The Occupation of Veracruz, Mexico

1914

Contents

Introduction

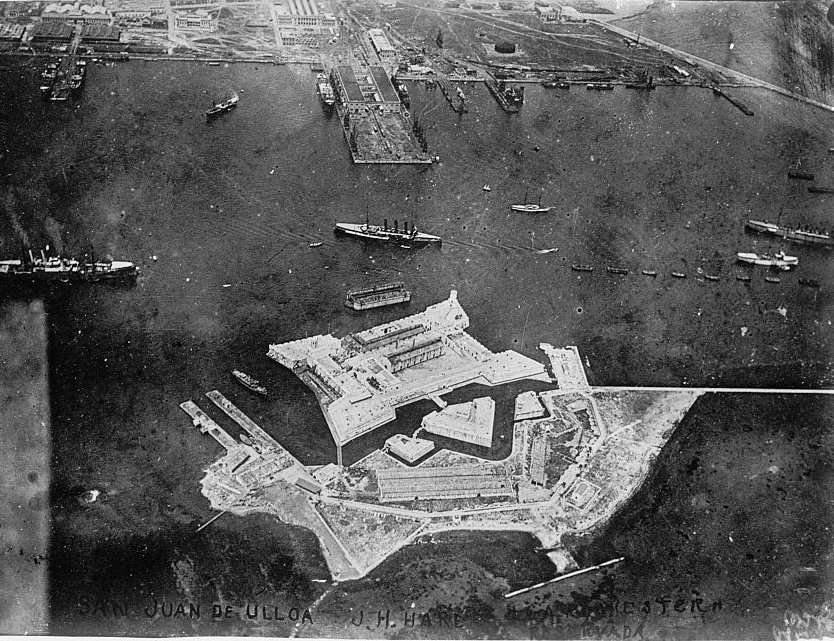

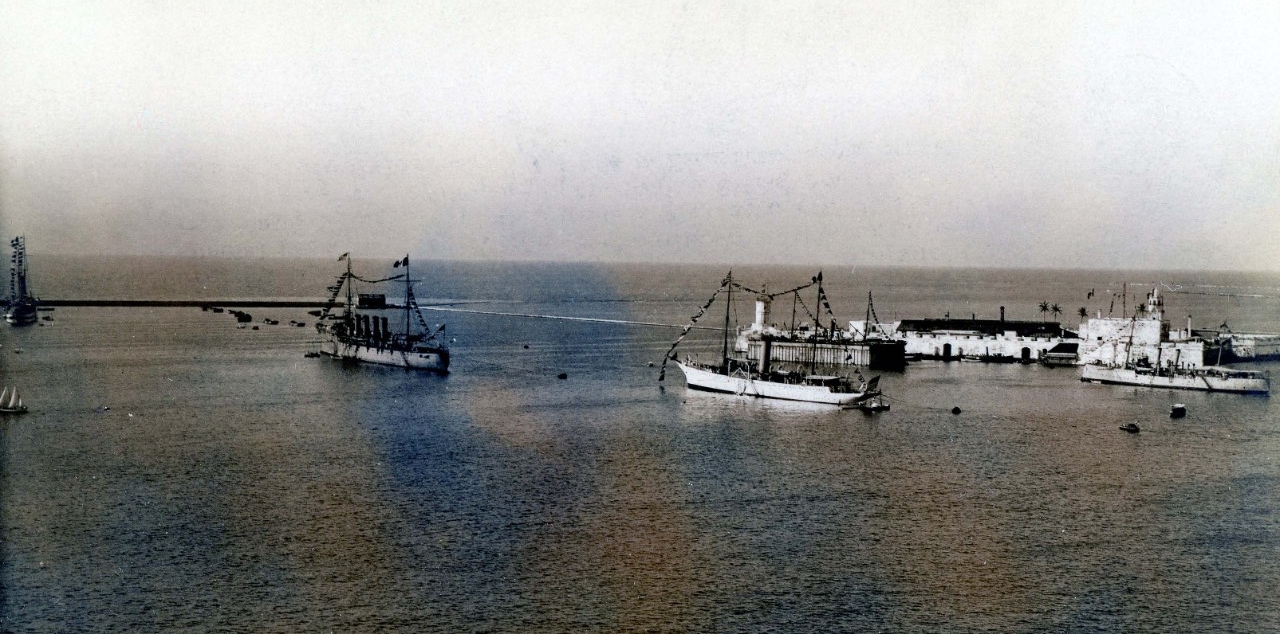

Veracruz was a city all too familiar with invasions.[1] The white-washed walls of the San Juan de Ulua fortress guarded its shoreline, but often failed to protect what lay beyond: narrow streets threading past newer homes of brick, granite, and concrete, and older homes painted in pastels or bright greens, reds, and blues. Since its founding in 1519 by Hernán Cortés, Veracruz had fallen victim to predations from various European nations. The city had fended off the English naval commander Sir John Hawkins and privateer Sir Francis Drake in 1568, but in 1838 the French had captured San Juan de Ulua and started the Pastry War (1838–1839). In 1847, the U.S. Army and Navy had paid a visit during the Mexican-American War (1846–1848), conducting the first major amphibious operation in American history and the largest prior to World War II. Army and Navy artillery batteries had worked together to lay siege to the city for 20 days, and more than 10,000 men had landed on shore in a span of five hours.[2] The Mexicans had surrendered and the U.S. military had occupied Veracruz, allowing General Winfield Scott’s forces to march on to Mexico City.

In 1914, U.S. Navy ships were once again visible along the Mexican gulf coast. At Tampico, a port city of mostly American expatriates lured by oil wells, Rear Admiral Henry T. Mayo commanded the Fifth Division of the U.S. Atlantic Fleet. At Veracruz, home of Mexico’s principal port, Rear Admiral Frank F. Fletcher commanded the U.S. Atlantic Fleet’s Fourth Division.

Mayo was 57 years old, and Fletcher was 58. Both men had spent more than 40 years in the naval service, advancing from midshipman to rear admiral. They held equal commands, neither superior to the other. Thus, Mayo could—and would—act without consulting Fletcher. A fellow officer described Mayo as “a man of business and action,” adding, “He does what he thinks is right, and as a rule he does not lose a lot of time doing it.”[3]

Fletcher had arrived in October 1913 to protect American lives and property as Mexico became embroiled in a civil war. Mayo had followed with his squadron in December of that year. General Victoriano Huerta had staged a coup d’état, overthrowing and assassinating Francisco Madero, the first democratically elected president of Mexico. Within days of Madero’s death, rival groups called Constitutionalists were revolting against Huerta, leaving the Americans in Mexico anxious about their oil holdings. The U.S. Navy’s presence brought a sense of calm to the American expatriates, but this was a false sense of security. Soon, a minor affair involving a handful of U.S. sailors would escalate to war.

The San Juan de Ulua fortress protecting the Veracruz shoreline. (Library of Congress [LC], LC-DIG-npcc-19703, https://www.loc.gov/item/2016821283/.)

The Tampico Affair

On 9 April 1914, near Tampico, eight bluejackets from Dolphin (PG-24) under the command of Assistant Paymaster Charles W. Copp traveled by a whaleboat flying American flags to a warehouse on the Pánuco River to pick up cans of gasoline. Two sailors remained in the boat while the rest carried the cans from the warehouse. Before they had finished, Mexican soldiers arrived to investigate their activities. Although the Americans were unarmed, the Mexican officer ordered them to stop loading their whaleboat. Then, he ordered the two sailors on the whaleboat to come ashore. When they hesitated, they found a row of rifles pointed at their chests. Ensign Copp told his men to obey, and the Americans were marched to the headquarters of Colonel Ramón H. Hinojosa.

Within minutes, Hinojosa released the bluejackets and allowed them to return to the warehouse, where they continued loading their whaleboat. However, they could not leave the warehouse without permission from General Ignacio Morelos Zaragoza, the Mexican commander at Tampico. The owner of the warehouse, a German named Max Tyron, hurried to Dolphin to inform Admiral Mayo of the incident. Mayo then sent Captain Ralph Earle and American consul Clarence Miller to lodge a complaint with General Zaragoza. Zaragoza was shocked at the news. He apologized profusely to Earle, but Mayo was not appeased. The whaleboat had been flying the American flag. In forcing the two sailors to leave the boat, the Mexican soldiers had abducted them from U.S. soil. Thus, Mayo believed, Zaragoza should publicly apologize to the United States of America.

Without deferring to Fletcher at Veracruz, Mayo sent a note to Zaragoza laying out his three demands: first, send Mayo a formal disavowal of the act and an apology; second, severely punish the Mexican officer responsible; and finally, raise the American flag in a prominent position on shore and salute it with 21 guns—a salute the Americans would then return. Mayo gave Zaragoza 24 hours to carry out his conditions, but agreed to an additional 24-hour extension.[4]

The American consul Miller believed Mayo’s demands to be excessive. However, he could not relay his opinion to the U.S. State Department. Diplomatic dispatches from Tampico to Washington went through Mayo’s radio to Fletcher at Veracruz, then on to the Navy’s land stations at Key West, and finally to the Secretary of State. Thus, the U.S. Navy was essentially in control of U.S. policy toward Mexico.[5]

Fletcher did not find out about Mayo’s plans until 1700 on 9 April, when Mayo sent a telegram containing sparse details of the bluejackets’ arrest along with his demands to Zaragoza. Fletcher forwarded the telegram to Washington. Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan then forwarded it to President Woodrow Wilson, who was in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia, for a weekend getaway with his family. Wilson did not consult with any of his advisors. He had long had a bone to pick with General Huerta. Both men had come to office the same year—Wilson popularly elected and Huerta through a violent coup. Wilson had immediately reversed his predecessor’s moderate policy toward Huerta, which would have eventually recognized the Mexican president, instead seeking to oust him and establish a democratically elected president in Mexico. When diplomatic efforts to remove Huerta had broken down, Wilson had imposed an arms embargo on Mexico. Mayo’s demands presented an opportunity for Wilson to put Huerta in his place.[6] He replied to the Secretary of State with a telegram that began with following sentence: “Mayo could not have done otherwise.”[7]

Like Wilson, Huerta saw opportunity in a confrontation with the United States. The rebel armies of the Constitutionalists posed a serious threat to his presidency, but a potential U.S. intervention posed a threat to all of Mexico. A common enemy could inspire the Constitutionalists to unite in support of Huerta.[8] Thus, Huerta refused Mayo’s demands.

