H-078-2: Renaming of USS Chancellorsville and USNS Maury

Background

The “Commission on the Naming of Items of the Department of Defense that Commemorate the Confederate States of America or any Person who Served Voluntarily with the Confederate States of America” (“Naming Commission” for short) was created by U.S. Congressional legislation and passed into law over veto by President Donald Trump, enacted in January 2021. The Naming Commission was chaired by Admiral Michelle Howard, U.S. Navy (Ret.). The Naming Commission recommended that two U.S. Navy ships be renamed, USS Chancellorsville (CG-62) and USNS Maury (T-AGS 66). On 6 October 2022, Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin issued a memo concurring with the Naming Commission recommendations. On 5 January 2023, the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment (USD [A&S]) directed the Department of Defense to implement all Naming Commission recommendations.

The Naming Commission recommended which ships (and buildings and streets) should be renamed for all Services, but in the case of the Navy left the decision of what the new name should be to the Secretary of the Navy. On 28 February, Secretary Carlos Del Toro announced that Chancellorsville would be renamed USS Robert Smalls.

On 8 March, Secretary Del Toro announced that USNS Maury would be renamed USNS Marie Tharp. (On 17 February, Secretary Del Toro previously announced the renaming of “Building 105” [formerly Maury Hall] at the U.S. Naval Academy, in accordance with the Naming Commission recommendation. Maury Hall was renamed after former President Jimmy Carter, the only U.S. president to graduate from the Naval Academy. Additional name changes for buildings and streets will be forthcoming.)

Of note, the Naming Commission hewed strictly to its remit (i.e., the Confederate States of America during the Civil War) and did not address ships named in honor of Southern slave-owning plantations (several of which were the homes of U.S. presidents) that are still in commission, nor did it address ships named in honor of persons with overtly segregationist views, that are also still in commission.

There is ample precedent for renaming U.S. Navy ships, although it has rarely been done since World War II. During the war, numerous ships were renamed while they were under construction in order to recycle names of ships lost in battle. Examples include Bon Homme Richard (CV-10) renamed Yorktown (CV-10) after the loss of Yorktown (CV-5) at the Battle of Midway. USS Cabot (CV-16) was renamed Lexington (CV-16) after the loss of Lexington (CV-2) at the Battle of the Coral Sea. The names Bon Homme Richard and Cabot were given to later carriers (Bon Homme Richard [CV-31], actually officially misspelled, and Cabot [CVL-28], which had originally been laid down as light cruiser Wilmington [CL-79] before being converted to a light carrier).

Although much more rare, there is precedent for renaming ships while the ship is in commission. By nautical lore, this is generally considered to be bad luck. The escort carrier Midway (CVE-63) was renamed St. Lo in October 1944 so that the name Midway could be used for the new large aircraft carrier Midway (CVB-41/CV-41). Two weeks later, St. Lo was sunk by a kamikaze during the Battle of Leyte Gulf. Anzio (CVE-57), formerly Coral Sea, fared much better than St. Lo.

The most recent example of renaming a U.S. Navy ship while in commission was Biddle (DDG-5), commissioned in 1962 and renamed Claude V. Ricketts in 1964 after the Vice Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Claude V. Ricketts, died in office in 1964. The name Biddle was subsequently given to Biddle (DLG-34, later CG-34), commissioned in 1967.

The aircraft carrier CVN-75 was originally authorized in 1988 as United States, but the name was changed to Harry S. Truman by Secretary of the Navy John Dalton in 1995, while under construction, prior to the carrier being commissioned in 1998. (Wags would say this was the second time a carrier named United States was killed by President Truman [see “Revolt of the Admirals”].)

Ships Named in Honor of Confederates

As a general rule, the U.S. Navy did not name ships after people until the 1890s with the construction of a significant number of torpedo boats and then destroyers that needed many names. Most of these ships were named after Navy heroes of the American Revolution and the War of 1812, but a fair number would be named after Civil War heroes of the Union Navy, and a lesser number were named after officers who served in the Confederate States Navy (CSN), in a supposed “spirit of reconciliation.” Other factors included a segregationist administration: President Woodrow Wilson and Secretary of the Navy (Josephus Daniels), as well as very powerful Southern senators and congressmen (such as Carl Vinson, John C. Stennis, Sam Rayburn, among others).

A number of Union and Confederate officers would have multiple ships named in their honor. An example on the Union side is Farragut, with five ships: Torpedo Boat No. 11, (1899-1919 ), Destroyer No. 300 (1920-1930), DD-348 (1934-1946), DLG-6/DDG-37 (1960-1992), and DDG-99 (2006-present). Another example is Porter: Torpedo Boat No. 6 (1897-1912), Destroyer No. 59 (1916-1934), DD-356 (1935—sunk in 1942), DD-800 (1944-1953), and DDG-78 (1999–present).

