Arkansas III (Battleship No. 33)

1912–1946

Arkansas was admitted to the Union as the 25th state on 15 June 1836. The French Jesuit missionary and explorer Father Jacques Marquette and his confreres recorded the term Arcansas as the plural of the word they transliterated as akansa, an Algonquian name for the Quapaw Native American people.

III

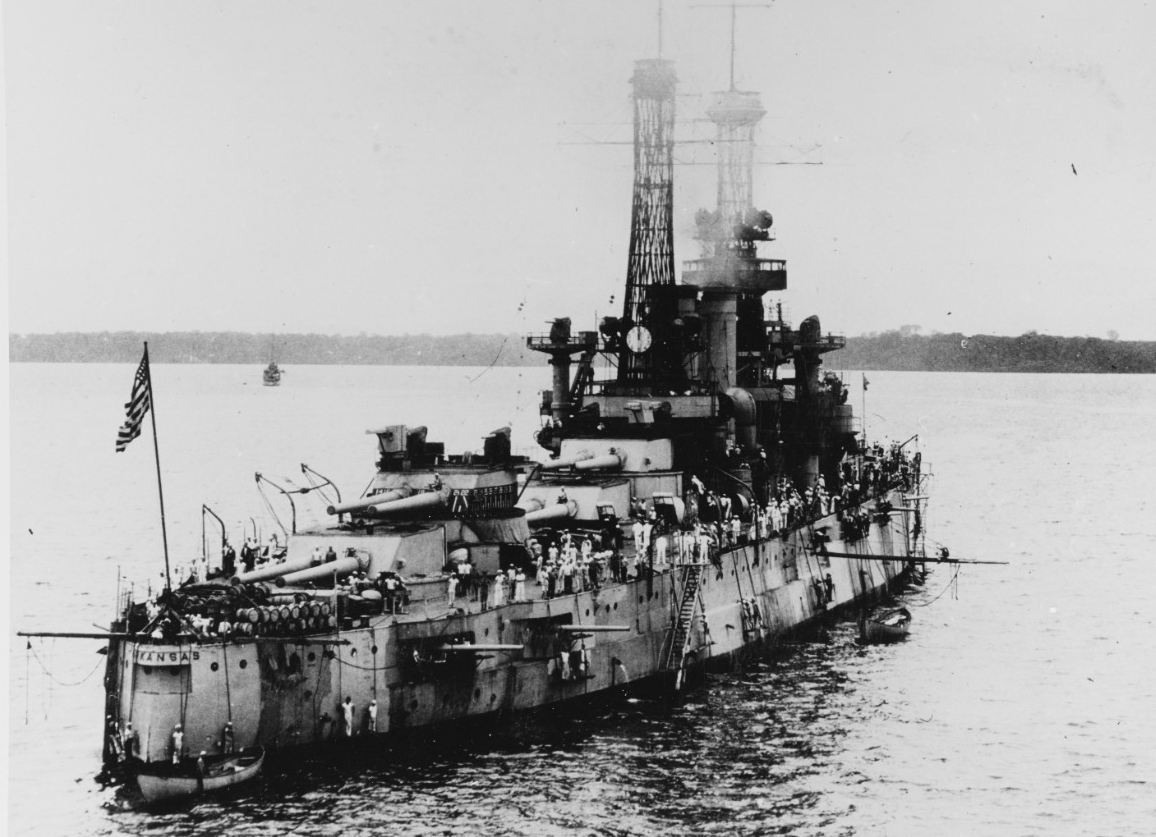

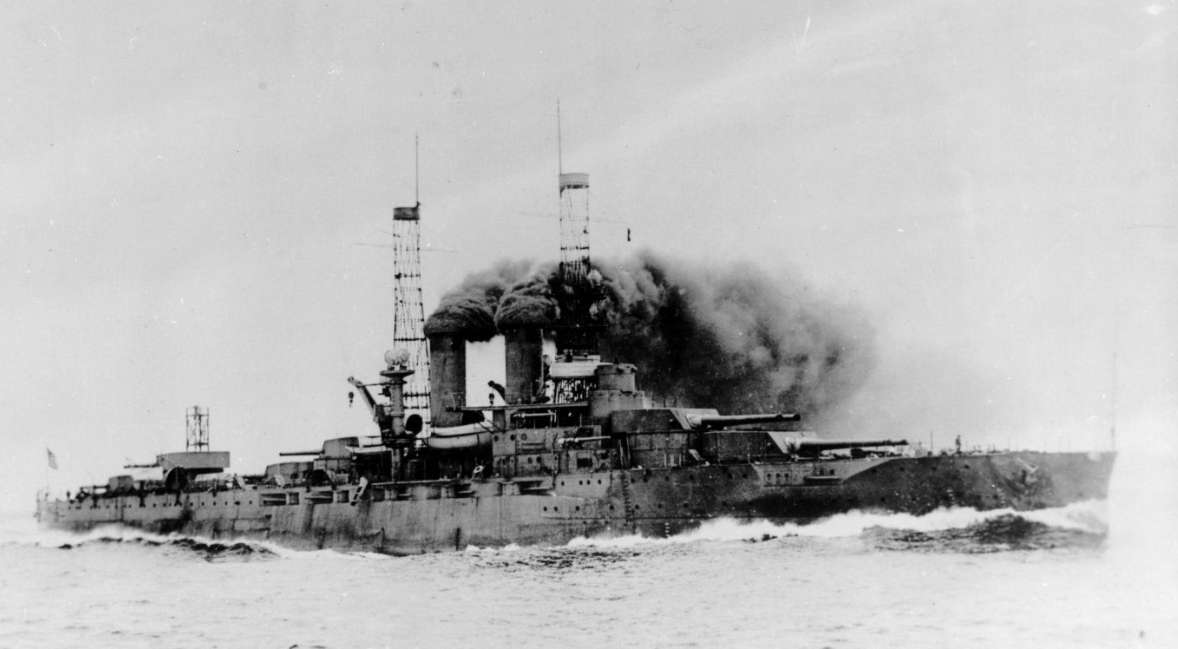

(Battleship No. 33: displacement 27,243; length 562'; beam 93'1'/2"; draft 28'6"; speed 21.05 knots; complement 1,036; armament 12 12-inch, 21 5-inch, 2 21-inch torpedo tubes (submerged); class Wyoming)

The third Arkansas (Battleship No. 33) was laid down on 25 January 1910 at Camden, N.J., by the New York Shipbuilding Co.; launched on 14 January 1911; and sponsored by Miss Nancy L. Macon of Helena, Ark., daughter of Representative Robert B. Macon (D., Ark.). While Arkansas carried out her builder’s trials and entered Penobscot Bay, Maine, she struck a rock on 4 June 1912. The mishap occurred just as she passed Two Bush Island outside the harbor of Rockland, and the rock gashed the hull for a length of nearly 45-feet abaft the bow on the port side, under the second engine room. Sailors manned pumps to dewater the flooded compartment so that inspectors could check the damage, and she subsequently resumed her trials. Investigators exonerated Capt. Charles A. Blair of Bath, Maine, the harbor pilot, and Capt. Roy C. Smith retained command of the ship. Arkansas was commissioned at the Philadelphia [Pa.] Navy Yard on 17 September 1912, Capt. Smith in command.

The new battleship fitted out until 6 October 1912, and then (8–15 October) took part in a fleet review by President William H. Taft and Secretary of the Navy George von L. Meyer in the North [Hudson] River off New York City on the 14th, and that day the chief executive briefly bordered her. Arkansas steamed back downriver and across Long Island Sound for a torpedo outfit at Newport, R.I. (16–21 October). On the 21st the ship tested her torpedoes in Narragansett Bay, returned to Newport the following day, and completed repairs and took on stores at New York Navy Yard (23 October–24 November). Arkansas next (25–26 November) began her shakedown cruise to Hampton Roads, Va., and shifted berths there while awaiting further orders through the end of the month. She then (1–3 December) carried out gunnery trials off Tangier Island in Chesapeake Bay, and returned to Hampton Roads to prepare to again take on board the chief executive.

Arkansas then (13–21 December 1912) steamed southerly courses along the east coast to Key West, Fla., where President Taft and his party boarded her for a trip (22–24 December) to Colón at the Panama Canal Zone to inspect the unfinished isthmian waterway. Arkansas landed the inspection party for Christmas and then (26–29 December) returned the President and his entourage to Key West. The battleship next stood out of the southernmost port of the continental United States to sail to Cuban waters to resume her shakedown training (30 December 1912–13 February 1913). The ship operated intermittently out of Guantánamo Bay (5–22 January 1913) and Guacanayabo Bay, Cuba (23 January–11 February).

Off Ceiba Cay, Cuba, on the 11th, however, Arkansas struck a coral head, which required her to return briefly for repairs at Guantánamo Bay, and from there to set out for the return voyage to Hampton Roads (20–25 February 1913). With no rest for the weary, Arkansas embarked the Trial Board upon her arrival and almost immediately continued north to the New York Navy Yard, where she accomplished more extensive repairs in Dry Dock No. 4 (28 February–25 May). The warship completed standardization and full power trials off Rockland (27–31 May), and then (2–4 June) swung around for Hampton Roads, where she rejoined the Atlantic Fleet for exercises. Arkansas also visited the Naval Academy at Annapolis, Md. (5–9 June), where midshipman embarked for their training cruise. Following that endeavor she (9 June–16 July), she welcomed Minas Geraes while the Brazilian battleship carried that country’s Minister of Foreign Affairs Lauro S. Müller to the United States, returning the visit that Secretary of State Elihu Root had made to the Brazilians seven years before. Arkansas escorted Minas Geraes to the North River at New York, and after that assignment joined the Atlantic Fleet for maneuvers along the east coast.

Arkansas carried out drills off Newport (17–21 July 1913), then on the 22nd off Block Island, Menensha Bight (22–24 July), swung around Block Island again on the 25th, and then (25 July–4 August) the laborious and filthy task of coaling, as well as taking on provisions, at Newport. The warship rendezvoused with the fleet for maneuvers off Point Judith, R.I. (5–8 August), Block Island (8–9 August), held drills and took on provisions at Newport (9–18 August), and next (18–22 August) fired her torpedoes at targets in Napeague Bay, N.Y. Arkansas charted southerly courses as she disembarked the midshipmen back at Annapolis (24–25 August), and then (25–28 August) conducted elementary torpedo practice at the Southern Drill Grounds, Va. The ship broke her rigorous regimen of training to coal at Hampton Roads (28 August–1 September), and furthermore prepared for gunnery practice at the Southern Drill Grounds (2–6 September), Cape Charles City, Va. (6–9 September), and Lynnhaven Roads, Va., on the 9th. As ready as she could ever be, the battleship held elementary target practice off the Southern Drill Grounds (9–14 September), and then (14–15 September) transferred targets at Hampton Roads. Arkansas did so because the ship required additional yard work and so she turned northward and entered dry dock at New York Navy Yard (10 September–2 October).

