H-008-5: Admiral Ernest J. King—Chief of Naval Operations, 1942

H-Gram 008, Attachment 5

Samuel J. Cox, Director NHHC

July 2017

“Brooke got good and nasty and King got good and sore. King about climbed over the table at Brooke. God he was mad. I wish he had socked him.” General Joseph “Vinegar Joe” Stillwell wrote this description of an encounter between Admiral Ernest J. King, Chief of Naval Operations and Commander-in-Chief U.S. Fleet (CNO/COMINCH) and General Sir Alan Brooke, Chief of the (British) Imperial General Staff, at the Cairo Conference in November 1943. Brooke described it as “the mother and father of a row.” So much for the “special relationship” between the United States and the United Kingdom. The issue in contention, as usual, was a dispute between King and the British regarding allocation of resources between the European and Pacific theaters of operations. Contrary to many historic interpretations, King was not opposed to the Allies’ “Defeat Germany first” strategy, nor was he especially anti-British. King was pretty much abrasive and rude to everyone (not just the British) and he believed that as long as the British resisted U.S. Army proposals to land in France as soon as possible, more resources should be shifted in the interim to the Pacific to take advantage of the stunning U.S. victory at Midway. King's view, in a nutshell, was that the Pacific should be getting 30 percent of available resources instead of the 15 percent he claimed it was getting. King was not hostile to the British, or British ideas, but the relationship was certainly far from harmonious, much of which stemmed from events of the first half of 1942.

King had become Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Atlantic Fleet, in the fall of 1940, when his career was resurrected by CNO Admiral Harold “Betty” Stark. Stark had gotten the CNO position instead of King in 1939, and King had been assigned to be a member of the General Board, generally regarded as a twilight tour for very senior admirals. King was highly intelligent (fourth in his USNA class of 1901) with extensive experience in submarines (he proposed and designed the “Dolphins” pin, although he never earned one), and was a qualified aviator. He had a long and distinguished record for being able to get things done. He also did not suffer fools (or anyone who disagreed with him) gladly, with a leadership style and a volcanic temperament that would probably not survive in today’s Navy. King’s leadership philosophy can be summed up by a quote when he was a two-star: “I don’t care how good they are. Unless they get a kick in the ass every six weeks, they’ll slack off.” President Roosevelt said that King, “shaves every morning with a blowtorch.” Even his own daughter (one of six) was quoted as saying of her father that “he is the most even tempered person in the United States Navy. He is always in a rage.” He also partied hard and had a reputation as a womanizer, and was even upbraided as junior officer by Rear Admiral Charles McVay (father of the skipper of Indianapolis—CA-35) for bringing women onboard his ship. Perhaps worst of all, King was an avid reader and proponent of the study of military history (as was Nimitz, for that matter).