In 1861, Admiral Franklin Buchanan, after a distinguished 46-year career in the U.S. Navy, chose to side with the Confederacy, becoming the senior officer in the Confederate Navy. Three U.S. Navy ships were later named in his honor: Destroyer No. 131 (1919-1941 ), DD-484 (1942-1948), and DDG-14 (1962-1991). Rear Admiral Raphael Semmes, commanding officer of CSS Alabama (the most successful commerce raider of all-time) had two ships named in his honor: Destroyer No. 189 (1918-1922), and DDG-18 (1962-1991). Commander James Waddell, the commanding officer of the Confederate raider CSS Shenandoah, had one ship named in his honor: DDG-24 (1964-1995). There are other examples of U.S. Navy ships named in honor of Confederates, including Commander Matthew Fontaine Maury—in his case, multiple ships. No ships named after Confederates are in commission today.

Naming Ships After Civil War Battles

The naming convention for aircraft carriers was initially battles (Lexington, Saratoga, and Yorktown) and famous U.S. Navy ships with distinguished battle records (Ranger, Enterprise, Wasp, and Hornet). Although a number of ships in the 1900s were named after people who served the Confederacy, naming aircraft carriers after Civil War battles or famous Civil War ships was considered too potentially controversial and divisive. One anomaly, in more ways than one, was Battleship No. 5, Kearsarge, named in honor of the Union warship that sank CSS Alabama during the Civil War. Kearsarge was also to only battleship not named after a state, and was in service 1900-1909 and 1915-1920. Congress, under considerable Southern influence, passed a law so that would never happen again, and Battleship No. 8 was named USS Alabama. (This law, that mandates all battleships must be named after states, is the only legal restriction on what the Secretary of the Navy can name ships—all other naming conventions are merely “traditions.” And, in the case of battleships, the law is moot.)

It was not until late in World War II that the name Kearsarge was recycled for Essex-class carrier CV-33 (1946-1970). Also, in a first, the Essex-class carrier Antietam (CV-36, 1945-1973) was named in honor of a costly Union victory in 1862. This did not go over well with Southern politicians, and no ship was named after a Civil War battle for another forty years.

The unwritten prohibition against naming U.S. Navy ships after Civil War battles came to an end during the President Ronald Reagan administration. The first six Ticonderoga-class (CG-47) Aegis guided-missile cruisers parted from the tradition of naming cruisers after cities. Five of the first six recycled names of aircraft carriers, with the exception being Thomas S. Gates (CG-51), named in honor of the Secretary of Defense serving at the end of the Eisenhower administration (Why him? There is no record of the decision).

Of 27 Aegis cruisers, seven were named after Civil War Battles: Mobile Bay (CG-53) Antietam (CG-54), Chancellorsville (CG-62), Gettysburg (CG-64), Shiloh (CG-67), Vicksburg (CG-69), and Port Royal (CG-73). Six of the seven were Union victories, although Shiloh is the Confederate name for the battle the Union called Pittsburg Landing (The national military park is “Shiloh”) and Port Royal is named in honor of both a Civil War battle and a battle during the American Revolution (inconclusive, except the British suffered higher casualties).

(Besides the seven Aegis cruisers, the amphibious assault ship Kearsarge [LHD-3], in commission since 1993, is the only other ship that has been named after a Civil War action.)

The exception above was the 1862 Battle of Chancellorsville in Virginia, a decisive Confederate victory, albeit at the cost of General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson killed by “friendly fire.” It is generally regarded as General Robert E. Lee’s most brilliant victory. Chancellorsville is the only U.S. Navy ship ever named for a battle the Confederates won. Technically, however, it is not named “in honor of” the Confederate victory. Rather, like other ships named after battles that the U.S. lost, it was named in honor of the Americans who died in the battle.

For example, Bunker Hill and Lexington were not named in honor of the British victories, nor were Bataan, Savo Island, Pearl Harbor, Kula Gulf, and others named in honor of the Japanese. They were named in honor of the Americans who gave their lives in those battles. In fact, the crest of Chancellorsville included a thin red line around the shield to symbolize “the blood of those who died to preserve the Union.”