President Wilson returned from White Sulphur Springs to the White House on 13 April.[9] On 14 April, he ordered additional ships of the U.S. Atlantic Fleet to enforce Fletcher and Mayo in Mexico. That evening, Rear Admiral Charles J. Badger, commander in chief of the Atlantic Fleet, departed Hampton Roads, Virginia, his flag flying from the new dreadnought battleship Arkansas (Battleship No. 33). Dreadnought battleships generally differed from their predecessors due to their armament of only big guns, which allowed them to engage at longer ranges, and oil-fired steam turbines, which provided greater power than steam engines. The predreadnoughts Vermont (Battleship No. 20), New Jersey (Battleship No. 16), and New Hampshire (Battleship No. 25) steamed with him. Meanwhile, dreadnought South Carolina (Battleship No. 26) sailed from Port-au-Prince, Haiti, joining Badger’s squadron as it passed Key West. The dreadnought Michigan (Battleship No. 27) departed from Philadelphia on the 15th and the predreadnought Louisiana (Battleship No. 19) left New York on the 16th. The predreadnought battleships Connecticut (Battleship No. 18) and Minnesota (Battleship No. 22) were already in Mexican waters at Tampico, and dreadnoughts Florida (Battleship No. 30) and Utah (Battleship No. 31) were at Veracruz.[10]

On 15 April, Huerta made a surprising concession. He agreed to fire the 21-gun salute on the condition that the Americans fire a simultaneous salute. President Wilson would not hear of a simultaneous salute. He gave Huerta an ultimatum: Fire the salute by 1800 on Sunday, 19 April, or else Wilson would take the matter to Congress.[11]

Huerta did not fire the salute, and Wilson addressed Congress on Monday afternoon. He asked for approval to use the U.S. military, if necessary, “to obtain from General Huerta and his adherents the fullest recognition of the rights and dignity of the United States.”[12] Wilson discussed the Tampico incident and also cited two other recent incidents of Mexican disrespect: the arrest of a uniformed sailor from Minnesota who was on shore to obtain the ship’s mail and the withholding of an official dispatch from the United States to its embassy in Mexico.[13] In a 16 April telegram reporting the sailor’s arrest, Fletcher had noted, “There is no cause for complaint against [Mexico] and the incident is without significance.”[14] Nevertheless, Wilson stressed that such “offenses” could heighten in severity until “something happened of so gross and intolerable a sort as to lead directly and inevitable to armed conflict.”[15]

Wilson omitted a key piece of intelligence from his address. On 18 April, the U.S. consul at Veracruz, William W. Canada, had cabled the State Department reporting the SS Ypiranga, a Hamburg-American Line steamer, would arrive in Veracruz on 21 April with the largest shipment of arms and ammunition ever to be delivered to a Mexican port: a total of 17,899 cases.[16] Within those cases were a reported 200 machine guns and 15 million cartridges.[17]

The House of Representatives quickly passed Wilson’s resolution on the use of force by a vote of 337 to 37. However, in the Senate, Republicans led by Elihu Root and Henry Cabot Lodge proposed an amendment authorizing the use of force not only against Huerta, but in any situation in Mexico that threatened American interests. The senators debated past midnight, placing the resolution at the head of their agenda for Tuesday, 21 April. By the time they reconvened, U.S. sailors had landed in Veracruz.[18]

A little after 0200 EST on 21 April, the State Department received a coded message from Consul Canada. It reported that Ypiranga would land around 1030 that morning and that three trains were waiting at the dock to carry the arms shipment to Mexico City. Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan called Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels, who agreed that if U.S. Navy forces were to intercept the arms shipment, they could not wait for Congress’s approval. White House servants roused President Wilson and arranged a conference call with Bryan and Daniels. Wilson agreed with their recommendation of a naval landing. “There is no alternative but to land…,” Wilson said. “Take Veracruz at once.”[19]

Rear Admiral Fletcher received Daniels’s brief radiogram at 0800 local time: “Seize Customs House. Do not permit war supplies to reach Huerta or any other party.”[20]

The Naval Landing at Veracruz

Secretary Daniels’s message ordering the seizure of the customhouse caught Rear Admiral Fletcher by surprise. During the days leading up to the diplomatic impasse, both Fletcher and Mayo had anticipated a naval landing at Tampico. This miscalculation had led the U.S. Navy to bolster Mayo’s forces at Tampico with the troop transport Hancock and its complement of nearly 1,000 U.S. Marines under future commandant of the Marine Corps Colonel John A. Lejeune. Badger’s squadron had also been steaming for Tampico and was still a day’s sail from Veracruz.[21]

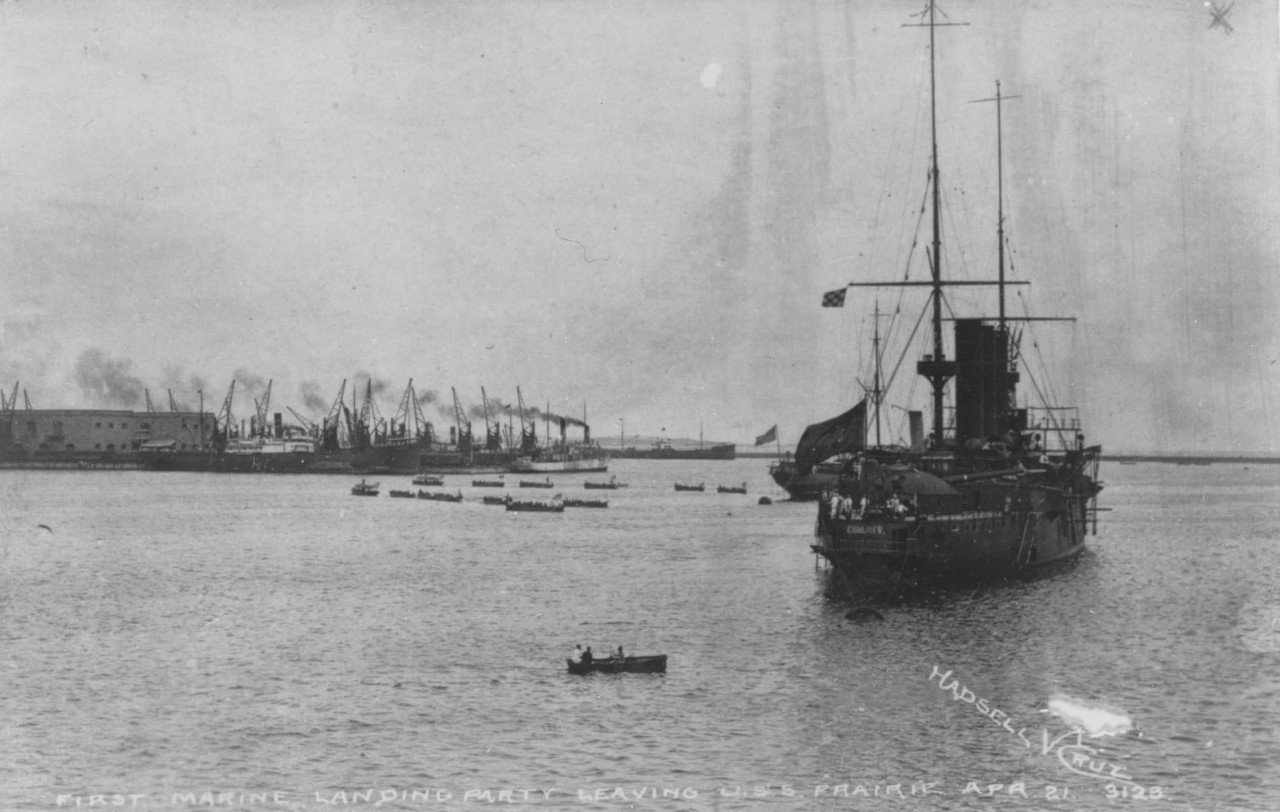

On the overcast morning of 21 April, Rear Admiral Fletcher had command of the battleships Florida and Utah and the gunboat Prairie. He wanted to wait for reinforcements from Badger and Mayo before commencing a naval landing, but dark clouds, wind gusts, and choppy waters foretold a coming storm. Utah and Florida were too large to enter Veracruz’s harbor, requiring the landing force to take small boats to shore. This limitation meant the landing needed to occur before the weather took a turn for the worse.

Florida’s captain, William R. “Wild Bill” Rush, commanded the landing party of 787 officers and men, which included 502 marines. The marines from Florida, Utah, and Prairie formed the 1st Marine Regiment and were commanded by Lieutenant Wendell C. Neville from Prairie. Neville had previously fought in the Spanish-American War (1898) and the Boxer Rebellion (1900), and would succeed Lejeune as commandant of the Marine Corps in 1929. The battalions of sailors from Florida and Utah formed the 1st Seaman Regiment. However, Fletcher decided to hold the Utah battalion in reserve and stationed the battleship outside the Veracruz harbor to halt Ypiranga’s arrival.[22]

A U.S. Marine with a field marching pack equipped for landing at Veracruz. (Box 6, divider 28B, General Photographic File, 1900–1941, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps, Record Group 127, National Archives and Records Administration [NARA], College Park, MD.)

At 1112, the first boat of marines left Prairie. The harbor was soon filled with motor launches carrying marines and bluejackets. On shore, Consul Canada carried out his role in the landing, placing a call to General Gustavo Maas, the military commandant of Veracruz. Canada assured Maas the landing party would be confined to the waterfront area and would only fire if fired upon. He asked that Maas work with the landing party to maintain order in the city. An agitated Maas hung up the phone and immediately radioed the Mexican war ministry. Then, he mobilized his troops, ordering about 100 men to march toward the harbor and halt the naval landing. Maas had only two regular army units at Veracruz because he had also shifted forces to Tampico, then reinforced his units with prisoners from the San Juan de Ulua fortress. Now, he increased his numbers by arming men in the military prison “La Galera” and distributing Mauser and Winchester rifles to the people of Veracruz. When the Mexican minister of war received Maas’s dispatch, he ordered Maas to pull back his small force. But the message would arrive too late. The Mexicans and Americans were on a collision course.[23]

The first U.S. Marine landing party leaving Prairie, 21 April 1914. (Box 6, divider 28B, General Photographic File, 1900–1941, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps, Record Group 127, NARA, College Park, MD.)

The American boats converged on Pier Four, the first boat from Prairie making land at 1120. Mexicans and Americans alike gathered at the seawall to watch the landing. The American expatriates cheered as each boat landed, one woman waving a small American flag.

The Americans’ first objective was the railroad terminal north of the docks, where Fletcher hoped to seize the trains awaiting Ypiranga’s shipments, but the Mexicans had already withdrawn them. Next, Captain Rush occupied the Terminal Hotel, located next to the railroad station, and established his headquarters there. Navy signalmen climbed to the hotel’s flat rooftop, waving semaphore flags to communicate with Fletcher on board Florida. Other sailors and marines seized the city’s post office and cable station. Not a single shot was fired.[24]

Sailors entering the Veracruz post office. (LC, LC-DIG-ggbain-18235, https://www.loc.gov/resource/ggbain.18235/.)

The largest contingent, 57 men of Florida’s 1st Company under Ensign George M. Lowry, advanced along Morelos Street toward the main objective: the customhouse. Unbeknownst to Lowry, the Mexican troops sent by Maas trained their rifles at the Americans from Independencia Street. Meanwhile, armed prisoners and civilians aimed from the roofs of surrounding buildings.[25]

At 1157, the Americans moved into the Mexicans’ line of fire. A Mexican, identified in several sources as municipal police officer Aurelio Monffort, pulled the first trigger.[26] His shot set off a volley throughout the city. A bullet struck Private Daniel Aloysius Haggerty, a U.S. Marine guarding the Navy signalmen atop the Terminal Hotel. The impact knocked him partially off the rooftop. Electrician Third Class Edward A. Gisburne, wounded in both legs, crawled through fire to pull Haggerty fully onto the roof. Haggerty died in Gisburne’s arms, becoming the operation’s first casualty.[27]

An illustration published in the 9 May 1914 issue of Collier’s magazine depicting the moment Private Daniel Aloysius Haggerty was struck by a bullet atop the Terminal Hotel. (Box 6, divider 28D, General Photographic File, 1900–1941, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps, Record Group 127, NARA, College Park, MD.)