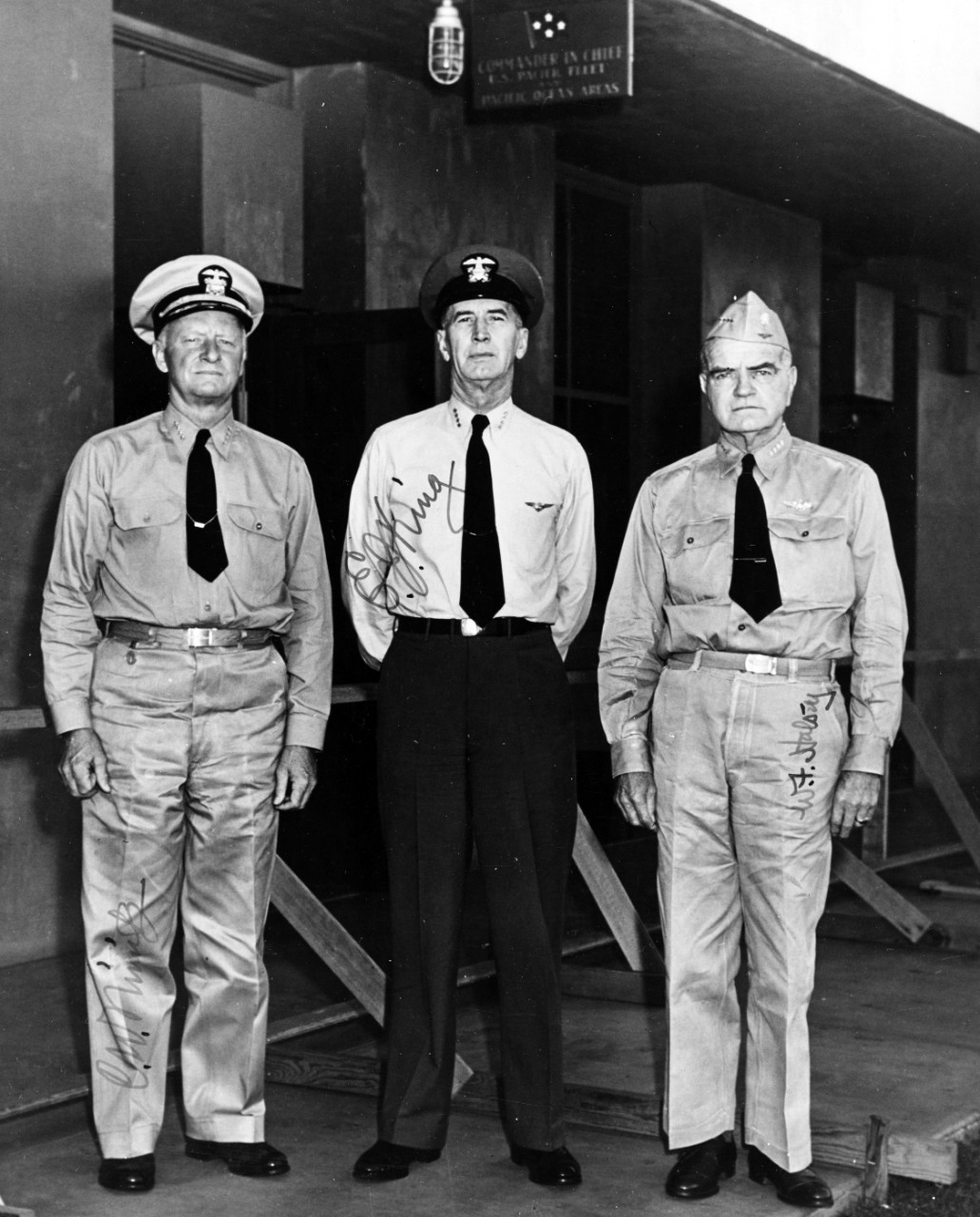

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, Admiral Husband Kimmel was relieved of his duties as Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Fleet (CINCUS) and Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Pacific Fleet (CINCPACFLT.) (Before World War II, CINCUS was the senior of the three U.S. Fleets—Pacific, Atlantic, and Asiatic—which was invariably CINCPACFLT.) However, after Kimmel’s relief, and in recognition of the “Germany first” strategy, the CINCUS title passed to CINC Atlantic Fleet Admiral King on 30 December 1941. On being tapped to be CINCUS, King was widely reputed throughout the Navy to have said, “When they get in trouble, they send for the sons of bitches.” When asked near the end of the war if he really said that, King replied that he hadn’t, but if he had thought of it, he would have. The CNO, Admiral Stark, was also a casualty of Pearl Harbor, although he received more gentle treatment than Kimmel. King was selected by President Roosevelt to relieve Stark, who retained four stars and was reassigned as the new Commander, U.S. Naval Forces Europe. On 18 March 1942, King became CNO and retained CINCUS responsibility, although he immediately changed the acronym from CINCUS (“Sink Us”) to COMINCH. King was the first and last to hold both positions simultaneously; he was also the first qualified aviator to serve as CNO. The Assistant CNO, Rear Admiral Royal Ingersoll (whose son would be killed in a “friendly fire” incident at Midway), received a third star and relieved King as CINCLANTFLT (and got his fourth star in July 1942).