However, references to General Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson were prevalent in the commissioning ceremony, and in a prominent painting aboard the ship honoring the two Confederate generals who renounced their oath of office and fought for the “right” of States to enslave their own people (and to which the crew was subjected). The motto, “Press On” was associated with Stonewall Jackson, and the crest included symbolism related to the Confederacy (a slight predominance of gray over blue, although the rest would require an understanding of heraldry to discern—such as the upturned wreath symbolized the death of Jackson). It may also be useful to note that of at least nine colonels from Virginia in the Federal army when the Civil War began, only Robert E. Lee sided with the Confederacy.

Chancellorsville is a unique case, as all other battles so honored involved a foreign adversary. This case juxtaposes honoring the fallen (on both sides) with perpetuating honoring those who took up arms against the United States. The Secretary of the Navy had to make a decision. My advice during this process included the recommendation to never again name ships after battles involving Americans killing other Americans.

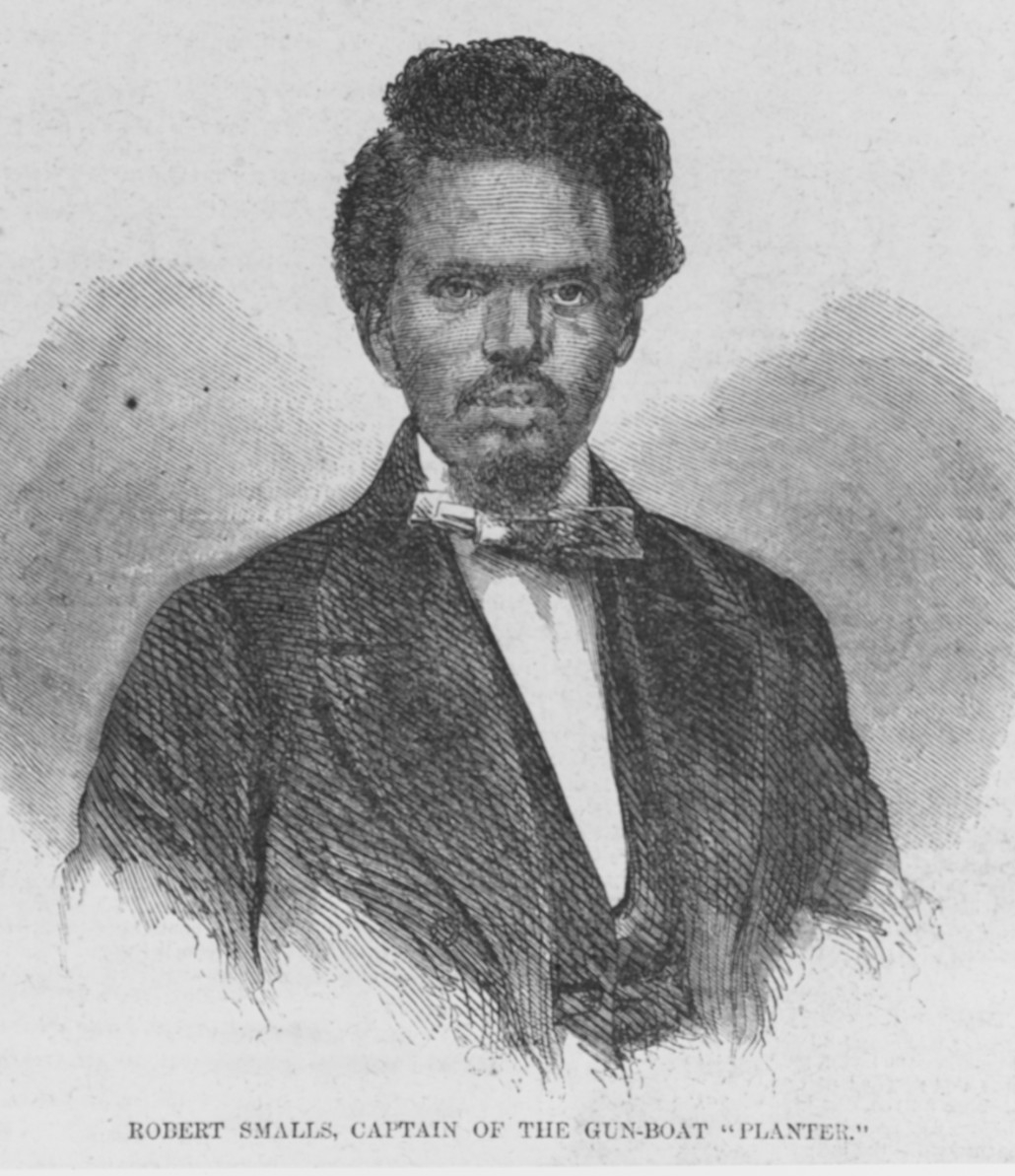

From a range of options, the Secretary of the Navy chose to rename Chancellorsville after Robert Smalls.

