H-063-3: The Battle of Shimonoseki Strait, Japan, 1863

Background: The Opening of Japan and Commodore Perry’s “Black Ships”

When the great “kamikaze” typhoons of 1274 and 1281 wrecked two invading Mongol fleets, the Japanese killed anyone who made it to shore, except southern Chinese, whom the Japanese enslaved, believing the Chinese had been coerced by the Mongols and were entitled to a little mercy. For centuries, this was pretty much the standard Japanese welcome to anyone who washed up on their shores, including shipwrecked sailors. Almost from the very beginning of contact with Western nations, the Japanese were eager to adopt foreign weapons technology (to use on each other) but had no inclination to allow foreigners on to Japanese soil.

The Portuguese made the first successful Western trade inroads with Japan, beginning in 1543. The Japanese were keen to acquire matchlock firearms from the Portuguese, less keen about the Portuguese spread of Catholicism. The weapons played a key role in the unification of Japan during the Battle of Nagashino in 1575 (see the 1980 Akira Kurosawa movie Kagemusha), a process completed in 1603 by Tokugawa Ieyasu, who became the shogun of a united Japan. Technically the Shogun was the prime minister appointed by the Emperor, but, in effect, the shogun was the military ruler of Japan (the emperor was “divine” but the shogun had the armies, and later, the guns and cannons). Christians were persecuted (and a number crucified) during the early years of the Tokugawa shogunate, especially after the death of Tokugawa Ieyasu. In 1638, the Portuguese were invited not to come back. For over 200 years after that, only the Dutch (enemies of the Portuguese) were allowed to trade with Japan, all limited to a small island off Nagasaki.

The first official attempt by the United States to open trade with Japan occurred in 1846. That year, Commodore James Biddle, commander of the U.S. East Indies squadron, successfully concluded the first American commercial treaty with China. Eager to replicate that success with Japan, Commodore Biddle arrived in Edo Bay (now Tokyo Bay) with USS Columbus and sloop-of-war USS Vincennes (the first U.S. Navy ship to circumnavigate the globe, in 1826–30 before serving as flagship for Lieutenant Charles Wilkes’ U.S. Exploring Expedition in 1838–42. See H-Gram 062). As a 90-gun ship-of-the-line, Columbus was one of the two largest and impressive ships in commission in the U.S. Navy at the time (the other was USS Ohio. Of nine ships-of-the line built in the U.S. in the aftermath of the War of 1812, almost all spent virtually their entire service lives laid up due to lack of funding and crewmen).

The Japanese were not impressed. Biddle’s two ships were quickly surrounded by a hundred or so small Japanese boats. The Japanese refused to allow anyone off the U.S. ships, until finally Biddle was invited to go aboard a Japanese junk to receive the Tokugawa shogunate’s official response. Due to translation difficulty, a brief scuffle ensued between Biddle and a Japanese samurai guard (who drew his sword) as Biddle tried to board the Japanese junk, and Biddle withdrew to his own ship. Regardless, the Japanese answer was “ee-ye” (one of 20 ways in Japanese to say “no”). Due to adverse winds, the U.S. ships required tow by the Japanese guardboats in order to leave the bay.

In 1849, Commodore David Geisinger, commander of the U.S. Far East Squadron, ordered Captain James Glynn, commander of 16-gun sloop-of-war USS Preble, to proceed to Nagasaki and attempt to negotiate for the release of a reported 15 American sailors of the whaler Lagoda, shipwrecked and imprisoned under very harsh conditions by the Japanese (several died of exposure and one hung himself, and the Japanese left him hanging). The Japanese tried to prevent Preble from entering the harbor, but she forced her way through a line of Japanese boats. With the help of Dutch interpreters, Glynn succeeded in gaining release of 14 surviving sailors (their harrowing story caused a sensation in the U.S. press, although it turned out 13 had actually deserted from Lagoda, not been shipwrecked). In his after-action report, Glynn recommended that any future attempt to open Japan to U.S. trade to be accompanied by a sizable show of force.

In 1851, Secretary of State Daniel Webster drafted a letter, signed by President Millard Fillmore (and you thought he did absolutely nothing during his presidency) to the Emperor of Japan requesting “friendship and commerce” with no religious purpose. Commodore John Aulick, commander of the U.S. East Indies Squadron, was authorized to deliver the letter and attempt to negotiate with the Japanese. However, Aulick was relieved of command, apparently due to a quarrelsome and undiplomatic nature. Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry (younger brother of War of 1812 hero, Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry), who had extensive diplomatic experience, was selected to replace Aulick. Perry avidly devoured every bit of “Intelligence” he could find about Japan in order to prepare for the voyage (much of it in books acquired by the Navy Department Library, now part of NHHC). As a result of understanding his “adversary,” Perry took large stocks of arms and ammunition as his trade items (such as 100 Colt revolvers).

Perry also took to heart Glynn’s advice on the need for a show of force. His flotilla included three sidewheel steam frigates: USS Mississippi, USS Susquehanna and USS Powhatan. Mississippi was armed with eight 8-inch Paixhans shell guns. Susquehanna had two 150-pounder Parrott rifles and twelve 9-inch Dahlgren smoothbore guns. Powhatan had one 11-inch Dahlgren gun and ten 9-inch Dahlgren guns. (Not surprisingly, ammunition logistics in the U.S. Navy was a real challenge at the time.)

Perry’s force also included the armed store steamships Lexington, Supply, and Southhampton, and the sailing sloops Macedonian (36-gun), Plymouth (4 8-inch shell guns and 18 32-pounder guns), and Saratoga (same armament as Plymouth). Perry also hand-picked most of the commanding officers of the flotilla, including Commander Franklin Buchanan of Susquehanna. (Buchanan would go on to found the “Naval School” which became the U.S. Naval Academy and later to go on as the senior officer in the Confederate States Navy.) The commander of the Marine detachment was Major Jacob Zeilin, who would go on to be the seventh Commandant of the Marine Corps (1864–76), and the first non-brevet (i.e., permanent) flag officer in the Marine Corps.