In the streets, Lowry’s men took cover, returning fire. From the yard of the Mexican naval academy, Lieutenant of Naval Artillery José Azueta, son of the Mexican commodore, fired a machine gun. Boatswain’s Mate Second Class Joseph G. Harner hit Azueta three times, mortally wounding him.[28] Lowry then called for five volunteers to advance with him down an alley by the customhouse. In the alley, they came under fire from the customhouse and from a machine gun in the second-story window of Hotel Oriente. Lowry ordered his men to fire on the machine gunner. In the exchange, two bluejackets were wounded, one mortally. Lowry was nearly killed when a bullet struck the button of his cap. Then, a Mexican policeman tumbled from the window, and the machine gun fell silent. Lowry’s men continued down the alley to the customhouse, breaking a window and climbing through. Inside, the customs officials laid down their weapons.[29]

A U.S. Navy machine gun squad guarding the Veracruz customhouse. (LC, LC-USZ62-49077, https://www.loc.gov/item/2006685909/.)

All the objectives had been occupied, but fighting now broke out across the city. A group of U.S. Marines battered their way through the iron barricade of a Spanish import house and commandeered sacks of rice and coffee to build barricades in the streets. The Americans placed machine guns at the main intersections and a light fieldpiece in front of the American consulate. At 1245, Fletcher ordered the battalion still aboard Utah to land, but as the landing party’s boats neared the shore, they came under fire from cadets inside the two-story Mexican naval academy. Their daring attack was likely inspired by the Chapultepec military academy cadets, revered in Mexican history for fighting to the death against General Winfield Scott’s troops during the Mexican-American War. In reply, three U.S. picket boats poured their 1-pound guns into the naval academy. Then Prairie opened fire with 3-inch guns. Inside, the teenage cadets sheltered behind mattresses and furniture they had pushed against the windows. One cadet, 16-year-old Virgilio Uribe, was killed in the barrage. The rest evacuated Veracruz, joining General Maas in Tejería, where he was destroying the railroad track between Tejería and Veracruz to prevent the Americans from reaching Mexico City.[30]

The Utah battalion landed at 1340. Ensign Paul F. Foster led a company of bluejackets to relieve Lowry and his men at the customhouse. At the warehouse next door, the sailors discovered bales of cotton, sacks of rice and sugar, and rum and molasses. Foster ordered his men to pile the stores onto the warehouse’s hand trucks, creating mobile barricades. Less than an hour later, the bluejackets had rolled their barricades to a point within a block from a Mexican stronghold at the Plaza Constitución.[31]

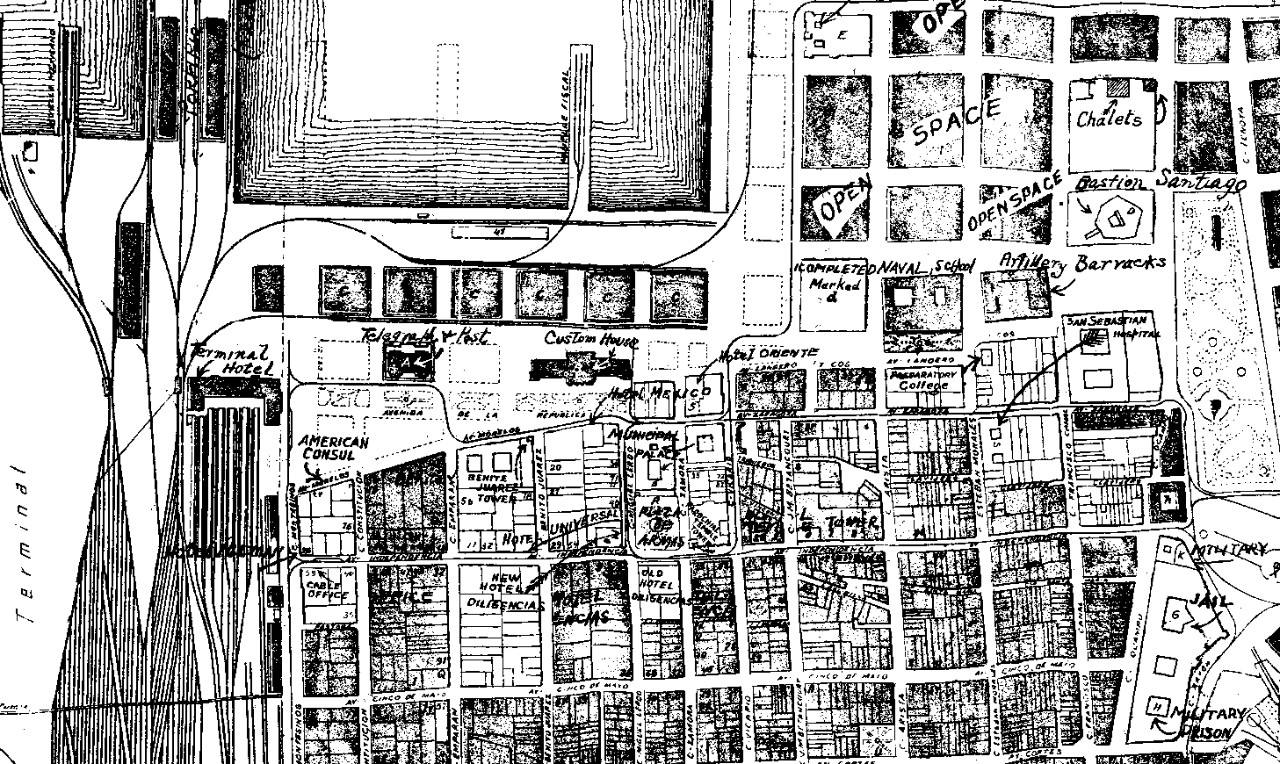

Section of a map of Veracruz showing the buildings occupied on 21 April. Note the Terminal Hotel, post office, cable office, customhouse, and Hotel Oriente. Click on this image to view the full map. (R. W. McNeely, trans., The Tragic Days of Vera Cruz: The First Published Native Account of the Seizure of Vera Cruz by the U.S. Naval Force under Rear Admiral Fletcher, U.S. Navy [Annapolis: United States Naval Institute Proceedings, 1914; repr., (Annapolis?): n.d.], map insert, Navy Department Library [NDL], NHHC.)

To avoid further bloodshed, Admiral Fletcher sent a messenger to Consul Canada to see if an armistice could be reached. However, the man with the authority to negotiate for peace, General Maas, had left Veracruz. Consul Canada sent two Mexican envoys carrying white flags into Veracruz. The first never returned—the Americans later learned he had been shot. The second broke into the mayor’s house and found the mayor barricaded in his bathroom. The mayor said he had no authority to end the fighting, and that the envoy should seek out the chief of police, but the chief of police could not be found.[32]

Fletcher decided to hold his forces in their current positions, as to advance further would bring the fighting to the densest section of the city after nightfall. Furthermore, reinforcements would soon arrive, bringing the total number of sailors and marines on shore to more than 4,000.[33] On the first day of fighting, U.S. casualties were 4 killed and 22 wounded. The wounded were treated aboard Prairie and at the field hospital established in a building at Pier Four.[34]

Outside the harbor, Ypiranga bobbed at anchor. The vessel had arrived at 1330, at the height of the day’s conflict. When a Utah officer boarded, he discovered the weapons shipment had originated from New York. To circumvent Wilson’s embargo, Huerta’s agents had first shipped the Remington-made weapons from New York to Germany.[35]

Throughout the night, U.S. Navy ships in Veracruz’s inner harbor shone their searchlights onto the city, and the Americans occupying the power station kept the streetlights on to hinder snipers. Prairie’s 3-inch guns opened up on pockets of Mexican resistance that dared to open fire.[36]

At 2030, the mine planter San Francisco arrived from Tampico, anchored near Prairie, and sent a landing party of 125 officers and enlisted men ashore. The two companies from San Francisco took a position left of Utah’s battalion and began building a barricade.[37] Shortly after midnight, the cruiser Chester (Cruiser No. 1) also arrived from Tampico carrying its complement of sailors and additional marines. On the short voyage, Chester had passed the Mexican gunboats Bravo and Zaragoza with the crew at battle stations and guns trained and loaded. Luckily, only salutes were exchanged. As Chester approached Veracruz, the captain, Commander William A. Moffett, received a wireless order to moor inside the breakwater. The crew extinguished all lights on the ship, and Moffett succeeded in mooring Chester several hundred yards from shore with the broadside facing the beach, only a short distance from the yellow façade of the Mexican naval academy. The maneuver was a challenge as the night was black and the light of the Veracruz lighthouse had been extinguished.[38]