As CINCUS, King had responsibilities in both the Atlantic and the Pacific, and faced extreme challenges in both. Exercising oversight of both Admiral Nimitz in the Pacific and Vice Admiral Ingersoll in the Atlantic, King found the situation dire in both. Previous H-Grams have covered the situation in the Pacific, and in one I described the beginnings of the “Second Happy Time” for German U-boats on the U.S. East Coast. After Germany declared war on the United States, and the United States reciprocated, the head of the German submarine force, Vizeadmiral Karl Dönitz, wasted no time in seizing an opportunity to take the war to our shores before we were ready. Operation Paukenschlag (literally “Timpani Beat,” although usually translated as “Drumbeat”) commenced in January 1942 with the arrival of five Type IX long-range U-boats. Although the Type VIIs were much more numerous, they lacked the endurance to sustain patrols off the U.S. East Coast, at least initially (by mid-1942, the innovative Germans had figured out ways to do it). Although Dönitz’s assets were limited, the first few U-boats ran amok. Successive waves of U-boats also had great success, and, in the late spring, U-boats began operating in the Caribbean (threatening oil supplies from Venezuela) and even in the Gulf of Mexico (Operation Neuland). During 1942, U-boats would sink over 600 ships (over 3 million tons,) killing thousands of merchant seamen. Although the scale of losses did not equal that of the unrestricted U-boat boat campaign in 1917, which almost brought Britain to its knees, and brought the United States into World War I, it did represent about a quarter of all losses to U-boats during World War II. The Germans lost about 22 U-boats in the process, although very few in the opening months.

The fact that the U.S. Navy was so unprepared to deal with the arrival of U-boats on the U.S. East Coast has been roundly criticized by many historians, especially since the U.S. Navy had been engaged in an undeclared war with U-boats for many months before Pearl Harbor. Much of the blame has been heaped on King, some deserved, most not. The unlikeable King makes for an easy target, but there were many factors that resulted in what was effectively a disaster as great as Pearl Harbor in terms of ships sunk and lives lost. British naval Intelligence provided timely warning to the U.S. that the first U-boats were on the way, but little was done with it. The Commander of the U.S. Eastern Sea Frontier, Rear Admiral Adolphus Andrews, had very little to work with, at least initially, with only 100 or so aircraft along the entire coast, and a number of U.S. Coast Guard cutters that were brought under Navy command. Given the lessons learned from World War I, the U.S. failure to immediately implement a convoy system along the U.S. East Coast has attracted a lot of historical “analysis.” There were certainly cases in which U.S. destroyers were inappropriately apportioned, and some were occasionally idle in port while merchant ships were being sunk almost within sight. Nevertheless, the destroyer force was actually heavily tasked and generally in very short supply. Most were committed to escorting transatlantic convoys providing troops and critical war materials to the British war effort, and others to escorting U.S. Navy ships operating in the Atlantic to guard against forays by the German surface navy, as the battleship Bismarck had done earlier in 1941.

What the U.S. sorely lacked was the large number of small anti-submarine craft (“sub-chasers”) like the hundreds that had been hastily built in World War I, but no longer existed. With insufficient escorts, King, Ingersoll, and Andrews reasoned that congregating coastal merchant ships into inadequately protected convoys would only make the U-boats’ job of sinking large numbers of ships even easier and more efficient. This was not because King was anti-British or anti-convoy, but a matter of scarce resource allocation. It was, however, arguably arrogant on King’s part to initially refuse the British offer to send smaller escort ships to the U.S. east coast. By this point in the war, the British had those types of small escorts in comparative abundance, which is how they had ended the U-boats' first “Happy Time” in 1940. Eventually, the U.S. relented, and in March 1942, the British deployed 24 anti-submarine trawlers and 10 corvettes to the U.S. East Coast to assist, and 53 Squadron of the Royal Air Force Coastal Command (flying U.S.-made Lockheed Hudson aircraft) operated out of Quonset Point, Rhode Island.

The critical situation was also not helped by the initial refusal of the U.S. government to order coastal cities to turn out their lights at night, because of counter-arguments that this was bad for tourism and business. The German U-boats’ tactical preference was to attack ships on the surface at night with deck guns so as to conserve torpedoes for the most lucrative targets. With lone coastal merchant ships backlit by coastal cities, the U-boats had easy pickings, sinking ships within sight of the U.S. coast. Eventually coastal blackouts were implemented (and implementation of strict gas rationing pretty much solved the tourist problem.) Some improvement was noted in April 1942 after Rear Admiral Andrews issued enforceable orders that coastal shipping traffic could only transit during daylight hours between protected ports. Numerous small craft were requisitioned by the Navy and put into service as coastal patrol boats. However, the first coastal convoy did not occur until 14 May. The implementation of escorted convoys on the East Coast had rapid positive effect, which is what prompted the Germans to shift their main effort to the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico. Eventually the extension of the convoy system to those areas as well significantly cut down on losses to U-boat attacks, and brought about the end of the “Second Happy Time.”

