The U.S. Navy in the Far East

The U.S. Asiatic Fleet: From Its Origins to World War II

U.S. Asiatic Fleet destroyers off Hankow, China, circa April-May 1923 The destroyers are, from left to right: Pruitt (DD-347) Stewart (DD-224) Preble (DD-345) Hulbert (DD-342), and William B. Preston (DD-344). The Japan-China Steamship Company (N.K.K. - Nisshin Kisen Kaisha) docks are in the foreground, with a river steamer alongside in the center and an ocean-going freighter at right. Many local small craft are also present (NH 67242).

The U.S. Navy’s Asiatic Fleet traces its origins back to the East India Squadron which began deploying to the Far East in the 1830s. As early as 1831, piracy and other dangers threatened the expansion of American trade routes in Asia. President Andrew Jackson established the East India Squadron in 1835 to protect American lives and property.

In March 1842, Captain Lawrence Kearny, commander of the East India Squadron, arrived in the Far East with his flagship Constellation and the sloop-of-war Boston. Kearny was in China to safeguard American lives and property during the First Opium War and to negotiate commercial treaties. On 29 Aug 1842, at the conclusion of the First Opium War, Great Britain and China signed the Treaty of Nanking, which opened four additional trading ports to the English. Captain Kearny sought assurances from the Chinese that Americans would receive access to the same trade privileges.

The Treaty of Wanghia, which was signed 3 July 1844, granted American vessels access to the Chinese ports of Ningpo, Amoy, Fuchow, Shanghai, and Canton. Diplomat Caleb Cushing traveled to China in 1843 to negotiate the terms of the treaty. The East India Squadron was responsible for protecting its terms. On 31 December 1845, the commander of the East India Squadron, Commodore James Biddle, exchanged ratified copies of the treaty with the Chinese in a ceremony in Canton, formalizing the first American commercial treaty with China.

Commodore Biddle remained in China to aid diplomatic efforts until April 1846, when he left for Japan with the ship-of-the-line Columbus and the sloop-of-war Vincennes. Biddle hoped to open trade relations with Japan, but upon his arrival in Edo Bay (Tokyo Bay) in late July 1846, Japanese vessels surrounded the two American ships. The Japanese declined to discuss a trade agreement with the commodore. The squadron departed on 29 July 1846.

In 1848, Captain James Glynn, commander of the sloop-of-war Preble, left the East Indies to sail north to Japan. His orders were to negotiate for the release of 15 Americans from the whaling vessel Lagoda who were being held as prisoners in Nagasaki, Japan. Although the Japanese initially tried to block Preble from entering the harbor, the ship forced her way in. With the help of a Dutch translator, Captain Glynn was successful in negotiating the release of the American seamen. Preble then returned to Shanghai, China, to join the rest of the East India Squadron.

The East India Squadron returned to Tokyo Bay again in July 1853, this time with Commodore Matthew Perry at the helm. Perry delivered a draft of a trade treaty and a letter from U.S. President Millard Fillmore to the Emperor of Japan. President Fillmore’s letter requested “friendship and commerce” with Japan. The Japanese accepted the letter and agreed to think about the President’s proposal for a treaty. Commodore Perry promised to return in the spring to receive an answer.

Commodore Perry returned to Tokyo Bay on 11 February 1854, and after a month and a half of deliberations, the United States and Japan signed the Treaty of Kanagawa on 31 March 1854. The treaty opened two Japanese ports to U.S. ships for supplies and refueling, which allowed American citizens to conduct trade and move freely within the treaty ports. It also stipulated that shipwrecked sailors would be returned to American representatives. This protection for American seamen was necessary as the American whaling industry had expanded into the North Pacific by that time and the United States sought safe harbors. In addition, the opening of two harbors to American ships was advantageous as Japan was rumored to have a large coal supply and American merchant ships needed to replenish coal and other supplies on the voyage to China.

In 1856, the Second Opium War broke out with France siding with Great Britain against China’s Qing dynasty. Although the United States remained neutral through the conflict, the American consul in Canton, China, worried about the safety of Americans living in the city. The consul requested help from Commander Andrew Hull Foote, commanding officer of the sloop-of-war Portsmouth, which was anchored off Whampoa, China. On 23 October 1856, a landing party of sailors and Marines disembarked from Portsmouth to travel up the Pearl River to Canton. Their orders were to protect the American compound there. The compound consisted of offices and warehouses, called “factories,” where Americans conducted trade. The Navy-Marine force posted guards on rooftops around the compound.