Perry arrived at the entrance to Edo Bay on 8 July 1853, with four ships, Susquehanna (flagship), Mississippi, Plymouth, and Saratoga. The Japanese had not seen steamships before the “Black Ships,” and their arrival got their attention (in fact, they quickly entered into negotiations with the Dutch to acquire steamships of their own). The other thing that drew the attention of the Japanese was that the steamships blew right past the Japanese guardships, with their guns trained on the first fortified Japanese village (Uraga) as they cut loose with blank shots from the 73 guns and cannons in the force, supposedly in honor of U.S. Independence Day. Perry had absorbed the lessons from Biddle’s visit, particularly regarding Japanese hierarchy, specifically which emissaries to refuse to meet (as they were too junior) and which to meet with (as they had sufficient status). Perry also threatened the use of force against the Japanese capital (Edo) if his messages were not delivered at the appropriate level or responded to in a timely manner.

Perry’s visit caught the Japanese at a particularly weak moment due to the illness of Shogun Tokugawa Ieyoshi, which resulted in government indecision. The Japanese had also obtained intelligence of their own regarding the relative ease with which the Americans had defeated Mexico in the Mexican-American War. They also realized they had no counter to steam warships armed with Paixhan and Dahlgren shell guns. The Japanese concluded that it would not violate their sovereignty to accept President Fillmore’s letter and draft of a trade treaty. The Japanese then agreed to let Perry land at Kurihama, near Yokosuka, to formally deliver the letter, which was done with much pomp and circumstance on both sides (which was pretty much “kabuki” as the Japanese were stalling for time). Perry agreed to depart and give the Japanese time to think about it, promising he would return, leaving Edo Bay on 17 July.

Perry’s proposals caused major splits among Japanese leaders, and the only thing they agreed on was the need to quickly bolster their coastal fortifications and to improve the defenses of the seaward approaches to Edo. Tokugawa Ieyoshi died a few days after, and he was replaced by his weak and sickly son, Tokugawa Iesada, leaving decisions in the hands of a council of elders. In a first for the Tokogawa Shogunate, all the major daimyos (feudal warlords) were actually asked their opinion about whether to accept Perry’s demands. (Rather than being grateful for the “democratic” opportunity, a number of daimyos concluded that the Tokugawa Shoganate was weak, and ripe to be challenged by some of the stronger and more independent-minded daimyos. The result of the vote was 19 for, 19 against, 14 vague, seven suggesting temporary concessions, and two “whatever.”)

True to his word, Perry returned to Edo Bay (actually ahead of schedule) on 13 February 1854, this time with eight ships and 1,600 men. Susquehanna, Mississippi, and Saratoga made their second visit, joined by Powhatan, Lexington, Macedonian, sloop-of-war Vandalia, and store ship Southhampton, and joined later by Supply. By this time, the Japanese agreed it was best to agree to American demands, although negotiations for a site for negotiations dragged on for weeks, prompting Perry to threaten to bring 100 ships within 20 days to take Edo (this was more ships than the entire U.S. Navy). Finally, a compromise was reached to conduct negotiations at Yokohama. On 8 March, Perry landed 500 Sailors and Marines in 27 boats to help with the discussions. Finally, after three weeks of massive gift exchanging, the negotiations concluded with the Convention of Kanagawa, which opened the ports of Shimoda and Hakodate to American trade, with provisions for the proper care of shipwrecked Sailors.

Despite all the bowing, exchanges of extravagant gifts and signing of papers, the contact with Perry and the U.S. resulted in major upheaval and dissension within Japan. Emperor Komei (121st in the line of Emperors) had come to the throne in March 1846 and was dead set against opening Japan to foreigners (weapons were OK). With the Tokugawa shogunate at its weakest level in 200 years, more and more daimyos began to gradually side with the Emperor. Much of the Japanese populace was of the same mind as the Emperor, and incidents of violence directed at foreigners (other European nations had piled on with trade treaties after Perry) became increasingly common in the early 1860’s. Increasingly assertive, Komei broke with centuries of tradition by becoming actively involved in the affairs of state.

In an increasingly strong position, Emperor Komei issued a decree in March 1863 that all foreigners should leave Japan. In April 1863, Komei issued the “Order to Expel Barbarians” with the date of 25 June for all foreigners to leave. Anti-foreign riots broke out in Edo and elsewhere, and the American legation in Edo was burned. The American Consul in Edo moved to Yokohama as the Japanese made clear his safety could no longer be guaranteed in Edo.

Upon the outbreak of the American Civil War in the United States in 1861, almost all U.S. ships were recalled from far-flung regions of the world to support the blockade of Confederate ports. In the Far East, only the steam side-wheel sloop USS Saginaw (see H-Gram 057) remained on station. Saginaw was the first ship built at the Mare Island Navy Yard, in 1860. In July 1861, Saginaw was searching for a missing boat and sailors from the American bark Myrtle when she was fired on by Vietnamese batteries at the entrance to Qui Nhon Bay, Cochin China (now Vietnam). Saginaw raised a white flag to show peaceful intent, but the battery continued to fire. Saginaw returned fire for 20 minutes when there was a major secondary explosion in the Vietnamese-held fort. Saginaw continued to fire for another 30 minutes until the fort was completely wrecked. (And you probably thought it all began with the Gulf of Tonkin incident in 1964.)

During USS Constitution’s around-the-world cruise (1844–46), she stopped in Turon Bay, Cochin China (near present day Danang, Vietnam) on 10 May 1845 to provision and to bury a sailor who died from dysentery, Seaman William Cooke. (Cooke was one of 234 Sailors who died aboard Constitution from illness and a few accidents during her history; only 26 actually died during or the result of combat.) When informed that the Vietnamese were reportedly holding a French missionary under sentence of death, Constitution’s skipper, Captain John “Mad Jack” Percival, responded by demanding the missionary’s release and taking three local officials (“mandarins”) hostage along with three of the Cochin Emperor’s war junks. The junks escaped during foul weather but were recaptured. Over the next days there were several incidents in which Constitution crewmen fired on local soldiers with muskets; the Vietnamese claimed scores were killed.