Arkansas emerged from the navy yard and steamed southward to anchor overnight on the 3rd and 4th off Cape Henry, Va. The warship coaled at Hampton Roads 4–7 October) and rejoined the fleet off Cape Henry (7–9 October), the Southern Drill Grounds (9–11 October), and Old Plantation Flats, Va. (11–13 October), the latter in company with the 1st Division as they prepared for division practice. Arkansas embarked passengers at Hampton Roads (15–16 October) to observe her fall of shot, and she then on the 16th carried out target practice off Lynnhaven Roads. The ship rendezvoused with her consorts for division practice off the Southern Drill Grounds (17–18 October), and then coaled and took on stores at Hampton Roads (18–25 October).

The reason that Arkansas required such extensive provisioning is that the ship began her first overseas cruise when she set out with the 1st and 4th Divisions for a voyage into European waters (25 October–15 December 1913). Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt visited the battleship just before she departed. Hospital ship Solace and three colliers stood out to sea at noon on the 25th, and at 1:30 p.m. Arkansas weighed anchor and headed down the channel with the fleet. Roosevelt saw the fleet off from dispatch boat Dolphin and signaled “Good bye, pleasant voyage” from her yard arm. The battleship’s crew exercised each morning except Sundays, when they celebrated a day of worship and rest. In particular, the Navy had just introduced a Swedish exercise regimen which stressed fun as well as physical health. Acclaimed Swedish-American painter Henry Reuterdahl traveled on board Arkansas during the voyage, and illustrated and wrote of his experiences. The ships crossed the Atlantic in calm weather until just before they reached the Strait of Gibraltar, when a storm pounded them mercilessly, even tossing the dreadnaughts. Consequently, they increased speed and passed through the strategic strait that night, to the dismay of many of the sailors and marines, who had otherwise looked forward to a glimpse of “The Rock.” Arkansas then crossed the Western Mediterranean and while she steamed along the Italian coast a new order, authored by someone who appreciated Greek mythology, appeared on the bulletin board:

“All Benedicts must wear cotton in their ears tomorrow. We are approaching Scylla and Charybidis, and the Sirens are still singing their persuasive songs. Lest some, too soft hearted, should be beguiled, it is ordered, in the interest of the waiting Penelope, that the married men of the Arkansas should vie with Ulysses in the stern refusal of their enticements.”

Arkansas visited several Italian ports and her liberty parties toured Rome, Florence, Naples, Pompeii, and Venice. While moored at the Breakwater at Naples (8–30 November) on the 11th the ship celebrated Italian King Victor Emmanuel III’s birthday. During the cruise the men of Turret IV received the coveted Battle Efficiency “E” award, and the ship herself outdid all of her consorts and won both the Engineering and Radio competitions. Men nonetheless complained about the lack of milk in their tea “Since the cute little stranger arrived,” a jibe about their new goat mascot. Revolution, meanwhile, tore Mexico apart as disparate groups lunged vengefully at each other and the crew eagerly listened to news broadcasts. Rumors did not credit Arkansas with deploying during the crisis, but her battalion nevertheless carried out daily drills as the ship steamed homeward.

Following the long miles of steaming the vessel required work and upon her return entered New York Navy Yard for an overhaul (15 December 1913–2 April 1914). Arkansas accomplished the yard work but battled the flood tide while leaving Brooklyn, which swung her bow around dangerously toward a car float. Several tugs rendered assistance and turned her down channel so that she could safely depart the busy harbor. The ship sailed to Hampton Roads and then (6–11 April) held spring battle practice off the Southern Drill Grounds, Hampton Roads (11–13 April), and the Southern Drill Grounds again (13–14 April). Arkansas would need the training for her next venture.

As the Mexican Revolution raged across the country, Gen. Victoriano Huerta, one of the strongmen, ruthlessly eliminated rivals and ambitiously amassed power among the Federales (government troops). The chaos endangered U.S. citizens caught in the midst of the war and pushed President Woodrow Wilson beyond forbearance, and he called on U.S. warships to protect, and, if necessary, evacuate Americans. Dolphin (Lt. Comdr. Ralph Earle, commanding) anchored at Tampico, Mexico, on 6 April 1914. Earle sent his paymaster and a boat ashore, but Mexican soldiers arrested the nine men because they landed in a “forbidden area” and paraded them through the streets. Mexicans incarcerated an orderly from Minnesota (Battleship No. 22) when he went ashore for the mail at Veracruz a few days later.

Rear Adm. Henry T. Mayo, Commander, Fourth Division, demanded a 21-gun salute in apology over the “Tampico Incident,” and on 14 April 1914 President Wilson ordered the Atlantic Fleet to send an expedition. The following day, Wilson wired an ultimatum as the lead ships of the Atlantic Fleet arrived in Mexican waters. The Mexicans could salute the flag prior to 6:00 p.m. the following day or suffer the consequences—they apologized and rendered the salute. Rumors circulated, however, that German interests were attempting to smuggle 250 machine guns, 20,000 rifles, and 15 million rounds of ammunition on board the 8,142 ton German-flagged cargo steamer Ypiranga of the Hamburg-Amerika Linie [Hamburg America Line] into Veracruz.

Wilson therefore directed Rear Adm. Charles J. Badger, Commander, Atlantic Fleet, to seize the custom house at Veracruz. On the morning of 19 April 1914, U.S. Consul William W. Canada notified Gen. Gustavo Maass, who led the port’s garrison, of the planned landings to avoid bloodshed. Huerta disregarded the warning and ordered Maass to make a show of force to influence foreign opinion among the observers on board the ships in the outer harbor, which included British and French armored cruisers Essex and Condé, respectively, and Spanish gunboat Carlos V.

Arkansas, New Hampshire (Battleship No. 25), New Jersey (Battleship No. 16), South Carolina (Battleship No. 26), Vermont (Battleship No. 20), Chester (Cruiser No. 1), and cruiser San Francisco reached Veracruz after nightfall on the 21st. The following morning [22 April 1914], the ships put ashore their detachments of sailors and marines. Capt. William R. Rush, the commanding officer of Florida (Battleship No. 30), led the landing force. Maj. Smedley D. Butler, USMC, commanded the marines ashore, and Rear Adm. Frank F. Fletcher, Commander, 1st Division, shifted his flag to transport Prairie to monitor the battle. The landing force included the First Seaman Regiment, Lt. Cmdr. Allen Buchanan (who later received the Medal of Honor), Second Seaman Regiment, Capt. Edwin A. Anderson Jr. (who also received the Medal of Honor for his “extraordinary heroism” during the battle), and the Second Marine Advanced Base Regiment. Arkansas contributed a battalion of four companies of bluejackets, 17 officers and 313 enlisted men under the command of Lt. Cmdr. Arthur B. Keating.

Reinforcing the sailors and marines already ashore raised the strength of the naval brigade to nearly 4,000 men, and at 7:45 a.m. they began to advance into the heart of the city. Mexican troops, especially the naval cadets under Commodore Manuel Azueta P., fought determinedly and repelled the initial advance of the Second Seaman Regiment until Chester opened fire. The bluejackets and marines established blocking positions across the streets leading toward the Plaza de la Constitucion, the main square. The Mexicans turned several buildings into strongholds and snipers shot at the invaders from vantage points at the Benito Juarez lighthouse and Naval Academy, and from boxcars and warehouses along the waterfront, although gunfire from the ships broke up troop concentrations. Arkansas’s men moved forward through the slow, methodical street fighting that eventually secured the city.

The ship’s junior officers included Lt. (j.g.) Jonas H. Ingram, who received the Medal of Honor for his heroism at Veracruz, as would Lt. John Grady, who commanded the artillery of the Second Seaman Regiment. Ingram’s service grew increasingly “conspicuous” during the second day’s fighting for his “skillful and efficient handling of the artillery and machine guns of the Arkansas battalion, for which he was repeatedly commended in reports.” Grady performed “eminent and conspicuous” service on the second day when from “necessarily exposed positions, he shelled the enemy from the strongest position.” Two Arkansas sailors, Ordinary Seamen Louis O. Fried and William L. Watson, died of their wounds on 22 April. The Americans suffered 17 dead and 63 wounded, and at least 126 Mexicans fell and another 195 sustained wounds.

Arkansas’s battalion returned to the ship on 30 April 1914, although the ship continued to operate in Mexican waters through the summer. During her stay at Veracruz, she received calls from German military attaché to the U.S. and Mexico Capt. Franz von Papen, and British Rear Adm. Sir Christopher G. F. M. Cradock, RN, Commander, Fourth Cruiser Squadron, on 10 and 30 May 1914, respectively. Cradock had already evacuated a number of refugees from Tampico, and during the additional fighting he rescued nearly 1,500 more from Mexico City, Tampico, and Veracruz. While Arkansas was operating in Mexican waters, Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels issued General Order No. 99 on 1 June. The order annulled article 826 of the Naval Instructions, effective on 1 July, by substituting it with the following instruction: “The use or introduction for drinking purposes of alcoholic liquors on board any naval vessel, or within any navy yard or station, is strictly prohibited, and commanding officers will be held responsible for the enforcement of this order.”

The Americans seized Ypiranga and temporarily cut off Huerta from his supplies, but the arms on board eventually reached the general. The invaders also left behind valuable stores. President Wilson shrewdly allowed the rival Constitutionalists to receive supplies, enabling them to snatch control from Huerta, who resigned on 17 July 1914 and fled into exile—although the Americans occupied Veracruz until November. Arkansas set course to return to the east coast on 30 September and on 7 October reached Hampton Roads. Following a week of exercises, Arkansas sailed to New York Navy Yard for repairs and alterations. She returned to the Virginia capes area for maneuvers on the Southern Drill Grounds and on 12 December 1914, returned to the yard at New York for further repairs.