Who Was Robert Smalls?

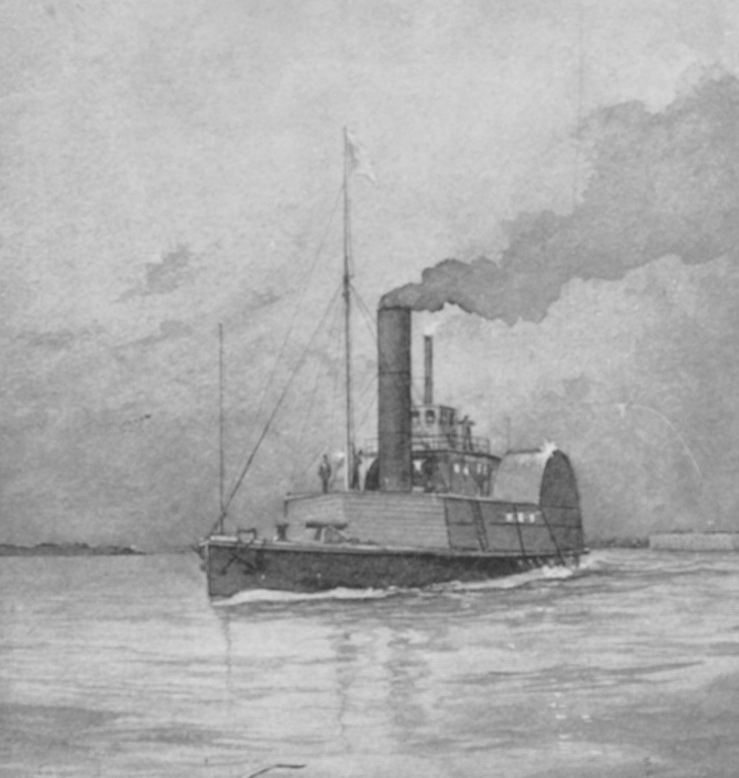

Robert Smalls was born into slavery in Beaufort, South Carolina, on 5 April 1839. As a youth, he worked as a longshoreman, rigger, and sailmaker, eventually becoming a “helmsman,” although slaves were not permitted that title. He developed considerable expertise in navigating the waters around Charleston, South Carolina. At the outbreak of the Civil War, Smalls was assigned (not that he had any choice) to steer the armed Confederate military transport, CSS Planter. Armed with a 32-pounder long gun and a 24-pounder howitzer, Planter’s mission included laying mines, surveying waterways, and transporting troops, dispatches, and supplies. Smalls acted loyal to the owners of the boat and three assigned Confederate officers, but he began planning an escape to reach the visible line of Union warships blockading Charleston.

On 12 May 1862, Planter embarked a cargo of four large guns, 200-pounds of ammunition and some firewood, before docking at the usual wharf below the headquarters of the Confederate commandant of the Charleston district. Lulled into complacency, the three officers spent the night ashore as they had become accustomed to doing (and for which they would later be court-martialed). Smalls asked the senior officer if families of the enslaved crew could visit, which had been done before. When the families arrived, Smalls revealed the plan (all but one of the enslaved crew had been “read in”). Despite substantial fear amongst the families, Smalls then executed the plan.

Three of the crewmen escorted the families back to their camp prior to curfew so as not to arouse suspicion (and for them to gather belongings). Smalls then put on the Confederate captain’s uniform and distinctive straw hat, and got the vessel underway with seven of the eight crewman (not clear what happened to the one who was not trusted). Planter then stopped at a wharf to pick up families.

Smalls then steamed past five Confederate harbor forts and then directly under the guns of Fort Sumter (in Confederate hands) making every effort to appear normal (i.e., a “wide berth” would have been unusual and suspicious). Fort Sumter flashed a challenge signal, and Smalls gave the correct ship’s whistle and hand-signal response. By the time the Confederates in the fort realized Planter was heading for the Union ships instead of turning east toward Morris Island, it was too late, although the guns on Morris Island did open fire. As part of the plan, Smalls’ wife had brought a white bedsheet, which was hauled up in place of the Confederate flag. (Other accounts state the bedsheet belonged to the Confederate captain of Planter.)

Planter was sighted by the armed clipper USS Onward, which prepared to open fire on the unknown approaching vessel. At almost the last moment, there was enough light from the approaching dawn that a crewman spotted the white sheet, and Onward held fire. Onward’s captain boarded the Planter and accepted the “surrender” of the vessel. In addition to the cargo of guns and ammunition, Smalls also turned over Confederate code books, and charts with the location of mines and “torpedoes” (command-detonated mines) laid around Charleston harbor. Smalls also provide very detailed information regarding Confederate fortifications and troop dispositions around Charleston, which enabled Union forces to capture a string of fortifications on Cole’s Island a week later, without a fight.