The Vietnamese refused to produce the missionary (who was not actually what he was claimed to be), but additional war junks arrived, along with preparations at the forts for battle, and the arrival of reinforcing Vietnamese troops. On 26 May, with obvious Vietnamese intent to defend against any further incursions and no sign of the missionary, Captain Percival opted to depart. Upon return to the United States, Percival was rebuked for his actions, and President Zachary Taylor issued a formal apology to the Cochin Emperor for Percival’s actions, which may be unique in U.S. diplomacy in the 1800s. In the meantime, Vietnamese locals carefully tended Seaman Cooke’s grave for over 160 years until it was apparently bulldozed for beachfront development within the last ten years. One of Constitution’s officers summed up the first U.S. armed conflict in Vietnam thus, “It seems…to have shown a sad want of ‘sound discretion’ in commencing an affair of this kind, without carrying it through to a successful conclusion,” words that could have been spoken in 1975.

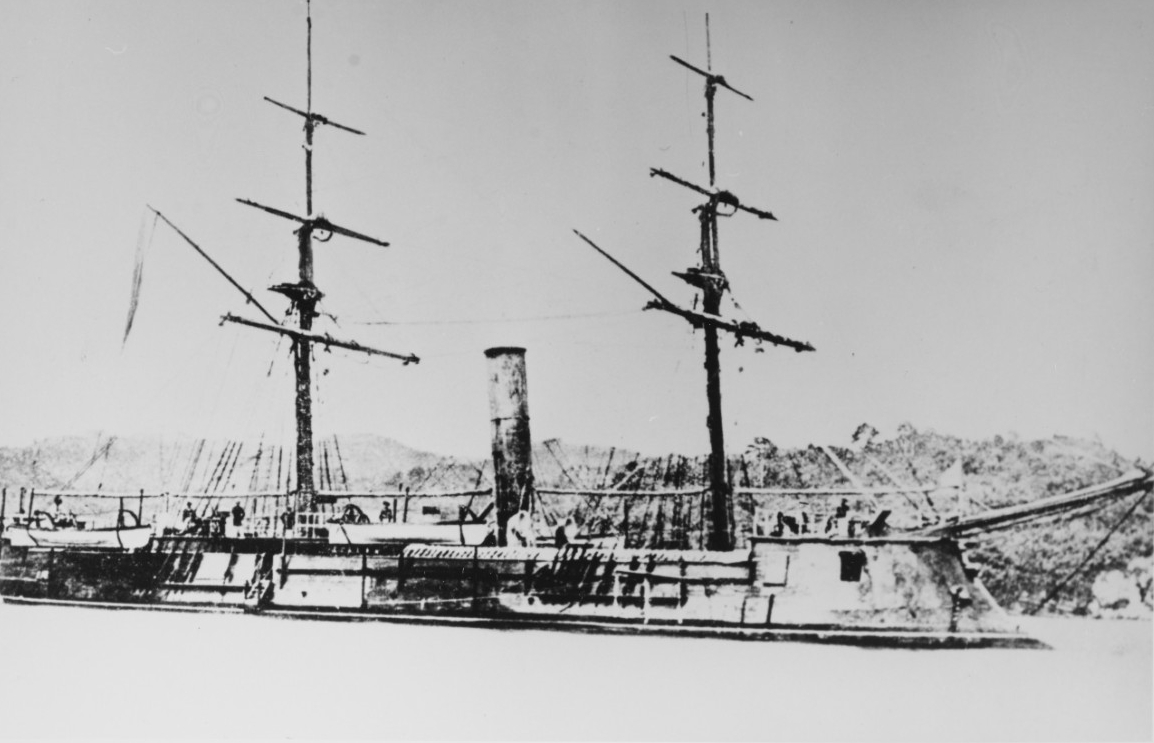

Meanwhile, back in the Far East during the U.S. Civil War, Saginaw was recalled to the U.S. West Coast in 1862, to protect American whalers in the eastern Pacific, temporarily leaving no U.S. Navy presence in Asia. However, reports were subsequently received that a Confederate raider was operating in Far Eastern Waters. Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles directed the commandant of the Mare Island shipyard to hasten the repair of the screw-sloop USS Wyoming and prepare her for 30-months of overseas service. Ordered to depart in June 1862, Wyoming was a new steam-powered vessel, commissioned in 1859, capable of 11 knots. She had a crew of about 200 and was armed with two 11-inch Dahlgren smoothbore guns (which could pivot from side-to-side), a 60-pounder Parrott rifle (an earlier shell gun of about 5.3-inch bore), and three 32-pounder broadside guns. Wyoming was named after a valley in Pennsylvania, as the state of Wyoming did not exist at that time.

Wyoming was under the command of Commander David Stockton McDougal. McDougal entered the U.S. Navy as a midshipman in 1828. He had extensive service in the Mediterranean, West Indies, Home and Great Lakes Squadrons. During the Mexican-American War, he served in Commodore Mathew Perry’s “Mosquito Fleet” (capturing inland objectives via small-boat riverine operations) as well as participating in the blockade and siege of Vera Cruz. His first command was the sloop-of-war USS Warren in 1854-56, followed by command of the steam tug USS John Hancock in 1856. He assumed command of Wyoming in 1861.

Wyoming arrived in the Philippines in August 1862 and, after a search, determined that the reports of a Confederate raider were false. The raider CSS Alabama was still in the West Indies at the time. Nevertheless, Wyoming remained on station. In March 1863, Wyoming struck a rock near Swatow, China. MacDougal ran her aground to keep her from sinking. She was repaired and refloated. Wyoming was preparing to return to the U.S. West Coast when the situation in Japan boiled over.