She was underway again on 16 January 1915, and returned to the Southern Drill Grounds for exercises there (19–21 January). Upon completing the training, Arkansas sailed to Guantánamo Bay for fleet exercises. Returning to Hampton Roads on 7 April, the battleship began another training period in the Southern Drill Grounds. On 23 April she headed to New York Navy Yard for a two-month repair period. Arkansas left New York on 25 June bound for Newport, where she conducted torpedo practice and tactical maneuvers in Narragansett Bay through late August. Throughout this period she operated in the Atlantic Fleet’s First Division, which at times also included Delaware (Battleship No. 28), North Dakota (Battleship No. 29), Texas (Battleship No. 35), and Wyoming (Battleship No. 32).

Returning to Hampton Roads on 27 August 1915 the battleship engaged in maneuvers in the Norfolk, Va., area through 4 October, then sailed once again to Newport. There, Arkansas carried out strategic exercises (5–14 October). On the 15th the battleship arrived at New York Navy Yard for drydocking through 8 November, when she returned to Hampton Roads. After a period of routine operations, Arkansas went back to Brooklyn for repairs on 19 October. The ship stood out on 5 January 1916, for Hampton Roads but pausing there only briefly, pushed on to the Caribbean for winter maneuvers. Arkansas visited the West Indies and Guantánamo Bay before returning to the United States on 12 March 1917, and held torpedo practice off Mobile Bay, Ala. She served largely in Squadron Four’s Seventh Division while carrying out these programs. The battleship steamed back to Guantánamo Bay on 20 March and three days later Capt. Louis R. De Steiguer relieved Capt. William H. G. Bullard as the ship’s commanding officer. Bullard subsequently (17–23 August) detached and traveled to Malta to take command with the temporary rank of rear admiral of Naval Forces Eastern Mediterranean.

Meanwhile, on 6 April 1917, the U.S. entered the Great War on the side of the Allied and Associated Powers. The declaration of war found Arkansas attached to Battleship Division (BatDiv) 7 and patrolling the York River in Virginia. The ship further prepared for hostilities by accomplishing an overhaul at New York Navy Yard, beginning on 15 April. Being stationed at the thrilling and busy metropolis brought with it additional hazards, however, and a car struck and killed FN3c Clifford T. Pocklington on 25 May. For the next 13 months, Arkansas carried out patrol duty along the east coast and trained gun crews for duty on armed merchantmen. Adm. William S. Benson, Chief of Naval Operations (CNO), ordered Arkansas, Arizona (Battleship No. 39), Kearsarge (Battleship No. 5), Kentucky (Battleship No. 6), Nevada (Battleship No. 36), Oklahoma (Battleship No. 37), Pennsylvania (Battleship No. 38), and Texas each to remove two 5-inch guns, mounts, accessories, and spare parts on 7 December.

The worldwide influenza epidemic caused millions of deaths during this period. Navy medical facilities treated 121,225 USN and USMC victims including 4,158 fatalities during 1918. “The morgues were packed almost to the ceiling with bodies stacked one on top of another,” Navy Nurse Josie Brown of Naval Hospital, Great Lakes, Ill., recalled. The dreaded disease infected a number of men of Arkansas’ ship’s company, and FN3c William F. Madden succumbed to influenza on 13 June 1918, followed on 6 September by FN3c Christian H. Rice.

In July 1918, Arkansas received orders to proceed to Rosyth, Scotland, to relieve her old friend Delaware. Fourteen members of the House Naval Committee boarded Arkansas for the voyage as she crossed the Atlantic for Scottish waters (14–28 July). On the eve of her arrival there, the ship opened fire on what lookouts believed to be the periscope wake of a German U-boat (submarine). Her escorting destroyers also dropped depth charges but scored no hits, and Arkansas then proceeded without further incident and dropped anchor at Rosyth. The committee members disembarked and began a tour of U.S. naval stations across Europe, and Arkansas relieved Delaware and the latter turned for home on the 30th. Throughout the remaining three and one-half months of war, Arkansas and the other American battleships in Rosyth operated as part of the British Grand Fleet as the Sixth Battle Squadron. The armistice ending World War I became effective on 11 November, and the Sixth Battle Squadron joined British Royal Navy ships as they sailed to a point some 40 miles east of May Island at the entrance of the Firth of Forth to observe the internment of the German High Seas Fleet in the Firth of Forth on 21 November.

The U.S. battleships were detached from the British Grand Fleet on 1 December 1918. From the Firth of Forth, Arkansas sailed to Portland, England, and thence out to sea to meet the troop transport George Washington (Id. No. 3018) (Capt. Edwin T. Pollock, commanding) as she carried President Wilson and the U.S. representatives to the Paris Peace Conference. Pennsylvania protected the chief executive and his entourage as they crossed the Atlantic. Arkansas rendezvoused with Pennsylvania and her charge to join seven other battleships and several divisions of destroyers in an impressive demonstration of U.S. naval strength as they escorted George Washington and her important passengers into Brest, France, on 13 December. From that French port, Arkansas sailed to New York City, where she arrived to a tumultuous welcome on 26 December 1918. Secretary Daniels reviewed the assembled battleship fleet from yacht Mayflower.

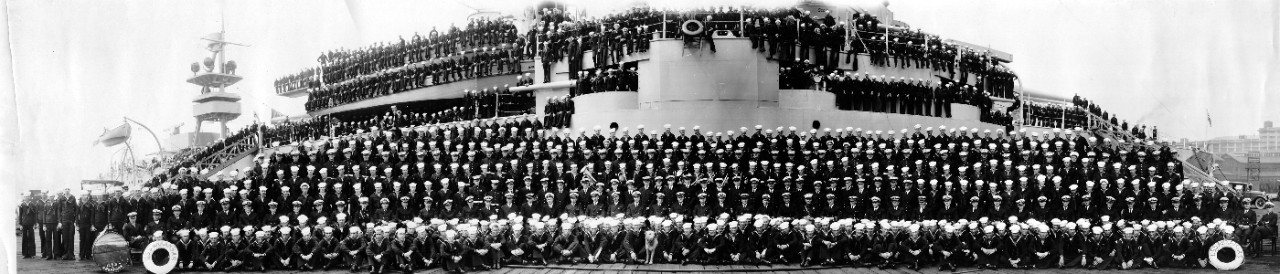

Arkansas bluejackets and marines marched in a parade down Fifth Avenue as Secretary Daniels and Secretary of War Newton D. Baker oversaw an enormous New York crowd that welcomed some of the returning veterans on 5 January 1919. Boy Scouts sang what the New York Times described as “rollicking marching songs” as the men proudly paraded past the reviewing stand and the boisterous crowd. The accolades and honors continued to shower Arkansas after her return from the Great War, and on 23 April Daisy N. Dalony, a representative of the Arkansas Travelers’ Association and on behalf of Arkansas’ Gov. Charles H. Brough, presented a silver service valued at $10,000 to the ship at New York from her namesake state in gratitude for her wartime service. Capt. Smith, the first commanding officer, Capt. De Steiguer, the current one, and Rear Adm. Edward W. Eberle, Commander, BatDiv 5, Atlantic Fleet, spoke at the ceremony. A “trophy” cup given by the Daughters of the American Revolution took pride of place in the set. The Navy later loaned the service back to the state of Arkansas, where it rests in the Governor’s Mansion in Little Rock at the time of writing.

Following an overhaul at Norfolk Navy Yard, Portsmouth, Va., Arkansas joined the fleet in Cuban waters for winter maneuvers. Soon thereafter, the battleship got underway to cross the Atlantic. On 12 May 1919, she reached Plymouth, England; thence she headed back out in the Atlantic to take weather observations on 19 May and to act as a reference vessel for the flight of the three operational Navy Curtiss (NC) flying boats (the men cannibalized NC-2 for the other planes) of Seaplane Division 1 from Trepassey Bay, Newfoundland, to Europe, as they attempted to secure their place in aviation history as the first aircraft to fly across the Atlantic. The Navy deployed four other battleships and a variety of vessels to aid the intrepid fliers including destroyers stationed at intervals to guide them, or at least planners so envisioned the operation.

“Those who think that having destroyers 50 miles apart made navigation as easy as ‘walking down Broadway’ should have been with us that evening [16 May],” Cmdr. John H. Towers, who commanded NC-3, the division’s flagship, later recalled. “It was not until darkness came on and they began to fire star shells at five-minute intervals that I could think of anything but finding the next destroyer. They could not be expected to be exactly on position, and if we didn’t find them just where we expected them, there was always the question, are they wrong or are we?” Sometimes both were.”

The plans instructed the ships to report by radio as the planes passed. At each report, the next ship in line would begin firing star shells. Then, as the planes approached, she would swing a searchlight repeatedly, from horizontal to straight up, in the direction of the prevailing surface wind. Electric lights would spell out the station number in eight-foot numerals and be situated so as to be viewed from the stern. Each ship would steam slowly along the course of the flight when planes were nearby. Planners also directed the destroyers to fire their guns to the northwest, at an angle of 75° with fuses set for 4,000 feet. The planes were supposed to pass to southward, thereby minimizing danger, or so Towers thought.

“I had set a course,” Towers explained, “which was taking us by the destroyers, just south of them, like clockwork, when finally as we approached one, it was apparent we would pass to north of it. I thought it was out of position and was reluctant to change my heading. Besides, I could see through the thin clouds and thought they could see us, too, so I kept right on. Having timed their shooting, I knew they were due to fire just about as we were in line. Either the destroyer didn’t see us or they didn’t believe in deviating one iota from their instructions for, right on the second, I saw the flash from the gun. The star shell exploded just under us. I glanced back and in the moonlight both [Cmdr. Holden C.] Richardson [CC] and [Lt. David H.] McCulloch [USNRF] looked as though they would like to take the navigation out of my hands.”

Despite their crew’s determination NC-1 and NC-3 failed to complete the perilous flight but NC-4 (BuNo A-2294), Lt. Cmdr. Albert C. Read, and crewmembers Lt. James L. Breese, Lt. Elmer F. Stone, USCG, Lt. (j.g.) Walter K. Hinton, Ens. Herbert C. Rodd, and MMC Eugene S. Rhoads became the first aircraft to cross the Atlantic when she reached Lisbon, Portugal, at 2100 on 27 May. Arkansas steamed to sea to render assistance to the fliers and her role in that epochal venture completed, she proceeded to Brest to embark Adm. and Mrs. Mary A. Benson on 10 June, as the admiral returned from the Peace Conference in Paris. The ship carried her passengers to New York, where she arrived on 20 June.