Nevertheless, convoys were not a panacea, and the experience of Arctic convoy PQ-17 in early July 1942, as the first joint U.S. and British effort under British command, was a total disaster, and served to further sour relations between King and the British. PQ-17 was a 35-ship convoy that departed from Iceland on 27 June 1942 en route to the Soviet Arctic port of Arkhangelsk, carrying desperately needed war supplies to the Russians, then facing a second summer of offensive operations by the German army. The convoy included 23 U.S. merchant ships, with close escort provided by British ships. A covering force consisting of British cruisers and destroyers, and the U.S. cruisers Tuscaloosa (CA-37) and Wichita (CA-45), and two American destroyers trailed behind to guard against any sortie by German surface combatants, including the battleship Tirpitz, which were then based in northern Norway. An additional heavy covering force was also on alert, which included a British aircraft carrier and battleship, and the new U.S. battleship Washington (BB-56.) Washington had been detached from U.S. Task Force 39, which had been established by King and also included the U.S. aircraft carrier Wasp (CV-7.) The battleship would go on to a stellar combat record in the Pacific, but began her career with the dubious distinction as the only U.S. ship to lose an admiral overboard. On 27 March 1942, the first commander of TF-39, Rear Admiral John W. Wilcox, Jr., was washed overboard in heavy seas, and his body was never recovered. The board of inquiry was unable to determine exactly how and why it happened.

Although 12 previous convoys had gone from Great Britain to Russia with the loss of only one ship out of 105, German intelligence provided ample warning of PQ-17 and the Germans were ready. The Germans also ignored a returning convoy in ballast, and either failed to detect or ignored two decoy convoys. Initially, convoy PQ-17 went reasonably well; a couple of ships turned back due to engine casualty or ice damage, and a couple were lost to U-boats. On 4 July, concerted German air attacks by dive bombers and torpedo bombers went after the convoy. During the attacks, the American destroyer Wainwright (DD-419) distinguished herself by damaging multiple German aircraft and severely disrupting multiple waves of German torpedo bombers (including a last wave of 25 Heinkel He-111 bombers) so that only a few torpedoes found their mark on merchant ships. However, after that, everything went to hell.

German surface ships did sortie to intercept PQ-17, but that turned into a fiasco of its own, when the German heavy cruiser Lützow and three destroyers ran aground in fog, followed by some chaotic German command and control and return of the rest of the ships, including Tirpitz, to port without engaging. However, when British reconnaissance aircraft detected Tirpitz missing, the British First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir Dudley Pound, issued orders for the covering force to withdraw and for the convoy to scatter and continue to Russia. Scattering the convoy was deemed the best defense against surface ship attack. The result was a bloodbath as German bombers and U-boats picked off one lone merchant ship after another, and merchant ships were scattered all over the Barents Sea, some taking refuge in the ice, and some in inlets on Novaya Zemlya. It wasn’t until 25 July that the last of the surviving merchant ships made it into Arkhangelsk. Twenty-four of the merchant ships were sunk, with the loss of 153 merchant seamen in the frigid Arctic waters. Only five of the U.S. merchant ships made it to Russia, although one other ran aground and was recovered later. The Germans lost five aircraft.

The debacle of PQ-17 resulted in a suspension of Artic convoys, with the next one not leaving until September 1942, with a radical increase in close escorts, and overhaul of escort procedures. It also resulted in a diplomatic flap, as Soviet dictator Josef Stalin refused to believe that almost an entire convoy could be lost, and accused the Allies of lying about how many ships had been sent in the first place and reneging on their pledges of support. An investigation into the affair came to naught, since it was the First Sea Lord himself who had given the order to scatter, and it was considered politically unpalatable to hold him publically accountable. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill described the PQ-17 affair as “one of the most melancholy naval episodes of the whole war.” Rear Admiral Daniel V. Gallery, then based in Iceland, called it a “shameful page in naval history.” Admiral King was disgusted by the whole affair, withdrew TF-39, and sent Wasp and Washington to the Pacific (although he was probably looking for an excuse to do so anyway), where they served in the waters off Guadalcanal, which will be the subject of the next H-Gram.

And lastly, just for my friends at CHINFO: When asked about the U.S. Navy’s public relations strategy for dealing with the press early in the war, King responded, “Don’t tell them anything. When it’s over, tell them who won.”