Operation “Expel the Barbarians”

Two of the most powerful daimyo clans, the Satsuma and Choshu, decided to side with the Emperor in defiance of the Tokugawa shogunate (which was viewed as the legitimate Japanese government by the United States and other Western nations). Under Prince Mori, the Choshu controlled the northern side of the narrow Shimonoseki Strait, which separates the main island of Honshu on the north and Kyushu on the south and forms the western entrance/exit between the East China Sea to the west and the Japanese Inland Sea to the east. The Choshu had fortified the north shore of Shimonoseki Strait with six forts, armed mostly with older round-ball cannons, including five 8-inch Dahlgren smoothbore guns (courtesy of the United States). (Like Iranian Harpoon missiles and F-14s, we never learn.) The Choshu had also purchased three armed ships from the United States: the 6-gun bark Daniel Webster (Japanese name unknown), the 10-gun brig Kosei (originally Lanrick) and the 4-gun steamer Koshin (originally Lancefield).

In accordance with the Emperor’s “expel the barbarian” order, the Choshu commenced action against foreigners on the night of 25–26 June 1863. At about 0100, two of the Choshu ships (still flying the flag of the Shogunate) opened fire on the American merchant Pembroke, which was anchored at the eastern end of the strait awaiting a pilot and turn of the tide. Pembroke was able to slip her anchor and backtrack into the Inland Sea and exit via the Bungo Strait (between Kyushu and Shikoku), suffering only minor damage. Pembroke continued her voyage to Shanghai, although she skipped a planned stop in Nagasaki, Japan.

Reports of the attack on Pembroke first reached American Consul in Yokohama on 10 July, and in keeping with the adage that “first reports are always wrong,” the report was that Pembroke had been sunk with all hands. The next day, mail from Shanghai arrived, confirming that the attack took place, but that Pembroke had survived. By this time, Wyoming had arrived at Yokohama from Hong Kong after receiving word of the burning of the American legation in Edo. Pryun, with McDougal present, delivered a diplomatic protest to the Tokugawa Minster of Foreign Affairs, who begged for more time to deal with the situation. It appeared to the Americans that the Tokugawa either could not or wouldn’t control the Choshu (and Satsuma). Actually, they could not. Although Wyoming was under orders to return to the States, McDougal informed Pryun that Wyoming would depart immediately for Shimonoseki Strait to take action, and Pryun agreed. (No need to wait for Washington.)

Unknown to the Americans at the time, the Choshu continued to attack ships trying to pass through the strait. Shortly after the Pembroke was fired on, the French dispatch boat Kien-Chang was hit and nearly sunk in the channel. The next ship through was the Dutch 16-gun steam frigate Medusa, under the command of Captain Casembroot. Because of the long centuries of friendly trade between the Japanese and the Dutch, Casembroot made the assumption he would be able to negotiate. Instead, Medusa encountered a hail of accurate fire, and was hit in the hull 31 times, suffering four dead and 16 wounded before she was able to extract herself from the situation. A couple days later, a French gunboat was hit in the hull three times. Then the Choshu mistakenly sank a Satsuma ship. In response to these attacks, the British, French and Dutch were gearing up for a coordinated response, but Wyoming got there first.

The First Battle of Shimonoseki Strait, July 1863

Wyoming planned to get underway from Yokohama at 0500 on 13 July 1863, but tarried an hour awaiting the arrival of the Tokugawa Foreign Minister, who was supposed to embark in order help with any negotiations. However, the Foreign Minister missed ships movement, later reportedly due to a severe case of diarrhea. Wyoming anchored off the island of Hime Shima, east of the approaches to Shimonoseki Strait, on the evening 15 July 1863. In discussions with a Japanese national who worked for the American legation, McDougal was informed (and convinced) that the Choshu would not negotiate and would fire on his ship. As a result, Wyoming’s crew made all preparations to be ready for battle.

At 0500 16 July 1863, Wyoming was underway from Hime Shima. At 0900, the crew went to general quarters, with the pivot guns loaded and cleared for action, although the guns were kept under tarps in attempt to give the ship an appearance of being a merchant. At 1000, Wyoming commenced an approach to the channel, sighting the two Choshu sailing ships and one steam ship at the far end of the channel. The vessels were noted flying the Tokugawa and Choshu banners. Wyoming entered the channel at 1045, at which point Japanese signal guns ashore fired. Wyoming then hoisted her colors.

As soon as the Wyoming was in range, the Japanese forts opened fire with an intense bombardment. McDougal correctly deduced that stakes in the channel indicated that the Japanese had already calculated the range for ships in the channel and aimed their guns accordingly. As a result, McDougal steered so close to the north shore that the forts’ guns could not depress enough, and numerous Japanese rounds whizzed by 10–15 feet overhead through the rigging. (The Japanese pilots aboard Wyoming had essentially gone catatonic by this point.)

As Wyoming passed through the narrowest point of the channel, McDougal aimed directly for the Choshu ships, which were still at anchor, and were heavily manned by what appeared to be highly motivated Japanese trying to get underway. The bark was anchored just off the town of Shimonoseki and the brig KOSEI about 50 yards beyond. The steamer Koshin was anchored beyond the two sail ships, anchored a bit further south in the channel. McDougal aimed to engage the two sail ships to starboard and the steamer to port. Wyoming passed the bark at pistol-shot range, as Wyoming’s Marines picked off Japanese with musket fire. The muzzles of the big 11-inch guns were so close to the Japanese they almost touched. The parrot gun and 32-pounders blew holes in the bark. The bark put up a spirited fight, getting off three broadsides as Wyoming passed. Wyoming then did the same to the brig. It was during these exchanges that Wyoming suffered most of her casualties. The forward gun had six men down, including one dead, and a Marine was killed by shrapnel.