Union officers, who probably had stereotypical low expectations, were highly impressed by Smalls’ innate intelligence. Smalls’ exploit was lauded in the Northern press and he quickly became a famous hero. Congress passed a law giving Smalls and his crewmen the prize money for Planter, unheard of at the time for an enslaved person. Over the next months, Smalls would work as a civilian pilot for the U.S. Navy, but also would be taken to Washington, DC, by a group attempting to persuade President Lincoln to allow Blacks to serve in the Federal army; his example was instrumental in Lincoln’s eventual decision to allow Blacks to serve under arms in the U.S. Army. (It should be noted that the U.S. Navy was fully integrated at the enlisted ranks all the way back to the American Revolution, and despite the occasional efforts of the secretaries of the Navy to ban Blacks from serving aboard ship.)

At times, Smalls continued to pilot USS Planter as well as the screw steamer USS Crusader, engaging in multiple battles. On 7 April 1863, Smalls was the pilot of the experimental ironclad screw steamer USS Keokuk during an attack on Fort Sumter, involving nine Union ironclads, including seven monitors. Confederate obstructions, accurate gunfire, and a strong flood tide caused the attack to go badly from the beginning. Keokuk was hit 96 times before withdrawing, sinking the next morning as the weather deteriorated.

As a result of a change of the Union command structure around Charleston in June 1863, Smalls was placed under the U.S. Army quartermaster department, although he continued to pilot Planter as well as screw-steamer USS Isaac Smith. On 1 December, while piloting Planter under the command of a U.S. army officer, the vessel came under heavy Confederate fire. The officer directed the ship to surrender, but Smalls refused, believing (almost certainly rightly) that if he and the other formerly enslaved crewmen were taken prisoner they would be summarily executed. The officer took refuge in the “coal bunker” according to some accounts (although Planter burned wood). Regardless, Smalls took command of the ship and got it to safety. He was reportedly promoted to captain (U.S. Army), but unclear if he ever received a commission. He was designated “acting captain” of Planter.

In 1864, Smalls served as an unofficial delegate to the Republican National Convention in Baltimore, Maryland. He then took Planter to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, for overhaul. While in Philadelphia, he was once ordered to give up his seat on a streetcar to a white passenger, choosing instead to get off (which then apparently led to a boycott). The humiliation of a heroic veteran was cited during debates after the war that led to integration of Pennsylvania’s public transportation in 1867.

In December 1864, Smalls brought Planter to Savannah, Georgia, to assist with General William Sherman’s “March to the Sea.” He piloted several other Union vessels including steam gunboats USS Huron and USS Paul Jones. He was in Charleston Harbor on Planter in April 1865 to witness the ceremony raising the U.S. flag over Fort Sumter at the end of the war.

The story of whether Smalls was ever formally commissioned or not, or whether he ever received fair compensation for the surrender of Planter (he almost certainly did not receive fair value) is subject to contradictory accounts, and is a fairly ugly tale, typical of the treatment of Black people at the time. In 1897, a special act of Congress finally granted him a pension equivalent to a Navy captain.

After the Civil War, Smalls returned to Beaufort, where he founded the Republican Party of South Carolina and won election as a Republican to the South Carolina House of Representatives in November 1868, and then to the South Carolina Senate in November 1870. Beginning in March 1875, he served five terms in the U.S. House of Representatives until March 1887, with a gap between 1879 and 1882 due to “redistricting.” He also served in the South Carolina State Militia, reaching the rank of major general just as the Democrats took control of State government in 1877, and barred Blacks from senior State positions.

Smalls’ actions during Reconstruction and post-Reconstruction are worth their own book, but are beyond the scope of this article, but he advocated strongly against the imposition of discriminatory “Jim Crow” laws in the South. On 23 February 1915, Smalls died of malaria and diabetes in Beaufort.

During World War II, Camp Robert Smalls was established at Great Lakes Naval Training Center in June 1942 as a segregated training facility for Black sailors. In January 1944, Camp Robert Smalls was the location for the first 16 Black U.S. Navy officer candidates (all 16 passed, despite the course being rigged for them to fail, but only 13 were commissioned).