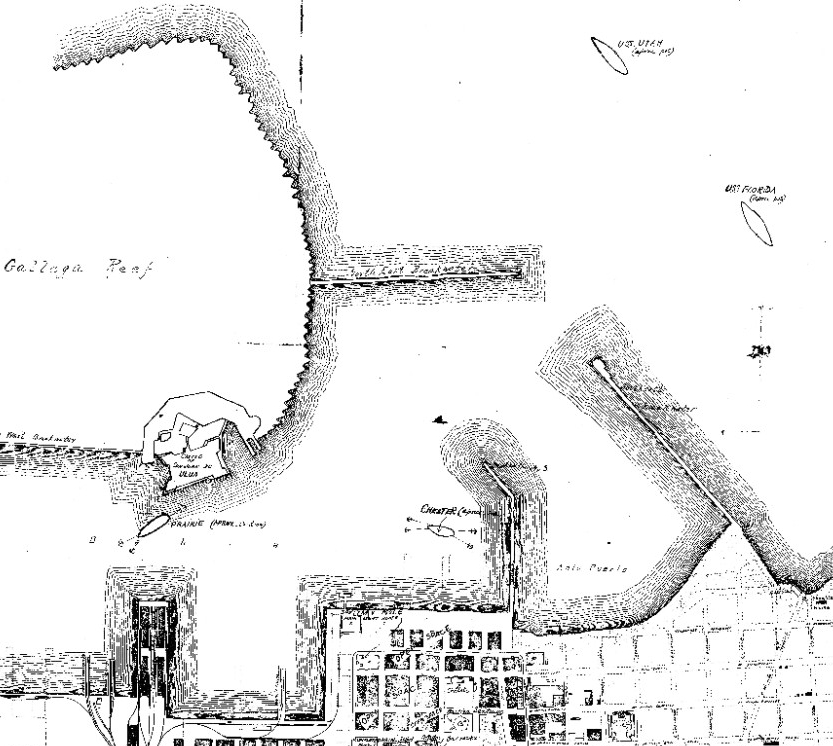

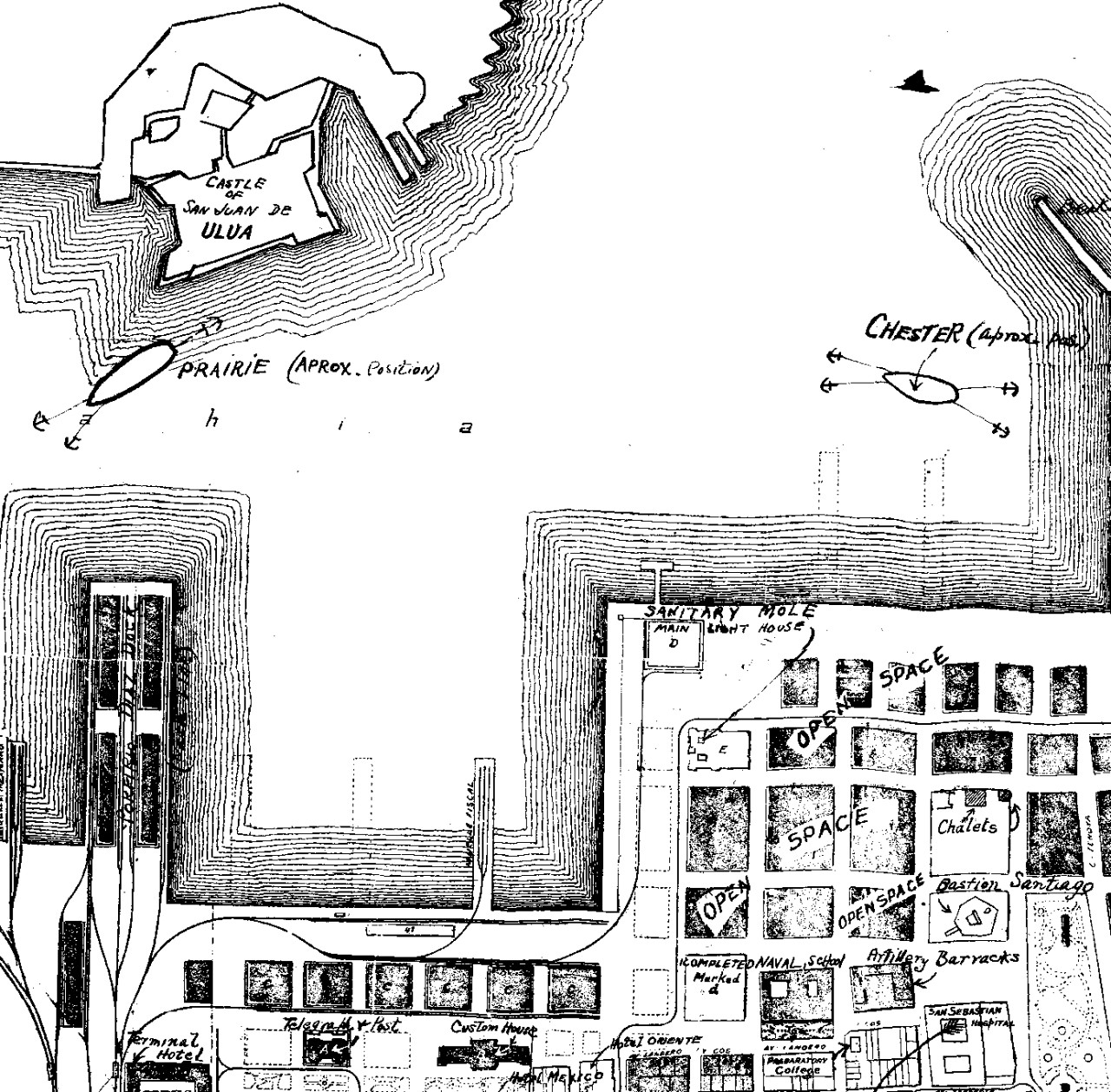

Section of historic Veracruz map showing the positions of U.S. Navy ships in the inner and outer harbor on 22 April 1914. Click on this image to view the full map. (R. W. McNeely, trans., The Tragic Days of Vera Cruz: The First Published Native Account of the Seizure of Vera Cruz by the U.S. Naval Force under Rear Admiral Fletcher, U.S. Navy [Annapolis: United States Naval Institute Proceedings, 1914; repr., (Annapolis?): n.d.], map insert, NDL, NHHC.)

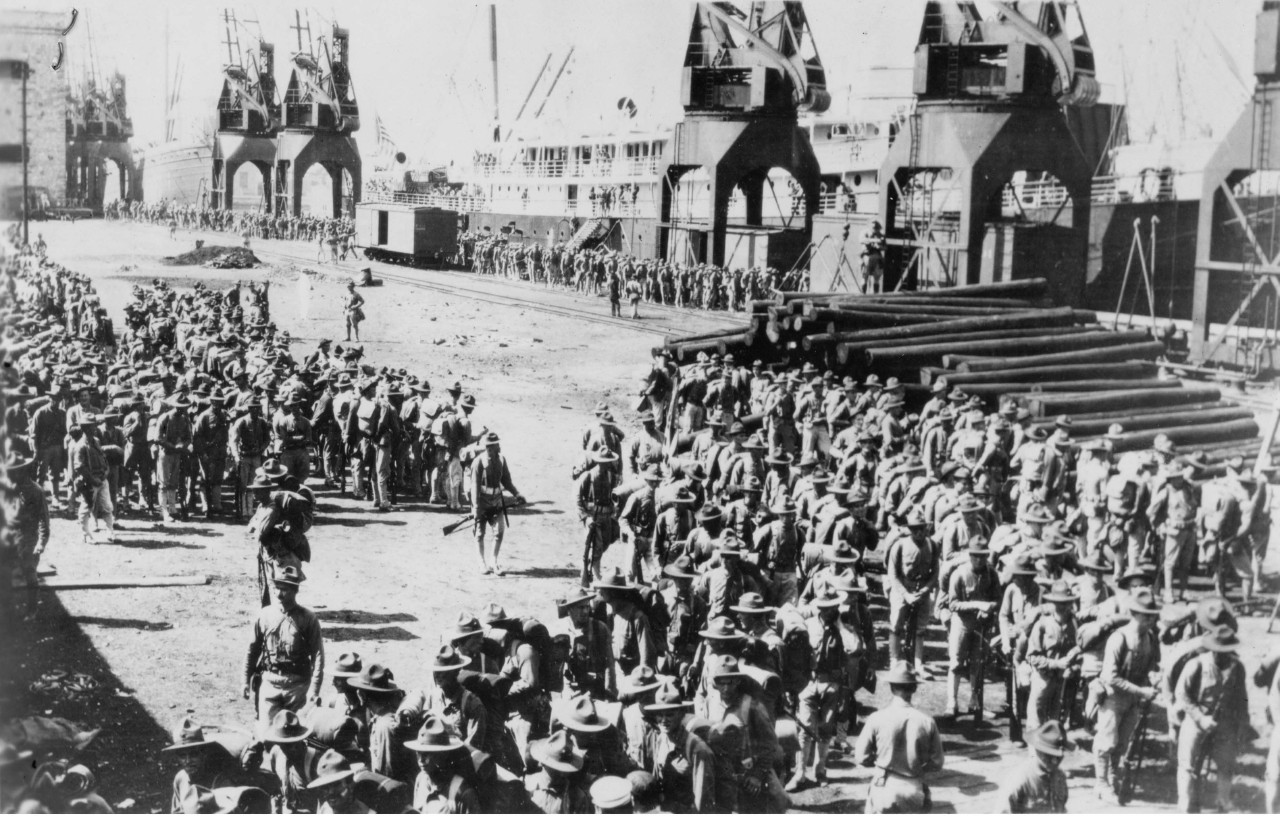

About an hour later, Badger’s squadron of battleships from Hampton Roads steamed into the outer harbor, followed later by battleship Minnesota and transport Hancock from Tampico. Aboard Hancock was Colonel Lejeune, who assumed overall command of the U.S. Marines at Veracruz.[39]

On the voyage to Veracruz, Badger’s bluejacket battalions had dyed their white uniforms with a ferrous sulfate solution to turn them khaki colored, thus making themselves less conspicuous targets.[40] By nightfall, their uniforms had been “dyed and dried,” their knapsacks packed, and rifles and ammunition distributed.[41] Fletcher boarded Arkansas around 0200 and offered to relinquish command to Badger. Badger replied that Fletcher should retain command given his familiarity with the situation. The two officers then drew up plans for taking the city. They decided the battalion of sailors from Arkansas would join the 1st Seamen Regiment, and the sailors from New Hampshire, South Carolina, Vermont, and New Jersey would form the 1,246-strong 2nd Seamen Regiment under Captain E. A. Anderson. The 300 newly arrived fleet marines would join Neville’s regiment.[42]

It was a calm night, the air and sea still and quiet. On New Hampshire, the men wrote letters home, spoke in hushed whispers, or distracted themselves with games of cards.[43] One young ordinary seaman, Esan Frohlichstein, predicted he would be the first man killed and wrote home, “It may be that I will be killed, but I will die like a man.”[44]

The morning of 22 April came and Consul Canada made one final failed attempt to secure an armistice. By 0730, all the reinforcements had landed. Fifteen minutes later, Fletcher signaled that Captain Rush could advance his naval brigade through Veracruz. The 1st Marine Regiment marched on the right, the 1st Seaman Regiment in the center, and the 2nd Seaman Regiment on the left. Each regiment had been assigned a specific area to secure, and each battalion had a section of several square blocks to occupy.[45]

The 1st Marine Regiment advanced along the streets north of Independencia until they encountered heavy fire from rifleman in houses and atop buildings. They hacked through the adobe walls one building at a time, clearing out a structure before moving to the next. The 1st Seaman Regiment also made rapid progress through their sector, occupying Plaza Constitución by 0930.[46]

The 2nd Seaman Regiment met the greatest resistance. Under Captain Anderson, the sailors marched in parade formation, despite Captain Rush’s warning to deploy an advance guard. The New Hampshire battalion formed the advance of the column, followed by the Vermont battalion, the South Carolina battalion, the New Jersey battalion, and an artillery battalion commanded by Lieutenant John Grady. Medical personnel formed the rear of the half-mile-long column.[47]

As the regiment neared the Mexican naval academy, machine gun, rifle, and 1-pounder fire flew from the academy buildings to the column’s right and rear, an arsenal to their left, and the San Sebastian Hospital directly in front of them. It was an ambush, and the Mexicans, firing with smokeless powder, were impossible to pinpoint. Bluejackets fell wounded or dead, the heaviest losses among the New Hampshire battalion.[48] Ordinary Seaman Esan Frohlichstein, who had predicted his own death the night before, was shot through the head.[49] The Vermont, South Carolina, and New Jersey battalions fell back, followed by the New Hampshire battalion. To the sailors, “It seemed that every stone building on all sides for blocks were filled with Mexican troops and machine guns.”[50] As the 2nd Seaman Regiment retreated, Ensign Oliver Bagby led a squad from New Hampshire’s 3rd Company to shoot the lock off the arsenal, pursue the Mexicans inside, and capture them on the arsenal’s rooftop.[51]

Section of historic Veracruz map showing the naval academy buildings, artillery barracks, and San Sebastian Hospital from which the Mexcians ambushed the 2nd Seaman Regiment on 22 April 1914. Click on this image to view the full map. (R. W. McNeely, trans., The Tragic Days of Vera Cruz: The First Published Native Account of the Seizure of Vera Cruz by the U.S. Naval Force under Rear Admiral Fletcher, U.S. Navy [Annapolis: United States Naval Institute Proceedings, 1914; repr., (Annapolis?): n.d.], map insert, NDL, NHHC.)