The sloop-of-war Levant arrived four days later followed by the screw frigate San Jacinto, with the commander of the East India Squadron, Commodore James Armstrong, aboard. Levant and San Jacinto also sent landing parties ashore.

Although Commodore Armstrong concurred with Commander Foote’s decision to send landing forces to protect the American compounds, the squadron commander worried that this action would provoke the Chinese and possibly lead them to attack U.S. military personnel from the forts along the Pearl River. To prevent this, the commodore opened negotiations with the Chinese authorities in Canton. The American consul and Chinese authorities in Canton agreed that if the United States remained neutral in the war between China and Britain and France, the Chinese would guarantee the safety of U.S. interests in Canton. As a result, the Americans agreed to withdraw the Navy-Marine force from the city, leaving only a small number of Marines behind.

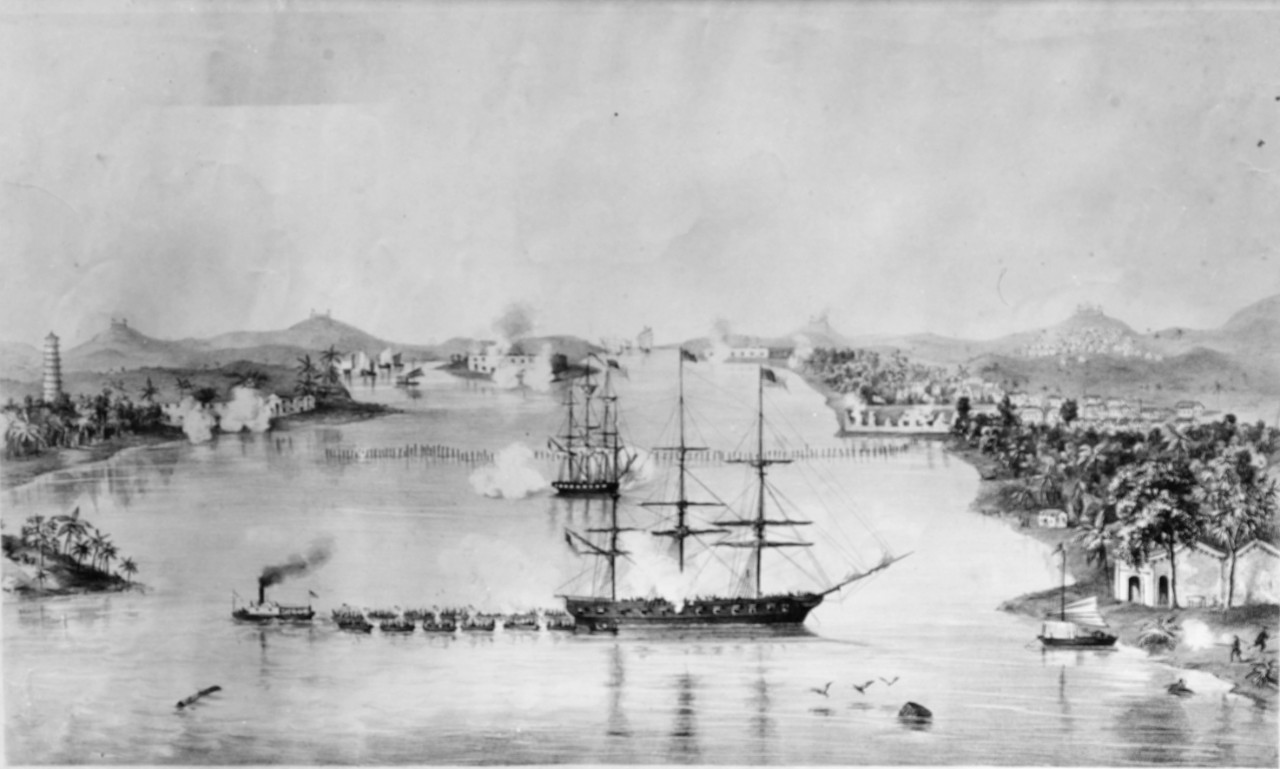

On 15 November 1856, in violation of the agreement, Chinese forces fired on a small boat carrying Commander Foote back to Portsmouth. The next day, the Chinese fired on an unarmed small boat from San Jacinto that was traveling up river to take soundings. In response, Commodore Armstrong ordered Portsmouth and Levant to bombard the forts. Throughout the day on 16 November, the two ships exchanged fire with the Chinese. On 20 November, Foote led a force of sailors and Marines ashore to storm the forts. The joint force fended off ferocious attacks by the Chinese over the week but eventually overpowered all four forts. Once all forts were abandoned by the Chinese, Foote’s men destroyed them. (For a more detailed summary, read H-063-1: The Battle of the Pearl River Forts, China, 1856.)

The attack on the barrier forts near Canton, China, by the East India Squadron, led by Commodore James Armstrong, on 21 November 1856. The force consists of Portsmouth, Levant, and the steam frigate San Jacinto. Leading parties were commanded by Commander Foote (Portsmouth), Captain Bell (San Jacinto), and Commander Smith (Levant) (NH 56895).

Two years later, Great Britain and France signed the Treaty of Tianjin (Tientsin) with the Chinese, which expanded privileges for foreign powers in China. Although China was forced to sign the treaty, it was another two years before they ceased to resist its terms and to ratify the treaty. In 1859, U.S. diplomat John Ward exchanged treaty ratifications which granted the United States and other foreign powers access to more Chinese coastal ports, as well as the Yangtze River. This new opening of China’s longest river provided foreign businessmen and missionaries unprecedented access to the Chinese interior. In addition, foreign diplomats were allowed to establish legations in Beijing.