As Wyoming opened the range from the brig, aiming for the steamship, the brig was already starting to sink, but kept on firing. Wyoming then fired into the steamer with her portside guns. As Wyoming passed the steamer, she turned to port to make a second pass at greater range and to bring the 11-inch guns to bear. At this point, Wyoming ran aground. As Wyoming tried to back off, the steamer Koshin slipped her anchor and made a run at Wyoming in an apparent attempt to either ram or board. Wyoming freed herself before the on-rushing steamer could get too close. McDougal gave repeated orders to the closest 11-inch to fire, which the gun captain seemed to ignore. Finally, the gun captain fired, and an exquisitely aimed round hit the steamer right at the waterline into her boiler (and out the other side), but the boiler exploded, sending the steamer Koshin to the bottom in less than two minutes.

Having reversed course, Wyoming engaged the sinking brig Kosei with the 11-inch Dahlgrens, hitting her twice in the hull and expediting her trip to the bottom. Wyoming then inflicted more punishment on the bark, which was still afloat at the end of the engagement, but effectively destroyed. Wyoming then bombarded the forts with accurate fire until all were silenced. Wyoming ceased fire at 1220 and steamed out without further interference from Japanese guns.

During the one hour and 10 minute engagement, Wyoming fired 55 rounds of shot and shell (actually with very judicious and well-aimed fire, as it was still necessary to conserve ammunition in the event of an encounter with a Confederate raider). The Choshu had fired 130 rounds, of which only 22 were damaging; Wyoming had been hit in the hull 11 times without serious effect, although her rigging was extensively shot up and her smokestack perforated. Wyoming suffered four killed and seven wounded, although one of the wounded subsequently died. McDougal initially considered burying his dead ashore, but decided against it, and all were buried at sea.

It should be noted that almost none of Wyoming’s crew had any combat experience, yet performed with great coolness under fire. McDougal’s astute tactical judgment in avoiding the worst of Japanese shore-based fire and in defeating three ships at once got him absolutely nothing in the way of commendation or promotion, with this battle being fought only three days after Gettysburg. President Theodore Roosevelt would later write, “had that action taken place at any other time than the Civil War, its fame would have echoed all over the world.” In McDougal’s after action report to Gideon Welles, he wrote, “the punishment inflicted…will I trust teach him a lesson that will not be forgotten.”

Wyoming was the first foreign warship to respond to the Japanese violation of treaties (that the Japanese had mostly signed under duress, viewing them as “unequal”). A few days later, a French force showed up to respond to the attacks on their shipping. Led by French admiral Constant Jaures aboard his flagship, 34-gun steam frigate Semiramis, accompanied by gunboat Tancrede, the French bombarded the forts and put troops ashore while under fire. The French destroyed an ammunition magazine and burned the nearby village. Wyoming, in particular, taught the Japanese a lesson they did not forget; however, the Japanese, being Japanese, did not give up. The two sunken ships were raised in 1864, the forts repaired, and shelling of foreign ships continued, effectively blocking the strait for another 15 months.

The British Royal Navy took its own unilateral action in August 1863, as a delayed reaction to the killing of a British merchant by samurai of the Satsumo daimyo. On 15 August 1863, a Royal Navy squadron entered the harbor of Kagoshima (on southern Kyushu), the Satsumo capital, to extract reparations by force, seizing several Satsuma ships. The Satsuma fired on the British, who in turn bombarded Kagoshima (which the Japanese had evacuated). Three Satsuma steamships were sunk and about 500 houses destroyed, but the British actually suffered more casualties, with 11 dead. A single Japanese cannonball decapitated both the captain and second-in-command of Acting Vice Admiral Augustus Kuper’s flagship, screw frigate HMS Euryalus. The British essentially ran out of ammunition and left, leaving the Satsuma to boast that they had driven the British off without paying anything.

Hunt for CSS Alabama

Wyoming’s orders to return to the U.S. were rescinded with reports that the Confederate raider CSS Alabama was heading toward the Far East. Alabama was a screw steam sloop built in Britain (she never entered a Confederate port) with a crew of about 145 and capable of 13 knots. She was armed with one pivoting 110-pounder 7-inch Blakely muzzle-loader forward, and a pivoting 8-inch smoothbore gun aft, along with six 32-pounder broadside guns. Under the command of Captain Rafael Semmes, Alabama was the most successful commerce raider of all time. By the time she was ultimately sunk by USS Kearsarge off Cherbourg, France on 19 June 1864, Alabama had been in service for 657 days, 534 of which were underway. She had boarded about 450 vessels, captured 65 Union merchant ships (valued in current dollars at 99 million) and burned most, taking more than 2,000 prisoners without loss of a single life of passengers and crew.

Once Alabama was in the Indian Ocean, Wyoming was ordered to wait in the Sunda Strait between Sumatra and Java in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) and remained there for about a month. Semmes was aware that Wyoming was waiting and was actually eager to do battle, believing his ship matched up well with Wyoming. Semmes’ plan was to catch Wyoming by moonlight while she was anchored off the volcanic island of Krakatoa in the Sunda Strait. However, on 10 November 1863, Wyoming received word to investigate Christmas Island (south of Java) based on a report from the U.S. Consul in Melbourne, Australia that the island was being used to stockpile stores for the Alabama. As it turned out, Wyoming left Sunda Strait the day before Alabama passed through. The two ships were within 25 miles, but never saw each other. Wyoming found absolutely nothing at Christmas Island. Wyoming subsequently called at Singapore in late November, where local officials mistook her for Alabama and delivered Alabama’s mail to Wyoming, the first confirmation that Alabama had entered the Java Sea and was operating in the Far East.

The Far East proved to be not very lucrative for Alabama and she took only three prizes near the Sunda Strait before departing. Despite aggressively searching, Wyoming never found Alabama, and McDougal arguably missed his chance at immortality (one way or the other). With her boilers in serious need of major work, Wyoming commenced a three-month voyage home to the U.S. East Coast, arriving in Philadelphia in July 1864, after circumnavigating the globe.

The departure of Wyoming left the sail sloop USS Jamestown as the only U.S. warship in the Far East. Under the command of Captain Cicero Price, Jamestown had reached the Far East in June 1863. First commissioned in 1844, Jamestown was armed with four 8-inch shell guns and 18 32-pounder broadside guns. However, her lack of steam power essentially rendered her obsolete for her mission.