The retreat halted at a field, where the sailors lay flat on the ground and fired at “every flash of a rifle from the stone buildings.”[52] The enemy fire increased as bullets poured from buildings and from tugs and barges in the harbor. Casualties mounted. Blood was staunched with first aid bandages until the wounded could be carried to the hospitalmen and surgeons at the rear.[53]

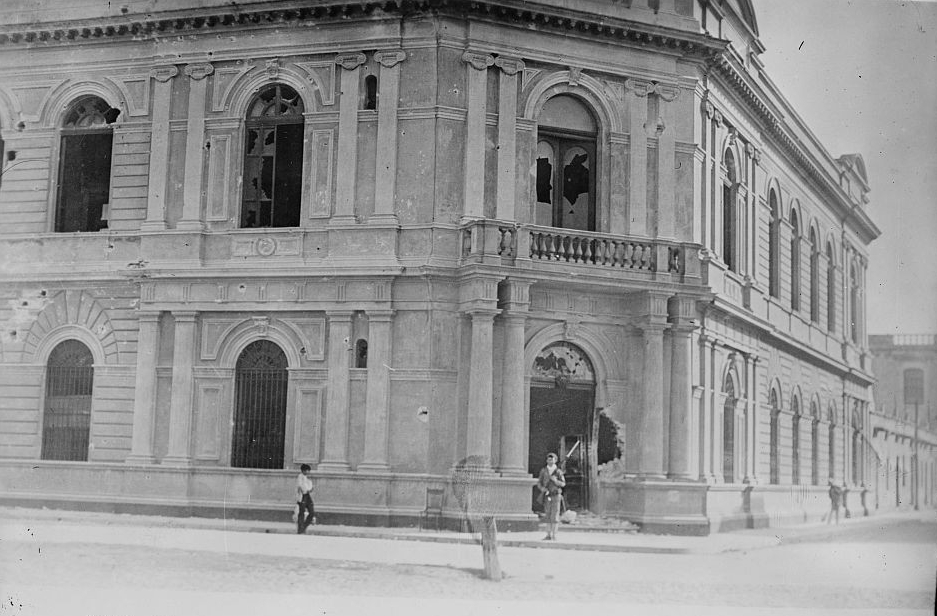

Then, the tide turned. Captain Moffett of Chester had been occupied with replying to fire from barges and woodpiles along the waterfront and from stately buildings on the shore. But when Moffett saw the 2nd Regiment’s dire situation, he turned Chester’s 5-inch and 3-inch guns on the Mexican naval academy and surrounding buildings.[54] San Francisco and Prairie joined in, and the 2nd Regiment retired to the waterfront to avoid falling victim to the bombardment. There, they were greeted by fire from several buildings, including one flying a Greek consular flag, and from the steamship Haakon, flying the Norwegian flag. A bullet struck Lieutenant James Lannon, commander of the New Hampshire battalion, who was carried to safety by his men.[55] Chester hailed the Norwegian steamship with an ultimatum: “Fire another shot and you will be sunk.”[56] Haakon began to steam out of the harbor, but not before the ship was overtaken by a U.S. Navy steam launch. Chester then addressed the barges by sending boarding parties to each and taking all hands as prisoners. Now, only fire from three buildings remained. Lieutenant Grady trained his artillery on the structures and made short work of the Greek consulate’s ornate façade. A company charged inside the building. When figures appeared in the tall grass behind it, U.S. Navy sharpshooters picked them off. Then, the regiment searched the Mexican naval academy and surrounding buildings. Inside, they found dead bodies and stockpiles of arms and ammunition. They carried their own dead and wounded to the Veracruz lighthouse building. Four of the dead and 11 of the wounded were from the New Hampshire battalion.[57]

Front of the Mexican naval academy after bombardment by Chester. (LC, LC-DIG-ggbain-16373, https://www.loc.gov/item/2014696349/.)

The New Jersey battalion held the captured buildings, and the remaining battalions continued their march south, Captain Anderson at the front. At Hernandez Avenue, the column came under fire from Mexican regulars and irregulars running atop the roofs of houses.[58] The 2nd Regiment split up with orders to march in “street riot formation, with a fieldpiece in the center” and rendezvous at the military barracks.[59] As the New Hampshire battalion marched toward Reforma Street, snipers opened fire and killed Seaman Francis DeLowry. When the battalion neared the military barracks, a lone Mexican man walked into the street, dropped behind the curb, and opened fire at a distance of 500 yards. Captain Anderson fired, but his bullets fell short. Then, Ensign W. A. Lee took a rifle from one of his men, walked into the middle of the street, and fired. His first shot flew inches from the man’s head, causing him to run. Ensign Lee’s second shot struck his head.[60]

The march continued under heavy fire from armed Mexican prisoners and from civilians, including women. The sailors battered down doors, captured those inside, and shot anyone who resisted. As they advanced, the parapets of the military barracks appeared.[61] Three regiments of Mexican soldiers were typically stationed inside the imposing structure, which spanned two city blocks and was “built so only a handful of determined men could stand off a regiment.”[62] Here, the bluejackets anticipated the Mexicans would make their last stand. The barracks were located in the center of the city, so this time, the sailors would not be supported by the guns of U.S. Navy ships. The battalions converged. The artillery battalion positioned their guns. The bluejackets charged.

Only a few Mexicans were found within the barracks, along with tons of ammunition and 100 horses. Adjoining the barracks was General Maas’s residence, where finery lay scattered about, a sign of the residents’ quick flight. There, Anderson established his headquarters and discovered relics dating back to Hernán Cortés.[63]

By noon, the entire city of Veracruz was in the hands of the Americans, but the day was not yet finished. A late-afternoon report indicated that General Maas was marching on Veracruz with a 10,000-strong force.[64]

A guard of one infantry company and a section of artillery remained at the barracks while Captain Anderson led the rest of the 2nd Regiment to the outskirts of the city. Battalions from Minnesota and Michigan were sent to the 2nd Regiment for temporary service, the Michigan sailors reinforcing the small contingent at the barracks. The Vermont and artillery battalions were stationed at Los Cocas Station two miles outside of Veracruz, erecting barricades and positioning fieldpieces to control the railroad in either direction. The New Jersey battalion occupied the tower of the Veracruz lighthouse. The New Hampshire, South Carolina, and Minnesota battalions continued to a hill a mile from the railroad, entrenching their position throughout the night.[65]

The forces of General Maas never appeared, but a train carrying American refugees from Mexico City erupted with cheers.[66] The military and civilian leaders of Veracruz had abandoned their posts, as a law from the French intervention of the 1860s made it illegal for Mexican citizens to serve under foreign occupiers. Sniping continued throughout the city, which had been reduced to shell-blasted buildings and deserted streets strewn with dead bodies. On 25 April, Fletcher issued a proclamation ordering the populace to turn in their weapons. On 26 April, he declared martial law, and thousands of Veracruzanos formed a line before the Municipal Palace, bearing an assortment of weapons. In total at Veracruz, the U.S. military seized 13,000 arms of various calibers, 150,000 rounds of ammunition, and thousands of pounds of powder.[67] On 27 April, the American flag was raised over the U.S. military’s headquarters at the Terminal Hotel. The naval landing force now found themselves with a city to run.

Sailors and marines raising the American flag over the Terminal Hotel on 27 April 1914. (LC, LC-DIG-ggbain-15834, https://www.loc.gov/resource/ggbain.15834/.)

Aftermath

U.S. Navy casualties at Veracruz from 21 to 22 April totaled 17 dead and 63 wounded. Wounded sailors and marines sailed on the hospital ship Solace to Naval Hospital New York for treatment, but two died on the ship, bringing the total killed to 19.[68] Of the dead, 13 were 22 years old or younger. The 2nd Seaman Regiment sustained the heaviest casualties of 8 killed and 28 wounded, and of that regiment the New Hampshire battalion had the greatest losses: 5 killed and 14 wounded.[69]

The final cruise for the men killed at Veracruz began aboard the armored cruiser Montana (Armored Cruiser No. 13) on 3 May. Each of the seventeen caskets rested on the deck and was draped with an American flag. The U.S. battleships formed a solemn column for Montana to steam through, and all U.S. and foreign ships present flew their flags at half-mast. Admiral Fletcher stood at the rail of Florida, his staff behind him at a distance. The deck of New Hampshire was lined with men dressed in white and standing in silence, their hats removed. At quarterdeck, the marine guard presented arms, remaining motionless until Montana passed. New Hampshire’s band broke out with Chopin’s funeral march to say farewell to the five men who days before had served among them.[70]

Seventeen flag-draped caskets on the deck of Montana (LC, LC-USZ62-49085, https://www.loc.gov/item/2006685917/.)

Montana was met at sea by the President’s yacht Mayflower with Secretary Daniels on board and by the battleship Wisconsin (Battleship No. 9). The vessels convoyed Montana to New York, where on 11 May the battleship anchored off the Battery and transferred the caskets to caissons. President Wilson and his cabinet, delegations from the Senate and the House of Representatives, and both the governor of New York and mayor of New York City rode with the funeral procession from the Battery across the Manhattan Bridge to the Brooklyn Navy Yard, the streets lined with Americans. At the navy yard, funeral rites were performed and Wilson spoke.[71] “We have gone down to Mexico to serve mankind if we can, because we know how we would like to be free, and how we would like to be served if there were friends standing by in such case ready to serve us,” he declared. “A war of aggression is not a war in which it is a proud thing to die, but a war of service is a thing in which it is a proud thing to die.”[72]

Wyoming convoys Montana and its precious cargo to New York City (LC, LC-DIG-ggbain-16205, https://www.loc.gov/item/2014696182/.)

President Woodrow Wilson (second from right) rides in the funeral procession with his private secretary Joseph Patrick Tumulty (second from left) and New York City mayor John Purroy Mitchell (far right). (LC, LC-DIG-ggbain-16193, https://www.loc.gov/item/2014696170/.)

Funeral procession through the streets of Brooklyn. (Box 6, divider 28H, General Photographic File, 1900–1941, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps, Record Group 127, NARA, College Park, MD.)

Funeral ceremony at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. (Box 6, divider 28H, General Photographic File, 1900–1941, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps, Record Group 127, NARA, College Park, MD.)