In May 1861, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles recalled most of the U.S. warships patrolling abroad at the onset of the American Civil War. Only Saginaw and Wyoming rotated through the waters of the Far East over the next four years. Following this conflict, the Navy attempted to reassert prewar protection levels for overseas commercial shipping routes despite a postwar decline in personnel, vessels, and funding.

In the squadron’s absence, the friendly relations between United States and Japan unraveled. Emperor Komei disagreed with the Japanese government’s decision to open the country to foreigners, and issued a decree in March 1863 that all foreigners should leave Japan. Japanese daimyo clans (feudal warlords) sided with the emperor and began attacking foreign ships in Japanese waters.

The first incident of an attack on an American ship occurred in June 1863, on the merchant ship Pembroke. The sloop-of-war Wyoming, which had originally been sent to the Asia to chase down a Confederate ship rumored to be operating in Far East, engaged in battle with the Choshu daimyo clan ships at Shimonoseki Strait in July 1863. Attacks on foreign ships in Japanese waters continued through September 1864. (For a more detailed summary, read H-063-3: The Battle of Shimonoseki Strait, Japan, 1863.)

Other European countries with interests in the area (Great Britain, France, and the Netherlands) joined forces with the United States to fight the Japanese clans in a series of battles from 1863 to 1864. The allied force overcame the Japanese in the second battle held in the Shimonoseki Strait, which ended with the Japanese surrendering on 8 September 1864. As a result, the Japanese were forced to open one more treaty port and to grant the Western powers additional trade privileges.

In July 1865, Commodore Henry H. Bell was assigned to command the East India Squadron. In 1868, the squadron was reorganized and renamed Asiatic Squadron. A lack of legislative funding kept the size of overseas squadron to a minimum through the end of the nineteenth century. In the years following the Civil War, the small squadron continued its antipiracy mission in an area spanning from Japan to the South China Sea.

As more ports of call opened up along the Yangtze River, the expansion of American trade interests necessitated the expansion of maritime control by the Asiatic squadron along China’s longest river. On 23 March 1871, the sidewheel gunboat Monocacy began to chart the lower Yangtze River. Three years later its sister ship Ashuelot, surveyed the Yangtze River from Shanghai to Ichang—nearly a thousand miles upriver from Shanghai. Her efforts blazed the way for the future riverine craft of the Yangtze Patrol.