The Second Battle of Shimonoseki Strait, September 1864

By the summer of 1864, the European powers finally resolved to take coordinated action against the Choshu and Satsuma, and planning commenced. Britain, France and the Dutch all agreed to participate. Although the American Civil War was still raging, the United States agreed to a token participation. However, all the ships of the other navies were steam-powered by this time, making sail-powered Jamestown more of a liability than a help. As result, Captain Price charted the steamship Ta-Kiang, armed it with a 30-pounder Parrott gun with a crew of 70 (18 were Americans) under the command of Lieutenant Frederick Pearson, and placed the ship under the command of British Admiral Augustus Kuper (which may have been a first for the U.S. Navy).

In late August, most of the force departed Yokohama. Jamestown remained behind to protect the foreign enclave at Yokohama. USS Ta-Kiang rendezvoused with the force at Hime Shima Island. The fleet included eight British steam warships, led by Admiral Kuper on screw frigate HMS Euryalus and included the ponderous 89-gun steam ship-of-the-line HMS Conqueror. The French contributed three steam warships under the command Admiral C. Jaures, including screw frigate Semiramis. The Dutch contributed four screw corvettes. As the Choshu were considered the strongest and most aggressive of the rebellious daimyo, the first objective of the force was Shimonoseki Strait.

On 4 September 1864, the allied force formed up into three columns based on nationality, with Ta-Kiang bringing up the rear of the French column. The force then anchored in sight of the Choshu gun batteries, in an ostentatious show of force. On 5 September, the allied force arrayed itself with medium sized ships in range of the Choshu batteries, the smaller ships arrayed to provide flanking fire on the fortifications, and the two flagships, Euryalus and Semiramis and ship-of-the line Conqueror a bit further out, all with no reaction from the Japanese. However, with the first opening shot by Euryalus in the afternoon, eight Choshu gun batteries immediately returned fire. In the ensuing three-hour gunnery duel, in which neither side accomplished much of anything, Ta-Kiang contributed 18 rounds from the Parrott gun. The Japanese guns finally fell silent, but the British and French admirals decided it was too late to put a landing force ashore.

At dawn on 6 September, the Japanese had the temerity to open fire first, quickly scoring multiple hits on two ships, before being overpowered by the combined guns of the allied force. Once the Japanese fire had been suppressed, Ta-Kiang and seven of the smaller ships towed boats with 1,000 Royal Marines and armed British, French and Dutch sailors to shore. The landing went off without a hitch, but the 17-gun corvette HMS Perseus was swept aground (she was later successfully refloated). The landing force overpowered opposition as it sequentially rolled up the Japanese batteries, spiking the guns and blowing up magazines. With the French and Dutch troops already re-embarking their ships, the last group of British sailors started their march back to the shore. A sudden surprise Japanese counter-attack threatened the British sailors, but was beaten off by Royal Marines.

Further attempts at Choshu resistance were met with overwhelming firepower from the ships. On 7 September, the allies carted off 62 Choshu cannons and destroyed the rest. On 8 September, the Choshu forces surrendered. Ta-Kiang (which had Jamestown’s surgeon embarked), served as a hospital ship for the allied force, returning 23 wounded personnel to Yokohama.

The accord drawn up after the cease fire was extremely punitive, requiring the Tokugawa shogunate to pay equivalent of 3 million dollars (even through the Choshu were operating in defiance of Tokugawa control – although a number of Choshu leaders ended up beheaded). The Tokugawa could not pay; they were forced to open another treaty port and make other trade concessions to the Western powers, further weakening the shogunate in relation to growing Imperial power, finally resulting in the Boshin War of 1868-1869 between the shogunate and forces loyal to Emperor Komei’s son Emperor Meiji (Komei died in 1867). Emperor Meiji would rule Japan from 1867 to 1912, a period of rapid modernization known as the “Meiji Restoration.” In 1883, the U.S. government returned the 750,000-dollar American share of the Shimonoseki indemnity to the Japanese.

The second battle of Shimonoseki Strait cost the allies 72 casualties. (The British suffered eight killed and 30 wounded.) The Japanese reportedly suffered 47 casualties. Three Victoria Crosses (Britain’s highest award for valor) were awarded as a result of the action. One was American-born Ordinary Seaman William Seeley (serving in the Royal Navy) for a daring reconnaissance of a Japanese position, and although wounded, he continued in the final assault on the battery. Seeley was the first American to be awarded the Victoria Cross.

More Raider Chasing

Within days of her return to the United States, McDougal and Wyoming were ordered back to sea to hunt for confederate raider CSS Florida. However, after five days, her boilers (long overdue for serious repair) finally gave out. (Screw-sloop USS Wachusett captured Confederate raider CSS Florida on 4 October 1864 when Commander Napoleon Collins took Wachusett right into Bahia Harbor (in flagrant violation of Brazilian neutrality and territorial water) where Florida had taken refuge. After a brief exchange of gunfire, Florida surrendered. Brazilian guns fired on Wachusett as she towed Florida to sea. Commander Collins was subsequently court-martialed, and then immediately restored to his command by Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles).

Wyoming remained in overhaul until the spring of 1865 when she was sent back to the Pacific in pursuit of Confederate raider CSS Shenandoah. After the war, Wyoming remained in the Far East (1865-1868), then served in the North Atlantic, and European Squadrons, before being decommissioned in 1882, serving as a training ship at the Naval Academy until 1892. Commander McDougal received little acclaim at the time for the action in Shimonoseki strait; in 1869, he assumed command of the South Pacific Squadron; he was placed on the retired list in 1871 and promoted to rear admiral in retired status in 1874. Two ships were named for McDougal; O’Brien-class destroyer DD-54 (1914–36), and Porter-class destroyer DD-358 (1936–46).

