Uniforms of the U.S. Navy 1776-1783

At the outbreak of the American Revolution in 1775, there were no warships available for use by the revolting colonists, but Americans had had long experience in maritime affairs. Much of the British trade had been carried in American bottoms, and North Americans had made up a large portion of the seamen in the Royal Navy. Although no ship larger than a frigate had ever been built in the colonies, it was not long before commerce raiders, flying the flag of the new country, were on the high seas. Various states created navies, primarily small vessels in an attempt to protect their shores and shipping from the British, and issued letters of marque to privateers.

The first attempt to place a Continental naval force afloat was instituted by George Washington as Commander-in-Chief of American forces at Boston in 1775. Small rented vessels, manned by New England seamen from Washington’s army, made some important captures of badly needed military supplies. Congress, realizing the need for a naval force, appointed a Naval Committee on 5 October 1775, to manage all seaborne military activities and in the same month, authorized the procurement of four ships to be used against the British. By a Resolution of 13 December 1775, Congress authorized the construction of thirteen frigates, ranging from 24 to 32 guns. Although the naval strength of the new republic was never great, the combination of the Continental Navy, the State forces and the privateers caused great injury to the British war effort and shipping, not only in North American waters, but also near the British Isles. The loss to British trade has been estimated at $90,000,000 and many valuable cargoes were diverted to American use.

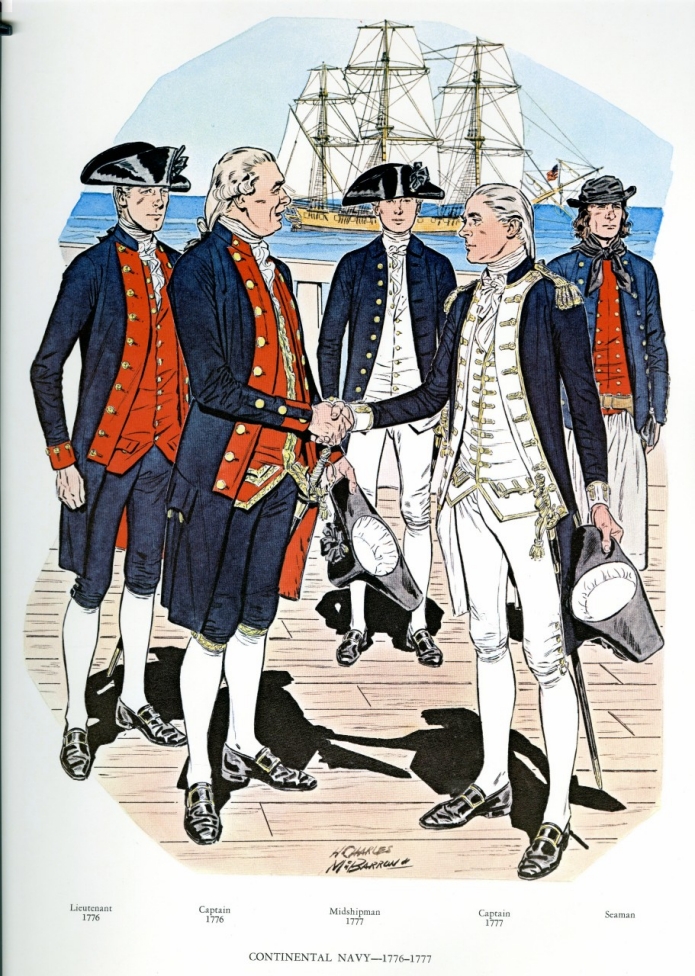

The Naval Committee, known generally as the Marine Committee, was responsible not only for the procurement of ships, but also for all other functions relative to forces afloat. A uniform instruction was issued on 5 September 1776, making the following uniform provision:

“Captains—Blue cloth, with red lappels, slash cuff, stand-up collar, flat yellow buttons, blue breeches, red waistcoat, with narrow lace.

Lieutenants—Blue with red lappels, round cuff, faced with red, standup collar, yellow buttons, blue breeches and red waistcoat, plain.

Masters—Blue with lappels, round cuff, blue breeches, and red waistcoats.

Midshipmen—Blue lapelled coat, round cuff faced with red, stand-up collar, red at the button and buttonhole, breeches and red waistcoat.”

It is to be noted that no provision was made for epaulets although the same order directed that Marine Corps officers wear a silver epaulet on the right shoulder of their white faced, green coats. No instructions were issued for the dress of petty officers or seamen. While a uniform was prescribed for the Navy, in this period of material shortages many officers wore whatever they could procure and did not always conform to official instructions. This of course was also true of the dress of the Continental Army, for both officers and the rank and file.

Evidently the blue and red uniform prescribed by Congress was not to the liking of all officers, for a group of captains, including John Paul Jones, met in Boston in 1777 and agreed upon a new dress. The uniform selected bore a close resemblance to that of the Royal Navy and the reports of British captains of contacts with Continental men-of-war commented that it was difficult at times to distinguish between friend and foe insofar as the dress of American officers was concerned. Under the unofficial agreement, captains’ coats were to be blue, lined and faced with white, and trimmed with gold lace or embroidery. The upper part of the lapel was to button on the shoulder, a British touch. A captain was to wear an epaulet on the right shoulder. The blue coat was to be worn with a white waistcoat and breeches. Lieutenants wore the dress of a captain, without lace or embroidery, and without the epaulet. Masters and midshipmen had the same uniform as lieutenants without the white lapel facings and with turndown instead of stand-up collars.

The captain and lieutenant in the paintings on the left are shown in the uniform authorized by Congress—blue coats, faced red, with blue breeches and red vests. The captain shows a modification of the Congressional order for he has the red patch at the button and buttonhole of the collar as specified for midshipmen. There are contemporary portraits of officers of the Continental Navy which show how the official instructions were interpreted by various officers. A painting of Commodore Abraham Whipple by Edward Savage shows the official coat with red collar patches. C. W. Peale’s portrait of Captain Joshua Barney also shows the collar patches and single epaulet. Peale’s portraits of Nicholas Biddle and William Stone show them in the uniform as prescribed by the official order. Paintings of John Paul Jones show him in a variety of uniforms—the red and blue official dress, the unofficial blue and white, without an epaulet and with one or two epaulets.

The officers shown in the blue and white uniform “adopted” in 1777 represent Captain John Paul Jones and one of his midshipmen. It is to be noted that Jones is displaying two epaulets as he was depicted in contemporary paintings and busts done in France. As a “commodore” in command of a squadron of ships, Jones probably added the second epaulet to indicate his rank as that above a captain. John Adams, in an entry in his diary of 13 May 1779, wrote, after having dinner with Jones in Lorient, “…You see the Character of the Man in his uniform, and that of his officers and Marines—variant from the Uniforms established by Congress. Golden Button holes for himself—two Epaulets—Marines in red and white, instead of Green…” Since the marines were French, they naturally wore their prescribed uniform, red coat, white waistcoat and breeches. Actually the Americans serving under Jones at this time were in the minority for the crews included men from many other countries, some being British and East Indian.

Although it would be many years before the dress of enlisted men would be covered by uniform instructions in either the American or British Navies, there was a degree of uniformity in the men’s dress. In the navies and merchant services, a typical costume had developed—a short jacket, waistcoat, shirt, long full trousers or petticoat breeches, neckerchiefs and brimmed, flat topped hats. This dress is shown on the seaman behind Captain Jones.