Arkansas shifted to the Pacific Fleet and sailed from Hampton Roads on 19 July 1919. Proceeding via the Panama Canal (25–26 July), the battleship steamed to San Francisco, Calif., where, on 6 September 1919, she embarked Secretary of the Navy and Mrs. Adelaide W. B. Daniels. Arkansas disembarked the secretary and his wife at Blakely Harbor, Wash., on the 12th, and the following day President Wilson reviewed the warship, the chief executive embarked in Oregon (Battleship No. 3). On 19 September 1919, Arkansas began a general overhaul at Puget Sound Navy Yard, Bremerton, Wash.

Resuming her operations with the fleet in May 1920, Arkansas operated off the California coast. Arkansas was reclassified to BB-33 as the ships of the fleet received alphanumeric designations on 17 July 1920. That September, she cruised to Hawaiian waters for the first time. Following those exercises, Arkansas, New York (BB-34), Texas (BB-35), and Wyoming (BB-32) anchored in what their sailors dubbed “Man O’ War Row” while they spent Christmas at San Francisco. Early in 1921, the ship visited Valparaiso, Chile, her crew manning the rail in honor of Chilean President Arturo F. A. Palma.

Arkansas’s peacetime routine consisted of an annual cycle of training interspersed with periods of upkeep or overhaul. The battleship’s schedule also included competitions in gunnery and engineering and an annual fleet problem. The annual tactical evolutions concentrated the Navy’s power to conduct maneuvers on the largest scale and under the most realistic conditions attainable. Becoming the flagship for Adm. Hilary P. Jones, Commander, Battleship Force, Atlantic Fleet, in the summer of 1921, Arkansas began operations off the east coast that August. A year later, on 1 August 1922, Arkansas and Wyoming anchored in the Hudson River off 96th Street for liberty at New York.

Arkansas, North Dakota (BB-29), and Wyoming took part in experimental aerial attacks against ships about 50 miles off Cape Henry on the clear and calm day of 27 September 1922. Lt. Harold T. Bartlett led a team that spent a year and a half examining the various operational aspects of using planes to attack ships with torpedoes. Eighteen Naval Aircraft Factory PT seaplanes of Torpedo and Bombing Plane Squadron 1 flew about 90 miles from their station at Hampton Roads and carried out what became the first mass torpedo practice against live targets. The trio of battleships steamed in formation but Arkansas, the principal target, stationed observers at key points around the vessel to watch where the planes dropped their Mk VII Model 1 “A” practice torpedoes, as the bombers flew at an altitude of about 2,000 feet and then swept in to release their weapons at distances of 500–1,000 yards during the 25 minute attack. The battleship’s men then telephoned the bridge and the navigator attempted to swing the ship hard over and dodged three of the torpedoes, while a fourth hurtled past Arkansas and accidently impacted North Dakota. Nonetheless, the planes scored eight ‘hits’ on Arkansas. Rear Adm. William A. Moffett, Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics, observed the tests while from Arkansas’ bridge, and noted satisfactorily the confusion that the attackers caused the battleships. Subsequent analysis emphasized artificialities which prevented the practice from demonstrating the combat capabilities of either the surface or air servicemembers, however, though the bombing runs demonstrated the capabilities of planes to launch torpedoes—and of the weapons to run straight.

Arkansas completed work in Dry Dock No. 4 at the New York Navy Yard through May 1923. For a number of years, Arkansas was detailed to take midshipmen from the Naval Academy on their summer cruises. In 1923, the battleship steamed to Europe and called on Copenhagen, Denmark, where Danish King Christian X visited her on 2 July 1923. She also put in to Lisbon and Gibraltar. Arkansas conducted another midshipman training cruise to European waters the following year in 1924. In 1925, she cruised to the west coast.

An earthquake devastated Santa Barbara, Calif., on 29 June 1925. The quake levelled most of the city’s historic district and killed at least 13 people. Some of the vessels sailing offshore reported seeing a small tsunami roll toward the coast, and the tremors also cut the telephone and telegraph lines, which all but isolated Santa Barbara from the outside world and compelled people to rely on the handful of shortwave radios available. The following day, Arkansas arrived at Santa Barbara, and, along with the destroyer McCawley (DD-276) and Eagle 34 (PE-34), landed a patrol of bluejackets for policing the city, and to establish a temporary radio station ashore for transmitting messages. Naval reservists from the city’s Naval Reserve Center and American Legionnaires, together with fire-fighters and policemen from nearby Los Angeles, Calif., also helped restore order in the aftermath of the earthquake.

Upon completing the 1925 midshipman cruise, Arkansas entered the Philadelphia Navy Yard for modernization. Workers replaced the coal-burning boilers with oil-fired ones, installed additional deck armor, plated over a number of the gun casemates, substituted a single stack for the original pair, replaced the after cage mast with a low tripod, and slightly lowered the main mast top to reduce the funnel gasses that enveloped the top when the ship steamed at high speed. Arkansas left the yard in November 1926, and after a shakedown cruise along the eastern seaboard and to Cuban waters, returned to Philadelphia to run acceptance trials. Resuming her duty with the fleet soon thereafter, she operated from Maine to the Caribbean.

Fighting between rival Nicaraguan factions broke out throughout the decade and the struggling government invited American assistance on more than one occasion. Revolutionary Augusto C. Sandino proved intractable and led guerilla warfare against U.S. Marines and the Nicaraguan Guardia Nacional. Trenton (CL-11) thus transported a company-sized battalion of 200 marines of the Arkansas, Florida (BB-30), and Texas ship’s companies to Nicaragua, where they arrived on 21 February 1927, to guard the railway towns of Chinindega and León.

President Calvin Coolidge reviewed the fleet including Arkansas off Hampton Roads on 4 June 1927. The following month the ship reported that she carried two Vought UO-1 and one UO-1C scout-observation planes. On 5 September 1927, Arkansas observed ceremonies unveiling a memorial tablet honoring the French soldiers and sailors who died during the campaign at Yorktown in 1781. In May 1928, Arkansas again embarked midshipmen for their practice cruise along the eastern seaboard and down into Cuban waters. The ship operated a single Loening OL-6 amphibian of Observation Squadron (VO) 5S on 2 June. During the first part of 1929, she steamed near the Panama Canal Zone and in the Caribbean, returning in May 1929 to New York Navy Yard for an overhaul. After embarking midshipmen at Annapolis, Arkansas carried out her 1929 practice cruise to Mediterranean and English waters, returning in August to operate with the Scouting Fleet off the east coast. Toward the end of the year in December 1929, she operated an average of one–two Vought O2U-1 Corsairs of VO-2S.

Arkansas took part in a review by President Herbert C. Hoover off the Virginia capes on 19 May 1930. The fleet passed in review, deployed, and conducted tactical exercises. That summer she again carried out a midshipmen’s practice cruise and visited Cherbourg, France; Kiel, Germany; Oslo, Norway; and Edinburgh, Scotland. The following year, the warship again embarked midshipmen and took them to Copenhagen; Greenock, Scotland; and Cádiz, Spain, as well as Gibraltar.

The participating ships, submarines, and aircraft fought across the Eastern Pacific toward Panamanian waters during Fleet Problem XII, which comprised strategic scouting, employing carriers and light cruisers, defending a coast line, and attacking and defending a convoy (15–21 February 1931). Adm. William V. Pratt, the CNO, Secretary of the Navy Charles F. Adams III, Assistant Secretary of the Navy Ernest L. Jahncke, and a number of ships from the British Atlantic Fleet including battleship Nelson (28), the flagship, observed the problem and thus generated considerable press coverage.

The essence of Fleet Problem XII concerned action between a fleet strong in aircraft and weak in battleships, and a fleet that reversed these strengths. Vice Adm. Arthur L. Willard, Commander, Scouting Force, U.S. Fleet, broke his flag in Arkansas as he led the Blue Fleet. Willard operated with vessels mainly drawn from the Scouting Force and the Control Force, which meant that he deployed an aviation heavy force that otherwise fought with limited surface strength, as Arkansas comprised his only battleship—a theoretical squadron of battleships operated in home waters but not directly in the problem. Lexington (CV-2), Saratoga (CV-3), aircraft tenders, rigid airship Los Angeles (ZR-3), and planes flying from ashore provided him an extensive offensive punch, and Arkansas added her trio of O2U-4s of VO-2S to the overall total of nearly 185 Blue aircraft. Los Angeles’s participation as a scout marked her first in a fleet problem but her “extreme vulnerability” generated controversy.

And. Frank A. Schofield, Commander, Battle Fleet, led the Black Fleet, a powerful and predominately surface force built around nine battleships and their cruiser and destroyer screen, augmented by a number of additional ships including Langley (CV-1). The opposing fleet thus deployed only 72 aircraft, most of them embarked on board the battlewagons and their cruiser consorts, but they also counted an impressive (constructive) expeditionary force of 15,000 men to seize airfields from where planes could attack Blue forces in Nicaragua and the Panama Canal. Schofield took the Black Fleet to sea from southern California on 7 February, and three days later after various preliminary operations and scouting, Willard took the Blue ships out from Hampton Roads.

Blue planes spotted the Black Fleet northwest of the Galapagos Islands about 850 nautical miles southwest of the Gulf of Panama on 15 February. Schofield divided his fleet into three forces, along with the expeditionary force. Willard wisely chose not to engage, if at all possible, the superior enemy battle strength but to lunge for the expeditionary force’s vulnerable transports. He thus steamed Arkansas to the southward of Panama while Rear Adm. Joseph M. Reeves, who broke his flag in Saratoga, led the carriers to envelop Schofield’s ships, screened by patrols of cruisers, destroyers, and submarines. Capt. Ernest J. King led one of the task forces and broke his flag in Lexington. Both sides attempted to outmaneuver the other and during the first dog watch on the 18th, Black heavy cruisers Northampton (CA-26) and Pensacola (CA-24) of Cruiser Division 4 raided into the Gulf of Chiriquí near the Panamanian coast, where they surprised and sank a minesweeper and an oiler. Aircraft tender Wright (AV-1) hurled her planes against the intruders but they unsuccessfully counterattacked the cruisers. Northampton and Pensacola came about and along the way sighted Arkansas, and the three ships inconclusively engaged salvoes as the cruisers made good their escape into the gathering dusk.