In May 1871, Monocacy, Palos, Alaska, and Benicia departed Japan for Korea—which was closed to foreigners at that time. The U.S. minister to China, Frederick Low, traveled on the squadron’s flagship Colorado to negotiate a trade arrangement with the Koreans and investigate what happened to the crew of General Sherman. General Sherman was an American-owned merchant ship which had sailed to Korea’s western coast in 1866, but never returned.

Upon the squadron’s arrival off the coast of Korea on 24 May 1871, Low delivered a letter to Korean authorities announcing the reason for the squadron’s visit. A messenger on a Korean junk sent word that Low’s letter had been received and he would be contacted by three emissaries. Low declined a meeting with the three emissaries, stating they were too junior and requested a meeting with higher-level diplomats. He also warned that U.S. Navy boats would be surveying the Salee River, and that the Korean forts on both sides of the river should be instructed not to fire on them. On 1 June 1871, the squadron’s steam launches entered the Salee River to conduct surveys and were fired upon by personnel in the Korean forts. Over the next 12 days, the U.S. Navy and Marines fought the Korean forts during The Battle of Ganghwa. On 12 June 1871, the U.S. force succeeded in overpowering the Korean force and withdrew to their ships. Fifteen Medals of Honor were awarded to Navy and Marine personnel for their actions during battle—with nine going to Navy personnel and six to Marines.

More than 10 years after this incident, on 12 May 1882, Commodore Robert Shufeldt arrives in Korea to negotiate the first commerce treaty between Korea and a Western power. The treaty is signed May 22, 1882, opening Korea to western trade.

As the end of the nineteenth century drew near, the mission of the Asiatic Squadron expanded as the U.S. presence (traders and missionaries) increased in the Indo-Pacific.

In May 1898, Admiral George Dewey led the Asiatic Squadron into Manila Bay, Philippines, to confront the Spanish in the Battle of Manila Bay. After defeating the Spanish fleet, the squadron took control of the former Spanish naval shipyard at Cavite, which became the squadron’s homeport. Cavite Navy Yard provided the Navy with a strategically important base in Asia.

Following Admiral Dewey’s victory in the Spanish-American War, Spain ceded the Philippines to the United States in the Treaty of Paris. The colonization of the Philippines by the United States led to an insurrection by Filipino nationalists who sought independence for the islands. At the onset of the Philippine-American War, the Asiatic Squadron transported U.S. troops to various islands in the Philippines to battle Filipino revolutionaries. Concurrently, other Asiatic Squadron ships provided support to U.S. forces in the Boxer Rebellion in China in an effort to quell the attacks on foreign nationalists living in the area, many of whom were American missionaries.

In 1902, the Asiatic Squadron was redesignated the Asiatic Fleet. The mission remained the same: protect American interests. These interests included American lives, commerce, property, diplomatic outposts, and treaty rights in East Asia. In addition, the United States hoped to promote friendly relations with the Chinese.

In 1907, U.S. Navy combined the Asiatic Fleet and the Pacific Squadron together to form the new Pacific Fleet. However, with the growing tensions in the China, the Navy once again saw the need to establish a naval presence. The fleet was based at Manila in the winter and at Chefoo during the warmer months.

In 1910, the Asiatic Fleet was re-established. Owing to increased American-flagged shipping on the Yangtze—particularly in the oil and kerosene trade—the Navy restarted the Yangtze Patrol. This flotilla of gunboats and monitors dates back to 1854 when side-wheel steam frigate Susquehanna became the first U.S. Navy warship to travel up the Yangtze River.

The Navy officially acknowledged the Yangtze Patrol and the South China Patrol as part of the Asiatic Fleet on 25 December 1919. By then, half a dozen gunboats were patrolling China’s rivers, including the West River in South China. In 1920, more than half of America’s imports and exports to China were shipped on the Yangtze River, which is navigable for 1,750 miles. Gunboats traveled the Yangtze River from Shanghai to Chungking, protecting American-shipping from bandits, pirates, and other lawless elements during an era of political unrest.

Members of a landing force from Pittsburgh (CA-4) in a boat, off Shanghai, China, in 1927. Note steel helmets and M1910 infantry equipment worn by these men. Several picks are in evidence, but few spades. Sailor on the left of the group seated on the gunwale has a non-standard entrenching axe on his pack. There are also three litter bearers present (at left), and a number of Chinese men on the far side of the boat (NH 50794).