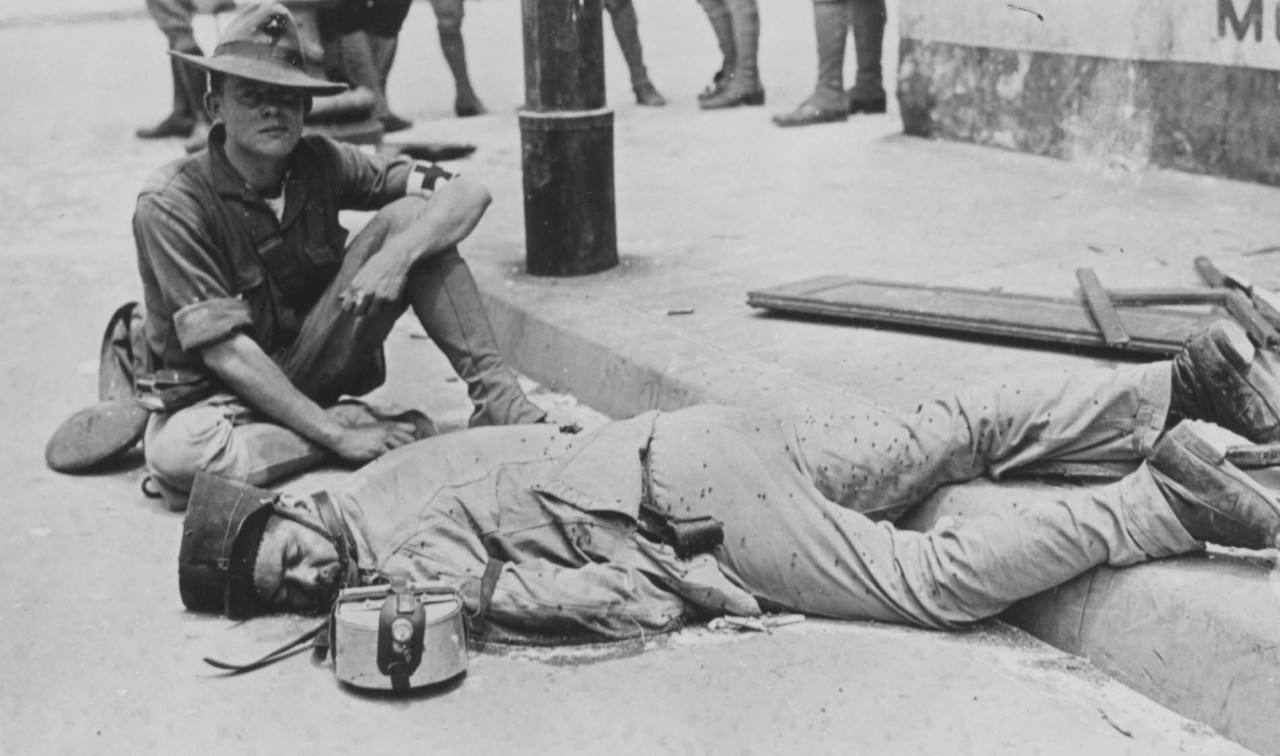

Veracruz hospital records showed Mexican casualties of 126 dead and 195 wounded, many of whom were civilians.[73] However, the true number was likely much higher. After the occupation was complete, the next major task became cleaning up the city. Bodies lying in the streets drew dogs and vultures, and the most efficient way to dispose of corpses was to pile them in mounds that were doused with oil and set ablaze.[74]

A U.S. Navy hospital corpsman serving with the U.S. Marines and wearing a Marine Corps uniform attends to a wounded Mexican army soldier. (Box 6, divider 28D, General Photographic File, 1900–1941, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps, Record Group 127, NARA, College Park, MD.)

On the evening of 27 April, with the American flag flying at the Terminal Hotel, U.S. Army transports from Galveston, Texas, under General Frederick Funston arrived in the Veracruz harbor to take over the occupation. Before the troops could be put ashore, the Army and Navy had to agree on what to do with the Marine Corps. Admiral Badger recommended the more than 3,000 marines at Veracruz remain on shore under the command of Admiral Fletcher. However, the Army wanted a unified command, which would place all troops under General Funston. The issue reached Washington, with the Secretary of the Navy and Secretary of War making their cases before President Wilson. Wilson ruled in the Army’s favor, ordering the marines to be detached from the Atlantic Fleet and detailed to the Army until the occupation had concluded. On 30 April, U.S. soldiers disembarked from their transports and paraded through the streets of Veracruz. The marines remained on shore under the command of Colonel James E. Mahoney, who would soon be superseded by the arrival of Littleton W. T. Waller, the senior line colonel in the corps.[75] Meanwhile, the bluejackets assembled along the Sanidad Wharf, and with cameras and moving picture machines recording their movement, embarked on Lebanon, which transported them to their respective ships. The Atlantic Fleet maintained a presence at Veracruz throughout the summer, ready to reinforce the Army if necessary.[76] The main threat to the soldiers and marines on shore came from diarrhea and dysentery, but as the U.S. military cleaned the city and enforced sanitation rules, the sick list decreased from 3.18 percent in 3 June to 1.9 percent on 25 August.[77]

The Navy turns over Veracruz to the Army. (LC, LC-DIG-ggbain-16382, https://www.loc.gov/item/2014696358/.)

Only a small U.S. Navy contingent was stationed on land with the Army and Marine Corps: an aviation detachment with seaplanes that had arrived on 24 April on the predreadnought Mississippi (Battleship No. 23). Mississippi was not an aircraft carrier, so en route to Veracruz, the crew had rigged an extension boom to lower planes off the deck and into the water. When Fletcher requested an aerial sweep of the Veracruz harbor for mines, Lieutenant Patrick N. L. Bellinger took a solo flight in a Curtiss C-33 (AH-3) hydroaeroplane. He also flew a Model F C-3 (AB-3) flying boat over the coastline accompanied by Ensign Walter D. Lamont, who took the first recorded aerial photographs during wartime conditions.[78]

Outside Veracruz, news of the American landing inspired a swift spike in anti-American sentiment. In Mexico City, outraged citizens smashed the windows of American businesses and toppled a statue of George Washington.[79] In the minds of the Mexican people, the boys who had died defending the Mexican naval academy were national heroes. Lieutenant José Azueta, the son of Commodore Azueta, languished in a makeshift hospital from his bullet wounds. When Admiral Fletcher heard of his condition, he offered the services and supplies of the Atlantic Fleet’s surgeons, but Azueta refused. He died on 10 May, and on 12 May, 5,000 Veracruzanos packed into the narrow streets for his funeral.[80]

At Tampico, alarmed by Consul Miller’s reports of rioting, Admiral Mayo decided to take on board American refugees. To avoid the appearance of a second American landing, British and German officers flew the flags of their nations on private vessels and shuttled American refugees to Mayo. The American citizens believed they would be able to return to Mexico within a few days’ time. They were dismayed to find themselves taken to Galveston, Texas. They signed letters of protest and sent telegrams to members of Congress, prompting the Secretary of the Navy to make a statement placing blame for the disorganization in Tampico on Mayo.[81]

Ypiranga remained anchored outside the Veracruz harbor until early May. Commander Herman O. Stickney, appointed by Fletcher as administrator of customs, was to oversee the landing of the ship and the seizure of its cargo. However, Ypiranga’s captain refused to land. Instead, he said he would return the arms to Germany. On 3 May, Ypiranga sailed from the Veracruz harbor to Tampico; then to Mobile, Alabama; then on to Puerto, México (today Coatzacoalcos). There, Ypiranga discharged its arms shipments, which were ferried on to Mexico City and, presumably, to President Huerta. Ypiranga then dared to return to Veracruz, where an upset Stickney imposed a fine of nearly 900,000 pesos against the Hamburg-American line. Not wanting to provoke Germany, President Wilson revoked the fine.[82]

When it came to Mexico, Wilson was less concerned with provocation. On 24 April, he had accepted a mediation offer by the ABC Powers—Argentina, Brazil, and Chile. However, he clarified that the United States was not a party to the mediation. Rather, the purpose was to find a Mexican regime suitable to all factions. Huerta, meanwhile, believed the mediation was to settle the differences between Mexico and the United States. The first mediation session was held at the Niagara Falls’ Clifton House on 21 May. At the end of June, the mediators recessed indefinitely. Huerta opposed a revolutionary Constitutionalist serving as a provisional Mexican president, and Wilson refused to withdraw his forces from Veracruz until Huerta resigned as president. Compromise was impossible.[83]

The ultimate resolution was to occur on the battlefield. On 15 July 1914, the Constitutionalists defeated Huerta’s forces, and Huerta resigned from office. Venustiano Carranza, leader of a Constitutionalist faction, became the provisional president of Mexico. With Huerta gone, the United States no longer had a reason to hold Veracruz. Army transports arrived to ferry the soldiers and marines home. Still, Wilson delayed. He tried to secure guarantees that Carranza would not punish Mexicans who had worked with the U.S. military government, nor levy import duties on merchants who had already paid the U.S. military government. In his negotiations with the United States, Carranza proved similar to his predecessor: he did not want the United States making decisions for Mexico. In fact, the landing at Veracruz was a diplomatic disaster that would strain Mexican-American relations for decades to come. Carranza did not agree to Wilson’s conditions until threats to his provisional presidency from rival Constitutionalist factions made him desperate to flee Mexico City and take refuge in Veracruz. At last, on the morning of 23 November, the 7,000 American servicemen in Veracruz marched through the streets to the music of a military band. By 1400 local time, all Americans had boarded the transports, which sailed from the Veracruz harbor.[84]

U.S. Marines leaving Veracruz on 23 November 1914. (Box 6, divider 28B, General Photographic File, 1900–1941, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps, Record Group 127, NARA, College Park, MD.)

Medal of Honor Controversy

More Medals of Honor were awarded for the landing at Veracruz than for any other single engagement in American military history.[85] In total, 37 officers and 18 enlisted men earned the highest military honor, a total of 55 Medals of Honor. Enlisted sailors and marines received their medals in 1914. However, officers were awarded their medals retroactively in 1915. Prior to that year, U.S. Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard officers were ineligible—despite the fact that U.S. Army officers had been eligible since the Medal of Honor became a permanent award in 1863.

Prior to the Spanish-American War, the Senate Committee for Naval Affairs had supported a resolution that would have expanded Medal of Honor eligibility to U.S. Navy officers, but the resolution failed in Congress despite favorable press coverage. After the war, Admiral George Dewey, who had led the United States to victory in the Battle of Manila Bay, took up the cause. He wrote to the Senate Committee for Naval Affairs that Navy officers should receive the same honors as Army officers, and that there should be two Medal of Honor categories: one for acts performed in peacetime, the other for heroism during wartime. The proposed law failed in 1905 despite Dewey’s efforts, and a similar bill failed in 1912. Though congressional testimony did not identify a reason for Congress finally remedying the inequity between the services, correspondence with Congress reveals the Navy Department wished to award officers who had served at Veracruz.[86] In addition, the Annual Reports of the Navy Department for the Fiscal Year 1914 expresses, “It is earnestly hoped that Congress will vote medals to the officers who showed gallantry.”[87]

In his history of the Medal of Honor, military historian Dwight S. Mears declares Veracruz was “undeniably the proximate motivation.”[88] Mears adds, “It is unclear why this clash was any more persuasive,” partly because Veracruz did not involve traditional naval battles and partly because the conflict largely resulted from “poor diplomacy by senior Navy officers.”[89]

The 1915 law expanding eligibility to naval officers required an awardee to have “distinguished himself in battle or displayed extraordinary heroism in the line of his profession.[90] However, Mears notes, “Many of the decorated officers had apparently performed no more than ordinary duty-bound actions.”[91] To illustrate his point, Mears offers the citation for Admiral Fletcher, which lauds him for being “at times on shore and under fire.”[92] Other notable examples include Commander Moffett, captain of Chester, whose citation notes both that “his skill in mooring his ship at night was especially noticeable” and that he was “in a position on the morning of the 22d to use his guns at a critical time with telling effect.”[93] Similarly, Surgeon Stuart Ellicott was awarded for “the efficient establishment and operation of the base hospital.”[94] While these actions no doubt reduced casualties at Veracruz, whether they merited the Medal of Honor is debatable.