“I had expected that any heavy cruiser falling in with the Arkansas…” Schofield later mused, “would be able to defeat that vessel by staying out of range of that vessel’s guns, and by raining 8" shells on her. The difference in range of the guns of these two vessels is 10,000 yards in favor of the cruiser, but without plane spot these cruisers lost all that advantage.” Foul weather and catapult issues impeded the cruisers’ efforts to launch Northampton’s four O2U-4s and Pensacola’s four O3U-1s of Scouting Squadron (VS) 9S. “I was greatly disappointed,” the admiral continued, “to find that our 8" cruisers have such acrobatic characteristics that they could not launch their planes and recover them at sea. This took away from their great advantage of long range fire.”

Arkansas’ apparent good fortune did not continue, however, and early on the evening of the 19th an enemy submarine penetrated the screen and torpedoed her. The umpires ruled that the resulting damage sank the ship, taking Willard to the bottom with her. Command of the Blue Fleet devolved upon Reeves, who aggressively resumed the fighting. Aircraft checked but did not stop the advance of the battleship fleet and despite inferior air support umpires ruled that the battleship fleet largely defeated the carrier fleet. The limitations of carriers became apparent in that their aircraft expended half of their fuel and ammunition in just two days and without replenishment the carriers would have been forced to retreat had the exercise continued. In addition, Northampton and Pensacola demonstrated that many heavy cruisers lacked sufficient stability for catapult and recovery operations.

Following the problem the fleets united and carried out a series of primarily naval aviation exercises in Panamanian waters with the goal of merging their operations to ensure increased efficiency in light of the lessons learned. The participants developed a variety of scenarios and on 28 March 1931, Arkansas simulated a force of four battleships and, supported by Langley and their screens, maneuvered against Lexington and her escorts. Planners kicked off another exercise on the 30th in which Arkansas again operated as four battlewagons, this time in company with Lexington, Langley, six light cruisers, and some destroyers, and they fought their way through Saratoga, a half dozen light cruisers, and their escorting destroyers as they attempted to defend some coastline against the attackers.

Arkansas continued to train along the east coast and steamed northward to visit Halifax, Nova Scotia in September 1931. The following month she participated in the Yorktown Sesquicentennial celebrating the 150th anniversary of the Siege of Yorktown against the British during the Revolutionary War. President Hoover and his party boarded Arkansas at Hampton Roads and she carried them to the exposition (17–18 October). The battleship later transported the chief executive and his entourage back to Annapolis (19–20 October). Upon the return, she entered dry dock at Philadelphia Navy Yard for an overhaul until January 1932.

Following the yard work Arkansas set out for the west coast, calling at New Orleans, La., en route, to participate in the Mardi Gras celebration in the second week of February 1932. Arkansas operated continuously on the west coast of the U.S. into the spring of 1934, at which time she passed back through the Panama Canal and returned to the east coast to serve as flagship of the Training Squadron, Atlantic Fleet. In the summer of 1934, the battleship conducted a midshipman practice cruise to Plymouth, England; Nice, France; Naples, and to Gibraltar, returning to Annapolis in August. The warship proceeded thence to Newport, where she manned the rail for President Franklin Roosevelt as he passed on board yacht Nourmalhal. She then (15–25 September) observed the International Yacht Race. Under authority of law, Secretary of Commerce Daniel C. Roper requested that the Coast Guard patrol and enforce the regatta laws during the event, and Arkansas, six other naval vessels, and a Navy seaplane reinforced 14 Coast Guard vessels and several private craft as they patrolled the area. Not to be outdone, Arkansas’s cutter took part in the race and defeated the cutter from British light cruiser Dragon (D-46) for the coveted Battenberg Cup, and the City of Newport Cup.

Arkansas resumed training and transported the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines, to Culebra Island, P.R., for Fleet Landing Exercise No. 1 early in the New Year in January 1935. In June she carried out a midshipman practice cruise to Europe, calling at Edinburgh, Oslo, where Norwegian King Haakon VII (the brother of King Christian of Denmark, a previous visitor) visited the ship, Copenhagen, Gibraltar, and Funchal on the island of Madeira. After disembarking the midshipmen at the Naval Academy at Annapolis in August, Arkansas proceeded to New York. There she embarked reservists from the New York area for a Naval Reserve cruise to Halifax in September. Upon completing that duty, she underwent repairs and alterations at New York Navy Yard in October. Early the following year (4 January–24 February 1936), Arkansas participated in Fleet Landing Exercise No. 2 at Culebra and then visited New Orleans for the Mardi Gras festivities before she returned to Norfolk for a navy yard overhaul which lasted through the spring. That summer she carried out a midshipman training cruise to Portsmouth, England; Göteborg [Gothenburg], Sweden; and Cherbourg, before she returned to Annapolis that August. Steaming thence to Boston, Mass., the battleship conducted a Naval Reserve training cruise before putting into Norfolk Navy Yard for an overhaul that October.

The following year, 1937, saw Arkansas, New York, and Wyoming (AG-17) embarked more than 1,000 midshipman for a practice cruise to European waters, visiting German and British ports, before she returned to the east coast of the U.S. for local operations out of Norfolk. During the latter part of the year, the warship also ranged from Philadelphia and Boston to St. Thomas in the Virgin Islands, and Cuban waters. During 1938 and 1939, the pattern of operations largely repeated that of the previous years, her duties in the Training Squadron usually confining her to the waters of the eastern seaboard.

The Atlantic Squadron, Rear Adm. Alfred W. Johnson in command, was established in January 1939. The outbreak of war in Europe in September of that year found the squadron comprising Arkansas, New York, Texas, and Wyoming under Johnson’s immediate command, Ranger (CV-4) and Wasp (CV-7), the latter not yet in commission and her planes consequently ashore, Cruiser Division 7, Rear Adm. Andrew C. Pickens, counting heavy cruisers Quincy (CA-39), San Francisco (CA-38), Tuscaloosa (CA-37), and Vincennes (CA-44), and Destroyer Squadron 10, Capt. William G. Greenman, as well as various auxiliaries. Arkansas herself lay at Hampton Roads, preparing for a Naval Reserve cruise to be completed in company with her traditional consorts, New York, Texas, and Wyoming. She soon got underway and transported seaplane moorings and aviation equipment from Naval Air Station (NAS) Norfolk to Quonset Point, a low sandy promontory on the western shore of Narragansett Bay, where the Navy was in the process of establishing a seaplane base. The project including substantial building and dredging, and the seaplane facilities comprised two hangars earmarked for the seaborne aircraft. While at nearby Newport, Arkansas took on board ordnance material for destroyers and brought it back to Hampton Roads.

Arkansas stood out of Norfolk in company with New York and Texas on 11 January 1940, and proceeded thence to Guantánamo Bay for fleet exercises. The next month she participated in landing exercises at Culebra, returning via St. Thomas and Culebra to Norfolk. Following an overhaul at Norfolk Navy Yard (18 March–24 May), Arkansas shifted to Naval Operating Base (NOB) Norfolk, where she remained until 30 May. Sailing on that day for Annapolis, the battleship, along with New York and Texas, charted a course for a midshipman training cruise to Panama and Venezuela that summer. Before the year was out, Arkansas would conduct three V-7 Naval Reserve training cruises, the voyages taking her to Guantánamo Bay, the Panama Canal Zone, and Chesapeake Bay.

The United States gradually edged toward war in the Atlantic over the months that followed. On 16 June 1941, President Roosevelt directed the U.S. armed forces to relieve the British garrison of Iceland. The American reinforcements would enable the British to deploy their troops elsewhere, while simultaneously expanding the U.S. forward presence in the Battle of the Atlantic. The Americans launched the operation under great secrecy, before the Icelanders invited them and while the U. S. Senate debated the decision.

The 4,095 men of the 1st Marine Brigade (Provisional), Brig. Gen. John Marston VI, USMC, formed the main element of the expeditionary force. Transports Fuller (AP-14), Heywood (AP-12), and William P. Biddle (AP-15) brought the Sixth Marines, which comprised the principal strength of the brigade, from the West Coast to Charleston, S.C.—some arrived by rail. There they met the rest of the brigade, boarded their expeditionary ships, and set out on 22 June. Later that day they rendezvoused with Task Force (TF) 19, Rear Adm. David M. LeBreton, formed around Arkansas, New York, and the light cruisers Brooklyn (CL-40) and Nashville (CL-43).

Capt. James L. Kauffman, Commander, Destroyer Squadron 7, broke his flag in Plunkett (DD-431) in command of the inner screen around the battleships and transports: Destroyer Division (DesDiv) 13, Cmdr. Dennis L. Ryan, Benson (DD-421), Gleaves (DD-423), Mayo (DD-422), and Niblack (DD-424); and DesDiv 14, Cmdr. Fred D. Kirtland, Charles F. Hughes (DD-428), Hilary P. Jones (DD-427), and Lansdale (DD-426). DesDiv 60, Cmdr. John B. Heffernan, formed the outer screen, which steamed 10,000 yards ahead of the task force and comprised Bernadou (DD-153), Buck (DD-420), Ellis (DD-154), Lea (DD-118), and Upshur (DD-144).

Capt. Frank A. Braisted led the Transport Base Force, which counted Fuller, Heywood, Orizaba (AP-24) (a veteran of the Great War), and William P. Biddle, cargo ships Arcturus (AK-18) and Hamul (AK-30), oiler Salamonie (AO-26), and fleet tug Cherokee (AT-66). The ships stopped at Argentia, Newfoundland, on the 27th to top off with fuel, and three days later stood down the channel and turned for Iceland.

On 1 July 1941 meanwhile, Adm. King, Commander in Chief, Atlantic Fleet, organized task forces to further support the defense of Iceland and to escort convoys between the U.S. and that country. TF 1, Rear Adm. LeBreton, was to operate from Narragansett Bay and Boston; TF 2, Rear Adm. Arthur B. Cook, was to be based at Bermuda and Hampton Roads; TF 3, Rear Adm. Jonas H. Ingram, was to deploy to San Juan, P.R., and Guantánamo Bay; TF 4, Rear Adm. Arthur L. Bristol, was also to operate from Narragansett Bay; and TF 7, Rear Adm. Ferdinand L. Reichmuth, was to be based at Bermuda. Additional forces comprised TF 5, Rear Adm. Richard S. Edwards; TF 6 and TF 8, Rear Adm. Edward D. McWhorter; TF 9, Rear Adm. Randall Jacobs; and TF 10, Maj. Gen. Holland M. Smith, USMC.

