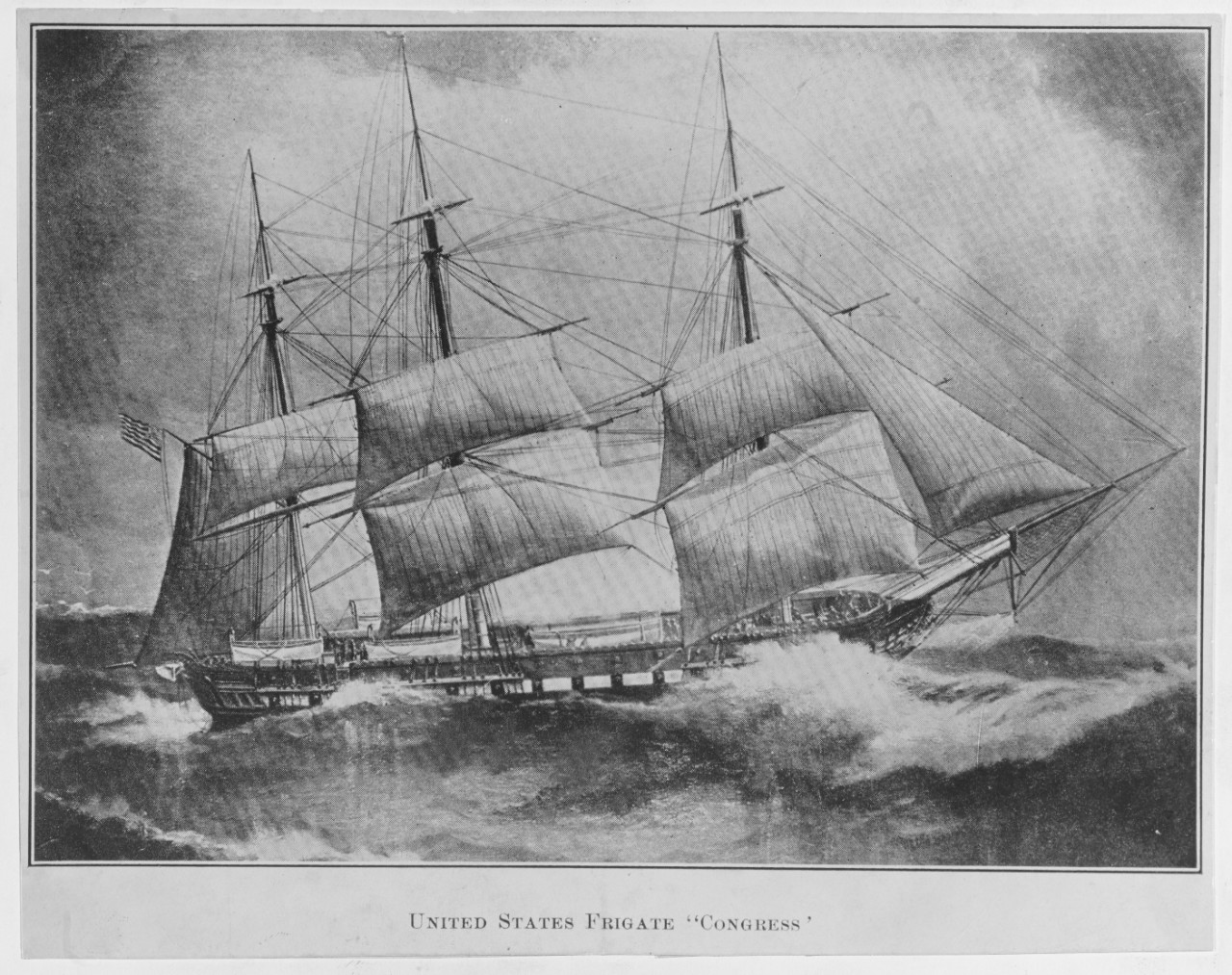

In 1845, President John Tyler selected Stockton to carry the congressional resolutions on the U.S. annexation of Texas to Galveston aboard Princeton. Stockton was successful in this diplomatic mission. While in Texas, however, he became convinced of an inevitable war with Mexico and, after his return, his impressed on Tyler his desire to take an active part in any forthcoming hostilities. Tyler subsequently had Stockton dispatched to the coast of California in command of the frigate Congress. In July 1846, Commodore Stockton took command of the Pacific Squadron from Commodore John Sloat, who had already claimed Monterey for the United States. Stockton combined his landing force with Army units commanded by Brigadier General Stephen Kearny in 1846. This force was eventually augmented with American “Bear Republic” volunteers led by John Fremont. The combined American forces took control of Alta, California (now the modern states of California, Nevada, and Utah, as well as parts of Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Wyoming). The Treaty of Cahuenga of 13 January 1847 ended hostilities with Mexico and placed California and surrounding territories under the control of the U.S. government.[14]