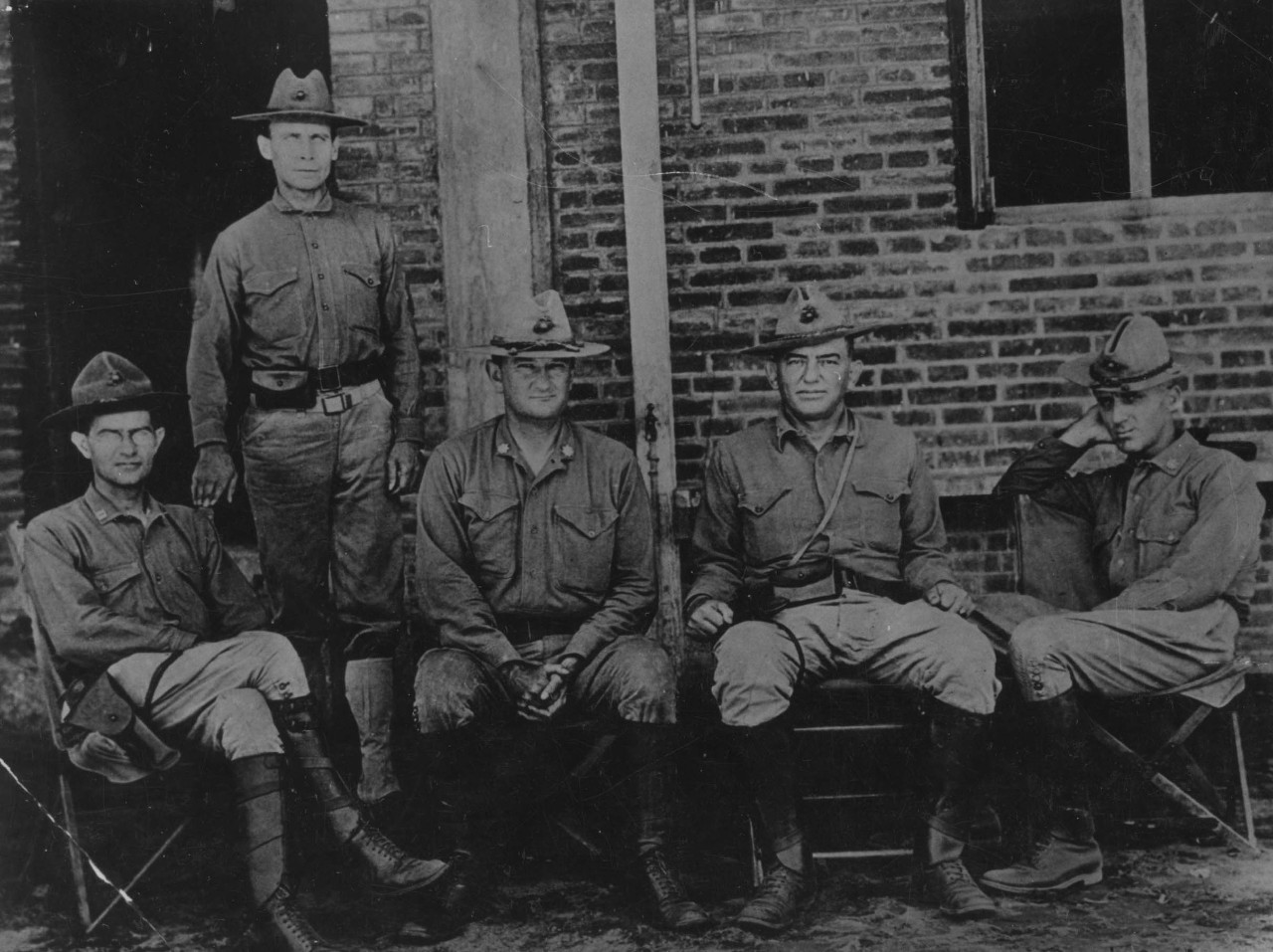

A handful of Navy and Marine Corps officers certainly opposed the high medal count. In May 1915, a Washington Herald article reported some officers slated to receive the award believed their service during the naval landing was “not of such a nature as to be considered either conspicuous or exceptional.”[95] When Major Smedley Butler received his, he wrote a scathing letter to his mother:

I, even in my most puffed up moments, can not remember a single action, or in fact any collection of actions, of mine that in the slightest degree warranted such a decoration. I did my duty as best I could in Vera Cruz but there was absolutely nothing heroic in it. The Medal of Honor is the prize for which all of us soldiers strive and risk our lives and to have it thrown around broad cast is an unutterably foul perversion of Our Country’s greatest gift.[96]

Butler sent his award back, but the Navy Department returned it with the reply that he would keep his Medal of Honor—and he would wear it.[97] Thus, Butler earned the first of his two Medals of Honor. The second would come from action in Haiti in 1915, and would make him one of only two U.S. Marines to earn a Medal of Honor for two separate actions. Had U.S. Navy officers been eligible in 1900, Butler might have earned a third medal for his actions during the Boxer Rebellion. Instead, he had been brevetted a captain and advanced two precedence numbers on the Marine Corps officers list.[98]

Major Smedley Darlington Butler (far right) with fellow U.S. Marine officers at Veracruz. Left to right: Captain F. H. Delario, Sergeant Major John H. Quick (standing), Lieutenant Colonel Wendell C. Neville, Colonel John A. Lejeune, and Butler. (Box 6, divider 28F, General Photographic File, 1900–1941, Records of the U.S. Marine Corps, Record Group 127, NARA, College Park, MD.)

The excessive number of medals awarded by the Navy Department and the backlash from officers pointed toward a lack of military decorations. A hierarchy of awards was needed so that men could be recognized for exemplary service even if their heroism did not merit the Medal of Honor. The Medal of Honor remained the only medal for valor available to U.S. service members until the last year of World War I, when General John G. Pershing and other military commanders urged Congress to legislate new medals, including the Navy Cross, Silver Star, and Distinguished Service Medal. However, the Navy would lack a medal to honor sacrifice until Pearl Harbor galvanized President Franklin Delano Roosevelt to authorize the Purple Heart for the U.S. Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard by executive order.[99]

Lessons Learned

Perhaps the greatest lesson learned from the naval landing at Veracruz was that U.S. Navy officers should consult U.S. diplomats in theater before making decisions that would influence—or strain—diplomatic relations. The U.S. consul in Tampico, Clarence Miller, understood Admiral Mayo’s demands to be excessive in proportion to the Tampico Affair. If decision-making had been shaped by diplomats with the expertise to accurately assess the situation in country, bloodshed could have been avoided altogether. Yet Consul Miller could not voice his position to the State Department because his only channel of communication was Mayo’s radio. Thus, the individual shaping policy in Washington was a U.S. Navy admiral with little understanding of Mexican-American relations. In the early twentieth century, as the United States navigated its newfound position as a global power, U.S. Navy operations were increasingly a matter of international diplomacy. As previously demonstrated during the Boxer Rebellion, the U.S. military and State Department needed to establish protocols for cooperation between officers and diplomats in theater. Furthermore, the U.S. Navy should not have had complete control over radio transmissions the State Department relied upon to conduct matters of diplomacy. Despite his inferior position to Mayo, Consul Miller should have been able to deliver his dissenting opinion to Washington.

The conflict itself also provided useful lessons for the U.S. Navy, namely that its sailors were unprepared for urban street fighting. Incidents of bluejackets bunching together in the streets or marching in parade formation and neglecting to send an advance guard made them easy targets for snipers. Furthermore, the sailors’ white summer uniforms could be seen by the enemy from afar, inspiring some men arriving in theater to hastily dye their uniforms. The U.S. Navy needed to better prepare its officers and enlisted men for the possibility of fighting on land, and it needed to provide them uniforms appropriate for land combat—perhaps the khaki or forest green recommended by the Annual Reports of the Navy Department for the Fiscal Year 1914.[100]

Sailors from Florida dressed in white summer uniforms guarding the Navy's headquarters at the Terminal Hotel. (Box 1, folder 19-VC-Y, Miscellaneous Views Taken at Veracruz, Mexico, 1914–1920, Records of the Bureau of Ships, Record Group 19, NARA, College Park, MD.)

The Navy Department’s report additionally noted that in the early days of the Veracruz occupation, the hospital ship Solace had to sail north for machinery repairs, leaving the Atlantic Fleet and the forces on shore without the vessel’s medical facilities. While a catastrophe did not occur in Solace’s absence, the mere possibility made a strong case for a second hospital ship being attached to the Atlantic Fleet.[101] The fighting and occupation at Veracruz also “taxed to the limit both the supplies and the personnel of the Medical Department,” almost entirely depleting the medical supply depot at Brooklyn. Had the occupation been longer or larger in scope, the Navy would have required contributions from the Red Cross or been forced to purchase large quantities of supplies “at a considerably advanced price.”[102] Thus, Veracruz illuminated a need for the Navy to keep larger stockpiles of medical supplies and employ a higher number of medical personnel.

Left to right: Solace, Chester, Mayflower, and Bravo at Veracruz. Note the San Juan de Ulua in the right background. (Box 1, folder 19-VC-D, Miscellaneous Views Taken at Veracruz, Mexico, 1914–1920, Records of the Bureau of Ships, Record Group 19, NARA, College Park, MD.)

Moreover, Veracruz revealed that the U.S. Navy’s current organization hindered effective operations by the U.S. Marine Corps. Marines arrived scattered among various Navy ships, which prevented the service from organizing itself as a single task force and forced it to undergo multiple rapid transfers of command. Only the troop transport Hancock under Colonel Lejeune had carried a robust complement of Marines, and upon its arrival on 22 April, command of the Marine Corps contingent had quickly changed hands from Neville to Lejeune. To realize the Marines Corps’ potential as an amphibious force, the Navy needed to build additional troop transports dedicated to its sister service. In fact, Veracruz was the last amphibious landing in U.S. military history in which a significant portion of the troops put ashore were sailors.[103] In the 1920s, Lejeune would become commandant of the Marine Corps and develop the doctrine and organization that forged the U.S. Marines into the service responsible for projecting power ashore.

Finally, the Navy needed to improve its ability to coordinate joint operations. At Veracruz, the transfer of command from the Navy to the Army had been delayed for several days as the services squabbled over control of the Marine Corps. Unable to resolve the issue between themselves, the Secretary of the Navy and Secretary of War had looked to President Wilson. Moving forward, joint operation protocols were imperative so that the President of the United States did not have to serve as a mediator.