While that reorganization was taking place the expeditionary force dropped anchor in the outer roadstead of Reykjavik on 7 July 1941, just as the British persuaded the Althing (Icelandic parliament) to agree to the landings, and President Roosevelt announced the agreement to Congress. The marines went ashore the next day. The cargo ships began to unload their supplies at the limited dock space in Reykjavik harbor, and by the evening of 12 July unloaded their cargo and all of the marines had gone ashore. The following day TF 19 and the transports turned back for home. The landings infuriated Großadmiral Erich J.A. Raeder, the Kriegsmarine’s commander-in-chief, but the Allies continued to develop bases on Iceland that sustained their operations throughout the war.

Following that assignment, Arkansas sailed to Casco Bay, Maine, to take part (8–14 August 1941) in the momentous meeting between the American and British leaders that led to the Atlantic Charter. President Roosevelt’s flag continued to fly from presidential yacht Potomac (AG-25) to conceal the chief executive’s departure on 5 August, with Augusta (CA-31), Tuscaloosa, and five destroyers. Augusta embarked three Curtiss SOC-1 Seagulls and one SOC-2 of her Aviation Unit, while Tuscaloosa operated one SOC-3 and three Naval Aircraft Factory SON-1s of Cruiser Scouting Squadron (VCS) 7. The ships reached Placentia Bay at Newfoundland on the 7th, and on the morning of 9 August British battleship Prince of Wales (53), destroyers Reading (G-71), ex-Bailey (DD-269), and Ripley (G-79), ex-Shubrick (DD-268), and Canadian destroyers Assiniboine (D-18) and Restigouche (H-00) arrived at Argentia with Prime Minister Winston L. S. Churchill and senior British leaders embarked including Admiral of the Fleet Sir Dudley P. R. Pound, RN, First Sea Lord, Field Marshal Sir John G. Dill, Chief of the Imperial General Staff, Air Chief Marshall Sir Wilfrid R. Freeman, RAF, Sir Alexander M. G. Cadogan, Permanent Under-Secretary of State at the Foreign Office, Frederick A. Lindemann, Lord Cherwell, Churchill’s scientific advisor, Henry V. Morton, a journalist and travel writer, and Howard Spring, a novelist. Harry L. Hopkins, Roosevelt’s principal emissary to Churchill, also travelled on board the British battleship.

Additional personages present included Adm. Harold R. Stark, the CNO, and Ens. Franklin D. Roosevelt Jr., USNR, the President’s son and temporarily detached from Mayrant (DD-403). During the conference, Arkansas provided accommodations for Under Secretary of State B. Sumner Welles and for W. Averell Harriman, the President’s special envoy. The discussions included a joint declaration subsequently known as the Atlantic Charter that included the Allies’ goal for the “final destruction of Nazi tyranny.” President Roosevelt also offered the Prime Minister Naval Plan 4, in which U.S. planes and warships would escort British merchant ships between the U.S. and Iceland. The conference concluded on 12 August. Prime Minister Churchill departed on board Prince of Wales, while the President set out with Augusta to rendezvous with Potomac at Blue Hill Bay, Maine.

Arkansas continued to train along the east coast until the outbreak of war with the Japanese attack upon the Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, T.H., on 7 December 1941, which found her at anchor in Casco Bay. The ship operated up to three Vought OS2U-1 Kingfishers or OS2U-3s of VO-5. One week later (15–16 December), Canadian Troop Convoy TC 16, consisting of a trio of steamers, Cuba, Letitia, and Pasteur, escorted by a trio of U.S. destroyers, Ericsson (DD-440), Ingraham (DD-444), and Ludlow (DD-438), set out from Halifax for the United Kingdom. Arkansas, Nashville, Eberle (DD-430), Livermore (DD-429), and high speed minesweeper Hamilton (DMS-18) rendezvoused with the convoy on the 16th and escorted the ships to Icelandic waters on the 22nd, where Ingraham detached. The ships led their charges into Hvalfjördur (Whale-fjord), Iceland, the following day. British destroyers Havelock (H-88) and Sherwood (I-80), ex-Rodgers (DD-254), along with Norwegian destroyer Newport (G-54), ex-Sigourney (DD-81), and Polish Blyskawica (H-34), meanwhile joined the troopships on 22nd and subsequently led them to British ports. On Christmas of 1941, Arkansas and her consorts stood out to sea for the return voyage to U.S. waters via Argentia.

The ships stayed at Argentia, however, because the Germans launched Operation Paukenschlag (Drumbeat)—an attack against Allied shipping off the East Coast of North America and in the West Indies. U-552, Kapitänleutnant Erich Topp, operating as part of Wolfpack Ziethen, torpedoed and sank British freighter Dayrose southwest of Cape Race, Newfoundland, on 15 January 1942. That same day U-203, Kapitänleutnant Rolf Mützelburg, also operating as part of that wolfpack, torpedoed and sank Portuguese motor fishing vessel Catalina southeast of Newfoundland. Arkansas, aircraft escort vessel Long Island (AVG-1), Philadelphia (CL-41), small seaplane tender Barnegat (AVP-10), and their destroyers were preparing to return to the United States on the 18th, but the news of the U-boat attacks electrified naval planners. Fearful of the large ships’ vulnerability, the Allies dispatched an eight-ship hunter-killer group comprising U.S. destroyers Badger (DD-126), Ellis (DD-154), Ericsson, and Greer (DD-145), along with four Canadian Flower-class corvettes, to rush to the waters off Cape Race and clear a course through the U-boats for the vessels at Argentia. The Germans aggressively continued their attacks and the Allied ships failed to sink the enemy boats, however, so the authorities delayed the ships from sailing until the 22nd. They then slipped out of Argentia and two days later on the 24th entered Boston safely.

On 29 January 1942, Arkansas served with New York and Texas in BatDiv 5, along with VO-5, all part of Battleships, Atlantic Fleet. Arkansas spent the month of February carrying out exercises in Casco Bay in preparation for her role as an escort for troop and cargo transports. She then turned southward and arrived at Norfolk on 6 March to begin an overhaul, which included replacing her distinctive “basket” foremast with a tripod. Underway on 2 July, Arkansas completed a shakedown cruise in Chesapeake Bay and then proceeded to New York City, where she arrived on 27 July.

The battleship sailed from New York on 6 August 1942, bound through U-boat-infested waters for Greenock along the Clyde Estuary, Scotland. Two days later, the ships paused at Halifax, then continued on through the stormy North Atlantic. The convoy reached Greenock on the 17th, and Arkansas returned to New York on 4 September. She escorted another Greenock-bound convoy across the Atlantic, then arrived back at New York on 20 October. Capt. Carleton F. Bryant, the ship’s commanding officer, also led TF 38, which generally comprised Arkansas, Brooklyn, and 7–11 destroyers. Rear Adm. Lyle A. Davidson led TF 37, which usually deployed New York, Philadelphia, and 6–12 destroyers. The two task forces escorted convoys averaging 8–15 transports or troopships packed with U.S. and Canadian soldiers from New York and Halifax to Lough Foyle and Londonderry, Northern Ireland, or to the Clyde or the Western Approaches Command at Liverpool on the Mersey Estuary.

The Allies meanwhile prepared for Operation Torch—the invasion of Vichy French-held North Africa. Cargo ship Almaack (AK-27) and transports Leedstown (AP-73) and Samuel Chase (AP-56) formed Transport Division 11 and sailed from Hampton Roads to New York on 19 September 1942. Arkansas and nine destroyers served in TF 38 and covered the trio as they set out as Convoy AT-26 to cross the Atlantic to Belfast, Northern Ireland (26 September–6 October). Almaack, Leedstown, and Samuel Chase waterproofed Army equipment and re-stowed their cargoes, while the soldiers drilled ashore, before they took part in training exercises and stood out for Torch.

Arkansas and nine destroyers in the meantime set out as the screen for a convoy that planners referred to as “the D plus 5 convoy,” meaning that they were supposed to reach their port of disembarkation at Casablanca, Morocco, five days after the initial landings. The fighting against the French damaged the port, however, and Allied engineers incurred delays as they laboriously cleared wrecked ships and repaired disabled facilities. The convoy reached the area but thus marked time steaming evasive courses offshore in heavy seas. The destroyers made multiple sonar contacts on possible U-boats but the convoy escaped any potential attacks, and French pilots and tugs aided the vessels as they finally slid into the harbor at Casablanca on the 18th. Arkansas and nine destroyers +escorted the 19 merchant ships and oilers of Convoy GUF-2, the second homeward-bound convoy, as they cleared Casablanca and returned to New York (29 November–11 December). Arkansas then accomplished an overhaul.

The battleship wrapped up the yard work early in the New Year and carried out gunnery drills in Chesapeake Bay (2–30 January 1943). She returned to New York and began loading supplies for yet another transatlantic trip, for which she made two runs between Casablanca and New York City (February–April). The following month, Arkansas completed voyage repairs and additional work in dry dock at the New York Navy Yard, emerging from that period of yard work to proceed to Norfolk on 26 May. When the ship completed yard work during the war it often involved installing additional light antiaircraft armament, most notably 20 and 40-millimeter guns. Arkansas assumed her new duty as a training ship for midshipmen, operating out of Norfolk. After four months of training cruises and drills in Chesapeake Bay, the battleship returned to New York to resume her role as a convoy escort. On 8 October the ship sailed for Bangor, Northern Ireland, where she remained throughout November before turning around to return to New York on the 1st of December. Arkansas then began some repairs on 12 December before setting out for more convoy duty.

Just two days before Christmas on the 23rd, German submarine U-471, Oberleutnant zur See Friedrich Kloevekorn, operated as part of Wolfpack Sylt and unsuccessfully attacked Arkansas while the battleship screened Convoy TU 5 in the North Atlantic, about 300 miles west of Rockall Bank. Kloevekorn and his men experienced a traumatic day because in addition to failing to attack the American battleship, a British Royal Air Force Coastal Command Consolidated B-24 Liberator of No. 120 Squadron assailed U-471 and wounded three men, though the submarine escaped. Clearing New York for Norfolk two days after Christmas of 1943, Arkansas closed the year in that port.