Renaming USNS Maury (T-AGS 66)

A strong case can be made that the USNS Maury (and four previous ships) were named in spite of Mathew Fontaine Maury’s service in the Confederate navy, not because of it. Rather, these ships were named in honor of his world-renowned (at the time) scientific contributions before the Civil War, such that he known as the “Father of Modern Oceanography” and his nickname at the time as “Pathfinder of the Seas.” However, the bronze plaque affixed to Maury Hall at the U.S. Naval Academy identified him as “Superintendent of the Naval Observatory” and “Commander, CSA,” i.e., Confederate States of America, which kind of shot a hole in that argument.

Born in 1806 in Virginia, Maury entered the U.S. Navy in 1825 as a midshipman on USS Brandywine as the ship took the French hero of the American Revolution, the Marquis de Lafayette back to France, following his visit. In 1826, Maury was aboard USS Vincennes for that ship’s four-year circumnavigation of the globe, the first for a U.S. Navy ship. His leg was badly injured in a stagecoach accident in 1839, which made him unfit for sea duty (He was riding on the outside of the coach after giving up his inside seat to an elderly Black woman).

Before the accident, Maury had already demonstrated substantial interest, and accomplishment, in the fields of navigation, meteorology, and the study of ocean, winds and currents. Following the accident, he devoted his life to this work, publishing numerous scholarly works, achieving wide acclaim throughout the United States and Europe, earning numerous honors and awards. (It is now fashionable to denigrate his work, but it was “ground-breaking” at the time.)

In 1842, Secretary of the Navy Upshur designated Lieutenant Maury to be the officer-in-charge of the Depot of Charts and Instruments of the Navy Department. With great zeal, Maury quickly turned what had been an unorganized attic of old logbooks into a “center of excellence” (to use a modern term). In that job, Maury focused on the four important fields related to the problems of navigation: astronomy, hydrography, magnetism, and meteorology. When new buildings for the Depot were completed in 1844, one of them included an observatory, and Maury was designated the first superintendent of the Naval Observatory, a position he would hold until the Civil War. His fame continued to grow as a world-renowned scientist.

During the 1850s, Maury concluded that the issue of slavery would eventually tear the United States apart. He did not own slaves and deplored slavery as a curse. His proposed solution (which would be considered unsavory today, but had plenty of company at the time) was to slowly shift Southern slave plantation culture to the Amazon, where slavery in Brazil already existed (and would be legal until 1888) in order to end slavery in the United States proper. (Brazil did not think this was such a keen idea.)

Maury was an outspoken opponent of secession and wrote to the governors of many states arguing against it. However, following the attack on Fort Sumter on 12 April 1861, Lieutenant Maury resigned his commission in the U.S. Navy on 20 April, the same day Colonel Robert E. Lee resigned from the U.S. Army.

On 23 April 1861, the governor of Virginia commissioned Maury as a commander in the Virginia navy. When the Virginia navy was subsequently rolled into the Confederate States navy, Maury retained his commander rank in the Confederate navy. He was then assigned as the chief of the Naval Bureau of Coast, Harbor, and River Defense.

Maury did not invent the electrically detonated sea mine (known at the time as “torpedoes”) but he developed enhancements that made it far more reliable and effective. Such mines are what Admiral Farragut’s famous quote, “Damn the torpedoes, Full speed ahead!” are referring to at the Battle of Mobile Bay in 1864 (actually, no one knows for sure what Farragut really said—this was the press version). Secretary of the (U.S.) Navy Gideon Welles claimed in 1865 that such mines cost the Union more vessels than all other causes combined. This is probably somewhat of an exaggeration, but the mines did account for many lost ships and lost Union lives.

Maury’s fame was such that there was a clamor for him to be named Secretary of the (Confederate) Navy, to the annoyance of the actual Confederate Secretary of the Navy, Stephen Mallory (who as a Senator from Florida before secession, had been Chairman of the U.S. Congressional Committee on Naval Affairs). To solve this problem, Maury was sent on a mission to Europe. Maury visited England, Ireland and France, and elsewhere in Europe, making friends with Emperor Napoleon III of France and Archduke Maximilian of Austria. He was engaged in the purchase and fitting out of vessels used for raiding U.S. commerce, as well as encouraging European nations to assist in bringing about a quick end to the war (which would have been favorable to the South).

Maury was on the way back to the Confederate States when the war ended, and he chose to go into voluntary exile in Mexico. There he served as imperial commissioner for colonization in the administration of Maximilian, who had been proclaimed Emperor of Mexico in 1864 (until he was overthrown and executed by the Mexicans in 1867). Maury’s mission in Mexico was to encourage Virginians to migrate to Mexico and establish a new Virginia. It was a bust, especially after Robert E. Lee declined to have anything to do with the idea.