The Confederate raider CSS Shenandoah, commanded by Commander James I. Waddell, CSN, arrived at Melbourne, Australia in February 1865 via the Cape of Good Hope. Shenandoah then headed for the north Pacific, capturing 20 of 58 American whalers operating in the Bering Sea, all more than a month after the war had ended (but word had not been received). In the spring of 1865, three Union steam warships were sent to the Pacific in pursuit of Shenandoah. Wyoming did not reach the Pacific until after the war ended. Screw-sloop USS Wachusett was delayed when she ran aground in the West Indies.

Screw sloop-of-war USS Iroquois rounded Cape Horn and finally reached Singapore in May 1865 and spent two months fruitlessly cruising near Sunda Strait, unaware of Shenandoah’s depredations in the Bering Sea. On 28 June 1865, Shenandoah fired the last shot of the Civil War, across the bow of a whaler in the Bering Sea. On 3 August, Shenandoah finally learned the war was definitely over (after having captured a total of 38 ships, burning most of them). Shenandoah exited the Pacific via Cape Horn disguised as a merchant. Having learned that all rebels had been pardoned, except the crew of Shenandoah, who were to be hanged as pirates if caught, Waddell steered clear of shipping lanes, until arriving at Liverpool, England, where her raiding voyage originated. Waddell surrendered the ship to 101-gun screw-ship-of-the-line HMS Donegal on 6 November 1865, lowering the Confederate flag (this was the last surrender of the Civil War and the last official lowering of a Confederate flag). The British paroled the ship’s crew. The Charles F. Adams–class guided missile destroyer DDG-24 (1964–92) was named for Waddell.

Jamestown remained in the Pacific until she departed Macao on 17 June 1865 to return to the United States; she was the last U.S. pure sailing warship to serve in the Far East. Jamestown was converted to a transport and store ship, serving in that capacity from 1866–1881, including being present at Sitka, Alaska, on 18 October 1867, when the U.S. took possession from Russia. She then served as a training and hospital ship until she burned at Norfolk Navy Shipyard in 1913. Jamestown’s commanding officer, Captain Cicero Price, was promoted to commodore in 1866 in command of the U.S. East Indies Squadron, before being statutorily retired in 1867 at age 62. He was court-martialed in 1866 for neglect of duty in preparing muster rolls, but his punishment was suspended.

Postscript: The Saga of CSS Stonewall

A Confederate ironclad ram, the CSS Stonewall, played a decisive role after being renamed Kotetsu as the flagship of Imperial Japanese Navy forces. She served in the defeat of rebel forces loyal to the former Tokugawa shogunate in the Naval Battle of Hakodate, Hokkaido, Japan on 4–10 May 1869, which ended the Boshin War (a civil war in Japan).

In June 1863, almost a year after the Battle of Hampton Roads between the ironclads USS Monitor and CSS Virginia, the Confederate commissioner to France, John Slidell, convinced Emperor Napoleon III of France to build ships for the Confederacy. Napoleon III agreed (to violate French law) on condition that the intended “end user” of the ships be kept secret, and that the ships be built in the yard of a personal friend. (John Slidell was one of two Confederate Commissioners taken from the British Royal Mail Ship Trent by Captain Charles Wilkes’s USS San Jacinto in November 1861, nearly leading to war with Great Britain [see H-Gram 062]). He was subsequently released by the Union. He was also the older brother of Lieutenant Commander Alexander Slidell Mackenzie, killed during the Formosa Expedition of 1867) (see H-063-4).

The French built two ironclads for the Confederacy under the phony names Sphinx and Cheops (to suggest they were destined for the Egyptian Navy). However, an informant in the shipyard alerted the U.S. government, which lodged a diplomatic protest with the French. With the cover blown, Napoleon III disavowed the effort. The two ships were subsequently sold to Prussia and Denmark (which were at war with each other in the Second Schleswig War, although neither ship was delivered before the war ended, in Prussia’s favor). The Cheops served in the Prussian Navy as Prinz Albert. Although Sphinx sailed to Denmark with a Danish crew as Staerkodder in June 1864, the Danes did not accept it in their Navy but rather sold it to the Confederacy in January 1865. On 6 January 1865, Lieutenant Thomas Jefferson Page of the Confederate States Navy took possession of Staerkodder (Page had been in command of the USS Water Witch during the Water Witch Affair with Paraguay [see H-Gram 062]). Staerkodder was underway the next day to France under a Danish captain. While off the coast of France to take on ammunition, provisions, and more crewmen, Lieutenant Page assumed command and the ship was commissioned as CSS Stonewall.

Stonewall was an ironclad ram. Her intended mission was to ram and sink Union ships on blockade duty off the Confederacy. The ship was steam powered, with a relatively new innovation – twin shafts, screws and rudders to improve maneuverability in restricted waters, and she could make 10.5 knots under steam. She was armed with a British-made 300-pounder 10-inch Armstrong rifled muzzle loader (RML), and two 70-pounder 6.4-inch RMLs. (These guns were accident-prone and were actually withdrawn from British service). The armor was designed to withstand hits by 15-inch guns and was 4.5-inches thick, backed by 15-inches of teak at its thickest. The ship also had “turrets” with 5.5-inch armor. Although called “turrets” they did not rotate but were actually fixed shelters with multiple gun ports, and the guns could swivel between the ports. Stonewall had a crew of about 135.

After leaving France, Stonewall ran into a severe storm in the Bay of Biscay, damaging her rudders, and forcing her to put into El Ferrol, Spain for extended repair. Union Intelligence quickly became aware, and within a few days, the steam frigate USS Niagara and steam-sloop Sacramento arrived off the port. On 21 March 1865, Stonewall was underway again en route Lisbon to re-coal. The wooden Niagara and Sacramento judiciously declined to engage in battle with the ironclad. Stonewall arrived in Nassau, Bahamas on 6 May 1865 and Havana, Spanish Cuba, on 11 May, where Lieutenant Page learned the war was over. Union ships arrived by 15 May to monitor Stonewall. Page turned over Stonewall to Spanish authorities in Cuba in exchange for enough money to pay off the crew. In November 1865, the U.S. reimbursed the Spanish and took possession of the Stonewall. On the way to the Washington Navy Yard, Stonewall accidentally rammed and sank a coal schooner in Chesapeake Bay; fortunately, no one was lost.