River gunboat duty in China in the early twentieth century was considered a desired assignment for a U.S. Navy sailor. Known as “river rats,” American sailors assigned to river gunboats in China were considered a “hard-drinking lot.” American sailors were paid in U.S. dollars, which went a long way in China. American enlisted men were known to spend their disposable income at the bars and cabarets in ports such as Hankow or Shanghai. In 1917, China had welcomed an influx of Russian, Polish, and Lithuanian refugees fleeing the Russian Empire as communism took hold. This led to an influx of Russian women, many of who were former dancers and performers, at the Shanghai dance halls and clubs which American service members frequented. Shanghai offered a variety of entertainment for men of all ranks—from theaters and dance halls to the exclusive Shanghai Club, and Astor Hotel, which included a lavish ballroom.

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, fighting between Chinese Nationalists and Communists often led to attacks on American lives and shipping. From 1925 to 1927, almost the entire Asiatic Fleet remained in Chinese waters to protect American interests. In 1928, upon the capture of Beijing by Nationalist forces, the Asiatic Fleet stationed 41 ships around northern Chinese ports to support the 3,000 Marines in Peking (Beijing) and Tientsin and protect nationals.

From 1930 to 1940, the Asiatic Fleet performed their normal functions, carrying out patrols on the Yangtze River in South China, while also conducting training cruises to the Philippine Islands.

On 12 December 1937, one month after Japanese forces invaded Shanghai, the gunboat Panay (PR-5) was escorting three American Standard Oil vessels on the Yangtze River when Japanese aircraft bombed and sank the American vessel. Two U.S. Navy sailors and one civilian were killed and 48 injured. The attack occurred a day after Panay rescued American and foreign nationals from Nanking, China, which was under attack by Japanese forces. Panay was the first U.S. ship in the 83 years of the Yangtze Patrol lost to enemy action.

As World War II approached, the United States began to draw down its forces in China. In late November 1940, all Asiatic Fleet dependents were sent home.

In November 1941, Admiral Thomas C. Hart, commander-in-chief of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet, ordered the withdrawal of all U.S. Navy gunboats in China. Five were transferred to Cavite, Philippines.

On 10 December 1941, Cavite Navy Yard was attacked, severely damaging several of the Asiatic Fleet’s ships and permanently destroying one submarine, Sealion (SS-195), and one ship, Bittern (AM-36).

After the Arcadia Conference (22 December 1941–14 January 1942), the Allies agreed to form the American-British-Dutch-Australian Command (ABDACOM) to defend territories in Southeast Asia and the Southwest Pacific from the Japanese.

The Battle of Java Sea and Sunda Strait (28 February–1 March 1942) was the final battle for the Navy’s Asiatic Fleet in World War II. After its defeat in the Netherlands East Indies, the remaining Asiatic Fleet vessels retreated to Australia where they fell under the South West Pacific Area command, which was later absorbed by the Navy’s Seventh Fleet in 1943.

—Wendy Arevalo, NHHC Communication and Outreach Division

NHHC Resources

H-063-01: The Battle of Pearl River Forts, China, 1856

H-063-3: The Battle of Shimonoseki Strait, July 1863

H-063-05—The Battle of Ganghwa, Korea, 1871

The Last Battle of USS Houston

Ready Seapower: A History of the U.S. Seventh Fleet

Yangtze River Patrol and Other U.S. Navy Asiatic Fleet Activities in China

Further Reading

Cole, Bernard D. “America’s Asiatic Fleet.” Naval History Magazine 25, no. 5 (October 2011): 1–9.

Crawley, Martha L. “Selected Resources in the Naval Historical Center on the Asiatic Squadron and the Asiatic Fleet in East Asia, 1865–1942,” Navy Department Library, Washington DC.

Herder, Brian Lane. US Navy Gunboats: 1885–1945. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2021.

Hoyt, Edwin P. The Lonely Ships: The Life and Death of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet. New York: David McKay Company, Inc., 1976.

Stires, Hunter. “‘They Were Playing Chicken’: The U.S. Asiatic Fleet’s Gray-Zone Deterrence Campaign Against Japan, 1937–40.” Naval War College Review 72, no. 3 (2019): 1–20.

Tolley, Kemp. Yangtze Patrol: The U.S. Navy in China. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1971.