Maury left Mexico for England in 1866. He returned to Virginia in 1868 as a result of a general amnesty offered by President Andrew Johnson including “full pardon and amnesty for the offense of treason against the United States, or of adhering to their enemies during the late civil war, with restoration of all rights, privileges and immunities . . . .” Actually, there were exceptions to this general amnesty, but Maury qualified. Maury then took a teaching position at Virginia Military Institute (VMI) and held the chair of the physics department. He continued to write and lecture. After one particularly strenuous lecture circuit, he took ill and died at home in Lexington, Virginia, on 1 February 1873.

In addition to the major academic hall at the U.S. Naval Academy named for Maury after it was built in 1907, the Navy saw fit to name five ships after him: Destroyer No. 100 (1918-1930), DD-401 (1938-1945), AGS-16 (1945-1969), T-AGS 39 (1989-1994), and T-AGS 66 (2016-present). In addition the steamer Commodore Maury (a rank he never held) served in non-commissioned status with the Fifth Naval District in World War I.

In 2022, the Naming Commission recommended that USNS Maury be renamed. The naming convention for oceanographic survey ships is famous oceanographers or other terms related to exploration of the seas. T-AGS 66 is a Pathfinder-class vessel. (The original Pathfinder (AGS-1) was a U.S. Coast Guard vessel commissioned into the U.S. Navy during World War II.) The Pathfinder-class ships are Pathfinder (T-AGS 60), Sumner (T-AGS 61), Bowditch (T-AGS 62), Henson (T-AGS 63), Bruce C. Heezen (T-AGS 64), Mary Sears (T-AGS 65), Maury (T-AGS 66), and the recently named Robert Ballard (T-AGS 67), which is not yet in service.

The name Marie Tharp has been on the Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC) list of recommended names for oceanographic survey ships for a number of years. NHHC recommends ship names to the Secretary in accordance with Secretary of the Navy Instruction 5030 (hence the use of the term “5030” for the formal naming document).

Who was Marie Tharp?

Marie Tharp was born 30 July 1920 in Ypsilanti, Michigan, moving many times during her youth. After graduating from high school, she worked on the family farm for several years before entering Ohio University in 1939. She graduated in 1943 with bachelor’s degrees in English and music. With so many men off to war, colleges were increasingly desperate to fill seats (and make money), and a number of colleges opened advanced degree programs to women for the first time. Tharp graduated from the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor with a master’s degree in petroleum geology.