Representatives from the Japanese Tokugawa shogunate (then viewed as the legitimate Japanese government) came to the U.S. in 1867 seeking to buy surplus ships, and bought Stonewall for $400,000 on 5 August 1867. The Japanese renamed her Kotetsu (literally, “Ironclad”). Kotetsu arrived at Shinegawa Harbor (near Edo (now Tokyo) on 22 January 1868, under Japanese flag but with an American crew. By then, however, the Boshin War was in full swing between forces aligned with the new resurgent Emperor Meiji and those aligned with the ruling Tokugawa Shogunate. The United States took a neutral stance in the civil war. The U.S. Resident Minister to Japan, Robert Van Valkenburg, refused to turn over the Kotetsu and she resumed flying the U.S. flag. When Imperial Meiji forces were finally in ascendance, Kotetsu was handed over to the Meiji government in March 1869.

In the meantime, the vice commander of the Tokugawa Navy, Admiral Enomoto Takeaki, refused to accept defeat. On 20 August 1868, Enomoto left Shinagawa with his flagship, steam frigate Kaiyo and three other steam warships and four steam transports, heading north along Honshu. They immediately ran into a typhoon and one steam transport was lost, and the corvette Kanrin Maru (Japan’s first screw driven warship, ordered in 1853 from the Dutch) was damaged and took refuge in a port, where she was bombarded and boarded by Imperial forces despite a white flag of surrender.

Enomoto’s naval force (with a number of French advisors) and about 3,000 troops ultimately reached Hakodate, Hokkaido, where they established the Ezo Republic (with a government modeled after the United States and Enomoto was elected president). The Meiji government refused to recognize the breakaway republic and began moving forces to attack. The Ezo navy suffered a major setback when Kaiyo was wrecked in a storm in November 1868, along with Shinsoku, which went to her rescue.

On 9 March 1869, an Imperial naval force departed Tokyo Bay made up of eight steam ships provided by some of the major daimyo (feudal warlords), bolstered by the new ironclad Kotetsu. This force included the steam paddlewheel warship Kasuga (built in the Britain), thee smaller steam corvettes and three steam supply ships. On Kotetsu, the Japanese had removed one of the Armstrong 70-pounders and replaced it with two smaller cannons and a Gatling gun (early machine gun).

Recognizing that his wooden ships were at a severe disadvantage to the Kotetsu, Admiral Enomoto devised a daring plan to capture her. The plan called for three Ezo ships to conduct a surprise night attack on Kotetsu while she was in port Miyako Bay in northern Honshu. The new Ezo flagship, the paddle-wheel corvette Kaiten (built in Germany), would lead the attack, flying the American-flag to confuse the Imperial ships. Each ship carried a boarding party of elite samurai. The plan went awry when Takao (former U.S. revenue cutter Ashuelot) developed engine trouble and Banryu became separated by bad weather. Kaiten pressed on with the attack alone, achieving the desired surprise (and hoisted her colors only at the last moment).

On 6 May 1869, Kaiten rammed Kotetsu as planned, and the elite Shinsengumi (“new select brigade”) began boarding Kotetsu. However, the nine-foot difference in deck height greatly impeded the boarding team, giving the Kotetsu’s crew time to overcome the shock of surprise and turn the Gatling gun on the boarding team, which was slaughtered, including the boarding team commander. Kaiten was able to pull away from Kotetsu and make a getaway, damaging three other ships on her way out, in what would be known as the Battle of Miyako Bay. Takao, slowed by engine trouble, showed up just in time to be beached and blown up to avoid capture (although her crew was captured).

On 9 April 1869, Imperial troops began landing near Hakodate, resulting in several land battles. The naval battle commenced on 4 May, with Kotetsu and Kusaga playing the key role with the Imperial forces. The Ezo ship Chiyoda ran aground and was captured by Imperial forces. The same day Ezo ship Banryu hit the Imperial Choya Maru in the gunpowder magazine, resulting in a massive blast that killed 86 of Choya Maru’s crewmen and sank her in about two minutes. However, Banryu had taken so many hits that her crew ran her aground and then burned her. By 6 May, Kaiten was so badly damaged, that she too was run aground and burned. By the time the series of actions were over, the entire Ezo force was sunk, burned or captured. The Ezo Republic surrendered in June 1869.

With the victory at Hakodate Bay, led by Stonewall, the Imperial Japanese Navy was formally established. Kotetsu would be renamed Azuma in 1871 and played a minor role in the Formosa Expedition of 1874, the first overseas expedition by the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy. Azuma was stricken in 1888 and sold for scrap in 1889. Although Admiral Enomoto was initially imprisoned as a traitor, the Meiji government recognized his considerable talents; he was pardoned and went on to serve in senior cabinet and other positions, and was a major leader in the modernization of Japanese communications and the Imperial Japanese Navy. And, aboard Kusaga at both Miyako Bay and Hakodate was junior officer Togo Heihachiro, who would achieve one of the most decisive victories in naval history, against the Imperial Russian Navy in the Battle of Tsushima in May 1905.

Sources include: Lieutenant Commander Thomas J. Cutler, U.S. Navy (Retired), “Lest We Forget: The Forgotten Battle of Shimonoseki Straits,” U.S. Naval Institute, Proceedings, January 2019; Carl Herzog, “Consigned to a Seaman’s Grave…” USS Constitution Museum, last modified 7 May 2019; Robert E. Johnson, Far China Station: The U.S. Navy in Asian Waters 1800–1898 (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2013); Elijah Palmer, “Unexpected Enemies in the Civil War: The Japanese (Part One/Part Two), Hampton Roads Naval Museum’s Blog; C.L. Veit, “The Battle of the Straits of Shimonoseki, July 16, 1863,” Navy and Marine Living History Association, On Deck.