President James K. Polk had succeeded Tyler by the end of the Mexican-American War, and placed Commodore Stockton in charge of the conquered territories. The 1846 Annual Report of the Secretary of War states, “Commodore Stockton took possession of the whole country as a conquest of the United States, and appointed Colonel Fremont governor, under the law of nations, to assume the functions of that office when he should return to the squadron.”[15]

In 1849, Stockton resigned his commission in the U.S. Navy and focused on a political future. Peace had been restored between the United States and Mexico the previous year (1848). Although the United States now had no quarrel with any foreign nation, the internal antagonisms preceding the Civil War were becoming more heated as the country expanded west and the balance of federal power was increasingly questioned. When nominated for a senate seat by the Democratic Party of New Jersey in 1850, Stockton declined. In his letter declining the nomination, he made his opinion on the high importance of preserving the Union clear: “Survive who may, perish who will, the Union must be preserved.”[16]

Despite Stockton’s rejection of his nomination, he was nonetheless elected as a senator representing New Jersey in Congress in 1851. Stockton became the first retired naval officer to be elected to Congress, but was not the first member of his family to serve in that institution.[17] Stockton’s father and grandfather had also served in Congress, and his grandfather, Richard Stockton, had been a signer of the Declaration of Independence.[18] (Delaware Senator Louis McLane had briefly served as a Navy lieutenant prior to being elected, but did not make a career in the service. He had a distinguished career in law prior to realizing his political ambitions.) Other members of Congress “were disposed to sneer at the election of a sailor to the Senate of the United States” when Stockton was first elected.[19]

Stockton resigned from the Senate in 1853 and took a position as president of the Delaware and Raritan Canal company until 1866. In 1856, he was a candidate for nomination in the short-lived American Party (the nomination went to former President Millard Fillmore.)[20] As differences between the North and the South intensified, Stockton embraced a role as peacekeeper in attempts to prevent a war, including serving as a delegate to the failed Peace Conference of 1861, when 131 politicians met in Washington, DC, on the eve of the Civil War in an unsuccessful attempt to preserve peace between the states. In 1863, he took command of the New Jersey militia following the Confederate army’s invasion of Pennsylvania.

Commodore Robert Stockton died on October 7, 1866, and is buried in Princeton Cemetery in Princeton, New Jersey. He served in the Navy for 39 years, from 1811−1850, and through two wars (not including his militia role in the Civil War). Stockton’s legacy includes three namesake ships (Torpedo Boat No. 32, Destroyer No. 73, and DD-646). Schools, streets, cities in California and Missouri, a New Jersey borough, and even a creek in California have been named in honor of Commodore Stockton. His legacy also includes the founding of Liberia, the abolition of flogging in the Navy, the first U.S. Navy steam-powered ship-of-war, and the creation of the American states of Texas and California. Although not without controversy in his views and his methods, Commodore Stockton’s legacy in U.S. Navy and the United States' history is without question.

__________________________

1 R. John Brockman. Commodore Robert F. Stockton, 1795-1866: Protean Man for a Protean Nation (Cambria Press, 2009).

2 Charles Oscar Paullin. “Dueling in the Old Navy,” USNI Proceedings, Vol. 35/4/132.

3 Amy Crawford. “How One Historian Located Liberia’s Elusive Founding Document,” Smithsonian Magazine, July/August 2022 (https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/liberias-founding-document-located-180980339/).

4 Ibid.

5 A Sketch of the Life of Com. Robert F. Stockton (Derby and Jackson, 1856), 46.

6 Ibid., 49-50

7 Ibid., 51-53

8 Ibid., 53

9 Ibid., 79-80

10 Dictionary of American Fighting Ships (DANFS)

11 Dictionary of American Fighting Ships (DANFS)

12 “Tyler narrowly escapes death on the USS Princeton,” https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/tyler-narrowly-escapes-death-on-the-uss-princeton

13 A Sketch of the Life of Com. Robert F. Stockton (Derby and Jackson, 1856), 92

14 Ibid., 142-156

15 Ibid., 155

16 Ibid., 185

17 Ibid., 187

18 Ibid., 9

19 Ibid., 187

20 Ibid., 198-210