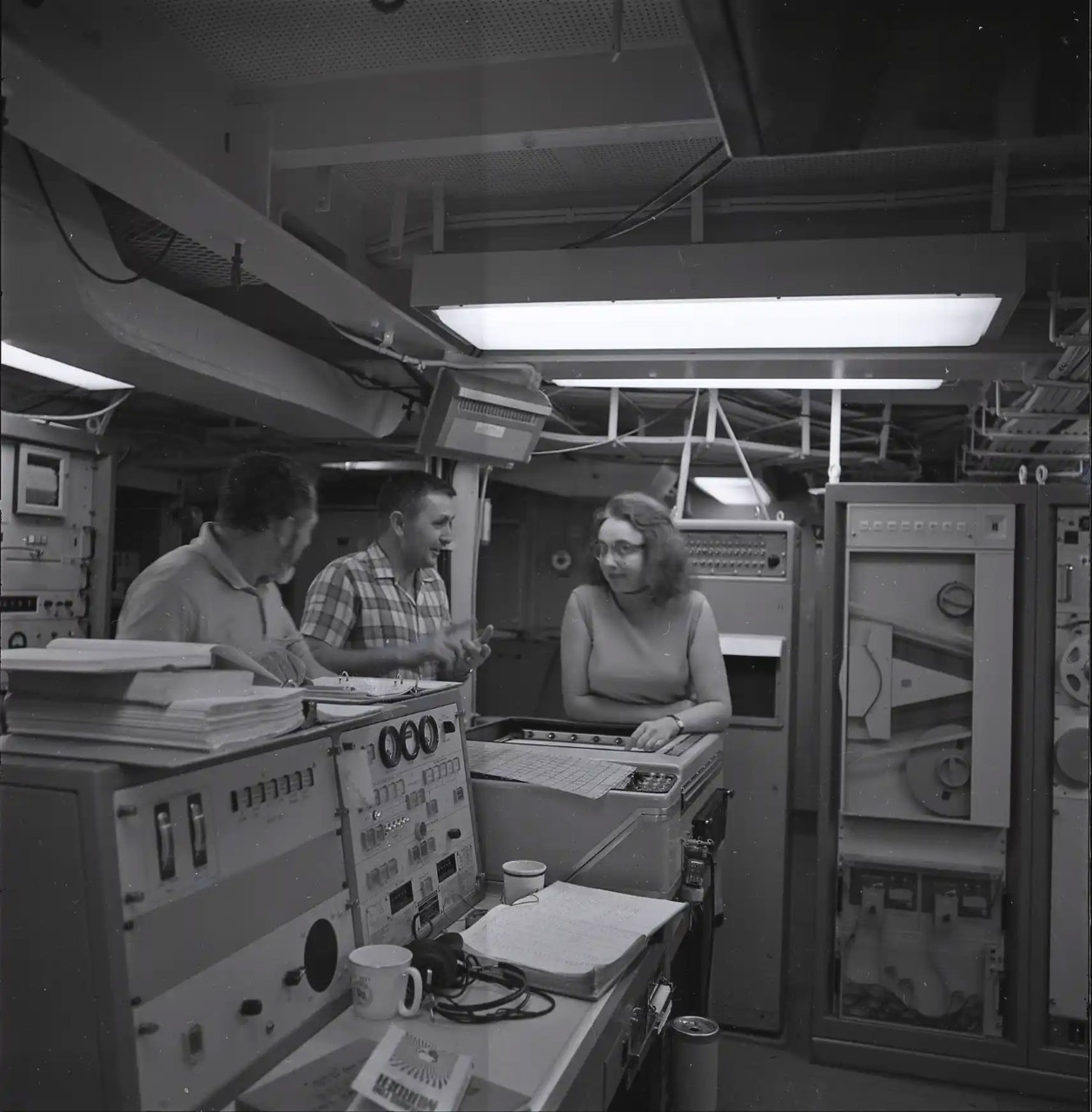

Tharp worked for four years as a geologist for Standard Oil, before ending up at the Lamont Geological Observatory at Columbia University in New York. While there, she worked with Bruce Heezen, and an early project was using aerial photography to locate and map aircraft downed during World War II. She would subsequently work for Heezen for over 18 years. Heezen collected bathymetric data aboard research ships, while Tharp drew maps based on the data since women were not allowed to work on ships at the time. (Tharp would get her first chance to “go to sea” in 1969, on the first deployment of USNS Kane [T-AGS 27].)

Although the presence of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge had been known since the mid-1800s, Tharp’s analysis of detailed sounding profiles in 1952 convinced her that a rift valley ran along the crest of the ridge, indicative of the ocean bottom being pulled apart. Heezen, however, was unconvinced, as was virtually the entire scientific community at the time, which held “continental drift” to be impossible. Tharp’s analysis was dismissed even by Heezen as “girl talk.” Subsequent data on earthquake epicenters along the ridge further convinced Tharp, and subsequently convinced Heezen, of what became known as “plate tectonics” and continental drift theory. In 1956, Heezen would get credit for the theory.

Despite her extensive work, Tharp’s name appeared in none of the major papers that Heezen and others published on plate tectonics between 1959 and 1963. Tharp’s analysis subsequently showed that the rift valley extended into the South Atlantic, Indian Ocean, Gulf of Aden, and the Red Sea, indicating a global oceanic rift zone.

In 1977, Heezen and Tharp jointly published their first map of the entire ocean floor with National Geographic. That same year, Heezen actually died of a heart attack while aboard the U.S. Navy’s deep-submergence, nuclear-powered submarine NR-1. Tharp finally got credit for her work with the award of the National Geographic Hubbard Medal in 1978, shared with Heezen (posthumously). In 1997, the Library of Congress would recognize Tharp as one of the four greatest cartographers of the 20th century.

In her later years, Tharp served on the faculty of Columbia University. After retiring from academia, she ran a map distribution business, and was belatedly recognized with more prestigious awards. She died from cancer on 23 August 2006 at age 86.

Secretary of the Navy Del Toro announced the renaming of USS Maury to USS Marie Tharp on International Women’s Day, 8 March 2023.

Sources include: Captain Miles P. DuVal, Jr., USN (Ret.), Matthew Fontaine Maury, Benefactor of Mankind (Washington, DC: Naval Historical Foundation, 1971); Erin Blakemore, “Seeing is Believing: How Marie Tharp Changed Geology Forever,” Smithsonian Magazine, 30 August 2016; NHHC Dictionary of American Fighting Ships (DANFS); Benjamin Armstrong, “Life and Times of Robert Smalls,” Proceedings Podcast (episode 208), U.S. Naval Institute, 18 February 2021; Benjamin Armstrong, “A Hero,” Naval History 35, No. 1 (February 2021).