The battleship sailed on 19 January 1944, with a convoy bound for Northern Ireland. After seeing the convoy safely to its destination, the ship reversed her course across the Atlantic and reached New York on 13 February. Arkansas then (28 March–11 April) went to Casco Bay for gunnery exercises. A number of ships operated in the area at times including battleships led by Rear Adm. Bryant, Commander, BatDiv 5: Arkansas, Nevada (BB-36), New York, and Texas; as well as Quincy, Tuscaloosa; Satterlee (DD-626), Thompson (DD-627), and a variety of escorts, minesweepers, and yard and district craft; along with British frigate Bahamas (K-503). Some of these vessels operated under the auspices of TF 22, Rear Adm. Morton L. Deyo. During the following days the ships prepared for war and carried out evolutions that included shore bombardment against Seal Island and daylight and nighttime antiaircraft practice. Following the training, Arkansas proceeded to Boston for repairs.

On 18 April 1944, she sailed once more for Bangor, and upon reaching Northern Ireland began training to prepare for her new role as a shore bombardment ship to support Operation Overlord—the Allied invasion of the German-occupied Norman coast. The gunner’s mates confidently wrote “You Name it Boss, We’ll Hit it!” on one of their 12-inch turrets as they prepared for what Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, USA, Supreme Allied Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force, announced as “this great and noble undertaking.” Arkansas sailed for the French coast and Overlord on 3 June.

“I am not under [any] delusions as to the risks involved in this most difficult of all operations...” British Adm. Sir Bertram H. Ramsay, RN, Naval Commander-in-Chief of the Allied Naval Expeditionary Force, penned in his diary on the night of the 5th. “Success will be in the balance. We must trust in our invisible assets to tip the balance in our favor.”

“We shall require all the help that God that can give us & I cannot believe that this will not be forthcoming.”

The battleship charted a course as part of the Western Task Force’s Bombarding Force O, Rear Adm. John L. Hall Jr., who had commanded her earlier in the war. As the ships of the force crossed the English Channel through passages swept for mines they deployed for their assigned tasks and turned toward the landing beaches. Texas led Bombardment Group, Task Group (TG) 124.9, Rear Adm. Bryant, followed (in order) by British light cruiser Glasgow (C-21), Arkansas, and Free French light cruisers Georges Leygues and Montcalm. Baldwin (DD-624), Carmick (DD-493), Doyle (DD-494), Frankford (DD-497), Harding (DD-625), McCook (DD-496), Satterlee (DD-626), Thompson (DD-627), and British Hunt-class destroyers Melbreak (L-73), Talybont (L-18), and Tanatside (L-69), at times screened the bombardment vessels and fired on the German defenders.

Arkansas entered the Baie de la Seine on the morning of 6 June 1944, took up a position 4,000 yards off Omaha beach, and at 0552 opened fire on the German soldiers. The enemy forces included four 150-millimeter guns, a captured Soviet 122-millimeter piece, and a trio of 20-millimeter antiaircraft guns of 4/Heeres-Küsten-Artillerie-Abteilung 1260 emplaced in Widerstandsnest (Nest of Resistance) WN-48 at Longues-sur-Mer, north of Bayeux on a bluff overlooking the beach. The German guns opened fire at British amphibious landing headquarters ship Bulolo (F-82) as she directed the British landings on nearby Gold Beach. British light cruisers Ajax (22) and Argonaut (61) bracketed the battery and the German gunners’ ceased fire while they sheltered from the shelling and repaired the damage. The gunners then resolutely starting shooting again, shifting their fire toward the Americans as they struggled ashore on Omaha. Arkansas, Georges Leygues, and Montcalm answered the call and hurled salvo after salvo at the position, knocking out one of the four casemates and damaging two others. The following morning Allied planes struck the battery again and then British soldiers of C Company, 2nd Devonshire Regiment, 231st Brigade, 50th Infantry Division, from Gold assaulted and captured the guns and their resolute defenders. Arkansas fired 163 armor piercing and 656 high capacity 12-inch rounds, along with 94 5-inch and 104 3-inch shells on D-Day (0605–1300).

Arkansas continued her fire support to the Allied soldiers as they fought their way inland over the ensuing days. On the 13th she shifted to a position off Grandcamp les Bains. A landing craft vehicle and personnel (LCVP) eased alongside Arkansas at one point and transferred wounded men to the battleship for medical treatment. Flares and starshells lit the horizon as the Germans struck back against Allied ships on the evening of 14 June. At 2300 a plane dropped two bombs, possibly Henschel Hs 293s, small but powerful radio-controlled glide bombs equipped with rocket motors to enable them to increase the range of their attacks, near Quincy. The first one splashed bearing 156° about 1,000 yards from the ship and 400 yards from Arkansas as she lay anchored in Berth E-51. The second glide bomb flew toward the ships at 2329 and splashed closer to Quincy, bearing 134° at 700 yards and 300 from Arkansas, and the boil of water rose as high as the battleship’s main deck. Combined headquarters and communications command ship Ancon (AGC-4) signaled incoming radio controlled bombs during the mid watch on 18 June, and Quincy helped jam the enemy wavelengths to disrupt their targeting the destructive devices. Arkansas, Nevada, and Texas came about for British waters later that night, and their departure left Quincy as one of the heaviest ships fighting off Omaha.

A storm meanwhile lashed the beachheads and destroyed Mulberry A, an artificial harbor that helped the Americans’ unload ships off Omaha Beach, and wreaked havoc with the vessels off the beachheads (19–22 June 1944). Arkansas weathered the tempest from her more sheltered anchorage in British waters, but the lack of an adequate port hindered Allied logistics and the storm compounded the delays in the build-up ashore in France. Consequently, the Allies desperately needed a port and dispatched a naval force to support the landward advance up the Cotentin Peninsula to Cherbourg.

Arkansas joined other vessels as they assembled into Rear Adm. Deyo’s Cherbourg Bombardment Force, TF 129, in Portland Harbour in southern England. Deyo divided the task force into two battle groups. Battle Group 1 comprised Nevada (Capt. Powell M. Rhea), Quincy, Tuscaloosa, and British light cruisers Enterprise (D-52) and Glasgow, in company with Ellyson (DD-454), Emmons (DD-457), Gherardi (DD-637), Hambleton (DD-455), Murphy (DD-603), and Rodman (DD-456). Bryant’s Battle Group 2 included Arkansas, Texas, Barton (DD-722), Hobson (DD-464), Laffey (DD-724), O’Brien (DD-725), and Plunkett (DD-431). The first group would attack the port while the second concentrated on nearby Marine-Küsten-Batterie Hamburg, emplaced on a hill near Fermanville, not far from Cap Levi and about six miles east of Cherbourg. In addition, at times ships of the 159th Minesweeping Flotilla and British 9th Minesweeping Flotilla took part in the operation.

Hitler declared Cherbourg a “fortress” and ordered Generalleutnant Karl-Wilhelm von Schlieben, whom the Allies had driven back from the beaches, to defend the city, but the landward defenses lacked strength against the overwhelming forces the Allies deployed against the port. Toward the sea, however, the Germans arrayed potentially heavier defenses, and emplaced four 11-inch guns and artillery ranging from 75, 88, and 150 millimeter guns and up around the area, often in casemated batteries—many of which could engage Allied ships. Both sides anticipated a bitter battle as the 25th of June opened as an otherwise beautiful and warm day. Haze restricted the view until the sun’s rays gradually broke through, and Quincy then logged the day as “bright and clear with a southeast wind of 8 knots.” The warship’s plan of the day called for breakfast and then succinctly summarized her goal as “neutralize Cherbourg.”

Allied planes including USN Consolidated PB4Y-1 Liberators and Eastern TBM Avengers searched for U-boats to the westward, while other planes, among them USAAF Lockheed P-38 Lightnings, flew protective flights over the ships, and still others including British Fleet Air Arm TBMs supported the attack. One of the Allied aircraft spotted what the pilot believed to be a midget submarine during the morning watch near 50°11ˈN, 2°2ˈW, which generated fears among the crews, but the (reported) enemy boat failed to maneuver into an attack position. As the ships of Battle Group 1 negotiated the treacherous minefields and awaited the advancing VII Corps’ calls for fire the German batteries opened up at 1206, the first rounds splashing 190° and about 3,000 yards from Quincy. The enemy guns continued and huge geysers of water erupted around some of the ships. Four 150 millimeter rounds passed over British minesweeper Sidmouth (J-47), the lead sweeper, and a three-gun salvo bracketed Nevada, one of the shells splashing within 100 yards. Rear Adm. Deyo ordered the ships to begin counter-battery fire, but the German gunners shot accurately, scoring a number of hits on some of the other task force ships, and the accompanying destroyers laid smoke.

The “enemy batteries opened fire with extreme accuracy,” Ramsay observed, “whilst the force was turning at slow speed from the approach channel into the fire support area. To avoid heavy damage destroyers had to make smoke and the heavier ships to manoeuvre at increased speed, and, in some cases, without regard to keeping inside swept water, in order to maintain manoeuvering searoom. Despite the accuracy of the enemy’s fire, by frequent use of helm and alterations in speed the Force managed to avoid any but minor casualties and damage, whilst at the same time continuing accurate fire on the enemy’s defences.”

German sailors manned four 11-inch guns at Target 2, Marine-Küsten-Batterie Hamburg, a strong position protected by steel shields—though not entirely enclosed in concrete casemates. Six 88 millimeter and a half dozen each light and heavy antiaircraft guns also protected the battery. Multiple ships including Arkansas and Texas fought Batterie Hamburg and disabled one of the 11-inch guns but failed to knock out the strong position, and Bryant requested that Deyo deploy Quincy from her other tasks to lend a hand. The latter so ordered the ship and a shore party and a plane spotted the fall of shot as the cruiser shifted fire and blasted the enemy, though apparently without effect (1330–1410). Deyo surmised that too many ships attacked the battery and that their gunfire prevented accurate spotting.

The Germans resisted stoutly and Oberleutnant zur See Rudi Gelbhaar of Marine-Artillerie-Abteilung 260, the battery’s commander, unleashed their 11-inch guns against Quincy. Salvoes tore the air barely 20 yards above Turret II, the rounds, one of them apparently a dud, narrowly missing the U.S. warship and splashing 50 yards abeam at 1340. Two minutes later, Deyo ordered Glasgow to come about from the battle and directed destroyers to screen the cruiser while she made repairs. Ellyson laid smoke to protect Quincy as the cruiser opened the range an additional 2,500 yards. Gelbhaar later received the Knight’s Cross for his fight against the Allied ships.