Although the landing at Veracruz highlighted critical areas for improvement, it also demonstrated the efficiency with which the U.S. Navy could mobilize. Within 24 hours of Admiral Badger receiving directions to sail, his squadron was underway—a feat that required moving “tens of thousands of tons of coal, supplies, provisions, ammunition, and war equipment” aboard the vessels while attending to “administrative details” and preparing each ship to sail.[104] The rapid movement of vessels and deployment of sailors and marines in Mexico provided evidence of the U.S. Navy’s readiness. Ships slipped into the Veracruz harbor under the cover of night, deploying landing parties that strengthened the men on shore and led to the swift capture of the city. Conflict could and should have been avoided, but when the United States and Mexico had passed the point of no return, the sailors and marines showed the world that the United States was a global power prepared for the conflicts of the twentieth century.

—Emily Abdow, NHHC Communication and Outreach Division

Available Online

Beazer, Dylan. “Navy Medial Corps Medal of Honor Recipients in the Battle of Vera Cruz.” NHHC. Last modified 24 February 2021.

Engel, Kati. “Aerial Reconnaissance at Veracruz, Mexico April–June 1914.” NHHC. Last modified 16 September 2022.

"Navy Medal of Honor: Mexican Campaign (Vera Cruz) 1914." NHHC. Last modified 20 September 2018.

Available at the Navy Department Library

Quirk, Robert E. An Affair of Honor: Woodrow Wilson and the Occupation of Veracruz. Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 2016.

Sweetman, Jack. The Landing at Veracruz: 1914. Annapolis: United States Naval Institute, 1968.

Wheatley, J. N., and H. T. Smith, comps. U.S.S. New Hampshire: Journal of Events Incident to the Capture and Occupation of Vera Cruz, Mexico, by United States Naval Forces, April 21–30. New Hampshire: The New Hampshire Press, 1914.

***

[1] In primary source accounts, the city’s name is often styled as “Vera Cruz.”

[2] Paul C. Clark Jr. and Edward H. Moseley, “D-Day Veracruz, 1847—A Grand Design,” Joint Forces Quarterly 10 (Winter 1995–96): 113.

[3] “Mayo at Tampico,” The Literary Digest, 2 May 1914, 1060.

[4] Robert E. Quirk, An Affair of Honor: Woodrow Wilson and the Occupation of Veracruz (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 2016), 20–26.

[5] Quirk, An Affair of Honor, 8, 27.

[6] Quirk, An Affair of Honor, 27–30.

[7] Quoted in Quirk, An Affair of Honor, 32.

[8] Quirk, An Affair of Honor, 41.

[9] Quirk, An Affair of Honor, 49.

[10] Jack Sweetman, “Take Veracruz at Once” Naval History Magazine, March 2014.

[11] Quirk, An Affair of Honor, 63.

[12] President Wilson’s Address to Congress, 20 April 1914, in U.S. Department of State, Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, with the Address of the President to Congress December 8, 1914, ed. Joseph V. Fuller (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office [GPO], 1922), Document 705.

[13] Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, Document 705.

[14] Admiral Fletcher to the Secretary of the Navy, 16 April 1915, in Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, Document 688.

[15] Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, Document 705.

[16] Sweetman, “Take Veracruz at Once.”

[17] Quirk, An Affair of Honor, 69.

[18] Quirk, An Affair of Honor, 76.

[19] Quoted in Sweetman, “Take Veracruz at Once.”

[20] Quoted in Sweetman, “Take Veracruz at Once.”

[21] Quirk, An Affair of Honor, 68, 85.

[22] Quirk, An Affair of Honor, 85–86; Sweetman, “Take Veracruz at Once.”

[23] Quirk, An Affair of Honor, 89–92.

[24] Quirk, An Affair of Honor, 92–94.

[25] Sweetman, “Take Veracruz at Once”; Quirk, An Affair of Honor, 94–95.

[26] Quirk, An Affair of Honor, 95; Jack Sweetman, The Landing at Veracruz: 1914 (Annapolis: United States Naval Institute, 1968), 69–71; Thos. Davis, “The American Invasion of Veracruz,” HistoryNet, last modified 19 February 2019.

[27] Davis, “The American Invasion of Veracruz”; Arthur Ruhl, “The Fall of Vera Cruz,” Collier’s, 9 May 1914, 5; “Edward A. Gisburne,” Congressional Medal of Honor Society, accessed 14 February 2023.

[28] Sweetman, The Landing at Veracruz: 1914, 71.

[29] Sweetman, “Take Veracruz at Once.”

[30] Quirk, An Affair of Honor, 96–97.

[31] Sweetman, “Take Veracruz at Once.”

[32] Quirk, An Affair of Honor, 97.

[33] Sweetman, “Take Veracruz at Once.”

[34] U.S. Navy Department, Annual Reports of the Navy Department for the Fiscal Year 1914 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1915), 358. The report mistakenly records 2 wounded rather than 22.

[35] Quirk, An Affair of Honor, 98.

[36] Quirk, An Affair of Honor, 99.

[37] “San Francisco I (Cruiser No. 5),” Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC), last modified 12 January 2018.

[38] J. N. Wheatley and H. T. Smith, comps., U.S.S. New Hampshire: Journal of Events Incident to the Capture and Occupation of Vera Cruz, Mexico, by United States Naval Forces, April 21–30 (New Hampshire: The New Hampshire Press, 1914), 24.

[39] Sweetman, “Take Veracruz at Once”; Quirk, An Affair of Honor, 100; Joseph Arthur Simon, The Greatest of All Leathernecks: John Archer Lejeune and the Making of the Modern Marine Corps (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2019), 93, Google Books, eBook.

[40] Wheatley and Smith, U.S.S. New Hampshire, 4; Annual Reports of the Navy Department, 352.

[41] Wheatley and Smith, U.S.S. New Hampshire, 4.

[42] Sweetman, “Take Veracruz at Once”; Wheatley and Smith, U.S.S. New Hampshire, 4.

[43] Wheatley and Smith, U.S.S. New Hampshire, 4–6.

[44] Wheatley and Smith, U.S.S. New Hampshire, 5.

[45] Quirk, An Affair of Honor, 100; Sweetman, “Take Veracruz at Once.”

[46] Sweetman, “Take Veracruz at Once.”

[47] Sweetman, “Take Veracruz at Once”; Wheatley and Smith, U.S.S. New Hampshire, 7.

[48] Wheatley and Smith, U.S.S. New Hampshire, 7–8.

[49] Wheatley and Smith, U.S.S. New Hampshire, 5.

[50] Wheatley and Smith, U.S.S. New Hampshire, 8.

[51] Wheatley and Smith, U.S.S. New Hampshire, 8.

[52] Wheatley and Smith, U.S.S. New Hampshire, 8.

[53] Wheatley and Smith, U.S.S. New Hampshire, 8–9.

[54] Wheatley and Smith, U.S.S. New Hampshire, 25.

[55] Wheatley and Smith, U.S.S. New Hampshire, 10, 27.

[56] Wheatley and Smith, U.S.S. New Hampshire, 10.

[57] Wheatley and Smith, U.S.S. New Hampshire, 10–11.

[58] Wheatley and Smith, U.S.S. New Hampshire, 11.

[59] Wheatley and Smith, U.S.S. New Hampshire, 12.

[60] Wheatley and Smith, U.S.S. New Hampshire, 12.

[61] Wheatley and Smith, U.S.S. New Hampshire, 12–13.

[62] Wheatley and Smith, U.S.S. New Hampshire, 13.

[63] Wheatley and Smith, U.S.S. New Hampshire, 13.

[64] Sweetman, “Take Veracruz at Once”; Wheatley and Smith, U.S.S. New Hampshire, 13–14.

[65] Wheatley and Smith, U.S.S. New Hampshire, 14, 29.

[66] Wheatley and Smith, U.S.S. New Hampshire, 15, 18.

[67] Wheatley and Smith, U.S.S. New Hampshire, 21.

[68] Annual Reports of the Navy Department, 358; Davis, “The American Invasion of Veracruz.”

[69] Wheatley and Smith, U.S.S. New Hampshire, 14–15, 30.

[70] Wheatley and Smith, U.S.S. New Hampshire, 31–32.

[71] Wheatley and Smith, U.S.S. New Hampshire, 32–33.

[72] Woodrow Wilson, Address of President Wilson at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, Brooklyn, N.Y., May 11, 1914 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1914), 4.

[73] Sweetman, “Take Veracruz at Once.”

[74] Quirk, An Affair of Honor, 103.

[75] Quirk, An Affair of Honor, 105–7; Simon, Greatest of All Leathernecks, 93.

[76] Wheatley and Smith, U.S.S. New Hampshire, 17. According to NHHC’s Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships, Vermont departed Veracruz in April; followed by Chester, Utah, and Michigan in June; Florida and San Francisco in July; Louisiana and New Jersey in August; and Arkansas and New Hampshire in September.

[77] Annual Reports of the Navy Department, 359.

[78] Kati Engel, “Aerial Reconnaissance at Veracruz, Mexico April–June 1914,” NHHC, last modified 16 September 2022.

[79] Quirk, An Affair of Honor, 108.

[80] Thos. Davis, “The American Invasion of Veracruz.” To this day on 13 September, the anniversary of the 1847 Battle of Chapultepec, the Mexican president reads the names of José Azueta, Virgilio Uribe, and the six Chapultepec cadets at the Monument to the Boy Heroes in Mexico City. Jonathan M. Katz; Gangsters of Capitalism: Smedley Butler, the Marines, and the Making and Breaking of America’s Empire (New York: St. Martin’s, 2022), chap. 10, Google Books, eBook.

[81] Quirk, An Affair of Honor, 110–13.

[82] Quirk, An Affair of Honor, 150–52.

[83] Quirk, An Affair of Honor, 118–19.

[84] Quirk, An Affair of Honor, 161–70.

[85] Philip Russell, The History of Mexico: From Pre-Conquest to Present (New York: Routledge, 2010), 326, Google Books, eBook.

[86] Dwight S. Mears, The Medal of Honor: The Evolution of America’s Highest Military Decoration (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2018), 46–50.

[87] Annual Reports of the Navy Department, 52.

[88] Mears, Medal of Honor, 49.

[89] Mears, Medal of Honor, 49.

[90] Record of Medals of Honor Issued to the Officers and Enlisted Men of the United States Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard (Washington, DC: GPO, 1917), 6.

[91] Mears, Medal of Honor, 50.

[92] Mears, Medal of Honor, 50.

[93] “Mexican Campaign (Vera Cruz), Full-Text Citations,” U.S. Army, accessed 14 February 2023.

[94] “Mexican Campaign (Vera Cruz),” U.S. Army.

[95] “Vera Cruz Medals,” The Washington Herald, 19 September 1915, 8.

[96] Anne Cipriano Venzon, ed., General Smedley Darlington Butler: The Letters of a Leatherneck, 1898–1934 (New York: Praeger, 1992), 163.

[97] Mears, Medal of Honor, 50.

[98] Chester M. Biggs Jr., The United States Marines in North China, 1894–1942 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2003), 119.

[99] Adam Bisno, “The Purple Heart,” NHHC, last modified 12 August 2019.

[100] Annual Reports of the Navy Department, 352.

[101] Annual Reports of the Navy Department, 353.

[102] Annual Reports of the Navy Department, 359.

[103] Simon, Greatest of All Leathernecks, 94–95. For an in-depth discussion of the Marine Corps' lessons learned at Veracruz, see Simon, Greatest of All Leathernecks, 90–95.

[104] Annual Reports of the Navy Department, 52.