“I regard the operation as highly successful,” Deyo said later that night. The ships of the task force hit 19 of their 21 primary targets with varying degrees of success. Their salvoes disabled some of the enemy positions so that they continued to face to sea (the Germans could have turned some of them inland on the advancing troops). The bombardment thus aided the landward assault and the Allies considered the battle a triumph. Their casualties and inability to knock out all of the defenses, however, weighed on some of their leaders.

“The important lesson to be learnt,” Ramsay summarized the battle, “is that duels between ships and coast defence guns are quite legitimate provided some or all of the above precautions [D-Day] are taken; owing to the prevailing conditions, it was not possible to take the necessary precautions before and during the bombardment,” adding ruefully that enemy gunfire hit some of the ships as a result.

The following morning, Von Schlieben reported to Generalfeldmarshall Erwin Rommel that “heavy fire from the sea” helped the Allies reduce the opposition at the port, and Adm. Theodore Krancke, Commander-in-Chief, Navy Group Command West, subsequently observed in his war diary that the “naval bombardment of a hitherto unequalled fierceness” rendered the defender’s resistance ineffective. The Germans subsequently surrendered Cherbourg but thoroughly wrecked and mined the port, and Allied engineers spent weeks laboriously restoring the facilities to capacity.

Arkansas retired to Weymouth, England, at 2220 that night, and on 30 June 1944 shifted to Bangor. The ship remained under Deyo’s overall command but some shifting placed her within TG 120.6, which also comprised Nevada, Quincy, Tuscaloosa (Deyo’s flagship), Ellyson, Emmons, Fitch (DD-462), Forrest (DD-461), Hambleton, Hobson, Plunkett, and Rodman. The ship then received the group’s Operation Order 8-44, which directed her to the Mediterranean.

The battleship sailed with the group auspiciously on Independence Day. Off the Mull of Cantyre [Kintyre], Scotland, they joined the Clyde Group of assault transports: Anne Arundel (AP-76), Barnett (APA-5), Charles Carroll (APA-28), Dorothea L. Dix (AP-67), Henrico (APA-45), Joseph P. Dickman (APA-13), Samuel Chase (APA-26), Thomas Jefferson (APA-30), and Thurston (AP-77). Two days later the Plymouth Group, consisting of Augusta (CA-31), Bayfield, and Achernar, joined the convoy. The ships passed through the Strait of Gibraltar overnight (9–10 July), and that evening anchored in Mers-el-Kébir near Oran, Algeria. Arkansas steamed to Taranto, Italy (18–21 July), where she remained until 6 August, when the venerable battleship shifted to Palermo, Sicily, on the 7th.

Arkansas did so in order to serve under Vice Adm. Henry K. Hewitt, Commander, Eighth Fleet and Western Task Force in Operation Dragoon—landings by the U.S. VI Corps, Gen. Lucian K. Truscott Jr., USA, and the French II Corps, Gen. Edgard de Larminat, between Cap Nègre and Fréjus in southern France. Arkansas joined Camel Force, TF 87, Rear Adm. Spencer S. Lewis, and supported landings by the 36th Infantry Division, Maj. Gen. John E. Dahlquist, USA, on Red Beach on the eastern (right) flank.

The ship operated as part of Rear Adm. Deyo’s Bombardment Group, which also included at times Tuscaloosa, Marblehead (CL-12), British light cruiser Argonaut (61), and French light cruisers Duguay-Trouin and Émile Bertin, screened by the ships of DesRon 16: flagship Parker (DD-604), Boyle (DD-600),Champlin (DD-601), Edison (DD-439), Kendrick (DD-612), Ludlow (DD-438), MacKenzie (DD-614), McLanahan (DD-615), Nields (DD-616), Ordronaux (DD-617), Parker (DD-604), and Woolsey (DD-437).

Previous Allied landings in North Africa, Sicily, and Italy experienced problems coordinating naval gunfire support between the various navies. The soldiers fighting ashore “became well acquainted with naval gunfire and appreciated its capabilities,” Vice Adm. Hewitt observed in his report on Dragoon. “Both British Forward Observer Bombardment officers, Naval Gunfire Liaison officers, and air spot were used, and the need for a common shore bombardment procedure and code became more apparent.” Hewitt therefore worked with U.S., British, and French naval, air, and army representatives and published and promulgated the Mediterranean Bombardment Code, under which Arkansas operated during the landings.

German Army Group G, Gen. Johannes Blaskowitz, opposed the landings and consisted of the Nineteenth Army, Gen. Friedrich Wiese, deployed along the Riviera coast, and the First Army, Gen. der Infanterie Kurt von der Chevellerie, along the Biscay coastline. “The main line of defense is and will remain the beach,” Wiese ordered his men, adding defiantly that they were “to fight to the last man and the last bullet.” The Germans detached many troops northward to battle the Allies in Normandy, however, and the balance comprised mostly poorly equipped soldiers, including some Ost-Bataillone (eastern battalions) of Soviet émigrés of doubtful combat value. In addition, French Maquis resistance fighters wreaked havoc with their supply lines.

Quincy noted that the night (14–15 August 1944) as they moved into position was “practically cloudless” but light fog lingered in the area. German search radar trained on the heavy cruiser in an effort to track her during the mid watch, and the ship made several attempts to jam the radar. “Sea conditions for craft were ideal,” the Eighth Fleet reported, “being almost calm in the Transport Area. Visibility about 5 to 6 miles with some ground mist…A slight ground haze made beach recognition extremely difficult and prevented the Scout Officer’s light (which had been successfully tried on the rehearsals) being seen. An unexpectedly strong Westerly set close inshore resulted in the landings in some cases being made somewhat to the Westward of the intended positions.”

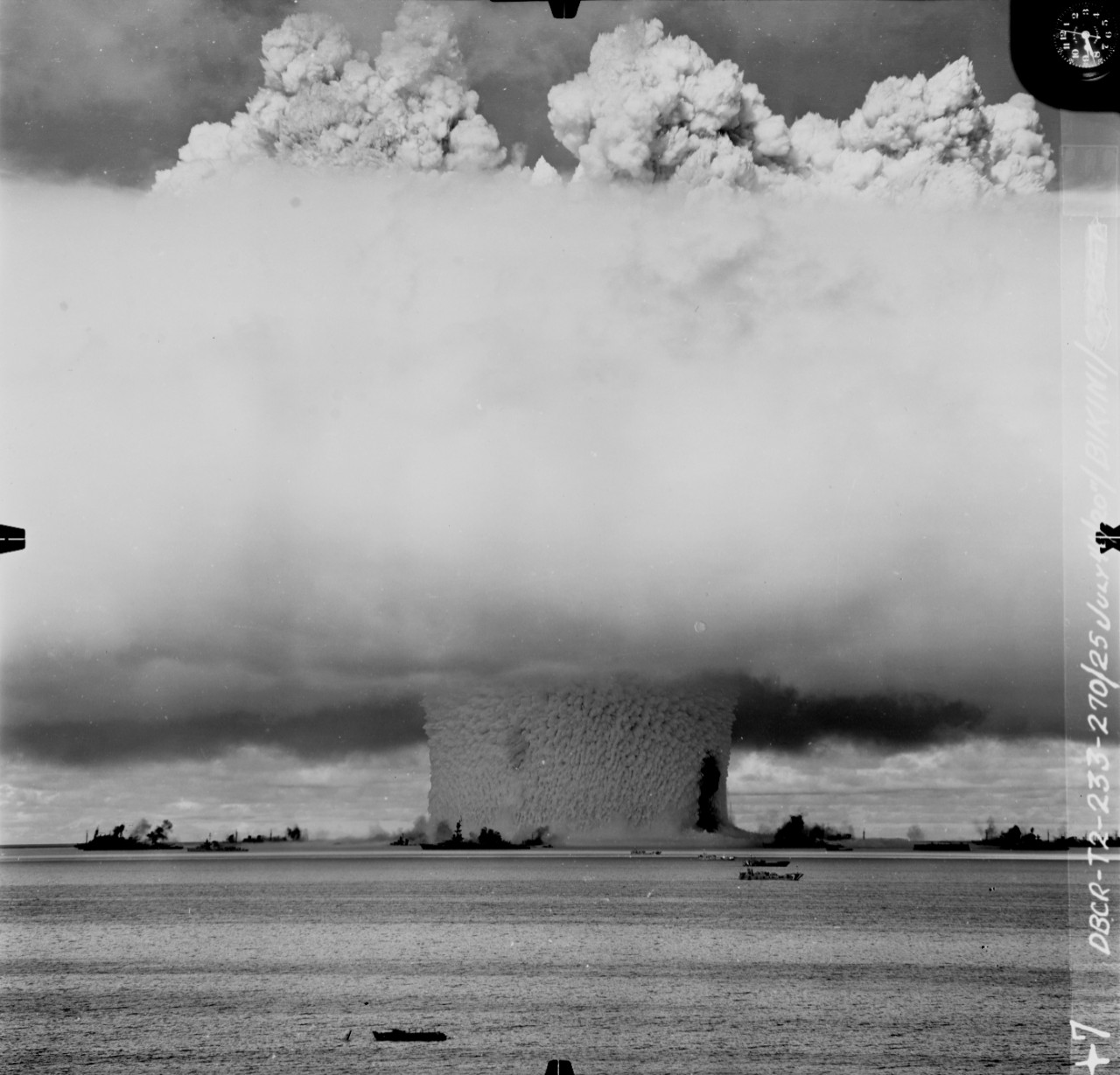

The Allied soldiers stormed ashore against relatively light resistance for the most part, and many of the Soviet émigrés deserted or surrendered. The landings did not all progress smoothly, however, and the enemy at Saint-Raphaël defied a bombardment by Tuscaloosa, Brooklyn, Argonaut, Duguay-Trouin, and Émile Bertin, as well as an attack by 90 USAAF B-24 Liberators. The Germans defiantly trained their coastal and antiaircraft guns in a withering fire on the invaders. The assault troops thus bypassed those beaches and landed at Agay, Cap Dramont, and Nartelle, pushed inland and enveloped the beach defenses from the rear the following day.